Advertisement

Measuring the effect of social media on student academic performance using a social media influence factor model

- Published: 18 July 2022

- Volume 28 , pages 1165–1188, ( 2023 )

Cite this article

- Mohammed Nurudeen ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-6711-6735 1 ,

- Siddique Abdul-Samad 2 ,

- Emmanuel Owusu-Oware 1 ,

- Godfred Yaw Koi-Akrofi 1 &

- Hannah Ayaba Tanye 1

3772 Accesses

6 Citations

Explore all metrics

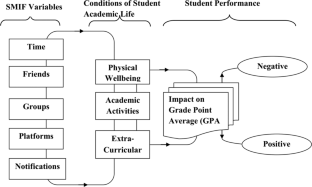

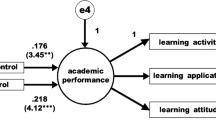

With the advent of smartphones and fourth generation mobile technologies, the effect of social media on society has stirred up some debate and researchers across various disciplines have drawn different conclusions. Social media provides university students with a convenient platform to create and share educational content. However, social media may have an addicting effect that may lead to poor health, poor concentration in class, poor time management and consequently poor academic performance. Using a random sample of 623 students from the University of Professional Studies Accra, Ghana, this paper presents a social media influence factor (SMIF) model for measuring the effect of social media on student academic performance. The proposed model is examined using linear regression analysis and the results show a statistically significant negative relationship between SMIF variables and student grade point average (GPA). The model accounted for 30.7% of the variability in student GPA and it demonstrated a prediction quality of 55.4% given the data collected.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

The impact of smartphone use on learning effectiveness: A case study of primary school students

The use of cronbach’s alpha when developing and reporting research instruments in science education.

Theories of Motivation in Education: an Integrative Framework

Data availability.

The datasets generated during and analyzed during the study are available in figshare repository https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.14905089.v1

http://www.raosoft.com/samplesize.html

Abbas, J., Jaffar, A., Mohammad, N., & Shaher, B. (2019). The impact of social media on learning behavior for sustainable education: Evidence of students from selected Universities in Pakistan. Sustainability, 11 (6), 1683. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11061683

Article Google Scholar

Addei, C., & Kokroko, E. (2020). The Effect of Social Media Use on the Written English of University Students: The case of University of Mines and Technology (UMaT). 6th UMaTBIC, Ghana.Retrieved from http://conference.umat.edu.gh/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/The-Effect-of-Social-Media-Use-on-the-Written-English-of-University-Students.pdf

Al-Menayes, J. (2015). Social Media use, engagement and addiction as predictors of academic performance. International Journal of Psychological Studies., 7 , 86. https://doi.org/10.5539/ijps.v7n4p86

Alwagait, E., Shahzad, B., & Alim, S. (2015). Impact of social media usage on students academic performance in Saudi Arabia. Computers in Human Behavior, 51 , 1092–1097.

Ansari, J. A. N., & Khan, N. A. (2020). Exploring the role of social media in collaborative learning the new domain of learning. Smart Learning Environments, 7 , 9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40561-020-00118-7

Asare-Donkoh, F. (2018). Impact of social media on Ghanaian High School students. Library Philosophy and Practice (ejournal) , 1914. Retrieved from http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac/1914

Azizi, S. M., Soroush, A., & Khatony, A. (2019). The relationship between social networking addiction and academic performance in Iranian students of medical sciences: A cross-sectional study. BMC Psychol, 7 , 28. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-019-0305-0

Barry, C. T., & Wong, M. Y. (2020). Fear of missing out (FoMO): A generational phenomenon or an individual difference? Journal of Social and Personal Relationships., 37 (12), 2952–2966. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407520945394

Berryman, C., Ferguson, C. J., & Negy, C. (2018). Social media use and mental health among young adults. Psychiatric Quarterly, 89 , 307–314. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11126-017-9535-6

Boté-Vericad, J. (2021). Challenges for the educational system during lockdowns: A possible new framework for teaching and learning for the near future. Education for Information, 37 (1), 149–153. https://doi.org/10.3233/EFI-200008

Brown, L., & Kuss, D. J. (2020). Fear of missing out, mental wellbeing, and social connectedness: A seven-day social media abstinence trial. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17 (12), 4566. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17124566

Franchina, V., Vanden Abeele, M., van Rooij, A. J., Lo Coco, G., & De Marez, L. (2018). Fear of missing out as a predictor of problematic social media use and phubbing behavior among flemish adolescents. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15 (10), 2319. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15102319

Gall, C., Gall, I., & Jalali, A. (2020). Social media usage among university students during exams: Distraction or academic support. Education in Medicine Journal, 12 , 49–53. https://doi.org/10.21315/eimj2020.12.3.6

Global Web Index. (2021). Social media marketing trends in 2021. GWI . Retrieved from https://www.globalwebindex.com/reports/social

Hamat, A., Embi, M., & Hassan, H. (2012). The Use of Social Networking Sites among Malaysian University Students. International Education Studies. 5. https://doi.org/10.5539/ies.v5n3p56

Hayran, C., Anik L., & Gürhan-Canli, Z. (2020). A threat to loyalty: Fear of missing out (FOMO) leads to reluctance to repeat current experiences. PLoS One, 15 (4). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0232318

Karim, F., Oyewande, A. A., Abdalla, L. F., Chaudhry Ehsanullah, R., & Khan, S. (2020). Social media use and its connection to mental health: A systematic review. Cureus, 12 (6), e8627. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.8627

Kim, B., & Kim, Y. (2017). College students’ social media use and communication network heterogeneity: Implications for social capital and subjective well-being. Computers in Human Behavior, 73 , 620–628. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2017.03.033

Kiran, R. D. (2016). Total Quality Management: Key Concepts and Case Studies (1st ed.). Butterworth-Heinemann.

Koeske, Gary F.., & Koeske, Randi Daimon. (1993). A Preliminary Test of a Stress-Strain-Outcome Model for Reconceptualizing the Burnout Phenomenon. Journal of Social Service Research, 17 (3–4), 107–135. https://doi.org/10.1300/J079v17n03_06

Kolan, B. J., & Dzandza, P. E. (2018). Effect of social media on academic performance of students in Ghanaian Universities: A case study of university of Ghana, Legon. Library Philosophy and Practice (e-journal) , 1637. Retrieved from https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac/1637

Lau, W. (2017). Effects of social media usage and social media multitasking on the academic performance of university students. Computers in Human Behavior., 68 , 286–291. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.11.043

Lee, Y., & Song, J. (2021). Robustness of model averaging methods for the violation of standard linear regression assumptions. Communications for Statistical Applications and Methods, 28 (2), 189–204. https://doi.org/10.29220/CSAM.2021.28.2.189

Mancini, M. (2003). Time Management . Canberra: McGraw-Hill Professional.

Google Scholar

Manjur, K., Raisa, N. A. K., & Abdalla, A. (2021). Effect of social media use on learning, social interactions, and sleep duration among university students. Saudi Journal of Biological Sciences . Elsevier B.V.

Martínez-Cardama, S., & Caridad-Sebastián, M. (2019). Social media and new visual literacies: Proposal based on an innovative teaching project. Education for Information, 35 (3), 337–352. https://doi.org/10.3233/EFI-180214

Mingle, J., & Adams, M. (2015). Social media network participation and academic performance in senior high schools in Ghana. Library Philosophy and Practice (e-journal) . Paper 1286. Retrieved from http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac/1286

Moreno-Guerrero, A., Rodríguez, C., Navas-Parejo, M., Costa, R., & López-Belmonte, J. (2020). (2020). WhatsApp and google drive influence on pre-service students’ learning. Frontiers in Education , 5 . https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2020.00152

Owusu-Acheaw, M., & Larson, A.G. (2015). Reading habits among students and its effect on academic performance: A study of students of koforidua polytechnic. Journal of Education and Practice , 6 (6). Retrieved from https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1083595.pdf

Priya, V. K., Thirumagal, P., & Madhumita, G. (2020). Social media effect on students academic performance based on their usage. International Journal of Scientific & Technology Research., 8 , 2715.

