- USC Libraries

- Research Guides

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper

- 5. The Literature Review

- Purpose of Guide

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Independent and Dependent Variables

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Reading Research Effectively

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Academic Writing Style

- Applying Critical Thinking

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- Research Process Video Series

- Executive Summary

- The C.A.R.S. Model

- Background Information

- The Research Problem/Question

- Theoretical Framework

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tiertiary Sources

- Scholarly vs. Popular Publications

- Qualitative Methods

- Quantitative Methods

- Insiderness

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Limitations of the Study

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Writing Concisely

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

- Generative AI and Writing

- USC Libraries Tutorials and Other Guides

- Bibliography

A literature review surveys prior research published in books, scholarly articles, and any other sources relevant to a particular issue, area of research, or theory, and by so doing, provides a description, summary, and critical evaluation of these works in relation to the research problem being investigated. Literature reviews are designed to provide an overview of sources you have used in researching a particular topic and to demonstrate to your readers how your research fits within existing scholarship about the topic.

Fink, Arlene. Conducting Research Literature Reviews: From the Internet to Paper . Fourth edition. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE, 2014.

Importance of a Good Literature Review

A literature review may consist of simply a summary of key sources, but in the social sciences, a literature review usually has an organizational pattern and combines both summary and synthesis, often within specific conceptual categories . A summary is a recap of the important information of the source, but a synthesis is a re-organization, or a reshuffling, of that information in a way that informs how you are planning to investigate a research problem. The analytical features of a literature review might:

- Give a new interpretation of old material or combine new with old interpretations,

- Trace the intellectual progression of the field, including major debates,

- Depending on the situation, evaluate the sources and advise the reader on the most pertinent or relevant research, or

- Usually in the conclusion of a literature review, identify where gaps exist in how a problem has been researched to date.

Given this, the purpose of a literature review is to:

- Place each work in the context of its contribution to understanding the research problem being studied.

- Describe the relationship of each work to the others under consideration.

- Identify new ways to interpret prior research.

- Reveal any gaps that exist in the literature.

- Resolve conflicts amongst seemingly contradictory previous studies.

- Identify areas of prior scholarship to prevent duplication of effort.

- Point the way in fulfilling a need for additional research.

- Locate your own research within the context of existing literature [very important].

Fink, Arlene. Conducting Research Literature Reviews: From the Internet to Paper. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2005; Hart, Chris. Doing a Literature Review: Releasing the Social Science Research Imagination . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 1998; Jesson, Jill. Doing Your Literature Review: Traditional and Systematic Techniques . Los Angeles, CA: SAGE, 2011; Knopf, Jeffrey W. "Doing a Literature Review." PS: Political Science and Politics 39 (January 2006): 127-132; Ridley, Diana. The Literature Review: A Step-by-Step Guide for Students . 2nd ed. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE, 2012.

Types of Literature Reviews

It is important to think of knowledge in a given field as consisting of three layers. First, there are the primary studies that researchers conduct and publish. Second are the reviews of those studies that summarize and offer new interpretations built from and often extending beyond the primary studies. Third, there are the perceptions, conclusions, opinion, and interpretations that are shared informally among scholars that become part of the body of epistemological traditions within the field.

In composing a literature review, it is important to note that it is often this third layer of knowledge that is cited as "true" even though it often has only a loose relationship to the primary studies and secondary literature reviews. Given this, while literature reviews are designed to provide an overview and synthesis of pertinent sources you have explored, there are a number of approaches you could adopt depending upon the type of analysis underpinning your study.

Argumentative Review This form examines literature selectively in order to support or refute an argument, deeply embedded assumption, or philosophical problem already established in the literature. The purpose is to develop a body of literature that establishes a contrarian viewpoint. Given the value-laden nature of some social science research [e.g., educational reform; immigration control], argumentative approaches to analyzing the literature can be a legitimate and important form of discourse. However, note that they can also introduce problems of bias when they are used to make summary claims of the sort found in systematic reviews [see below].

Integrative Review Considered a form of research that reviews, critiques, and synthesizes representative literature on a topic in an integrated way such that new frameworks and perspectives on the topic are generated. The body of literature includes all studies that address related or identical hypotheses or research problems. A well-done integrative review meets the same standards as primary research in regard to clarity, rigor, and replication. This is the most common form of review in the social sciences.

Historical Review Few things rest in isolation from historical precedent. Historical literature reviews focus on examining research throughout a period of time, often starting with the first time an issue, concept, theory, phenomena emerged in the literature, then tracing its evolution within the scholarship of a discipline. The purpose is to place research in a historical context to show familiarity with state-of-the-art developments and to identify the likely directions for future research.

Methodological Review A review does not always focus on what someone said [findings], but how they came about saying what they say [method of analysis]. Reviewing methods of analysis provides a framework of understanding at different levels [i.e. those of theory, substantive fields, research approaches, and data collection and analysis techniques], how researchers draw upon a wide variety of knowledge ranging from the conceptual level to practical documents for use in fieldwork in the areas of ontological and epistemological consideration, quantitative and qualitative integration, sampling, interviewing, data collection, and data analysis. This approach helps highlight ethical issues which you should be aware of and consider as you go through your own study.

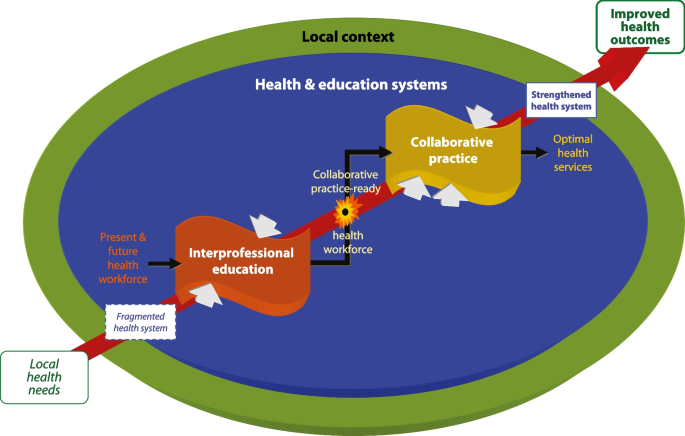

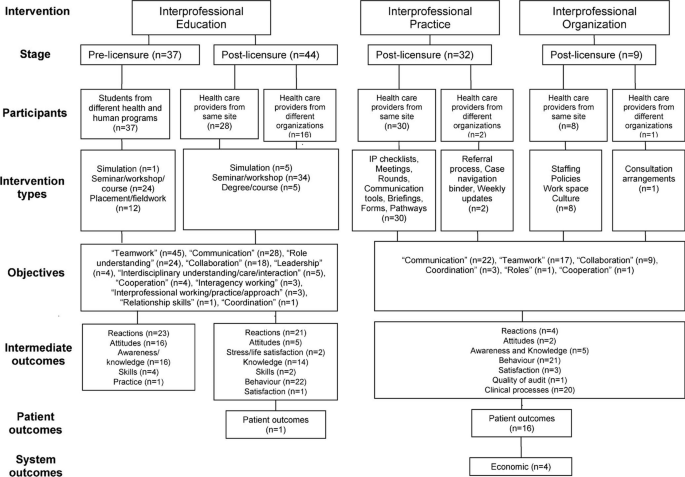

Systematic Review This form consists of an overview of existing evidence pertinent to a clearly formulated research question, which uses pre-specified and standardized methods to identify and critically appraise relevant research, and to collect, report, and analyze data from the studies that are included in the review. The goal is to deliberately document, critically evaluate, and summarize scientifically all of the research about a clearly defined research problem . Typically it focuses on a very specific empirical question, often posed in a cause-and-effect form, such as "To what extent does A contribute to B?" This type of literature review is primarily applied to examining prior research studies in clinical medicine and allied health fields, but it is increasingly being used in the social sciences.

