- Search Menu

- Advance articles

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- About Children & Schools

- About the National Association of Social Workers

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

Literature review, alive program, implications for school social work practice.

- < Previous

Trauma and Early Adolescent Development: Case Examples from a Trauma-Informed Public Health Middle School Program

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Jason Scott Frydman, Christine Mayor, Trauma and Early Adolescent Development: Case Examples from a Trauma-Informed Public Health Middle School Program, Children & Schools , Volume 39, Issue 4, October 2017, Pages 238–247, https://doi.org/10.1093/cs/cdx017

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Middle-school-age children are faced with a variety of developmental tasks, including the beginning phases of individuation from the family, building peer groups, social and emotional transitions, and cognitive shifts associated with the maturation process. This article summarizes how traumatic events impair and complicate these developmental tasks, which can lead to disruptive behaviors in the school setting. Following the call by Walkley and Cox for more attention to be given to trauma-informed schools, this article provides detailed information about the Animating Learning by Integrating and Validating Experience program: a school-based, trauma-informed intervention for middle school students. This public health model uses psychoeducation, cognitive differentiation, and brief stress reduction counseling sessions to facilitate socioemotional development and academic progress. Case examples from the authors’ clinical work in the New Haven, Connecticut, urban public school system are provided.

Within the U.S. school system there is growing awareness of how traumatic experience negatively affects early adolescent development and functioning ( Chanmugam & Teasley, 2014 ; Perfect, Turley, Carlson, Yohannan, & Gilles, 2016 ; Porche, Costello, & Rosen-Reynoso, 2016 ; Sibinga, Webb, Ghazarian, & Ellen, 2016 ; Turner, Shattuck, Finkelhor, & Hamby, 2017 ; Woodbridge et al., 2016 ). The manifested trauma symptoms of these students have been widely documented and include self-isolation, aggression, and attentional deficit and hyperactivity, producing individual and schoolwide difficulties ( Cook et al., 2005 ; Iachini, Petiwala, & DeHart, 2016 ; Oehlberg, 2008 ; Sajnani, Jewers-Dailley, Brillante, Puglisi, & Johnson, 2014 ). To address this vulnerability, school social workers should be aware of public health models promoting prevention, data-driven investigation, and broad-based trauma interventions ( Chafouleas, Johnson, Overstreet, & Santos, 2016 ; Johnson, 2012 ; Moon, Williford, & Mendenhall, 2017 ; Overstreet & Chafouleas, 2016 ; Overstreet & Matthews, 2011 ). Without comprehensive and effective interventions in the school setting, seminal adolescent developmental tasks are at risk.

This article follows the twofold call by Walkley and Cox (2013) for school social workers to develop a heightened awareness of trauma exposure's impact on childhood development and to highlight trauma-informed practices in the school setting. In reference to the former, this article will not focus on the general impact of toxic stress, or chronic trauma, on early adolescents in the school setting, as this work has been widely documented. Rather, it begins with a synthesis of how exposure to trauma impairs early adolescent developmental tasks. As to the latter, we will outline and discuss the Animating Learning by Integrating and Validating Experience (ALIVE) program, a school-based, trauma-informed intervention that is grounded in a public health framework. The model uses psychoeducation, cognitive differentiation, and brief stress reduction sessions to promote socioemotional development and academic progress. We present two clinical cases as examples of trauma-informed, school-based practice, and then apply their experience working in an urban, public middle school to explicate intervention theory and practice for school social workers.

Impact of Trauma Exposure on Early Adolescent Developmental Tasks

Social development.

Impact of Trauma on Early Adolescent Development

Traumatic experiences may create difficulty with developing and differentiating another person's point of view (that is, mentalization) due to the formation of rigid cognitive schemas that dictate notions of self, others, and the external world ( Frydman & McLellan, 2014 ). For early adolescents, the ability to diversify a single perspective with complexity is central to modulating affective experience. Without the capacity to diversify one's perspective, there is often difficulty differentiating between a nonthreatening current situation that may harbor reminders of the traumatic experience and actual traumatic events. Incumbent on the school social worker is the need to help students understand how these conflicts may trigger a memory of harm, abandonment, or loss and how to differentiate these past memories from the present conflict. This is of particular concern when these reactions are conflated with more common middle school behaviors such as withdrawing, blaming, criticizing, and gossiping ( Card, Stucky, Sawalani, & Little, 2008 ).

Encouraging cognitive discrimination is particularly meaningful given that the second social developmental task for early adolescents is the re-orientation of their primary relationships with family toward peers ( Henderson & Thompson, 2010 ). This shift may become complicated for students facing traumatic stress, resulting in a stunted movement away from familiar connections or a displacement of dysfunctional family relationships onto peers. For example, in the former, a student who has witnessed and intervened to protect his mother from severe domestic violence might believe he needs to sacrifice himself and be available to his mother, forgoing typical peer interactions. In the latter, a student who was beaten when a loud, intoxicated family member came home might become enraged, anxious, or anticipate violence when other students raise their voices.

Cognitive Development and Emotional Regulation

During normative early adolescent development, the prefrontal cortex undergoes maturational shifts in cognitive and emotional functioning, including increased impulse control and affect regulation ( Wigfield, Lutz, & Wagner, 2005 ). However, these developmental tasks can be negatively affected by chronic exposure to traumatic events. Stressful situations often evoke a fear response, which inhibits executive functioning and commonly results in a fight-flight-freeze reaction. If a student does not possess strong anxiety management skills to cope with reminders of the trauma, the student is prone to further emotional dysregulation, lowered frustration tolerance, and increased behavioral problems and depressive symptoms ( Iachini et al., 2016 ; Saltzman, Steinberg, Layne, Aisenberg, & Pynoos, 2001 ).

Typical cognitive development in early adolescence is defined by the ambiguity of a transitional stage between childhood remedial capacity and adult refinement ( Casey & Caudle, 2013 ; Van Duijvenvoorde & Crone, 2013 ). Casey and Caudle (2013) found that although adolescents performed equally as well as, if not better than, adults on a self-control task when no emotional information was present, the introduction of affectively laden social cues resulted in diminished performance. The developmental challenge for the early adolescent then is to facilitate the coordination of this ever-shifting dynamic between cognition and affect. Although early adolescents may display efficient and logically informed behaviors, they may struggle to sustain these behaviors, especially in the presence of emotional stimuli ( Casey & Caudle, 2013 ; Van Duijvenvoorde & Crone, 2013 ). Because trauma often evokes an emotional response ( Johnson & Lubin, 2015 ), these findings insinuate that those early adolescents who are chronically exposed will have ongoing regulation difficulties. Further empirical findings considering the cognitive effects of trauma exposure on the adolescent brain have highlighted detriments in working memory, inhibition, memory, and planning ability ( Moradi, Neshat Doost, Taghavi, Yule, & Dalgleish, 1999 ).

Using a Public Health Framework for School-Based, Trauma-Informed Services

The need for a more informed and comprehensive approach to addressing trauma within the schools has been widely articulated ( Chafouleas et al., 2016 ; Durlak, Weissberg, Dymnicki, Taylor, & Schellinger, 2011 ; Jaycox, Kataoka, Stein, Langley, & Wong, 2012 ; Overstreet & Chafouleas, 2016 ; Perry & Daniels, 2016 ). Overstreet and Matthews (2011) suggested that using a public health model to address trauma in schools will promote prevention, early identification, and data-driven investigation and yield broad-based intervention on a policy and communitywide level. A public health approach focuses on developing interventions that address the underlying causal processes that lead to social, emotional, and cognitive maladjustment. Opening the dialogue to the entire student body, as well as teachers and administrators, promotes inclusion and provides a comprehensive foundation for psychoeducation, assessment, and prevention.

ALIVE: A Comprehensive Public Health Intervention for Middle School Students

Note: ALIVE = Animating Learning by Integrating and Validating Experience.

