- Deakin University

- Learning and Teaching

Critical reflection for assessments and practice

- Critical reflection

Critical reflection for assessments and practice: Critical reflection

- Reflective practice

- How to reflect

- Critical reflection writing

- Recount and reflect

What is critical reflection?

"We don't see things as they are, we see them as we are".

Anais Nin - Seduction of the Minotour (1961)

Critical reflection can be defined in different ways but at core it's an extension of critical thinking. It involves learning from everyday experiences and situations. You need to ask questions of yourself and about your actions to better understand why things happened.

Critical reflection is active not passive

Critical reflection is active personal learning and development where you take time to engage with your thoughts, feelings and experiences. It helps us examine the past, look at the present and then apply learnings to future experiences or actions.

Critical reflection is also focused on a central question, “Can I articulate the doing that is shaped by the knowing.” What this means is that critical reflection and reflective practice are tied together. You can use critical reflection as a tool to analyse your reflections more critically which allows you to evaluate , inform and continually change your practice .

Critical reflection: think, feel, and do

The events, experiences or interactions you choose to critically reflect on can be either positive or negative. They may be an interesting interaction or an everyday occurrence.

No matter what it is, when you are critically reflecting it is a good idea to think about how the experience, event or interaction made you:

And what you can do to change your practice.

What you think, feel and do as a result of critical reflective learning will shape the what, how and why of future behaviours, actions and work.

Critical reflection: what influences your practice

Critical reflection also means thinking about why you make certain choices in your practice. Sometimes this may feel uncomfortable because it can highlight your assumptions, biases, views and behaviours. But it is important to take the time to think about how your own experiences influence your study, your work and your life in general. This involves you recognising how your perspectives and values influence the decisions you make.

Click on the plus (+) icons beneath each thought bubble to view some example assumptions that may influence practice.

Text version

Activity overview

This interactive hotspot activity provides examples of assumptions that may influence practice. The hotspots are displayed as plus (+) icons that can be clicked to reveal the examples, as follows

Assumption: People have their cameras and mics off for digital meetings to avoid active involvement.

Possibility: People may have low bandwidth and/or other people in their space and either cannot share camera view, or respect the privacy of others.

Assumption: Everyone in your professional workplace will be digitally literate.

Possibility: People have had differing experience of working with digital tools and in online environments.

Assumption: Having people work from home will cause a drop in productivity and loss of workplace culture.

Possibility: Productivity will maintain or increase. A new digital culture of connection emerges.

Assumption: All students hate group work.

Possibility: Some students prefer collaboration. They are stimulated by brainstorming, creating solutions and putting together assignments in a group.

Assumption: After emailing my work group with the finished report everyone will be aware of the project’s goals and outcomes, ready to discuss at our next team meeting.

Assumption: People who are quiet and don't ask questions in my class are having no problems with the content.

Assumption: Everyone can jump online at anytime to use the self-service portal.

Scaffolded approach to think, feel, and do in your practice

There is quite a bit to keep in mind with using critical reflective to shape your practice. Making critical reflection part of your everyday is easier if you have a framework to refer to.

This critical reflection and reflective practice framework is a handy resource for you to keep. Download the framework and use it as a prompt when doing critical reflective assessments at uni or as part of developing reflective practice in your work.

DOWNLOAD FRAMEWORK (PDF, 1MB)

Critical reflection includes research and evidence-base

Why you need to use academic literature in critical reflections can be hard to understand as you may feel that you don’t need to draw on other sources when discussing your own experiences. Critical reflections involve both personal perspective and theory = the need to use academic literature.

Personal plus theory underpins reflective practice

Keep in mind that when you are at university there is an expectation that you support the points you make by referring to information from relevant, credible sources.

You also need to think about how theories can influence and inform your practice. Reflective practice relies on evidence, with research informing your reflection and what changes to practice you intend to put into play. This means you will need to use academic literature to support what you are saying in your reflection.

Learn more about including literature in your writing. Deakin’s academic skills guide on Using Sources will help you weave academic literature into your critical reflection assessments. It’s focused on supporting evidence in your writing.

- << Previous: Reflective practice

- Next: How to reflect >>

- Last Updated: Jun 28, 2024 4:06 PM

- URL: https://deakin.libguides.com/critical-reflection-guide

- Rasmussen University

- Transferable Skills*

- Critical Thinking

- Steps 1 & 2: Reflection and Analysis

Critical Thinking: Steps 1 & 2: Reflection and Analysis

- Step 3: Acquisition of Information

- Step 4: Creativity

- Step 5: Structuring Arguments

- Step 6: Decision Making

- Steps 7 & 8: Commitment and Debate

- In the Classroom

- In the Workplace

Identify, Reflect, and Analyze

- Step 1: Reflect

- Step 2: Analyze

Step 1: Reflecting on the Issue, Problem, or Task

Reflection is an important early step in critical thinking. There are various kinds of reflection that promote deeper levels of critical thinking (click on the table to view larger):

Brockbank, A., & McGill, I. (2007). Facilitating Reflective Learning in Higher Education . Maidenhead, England: McGraw-Hill Education.

Ask yourself questions to identify the nature and essence of the issue, problem, or task. Why are you examining this subject? Why is it important that you solve this problem?

Reflective Thinking

Game: There is 1 random word below. Use it as inspiration to think of something it would be interesting if we never had in this world.

Challenge: For extra challenge, reply to someone else’s suggestion and predict how life would be different if it never was. Try and think big. Think about profound and extreme ways in which the world may be different.

Strategy: We often think about how life would be better if only we had X (X being something we would quite like). It can be a fun way to pass the time but it tends to involve adding something new to our lives. Let's go the other way around and subtract something instead. But instead of something desirable it will be something that we take for granted, something simple. Then trying to predict how it would have a profound effect changing the world around us becomes an act in following a chain reaction of influences. Creativity often involves having keen insights into how everything influences and affects everything around it in often unobvious ways. This little game is a good way to practice that thinking.

- << Previous: Steps to Critical Thinking

- Next: Step 3: Acquisition of Information >>

- Last Updated: Apr 24, 2024 8:30 AM

- URL: https://guides.rasmussen.edu/criticalthinking

Parent Portal

Extracurriculars

Reflective Practice: A Critical Thinking Study Method

In the ever-evolving landscape of education and self-improvement, the quest for effective study techniques is unceasing. One such technique that has gained substantial recognition is reflective practice. Rooted in the realms of experiential learning and critical thinking, reflective practice goes beyond pure memorisation and aims to foster a deeper understanding of concepts.

In this article, we’ll explore the essence of reflective practice as a study technique and how it can be harnessed to elevate the learning experience.

What is Reflective Learning?

The concept of reflective practice has been explored by many researchers , including John Dewey. His work states that reflective learning is more than just a simple review of study material. It's an intentional process that encourages students to examine their experiences, thoughts, and actions. This process aims to uncover insights and connections that lead to enhanced comprehension. The essence of reflective practice lies in its ability to turn information consumption into an active cognitive exercise that leads to the understanding and retention of information.

At its core, reflective learning involves several key steps:

- Experience : the first step to reflective learning is to engage with the material, whether it's a lecture, a reading, a discussion, or any other learning experience.

- Reflection : after engaging with the material to be understood it’s important to take time to ponder and evaluate the experience. This involves questioning what was learnt, why it was learnt, and how it fits into the larger context of the subject matter.

