Greater Good Science Center • Magazine • In Action • In Education

How to Empower Students to Take Action for Social Change

Young people are increasingly aware and concerned about the problems our world is confronting, from climate change to racial disparities in society. When facing social problems, how can educators transform a child’s sense of helplessness toward hope and action?

Educators must not allow our adolescents to languish in the face of social problems and injustice. In James Baldwin’s 1963 Talk to Teachers , he reminds us of this charge: “Our obligation as educators is to entrust in our students the abilities to create conscious citizens who are vocal about reexamining their society.” It is the moral imperative of public education to foster student agency to nurture an engaged citizenry.

At the Rutgers University Social-Emotional Character Development Laboratory’s Students Taking Action Together project , we have developed a social problem-solving and action strategy, PLAN, that makes it possible for teachers to transform students’ sense of hopelessness into empowerment. It allows students to investigate a particular social problem to get to the root cause, then design an action plan to challenge the dominant power structure to make change. It emphasizes considering the issue from multiple viewpoints to develop a solution that is inclusive and viable.

Below, we’ll describe the four components of PLAN and demonstrate how to use PLAN to empower students in grades 5-12 to take action. We hope these strategies can help you encourage your students to be more deeply engaged with today’s problems and inspired to take social action.

P: Create a Problem description

Problems are an inherent part of our daily lives, and one of the key problem-solving skills is the ability to define a problem.

To define a problem, students working collaboratively in groups of four or five start by reviewing background sources, such as articles, speeches, and podcast episodes, and then draft a problem description . They can discuss the following questions to frame their thinking. Not all questions will be answered, yet the discussion will guide and stretch their thinking to begin defining the problem:

- Is there a problem? How do you know?

- What is the problem?

- Who is impacted by the problem?

- What are the issues from each perspective/party involved? What is the impact on the different individuals/groups involved?

- Who is responsible for the problem? What internal and external factors might have influenced this issue?

- What is causing those responsible to use these practices?

- Who were the key people involved in making important decisions?

To illustrate this process, let’s use the example of a recent issue: Texas’s refusal of federal funding to expand health care under the Affordable Care Act for all citizens of the state. For this issue, students might write the following problem description:

Along with Texas, 13 other states have refused to accept federal funding to expand Medicaid for citizens under the Affordable Care Act (ACA). State refusals can be attributed to a variety of factors. State lawmakers fear the loss of support from voters and their political party if they accept the federal funding to expand access to health care for lower-income communities and communities of color. Public perceptions of expanding social programs and the political costs of supporting bi-partisan reform also play a role. Political obstructionism harms all citizens, causing people to go without needed medical care and perpetuating inequalities in public health.

L: Generate a List of options to solve the problem and consider the pros and cons

Organizing for change is a skill that can be taught, even though problem solving in the political arena may feel novel and uncertain for students. Stress that while there is no guarantee of a positive outcome as they tackle a problem, brainstorming effective and inclusive solutions can help stimulate deeper awareness and discussion on the need for change. According to Irving Tallman and his colleagues , this process teaches students to apply reasoning to anticipate how solutions may play out and, ultimately, arrive at an estimate of the probability of a specific result.

That’s where the second step of PLAN comes into play: listing the possible solutions and considering the optimal plan of action to pursue. Students will revisit the background sources that they consulted during step one to consider how the actual current-event problem has been addressed over time and reflect on their own solutions. We encourage you to facilitate a whole-class discussion, guided by the following questions:

- What options did the group consider to be acceptable ways to resolve the problem?

- What do you think about their solution?

- What would your solution be?

- What solution did they ultimately decide to pursue?

For example, here are some solutions that students may generate as they brainstorm around health care funding in Texas:

- Launch a letter writing campaign to Senators and Congressional representatives communicating that obstructionism of federal funding to expand health care hurts all citizens and public health.

- Develop a social media-based public service announcement about the costs of refusing federal funding to expand health care, tagging state Senators and local Congressional representatives.

- Team up with a public health advocacy organization and learn about how to support their work in key states.

Students would then weigh the pros and cons of each solution, as well as apply perspective-taking skills to consider the needs and interests of all relevant stakeholders (e.g., government officials, insurance companies, and patients) to select what they deem to be the most effective and inclusive option. In evaluating the pros and cons of all of the solutions presented above, they may determine:

- Solutions have direct routes to communicating to politicians and have a wide audience reach.

- Solutions build student’s advocacy skills and can send a clear message to lawmakers.

- Solutions enable students to rehearse the skills of correspondence, networking, and communicating their ideas and plans with outside agencies.

- Solutions require substantial time for additional research.

- In some solutions, students may not be addressing issues in the state they live.

- In the letter-writing solution, letters lack a broad reach and the identified state(s) may already be developing reasonable alternatives to accepting federal funds to expand health care access.

- The solutions will require efforts to be sustained over time and will demand additional time in or beyond the classroom to orchestrate.

This essential problem-solving skill will support students in making objective, thoughtful decisions.

A: Create an Action plan to solve the problem

After students select what they assess to be the most effective solution, they collaborate with one another to develop a specific, measurable, attainable goal and a step-by-step action plan to implement the solution. Together, researchers refer to this as the solution plan.

For example, the goal might be to develop a one-minute public service announcement about the costs of a state’s refusal to accept federal funding to expand Medicaid under the ACA.

The step-by-step solution plan should align with the goal to resolve the problem and increase positive consequences, while minimizing potential negative effects. Your students should keep the following in mind when developing their plans:

- Make steps as specific as possible.

- Consider who is responsible for implementing each step.

- Determine how long each action step will take to execute.

- Anticipate any challenges that you may face and how you will address them.

- Identify the data that you can collect to determine whether or not your action plan was successful.

Below is a sample action plan that students may develop to meet their public service announcement goal:

- Convene a group of students to conduct research on the ACA’s expansion of Medicaid and the states that have accepted federal aid and those that refused federal aid.

- Conduct research by interviewing school nurses, county health commissioners, and the state’s Department of Health for additional content.

- Collaborate with visual arts teachers and students to design and develop the video, and course-level teacher to review the video.

- Post the social media public service announcement on YouTube and share on social media, tagging the appropriate audiences.

N: Evaluate the action plan by Noticing successes

The final step of PLAN involves evaluating the success of the action plan, using the evidence collected throughout in order to notice successes. As a whole class, students consider how similar problems were solved historically, as compared to the success of their plan. They also consider aspects of the plan that went well and those that could be improved upon moving forward. Connecting to past examples of social action affirms the understanding that you don’t always get it right in the initial push for change, and that the legacy and knowledge of incomplete change is passed from one generation to the next.

A Sample Lesson

To check out how to infuse PLAN using a historic event, check out our ready-made lesson on Fredrick Douglass’s 1852 Speech: "What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?" .

Noticing successes is essential to instilling confidence in students to exercise their voice and choice by organizing for and taking social action. Research suggests that problem-solving skills help buffer against distress when people are experiencing stressful events in life. With PLAN, we have discovered that equipping our students with problem-solving skills is a strong predictor of student agency and social action . By teaching a deliberate social problem-solving strategy, we nurture hope that change can be made.

In her 2003 Teaching Community: A Pedagogy of Hope , bell hooks reminds us of the transformative power to upend the dominant power structure by bridging the gap between complaining and hope and action: “When we only name the problem, when we state a complaint without a constructive focus or resolution, we take away hope. In this way critique can become merely an expression of profound cynicism, which then works to sustain dominator culture.”

It is not enough to witness and criticize injustice. Students need to learn how to overcome injustice by developing solutions and gaining a sense of empowerment and agency.

