Background Essay: The Declaration of Independence

Background Essay: Declaration of Independence

Guiding Question: What were the philosophical bases and practical purposes of the Declaration of Independence?

- I can explain the major events that led the American colonists to question British rule.

- I can explain how the concepts of natural rights and self-government influenced the Founders and the drafting of the Declaration of Independence.

Essential Vocabulary

Directions: As you read the essay, highlight the events from the graphic organizer in Handout B in one color. Think about how each of these events led the American colonists further down the road to declaring independence. Highlight the impacts of those events in another color.

In 1825, Thomas Jefferson reflected on the meaning and principles of the Declaration of Independence. In a letter to a friend, Jefferson explained that the document was an “expression of the American mind.” He meant that it reflected the common sentiments shared by American colonists during the resistance against British taxes in the 1760s and 1770s The Road to Independence

After the conclusion of the French and Indian War, the British sought to increase taxes on their American colonies and passed the Stamp Act (1765) and Townshend Acts (1767). American colonists viewed the acts as British oppression that violated their traditional rights as English subjects as well as their inalienable natural rights. The colonists mostly complained of “taxation without representation,” meaning that Parliament taxed them without their consent. During this period, most colonists simply wanted to restore their rights and liberties within the British Empire. They wanted reconciliation, not independence. But they were also developing an American identity as a distinctive people, which added to the anger over their lack of representation in Parliament and self-government.

After the Boston Tea Party (1773), Parliament passed the Coercive Acts (1774), punishing Massachusetts by closing Boston Harbor and stripping away the right to self-government. As a result, the Continental Congress met in 1774 to consider a unified colonial response. The Congress issued a declaration of rights stating, “That they are entitled to life, liberty, & property, and they have never ceded [given] to any sovereign power whatever, a right to dispose of either without their consent.” Military clashes with British forces at Lexington, Concord, and Bunker Hill in Massachusetts showed that American colonists were willing to resort to force to vindicate their claim to their rights and liberties.

In January 1776, Thomas Paine wrote the best-selling pamphlet Common Sense which was a forceful expression of the growing desire of many colonists for independence. Paine wrote that a republican government that followed the rule of law would protect liberties better than a monarchy. The rule of law means that government and citizens all abide by the same laws regardless of political power.

The Second Continental Congress debated the question of independence that spring. On May 10, it adopted a resolution that seemed to support independence. It called on colonial assemblies and popular conventions to “adopt such government as shall, in the opinion of the representatives of the people, best conduce [lead] to the happiness and safety of their constituents in particular and America in general.”

Five days later, John Adams added his own even more radical preamble calling for independence: “It is necessary that the exercise of every kind of authority under the said Crown should be totally suppressed [brought to an end].” This bold declaration was essentially a break from the British.

“Free and Independent States”

On June 7, Richard Henry Lee rose in Congress and offered a formal resolution for independence: “That these United Colonies are, and of right ought to be, free and independent States, that they are absolved [set free] from all allegiance to the British Crown, and that all political connection between them and the State of Great Britain is, and ought to be, totally dissolved.” Congress appointed a committee to draft a Declaration of Independence, while states wrote constitutions and declarations of rights with similar republican and natural rights principles.

On June 12, for example, the Virginia Convention issued the Virginia Declaration of Rights , a document drafted in 1776 to proclaim the natural rights that all people are entitled to. The document was based upon the ideas of Enlightenment thinker John Locke about natural rights and republican government. It read: “That all men are by nature equally free and independent and have certain inherent rights … they cannot by any compact, deprive or divest [take away] their posterity [future generations]; namely, the enjoyment of life and liberty, with the means of acquiring and possessing property, and pursuing and obtaining happiness and safety.”

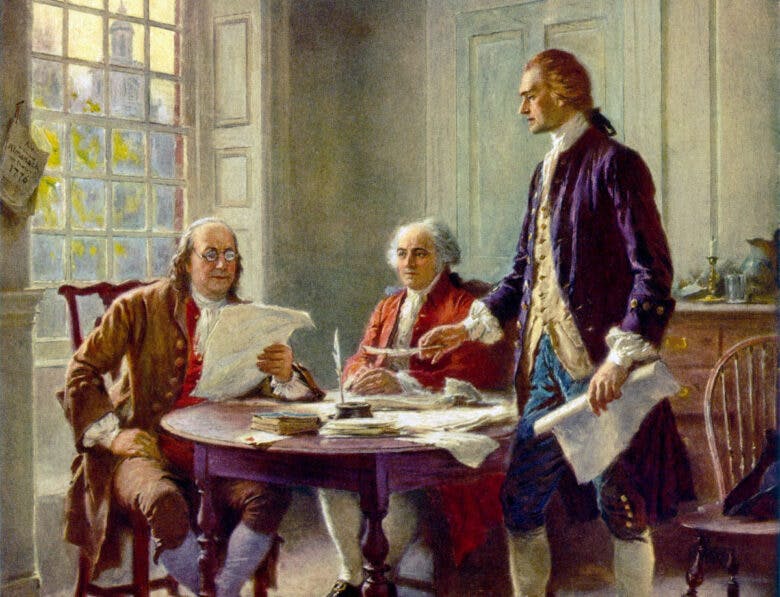

The Continental Congress’s drafting committee selected Thomas Jefferson to draft the Declaration of Independence because he was well-known for his writing ability. He knew the ideas of John Locke well and had a copy of the Virginia Declaration of Rights when he wrote the Declaration. Benjamin Franklin and John Adams were also members of the committee and edited the document before sending it to Congress.

Still, the desire for independence was not unanimous. John Dickinson and others still wished for reconciliation. On July 1, Dickinson and Adams and their respective allies debated whether America should declare independence. The next day, Congress voted for independence by passing Lee’s resolution. Over the next two days, Congress made several edits to the document, making it a collective effort of the Congress. It adopted the Declaration of Independence on July 4. The document expressed the natural rights principles of the independent American republic.

The Declaration opened by stating that the Americans were explaining the causes for separating from Great Britain and becoming an independent nation. It stated that they were entitled to the rights of the “Laws of Nature and of Nature’s God.”

The Declaration then asserted its universal ideals, which were closely related to the ideas of John Locke. It claimed that all human beings were created equal as a self-evident truth. They were equally “endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.” So whatever inequality that might exist in society (such as wealth, power, or status) does not justify one person or group getting more natural rights than anyone else. One way in which humans are equal is in possession of certain natural rights.

The equality of human beings also meant that they were equal in giving consent to their representatives to govern under a republican form of government. All authority flowed from the sovereign people equally. The purpose of that government was to protect the rights of the people. “That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed.” The people had the right to overthrow a government that violated their rights in a long series of abuses.

The Declaration claimed the reign of King George III had been a “history of repeated injuries and usurpations ” [illegal taking] of the colonists’ rights. The king exercised political tyranny against the American colonies. For example, he taxed them without their consent and dissolved [closed down] colonial legislatures and charters. Acts of economic tyranny included cutting off colonial trade. The colonists were denied equal justice when they lost their traditional right to a trial by jury in special courts. Acts of military tyranny included quartering , or forcing citizens to house, troops without consent; keeping standing armies in the colonies; waging war against the colonists; and hiring mercenaries , or paid foreign soldiers, to fight them. Repeated attempts by the colonists to petition king and Parliament to address their grievances were ignored or treated with disdain, so the time had come for independence.

In the final paragraph, the representatives appealed to the authority given to them by the people to declare that the united colonies were now free and independent. The new nation had the powers of a sovereign nation and could levy war, make treaties and alliances, and engage in foreign trade. The Declaration ends with the promise that “we mutually pledge to each other our Lives, our Fortunes and our sacred Honor.”

