Success Skills

Critical thinking, introduction, learning objectives.

- define critical thinking

- identify the role that logic plays in critical thinking

- apply critical thinking skills to problem-solving scenarios

- apply critical thinking skills to evaluation of information

Consider these thoughts about the critical thinking process, and how it applies not just to our school lives but also our personal and professional lives.

“Thinking Critically and Creatively”

Critical thinking skills are perhaps the most fundamental skills involved in making judgments and solving problems. You use them every day, and you can continue improving them.

The ability to think critically about a matter—to analyze a question, situation, or problem down to its most basic parts—is what helps us evaluate the accuracy and truthfulness of statements, claims, and information we read and hear. It is the sharp knife that, when honed, separates fact from fiction, honesty from lies, and the accurate from the misleading. We all use this skill to one degree or another almost every day. For example, we use critical thinking every day as we consider the latest consumer products and why one particular product is the best among its peers. Is it a quality product because a celebrity endorses it? Because a lot of other people may have used it? Because it is made by one company versus another? Or perhaps because it is made in one country or another? These are questions representative of critical thinking.

The academic setting demands more of us in terms of critical thinking than everyday life. It demands that we evaluate information and analyze myriad issues. It is the environment where our critical thinking skills can be the difference between success and failure. In this environment we must consider information in an analytical, critical manner. We must ask questions—What is the source of this information? Is this source an expert one and what makes it so? Are there multiple perspectives to consider on an issue? Do multiple sources agree or disagree on an issue? Does quality research substantiate information or opinion? Do I have any personal biases that may affect my consideration of this information?

It is only through purposeful, frequent, intentional questioning such as this that we can sharpen our critical thinking skills and improve as students, learners and researchers.

—Dr. Andrew Robert Baker, Foundations of Academic Success: Words of Wisdom

Defining Critical Thinking

Thinking comes naturally. You don’t have to make it happen—it just does. But you can make it happen in different ways. For example, you can think positively or negatively. You can think with “heart” and you can think with rational judgment. You can also think strategically and analytically, and mathematically and scientifically. These are a few of multiple ways in which the mind can process thought.

What are some forms of thinking you use? When do you use them, and why?

As a college student, you are tasked with engaging and expanding your thinking skills. One of the most important of these skills is critical thinking. Critical thinking is important because it relates to nearly all tasks, situations, topics, careers, environments, challenges, and opportunities. It’s not restricted to a particular subject area.

Imagine, for example, that you’re reading a history textbook. You wonder who wrote it and why, because you detect certain assumptions in the writing. You find that the author has a limited scope of research focused only on a particular group within a population. In this case, your critical thinking reveals that there are “other sides to the story.”

Who are critical thinkers, and what characteristics do they have in common? Critical thinkers are usually curious and reflective people. They like to explore and probe new areas and seek knowledge, clarification, and new solutions. They ask pertinent questions, evaluate statements and arguments, and they distinguish between facts and opinion. They are also willing to examine their own beliefs, possessing a manner of humility that allows them to admit lack of knowledge or understanding when needed. They are open to changing their mind. Perhaps most of all, they actively enjoy learning, and seeking new knowledge is a lifelong pursuit.

This may well be you!

No matter where you are on the road to being a critical thinker, you can always more fully develop your skills. Doing so will help you develop more balanced arguments, express yourself clearly, read critically, and absorb important information efficiently. Critical thinking skills will help you in any profession or any circumstance of life, from science to art to business to teaching.

| Critical Thinking IS | Critical Thinking is NOT |

|---|---|

| Skepticism | Memorizing |

| Examining assumptions | Group thinking |

| Challenging reasoning | Blind acceptance of authority |

| Uncovering biases |

Critical Thinking in Action

The following video, from Lawrence Bland, presents the major concepts and benefits of critical thinking.

Critical Thinking and Logic

Critical thinking is fundamentally a process of questioning information and data. You may question the information you read in a textbook, or you may question what a politician or a professor or a classmate says. You can also question a commonly-held belief or a new idea. With critical thinking, anything and everything is subject to question and examination.

Logic’s Relationship to Critical Thinking

The word logic comes from the Ancient Greek logike , referring to the science or art of reasoning. Using logic, a person evaluates arguments and strives to distinguish between good and bad reasoning, or between truth and falsehood. Using logic, you can evaluate ideas or claims people make, make good decisions, and form sound beliefs about the world. [1]

Questions of Logic in Critical Thinking

Let’s use a simple example of applying logic to a critical-thinking situation. In this hypothetical scenario, a man has a PhD in political science, and he works as a professor at a local college. His wife works at the college, too. They have three young children in the local school system, and their family is well known in the community.

The man is now running for political office. Are his credentials and experience sufficient for entering public office? Will he be effective in the political office? Some voters might believe that his personal life and current job, on the surface, suggest he will do well in the position, and they will vote for him.

In truth, the characteristics described don’t guarantee that the man will do a good job. The information is somewhat irrelevant. What else might you want to know? How about whether the man had already held a political office and done a good job? In this case, we want to ask, How much information is adequate in order to make a decision based on logic instead of assumptions?

The following questions, presented in Figure 1, below, are ones you may apply to formulating a logical, reasoned perspective in the above scenario or any other situation:

- What’s happening? Gather the basic information and begin to think of questions.

- Why is it important? Ask yourself why it’s significant and whether or not you agree.

- What don’t I see? Is there anything important missing?

- How do I know? Ask yourself where the information came from and how it was constructed.

- Who is saying it? What’s the position of the speaker and what is influencing them?

- What else? What if? What other ideas exist and are there other possibilities?

Problem-Solving With Critical Thinking

For most people, a typical day is filled with critical thinking and problem-solving challenges. In fact, critical thinking and problem-solving go hand-in-hand. They both refer to using knowledge, facts, and data to solve problems effectively. But with problem-solving, you are specifically identifying, selecting, and defending your solution. Below are some examples of using critical thinking to problem-solve:

- Your roommate was upset and said some unkind words to you, which put a crimp in your relationship. You try to see through the angry behaviors to determine how you might best support your roommate and help bring your relationship back to a comfortable spot.

- Your final art class project challenges you to conceptualize form in new ways. On the last day of class when students present their projects, you describe the techniques you used to fulfill the assignment. You explain why and how you selected that approach.

- Your math teacher sees that the class is not quite grasping a concept. She uses clever questioning to dispel anxiety and guide you to new understanding of the concept.

- You have a job interview for a position that you feel you are only partially qualified for, although you really want the job and you are excited about the prospects. You analyze how you will explain your skills and experiences in a way to show that you are a good match for the prospective employer.

- You are doing well in college, and most of your college and living expenses are covered. But there are some gaps between what you want and what you feel you can afford. You analyze your income, savings, and budget to better calculate what you will need to stay in college and maintain your desired level of spending.

Problem-Solving Action Checklist

Problem-solving can be an efficient and rewarding process, especially if you are organized and mindful of critical steps and strategies. Remember, too, to assume the attributes of a good critical thinker. If you are curious, reflective, knowledge-seeking, open to change, probing, organized, and ethical, your challenge or problem will be less of a hurdle, and you’ll be in a good position to find intelligent solutions.

| STRATEGIES | ACTION CHECKLIST | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Define the problem | |

| 2 | Identify available solutions | |

| 3 | Select your solution |

Evaluating Information With Critical Thinking

Evaluating information can be one of the most complex tasks you will be faced with in college. But if you utilize the following four strategies, you will be well on your way to success:

- Read for understanding by using text coding

- Examine arguments

- Clarify thinking

1. Read for Understanding Using Text Coding

When you read and take notes, use the text coding strategy . Text coding is a way of tracking your thinking while reading. It entails marking the text and recording what you are thinking either in the margins or perhaps on Post-it notes. As you make connections and ask questions in response to what you read, you monitor your comprehension and enhance your long-term understanding of the material.

With text coding, mark important arguments and key facts. Indicate where you agree and disagree or have further questions. You don’t necessarily need to read every word, but make sure you understand the concepts or the intentions behind what is written. Feel free to develop your own shorthand style when reading or taking notes. The following are a few options to consider using while coding text.

| Shorthand | Meaning |

|---|---|

| ! | Important |

| L | Learned something new |

| ! | Big idea surfaced |

| * | Interesting or important fact |

| ? | Dig deeper |

| ✓ | Agree |

| ≠ | Disagree |

See more text coding from PBWorks and Collaborative for Teaching and Learning .

2. Examine Arguments

When you examine arguments or claims that an author, speaker, or other source is making, your goal is to identify and examine the hard facts. You can use the spectrum of authority strategy for this purpose. The spectrum of authority strategy assists you in identifying the “hot” end of an argument—feelings, beliefs, cultural influences, and societal influences—and the “cold” end of an argument—scientific influences. The following video explains this strategy.

