Essay on Sexual Orientation And Gender Identity

Students are often asked to write an essay on Sexual Orientation And Gender Identity in their schools and colleges. And if you’re also looking for the same, we have created 100-word, 250-word, and 500-word essays on the topic.

Let’s take a look…

100 Words Essay on Sexual Orientation And Gender Identity

What is sexual orientation.

Sexual orientation refers to who you are attracted to emotionally and physically. It can be towards the opposite sex (heterosexuality), the same sex (homosexuality), or both sexes (bisexuality).

What is Gender Identity?

Gender identity refers to how you identify yourself in terms of being male, female, or something else. It is different from biological sex, which is determined by your chromosomes and reproductive organs.

Understanding Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity

Sexual orientation and gender identity are two distinct aspects of a person’s identity. One’s sexual orientation does not determine their gender identity, and vice versa.

Respecting Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity

It is important to respect everyone’s sexual orientation and gender identity. Everyone deserves to be treated with respect and dignity, regardless of who they are attracted to or how they identify themselves.

250 Words Essay on Sexual Orientation And Gender Identity

Sexual orientation.

People can be attracted to people of the opposite sex, the same sex, or both sexes. Some people may feel attracted to people regardless of their sex or gender identity.

Sexual orientation is not a choice. People are born with their sexual orientation, and it is not something they can change.

Gender Identity

Gender identity refers to an individual’s deeply felt sense of being male, female, a blend of both, or neither. It is not the same as biological sex, which is assigned at birth based on physical characteristics.

People may identify with a gender that is different from the sex they were assigned at birth. This is called being transgender.

Transgender people may experience discrimination and prejudice because of their gender identity. They may be denied jobs, housing, and healthcare. They may also be subjected to violence and harassment.

Importance of Understanding and Respecting Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity

No one should be discriminated against or harassed because of their sexual orientation or gender identity.

We should all work to create a more inclusive and welcoming society for everyone.

500 Words Essay on Sexual Orientation And Gender Identity

Sexual orientation: an overview, gender identity: understanding self-perception.

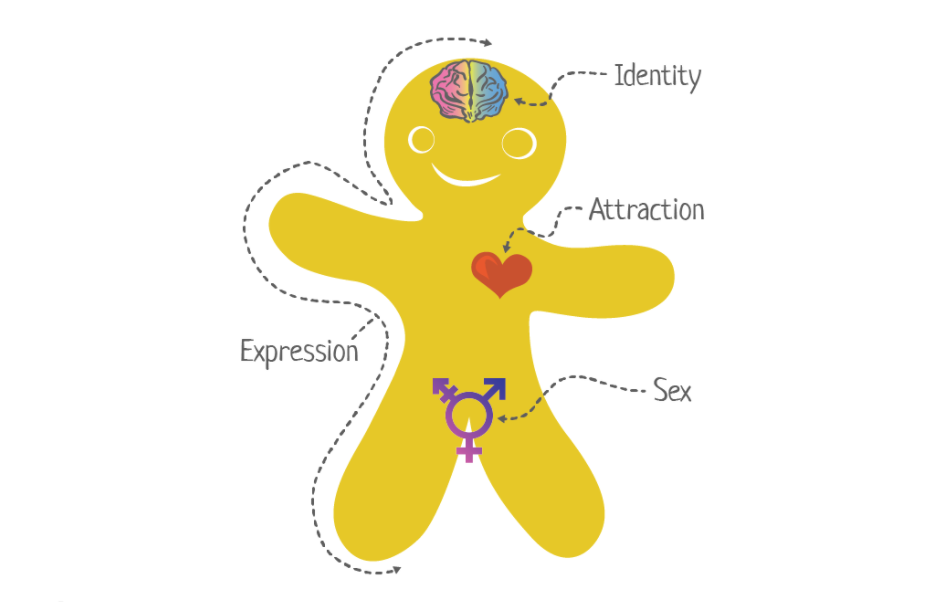

Gender identity refers to an individual’s sense of being male, female, both, or neither, regardless of their biological sex assigned at birth. It is a complex and personal experience that involves a person’s innermost sense of self. Gender identity is distinct from sexual orientation and can be expressed through various aspects of a person’s life, such as their name, pronouns, and outward appearance.

Social Acceptance and Discrimination

Sexual orientation and gender identity have been topics of discussion and debate throughout history. While some societies have shown acceptance and understanding, others have faced discrimination and prejudice. Discrimination based on sexual orientation or gender identity, often referred to as sexual orientation and gender identity (SOGI) discrimination, can manifest in various forms, including social exclusion, denial of rights, and even violence.

The Importance of Equality and Inclusion

Challenges and the way forward.

The journey towards full acceptance and equality for people of all sexual orientations and gender identities is ongoing. While progress has been made in many countries, challenges still exist. Efforts to educate and raise awareness about sexual orientation and gender identity are vital in combating discrimination and promoting understanding. Additionally, creating safe and supportive environments, both in schools and workplaces, is essential in fostering a sense of belonging and well-being among individuals from diverse backgrounds.

In conclusion, sexual orientation and gender identity are fundamental aspects of human diversity and should be recognized and respected. Promoting equality, inclusion, and acceptance for all individuals, regardless of their sexual orientation or gender identity, is a crucial step towards building a just and harmonious society.

That’s it! I hope the essay helped you.

Apart from these, you can look at all the essays by clicking here .

Happy studying!

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Understanding Gender, Sex, and Gender Identity

It's more important than ever to use this terminology correctly..

Posted February 27, 2021 | Reviewed by Kaja Perina

- The Fundamentals of Sex

- Find a sex therapist near me

Representative Marjorie Taylor Greene hung a sign outside her Capitol office door that said “There are TWO genders: MALE & FEMALE. ‘Trust the Science!’” There are many reasons to question hanging such a sign, but given that Rep. Taylor Greene invoked science in making her assertion, I thought it might be helpful to clarify by citing some actual science. Put simply, from a scientific standpoint, Rep. Taylor Greene’s statement is patently wrong. It perpetuates a common error by conflating gender with sex . Allow me to explain how psychologists scientifically operationalize these terms.

According to the American Psychological Association (APA, 2012), sex is rooted in biology. A person’s sex is determined using observable biological criteria such as sex chromosomes, gonads, internal reproductive organs, and external genitalia (APA, 2012). Most people are classified as being either biologically male or female, although the term intersex is reserved for those with atypical combinations of biological features (APA, 2012).

Gender is related to but distinctly different from sex; it is rooted in culture, not biology. The APA (2012) defines gender as “the attitudes, feelings, and behaviors that a given culture associates with a person’s biological sex” (p. 11). Gender conformity occurs when people abide by culturally-derived gender roles (APA, 2012). Resisting gender roles (i.e., gender nonconformity ) can have significant social consequences—pro and con, depending on circumstances.

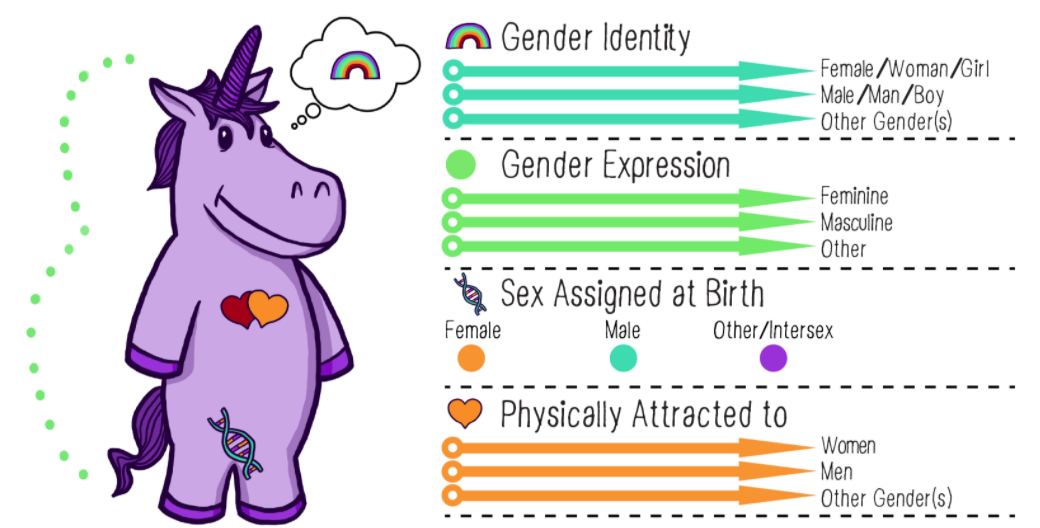

Gender identity refers to how one understands and experiences one’s own gender. It involves a person’s psychological sense of being male, female, or neither (APA, 2012). Those who identify as transgender feel that their gender identity doesn’t match their biological sex or the gender they were assigned at birth; in some cases they don’t feel they fit into into either the male or female gender categories (APA, 2012; Moleiro & Pinto, 2015). How people live out their gender identities in everyday life (in terms of how they dress, behave, and express themselves) constitutes their gender expression (APA, 2012; Drescher, 2014).

