- Games, topic printables & more

- The 4 main speech types

- Example speeches

- Commemorative

- Declamation

- Demonstration

- Informative

- Introduction

- Student Council

- Speech topics

- Poems to read aloud

- How to write a speech

- Using props/visual aids

- Acute anxiety help

- Breathing exercises

- Letting go - free e-course

- Using self-hypnosis

- Delivery overview

- 4 modes of delivery

- How to make cue cards

- How to read a speech

- 9 vocal aspects

- Vocal variety

- Diction/articulation

- Pronunciation

- Speaking rate

- How to use pauses

- Eye contact

- Body language

- Voice image

- Voice health

- Public speaking activities and games

- About me/contact

- How to end a speech effectively

How to end a speech memorably

3 ways to close a speech effectively.

By: Susan Dugdale | Last modified: 09-05-2022

Knowing how, and when, to end a speech is just as important as knowing how to begin. Truly.

What's on this page:

- why closing well is important

- 3 effective speech conclusions with examples and audio

- 7 common ways people end their speeches badly - what happens when you fail to plan to end a speech memorably

- How to end a Maid Honor speech: 20 examples

- links to research showing the benefits of finishing a speech strongly

Why ending a speech well is important

Research * tells us people most commonly remember the first and last thing they hear when listening to a speech, seminar or lecture.

Therefore if you want the audience's attention and, your speech to create a lasting impression sliding out with: "Well, that's all I've got say. My time's up anyway. Yeah - so thanks for listening, I guess.", isn't going to do it.

So what will?

* See the foot of the page for links to studies and articles on what and how people remember : primacy and recency.

Three effective speech conclusions

Here are three of the best ways to end a speech. Each ensures your speech finishes strongly rather than limping sadly off to sure oblivion.

You'll need a summary of your most important key points followed by the ending of your choice:

- a powerful quotation

- a challenge

- a call back

To work out which of these to use, ask yourself what you want audience members to do or feel as a result of listening to your speech. For instance;

- Do you want to motivate them to work harder?

- Do you want them to join the cause you are promoting?

- Do you want them to remember a person and their unique qualities?

What you choose to do with your last words should support the overall purpose of your speech.

Let's look at three different scenarios showing each of these ways to end a speech.

To really get a feel for how they work try each of them out loud yourself and listen to the recordings.

1. How to end a speech with a powerful quotation

Your speech purpose is to inspire people to join your cause. Specifically you want their signatures on a petition lobbying for change and you have everything ready to enable them to sign as soon as you have stopped talking.

You've summarized the main points and want a closing statement at the end of your speech to propel the audience into action.

Borrowing words from a revered and respected leader aligns your cause with those they fought for, powerfully blending the past with the present.

For example:

"Martin Luther King, Jr said 'The ultimate measure of a man is not where he stands in moments of comfort, but where he stands at times of challenge and controversy.'

Now is the time to decide. Now is the time to act.

Here's the petition. Here's the pen. And here's the space for your signature.

Now, where do you stand?"

Try it out loud and listen to the audio

Try saying this out loud for yourself. Listen for the cumulative impact of: an inspirational quote, plus the rhythm and repetition (two lots of 'Now is the time to...', three of 'Here's the...', three repeats of the word 'now') along with a rhetorical question to finish.

Click the link to hear a recording of it: sample speech ending with a powerful quotation .

2. How to end a speech with a challenge

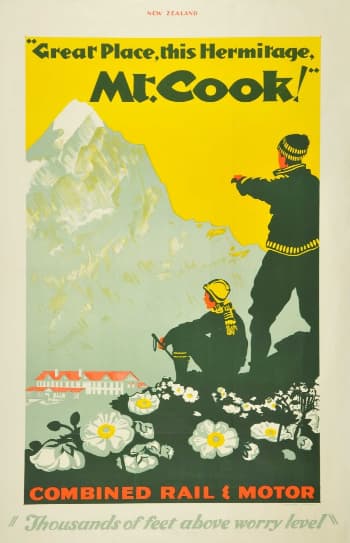

Your speech purpose is to motivate your sales force.

You've covered the main points in the body of it, including introducing an incentive: a holiday as a reward for the best sales figures over the next three weeks.

You've summarized the important points and have reached the end of your speech. The final words are a challenge, made even stronger by the use of those two extremely effective techniques: repetition and rhetorical questions.

"You have three weeks from the time you leave this hall to make that dream family holiday in New Zealand yours.

Can you do it?

Will you do it?

The kids will love it.

Your wife, or your husband, or your partner, will love it.

Do it now!"

Click the link to listen to a recording of it: sample speech ending with a challenge . And do give it a go yourself.

3. How to end a speech with a call back

Your speech purpose is to honor the memory of a dear friend who has passed away.

You've briefly revisited the main points of your speech and wish in your closing words to leave the members of the audience with a happy and comforting take-home message or image to dwell on.

Earlier in the speech you told a poignant short story. It's that you return to, or call back.

Here's an example of what you could say:

"Remember that idyllic picnic I told you about?

Every blue sky summer's day I'll see Amy in my mind.

Her red picnic rug will be spread on green grass under the shade of an old oak tree. There'll be food, friends and laughter.

I'll see her smile, her pleasure at sharing the simple good things of life, and I know what she'd say too. I can hear her.

"Come on, try a piece of pie. My passing is not the end of the world you know."

Click the link to hear a recording of it: sample speech ending with a call back . Try it out for yourself too. (For some reason, this one is a wee bit crackly. Apologies for that!)

When you don't plan how to end a speech...

That old cliché 'failing to plan is planning to fail' can bite and its teeth are sharp.

The 'Wing It' Department * delivers lessons learned the hard way. I know from personal experience and remember the pain!

How many of these traps have caught you?

- having no conclusion and whimpering out on a shrug of the shoulders followed by a weak, 'Yeah, well, that's all, I guess.', type of line.

- not practicing while timing yourself and running out of it long before getting to your prepared conclusion. (If you're in Toastmasters where speeches are timed you'll know when your allotted time is up, that means, finish. Stop talking now, and sit down. A few seconds over time can be the difference between winning and losing a speech competition.)

- ending with an apology undermining your credibility. For example: 'Sorry for going on so long. I know it can be a bit boring listening to someone like me.'

- adding new material just as you finish which confuses your audience. The introduction of information belongs in the body of your speech.

- making the ending too long in comparison to the rest of your speech.

- using a different style or tone that doesn't fit with what went before it which puzzles listeners.

- ending abruptly without preparing the audience for the conclusion. Without a transition, signal or indication you're coming to the end of your talk they're left waiting for more.

* Re The 'Wing It' Department

One of the most galling parts of ending a speech weakly is knowing it's avoidable. Ninety nine percent of the time it didn't have to happen that way. But that's the consequence of 'winging it', trying to do something without putting the necessary thought and effort in.

It's such a sod when there's no one to blame for the poor conclusion of your speech but yourself! ☺

How to end a Maid of Honor speech: 20 examples

More endings! These are for Maid of Honor speeches. There's twenty examples of varying types: funny, ones using Biblical and other quotations... Go to: how to end a Maid of Honor speech

How to write a speech introduction

Now that you know how to end a speech effectively, find out how to open one well. Discover the right hook to use to captivate your audience.

Find out more: How to write a speech introduction: 12 of the very best ways to open a speech .

More speech writing help

You do not need to flail around not knowing what to do, or where to start.

Visit this page to find out about structuring and writing a speech .

You'll find information on writing the body, opening and conclusion as well as those all important transitions. There's also links to pages to help you with preparing a speech outline, cue cards, rehearsal, and more.

Research on what, and how, people remember: primacy and recency

McLeod, S. A. (2008). Serial position effect . (Primacy and recency, first and last) Simply Psychology.

