- Conference key note

- Open access

- Published: 24 January 2019

Financial literacy and the need for financial education: evidence and implications

- Annamaria Lusardi 1

Swiss Journal of Economics and Statistics volume 155 , Article number: 1 ( 2019 ) Cite this article

411k Accesses

293 Citations

215 Altmetric

Metrics details

1 Introduction

Throughout their lifetime, individuals today are more responsible for their personal finances than ever before. With life expectancies rising, pension and social welfare systems are being strained. In many countries, employer-sponsored defined benefit (DB) pension plans are swiftly giving way to private defined contribution (DC) plans, shifting the responsibility for retirement saving and investing from employers to employees. Individuals have also experienced changes in labor markets. Skills are becoming more critical, leading to divergence in wages between those with a college education, or higher, and those with lower levels of education. Simultaneously, financial markets are rapidly changing, with developments in technology and new and more complex financial products. From student loans to mortgages, credit cards, mutual funds, and annuities, the range of financial products people have to choose from is very different from what it was in the past, and decisions relating to these financial products have implications for individual well-being. Moreover, the exponential growth in financial technology (fintech) is revolutionizing the way people make payments, decide about their financial investments, and seek financial advice. In this context, it is important to understand how financially knowledgeable people are and to what extent their knowledge of finance affects their financial decision-making.

An essential indicator of people’s ability to make financial decisions is their level of financial literacy. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) aptly defines financial literacy as not only the knowledge and understanding of financial concepts and risks but also the skills, motivation, and confidence to apply such knowledge and understanding in order to make effective decisions across a range of financial contexts, to improve the financial well-being of individuals and society, and to enable participation in economic life. Thus, financial literacy refers to both knowledge and financial behavior, and this paper will analyze research on both topics.

As I describe in more detail below, findings around the world are sobering. Financial literacy is low even in advanced economies with well-developed financial markets. On average, about one third of the global population has familiarity with the basic concepts that underlie everyday financial decisions (Lusardi and Mitchell, 2011c ). The average hides gaping vulnerabilities of certain population subgroups and even lower knowledge of specific financial topics. Furthermore, there is evidence of a lack of confidence, particularly among women, and this has implications for how people approach and make financial decisions. In the following sections, I describe how we measure financial literacy, the levels of literacy we find around the world, the implications of those findings for financial decision-making, and how we can improve financial literacy.

2 How financially literate are people?

2.1 measuring financial literacy: the big three.

In the context of rapid changes and constant developments in the financial sector and the broader economy, it is important to understand whether people are equipped to effectively navigate the maze of financial decisions that they face every day. To provide the tools for better financial decision-making, one must assess not only what people know but also what they need to know, and then evaluate the gap between those things. There are a few fundamental concepts at the basis of most financial decision-making. These concepts are universal, applying to every context and economic environment. Three such concepts are (1) numeracy as it relates to the capacity to do interest rate calculations and understand interest compounding; (2) understanding of inflation; and (3) understanding of risk diversification. Translating these concepts into easily measured financial literacy metrics is difficult, but Lusardi and Mitchell ( 2008 , 2011b , 2011c ) have designed a standard set of questions around these concepts and implemented them in numerous surveys in the USA and around the world.

Four principles informed the design of these questions, as described in detail by Lusardi and Mitchell ( 2014 ). The first is simplicity : the questions should measure knowledge of the building blocks fundamental to decision-making in an intertemporal setting. The second is relevance : the questions should relate to concepts pertinent to peoples’ day-to-day financial decisions over the life cycle; moreover, they must capture general rather than context-specific ideas. Third is brevity : the number of questions must be few enough to secure widespread adoption; and fourth is capacity to differentiate , meaning that questions should differentiate financial knowledge in such a way as to permit comparisons across people. Each of these principles is important in the context of face-to-face, telephone, and online surveys.

Three basic questions (since dubbed the “Big Three”) to measure financial literacy have been fielded in many surveys in the USA, including the National Financial Capability Study (NFCS) and, more recently, the Survey of Consumer Finances (SCF), and in many national surveys around the world. They have also become the standard way to measure financial literacy in surveys used by the private sector. For example, the Aegon Center for Longevity and Retirement included the Big Three questions in the 2018 Aegon Retirement Readiness Survey, covering around 16,000 people in 15 countries. Both ING and Allianz, but also investment funds, and pension funds have used the Big Three to measure financial literacy. The exact wording of the questions is provided in Table 1 .

2.2 Cross-country comparison

The first examination of financial literacy using the Big Three was possible due to a special module on financial literacy and retirement planning that Lusardi and Mitchell designed for the 2004 Health and Retirement Study (HRS), which is a survey of Americans over age 50. Astonishingly, the data showed that only half of older Americans—who presumably had made many financial decisions in their lives—could answer the two basic questions measuring understanding of interest rates and inflation (Lusardi and Mitchell, 2011b ). And just one third demonstrated understanding of these two concepts and answered the third question, measuring understanding of risk diversification, correctly. It is sobering that recent US surveys, such as the 2015 NFCS, the 2016 SCF, and the 2017 Survey of Household Economics and Financial Decisionmaking (SHED), show that financial knowledge has remained stubbornly low over time.

Over time, the Big Three have been added to other national surveys across countries and Lusardi and Mitchell have coordinated a project called Financial Literacy around the World (FLat World), which is an international comparison of financial literacy (Lusardi and Mitchell, 2011c ).

Findings from the FLat World project, which so far includes data from 15 countries, including Switzerland, highlight the urgent need to improve financial literacy (see Table 2 ). Across countries, financial literacy is at a crisis level, with the average rate of financial literacy, as measured by those answering correctly all three questions, at around 30%. Moreover, only around 50% of respondents in most countries are able to correctly answer the two financial literacy questions on interest rates and inflation correctly. A noteworthy point is that most countries included in the FLat World project have well-developed financial markets, which further highlights the cause for alarm over the demonstrated lack of the financial literacy. The fact that levels of financial literacy are so similar across countries with varying levels of economic development—indicating that in terms of financial knowledge, the world is indeed flat —shows that income levels or ubiquity of complex financial products do not by themselves equate to a more financially literate population.

Other noteworthy findings emerge in Table 2 . For instance, as expected, understanding of the effects of inflation (i.e., of real versus nominal values) among survey respondents is low in countries that have experienced deflation rather than inflation: in Japan, understanding of inflation is at 59%; in other countries, such as Germany, it is at 78% and, in the Netherlands, it is at 77%. Across countries, individuals have the lowest level of knowledge around the concept of risk, and the percentage of correct answers is particularly low when looking at knowledge of risk diversification. Here, we note the prevalence of “do not know” answers. While “do not know” responses hover around 15% on the topic of interest rates and 18% for inflation, about 30% of respondents—in some countries even more—are likely to respond “do not know” to the risk diversification question. In Switzerland, 74% answered the risk diversification question correctly and 13% reported not knowing the answer (compared to 3% and 4% responding “do not know” for the interest rates and inflation questions, respectively).

These findings are supported by many other surveys. For example, the 2014 Standard & Poor’s Global Financial Literacy Survey shows that, around the world, people know the least about risk and risk diversification (Klapper, Lusardi, and Van Oudheusden, 2015 ). Similarly, results from the 2016 Allianz survey, which collected evidence from ten European countries on money, financial literacy, and risk in the digital age, show very low-risk literacy in all countries covered by the survey. In Austria, Germany, and Switzerland, which are the three top-performing nations in term of financial knowledge, less than 20% of respondents can answer three questions related to knowledge of risk and risk diversification (Allianz, 2017 ).

Other surveys show that the findings about financial literacy correlate in an expected way with other data. For example, performance on the mathematics and science sections of the OECD Program for International Student Assessment (PISA) correlates with performance on the Big Three and, specifically, on the question relating to interest rates. Similarly, respondents in Sweden, which has experienced pension privatization, performed better on the risk diversification question (at 68%), than did respondents in Russia and East Germany, where people have had less exposure to the stock market. For researchers studying financial knowledge and its effects, these findings hint to the fact that financial literacy could be the result of choice and not an exogenous variable.

