Subscribe or renew today

Every print subscription comes with full digital access

Science News

Social media harms teens’ mental health, mounting evidence shows. what now.

Understanding what is going on in teens’ minds is necessary for targeted policy suggestions

Most teens use social media, often for hours on end. Some social scientists are confident that such use is harming their mental health. Now they want to pinpoint what explains the link.

Carol Yepes/Getty Images

Share this:

By Sujata Gupta

February 20, 2024 at 7:30 am

In January, Mark Zuckerberg, CEO of Facebook’s parent company Meta, appeared at a congressional hearing to answer questions about how social media potentially harms children. Zuckerberg opened by saying: “The existing body of scientific work has not shown a causal link between using social media and young people having worse mental health.”

But many social scientists would disagree with that statement. In recent years, studies have started to show a causal link between teen social media use and reduced well-being or mood disorders, chiefly depression and anxiety.

Ironically, one of the most cited studies into this link focused on Facebook.

Researchers delved into whether the platform’s introduction across college campuses in the mid 2000s increased symptoms associated with depression and anxiety. The answer was a clear yes , says MIT economist Alexey Makarin, a coauthor of the study, which appeared in the November 2022 American Economic Review . “There is still a lot to be explored,” Makarin says, but “[to say] there is no causal evidence that social media causes mental health issues, to that I definitely object.”

The concern, and the studies, come from statistics showing that social media use in teens ages 13 to 17 is now almost ubiquitous. Two-thirds of teens report using TikTok, and some 60 percent of teens report using Instagram or Snapchat, a 2022 survey found. (Only 30 percent said they used Facebook.) Another survey showed that girls, on average, allot roughly 3.4 hours per day to TikTok, Instagram and Facebook, compared with roughly 2.1 hours among boys. At the same time, more teens are showing signs of depression than ever, especially girls ( SN: 6/30/23 ).

As more studies show a strong link between these phenomena, some researchers are starting to shift their attention to possible mechanisms. Why does social media use seem to trigger mental health problems? Why are those effects unevenly distributed among different groups, such as girls or young adults? And can the positives of social media be teased out from the negatives to provide more targeted guidance to teens, their caregivers and policymakers?

“You can’t design good public policy if you don’t know why things are happening,” says Scott Cunningham, an economist at Baylor University in Waco, Texas.

Increasing rigor

Concerns over the effects of social media use in children have been circulating for years, resulting in a massive body of scientific literature. But those mostly correlational studies could not show if teen social media use was harming mental health or if teens with mental health problems were using more social media.

Moreover, the findings from such studies were often inconclusive, or the effects on mental health so small as to be inconsequential. In one study that received considerable media attention, psychologists Amy Orben and Andrew Przybylski combined data from three surveys to see if they could find a link between technology use, including social media, and reduced well-being. The duo gauged the well-being of over 355,000 teenagers by focusing on questions around depression, suicidal thinking and self-esteem.

Digital technology use was associated with a slight decrease in adolescent well-being , Orben, now of the University of Cambridge, and Przybylski, of the University of Oxford, reported in 2019 in Nature Human Behaviour . But the duo downplayed that finding, noting that researchers have observed similar drops in adolescent well-being associated with drinking milk, going to the movies or eating potatoes.

Holes have begun to appear in that narrative thanks to newer, more rigorous studies.

In one longitudinal study, researchers — including Orben and Przybylski — used survey data on social media use and well-being from over 17,400 teens and young adults to look at how individuals’ responses to a question gauging life satisfaction changed between 2011 and 2018. And they dug into how the responses varied by gender, age and time spent on social media.

Social media use was associated with a drop in well-being among teens during certain developmental periods, chiefly puberty and young adulthood, the team reported in 2022 in Nature Communications . That translated to lower well-being scores around ages 11 to 13 for girls and ages 14 to 15 for boys. Both groups also reported a drop in well-being around age 19. Moreover, among the older teens, the team found evidence for the Goldilocks Hypothesis: the idea that both too much and too little time spent on social media can harm mental health.

“There’s hardly any effect if you look over everybody. But if you look at specific age groups, at particularly what [Orben] calls ‘windows of sensitivity’ … you see these clear effects,” says L.J. Shrum, a consumer psychologist at HEC Paris who was not involved with this research. His review of studies related to teen social media use and mental health is forthcoming in the Journal of the Association for Consumer Research.

Cause and effect

That longitudinal study hints at causation, researchers say. But one of the clearest ways to pin down cause and effect is through natural or quasi-experiments. For these in-the-wild experiments, researchers must identify situations where the rollout of a societal “treatment” is staggered across space and time. They can then compare outcomes among members of the group who received the treatment to those still in the queue — the control group.

That was the approach Makarin and his team used in their study of Facebook. The researchers homed in on the staggered rollout of Facebook across 775 college campuses from 2004 to 2006. They combined that rollout data with student responses to the National College Health Assessment, a widely used survey of college students’ mental and physical health.

The team then sought to understand if those survey questions captured diagnosable mental health problems. Specifically, they had roughly 500 undergraduate students respond to questions both in the National College Health Assessment and in validated screening tools for depression and anxiety. They found that mental health scores on the assessment predicted scores on the screenings. That suggested that a drop in well-being on the college survey was a good proxy for a corresponding increase in diagnosable mental health disorders.

Compared with campuses that had not yet gained access to Facebook, college campuses with Facebook experienced a 2 percentage point increase in the number of students who met the diagnostic criteria for anxiety or depression, the team found.