Hopper, Elizabeth. "What Is the Recency Effect in Psychology?" ThoughtCo, Feb. 29, 2020.

ScienceDirect: Recency Effect - an overview of articles from academic Journals & Books covering the topic.

- Back to top of how to end a speech page

speaking out loud

Subscribe for FREE weekly alerts about what's new For more see speaking out loud

Top 10 popular pages

- Welcome speech

- Demonstration speech topics

- Impromptu speech topic cards

- Thank you quotes

- Impromptu public speaking topics

- Farewell speeches

- Phrases for welcome speeches

- Student council speeches

- Free sample eulogies

From fear to fun in 28 ways

A complete one stop resource to scuttle fear in the best of all possible ways - with laughter.

Useful pages

- Search this site

- About me & Contact

- Blogging Aloud

- Free e-course

- Privacy policy

©Copyright 2006-24 www.write-out-loud.com

Designed and built by Clickstream Designs

Speechwriting

10 Introductions and Conclusions

Starting and Ending Your Speech

One of the most fundamental components of any public speech is having a strong introduction and conclusion. Your introduction gives the audience their first impression of you. This is your best chance to build credibility. You need to grab the audience’s attention, introduce your topic, and preview how the speech will unfold. The conclusion needs to reiterate your main points and help the audience see how all your main points work together. Additionally, even if the audience got a bit lost or disengaged in the middle, a strong conclusion will leave them with an overall positive reaction to your speech.

Can you imagine how strange a speech would sound without an introduction? Or how jarring it would be if, after making a point, a speaker just walked away from the lectern and sat down? You would be confused, and the takeaway from that speech—even if the content were good—would likely be, “I couldn’t follow” or “That was a weird speech.”

This is just one of the reasons all speeches need introductions and conclusions. Introductions and conclusions serve to frame the speech and give it a clearly defined beginning and end. They help the audience to see what is to come in the speech, and then let them mentally prepare for the end. In doing this, introductions and conclusions provide a “preview/review” of your speech as a means to reiterate or re-emphasize to your audience what you are talking about.

Since speeches are auditory and live, you need to make sure the audience remembers what you are saying. One of the primary functions of an introduction is to preview what you will be covering in your speech, and one of the main roles of the conclusion is to review what you have covered. It may seem like you are repeating yourself and saying the same things over and over, but that repetition ensures that your audience understands and retains what you are saying.

The roles that introductions and conclusions fulfill are numerous, and, when done correctly, can make your speech stronger. The general rule is that the introduction and conclusion should each be about 10-15% of your total speech, leaving 80% for the body section. Let’s say that your informative speech has a time limit of 5-7 minutes: if we average that out to 6 minutes that gives you 360 seconds. Ten to 15 percent means that the introduction and conclusion should each be no more than 1-1/2 minutes.

In the following sections, we will discuss specifically what should be included in the introduction and conclusion and offer several options for accomplishing each.

The Five Elements of an Introduction

Intro element 1: attention-getter.

The first major purpose of an introduction is to gain your audience’s attention and make them interested in what you have to say. First impressions matter. When we meet someone for the first time, it can be only a matter of seconds before we find ourselves interested or disinterested in the person. The equivalent in speechwriting of “first impression” is what is called an attention-getter. This is a statement or question that piques the audience’s interest in what you have to say. There are several strategies you can choose from—verbal and non-verbal—to get the audience’s attention. Below are described the most popular types of attention-getters: quotations, questions, stories, humor, surprise, stories, and references. As well as non-verbal attention-getters involving images, sounds, or objects.

Quotations are a great way to start a speech. That’s why they are used so often as a strategy. Here’s an example that might be used in the opening of a commencement address:

The late actor, fashion icon, and social activist Audrey Hepburn once noted that, “Nothing is impossible. The word itself says ‘I’m possible’!”

If you use a quotation as your attention getter, be sure to give the source first (as in this example) so that it isn’t mistaken as your own wording.

We often hear speakers begin a speech with a question for the audience. As easy as it sounds, beginning with a question is somewhat tricky. You must decide if you are asking a question because you want a response from the audience, or, on the other hand, if you are asking a question that you will answer, or that will create a dramatic effect. We call these rhetorical questions .

The dangers with a direct question are many. There may be an awkward pause after your question because the audience doesn’t know if you actually want an answer. Or they don’t know how you want the response—a verbal response or a gesture such as a raised hand. Another reason direct questions are delicate is this obvious point: what you are going to do with the response. For example, imagine you have written a speech about the importance of forgiving student debt, and you begin your speech with this question for the audience: “How many of you have more than $10,000 in student loan debt?” You would be creating a problem for yourself if just a few people in the audience raised their hand. If you want to use a direct question, follow these rules:

- make it clear to the audience the means of response. “By a show of hands, how many of you have more than $10,000 in student loan debt?”

- prepare in advance how you will acknowledge different responses.

Contrary to a direct question, you could use a rhetorical question—a question to which no actual reply is expected. For example, a speaker talking about the history of Mother’s Day could start by asking the audience, “Do you remember the last time you told your mom you loved her?” In this case, the speaker does not expect the audience to shout out an answer, but rather to think about the question as the speech goes on.

Finally, when asking a rhetorical question, don’t pause after it, or the audience will get distracted wondering if you’re waiting for a response. Jump right into your speech:

“How many of you have more than $10,000 in student loan debt? If you’re like 78% of college seniors, your answer is probably a yes.”

Humor is an amazing tool when used properly but it’s a double-edged sword. If you don’t wield the sword carefully, you can turn your audience against you very quickly.

When using humor, you really need to know your audience and understand what they will find humorous. One of the biggest mistakes a speaker can make is to use some form of humor that the audience either doesn’t find funny or, worse, finds offensive. We always recommend that you test out humor of any kind on a sample of potential audience members prior to actually using it during a speech. If you do use a typical narrative “joke,” don’t say it happened to you. Anyone who heard the joke before will think you are less than truthful!

As with other attention-getting devices, you need to make sure your humor is relevant to your topic, as one of the biggest mistakes some novices make when using humor is to add humor that really doesn’t support the overall goal of the speech. Therefore, when looking for humorous attention getters, you want to make sure that the humor isn’t going to be offensive to your audience and relevant to your speech.

Another way to start your speech is to surprise your audience with information that will be surprising or startling to your audience. Often, startling statements come in the form of statistics and strange facts. For example, if you’re giving a speech about oil conservation, you could start by saying,

“A Boeing 747 airliner holds 57,285 gallons of fuel.”

That’s a surprising or startling fact. Another version of the surprise form of an attention-getter is to offer a strange fact. For example, you could start a speech on the gambling industry by saying, “There are no clocks in any casinos in Las Vegas.” You could start a speech on the Harlem Globetrotters by saying, “In 2000, Pope John Paul II became the most famous honorary member of the Harlem Globetrotters.” (These examples come from a great website for strange facts ( http://www. strangefacts.com ).

Although such statements are fun, it’s important to use them ethically. First, make sure that your startling statement is factual. The Internet is full of startling statements and claims that are simply not factual, so when you find a statement that you’d like to use, you have an ethical duty to ascertain its truth before you use it and to provide a reliable citation. Second, make sure that your startling statement is relevant to your speech and not just thrown in for shock value. We’ve all heard startling claims made in the media that are clearly made for purposes of shock or fear mongering, such as “Do you know what common household appliance could kill you? Film at 11:00.” As speakers, we have an ethical obligation to avoid playing on people’s emotions in this way.

