Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Review Article

- Published: 27 September 2021

Why lockdown and distance learning during the COVID-19 pandemic are likely to increase the social class achievement gap

- Sébastien Goudeau ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-7293-0977 1 ,

- Camille Sanrey ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-3158-1306 1 ,

- Arnaud Stanczak ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-2596-1516 2 ,

- Antony Manstead ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-7540-2096 3 &

- Céline Darnon ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-2613-689X 2

Nature Human Behaviour volume 5 , pages 1273–1281 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

115k Accesses

148 Citations

129 Altmetric

Metrics details

The COVID-19 pandemic has forced teachers and parents to quickly adapt to a new educational context: distance learning. Teachers developed online academic material while parents taught the exercises and lessons provided by teachers to their children at home. Considering that the use of digital tools in education has dramatically increased during this crisis, and it is set to continue, there is a pressing need to understand the impact of distance learning. Taking a multidisciplinary view, we argue that by making the learning process rely more than ever on families, rather than on teachers, and by getting students to work predominantly via digital resources, school closures exacerbate social class academic disparities. To address this burning issue, we propose an agenda for future research and outline recommendations to help parents, teachers and policymakers to limit the impact of the lockdown on social-class-based academic inequality.

Similar content being viewed by others

Large socio-economic, geographic and demographic disparities exist in exposure to school closures

Elementary school teachers’ perspectives about learning during the COVID-19 pandemic

Uncovering Covid-19, distance learning, and educational inequality in rural areas of Pakistan and China: a situational analysis method

The widespread effects of the COVID-19 pandemic that emerged in 2019–2020 have drastically increased health, social and economic inequalities 1 , 2 . For more than 900 million learners around the world, the pandemic led to the closure of schools and universities 3 . This exceptional situation forced teachers, parents and students to quickly adapt to a new educational context: distance learning. Teachers had to develop online academic materials that could be used at home to ensure educational continuity while ensuring the necessary physical distancing. Primary and secondary school students suddenly had to work with various kinds of support, which were usually provided online by their teachers. For college students, lockdown often entailed returning to their hometowns while staying connected with their teachers and classmates via video conferences, email and other digital tools. Despite the best efforts of educational institutions, parents and teachers to keep all children and students engaged in learning activities, ensuring educational continuity during school closure—something that is difficult for everyone—may pose unique material and psychological challenges for working-class families and students.

Not only did the pandemic lead to the closure of schools in many countries, often for several weeks, it also accelerated the digitalization of education and amplified the role of parental involvement in supporting the schoolwork of their children. Thus, beyond the specific circumstances of the COVID-19 lockdown, we believe that studying the effects of the pandemic on academic inequalities provides a way to more broadly examine the consequences of school closure and related effects (for example, digitalization of education) on social class inequalities. Indeed, bearing in mind that (1) the risk of further pandemics is higher than ever (that is, we are in a ‘pandemic era’ 4 , 5 ) and (2) beyond pandemics, the use of digital tools in education (and therefore the influence of parental involvement) has dramatically increased during this crisis, and is set to continue, there is a pressing need for an integrative and comprehensive model that examines the consequences of distance learning. Here, we propose such an integrative model that helps us to understand the extent to which the school closures associated with the pandemic amplify economic, digital and cultural divides that in turn affect the psychological functioning of parents, students and teachers in a way that amplifies academic inequalities. Bringing together research in social sciences, ranging from economics and sociology to social, cultural, cognitive and educational psychology, we argue that by getting students to work predominantly via digital resources rather than direct interactions with their teachers, and by making the learning process rely more than ever on families rather than teachers, school closures exacerbate social class academic disparities.

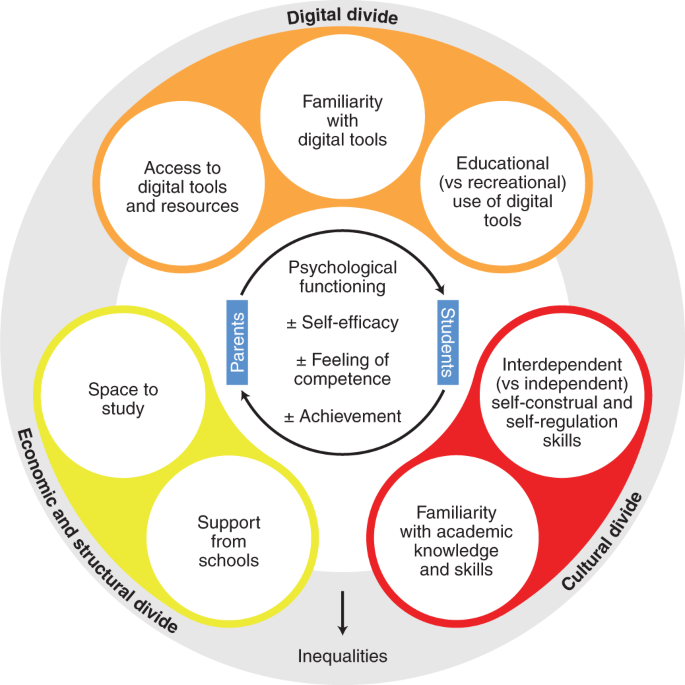

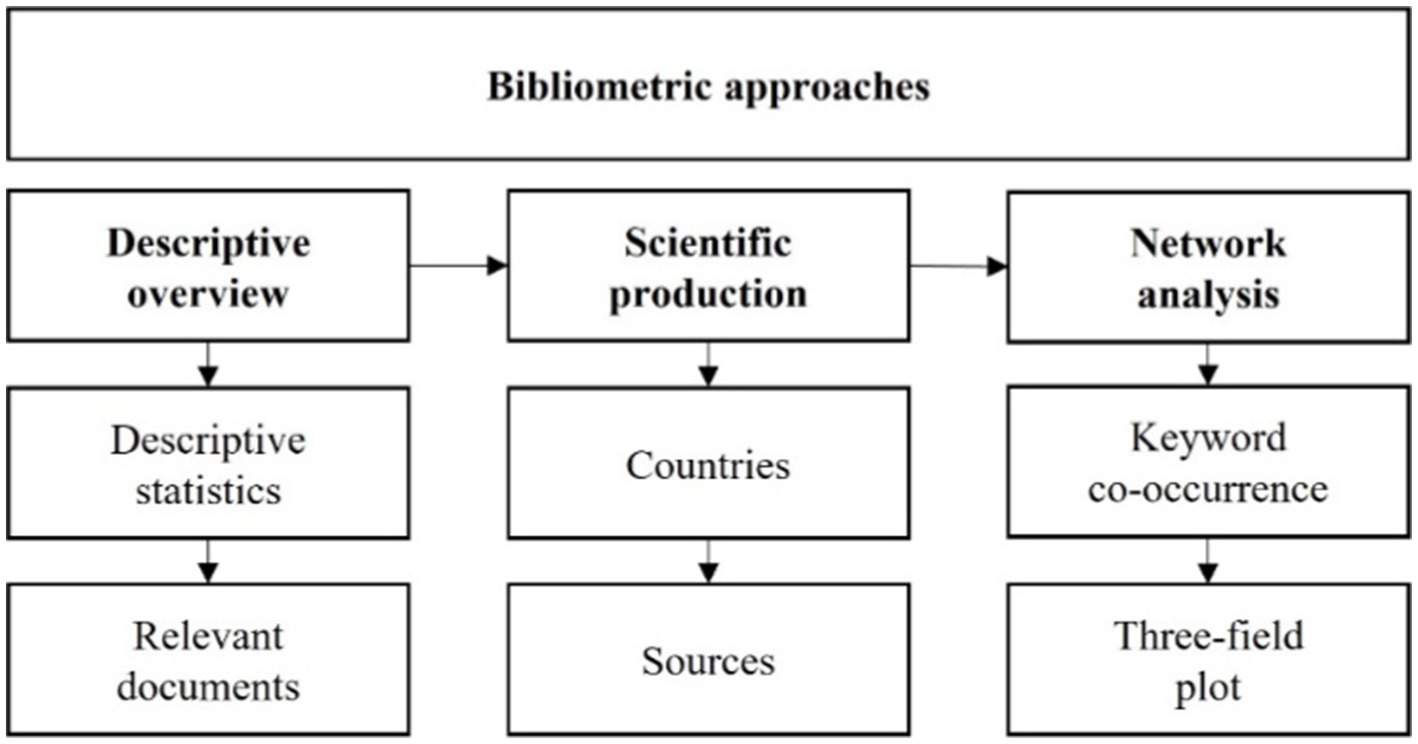

First, we review research showing that social class is associated with unequal access to digital tools, unequal familiarity with digital skills and unequal uses of such tools for learning purposes 6 , 7 . We then review research documenting how unequal familiarity with school culture, knowledge and skills can also contribute to the accentuation of academic inequalities 8 , 9 . Next, we present the results of surveys conducted during the 2020 lockdown showing that the quality and quantity of pedagogical support received from schools varied according to the social class of families (for examples, see refs. 10 , 11 , 12 ). We then argue that these digital, cultural and structural divides represent barriers to the ability of parents to provide appropriate support for children during distance learning (Fig. 1 ). These divides also alter the levels of self-efficacy of parents and children, thereby affecting their engagement in learning activities 13 , 14 . In the final section, we review preliminary evidence for the hypothesis that distance learning widens the social class achievement gap and we propose an agenda for future research. In addition, we outline recommendations that should help parents, teachers and policymakers to use social science research to limit the impact of school closure and distance learning on the social class achievement gap.

