Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 29 October 2020

Urban and air pollution: a multi-city study of long-term effects of urban landscape patterns on air quality trends

- Lu Liang 1 &

- Peng Gong 2 , 3 , 4

Scientific Reports volume 10 , Article number: 18618 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

62k Accesses

113 Citations

320 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Environmental impact

- Environmental sciences

Most air pollution research has focused on assessing the urban landscape effects of pollutants in megacities, little is known about their associations in small- to mid-sized cities. Considering that the biggest urban growth is projected to occur in these smaller-scale cities, this empirical study identifies the key urban form determinants of decadal-long fine particulate matter (PM 2.5 ) trends in all 626 Chinese cities at the county level and above. As the first study of its kind, this study comprehensively examines the urban form effects on air quality in cities of different population sizes, at different development levels, and in different spatial-autocorrelation positions. Results demonstrate that the urban form evolution has long-term effects on PM 2.5 level, but the dominant factors shift over the urbanization stages: area metrics play a role in PM 2.5 trends of small-sized cities at the early urban development stage, whereas aggregation metrics determine such trends mostly in mid-sized cities. For large cities exhibiting a higher degree of urbanization, the spatial connectedness of urban patches is positively associated with long-term PM 2.5 level increases. We suggest that, depending on the city’s developmental stage, different aspects of the urban form should be emphasized to achieve long-term clean air goals.

Similar content being viewed by others

Widespread societal and ecological impacts from projected Tibetan Plateau lake expansion

Positive effects of COVID-19 lockdown on air quality of industrial cities (Ankleshwar and Vapi) of Western India

A unifying modelling of multiple land degradation pathways in Europe

Introduction.

Air pollution represents a prominent threat to global society by causing cascading effects on individuals 1 , medical systems 2 , ecosystem health 3 , and economies 4 in both developing and developed countries 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 . About 90% of global citizens lived in areas that exceed the safe level in the World Health Organization (WHO) air quality guidelines 9 . Among all types of ecosystems, urban produce roughly 78% of carbon emissions and substantial airborne pollutants that adversely affect over 50% of the world’s population living in them 5 , 10 . While air pollution affects all regions, there exhibits substantial regional variation in air pollution levels 11 . For instance, the annual mean concentration of fine particulate matter with an aerodynamic diameter of less than 2.5 \(\upmu\mathrm{m}\) (PM 2.5 ) in the most polluted cities is nearly 20 times higher than the cleanest city according to a survey of 499 global cities 12 . Many factors can influence the regional air quality, including emissions, meteorology, and physicochemical transformations. Another non-negligible driver is urbanization—a process that alters the size, structure, and growth of cities in response to the population explosion and further leads to lasting air quality challenges 13 , 14 , 15 .

With the global trend of urbanization 16 , the spatial composition, configuration, and density of urban land uses (refer to as urban form) will continue to evolve 13 . The investigation of urban form impacts on air quality has been emerging in both empirical 17 and theoretical 18 research. While the area and density of artificial surface areas have well documented positive relationship with air pollution 19 , 20 , 21 , the effects of urban fragmentation on air quality have been controversial. In theory, compact cities promote high residential density with mixed land uses and thus reduce auto dependence and increase the usage of public transit and walking 21 , 22 . The compact urban development has been proved effective in mitigating air pollution in some cities 23 , 24 . A survey of 83 global urban areas also found that those with highly contiguous built-up areas emitted less NO 2 22 . In contrast, dispersed urban form can decentralize industrial polluters, improve fuel efficiency with less traffic congestion, and alleviate street canyon effects 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 . Polycentric and dispersed cities support the decentralization of jobs that lead to less pollution emission than compact and monocentric cities 29 . The more open spaces in a dispersed city support air dilution 30 . In contrast, compact cities are typically associated with stronger urban heat island effects 31 , which influence the availability and the advection of primary and secondary pollutants 32 .

The mixed evidence demonstrates the complex interplay between urban form and air pollution, which further implies that the inconsistent relationship may exist in cities at different urbanization levels and over different periods 33 . Few studies have attempted to investigate the urban form–air pollution relationship with cross-sectional and time series data 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 . Most studies were conducted in one city or metropolitan region 38 , 39 or even at the country level 40 . Furthermore, large cities or metropolitan areas draw the most attention in relevant studies 5 , 41 , 42 , and the small- and mid-sized cities, especially those in developing countries, are heavily underemphasized. However, virtually all world population growth 43 , 44 and most global economic growth 45 , 46 are expected to occur in those cities over the next several decades. Thus, an overlooked yet essential task is to account for various levels of cities, ranging from large metropolitan areas to less extensive urban area, in the analysis.

This study aims to improve the understanding of how the urban form evolution explains the decadal-long changes of the annual mean PM 2.5 concentrations in 626 cities at the county-level and above in China. China has undergone unprecedented urbanization over the past few decades and manifested a high degree of heterogeneity in urban development 47 . Thus, Chinese cities serve as a good model for addressing the following questions: (1) whether the changes in urban landscape patterns affect trends in PM 2.5 levels? And (2) if so, do the determinants vary by cities?

City boundaries

Our study period spans from the year 2000 to 2014 to keep the data completeness among all data sources. After excluding cities with invalid or missing PM 2.5 or sociodemographic value, a total of 626 cities, with 278 prefecture-level cities and 348 county-level cities, were selected. City boundaries are primarily based on the Global Rural–Urban Mapping Project (GRUMP) urban extent polygons that were defined by the extent of the nighttime lights 48 , 49 . Few adjustments were made. First, in the GRUMP dataset, large agglomerations that include several cities were often described in one big polygon. We manually split those polygons into individual cities based on the China Administrative Regions GIS Data at 1:1 million scales 50 . Second, since the 1978 economic reforms, China has significantly restructured its urban administrative/spatial system. Noticeable changes are the abolishment of several prefectures and the promotion of many former county-level cities to prefecture-level cities 51 . Thus, all city names were cross-checked between the year 2000 and 2014, and the mismatched records were replaced with the latest names.

PM 2.5 concentration data

The annual mean PM 2.5 surface concentration (micrograms per cubic meter) for each city over the study period was calculated from the Global Annual PM 2.5 Grids at 0.01° resolution 52 . This data set combines Aerosol Optical Depth retrievals from multiple satellite instruments including the NASA Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS), Multi-angle Imaging SpectroRadiometer (MISR), and the Sea-Viewing Wide Field-of-View Sensor (SeaWiFS). The global 3-D chemical transport model GEOS-Chem is further applied to relate this total column measure of aerosol to near-surface PM 2.5 concentration, and geographically weighted regression is finally used with global ground-based measurements to predict and adjust for the residual PM 2.5 bias per grid cell in the initial satellite-derived values.

Human settlement layer

The urban forms were quantified with the 40-year (1978–2017) record of annual impervious surface maps for both rural and urban areas in China 47 , 53 . This state-of-art product provides substantial spatial–temporal details on China’s human settlement changes. The annual impervious surface maps covering our study period were generated from 30-m resolution Landsat images acquired onboard Landsat 5, 7, and 8 using an automatic “Exclusion/Inclusion” mapping framework 54 , 55 . The output used here was the binary impervious surface mask, with the value of one indicating the presence of human settlement and the value of zero identifying non-residential areas. The product assessment concluded good performance. The cross-comparison against 2356 city or town locations in GeoNames proved an overall high agreement (88%) and approximately 80% agreement was achieved when compared against visually interpreted 650 urban extent areas in the year 1990, 2000, and 2010.

Control variables

To provide a holistic assessment of the urban form effects, we included control variables that are regarded as important in influencing air quality to account for the confounding effects.

Four variables, separately population size, population density, and two economic measures, were acquired from the China City Statistical Yearbook 56 (National Bureau of Statistics 2000–2014). Population size is used to control for the absolute level of pollution emissions 41 . Larger populations are associated with increased vehicle usage and vehicle-kilometers travels, and consequently boost tailpipes emissions 5 . Population density is a useful reflector of transportation demand and the fraction of emissions inhaled by people 57 . We also included gross regional product (GRP) and the proportion of GRP generated from the secondary sector (GRP2). The impact of economic development on air quality is significant but in a dynamic way 58 . The rising per capita income due to the concentration of manufacturing industrial activities can deteriorate air quality and vice versa if the stronger economy is the outcome of the concentration of less polluting high-tech industries. Meteorological conditions also have short- and long-term effects on the occurrence, transport, and dispersion of air pollutants 59 , 60 , 61 . Temperature affects chemical reactions and atmospheric turbulence that determine the formation and diffusion of particles 62 . Low air humidity can lead to the accumulation of air pollutants due to it is conducive to the adhesion of atmospheric particulate matter on water vapor 63 . Whereas high humidity can lead to wet deposition processes that can remove air pollutants by rainfall. Wind speed is a crucial indicator of atmospheric activity by greatly affect air pollutant transport and dispersion. All meteorological variables were calculated based on China 1 km raster layers of monthly relative humidity, temperature, and wind speed that are interpolated from over 800 ground monitoring stations 64 . Based on the monthly layer, we calculated the annual mean of each variable for each year. Finally, all pixels falling inside of the city boundary were averaged to represent the overall meteorological condition of each city.