- Analysis : once the information has been questioned, it’s important to dive deeper into the experience by analysing the components, concepts, and connections. Explore how the new information relates to what you already know.

- Synthesis : it’s then time to integrate the new knowledge with your existing understanding, creating a cohesive mental framework that bridges the gaps between concepts.

- Application : it’s then important to consider how this newly acquired knowledge can be applied in real-life scenarios or to solve problems, thus enhancing its practical relevance.

- Feedback and adjustment : the final step is to reflect on the effectiveness of the learning process. What worked well? What could be improved? This step encourages continuous refinement of your study techniques.

The Benefits of Reflective Practice

There are a variety of benefits that reflective practice can offer students as they attempt to understand and retain new information, making the studying process much more effective.

Deeper Understanding

Reflective practice prompts students to go beyond surface-level comprehension. By dissecting and analysing the material, students are able to gain a more profound understanding of the subject matter. When engaging in reflective practice, you're not just skimming the surface of the information; you're actively delving into the core concepts, identifying underlying relationships, and unravelling the intricacies of the topic.

Imagine you're reading a challenging chapter in your history textbook.Rather than quickly flipping through the pages, using reflective practice would mean taking a moment to think about why this historical event is important. You might wonder how it connects to events you've learnt about before, and how it might have shaped the world we live in today. By taking the time to really think about these things, you'll start to see patterns and connections that make the topic much more interesting and understandable.

Critical Thinking

This technique nurtures critical thinking skills by encouraging individuals to evaluate and question information, enhancing their ability to think logically and make informed judgements. Critical thinking involves analysing information, assessing its validity and reliability, and discerning its relevance. Reflective practice compels you to question the material, explore its underlying assumptions, and consider different perspectives.

If we once again use history as an example, a reflective practice will prompt you to question the biases of the sources, evaluate the motivations of the individuals involved, and critically assess the long-term impact of the event. These analytical skills extend beyond academia, enriching your ability to evaluate information in everyday situations and make informed decisions.

Long-Tern Retention

Engaging with material on a reflective level enhances memory retention. When you actively connect new information to existing knowledge, it becomes more ingrained in your memory. This process is often referred to as ‘elaborative rehearsal’, where you link new information to what you already know, creating meaningful connections that make the material easier to recall in the future.

For example, when learning a new language, reflecting on how certain words or phrases relate to your native language or personal experiences can help you remember them more effectively.

Personalisation

Reflective practice is adaptable to various learning styles. It allows students to tailor their approach to fit their strengths, preferences, and pace. This is because reflective practice is a self-directed process, allowing you to shape it in ways that align with your individual learning style .

For instance, if you're a visual learner, you might create concept maps or diagrams during your reflective sessions to visually represent the connections between ideas. However, if you're an auditory learner, you might prefer recording your reflections as spoken thoughts.

Real-Life Application

By encouraging students to consider how knowledge can be applied practically, reflective practice bridges the gap between theoretical learning and real-world scenarios. This benefit is especially valuable as you are preparing to tackle challenges beyond the classroom .

For example, if you're studying economics, reflective practice prompts you to think about how the principles you're learning can be applied to analyse current economic issues or make informed personal financial decisions.

Self-Awareness

Reflective practice cultivates self-awareness, as students learn about their thought processes, learning preferences, and areas of growth. As you reflect on your learning experiences, you become attuned to how you absorb information, what strategies work best for you, and where you might encounter challenges.

How to Apply Reflective Learning

Reflective learning can easily be integrated into your study routine, all it takes is a bit of planning, time and patience in order to get used to it.

Set Aside Time

Dedicate specific time slots for reflective practice in your study routine. This could be after a lecture, reading a chapter, or completing an assignment.

Allocating dedicated time for reflective practice ensures that you prioritise this valuable technique in your learning process. After engaging with new material, take a few moments to step back and contemplate what you've learnt. This practice prevents information overload and provides an opportunity for your brain to process and make connections.

For example, if you've just attended a lecture, set aside 10–15 minutes afterwards, or as soon as you can, to reflect on the main points, key takeaways, and any questions that arose during the session.

Create a Reflection Space

Creating a conducive environment for reflection is crucial. Find a quiet and comfortable space where you can concentrate without interruptions. Having a designated journal or digital note-taking app allows you to capture your thoughts systematically.

A voice recorder can be particularly helpful for those who prefer verbalising their reflections.

The act of recording your reflections also adds a layer of accountability, making it easier to track your progress over time.

Ask Thoughtful Questions

Asking insightful questions is at the heart of reflective practice. Challenge yourself to go beyond the superficial understanding of a concept by posing thought-provoking inquiries.

For instance, if you've just read a chapter in a textbook, consider why the concepts covered are significant in the larger context of the subject. Reflect on how these ideas relate to your prior knowledge and experiences. Additionally, explore real-world scenarios where you could apply the newfound knowledge. This will enhance your comprehension and problem-solving skills.

Review Regularly

Revisiting your reflections is akin to reviewing your study notes. Regularly returning to your reflections reinforces your understanding of the material. Over time, you might notice patterns in your thinking, areas where you consistently struggle, or subjects that spark your curiosity.

This insight can guide your future study sessions and help you allocate more time to topics that need a little more attention.

Engage in Dialogue

Sharing your reflections with others opens the door to valuable discussions. Conversations with peers, parents, teachers, or mentors offer different viewpoints and insights you might not have considered on your own. Explaining your thoughts aloud also helps consolidate your understanding, as articulating concepts requires a deeper level of comprehension.

Ultimately, engaging in dialogue enriches your learning experience and enables you to refine your thoughts through constructive feedback.

A Reflective Learner is A Life Long Learner

Reflective learning has the remarkable ability to cultivate a love for learning and foster a lifelong learner mindset.

This method will encourage you to actively engage with your learning experiences, critically examine your knowledge, and apply insights to real-life situations. This process of examination, questioning, and application will nurture intrinsic motivation , curiosity, and ownership of learning.

This will also empower you to view challenges as opportunities for growth and to embrace a mindset of continuous improvement. This joy of discovery, combined with collaborative interactions, can also strengthen your sense of community and amplify the satisfaction you derive from the learning process.

Ultimately, reflective practice instils a belief in the value of lifelong learning, encouraging you to seek out new knowledge, explore diverse fields, and continuously evolve intellectually and personally.

Download Your Free Printable Homeschool Planner

Everything you need to know about setting up your homeschooling schedule with a free printable PDF planner.

Other articles

- The Open University

- Accessibility hub

- Guest user / Sign out

- Study with The Open University

My OpenLearn Profile

Personalise your OpenLearn profile, save your favourite content and get recognition for your learning

About this free course

Become an ou student, download this course, share this free course.

Start this free course now. Just create an account and sign in. Enrol and complete the course for a free statement of participation or digital badge if available.

4 Models of reflection – core concepts for reflective thinking

The theories behind reflective thinking and reflective practice are complex. Most are beyond the scope of this course, and there are many different models. However, an awareness of the similarities and differences between some of these should help you to become familiar with the core concepts, allow you to explore deeper level reflective questions, and provide a way to better structure your learning.