About the Authors

Lauren Fullmer

Lauren Fullmer, Ed.D. , is the math curriculum chair and middle school math teacher at the Willow School in Gladstone, NJ; instructor for The Academy for Social-Emotional Learning in Schools—a partnership between Rutgers University and St. Elizabeth University—adjunct professor at the University of Dayton’s doctoral program, and a consulting field expert for the Rutgers Social-Emotional Character Development (SECD) Lab.

Laura Bond, M.A. , has served as a K–8 curriculum supervisor in central New Jersey. She has taught 6–12 Social Studies and worked as an assistant principal at both the elementary and secondary level. Currently, she is a field consultant for Rutgers Social Emotional Character Development Lab and serves on her local board of education.

You May Also Enjoy

These Kids Are Learning How to Have Bipartisan Conversations

Three Strategies for Helping Students Discuss Controversial Issues

How to Talk about Ethical Issues in the Classroom

Nine Ways to Help Students Discuss Guns and Violence

How to Inspire Students to Become Better Citizens

Three SEL Skills You Need to Discuss Race in Classrooms

The Seekers

- Posted November 7, 2022

- By Lory Hough

- Entrepreneurship

In the education world, it’s easy to identify problems, less easy to find solutions. Everyone has a different idea of what could or should happen, and change is never simple — or fast. But solutions are out there, especially if you look close to the source: people who have been impacted in some way by the problem. Meet eight current students and recent graduates who experienced something — sometimes pain, sometimes frustration, sometimes hope — and are now working on ways to help others.

SEEKER: Elijah Armstrong, Ed.M.'20

“This motivated me to become an activist in the space of disability and education,” he says. “Education is supposed to act as a gateway for students, but far too often, for people with disabilities, it acts as a barrier.”

His experience led him to start a nonprofit while he was in college at Penn State called Equal Opportunities for Students “as a way to help tell the stories of marginalized students in education.” Then last year, he won the 2021 Paul G. Hearne Emerging Leader Award, an award given by the American Association of People with Disabilities that recognizes up and coming leaders with disabilities. With his prize money, Armstrong started his own award program: the Heumann-Armstrong Educational Awards, named partly for disability rights activist Judy Heumann. The award is given annually to students (sixth grade and up) who have experienced ableism — the social prejudice against people with disabilities — and have fought against it.

“Students with disabilities face barriers in education that aren’t faced by their non-disabled peers,” he says. “At all levels of education, students are forced to do intense emotional and logistical labor to fight for accommodations or go without accommodations at all. This is on top of the day-to-day challenges of having a disability or chronic illness, and the challenges that go along with that. Students with disabilities should have ways of being compensated for that labor and denoting that labor on resumes.”

One of the unique aspects of the award program, he says, is that winners aren’t restricted on how they can use their award money, although several from the inaugural round have used it to fund their own activism. For example, Otto Lana, a high school student, started a company called Otto’s Mottos that sells T-shirts and letterboards to help purchase communication devices for non-speaking students who can’t afford them. Himani Hitendra, a middle schooler, has been producing videos to educate her teachers and classmates about her disability, as well as ways they can be more inclusive. Jennifer Lee, a Princeton student, founded the Asian Americans with Disabilities Initiative.

Armstrong, who is also currently living and working in Washington, D.C. as a fellow with the Congressional Black Caucus Foundation, says beyond awarding money to other young activists, one of the biggest and most impactful ways he thinks he’s helping to challenge the education system is through the videos his nonprofit produces for each of the winners.

“We highlight the award winners and give them a platform to tell their stories in a way that gives them agency,” he says. “Education doesn’t often take the voices or experiences of disabled students into account when discussing accessibility in education. We want to make sure we develop a platform that gives voice to the narratives of these students, so that everyone can listen to and learn from them.”

Learn about his nonprofit: equalopportunitiesforstudents.org

SEEKER: Elisa Guerra, Ed.M.’21

In the early 2000s, Guerra wasn’t finding the kind of educational experience for her young children near her home in Aguascalientes, México, that she was looking for — one that was warm, but also ambitious and fun and stimulating.

“I saw a gap between what schools offered at that time and what parents like me were dreaming of for their young,” she says. “After my son went through three different schools and none was a true fit, I decided that I needed to imagine and create the school I wanted for my children.”

So Guerra, without any formal teaching experience, started Colegio Valle de Filadelfia, a small preschool with 17 kids that was based on what she was doing informally at home with her ownchildren. Those first few years, she says she pretty much did every job the school had, learning along the way.

“I taught. I answered the phone. I designed our programs. I managed promotion and enrollment,” she says. “I also changed diapers, cleaned noses, and mopped puke.” For many years, she served as the principal.

She also fine-tuned their learning model, what they started calling Método Filadelfia , or the Philadelphia Method. Based on the work of Glenn Doman and The Institutes for the Achievement of Human Potential, their model isn’t your typical approach for helping young children learn.

“We teach — playfully and respectfully — tiny children, starting at age three, to read, and [we also teach] art, physical excellence, and world cultures as the first steps of global citizenship,” she says. Music lessons, including violin, are started at the preschool level, and classes are taught in two foreign languages in addition to a student’s first language. When Guerra first started the school, there were no commercial textbooks that fit what she was trying to do, so she wrote her own.

Since then, schools across Mexico, as well as Costa Rica, Colombia, Brazil, Bolivia, and Ecuador now use her textbooks. Al Jazeera made a documentary about her as part of their Rebel Educator series. Twice she was a finalist for Global Teacher of the Year. Just before the pandemic hit, she was appointed to unesco’s International Commission on the Futures of Education, a small group that includes writers, activists, professors (including Professor Fernando Reimers, Ed.M.’84, Ed.D.’88), anthropologists, entrepreneurs, and country presidents. (When UNESCO first reached out to her, she thought it was a scam and almost didn’t respond back to them.)

And it all started 23 years ago with an idea and, as she says, some naivete.

“In retrospect, it was crazy. Most people I know who have opened schools have done it ‘the right way,’ if such a thing exists,” Guerra says. “They were experienced teachers, or they even ran schools as principals, before jumping out to create a new one. They could do better because they knew better. I did not have that advantage. I had so much to learn myself. But in a way, that was also a blessing because I also had much less to ‘unlearn.’ …I said before that I became a teacher accidentally, but that is only partly accurate. Indeed, I was not expecting my life to take the path of education. But once I found myself there, it was my decision to stay. The discovery of a passion for teaching was the accident. To embrace the teaching profession was a choice.”

Read more about her work: elisaguerra.net/english/

SEEKER: Cynthia Hagan, Ed.M.’22

“I’ve lived here for 35 years and have witnessed the impact of poverty and the opioid crisis on our communities,” she says, “both on current realities and hopes for the future.”

Initially, when she first applied to Harvard, she thought she’d create a children’s program using puppets, inspired, in part, by Sesame Street , but after taking a few classes, Hagan’s ideas on how to help children in her state evolved.

“I became fascinated with the concept of designing for joy as introduced to us in the course What Learning Designers Do,” taught by Senior Lecturer Joe Blatt, she says. “Joy is an often-overlooked ingredient for learning.” The power of story also began to stick.

After creating a class project called Adventure Box, focused on increasing third-grade reading levels for children experiencing homelessness, Hagan’s idea for Book Joy emerged.

Research shows that children who are not proficient in reading by the third grade, when they transition from learning to read to reading to learn, are four times more likely to drop out of high school, and six times as likely to be incarcerated as an adult.

“I knew that the overall thirdgrade reading levels of children experiencing poverty in rural Appalachia were significantly lagging,” she says. “It just seemed like a logical move to modify Adventure Box to meet the needs of this population.”

She decided to focus first on McDowell County, West Virginia, once one of the largest coal producing areas in the world, where the child poverty rate in 2019 was a staggering 48.6%.