Ra, C., Cho, J., Stone, M., Cerda, J., Goldenson, N., Moroney, E., Tung, I., Lee, S., & Leventhal, A. (2018). Association of digital media use with subsequent symptoms of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder among adolescents. JAMA Journal of the American Medical Association, 320 , 255–263. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2018.8931

Sankar, V., & Pushpa, B. (2020). Impact of social media on academic performance of university students-a field survey of academic development. TechnoLearn an International Journal of Educational Technology , 10 (1&2). https://doi.org/10.30954/2231-4105.02.2020.1

Sela, Y., Zach, M., Amichay-Hamburger, Y., Mishali, M., & Omer, Haim. (2019). Family environment and problematic internet use among adolescents: The mediating roles of depression and fear of missing out. Computers in Human Behavior , 106 . https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2019.106226

Shakya, H. B., & Christakis, N. A. (2017). Association of Facebook use with compromised well-being: A longitudinal study. American Journal of Epidemiology , 185 (3). https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kww189

Shi, C., Yu, L., Wang, N., Cheng, B., & Cao, X. (2020). Effects of social media overload on academic performance: A stressor-strain-outcome perspective. Asian Journal of Communication, 30 (2), 179–197.

Simon, K. (2021a). Digital 2021a: Global Overview Report. Datareportal . Retrieved from https://www.slideshare.net/DataReportal/digital-2021-global-overview-report-january-2021-v03?ref=https://datareportal.com/ .

Simon, K. (2021b). Digital 2021b report for Ghana. Datareportal. Retrieved from https://www.slideshare.net/DataReportal/digital-2021-ghana-january-2021-v01?qid=bb2421dd-a89a-41c5-a8b9-18c3571cf67f&v=&b=&from_search=1

Songxaba, S. L., & Sincuba, L. (2019). The effect of social media on English second language essay writing with special reference to WhatsApp. Reading & Writing - Journal of the Reading Association of South Africa, 10 (1), a179. https://doi.org/10.4102/rw.v10i1.1799

Twenge, J. M., & Campbell, W. K. (2019). Media use is linked to lower psychological well-being: Evidence from three datasets. Psychiatric Quarterly, 90 , 311–331. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11126-019-09630-7

Vannucci, A., Flannery, K. M., & Ohannessian, C. M. C. (2017). Social media use and anxiety in emerging adults. Journal of Affective Disorders, 207 , 163–166. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2016.08.040

Washington, S., Karlaftis, M., Mannering, F., & Anastasopoulos, P. (2020). Violations of Regression Assumptions. https://doi.org/10.1201/9780429244018-6

Wright, J. (2002). Time management: The pickle jar theory. A List Apart, 146, 1–5. Retrieved from file file:///C:/Users/JEFF/Downloads/Time-Management-The-Pickle-Jar-Theory.pdf.

Download references

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank the respondents who took the time to respond to this survey and the University of Professional Studies Accra, Ghana

This research was conducted using the researchers’ annual research allowance which is funding given by the Government of Ghana to all academic staffs in Ghanaian public universities. The research was therefore conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest. Also, no funding body played any role in the design of the study, collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

IT-Department, FITCS, University of Professional Studies, Accra (UPSA), Legon, P. O. Box LG 149, Accra, Ghana

Mohammed Nurudeen, Emmanuel Owusu-Oware, Godfred Yaw Koi-Akrofi & Hannah Ayaba Tanye

University of Professional Studies, Accra (UPSA), Accra, Ghana

Siddique Abdul-Samad

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

All authors contributed equally to this work and all authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Mohammed Nurudeen .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

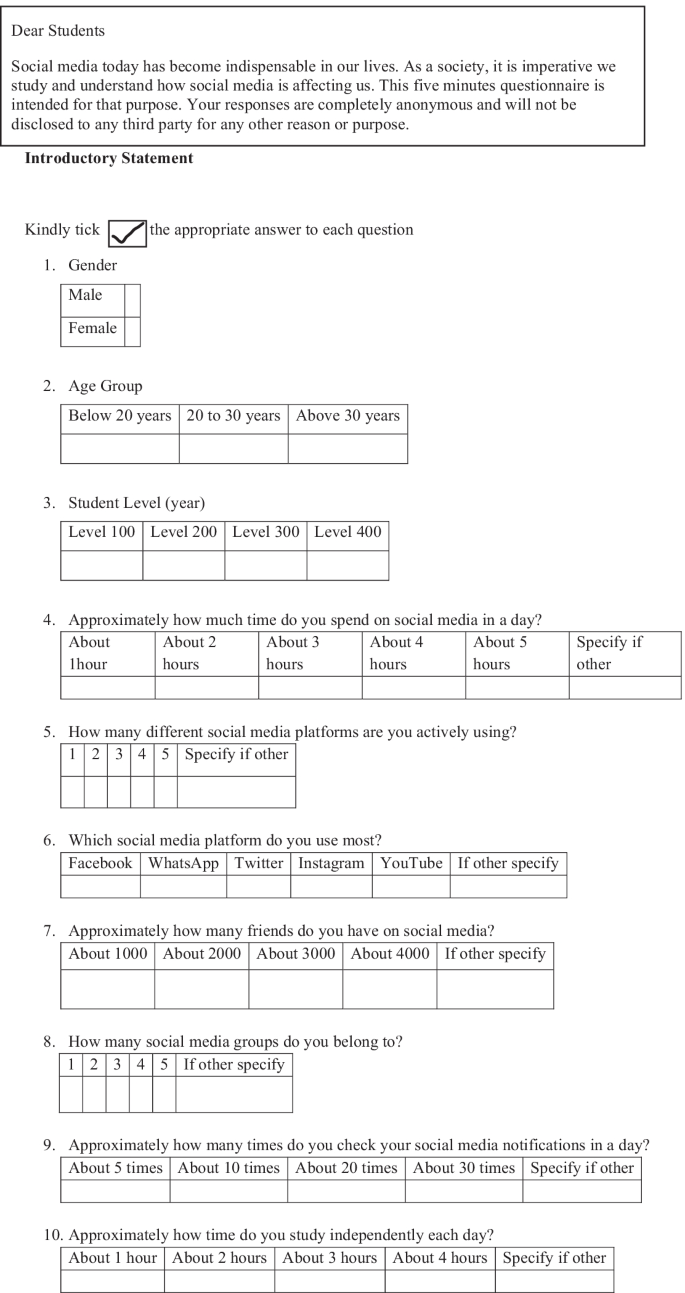

Questionnaire

1.1 appendix.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Nurudeen, M., Abdul-Samad, S., Owusu-Oware, E. et al. Measuring the effect of social media on student academic performance using a social media influence factor model. Educ Inf Technol 28 , 1165–1188 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-022-11196-0

Download citation

Received : 17 January 2022

Accepted : 28 June 2022

Published : 18 July 2022

Issue Date : January 2023

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-022-11196-0

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Social media use

- Social media effects

- Social media influence factors

- Higher education

- Student academic performance

- Regression analysis and UPSA

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 22 October 2022

Comparative sensitivity of social media data and their acceptable use in research

- Libby Hemphill ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-3793-7281 1 , 2 ,

- Angela Schöpke-Gonzalez ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-7912-1371 1 &

- Anmol Panda 1

Scientific Data volume 9 , Article number: 643 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

5107 Accesses

4 Citations

28 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Research data

Social media data offer a rich resource for researchers interested in public health, labor economics, politics, social behaviors, and other topics. However, scale and anonymity mean that researchers often cannot directly get permission from users to collect and analyze their social media data. This article applies the basic ethical principle of respect for persons to consider individuals’ perceptions of acceptable uses of data. We compare individuals’ perceptions of acceptable uses of other types of sensitive data, such as health records and individual identifiers, with their perceptions of acceptable uses of social media data. Our survey of 1018 people shows that individuals think of their social media data as moderately sensitive and agree that it should be protected. Respondents are generally okay with researchers using their data in social research but prefer that researchers clearly articulate benefits and seek explicit consent before conducting research. We argue that researchers must ensure that their research provides social benefits worthy of individual risks and that they must address those risks throughout the research process.

Similar content being viewed by others

Variation in social media sensitivity across people and contexts

A value-driven approach to addressing misinformation in social media

Public attitudes towards algorithmic personalization and use of personal data online: evidence from Germany, Great Britain, and the United States

Introduction.