Theoretical Review The purpose of this form is to examine the corpus of theory that has accumulated in regard to an issue, concept, theory, phenomena. The theoretical literature review helps to establish what theories already exist, the relationships between them, to what degree the existing theories have been investigated, and to develop new hypotheses to be tested. Often this form is used to help establish a lack of appropriate theories or reveal that current theories are inadequate for explaining new or emerging research problems. The unit of analysis can focus on a theoretical concept or a whole theory or framework.

NOTE: Most often the literature review will incorporate some combination of types. For example, a review that examines literature supporting or refuting an argument, assumption, or philosophical problem related to the research problem will also need to include writing supported by sources that establish the history of these arguments in the literature.

Baumeister, Roy F. and Mark R. Leary. "Writing Narrative Literature Reviews." Review of General Psychology 1 (September 1997): 311-320; Mark R. Fink, Arlene. Conducting Research Literature Reviews: From the Internet to Paper . 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2005; Hart, Chris. Doing a Literature Review: Releasing the Social Science Research Imagination . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 1998; Kennedy, Mary M. "Defining a Literature." Educational Researcher 36 (April 2007): 139-147; Petticrew, Mark and Helen Roberts. Systematic Reviews in the Social Sciences: A Practical Guide . Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishers, 2006; Torracro, Richard. "Writing Integrative Literature Reviews: Guidelines and Examples." Human Resource Development Review 4 (September 2005): 356-367; Rocco, Tonette S. and Maria S. Plakhotnik. "Literature Reviews, Conceptual Frameworks, and Theoretical Frameworks: Terms, Functions, and Distinctions." Human Ressource Development Review 8 (March 2008): 120-130; Sutton, Anthea. Systematic Approaches to a Successful Literature Review . Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publications, 2016.

Structure and Writing Style

I. Thinking About Your Literature Review

The structure of a literature review should include the following in support of understanding the research problem :

- An overview of the subject, issue, or theory under consideration, along with the objectives of the literature review,

- Division of works under review into themes or categories [e.g. works that support a particular position, those against, and those offering alternative approaches entirely],

- An explanation of how each work is similar to and how it varies from the others,

- Conclusions as to which pieces are best considered in their argument, are most convincing of their opinions, and make the greatest contribution to the understanding and development of their area of research.

The critical evaluation of each work should consider :

- Provenance -- what are the author's credentials? Are the author's arguments supported by evidence [e.g. primary historical material, case studies, narratives, statistics, recent scientific findings]?

- Methodology -- were the techniques used to identify, gather, and analyze the data appropriate to addressing the research problem? Was the sample size appropriate? Were the results effectively interpreted and reported?

- Objectivity -- is the author's perspective even-handed or prejudicial? Is contrary data considered or is certain pertinent information ignored to prove the author's point?

- Persuasiveness -- which of the author's theses are most convincing or least convincing?

- Validity -- are the author's arguments and conclusions convincing? Does the work ultimately contribute in any significant way to an understanding of the subject?

II. Development of the Literature Review

Four Basic Stages of Writing 1. Problem formulation -- which topic or field is being examined and what are its component issues? 2. Literature search -- finding materials relevant to the subject being explored. 3. Data evaluation -- determining which literature makes a significant contribution to the understanding of the topic. 4. Analysis and interpretation -- discussing the findings and conclusions of pertinent literature.

Consider the following issues before writing the literature review: Clarify If your assignment is not specific about what form your literature review should take, seek clarification from your professor by asking these questions: 1. Roughly how many sources would be appropriate to include? 2. What types of sources should I review (books, journal articles, websites; scholarly versus popular sources)? 3. Should I summarize, synthesize, or critique sources by discussing a common theme or issue? 4. Should I evaluate the sources in any way beyond evaluating how they relate to understanding the research problem? 5. Should I provide subheadings and other background information, such as definitions and/or a history? Find Models Use the exercise of reviewing the literature to examine how authors in your discipline or area of interest have composed their literature review sections. Read them to get a sense of the types of themes you might want to look for in your own research or to identify ways to organize your final review. The bibliography or reference section of sources you've already read, such as required readings in the course syllabus, are also excellent entry points into your own research. Narrow the Topic The narrower your topic, the easier it will be to limit the number of sources you need to read in order to obtain a good survey of relevant resources. Your professor will probably not expect you to read everything that's available about the topic, but you'll make the act of reviewing easier if you first limit scope of the research problem. A good strategy is to begin by searching the USC Libraries Catalog for recent books about the topic and review the table of contents for chapters that focuses on specific issues. You can also review the indexes of books to find references to specific issues that can serve as the focus of your research. For example, a book surveying the history of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict may include a chapter on the role Egypt has played in mediating the conflict, or look in the index for the pages where Egypt is mentioned in the text. Consider Whether Your Sources are Current Some disciplines require that you use information that is as current as possible. This is particularly true in disciplines in medicine and the sciences where research conducted becomes obsolete very quickly as new discoveries are made. However, when writing a review in the social sciences, a survey of the history of the literature may be required. In other words, a complete understanding the research problem requires you to deliberately examine how knowledge and perspectives have changed over time. Sort through other current bibliographies or literature reviews in the field to get a sense of what your discipline expects. You can also use this method to explore what is considered by scholars to be a "hot topic" and what is not.

III. Ways to Organize Your Literature Review

Chronology of Events If your review follows the chronological method, you could write about the materials according to when they were published. This approach should only be followed if a clear path of research building on previous research can be identified and that these trends follow a clear chronological order of development. For example, a literature review that focuses on continuing research about the emergence of German economic power after the fall of the Soviet Union. By Publication Order your sources by publication chronology, then, only if the order demonstrates a more important trend. For instance, you could order a review of literature on environmental studies of brown fields if the progression revealed, for example, a change in the soil collection practices of the researchers who wrote and/or conducted the studies. Thematic [“conceptual categories”] A thematic literature review is the most common approach to summarizing prior research in the social and behavioral sciences. Thematic reviews are organized around a topic or issue, rather than the progression of time, although the progression of time may still be incorporated into a thematic review. For example, a review of the Internet’s impact on American presidential politics could focus on the development of online political satire. While the study focuses on one topic, the Internet’s impact on American presidential politics, it would still be organized chronologically reflecting technological developments in media. The difference in this example between a "chronological" and a "thematic" approach is what is emphasized the most: themes related to the role of the Internet in presidential politics. Note that more authentic thematic reviews tend to break away from chronological order. A review organized in this manner would shift between time periods within each section according to the point being made. Methodological A methodological approach focuses on the methods utilized by the researcher. For the Internet in American presidential politics project, one methodological approach would be to look at cultural differences between the portrayal of American presidents on American, British, and French websites. Or the review might focus on the fundraising impact of the Internet on a particular political party. A methodological scope will influence either the types of documents in the review or the way in which these documents are discussed.

