Dissertation Structure & Layout 101: How to structure your dissertation, thesis or research project.

By: Derek Jansen (MBA) Reviewed By: David Phair (PhD) | July 2019

So, you’ve got a decent understanding of what a dissertation is , you’ve chosen your topic and hopefully you’ve received approval for your research proposal . Awesome! Now its time to start the actual dissertation or thesis writing journey.

To craft a high-quality document, the very first thing you need to understand is dissertation structure . In this post, we’ll walk you through the generic dissertation structure and layout, step by step. We’ll start with the big picture, and then zoom into each chapter to briefly discuss the core contents. If you’re just starting out on your research journey, you should start with this post, which covers the big-picture process of how to write a dissertation or thesis .

*The Caveat *

In this post, we’ll be discussing a traditional dissertation/thesis structure and layout, which is generally used for social science research across universities, whether in the US, UK, Europe or Australia. However, some universities may have small variations on this structure (extra chapters, merged chapters, slightly different ordering, etc).

So, always check with your university if they have a prescribed structure or layout that they expect you to work with. If not, it’s safe to assume the structure we’ll discuss here is suitable. And even if they do have a prescribed structure, you’ll still get value from this post as we’ll explain the core contents of each section.

Overview: S tructuring a dissertation or thesis

- Acknowledgements page

- Abstract (or executive summary)

- Table of contents , list of figures and tables

- Chapter 1: Introduction

- Chapter 2: Literature review

- Chapter 3: Methodology

- Chapter 4: Results

- Chapter 5: Discussion

- Chapter 6: Conclusion

- Reference list

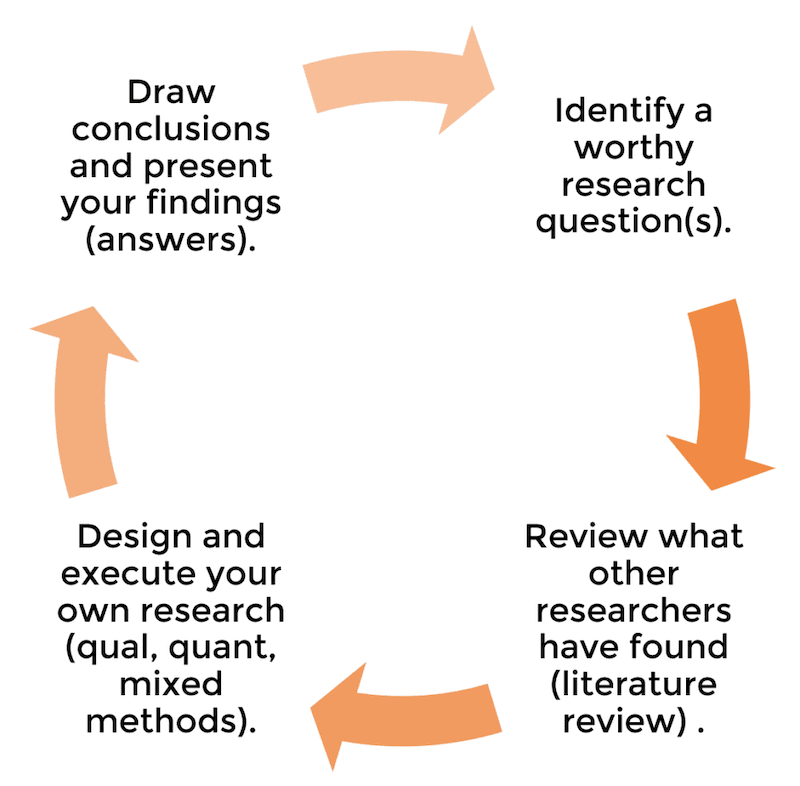

As I mentioned, some universities will have slight variations on this structure. For example, they want an additional “personal reflection chapter”, or they might prefer the results and discussion chapter to be merged into one. Regardless, the overarching flow will always be the same, as this flow reflects the research process , which we discussed here – i.e.:

- The introduction chapter presents the core research question and aims .

- The literature review chapter assesses what the current research says about this question.

- The methodology, results and discussion chapters go about undertaking new research about this question.

- The conclusion chapter (attempts to) answer the core research question .

In other words, the dissertation structure and layout reflect the research process of asking a well-defined question(s), investigating, and then answering the question – see below.

To restate that – the structure and layout of a dissertation reflect the flow of the overall research process . This is essential to understand, as each chapter will make a lot more sense if you “get” this concept. If you’re not familiar with the research process, read this post before going further.

Right. Now that we’ve covered the big picture, let’s dive a little deeper into the details of each section and chapter. Oh and by the way, you can also grab our free dissertation/thesis template here to help speed things up.

The title page of your dissertation is the very first impression the marker will get of your work, so it pays to invest some time thinking about your title. But what makes for a good title? A strong title needs to be 3 things:

- Succinct (not overly lengthy or verbose)

- Specific (not vague or ambiguous)

- Representative of the research you’re undertaking (clearly linked to your research questions)

Typically, a good title includes mention of the following:

- The broader area of the research (i.e. the overarching topic)

- The specific focus of your research (i.e. your specific context)

- Indication of research design (e.g. quantitative , qualitative , or mixed methods ).

For example:

A quantitative investigation [research design] into the antecedents of organisational trust [broader area] in the UK retail forex trading market [specific context/area of focus].

Again, some universities may have specific requirements regarding the format and structure of the title, so it’s worth double-checking expectations with your institution (if there’s no mention in the brief or study material).

Acknowledgements

This page provides you with an opportunity to say thank you to those who helped you along your research journey. Generally, it’s optional (and won’t count towards your marks), but it is academic best practice to include this.

So, who do you say thanks to? Well, there’s no prescribed requirements, but it’s common to mention the following people:

- Your dissertation supervisor or committee.

- Any professors, lecturers or academics that helped you understand the topic or methodologies.

- Any tutors, mentors or advisors.

- Your family and friends, especially spouse (for adult learners studying part-time).

There’s no need for lengthy rambling. Just state who you’re thankful to and for what (e.g. thank you to my supervisor, John Doe, for his endless patience and attentiveness) – be sincere. In terms of length, you should keep this to a page or less.

Abstract or executive summary

The dissertation abstract (or executive summary for some degrees) serves to provide the first-time reader (and marker or moderator) with a big-picture view of your research project. It should give them an understanding of the key insights and findings from the research, without them needing to read the rest of the report – in other words, it should be able to stand alone .

For it to stand alone, your abstract should cover the following key points (at a minimum):

- Your research questions and aims – what key question(s) did your research aim to answer?

- Your methodology – how did you go about investigating the topic and finding answers to your research question(s)?

- Your findings – following your own research, what did do you discover?

- Your conclusions – based on your findings, what conclusions did you draw? What answers did you find to your research question(s)?

So, in much the same way the dissertation structure mimics the research process, your abstract or executive summary should reflect the research process, from the initial stage of asking the original question to the final stage of answering that question.

In practical terms, it’s a good idea to write this section up last , once all your core chapters are complete. Otherwise, you’ll end up writing and rewriting this section multiple times (just wasting time). For a step by step guide on how to write a strong executive summary, check out this post .

Need a helping hand?

Table of contents

This section is straightforward. You’ll typically present your table of contents (TOC) first, followed by the two lists – figures and tables. I recommend that you use Microsoft Word’s automatic table of contents generator to generate your TOC. If you’re not familiar with this functionality, the video below explains it simply:

If you find that your table of contents is overly lengthy, consider removing one level of depth. Oftentimes, this can be done without detracting from the usefulness of the TOC.