To summarize, financial literacy is low across the world and higher national income levels do not equate to a more financially literate population. The design of the Big Three questions enables a global comparison and allows for a deeper understanding of financial literacy. This enhances the measure’s utility because it helps to identify general and specific vulnerabilities across countries and within population subgroups, as will be explained in the next section.

2.3 Who knows the least?

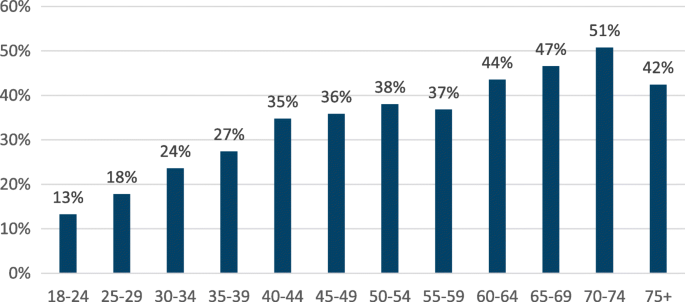

Low financial literacy on average is exacerbated by patterns of vulnerability among specific population subgroups. For instance, as reported in Lusardi and Mitchell ( 2014 ), even though educational attainment is positively correlated with financial literacy, it is not sufficient. Even well-educated people are not necessarily savvy about money. Financial literacy is also low among the young. In the USA, less than 30% of respondents can correctly answer the Big Three by age 40, even though many consequential financial decisions are made well before that age (see Fig. 1 ). Similarly, in Switzerland, only 45% of those aged 35 or younger are able to correctly answer the Big Three questions. Footnote 1 And if people may learn from making financial decisions, that learning seems limited. As shown in Fig. 1 , many older individuals, who have already made decisions, cannot answer three basic financial literacy questions.

Financial literacy across age in the USA. This figure shows the percentage of respondents who answered correctly all Big Three questions by age group (year 2015). Source: 2015 US National Financial Capability Study

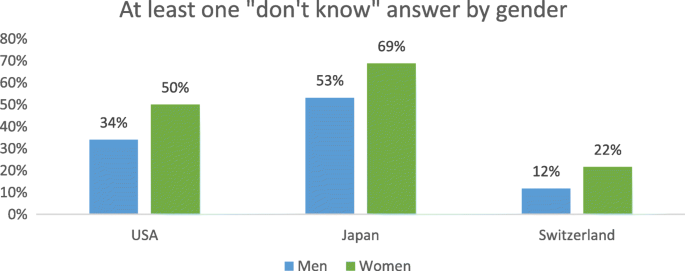

A gender gap in financial literacy is also present across countries. Women are less likely than men to answer questions correctly. The gap is present not only on the overall scale but also within each topic, across countries of different income levels, and at different ages. Women are also disproportionately more likely to indicate that they do not know the answer to specific questions (Fig. 2 ), highlighting overconfidence among men and awareness of lack of knowledge among women. Even in Finland, which is a relatively equal society in terms of gender, 44% of men compared to 27% of women answer all three questions correctly and 18% of women give at least one “do not know” response versus less than 10% of men (Kalmi and Ruuskanen, 2017 ). These figures further reflect the universality of the Big Three questions. As reported in Fig. 2 , “do not know” responses among women are prevalent not only in European countries, for example, Switzerland, but also in North America (represented in the figure by the USA, though similar findings are reported in Canada) and in Asia (represented in the figure by Japan). Those interested in learning more about the differences in financial literacy across demographics and other characteristics can consult Lusardi and Mitchell ( 2011c , 2014 ).

Gender differences in the responses to the Big Three questions. Sources: USA—Lusardi and Mitchell, 2011c ; Japan—Sekita, 2011 ; Switzerland—Brown and Graf, 2013

3 Does financial literacy matter?

A growing number of financial instruments have gained importance, including alternative financial services such as payday loans, pawnshops, and rent to own stores that charge very high interest rates. Simultaneously, in the changing economic landscape, people are increasingly responsible for personal financial planning and for investing and spending their resources throughout their lifetime. We have witnessed changes not only in the asset side of household balance sheets but also in the liability side. For example, in the USA, many people arrive close to retirement carrying a lot more debt than previous generations did (Lusardi, Mitchell, and Oggero, 2018 ). Overall, individuals are making substantially more financial decisions over their lifetime, living longer, and gaining access to a range of new financial products. These trends, combined with low financial literacy levels around the world and, particularly, among vulnerable population groups, indicate that elevating financial literacy must become a priority for policy makers.

There is ample evidence of the impact of financial literacy on people’s decisions and financial behavior. For example, financial literacy has been proven to affect both saving and investment behavior and debt management and borrowing practices. Empirically, financially savvy people are more likely to accumulate wealth (Lusardi and Mitchell, 2014 ). There are several explanations for why higher financial literacy translates into greater wealth. Several studies have documented that those who have higher financial literacy are more likely to plan for retirement, probably because they are more likely to appreciate the power of interest compounding and are better able to do calculations. According to the findings of the FLat World project, answering one additional financial question correctly is associated with a 3–4 percentage point greater probability of planning for retirement; this finding is seen in Germany, the USA, Japan, and Sweden. Financial literacy is found to have the strongest impact in the Netherlands, where knowing the right answer to one additional financial literacy question is associated with a 10 percentage point higher probability of planning (Mitchell and Lusardi, 2015 ). Empirically, planning is a very strong predictor of wealth; those who plan arrive close to retirement with two to three times the amount of wealth as those who do not plan (Lusardi and Mitchell, 2011b ).

Financial literacy is also associated with higher returns on investments and investment in more complex assets, such as stocks, which normally offer higher rates of return. This finding has important consequences for wealth; according to the simulation by Lusardi, Michaud, and Mitchell ( 2017 ), in the context of a life-cycle model of saving with many sources of uncertainty, from 30 to 40% of US retirement wealth inequality can be accounted for by differences in financial knowledge. These results show that financial literacy is not a sideshow, but it plays a critical role in saving and wealth accumulation.

Financial literacy is also strongly correlated with a greater ability to cope with emergency expenses and weather income shocks. Those who are financially literate are more likely to report that they can come up with $2000 in 30 days or that they are able to cover an emergency expense of $400 with cash or savings (Hasler, Lusardi, and Oggero, 2018 ).

With regard to debt behavior, those who are more financially literate are less likely to have credit card debt and more likely to pay the full balance of their credit card each month rather than just paying the minimum due (Lusardi and Tufano, 2009 , 2015 ). Individuals with higher financial literacy levels also are more likely to refinance their mortgages when it makes sense to do so, tend not to borrow against their 401(k) plans, and are less likely to use high-cost borrowing methods, e.g., payday loans, pawn shops, auto title loans, and refund anticipation loans (Lusardi and de Bassa Scheresberg, 2013 ).

Several studies have documented poor debt behavior and its link to financial literacy. Moore ( 2003 ) reported that the least financially literate are also more likely to have costly mortgages. Lusardi and Tufano ( 2015 ) showed that the least financially savvy incurred high transaction costs, paying higher fees and using high-cost borrowing methods. In their study, the less knowledgeable also reported excessive debt loads and an inability to judge their debt positions. Similarly, Mottola ( 2013 ) found that those with low financial literacy were more likely to engage in costly credit card behavior, and Utkus and Young ( 2011 ) concluded that the least literate were more likely to borrow against their 401(k) and pension accounts.

Young people also struggle with debt, in particular with student loans. According to Lusardi, de Bassa Scheresberg, and Oggero ( 2016 ), Millennials know little about their student loans and many do not attempt to calculate the payment amounts that will later be associated with the loans they take. When asked what they would do, if given the chance to revisit their student loan borrowing decisions, about half of Millennials indicate that they would make a different decision.