3. Clarify Thinking

When you use critical thinking to evaluate information, you need to clarify your thinking to yourself and likely to others. Doing this well is mainly a process of asking and answering probing questions, such as the logic questions discussed earlier. Design your questions to fit your needs, but be sure to cover adequate ground. What is the purpose? What question are we trying to answer? What point of view is being expressed? What assumptions are we or others making? What are the facts and data we know, and how do we know them? What are the concepts we’re working with? What are the conclusions, and do they make sense? What are the implications?

4. Cultivate “Habits of Mind”

“Habits of mind” are the personal commitments, values, and standards you have about the principle of good thinking. Consider your intellectual commitments, values, and standards. Do you approach problems with an open mind, a respect for truth, and an inquiring attitude? Some good habits to have when thinking critically are being receptive to having your opinions changed, having respect for others, being independent and not accepting something is true until you’ve had the time to examine the available evidence, being fair-minded, having respect for a reason, having an inquiring mind, not making assumptions, and always, especially, questioning your own conclusions—in other words, developing an intellectual work ethic. Try to work these qualities into your daily life.

- "logic." Wordnik . n.d. Web. 16 Feb 2016 . ↵

- "Student Success-Thinking Critically In Class and Online." Critical Thinking Gateway . St Petersburg College, n.d. Web. 16 Feb 2016. ↵

- Outcome: Critical Thinking. Provided by : Lumen Learning. License : CC BY: Attribution

- Self Check: Critical Thinking. Provided by : Lumen Learning. License : CC BY: Attribution

- Foundations of Academic Success. Authored by : Thomas C. Priester, editor. Provided by : Open SUNY Textbooks. Located at : http://textbooks.opensuny.org/foundations-of-academic-success/ . License : CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

- Image of woman thinking. Authored by : Moyan Brenn. Located at : https://flic.kr/p/8YV4K5 . License : CC BY: Attribution

- Critical Thinking. Provided by : Critical and Creative Thinking Program. Located at : http://cct.wikispaces.umb.edu/Critical+Thinking . License : CC BY: Attribution

- Critical Thinking Skills. Authored by : Linda Bruce. Provided by : Lumen Learning. Project : https://courses.lumenlearning.com/lumencollegesuccess/chapter/critical-thinking-skills/. License : CC BY: Attribution

- Image of critical thinking poster. Authored by : Melissa Robison. Located at : https://flic.kr/p/bwAzyD . License : CC BY: Attribution

- Thinking Critically. Authored by : UBC Learning Commons. Provided by : The University of British Columbia, Vancouver Campus. Located at : http://www.oercommons.org/courses/learning-toolkit-critical-thinking/view . License : CC BY: Attribution

- Critical Thinking 101: Spectrum of Authority. Authored by : UBC Leap. Located at : https://youtu.be/9G5xooMN2_c . License : CC BY: Attribution

- Image of students putting post-its on wall. Authored by : Hector Alejandro. Located at : https://flic.kr/p/7b2Ax2 . License : CC BY: Attribution

- Image of man thinking. Authored by : Chad Santos. Located at : https://flic.kr/p/phLKY . License : CC BY: Attribution

- Critical Thinking.wmv. Authored by : Lawrence Bland. Located at : https://youtu.be/WiSklIGUblo . License : All Rights Reserved . License Terms : Standard YouTube License

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

1 Chapter 1 – Critical Reading

Elizabeth Browning

When you are eager to start on the coursework in a major that will prepare you for your chosen career, getting excited about an introductory college writing course can be difficult. However, regardless of your field of study, honing your writing, reading, and critical-thinking skills will give you a more solid foundation for success, both academically and professionally. In this chapter, you will learn about the concept of critical reading and why it is an important skill to have—not just in college but in everyday life. The same skills used for reading a textbook chapter or academic journal article are the same ones used for successfully reading an expense report, project proposal, or other professional document you may encounter in the career world.

This chapter will also cover reading, note-taking, and writing strategies, which are necessary skills for college students who often use reading assignments or research sources as the springboard for writing a paper, completing discussion questions, or preparing for class discussion.

1. What expectations should you have?

2. What is critical reading?

3. Why do you read critically?

4. How do you read critically?

4.1 Preparing for a reading assignment.

4.2 Establishing your purpose.

4.3 Right before you read.

4.4 While you read.

4.5 After you read .

5. Now what?

1. What expectations should you have?

In college, academic expectations change from what you may have experienced in high school. The quantity of work expected of you increases, and the quality of the work also changes. You must do more than just understand course material and summarize it on an exam. You will be expected to engage seriously with new ideas by reflecting on them, analyzing them, critiquing them, making connections, drawing conclusions, or finding new ways of thinking about them. Educationally, you are moving into deeper waters. Learning the basics of critical reading and writing will help you swim.

Figure 1.1 “High School versus College Assignments” summarizes other major differences between high school and college assignments.

2. What is critical reading?

Reading critically does not simply mean being moved, affected, informed, influenced, and persuaded by a piece of writing. It refers to analyzing and understanding the overall composition of the writing as well as how the writing has achieved its effect on the audience. This level of understanding begins with thinking critically about the texts you are reading. In this case, “critically” does not mean that you are looking for what is wrong with a work (although during your critical process, you may well do that). Instead, thinking critically means approaching a work as if you were a critic or commentator whose job it is to analyze a text beyond its surface.

A text is simply a piece of writing, or as Merriam-Webster defines it, “the main body of printed or written matter on a page.” In English classes, the term “text” is often used interchangeably with the words “reading” or “work.”

This step is essential in analyzing a text, and it requires you to consider many different aspects of a writer’s work. Do not just consider what the text says; think about what effect the author intends to produce in a reader or what effect the text has had on you as the reader. For example, does the author want to persuade, inspire, provoke humor, or simply inform his audience? Look at the process through which the writer achieves (or does not achieve) the desired effect and which rhetorical strategies he uses. These rhetorical strategies are covered in the next chapter . If you disagree with a text, what is the point of contention? If you agree with it, how do you think you can expand or build upon the argument put forth?

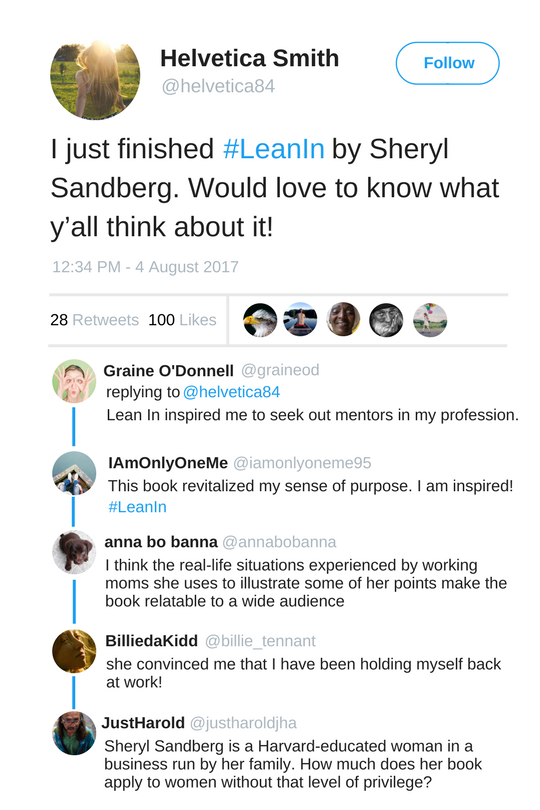

Consider this example: Which of the following tweets below are critical and which are uncritical? Figure 1.2 “Lean In Tweets”

3. Why do you read critically?

Critical reading has many uses. If applied to a work of literature, for example, it can become the foundation for a detailed textual analysis. With scholarly articles, critical reading can help you evaluate their potential reliability as future sources. Finding an error in someone else’s argument can be the point of destabilization you need to make a worthy argument of your own, illustrated in the final tweet from the previous image, for example. Critical reading can even help you hone your own argumentation skills because it requires you to think carefully about which strategies are effective for making arguments, and in this age of social media and instant publication, thinking carefully about what we say is a necessity.

4. How do you read critically?

How many times have you read a page in a book, or even just a paragraph, and by the end of it thought to yourself, “I have no idea what I just read; I can’t remember any of it”? Almost everyone has done it, and it’s particularly easy to do when you don’t care about the material, are not interested in the material, or if the material is full of difficult or new concepts. If you don’t feel engaged with a text, then you will passively read it, failing to pay attention to substance and structure. Passive reading results in zero gains; you will get nothing from what you have just read.

On the other hand, critical reading is based on active reading because you actively engage with the text, which means thinking about the text before you begin to read it, asking yourself questions as you read it as well as after you have read it, taking notes or annotating the text, summarizing what you have read, and, finally, evaluating the text. Completing these steps will help you to engage with a text, even if you don’t find it particularly interesting, which may be the case when it comes to assigned readings for some of your classes. In fact, active reading may even help you to develop an interest in the text even when you thought that you initially had none.