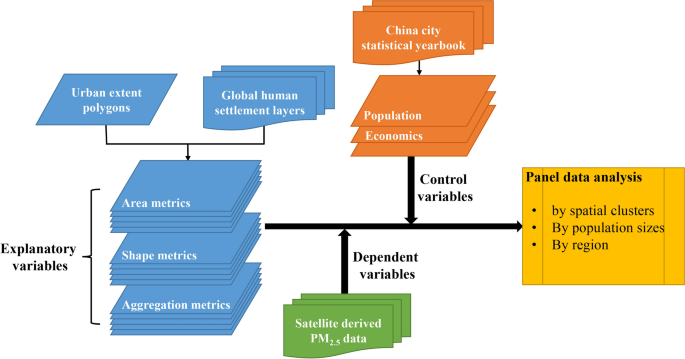

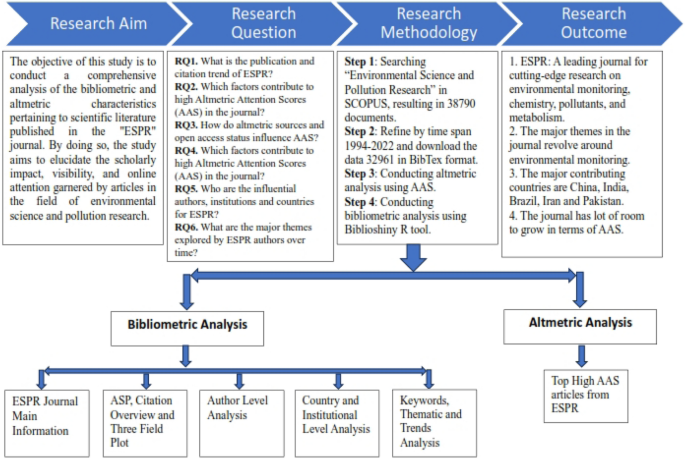

Considering the dynamic urban form-air pollution relationship evidenced from the literature review, our hypothesis is: the determinants of PM 2.5 level trends are not the same for cities undergoing different levels of development or in different geographic regions. To test this hypothesis, we first categorized city groups following (1) social-economic development level, (2) spatial autocorrelation relationship, and (3) population size. We then assessed the relationship between urban form and PM 2.5 level trends by city groups. Finally, we applied the panel data models to different city groups for hypothesis testing and key determinant identification (Fig. 1 ).

Methodology workflow.

Calculation of urban form metrics

Based on the previous knowledge 65 , 66 , 67 , fifteen landscape metrics falling into three categories, separately area, shape, and aggregation, were selected. Those metrics quantify the compositional and configurational characteristics of the urban landscape, as represented by urban expansion, urban shape complexity, and compactness (Table 1 ).

Area metrics gives an overview of the urban extent and the size of urban patches that are correlated with PM 2.5 20 . As an indicator of the urbanization degree, total area (TA) typically increases constantly or remains stable, because the urbanization process is irreversible. Number of patches (NP) refers to the number of discrete parcels of urban settlement within a given urban extent and Mean Patch Size (AREA_MN) measures the average patch size. Patch density (PD) indicates the urbanization stages. It usually increases with urban diffusion until coalescence starts, after which decreases in number 66 . Largest Patch Index (LPI) measures the percentage of the landscape encompassed by the largest urban patch.

The shape complexity of urban patches was represented by Mean Patch Shape Index (SHAPE_MN), Mean Patch Fractal Dimension (FRAC_MN), and Mean Contiguity Index (CONTIG_MN). The greater irregularity the landscape shape, the larger the value of SHAPE_MN and FRAC_MN. CONTIG_MN is another method of assessing patch shape based on the spatial connectedness or contiguity of cells within a patch. Larger contiguous patches will result in larger CONTIG_MN.

Aggregation metrics measure the spatial compactness of urban land, which affects pollutant diffusion and dilution. Mean Euclidean nearest-neighbor distance (ENN_MN) quantifies the average distance between two patches within a landscape. It decreases as patches grow together and increases as the urban areas expand. Landscape Shape Index (LSI) indicates the divergence of the shape of a landscape patch that increases as the landscape becomes increasingly disaggregated 68 . Patch Cohesion Index (COHESION) is suggestive of the connectedness degree of patches 69 . Splitting Index (SPLIT) and Landscape Division Index (DIVISION) increase as the separation of urban patches rises, whereas, Mesh Size (MESH) decreases as the landscape becomes more fragmented. Aggregation Index (AI) measures the degree of aggregation or clumping of urban patches. Higher values of continuity indicate higher building densities, which may have a stronger effect on pollution diffusion.

The detailed descriptions of these indices are given by the FRAGSTATS user’s guide 70 . The calculation input is a layer of binary grids of urban/nonurban. The resulting output is a table containing one row for each city and multiple columns representing the individual metrics.

Division of cities

Division based on the socioeconomic development level.

The socioeconomic development level in China is uneven. The unequal development of the transportation system, descending in topography from the west to the east, combined with variations in the availability of natural and human resources and industrial infrastructure, has produced significantly wide gaps in the regional economies of China. By taking both the economic development level and natural geography into account, China can be loosely classified into Eastern, Central, and Western regions. Eastern China is generally wealthier than the interior, resulting from closeness to coastlines and the Open-Door Policy favoring coastal regions. Western China is historically behind in economic development because of its high elevation and rugged topography, which creates barriers in the transportation infrastructure construction and scarcity of arable lands. Central China, echoing its name, is in the process of economic development. This region neither benefited from geographic convenience to the coast nor benefited from any preferential policies, such as the Western Development Campaign.

Division based on spatial autocorrelation relationship

The second type of division follows the fact that adjacent cities are likely to form air pollution clusters due to the mixing and diluting nature of air pollutants 71 , i.e., cities share similar pollution levels as its neighbors. The underlying processes driving the formation of pollution hot spots and cold spots may differ. Thus, we further divided the city into groups based on the spatial clusters of PM 2.5 level changes.

Local indicators of spatial autocorrelation (LISA) was used to determine the local patterns of PM 2.5 distribution by clustering cities with a significant association. In the presence of global spatial autocorrelation, LISA indicates whether a variable exhibits significant spatial dependence and heterogeneity at a given scale 72 . Practically, LISA relates each observation to its neighbors and assigns a value of significance level and degree of spatial autocorrelation, which is calculated by the similarity in variable \(z\) between observation \(i\) and observation \(j\) in the neighborhood of \(i\) defined by a matrix of weights \({w}_{ij}\) 7 , 73 :

where \({I}_{i}\) is the Moran’s I value for location \(i\) ; \({\sigma }^{2}\) is the variance of variable \(z\) ; \(\bar{z}\) is the average value of \(z\) with the sample number of \(n\) . The weight matrix \({w}_{ij}\) is defined by the k-nearest neighbors distance measure, i.e., each object’s neighborhood consists of four closest cites.

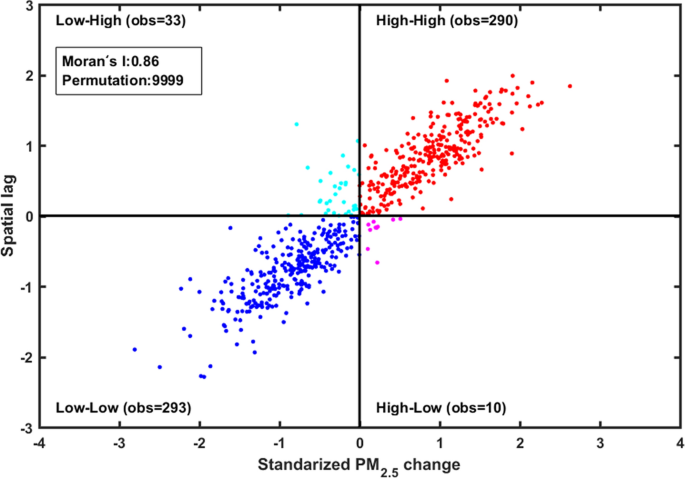

The computation of Moran’s I enables the identification of hot spots and cold spots. The hot spots are high-high clusters where the increase in the PM 2.5 level is higher than the surrounding areas, whereas cold spots are low-low clusters with the presence of low values in a low-value neighborhood. A Moran scatterplot, with x-axis as the original variable and y-axis as the spatially lagged variable, reflects the spatial association pattern. The slope of the linear fit to the scatter plot is an estimation of the global Moran's I 72 (Fig. 2 ). The plot consists of four quadrants, each defining the relationship between an observation 74 . The upper right quadrant indicates hot spots and the lower left quadrant displays cold spots 75 .

Moran’s I scatterplot. Figure was produced by R 3.4.3 76 .

Division based on population size

The last division was based on population size, which is a proven factor in changing per capita emissions in a wide selection of global cities, even outperformed land urbanization rate 77 , 78 , 79 . We used the 2014 urban population to classify the cities into four groups based on United Nations definitions 80 : (1) large agglomerations with a total population larger than 1 million; (2) mid-sized cities, 500,000–1 million; (3) small cities, 250,000–500,000, and (4) very small cities, 100,000–250,000.