Hagan’s idea with Book Joy is simple but potentially life altering for the young children they began targeting starting this past September: give each incoming kindergarten student a curated box filled with high-quality books (printed and audio) based on interest and reading level, plus fun related activities to conceptualize the reading experience, and then follow up with new boxes quarterly (December, March, June) until third grade. The goal is to significantly increase third-grade reading proficiency.

For the launch this fall, Book Joy partnered with Scholastic to get discounted books and with Random House for free books. McDowell’s assistant superintendent/federal programs manager has been actively involved. Twice a year, Book Joy will conduct assessments with the students, their parents, and their teachers, to see how each box is working, and then tweak the content. They’ll also use feedback to improve on future boxes and teachers can use assessments to provide individualized intervention, as needed.

“When their interests, reading levels, or personal circumstances change,” says Hagan, “so does the contents of their box.”

Another goal for Book Joy, beyond improving third-grade reading proficiency for children in one of the poorest districts in Hagan’s state, is something fundamental to this former librarian: to bring joy to reading and learning, hence the name, Book Joy.

“Each box is truly a gift created just for them. No two boxes will be alike because no two children are alike,” she says. “And we are designing these boxes from an edutainment perspective, putting as much focus on eliciting joy as we do in choosing the best aligned reading material. We want every design element of the box, from the moment the children lay eyes on it to the emptying of every item, to elicit joy.”

Discover how you can help: givebookjoy.org

SEEKER: Ben Mackey, Ed.M.’13

In 2020, the district unanimously passed the Environmental & Climate Resolution, a massive overhaul of how schools in the Dallas Independent School District approach climate change. It includes reviewing and revising current policies across all schools and setting goals for reducing the district’s environmental footprint, while also keeping an eye on spending.

Mackey, a former math teacher and principal, says that it was young people in the district who really got the ball rolling when it came to making sure the district was thinking about its impact on the environment and then making a plan for change — something few districts are doing.

“The genesis of this resolution and the work really started with students,” he says. “When I took office in 2019, there was a small but mighty group of students who had been coming and attending every board meeting and sharing their perspectives and imploring the school board to make strides in its sustainability work. I was able to work with these students to get this resolution drafted and passed by the school board.”

What passed is a 10-year plan to drastically improve the district’s sustainability practices, including some steps that have already been taken, including switching energy plans and contracting for 100% renewable energy, which is expected to save the district $1 million a year on top of the energy benefits. By 2027, all plates, utensils, and trash bags will be 100% compostable.

Longer term, the district has applied for a federal grant to pilot 25 electric busses and will begin moving away from gas-powered maintenance equipment. It will limit synthetic fertilizer. The district also created a set of policies that say any new school built or existing school remodeled must include LEED silver certified standards. Another goal is to plant more trees to combat the “heat island” effect that schools that are primarily blacktop experience.

“One area that stuck out to our community group and administration as they were formulating the recommendation is how the increase in tree canopy cover can combat carbon emissions, improve learning environments, and serve to decrease energy usage,” he says. “We’re aiming to increase canopy cover at all campuses to at least 30% and we’re working with a number of phenomenal partner organizations to get this started, including the Texas Trees Foundation and the Cool Schools Parks initiatives.”

Mackey, who is the executive director of a statewide education nonprofit called Texas Impact Network(in addition to being on the school board), says his advice to other districts that want to reduce their school’s climate footprint is to get buy-in across the district — and just get started.

“Dallas ISD’s process started with students at our board meetings, speaking every single month, about the need and importance for this to happen. These students reached out to trustees and school staff and continued to come forward with both a charge and ideas for what success looks like,” he says. “The hardest part is often to get it off the ground and I’d encourage all who care about this to call your school board trustees and be a consistent and sensible voice who will share their mind and provide concrete solutions to make this work happen.”

Sign up for his monthly newsletters: benfordisd.com

SEEKER: Michael Ángel Vázquez, Ed.M.’19, current Ph.D. student

That’s why he’s trying to make the graduate years, at least for Ed School students, less stressful.

“I just went through this huge burst of depression my first year, my master’s year,” he says, “and I realized that I wasn’t the only one that was going through that.”

Part of the problem, says Vázquez, a former teacher in the Navajo Nation, is that while universities often offer great resources, many students don’t know where to turn for help or don’t even think they should ask for help.

“There’s so much pressure to feel like you know everything and not admit when you don’t,” he says.

Vázquez decided to create a comprehensive student-to-student guidebook, based on resources he knew about and those shared by other students. This “labor of love,” as he calls it, includes everything from where to find books and readings to how to save money, including where to grocery shop, how to sign up for MassHealth, how to apply for snap benefits, and how to sell items to other students through the Harvard Grad Market. He has a section on job hunting. The mental health section offers tips for finding therapists, wellness options at Harvard, ways to combat vitamin D deficiencies, and advice for advocating for yourself. Other documents include ways to prep for graduation, must-have lists for living in a colder climate, and a link to local tenants’ rights.

“I just felt like it was important to do whatever was possible for the next group of students to have a safe, happy experience, because, ultimately, learning should be fun, should be exciting,” he says. Endemic to being back in school, with all of the pressure, “it’s very common for that fun and excitement of learning” to take a back seat. “I don’t want that be the case. This guidebook is just one way to mitigate that a little bit and make it more fun and exciting for people.”

None of this support and concern for the well-being of other students surprises Vázquez’s professors, who point out that he has been one of the most active students since he got to Harvard. He’s been especially in-tune with first-gen students (he’s first gen, starting with attending the University of Southern California) and for students of color, both at the Ed School and at the college, where he’s a tutor at Adams House. He’s also been a teaching fellow for ethnic studies classes at the Ed School since 2019 and will now help teach ethnic studies to undergraduates at Harvard starting this fall. He hopes creating and sharing his guide helps all of the students he’s around.

“As a student and as somebody who is a teaching fellow and who has worked in different organizing groups on campus and off campus, I see that grad school and organizing are often very stressful,” he says. “I really want to drill that it’s OK to not know something and that learning is shared, which is why I did this. There were things I didn’t know at first. I want to share that knowledge with others, and I want it to be community-built. When you admit you don’t know something, that’s when you truly learn something.”

SEEKER: Grace Kossia, Ed.M.’17

“Anytime one of my friends unconsciously has a math moment, I always yell out, ‘You’re a mathematician!’” she says. “Too many people are walking through this life convinced that they could never be good at math. Math isn’t meant to be something we’re good at — it’s simply something we do, and when mistakes happen, we learn.”

It’s this philosophy that she and her coworkers bring to their edtech nonprofit based in Brooklyn, New York, playfully called Almost Fun, which last year helped 1.5 million middle and high school students with free online math lessons.

“The title ‘Almost Fun’ winks at the way students perk up when they engage with our resources and find unexpected joy while learning math,” she says. “We value being real with our students, and part of that is understanding that math can be a hard pill to swallow and that schoolwork may not be the number one thing students are going to want to do. However, with the right approach, we can curate experiences that make math learning ‘almost fun’ and something to look forward to for even the least confident learners.”

The backbone of their approach includes explaining concepts using easy-to-understand examples, rather than through clinical, mathematical definitions. Their distributive property lesson, for example, relates expanding and factoring an expression to opening and closing an umbrella. Their functions lesson uses a vending machine to explain how functions represent the relationship between inputs and outputs. Another lesson compares absolute value to the overall power of a superhero or villain.

Kossia says their site is meant to complement existing online sites like Khan Academy, which she says has been a trailblazer in edtech that serves many students. But as helpful as Khan is, some students still need more help — or just a different approach.

“There is still a critical number of students who struggle with high levels of math anxiety and low math confidence, which limits their ability to take full advantage of the support online resources like Khan offer,” she says. “At Almost Fun, we want to position ourselves as a complement to these existing resources by using creative math analogies to explain foundational math concepts and bridge the gaps in students’ math confidence and motivation, so that they can better benefit from the support other resources offer.”

