- Open access

- Published: 04 July 2015

Universal health coverage from multiple perspectives: a synthesis of conceptual literature and global debates

- Gilbert Abotisem Abiiro 1 , 2 &

- Manuela De Allegri 1

BMC International Health and Human Rights volume 15 , Article number: 17 ( 2015 ) Cite this article

22k Accesses

76 Citations

18 Altmetric

Metrics details

There is an emerging global consensus on the importance of universal health coverage (UHC), but no unanimity on the conceptual definition and scope of UHC, whether UHC is achievable or not, how to move towards it, common indicators for measuring its progress, and its long-term sustainability. This has resulted in various interpretations of the concept, emanating from different disciplinary perspectives. This paper discusses the various dimensions of UHC emerging from these interpretations and argues for the need to pay attention to the complex interactions across the various components of a health system in the pursuit of UHC as a legal human rights issue.

The literature presents UHC as a multi-dimensional concept, operationalized in terms of universal population coverage, universal financial protection, and universal access to quality health care, anchored on the basis of health care as an international legal obligation grounded in international human rights laws. As a legal concept, UHC implies the existence of a legal framework that mandates national governments to provide health care to all residents while compelling the international community to support poor nations in implementing this right. As a humanitarian social concept, UHC aims at achieving universal population coverage by enrolling all residents into health-related social security systems and securing equitable entitlements to the benefits from the health system for all. As a health economics concept, UHC guarantees financial protection by providing a shield against the catastrophic and impoverishing consequences of out-of-pocket expenditure, through the implementation of pooled prepaid financing systems. As a public health concept, UHC has attracted several controversies regarding which services should be covered: comprehensive services vs. minimum basic package, and priority disease-specific interventions vs. primary health care.

As a multi-dimensional concept, grounded in international human rights laws, the move towards UHC in LMICs requires all states to effectively recognize the right to health in their national constitutions. It also requires a human rights-focused integrated approach to health service delivery that recognizes the health system as a complex phenomenon with interlinked functional units whose effective interaction are essential to reach the equilibrium called UHC.

Peer Review reports

Universal health coverage (UHC) has been acknowledged as a priority goal of every health system [ 1 – 5 ]. The importance of this goal is reflected in the consistent calls by the World Health Organization (WHO) for its member states to implement pooled prepaid health care financing systems that promote access to quality health care and provide households with the needed protection from the catastrophic consequences of out-of-pocket (OOP) health-related payments [ 2 , 6 – 8 ]. This call has also been endorsed by the United Nations [ 5 ].

In the existing literature, different conceptual terminology, such as universal health care [ 9 ], universal health care coverage [ 10 , 11 ], universal health system, universal health coverage, or simply universal coverage, have been used to refer to basically the same concept [ 9 , 12 – 14 ]. Stuckler et al. [ 15 ] noted that “universal health care” is often used to describe health care reforms in high income countries while “universal health coverage” is associated with health system reforms within low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). Given that the poor, marginalized and most vulnerable populations mostly reside in LMICs, this paper places relatively high emphasis on such settings. Hence, we adopt the term universal health coverage (UHC) [ 2 ] throughout the paper.

It is argued that health system reforms aimed at UHC can be traced back to the emergence of organized health care in the 19th century, in response to labor agitations calling for the implementation of social security systems [ 16 – 18 ]. This phenomenon first started in Germany under the leadership of Otto von Bismarck, and later spread throughout other parts of Europe such as Britain, France and Sweden [ 16 – 18 ]. Later in 1948, the concept of UHC was implicitly enshrined in the WHO constitution which recognized that “the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of health is one of the fundamental rights of every human being without distinction of race, religion, and political belief, economic or social condition ” [ 19 ]. This fundamental human right was reaffirmed in the “ Health for all ” declaration of the Alma Ata conference on primary health care in 1978 [ 20 ].

In 2005, the concept of UHC was once again acknowledged and for the first time explicitly endorsed by the World Health Assembly (WHA) as the goal of sustainable health care financing [ 6 ]. The World Health Assembly resolution (WHA58.33) explicitly called for the implementation of health care financing systems centered on prepaid and pooling mechanisms aimed at achieving UHC [ 6 ]. Based on this Resolution, WHO defined UHC as “access to key promotive, preventive, curative and rehabilitative health interventions for all at an affordable cost, thereby achieving equity in access” [ 6 ] . The 2008 World Health Report re-emphasized prepayment and pooling systems as essential instruments for UHC by categorically stating that UHC entails “ pooling pre-paid contributions collected on the basis of ability to pay, and using these funds to ensure that services are available, accessible and produce quality care for those who need them, without exposing them to the risk of catastrophic expenditures” [ 7 ] . In 2010, the World Health Report, further stressed the role of health system financing for UHC by arguing that “ countries must raise sufficient funds, reduce the reliance on direct payments to finance services, and improve efficiency and equity” [ 2 ] . The concept of UHC as reflected in these WHO reports seems to be focused more on improving the health care financing function of a health system. The 2013 World Health Report built on prior work resulting in a call for research evidence to facilitate the transition of countries towards UHC [ 8 ]. The United Nations, the World Bank, the Gates Foundation, Oxfam, United States Agency for International Development (USAID), the International Labour Organization, United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), Rockefeller Foundation, Results for Development Institute, the Joint Learning Network, among other international and regional development organizations have also in various ways recently endorsed and promoted the move towards UHC [ 5 , 21 – 25 ]. Considering the key role of the WHO and these other global actors in shaping the health policy debate at the global level, this recent history demonstrates a consistent and increasing international interest in the concept and debates surrounding UHC [ 2 , 26 ].

To date, the literature continues to present a clear consensus on the importance of UHC [ 23 , 27 – 29 ]. UHC was described by the Director General of WHO as “ the single most powerful concept that public health has to offer” [ 30 ]. Its potential to improve the health of the population, especially for the poor, has been demonstrated [ 31 , 32 ]. It is viewed as the phenomenon that will result in the third global transition and hence greatly influence the (re-) organization and financing of global health systems [ 29 ]. As an essential catalyst for poverty reduction and economic growth [ 14 , 33 , 34 ], UHC is regarded as a prerequisite for sustainable development [ 35 ]. It has therefore been advocated for as an important health goal in the post-2015 global development agenda [ 35 – 40 ]. The Lancet Commission on Investing in Health reports that this goal can be progressively attained by 2035 [ 34 ].

Despite the global consensus on its importance, consensus on the conceptual definition, meaning, and scope of UHC are still missing [ 12 , 26 , 41 ]. Likewise, no consensus exists on whether UHC is achievable or not; on how to move towards it [ 3 , 22 , 42 , 43 ]; on common indicators for measuring progress towards it [ 13 , 24 , 28 , 29 , 44 ]; and on its long-term sustainability [ 27 ]. The absence of a clear consensus on the conceptual definition of UHC has resulted in various interpretations of the concept, emanating from different disciplinary perspectives. These different interpretations reveal distinct, but interlinked dimensions of UHC [ 2 ]. This paper seeks to explore these various interpretations and representations of the concept of UHC from a multidimensional perspective and to discuss the various dimensions of UHC emerging from these interpretations. The arguments presented in this paper are based on a synthesis of the literature emerging from recent global debates on UHC. We adapted the WHO framework [ 2 ] to guide the presentation of our synthesis of the conceptual debates currently being advanced in the literature. Inspired by the WHO framework, our conceptual reasoning is that advancing UHC requires a healthy interaction across the three coverage dimensions: population coverage, financial protection and access to health services, held together by the view of health as a legal human right.

Discussions

Universal health coverage as a legal right to health.

