41+ Critical Thinking Examples (Definition + Practices)

Critical thinking is an essential skill in our information-overloaded world, where figuring out what is fact and fiction has become increasingly challenging.

But why is critical thinking essential? Put, critical thinking empowers us to make better decisions, challenge and validate our beliefs and assumptions, and understand and interact with the world more effectively and meaningfully.

Critical thinking is like using your brain's "superpowers" to make smart choices. Whether it's picking the right insurance, deciding what to do in a job, or discussing topics in school, thinking deeply helps a lot. In the next parts, we'll share real-life examples of when this superpower comes in handy and give you some fun exercises to practice it.

Critical Thinking Process Outline

Critical thinking means thinking clearly and fairly without letting personal feelings get in the way. It's like being a detective, trying to solve a mystery by using clues and thinking hard about them.

It isn't always easy to think critically, as it can take a pretty smart person to see some of the questions that aren't being answered in a certain situation. But, we can train our brains to think more like puzzle solvers, which can help develop our critical thinking skills.

Here's what it looks like step by step:

Spotting the Problem: It's like discovering a puzzle to solve. You see that there's something you need to figure out or decide.

Collecting Clues: Now, you need to gather information. Maybe you read about it, watch a video, talk to people, or do some research. It's like getting all the pieces to solve your puzzle.

Breaking It Down: This is where you look at all your clues and try to see how they fit together. You're asking questions like: Why did this happen? What could happen next?

Checking Your Clues: You want to make sure your information is good. This means seeing if what you found out is true and if you can trust where it came from.

Making a Guess: After looking at all your clues, you think about what they mean and come up with an answer. This answer is like your best guess based on what you know.

Explaining Your Thoughts: Now, you tell others how you solved the puzzle. You explain how you thought about it and how you answered.

Checking Your Work: This is like looking back and seeing if you missed anything. Did you make any mistakes? Did you let any personal feelings get in the way? This step helps make sure your thinking is clear and fair.

And remember, you might sometimes need to go back and redo some steps if you discover something new. If you realize you missed an important clue, you might have to go back and collect more information.

Critical Thinking Methods

Just like doing push-ups or running helps our bodies get stronger, there are special exercises that help our brains think better. These brain workouts push us to think harder, look at things closely, and ask many questions.

It's not always about finding the "right" answer. Instead, it's about the journey of thinking and asking "why" or "how." Doing these exercises often helps us become better thinkers and makes us curious to know more about the world.

Now, let's look at some brain workouts to help us think better:

1. "What If" Scenarios

Imagine crazy things happening, like, "What if there was no internet for a month? What would we do?" These games help us think of new and different ideas.

Pick a hot topic. Argue one side of it and then try arguing the opposite. This makes us see different viewpoints and think deeply about a topic.

3. Analyze Visual Data

Check out charts or pictures with lots of numbers and info but no explanations. What story are they telling? This helps us get better at understanding information just by looking at it.

4. Mind Mapping

Write an idea in the center and then draw lines to related ideas. It's like making a map of your thoughts. This helps us see how everything is connected.

There's lots of mind-mapping software , but it's also nice to do this by hand.

5. Weekly Diary

Every week, write about what happened, the choices you made, and what you learned. Writing helps us think about our actions and how we can do better.

6. Evaluating Information Sources

Collect stories or articles about one topic from newspapers or blogs. Which ones are trustworthy? Which ones might be a little biased? This teaches us to be smart about where we get our info.

There are many resources to help you determine if information sources are factual or not.

7. Socratic Questioning

This way of thinking is called the Socrates Method, named after an old-time thinker from Greece. It's about asking lots of questions to understand a topic. You can do this by yourself or chat with a friend.

Start with a Big Question:

"What does 'success' mean?"

Dive Deeper with More Questions:

"Why do you think of success that way?" "Do TV shows, friends, or family make you think that?" "Does everyone think about success the same way?"

"Can someone be a winner even if they aren't rich or famous?" "Can someone feel like they didn't succeed, even if everyone else thinks they did?"

Look for Real-life Examples:

"Who is someone you think is successful? Why?" "Was there a time you felt like a winner? What happened?"

Think About Other People's Views:

"How might a person from another country think about success?" "Does the idea of success change as we grow up or as our life changes?"

Think About What It Means:

"How does your idea of success shape what you want in life?" "Are there problems with only wanting to be rich or famous?"

Look Back and Think:

"After talking about this, did your idea of success change? How?" "Did you learn something new about what success means?"

8. Six Thinking Hats

Edward de Bono came up with a cool way to solve problems by thinking in six different ways, like wearing different colored hats. You can do this independently, but it might be more effective in a group so everyone can have a different hat color. Each color has its way of thinking:

White Hat (Facts): Just the facts! Ask, "What do we know? What do we need to find out?"

Red Hat (Feelings): Talk about feelings. Ask, "How do I feel about this?"

Black Hat (Careful Thinking): Be cautious. Ask, "What could go wrong?"

Yellow Hat (Positive Thinking): Look on the bright side. Ask, "What's good about this?"

Green Hat (Creative Thinking): Think of new ideas. Ask, "What's another way to look at this?"

Blue Hat (Planning): Organize the talk. Ask, "What should we do next?"

When using this method with a group:

- Explain all the hats.

- Decide which hat to wear first.

- Make sure everyone switches hats at the same time.

- Finish with the Blue Hat to plan the next steps.

9. SWOT Analysis

SWOT Analysis is like a game plan for businesses to know where they stand and where they should go. "SWOT" stands for Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, and Threats.

There are a lot of SWOT templates out there for how to do this visually, but you can also think it through. It doesn't just apply to businesses but can be a good way to decide if a project you're working on is working.

Strengths: What's working well? Ask, "What are we good at?"

Weaknesses: Where can we do better? Ask, "Where can we improve?"

Opportunities: What good things might come our way? Ask, "What chances can we grab?"

Threats: What challenges might we face? Ask, "What might make things tough for us?"

Steps to do a SWOT Analysis:

- Goal: Decide what you want to find out.

- Research: Learn about your business and the world around it.

- Brainstorm: Get a group and think together. Talk about strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats.

- Pick the Most Important Points: Some things might be more urgent or important than others.

- Make a Plan: Decide what to do based on your SWOT list.

- Check Again Later: Things change, so look at your SWOT again after a while to update it.

Now that you have a few tools for thinking critically, let’s get into some specific examples.

Everyday Examples

Life is a series of decisions. From the moment we wake up, we're faced with choices – some trivial, like choosing a breakfast cereal, and some more significant, like buying a home or confronting an ethical dilemma at work. While it might seem that these decisions are disparate, they all benefit from the application of critical thinking.

10. Deciding to buy something

Imagine you want a new phone. Don't just buy it because the ad looks cool. Think about what you need in a phone. Look up different phones and see what people say about them. Choose the one that's the best deal for what you want.

11. Deciding what is true

There's a lot of news everywhere. Don't believe everything right away. Think about why someone might be telling you this. Check if what you're reading or watching is true. Make up your mind after you've looked into it.

12. Deciding when you’re wrong

Sometimes, friends can have disagreements. Don't just get mad right away. Try to see where they're coming from. Talk about what's going on. Find a way to fix the problem that's fair for everyone.

13. Deciding what to eat

There's always a new diet or exercise that's popular. Don't just follow it because it's trendy. Find out if it's good for you. Ask someone who knows, like a doctor. Make choices that make you feel good and stay healthy.

14. Deciding what to do today

Everyone is busy with school, chores, and hobbies. Make a list of things you need to do. Decide which ones are most important. Plan your day so you can get things done and still have fun.

15. Making Tough Choices

Sometimes, it's hard to know what's right. Think about how each choice will affect you and others. Talk to people you trust about it. Choose what feels right in your heart and is fair to others.

16. Planning for the Future

Big decisions, like where to go to school, can be tricky. Think about what you want in the future. Look at the good and bad of each choice. Talk to people who know about it. Pick what feels best for your dreams and goals.

Job Examples

17. solving problems.

Workers brainstorm ways to fix a machine quickly without making things worse when a machine breaks at a factory.

18. Decision Making

A store manager decides which products to order more of based on what's selling best.

19. Setting Goals

A team leader helps their team decide what tasks are most important to finish this month and which can wait.

20. Evaluating Ideas

At a team meeting, everyone shares ideas for a new project. The group discusses each idea's pros and cons before picking one.

21. Handling Conflict

Two workers disagree on how to do a job. Instead of arguing, they talk calmly, listen to each other, and find a solution they both like.

22. Improving Processes

A cashier thinks of a faster way to ring up items so customers don't have to wait as long.

23. Asking Questions

Before starting a big task, an employee asks for clear instructions and checks if they have the necessary tools.

24. Checking Facts

Before presenting a report, someone double-checks all their information to make sure there are no mistakes.

25. Planning for the Future

A business owner thinks about what might happen in the next few years, like new competitors or changes in what customers want, and makes plans based on those thoughts.

26. Understanding Perspectives

A team is designing a new toy. They think about what kids and parents would both like instead of just what they think is fun.

School Examples

27. researching a topic.

For a history project, a student looks up different sources to understand an event from multiple viewpoints.

28. Debating an Issue

In a class discussion, students pick sides on a topic, like school uniforms, and share reasons to support their views.

29. Evaluating Sources

While writing an essay, a student checks if the information from a website is trustworthy or might be biased.

30. Problem Solving in Math

When stuck on a tricky math problem, a student tries different methods to find the answer instead of giving up.

31. Analyzing Literature

In English class, students discuss why a character in a book made certain choices and what those decisions reveal about them.

32. Testing a Hypothesis

For a science experiment, students guess what will happen and then conduct tests to see if they're right or wrong.

33. Giving Peer Feedback

After reading a classmate's essay, a student offers suggestions for improving it.

34. Questioning Assumptions

In a geography lesson, students consider why certain countries are called "developed" and what that label means.

35. Designing a Study

For a psychology project, students plan an experiment to understand how people's memories work and think of ways to ensure accurate results.

36. Interpreting Data

In a science class, students look at charts and graphs from a study, then discuss what the information tells them and if there are any patterns.

Critical Thinking Puzzles

Not all scenarios will have a single correct answer that can be figured out by thinking critically. Sometimes we have to think critically about ethical choices or moral behaviors.

Here are some mind games and scenarios you can solve using critical thinking. You can see the solution(s) at the end of the post.

37. The Farmer, Fox, Chicken, and Grain Problem

A farmer is at a riverbank with a fox, a chicken, and a grain bag. He needs to get all three items across the river. However, his boat can only carry himself and one of the three items at a time.

Here's the challenge:

- If the fox is left alone with the chicken, the fox will eat the chicken.

- If the chicken is left alone with the grain, the chicken will eat the grain.

How can the farmer get all three items across the river without any item being eaten?

38. The Rope, Jar, and Pebbles Problem

You are in a room with two long ropes hanging from the ceiling. Each rope is just out of arm's reach from the other, so you can't hold onto one rope and reach the other simultaneously.

Your task is to tie the two rope ends together, but you can't move the position where they hang from the ceiling.

You are given a jar full of pebbles. How do you complete the task?

39. The Two Guards Problem

Imagine there are two doors. One door leads to certain doom, and the other leads to freedom. You don't know which is which.

In front of each door stands a guard. One guard always tells the truth. The other guard always lies. You don't know which guard is which.

You can ask only one question to one of the guards. What question should you ask to find the door that leads to freedom?

40. The Hourglass Problem

You have two hourglasses. One measures 7 minutes when turned over, and the other measures 4 minutes. Using just these hourglasses, how can you time exactly 9 minutes?

41. The Lifeboat Dilemma

Imagine you're on a ship that's sinking. You get on a lifeboat, but it's already too full and might flip over.