Economic, structural, digital and cultural divides influence the psychological functioning of parents and students in a way that amplify inequalities.

The digital divide

Unequal access to digital resources.

Although the use of digital technologies is almost ubiquitous in developed nations, there is a digital divide such that some people are more likely than others to be numerically excluded 15 (Fig. 1 ). Social class is a strong predictor of digital disparities, including the quality of hardware, software and Internet access 16 , 17 , 18 . For example, in 2019, in France, around 1 in 5 working-class families did not have personal access to the Internet compared with less than 1 in 20 of the most privileged families 19 . Similarly, in 2020, in the United Kingdom, 20% of children who were eligible for free school meals did not have access to a computer at home compared with 7% of other children 20 . In 2021, in the United States, 41% of working-class families do not own a laptop or desktop computer and 43% do not have broadband compared with 8% and 7%, respectively, of upper/middle-class Americans 21 . A similar digital gap is also evident between lower-income and higher-income countries 22 .

Second, simply having access to a computer and an Internet connection does not ensure effective distance learning. For example, many of the educational resources sent by teachers need to be printed, thereby requiring access to printers. Moreover, distance learning is more difficult in households with only one shared computer compared with those where each family member has their own 23 . Furthermore, upper/middle-class families are more likely to be able to guarantee a suitable workspace for each child than their working-class counterparts 24 .

In the context of school closures, such disparities are likely to have important consequences for educational continuity. In line with this idea, a survey of approximately 4,000 parents in the United Kingdom confirmed that during lockdown, more than half of primary school children from the poorest families did not have access to their own study space and were less well equipped for distance learning than higher-income families 10 . Similarly, a survey of around 1,300 parents in the Netherlands found that during lockdown, children from working-class families had fewer computers at home and less room to study than upper/middle-class children 11 .

Data from non-Western countries highlight a more general digital divide, showing that developing countries have poorer access to digital equipment. For example, in India in 2018, only 10.7% of households possessed a digital device 25 , while in Pakistan in 2020, 31% of higher-education teachers did not have Internet access and 68.4% did not have a laptop 26 . In general, developing countries lack access to digital technologies 27 , 28 , and these difficulties of access are even greater in rural areas (for example, see ref. 29 ). Consequently, school closures have huge repercussions for the continuity of learning in these countries. For example, in India in 2018, only 11% of the rural and 40% of the urban population above 14 years old could use a computer and access the Internet 25 . Time spent on education during school closure decreased by 80% in Bangladesh 30 . A similar trend was observed in other countries 31 , with only 22% of children engaging in remote learning in Kenya 32 and 50% in Burkina Faso 33 . In Ghana, 26–32% of children spent no time at all on learning during the pandemic 34 . Beyond the overall digital divide, social class disparities are also evident in developing countries, with lower access to digital resources among households in which parental educational levels were low (versus households in which parental educational levels were high; for example, see ref. 35 for Nigeria and ref. 31 for Ecuador).

Unequal digital skills

In addition to unequal access to digital tools, there are also systematic variations in digital skills 36 , 37 (Fig. 1 ). Upper/middle-class families are more familiar with digital tools and resources and are therefore more likely to have the digital skills needed for distance learning 38 , 39 , 40 . These digital skills are particularly useful during school closures, both for students and for parents, for organizing, retrieving and correctly using the resources provided by the teachers (for example, sending or receiving documents by email, printing documents or using word processors).

Social class disparities in digital skills can be explained in part by the fact that children from upper/middle-class families have the opportunity to develop digital skills earlier than working-class families 41 . In member countries of the OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development), only 23% of working-class children had started using a computer at the age of 6 years or earlier compared with 43% of upper/middle-class children 42 . Moreover, because working-class people tend to persist less than upper/middle-class people when confronted with digital difficulties 23 , the use of digital tools and resources for distance learning may interfere with the ability of parents to help children with their schoolwork.

Unequal use of digital tools

A third level of digital divide concerns variations in digital tool use 18 , 43 (Fig. 1 ). Upper/middle-class families are more likely to use digital resources for work and education 6 , 41 , 44 , whereas working-class families are more likely to use these resources for entertainment, such as electronic games or social media 6 , 45 . This divide is also observed among students, whereby working-class students tend to use digital technologies for leisure activities, whereas their upper/middle-class peers are more likely to use them for academic activities 46 and to consider that computers and the Internet provide an opportunity for education and training 23 . Furthermore, working-class families appear to regulate the digital practices of their children less 47 and are more likely to allow screens in the bedrooms of children and teenagers without setting limits on times or practices 48 .

In sum, inequalities in terms of digital resources, skills and use have strong implications for distance learning. This is because they make working-class students and parents particularly vulnerable when learning relies on extensive use of digital devices rather than on face-to-face interaction with teachers.

The cultural divide

Even if all three levels of digital divide were closed, upper/middle-class families would still be better prepared than working-class families to ensure educational continuity for their children. Upper/middle-class families are more familiar with the academic knowledge and skills that are expected and valued in educational settings, as well as with the independent, autonomous way of learning that is valued in the school culture and becomes even more important during school closure (Fig. 1 ).

Unequal familiarity with academic knowledge and skills

According to classical social reproduction theory 8 , 49 , school is not a neutral place in which all forms of language and knowledge are equally valued. Academic contexts expect and value culture-specific and taken-for-granted forms of knowledge, skills and ways of being, thinking and speaking that are more in tune with those developed through upper/middle-class socialization (that is, ‘cultural capital’ 8 , 50 , 51 , 52 , 53 ). For instance, academic contexts value interest in the arts, museums and literature 54 , 55 , a type of interest that is more likely to develop through socialization in upper/middle-class families than in working-class socialization 54 , 56 . Indeed, upper/middle-class parents are more likely than working-class parents to engage in activities that develop this cultural capital. For example, they possess more books and cultural objects at home, read more stories to their children and visit museums and libraries more often (for examples, see refs. 51 , 54 , 55 ). Upper/middle-class children are also more involved in extra-curricular activities (for example, playing a musical instrument) than working-class children 55 , 56 , 57 .

Beyond this implicit familiarization with the school curriculum, upper/middle-class parents more often organize educational activities that are explicitly designed to develop academic skills of their children 57 , 58 , 59 . For example, they are more likely to monitor and re-explain lessons or use games and textbooks to develop and reinforce academic skills (for example, labelling numbers, letters or colours 57 , 60 ). Upper/middle-class parents also provide higher levels of support and spend more time helping children with homework than working-class parents (for examples, see refs. 61 , 62 ). Thus, even if all parents are committed to the academic success of their children, working-class parents have fewer chances to provide the help that children need to complete homework 63 , and homework is more beneficial for children from upper-middle class families than for children from working-class families 64 , 65 .

School closures amplify the impact of cultural inequalities

The trends described above have been observed in ‘normal’ times when schools are open. School closures, by making learning rely more strongly on practices implemented at home (rather than at school), are likely to amplify the impact of these disparities. Consistent with this idea, research has shown that the social class achievement gap usually greatly widens during school breaks—a phenomenon described as ‘summer learning loss’ or ‘summer setback’ 66 , 67 , 68 . During holidays, the learning by children tends to decline, and this is particularly pronounced in children from working-class families. Consequently, the social class achievement gap grows more rapidly during the summer months than it does in the rest of the year. This phenomenon is partly explained by the fact that during the break from school, social class disparities in investment in activities that are beneficial for academic achievement (for example, reading, travelling to a foreign country or museum visits) are more pronounced.

Therefore, when they are out of school, children from upper/middle-class backgrounds may continue to develop academic skills unlike their working-class counterparts, who may stagnate or even regress. Research also indicates that learning loss during school breaks tends to be cumulative 66 . Thus, repeated episodes of school closure are likely to have profound consequences for the social class achievement gap. Consistent with the idea that school closures could lead to similar processes as those identified during summer breaks, a recent survey indicated that during the COVID-19 lockdown in the United Kingdom, children from upper/middle-class families spent more time on educational activities (5.8 h per day) than those from working-class families (4.5 h per day) 7 , 69 .