Finally, a recent report on Millennials in the USA (18- to 34-year-olds) noted the impact of financial technology (fintech) on the financial behavior of young individuals. New and rapidly expanding mobile payment options have made transactions easier, quicker, and more convenient. The average user of mobile payments apps and technology in the USA is a high-income, well-educated male who works full time and is likely to belong to an ethnic minority group. Overall, users of mobile payments are busy individuals who are financially active (holding more assets and incurring more debt). However, mobile payment users display expensive financial behaviors, such as spending more than they earn, using alternative financial services, and occasionally overdrawing their checking accounts. Additionally, mobile payment users display lower levels of financial literacy (Lusardi, de Bassa Scheresberg, and Avery, 2018 ). The rapid growth in fintech around the world juxtaposed with expensive financial behavior means that more attention must be paid to the impact of mobile payment use on financial behavior. Fintech is not a substitute for financial literacy.

4 The way forward for financial literacy and what works

Overall, financial literacy affects everything from day-to-day to long-term financial decisions, and this has implications for both individuals and society. Low levels of financial literacy across countries are correlated with ineffective spending and financial planning, and expensive borrowing and debt management. These low levels of financial literacy worldwide and their widespread implications necessitate urgent efforts. Results from various surveys and research show that the Big Three questions are useful not only in assessing aggregate financial literacy but also in identifying vulnerable population subgroups and areas of financial decision-making that need improvement. Thus, these findings are relevant for policy makers and practitioners. Financial illiteracy has implications not only for the decisions that people make for themselves but also for society. The rapid spread of mobile payment technology and alternative financial services combined with lack of financial literacy can exacerbate wealth inequality.

To be effective, financial literacy initiatives need to be large and scalable. Schools, workplaces, and community platforms provide unique opportunities to deliver financial education to large and often diverse segments of the population. Furthermore, stark vulnerabilities across countries make it clear that specific subgroups, such as women and young people, are ideal targets for financial literacy programs. Given women’s awareness of their lack of financial knowledge, as indicated via their “do not know” responses to the Big Three questions, they are likely to be more receptive to financial education.

The near-crisis levels of financial illiteracy, the adverse impact that it has on financial behavior, and the vulnerabilities of certain groups speak of the need for and importance of financial education. Financial education is a crucial foundation for raising financial literacy and informing the next generations of consumers, workers, and citizens. Many countries have seen efforts in recent years to implement and provide financial education in schools, colleges, and workplaces. However, the continuously low levels of financial literacy across the world indicate that a piece of the puzzle is missing. A key lesson is that when it comes to providing financial education, one size does not fit all. In addition to the potential for large-scale implementation, the main components of any financial literacy program should be tailored content, targeted at specific audiences. An effective financial education program efficiently identifies the needs of its audience, accurately targets vulnerable groups, has clear objectives, and relies on rigorous evaluation metrics.

Using measures like the Big Three questions, it is imperative to recognize vulnerable groups and their specific needs in program designs. Upon identification, the next step is to incorporate this knowledge into financial education programs and solutions.

School-based education can be transformational by preparing young people for important financial decisions. The OECD’s Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA), in both 2012 and 2015, found that, on average, only 10% of 15-year-olds achieved maximum proficiency on a five-point financial literacy scale. As of 2015, about one in five of students did not have even basic financial skills (see OECD, 2017 ). Rigorous financial education programs, coupled with teacher training and high school financial education requirements, are found to be correlated with fewer defaults and higher credit scores among young adults in the USA (Urban, Schmeiser, Collins, and Brown, 2018 ). It is important to target students and young adults in schools and colleges to provide them with the necessary tools to make sound financial decisions as they graduate and take on responsibilities, such as buying cars and houses, or starting retirement accounts. Given the rising cost of education and student loan debt and the need of young people to start contributing as early as possible to retirement accounts, the importance of financial education in school cannot be overstated.

There are three compelling reasons for having financial education in school. First, it is important to expose young people to the basic concepts underlying financial decision-making before they make important and consequential financial decisions. As noted in Fig. 1 , financial literacy is very low among the young and it does not seem to increase a lot with age/generations. Second, school provides access to financial literacy to groups who may not be exposed to it (or may not be equally exposed to it), for example, women. Third, it is important to reduce the costs of acquiring financial literacy, if we want to promote higher financial literacy both among individuals and among society.

There are compelling reasons to have personal finance courses in college as well. In the same way in which colleges and university offer courses in corporate finance to teach how to manage the finances of firms, so today individuals need the knowledge to manage their own finances over the lifetime, which in present discounted value often amount to large values and are made larger by private pension accounts.

Financial education can also be efficiently provided in workplaces. An effective financial education program targeted to adults recognizes the socioeconomic context of employees and offers interventions tailored to their specific needs. A case study conducted in 2013 with employees of the US Federal Reserve System showed that completing a financial literacy learning module led to significant changes in retirement planning behavior and better-performing investment portfolios (Clark, Lusardi, and Mitchell, 2017 ). It is also important to note the delivery method of these programs, especially when targeted to adults. For instance, video formats have a significantly higher impact on financial behavior than simple narratives, and instruction is most effective when it is kept brief and relevant (Heinberg et al., 2014 ).

The Big Three also show that it is particularly important to make people familiar with the concepts of risk and risk diversification. Programs devoted to teaching risk via, for example, visual tools have shown great promise (Lusardi et al., 2017 ). The complexity of some of these concepts and the costs of providing education in the workplace, coupled with the fact that many older individuals may not work or work in firms that do not offer such education, provide other reasons why financial education in school is so important.

Finally, it is important to provide financial education in the community, in places where people go to learn. A recent example is the International Federation of Finance Museums, an innovative global collaboration that promotes financial knowledge through museum exhibits and the exchange of resources. Museums can be places where to provide financial literacy both among the young and the old.

There are a variety of other ways in which financial education can be offered and also targeted to specific groups. However, there are few evaluations of the effectiveness of such initiatives and this is an area where more research is urgently needed, given the statistics reported in the first part of this paper.

5 Concluding remarks

The lack of financial literacy, even in some of the world’s most well-developed financial markets, is of acute concern and needs immediate attention. The Big Three questions that were designed to measure financial literacy go a long way in identifying aggregate differences in financial knowledge and highlighting vulnerabilities within populations and across topics of interest, thereby facilitating the development of tailored programs. Many such programs to provide financial education in schools and colleges, workplaces, and the larger community have taken existing evidence into account to create rigorous solutions. It is important to continue making strides in promoting financial literacy, by achieving scale and efficiency in future programs as well.

In August 2017, I was appointed Director of the Italian Financial Education Committee, tasked with designing and implementing the national strategy for financial literacy. I will be able to apply my research to policy and program initiatives in Italy to promote financial literacy: it is an essential skill in the twenty-first century, one that individuals need if they are to thrive economically in today’s society. As the research discussed in this paper well documents, financial literacy is like a global passport that allows individuals to make the most of the plethora of financial products available in the market and to make sound financial decisions. Financial literacy should be seen as a fundamental right and universal need, rather than the privilege of the relatively few consumers who have special access to financial knowledge or financial advice. In today’s world, financial literacy should be considered as important as basic literacy, i.e., the ability to read and write. Without it, individuals and societies cannot reach their full potential.

See Brown and Graf ( 2013 ).

Abbreviations

Defined benefit (refers to pension plan)

Defined contribution (refers to pension plan)

Financial Literacy around the World

National Financial Capability Study

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

Programme for International Student Assessment

Survey of Consumer Finances

Survey of Household Economics and Financial Decisionmaking

Aegon Center for Longevity and Retirement. (2018). The New Social Contract: a blueprint for retirement in the 21st century. The Aegon Retirement Readiness Survey 2018. Retrieved from https://www.aegon.com/en/Home/Research/aegon-retirement-readiness-survey-2018/ . Accessed 1 June 2018.

Agnew, J., Bateman, H., & Thorp, S. (2013). Financial literacy and retirement planning in Australia. Numeracy, 6 (2).