By taking an actively critical approach to reading, you will be able to do the following:

- Stay focused while you read the text

- Understand the main idea of the text

- Understand the overall structure or organization of the text

- Retain what you have read

- Pose informed and thoughtful questions about the text

- Evaluate the effectiveness of ideas in the text

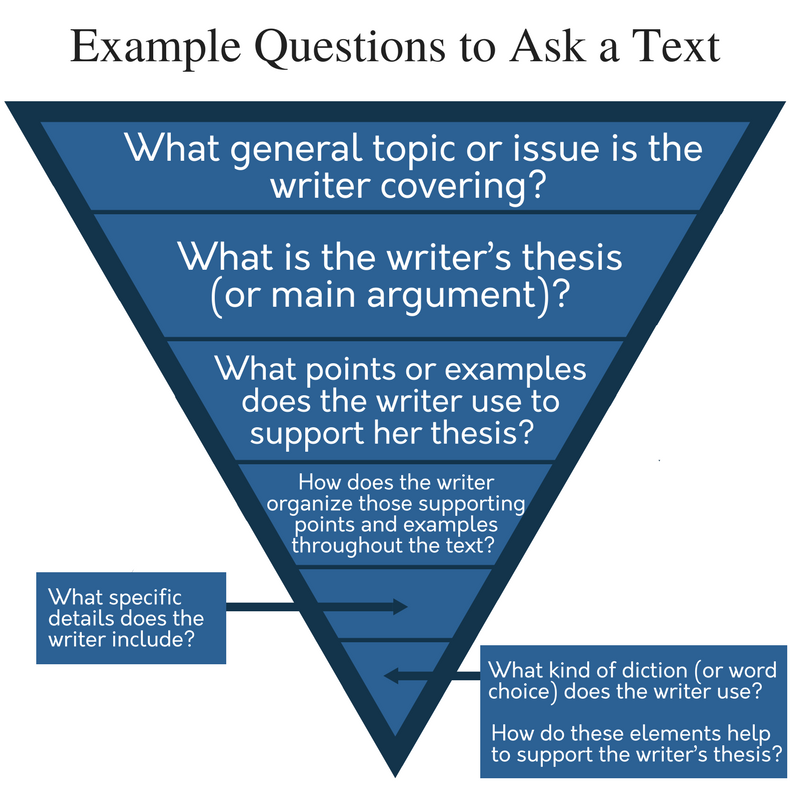

Specific questions generated by the text can guide your critical reading process. Use them when reading a text, and if asked to, use them in writing a formal analysis. When reading critically, you should begin with broad questions and then work towards more specific questions; after all, the ultimate purpose of engaging in critical reading is to turn you into an analyzer who asks questions that work to develop the purpose of the text.

Figure 1.3 “Example Questions to Ask a Text”

4.1 Preparing for a reading assignment

You need to make a plan before you read. Planning ahead is a necessary and smart step in various situations, inside or outside of the classroom. You wouldn’t want to jump into dark water head first before knowing how deep the water is, how cold it is, or what might be living below the surface. Instead, you would want to create a strategy, formulate a plan before you made that jump. The same goes for reading.

- Planning Your Reading

Have you ever stayed up all night cramming just before an exam or found yourself skimming a detailed memo from your boss five minutes before a crucial meeting? The first step in successful college reading is planning. This involves both managing your time and setting a purpose for your reading.

- Managing Your Reading Time

This step involves setting aside enough time for reading and breaking assignments into manageable chunks. If you are assigned a seventy-page chapter to read for next week’s class, try not to wait until the night before it’s due to get started. Give yourself at least a few days and tackle one section at a time.

The method for breaking up the assignment depends on the type of reading. If the text is dense and packed with unfamiliar terms and concepts, limit yourself to no more than five or ten pages in one sitting so that you can truly understand and process the information. With more user-friendly texts, you can handle longer sections—twenty to forty pages, for instance. Additionally, if you have a highly engaging reading assignment, such as a novel you cannot put down, you may be able to read lengthy passages in one sitting.

As the semester progresses, you will develop a better sense of how much time you need to allow for reading assignments in different subjects. Also consider previewing each assignment well in advance to assess its difficulty level and to determine how much reading time to set aside.

4.2 Establishing your purpose

Establishing why you read something helps you decide how to read it, which saves time and improves comprehension. This section lists some purposes for reading as well as different strategies to try at each stage of the reading process.

Purposes for Reading

In college and in your profession, you will read a variety of texts to gain and use information (e.g., scholarly articles, textbooks, reviews). Some purposes for reading might include the following:

- to scan for specific information

- to skim to get an overview of the text

- to relate new content to existing knowledge

- to write something (often depends on a prompt)

- to discuss in class

- to critique an argument

- to learn something

- for general comprehension

To skim a text means to look over a text briefly in order to get the gist or overall idea of it. When skimming, pay attention to these key parts:

●Introductory paragraph, which often contains the writer’s thesis or main idea

●Topic sentences of body paragraphs

●Conclusion paragraph

●Bold or italicized terms

Strategies differ from reader to reader. The same reader may use different strategies for different contexts because her purpose for reading changes. Ask yourself “why am I reading?” and “what am I reading?” when deciding which strategies work best.

Key Takeaways

- College-level reading and writing assignments differ from high school assignments not only in quantity but also in quality.

- Managing college reading assignments successfully requires you to plan and manage your time, set a purpose for reading, practice effective comprehension strategies, and use active reading strategies to deepen your understanding of the text.

- College writing assignments place greater emphasis on learning to think critically about a particular discipline and less emphasis on personal and creative writing.

4.3 Right before you read

Once you have established your purpose for reading, the next step is to preview the text . Previewing a text involves skimming over it and noticing what stands out so that you not only get an overall sense of the text, but you also learn the author’s main ideas before reading for details. Thus, because previewing a text helps you better understand it, you will have better success analyzing it.

Questions to ask when previewing may include the following:

- What is the title of the text? Does it give a clear indication of the text’s subject?

- Who is the author? Is the author familiar to you? Is any biographical information about the author included?

- If previewing a book, is there a summary on the back or inside the front of the book?

- What main idea emerges from the introductory paragraph? From the concluding paragraph?

- Are there any organizational elements that stand out, such as section headings, numbering, bullet points, or other types of lists?

- Are there any editorial elements that stand out, such as words in italics, bold print, or in a large font size?

- Are there any visual elements that give a sense of the subject, such as photos or illustrations?

Once you have formed a general idea about the text by previewing it, the next preparatory step for critical reading is to speculate about the author’s purpose for writing.

- What do you think the author’s aim might be in writing this text?

- What sort of questions do you think the author might raise?

Sample pre-reading guides (Word Document downloads) – K-W-L guide (https://tinyurl.com/y9pvlw9k)· Critical reading questionnaire ( https://tinyurl.com/y7ak9ygk )

4.4 While you read

Improving Your Comprehension

Thus far, you have blocked out time for your reading assignments, established a purpose for reading, and previewed the text. Now comes the challenge: making sure you actually understand all the information you are expected to process. Some of your reading assignments will be fairly straightforward. Others, however, will be longer and more complex, so you will need a plan for how to handle them.

For any expository writing—that is, nonfiction, informational writing—your first comprehension goal is to identify the main points and relate any details to those main points. Because college-level texts can be challenging, you should monitor your reading comprehension. That is, you should stop periodically to assess how well you understand what you have read. Finally, you can improve comprehension by taking time to determine which strategies work best for you and putting those strategies into practice.

Identifying the Main Points

In college, you will read a wide variety of materials, including the following:

- Textbooks. These usually include summaries, glossaries, comprehension questions, and other study aids.

- Nonfiction trade books, such as a biographical book. These are less likely to include the study features found in textbooks.

- Popular magazine, newspaper, or web articles. These are usually written for the general public.

- Scholarly books and journal articles. These are written for an audience of specialists in a given field.

Regardless of what type of expository text you are assigned to read, the primary comprehension goal is to identify the main point: the most important idea that the writer wants to communicate, often stated early on in the introduction and often re-emphasized in the conclusion. Finding the main point gives you a framework to organize the details presented in the reading and to relate the reading to concepts you learned in class or through other reading assignments. After identifying the main point, find the supporting points: the details, facts, and explanations that develop and clarify the main point.

Your instructor may use the term “main point” interchangeably with other terms, such as thesis, main argument, main focus, or core concept.

Some texts make the task of identifying the main point relatively easy. Textbooks, for instance, include the aforementioned features as well as headings and subheadings intended to make it easier for students to identify core concepts as well as the hierarchy of concepts (working from broad ideas to more focused ideas). Graphic features, such as sidebars, diagrams, and charts, help students understand complex information and distinguish between essential and inessential points. When assigned a textbook reading, be sure to use available comprehension aids to help you identify the main points.