Unequal dispositions for autonomy and self-regulation

School closures have encouraged autonomous work among students. This ‘independent’ way of studying is compatible with the family socialization of upper/middle-class students, but does not match the interdependent norms more commonly associated with working-class contexts 9 . Upper/middle-class contexts tend to promote cultural norms of independence whereby individuals perceive themselves as autonomous actors, independent of other individuals and of the social context, able to pursue their own goals 70 . For example, upper/middle-class parents tend to invite children to express their interests, preferences and opinions during the various activities of everyday life 54 , 55 . Conversely, in working-class contexts characterized by low economic resources and where life is more uncertain, individuals tend to perceive themselves as interdependent, connected to others and members of social groups 53 , 70 , 71 . This interdependent self-construal fits less well with the independent culture of academic contexts. This cultural mismatch between interdependent self-construal common in working-class students and the independent norms of the educational institution has negative consequences for academic performance 9 .

Once again, the impact of these differences is likely to be amplified during school closures, when being able to work alone and autonomously is especially useful. The requirement to work alone is more likely to match the independent self-construal of upper/middle-class students than the interdependent self-construal of working-class students. In the case of working-class students, this mismatch is likely to increase their difficulties in working alone at home. Supporting our argument, recent research has shown that working-class students tend to underachieve in contexts where students work individually compared with contexts where students work with others 72 . Similarly, during school closures, high self-regulation skills (for example, setting goals, selecting appropriate learning strategies and maintaining motivation 73 ) are required to maintain study activities and are likely to be especially useful for using digital resources efficiently. Research has shown that students from working-class backgrounds typically develop their self-regulation skills to a lesser extent than those from upper/middle-class backgrounds 74 , 75 , 76 .

Interestingly, some authors have suggested that independent (versus interdependent) self-construal may also affect communication with teachers 77 . Indeed, in the context of distance learning, working-class families are less likely to respond to the communication of teachers because their ‘interdependent’ self leads them to respect hierarchies, and thus perceive teachers as an expert who ‘can be trusted to make the right decisions for learning’. Upper/middle class families, relying on ‘independent’ self-construal, are more inclined to seek individualized feedback, and therefore tend to participate to a greater extent in exchanges with teachers. Such cultural differences are important because they can also contribute to the difficulties encountered by working-class families.

The structural divide: unequal support from schools

The issues reviewed thus far all increase the vulnerability of children and students from underprivileged backgrounds when schools are closed. To offset these disadvantages, it might be expected that the school should increase its support by providing additional resources for working-class students. However, recent data suggest that differences in the material and human resources invested in providing educational support for children during periods of school closure were—paradoxically—in favour of upper/middle-class students (Fig. 1 ). In England, for example, upper/middle-class parents reported benefiting from online classes and video-conferencing with teachers more often than working-class parents 10 . Furthermore, active help from school (for example, online teaching, private tutoring or chats with teachers) occurred more frequently in the richest households (64% of the richest households declared having received help from school) than in the poorest households (47%). Another survey found that in the United Kingdom, upper/middle-class children were more likely to take online lessons every day (30%) than working-class students (16%) 12 . This substantial difference might be due, at least in part, to the fact that private schools are better equipped in terms of online platforms (60% of schools have at least one online platform) than state schools (37%, and 23% in the most deprived schools) and were more likely to organize daily online lessons. Similarly, in the United Kingdom, in schools with a high proportion of students eligible for free school meals, teachers were less inclined to broadcast an online lesson for their pupils 78 . Interestingly, 58% of teachers in the wealthiest areas reported having messaged their students or their students’ parents during lockdown compared with 47% in the most deprived schools. In addition, the probability of children receiving technical support from the school (for example, by providing pupils with laptops or other devices) is, surprisingly, higher in the most advantaged schools than in the most deprived 78 .

In addition to social class disparities, there has been less support from schools for African-American and Latinx students. During school closures in the United States, 40% of African-American students and 30% of Latinx students received no online teaching compared with 10% of white students 79 . Another source of inequality is that the probability of school closure was correlated with social class and race. In the United States, for example, school closures from September to December 2020 were more common in schools with a high proportion of racial/ethnic minority students, who experience homelessness and are eligible for free/discounted school meals 80 .

Similarly, access to educational resources and support was lower in poorer (compared with richer) countries 81 . In sub-Saharan Africa, during lockdown, 45% of children had no exposure at all to any type of remote learning. Of those who did, the medium was mostly radio, television or paper rather than digital. In African countries, at most 10% of children received some material through the Internet. In Latin America, 90% of children received some remote learning, but less than half of that was through the internet—the remainder being via radio and television 81 . In Ecuador, high-school students from the lowest wealth quartile had fewer remote-learning opportunities, such as Google class/Zoom, than students from the highest wealth quartile 31 .

Thus, the achievement gap and its accentuation during lockdown are due not only to the cultural and digital disadvantages of working-class families but also to unequal support from schools. This inequality in school support is not due to teachers being indifferent to or even supportive of social stratification. Rather, we believe that these effects are fundamentally structural. In many countries, schools located in upper/middle-class neighbourhoods have more money than those in the poorest neighbourhoods. Moreover, upper/middle-class parents invest more in the schools of their children than working-class parents (for example, see ref. 82 ), and schools have an interest in catering more for upper/middle-class families than for working-class families 83 . Additionally, the expectation of teachers may be lower for working-class children 84 . For example, they tend to estimate that working-class students invest less effort in learning than their upper/middle-class counterparts 85 . These differences in perception may have influenced the behaviour of teachers during school closure, such that teachers in privileged neighbourhoods provided more information to students because they expected more from them in term of effort and achievement. The fact that upper/middle-class parents are better able than working-class parents to comply with the expectations of teachers (for examples, see refs. 55 , 86 ) may have reinforced this phenomenon. These discrepancies echo data showing that working-class students tend to request less help in their schoolwork than upper/middle-class ones 87 , and they may even avoid asking for help because they believe that such requests could lead to reprimands 88 . During school closures, these students (and their families) may in consequence have been less likely to ask for help and resources. Jointly, these phenomena have resulted in upper/middle-class families receiving more support from schools during lockdown than their working-class counterparts.

Psychological effects of digital, cultural and structural divides

Despite being strongly influenced by social class, differences in academic achievement are often interpreted by parents, teachers and students as reflecting differences in ability 89 . As a result, upper/middle-class students are usually perceived—and perceive themselves—as smarter than working-class students, who are perceived—and perceive themselves—as less intelligent 90 , 91 , 92 or less able to succeed 93 . Working-class students also worry more about the fact that they might perform more poorly than upper/middle-class students 94 , 95 . These fears influence academic learning in important ways. In particular, they can consume cognitive resources when children and students work on academic tasks 96 , 97 . Self-efficacy also plays a key role in engaging in learning and perseverance in the face of difficulties 13 , 98 . In addition, working-class students are those for whom the fear of being outperformed by others is the most negatively related to academic performance 99 .

The fact that working-class children and students are less familiar with the tasks set by teachers, and less well equipped and supported, makes them more likely to experience feelings of incompetence (Fig. 1 ). Working-class parents are also more likely than their upper/middle-class counterparts to feel unable to help their children with schoolwork. Consistent with this, research has shown that both working-class students and parents have lower feelings of academic self-efficacy than their upper/middle-class counterparts 100 , 101 . These differences have been documented under ‘normal’ conditions but are likely to be exacerbated during distance learning. Recent surveys conducted during the school closures have confirmed that upper/middle-class families felt better able to support their children in distance learning than did working-class families 10 and that upper/middle-class parents helped their children more and felt more capable to do so 11 , 12 .

Pandemic disparity, future directions and recommendations

The research reviewed thus far suggests that children and their families are highly unequal with respect to digital access, skills and use. It also shows that upper/middle-class students are more likely to be supported in their homework (by their parents and teachers) than working-class students, and that upper/middle-class students and parents will probably feel better able than working-class ones to adapt to the context of distance learning. For all these reasons, we anticipate that as a result of school closures, the COVID-19 pandemic will substantially increase the social class achievement gap. Because school closures are a recent occurrence, it is too early to measure with precision their effects on the widening of the achievement gap. However, some recent data are consistent with this idea.

Evidence for a widening gap during the pandemic

Comparing academic achievement in 2020 with previous years provides an early indication of the effects of school closures during the pandemic. In France, for example, first and second graders take national evaluations at the beginning of the school year. Initial comparisons of the results for 2020 with those from previous years revealed that the gap between schools classified as ‘priority schools’ (those in low-income urban areas) and schools in higher-income neighbourhoods—a gap observed every year—was particularly pronounced in 2020 in both French and mathematics 102 .