“Male” and “female” are the most common gender identities in Western culture; they form a dualistic way of thinking about gender that often informs the identity options that people feel are available to them (Prentice & Carranza, 2002). Anyone, regardless of biological sex, can closely adhere to culturally-constructed notions of “maleness” or “femaleness” by dressing, talking, and taking interest in activities stereotypically associated with traditional male or female gender identities. However, many people think “outside the box” when it comes to gender, constructing identities for themselves that move beyond the male-female binary. For examples, explore lists of famous “gender benders” from Oxygen , Vogue , More , and The Cut (not to mention Mr. and Mrs. Potato Head , whose evolving gender identities made headlines this week).

Whether society approves of these identities or not, the science on whether there are more than two genders is clear; there are as many possible gender identities as there are people psychologically forming identities. Rep. Taylor Greene’s insistence that there are just two genders merely reflects Western culture’s longstanding tradition of only recognizing “male” and “female” gender identities as “normal.” However, if we are to “trust the science” (as Rep. Taylor Greene’s recommends), then the first thing we need to do is stop mixing up biological sex and gender identity. The former may be constrained by biology, but the latter is only constrained by our imaginations.

American Psychological Association. (2012). Guidelines for psychological practice with lesbian, gay, and bisexual clients. American Psychologist , 67 (1), 10-42. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0024659

Drescher, J. (2014). Treatment of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender patients. In R. E. Hales, S. C. Yudofsky, & L. W. Roberts (Eds.), The American Psychiatric Publishing textbook of psychiatry (6th ed., pp. 1293-1318). American Psychiatric Publishing.

Moleiro, C., & Pinto, N. (2015). Sexual orientation and gender identity: Review of concepts, controversies and their relation to psychopathology classification systems. Frontiers in Psychology , 6 .

Prentice, D. A., & Carranza, E. (2002). What women should be, shouldn't be, are allowed to be, and don't have to be: The contents of prescriptive gender stereotypes. Psychology of Women Quarterly , 26 (4), 269-281. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-6402.t01-1-00066

Jonathan D. Raskin, Ph.D. , is a professor of psychology and counselor education at the State University of New York at New Paltz.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Online Therapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Self Tests NEW

- Therapy Center

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

At any moment, someone’s aggravating behavior or our own bad luck can set us off on an emotional spiral that could derail our entire day. Here’s how we can face triggers with less reactivity and get on with our lives.

- Emotional Intelligence

- Gaslighting

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

Pride Month

A guide to gender identity terms.

Laurel Wamsley

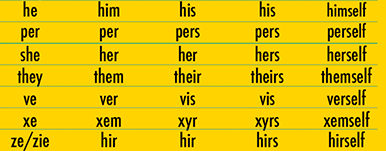

"Pronouns are basically how we identify ourselves apart from our name. It's how someone refers to you in conversation," says Mary Emily O'Hara, a communications officer at GLAAD. "And when you're speaking to people, it's a really simple way to affirm their identity." Kaz Fantone for NPR hide caption

"Pronouns are basically how we identify ourselves apart from our name. It's how someone refers to you in conversation," says Mary Emily O'Hara, a communications officer at GLAAD. "And when you're speaking to people, it's a really simple way to affirm their identity."

Issues of equality and acceptance of transgender and nonbinary people — along with challenges to their rights — have become a major topic in the headlines. These issues can involve words and ideas and identities that are new to some.

That's why we've put together a glossary of terms relating to gender identity. Our goal is to help people communicate accurately and respectfully with one another.

Proper use of gender identity terms, including pronouns, is a crucial way to signal courtesy and acceptance. Alex Schmider , associate director of transgender representation at GLAAD, compares using someone's correct pronouns to pronouncing their name correctly – "a way of respecting them and referring to them in a way that's consistent and true to who they are."

Glossary of gender identity terms

This guide was created with help from GLAAD . We also referenced resources from the National Center for Transgender Equality , the Trans Journalists Association , NLGJA: The Association of LGBTQ Journalists , Human Rights Campaign , InterAct and the American Psychological Association . This guide is not exhaustive, and is Western and U.S.-centric. Other cultures may use different labels and have other conceptions of gender.

One thing to note: Language changes. Some of the terms now in common usage are different from those used in the past to describe similar ideas, identities and experiences. Some people may continue to use terms that are less commonly used now to describe themselves, and some people may use different terms entirely. What's important is recognizing and respecting people as individuals.

Jump to a term: Sex, gender , gender identity , gender expression , cisgender , transgender , nonbinary , agender , gender-expansive , gender transition , gender dysphoria , sexual orientation , intersex

Jump to Pronouns : questions and answers

Sex refers to a person's biological status and is typically assigned at birth, usually on the basis of external anatomy. Sex is typically categorized as male, female or intersex.

Gender is often defined as a social construct of norms, behaviors and roles that varies between societies and over time. Gender is often categorized as male, female or nonbinary.

Gender identity is one's own internal sense of self and their gender, whether that is man, woman, neither or both. Unlike gender expression, gender identity is not outwardly visible to others.

For most people, gender identity aligns with the sex assigned at birth, the American Psychological Association notes. For transgender people, gender identity differs in varying degrees from the sex assigned at birth.

Gender expression is how a person presents gender outwardly, through behavior, clothing, voice or other perceived characteristics. Society identifies these cues as masculine or feminine, although what is considered masculine or feminine changes over time and varies by culture.

Cisgender, or simply cis , is an adjective that describes a person whose gender identity aligns with the sex they were assigned at birth.

Transgender, or simply trans, is an adjective used to describe someone whose gender identity differs from the sex assigned at birth. A transgender man, for example, is someone who was listed as female at birth but whose gender identity is male.

Cisgender and transgender have their origins in Latin-derived prefixes of "cis" and "trans" — cis, meaning "on this side of" and trans, meaning "across from" or "on the other side of." Both adjectives are used to describe experiences of someone's gender identity.

Nonbinary is a term that can be used by people who do not describe themselves or their genders as fitting into the categories of man or woman. A range of terms are used to refer to these experiences; nonbinary and genderqueer are among the terms that are sometimes used.

Agender is an adjective that can describe a person who does not identify as any gender.

Gender-expansive is an adjective that can describe someone with a more flexible gender identity than might be associated with a typical gender binary.

Gender transition is a process a person may take to bring themselves and/or their bodies into alignment with their gender identity. It's not just one step. Transitioning can include any, none or all of the following: telling one's friends, family and co-workers; changing one's name and pronouns; updating legal documents; medical interventions such as hormone therapy; or surgical intervention, often called gender confirmation surgery.

Gender dysphoria refers to psychological distress that results from an incongruence between one's sex assigned at birth and one's gender identity. Not all trans people experience dysphoria, and those who do may experience it at varying levels of intensity.

Gender dysphoria is a diagnosis listed in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Some argue that such a diagnosis inappropriately pathologizes gender incongruence, while others contend that a diagnosis makes it easier for transgender people to access necessary medical treatment.