Nearby in the water, five people are struggling: a scientist close to finding a cure for a sickness, an old couple who've been together for a long time, a mom with three kids waiting at home, and a tired teenager who helped save others but is now in danger.

You can only save one person without making the boat flip. Who would you choose?

42. The Tech Dilemma

You work at a tech company and help make a computer program to help small businesses. You're almost ready to share it with everyone, but you find out there might be a small chance it has a problem that could show users' private info.

If you decide to fix it, you must wait two more months before sharing it. But your bosses want you to share it now. What would you do?

43. The History Mystery

Dr. Amelia is a history expert. She's studying where a group of people traveled long ago. She reads old letters and documents to learn about it. But she finds some letters that tell a different story than what most people believe.

If she says this new story is true, it could change what people learn in school and what they think about history. What should she do?

The Role of Bias in Critical Thinking

Have you ever decided you don’t like someone before you even know them? Or maybe someone shared an idea with you that you immediately loved without even knowing all the details.

This experience is called bias, which occurs when you like or dislike something or someone without a good reason or knowing why. It can also take shape in certain reactions to situations, like a habit or instinct.

Bias comes from our own experiences, what friends or family tell us, or even things we are born believing. Sometimes, bias can help us stay safe, but other times it stops us from seeing the truth.

Not all bias is bad. Bias can be a mechanism for assessing our potential safety in a new situation. If we are biased to think that anything long, thin, and curled up is a snake, we might assume the rope is something to be afraid of before we know it is just a rope.

While bias might serve us in some situations (like jumping out of the way of an actual snake before we have time to process that we need to be jumping out of the way), it often harms our ability to think critically.

How Bias Gets in the Way of Good Thinking

Selective Perception: We only notice things that match our ideas and ignore the rest.

It's like only picking red candies from a mixed bowl because you think they taste the best, but they taste the same as every other candy in the bowl. It could also be when we see all the signs that our partner is cheating on us but choose to ignore them because we are happy the way we are (or at least, we think we are).

Agreeing with Yourself: This is called “ confirmation bias ” when we only listen to ideas that match our own and seek, interpret, and remember information in a way that confirms what we already think we know or believe.

An example is when someone wants to know if it is safe to vaccinate their children but already believes that vaccines are not safe, so they only look for information supporting the idea that vaccines are bad.

Thinking We Know It All: Similar to confirmation bias, this is called “overconfidence bias.” Sometimes we think our ideas are the best and don't listen to others. This can stop us from learning.

Have you ever met someone who you consider a “know it”? Probably, they have a lot of overconfidence bias because while they may know many things accurately, they can’t know everything. Still, if they act like they do, they show overconfidence bias.

There's a weird kind of bias similar to this called the Dunning Kruger Effect, and that is when someone is bad at what they do, but they believe and act like they are the best .

Following the Crowd: This is formally called “groupthink”. It's hard to speak up with a different idea if everyone agrees. But this can lead to mistakes.

An example of this we’ve all likely seen is the cool clique in primary school. There is usually one person that is the head of the group, the “coolest kid in school”, and everyone listens to them and does what they want, even if they don’t think it’s a good idea.

How to Overcome Biases

Here are a few ways to learn to think better, free from our biases (or at least aware of them!).

Know Your Biases: Realize that everyone has biases. If we know about them, we can think better.

Listen to Different People: Talking to different kinds of people can give us new ideas.

Ask Why: Always ask yourself why you believe something. Is it true, or is it just a bias?

Understand Others: Try to think about how others feel. It helps you see things in new ways.

Keep Learning: Always be curious and open to new information.

In today's world, everything changes fast, and there's so much information everywhere. This makes critical thinking super important. It helps us distinguish between what's real and what's made up. It also helps us make good choices. But thinking this way can be tough sometimes because of biases. These are like sneaky thoughts that can trick us. The good news is we can learn to see them and think better.

There are cool tools and ways we've talked about, like the "Socratic Questioning" method and the "Six Thinking Hats." These tools help us get better at thinking. These thinking skills can also help us in school, work, and everyday life.

We’ve also looked at specific scenarios where critical thinking would be helpful, such as deciding what diet to follow and checking facts.

Thinking isn't just a skill—it's a special talent we improve over time. Working on it lets us see things more clearly and understand the world better. So, keep practicing and asking questions! It'll make you a smarter thinker and help you see the world differently.

Critical Thinking Puzzles (Solutions)

The farmer, fox, chicken, and grain problem.

- The farmer first takes the chicken across the river and leaves it on the other side.

- He returns to the original side and takes the fox across the river.

- After leaving the fox on the other side, he returns the chicken to the starting side.

- He leaves the chicken on the starting side and takes the grain bag across the river.

- He leaves the grain with the fox on the other side and returns to get the chicken.

- The farmer takes the chicken across, and now all three items -- the fox, the chicken, and the grain -- are safely on the other side of the river.

The Rope, Jar, and Pebbles Problem

- Take one rope and tie the jar of pebbles to its end.

- Swing the rope with the jar in a pendulum motion.

- While the rope is swinging, grab the other rope and wait.

- As the swinging rope comes back within reach due to its pendulum motion, grab it.

- With both ropes within reach, untie the jar and tie the rope ends together.

The Two Guards Problem

The question is, "What would the other guard say is the door to doom?" Then choose the opposite door.

The Hourglass Problem

- Start both hourglasses.

- When the 4-minute hourglass runs out, turn it over.

- When the 7-minute hourglass runs out, the 4-minute hourglass will have been running for 3 minutes. Turn the 7-minute hourglass over.

- When the 4-minute hourglass runs out for the second time (a total of 8 minutes have passed), the 7-minute hourglass will run for 1 minute. Turn the 7-minute hourglass again for 1 minute to empty the hourglass (a total of 9 minutes passed).

The Boat and Weights Problem

Take the cat over first and leave it on the other side. Then, return and take the fish across next. When you get there, take the cat back with you. Leave the cat on the starting side and take the cat food across. Lastly, return to get the cat and bring it to the other side.

The Lifeboat Dilemma

There isn’t one correct answer to this problem. Here are some elements to consider:

- Moral Principles: What values guide your decision? Is it the potential greater good for humanity (the scientist)? What is the value of long-standing love and commitment (the elderly couple)? What is the future of young children who depend on their mothers? Or the selfless bravery of the teenager?

- Future Implications: Consider the future consequences of each choice. Saving the scientist might benefit millions in the future, but what moral message does it send about the value of individual lives?

- Emotional vs. Logical Thinking: While it's essential to engage empathy, it's also crucial not to let emotions cloud judgment entirely. For instance, while the teenager's bravery is commendable, does it make him more deserving of a spot on the boat than the others?

- Acknowledging Uncertainty: The scientist claims to be close to a significant breakthrough, but there's no certainty. How does this uncertainty factor into your decision?

- Personal Bias: Recognize and challenge any personal biases, such as biases towards age, profession, or familial status.

The Tech Dilemma

Again, there isn’t one correct answer to this problem. Here are some elements to consider:

- Evaluate the Risk: How severe is the potential vulnerability? Can it be easily exploited, or would it require significant expertise? Even if the circumstances are rare, what would be the consequences if the vulnerability were exploited?

- Stakeholder Considerations: Different stakeholders will have different priorities. Upper management might prioritize financial projections, the marketing team might be concerned about the product's reputation, and customers might prioritize the security of their data. How do you balance these competing interests?

- Short-Term vs. Long-Term Implications: While launching on time could meet immediate financial goals, consider the potential long-term damage to the company's reputation if the vulnerability is exploited. Would the short-term gains be worth the potential long-term costs?

- Ethical Implications : Beyond the financial and reputational aspects, there's an ethical dimension to consider. Is it right to release a product with a known vulnerability, even if the chances of it being exploited are low?

- Seek External Input: Consulting with cybersecurity experts outside your company might be beneficial. They could provide a more objective risk assessment and potential mitigation strategies.

- Communication: How will you communicate the decision, whatever it may be, both internally to your team and upper management and externally to your customers and potential users?

The History Mystery

Dr. Amelia should take the following steps:

- Verify the Letters: Before making any claims, she should check if the letters are actual and not fake. She can do this by seeing when and where they were written and if they match with other things from that time.

- Get a Second Opinion: It's always good to have someone else look at what you've found. Dr. Amelia could show the letters to other history experts and see their thoughts.

- Research More: Maybe there are more documents or letters out there that support this new story. Dr. Amelia should keep looking to see if she can find more evidence.

- Share the Findings: If Dr. Amelia believes the letters are true after all her checks, she should tell others. This can be through books, talks, or articles.

- Stay Open to Feedback: Some people might agree with Dr. Amelia, and others might not. She should listen to everyone and be ready to learn more or change her mind if new information arises.

Ultimately, Dr. Amelia's job is to find out the truth about history and share it. It's okay if this new truth differs from what people used to believe. History is about learning from the past, no matter the story.

Related posts:

- Experimenter Bias (Definition + Examples)

- Hasty Generalization Fallacy (31 Examples + Similar Names)

- Ad Hoc Fallacy (29 Examples + Other Names)

- Confirmation Bias (Examples + Definition)

- Equivocation Fallacy (26 Examples + Description)

Reference this article:

About The Author

Free Personality Test

Free Memory Test

Free IQ Test

PracticalPie.com is a participant in the Amazon Associates Program. As an Amazon Associate we earn from qualifying purchases.

Follow Us On:

Youtube Facebook Instagram X/Twitter

Psychology Resources

Developmental

Personality

Relationships

Psychologists

Serial Killers

Psychology Tests

Personality Quiz

Memory Test

Depression test

Type A/B Personality Test

© PracticalPsychology. All rights reserved

Privacy Policy | Terms of Use

The 23 Most Impactful Advertising Campaign Examples Ever

By Joe Weller | September 19, 2023

- Share on Facebook

- Share on LinkedIn

Link copied

Creating an ad campaign is similar to getting ready for speed dating: You have 30 seconds to make your mark, or your audience will leave bored and never remember your name — or tagline.

But how do you make a good first impression when your audience consumes between 4,000 and 8,000 ads per day? Inspiration can strike anywhere at any time, so with the help of experts we’ve curated a list of 23 impactful advertising campaign examples to help you understand what an ad campaign is , the types of campaigns you can create, and the elements you should include in a successful advertising campaign.

1. Nike: Just Do It Campaign

In the 1980s, Nike’s biggest competitor was outselling the now-famous athletic brand. Nike was advertising almost exclusively to marathon runners, and it was losing the race. Enter “Just Do It”: the advertising campaign designed with everyone in mind. By expanding its target audience to athletes and nonathletes alike, Nike’s new tagline embodied the universal drive people feel while exercising. In doing so, they substantially increased their sales and created a long-lasting campaign that continues to resonate with the brand’s audience.

Launch Year: 1988 Campaign Medium: All Expert Takeaway: “The slogan itself is simple and powerful, encouraging individuals to take action and push their limits. Moreover, Nike has consistently featured inspiring athletes in their advertisements, which helps to create an emotional connection with consumers. Overall, the ‘Just Do It’ campaign is memorable, motivating, and has had a lasting impact on advertising.” — Bridget Reed, co-founder at The Word Counter

2. McDonald’s: I’m Lovin’ It Campaign

While visual imagery is vital when creating an advertising campaign, sound can be just as effective. In 2003, McDonald’s ran an international ad campaign competition to update its current branding. Originally sung by Justin Timberlake before receiving one of the most famous upgrades in history, the jingle “Ba da ba ba ba, I’m lovin’ it” was awarded a permanent spot in McDonald’s advertisements.