Similarly, in the Netherlands, national assessments take place twice a year. In 2020, they took place both before and after school closures. A recent analysis compared progress during this period in 2020 in mathematics/arithmetic, spelling and reading comprehension for 7–11-year-old students within the same period in the three previous years 103 . Results indicated a general learning loss in 2020. More importantly, for the 8% of working-class children, the losses were 40% greater than they were for upper/middle-class children.

Similar results were observed in Belgium among students attending the final year of primary school. Compared with students from previous cohorts, students affected by school closures experienced a substantial decrease in their mathematics and language scores, with children from more disadvantaged backgrounds experiencing greater learning losses 104 . Likewise, oral reading assessments in more than 100 school districts in the United States showed that the development of this skill among children in second and third grade significantly slowed between Spring and Autumn 2020, but this slowdown was more pronounced in schools from lower-achieving districts 105 .

It is likely that school closures have also amplified racial disparities in learning and achievement. For example, in the United States, after the first lockdown, students of colour lost the equivalent of 3–5 months of learning, whereas white students were about 1–3 months behind. Moreover, in the Autumn, when some students started to return to classrooms, African-American and Latinx students were more likely to continue distance learning, despite being less likely to have access to the digital tools, Internet access and live contact with teachers 106 .

In some African countries (for example, Ethiopia, Kenya, Liberia, Tanzania and Uganda), the COVID-19 crisis has resulted in learning loss ranging from 6 months to more 1 year 107 , and this learning loss appears to be greater for working-class children (that is, those attending no-fee schools) than for upper/middle-class children 108 .

These findings show that school closures have exacerbated achievement gaps linked to social class and ethnicity. However, more research is needed to address the question of whether school closures differentially affect the learning of students from working- and upper/middle-class families.

Future directions

First, to assess the specific and unique impact of school closures on student learning, longitudinal research should compare student achievement at different times of the year, before, during and after school closures, as has been done to document the summer learning loss 66 , 109 . In the coming months, alternating periods of school closure and opening may occur, thereby presenting opportunities to do such research. This would also make it possible to examine whether the gap diminishes a few weeks after children return to in-school learning or whether, conversely, it increases with time because the foundations have not been sufficiently acquired to facilitate further learning 110 .

Second, the mechanisms underlying the increase in social class disparities during school closures should be examined. As discussed above, school closures result in situations for which students are unevenly prepared and supported. It would be appropriate to seek to quantify the contribution of each of the factors that might be responsible for accentuating the social class achievement gap. In particular, distinguishing between factors that are relatively ‘controllable’ (for example, resources made available to pupils) and those that are more difficult to control (for example, the self-efficacy of parents in supporting the schoolwork of their children) is essential to inform public policy and teaching practices.

Third, existing studies are based on general comparisons and very few provide insights into the actual practices that took place in families during school closure and how these practices affected the achievement gap. For example, research has documented that parents from working-class backgrounds are likely to find it more difficult to help their children to complete homework and to provide constructive feedback 63 , 111 , something that could in turn have a negative impact on the continuity of learning of their children. In addition, it seems reasonable to assume that during lockdown, parents from upper/middle-class backgrounds encouraged their children to engage in practices that, even if not explicitly requested by teachers, would be beneficial to learning (for example, creative activities or reading). Identifying the practices that best predict the maintenance or decline of educational achievement during school closures would help identify levers for intervention.

Finally, it would be interesting to investigate teaching practices during school closures. The lockdown in the spring of 2020 was sudden and unexpected. Within a few days, teachers had to find a way to compensate for the school closure, which led to highly variable practices. Some teachers posted schoolwork on platforms, others sent it by email, some set work on a weekly basis while others set it day by day. Some teachers also set up live sessions in large or small groups, providing remote meetings for questions and support. There have also been variations in the type of feedback given to students, notably through the monitoring and correcting of work. Future studies should examine in more detail what practices schools and teachers used to compensate for the school closures and their effects on widening, maintaining or even reducing the gap, as has been done for certain specific literacy programmes 112 as well as specific instruction topics (for example, ecology and evolution 113 ).

Practical recommendations

We are aware of the debate about whether social science research on COVID-19 is suitable for making policy decisions 114 , and we draw attention to the fact that some of our recommendations (Table 1 ) are based on evidence from experiments or interventions carried out pre-COVID while others are more speculative. In any case, we emphasize that these suggestions should be viewed with caution and be tested in future research. Some of our recommendations could be implemented in the event of new school closures, others only when schools re-open. We also acknowledge that while these recommendations are intended for parents and teachers, their implementation largely depends on the adoption of structural policies. Importantly, given all the issues discussed above, we emphasize the importance of prioritizing, wherever possible, in-person learning over remote learning 115 and where this is not possible, of implementing strong policies to support distance learning, especially for disadvantaged families.

Where face-to face teaching is not possible and teachers are responsible for implementing distance learning, it will be important to make them aware of the factors that can exacerbate inequalities during lockdown and to provide them with guidance about practices that would reduce these inequalities. Thus, there is an urgent need for interventions aimed at making teachers aware of the impact of the social class of children and families on the following factors: (1) access to, familiarity with and use of digital devices; (2) familiarity with academic knowledge and skills; and (3) preparedness to work autonomously. Increasing awareness of the material, cultural and psychological barriers that working-class children and families face during lockdown should increase the quality and quantity of the support provided by teachers and thereby positively affect the achievements of working-class students.

In addition to increasing the awareness of teachers of these barriers, teachers should be encouraged to adjust the way they communicate with working-class families due to differences in self-construal compared with upper/middle-class families 77 . For example, questions about family (rather than personal) well-being would be congruent with interdependent self-construals. This should contribute to better communication and help keep a better track of the progress of students during distance learning.

It is also necessary to help teachers to engage in practices that have a chance of reducing inequalities 53 , 116 . Particularly important is that teachers and schools ensure that homework can be done by all children, for example, by setting up organizations that would help children whose parents are not in a position to monitor or assist with the homework of their children. Options include homework help groups and tutoring by teachers after class. When schools are open, the growing tendency to set homework through digital media should be resisted as far as possible given the evidence we have reviewed above. Moreover, previous research has underscored the importance of homework feedback provided by teachers, which is positively related to the amount of homework completed and predictive of academic performance 117 . Where homework is web-based, it has also been shown that feedback on web-based homework enhances the learning of students 118 . It therefore seems reasonable to predict that the social class achievement gap will increase more slowly (or even remain constant or be reversed) in schools that establish individualized monitoring of students, by means of regular calls and feedback on homework, compared with schools where the support provided to pupils is more generic.

Given that learning during lockdown has increasingly taken place in family settings, we believe that interventions involving the family are also likely to be effective 119 , 120 , 121 . Simply providing families with suitable material equipment may be insufficient. Families should be given training in the efficient use of digital technology and pedagogical support. This would increase the self-efficacy of parents and students, with positive consequences for achievement. Ideally, such training would be delivered in person to avoid problems arising from the digital divide. Where this is not possible, individualized online tutoring should be provided. For example, studies conducted during the lockdown in Botswana and Italy have shown that individual online tutoring directly targeting either parents or students in middle school has a positive impact on the achievement of students, particularly for working-class students 122 , 123 .

Interventions targeting families should also address the psychological barriers faced by working-class families and children. Some interventions have already been designed and been shown to be effective in reducing the social class achievement gap, particularly in mathematics and language 124 , 125 , 126 . For example, research showed that an intervention designed to train low-income parents in how to support the mathematical development of their pre-kindergarten children (including classes and access to a library of kits to use at home) increased the quality of support provided by the parents, with a corresponding impact on the development of mathematical knowledge of their children. Such interventions should be particularly beneficial in the context of school closure.

Beyond its impact on academic performance and inequalities, the COVID-19 crisis has shaken the economies of countries around the world, casting millions of families around the world into poverty 127 , 128 , 129 . As noted earlier, there has been a marked increase in economic inequalities, bringing with it all the psychological and social problems that such inequalities create 130 , 131 , especially for people who live in scarcity 132 . The increase in educational inequalities is just one facet of the many difficulties that working-class families will encounter in the coming years, but it is one that could seriously limit the chances of their children escaping from poverty by reducing their opportunities for upward mobility. In this context, it should be a priority to concentrate resources on the most deprived students. A large proportion of the poorest households do not own a computer and do not have personal access to the Internet, which has important consequences for distance learning. During school closures, it is therefore imperative to provide such families with adequate equipment and Internet service, as was done in some countries in spring 2020. Even if the provision of such equipment is not in itself sufficient, it is a necessary condition for ensuring pedagogical continuity during lockdown.