Americans had asserted their natural rights, right to self-government, and reasons for splitting from Great Britain. They now faced a long and difficult fight against the most powerful empire in the world to preserve that liberty and independence.

Related Content

The Declaration of Independence Answer Key

The Declaration of Independence

America's Founders looked to the lessons of human nature and history to determine how best to structure a government that would promote liberty. They started with the principle of consent of the governed: the only legitimate government is one which the people themselves have authorized. But the Founders also guarded against the tendency of those in power to abuse their authority, and structured a government whose power is limited and divided in complex ways to prevent a concentration of power. They counted on citizens to live out virtues like justice, honesty, respect, humility, and responsibility.

Background Essay Graphic Organizer and Questions: The Declaration of Independence

Declaration Preamble and Grievances Organizer: Versions A and B

Thomas Jefferson Looks Back on the Declaration of Independence

- Utility Menu

Text of the Declaration of Independence

Note: The source for this transcription is the first printing of the Declaration of Independence, the broadside produced by John Dunlap on the night of July 4, 1776. Nearly every printed or manuscript edition of the Declaration of Independence has slight differences in punctuation, capitalization, and even wording. To find out more about the diverse textual tradition of the Declaration, check out our Which Version is This, and Why Does it Matter? resource.

WHEN in the Course of human Events, it becomes necessary for one People to dissolve the Political Bands which have connected them with another, and to assume among the Powers of the Earth, the separate and equal Station to which the Laws of Nature and of Nature’s God entitle them, a decent Respect to the Opinions of Mankind requires that they should declare the causes which impel them to the Separation. We hold these Truths to be self-evident, that all Men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Happiness—-That to secure these Rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just Powers from the Consent of the Governed, that whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these Ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new Government, laying its Foundation on such Principles, and organizing its Powers in such Form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their Safety and Happiness. Prudence, indeed, will dictate that Governments long established should not be changed for light and transient Causes; and accordingly all Experience hath shewn, that Mankind are more disposed to suffer, while Evils are sufferable, than to right themselves by abolishing the Forms to which they are accustomed. But when a long Train of Abuses and Usurpations, pursuing invariably the same Object, evinces a Design to reduce them under absolute Despotism, it is their Right, it is their Duty, to throw off such Government, and to provide new Guards for their future Security. Such has been the patient Sufferance of these Colonies; and such is now the Necessity which constrains them to alter their former Systems of Government. The History of the present King of Great-Britain is a History of repeated Injuries and Usurpations, all having in direct Object the Establishment of an absolute Tyranny over these States. To prove this, let Facts be submitted to a candid World. He has refused his Assent to Laws, the most wholesome and necessary for the public Good. He has forbidden his Governors to pass Laws of immediate and pressing Importance, unless suspended in their Operation till his Assent should be obtained; and when so suspended, he has utterly neglected to attend to them. He has refused to pass other Laws for the Accommodation of large Districts of People, unless those People would relinquish the Right of Representation in the Legislature, a Right inestimable to them, and formidable to Tyrants only. He has called together Legislative Bodies at Places unusual, uncomfortable, and distant from the Depository of their public Records, for the sole Purpose of fatiguing them into Compliance with his Measures. He has dissolved Representative Houses repeatedly, for opposing with manly Firmness his Invasions on the Rights of the People. He has refused for a long Time, after such Dissolutions, to cause others to be elected; whereby the Legislative Powers, incapable of Annihilation, have returned to the People at large for their exercise; the State remaining in the mean time exposed to all the Dangers of Invasion from without, and Convulsions within. He has endeavoured to prevent the Population of these States; for that Purpose obstructing the Laws for Naturalization of Foreigners; refusing to pass others to encourage their Migrations hither, and raising the Conditions of new Appropriations of Lands. He has obstructed the Administration of Justice, by refusing his Assent to Laws for establishing Judiciary Powers. He has made Judges dependent on his Will alone, for the Tenure of their Offices, and the Amount and Payment of their Salaries. He has erected a Multitude of new Offices, and sent hither Swarms of Officers to harrass our People, and eat out their Substance. He has kept among us, in Times of Peace, Standing Armies, without the consent of our Legislatures. He has affected to render the Military independent of and superior to the Civil Power. He has combined with others to subject us to a Jurisdiction foreign to our Constitution, and unacknowledged by our Laws; giving his Assent to their Acts of pretended Legislation: For quartering large Bodies of Armed Troops among us: For protecting them, by a mock Trial, from Punishment for any Murders which they should commit on the Inhabitants of these States: For cutting off our Trade with all Parts of the World: For imposing Taxes on us without our Consent: For depriving us, in many Cases, of the Benefits of Trial by Jury: For transporting us beyond Seas to be tried for pretended Offences: For abolishing the free System of English Laws in a neighbouring Province, establishing therein an arbitrary Government, and enlarging its Boundaries, so as to render it at once an Example and fit Instrument for introducing the same absolute Rule into these Colonies: For taking away our Charters, abolishing our most valuable Laws, and altering fundamentally the Forms of our Governments: For suspending our own Legislatures, and declaring themselves invested with Power to legislate for us in all Cases whatsoever. He has abdicated Government here, by declaring us out of his Protection and waging War against us. He has plundered our Seas, ravaged our Coasts, burnt our Towns, and destroyed the Lives of our People. He is, at this Time, transporting large Armies of foreign Mercenaries to compleat the Works of Death, Desolation, and Tyranny, already begun with circumstances of Cruelty and Perfidy, scarcely paralleled in the most barbarous Ages, and totally unworthy the Head of a civilized Nation. He has constrained our fellow Citizens taken Captive on the high Seas to bear Arms against their Country, to become the Executioners of their Friends and Brethren, or to fall themselves by their Hands. He has excited domestic Insurrections amongst us, and has endeavoured to bring on the Inhabitants of our Frontiers, the merciless Indian Savages, whose known Rule of Warfare, is an undistinguished Destruction, of all Ages, Sexes and Conditions. In every stage of these Oppressions we have Petitioned for Redress in the most humble Terms: Our repeated Petitions have been answered only by repeated Injury. A Prince, whose Character is thus marked by every act which may define a Tyrant, is unfit to be the Ruler of a free People. Nor have we been wanting in Attentions to our British Brethren. We have warned them from Time to Time of Attempts by their Legislature to extend an unwarrantable Jurisdiction over us. We have reminded them of the Circumstances of our Emigration and Settlement here. We have appealed to their native Justice and Magnanimity, and we have conjured them by the Ties of our common Kindred to disavow these Usurpations, which, would inevitably interrupt our Connections and Correspondence. They too have been deaf to the Voice of Justice and of Consanguinity. We must, therefore, acquiesce in the Necessity, which denounces our Separation, and hold them, as we hold the rest of Mankind, Enemies in War, in Peace, Friends. We, therefore, the Representatives of the UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, in General Congress, Assembled, appealing to the Supreme Judge of the World for the Rectitude of our Intentions, do, in the Name, and by Authority of the good People of these Colonies, solemnly Publish and Declare, That these United Colonies are, and of Right ought to be, Free and Independent States; that they are absolved from all Allegiance to the British Crown, and that all political Connection between them and the State of Great-Britain, is and ought to be totally dissolved; and that as Free and Independent States, they have full Power to levy War, conclude Peace, contract Alliances, establish Commerce, and to do all other Acts and Things which Independent States may of right do. And for the support of this Declaration, with a firm Reliance on the Protection of divine Providence, we mutually pledge to each other our Lives, our Fortunes, and our sacred Honor.

Signed by Order and in Behalf of the Congress, JOHN HANCOCK, President.

Attest. CHARLES THOMSON, Secretary.