Launch Year: 2003 Campaign Medium: All Key Takeaway: Consider mixing audio into your advertising campaigns, including media or social media assets. When creating ad campaigns, user-generated content can be incredibly successful — jingles, social media posts, comments, and more. One of a brand’s strongest assets is an audience that advocates for the products and services they love.

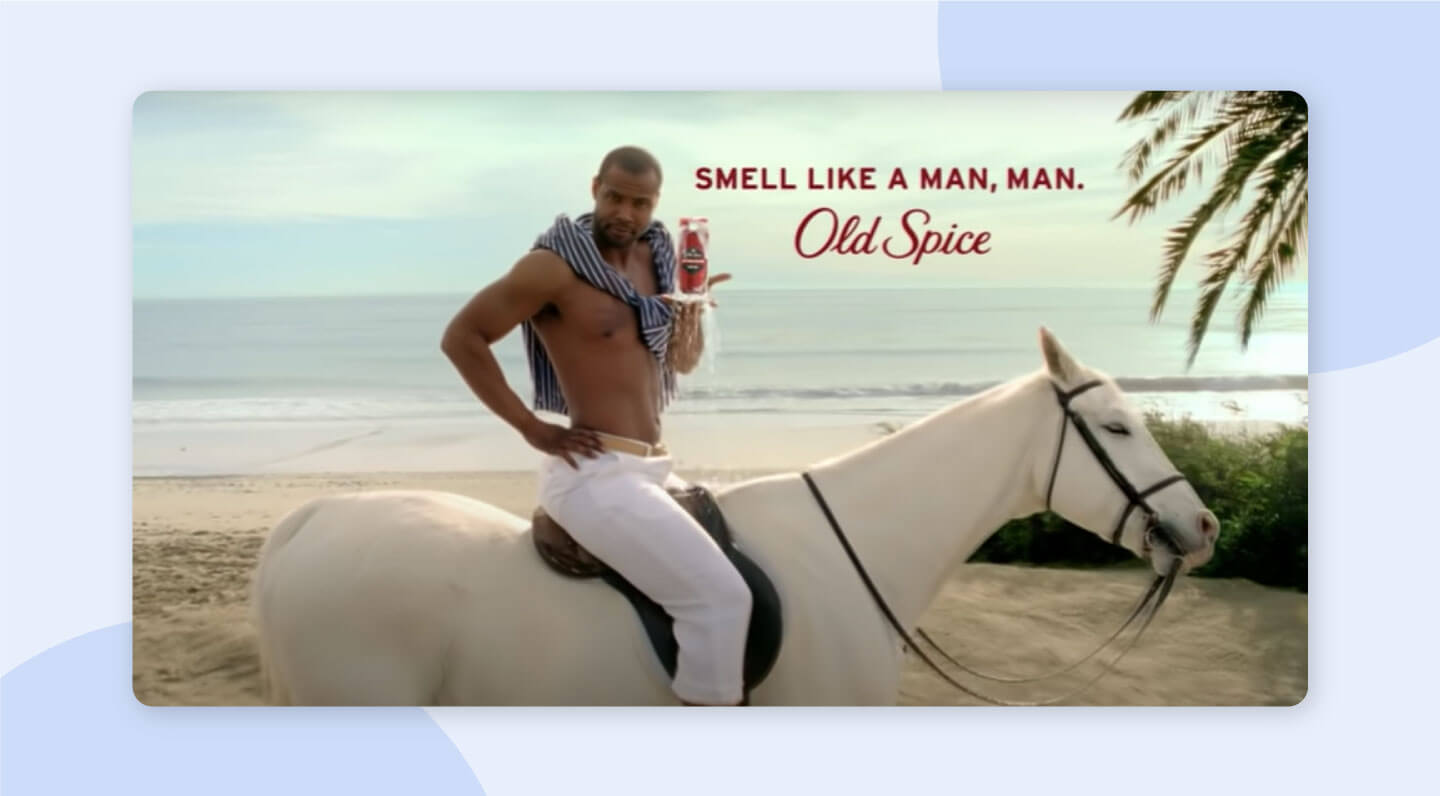

3. Old Spice: The Man Your Man Could Smell Like Campaign

After Old Spice’s initial “Smell like a man, man” campaign went viral in early 2010, the brand jumped to social media to ride the wave. The Old Spice Man created interactive videos responding to comments on various social media platforms, including Facebook and Twitter, all while remaining in character and nailing the brand’s voice. While advertising Old Spice’s products, this ad campaign also increased their target audience and social media followers by thousands of people.

Launch Year: 2010 Campaign Medium: Media and social media Expert Takeaway: Old Spice’s campaign is best “known for its humor, creativity, and viral impact. By targeting both men and women with witty and entertaining commercials, it created memorable moments and engaged viewers effectively.” — Olivia Lin, marketing specialist at Tabrick

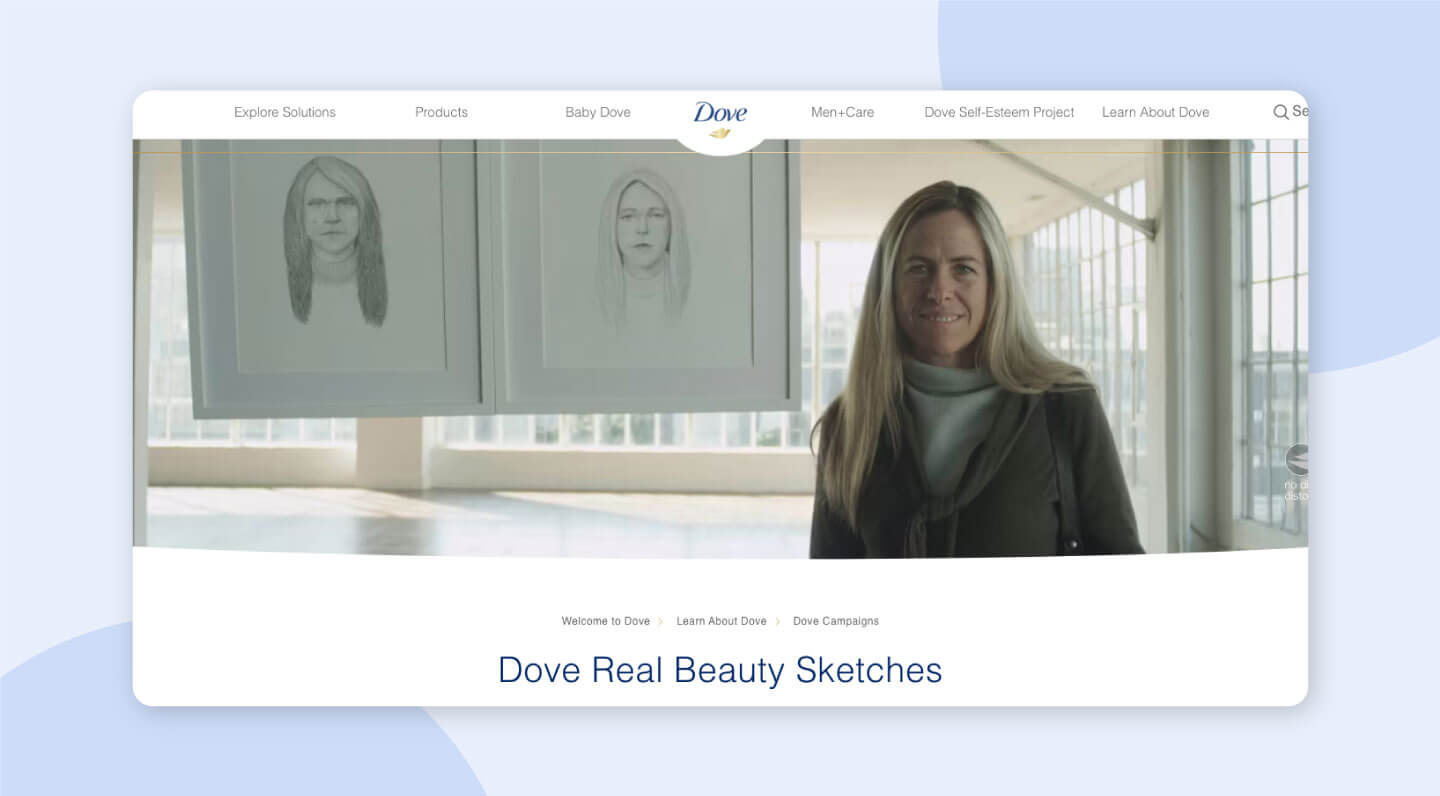

4. Dove: Real Beauty Campaign

Some ad campaigns challenge society while others simply move with the current, and Dove’s Real Beauty campaign was designed to do the former. This ad campaign challenged the beauty industry’s incredibly high — often impossible — standards of female beauty. In a series of videos, advertisements, projects, and sketches, this still-evolving ad campaign increased the brand’s profits by almost $2 billion while celebrating, supporting, and standing with women.

Launch Year: 2004 Campaign Medium: Media and social media Expert Takeaway: The Real Beauty campaign “challenged traditional beauty standards and promoted self-acceptance. It featured diverse women of different ages, sizes, and ethnicities, celebrating their unique beauty. This campaign resonated with audiences as it challenged the narrow definition of beauty portrayed in the media, making it compelling by promoting inclusivity and empowering women to embrace their natural beauty.” — Oliver Andrews, editor at OA Design Services

5. Snickers: You’re Not You When You’re Hungry Campaign

Beloved celebrities like Betty White and Elton John joined Snickers in one of the company’s most successful ad campaigns. In a series of video commercials, the brand used celebrities to portray unlikely behaviors caused by hunger. After receiving a Snickers candy bar, the celebrities transformed into everyday people acting normally, which solidified Snickers as a hunger-beating snack option rather than a simple candy bar.

Launch Year: 2010 Campaign Medium: Media Key Takeaway: Clever ads that also provide solutions to customer issues frequently perform well. Learning your target audience’s pain points and providing simple, straightforward solutions through ad campaigns can help build brand loyalty and trust.

