Essay on Entrepreneurship

Introduction to Entrepreneurship

Entrepreneurship is the cornerstone of innovation, economic growth, and societal progress. Entrepreneurship embodies risk-taking, innovation, and determination as entrepreneurs actively identify, create, and pursue opportunities to build and scale ventures. From the inception of small startups to the expansion of multinational corporations, entrepreneurial endeavors permeate every facet of our global economy.

This essay delves into the complex world of entrepreneurship, examining its importance, traits of prosperous businesspeople, function in economic growth, kinds of entrepreneurship, how to start one, obstacles to overcome, the ecosystem surrounding entrepreneurship, and motivational success stories of well-known businesspeople. Through this exploration, we aim to shed light on the dynamic nature of entrepreneurship and its profound impact on shaping our world.

Watch our Demo Courses and Videos

Valuation, Hadoop, Excel, Mobile Apps, Web Development & many more.

Historical Context of Entrepreneurship

Entrepreneurship, as a concept, has roots that stretch back centuries. It evolved in response to changing economic, social, and technological landscapes. While the term “Entrepreneurship” may be relatively modern, the spirit of entrepreneurship has been evident throughout human history.

1. Early Civilization and Trade

- Ancient Mesopotamia and Egypt: Merchants in ancient civilizations like Mesopotamia and Egypt actively engaged in trade, barter, and commerce, marking the earliest forms of entrepreneurship.

- Medieval Guilds: During the Middle Ages, guilds emerged as entrepreneurship centers, bringing together artisans and craftsmen to regulate trade, ensure quality standards, and foster innovation.

2. Age of Exploration and Colonization

- Age of Exploration: During the Age of Exploration, which lasted between the 15th and 16th centuries, international trade networks were formed, and as explorers looked for new trade routes, this encouraged commercial ventures.

- Colonialism: European colonial expansion in the 17th and 18th centuries created opportunities for entrepreneurial endeavors in trade, agriculture , and resource extraction, albeit often at the expense of indigenous populations.

3. Industrial Revolution

- Transition to Industrialization: The emergence of factories, mechanization, and mass production during the Industrial Revolution of the 18th and 19th centuries drove economic expansion and urbanization, so ushering in a revolutionary era for entrepreneurship.

- Innovations and Entrepreneurs: Visionary entrepreneurs like James Watt, Thomas Edison , and Henry Ford revolutionized industries through technological innovations, shaping the modern world.

4. 20th Century and Beyond

- Post-World War II Reconstruction: The aftermath of World War II saw a resurgence of entrepreneurship driven by reconstruction efforts, technological advancements, and the rise of consumer culture.

- Digital Revolution: The digital revolution, which began in the late 20th century and was marked by the widespread use of computers, the Internet, and information technology, fostered a new era of entrepreneurship focused on innovation, startups, and digital commerce.

5. Contemporary Entrepreneurship

- Globalization: In the 21st century, globalization has expanded opportunities for entrepreneurship, enabling businesses to operate across borders, access global markets, and collaborate on a scale never before seen.

- Social Entrepreneurship: Alongside traditional business ventures, the rise of social entrepreneurship reflects a growing emphasis on addressing societal challenges, promoting sustainability, and creating positive social impact.

Characteristics of Successful Entrepreneurs

- Visionary Leadership : Successful entrepreneurs have a clear vision of their goals and are adept at inspiring others to share. They can successfully communicate their vision and mobilize stakeholders behind it.

- Resilience and Persistence : Entrepreneurship is fraught with setbacks and obstacles, but successful entrepreneurs exhibit resilience in adversity. Despite obstacles, they continue to work toward their objectives and see setbacks as teaching opportunities.

- Risk-taking Propensity : Risk is a natural part of entrepreneurship, and prosperous businesspeople aren’t afraid to take calculated chances to seize opportunities. They possess the courage to step outside their comfort zones and embrace uncertainty.

- Creativity and Innovation : Entrepreneurs are creative people who are always looking for innovative approaches to addressing issues and satisfying consumer demands. Their imaginative mindset enables them to come up with original ideas and think outside the box.

- Adaptability and Flexibility : The business landscape is dynamic, and successful entrepreneurs demonstrate adaptability in response to changing circumstances. They are flexible and willing to pivot and adjust strategies as needed.

- Passion and Commitment : Passion fuels the entrepreneurial journey, driving entrepreneurs to pour their time, energy, and resources into their ventures. Successful entrepreneurs are deeply committed to their work and willing to make sacrifices to succeed.

- Strong Work Ethic : Entrepreneurship requires hard work, dedication, and perseverance. Successful entrepreneurs are willing to work long hours and exert the effort to build and grow their businesses.

- Effective Communication Skills : Effective communication depends on establishing and maintaining connections, obtaining funding, and promoting goods and services. Successful entrepreneurs possess strong communication skills, both verbal and written, enabling them to convey their ideas persuasively.

- Empathy and Emotional Intelligence : Understanding the needs and perspectives of others is crucial in entrepreneurship. Empathy and emotional intelligence are hallmarks of successful entrepreneurs. They build strong relationships with employees, customers, and partners.

- Strategic Thinking : Entrepreneurs must think strategically to navigate complex business environments and make informed decisions. Successful entrepreneurs possess strategic thinking skills, enabling them to set clear objectives, prioritize tasks, and allocate resources effectively.

The Entrepreneurial Process

The entrepreneurial process encompasses the journey from ideation to establishing and growing a successful venture. Entrepreneurs must go through several phases and processes to realize their ideas and add value to the market.

- Opportunity Identification : The entrepreneurial process often begins with identifying opportunities in the market or recognizing unmet needs and problems. Entrepreneurs may draw inspiration from personal experiences, industry trends, market gaps, or technological advancements.

- Market Research and Validation : Once entrepreneurs identify an opportunity, they conduct thorough market research to assess the viability of their ideas. It involves analyzing target markets, understanding customer preferences, evaluating competitors, and validating demand for the proposed product or service.

- Business Planning : With a clear understanding of the market opportunity, entrepreneurs develop a comprehensive business plan outlining their vision, goals, strategies, and operational plans. The business plan serves as a roadmap for the venture, guiding decision-making and resource allocation.

- Resource Acquisition : Entrepreneurs must secure the resources necessary to realize their ideas. This may involve raising capital through investments, loans, or crowdfunding, recruiting talent, acquiring technology or equipment, and establishing partnerships.

- Venture Launch : The launch phase marks the official start of the venture, where entrepreneurs execute their business plans and introduce their products or services to the market, involving product development, marketing and branding efforts, setting up operations, and launching sales channels.

- Growth and Scaling : As the venture gains traction and generates revenue, entrepreneurs focus on scaling operations and expanding their market reach, often involving refining business processes, optimizing efficiency, entering new markets, and diversifying product offerings.

- Risk Management : Entrepreneurship inherently involves risk, and successful entrepreneurs must proactively identify, assess, and manage risks throughout the venture lifecycle. They must also implement risk mitigation strategies, diversify revenue streams, and maintain financial resilience.

- Innovation and Adaptation : In a rapidly evolving corporate environment, entrepreneurs need to innovate and adapt to stay competitive continuously. It includes launching new goods and services, utilizing cutting-edge technologies, and reacting to shifting consumer demands and industry trends.

- Network Building and Relationship Management : Entrepreneurs must build a strong network of relationships to access resources, expertise, and opportunities. It includes cultivating relationships with investors, customers, suppliers, mentors, and other stakeholders.

- Continuous Learning and Improvement : Entrepreneurship is a dynamic and iterative process, and successful entrepreneurs are committed to lifelong learning and improvement. They seek feedback, learn from failures and successes, and adapt their strategies based on new insights and experiences.

