- - Google Chrome

Intended for healthcare professionals

- Access provided by Google Indexer

- My email alerts

- BMA member login

- Username * Password * Forgot your log in details? Need to activate BMA Member Log In Log in via OpenAthens Log in via your institution

Search form

- Advanced search

- Search responses

- Search blogs

- Effectiveness of...

Effectiveness of weight management interventions for adults delivered in primary care: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials

- Related content

- Peer review

- Claire D Madigan , senior research associate 1 ,

- Henrietta E Graham , doctoral candidate 1 ,

- Elizabeth Sturgiss , NHMRC investigator 2 ,

- Victoria E Kettle , research associate 1 ,

- Kajal Gokal , senior research associate 1 ,

- Greg Biddle , research associate 1 ,

- Gemma M J Taylor , reader 3 ,

- Amanda J Daley , professor of behavioural medicine 1

- 1 Centre for Lifestyle Medicine and Behaviour (CLiMB), The School of Sport, Exercise and Health Sciences, Loughborough University, Loughborough LE11 3TU, UK

- 2 School of Primary and Allied Health Care, Monash University, Melbourne, Australia

- 3 Department of Psychology, Addiction and Mental Health Group, University of Bath, Bath, UK

- Correspondence to: C D Madigan c.madigan{at}lboro.ac.uk (or @claire_wm and @lboroclimb on Twitter)

- Accepted 26 April 2022

Objective To examine the effectiveness of behavioural weight management interventions for adults with obesity delivered in primary care.

Design Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials.

Eligibility criteria for selection of studies Randomised controlled trials of behavioural weight management interventions for adults with a body mass index ≥25 delivered in primary care compared with no treatment, attention control, or minimal intervention and weight change at ≥12 months follow-up.

Data sources Trials from a previous systematic review were extracted and the search completed using the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, Medline, PubMed, and PsychINFO from 1 January 2018 to 19 August 2021.

Data extraction and synthesis Two reviewers independently identified eligible studies, extracted data, and assessed risk of bias using the Cochrane risk of bias tool. Meta-analyses were conducted with random effects models, and a pooled mean difference for both weight (kg) and waist circumference (cm) were calculated.

Main outcome measures Primary outcome was weight change from baseline to 12 months. Secondary outcome was weight change from baseline to ≥24 months. Change in waist circumference was assessed at 12 months.

Results 34 trials were included: 14 were additional, from a previous review. 27 trials (n=8000) were included in the primary outcome of weight change at 12 month follow-up. The mean difference between the intervention and comparator groups at 12 months was −2.3 kg (95% confidence interval −3.0 to −1.6 kg, I 2 =88%, P<0.001), favouring the intervention group. At ≥24 months (13 trials, n=5011) the mean difference in weight change was −1.8 kg (−2.8 to −0.8 kg, I 2 =88%, P<0.001) favouring the intervention. The mean difference in waist circumference (18 trials, n=5288) was −2.5 cm (−3.2 to −1.8 cm, I 2 =69%, P<0.001) in favour of the intervention at 12 months.

Conclusions Behavioural weight management interventions for adults with obesity delivered in primary care are effective for weight loss and could be offered to members of the public.

Systematic review registration PROSPERO CRD42021275529.

Introduction

Obesity is associated with an increased risk of diseases such as cancer, type 2 diabetes, and heart disease, leading to early mortality. 1 2 3 More recently, obesity is a risk factor for worse outcomes with covid-19. 4 5 Because of this increased risk, health agencies and governments worldwide are focused on finding effective ways to help people lose weight. 6

Primary care is an ideal setting for delivering weight management services, and international guidelines recommend that doctors should opportunistically screen and encourage patients to lose weight. 7 8 On average, most people consult a primary care doctor four times yearly, providing opportunities for weight management interventions. 9 10 A systematic review of randomised controlled trials by LeBlanc et al identified behavioural interventions that could potentially be delivered in primary care, or involved referral of patients by primary care professionals, were effective for weight loss at 12-18 months follow-up (−2.4 kg, 95% confidence interval −2.9 to−1.9 kg). 11 However, this review included trials with interventions that the review authors considered directly transferrable to primary care, but not all interventions involved primary care practitioners. The review included interventions that were entirely delivered by university research employees, meaning implementation of these interventions might differ if offered in primary care, as has been the case in other implementation research of weight management interventions, where effects were smaller. 12 As many similar trials have been published after this review, an updated review would be useful to guide health policy.

We examined the effectiveness of weight loss interventions delivered in primary care on measures of body composition (weight and waist circumference). We also identified characteristics of effective weight management programmes for policy makers to consider.

This systematic review was registered on PROSPERO and is reported according to the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) statement. 13 14

Eligibility criteria

We considered studies to be eligible for inclusion if they were randomised controlled trials, comprised adult participants (≥18 years), and evaluated behavioural weight management interventions delivered in primary care that focused on weight loss. A primary care setting was broadly defined as the first point of contact with the healthcare system, providing accessible, continued, comprehensive, and coordinated care, focused on long term health. 15 Delivery in primary care was defined as the majority of the intervention being delivered by medical and non-medical clinicians within the primary care setting. Table 1 lists the inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Study inclusion and exclusion criteria

- View inline

We extracted studies from the systematic review by LeBlanc et al that met our inclusion criteria. 11 We also searched the exclusions in this review because the researchers excluded interventions specifically for diabetes management, low quality trials, and only included studies from an Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development country, limiting the scope of the findings.

We searched for studies in the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, Medline, PubMed, and PsychINFO from 1 January 2018 to 19 August 2021 (see supplementary file 1). Reference lists of previous reviews 16 17 18 19 20 21 and included trials were hand searched.

Data extraction

Results were uploaded to Covidence, 22 a software platform used for screening, and duplicates removed. Two independent reviewers screened study titles, abstracts, and full texts. Disagreements were discussed and resolved by a third reviewer. All decisions were recorded in Covidence, and reviewers were blinded to each other’s decisions. Covidence calculates proportionate agreement as a measure of inter-rater reliability, and data are reported separately by title or abstract screening and full text screening. One reviewer extracted data on study characteristics (see supplementary table 1) and two authors independently extracted data on weight outcomes. We contacted the authors of four included trials (from the updated search) for further information. 23 24 25 26

Outcomes, summary measures, and synthesis of results

The primary outcome was weight change from baseline to 12 months. Secondary outcomes were weight change from baseline to ≥24 months and from baseline to last follow-up (to include as many trials as possible), and waist circumference from baseline to 12 months. Supplementary file 2 details the prespecified subgroup analysis that we were unable to complete. The prespecified subgroup analyses that could be completed were type of healthcare professional who delivered the intervention, country, intensity of the intervention, and risk of bias rating.

Healthcare professional delivering intervention —From the data we were able to compare subgroups by type of healthcare professional: nurses, 24 26 27 28 general practitioners, 23 29 30 31 and non-medical practitioners (eg, health coaches). 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 Some of the interventions delivered by non-medical practitioners were supported, but not predominantly delivered, by GPs. Other interventions were delivered by a combination of several different practitioners—for example, it was not possible to determine whether a nurse or dietitian delivered the intervention. In the subgroup analysis of practitioner delivery, we refer to this group as “other.”

Country —We explored the effectiveness of interventions by country. Only countries with three or more trials were included in subgroup analyses (United Kingdom, United States, and Spain).

Intensity of interventions —As the median number of contacts was 12, we categorised intervention groups according to whether ≤11 or ≥12 contacts were required.

Risk of bias rating —Studies were classified as being at low, unclear, and high risk of bias. Risk of bias was explored as a potential influence on the results.