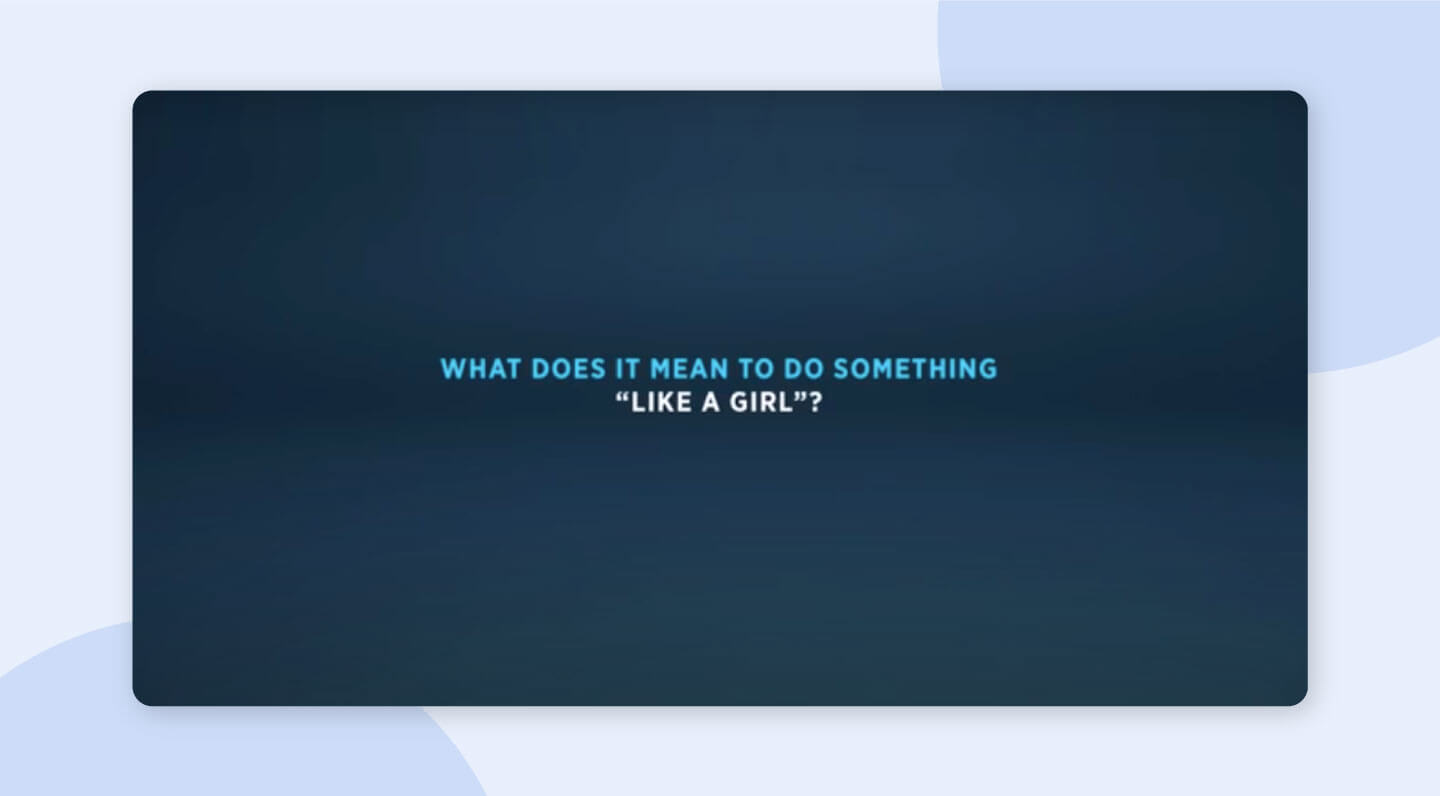

6. Always: #LikeAGirl Campaign

There’s nothing like a strong hashtag with a compelling message, and that’s exactly what Always created with their 2014 #LikeAGirl advertising campaign. This simple yet powerful campaign compared men’s and women’s abilities and proved that women — no matter their age — are just as capable as men. The campaign became wildly successful by fighting gender stereotypes.

Year: 2014 Campaign Medium: Media and social media Expert Takeaway: “The #LikeAGirl campaign drove self-confidence and empowerment in girls. This 2014 campaign targeted the stereotypes that girls are weak and not powerful enough to achieve milestones. It also shows that the brand shares similar values with its customers, [which] fosters brand loyalty and gives meaning to the products.” — Jessica Shee, marketing manager at iBoysoft

7. Coca-Cola: Share A Coke Campaign

Gift shops are full of personalized keychains emblazoned with popular names like Mary, John, Rebecca, and David. Coca-Cola understood that people love to find and purchase items with specific names, so they created the Share a Coke campaign designed with personality in mind. Using various advertising platforms, Coca-Cola saw the massive impact personalization could have on its brand after selling more than 250 million bottles in the first few months of its original Australian release.

Year: 2011 Campaign Medium: Print, media, and social media Expert Takeaway: “What actually made this campaign particularly compelling was its clever use of personalization, its ability to capture the attention of customers, and its effective use of social media. The Share a Coke campaign is one of the most successful and compelling ad campaigns of all time.” — Jaden Oh, chief of marketing at Traffv

8. Dos Equis: The Most Interesting Man In The World Campaign

Combining catchy taglines and unforgettable characters is a surefire way to create memorable advertising campaigns. When Dos Equis introduced its “The Most Interesting Man in the World” campaign in 2006, it slowly and subtly changed how customers viewed the brand’s product. With an indulgent character showcasing his preference for Dos Equis beer, ad viewers were introduced to a new way of thinking about potential vices, like alcohol and cigars.

Year: 2006 Campaign Medium: Print, media, and social media Key Takeaway: Characterization can make an advertising campaign memorable. Dos Equis’s Most Interesting Man in the World is hard to forget — even though the original has since been replaced. Additionally, the original characterization gave the brand a specific energy that customers could only associate with Dos Equis beer.

9. Google: Year in Search Campaign

Google’s “Year in Search” campaign is an experiment in current events and relationships — what captured the globe’s attention in a single calendar year? By recognizing the brand’s most searched queries and connecting strangers or groups of people based on their search history, Google effectively communicated the message that nobody is truly alone. Using sources that range from local to global, the “Year in Search” campaign continues to unite Google’s users.

Year: 2010 Campaign Medium: Media Key Takeaway: New, old, and potential customers want to feel seen and heard. Google’s “Year in Search” campaign shows its audience that it hears their desires. Additionally, this campaign showcases the brand’s humanity by connecting with its users, and connecting them with each other.

10. Wendy’s: Where’s the Beef? Campaign

In 1984, the phrase, “Where’s the beef?” took the world by storm. Instead of focusing solely on its products and offerings, Wendy’s dared to call out its competitor’s products in this famous ad campaign. The phrase stuck, but the brand didn’t wear it out or continue to knock its competitors. Instead, they let word-of-mouth advertising continue promoting this campaign while professionally creating new, improved, brand-focused advertisements.

Year: 1984 Campaign Medium: Media Key Takeaway: Knocking a competitor’s product can be a component of a successful advertising campaign, but businesses must do it with tact. Once an initial statement has run its course, sometimes a brand should brainstorm new ad ideas instead of reprising successful campaigns.

11. TOMS: One For One

In 2006, TOMS introduced its One For One advertising campaign, which operated on a buy-one-give-one model. Under this model, TOMS promised to give a pair of shoes to communities in need for every pair bought. The brand later expanded this initiative to help support education, health, and community development projects.

Year: 2006 Campaign Medium: Print and media Expert Takeaway: TOMS’ One For One campaign “is not just about selling shoes; it's about selling a cause. It makes consumers feel they are contributing to a positive change, adding a significant emotional value to each purchase. The key takeaway here is the power of purpose-driven marketing. In today's world, consumers are looking for more than just products; they're looking for brands that align with their values and make them feel good about their purchases.” — Kacper Rafalski, demand generation team leader at Netguru

12. Dunkin’: America Runs on Dunkin’ Campaign

It’s no secret that coffee is an important part of many people’s lives. In 2006, Dunkin’ (then Dunkin’ Donuts) coined the phrase “America runs on Dunkin’,” which highlighted how the brand could help anyone — from average customers to other businesses or organizations. This ad campaign successfully painted Dunkin’ in a new light and propelled the brand into the hands of new and returning customers.

Year: 2006 Campaign Medium: Print and media Key Takeaway: Dunkin’ released its new tagline and an updated business plan. While an ad campaign can reach new customers and be successful on its own, it’s sometimes necessary to pair a campaign plan with a company rebrand.

13. ALS: Ice Bucket Challenge

Not every ad campaign needs to start with great aspirations — some of the greatest campaigns in history have been organic movements that went viral. For example, the ALS ice bucket challenge in 2014 gained notoriety due less to paid advertising and more to social media and influencer marketing. With celebrity endorsements like Bill Gates, Chris Pratt, and LeBron James, the ALS ice bucket challenge soared, and proved how successful advertising campaigns could be when they engaged audiences in an activity or competition.

Year: 2014 Campaign Medium: Media and social media Key Takeaway: Don’t be afraid to leverage social media to help increase the success of an ad campaign. Experiential marketing elements like challenges and giveaways can encourage engagement, while other marketing tactics like influencer and affiliate marketing can increase an ad campaign’s reach.

14. Red Bull: Stratos Campaign

Red Bull’s Stratos campaign is one of the most famous and successful examples of collaboration marketing at work inside an advertising campaign. While staying true to its target audience and values, the company planned and funded an extreme skydiving stunt, which took place in 2012. The three-hour livestream — now an on-demand video — included extensive Red Bull advertising, which cemented the brand as a daring, risk-taking company.

Year: 2012 Campaign Medium: Media and social media Key Takeaway: Even though Red Bull’s Stratos experiment became a record-breaking experience, it’s possible to use smaller-scale stunts to promote brands. If it aligns with your values and the interests of your target audience, consider weaving a new or daring event into the planning of your ad campaign.

15. Dollar Shave Club: Everyman’s Brand Campaign

After officially launching the brand in 2011, Dollar Shave Club took to the screens and produced one of the best advertising campaigns ever. With a budget of $4,500, the brand created a simple video advertisement showcasing the company’s durable products and affordable prices, which helped cement Dollar Shave Club as an “everyman” brand — or a brand designed for every person, everywhere. The video went viral, and the company got acquired for $1 billion in 2016.

Year: 2012 Campaign Medium: Media and social media Expert Takeaway: “Despite working with a relatively modest budget, the Dollar Shave Club managed to use humor and authenticity to resonate deeply with its target audience. Rather than resorting to the glossy, polished ads typical of many razor companies, they positioned themselves as the 'everyman’s brand', and it worked phenomenally well. It's a great example of how sincere messaging can catapult a brand to remarkable heights. That debut video wasn't just an ad; it was the start of a billion-dollar story.” — Kyle Roof, co-founder of PageOptimizer Pro

16. California Milk Processor Board: Got Milk? Campaign

People typically view everyday products as necessities rather than luxuries. For children, milk is a necessary part of a balanced diet, and the California Milk Processor Board used this knowledge to target milk drinkers in its now-famous “Got Milk?” advertising campaign. Its celebrity-studded, milk-mustachioed campaign used various marketing tactics — including co-branding and early influencer marketing — to convince current milk users that the beverage was worth investing in and advocating for.

Year: 1994 Campaign Medium: Print, media, email, and social media Key Takeaway: Instead of focusing its ad campaign on new customers, the California Milk Processor Board targeted former and current customers by advertising why they should continue using its product. In some cases, an ad campaign can extend its reach outside its current audience simply by focusing its efforts on those already interacting with its products.

17. Apple: Think Different Campaign

What do famous greats like Einstein, Gandhi, and Picasso have in common? Well, one thing: they each changed the world in their respective areas while fielding insults and disapproval at every step. Apple’s 1997 “Think Different” campaign highlighted these heroes — and others — to elevate the ideas behind innovation and individuality. As a brand going against the technological status quo, Apple’s ad campaign proved how successful thinking differently could be.

Year: 1997 Campaign Medium: Media Expert Takeaway: “This campaign was revolutionary in simplicity and impact. It featured iconic figures such as Albert Einstein and Martin Luther King, Jr., celebrating individuals who challenged the status quo and changed the world. The campaign inspired people to think differently and embrace innovation. Apple effectively conveyed its brand values of creativity, individuality, and non-conformity through this campaign.” — Jonathan Zacharias, founder at GR0

18. FedEx: When It Absolutely, Positively Has To Be There Overnight Campaign

When ordering online or mailing packages across the country, from forgotten costumes or presents to items with short expiration dates, time is truly of the essence. Plenty of customers have experienced the need for overnight delivery. In 1978, FedEx created an ad campaign focused on the company’s delivery time rather than its prices, which eventually helped lead to the company’s shipping notoriety and brand success.

Year: 1978 Campaign Medium: Media Key Takeaway: Consider creating an ad campaign to help solve a specific problem or answer a question. Your target audience is more likely to engage with your brand or ad campaign if they benefit from the interaction.