Researchers have used social media data in myriad ways and through different means. For instance, Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, Reddit, and Wikipedia are the top five platforms used by social media researchers for gathering data 1 . Prior work also enumerates different ways researchers procure social media data, including web scraping using Python or R, services such as NVivo, Discovertext, NodeXL, TAGS, IFTTT, Social Feed Manager, Zapier, Hydrator, WebRecorder.io, platform APIs, and even screenshots 1 , 2 .

Tools for providing access to social media data are evolving. For instance, in early 2022, Twitter released its no-code API, making it possible for researchers to access Twitter data without needing to have programming expertise. Twitter data is now more accessible for a wider range of researchers to study topics like social capital 3 , political agendas 4 , labor economics 5 , and public health 6 . Likewise, the launch of the Twitter Academic API has significantly expanded the scope of Twitter data that researchers can utilize, while also affording access to the full archive of tweets previously available only through the Enterprise version.

Increased data availability makes ethical questions about social media data use for research all the more pressing. For example, should researchers be collecting social media data? If so, when and how ought researchers use it? Legally, social media users grant broad permissions for their data to be used when they agree to platforms’ terms of service (TOS). However, users often do not actually read or understand TOS 7 , may not think of their data as public 8 , and may not realize that researchers are among that public 9 , 10 . Prior work finds that users actually prefer to grant explicit consent to use their data in research despite agreeing to TOS 8 , and their attitudes toward acceptable data uses depend heavily on the research context and goals 11 . How can social media researchers reconcile legal ability to use social media data and its ready availability with individuals’ preferences about their social media data being used for research?

A basic principle in research called respect for persons can bring clarity to how researchers can think about ethical social media data use practices. Respect for persons 12 requires that researchers orient their practices around individuals’ perceptions of acceptable uses of data. Respect for persons is often addressed through informed consent processes that obtain explicit permission from individuals to use their data. Explicit consent serves to inform individuals of the opportunity to have data about them collected for research, and to express their preferences about their data being collected by accepting or declining participation.

Though researchers recognize that informed consent is a consideration, along with balancing risks and benefits and protecting individuals 13 , explicit consent processes with social media users are often infeasible. The scale and anonymity of social media mean that researchers often cannot directly elicit individuals’ perceptions about the acceptable uses of data they generate on social media. One exception is the Documenting the Now Project, which created “Social Humans” labels to attach explicit use permissions to content and analyses from social media 14 . Social Humans labels aim to bridge the gap between the legal permissions users grant when agreeing to platforms’ TOS and content creators’ wishes. However, this method has yet to be widely adopted, meaning even explicit use permissions like Social Humans labels cannot effectively guide researchers about how to ensure that they are respecting individuals’ preferences about use of their data.

To understand how we can realize respect for persons in the particular context of social media data research, we look to scholarship on users’ perceptions about acceptable uses of other types of sensitive yet widely available data. Prior work finds that social media data users think of their social media data similarly to how they think about widely-recognized sensitive data types 15 , 16 like voter files 17 , cell phone records 18 , and large-scale surveys 19 . Comparing individuals’ acceptable use perceptions for their social media data with these other types of sensitive data opens opportunities for us to learn from existing respect-for-persons best practices aside from explicit consent developed to support sensitive data. Our survey study thus addresses the following research questions:

RQ1: How do participants perceptions of acceptable social media data use compare to other types of sensitive data about them?

RQ2: How do participants’ perceptions of acceptable social media data use relate to the data analyst , their purpose for using the data, and perceptions of sensitivity ?

Answering RQ1 allows us to assess social media data’s relative sensitivity, and to understand whether other sensitive data types are an appropriate context from which to seek wisdom about how researchers can approach social media data use. Answering RQ2 allows us to clarify sensitivity and other variables’ relationships to acceptable use. Together, the answers to these questions provide insights for social media researchers about which best practices to follow when working with social media data to ensure respect-for-persons.

Factors Affecting Perceptions of Acceptable Use

Prior work argues that individuals’ willingness to share their personal data is a function of: data sensitivity, who will use the data (data analyst), what users hope to gain and who who else will benefit from using the data (data use purpose), which data will be used (data type), and personal characteristics of the person sharing the data (data sharer characteristics). The following subsections review each of these factors.

Data sensitivity: risk perception

Data sensitivity describes how risky a person perceives sharing their data to be. Prior work on consumer willingness to share data with marketers 15 , 16 identifies four types of risk that may be particularly important for people’s characterization of data as sensitive: monetary, psychological, physical, and social risk. A person’s perceptions of how sensitive a type of data is–or how much risk they perceive they will incur by sharing that type of data–may inform how willing that person may be to share their data. However, while this correlation is implied by marketing literature, the existence and quality of this relationship have yet to be empirically evaluated. Further, whether a person characterizes data about themselves as sensitive is not a fixed characteristic, but rather can change according to the contexts in which data might be used and the data sharer’s personal characteristics 15 , 16 .

Data analyst: known identities

Knowing who will use their data shapes data sharers’ perceptions of acceptable use. People tend to find use of their social media data by known data analysts more acceptable than unknown data analysts. While social media users try to limit who sees and uses their data to only intended audiences, their data are still often seen by unintended or unknown audiences 10 . When people learn that these unintended audiences - among them researchers - use their data, they tend to find this use less acceptable than if their data is used by intended audiences 20 .

Beyond known versus unknown data analysts, other data analyst identities can further affect sharers’ perceptions of acceptable use. For example, Gilbert and colleagues 11 asked respondents to rate the appropriateness of their personal Facebook data’s use for research according to the discipline using it. They found that respondents were more concerned about studies in Computer Science, Gender Studies, and Psychology using their data than studies in Health Sciences. A related study about UK public health research shows that participants were much more willing to share their personal data for research by the UK’s National Health Service than with a commercial company 21 . Aside from explicitly intended audiences, people are most comfortable with their data being used by health researchers relative to other analysts. Overall, whether a data analyst is known or unknown and which discipline or professional domain they are affiliated with can affect individuals’ perceptions of acceptable use.

Data use purpose: benefit and process

Literature suggests that individuals’ perceptions of acceptable use also vary across data use purposes like health research or marketing. For example, a study about UK public health research found that when participants were told that mandating consent could lead to selection bias and adversely impact public health research, participants were more willing to share their data without explicit consent 21 . For both health data 21 , 22 , 23 and social media data 11 , 24 , how much participants believe that sharing their data will contribute to a purpose that will benefit society affects how acceptable they find the use of their data.

In addition to public benefits, people are more likely to find data use acceptable when it offers personal benefits like discounts or personalized service. Researchers studying public conversations about privacy controversies found that many discussants understand themselves and their data as a “product” that for-profit companies use for the purpose of making money, and in return they receive some digital service–a personal benefit 25 . Discussants found this type of data use purpose acceptable. In another example, a study of journalists’ use of social media data suggests that the more social media users want to feel heard, the more likely they are to find journalists’ use of their data acceptable. The personal benefits of receiving digital services and “feeling heard” mediated individuals’ perceptions of different data use purposes’ acceptability 26 .

Beyond general use purpose (e.g., for public health research, for marketing, for public awareness, etc.), people’s understanding of exactly how their social media data will be used also affects their perceptions of its acceptable use. When participants know which analysis methods and data security measures researchers will use, they feel better about their data being used for research 22 . Fiesler and Proferes 25 found that people who indicated understanding how their social media data would be used, including for research, were less concerned about its use relative to those who were unaware of how their data was later used. In general, when individuals are asked explicitly for their permission and understand what research will be conducted (i.e., data use purpose), they usually agree that their social media data can be used in research 8 , 11 .

Data type: keys to personal identity and social networks

In addition to who will use their data and for what purposes, sharers care about which specific data will be used. Two studies examined U.S. consumers’ willingness to share different types of information with marketers 15 , 16 . Using a nationally representative survey, they found that respondents were just as unwilling to share their credit card number, financial account details, and driver’s license information–unique identifiers or keys that are directly tied to a specific individual–as they were to share their social network profile, profile picture, and information about their friends or family. Respondents also considered their social media profile more sensitive–or risky to share–than basic demographics such as height, place of birth, and their occupation–data that when linked to other data can increase the risk that a specific individual can be identified. When they asked respondents to rate the appropriateness of uses of their personal data for research by type of data, researchers found that respondents were most concerned about researchers using their photos and videos, data about sexual habits, data about preferences and behaviours, and posts about their friends or family members 11 . These studies show that people weigh the riskiness and acceptability of sharing various types of social media data differently.