When it comes to showing a causal link between social media use in teens and worse mental health, “that study really is the crown jewel right now,” says Cunningham, who was not involved in that research.

A need for nuance

The social media landscape today is vastly different than the landscape of 20 years ago. Facebook is now optimized for maximum addiction, Shrum says, and other newer platforms, such as Snapchat, Instagram and TikTok, have since copied and built on those features. Paired with the ubiquity of social media in general, the negative effects on mental health may well be larger now.

Moreover, social media research tends to focus on young adults — an easier cohort to study than minors. That needs to change, Cunningham says. “Most of us are worried about our high school kids and younger.”

And so, researchers must pivot accordingly. Crucially, simple comparisons of social media users and nonusers no longer make sense. As Orben and Przybylski’s 2022 work suggested, a teen not on social media might well feel worse than one who briefly logs on.

Researchers must also dig into why, and under what circumstances, social media use can harm mental health, Cunningham says. Explanations for this link abound. For instance, social media is thought to crowd out other activities or increase people’s likelihood of comparing themselves unfavorably with others. But big data studies, with their reliance on existing surveys and statistical analyses, cannot address those deeper questions. “These kinds of papers, there’s nothing you can really ask … to find these plausible mechanisms,” Cunningham says.

One ongoing effort to understand social media use from this more nuanced vantage point is the SMART Schools project out of the University of Birmingham in England. Pedagogical expert Victoria Goodyear and her team are comparing mental and physical health outcomes among children who attend schools that have restricted cell phone use to those attending schools without such a policy. The researchers described the protocol of that study of 30 schools and over 1,000 students in the July BMJ Open.

Goodyear and colleagues are also combining that natural experiment with qualitative research. They met with 36 five-person focus groups each consisting of all students, all parents or all educators at six of those schools. The team hopes to learn how students use their phones during the day, how usage practices make students feel, and what the various parties think of restrictions on cell phone use during the school day.

Talking to teens and those in their orbit is the best way to get at the mechanisms by which social media influences well-being — for better or worse, Goodyear says. Moving beyond big data to this more personal approach, however, takes considerable time and effort. “Social media has increased in pace and momentum very, very quickly,” she says. “And research takes a long time to catch up with that process.”

Until that catch-up occurs, though, researchers cannot dole out much advice. “What guidance could we provide to young people, parents and schools to help maintain the positives of social media use?” Goodyear asks. “There’s not concrete evidence yet.”

More Stories from Science News on Science & Society

Privacy remains an issue with several women’s health apps

Should we use AI to resurrect digital ‘ghosts’ of the dead?

A hidden danger lurks beneath Yellowstone

Online spaces may intensify teens’ uncertainty in social interactions

Want to see butterflies in your backyard? Try doing less yardwork

Ximena Velez-Liendo is saving Andean bears with honey

‘Flavorama’ guides readers through the complex landscape of flavor

Rain Bosworth studies how deaf children experience the world

Subscribers, enter your e-mail address for full access to the Science News archives and digital editions.

Not a subscriber? Become one now .

Advertisement

Misinformation, manipulation, and abuse on social media in the era of COVID-19

- Published: 22 November 2020

- Volume 3 , pages 271–277, ( 2020 )

Cite this article

- Emilio Ferrara 1 ,

- Stefano Cresci 2 &

- Luca Luceri 3

30k Accesses

93 Citations

40 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

The COVID-19 pandemic represented an unprecedented setting for the spread of online misinformation, manipulation, and abuse, with the potential to cause dramatic real-world consequences. The aim of this special issue was to collect contributions investigating issues such as the emergence of infodemics, misinformation, conspiracy theories, automation, and online harassment on the onset of the coronavirus outbreak. Articles in this collection adopt a diverse range of methods and techniques, and focus on the study of the narratives that fueled conspiracy theories, on the diffusion patterns of COVID-19 misinformation, on the global news sentiment, on hate speech and social bot interference, and on multimodal Chinese propaganda. The diversity of the methodological and scientific approaches undertaken in the aforementioned articles demonstrates the interdisciplinarity of these issues. In turn, these crucial endeavors might anticipate a growing trend of studies where diverse theories, models, and techniques will be combined to tackle the different aspects of online misinformation, manipulation, and abuse.

Similar content being viewed by others

Fake news, disinformation and misinformation in social media: a review

Fake news on Social Media: the Impact on Society

Sexist Slurs: Reinforcing Feminine Stereotypes Online

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Malicious and abusive behaviors on social media have elicited massive concerns for the negative repercussions that online activity can have on personal and collective life. The spread of false information [ 8 , 14 , 19 ] and propaganda [ 10 ], the rise of AI-manipulated multimedia [ 3 ], the presence of AI-powered automated accounts [ 9 , 12 ], and the emergence of various forms of harmful content are just a few of the several perils that social media users can—even unconsciously—encounter in the online ecosystem. In times of crisis, these issues can only get more pressing, with increased threats for everyday social media users [ 20 ]. The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic makes no exception and, due to dramatically increased information needs, represents the ideal setting for the emergence of infodemics —situations characterized by the undisciplined spread of information, including a multitude of low-credibility, fake, misleading, and unverified information [ 24 ]. In addition, malicious actors thrive on these wild situations and aim to take advantage of the resulting chaos. In such high-stakes scenarios, the downstream effects of misinformation exposure or information landscape manipulation can manifest in attitudes and behaviors with potentially dramatic public health consequences [ 4 , 21 ].