Psychoeducation

The classroom is a place traditionally dedicated to academic pursuits; however, it also serves as an indicator of trauma's impact on cognitive functioning evidenced by poor grades, behavioral dysregulation, and social turbulence. ALIVE practitioners conduct weekly trauma-focused dialogues in the classroom to normalize conversations addressing trauma, to recruit and rehearse more adaptive cognitive skills, and to engage in an insight-oriented process ( Sajnani et al., 2014 ).

Using a parable as a projective tool for identification and connection, the model helps students tolerate direct discussions about adverse experiences. The ALIVE practitioner begins each academic year by telling the parable of a woman named Miss Kendra, who struggled to cope with the loss of her 10-year-old child. Miss Kendra is able to make meaning out of her loss by providing support for schoolchildren who have encountered adverse experiences, serving as a reminder of the strength it takes to press forward after a traumatic event. The intention of this parable is to establish a metaphor for survival and strength to fortify the coping skills already held by trauma-exposed middle school students. Furthermore, Miss Kendra offers early adolescents an opportunity to project their own needs onto the story, creating a personalized figure who embodies support for socioemotional growth.

Following this parable, the students’ attention is directed toward Miss Kendra's List, a poster that is permanently displayed in the classroom. The list includes a series of statements against adolescent maltreatment, comprehensively identifying various traumatic stressors such as witnessing domestic violence; being physically, verbally, or sexually abused; and losing a loved one to neighborhood violence. The second section of the list identifies what may happen to early adolescents when they experience trauma from emotional, social, and academic perspectives. The practitioner uses this list to provide information about the nature and impact of trauma, while modeling for students and staff the ability to discuss difficult experiences as a way of connecting with one another with a sense of hope and strength.

Furthermore, creating a dialogue about these issues with early adolescents facilitates a culture of acceptance, tolerance, and understanding, engendering empathy and identification among students. This fostering of interpersonal connection provides a reparative and differentiated experience to trauma ( Hartling & Sparks, 2008 ; Henderson & Thompson, 2010 ; Johnson & Lubin, 2015 ) and is particularly important given the peer-focused developmental tasks of early adolescence. The positive feelings evoked through classroom-based conversation are predicated on empathic identification among the students and an accompanying sense of relief in understanding the scope of trauma's impact. Furthermore, the consistent appearance of and engagement by the ALIVE practitioner, and the continual presence of Miss Kendra's list, effectively counters traumatically informed expectations of abandonment and loss while aligning with a public health model that attends to the impact of trauma on a regular, systemwide basis.

Participatory and Somatic Indicators for Informal Assessment during the Psychoeducation Component of the ALIVE Intervention

Notes: ALIVE = Animating Learning by Integrating and Validating Experience. Examples are derived from authors’ clinical experiences.

In addition to behavioral symptoms, the content of conversation is considered. All practitioners in the ALIVE program are mandated reporters, and any content presented that meets criteria for suspicion of child maltreatment is brought to the attention of the school leadership and ALIVE director. According to Johnson (2012) , reports of child maltreatment to the Connecticut Department of Child and Family Services have actually decreased in the schools where the program has been implemented “because [the ALIVE program is] catching problems well before they have risen to the severity that would require reporting” (p. 17).

Case Example 1

The following demonstrates a middle school classroom psychoeducation session and assessment facilitated by an ALIVE practitioner (the first author). All names and identifying characteristics have been changed to protect confidentiality.

Ms. Skylar's seventh grade class comprised many students living in low-income housing or in a neighborhood characterized by high poverty and frequent criminal activity. During the second week of school, I introduced myself as a practitioner who was here to speak directly about difficult experiences and how these instances might affect academic functioning and students’ thoughts about themselves, others, and their environment.

After sharing the Miss Kendra parable and list, I invited the students to share their thoughts about Miss Kendra and her journey. Tyreke began the conversation by wondering whether Miss Kendra lost her child to gun violence, exploring the connection between the list and the story and his own frequent exposure to neighborhood shootings. To transition a singular connection to a communal one, I asked the students if this was a shared experience. The majority of students nodded in agreement. I referred the students back to the list and asked them to identify how someone's school functioning or mood may be affected by ongoing neighborhood gun violence. While the students read the list, I actively monitored reactions and scanned for inattention and active avoidance. Performing both active facilitation of discussion and monitoring students’ reactions is critical in accomplishing the goals of providing quality psychoeducation and identifying at-risk students for intervention.

After inspection, Cleo remarked that, contrary to a listed outcome on Miss Kendra's list, neighborhood gun violence does not make him feel lonely; rather, he “doesn't care about it.” Slumped down in his chair, head resting on his crossed arms on the desk in front of him, Cleo's body language suggested a somatized disengagement. I invited other students to share their individual reactions. Tyreke agreed that loneliness is not the identified affective experience; rather, for him, it's feeling “mad or scared.” Immediately, Greg concurred, expressing that “it makes me more mad, and I think about my family.”

Encouraging a variety of viewpoints, I stated, “It sounds like it might make you mad, scared, and may even bring up thoughts about your family. I wonder why people have different reactions?” Doing so moved the conversation into a phase of deeper reflection, simultaneously honoring the students’ voiced experience while encouraging critical thinking. A number of students responded by offering connections to their lives, some indicating they had difficulty identifying feelings. I reflected back, “Sometimes people feel something, but can't really put their finger on it, and sometimes they know exactly how they feel or who it makes them think about.”

I followed with a question: “How do you think it affects your schoolwork or feelings when you're in school?” Greg and Natalia both offered that sometimes difficult or confusing thoughts can consume their whole day, even while in class. Sharon began to offer a related comment when Cleo interrupted by speaking at an elevated volume to his desk partner, Tyreke. The two began to snicker and pull focus. By the time they gained the class's full attention, Cleo was openly laughing and pushing his chair back, stating, “No way! She DID!? That's crazy”; he began to stand up, enlisting Tyreke in the process. While this disruption may be viewed as a challenge to the discussion, it is essential to understand all behavior in context of the session's trauma content. Therefore, Cleo's outburst was interpreted as a potential avenue for further exploration of the topic regarding gun violence and difficulties concentrating. In turn, I posed this question to the class: “Should we talk about this stuff? I wonder if sometimes people have a hard time tolerating it. Can anybody think of why it might be important? Sharon, I think you were saying something about this.” While Sharon continued to share, Cleo and Tyreke gradually shifted their attention back to the conversation. I noted the importance of an individual follow-up with Cleo.

Natalia jumped back in the conversation, stating, “I think we talk about stuff like this so we know about it and can help people with it.” I checked in with the rest of the class about this strategy for coping with the impact of trauma exposure on school functioning: “So it sounds like these thoughts have a pretty big impact on your day. If that's the case, how do you feel less worried or mad or scared?” Marta quickly responded, “You could talk to someone.” I responded, “Part of my job here is to be a person to talk to one-on-one about these things. Hopefully, it will help you feel better to get some of that stuff off your chest.” The students nodded, acknowledging that I would return to discuss other items on the list and that there would be opportunities to check in with me individually if needed.

On reflection, Cleo's disruption in the discussion may be attributed to his personal difficulty emotionally managing intrusive thoughts while in school. This clinical assumption was not explicitly named in the moment, but was noted as information for further individual follow-up. When I met individually with Cleo, Cleo reported that his cousin had been shot a month ago, causing him to feel confused and angry. I continued to work with him individually, which resulted in a reduction of behavioral disruptions in the classroom.

In the preceding case example, the practitioner performed a variety of public health tasks. Foremost was the introduction of how traumatic experience may affect individuals and their relationships with others and their role as a student. Second, the practitioner used Miss Kendra and her list as a foundational mechanism to ground the conversation and serve as a reference point for the students’ experience. Finally, the practitioner actively monitored individual responses to the material as a means of identifying students who may require more support. All three of these processes are supported within the public health framework as a means toward assessment and early intervention for early adolescents who may be exposed to trauma.