Another common type of attention-getter is an account or story of an interesting or humorous event. Notice the emphasis here is on the word “brief.” A common mistake speakers make when telling an anecdote is to make the anecdote too long. An example of an anecdote used in a speech about the pervasiveness of technology might look something like this:

“In July 2009, a high school student named Miranda Becker was walking along a main boulevard near her home on Staten Island, New York, typing in a message on her cell phone. Not paying attention to the world around her, she took a step and fell right into an open maintenance hole.”

Notice that the anecdote is short and has a clear point. From here the speaker can begin to make their point about how technology is controlling our lives.

A personal story is another option here. This is a story about yourself or someone you know that is relevant to your topic. For example, if you had a gastric bypass surgery and you wanted to give an informative speech about the procedure, you could introduce your speech in this way:

“In the fall of 2015, I decided that it was time that I took my life into my own hands. After suffering for years with the disease of obesity, I decided to take a leap of faith and get a gastric bypass in an attempt to finally beat the disease.”

Two primary issues that you should be aware of often arise with using stories as attention getters. First, you shouldn’t let your story go on for too long. If you are going to use a story to begin your speech, you need to think of it more in terms of summarizing the story rather than recounting it in its entirety. The second issue with using stories as attention getters is that the story must in some way relate to your speech. If you begin your speech by recounting the events in “Goldilocks and the Three Bears,” your speech will in some way need to address such topics as finding balance or coming to a compromise. If your story doesn’t relate to your topic, you will confuse your audience and they may spend the remainder of your speech trying to figure out the connection rather than listening to what you have to say.

You can catch the attention of the audience by referencing information of special interest. This includes references to the audience itself, and their interests. It can also mean references to current events or events in the past.

Your audience is a factor of utmost importance when crafting your speech, so it makes sense that one approach to opening your speech is to make a direct reference to the audience. In this case, the speaker has a clear understanding of the audience and points out that there is something unique about the audience that should make them interested in the speech’s content. Here’s an example:

“As students at State College, you and I know the importance of selecting a major that will benefit us in the future. In today’s competitive world, we need to study a topic that will help us be desirable to employers and provide us with lucrative and fulfilling careers. That’s why I want you all to consider majoring in communication.”

Referring to a current news event that relates to your topic is often an effective way to capture attention, as it immediately makes the audience aware of how relevant the topic is in today’s world. For example, consider this attention getter for a persuasive speech on frivolous lawsuits:

“On January 10 of this year, two prisoners escaped from a Pueblo, Colorado, jail. During their escape, the duo attempted to rappel from the roof of the jail using a makeshift ladder of bed sheets. During one prisoner’s attempt to scale the building, he slipped, fell forty feet, and injured his back. After being quickly apprehended, he filed a lawsuit against the jail for making it too easy for him to escape.”

In this case, the speaker is highlighting a news event that illustrates what a frivolous lawsuit is, setting up the speech topic of a need for change in how such lawsuits are handled.

A variation of this kind of reference is to open your speech with a reference about something that happened in the past. For example, if you are giving a speech on the perception of modern music as crass or having no redeeming values, you could refer to Elvis Presley and his musical breakout in the 1950s as a way of making a comparison:

“During the mid-1950s, Elvis Presley introduced the United States to a new genre of music: rock and roll. It was initially viewed as distasteful, and Presley was himself chastised for his gyrating dance moves and flashy style. Today he is revered as “The King of Rock ‘n Roll.” So, when we criticize modern artists for being flamboyant or over the top, we may be ridiculing some of the most important musical innovators we will know in our lifetimes.”

In this example, the speaker is evoking the audience’s knowledge of Elvis to raise awareness of similarities to current artists that may be viewed today as he was in the 1950s.

Non-Verbal Attention-Getters

The last variation of attention-getter discussed here is the non-verbal sort. You can get the audience interested in your speech by beginning with an image on a slide, music, sound, and even objects. As with all attention-getters, a non-verbal choice should be relevant to the topic of your speech and appropriate for your audience. The use of visual images and sounds shouldn’t be used if they require a trigger warning or content advisory.

This list of attention-getting devices represents a thorough, but not necessarily exhaustive, range of ways that you can begin your speech. Again, as mentioned earlier, your selection of attention getter isn’t only dependent on your audience, your topic, and the occasion, but also on your preferences and skills as a speaker. If you know that you are a bad storyteller, you might elect not to start your speech with a story. If you tend to tell jokes that no one laughs at, avoid starting your speech off with humor.

Intro Element 2: Establish Your Credibility

Whether you are informing, persuading, or entertaining an audience, one of the things they’ll be expecting is that you know what you’re talking about or that you have some special interest in the speech topic. To do this, you will need to convey to your audience, not only what you know, but how you know what you know about your topic.

Sometimes, this will be simple. If you’re informing your audience how a baseball is thrown and you have played baseball since you were eight years old, that makes you a very credible source. In your speech, you can say something like this:

“Having played baseball for over ten years, including two years as the starting pitcher on my high school’s varsity team, I can tell you about the ways that pitchers throw different kind of balls in a baseball game.”

In another example, if you were trying to convince your audience to join Big Brothers Big Sisters and you have been volunteering for years, you could say:

“I’ve been serving with Big Brothers Big Sisters for the last two years, and I can tell you that the experience is very rewarding.”

However, sometimes you will be speaking on a topic with which you have no experience. In these cases, use your interest in the subject as your credibility. For example, imagine you are planning a speech on the history of how red, yellow, and green traffic signals came to be used in the United States. You chose that topic because you plan to major in Urban Planning. In this case you might say something like:

“As someone who has always been interested in the history of transportation, and as a future Urban Studies major, I will share with you what I’ve been learning about the invention of traffic signals in America.”

It is around the credibility statement that you can usually find the moment to introduce yourself:

“Hi, I’m Josh Cohen, a sophomore studying Psychology here at North State University. I’ve been serving with Big Brothers Big Sisters for the last two years, and I can tell you that the experience is very rewarding.”

Establishing credibility as a speaker has a broader meaning, explained in depth in the chapter “ Ethics in Public Speaking. ”

Intro Element 3: Establish Rapport

Credibility is about establishing the basis of your knowledge, so that the audience can trust in the reliability of what you say. Rapport is about establishing a connection with the audience, so that the audience can trust who you are.

Rapport means the relationship or connection you make with your audience. To make a good connection, you’ll need to convey to your audience that you understand their interests, share them, and have a speech that will benefit them. Here is an example from an informative speech on the poet Lord Byron:

“You may be asking yourselves why you need to know about Lord Byron. If you take Humanities 120 as I did last semester, you’ll be discussing his life and works. After listening to my speech today, you’ll have a good basis for better learning in that course.”

In this example, the speaker connects to the audience with a shared interest and conveyed in these sentences the idea that the speaker has the best interests of the audience in mind by giving them information that would benefit them in a future course they might take.

The way that a speaker establishes connection with the audience is often by leaning in on the demographic of group affiliation.

“As college students, we all know the challenge of finding time to get our homework done.”

Intro Element 4: Preview Purpose & Central Idea

The fourth essential element of an introduction is to reveal the purpose and thesis of your speech to your audience. Have you ever come away after a speech and had no idea what the speech was about (purpose)? Have you ever sat through a speech wondering what the point was (central idea)? An introduction should provide this information from the beginning, so that the audience doesn’t have to figure it out. (If you’re still not certain what purpose and thesis are, now is good time to review this chapter ).

Whether you’re writing a speech or drafting an essay, previewing is essential. Like a sign on a highway that tells. you what’s ahead, a preview is a succinct statement that reveals the content to come. The operative word here is “succinct.” A preview statement for a short speech should be no more than two or three sentences. Consider the following example:

“In my speech today, I’m going to paint a profile of Abraham Lincoln, a man who overcame great adversity to become the President of the United States. During his time in office, he faced increasing opposition from conservative voices in government, as well as some dissension among his own party, all while being thrust into a war he didn’t want.”