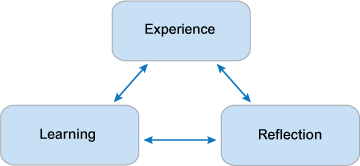

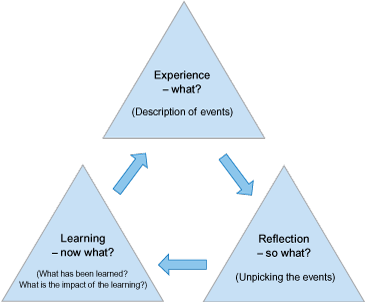

Boud’s triangular representation (Figure 2) can be viewed as perhaps the simplest model. This cyclic model represents the core notion that reflection leads to further learning. Although it captures the essentials (that experience and reflection lead to learning), the model does not guide us as to what reflection might consist of, or how the learning might translate back into experience. Aligning key reflective questions to this model would help (Figure 3).

This figure contains three boxes, with arrows linking each box. In the boxes are the words ‘Experience’, ‘Learning’ and ‘Reflection’.

This figure contains three triangles, with arrows linking each one. In the top triangle is the text ‘Experience - what? (Description of events)’. In the bottom-left triangle is the text ‘Learning - now what? (What has been learned? What is the impact of the learning?’. In the bottom-right triangle is the text ‘Reflection - so what? (Unpicking the events)’.

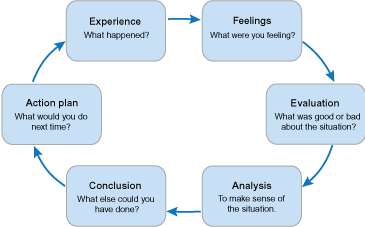

Gibbs’ reflective cycle (Figure 4) breaks this down into further stages. Gibbs’ model acknowledges that your personal feelings influence the situation and how you have begun to reflect on it. It builds on Boud’s model by breaking down reflection into evaluation of the events and analysis and there is a clear link between the learning that has happened from the experience and future practice. However, despite the further break down, it can be argued that this model could still result in fairly superficial reflection as it doesn’t refer to critical thinking or analysis. It doesn’t take into consideration assumptions that you may hold about the experience, the need to look objectively at different perspectives, and there doesn’t seem to be an explicit suggestion that the learning will result in a change of assumptions, perspectives or practice. You could legitimately respond to the question ‘what would you do or decide next time?’ by answering that you would do the same, but does that constitute deep level reflection?

This figure shows a number of boxes containing text, with arrows linking the boxes. From the top left (and going clockwise) the boxes display the following text: ‘Experience. What happened?’; ‘Feeling. What were you feeling?’; ‘Evaluation. What was good or bad about the situation?’; ‘Analysis. To make sense of the situation’; ‘Conclusion. What else could you have done?’; ‘Action plan. What would you do next time?’.

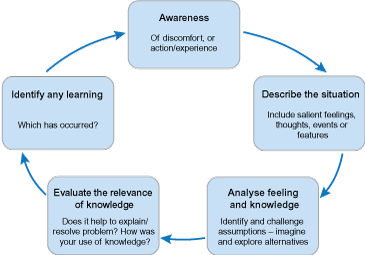

Atkins and Murphy (1993) address many of these criticisms with their own cyclical model (Figure 5). Their model can be seen to support a deeper level of reflection, which is not to say that the other models are not useful, but that it is important to remain alert to the need to avoid superficial responses, by explicitly identifying challenges and assumptions, imagining and exploring alternatives, and evaluating the relevance and impact, as well as identifying learning that has occurred as a result of the process.

This figure shows a number of boxes containing text, with arrows linking the boxes. From the top (and going clockwise) the boxes display the following text: ‘Awareness. Of discomfort, or action/experience’; ‘Describe the situation. Include saliant feelings, thoughts, events or features’; ‘Analyse feeling and knowledge. Identify and challenge assumptions - imagine and explore alternatives’; ‘Evaluate the relevance of knowledge. Does it help to explain/resolve the problem? How was your use of knowledge?’; ‘Identify any learning. Which has occurred?’

You will explore how these models can be applied to professional practice in Session 7.

Critical Thinking and Evaluating Information

- Introduction

- What Is Critical Thinking?

- Words Of Wisdom

Critical Thinking and Reflective Judgment

Stages of reflective judgment.

- Problem Solving Skills

- Critical Reading

- Critical Writing

- Use the CRAAP Test

- Evaluating Fake News

- Explore Different Viewpoints

- The Peer-Review Process

- Critical ThinkingTutorials

- Books on Critical Thinking

- Explore More With These Links

Live Chat with a Librarian 24/7

Text a Librarian at 912-600-2782

What is Reflective Judgment?

Critical thinking is "thinking about thinking." To apply critical thinking skills, skills to a particular problem implies a reflective sensibility and the capacity for reflective judgment (King & Kitchener, 1994). The simplest description of reflective judgment is that of ‘taking a step back.’ ( Dwyer, 2017)

Reflective judgment is the ability to evaluate and process information in order to draw plausible conclusions.

It can be defined more concisely in the video below:

Video Source and Credit: Bill Garris, Ph.D

| Stage | Developmental Period | View Of Knowledge | Concept of Justification | Statement |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Pre-Reflective Reasoning | Knowledge exists absolutely and concretely. It can be obtained by direct observation. | No verification is needed. There are no alternate beliefs to be perceived | "I know what I have seen." |

| 2 | Pre-Reflective Reasoning | Knowledge is assumed to be absolutely certain or certain but not immediately available. Knowledge can be obtained directly through the senses (as in direct observation) or via authority figures. | Most issues are assumed to have a right answer, so there is little or no conflict in making decisions about disputed issues. | “If it is on the news, it has to be true.” |

| 3 | Pre-Reflective Reasoning | Knowledge is assumed to be absolutely certain or temporarily uncertain. In areas of temporary uncertainty, only personal beliefs can be known until absolute knowledge is obtained. In areas of absolute certainty, knowledge is obtained from authorities. | In areas in which certain answers exist, beliefs are justified by reference to authorities' views. In areas in which answers do not exist, beliefs are defended as personal opinions since the link between evidence and beliefs is unclear. | "When there is evidence that people can give to convince everybody one way or another, then it will be knowledge, until then, it's just a guess." |

| 4 | Quasi-Reflective Reasoning | Knowledge is uncertain and knowledge claims are idiosyncratic to the individual since situational variables (such as incorrect reporting of data, data lost over time, or disparities in access to information) dictate that knowing always involves an element of ambiguity. | Beliefs are justified by giving reasons and using evidence, but the arguments and choice of evidence are idiosyncratic (for example, choosing evidence that fits an established belief). | "I'd be more inclined to believe evolution if they had proof. It's just like the pyramids: I don't think we'll ever know. Who are you going to ask? No one was there." |

| 5 | Quasi-Reflective Reasoning | Knowledge is contextual and subjective since it is filtered through a person's perceptions and criteria for judgment. Only interpretations of evidence, events, or issues may be known. | Beliefs are justified within a particular context by means of the rules of inquiry for that context and by the context-specific interpretations as evidence. Specific beliefs are assumed to be context specific or are balanced against other interpretations, which complicates (and sometimes delays) conclusions. | "People think differently and so they attack the problem differently. Other theories could be as true as my own, but based on different evidence." |