Allianz (2017). When will the penny drop? Money, financial literacy and risk in the digital age. Retrieved from http://gflec.org/initiatives/money-finlit-risk/ . Accessed 1 June 2018.

Almenberg, J., & Säve-Söderbergh, J. (2011). Financial literacy and retirement planning in Sweden. Journal of Pension Economics & Finance, 10 (4), 585–598.

Article Google Scholar

Arrondel, L., Debbich, M., & Savignac, F. (2013). Financial literacy and financial planning in France. Numeracy, 6 (2).

Beckmann, E. (2013). Financial literacy and household savings in Romania. Numeracy, 6 (2).

Boisclair, D., Lusardi, A., & Michaud, P. C. (2017). Financial literacy and retirement planning in Canada. Journal of Pension Economics & Finance, 16 (3), 277–296.

Brown, M., & Graf, R. (2013). Financial literacy and retirement planning in Switzerland. Numeracy, 6 (2).

Bucher-Koenen, T., & Lusardi, A. (2011). Financial literacy and retirement planning in Germany. Journal of Pension Economics & Finance, 10 (4), 565–584.

Clark, R., Lusardi, A., & Mitchell, O. S. (2017). Employee financial literacy and retirement plan behavior: a case study. Economic Inquiry, 55 (1), 248–259.

Crossan, D., Feslier, D., & Hurnard, R. (2011). Financial literacy and retirement planning in New Zealand. Journal of Pension Economics & Finance, 10 (4), 619–635.

Fornero, E., & Monticone, C. (2011). Financial literacy and pension plan participation in Italy. Journal of Pension Economics & Finance, 10 (4), 547–564.

Hasler, A., Lusardi, A., and Oggero, N. (2018). Financial fragility in the US: evidence and implications. GFLEC working paper n. 2018–1.

Heinberg, A., Hung, A., Kapteyn, A., Lusardi, A., Samek, A. S., & Yoong, J. (2014). Five steps to planning success: experimental evidence from US households. Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 30 (4), 697–724.

Kalmi, P., & Ruuskanen, O. P. (2017). Financial literacy and retirement planning in Finland. Journal of Pension Economics & Finance, 17 (3), 1–28.

Klapper, L., Lusardi, A., & Van Oudheusden, P. (2015). Financial literacy around the world. In Standard & Poor’s Ratings Services Global Financial Literacy Survey (GFLEC working paper).

Google Scholar

Klapper, L., & Panos, G. A. (2011). Financial literacy and retirement planning: The Russian case. Journal of Pension Economics & Finance, 10 (4), 599–618.

Lusardi, A., & de Bassa Scheresberg, C. (2013). Financial literacy and high-cost borrowing in the United States, NBER Working Paper n. 18969, April .

Book Google Scholar

Lusardi, A., de Bassa Scheresberg, C., and Avery, M. 2018. Millennial mobile payment users: a look into their personal finances and financial behaviors. GFLEC working paper.

Lusardi, A., de Bassa Scheresberg, C., & Oggero, N. (2016). Student loan debt in the US: an analysis of the 2015 NFCS Data, GFLEC Policy Brief, November .

Lusardi, A., Michaud, P. C., & Mitchell, O. S. (2017). Optimal financial knowledge and wealth inequality. Journal of Political Economy, 125 (2), 431–477.

Lusardi, A., & Mitchell, O. S. (2008). Planning and financial literacy: how do women fare? American Economic Review, 98 , 413–417.

Lusardi, A., & Mitchell, O. S. (2011a). The outlook for financial literacy. In O. S. Mitchell & A. Lusardi (Eds.), Financial literacy: implications for retirement security and the financial marketplace (pp. 1–15). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Chapter Google Scholar

Lusardi, A., & Mitchell, O. S. (2011b). Financial literacy and planning: implications for retirement wellbeing. In O. S. Mitchell & A. Lusardi (Eds.), Financial literacy: implications for retirement security and the financial marketplace (pp. 17–39). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Lusardi, A., & Mitchell, O. S. (2011c). Financial literacy around the world: an overview. Journal of Pension Economics and Finance, 10 (4), 497–508.

Lusardi, A., & Mitchell, O. S. (2014). The economic importance of financial literacy: theory and evidence. Journal of Economic Literature, 52 (1), 5–44.

Lusardi, A., Mitchell, O. S., & Oggero, N. (2018). The changing face of debt and financial fragility at older ages. American Economic Association Papers and Proceedings, 108 , 407–411.

Lusardi, A., Samek, A., Kapteyn, A., Glinert, L., Hung, A., & Heinberg, A. (2017). Visual tools and narratives: new ways to improve financial literacy. Journal of Pension Economics & Finance, 16 (3), 297–323.

Lusardi, A., & Tufano, P. (2009). Teach workers about the peril of debt. Harvard Business Review , 22–24.

Lusardi, A., & Tufano, P. (2015). Debt literacy, financial experiences, and overindebtedness. Journal of Pension Economics & Finance, 14 (4), 332–368.

Mitchell, O. S., & Lusardi, A. (2015). Financial literacy and economic outcomes: evidence and policy implications. The Journal of Retirement, 3 (1).

Moore, Danna. 2003. Survey of financial literacy in Washington State: knowledge, behavior, attitudes and experiences. Washington State University Social and Economic Sciences Research Center Technical Report 03–39.

Mottola, G. R. (2013). In our best interest: women, financial literacy, and credit card behavior. Numeracy, 6 (2).

Moure, N. G. (2016). Financial literacy and retirement planning in Chile. Journal of Pension Economics & Finance, 15 (2), 203–223.

OECD. (2017). PISA 2015 results (Volume IV): students’ financial literacy . Paris: PISA, OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264270282-en .

Sekita, S. (2011). Financial literacy and retirement planning in Japan. Journal of Pension Economics & Finance, 10 (4), 637–656.

Urban, C., Schmeiser, M., Collins, J. M., & Brown, A. (2018). The effects of high school personal financial education policies on financial behavior. Economics of Education Review . https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0272775718301699 .

Utkus, S., & Young, J. (2011). Financial literacy and 401(k) loans. In O. S. Mitchell & A. Lusardi (Eds.), Financial literacy: implications for retirement security and the financial marketplace (pp. 59–75). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Van Rooij, M. C., Lusardi, A., & Alessie, R. J. (2011). Financial literacy and retirement preparation in the Netherlands. Journal of Pension Economics and Finance, 10 (4), 527–545.

Download references

Acknowledgements

This paper represents a summary of the keynote address I gave to the 2018 Annual Meeting of the Swiss Society of Economics and Statistics. I would like to thank Monika Butler, Rafael Lalive, anonymous reviewers, and participants of the Annual Meeting for useful discussions and comments, and Raveesha Gupta for editorial support. All errors are my responsibility.

Not applicable

Availability of data and materials

Author information, authors and affiliations.