Meta-analyses

Meta-analyses were conducted using Review Manager 5.4. 40 As we expected the treatment effects to differ because of the diversity of intervention components and comparator conditions, we used random effects models. A pooled mean difference was calculated for each analysis, and variance in heterogeneity between studies was compared using the I 2 and τ 2 statistics. We generated funnel plots to evaluate small study effects. If more than two intervention groups existed, we divided the number of participants in the comparator group by the number of intervention groups and analysed each individually. Nine trials were cluster randomised controlled trials. The trials had adjusted their results for clustering, or adjustment had been made in the previous systematic review by LeBlanc et al. 11 One trial did not report change in weight by group. 26 We calculated the mean weight change and standard deviation using a standard formula, which imputes a correlation for the baseline and follow-up weights. 41 42 In a non-prespecified analysis, we conducted univariate and multivariable metaregression (in Stata) using a random effects model to examine the association between number of sessions and type of interventionalist on study effect estimates.

Risk of bias

Two authors independently assessed the risk of bias using the Cochrane risk of bias tool v2. 43 For incomplete outcome data we defined a high risk of bias as ≥20% attrition. Disagreements were resolved by discussion or consultation with a third author.

Patient and public involvement

The study idea was discussed with patients and members of the public. They were not, however, included in discussions about the design or conduct of the study.

The search identified 11 609 unique study titles or abstracts after duplicates were removed ( fig 1 ). After screening, 97 full text articles were assessed for eligibility. The proportionate agreement ranged from 0.94 to 1.0 for screening of titles or abstracts and was 0.84 for full text screening. Fourteen new trials met the inclusion criteria. Twenty one studies from the review by LeBlanc et al met our eligibility criteria and one study from another systematic review was considered eligible and included. 44 Some studies had follow-up studies (ie, two publications) that were found in both the second and the first search; hence the total number of trials was 34 and not 36. Of the 34 trials, 27 (n=8000 participants) were included in the primary outcome meta-analysis of weight change from baseline to 12 months, 13 (n=5011) in the secondary outcome from baseline to ≥24 months, and 30 (n=8938) in the secondary outcome for weight change from baseline to last follow-up. Baseline weight was accounted for in 18 of these trials, but in 14 24 26 29 30 31 32 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 it was unclear or the trials did not consider baseline weight. Eighteen trials (n=5288) were included in the analysis of change in waist circumference at 12 months.

Studies included in systematic review of effectiveness of behavioural weight management interventions in primary care. *Studies were merged in Covidence if they were from same trial

- Download figure

- Open in new tab

- Download powerpoint

Study characteristics

Included trials (see supplementary table 1) were individual randomised controlled trials (n=25) 24 25 26 27 28 29 32 33 34 35 38 39 41 44 45 46 47 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 59 or cluster randomised controlled trials (n=9). 23 30 31 36 37 48 49 57 58 Most were conducted in the US (n=14), 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 45 48 51 54 55 UK (n=7), 27 28 38 41 47 57 58 and Spain (n=4). 25 44 46 49 The median number of participants was 276 (range 50-864).

Four trials included only women (average 65.9% of women). 31 48 51 59 The mean BMI at baseline was 35.2 (SD 4.2) and mean age was 48 (SD 9.7) years. The interventions lasted between one session (with participants subsequently following the programme unassisted for three months) and several sessions over three years (median 12 months). The follow-up period ranged from 12 months to three years (median 12 months). Most trials excluded participants who had lost weight in the past six months and were taking drugs that affected weight.

Meta-analysis

Overall, 27 trials were included in the primary meta-analysis of weight change from baseline to 12 months. Three trials could not be included in the primary analysis as data on weight were only available at two and three years and not 12 months follow-up, but we included these trials in the secondary analyses of last follow-up and ≥24 months follow-up. 26 44 50 Four trials could not be included in the meta-analysis as they did not present data in a way that could be synthesised (ie, measures of dispersion). 25 52 53 58 The mean difference was −2.3 kg (95% confidence interval −3.0 to −1.6 kg, I 2 =88%, τ 2 =3.38; P<0.001) in favour of the intervention group ( fig 2 ). We found no evidence of publication bias (see supplementary fig 1). Absolute weight change was −3.7 (SD 6.1) kg in the intervention group and −1.4 (SD 5.5) kg in the comparator group.

Mean difference in weight at 12 months by weight management programme in primary care (intervention) or no treatment, different content, or minimal intervention (control). SD=standard deviation

Supplementary file 2 provides a summary of the main subgroup analyses.

Weight change

The mean difference in weight change at the last follow-up was −1.9 kg (95% confidence interval −2.5 to −1.3 kg, I 2 =81%, τ 2 =2.15; P<0.001). Absolute weight change was −3.2 (SD 6.4) kg in the intervention group and −1.2 (SD 6.0) kg in the comparator group (see supplementary figs 2 and 3).

At the 24 month follow-up the mean difference in weight change was −1.8 kg (−2.8 to −0.8 kg, I 2 =88%, τ 2 =3.13; P<0.001) (see supplementary fig 4). As the weight change data did not differ between the last follow-up and ≥24 months, we used the weight data from the last follow-up in subgroup analyses.

In subgroup analyses of type of interventionalist, differences were significant (P=0.005) between non-medical practitioners, GPs, nurses, and other people who delivered interventions (see supplementary fig 2).

Participants who had ≥12 contacts during interventions lost significantly more weight than those with fewer contacts (see supplementary fig 6). The association remained after adjustment for type of interventionalist.

Waist circumference

The mean difference in waist circumference was −2.5 cm (95% confidence interval −3.2 to −1.8 cm, I 2 =69%, τ 2 =1.73; P<0.001) in favour of the intervention at 12 months ( fig 3 ). Absolute changes were −3.7 cm (SD 7.8 cm) in the intervention group and −1.3 cm (SD 7.3) in the comparator group.

Mean difference in waist circumference at 12 months. SD=standard deviation

Risk of bias was considered to be low in nine trials, 24 33 34 35 39 41 47 55 56 unclear in 12 trials, 25 27 28 29 32 45 46 50 51 52 54 59 and high in 13 trials 23 26 30 31 36 37 38 44 48 49 53 57 58 ( fig 4 ). No significant (P=0.65) differences were found in subgroup analyses according to level of risk of bias from baseline to 12 months (see supplementary fig 7).

Risk of bias in included studies

Worldwide, governments are trying to find the most effective services to help people lose weight to improve the health of populations. We found weight management interventions delivered by primary care practitioners result in effective weight loss and reduction in waist circumference and these interventions should be considered part of the services offered to help people manage their weight. A greater number of contacts between patients and healthcare professionals led to more weight loss, and interventions should be designed to include at least 12 contacts (face-to-face or by telephone, or both). Evidence suggests that interventions delivered by non-medical practitioners were as effective as those delivered by GPs (both showed statistically significant weight loss). It is also possible that more contacts were made with non-medical interventionalists, which might partially explain this result, although the metaregression analysis suggested the effect remained after adjustment for type of interventionalist. Because most comparator groups had fewer contacts than intervention groups, it is not known whether the effects of the interventions are related to contact with interventionalists or to the content of the intervention itself.

Although we did not determine the costs of the programme, it is likely that interventions delivered by non-medical practitioners would be cheaper than GP and nurse led programmes. 41 Most of the interventions delivered by non-medical practitioners involved endorsement and supervision from GPs (ie, a recommendation or checking in to see how patients were progressing), and these should be considered when implementing these types of weight management interventions in primary care settings. Our findings suggest that a combination of practitioners would be most effective because GPs might not have the time for 12 consultations to support weight management.

Although the 2.3 kg greater weight loss in the intervention group may seem modest, just 2-5% in weight loss is associated with improvements in systolic blood pressure and glucose and triglyceride levels. 60 The confidence intervals suggest a potential range of weight loss and that these interventions might not provide as much benefit to those with a higher BMI. Patients might not find an average weight loss of 3.7 kg attractive, as many would prefer to lose more weight; explaining to patients the benefits of small weight losses to health would be important.