| 6 | Reflective Reasoning | Knowledge is constructed into individual conclusions about ill-structured problems on the basis of information from a variety of sources. Interpretations that are based on evaluations of evidence across contexts and on the evaluated opinions of reputable others can be known. | Beliefs are justified by comparing evidence and opinion from different perspectives on an issue or across different contexts and by constructing solutions that are evaluated by criteria such as the weight of the evidence, the utility of the solution, and the pragmatic need for action. | "It's very difficult in this life to be sure. There are degrees of sureness. You come to a point at which you are sure enough for a personal stance on the issue." |

| 7 | Reflective Reasoning | Knowledge is the outcome of a process of reasonable inquiry in which solutions to ill-structured problems are constructed. The adequacy of those solutions is evaluated in terms of what is most reasonable or probable according to the current evidence, and it is reevaluated when relevant new evidence, perspectives, or tools of inquiry become available. | Beliefs are justified probabilistically on the basis of a variety of interpretive considerations, such as the weight of the evidence, the explanatory value of the interpretations, the risk of erroneous conclusions, the consequences of alternative judgments, and the interrelationships of these factors. Conclusions are defended as representing the most complete, plausible, or compelling understanding of an issue on the basis of the available evidence. | "One can judge an argument by how well thought-out the positions are, what kinds of reasoning and evidence are used to support it, and how consistent the way one argues on this topic is as compared with other topics." |

Source: King, P.M. & Kitchener, K.S. (1994). Developing Reflective Judgment. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers, pp. 14-16. Source hosted by Univerity of Michigan

- << Previous: What Is Critical Thinking?

- Next: Problem Solving Skills >>

- Last Updated: Mar 25, 2024 8:18 AM

- URL: https://libguides.coastalpines.edu/thinkcritically

A Step-by-Step Guide to Critical Reflection

Introduction

Critical reflection is the process of analyzing and evaluating an experience in order to gain a deeper understanding of oneself and the situation. It involves taking a step back, examining the experience from different perspectives, and considering the different factors that influenced the outcome. Critical reflection helps us to learn from our experiences and make better choices in the future.

The importance of critical reflection cannot be overstated. It is a vital tool for personal and professional development, and it is essential for anyone who wants to grow and improve. This guide will provide a step-by-step process for practicing critical reflection, as well as tips and strategies for making the most of the process.

If you’re ready to start your journey of self-improvement and growth, this guide is for you. By following the steps outlined here and investing time and effort into the process of critical reflection, you can gain a deeper understanding of yourself, your experiences, and the world around you. So let’s get started!

What is Critical Reflection?

Critical reflection is a process of analyzing and evaluating a particular experience, situation, or problem in a thoughtful and structured way. It involves identifying your own assumptions and biases, as well as considering alternative perspectives and potential areas for improvement.

Definition of Critical Reflection

Simply put, critical reflection is a process of thinking deeply and critically about a particular experience or issue in order to gain insight and improve future outcomes. It is a self-directed and ongoing process that encourages individuals to evaluate their own actions, beliefs, and assumptions in a non-judgmental way.

Characteristics of Critical Reflection

Critical reflection is characterized by several important qualities, including:

- Critical thinking: It involves analyzing and evaluating information in a thoughtful and objective manner.

- Self-awareness: It requires individuals to be aware of their own assumptions and biases, as well as the impact of their actions on others.

- Open-mindedness: It encourages individuals to consider alternative perspectives and ideas, rather than relying solely on their own experiences and beliefs.

- Reflection: It involves taking the time to reflect on a particular experience or issue in order to gain insight and improve performance.

Process of Critical Reflection

Critical reflection is a process that involves several steps to analyze an experience or problem. Below is a step-by-step guide for critical reflection:

Identify the problem or experience to reflect on: The first step in critical reflection is to identify a particular experience or problem to reflect on. This could be a work-related issue, a personal experience, or a situation that occurred in your community.

Describe the experience in detail: Once you have identified the experience or problem to reflect on, the next step is to describe it in detail. This involves identifying the key players, events, and outcomes. Write down your thoughts, feelings, and reactions to the experience.

Analyze the experience: In this step, you need to analyze the experience by reflecting on the following questions: What happened? Why did it happen? What did you think and feel about it? What were the consequences of your actions? What were the consequences of others’ actions? Use critical thinking skills to examine the experience from multiple perspectives.

Evaluate your own role and actions: After analyzing the experience, evaluate your own role and actions. Ask yourself: What did I do well? What actions could I have done differently? What are the implications of my actions for myself and others? This step requires you to be honest and self-reflective.

Identify alternative actions: After evaluating your own role and actions, think about alternative actions that you could have taken. Ask yourself: What could I have done differently? How would that have changed the outcome? What did I learn from this experience?

Conclusion - What did you learn?: The final step in critical reflection is to draw conclusions from your reflection. Identify what you learned from the experience and how you can apply this learning in the future. This step is essential for personal growth and development.

Remember that critical reflection is not a one-time event. It is an ongoing process that requires regular practice. By engaging in critical reflection, you can develop improved communication, problem-solving, and decision-making skills.

Benefits of Critical Reflection

Critical reflection provides numerous benefits for personal and professional development. Here are some of the most common advantages of the process:

Personal growth and development : Critical reflection enables individuals to learn from their experiences and mistakes. This learning process fosters personal growth and development, as individuals are encouraged to examine their values, beliefs, and assumptions.

Improved decision-making skills : Critical reflection helps individuals make more informed and deliberate decisions. By analyzing their experiences and evaluating different courses of action, individuals are better equipped to make decisions that align with their goals and values.

Improved problem solving skills : Critical reflection also enhances problem-solving skills. By systematically examining a problem or experience, individuals can identify the underlying issues and develop more effective solutions.

Improved communication skills : Critical reflection requires individuals to articulate their thoughts and feelings clearly and concisely. This ability to communicate effectively can benefit individuals in a range of contexts, from personal relationships to professional settings.

Overall, critical reflection is a powerful tool for personal and professional development. The benefits of critical reflection extend beyond the individual, as they also enhance the quality of work and relationships with others.

Tips for Effective Critical Reflection

Here are some tips to help you engage in effective critical reflection:

Be Open-minded

Approach the reflection process with an open mind. Be receptive to new ideas and perspectives, and be willing to challenge your own assumptions or beliefs. This will help you gain a deeper understanding of the experience and identify alternative ways of thinking and behaving.

Use a Structured Process

Use a structured process or template to guide your reflection. This can help ensure that you cover all the necessary steps and stay focused on the key issues. It can also make the process more efficient and effective.

Be Honest with Yourself

Be honest and objective when reflecting on your experience. Don’t shy away from acknowledging your own mistakes or limitations, as this can help you grow and improve. However, be sure to also recognize your strengths and accomplishments, as this can help build confidence and motivation.

Practice Regularly

Make reflection a regular habit. Don’t wait for a major crisis or challenge to start reflecting on your experiences. Instead, try to incorporate reflection into your daily routine. This can help you identify patterns or trends over time and make continuous improvements.

By following these tips, you can enhance the effectiveness and impact of your critical reflection process.

In conclusion, critical reflection is an essential part of personal growth and development. Through the process of critical reflection, we can identify areas for improvement, evaluate our own actions and decisions, and come up with alternative solutions to challenging situations.