Panel data analysis

The panel data analysis is an analytical method that deals with observations from multiple entities over multiple periods. Its capacity in analyzing the characteristics and changes from both the time-series and cross-section dimensions of data surpasses conventional models that purely focus on one dimension 81 , 82 . The estimation equation for the panel data model in this study is given as:

where the subscript \(i\) and \(t\) refer to city and year respectively. \(\upbeta _{{0}}\) is the intercept parameter and \(\upbeta _{{1}} - { }\upbeta _{{{18}}}\) are the estimates of slope coefficients. \(\varepsilon \) is the random error. All variables are transformed into natural logarithms.

Two methods can be used to obtain model estimates, separately fixed effects estimator and random effects estimator. The fixed effects estimator assumes that each subject has its specific characteristics due to inherent individual characteristic effects in the error term, thereby allowing differences to be intercepted between subjects. The random effects estimator assumes that the individual characteristic effect changes stochastically, and the differences in subjects are not fixed in time and are independent between subjects. To choose the right estimator, we run both models for each group of cities based on the Hausman specification test 83 . The null hypothesis is that random effects model yields consistent and efficient estimates 84 : \({H}_{0}{:}\,E\left({\varepsilon }_{i}|{X}_{it}\right)=0\) . If the null hypothesis is rejected, the fixed effects model will be selected for further inferences. Once the better estimator was determined for each model, one optimal panel data model was fit to each city group of one division type. In total, six, four, and eight runs were conducted for socioeconomic, spatial autocorrelation, and population division separately and three, two, and four panel data models were finally selected.

Spatial patterns of PM 2.5 level changes

During the period from 2000 to 2014, the annual mean PM 2.5 concentration of all cities increases from 27.78 to 42.34 µg/m 3 , both of which exceed the World Health Organization recommended annual mean standard (10 µg/m 3 ). It is worth noting that the PM 2.5 level in the year 2014 also exceeds China’s air quality Class 2 standard (35 µg/m 3 ) that applies to non-national park places, including urban and industrial areas. The standard deviation of annual mean PM 2.5 values for all cities increases from 12.34 to 16.71 µg/m 3 , which shows a higher variability of inter-urban PM 2.5 pollution after a decadal period. The least and most heavily polluted cities in China are Delingha, Qinghai (3.01 µg/m 3 ) and Jizhou, Hubei (64.15 µg/m 3 ) in 2000 and Hami, Xinjiang (6.86 µg/m 3 ) and Baoding, Hubei (86.72 µg/m 3 ) in 2014.

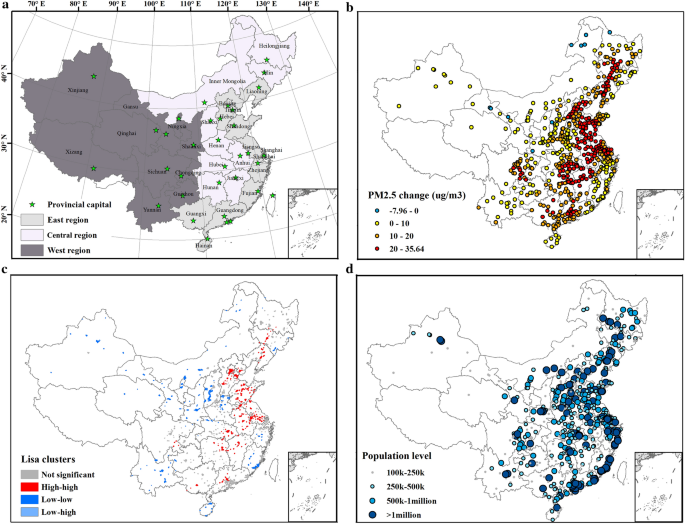

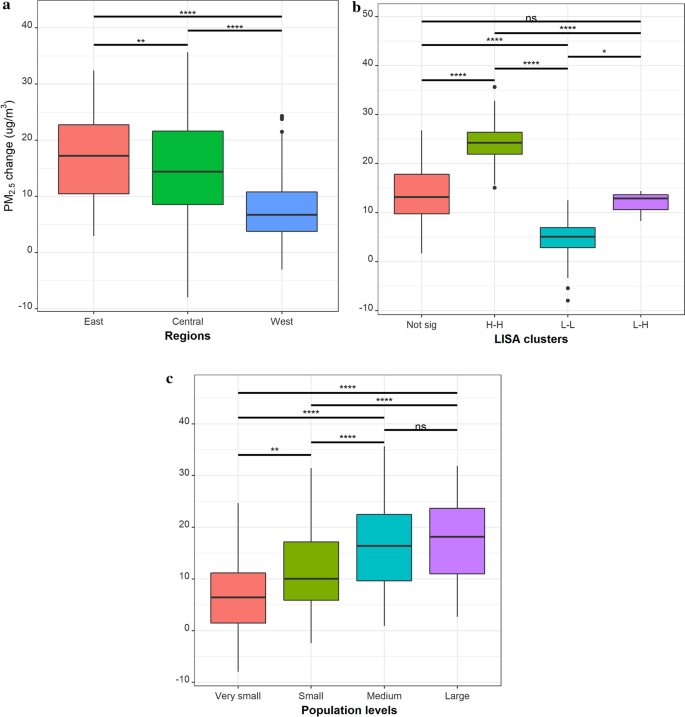

Spatially, the changes in PM 2.5 levels exhibit heterogeneous patterns across cities (Fig. 3 b). According to the socioeconomic level division (Fig. 3 a), the Eastern, Central, and Western region experienced a 38.6, 35.3, and 25.5 µg/m 3 increase in annual PM 2.5 mean , separately, and the difference among regions is significant according to the analysis of variance (ANOVA) results (Fig. 4 a). When stratified by spatial autocorrelation relationship (Fig. 3 c), the differences in PM 2.5 changes among the spatial clusters are even more dramatic. The average PM 2.5 increase in cities belonging to the high-high cluster is approximately 25 µg/m 3 , as compared to 5 µg/m 3 in the low-low clusters (Fig. 4 b). Finally, cities at four different population levels have significant differences in the changes of PM 2.5 concentration (Fig. 3 d), except for the mid-sized cities and large city agglomeration (Fig. 4 c).

( a ) Division of cities in China by socioeconomic development level and the locations of provincial capitals; ( b ) Changes in annual mean PM 2.5 concentrations between the year 2000 and 2014; ( c ) LISA cluster maps for PM 2.5 changes at the city level; High-high indicates a statistically significant cluster of high PM 2.5 level changes over the study period. Low-low indicates a cluster of low PM 2.5 inter-annual variation; No high-low cluster is reported; Low–high represents cities with high PM 2.5 inter-annual variation surrounded by cities with low variation; ( d ) Population level by cities in the year 2014. Maps were produced by ArcGIS 10.7.1 85 .

Boxplots of PM 2.5 concentration changes between 2000 and 2014 for city groups that are formed according to ( a ) socioeconomic development level division, ( b ) LISA clusters, and ( c ) population level. Asterisk marks represent the p value of ANOVA significant test between the corresponding pair of groups. Note ns not significant; * p value < 0.05; ** p value < 0.01; *** p value < 0.001; H–H high-high cluster, L–H low–high cluster, L–L denotes low–low cluster.

The effects of urban forms on PM 2.5 changes

The Hausman specification test for fixed versus random effects yields a p value less than 0.05, suggesting that the fixed effects model has better performance. We fit one panel data model to each city group and built nine models in total. All models are statistically significant at the p < 0.05 level and have moderate to high predictive power with the R 2 values ranging from 0.63 to 0.95, which implies that 63–95% of the variation in the PM 2.5 concentration changes can be explained by the explanatory variables (Table 2 ).

The urban form—PM 2.5 relationships differ distinctly in Eastern, Central, and Western China. All models reach high R 2 values. Model for Eastern China (refer to hereafter as Eastern model) achieves the highest R 2 (0.90), and the model for the Western China (refer to hereafter as Western model) reaches the lowest R 2 (0.83). The shape metrics FRAC and CONTIG are correlated with PM 2.5 changes in the Eastern model, whereas the area metrics AREA demonstrates a positive effect in the Western model. In contrast to the significant associations between shape, area metrics and PM 2.5 level changes in both Eastern and Western models, no such association was detected in the Central model. Nonetheless, two aggregation metrics, LSI and AI, play positive roles in determining the PM 2.5 trends in the Central model.

For models built upon the LISA clusters, the H–H model (R 2 = 0.95) reaches a higher fitting degree than the L–L model (R 2 = 0.63). The estimated coefficients vary substantially. In the H–H model, the coefficient of CONTIG is positive, which indicates that an increase in CONTIG would increase PM 2.5 pollution. In contrast, no shape metrics but one area metrics AREA is significant in the L–L model.