Individual data sharer characteristics

Research reports that perceptions of acceptable data use also vary based on a data sharer’s personal characteristics. For example, studies find that how much people trust institutions–a type of data analyst–affects whether individuals are okay with those institutions using their social media data 8 , 11 , 27 . For both health data 21 , 22 , 23 and social media data 11 , 24 , how much people trust researchers in general also affects how acceptable they find their data’s use. Studies find mixed results concerning the effects on demographic characteristics on perceptions of acceptable use. For example, Fiesler and Proferes 8 found that demographic characteristics have no statistically significant effect on survey respondents’ attitudes toward their Twitter data being used in various types of research. In contrast, Gilbert, Vitak, and Shilton 11 showed that gender, age, education level, and frequency of social media use have significant effects on individuals’ attitudes toward their Facebook data being used in various type of research. A comparative study of sensitivity perceptions in Brazil and the United States found that perceptions do vary based on an individual’s country of residence (i.e., Brazil or the US) and age affect their willingness to share personal data 16 . Others also reported significant effects for sex and education level on willingness to share data in their US-based survey 15 . Finally, literature shows that pre-existing attitudes toward privacy 8 may affect perceptions of acceptable use. These data sharer characteristics can mediate the effects of the data analyst, data use purpose, and data type on individuals’ perceptions of acceptable use.

Summary of factors affecting perceptions of acceptable use

Overall, social media users’ perceptions of of whether using their data is acceptable may be mediated by how sensitive they perceive their data to be, the data analyst, data use purpose, data type, and their personal characteristics. This web of factors shapes the challenges that researchers face in balancing respect for persons with research needs. Our study draws from existing scholarship’s insights on sensitive data and acceptable use to learn specifically about how people feel about their social media data’s use relative to other data types that people have indicated is sensitive to them like health records 21 and location 28 .

To understand participants’ perceptions about acceptable social media data use, we surveyed 1018 people through Qualtrics panels and Mechanical Turk 29 . Table 6 offers summary descriptive statistics about our sample. We used statistical analyses to identify patterns in survey responses, specifically regarding (a) the sensitivity of individuals’ online identifiers relative to other personal identifiers, and (b) whether or not participants perceive a particular data analyst using a specific type of data for a purpose is acceptable or not. Section 5 provides additional details about our survey design, variables, and analysis techniques. We address each research question in its own section below. In each case, we have provided the regression models of best fit.

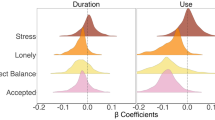

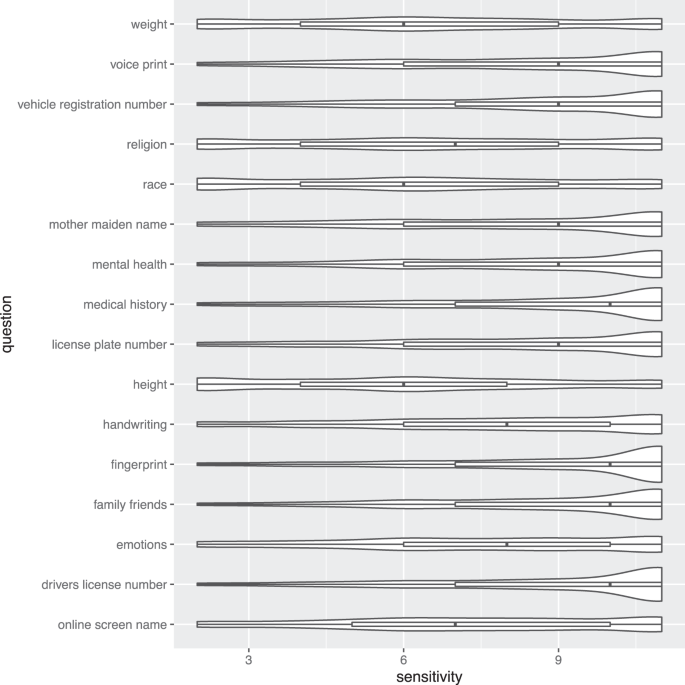

We calculated cumulative link mixed model (CLMM) using the ordinal package in R 30 to compare the relative sensitivity of a key to one’s social media data - one’s screen name - with other types of similar keys to potentially sensitive data about individuals (e.g., driver’s license number or social security number). We also compare the sensitivity of one’s screen name with data that in aggregate could be linked to a specific individual’s identity (e.g., race, weight). Our results, presented in Table 1 and Fig. 1 , show that a screen name is more sensitive than demographic details such as race (OR = 0.36, p < 0.001), religion (OR = 0.50 p < 0.001), and weight (OR = 0.47 p < 0.001), but less sensitive than identifiers such as a driver’s license number (OR = 4.67, p < 0.001) or data from one’s medical history (OR = 4.46, p < 0.001). Figure 2 also shows that individuals exhibited more variation in the sensitivity of their online screen name than other types of data such as fingerprints or medical history that may also provide access to data about their behaviors.

Violin plots showing the distribution, median, and quartiles for sensitivity of various types of data where 10 = ‘very sensitive’.

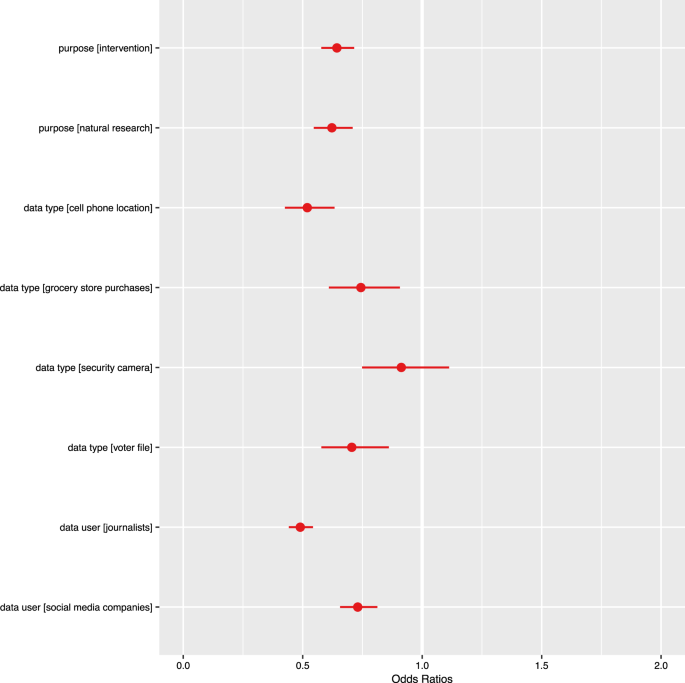

Odds ratio plot where DV = “is ok” on each data analyst, data type, purpose combination.

Table 1 also indicates that respondents who were men and those with higher trust in institutions were less likely to find their online screen name sensitive. Respondents from Qualtrics who had higher digital privacy concerns, more privacy behaviors, were neither Black nor White, were straight, older, more educated, and/or had a higher income were more likely to find their online screen name sensitive.

RQ2: How do participants’ perceptions of acceptable use relate to data type, data analyst, data use purpose, and sensitivity?

We calculated a mixed effects logistic regression (MELR) using the glmer function from lme4 31 to understand whether respondents indicated that a particular combination of data analyst, data type, and purpose was acceptable. In this model, the dependent variable was whether respondents answered “yes” to a specific question, and the questions were the only fixed effect. We included random effects for respondent and source (Qualtrics or Mechanical Turk). The coefficient for source’s random effects was nearly zero, indicating that between-subject differences based on source could be almost entirely explained by the other variables we assessed in our model. We also included demographic controls and scales for our questions about trust, digital privacy concerns, and privacy behaviors. According to ANOVA analyses, the model of best fit did not include sensitivity as a predictor.

The results (see Table 2 indicate respondents found only one combination clearly unacceptable (i.e., significantly lower odds ratio):

Is it ok for journalists to use posts you’ve deleted from social media in a story about natural disasters?

Overall, respondents said that it was more acceptable to use their social media data than other types of data (see Table 3 ).