Kossia remembers the gaps she struggled to fill after she immigrated to the United States from the Democratic Republic of the Congo. At the time, she was good at math, and decided to major in mechanical engineering in college. She had a hard time.

“I quickly realized that I had many gaps in my understanding of math and physics, which were essential skills I needed in this journey,” she says. “This chipped away at my confidence, but I was determined not to give up. I wanted to prove to myself and other people like me, especially Black women, that it could be done.” Later, when she worked as a physics teacher, her struggles helped her relate to students who were anxious about physics and pushed her to design creative lessons that focused on learning by doing, as opposed to learning by memorizing.

“At Almost Fun, I do the same thing but with math as the primary focus,” she says. “We believe math is more than just sets of memorized steps; it’s a way of describing relationships between things in our world.”

Access resources and lesson plans: almostfun.org

SEEKER: Shaina Lu, Ed.M.’17

“Learning about gentrification is unavoidable in placebased learning in a place like Chinatown,” Lu says. “However, it could be kind of a drag to spend your fourth-grade summer learning about gentrification.”

So Lu, an artist and former media arts teacher in Boston Public Schools, decided to make learning about this heavy topic more interesting: she created a graphic novel.

“ Noodle and Bao was my response to that feeling. I wanted to write and draw a story that elementary kids would devour and love — There’s a cat selling food in a cart! Neighborhood kids dress up and infiltrate a snobby restaurant! — but would also pay homage to some of these inspirational histories and present-day struggles they were learning about,” she says. While the novel isn’t specifically set in Boston’s Chinatown — it’s set in a fictional Town — Lu says it’s inspired by the many residents, activists, and community members of Boston’s Chinatown that she has met and worked with over the years — people who “have done so much exciting work that is more than comic book-worthy.”

Set to publish in the fall of 2024 by HarperCollins, Noodle and Bao also explores historical events from Boston’s Chinatown, most notably a fight for the land that now houses the community center where Lu worked and where elderly residents passionately voiced their displeasure to hotel developers at a meeting.

Lu says the graphic novel is just one example of something that has been important to her for many years: the intersection of art, education, and activism. Another example is a creative placemaking project she recently worked on in Chinatown with a local student in partnership with a local resident.

“The resident, youth, and I painted a community mural that featured [the resident’s] personal lens on the history of Chinatown,” she says. “The mural was painted on a condemned building on a border of Chinatown that is elslowly being eroded away by the neighboring district. It’s hard to parse out which separate part was ‘art’ or ‘activism,’ or ‘education,’ so I feel like they’re interwoven.”

Although she’s interested in teaching, Lu says classrooms are tricky places. “There’s an inherent power structure with the teacher as the fountain of knowledge and students as recipients of that.” Instead, “I’m interested in disrupting the capitalist status quo of education with ‘winners and losers’ as described by activist- philosopher Grace Lee Boggs in her 1970 essay, Education: The Great Obsession .”

She’s not interested, though, in disrupting the system on her own. “I hope to be, alongside others, building a new system, where people’s needs and interests and social responsibility define their learning, rather than their ability to produce,” she says. “There’s actually so much incredible person- centered education out there, both in and out of schools. I’ve worked with teachers who engaged students with civics project-based learning about gentrification, youth workers who have helped young people organize community gardens for their neighborhoods, and more.”

Learn about her art: shainadoesart.com

SEEKER: Justis Lopez, Current Ed.L.D. student

“I hold near to me that there are ancestors that wanted to study, but didn’t get the chance to,” he says. “There are relatives that wanted to pursue their dreams, but they put food on the table instead so that I could pursue mine, and for that I am eternally grateful and full of joy.”

It’s this gratitude and happiness for life that Lopez, a DJ known as DJ Faro (for the Spanish word, lightkeeper), is bringing to his time at the Ed School and to Project Happyvism, the culturally responsive nonprofit he started with his friend, Ryan Parker, a youth empowerment teacher and activist, that is rooted in hip hop and is a combination of happiness + activism.

“Project Happyvism is a feeling, a philosophy, and a movement that centers joy and love as a radical form of activism,” he says, meaning the commitment to loving yourself and those around you unconditionally.

“The organization embraces the beauty and need for joy,” he says, “and emphasizes the fact that maintaining happiness about who you are and what you think, say, and do in a world that consistently goes against the grain of your identity is a form of activism in itself, hence: happyvism.”

The project started from a song and video that Lopez and Parker wrote and produced and has since expanded to include helping others write songs (what they call “joy anthems”) in their recording studio, publishing a children’s book, Happyvism: A Story About Choosing Joy , and working with K–12 districts on related curriculum. They also started Joy Lab, a community gathering space in Manchester, Connecticut, where Lopez grew up, that offers yoga, wellness and equity workshops, and book readings. He plans on starting a Joy Lab at the Ed School during his time here.

“I’m just trying to create the spaces I wish I had for myself growing up,” Lopez says. “Spaces that center healing, hope, and hip hop.”

Although this is his first year as a student at the Ed School, Lopez has been involved with the school in the past, including as an organizer, MC, and DJ at the Alumni of Color Conference, thanks to Lecturer Christina Villarreal, Ed.M.’05, who later convinced him that getting into Harvard was a possibility. He also attended the Hip Hop Experience Lab conference run by Lecturer Aysha Upchurch, Ed.M.’15.

Previously, Lopez was a high school social studies teacher in Connecticut and created a hip hop class and afterschool program in the Bronx. He worked in the Hartford public schools as a climate, culture, and equity strategist, and was an adjunct professor at Stephen F. Austin State University in Texas. One day, he’d like to reach even higher and become the secretary of education for the United States.

“Policy is created by people and it’s important to have people in positions of leadership that understand the experiences of the students and educators they serve,” he says. “An important factor of that being a classroom teacher. When you have taught in the classroom you understand the human-centered perspective that is needed in education that goes beyond any policy. Of the last 11 U.S. secretaries of education, only three have been classroom teachers. Secretary Cardona makes the fourth. I want to build upon the human-centered approach he has brought to the role.”

Find your joy and watch their music video: projecthappyvism.com

Ed. Magazine

The magazine of the Harvard Graduate School of Education

Related Articles

Up Next: CubbyCase

A subscription box filled with education products and activities

Every Child Has a Voice

Building social-emotional learning skills through the arts

A Pitch for Improving Special Education

- Chronicle Conversations

- Article archives

- Issue archives

- Join our mailing list

Recognizing and Overcoming Inequity in Education

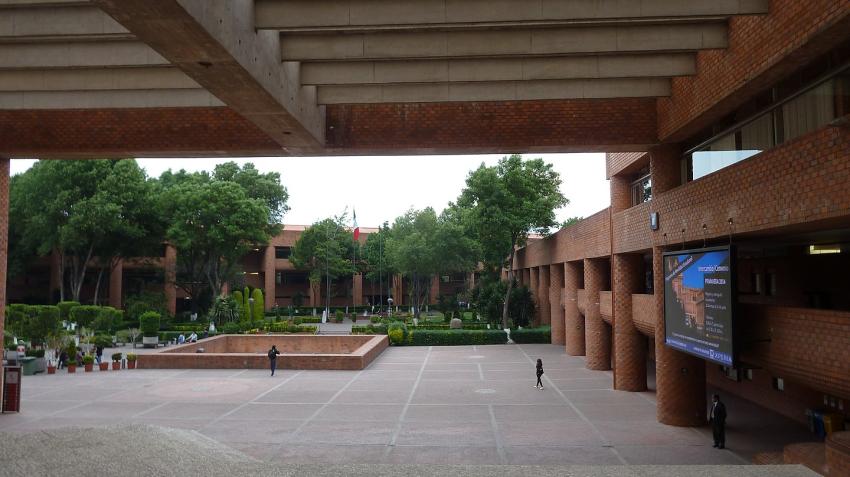

About the author, sylvia schmelkes.