Individualized Stress Reduction Intervention

Students are seen for individualized support if they display significant externalizing or internalizing trauma-related behavior. Students are either self-referred; referred by a teacher, administrator, or staff member; or identified by an ALIVE practitioner. Following the principle of immediate engagement based on emergent traumatic material, individual sessions are brief, lasting only 15 to 20 minutes. Using trauma-centered psychotherapy ( Johnson & Lubin, 2015 ), a brief inquiry addressing the current problem is conducted to identify the trauma trigger connected to the original harm, fostering cognitive discrimination. Conversation about the adverse experience proceeds in a calm, direct way focusing on differentiating between intrusive memories and the current situation at school ( Sajnani et al., 2014 ). Once the student exhibits greater emotional regulation, the ALIVE practitioner returns the student to the classroom in a timely manner and may provide either brief follow-up sessions for preventive purposes or, when appropriate, refer the student to more regular, clinical support in or out of the school.

Case Example 2

The following case example is representative of the brief, immediate, and open engagement with traumatic material and encouragement of cognitive discrimination. This intervention was conducted with a sixth grade student, Jacob (name and identifying information changed to ensure confidentiality), by an ALIVE practitioner (the second author).

I found Jacob in the hallway violently shaking a trash can, kicking the classroom door, and slamming his hands into the wall and locker. His teacher was standing at the door, distressed, stating, “Jacob, you need to calm down and go to the office, or I'm calling home!” Jacob yelled, “It's not fair, it was him, not me! I'm gonna fight him!” As I approached, I asked what was making him so angry, but he said, “I don't want to talk about it.” Rather than asking him to calm down or stop slamming objects, I instead approached the potential memory agitating him, stating, “My guess is that you are angry for a very good reason.” Upon this simple connection, he sighed and stopped kicking the trash can and slamming the wall. Jacob continued to demonstrate physical and emotional activation, pacing the hallway and making a fist; however, he was able to recount putting trash in the trash can when a peer pushed him from behind, causing him to yell. Jacob explained that his teacher heard him yelling and scolded him, making him more mad. Jacob stated, “She didn't even know what happened and she blamed me. I was trying to help her by taking out all of our breakfast trash. It's not fair.”

The ALIVE practitioner listens to students’ complaints with two ears, one for the current complaint and one for affect-laden details that may be connected to the original trauma to inquire further into the source of the trigger. Affect-laden details in case example 2 include Jacob's anger about being blamed (rather than toward the student who pushed him), his original intention to help, and his repetition of the phrase “it's not fair.” Having met with Jacob previously, I was aware that his mother suffers from physical and mental health difficulties. When his mother is not doing well, he (as the parentified child) typically takes care of the household, performing tasks like cooking, cleaning, and helping with his two younger siblings and older autistic brother. In the past, Jacob has discussed both idealizing his mother and holding internalized anger that he rarely expresses at home because he worries his anger will “make her sick.”

I know sometimes when you are trying to help mom, there are times she gets upset with you for not doing it exactly right, or when your brothers start something, she will blame you. What just happened sounds familiar—you were trying to help your teacher by taking out the garbage when another student pushed you, and then you were the one who got in trouble.

Jacob nodded his head and explained that he was simply trying to help.

I moved into a more detailed inquiry, to see if there was a more recent stressor I was unaware of. When I asked how his mother was doing this week, Jacob revealed that his mother's health had deteriorated and his aunt had temporarily moved in. Jacob told me that he had been yelled at by both his mother and his aunt that morning, when his younger brother was not ready for school. I asked, “I wonder if when the student pushed you it reminded you of getting into trouble because of something your little brother did this morning?” Jacob nodded. The displacement was clear: He had been reminded of this incident at school and was reacting with anger based on his family dynamic, and worries connected to his mother.

My guess is that you were a mix of both worried and angry by the time you got to school, with what's happening at home. You were trying to help with the garbage like you try to help mom when she isn't doing well, so when you got pushed it was like your brother being late, and then when you got blamed by your teacher it was like your mom and aunt yelling, and it all came flooding back in. The problem is, you let out those feelings here. Even though there are some similar things, it's not totally the same, right? Can you tell me what is different?

Jacob nodded and was able to explain that the other student was probably just playing and did not mean to get him into trouble, and that his teacher did not usually yell at him or make him worried. Highlighting this important differentiation, I replied, “Right—and fighting the student or yelling at the teacher isn't going to solve this, but more importantly, it isn't going to make your mom better or have your family go any easier on you either.” Jacob stated that he knew this was true.

I reassured Jacob that I could help him let out those feelings of worry and anger connected to home so they did not explode out at school and planned to meet again. Jacob confirmed that he was willing to do that. He was able to return to the classroom without incident, with the entire intervention lasting less than 15 minutes.

In case example 2, the practitioner was available for an immediate engagement with disturbing behaviors as they were happening by listening for similarities between the current incident and traumatic stressors; asking for specific details to more effectively help Jacob understand how he was being triggered in school; providing psychoeducation about how these two events had become confused and aiding him in cognitively differentiating between the two; and, last, offering to provide further support to reduce future incidents.

Germane to the practice of school social work is the ability to work flexibly within a public health model to attend to trauma within the school setting. First, we suggest that a primary implication for school social workers is not to wait for explicit problems related to known traumatic experiences to emerge before addressing trauma in the school, but, rather, to follow a model of prevention-assessment-intervention. School social workers are in a unique position within the school system to disseminate trauma-informed material to both students and staff in a preventive capacity. Facilitating this implementation will help to establish a tone and sharpened focus within the school community, norming the process of articulating and engaging with traumatic material. In the aforementioned classroom case example, we have provided a sample of how school social workers might work with entire classrooms on a preventive basis regarding trauma, rather than waiting for individual referrals.

Second, in addition to functional behavior assessments and behavior intervention plans, school social workers maintain a keen eye for qualitative behavioral assessment ( National Association of Social Workers, 2012 ). Using this skill set within a trauma-informed model will help to identify those students in need who may be reluctant or resistant to explicitly ask for help. As called for by Walkley and Cox (2013) , we suggest that using the information presented in Table 1 will help school social workers understand, identify, and assess the impact of trauma on early adolescent developmental tasks. If school social workers engage on a classroom level in trauma psychoeducation and conversations, the information in Table 3 may assist with assessment of children and provide a basis for checking in individually with students as warranted.

Third, school social workers are well positioned to provide individual targeted, trauma-informed interventions based on previous knowledge of individual trauma and through widespread assessment ( Walkley & Cox, 2013 ). The individual case example provides one way of immediately engaging with students who are demonstrating trauma-based behaviors. In this model, school social workers engage in a brief inquiry addressing the current trauma to identify the trauma trigger, discuss the adverse experience in a calm but direct way, and help to differentiate between intrusive memories and the current situation at school. For this latter component, the focus is on cognitive discrimination and emotional regulation so that students can reengage in the classroom within a short time frame.