Strengths and limitations of this review

Our conclusions are based on a large sample of about 8000 participants, and 12 of these trials were published since 2018. It was occasionally difficult to distinguish who delivered the interventions and how they were implemented. We therefore made some assumptions at the screening stage about whether the interventionalists were primary care practitioners or if most of the interventions were delivered in primary care. These discussions were resolved by consensus. All included trials measured weight, and we excluded those that used self-reported data. Dropout rates are important in weight management interventions as those who do less well are less likely to be followed-up. We found that participants in trials with an attrition rate of 20% or more lost less weight and we are confident that those with high attrition rates have not inflated the results. Trials were mainly conducted in socially economic developed countries, so our findings might not be applicable to all countries. The meta-analyses showed statistically significant heterogeneity, and our prespecified subgroups analysis explained some, but not all, of the variance.

Comparison with other studies

The mean difference of −2.3 kg in favour of the intervention group at 12 months is similar to the findings in the review by LeBlanc et al, who reported a reduction of −2.4 kg in participants who received a weight management intervention in a range of settings, including primary care, universities, and the community. 11 61 This is important because the review by LeBlanc et al included interventions that were not exclusively conducted in primary care or by primary care practitioners. Trials conducted in university or hospital settings are not typically representative of primary care populations and are often more intensive than trials conducted in primary care as a result of less constraints on time. Thus, our review provides encouraging findings for the implementation of weight management interventions delivered in primary care. The findings are of a similar magnitude to those found in a trial by Ahern et al that tested primary care referral to a commercial programme, with a difference of −2.7 kg (95% confidence interval −3.9 to −1.5 kg) reported at 12 month follow-up. 62 The trial by Ahern et al also found a difference in waist circumference of −4.1 cm (95% confidence interval −5.5 to −2.3 cm) in favour of the intervention group at 12 months. Our finding was smaller at −2.5 cm (95% confidence interval −3.2 to −1.8 cm). Some evidence suggests clinical benefits from a reduction of 3 cm in waist circumference, particularly in decreased glucose levels, and the intervention groups showed a 3.7 cm absolute change in waist circumference. 63

Policy implications and conclusions

Weight management interventions delivered in primary care are effective and should be part of services offered to members of the public to help them manage weight. As about 39% of the world’s population is living with obesity, helping people to manage their weight is an enormous task. 64 Primary care offers good reach into the community as the first point of contact in the healthcare system and the remit to provide whole person care across the life course. 65 When developing weight management interventions, it is important to reflect on resource availability within primary care settings to ensure patients’ needs can be met within existing healthcare systems. 66

We did not examine the equity of interventions, but primary care interventions may offer an additional service and potentially help those who would not attend a programme delivered outside of primary care. Interventions should consist of 12 or more contacts, and these findings are based on a mixture of telephone and face-to-face sessions. Previous evidence suggests that GPs find it difficult to raise the issue of weight with patients and are pessimistic about the success of weight loss interventions. 67 Therefore, interventions should be implemented with appropriate training for primary care practitioners so that they feel confident about helping patients to manage their weight. 68

Unanswered questions and future research

A range of effective interventions are available in primary care settings to help people manage their weight, but we found substantial heterogeneity. It was beyond the scope of this systematic review to examine the specific components of the interventions that may be associated with greater weight loss, but this could be investigated by future research. We do not know whether these interventions are universally suitable and will decrease or increase health inequalities. As the data are most likely collected in trials, an individual patient meta-analysis is now needed to explore characteristics or factors that might explain the variance. Most of the interventions excluded people prescribed drugs that affect weight gain, such as antipsychotics, glucocorticoids, and some antidepressants. This population might benefit from help with managing their weight owing to the side effects of these drug classes on weight gain, although we do not know whether the weight management interventions we investigated would be effective in this population. 69

What is already known on this topic

Referral by primary care to behavioural weight management programmes is effective, but the effectiveness of weight management interventions delivered by primary care is not known

Systematic reviews have provided evidence for weight management interventions, but the latest review of primary care delivered interventions was published in 2014

Factors such as intensity and delivery mechanisms have not been investigated and could influence the effectiveness of weight management interventions delivered by primary care

What this study adds

Weight management interventions delivered by primary care are effective and can help patients to better manage their weight

At least 12 contacts (telephone or face to face) are needed to deliver weight management programmes in primary care

Some evidence suggests that weight loss after weight management interventions delivered by non-medical practitioners in primary care (often endorsed and supervised by doctors) is similar to that delivered by clinician led programmes

Ethics statements

Ethical approval.

Not required.

Data availability statement

Additional data are available in the supplementary files.

Contributors: CDM and AJD conceived the study, with support from ES. CDM conducted the search with support from HEG. CDM, AJD, ES, HEG, KG, GB, and VEK completed the screening and full text identification. CDM and VEK completed the risk of bias assessment. CDM extracted data for the primary outcome and study characteristics. HEJ, GB, and KG extracted primary outcome data. CDM completed the analysis in RevMan, and GMJT completed the metaregression analysis in Stata. CDM drafted the paper with AJD. All authors provided comments on the paper. CDM acts as guarantor. The corresponding author attests that all listed authors meet authorship criteria and that no others meeting the criteria have been omitted.

Funding: AJD is supported by a National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) research professorship award. This research was supported by the NIHR Leicester Biomedical Research Centre. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR, or the Department of Health and Social Care. ES’s salary is supported by an investigator grant (National Health and Medical Research Council, Australia). GT is supported by a Cancer Research UK fellowship. The funders had no role in considering the study design or in the collection, analysis, interpretation of data, writing of the report, or decision to submit the article for publication.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/disclosure-of-interest/ and declare: This research was supported by the National Institute for Health and Care Research Leicester Biomedical Research Centre; no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years, no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

The lead author (CDM) affirms that the manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported, and that no important aspects of the study have been omitted.

Dissemination to participants and related patient and public communities: We plan to disseminate these research findings to a wider community through press releases, featuring on the Centre for Lifestyle Medicine and Behaviour website ( www.lboro.ac.uk/research/climb/ ) via our policy networks, through social media platforms, and presentation at conferences.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

- Renehan AG ,

- Heller RF ,

- Bansback N ,

- Birmingham CL ,

- Abdullah A ,

- Peeters A ,

- de Courten M ,

- Stoelwinder J

- Aghili SMM ,

- Ebrahimpur M ,

- Arjmand B ,

- KETLAK Study Group

- ↵ Department of Health and Social Care. New specialised support to help those living with obesity to lose weight UK2021. www.gov.uk/government/news/new-specialised-support-to-help-those-living-with-obesity-to-lose-weight [accessed 08/02/2021].

- U.S. Preventive Services Task Force

- ↵ National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Maintaining a Healthy Weight and Preventing Excess Weight Gain in Children and Adults. Cost Effectiveness Considerations from a Population Modelling Viewpoint. 2014, NICE. www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng7/evidence/evidence-review-2-qualitative-evidence-review-of-the-most-acceptable-ways-to-communicate-information-about-individually-modifiable-behaviours-to-help-maintain-a-healthy-weight-or-prevent-excess-weigh-8733713.

- ↵ The Health Foundation. Use of primary care during the COVID-19 pandemic. 17/09/2020: The Health Foundation, 2020.

- ↵ Australian Bureau of Statistics. Patient Experiences in Australia: Summary of Findings, 2017-18. 2019 ed. Canberra, Australia, 2018. www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/[email protected]/Lookup/4839.0Main+Features12017-18?OpenDocument.

- LeBlanc ES ,

- Patnode CD ,

- Webber EM ,

- Redmond N ,

- Rushkin M ,

- O’Connor EA

- Damschroder LJ ,

- Liberati A ,

- Tetzlaff J ,

- Altman DG ,

- PRISMA Group

- McKenzie JE ,

- Bossuyt PM ,

- ↵ WHO. Main terminology: World Health Organization; 2004. www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/Health-systems/primary-health-care/main-terminology [accessed 09.12.21].

- Aceves-Martins M ,

- Robertson C ,

- REBALANCE team

- Glasziou P ,

- Isenring E ,

- Chisholm A ,

- Wakayama LN ,

- Kettle VE ,

- Madigan CD ,

- ↵ Covidence [program]. Melbourne, 2021.

