Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 28 February 2018

Quantitative account of social interactions in a mental health care ecosystem: cooperation, trust and collective action

- Anna Cigarini 1 , 2 ,

- Julián Vicens ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-0643-0469 1 , 2 , 3 ,

- Jordi Duch ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-2639-6333 3 , 4 ,

- Angel Sánchez 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 &

- Josep Perelló ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-8533-6539 1 , 2

Scientific Reports volume 8 , Article number: 3794 ( 2018 ) Cite this article

9469 Accesses

10 Citations

51 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Applied mathematics

- Human behaviour

- Psychology and behaviour

- Public health

An Author Correction to this article was published on 26 September 2018

This article has been updated

Mental disorders have an enormous impact in our society, both in personal terms and in the economic costs associated with their treatment. In order to scale up services and bring down costs, administrations are starting to promote social interactions as key to care provision. We analyze quantitatively the importance of communities for effective mental health care, considering all community members involved. By means of citizen science practices, we have designed a suite of games that allow to probe into different behavioral traits of the role groups of the ecosystem. The evidence reinforces the idea of community social capital, with caregivers and professionals playing a leading role. Yet, the cost of collective action is mainly supported by individuals with a mental condition - which unveils their vulnerability. The results are in general agreement with previous findings but, since we broaden the perspective of previous studies, we are also able to find marked differences in the social behavior of certain groups of mental disorders. We finally point to the conditions under which cooperation among members of the ecosystem is better sustained, suggesting how virtuous cycles of inclusion and participation can be promoted in a ‘care in the community’ framework.

Similar content being viewed by others

Reformulating computational social science with citizen social science: the case of a community-based mental health care research

Investigation of turning points in the effectiveness of Covid-19 social distancing

An agent-based model of social care provision during the early stages of Covid-19

Introduction.

Approximately one fifth of the world population will suffer some mental disorder (MD) at some point in their lives, such as anxiety or depression 1 . The direct economic costs of MD, including care and indirect effects, is estimated to reach $6 trillion in 2030, which is more than cancer, diabetes, and respiratory diseases combined 2 . As part of a global effort to scale up services and bring down costs, reliance is increasingly made upon informal social networks 3 . A holistic approach to mental health promotion and care provision is then necessary, and emphasis is placed on the idea of individuals-in-community: individuals with MD are defined not just alone but in relationship to others 4 . Such a paradigm shift implies superseding the traditional physician-patient dyad to include caregivers, relatives, social workers, and the community as a whole, recognizing their crucial role in the recovery process.

A key aspect in the definition and aetiology of MD has to do with social behavior 5 : behavioral symptoms, or consequences at the behavioral level, characterize most MD. For instance, autism, social phobia, or personality disorders are determined by the presence of impairments in social interaction. Other disorders result in significant difficulties in the social domain, such as depression or psychotic disorders. Further, conditions that are intrinsically behavioral (as for eating disorders or substance abuse) seem to be exacerbated by the influence of social peers. A large body of research has therefore looked at the neural basis of social decision-making among individuals with MD to identify objective biomarkers that may prove useful for its diagnosis, therapy evaluation, and understanding 6 , 7 , 8 . However, such a methodology does not well fit into the individuals-in-community paradigm. We argue that an agent-based approach which draws upon experimental game theory might prove insightful and ecologically valid for the study of behavior in a given social environment.

Within the mental health literature, the use of game theory as a way to understand the multi-faceted dimensions of behavior has received already quite some attention 9 , 10 . Most research addressed the issue of behavioral differences between individuals with MD and healthy populations 6 , 7 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 . These works, that point to cognitive and affective processing impairments 6 , 16 , 17 , further support the idea that MDs are associated with significant and pervasive difficulties in social cognition and altered decision-making at various levels. Yet, despite these studies are of very much interest, they are primarly concerned with dyadic interactions among people with specific MDs. That is, they lack insights into the complexity of individual behaviors of MD within a specific social context.

Here we adopt a novel community perspective. Our objective is twofold: First, we aim to develop a thorough taxonomy of the behavioral traits of role groups within the collective. We thus account for both the heterogeneity of actors, and for multiple types of social interactions. We strongly believe that to predict and understand behavior is necessary to consider the relationship context in which individuals are embedded. Therefore diversity of roles, motivations or capabilities, must be taken into account. Also, real life social interactions occur in different forms; sometimes people must work together, some others they have to coordinate or anti-coordinate their behaviors, yet in other situations they find themselves in more or less disadvantaged positions. It is therefore of crucial importance to encompass a comprehensive range of strategic situations if we are to appreciate behavior. That is, traits such as trust, altruism, or reciprocity, along with the person’s own expectations, all play a role in the process of decision making in social contexts. This calls for an experimental approach in which participants face several strategic settings. Our second objective is to provide quantitative accounts of social capital within the mental health community, bringing the notion of social capital into the forefront of mental health care. Far from being universally defined, its core contention is that social networks are a valuable asset, providing a basis for social cohesion and cooperation towards a common goal 18 (which is, in our case, mental care provision). It thus encompasses those norms and forces that shape social interactions, serving as the glue that holds society together 19 .

For these purposes, we have designed an experimental setup that probes into the complexity of the interdependencies at play within the mental health ecosystem. Accordingly, our experiments take place in a socialized, lab-in-the-field setting 20 , in order to be as close as possible to the dynamic and unique nature of real-life social interactions. The design of our socialized setup is based on a participatory process and citizen science practices 20 which counted on the collaboration of all stakeholders of the mental health ecosystem. By combining all these ingredients, we have developed a framework that, as will be shown below, allows to capture some difficult-to-observe aspects of behavior and social capital within mental health ecosystems as a way to understand how communities contribute to care and resocialization.

A full description of the games we implemented can be found in the Methods section below, but for clarity we briefly describe here the games we used. We had participants play two dyadic games, namely the Trust game, in which they had to lend money to another player who then obtains a return, and has the option to send some money back to the lender; players played in both roles. They also played the well known Prisoner’s Dilemma, in which they had to choose to cooperate or to try to benefit from the other’s cooperation. Finally, they played a collective risk dilemma, in which the whole group had to reach a common goal to avert a catastrophe that most likely would wipe out their money. Participants belonging to the mental health ecosystem played with each other in group of six players. However, they could by no means guess with whom they were actually playing.

We begin the presentation of our results from the dyadic games of our suite of strategic interactions. Aggregate behavioral measures point to systematic deviations from self-interested predictions which are in line with previous literature on experimental game play 21 . In the Prisoner’s Dilemma (PD), the average cooperation rate across all individuals is c = 0.61 ± 0.03 (standard error of the mean), which is notoriously well above the Nash equilibrium prediction of c = 0. Participants behavior in the PD is also significantly associated with their estimates about the likely cooperation of the partner ( \({\chi }^{2}=32.48\) , p = 1.2 · 10 8 ), with 44% of all participants expecting the partner to cooperate, and thus cooperating themselves. This points to the crucial role of positive expectations on cooperative behavior 22 . Further, participants trust and reciprocate positive amounts in the Trust Game (5.79 ± 0.15 monetary units (MU) and 41.3 ± 1.37% of the amount available to return, respectively), again departing largely from Nash equilibrium conjectures of 0 MU transferred. The results also suggest that in considering the mental health community in its whole, thus accounting for the diversity of actors and roles, the global picture does not substantially differ from society at large.

Sectorial and dyadic behavior

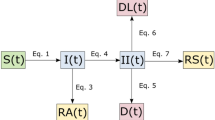

As we stated above, our main interest is to delve into the behavior of the different actors who make up the mental health ecosystem Fig. 1 summarizes the results for the five groups of individuals concerned. The heatmap yields several insights that are worth commenting upon.

Heatmap of behavioural traits’ average and deviation of the mean across games. Collectivity refers to the ratio of contribution in the Collective-Risk Social Dilemma. Cooperation and Optimism refers to the ratio of cooperation and expected cooperation, respectively, in Prisoner’s Dilemma. Trust and Reciprocity refers to the ratio of capital trusted and reciprocated in Trust Game. The left part shows the ratio of individuals without mental conditions: caregivers (professionals and relatives with caregiving tasks) and non-caregivers (relatives without caregiving tasks, friends and others). The right part shows the actions of individuals with mental conditions. Therefore, the number in each cell indicates the ratio of social preferences per subjects in each social dilemma and the color scale shows the deviation of the mean measured in SD units.

In one-shot dyadic interactions some marked differences in the frequency of cooperative behaviors (PD) arise within the collective formed by affected with MD, caregivers, non-caregivers (Kruskal-Wallis rank sum test, \(H=6.04,df=2,p=0.0488\) ). Further pairwise comparisons (see Supplementary Table S1 ) show that participants with anxiety and caregivers are more likely to opt for the cooperative strategy compared to participants with bipolar disorder, psychosis or other members of the collective. Participants with anxiety are also the ones with the most positive expectations about the partner’s behavior compared to all but caregivers (see Supplementary Table S2 ). Also, relatives, friends and other members with no MD defect more than caregivers (Mann-Whitney U test, \(U=1352,p=0.02839\) ), being relatives remarkably less cooperative than the rest of the collective c = 0.33 ± 0.16. This suggests that cooperation among members of the mental health ecosystem is contextually based, depending on the role that actors play in the recovery process. It also varies across diagnostics, revealing a marked cooperativeness and optimism of individuals with anxiety disorders.

On the other hand, in sequential dyadic interactions (TG) all participants trust more than half of their endowment, being the distribution of initial transfers similar across groups. No variation is indeed found in trust levels between participants with MD, caregivers and non caregivers (Kruskal-Wallis rank sum test, \(H=2.75,df=2,p=0.25\) ). Yet, at the time of reciprocating the partner’s behavior, participants with anxiety and depression return the least (37.5 ± 3.3%). The difference is significant if compared to return transfers of participants with psychosis or other diagnostics (see Supplementary Table S4 ).

Group interaction

Our experimental setup has proven extremely informative in its most novel section, namely the analysis of group interactions framed within the Collective Risk Dilemma (CRD), with no prior result within the mental health literature. In global terms, the average amount contributed to the public good (22.6 MUs) is much more than the fair contribution of 20 MUs, where by fair we understand sharing equally the total amount needed for the threshold (120 MUs) among all six participants. Here it is important to keep in mind that participants were told that all money contributed would go to reforestation projects, so it is not irrational to keep contributing beyond the threshold as many of our subjects did. The key result in the CRD is that large, significant differences (t-test, \(t=2.85,df=242,p=0.0047\) ) are found between participants with and without mental disorders. The former contribute with 22.95 ± 0.63 MUs compared to 20.34 ± 0.68 MUs from the latter, and therefore it appears that when repeated interaction and sustained teamwork (CRD) are required, people with MD contribute much more to the common goal (See Supplementary Section 1.6.2).

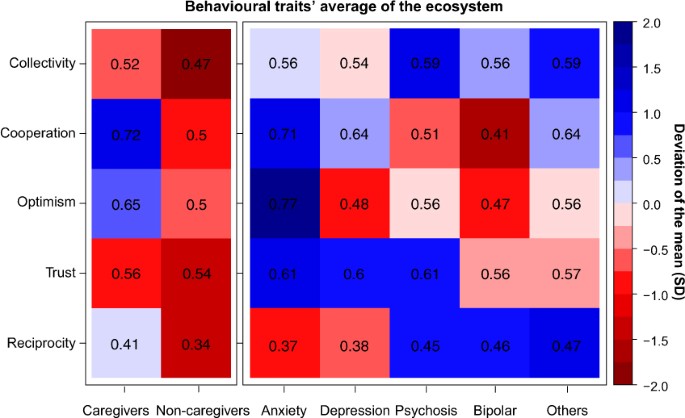

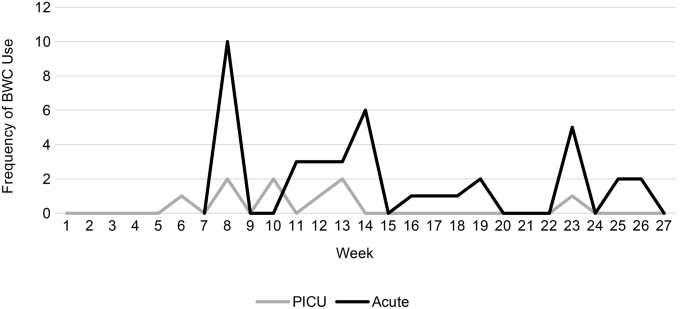

Contribution dynamics vary according to group composition in terms of number of participants with mental disorder conditions and other actors involved in the recovery process. All groups successfully reach the target collecting on average 135.64 ± 1.75 MUs (see Supplementary Section 1.6.1). Similarly to other public good experiments, contributions decrease over time 23 . While in the first round participants contribute around 56.3% of the allowed contribution per round (2.2 ± 0.07 MUs, where the social optimum is 2 MU), contributions drop when the endgame effect sets in. A Spearman’s rank-order correlation of contributions over rounds corroborates this negative time trend ( \(\rho =-0.757,p < 0.05\) ). Both patients and actors involved in the recovery process reduce their contributions by the end of the game. However, in almost all rounds, participants with a mental condition contribute more than caregivers and non caregivers, for whom motivations to contribute decline steadily (see Fig. 2 ).

(a) Individual contribution over rounds. Evolution of contributions (mean and standard error of the mean) during the game between participants with mental disorder conditions, caregivers and non-caregivers. We can see that all groups behave similarly and in an identical way to a previous experiment run outside the mental health ecosystem 40 . (b) Average individual contribution per round. Average contribution and standard error of the mean in the mental health ecosystem. There are significant differences between participant with MD and the rest of actors, caregivers (t-test, \(t=2.107,df=155,p < 0.0294\) ) and non-caregivers (t-test, \(t=2.499,df=48,p=0.01588\) ). Distribution of choices by participants with MD ( c ), caregivers (d) and non-caregivers ( e ). The most of participants with MD (43.6%) selected the maximum contribution (4), while the caregivers (46.5%) and non-caregivers (48.9%) mostly selected the fair contribution (2).

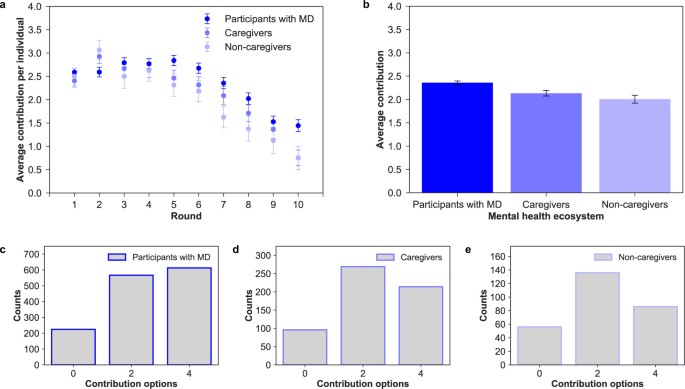

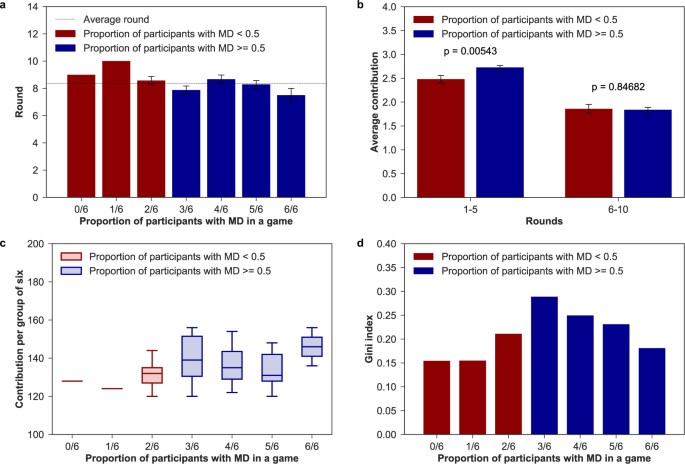

In terms of the group composition, groups where individuals with MD conditions constitute half or the majority of the group (n = 36) do much better in sustaining cooperation compared to groups where firsthand affected are the minority (n = 9). It is here worth to mention that participants may see who the rest of the members are but ignore who is exactly making the choice in the game (see Methods for further details). As Fig. 3b shows, while average individual contributions are similar in the last periods (rounds 6–10 t-test, t = 0.19, p = 0.85), groups with half or more individuals with MD contribute significantly more at the beginning of the game (rounds 1–5 t-test, t = 2.79, p = 0.0054). Hence, the presence of three or more individuals with a mental condition in the group has a positive and stabilizing effect on average individual contributions. Likewise, in games with a low proportion of participants affected with MD the group achieved the goal, on average, later than in games with more than 50% of participants affected with MD (see Fig. 3a ).

(a) Average round of achievement. Round (mean and standard error of the mean) in which the group of six achieved the target. (b) Aggregated contributions per group composition. Contributions (mean and standard error of the mean) in the first and last five-rounds per number of individuals with MD in a group. There are significant differences (t-test p < 0.01) in contributions in the first part of the game. (c ) Contributions per group of six. Total group contributions by number of individuals with mental conditions in the group. (d ) Gini index of final payoff within groups. Level of inequality in final payoff based on the number of individuals with MD in each group.

If we then break down the analysis by group type, we find that group members contribute and benefit differently from cooperation (see Fig. 3c ). Indeed, final payoffs within groups are far from being equally distributed (see Fig. 3d ), with the highest inequality found in the group where the number of patients equals the number of actors involved in the recovery process (Gini coefficient = 0.289). We thus see clearly that the cost of collective action is mainly supported by individuals with a mental disorder. Given that they contribute the most within all groups, lower investments are needed for other members of the collective to reach the common target. Yet, in 4/6 and 5/6 groups caregivers reduce average individual contributions while non-caregivers pay more than their fair share. In 1/6 and 2/6 groups, on the other hand, caregivers are the ones who compensate the unfair contributions of other members. These last groups are the ones that ensure the lowest inequality in final payoffs. Therefore, while our results are unambiguous about the larger readiness for collective action among people with MD, we cannot claim nothing about the rest of the collective.

Let us now turn to the discussion of the above results and their implications (see Table 1 for a summary of the key findings). As a first general remark, through our lab-in-the field experiment we found that an ecosystem approach to mental health care brings with it a quite complex scenario with several interesting insights. To begin with, participants with anxiety symptoms display a markedly different behavior compared to other diagnostics: they are more likely to opt for the cooperative strategy compared to individuals with bipolar disorder or depression, and return significantly less than participants with psychosis or other disorders. Since the current study is the first to investigate social decision-making within a heterogeneous population of individuals diagnosed with MD, a comparison with previous research is only possible referring to studies focusing on specific clinical and quite homogeneous populations. Several experiments have demonstrated deficits in cooperative behavior among individuals with anxiety or depression when playing iterated versions of the PD 11 , 17 , 24 , 25 , but results about altruism (Ultimatum Game) and trust are inconsistent between studies 6 , 7 , 11 , 12 , 17 , 26 . Individuals with major depressive disorders (which include anxiety and depressive symptoms) have also been found to systematically differ when their emotional responses to fairness are compared 6 , 17 , showing higher levels of negative feelings when faced with unfair treatments. One of the hypothesis advanced to explain the systematic behavioral differences of individuals with anxiety relates to a potentiated sensitivity to negative stimuli as well as a tendency to treat neutral or ambiguous stimuli as negative or as less positive 6 , 12 , 17 , 27 . This hypothesis might find support in our results as for the low returns in the Trust Game, despite displaying relatively high trust in the partner’s behavior and very high expectations. Indeed, participants with depressive or anxiety symptoms in our experiment significantly over-punish trustee transfers, but the low returns are independent of the amount received. This seems to imply that participants with mood disorders respond negatively to their partner behavior, as if they interpret their partner’s choice in a negative sense. Alternatively, fairness considerations may be playing a role: low returns of participants with mood disorders might therefore be due to different fairness perceptions 6 , 12 , 17 , which result in a bias towards negative reactions rather than positive rewarding.

Deficits in economic game play have also been documented for individuals with bipolar disorder. Studies report low and decreasing trust levels over sequential interactions, skeptical beliefs about the partner’s behavior and a tendency to break cooperative interactions 28 , 29 . Again, this is partly supported by our results. Negative expectations of participants with bipolar disorder indeed agree with a low frequency of cooperative choices, little amounts of money sent to trustees, and low contributions to collective action. In line with King-Casas et al . results 29 , while individuals with depression trust in the cooperativeness of other people, those with bipolar personality disorders do not. Cognitive dysfunctions (insula response) might possibly reflect an atypical social norm in this group 29 . Consequently, defection by partners might not violate the social expectations of individuals with BPD. In contrast, in our experiment, participants with bipolar disorder return the most within the group of individuals with a mental disorder. That is, they report a strong willingness to positively respond to a norm of trust as to signal their partner trustworthiness. Therefore, conditioned on the previous action of the partner, it seems that individuals with BPD are willing to show cooperative behavior. Considering now individuals with high levels of psychopathy, they have been found to make less fair offers, accept less fair offers, and show very high levels of defection 15 , 16 , 30 . Major explanations for such behavior point to deficits in emotion regulations (amygdala dysfunctions), which would lead to lack of anxiety, empathy, and guilt, coupled with exaggerated levels of anger and frustration 30 and to the absence of prepotent biases toward minimizing the distress of others 16 . In this case, our experiments do not confirm those previous results: Indeed, participants with psychosis are the ones who trust, contribute the most to the public good, and are willing to take costly actions to reciprocate their partner’s behavior. It could be possible that, as psychopathic disorders are in fact a large group of different ones, behavioral differences among subgroups may lead to this discrepancy. In connection with these results, it is interesting to note that recent results on a large population of patients with paranoia suggest that distrust is not the best explanation for reduced cooperation and alternative explanations incorporating self-interest might be more relevant 31 , 32 . This calls for further research into this particular family of MD to clarify whether or not the behavioral characterization applies to all or to a subclass of them.

However, pointing to deficits in social cognition can only account for a partial explanation of individual behavior, and does not contribute to community care narratives. The fact that nothing in this direction has been reported before also reinforces the need to adopt a more holistic view on the interdependencies at play within the mental health collective. Indeed, if statistically relevant differences in cooperative behavior are found across diagnostics, they also depend on the role that actors play in the recovery process. That is, caregivers display exceedingly large degrees of cooperativeness and optimism in one-shot interactions. Caregivers can be thus considered the strong ties of the mental health ecosystem, of particular value when one seeks emotional support. With the de-institutionalization of health systems, caregivers have indeed become key players in care provision. Taking into account their behavior and expectations is therefore of particular interest to extend the support tailored to their needs. These actions should improve the effectiveness of their role by guiding them 33 . Yet, relatives who do not strictly contribute to caregiving practices turn out to be the weak links. It is thus likely that interventions designed to increase their participation in the community might help improve the recovery process.

Also, members of the mental health ecosystem do not equally contribute and benefit from collective action. Rather, systematic behavioral differences arise as the number of social interactions increase, i.e., when teamwork is required for the collective to benefit as a whole. This suggests that considering repeated games may prove extremely insightful for the purpose of the research. Indeed, our experiments show that individuals with MD are the ones who contribute the most to the public good: they make larger efforts towards reaching the collective goal, thus playing a leading role for the functioning of the ecosystem. As a consequence, groups with half or more participants with MD do better in sustaining cooperation in the first rounds, which implies that a community care setting might prove successful for capability building. Yet, large proportions of individuals with MD in a group result in higher inequalities in final gains, which reach the maximum when the number of individuals with MD equals the number of caregivers or relatives. This means that community care perspectives might also take account of group composition to deal with potential inequalities arising from differential capabilities. In summary, we have explored the behavior of all individuals and role groups who make up the mental health ecosystem through an extensive suite of games that simulate strategic social situations. Overall, the results point to the availability of large social capital in the mental health community that can make a difference in the welfare and recovery process of firsthand affected, and suggest that the community-centered approach to mental care may turn out to be very beneficial. Indeed, the behavior of individuals with MD can be better explained by examining not only their cognitive abilities, but also the web of relationships in which they are embedded. Yet, that web of relationships presents opportunities and imposes constraints.

Though we depicted some behavioral differences in dyadic interactions, most importantly we found that individuals with MD show a remarkably larger disposition towards sustaining cooperation within groups. The larger readiness of individuals with MD to contribute to the collective action problem can thus be seen as a way to claim their place in the community. By having participants unaware of their partner’s identity, we could indeed measure participants decisions based solely on the value they placed on the group’s welfare, independently of its composition or other factors. Yet, the fact that participants with MD contribute the most implies for other members of the group lower investments to reach the common target. This, on the other hand, unveils the vulnerability of individuals with a diagnosis of MD. Repeated or periodic and more situated experiments with digital platforms 34 , in the future, can surely provide further valuable insights into the effect of participants prior knowledge of and relation with the partner on their behavior. We are indeed sure that our experimental setup can prove helpful in complementing the diagnostic process of physicians and health professionals and even to evaluate care service providers. On the other hand, other possible application of this approach arises in the realm of behavior change interventions 35 , that should focus on the aspects that are more specific of every disorder.

In conclusion, the results reinforce the idea of community social capital as a key approach to the recovery process based on an ecosystem paradigm (see also the recent results in ref. 36 about the role and impact of family and community social capital on MD in children and adolescents). Also, if on the one hand the fact that the results of our dyadic games are in general agreement with previous studies validates our procedure; on the other hand it supports the validity and contributions of neuroeconomics and experimental approaches to the study of MD. Finally, given that our work has been carried out in a fully socialized context, this approach can be applied to any similar’ ‘care in the community’ initiative. The adoption of our setup could lead to the identification of core groups that can boost and sustain cooperation within a given community. It can also help in discriminating among different communities in order to identify best practices and optimize resource allocation 37 .

All participants were fully informed about the purpose, methods and intended uses of the research. No participant could approach any experimental station without having signed a written informed consent. The use of pseudonyms ensured the anonymity of participants’ identity, in agreement with the Spanish Law for Personal Data Protection. No association was ever made between the participants’ real names and the results. The whole procedure was approved by the Ethics Committee of Universitat de Barcelona. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Experimental design

As indicated in the main text, the dialogue with the main stakeholders of the mental health ecosystem was at the centre of the project. Around 20 representatives including members of the Catalonia Federation of Mental Health (Federació Salut Mental Catalunya), firsthand affected, relatives, caregivers, and other professionals related to both the health and social sector, informed and validated the whole research through focus groups and further discussions, leading to the largest experiment of this kind ever carried out. Citizen science principles guided the whole experimental design process in order to raise concerns grounded in the daily life of mental health professionals and service users, and to increase public awareness. The experimental dilemmas being proposed served both to advance in knowledge on the social dynamics at play within ‘care in the community’ settings and as a self-reflection experience for all participants. The experimental design process developed in four main phases: (i) identification of the behavioral traits perceived as of fundamental importance within the community, (ii) operationalization of those same behavioral traits thorugh game theoretical paradigms and literature reviews, (iii) definition of the socio-demographic information relevant for the analysis, and (iv) a beta testing of the digital interface (including contents, time duration, and language used). The locations where the experiments took place were accorded with the Catalonia Federation of Mental Health in an attempt to explore the functioning of some communities of interest for inclusive and effective policy making. The Federation provided a fundamental support throughout the whole experiments’ implementation, serving as a crucial intermediaire between the scientists and different mental health collectives. It also provided valuable insights to better interpret the data obtained.

Participants and procedure

To our knowledge, experimental work on this issue has been conducted only recently and on specific collectives of orders of magnitude smaller. A total of 270 individuals participated in the experiments, that were run over 45 sessions between October 2016 and March 2017. The experiments were carried out in Girona (n = 60), Lleida (n = 120), Sabadell (n = 48) and Valls (n = 42). Participants were either diagnosed with a mental condition (n = 169) or members of the broader mental health ecosystem (n = 101), including professionals of the health and social sector (n = 52), formal and informal caregivers (n = 17), relatives (n = 9), friends (n = 4) and other members of the collective (n = 19). Individuals with a mental condition had to self-assess their diagnosis selecting one from a spectrum of options agreed upon with representatives of the mental health ecosystem during the co-design phases of the experiment. Those participants who had received more than one diagnosis had to select the one they considered to be the most relevant. Overall, they had received a diagnosis of psychosis (n = 63), depression (n = 33), anxiety (n = 31), bipolar disorder (n = 17) or other unspecified diagnosis (n = 25). They ranged in age from 21 to 77 years old (these are weighted values since for ethical and privacy reasons participants were only asked to choose among different age ranges) with 47.2 years on average. Further, 55.6% were men and 44.4% were women. Yet, actors involved in the recovery process were predominantly women (76.2%), and up to 21.8% of them was over 60 years old (see Supplementary Section 1.1). Participants were told that they would play against each others a set of games meant to explore human decision-making processes. They played in random groups of six players through a web interface specifically developed for the research. They were informed that they had to make a decision under different conditions and against different opponents in every round. Every game represented an interactive situation requiring the participants to make a decision, the result of which depended also on the opponent’s behavior. To incentivize the participation, they would earn a voucher worth their final score (the experimental settings and instructions, can be found in the Supplementary Section 1.2 and 1.3 respectively). First, participants participated in a Collective Risk Dilemma 23 against five opponents. Briefly, the game is a public goods game with threshold: If the participants’ total contribution after 10 rounds is lower than a given threshold, they loose all the money they kept with a probability of 90%. Otherwise, they are told that the money collected in the common fund are spent in reforesting land plots in Catalonia, where the experimental sessions took place, and each participants earns the money left in the personal account. After completing the task, participants played one round of the Trust Game 38 in both roles: as trustors and as trustees. They played against different partners in each role. Finally, they played one round of a Prisoner Dilemma 39 with (unincentivized) belief elicitation about their counterpart’s behavior prior to playing. Before starting the games, participants had to complete a brief survey covering some key dimensions of their sociodemographic background. The assignment of players’ partners in the dyadic games was completely random and every action was made with a different partner. The average (standard error of the mean) time for completing the three experiments (CRD, PD and TG and tutorials) is around 12 minutes, 705.86 ± 17.93 s. At the end of each session, participants received a gift card worth their earnings. The average individual earning is 46.84 ± 0.77 MUs equivalent to a 4.04 ± 0.077 EUR voucher. The behavioral patterns that emerged do not reveal significant variation across the different experiments, which may suggest that our results are robust to generalizations (see Supplementary Section 1.7).

Statistical analysis

Results were analyzed at two levels: first, we tested for behavioral differences between the whole group of individuals with mental condition compared to members of the mental health ecosystem; we then checked for systematic behavioral variation across diagnostics and role played in the recovery process. In one shot, two-person dyadic interactions we performed Mann-Whitney-U tests for independent groups to compare the distributions of cooperative choices (PD), and initial and back transfers (TG), between individuals with and without a mental condition. We then checked for marginal differences within groups using Kruskal-Wallis tests, and post-hoc comparisons were run with Mann-Whitney-U tests adjusting for p-values with the Holm-Bonferroni method. Welch’s two-tailed t-tests were performed to check for differences in average contributions (CRD) between participants with and without a MD, controlling for unequal variances and sample sizes. Finally, ANOVA and further Tukey HSD post-hoc comparisons served to check for differences in average contributions over round across diagnostics and members of the mental health community.

Accession codes

Data is available in an structured way at Zenodo public repository with DOI 10.5281/zenodo.1175627.

Change history

26 september 2018.

A correction to this article has been published and is linked from the HTML and PDF versions of this paper. The error has not been fixed in the paper.

Steel, Z. et al . The global prevalence of common mental disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis 1980–2013. Int. J. Epidemiol. 43 , 476–493 (2014).

Article Google Scholar

Insel, T. R., Collins, P. Y. & Hyman, S. E. Darkness invisible: The hidden global costs of mental illness. Foreign Affairs 94 (2015).

White, R. G., Jain, S., Orr, D. M. R. & Read, U. M. The Palgrave handbook of sociocultural perspectives on global mental health. The Palgrave handbook of sociocultural perspectives on global mental health. (2017).

Chapter Google Scholar

World Health Organisation. The World Health Report 2001: mental health, new understanding, new hope. World Health Report 1–169 (2001).

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 4th edition TR. (2000).

Gradin, V. B. et al . Abnormal brain responses to social fairness in depression: an fMRI study using the Ultimatum Game. Psychol. Med. 45 , 1241–51 (2015).

Article CAS Google Scholar

Shao, R., Zhang, H. & Lee, T. M. C. The neural basis of social risky decision making in females with major depressive disorder. Neuropsychologia 67 , 100–10 (2015).

Guroglu, B., van den Bos, W., Rombouts, S. A. R. B. & Crone, E. A. Unfair? It depends: Neural correlates of fairness in social context. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 5 , 414–423 (2010).

Wang, Y., Yang, L. –Q., Li, S. & Zhou, Y. Game Theory Paradigm: A New Tool for Investigating Social Dysfunction in Major Depressive Disorders. Front. Psychiatry 6 , 128 (2015).

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

King–Casas, B. & Chiu, P. H. Understanding interpersonal function in psychiatric illness through multiplayer economic games. Biol. Psychiatry 72 , 119–125 (2012).

Pulcu, E. et al . Social–economical decision making in current and remitted major depression. Psychol. Med. 45 , 1–13 (2015).

Wang, Y. et al . Impaired social decision making in patients with major depressive disorder. BMC Psychiatry 14 , 18 (2014).

Csukly, G., Polgár, P., Tombor, L., Réthelyi, J. & Kéri, S. Are patients with schizophrenia rational maximizers? Evidence from an ultimatum game study. Psychiatry Res. 187 , 11–17 (2011).

Agay, N., Kron, S., Carmel, Z., Mendlovic, S. & Levkovitz, Y. Ultimatum bargaining behavior of people affected by schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 157 , 39–46 (2008).

Mokros, A. et al . Diminished cooperativeness of psychopaths in a prisoner’s dilemma game yields higher rewards. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 117 , 406–413 (2008).

Rilling, J. K. et al . Neural Correlates of Social Cooperation and Non-Cooperation as a Function of Psychopathy. Biol. Psychiatry 61 , 1260–1271 (2007).

Scheele, D., Mihov, Y., Schwederski, O., Maier, W. & Hurlemann, R. A negative emotional and economic judgment bias in major depression. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 263 , 675–683 (2013).

Putnam, R. D. Bowling Aalone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community. J. Democr. 6 , 1–18 (2000).

Google Scholar

Ostrom, E. In Handbook of Social Capital: The troika of sociology, political science and economics, pp. 17–35 (2009).

Sagarra, O., Gutiérrez-Roig, M., Bonhoure, I. & Perelló, J. Citizen science practices for computational social science research: The conceptualization of pop-up experiments. Front. Phys. 3 , 93 (2016).

Camerer, C.F., Behavioral Game Theory: Experiments in Strategic Interaction (Princeton University Press, 2003).

Brañas-Garza, P., Rodríguez-Lara, I. & Sánchez, A. Humans expect generosity. Sci. Rep. 7 , 42446 (2017).

Article ADS Google Scholar

Milinski, M., Sommerfeld, R. D., Krambeck, H.-J., Reed, F. A. & Marotzke, J. The collective-risk social dilemma and the prevention of simulated dangerous climate change. Proc. Nat’l. Acad. Sci. USA 105 , 2291–2294 (2008).

Article ADS CAS Google Scholar

Surbey, M. K. Adaptive significance of low levels of self-deception and cooperation in depression. Evol. Hum. Behav. 32 , 29–40 (2011).

Clark, C. B., Thorne, C. B., Hardy, S. & Cropsey, K. L. Cooperation and depressive symptoms. J. Affect. Disord. 150 , 1184–1187 (2013).

Destoop, M., Schrijvers, D., De Grave, C., Sabbe, B. & De Bruijn, E. R. A. Better to give than to take? Interactive social decision–making in severe major depressive disorder. J. Affect. Disord. 137 , 98–105 (2012).

Harlé, K. M., Allen, J. J. B., Sanfey, A. G., Harlé, K. M. & Sanfey, A. G. The impact of depression on social economic decision making. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 119 , 440–446 (2010).

Unoka, Z., Seres, I., Aspán, N., Bódi, N. & Kéri, S. Trust game reveals restricted interpersonal transactions in patients with borderline personality disorder. J. Pers. Disord. 23 , 399–409 (2009).

King-Casas, B. et al . The rupture and repair of cooperation in borderline personality disorder. Science 321 , 806–810 (2008).

Koenigs, M., Kruepke, M. & Newman, J. P. Economic decision-making in psychopathy: A comparison with ventromedial prefrontal lesion patients. Neuropsychologia 48 , 2198–2204 (2010).

Raihani, N. J. & Bell, V. Paranoia and the social representation of others: a large-scale game theory approach. Scientific Reports 7 , 4544, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-04805-3 (2017).

Article ADS CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Raihani, N. J. & Bell, V. Conflict and cooperation in paranoia: a large-scale behavioural experiment. Psychological Medicine 1–11, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291717003075 (2017).

Collins, L. G. & Swartz, K. Caregiver care. American family physician 83 , 1309–1317 (2011).

PubMed Google Scholar

Aledwood, T. et al . Data collection for mental health studies through digital platforms: requirements and design of a prototype. JMIR research protocols 6 (6), 1–11 (2017).

Blaga, O. M., Vasilescu, L. & Chereches, R. M. Use and effectiveness of behavioural economics in interventions for lifestyle risk factors of non-communicable diseases: a systematic review with policy implications. Perspectives in Public Health 20 (10), 1–11 (2017).

McPherson, K. E. et al . The association between social capital and mental health and behavioural problems in children and adolescents: an integrative systematic review. BMC psychology 2 , 7, https://doi.org/10.1186/2050-7283-2-7 (2014).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Almedom, A. M. Social capital and mental health: An interdisciplinary review of primary evidence. Social Science and Medicine 61 , 943–964 (2005).

Berg, J., Dickhaut, J. & McCabe, K. Trust, reciprocity, and social history. Games Econ. Behav. 10 , 122–142 (1995).

Rapoport, A. & Chammah, A. M. Prisoner’s Dilemma (University of Michigan Press, 1965).

Vicens, J. et al . Resource heterogeneity leads to unjust effort distribution in climate change mitigation. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/1709.02857 (2017).

Download references

Acknowledgements

We thank the community of patients, caregivers and families working within the Federació de Salut Mental Catalunya (Catalonia Mental Health Federation) for the enthusiasm and for their invaluable help in the design and realization of the experiments. We are also especially thankful to I Bonhoure for the necessary logistics to make the experiments possible, to F Español for contributing in the first steps in the experimental design, to M Poll for always giving us the institutional support from inside the Federation, to both E Ferrer and F Muñoz for building the bridge between us and the mental health ecosystem and to X Trabado for encouraging us to run this research. This work was partially supported by Federació de Salut Mental Catalunya; by MINEICO (Spain), Agencia Estatal de Investigación (AEI) and Fondo Europeo de Desarrollo Regional (FEDER) through grants FIS2013-47532-C3-1-P (JD), FIS2016-78904-C3-1-P (JD), FIS2013-47532-C3-2-P (JP), FIS2016-78904-C3-2-P (JP, AC); by Generalitat de Catalunya (Spain) through Complexity Lab Barcelona (contract no. 2014 SGR 608, JP) and through Secretaria d’Universitats i Recerca (contract no. 2013 DI 49, JD, JV); and by the EU through FET Open Project IBSEN (contract no. 662725, AS) and FET-Proactive Project DOLFINS (contract no. 640772, AS).

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Departament de Física de la Matèria Condensada, Universitat de Barcelona, 08028, Barcelona, Spain

Anna Cigarini, Julián Vicens & Josep Perelló

Universitat de Barcelona Institute of Complex Systems UBICS, 08028, Barcelona, Spain

Departament d’Enginyeria Informàtica i Matemàtiques, Universitat Rovira i Virgili, 43007, Tarragona, Spain

Julián Vicens & Jordi Duch

Northwestern Institute on Complex Systems (NICO), Northwestern University, 60208, Evanston, IL, USA

Grupo Interdisciplinar de Sistemas Complejos (GISC), Unidad de Matemática, Modelización y Ciencia Computacional, Universidad Carlos III de Madrid, 28911, Leganés, Spain

Angel Sánchez

Unidad Mixta Interdisciplinar de Comportamiento y Complejidad Social (UMICCS) UC3M-UV-UZ, Universidad Carlos III de Madrid, 28911, Leganés, Spain

Institute UC3M-BS of Financial Big Data, Universidad Carlos III de Madrid, 28903, Getafe, Spain

Instituto de Biocomputación y Física de Sistemas Complejos (BIFI), Universidad de Zaragoza, 50009, Zaragoza, Spain

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

J.D., A.S., and J.P. conceived the original idea for the experiment; J.V. and J.D. prepared the software for the final experimental setup; A.C. and J.V. analyzed the data; and all authors carried out the experiments, discussed the analysis results, and wrote the paper.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Josep Perelló .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information, rights and permissions.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Cigarini, A., Vicens, J., Duch, J. et al. Quantitative account of social interactions in a mental health care ecosystem: cooperation, trust and collective action. Sci Rep 8 , 3794 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-21900-1

Download citation

Received : 15 November 2017

Accepted : 01 February 2018

Published : 28 February 2018

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-21900-1

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Mental Health

- Community Social Capital

- Group Roles

- Dyadic Games

- Average Individual Contribution

This article is cited by

Gender-based pairings influence cooperative expectations and behaviours.

- Anna Cigarini

- Julián Vicens

- Josep Perelló

Scientific Reports (2020)

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines . If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing: AI and Robotics newsletter — what matters in AI and robotics research, free to your inbox weekly.

Advertisement

Quantitative needs assessment tools for people with mental health problems: a systematic scoping review

- Open access

- Published: 12 March 2024

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Irena Makivić ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-2748-5522 1 ,

- Anja Kragelj 1 &

- Antonio Lasalvia ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-9963-6081 2

779 Accesses

Explore all metrics

Needs assessment in mental health is a complex and multifaceted process that involves different steps, from assessing mental health needs at the population or individual level to assessing the different needs of individuals or groups of people. This review focuses on quantitative needs assessment tools for people with mental health problems. Our aim was to find all possible tools that can be used to assess different needs within different populations, according to their diverse uses. A comprehensive literature search with the Boolean operators “Mental health” AND “Needs assessment” was conducted in the PubMed and PsychINFO electronic databases. The search was performed with the inclusion of all results without time or other limits. Only papers addressing quantitative studies on needs assessment in people with mental health problems were included. Additional articles were added through a review of previous review articles that focused on a narrower range of such needs and their assessment. Twenty-nine different need-assessment tools specifically designed for people with mental health problems were found. Some tools can only be used by professionals, some by patients, some even by caregivers, or a combination of all three. Within each recognized tool, there are different fields of needs, so they can be used for different purposes within the needs assessment process, according to the final research or clinical aims. The added value of this review is that the retrieved tools can be used for assessment at the individual level, research purposes or evaluation at the outcome level. Therefore, best needs assessment tool can be chosen based on the specific goals or focus of the related needs assessment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Access to health services among culturally and linguistically diverse populations in the Australian universal health care system: issues and challenges

Characterising and justifying sample size sufficiency in interview-based studies: systematic analysis of qualitative health research over a 15-year period

The Biopsychosocial Approach: Towards Holistic, Person-Centred Psychiatric/Mental Health Nursing Practice

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Mental disorders are the largest contributor to the disease burden in Europe (Wykes et al., 2021 ), and mortality related to such conditions increases the overall economic burden (McGorry & Hamilton, 2016 ). Mental disorders affect various life domains, from physical health to daily living, friends, family situations, and education, and are associated with greater unemployment and economic problems (Wykes et al., 2021 ).

In order to plan and carry out successful mental health care, it is necessary to have a good mental health information system that also includes data about related needs (Wykes et al., 2021 ). When a need is identified, an action can be (re)organized to address it. Such action, based on the needs identified by the affected individuals, professionals or society, results in either satisfaction or dissatisfaction if the needs continue to be present (Endacott, 1997 ). Assessing needs might also be used to assess the adequacy and prioritization of mental health services at the population level (Ashaye et al., 2003 ; Hamid et al., 2009 ) as well as for the evaluation of mental health care (Hamid et al., 2009 ).

When considering mental health, a need represents a gap between what is and what should be (Witkin & Altschuld, 1995 ), and any changes that are made to the system should thus work to reduce this gap. There are various definitions of both “need” and “assessment” (Royse & Drude, 1982 ). Kahn (1969) considered needs from a social perspective to represent what someone requires in a broader bio-psycho-social context to be able to fully and productively participate in a social process (Royse & Drude, 1982 ). Brewin conceptualised needs (Lesage, 2017 ) as assessing what kind of social disability an individual has for professionals to be able to use an adequate model of care. Disability in this context is the result of interactions between people and the environment, and thus a disability can be seen as a lack of appropriate care models in relation to recognized needs. The concept of “need” in mental health care may be defined according to different points of view: a “normative need” is defined by professionals, while a “felt need” is what people with mental health problems experience and ask to be met (Endacott, 1997 ). What patients request and what they really need may differ, as they can only get what is available and provided at the system level, and what is the most beneficial for them in the current situation. Moreover, what they ask for is not always feasible. However, according to Bradshaw, what an individual requests is important and should be considered as felt needs (Endacott, 1997 ). Bearing in mind Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, only a combination of assessments from different points of view can provide a comprehensive needs assessment: needs assessed at the individual level from service users, their family members, caregivers, practitioners, and other professionals (Endacott, 1997 ). Indicators of needs at the individual level include functioning on different levels, symptoms, diagnoses, quality of life and, access to services (Aoun et al., 2004 ). Patient-centredness is vital to ensure the highest quality of care through monitoring performance (Kilbourne et al., 2018 ). Taking into account the patients’ perspective is also important to assess needs correctly, since such an assessment is more than just the professionals’ perception. An assessment of needs, as Thornicroft ( 1991 ) pointed out, provides care in the community with an emphasis on the provider-user relationship as a key component through which effective care is organized (Carter et al., 1995 ). According to Slade ( 1994 ), the concept of a need in mental health has no single correct definition, but it should rather be seen s a “socially-negotiated concept” (Thornicroft & Slade, 2002 ). Additionally, needs have to be assessed through the bio-psycho-social model (Makivić & Klemenc-Ketiš, 2022 ), including not just medical needs but also a wide array of social needs.

Initially, the assessment of needs (Balacki, 1988 ) in the community was seen as an approach using different forms of analysis to gain insights into the use of services, characteristics of people, incidence and prevalence rates and indicators to recognize crucial determinants that lead to the worsening of mental health. The assessment of mental health needs in Western societies began in 1775 with the analysis of public health data contained in the case registers (Royse & Drude, 1982 ). In the mid-1970s, with the beginning of the transition to care for mental health in the community (and the launch of community mental health service organizations), needs assessment was required within the evaluation process to help meet the patients’ needs. Needs assessment also represents a crucial part of mental health planning (Royse & Drude, 1982 ), where different needs must be considered, especially those felt by individuals. At the end of seventies, Kimmel pointed out that this area of needs assessment had no systematic procedures (Royse & Drude, 1982 ). However, several mental health needs assessment tools have been developed over the last thirty years.

The MRC Needs for Care Assessment (NFCAS) (by Brewin, 1987) was the first attempt to introduce a standardized assessment of the needs of the severely mentally ill (Lesage, 2017 ). Subsequently, a reduced version of the instrument applicable to common mental disorders was developed – i.e., the Needs for Care Assessment Schedule-Community version (NFCAS-C) (Bebbington et al., 1996 ). The shortened version of NFCAS was the Cardinal Needs Schedule (CNS), which is used to assess needs to address them with appropriate interventions (Marshall et al., 1995 ). Later the self-administered Perceived Needs for Care Questionnaire (PNCQ) was developed for use at the population level (Meadows et al., 2000 ), while in 1995 the Camberwell Assessment of Need (CAN) (Phelan et al., 1995 ) was published. After this time the focus shifted more to people-centred approaches, and therefore the assessment of needs also moved beyond psychiatric symptomatology to bring in “consumers”, i.e. patients and their caregivers. Other scales have also been used as needs assessment tools, such as the HoNOS scale (Joska & Flisher, 2005 ) which was designed to evaluate the clinical and social outcomes of mental health care.

Needs assessment is not always a clear and straightforward process with one approach and one goal. Therefore, different tools and approaches may be used to assess needs from different perspectives at different levels and with the help of different tools. The problem with using different techniques is that there is a lack of comparability and a consequent danger of not using the needs assessment outcome data as intended (Stewart, 1979 ); thus, it is important to have a good overview of the available tools.

To the best of our knowledge, only six reviews on needs assessment in people with mental health problems have been published to date (Davies et al., 2018 , 2019 ; Dobrzyńska et al., 2008b ; Joska & Flisher, 2005 ; Keulen-de Vos & Schepers, 2016 ; Lasalvia et al., 2000b ). Four additional reviews focused on the general needs or general health needs of people without mental health problems (Asadi-Lari & Gray, 2005 ; Carvacho et al., 2021 ; Lasalvia et al., 2000a ; Ravaghi et al., 2023 ), which was not focus group of our review. Finally, another article was considered inadequate for this study’s purposes, as it was published in Polish (as the one above) and is not a review paper (Dobrzyńska et al., 2008a ). None of the reviews published thus far have focused on the different assessment tools available for assessing the needs of people with different mental disorders. To date, no study has attempted to review all the available published studies on the various needs assessment processes to systematize the topic. The reviews mentioned above deal with only one specific population (patients with first-episode psychosis; forensic patients), or with specific needs (need for mental health services, supportive care needs, or individual needs for care). Thus, this study aimed to review all studies addressing needs assessment tools specifically designed for people with mental health problems, regardless of their diagnoses. The added value of this study is especially because of its wholeness in presenting different tools that can be used on different populations and by different groups. Thus this study may serve as a framework for starting different needs-assessment processes.

Search strategy

A comprehensive literature search using the Boolean operators “Mental health” AND “Needs assessment” was conducted in electronic bibliographic databases PubMed [Needs Assessment (Mesh Terms) AND Mental Health (Mesh Terms); Mental Health (Title/Abstract) AND Needs assessment (Title/Abstract);] and PsychINFO [Needs assessment AND Mental health in keywords; Needs assessment AND Mental health in Title; Needs assessment AND Mental health in Abstract]. Searching was carried out with the inclusion of all results without time or other limits in August 2021. The search strategy was based on the needs from a clinical context as well as some research priorities in the field of mental health. After the first systematic search we collected additional papers with an overview of six review articles (Davies et al., 2018 , 2019 ; Dobrzyńska et al., 2008b ; Joska & Flisher, 2005 ; Keulen-de Vos & Schepers, 2016 ; Lasalvia et al., 2000b ) and their results, and by searching PubMed within all connected articles. This was important since keywords changed over all this broad timeframe.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

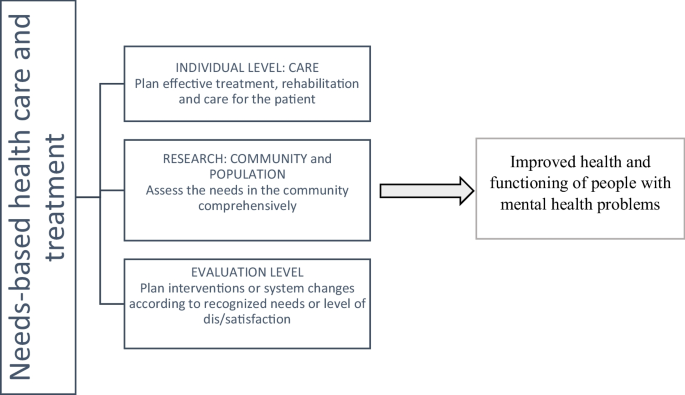

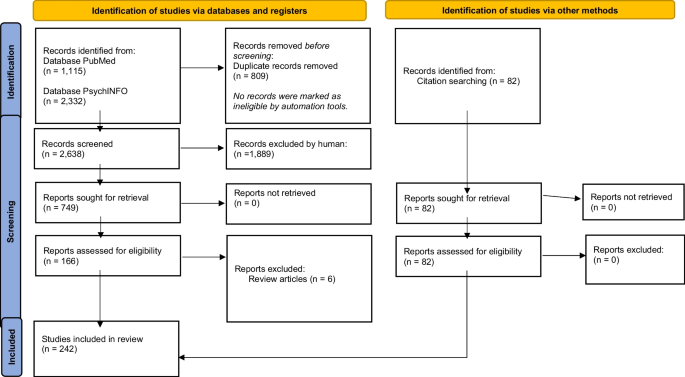

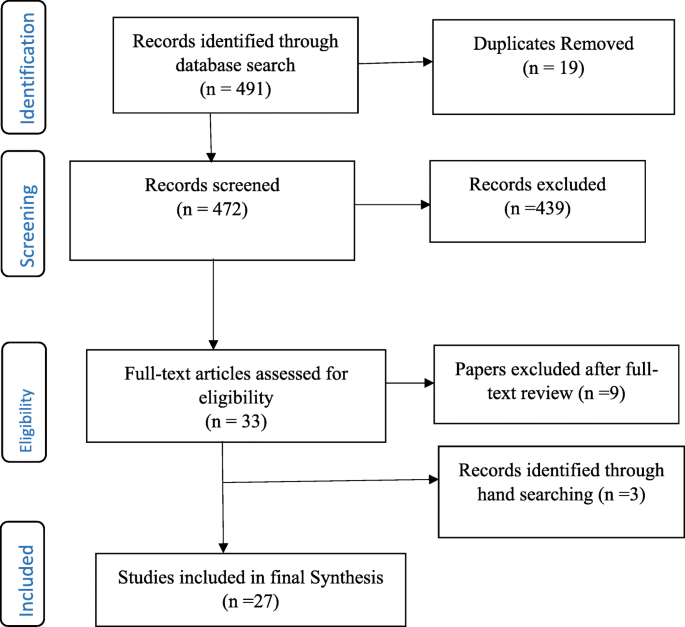

Our research exclusively focused on quantitative studies. We thus excluded all theoretical/conceptual articles, editorials, books, book commentaries or dissertations. Studies assessing the needs of patients with dementia and groups of people with physical and psychological disabilities were also excluded. We did not include papers related to 1) only general health (care), 2) other needs of the general population, 3) screening, prevalence, general diagnostic tools, and 4) tools for assessing caregivers’ needs. All those steps were done comprehensively by two researchers (IM, AK) independently. When there was a disagreement on the inclusion or exclusion of an article, both researchers looked at it again before reaching a consensus. We then manually added all relevant articles that could have been missed during the electronic search. We added articles that were cited within or were related with all the six mentioned reviews, but were not yet retrieved in the first search. These review articles were not included in the final number of all the articles examined in this study with the aim of exploring the different tools used for needs assessment of people with mental health problems. The aim of this process is to first obtain an overview of all the tools available, as this will make it possible to better use them within clinical settings, as well as for research and development purposes in order to plan a system or intervention that addresses the recognized needs (Fig. 1 ).

Concept of patient-centred care based on needs

Scoping studies, as Arksey and O'Malley ( 2005 ) mentioned, follow five steps, which we also took into consideration. First (step one) we identified the research question, which was “What are all different needs assessment tools that have been used in the population of people with mental health problems within different studies”. We then identified the relevant studies within recognised databases, as well as manually searching and adding the relevant articles (step two). We selected the appropriate studies (step three) as described within the search strategy process, with all inclusion and exclusion criteria. Finally, we presented the results (step four) in the chart flow in Fig. 2 , and Tables 1 , 2 and 3 , which corresponds to the concept of patient-centred care based on needs (Fig. 1 ). Because our focus was on different tools, we prepared the tables accordingly. There was no other relevant information in the original 242 articles to be presented at this occasion, other than those about the usage of different needs assessment tools, as this was the goal of the scoping review. The presentation of the results is based on the use of all recognized needs assessment tools, since geographical studies have been presented elsewhere (Makivić & Kragelj, 2023 ).

Research process within the databases

The analysis was multi-structured to provide an overview of all the recognized tools and the related time trends, country use and population of the most frequently used assessment methods.

The study selection process is shown in Fig. 2 . PubMed provided 578 records within the Mesh search and 537 within the title/abstract search, with after duplicates were removed this gave 1,090 results. Searching in PsychINFO provided 650 results from a search within the Abstract, 232 within Keywords and 1450 within Title; after combining these and removing duplicates, a total of 1,548 results were obtained.

The first selection was made within the final database (n = 2,638) by reading the abstracts and excluding all studies covering topics not relevant for this review. After this was completed, 166 articles remained. These were reviews and research articles covering the needs assessment of people with mental disorders (MD). After this, we eliminated review articles (n = 6) and used them for additional search to manually add all relevant articles that could have been missed during the electronic search, mainly because of the use of different keywords. Specifically, we added the articles that were cited within or were related to all the six mentioned reviews, but were not found in the first search (n = 82). After this process, a total of 242 articles were included in the final review.