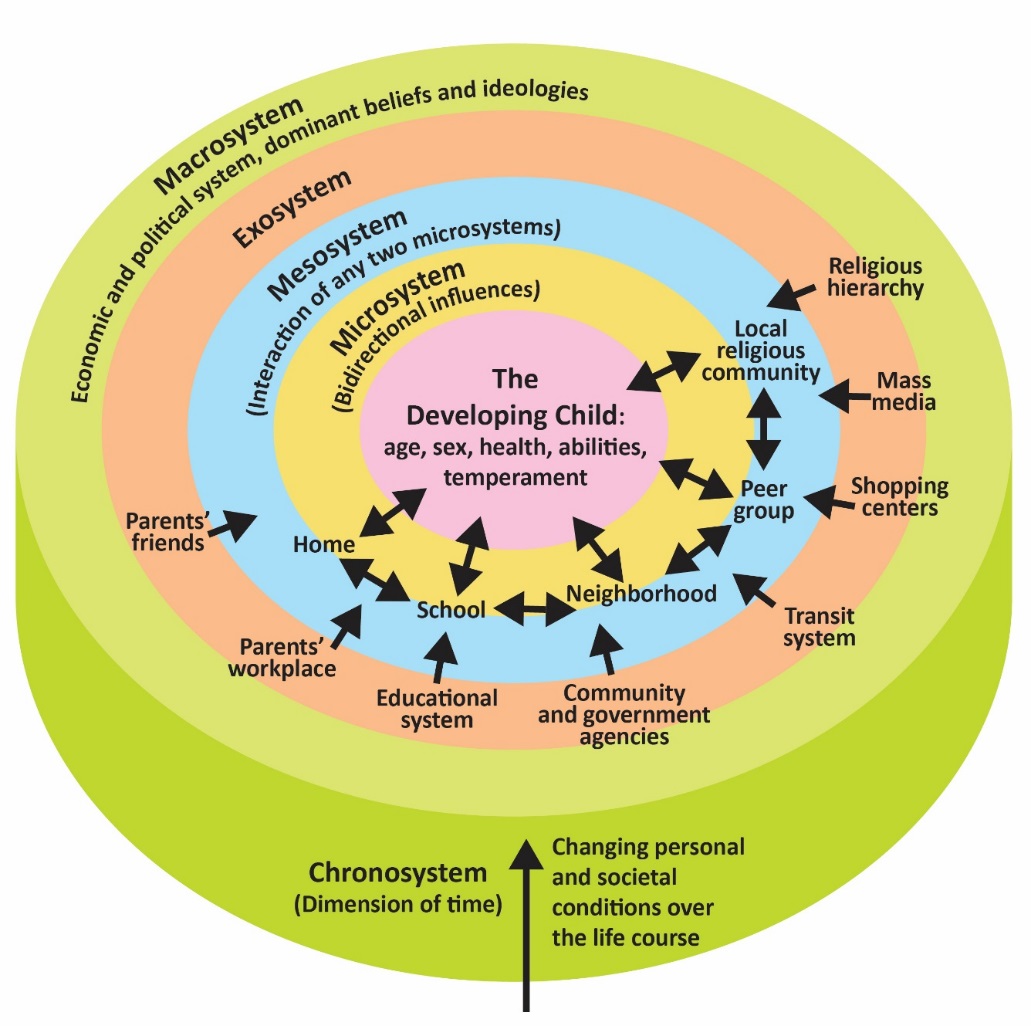

Fourth, given social work's roots in collaboration and community work, school social workers are encouraged to use a systems-based approach in partnering with allied practitioners and institutions ( D'Agostino, 2013 ), thus supporting the public health tenet of establishing and maintaining a link to the wider community. This may include referring students to regular clinical support in or out of the school. Although the implementation of a trauma-informed program will vary across schools, we suggest that school social workers have the capacity to use a public health school intervention model to ecologically address the psychosocial and behavioral issues stemming from trauma exposure.

As increasing attention is being given to adverse childhood experiences, a tiered approach that uses a public health framework in the schools is necessitated. Nevertheless, there are some limitations to this approach. First, although the interventions outlined here are rooted in prevention and early intervention, there are times when formal, intensive treatment outside of the school setting is warranted. Second, the ALIVE program has primarily been implemented by ALIVE practitioners; the results from piloting this public health framework in other school settings with existing school personnel, such as school social workers, will be necessary before widespread replication.

The public health framework of prevention-assessment-intervention promotes continual engagement with middle school students’ chronic exposure to traumatic stress. There is a need to provide both broad-based and individualized support that seeks to comprehensively ameliorate the social, emotional, and cognitive consequences on early adolescent developmental milestones associated with traumatic experiences. We contend that school social workers are well positioned to address this critical public health issue through proactive and widespread psychoeducation and assessment in the schools, and we have provided case examples to demonstrate one model of doing this work within the school day. We hope that this article inspires future writing about how school social workers individually and systemically address trauma in the school system. In alignment with Walkley and Cox (2013) , we encourage others to highlight their practice in incorporating trauma-informed, school-based programming in an effort to increase awareness of effective interventions.

Card , N. A. , Stucky , B. D. , Sawalani , G. M. , & Little , T. D. ( 2008 ). Direct and indirect aggression during childhood and adolescence: A meta-analytic review of gender difference, intercorrelations, and relations to maladjustment . Child Development, 79 , 1185 – 1229 .

Google Scholar

Casey , B. J. , & Caudle , K. ( 2013 ). The teenage brain: Self control . Current Directions in Psychological Science, 22 ( 2 ), 82 – 87 .

Chafouleas , S. M. , Johnson , A. H. , Overstreet , S. , & Santos , N. M. ( 2016 ). Toward a blueprint for trauma-informed service delivery in schools . School Mental Health, 8 ( 1 ), 144 – 162 .

Chanmugam , A. , & Teasley , M. L. ( 2014 ). What should school social workers know about children exposed to intimate partner violence? [Editorial]. Children & Schools, 36 , 195 – 198 .

Cook , A. , Spinazzola , J. , Ford , J. , Lanktree , C. , Blaustein , M. , Cloitre , M. , et al. . ( 2005 ). Complex trauma in children and adolescents . Psychiatric Annals, 35 , 390 – 398 .

D'Agostino , C. ( 2013 ). Collaboration as an essential social work skill [Resources for Practice] . Children & Schools, 35 , 248 – 251 .

Durlak , J. A. , Weissberg , R. P. , Dymnicki , A. B. , Taylor , R. D. , & Schellinger , K. B. ( 2011 ). The impact of enhancing students’ social and emotional learning: A meta-analysis of school-based universal interventions . Child Development, 82 , 405 – 432 .

Frydman , J. S. , & McLellan , L. ( 2014 ). Complex trauma and executive functioning: Envisioning a cognitive-based, trauma-informed approach to drama therapy. In N. Sajnani & D. R. Johnson (Eds.), Trauma-informed drama therapy: Transforming clinics, classrooms, and communities (pp. 179 – 205 ). Springfield, IL : Charles C Thomas .

Google Preview

Hartling , L. , & Sparks , J. ( 2008 ). Relational-cultural practice: Working in a nonrelational world . Women & Therapy, 31 , 165 – 188 .

Henderson , D. , & Thompson , C. ( 2010 ). Counseling children (8th ed.). Belmont, CA : Brooks-Cole .

Iachini , A. L. , Petiwala , A. F. , & DeHart , D. D. ( 2016 ). Examining adverse childhood experiences among students repeating the ninth grade: Implications for school dropout prevention . Children & Schools, 38 , 218 – 227 .

Jaycox , L. H. , Kataoka , S. H. , Stein , B. D. , Langley , A. K. , & Wong , M. ( 2012 ). Cognitive behavioral intervention for trauma in schools . Journal of Applied School Psychology, 28 , 239 – 255 .

Johnson , D. R. ( 2012 ). Ask every child: A public health initiative addressing child maltreatment [White paper]. Retrieved from http://www.traumainformedschools.org/publications.html

Johnson , D. R. , & Lubin , H. ( 2015 ). Principles and techniques of trauma-centered psychotherapy . Arlington, VA : American Psychiatric Publishing .

Moon , J. , Williford , A. , & Mendenhall , A. ( 2017 ). Educators’ perceptions of youth mental health: Implications for training and the promotion of mental health services in schools . Child and Youth Services Review, 73 , 384 – 391 .

Moradi , A. R. , Neshat Doost , H. T. , Taghavi , M. R. , Yule , W. , & Dalgleish , T. ( 1999 ). Everyday memory deficits in children and adolescents with PTSD: Performance on the Rivermead Behavioural Memory Test . Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 40 , 357 – 361 .

National Association of Social Workers . ( 2012 ). NASW standards for school social work services . Retrieved from http://www.naswdc.org/practice/standards/NASWSchoolSocialWorkStandards.pdf

Oehlberg , B. ( 2008 ). Why schools need to be trauma informed . Trauma and Loss: Research and Interventions, 8 ( 2 ), 1 – 4 .