Trade books and popular articles may not be written specifically for an educational purpose; nevertheless, they also include features that can help you identify the main ideas. These features include the following:

- Trade books . Many trade books include an introduction that presents the writer’s main ideas and purpose for writing. Reading chapter titles (and any subtitles within the chapter) provides a broad sense of what is covered. Reading the beginning and ending paragraphs of a chapter closely can also help comprehension because these paragraphs often sum up the main ideas presented.

- Popular articles . Reading headings and introductory paragraphs carefully is crucial. In magazine articles, these features–along with the closing paragraphs–present the main concepts. Hard news articles in newspapers present the gist of the news story in the lead paragraph, while subsequent paragraphs present increasingly general bits of information.

At the far end of the reading difficulty scale are scholarly books and journal articles. Because these texts are written for a specialized, highly educated audience, the authors presume their readers are already familiar with the topic. The language and writing style are sophisticated and sometimes dense.

When you read scholarly books and journal articles, you should apply the same strategies discussed earlier. The introduction usually presents the writer’s thesis, the idea or hypothesis the writer is trying to prove. Headings and subheadings can reveal how the writer has organized support for his or her thesis. If the text contains neither headings nor subheadings, however, then topic sentences of paragraphs can reveal the writer’s sense of organization. Additionally, academic journal articles often include a summary at the beginning, called an abstract, and electronic databases include summaries of articles, too.

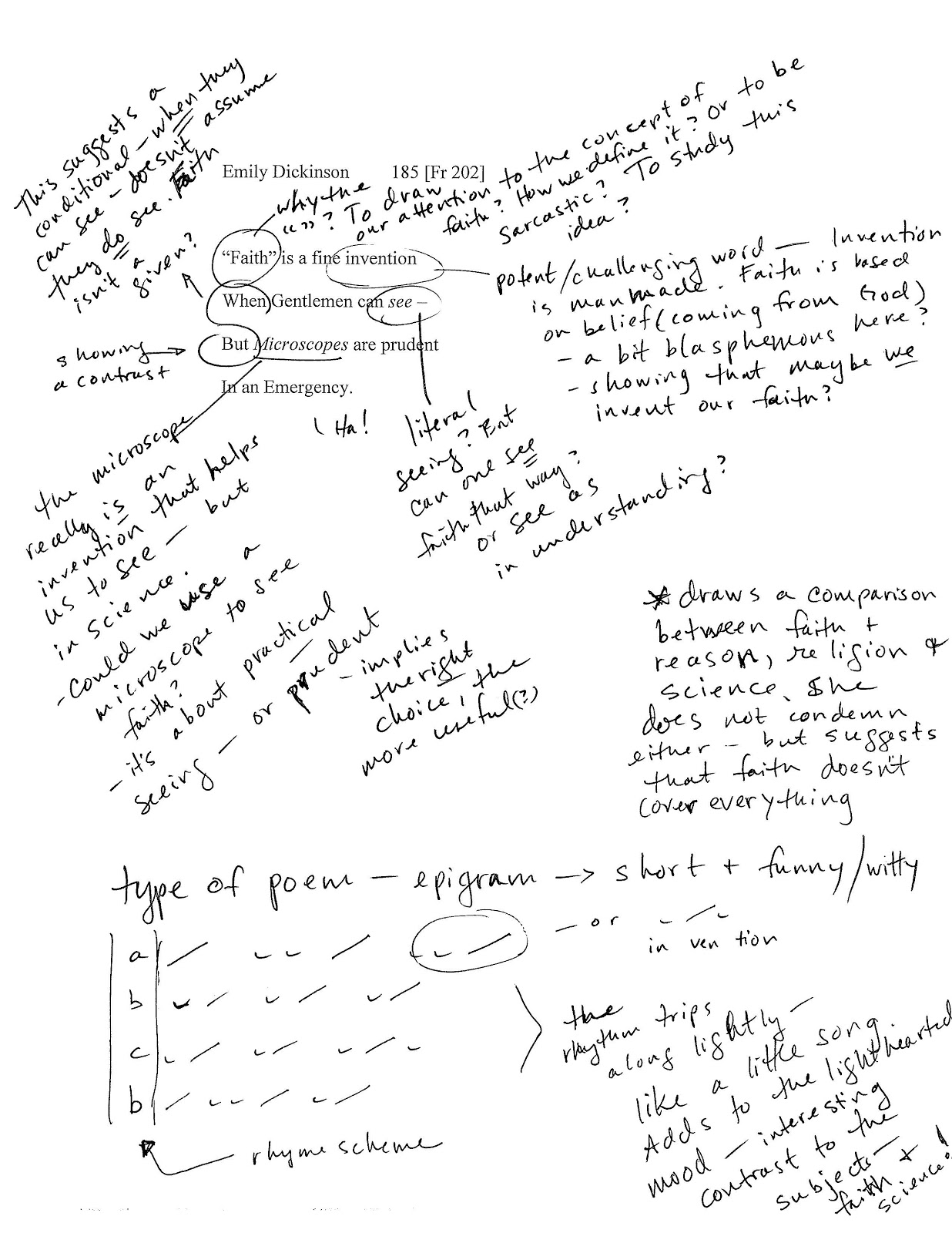

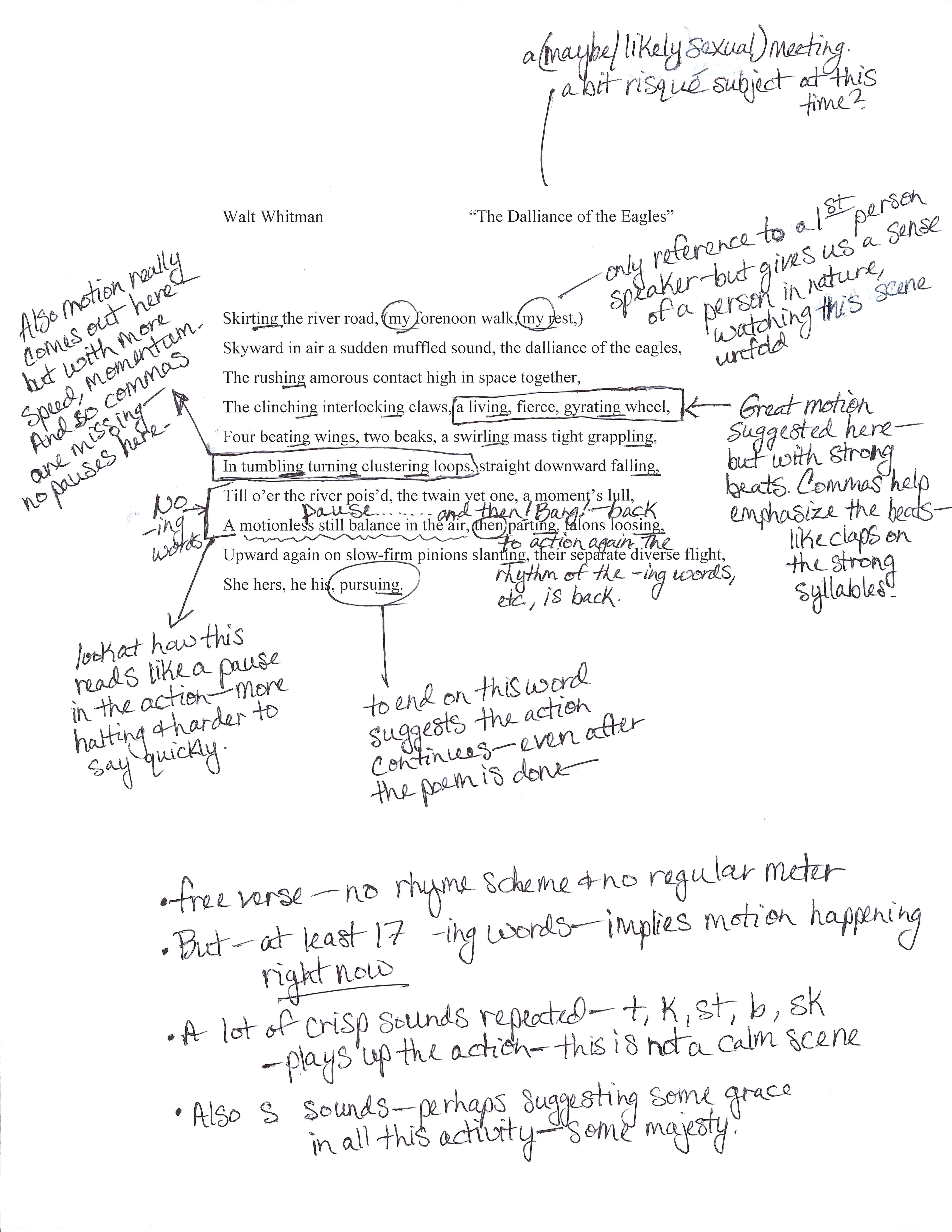

Annotating a text means that you actively engage with it by taking notes as you read, usually by marking the text in some way (underlining, highlighting, using symbols such as asterisks) as well as by writing down brief summaries, thoughts, or questions in the margins of the page. If you are working with a textbook and prefer not to write in it, annotations can be made on sticky notes or on a separate sheet of paper. Regardless of what method you choose, annotating not only directs your focus, but it also helps you retain that information. Furthermore, annotating helps you to recall where important points are in the text if you must return to it for a writing assignment or class discussion.