We hope that this step-by-step guide has provided you with a helpful roadmap for engaging in critical reflection. Remember to be open-minded, use a structured process, and be honest with yourself. By practicing critical reflection regularly, you can improve your decision-making and problem-solving skills, as well as your communication with others.

If you want to learn more about critical reflection, there are many additional resources available. We encourage you to continue to explore this topic and to incorporate critical reflection into your daily life.

Are You a Stoic Thinker?

Redefining your life's purpose through introspection, critical reflection for grad students seeking a career change, why is critical reflection so important ask yourself these questions, exclusive insights from experts on the power of critical reflection, creating anticipation in critical reflection: how to build momentum for change.

Tips for Online Students , Tips for Students

Reflective Thinking: Revealing What Really Matters

Updated: June 19, 2024

Published: April 1, 2020

You may have heard of the term reflective thinking, and you also may have struggled to understand what it truly is — and you’re not alone. After all, it can appear to be one seriously abstract concept. But truth be told, it’s a lot simpler than you think. In short, it’s defined as constantly thinking and analyzing what you’re doing, what you’ve done, what you’ve experienced, what you’ve learned, and how you’ve learned it.

What Exactly Is Reflection?

Reflection is looking back at an experience or a situation, and learning from it in order to improve for the next time around.

There are three main aspects of reflection:

1. Being Self-Aware

Reflection starts with self-awareness, being in touch with yourself, your experiences, and what’s shaped your worldview.

2. Constantly Improving

The next step of reflection is self-improvement. Once you’re aware of where your strengths and weaknesses are, you can know where to shift your focus.

3. Empower Yourself

Reflection gives you power to take control and make the necessary changes in your life.

What Is Reflective Thinking?

Reflective thinking means taking the bigger picture and understanding all of its consequences. It doesn’t mean that you’re just going to simply write down your future plans or what you’ve done in the past. It means truly trying to understand why you did what you did, and why that’s important. This often includes delving into your feelings, reactions, and emotions.

Photo by David McEachan from Pexels

A note on critical thinking.

Reflective thinking and critical thinking are often used synonymously. Critical thinking , however, is the systematic process of analyzing information in order to form an opinion or make a decision, and it varies based on its underlying motivation.

We all think endlessly, but much of that is done so with biases as misinformation, which is where critical thinking comes in.

Examples Of Reflective Thinking

What is reflective thinking? If you haven’t yet quite understood the process of reflective thinking, here are some straight-forward examples that can clarify what it truly means.

People often keep a journal in order to write about their experiences and make sense of them. For example, Jessica and her boyfriend have been having several disagreements lately, and she’s upset about the situation. By having the ability to express her feelings and see the bigger picture (their future together, the cause of their fights, and what makes him happy), she is practicing reflective thinking and providing herself with a rewarding mental activity.

Another example of reflective thinking would be in a class. A science teacher spends an hour teaching about a specific concept. Students are then given a few minutes to write a reflective piece about what they’ve learned, including any questions they may have. By giving them the chance to reflect on the material, they can not only remember it, but also truly understand it.

Environmental Characteristics that Support Reflective Thinking

In order for reflective thinking to be made possible, we need to be given the right environment to do so. Some of these environmental characteristics include having enough time to properly reflect when responding, as well as having enough emotional support (in a classroom, for example) to encourage reflection and reevaluation of conclusions.

Prompting reviews of the situation can also help encourage reflective thinking, discussing what is known, what’s been learned, and what is yet to be learned.

Providing social-learning groups are also highly beneficial to promote the ability to see other perspectives and points of view.

Photo by Keegan Houser from Pexels

How to think reflectively.

What are some popular theories on the reflective thinking method and on learning ?

Kolb’s Learning Cycle

David Kolb published his learning cycle model in 1984, and it tends to be represented by a four-stage learning cycle .

The learner is intended to touch all bases of the cycle, which include:

- Concrete experience (having a new experience)

- Reflective observation (reflecting on that experience)

- Abstract conceptualization (learning from that experience)

- Abstract experimentation (apply what you’ve learned from that experience).

Kolb views learning as a process in which each stage supports the next, and that it’s possible to enter the learning cycle at any of the 4 stages.

Schön’s model

Schön’s model of the reflective thinking process, presented in 1991, is based on the concepts of ‘reflection-in-action’ and ‘reflection-on-action’. What do these mean exactly?

Reflection-in-action

Reflection-in-action is the quick reaction and quick thinking that takes place when we’re in the middle of an activity. This type of reflection allows us to look at a situation, understand why it’s occurring, and respond accordingly.

One example of reflection-in-action would be if you’re trying to focus in class, but keep thinking about your weekend plans.

Reflection-on-action

Reflection-on-action, on the other hand, is the type of reflection that takes place when we look back at the activity, rather than our reflections during. Generally, in this type of reflection, you are likely to think more deeply about the way you were feeling, and what caused those feelings.

An example of reflection-on-action would be deciding to take notes in class in order to better focus after noticing that you’ve been struggling.

What Are The Benefits Of Reflective Thinking?

Why is reflective thinking so important for you to practice? Here are a few of the many benefits.

1. Broaden Your Perspective

Reflective thinking can help you become more open-minded towards others, and better understand where they are coming from.

2. Change & Improve

Reflective thinking is key to making improvements, both on a personal and professional level. By becoming more self-aware and understanding yourself, you can know where to best focus your efforts.

3. Take On New Challenges

Being a reflective thinker can make you more motivated since you will truly understand what you’re trying to achieve, and why. In turn, you are likely to be willing to take on new challenges and fear them less.

4. Apply Knowledge To Other Situations

Reflective thinkers know how to extend their understanding of situations to other topics and experience, relating new concepts to past experiences, making you overall more informed and confident.

What Is The Cycle Of Reflective Learning?

The cycle of reflective learning never stops. You take what you’ve learned and apply it, and then continue to reflectively think and further develop your understanding.

Think about how others have approached similar challenges and tasks, and take this understanding to accordingly form your own plan of action.

Apply what you’ve set up for yourself in your plan, but be ready to make any necessary changes along the way.

Review what you’ve done and what the results of your actions are. Make an objective description of the situation.

Reflect upon your actions, including your strengths and weaknesses — what did you do, and how did you do it? Did you achieve your goals? Maybe your goals even changed throughout.

5. Plan All Over Again

Back to the beginning! Set yourself a new plan based on what you’ve learned from your previous experience.

How Can You Develop Your Reflective Insights?

Reflective insights are a skill that can be developed over time if certain actions are taken.

Prepare Yourself

Be prepared to develop your reflective insights. Take a step back, and aim to be as objective as possible in your thinking, always being critical of your own actions. Always think of another explanation for what happened, and look towards a variety of sources. Accept the fact that your beliefs may change over time, and always maintain healthy discussion to keep an open-mind. Continue asking yourself the right kinds of questions no matter what.

Ask These Questions

What are the ‘right’ kinds of questions that you should be asking yourself? Perhaps why you responded in such a way, what you were feeling and thinking in the moment, and how it influenced you? What other actions could you have taken instead? Maybe even consider what you or someone else would have done in a similar situation.

What Are The Main Features Of Reflection?

There are four main features of reflection, which include:

- Leads To Learning: Reflection can change your ideas and understanding of a situation.

- Dynamic & Active: Reflection is not a static process, but rather a dynamic and active one that can be either be on a past experience, during an experience, or even for a future experience.