However, respondents generally found academic researchers using social media data about them acceptable except for two scenarios (no significant difference between acceptable and not acceptable):

images you’ve uploaded to social media to train facial recognition software?

metadata from your photos in social media to create a public map of peony gardens in your area?

Respondents with higher scores on the digital privacy concern scale were less likely to agree that it their data’s use is acceptable (OR = 0.892). Those who had higher institutional trust scores (OR = 1.041) and privacy behavior scores (OR = 1.112) were more likely to indicate that using their data was acceptable.

Among our demographic controls, only straight (OR = 0.265) and older respondents (OR = 0.618) were less likely to answer that it was acceptable for their data to be used. Men were significantly more likely than women and other gender identities (OR = 1.980) to say it was acceptable for their data to be used. Individuals of races other than White and Black (OR = 2.116) were also more likely to find their data’s use acceptable. We observed no significant effects for income level.

We also fit a model where we collapsed our data type and purpose variables into categories. According to ANOVA analyses, we found that the best model included data type, use purpose, data analyst, behavioral scales, and demographics but not sensitivity as predictors of respondents finding their social media data’s use by researchers acceptable for social/behavioral research. In this model, presented in Table 3 and Fig. 2 , we use academic researchers , social media data , and social research as the reference categories for data analyst, data type, and purpose respectively. We included a random effect for respondent and another for source (Qualtrics or Mechanical Turk). The variance between sources was nearly zero, indicating that between-source differences could be almost entirely explained by the other variables we assessed in our model. Table 3 shows that respondents were more accepting of their data being used for social research than to generate interventions or research about the natural world.

We saw similar patterns among the control variables (trust, digital privacy, privacy behavior, and demographics) in both of our models. Individuals with concerns about digital privacy (e.g., they hesitate to provide information when its requested) were less likely to be accepting of their data being used. Individuals who generally trust institutions and governments accepted their data being used by these entities. Individuals who engaged in more privacy-protecting behaviors (e.g., removing cookies from their web browser, watching for ways to control what emails they receive) were more likely to agree that their data could be used. We find that information about how sensitive someone considers their online screen name does not provide statistically significant information about how acceptable they think a combination of data, user, and purpose are.

Our results suggest that individuals are generally accepting of academic researchers using social media data and that online screen names are less sensitive than many other types of data, including individual identifiers such as driver’s license numbers and medical histories, but more sensitive than height, weight, race, and religion. Individuals indicated that academic researchers using their data was acceptable in more scenarios than journalists or social media companies doing so. Prior work on internet fandom similarly indicated more trust for researchers than for private companies and journalists 32 .

One implication of our findings is that social media researchers can leverage the expertise and practices of researchers who use other types of sensitive or moderately sensitive data such as health records. However, one potential limitation of our study and Gilbert’s 11 is that our survey instruments clearly communicated the user, data, and purpose. In doing so, the instruments may have been specific enough that users found these scenarios acceptable; had we asked more generally about social media researchers using their data, they may not have been as accepting. We address findings about the comparative sensitivity of social media data and the relationships between sensitivity and acceptable data use below.

Sensitivity comparison

Prior work on social media data use in research 11 , 25 examines social media data on its own rather than in the context of private and/or sensitive personal information. Our survey instrument allowed us to compare individuals’ reports about the sensitivity of different types of data so that we can understand how social media data is similar to (or dissimilar from) other data often used in research. Looking at a specific type of social media data - one’s online screen name or the “key” to accessing one’s social media data, similar to one’s “offline” name–respondents suggest that their online screen name is more sensitive than demographic characteristics (e.g., one’s race) and less sensitive than other personally-identifiable data that can be linked to an individual and her behavior (e.g., one’s driver’s license number). Respondents also found online identifiers less sensitive than mental health and health records. There was also more variation in respondents’ perceptions of their online screen name’s sensitivity relative to other types of data like fingerprints or medical history that may also provide access to data about their behaviors. This variability may indicate uncertainty among individuals or true variation in our sample, and future work could attempt to verify this distribution and its causes.

Acceptable use comparison

To evaluate perceptions of social media data’s acceptable use relative to other widely used sensitive data types, we compared social media data with examples like cell phone data and voter files that carry varying re-identification risks. Compared to these other types of sensitive data, respondents were most comfortable with their social media data being used, and least comfortable with their cell phone location data being used. This finding resonates with prior work on location data arguing that individuals expect privacy even in public 28 , and this expectation extends to automatically collected data like location captured by cell phones and social media. Relative to social media data, respondents were also less likely to agree that it’s acceptable to use their voter file or security camera footage of them. While voter files are widely used in political science research 33 , 34 , researchers have made important efforts to protect data sharers’ privacy expectations including disclosure risk mitigation techniques like aggregation to avoid revealing personally identifiable information.

Sensitivity and acceptable use

We found that sensitivity is not a good predictor of whether individuals thought it was acceptable for researchers to use social media data. This result is somewhat unexpected given prior literature that suggested sensitivity mediates acceptable use 16 . One possible explanation is that ‘online screen name’ is not a useful example of social media data to ask about. It is possible, for example, that respondents may not understand how much data can be accessed when one’s online screen name is known (e.g., one’s tweet history or one’s Reddit comment history, which may reveal other types of sensitive data like religion, mental health status, etc.). Another explanation is that for other types of data, sensitivity may predict acceptable use, but for social media data, acceptable use is a function of the data analyst, data type, and purpose of data use 11 .

Concerning data analyst, type, and use purpose, our findings echo earlier results indicating users accept their social media data being used in research when told about who will use it and for what purpose 8 , 11 . Our respondents were generally more accepting of researchers using their data than social media companies or journalists (see Table 2 ). We expect that this pattern holds because users better are able to imagine benefits from research. Given the increasing distrust of journalists in the United States 35 , 36 , it’s not surprising that our respondents did not welcome journalists using their data. In line with prior research about sensitive data use in health research 27 and marketing 16 , our respondents were more comfortable sharing data with researchers looking to produce social benefit and understanding than with for-profit companies using their data for similar purposes.

Given these findings, rather than looking to similarly sensitive data for guidance on respect-for-persons practices with social media data, our research points us to data whose analysts have clearly communicated their use purposes’ benefits and cultivated trust among prospective sharers. In fact, for both our survey and Gilbert, et al .‘s 11 , articulating data use scenarios explicitly may drive much of the acceptance individuals expressed.

Acceptable use and personal characteristics

In our results, men were more likely to report that researchers could use their data without explicit permission, and that most uses of their data were acceptable. Related prior research on individuals’ willingness to share data with marketers found that sensitivity was a function of perceived privacy controls and cultural context such as masculinity values and long-term orientation 16 . The importance of masculinity values (e.g., “ It is more important for men to have a professional career than for women.”) in predicting sensitivity may explain why we observed differences between men and other gender identities. Women and members of gender identity minorities face greater risks when engaging in social media; 37 , 38 those risks may lead them to be more conservative in their data sharing beliefs. As Mikal and colleagues 39 point out, we must carefully consider who may opt-out of using social media publicly whenever we think of social media data.

We also found that older adults and straight respondents oppose the use of their data without explicit permission when asked about research generally. In another study, Dym and Fiesler 32 found in their survey about data from online fandom communities–majority LGBTQ spaces–and their use in research that less than ten percent of their respondents used their real names in online fandom. It is possible that LGBTQ users employ privacy-protecting strategies like pseudonyms to disconnect their online screen names from their offline identities, rendering their screen names less sensitive. It is also possible that members of marginalized demographic groups may be more willing to share their data because they seek inclusion or because they see efforts to avoid surveillance as futile. Benjamin 40 provides a thorough discussion of the differential impacts of surveillance among racial groups, for instance.

Realizing respect for persons in social media research

Our results have two implications for realizing respect for persons in social media research. First, whenever possible, researchers should elicit informed consent from social media users to use their data in research. However, if researchers use data only from those individuals who have provided explicit permission and who are generally accepting of their data being used in research, their data will likely skew male, younger, more educated, and less straight. While bias in data cannot be eliminated and is not inherently bad, demographically-biased social media data limit their utility for population-level studies. Because individuals are generally more comfortable with population-level research than with individual-level research 8 , 20 , this tension is especially important for researchers to consider. Given the burden of obtaining informed consent and the biases it introduces, when it is not possible to obtain, researchers should work to anonymize data as much as possible to reduce the risks of reidentification. Existing work such as Williams, Burnap and Sloan 20 , the AOIR Ethics Guidelines 41 , and the STEP framework 42 provide useful tools for thinking through research processes, when and how to get consent, and how to mitigate risks to individuals.