Annotations should not consist of JUST symbols, highlighting, or underlining. Successful and thorough annotations should combine those visual elements with notes in the margin and written summaries; otherwise, you may not remember why you highlighted that word or sentence in the first place.

How to Annotate:

- Underline, highlight, or mark sections of the text that seem important, interesting, or confusing.

- Be selective about which sections to mark; if you end up highlighting most of a page or even most of a paragraph, nothing will stand out, and you will have defeated the purpose of annotating.

- Use symbols to represent your thoughts.

- Asterisks or stars might go next to an important sentence or idea.

- Question marks might indicate a point or section that you find confusing or questionable in some way.

- Exclamation marks might go next to a point that you find surprising.

- Abbreviations can represent your thoughts in the same way symbols can

- For example, you may write “Def.” or “Bkgnd” in the margins to label a section that provides definition or background info for an idea or concept.

- Think of typical terms that you would use to summarize or describe sections or ideas in a text, and come up with abbreviations that make sense to you.

- Write down questions that you have as you read.

- Identify transitional phrases or words that connect ideas or sections of the text.

- Mark words that are unfamiliar to you or keep a running list of those words in your notebook.

- Mark key terms or main ideas in topic sentences.

- Identify key concepts pertaining to the course discipline (i.e.–look for literary devices, such as irony, climax, or metaphor, when reading a short story in an English class).

- Identify the thesis statement in the text (if it is explicitly stated).

Links to sample annotated texts – Journal article (https://tinyurl.com/ybfz7uke) · Book chapter excerpt (https://tinyurl.com/yd7pj379)

Figure 1.4 Sample Annotated Emily Dickinson Poem

Sample Annotated Emily Dickinson Poem

Figure 1.5 Sample Annotated Walt Whitman Poem “The Dalliance of the Eagles”

Sample Annotated Walt Whitman Poem “The Dalliance of the Eagles”

For three different but equally helpful videos on how to read actively and annotate a text, click on one of the links below:

“ How to Annotate ” (https://youtu.be/muZcJXlfCWs, transcript here )

“ 5 Active Reading Strategies ” (https://youtu.be/JL0pqJeE4_w, transcript here )

“ 10 Active Reading Strategies ” (https://youtu.be/5j8H3F8EMNI, transcript here )

4.5 After you read

Once you’ve finished reading, take time to review your initial reactions from your first preview of the text. Were any of your earlier questions answered within the text? Was the author’s purpose similar to what you had speculated it would be?

The following steps will help you process what you have read so that you can move onto the next step of analyzing the text.

- Summarize the text in your own words (note your impressions, reactions, and what you learned) in an outline or in a short paragraph

- Talk to someone, like a classmate, about the author’s ideas to check your comprehension

- Identify and reread difficult parts of the text

- Review your annotations

- Try to answer some of your own questions from your annotations that were raised while you were reading

- Define words on your vocabulary list and practice using them (to define words, try a learner’s dictionary, such as Merriam-Webster’s )

Critical Reading Practice Exercises

Choose any text that you have been assigned to read for one of your college courses. In your notes, complete the following tasks:

1. Follow the steps in the bulleted lists beginning under Section 3, “How do you read critically?” (For an in-class exercise, you may want to start with “Establishing Your Purpose.”)

- Before you read: Establish your purpose; preview the text.

- While you read: Identify the main point of the text; annotate the text.

- After you read: Summarize the main points of the text in two to three sentences; review your annotations.

2. Write down two to three questions about the text that you can bring up during class discussion. (Reviewing your annotations and identifying what stood out to you in the text should help you figure out what questions you want to ask.)

Students are often reluctant to seek help. They believe that doing so marks them as slow, weak, or demanding. The truth is, every learner occasionally struggles. If you are sincerely trying to keep up with the course reading but feel like you are in over your head, seek out help. Speak up in class, schedule a meeting with your instructor, or visit your university learning center for assistance. Deal with the problem as early in the semester as you can. Instructors respect students who are proactive about their own learning. Most instructors will work hard to help students who make the effort to help themselves.

To access a list of Virginia Western Community College’s learning resources, visit The Academic Link’s webpage (https://tinyurl.com/yccryaky)

5. Now what?

After you have taken the time to read a text critically, the next step, which is covered in the next chapter , is to analyze the text rhetorically to establish a clear idea of what the author wrote and how the author wrote it, as well as how effectively the author communicated the overall message of the text.

- Finding the main idea and paying attention to textual features as you read helps you figure out what you should know. Just as important, however, is being able to figure out what you do not know and developing a strategy to deal with it.

- Textbooks often include comprehension questions in the margins or at the end of a section or chapter. As you read, stop occasionally to answer these questions on paper or in your head. Use them to identify sections you may need to reread, read more carefully, or ask your instructor about later.

- Even when a text does not have built-in comprehension features, you can actively monitor your own comprehension. Try these strategies, adapting them as needed to suit different kinds of texts:

- Summarize. At the end of each section, pause to summarize the main points in a few sentences. If you have trouble doing so, revisit that section.

- Ask and answer questions. When you begin reading a section, try to identify two to three questions you should be able to answer after you finish it. Write down your questions and use them to test yourself on the reading. If you cannot answer a question, try to determine why. Is the answer buried in that section of reading but just not coming across to you, or do you expect to find the answer in another part of the reading?

- Do not read in a vacuum. Simply put, don’t rely solely on your own interpretation. Look for opportunities to discuss the reading with your classmates. Many instructors set up online discussion forums or blogs specifically for that purpose. Participating in these discussions can help you determine whether your understanding of the main points is the same as your peers’.

- Class discussions of the reading can serve as a reality check. If everyone in the class struggled with the reading, it may be exceptionally challenging. If it was easy for everyone but you, you may need to see your instructor for help.

CC Licensed Content, Shared Previously

English Composition I , Lumen Learning, CC-BY 4.0.

Rhetoric and Composition , John Barrett, et al., CC-BY-SA 3.0.

Writing for Success , CC-BY-NC-SA 3.0.

Image Credits

Figure 1.1 “High School versus College Assignments,” Kalyca Schultz, Virginia Western Community College, CC-BY-NC-SA 3.0, derivative image from “High School Versus College Assignments,” Writing for Success , CC-BY-NC-SA 3.0.

Figure 1.2 “Lean In Tweets,” Kalyca Schultz, Virginia Western Community College, CC-0.

Figure 1.3 “Example Questions to Ask a Text,” Kalyca Schultz, Virginia Western Community College, CC-0 .

Figure 1.4 “Sample Annotated Emily Dickinson Poem,” Kirsten DeVries and Kalyca Schultz, Virginia Western Community College, CC-0.

Figure 1.5 “Sample Annotated Walt Whitman Poem ‘The Dalliance of the Eagles,’” Kirsten DeVries and Kalyca Schultz, Virginia Western Community College, CC-0.

English 101 Copyright © 2018 by Elizabeth Browning is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Academic Writing

Inquiry, rhetoric and conversation are the core of UMD English’s Academic Writing Program.

Related Resources

- UTA Internship (ENGL388V)

- Blended Learning

- English 101 Exemptions

- Classes to take after English 101

While characteristics of academic writing vary across university disciplines, successful academic writing largely relies on using inquiry and rhetoric to engage in a scholarly conversation.

English 101 at the University of Maryland prepares students to write effectively within academic contexts. This course also invites students to make connections between academic and public contexts, exploring the public stakes of academic inquiry and argument.

Academic Writing Course

About the course.

The goal of English 101 is to familiarize students with the kind of writing they will have to do in college, broadly referred to as academic writing. Inquiry, rhetoric and conversation are the three major concerns of English 101. To start the course, students first inquire: they determine what is known—and credible—about a topic or issue by conducting research to assess the conversation. As students engage in this inquiry, they gain expertise in rhetoric: the art of knowledge-making and persuasion. By analyzing and practicing rhetorical strategies, students learn how to use writing to make sense of their inquiries, consider alternate perspectives, engage audiences and craft persuasive arguments they believe their audiences should consider. The ultimate work of the course is for students to learn how to participate thoughtfully, critically and persuasively in academic conversations.

English 101 is a rhetorically based course. Here, students not only gain the knowledge and skills to form arguments and persuade audiences, but they also learn to inquire, listen, reconsider and reflect on an issue of their choice and their evolving positions within that issue. Students will thus learn to ask good questions, conduct effective research, explore possible arguments, consider counter arguments, form claims and then reflect on those claims as they craft their positions.