The results of the regression models built for cities at different population levels exhibit a distinct pattern. No urban form metrics was identified to have a significant relationship with the PM 2.5 level changes in groups of very small and mid-sized cities. For small size cities, the aggregation metrics COHESION was positively associated whereas AI was negatively related. For mid-sized cities and large agglomerations, CONTIG is the only significant variable that is positively related to PM 2.5 level changes.

Urban form is an effective measure of long-term PM 2.5 trends

All panel data models are statistically significant regardless of the data group they are built on, suggesting that the associations between urban form and ambient PM 2.5 level changes are discernible at all city levels. Importantly, these relationships are found to hold when controlling for population size and gross domestic product, implying that the urban landscape patterns have effects on long-term PM 2.5 trends that are independent of regional economic performance. These findings echo with the local, regional, and global evidence of urban form effect on various air pollution types 5 , 14 , 21 , 22 , 24 , 39 , 78 .

Although all models demonstrate moderate to high predictive power, the way how different urban form metrics respond to the dependent variable varies. Of all the metrics tested, shape metrics, especially CONTIG has the strongest effect on PM 2.5 trends in cities belonging to the high-high cluster, Eastern, and large urban agglomerations. All those regions have a strong economy and higher population density 86 . In the group of cities that are moderately developed, such as the Central region, as well as small- and mid-sized cities, aggregation metrics play a dominant negative role in PM 2.5 level changes. In contrast, in the least developed cities belonging to the low-low cluster regions and Western China, the metrics describing size and number of urban patches are the strongest predictors. AREA and NP are positively related whereas TA is negatively associated.

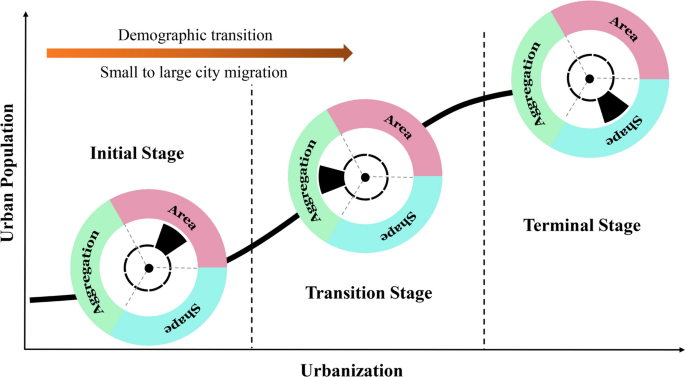

The impacts of urban form metrics on air quality vary by urbanization degree

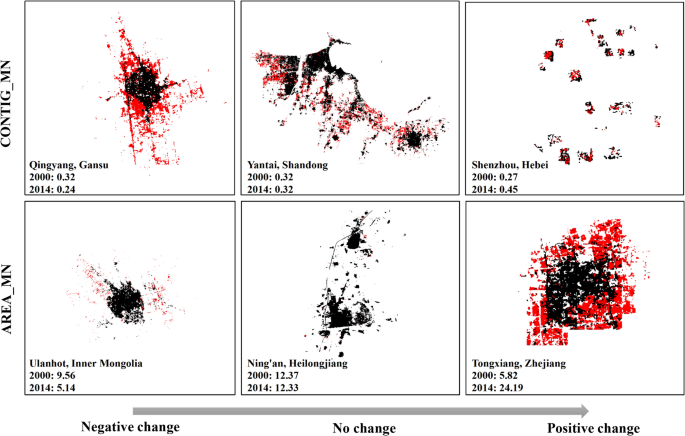

Based on the above observations, how urban form affects within-city PM 2.5 level changes may differ over the urbanization stages. We conceptually summarized the pattern in Fig. 5 : area metrics have the most substantial influence on air pollution changes at the early urban development stage, and aggregation metrics emerge at the transition stage, whereas shape metrics affect the air quality trends at the terminal stage. The relationship between urban form and air pollution has rarely been explored with such a wide range of city selections. Most prior studies were focused on large urban agglomeration areas, and thus their conclusions are not representative towards small cities at the early or transition stage of urbanization.

The most influential metric of urban form in affecting PM 2.5 level changes at different urbanization stages.

Not surprisingly, the area metrics, which describe spatial grain of the landscape, exert a significant effect on PM 2.5 level changes in small-sized cities. This could be explained by the unusual urbanization speed of small-sized cities in the Chinese context. Their thriving mostly benefited from the urbanization policy in the 1980s, which emphasized industrialization of rural, small- and mid-sized cities 87 . With the large rural-to-urban migration and growing public interest in investing real estate market, a side effect is that the massive housing construction that sometimes exceeds market demand. Residential activities decline in newly built areas of smaller cities in China, leading to what are known as ghost cities 88 . Although ghost cities do not exist for all cities, high rate of unoccupied dwellings is commonly seen in cities under the prefectural level. This partly explained the negative impacts of TA on PM 2.5 level changes, as an expanded while unoccupied or non-industrialized urban zones may lower the average PM 2.5 concentration within the city boundary, but it doesn’t necessarily mean that the air quality got improved in the city cores.

Aggregation metrics at the landscape scale is often referred to as landscape texture that quantifies the tendency of patch types to be spatially aggregated; i.e., broadly speaking, aggregated or “contagious” distributions. This group of metrics is most effective in capturing the PM 2.5 trends in mid-sized cities (population range 25–50 k) and Central China, where the urbanization process is still undergoing. The three significant variables that reflect the spatial property of dispersion, separately landscape shape index, patch cohesion index, and aggregation index, consistently indicate that more aggregated landscape results in a higher degree of PM 2.5 level changes. Theoretically, the more compact urban form typically leads to less auto dependence and heavier reliance on the usage of public transit and walking, which contributes to air pollution mitigation 89 . This phenomenon has also been observed in China, as the vehicle-use intensity (kilometers traveled per vehicle per year, VKT) has been declining over recent years 90 . However, VKT only represents the travel intensity of one car and does not reflect the total distance traveled that cumulatively contribute to the local pollution. It should be noted that the private light-duty vehicle ownership in China has increased exponentially and is forecast to reach 23–42 million by 2050, with the share of new-growth purchases representing 16–28% 90 . In this case, considering the increased total distance traveled, the less dispersed urban form can exert negative effects on air quality by concentrating vehicle pollution emissions in a limited space.

Finally, urban contiguity, observed as the most effective shape metric in indicating PM 2.5 level changes, provides an assessment of spatial connectedness across all urban patches. Urban contiguity is found to have a positive effect on the long-term PM 2.5 pollution changes in large cities. Urban contiguity reflects to which degree the urban landscape is fragmented. Large contiguous patches result in large CONTIG_MN values. Among the 626 cities, only 11% of cities experience negative changes in urban contiguity. For example, Qingyang, Gansu is one of the cities-featuring leapfrogs and scattered development separated by vacant land that may later be filled in as the development continues (Fig. 6 ). Most Chinese cities experienced increased urban contiguity, with less fragmented and compacted landscape. A typical example is Shenzhou, Hebei, where CONTIG_MN rose from 0.27 to 0.45 within the 14 years. Although the 13 counties in Shenzhou are very far scattered from each other, each county is growing intensively internally rather than sprawling further outside. And its urban layout is thus more compact (Fig. 6 ). The positive association revealed in this study contradicts a global study indicating that cities with highly contiguous built-up areas have lower NO 2 pollution 22 . We noticed that the principal emission sources of NO 2 differ from that of PM 2.5. NO 2 is primarily emitted with the combustion of fossil fuels (e.g., industrial processes and power generation) 6 , whereas road traffic attributes more to PM 2.5 emissions. Highly connected urban form is likely to cause traffic congestion and trap pollution inside the street canyon, which accumulates higher PM 2.5 concentration. Computer simulation results also indicate that more compact cities improve urban air quality but are under the premise that mixed land use should be presented 18 . With more connected impervious surfaces, it is merely impossible to expect increasing urban green spaces. If compact urban development does not contribute to a rising proportion of green areas, then such a development does not help mitigating air pollution 41 .

Six cities illustrating negative to positive changes in CONTIG_MN and AREA_MN. Pixels in black show the urban areas in the year 2000 and pixels in red are the expanded urban areas from the year 2000 to 2014. Figure was produced by ArcGIS 10.7.1 85 .

Conclusions

This study explores the regional land-use patterns and air quality in a country with an extraordinarily heterogeneous urbanization pattern. Our study is the first of its kind in investigating such a wide range selection of cities ranging from small-sized ones to large metropolitan areas spanning a long time frame, to gain a comprehensive insight into the varying effects of urban form on air quality trends. And the primary insight yielded from this study is the validation of the hypothesis that the determinants of PM 2.5 level trends are not the same for cities at various developmental levels or in different geographic regions. Certain measures of urban form are robust predictors of air quality trends for a certain group of cities. Therefore, any planning strategy aimed at reducing air pollution should consider its current development status and based upon which, design its future plan. To this end, it is also important to emphasize the main shortcoming of this analysis, which is generally centered around the selection of control variables. This is largely constrained by the available information from the City Statistical Yearbook. It will be beneficial to further polish this study by including other important controlling factors, such as vehicle possession.