Finally, after prolonged periods of school closure, many students may not have acquired the skills needed to pursue their education. A possible consequence would be an increase in the number of students for whom teachers recommend class repetitions. Class repetitions are contentious. On the one hand, class repetition more frequently affects working-class children and is not efficient in terms of learning improvement 133 . On the other hand, accepting lower standards of academic achievement or even suspending the practice of repeating a class could lead to pupils pursuing their education without mastering the key abilities needed at higher grades. This could create difficulties in subsequent years and, in this sense, be counterproductive. We therefore believe that the most appropriate way to limit the damage of the pandemic would be to help children catch up rather than allowing them to continue without mastering the necessary skills. As is being done in some countries, systematic remedial courses (for example, summer learning programmes) should be organized and financially supported following periods of school closure, with priority given to pupils from working-class families. Such interventions have genuine potential in that research has shown that participation in remedial summer programmes is effective in reducing learning loss during the summer break 134 , 135 , 136 . For example, in one study 137 , 438 students from high-poverty schools were offered a multiyear summer school programme that included various pedagogical and enrichment activities (for example, science investigation and music) and were compared with a ‘no-treatment’ control group. Students who participated in the summer programme progressed more than students in the control group. A meta-analysis 138 of 41 summer learning programmes (that is, classroom- and home-based summer interventions) involving children from kindergarten to grade 8 showed that these programmes had significantly larger benefits for children from working-class families. Although such measures are costly, the cost is small compared to the price of failing to fulfil the academic potential of many students simply because they were not born into upper/middle-class families.

The unprecedented nature of the current pandemic means that we lack strong data on what the school closure period is likely to produce in terms of learning deficits and the reproduction of social inequalities. However, the research discussed in this article suggests that there are good reasons to predict that this period of school closures will accelerate the reproduction of social inequalities in educational achievement.

By making school learning less dependent on teachers and more dependent on families and digital tools and resources, school closures are likely to greatly amplify social class inequalities. At a time when many countries are experiencing second, third or fourth waves of the pandemic, resulting in fresh periods of local or general lockdowns, systematic efforts to test these predictions are urgently needed along with steps to reduce the impact of school closures on the social class achievement gap.

Bambra, C., Riordan, R., Ford, J. & Matthews, F. The COVID-19 pandemic and health inequalities. J. Epidemiol. Commun. Health 74 , 964–968 (2020).

Google Scholar

Johnson, P, Joyce, R & Platt, L. The IFS Deaton Review of Inequalities: A New Year’s Message (Institute for Fiscal Studies, 2021).

Education: from disruption to recovery. https://en.unesco.org/covid19/educationresponse (UNESCO, 2020).

Daszak, P. We are entering an era of pandemics—it will end only when we protect the rainforest. The Guardian (28 July 2020); https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2020/jul/28/pandemic-era-rainforest-deforestation-exploitation-wildlife-disease

Dobson, A. P. et al. Ecology and economics for pandemic prevention. Science 369 , 379–381 (2020).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Harris, C., Straker, L. & Pollock, C. A socioeconomic related ‘digital divide’ exists in how, not if, young people use computers. PLoS ONE 12 , e0175011 (2017).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Zhang, M. Internet use that reproduces educational inequalities: evidence from big data. Comput. Educ. 86 , 212–223 (2015).

Article Google Scholar

Bourdieu, P. & Passeron, J. C. Reproduction in Education, Society and Culture (Sage, 1990).

Stephens, N. M., Fryberg, S. A., Markus, H. R., Johnson, C. S. & Covarrubias, R. Unseen disadvantage: how American universities’ focus on independence undermines the academic performance of first-generation college students. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 102 , 1178–1197 (2012).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Andrew, A. et al. Inequalities in children’s experiences of home learning during the COVID-19 lockdown in England. Fisc. Stud. 41 , 653–683 (2020).

Bol, T. Inequality in homeschooling during the Corona crisis in the Netherlands. First results from the LISS Panel. Preprint at SocArXiv https://doi.org/10.31235/osf.io/hf32q (2020).

Cullinane, C. & Montacute, R. COVID-19 and Social Mobility. Impact Brief #1: School Shutdown (The Sutton Trust, 2020).

Bandura, A. Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol. Rev. 84 , 191–215 (1977).

Prior, D. D., Mazanov, J., Meacheam, D., Heaslip, G. & Hanson, J. Attitude, digital literacy and self efficacy: low-on effects for online learning behavior. Internet High. Educ. 29 , 91–97 (2016).

Robinson, L. et al. Digital inequalities 2.0: legacy inequalities in the information age. First Monday https://doi.org/10.5210/fm.v25i7.10842 (2020).

Cruz-Jesus, F., Vicente, M. R., Bacao, F. & Oliveira, T. The education-related digital divide: an analysis for the EU-28. Comput. Hum. Behav. 56 , 72–82 (2016).

Rice, R. E. & Haythornthwaite, C. In The Handbook of New Media (eds Lievrouw, L. A. & Livingstone S. M.), 92–113 (Sage, 2006).

Yates, S., Kirby, J. & Lockley, E. Digital media use: differences and inequalities in relation to class and age. Sociol. Res. Online 20 , 71–91 (2015).

Legleye, S. & Rolland, A. Une personne sur six n’utilise pas Internet, plus d’un usager sur trois manques de compétences numériques de base [One in six people do not use the Internet, more than one in three users lack basic digital skills] (INSEE Première, 2019).

Green, F. Schoolwork in lockdown: new evidence on the epidemic of educational poverty (LLAKES Centre, 2020); https://www.llakes.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/RP-67-Francis-Green-Research-Paper-combined-file.pdf

Vogels, E. Digital divide persists even as americans with lower incomes make gains in tech adoption (Pew Research Center, 2021); https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2021/06/22/digital-divide-persists-even-as-americans-with-lower-incomes-make-gains-in-tech-adoption/

McBurnie, C., Adam, T. & Kaye, T. Is there learning continuity during the COVID-19 pandemic? A synthesis of the emerging evidence. J. Learn. Develop. http://dspace.col.org/handle/11599/3720 (2020).

Baillet, J., Croutte, P. & Prieur, V. Baromètre du numérique 2019 [Digital barometer 2019] (Sourcing Crédoc, 2019).

Giraud, F., Bertrand, J., Court, M. & Nicaise, S. In Enfances de Classes. De l’inégalité Parmi les Enfants (ed. Lahire, B.) 933–952 (Seuil, 2019).

Ahamed, S. & Siddiqui, Z. Disparity in access to quality education and the digital divide (Ideas for India, 2020); https://www.ideasforindia.in/topics/macroeconomics/disparity-in-access-to-quality-education-and-the-digital-divide.html

Soomro, K. A., Kale, U., Curtis, R., Akcaoglu, M. & Bernstein, M. Digital divide among higher education faculty. Int. J. Educ. Tech. High. Ed. 17 , 21 (2020).

Meng, Q. & Li, M. New economy and ICT development in China. Inf. Econ. Policy 14 , 275–295 (2002).

Chinn, M. D. & Fairlie, R. W. The determinants of the global digital divide: a cross-country analysis of computer and internet penetration. Oxf. Econ. Pap. 59 , 16–44 (2006).

Lembani, R., Gunter, A., Breines, M. & Dalu, M. T. B. The same course, different access: the digital divide between urban and rural distance education students in South Africa. J. Geogr. High. Educ. 44 , 70–84 (2020).

Asadullah, N., Bhattacharjee, A., Tasnim, M. & Mumtahena, F. COVID-19, schooling, and learning (BRAC Institute of Governance & Development, 2020); https://bigd.bracu.ac.bd/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/COVID-19-Schooling-and-Learning_June-25-2020.pdf

Asanov, I., Flores, F., McKenzie, D., Mensmann, M. & Schulte, M. Remote-learning, time-use, and mental health of Ecuadorian high-school students during the COVID-19 quarantine. World Dev. 138 , 105225 (2021).

Kihui, N. Kenya: 80% of students missing virtual learning amid school closures—study. AllAfrica (18 May 2020); https://allafrica.com/stories/202005180774.html

Debenedetti, L., Hirji, S., Chabi, M. O. & Swigart, T. Prioritizing evidence-based responses in Burkina Faso to mitigate the economic effects of COVID-19: lessons from RECOVR (Innovations for Poverty Action, 2020); https://www.poverty-action.org/blog/prioritizing-evidence-based-responses-burkina-faso-mitigate-economic-effects-covid-19-lessons

Bosumtwi-Sam, C. & Kabay, S. Using data and evidence to inform school reopening in Ghana (Innovations for Poverty Action, 2020); https://www.poverty-action.org/blog/using-data-and-evidence-inform-school-reopening-ghana

Azubuike, O. B., Adegboye, O. & Quadri, H. Who gets to learn in a pandemic? Exploring the digital divide in remote learning during the COVID-19 pandemic in Nigeria. Int. J. Educ. Res. Open 2 , 100022 (2021).