Because a good deal of English 101 is dedicated to exploring the various positions people hold around an issue, a priority for the course is for students to step beyond the realities they know best and consider how others experience the world. A main goal of the course, then, is for students to learn to listen and write “across difference.” Students work on genuinely considering what others who hold positions different from their own have to say and craft their own arguments based on reflection. Ultimately, English 101 is a course in which students learn how to engage in academic and public discussions with generosity and rigor, exploring ways to make positive change in the world around them.

Learning Outcomes

Upon completion of an academic writing course, students will be able to:

- Demonstrate understanding of writing as a series of tasks, including finding, evaluating, analyzing and synthesizing appropriate sources, and as a process that involves composing, editing and revising.

- Demonstrate critical reading and analytical skills, including understanding an argument's major assertions and assumptions and how to evaluate its supporting evidence.

- Demonstrate facility with the fundamentals of persuasion, especially as they are adapted to a variety of special situations and audiences in academic writing.

- Demonstrate research skills, integrate your own ideas with those of others and apply the conventions of attribution and citation correctly.

- Use standard written English and revise and edit your own writing for appropriateness. You will take responsibility for such features as format, syntax, grammar, punctuation and spelling.

- Demonstrate an understanding of the connection between writing and thinking and use writing and reading for inquiry, learning, thinking and communicating in an academic setting.

University Resources

Get Academic Writing Support

Academic Integrity Policy at the University of Maryland

McKeldin Library Resources for English 101

The Purdue Online Writing Lab

The Writing Center

Disability Support Services

Maryland English Institute

Interpolations

One way to learn how to compose effectively in academic and public contexts is to study both the genre characteristics of specific kinds of writing and the effective rhetorical strategies used by successful writers. Interpolations showcases model projects from English 101 composed by UMD students. The intent for this publication is to offer current students the opportunity to see how those before them have, in their own unique ways, composed within the genres assigned in English 101. This publication also celebrates exemplary student writing in UMD’s academic writing courses.

Academic Writing Team/Staff

Scott eklund.

Administrative Coordinator, Academic Writing, English Managing Editor, Interpolations, English

1116 Tawes Hall College Park MD, 20742

Jessica Enoch

Professor, English Affiliate Professor, The Harriet Tubman Department of Women, Gender, and Sexuality Studies

Joshua Weiss

Senior Lecturer, English Administrative Fellow, English

2232 Tawes Hall College Park MD, 20742

- Academic Programs

Composition

- Journals & Series

- Directories

Quick Links

- Directories Home

- Colleges, Schools, and Departments

- Administrative Units

- Research Centers and Institutes

- Resources and Services

- Employee Directory

- Contact UNLV

- Social Media Directory

- UNLV Mobile Apps

- English Home

Program Information

All UNLV degree-seeking students must satisfy the composition requirements of ENG 101 and ENG 102, usually during the first year of college. This requirement, which is managed by the UNLV Composition Program, is based on the belief that the ability to read difficult texts, to analyze those texts, and to respond in writing is essential for success in college. The principles of good research also contribute to this success. English 101 and 102 are designed to provide the basics of these skills, which will continue to develop throughout the student's undergraduate career.

Course Descriptions

UNLV offers courses to provide instruction and support for students with a range of experiences with reading, writing, and language:

- ENG 101 Composition I: (3 credits) English 101 is a writing-intensive course designed to improve critical thinking, reading, and writing skills across disciplines. Students develop strategies for turning their experience, observations, and analyses into evidence suitable for writing in a variety of genres.

- ENG 100L Composition Intensive Lab: (1 credit) ENG 100L is a corequisite lab that reinforces the writing skills taught in ENG 101 by providing additional opportunities for guided practice.

- ENG 105L Critical Reading Lab: (1 credit) ENG 105L is a corequisite lab that reinforces the critical reading skills taught in ENG 101 by providing additional opportunities for guided practice.

- ENG 102 Composition II: (3 credits) ENG 102 builds upon the critical thinking, reading, and writing skills that students develop in ENG 101. Students develop strategies to develop arguments by identifying a research question, finding, evaluating, and citing research materials; and incorporating evidence effectively into their writing.

The English Language Center (ELC) provides equivalent composition courses for international and multilingual students. Students can contact the English Language Center at 702-895-3925 or [email protected] for more information.

Students place into composition courses based on their highest official score for any of these assessments:

| Courses | ACT English | SAT Evidence- Based Reading & Writing | AP Composition Exams | UNLV English Placement Assessment* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exams ENG 101 Composition I + 100L Composition Intensive Lab + 105L Critical Reading Lab All three classes (5 credits total) must be taken during the same semester | 1 - 17 | 200 - 470 | 5 - 8 | |

| ENG 101 Composition I | 18 - 29 | 480 - 650 | 9 -12 | |

| ENG 102 Composition II | 30 - 36 | 660 - 800 | 3 - 5 |

* The UNLV English Placement Assessment allows students to demonstrate their preparation for ENG 101 by submitting a reflective self-assessment letter online through WebCampus using their ACE account .

Once enrolled, students will also have access to detailed information about the curriculum for ENG 101 and the instructions for submitting the assessment letter in the WebCampus English Placement Assessment module. New students should complete their English Placement Assessment as soon as possible. Assessment scores will be used for English course placement before New Student Orientation.

To complete the UNLV English Placement Assessment :

- Activate your ACE account (if you haven't done so already).

- Log in using your ACE credentials.

- Click on the Enroll in Course button.

- Now you can visit your dashboard and click on the course to get started!

Transfer Credits

Classes taken at another college may serve as a prerequisite or fulfill the requirements for ENG 101 or ENG 102. Submit an official college transcript to the Office of Admissions for each institution you have attended. Sending official transcripts through secure electronic delivery is highly preferred, if possible. The webpage for the Office of Admissions provides more information about submitting transcripts. You can also contact your Academic Advising Center if you have questions.

The UNLV Composition Program office is located in the Beverly Rogers Literature and Law Building (RLL) , Room 264. Please call 702-895-3799 or email [email protected] for more information.

College Composition

The College Composition exam covers material usually taught in a one-semester college course in composition and features essays graded by the College Board.

Register for $93.00

The College Composition exam uses multiple-choice questions and essays to assess writing skills taught in most first-year college composition courses. Those skills include analysis, argumentation, synthesis, usage, ability to recognize logical development, and research.

The College Composition exam has a total testing time of 125 minutes and contains:

- 50 multiple-choice questions to be answered in 55 minutes

- 2 essays to be written in 70 minutes

Essays are scored twice a month by college English faculty from throughout the country via an online scoring system. Each essay is scored by at least two different readers, and the scores are then combined.

This combined score is weighted equally with the score from the multiple-choice section. These scores are then combined to yield the test taker's score. The resulting combined score is reported as a single scaled score between 20 and 80. Separate scores are not reported for the multiple-choice and essay sections.

Note: Although scores are provided immediately upon completion for other CLEP exams, scores for the College Composition exam are available to test takers one to two weeks after the test date. View the complete College Composition Scoring and Score Availability Dates .

The exam includes some pretest multiple-choice questions that won't be counted toward the test taker's score.

Colleges set their own credit-granting policies and therefore differ with regard to their acceptance of the College Composition exam. Most colleges will grant course credit for a first-year composition or English course that emphasizes expository writing; others will grant credit toward satisfying a liberal arts or distribution requirement in English.

Knowledge and Skills Required

The exam measures test takers' knowledge of the fundamental principles of rhetoric and composition and their ability to apply Standard Written English principles. In addition, the exam requires a familiarity with research and reference skills. In one of the two essays, test takers must develop a position by building an argument in which they synthesize information from two provided sources, which they must cite. The requirement that test takers cite the sources they use reflects the recognition of source attribution as an essential skill in college writing courses.

The skills assessed in the College Composition exam follow. The numbers in parentheses indicate the approximate percentages of exam questions on those topics. The bulleted lists under each topic are meant to be representative rather than prescriptive.