A group of scholars, building their opinions from a legal and human rights perspective, enshrined in various international covenants and treaties [ 45 – 49 ], argue that the concept of UHC implies the existence of a legal framework to ensure that every resident gets access to affordable health care [ 15 , 50 , 51 ]. This portrays UHC as a reformulation of the “ health for all” goal of the Alma Ata Declaration [ 15 , 22 , 52 – 54 ]. The view of UHC as a legal obligation imposed on all states that ratified the convention on the right to health [ 45 ], implies that UHC calls for all States to create legal entitlements to health care for all their residents [ 50 , 55 , 56 ], thereby placing the responsibility for the delivery of UHC on national governments [ 5 , 17 , 57 ]. To guarantee a comprehensive right to health, the legal obligation of the state needs to reach beyond mere health service provision to include deliberate efforts to advance improvements in structures which are recognized to act as important social determinants of health such as, education, housing, sanitation and portable water as well as equitable gender and power relations [ 58 – 60 ]. The goal of UHC and the responsibility of moving towards it, therefore, need to be mandated by national laws [ 4 , 61 , 62 ]. Backman et al. [ 63 ] report that only 56 states have constitutional provisions that legally recognize the right to health and argue that even within these states, much work is still needed to ensure that this right is guaranteed in actual practice for all. Kingston et al. [ 55 ] also argue that even the state-centered view of the right to health is based on a false assumption that all people have legal nationalities. They insist that this false assumption is the cause for the medical exclusion of some migrants, especially illegal immigrants, from accessing institutionalized health care within their countries of residence. This situation is even more serious in LIMCs, where states find it difficult to raise sufficient revenues to finance health care for their legal citizenry. The vague definition of the right to health for non-nationals premised on the individual state’s economic ability and willingness to guarantee it [ 46 ], is therefore a potential recipe for social exclusion on the basis of nationality. Current debates on UHC therefore need to seriously reflect on ways by which the rights of stateless individuals to health care can also be guaranteed within the framework of UHC.

Acknowledging financial constraints to enforcing the right to health within poor-resource settings, some scholars explicitly call for international assistance for health as a way of strengthening the right to health component of UHC [ 62 , 64 ]. This, they argue, can be implemented through the establishment of a global fund to finance UHC [ 65 ] thereby presenting health as a global public good [ 66 ]. The notion of creating a common fund for UHC also recognizes the transnational nature of emerging global health problems and the inherent global interdependency needed to deal with such problems [ 67 ]. The possibility of funding global efforts towards UHC from this global fund is being explored. Initial results reveal conflicting expectations and interests between the potential donors/financiers and beneficiary countries [ 65 ]. The rights-based arguments for UHC therefore suggest a shift on the ethical spectrum of international assistance for health, from the concept of international health, where international assistance for health is viewed as a form of charity, towards that of global health [ 62 , 67 – 69 ] which is driven by the cosmopolitan ethical preposition that states should assist each other on the basis of humanitarian responsibility [ 68 , 69 ] and solidarity [ 67 ]. This cosmopolitan ethical view has the potential of facilitating efforts at raising more international assistance to facilitate UHC within its broader dimensions currently being advanced by WHO and other global experts.

Population coverage as a dimension of universal health coverage

Another group of scholars [ 22 , 61 ], also supportive of the rights-based perspective, argue that UHC implies “ equal or same entitlements” to the benefits of a health system. This reflects the notion of universal enrollment into health-related social security or risk protection systems [ 17 , 70 ] or population coverage under public health financing systems [ 2 ]. This notion therefore puts people (population) at the center of UHC [ 71 ]. Universal population coverage is to be understood in relation to the tenets of the right to health [ 45 ] as the absence of systemic exclusion of certain population groups (especially the poor and vulnerable) from the coverage of public prepaid funds and the ability of all residents to enjoy the same entitlements to the benefits of such public funding, irrespective of their nationality, race, sexual orientation, gender, political affiliations, socio-economic status or geographic locations [ 2 , 12 , 22 , 53 , 55 , 61 , 72 – 74 ].

To distinguish between aggregate and equity-based measures of population coverage, both WHO & the World Bank [ 24 ] have defined population coverage along two dimensions. Thus; achieving a 100 % coverage of the total population as an aggregate measure, or ensuring a relatively good proportion of coverage of the poorest 40 % compared to the rest of the population as an equity-based measure [ 24 ]. The overall notion of equity, defined as progressive income-rated contributions to health financing and need-based entitlements to health services, is embedded in almost all conceptual definitions of universal population coverage [ 2 , 4 , 75 – 77 ]. Implicit in the notion of equity is the concept of income and risk cross-subsidization [ 78 ], whereby the rich cross-subsidize the poor, whilst the healthy cross-subsidize the sick [ 61 ]. Notwithstanding this, other scholars have warned that universal population coverage, although desirable, must be carefully pursued to avoid creating a situation of which official entitlements will be offered to all people yet the existing health system may not have sufficient capacity to deliver quality health care for all the population [ 79 , 80 ]. This is referred to as adverse incorporation or inclusion [ 79 ].

Financial protection as a dimension of universal health coverage

From the perspective of health economics, UHC is viewed as a means of protection against the economic consequences of ill health [ 81 , 82 ]. A guaranteed financial protection requires the implementation of a health care financing mechanism that does not require direct (substantial) out-of-pocket (OOP) payments, official or informal, such as user fees, copayments and deductibles, for health care at the point of use [ 23 , 74 , 81 , 83 ]. This is the reason why the international community has endorsed financing health care from pooled prepaid mechanisms such as tax (general or dedicated) revenue, and contributions from social health insurance (usually for formal sector employees), private health insurance, and micro health insurance as essential pre-requisites for moving towards universal financial protection [ 6 ]. The existing literature does not reveal a consensus on the best prepayment mechanism or the right mix of prepayment systems that will guarantee adequate financial protection [ 22 , 84 ]. A report by Oxfam [ 22 ] suggests that within the context of LMICs, different development partners each promote their ideologically favored prepayment mechanisms as a strategy towards achieving UHC. Both the WHO and the academic community, however, recommend that such ideological prescriptions should be abandoned in favor of mixed pooling systems that can coordinate funds from different prepaid sources, in a manner that reflects context-specific UHC needs [ 2 , 28 ]. This recommendation is also rooted in the recognition that no country, not even high income ones, has achieved complete coverage, relying solely on one single financing strategy [ 4 ]. Within a mixed pooling system, there is the need to ensure proper monitory of both private and public inputs that go into the financing system.

The WHO recommends two measures for assessing progress towards financial protection: the incidence of catastrophic health care expenditure and the incidence of impoverishment resulting from OOP payments for health care [ 25 ]. The proportion of total health care expenditure incurred through OOP payments is normally used as an indicator of financial protection at the national level [ 2 ]. WHO recommends a maximum OOP expenditure threshold of 15–20 % of total health care expenditure as a requirement for financial protection [ 2 ]. At the household level, a quantitative measure of financial protection is the proportion of households incurring OOP healthcare expenditure exceeding 40 % of their household’s non-subsistence (i.e., non-food) expenditure [ 85 ] or 10 % of total household expenditure [ 86 ]. It must be noted that direct medical cost of seeking health care is not the only barrier to financial protection. A good estimate of catastrophic health care expenditure must therefore reflect all relevant costs including non-medical costs such as the cost of travelling to a health facility and loss of earnings while being treated among others. These quantitative measures, estimated on the basis of actual health care cost incurred, however, only reflect the true situation of financial risk protection if all those who need care can actually utilize health services [ 87 ]. It is argued that, such utilization-focused quantitative cost estimates are often not able to capture the quantum of needed healthcare that is forgone due to fear of impoverishment associated with utilization [ 87 ]. Effective universal financial protection can, therefore, be attained not only if the population does not incur (substantial) OOP payments and critical income losses due to payment for health care, but if there are no fears of and delays in seeking healthcare due to financial reasons, no borrowing and sale of valuable assets to pay for healthcare, and no detentions in hospitals for non-payment of bills [ 2 , 61 , 80 , 86 , 88 – 90 ].

Access to services as a dimension of universal health coverage

From the perspective of public health, it is argued that a UHC package should include a comprehensive spectrum of health services in line with the WHO’s conceptualization of UHC as “ access to key promotive, preventive, curative and rehabilitative health interventions … ” [ 2 , 6 ]. From a feasibility view point, other scholars, however, argue that the focus should be on the provision of a minimum basic package to cover priority health needs for which there are effective low-cost interventions [ 91 ] . Some of these scholars insist that this package should include priority services in line with the health-related Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) [ 14 , 24 ], thereby suggesting a continuous focus on vertical disease-specific interventions. While some of these scholars argue that the expansion and effective implementation of disease-specific interventions, especially those focused on prevention, can improve health and reduce health system costs, opponents insist that all disease-specific interventions create fragmentation and undermine broader efforts aimed at system-wide strengthening [ 92 , 93 ]. The opposing scholars call for a focus on primary health care [ 7 , 15 , 94 ], to the extent that Yates [ 74 ] calls for a clear timetable, proposing 2015 as deadline, for the achievement of universal access to primary health care.

A number of authors further distinguish between official health service coverage, defined in terms of entitlement to services, and actual effective coverage, defined in terms of real access and utilization of health services according to need [ 13 , 44 , 51 ]. It follows that attempts to measure UHC should focus on indicators that measure actual effective service coverage in relation to people’s ability to obtain real access to services, without facing barriers on both the demand and the supply side [ 13 , 51 , 70 ]. Real access, is further defined as access in relation to the availability of health services, personnel and facilities; geographical accessibility of health services; acceptability defined in relation to appropriate client-provider interactions, timeliness, appropriateness and quality of services; and affordability in terms of medical and transport costs of services relative to clients’ ability-to-pay [ 73 , 80 , 95 – 106 ]. A guaranteed sufficient capacity of the local health system, in terms of adequate health infrastructure, qualified human resources, equipment and tools, to deliver quality health care is therefore an essential component of the access dimension of UHC [ 2 , 11 , 107 ]. It is interesting to note that “ Availability, Acceptability, Affordability and Quality (AAAQ)” of health services as essential sub-components of real access are directly rooted in the human rights conceptual framework and captured in broader discussions on the right to health [ 45 , 63 ].

Considering its interactive facets, it can be concluded that UHC emerges from the literature as a multi-dimensional concept, operationalized in terms of population coverage of health-related social security systems, financial protection, and access to quality health care according to need [ 17 ], and pursued within the framework of health care as an international legal obligation grounded in international human rights laws [ 45 , 46 , 48 , 49 ]. As an essential pre-condition for moving towards UHC in LMICs, there is therefore the need for all states to abide by the international human rights obligation imposed on them and thereby legally recognize the right to health in their national constitutions. It is only on this basis that the needed national and political commitment can be enhanced for a successful move towards universal population coverage of health-related social security systems, financial protection and access to services, which are essential components of a guaranteed comprehensive right to health and hence UHC. UHC can thus be understood as a broad legal, rights-based, social humanitarian, health economics and public health concept [ 15 , 17 , 27 , 42 ]. As such, it transcends a mere legal extension of the coverage of prepaid financing systems such as health insurance or tax-based systems to all residents, to ensuring that other financial and health system bottlenecks are removed to enhance effective financial protection and equitable access to services for all. As an overall health system strengthening tool, UHC can only be achieved through a human rights-focused integrated approach that recognizes the health system as a complex phenomenon with interlinked functional units whose effective interaractions are essential to reach the equilibrium called UHC. It follows that in LMICs, interventions aimed at strengthening health systems need to attract as much attention and funding as currently being deployed towards disease-specific interventions within the framework of the MDGs. Such an action has the capability of improving local service delivery capacity and hence of building resilient and responsive health systems to facilitate the move towards UHC. The move towards UHC should therefore be conceptualized as a continuous process of identifying gaps in the various interactive UHC dimensions, and designing context-specific strategies to address these gaps in accordance with the international legal obligations imposed on states by international agreements on the right to health. As a global issue, international assistance based on the principle of global solidarity is indispensable in the move towards UHC in LMICs.

Abbreviations

Availability, Acceptability, Affordability, Quality

Low - and Middle-Income Countries

Millennium Development Goals

Out-of-pocket

Universal Health coverage

United Nations Children’s Fund

United States Agency for International Development

World Health Assembly

World Health Organization

Garrett L, Chowdhury AMR, Pablos-Méndez A. All for universal health coverage. Lancet. 2009;374:1294–9.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

WHO. The World Health Report 2010 - Health Systems Financing: the path to universal coverage. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010.

Google Scholar

Mills A, Ally M, Goudge J, Gyapong J, Mtei G. Progress towards universal coverage: the health systems of Ghana, South Africa and Tanzania. Health Policy Plan. 2012;27 suppl 1:i4–12.

Kutzin J. Health financing for universal coverage and health system performance: concepts and implications for policy. Bull World Health Organ. 2013;91:602–11.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

United Nations’ General Assembly. Global Health and Foreign policy. Agenda item 123. The Sixty-seventh session (A/67/L.36). New York: United Nations; 2012.

World Health Organization. Sustainable health financing, universal coverage and social health insurance. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2005.

WHO. World Health Report 2008 - primary health care - now more than ever. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2008.

WHO. WHO | World Health Report 2013: research for universal health coverage. Genena: World Health Organization; 2013.

Reddy KS, Patel V, Jha P, Paul VK, Kumar AKS, Dandona L. Towards achievement of universal health care in India by 2020. A call to action. Lancet. 2011;377:760–8.

Gorin S. Universal health care coverage in the United States: Barriers, prospects, and implications. Health Soc Work. 1997;22:223–30.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Collet T-H, Salamin S, Zimmerli L, Kerr EA, Clair C, Picard-Kossovsky M, et al. The quality of primary care in a country with universal health care coverage. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26:724–30.

O’Connell T, Rasanathan K, Chopra M. What does universal health coverage mean? Lancet. 2013;6736:13–5.

de Noronha JC. Universal health coverage: how to mix concepts, confuse objectives, and abandon principles. Cad Saúde Pública. 2013;29:847–9.

Kieny M-P, Evans DB. Universal health coverage. East Mediterr Health J. 2013;19:305-6.

Stuckler D, Feigl AB, Basu S, McKee M. The political economy of universal health coverage. In: Background paper for the global symposium on health systems research. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010.

Bärnighausen T, Sauerborn R. One hundred and eighteen years of the German health insurance system. Are there any lessons for middle-and low-income countries. Soc Sci Med. 2002;54:1559–87.

Savedoff W, de Ferranti D, Smith A, Fan V. Political and economic aspects of the transition to universal health coverage. Lancet. 2012;380:924–32.

McKee M, Balabanova D, Basu S, Ricciardi W, Stuckler D. Universal health coverage: a quest for all countries but under threat in some. Value Health. 2013;16(1, Supplement):S39–45.

WHO. Constitution of the World Health Organization. Geneva: World Health Organisation; 1948.

Declaration of Alma-Ata. International Conference on Primary Health Care, Al ma-Ata, USSR, 6–12 September 1978. http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0009/113877/E93944.pdf . Accessed 4 May, 2015.

Bristol N. Global action towards Universal health coverage: a report for the CSIS Global Health Policy Center. Washington DC: Centre for strategic and International Studies; 2014.

Oxfam. Universal Health Coverage : Why health insurance schemes are leaving the poor behind. Oxford: Oxfam International; 2013.

World Bank WHO. WHO/World Bank Ministerial-level Meeting on Universal Health Coverage 18–19 February 2013. Geneva: World Health Organization’s headquarters; 2013.

WHO, World Bank. Monitoring Progress towards Universal Health Coverage at Country and Global Levels: A Framework. Joint WHO/World Bank Group Discussion Paper. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2013.

World Bank, WHO. Towards Universal Health Coverage by 2030. Washington DC: World Bank Group; 2014.

Latko B, Temporão JG, Frenk J, Evans TG, Chen LC, Pablos-Mendez A, et al. The growing movement for universal health coverage. Lancet. 2011;377:2161–3.

Borgonovi E, Compagni A. Sustaining universal health coverage: the interaction of social, political, and economic sustainability. Value Health. 2013;16(1, Supplement):S34–8.

Kutzin J. Anything goes on the path to universal health coverage? No. Bull World Health Organ. 2012;90:867–8.

Rodin J, de Ferranti D. Universal health coverage. The third global health transition? Lancet. 2012;380:861–2.

Chan M. Best days for public health are ahead of us, says WHO Director-General. Geneva, Switzerland: Address to the 65th World Health Assembly; 2012.

Lee Y-C, Huang Y-T, Tsai Y-W, Huang S-M, Kuo KN, McKee M, et al. The impact of universal National Health Insurance on population health: the experience of Taiwan. BMC Health Serv Res. 2010;10:225.

Moreno-Serra R, Smith PC. Does progress towards universal health coverage improve population health? Lancet. 2012;380:917–23.

The World Bank. World Development Report 1993. Investing in Health. New York: Oxford University Press; 1993.

Book Google Scholar

Jamison DT, Summers LH, Alleyne G, Arrow KJ, Berkley S, Binagwaho A, et al. Global health 2035: a world converging within a generation. Lancet. 2013;382:1898–955.

Evans DB, Marten R, Etienne C. Universal health coverage is a development issue. Lancet. 2012;380:864–5.

D’Ambruoso L. Global health post-2015: the case for universal health equity. Global Health Action. 2013;6:19661.

Sheikh M, Cometto G, Duvivier R. Universal health coverage and the post 2015 agenda. Lancet. 2013;381:725–6.

United Nations. Adopting consensus text, General Assembly encourages member states to plan, pursue transition of National Health Care Systems towards Universal Coverage. In: Sixty-seventh General Assembly Plenary 53rd Meeting (AM). New York: Department of Public Information • News and Media Division; 2012.

Vega J. Universal health coverage. The post-2015 development agenda. Lancet. 2013;381:179–80.

Victora C, Saracci R, Olsen J. Universal health coverage and the post-2015 agenda. Lancet. 2013;381:726.

Sengupta M. Universal Health Coverage: Beyond rhetoric. In: McDonald DA, Ruiters G, editors. Municipal Services Project, Occasional Paper No 20 - November 2013. http://www.alames.org/documentos/uhcamit.pdf . Accessed 14 May, 2015.

Holmes D. Margaret Chan: committed to universal health coverage. Lancet. 2012;380:879.

Horton R, Das P. Universal health coverage: not why, what, or when—but how? Lancet. 2014;384:2101.

Article Google Scholar

Lagomarsino G, Garabrant A, Adyas A, Muga R, Otoo N. Moving towards universal health coverage: health insurance reforms in nine developing countries in Africa and Asia. Lancet. 2012;380:933–43.

Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, WHO. The Right to Health: Joint Fact Sheet WHO/OHCHR/323. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2007.

United Nations’ General Assemby. International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights: Adopted and opened for signature, ratification and accession by General Assembly resolution 2200A (XXI) of 16 December 1966 entry into force 3 January 1976, in accordance with article 27. New York: United Nations; 1966.

Young S, The U.S. Fund for UNICEF Education Department. The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child: An Introduction -A Middle School Unit (Grades 6–8). U.S. Malawi: Fund for UNICEF/Mia Brandt; 2006.

United Nations. Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. New York: United Nations; 2006.

United Nations General Assemby. Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women. New York: United Nations; 1979.

Bárcena A. Health protection as a citizen’s right. Lancet. 2014;6736:61771–2.

Scheil-Adlung X, Bonnet F. Beyond legal coverage: assessing the performance of social health protection. Int Soc Secur Rev. 2011;64:21–38.

Forman L, Ooms G, Chapman A, Friedman E, Waris A, Lamprea E, et al. What could a strengthened right to health bring to the post-2015 health development agenda?: interrogating the role of the minimum core concept in advancing essential global health needs. BMC Int Health Hum Rights. 2013;13:48.

Fried ST, Khurshid A, Tarlton D, Webb D, Gloss S, Paz C, et al. Universal health coverage: necessary but not sufficient. Reprod Health Matters. 2013;21:50–60.

Hammonds R, Ooms G. The emergence of a global right to health norm - the unresolved case of universal access to quality emergency obstetric care. BMC Int Health Hum Rights. 2014;14:4.

Kingston LN, Cohen EF, Morley CP. Debate: limitations on universality: the “right to health” and the necessity of legal nationality. BMC Int Health Hum Rights. 2010;10:11.

Yamin AE, Frisancho A. Human-rights-based approaches to health in Latin America. Lancet. 2014;6736(14):61280.

Rosen G. A History of Public Health. Maryland: John Hopkins University Press; 1993.

Wilkinson R, Marmot M. Social determinants of health. The solid facts. Copenhagen: World Health Organization; 1998.

Marmot M, Wilkinson R. Social determinants of health. New York: Oxford University Press; 2005.

WHO. Social determinants of health: report by the Secretariat EB132/14. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2012.

McIntyre D. Health service financing for universal coverage in east and southern Africa, EQUINET Discussion Paper 95. Harare: Regional Network for Equity in Health in East and Southern Africa (EQUINET); 2012.

Ooms G. From international health to global health: how to foster a better dialogue between empirical and normative disciplines. BMC Int Health Hum Rights. 2014; 14:36.

Backman G, Hunt P, Khosla R, Jaramillo-Strouss C, Fikre BM, Rumble C, et al. Health systems and the right to health: an assessment of 194 countries. Lancet. 2008;372:2047–85.

Ooms G, Latif LA, Waris A, Brolan CE, Hammonds R, Friedman EA, et al. Is universal health coverage the practical expression of the right to health care? BMC Int Health Hum Rights. 2014; 14:3.

Ooms G, Hammonds R. Financing Global Health Through a Global Fund for Health? Working Group on Financing | PAPER 4. London: CHATHAM HOUSE (The Royal Institute of International Affairs); 2014.

Chen LC, Evans T, Cash R. Health as a global public good. In: Kaul I, Stern M, Grunberg I, editors. Global public goods: international cooperation in the 21st century. New York: Oxford University Press; 1999. p. 284–304.

Chapter Google Scholar

Frenk J, Gómez-Dantés O, Moon S. From sovereignty to solidarity: a renewed concept of global health for an era of complex interdependence. Lancet. 2014;383:94–7.

Stuckler D, McKee M. Five metaphors about global-health policy. Lancet. 2008;372:95–7.

Lencucha R. Cosmopolitanism and foreign policy for health: ethics for and beyond the state. BMC Int Health Hum Rights. 2013;13:29.

Knaul FM, González-Pier E, Gómez-Dantés O, García-Junco D, Arreola-Ornelas H, Barraza-Lloréns M, et al. The quest for universal health coverage: achieving social protection for all in Mexico. Lancet. 2012;380:1259–79.

The Lancet. Universal health coverage post-2015: putting people first. Lancet. 2014;384:2083.

Allotey P, Verghis S, Alvarez-Castillo F, Reidpath DD. Vulnerability, equity and universal coverage – a concept note. BMC Public Health. 2012;12 Suppl 1:S2.

Ravindran TS. Universal access: making health systems work for women. BMC Public Health. 2012;12 Suppl 1:S4.

Yates R. Universal health care and the removal of user fees. Lancet. 2009;373:2078–81.

McIntyre D. What healthcare financing changes are needed to reach universal coverage in South Africa? SAMJ: S Afr Med J. 2012;102:489–90.

Mills A, Ataguba JE, Akazili J, Borghi J, Garshong B, Makawia S, et al. Equity in financing and use of health care in Ghana, South Africa, and Tanzania: implications for paths to universal coverage. Lancet. 2012;380:126–33.

Rodney AM, Hill PS. Achieving equity within universal health coverage: a narrative review of progress and resources for measuring success. Int J Equity Health. 2014;13:1–72.

Goudge J, Akazili J, Ataguba J, Kuwawenaruwa A, Borghi J, Harris B, et al. Social solidarity and willingness to tolerate risk- and income-related cross-subsidies within health insurance: experiences from Ghana, Tanzania and South Africa. Health Policy Plan. 2012;27 suppl 1:i55–63.

Hickey S, Du Toit A. Adverse incorporation, social exclusion and chronic poverty, CPRC Working Paper 81. Chronic Poverty Research Centre: Manchester, UK; 2007.

Abiiro GA, Mbera GB, De Allegri M. Gaps in universal health coverage in Malawi: a qualitative study in rural communities. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:234.

Palmer N, Mueller DH, Gilson L, Mills A, Haines A. Health financing to promote access in low income settings—how much do we know? Lancet. 2004;364:1365–70.

Xu K, Evans DB, Kawabata K, Zeramdini R, Klavus J, Murray CJL. Household catastrophic health expenditure. A multicountry analysis. Lancet. 2003;362:111–7.

McIntyre D, Ranson MK, Aulakh BK, Honda A. Promoting universal financial protection: evidence from seven low-and middle-income countries on factors facilitating or hindering progress. Health Res Policy Syst. 2013;11:36.

Kutzin J, Ibraimova A, Jakab M, O’Dougherty S. Bismarck meets Beveridge on the Silk Road: coordinating funding sources to create a universal health financing system in Kyrgyzstan. Bull World Health Organ. 2009;87:549–54.

Xu K, Evans DB, Carrin G, Aguilar-Rivera AM, Musgrove P, Evans T. Protecting households from catastrophic health spending. Health Affair. 2007;26:972–83.

Cleary S, Birch S, Chimbindi N, Silal S, McIntyre D. Investigating the affordability of key health services in South Africa. Soc Sci Med. 2013;80:37–46.

Moreno-Serra R, Millett C, Smith PC. Towards improved measurement of financial protection in health. PLoS Med. 2011;8, e1001087.

Dekker M, Wilms A. Health insurance and other risk-coping strategies in Uganda. The case of Microcare Insurance Ltd. World Dev. 2009;38:369–78.

Kruk ME, Goldmann E, Galea S. Borrowing and selling to pay for health care in low- and middle-income countries. Health Aff. 2009;28:1056–66.

Leive A, Xu K. Coping with out-of-pocket health payments: empirical evidence from 15 African countries. Bull World Health Organ. 2008;86:849–56.

Sachs JD. Achieving universal health coverage in low-income settings. Lancet. 2012;380:944–7.

Adam T, Hsu J, de Savigny D, Lavis JN, Røttingen J-A, Bennett S. Evaluating health systems strengthening interventions in low-income and middle-income countries: are we asking the right questions? Health Policy Plan. 2012;27 suppl 4:iv9–19.

PubMed Google Scholar

Rao KD, Ramani S, Hazarika I, George S. When do vertical programmes strengthen health systems? A comparative assessment of disease-specific interventions in India. Health Policy Plan. 2014;29:495–505.

Sustainable Development Solutions Network. Health in the framework of development: Technical Report for the Post-2015 Development Agenda. New York: Sustainable Development Solutions Network: Global Inititative for the United Nation; 2014.

Aday LA, Andersen R. A framework for the study of access to medical care. Health Serv Res. 1974;9:208–20.

CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Arnold C, Theede J, Gagnon A. A qualitative exploration of access to urban migrant healthcare in Nairobi, Kenya. Soc Sci Med. 2014;110:1–9.

Dillip A, Alba S, Mshana C, Hetzel MW, Lengeler C, Mayumana I, et al. Acceptability – a neglected dimension of access to health care: findings from a study on childhood convulsions in rural Tanzania. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12:113.

Ensor T, Cooper S. Overcoming barriers to health service access: influencing the demand side. Health Policy Plan. 2004;19:69–79.

Evans DB, Hsu J, Boerma T. Universal health coverage and universal access. Bull World Health Organ. 2013;91:546–546A.

Goudge J, Gilson L, Russell S, Gumede T, Mills A. Affordability, availability and acceptability barriers to health care for the chronically ill: longitudinal case studies from South Africa. BMC Health Serv Res. 2009;9:75.

Jacobs B, Ir P, Bigdeli M, Annear PL, Damme WV. Addressing access barriers to health services: an analytical framework for selecting appropriate interventions in low-income Asian countries. Health Policy Plan. 2012;27:288–300.

Macha J, Harris B, Garshong B, Ataguba JE, Akazili J, Kuwawenaruwa A, et al. Factors influencing the burden of health care financing and the distribution of health care benefits in Ghana, Tanzania and South Africa. Health Policy Plan. 2012;27 suppl 1:i46–54.

McIntyre D, Thiede M, Birch S. Access as a policy-relevant concept in low- and middle-income countries. Health Econ Policy Law. 2009;4(Pt 2):179–93.

O’Donnell O. Access to health care in developing countries: breaking down demand side barriers. Cad Saúde Pública. 2007;23:2820–34.

Penchansky R, Thomas JW. The concept of access: definition and relationship to consumer satisfaction. Med Care. 1981;19:127–40.

Silal SP, Penn-Kekana L, Harris B, Birch S, McIntyre D. Exploring inequalities in access to and use of maternal health services in South Africa. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12:120.

Meessen B, Malanda B. No universal health coverage without strong local health systems. Bull World Health Organ. 2014;92:78–78A.

Download references

Acknowledgement

GAA was funded by a scientific contract from the Institute of Public Health, University of Heidelberg, Germany, and a senior research assistant contract from the University for Development Studies, Ghana. MDA is fully funded by a core position in the Medical Faculty of the University of Heidelberg, Germany.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Institute of Public Health, Medical Faculty, University of Heidelberg, Heidelberg, Germany

Gilbert Abotisem Abiiro & Manuela De Allegri

Department of Planning and Management, Faculty of Planning and Land Management, University for Development Studies, University Post Box 3, Wa, Upper West Region, Ghana

Gilbert Abotisem Abiiro

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Gilbert Abotisem Abiiro .

Additional information

Competing interests.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

GAA conceptualized and designed the study, undertook the literature search, data extraction and analysis, and drafted the paper. MDA supported the conceptualization and design of the study and paper drafting, and critically reviewed the drafts and contributed to its finalization. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly credited. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Abiiro, G.A., De Allegri, M. Universal health coverage from multiple perspectives: a synthesis of conceptual literature and global debates. BMC Int Health Hum Rights 15 , 17 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12914-015-0056-9

Download citation

Received : 15 January 2015

Accepted : 29 June 2015

Published : 04 July 2015

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12914-015-0056-9

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Universal health coverage

- Multi-dimensional concept

- Rights-based

- Population coverage

- Financial protection

- Access to health services

- Health system

- Conceptual literature

- Global debates

BMC International Health and Human Rights

ISSN: 1472-698X

- General enquiries: [email protected]

- Open access

- Published: 23 March 2023

Quality of care in the context of universal health coverage: a scoping review

- Bernice Yanful ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-6824-6694 1 ,

- Abirami Kirubarajan 2 ,

- Dominika Bhatia 2 ,

- Sujata Mishra 2 ,

- Sara Allin 2 &

- Erica Di Ruggiero 1 , 2 , 3

Health Research Policy and Systems volume 21 , Article number: 21 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

8646 Accesses

2 Citations

7 Altmetric

Metrics details

Introduction

Universal health coverage (UHC) is an emerging priority of health systems worldwide and central to Sustainable Development Goal 3 (target 3.8). Critical to the achievement of UHC, is quality of care. However, current evidence suggests that quality of care is suboptimal, particularly in low- and middle-income countries. The primary objective of this scoping review was to summarize the existing conceptual and empirical literature on quality of care within the context of UHC and identify knowledge gaps.

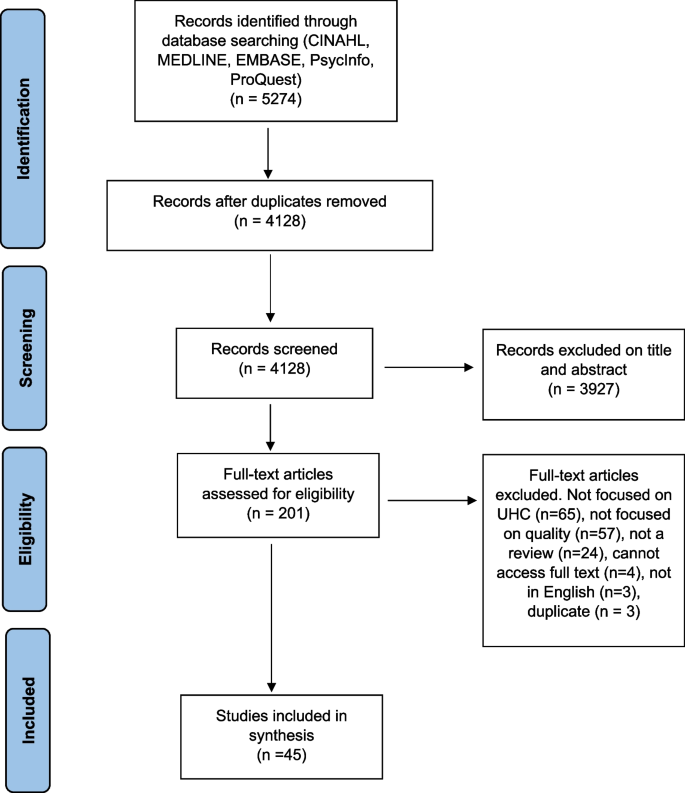

We conducted a scoping review using the Arksey and O’Malley framework and further elaborated by Levac et al. and applied the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) Extension for Scoping Reviews reporting guidelines. We systematically searched MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL-Plus, PAIS Index, ProQuest and PsycINFO for reviews published between 1 January 1995 and 27 September 2021. Reviews were eligible for inclusion if the article had a central focus on UHC and discussed quality of care. We did not apply any country-based restrictions. All screening, data extraction and analyses were completed by two reviewers.

Of the 4128 database results, we included 45 studies that met the eligibility criteria, spanning multiple geographic regions. We synthesized and analysed our findings according to Kruk et al.’s conceptual framework for high-quality systems, including foundations, processes of care and quality impacts. Discussions of governance in relation to quality of care were discussed in a high number of studies. Studies that explored the efficiency of health systems and services were also highly represented in the included reviews. In contrast, we found that limited information was reported on health outcomes in relation to quality of care within the context of UHC. In addition, there was a global lack of evidence on measures of quality of care related to UHC, particularly country-specific measures and measures related to equity.

There is growing evidence on the relationship between quality of care and UHC, especially related to the governance and efficiency of healthcare services and systems. However, several knowledge gaps remain, particularly related to monitoring and evaluation, including of equity. Further research, evaluation and monitoring frameworks are required to strengthen the existing evidence base to improve UHC.

Peer Review reports

According to the World Health Organization, universal health coverage (UHC) is achieved when ‘all people and communities can use the promotive, preventive, curative, rehabilitative and palliative health services they need, of sufficient quality to be effective, while also ensuring that the use of these services does not expose the user to financial hardship’ [ 1 ]. UHC has gained renewed attention from researchers and policymakers following its inclusion in the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (SDGs). SDG target 3.8 calls for achieving ‘universal health coverage, including financial risk protection, access to quality essential healthcare services and access to safe, effective, quality and affordable essential medicines and vaccines for all’ [ 2 ].

While there is growing evidence linking UHC to different health, economic and social outcomes, recent estimates suggest that about 800 million people globally still do not have access to full financial coverage of essential health services, including but not limited to high-income countries [ 3 ]. The WHO’s well-established UHC cube identifies three dimensions of UHC: (1) population (who is covered); (2) services (services that are covered); (3) direct costs (the proportion of the costs that are covered) [ 4 ]. Absent from the cube is the explicit inclusion of quality of care. However, without attention to the quality of care provided, increasing service coverage alone is unlikely to produce better health outcomes. As such, quality of care is critical to the achievement of UHC. A high-quality health system has been defined as one ‘that optimises health care in a given context by consistently delivering care that improves or maintains health outcomes, by being valued and trusted by all people, and by responding to changing population needs’ [ 5 , p. e1200].

Current evidence suggests that quality of care is suboptimal, particularly in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) [ 6 ]. While the era of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) expanded access to essential health services in LMICs, poor quality of care remains a significant problem, and explains persistently high levels of maternal and child mortality [ 6 ]. In addition, poor quality of care is estimated to cause between 5.7 and 8.4 million deaths yearly in LMICs [ 7 ]. Low-quality services are also an issue in high-income countries (HICs), particularly for disadvantaged populations such as immigrant and Indigenous groups [ 6 , 8 ].

As such, efforts to achieve UHC focused solely on expanding access to care are insufficient. Achieving UHC will require a more deliberate focus on quality of care across its various dimensions including effectiveness, safety, people-centredness, timeliness, equity, integration of care and efficiency [ 6 ]. However, existing literature synthesizing evidence on the quality of care within the context of UHC is more limited.

The primary objective of this scoping review is to synthesize and analyse the existing conceptual and empirical literature on quality of care within the context of UHC. The secondary objective is to identify knowledge gaps on quality of care within the context of advancing UHC and highlight areas for further inquiry.

We conducted a scoping review using the five-stage scoping review framework proposed by Arksey and O’Malley [ 9 ] and further elaborated by Levac et al. with the following stages [ 10 ]: (1) formulating the research question; (2) searching for relevant studies; (3) selection of eligible studies; (4) data extraction and (5) analysing and describing the results. In addition, we followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) Extension for Scoping Reviews reporting guidelines [ 11 ]. In accordance with the guidelines, our protocol is publicly available through Open Science Forum [ 12 ]. The scoping review methodology was selected due to its relevance to both identifying emerging and established content areas, and integration of diverse study methodologies [ 13 ]. As such, our methodology was well-aligned with the exploratory aims of our study.

To synthesize the existing knowledge on quality of care within the context of UHC, we focused on retrieving and analysing relevant reviews (as opposed to primary research studies). Bennett et al. [ 14 ] applied this overview of reviews approach in identifying health policy and system research priorities for the SDGs.

Information sources and search strategy

We developed the search strategy in consultation with a research librarian with expertise in public health and health systems. After finalizing our search in MEDLINE (Ovid) through an iterative process involving pilot tests, we completed a systematic search of MEDLINE (Ovid), EMBASE (Ovid), CINAHL-Plus (EBSCO), PAIS Index, ProQuest and PsycINFO (Ovid) for articles published from 1 January 1995 to 27 September 2021. The date cut-off of 1995 was selected to capture articles published during the period leading up to the adoption of the MDGs. We applied adapted search filters from the InterTASC Information Specialists’ Subgroup Search Filter Resource for each database [ 15 ].

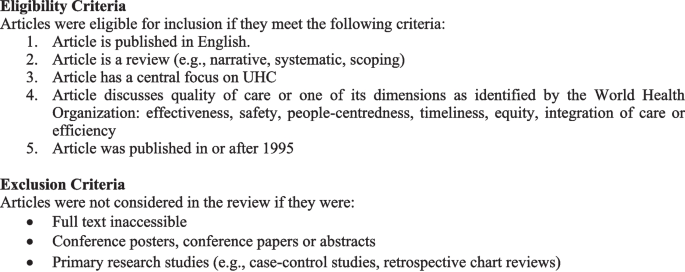

Our searches combined terms related to the concepts of (1) UHC (e.g. universal health insurance, universal coverage) and (2) quality of care and its seven dimensions (e.g. equity, safety, people-centredness). Our search strategy is available in Appendix A. Figure 1 outlines the eligibility criteria we used to assess studies for inclusion in the review.

Eligibility and exclusion criteria

Data management

Results from database searches were managed through Covidence ( www.covidence.org ) for deduplication and screening.

Study selection

Two reviewers (BY&AK) independently assessed studies against the eligibility criteria in two phases: (1) titles and abstracts and (2) full-text articles. A pilot test of the title and abstract screening was completed for approximately the first 100 search results. The two reviewers discussed disagreements to revise eligibility criteria as required. Any disagreements were resolved via consensus and in consultation with senior co-authors.

Data extraction

BY & AK independently completed data extraction for the first 10 articles using a standardized form. Following the pilot, the full data extraction was completed by the two reviewers in parallel. We extracted data on key study characteristics and according to each domain and subcomponent identified in Kruk et al.’s [ 5 ] framework described in the following section. The process of data extraction was iterative, with the form subject to revisions. Geographic regions were classified either by WHO regions [ 16 ] or through self-identification by the articles, such as a global focus, LMICs, HICs, ‘developing’ or ‘developed’.

Data synthesis

We synthesized the results through both a descriptive summary and a qualitative, narrative synthesis. We anchored our narrative synthesis in Kruk et al.’s [ 5 ] conceptual framework for high-quality health systems. The framework draws from Donabedian’s well-known conceptual model of quality of care, which was first developed in the 1960s and identifies structures, processes and outcomes as three components of quality of care. Kruk et al. [ 5 ] offer a new evidence-based framework relevant to present-day health systems, recognizing the heterogeneity of health systems across HIC and LMIC contexts.

They define three key domains of a high-quality health system, which they argue should be at the core of implementing and advancing UHC: foundations, processes of care and quality impacts. Foundations refer to the context and resources required to lead a high-quality health system. Processes of care include competent care and systems, relating to evidence-based effective care and health systems’ ability to respond to patient needs. Quality impacts include both patient and provider-reported health outcomes and client confidence in the health system, as well as economic benefits such as a reduction of resource waste and financial risk protection. The Kruk et al. [ 5 ] framework does not explicitly address equity; however, the authors state that equity in the quality of healthcare is critical, which they define as ‘the absence of disparities in the quality of health services between individuals and groups with different levels of underlying social disadvantage [p. e1214].’ When compared with Donabedian’s model for evaluating the quality of care [ 17 ], Kruk et al. [ 5 ] offer a much more elaborated framework that explicitly names a range of subcomponents to guide quality measurement and improvement (e.g. governance, positive user experience, etc.).

As our scoping review examines the existing literature on quality of care within the context of UHC and identifies knowledge gaps, Kruk et al.’s [ 5 ] framework provided a useful analytic tool by which to organize and interpret our findings.

We organized the results from our narrative synthesis according to each component of the framework (foundations, processes of care and quality impacts), addressing equity as a cross-cutting theme across these components. Table 1 summarizes the components and subcomponents of the framework.

Description of included reviews

The database searches yielded 4128 results after deduplication. Following screening, 45 articles that met eligibility criteria were included in the review. The search results are shown in Appendix A and a summary of each article is presented in Table 2 . Narrative reviews comprised 40.0% of the studies ( n = 18), 35.6% were systematic reviews (n = 16), while 20.0% were scoping reviews ( n = 9), and 4.4% were overviews of systematic reviews ( n = 2). Of the 45 reviews, 28 covered multiple WHO regions (62.2%). This included reviews with a broad global focus, reviews focused on LMICs, ‘developing’ or ‘developed’ countries, as well as reviews with an explicit focus on more than one of six WHO regions. Regarding the dimensions of quality of care, equity was the most well represented, examined by 40 of the studies (88.9%). Integration of care and safety were the least represented across the studies, each examined by 11 of the reviews (24.4%). We did not formally appraise the quality of studies included in our review, which is not required for a scoping review given its overarching aim to map the scope and size of the available literature on a given topic.

Narrative synthesis of results

Conceptualizing universal healthcare/coverage and quality of care.

The included studies highlighted varying definitions of UHC and quality of care. A common definition of UHC was that all people who require any essential healthcare services, including but not limited to promotion, prevention and treatment, are able to access services without financial stress [ 18 , 19 , 20 ]. One study further expanded this definition to include that UHC was the desired outcome of health system performance [ 18 ]. Some studies specified the definition was outlined in the Alma Ata declaration [ 21 , 22 ].

Definitions of quality of care also varied. One study distinguished between service quality (e.g. patient satisfaction, responsiveness) and technical quality (e.g. adherence to clinical guidelines) [ 23 ]. Another study defined high-quality healthcare as ‘providing the highest possible level of health with the available resources’ [ 24 , p. 142]. However, most studies did not provide a working definition of quality of care, and instead used proxy indicators such as infant mortality [ 25 ] to highlight quality-related outcomes.

Synthesis according to Kruk et al. Conceptual framework

Below, we synthesize findings from the studies according to the components of Kruk et al.’s [ 5 ] conceptual framework (foundations, processes of care and impacts). We highlight the most common themes that we identified in the literature for each domain and provide illustrative examples. Unless specified, findings were not specific to LMIC or HIC contexts.

Foundations

Governance: leaders, policies, processes and procedures providing direction and oversight of health system(s).

A common theme across the literature was health system governance at local, regional and national scales, and its relationship to quality of care within the context of UHC. Naher et al. [ 26 ] identified transparency, accountability, laws and regulations, and citizen engagement as critical components of governance. The articles discussed both poor and good governance, their underlying determinants and drivers, as well as interventions to improve governance and thus quality of care [ 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 , 40 , 41 , 42 , 43 , 44 , 45 , 46 , 47 , 48 , 49 , 50 , 51 , 52 , 53 , 54 ].

The literature suggests that poor governance is a common issue across health systems, and is both a cause and indicator of poor-quality care. Causes and forms of poor governance include weak supervision of, and inadequate incentives and remuneration for healthcare providers; lack of transparency and accountability in decision-making; and insufficient financial capacity; in addition to fragmented regulations and policies. Poor governance has also been found to result in low patient trust and confidence in the health system, wasted resources and poor patient outcomes [ 26 , 40 , 44 ]. In contrast, the reviewed literature described strong governance as critical to effective healthcare services [ 26 ] and the basis for achieving UHC [ 32 ].

Interventions to improve governance described by the reviewed literature include decentralization, social accountability mechanisms, such as social audits, and policy reforms to strengthen provider incentives and service integration [ 26 , 28 , 31 , 45 , 47 , 53 ]. However, the evidence regarding the effectiveness of these interventions on governance and quality of care was largely inconclusive. Regarding integration, White [ 45 ] noted the need to ensure adequate leadership and organizational capacity before integrating services, as a key determinant of success.

Quality of care measures

Six studies identified measures and/or measurement instruments to assess quality of care or its various dimensions within the context of UHC [ 19 , 22 , 27 , 30 , 42 , 51 ]. These measures differed based on their service areas of focus (e.g. family planning, primary care), the geographic contexts for which they are intended and whether they assessed foundations, processes of care or quality impacts. The reviewed literature identified a lack of standardized quality assessment tools as a significant barrier to the realization of UHC [ 22 , 42 ]. However, researchers also noted the need for country-specific indicators reflective of a country’s unique social, political and economic circumstances, and population needs and expectations [ 18 , 22 , 30 , 39 , 51 ]. Studies also emphasized the importance of integrating equity as an explicit component in the measurement and monitoring of UHC through for example, disaggregation of data by key socioeconomic and demographic variables including place of residence, occupation, religion, ethnicity and migration status [ 18 , 27 , 30 , 35 ]. Table 3 maps the measures identified in the studies according to the domains and subdomains of Kruk et al.’s framework.

Skills and availability of health system workers

Several studies also identified critical health workforce shortages and inequities in the distribution of appropriately qualified staff between urban and rural areas as significant constraints to the provision of high-quality, equitable care within the context of UHC, particularly in LMIC contexts [ 21 , 23 , 25 , 29 , 31 , 38 , 40 , 43 , 44 , 46 , 47 , 48 , 49 , 50 , 53 ]. Strategies discussed to address these concerns included (i) improving recruitment and retention of health system staff for rural and remote areas [ 21 , 46 , 47 , 50 ]; (ii) recruiting and training community health workers, while increasing the skills of lay health workers [ 21 ]; (iii) training traditional medicine practitioners in conventional medicine and utilizing them as community health workers [ 49 ]; and (iv) increasing task shifting, through delegating tasks to less specialized health workers [ 21 , 31 ], for which supportive supervision and adequate training is required [ 21 ].

Processes of care

Access to competent care and systems, incentives to improve quality of care delivery.

Evidence from the reviewed studies suggests that poor provider competence across a range of health services remains an ongoing issue, particularly in LMICs, posing a considerable barrier to the provision of timely, safe and effective quality of care [ 22 , 23 , 29 , 31 , 33 , 39 , 40 , 46 , 47 , 49 ]. For example, in China, a study with standardized patients found that providers in village hospitals provided correct treatment for tuberculosis only 28% of the time [ 47 ].

Within health systems seeking to provide UHC, significant inequities remain in both LMICs and HICs regarding the quality of care received by different populations. Vulnerable populations, who are more likely to receive care from lower-level health facilities, such as health centres, are disproportionately impacted by incompetent care and systems, having already constrained access to care [ 26 ], fewer options regarding providers and being more likely to receive inappropriate referrals [ 40 ], all indicators of lower-quality care.

Four studies described organizational factors influencing provider competence, including performance appraisal, continuing education, incentives, and remuneration and payment mechanisms [ 27 , 31 , 40 , 46 ]. For example, Sanogo et al. [ 40 ] discussed how delays in provider reimbursement as observed in Ghana, can demotivate healthcare providers, which Agarwal et al. [ 27 ] noted may decrease providers’ willingness to exert maximum effort on assigned tasks, compromising the quality of care.

Regarding incentives to improve motivation and quality of care delivery, Yip et al. [ 47 ] suggested a pay-for-performance system in China, as physicians are traditionally incentivized for treatment-based care through fee-for-service. However, the systematic review from Wiysonge et al. [ 46 ] noted a lack of evidence to support whether financial incentives for healthcare providers would improve quality of care in low-income countries.

User experience: wait times and people centredness

Wait times, a core component of quality of care, were noted as ongoing concerns in HICs and LMICs [ 21 , 23 , 33 , 39 , 40 , 47 , 48 , 55 , 56 ]. In HICs such as Norway and the United Kingdom, long wait times have been found to increase the demand for duplicative voluntary private health insurance, which Kiil argues may threaten the overall quality of public-sector driven UHC and exacerbate inequities [ 56 ]. In LMICs, evidence has shown that service quality is often superior in the private sector compared with the public sector, defined in relation to shorter wait times, better hospitality and increased time spent with providers [ 23 ].

Several studies described the relationship between positive user experience and people-centred care, which focuses on the needs and preferences of populations served while engaging them in shaping health policies and services. In addition, people centredness has been linked to improved mental and physical health, and reduced health inequities among other outcomes [ 20 , 22 , 31 , 35 , 57 ].

One study presented a people-centred care partnership model intended to support the work of advanced practice nurses in sustaining UHC, identifying nine attributes of people centredness including mutual trust and shared decision-making [ 20 ].

Several studies also discussed strategies aimed at increasing patient/community voice and engagement and the people centredness of health systems. These strategies included citizenship endorsement groups in Mexico [ 34 ] and various public forums to foster accountability and transparency [ 26 ]. However, McMichael et al. [ 35 ] cautioned that approaches to increase the voice of patients and communities risk excluding the most vulnerable, as those facing the greatest barriers to participation in such initiatives are often the most disadvantaged in their access and use of health services.

Quality impacts

Quality of care outcomes.

A few of the reviewed articles reported on empirical studies that analyzed patient and population health outcomes in relation to quality of care in the context of UHC. Where reported, these outcomes were discussed in reference to (i) specific programmes intended to improve quality of care and advance UHC, (ii) the impacts of health insurance schemes or health system reforms, (iii) private versus public sector provision of healthcare and/or (iv) the effects of specific service delivery models.

Regarding programmes intended to improve the quality of care, a community health extension programme in Ethiopia was associated with increased perinatal survival and decreased prevalence of communicable diseases. Though resource constraints such as inadequate medical supplies and limited supervision of health extension workers were noted as challenges, a key success factor included strong community engagement [ 29 ].

Another six studies examined health outcomes in relation to health insurance schemes or health system reforms [ 25 , 40 , 46 , 47 , 48 , 55 ]. Some improvements in health outcomes were noted. For example, in China, health system reforms aimed at achieving UHC have been associated with decreased maternal mortality rates [ 25 ]. However, the burden of noncommunicable diseases such as diabetes is rising amid significant gaps in their detection and treatment [ 47 ].

Studies also compared patient outcomes in relation to private versus public sector healthcare provision [ 24 , 56 , 58 ]. How the private sector was conceptualized varied across the studies, both in terms of how it was categorized (e.g. for-profit versus not-for-profit), as well as its role in healthcare financing and delivery. Given this heterogeneity, whether the public or private sector leads to higher-quality care and consequently, better health outcomes, is unclear in the reviewed literature. However, the private sector, when financed through out-of-pocket payments, is more likely to exacerbate inequities in access to healthcare.

Finally, two studies examined integrated models of care and their relationship to health outcomes [ 52 , 54 ]. According to these studies, different forms of service integration may positively impact health, for example, through slowed disease progression [ 54 ] and decreased preterm births [ 52 ].

Patient-reported satisfaction and trust in health system

Reports of poor perceived quality of care and low patient satisfaction as barriers to healthcare uptake and enrollment in health insurance schemes were common across the reviewed studies [ 26 , 28 , 36 , 40 , 44 , 47 , 55 , 56 ]. For instance, Alhassan et al. [ 28 ] found that perceived low quality of care, long wait times and poor treatment by healthcare providers reduced clients’ trust in Ghana’s National Health Insurance Scheme, reducing subsequent re-enrollment rates. In Ghana, perceived quality of care was found to exert a greater influence on men’s decisions regarding care uptake than on women’s decisions [ 36 , 44 ]. O’Connell et al. [ 36 ] suggested this gendered difference may be due to men’s care being more likely to be prioritized within household financial decisions, affording them the opportunity to be more discerning regarding the quality of care.

Several studies also discussed the effects of health system reforms and different service delivery models on patient satisfaction and trust in healthcare systems [ 23 , 28 , 29 , 31 , 38 , 43 , 47 , 54 , 57 ]. Yip et al. noted that despite reforms aimed at expanding access to care across China, many patients have chosen to forgo care at primary healthcare facilities altogether due to a lack of trust and dissatisfaction with quality of care [ 47 ]. Similarly, Ravaghi et al. identified contradictory results regarding the effects of hospital autonomy reforms on patient satisfaction. Two studies in Indonesia cited in Ravaghi’s review reported improvements, while others noted decreased or no change in patient satisfaction [ 38 ]. In contrast, four reviews found that integrated, people-centred health services may positively impact patient satisfaction [ 29 , 31 , 54 , 57 ].

Efficiency of healthcare services and systems

Twenty-seven studies addressed the efficiency of healthcare systems and services, which the review by Morgan et al., defined as ‘the extent to which resources are used effectively or are wasted’ [ 23 , p. 608]. These studies discussed inefficiencies in health systems [ 22 , 26 , 28 , 29 , 44 , 48 ], the possible effects of health reforms and other interventions on efficiency [ 21 , 25 , 31 , 37 , 38 , 41 , 44 , 45 , 46 , 47 , 50 , 53 , 54 , 55 , 58 , 59 ], efficiency as a criterion in health policymaking [ 32 ], and the measurement of efficiency [ 22 , 30 , 42 , 51 ], an example of which, as cited in Rezapour et al.’s study, was the percentage of prescriptions including antibiotics in health centres and health posts [ 51 ].

Additionally, some studies compared the efficiency of public and private sector healthcare provision, reporting mixed results [ 23 , 24 , 48 , 58 , 61 ]. For example, higher overhead costs and lower quality of care outcomes, including higher death rates, have been observed in private hospitals compared with public hospitals in the United States [ 24 ]. In contrast, research on the National Health Service in England has suggested that privatization and market-oriented reforms have improved the efficiency of hospital care through cost cutting without evidence of reduced quality [ 58 ].

In LMICs, the private sector has been linked to increased service costs related to overprescribing and use of unnecessary and expensive procedures [ 23 ]. However, Morgan et al. noted that studies assessing private sector performance in LMICs have often focused on unqualified or informal small private providers, such as small drug shops, operating amid weak public health systems and poor regulation, providing an incomplete picture of the role of the private sector in progress towards UHC [ 23 ]. Table 4 captures a high-level overview of the key highlights related to each domain and subdomain of Kruk et al.’s [ 5 ] framework discussed in the studies.

Identified evidence gaps and priorities for future research

Substantial evidence gaps that were identified in the reviewed literature are grouped thematically below. Themes are ordered by how frequently they were discussed by the reviewed studies.

Gap 1: How to measure and monitor UHC, with particular attention to quality of care and equity

Several studies identified the need for additional research to inform the development, selection and use of monitoring and evaluation frameworks and measures to assess quality of care and equity in relation to UHC in various geographic contexts at multiple levels of the health system, including facility and institutional levels [ 22 , 30 , 31 , 34 , 39 , 42 ]. For example, Rodney et al. stressed that countries should select contextually relevant indicators, and pay particular attention to the measurement of equity within UHC, cautioning that measuring equity based solely on wealth quintiles may mask inequities related to other factors such as race or disability [ 39 ]. In addition, two studies discussed the lack of client-reported measurements and advocated for further research to integrate data from household surveys and user-experience surveys [ 22 , 30 ].

Gap 2: Comparative information on the efficiency and effectiveness of public and private health provision and appropriate mix of public and private healthcare

Researchers noted the need for more conclusive evidence comparing the efficiency and effectiveness of public and private health sector provision, and the role of the private sector in contributing to UHC [ 21 , 23 , 56 , 57 , 62 ]. For example, Morgan et al. highlighted the need for greater evidence on how system-level influences such as regulations, may be used to create a public–private healthcare mix that promotes high-quality care and supports the achievement of UHC [ 23 ].

Gap 3: Effects of financial and insurance schemes on quality-of-care delivery and patient outcomes

The reviewed literature identified a lack of evidence regarding the impacts of different financial and insurance schemes on quality-of-care delivery and patient outcomes, particularly for vulnerable groups including women-headed households, children with special needs and migrants [ 34 , 46 , 55 , 62 ]. For example, van Hees et al. noted a lack of evidence regarding the impacts of financial schemes, such as pooling of funds and cost sharing, on equity [ 55 ].

Gap 4: Effects of integrated service delivery models

Studies identified the need for more robust evidence related to the effects of integrated service delivery models on access to quality care, as well as patient and population health outcomes [ 22 , 37 , 52 , 54 ]. Lê et al. specifically highlighted the lack of evidence on equity outcomes related to service integration, suggesting the need for further research in this area [ 54 ].

Gap 5: Mechanisms and contexts that enable and hinder implementation of quality-related interventions