- Welzel FD ,

- Carrington MJ ,

- Fernández-Ruiz VE ,

- Ramos-Morcillo AJ ,

- Solé-Agustí M ,

- Paniagua-Urbano JA ,

- Armero-Barranco D

- Bräutigam-Ewe M ,

- Hildingh C ,

- Yardley L ,

- Christian JG ,

- Bessesen DH ,

- Christian KK ,

- Goldstein MG ,

- Martin PD ,

- Dutton GR ,

- Horswell RL ,

- Brantley PJ

- Wadden TA ,

- Rogers MA ,

- Berkowitz RI ,

- Kumanyika SK ,

- Morales KH ,

- Allison KC ,

- Rozenblum R ,

- De La Cruz BA ,

- Katzmarzyk PT ,

- Martin CK ,

- Newton RL Jr . ,

- Nanchahal K ,

- Holdsworth E ,

- ↵ RevMan [program]. 5.4 version: Copenhagen, 2014.

- Sterne JAC ,

- Savović J ,

- Gomez-Huelgas R ,

- Jansen-Chaparro S ,

- Baca-Osorio AJ ,

- Mancera-Romero J ,

- Tinahones FJ ,

- Bernal-López MR

- Delahanty LM ,

- Tárraga Marcos ML ,

- Panisello Royo JM ,

- Carbayo Herencia JA ,

- Beeken RJ ,

- Leurent B ,

- Vickerstaff V ,

- Hagobian T ,

- Brannen A ,

- Rodriguez-Cristobal JJ ,

- Alonso-Villaverde C ,

- Panisello JM ,

- Conroy MB ,

- Spadaro KC ,

- Takasawa N ,

- Mashiyama Y ,

- Pritchard DA ,

- Hyndman J ,

- Jarjoura D ,

- Smucker W ,

- Baughman K ,

- Bennett GG ,

- Steinberg D ,

- Zaghloul H ,

- Chagoury O ,

- Leslie WS ,

- Barnes AC ,

- Summerbell CD ,

- Greenwood DC ,

- Huseinovic E ,

- Leu Agelii M ,

- Hellebö Johansson E ,

- Winkvist A ,

- Look AHEAD Research Group

- LeBlanc EL ,

- Wheeler GM ,

- Aveyard P ,

- de Koning L ,

- Chiuve SE ,

- Willett WC ,

- ↵ World Health Organization. Obesity and Overweight, 2021, www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight

- Starfield B ,

- Sturgiss E ,

- Dewhurst A ,

- Devereux-Fitzgerald A ,

- Haesler E ,

- van Weel C ,

- Gulliford MC

- Fassbender JE ,

- Sarwer DB ,

- Brekke HK ,

An official website of the United States government

Here’s how you know

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( A locked padlock ) or https:// means you’ve safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Heart-Healthy Living

- High Blood Pressure

- Sickle Cell Disease

- Sleep Apnea

- Information & Resources on COVID-19

- The Heart Truth®

- Learn More Breathe Better®

- Blood Diseases and Disorders Education Program

- Publications and Resources

- Blood Disorders and Blood Safety

- Sleep Science and Sleep Disorders

- Lung Diseases

- Health Disparities and Inequities

- Heart and Vascular Diseases

- Precision Medicine Activities

- Obesity, Nutrition, and Physical Activity

- Population and Epidemiology Studies

- Women’s Health

- Research Topics

- Clinical Trials

- All Science A-Z

- Grants and Training Home

- Policies and Guidelines

- Funding Opportunities and Contacts

- Training and Career Development

- Email Alerts

- NHLBI in the Press

- Research Features

- Past Events

- Upcoming Events

- Mission and Strategic Vision

- Divisions, Offices and Centers

- Advisory Committees

- Budget and Legislative Information

- Jobs and Working at the NHLBI

- Contact and FAQs

- NIH Sleep Research Plan

- < Back To Research Topics

Obesity Research

Language switcher.

Over the years, NHLBI-supported research on overweight and obesity has led to the development of evidence-based prevention and treatment guidelines for healthcare providers. NHLBI research has also led to guidance on how to choose a behavioral weight loss program.

Studies show that the skills learned and support offered by these programs can help most people make the necessary lifestyle changes for weight loss and reduce their risk of serious health conditions such as heart disease and diabetes.

Our research has also evaluated new community-based programs for various demographics, addressing the health disparities in overweight and obesity.

NHLBI research that really made a difference

- In 1991, the NHLBI developed an Obesity Education Initiative to educate the public and health professionals about obesity as an independent risk factor for cardiovascular disease and its relationship to other risk factors, such as high blood pressure and high blood cholesterol. The initiative led to the development of clinical guidelines for treating overweight and obesity.

- The NHLBI and other NIH Institutes funded the Obesity-Related Behavioral Intervention Trials (ORBIT) projects , which led to the ORBIT model for developing behavioral treatments to prevent or manage chronic diseases. These studies included families and a variety of demographic groups. A key finding from one study focuses on the importance of targeting psychological factors in obesity treatment.

Current research funded by the NHLBI

The Division of Cardiovascular Sciences , which includes the Clinical Applications and Prevention Branch, funds research to understand how obesity relates to heart disease. The Center for Translation Research and Implementation Science supports the translation and implementation of research, including obesity research, into clinical practice. The Division of Lung Diseases and its National Center on Sleep Disorders Research fund research on the impact of obesity on sleep-disordered breathing.

Find funding opportunities and program contacts for research related to obesity and its complications.

Current research on obesity and health disparities

Health disparities happen when members of a group experience negative impacts on their health because of where they live, their racial or ethnic background, how much money they make, or how much education they received. NHLBI-supported research aims to discover the factors that contribute to health disparities and test ways to eliminate them.

- NHLBI-funded researchers behind the RURAL: Risk Underlying Rural Areas Longitudinal Cohort Study want to discover why people in poor rural communities in the South have shorter, unhealthier lives on average. The study includes 4,000 diverse participants (ages 35–64 years, 50% women, 44% whites, 45% Blacks, 10% Hispanic) from 10 of the poorest rural counties in Kentucky, Alabama, Mississippi, and Louisiana. Their results will support future interventions and disease prevention efforts.

- The Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos (HCHS/SOL) is looking at what factors contribute to the higher-than-expected numbers of Hispanics/Latinos who suffer from metabolic diseases such as obesity and diabetes. The study includes more than 16,000 Hispanic/Latino adults across the nation.

Find more NHLBI-funded studies on obesity and health disparities at NIH RePORTER.

Read how African Americans are learning to transform soul food into healthy, delicious meals to prevent cardiovascular disease: Vegan soul food: Will it help fight heart disease, obesity?

Current research on obesity in pregnancy and childhood

- The NHLBI-supported Fragile Families Cardiovascular Health Follow-Up Study continues a study that began in 2000 with 5,000 American children born in large cities. The cohort was racially and ethnically diverse, with approximately 40% of the children living in poverty. Researchers collected socioeconomic, demographic, neighborhood, genetic, and developmental data from the participants. In this next phase, researchers will continue to collect similar data from the participants, who are now young adults.

- The NHLBI is supporting national adoption of the Bright Bodies program through Dissemination and Implementation of the Bright Bodies Intervention for Childhood Obesity . Bright Bodies is a high-intensity, family-based intervention for childhood obesity. In 2017, a U.S. Preventive Services Task Force found that Bright Bodies lowered children’s body mass index (BMI) more than other interventions did.

- The NHLBI supports the continuation of the nuMoM2b Heart Health Study , which has followed a diverse cohort of 4,475 women during their first pregnancy. The women provided data and specimens for up to 7 years after the birth of their children. Researchers are now conducting a follow-up study on the relationship between problems during pregnancy and future cardiovascular disease. Women who are pregnant and have obesity are at greater risk than other pregnant women for health problems that can affect mother and baby during pregnancy, at birth, and later in life.