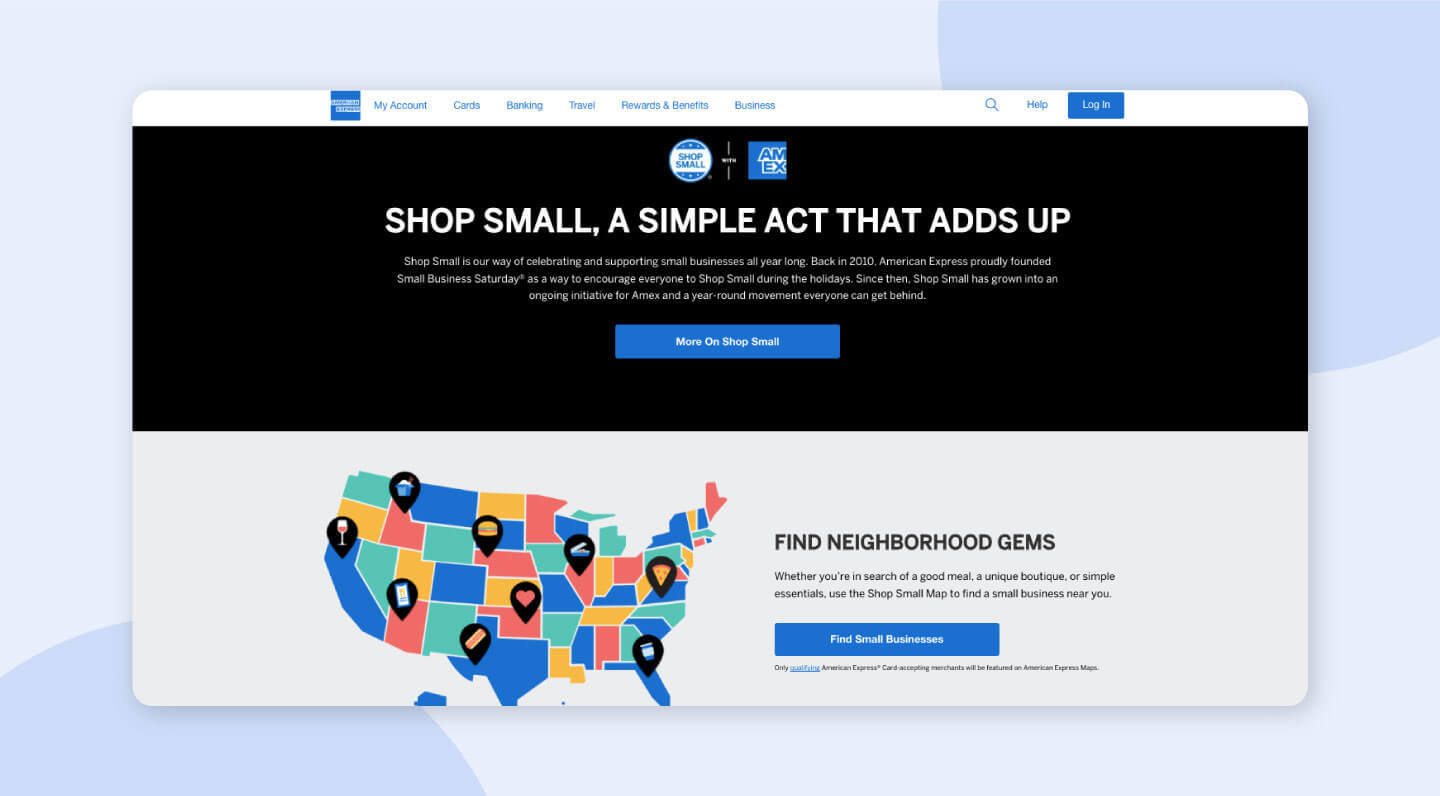

19. American Express: Shop Small Campaign

As a reaction to Black Friday, American Express began promoting Small Business Saturday in 2010. Its “Shop Small” ad campaign was created to help counteract the recession at the time, and the campaign was officially recognized by the U.S. Senate the following year. American Express aligned its goals and values with those of small, local communities, which helped create a lasting, successful advertising campaign.

Year: 2010 Campaign Medium: Media and social media Key Takeaway: American Express’s “Shop Small” campaign did more than encourage shoppers to purchase products from small businesses — it highlighted the growing scarcity of local businesses and the difficult climate created by the recession. The brand’s campaign advertised the needs of the country’s local communities rather than its own, which promoted brand awareness and increased loyalty and trust.

20. Volkswagen: “Think Small” Campaign

Advertising campaigns are not just a marketing campaign of the present and future — Volkswagen’s “Think Small” campaign rocked the boat in the middle of the 20th century. Sticking with an honest, authentic approach, this brand never marketed itself as something it wasn’t. Instead, it aimed to convince its audience that different wasn’t bad — that it was, in fact, a major benefit of the brand. With its minimalist marketing design, Volkswagen changed the advertising world and the opinions of its critical market.

Year: 1959 Campaign Medium: Print and media Expert Takeaway: “This campaign challenged car advertising norms by highlighting the Volkswagen Beetle's compact size. Its clever and minimalistic approach stood out and redefined how cars were marketed.” — Alana Armstrong, co-founding partner at Alan Aldous

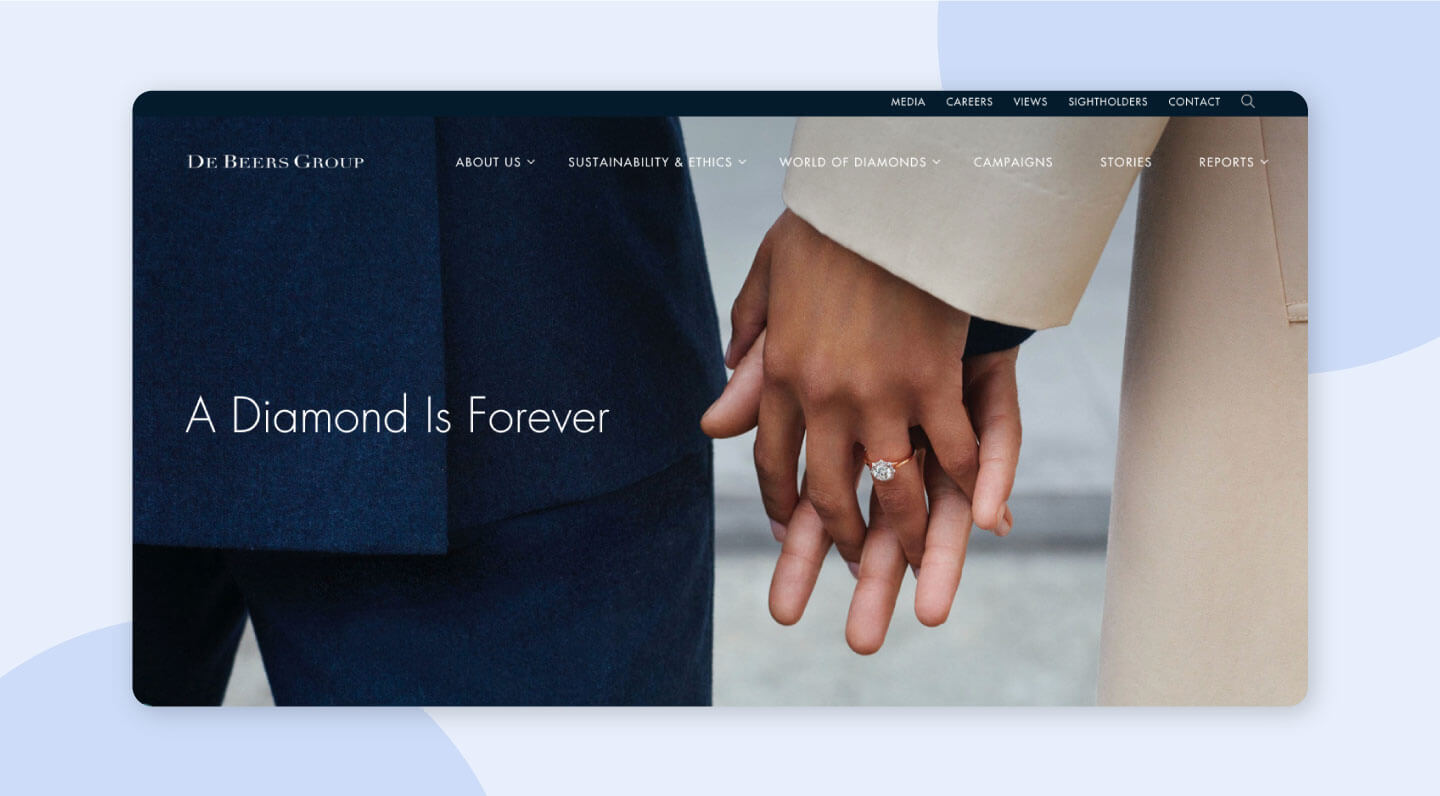

21. De Beers: A Diamond Is Forever

Named the most memorable ad slogan of the century in 1999, De Beers’s “A Diamond Is Forever” campaign targeted men of marrying age. It communicated that every marriage deserves a diamond ring, and as a diamond lasts forever, so should a marriage with a diamond ring. This ad campaign’s message mixed necessity with luxury and changed the course of the jewelry industry.

Year: 1948 Campaign Medium: Print Expert Takeaway: Attempting to counteract decreasing diamond purchases, De Beers created a campaign designed to showcase the longevity of diamonds and their enduring value. “De Beers’s ‘A Diamond Is Forever’ campaign targeted young men who wanted to demonstrate their status and present something extra special to the significant woman in their lives.” — Khaled Bentoumi, co-founder of *anyIP*

22. InVision: Design Disruptors

As technology and technology-focused industries increase, InVision recognized the need to expand design beyond its current limits. Its documentary and ad campaign — Design Disruptors — featured 15 designers from unique companies. This campaign helped transform plenty of industry expectations concerning brand design by focusing on innovations in product design.

Year: 2016 Campaign Medium: Media and social media Expert Takeaway: “InVision effectively used Facebook’s retargeting capabilities to guide viewers through the series, building brand credibility by providing valuable industry insights. By offering a downloadable resource at the end of the series, they captured leads and nurtured these relationships beyond the initial interaction. What's compelling is their strategic use of Facebook’s tools and video content to simultaneously position themselves as a thought leader, build a community, and generate leads. This campaign is a testament to the potential of social media marketing when aligned with a brand’s broader goals.” — George Panayides, digital marketing technician at The Digital XX