By affecting the very fabric of our socio-technical systems, these problems are intrinsically interdisciplinary and require joint efforts to investigate and address both the technical (e.g., how to thwart automated accounts and the spread of low-quality information, how to develop algorithms for detecting deception, automation, and manipulation), as well as the socio-cultural aspects (e.g., why do people believe in and share false news, how do interference campaigns evolve over time) [ 7 , 15 ]. Fortunately, in the case of COVID-19, several open datasets were promptly made available to foster research on the aforementioned matters [ 1 , 2 , 6 , 16 ]. Such assets bootstrapped the first wave of studies on the interplay between a global pandemic and online deception, manipulation, and automation.

Contributions

In light of the previous considerations, the purpose of this special issue was to collect contributions proposing models, methods, empirical findings, and intervention strategies to investigate and tackle the abuse of social media along several dimensions that include (but are not limited to) infodemics, misinformation, automation, online harassment, false information, and conspiracy theories about the COVID-19 outbreak. In particular, to protect the integrity of online discussions on social media, we aimed to stimulate contributions along two interlaced lines. On one hand, we solicited contributions to enhance the understanding on how health misinformation spreads, on the role of social media actors that play a pivotal part in the diffusion of inaccurate information, and on the impact of their interactions with organic users. On the other hand, we sought to stimulate research on the downstream effects of misinformation and manipulation on user perception of, and reaction to, the wave of questionable information they are exposed to, and on possible strategies to curb the spread of false narratives. From ten submissions, we selected seven high-quality articles that provide important contributions for curbing the spread of misinformation, manipulation, and abuse on social media. In the following, we briefly summarize each of the accepted articles.

The COVID-19 pandemic has been plagued by the pervasive spread of a large number of rumors and conspiracy theories, which even led to dramatic real-world consequences. “Conspiracy in the Time of Corona: Automatic Detection of Emerging COVID-19 Conspiracy Theories in Social Media and the News” by Shahsavari, Holur, Wang, Tangherlini, and Roychowdhury grounds on a machine learning approach to automatically discover and investigate the narrative frameworks supporting such rumors and conspiracy theories [ 17 ]. Authors uncover how the various narrative frameworks rely on the alignment of otherwise disparate domains of knowledge, and how they attach to the broader reporting on the pandemic. These alignments and attachments are useful for identifying areas in the news that are particularly vulnerable to reinterpretation by conspiracy theorists. Moreover, identifying the narrative frameworks that provide the generative basis for these stories may also contribute to devise methods for disrupting their spread.

The widespread diffusion of rumors and conspiracy theories during the outbreak has also been analyzed in “Partisan Public Health: How Does Political Ideology Influence Support for COVID-19 Related Misinformation?” by Nicholas Havey. The author investigates how political leaning influences the participation in the discourse of six COVID-19 misinformation narratives: 5G activating the virus, Bill Gates using the virus to implement a global surveillance project, the “Deep State” causing the virus, bleach, and other disinfectants as ingestible protection against the virus, hydroxychloroquine being a valid treatment for the virus, and the Chinese Communist party intentionally creating the virus [ 13 ]. Results show that conservative users dominated most of these discussions and pushed diverse conspiracy theories. The study further highlights how political and informational polarization might affect the adherence to health recommendations and can, thus, have dire consequences for public health.

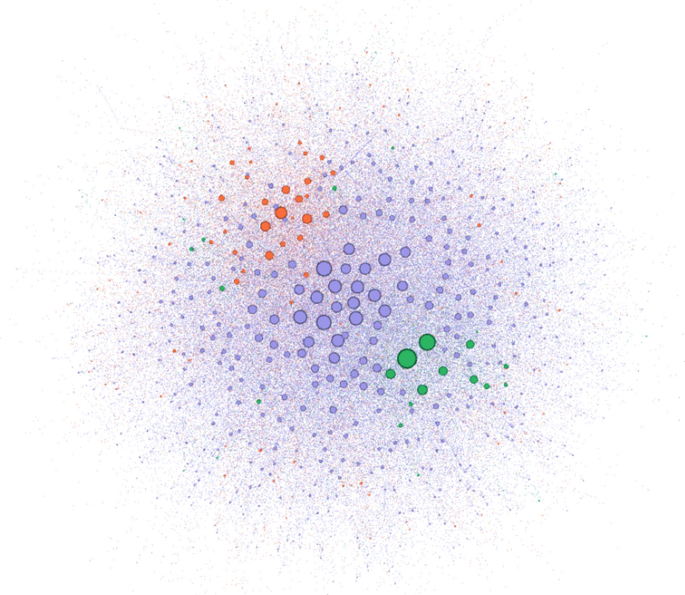

Network based on the web-page URLs shared on Twitter from January 16, 2020 to April 15, 2020 [ 18 ]. Each node represents a web-page URL, while connections indicate links among web-pages. The purple nodes represent traditional news sources, the orange nodes indicate the low-quality and misinformation news sources, and the green nodes represent authoritative health sources. The edges take the color of the source, while the node size is based on the degree

“Understanding High and Low Quality URL Sharing on COVID-19 Twitter Streams” by Singh, Bode, Budak, Kawintiranon, Padden, and Vraga investigate URL sharing patterns during the pandemic, for different categories of websites [ 18 ]. Specifically, authors categorize URLs as either related to traditional news outlets, authoritative health sources, or low-quality and misinformation news sources. Then, they build networks of shared URLs (see Fig. 1 ). They find that both authoritative health sources and low-quality/misinformation ones are shared much less than traditional news sources. However, COVID-19 misinformation is shared at a higher rate than news from authoritative health sources. Moreover, the COVID-19 misinformation network appears to be dense (i.e., tightly connected) and disassortative. These results can pave the way for future intervention strategies aimed at fragmenting networks responsible for the spread of misinformation.