Notice that this preview provides the purpose of this informative speech and its central idea of struggle. While it’s constructed from the specific purpose statement and central thesis, it presents them more smoothly, less awkwardly. Here is how purpose and thesis statements are smoothly combined in a preview:

| Specific Purpose: My purpose is to inform my audience about the life of Abraham Lincoln. | In my speech, today, I’m going to paint a profile of Abraham Lincoln, |

| Central Idea/Thesis: Abraham Lincoln was a great president even though he was faced with great adversity.

| a man who overcame great adversity to become the President of the United States. During his time in office, he faced increasing opposition from conservative voices in government, as well as some dissension among his own party, all while being thrust into a war he didn’t want.” |

Intro Element 5: Preview Your Main Points

Just like previewing your topic, previewing your main points helps your audience know what to expect throughout the course of your speech and prepares them to listen.

Your preview of the main points should be clear and easy to follow so that there is no question in your audience’s minds about what they are. Be succinct and simple: “Today, in my discussion of Abraham Lincoln’s life, I will look at his birth, his role a president, and his assassination.” If you want to be extra sure the audiences hears these, you can always enumerate your main points by using signposts (first, second, third, and so on): “In discussing how to make chocolate chip cookies, first we will cover what ingredients you need, second we will talk about how to mix them, and third we will look at baking them.”

Tips for Introductions

Together, these five elements of introduction prepare your audience by getting them interested in your speech (#1 attention-getter); conveying your knowledge (#2 credibility); conveying your good will (#3 rapport); letting them what you’ll be talking about and why (#4 preview topic and thesis); and finally, that to expect in the body of the speech (#5 preview of main points). Including all five elements starts your speech off on solid ground. Here are some additional tips:

- Writers often find it best to write an introduction after the other parts of the speech are drafted.

- When selecting an attention-getting device, you want to make sure that the option you choose is appropriate to your audience and relevant to your topic.

- Avoid starting a speech by saying your name. Instead choose a good attention-getter and put your self-introduction after it.

- You cannot “wing it” on an introduction. It needs to be carefully planned. Even if you are speaking extemporaneously, consider writing out the entire introduction.

- Avoid saying the specific purpose statement, especially as first words. Instead, shape your specific purpose and thesis statement into a smooth whole.

- don’t begin to talk as you approach the platform or lectern; instead, it’s preferable to reach your destination, pause, smile, and then begin;

- don’t just read your introduction from your notes; instead, it’s vital to establish eye contact in the introduction, so knowing it very well is important;

- don’t talk too fast; instead, go a little slower at the beginning of your speech and speak clearly. This will let your audience get used to your voice.

Here are two examples of a complete introduction, containing all five elements:

Example #1: “My parents knew that something was really wrong when my mom received a call from my home economics teacher saying that she needed to get to the school immediately and pick me up. This was all because of an allergy, something that everyone in this room is either vaguely or extremely familiar with. Hi, I’m Alison. I’m a physician assistant from our Student Health Center and an allergy sufferer. Allergies affect a large number of people, and three very common allergies include pet and animal allergies, seasonal allergies, and food allergies. All three of these allergies take control over certain areas of my life, as all three types affect me, starting when I was just a kid and continuing today. Because of this, I have done extensive research on the subject, and would like to share some of what I’ve learned with all of you today. Whether you just finished your first year of college, you are a new parent, or you have kids that are grown and out of the house, allergies will most likely affect everyone in this room at some point. So, it will benefit you all to know more about them, specifically the three most common sources of allergies and the most recent approaches to treating them.”

Example #2 “When winter is approaching and the days are getting darker and shorter, do you feel a dramatic reduction in energy, or do you sleep longer than usual during the fall or winter months? If you answered “yes” to either of these questions, you may be one of the millions of people who suffer from Seasonal Affective Disorder, or SAD. For most people, these problems don’t cause great suffering in their life, but for an estimated six percent of the United States population these problems can result in major suffering. Hi, I’m Derrick and as a student in the registered nursing program here at State College, I became interested in SAD after learning more about it. I want to share this information with all of you in case you recognize some of these symptoms in yourself or someone you love. In order to fully understand SAD, it’s important to look at the medical definition of SAD, the symptoms of this disorder, and the measures that are commonly used to ease symptoms.”

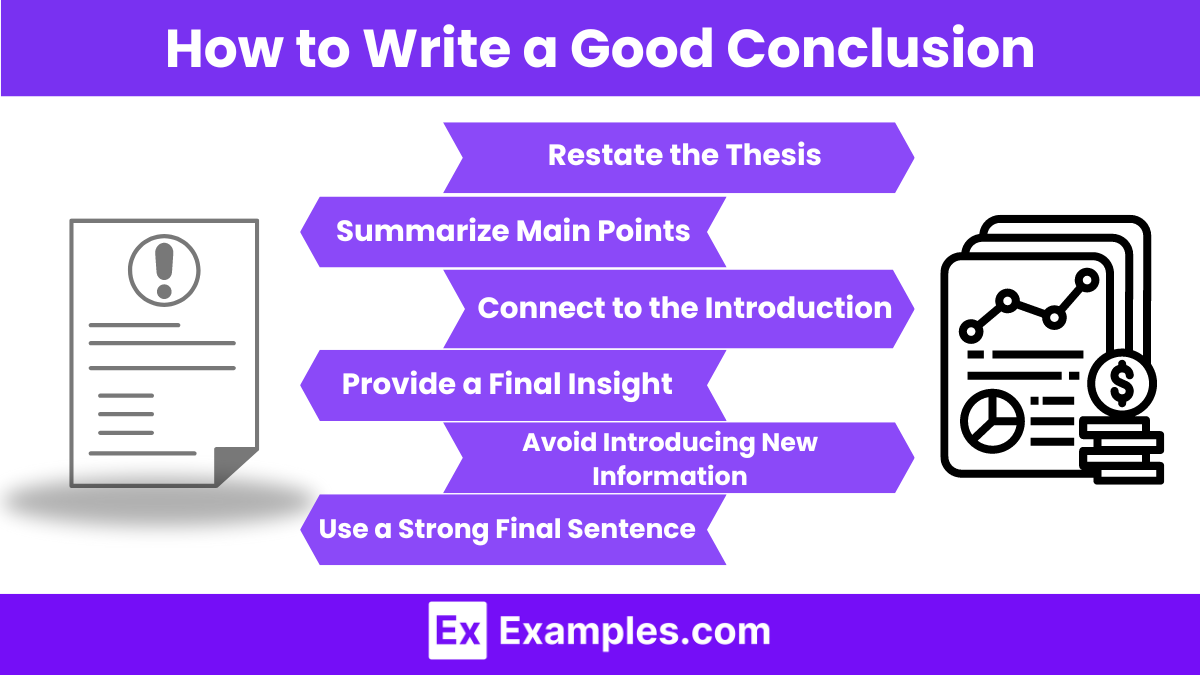

The Three Elements of a Conclusion

Like an introduction, the conclusion has specific elements that you must incorporate in order to make it as strong as possible. Given the nature of these elements and what they do, these should be incorporated into your conclusion in the order they are presented below.

Conclusion Element 1: Signal the End

The first thing a good conclusion should do is to signal the end of a speech. You may be thinking that telling an audience that you’re about to stop speaking is a “no brainer,” but many speakers really don’t prepare their audience for the end. When a speaker just suddenly stops speaking, the audience is left confused and disappointed. Instead, you want to make sure that audiences are left knowledgeable and satisfied with your speech. In a way, it gives them time to begin mentally organizing and cataloging all the points you have made for further consideration later.