Other Sections of Your Literature Review Once you've decided on the organizational method for your literature review, the sections you need to include in the paper should be easy to figure out because they arise from your organizational strategy. In other words, a chronological review would have subsections for each vital time period; a thematic review would have subtopics based upon factors that relate to the theme or issue. However, sometimes you may need to add additional sections that are necessary for your study, but do not fit in the organizational strategy of the body. What other sections you include in the body is up to you. However, only include what is necessary for the reader to locate your study within the larger scholarship about the research problem.

Here are examples of other sections, usually in the form of a single paragraph, you may need to include depending on the type of review you write:

- Current Situation : Information necessary to understand the current topic or focus of the literature review.

- Sources Used : Describes the methods and resources [e.g., databases] you used to identify the literature you reviewed.

- History : The chronological progression of the field, the research literature, or an idea that is necessary to understand the literature review, if the body of the literature review is not already a chronology.

- Selection Methods : Criteria you used to select (and perhaps exclude) sources in your literature review. For instance, you might explain that your review includes only peer-reviewed [i.e., scholarly] sources.

- Standards : Description of the way in which you present your information.

- Questions for Further Research : What questions about the field has the review sparked? How will you further your research as a result of the review?

IV. Writing Your Literature Review

Once you've settled on how to organize your literature review, you're ready to write each section. When writing your review, keep in mind these issues.

Use Evidence A literature review section is, in this sense, just like any other academic research paper. Your interpretation of the available sources must be backed up with evidence [citations] that demonstrates that what you are saying is valid. Be Selective Select only the most important points in each source to highlight in the review. The type of information you choose to mention should relate directly to the research problem, whether it is thematic, methodological, or chronological. Related items that provide additional information, but that are not key to understanding the research problem, can be included in a list of further readings . Use Quotes Sparingly Some short quotes are appropriate if you want to emphasize a point, or if what an author stated cannot be easily paraphrased. Sometimes you may need to quote certain terminology that was coined by the author, is not common knowledge, or taken directly from the study. Do not use extensive quotes as a substitute for using your own words in reviewing the literature. Summarize and Synthesize Remember to summarize and synthesize your sources within each thematic paragraph as well as throughout the review. Recapitulate important features of a research study, but then synthesize it by rephrasing the study's significance and relating it to your own work and the work of others. Keep Your Own Voice While the literature review presents others' ideas, your voice [the writer's] should remain front and center. For example, weave references to other sources into what you are writing but maintain your own voice by starting and ending the paragraph with your own ideas and wording. Use Caution When Paraphrasing When paraphrasing a source that is not your own, be sure to represent the author's information or opinions accurately and in your own words. Even when paraphrasing an author’s work, you still must provide a citation to that work.

V. Common Mistakes to Avoid

These are the most common mistakes made in reviewing social science research literature.

- Sources in your literature review do not clearly relate to the research problem;

- You do not take sufficient time to define and identify the most relevant sources to use in the literature review related to the research problem;

- Relies exclusively on secondary analytical sources rather than including relevant primary research studies or data;

- Uncritically accepts another researcher's findings and interpretations as valid, rather than examining critically all aspects of the research design and analysis;

- Does not describe the search procedures that were used in identifying the literature to review;

- Reports isolated statistical results rather than synthesizing them in chi-squared or meta-analytic methods; and,

- Only includes research that validates assumptions and does not consider contrary findings and alternative interpretations found in the literature.

Cook, Kathleen E. and Elise Murowchick. “Do Literature Review Skills Transfer from One Course to Another?” Psychology Learning and Teaching 13 (March 2014): 3-11; Fink, Arlene. Conducting Research Literature Reviews: From the Internet to Paper . 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2005; Hart, Chris. Doing a Literature Review: Releasing the Social Science Research Imagination . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 1998; Jesson, Jill. Doing Your Literature Review: Traditional and Systematic Techniques . London: SAGE, 2011; Literature Review Handout. Online Writing Center. Liberty University; Literature Reviews. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina; Onwuegbuzie, Anthony J. and Rebecca Frels. Seven Steps to a Comprehensive Literature Review: A Multimodal and Cultural Approach . Los Angeles, CA: SAGE, 2016; Ridley, Diana. The Literature Review: A Step-by-Step Guide for Students . 2nd ed. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE, 2012; Randolph, Justus J. “A Guide to Writing the Dissertation Literature Review." Practical Assessment, Research, and Evaluation. vol. 14, June 2009; Sutton, Anthea. Systematic Approaches to a Successful Literature Review . Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publications, 2016; Taylor, Dena. The Literature Review: A Few Tips On Conducting It. University College Writing Centre. University of Toronto; Writing a Literature Review. Academic Skills Centre. University of Canberra.

Writing Tip

Break Out of Your Disciplinary Box!

Thinking interdisciplinarily about a research problem can be a rewarding exercise in applying new ideas, theories, or concepts to an old problem. For example, what might cultural anthropologists say about the continuing conflict in the Middle East? In what ways might geographers view the need for better distribution of social service agencies in large cities than how social workers might study the issue? You don’t want to substitute a thorough review of core research literature in your discipline for studies conducted in other fields of study. However, particularly in the social sciences, thinking about research problems from multiple vectors is a key strategy for finding new solutions to a problem or gaining a new perspective. Consult with a librarian about identifying research databases in other disciplines; almost every field of study has at least one comprehensive database devoted to indexing its research literature.

Frodeman, Robert. The Oxford Handbook of Interdisciplinarity . New York: Oxford University Press, 2010.

Another Writing Tip

Don't Just Review for Content!

While conducting a review of the literature, maximize the time you devote to writing this part of your paper by thinking broadly about what you should be looking for and evaluating. Review not just what scholars are saying, but how are they saying it. Some questions to ask:

- How are they organizing their ideas?

- What methods have they used to study the problem?

- What theories have been used to explain, predict, or understand their research problem?

- What sources have they cited to support their conclusions?

- How have they used non-textual elements [e.g., charts, graphs, figures, etc.] to illustrate key points?

When you begin to write your literature review section, you'll be glad you dug deeper into how the research was designed and constructed because it establishes a means for developing more substantial analysis and interpretation of the research problem.

Hart, Chris. Doing a Literature Review: Releasing the Social Science Research Imagination . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 1 998.

Yet Another Writing Tip

When Do I Know I Can Stop Looking and Move On?

Here are several strategies you can utilize to assess whether you've thoroughly reviewed the literature:

- Look for repeating patterns in the research findings . If the same thing is being said, just by different people, then this likely demonstrates that the research problem has hit a conceptual dead end. At this point consider: Does your study extend current research? Does it forge a new path? Or, does is merely add more of the same thing being said?

- Look at sources the authors cite to in their work . If you begin to see the same researchers cited again and again, then this is often an indication that no new ideas have been generated to address the research problem.

- Search Google Scholar to identify who has subsequently cited leading scholars already identified in your literature review [see next sub-tab]. This is called citation tracking and there are a number of sources that can help you identify who has cited whom, particularly scholars from outside of your discipline. Here again, if the same authors are being cited again and again, this may indicate no new literature has been written on the topic.

Onwuegbuzie, Anthony J. and Rebecca Frels. Seven Steps to a Comprehensive Literature Review: A Multimodal and Cultural Approach . Los Angeles, CA: Sage, 2016; Sutton, Anthea. Systematic Approaches to a Successful Literature Review . Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publications, 2016.