Attewell, P. Comment: the first and second digital divides. Sociol. Educ. 74 , 252–259 (2001).

DiMaggio, P., Hargittai, E., Neuman, W. R. & Robinson, J. P. Social implications of the Internet. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 27 , 307–336 (2001).

Hargittai, E. Digital na(t)ives? Variation in Internet skills and uses among members of the ‘Net Generation’. Sociol. Inq. 80 , 92–113 (2010).

Iivari, N., Sharma, S. & Ventä-Olkkonen, L. Digital transformation of everyday life—how COVID-19 pandemic transformed the basic education of the young generation and why information management research should care? Int. J. Inform. Manag. 55 , 102183 (2020).

Wei, L. & Hindman, D. B. Does the digital divide matter more? Comparing the effects of new media and old media use on the education-based knowledge gap. Mass Commun. Soc. 14 , 216–235 (2011).

Octobre, S. & Berthomier, N. L’enfance des loisirs [The childhood of leisure]. Cult. Études 6 , 1–12 (2011).

Education at a glance 2015: OECD indicators (OECD, 2015); https://doi.org/10.1787/eag-2015-en

North, S., Snyder, I. & Bulfin, S. Digital tastes: social class and young people’s technology use. Inform. Commun. Soc. 11 , 895–911 (2008).

Robinson, L. & Schulz, J. Net time negotiations within the family. Inform. Commun. Soc. 16 , 542–560 (2013).

Bonfadelli, H. The Internet and knowledge gaps: a theoretical and empirical investigation. Eur. J. Commun. 17 , 65–84 (2002).

Drabowicz, T. Social theory of Internet use: corroboration or rejection among the digital natives? Correspondence analysis of adolescents in two societies. Comput. Educ. 105 , 57–67 (2017).

Nikken, P. & Jansz, J. Developing scales to measure parental mediation of young children’s Internet use. Learn. Media Technol. 39 , 250–266 (2014).

Danic, I., Fontar, B., Grimault-Leprince, A., Le Mentec, M. & David, O. Les espaces de construction des inégalités éducatives [The areas of construction of educational inequalities] (Presses Univ. de Rennes, 2019).

Goudeau, S. Comment l'école reproduit-elle les inégalités? [How does school reproduce inequalities?] (Univ. Grenoble Alpes Editions/Presses Univ. de Grenoble, 2020).

Bernstein, B. Class, Codes, and Control (Routledge, 1975).

Gaddis, S. M. The influence of habitus in the relationship between cultural capital and academic achievement. Soc. Sci. Res. 42 , 1–13 (2013).

Lamont, M. & Lareau, A. Cultural capital: allusions, gaps and glissandos in recent theoretical developments. Sociol. Theory 6 , 153–168 (1988).

Stephens, N. M., Markus, H. R. & Phillips, L. T. Social class culture cycles: how three gateway contexts shape selves and fuel inequality. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 65 , 611–634 (2014).

Lahire, B. Enfances de classe. De l’inégalité parmi les enfants [Social class childhood. Inequality among children] (Le Seuil, 2019).

Lareau, A. Unequal Childhoods: Class, Race, and Family Life (Univ. of California Press, 2003).

Bourdieu, P. La distinction. Critique sociale du jugement [Distinction: a social critique of the judgement of taste] (Éditions de Minuit, 1979).

Bradley, R. H., Corwyn, R. F., McAdoo, H. P. & Garcia Coll, C. The home environments of children in the United States part I: variations by age, ethnicity, and poverty status. Child Dev. 72 , 1844–1867 (2001).

Blevins‐Knabe, B. & Musun‐Miller, L. Number use at home by children and their parents and its relationship to early mathematical performance. Early Dev. Parent. 5 , 35–45 (1996).

LeFevre, J. A. et al. Pathays to mathematics: longitudinal predictors of performance. Child Dev. 81 , 1753–1767 (2010).

Lareau, A. Home Advantage. Social Class and Parental Intervention in Elementary Education (Falmer Press, 1989).

Guryan, J., Hurst, E. & Kearney, M. Parental education and parental time with children. J. Econ. Perspect. 22 , 23–46 (2008).

Hill, C. R. & Stafford, F. P. Allocation of time to preschool children and educational opportunity. J. Hum. Resour. 9 , 323–341 (1974).

Calarco, J. M. A Field Guide to Grad School: Uncovering the Hidden Curriculum (Princeton Univ. Press, 2020).

Daw, J. Parental income and the fruits of labor: variability in homework efficacy in secondary school. Res. Soc. Strat. Mobil. 30 , 246–264 (2012).

Rønning, M. Who benefits from homework assignments? Econ. Educ. Rev. 30 , 55–64 (2011).

Alexander, K. L., Entwisle, D. R. & Olson, L. S. Lasting consequences of the summer learning gap. Am. Sociol. Rev. 72 , 167–180 (2007).

Cooper, H., Nye, B., Charlton, K., Lindsay, J. & Greathouse, S. The effects of summer vacation on achievement test scores: a narrative and meta-analytic review. Rev. Educ. Res. 66 , 227–268 (1996).

Stewart, H., Watson, N. & Campbell, M. The cost of school holidays for children from low income families. Childhood 25 , 516–529 (2018).

Pensiero, N., Kelly, A. & Bokhove, C. Learning inequalities during the Covid-19 pandemic: how families cope with home-schooling (University of Southampton, 2020); https://doi.org/10.5258/SOTON/P0025

Stephens, N. M., Markus, H. R. & Townsend, S. S. Choice as an act of meaning: the case of social class. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 93 , 814–830 (2007).

Kraus, M. W., Piff, P. K. & Keltner, D. Social class, sense of control, and social explanation. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 97 , 992–1004 (2009).

Dittmann, A. G., Stephens, N. M. & Townsend, S. S. Achievement is not class-neutral: working together benefits pople from working-class contexts. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 119 , 517–539 (2020).

Zimmerman, B. J. Investigating self-regulation and motivation: historical background, methodological developments, and future prospects. Am. Educ. Res. J. 45 , 166–183 (2008).

Backer-Grøndahl, A., Nærde, A., Ulleberg, P. & Janson, H. Measuring effortful control using the children’s behavior questionnaire–very short form: modeling matters. J. Pers. Assess. 98 , 100–109 (2016).

Johnson, S. E., Richeson, J. A. & Finkel, E. J. Middle class and marginal? Socioeconomic status, stigma, and self-regulation at an elite university. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 100 , 838–852 (2011).

Størksen, I., Ellingsen, I. T., Wanless, S. B. & McClelland, M. M. The influence of parental socioeconomic background and gender on self-regulation among 5-year-old children in Norway. Early Educ. Dev. 26 , 663–684 (2015).

Brady, L. et al. 7 ways for teachers to truly connect with parents. Education Week (31 December 2020); https://www.edweek.org/leadership/opinion-7-ways-for-teachers-to-truly-connect-with-parents/2020/12

Montacute, R. Social mobility and Covid-19: implications of the Covid-19 crisis for educational inequality (Sutton Trust, 2020); https://dera.ioe.ac.uk/35323/2/COVID-19-and-Social-Mobility-1.pdf

Dorn, E., Hancock, B., Sarakatsannis, J. & Viruleg, E. COVID-19 and student learning in the United States: the hurt could last a lifetime (McKinsey & Company, 2020); https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/public-and-social-sector/our-insights/covid-19-and-student-learning-in-the-united-states-the-hurt-could-last-a-lifetime

Parolin, Z. & Lee, E. K. Large socio-economic, geographic and demographic disparities exist in exposure to school closures. Nat. Hum. Behav. 5 , 522–528 (2021).

Saavedra, J. A silent and unequal education crisis. And the seeds for its solution (World Bank, 2021); https://blogs.worldbank.org/education/silent-and-unequal-education-crisis-and-seeds-its-solution

Murray, B., Domina, T., Renzulli, L. & Boylan, R. Civil society goes to school: parent–teacher associations and the equality of educational opportunity. Russell Sage Found. J. Soc. Sci. 5 , 41–63 (2019).

Calarco, J. M. Avoiding us versus them: how schools’ dependence on privileged ‘helicopter’ parents influences enforcement of rules. Am. Sociol. Rev. 85 , 223–246 (2020).

Rist, R. Student social class and teacher expectations: the self-fulfilling prophecy in ghetto education. Harv. Educ. Rev. 40 , 411–451 (1970).

Tobisch, A. & Dresel, M. Negatively or positively biased? Dependencies of teachers’ judgments and expectations based on students’ ethnic and social backgrounds. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 20 , 731–752 (2017).