Lim, C. C. et al. Association between long-term exposure to ambient air pollution and diabetes mortality in the US. Environ. Res. 165 , 330–336 (2018).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Yang, J. & Zhang, B. Air pollution and healthcare expenditure: implication for the benefit of air pollution control in China. Environ. Int. 120 , 443–455 (2018).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Bell, J. N. B., Power, S. A., Jarraud, N., Agrawal, M. & Davies, C. The effects of air pollution on urban ecosystems and agriculture. Int. J. Sust. Dev. World 18 (3), 226–235 (2011).

Article Google Scholar

Matus, K. et al. Health damages from air pollution in China. Glob. Environ. Change 22 (1), 55–66 (2012).

Bereitschaft, B. & Debbage, K. Urban form, air pollution, and CO 2 emissions in large US metropolitan areas. Prof Geogr. 65 (4), 612–635 (2013).

Bozkurt, Z., Üzmez, Ö. Ö., Döğeroğlu, T., Artun, G. & Gaga, E. O. Atmospheric concentrations of SO2, NO2, ozone and VOCs in Düzce, Turkey using passive air samplers: sources, spatial and seasonal variations and health risk estimation. Atmos. Pollut. Res. 9 (6), 1146–1156 (2018).

Article CAS Google Scholar

Fang, C., Liu, H., Li, G., Sun, D. & Miao, Z. Estimating the impact of urbanization on air quality in China using spatial regression models. Sustainability 7 (11), 15570–15592 (2015).

Khaniabadi, Y. O. et al. Mortality and morbidity due to ambient air pollution in Iran. Clin. Epidemiol. Glob. Health 7 (2), 222–227 (2019).

Health Effects Institute. State of Global Air 2019 . Special Report (Health Effects Institute, Boston, 2019). ISSN 2578-6873.

O’Meara, M. & Peterson, J. A. Reinventing Cities for People and the Planet (Worldwatch Institute, Washington, 1999).

Google Scholar

World Health Organization. Ambient Air Pollution: A Global Assessment of Exposure and Burden of Disease . ISBN: 9789241511353 (2016).

Liu, C. et al. Ambient particulate air pollution and daily mortality in 652 cities. N. Engl. J. Med. 381 (8), 705–715 (2019).

Anderson, W. P., Kanaroglou, P. S. & Miller, E. J. Urban form, energy and the environment: a review of issues, evidence and policy. Urban Stud. 33 (1), 7–35 (1996).

Hart, R., Liang, L. & Dong, P. L. Monitoring, mapping, and modeling spatial–temporal patterns of PM2.5 for improved understanding of air pollution dynamics using portable sensing technologies. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health . 17 (14), 4914 (2020).

Article PubMed Central Google Scholar

Environmental Protection Agency. Our Built and Natural Environments: A Technical Review of the Interactions Between Land Use, Transportation and Environmental Quality (2nd edn.). Report 231K13001 (Environmental Protection Agency, Washington, 2013).

Chen, M., Zhang, H., Liu, W. & Zhang, W. The global pattern of urbanization and economic growth: evidence from the last three decades. PLoS ONE 9 (8), e103799 (2014).

Article ADS PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar

Wang, S., Liu, X., Zhou, C., Hu, J. & Ou, J. Examining the impacts of socioeconomic factors, urban form, and transportation networks on CO 2 emissions in China’s megacities. Appl. Energy. 185 , 189–200 (2017).

Borrego, C. et al. How urban structure can affect city sustainability from an air quality perspective. Environ. Model. Softw. 21 (4), 461–467 (2006).

Bart, I. Urban sprawl and climate change: a statistical exploration of cause and effect, with policy options for the EU. Land Use Policy 27 (2), 283–292 (2010).

Feng, H., Zou, B. & Tang, Y. M. Scale- and region-dependence in landscape-PM 2.5 correlation: implications for urban planning. Remote Sens. 9 , 918. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs9090918 (2017).

Rodríguez, M. C., Dupont-Courtade, L. & Oueslati, W. Air pollution and urban structure linkages: evidence from European cities. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 53 , 1–9 (2016).

Bechle, M. J., Millet, D. B. & Marshall, J. D. Effects of income and urban form on urban NO2: global evidence from satellites. Environ. Sci. Technol. 45 (11), 4914–4919 (2011).

Article ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Martins, H., Miranda, A. & Borrego, C. Urban structure and air quality. In Air Pollution-A Comprehensive Perspective (2012).

Stone, B. Jr. Urban sprawl and air quality in large US cities. J. Environ. Manag. 86 (4), 688–698 (2008).

Breheny, M. Densities and sustainable cities: the UK experience. In Cities for the new millennium , 39–51 (2001).

Glaeser, E. L. & Kahn, M. E. Sprawl and urban growth. In Handbook of regional and urban economics , vol. 4, 2481–2527 (Elsevier, Amsterdam, 2004).

Manins, P. C. et al. The impact of urban development on air quality and energy use. Clean Air 18 , 21 (1998).

Troy, P. N. Environmental stress and urban policy. The compact city: a sustainable urban form, 200–211 (1996).

Gaigné, C., Riou, S. & Thisse, J. F. Are compact cities environmentally friendly?. J. Urban Econ. 72 (2–3), 123–136 (2012).

Wood, C. Air pollution control by land use planning techniques: a British-American review. Int. J. Environ. Stud. 35 (4), 233–243 (1990).

Zhou, B., Rybski, D. & Kropp, J. P. The role of city size and urban form in the surface urban heat island. Sci. Rep. 7 (1), 4791 (2017).

Sarrat, C., Lemonsu, A., Masson, V. & Guedalia, D. Impact of urban heat island on regional atmospheric pollution. Atmos. Environ. 40 (10), 1743–1758 (2006).

Article ADS CAS Google Scholar

Liu, Y., Wu, J., Yu, D. & Ma, Q. The relationship between urban form and air pollution depends on seasonality and city size. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 25 (16), 15554–15567 (2018).

Cavalcante, R. M. et al. Influence of urbanization on air quality based on the occurrence of particle-associated polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in a tropical semiarid area (Fortaleza-CE, Brazil). Air Qual. Atmos. Health. 10 (4), 437–445 (2017).

Han, L., Zhou, W. & Li, W. Fine particulate (PM 2.5 ) dynamics during rapid urbanization in Beijing, 1973–2013. Sci. Rep. 6 , 23604 (2016).

Article ADS CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Tuo, Y., Li, X. & Wang, J. Negative effects of Beijing’s air pollution caused by urbanization on residents’ health. In 2nd International Conference on Science and Social Research (ICSSR 2013) , 732–735 (Atlantis Press, 2013).

Zhou, C. S., Li, S. J. & Wang, S. J. Examining the impacts of urban form on air pollution in developing countries: a case study of China’s megacities. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 15 (8), 1565 (2018).

Article PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar

Cariolet, J. M., Colombert, M., Vuillet, M. & Diab, Y. Assessing the resilience of urban areas to traffic-related air pollution: application in Greater Paris. Sci. Total Environ. 615 , 588–596 (2018).

She, Q. et al. Air quality and its response to satellite-derived urban form in the Yangtze River Delta, China. Ecol. Indic. 75 , 297–306 (2017).

Yang, D. et al. Global distribution and evolvement of urbanization and PM 2.5 (1998–2015). Atmos. Environ. 182 , 171–178 (2018).

Cho, H. S. & Choi, M. Effects of compact urban development on air pollution: empirical evidence from Korea. Sustainability 6 (9), 5968–5982 (2014).

Li, C., Wang, Z., Li, B., Peng, Z. R. & Fu, Q. Investigating the relationship between air pollution variation and urban form. Build. Environ. 147 , 559–568 (2019).

Montgomery, M. R. The urban transformation of the developing world. Science 319 (5864), 761–764 (2008).

United Nations. World Urbanization Prospects: The 2009 Revision (United Nations Publication, New York, 2010).

Jiang, L. & O’Neill, B. C. Global urbanization projections for the shared socioeconomic pathways. Glob. Environ. Change 42 , 193–199 (2017).

Martine, G., McGranahan, G., Montgomery, M. & Fernandez-Castilla, R. The New Global Frontier: Urbanization, Poverty and Environment in the 21st Century (Earthscan, London, 2008).

Gong, P., Li, X. C. & Zhang, W. 40-Year (1978–2017) human settlement changes in China reflected by impervious surfaces from satellite remote sensing. Sci. Bull. 64 (11), 756–763 (2019).

Center for International Earth Science Information Network—CIESIN—Columbia University, C. I.-C.-I.. Global Rural–Urban Mapping Project, Version 1 (GRUMPv1): Urban Extent Polygons, Revision 01 . Palisades, NY: NASA Socioeconomic Data and Applications Center (SEDAC) (2017). https://doi.org/10.7927/H4Z31WKF . Accessed 10 April 2020.

Balk, D. L. et al. Determining global population distribution: methods, applications and data. Adv Parasit. 62 , 119–156. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-308X(05)62004-0 (2006).