- Non-Linear Process: Reflection can help formulate new ideas and concepts to help you plan your future learning stages, making it a cyclic process.

- Take On Different Perspectives: Reflective thinking helps us to criticize our own thoughts, and see situations from the bigger picture.

Now that you know all about reflective thinking, you can start to make it a natural part of your daily life, and a core part of your thought process. Allow yourself to constantly learn and grow from your experiences, always improving for the next time around. That’s what reflective thinking is all about!

At UoPeople, our blog writers are thinkers, researchers, and experts dedicated to curating articles relevant to our mission: making higher education accessible to everyone.

Related Articles

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Critical Reflection

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

Writing Critical Reflection

Reflective writing is a common genre in classrooms across disciplines. Reflections often take the form of narrative essays that summarize an experience or express changes in thinking over time. Initially, reflective writing may seem pretty straightforward; but since reflective writing summarizes personal experience, reflections can easily lose their structure and resemble stream-of-consciousness journals capturing disjointed musings focused on only the self or the past.

Critical reflection still requires a writer to consider the self and the past but adopts an argumentative structure supported by readings, theories, discussions, demonstrated changes in material conditions, and resources like post-collaboration assessments, testimonial evidence, or other data recorded during the collaboration . Common arguments in critical reflections present evidence to demonstrate learning, contextualize an experience, and evaluate impact. While critical reflections still require authors to reflect inwardly, critical reflection go es beyond the self and examine s any relevant contexts that informed the experience. Then, writers should determine how effectively their project addressed these contexts. In other words, critical reflection considers the “impact” of their project: How did it impact the writer? How did it impact others? Why is the project meaningful on a local, historical, global, and/or societal level? H ow can that impact be assessed?

In short: reflection and critical reflection both identify the facts of an experience and consider how it impacts the self. Critical reflection goes beyond this to conceive of the project’s impact at numerous levels and establish an argument for the project’s efficacy. In addition, critical reflection encourages self-assessment—we critically reflect to change our actions, strategies, and approaches and potentially consider these alternative methods.

Collecting Your Data: Double-Entry Journaling

Double-entry journaling is a helpful strategy for you to document data, observations, and analysis throughout the entire course of a community-based project. It is a useful practice for projects involving primary research, secondary research, or a combination of both. In its most basic form, a double-entry journal is a form of notetaking where a writer can keep track of any useful sources, notes on those sources, observations, thoughts, and feelings—all in one place.

For community-based projects, this might involve:

- Recording your observations during or after a community partner meeting in one column of the journal.

- Recording any of your thoughts or reactions about those observations in a second column.

- Writing any connections you make between your observations, thoughts, and relevant readings from class in a third column.

This allows you to document both your data and your analysis of that data throughout the life of the project. This activity can act as a blueprint for your critical reflection by providing you with a thorough account of how your thinking developed throughout the life of a project.

The format of a double-entry journal is meant to be flexible, tailored to both your unique notetaking practice and your specific project. It can be used to analyze readings from class, observations from research, or even quantitative data relevant to your project.

Just the Facts, Please: What, So What, Now What

Getting started is often the hardest part in writing. To get your critical reflection started, you can identify the What , So What , and Now What? of your project. The table below presents questions that can guide your inquiry . If you’re currently drafting, we have a freewriting activity below to help you develop content.

|

| |

|

| |

|

|

Freewrite your answers to these questions; that is, respond to these questions without worrying about grammar, sentence structure, or even the quality of your ideas. At this stage, your primary concern is getting something on the page. Once you’re ready to begin drafting your critical reflection, you can return to these ideas and refine them.

Below are some additional prompts you can use to begin your freewriting. These reflection stems can organize the ideas that you developed while freewriting and place them in a more formal context.

- I observed that...

- My understanding of the problem changed when...

- I became aware of (x) when....

- I struggled to...

- The project's biggest weakness was…

- The project's greatest strength was… I learned the most when...

- I couldn't understand...

- I looked for assistance from...

- I accounted for (x) by...

- I connected (concept/theory) to...

- (Specific skill gained) will be useful in a professional setting through…

Analyzing Your Experience: A Reflective Spectrum

Y our critical reflection is a space to make an argument about the impact of your project . This means your primary objective is to determine what kind of impact your project had on you and the world around you. Impact can be defined as the material changes, either positive or negative, that result from an intervention , program , or initiative . Impact can be considered at three different reflective levels: inward, outward, and exploratory.

Inward reflection requires the writer to examine how the project affected the self. Outward reflection explores the impact the project had on others. Additionally, you can conceptualize your project’s impact in relation to a specific organization or society overall, depending on the project’s scope. Finally, exploratory reflection asks writers to consider how impact is measured and assessed in the context of their project to ultimately determine: What does impact look like for the work that I’m doing? How do I evaluate this? How do we store, archive, or catalog this work for institutional memory? And what are the next steps?

This process is cyclical in nature; in other words, it’s unlikely you will start with inward reflection, move to outward reflection, and finish with exploratory reflection. As you conceptualize impact and consider it at each level, you will find areas of overlap between each reflective level.

Finally, if you’re having trouble conceptualizing impact or determining how your project impacted you and the world around you, ask yourself:

- What metrics did I use to assess the "impact" of this project? Qualitative? Quantitative? Mixed-methods? How do those metrics illustrate meaningful impact?

- How did the intended purpose of this project affect the types of impact that were feasible, possible, or recognized?

- At what scope (personal, individual, organizational, local, societal) did my outcomes have the most "impact"?

These questions can guide additional freewriting about your project. Once you’ve finished freewriting responses to these questions, spend some time away from the document and return to it later. Then, analyze your freewriting for useful pieces of information that could be incorporated into a draft.

Drafting Your Critical Reflection

Now that you have determined the “What, So What, Now What” of your project and explored its impact at different reflective levels, you are ready to begin drafting your critical reflection.

If you’re stuck or find yourself struggling to structure your critical reflection, the OWL’s “ Writing Process ” [embe ded link ] resource may offer additional places to start. That said, another drafting strategy is centering the argument you intend to make.

Your critical reflection is an argument for the impact your project has made at multiple levels; as such, much of your critical reflections will include pieces of evidence to support this argument. To begin identifying these pieces of evidence, return to your “reflection stem” responses . Your evidence might include :

- H ow a particular reading or theory informed the actions during your partnership ;

- How the skills, experiences, or actions taken during this partnerhsip will transfer to new contexts and situations;

- Findings from y our evaluation of the project;

- Demonstrated changes in thoughts, beliefs, and values, both internally and externally;

- And, of course, specific ways your project impacted you, other individuals, your local community, or any other community relevant to the scope of your work.

As you compile this evidence, you will ulti mately be compiling ways to support an argument about your project’s efficacy and impact .

Sharing Your Critical Reflection

Reflective writing and critical reflections are academic genres that offer value to the discourse of any field. Oftentimes, these reflective texts are composed for the classroom, but there are other venues for your critical reflections, too.

For example, Purdue University is home to the Purdue Journal of Service-Learning and International Engagement ( PJSL ) which publishes student reflective texts and reflections with research components. Although PJSL only accepts submissions from Purdue students, other journals like this one may exist at your campus. Other venues like the Journal of Higher Education Outreach and Impact publish reflective essays from scholars across institutions, and journals in your chosen discipline may also have interest in reflective writing.