- << Previous: Theoretical Framework

- Next: Citation Tracking >>

- Last Updated: May 30, 2024 9:38 AM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide

Eugene McDermott Library

Literature review.

- Collecting Resources for a Literature Review

- Organizing the Literature Review

- Writing the Literature Review

- Examples of Literature Reviews

Organization

Organization of your Literature Review

What is the most effective way of presenting the information? What are the most important topics, subtopics, etc., that your review needs to include? What order should you present them?

Basic Outline of a Literature Review

Just like most academic papers, literature reviews must contain at least three basic elements: an introduction or background information section; the body of the review containing the discussion of sources; and, finally, a conclusion and/or recommendations section to end the paper.

Introduction: Gives a quick idea of the topic of the literature review, such as the central theme or organizational pattern.

Body: Contains your discussion of sources and is organized either chronologically, thematically, or methodologically (see below for more information on each).

Conclusions/Recommendations: Discuss what you have drawn from reviewing the literature so far. Where might the discussion proceed ? ( " Literature Reviews" from The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill )

Organizing the Body

Once you have the basic categories in place, then you must consider how you will present the sources themselves within the body of your paper. Create an organizational method to focus this section even further.

To help you come up with an overall organizational framework for your review, consider the following scenario and then three typical ways of organizing the sources into a review:

You've decided to focus your literature review on materials dealing with sperm whales. This is because you've just finished reading Moby Dick, and you wonder if that whale's portrayal is really real. You start with some articles about the physiology of sperm whales in biology journals written in the 1980's. But these articles refer to some British biological studies performed on whales in the early 18th century. So you check those out. Then you look up a book written in 1968 with information on how sperm whales have been portrayed in other forms of art, such as in Alaskan poetry, in French painting, or on whale bone, as the whale hunters in the late 19th century used to do. This makes you wonder about American whaling methods during the time portrayed in Moby Dick, so you find some academic articles published in the last five years on how accurately Herman Melville portrayed the whaling scene in his novel.

Chronological

If your review follows the chronological method, you could write about the materials above according to when they were published. For instance, first you would talk about the British biological studies of the 18th century, then about Moby Dick, published in 1851, then the book on sperm whales in other art (1968), and finally the biology articles (1980s) and the recent articles on American whaling of the 19th century. But there is relatively no continuity among subjects here. And notice that even though the sources on sperm whales in other art and on American whaling are written recently, they are about other subjects/objects that were created much earlier. Thus, the review loses its chronological focus.

By publication

Order your sources chronologically by publication if the order demonstrates a more important trend. For instance, you could order a review of literature on biological studies of sperm whales if the progression revealed a change in dissection practices of the researchers who wrote and/or conducted the studies.

Another way to organize sources chronologically is to examine the sources under a trend, such as the history of whaling. Then your review would have subsections according to eras within this period. For instance, the review might examine whaling from pre-1600-1699, 1700-1799, and 1800-1899. Using this method, you would combine the recent studies on American whaling in the 19th century with Moby Dick itself in the 1800-1899 category, even though the authors wrote a century apart.

Thematic reviews of literature are organized around a topic or issue, rather than the progression of time. However, progression of time may still be an important factor in a thematic review. For instance, the sperm whale review could focus on the development of the harpoon for whale hunting. While the study focuses on one topic, harpoon technology, it will still be organized chronologically. The only difference here between a "chronological" and a "thematic" approach is what is emphasized the most: the development of the harpoon or the harpoon technology.

More authentic thematic reviews tend to break away from chronological order. For instance, a thematic review of material on sperm whales might examine how they are portrayed as "evil" in cultural documents. The subsections might include how they are personified, how their proportions are exaggerated, and their behaviors misunderstood. A review organized in this manner would shift between time periods within each section according to the point made.

Methodological

A methodological approach differs from the two above in that the focusing factor usually does not have to do with the content of the material. Instead, it focuses on the "methods" of the researcher or writer. For the sperm whale project, one methodological approach would be to look at cultural differences between the portrayal of whales in American, British, and French art work. Or the review might focus on the economic impact of whaling on a community. A methodological scope will influence either the types of documents in the review or the way in which these documents are discussed.

Once you've decided on the organizational method for the body of the review, the sections you need to include in the paper should be easy to figure out. They should arise out of your organizational strategy. In other words, a chronological review would have subsections for each vital time period. A thematic review would have subtopics based upon factors that relate to the theme or issue.

( "Literature Reviews" from The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill )

Other Sections to Include in a Literature Review

Sometimes, though, you might need to add additional sections that are necessary for your study, but do not fit in the organizational strategy of the body. What other sections you include in the body is up to you. Put in only what is necessary. Here are a few other sections you might want to consider:

Current Situation: Information necessary to understand the topic or focus of the literature review.

History: The chronological progression of the field, the literature, or an idea that is necessary to understand the literature review, if the body of the literature review is not already a chronology.

Methods and/or Standards: The criteria you used to select the sources in your literature review or the way in which you present your information. For instance, you might explain that your review includes only peer-reviewed articles and journals.

Questions for Further Research: What questions about the field has the review sparked? How will you further your research as a result of the review?

( " Literature Reviews" from The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill )

- << Previous: Collecting Resources for a Literature Review

- Next: Writing the Literature Review >>

- Last Updated: Mar 22, 2024 12:28 PM

- URL: https://libguides.utdallas.edu/literature-review

Organizing and Creating Information

- Citation and Attribution

What Is a Literature Review?

Review the literature, write the literature review, further reading, learning objectives, attribution.

This guide is designed to:

- Identify the sections and purpose of a literature review in academic writing

- Review practical strategies and organizational methods for preparing a literature review

A literature review is a summary and synthesis of scholarly research on a specific topic. It should answer questions such as:

- What research has been done on the topic?

- Who are the key researchers and experts in the field?

- What are the common theories and methodologies?

- Are there challenges, controversies, and contradictions?

- Are there gaps in the research that your approach addresses?

The process of reviewing existing research allows you to fine-tune your research question and contextualize your own work. Preparing a literature review is a cyclical process. You may find that the research question you begin with evolves as you learn more about the topic.

Once you have defined your research question , focus on learning what other scholars have written on the topic.

In order to do a thorough search of the literature on the topic, define the basic criteria:

- Databases and journals: Look at the subject guide related to your topic for recommended databases. Review the tutorial on finding articles for tips.

- Books: Search BruKnow, the Library's catalog. Steps to searching ebooks are covered in the Finding Ebooks tutorial .

- What time period should it cover? Is currency important?

- Do I know of primary and secondary sources that I can use as a way to find other information?

- What should I be aware of when looking at popular, trade, and scholarly resources ?

One strategy is to review bibliographies for sources that relate to your interest. For more on this technique, look at the tutorial on finding articles when you have a citation .

Tip: Use a Synthesis Matrix

As you read sources, themes will emerge that will help you to organize the review. You can use a simple Synthesis Matrix to track your notes as you read. From this work, a concept map emerges that provides an overview of the literature and ways in which it connects. Working with Zotero to capture the citations, you build the structure for writing your literature review.

How do I know when I am done?

A key indicator for knowing when you are done is running into the same articles and materials. With no new information being uncovered, you are likely exhausting your current search and should modify search terms or search different catalogs or databases. It is also possible that you have reached a point when you can start writing the literature review.