Sylvia Schmelkes is Provost of the Universidad Iberoamericana in Mexico City.

22 January 2020 Introduction

I nequity is perhaps the most serious problem in education worldwide. It has multiple causes, and its consequences include differences in access to schooling, retention and, more importantly, learning. Globally, these differences correlate with the level of development of various countries and regions. In individual States, access to school is tied to, among other things, students' overall well-being, their social origins and cultural backgrounds, the language their families speak, whether or not they work outside of the home and, in some countries, their sex. Although the world has made progress in both absolute and relative numbers of enrolled students, the differences between the richest and the poorest, as well as those living in rural and urban areas, have not diminished. 1

These correlations do not occur naturally. They are the result of the lack of policies that consider equity in education as a principal vehicle for achieving more just societies. The pandemic has exacerbated these differences mainly due to the fact that technology, which is the means of access to distance schooling, presents one more layer of inequality, among many others.

The dimension of educational inequity

Around the world, 258 million, or 17 per cent of the world’s children, adolescents and youth, are out of school. The proportion is much larger in developing countries: 31 per cent in sub-Saharan Africa and 21 per cent in Central Asia, vs. 3 per cent in Europe and North America. 2 Learning, which is the purpose of schooling, fares even worse. For example, it would take 15-year-old Brazilian students 75 years, at their current rate of improvement, to reach wealthier countries’ average scores in math, and more than 260 years in reading. 3 Within countries, learning results, as measured through standardized tests, are almost always much lower for those living in poverty. In Mexico, for example, 80 per cent of indigenous children at the end of primary school don’t achieve basic levels in reading and math, scoring far below the average for primary school students. 4

The causes of educational inequity

There are many explanations for educational inequity. In my view, the most important ones are the following:

- Equity and equality are not the same thing. Equality means providing the same resources to everyone. Equity signifies giving more to those most in need. Countries with greater inequity in education results are also those in which governments distribute resources according to the political pressure they experience in providing education. Such pressures come from families in which the parents attended school, that reside in urban areas, belong to cultural majorities and who have a clear appreciation of the benefits of education. Much less pressure comes from rural areas and indigenous populations, or from impoverished urban areas. In these countries, fewer resources, including infrastructure, equipment, teachers, supervision and funding, are allocated to the disadvantaged, the poor and cultural minorities.

- Teachers are key agents for learning. Their training is crucial. When insufficient priority is given to either initial or in-service teacher training, or to both, one can expect learning deficits. Teachers in poorer areas tend to have less training and to receive less in-service support.

- Most countries are very diverse. When a curriculum is overloaded and is the same for everyone, some students, generally those from rural areas, cultural minorities or living in poverty find little meaning in what is taught. When the language of instruction is different from their native tongue, students learn much less and drop out of school earlier.

- Disadvantaged students frequently encounter unfriendly or overtly offensive attitudes from both teachers and classmates. Such attitudes are derived from prejudices, stereotypes, outright racism and sexism. Students in hostile environments are affected in their disposition to learn, and many drop out early.

It doesn’t have to be like this

When left to inertial decision-making, education systems seem to be doomed to reproduce social and economic inequity. The commitment of both governments and societies to equity in education is both necessary and possible. There are several examples of more equitable educational systems in the world, and there are many subnational examples of successful policies fostering equity in education.

Why is equity in education important?

Education is a basic human right. More than that, it is an enabling right in the sense that, when respected, allows for the fulfillment of other human rights. Education has proven to affect general well-being, productivity, social capital, responsible citizenship and sustainable behaviour. Its equitable distribution allows for the creation of permeable societies and equity. The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development includes Sustainable Development Goal 4, which aims to ensure “inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all”. One hundred eighty-four countries are committed to achieving this goal over the next decade. 5 The process of walking this road together has begun and requires impetus to continue, especially now that we must face the devastating consequences of a long-lasting pandemic. Further progress is crucial for humanity.

Notes 1 United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization , Inclusive Education. All Means All , Global Education Monitoring Report 2020 (Paris, 2020), p.8. Available at https://en.unesco.org/gem-report/report/2020/inclusion . 2 Ibid., p. 4, 7. 3 World Bank Group, World Development Report 2018: Learning to Realize Education's Promise (Washington, DC, 2018), p. 3. Available at https://www.worldbank.org/en/publication/wdr2018 . 4 Instituto Nacional para la Evaluación de la Educación, "La educación obligatoria en México", Informe 2018 (Ciudad de México, 2018), p. 72. Available online at https://www.inee.edu.mx/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/P1I243.pdf . 5 United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization , “Incheon Declaration and Framework for Action for the implementation of Sustainable Development Goal 4” (2015), p. 23. Available at https://iite.unesco.org/publications/education-2030-incheon-declaration-framework-action-towards-inclusive-equitable-quality-education-lifelong-learning/ The UN Chronicle is not an official record. It is privileged to host senior United Nations officials as well as distinguished contributors from outside the United Nations system whose views are not necessarily those of the United Nations. Similarly, the boundaries and names shown, and the designations used, in maps or articles do not necessarily imply endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations.

Thirty Years On, Leaders Need to Recommit to the International Conference on Population and Development Agenda

With the gains from the Cairo conference now in peril, the population and development framework is more relevant than ever. At the end of April 2024, countries will convene to review the progress made on the ICPD agenda during the annual session of the Commission on Population and Development.

The LDC Future Forum: Accelerating the Attainment of the Sustainable Development Goals in the Least Developed Countries

The desired outcome of the LDC Future Forums is the dissemination of practical and evidence-based case studies, solutions and policy recommendations for achieving sustainable development.

From Local Moments to Global Movement: Reparation Mechanisms and a Development Framework

For two centuries, emancipated Black people have been calling for reparations for the crimes committed against them.

Documents and publications

- Yearbook of the United Nations

- Basic Facts About the United Nations

- Journal of the United Nations

- Meetings Coverage and Press Releases

- United Nations Official Document System (ODS)

- Africa Renewal

Libraries and Archives

- Dag Hammarskjöld Library

- UN Audiovisual Library

- UN Archives and Records Management

- Audiovisual Library of International Law

- UN iLibrary

News and media

- UN News Centre

- UN Chronicle on Twitter

- UN Chronicle on Facebook

The UN at Work

- 17 Goals to Transform Our World

- Official observances

- United Nations Academic Impact (UNAI)

- Protecting Human Rights

- Maintaining International Peace and Security

- The Office of the Secretary-General’s Envoy on Youth

- United Nations Careers

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

current events conversation

What Students Are Saying About How to Improve American Education

An international exam shows that American 15-year-olds are stagnant in reading and math. Teenagers told us what’s working and what’s not in the American education system.

By The Learning Network

Earlier this month, the Program for International Student Assessment announced that the performance of American teenagers in reading and math has been stagnant since 2000 . Other recent studies revealed that two-thirds of American children were not proficient readers , and that the achievement gap in reading between high and low performers is widening.

We asked students to weigh in on these findings and to tell us their suggestions for how they would improve the American education system.

Our prompt received nearly 300 comments. This was clearly a subject that many teenagers were passionate about. They offered a variety of suggestions on how they felt schools could be improved to better teach and prepare students for life after graduation.

While we usually highlight three of our most popular writing prompts in our Current Events Conversation , this week we are only rounding up comments for this one prompt so we can honor the many students who wrote in.

Please note: Student comments have been lightly edited for length, but otherwise appear as they were originally submitted.

Put less pressure on students.