Chinese Academy of Surveying and Mapping—CASM China in Time and Space—CITAS—University of Washington, a. C.-C. (1996). China Dimensions Data Collection: China Administrative Regions GIS Data: 1:1M, County Level, 1 July 1990 . Palisades, NY: NASA Socioeconomic Data and Applications Center (SEDAC). https://doi.org/10.7927/H4GT5K3V . Accessed 10 April 2020.

Ma, L. J. Urban administrative restructuring, changing scale relations and local economic development in China. Polit. Geogr. 24 (4), 477–497 (2005).

Article MathSciNet Google Scholar

Van Donkelaar, A. et al. Global estimates of fine particulate matter using a combined geophysical-statistical method with information from satellites, models, and monitors. Environ. Sci. Technol. 50 (7), 3762–3772 (2016).

Article ADS PubMed CAS Google Scholar

Gong, P. et al. Annual maps of global artificial impervious area (GAIA) between 1985 and 2018. Remote Sens. Environ 236 , 111510 (2020).

Article ADS Google Scholar

Li, X. C., Gong, P. & Liang, L. A 30-year (1984–2013) record of annual urban dynamics of Beijing City derived from Landsat data. Remote Sens. Environ. 166 , 78–90 (2015).

Li, X. C. & Gong, P. An, “exclusion-inclusion” framework for extracting human settlements in rapidly developing regions of China from Landsat images. Remote Sens. Environ. 186 , 286–296 (2016).

National Bureau of Statistics 2000–2014. China City Statistical Yearbook (China Statistics Press). ISBN: 978-7-5037-6387-8

Lai, A. C., Thatcher, T. L. & Nazaroff, W. W. Inhalation transfer factors for air pollution health risk assessment. J. Air Waste Manag. Assoc. 50 (9), 1688–1699 (2000).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Luo, Y. et al. Relationship between air pollutants and economic development of the provincial capital cities in China during the past decade. PLoS ONE 9 (8), e104013 (2014).

Hart, R., Liang, L. & Dong, P. Monitoring, mapping, and modeling spatial–temporal patterns of PM2.5 for improved understanding of air pollution dynamics using portable sensing technologies. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 17 (14), 4914 (2020).

Wang, X. & Zhang, R. Effects of atmospheric circulations on the interannual variation in PM2.5 concentrations over the Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei region in 2013–2018. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 20 (13), 7667–7682 (2020).

Xu, Y. et al. Impact of meteorological conditions on PM 2.5 pollution in China during winter. Atmosphere 9 (11), 429 (2018).

Hernandez, G., Berry, T.A., Wallis, S. & Poyner, D. Temperature and humidity effects on particulate matter concentrations in a sub-tropical climate during winter. In Proceedings of the International Conference of the Environment, Chemistry and Biology (ICECB 2017), Queensland, Australia, 20–22 November 2017; Juan, L., Ed.; IRCSIT Press: Singapore, 2017.

Zhang, Y. Dynamic effect analysis of meteorological conditions on air pollution: a case study from Beijing. Sci. Total. Environ. 684 , 178–185 (2019).

National Earth System Science Data Center. National Science & Technology Infrastructure of China . https://www.geodata.cn . Accessed 6 Oct 2020.

Bhatta, B., Saraswati, S. & Bandyopadhyay, D. Urban sprawl measurement from remote sensing data. Appl. Geogr. 30 (4), 731–740 (2010).

Dietzel, C., Oguz, H., Hemphill, J. J., Clarke, K. C. & Gazulis, N. Diffusion and coalescence of the Houston Metropolitan Area: evidence supporting a new urban theory. Environ. Plan. B Plan. Des. 32 (2), 231–246 (2005).

Li, S., Zhou, C., Wang, S. & Hu, J. Dose urban landscape pattern affect CO2 emission efficiency? Empirical evidence from megacities in China. J. Clean. Prod. 203 , 164–178 (2018).

Gyenizse, P., Bognár, Z., Czigány, S. & Elekes, T. Landscape shape index, as a potencial indicator of urban development in Hungary. Acta Geogr. Debrecina Landsc. Environ. 8 (2), 78–88 (2014).

Rutledge, D. T. Landscape indices as measures of the effects of fragmentation: can pattern reflect process? DOC Science Internal Series . ISBN 0-478-22380-3 (2003).

Mcgarigal, K. & Marks, B. J. Spatial pattern analysis program for quantifying landscape structure. Gen. Tech. Rep. PNW-GTR-351. US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Research Station, 1–122 (1995).

Chan, C. K. & Yao, X. Air pollution in mega cities in China. Atmos. Environ. 42 (1), 1–42 (2008).

Anselin, L. The Moran Scatterplot as an ESDA Tool to Assess Local Instability in Spatial Association. In Spatial Analytical Perspectives on Gis in Environmental and Socio-Economic Sciences (eds Fischer, M. et al. ) 111–125 (Taylor; Francis, London, 1996).

Zou, B., Peng, F., Wan, N., Mamady, K. & Wilson, G. J. Spatial cluster detection of air pollution exposure inequities across the United States. PLoS ONE 9 (3), e91917 (2014).

Bone, C., Wulder, M. A., White, J. C., Robertson, C. & Nelson, T. A. A GIS-based risk rating of forest insect outbreaks using aerial overview surveys and the local Moran’s I statistic. Appl. Geogr. 40 , 161–170 (2013).

Anselin, L., Syabri, I. & Kho, Y. GeoDa: an introduction to spatial data analysis. Geogr. Anal. 38 , 5–22 (2006).

R Core Team. R A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, 2013).

Cole, M. A. & Neumayer, E. Examining the impact of demographic factors on air pollution. Popul. Environ. 26 (1), 5–21 (2004).

Liu, Y., Arp, H. P. H., Song, X. & Song, Y. Research on the relationship between urban form and urban smog in China. Environ. Plan. B Urban Anal. City Sci. 44 (2), 328–342 (2017).

York, R., Rosa, E. A. & Dietz, T. STIRPAT, IPAT and ImPACT: analytic tools for unpacking the driving forces of environmental impacts. Ecol. Econ. 46 (3), 351–365 (2003).

United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs Population Division 2011: the 2010 Revision (United Nations Publications, New York, 2011)

Ahn, S. C. & Schmidt, P. Efficient estimation of models for dynamic panel data. J. Econ. 68 (1), 5–27 (1995).

Article MathSciNet MATH Google Scholar

Du, L., Wei, C. & Cai, S. Economic development and carbon dioxide emissions in China: provincial panel data analysis. China Econ. Rev. 23 (2), 371–384 (2012).

Hausman, J. A. Specification tests in econometrics. Econ. J. Econ. Soc. 46 (6), 1251–1271 (1978).

Greene, W. H. Econometric Analysis (Pearson Education India, New Delhi, 2003).

ArcGIS GIS 10.7.1. (Environmental Systems Research Institute, Inc., Redlands, 2010).

Lao, X., Shen, T. & Gu, H. Prospect on China’s urban system by 2020: evidence from the prediction based on internal migration network. Sustainability 10 (3), 654 (2018).

Henderson, J.V., Logan, J.R. & Choi, S. Growth of China's medium-size cities . Brookings-Wharton Papers on Urban Affairs, 263–303 (2005).

Lu, H., Zhang, C., Liu, G., Ye, X. & Miao, C. Mapping China’s ghost cities through the combination of nighttime satellite data and daytime satellite data. Remote Sens. 10 (7), 1037 (2018).

Frank, L. D. et al. Many pathways from land use to health: associations between neighborhood walkability and active transportation, body mass index, and air quality. JAPA. 72 (1), 75–87 (2006).

Huo, H. & Wang, M. Modeling future vehicle sales and stock in China. Energy Policy 43 , 17–29 (2012).

Download references

Acknowledgements

Lu Liang received intramural research funding support from the UNT Office of Research and Innovation. Peng Gong is partially supported by the National Research Program of the Ministry of Science and Technology of the People’s Republic of China (2016YFA0600104), and donations from Delos Living LLC and the Cyrus Tang Foundation to Tsinghua University.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Geography and the Environment, University of North Texas, 1155 Union Circle, Denton, TX, 76203, USA

Ministry of Education Key Laboratory for Earth System Modeling, Department of Earth System Science, Tsinghua University, Beijing, China

Tsinghua Urban Institute, Tsinghua University, Beijing, 100084, China

Center for Healthy Cities, Institute for China Sustainable Urbanization, Tsinghua University, Beijing, 100084, China

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

L.L. and P.G. wrote the main manuscript text. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Lu Liang .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Liang, L., Gong, P. Urban and air pollution: a multi-city study of long-term effects of urban landscape patterns on air quality trends. Sci Rep 10 , 18618 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-74524-9

Download citation

Received : 11 June 2020

Accepted : 24 August 2020

Published : 29 October 2020

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-74524-9

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

This article is cited by

Spatial–temporal distribution patterns and influencing factors analysis of comorbidity prevalence of chronic diseases among middle-aged and elderly people in china: focusing on exposure to ambient fine particulate matter (pm2.5).