Tip: Manage Your Citations

These citation management tools also create citations, footnotes, and bibliographies with just a few clicks:

Zotero Tutorial

Endnote Tutorial

Your literature review should be focused on the topic defined in your research question. It should be written in a logical, structured way and maintain an objective perspective and use a formal voice.

Review the Summary Table you created for themes and connecting ideas. Use the following guidelines to prepare an outline of the main points you want to make.

- Synthesize previous research on the topic.

- Aim to include both summary and synthesis.

- Include literature that supports your research question as well as that which offers a different perspective.

- Avoid relying on one author or publication too heavily.

- Select an organizational structure, such as chronological, methodological, and thematic.

The three elements of a literature review are introduction, body, and conclusion.

Introduction

- Define the topic of the literature review, including any terminology.

- Introduce the central theme and organization of the literature review.

- Summarize the state of research on the topic.

- Frame the literature review with your research question.

- Focus on ways to have the body of literature tell its own story. Do not add your own interpretations at this point.

- Look for patterns and find ways to tie the pieces together.

- Summarize instead of quote.

- Weave the points together rather than list summaries of each source.

- Include the most important sources, not everything you have read.

- Summarize the review of the literature.

- Identify areas of further research on the topic.

- Connect the review with your research.

- DeCarlo, M. (2018). 4.1 What is a literature review? In Scientific Inquiry in Social Work. Open Social Work Education. https://scientificinquiryinsocialwork.pressbooks.com/chapter/4-1-what-is-a-literature-review/

- Literature Reviews (n.d.) https://writingcenter.unc.edu/tips-and-tools/literature-reviews/ Accessed Nov. 10, 2021

This guide was designed to:

- Identify the sections and purpose of a literature review in academic writing

- Review practical strategies and organizational methods for preparing a literature review

Content on this page adapted from:

Frederiksen, L. and Phelps, S. (2017). Literature Reviews for Education and Nursing Graduate Students. Licensed CC BY 4.0

- << Previous: EndNote

- Last Updated: May 24, 2024 10:37 AM

- URL: https://libguides.brown.edu/organize

Brown University Library | Providence, RI 02912 | (401) 863-2165 | Contact | Comments | Library Feedback | Site Map

Library Intranet

How To Structure Your Literature Review

3 options to help structure your chapter.

By: Amy Rommelspacher (PhD) | Reviewer: Dr Eunice Rautenbach | November 2020 (Updated May 2023)

Writing the literature review chapter can seem pretty daunting when you’re piecing together your dissertation or thesis. As we’ve discussed before , a good literature review needs to achieve a few very important objectives – it should:

- Demonstrate your knowledge of the research topic

- Identify the gaps in the literature and show how your research links to these

- Provide the foundation for your conceptual framework (if you have one)

- Inform your own methodology and research design

To achieve this, your literature review needs a well-thought-out structure . Get the structure of your literature review chapter wrong and you’ll struggle to achieve these objectives. Don’t worry though – in this post, we’ll look at how to structure your literature review for maximum impact (and marks!).

But wait – is this the right time?

Deciding on the structure of your literature review should come towards the end of the literature review process – after you have collected and digested the literature, but before you start writing the chapter.

In other words, you need to first develop a rich understanding of the literature before you even attempt to map out a structure. There’s no use trying to develop a structure before you’ve fully wrapped your head around the existing research.

Equally importantly, you need to have a structure in place before you start writing , or your literature review will most likely end up a rambling, disjointed mess.

Importantly, don’t feel that once you’ve defined a structure you can’t iterate on it. It’s perfectly natural to adjust as you engage in the writing process. As we’ve discussed before , writing is a way of developing your thinking, so it’s quite common for your thinking to change – and therefore, for your chapter structure to change – as you write.

Need a helping hand?

Like any other chapter in your thesis or dissertation, your literature review needs to have a clear, logical structure. At a minimum, it should have three essential components – an introduction , a body and a conclusion .

Let’s take a closer look at each of these.

1: The Introduction Section

Just like any good introduction, the introduction section of your literature review should introduce the purpose and layout (organisation) of the chapter. In other words, your introduction needs to give the reader a taste of what’s to come, and how you’re going to lay that out. Essentially, you should provide the reader with a high-level roadmap of your chapter to give them a taste of the journey that lies ahead.

Here’s an example of the layout visualised in a literature review introduction:

Your introduction should also outline your topic (including any tricky terminology or jargon) and provide an explanation of the scope of your literature review – in other words, what you will and won’t be covering (the delimitations ). This helps ringfence your review and achieve a clear focus . The clearer and narrower your focus, the deeper you can dive into the topic (which is typically where the magic lies).

Depending on the nature of your project, you could also present your stance or point of view at this stage. In other words, after grappling with the literature you’ll have an opinion about what the trends and concerns are in the field as well as what’s lacking. The introduction section can then present these ideas so that it is clear to examiners that you’re aware of how your research connects with existing knowledge .

2: The Body Section

The body of your literature review is the centre of your work. This is where you’ll present, analyse, evaluate and synthesise the existing research. In other words, this is where you’re going to earn (or lose) the most marks. Therefore, it’s important to carefully think about how you will organise your discussion to present it in a clear way.

The body of your literature review should do just as the description of this chapter suggests. It should “review” the literature – in other words, identify, analyse, and synthesise it. So, when thinking about structuring your literature review, you need to think about which structural approach will provide the best “review” for your specific type of research and objectives (we’ll get to this shortly).

There are (broadly speaking) three options for organising your literature review.

Option 1: Chronological (according to date)

Organising the literature chronologically is one of the simplest ways to structure your literature review. You start with what was published first and work your way through the literature until you reach the work published most recently. Pretty straightforward.

The benefit of this option is that it makes it easy to discuss the developments and debates in the field as they emerged over time. Organising your literature chronologically also allows you to highlight how specific articles or pieces of work might have changed the course of the field – in other words, which research has had the most impact . Therefore, this approach is very useful when your research is aimed at understanding how the topic has unfolded over time and is often used by scholars in the field of history. That said, this approach can be utilised by anyone that wants to explore change over time .

For example , if a student of politics is investigating how the understanding of democracy has evolved over time, they could use the chronological approach to provide a narrative that demonstrates how this understanding has changed through the ages.

Here are some questions you can ask yourself to help you structure your literature review chronologically.

- What is the earliest literature published relating to this topic?

- How has the field changed over time? Why?

- What are the most recent discoveries/theories?

In some ways, chronology plays a part whichever way you decide to structure your literature review, because you will always, to a certain extent, be analysing how the literature has developed. However, with the chronological approach, the emphasis is very firmly on how the discussion has evolved over time , as opposed to how all the literature links together (which we’ll discuss next ).

Option 2: Thematic (grouped by theme)

The thematic approach to structuring a literature review means organising your literature by theme or category – for example, by independent variables (i.e. factors that have an impact on a specific outcome).

As you’ve been collecting and synthesising literature , you’ll likely have started seeing some themes or patterns emerging. You can then use these themes or patterns as a structure for your body discussion. The thematic approach is the most common approach and is useful for structuring literature reviews in most fields.

For example, if you were researching which factors contributed towards people trusting an organisation, you might find themes such as consumers’ perceptions of an organisation’s competence, benevolence and integrity. Structuring your literature review thematically would mean structuring your literature review’s body section to discuss each of these themes, one section at a time.