One of the biggest flaws in the American education system is the amount of pressure that students have on them to do well in school, so they can get into a good college. Because students have this kind of pressure on them they purely focus on doing well rather than actually learning and taking something valuable away from what they are being taught.

— Jordan Brodsky, Danvers, MA

As a Freshman and someone who has a tough home life, I can agree that this is one of the main causes as to why I do poorly on some things in school. I have been frustrated about a lot that I am expected to learn in school because they expect us to learn so much information in such little time that we end up forgetting about half of it anyway. The expectations that I wish that my teachers and school have of me is that I am only human and that I make mistakes. Don’t make me feel even worse than I already am with telling me my low test scores and how poorly I’m doing in classes.

— Stephanie Cueva, King Of Prussia, PA

I stay up well after midnight every night working on homework because it is insanely difficult to balance school life, social life, and extracurriculars while making time for family traditions. While I don’t feel like making school easier is the one true solution to the stress students are placed under, I do feel like a transition to a year-round schedule would be a step in the right direction. That way, teachers won’t be pressured into stuffing a large amount of content into a small amount of time, and students won’t feel pressured to keep up with ungodly pacing.

— Jacob Jarrett, Hoggard High School in Wilmington, NC

In my school, we don’t have the best things, there are holes in the walls, mice, and cockroaches everywhere. We also have a lot of stress so there is rarely time for us to study and prepare for our tests because we constantly have work to do and there isn’t time for us to relax and do the things that we enjoy. We sleep late and can’t ever focus, but yet that’s our fault and that we are doing something wrong. School has become a place where we just do work, stress, and repeat but there has been nothing changed. We can’t learn what we need to learn because we are constantly occupied with unnecessary work that just pulls us back.

— Theodore Loshi, Masterman School

As a student of an American educational center let me tell you, it is horrible. The books are out dated, the bathrooms are hideous, stress is ever prevalent, homework seems never ending, and worst of all, the seemingly impossible feat of balancing school life, social life, and family life is abominable. The only way you could fix it would be to lessen the load dumped on students and give us a break.

— Henry Alley, Hoggard High School, Wilmington NC

Use less technology in the classroom (…or more).

People my age have smaller vocabularies, and if they don’t know a word, they just quickly look it up online instead of learning and internalizing it. The same goes for facts and figures in other subjects; don’t know who someone was in history class? Just look ‘em up and read their bio. Don’t know how to balance a chemical equation? The internet knows. Can’t solve a math problem by hand? Just sneak out the phone calculator.

My largest grievance with technology and learning has more to do with the social and psychological aspects, though. We’ve decreased ability to meaningfully communicate, and we want everything — things, experiences, gratification — delivered to us at Amazon Prime speed. Interactions and experiences have become cheap and 2D because we see life through a screen.

— Grace Robertson, Hoggard High School Wilmington, NC

Kids now a days are always on technology because they are heavily dependent on it- for the purpose of entertainment and education. Instead of pondering or thinking for ourselves, our first instinct is to google and search for the answers without giving it any thought. This is a major factor in why I think American students tests scores haven’t been improving because no one wants to take time and think about questions, instead they want to find answers as fast as they can just so they can get the assignment/ project over with.

— Ema Thorakkal, Glenbard West HS IL

There needs to be a healthier balance between pen and paper work and internet work and that balance may not even be 50:50. I personally find myself growing as a student more when I am writing down my assignments and planning out my day on paper instead of relying on my phone for it. Students now are being taught from preschool about technology and that is damaging their growth and reading ability. In my opinion as well as many of my peers, a computer can never beat a book in terms of comprehension.

— Ethan, Pinkey, Hoggard High School in Wilmington, NC

Learning needs to be more interesting. Not many people like to study from their textbooks because there’s not much to interact with. I think that instead of studying from textbooks, more interactive activities should be used instead. Videos, websites, games, whatever might interest students more. I’m not saying that we shouldn’t use textbooks, I’m just saying that we should have a combination of both textbooks and technology to make learning more interesting in order for students to learn more.

— Vivina Dong, J. R. Masterman

Prepare students for real life.

At this point, it’s not even the grades I’m worried about. It feels like once we’ve graduated high school, we’ll be sent out into the world clueless and unprepared. I know many college students who have no idea what they’re doing, as though they left home to become an adult but don’t actually know how to be one.

The most I’ve gotten out of school so far was my Civics & Economics class, which hardly even touched what I’d actually need to know for the real world. I barely understand credit and they expect me to be perfectly fine living alone a year from now. We need to learn about real life, things that can actually benefit us. An art student isn’t going to use Biology and Trigonometry in life. Exams just seem so pointless in the long run. Why do we have to dedicate our high school lives studying equations we’ll never use? Why do exams focusing on pointless topics end up determining our entire future?

— Eliana D, Hoggard High School in Wilmington, NC

I think that the American education system can be improved my allowing students to choose the classes that they wish to take or classes that are beneficial for their future. Students aren’t really learning things that can help them in the future such as basic reading and math.

— Skye Williams, Sarasota, Florida

I am frustrated about what I’m supposed to learn in school. Most of the time, I feel like what I’m learning will not help me in life. I am also frustrated about how my teachers teach me and what they expect from me. Often, teachers will give me information and expect me to memorize it for a test without teaching me any real application.

— Bella Perrotta, Kent Roosevelt High School

We divide school time as though the class itself is the appetizer and the homework is the main course. Students get into the habit of preparing exclusively for the homework, further separating the main ideas of school from the real world. At this point, homework is given out to prepare the students for … more homework, rather than helping students apply their knowledge to the real world.

— Daniel Capobianco, Danvers High School

Eliminate standardized tests.

Standardized testing should honestly be another word for stress. I know that I stress over every standardized test I have taken and so have most of my peers. I mean they are scary, it’s like when you take these tests you bring your No. 2 pencil and an impending fail.

— Brennan Stabler, Hoggard High School in Wilmington, NC

Personally, for me I think standardized tests have a negative impact on my education, taking test does not actually test my knowledge — instead it forces me to memorize facts that I will soon forget.

— Aleena Khan, Glenbard West HS Glen Ellyn, IL

Teachers will revolve their whole days on teaching a student how to do well on a standardized test, one that could potentially impact the final score a student receives. That is not learning. That is learning how to memorize and become a robot that regurgitates answers instead of explaining “Why?” or “How?” that answer was found. If we spent more time in school learning the answers to those types of questions, we would become a nation where students are humans instead of a number.

— Carter Osborn, Hoggard High School in Wilmington, NC

In private school, students have smaller class sizes and more resources for field trips, computers, books, and lab equipment. They also get more “hand holding” to guarantee success, because parents who pay tuition expect results. In public school, the learning is up to you. You have to figure stuff out yourself, solve problems, and advocate for yourself. If you fail, nobody cares. It takes grit to do well. None of this is reflected in a standardized test score.

— William Hudson, Hoggard High School in Wilmington, NC

Give teachers more money and support.

I have always been told “Don’t be a teacher, they don’t get paid hardly anything.” or “How do you expect to live off of a teachers salary, don’t go into that profession.” As a young teen I am being told these things, the future generation of potential teachers are being constantly discouraged because of the money they would be getting paid. Education in Americans problems are very complicated, and there is not one big solution that can fix all of them at once, but little by little we can create a change.

— Lilly Smiley, Hoggard High School

We cannot expect our grades to improve when we give teachers a handicap with poor wages and low supplies. It doesn’t allow teachers to unleash their full potential for educating students. Alas, our government makes teachers work with their hands tied. No wonder so many teachers are quitting their jobs for better careers. Teachers will shape the rest of their students’ lives. But as of now, they can only do the bare minimum.