Conventions of Standard Written English (10%)

This section measures test takers' awareness of a variety of logical, structural, and grammatical relationships within sentences. The questions test recognition of acceptable usage relating to the items below:

- Syntax (parallelism, coordination, subordination)

- Sentence boundaries (comma splices, run-ons, sentence fragments)

- Recognition of correct sentences

- Concord/agreement (pronoun reference, case shift, and number; subject-verb; verb tense)

- Active/passive voice

- Lack of subject in modifying word group

- Logical comparison

- Logical agreement

- Punctuation

Revision Skills (40%)

This section measures test takers' revision skills in the context of works in progress (early drafts of essays):

- Organization

- Evaluation of evidence

- Awareness of audience, tone, and purpose

- Level of detail

- Coherence between sentences and paragraphs

- Sentence variety and structure

- Main idea, thesis statements, and topic sentences

- Rhetorical effects and emphasis

- Use of language

- Evaluation of author's authority and appeal

- Evaluation of reasoning

- Consistency of point of view

- Transitions

- Sentence-level errors primarily relating to the conventions of Standard Written English

Ability to Use Source Materials (25%)

This section measures test takers' familiarity with elements of the following basic reference and research skills, which are tested primarily in sets but may also be tested through stand-alone questions. In the passage-based sets, the elements listed under Revision Skills and Rhetorical Analysis may also be tested. In addition, this section will cover the following skills:

- Use of reference materials

- Evaluation of sources

- Integration of resource material

- Documentation of sources (including, but not limited to, MLA, APA, and Chicago manuals of style)

Rhetorical Analysis (25%)

This section measures test takers' ability to analyze writing. This skill is tested primarily in passage-based questions pertaining to critical thinking, style, purpose, audience, and situation:

- Organization/structure

- Rhetorical effects

In addition to the multiple-choice section, the College Composition exam includes a mandatory essay section that tests skills of argumentation, analysis, and synthesis. This section of the exam consists of two essays, both of which measure a test taker's ability to write clearly and effectively. The first essay is based on the test taker's reading, observation, or experience, while the second requires test takers to synthesize and cite two sources that are provided. Test takers have 30 minutes to write the first essay and 40 minutes to read the two sources and write the second essay. The essays must be typed on the computer.

First Essay: Directions

Write an essay in which you discuss the extent to which you agree or disagree with the statement provided. Support your discussion with specific reasons and examples from your reading, experience, or observations.

Second Essay: Directions

This assignment requires you to write a coherent essay in which you synthesize the two sources provided. Synthesis refers to combining the sources and your position to form a cohesive, supported argument. You must develop a position and incorporate both sources. You must cite the sources whether you are paraphrasing or quoting. Refer to each source by the author’s last name, the title, or by any other means that adequately identifies it.

Essay Scoring Guidelines

Readers will assign scores based on the following scoring guide.

Score of 6

Essays that score a 6 demonstrate a high degree of competence and sustained control, although it may have a few minor errors.

A typical essay in this category:

- addresses the writing task very effectively

- develops ideas thoroughly, using well-chosen reasons, examples, or details for support

- is clearly focused and well-organized

- demonstrates superior facility with language, using effective vocabulary and sentence variety

- demonstrates strong control of the standard conventions of grammar, usage, and mechanics, though it may contain minor errors

Score of 5

Essays that score a 5 demonstrate a generally high degree of competence, although it will have occasional lapses in quality.

- addresses the writing task effectively

- develops ideas consistently, using appropriate reasons, examples, or details for support

- is focused and organized

- demonstrates facility with language, using appropriate vocabulary and some sentence variety

- demonstrates consistent control of the standard conventions of grammar, usage, and mechanics, though it may contain minor errors

Score of 4

Essays that score a 4 demonstrate competence with some errors and lapses in quality.

- addresses the writing task adequately

- develops ideas adequately, using generally relevant reasons, examples, or details for support

- is generally focused and organized

- demonstrates competence with language, using adequate vocabulary and minimal sentence variety

- demonstrates adequate control of the standard conventions of grammar, usage, and mechanics; errors do not interfere with meaning

Score of 3

Essays that score a 3 demonstrate limited competence.

A typical essay in this category exhibits one or more of the following weaknesses:

- addresses the writing task, but may fail to sustain a focus or viewpoint

- develops ideas unevenly, often using assertions rather than relevant reasons, examples, or details for support

- is poorly focused and/or poorly organized

- displays frequent problems in the use of language, using unvaried diction and syntax

- demonstrates some control of grammar, usage, and mechanics, but with occasional shifts and inconsistencies

Score of 2

Essays that score a 2 are seriously flawed.

- addresses the writing task in a seriously limited or unclear manner

- develops ideas thinly, providing few or no relevant reasons, examples, or details for support

- is unfocused and/or disorganized

- displays frequent serious language errors that may interfere with meaning

- demonstrates a lack of control of standard grammar, usage, and mechanics

Score of 1

Essays that score a 1 are fundamentally deficient.

- does not address the writing task in a meaningful way

- does not develop ideas with relevant reasons, examples, or details

- displays a fundamental lack of control of language that may seriously interfere with meaning

Score of 0

Essays that score a 0 are off-topic.

Provides no evidence of an attempt to respond to the assigned topic, is written in a language other than English, merely copies the prompt, or consists of only keystroke characters.

Note: For the purposes of scoring, synthesis refers to combining the sources and the writer’s position to form a cohesive, supported argument.

Score Information

Ace recommendation for college composition.

| Credit-granting Score | 50 |

| Semester Hours | 6 |

Note: Each institution reserves the right to set its own credit-granting policy, which may differ from the American Council on Education (ACE) . Contact your college to find out the score required for credit and the number of credit hours granted.

Add Study Guides

Clep college composition and college composition modular examination guide.

This guide provides practice questions for the CLEP College Composition and College Composition Modular Exams.

Study Resources: College Composition

A study plan and list of online resources.

College Composition Resource Guide and Sample Questions

Details about the exam breakdown, credit recommendations, and free sample questions.

CLEP Practice App

Official CLEP eguides from examIam.

- Go to examIam

College Composition Scoring and Score Availability Dates

Access scoring dates for the current academic year as well as dates for when scores will be made available to students and mailed to institutions.

What Your CLEP Score Means

Guide to understanding how CLEP scores are calculated and credit-granting recommendations for all exams.

ACE Credit Recommendations

Recommendations for credit-granting scores from the American Council on Education.

Your Shopping Cart

Item added to your cart.

Not ready to checkout?

- Future Students

- Board Agenda

Home > Academics > English > Course Sequence Chart > English 102

ENGLISH 102

English 102 builds on the critical thinking, reading, and writing practice begun in English 101. This class includes critical analysis, interpretation, and evaluation of literary works, along with writing of argumentative essays about literary works.

The Student Learning Outcomes for English 102 are:

- Compose well-structured, grammatically-correct essays which assert the reader's analytical interpretation of a literary work and support that interpretation with convincing textual evidence.

- Apply critical thinking, specifically multiple perspectives and elements of argument, to the analysis and interpretation of literature.

To achieve these goals, students will learn to:

- Analyze the relationship between literary genre and meaning.

- Analyze the effect of point of view, character, diction, tone, imagery, figurative language, plot, and structure on the theme of the literary work.

- Relate the texts values and assumptions to the social, historical, ethical, psychological, philosophical, or religious context of the work.

- Compare ones own values and assumptions to those of the text, and debate the extent to which the literary works values and assumptions challenge those of the reader.

- Evaluate the formal and stylistic aspects of the literary work.

- Create a thesis that argues and assembles the readers interpretation of a literary work or works, and assemble supporting evidence to validate that interpretation.

- Assess and revise one's own arguments about literary works with attention to issues of organization, clarity, mechanics, and style based on peer evaluation of, and self-reflection on, composition strengths and weaknesses.

- Examine logical fallacies in literary works and in the interpretations of those works.

- Analyze and evaluate other elements of reasoning, such as quality of evidence and underlying assumptions, in literature and arguments about literature.

- Compare and contrast literary theories, and apply literary theory to analyze and interpret literature.

Course Sequence Chart

English 101

English 103

English 110

English 112

English 110: Critical Thinking, Reading and Writing Through Literature

Your assignment, what is literary criticism, guides to writing literary criticism.

- Choosing Topics

- Search Strategies

- Find Articles

- Use Websites

- Scholarly Sources

- Primary vs. Secondary Sources

- Annotated Bibliographies

For research help and more: Ask a GWC Librarian!

During library open hours :

Call: (714) 895-8741 x55184

Text: 714-882-5425

Visit: Reference Desk/LRC 2nd Floor

Library Hours: Spring 2024

Library building :, mon - thurs: 8 am - 5 pm, friday: 8 am - 12:30 pm, online research help:, mon - thurs: 8 am - 8 pm*, friday: 8 am - 12:30 pm.

*New later hours!

*January 29 - May 24*

Library Hours: Summer 2024

Mon - wed: 9 am - 1 pm.

* June 10 - August 16 *

English 110: Instructor Jereb - Textbook Citation Example

Dickinson, Emily. “Because I Could Not Stop for Death.” Literature and Its Writers: An Introduction to Fiction, Poetry, and Drama , edited by Ann Charters and Samuel Charters, 6th ed., Bedford/St. Martin's, 2013, p. 849.

Your assignment is to identify, evaluate, and select research material relevant about an author and their literary work or a literary movement. You are also expected to properly compile this material in order to write a research paper using MLA format.

This guide has been designed to highlight library resources to help you achieve these goals!

Literary Criticism is the discussion, analysis or appraisal of a literary work-whether a novel, poem, play, short story or essay.

As a literary critic, you will read and study a piece of literature and attempt to:

The guide will help you find biographical and critical information about authors and their works.