Sexual orientation refers to the enduring physical, romantic and/or emotional attraction to members of the same and/or other genders, including lesbian, gay, bisexual and straight orientations.

People don't need to have had specific sexual experiences to know their own sexual orientation. They need not have had any sexual experience at all. They need not be in a relationship, dating or partnered with anyone for their sexual orientation to be validated. For example, if a bisexual woman is partnered with a man, that does not mean she is not still bisexual.

Sexual orientation is separate from gender identity. As GLAAD notes , "Transgender people may be straight, lesbian, gay, bisexual or queer. For example, a person who transitions from male to female and is attracted solely to men would typically identify as a straight woman. A person who transitions from female to male and is attracted solely to men would typically identify as a gay man."

Intersex is an umbrella term used to describe people with differences in reproductive anatomy, chromosomes or hormones that don't fit typical definitions of male and female.

Intersex can refer to a number of natural variations, some of them laid out by InterAct . Being intersex is not the same as being nonbinary or transgender, which are terms typically related to gender identity.

The Picture Show

Nonbinary photographer documents gender dysphoria through a queer lens, pronouns: questions and answers.

What is the role of pronouns in acknowledging someone's gender identity?

Everyone has pronouns that are used when referring to them – and getting those pronouns right is not exclusively a transgender issue.

"Pronouns are basically how we identify ourselves apart from our name. It's how someone refers to you in conversation," says Mary Emily O'Hara , a communications officer at GLAAD. "And when you're speaking to people, it's a really simple way to affirm their identity."

"So, for example, using the correct pronouns for trans and nonbinary youth is a way to let them know that you see them, you affirm them, you accept them and to let them know that they're loved during a time when they're really being targeted by so many discriminatory anti-trans state laws and policies," O'Hara says.

"It's really just about letting someone know that you accept their identity. And it's as simple as that."

Getting the words right is about respect and accuracy, says Rodrigo Heng-Lehtinen, deputy executive director of the National Center for Transgender Equality. Kaz Fantone for NPR hide caption

Getting the words right is about respect and accuracy, says Rodrigo Heng-Lehtinen, deputy executive director of the National Center for Transgender Equality.

What's the right way to find out a person's pronouns?

Start by giving your own – for example, "My pronouns are she/her."

"If I was introducing myself to someone, I would say, 'I'm Rodrigo. I use him pronouns. What about you?' " says Rodrigo Heng-Lehtinen , deputy executive director of the National Center for Transgender Equality.

O'Hara says, "It may feel awkward at first, but eventually it just becomes another one of those get-to-know-you questions."

Should people be asking everyone their pronouns? Or does it depend on the setting?

Knowing each other's pronouns helps you be sure you have accurate information about another person.

How a person appears in terms of gender expression "doesn't indicate anything about what their gender identity is," GLAAD's Schmider says. By sharing pronouns, "you're going to get to know someone a little better."

And while it can be awkward at first, it can quickly become routine.

Heng-Lehtinen notes that the practice of stating one's pronouns at the bottom of an email or during introductions at a meeting can also relieve some headaches for people whose first names are less common or gender ambiguous.

"Sometimes Americans look at a name and are like, 'I have no idea if I'm supposed to say he or she for this name' — not because the person's trans, but just because the name is of a culture that you don't recognize and you genuinely do not know. So having the pronouns listed saves everyone the headache," Heng-Lehtinen says. "It can be really, really quick once you make a habit of it. And I think it saves a lot of embarrassment for everybody."

Might some people be uncomfortable sharing their pronouns in a public setting?

Schmider says for cisgender people, sharing their pronouns is generally pretty easy – so long as they recognize that they have pronouns and know what they are. For others, it could be more difficult to share their pronouns in places where they don't know people.

But there are still benefits in sharing pronouns, he says. "It's an indication that they understand that gender expression does not equal gender identity, that you're not judging people just based on the way they look and making assumptions about their gender beyond what you actually know about them."

How is "they" used as a singular pronoun?

"They" is already commonly used as a singular pronoun when we are talking about someone, and we don't know who they are, O'Hara notes. Using they/them pronouns for someone you do know simply represents "just a little bit of a switch."

"You're just asking someone to not act as if they don't know you, but to remove gendered language from their vocabulary when they're talking about you," O'Hara says.

"I identify as nonbinary myself and I appear feminine. People often assume that my pronouns are she/her. So they will use those. And I'll just gently correct them and say, hey, you know what, my pronouns are they/them just FYI, for future reference or something like that," they say.

O'Hara says their family and friends still struggle with getting the pronouns right — and sometimes O'Hara struggles to remember others' pronouns, too.

"In my community, in the queer community, with a lot of trans and nonbinary people, we all frequently remind each other or remind ourselves. It's a sort of constant mindfulness where you are always catching up a little bit," they say.

"You might know someone for 10 years, and then they let you know their pronouns have changed. It's going to take you a little while to adjust, and that's fine. It's OK to make those mistakes and correct yourself, and it's OK to gently correct someone else."

What if I make a mistake and misgender someone, or use the wrong words?

Simply apologize and move on.

"I think it's perfectly natural to not know the right words to use at first. We're only human. It takes any of us some time to get to know a new concept," Heng-Lehtinen says. "The important thing is to just be interested in continuing to learn. So if you mess up some language, you just say, 'Oh, I'm so sorry,' correct yourself and move forward. No need to make it any more complicated than that. Doing that really simple gesture of apologizing quickly and moving on shows the other person that you care. And that makes a really big difference."

Why are pronouns typically given in the format "she/her" or "they/them" rather than just "she" or "they"?

The different iterations reflect that pronouns change based on how they're used in a sentence. And the "he/him" format is actually shorter than the previously common "he/him/his" format.

"People used to say all three and then it got down to two," Heng-Lehtinen laughs. He says staff at his organization was recently wondering if the custom will eventually shorten to just one pronoun. "There's no real rule about it. It's absolutely just been habit," he says.

Amid Wave Of Anti-Trans Bills, Trans Reporters Say 'Telling Our Own Stories' Is Vital

But he notes a benefit of using he/him and she/her: He and she rhyme. "If somebody just says he or she, I could very easily mishear that and then still get it wrong."

What does it mean if a person uses the pronouns "he/they" or "she/they"?

"That means that the person uses both pronouns, and you can alternate between those when referring to them. So either pronoun would be fine — and ideally mix it up, use both. It just means that they use both pronouns that they're listing," Heng-Lehtinen says.

Schmider says it depends on the person: "For some people, they don't mind those pronouns being interchanged for them. And for some people, they are using one specific pronoun in one context and another set of pronouns in another, dependent on maybe safety or comfortability."

The best approach, Schmider says, is to listen to how people refer to themselves.

Why might someone's name be different than what's listed on their ID?

Heng-Lehtinen notes that there's a perception when a person comes out as transgender, they change their name and that's that. But the reality is a lot more complicated and expensive when it comes to updating your name on government documents.

"It is not the same process as changing your last name when you get married. There is bizarrely a separate set of rules for when you are changing your name in marriage versus changing your name for any other reason. And it's more difficult in the latter," he says.

"When you're transgender, you might not be able to update all of your government IDs, even though you want to," he says. "I've been out for over a decade. I still have not been able to update all of my documents because the policies are so onerous. I've been able to update my driver's license, Social Security card and passport, but I cannot update my birth certificate."

"Just because a transgender person doesn't have their authentic name on their ID doesn't mean it's not the name that they really use every day," he advises. "So just be mindful to refer to people by the name they really use regardless of their driver's license."

NPR's Danielle Nett contributed to this report.

- transgender

- gender identity

- Table of Contents

- Random Entry

- Chronological

- Editorial Information

- About the SEP

- Editorial Board

- How to Cite the SEP

- Special Characters

- Advanced Tools

- Support the SEP

- PDFs for SEP Friends

- Make a Donation

- SEPIA for Libraries

- Entry Contents

Bibliography

Academic tools.