America's Founding Documents

Declaration of Independence: A Transcription

Note: The following text is a transcription of the Stone Engraving of the parchment Declaration of Independence (the document on display in the Rotunda at the National Archives Museum .) The spelling and punctuation reflects the original.

In Congress, July 4, 1776

The unanimous Declaration of the thirteen united States of America, When in the Course of human events, it becomes necessary for one people to dissolve the political bands which have connected them with another, and to assume among the powers of the earth, the separate and equal station to which the Laws of Nature and of Nature's God entitle them, a decent respect to the opinions of mankind requires that they should declare the causes which impel them to the separation.

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.--That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed, --That whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new Government, laying its foundation on such principles and organizing its powers in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their Safety and Happiness. Prudence, indeed, will dictate that Governments long established should not be changed for light and transient causes; and accordingly all experience hath shewn, that mankind are more disposed to suffer, while evils are sufferable, than to right themselves by abolishing the forms to which they are accustomed. But when a long train of abuses and usurpations, pursuing invariably the same Object evinces a design to reduce them under absolute Despotism, it is their right, it is their duty, to throw off such Government, and to provide new Guards for their future security.--Such has been the patient sufferance of these Colonies; and such is now the necessity which constrains them to alter their former Systems of Government. The history of the present King of Great Britain is a history of repeated injuries and usurpations, all having in direct object the establishment of an absolute Tyranny over these States. To prove this, let Facts be submitted to a candid world.

He has refused his Assent to Laws, the most wholesome and necessary for the public good.

He has forbidden his Governors to pass Laws of immediate and pressing importance, unless suspended in their operation till his Assent should be obtained; and when so suspended, he has utterly neglected to attend to them.

He has refused to pass other Laws for the accommodation of large districts of people, unless those people would relinquish the right of Representation in the Legislature, a right inestimable to them and formidable to tyrants only.

He has called together legislative bodies at places unusual, uncomfortable, and distant from the depository of their public Records, for the sole purpose of fatiguing them into compliance with his measures.

He has dissolved Representative Houses repeatedly, for opposing with manly firmness his invasions on the rights of the people.

He has refused for a long time, after such dissolutions, to cause others to be elected; whereby the Legislative powers, incapable of Annihilation, have returned to the People at large for their exercise; the State remaining in the mean time exposed to all the dangers of invasion from without, and convulsions within.

He has endeavoured to prevent the population of these States; for that purpose obstructing the Laws for Naturalization of Foreigners; refusing to pass others to encourage their migrations hither, and raising the conditions of new Appropriations of Lands.

He has obstructed the Administration of Justice, by refusing his Assent to Laws for establishing Judiciary powers.

He has made Judges dependent on his Will alone, for the tenure of their offices, and the amount and payment of their salaries.

He has erected a multitude of New Offices, and sent hither swarms of Officers to harrass our people, and eat out their substance.

He has kept among us, in times of peace, Standing Armies without the Consent of our legislatures.

He has affected to render the Military independent of and superior to the Civil power.

He has combined with others to subject us to a jurisdiction foreign to our constitution, and unacknowledged by our laws; giving his Assent to their Acts of pretended Legislation:

For Quartering large bodies of armed troops among us:

For protecting them, by a mock Trial, from punishment for any Murders which they should commit on the Inhabitants of these States:

For cutting off our Trade with all parts of the world:

For imposing Taxes on us without our Consent:

For depriving us in many cases, of the benefits of Trial by Jury:

For transporting us beyond Seas to be tried for pretended offences

For abolishing the free System of English Laws in a neighbouring Province, establishing therein an Arbitrary government, and enlarging its Boundaries so as to render it at once an example and fit instrument for introducing the same absolute rule into these Colonies:

For taking away our Charters, abolishing our most valuable Laws, and altering fundamentally the Forms of our Governments:

For suspending our own Legislatures, and declaring themselves invested with power to legislate for us in all cases whatsoever.

He has abdicated Government here, by declaring us out of his Protection and waging War against us.

He has plundered our seas, ravaged our Coasts, burnt our towns, and destroyed the lives of our people.

He is at this time transporting large Armies of foreign Mercenaries to compleat the works of death, desolation and tyranny, already begun with circumstances of Cruelty & perfidy scarcely paralleled in the most barbarous ages, and totally unworthy the Head of a civilized nation.

He has constrained our fellow Citizens taken Captive on the high Seas to bear Arms against their Country, to become the executioners of their friends and Brethren, or to fall themselves by their Hands.

He has excited domestic insurrections amongst us, and has endeavoured to bring on the inhabitants of our frontiers, the merciless Indian Savages, whose known rule of warfare, is an undistinguished destruction of all ages, sexes and conditions.

In every stage of these Oppressions We have Petitioned for Redress in the most humble terms: Our repeated Petitions have been answered only by repeated injury. A Prince whose character is thus marked by every act which may define a Tyrant, is unfit to be the ruler of a free people.

Nor have We been wanting in attentions to our Brittish brethren. We have warned them from time to time of attempts by their legislature to extend an unwarrantable jurisdiction over us. We have reminded them of the circumstances of our emigration and settlement here. We have appealed to their native justice and magnanimity, and we have conjured them by the ties of our common kindred to disavow these usurpations, which, would inevitably interrupt our connections and correspondence. They too have been deaf to the voice of justice and of consanguinity. We must, therefore, acquiesce in the necessity, which denounces our Separation, and hold them, as we hold the rest of mankind, Enemies in War, in Peace Friends.

We, therefore, the Representatives of the united States of America, in General Congress, Assembled, appealing to the Supreme Judge of the world for the rectitude of our intentions, do, in the Name, and by Authority of the good People of these Colonies, solemnly publish and declare, That these United Colonies are, and of Right ought to be Free and Independent States; that they are Absolved from all Allegiance to the British Crown, and that all political connection between them and the State of Great Britain, is and ought to be totally dissolved; and that as Free and Independent States, they have full Power to levy War, conclude Peace, contract Alliances, establish Commerce, and to do all other Acts and Things which Independent States may of right do. And for the support of this Declaration, with a firm reliance on the protection of divine Providence, we mutually pledge to each other our Lives, our Fortunes and our sacred Honor.

Button Gwinnett

George Walton

North Carolina

William Hooper

Joseph Hewes

South Carolina

Edward Rutledge

Thomas Heyward, Jr.

Thomas Lynch, Jr.

Arthur Middleton

Massachusetts

John Hancock

Samuel Chase

William Paca

Thomas Stone

Charles Carroll of Carrollton

George Wythe

Richard Henry Lee

Thomas Jefferson

Benjamin Harrison

Thomas Nelson, Jr.

Francis Lightfoot Lee

Carter Braxton

Pennsylvania

Robert Morris

Benjamin Rush

Benjamin Franklin

John Morton

George Clymer

James Smith

George Taylor

James Wilson

George Ross

Caesar Rodney

George Read

Thomas McKean

William Floyd

Philip Livingston

Francis Lewis

Lewis Morris

Richard Stockton

John Witherspoon

Francis Hopkinson

Abraham Clark

New Hampshire

Josiah Bartlett

William Whipple

Samuel Adams

Robert Treat Paine

Elbridge Gerry

Rhode Island

Stephen Hopkins

William Ellery

Connecticut

Roger Sherman

Samuel Huntington

William Williams

Oliver Wolcott

Matthew Thornton

Back to Main Declaration Page

- Introduction

- Related Information

- Jefferson's Account

- Declaration House

- Declaration Timeline

- Rev. War Timeline

- More Resources

- Lesson Plan

The Declaration of Independence

- USHistory Home

Reading the Declaration

The Declaration of Independence has been read and talked about more than any other American document. There are many books, essays, and treatises written about it. And yet, there are many different opinions about what the ideas in it really mean. Even today all new American citizens study the meaning of this important document. It helps to give a look into what it means to be American.