Right, now that the “admin” sections are out of the way, its time to move on to your core chapters. These chapters are the heart of your dissertation and are where you’ll earn the marks. The first chapter is the introduction chapter – as you would expect, this is the time to introduce your research…

It’s important to understand that even though you’ve provided an overview of your research in your abstract, your introduction needs to be written as if the reader has not read that (remember, the abstract is essentially a standalone document). So, your introduction chapter needs to start from the very beginning, and should address the following questions:

- What will you be investigating (in plain-language, big picture-level)?

- Why is that worth investigating? How is it important to academia or business? How is it sufficiently original?

- What are your research aims and research question(s)? Note that the research questions can sometimes be presented at the end of the literature review (next chapter).

- What is the scope of your study? In other words, what will and won’t you cover ?

- How will you approach your research? In other words, what methodology will you adopt?

- How will you structure your dissertation? What are the core chapters and what will you do in each of them?

These are just the bare basic requirements for your intro chapter. Some universities will want additional bells and whistles in the intro chapter, so be sure to carefully read your brief or consult your research supervisor.

If done right, your introduction chapter will set a clear direction for the rest of your dissertation. Specifically, it will make it clear to the reader (and marker) exactly what you’ll be investigating, why that’s important, and how you’ll be going about the investigation. Conversely, if your introduction chapter leaves a first-time reader wondering what exactly you’ll be researching, you’ve still got some work to do.

Now that you’ve set a clear direction with your introduction chapter, the next step is the literature review . In this section, you will analyse the existing research (typically academic journal articles and high-quality industry publications), with a view to understanding the following questions:

- What does the literature currently say about the topic you’re investigating?

- Is the literature lacking or well established? Is it divided or in disagreement?

- How does your research fit into the bigger picture?

- How does your research contribute something original?

- How does the methodology of previous studies help you develop your own?

Depending on the nature of your study, you may also present a conceptual framework towards the end of your literature review, which you will then test in your actual research.

Again, some universities will want you to focus on some of these areas more than others, some will have additional or fewer requirements, and so on. Therefore, as always, its important to review your brief and/or discuss with your supervisor, so that you know exactly what’s expected of your literature review chapter.

Now that you’ve investigated the current state of knowledge in your literature review chapter and are familiar with the existing key theories, models and frameworks, its time to design your own research. Enter the methodology chapter – the most “science-ey” of the chapters…

In this chapter, you need to address two critical questions:

- Exactly HOW will you carry out your research (i.e. what is your intended research design)?

- Exactly WHY have you chosen to do things this way (i.e. how do you justify your design)?

Remember, the dissertation part of your degree is first and foremost about developing and demonstrating research skills . Therefore, the markers want to see that you know which methods to use, can clearly articulate why you’ve chosen then, and know how to deploy them effectively.

Importantly, this chapter requires detail – don’t hold back on the specifics. State exactly what you’ll be doing, with who, when, for how long, etc. Moreover, for every design choice you make, make sure you justify it.

In practice, you will likely end up coming back to this chapter once you’ve undertaken all your data collection and analysis, and revise it based on changes you made during the analysis phase. This is perfectly fine. Its natural for you to add an additional analysis technique, scrap an old one, etc based on where your data lead you. Of course, I’m talking about small changes here – not a fundamental switch from qualitative to quantitative, which will likely send your supervisor in a spin!

You’ve now collected your data and undertaken your analysis, whether qualitative, quantitative or mixed methods. In this chapter, you’ll present the raw results of your analysis . For example, in the case of a quant study, you’ll present the demographic data, descriptive statistics, inferential statistics , etc.

Typically, Chapter 4 is simply a presentation and description of the data, not a discussion of the meaning of the data. In other words, it’s descriptive, rather than analytical – the meaning is discussed in Chapter 5. However, some universities will want you to combine chapters 4 and 5, so that you both present and interpret the meaning of the data at the same time. Check with your institution what their preference is.

Now that you’ve presented the data analysis results, its time to interpret and analyse them. In other words, its time to discuss what they mean, especially in relation to your research question(s).

What you discuss here will depend largely on your chosen methodology. For example, if you’ve gone the quantitative route, you might discuss the relationships between variables . If you’ve gone the qualitative route, you might discuss key themes and the meanings thereof. It all depends on what your research design choices were.

Most importantly, you need to discuss your results in relation to your research questions and aims, as well as the existing literature. What do the results tell you about your research questions? Are they aligned with the existing research or at odds? If so, why might this be? Dig deep into your findings and explain what the findings suggest, in plain English.

The final chapter – you’ve made it! Now that you’ve discussed your interpretation of the results, its time to bring it back to the beginning with the conclusion chapter . In other words, its time to (attempt to) answer your original research question s (from way back in chapter 1). Clearly state what your conclusions are in terms of your research questions. This might feel a bit repetitive, as you would have touched on this in the previous chapter, but its important to bring the discussion full circle and explicitly state your answer(s) to the research question(s).

Next, you’ll typically discuss the implications of your findings . In other words, you’ve answered your research questions – but what does this mean for the real world (or even for academia)? What should now be done differently, given the new insight you’ve generated?

Lastly, you should discuss the limitations of your research, as well as what this means for future research in the area. No study is perfect, especially not a Masters-level. Discuss the shortcomings of your research. Perhaps your methodology was limited, perhaps your sample size was small or not representative, etc, etc. Don’t be afraid to critique your work – the markers want to see that you can identify the limitations of your work. This is a strength, not a weakness. Be brutal!

This marks the end of your core chapters – woohoo! From here on out, it’s pretty smooth sailing.

The reference list is straightforward. It should contain a list of all resources cited in your dissertation, in the required format, e.g. APA , Harvard, etc.

It’s essential that you use reference management software for your dissertation. Do NOT try handle your referencing manually – its far too error prone. On a reference list of multiple pages, you’re going to make mistake. To this end, I suggest considering either Mendeley or Zotero. Both are free and provide a very straightforward interface to ensure that your referencing is 100% on point. I’ve included a simple how-to video for the Mendeley software (my personal favourite) below:

Some universities may ask you to include a bibliography, as opposed to a reference list. These two things are not the same . A bibliography is similar to a reference list, except that it also includes resources which informed your thinking but were not directly cited in your dissertation. So, double-check your brief and make sure you use the right one.

The very last piece of the puzzle is the appendix or set of appendices. This is where you’ll include any supporting data and evidence. Importantly, supporting is the keyword here.

Your appendices should provide additional “nice to know”, depth-adding information, which is not critical to the core analysis. Appendices should not be used as a way to cut down word count (see this post which covers how to reduce word count ). In other words, don’t place content that is critical to the core analysis here, just to save word count. You will not earn marks on any content in the appendices, so don’t try to play the system!

Time to recap…

And there you have it – the traditional dissertation structure and layout, from A-Z. To recap, the core structure for a dissertation or thesis is (typically) as follows:

- Acknowledgments page

Most importantly, the core chapters should reflect the research process (asking, investigating and answering your research question). Moreover, the research question(s) should form the golden thread throughout your dissertation structure. Everything should revolve around the research questions, and as you’ve seen, they should form both the start point (i.e. introduction chapter) and the endpoint (i.e. conclusion chapter).

I hope this post has provided you with clarity about the traditional dissertation/thesis structure and layout. If you have any questions or comments, please leave a comment below, or feel free to get in touch with us. Also, be sure to check out the rest of the Grad Coach Blog .

Psst... there’s more!