The relationship between news sentiment and real-world events is a long-studied matter that has serious repercussions for agenda setting and (mis-)information spreading. In “Around the world in 60 days: An exploratory study of impact of COVID-19 on online global news sentiment” , Chakraborty and Bose explore this relationship for a large set of worldwide news articles published during the COVID-19 pandemic [ 5 ]. They apply unsupervised and transfer learning-based sentiment analysis techniques and they explore correlations between news sentiment scores and the global and local numbers of infected people and deaths. Specific case studies are also conducted for countries, such as China, the US, Italy, and India. Results of the study contribute to identify the key drivers for negative news sentiment during an infodemic, as well as the communication strategies that were used to curb negative sentiment.

Farrell, Gorrell, and Bontcheva investigate one of the most damaging sides of online malicious content: online abuse and hate speech. In “Vindication, Virtue and Vitriol: A study of online engagement and abuse toward British MPs during the COVID-19 Pandemic” , they adopt a mixed methods approach to analyze citizen engagement towards British MPs online communications during the pandemic [ 11 ]. Among their findings is that certain pressing topics, such as financial concerns, attract the highest levels of engagement, although not necessarily negative. Instead, other topics such as criticism of authorities and subjects like racism and inequality tend to attract higher levels of abuse, depending on factors such as ideology, authority, and affect.

Yet, another aspect of online manipulation—that is, automation and social bot interference—is tackled by Uyheng and Carley in their article “Bots and online hate during the COVID-19 pandemic: Case studies in the United States and the Philippines” [ 22 ]. Using a combination of machine learning and network science, the authors investigate the interplay between the use of social media automation and the spread of hateful messages. They find that the use of social bots yields more results when targeting dense and isolated communities. While the majority of extant literature frames hate speech as a linguistic phenomenon and, similarly, social bots as an algorithmic one, Uyheng and Carley adopt a more holistic approach by proposing a unified framework that accounts for disinformation, automation, and hate speech as interlinked processes, generating insights by examining their interplay. The study also reflects on the value of taking a global approach to computational social science, particularly in the context of a worldwide pandemic and infodemic, with its universal yet also distinct and unequal impacts on societies.

It has now become clear that text is not the only way to convey online misinformation and propaganda [ 10 ]. Instead, images such as those used for memes are being increasingly weaponized for this purpose. Based on this evidence, Wang, Lee, Wu, and Shen investigate US-targeted Chinese COVID propaganda, which happens to rely heavily on text images [ 23 ]. In their article “Influencing Overseas Chinese by Tweets: Text-Images as the Key Tactic of Chinese Propaganda” , they tracked thousands of Twitter accounts involved in the #USAVirus propaganda campaign. A large percentage ( \(\simeq 38\%\) ) of those accounts was later suspended by Twitter, as part of their efforts for contrasting information operations. Footnote 1 Authors studied the behavior and content production of suspended accounts. They also experimented with different statistical and machine learning models for understanding which account characteristics mostly determined their suspension by Twitter, finding that the repeated use of text images played a crucial part.

Overall, the great interest around the COVID-19 infodemic and, more broadly, about research themes such as online manipulation, automation, and abuse, combined with the growing risks of future infodemics, make this special issue a timely endeavor that will contribute to the future development of this crucial area. Given the recent advances and breadth of the topic, as well as the level of interest in related events that followed this special issue—such as dedicated panels, webinars, conferences, workshops, and other special issues in journals—we are confident that the articles selected in this collection will be both highly informative and thought provoking for readers. The diversity of the methodological and scientific approaches undertaken in the aforementioned articles demonstrates the interdisciplinarity of these issues, which demand renewed and joint efforts from different computer science fields, as well as from other related disciplines such as the social, political, and psychological sciences. To this regard, the articles in this collection testify and anticipate a growing trend of interdisciplinary studies where diverse theories, models, and techniques will be combined to tackle the different aspects at the core of online misinformation, manipulation, and abuse.

https://blog.twitter.com/en_us/topics/company/2020/information-operations-june-2020.html .

Alqurashi, S., Alhindi, A., & Alanazi, E. (2020). Large Arabic Twitter dataset on COVID-19. arXiv preprint arXiv:2004.04315 .

Banda, J.M., Tekumalla, R., Wang, G., Yu, J., Liu, T., Ding, Y., & Chowell, G. (2020). A large-scale COVID-19 Twitter chatter dataset for open scientific research—An international collaboration. arXiv preprint arXiv:2004.03688 .

Boneh, D., Grotto, A. J., McDaniel, P., & Papernot, N. (2019). How relevant is the Turing test in the age of sophisbots? IEEE Security & Privacy, 17 (6), 64–71.

Article Google Scholar

Broniatowski, D. A., Jamison, A. M., Qi, S., AlKulaib, L., Chen, T., Benton, A., et al. (2018). Weaponized health communication: Twitter bots and Russian trolls amplify the vaccine debate. American Journal of Public Health, 108 (10), 1378–1384.

Chakraborty, A., & Bose, S. (2020). Around the world in sixty days: An exploratory study of impact of COVID-19 on online global news sentiment. Journal of Computational Social Science .