The George Washington University School of Business Global Financial Literacy Excellence Center and Italian Committee for Financial Education, Washington, D.C., USA

Annamaria Lusardi

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

The author read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Annamaria Lusardi .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The author declares that she has no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Lusardi, A. Financial literacy and the need for financial education: evidence and implications. Swiss J Economics Statistics 155 , 1 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41937-019-0027-5

Download citation

Received : 22 October 2018

Accepted : 07 January 2019

Published : 24 January 2019

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s41937-019-0027-5

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

About Stanford GSB

- The Leadership

- Dean’s Updates

- School News & History

- Commencement

- Business, Government & Society

- Centers & Institutes

- Center for Entrepreneurial Studies

- Center for Social Innovation

- Stanford Seed

About the Experience

- Learning at Stanford GSB

- Experiential Learning

- Guest Speakers

- Entrepreneurship

- Social Innovation

- Communication

- Life at Stanford GSB

- Collaborative Environment

- Activities & Organizations

- Student Services

- Housing Options

- International Students

Full-Time Degree Programs

- Why Stanford MBA

- Academic Experience

- Financial Aid

- Why Stanford MSx

- Research Fellows Program

- See All Programs

Non-Degree & Certificate Programs

- Executive Education

- Stanford Executive Program

- Programs for Organizations

- The Difference

- Online Programs

- Stanford LEAD

- Seed Transformation Program

- Aspire Program

- Seed Spark Program

- Faculty Profiles

- Academic Areas

- Awards & Honors

- Conferences

Faculty Research

- Publications

- Working Papers

- Case Studies

Research Hub

- Research Labs & Initiatives

- Business Library

- Data, Analytics & Research Computing

- Behavioral Lab

Research Labs

- Cities, Housing & Society Lab

- Golub Capital Social Impact Lab

Research Initiatives

- Corporate Governance Research Initiative

- Corporations and Society Initiative

- Policy and Innovation Initiative

- Rapid Decarbonization Initiative

- Stanford Latino Entrepreneurship Initiative

- Value Chain Innovation Initiative

- Venture Capital Initiative

- Career & Success

- Climate & Sustainability

- Corporate Governance

- Culture & Society

- Finance & Investing

- Government & Politics

- Leadership & Management

- Markets and Trade

- Operations & Logistics

- Opportunity & Access

- Technology & AI

- Opinion & Analysis

- Email Newsletter

Welcome, Alumni

- Communities

- Digital Communities & Tools

- Regional Chapters

- Women’s Programs

- Identity Chapters

- Find Your Reunion

- Career Resources

- Job Search Resources

- Career & Life Transitions

- Programs & Services

- Career Video Library

- Alumni Education

- Research Resources

- Volunteering

- Alumni News

- Class Notes

- Alumni Voices

- Contact Alumni Relations

- Upcoming Events

Admission Events & Information Sessions

- MBA Program

- MSx Program

- PhD Program

- Alumni Events

- All Other Events

- Operations, Information & Technology

- Organizational Behavior

- Political Economy

- Classical Liberalism

- The Eddie Lunch

- Accounting Summer Camp

- Videos, Code & Data

- California Econometrics Conference

- California Quantitative Marketing PhD Conference

- California School Conference

- China India Insights Conference

- Homo economicus, Evolving

- Political Economics (2023–24)

- Scaling Geologic Storage of CO2 (2023–24)

- A Resilient Pacific: Building Connections, Envisioning Solutions

- Adaptation and Innovation

- Changing Climate

- Civil Society

- Climate Impact Summit

- Climate Science

- Corporate Carbon Disclosures

- Earth’s Seafloor

- Environmental Justice

- Operations and Information Technology

- Organizations

- Sustainability Reporting and Control

- Taking the Pulse of the Planet

- Urban Infrastructure

- Watershed Restoration

- Junior Faculty Workshop on Financial Regulation and Banking

- Ken Singleton Celebration

- Marketing Camp

- Quantitative Marketing PhD Alumni Conference

- Presentations

- Theory and Inference in Accounting Research

- Stanford Closer Look Series

- Quick Guides

- Core Concepts

- Journal Articles

- Glossary of Terms

- Faculty & Staff

- Researchers & Students

- Research Approach

- Charitable Giving

- Financial Health

- Government Services

- Workers & Careers

- Short Course

- Adaptive & Iterative Experimentation

- Incentive Design

- Social Sciences & Behavioral Nudges

- Bandit Experiment Application

- Conferences & Events

- Get Involved

- Reading Materials

- Teaching & Curriculum

- Energy Entrepreneurship

- Faculty & Affiliates

- SOLE Report

- Responsible Supply Chains

- Current Study Usage

- Pre-Registration Information

- Participate in a Study

Financial Literacy and the Need for Financial Education: Evidence and Implications

Throughout their lifetime, individuals today are more responsible for their personal finances than ever before. With life expectancies rising, pension and social welfare systems are being strained. In many countries, employer-sponsored defined benefit (DB) pension plans are swiftly giving way to private defined contribution (DC) plans, shifting the responsibility for retirement saving and investing from employers to employees. Individuals have also experienced changes in labor markets. Skills are becoming more critical, leading to divergence in wages between those with a college education, or higher, and those with lower levels of education. Simultaneously, financial markets are rapidly changing, with developments in technology and new and more complex financial products. From student loans to mortgages, credit cards, mutual funds, and annuities, the range of financial products people have to choose from is very different from what it was in the past, and decisions relating to these financial products have implications for individual well-being. Moreover, the exponential growth in financial technology (fintech) is revolutionizing the way people make payments, decide about their financial investments, and seek financial advice. In this context, it is important to understand how financially knowledgeable people are and to what extent their knowledge of finance affects their financial decision-making.

An essential indicator of people’s ability to make financial decisions is their level of financial literacy. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) aptly defines financial literacy as not only the knowledge and understanding of financial concepts and risks but also the skills, motivation, and confidence to apply such knowledge and understanding in order to make effective decisions across a range of financial contexts, to improve the financial well-being of individuals and society, and to enable participation in economic life. Thus, financial literacy refers to both knowledge and financial behavior, and this paper will analyze research on both topics.

As I describe in more detail below, findings around the world are sobering. Financial literacy is low even in advanced economies with well-developed financial markets. On average, about one third of the global population has familiarity with the basic concepts that underlie everyday financial decisions (Lusardi and Mitchell, 2011c ). The average hides gaping vulnerabilities of certain population subgroups and even lower knowledge of specific financial topics. Furthermore, there is evidence of a lack of confidence, particularly among women, and this has implications for how people approach and make financial decisions. In the following sections, I describe how we measure financial literacy, the levels of literacy we find around the world, the implications of those findings for financial decision-making, and how we can improve financial literacy.