Overstreet , S. , & Chafouleas , S. M. ( 2016 ). Trauma-informed schools: Introduction to the special issue . School Mental Health, 8 ( 1 ), 1 – 6 .

Overstreet , S. , & Matthews , T. ( 2011 ). Challenges associated with exposure to chronic trauma: Using a public health framework to foster resilient outcomes among youth . Psychology in the Schools, 48 , 738 – 754 .

Perfect , M. , Turley , M. , Carlson , J. S. , Yohannan , J. , & Gilles , M. S. ( 2016 ). School-related outcomes of traumatic event exposure and traumatic stress symptoms in students: A systematic review of research from 1990 to 2015 . School Mental Health, 8 ( 1 ), 7 – 43 .

Perry , D. L. , & Daniels , M. L. ( 2016 ). Implementing trauma-informed practices in the school setting: A pilot study . School Mental Health, 8 ( 1 ), 177 – 188 .

Porche , M. V. , Costello , D. M. , & Rosen-Reynoso , M. ( 2016 ). Adverse family experiences, child mental health, and educational outcomes for a national sample of students . School Mental Health, 8 ( 1 ), 44 – 60 .

Sajnani , N. , Jewers-Dailley , K. , Brillante , A. , Puglisi , J. , & Johnson , D. R. ( 2014 ). Animating Learning by Integrating and Validating Experience. In N. Sajnani & D. R. Johnson (Eds.), Trauma-informed drama therapy: Transforming clinics, classrooms, and communities (pp. 206 – 242 ). Springfield, IL : Charles C Thomas .

Saltzman , W. R. , Steinberg , A. M. , Layne , C. M. , Aisenberg , E. , & Pynoos , R. S. ( 2001 ). A developmental approach to school-based treatment of adolescents exposed to trauma and traumatic loss . Journal of Child and Adolescent Group Therapy, 11 ( 2–3 ), 43 – 56 .

Sibinga , E. M. , Webb , L. , Ghazarian , S. R. , & Ellen , J. M. ( 2016 ). School-based mindfulness instruction: An RCT . Pediatrics, 137 ( 1 ), e20152532 .

Tucker , C. , Smith-Adcock , S. , & Trepal , H. C. ( 2011 ). Relational-cultural theory for middle school counselors . Professional School Counseling, 14 , 310 – 316 .

Turner , H. A. , Shattuck , A. , Finkelhor , D. , & Hamby , S. ( 2017 ). Effects of poly-victimization on adolescent social support, self-concept, and psychological distress . Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 32 , 755 – 780 .

van der Kolk , B. A. ( 2005 ). Developmental trauma disorder: Toward a rational diagnosis for children with complex trauma histories . Psychiatric Annals, 35 , 401 – 408 .

Van Duijvenvoorde , A.C.K. , & Crone , E. A. ( 2013 ). The teenage brain: A neuroeconomic approach to adolescent decision making . Current Directions in Psychological Science, 22 ( 2 ), 114 – 120 .

Walkley , M. , & Cox , T. L. ( 2013 ). Building trauma-informed schools and communities [Trends & Resources] . Children & Schools, 35 , 123 – 126 .

Wigfield , A. W. , Lutz , S. L. , & Wagner , L. ( 2005 ). Early adolescents’ development across the middle school years: Implications for school counselors . Professional School Counseling, 9 ( 2 ), 112 – 119 .

Woodbridge , M. W. , Sumi , W. C. , Thornton , S. P. , Fabrikant , N. , Rouspil , K. M. , Langley , A. K. , & Kataoka , S. H. ( 2016 ). Screening for trauma in early adolescence: Findings from a diverse school district . School Mental Health, 8 ( 1 ), 89 – 105 .

Email alerts

Citing articles via.

- About Children & Schools

- Recommend to your Library

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1545-682X

- Print ISSN 1532-8759

- Copyright © 2024 National Association of Social Workers

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

Module 13: Disorders of Childhood and Adolescence

Case studies: disorders of childhood and adolescence, learning objectives.

- Identify disorders of childhood and adolescence in case studies

Case Study: Jake

Jake was born at full term and was described as a quiet baby. In the first three months of his life, his mother became worried as he was unresponsive to cuddles and hugs. He also never cried. He has no friends and, on occasions, he has been victimized by bullying at school and in the community. His father is 44 years old and describes having had a difficult childhood; he is characterized by the family as indifferent to the children’s problems and verbally violent towards his wife and son, but less so to his daughters. The mother is 41 years old, and describes herself as having a close relationship with her children and mentioned that she usually covers up for Jake’s difficulties and makes excuses for his violent outbursts. [1]

During his stay (for two and a half months) in the inpatient unit, Jake underwent psychiatric and pediatric assessments plus occupational therapy. He took part in the unit’s psycho-educational activities and was started on risperidone, two mg daily. Risperidone was preferred over an anti-ADHD agent because his behavioral problems prevailed and thus were the main target of treatment. In addition, his behavioral problems had undoubtedly influenced his functionality and mainly his relations with parents, siblings, peers, teachers, and others. Risperidone was also preferred over other atypical antipsychotics for its safe profile and fewer side effects. Family meetings were held regularly, and parental and family support along with psycho-education were the main goals. Jake was aided in recognizing his own emotions and conveying them to others as well as in learning how to recognize the emotions of others and to become aware of the consequences of his actions. Improvement was made in rule setting and boundary adherence. Since his discharge, he received regular psychiatric follow-up and continues with the medication and the occupational therapy. Supportive and advisory work is done with the parents. Marked improvement has been noticed regarding his social behavior and behavior during activity as described by all concerned. Occasional anger outbursts of smaller intensity and frequency have been reported, but seem more manageable by the child with the support of his mother and teachers.

In the case presented here, the history of abuse by the parents, the disrupted family relations, the bullying by his peers, the educational difficulties, and the poor SES could be identified as additional risk factors relating to a bad prognosis. Good prognostic factors would include the ending of the abuse after intervention, the child’s encouragement and support from parents and teachers, and the improvement of parental relations as a result of parent training and family support by mental health professionals. Taken together, it appears that also in the case of psychiatric patients presenting with complex genetic aberrations and additional psychosocial problems, traditional psychiatric and psychological approaches can lead to a decrease of symptoms and improved functioning.

Case Study: Kelli

Kelli may benefit from a course of comprehensive behavioral intervention for her tics in addition to psychotherapy to treat any comorbid depression she experiences from isolation and bullying at school. Psychoeducation and approaches to reduce stigma will also likely be very helpful for both her and her family, as well as bringing awareness to her school and those involved in her education.

- Kolaitis, G., Bouwkamp, C.G., Papakonstantinou, A. et al. A boy with conduct disorder (CD), attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), borderline intellectual disability, and 47,XXY syndrome in combination with a 7q11.23 duplication, 11p15.5 deletion, and 20q13.33 deletion. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health 10, 33 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13034-016-0121-8 ↵

- Case Study: Childhood and Adolescence. Authored by : Chrissy Hicks for Lumen Learning. Provided by : Lumen Learning. License : CC BY: Attribution

- A boy with conduct disorder (CD), attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), borderline intellectual disability.... Authored by : Gerasimos Kolaitis, Christian G. Bouwkamp, Alexia Papakonstantinou, Ioanna Otheiti, Maria Belivanaki, Styliani Haritaki, Terpsihori Korpa, Zinovia Albani, Elena Terzioglou, Polyxeni Apostola, Aggeliki Skamnaki, Athena Xaidara, Konstantina Kosma, Sophia Kitsiou-Tzeli, Maria Tzetis . Provided by : Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health. Located at : https://capmh.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13034-016-0121-8 . License : CC BY: Attribution

- Angry boy. Located at : https://www.pxfuel.com/en/free-photo-jojfk . License : Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Frustrated girl. Located at : https://www.pickpik.com/book-bored-college-education-female-girl-1717 . License : Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- High contrast

- Press Centre

Search UNICEF

Adolescent development: case studies, investing in adolescents builds strong economies, inclusive communities and vibrant societies..

- Case studies

Adolescent development case studies

Advancing child-centred public policy in brazil through adolescent civic engagement in local governance, mainstreaming adolescent mental health & suicide prevention, adolescents take action to mitigate air pollution in vietnam, adolescent mental health knowledge summary: time for action.

Child Growth and Development

(12 reviews)

Jennifer Paris

Antoinette Ricardo

Dawn Rymond

Alexa Johnson

Copyright Year: 2018

Last Update: 2019

Publisher: College of the Canyons

Language: English

Formats Available

Conditions of use.

Learn more about reviews.

Reviewed by Mistie Potts, Assistant Professor, Manchester University on 11/22/22

This text covers some topics with more detail than necessary (e.g., detailing infant urination) yet it lacks comprehensiveness in a few areas that may need revision. For example, the text discusses issues with vaccines and offers a 2018 vaccine... read more

Comprehensiveness rating: 4 see less

This text covers some topics with more detail than necessary (e.g., detailing infant urination) yet it lacks comprehensiveness in a few areas that may need revision. For example, the text discusses issues with vaccines and offers a 2018 vaccine schedule for infants. The text brushes over “commonly circulated concerns” regarding vaccines and dispels these with statements about the small number of antigens a body receives through vaccines versus the numerous antigens the body normally encounters. With changes in vaccines currently offered, shifting CDC viewpoints on recommendations, and changing requirements for vaccine regulations among vaccine producers, the authors will need to revisit this information to comprehensively address all recommended vaccines, potential risks, and side effects among other topics in the current zeitgeist of our world.

Content Accuracy rating: 3

At face level, the content shared within this book appears accurate. It would be a great task to individually check each in-text citation and determine relevance, credibility and accuracy. It is notable that many of the citations, although this text was updated in 2019, remain outdated. Authors could update many of the in-text citations for current references. For example, multiple in-text citations refer to the March of Dimes and many are dated from 2012 or 2015. To increase content accuracy, authors should consider revisiting their content and current citations to determine if these continue to be the most relevant sources or if revisions are necessary. Finally, readers could benefit from a reference list in this textbook. With multiple in-text citations throughout the book, it is surprising no reference list is provided.

Relevance/Longevity rating: 4

This text would be ideal for an introduction to child development course and could possibly be used in a high school dual credit or beginning undergraduate course or certificate program such as a CDA. The outdated citations and formatting in APA 6th edition cry out for updating. Putting those aside, the content provides a solid base for learners interested in pursuing educational domains/careers relevant to child development. Certain issues (i.e., romantic relationships in adolescence, sexual orientation, and vaccination) may need to be revisited and updated, or instructors using this text will need to include supplemental information to provide students with current research findings and changes in these areas.

Clarity rating: 4

The text reads like an encyclopedia entry. It provides bold print headers and brief definitions with a few examples. Sprinkled throughout the text are helpful photographs with captions describing the images. The words chosen in the text are relatable to most high school or undergraduate level readers and do not burden the reader with expert level academic vocabulary. The layout of the text and images is simple and repetitive with photographs complementing the text entries. This allows the reader to focus their concentration on comprehension rather than deciphering a more confusing format. An index where readers could go back and search for certain terms within the textbook would be helpful. Additionally, a glossary of key terms would add clarity to this textbook.

Consistency rating: 5

Chapters appear in a similar layout throughout the textbook. The reader can anticipate the flow of the text and easily identify important terms. Authors utilized familiar headings in each chapter providing consistency to the reader.

Modularity rating: 4

Given the repetitive structure and the layout of the topics by developmental issues (physical, social emotional) the book could be divided into sections or modules. It would be easier if infancy and fetal development were more clearly distinct and stages of infant development more clearly defined, however the book could still be approached in sections or modules.

Organization/Structure/Flow rating: 4

The text is organized in a logical way when we consider our own developmental trajectories. For this reason, readers learning about these topics can easily relate to the flow of topics as they are presented throughout the book. However, when attempting to find certain topics, the reader must consider what part of development that topic may inhabit and then turn to the portion of the book aligned with that developmental issue. To ease the organization and improve readability as a reference book, authors could implement an index in the back of the book. With an index by topic, readers could quickly turn to pages covering specific topics of interest. Additionally, the text structure could be improved by providing some guiding questions or reflection prompts for readers. This would provide signals for readers to stop and think about their comprehension of the material and would also benefit instructors using this textbook in classroom settings.

Interface rating: 4

The online interface for this textbook did not hinder readability or comprehension of the text. All information including photographs, charts, and diagrams appeared to be clearly depicted within this interface. To ease reading this text online authors should create a live table of contents with bookmarks to the beginning of chapters. This book does not offer such links and therefore the reader must scroll through the pdf to find each chapter or topic.

Grammatical Errors rating: 5

No grammatical errors were found in reviewing this textbook.

Cultural Relevance rating: 3

Cultural diversity is represented throughout this text by way of the topics described and the images selected. The authors provide various perspectives that individuals or groups from multiple cultures may resonate with including parenting styles, developmental trajectories, sexuality, approaches to feeding infants, and the social emotional development of children. This text could expand in the realm of cultural diversity by addressing current issues regarding many of the hot topics in our society. Additionally, this textbook could include other types of cultural diversity aside from geographical location (e.g., religion-based or ability-based differences).

While this text lacks some of the features I would appreciate as an instructor (e.g., study guides, review questions, prompts for critical thinking/reflection) and it does not contain an index or glossary, it would be appropriate as an accessible resource for an introduction to child development. Students could easily access this text and find reliable and easily readable information to build basic content knowledge in this domain.

Reviewed by Caroline Taylor, Instructor, Virginia Tech on 12/30/21

Each chapter is comprehensively described and organized by the period of development. Although infancy and toddlerhood are grouped together, they are logically organized and discussed within each chapter. One helpful addition that would largely... read more

Each chapter is comprehensively described and organized by the period of development. Although infancy and toddlerhood are grouped together, they are logically organized and discussed within each chapter. One helpful addition that would largely contribute to the comprehensiveness is a glossary of terms at the end of the text.

From my reading, the content is accurate and unbiased. However, it is difficult to confidently respond due to a lack of references. It is sometimes clear where the information came from, but when I followed one link to a citation the link was to another textbook. There are many citations embedded within the text, but it would be beneficial (and helpful for further reading) to have a list of references at the end of each chapter. The references used within the text are also older, so implementing updated references would also enhance accuracy. If used for a course, instructors will need to supplement the textbook readings with other materials.

This text can be implemented for many semesters to come, though as previously discussed, further readings and updated materials can be used to supplement this text. It provides a good foundation for students to read prior to lectures.

Clarity rating: 5

This text is unique in its writing style for a textbook. It is written in a way that is easily accessible to students and is also engaging. The text doesn't overly use jargon or provide complex, long-winded examples. The examples used are clear and concise. Many key terms are in bold which is helpful to the reader.

For the terms that are in bold, it would be helpful to have a definition of the term listed separately on the page within the side margins, as well as include the definition in a glossary at the end.

Each period of development is consistently described by first addressing physical development, cognitive development, and then social-emotional development.

Modularity rating: 5

This text is easily divisible to assign to students. There were few (if any) large blocks of texts without subheadings, graphs, or images. This feature not only improves modularity but also promotes engagement with the reading.

Organization/Structure/Flow rating: 5

The organization of the text flows logically. I appreciate the order of the topics, which are clearly described in the first chapter by each period of development. Although infancy and toddlerhood are grouped into one period of development, development is appropriately described for both infants and toddlers. Key theories are discussed for infants and toddlers and clearly presented for the appropriate age.

Interface rating: 5

There were no significant interface issues. No images or charts were distorted.