Types of Entrepreneurship

Entrepreneurship manifests in various forms, each characterized by distinct goals, approaches, and impacts on society and the economy. Understanding the different types of entrepreneurship provides insights into how individuals and organizations engage in entrepreneurial activities to create value and drive innovation.

1. Small Business Entrepreneurship : Small business entrepreneurship involves creating and managing small-scale enterprises typically operated by a single individual or a small team. These ventures often serve local markets and focus on providing goods or services tailored to specific customer needs.

Examples: Family-owned businesses, local restaurants, independent retailers, and service providers such as plumbers or electricians actively operate within their respective domains.

2. Social Entrepreneurship : Social entrepreneurship blends entrepreneurial principles that address social, environmental, or humanitarian challenges. These ventures aim to create a positive social impact while generating sustainable financial returns.

Examples: Nonprofit organizations, social enterprises, and initiatives focused on poverty alleviation, environmental conservation, healthcare access, education, and community development.

3. Corporate Entrepreneurship : Corporate entrepreneurship refers to activities undertaken within established organizations, including corporations, companies, and institutions. These activities foster innovation, explore new business opportunities, and drive organizational growth and competitiveness.

Examples: Corporate innovation labs, intrapreneurship programs, new product development initiatives, and strategic partnerships with startups or external innovators drive innovation within established organizations.

4. Technology Entrepreneurship : Technology entrepreneurship revolves around the development, commercialization, and utilization of technological innovations to create new products, services, or solutions. These ventures often operate at the intersection of science, engineering, and business.

Examples: Software-development startups, biotechnology companies, hardware producers, and businesses concentrating on cutting-edge technologies like blockchain, artificial intelligence, and renewable energy are some examples of tech startups.

5. Serial Entrepreneurship : Serial entrepreneurship involves individuals who repeatedly start, grow, and exit multiple ventures throughout their careers. These entrepreneurs leverage their experience, networks, and insights from previous ventures to launch new initiatives.

Examples: Entrepreneurs who have founded and successfully scaled multiple startups across different industries or sectors, such as Elon Musk (PayPal, SpaceX, Tesla) and Richard Branson (Virgin Group).

6. Innovative Entrepreneurship : Innovative entrepreneurship emphasizes the creation of groundbreaking innovations and disruptive technologies that transform industries and markets. These ventures challenge existing norms and paradigms and introduce novel solutions to complex problems.

Examples: Startups like Airbnb, Uber, and SpaceX are pioneering revolutionary technologies or business models, such as peer-to-peer lodging, ride-sharing, and space exploration and transportation, respectively.

7. Cultural Entrepreneurship : Cultural entrepreneurship involves the creation, preservation, and promotion of cultural products, experiences, and heritage. These ventures contribute to the enrichment of cultural diversity, identity, and expression.

Examples: Art galleries, museums, cultural festivals, heritage tourism initiatives, and creative industries like film, music, literature, and fashion contribute actively to the enrichment of cultural diversity, identity, and expression.

Challenges Faced by Entrepreneurs

1. Financial Constraints

- Limited Capital: Accessing sufficient funding to start and sustain operations is a common challenge for entrepreneurs, especially in the early stages of venture development.

- Cash Flow Management: A company’s capacity to remain viable and sustainable depends on its ability to manage cash flow, especially in times of variable revenue and expenses.

2. Market Competition

- Competitive Landscape: Entrepreneurs must contend with intense competition from existing incumbents, emerging startups, and disruptive innovators who are vying for market share and customer attention.

- Market Saturation: Saturated markets pose challenges for entrepreneurs seeking to differentiate their offerings and carve out a niche amidst a crowded marketplace.

3. Regulatory and Legal Hurdles

- Compliance Requirements: Entrepreneurs must navigate complex regulatory frameworks and legal requirements governing business operations, taxation, licensing, permits, and intellectual property rights.

- Litigation Risks: Legal disputes, lawsuits, and regulatory penalties can pose significant risks to entrepreneurs, requiring proactive risk management and legal counsel.

4. Failure and Resilience

- Fear of Failure: Fear of failure can immobilize business owners and inhibit their willingness to take risks, which keeps them from taking advantage of chances and exploring novel concepts.

- Resilience and Grit: Building resilience and maintaining a positive mindset are essential for overcoming setbacks, learning from failures, and persevering in adversity.

5. Market Uncertainty and Volatility

- Economic Fluctuations: Entrepreneurs must navigate economic uncertainties, market downturns, and macroeconomic factors that impact consumer spending, business investment, and market demand.

- Technological Disruption: Rapid technological advancements and disruptive innovations can render existing business models obsolete, requiring entrepreneurs to adapt and innovate to stay competitive.

6. Talent Acquisition and Retention

- Recruitment Challenges: Hiring and retaining skilled talent is a persistent challenge for entrepreneurs, particularly in competitive industries and niche sectors with high demand for specialized expertise.

- Team Building and Management: Building cohesive teams, fostering a positive work culture, and managing interpersonal dynamics are essential for organizational success and employee engagement.

7. Scaling and Growth

- Operational Scalability: Scaling operations to accommodate growth while maintaining efficiency and quality requires strategic planning, infrastructure investment, and process optimization.

- Resource Allocation: Entrepreneurs at every stage of venture development face the strategic challenge of effectively allocating resources to support growth initiatives, expand market reach, and capitalize on new opportunities.

8. Market Disruption and Adaptation

- Disruptive Forces: Entrepreneurs must foresee and react to disruptive factors that have the potential to transform sectors and jeopardize established business models. These forces include technology innovation, shifting customer preferences, and shifting market dynamics.

- Adaptability and Agility: It takes agility, flexibility, and capacity to change course in reaction to shifting market conditions so business owners can stay ahead of the curve and profit from new trends.

9. Mental Health and Well-being

- Stress and Burnout: Entrepreneurship can damage mental health and well-being due to the pressures of running a business, managing uncertainties, and balancing work-life demands.

- Self-care and Support Systems: Long-term business success depends on prioritizing self-care, getting help from peers, mentors, and mental health specialists, and maintaining a healthy work-life balance.

The Role of Entrepreneurship in Economic Development

- Job Creation : Entrepreneurship is a primary engine of job creation, as new ventures often require a workforce to support their operations. Entrepreneurs generate employment opportunities, reduce unemployment rates, and promote economic inclusion by starting and expanding existing businesses.

- Innovation and Technological Advancement : Entrepreneurs are at the forefront of innovation, pioneering new technologies, products, and services that disrupt industries and drive progress. Entrepreneurs introduce novel solutions to market needs through research, experimentation, and risk-taking, fueling technological advancement and enhancing productivity.

- Wealth Creation and Economic Growth : Successful entrepreneurship leads to wealth creation, as ventures generate profits, attract investment, and increase the overall wealth of individuals and communities. This wealth is reinvested in the economy through spending, savings, and investment, contributing to economic growth and prosperity.

- Regional Development and Economic Diversification : Entrepreneurship promotes regional development by spurring economic activity in previously underserved or marginalized areas. By establishing businesses and investing in local infrastructure, entrepreneurs contribute to diversifying regional economies, reducing dependence on specific industries, and enhancing resilience to economic shocks.

- Income Generation and Poverty Alleviation : Entrepreneurship allows people from various backgrounds to increase their wealth, create income, and enhance their quality of life. By creating self-employment opportunities and empowering marginalized groups, entrepreneurship serves as a pathway out of poverty and promotes social mobility.

- Export Promotion and International Trade : Entrepreneurial ventures often engage in international trade, exporting goods and services to foreign markets and contributing to trade balances. By tapping into global markets, entrepreneurs access new growth opportunities, expand their customer base, and drive economic integration and globalization.