- Liangwen Zhang

- Linjiang Wei

BMC Public Health (2024)

The impact of mobility costs on cooperation and welfare in spatial social dilemmas

- Jacques Bara

- Fernando P. Santos

- Paolo Turrini

Scientific Reports (2024)

The association between ambient air pollution exposure and connective tissue sarcoma risk: a nested case–control study using a nationwide population-based database

- Wei-Yi Huang

- Yu-Fen Chen

- Kuo-Yuan Huang

Environmental Science and Pollution Research (2024)

Systematic review of ecological research in Philippine cities: assessing the present status and charting future directions

- Anne Olfato-Parojinog

- Nikki Heherson A. Dagamac

Discover Environment (2024)

The evolution of atmospheric particulate matter in an urban landscape since the Industrial Revolution

- Ann L. Power

- Richard K. Tennant

Scientific Reports (2023)

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines . If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing: Anthropocene newsletter — what matters in anthropocene research, free to your inbox weekly.

- News & Events

- Eastern and Southern Africa

- Eastern Europe and Central Asia

- Mediterranean

- Mexico, Central America and the Caribbean

- North America

- South America

- West and Central Africa

- IUCN Academy

- IUCN Contributions for Nature

- IUCN Library

- IUCN Red List of Threatened Species TM

- IUCN Green List of Protected and Conserved Areas

- IUCN World Heritage Outlook

- IUCN Leaders Forum

- Protected Planet

- Union Portal (login required)

- IUCN Engage (login required)

- Commission portal (login required)

Data, analysis, convening and action.

- Open Project Portal

- SCIENCE-LED APPROACH

- INFORMING POLICY

- SUPPORTING CONSERVATION ACTION

- GEF AND GCF IMPLEMENTATION

- IUCN CONVENING

- IUCN ACADEMY

The world’s largest and most diverse environmental network.

CORE COMPONENTS

- Expert Commissions

- Secretariat and Director General

- IUCN Council

- IUCN WORLD CONSERVATION CONGRESS

- REGIONAL CONSERVATION FORA

- CONTRIBUTIONS FOR NATURE

- IUCN ENGAGE (LOGIN REQUIRED)

IUCN tools, publications and other resources.

Get involved

Four IUCN economic case studies show the impacts of plastic pollution in the marine environment on biodiversity, livelihoods, and more in Africa and Asia

Research into the economic aspects of the Marine Plastics and Coastal Communities project, to contain and reduce plastic pollution in the ocean, delivers insight into the true costs of plastic pollution on communities, livelihoods, coasts, and the global ocean.

Photo: Adobe Stock Image

The objective

The Marine Plastics and Coastal Communities (MARPLASTICCs) project goal was to assist governments and regional bodies in Eastern and Southern Africa and Asia to promote, enact, and enforce legislation and other effective measures to contain and reduce plastic pollution in the ocean. Part of the research completed included defining an economic assessment approach and producing economics case studies that reflected the impacts of plastic pollution on the marine environment, on coastal livelihoods, and more.

National case studies

Four national level economic case studies are available: for Mozambique, South Africa, Thailand, and Viet Nam. The important economic sectors of fisheries and tourism were studied, using different lenses to examine how plastic pollution causes detrimental economic impacts at national and local levels. Each assessment differs and explores wide-ranging economic dimensions that should be considered when creating a national plan of action to mitigate marine litter and plastic pollution in the environment. From impacts upon export revenue, employment and food security, to the economic efficiency of beach cleaning in conjunction with deposit refund schemes, and the impact of ghost gear on fisheries, these four case studies take a reader into the true costs of plastic pollution on our global ocean and coastal communities.

Mozambique Economic Report

What is the impact of plastic pollution on fisheries – including the broader economic dimension relating to export revenue, employment, food security, and marine ecosystems, and biodiversity? This economic policy brief explains these impacts within the Republic of Mozambique.

South Africa: Efficiency of beach clean-ups and deposit refund schemes (DRS) to avoid damages from plastic pollution on the tourism sector in Cape Town, South Africa (2021)

What are the impacts of plastic pollution on tourism revenue and tourism employment? What is the efficiency of beach cleaning with the implementation of a DRS? What is the impact on employment after DRS implementation? This economic policy brief explains these impacts within the context of the city of Cape Town, South Africa.

Case study on net fisheries in the Gulf of Thailand

This issues brief presents the results of a study that estimated the impact of marine macroplastic on Thai net fisheries operating in the Gulf of Thailand. The study has estimated the reduction in the net fisheries’ revenue due to the plastic stock and annual flow into the fishing zone/Thai Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) (Gulf of Thailand).

The economic impact of marine plastics, including ghost fishing, on fishing boats in Phước Tinh and Loc An, Ba Ria Vung Tau Province, Viet Nam (2022)

What are the impacts of plastic pollution caused by abandoned, lost or otherwise discarded fishing gear (ALDFG), also known as ‘ghost gear’? What are the costs to biodiversity of ghost gear? This economic policy brief explains the impacts on fishing boats in Phước Tinh and Loc An, Ba Ria Vung Tau Province, Viet Nam.

On-the-ground work

The work IUCN is doing on the impacts of plastic pollution, especially on tourism, fisheries, and waste management aims to identify the plastic applications and polymers and the waste management gaps that are contributing to the global problem.

IUCN works on-the-ground with partners from NGOs, the private sector, and national governments, in order to determine the priority problems and the most effective interventions, to advise countries how to stop the problem within their specific national context. IUCN bring science and knowledge together with policy, for action, in this case economic policies can be examined for their role in dealing with plastic pollution.

As the world is now focused on the establishment of a global plastic pollution treaty , understanding the scope of the impacts and prioritising interventions – including economic interventions – will be needed.

Acknowledgments and Support

The Marine Plastics and Coastal Communities project (MARPLASTICCs), generously supported by the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (Sida), provided support for the research and production of these Economic Case Studies.

For further information

Related content

Today the European Commission proposed a new nature restoration law with binding targets on…

The BIODEV2030 project, launched in early 2020 supports the country's development ambition, while…

From 4 to 6 October in Malaga (Spain), the “International Bycatch Meeting” will demonstrate the…

Sign up for an IUCN newsletter

Suggested citation: Khan, Adeel, Uday Suryanarayanan, Tanushree Ganguly, and Karthik Ganesan. Improving Air Quality Management through Forecasts: A Case Study of Delhi’s Air Pollution of Winter 2021. New Delhi: Council on Energy, Environment and Water.

This study assesses Delhi’s air pollution scenario in the winter of 2021 and the actions to tackle it. Winter 2021 was unlike previous winters as the control measures mandated by the Commission of Air Quality Management (CAQM) in Delhi National Capital Region and adjoining areas were rolled out. These measures included the Graded Response Action Plan (GRAP) and additional emergency responses instituted on the basis of air quality and meteorological forecasts. Given that the forecasts play a major role in emergency response measures, the study assesses the reliability of different forecasts. Further, it gauges the impact of the emergency measures on Delhi’s air quality levels. It also discusses the primary driver of air pollution in winter 2021.

Key Findings

- While air quality forecasts picked up the pollution trends, they are not yet very accurate in predicting high pollution episodes ('very poor' and 'severe' air quality days)

- When the restrictions were in place like ban on entry of trucks, construction & demolition activities and others, air quality did not descend into the ‘severe +’ category. Moreover, air quality improved from ‘severe’ to ‘poor’ when all the restrictions were in place simultaneously, aided by better meteorology.

- However, when the restrictions were finally lifted, the air quality spiralled back into the ‘severe’ category resulting in the longest six days ‘severe’ air quality spell of the season.

- There has been no significant improvement in Delhi's winter air quality since 2019. In winter 2021, air quality was in the ‘very poor’ to ‘severe’ category on about 75 per cent of days.

- In the winter of 2021, transport(∼ 12 per cent), dust (∼ 7 per cent) and domestic biomass burning (∼ 6 per cent) were the largest local contributors.

- About 64 per cent of Delhi’s winter pollution load comes from outside of Delhi’s boundaries.

HAVE A QUERY?

Executive Summary

With every passing winter, the need to address Delhi’s air pollution grows more urgent. During the winter of 2021, the Supreme Court, the Delhi Government, and the Commission for Air Quality Management in the NCR and Adjoining Areas (CAQM), all sprang into action to arrest rising pollution levels in Delhi. The interventions ranged from shutting down power plants and restricting the entry of trucks into Delhi to school closures and using forecasts to pre-emptively roll out emergency measures. However, the impact of these interventions on Delhi’s air quality begs further investigation.

Through this study, we intend to examine what worked and what did not this season. As is the case every year, meteorological conditions played an important role in both aggravating and alleviating pollution levels. To assess the impact of meteorological conditions on pollution levels, we analysed pollution levels during the months of October to January vis-a-vis meteorological parameters. To understand the driving causes of pollution in the winter of 2021, we tracked the changes in relative contribution of various polluting sources as the season progressed.

While pre-emptive actions based on forecasts was a step in the right direction, an assessment of forecast performance is a prerequisite to integrating them in decision-making. We also assessed the performance of forecasts by comparing them with the measured onground concentrations. We also studied the timing and effectiveness of emergency directions issued in response to forecasts.