So, what is the best way to examine the Declaration? There are a number of different views.

It could be interpreted as an expression of John Locke’s ideas. Locke was a big influence on the writers of the Declaration.

It also could be seen as a new and original statement about government.

Some believe the declaration is all about individualism. Others see it as promoting civic engagement and participation in groups.

Historians see the Declaration as a way to define who an American is. Judges and lawyers use the document in the political process when creating and interpreting laws.

The Declaration is a beautifully written document that officially announced that the United States were no longer part of Great Britain. That these United States were establishing a new idea of government; one whose leadership did not govern by divine right, but was chosen by the people for the people themselves. This new government's job was to protect the "Rights” of its citizens.

In the sections that follow, you will get the chance to try to decide on your own point of view. To do this, we are going to ask you to do carefully read the Declaration.

In order to assist your exploration, we have explored each of the five parts of the Declaration separately:

BUY A DECLARATION POSTER

Start page | The Document | A Reading | Signers | Related Information | Jefferson's Account | Declaration House | Declaration Timeline | Rev. War Timeline | More Resources | Lesson Plan |

Buy a Declaration

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Why Was the Declaration of Independence Written?

By: Sarah Pruitt

Updated: June 22, 2023 | Original: June 29, 2018

When the first skirmishes of the Revolutionary War broke out in Massachusetts in April 1775, few people in the American colonies wanted to separate from Great Britain entirely. But as the war continued, and Britain called out massive armed forces to enforce its will, more and more colonists came to accept that asserting independence was the only way forward.

And the Declaration of Independence would play a critical role in unifying the colonies from the bloody struggle they now faced.

The Road to Revolution Was Paved with Taxes

Over the decade following the passage of the Stamp Act in 1765, a series of unpopular British laws met with stiff opposition in the colonies, fueling a bitter struggle over whether Parliament had the right to tax the colonists without the consent of the representative colonial governments. This struggle erupted into violence in 1770 when British troops killed five colonists in the Boston Massacre .

Three years later, outrage over the Tea Act of 1773 prompted colonists to board an East India Company ship in Boston Harbor and dump its cargo into the sea in the now-infamous Boston Tea Party .

In response, Britain cracked down further with the Coercive Acts, going so far as to revoke the colonial charter of Massachusetts and close the port of Boston. Resistance to the Intolerable Acts, as they became known, led to the formation of the First Continental Congress in Philadelphia in 1774, which denounced “taxation without representation” - but stopped short of demanding independence from Britain.

Would Colonists Reconcile or Separate?

Then the first shots rang out between colonial and British forces at Lexington and Concord, and the Battle of Bunker Hill cost hundreds of American lives, along with 1,000 killed on the British side.

Some 20,000 troops under General George Washington faced off against a British garrison in the Boston Siege, which ended when the British evacuated in March 1776. Washington then moved his Continental Army to New York, where he assumed (correctly) that a major British invasion would soon take place.

Meanwhile, many in the Continental Congress still clung to the assumption that reconciliation with Britain was the ultimate goal. This would soon change, thanks in part to the actions of King George III , who in October 1775 denounced the colonies in front of Parliament and began building up his army and navy to crush their rebellion.

In order to have any hope of defeating Britain, the colonists would need support from foreign powers (especially France), which Congress knew they could only get by declaring themselves a separate nation.

Thomas Paine Disavowed the Monarchy

In his bestselling pamphlet, “Common Sense,” a recent English immigrant named Thomas Paine also helped push the colonists along on their path toward independence.

“His argument was that we had to break from Britain because the system of the British constitution was hopelessly flawed,” the late Pauline Maier , professor of history at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), said in a 2013 lecture on “The Making of the Declaration of Independence.”

“[Britain] had hereditary rule, it had kings—you could never have freedom so long as you had hereditary rule.”

After Virginia delegate Richard Henry Lee introduced a motion to declare independence on June 7, 1776, Congress formed a committee to draft a statement justifying the break with Great Britain.

Who Wrote the Declaration of Independence?

The initial draft of the Declaration of Independence was written by Thomas Jefferson and was presented to the entire Congress on June 28 for debate and revision.

In addition to Jefferson’s eloquent preamble, the document included a long list of grievances against King George III, who was accused of committing many “injuries and usurpations” in his quest to establish “an absolute tyranny over these States.”

The Declaration of Independence United the Colonists

After two days of editing and debate, the Congress adopted the Declaration of Independence on July 4, 1776, even as a large British fleet and more than 34,000 troops prepared to invade New York. By the time it was formally signed on August 2, printed copies of the document were spreading around the country, being reprinted in newspapers and publicly read aloud.

While the road to independence had been long and twisted, the effect of its declaration made an impact right away.

“It changed the whole character of the war,” Maier said. “These were people who for a year had been making war against a king with whom they were trying to effect a reconciliation, to whom they were publicly professing loyalty. Now heart and hand, as one person said, could move together. They had a cause to fight for.”

HISTORY Vault: The American Revolution

Stream American Revolution documentaries and your favorite HISTORY series, commercial-free.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

Declaration of Independence in American History Essay

- To find inspiration for your paper and overcome writer’s block

- As a source of information (ensure proper referencing)

- As a template for you assignment

The United States declared independence on 4th July 1776. Being an independent state, one of the dreams they had at that time was for its citizens to live in freedom and have equal opportunity in all aspects of life. They believed that all men and women are equal, and that the Creator has endowed them with equal rights.

The question as to whether the United States has lived up to the promise of liberty and opportunity for all its citizens can be analyzed by critically looking into a number of issues that the United States is currently facing. These include the following: Do all citizens have access to basic necessities? Do all citizens have the right to own property?

Do we have a right to decide what is right for our children or does the government dictate for us through the school systems and Planned Parenthood? Do we have a gap between the poor and the rich? Are government policies put forth for the benefit of all citizens or just for a few elites? And, is modernization threatening the dream the United States once had?

From my point of view, the United States has failed to live up to the promise of liberty and opportunity for all its citizens. Looking at its economy, which is currently in crisis, there are rising income inequalities and rising unemployment rates.

With such a scenario, citizens have limited choices to exercise their freedom, for instance in choosing where to live, which school to take their children, or which hospital to seek treatment. To my view, is against the dream of equal opportunity for all that the United States had at the time of declaration of independence.

Another issue that threatens the freedom of US citizens is war and terror. The US citizens have lived in constant fear of war and terror following the attack of 11th September 2001. It is evident from the huge investment they are putting together to counter war and crime that this issue has certainly threatened their freedom.

Modernization has brought about a change in the behavior of people. With these changes, most people desire to do things that the constitution of the US deem illegal. For example, let us look at prostitution.

There are people who believe that it is there right; but unless the constitution is amended, the practice remains unlawful to the government. Thus, with the ever-changing behavioral needs of people due to modernization verses the law of the State, which is rather static, citizens have been deprived off their freedom in one way or the other.

Political interference is also a factor depriving the citizen’s liberty they so hoped for. For instance, the two political parties in the US, the Republican, and Democrats have polarized the society to such degree that a registered Democrat or Republican citizen cannot see the failings of their own parties.

This has created a potentially dangerous environment where the policies that are put forth do not connect to the citizens’ welfare, but instead to a select few. Nevertheless, if the policies happen to serve the citizens, the means are inconsistent with individuals’ liberty.

In conclusion, it is apparent that the US is experiencing problems of inequality and freedom, but compared to other countries in the world, the US is performing better than they are in terms of democracy and freedom. Even though there is more still to be done to fulfill their dream of liberty and opportunity for all citizens.