It would be helpful to the reader if the table of contents included a navigation option, but this doesn't detract from the overall interface.

I did not see any grammatical errors.

This text includes some cultural examples across each area of development, such as differences in first words, parenting styles, personalities, and attachments styles (to list a few). The photos included throughout the text are inclusive of various family styles, races, and ethnicities. This text could implement more cultural components, but does include some cultural examples. Again, instructors can supplement more cultural examples to bolster the reading.

This text is a great introductory text for students. The text is written in a fun, approachable way for students. Though the text is not as interactive (e.g., further reading suggestions, list of references, discussion points at the end of each chapter, etc.), this is a great resource to cover development that is open access.

Reviewed by Charlotte Wilinsky, Assistant Professor of Psychology, Holyoke Community College on 6/29/21

This text is very thorough in its coverage of child and adolescent development. Important theories and frameworks in developmental psychology are discussed in appropriate depth. There is no glossary of terms at the end of the text, but I do not... read more

Comprehensiveness rating: 5 see less

This text is very thorough in its coverage of child and adolescent development. Important theories and frameworks in developmental psychology are discussed in appropriate depth. There is no glossary of terms at the end of the text, but I do not think this really hurts its comprehensiveness.

Content Accuracy rating: 5

The citations throughout the textbook help to ensure its accuracy. However, the text could benefit from additional references to recent empirical studies in the developmental field.

It seems as if updates to this textbook will be relatively easy and straightforward to implement given how well organized the text is and its numerous sections and subsections. For example, a recent narrative review was published on the effects of corporal punishment (Heilmann et al., 2021). The addition of a reference to this review, and other more recent work on spanking and other forms of corporal punishment, could serve to update the text's section on spanking (pp. 223-224; p. 418).

The text is very clear and easily understandable.

Consistency rating: 4

There do not appear to be any inconsistencies in the text. The lack of a glossary at the end of the text may be a limitation in this area, however, since glossaries can help with consistent use of language or clarify when different terms are used.

This textbook does an excellent job of dividing up and organizing its chapters. For example, chapters start with bulleted objectives and end with a bulleted conclusion section. Within each chapter, there are many headings and subheadings, making it easy for the reader to methodically read through the chapter or quickly identify a section of interest. This would also assist in assigning reading on specific topics. Additionally, the text is broken up by relevant photos, charts, graphs, and diagrams, depending on the topic being discussed.

This textbook takes a chronological approach. The broad developmental stages covered include, in order, birth and the newborn, infancy and toddlerhood, early childhood, middle childhood, and adolescence. Starting with the infancy and toddlerhood stage, physical, cognitive, and social emotional development are covered.

There are no interface issues with this textbook. It is easily accessible as a PDF file. Images are clear and there is no distortion apparent.

I did not notice any grammatical errors.

Cultural Relevance rating: 4

This text does a good job of including content relevant to different cultures and backgrounds. One example of this is in the "Cultural Influences on Parenting Styles" subsection (p. 222). Here the authors discuss how socioeconomic status and cultural background can affect parenting styles. Including references to specific studies could further strengthen this section, and, more broadly, additional specific examples grounded in research could help to fortify similar sections focused on cultural differences.

Overall, I think this is a terrific resource for a child and adolescent development course. It is user-friendly and comprehensive.

Reviewed by Lois Pribble, Lecturer, University of Oregon on 6/14/21

This book provides a really thorough overview of the different stages of development, key theories of child development and in-depth information about developmental domains. read more

This book provides a really thorough overview of the different stages of development, key theories of child development and in-depth information about developmental domains.

The book provides accurate information, emphasizes using data based on scientific research, and is stated in a non-biased fashion.

Relevance/Longevity rating: 5

The book is relevant and provides up-to-date information. There are areas where updates will need to be made as research and practices change (e.g., autism information), but it is written in a way where updates should be easy to make as needed.

The book is clear and easy to read. It is well organized.

Good consistency in format and language.

It would be very easy to assign students certain chapters to read based on content such as theory, developmental stages, or developmental domains.

Very well organized.

Clear and easy to follow.

I did not find any grammatical errors.

Cultural Relevance rating: 5

General content related to culture was infused throughout the book. The pictures used were of children and families from a variety of cultures.

This book provides a very thorough introduction to child development, emphasizing child development theories, stages of development, and developmental domains.

Reviewed by Nancy Pynchon, Adjunct Faculty, Middlesex Community College on 4/14/21

Overall this textbook is comprehensive of all aspects of children's development. It provided a brief introduction to the different relevant theorists of childhood development . read more

Overall this textbook is comprehensive of all aspects of children's development. It provided a brief introduction to the different relevant theorists of childhood development .

Content Accuracy rating: 4

Most of the information is accurately written, there is some outdated references, for example: Many adults can remember being spanked as a child. This method of discipline continues to be endorsed by the majority of parents (Smith, 2012). It seems as though there may be more current research on parent's methods of discipline as this information is 10 years old. (page 223).

The content was current with the terminology used.

Easy to follow the references made in the chapters.

Each chapter covers the different stages of development and includes the theories of each stage with guided information for each age group.

The formatting of the book makes it reader friendly and easy to follow the content.

Very consistent from chapter to chapter.

Provided a lot of charts and references within each chapter.

Formatted and written concisely.

Included several different references to diversity in the chapters.

There was no glossary at the end of the book and there were no vignettes or reflective thinking scenarios in the chapters. Overall it was a well written book on child development which covered infancy through adolescents.

Reviewed by Deborah Murphy, Full Time Instructor, Rogue Community College on 1/11/21

The text is excellent for its content and presentation. The only criticism is that neither an index nor a glossary are provided. read more

Comprehensiveness rating: 3 see less

The text is excellent for its content and presentation. The only criticism is that neither an index nor a glossary are provided.

The material seems very accurate and current. It is well written. It is very professionally done and is accessible to students.

This text addresses topics that will serve this field in positive ways that should be able to address the needs of students and instructors for the next several years.

Complex concepts are delivered accurately and are still accessible for students . Figures and tables complement the text . Terms are explained and are embedded in the text, not in a glossary. I do think indices and glossaries are helpful tools. Terminology is highlighted with bold fonts to accentuate definitions.

Yes the text is consistent in its format. As this is a text on Child Development it consistently addresses each developmental domain and then repeats the sequence for each age group in childhood. It is very logically presented.

Yes this text is definitely divisible. This text addresses development from conception to adolescents. For the community college course that my department wants to use it is very adaptable. Our course ends at middle school age development; our courses are offered on a quarter system. This text is adaptable for the content and our term time schedule.

This text book flows very clearly from Basic principles to Conception. It then divides each stage of development into Physical, Cognitive and Social Emotional development. Those concepts and information are then repeated for each stage of development. e.g. Infants and Toddler-hood, Early Childhood, and Middle Childhood. It is very clearly presented.

It is very professionally presented. It is quite attractive in its presentation .

I saw no errors

The text appears to be aware of being diverse and inclusive both in its content and its graphics. It discusses culture and represents a variety of family structures representing contemporary society.

It is wonderfully researched. It will serve our students well. It is comprehensive and constructed very well. I have enjoyed getting familiar with this text and am looking forward to using it with my students in this upcoming term. The authors have presented a valuable, well written book that will be an addition to our field. Their scholarly efforts are very apparent. All of this text earns high grades in my evaluation. My only criticism is, as mentioned above, is that there is not a glossary or index provided. All citations are embedded in the text.

Reviewed by Ida Weldon, Adjunct Professor, Bunker Hill Community College on 6/30/20

The overall comprehensiveness was strong. However, I do think some sections should have been discussed with more depth read more

The overall comprehensiveness was strong. However, I do think some sections should have been discussed with more depth

Most of the information was accurate. However, I think more references should have been provided to support some claims made in the text.

The material appeared to be relevant. However, it did not provide guidance for teachers in addressing topics of social justice, equality that most children will ask as they try to make sense of their environment.