Second, as Kass et al . 27 suggest, educating the public about why research is important and why it requires their data is vital to ensuring individuals’ comfort with their data being used. As earlier studies 11 , 24 and now our work show, how much data sharers trust researchers affects their perceptions of acceptable use. People who place more trust in institutions were more likely to accept their data being used. We can learn from health research that has been able to explain to individuals how and why their medical records are necessary for understanding diseases such as cancer. People now tend to find their data’s use for health research more acceptable than for other uses 11 , 21 .

Researchers who leverage social media data can engage in similar outreach and engagement efforts to understand individuals’ hesitations and preferences. We do not, however, suggest that researchers try to cajole or coerce potential participants. Instead, social media researchers must work to ensure that their research does actually provide social benefits worthy of individual risks, and that they are consequently able to articulate the significance of their work so that individuals can decide whether that benefit is worth their risks. As Sloan and colleagues 43 argue, the principles outlined in the Belmont Report apply even to social media research, and researchers have a responsibility to ensure that individuals understand their own data, how it could be used, and the risks associated with use.

In one example, Xafis 44 demonstrated how they helped individuals understand how their data could be used and potentially competing interests between researchers and individuals represented in data. Their research showed that individuals could understand data linkage processes and the potential trade-offs quickly. Because it is not feasible to educate each potential participant that might share their social media data, the burden of education lies on researchers collectively. Researchers need to articulate the social benefits of their work so that individuals understand why disclosure and reputation risks are worth taking; if the benefits do not outweigh the risks, researchers need to be willing to abandon or avoid particular projects.

Contextual integrity in social media research

Our work shows that beyond considering individuals’ preferences for their data’s use under a respect for persons framework, social media researchers must also attend to the contexts in which user data are generated and used. Our results confirm that contexts in which user data are used impact individuals’ perceptions of acceptable use. Specifically, they indicate relatively less comfort with their data being used for natural research or to develop interventions than with their use in social research. These findings resonate with earlier work in online fan communities, where fans expressed concerns about the contexts in which their data could be used (e.g., articles about fandom) because their identities carry different risks (e.g., fandom vs physical communities for LGBTQ folks) 32 . It also echoes prior work about Facebook data, specifically, where users expressed comfort with their data being used to improve services but not to evaluate mental health 11 . To address concerns about mismatch between data generation and use contexts, Nissenbaum 45 offers the principle of “contextual integrity” to refer to the challenges inherent in using data generated in one context (e.g., an online discussion) in another (e.g., a research study).

Legal constructs that impact social media data use

Recent developments in regulations, such as the EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) 46 , the Digital Services Act (DSA) 47 , and proposed bills in the United States encode ethical principles in governments’ policies. For instance, GDPR specifically requires that researchers provide privacy notices and consent documents. Similarly, the DSA demands that social media companies attend to the risks related to data’s collection and use. Researchers’ obligations under GDPR, DSA, and their analogues in other jurisdictions are not yet settled, but it is clear that researchers will have regulatory requirements to meet 48 . As these regulations begin to take effect, our work based on a respect-for-persons framework suggests that future policy efforts would benefit from soliciting public input on appropriate uses of data to balance users’ expectations and preferences with researchers’ interests and goals. A one-size-fits-all approach to data reuse policy could potentially stifle research that users found acceptable and from which society could benefit.

We began this article with an example of increased accessibility of Twitter data and raised questions for social media researchers such as: should they use social media data in their research? If so, when and how ? As with other large-scale data, it is not always possible to ask all prospective study participants to explicitly consent to use their social media data in research. However, through surveying individuals, our study offers a benchmark of individuals’ perceptions of their social media data’s sensitivity and acceptable use from which social media data researchers can cultivate general respect-for-persons practices. We show that people generally find their social media data moderately sensitive relative to other widely used data types. People generally find it acceptable for researchers to use their social media data but prefer that researchers clearly articulate the benefits of their work. Individuals are most concerned about who, why , and which data will be used. When these factors are clearly communicated, individuals are more likely to find their data’s use for research acceptable.

Given our findings that individuals find their social media data moderately sensitive, our study invites social media researchers to learn from well-established best practices for using sensitive data and increasing public awareness about the benefits of research with social media data. Researchers must be clear with themselves and with the public about why social media data is necessary for their work and what benefits that work provides for society, especially for the individuals who carry risks by being included in the data. By using contemporary strategies to balance social media data’s use risks to individuals with the benefits to society, social media researchers can more effectively realize respect for persons, ensuring greater public support for significant advances in research.

To understand participants’ perceptions about acceptable social media data use, we surveyed 1018 people through Qualtrics panels and Mechanical Turk 29 . Qualtrics recruitment targeted U.S. adults who posted publicly to social media at least once per week. We also used quotas for racial identity to ensure our sample was at least 10% African American individuals and at maximum was 80% white-only. We did not use targeting in recruiting MTurk participants.

We used statistical analyses to identify patterns in survey responses, specifically regarding (a) the sensitivity of individuals’ online identifiers relative to other personal identifiers, and (b) whether or not participants perceive a particular data analyst using a specific type of data for a purpose as acceptable or not.

Survey population and sample size

We used the easypower 49 package to estimate the appropriate size of our survey sample using a significance criterion of α = 0.05 and power = 0.80 and determined we needed at least 426 respondents to detect significant differences in the effect of the interaction of analyst, data type, and purpose. We contracted with Qualtrics to solicit responses from 586 survey panelists. Using a Qualtrics panel enabled us to set minimum quotas for our independent variables (e.g., non-white respondents) to ensure variability. We then used the same instrument to survey 432 crowdworkers through Amazon’s Mechanical Turk. We recruited panels through both Qualtrics and Mechanical Turk to determine whether recruitment platform influenced findings. In our analyses, we include random effects for recruitment source to detect differences between the samples and their impacts on our observations 50 .

Instrument design and variables

Our survey instrument measured relationships between acceptable use and relevant constructs like data sensitivity, and personal characteristics like trust in institutions. Table 4 summarizes the various measures we included in our instrument. The following subsections explain how we developed each measure.

Acceptable use

We developed a measure of acceptable use perceptions motivated by existing work that uses scenarios. However, existing acceptable use scenarios did not explicitly vary three constructs that other literature proposes affect acceptable use perceptions (“data analyst”, “data type”, and “data use purpose”). Therefore, we developed our own set of scenarios to evaluate the effects of these three constructs (see Table 5 for a summary of how we operationalized these constructs). Specifically, we varied scenarios according to three data analysts : academic researchers, social media companies 21 , and journalists 26 . We varied data types to include social media content 15 , cell phone location 51 , 52 , voter file 53 , survey 33 , security camera 54 , and grocery store purchase data 55 because they are used widely in contemporary research. We included three data use purposes : social/behavioral research, research about the natural world, and interventions designed to change individual behavior 11 . Scenarios describing these purposes include real-world research use such as vegetation phenology 56 , emotional contagion 57 , and consumer spending 58 . They also mirror vignettes used in prior work on attitudes toward Facebook and Twitter users’ data 8 , 11 and individuals’ location data 28 . We requested binary responses rather than scale-based responses to our questions about whether data use was acceptable in a scenario because scales are more difficult for respondents to interpret and answer 59 , 60 .

Data sensitivity

In studying the relative sensitivity of respondents’ data, we include items from Milne, et al .‘s 15 study of information sensitivity and willingness to provide it to various institutions for different purposes. Their study evaluated respondents’ relationships to a specific kind of social media data: the online screen name . Evaluating respondents’ relationships to their online screen name does not encompass all types of social media data. However, this particular social media data type, like a driver’s license number, can be a key to accessing other data about a person. Online screen names thus offer a point of comparison with similarly sensitive data types. We mirror earlier surveys’ 15 focus on the online screen name to facilitate comparisons to earlier work and other types of sensitive data. We compare the sensitivity of the online screen name to other data that can uniquely identify a specific person (e.g., driver’s license number) and to data that through linkage or in aggregate can be used to identify a specific person (e.g., race, religion, income, etc.) 61 . Sensitivity acts as a dependent variable in analyses responding to RQ1, and independent variable in analyses responding to RQ2.