Find more NHLBI-funded studies on obesity in pregnancy and childhood at NIH RePORTER.

Learn about the largest public health nonprofit for Black and African American women and girls in the United States: Empowering Women to Get Healthy, One Step at a Time .

Current research on obesity and sleep

- An NHLBI-funded study is looking at whether energy balance and obesity affect sleep in the same way that a lack of good-quality sleep affects obesity. The researchers are recruiting equal numbers of men and women to include sex differences in their study of how obesity affects sleep quality and circadian rhythms.

- NHLBI-funded researchers are studying metabolism and obstructive sleep apnea . Many people with obesity have sleep apnea. The researchers will look at the measurable metabolic changes in participants from a previous study. These participants were randomized to one of three treatments for sleep apnea: weight loss alone, positive airway pressure (PAP) alone, or combined weight loss and PAP. Researchers hope that the results of the study will allow a more personalized approach to diagnosing and treating sleep apnea.

- The NHLBI-funded Lipidomics Biomarkers Link Sleep Restriction to Adiposity Phenotype, Diabetes, and Cardiovascular Risk study explores the relationship between disrupted sleep patterns and diabetes. It uses data from the long-running Multiethnic Cohort Study, which has recruited more than 210,000 participants from five ethnic groups. Researchers are searching for a cellular-level change that can be measured and can predict the onset of diabetes in people who are chronically sleep deprived. Obesity is a common symptom that people with sleep issues have during the onset of diabetes.

Find more NHLBI-funded studies on obesity and sleep at NIH RePORTER.

Learn about a recent study that supports the need for healthy sleep habits from birth: Study finds link between sleep habits and weight gain in newborns .

Obesity research labs at the NHLBI

The Cardiovascular Branch and its Laboratory of Inflammation and Cardiometabolic Diseases conducts studies to understand the links between inflammation, atherosclerosis, and metabolic diseases.

NHLBI’s Division of Intramural Research , including its Laboratory of Obesity and Aging Research , seeks to understand how obesity induces metabolic disorders. The lab studies the “obesity-aging” paradox: how the average American gains more weight as they get older, even when food intake decreases.

Related obesity programs and guidelines

- Aim for a Healthy Weight is a self-guided weight-loss program led by the NHLBI that is based on the psychology of change. It includes tested strategies for eating right and moving more.

- The NHLBI developed the We Can! ® (Ways to Enhance Children’s Activity & Nutrition) program to help support parents in developing healthy habits for their children.

- The Accumulating Data to Optimally Predict obesity Treatment (ADOPT) Core Measures Project standardizes data collected from the various studies of obesity treatments so the data can be analyzed together. The bigger the dataset, the more confidence can be placed in the conclusions. The main goal of this project is to understand the individual differences between people who experience the same treatment.

- The NHLBI Director co-chairs the NIH Nutrition Research Task Force, which guided the development of the first NIH-wide strategic plan for nutrition research being conducted over the next 10 years. See the 2020–2030 Strategic Plan for NIH Nutrition Research .

- The NHLBI is an active member of the National Collaborative on Childhood Obesity (NCCOR) , which is a public–private partnership to accelerate progress in reducing childhood obesity.

- The NHLBI has been providing guidance to physicians on the diagnosis, prevention, and treatment of obesity since 1977. In 2017, the NHLBI convened a panel of experts to take on some of the pressing questions facing the obesity research community. See their responses: Expert Panel on Integrated Guidelines for Cardiovascular Health and Risk Reduction in Children and Adolescents (PDF, 3.69 MB).

- In 2021, the NHLBI held a Long Non-coding (lnc) RNAs Symposium to discuss research opportunities on lnc RNAs, which appear to play a role in the development of metabolic diseases such as obesity.

- The Muscatine Heart Study began enrolling children in 1970. By 1981, more than 11,000 students from Muscatine, Iowa, had taken surveys twice a year. The study is the longest-running study of cardiovascular risk factors in children in the United States. Today, many of the earliest participants and their children are still involved in the study, which has already shown that early habits affect cardiovascular health later in life.

- The Jackson Heart Study is a unique partnership of the NHLBI, three colleges and universities, and the Jackson, Miss., community. Its mission is to discover what factors contribute to the high prevalence of cardiovascular disease among African Americans. Researchers aim to test new approaches for reducing this health disparity. The study incudes more than 5,000 individuals. Among the study’s findings to date is a gene variant in African Americans that doubles the risk of heart disease.

Explore more NHLBI research on overweight and obesity

The sections above provide you with the highlights of NHLBI-supported research on overweight and obesity . You can explore the full list of NHLBI-funded studies on the NIH RePORTER .

To find more studies:

- Type your search words into the Quick Search box and press enter.

- Check Active Projects if you want current research.

- Select the Agencies arrow, then the NIH arrow, then check NHLBI .

If you want to sort the projects by budget size — from the biggest to the smallest — click on the FY Total Cost by IC column heading.

- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 05 July 2019

Obesity prevention and the role of hospital and community-based health services: a scoping review

- Claire Pearce ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-2129-467X 1 , 2 , 3 ,

- Lucie Rychetnik 1 , 2 , 4 ,

- Sonia Wutzke 1 an1 &

- Andrew Wilson 1 , 2

BMC Health Services Research volume 19 , Article number: 453 ( 2019 ) Cite this article

31k Accesses

31 Citations

5 Altmetric

Metrics details

Control of obesity is an important priority to reduce the burden of chronic disease. Clinical guidelines focus on the role of primary healthcare in obesity prevention. The purpose of this scoping review is to examine what the published literature indicates about the role of hospital and community based health services in adult obesity prevention in order to map the evidence and identify gaps in existing research.

Databases were searched for articles published in English between 2006 and 2016 and screened against inclusion and exclusion criteria. Further papers were highlighted through a manual search of the reference lists. Included papers evaluated interventions aimed at preventing overweight and obesity in adults that were implemented within and/or by hospital and community health services; were an empirical description of obesity prevention within a health setting or reported health staff perceptions of obesity and obesity prevention.

The evidence supports screening for obesity of all healthcare patients, combined with referral to appropriate intervention services but indicates that health professionals do not typically adopt this practice. As well as practical issues such as time and resourcing, implementation is impacted by health professionals’ views about the causes of obesity and doubts about the benefits of the health sector intervening once someone is already obese. As well as lacking confidence or knowledge about how to integrate prevention into clinical care, health professional judgements about who might benefit from prevention and negative views about effectiveness of prevention hinder the implementation of practice guidelines. This is compounded by an often prevailing view that preventing obesity is a matter of personal responsibility and choice.

Conclusions

This review highlights that whilst a population health approach is important to address the complexity of obesity, it is important that the remit of health services is extended beyond medical treatment to incorporate obesity prevention through screening and referral. Further research into the role of health services in obesity prevention should take a systems approach to examine how health service structures, policy and practice interrelationships, and service delivery boundaries, processes and perspectives impact on changing models of care.

Peer Review reports

Chronic diseases place a significant burden on the Australian healthcare system. They account for 90% of all deaths [ 1 ] and significantly reduce quality of life [ 2 ]. Being obese is a major risk factor for many chronic diseases including heart disease, cancer, kidney failure, pulmonary disease and diabetes [ 3 , 4 ]. Being overweight can impede the management of chronic conditions and is the second highest contributor to burden of disease. Obesity has been shown to reduce quality-adjusted life expectancy [ 5 ].

The World Health Organisation (WHO) highlights prevention of obesity as an important priority to reduce the impact of non-communicable disease. Both supporting people who are currently overweight to attain modest weight loss as well as preventing further increases in weight may eventually see a decrease in overall rates of obesity and a reduction in the rates of chronic diseases [ 6 ] and therefore a decrease in associated costs [ 7 ].