Chen, E., Lerman, K., & Ferrara, E. (2020). Tracking social media discourse about the COVID-19 pandemic: Development of a public coronavirus Twitter data set. JMIR Public Health and Surveillance, 6 (2), e19273.

Ciampaglia, G. L. (2018). Fighting fake news: A role for computational social science in the fight against digital misinformation. Journal of Computational Social Science, 1 (1), 147–153.

Cinelli, M., Cresci, S., Galeazzi, A., Quattrociocchi, W., & Tesconi, M. (2020). The limited reach of fake news on Twitter during 2019 European elections. PLoS One, 15 (6), e0234689.

Cresci, S. (2020). A decade of social bot detection. Communications of the ACM, 63 (10), 61–72.

Da San M., G., Cresci, S., Barrón-Cedeño, A., Yu, S., Di Pietro, R., & Nakov, P. (2020). A survey on computational propaganda detection. In: The 29th International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence (IJCAI’20), pp. 4826–4832.

Farrell, T., Gorrell, G., & Bontcheva, K. (2020). Vindication, virtue and vitriol: A study of online engagement and abuse toward British MPs during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Journal of Computational Social Science .

Ferrara, E., Varol, O., Davis, C., Menczer, F., & Flammini, A. (2016). The rise of social bots. Communications of the ACM, 59 (7), 96–104.

Havey, N. (2020). Partisan public health: How does political ideology influence support for COVID-19 related misinformation?. Journal of Computational Social Science .

Lazer, D. M., Baum, M. A., Benkler, Y., Berinsky, A. J., Greenhill, K. M., Menczer, F., et al. (2018). The science of fake news. Science, 359 (6380), 1094–1096.

Luceri, L., Deb, A., Giordano, S., & Ferrara, E. (2019). Evolution of bot and human behavior during elections. First Monday, 24 , 9.

Google Scholar

Qazi, U., Imran, M., & Ofli, F. (2020). GeoCoV19: a dataset of hundreds of millions of multilingual COVID-19 tweets with location information. ACM SIGSPATIAL Special, 12 (1), 6–15.

Shahsavari, S., Holur, P., Wang, T., Tangherlini, T. R., & Roychowdhury, V. (2020). Conspiracy in the time of corona: Automatic detection of emerging COVID-19 conspiracy theories in social media and the news. Journal of Computational Social Science .

Singh, L., Bode, L., Budak, C., Kawintiranon, K., Padden, C., & Vraga, E. (2020). Understanding high and low quality URL sharing on COVID-19 Twitter streams. Journal of Computational Social Science .

Starbird, K. (2019). Disinformation’s spread: Bots, trolls and all of us. Nature, 571 (7766), 449–450.

Starbird, K., Dailey, D., Mohamed, O., Lee, G., & Spiro, E.S. (2018). Engage early, correct more: How journalists participate in false rumors online during crisis events. In: Proceedings of the 2018 ACM CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI’18), pp. 1–12. ACM.

Swire-Thompson, B., & Lazer, D. (2020). Public health and online misinformation: challenges and recommendations. Annual Review of Public Health, 41 , 433–451.

Uyheng, J., & Carley, K. M. (2020). Bots and online hate during the COVID-19 pandemic: Case studies in the United States and the Philippines. Journal of Computational Social Science .

Wang, A. H. E., Lee, M. C., Wu, M. H., & Shen, P. (2020). Influencing overseas Chinese by tweets: Text-Images as the key tactic of Chinese propaganda. Journal of Computational Social Science .

Zarocostas, J. (2020). How to fight an infodemic. The Lancet, 395 (10225), 676.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA, 90007, USA

Emilio Ferrara

Institute of Informatics and Telematics, National Research Council (IIT-CNR), 56124, Pisa, Italy

Stefano Cresci

University of Applied Sciences and Arts of Southern Switzerland (SUPSI), Manno, Switzerland

Luca Luceri

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Emilio Ferrara .

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Ferrara, E., Cresci, S. & Luceri, L. Misinformation, manipulation, and abuse on social media in the era of COVID-19. J Comput Soc Sc 3 , 271–277 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42001-020-00094-5

Download citation

Received : 19 October 2020

Accepted : 23 October 2020

Published : 22 November 2020

Issue Date : November 2020

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s42001-020-00094-5

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Misinformation

- Social bots

- Social media

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

- Search Menu

Sign in through your institution

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Acquisition

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Religion

- Music and Media

- Music and Culture

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Medical Ethics

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Strategy

- Business Ethics

- Business History

- Business and Government

- Business and Technology

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic Systems

- Economic History

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Theory

- Politics and Law

- Politics of Development

- Public Administration

- Public Policy

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous

- Next chapter >

Regulating Harmful Speech on Social Media: The Current Legal Landscape and Policy Proposals

- Published: August 2022

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Social media platforms have transformed how we communicate with one another. They allow us to talk easily and directly to countless others at lightning speed, with no filter and essentially no barriers to transmission. With their enormous user bases and proprietary algorithms that are designed both to promote popular content and to display information based on user preferences, they far surpass any historical antecedents in their scope and power to spread information and ideas.

The benefits of social media platforms are obvious and enormous. They foster political and public discourse and civic engagement in the United States and around the world. 1 Close Social media platforms give voice to marginalized individuals and groups, allowing them to organize, offer support, and hold powerful people accountable. 2 Close And they allow individuals to communicate with and form communities with others who share their interests but might otherwise have remained disconnected from one another.