- Ecosystem Development and Knowledge Spillovers : Entrepreneurship fosters the development of vibrant ecosystems comprised of startups, investors, incubators, accelerators, and support organizations. These ecosystems facilitate knowledge sharing, collaboration, and networking, leading to the diffusion of ideas and best practices across industries and regions.

- Cultural and Social Impact : Entrepreneurship transcends economic boundaries, shaping cultural norms, values, and attitudes towards innovation and risk-taking. Successful entrepreneurs are role models, inspiring others to pursue their aspirations and contribute to societal progress.

Entrepreneurship and Innovation

- Catalysts of Change : Entrepreneurship acts as a catalyst for innovation, sparking the creation of groundbreaking ideas, technologies, and business models. Innovators, in turn, fuel entrepreneurial endeavors by presenting new solutions and opportunities ripe for exploration.

- Market Disruption : Entrepreneurs often disrupt markets through innovative products or services, challenging established norms and creating new market segments. This disruption prompts further innovation as incumbents respond with their advancements, leading to a cycle of continuous improvement and evolution.

- Risk-Taking and Experimentation : Entrepreneurship thrives on risk-taking and experimentation, essential ingredients for innovation. Recognizing that failure is often a prerequisite for eventual success, entrepreneurs strategically take calculated risks to transform their creative visions into reality.

- Ecosystem Collaboration : Vibrant entrepreneurial ecosystems foster collaboration between entrepreneurs, researchers, investors, and policymakers. By combining varied knowledge and resources, these collaborations promote innovation by quickening the development and commercialization of innovative ideas.

- Customer-Centric Solutions : Successful entrepreneurs understand the importance of innovation in addressing customer needs and pain points. They leverage innovation to create customer-centric solutions, driving adoption and loyalty while continuously refining their offerings based on feedback and market insights.

- Technological Advancements : Entrepreneurial ventures often drive the adoption and commercialization of emerging technologies. Entrepreneurs propel technological advancements forward by recognizing new technologies’ potential and integrating them into innovative products or processes.

- Social and Environmental Impact : Entrepreneurship and innovation increasingly address pressing social and environmental challenges. Social entrepreneurs leverage innovative business models to tackle issues such as poverty, healthcare, education, and environmental sustainability, creating positive change on a global scale.

- Economic Resilience and Competitiveness : Nations with thriving entrepreneurial ecosystems and a culture of innovation are better positioned to adapt to economic disruptions and maintain competitiveness in the global marketplace. Entrepreneurship and innovation foster economic resilience by driving productivity, creating jobs, and fostering economic diversification.

Ethical Considerations in Entrepreneurship

- Transparency and Honesty : Entrepreneurs should prioritize transparency and honesty in their dealings with stakeholders, including customers, employees, investors, and partners. Providing accurate information, being truthful about risks, and avoiding deceptive practices build trust and credibility.

- Fair Treatment of Stakeholders : Entrepreneurs should treat all stakeholders fairly and equitably, considering the interests and well-being of employees, suppliers, customers, and the community. Fair labor practices, non-discriminatory policies, and responsible supply chain management demonstrate a commitment to ethical conduct.

- Responsible Innovation : Entrepreneurs should pursue innovation responsibly, actively considering the potential social, environmental, and ethical implications. Entrepreneurs should consider the broader impact of their products or services, prioritizing safety, sustainability, and ethical use.

- Respect for Intellectual Property : Entrepreneurs must respect intellectual property rights and avoid infringing on others’ patents, trademarks, copyrights, or trade secrets. Protecting intellectual property created by the venture also safeguards against unfair competition and promotes innovation.

- Environmental Sustainability : Entrepreneurs should integrate environmental sustainability into their business practices, minimizing negative environmental impacts and promoting resource efficiency. Sustainable sourcing, eco-friendly manufacturing processes, and carbon footprint reduction initiatives demonstrate a commitment to environmental stewardship.

- Social Responsibility : Entrepreneurs are responsible for contributing positively to society, addressing social issues, and supporting community development. Socially responsible initiatives such as charitable giving, volunteerism, and ethical sourcing enhance the venture’s reputation and foster goodwill among stakeholders.

- Ethical Marketing and Advertising : Entrepreneurs should adhere to ethical standards in marketing and advertising, avoiding deceptive or manipulative tactics that mislead consumers. Clear and truthful communication, respecting consumer privacy, and avoiding false claims uphold integrity in marketing practices.

- Data Privacy and Security : Entrepreneurs must prioritize protecting customer and employee data, respecting privacy rights, and implementing robust cybersecurity measures. Safeguarding sensitive information against unauthorized access, breaches, or misuse is essential for maintaining trust and compliance with data protection regulations.

- Corporate Governance and Accountability : Entrepreneurs should establish sound corporate governance practices that promote accountability, integrity, and ethical behavior within the organization. Transparent decision-making processes, independent oversight, and ethical leadership foster a culture of accountability and responsibility .

- Continuous Ethical Reflection and Improvement : Entrepreneurs should actively integrate ethical considerations into the fabric of their ventures, engaging in continuous reflection and improvement. Regular ethical assessments, stakeholder engagement, and responsiveness to feedback help ensure ethical conduct remains a priority as the venture evolves.

Case Studies

Success Stories of Entrepreneurs and Lessons Learned from Failures

1. Steve Jobs (Apple Inc.)

- Success Story: Steve Jobs co-founded Apple Inc., leading it to become one of the world’s most valuable companies. He revolutionized industries with products like the iPhone, iPad, and Macintosh.

- Lessons Learned from Failure: Throughout his career, Jobs experienced many failures, including being fired from Apple in 1985 due to internal strife. However, in 1997, Steve returned to Apple, helping it achieve remarkable success. However, he returned to Apple in 1997, leading it to unprecedented success. His failures taught him the importance of perseverance, innovation, and resilience in adversity.

2. Sara Blakely (Spanx)

- Success Story: Sara Blakely transformed the fashion industry and empowered women worldwide by founding Spanx, a multi-billion-dollar shapewear company.

- Lessons Learned from Failure: Blakely faced multiple rejections when pitching her idea to manufacturers and investors. However, she persisted, self-funding her venture and learning from each rejection. Her experience taught her the value of persistence, self-belief, and resilience in overcoming obstacles.

3. Elon Musk (SpaceX, Tesla)

- Success Story: Elon Musk co-founded SpaceX, which revolutionized space exploration, and Tesla, which pioneered electric vehicles and sustainable energy solutions.

- Lessons Learned from Failure: Musk experienced numerous setbacks and near-bankruptcy with SpaceX and Tesla. Despite facing criticism and skepticism, he remained steadfast in his vision, learning from failures and leveraging them to fuel future successes. His journey underscores the importance of resilience, risk-taking, and relentless pursuit of goals.

4. JK Rowling (Harry Potter)

- Success Story: The Harry Potter series, authored by J.K. Rowling, became a global phenomenon, inspiring generations of readers and selling over 500 million copies worldwide.

- Lessons Learned from Failure: Rowling faced rejection from multiple publishers before finally securing a book deal for Harry Potter. Her experiences taught her the value of perseverance, belief in oneself, and the transformative power of resilience. Rowling’s journey exemplifies the importance of resilience in facing rejection and adversity.

5. Jeff Bezos (Amazon)

- Success Story: Jeff Bezos founded Amazon, which he turned from an online bookshop into the biggest e-commerce platform in the world and one of the most valuable firms.

- Lessons Learned from Failure: Bezos experienced failures and setbacks throughout Amazon’s journey, including failed product launches and financial challenges. However, he embraced failure as a learning opportunity, iterating on ideas and remaining focused on long-term goals. Bezos’ experience underscores the importance of adaptability, customer obsession, and a willingness to experiment.