- The Way the American Flag Was Deployed Culturally Following Sept 11th

- A Critical Review of "The WJ 4th Edition"

- September 11th 2001 Analysis

- Awakenings" by Judith Vecchione

- Slavery and the Civil War Relationship

- Importance of US Foreign Policy between 1890-1991

- Columbus’s Encounter With Caribbean Natives

- The Vision of Reconstruction Issues in US

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2020, April 28). Declaration of Independence in American History. https://ivypanda.com/essays/declaration-of-independence-in-american-history/

"Declaration of Independence in American History." IvyPanda , 28 Apr. 2020, ivypanda.com/essays/declaration-of-independence-in-american-history/.

IvyPanda . (2020) 'Declaration of Independence in American History'. 28 April.

IvyPanda . 2020. "Declaration of Independence in American History." April 28, 2020. https://ivypanda.com/essays/declaration-of-independence-in-american-history/.

1. IvyPanda . "Declaration of Independence in American History." April 28, 2020. https://ivypanda.com/essays/declaration-of-independence-in-american-history/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Declaration of Independence in American History." April 28, 2020. https://ivypanda.com/essays/declaration-of-independence-in-american-history/.

The Declaration of Independence

21 pages • 42 minutes read

A modern alternative to SparkNotes and CliffsNotes, SuperSummary offers high-quality Study Guides with detailed chapter summaries and analysis of major themes, characters, and more.

Essay Analysis

Key Figures

Symbols & Motifs

Literary Devices

Important Quotes

Essay Topics

Discussion Questions

In what ways is the Declaration of Independence a timeless document, and in what ways is it a product of a specific time and place? Is it primarily a historical document, or is it relevant to the modern era?

How does the Declaration of Independence define a tyrant? And how convincing is the argument the signers make that George III was a tyrant?

The Declaration of Independence does not establish any laws for the United States. But how do its ideas influence the Constitution or other documents that do establish laws?

Don't Miss Out!

Access Study Guide Now

Related Titles

By Thomas Jefferson

Notes on the State of Virginia

Thomas Jefferson

Featured Collections

American Revolution

View Collection

Books on Justice & Injustice

Books on U.S. History

Nation & Nationalism

Politics & Government

Required Reading Lists

Self-Paced Courses : Explore American history with top historians at your own time and pace!

- AP US History Study Guide

- History U: Courses for High School Students

- History School: Summer Enrichment

- Lesson Plans

- Classroom Resources

- Spotlights on Primary Sources

- Professional Development (Academic Year)

- Professional Development (Summer)

- Book Breaks

- Inside the Vault

- Self-Paced Courses

- Browse All Resources

- Search by Issue

- Search by Essay

- Become a Member (Free)

- Monthly Offer (Free for Members)

- Program Information

- Scholarships and Financial Aid

- Applying and Enrolling

- Eligibility (In-Person)

- EduHam Online

- Hamilton Cast Read Alongs

- Official Website

- Press Coverage

- Veterans Legacy Program

- The Declaration at 250

- Black Lives in the Founding Era

- Celebrating American Historical Holidays

- Browse All Programs

- Donate Items to the Collection

- Search Our Catalog

- Research Guides

- Rights and Reproductions

- See Our Documents on Display

- Bring an Exhibition to Your Organization

- Interactive Exhibitions Online

- About the Transcription Program

- Civil War Letters

- Founding Era Newspapers

- College Fellowships in American History

- Scholarly Fellowship Program

- Richard Gilder History Prize

- David McCullough Essay Prize

- Affiliate School Scholarships

- Nominate a Teacher

- Eligibility

- State Winners

- National Winners

- Gilder Lehrman Lincoln Prize

- Gilder Lehrman Military History Prize

- George Washington Prize

- Frederick Douglass Book Prize

- Our Mission and History

- Annual Report

- Contact Information

- Student Advisory Council

- Teacher Advisory Council

- Board of Trustees

- Remembering Richard Gilder

- President's Council

- Scholarly Advisory Board

- Internships

- Our Partners

- Press Releases

History Resources

The Declaration of Independence in Global Perspective

By david armitage.

The Declaration was addressed as much to "mankind" as it was to the population of the colonies. In the opening paragraph, the authors of the Declaration—Thomas Jefferson, the five-member Congressional committee of which he was part, and the Second Continental Congress itself—addressed "the opinions of Mankind" as they announced the necessity for

. . . one People to dissolve the Political Bands which have connected them with another, and to assume among the Powers of the Earth, the separate and equal Station to which the Laws of Nature and of Nature’s God entitle them. . . .

After stating the fundamental principles—the "self-evident" truths—that justified separation, they submitted an extensive list of facts to "a candid world" to prove that George III had acted tyrannically. On the basis of those facts, his colonial subjects could now rightfully leave the British Empire. The Declaration therefore "solemnly Publish[ed] and Declare[d], That these United Colonies are, and of Right ought to be, FREE AND INDEPENDENT STATES" and concluded with a statement of the rights of such states that was similar to the enumeration of individual rights in the Declaration’s second paragraph in being both precise and open-ended:

. . . that as FREE AND INDEPENDENT STATES, they have full Power to levy War, conclude Peace, contract Alliances, establish Commerce, and to do all other Acts and Things which INDEPENDENT STATES may of right do.

This was what the Declaration declared to the colonists who could now become citizens rather than subjects, and to the powers of the earth who were being asked to choose whether or not to acknowledge the United States of America among their number.

The final paragraph of the Declaration announced that the United States of America were now available for alliances and open for business. The colonists needed military, diplomatic, and commercial help in their revolutionary struggle against Great Britain; only a major power, like France or Spain, could supply that aid. Thomas Paine had warned in Common Sense in January 1776 that "the custom of all courts is against us, and will be so, until by an independence, we take rank with other nations." So long as the colonists remained within the empire, they would be treated as rebels; if they organized themselves into political bodies with which other powers could engage, then they might become legitimate belligerents in an international conflict rather than treasonous combatants within a British civil war.

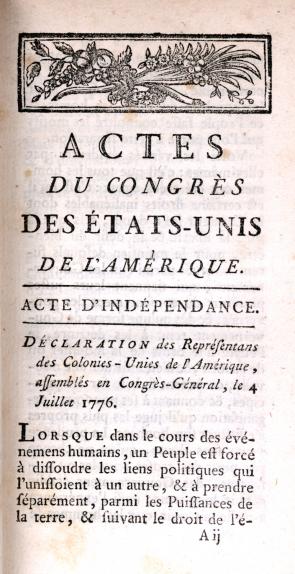

The Declaration of Independence was primarily a declaration of interdependence with the other powers of the earth. It marked the entry of one people, constituted into thirteen states, into what we would now call international society. It did so in the conventional language of the contemporary law of nations drawn from the hugely influential book of that title (1758) by the Swiss jurist Emer de Vattel, a copy of which Benjamin Franklin had sent to Congress in 1775. Vattel’s was a language of rights and freedom, sovereignty and independence, and the Declaration’s use of his terms was designed to reassure the world beyond North America that the United States would abide by the rules of international behavior. The goal of the Declaration’s authors was still quite revolutionary: to extend the sphere of European international relations across the Atlantic Ocean by turning dependent colonies into independent political actors. The historical odds were greatly against them; as they knew well, no people had managed to secede from an empire since the United Provinces had revolted from Spain almost two centuries before, and no overseas colony had done so in modern times.