- Friends PDF Preview

- Author and Citation Info

- Back to Top

Feminist Perspectives on Sex and Gender

Feminism is said to be the movement to end women’s oppression (hooks 2000, 26). One possible way to understand ‘woman’ in this claim is to take it as a sex term: ‘woman’ picks out human females and being a human female depends on various biological and anatomical features (like genitalia). Historically many feminists have understood ‘woman’ differently: not as a sex term, but as a gender term that depends on social and cultural factors (like social position). In so doing, they distinguished sex (being female or male) from gender (being a woman or a man), although most ordinary language users appear to treat the two interchangeably. In feminist philosophy, this distinction has generated a lively debate. Central questions include: What does it mean for gender to be distinct from sex, if anything at all? How should we understand the claim that gender depends on social and/or cultural factors? What does it mean to be gendered woman, man, or genderqueer? This entry outlines and discusses distinctly feminist debates on sex and gender considering both historical and more contemporary positions.

1.1 Biological determinism

1.2 gender terminology, 2.1 gender socialisation, 2.2 gender as feminine and masculine personality, 2.3 gender as feminine and masculine sexuality, 3.1.1 particularity argument, 3.1.2 normativity argument, 3.2 is sex classification solely a matter of biology, 3.3 are sex and gender distinct, 3.4 is the sex/gender distinction useful, 4.1.1 gendered social series, 4.1.2 resemblance nominalism, 4.2.1 social subordination and gender, 4.2.2 gender uniessentialism, 4.2.3 gender as positionality, 5. beyond the binary, 6. conclusion, other internet resources, related entries, 1. the sex/gender distinction..

The terms ‘sex’ and ‘gender’ mean different things to different feminist theorists and neither are easy or straightforward to characterise. Sketching out some feminist history of the terms provides a helpful starting point.

Most people ordinarily seem to think that sex and gender are coextensive: women are human females, men are human males. Many feminists have historically disagreed and have endorsed the sex/ gender distinction. Provisionally: ‘sex’ denotes human females and males depending on biological features (chromosomes, sex organs, hormones and other physical features); ‘gender’ denotes women and men depending on social factors (social role, position, behaviour or identity). The main feminist motivation for making this distinction was to counter biological determinism or the view that biology is destiny.

A typical example of a biological determinist view is that of Geddes and Thompson who, in 1889, argued that social, psychological and behavioural traits were caused by metabolic state. Women supposedly conserve energy (being ‘anabolic’) and this makes them passive, conservative, sluggish, stable and uninterested in politics. Men expend their surplus energy (being ‘katabolic’) and this makes them eager, energetic, passionate, variable and, thereby, interested in political and social matters. These biological ‘facts’ about metabolic states were used not only to explain behavioural differences between women and men but also to justify what our social and political arrangements ought to be. More specifically, they were used to argue for withholding from women political rights accorded to men because (according to Geddes and Thompson) “what was decided among the prehistoric Protozoa cannot be annulled by Act of Parliament” (quoted from Moi 1999, 18). It would be inappropriate to grant women political rights, as they are simply not suited to have those rights; it would also be futile since women (due to their biology) would simply not be interested in exercising their political rights. To counter this kind of biological determinism, feminists have argued that behavioural and psychological differences have social, rather than biological, causes. For instance, Simone de Beauvoir famously claimed that one is not born, but rather becomes a woman, and that “social discrimination produces in women moral and intellectual effects so profound that they appear to be caused by nature” (Beauvoir 1972 [original 1949], 18; for more, see the entry on Simone de Beauvoir ). Commonly observed behavioural traits associated with women and men, then, are not caused by anatomy or chromosomes. Rather, they are culturally learned or acquired.

Although biological determinism of the kind endorsed by Geddes and Thompson is nowadays uncommon, the idea that behavioural and psychological differences between women and men have biological causes has not disappeared. In the 1970s, sex differences were used to argue that women should not become airline pilots since they will be hormonally unstable once a month and, therefore, unable to perform their duties as well as men (Rogers 1999, 11). More recently, differences in male and female brains have been said to explain behavioural differences; in particular, the anatomy of corpus callosum, a bundle of nerves that connects the right and left cerebral hemispheres, is thought to be responsible for various psychological and behavioural differences. For instance, in 1992, a Time magazine article surveyed then prominent biological explanations of differences between women and men claiming that women’s thicker corpus callosums could explain what ‘women’s intuition’ is based on and impair women’s ability to perform some specialised visual-spatial skills, like reading maps (Gorman 1992). Anne Fausto-Sterling has questioned the idea that differences in corpus callosums cause behavioural and psychological differences. First, the corpus callosum is a highly variable piece of anatomy; as a result, generalisations about its size, shape and thickness that hold for women and men in general should be viewed with caution. Second, differences in adult human corpus callosums are not found in infants; this may suggest that physical brain differences actually develop as responses to differential treatment. Third, given that visual-spatial skills (like map reading) can be improved by practice, even if women and men’s corpus callosums differ, this does not make the resulting behavioural differences immutable. (Fausto-Sterling 2000b, chapter 5).

In order to distinguish biological differences from social/psychological ones and to talk about the latter, feminists appropriated the term ‘gender’. Psychologists writing on transsexuality were the first to employ gender terminology in this sense. Until the 1960s, ‘gender’ was often used to refer to masculine and feminine words, like le and la in French. However, in order to explain why some people felt that they were ‘trapped in the wrong bodies’, the psychologist Robert Stoller (1968) began using the terms ‘sex’ to pick out biological traits and ‘gender’ to pick out the amount of femininity and masculinity a person exhibited. Although (by and large) a person’s sex and gender complemented each other, separating out these terms seemed to make theoretical sense allowing Stoller to explain the phenomenon of transsexuality: transsexuals’ sex and gender simply don’t match.

Along with psychologists like Stoller, feminists found it useful to distinguish sex and gender. This enabled them to argue that many differences between women and men were socially produced and, therefore, changeable. Gayle Rubin (for instance) uses the phrase ‘sex/gender system’ in order to describe “a set of arrangements by which the biological raw material of human sex and procreation is shaped by human, social intervention” (1975, 165). Rubin employed this system to articulate that “part of social life which is the locus of the oppression of women” (1975, 159) describing gender as the “socially imposed division of the sexes” (1975, 179). Rubin’s thought was that although biological differences are fixed, gender differences are the oppressive results of social interventions that dictate how women and men should behave. Women are oppressed as women and “by having to be women” (Rubin 1975, 204). However, since gender is social, it is thought to be mutable and alterable by political and social reform that would ultimately bring an end to women’s subordination. Feminism should aim to create a “genderless (though not sexless) society, in which one’s sexual anatomy is irrelevant to who one is, what one does, and with whom one makes love” (Rubin 1975, 204).

In some earlier interpretations, like Rubin’s, sex and gender were thought to complement one another. The slogan ‘Gender is the social interpretation of sex’ captures this view. Nicholson calls this ‘the coat-rack view’ of gender: our sexed bodies are like coat racks and “provide the site upon which gender [is] constructed” (1994, 81). Gender conceived of as masculinity and femininity is superimposed upon the ‘coat-rack’ of sex as each society imposes on sexed bodies their cultural conceptions of how males and females should behave. This socially constructs gender differences – or the amount of femininity/masculinity of a person – upon our sexed bodies. That is, according to this interpretation, all humans are either male or female; their sex is fixed. But cultures interpret sexed bodies differently and project different norms on those bodies thereby creating feminine and masculine persons. Distinguishing sex and gender, however, also enables the two to come apart: they are separable in that one can be sexed male and yet be gendered a woman, or vice versa (Haslanger 2000b; Stoljar 1995).

So, this group of feminist arguments against biological determinism suggested that gender differences result from cultural practices and social expectations. Nowadays it is more common to denote this by saying that gender is socially constructed. This means that genders (women and men) and gendered traits (like being nurturing or ambitious) are the “intended or unintended product[s] of a social practice” (Haslanger 1995, 97). But which social practices construct gender, what social construction is and what being of a certain gender amounts to are major feminist controversies. There is no consensus on these issues. (See the entry on intersections between analytic and continental feminism for more on different ways to understand gender.)

2. Gender as socially constructed

One way to interpret Beauvoir’s claim that one is not born but rather becomes a woman is to take it as a claim about gender socialisation: females become women through a process whereby they acquire feminine traits and learn feminine behaviour. Masculinity and femininity are thought to be products of nurture or how individuals are brought up. They are causally constructed (Haslanger 1995, 98): social forces either have a causal role in bringing gendered individuals into existence or (to some substantial sense) shape the way we are qua women and men. And the mechanism of construction is social learning. For instance, Kate Millett takes gender differences to have “essentially cultural, rather than biological bases” that result from differential treatment (1971, 28–9). For her, gender is “the sum total of the parents’, the peers’, and the culture’s notions of what is appropriate to each gender by way of temperament, character, interests, status, worth, gesture, and expression” (Millett 1971, 31). Feminine and masculine gender-norms, however, are problematic in that gendered behaviour conveniently fits with and reinforces women’s subordination so that women are socialised into subordinate social roles: they learn to be passive, ignorant, docile, emotional helpmeets for men (Millett 1971, 26). However, since these roles are simply learned, we can create more equal societies by ‘unlearning’ social roles. That is, feminists should aim to diminish the influence of socialisation.

Social learning theorists hold that a huge array of different influences socialise us as women and men. This being the case, it is extremely difficult to counter gender socialisation. For instance, parents often unconsciously treat their female and male children differently. When parents have been asked to describe their 24- hour old infants, they have done so using gender-stereotypic language: boys are describes as strong, alert and coordinated and girls as tiny, soft and delicate. Parents’ treatment of their infants further reflects these descriptions whether they are aware of this or not (Renzetti & Curran 1992, 32). Some socialisation is more overt: children are often dressed in gender stereotypical clothes and colours (boys are dressed in blue, girls in pink) and parents tend to buy their children gender stereotypical toys. They also (intentionally or not) tend to reinforce certain ‘appropriate’ behaviours. While the precise form of gender socialization has changed since the onset of second-wave feminism, even today girls are discouraged from playing sports like football or from playing ‘rough and tumble’ games and are more likely than boys to be given dolls or cooking toys to play with; boys are told not to ‘cry like a baby’ and are more likely to be given masculine toys like trucks and guns (for more, see Kimmel 2000, 122–126). [ 1 ]

According to social learning theorists, children are also influenced by what they observe in the world around them. This, again, makes countering gender socialisation difficult. For one, children’s books have portrayed males and females in blatantly stereotypical ways: for instance, males as adventurers and leaders, and females as helpers and followers. One way to address gender stereotyping in children’s books has been to portray females in independent roles and males as non-aggressive and nurturing (Renzetti & Curran 1992, 35). Some publishers have attempted an alternative approach by making their characters, for instance, gender-neutral animals or genderless imaginary creatures (like TV’s Teletubbies). However, parents reading books with gender-neutral or genderless characters often undermine the publishers’ efforts by reading them to their children in ways that depict the characters as either feminine or masculine. According to Renzetti and Curran, parents labelled the overwhelming majority of gender-neutral characters masculine whereas those characters that fit feminine gender stereotypes (for instance, by being helpful and caring) were labelled feminine (1992, 35). Socialising influences like these are still thought to send implicit messages regarding how females and males should act and are expected to act shaping us into feminine and masculine persons.

Nancy Chodorow (1978; 1995) has criticised social learning theory as too simplistic to explain gender differences (see also Deaux & Major 1990; Gatens 1996). Instead, she holds that gender is a matter of having feminine and masculine personalities that develop in early infancy as responses to prevalent parenting practices. In particular, gendered personalities develop because women tend to be the primary caretakers of small children. Chodorow holds that because mothers (or other prominent females) tend to care for infants, infant male and female psychic development differs. Crudely put: the mother-daughter relationship differs from the mother-son relationship because mothers are more likely to identify with their daughters than their sons. This unconsciously prompts the mother to encourage her son to psychologically individuate himself from her thereby prompting him to develop well defined and rigid ego boundaries. However, the mother unconsciously discourages the daughter from individuating herself thereby prompting the daughter to develop flexible and blurry ego boundaries. Childhood gender socialisation further builds on and reinforces these unconsciously developed ego boundaries finally producing feminine and masculine persons (1995, 202–206). This perspective has its roots in Freudian psychoanalytic theory, although Chodorow’s approach differs in many ways from Freud’s.

Gendered personalities are supposedly manifested in common gender stereotypical behaviour. Take emotional dependency. Women are stereotypically more emotional and emotionally dependent upon others around them, supposedly finding it difficult to distinguish their own interests and wellbeing from the interests and wellbeing of their children and partners. This is said to be because of their blurry and (somewhat) confused ego boundaries: women find it hard to distinguish their own needs from the needs of those around them because they cannot sufficiently individuate themselves from those close to them. By contrast, men are stereotypically emotionally detached, preferring a career where dispassionate and distanced thinking are virtues. These traits are said to result from men’s well-defined ego boundaries that enable them to prioritise their own needs and interests sometimes at the expense of others’ needs and interests.

Chodorow thinks that these gender differences should and can be changed. Feminine and masculine personalities play a crucial role in women’s oppression since they make females overly attentive to the needs of others and males emotionally deficient. In order to correct the situation, both male and female parents should be equally involved in parenting (Chodorow 1995, 214). This would help in ensuring that children develop sufficiently individuated senses of selves without becoming overly detached, which in turn helps to eradicate common gender stereotypical behaviours.

Catharine MacKinnon develops her theory of gender as a theory of sexuality. Very roughly: the social meaning of sex (gender) is created by sexual objectification of women whereby women are viewed and treated as objects for satisfying men’s desires (MacKinnon 1989). Masculinity is defined as sexual dominance, femininity as sexual submissiveness: genders are “created through the eroticization of dominance and submission. The man/woman difference and the dominance/submission dynamic define each other. This is the social meaning of sex” (MacKinnon 1989, 113). For MacKinnon, gender is constitutively constructed : in defining genders (or masculinity and femininity) we must make reference to social factors (see Haslanger 1995, 98). In particular, we must make reference to the position one occupies in the sexualised dominance/submission dynamic: men occupy the sexually dominant position, women the sexually submissive one. As a result, genders are by definition hierarchical and this hierarchy is fundamentally tied to sexualised power relations. The notion of ‘gender equality’, then, does not make sense to MacKinnon. If sexuality ceased to be a manifestation of dominance, hierarchical genders (that are defined in terms of sexuality) would cease to exist.

So, gender difference for MacKinnon is not a matter of having a particular psychological orientation or behavioural pattern; rather, it is a function of sexuality that is hierarchal in patriarchal societies. This is not to say that men are naturally disposed to sexually objectify women or that women are naturally submissive. Instead, male and female sexualities are socially conditioned: men have been conditioned to find women’s subordination sexy and women have been conditioned to find a particular male version of female sexuality as erotic – one in which it is erotic to be sexually submissive. For MacKinnon, both female and male sexual desires are defined from a male point of view that is conditioned by pornography (MacKinnon 1989, chapter 7). Bluntly put: pornography portrays a false picture of ‘what women want’ suggesting that women in actual fact are and want to be submissive. This conditions men’s sexuality so that they view women’s submission as sexy. And male dominance enforces this male version of sexuality onto women, sometimes by force. MacKinnon’s thought is not that male dominance is a result of social learning (see 2.1.); rather, socialization is an expression of power. That is, socialized differences in masculine and feminine traits, behaviour, and roles are not responsible for power inequalities. Females and males (roughly put) are socialised differently because there are underlying power inequalities. As MacKinnon puts it, ‘dominance’ (power relations) is prior to ‘difference’ (traits, behaviour and roles) (see, MacKinnon 1989, chapter 12). MacKinnon, then, sees legal restrictions on pornography as paramount to ending women’s subordinate status that stems from their gender.

3. Problems with the sex/gender distinction

3.1 is gender uniform.

The positions outlined above share an underlying metaphysical perspective on gender: gender realism . [ 2 ] That is, women as a group are assumed to share some characteristic feature, experience, common condition or criterion that defines their gender and the possession of which makes some individuals women (as opposed to, say, men). All women are thought to differ from all men in this respect (or respects). For example, MacKinnon thought that being treated in sexually objectifying ways is the common condition that defines women’s gender and what women as women share. All women differ from all men in this respect. Further, pointing out females who are not sexually objectified does not provide a counterexample to MacKinnon’s view. Being sexually objectified is constitutive of being a woman; a female who escapes sexual objectification, then, would not count as a woman.

One may want to critique the three accounts outlined by rejecting the particular details of each account. (For instance, see Spelman [1988, chapter 4] for a critique of the details of Chodorow’s view.) A more thoroughgoing critique has been levelled at the general metaphysical perspective of gender realism that underlies these positions. It has come under sustained attack on two grounds: first, that it fails to take into account racial, cultural and class differences between women (particularity argument); second, that it posits a normative ideal of womanhood (normativity argument).

Elizabeth Spelman (1988) has influentially argued against gender realism with her particularity argument. Roughly: gender realists mistakenly assume that gender is constructed independently of race, class, ethnicity and nationality. If gender were separable from, for example, race and class in this manner, all women would experience womanhood in the same way. And this is clearly false. For instance, Harris (1993) and Stone (2007) criticise MacKinnon’s view, that sexual objectification is the common condition that defines women’s gender, for failing to take into account differences in women’s backgrounds that shape their sexuality. The history of racist oppression illustrates that during slavery black women were ‘hypersexualised’ and thought to be always sexually available whereas white women were thought to be pure and sexually virtuous. In fact, the rape of a black woman was thought to be impossible (Harris 1993). So, (the argument goes) sexual objectification cannot serve as the common condition for womanhood since it varies considerably depending on one’s race and class. [ 3 ]

For Spelman, the perspective of ‘white solipsism’ underlies gender realists’ mistake. They assumed that all women share some “golden nugget of womanness” (Spelman 1988, 159) and that the features constitutive of such a nugget are the same for all women regardless of their particular cultural backgrounds. Next, white Western middle-class feminists accounted for the shared features simply by reflecting on the cultural features that condition their gender as women thus supposing that “the womanness underneath the Black woman’s skin is a white woman’s, and deep down inside the Latina woman is an Anglo woman waiting to burst through an obscuring cultural shroud” (Spelman 1988, 13). In so doing, Spelman claims, white middle-class Western feminists passed off their particular view of gender as “a metaphysical truth” (1988, 180) thereby privileging some women while marginalising others. In failing to see the importance of race and class in gender construction, white middle-class Western feminists conflated “the condition of one group of women with the condition of all” (Spelman 1988, 3).

Betty Friedan’s (1963) well-known work is a case in point of white solipsism. [ 4 ] Friedan saw domesticity as the main vehicle of gender oppression and called upon women in general to find jobs outside the home. But she failed to realize that women from less privileged backgrounds, often poor and non-white, already worked outside the home to support their families. Friedan’s suggestion, then, was applicable only to a particular sub-group of women (white middle-class Western housewives). But it was mistakenly taken to apply to all women’s lives — a mistake that was generated by Friedan’s failure to take women’s racial and class differences into account (hooks 2000, 1–3).

Spelman further holds that since social conditioning creates femininity and societies (and sub-groups) that condition it differ from one another, femininity must be differently conditioned in different societies. For her, “females become not simply women but particular kinds of women” (Spelman 1988, 113): white working-class women, black middle-class women, poor Jewish women, wealthy aristocratic European women, and so on.

This line of thought has been extremely influential in feminist philosophy. For instance, Young holds that Spelman has definitively shown that gender realism is untenable (1997, 13). Mikkola (2006) argues that this isn’t so. The arguments Spelman makes do not undermine the idea that there is some characteristic feature, experience, common condition or criterion that defines women’s gender; they simply point out that some particular ways of cashing out what defines womanhood are misguided. So, although Spelman is right to reject those accounts that falsely take the feature that conditions white middle-class Western feminists’ gender to condition women’s gender in general, this leaves open the possibility that women qua women do share something that defines their gender. (See also Haslanger [2000a] for a discussion of why gender realism is not necessarily untenable, and Stoljar [2011] for a discussion of Mikkola’s critique of Spelman.)

Judith Butler critiques the sex/gender distinction on two grounds. They critique gender realism with their normativity argument (1999 [original 1990], chapter 1); they also hold that the sex/gender distinction is unintelligible (this will be discussed in section 3.3.). Butler’s normativity argument is not straightforwardly directed at the metaphysical perspective of gender realism, but rather at its political counterpart: identity politics. This is a form of political mobilization based on membership in some group (e.g. racial, ethnic, cultural, gender) and group membership is thought to be delimited by some common experiences, conditions or features that define the group (Heyes 2000, 58; see also the entry on Identity Politics ). Feminist identity politics, then, presupposes gender realism in that feminist politics is said to be mobilized around women as a group (or category) where membership in this group is fixed by some condition, experience or feature that women supposedly share and that defines their gender.

Butler’s normativity argument makes two claims. The first is akin to Spelman’s particularity argument: unitary gender notions fail to take differences amongst women into account thus failing to recognise “the multiplicity of cultural, social, and political intersections in which the concrete array of ‘women’ are constructed” (Butler 1999, 19–20). In their attempt to undercut biologically deterministic ways of defining what it means to be a woman, feminists inadvertently created new socially constructed accounts of supposedly shared femininity. Butler’s second claim is that such false gender realist accounts are normative. That is, in their attempt to fix feminism’s subject matter, feminists unwittingly defined the term ‘woman’ in a way that implies there is some correct way to be gendered a woman (Butler 1999, 5). That the definition of the term ‘woman’ is fixed supposedly “operates as a policing force which generates and legitimizes certain practices, experiences, etc., and curtails and delegitimizes others” (Nicholson 1998, 293). Following this line of thought, one could say that, for instance, Chodorow’s view of gender suggests that ‘real’ women have feminine personalities and that these are the women feminism should be concerned about. If one does not exhibit a distinctly feminine personality, the implication is that one is not ‘really’ a member of women’s category nor does one properly qualify for feminist political representation.

Butler’s second claim is based on their view that“[i]dentity categories [like that of women] are never merely descriptive, but always normative, and as such, exclusionary” (Butler 1991, 160). That is, the mistake of those feminists Butler critiques was not that they provided the incorrect definition of ‘woman’. Rather, (the argument goes) their mistake was to attempt to define the term ‘woman’ at all. Butler’s view is that ‘woman’ can never be defined in a way that does not prescribe some “unspoken normative requirements” (like having a feminine personality) that women should conform to (Butler 1999, 9). Butler takes this to be a feature of terms like ‘woman’ that purport to pick out (what they call) ‘identity categories’. They seem to assume that ‘woman’ can never be used in a non-ideological way (Moi 1999, 43) and that it will always encode conditions that are not satisfied by everyone we think of as women. Some explanation for this comes from Butler’s view that all processes of drawing categorical distinctions involve evaluative and normative commitments; these in turn involve the exercise of power and reflect the conditions of those who are socially powerful (Witt 1995).

In order to better understand Butler’s critique, consider their account of gender performativity. For them, standard feminist accounts take gendered individuals to have some essential properties qua gendered individuals or a gender core by virtue of which one is either a man or a woman. This view assumes that women and men, qua women and men, are bearers of various essential and accidental attributes where the former secure gendered persons’ persistence through time as so gendered. But according to Butler this view is false: (i) there are no such essential properties, and (ii) gender is an illusion maintained by prevalent power structures. First, feminists are said to think that genders are socially constructed in that they have the following essential attributes (Butler 1999, 24): women are females with feminine behavioural traits, being heterosexuals whose desire is directed at men; men are males with masculine behavioural traits, being heterosexuals whose desire is directed at women. These are the attributes necessary for gendered individuals and those that enable women and men to persist through time as women and men. Individuals have “intelligible genders” (Butler 1999, 23) if they exhibit this sequence of traits in a coherent manner (where sexual desire follows from sexual orientation that in turn follows from feminine/ masculine behaviours thought to follow from biological sex). Social forces in general deem individuals who exhibit in coherent gender sequences (like lesbians) to be doing their gender ‘wrong’ and they actively discourage such sequencing of traits, for instance, via name-calling and overt homophobic discrimination. Think back to what was said above: having a certain conception of what women are like that mirrors the conditions of socially powerful (white, middle-class, heterosexual, Western) women functions to marginalize and police those who do not fit this conception.

These gender cores, supposedly encoding the above traits, however, are nothing more than illusions created by ideals and practices that seek to render gender uniform through heterosexism, the view that heterosexuality is natural and homosexuality is deviant (Butler 1999, 42). Gender cores are constructed as if they somehow naturally belong to women and men thereby creating gender dimorphism or the belief that one must be either a masculine male or a feminine female. But gender dimorphism only serves a heterosexist social order by implying that since women and men are sharply opposed, it is natural to sexually desire the opposite sex or gender.

Further, being feminine and desiring men (for instance) are standardly assumed to be expressions of one’s gender as a woman. Butler denies this and holds that gender is really performative. It is not “a stable identity or locus of agency from which various acts follow; rather, gender is … instituted … through a stylized repetition of [habitual] acts ” (Butler 1999, 179): through wearing certain gender-coded clothing, walking and sitting in certain gender-coded ways, styling one’s hair in gender-coded manner and so on. Gender is not something one is, it is something one does; it is a sequence of acts, a doing rather than a being. And repeatedly engaging in ‘feminising’ and ‘masculinising’ acts congeals gender thereby making people falsely think of gender as something they naturally are . Gender only comes into being through these gendering acts: a female who has sex with men does not express her gender as a woman. This activity (amongst others) makes her gendered a woman.

The constitutive acts that gender individuals create genders as “compelling illusion[s]” (Butler 1990, 271). Our gendered classification scheme is a strong pragmatic construction : social factors wholly determine our use of the scheme and the scheme fails to represent accurately any ‘facts of the matter’ (Haslanger 1995, 100). People think that there are true and real genders, and those deemed to be doing their gender ‘wrong’ are not socially sanctioned. But, genders are true and real only to the extent that they are performed (Butler 1990, 278–9). It does not make sense, then, to say of a male-to-female trans person that s/he is really a man who only appears to be a woman. Instead, males dressing up and acting in ways that are associated with femininity “show that [as Butler suggests] ‘being’ feminine is just a matter of doing certain activities” (Stone 2007, 64). As a result, the trans person’s gender is just as real or true as anyone else’s who is a ‘traditionally’ feminine female or masculine male (Butler 1990, 278). [ 5 ] Without heterosexism that compels people to engage in certain gendering acts, there would not be any genders at all. And ultimately the aim should be to abolish norms that compel people to act in these gendering ways.

For Butler, given that gender is performative, the appropriate response to feminist identity politics involves two things. First, feminists should understand ‘woman’ as open-ended and “a term in process, a becoming, a constructing that cannot rightfully be said to originate or end … it is open to intervention and resignification” (Butler 1999, 43). That is, feminists should not try to define ‘woman’ at all. Second, the category of women “ought not to be the foundation of feminist politics” (Butler 1999, 9). Rather, feminists should focus on providing an account of how power functions and shapes our understandings of womanhood not only in the society at large but also within the feminist movement.

Many people, including many feminists, have ordinarily taken sex ascriptions to be solely a matter of biology with no social or cultural dimension. It is commonplace to think that there are only two sexes and that biological sex classifications are utterly unproblematic. By contrast, some feminists have argued that sex classifications are not unproblematic and that they are not solely a matter of biology. In order to make sense of this, it is helpful to distinguish object- and idea-construction (see Haslanger 2003b for more): social forces can be said to construct certain kinds of objects (e.g. sexed bodies or gendered individuals) and certain kinds of ideas (e.g. sex or gender concepts). First, take the object-construction of sexed bodies. Secondary sex characteristics, or the physiological and biological features commonly associated with males and females, are affected by social practices. In some societies, females’ lower social status has meant that they have been fed less and so, the lack of nutrition has had the effect of making them smaller in size (Jaggar 1983, 37). Uniformity in muscular shape, size and strength within sex categories is not caused entirely by biological factors, but depends heavily on exercise opportunities: if males and females were allowed the same exercise opportunities and equal encouragement to exercise, it is thought that bodily dimorphism would diminish (Fausto-Sterling 1993a, 218). A number of medical phenomena involving bones (like osteoporosis) have social causes directly related to expectations about gender, women’s diet and their exercise opportunities (Fausto-Sterling 2005). These examples suggest that physiological features thought to be sex-specific traits not affected by social and cultural factors are, after all, to some extent products of social conditioning. Social conditioning, then, shapes our biology.

Second, take the idea-construction of sex concepts. Our concept of sex is said to be a product of social forces in the sense that what counts as sex is shaped by social meanings. Standardly, those with XX-chromosomes, ovaries that produce large egg cells, female genitalia, a relatively high proportion of ‘female’ hormones, and other secondary sex characteristics (relatively small body size, less body hair) count as biologically female. Those with XY-chromosomes, testes that produce small sperm cells, male genitalia, a relatively high proportion of ‘male’ hormones and other secondary sex traits (relatively large body size, significant amounts of body hair) count as male. This understanding is fairly recent. The prevalent scientific view from Ancient Greeks until the late 18 th century, did not consider female and male sexes to be distinct categories with specific traits; instead, a ‘one-sex model’ held that males and females were members of the same sex category. Females’ genitals were thought to be the same as males’ but simply directed inside the body; ovaries and testes (for instance) were referred to by the same term and whether the term referred to the former or the latter was made clear by the context (Laqueur 1990, 4). It was not until the late 1700s that scientists began to think of female and male anatomies as radically different moving away from the ‘one-sex model’ of a single sex spectrum to the (nowadays prevalent) ‘two-sex model’ of sexual dimorphism. (For an alternative view, see King 2013.)

Fausto-Sterling has argued that this ‘two-sex model’ isn’t straightforward either (1993b; 2000a; 2000b). Based on a meta-study of empirical medical research, she estimates that 1.7% of population fail to neatly fall within the usual sex classifications possessing various combinations of different sex characteristics (Fausto-Sterling 2000a, 20). In her earlier work, she claimed that intersex individuals make up (at least) three further sex classes: ‘herms’ who possess one testis and one ovary; ‘merms’ who possess testes, some aspects of female genitalia but no ovaries; and ‘ferms’ who have ovaries, some aspects of male genitalia but no testes (Fausto-Sterling 1993b, 21). (In her [2000a], Fausto-Sterling notes that these labels were put forward tongue–in–cheek.) Recognition of intersex people suggests that feminists (and society at large) are wrong to think that humans are either female or male.

To illustrate further the idea-construction of sex, consider the case of the athlete Maria Patiño. Patiño has female genitalia, has always considered herself to be female and was considered so by others. However, she was discovered to have XY chromosomes and was barred from competing in women’s sports (Fausto-Sterling 2000b, 1–3). Patiño’s genitalia were at odds with her chromosomes and the latter were taken to determine her sex. Patiño successfully fought to be recognised as a female athlete arguing that her chromosomes alone were not sufficient to not make her female. Intersex people, like Patiño, illustrate that our understandings of sex differ and suggest that there is no immediately obvious way to settle what sex amounts to purely biologically or scientifically. Deciding what sex is involves evaluative judgements that are influenced by social factors.

Insofar as our cultural conceptions affect our understandings of sex, feminists must be much more careful about sex classifications and rethink what sex amounts to (Stone 2007, chapter 1). More specifically, intersex people illustrate that sex traits associated with females and males need not always go together and that individuals can have some mixture of these traits. This suggests to Stone that sex is a cluster concept: it is sufficient to satisfy enough of the sex features that tend to cluster together in order to count as being of a particular sex. But, one need not satisfy all of those features or some arbitrarily chosen supposedly necessary sex feature, like chromosomes (Stone 2007, 44). This makes sex a matter of degree and sex classifications should take place on a spectrum: one can be more or less female/male but there is no sharp distinction between the two. Further, intersex people (along with trans people) are located at the centre of the sex spectrum and in many cases their sex will be indeterminate (Stone 2007).

More recently, Ayala and Vasilyeva (2015) have argued for an inclusive and extended conception of sex: just as certain tools can be seen to extend our minds beyond the limits of our brains (e.g. white canes), other tools (like dildos) can extend our sex beyond our bodily boundaries. This view aims to motivate the idea that what counts as sex should not be determined by looking inwards at genitalia or other anatomical features. In a different vein, Ásta (2018) argues that sex is a conferred social property. This follows her more general conferralist framework to analyse all social properties: properties that are conferred by others thereby generating a social status that consists in contextually specific constraints and enablements on individual behaviour. The general schema for conferred properties is as follows (Ásta 2018, 8):

Conferred property: what property is conferred. Who: who the subjects are. What: what attitude, state, or action of the subjects matter. When: under what conditions the conferral takes place. Base property: what the subjects are attempting to track (consciously or not), if anything.

With being of a certain sex (e.g. male, female) in mind, Ásta holds that it is a conferred property that merely aims to track physical features. Hence sex is a social – or in fact, an institutional – property rather than a natural one. The schema for sex goes as follows (72):

Conferred property: being female, male. Who: legal authorities, drawing on the expert opinion of doctors, other medical personnel. What: “the recording of a sex in official documents ... The judgment of the doctors (and others) as to what sex role might be the most fitting, given the biological characteristics present.” When: at birth or after surgery/ hormonal treatment. Base property: “the aim is to track as many sex-stereotypical characteristics as possible, and doctors perform surgery in cases where that might help bring the physical characteristics more in line with the stereotype of male and female.”

This (among other things) offers a debunking analysis of sex: it may appear to be a natural property, but on the conferralist analysis is better understood as a conferred legal status. Ásta holds that gender too is a conferred property, but contra the discussion in the following section, she does not think that this collapses the distinction between sex and gender: sex and gender are differently conferred albeit both satisfying the general schema noted above. Nonetheless, on the conferralist framework what underlies both sex and gender is the idea of social construction as social significance: sex-stereotypical characteristics are taken to be socially significant context specifically, whereby they become the basis for conferring sex onto individuals and this brings with it various constraints and enablements on individuals and their behaviour. This fits object- and idea-constructions introduced above, although offers a different general framework to analyse the matter at hand.

In addition to arguing against identity politics and for gender performativity, Butler holds that distinguishing biological sex from social gender is unintelligible. For them, both are socially constructed:

If the immutable character of sex is contested, perhaps this construct called ‘sex’ is as culturally constructed as gender; indeed, perhaps it was always already gender, with the consequence that the distinction between sex and gender turns out to be no distinction at all. (Butler 1999, 10–11)

(Butler is not alone in claiming that there are no tenable distinctions between nature/culture, biology/construction and sex/gender. See also: Antony 1998; Gatens 1996; Grosz 1994; Prokhovnik 1999.) Butler makes two different claims in the passage cited: that sex is a social construction, and that sex is gender. To unpack their view, consider the two claims in turn. First, the idea that sex is a social construct, for Butler, boils down to the view that our sexed bodies are also performative and, so, they have “no ontological status apart from the various acts which constitute [their] reality” (1999, 173). Prima facie , this implausibly implies that female and male bodies do not have independent existence and that if gendering activities ceased, so would physical bodies. This is not Butler’s claim; rather, their position is that bodies viewed as the material foundations on which gender is constructed, are themselves constructed as if they provide such material foundations (Butler 1993). Cultural conceptions about gender figure in “the very apparatus of production whereby sexes themselves are established” (Butler 1999, 11).

For Butler, sexed bodies never exist outside social meanings and how we understand gender shapes how we understand sex (1999, 139). Sexed bodies are not empty matter on which gender is constructed and sex categories are not picked out on the basis of objective features of the world. Instead, our sexed bodies are themselves discursively constructed : they are the way they are, at least to a substantial extent, because of what is attributed to sexed bodies and how they are classified (for discursive construction, see Haslanger 1995, 99). Sex assignment (calling someone female or male) is normative (Butler 1993, 1). [ 6 ] When the doctor calls a newly born infant a girl or a boy, s/he is not making a descriptive claim, but a normative one. In fact, the doctor is performing an illocutionary speech act (see the entry on Speech Acts ). In effect, the doctor’s utterance makes infants into girls or boys. We, then, engage in activities that make it seem as if sexes naturally come in two and that being female or male is an objective feature of the world, rather than being a consequence of certain constitutive acts (that is, rather than being performative). And this is what Butler means in saying that physical bodies never exist outside cultural and social meanings, and that sex is as socially constructed as gender. They do not deny that physical bodies exist. But, they take our understanding of this existence to be a product of social conditioning: social conditioning makes the existence of physical bodies intelligible to us by discursively constructing sexed bodies through certain constitutive acts. (For a helpful introduction to Butler’s views, see Salih 2002.)

For Butler, sex assignment is always in some sense oppressive. Again, this appears to be because of Butler’s general suspicion of classification: sex classification can never be merely descriptive but always has a normative element reflecting evaluative claims of those who are powerful. Conducting a feminist genealogy of the body (or examining why sexed bodies are thought to come naturally as female and male), then, should ground feminist practice (Butler 1993, 28–9). Feminists should examine and uncover ways in which social construction and certain acts that constitute sex shape our understandings of sexed bodies, what kinds of meanings bodies acquire and which practices and illocutionary speech acts ‘make’ our bodies into sexes. Doing so enables feminists to identity how sexed bodies are socially constructed in order to resist such construction.

However, given what was said above, it is far from obvious what we should make of Butler’s claim that sex “was always already gender” (1999, 11). Stone (2007) takes this to mean that sex is gender but goes on to question it arguing that the social construction of both sex and gender does not make sex identical to gender. According to Stone, it would be more accurate for Butler to say that claims about sex imply gender norms. That is, many claims about sex traits (like ‘females are physically weaker than males’) actually carry implications about how women and men are expected to behave. To some extent the claim describes certain facts. But, it also implies that females are not expected to do much heavy lifting and that they would probably not be good at it. So, claims about sex are not identical to claims about gender; rather, they imply claims about gender norms (Stone 2007, 70).

Some feminists hold that the sex/gender distinction is not useful. For a start, it is thought to reflect politically problematic dualistic thinking that undercuts feminist aims: the distinction is taken to reflect and replicate androcentric oppositions between (for instance) mind/body, culture/nature and reason/emotion that have been used to justify women’s oppression (e.g. Grosz 1994; Prokhovnik 1999). The thought is that in oppositions like these, one term is always superior to the other and that the devalued term is usually associated with women (Lloyd 1993). For instance, human subjectivity and agency are identified with the mind but since women are usually identified with their bodies, they are devalued as human subjects and agents. The opposition between mind and body is said to further map on to other distinctions, like reason/emotion, culture/nature, rational/irrational, where one side of each distinction is devalued (one’s bodily features are usually valued less that one’s mind, rationality is usually valued more than irrationality) and women are associated with the devalued terms: they are thought to be closer to bodily features and nature than men, to be irrational, emotional and so on. This is said to be evident (for instance) in job interviews. Men are treated as gender-neutral persons and not asked whether they are planning to take time off to have a family. By contrast, that women face such queries illustrates that they are associated more closely than men with bodily features to do with procreation (Prokhovnik 1999, 126). The opposition between mind and body, then, is thought to map onto the opposition between men and women.