Here are some questions to ask yourself when structuring your literature review by themes:

- Are there any patterns that have come to light in the literature?

- What are the central themes and categories used by the researchers?

- Do I have enough evidence of these themes?

PS – you can see an example of a thematically structured literature review in our literature review sample walkthrough video here.

Option 3: Methodological

The methodological option is a way of structuring your literature review by the research methodologies used . In other words, organising your discussion based on the angle from which each piece of research was approached – for example, qualitative , quantitative or mixed methodologies.

Structuring your literature review by methodology can be useful if you are drawing research from a variety of disciplines and are critiquing different methodologies. The point of this approach is to question how existing research has been conducted, as opposed to what the conclusions and/or findings the research were.

For example, a sociologist might centre their research around critiquing specific fieldwork practices. Their literature review will then be a summary of the fieldwork methodologies used by different studies.

Here are some questions you can ask yourself when structuring your literature review according to methodology:

- Which methodologies have been utilised in this field?

- Which methodology is the most popular (and why)?

- What are the strengths and weaknesses of the various methodologies?

- How can the existing methodologies inform my own methodology?

3: The Conclusion Section

Once you’ve completed the body section of your literature review using one of the structural approaches we discussed above, you’ll need to “wrap up” your literature review and pull all the pieces together to set the direction for the rest of your dissertation or thesis.

The conclusion is where you’ll present the key findings of your literature review. In this section, you should emphasise the research that is especially important to your research questions and highlight the gaps that exist in the literature. Based on this, you need to make it clear what you will add to the literature – in other words, justify your own research by showing how it will help fill one or more of the gaps you just identified.

Last but not least, if it’s your intention to develop a conceptual framework for your dissertation or thesis, the conclusion section is a good place to present this.

Example: Thematically Structured Review

In the video below, we unpack a literature review chapter so that you can see an example of a thematically structure review in practice.

Let’s Recap

In this article, we’ve discussed how to structure your literature review for maximum impact. Here’s a quick recap of what you need to keep in mind when deciding on your literature review structure:

- Just like other chapters, your literature review needs a clear introduction , body and conclusion .

- The introduction section should provide an overview of what you will discuss in your literature review.

- The body section of your literature review can be organised by chronology , theme or methodology . The right structural approach depends on what you’re trying to achieve with your research.

- The conclusion section should draw together the key findings of your literature review and link them to your research questions.

If you’re ready to get started, be sure to download our free literature review template to fast-track your chapter outline.

Psst… there’s more!

This post is an extract from our bestselling short course, Literature Review Bootcamp . If you want to work smart, you don't want to miss this .

You Might Also Like:

27 Comments

Great work. This is exactly what I was looking for and helps a lot together with your previous post on literature review. One last thing is missing: a link to a great literature chapter of an journal article (maybe with comments of the different sections in this review chapter). Do you know any great literature review chapters?

I agree with you Marin… A great piece

I agree with Marin. This would be quite helpful if you annotate a nicely structured literature from previously published research articles.

Awesome article for my research.

I thank you immensely for this wonderful guide

It is indeed thought and supportive work for the futurist researcher and students

Very educative and good time to get guide. Thank you

Great work, very insightful. Thank you.

Thanks for this wonderful presentation. My question is that do I put all the variables into a single conceptual framework or each hypothesis will have it own conceptual framework?

Thank you very much, very helpful

This is very educative and precise . Thank you very much for dropping this kind of write up .

Pheeww, so damn helpful, thank you for this informative piece.

I’m doing a research project topic ; stool analysis for parasitic worm (enteric) worm, how do I structure it, thanks.

comprehensive explanation. Help us by pasting the URL of some good “literature review” for better understanding.

great piece. thanks for the awesome explanation. it is really worth sharing. I have a little question, if anyone can help me out, which of the options in the body of literature can be best fit if you are writing an architectural thesis that deals with design?

I am doing a research on nanofluids how can l structure it?

Beautifully clear.nThank you!

Lucid! Thankyou!

Brilliant work, well understood, many thanks

I like how this was so clear with simple language 😊😊 thank you so much 😊 for these information 😊

Insightful. I was struggling to come up with a sensible literature review but this has been really helpful. Thank you!

You have given thought-provoking information about the review of the literature.

Thank you. It has made my own research better and to impart your work to students I teach

I learnt a lot from this teaching. It’s a great piece.

I am doing research on EFL teacher motivation for his/her job. How Can I structure it? Is there any detailed template, additional to this?

You are so cool! I do not think I’ve read through something like this before. So nice to find somebody with some genuine thoughts on this issue. Seriously.. thank you for starting this up. This site is one thing that is required on the internet, someone with a little originality!

I’m asked to do conceptual, theoretical and empirical literature, and i just don’t know how to structure it

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

- University Libraries

- Research Guides

- Subject Guides

What is a literature review?

- Organization

- Getting Started

- Finding the Literature

A Process for Organizing Your Review of the Literature

Tools to help organize your literature review.

- Connect with Your Librarian

- More Information

Citation Management

- Zotero: A Beginner's Guide by Todd Quinn Last Updated Mar 29, 2024 20046 views this year

- Zotero v. EndNote v. Mendeley by Todd Quinn Last Updated Mar 13, 2023 467 views this year

- EndNote Software: Beginner's Guide by Todd Quinn Last Updated Jan 24, 2024 3606 views this year

More information

- Literature review assignments A video on how to organize literature reviews.

- Select the most relevant material from your sources With your research question in mind, read each of your sources and identify the material that is most relevant to that question. This might be material that answers the question directly, but it might also be material that helps explain why it’s important to ask the question or that is otherwise relevant to your question. When you pull this material from your source, you can extract it as a direct quotation, or you can paraphrase the passage or idea. (Make sure you enclose direct quotations in quotation marks!) A single source may have more than one idea relevant to your question.

- Arrange that material so you can focus on it apart from the source text itself Many writers put the material they have selected into a grid. They place each quotation or paraphrase in a cell in that grid. Arranging your selected material in a grid has two benefits: first, you can view your relevant material away from the source text (meaning you are now working with fewer words and pages!). Second, you can view all of the material that will go into your lit review in one place.

Once you have created these groups of ideas, approaches, or themes, give each one a label. The labels describe the points, themes, or topics that are the backbone of your paper’s structure.

Now that you have identified the topics you will discuss in your lit review, look them over as a whole. Do you see any gaps that you should fill by finding additional sources? If so, do that research and add those sources to your groupings.

Once you have an assertion for each of your groupings, put those assertions in the order that you want to use in the lit review. This may be the order that has the best logical flow, or the order that tells the story you want to tell in the lit review.

Source: Organizing Literature Reviews: The Basics from George Mason University

- Bubbl.us Bubbl.us makes it easy to organize your ideas visually in a way that makes sense to you and others.

- Coggle Coggle is online software for creating and sharing mindmaps and flowcharts.

- Google Sheets Create a matrix with author names across the top (columns), themes on the left side (rows).

- Microsoft Excel Create a matrix with author names across the top (columns), themes on the left side (rows).

- Mind42 Mind42 is a free online mind mapping software. In short: Mind42 offers you a software that runs in your browser to create mind maps - a special form of a structured diagram to visually organize information.

- Popplet Mind maps, flow charts, timelines, story boards and more.