- Priorities for the GSB's Future

- See the Current DEI Report

- Supporting Data

- Research & Insights

- Share Your Thoughts

- Search Fund Primer

- Affiliated Faculty

- Faculty Advisors

- Louis W. Foster Resource Center

- Defining Social Innovation

- Impact Compass

- Global Health Innovation Insights

- Faculty Affiliates

- Student Awards & Certificates

- Changemakers

- Dean Jonathan Levin

- Dean Garth Saloner

- Dean Robert Joss

- Dean Michael Spence

- Dean Robert Jaedicke

- Dean Rene McPherson

- Dean Arjay Miller

- Dean Ernest Arbuckle

- Dean Jacob Hugh Jackson

- Dean Willard Hotchkiss

- Faculty in Memoriam

- Stanford GSB Firsts

- Certificate & Award Recipients

- Teaching Approach

- Analysis and Measurement of Impact

- The Corporate Entrepreneur: Startup in a Grown-Up Enterprise

- Data-Driven Impact

- Designing Experiments for Impact

- Digital Business Transformation

- The Founder’s Right Hand

- Marketing for Measurable Change

- Product Management

- Public Policy Lab: Financial Challenges Facing US Cities

- Public Policy Lab: Homelessness in California

- Lab Features

- Curricular Integration

- View From The Top

- Formation of New Ventures

- Managing Growing Enterprises

- Startup Garage

- Explore Beyond the Classroom

- Stanford Venture Studio

- Summer Program

- Workshops & Events

- The Five Lenses of Entrepreneurship

- Leadership Labs

- Executive Challenge

- Arbuckle Leadership Fellows Program

- Selection Process

- Training Schedule

- Time Commitment

- Learning Expectations

- Post-Training Opportunities

- Who Should Apply

- Introductory T-Groups

- Leadership for Society Program

- Certificate

- 2024 Awardees

- 2023 Awardees

- 2022 Awardees

- 2021 Awardees

- 2020 Awardees

- 2019 Awardees

- 2018 Awardees

- Social Management Immersion Fund

- Stanford Impact Founder Fellowships and Prizes

- Stanford Impact Leader Prizes

- Social Entrepreneurship

- Stanford GSB Impact Fund

- Economic Development

- Energy & Environment

- Stanford GSB Residences

- Environmental Leadership

- Stanford GSB Artwork

- A Closer Look

- California & the Bay Area

- Voices of Stanford GSB

- Business & Beneficial Technology

- Business & Sustainability

- Business & Free Markets

- Business, Government, and Society Forum

- Second Year

- Global Experiences

- JD/MBA Joint Degree

- MA Education/MBA Joint Degree

- MD/MBA Dual Degree

- MPP/MBA Joint Degree

- MS Computer Science/MBA Joint Degree

- MS Electrical Engineering/MBA Joint Degree

- MS Environment and Resources (E-IPER)/MBA Joint Degree

- Academic Calendar

- Clubs & Activities

- LGBTQ+ Students

- Military Veterans

- Minorities & People of Color

- Partners & Families

- Students with Disabilities

- Student Support

- Residential Life

- Student Voices

- MBA Alumni Voices

- A Week in the Life

- Career Support

- Employment Outcomes

- Cost of Attendance

- Knight-Hennessy Scholars Program

- Yellow Ribbon Program

- BOLD Fellows Fund

- Application Process

- Loan Forgiveness

- Contact the Financial Aid Office

- Evaluation Criteria

- GMAT & GRE

- English Language Proficiency

- Personal Information, Activities & Awards

- Professional Experience

- Letters of Recommendation

- Optional Short Answer Questions

- Application Fee

- Reapplication

- Deferred Enrollment

- Joint & Dual Degrees

- Entering Class Profile

- Event Schedule

- Ambassadors

- New & Noteworthy

- Ask a Question

- See Why Stanford MSx

- Is MSx Right for You?

- MSx Stories

- Leadership Development

- Career Advancement

- Career Change

- How You Will Learn

- Admission Events

- Personal Information

- Information for Recommenders

- GMAT, GRE & EA

- English Proficiency Tests

- After You’re Admitted

- Daycare, Schools & Camps

- U.S. Citizens and Permanent Residents

- Requirements

- Requirements: Behavioral

- Requirements: Quantitative

- Requirements: Macro

- Requirements: Micro

- Annual Evaluations

- Field Examination

- Research Activities

- Research Papers

- Dissertation

- Oral Examination

- Current Students

- Education & CV

- International Applicants

- Statement of Purpose

- Reapplicants

- Application Fee Waiver

- Deadline & Decisions

- Job Market Candidates

- Academic Placements

- Stay in Touch

- Faculty Mentors

- Current Fellows

- Standard Track

- Fellowship & Benefits

- Group Enrollment

- Program Formats

- Developing a Program

- Diversity & Inclusion

- Strategic Transformation

- Program Experience

- Contact Client Services

- Campus Experience

- Live Online Experience

- Silicon Valley & Bay Area

- Digital Credentials

- Faculty Spotlights

- Participant Spotlights

- Eligibility

- International Participants

- Stanford Ignite

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Founding Donors

- Location Information

- Participant Profile

- Network Membership

- Program Impact

- Collaborators

- Entrepreneur Profiles

- Company Spotlights

- Seed Transformation Network

- Responsibilities

- Current Coaches

- How to Apply

- Meet the Consultants

- Meet the Interns

- Intern Profiles

- Collaborate

- Research Library

- News & Insights

- Program Contacts

- Databases & Datasets

- Research Guides

- Consultations

- Research Workshops

- Career Research

- Research Data Services

- Course Reserves

- Course Research Guides

- Material Loan Periods

- Fines & Other Charges

- Document Delivery

- Interlibrary Loan

- Equipment Checkout

- Print & Scan

- MBA & MSx Students

- PhD Students

- Other Stanford Students

- Faculty Assistants

- Research Assistants

- Stanford GSB Alumni

- Telling Our Story

- Staff Directory

- Site Registration

- Alumni Directory

- Alumni Email

- Privacy Settings & My Profile

- Success Stories

- The Story of Circles

- Support Women’s Circles

- Stanford Women on Boards Initiative

- Alumnae Spotlights

- Insights & Research

- Industry & Professional

- Entrepreneurial Commitment Group

- Recent Alumni

- Half-Century Club

- Fall Reunions

- Spring Reunions

- MBA 25th Reunion

- Half-Century Club Reunion

- Faculty Lectures

- Ernest C. Arbuckle Award

- Alison Elliott Exceptional Achievement Award

- ENCORE Award

- Excellence in Leadership Award

- John W. Gardner Volunteer Leadership Award

- Robert K. Jaedicke Faculty Award

- Jack McDonald Military Service Appreciation Award

- Jerry I. Porras Latino Leadership Award

- Tapestry Award

- Student & Alumni Events

- Executive Recruiters

- Interviewing

- Land the Perfect Job with LinkedIn

- Negotiating

- Elevator Pitch

- Email Best Practices

- Resumes & Cover Letters

- Self-Assessment

- Whitney Birdwell Ball

- Margaret Brooks

- Bryn Panee Burkhart

- Margaret Chan

- Ricki Frankel

- Peter Gandolfo

- Cindy W. Greig

- Natalie Guillen

- Carly Janson

- Sloan Klein

- Sherri Appel Lassila

- Stuart Meyer

- Tanisha Parrish

- Virginia Roberson

- Philippe Taieb

- Michael Takagawa

- Terra Winston

- Johanna Wise

- Debbie Wolter

- Rebecca Zucker

- Complimentary Coaching

- Changing Careers

- Work-Life Integration

- Career Breaks

- Flexible Work

- Encore Careers

- Join a Board

- D&B Hoovers

- Data Axle (ReferenceUSA)

- EBSCO Business Source

- Global Newsstream

- Market Share Reporter

- ProQuest One Business

- Student Clubs

- Entrepreneurial Students

- Stanford GSB Trust

- Alumni Community

- How to Volunteer

- Springboard Sessions

- Consulting Projects

- 2020 – 2029

- 2010 – 2019

- 2000 – 2009

- 1990 – 1999

- 1980 – 1989

- 1970 – 1979

- 1960 – 1969

- 1950 – 1959

- 1940 – 1949

- Service Areas

- ACT History

- ACT Awards Celebration

- ACT Governance Structure

- Building Leadership for ACT

- Individual Leadership Positions

- Leadership Role Overview

- Purpose of the ACT Management Board

- Contact ACT

- Business & Nonprofit Communities

- Reunion Volunteers

- Ways to Give

- Fiscal Year Report

- Business School Fund Leadership Council

- Planned Giving Options

- Planned Giving Benefits

- Planned Gifts and Reunions

- Legacy Partners

- Giving News & Stories

- Giving Deadlines

- Development Staff

- Submit Class Notes

- Class Secretaries

- Board of Directors

- Health Care

- Sustainability

- Class Takeaways

- All Else Equal: Making Better Decisions

- If/Then: Business, Leadership, Society

- Grit & Growth

- Think Fast, Talk Smart

- Spring 2022

- Spring 2021

- Autumn 2020

- Summer 2020

- Winter 2020

- In the Media

- For Journalists

- DCI Fellows

- Other Auditors

- Academic Calendar & Deadlines

- Course Materials

- Entrepreneurial Resources

- Campus Drive Grove

- Campus Drive Lawn

- CEMEX Auditorium

- King Community Court

- Seawell Family Boardroom

- Stanford GSB Bowl

- Stanford Investors Common

- Town Square

- Vidalakis Courtyard

- Vidalakis Dining Hall

- Catering Services

- Policies & Guidelines

- Reservations

- Contact Faculty Recruiting

- Lecturer Positions

- Postdoctoral Positions

- Accommodations

- CMC-Managed Interviews

- Recruiter-Managed Interviews

- Virtual Interviews

- Campus & Virtual

- Search for Candidates

- Think Globally

- Recruiting Calendar

- Recruiting Policies

- Full-Time Employment

- Summer Employment

- Entrepreneurial Summer Program

- Global Management Immersion Experience

- Social-Purpose Summer Internships

- Process Overview

- Project Types

- Client Eligibility Criteria

- Client Screening

- ACT Leadership

- Social Innovation & Nonprofit Management Resources

- Develop Your Organization’s Talent

- Centers & Initiatives

- Student Fellowships

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 27 May 2024

Knowledge creates value: the role of financial literacy in entrepreneurial behavior