Selection of books in the library:

Click on the titles to see chapter titles and more.

- Next: Choosing Topics >>

- Last Updated: Jun 18, 2024 12:51 PM

- URL: https://goldenwestcollege.libguides.com/english110

Jump to navigation

Multi-level Slide Menu

Search form.

- ‹ Back

- Orientation & Placement

- Fees & Registration

- Financial Aid

- Returning Students

- Health Science Students

- International Students

- Military Veterans

- Dual Enrollment Program

- Early College HS Program

- Class Schedule

- Important Dates

- Transcripts

- Degrees & Certificates

- Noncredit Courses

- Career Education

- Curriculum Guides

- Office of Academic Affairs

- Tutoring & Labs

- Transfer Center

- Career Center

- Academic Calendar

- Academic Departments

- Community Education

- Corporate Education

- Student Support

- Counseling Services

- Basic Needs Resource Center

- Health Services

- Office of Student Services

- Student Life & Activities

- Student Accessibility Services

- Extended Opportunity Programs and Services

- Dreamers (AB540 Students)

- Multicultural Student Center

- Campus Police Services

- Technology Support

- Parking Permit & Information

- Justice Involved Students Pathway Program

- Quick Facts

- Vision & Mission

- History of Ohlone College

- Careers at Ohlone

- Board of Trustees

- Office of the President

- College Administration

- College Council

- Campus Maps

- News Center

- Ohlone Foundation

- Campus Events

- Facility Rentals

- MyOhlone Login

- MyOhlone Resources

- Retrieve Account

- Reset Password

Information For

- Prospective Students

- Current Students

- Employees & Potential Employees

- External Community

- Business and Industry

- A - Z Index

- Search for Classes

- Student Email

- New O365 Employee Email

- Report Positive COVID-19

- Select Language

- Enrolling at Ohlone

- Create Account / Reset Password

- O365 Employee Email

- Employee Directory

- Career Coach

- Chancellor’s Office

- Lytton Center

- Ohlone Bond Measure

Term Offered: SP,FA,SU Students will learn critical thinking skills and use them to read and evaluate essays in a precise, logical way. The emphasis will be upon critical analysis and upon the students' development of effective, written arguments.

- Terms of Use

- Accessibility

© 2024 Ohlone Community College District

- English Composition Courses

- English & ESL Scholarships

- The Citadel

- Writing Contest

- English Faculty & Staff

- Credit ESL Faculty & Staff

College Composition (First Semester)

All college freshmen are required to take a transfer-level college composition course. We highly recommend that you take this course during your first semester at LACC. The LACC English & ESL Department offers a variety of options to fulfill this requirement. You may choose one of the following: English 101 , English 101z , or E.S.L 110 . Please read the options below to determine which course best suits your needs:

English 101: College Reading and Composition 1

English 101 (3 Units) is designed for students who are strong readers and writers with a working understanding of research methods and MLA formatting. If you answer yes to the following questions, English 101 might be for you:

- Are you a recent High School graduate who had success in English coursework?

- Are you an independent worker who can succeed without additional support?

Transfer Credit: CSU (CSUGE Area A2), UC (IGETC Area 1A), C-ID (ENGL 100 or ENGL 110) / Meets Written Expression Competency

English 101Z: College Reading and Composition 1 (With 3-Hour Lab)

English 101z (4 Units) provides students with three additional hours of instructional time with your professor to work on reading, writing, research, and MLA formatting. If you answer yes to the following questions, English 101z might be for you:

- Would you like more time to master concepts?

- Would you like additional support and instruction from your professor?

- Has it been a long time since your last English class?

E.S.L. 110: College Composition for Non-Native Speakers

E.S.L. 110 (4 units) is the equivalent of English 101 but includes an additional focus on integrated grammar and academic vocabulary instruction based on needs typical of second-language learners. The following students are eligible to enroll in E.S.L. 110:

- Credit ESL students who have passed E.S.L. 8 with a grade of “C” or higher.

- Incoming students who have placed in E.S.L. 110 through the ESL Guided Self-Placement Process.

- U.S. high school graduates who are non-native speakers and who would like to receive additional language support.

Note: If you are an International (F-1 Visa) Student, we recommend that you follow our Guided Self-Placement process to determine the most appropriate level within the credit ESL course sequence (ESL 3, 4, 5, 6, 8, or 110) based on your English language proficiency.

Transfer Credit: CSU (CSUGE Area A2), UC (IGETC Area 1A) / Meets Written Expression Competency

College Composition (Second Semester)

Students wishing to transfer to a four-year university will also need to take either English 102 or English 103 . In addition to the course information provided below, you can obtain detailed information regarding lower division courses required for transfer to a University of California (UC) or California State University (CSU) campus at ASSIST . Please meet with a counselor in the Transfer Center for information about private or out-of-state colleges and universities.

English 102: College Reading and Composition 2

English 102 is designed to offer students an overview of literature , introducing students to three primary genres: prose, poetry, and drama. This course examines literature from various time periods and diverse voices.

English 102 is required for English and Creative Writing degrees, so it is ideal for students pursuing further education in those fields.

Transfer Credit: CSU (CSUGE Area C2, A3), UC (IGETC Area 1B,3B), C-ID (ENGL 120 or ENGL LIT 100)

Prerequisite: ENGLISH 101 or ENGLISH 101Z or E.S.L. 110 or by Appropriate Placement

Units: 3 units

English 103: Composition and Critical Thinking

English 103 is an introduction to critical thinking related to reading and writing. Students will examine the invisible, ideological structures that shape our world. Rhetorical strategies will be studied in order to provide students with a framework for further sharpening their academic writing to apply to diverse fields.

English 103 is ideal for students pursuing a degree outside the field of English, as it fulfills general requirements for many other degrees and transfer.

Transfer Credit: CSU (CSUGE Area A3), UC (IGETC Area 1B), C-ID (ENGL 105 or 115)

Meet Our Professors

English Faculty & Staff Page

Credit ESL Faculty & Staff Page

Useful Links

English & esl department.

Writing Support Center

Schedule of Classes

Office Hours and Location

Mondays to Thursdays: 8:00AM - 4:00PM Fridays to Sundays: Closed

We are located on the 3rd Floor of Jefferson Hall in room JH 301.

Jeffrey M. Nishimura, Department Chair Email: @email Phone: (323) 953-4000 ext. 2706

The Chair usually attends meetings in the afternoon, so please call before you come.

Jasminee Haywood-Daley, Secretary Email: @email Phone: (323) 953-4000 ext. 2700

Facebook Instagram

English (ENGL)

0.5 Units (LBE 24-27)

This class is open to students who feel they need review or additional support while concurrently enrolled in English 101. This course will focus on study skills, college-level reading strategies, essay structure, and grammar through more individualized attention and instruction. Offered as pass/no pass only.

Corequisite: ENGL-101 .

Not transferable

Offered as Pass/No Pass Only

3 Units (LBE 24-27, LEC 40-45)

This course offers instruction in expository and argumentative writing, including appropriate and effective use of language, close reading, cogent thinking, research strategies, information literacy, and documentation.

Prerequisite: Eligibility for college-level composition as determined by college assessment or other appropriate method.

Transfers to both UC/CSU

C-ID: ENGL 100

IGETC Area(s): 1A

CSU Area(s): A2

AA/AS General Education: AA/AS D1

Prerequisite: Acceptance into the Honors Enrichment Program., Eligibility for college-level composition as determined by college assessment or other appropriate method.

This course provides continuing practice in the analytic writing begun in English 101. The course develops critical thinking, reading, and writing skills as they apply to the analysis of written texts (literature and/or non-fiction) from diverse cultural sources and perspectives. The techniques and principles of effective written argument as they apply to the written text will be emphasized. Some research is required.

Prerequisite: ENGL-101 (with a grade of C or better).

C-ID: ENGL 105 C-ID: ENGL 110

IGETC Area(s): 1B

CSU Area(s): A3

AA/AS General Education: AA/AS D2

Prerequisite: ENGL-101 (with a grade of C or better)., Acceptance into the Honors Enrichment Program.

C-ID: ENGL 105

3 Units (LEC 48-54)

This course introduces students to styles, formats, and interactive media writing, including scripts and treatments for fiction and non-fiction film, television, and electronic media. Students evaluate sample scripts and electronic media as models for their own writings, thus readings draw from diverse authors, themes, and contexts to foster consideration of race, ethnicity, gender and sexuality, ability, language, belief systems, class, position, intersectionality, and power. The course emphasizes the importance of audience engagement, including how to connect with diverse audiences and points of view in terms of how a work is written and received.

This course encourages individual exploration into creative writing in several core genres- particularly poetry and short fiction. The course includes writing in journals, composing creative works, reading works of literature, and actively participating in peer workshops.

C-ID: ENGL 200

CSU Area(s): C2