Independent variables

To understand whether perceptions of acceptable use vary by mediating factors, we included independent variables motivated by existing literature. Based on existing research, we expected participants’ perspectives to vary based on personal characteristics like their trust in institutions generally 62 , their existing privacy practices and concerns 63 , their demographics 62 , 64 , and their social media use 65 . Assessing these independent variables’ effects also allows us to compare our findings with existing research on personal data sharing and sensitivity 8 , 11 , 15 , 27 .

We used generalized linear mixed models (GLMM)–specifically a cumulative link mixed model (CLMM) for ordinal outcome variables and a mixed effects logistic regression (MELR) for binary outcome variables–to analyze our survey’s results. Through the ability to include random effects, GLMMs enabled us to understand whether individual variation among participants, in addition to personal characteristics like demographics and institutional trust that we measured, impacted participants’ responses. We included a random effect for response platform (Qualtrics or MTurk) and for individual respondent. We estimated models for different combinations of independent variables, their interactions, and control variables. We include the models of best fit, determined by ANOVA, in the main text below.

Limitations

Our survey method likely underestimates individuals’ agreement with various data uses because they may not be familiar with ways that data are used or the methods employed in analysis. For instance, prior studies of patient records 23 and commercial access to health data 66 found that users increased their willingness to share health data after they understood the potential for public benefit and data security measures.

We adopted the variable ‘online screen name’ from prior surveys. Had we included the specific data types we asked about in scenarios (e.g., social media posts) in the sensitivity questions, we may have gotten different results. We chose ‘online screen name’ because it enabled comparison to prior studies 15 , 16 , and because it is analogous to other linkable personal identifiers such as driver’s license number. Future work could examine the sensitivity of specific types of social media data.

Data availability

The survey data 29 that support the findings of this study are available in Deep Blue Data with the identifier 10.7302/6vjf-av59. The University of Michigan IRB HSBS has reviewed this study and determined that it is exempt from ongoing IRB review per federal exemption category: EXEMPTION 2(i) and/or 2(ii) at 45 CFR 46.104(d) (IRB: HUM00204213).

Code availability

Code 67 used to perform the data preparation and analysis for this paper is available on GitHub at https://github.com/casmlab/personal-data-survey and through Zenodo with the identifier https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6807258 .

Hemphill, L., Hedstrom, M. L. & Leonard, S. H. Saving social media data: understanding data management practices among social media researchers and their implications for archives. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology 72 , 97–109 (2021).

Article Google Scholar

Proferes, N., Jones, N., Gilbert, S., Fiesler, C. & Zimmer, M. Studying Reddit: a systematic overview of disciplines, approaches, methods, and ethics. Social Media + Society 7 , 20563051211019004 (2021).

Google Scholar

Steinfield, C., Ellison, N. B. & Lampe, C. Social capital, self-esteem, and use of online social network sites: a longitudinal analysis. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 29 , 434–445 (2008).

Hemphill, L., Russell, A. & Schöpke-Gonzalez, A. M. What drives U.S. congressional members’ policy attention on Twitter? Policy & Internet 13 , 233–256 (2020).

Antenucci, D. et al . Ringtail: a generalized nowcasting system. Proc. VLDB Endow. 6 , 1358–1361, https://doi.org/10.14778/2536274.2536315 (2013).

Ordun, C. et al . Open source health intelligence (OSHINT) for foodborne illness event characterization. Online J. Public Health Inform . 5 (2013).

Obar, J. A. & Oeldorf-Hirsch, A. The biggest lie on the internet: ignoring the privacy policies and terms of service policies of social networking services. Inf. Commun. Soc. 23 , 128–147 (2020).

Fiesler, C. & Proferes, N. “Participant” perceptions of Twitter research ethics. Social Media + Society 4 , 1–14 (2018).

Bernstein, M. S., Bakshy, E., Burke, M. & Karrer, B. Quantifying the invisible audience in social networks. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems , CHI ‘13, 21–30 (Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 2013).

Marwick, A. E. & Boyd, D. I tweet honestly, I tweet passionately: Twitter users, context collapse, and the imagined audience. New Media & Society 13 , 114–133 (2010).

Gilbert, S., Vitak, J. & Shilton, K. Measuring Americans’ comfort with research uses of their social media data. Social Media + Society 7 , 1–13 (2021).

Office for Human Research Protections (OHRP). Read the Belmont report. https://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/regulations-and-policy/belmont-report/read-the-belmont-report/index.html . Accessed: 2021-12-5.

Vitak, J., Shilton, K. & Ashktorab, Z. Beyond the Belmont principles: ethical challenges, practices, and beliefs in the online data research community. In Proceedings of the 19th ACM Conference on Computer-Supported Cooperative Work & Social Computing , CSCW ‘16, 941–953 (Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 2016).

Documenting the Now. Social humans labels. https://www.docnow.io/social-humans/index.html . Accessed: 2021-12-14.

Milne, G. R., Pettinico, G., Hajjat, F. M. & Markos, E. Information sensitivity typology: mapping the degree and type of risk consumers perceive in personal data sharing. J. Consum. Aff. 51 , 133–161 (2017).

Markos, E., Milne, G. R. & Peltier, J. W. Information sensitivity and willingness to provide continua: a comparative privacy study of the united states and brazil. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing 36 , 79–96 (2017).

Rubinstein, I. S. Voter privacy in the age of big data. Wis. L. Rev . 861 (2014).

Richards, N. M. & King, J. H. Big data ethics. Wake Forest L. Rev. 49 , 393 (2014).

Kenny, C. T. et al . The use of differential privacy for census data and its impact on redistricting: the case of the 2020 U.S. census. Science Advances 7 , eabk3283, https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.abk3283 (2021).

Article ADS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Williams, M. L., Burnap, P. & Sloan, L. Towards an ethical framework for publishing Twitter data in social research: taking into account users’ views, online context and algorithmic estimation. Sociology 51 , 1149–1168 (2017).

Hill, E. M., Turner, E. L., Martin, R. M. & Donovan, J. L. “Let’s get the best quality research we can”: public awareness and acceptance of consent to use existing data in health research: a systematic review and qualitative study. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 13 , 72 (2013).

Howe, N., Giles, E., Newbury-Birch, D. & McColl, E. Systematic review of participants’ attitudes towards data sharing: a thematic synthesis. J. Health Serv. Res. Policy 23 , 123–133 (2018).

Tully, M. P. et al . Investigating the extent to which patients should control access to patient records for research: a deliberative process using citizens’ juries. J. Med. Internet Res. 20 , e112 (2018).

Chen, Y., Chen, C. & Li, S. Determining factors of participants’ attitudes toward the ethics of social media data research. Online Information Review 46 , 164–181, https://doi.org/10.1108/OIR-11-2020-0514 (2021).

Fiesler, C. & Hallinan, B. “We are the product”: public reactions to online data sharing and privacy controversies in the media. In Proceedings of the 2018 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems , no. 53 in CHI ‘18, 1–13 (Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 2018).

Dubois, E., Gruzd, A. & Jacobson, J. Journalists’ use of social media to infer public opinion: the citizens’ perspective. Soc. Sci. Comput. Rev. 38 , 57–74 (2020).

Kass, N. E. et al . The use of medical records in research: what do patients want? J. Law Med. Ethics 31 , 429–433 (2003).

Martin, K. E. & Nissenbaum, H. What is it about location? Berkeley Technol. Law J . 35 (2020).

Hemphill, L. Personal and social media data survey [data set]. University of Michigan - Deep Blue Data https://doi.org/10.7302/6vjf-av59 (2022).

Christensen, R. H. B. Ordinal–regression models for ordinal data R package version 2019.12-10. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=ordinal (2019).

Bates, D., Mächler, M., Bolker, B. & Walker, S. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. Journal of Statistical Software 67 , 1–48, https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v067.i01 (2015).

Dym, B. & Fiesler, C. Ethical and privacy considerations for research using online fandom data. TWC 33 (2020).