Entrepreneurship is a beacon of innovation, economic dynamism, and societal progress. From the visionary leadership of pioneers like Steve Jobs to the relentless determination of trailblazers like Sara Blakely, the entrepreneurial journey is marked by triumphs forged from failures. Aspiring entrepreneurs must embrace resilience, creativity, and ethical conduct to navigate the challenges and opportunities that lie ahead in shaping a brighter future through entrepreneurship.

*Please provide your correct email id. Login details for this Free course will be emailed to you

By signing up, you agree to our Terms of Use and Privacy Policy .

Valuation, Hadoop, Excel, Web Development & many more.

Forgot Password?

This website or its third-party tools use cookies, which are necessary to its functioning and required to achieve the purposes illustrated in the cookie policy. By closing this banner, scrolling this page, clicking a link or continuing to browse otherwise, you agree to our Privacy Policy

Explore 1000+ varieties of Mock tests View more

Submit Next Question

🚀 Limited Time Offer! - 🎁 ENROLL NOW

Home » Home » Essay » Essay on entrepreneurship (100, 200, 300, & 500 Words)

Essay on entrepreneurship (100, 200, 300, & 500 Words)

Essay on entrepreneurship (100 words), essay on entrepreneurship (200 words), essay on entrepreneurship (300 words), the importance of entrepreneurship.

- Economic Growth : Entrepreneurship plays a crucial role in driving economic growth by creating new businesses, products, and services. It fosters competition and encourages innovation, leading to increased productivity and efficiency in the economy.

- Job Creation : Entrepreneurs are job creators. They not only create jobs for themselves but also generate employment opportunities for others. Startups and small businesses are known to be significant contributors to job creation, especially in developing economies.

- Innovation and Technology : Entrepreneurs are at the forefront of innovation and technological advancements. They constantly challenge the status quo and introduce new ideas, products, and processes, driving progress in various industries.

- Societal Development : Entrepreneurship has a positive impact on society by addressing social problems and meeting unmet needs. Social entrepreneurs focus on creating ventures that tackle issues like poverty, education, healthcare, and environmental sustainability.

Qualities of Successful Entrepreneurs

- Passion and Motivation : Successful entrepreneurs are driven by a strong passion for their ideas, products, or services. They are motivated to overcome challenges and persevere through setbacks, fueling their determination to succeed.

- Creativity and Innovation : Entrepreneurs possess a high degree of creativity and are constantly seeking new and innovative solutions. They think outside the box, challenge conventions, and find unique ways to add value to the market.

- Risk-taking and Resilience : Entrepreneurs are willing to take calculated risks and step out of their comfort zones. They understand that failure is a part of the journey and are resilient enough to bounce back from setbacks and learn from their mistakes.

- Adaptability and Flexibility : The business landscape is ever-evolving, and successful entrepreneurs are adaptable and flexible. They embrace change, pivot when necessary, and stay ahead of market trends and customer demands.

- Leadership and Vision : Entrepreneurs are visionaries who can inspire and lead their teams. They have a clear vision of what they want to achieve and possess the ability to communicate and align their goals with others, turning their vision into reality.

Key Steps in the Entrepreneurial Journey

- Identifying Opportunities : Successful entrepreneurs have a keen eye for identifying market gaps, unsolved problems, and emerging trends. They conduct thorough market research to understand customer needs and assess the viability of their ideas.

- Business Planning : Once an opportunity is identified, entrepreneurs develop a comprehensive business plan. This includes defining their target market, analyzing competitors, outlining their value proposition, and formulating a strategic roadmap.

- Securing Funding : Entrepreneurs often require financial resources to launch and grow their ventures. They explore different funding options such as bootstrapping, seeking loans, attracting investors, or crowdfunding to secure the necessary capital.

- Building a Team : Entrepreneurship is rarely a solo journey. Successful entrepreneurs build a team of skilled individuals who complement their strengths and contribute towards achieving the company’s goals. They understand the importance of delegation and collaboration.

- Execution and Iteration : Entrepreneurs turn their ideas into action by executing their plans and continuously iterating their products or services based on customer feedback. They are agile and adaptable, making changes and improvements as they learn from the market.

- Scaling and Growth : As the venture gains traction, entrepreneurs focus on scaling their operations. They explore opportunities for expansion, enter new markets, and invest in resources to support growth while maintaining a strong customer-centric approach.

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

So You Want to Be an Entrepreneur?

- Emily Heyward

One founder’s advice on what you should know before you quit your day job.

Starting a business is not easy, and scaling it is even harder. You may think you’re sitting on a completely original idea, but chances are the same cultural forces that led you to your business plan are also influencing someone else. That doesn’t mean you should give up, or that you should rush to market before you’re ready. It’s not about who’s first, it’s about who does it best, and best these days is the business that delivers the most value to the consumer. Consumers have more power and choice than ever before, and they’re going to choose and stick with the companies who are clearly on their side. How will you make their lives easier, more pleasant, more meaningful? How will you go out of your way for them at every turn? When considering your competitive advantage, start with the needs of the people you’re ultimately there to serve. If you have a genuine connection to your idea, and you’re solving a real problem in a way that adds more value to people’s lives, you’re well on your way.

When I graduated from college in 2001, I didn’t have a single friend whose plan was to start his or her own business. Med school, law school, finance, consulting: these were the coveted jobs, the clear paths laid out before us. I took a job in advertising, which was seen as much more rebellious than the reality. I worked in advertising for a few years, and learned an incredible amount about how brands get built and communicated. But I grew restless and bored, tasked with coming up with new campaigns for old and broken products that lacked relevance, unable to influence the products themselves. During that time, I was lucky to have an amazing boss who explained a simple principle that fundamentally altered my path. What she told me was that stress is not about how much you have on your plate; it’s about how much control you have over the outcomes. Suddenly I realized why every Sunday night I was overcome with a feeling of dread. It wasn’t because I had too much going on at work. It was because I had too little power to effect change.

- EH Emily Heyward is the author of Obsessed: Building a Brand People Love from Day One (Portfolio; June 9, 2020). She is the co-founder and chief brand officer at Red Antler, a full-service brand company based in Brooklyn. Emily was named among the Most Important Entrepreneurs of the Decade by Inc. magazine, and has also been recognized as a Top Female Founder by Inc. and one of Entrepreneur’s Most Powerful Women of 2019.

Partner Center

- Entertainment

- Environment

- Information Science and Technology

- Social Issues

Home Essay Samples Business

Essay Samples on Entrepreneurship

What is entrepreneurship in your own words.

What is entrepreneurship in your own words? To me, entrepreneurship is the art of turning imagination into reality, the courage to chart unexplored territories, and the commitment to leave a lasting mark on the world. It's a journey of boundless creativity, relentless innovation, and unwavering...

- Entrepreneurship

What is Entrepreneurship: Unveiling the Essence

What is entrepreneurship? This seemingly straightforward question encapsulates a world of innovation, risk-taking, and enterprise. Entrepreneurship is not merely a business concept; it's a mindset, a journey, and a force that drives economic growth and societal progress. In this essay, we delve into the multifaceted...

Social Entrepreneurship: Harnessing Innovation

Social entrepreneurship is a transformative approach that merges business principles with social consciousness to address pressing societal challenges. This unique form of entrepreneurship goes beyond profit-seeking and focuses on generating innovative solutions that create positive change in communities. In this essay, we explore the concept...

Evolution of Entrepreneurship: Economic Progress

Evolution of entrepreneurship is a fascinating journey that mirrors the changes in society, economy, and technology throughout history. From humble beginnings as small-scale trade to the modern era of startups, innovation hubs, and global business networks, entrepreneurship has continuously adapted to the dynamic landscape. This...

Importance of Entrepreneurship: Economic Growth and Societal Transformation

Importance of entrepreneurship transcends its role as a mere business activity; it stands as a driving force behind innovation, economic growth, and societal transformation. Entrepreneurship fosters the creation of new products, services, and industries, while also generating employment opportunities and catalyzing economic development. This essay...