This post was based on one of our popular Research Bootcamps . If you're working on a research project, you'll definitely want to check this out ...

You Might Also Like:

36 Comments

many thanks i found it very useful

Glad to hear that, Arun. Good luck writing your dissertation.

Such clear practical logical advice. I very much needed to read this to keep me focused in stead of fretting.. Perfect now ready to start my research!

what about scientific fields like computer or engineering thesis what is the difference in the structure? thank you very much

Thanks so much this helped me a lot!

Very helpful and accessible. What I like most is how practical the advice is along with helpful tools/ links.

Thanks Ade!

Thank you so much sir.. It was really helpful..

You’re welcome!

Hi! How many words maximum should contain the abstract?

Thank you so much 😊 Find this at the right moment

You’re most welcome. Good luck with your dissertation.

best ever benefit i got on right time thank you

Many times Clarity and vision of destination of dissertation is what makes the difference between good ,average and great researchers the same way a great automobile driver is fast with clarity of address and Clear weather conditions .

I guess Great researcher = great ideas + knowledge + great and fast data collection and modeling + great writing + high clarity on all these

You have given immense clarity from start to end.

Morning. Where will I write the definitions of what I’m referring to in my report?

Thank you so much Derek, I was almost lost! Thanks a tonnnn! Have a great day!

Thanks ! so concise and valuable

This was very helpful. Clear and concise. I know exactly what to do now.

Thank you for allowing me to go through briefly. I hope to find time to continue.

Really useful to me. Thanks a thousand times

Very interesting! It will definitely set me and many more for success. highly recommended.

Thank you soo much sir, for the opportunity to express my skills

Usefull, thanks a lot. Really clear

Very nice and easy to understand. Thank you .

That was incredibly useful. Thanks Grad Coach Crew!

My stress level just dropped at least 15 points after watching this. Just starting my thesis for my grad program and I feel a lot more capable now! Thanks for such a clear and helpful video, Emma and the GradCoach team!

Do we need to mention the number of words the dissertation contains in the main document?

It depends on your university’s requirements, so it would be best to check with them 🙂

Such a helpful post to help me get started with structuring my masters dissertation, thank you!

Great video; I appreciate that helpful information

It is so necessary or avital course

This blog is very informative for my research. Thank you

Doctoral students are required to fill out the National Research Council’s Survey of Earned Doctorates

wow this is an amazing gain in my life

This is so good

How can i arrange my specific objectives in my dissertation?

Trackbacks/Pingbacks

- What Is A Literature Review (In A Dissertation Or Thesis) - Grad Coach - […] is to write the actual literature review chapter (this is usually the second chapter in a typical dissertation or…

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

Tips for writing a PhD dissertation: FAQs answered

From how to choose a topic to writing the abstract and managing work-life balance through the years it takes to complete a doctorate, here we collect expert advice to get you through the PhD writing process

Campus team

Additional links.

You may also like

Popular resources

.css-1txxx8u{overflow:hidden;max-height:81px;text-indent:0px;} Students using generative AI to write essays isn't a crisis

How students’ genai skills affect assignment instructions, turn individual wins into team achievements in group work, access and equity: two crucial aspects of applied learning, emotions and learning: what role do emotions play in how and why students learn.

Embarking on a PhD is “probably the most challenging task that a young scholar attempts to do”, write Mark Stephan Felix and Ian Smith in their practical guide to dissertation and thesis writing. After years of reading and research to answer a specific question or proposition, the candidate will submit about 80,000 words that explain their methods and results and demonstrate their unique contribution to knowledge. Here are the answers to frequently asked questions about writing a doctoral thesis or dissertation.

What’s the difference between a dissertation and a thesis?

Whatever the genre of the doctorate, a PhD must offer an original contribution to knowledge. The terms “dissertation” and “thesis” both refer to the long-form piece of work produced at the end of a research project and are often used interchangeably. Which one is used might depend on the country, discipline or university. In the UK, “thesis” is generally used for the work done for a PhD, while a “dissertation” is written for a master’s degree. The US did the same until the 1960s, says Oxbridge Essays, when the convention switched, and references appeared to a “master’s thesis” and “doctoral dissertation”. To complicate matters further, undergraduate long essays are also sometimes referred to as a thesis or dissertation.

The Oxford English Dictionary defines “thesis” as “a dissertation, especially by a candidate for a degree” and “dissertation” as “a detailed discourse on a subject, especially one submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of a degree or diploma”.

- Ten platinum rules for PhD supervisors

- Fostering freedom in PhD students: how supervisors can shape accessible paths for doctoral research

- Lessons from students on effective research supervision

The title “doctor of philosophy”, incidentally, comes from the degree’s origins, write Dr Felix, an associate professor at Mahidol University in Thailand, and Dr Smith, retired associate professor of education at the University of Sydney , whose co-authored guide focuses on the social sciences. The PhD was first awarded in the 19th century by the philosophy departments of German universities, which at that time taught science, social science and liberal arts.

How long should a PhD thesis be?

A PhD thesis (or dissertation) is typically 60,000 to 120,000 words ( 100 to 300 pages in length ) organised into chapters, divisions and subdivisions (with roughly 10,000 words per chapter) – from introduction (with clear aims and objectives) to conclusion.

The structure of a dissertation will vary depending on discipline (humanities, social sciences and STEM all have their own conventions), location and institution. Examples and guides to structure proliferate online. The University of Salford , for example, lists: title page, declaration, acknowledgements, abstract, table of contents, lists of figures, tables and abbreviations (where needed), chapters, appendices and references.

A scientific-style thesis will likely need: introduction, literature review, materials and methods, results, discussion, bibliography and references.

As well as checking the overall criteria and expectations of your institution for your research, consult your school handbook for the required length and format (font, layout conventions and so on) for your dissertation.

A PhD takes three to four years to complete; this might extend to six to eight years for a part-time doctorate.

What are the steps for completing a PhD?

Before you get started in earnest , you’ll likely have found a potential supervisor, who will guide your PhD journey, and done a research proposal (which outlines what you plan to research and how) as part of your application, as well as a literature review of existing scholarship in the field, which may form part of your final submission.

In the UK, PhD candidates undertake original research and write the results in a thesis or dissertation, says author and vlogger Simon Clark , who posted videos to YouTube throughout his own PhD journey . Then they submit the thesis in hard copy and attend the viva voce (which is Latin for “living voice” and is also called an oral defence or doctoral defence) to convince the examiners that their work is original, understood and all their own. Afterwards, if necessary, they make changes and resubmit. If the changes are approved, the degree is awarded.

The steps are similar in Australia , although candidates are mostly assessed on their thesis only; some universities may include taught courses, and some use a viva voce. A PhD in Australia usually takes three years full time.

In the US, the PhD process begins with taught classes (similar to a taught master’s) and a comprehensive exam (called a “field exam” or “dissertation qualifying exam”) before the candidate embarks on their original research. The whole journey takes four to six years.

A PhD candidate will need three skills and attitudes to get through their doctoral studies, says Tara Brabazon , professor of cultural studies at Flinders University in Australia who has written extensively about the PhD journey :

- master the academic foundational skills (research, writing, ability to navigate different modalities)

- time-management skills and the ability to focus on reading and writing

- determined motivation to do a PhD.

How do I choose the topic for my PhD dissertation or thesis?

It’s important to find a topic that will sustain your interest for the years it will take to complete a PhD. “Finding a sustainable topic is the most important thing you [as a PhD student] would do,” says Dr Brabazon in a video for Times Higher Education . “Write down on a big piece of paper all the topics, all the ideas, all the questions that really interest you, and start to cross out all the ones that might just be a passing interest.” Also, she says, impose the “Who cares? Who gives a damn?” question to decide if the topic will be useful in a future academic career.

The availability of funding and scholarships is also often an important factor in this decision, says veteran PhD supervisor Richard Godwin, from Harper Adams University .

Define a gap in knowledge – and one that can be questioned, explored, researched and written about in the time available to you, says Gina Wisker, head of the Centre for Learning and Teaching at the University of Brighton. “Set some boundaries,” she advises. “Don’t try to ask everything related to your topic in every way.”

James Hartley, research professor in psychology at Keele University, says it can also be useful to think about topics that spark general interest. If you do pick something that taps into the zeitgeist, your findings are more likely to be noticed.

You also need to find someone else who is interested in it, too. For STEM candidates , this will probably be a case of joining a team of people working in a similar area where, ideally, scholarship funding is available. A centre for doctoral training (CDT) or doctoral training partnership (DTP) will advertise research projects. For those in the liberal arts and social sciences, it will be a matter of identifying a suitable supervisor .

Avoid topics that are too broad (hunger across a whole country, for example) or too narrow (hunger in a single street) to yield useful solutions of academic significance, write Mark Stephan Felix and Ian Smith. And ensure that you’re not repeating previous research or trying to solve a problem that has already been answered. A PhD thesis must be original.

What is a thesis proposal?

After you have read widely to refine your topic and ensure that it and your research methods are original, and discussed your project with a (potential) supervisor, you’re ready to write a thesis proposal , a document of 1,500 to 3,000 words that sets out the proposed direction of your research. In the UK, a research proposal is usually part of the application process for admission to a research degree. As with the final dissertation itself, format varies among disciplines, institutions and countries but will usually contain title page, aims, literature review, methodology, timetable and bibliography. Examples of research proposals are available online.

How to write an abstract for a dissertation or thesis

The abstract presents your thesis to the wider world – and as such may be its most important element , says the NUI Galway writing guide. It outlines the why, how, what and so what of the thesis . Unlike the introduction, which provides background but not research findings, the abstract summarises all sections of the dissertation in a concise, thorough, focused way and demonstrates how well the writer understands their material. Check word-length limits with your university – and stick to them. About 300 to 500 words is a rough guide – but it can be up to 1,000 words.

The abstract is also important for selection and indexing of your thesis, according to the University of Melbourne guide , so be sure to include searchable keywords.

It is the first thing to be read but the last element you should write. However, Pat Thomson , professor of education at the University of Nottingham , advises that it is not something to be tackled at the last minute.

How to write a stellar conclusion

As well as chapter conclusions, a thesis often has an overall conclusion to draw together the key points covered and to reflect on the unique contribution to knowledge. It can comment on future implications of the research and open up new ideas emanating from the work. It is shorter and more general than the discussion chapter , says online editing site Scribbr, and reiterates how the work answers the main question posed at the beginning of the thesis. The conclusion chapter also often discusses the limitations of the research (time, scope, word limit, access) in a constructive manner.

It can be useful to keep a collection of ideas as you go – in the online forum DoctoralWriting SIG , academic developer Claire Aitchison, of the University of South Australia , suggests using a “conclusions bank” for themes and inspirations, and using free-writing to keep this final section fresh. (Just when you feel you’ve run out of steam.) Avoid aggrandising or exaggerating the impact of your work. It should remind the reader what has been done, and why it matters.

How to format a bibliography (or where to find a reliable model)

Most universities use a preferred style of references , writes THE associate editor Ingrid Curl. Make sure you know what this is and follow it. “One of the most common errors in academic writing is to cite papers in the text that do not then appear in the bibliography. All references in your thesis need to be cross-checked with the bibliography before submission. Using a database during your research can save a great deal of time in the writing-up process.”

A bibliography contains not only works cited explicitly but also those that have informed or contributed to the research – and as such illustrates its scope; works are not limited to written publications but include sources such as film or visual art.

Examiners can start marking from the back of the script, writes Dr Brabazon. “Just as cooks are judged by their ingredients and implements, we judge doctoral students by the calibre of their sources,” she advises. She also says that candidates should be prepared to speak in an oral examination of the PhD about any texts included in their bibliography, especially if there is a disconnect between the thesis and the texts listed.

Can I use informal language in my PhD?

Don’t write like a stereotypical academic , say Kevin Haggerty, professor of sociology at the University of Alberta , and Aaron Doyle, associate professor in sociology at Carleton University , in their tongue-in-cheek guide to the PhD journey. “If you cannot write clearly and persuasively, everything about PhD study becomes harder.” Avoid jargon, exotic words, passive voice and long, convoluted sentences – and work on it consistently. “Writing is like playing guitar; it can improve only through consistent, concerted effort.”

Be deliberate and take care with your writing . “Write your first draft, leave it and then come back to it with a critical eye. Look objectively at the writing and read it closely for style and sense,” advises THE ’s Ms Curl. “Look out for common errors such as dangling modifiers, subject-verb disagreement and inconsistency. If you are too involved with the text to be able to take a step back and do this, then ask a friend or colleague to read it with a critical eye. Remember Hemingway’s advice: ‘Prose is architecture, not interior decoration.’ Clarity is key.”

How often should a PhD candidate meet with their supervisor?

Since the PhD supervisor provides a range of support and advice – including on research techniques, planning and submission – regular formal supervisions are essential, as is establishing a line of contact such as email if the candidate needs help or advice outside arranged times. The frequency varies according to university, discipline and individual scholars.

Once a week is ideal, says Dr Brabazon. She also advocates a two-hour initial meeting to establish the foundations of the candidate-supervisor relationship .

The University of Edinburgh guide to writing a thesis suggests that creating a timetable of supervisor meetings right at the beginning of the research process will allow candidates to ensure that their work stays on track throughout. The meetings are also the place to get regular feedback on draft chapters.

“A clear structure and a solid framework are vital for research,” writes Dr Godwin on THE Campus . Use your supervisor to establish this and provide a realistic view of what can be achieved. “It is vital to help students identify the true scientific merit, the practical significance of their work and its value to society.”

How to proofread your dissertation (what to look for)

Proofreading is the final step before printing and submission. Give yourself time to ensure that your work is the best it can be . Don’t leave proofreading to the last minute; ideally, break it up into a few close-reading sessions. Find a quiet place without distractions. A checklist can help ensure that all aspects are covered.

Proofing is often helped by a change of format – so it can be easier to read a printout rather than working off the screen – or by reading sections out of order. Fresh eyes are better at spotting typographical errors and inconsistencies, so leave time between writing and proofreading. Check with your university’s policies before asking another person to proofread your thesis for you.

As well as close details such as spelling and grammar, check that all sections are complete, all required elements are included , and nothing is repeated or redundant. Don’t forget to check headings and subheadings. Does the text flow from one section to another? Is the structure clear? Is the work a coherent whole with a clear line throughout?

Ensure consistency in, for example, UK v US spellings, capitalisation, format, numbers (digits or words, commas, units of measurement), contractions, italics and hyphenation. Spellchecks and online plagiarism checkers are also your friend.

How do you manage your time to complete a PhD dissertation?

Treat your PhD like a full-time job, that is, with an eight-hour working day. Within that, you’ll need to plan your time in a way that gives a sense of progress . Setbacks and periods where it feels as if you are treading water are all but inevitable, so keeping track of small wins is important, writes A Happy PhD blogger Luis P. Prieto.

Be specific with your goals – use the SMART acronym (specific, measurable, attainable, relevant and timely).

And it’s never too soon to start writing – even if early drafts are overwritten and discarded.

“ Write little and write often . Many of us make the mistake of taking to writing as one would take to a sprint, in other words, with relatively short bursts of intense activity. Whilst this can prove productive, generally speaking it is not sustainable…In addition to sustaining your activity, writing little bits on a frequent basis ensures that you progress with your thinking. The comfort of remaining in abstract thought is common; writing forces us to concretise our thinking,” says Christian Gilliam, AHSS researcher developer at the University of Cambridge ’s Centre for Teaching and Learning.

Make time to write. “If you are more alert early in the day, find times that suit you in the morning; if you are a ‘night person’, block out some writing sessions in the evenings,” advises NUI Galway’s Dermot Burns, a lecturer in English and creative arts. Set targets, keep daily notes of experiment details that you will need in your thesis, don’t confuse writing with editing or revising – and always back up your work.

What work-life balance tips should I follow to complete my dissertation?

During your PhD programme, you may have opportunities to take part in professional development activities, such as teaching, attending academic conferences and publishing your work. Your research may include residencies, field trips or archive visits. This will require time-management skills as well as prioritising where you devote your energy and factoring in rest and relaxation. Organise your routine to suit your needs , and plan for steady and regular progress.

How to deal with setbacks while writing a thesis or dissertation

Have a contingency plan for delays or roadblocks such as unexpected results.

Accept that writing is messy, first drafts are imperfect, and writer’s block is inevitable, says Dr Burns. His tips for breaking it include relaxation to free your mind from clutter, writing a plan and drawing a mind map of key points for clarity. He also advises feedback, reflection and revision: “Progressing from a rough version of your thoughts to a superior and workable text takes time, effort, different perspectives and some expertise.”

“Academia can be a relentlessly brutal merry-go-round of rejection, rebuttal and failure,” writes Lorraine Hope , professor of applied cognitive psychology at the University of Portsmouth, on THE Campus. Resilience is important. Ensure that you and your supervisor have a relationship that supports open, frank, judgement-free communication.

If you would like advice and insight from academics and university staff delivered direct to your inbox each week, sign up for the Campus newsletter .

Authoring a PhD Thesis: How to Plan, Draft, Write and Finish a Doctoral Dissertation (2003), by Patrick Dunleavy

Writing Your Dissertation in Fifteen Minutes a Day: A Guide to Starting, Revising, and Finishing Your Doctoral Thesis (1998), by Joan Balker

Challenges in Writing Your Dissertation: Coping with the Emotional, Interpersonal, and Spiritual Struggles (2015), by Noelle Sterne

Students using generative AI to write essays isn't a crisis

Eleven ways to support international students, indigenising teaching through traditional knowledge, seven exercises to use in your gender studies classes, rather than restrict the use of ai, embrace the challenge, how hard can it be testing ai detection tools.

Register for free

and unlock a host of features on the THE site

- Manuscript Preparation

Know How to Structure Your PhD Thesis

- 4 minute read

- 35.4K views

Table of Contents

In your academic career, few projects are more important than your PhD thesis. Unfortunately, many university professors and advisors assume that their students know how to structure a PhD. Books have literally been written on the subject, but there’s no need to read a book in order to know about PhD thesis paper format and structure. With that said, however, it’s important to understand that your PhD thesis format requirement may not be the same as another student’s. The bottom line is that how to structure a PhD thesis often depends on your university and department guidelines.

But, let’s take a look at a general PhD thesis format. We’ll look at the main sections, and how to connect them to each other. We’ll also examine different hints and tips for each of the sections. As you read through this toolkit, compare it to published PhD theses in your area of study to see how a real-life example looks.

Main Sections of a PhD Thesis

In almost every PhD thesis or dissertation, there are standard sections. Of course, some of these may differ, depending on your university or department requirements, as well as your topic of study, but this will give you a good idea of the basic components of a PhD thesis format.

- Abstract : The abstract is a brief summary that quickly outlines your research, touches on each of the main sections of your thesis, and clearly outlines your contribution to the field by way of your PhD thesis. Even though the abstract is very short, similar to what you’ve seen in published research articles, its impact shouldn’t be underestimated. The abstract is there to answer the most important question to the reviewer. “Why is this important?”

- Introduction : In this section, you help the reviewer understand your entire dissertation, including what your paper is about, why it’s important to the field, a brief description of your methodology, and how your research and the thesis are laid out. Think of your introduction as an expansion of your abstract.

- Literature Review : Within the literature review, you are making a case for your new research by telling the story of the work that’s already been done. You’ll cover a bit about the history of the topic at hand, and how your study fits into the present and future.

- Theory Framework : Here, you explain assumptions related to your study. Here you’re explaining to the review what theoretical concepts you might have used in your research, how it relates to existing knowledge and ideas.

- Methods : This section of a PhD thesis is typically the most detailed and descriptive, depending of course on your research design. Here you’ll discuss the specific techniques you used to get the information you were looking for, in addition to how those methods are relevant and appropriate, as well as how you specifically used each method described.

- Results : Here you present your empirical findings. This section is sometimes also called the “empiracles” chapter. This section is usually pretty straightforward and technical, and full of details. Don’t shortcut this chapter.

- Discussion : This can be a tricky chapter, because it’s where you want to show the reviewer that you know what you’re talking about. You need to speak as a PhD versus a student. The discussion chapter is similar to the empirical/results chapter, but you’re building on those results to push the new information that you learned, prior to making your conclusion.

- Conclusion : Here, you take a step back and reflect on what your original goals and intentions for the research were. You’ll outline them in context of your new findings and expertise.

Tips for your PhD Thesis Format

As you put together your PhD thesis, it’s easy to get a little overwhelmed. Here are some tips that might keep you on track.

- Don’t try to write your PhD as a first-draft. Every great masterwork has typically been edited, and edited, and…edited.

- Work with your thesis supervisor to plan the structure and format of your PhD thesis. Be prepared to rewrite each section, as you work out rough drafts. Don’t get discouraged by this process. It’s typical.

- Make your writing interesting. Academic writing has a reputation of being very dry.

- You don’t have to necessarily work on the chapters and sections outlined above in chronological order. Work on each section as things come up, and while your work on that section is relevant to what you’re doing.

- Don’t rush things. Write a first draft, and leave it for a few days, so you can come back to it with a more critical take. Look at it objectively and carefully grammatical errors, clarity, logic and flow.

- Know what style your references need to be in, and utilize tools out there to organize them in the required format.

- It’s easier to accidentally plagiarize than you think. Make sure you’re referencing appropriately, and check your document for inadvertent plagiarism throughout your writing process.

PhD Thesis Editing Plus

Want some support during your PhD writing process? Our PhD Thesis Editing Plus service includes extensive and detailed editing of your thesis to improve the flow and quality of your writing. Unlimited editing support for guaranteed results. Learn more here , and get started today!

- Publication Process

Journal Acceptance Rates: Everything You Need to Know

- Publication Recognition

How to Make a PowerPoint Presentation of Your Research Paper

You may also like.

Make Hook, Line, and Sinker: The Art of Crafting Engaging Introductions

Can Describing Study Limitations Improve the Quality of Your Paper?

A Guide to Crafting Shorter, Impactful Sentences in Academic Writing

6 Steps to Write an Excellent Discussion in Your Manuscript

How to Write Clear and Crisp Civil Engineering Papers? Here are 5 Key Tips to Consider

The Clear Path to An Impactful Paper: ②

The Essentials of Writing to Communicate Research in Medicine

Changing Lines: Sentence Patterns in Academic Writing

Input your search keywords and press Enter.

- What Is a PhD Thesis?

- Doing a PhD

This page will explain what a PhD thesis is and offer advice on how to write a good thesis, from outlining the typical structure to guiding you through the referencing. A summary of this page is as follows:

- A PhD thesis is a concentrated piece of original research which must be carried out by all PhD students in order to successfully earn their doctoral degree.

- The fundamental purpose of a thesis is to explain the conclusion that has been reached as a result of undertaking the research project.

- The typical PhD thesis structure will contain four chapters of original work sandwiched between a literature review chapter and a concluding chapter.

- There is no universal rule for the length of a thesis, but general guidelines set the word count between 70,000 to 100,000 words .

What Is a Thesis?

A thesis is the main output of a PhD as it explains your workflow in reaching the conclusions you have come to in undertaking the research project. As a result, much of the content of your thesis will be based around your chapters of original work.

For your thesis to be successful, it needs to adequately defend your argument and provide a unique or increased insight into your field that was not previously available. As such, you can’t rely on other ideas or results to produce your thesis; it needs to be an original piece of text that belongs to you and you alone.

What Should a Thesis Include?

Although each thesis will be unique, they will all follow the same general format. To demonstrate this, we’ve put together an example structure of a PhD thesis and explained what you should include in each section below.

Acknowledgements

This is a personal section which you may or may not choose to include. The vast majority of students include it, giving both gratitude and recognition to their supervisor, university, sponsor/funder and anyone else who has supported them along the way.

1. Introduction

Provide a brief overview of your reason for carrying out your research project and what you hope to achieve by undertaking it. Following this, explain the structure of your thesis to give the reader context for what he or she is about to read.

2. Literature Review

Set the context of your research by explaining the foundation of what is currently known within your field of research, what recent developments have occurred, and where the gaps in knowledge are. You should conclude the literature review by outlining the overarching aims and objectives of the research project.

3. Main Body

This section focuses on explaining all aspects of your original research and so will form the bulk of your thesis. Typically, this section will contain four chapters covering the below:

- your research/data collection methodologies,

- your results,

- a comprehensive analysis of your results,

- a detailed discussion of your findings.

Depending on your project, each of your chapters may independently contain the structure listed above or in some projects, each chapter could be focussed entirely on one aspect (e.g. a standalone results chapter). Ideally, each of these chapters should be formatted such that they could be translated into papers for submission to peer-reviewed journals. Therefore, following your PhD, you should be able to submit papers for peer-review by reusing content you have already produced.

4. Conclusion

The conclusion will be a summary of your key findings with emphasis placed on the new contributions you have made to your field.

When producing your conclusion, it’s imperative that you relate it back to your original research aims, objectives and hypotheses. Make sure you have answered your original question.

Finding a PhD has never been this easy – search for a PhD by keyword, location or academic area of interest.

How Many Words Is a PhD Thesis?

A common question we receive from students is – “how long should my thesis be?“.

Every university has different guidelines on this matter, therefore, consult with your university to get an understanding of their full requirements. Generally speaking, most supervisors will suggest somewhere between 70,000 and 100,000 words . This usually corresponds to somewhere between 250 – 350 pages .

We must stress that this is flexible, and it is important not to focus solely on the length of your thesis, but rather the quality.

How Do I Format My Thesis?

Although the exact formatting requirements will vary depending on the university, the typical formatting policies adopted by most universities are:

What Happens When I Finish My Thesis?

After you have submitted your thesis, you will attend a viva . A viva is an interview-style examination during which you are required to defend your thesis and answer questions on it. The aim of the viva is to convince your examiners that your work is of the level required for a doctoral degree. It is one of the last steps in the PhD process and arguably one of the most daunting!

For more information on the viva process and for tips on how to confidently pass it, please refer to our in-depth PhD Viva Guide .

How Do I Publish My Thesis?

Unfortunately, you can’t publish your thesis in its entirety in a journal. However, universities can make it available for others to read through their library system.

If you want to submit your work in a journal, you will need to develop it into one or more peer-reviewed papers. This will largely involve reformatting, condensing and tailoring it to meet the standards of the journal you are targeting.

Browse PhDs Now

Join thousands of students.

Join thousands of other students and stay up to date with the latest PhD programmes, funding opportunities and advice.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Dissertation

How to Write a Dissertation | A Guide to Structure & Content

A dissertation or thesis is a long piece of academic writing based on original research, submitted as part of an undergraduate or postgraduate degree.

The structure of a dissertation depends on your field, but it is usually divided into at least four or five chapters (including an introduction and conclusion chapter).

The most common dissertation structure in the sciences and social sciences includes:

- An introduction to your topic

- A literature review that surveys relevant sources

- An explanation of your methodology

- An overview of the results of your research

- A discussion of the results and their implications

- A conclusion that shows what your research has contributed

Dissertations in the humanities are often structured more like a long essay , building an argument by analysing primary and secondary sources . Instead of the standard structure outlined here, you might organise your chapters around different themes or case studies.

Other important elements of the dissertation include the title page , abstract , and reference list . If in doubt about how your dissertation should be structured, always check your department’s guidelines and consult with your supervisor.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Be assured that you'll submit flawless writing. Upload your document to correct all your mistakes.

Table of contents

Acknowledgements, table of contents, list of figures and tables, list of abbreviations, introduction, literature review / theoretical framework, methodology, reference list.

The very first page of your document contains your dissertation’s title, your name, department, institution, degree program, and submission date. Sometimes it also includes your student number, your supervisor’s name, and the university’s logo. Many programs have strict requirements for formatting the dissertation title page .

The title page is often used as cover when printing and binding your dissertation .

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

The acknowledgements section is usually optional, and gives space for you to thank everyone who helped you in writing your dissertation. This might include your supervisors, participants in your research, and friends or family who supported you.

The abstract is a short summary of your dissertation, usually about 150-300 words long. You should write it at the very end, when you’ve completed the rest of the dissertation. In the abstract, make sure to:

- State the main topic and aims of your research

- Describe the methods you used

- Summarise the main results

- State your conclusions

Although the abstract is very short, it’s the first part (and sometimes the only part) of your dissertation that people will read, so it’s important that you get it right. If you’re struggling to write a strong abstract, read our guide on how to write an abstract .

In the table of contents, list all of your chapters and subheadings and their page numbers. The dissertation contents page gives the reader an overview of your structure and helps easily navigate the document.

All parts of your dissertation should be included in the table of contents, including the appendices. You can generate a table of contents automatically in Word.

The only proofreading tool specialized in correcting academic writing

The academic proofreading tool has been trained on 1000s of academic texts and by native English editors. Making it the most accurate and reliable proofreading tool for students.

Correct my document today

If you have used a lot of tables and figures in your dissertation, you should itemise them in a numbered list . You can automatically generate this list using the Insert Caption feature in Word.

If you have used a lot of abbreviations in your dissertation, you can include them in an alphabetised list of abbreviations so that the reader can easily look up their meanings.

If you have used a lot of highly specialised terms that will not be familiar to your reader, it might be a good idea to include a glossary . List the terms alphabetically and explain each term with a brief description or definition.

In the introduction, you set up your dissertation’s topic, purpose, and relevance, and tell the reader what to expect in the rest of the dissertation. The introduction should:

- Establish your research topic , giving necessary background information to contextualise your work

- Narrow down the focus and define the scope of the research

- Discuss the state of existing research on the topic, showing your work’s relevance to a broader problem or debate

- Clearly state your objectives and research questions , and indicate how you will answer them

- Give an overview of your dissertation’s structure

Everything in the introduction should be clear, engaging, and relevant to your research. By the end, the reader should understand the what , why and how of your research. Not sure how? Read our guide on how to write a dissertation introduction .

Before you start on your research, you should have conducted a literature review to gain a thorough understanding of the academic work that already exists on your topic. This means:

- Collecting sources (e.g. books and journal articles) and selecting the most relevant ones

- Critically evaluating and analysing each source

- Drawing connections between them (e.g. themes, patterns, conflicts, gaps) to make an overall point

In the dissertation literature review chapter or section, you shouldn’t just summarise existing studies, but develop a coherent structure and argument that leads to a clear basis or justification for your own research. For example, it might aim to show how your research:

- Addresses a gap in the literature

- Takes a new theoretical or methodological approach to the topic

- Proposes a solution to an unresolved problem

- Advances a theoretical debate

- Builds on and strengthens existing knowledge with new data

The literature review often becomes the basis for a theoretical framework , in which you define and analyse the key theories, concepts and models that frame your research. In this section you can answer descriptive research questions about the relationship between concepts or variables.

The methodology chapter or section describes how you conducted your research, allowing your reader to assess its validity. You should generally include:

- The overall approach and type of research (e.g. qualitative, quantitative, experimental, ethnographic)

- Your methods of collecting data (e.g. interviews, surveys, archives)

- Details of where, when, and with whom the research took place

- Your methods of analysing data (e.g. statistical analysis, discourse analysis)

- Tools and materials you used (e.g. computer programs, lab equipment)

- A discussion of any obstacles you faced in conducting the research and how you overcame them

- An evaluation or justification of your methods

Your aim in the methodology is to accurately report what you did, as well as convincing the reader that this was the best approach to answering your research questions or objectives.

Next, you report the results of your research . You can structure this section around sub-questions, hypotheses, or topics. Only report results that are relevant to your objectives and research questions. In some disciplines, the results section is strictly separated from the discussion, while in others the two are combined.

For example, for qualitative methods like in-depth interviews, the presentation of the data will often be woven together with discussion and analysis, while in quantitative and experimental research, the results should be presented separately before you discuss their meaning. If you’re unsure, consult with your supervisor and look at sample dissertations to find out the best structure for your research.

In the results section it can often be helpful to include tables, graphs and charts. Think carefully about how best to present your data, and don’t include tables or figures that just repeat what you have written – they should provide extra information or usefully visualise the results in a way that adds value to your text.

Full versions of your data (such as interview transcripts) can be included as an appendix .

The discussion is where you explore the meaning and implications of your results in relation to your research questions. Here you should interpret the results in detail, discussing whether they met your expectations and how well they fit with the framework that you built in earlier chapters. If any of the results were unexpected, offer explanations for why this might be. It’s a good idea to consider alternative interpretations of your data and discuss any limitations that might have influenced the results.

The discussion should reference other scholarly work to show how your results fit with existing knowledge. You can also make recommendations for future research or practical action.

The dissertation conclusion should concisely answer the main research question, leaving the reader with a clear understanding of your central argument. Wrap up your dissertation with a final reflection on what you did and how you did it. The conclusion often also includes recommendations for research or practice.

In this section, it’s important to show how your findings contribute to knowledge in the field and why your research matters. What have you added to what was already known?

You must include full details of all sources that you have cited in a reference list (sometimes also called a works cited list or bibliography). It’s important to follow a consistent reference style . Each style has strict and specific requirements for how to format your sources in the reference list.

The most common styles used in UK universities are Harvard referencing and Vancouver referencing . Your department will often specify which referencing style you should use – for example, psychology students tend to use APA style , humanities students often use MHRA , and law students always use OSCOLA . M ake sure to check the requirements, and ask your supervisor if you’re unsure.

To save time creating the reference list and make sure your citations are correctly and consistently formatted, you can use our free APA Citation Generator .

Your dissertation itself should contain only essential information that directly contributes to answering your research question. Documents you have used that do not fit into the main body of your dissertation (such as interview transcripts, survey questions or tables with full figures) can be added as appendices .

Is this article helpful?

Other students also liked.

- What Is a Dissertation? | 5 Essential Questions to Get Started

- What is a Literature Review? | Guide, Template, & Examples

- How to Write a Dissertation Proposal | A Step-by-Step Guide

More interesting articles

- Checklist: Writing a dissertation

- Dissertation & Thesis Outline | Example & Free Templates

- Dissertation binding and printing

- Dissertation Table of Contents in Word | Instructions & Examples

- Dissertation title page

- Example Theoretical Framework of a Dissertation or Thesis

- Figure & Table Lists | Word Instructions, Template & Examples

- How to Choose a Dissertation Topic | 8 Steps to Follow

- How to Write a Discussion Section | Tips & Examples

- How to Write a Results Section | Tips & Examples

- How to Write a Thesis or Dissertation Conclusion

- How to Write a Thesis or Dissertation Introduction

- How to Write an Abstract | Steps & Examples

- How to Write Recommendations in Research | Examples & Tips

- List of Abbreviations | Example, Template & Best Practices

- Operationalisation | A Guide with Examples, Pros & Cons

- Prize-Winning Thesis and Dissertation Examples

- Relevance of Your Dissertation Topic | Criteria & Tips

- Research Paper Appendix | Example & Templates

- Thesis & Dissertation Acknowledgements | Tips & Examples

- Thesis & Dissertation Database Examples

- What is a Dissertation Preface? | Definition & Examples

- What is a Glossary? | Definition, Templates, & Examples

- What Is a Research Methodology? | Steps & Tips

- What is a Theoretical Framework? | A Step-by-Step Guide

- What Is a Thesis? | Ultimate Guide & Examples

Skip to content. | Skip to navigation

Personal tools

- Log in/Register Register

https://www.vitae.ac.uk/doing-research/doing-a-doctorate/completing-your-doctorate/writing-and-submitting-your-doctoral-thesis/structuring-your-thesis

This page has been reproduced from the Vitae website (www.vitae.ac.uk). Vitae is dedicated to realising the potential of researchers through transforming their professional and career development.

- Vitae members' area

Structuring your thesis

Time spent thinking about and planning how you will structure your thesis is time well spent. Start to organise the material that you have already written into folders relating to each chapter. The following techniques may help you to decide upon a structure.

- Discuss the structure with a colleague, explaining it as a continuous story you're trying to write

- Use visual techniques like mind-mapping

- Create a storyboard for your thesis. This tells the ‘story' of the thesis in a small number of panels that mix text and pictures

- Sort index cards with key ideas into a coherent structure

- Use post-it notes with key ideas on a whiteboard to make connections with lines and colours.

Analysing existing theses is a good starting point to get an idea of typical structures in your field. Theses will usually contain most or all of the following sections:

- Acknowledgements

- Contents page(s)

- Introduction

- Literature review (sometimes within the introduction)

- Materials/sources and methods (can be part of every chapter if these are different per chapter)

- Themed topic chapters

- Discussion or Findings

- Conclusions

- Your publications

Once a rough structure is sketched out, it is a good idea to assign each chapter a likely word length and, if possible, a deadline for a first draft.

Writing preferences

People have different preferences in terms of writing. Think about the approach that will work best for you. For example here are two examples of writing preferences.

Planning writers tend to have a highly structured approach to writing and if this is your approach you may find the following tips helpful.

- Under each chapter heading define a series of sections

- Break these into sub-sections and keep breaking these down until you are almost at the paragraph level

- You can now work methodically through this set of short sections

- Check completed sections or chapters agree with your plan

Generative writers prefer to g et ideas down on paper and then organise them afterwards. If this approach suits you try the following approach.

- Choose a chapter and just start typing

- Then you need to do some work to impose a structure

- Summarise each paragraph as a bullet point

- Use this summary to gain an overview of the structure

- Re-order the writing and strengthen the structure by adding sub-headings and revising what you have written to make the argument clearer

Reviewing your structure

As your research and writing develop you will want to revise and rework your structure. Try to review do this on a regular basis and amend plans for future chapters as you become more aware of what the thesis must contain.

Bookmark & Share

- Formatting Your Dissertation

- Introduction

Harvard Griffin GSAS strives to provide students with timely, accurate, and clear information. If you need help understanding a specific policy, please contact the office that administers that policy.

- Application for Degree

- Credit for Completed Graduate Work

- Ad Hoc Degree Programs

- Acknowledging the Work of Others

- Advanced Planning

- Dissertation Advisory Committee

- Dissertation Submission Checklist

- Publishing Options

- Submitting Your Dissertation

- English Language Proficiency

- PhD Program Requirements

- Secondary Fields

- Year of Graduate Study (G-Year)

- Master's Degrees

- Grade and Examination Requirements

- Conduct and Safety

- Financial Aid

- Non-Resident Students

- Registration

On this page:

Language of the Dissertation

Page and text requirements, body of text, tables, figures, and captions, dissertation acceptance certificate, copyright statement.

- Table of Contents

Front and Back Matter

Supplemental material, dissertations comprising previously published works, top ten formatting errors, further questions.

- Related Contacts and Forms

When preparing the dissertation for submission, students must follow strict formatting requirements. Any deviation from these requirements may lead to rejection of the dissertation and delay in the conferral of the degree.

The language of the dissertation is ordinarily English, although some departments whose subject matter involves foreign languages may accept a dissertation written in a language other than English.

Most dissertations are 100 to 300 pages in length. All dissertations should be divided into appropriate sections, and long dissertations may need chapters, main divisions, and subdivisions.

- 8½ x 11 inches, unless a musical score is included

- At least 1 inch for all margins

- Body of text: double spacing

- Block quotations, footnotes, and bibliographies: single spacing within each entry but double spacing between each entry

- Table of contents, list of tables, list of figures or illustrations, and lengthy tables: single spacing may be used

Fonts and Point Size

Use 10-12 point size. Fonts must be embedded in the PDF file to ensure all characters display correctly.

Recommended Fonts

If you are unsure whether your chosen font will display correctly, use one of the following fonts:

If fonts are not embedded, non-English characters may not appear as intended. Fonts embedded improperly will be published to DASH as-is. It is the student’s responsibility to make sure that fonts are embedded properly prior to submission.

Instructions for Embedding Fonts

To embed your fonts in recent versions of Word, follow these instructions from Microsoft:

- Click the File tab and then click Options .

- In the left column, select the Save tab.

- Clear the Do not embed common system fonts check box.

For reference, below are some instructions from ProQuest UMI for embedding fonts in older file formats:

To embed your fonts in Microsoft Word 2010:

- In the File pull-down menu click on Options .

- Choose Save on the left sidebar.

- Check the box next to Embed fonts in the file.

- Click the OK button.

- Save the document.

Note that when saving as a PDF, make sure to go to “more options” and save as “PDF/A compliant”

To embed your fonts in Microsoft Word 2007:

- Click the circular Office button in the upper left corner of Microsoft Word.

- A new window will display. In the bottom right corner select Word Options .

- Choose Save from the left sidebar.

Using Microsoft Word on a Mac:

Microsoft Word 2008 on a Mac OS X computer will automatically embed your fonts while converting your document to a PDF file.

If you are converting to PDF using Acrobat Professional (instructions courtesy of the Graduate Thesis Office at Iowa State University):

- Open your document in Microsoft Word.

- Click on the Adobe PDF tab at the top. Select "Change Conversion Settings."

- Click on Advanced Settings.

- Click on the Fonts folder on the left side of the new window. In the lower box on the right, delete any fonts that appear in the "Never Embed" box. Then click "OK."

- If prompted to save these new settings, save them as "Embed all fonts."

- Now the Change Conversion Settings window should show "embed all fonts" in the Conversion Settings drop-down list and it should be selected. Click "OK" again.

- Click on the Adobe PDF link at the top again. This time select Convert to Adobe PDF. Depending on the size of your document and the speed of your computer, this process can take 1-15 minutes.

- After your document is converted, select the "File" tab at the top of the page. Then select "Document Properties."

- Click on the "Fonts" tab. Carefully check all of your fonts. They should all show "(Embedded Subset)" after the font name.

- If you see "(Embedded Subset)" after all fonts, you have succeeded.

The font used in the body of the text must also be used in headers, page numbers, and footnotes. Exceptions are made only for tables and figures created with different software and inserted into the document.

Tables and figures must be placed as close as possible to their first mention in the text. They may be placed on a page with no text above or below, or they may be placed directly into the text. If a table or a figure is alone on a page (with no narrative), it should be centered within the margins on the page. Tables may take up more than one page as long as they obey all rules about margins. Tables and figures referred to in the text may not be placed at the end of the chapter or at the end of the dissertation.

- Given the standards of the discipline, dissertations in the Department of History of Art and Architecture and the Department of Architecture, Landscape Architecture, and Urban Planning often place illustrations at the end of the dissertation.

Figure and table numbering must be continuous throughout the dissertation or by chapter (e.g., 1.1, 1.2, 2.1, 2.2, etc.). Two figures or tables cannot be designated with the same number. If you have repeating images that you need to cite more than once, label them with their number and A, B, etc.

Headings should be placed at the top of tables. While no specific rules for the format of table headings and figure captions are required, a consistent format must be used throughout the dissertation (contact your department for style manuals appropriate to the field).

Captions should appear at the bottom of any figures. If the figure takes up the entire page, the caption should be placed alone on the preceding page, centered vertically and horizontally within the margins.

Each page receives a separate page number. When a figure or table title is on a preceding page, the second and subsequent pages of the figure or table should say, for example, “Figure 5 (Continued).” In such an instance, the list of figures or tables will list the page number containing the title. The word “figure” should be written in full (not abbreviated), and the “F” should be capitalized (e.g., Figure 5). In instances where the caption continues on a second page, the “(Continued)” notation should appear on the second and any subsequent page. The figure/table and the caption are viewed as one entity and the numbering should show correlation between all pages. Each page must include a header.

Landscape orientation figures and tables must be positioned correctly and bound at the top so that the top of the figure or table will be at the left margin. Figure and table headings/captions are placed with the same orientation as the figure or table when on the same page. When on a separate page, headings/captions are always placed in portrait orientation, regardless of the orientation of the figure or table. Page numbers are always placed as if the figure were vertical on the page.

If a graphic artist does the figures, Harvard Griffin GSAS will accept lettering done by the artist only within the figure. Figures done with software are acceptable if the figures are clear and legible. Legends and titles done by the same process as the figures will be accepted if they too are clear, legible, and run at least 10 or 12 characters per inch. Otherwise, legends and captions should be printed with the same font used in the text.

Original illustrations, photographs, and fine arts prints may be scanned and included, centered between the margins on a page with no text above or below.

Use of Third-Party Content