Most studies addressing needs assessment tools retrieved with both electronic and manual searches were published in English (n = 231), although some were published in German (n = 3), Spanish (n = 3), and Italian (n = 2). Only one article each was published in Dutch, French and Turkish. Regarding the geographical distribution, most studies were published from European groups (n = 163), while 43 studies were conducted in America, 22 in Australia or New Zealand, 11 in Asia and only three in Africa. Some of the studies were published in collaboration among researchers from different countries. Regarding the publication period, the first studies on this issue were published in 1978, 52.9% of the studies were published from 2000 to 2012, and 66.1% had been published further by 2016.

Through the search performed in this study we found 29 different needs assessment tools, as shown in Table 1 in alphabetical order. We have made and additional search in order to find original sources and the information about the validation. Original sources for each of the recognized tools are listed in Supplementary information ( SI 1 ). Some tools, additional to those 29, were developed for the purposes of a single research study and its specific aims and the information about the validation were not available (n = 11), and thus we eliminated those tools at this point, although they will later be presented elsewhere in another study.

The retrieved tools and their respective constructs of need are presented in Table 2 . The various needs assessment tools are listed in alphabetical order. The tools are presented with regard to (1) who can answer the scale, (2) who the target population is, and (3) the domains addressed. Table 2 provides information on the various needs assessment tools, listed in alphabetical order. The tools are presented with regard to (1) who can answer the scale, (2) who the target population is, and (3) the domains addressed.

Service needs (Hamid et al., 2009 ) are defined as care requirements for prevention, treatment and rehabilitation. These needs can either be assessed by waiting lists or by only asking a simple question (e.g. “Do you think that you require any professional mental health services?”) along with the screening for mental and physical health problems (Yu et al., 2019 ) or social problems, with the help of the tools listed below. Moreover, there are different bio-psycho-social needs that are related to various mental health, physical health, and quality of life factors, as well as personal interests or abilities and social factors (Keulen-de Vos & Schepers, 2016 ), and these can be measured for different purposes. Social needs can be assessed by tools such as the Social Behavioral Schedule or REHAB Schedules, and therefore the need for rehabilitation can also be assessed (Hamid et al., 2009 ) using the comprehensive tools mentioned in our review.

Most of the needs assessment tools were self-completed by the patients (n = 85), completed by professionals (n = 41), or by combination of both (n = 78). Some tools were also completed by the patients and their caregivers (n = 12) or by the patients, caregivers, and professionals at the same time (n = 12). There were few studies where the researchers completed the needs assessment tool (n = 5). The majority of the tools were developed for assessing needs in an adult population with mental health problems (n = 193), either with severe mental disorders or with some other mental health diagnosis. Seventeen studies focused on an elderly population with mental health problems, and six on children with mental health problems. Some needs assessment tools for specific populations were found, such as tools for assessing the needs of forensic patients with mental health problems (n = 18), homeless people and migrants with a mental health diagnosis (n = 4), and mothers or pregnant women with a severe mental disorder (n = 1). In some studies, there was a combination of all these different populations and even people without a diagnosis, which we assigned to each of the mentioned groups.

In the second Supplementary information ( SI 2 ) there are reported the studies found in the literature search that used recognized needs assessment tools (n = 227). In this presentation some of the studies are not presented, namely those without validated tools (n = 11) as already mentioned and all articles using mentioned three different models (n = 4). In some studies, more tools have been used and in this case the study is counted within each tool in the total number of studies. Among the different needs-assessment tool, the CAN is mentioned as the most frequently used scale and, to the best of our knowledge, it has the highest number of different versions. The tools are presented based on their frequency of recognized use within this scoping review, from the most frequent to the least.

The recognized tools can be used in different contexts. Table 3 , groups the needs assessment tools according to their use at the care, research, and system levels.

This scoping review addressed all the published needs assessment tools specifically designed for use in mental health field. Nevertheless, some of the reviewed tools had also been used on the populations without a mental health diagnosis (Carvacho et al., 2021 ). Overall, we found twenty-nine different tools measuring needs in various mental health populations. The list of authors of the originally developed scales mentioned below are provided in the Supplementary information ( SI 1 ).

The reviewed literature highlights that the majority of needs assessment tools have been developed and used in Europe as the adoption of a community psychiatry model is relatively more widespread in this region than in other world regions; some tools, however, have been also used in America, Australia, and New Zealand.

Some scales had been developed with the aim to simplify or shorten previously published needs assessment tools, such as the Camberwell Assessment of Need (CAN) derived from the MRC Needs for Care Assessment Schedule. Similarly, the Difficulties and Needs Self-Assessment Tool was derived from the CAN, where some items are identical, some are a combination of several items of the CAN and some were added as new ones (on work, public places, family and friendship). Some tools, like the Montreal Assessment of Needs Questionnaire, were also developed from the CAN and had different aims, like enhancing data variability to broaden outcome measures for service planning, or simply because the organization of the related system is different and other tools are more appropriate. On the other hand, some tools are based on the CAN, but have been designed for use on a larger scale at the population level, like the Needs Assessment Scale. While most of the tools are used within health care services, the Resident Assessment Instrument Mental Health is a tool developed to support a seamless approach to person-centred health and social care. Some of the tools can also be used outside of the mental health field – such as the Child and Adolescent Needs and Strengths, which can be used in juvenile justice, intervention applications and child welfare – and the abovementioned CAN and others.

There are slightly different ideas regarding the needs and concepts about measuring needs. Many tools include a combination of needs assessed from different perspectives, such as the Bangor Assessment of Need Profile and the CAN. In some tools, like the Community Placement Questionnaire, it is predicted that various people rate the situation for one patient to eliminate any inaccuracies. On the other hand, some tools presented here, like the Self-Sufficiency Matrix, measure needs indirectly through self-sufficiency. When there is higher self-sufficiency for a certain life domain then there is less need presented for this area. Some tools, like Services Needed, Available, Planned, Offered, are complicated to use, since they include an investigation method with the review of the tool and assessment of the service use after the needs have been recognized. But this can be a good approach for the evaluation of the performance of community mental health centres about meeting the needs of their patients. Although we must bear in mind that such a tool is not directly transferable to every community mental health centre, as this depends on how each system is organized.

Needs can be evaluated according to different points of view, from patients themselves and their caregivers, as well as professionals. Studies show there are different outcomes based on the assessor (Lasalvia et al., 2000a , b , c ; Macpherson et al., 2003 ), and that professionals may see the needs differently to the users. Therefore, it is important not only what the tool is being used, but also who can complete it. Therefore, the most useful tools are the ones that can be used by various different people, so that the needs are assessed (also) from the patients’ standpoints (Larson et al., 2001 ).

Although the CAN is the most widely used tool, the research shows that sometimes there is not a very high agreement between staff and patients about needs, as was also found with the Health of the Nation Outcome Scales (HoNOS), which is the reason why some additional scales, such as the Profile of Community Psychiatry Clients, were developed. There are also some tools, such as the HoNOS, that indirectly measure needs for care, so they can be used as either a clinical or needs assessment tool.

Needs assessment tools are generally used by community psychiatry organizations and are also used to support changes to the organizations of countries’ related systems. The tools have already been used in order to assess the needs within clinical procedures, as well as at higher organizational levels in order to supplement services and direct programming (Royse & Drude, 1982 ). Different tools have good potential to evaluate community mental health services through assessing if patients’ needs have been met. Therefore, this study also aims at answering the question of which tool(s) can be most appropriate regarding different goals.

Within this review, we identified three systematic approaches to needs assessment which encompass different tools. The first is the DISC (Developing Individual Services in the Community) Framework (Smith, 1998 ), which includes the CAN and the Avon Self-Assessment Measure. The second is the Cumulative Needs for Care Monitor (Drukker et al., 2010 ), developed in order to choose the best treatment for each person. This one also uses the CAN and other more clinical tools and outcome measures (such as quality of life). The third is the Colorado Client Assessment Record (Ellis et al., 1984 ), which includes different measures of social functioning, such as the Denver Community of Mental Health Questionnaire, the Community Adjustment Profile, the Fort Logan Evaluation Screen, the Personal Role Skills Scale and the Global Assessment Scale.