— Jeffery Austin, Hoggard High School

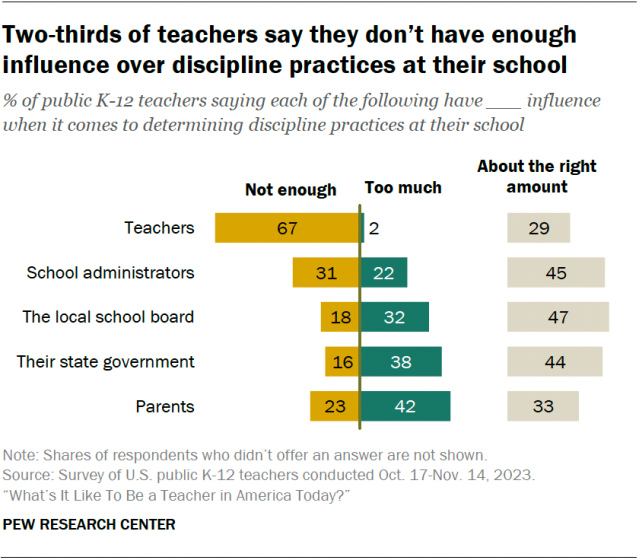

The answer to solving the American education crisis is simple. We need to put education back in the hands of the teachers. The politicians and the government needs to step back and let the people who actually know what they are doing and have spent a lifetime doing it decide how to teach. We wouldn’t let a lawyer perform heart surgery or construction workers do our taxes, so why let the people who win popularity contests run our education systems?

— Anders Olsen, Hoggard High School, Wilmington NC

Make lessons more engaging.

I’m someone who struggles when all the teacher does is say, “Go to page X” and asks you to read it. Simply reading something isn’t as effective for me as a teacher making it interactive, maybe giving a project out or something similar. A textbook doesn’t answer all my questions, but a qualified teacher that takes their time does. When I’m challenged by something, I can always ask a good teacher and I can expect an answer that makes sense to me. But having a teacher that just brushes off questions doesn’t help me. I’ve heard of teachers where all they do is show the class movies. At first, that sounds amazing, but you don’t learn anything that can benefit you on a test.

— Michael Huang, JR Masterman

I’ve struggled in many classes, as of right now it’s government. What is making this class difficult is that my teacher doesn’t really teach us anything, all he does is shows us videos and give us papers that we have to look through a textbook to find. The problem with this is that not everyone has this sort of learning style. Then it doesn’t help that the papers we do, we never go over so we don’t even know if the answers are right.

— S Weatherford, Kent Roosevelt, OH

The classes in which I succeed in most are the ones where the teachers are very funny. I find that I struggle more in classes where the teachers are very strict. I think this is because I love laughing. Two of my favorite teachers are very lenient and willing to follow the classes train of thought.

— Jonah Smith Posner, J.R. Masterman

Create better learning environments.

Whenever they are introduced to school at a young age, they are convinced by others that school is the last place they should want to be. Making school a more welcoming place for students could better help them be attentive and also be more open minded when walking down the halls of their own school, and eventually improve their test scores as well as their attitude while at school.

— Hart P., Bryant High School

Students today feel voiceless because they are punished when they criticize the school system and this is a problem because this allows the school to block out criticism that can be positive leaving it no room to grow. I hope that in the near future students can voice their opinion and one day change the school system for the better.

— Nico Spadavecchia, Glenbard West Highschool Glen Ellyn IL

The big thing that I have struggled with is the class sizes due to overcrowding. It has made it harder to be able to get individual help and be taught so I completely understand what was going on. Especially in math it builds on itself so if you don’t understand the first thing you learn your going to be very lost down the road. I would go to my math teacher in the morning and there would be 12 other kids there.

— Skyla Madison, Hoggard High School in Wilmington, NC

The biggest issue facing our education system is our children’s lack of motivation. People don’t want to learn. Children hate school. We despise homework. We dislike studying. One of the largest indicators of a child’s success academically is whether or not they meet a third grade reading level by the third grade, but children are never encouraged to want to learn. There are a lot of potential remedies for the education system. Paying teachers more, giving schools more funding, removing distractions from the classroom. All of those things are good, but, at the end of the day, the solution is to fundamentally change the way in which we operate.

Support students’ families.

I say one of the biggest problems is the support of families and teachers. I have heard many success stories, and a common element of this story is the unwavering support from their family, teachers, supervisors, etc. Many people need support to be pushed to their full potential, because some people do not have the will power to do it on their own. So, if students lived in an environment where education was supported and encouraged; than their children would be more interested in improving and gaining more success in school, than enacting in other time wasting hobbies that will not help their future education.

— Melanie, Danvers

De-emphasize grades.

I wish that tests were graded based on how much effort you put it and not the grade itself. This would help students with stress and anxiety about tests and it would cause students to put more effort into their work. Anxiety around school has become such a dilemma that students are taking their own life from the stress around schoolwork. You are told that if you don’t make straight A’s your life is over and you won’t have a successful future.

— Lilah Pate, Hoggard High School in Wilmington, NC

I personally think that there are many things wrong with the American education system. Everyone is so worried about grades and test scores. People believe that those are the only thing that represents a student. If you get a bad grade on something you start believing that you’re a bad student. GPA doesn’t measure a students’ intelligence or ability to learn. At young ages students stop wanting to come to school and learn. Standardized testing starts and students start to lose their creativity.

— Andrew Gonthier, Hoggard High School in Wilmington, NC

Praise for great teachers

Currently, I’m in a math class that changed my opinion of math. Math class just used to be a “meh” for me. But now, my teacher teachers in a way that is so educational and at the same time very amusing and phenomenal. I am proud to be in such a class and with such a teacher. She has changed the way I think about math it has definitely improve my math skills. Now, whenever I have math, I am so excited to learn new things!

— Paulie Sobol, J.R Masterman

At the moment, the one class that I really feel supported in is math. My math teachers Mrs. Siu and Ms. Kamiya are very encouraging of mistakes and always are willing to help me when I am struggling. We do lots of classwork and discussions and we have access to amazing online programs and technology. My teacher uses Software called OneNote and she does all the class notes on OneNote so that we can review the class material at home. Ms. Kamiya is very patient and is great at explaining things. Because they are so accepting of mistakes and confusion it makes me feel very comfortable and I am doing very well in math.

— Jayden Vance, J.R. Masterman

One of the classes that made learning easier for me was sixth-grade math. My teacher allowed us to talk to each other while we worked on math problems. Talking to the other students in my class helped me learn a lot quicker. We also didn’t work out of a textbook. I feel like it is harder for me to understand something if I just read it out of a textbook. Seventh-grade math also makes learning a lot easier for me. Just like in sixth-grade math, we get to talk to others while solving a problem. I like that when we don’t understand a question, our teacher walks us through it and helps us solve it.

— Grace Moan, J R Masterman

My 2nd grade class made learning easy because of the way my teacher would teach us. My teacher would give us a song we had to remember to learn nouns, verbs, adjectives, pronouns, etc. which helped me remember their definitions until I could remember it without the song. She had little key things that helped us learn math because we all wanted to be on a harder key than each other. She also sang us our spelling words, and then the selling of that word from the song would help me remember it.

— Brycinea Stratton, J.R. Masterman

Featured Topics

Featured series.

A series of random questions answered by Harvard experts.

Explore the Gazette

Read the latest.

Should NATO step up role in Russia-Ukraine war?

It’s on Facebook, and it’s complicated

How far has COVID set back students?

The costs of inequality: education’s the one key that rules them all.

When there’s inequity in learning, it’s usually baked into life, Harvard analysts say

Corydon Ireland

Harvard Correspondent

Third in a series on what Harvard scholars are doing to identify and understand inequality, in seeking solutions to one of America’s most vexing problems.