- Economic Growth

Stressed out with your paper?

Consider using writing assistance:

- 100% unique papers

- 3 hrs deadline option

Entrepreneurship as a Career: Navigating the Path of Innovation

Entrepreneurship as a career is a compelling journey that offers individuals the opportunity to create their own path, shape their destiny, and contribute to the economy through innovation. While the road to entrepreneurship is laden with challenges and uncertainties, it is also marked by the...

Corporate Entrepreneurship: Fostering Innovation

Corporate entrepreneurship represents a strategic approach that empowers established organizations to embrace innovation, take calculated risks, and explore new opportunities. In an ever-evolving business landscape, the concept of corporate entrepreneurship has gained prominence as companies seek to maintain their competitive edge and adapt to changing...

Challenges Faced by Entrepreneurs: Innovation and Success

Challenges faced by entrepreneurs are a testament to the intricate journey of turning visionary ideas into tangible realities. While entrepreneurship is often associated with innovation and opportunity, it's also characterized by a multitude of hurdles and obstacles that test an entrepreneur's resilience and determination. In...

300 Words About Entrepreneurship: Navigating Innovation and Opportunity

About entrepreneurship is a dynamic journey that involves the pursuit of innovation, creation, and the realization of opportunities. It is the process of identifying gaps in the market, envisioning solutions, and taking calculated risks to bring new products, services, or ventures to life. Entrepreneurs are...

Best topics on Entrepreneurship

1. What is Entrepreneurship in Your Own Words

2. What is Entrepreneurship: Unveiling the Essence

3. Social Entrepreneurship: Harnessing Innovation

4. Evolution of Entrepreneurship: Economic Progress

5. Importance of Entrepreneurship: Economic Growth and Societal Transformation

6. Entrepreneurship as a Career: Navigating the Path of Innovation

7. Corporate Entrepreneurship: Fostering Innovation

8. Challenges Faced by Entrepreneurs: Innovation and Success

9. 300 Words About Entrepreneurship: Navigating Innovation and Opportunity

- Advertising

- Comparative Analysis

- Business Analysis

- SWOT Analysis

- Mystery Shopper

- Black Friday

Need writing help?

You can always rely on us no matter what type of paper you need

*No hidden charges

100% Unique Essays

Absolutely Confidential

Money Back Guarantee

By clicking “Send Essay”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement. We will occasionally send you account related emails

You can also get a UNIQUE essay on this or any other topic

Thank you! We’ll contact you as soon as possible.

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

Margin Size

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

1.10: Chapter 10 – The Entrepreneurial Environment

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 21262

- Lee A. Swanson

- University of Saskatchewan

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

Entrepreneurs adopt the ways of the adept and adapt to a changing environment. Actually, entrepreneurs are more entrepreneurs, because they are forever entering into new territory. – Jarod Kintz

Entrepreneurship rests on a theory of economy and society. The theory sees change as normal and indeed as healthy. And it sees the major task in society—and especially in the economy—as doing something different rather than doing better what is already being done. That is basically what Say, two hundred years ago, meant when he coined the term entrepreneur. It was intended as a manifesto and as a declaration of dissent: the entrepreneur upsets and disorganizes. As Joseph Schumpeter formulated it, his task is “creative destruction. – Peter Drucker

Learning Objectives

After completing this chapter you will be able to

- Explain what an entrepreneurial ecosystem is as a form of complex adaptive system while explaining its relevance to the study of entrepreneurship

- Describe various entrepreneurship concepts, such as intrapreneurship and social entrepreneurship, while explaining their relevance to the study of entrepreneurship

In this chapter several entrepreneurship topics are introduced, including: entrepreneurial ecosystems, intrapreneurship, social entrepreneurship, Indigenous entrepreneurship, community-based entrepreneurship, and family business. This overview of just a few of the branches of entrepreneurship thought and research is intended to provide the reader with an idea of the breadth of this field of study. There are many other categories of entrepreneurship, from women entrepreneurs to technology entrepreneurs, which provide interesting and important study topics.

The Entrepreneurial Environment

Entrepreneurial ecosystems.

An entrepreneurial ecosystem might be viewed as a complex adaptive system that can be compared to a natural ecosystem, like a forest. This complexity theory perspective can help us better understand the nature of an entrepreneurial ecosystem.

A forest is a complex adaptive system made up of many, many different elements, including the plants and animals that live in it or otherwise influence how it works. Those many different elements behave autonomously from each other in most ways; but as they do what is necessary to ensure their own survival—and as they attempt to thrive—the end result of their collective behaviours is a forest that exists in a somewhat stable state of being.

The forest is in a somewhat stable state because it is ever evolving and changing to some degree as variables change. Changing variables include new insect species that move in and out, new plants that try to establish roots there, and similar changes that regularly happen to cause some change, but that don’t necessarily change the fundamental nature of the forest.

Sometimes, however, a parameter change occurs when something more substantial happens, like a forest fire. When a fire burns down the plants and chases many of the animals away, the forest fundamentally changes to a very different state (the change from the first state to a new and very different one is called bifurcation ).

An entrepreneurial ecosystem is similar in that the nature of entrepreneurship—thriving or not—across a geographic region remains in a somewhat stable state of being even though it is made up of a complex network of independent elements that continually adapt to the organizational environments in which they operate; it is a complex adaptive system. The variable changes, including new leaders that replace the old ones, new rules and regulations, and entrepreneurial support systems that come and go do not necessarily change the fundamental nature of the entrepreneurial ecosystem (although the residents of the region might actually want substantial change leading to a more vibrant economic situation). A parameter change, however, might cause a bifurcation that leaves the system in a very different state—maybe one where entrepreneurship thrives and prosperity prevails much more than it did before. The introduction of a major new project that, in turn, spawns new spin-off businesses and gives the region a needed economic boost, and maybe even leaves it with a new entrepreneurial culture, is an example of a parameter change.

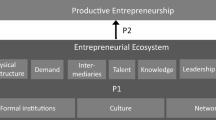

In a more formal sense, an entrepreneurial ecosystem can be described as

a set of interconnected entrepreneurial actors (both potential and existing), entrepreneurial organisations (e.g. firms, venture capitalists, business angels, banks), institutions (universities, public sector agencies, financial bodies) and entrepreneurial processes (e.g. the business birth rate, numbers of high growth firms, levels of ‘blockbuster entrepreneurship’, number of serial entrepreneurs, degree of sell-out mentality within firms and levels of entrepreneurial ambition) which formally and informally coalesce to connect, mediate and govern the performance within the local entrepreneurial environment (Mason & Brown, 2014, p. 5).

Definitions of entrepreneurial ecosystems can include the suppliers, customers and others that any particular firm in that ecosystem directly interacts with as well as other individuals, firms, and organizations that the firm might not directly interact with, but that play a role in shaping the ecosystem. While framing it as an innovation ecosystem rather than an entrepreneurial ecosystem, Matthews and Brueggemann (2015) described an internal ecosystem as a company’s activities that are independent of other companies and an external ecosystem that includes all of the other actors that the company is dependent upon in some way.

While some researchers have studied how entrepreneurial ecosystems can generate geographic clusters of technology-based ventures, like in Silicon Valley (Cohen, 2006) or how these ecosystems can facilitate growth in entrepreneurship in cities and similarly defined regions (Neck, Meyer, Cohen, & Corbett, 2004), Mason and Brown (2014) suggest that even traditional industries can “provide the platform to create dynamic, high-value-added entrepreneurial ecosystems” (p. 19).

Types of Entrepreneurship

Intrapreneurship.