International guidelines recommend that preventive care be provided across the whole health system, integrated into ‘curative’ or disease management focused consultations, regardless of age or health status [ 8 ]. For obesity prevention, there are specific guidelines for the role of the general practitioner, for example the Royal Australian College of General Practitioners ‘Guidelines for preventive activities in general practice’ [ 9 ]. However, the prevention role of hospital and community health services is not as clearly articulated, particularly in relation to an adult population.

In this research we present a review of published literature investigating the role of hospital and community based health services in adult obesity prevention. The aim is to improve understanding of the role for hospital and community based health services in prevention as well as the potential enablers and barriers to the delivery of preventive health services in order to inform future research to support the development of obesity prevention guidelines applicable to a range of health service settings.

A scoping review [ 10 ] was conducted to map evidence and identify gaps in the extent, range, and nature of research undertaken in relation to the role of health services in obesity prevention. The focus of the review was on hospital and community based health services as unlike primary care, the roles of these services in obesity prevention are not clearly outlined in clinical guidelines.

Research question

The overarching question for this scoping study was: What does the peer reviewed literature reveal about the role of adult health services (excluding general practice) in the provision of obesity prevention and what are the key elements of implementation?

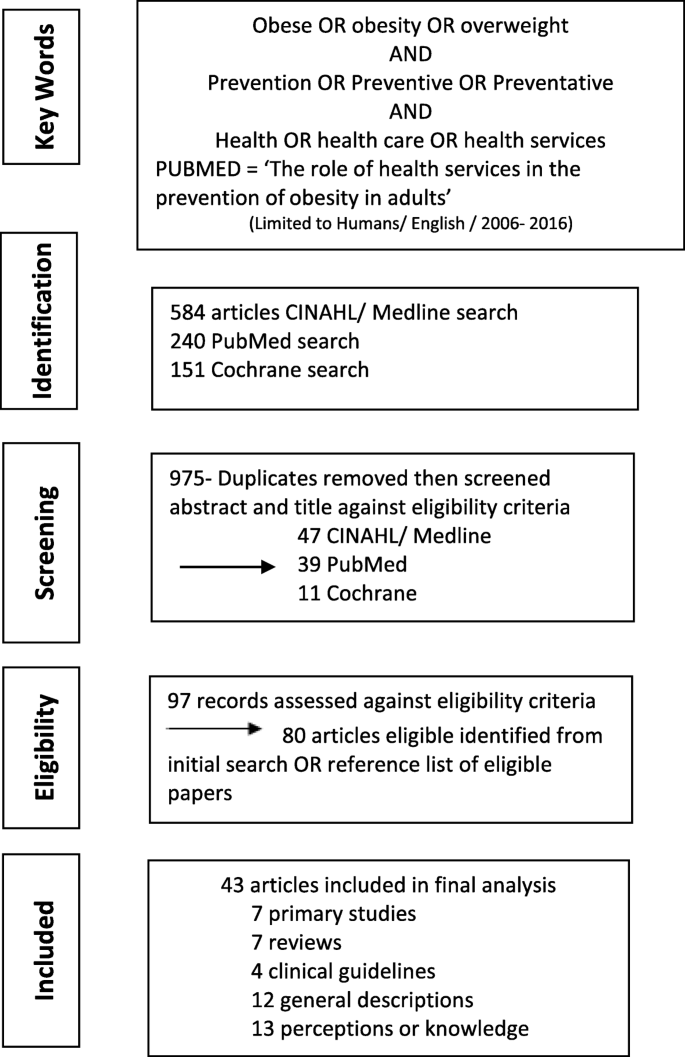

Data sources and search

Three databases (CINAHL and Medline concurrently and PubMed) were searched for references containing the words “obese” AND “prevent*” AND “healthcare/ health services” AND “adult”. Medline and CINAHL were searched concurrently to cover medical, nursing and allied health research. PubMed was searched to pick up those articles not yet assigned MESH headings. For practical reasons, the scope was limited to articles published in English between 2006 and 2016 (November). The Cochrane database was searched using the phrase “Prevention of overweight and obesity” to include systematic reviews conducted in the last 10 years.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

As the aim of the review was to highlight clinical interventions as well as issues relating to implementation, papers were included if they fell into any of the following categories: (1) Evaluation of a specific hospital or community health based obesity prevention intervention; (2) Clinical guidelines featuring obesity prevention; (3) Systematic or scoping reviews of health service based obesity prevention or (4) Empirical description of obesity prevention within a health setting. A fifth category was identified in the process of undertaking the review: (5) Health staff or health service consumer perceptions of and beliefs about obesity and obesity prevention. For each of these categories, the focus of the intervention was on services for adults. We included primary studies as well as literature reviews.

Articles that were excluded were those that:

focused on prevention of childhood obesity;

were medical treatments aimed solely at weight loss, such as surgical or pharmaceutical interventions;

described an intervention that did not take place in a health setting or if that setting was focused solely on the role of general practitioners.

Papers were also excluded if they described obesity or associated disease but did not focus on interventions with a goal of prevention or if the focus was on population health initiatives that were not within the remit of health services, such as introducing food taxes. Opinion pieces and editorials were not included.

Data extraction

All articles were reviewed and divided into the categories described above. Information was summarised using a standardised extraction form developed for the review (see Tables 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 ) to identify the clinical areas where prevention is effective and the fundamental elements of implementation.

The primary aim of analysis was to determine the main factors in delivering adult obesity prevention within a health setting. Analysis commenced with an examination of intervention type, sample size, setting and duration. Studies were then grouped into categories that were empirically derived from the type of studies identified as summarised in Tables 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 . Analysis has been framed with the 5As framework [ 9 ] which is utilised as a preventative healthcare tool to identify risk factors for chronic disease. It originated as a smoking cessation tool but has been adapted for use with obesity.

Literature search

An initial PubMed search using the search terms “obese” AND “prevent*” AND “healthcare/ health services” AND “adult”, produced 710 articles. The first 40 of these articles were screened and found to be highly irrelevant. Subsequently, the PubMed search was changed to a title search “The Role of Health Services in the Prevention of Overweight and Obesity in Adults”. This produced 240 references, which on initial scan appeared to highlight more relevant documents. CINAHL and Medline searches using the same search terms produced 584 articles which on screening appeared to hold relevant studies. The Cochrane database search resulted in 151 references.

All references were then screened for duplicates before being assessed against the specific inclusion/ exclusion criteria. Further references were highlighted through a manual search of the reference list of those references which met the inclusion criteria. In all, 43 articles were included for review. Figure 1 presents the review flow chart.

Scoping review flow chart

Scope of literature by category

Of the 43 papers included in the review, seven were primary studies of a specific health based obesity prevention intervention (Category 1) and seven were scoping or systematic reviews of specific health based obesity prevention interventions (Category 2). Four clinical guidelines were included (Category 3); two specific to the Australian context [ 9 , 41 ], one from the United States [ 42 ] and one from the United Kingdom [ 43 ]. One guideline, the Royal Australian Council of General Practitioners (RACGP) Red Book [ 44 ] focussed on primary healthcare but was included as it does examine implementation of the 5As framework. This framework is frequently utilised in preventive care and though most commonly used in primary care, is one which is applicable to a range of health services. The other three focus on primary healthcare, but also consider other health services. A group of 12 papers (Category 4) provided general descriptions of obesity prevention interventions within health settings. Thirteen papers (Category 5) surveyed health professionals or consumers about their perceptions or knowledge of obesity and/or obesity prevention. A summary of the papers in each category, and the extracted data can be found in Tables 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 .

How the 5A framework informs obesity prevention

The specific health based obesity prevention interventions (Category 1 and 2), were examined using the 5As framework [ 44 ]. The 5As framework is used to identify risk factors for chronic disease, including obesity, and to plan interventions to take into account the behavioural and physiological elements to be addressed [ 45 ]. The 5As refer to Ask (about risk factors); Assess (level of risk factors, health literacy and readiness to change); Advise/ Agree (use motivational interviewing to agree goals); Assist (develop a plan to address goals) and Arrange (organise support to achieve goals and maintain change) [ 44 ].