Before Deval Patrick ’78, J.D. ’82, was the popular and successful two-term governor of Massachusetts, before he was managing director of high-flying Bain Capital, and long before he was Harvard’s most recent Commencement speaker , he was a poor black schoolchild in the battered housing projects of Chicago’s South Side.

The odds of his escaping a poverty-ridden lifestyle, despite innate intelligence and drive, were long. So how did he help mold his own narrative and triumph over baked-in societal inequality ? Through education.

“Education has been the path to better opportunity for generations of American strivers, no less for me,” Patrick said in an email when asked how getting a solid education, in his case at Milton Academy and at Harvard, changed his life.

“What great teachers gave me was not just the skills to take advantage of new opportunities, but the ability to imagine what those opportunities could be. For a kid from the South Side of Chicago, that’s huge.”

If inequality starts anywhere, many scholars agree, it’s with faulty education. Conversely, a strong education can act as the bejeweled key that opens gates through every other aspect of inequality , whether political, economic , racial, judicial, gender- or health-based.

Simply put, a top-flight education usually changes lives for the better. And yet, in the world’s most prosperous major nation, it remains an elusive goal for millions of children and teenagers.

Plateau on educational gains

The revolutionary concept of free, nonsectarian public schools spread across America in the 19th century. By 1970, America had the world’s leading educational system, and until 1990 the gap between minority and white students, while clear, was narrowing.

But educational gains in this country have plateaued since then, and the gap between white and minority students has proven stubbornly difficult to close, says Ronald Ferguson, adjunct lecturer in public policy at Harvard Kennedy School (HKS) and faculty director of Harvard’s Achievement Gap Initiative. That gap extends along class lines as well.

“What great teachers gave me was not just the skills to take advantage of new opportunities, but the ability to imagine what those opportunities could be. For a kid from the South Side of Chicago, that’s huge.” — Deval Patrick

In recent years, scholars such as Ferguson, who is an economist, have puzzled over the ongoing achievement gap and what to do about it, even as other nations’ school systems at first matched and then surpassed their U.S. peers. Among the 34 market-based, democracy-leaning countries in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), the United States ranks around 20th annually, earning average or below-average grades in reading, science, and mathematics.

By eighth grade, Harvard economist Roland G. Fryer Jr. noted last year, only 44 percent of American students are proficient in reading and math. The proficiency of African-American students, many of them in underperforming schools, is even lower.

“The position of U.S. black students is truly alarming,” wrote Fryer, the Henry Lee Professor of Economics, who used the OECD rankings as a metaphor for minority standing educationally. “If they were to be considered a country, they would rank just below Mexico in last place.”

Harvard Graduate School of Education (HGSE) Dean James E. Ryan, a former public interest lawyer, says geography has immense power in determining educational opportunity in America. As a scholar, he has studied how policies and the law affect learning, and how conditions are often vastly unequal.

His book “Five Miles Away, A World Apart” (2010) is a case study of the disparity of opportunity in two Richmond, Va., schools, one grimly urban and the other richly suburban. Geography, he says, mirrors achievement levels.

A ZIP code as predictor of success

“Right now, there exists an almost ironclad link between a child’s ZIP code and her chances of success,” said Ryan. “Our education system, traditionally thought of as the chief mechanism to address the opportunity gap, instead too often reflects and entrenches existing societal inequities.”

Urban schools demonstrate the problem. In New York City, for example, only 8 percent of black males graduating from high school in 2014 were prepared for college-level work, according to the CUNY Institute for Education Policy, with Latinos close behind at 11 percent. The preparedness rates for Asians and whites — 48 and 40 percent, respectively — were unimpressive too, but nonetheless were firmly on the other side of the achievement gap.

In some impoverished urban pockets, the racial gap is even larger. In Washington, D.C., 8 percent of black eighth-graders are proficient in math, while 80 percent of their white counterparts are.

Fryer said that in kindergarten black children are already 8 months behind their white peers in learning. By third grade, the gap is bigger, and by eighth grade is larger still.

According to a recent report by the Education Commission of the States, black and Hispanic students in kindergarten through 12th grade perform on a par with the white students who languish in the lowest quartile of achievement.

There was once great faith and hope in America’s school systems. The rise of quality public education a century ago “was probably the best public policy decision Americans have ever made because it simultaneously raised the whole growth rate of the country for most of the 20th century, and it leveled the playing field,” said Robert Putnam, the Peter and Isabel Malkin Professor of Public Policy at HKS, who has written several best-selling books touching on inequality, including “Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of the American Community” and “Our Kids: The American Dream in Crisis.”

Historically, upward mobility in America was characterized by each generation becoming better educated than the previous one, said Harvard economist Lawrence Katz. But that trend, a central tenet of the nation’s success mythology, has slackened, particularly for minorities.

“Thirty years ago, the typical American had two more years of schooling than their parents. Today, we have the most educated group of Americans, but they only have about .4 more years of schooling, so that’s one part of mobility not keeping up in the way we’ve invested in education in the past,” Katz said.

As globalization has transformed and sometimes undercut the American economy, “education is not keeping up,” he said. “There’s continuing growth of demand for more abstract, higher-end skills” that schools aren’t delivering, “and then that feeds into a weakening of institutions like unions and minimum-wage protections.”

“The position of U.S. black students is truly alarming.” — Roland G. Fryer Jr.

Fryer is among a diffuse cohort of Harvard faculty and researchers using academic tools to understand the achievement gap and the many reasons behind problematic schools. His venue is the Education Innovation Laboratory , where he is faculty director.

“We use big data and causal methods,” he said of his approach to the issue.

Fryer, who is African-American, grew up poor in a segregated Florida neighborhood. He argues that outright discrimination has lost its power as a primary driver behind inequality, and uses economics as “a rational forum” for discussing social issues.

Better schools to close the gap

Fryer set out in 2004 to use an economist’s data and statistical tools to answer why black students often do poorly in school compared with whites. His years of research have convinced him that good schools would close the education gap faster and better than addressing any other social factor, including curtailing poverty and violence, and he believes that the quality of kindergarten through grade 12 matters above all.

Supporting his belief is research that says the number of schools achieving excellent student outcomes is a large enough sample to prove that much better performance is possible. Despite the poor performance by many U.S. states, some have shown that strong results are possible on a broad scale. For instance, if Massachusetts were a nation, it would rate among the best-performing countries.

At HGSE, where Ferguson is faculty co-chair as well as director of the Achievement Gap Initiative, many factors are probed. In the past 10 years, Ferguson, who is African-American, has studied every identifiable element contributing to unequal educational outcomes. But lately he is looking hardest at improving children’s earliest years, from infancy to age 3.

In addition to an organization he founded called the Tripod Project , which measures student feedback on learning, he launched the Boston Basics project in August, with support from the Black Philanthropy Fund, Boston’s mayor, and others. The first phase of the outreach campaign, a booklet, videos, and spot ads, starts with advice to parents of children age 3 or younger.

“Maximize love, manage stress” is its mantra and its foundational imperative, followed by concepts such as “talk, sing, and point.” (“Talking,” said Ferguson, “is teaching.”) In early childhood, “The difference in life experiences begins at home.”

At age 1, children score similarly

Fryer and Ferguson agree that the achievement gap starts early. At age 1, white, Asian, black, and Hispanic children score virtually the same in what Ferguson called “skill patterns” that measure cognitive ability among toddlers, including examining objects, exploring purposefully, and “expressive jabbering.” But by age 2, gaps are apparent, with black and Hispanic children scoring lower in expressive vocabulary, listening comprehension, and other indicators of acuity. That suggests educational achievement involves more than just schooling, which typically starts at age 5.

Key factors in the gap, researchers say, include poverty rates (which are three times higher for blacks than for whites), diminished teacher and school quality, unsettled neighborhoods, ineffective parenting, personal trauma, and peer group influence, which only strengthens as children grow older.