- Shulin Xu 1 &

- Kangqi Jiang 2

Humanities and Social Sciences Communications volume 11 , Article number: 679 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

398 Accesses

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

Under the backdrop of economic globalization and the digital economy, entrepreneurial behavior has emerged not only as a focal point of management research but also as an urgent topic within the domain of family finance. This paper scrutinizes the ramifications of financial literacy on household entrepreneurial behavior utilizing data from China’s sample of the China Household Finance Survey spanning the years 2015 and 2017. Employing the ordered Probit model, we pursue our research objectives. Our findings suggest that financial literacy exerts immediate, persistent, and evolving positive effects on households’ engagement in entrepreneurial activities and their proclivity toward entrepreneurship. Through the mitigation of endogeneity in the regression model, the outcomes of the two-stage regression corroborate the primary regression results. An examination of heterogeneity unveils noteworthy disparities between urban and rural areas, as well as gender discrepancies, in how financial literacy influences household entrepreneurial behavior. Furthermore, this study validates three potential pathways—namely income, social network, and risk attitude channels—demonstrating that financial literacy significantly augments household income, expands social networks, and enhances risk attitudes. Moreover, through supplementary analysis, we ascertain that financial education amplifies the impact of financial literacy on entrepreneurial behavior. Our study contributes to the enrichment of human capital theory and modern entrepreneurship theory. It advocates for robust efforts by governments and financial institutions to widely disseminate financial knowledge and foster family entrepreneurship, thereby fostering the robust and stable operation of both the global financial market and the job market.

Similar content being viewed by others

The influence of psychological capital and social capital on women entrepreneurs’ intentions: the mediating role of attitude

Improving the entrepreneurial ability of rural migrant workers returning home in China: Study based on 5,675 questionnaires

Similar but yet different: individual cognitive traits and family contingencies as antecedents of intrapreneurship and self-employment

Introduction.

With the advancement of the global digital economy, entrepreneurship has increasingly emerged as a pivotal strategy for corporate strategic development (Cheng et al., 2024 ) and for the accumulation of residents’ wealth. Entrepreneurial behavior entails the optimization and integration of one’s own resources to generate substantial economic or social value. Individuals are expected to possess organizational and managerial abilities and to deliberate upon and determine the operational strategies for services, technologies, and equipment to engage in rational entrepreneurial endeavors (Levesque and Minniti, 2006 ). Entrepreneurial activities play a crucial role in fostering labor market prosperity, achieving social equity, enhancing the flow of social capital, and sustaining the healthy and stable functioning of the social economy (Hombert et al., 2020 ; Schmitz, 1989 ). They also hold promise for alleviating the current economic crisis through the exploitation of renewable energy sources (Abou Houran, 2023 ) and enhancing firm productivity (Tao et al., 2023 ). According to human capital theory, as posited by Becker ( 2009 ), human capital encompasses the cumulative knowledge, skills, cultural sophistication, and health status of an individual. Financial literacy, as a form of scarce human capital, constitutes a significant driver of entrepreneurial decision-making and motivation. On the one hand, the migration of individuals possessing high financial literacy fosters the transfer of theoretical knowledge and technical expertise, while the symbiotic interaction of knowledge, skills, and capabilities nurtures a reservoir of knowledge and entrepreneurial dynamism. On the other hand, individuals with elevated financial literacy are more likely to enhance their awareness and identification of opportunities within an imbalanced market, thereby bolstering their self-awareness and catalyzing independent innovation and entrepreneurship. Moreover, in line with modern entrepreneurship theory, Alvarez and Busenitz ( 2001 ) contend that entrepreneurial opportunities are endogenous. Entrepreneurs equipped with the requisite skills and knowledge pertaining to entrepreneurship are better positioned to identify and exploit opportunities. Additionally, they possess extensive and efficacious social networks, enabling them to access valuable information and resources conducive to enhancing entrepreneurial performance. Against the backdrop of economic globalization and the digital economy, governments worldwide are actively encouraging entrepreneurial engagement. They have enacted financial support policies and preferential tax measures to enhance the domestic entrepreneurial ecosystem and to galvanize individuals’ entrepreneurial potential. For instance, the Chinese government introduced numerous policies aimed at fostering entrepreneurial endeavors in 2018. Similarly, the U.S. government is proactively implementing several initiatives to foster an environment conducive to the flourishing of small and medium-sized enterprises, striving to institute permanent tax relief measures for small businesses.

However, the enhancement of the entrepreneurial environment can engender a proliferation of entrepreneurial opportunities (Segaf, 2023 ). Yet, the ability of entrepreneurs to seize such opportunities for proactive entrepreneurship remains constrained by numerous factors, including the development of the digital economy (Sussan and Acs, 2017 ; Firmansyah et al., 2023 ; Zhao and Weng, 2024 ), social networks (Karlan, 2007 ; Qi and Chun, 2017 ), human capital (Dawson et al., 2014 ), risk attitudes (Osman, 2014 ), government regulations (Black and Strahan, 2002 ), institutional environments (Burtch et al., 2018 ; Lan et al., 2018 ), institutional changes within universities (Eesley et al., 2016 ), financial constraints (Hurst and Lusardi, 2004 ; Asongu et al., 2020 ), policy interventions (Sharipov and Zaynuidinova, 2020 ), cognitive abilities (Haynie et al., 2012 ), personal beliefs regarding character and opportunity (Pidduck et al., 2023 ), household background, income levels, and trust (Kwon and Arenius, 2010 ). Entrepreneurial activities entail the identification and exploitation of entrepreneurial opportunities and the utilization of entrepreneurial resources. These endeavors invariably entail considerations of business management, financial matters, and professional concerns. Entrepreneurs must possess adequate financial literacy to ensure the rationality of entrepreneurial decision-making, the judicious allocation of entrepreneurial resources, the mitigation of venture capital risks, and the effective operation of enterprises. Drawing from a review of international experiences, scholars predominantly emphasize macroeconomic environments (Arin et al., 2015 ), institutional frameworks, cultural disparities (Liang et al., 2018 ), credit constraints (Ma et al., 2018 ), liquidity constraints (Beck et al., 2018 ), as well as micro-level factors such as social networks (Yueh, 2009 ), and information availability (Companys and McMullen, 2007 ), when examining the determinants of entrepreneurial activities.

From a current static perspective, existing studies indicate a close association between financial literacy and a range of financial behaviors and economic outcomes. A wealth of evidence demonstrates that financial literacy fosters household income growth (Behrman et al., 2012 ), facilitates the expansion of social networks (Kinnan and Townsend, 2012 ; Suresh, 2024 ), and enhances residents’ risk attitudes (Mishra, 2018 ), all of which can also impact entrepreneurial behavior. Thus, we posit that financial literacy may influence household entrepreneurial activities through three primary channels. Firstly, prior research has affirmed that higher levels of financial literacy correlate with enhanced information acquisition and processing abilities, leading to more informed decision-making (Forbes and Kara, 2010 ; Molina-García et al., 2023 ), fostering healthier and more rational investment philosophies and habits. These factors, in turn, contribute to improved investment returns and elevated household income levels. Household entrepreneurial activities necessitate sufficient financial support for use as entrepreneurial funds, and throughout the entrepreneurial process, a continuous stream of funds is required for operational and managerial purposes. Household wealth and income serve as the principal resources for family entrepreneurship, indispensable for entrepreneurial endeavors.