Document explaining the theories, concepts, literature, strategies that informed the creation of this content page.

Critical Thinking and Reflective Thinking

Critical and Reflective Thinking encompasses a set of abilities that students use to examine their own thinking and that of others. This involves making judgments based on reasoning, where students consider options, analyze options using specific criteria, and draw conclusions.

People who think critically and reflectively are analytical and investigative, willing to question and challenge their own thoughts, ideas, and assumptions and challenge those of others. They reflect on the information they receive through observation, experience, and other forms of communication to solve problems, design products, understand events, and address issues. A critical thinker uses their ideas, experiences, and reflections to set goals, make judgments, and refine their thinking.

- Back to Thinking

- Connections

- Illustrations

Analyzing and critiquing

Students learn to analyze and make judgments about a work, a position, a process, a performance, or another product or act. They reflect to consider purpose and perspectives, pinpoint evidence, use explicit or implicit criteria, make defensible judgments or assessments, and draw conclusions. Students have opportunities for analysis and critique through engagement in formal tasks, informal tasks, and ongoing activities.

Questioning and investigating

Students learn to engage in inquiry when they identify and investigate questions, challenges, key issues, or problematic situations in their studies, lives, and communities and in the media. They develop and refine questions; create and carry out plans; gather, interpret, and synthesize information and evidence; and reflect to draw reasoned conclusions. Critical thinking activities may focus on one part of the process, such as questioning, and reach a simple conclusion, while others may involve more complex inquiry requiring extensive thought and reflection.

Designing and developing

Students think critically to develop ideas. Their ideas may lead to the designing of products or methods or the development of performances and representations in response to problems, events, issues, and needs. They work with clear purpose and consider the potential uses or audiences of their work. They explore possibilities, develop and reflect on processes, monitor progress, and adjust procedures in light of criteria and feedback.

Reflecting and assessing

Students apply critical, metacognitive, and reflective thinking in given situations, and relate this thinking to other experiences, using this process to identify ways to improve or adapt their approach to learning. They reflect on and assess their experiences, thinking, learning processes, work, and progress in relation to their purposes. Students give, receive, and act on feedback and set goals individually and collaboratively. They determine the extent to which they have met their goals and can set new ones.

I can explore.

I can explore materials and actions. I can show whether I like something or not.

I can use evidence to make simple judgments.

I can ask questions, make predictions, and use my senses to gather information. I can explore with a purpose in mind and use what I learn. I can tell or show others something about my thinking. I can contribute to and use simple criteria. I can find some evidence and make judgments. I can reflect on my work and experiences and tell others about something I learned.

I can ask questions and consider options. I can use my observations, experience, and imagination to draw conclusions and make judgments.

I can ask open-ended questions, explore, and gather information. I experiment purposefully to develop options. I can contribute to and use criteria. I use observation, experience, and imagination to draw conclusions, make judgments, and ask new questions. I can describe my thinking and how it is changing. I can establish goals individually and with others. I can connect my learning with my experiences, efforts, and goals. I give and receive constructive feedback.

I can gather and combine new evidence with what I already know to develop reasoned conclusions, judgments, or plans.

I can use what I know and observe to identify problems and ask questions. I explore and engage with materials and sources. I can develop or adapt criteria, check information, assess my thinking, and develop reasoned conclusions, judgments, or plans. I consider more than one way to proceed and make choices based on my reasoning and what I am trying to do. I can assess my own efforts and experiences and identify new goals. I give, receive, and act on constructive feedback.

I can evaluate and use well-chosen evidence to develop interpretations; identify alternatives, perspectives, and implications; and make judgments. I can examine and adjust my thinking.

I can ask questions and offer judgments, conclusions, and interpretations supported by evidence I or others have gathered. I am flexible and open-minded; I can explain more than one perspective and consider implications. I can gather, select, evaluate, and synthesize information. I consider alternative approaches and make strategic choices. I take risks and recognize that I may not be immediately successful. I examine my thinking, seek feedback, reassess my work, and adjust. I represent my learning and my goals and connect these with my previous experiences. I accept constructive feedback and use it to move forward.

I can examine evidence from various perspectives to analyze and make well-supported judgments about and interpretations of complex issues.

I can determine my own framework and criteria for tasks that involve critical thinking. I can compile evidence and draw reasoned conclusions. I consider perspectives that do not fit with my understandings. I am open-minded and patient, taking the time to explore, discover, and understand. I make choices that will help me create my intended impact on an audience or situation. I can place my work and that of others in a broader context. I can connect the results of my inquiries and analyses with action. I can articulate a keen awareness of my strengths, my aspirations and how my experiences and contexts affect my frameworks and criteria. I can offer detailed analysis, using specific terminology, of my progress, work, and goals.

The Core Competencies relate to each other and with every aspect of learning.

Connections among Core Competencies

The Core Competencies are interrelated and interdependent. Taken together, the competencies are foundational to every aspect of learning. Communicating is intertwined with the other Core Competencies.

Critical and Reflective Thinking is one of the Thinking Core Competency’s two interrelated sub-competencies, Creative Thinking and Critical and Reflective Thinking.

Critical and Reflective Thinking and Creative Thinking overlap. For example:

- Students use creative thinking to generate new ideas when solving problems and addressing constraints that arise as they question and investigate, and design and develop

- Students use critical thinking to analyze and reflect on creative ideas to determine whether they have value and should be developed, engaging in ongoing reflection as they develop their creative ideas

Communication

Critical and Reflective Thinking is closely related to the two Communication sub-competencies: Communicating and Collaborating. For example:

- Students apply critical thinking to acquire and interpret information, and to make choices about how to communicate their ideas

- Students often collaborate as they work in groups to analyze and critique, and design and develop

Personal and Social

Critical and Reflective Thinking is closely related to the three Personal and Social sub-competencies, Personal Awareness and Responsibility, Social Awareness and Responsibility, and Positive Personal and Cultural Identity. For example:

- Students think critically to determine their personal and social responsibilities

- Students apply their personal awareness as they reflect on their efforts and goals

Connections with areas of learning

Critical and Reflective Thinking is embedded within the curricular competencies of the concept-based, competency-driven curriculum. Curricular competencies are focused on the “doing” within the area of learning and include skills, processes, and habits of mind required by the discipline. For example, the Critical and Reflective Thinking sub-competency can be seen in the sample inquiry questions that elaborate on the following Big Ideas in Science:

- Light and sound can be produced and their properties can be changed: How can you explore the properties of light and sound? What discoveries did you make? (Science 1)

- Matter has mass, takes up space, and can change phase: How can you explore the phases of matter? How does matter change phases? How does heating and cooling affect phase changes? (Science 4)

- Elements consist of one type of atom, and compounds consist of atoms of different elements chemically combined: What are the similarities and differences elements and compounds? How can you investigate the properties of elements and compounds? (Science 7)

- The formation of the universe can be explained by the big bang theory: How could you model the formation of the universe? (Science 10)

Une élève, inspirée par un roman sur l’expérience d’une jeune fille dans un pensionnat indien, rassemble de plus amples renseignements et, quatre ans plus tard, organise une Journée du chandail orange dans son école.

Une élève a enquêté sur la façon dont les artistes s’expriment et a créé une œuvre authentique.