Whilst not all the papers explicitly referred to the 5As, elements of the framework were noted in each of the seven primary studies and three of the six literature reviews concerned with health service based prevention interventions. In the section below we apply the 5A framework to consider different elements of obesity prevention and how these have been reported in the literature.

Ask and assess

For this review, Ask and Assess have been considered together as both focus on gathering the initial information which will determine the next step. A focus on screening is supported by evidence which shows that weighing people and discussing the risks associated with putting on excess weight has an impact on individual knowledge and readiness for change which are basic factors if obesity prevention is to be effective [ 36 , 46 ]. The US Preventive Task Force and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute guidelines recommend health services screen all adults for obesity [ 42 ].

Screening should include not only identifying risk factors but also ascertaining if a person is wanting to make changes to address the risk factors and their ability to do so based on factors such as health literacy, which is an individual’s ability to understand, interpret and apply information to their own health and healthcare [ 47 ]. In the included studies, there was a focus on determining risk factors but not on establishing an individual’s health literacy. The seven evaluation based papers identified a need to assess for obesity risk factors and the potential impact of these on health but only one [ 12 ] specifically concluded that there is a need to train staff in issues such as health literacy and readiness for change. This factor was missing all together from the systematic review summarising best practice in applying the framework [ 23 ].

All the primary study papers (Category 1) concluded that there is a role for health professionals in the provision of prevention advice and five of these seven studies discussed providing specific training to support this role [ 12 , 13 , 15 , 16 , 17 ]. However, targeted training does not automatically change practice. Two studies, one with community health staff and one with mental health clinicians, found that training changed practice in terms of assessment of risk factors but did not change practice in relation to providing advice [ 16 , 17 ]. In studies which reported that clinicians did provide advice, in most cases patients could recall that advice but these papers did not report on whether the people receiving the advice changed their behaviour or on the long term retention of that advice [ 11 , 12 , 13 , 15 ]. One systematic review [ 23 ] framed ‘advise’ in terms of telling people they needed to lose weight and how they should do that on the basis that sustained weight loss has the most significant impact on health. It did not consider supporting people to set their own goals around their weight or risk factors. The remaining six literature reviews did not report on health professionals providing advice.

The next step of the 5As framework is providing intervention aimed at assisting people to set goals to self-manage lifestyle changes. The primary studies (category 1) did not address this element, instead framing the role of health services not as providing support but instead referring to other agencies to provide this support. One literature review concluded that intensive long term support was required to assist people to embed changes but did not provide specific details of what this might look like [ 23 ]. Another concluded that assisting people to set goals related to weight management achieves better outcomes than linking goals to more general improvements in health [ 20 ]. The remaining literature reviews did not address the ‘assist’ element.

The final step of the 5As framework recommends providing support to help people achieve and maintain their weight goals. Three of the Category 1 health service evaluations focussed specifically on this step. All were unsuccessful in increasing health professional’s rate of referral to support services. [ 15 , 16 , 17 ]. For example, a recent study undertaken across several community health centres focussed on supporting community health staff to incorporate assessment, brief advice and referral in relation to addressing chronic disease risk factors, including obesity risk factors. The intervention was well supported over the 12 months of implementation by a range of initiatives including pre-intervention policy change, electronic resources and staff training. The intervention was successful in getting staff to undertake more assessments for risk factors but did not change practice in relation to brief advice or referral for intervention [ 17 ] . Similar results were obtained within a community mental health setting, concluding that even when clinical guidelines explicitly direct clinicians to incorporate preventive care into interactions, rates of care given around issues such as fruit and vegetable intake or physical activity remain low [ 16 ]. The study concluded that prevention may need to be delivered within a different model of care [ 16 ]. Two of the systematic reviews concluded that successful obesity prevention needs to include the provision of or referral to intensive, multicomponent behavioural interventions which aim to support weight loss and management [ 21 , 23 ].

Clinical areas in which obesity prevention may be warranted

The National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Clinical Practice Guidelines [ 6 ] identify different life stages where there is a greater risk of weight gain. The empirical studies were therefore analysed to identify the clinical areas where prevention may have the most significant impact and the specific elements key to working with these clinical groups. Fifteen of the papers included in the review focused on a particular life stage or cohort of patients. The clinical areas identified were maternity, which has received the most focus but has not been rigorously evaluated [ 13 , 14 , 26 , 27 , 31 , 33 , 34 , 36 , 48 ] and mental health [ 37 ]. Definitive evidence of how obesity prevention should be delivered in mental health services was not available.

The papers which focussed on maternity based services highlight the immediate consequences of maternal obesity including higher rates of gestational diabetes, high blood pressure and pre-eclampsia and higher risk births. Excess weight gain in pregnancy combined with not losing the weight after pregnancy are predictors of long-term maternal obesity and increases the risk of the child developing obesity whilst mothers with gestational diabetes are more likely to develop type 2 diabetes later in life [ 36 ]. Along with the individual risks to mother and child, there is an increased demand for services and a requirement for more specialised services to support woman and baby both during and after the birth [ 18 , 26 , 30 , 31 , 33 , 34 ].

Only one of the papers targeting obesity prevention in maternity care settings reported on a specific intervention. This found that women at risk of gestational diabetes who receive advice in relation to limiting weight gain during pregnancy are less likely to develop diabetes despite no significant difference in weight gain compared with a control group [ 13 ]. The other maternity focussed papers were more descriptive, providing a broad overview of implementation factors including the need for a multidisciplinary approach to reinforce the benefits of diet and physical activity beyond weight management. For example, obese pregnant women who are physically active have been shown to experience less depressive symptoms and report higher quality of life to obese women who are not physically active in pregnancy [ 14 ]. Two papers stated that discussions about safe weight gain and weight management needs to be done in a way that does not stigmatise or cause feelings of shame [ 27 , 33 ].

Only one paper looked at a life stage other than child bearing years, namely older adults [ 29 ]. This paper summarised the results of a large survey, focussing specifically on older persons’ perceptions of receiving weight management advice. As with similar studies looking at the adult population more generally [ 28 ], it was found that older adults were more likely to receive lifestyle advice if they were already obese or had a number of chronic conditions [ 29 ]. The disadvantage of many of the survey based studies was the reliance on self-reported weight and height.

In terms of specific clinical areas, studies have been conducted in mental health and community health services. It was reported that it is very difficult to change the practice of mental health staff to include a focus of physical health risk factors [ 16 ] with mental health clinicians not necessarily seeing this as their role [ 37 ] despite the fact that people with mental illness do want to reduce their risk factors [ 40 ]. Similarly in services delivering general community health care, despite the presence of risk factors and an openness by clients to receive preventive advice, community health staff do not deliver opportunistic prevention, particularly in relation to diet [ 8 , 17 ].

Perceptions and beliefs towards obesity prevention in health services

This review found that along with practical barriers to changing practice including a lack of time, resources or clinical guidelines [ 34 , 38 , 39 , 49 ], a key barrier to healthcare based obesity prevention is the perceptions and beliefs of health professionals towards obesity. As well as lacking confidence or knowledge about how to integrate prevention into clinical care, health professionals may simply not see it is their role [ 37 ]. There is also an issue with judgements being made in relation to who might benefit from prevention along with a negative view of the effectiveness of prevention, compounded by a view that preventing obesity is a matter of personal responsibility and choice [ 25 , 38 ].

The 13 studies which specifically looked at this issue are summarised in Category 5 of Tables 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 . These papers used a range of methods to ascertain attitudes, including questionnaires or surveys [ 8 , 32 , 36 , 37 , 39 , 40 , 46 , 49 , 50 ] and semi-structured interviews or focus groups [ 33 , 34 , 35 , 38 ] and were conducted with health professionals [ 33 , 34 , 35 , 37 , 38 , 39 , 49 , 50 ] and consumers [ 8 , 32 , 36 , 40 , 46 ]. Due to the range of methods and small numbers of many of the studies the results are not necessarily generalisable but a recurrence of themes indicates that perceptions and beliefs should be considered when incorporating obesity prevention into health care services.