At the same time, social media platforms, with their directness, immediacy, and lack of a filter, enable harmful speech to flourish—including wild conspiracy theories, deliberately false information, foreign propaganda, and hateful rhetoric. The platforms’ algorithms and massive user bases allow such “harmful speech” to be disseminated to millions of users at once and then shared by those users at an exponential rate. This widespread and frictionless transmission of harmful speech has real-world consequences. Conspiracy theories and false information spread on social media have helped sow widespread rejection of COVID-19 public-health measures 3 Close and fueled the lies about the 2020 US presidential election and its result. 4 Close Violent, racist, and anti-Semitic content on social media has played a role in multiple mass shootings. 5 Close Social media have also facilitated speech targeted at specific individuals, including doxing (the dissemination of private information, such as home addresses, for malevolent purposes) and other forms of harassment, including revenge porn and cyberbullying.

Signed in as

Institutional accounts.

- Google Scholar Indexing

- GoogleCrawler [DO NOT DELETE]

Personal account

- Sign in with email/username & password

- Get email alerts

- Save searches

- Purchase content

- Activate your purchase/trial code

- Add your ORCID iD

Institutional access

Sign in with a library card.

- Sign in with username/password

- Recommend to your librarian

- Institutional account management

- Get help with access

Access to content on Oxford Academic is often provided through institutional subscriptions and purchases. If you are a member of an institution with an active account, you may be able to access content in one of the following ways:

IP based access

Typically, access is provided across an institutional network to a range of IP addresses. This authentication occurs automatically, and it is not possible to sign out of an IP authenticated account.

Choose this option to get remote access when outside your institution. Shibboleth/Open Athens technology is used to provide single sign-on between your institution’s website and Oxford Academic.

- Click Sign in through your institution.

- Select your institution from the list provided, which will take you to your institution's website to sign in.

- When on the institution site, please use the credentials provided by your institution. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

- Following successful sign in, you will be returned to Oxford Academic.

If your institution is not listed or you cannot sign in to your institution’s website, please contact your librarian or administrator.

Enter your library card number to sign in. If you cannot sign in, please contact your librarian.

Society Members

Society member access to a journal is achieved in one of the following ways:

Sign in through society site

Many societies offer single sign-on between the society website and Oxford Academic. If you see ‘Sign in through society site’ in the sign in pane within a journal:

- Click Sign in through society site.

- When on the society site, please use the credentials provided by that society. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

If you do not have a society account or have forgotten your username or password, please contact your society.

Sign in using a personal account

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members. See below.

A personal account can be used to get email alerts, save searches, purchase content, and activate subscriptions.

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members.

Viewing your signed in accounts

Click the account icon in the top right to:

- View your signed in personal account and access account management features.

- View the institutional accounts that are providing access.

Signed in but can't access content

Oxford Academic is home to a wide variety of products. The institutional subscription may not cover the content that you are trying to access. If you believe you should have access to that content, please contact your librarian.

For librarians and administrators, your personal account also provides access to institutional account management. Here you will find options to view and activate subscriptions, manage institutional settings and access options, access usage statistics, and more.

Our books are available by subscription or purchase to libraries and institutions.

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Rights and permissions

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

- Skip to content

- Skip to navigation

Header Menu

Search form

You are here, why ai struggles to recognize toxic speech on social media.

Automated speech police can score highly on technical tests but miss the mark with people, new research shows.

Facebook says its artificial intelligence models identified and pulled down 27 million pieces of hate speech in the final three months of 2020 . In 97 percent of the cases, the systems took action before humans had even flagged the posts.

That’s a huge advance, and all the other major social media platforms are using AI-powered systems in similar ways. Given that people post hundreds of millions of items every day, from comments and memes to articles, there’s no real alternative. No army of human moderators could keep up on its own.

But a team of human-computer interaction and AI researchers at Stanford sheds new light on why automated speech police can score highly accurately on technical tests yet provoke a lot dissatisfaction from humans with their decisions. The main problem: There is a huge difference between evaluating more traditional AI tasks, like recognizing spoken language, and the much messier task of identifying hate speech, harassment, or misinformation — especially in today’s polarized environment.

Read the study: The Disagreement Deconvolution: Bringing Machine Learning Performance Metrics In Line With Reality

“It appears as if the models are getting almost perfect scores, so some people think they can use them as a sort of black box to test for toxicity,’’ says Mitchell Gordon, a PhD candidate in computer science who worked on the project. “But that’s not the case. They’re evaluating these models with approaches that work well when the answers are fairly clear, like recognizing whether ‘java’ means coffee or the computer language, but these are tasks where the answers are not clear.”

The team hopes their study will illuminate the gulf between what developers think they’re achieving and the reality — and perhaps help them develop systems that grapple more thoughtfully with the inherent disagreements around toxic speech.

Too Much Disagreement

There are no simple solutions, because there will never be unanimous agreement on highly contested issues. Making matters more complicated, people are often ambivalent and inconsistent about how they react to a particular piece of content.

In one study, for example, human annotators rarely reached agreement when they were asked to label tweets that contained words from a lexicon of hate speech. Only 5 percent of the tweets were acknowledged by a majority as hate speech, while only 1.3 percent received unanimous verdicts. In a study on recognizing misinformation, in which people were given statements about purportedly true events, only 70 percent agreed on whether most of the events had or had not occurred.