Hughes, A. G. et al . Using administrative records and survey data to construct samples of tweeters and tweets. Public Opin. Q. 85 , 323–346 (2021).

Nyhan, B., Skovron, C. & Titiunik, R. Differential registration bias in voter file data: a sensitivity analysis approach. Am. J. Pol. Sci. 61 , 744–760 (2017).

Fink, K. The biggest challenge facing journalism: a lack of trust. Journalism 20 , 40–43 (2019).

Usher, N. Putting “place” in the center of journalism research: a way forward to understand challenges to trust and knowledge in news. Journal. Commun. Monogr. 21 , 84–146 (2019).

Boulianne, S., Koc-Michalska, K., Vedel, T., Nadim, M. & Fladmoe, A. Silencing women? Gender and online harassment. Soc. Sci. Comput. Rev. 39 , 245–258 (2021).

Duggan, M. Online harassment 2017. Pew Research Center (2017).

Mikal, J., Hurst, S. & Conway, M. Ethical issues in using Twitter for population-level depression monitoring: a qualitative study. BMC Med. Ethics 17 , 22 (2016).

Benjamin, R. Race After Technology: Abolitionist Tools for the New Jim Code (Polity Books, New York, NY, USA, 2019).

Franzke, A. S., Bechmann, A., Zimmer, M., Ess, C. & the Association of Internet Researchers. Internet Research: Ethical Guidelines 3.0. Tech. Rep. (2020).

Mannheimer, S. & Hull, E. A. Sharing selves: developing an ethical framework for curating social media data. International Journal of Digital Curation 12 , 196–209 (2018).

Sloan, L., Jessop, C., Al Baghal, T. & Williams, M. Linking survey and Twitter data: informed consent, disclosure, security, and archiving. J. Empir. Res. Hum. Res. Ethics 15 , 63–76 (2020).

Xafis, V. The acceptability of conducting data linkage research without obtaining consent: lay people’s views and justifications. BMC Med. Ethics 16 , 79 (2015).

Nissenbaum, H. Privacy as contextual integrity. Wash Law Rev. 79 , 119 (2004).

European Commission. General Data Protection Regulation. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:02016R0679-20160504 Accessed: 2022-09-19 (2016).

European Commission. Digital Services Act. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/en/TXT/?uri=COM:2020:825:FIN (2020).

Kotsios, A., Magnani, M., Vega, D., Rossi, L. & Shklovski, I. An analysis of the consequences of the General Data Protection Regulation on social network research. Trans. Soc. Comput. 2 , 1–22 (2019).

McGarvey, A. easypower: Sample Size Estimation for Experimental Designs . R package version 1.0.1 (2015).

McKone, M. J. & Lively, C. M. Statistical analysis of experiments conducted at multiple sites. Oikos 67 , 184–186 (1993).

Arie, Y. & Mesch, G. S. Spatial distance and mobile business social network density. Inf. Commun. Soc. 19 , 1572–1586 (2016).

Ratti, C., Frenchman, D., Pulselli, R. M. & Williams, S. Mobile landscapes: using location data from cell phones for urban analysis. Environ. Plann. B Plann. Des. 33 , 727–748 (2006).

Fraga, B. & Holbein, J. Measuring youth and college student voter turnout. Electoral Studies 65 , 102086 (2020).

Schiff, J., Meingast, M., Mulligan, D. K., Sastry, S. & Goldberg, K. Respectful cameras: detecting visual markers in real-time to address privacy concerns. In Protecting privacy in video surveillance , 65–89 (Springer, 2009).

Ozgormus, E. & Smith, A. E. A data-driven approach to grocery store block layout. Comput. Ind. Eng. 139 , 105562 (2020).

Silva, S. J., Barbieri, L. K. & Thomer, A. K. Observing vegetation phenology through social media. PLoS One 13 , e0197325 (2018).

Kramer, A. D. I., Guillory, J. E. & Hancock, J. T. Experimental evidence of massive-scale emotional contagion through social networks. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 111 , 8788–8790 (2014).

Article ADS CAS Google Scholar

Hui, S. K., Bradlow, E. T. & Fader, P. S. Testing behavioral hypotheses using an integrated model of grocery store shopping path and purchase behavior. J. Consum. Res. 36 , 478–493 (2009).

Singer, E. et al . The effect of question framing and response options on the relationship between racial attitudes and beliefs about genes as causes of behavior. Public Opin. Q. 74 , 460–476 (2010).

Couper, M. P., Tourangeau, R., Conrad, F. G. & Singer, E. Evaluating the effectiveness of visual analog scales: a web experiment. Soc. Sci. Comput. Rev. 24 , 227–245 (2006).

Schöpke-Gonzalez, A. M. & Schaub, F. Mobile phones at borders: logics of deterrence and survival in the mediterranean sea and sonoran desert. Information, Communication & Society 0 , 1–17, https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2022.2113818 (2022).

NORC. Documentation questionnaire. https://gss.norc.org/get-documentation/questionnaires . Accessed: 2022-2-24 (2021).

Steinbart, P., Keith, M. & Babb, J. Measuring privacy concern and the right to be forgotten. In Proceedings of the 50th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences (2017) , 4967–4976 (Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, 2017).

ANES. User guide and codebook. https://electionstudies.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/anes_timeseries_2016_userguidecodebook.pdf (2019).

Auxier, B. & Anderson, M. Social Media Use in 2021. Pew Research Center (2021).

Ipsos MORI. The One-Way mirror: public attitudes to commercial access to health data. Tech. Rep., Ipsos MORI (2016).

Hemphill, L. Personal and social media data survey [code]. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6807258 (2022).

Download references

Acknowledgements

We are thankful for our colleagues’ help and feedback on this project: Nazanin Andalibi, Ricardo Punzalan, and Kat Roemmich helped draft the survey questions. The Statistical Design Group directed by Brady West and James Wagner consulted on the structure and statistical design of our survey instrument. Lizhou (Leo) Fan provided comments on an earlier draft. Andrew Schrock provided editing services. Staff at Consulting for Statistics, Computing, and Analytics Research (CSCAR) at the University of Michigan advised on statistical analysis. This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant No. 1839868. Additional funding was provided by the Propelling Original Data Science (PODS) grant program from the Michigan Institute for Data Science.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

University of Michigan, School of Information, Ann Arbor, MI, 48109, USA

Libby Hemphill, Angela Schöpke-Gonzalez & Anmol Panda

University of Michigan, ICPSR, Ann Arbor, MI, 48104, USA

Libby Hemphill

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

Libby Hemphill: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Formal Analysis, Resources, Data Curation, Writing - Original Draft, Writing - Review and Editing, Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition; Angela Schöpke-Gonzalez: Validation, Writing - Original Draft, Writing - Review and Editing; Anmol Panda: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing - Review and Editing.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Libby Hemphill .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Hemphill, L., Schöpke-Gonzalez, A. & Panda, A. Comparative sensitivity of social media data and their acceptable use in research. Sci Data 9 , 643 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-022-01773-w

Download citation

Received : 08 July 2022

Accepted : 12 October 2022

Published : 22 October 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-022-01773-w

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Using Social Media Data in Academic Research

The Mixed Blessing of Social Media Data

The phenomenal growth in utilization rates of popular social networking sites such as Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram, offer academic researchers an absolute treasure trove of consumer-generated content for analysis. However, access to that data isn’t without challenges—all providers have unique policies and procedures on data collection, sharing and publication.

The Potential of Social Media Data

Assuming the challenges to access data can be overcome, social media data offers several advantages over data gathered by more traditional research methods :

- Topical information that is potentially available in real time

- Information that is unfiltered by survey tools and other potential biases

- Naturally occurring data collected from an actively engaged population

- Clearly identified, albeit narrow user demographics

Ethical Challenges

Beyond the default privacy settings established by the respective social networking sites (which offer varied customization options to users), critics of social media data mining raise concerns about the issue of consent. Does the fact that the posts are made to public sites with the potential for re-posting constitute a de facto grant of consent? Should consent be sought from each user? Is that even feasible when software programs are scraping tens of thousand of posts per minute?

Is there some middle ground where the anonymity of your username can be seen to allay fears about identity protection? Is your Twitter user name sufficiently anonymous, or should that name be kept anonymous too?