- Scapple Ever scribbled ideas on a piece of paper and drawn lines between related thoughts? Then you already know what Scapple does. It's a virtual sheet of paper that lets you make notes anywhere and connect them using lines or arrows.

- XMind The full-featured mind mapping and brainstorming app.

- << Previous: Finding the Literature

- Next: Connect with Your Librarian >>

- Last Updated: Aug 17, 2023 9:45 AM

- URL: https://libguides.unm.edu/litreview

Literature Reviews

- 6. Write the review

- Getting started

- Types of reviews

- 1. Define your research question

- 2. Plan your search

- 3. Search the literature

- 4. Organize your results

- 5. Synthesize your findings

- Artificial intelligence (AI) tools

- Thompson Writing Studio This link opens in a new window

- Need to write a systematic review? This link opens in a new window

Contact a Librarian

Ask a Librarian

Organize your review according to the following structure:

- Provide a concise overview of your primary thesis and the studies you explore in your review.

- Present the subject of your review

- Outline the key points you will address in the review

- Use your thesis to frame your paper

- Explain the significance of reviewing the literature in your chosen topic area (e.g., to find research gaps? Or to update your field on the current literature?)

- Consider dividing it into sections, particularly if examining multiple methodologies

- Examine the literature thoroughly and systematically, maintaining organization — don't just paraphrase researchers, add your own interpretation and discuss the significance of the papers you found)

- Reiterate your thesis

- Summarize your key findings

- Ensure proper formatting of your references (stick to a single citation style — be consistent!)

- Use a citation manager, such as Zotero or EndNote, for easy formatting!

Check out UNC's guide on literature reviews, especially the section " Organizing the Body ."

- << Previous: 5. Synthesize your findings

- Next: Artificial intelligence (AI) tools >>

- Last Updated: May 17, 2024 8:42 AM

- URL: https://guides.library.duke.edu/litreviews

Services for...

- Faculty & Instructors

- Graduate Students

- Undergraduate Students

- International Students

- Patrons with Disabilities

- Harmful Language Statement

- Re-use & Attribution / Privacy

- Support the Libraries

How to Do a Literature Review: Organization & Writing

- Introduction

- Where to Begin

- Organization & Writing

Preparing to Write

What are you writing? A literature review is not a one-by-one summary of your sources, but a synthesis or integration of them all. For a literature review, you want to focus on analyzing the sources you have examined from the point of view of your thesis/hypothesis. Keep in mind that the purpose of analyzing your reviewed sources is to convince your reader that your thesis or hypothesis is a good one.

How are you writing it? There are many ways to organize a literature review. You many want to group you sources in the form of a debate or compare and contrast, highlighting the similarities and differences between them. You could also decide to present your sources as they connect to the subtopics you establish as key to your thesis/hypothesis. Another possibility might be to discuss the sources in chronological order by their date of publication to show how a specific position or approach or concept important to your thesis/hypothesis may have come about.

On this page you will find a guide to the general structure of a literature review as well as suggestions for note-taking and outlining.

Parts of the Literature Review

The introduction

- Define or identify the general topic, issue, or area of concern.

- Establish your reason (point of view) for reviewing the literature, i.e. testing the hypothesis of your research project against the available published research pertinent to it.

- State trends, points of agreement and disagreement in the sources you reviewed

- Decide what organizing principle you will use to present your sources: Will you group sources by concept, by your own subtopic, by trends, by shared methodologies, by schools of thought, by chronology?

- Summarize individual studies or articles with as much or as little detail as each merits in your argument

- Make sure you discuss more than one source in each section of your literature review

- Provide the reader with strong "signal sentences at beginnings of paragraphs or "signposts" that make the overall topic of the paragraph clear

- End each paragraph with a reflection on what the sources reviewed show in relation to your hypothesis or research focus.

The conclusion

- Articulate how your review of your sources sheds light on your hypothesis or research focus

- Point to aspects of your research focus that are not covered in depth or at all in the sources you reviewed and merit more research

-Loosely adapted from the Writing Center at the University of Wisconsin, Madison

Outlining Your Literature Review

- What is your topic and why is it important?

- What is the thesis you want to establish or the proposal you want to lay out or the hypothesis you want to test?

- What is the range of sources you reviewed (publication dates, types of articles)?

- How does source #1 in relation to your main point #1?

- How does source #2 in relation to your main point #1 and in relation to source #1?

- How does source #3 in relation to your main point #1 and in relation to sources #1 & # 2?

- What does the research reviewed here show about your overall thesis, proposal, or hypothesis?

- What points or trends stood out to you most in reviewing the published research related to your topic and why?

- How did the research you reviewed help you shape, refine, revise, strengthen, justify your thesis, proposal, hypothesis?

Taking Notes: The Organizational Synthesis Chart

- Literature Review Note-Taker:The Synthesis Matrix

Remember that the literature review is about identifying patterns of connection in the published research on an issue or question. The following note-taking tool can help you visualize those patterns better. At the same time, this tool will help you translate the research into the terms of your own research project and facilitate your in-text citation when you begin to write. See below and download above.

For more information on how synthesis works in writing a literature review, watch this excellent short video: Synthesis for Literature Reviews by USU Libraries.

- << Previous: Where to Begin

- Next: Resources >>

- Last Updated: Mar 4, 2021 10:44 AM

- URL: https://libguides.mcny.edu/literaturereview

- Process: Literature Reviews

- Literature Review

- Managing Sources

Ask a Librarian

Does your assignment or publication require that you write a literature review? This guide is intended to help you understand what a literature is, why it is worth doing, and some quick tips composing one.

Understanding Literature Reviews

What is a literature review .

Typically, a literature review is a written discussion that examines publications about a particular subject area or topic. Depending on disciplines, publications, or authors a literature review may be:

A summary of sources An organized presentation of sources A synthesis or interpretation of sources An evaluative analysis of sources

A Literature Review may be part of a process or a product. It may be:

A part of your research process A part of your final research publication An independent publication

Why do a literature review?

The Literature Review will place your research in context. It will help you and your readers:

Locate patterns, relationships, connections, agreements, disagreements, & gaps in understanding Identify methodological and theoretical foundations Identify landmark and exemplary works Situate your voice in a broader conversation with other writers, thinkers, and scholars

The Literature Review will aid your research process. It will help you to:

Establish your knowledge Understand what has been said Define your questions Establish a relevant methodology Refine your voice Situate your voice in the conversation

What does a literature review look like?

The Literature Review structure and organization may include sections such as:

An introduction or overview A body or organizational sub-divisions A conclusion or an explanation of significance

The body of a literature review may be organized in several ways, including:

Chronologically: organized by date of publication Methodologically: organized by type of research method used Thematically: organized by concept, trend, or theme Ideologically: organized by belief, ideology, or school of thought

- Find a focus

- Find models

- Review your target publication

- Track citations

- Read critically

- Manage your citations

- Ask friends, faculty, and librarians

Additional Sources

- Reviewing the literature. Project Planner.