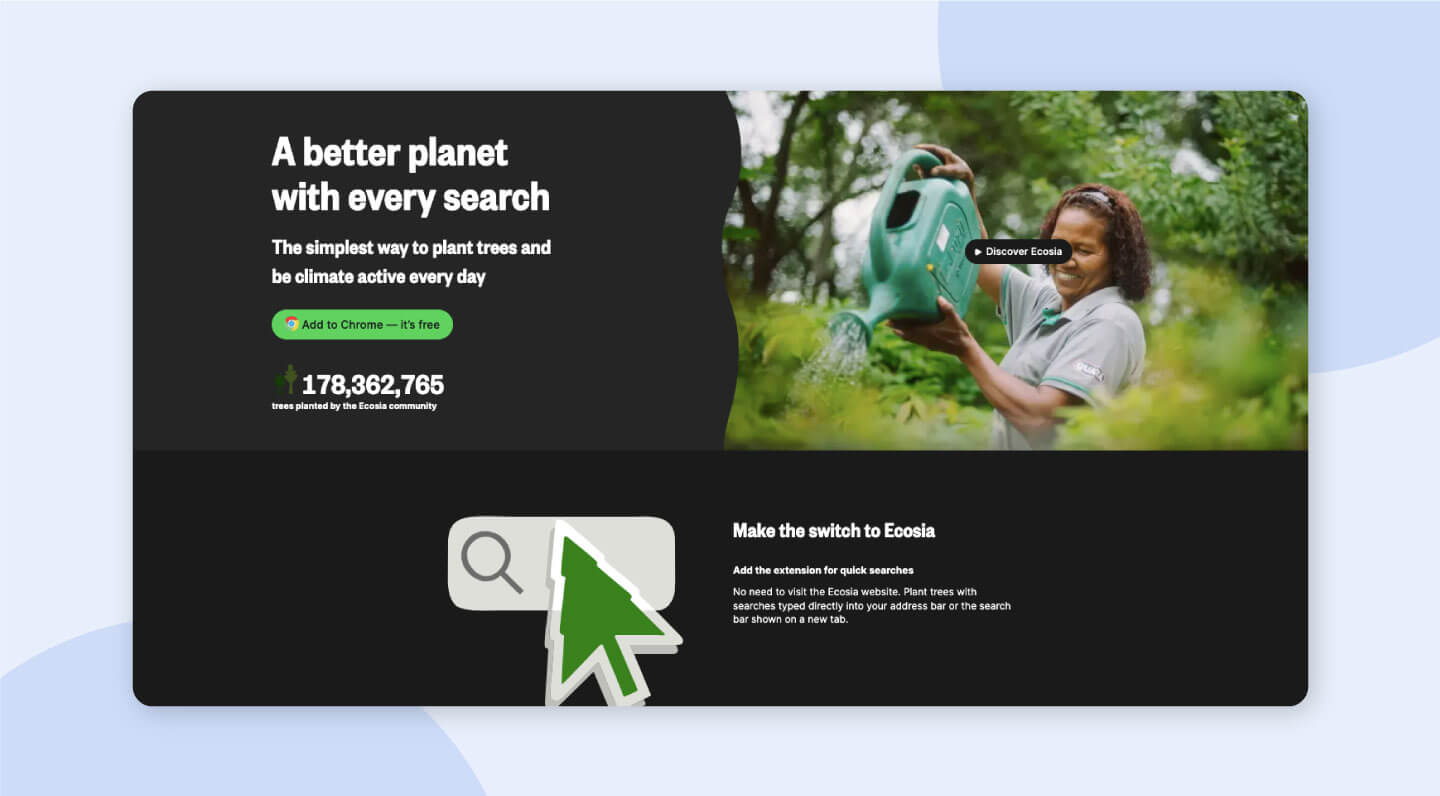

23. Ecosia: Plant Trees While You Search

Looking to create a better world, Ecosia launched its “Plant Trees While You Search” initiative, which plants trees for every online search made by its users. This ad campaign positions the brand as an eco-aware online tool that uplifts local communities in more than 35 countries. Instead of focusing solely on its users’ actions, this campaign extends Ecosia’s contentious thinking beyond the borders of the search bar.

Year: 2009 Campaign Medium: Media Expert Takeaway: “Its simplicity and impactful message make it compelling. It's not just about promoting a product but about making a difference in the world. [Ecosia’s] campaign success lies in its ability to connect with the audience on a deeper, emotional level, making it a powerful example of purpose-driven marketing.” — Sarah Berthe, founder at SEO with Sarah

What Is An Ad Campaign?

An ad campaign refers to a collection of advertisements that use similar tones, messaging, and design assets to portray a similar message. Businesses can optimize specific portions of an ad campaign for different platforms, which can help brands continue to promote their messages through a product’s lifecycle without boring or frustrating their audience.

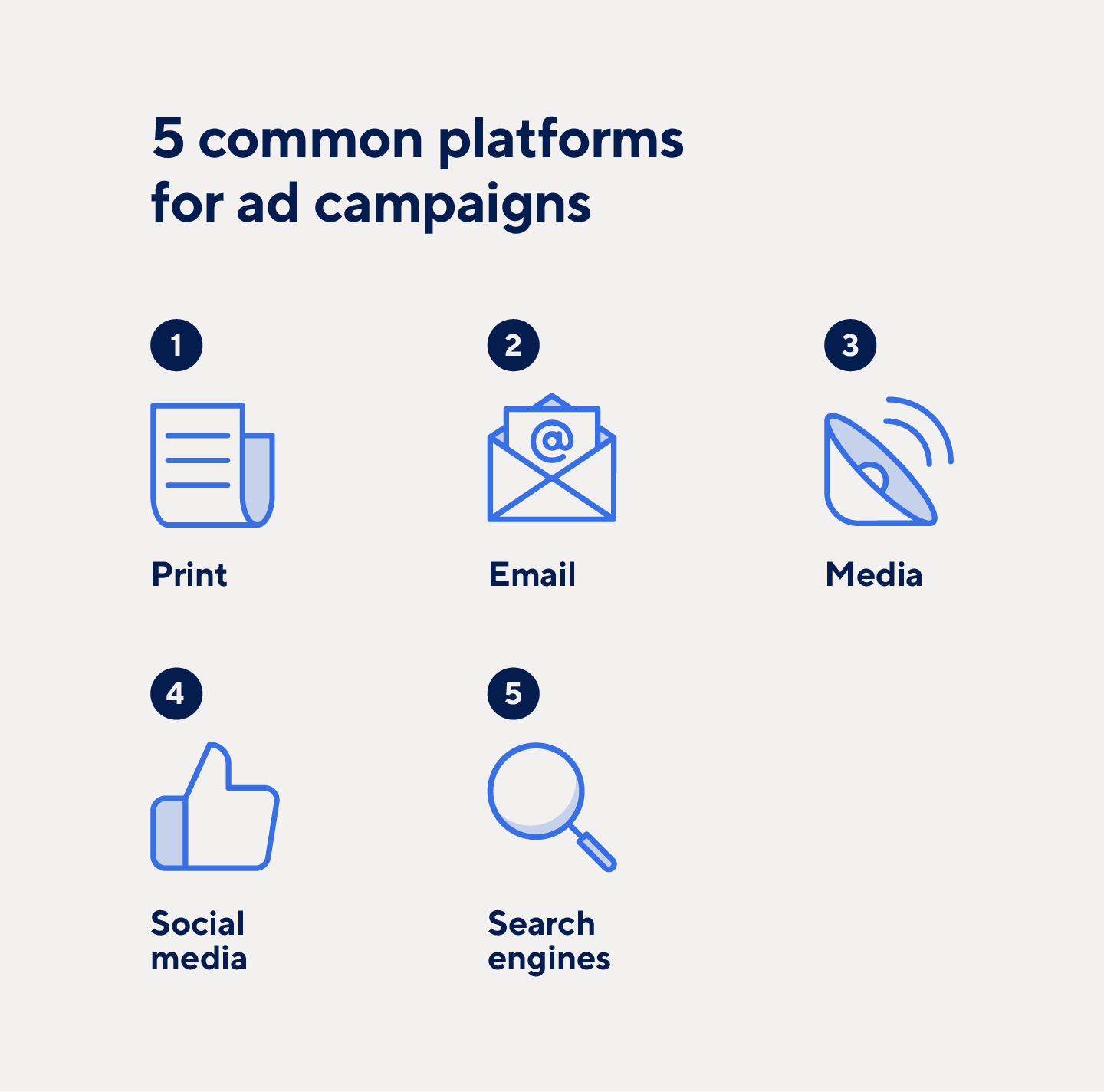

The most common platforms marketers include in ad campaigns include the following:

- Print: Newspaper ads, physical mail, and magazine advertisements are some of the most common forms of print advertising.

- Email: Catchy subject lines and time-sensitive messages usually comprise email ads that users can view on smart devices from virtually anywhere.

- Media: Many marketers will design media-specific campaigns, from television to radio. These types of campaigns can even show up on social media platforms.

- Social Media: From in-app advertisements to pop-up notifications and video ads, social media has become one of the most popular platforms for ad campaigns.

- Search Engines: Search engines use an auction-based system to allow marketers to bid on keywords and advertise services or products on search engine results pages.

Types of Ad Campaigns

Before creating an ad campaign , it’s important to understand the different types of campaigns and when to use them. There are four main types of ad campaigns:

- Informative: Informative campaigns are meant to inform customers about products, services, promotions, and more. These campaigns usually aim to increase brand awareness, authority, trust, and loyalty.

- Persuasive: Persuasive campaigns are designed to encourage readers to make a decision. These campaigns can target products, sales, subscriptions, time-sensitive promotions, and other conversion-centric decisions.

- Reminders: With so many advertisements flooding the average person’s day-to-day life, reminder ads simply remind audience members of their purchasing options — including expiration dates for rewards and promotions.

- Reinforcement: The purpose of reinforcement ads is to reassure customers of their decisions and provide guidance about the best ways to use or enhance their product experience after purchasing.

Elements of a Successful Ad Campaign

No matter what ad campaign you create, there are usually two key components: a target audience, and campaign goals. Whether your campaign is designed to sell a product or promote a service, including these elements in your campaign’s design can help you succeed.

Audience-Centric

A successful ad campaign keeps its audience in mind, and always engaged. Whether your campaign aims to increase brand awareness, attract new customers, or keep the interest of previous customers, you need to know and understand your target audience to create an audience-centric campaign.

While an ad campaign uses various types of advertisements across different platforms, it is still a singular campaign attempting to reach specific goals. To be successful, each component of the campaign must be cohesive — even if you design them for different audiences or platforms. A creative project management plan for an advertising campaign can ensure that your language, tone, design assets, and other campaign elements follow a singular set of guidelines.

Visually Appealing

Unless you are solely advertising on audio-only platforms, the visual appeal of your ads can greatly affect their success. Using engaging colors, unique fonts, and fun illustration styles can increase the appeal of an ad campaign’s offerings. Plus, by prioritizing color contrast and character representation in a campaign’s designs, marketers can make advertisements both accessible and appealing — this can greatly increase a campaign’s potential reach while respecting individual needs.

Clear Messaging

All components of a single campaign need to focus on and prioritize a single message. Whether promoting a new product, giving away a free trial, or increasing brand awareness, your advertisements should all use clear, straightforward messaging focused on the same outcome.

Goal-Focused

Along with clear messaging, an ad campaign should be focused on a specific goal, or goals. Your messaging will change depending on the action you want your audience to take. For example, if you want your audience to trust you, you must create informational, researched-based advertisements designed with their needs in mind. Before creating any promotional material, decide on a campaign’s goal and adjust your language, visuals, and medium choices.

Empower your people to go above and beyond with a flexible platform designed to match the needs of your team — and adapt as those needs change.

The Smartsheet platform makes it easy to plan, capture, manage, and report on work from anywhere, helping your team be more effective and get more done. Report on key metrics and get real-time visibility into work as it happens with roll-up reports, dashboards, and automated workflows built to keep your team connected and informed.

When teams have clarity into the work getting done, there’s no telling how much more they can accomplish in the same amount of time. Try Smartsheet for free, today.

Discover why over 90% of Fortune 100 companies trust Smartsheet to get work done.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Visual Arguments, Media and Advertising

This week, we will be exploring the use of visuals (images, charts, graphs, etc.) in the presentation of arguments. Like any other piece of support, images and other visuals are compelling when used correctly. They also can be used in ways that contribute to all of the flaws, fallacies and faulty reasoning we have been exploring all term. Images can support written or spoken arguments or become the arguments themselves. They hold great power, in advertising, journalism and many other aspects of our media-managed perceptions of the world around us. As such they deserve our attention here as we finish our discussion of the analysis and construction of arguments.

In the modern era, not all arguments come to us in the form of words: written or spoken. Increasingly, images play an important role in the development and understanding of arguments. This unit explores how visual arguments are constructed and employed to sustain and bolster other forms of argument. This week, we will be exploring the use of visuals (images, charts, graphs, etc.) in the presentation of arguments. Like any other piece of support, images and other visuals are compelling when used correctly. They also can be used in ways that contribute to all of the flaws, fallacies and faulty reasoning we have been exploring all term.