Un élève fait une réflexion approfondie sur ses expériences d’apprentissage comme examen final d’un programme STIM (sciences, technologie, ingénierie, mathématiques).

Un élève construit une maquette d’aquarium qui garderait les poissons heureux et en santé.

Après avoir rencontré d’anciens combattants lors d’un événement du jour du Souvenir, un élève forme un groupe consacré aux liens intergénérationnels entre élèves et anciens combattants.

Au fil du temps, l’élève réalise un ensemble d’œuvres créatives sur le thème de l’identité.

A student uses “loose parts” to record his observations of seasonal changes in the local environment.

A student explores magnetic properties using a magnetic wand.

A student creates a presentation reflecting on their school experience and goals for the future.

A student explains how he learned to be persistent and why that trait is important to him.

A student writes an essay in response to the prompt “How We Know Who We Are”.

Students present their application for the Mars One project, explaining how they would be suited to the project and how they would deal with issues they would likely face.

A student reflects on the personal experiences that have changed his goals and aspirations.

During a portfolio review, students reflect on their writing, set goals, and create a plan for moving forward.

A student approaches a teacher with her concerns about her progress in math.

Students explore issues related to the manufacturing of jeans in sweatshops.

After creating submersibles, students reflected on their creation process and the challenges they encountered.

Students create a mind map to assess and reflect on their learning.

A student shares his reasoning about which group of dinosaurs would win a battle.

A student creates a one-page representation of the story “ The Lost Thing”.

Students generate and develop a variety of ideas when challenged to see how high they can stack provided materials.

Students work together to solve an open-ended problem about sharing cookies.

As part of an engineering study, students work collaboratively to build, test, and adapt roller coasters.

Students work in small groups to design an experiment that explores the effects of different salt solutions on gummy bears.

A student applies what he knows about genetics to critique the movie "Gattaca".

A student develops, evaluates, and revises a process for calculating the area under a curve.

A student uses her senses to explore a toy bear and rocks.

Students create documentaries that explore the pros and cons of the Site C dam while considering the various stakeholders.

Students reflect on the process they used to make pinhole cameras and the variables that affected its effectiveness.

During an architecture project, a student uses found materials to represent that hotels simultaneously act as public space and private refuge.

A student designs a snake made of pull-tabs in response to a class challenge.

A student extends a classroom assignment by designing a fire starter for campers.

A student works with classmates to build a cardboard vending machine to deliver secret Santa presents.

A student creates a political cartoon to encourage community members to support a ban of shark fin products.

After doing a report on robots and assembling a robot from a kit, a student designs his own robot.

A student makes duct tape wallets as a hobby.

A group of students engage in a multi-stage design process to make a working model of a construction crane.

Students build mousetrap cars made from household materials and participated in a Mousetrap Car Competition.

- Campus Life

- ...a student.

- ...a veteran.

- ...an alum.

- ...a parent.

- ...faculty or staff.

- UTC Learn (Canvas)

- Class Schedule

- Crisis Resources

- People Finder

- Change Password

UTC RAVE Alert

Critical reflection.

Critical reflection is a reasoning process to make meaning of an experience.

Critical reflection is descriptive, analytical, and critical, and can be articulated in a number of ways such as in written form, orally, or as an artistic expression. In short, this process adds depth and breadth to experience and builds connections between course content and the experience.

Often, a reflection activity is guided by a set of written prompts. A best practice for critical reflection is that students respond to prompts before, during, and after their experience; therefore, the prompts should be adjusted to match the timing of the reflection. Critical reflection can be integrated into any type of experiential learning activity - inside the classroom or outside the classroom.

It is important to understand what critical reflection is NOT. It is not a reading assignment, it is not an activity summary, and it is not an emotional outlet without other dimensions of experience described and analyzed. Critical reflection should be carefully designed by the instructor to generate and document student learning before, during, and after the experience.

If you are considering using critical reflection, there are four steps to think about:

1. Identify the student learning outcomes related to the experience. What do you expect students to gain as a result of this activity? Understand multiple points of view? Be able to propose solutions to a problem?

2. Once you identify the outcomes, then you can design the reflection activities to best achieve the outcomes. Remember, that critical reflection is a continuous process.

3. Engage students in critical reflection before, during, and after the experience.

4. Assess their learning . A rubric that outlines the criteria for evaluation and levels of performance for each criterion can be useful for grading reflection products and providing detailed feedback to students.

Additional Resources

Bart, M. (2011, May 11). Critical reflection adds depth and breadth to student learning. Faculty Focus. Retrieved from http://www.facultyfocus.com/articles/instructional-design/critical-reflection-adds-depth-and-breadth-to-student-learning/ .

Colorado Mountain College. (2007). Critical reflection. Retrieved from http://faculty.coloradomtn.edu/orl/critical_reflection.htm .

Jacoby, B. (2010). How can I promote deep learning through critical reflection? Magna Publications. Retrieved from http://www.magnapubs.com/mentor-commons/?video=25772a92#.UjnHBazD-70 .

Walker Center for Teaching and Learning

- 433 Library

- Dept 4354

- 615 McCallie Ave

- 423-425-4188

Inquiry: Critical Thinking Across the Disciplines

Volume 26, issue 2, summer 2011.

Critical Thinking Reflection and Perspective Part II

This is the second part of a two-part reflection by Robert Ennis on his involvement in, and the progress of, the critical thinking movement. It provides a summary of Part I (Ennis 2011), including his definition/conception of critical thinking, the definition being “reasonable reflective thinking focused on deciding what to believe or do.” It then examines the assessment and the teaching of critical thinking (including incorporation in a curriculum), and makes suggestions regarding the future of critical thinking. He urges that now is the time to make a major effort in promoting critical thinking. Later may be too late. He also suggests a number of things to do. An Appendix, which provides a detailed elaboration of the nature of critical thinking, is at the end of Part I, but summaries are provided here.

Home — Essay Samples — Education — Critical Thinking — Reflection On Critical Thinking

Reflection on Critical Thinking

- Categories: Critical Thinking

About this sample

Words: 664 |

Published: Mar 14, 2024

Words: 664 | Page: 1 | 4 min read

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Dr Jacklynne

Verified writer

- Expert in: Education

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

2 pages / 1099 words

3 pages / 1286 words

2 pages / 789 words

8 pages / 3586 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Critical Thinking

In the realm of intellectual discourse, the ability to construct a cogent argument is a skill that cannot be understated. Whether in the classroom, the courtroom, or the conference room, the power of a well-reasoned argument can [...]

Imagine yourself sitting in a jury room, surrounded by eleven other individuals, all with differing opinions and perspectives. You are tasked with deciding the fate of a young man accused of murder. The evidence seems [...]

The text in consideration is “Burkean Identification: Rhetorical Inquiry and Literacy Practices in Social Media”, which profoundly explores the opportunity of describing the interactions within the domain of social networking as [...]

The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) stands as one of the most prestigious and enigmatic institutions in the world, renowned for its secretive operations and critical role in national security. Applying for a position within [...]

Reginald Rose's play "12 Angry Men" explores the complexities of the human mind and the dynamics of group decision-making. At the heart of this powerful drama is Juror 8, a character who stands alone in his belief and [...]

In my critical analysis essay based on the article Some Lessons from the Assembly Line by Andrew Braaksma, my target audience will be graduating high school seniors. This audience will consist of adolescents between the ages of [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique