8.2 The Topic, General Purpose, Specific Purpose, and Thesis

Before any work can be done on crafting the body of your speech or presentation, you must first do some prep work—selecting a topic, formulating a general purpose, a specific purpose statement, and crafting a central idea, or thesis statement. In doing so, you lay the foundation for your speech by making important decisions about what you will speak about and for what purpose you will speak. These decisions will influence and guide the entire speechwriting process, so it is wise to think carefully and critically during these beginning stages.

Understanding the General Purpose

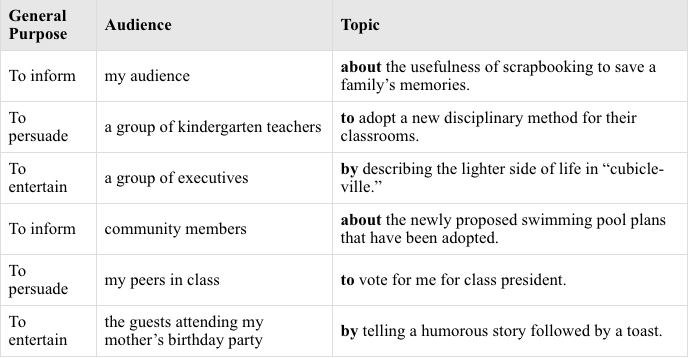

Before any work on a speech can be done, the speaker needs to understand the general purpose of the speech. The general purpose is what the speaker hopes to accomplish and will help guide in the selection of a topic. The instructor generally provides the general purpose for a speech, which falls into one of three categories. A general purpose to inform would mean that the speaker is teaching the audience about a topic, increasing their understanding and awareness, or providing new information about a topic the audience might already know. Informative speeches are designed to present the facts, but not give the speaker’s opinion or any call to action. A general purpose to persuade would mean that the speaker is choosing the side of a topic and advocating for their side or belief. The speaker is asking the audience to believe in their stance, or to take an action in support of their topic. A general purpose to entertain often entails short speeches of ceremony, where the speaker is connecting the audience to the celebration. You can see how these general purposes are very different. An informative speech is just facts, the speaker would not be able to provide an opinion or direction on what to do with the information, whereas a persuasive speech includes the speaker’s opinions and direction on what to do with the information. Before a speaker chooses a topic, they must first understand the general purpose.

Selecting a Topic

Generally, speakers focus on one or more interrelated topics—relatively broad concepts, ideas, or problems that are relevant for particular audiences. The most common way that speakers discover topics is by simply observing what is happening around them—at their school, in their local government, or around the world. Opportunities abound for those interested in engaging speech as a tool for change. Perhaps the simplest way to find a topic is to ask yourself a few questions, including:

- What important events are occurring locally, nationally, and internationally?

- What do I care about most?

- Is there someone or something I can advocate for?

- What makes me angry/happy?

- What beliefs/attitudes do I want to share?

- Is there some information the audience needs to know?

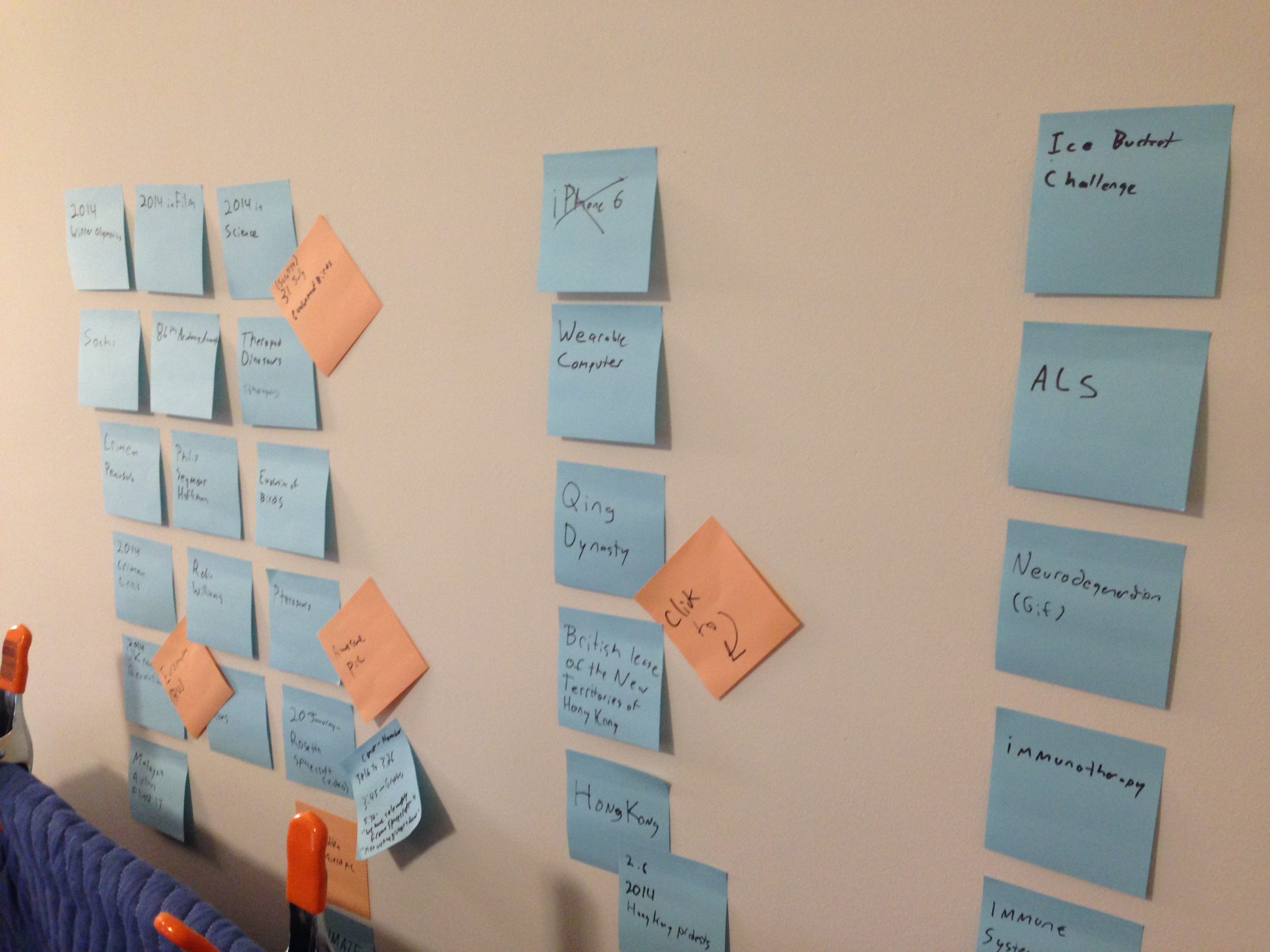

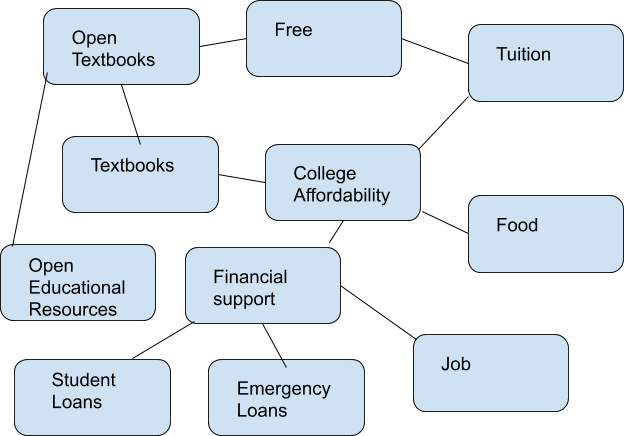

Students speak about what is interesting to them and their audiences. What topics do you think are relevant today? There are other questions you might ask yourself, too, but these should lead you to at least a few topical choices. The most important work that these questions do is to locate topics within your pre-existing sphere of knowledge and interest. Topics should be ideas that interest the speaker or are part of their daily lives. In order for a topic to be effective, the speaker needs to have some credibility or connection to the topic; it would be unfair to ask the audience to donate to a cause that the speaker has never donated to. There must be a connection to the topic for the speaker to be seen as credible. David Zarefsky (2010) also identifies brainstorming as a way to develop speech topics, a strategy that can be helpful if the questions listed above did not yield an appropriate or interesting topic. Brainstorming involves looking at your daily activities to determine what you could share with an audience. Perhaps if you work out regularly or eat healthy, you could explain that to an audience, or demonstrate how to dribble a basketball. If you regularly play video games, you may advocate for us to take up video games or explain the history of video games. Anything that you find interesting or important might turn into a topic. Starting with a topic you are already interested in will make writing and presenting your speech a more enjoyable and meaningful experience. It means that your entire speechwriting process will focus on something you find important and that you can present this information to people who stand to benefit from your speech. At this point, it is also important to consider the audience before choosing a topic. While we might really enjoy a lot of different things that could be topics, if the audience has no connection to that topic, then it wouldn’t be meaningful for the speaker or audience. Since we always have a diverse audience, we want to make sure that everyone in the audience can gain some new information from the speech. Sometimes, a topic might be too complicated to cover in the amount of time we have to present, or involve too much information then that topic might not work for the assignment, and finally if the audience can not gain anything from a topic then it won’t work. Ultimately, when we choose a topic we want to pick something that we are familiar with and enjoy, we have credibility and that the audience could gain something from. Once you have answered these questions and narrowed your responses, you are still not done selecting your topic. For instance, you might have decided that you really care about breeds of dogs. This is a very broad topic and could easily lead to a dozen different speeches. To resolve this problem, speakers must also consider the audience to whom they will speak, the scope of their presentation, and the outcome they wish to achieve.

Formulating the Purpose Statements

By honing in on a very specific topic, you begin the work of formulating your purpose statement. In short, a purpose statement clearly states what it is you would like to achieve. Purpose statements are especially helpful for guiding you as you prepare your speech. When deciding which main points, facts, and examples to include, you should simply ask yourself whether they are relevant not only to the topic you have selected, but also whether they support the goal you outlined in your purpose statement. The general purpose statement of a speech may be to inform, to persuade, to celebrate, or to entertain. Thus, it is common to frame a specific purpose statement around one of these goals. According to O’Hair, Stewart, and Rubenstein, a specific purpose statement “expresses both the topic and the general speech purpose in action form and in terms of the specific objectives you hope to achieve” (2004). The specific purpose is a single sentence that states what the audience will gain from this speech, or what will happen at the end of the speech. The specific purpose is a combination of the general purpose and the topic and helps the speaker to focus in on what can be achieved in a short speech.

To go back to the topic of a dog breed, the general purpose might be to inform, a specific purpose might be: To inform the audience about how corgis became household pets. If the general purpose is to persuade the specific purpose might be: to persuade the audience that dog breeds deemed “dangerous” should not be excluded from living in the cities. In short, the general purpose statement lays out the broader goal of the speech while the specific purpose statement describes precisely what the speech is intended to do. The specific purpose should focus on the audience and be measurable, if I were to ask the audience before I began the speech how many people know how corgis became household pets, they could raise their hand, and if I ask at the end of my speech how many people know how corgis became household pets, I should see a lot more hands. The specific purpose is the “so what” of the speech, it helps the speaker focus on the audience and take a bigger idea of a topic and narrow it down to what can be accomplished in a short amount of time.

Writing the Thesis Statement

The specific purpose statement is a tool that you will use as you write your speech, but it is unlikely that it will appear verbatim in your speech. Instead, you will want to convert the specific purpose statement into a central idea, or thesis statement that you will share with your audience. Just like in a written paper, where the thesis comes in the first part of the paper, in a speech, the thesis comes within the first few sentences of the speech. The thesis must be stated and tells the audience what to expect in this speech. A thesis statement may encapsulate the main idea of a speech in just a sentence or two and be designed to give audiences a quick preview of what the entire speech will be about. The thesis statement should be a single, declarative statement followed by a separate preview statement. If you are a Harry Potter enthusiast, you may write a thesis statement (central idea) the following way using the above approach: J.K. Rowling is a renowned author of the Harry Potter series with a Cinderella-like story of a rise to fame.

Writing the Preview Statement

A preview statement (or series of statements) is a guide to your speech. This is the part of the speech that literally tells the audience exactly what main points you will cover. If you were to get on any freeway, there would be a green sign on the side of the road that tells you what cities are coming up—this is what your preview statement does; it tells the audience what points will be covered in the speech. Best of all, you would know what to look for! So, if we take our J.K Rowling example, the thesis and preview would look like this: J.K. Rowling is a renowned author of the Harry Potter series with a Cinderella-like rags-to-riches story. First, I will tell you about J.K. Rowling’s humble beginnings. Then, I will describe her personal struggles as a single mom. Finally, I will explain how she overcame adversity and became one of the richest women in the United Kingdom.

Writing the Body of Your Speech

Once you have finished the important work of deciding what your speech will be about, as well as formulating the purpose statement and crafting the thesis, you should turn your attention to writing the body of your speech. The body of your speech consists of 3–4 main points that support your thesis and help the audience to achieve the specific purpose. Creating main points helps to chunk the information you are sharing with your audience into an easy-to-understand organization. Choosing your main points will help you focus in on what information you want to share with the audience in order to prove your thesis. Since we can’t tell the audience everything about our topic, we need to choose our main points to make sure we can share the most important information with our audience. All of your main points are contained in the body, and normally this section is prepared well before you ever write the introduction or conclusion. The body of your speech will consume the largest amount of time to present, and it is the opportunity for you to elaborate on your supporting evidence, such as facts, statistics, examples, and opinions that support your thesis statement and do the work you have outlined in the specific purpose statement. Combining these various elements into a cohesive and compelling speech, however, is not without its difficulties, the first of which is deciding which elements to include and how they ought to be organized to best suit your purpose.

clearly states what it is you would like to achieve

“expresses both the topic and the general speech purpose in action form and in terms of the specific objectives you hope to achieve” (O'Hair, Stewart, & Rubenstein, 2004)

single, declarative sentence that captures the essence or main point of your entire presentation

It’s About Them: Public Speaking in the 21st Century Copyright © 2022 by LOUIS: The Louisiana Library Network is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Module 5: Choosing and Researching a Topic

Finding the purpose and central idea of your speech, learning objectives.

- Identify the specific purpose of a speech.

- Explain how to formulate a central idea statement for a speech.

General Purpose

The general purpose of most speeches will fall into one of four categories: to inform , to persuade , to entertain , and to commemorate or celebrate . The first step of defining the purpose of your speech is to think about which category best describes your overall goal with the speech. What do you want your audience to think, feel, or do as a consequence of hearing you speak? Often, the general purpose of your speech will be defined by the speaking situation. If you’re asked to run a training session at work, your purpose isn’t to entertain but rather to inform. Likewise, if you are invited to introduce the winner of an award, you’re not trying to change the audience’s mind about something; you’re honoring the recipient of the award. In a public speaking class, your general purpose may be included in the assignment: for instance, “Give a persuasive speech about . . . .” When you’re assigned a speech project, you should always make sure you know whether the general purpose is included in the assignment or whether you need to decide on the general purpose yourself.

Specific Purpose

Now that you know your general purpose (to inform, to persuade, or to entertain), you can start to move in the direction of the specific purpose. A specific purpose statement builds on your general purpose and makes it more specific (as the name suggests). So if your first speech is an informative speech, your general purpose will be to inform your audience about a very specific realm of knowledge.

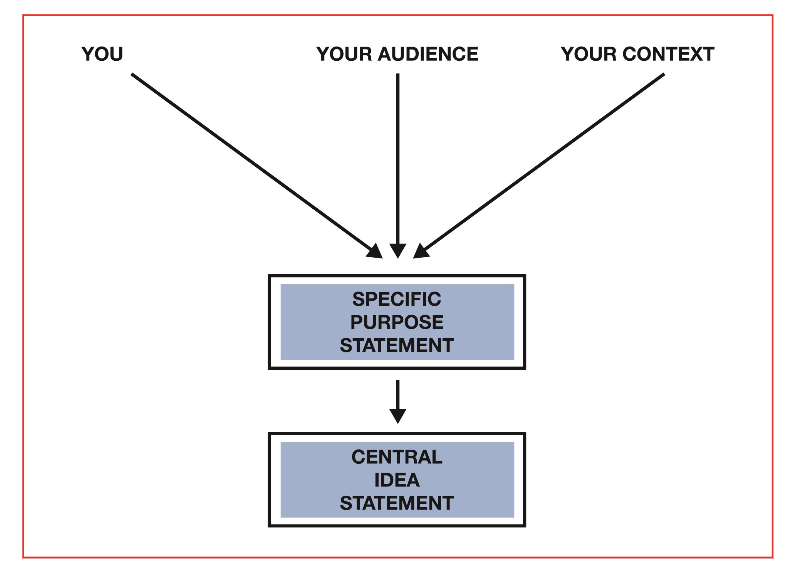

In writing your specific purpose statement, you will take three contributing elements and bring them together to help you determine your specific purpose :

- You (your interests, your background, experience, education, etc.)

- Your audience

- The context or setting

There are three elements that combine to create a specific purpose statements: your own interests and knowledge, the interests and needs of your audience, and the context or setting in which you will be speaking.

Keeping these three inputs in mind, you can begin to write a specific purpose statement, which will be the foundation for everything you say in the speech and a guide for what you do not say. This formula will help you in putting together your specific purpose statement:

To _______________ [ Specific Communication Word (inform, explain, demonstrate, describe, define, persuade, convince, prove, argue)] _______________ [ Target Audience (my classmates, the members of the Social Work Club, my coworkers] __________________. [ The Content (how to bake brownies, that Macs are better than PCs].

Example: The purpose of my presentation is to demonstrate to my coworkers the value of informed intercultural communication .

Formulating a Central Idea Statement

While you will not actually say your specific purpose statement during your speech, you will need to clearly state what your focus and main points are going to be. The statement that reveals your main points is commonly known as the central idea statement (or just the central idea). Just as you would create a thesis statement for an essay or research paper, the central idea statement helps focus your presentation by defining your topic, purpose, direction, angle, and/or point of view. Here are two examples:

- Central Idea—When elderly persons lose their animal companions, they can experience serious psychological, emotional, and physical effects.

- Central Idea—Your computer keyboard needs regular cleaning to function well, and you can achieve that in four easy steps.

Please note that your central idea will emerge and evolve as you research and write your speech, so be open to where your research takes you and anticipate that formulating your central idea will be an ongoing process.

Below are four guidelines for writing a strong central idea.

- Your central idea should be one, full sentence.

- Your central idea should be a statement, not a question.

- Your central idea should be specific and use concrete language.

- Each element of your central idea should be related to the others.

Using the topic “Benefits of Yoga for College Students’ Stress,” here are some correct and incorrect ways to write a central idea.

| Yoga practice can help college students improve the quality of their sleep, improve posture, and manage anxiety. | Yoga is great for many things. It can help you sleep better and not be so stiff. Yoga also helps you feel better. (This central idea is not one sentence and uses vague words.) |

| Yoga practice can help college students focus while studying, manage stress, and increase mindfulness. | What are the benefits of yoga for college students? (This central idea should be a statement, not a question.) |

| Yoga is an inclusive, low-impact practice that offers mental and physical benefits for a beginning athlete, a highly competitive athlete, and everyone in between. | Yoga is great and everyone should try it! (This central idea uses vague language.) |

| Yoga practice can help college students develop mindfulness so they can manage anxiety, increase their sense of self-worth, and improve decision-making. | Yoga practice increases mindfulness, but can lead to some injuries and it takes at least 200 hours of training to become an instructor. (The elements of this central idea are not related to one another.) |

A strong central idea shows that your speech is focused around a clear and concise topic and that you have a strong sense of what you want your audience to know and understand as a result of your speech. Again, it is unlikely that you will have a final central idea before you begin your research. Instead, it will come together as you research your topic and develop your main points.

- Purpose and Central Idea Statements. Provided by : eCampusOntario. Project : Communication for Business Professionals. License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Finding the Purpose of Your Speech. Authored by : Susan Bagley-Koyle with Lumen Learning. License : CC BY: Attribution

14 Crafting a Thesis Statement

Learning Objectives

- Craft a thesis statement that is clear, concise, and declarative.

- Narrow your topic based on your thesis statement and consider the ways that your main points will support the thesis.

Crafting a Thesis Statement

A thesis statement is a short, declarative sentence that states the purpose, intent, or main idea of a speech. A strong, clear thesis statement is very valuable within an introduction because it lays out the basic goal of the entire speech. We strongly believe that it is worthwhile to invest some time in framing and writing a good thesis statement. You may even want to write your thesis statement before you even begin conducting research for your speech. While you may end up rewriting your thesis statement later, having a clear idea of your purpose, intent, or main idea before you start searching for research will help you focus on the most appropriate material. To help us understand thesis statements, we will first explore their basic functions and then discuss how to write a thesis statement.

Basic Functions of a Thesis Statement

A thesis statement helps your audience by letting them know, clearly and concisely, what you are going to talk about. A strong thesis statement will allow your reader to understand the central message of your speech. You will want to be as specific as possible. A thesis statement for informative speaking should be a declarative statement that is clear and concise; it will tell the audience what to expect in your speech. For persuasive speaking, a thesis statement should have a narrow focus and should be arguable, there must be an argument to explore within the speech. The exploration piece will come with research, but we will discuss that in the main points. For now, you will need to consider your specific purpose and how this relates directly to what you want to tell this audience. Remember, no matter if your general purpose is to inform or persuade, your thesis will be a declarative statement that reflects your purpose.

How to Write a Thesis Statement

Now that we’ve looked at why a thesis statement is crucial in a speech, let’s switch gears and talk about how we go about writing a solid thesis statement. A thesis statement is related to the general and specific purposes of a speech.

Once you have chosen your topic and determined your purpose, you will need to make sure your topic is narrow. One of the hardest parts of writing a thesis statement is narrowing a speech from a broad topic to one that can be easily covered during a five- to seven-minute speech. While five to seven minutes may sound like a long time for new public speakers, the time flies by very quickly when you are speaking. You can easily run out of time if your topic is too broad. To ascertain if your topic is narrow enough for a specific time frame, ask yourself three questions.

Is your speech topic a broad overgeneralization of a topic?

Overgeneralization occurs when we classify everyone in a specific group as having a specific characteristic. For example, a speaker’s thesis statement that “all members of the National Council of La Raza are militant” is an overgeneralization of all members of the organization. Furthermore, a speaker would have to correctly demonstrate that all members of the organization are militant for the thesis statement to be proven, which is a very difficult task since the National Council of La Raza consists of millions of Hispanic Americans. A more appropriate thesis related to this topic could be, “Since the creation of the National Council of La Raza [NCLR] in 1968, the NCLR has become increasingly militant in addressing the causes of Hispanics in the United States.”

Is your speech’s topic one clear topic or multiple topics?

A strong thesis statement consists of only a single topic. The following is an example of a thesis statement that contains too many topics: “Medical marijuana, prostitution, and Women’s Equal Rights Amendment should all be legalized in the United States.” Not only are all three fairly broad, but you also have three completely unrelated topics thrown into a single thesis statement. Instead of a thesis statement that has multiple topics, limit yourself to only one topic. Here’s an example of a thesis statement examining only one topic: Ratifying the Women’s Equal Rights Amendment as equal citizens under the United States law would protect women by requiring state and federal law to engage in equitable freedoms among the sexes.

Does the topic have direction?

If your basic topic is too broad, you will never have a solid thesis statement or a coherent speech. For example, if you start off with the topic “Barack Obama is a role model for everyone,” what do you mean by this statement? Do you think President Obama is a role model because of his dedication to civic service? Do you think he’s a role model because he’s a good basketball player? Do you think he’s a good role model because he’s an excellent public speaker? When your topic is too broad, almost anything can become part of the topic. This ultimately leads to a lack of direction and coherence within the speech itself. To make a cleaner topic, a speaker needs to narrow her or his topic to one specific area. For example, you may want to examine why President Obama is a good public speaker.

Put Your Topic into a Declarative Sentence

You wrote your general and specific purpose. Use this information to guide your thesis statement. If you wrote a clear purpose, it will be easy to turn this into a declarative statement.

General purpose: To inform

Specific purpose: To inform my audience about the lyricism of former President Barack Obama’s presentation skills.

Your thesis statement needs to be a declarative statement. This means it needs to actually state something. If a speaker says, “I am going to talk to you about the effects of social media,” this tells you nothing about the speech content. Are the effects positive? Are they negative? Are they both? We don’t know. This sentence is an announcement, not a thesis statement. A declarative statement clearly states the message of your speech.

For example, you could turn the topic of President Obama’s public speaking skills into the following sentence: “Because of his unique sense of lyricism and his well-developed presentational skills, President Barack Obama is a modern symbol of the power of public speaking.” Or you could state, “Socal media has both positive and negative effects on users.”

Adding your Argument, Viewpoint, or Opinion

If your topic is informative, your job is to make sure that the thesis statement is nonargumentative and focuses on facts. For example, in the preceding thesis statement, we have a couple of opinion-oriented terms that should be avoided for informative speeches: “unique sense,” “well-developed,” and “power.” All three of these terms are laced with an individual’s opinion, which is fine for a persuasive speech but not for an informative speech. For informative speeches, the goal of a thesis statement is to explain what the speech will be informing the audience about, not attempting to add the speaker’s opinion about the speech’s topic. For an informative speech, you could rewrite the thesis statement to read, “Barack Obama’s use of lyricism in his speech, ‘A World That Stands as One,’ delivered July 2008 in Berlin demonstrates exceptional use of rhetorical strategies.

On the other hand, if your topic is persuasive, you want to make sure that your argument, viewpoint, or opinion is clearly indicated within the thesis statement. If you are going to argue that Barack Obama is a great speaker, then you should set up this argument within your thesis statement.

For example, you could turn the topic of President Obama’s public speaking skills into the following sentence: “Because of his unique sense of lyricism and his well-developed presentational skills, President Barack Obama is a modern symbol of the power of public speaking.” Once you have a clear topic sentence, you can start tweaking the thesis statement to help set up the purpose of your speech.

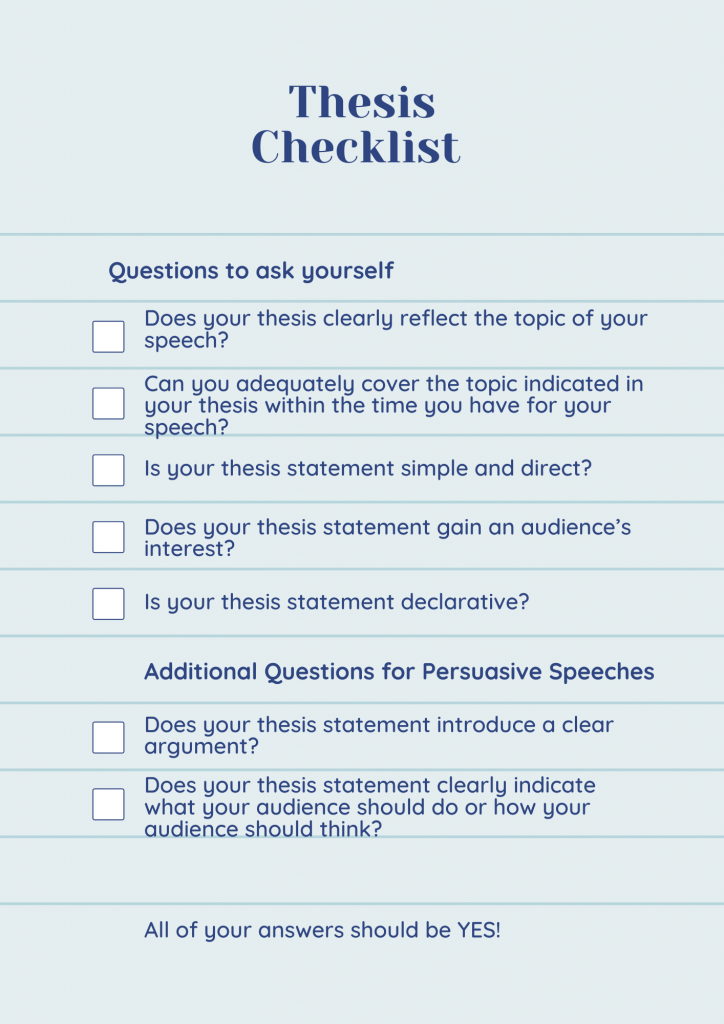

Thesis Checklist

Once you have written a first draft of your thesis statement, you’re probably going to end up revising your thesis statement a number of times prior to delivering your actual speech. A thesis statement is something that is constantly tweaked until the speech is given. As your speech develops, often your thesis will need to be rewritten to whatever direction the speech itself has taken. We often start with a speech going in one direction, and find out through our research that we should have gone in a different direction. When you think you finally have a thesis statement that is good to go for your speech, take a second and make sure it adheres to the criteria shown below.

Preview of Speech

The preview, as stated in the introduction portion of our readings, reminds us that we will need to let the audience know what the main points in our speech will be. You will want to follow the thesis with the preview of your speech. Your preview will allow the audience to follow your main points in a sequential manner. Spoiler alert: The preview when stated out loud will remind you of main point 1, main point 2, and main point 3 (etc. if you have more or less main points). It is a built in memory card!

For Future Reference | How to organize this in an outline |

Introduction

Attention Getter: Background information: Credibility: Thesis: Preview:

Key Takeaways

Introductions are foundational to an effective public speech.

- A thesis statement is instrumental to a speech that is well-developed and supported.

- Be sure that you are spending enough time brainstorming strong attention getters and considering your audience’s goal(s) for the introduction.

- A strong thesis will allow you to follow a roadmap throughout the rest of your speech: it is worth spending the extra time to ensure you have a strong thesis statement.

Stand up, Speak out by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Public Speaking Copyright © by Dr. Layne Goodman; Amber Green, M.A.; and Various is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

7.2 The Topic, General Purpose, Specific Purpose, and Thesis

Click below to play an audio file of this section of the chapter sponsored by the Women for OSU Partnering to Impact grant.

Before any work can be done on crafting the body of your speech or presentation, you must first do some prep work—selecting a topic, formulating a general purpose, a specific purpose statement, and crafting a central idea, or thesis statement. In doing so, you lay the foundation for your speech by making important decisions about what you will speak about and for what purpose you will speak. These decisions will influence and guide the entire speechwriting process, so it is wise to think carefully and critically during these beginning stages.

Selecting a Topic

Generally, speakers focus on one or more interrelated topics—relatively broad concepts, ideas, or problems that are relevant for particular audiences. The most common way that speakers discover topics is by simply observing what is happening around them—at their school, in their local government, or around the world. Student government leaders, for example, speak or write to other students when their campus is facing tuition or fee increases, or when students have achieved something spectacular, like lobbying campus administrators for lower student fees and succeeding. In either case, it is the situation that makes their speeches appropriate and useful for their audience of students and university employees. More importantly, they speak when there is an opportunity to change a university policy or to alter the way students think or behave in relation to a particular event on campus.

But you need not run for president or student government in order to give a meaningful speech. On the contrary, opportunities abound for those interested in engaging speech as a tool for change. Perhaps the simplest way to find a topic is to ask yourself a few questions, including:

• What important events are occurring locally, nationally and internationally? • What do I care about most? • Is there someone or something I can advocate for? • What makes me angry/happy? • What beliefs/attitudes do I want to share? • Is there some information the audience needs to know?

Students speak about what is interesting to them and their audiences. What topics do you think are relevant today? There are other questions you might ask yourself, too, but these should lead you to at least a few topical choices. The most important work that these questions do is to locate topics within your pre-existing sphere of knowledge and interest. David Zarefsky (2010) also identifies brainstorming as a way to develop speech topics, a strategy that can be helpful if the questions listed above did not yield an appropriate or interesting topic. Starting with a topic you are already interested in will likely make writing and presenting your speech a more enjoyable and meaningful experience. It means that your entire speechwriting process will focus on something you find important and that you can present this information to people who stand to benefit from your speech.

Once you have answered these questions and narrowed your responses, you are still not done selecting your topic. For instance, you might have decided that you really care about breeds of dogs. This is a very broad topic and could easily lead to a dozen different speeches. To resolve this problem, speakers must also consider the audience to whom they will speak, the scope of their presentation, and the outcome they wish to achieve.

Formulating the Purpose Statements

By honing in on a very specific topic, you begin the work of formulating your purpose statement . In short, a purpose statement clearly states what it is you would like to achieve. Purpose statements are especially helpful for guiding you as you prepare your speech. When deciding which main points, facts, and examples to include, you should simply ask yourself whether they are relevant not only to the topic you have selected, but also whether they support the goal you outlined in your purpose statement. The general purpose statement of a speech may be to inform, to persuade, to celebrate, or to entertain. Thus, it is common to frame a specific purpose statement around one of these goals. According to O’Hair, Stewart, and Rubenstein, a specific purpose statement “expresses both the topic and the general speech purpose in action form and in terms of the specific objectives you hope to achieve” (2004). For instance, the home design enthusiast might write the following specific purpose statement: At the end of my speech, the audience will learn the pro’s and con’s of flipping houses. In short, the general purpose statement lays out the broader goal of the speech while the specific purpose statement describes precisely what the speech is intended to do. Some of your professors may ask that you include the general purpose and add the specific purpose.

Writing the Thesis Statement

The specific purpose statement is a tool that you will use as you write your talk, but it is unlikely that it will appear verbatim in your speech. Instead, you will want to convert the specific purpose statement into a central idea, or thesis statement that you will share with your audience.

Depending on your instructor’s approach, a thesis statement may be written two different ways. A thesis statement may encapsulate the main points of a speech in just a sentence or two, and be designed to give audiences a quick preview of what the entire speech will be about. The thesis statement for a speech, like the thesis of a research-based essay, should be easily identifiable and ought to very succinctly sum up the main points you will present. Some instructors prefer that your thesis, or central idea, be a single, declarative statement providing the audience with an overall statement that provides the essence of the speech, followed by a separate preview statement.

If you are a Harry Potter enthusiast, you may write a thesis statement (central idea) the following way using the above approach: J.K. Rowling is a renowned author of the Harry Potter series with a Cinderella like story having gone from relatively humble beginnings, through personal struggles, and finally success and fame.

Writing the Preview Statement

However, some instructors prefer that you separate your thesis from your preview statement . A preview statement (or series of statements) is a guide to your speech. This is the part of the speech that literally tells the audience exactly what main points you will cover. If you were to open your Waze app, it would tell you exactly how to get there. Best of all, you would know what to look for! So, if we take our J.K Rowling example, let’s rewrite that using this approach separating out the thesis and preview:

J.K. Rowling is a renowned author of the Harry Potter series with a Cinderella like rags to riches story. First, I will tell you about J.K. Rowling’s humble beginnings. Then, I will describe her personal struggles as a single mom. Finally, I will explain how she overcame adversity and became one of the richest women in the United Kingdom.

There is no best way to approach this. This is up to your instructor.

Writing the Body of Your Speech

Once you have finished the important work of deciding what your speech will be about, as well as formulating the purpose statement and crafting the thesis, you should turn your attention to writing the body of your speech. All of your main points are contained in the body, and normally this section is prepared well before you ever write the introduction or conclusion. The body of your speech will consume the largest amount of time to present; and it is the opportunity for you to elaborate on facts, evidence, examples, and opinions that support your thesis statement and do the work you have outlined in the specific purpose statement. Combining these various elements into a cohesive and compelling speech, however, is not without its difficulties, the first of which is deciding which elements to include and how they ought to be organized to best suit your purpose.

clearly states what it is you would like to achieve

“expresses both the topic and the general speech purpose in action form and in terms of the specific objectives you hope to achieve" (O'Hair, Stewart, & Rubenstein, 2004)

single, declarative sentence that captures the essence or main point of your entire presentation

the part of the speech that literally tells the audience exactly what main points you will cover

Introduction to Speech Communication Copyright © 2021 by Individual authors retain copyright of their work. is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Chapter 5: Presentation Organization

32 Purpose and Central Idea Statements

Speeches have traditionally been seen to have one of three broad purposes: to inform, to persuade, and — well, to be honest, different words are used for the third kind of speech purpose: to inspire, to amuse, to please, or to entertain. These broad goals are commonly known as a speech’s general purpose, since, in general, you are trying to inform, persuade, or entertain your audience without regard to specifically what the topic will be. Perhaps you could think of them as appealing to the understanding of the audience (informative), the will or action (persuasive), and the emotion or pleasure.

Now that you know your general purpose (to inform, to persuade, or to entertain), you can start to move in the direction of the specific purpose. A specific purpose statement builds on your general purpose (to inform) and makes it more specific (as the name suggests). So if your first speech is an informative speech, your general purpose will be to inform your audience about a very specific realm of knowledge.

In writing your specific purpose statement, you will take three contributing elements (shown in figure 5.3) that will come together to help you determine your specific purpose :

- You (your interests, your background, past jobs, experience, education, major),

- Your audience

- The context or setting.

Putting It Together

Keeping these three inputs in mind, you can begin to write a specific purpose statement , which will be the foundation for everything you say in the speech and a guide for what you do not say. This formula will help you in putting together your specific purpose statement:

To _______________ [Specific Communication Word (inform, explain, demonstrate, describe, define, persuade, convince, prove, argue)] my [ Target Audience (my classmates, the members of the Social Work Club, my coworkers] __________________. [T he Content (how to bake brownies, that Macs are better than PCs].

Example: The purpose of my presentation is to demonstrate for my coworkers the value of informed intercultural communication.

Formulating a Central Idea Statement

While you will not actually say your specific purpose statement during your speech, you will need to clearly state what your focus and main points are going to be. The statement that reveals your main points is commonly known as the central idea statement (or just the central idea). Just as you would create a thesis statement for an essay or research paper, the central idea statement helps focus your presentation by defining your topic, purpose, direction, angle and/or point of view. Here are two examples:

Specific Purpose – To explain to my classmates the effects of losing a pet on the elderly.

Central Idea – When elderly persons lose their animal companions, they can experience serious psychological, emotional, and physical effects.

Specific Purpose – To demonstrate to my audience the correct method for cleaning a computer keyboard.

Central Idea – Your computer keyboard needs regular cleaning to function well, and you can achieve that in four easy steps.

Communication for Business Professionals Copyright © 2018 by eCampusOntario is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

BUS210: Business Communication

Preparing your speech to inform.

Read this section, which describes how to give an ethical speech, especially when the purpose of that speech is to inform. It is important to be non-judgemental and honest in your approach. After you read, try the exercises at the end of the section.

Learning Objectives

- Discuss and provide examples of ways to incorporate ethics in a speech.

- Construct an effective speech to inform.

Now that we've covered issues central to the success of your informative speech, there's no doubt you want to get down to work. Here are five final suggestions to help you succeed.

Start with What You Know

Are you taking other classes right now that are fresh in your memory? Are you working on a challenging chemistry problem that might lend itself to your informative speech? Are you reading a novel by Gabriel García Márquez that might inspire you to present a biographical speech, informing your audience about the author? Perhaps you have a hobby or outside interest that you are excited about that would serve well. Regardless of where you draw the inspiration, it's a good strategy to start with what you know and work from there. You'll be more enthusiastic, helping your audience to listen intently, and you'll save yourself time. Consider the audience's needs, not just your need to cross a speech off your "to-do" list. This speech will be an opportunity for you to take prepared material and present it, gaining experience and important feedback. In the "real world," you often lack time and the consequences of a less than effective speech can be serious. Look forward to the opportunity and use what you know to perform an effective, engaging speech.

Consider Your Audience's Prior Knowledge

You don't want to present a speech on the harmful effects of smoking when no one in the audience smokes. You may be more effective addressing the issue of secondhand smoke, underscoring the relationship to relevance and addressing the issue of importance with your audience. The audience will want to learn something from you, not hear everything they have heard before. It's a challenge to assess what they've heard before, and often a class activity is conducted to allow audience members to come to know each other. You can also use their speeches and topic selection as points to consider. Think about age, gender, and socioeconomic status, as well as your listeners' culture or language. Survey the audience if possible, or ask a couple of classmates what they think of the topics you are considering. In the same way, when you prepare a speech in a business situation, do your homework. Access the company Web site, visit the location and get to know people, and even call members of the company to discuss your topic. The more information you can gather about your audience, the better you will be able to adapt and present an effective speech.

Adapting Jargon and Technical Terms

You may have a topic in mind from another class or an outside activity, but chances are that there are terms specific to the area or activity. From wakeboarding to rugby to a chemical process that contributes to global warming, there will be jargon and technical terms. Define and describe the key terms for your audience as part of your speech and substitute common terms where appropriate. Your audience will enjoy learning more about the topic and appreciate your consideration as you present your speech.

Using Outside Information

Even if you think you know everything there is to know about your topic, using outside sources will contribute depth to your speech, provide support for your main points, and even enhance your credibility as a speaker. "According to ____________" is a normal way of attributing information to a source, and you should give credit where credit is due. There is nothing wrong with using outside information as long as you clearly cite your sources and do not present someone else's information as your own.

Presenting Information Ethically

A central but often unspoken expectation of the speaker is that we will be ethical. This means, fundamentally, that we perceive one another as human beings with common interests and needs, and that we attend to the needs of others as well as our own. An ethical informative speaker expresses respect for listeners by avoiding prejudiced comments against any group, and by being honest about the information presented, including information that may contradict the speaker's personal biases. The ethical speaker also admits it when he or she does not know something. The best salespersons recognize that ethical communication is the key to success, as it builds a healthy relationship where the customer's needs are met, thereby meeting the salesperson's own needs.

Reciprocity

Tyler discusses ethical communication and specifically indicates reciprocity as a key principle. Reciprocity , or a relationship of mutual exchange and interdependence, is an important characteristic of a relationship, particularly between a speaker and the audience. We've examined previously the transactional nature of communication, and it is important to reinforce this aspect here. We exchange meaning with one another in conversation, and much like a game, it takes more than one person to play. This leads to interdependence, or the dependence of the conversational partners on one another. Inequality in the levels of dependence can negatively impact the communication and, as a result, the relationship. You as the speaker will have certain expectations and roles, but dominating your audience will not encourage them to fulfill their roles in terms of participation and active listening. Communication involves give and take, and in a public speaking setting, where the communication may be perceived as "all to one," don't forget that the audience is also communicating in terms of feedback with you. You have a responsibility to attend to that feedback, and develop reciprocity with your audience. Without them, you don't have a speech.

Mutuality means that you search for common ground and understanding with the audience, establishing this space and building on it throughout the speech. This involves examining viewpoints other than your own, and taking steps to insure the speech integrates an inclusive, accessible format rather than an ethnocentric one.

Nonjudgmentalism

Nonjudgmentalism underlines the need to be open-minded, an expression of one's willingness to examine diverse perspectives. Your audience expects you to state the truth as you perceive it, with supporting and clarifying information to support your position, and to speak honestly. They also expect you to be open to their point of view and be able to negotiate meaning and understanding in a constructive way. Nonjudgmentalism may include taking the perspective that being different is not inherently bad and that there is common ground to be found with each other. While this characteristic should be understood, we can see evidence of breakdowns in communication when audiences perceive they are not being told the whole truth. This does not mean that the relationship with the audience requires honesty and excessive self-disclosure. The use of euphemisms and displays of sensitivity are key components of effective communication, and your emphasis on the content of your speech and not yourself will be appreciated. Nonjudgmentalism does underscore the importance of approaching communication from an honest perspective where you value and respect your audience.

Honesty , or truthfulness, directly relates to trust, a cornerstone in the foundation of a relationship with your audience. Without it, the building (the relationship) would fall down. Without trust, a relationship will not open and develop the possibility of mutual understanding. You want to share information and the audience hopefully wants to learn from you. If you "cherry-pick" your data, only choosing the best information to support only your point and ignore contrary or related issues, you may turn your informative speech into a persuasive one with bias as a central feature. Look at the debate over the U.S. conflict with Iraq. There has been considerable discussion concerning the cherry-picking of issues and facts to create a case for armed intervention. To what degree the information at the time was accurate or inaccurate will continue to be a hotly debated issue, but the example holds in terms on an audience's response to a perceived dishonestly. Partial truths are incomplete and often misleading, and you don't want your audience to turn against you because they suspect you are being less than forthright and honest.

Respect should be present throughout a speech, demonstrating the speaker's high esteem for the audience. Respect can be defined as an act of giving and displaying particular attention to the value you associate with someone or a group. This definition involves two key components. You need to give respect in order to earn from others, and you need to show it. Displays of respect include making time for conversation, not interrupting, and even giving appropriate eye contact during conversations.

Communication involves sharing and that requires trust. Trust means the ability to rely on the character or truth of someone, that what you say you mean and your audience knows it. Trust is a process, not a thing. It builds over time, through increased interaction and the reduction of uncertainty. It can be lost, but it can also be regained. It should be noted that it takes a long time to build trust in a relationship and can be lost in a much shorter amount of time. If your audience suspects you mislead them this time, how will they approach your next presentation? Acknowledging trust and its importance in your relationship with the audience is the first step in focusing on this key characteristic.

Avoid Exploitation

Finally, when we speak ethically, we do not intentionally exploit one another. Exploitation means taking advantage, using someone else for one's own purposes. Perceiving a relationship with an audience as a means to an end and only focusing on what you get out of it, will lead you to treat people as objects. The temptation to exploit others can be great in business situations, where a promotion, a bonus, or even one's livelihood are at stake. Suppose you are a bank loan officer. Whenever a customer contacts the bank to inquire about applying for a loan, your job is to provide an informative presentation about the types of loans available, their rates and terms. If you are paid a commission based on the number of loans you make and their amounts and rates, wouldn't you be tempted to encourage them to borrow the maximum amount they can qualify for? Or perhaps to take a loan with confusing terms that will end up costing much more in fees and interest than the customer realizes? After all, these practices are within the law; aren't they just part of the way business is done? If you are an ethical loan officer, you realize you would be exploiting customers if you treated them this way. You know it is more valuable to uphold your long-term relationships with customers than to exploit them so that you can earn a bigger commission. Consider these ethical principles when preparing and presenting your speech, and you will help address many of these natural expectations of others and develop healthier, more effective speeches.

Sample Informative Presentation

Here is a generic sample speech in outline form with notes and suggestions.

Attention Statement

Show a picture of a goldfish and a tomato and ask the audience, "What do these have in common?"

Introduction

Briefly introduce genetically modified foods.

- State your topic and specific purpose: "My speech today will inform you on genetically modified foods that are increasingly part of our food supply".

- Introduce your credibility and the topic: "My research on this topic has shown me that our food supply has changed but many people are unaware of the changes".

- State your main points: "Today I will define genes, DNA, genome engineering and genetic manipulation, discuss how the technology applies to foods, and provide common examples".

- Information. Provide a simple explanation of the genes, DNA and genetic modification in case there are people who do not know about it. Provide clear definitions of key terms.

- Genes and DNA. Provide arguments by generalization and authority.

- Genome engineering and genetic manipulation. Provide arguments by analogy, cause, and principle.

- Case study. In one early experiment, GM (genetically modified) tomatoes were developed with fish genes to make them resistant to cold weather, although this type of tomato was never marketed.

- Highlight other examples.

Reiterate your main points and provide synthesis, but do not introduce new content.

Residual Message

"Genetically modified foods are more common in our food supply than ever before".

Key Takeaway

In preparing an informative speech, use your knowledge and consider the audience's knowledge, avoid unnecessary jargon, give credit to your sources, and present the information ethically.

- Identify an event or issue in the news that interests you. On at least three different news networks or Web sites, find and watch video reports about this issue. Compare and contrast the coverage of the issue. Do the networks or Web sites differ in their assumptions about viewers' prior knowledge? Do they give credit to any sources of information? To what extent do they each measure up to the ethical principles described in this section? Discuss your findings with your classmates.

- Find an example of reciprocity in a television program and write two to three paragraphs describing it. Share and compare with your classmates.

- Find an example of honesty in a television program and write two to three paragraphs describing it. Share and compare with your classmates.

- Find an example of exploitation depicted in the media. Describe how the exploitation is communicated with words and images and share with the class.

- Compose a general purpose statement and thesis statement for a speech to inform. Now create a sample outline. Share with a classmate and see if he or she offers additional points to consider.

Speech Thesis Statement

Speech thesis statement generator.

In the realm of effective communication, crafting a well-structured and compelling speech thesis statement is paramount. A speech thesis serves as the bedrock upon which impactful oratory is built, encapsulating the core message, purpose, and direction of the discourse. This exploration delves into diverse speech thesis statement examples, offering insights into the art of formulating them. Moreover, it provides valuable tips to guide you in crafting speeches that resonate powerfully with your audience and leave a lasting impact.

What is a Speech Thesis Statement? – Definition

A speech thesis statement is a succinct and focused declaration that encapsulates the central argument, purpose, or message of a speech. It outlines the primary idea the speaker intends to convey to the audience, serving as a guide for the content and structure of the speech.

What is an Example of Speech Thesis Statement?

“In this speech, I will argue that implementing stricter gun control measures is essential for reducing gun-related violence and ensuring public safety. By examining statistical data, addressing common misconceptions, and advocating for comprehensive background checks, we can take meaningful steps toward a safer society.”

In this example, the speech’s main argument, key points (statistics, misconceptions, background checks), and the intended impact (safer society) are all succinctly conveyed in the thesis statement.

100 Speech Thesis Statement Examples

- “Today, I will convince you that renewable energy sources are the key to a sustainable and cleaner future.”

- “In this speech, I will explore the importance of mental health awareness and advocate for breaking the stigma surrounding it.”

- “My aim is to persuade you that adopting a plant-based diet contributes not only to personal health but also to environmental preservation.”

- “In this speech, I will discuss the benefits of exercise on cognitive function and share practical tips for integrating physical activity into our daily routines.”

- “Today, I’ll argue that access to quality education is a fundamental right for all, and I’ll present strategies to bridge the educational gap.”

- “My speech centers around the significance of arts education in fostering creativity, critical thinking, and overall cognitive development in students.”

- “Through this speech, I’ll shed light on the impact of plastic pollution on marine ecosystems and inspire actionable steps toward plastic reduction.”

- “My aim is to persuade you that stricter regulations on social media platforms are imperative to combat misinformation and protect user privacy.”

- “Today, I’ll discuss the importance of empathy in building strong interpersonal relationships and provide techniques to cultivate empathy in daily interactions.”

- “In this speech, I’ll present the case for implementing universal healthcare, emphasizing its benefits for both individual health and societal well-being.”

- “My speech highlights the urgency of addressing climate change and calls for international collaboration in reducing carbon emissions.”

- “I will argue that the arts play a crucial role in fostering cultural understanding, breaking down stereotypes, and promoting global harmony.”

- “Through this speech, I’ll advocate for the preservation of endangered species and offer strategies to contribute to wildlife conservation efforts.”

- “Today, I’ll discuss the power of effective time management in enhancing productivity and share practical techniques to prioritize tasks.”

- “My aim is to convince you that raising the minimum wage is vital to reducing income inequality and improving the overall quality of life.”

- “In this speech, I’ll explore the societal implications of automation and artificial intelligence and propose strategies for a smooth transition into the future.”

- “Through this speech, I’ll emphasize the significance of volunteering in community development and suggest ways to get involved in meaningful initiatives.”

- “I will argue that stricter regulations on fast food advertising are necessary to address the growing obesity epidemic among children and adolescents.”

- “Today, I’ll discuss the importance of financial literacy in personal empowerment and provide practical advice for making informed financial decisions.”

- “My speech focuses on the value of cultural diversity in enriching society, fostering understanding, and promoting a more inclusive world.”

- “In this speech, I’ll present the case for investing in renewable energy technologies to mitigate the adverse effects of climate change on future generations.”

- “I will argue that embracing failure as a stepping stone to success is crucial for personal growth and achieving one’s fullest potential.”

- “Through this speech, I’ll examine the impact of social media on mental health and offer strategies to maintain a healthy online presence.”

- “Today, I’ll emphasize the importance of effective communication skills in professional success and share tips for honing these skills.”

- “My aim is to persuade you that stricter gun control measures are essential to reduce gun-related violence and ensure public safety.”

- “In this speech, I’ll discuss the significance of cultural preservation and the role of heritage sites in maintaining the identity and history of communities.”

- “I will argue that promoting diversity and inclusion in the workplace leads to enhanced creativity, collaboration, and overall organizational success.”

- “Through this speech, I’ll explore the impact of social media on political engagement and discuss ways to critically evaluate online information sources.”

- “Today, I’ll present the case for investing in public transportation infrastructure to alleviate traffic congestion, reduce pollution, and enhance urban mobility.”

- “My aim is to persuade you that implementing mindfulness practices in schools can improve students’ focus, emotional well-being, and overall academic performance.”

- “In this speech, I’ll discuss the importance of supporting local businesses for economic growth, community vibrancy, and sustainable development.”

- “I will argue that fostering emotional intelligence in children equips them with crucial skills for interpersonal relationships, empathy, and conflict resolution.”

- “Through this speech, I’ll emphasize the need for comprehensive sex education that addresses consent, healthy relationships, and informed decision-making.”

- “Today, I’ll explore the benefits of embracing a minimalist lifestyle for mental clarity, reduced stress, and a more mindful and sustainable way of living.”

- “My aim is to persuade you that sustainable farming practices are essential for preserving ecosystems, ensuring food security, and mitigating climate change.”

- “In this speech, I’ll discuss the importance of civic engagement in democracy and provide strategies for individuals to get involved in their communities.”

- “I will argue that investing in early childhood education not only benefits individual children but also contributes to a stronger and more prosperous society.”

- “Through this speech, I’ll examine the impact of social media on body image dissatisfaction and offer strategies to promote body positivity and self-acceptance.”

- “Today, I’ll present the case for stricter regulations on e-cigarette marketing and sales to curb youth vaping and protect public health.”

- “My aim is to persuade you that exploring nature and spending time outdoors is essential for mental and physical well-being in our technology-driven world.”

- “In this speech, I’ll discuss the implications of automation on employment and suggest strategies for reskilling and preparing for the future of work.”

- “I will argue that embracing failure as a valuable learning experience fosters resilience, innovation, and personal growth, leading to ultimate success.”

- “Through this speech, I’ll emphasize the significance of media literacy in discerning credible information from fake news and ensuring informed decision-making.”

- “Today, I’ll explore the benefits of implementing universal healthcare, focusing on improved access to medical services and enhanced public health outcomes.”

- “My aim is to persuade you that embracing sustainable travel practices can minimize the environmental impact of tourism and promote cultural exchange.”

- “In this speech, I’ll present the case for criminal justice reform, highlighting the importance of alternatives to incarceration for nonviolent offenders.”

- “I will argue that instilling a growth mindset in students enhances their motivation, learning abilities, and willingness to face challenges.”

- “Through this speech, I’ll discuss the implications of artificial intelligence on the job market and propose strategies for adapting to automation-driven changes.”

- “Today, I’ll emphasize the importance of digital privacy awareness and provide practical tips to safeguard personal information online.”

- “My aim is to persuade you that investing in renewable energy sources is crucial not only for environmental sustainability but also for economic growth.”

- “In this speech, I’ll discuss the significance of cultural preservation and the role of heritage sites in maintaining a sense of identity and history.”

- “I will argue that promoting diversity and inclusion in the workplace leads to improved creativity, collaboration, and overall organizational performance.”

- “Through this speech, I’ll explore the impact of social media on political engagement and offer strategies to critically assess online information.”

- “Today, I’ll present the case for investing in public transportation to alleviate traffic congestion, reduce emissions, and enhance urban mobility.”

- “My aim is to persuade you that implementing mindfulness practices in schools can enhance students’ focus, emotional well-being, and academic achievement.”

- “In this speech, I’ll discuss the importance of supporting local businesses for economic growth, community vitality, and sustainable development.”

- “I will argue that fostering emotional intelligence in children equips them with essential skills for healthy relationships, empathy, and conflict resolution.”

- “Through this speech, I’ll emphasize the need for comprehensive sex education that includes consent, healthy relationships, and informed decision-making.”

- “My aim is to persuade you that sustainable farming practices are vital for preserving ecosystems, ensuring food security, and combating climate change.”

- “In this speech, I’ll discuss the importance of civic engagement in democracy and provide strategies for individuals to actively participate in their communities.”

- “I will argue that investing in early childhood education benefits not only individual children but also contributes to a stronger and more prosperous society.”

- “Through this speech, I’ll examine the impact of social media on body image dissatisfaction and suggest strategies to promote body positivity and self-acceptance.”

- “Today, I’ll present the case for stricter regulations on e-cigarette marketing and sales to combat youth vaping and protect public health.”

- “My aim is to persuade you that connecting with nature and spending time outdoors is essential for mental and physical well-being in our technology-driven world.”

- “In this speech, I’ll discuss the implications of automation on employment and suggest strategies for reskilling and adapting to the changing job landscape.”

- “I will argue that embracing failure as a valuable learning experience fosters resilience, innovation, and personal growth, ultimately leading to success.”

- “Through this speech, I’ll emphasize the significance of media literacy in discerning credible information from fake news and making informed decisions.”

- “Today, I’ll explore the benefits of implementing universal healthcare, focusing on improved access to medical services and better public health outcomes.”

- “My aim is to persuade you that adopting sustainable travel practices can minimize the environmental impact of tourism and promote cultural exchange.”

- “I will argue that instilling a growth mindset in students enhances their motivation, learning abilities, and readiness to tackle challenges.”

- “Through this speech, I’ll discuss the implications of artificial intelligence on the job market and propose strategies for adapting to the changing landscape.”

- “Today, I’ll emphasize the importance of digital privacy awareness and provide practical tips to safeguard personal information in the online world.”

- “My aim is to persuade you that investing in renewable energy sources is essential for both environmental sustainability and economic growth.”

- “In this speech, I’ll discuss the transformative power of art therapy in promoting mental well-being and share real-life success stories.”

- “I will argue that promoting gender equality not only empowers women but also contributes to economic growth and social progress.”

- “Through this speech, I’ll explore the impact of technology on interpersonal relationships and offer strategies to maintain meaningful connections.”

- “Today, I’ll present the case for sustainable fashion choices, emphasizing their positive effects on the environment and ethical manufacturing practices.”

- “My aim is to persuade you that investing in early childhood education is an investment in the future, leading to a more educated and equitable society.”

- “In this speech, I’ll discuss the significance of community service in building strong communities and share personal stories of volunteering experiences.”

- “I will argue that fostering emotional intelligence in children lays the foundation for a harmonious and empathetic society.”

- “Through this speech, I’ll emphasize the importance of teaching critical thinking skills in education and how they empower individuals to navigate a complex world.”

- “Today, I’ll explore the benefits of embracing a growth mindset in personal and professional development, leading to continuous learning and improvement.”

- “My aim is to persuade you that conscious consumerism can drive positive change in industries by supporting ethical practices and environmentally friendly products.”

- “In this speech, I’ll present the case for renewable energy as a solution to energy security, reduced carbon emissions, and a cleaner environment.”

- “I will argue that investing in mental health support systems is essential for the well-being of individuals and society as a whole.”

- “Through this speech, I’ll discuss the role of music therapy in enhancing mental health and promoting emotional expression and healing.”

- “Today, I’ll emphasize the importance of embracing cultural diversity to foster global understanding, harmony, and peaceful coexistence.”

- “My aim is to persuade you that incorporating mindfulness practices into daily routines can lead to reduced stress and increased overall well-being.”

- “In this speech, I’ll discuss the implications of genetic engineering and gene editing technologies on ethical considerations and future generations.”

- “I will argue that investing in renewable energy infrastructure not only mitigates climate change but also generates job opportunities and economic growth.”

- “Through this speech, I’ll explore the impact of social media on political polarization and offer strategies for promoting constructive online discourse.”

- “Today, I’ll present the case for embracing experiential learning in education, focusing on hands-on experiences that enhance comprehension and retention.”

- “My aim is to persuade you that practicing gratitude can lead to improved mental health, increased happiness, and a more positive outlook on life.”

- “In this speech, I’ll discuss the importance of teaching financial literacy in schools to equip students with essential money management skills.”

- “I will argue that promoting sustainable agriculture practices is essential to ensure food security, protect ecosystems, and combat climate change.”

- “Through this speech, I’ll emphasize the need for greater awareness of mental health issues in society and the importance of reducing stigma.”

- “Today, I’ll explore the benefits of incorporating arts and creativity into STEM education to foster innovation, critical thinking, and problem-solving.”

- “My aim is to persuade you that practicing mindfulness and meditation can lead to improved focus, reduced anxiety, and enhanced overall well-being.”

Speech Thesis Statement for Introduction

Introductions set the tone for impactful speeches. These thesis statements encapsulate the essence of opening remarks, laying the foundation for engaging discourse.

- “Welcome to an exploration of the power of storytelling and its ability to bridge cultures and foster understanding across diverse backgrounds.”

- “In this introductory speech, we delve into the realm of artificial intelligence, examining its potential to reshape industries and redefine human capabilities.”

- “Join us as we navigate the fascinating world of space exploration and the role of technological advancements in uncovering the mysteries of the universe.”

- “Through this speech, we embark on a journey through history, highlighting pivotal moments that have shaped civilizations and continue to inspire change.”

- “Today, we embark on a discussion about the significance of empathy in our interactions, exploring how it can enrich our connections and drive positive change.”

- “In this opening address, we dive into the realm of sustainable living, exploring practical steps to reduce our environmental footprint and promote eco-consciousness.”

- “Join us as we explore the evolution of communication, from ancient symbols to modern technology, and its impact on how we connect and convey ideas.”

- “Welcome to an exploration of the intricate relationship between art and emotion, uncovering how artistic expression transcends language barriers and unites humanity.”

- “In this opening statement, we examine the changing landscape of work and career, discussing strategies to navigate career transitions and embrace lifelong learning.”

- “Today, we delve into the concept of resilience and its role in facing adversity, offering insights into how resilience can empower us to overcome challenges.”

Speech Thesis Statement for Graduation

Graduation speeches mark significant milestones. These thesis statements encapsulate the achievements, aspirations, and challenges faced by graduates as they move forward.

- “As we stand on the threshold of a new chapter, let’s reflect on our journey, celebrate our achievements, and embrace the uncertainties that lie ahead.”

- “In this graduation address, we celebrate not only our academic accomplishments but also the personal growth, resilience, and friendships that have enriched our years here.”

- “As we step into the world beyond academia, let’s remember that learning is a lifelong journey, and the skills we’ve honed will propel us toward success.”

- “Today, we bid farewell to the familiar and embrace the unknown, armed with the knowledge that every challenge we face is an opportunity for growth.”

- “In this commencement speech, we acknowledge the collective accomplishments of our class and embrace the responsibility to contribute positively to the world.”

- “As we graduate, let’s carry with us the values instilled by our education, applying them not only in our careers but also in shaping a more just and compassionate society.”

- “Join me in celebrating the diversity of talents and perspectives that define our graduating class, and let’s channel our unique strengths to make a meaningful impact.”

- “Today, we honor the culmination of our academic pursuits and embrace the journey of continuous learning that will shape our personal and professional paths.”

- “In this graduation address, we acknowledge the support of our families, educators, and peers, recognizing that our successes are a testament to shared effort.”

- “As we don our caps and gowns, let’s remember that our education equips us not only with knowledge but also with the power to effect positive change in the world.”

Speech Thesis Statement For Acceptance

Acceptance speeches express gratitude and acknowledge achievements. These thesis statements capture the essence of acknowledgment, appreciation, and commitment.

- “I am humbled and honored by this recognition, and I pledge to use this platform to amplify the voices of the marginalized and work toward equity.”

- “As I accept this award, I express my gratitude to those who believed in my potential, and I commit to using my skills to contribute meaningfully to our community.”

- “Receiving this honor is a testament to the collaborative efforts that make achievements possible. I am dedicated to sharing this success with those who supported me.”

- “Accepting this award, I am reminded of the responsibility that accompanies it. I vow to continue striving for excellence and inspiring those around me.”

- “As I receive this recognition, I extend my deepest appreciation to my mentors, colleagues, and family, and I promise to pay it forward by mentoring the next generation.”

- “Accepting this accolade, I recognize that success is a team effort. I commit to fostering a culture of collaboration and innovation in all my endeavors.”

- “Receiving this honor, I am reminded of the privilege I have to effect change. I dedicate myself to leveraging this platform for the betterment of society.”

- “Accepting this award, I am grateful for the opportunities that have shaped my journey. I am committed to using my influence to uplift others and drive positive change.”

- “As I stand here, I am deeply moved by this recognition. I pledge to use this honor as a catalyst for making a meaningful impact on the lives of those I encounter.”

- “Accepting this distinction, I embrace the responsibility it brings. I promise to uphold the values that guided me to this moment and channel my efforts toward progress.”

Speech Thesis Statement in Extemporaneous

Extemporaneous speeches require quick thinking and concise communication. These thesis statements capture the essence of on-the-spot analysis and delivery.

- “On the topic of technological disruption, we explore its effects on job markets, emphasizing the importance of upskilling for the workforce’s evolving demands.”

- “In this impromptu speech, we dissect the complexities of global climate agreements, assessing their impact on environmental sustainability and international cooperation.”