The other powers of the earth were naturally curious about what the Declaration said. By August 1776, news of American independence and copies of the Declaration itself had reached London, Edinburgh, and Dublin, as well as the Dutch Republic and Austria. By the fall of that year, Danish, Italian, Swiss, and Polish readers had heard the news and many could now read the Declaration in their own language as translations appeared across Europe. The document inspired diplomatic debate in France but that potential ally only began serious negotiations after the American victory at the Battle of Saratoga in October 1777. The Franco-American Treaty of Amity and Commerce of February 1778 was the first formal recognition of the United States as "free and independent states." French assistance would, of course, be crucial to the success of the American cause. It also turned the American war into a global conflict involving Britain, France, Spain, and the Dutch Republic in military operations around the globe that would shape the fate of empires in the Atlantic, Pacific, and Indian Ocean worlds.

The ultimate success of American independence was swiftly acknowledged to be of world-historical significance. "A great revolution has happened—a revolution made, not by chopping and changing of power in any one of the existing states, but by the appearance of a new state, of a new species, in a new part of the globe," wrote the British politician Edmund Burke. With Sir William Herschel’s recent discovery of the ninth planet, Uranus, in mind, he continued: "It has made as great a change in all the relations, and balances, and gravitation of power, as the appearance of a new planet would in the system of the solar world." However, it is a striking historical irony that the Declaration itself almost immediately sank into oblivion, "old wadding left to rot on the battle-field after the victory is won," as Abraham Lincoln put it in 1857. The Fourth of July was widely celebrated but not the Declaration itself. Even in the infant United States, the Declaration was largely forgotten until the early 1790s, when it re-emerged as a bone of political contention in the partisan struggles between pro-British Federalists and pro-French Republicans after the French Revolution. Only after the War of 1812 and the end of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815, did it become revered as the foundation of a newly emergent American patriotism.

Imitations of the Declaration were also slow in coming. Within North America, there was only one other early declaration of independence—Vermont’s, in January 1777—and no similar document appeared outside North America until after the French Revolution. In January 1790, the Austrian province of Flanders expressed a desire to become a free and independent state in a document whose concluding lines drew directly on a French translation of the American Declaration. The allegedly self-evident truths of the Declaration’s second paragraph did not appear in this Flemish manifesto nor would they in most of the 120 or so declarations of independence issued around the world in the following two centuries. The French Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Citizen would have greater global impact as a charter of individual rights. The sovereignty of states, as laid out in the opening and closing paragraphs of the American Declaration, was the main message other peoples beyond America heard in the document after 1776.

More than half of the 192 countries now represented at the United Nations have a founding document that can be called a declaration of independence. Most of those countries came into being from the wreckage of empires or confederations, from Spanish America in the 1810s and 1820s to the Soviet Union and the former Yugoslavia in the 1990s. Their declarations of independence, like the American Declaration, informed the world that one people or state was now asserting—or, in many cases in the second half of the twentieth century re-asserting—its sovereignty and independence. Many looked back directly to the American Declaration for inspiration. For example, in 1811, Venezuela’s representatives declared "that these united Provinces are, and ought to be, from this day, by act and right, Free, Sovereign, and Independent States." The Texas declaration of independence (1836) likewise followed the American in listing grievances and claiming freedom and independence. In the twentieth century, nationalists in Central Europe and Korea after the First World War staked their claims to sovereignty by going to Independence Hall in Philadelphia. Even the white minority government of Southern Rhodesia in 1965 made their unilateral declaration of independence from the British Parliament by adopting the form of the 1776 Declaration, though they ended it with a royalist salutation: "God Save the Queen!" The international community did not recognize that declaration because, unlike many similar pronouncements made during the process of decolonization by other African countries, it did not speak on behalf of all the people of their country.

Invocations of the American Declaration’s second paragraph in later declarations of independence are conspicuous by their scarcity. Among the few are those of Liberia (1847) and Vietnam (1945). The Liberian declaration of independence recognized "in all men, certain natural and inalienable rights: among these are life, liberty, and the right to acquire, possess, and enjoy property": a significant amendment to the original Declaration’s right to happiness by the former slaves who had settled Liberia under the aegis of the American Colonization Society. Almost a century later, in September 1945, the Vietnamese leader Ho Chi Minh opened his declaration of independence with the "immortal statement" from the 1776 Declaration: "All men are created equal. They are endowed by their Creator with certain inalienable rights, among these are Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness." However, Ho immediately updated those words: "In a broader sense, this means: All the peoples of the earth are equal from birth, all the peoples have a right to live, to be happy and free." It would be hard to find a more concise summary of the message of the Declaration for the post-colonial predicaments of the late twentieth century.

The global history of the Declaration of Independence is a story of the spread of sovereignty and the creation of states more than it is a narrative of the diffusion and reception of ideas of individual rights. The farflung fortunes of the Declaration remind us that independence and popular sovereignty usually accompanied each other, but also that there was no necessary connection between them: an independent Mexico became an empire under a monarchy between 1821 and 1823, Brazil’s independence was proclaimed by its emperor, Dom Pedro II in 1822, and, as we have seen, Ian Smith’s Rhodesian government threw off parliamentary authority while professing loyalty to the British Crown. How to protect universal human rights in a world of sovereign states, each of which jealously guards itself from interference by outside authorities, remains one of the most pressing dilemmas in contemporary politics around the world.

So long as a people comes to believe their rights have been assaulted in a "long Train of Abuses and Usurpations," they will seek to protect those rights by forming their own state, for which international custom demands a declaration of independence. In February 2008, the majority Albanian population of Kosovo declared their independence of Serbia in a document designed to reassure the world that their cause offered no precedent for any similar separatist or secessionist movements. Fewer than half of the current powers of the earth have so far recognized this Kosovar declaration. The remaining countries, among them Russia, China, Spain, and Greece, have resisted for fear of encouraging the break-up of their own territories. The explosive potential of the American Declaration was hardly evident in 1776 but a global perspective reveals its revolutionary force in the centuries that followed. Thomas Jefferson’s assessment of its potential, made weeks before his death on July 4, 1826, surely still holds true today: "an instrument, pregnant with our own and the fate of the world."

David Armitage is the Lloyd C. Blankfein Professor of History and Director of Graduate Studies in History at Harvard University. He is also an Honorary Professor of History at the University of Sydney. Among his books are The Declaration of Independence: A Global History (2007) and The Age of Revolutions in Global Context, c. 1760–1860 (2010).

Stay up to date, and subscribe to our quarterly newsletter.

Learn how the Institute impacts history education through our work guiding teachers, energizing students, and supporting research.

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Spain Approves Amnesty for Separatists in 2017 Catalan Independence Vote

The measure has divided Spain in recent months, and opponents vowed to keep trying to block it.

By Rachel Chaundler

Reporting from Zaragoza, Spain

Spain’s Parliament approved a landmark law on Thursday that grants amnesty to Catalan separatists involved in the illegal October 2017 independence referendum , a reprieve that could apply to hundreds of people, including Carles Puigdemont, the former Catalan leader who has been living in self-imposed exile for seven years.

The measure had met with resistance from opposition parties in recent months, and led to widespread anger and huge demonstrations in cities around Spain, with opponents denouncing it as a ploy by Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez to remain in power. Mr. Sánchez brokered the amnesty deal with the Catalan separatist party Together for Catalonia after his own party fell short of a majority in last July’s general elections.

Cries of “traitor” could be heard from several lawmakers in Parliament when Mr. Sánchez cast his vote on Thursday.

Spain’s judges now have two months to apply the new law, although its opponents vowed to continue trying to block it. Some argue that the measure violates the Constitution’s principle of equality because it is unfair to other people facing legal proceedings.

The regional president of Madrid, Isabel Ayuso, said in a radio interview on Thursday that her government would take steps to hinder implementation of the new law and present an appeal on the grounds that it is unconstitutional.

Pablo Simón, a political scientist at Carlos III University in Madrid, said that judges could also bring legal challenges if they considered granting general legal amnesty to be discriminatory.