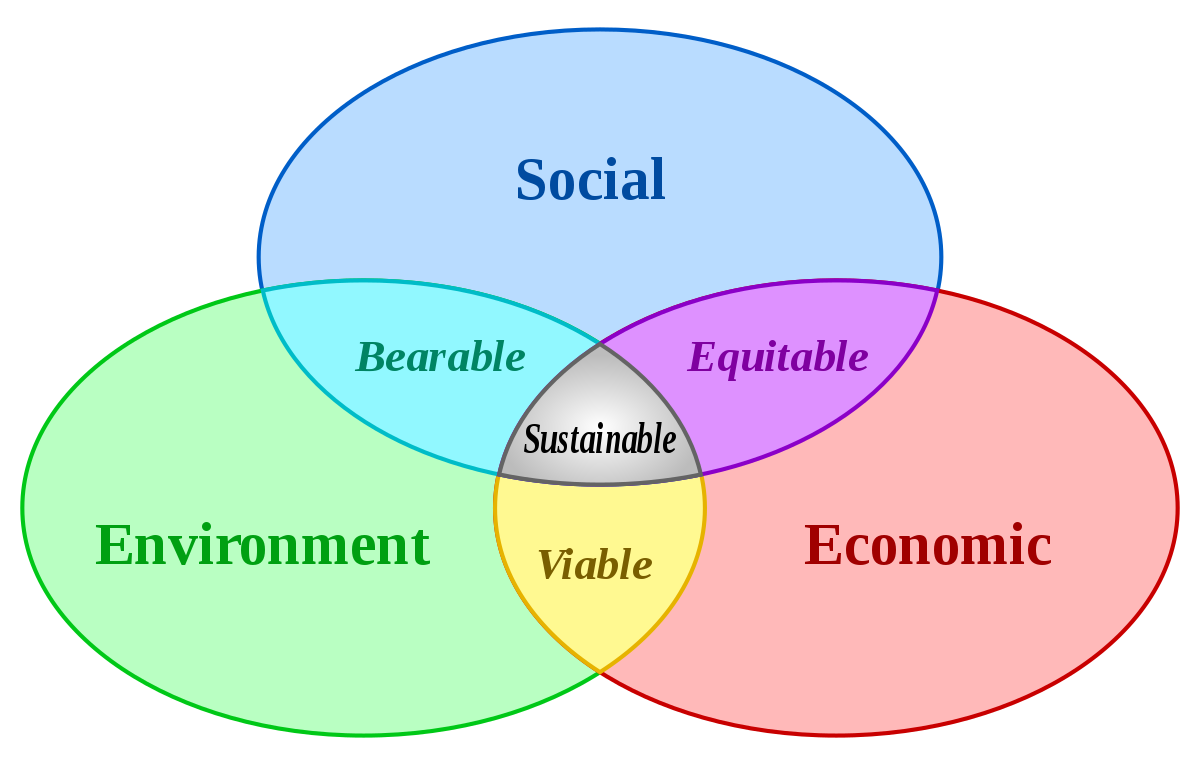

The Venn diagram above is a great example of how an image can be used effectively to communicate a complicated idea rather quickly and efficiently. Here, we can see that “sustainability” is defined as the intersection of environmental, economic and social concerns, for instance. Proper use of visuals can help us connect with an audience’s emotions and values, build credibility and share data and logical information in memorable and engaging ways.

- View the film: The Codes of Gender

- View the film: Generation Like https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JqamKb7gTWY

- View the video: Visual Arguments Essay https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4rudEk92goc

- Use the outside link: Visual Arguments https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xCYf3J88EzA

- Review the handout: Ideographs

Critical Thinking Copyright © 2019 by Andrew Gurevich is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 30 June 2023

Do I question what influencers sell me? Integration of critical thinking in the advertising literacy of Spanish adolescents

- Beatriz Feijoo ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5287-3813 1 ,

- Luisa Zozaya 1 &

- Charo Sádaba 2

Humanities and Social Sciences Communications volume 10 , Article number: 363 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

2111 Accesses

3 Citations

6 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Cultural and media studies

Engaging with influencer posts has become a prevalent practice among adolescents on social media, exposing them to the combined elements of promotional content and entertainment in influencer marketing. However, the versatile and appealing nature of this content may hinder adolescents’ ability to engage in critical thinking and accurately interpret this hybrid form of advertising. This study aims to investigate adolescents’ capacity to critically process persuasive content shared by influencers, utilizing the five components of digital critical thinking outlined by Van Laar ( 2019 ): clarification, evaluation, justification, linking of ideas, and novelty. To analyze minors’ online experiences, a qualitative approach was employed involving twelve discussion groups with a total of 62 children and adolescents aged 11 to 17 in Spain. The findings indicate that the exercise of critical thinking in response to influencer marketing is closely associated with the cognitive and affective dimensions of advertising literacy in adolescents, while wamong them.

Similar content being viewed by others

Exploring the dynamics of consumer engagement in social media influencer marketing: from the self-determination theory perspective

Is visual content modality a limiting factor for social capital? Examining user engagement within Instagram-based brand communities

Exploring the effects of audience and strategies used by beauty vloggers on behavioural intention towards endorsed brands

Introduction.

In a consumer society, the cultivation of advertising literacy has long been recognized as culturally and socially necessary (Malmelin, 2010 ; Rozendaal et al., 2011 ). However, the relevance of advertising literacy has significantly increased with the widespread influence of digital technology throughout all stages of the consumer journey encompassing discovery, information search, offer evaluation, purchase decisions and product/service recommendation (Kietzmann et al., 2018 ; Shavitt and Barnes, 2020 ). The urgency for adolescents to develop advertising literacy has intensified due to the omnipresence of commercial information in various formats (Braun and Garriga, 2018 ; Cheng and Anderson, 2021 ; Humphreys et al., 2021 ; Kietzmann et al., 2018 ), such as the emergence of hybrid advertising that poses challenges in identification (Feijoo and Sádaba, 2022 ; Ikonen et al., 2017 ). Additionally, the accessibility of technology to audiences, of all age groups, including adolescents, and across various educational levels, particularly through mobile devices (An and Kang, 2014 ; Chen et al., 2013 ; Terlutter and Capella, 2013 ), exacerbates the need for promoting advertising literacy. The personal nature of screens and the exposure to commercial content amplify the urgency of addressing this issue (Oates et al., 2014 ).

Advertising literacy, which has existed even before the digital era, has now emerged as a distinct category among the various literacies that have evolved (Malmelin, 2010 ) due to the increasing digitalization of our daily lives (Selber and Selber, 2004 ). In addition to advertising literacy, other important literacies include algorithmic literacy (Dogruel et al., 2022 ; Shin et al., 2021 ), visual literacy (Avgerinou and Ericson, 1997 ), informational literacy (Behrens, 1994 ), and data literacy (Sagirolu and Sinanc, 2013 ), among others. While these literacies may primarily focus on specific perspectives that are currently of great interest, the knowledge, skills, and attitudes required for acquiring these literacies can be widely applicable across various domains. Some scholars argue that simplification is necessary to facilitate efforts in operationalizing these literacies (Kacinova and Sádaba, 2022 ).

Numerous studies on advertising literacy have emphasized that understanding advertising is necessary but insufficient for accurately processing digital messages (Rozendaal et al., 2011 ; An et al., 2014 ; Rozendaal et al., 2013 ; Vanwesenbeeck et al., 2017 ; Van Reijmersdal, 2017 ). This holds true particularly for content where the persuasive intent is more subtle, such as influencer marketing (Borchers, 2022 ; Van Dam and Van Reijmersdal, 2019 ). In addition to the cognitive dimension, considering the attitudinal dimension of advertising literacy is crucial as it plays a significant role in encouraging children to question and interpret advertisements. Attitudes such as skepticism (valuing a critical approach to advertising) or liking/disliking the phenomenon are instrumental in facilitating low-effort processing when children encounter new advertising formats. However, an examination of the results from the latest EU Kids Online questionnaire reveals that Spanish children aged 12–16 demonstrate some of the lowest levels of browsing and critical appraisal skills in Europe (Smahel et al., 2020 ).

Hence, programs aimed at enhancing advertising literacy among adolescents should not solely focus on the cognitive aspects but should also encompass the attitudinal domain, where critical thinking skills play a pivotal role. This article seeks to contribute to the ongoing discourse on advertising literacy in adolescents by employing a qualitative approach to assess their level of critical competence when confronted with influencer-generated branded content, characterized by subtle persuasive intent. The World Health Organization has coined the term “infodemic” to describe the overwhelming abundance of information individuals encounter on the internet, particularly on social networks. Therefore, it is imperative for individuals, especially children who are vulnerable during their formative years, to develop essential skills such as discerning content, identifying and selecting credible sources, curbing the spread of misinformation, and refraining from propagating falsehoods. All these skills foster responsible digital consumption.

The attitudinal and ethical dimension of adolescents’ advertising literacy in the face of influencer marketing

Leisure and social relations content holds significant relevance for children and adolescents in today’s digital landscape. Although screens have been used for educational purposes, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic, entertainment continues to be a prominent component of digital device usage (IAB Spain, 2022 ), particularly among adolescents. The content consumed by minors on social networks often consists of sponsored posts and advertisements, encompassing both traditional and hybrid formats. Influencers frequently utilize this combination of formats to produce content that appeals to the varied interests of young audiences.

The traditional understanding of advertising literacy in children encompasses both cognitive and attitudinal dimensions (Rozendaal et al., 2011 ). The cognitive dimension requires the awareness of specific elements such as recognizing the intent to sell, the source, the persuasive intent, the employed tactics, and the advertising bias (Friestad and Wright, 1994 ; Livingstone and Helsper, 2006 ; Rozendaal et al., 2011 ). However, the rapid evolution of commercial tactics presents challenges in accurately processing advertising. Advertisers now employ branded content, adgames and influencer-generated content to quickly capture consumer attention and intention (van Berlo et al., 2021 ; van Dam and Van Reijmersdal, 2019 ; Hudders et al., 2016 ). Strategies used by advertisers include strategically placing content, appealing to audience emotions, offering customized experiences, and providing rewards and gifts in exchange for exposure (Feijoo and Sádaba, 2021 ). The increasing demands for stricter regulations in digital advertising sometimes surpassing those of television (Feijoo et al., 2020 ), and the suggestion of timely labeling of commercial content to facilitate identification (Lou and Yuan, 2019 ; Zozaya and Sádaba, 2022 ) further emphasize the need to address evolving advertising formats. Given the rapid evolution and ubiquity of advertising formats, developing persuasive knowledge is crucial for navigating this content, particularly among vulnerable audiences.

The attitudinal dimension of advertising literacy encompasses fostering a healthy level of skepticism and promoting critical reflection on the content individuals hear or see in terms of biases and persuasive intentions (Waiguny et al., 2014 ). Ideally, through this process of critical analysis, individuals would develop an informed response to advertising exposure.

When children come across formats that combine advertising and entertainment, they tend to engage in low-effort cognitive processing and fail to activate their developed associative knowledge network regarding the phenomenon (Mallinckrodt and Mizerski, 2007 ; Rozendaal et al., 2011 ; Rozendaal et al., 2013 ; An et al., 2014 ; Vanwesenbeeck et al., 2017 ; Van Reijmersdal et al., 2017 ). Numerous studies have focused on advergaming formats and have shown that merely recognizing the advertising intent of a message does not automatically translate into the ability to question or interpret the received content. This limited cognitive processing of non-traditional advertising formats is further influenced by several factors, such as the child’s primary attention being directed toward the recreational aspect of the format, often overshadowing the processing of the persuasive message. Consequently, advertising literacy programs should adopt an attitudinal perspective, emphasizing the promotion of critical attitudes towards advertising (Hudders et al., 2017 ; Vanwesenbeeck et al., 2017 ; Van Reijmersdal et al., 2017 ).