The easiest way to signal that it’s the end of your speech is to begin your conclusion with the words, “In conclusion.” Similarly, “In summary” or “To conclude” work just as well.

Conclusion Element 2: Restate Main Points

In the introduction of a speech, you delivered a preview of your main points; now in the conclusion you will deliver a review. One of the biggest differences between written and oral communication is the necessity of repetition in oral communication (the technique of “planned redundancy” again). When you preview your main points in the introduction, effectively make transitions to your main points during the body of the speech, and finally, review the main points in the conclusion, you increase the likelihood that the audience will understand and retain your main points after the speech is over.

Because you are trying to remind the audience of your main points, you want to be sure not to bring up any new material or ideas . For example, if you said, “There are several other issues related to this topic, such as…but I don’t have time for them,” that would just make the audience confused. Or, if you were giving a persuasive speech on wind energy, and you ended with “Wind energy is the energy of the future, but there are still a few problems with it, such as noise and killing lots of birds,” then you are bringing up an argument that should have been dealt with in the body of the speech.

As you progress as a public speaker, you will want to learn to rephrase your summary statement so that it doesn’t sound like an exact repeat of the preview. For example, if your preview was:

“The three arguments in favor of medical marijuana that I will present are that it would make necessary treatments available to all, it would cut down on the costs to law enforcement, and it would bring revenue to state budgets.”

Your summary might be:

“In the minutes we’ve had together, I have shown you that approving medical marijuana in our state will greatly help persons with a variety of chronic and severe conditions. Also, funds spent on law enforcement to find and convict legitimate marijuana users would go down as revenues from medical marijuana to the state budget would go up.”

Conclusion Element 3: Clinchers

The third element of your conclusion is the clincher. This is something memorable with which to conclude your speech. The clincher is sometimes referred to as a concluding device . These are the very last words you will say in your speech, so you need to make them count. It will make your speech more memorable.

In many ways the clincher is like the inverse of the attention getter. You want to start the speech off with something strong, and you want to end the speech with something strong.

To that end, like what we discussed above with attention getters, there are several common strategies you can use to make your clincher strong and memorable: quotation, question, call to action, visualizing the future, refer back to the introduction, or appeal to audience self-interest.

As in starting a speech with a quotation, ending the speech with one allows you to summarize your main point or provoke thought.

I’ll leave you with these inspirational words by Eleanor Roosevelt: “The future belongs to those who believe in the beauty of their dreams.”

Some quotations will inspire your audience to action:

I urge you to sponsor a child in a developing country. Remember the words by Forest Witcraft, who said, “A hundred years from now it will not matter what my bank account was, the sort of house I lived in, or the kind of car I drove. But the world may be different because I was important in the life of a child.”

In this case, the quotation leaves the audience with the message that monetary sacrifices are worth making.

Another way you can end a speech is to ask a rhetorical question that forces the audience to ponder an idea. Maybe you are giving a speech on the importance of the environment, so you end the speech by saying, “Think about your children’s future. What kind of world do you want them raised in? A world that is clean, vibrant, and beautiful—or one that is filled with smog, pollution, filth, and disease?” Notice that you aren’t asking the audience to answer the question verbally or nonverbally, so it’s a rhetorical question.

Call to Action

Calls to action are used specifically in persuasive speeches. It is something you want the audience to do, either immediately or in the future. If a speaker wants to see a new traffic light placed at a dangerous intersection, the clincher would be to ask all the audience members to sign a petition right then and there. For a speech about buying an electric vehicle, the clincher would ask the audience to keep in mind an electric vehicle the “next time they buy a car.”

Another kind of call to action takes the form of a challenge. In a speech on the necessity of fundraising, a speaker could conclude by challenging the audience to raise 10 percent more than their original projections. In a speech on eating more vegetables, you could challenge your audience to increase their current intake of vegetables by two portions daily. In both these challenges, audience members are being asked to go out of their way to do something different that involves effort on their part.

Visualizing the Future

The purpose of a conclusion that refers to the future is to help your audience imagine the future you believe can occur. If you are giving a speech on the development of video games for learning, you could conclude by depicting the classroom of the future where video games are perceived as true learning tools. More often, speakers use visualization of the future to depict how society or how individual listeners’ lives would be different if the audience accepts and acts on the speaker’s main idea. For example, if a speaker proposes that a solution to illiteracy is hiring more reading specialists in public schools, the speaker could ask their audience to imagine a world without illiteracy.

Refer Back to Introduction

This method provides a good sense of closure to the speech. If you started the speech with a startling statistic or fact, such as “Last year, according to the official website of the American Humane Society, four million pets were euthanized in shelters in the United States,” in the end you could say, “Remember that shocking number of four million euthanized pets? With your donation of time or money to the Northwest Georgia Rescue Shelter, you can help lower that number in our region.”

Appeal to Audience Self-Interest

The last concluding device involves a direct reference to your audience. This concluding device is used when a speaker attempts to answer the basic audience question, “What’s in it for me?” (WIIFM). The goal of this concluding device is to spell out the direct benefits a behavior or thought change has for audience members. For example, a speaker talking about stress reduction techniques could have a clincher like this: “If you want to better a better immune system, better heart health, and more happiness, all it takes are following the techniques I talked about today.”

Tips for Conclusions

In terms of the conclusions, be careful NOT to:

- signal the end multiple times. In other words, no “multiple conclusions.”

- ramble: if you signal the end, then end your speech;

- talking as you leave the platform or lectern.

- indicating with facial expression or body language that you were not happy with the speech.

Some examples of conclusions:

Conclusion Example #1: “Anxiety is a complex emotion that afflicts people of all ages and social backgrounds and is experienced uniquely by each individual. We have seen that there are multiple symptoms, causes, and remedies, all of which can often be related either directly or indirectly to cognitive behaviors. While most people don’t enjoy anxiety, it seems to be part of the universal human experience, so realize that you are not alone, but also realize that you are not powerless against it. With that said, the following quote, attributed to an anonymous source, could not be truer, ‘Worry does not relieve tomorrow of its stress; it merely empties today of its strength.’ “

Conclusion Example #2: “I believe you should adopt a rescue animal because it helps stop forms of animal cruelty, you can add a healthy companion to your home, and it’s a relatively simple process that can save a life. Each and every one of you should go to your nearest animal shelter, which may include the Catoosa Citizens for Animal Care, the Humane Society of NWGA in Dalton, the Murray County Humane Society, or the multiple other shelters in the area to bring a new animal companion into your life. I’ll leave you with a paraphrased quote from Deborah Jacobs’s article “Westminster Dog Show Junkie” on Forbes.com: ‘You may start out thinking that you are rescuing the animal, and ultimately find that the animal rescues you right back.’ “

Public Speaking as Performance Copyright © 2023 by Mechele Leon is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

8 Effective Introductions and Powerful Conclusions

Learning objectives.

- Identify the functions of introductions and conclusions.

- Understand the key parts of an introduction and a conclusion.

- Explore techniques to create your own effective introductions and conclusions.

Introductions and conclusions can be challenging. One of the most common complaints novice public speakers have is that they simply don’t know how to start or end a speech. It may feel natural to start crafting a speech at the beginning, but it can be difficult to craft an introduction for something which doesn’t yet exist. Many times, creative and effective ideas for how to begin a speech will come to speakers as they go through the process of researching and organizing ideas. Similarly, a conclusion needs to be well considered and leave audience members with a sense of satisfaction.

In this chapter, we will explore why introductions and conclusions are important, and we will identify various ways speakers can create impactful beginnings and endings. There is not a “right” way to start or end a speech, but we can provide some helpful guidelines that will make your introductions and conclusions much easier for you as a speaker and more effective for your audience.