- Literature Review: By UNC Writing Center

- PhD on Track

- CU Graduate Students Thesis & Dissertation Guidance

- CU Honors Thesis Guidance

- Next: Managing Sources >>

- University of Colorado Boulder Libraries

- Research Guides

- Research Strategies

- Last Updated: May 31, 2024 4:45 PM

- URL: https://libguides.colorado.edu/strategies/litreview

- © Regents of the University of Colorado

How do I Write a Literature Review?: #5 Writing the Review

- Step #1: Choosing a Topic

- Step #2: Finding Information

- Step #3: Evaluating Content

- Step #4: Synthesizing Content

- #5 Writing the Review

- Citing Your Sources

WRITING THE REVIEW

You've done the research and now you're ready to put your findings down on paper. When preparing to write your review, first consider how will you organize your review.

The actual review generally has 5 components:

Abstract - An abstract is a summary of your literature review. It is made up of the following parts:

- A contextual sentence about your motivation behind your research topic

- Your thesis statement

- A descriptive statement about the types of literature used in the review

- Summarize your findings

- Conclusion(s) based upon your findings

Introduction : Like a typical research paper introduction, provide the reader with a quick idea of the topic of the literature review:

- Define or identify the general topic, issue, or area of concern. This provides the reader with context for reviewing the literature.

- Identify related trends in what has already been published about the topic; or conflicts in theory, methodology, evidence, and conclusions; or gaps in research and scholarship; or a single problem or new perspective of immediate interest.

- Establish your reason (point of view) for reviewing the literature; explain the criteria to be used in analyzing and comparing literature and the organization of the review (sequence); and, when necessary, state why certain literature is or is not included (scope) -

Body : The body of a literature review contains your discussion of sources and can be organized in 3 ways-

- Chronological - by publication or by trend

- Thematic - organized around a topic or issue, rather than the progression of time

- Methodical - the focusing factor usually does not have to do with the content of the material. Instead, it focuses on the "methods" of the literature's researcher or writer that you are reviewing

You may also want to include a section on "questions for further research" and discuss what questions the review has sparked about the topic/field or offer suggestions for future studies/examinations that build on your current findings.

Conclusion : In the conclusion, you should:

Conclude your paper by providing your reader with some perspective on the relationship between your literature review's specific topic and how it's related to it's parent discipline, scientific endeavor, or profession.

Bibliography : Since a literature review is composed of pieces of research, it is very important that your correctly cite the literature you are reviewing, both in the reviews body as well as in a bibliography/works cited. To learn more about different citation styles, visit the " Citing Your Sources " tab.

- Writing a Literature Review: Wesleyan University

- Literature Review: Edith Cowan University

- << Previous: Step #4: Synthesizing Content

- Next: Citing Your Sources >>

- Last Updated: Aug 22, 2023 1:35 PM

- URL: https://libguides.eastern.edu/literature_reviews

About the Library

- Collection Development

- Circulation Policies

- Mission Statement

- Staff Directory

Using the Library

- A to Z Journal List

- Library Catalog

- Research Guides

Interlibrary Services

- Research Help

Warner Memorial Library

Library & Information Services

Literature reviews: parts & organization of a literature review.

- Back to Lovejoy Library

- Literature Reviews

Parts & Organization of a Literature Review

- Why are Literature Reviews Important

Literature reviews typically follow the introduction-body-conclusion format. If your literature review is part of a larger project or paper, the introduction and conclusion of the lit review may be just a few sentences, while you focus most of your attention on the body. If it is a standalone piece, then the introduction and conclusion may take up more space.

A literature review typically follows this model:

Introduction:

- An introductory paragraph that explains what your working topic and thesis is.

- Noting key topics or texts that will appear in the review.

- A potential description of how you found your sources, and how you chose them for inclusion and discussion for your review.

- Summarize and synthesize : Give an overview of the main points of each source and combine them into a coherent whole.

- Analyze and interpret : Don’t just paraphrase other researchers and their voices – add your own interpretations where possible, discussing the significance of findings in relation to the literature as a whole.

- Critically Evaluate : Mention strengths and weaknesses of your sources.

- Write in well-structured paragraphs : Use this body paragraph space to draw and show connections, comparisons, and contrasts between your selected sources.

Conclusion:

- Summarize the key findings you have taken from the literature and emphasize their significance.

- Connect it back to your primary research question. Remind readers what your thesis is.

Purdue University – Purdue Online Writing Lab. (n.d.). What are the Parts of a Lit Review?; How Should I Organize My Lit Review?. Retrieved from: https://owl.purdue.edu/owl/research_and_citation/conducting_research/writing_a_literature_review.html

- << Previous: Why are Literature Reviews Important

- Next: Example >>

- Last Updated: Sep 9, 2021 3:29 PM

- URL: https://libguides.siue.edu/litreview

- About the LSE Impact Blog

- Comments Policy

- Popular Posts

- Recent Posts

- Subscribe to the Impact Blog

- Write for us

- LSE comment

Neal Haddaway

October 19th, 2020, 8 common problems with literature reviews and how to fix them.

3 comments | 315 shares

Estimated reading time: 5 minutes

Literature reviews are an integral part of the process and communication of scientific research. Whilst systematic reviews have become regarded as the highest standard of evidence synthesis, many literature reviews fall short of these standards and may end up presenting biased or incorrect conclusions. In this post, Neal Haddaway highlights 8 common problems with literature review methods, provides examples for each and provides practical solutions for ways to mitigate them.

Enjoying this blogpost? 📨 Sign up to our mailing list and receive all the latest LSE Impact Blog news direct to your inbox.

Researchers regularly review the literature – it’s an integral part of day-to-day research: finding relevant research, reading and digesting the main findings, summarising across papers, and making conclusions about the evidence base as a whole. However, there is a fundamental difference between brief, narrative approaches to summarising a selection of studies and attempting to reliably and comprehensively summarise an evidence base to support decision-making in policy and practice.

So-called ‘evidence-informed decision-making’ (EIDM) relies on rigorous systematic approaches to synthesising the evidence. Systematic review has become the highest standard of evidence synthesis and is well established in the pipeline from research to practice in the field of health . Systematic reviews must include a suite of specifically designed methods for the conduct and reporting of all synthesis activities (planning, searching, screening, appraising, extracting data, qualitative/quantitative/mixed methods synthesis, writing; e.g. see the Cochrane Handbook ). The method has been widely adapted into other fields, including environment (the Collaboration for Environmental Evidence ) and social policy (the Campbell Collaboration ).

Despite the growing interest in systematic reviews, traditional approaches to reviewing the literature continue to persist in contemporary publications across disciplines. These reviews, some of which are incorrectly referred to as ‘systematic’ reviews, may be susceptible to bias and as a result, may end up providing incorrect conclusions. This is of particular concern when reviews address key policy- and practice- relevant questions, such as the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic or climate change.

These limitations with traditional literature review approaches could be improved relatively easily with a few key procedures; some of them not prohibitively costly in terms of skill, time or resources.

In our recent paper in Nature Ecology and Evolution , we highlight 8 common problems with traditional literature review methods, provide examples for each from the field of environmental management and ecology, and provide practical solutions for ways to mitigate them.

There is a lack of awareness and appreciation of the methods needed to ensure systematic reviews are as free from bias and as reliable as possible: demonstrated by recent, flawed, high-profile reviews. We call on review authors to conduct more rigorous reviews, on editors and peer-reviewers to gate-keep more strictly, and the community of methodologists to better support the broader research community. Only by working together can we build and maintain a strong system of rigorous, evidence-informed decision-making in conservation and environmental management.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of the LSE Impact Blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please review our comments policy if you have any concerns on posting a comment below