“Each judge has different criteria,” Mr. Simón said, adding that they could also appeal for intervention from the European Court of Justice “if they consider that giving a general legal pardon is discriminatory,” in which case “the law could be paralyzed.”

The amnesty law applies to people involved in the Catalan independence movement, which came to a head in October 2017, when the region’s separatist government, led by Mr. Puigdemont, ignored Spanish court orders and moved ahead with a referendum.

Numerous voters were injured by violent police intervention, and a declaration of independence followed the balloting — as did a crackdown by the Spanish government, which fired the Catalan government and imposed direct control. Nine political leaders were jailed for crimes including sedition, while Mr. Puigdemont fled across the border to France, and then to Belgium, narrowly avoiding arrest.

Although Mr. Sánchez’s government has already granted pardons to the political leaders and activists who were jailed, the amnesty goes a step further. It will dismiss cases against people who are facing prosecution on a wide range of charges, including misuse of public funds to finance the 2017 referendum; civil disobedience — for example, by teachers who opened schools to be used as polling stations; and resisting authority by participating in riots that prevented Spanish law enforcement from gathering evidence.

The only exceptions to the new amnesty legislation are cases relating to terrorism.

The measure was approved by the governing Socialist Party and its coalition partners after a monthslong parliamentary process. It had earlier been vetoed by Spain’s upper house, which has limited powers and is controlled by the opposition People’s Party.

Mr. Sánchez and his allies have defended the amnesty as the best way forward for peaceful coexistence in Catalonia. Félix Bolaños, the minister of the presidency, called the law “a definitive step toward closing a difficult period and opening a period of prosperity.”

Míriam Nogueras, the spokeswoman for Mr. Puigdemont’s party, said during the morning’s parliamentary debate that passing the bill was “not pardon or clemency” but a “victory” for democracy.

But Alberto Núñez Feijóo, the leader of the People’s Party, dismissed the measure as an “exchange of power” for “privileges and impunity.” He said during the debate, “Don’t dare call it coexistence.” Santiago Abascal, the leader of the far-right Vox party, said the law “legitimizes political violence in Spain.”

Despite the political and social backlash, Mr. Sánchez’s gamble seems to be paying off. In regional elections on May 12, the branch of his Socialist Party in Catalonia made history by winning enough votes to be able to form the region’s first government in over a decade that is led by a party opposed to Catalan independence.

That did not seem to deter Gabriel Rufían, a lawmaker with the Republican Left of Catalonia, who told Parliament on Wednesday that separatists in the region would use the momentum to press again for independence. “Next stop, referendum,” he said.

Ms. Nogueras, the spokeswoman for Mr. Puigdemont’s party, called the passage of the law “a historic day.” But the legal path for Mr. Puigdemont, who has also served as a member of the European Parliament since 2019, remains uncertain.

Mr. Simón, the political analyst, speculated that if judges were to link Mr. Puigdemont to the 2019 riots organized by Tsunami Democràtic , a Catalan protest group, at Barcelona’s airport, he and others could potentially be charged with terrorism and therefore be excluded from the amnesty law.

“Let’s see what happens,” Mr. Simón said.

A Thorough Look at the Declaration of Sentiments

This essay about the Declaration of Sentiments discusses its significance as a foundational document in the women’s rights movement in the United States. Drafted in 1848 at the Seneca Falls Convention, the Declaration outlined the systemic inequalities faced by women and demanded equal rights. It mirrored the Declaration of Independence, asserting that women deserved the same rights as men. Key issues addressed include women’s suffrage, legal inequality, lack of educational and employment opportunities, and societal double standards. The essay highlights the document’s impact on subsequent advocacy efforts and its enduring legacy in the fight for gender equality.

How it works

The Declaration of Sentiments, drafted in 1848 at the Seneca Falls Convention, marks a pivotal moment in the history of women’s rights in the United States. Modeled after the Declaration of Independence, this document articulated the grievances and demands of women, highlighting the systemic inequalities they faced and calling for equal rights. Its creation and adoption were led by prominent activists like Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Lucretia Mott, who sought to challenge the societal norms that relegated women to subordinate roles.

The document begins with a powerful preamble that mirrors the language of the Declaration of Independence, asserting that “all men and women are created equal.” This deliberate choice underscores the foundational belief that women deserve the same rights and opportunities as men. The preamble sets the stage for a series of grievances that detail the various ways in which women were oppressed and discriminated against in mid-19th century America.

One of the primary grievances outlined in the Declaration of Sentiments is the lack of women’s suffrage. The document condemns the fact that women were denied the right to vote, arguing that this exclusion from the political process left them without a voice in the laws that governed their lives. This call for women’s suffrage was revolutionary at the time and laid the groundwork for future movements that eventually secured this right with the 19th Amendment in 1920.

The Declaration also addresses the issue of legal inequality. It points out that women had no legal identity separate from their husbands, effectively rendering them invisible in the eyes of the law. Married women could not own property, enter into contracts, or earn wages in their own right. This lack of legal recognition deprived women of autonomy and economic independence, reinforcing their dependence on men.

Educational and employment opportunities for women were also significant concerns highlighted in the document. The Declaration criticizes the limited access to education for women, which restricted their intellectual and professional growth. It calls for equal opportunities in education and the workforce, arguing that women should be allowed to pursue any occupation and achieve financial independence. This demand for educational and professional equality was crucial in challenging the traditional roles assigned to women and advocating for their right to self-determination.

Furthermore, the Declaration of Sentiments addresses the double standards and moral expectations imposed on women. It condemns the societal norms that judged women harshly for behaviors deemed acceptable in men. This criticism extends to the religious sphere, where the document denounces the exclusion of women from church leadership roles and the interpretation of religious texts that justified women’s subordination.

The impact of the Declaration of Sentiments was profound, both in the immediate aftermath of the Seneca Falls Convention and in the broader context of the women’s rights movement. While it faced significant opposition and skepticism at the time, the document galvanized activists and provided a clear set of goals for the movement. It served as a blueprint for future advocacy, inspiring subsequent generations to continue the fight for gender equality.

In the years following its adoption, the Declaration of Sentiments influenced numerous other women’s rights conventions and reform efforts. It helped to frame the discourse around women’s rights and provided a rallying point for activists seeking to challenge the status quo. The issues raised in the document, such as suffrage, legal equality, and access to education and employment, remained central to the women’s rights movement for decades.

The legacy of the Declaration of Sentiments extends beyond the specific grievances it addressed. It represents a broader assertion of women’s humanity and their right to participate fully in all aspects of society. The document’s emphasis on equality, justice, and human dignity continues to resonate in contemporary discussions about gender equality and women’s rights.

In conclusion, the Declaration of Sentiments is a landmark document in the history of the women’s rights movement. Its eloquent articulation of the injustices faced by women and its bold demands for equality laid the foundation for subsequent advocacy and reform. The Declaration’s enduring legacy is a testament to the courage and vision of the women who drafted it and the generations of activists who have continued to fight for the rights and opportunities it championed. By understanding and appreciating the significance of the Declaration of Sentiments, we can better appreciate the ongoing struggle for gender equality and the progress that has been made over the past century and a half.