The view of health professionals, that prevention is not their role, may be reinforced by the fact that they will probably not have had specific training in assessment and advice [ 16 ]. They may make judgements on who would benefit from preventive advice and tend to only raise the issue of weight if they know the patient [ 38 ]. Whilst health professionals are aware of the health implications of excess weight there may be a perception that they cannot be effective in their role due to a lack of patient motivation to enact change [ 25 ]. Other studies have shown that patients may not be told they are overweight or have the health consequences of being overweight discussed [ 21 , 32 ]. This is despite evidence to suggest that being told firstly they are overweight and secondly the health risks of excess weight can impact on an individual’s readiness to make changes to diet and levels of physical activity [ 28 ]. When discussions do occur, they are more likely to be with people who are already obese [ 24 , 28 ] or who have more frequent health encounters indicating that they have more complex health problems [ 29 ]. By clinicians not discussing weight and lifestyle with people before it becomes a significant problem there is a missed opportunity to prevent illness development based on known risk factors.

The uptake of prevention may also be impacted by a view that obesity is an issue of lifestyle choice and personal responsibility and therefore not the responsibility of health services unless linked to the treatment of a specific clinical condition [ 35 , 38 ]. Clinical guidelines may not be consistently followed because of a lack of knowledge of the guidelines existence or a belief that the guidelines will be ineffective due to pre-conceived ideas about the group of clients being targeted or a lack of confidence in the guidelines [ 19 , 35 ] . Specific to maternity services, clinicians acknowledge that weight gain in pregnancy is an issue but do not perceive that their patients see it as a problem [ 30 ]. In some instances, health professionals don’t feel confident talking to their patients about excess weight [ 35 , 38 , 39 , 51 ]. These findings occur even in areas where policy is in place directing clinicians to incorporate prevention, highlighting the need for more comprehensive, multi component change management strategies to enable health professionals to develop their practice to incorporate prevention routinely into interventions [ 8 ].

Without further training, baseline knowledge on appropriate interventions to support obesity prevention is generally poor [ 39 ] and advice may be given based on the clinicians own experience of weight management [ 38 ]. Educating staff about prevention may lead to an increase in assessment of risk but not a significant increase in brief advice or referral to other services for prevention intervention [ 15 , 17 ]. Both of these later elements are key to impacting on an individual’s chronic disease risk profile [ 16 ]. Training of staff may need to extend beyond principles of prevention and also include training on communicating complex information to people with low health literacy. This should include teaching techniques to ensure health professionals clarify their patient has understood information, [ 12 ] as this is a significant element in someone being able to adopt and follow preventive care advice [ 45 ].

However, the evidence of what education strategies are most effective, particularly in relation to increasing assessment and referral across all risk factors, is limited [ 52 ]. A systematic review of interventions to change the behaviour of health professionals found just six randomised control trials and the combined results of these were ambiguous [ 19 ]. When specifically looking at factors influencing health professionals decision to provide counselling regarding physical activity, the health professionals own levels of physical activity, whether or not they have specific training, knowing the patient well and the patient having risk factors for chronic disease were all influencing factors [ 22 ].

This review examined the literature in order to ascertain the role of hospital and community- based health services in adult obesity prevention as well as the potential enablers and barriers to the delivery of preventive health services. Whilst it is acknowledged that the health care system alone is not the answer to reducing the population impact of obesity [ 53 ], there is evidence that health services can significantly contribute to obesity prevention commencing with screening all patients for risk factors and providing brief advice. This should be followed up with referral to a service which provides long term follow-up with a focus on lifestyle change rather than just weight loss and should include consideration of an individual’s health literacy [ 41 , 42 , 43 , 44 ].

However, the reviewed evidence indicates that existing clinical guidelines, including the application of the 5As framework, are not being fully implemented. Where training and resources have focussed on prevention, there is an increase in the rate of screening provided but only a limited change in the rates of brief advice or referral to an intervention service [ 12 , 15 , 16 , 17 ]. Whilst assessment of risk factors may offer some benefits, greater change is achieved when this is followed up by advice and clear, individualised input to assist people to apply the advice to their own circumstances [ 54 ].

In taking a scoping approach to the role of health services, this review was able to draw out that a significant barrier to the implementation of prevention guidelines are the perceptions of health professionals. They may not see prevention as their role [ 16 ], make judgements about the causes of and responsibility for an individual’s weight, or make subjective decisions about who will benefit from their advice [ 25 , 35 , 38 ]. Health professionals may also not feel sufficiently confident to raise the issue of weight because of the social meanings attached or lack of knowledge [ 35 , 38 , 39 , 51 ]. Our review reveals these issues are common to nursing, allied health and medical staff.

Health care is predominantly delivered within a reactive model of care which is at odds with the concept of prevention [ 55 ]. Whilst there are obesity prevention guidelines which highlight the need to apply a framework such as the 5As, this fundamentally linear tool is designed to work within a traditional health care approach which focusses on the diagnosis and treatment of acute disease. As has been shown by this review, health professionals’ willingness or ability to change practice may be influenced by a range of factors, including their personal perceptions of obesity and of the potential value of prevention. So, whilst at a macro level policy and guidelines may be in place, implementation is hindered at a meso level by the mismatch between the medical model and the multifactorial causes of obesity and at a micro level by the impact of personal beliefs on patient interaction. Each of the factors dynamically influence the others so need should not be considered in isolation [ 53 ].

Changing the health system to implement effective action for the prevention of obesity therefore calls for an examination of the issues through a systems lens rather than taking a simple problem-solution driven approach. Health services are a complex system, constituted of a range of people, processes, activities, settings and structures. The interrelationships, boundaries, processes and perspectives connect in dynamic and non-linear ways which may result in emergent self-organised behaviour [ 56 ]. Importantly it should be acknowledged that systems are often nested within other systems with their own dynamics at play. Consequently, a search for solutions means identifying multiple causes as well as multiple points for intervention and being aware of unintended consequences [ 2 , 57 ]. The studies identified by this review focussed on a linear approach to implementing guidelines or examined the perspectives of just one clinical team or group within a system. There is a need for research to be undertaken which, using a systems approach, examines the opportunities and threats to prevention from the perspective of a range of players within the system and considers how these perspectives might be influenced by policy and guidelines, as well as each other. This could include looking at moving beyond traditional structural boundaries to look at alternative models of care to the medical model including the use of support roles outside of those typically considered to be health professionals, particularly in the role of ongoing support [ 56 , 58 ].

Obesity is often described as a ‘wicked’ problem due to the multifactorial causes requiring complex solutions. Whilst a population health approach is important to address this complexity, it is important that the remit of health services is extended beyond medical treatment to incorporate obesity prevention. [ 59 ]. Though this scoping review has demonstrated that there is evidence for incorporating obesity prevention into clinical care, research to date has taken a linear approach to the implementation of guidelines without explicitly factoring in the impact of the perceptions of clinicians and managers to the prevention role or addressing the individual responsibility discourse. Further research into the role of health services in obesity prevention should take a systems approach to examine the impacts of changing models of care whilst also taking into account the perceptions of health staff towards obesity and obesity prevention and the breadth of issues impacting on each individual’s ability to make lifestyle changes.

Strengths and limitations of the reviews

This review contributes to an understanding of the role of health services in obesity prevention by specifically focussing on services outside of primary health. The use of a scoping review allowed for broad coverage of the literature in order that the main issues could be highlighted in order to inform health policy, clinical practice and future research. The broad aims of the review may impact on attempts to replicate the review. Limiting the review to English language references may have excluded some evidence.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable

Abbreviations

National Health and Medical Research Council

Royal Australian College of General Practitioners

World Health Organisation

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Premature mortaility from chronic disease. Canberra: AIHW; 2010.

Google Scholar