Despite this challenge for human moderators, conventional AI models achieve high scores on recognizing toxic speech — .95 “ROCAUC” — a popular metric for evaluating AI models in which 0.5 means pure guessing and 1.0 means perfect performance. But the Stanford team found that the real score is much lower — at most .73 — if you factor in the disagreement among human annotators.

Reassessing the Models

In a new study, the Stanford team re-assesses the performance of today’s AI models by getting a more accurate measure of what people truly believe and how much they disagree among themselves.

The study was overseen by Michael Bernstein and Tatsunori Hashimoto , associate and assistant professors of computer science and faculty members of the Stanford Institute for Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence (HAI). In addition to Gordon, Bernstein, and Hashimoto, the paper’s co-authors include Kaitlyn Zhou, a PhD candidate in computer science, and Kayur Patel, a researcher at Apple Inc.

To get a better measure of real-world views, the researchers developed an algorithm to filter out the “noise” — ambivalence, inconsistency, and misunderstanding — from how people label things like toxicity, leaving an estimate of the amount of true disagreement. They focused on how repeatedly each annotator labeled the same kind of language in the same way. The most consistent or dominant responses became what the researchers call "primary labels," which the researchers then used as a more precise dataset that captures more of the true range of opinions about potential toxic content.

The team then used that approach to refine datasets that are widely used to train AI models in spotting toxicity, misinformation, and pornography. By applying existing AI metrics to these new “disagreement-adjusted” datasets, the researchers revealed dramatically less confidence about decisions in each category. Instead of getting nearly perfect scores on all fronts, the AI models achieved only .73 ROCAUC in classifying toxicity and 62 percent accuracy in labeling misinformation. Even for pornography — as in, “I know it when I see it” — the accuracy was only .79.

Someone Will Always Be Unhappy. The Question Is Who?

Gordon says AI models, which must ultimately make a single decision, will never assess hate speech or cyberbullying to everybody’s satisfaction. There will always be vehement disagreement. Giving human annotators more precise definitions of hate speech may not solve the problem either, because people end up suppressing their real views in order to provide the “right” answer.

But if social media platforms have a more accurate picture of what people really believe, as well as which groups hold particular views, they can design systems that make more informed and intentional decisions.

In the end, Gordon suggests, annotators as well as social media executives will have to make value judgments with the knowledge that many decisions will always be controversial.

“Is this going to resolve disagreements in society? No,” says Gordon. “The question is what can you do to make people less unhappy. Given that you will have to make some people unhappy, is there a better way to think about whom you are making unhappy?”

Stanford HAI's mission is to advance AI research, education, policy and practice to improve the human condition. Learn more .

Why AI Struggles To Recognize Toxic Speech on Social Media - by Edmund L. Andrews - Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence - July 13, 2021

Via : hai.stanford.edu

- Maps & Directions

- Search Stanford

- Terms of Use

- Copyright Complaints

© Stanford University , Stanford , California 94305

- All Stories

- Journalists

- Expert Advisories

- Media Contacts

- X (Twitter)

- Arts & Culture

- Business & Economy

- Education & Society

- Environment

- Law & Politics

- Science & Technology

- International

- Michigan Minds Podcast

- Michigan Stories

- 2024 Elections

- Artificial Intelligence

- Abortion Access

- Mental Health

Hate speech in social media: How platforms can do better

- Morgan Sherburne

With all of the resources, power and influence they possess, social media platforms could and should do more to detect hate speech, says a University of Michigan researcher.

Libby Hemphill

In a report from the Anti-Defamation League , Libby Hemphill, an associate research professor at U-M’s Institute for Social Research and an ADL Belfer Fellow, explores social media platforms’ shortcomings when it comes to white supremacist speech and how it differs from general or nonextremist speech, and recommends ways to improve automated hate speech identification methods.

“We also sought to determine whether and how white supremacists adapt their speech to avoid detection,” said Hemphill, who is also a professor at U-M’s School of Information. “We found that platforms often miss discussions of conspiracy theories about white genocide and Jewish power and malicious grievances against Jews and people of color. Platforms also let decorous but defamatory speech persist.”

How platforms can do better

White supremacist speech is readily detectable, Hemphill says, detailing the ways it is distinguishable from commonplace speech in social media, including:

- Frequently referencing racial and ethnic groups using plural noun forms (whites, etc.)

- Appending “white” to otherwise unmarked terms (e.g., power)

- Using less profanity than is common in social media to elude detection based on “offensive” language

- Being congruent on both extremist and mainstream platforms

- Keeping complaints and messaging consistent from year to year

- Describing Jews in racial, rather than religious, terms

“Given the identifiable linguistic markers and consistency across platforms, social media companies should be able to recognize white supremacist speech and distinguish it from general, nontoxic speech,” Hemphill said.

The research team used commonly available computing resources, existing algorithms from machine learning and dynamic topic modeling to conduct the study.

“We needed data from both extremist and mainstream platforms,” said Hemphill, noting that mainstream user data comes from Reddit and extremist website user data comes from Stormfront.

What should happen next?

Even though the research team found that white supremacist speech is indentifiable and consistent—with more sophisticated computing capabilities and additional data—social media platforms still miss a lot and struggle to distinguish nonprofane, hateful speech from profane, innocuous speech.

“Leveraging more specific training datasets, and reducing their emphasis on profanity can improve platforms’ performance,” Hemphill said.

The report recommends that social media platforms: 1) enforce their own rules; 2) use data from extremist sites to create detection models; 3) look for specific linguistic markers; 4) deemphasize profanity in toxicity detection; and 5) train moderators and algorithms to recognize that white supremacists’ conversations are dangerous and hateful.