We sourced data on pollution levels from Central Pollution Control Board’s (CPCB) real-time air quality data portal and meteorological information from ECMWF Reanalysis v5 (ERA5). For information on modelled concentration and source contributions, we used data from publicly available air quality forecasts, including Delhi’s Air Quality Early Warning System (AQ-EWS) (3-day and 10-day), the Decision Support System for Air Quality Management in Delhi (DSS), and UrbanEmissions.Info (UE).

Figure ES1 In Delhi, 75% of Winter 2021 saw 'very poor' to 'severe' air quality

Source: Authors’ analysis, data from Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB). Note: Air quality index (AQI) for the day is calculated using the PM2.5 concentration at the same stations with a minimum of 75 per cent of the data being available.

A. 75 per cent of days were in ‘Very poor’ to ‘Severe’ air quality during winter 2021

The number of ‘Severe’ plus ‘Very poor’ air quality days during the winter has not decreased in the last three years (Figure ES1). During the winter of 2021 (15 October 2021 - 15 January 2022), about 75 per cent of the days, air quality were in the ‘Very poor’ to ‘Severe’ category. Interestingly, despite more farm fire incidents in Punjab, Haryana, and Uttar Pradesh in 2021 compared to 2020, Delhi’s PM2.5 concentration during the stubble burning phase (i.e., 15 October to 15 November) was lesser in 2021. This was primarily due to better meteorological conditions like higher wind speed and more number of rainy days during this period.

B. Regional influence predominant; Transport, dust, and domestic biomass burning are the largest local contributors to air pollution

We find that about 64 per cent of Delhi’s winter pollution load comes from outside Delhi’s boundaries (Figure ES2(a). Biomass burning of agricultural waste during the stubble burning phase and burning for heating and cooking needs during peak winter are estimated to be the major sources of air pollution from outside the city according to UE (Figure ES2(b). Locally, transport (12 per cent), dust (7 per cent), and domestic biomass burning (6 per cent) contribute the most to the PM2.5 pollution load of the city. While transport and dust are perennial sources of pollution in the city, the residential space heating component is a seasonal source. However, this seasonal contribution is so significant that as the use of biomass as a heat source in and around Delhi starts going up as winter progresses, the residential sector becomes the single-largest contributor by 15 December (Figure ES2(b)). This indicates the need to ramp up programmes to encourage households to shift to cleaner fuels for cooking and space heating.

Figure ES 2(a) Transport, dust, and domestic biomass burning are the largest local contributors to the PM2.5 pollution load in Delhi

Source: Authors’ analysis, source contribution data from DSS and UE. Note: Modelled estimates of relative source contributions retrieved from UE and DSS.

Figure ES 2(b) Both local and regional sources need to be targeted for reducing Delhi’s pollution

Source: Authors’ analysis, source contribution data from UE. Note: Source contribution data retrieved from UE district products which have larger geographical cover and lower resolution.

C. Forecasts picked up the pollution trend but could not predict high pollution episodes

The availability of multiple forecasts provides decisionmakers with a range of options to choose from. At the same time, this is an obstacle to effective onground action. To streamline the flow of relevant information from forecasters to decision-makers, it is important to analyse the forecasts and assess their reliability. We found that all the forecasts identified pollution trends accurately (Figure ES3) but their accuracy in predicting pollution episodes (‘Severe’ and ‘Very Poor’ air quality days) decreases with future time horizon.

D. Though forecasts were used to impose restrictions, the lifting of the curbs was ill-timed

In November–December 2021, apart from the Graded Response Action Plan (GRAP) coming into effect in DelhiNCR, the CAQM introduced several emergency response measures through a series of directions and orders. The Supreme Court also stepped in from time to time to direct the authorities to act on air pollution.

As a first, the CAQM used air quality and meteorological forecasts to time and tailor emergency response actions. The first set of restrictions was put in place on 16 November 2021, and all were lifted by 20 December 2021, save the one on industrial operations.

Figure ES3 All the forecasts can predict the trend accurately

Source: Authors’ analysis, data from Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB), AQ-EWS, and UE. Note: r represents correlation.

During this period, all the forecasts except AQ-EWS (3-day) underpredicted PM2.5 levels. Therefore, by looking at the difference between forecasted and measured concentrations, it is not possible to gauge the effectiveness of the restrictions conclusively. Hence, multiple models or different modelling experiments are needed to estimate the impact of the intervention.

It should be noted that during the restriction period, air quality did not descend into the ‘Severe +’ category. Further, when all the restrictions were in place along with better meteorology, air quality did improve from ‘Severe’ to ‘Poor’. The first prolonged ‘Severe’ air quality period in December was witnessed between 21 December and 26 December. While the forecasts sounded an alarm for high pollution levels during this period, all restrictions barring those on industrial activities were lifted. Subsequently, PM2.5 levels remained above 250 µgm -3 for six straight days resulting in the longest ‘Severe’ air quality spell of the season. (Figure ES4).

Figure ES4 The lifting of the restrictions was ill-timed with high pollution levels forecasted in the following days

Source: Authors’ analysis, data from Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB). Note: C&D stands for construction and demolition activities. Work from home (WFH) stands for the 50% cap on employee attendance in the office. Industrial restrictions stand for compulsory switching over to Piped Natural Gas (PNG) or other cleaner fuels within industries and non-compliant industries being allowed to operate restrictively.

The discussion above highlights that despite the emergency measures taken in winter 2021, the air quality conditions were far from satisfactory. Calibrating emergency responses to forecasted source contributions may result in a greater impact on air quality. Our study recommends the following to help the Government of National Capital Territory of Delhi ( GNCTD) and CAQM plan and execute emergency responses better:

- GRAP implementation must be based strictly on modelled source contributions obtained from forecasts and timed accordingly. This will eliminate the need for ad-hoc emergency directions to restrict various activities. For instance, restrictions on private vehicles can be brought in when the air quality is forecasted to be ‘Very poor’ as transport is a significant contributor.

- Surveys or assessments are required in the residential areas across NCR to explore the prevalence of biomass usage for heating and cooking purposes. Based on this, a targeted support mechanism is required to allow households and others to use clean fuels for cooking and heating. There is also a need to assess and promote alternatives for space heating.

- Air quality forecasts should be relayed to the public via social media platforms to encourage them to take preventive measures such as avoiding unnecessary travel and wearing masks when stepping out. This will help reduce individual exposure and activity levels in the city.

- Ground level data and insights need to be incorporated in forecasting models. Data from sources like social media posts (text and photos), camera feeds from public places, and pollution related grievance portals like SAMEER, Green Delhi, and SDMC 311 can provide near-real time information on pollution sources. Then aggregated representation of polluting activities based on recent days or weeks can be used as an input in models. Ultimately, a crowd-sourced emissions inventory for NCT/NCR will benefit modellers and policymakers alike while also making pollution curtailment efforts transparent.

- Combining the available air quality forecasts through an ensemble approach can help improve the accuracy of the forecasts and prompt better coordination within the modelling community.

Sign up for the latest on our pioneering research

Explore related publications.

Assessing Effectiveness of India’s Industrial Emission Monitoring Systems

Hemant Mallya, Sankalp Kumar, Sabarish Elango

Catalysing Local Action for Clean Air

Sairam D, Priyanka Singh, Satyateja Subbarao, KS Jayachandran

Best Practices in CEM (Continuous Emission Monitoring)

Sanjeev K Kanchan

What is Polluting India’s Air? The Need for an Official Air Pollution Emissions Database

Tanushree Ganguly, Adeel Khan and Karthik Ganesan

Why Paddy Stubble Continues to be Burnt in Punjab?

L. S. Kurinji, Srish Prakash

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Int J Environ Res Public Health

A Case Study of Environmental Injustice: The Failure in Flint

Carla campbell.

1 Department of Public Health Sciences, Room 408, College of Health Sciences, University of Texas at El Paso, 500 W. University Ave, El Paso, TX 79968, USA

Rachael Greenberg

2 National Nurse-led Care Consortium (NNCC), Philadelphia, PA 19102, USA; su.ccnn@grebneergr

Deepa Mankikar

3 Research and Evaluation Group, Public Health Management Corporation, Philadelphia, PA 19102, USA; gro.cmhp@rakiknamd

Ronald D. Ross

4 Occupational and Environmental Medicine Consultant, Las Cruces, NM 88001, USA; [email protected]

The failure by the city of Flint, Michigan to properly treat its municipal water system after a change in the source of water, has resulted in elevated lead levels in the city’s water and an increase in city children’s blood lead levels. Lead exposure in young children can lead to decrements in intelligence, development, behavior, attention and other neurological functions. This lack of ability to provide safe drinking water represents a failure to protect the public’s health at various governmental levels. This article describes how the tragedy happened, how low-income and minority populations are at particularly high risk for lead exposure and environmental injustice, and ways that we can move forward to prevent childhood lead exposure and lead poisoning, as well as prevent future Flint-like exposure events from occurring. Control of the manufacture and use of toxic chemicals to prevent adverse exposure to these substances is also discussed. Environmental injustice occurred throughout the Flint water contamination incident and there are lessons we can all learn from this debacle to move forward in promoting environmental justice.

1. Description of the Flint Water Crisis