The Importance of an Introduction

The introduction of a speech is incredibly important because it needs to establish the topic and purpose, set up the reason your audience should listen to you and set a precedent for the rest of the speech. Imagine the first day of a semester long class. You will have a different perception of the course if the teacher is excited, creative and clear about what is to come then if the teacher recites to you what the class is about and is confused or disorganized about the rest of the semester. The same thing goes for a speech. The introduction is an important opportunity for the speaker to gain the interest and trust of the audience.

Overall, an effective introduction serves five functions. Let’s examine each of these.

Gain Audience Attention and Interest

The first major purpose of an introduction is to gain your audience’s attention and get them interested in what you have to say. While your audience may know you, this is your speeches’ first impression! One common incorrect assumption beginning speakers make that people will naturally listen because the speaker is speaking. While many audiences may be polite and not talk while you’re speaking, actually getting them to listen and care about what you are saying is a completely different challenge. Think to a time when you’ve tuned out a speaker because you were not interested in what they had to say or how they were saying it. However, I’m sure you can also think of a time someone engaged you in a topic you wouldn’t have thought was interesting, but because of how they presented it or their energy about the subject, you were fascinated. As the speaker, you have the ability to engage the audience right away.

State the Purpose of Your Speech

The second major function of an introduction is to reveal the purpose of your speech to your audience. Have you ever sat through a speech wondering what the basic point was? Have you ever come away after a speech and had no idea what the speaker was talking about? An introduction is critical for explaining the topic to the audience and justifying why they should care about it. The speaker needs to have an in-depth understanding of the specific focus of their topic and the goals they have for their speech. Robert Cavett, the founder of the National Speaker’s Association, used the analogy of a preacher giving a sermon when he noted, “When it’s foggy in the pulpit, it’s cloudy in the pews.” The specific purpose is the one idea you want your audience to remember when you are finished with your speech. Your specific purpose is the rudder that guides your research, organization, and development of main points. The more clearly focused your purpose is, the easier it will be both for you to develop your speech and your audience to understand your core point. To make sure you are developing a specific purpose, you should be able to complete the sentence: “I want my audience to understand…” Notice that your specific speech purpose is phrased in terms of expected audience responses, not in terms of your own perspective.

Establish Credibility

One of the most researched areas within the field of communication has been Aristotle’s concept of ethos or credibility. First, and foremost, the idea of credibility relates directly to audience perception. You may be the most competent, caring, and trustworthy speaker in the world on a given topic, but if your audience does not perceive you as credible, then your expertise and passion will not matter to them. As public speakers, we need to communicate to our audiences why we are credible speakers on a given topic. James C. McCroskey and Jason J. Teven have conducted extensive research on credibility and have determined that an individual’s credibility is composed of three factors: competence, trustworthiness, and caring/goodwill (McCroskey & Teven, 1999). Competence is the degree to which a speaker is perceived to be knowledgeable or expert in a given subject by an audience member.

The second factor of credibility noted by McCroskey and Teven is trustworthiness or the degree to which an audience member perceives a speaker as honest. Nothing will turn an audience against a speaker faster than if the audience believes the speaker is lying. When the audience does not perceive a speaker as trustworthy, the information coming out of the speaker’s mouth is automatically perceived as deceitful.

Finally, caring/goodwill is the last factor of credibility noted by McCroskey and Teven. Caring/goodwill refers to the degree to which an audience member perceives a speaker as caring about the audience member. As indicated by Wrench, McCroskey, and Richmond, “If a receiver does not believe that a source has the best intentions in mind for the receiver, the receiver will not see the source as credible. Simply put, we are going to listen to people who we think truly care for us and are looking out for our welfare” (Wrench, McCroskey & Richmond, 2008). As a speaker, then, you need to establish that your information is being presented because you care about your audience and are not just trying to manipulate them. We should note that research has indicated that caring/goodwill is the most important factor of credibility. This understanding means that if an audience believes that a speaker truly cares about the audience’s best interests, the audience may overlook some competence and trust issues.

Credibility relates directly to audience perception. You may be the most competent, caring, and trustworthy speaker in the world on a given topic, but if your audience does not perceive you as credible, then your expertise and passion will not matter to them.

Trustworthiness is the degree to which an audience member perceives a speaker as honest.

Caring/goodwill is the degree to which an audience member perceives a speaker as caring about the audience member.

Provide Reasons to Listen

The fourth major function of an introduction is to establish a connection between the speaker and the audience, and one of the most effective means of establishing a connection with your audience is to provide them with reasons why they should listen to your speech. The idea of establishing a connection is an extension of the notion of caring/goodwill. In the chapters on Language and Speech Delivery, we’ll spend a lot more time talking about how you can establish a good relationship with your audience. This relationship starts the moment you step to the front of the room to start speaking.

Instead of assuming the audience will make their own connections to your material, you should explicitly state how your information might be useful to your audience. Tell them directly how they might use your information themselves. It is not enough for you alone to be interested in your topic. You need to build a bridge to the audience by explicitly connecting your topic to their possible needs.

Preview Main Ideas

The last major function of an introduction is to preview the main ideas that your speech will discuss. A preview establishes the direction your speech will take. We sometimes call this process signposting because you’re establishing signs for audience members to look for while you’re speaking. In the most basic speech format, speakers generally have three to five major points they plan on making. During the preview, a speaker outlines what these points will be, which demonstrates to the audience that the speaker is organized.

A study by Baker found that individuals who were unorganized while speaking were perceived as less credible than those individuals who were organized (Baker, 1965). Having a solid preview of the information contained within one’s speech and then following that preview will help a speaker’s credibility. It also helps your audience keep track of where you are if they momentarily daydream or get distracted.

Putting Together a Strong Introduction

Now that we have an understanding of the functions of an introduction, let’s explore the details of putting one together. As with all aspects of a speech, these may change based on your audience, circumstance, and topic. But this will give you a basic understanding of the important parts of an intro, what they do, and how they work together.

Attention Getting Device

An attention-getter is the device a speaker uses at the beginning of a speech to capture an audience’s interest and make them interested in the speech’s topic. Typically, there are four things to consider in choosing a specific attention-getting device:

- Topic and purpose of the speech

- Appropriateness or relevance to the audience

First, when selecting an attention-getting device is considering your speech topic and purpose. Ideally, your attention-getting device should have a relevant connection to your speech. Imagine if a speaker pulled condoms out of his pocket, yelled “Free sex!” and threw the condoms at the audience. This act might gain everyone’s attention, but would probably not be a great way to begin a speech about the economy. Thinking about your topic because the interest you want to create needs to be specific to your subject. More specifically, you want to consider the basic purpose of your speech. When selecting an attention getter, you want to make sure that you select one that corresponds with your basic purpose. If your goal is to entertain an audience, starting a speech with a quotation about how many people are dying in Africa each day from malnutrition may not be the best way to get your audience’s attention. Remember, one of the goals of an introduction is to prepare your audience for your speech . If your attention-getter differs drastically in tone from the rest of your speech the disjointedness may cause your audience to become confused or tune you out completely.

Possible Attention Getters

These will help you start brainstorming ideas for how to begin your speech. While not a complete list, these are some of the most common forms of attention-getters:

- Reference to Current Events

- Historical Reference

- Startling Fact

- Rhetorical Question

- Hypothetical Situation

- Demonstration

- Personal Reference

- Reference to Audience

- Reference to Occasion

Second, when selecting an attention-getting device, you want to make sure you are being appropriate and relevant to your specific audience. Different audiences will have different backgrounds and knowledge, so you should keep your audience in mind when determining how to get their attention. For example, if you’re giving a speech on family units to a group of individuals over the age of sixty-five, starting your speech with a reference to the television show Gossip Girl may not be the best idea because the television show may not be relevant to that audience.