The information was presented (use of language) that added to its understand-ability. However, I think more discussions and examples would be helpful.

The text appeared to be consistent. The purpose and intent of the text was understandable throughout.

The text can easily be divided into smaller reading sections or restructured to meet the needs of the professor.

The organization of the text adds to its consistency. However, some sections can be included in others decreasing the length of the text.

Interface issues were not visible.

The text appears to be free of grammatical errors.

While cultural differences are mentioned, more time can be given to helping teachers understand and create a culturally and ethnically focused curriculum.

The textbook provides a comprehensive summary of curriculum planing for preschool age children. However, very few chapters address infant/toddlers.

Reviewed by Veronica Harris, Adjunct Faculty, Northern Essex Community College on 6/28/20

This text explores child development from genetics, prenatal development and birth through adolescence. The text does not contain a glossary. However, the Index is clear. The topics are sequential. The text addresses the domains of physical,... read more

This text explores child development from genetics, prenatal development and birth through adolescence. The text does not contain a glossary. However, the Index is clear. The topics are sequential. The text addresses the domains of physical, cognitive and social emotional development. It is thorough and easy to read. The theories of development are inclusive to give the reader a broader understanding on how the domains of development are intertwined. The content is comprehensive, well - researched and sequential. Each chapter begins with the learning outcomes for the upcoming material and closes with an outline of the topics covered. Furthermore, a look into the next chapter is discussed.

The content is accurate, well - researched and unbiased. An historical context is provided putting content into perspective for the student. It appears to be unbiased.

Updated and accurate research is evidenced in the text. The text is written and organized in such a way that updates can be easily implemented. The author provides theoretical approaches in the psychological domains with examples along with real - life scenarios providing meaningful references invoking understanding by the student.

The text is written with clarity and is easily understood. The topics are sequential, comprehensive and and inclusive to all students. This content is presented in a cohesive, engaging, scholarly manner. The terminology used is appropriate to students studying Developmental Psychology spanning from birth through adolescents.

The book's approach to the content is consistent and well organized. . Theoretical contexts are presented throughout the text.

The text contains subheadings chunking the reading sections which can be assigned at various points throughout the course. The content flows seamlessly from one idea to the next. Written chronologically and subdividing each age span into the domains of psychology provides clarity without overwhelming the reader.

The book begins with an overview of child development. Next, the text is divided logically into chapters which focus on each developmental age span. The domains of each age span are addressed separately in subsequent chapters. Each chapter outlines the chapter objectives and ends with an outline of the topics covered and share an idea of what is to follow.

Pages load clearly and consistently without distortion of text, charts and tables. Navigating through the pages is met with ease.

The text is written with no grammatical or spelling errors.

The text did not present with biases or insensitivity to cultural differences. Photos are inclusive of various cultures.

The thoroughness, clarity and comprehensiveness promote an approach to Developmental Psychology that stands alongside the best of texts in this area. I am confident that this text encompasses all the required elements in this area.

Reviewed by Kathryn Frazier, Assistant Professor, Worcester State University on 6/23/20

This is a highly comprehensive, chronological text that covers genetics and conception through adolescence. All major topics and developmental milestones in each age range are given adequate space and consideration. The authors take care to... read more

This is a highly comprehensive, chronological text that covers genetics and conception through adolescence. All major topics and developmental milestones in each age range are given adequate space and consideration. The authors take care to summarize debates and controversies, when relevant and include a large amount of applied / practical material. For example, beyond infant growth patterns and motor milestone, the infancy/toddler chapters spend several pages on the mechanics of car seat safety, best practices for introducing solid foods (and the rationale), and common concerns like diaper rash. In addition to being generally useful information for students who are parents, or who may go on to be parents, this text takes care to contextualize the psychological research in the lived experiences of children and their parents. This is an approach that I find highly valuable. While the text does not contain an index, the search & find capacity of OER to make an index a deal-breaker for me.

The text includes accurate information that is well-sourced. Relevant debates, controversies and historical context is also provided throughout which results in a rich, balanced text.

This text provides an excellent summary of classic and updated developmental work. While the majority of the text is skewed toward dated, classic work, some updated research is included. Instructors may wish to supplement this text with more recent work, particularly that which includes diverse samples and specifically addresses topics of class, race, gender and sexual orientation (see comment below regarding cultural aspects).

The text is written in highly accessible language, free of jargon. Of particular value are the many author-generated tables which clearly organize and display critical information. The authors have also included many excellent figures, which reinforce and visually organize the information presented.

This text is consistent in its use of terminology. Balanced discussion of multiple theoretical frameworks are included throughout, with adequate space provided to address controversies and debates.

The text is clearly organized and structured. Each chapter is self-contained. In places where the authors do refer to prior or future chapters (something that I find helps students contextualize their reading), a complete discussion of the topic is included. While this may result in repetition for students reading the text from cover to cover, the repetition of some content is not so egregious that it outweighs the benefit of a flexible, modular textbook.

Excellent, clear organization. This text closely follows the organization of published textbooks that I have used in the past for both lifespan and child development. As this text follows a chronological format, a discussion of theory and methods, and genetics and prenatal growth is followed by sections devoted to a specific age range: infancy and toddlerhood, early childhood (preschool), middle childhood and adolescence. Each age range is further split into three chapters that address each developmental domain: physical, cognitive and social emotional development.

All text appears clearly and all images, tables and figures are positioned correctly and free of distortion.

The text contains no spelling or grammatical errors.

While this text provides adequate discussion of gender and cross-cultural influences on development, it is not sufficient. This is not a problem unique to this text, and is indeed a critique I have of all developmental textbooks. In particular, in my view this text does not adequately address the role of race, class or sexual orientation on development.

All in all, this is a comprehensive and well-written textbook that very closely follows the format of standard chronologically-organized child development textbooks. This is a fantastic alternative for those standard texts, with the added benefit of language that is more accessible, and content that is skewed toward practical applications.

Reviewed by Tony Philcox, Professor, Valencia College on 6/4/20

The subject of this book is Child Growth and Development and as such covers all areas and ideas appropriate for this subject. This book has an appropriate index. The author starts out with a comprehensive overview of Child Development in the... read more

The subject of this book is Child Growth and Development and as such covers all areas and ideas appropriate for this subject. This book has an appropriate index. The author starts out with a comprehensive overview of Child Development in the Introduction. The principles of development were delineated and were thoroughly presented in a very understandable way. Nine theories were presented which gave the reader an understanding of the many authors who have contributed to Child Development. A good backdrop to start a conversation. This book discusses the early beginnings starting with Conception, Hereditary and Prenatal stages which provides a foundation for the future developmental stages such as infancy, toddler, early childhood, middle childhood and adolescence. The three domains of developmental psychology – physical, cognitive and social emotional are entertained with each stage of development. This book is thoroughly researched and is written in a way to not overwhelm. Language is concise and easily understood.

This book is a very comprehensive and detailed account of Child Growth and Development. The author leaves no stone unturned. It has the essential elements addressed in each of the developmental stages. Thoroughly researched and well thought out. The content covered was accurate, error-free and unbiased.

The content is very relevant to the subject of Child Growth and Development. It is comprehensive and thoroughly researched. The author has included a number of relevant subjects that highlight the three domains of developmental psychology, physical, cognitive and social emotional. Topics are included that help the student see the relevancy of the theories being discussed. Any necessary updates along the way will be very easy and straightforward to insert.

The text is easily understood. From the very beginning of this book, the author has given the reader a very clear message that does not overwhelm but pulls the reader in for more information. The very first chapter sets a tone for what is to come and entices the reader to learn more. Well organized and jargon appropriate for students in a Developmental Psychology class.

This book has all the ingredients necessary to address Child Growth and Development. Even at the very beginning of the book the backdrop is set for future discussions on the stages of development. Theorists are mentioned and embellished throughout the book. A very consistent and organized approach.