According to Martiarena (2013) “the recognition of intrapreneurial activities has widened the notion of entrepreneurship by incorporating entrepreneurial activities undertaken within established organisations to the usual view of entrepreneurship as new independent business creation.” (p. 27). Intrapreneurship, then, is a form of entrepreneurship that occurs within existing organizations, but intrapreneurs are generally considered to be “significantly more risk-averse than entrepreneurs, earn lower incomes, perceive less business opportunities in the short term and do not consider that they have enough skills to succeed in setting up a business” (Martiarena, 2013, p. 33).

Merriam-Webster (n.d.) defines an intrepreneur as “a corporate executive who develops new enterprises within the corporation” (Intrapreneur, n.d.); however some might consider some employees who are not corporate executives to also be intrapreneurs if they demonstrate entrepreneurial behaviour within the company they work for.

Social Entrepreneurship

Social entrepreneurship involves employing the principles of entrepreneurship to create organizations that address social issues.

Martin and Osberg (2007) defined a social entrepreneur as an individual who

targets an unfortunate but stable equilibrium that causes the neglect, marginalization, or suffering of a segment of humanity; who brings to bear on this situation his or her inspiration, direct action, creativity, courage, and fortitude; and who aims for and ultimately affects the establishment of a new stable equilibrium that secures permanent benefit for the targeted group and society at large. (p. 39)

Martin and Osberg’s (2007) definition encompasses for-profit and not-for-profit organizations created by these entrepreneurs and also some government initiatives, but it excludes entities that exist solely to provide social services and groups formed to engage in social activism.

An idealized definition of social entrepreneurship developed by Dees (2001) is informative in that it supports Martin and Osberg’s (2007) definition while complementing it with a set of criteria against which organizations can be assessed to determine whether they are socially entrepreneurial.

Social entrepreneurs play the role of change agents in the social sector, by

- adopting a mission to create and sustain social value (not just private value)

- recognizing and relentlessly pursuing new opportunities to serve that mission

- engaging in a process of continuous innovation, adaptation, and learning

- acting boldly without being limited by resources currently in hand

- exhibiting heightened accountability to the constituencies served and for the outcomes created (Dees, 2001, p. 4)

Social entrepreneurs “use their skills not only to create profitable business ventures, but also to achieve social and environmental goals for the common good” (Zimmerer & Scarborough, 2008, p. 25). They are “people who start businesses so that they can create innovative solutions to society’s most vexing problems, see themselves as change agents for society” (Scarborough, Wilson, & Zimmer, 2009, p. 745).

Social entrepreneurship

- addresses social problems or needs that are unmet by private markets or governments

- is motivated primarily by social benefit

- generally works with—not against—market forces (Brooks, 2009, p. 4)

A social entrepreneur might

- start a new product or service

- expand an existing product or service

- expand an existing activity for a new group of people

- expand an existing activity to a new geographic area

- merge with an existing business (Brooks, 2009, p. 8)

What social entrepreneurship is not: it is not anti-business:

- Many social entrepreneurs came from the commercial business world.

- Sometimes commercial and nonprofit missions align for mutual benefit.

- The difference between it and commercial entrepreneurship is not greed.

- There is no evidence commercial entrepreneurs are especially greedy—they are more likely to be goal-obsessed than money-obsessed.

- Social entrepreneurs are also commercial entrepreneurs.

- Social entrepreneurs do not only run non-profits.

- Social entrepreneurship can occur in any sector and with any legal status. (Brooks, 2009, pp. 16-17)

The social entrepreneurship zone:

From Swanson and Zhang (2010, 2011, 2012)

Figure 7 – The Social Entrepreneurship Zone (Illustration by Lee A. Swanson)

Aboriginal (Indigenous) Entrepreneurship

Swanson and Zhang (2014) described a range of perspectives on what Indigenous entrepreneurship means and what implications it holds for social and economic development for Indigenous people.

Indigenous entrepreneurship might simply be entrepreneurship carried out by Indigenous people (Peredo & Anderson, 2006), but it can also refer to the common situation where Indigenous entrepreneurs—sometimes through community-based enterprises—start businesses that are largely intended to preserve and promote their culture and values (Anderson, Dana, & Dana, 2006; Christie & Honig, 2006; Swanson & Zhang, 2011). Dana and Anderson (2007) expanded upon that notion when they described Indigenous entrepreneurship as follows:

There is rich heterogeneity among Indigenous peoples, and some of their cultural values are often incompatible with the basic assumptions of mainstream theories. Indigenous entrepreneurship often has non-economic explanatory variables. Some Indigenous communities’ economies display elements of egalitarianism, sharing and communal activity. Indigenous entrepreneurship is usually environmentally sustainable; this often allows Indigenous people to rely on immediate available resources and, consequently, work in Indigenous communities is often irregular. Social organization among Indigenous peoples is often based on kinship ties, not necessarily created in response to market needs. (p. 601)

Lindsay (2005) described Indigenous entrepreneurship as something even more complex:

Significant cultural pressures are placed on Indigenous entrepreneurs. These pressures will manifest themselves in new venture creation and development behavior that involve the community at a range of levels that contribute toward self-determination while incorporating heritage, and where cultural values are an inextricable part of the very fabric of these ventures. Thus, the Indigenous “team” involved in new venture creation and development may involve not only the entrepreneur and the business’ entrepreneurial team but also the entrepreneur’s family, extended family, and/or the community. Thus, in Indigenous businesses, there are more stakeholders involved than with non-Indigenous businesses. For this reason, Indigenous businesses can be regarded as more complex than non-Indigenous businesses and this complexity needs to be reflected in defining entrepreneurship from an Indigenous perspective. (p. 2)

Community-Based Enterprises and Community-Based Entrepreneurship

Peredo and Chrisman (2006) described community-based enterprises (CBEs) as emerging from “a process in which the community acts entrepreneurially to create and operate a new enterprise embedded in its existing social structure” (p. 310). CBEs emerge when a community works collaboratively to “create or identify a market opportunity and organize themselves in order to respond to it” (p. 315). These ventures “are managed and governed to pursue the economic and social goals of a community in a manner that is meant to yield sustainable individual and group benefits over the short and long term” (p. 310). CBEs are positioned in a sector of the economy that is not dominated by a profit motive, often because there is little profit to be made, or by government. As illustrated in the next paragraphs, they also serve what we can refer to as the social commons .

Modern societies are comprised of three distinct, but overlapping sectors (Mook, Quarter, & Richmond, 2007; Quarter, Mook, & Armstrong, 2009; Quarter, Mook, & Ryan, 2010). Businesses operating in the private sector primarily strive to generate profits for their owners by providing goods and services in response to market demands. “While this sector provides jobs, innovation, and overall wealth, it is not suited to addressing most social problems because there is usually no profit to be made by doing so” (Swanson & Zhang, 2012, p. 177). The public sector redistributes the money it collects in taxes to provide public goods and to serve needs not met by the private sector. “While this sector provides defence, public safety, education and a range of other public needs and social services, it has limited capacity to recognize and solve all social needs” (Swanson & Zhang, 2012, p. 177). The remaining sector—referred to by a variety of names including the third sector, the citizens’ sector, the voluntary sector, the non-profit sector, and more recently by Mintzberg, the plural sector (Mintzberg, 2013; Mintzberg & Azevedo, 2012)—is comprised of organizations that deliver goods and services the other sectors do not provide and are either owned by their members (with limited or no potential for individuals or small groups to gain a controlling interest in the organization) or not owned by any individuals, governments, businesses, other organizations, or any particular entity at all.

Bollier (2002) used the term the commons to distinguish the collaborative community-based concern for particular kinds of resources from the management interests in resources assumed by the markets and governments. He pointed out that “people have interests apart from those of government and markets” (p. 12). One of his categories of the commons is the social commons, which involves “pursuing a shared mission as a social or civic organism” (p. 12). The social commons is comprised of community members who contribute energy and resources as they work together to create value.

Scholars have studied CBEs’ role in promoting socio-economic development in developing countries (Manyara & Jones, 2007; Torri, 2010) and some have conceptualized Indigenous entrepreneurship as based on a community-based orientation (Kerins & Jordan, 2010; Peredo & Anderson, 2006; Peredo, Anderson, Galbraith, Honig, & Dana, 2004). Social enterprises are sometimes considered to be a form of CBE (Leadbeater, 1997); however, Somerville and McElwee (2011) interpreted Peredo and Chrisman’s (2006) work to mean that a CBE is “a special kind of community enterprise where the community itself is the enterprise and is also the entrepreneur. Consequently, a CBE is an enterprise whose social base (the social structure of the community) lies in the CBE itself” (Somerville & McElwee, 2011, p. 320). This interpretation might distinguish CBEs from some types of social enterprises.

Some scholars refer to CBEs as being owned by the community while others indicate they can be owned by individuals or groups of people on behalf of the communities they serve. Lehman and Lento (1992) referred to “owners and managers” (p. 70) of CBEs when they argued that the value generated by these types of enterprises often benefit neighbouring residents and businesses more so than the direct owners.

While CBEs in the form of cooperatives have proven to be both prominent and resilient in many parts of the world (Birchall & Hammond Ketilson, 2009), there are also other forms of community-based or mutually owned enterprises as described by Woodin, Crook, and Carpentier (2010). They identified five general models of community-based or mutual ownership while explaining that new models continue to develop.

CBEs involved with housing developments, energy production initiatives, financial services, retail and wholesale trade, health care and social services, education, and other types of activities is relatively well documented (Woodin et al., 2010). There are also examples of symphony orchestras (Boyle, 2003) and other arts organizations that are community-based, sometimes through direct community ownership. Examples of community-owned sports franchises in Canada include the Saskatchewan Roughriders (Saskatchewan Roughrider Football Club Inc., 2012), Edmonton Eskimos (Edmonton Eskimos, 2011), and Winnipeg Blue Bombers (Winnipeg Blue Bombers, 2012) of the Canadian Football League. The Green Bay Packers, a professional American football team in the United States is also community-owned (Green Bay Packers, 2012). In the association football (soccer) world, the Victoria Highlanders’ F. C. (Dheensaw, 2011) and F. C. Barcelona (Schoenfeld, 2000) are examples of community-owned teams.

The Role of Community-Based Enterprises

According to Gates (1999), the free enterprise system that has dominated the economic landscape of many developed countries since the end of the Cold War has often proven to be insensitive to the needs of communities. “The result is to endanger sustainability across five overlapping domains: fiscal, constitutional, civil, social and environmental” (p. 437). He suggested that the policy environment should be adjusted to encourage more connection between people and the results from the investments they make. With a revised capitalist goal to improve societal well-being rather than the current imperative to maximize financial returns with little or no regard for the associated public outcomes, the current and growing divide between our richest and poorest should narrow and we should end up with a more sustainable economic system.

Gates (1999) suggested that one approach to establishing a closer connection between people and the effects from their investments is to re-engineer capitalism in a way that encourages a shift in ownership types toward more members of society directly and collectively owning elements of the organizations that affect their lives through the social, environmental, and other impacts they have. CBEs appear to be one form of organization that can fulfill part of the role advocated by Gates (1999).

Community context plays an important role in how entrepreneurial processes evolve and in their resulting outcomes. According to Hindle (2010), to understand the community context requires an “examination of the nature and interrelationship of three generic institutional components of any community: physical resources, human resources and property rights, and three generic human factors: human resources, social networks and the ability to span boundaries” (p. 599). When communities face social and economic challenges, some are able to mobilize physical and human resources, particularly when these communities “are rich in social capital and are able to learn from collective experiences” (Ring, Peredo, & Chrisman, 2010, p. 5). Communities within this context are often equipped to identify opportunities and capitalize on them. This can give rise to CBEs that can contribute to capacity building in their communities (Peredo & Chrisman, 2006).

Community Capacity Building through Community-Based Enterprises

Similar to entrepreneurial capacity in that it refers to evaluating and capitalizing upon the potential to create value (Hindle, 2007), community capacity “is the interaction of human capital, organizational resources, and social capital existing within a given community that can be leveraged to solve collective problems and improve or maintain the well-being of a given community” (Chaskin, 2001, p. 295). Borch et al. (2008) indicated that CBEs play a community-capacity-building role when they mobilize physical, financial, organizational and human resources. Their role in organizing “voluntary efforts and other non-market resources” (p. 120) is also of particular importance in this regard.

Economists have generally suggested that for-profit, privately held organizations occupy different market segments than publicly funded and community-based organizations. For-profit entities normally seek markets that are easiest to access and profit from, but their activities in these markets do not necessarily generate social return beyond that provided by increased employment and the services that are funded by the taxes they pay. On the other hand, publicly funded and community-based organizations generally serve a different market segment focused on generating some sort of social return (Abzug & Webb, 1999).

For-profit entities are usually subject to significant influence from the suppliers of the capital used to support the organization’s operations. Sometimes these supply-side stakeholders have little interest in the service or product delivered provided that it generates an adequate financial return for them. CBEs and not-for-profit organizations primarily answer to demand-side stakeholders who might use the products or services these organizations deliver or who will benefit from their provision. This can mean that CBEs play an important role in building community capacity when their demand-side stakeholders turn to them when “for-profit organizations fail to provide products and services that stakeholders trust; and where they provide insufficient quantity or quality, and government provision fails to compensate for this market failure” (Abzug & Webb, 1999, p. 421).

One major difference between for-profit and CBEs and not-for-profit organizations is in the distribution of the accounting profit. Unlike for-profits, CBEs and non-profits generally do not distribute profits to equity holders and they enjoy some competitive advantages, including tax exemptions and the ability to receive private donations (Sloan, 2000). Transparency in reporting financial returns is especially important in community-held entities. These entities must report to a vast group of stakeholders who evaluate the organization’s success based on social return as well as financial efficiency (De Alwis, 2012).

CBEs can also represent an extension of the private sector that plays an important role in supporting them (Abzug & Webb, 1999). In the case of the Lloydminster Bobcats, the private sector supported the team by providing volunteers, advertising dollars, financial resources, and management and board expertise because it believed the team made the community more attractive. The team provided a form of entertainment that could help attract private sector employees to the community and retain them after they arrived.

Family Businesses

Chua, Chrisman, and Steier (2003) reported that “family-owned firms account for a large percentage of the economic activities in the United States and Canada. Estimates run from 40 to 60 percent of the U.S. gross national product (Neubauer & Lank, 1998), in addition to employment for up to six million Canadians (Deloitte & Touche, 1999). Their influence is likely even larger elsewhere” (p. 331). Besides the significant component of Canadian and other economies that are made up of family-owned businesses, these entities might be distinct from other forms of entrepreneurship in several ways. While more research is required to better understand the distinctions, family businesses might be characterized by the unique influences family members have on how their firms operate and by the distinctive challenges they face that make them behave and perform differently than other categories of businesses (Chua et al., 2003).

One of the unique and most important challenges faced by family businesses is managing succession so that leadership can be transferred to future generations to preserve family ownership while maintaining family harmony. This is particularly important as the survival rate of family businesses decline as new generations take over (Davis & Harveston, 1998).