Finally, the last consideration involves the speech occasion. Different occasions will necessitate different tones or particular styles or manners of speaking. For example, giving a eulogy at a funeral will have a very different feel than a business presentation. This understanding doesn’t mean certain situations are always the same, but rather taking into account the details of your circumstances will help you craft an effective beginning to your speech. When selecting an attention-getter, you want to make sure that the attention-getter sets the tone for the speech and situation.

Tones are particular styles or manners of speaking determined by the speech’s occasion.

Link to Topic

The link to the topic occurs when a speaker demonstrates how an attention-getting device relates to the topic of a speech. This presentation of the relationship works to transition your audience from the attention getter to the larger issue you are discussing. Often the attention-getter and the link to the topic are very clear. But other times, there may need to be a more obvious connection between how you began your attention-getting device and the specific subject you are discussing. You may have an amazing attention-getter, but if you can’t connect it to the main topic and purpose of your speech, it will not be as effective.

Significance

Once you have linked an attention-getter to the topic of your speech, you need to explain to your audience why your topic is important and why they should care about what you have to say. Sometimes you can include the significance of your topic in the same sentence as your link to the topic, but other times you may need to spell out in one or two sentences why your specific topic is important to this audience.

Thesis Statement

A thesis statement is a short, declarative sentence that states the purpose, intent, or main idea of a speech. A strong, clear thesis statement is very valuable within an introduction because it lays out the basic goal of the entire speech. We strongly believe that it is worthwhile to invest some time in framing and writing a good thesis statement. You may even want to write a version of your thesis statement before you even begin conducting research for your speech in order to guide you. While you may end up rewriting your thesis statement later, having a clear idea of your purpose, intent, or main idea before you start searching for research will help you focus on the most appropriate material.

Preview of Speech

The final part of an introduction contains a preview of the major points to be covered by your speech. I’m sure we’ve all seen signs that have three cities listed on them with the mileage to reach each city. This mileage sign is an indication of what is to come. A preview works the same way. A preview foreshadows what the main body points will be in the speech. For example, to preview a speech on bullying in the workplace, one could say, “To understand the nature of bullying in the modern workplace, I will first define what workplace bullying is and the types of bullying, I will then discuss the common characteristics of both workplace bullies and their targets, and lastly, I will explore some possible solutions to workplace bullying.” In this case, each of the phrases mentioned in the preview would be a single distinct point made in the speech itself. In other words, the first major body point in this speech would examine what workplace bullying is and the types of bullying; the second major body point in this speech would discuss the characteristics of both workplace bullies and their targets; and lastly, the third body point in this speech would explore some possible solutions to workplace bullying.

Putting it all together

The importance of introductions often leads speakers to work on them first, attending to every detail. While it is good to have some ideas and notes about the intro, specifically the thesis statement, it is often best to wait until the majority of the speech is crafted before really digging into the crafting of the introduction. This timeline may not seem intuitive, but remember, the intro is meant to introduce your speech and set up what is to come. It is difficult to introduce something that you haven’t made yet. This is why working on your main points first can help lead to an even stronger introduction.

Why Conclusions Matter

Willi Heidelbach – Puzzle2 – CC BY 2.0.

As public speaking professors and authors, we have seen many students give otherwise good speeches that seem to fall apart at the end. We’ve seen students end their three main points by saying things such as “OK, I’m done”; “Thank God that’s over!”; or “Thanks. Now what? Do I just sit down?” It’s understandable to feel relief at the end of a speech, but remember that as a speaker, your conclusion is the last chance you have to drive home your ideas. When a speaker opts to end the speech with an ineffective conclusion, or no conclusion at all, the speech loses the energy that’s been created, and the audience is left confused and disappointed. Instead of falling prey to emotional exhaustion, remind yourself to keep your energy up as you approach the end of your speech, and plan ahead so that your conclusion will be an effective one.

Of course, a good conclusion will not rescue a poorly prepared speech. Thinking again of the chapters in a novel, if one bypasses all the content in the middle, the ending often isn’t very meaningful or helpful. So to take advantage of the advice in this chapter, you need to keep in mind the importance of developing a speech with an effective introduction and an effective body. If you have these elements, you will have the foundation you need to be able to conclude effectively. Just as a good introduction helps bring an audience member into the world of your speech, and a good speech body holds the audience in that world, a good conclusion helps bring that audience member back to the reality outside of your speech.

In this section, we’re going to examine the functions fulfilled by the conclusion of a speech. A strong conclusion serves to signal the end of the speech and helps your listeners remember your speech.

Signals the End

The first thing a good conclusion can do is to signal the end of a speech. You may be thinking that showing an audience that you’re about to stop speaking is a “no brainer,” but many speakers don’t prepare their audience for the end. When a speaker just suddenly stops speaking, the audience is left confused and disappointed. Instead, we want to make sure that audiences are left knowledgeable and satisfied with our speeches. In the next section, we’ll explain in great detail about how to ensure that you signal the end of your speech in a manner that is both effective and powerful.

Aids Audience’s Memory of Your Speech

The second reason for a good conclusion stems out of some research reported by the German psychologist Hermann Ebbinghaus back in 1885 in his book Memory: A Contribution to Experimental Psychology (Ebbinghaus, 1885). Ebbinghaus proposed that humans remember information in a linear fashion, which he called the serial position effect. He found an individual’s ability to remember information in a list (e.g. a grocery list, a chores list, or a to-do list) depends on the location of an item on the list. Specifically, he found that items toward the top of the list and items toward the bottom of the list tended to have the highest recall rates. The serial position effect finds that information at the beginning of a list (primacy) and information at the end of the list (recency) are easier to recall than information in the middle of the list.

So what does this have to do with conclusions? A lot! Ray Ehrensberger wanted to test Ebbinghaus’ serial position effect in public speaking. Ehrensberger created an experiment that rearranged the ordering of a speech to determine the recall of information (Ehrensberger, 1945). Ehrensberger’s study reaffirmed the importance of primacy and recency when listening to speeches. In fact, Ehrensberger found that the information delivered during the conclusion (recency) had the highest level of recall overall.

Steps of a Conclusion

Matthew Culnane – Steps – CC BY-SA 2.0.

In the previous sections, we discussed the importance a conclusion has on a speech. In this section, we’re going to examine the three steps to building an effective conclusion.

Restatement of the Thesis

Restating a thesis statement is the first step to a powerful conclusion. As we explained earlier, a thesis statement is a short, declarative sentence that states the purpose, intent, or main idea of a speech. When we restate the thesis statement at the conclusion of our speech, we’re attempting to reemphasize what the overarching main idea of the speech has been. Suppose your thesis statement was, “I will analyze Barack Obama’s use of lyricism in his July 2008 speech, ‘A World That Stands as One.’” You could restate the thesis in this fashion at the conclusion of your speech: “In the past few minutes, I have analyzed Barack Obama’s use of lyricism in his July 2008 speech, ‘A World That Stands as One.’” Notice the shift in tense. The statement has gone from the future tense (this is what I will speak about) to the past tense (this is what I have spoken about). Restating the thesis in your conclusion reminds the audience of the main purpose or goal of your speech, helping them remember it better.

Review of Main Points

After restating the speech’s thesis, the second step in a powerful conclusion is to review the main points from your speech. One of the biggest differences between written and oral communication is the necessity of repetition in oral communication. When we preview our main points in the introduction, effectively discuss and make transitions to our main points during the body of the speech, and review the main points in the conclusion, we increase the likelihood that the audience will retain our main points after the speech is over.

In the introduction of a speech, we deliver a preview of our main body points, and in the conclusion, we deliver a review . Let’s look at a sample preview:

In order to understand the field of gender and communication, I will first differentiate between the terms biological sex and gender. I will then explain the history of gender research in communication. Lastly, I will examine a series of important findings related to gender and communication.