“Social media platforms can enable social support, political dialogue and productive collective action. But the companies behind them have civic responsibilities to combat abuse and prevent hateful users and groups from harming others,” Hemphill said. “We hope these findings and recommendations help platforms fulfill these responsibilities now and in the future.”

More information:

- Report: Very Fine People: What Social Media Platforms Miss About White Supremacist Speech

- Related: Video: ISR Insights Speaker Series: Detecting white supremacist speech on social media

- Podcast: Data Brunch Live! Extremism in Social Media

412 Maynard St. Ann Arbor, MI 48109-1399 Email [email protected] Phone 734-764-7260 About Michigan News

- Engaged Michigan

- Global Michigan

- Michigan Medicine

- Public Affairs

Publications

- Michigan Today

- The University Record

Office of the Vice President for Communications © 2024 The Regents of the University of Michigan

How should social media platforms combat misinformation and hate speech?

Subscribe to the center for technology innovation newsletter, niam yaraghi niam yaraghi nonresident senior fellow - governance studies , center for technology innovation @niamyaraghi.

April 9, 2019

Social media companies are under increased scrutiny for their mishandling of hateful speech and fake news on their platforms. There are two ways to consider a social media platform: On one hand, we can view them as technologies that merely enable individuals to publish and share content, a figurative blank sheet of paper on which anyone can write anything. On the other hand, one can argue that social media platforms have now evolved curators of content. I argue that these companies should take some responsibility over the content that is published on their platforms and suggest a set of strategies to help them with dealing with fake news and hate speech.

Artificial and Human Intelligence together

At the beginning, social media companies established themselves not to hold any accountability over the content being published on its platform. In the intervening years, they have since set up a mix of automated and human driven editorial processes to promote or filter certain types of content. In addition to that, their users are increasingly using these platforms as the primary source of getting their news. Twitter moments , in which you can see a brief snapshot of the daily news, is a prime example of how Twitter is getting closer to becoming a news media. As social media practically become news media, their level of responsibility over the content which they distribute should increase accordingly.

While I believe it is naïve to consider social media as merely neutral content sharing technologies with no responsibility, I do not believe that we should either have the same level of editorial expectation from social media that we have from traditional news media.

The sheer volume of content shared on social media makes it impossible to establish a comprehensive editorial system. Take Twitter as an example: It is estimated that 500 million tweets are sent per day. Assuming that each tweet contains 20 words on average, the volume of content published on Twitter in one single day will be equivalent to that of New York Times in 182 years. The terminology and focus of the hate speech changes over time, and most fake news articles contain some level of truthfulness in them. Therefore, social media companies cannot solely rely on artificial intelligence or humans to monitor and edit their content. They should rather develop approaches that utilize artificial and human intelligence together.

Finding the needle in a haystack

To overcome the editorial challenges of so much content, I suggest that the companies focus on a limited number of topics which are deemed important with significant consequences. The anti-vaccination movement and those who believe in flat-earth theory are both spreading anti-scientific and fake content. However, the consequences of believing that vaccines cause harm are eminently more dangerous than believing that the earth is flat. The former creates serious public health problems, the latter makes for a good laugh at a bar. Social media companies should convene groups of experts in various domains to constantly monitor the major topics in which fake news or hate speech may cause serious harm.

It is also important to consider how recommendation algorithms on social media platforms may inadvertently promote fake and hateful speech. At their core, these recommendation systems group users based on their shared interests and then promote the same type of content to all users within each group. If most of the users in one group have interests in, say, flat-earth theory and anti-vaccination hoaxes, then the algorithm will promote the anti-vaccination content to the users in the same group who may only be interested in flat-earth theory. Over time, the exposure to such promoted content could persuade the users who initially believed in vaccines to become skeptical about them. Once the major areas of focus for combating the fake and hateful speech is determined, the social media companies can tweak their recommendation systems fairly easily so that they will not nudge users to the harmful content.

Once those limited number of topics are identified, social media companies should decide on how to fight the spread of such content. In rare instances, the most appropriate response is to censor and ban the content with no hesitation. Examples include posts that incite violence or invite others to commit crimes. The recent New Zealand incident in which the shooter live broadcasted his heinous crimes on Facebook is the prime example of the content which should have never been allowed to be posted and shared on the platform.

Facebook currently relies on its community of users to flag such content and then uses an army of real humans to monitor such content within 24 hours to determine if they are actually in violation of its terms of use. Live content is monitored by humans once it reaches a certain level of popularity. While it is easier to use artificial intelligence to monitor textual content in real-time, our technologies to analyze images and videos are quickly advancing. For example, Yahoo! has recently made its algorithms to detect offensive and adult images public. The AI algorithms of Facebook are getting smart enough to detect and flag non-consensual intimate images .

Fight misinformation with information

Currently, social media companies have adopted two approaches to fight misinformation. The first one is to block such content outright. For example, Pinterest bans anti-vaccination content and Facebook bans white supremacist content. The other is to provide alternative information alongside the content with fake information so that the users are exposed to the truth and correct information. This approach, which is implemented by YouTube, encourages users to click on the links with verified and vetted information that would debunk the misguided claims made in fake or hateful content. If you search “Vaccines cause autism” on YouTube, while you still can view the videos posted by anti-vaxxers, you will also be presented with a link to the Wikipedia page of MMR vaccine that debunks such beliefs.