Advertisement

The influence of ecosystems on the entrepreneurship process: a comparison across developed and developing economies

- Open access

- Published: 21 August 2020

- Volume 57 , pages 1733–1759, ( 2021 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Maribel Guerrero ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-7387-1999 1 , 2 ,

- Francisco Liñán ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-6212-1375 3 , 4 &

- F. Rafael Cáceres-Carrasco ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-6240-3900 3

21k Accesses

90 Citations

8 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

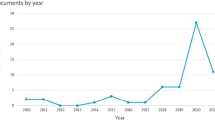

Over the past 30 years, the academic literature has legitimised the significant impact of environmental conditions on entrepreneurial activity. In the past 5 years, in particular, the academic debate has focused on the elements that configure entrepreneurship ecosystems and their influence on the creation of high-growth ventures. Previous studies have also recognised the heterogeneity of environmental conditions (including policies, support programs, funding, culture, professional infrastructure, university support, labour market, R&D, and market dynamics) across regions/countries. Yet, an in-depth discussion is required to address how environmental conditions vary per entrepreneurial stage of enterprises within certain regions/countries, as well as how these conditions determine the technological factor of the entrepreneurial process. By reviewing the literature from 2000 to 2017, this paper analyses the environmental conditions that have influenced the transitions towards becoming potential entrepreneurs, nascent/new entrepreneurs, and established/consolidated entrepreneurs in both developed and developing economies. Our findings show why diversity in entrepreneurship and context is significant. Favourable conditions include professional support, incubators/accelerators, networking with multiple agents, and R&D investments. Less favourable conditions include a lack of funding sources, labour market conditions, and social norms. Our paper contributes by proposing a research agenda and implications for stakeholders.

Similar content being viewed by others

Entrepreneurial ecosystem elements

The impact of entrepreneurship on economic, social and environmental welfare and its determinants: a systematic review

Economic effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on entrepreneurship and small businesses

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

In the past three decades, the literature has outlined the critical impact of environmental conditions on entrepreneurship and economic growth (Urbano et al. 2019 ). In the past 5 years especially, academic and public actors have focused on the configuration of thriving entrepreneurial ecosystems (Autio et al. 2014 ; Acs et al. 2017 ). It explains why the Silicon Valley entrepreneurial ecosystem has captured the attention of the international public policy community who wish to emulate it (Audretsch 2019 ). However, scholars worldwide argue that this model of entrepreneurship has several limitations when addressing the most compelling contemporary global problems.

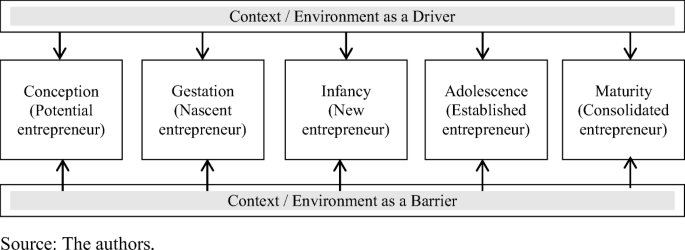

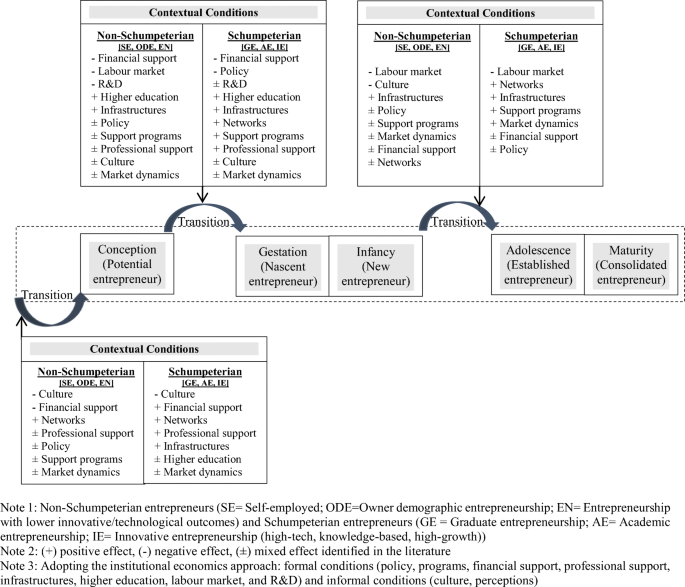

By analysing the existing literature, it is possible to identify the conditions that act as drivers or barriers for entrepreneurship around the world. Although relevant insights can be gained, it is not yet clear which environmental conditions (policies, support programs, funding, culture, professional infrastructure, university support, labour market, infrastructure, networks, R&D, and market dynamics) exert an influence during the exploration, exploitation, and consolidation of entrepreneurial initiatives (technological vs. non-technological) per type of economy (developed vs. developing economies) (Guerrero and Urbano 2019b ). In this vein, Welter et al. ( 2017 : p. 318) highlight that there is no single type of entrepreneurship, no ideal context, and no ideal type of entrepreneur. Therefore, differences matter; and where, when, and why those differences matter most need to be ascertained. It opens up the discussion on the diversity of contexts and types of entrepreneurship that should be understood by analysing their nature, richness, and dynamics (Welter 2011 ; Karlsson et al. 2019 ).

Inspired by this academic gap, in this paper, we review the previous literature in order to identify which environmental conditions have been affecting entrepreneurial processes per type of economy. Specifically, we analyse 67 manuscripts, published from 2000 to 2017, that focus mainly on the barriers, facilitators, and triggers found in the developmental stages of diverse entrepreneurial types per socioeconomic context. Our analysis highlights the elements of entrepreneurial ecosystems associated with each developmental stage of diverse initiatives in developed and developing countries. Our results contribute to the academic discussion about the definitions/measures of entrepreneurship (Iversen et al. 2007 ; Henrekson and Sanandaji 2019 ), entrepreneurial process (Busenitz et al. 2014 ), entrepreneurial ecosystems (Acs et al. 2017 ; Audretsch 2019 ), diversity of entrepreneurship (Welter et al. 2017 ; Karlsson et al. 2019 ), and economic development (Urbano et al. 2019 ). A research agenda is proposed for the analysis of those gaps identified across the entrepreneurial processes and types of economy. Moreover, several contributions for stakeholders emerge from our results.

Following this introduction, the paper is structured as follows: Section 2 describes the theoretical foundations linking the entrepreneurial process with the environmental conditions. Section 3 presents the methodological design regarding data collection and analysis. Section 4 shows the insights obtained from the influence of the context on the entrepreneurial process across socioeconomic stages. Section 5 discusses the findings in light of previous studies and sets a research agenda. This section also provides several implications that have emerged from this study. Section 6 concludes by providing insights regarding the contributions to the academic debate in the field of entrepreneurship.

2 Diversity in the entrepreneurial process and context

According to Gartner ( 1990 ) and Morris et al. ( 1994 ), entrepreneurship encompasses the creation of enterprises, wealth, innovation, change, employment, value, and growth. Distinguishing between Schumpeterian entrepreneurship and other business activities may, therefore, facilitate the differentiation between low-impact and high-impact entrepreneurship in terms of outcomes, such as employment, sales, innovation, and the wealth of the founders (Henrekson and Sanandaji 2019 ). By understanding the diversity inherent in entrepreneurship (Iversen et al. 2007 ; Welter 2011 ; Dencker et al. 2019 ) and capturing the notion of Schumpeterian entrepreneurship (Henrekson and Sanandaji 2019 ; Karlsson et al. 2019 ), this research categorises entrepreneurship into either (a) non-Schumpeterian entrepreneurship or (b) Schumpeterian entrepreneurship. The first category (non-Schumpeterian entrepreneurship) is characterised by self-employment (individuals who do not generate employment and with outcomes that merely allow them to survive) and traditional entrepreneurs (individuals who generate lower impacts/outcomes). Footnote 1 The second category (Schumpeterian entrepreneurship) comprises academic/graduate entrepreneurs (individuals who generate entrepreneurial innovations within a university or after graduation) and innovative entrepreneurs (individuals who generate a technological-based venture that is looking for high-level impacts and outcomes).