In this preview, we have three clear main points. Let’s see how we can review them at the conclusion of our speech:

Today, we have differentiated between the terms biological sex and gender, examined the history of gender research in communication, and analyzed a series of research findings on the topic.

In the past few minutes, I have explained the difference between the terms “biological sex” and “gender,” discussed the rise of gender research in the field of communication, and examined a series of groundbreaking studies in the field.

Notice that both of these conclusions review the main points initially set forth. Both variations are equally effective reviews of the main points, but you might like the linguistic turn of one over the other. Remember, while there is a lot of science to help us understand public speaking, there’s also a lot of art as well. You are always encouraged to choose the wording that you think will be most effective for your audience.

Concluding Device

The final part of a powerful conclusion is the concluding device. A concluding device is a final thought you want your audience members to have when you stop speaking. It also provides a definitive sense of closure to your speech. One of the authors of this text often makes an analogy between a gymnastics dismount and the concluding device in a speech. Just as a gymnast dismounting the parallel bars or balance beam wants to stick the landing and avoid taking two or three steps, a speaker wants to “stick” the ending of the presentation by ending with a concluding device instead of with, “Well, umm, I guess I’m done.” Miller observed that speakers tend to use one of ten concluding devices when ending a speech (Miller, 1946). The rest of this section is going to examine these ten concluding devices and one additional device that we have added.

Conclude with a Challenge

The first way that Miller found that some speakers end their speeches is with a challenge. A challenge is a call to engage in some activity that requires a special effort. In a speech on the necessity of fund-raising, a speaker could conclude by challenging the audience to raise 10 percent more than their original projections. In a speech on eating more vegetables, you could challenge your audience to increase their current intake of vegetables by two portions daily. In both of these challenges, audience members are being asked to go out of their way to do something different that involves effort on their part.

Conclude with a Quotation

A second way you can conclude a speech is by reciting a quotation relevant to the speech topic. When using a quotation, you need to think about whether your goal is to end on a persuasive note or an informative note. Some quotations will have a clear call to action, while other quotations summarize or provoke thought. For example, let’s say you are delivering an informative speech about dissident writers in the former Soviet Union. You could end by citing this quotation from Alexander Solzhenitsyn: “A great writer is, so to speak, a second government in his country. And for that reason, no regime has ever loved great writers” (Solzhenitsyn, 1964). Notice that this quotation underscores the idea of writers as dissidents, but it doesn’t ask listeners to put forth the effort to engage in any specific thought process or behavior. If, on the other hand, you were delivering a persuasive speech urging your audience to participate in a very risky political demonstration, you might use this quotation from Martin Luther King Jr.: “If a man hasn’t discovered something that he will die for, he isn’t fit to live” (King, 1963). In this case, the quotation leaves the audience with the message that great risks are worth taking, that they make our lives worthwhile, and that the right thing to do is to go ahead and take that great risk.

Conclude with a Summary

When a speaker ends with a summary, they are simply elongating the review of the main points. While this may not be the most exciting concluding device, it can be useful for information that was highly technical or complex or for speeches lasting longer than thirty minutes. Typically, for short speeches (like those in your class), this summary device should be avoided.

Conclude by Visualizing the Future

The purpose of a conclusion that refers to the future is to help your audience imagine the future you believe can occur. If you are giving a speech on the development of video games for learning, you could conclude by depicting the classroom of the future where video games are perceived as true learning tools and how those tools could be utilized. More often, speakers use visualization of the future to depict how society would be, or how individual listeners’ lives would be different if the speaker’s persuasive attempt worked. For example, if a speaker proposes that a solution to illiteracy is hiring more reading specialists in public schools, the speaker could ask her or his audience to imagine a world without illiteracy. In this use of visualization, the goal is to persuade people to adopt the speaker’s point of view. By showing that the speaker’s vision of the future is a positive one, the conclusion should help to persuade the audience to help create this future.

Conclude with an Appeal for Action

Probably the most common persuasive concluding device is the appeal for action or the call to action. In essence, the appeal for action occurs when a speaker asks their audience to engage in a specific behavior or change in thinking. When a speaker concludes by asking the audience “to do” or “to think” in a specific manner, the speaker wants to see an actual change. Whether the speaker appeals for people to eat more fruit, buy a car, vote for a candidate, oppose the death penalty, or sing more in the shower, the speaker is asking the audience to engage in action.

One specific type of appeal for action is the immediate call to action. Whereas some appeals ask for people to engage in behavior in the future, an immediate call to action asks people to engage in behavior right now. If a speaker wants to see a new traffic light placed at a dangerous intersection, he or she may conclude by asking all the audience members to sign a digital petition right then and there, using a computer the speaker has made available ( http://www.petitiononline.com ). Here are some more examples of immediate calls to action:

- In a speech on eating more vegetables, pass out raw veggies and dip at the conclusion of the speech.

- In a speech on petitioning a lawmaker for a new law, provide audience members with a prewritten e-mail they can send to the lawmaker.

- In a speech on the importance of using hand sanitizer, hand out little bottles of hand sanitizer and show audience members how to correctly apply the sanitizer.

- In a speech asking for donations for a charity, send a box around the room asking for donations.

These are just a handful of different examples we’ve seen students use in our classrooms to elicit an immediate change in behavior. These immediate calls to action may not lead to long-term change, but they can be very effective at increasing the likelihood that an audience will change behavior in the short term.

Conclude by Inspiration

By definition, the word inspire means to affect or connect with someone emotionally. Both affect and arouse have strong emotional connotations. The ultimate goal of an inspiration concluding device is similar to an “appeal for action,” but the ultimate goal is more lofty or ambiguous. The goal is to stir someone’s emotions in a specific manner. Maybe a speaker is giving an informative speech about the prevalence of domestic violence in our society today. That speaker could end the speech by reading Paulette Kelly’s powerful poem “I Got Flowers Today.” “I Got Flowers Today” is a poem that evokes strong emotions because it’s about an abuse victim who received flowers from her abuser every time she was victimized. The poem ends by saying, “I got flowers today… Today was a special day. It was the day of my funeral. Last night he killed me” (Kelly, 1994).

Conclude with Advice

The next concluding device is one that should be used primarily by speakers who are recognized as expert authorities on a given subject. Advice is a speaker’s opinion about what should or should not be done. The problem with opinions is that everyone has one, and one person’s opinion is not necessarily any more correct than another’s. There needs to be a really good reason for your opinion. Your advice should matter to your audience. If, for example, you are an expert in nuclear physics, you might conclude a speech on energy by giving advice about the benefits of nuclear energy.

Conclude by Proposing a Solution

Another way a speaker can conclude a speech powerfully is to offer a solution to the problem discussed within a speech. For example, perhaps a speaker has been discussing the problems associated with the disappearance of art education in the United States. The speaker could then propose a solution for creating more community-based art experiences for school children as a way to fill this gap. Although this can be a compelling conclusion, a speaker must ask themselves whether the solution should be discussed in more depth as a stand-alone main point within the body of the speech so that audience concerns about the proposed solution may be addressed.

Conclude with a Question

Another way you can end a speech is to ask a rhetorical question that forces the audience to ponder an idea. Maybe you are giving a speech on the importance of the environment, so you end the speech by saying, “Think about your children’s future. What kind of world do you want them raised in? A world that is clean, vibrant, and beautiful—or one that is filled with smog, pollution, filth, and disease?” Notice that you aren’t asking the audience to verbally or nonverbally answer the question. The goal of this question is to force the audience into thinking about what kind of world they want for their children.

Conclude with a Reference to Audience