Cite this page

A Thorough Look at the Declaration of Sentiments. (2024, Jun 01). Retrieved from https://papersowl.com/examples/a-thorough-look-at-the-declaration-of-sentiments/

"A Thorough Look at the Declaration of Sentiments." PapersOwl.com , 1 Jun 2024, https://papersowl.com/examples/a-thorough-look-at-the-declaration-of-sentiments/

PapersOwl.com. (2024). A Thorough Look at the Declaration of Sentiments . [Online]. Available at: https://papersowl.com/examples/a-thorough-look-at-the-declaration-of-sentiments/ [Accessed: 4 Jun. 2024]

"A Thorough Look at the Declaration of Sentiments." PapersOwl.com, Jun 01, 2024. Accessed June 4, 2024. https://papersowl.com/examples/a-thorough-look-at-the-declaration-of-sentiments/

"A Thorough Look at the Declaration of Sentiments," PapersOwl.com , 01-Jun-2024. [Online]. Available: https://papersowl.com/examples/a-thorough-look-at-the-declaration-of-sentiments/. [Accessed: 4-Jun-2024]

PapersOwl.com. (2024). A Thorough Look at the Declaration of Sentiments . [Online]. Available at: https://papersowl.com/examples/a-thorough-look-at-the-declaration-of-sentiments/ [Accessed: 4-Jun-2024]

Don't let plagiarism ruin your grade

Hire a writer to get a unique paper crafted to your needs.

Our writers will help you fix any mistakes and get an A+!

Please check your inbox.

You can order an original essay written according to your instructions.

Trusted by over 1 million students worldwide

1. Tell Us Your Requirements

2. Pick your perfect writer

3. Get Your Paper and Pay

Hi! I'm Amy, your personal assistant!

Don't know where to start? Give me your paper requirements and I connect you to an academic expert.

short deadlines

100% Plagiarism-Free

Certified writers

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Declaration of Independence, in U.S. history, document that was approved by the Continental Congress on July 4, 1776, and that announced the separation of 13 North American British colonies from Great Britain. It explained why the Congress on July 2 "unanimously" by the votes of 12 colonies (with New York abstaining) had resolved that "these United Colonies are, and of right ought to be ...

The Declaration of Independence is the foundational document of the United States of America. Written primarily by Thomas Jefferson, it explains why the Thirteen Colonies decided to separate from Great Britain during the American Revolution (1765-1789). It was adopted by the Second Continental Congress on 4 July 1776, the anniversary of which is celebrated in the US as Independence Day.

The U.S. Declaration of Independence, adopted July 4, 1776, was the first formal statement by a nation's people asserting the right to choose their government.

Writing of Declaration of Independence. The 33-year-old Jefferson may have been a shy, awkward public speaker in Congressional debates, but he used his skills as a writer and correspondent to ...

The next day, Congress voted for independence by passing Lee's resolution. Over the next two days, Congress made several edits to the document, making it a collective effort of the Congress. It adopted the Declaration of Independence on July 4. The document expressed the natural rights principles of the independent American republic.

The Declaration of Independence states three basic ideas: (1) God made all men equal and gave them the rights of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness; (2) the main business of government is to protect these rights; (3) if a government tries to withhold these rights, the people are free to revolt and to set up a new government.

The Declaration of Independence, formally titled The unanimous Declaration of the thirteen united States of America (in the engrossed version but also the original printing), is the founding document of the United States.On July 4, 1776, it was adopted unanimously by the 56 delegates to the Second Continental Congress, who had convened at the Pennsylvania State House, later renamed ...

He has abdicated Government here, by declaring us out of his Protection and waging War against us. He has plundered our Seas, ravaged our Coasts, burnt our Towns, and destroyed the Lives of our People. He is, at this Time, transporting large Armies of foreign Mercenaries to compleat the Works of Death, Desolation, and Tyranny, already begun ...

The Declaration of Independence: A History. Nations come into being in many ways. Military rebellion, civil strife, acts of heroism, acts of treachery, a thousand greater and lesser clashes between defenders of the old order and supporters of the new--all these occurrences and more have marked the emergences of new nations, large and small.

In Congress, July 4, 1776. The unanimous Declaration of the thirteen united States of America, When in the Course of human events, it becomes necessary for one people to dissolve the political bands which have connected them with another, and to assume among the powers of the earth, the separate and equal station to which the Laws of Nature and of Nature's God entitle them, a decent respect to ...

Effects. The Declaration of Independence put forth the doctrines of natural rights and of government under social contract. The document claimed that Parliament never truly possessed sovereignty over the colonies and that George III had persistently violated the agreement between himself as governor and the Americans as the governed.

The Declaration of Independence has been read and talked about more than any other American document. There are many books, essays, and treatises written about it. And yet, there are many different opinions about what the ideas in it really mean. Even today all new American citizens study the meaning of this important document.

Therefore, the document marked the independence of the thirteen colonies of America, a condition which had caused revolutionary war. America celebrates its day of independence on 4 th July, the day when the congress approved the Declaration for Independence (Becker, 2008). With that background in mind, this essay shall give an analysis of the key issues closely linked to the United States ...

The Declaration of Independence is one of the founding documents of the United States of America. The text was written primarily by Thomas Jefferson in June of 1776 after the Second Continental Congress appointed him the chair of the Committee of Five (the others were John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, Robert Livingston, and Roger Sherman), a group designated to draft a statement declaring the ...

The initial draft of the Declaration of Independence was written by Thomas Jefferson and was presented to the entire Congress on June 28 for debate and revision. In addition to Jefferson's ...

Drafting the Documents. Thomas Jefferson drafted the Declaration of Independence in Philadelphia behind a veil of Congressionally imposed secrecy in June 1776 for a country wracked by military and political uncertainties. In anticipation of a vote for independence, the Continental Congress on June 11 appointed Thomas Jefferson, John Adams ...

Declaration of Independence in American History Essay. The United States declared independence on 4th July 1776. Being an independent state, one of the dreams they had at that time was for its citizens to live in freedom and have equal opportunity in all aspects of life. They believed that all men and women are equal, and that the Creator has ...

Unit Objective. Exact facsimile of the original Declaration of Independence, reproduced in 1823 by William Stone. (Gilder Lehrman Collection) This unit is part of Gilder Lehrman's series of Common Core State Standards-based teaching resources. These units were written to enable students to understand, summarize, and analyze original texts ...

Get unlimited access to SuperSummaryfor only $0.70/week. Thanks for exploring this SuperSummary Study Guide of "The Declaration of Independence" by Thomas Jefferson. A modern alternative to SparkNotes and CliffsNotes, SuperSummary offers high-quality Study Guides with detailed chapter summaries and analysis of major themes, characters, and ...

Declaring Independence. Not much is known about the conversations that took place between John Adams, Benjamin Franklin and Thomas Jefferson during the drafting of the Declaration of Independence ...

This essay about the Declaration of Independence explores its enduring significance in shaping the principles of liberty, equality, and self-governance. It highlights how the document's proclamation of natural rights and call for popular sovereignty resonated globally, despite its historical contradictions. ... short deadlines. 100% ...

The Liberian declaration of independence recognized "in all men, certain natural and inalienable rights: among these are life, liberty, and the right to acquire, possess, and enjoy property": a significant amendment to the original Declaration's right to happiness by the former slaves who had settled Liberia under the aegis of the American ...

24 essay samples found. The Declaration of Independence, signed on July 4, 1776, is a fundamental document that proclaimed the thirteen American colonies' independence from British rule. An essay on this topic could explore the historical context leading to its adoption, its philosophical underpinnings, and its influence on the American ...

Essay Example: In the annals of American history, few names evoke the spirit of revolution and the fervor of independence like that of John Hancock. Though often remembered for the flamboyant flourish of his signature on the Declaration of Independence, Hancock's legacy extends far beyond mere

Essay Example: Thomas Jefferson, the tertiary President of the United States and a pivotal architect of the Declaration of Independence, etched an enduring imprint on the nascent Republic. His accolades traversed diverse domains, spanning politics, academia, architectural ingenuity, and scientific

Susana Vera/Reuters. Spain's Parliament approved a landmark law on Thursday that grants amnesty to Catalan separatists involved in the illegal October 2017 independence referendum, a reprieve ...