Secondly, studies by Korkmaz et al. ( 2021 ), Mishra ( 2018 ), and Mushafiq et al. ( 2023 ) reveal that heightened levels of financial literacy correlate with an increased likelihood of risk-taking or risk-neutrality and diminished tendencies toward risk aversion. This indicates that enhancing financial literacy significantly bolsters individuals’ risk appetites and reduces risk aversion. Entrepreneurship inherently entails risk-taking behavior and a willingness to embark on new ventures. Therefore, risk attitudes are intricately linked to entrepreneurial behavior. Research by Van Praag and Cramer ( 2001 ), as well as Long et al. ( 2023 ), spanning a 41-year study of 5800 Danish students, illustrates significant disparities in entrepreneurial willingness among individuals with varying risk preferences, with risk-conscious individuals exhibiting stronger inclinations towards entrepreneurship. Thirdly, Hong et al. ( 2004 ) and Chen et al. ( 2023 ) posit that financial literacy may proliferate through word-of-mouth or observational learning methods, thereby expanding social network structures. Social networks, as a distinct form of family capital alongside physical and human capital, facilitate risk-sharing (Munshi and Rosenzweig, 2016 ) and augment the likelihood of accessing formal or informal financing (Kinnan and Townsend, 2012 ). It is widely acknowledged that family entrepreneurial activities, to some extent, depend on the support offered by family members, relatives, and friends in terms of information, financing, and business operations and management (Munshi and Rosenzweig, 2016 ). Consequently, broader family social networks correlate with heightened probabilities of choosing entrepreneurship. Financial literacy can effectively mitigate information asymmetry in financial markets by enhancing family social networks, reducing monitoring costs and risky borrowing, and addressing adverse selection and moral hazard issues, thereby alleviating financing constraints and fostering family entrepreneurial activities.

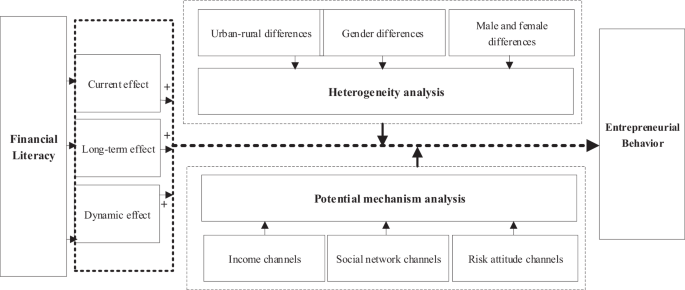

The aforementioned analysis offers insights into the impact of financial literacy on household entrepreneurial activities. Nevertheless, a pivotal inquiry remains: can financial literacy effectively bolster the likelihood of family entrepreneurial choices and entrepreneurial motivation in the long term, thereby dynamically enhancing family entrepreneurial behavior? Furthermore, the urban–rural dichotomy and gender disparities in financial literacy prevalent in numerous countries may introduce variations in the current, long-term, and dynamic effects of financial literacy on residents’ entrepreneurial behavior. This prompts us to explore the existence of such disparities and whether the mechanisms underlying these differences are mediated through income, social networks, and risk attitudes. To address these gaps in the literature and elucidate the raised questions, we propose to establish a robust empirical framework. This framework will enable us to examine how financial literacy influences local households’ entrepreneurial behavior. Figure 1 illustrates our theoretical framework, delineating how financial literacy impacts household entrepreneurial activities through three primary channels.

Theoretical design and framework.

This study empirically examines the immediate, long-term, and evolving impacts of financial literacy on household entrepreneurial activities using data from the China Household Finance Survey (CHFS) for the years 2015 and 2017. We employ the ordered Probit model to fulfill our research objectives. The findings indicate that financial literacy exerts immediate, enduring, and evolving positive effects on households’ involvement in entrepreneurial activities and their propensity toward entrepreneurship. Accounting for the endogeneity of the regression model, the results from the two-stage regression reinforce the primary regression outcomes. Heterogeneity analysis reveals significant urban–rural disparities and gender differences in the influence of financial literacy on household entrepreneurial behavior. Additionally, this research substantiates three potential pathways: income, social network, and risk attitude channels. It demonstrates that financial literacy significantly enhances household income, expands social networks, and improves risk attitudes. Further analysis reveals that financial education amplifies the impact of financial literacy on entrepreneurial behavior.

Our contributions are multifaceted: Firstly, this study advances the understanding of entrepreneurial behavior in several dimensions. Previous research primarily focuses on factors influencing entrepreneurial behavior, such as social networks (Karlan, 2007 ), human capital (Dawson et al., 2014 ), risk attitudes (Osman, 2014 ), government regulation (Black and Strahan, 2002 ), institutional environments (Lu and Tao, 2010 ), financial constraints (Hurst and Lusardi, 2004 ), cognitive ability (Haynie et al., 2012 ), household background, and trust (Kwon and Arenius, 2010 ). Few studies delve into the influence of financial literacy on entrepreneurial behaviors. We address this gap and find that financial literacy positively impacts entrepreneurial behaviors. Secondly, we measure entrepreneurial behavior at the family level, including initiative entrepreneurship in the household finance domain, thereby expanding the existing literature beyond the use of new ventures as a measurement indicator. Most importantly, our study contributes to the enrichment of human capital theory and entrepreneurship theory within the realm of household finance, providing valuable insights into the theoretical understanding of the relationship between financial literacy and entrepreneurial behavior. Thirdly, in mechanism analysis, our study is the first to investigate the three channels through which financial literacy affects household entrepreneurial behavior using CHFS data from 2015 and 2017. Lastly, our study conducts heterogeneity analysis and presents evidence of significant urban-rural disparities and gender heterogeneity in the impact of financial literacy on household entrepreneurial behavior. Furthermore, this research enhances the comprehension of the relationship between financial literacy and financial behavior. While prior studies predominantly focus on the immediate effect of financial literacy on financial behavior, our study delves deeper. We not only explore the immediate impact of financial literacy on entrepreneurial behavior but also probe into its long-term and dynamic improvement characteristics, elucidating the internal mechanisms driving these effects. For policymakers, our research provides a theoretical foundation and empirical validation to formulate entrepreneurship policies. By comprehensively understanding how financial literacy influences household entrepreneurial behavior and acknowledging the heterogeneous effects across urban–rural divides and gender disparities, governments can tailor policies to effectively support and promote entrepreneurship, thereby fostering economic growth and development. Based on the conclusions of this study, governments can fully consider residents’ financial literacy and enhance various influencing channels while encouraging innovation and entrepreneurship, thereby facilitating wealth accumulation, enhancing family welfare, and elevating the national level of innovation and entrepreneurship in entrepreneurial activities. For businesses, our research underscores the pivotal role of financial literacy in entrepreneurial activities, constituting an indispensable aspect of “entrepreneurship.” In the actual operation and management processes of enterprises, managers should prioritize the cultivation of financial literacy, as it can aid in cost reduction and the expansion of social networks, thereby realizing the healthy and stable operation of enterprises.

In the rest of this paper, the section “Literature review” reviews the relevant literature. Section “Methodology” outlines the empirical model and introduces the variables and datasets. Section “Empirical results” describes and discusses the empirical results. Section “Heterogeneity analysis” reports a heterogeneous analysis in geography, gender and income level. The section “Potential mechanism analysis” and “Further analysis: the role of financial education” discusses three channels and analyses. Section “Conclusion” concludes and policy implications.

Literature review

Factors affecting financial literacy.

The financial literacy level of respondents is primarily influenced by both micro and macro environments. Concerning microelements, empirical evidence provided by Lusardi and Mitchell ( 2014 ) suggests that men tend to exhibit higher financial literacy levels than women, largely due to women’s perceived lack of self-confidence. Notably, only elderly women demonstrate high levels of self-assurance, alongside robust investment motivation and financial management interest (Bucher‐Koenen et al., 2017 ). Furthermore, Van Rooij et al. ( 2011 ) contend that age and financial literacy follow a hump-shaped distribution pattern, indicating that young individuals under 15 and seniors over 60 typically exhibit the lowest levels of financial literacy, while the middle-aged group tends to have the highest level. The accumulation of social experience serves to enhance the financial literacy level of the middle-aged demographic (Fong et al., 2021 ; Gamble et al., 2015 ). Moreover, Lusardi et al. ( 2012 ) found a positive correlation between the number of years of education and financial literacy, implying that higher levels of education contribute to the advancement of financial literacy.