Brantlinger, E. Dividing Classes: How the Middle-class Negotiates and Rationalizes School Advantage (Routledge, 2003).

Calarco, J. M. ‘I need help!’ Social class and children’s help-seeking in elementary school. Am. Sociol. Rev. 76 , 862–882 (2011).

Calarco, J. M. The inconsistent curriculum: cultural tool kits and student interpretations of ambiguous expectations. Soc. Psychol. Quart. 77 , 185–209 (2014).

Goudeau, S. & Cimpian, A. How do young children explain differences in the classroom? Implications for achievement, motivation, and educational equity. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 16 , 533–552 (2021).

Croizet, J. C., Goudeau, S., Marot, M. & Millet, M. How do educational contexts contribute to the social class achievement gap: documenting symbolic violence from a social psychological point of view. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 18 , 105–110 (2017).

Goudeau, S. & Croizet, J.-C. Hidden advantages and disadvantages of social class: how classroom settings reproduce social inequality by staging unfair comparison. Psychol. Sci. 28 , 162–170 (2017).

Kudrna, L., Furnham, A. & Swami, V. The influence of social class salience on self-assessed intelligence. Soc. Behav. Personal. 38 , 859–864 (2010).

Wiederkehr, V., Darnon, C., Chazal, S., Guimond, S. & Martinot, D. From social class to self-efficacy: internalization of low social status pupils’ school performance. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 18 , 769–784 (2015).

Jury, M., Smeding, A., Court, M. & Darnon, C. When first-generation students succeed at university: on the link between social class, academic performance, and performance-avoidance goals. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 41 , 25–36 (2015).

Jury, M., Quiamzade, A., Darnon, C. & Mugny, G. Higher and lower status individuals’ performance goals: the role of hierarchy stability. Motiv. Sci. 5 , 52–65 (2019).

Autin, F. & Croizet, J.-C. Improving working memory efficiency by reframing metacognitive interpretation of task difficulty. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 141 , 610–618 (2012).

Schmader, T., Johns, M. & Forbes, C. An integrated process model of stereotype threat effects on performance. Psychol. Rev. 115 , 336–356 (2008).

Usher, E. L. & Pajares, F. Self-efficacy for self-regulated learning: a validation study. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 68 , 443–463 (2008).

Bruno, A., Jury, M., Toczek-Capelle, M.-C. & Darnon, C. Are performance-avoidance goals always deleterious for academic achievement in college? The moderating role of social class. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 22 , 539–555 (2019).

Holloway, S. D. et al. Parenting self-efficacy and parental involvement: mediators or moderators between socioeconomic status and children’s academic competence in Japan and Korea? Res. Hum. Dev. 13 , 258–272 (2016).

Tazouti, Y. & Jarlégan, A. The mediating effects of parental self-efficacy and parental involvement on the link between family socioeconomic status and children’s academic achievement. J. Fam. Stud. 25 , 250–266 (2019).

Andreu, S. et al. Évaluations 2020, repères CP, CE1: premiers résultats [2020 assessments, first and second grades benchmarks: first results] (Ministère de l’Éducation nationale, de la Jeunesse et des Sports, 2020); https://www.education.gouv.fr/evaluations-2020-reperes-cp-ce1-premiers-resultats-307122

Engzell, P., Frey, A. & Verhagen, M. D. Learning loss due to school closures during the COVID-19 pandemic. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 118 , e2022376118 (2021).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Maldonado, J. E. & De Witte, K. The effect of school closures on standardized student test outcomes (KU Leuven—Faculty of Economics and Business, 2020); https://limo.libis.be/primo-explore/fulldisplay?docid=LIRIAS3189074&context=L&vid=Lirias&search_scope=Lirias&tab=default_tab&lang=en_US

Domingue, B., Hough, H. J., Lang, D. & Yeatman, J. Changing patterns of growth in oral reading fluency during the COVID-19 pandemic (PACE, 2021); https://edpolicyinca.org/publications/changing-patterns-growth-oral-reading-fluency-during-covid-19-pandemic

Dorn, E., Hancock, B., Sarakatsannis, J. & Viruleg, E. COVID-19 and learning loss—disparities grow and students need help (McKinsey & Company, 2020); https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/public-and-social-sector/our-insights/covid-19-and-learning-loss-disparities-grow-and-students-need-help

Angrist, N. et al. Building back better to avert a learning catastrophe: estimating learning loss from COVID-19 school shutdowns in Africa and facilitating short-term and long-term learning recovery. Int. J. Educ. Dev. 84 , 102397 (2021).

Reddy, V., Soudien, C. & Winnaar, L. Disrupted learning during COVID-19: the impact of school closures on education outcomes in South Africa (The Conversation, 2020); https://theconversation.com/impact-of-school-closures-on-education-outcomes-in-south-africa-136889

Entwisle, D. R. & Alexander, K. L. Summer setback: race, poverty, school composition, and mathematics achievement in the first two years of school. Am. Sociol. Rev. 57 , 72–84 (1992).

Kieffer, M. J. Catching up or falling behind? Initial English proficiency, concentrated poverty, and the reading growth of language minority learners in the United States. J. Educ. Psychol. 100 , 851–868 (2008).

Calarco, J. M., Horn, I. & Chen, G. A. ‘You need to be more responsible’: how math homework operates as a status-reinforcing process in school. Preprint at SocArXiv https://doi.org/10.31235/osf.io/xf96q (2020).

Kaiper-Marquez, A. et al. On the fly: adapting quickly to emergency remote instruction in a family literacy program. Int. Rev. Educ. 66 , 1–23 (2020).

Barton, D. C. Impacts of the COVID‐19 pandemic on field instruction and remote teaching alternatives: results from a survey of instructors. Ecol. Evol. 10 , 12499–12507 (2020).

Article PubMed Central Google Scholar

IJzerman, H. et al. Use caution when applying behavioural science to policy. Nat. Hum. Behav. 4 , 1092–1094 (2020).

Taylor, J. & Mallery, J. In person and online learning go together (Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research, 2020); https://siepr.stanford.edu/research/publications/person-and-online-learning-go-together

Dietrichson, J., Bøg, M., Filges, T. & Klint Jørgensen, A. M. Academic interventions for elementary and middle school students with low socioeconomic status: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Rev. Educ. Res. 87 , 243–282 (2017).

Núñez, J. C. et al. Teachers’ feedback on homework, homework-related behaviors, and academic achievement. J. Educ. Res. 108 , 204–216 (2015).

Singh, R. et al. In Artificial Intelligence in Education (eds Biswas, G.et al.) 328–336 (Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2011).

Harackiewicz, J. M., Rozek, C. S., Hulleman, C. S. & Hyde, J. S. Helping parents to motivate adolescents in mathematics and science: an experimental test of a utility-value intervention. Psychol. Sci. 23 , 899–906 (2012).

Jeynes, W. A meta-analysis of the efficacy of different types of parental involvement programs for urban students. Urban Educ. 47 , 706–742 (2012).

Mol, S. E., Bus, A. G., De Jong, M. T. & Smeets, D. J. Added value of dialogic parent–child book readings: a meta-analysis. Early Educ. Dev. 19 , 7–26 (2008).

Angrist, N., Bergman, P. & Matsheng, M. School’s out: experimental evidence on limiting learning loss using “low-tech” in a pandemic (National Bureau of Economic Research, 2021); https://www.nber.org/papers/w28205

Carlana, M. & La Ferrara, E. Apart but connected: online tutoring and student outcomes during the COVID-19 pandemic (Institute of Labor Economics, 2021); http://hdl.handle.net/10419/232846

Pagan, S. & Sénéchal, M. Involving parents in a summer book reading program to promote reading comprehension, fluency, and vocabulary in grade 3 and grade 5 children. Can. J. Educ. 37 , 1–31 (2014).

Sénéchal, M. & LeFevre, J. A. Parental involvement in the development of children’s reading skill: a five‐year longitudinal study. Child Dev. 73 , 445–460 (2002).

Starkey, P. & Klein, A. Fostering parental support for children’s mathematical development: an intervention with Head Start families. Early Educ. Dev. 11 , 659–680 (2000).

Buheji, M. et al. The extent of Covid-19 pandemic socio-economic impact on global poverty: a global integrative multidisciplinary review. Am. J. Econ. 10 , 213–224 (2020).

The world economy on a tightrope (OECD, 2020); http://www.oecd.org/economic-outlook/june-2020/

Martin, A., Markhvida, M., Hallegatte, S. & Walsh, B. Socio-economic impacts of COVID-19 on household consumption and poverty. Econ. Disasters Clim. Change 4 , 453–479 (2020).

Jetten, J., Mols, F. & Selvanathan, H. P. How economic inequality fuels the rise and persistence of the Yellow Vest movement. Int. Rev. Soc. Psychol. 33 , 2 (2020).