In recent years, the dimension of ethics has been recognized as a crucial aspect of advertising literacy (Adams et al., 2017 ; Hudders et al., 2017 ; De Jans et al., 2018 ; Sweeney et al., 2022 ; Zarouali et al., 2019 ). This addition reflects the growing pressure and diversification of advertising messages, as well as the utilization of various elements and resources aimed at achieving commercial objectives. Some advertising campaigns employ images, stories or tactics that deviate from social values or norms in order to capture the attention of potential consumers. Others attempt to circumvent legal restrictions by employing hybrid or inaccurately labeled formats or promoting unethical or illegal products or services, which may vary across cultures (Lee et al., 2011 ). To assess the potential impact of an advertising message or action on themselves, others, or society as a whole, consumers must enhance their ethical dimension (Adams et al., 2017 ; Zarouali et al., 2019 ).

The increasing digitization and its impact on consumption practices underscore the heightened necessity of advertising literacy across its three dimensions (Sweeney et al., 2022 ). Therefore, this study aims to integrate advertising literacy with the development of digital competence by emphasizing its interconnectedness with critical thinking. This integrated approach seeks to facilitate the comprehensive advancement of all three dimensions of advertising literacy. By exploring these synergies, the research intends to equip citizens, particularly adolescents as consumers of commercial content, with the ability to engage with such content in a healthy and conscientious manner. This endeavor aligns with prior research that examines the essential skills adolescents need to cultivate in the face of ubiquitous and pervasive commercial content (Hudders et al., 2017 ).

Critical thinking as a key competency in advertising literacy for adolescents

The development of critical thinking is recognized as a fundamental skill for educating new generations. Critical thinking entails an intellectually disciplined process of conceptualizing, applying, analyzing, synthesizing, and actively evaluating information derived from reflection, reasoning, or communication which serves as a guide to belief and action (Scriven and Paul, 2007 ). It involves acquiring skills such as identifying the source of information, analyzing credibility, reflecting on information, and drawing conclusions (Linn, 2000 ; Shin et al., 2015 ). Additionally, critical thinking encompasses attitudes towards inquiry, a commitment to the accuracy of evidence, and the practical application of these attitudes and knowledge (Watson and Glaser, 1980 ).

During adolescence, the development of critical thinking becomes more prominent, relying on the advancement of formal thinking. It represents a sophisticated ability to solve complex problems, but prior training is essential to cultivate the skills necessary for evaluating one’s own thinking and the thinking of others (Delval, 1999 ). In Spain, the Royal Decree 1105/2014 of 26 December establishes the basic curriculum for Compulsory Secondary Education and the Baccalaureate. While critical thinking competency is not considered fundamental throughout the curriculum, it is addressed in a cross-cutting manner within the Secondary and Baccalaureate content.

The constant participation and immersion in the global online environment have elevated critical thinking to one of the seven essential digital skills necessary for engaging with 21st-century online content. Consequently, critical thinking is considered a priority competency by the European Union’s Innovation, Research, Culture, Education, and Youth Council ( 2022 ) in their efforts to promote digital literacy and combat misinformation. In the digital context, critical thinking serves as the foundation for developing reflective reasoning, which relies on evidence to validate or challenge the encountered information. This enables users to make informed judgments and decisions by considering the intentions behind publications and examining multiple perspectives (Amabile and Pillemer, 2012 ; Van Laar, 2019 ). An essential characteristic of critical thinking is the ability to independently evaluate arguments and evidence, detached from personal beliefs. This capacity to contrast ideas fosters the emergence of new viewpoints and contributes to meaningful discussions (Voskoglou and Buckley, 2012 ).

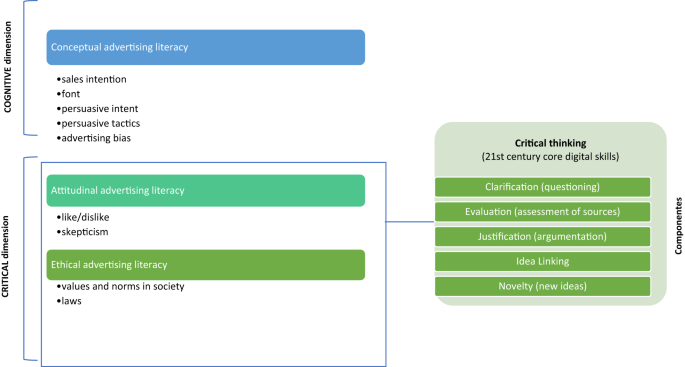

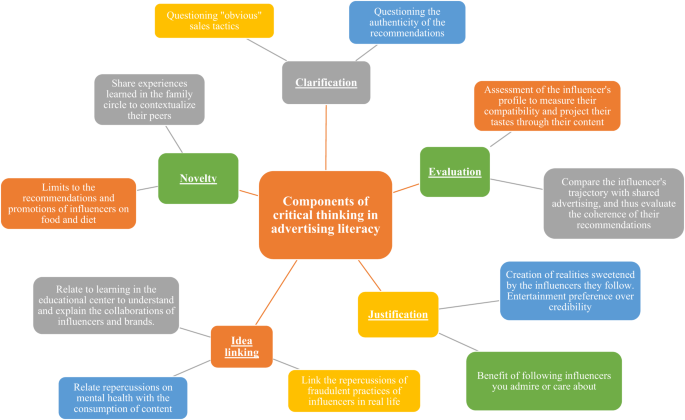

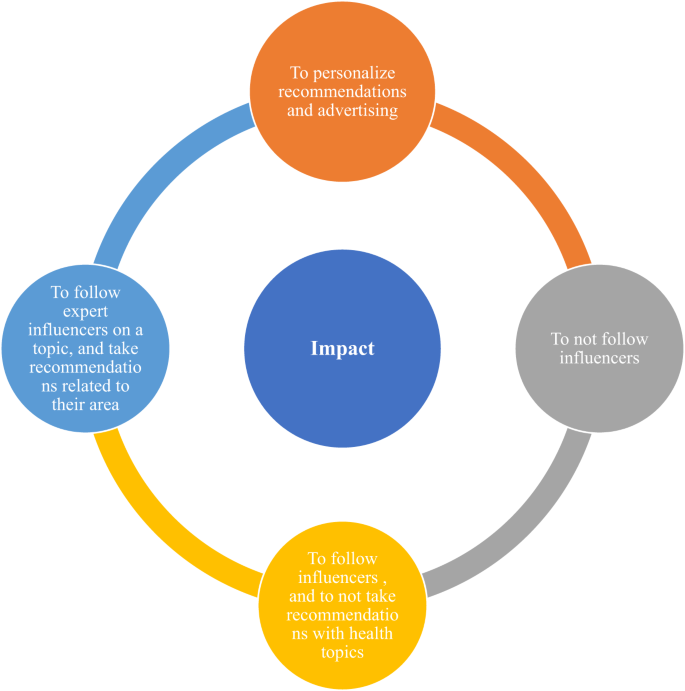

Van Laar ( 2019 ) identifies five components of digital critical thinking: clarification (asking and answering clarifying questions), evaluation (assessing the credibility of sources), justification (providing arguments based on personal experiences, reasoning, etc.), idea linking (connecting facts and ideas from personal experiences), and novelty (suggesting new ideas for discussion).

Figure 1 illustrates the advertising literacy model that serves as the foundation for this study (Rozendaal et al., 2011 ; Hudders et al., 2017 ). This model outlines the components of digital critical thinking that play a vital role in the attitudinal and ethical dimensions of the literacy process.

Advertising literacy model used in this study, which includes Van Laar’s critical thinking components.

However, evidence from the European research network EU Kids Online (Garmendia et al., 2011 , 2016 , and 2019 ; Livingstone et al., 2011 ; Smahel et al., 2020 ) indicates that Spanish children consistently demonstrate the lowest levels of critical information literacy in Europe. These findings have remained consistent since 2015 (Garmendia et al., 2016 ) when Spanish children aged 9 to 16 displayed significantly lower levels of information literacy skills, such as contrasting information from different sources, compared to other activities. Only 48% of 9 to 16 year olds claimed to possess this ability, with notable gender and age differences. The most recent EU Kids Online questionnaire, which compares digital skills among children in 18 European countries, reveals alarming results, particularly for Spain. Spanish children aged 12 to 16 exhibit the lowest levels of browsing skills and critical appraisal in Europe (Smahel et al., 2020 ). Authors such as Van Deursen et al. ( 2016 ) argue for the necessity of new qualitative studies that enable a more in-depth exploration of digital skills, particularly those related to Web 2.0 activities and the technical aspects of internet use, to avoid oversimplifying the findings.

Adolescents may encounter difficulties in recognizing dynamic or entertaining advertising formats as advertisements and may face challenges in developing critical attitudes towards them. This is particularly evident in the case of influencer marketing, where influencers serve as brand ambassadors and promote products and services aligned with their personal profiles. They engage with their followers in a manner that resembles recommendations rather than sales pitches. Consequently, distinguishing between genuine product suggestions and paid collaborations can become challenging for the audience (van Dam and van Reijmersdal, 2019 ; Feijoo and Sádaba, 2021 ).

Previous research has investigated adolescents’ ability to recognize and respond to influencer-generated content with persuasive intent (Boerman and Van Reijmersdal, 2020 ; De Jans and Hudders, 2020 ; Van Reijmersdal and Rozendaal, 2020 ; Van Dam and Van Reijmersdal, 2019 ; van der Bend et al., 2023 ). Qualitative research conducted by Borchers ( 2022 ) with 132 German adolescents aged eleven to fifteen revealed their awareness of sponsored influencer posts. However, the study highlighted a tension between their understanding that sponsored content is advertising and the need to critically scrutinize it. Consequently, there is an urgent need for additional qualitative studies exploring adolescents’ online behavior and the strategies they employ to navigate the impact of persuasive content disseminated by influencers. Adopting an advertising literacy approach and aiming to foster the development of critical consumers, it is crucial to gather data on the presence of critical thinking dimensions when children and adolescents encounter messages disguised as entertainment but containing commercial intent (Feijoo and Sádaba, 2021 ).

The acquisition and development of critical thinking skills among adolescents are fundamental for advancing their advertising literacy. This serves as a crucial foundation for enhancing media and digital competence, especially considering the significant portion of content exposure occurring through internet-connected screens. Examining how critical thinking evolves during exposure to influencer marketing enables questioning, investigation, and learning. This perspective helps envision approaches that go beyond automatic responses influenced by biases against the commercial relationship between advertising and celebrities (McShane et al., 2013 ).

In light of these underlying factors, this article aims to address the following research question:

RQ1. To what extent do adolescents’ reactions to commercial content created by influencers encompass the components of critical thinking as defined by Van Laar ( 2019 )?

Methodology

The objective of this study is to investigate how adolescents use critical thinking when exposed to influencer-generated content. A qualitative methodology will be employed to accomplish this aim. In assessing critical thinking, the study will adopt the five dimensions proposed by Van Laar ( 2019 ) as a framework.

Participants and selection process

For this study, a sample of 62 students between the ages of 11 and 17 ( M = 14.14, SD = 1.9) was selected, comprising 59.7% female participants and 40.3% male participants. These students were drawn from multiple schools located across different regions of Spain, with 41.9% from the South, 22.6% from the Levante region, 19.3% from the North, 9.7% from the Canary Islands, and 6.5% from the central area.