Wilkinson, R. G. & Pickett, K. E. Income inequality and social dysfunction. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 35 , 493–511 (2009).

Sommet, N., Morselli, D. & Spini, D. Income inequality affects the psychological health of only the people facing scarcity. Psychol. Sci. 29 , 1911–1921 (2018).

Hattie, J. Visible Learning: A Synthesis of over 800 Meta-analyses Relating to Achievement (Routledge, 2008).

Cooper, H., Charlton, K., Valentine, J. C., Muhlenbruck, L. & Borman, G. D. Making the most of summer school: a meta-analytic and narrative review. Monogr. Soc. Res. Child 65 , 1–127 (2000).

Heyns, B. Schooling and cognitive development: is there a season for learning? Child Dev. 58 , 1151–1160 (1987).

McCombs, J. S., Augustine, C. H. & Schwartz, H. L. Making Summer Count: How Summer Programs can Boost Children’s Learning (Rand Education, 2011).

Borman, G. D. & Dowling, N. M. Longitudinal achievement effects of multiyear summer school: evidence from the teach Baltimore randomized field trial. Educ. Eval. Policy 28 , 25–48 (2006).

Kim, J. S. & Quinn, D. M. The effects of summer reading on low-income children’s literacy achievement from kindergarten to grade 8: a meta-analysis of classroom and home interventions. Rev. Educ. Res. 83 , 386–431 (2013).

Download references

Acknowledgements

We thank G. Reis for editing the figure. The writing of this manuscript was supported by grant ANR-19-CE28-0007–PRESCHOOL from the French National Research Agency (S.G.).

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Université de Poitiers, CNRS, CeRCA, Centre de Recherches sur la Cognition et l’Apprentissage, Poitiers, France

Sébastien Goudeau & Camille Sanrey

Université Clermont Auvergne, CNRS, LAPSCO, Laboratoire de Psychologie Sociale et Cognitive, Clermont-Ferrand, France

Arnaud Stanczak & Céline Darnon

School of Psychology, Cardiff University, Cardiff, UK

Antony Manstead

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Sébastien Goudeau .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Peer review information Nature Human Behaviour thanks Daniele Checchi and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Goudeau, S., Sanrey, C., Stanczak, A. et al. Why lockdown and distance learning during the COVID-19 pandemic are likely to increase the social class achievement gap. Nat Hum Behav 5 , 1273–1281 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-021-01212-7

Download citation

Received : 15 March 2021

Accepted : 06 September 2021

Published : 27 September 2021

Issue Date : October 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-021-01212-7

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

This article is cited by

Socioeconomic inequalities in psychosocial well-being among adolescents under the covid-19 pandemic: a cross-regional comparative analysis in hong kong, mainland china, and the netherlands.

- Gary Ka-Ki Chung

- Xiaoting Liu

- Roger Yat-Nork Chung

Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology (2024)

Digital gender gaps in Students’ knowledge, attitudes and skills: an integrative data analysis across 32 Countries

- Diego G. Campos

- Ronny Scherer

Education and Information Technologies (2024)

Microlearning as a Concept to Optimize Integrated Services for Racially/Ethnically Diverse Families of Autistic Children

- Zhiwen Xiao

- Sandra Vanegas

Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities (2024)

The ethicality of the COVID-19 response in children and adolescents

- Fiona McNicholas

Irish Journal of Medical Science (1971 -) (2024)

Health-related quality of life of young refugees in Germany during the COVID-19 pandemic: comparisons to non-refugees and pre-pandemic times

- Johanna Braig

- Pia Schmees

- Heike Eschenbeck

Current Psychology (2024)

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

The COVID-19 pandemic has changed education forever. This is how

With schools shut across the world, millions of children have had to adapt to new types of learning. Image: REUTERS/Gonzalo Fuentes

.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo{-webkit-transition:all 0.15s ease-out;transition:all 0.15s ease-out;cursor:pointer;-webkit-text-decoration:none;text-decoration:none;outline:none;color:inherit;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:hover,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-hover]{-webkit-text-decoration:underline;text-decoration:underline;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:focus,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-focus]{box-shadow:0 0 0 3px rgba(168,203,251,0.5);} Cathy Li

Farah lalani.

.chakra .wef-9dduvl{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-9dduvl{font-size:1.125rem;}} Explore and monitor how .chakra .wef-15eoq1r{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;color:#F7DB5E;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-15eoq1r{font-size:1.125rem;}} Education, Gender and Work is affecting economies, industries and global issues

.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;color:#2846F8;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{font-size:1.125rem;}} Get involved with our crowdsourced digital platform to deliver impact at scale

Stay up to date:, education, gender and work.

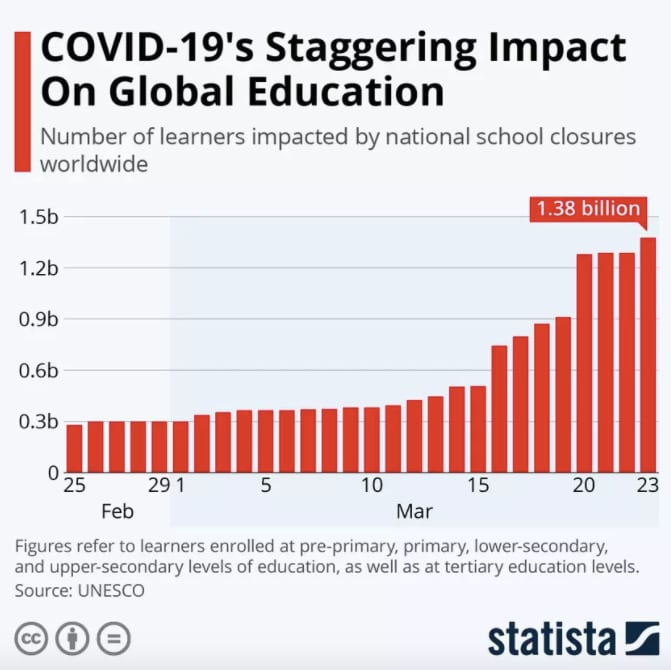

- The COVID-19 has resulted in schools shut all across the world. Globally, over 1.2 billion children are out of the classroom.

- As a result, education has changed dramatically, with the distinctive rise of e-learning, whereby teaching is undertaken remotely and on digital platforms.

- Research suggests that online learning has been shown to increase retention of information, and take less time, meaning the changes coronavirus have caused might be here to stay.

While countries are at different points in their COVID-19 infection rates, worldwide there are currently more than 1.2 billion children in 186 countries affected by school closures due to the pandemic. In Denmark, children up to the age of 11 are returning to nurseries and schools after initially closing on 12 March , but in South Korea students are responding to roll calls from their teachers online .

With this sudden shift away from the classroom in many parts of the globe, some are wondering whether the adoption of online learning will continue to persist post-pandemic, and how such a shift would impact the worldwide education market.

Even before COVID-19, there was already high growth and adoption in education technology, with global edtech investments reaching US$18.66 billion in 2019 and the overall market for online education projected to reach $350 Billion by 2025 . Whether it is language apps , virtual tutoring , video conferencing tools, or online learning software , there has been a significant surge in usage since COVID-19.

How is the education sector responding to COVID-19?

In response to significant demand, many online learning platforms are offering free access to their services, including platforms like BYJU’S , a Bangalore-based educational technology and online tutoring firm founded in 2011, which is now the world’s most highly valued edtech company . Since announcing free live classes on its Think and Learn app, BYJU’s has seen a 200% increase in the number of new students using its product, according to Mrinal Mohit, the company's Chief Operating Officer.

Tencent classroom, meanwhile, has been used extensively since mid-February after the Chinese government instructed a quarter of a billion full-time students to resume their studies through online platforms. This resulted in the largest “online movement” in the history of education with approximately 730,000 , or 81% of K-12 students, attending classes via the Tencent K-12 Online School in Wuhan.

Have you read?

The future of jobs report 2023, how to follow the growth summit 2023.

Other companies are bolstering capabilities to provide a one-stop shop for teachers and students. For example, Lark, a Singapore-based collaboration suite initially developed by ByteDance as an internal tool to meet its own exponential growth, began offering teachers and students unlimited video conferencing time, auto-translation capabilities, real-time co-editing of project work, and smart calendar scheduling, amongst other features. To do so quickly and in a time of crisis, Lark ramped up its global server infrastructure and engineering capabilities to ensure reliable connectivity.

Alibaba’s distance learning solution, DingTalk, had to prepare for a similar influx: “To support large-scale remote work, the platform tapped Alibaba Cloud to deploy more than 100,000 new cloud servers in just two hours last month – setting a new record for rapid capacity expansion,” according to DingTalk CEO, Chen Hang.