Europe PMC requires Javascript to function effectively.

Either your web browser doesn't support Javascript or it is currently turned off. In the latter case, please turn on Javascript support in your web browser and reload this page.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- My Bibliography

- Collections

- Citation manager

Save citation to file

Email citation, add to collections.

- Create a new collection

- Add to an existing collection

Add to My Bibliography

Your saved search, create a file for external citation management software, your rss feed.

- Search in PubMed

- Search in NLM Catalog

- Add to Search

How to...write a paper

Affiliation.

- 1 Department of Orthodontics, Eastman Dental Institute for Oral Health Care Sciences, University College, London, UK. [email protected]

- PMID: 15071152

- DOI: 10.1179/146531204225011328

Writing a paper may seem like a daunting process for the inexperienced researcher (and sometimes for those who are experienced!). However, this does not need to be the case if the approach is logical and systematic. This article covers some of the most important aspects of writing a scientific paper.

PubMed Disclaimer

Similar articles

- [How do I write a scientific article--advice to a young researcher]. Auvinen A. Auvinen A. Duodecim. 2015;131(16):1460-6. Duodecim. 2015. PMID: 26485939 Review. Finnish.

- How to write a problem solving in clinical practice paper. Skinner GJ. Skinner GJ. Arch Dis Child Educ Pract Ed. 2013 Jun;98(3):82-3. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2012-303453. Epub 2013 Mar 13. Arch Dis Child Educ Pract Ed. 2013. PMID: 23487513 Review.

- Authorship and acknowledgements. Peh WC, Ng KH. Peh WC, et al. Singapore Med J. 2009 Jun;50(6):563-5; quiz 566. Singapore Med J. 2009. PMID: 19551307

- Writing a scientific paper: getting to the basics. Nte AR, Awi DD. Nte AR, et al. Niger J Med. 2007 Jul-Sep;16(3):212-8. Niger J Med. 2007. PMID: 17937155

- Writing for publication--a guide for new authors. Dixon N. Dixon N. Int J Qual Health Care. 2001 Oct;13(5):417-21. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/13.5.417. Int J Qual Health Care. 2001. PMID: 11669570

- The Principles of Biomedical Scientific Writing: Results. Bahadoran Z, Mirmiran P, Zadeh-Vakili A, Hosseinpanah F, Ghasemi A. Bahadoran Z, et al. Int J Endocrinol Metab. 2019 Apr 24;17(2):e92113. doi: 10.5812/ijem.92113. eCollection 2019 Apr. Int J Endocrinol Metab. 2019. PMID: 31372173 Free PMC article. Review.

- Ten simple (empirical) rules for writing science. Weinberger CJ, Evans JA, Allesina S. Weinberger CJ, et al. PLoS Comput Biol. 2015 Apr 30;11(4):e1004205. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1004205. eCollection 2015 Apr. PLoS Comput Biol. 2015. PMID: 25928031 Free PMC article. No abstract available.

- Search in MeSH

LinkOut - more resources

Full text sources.

- Ovid Technologies, Inc.

- Taylor & Francis

- Citation Manager

NCBI Literature Resources

MeSH PMC Bookshelf Disclaimer

The PubMed wordmark and PubMed logo are registered trademarks of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Unauthorized use of these marks is strictly prohibited.

- DOI: 10.1179/146531204225020445

- Corpus ID: 43189555

How to Write a Thesis

- S. Cunningham

- Published in Journal of orthodontics 1 June 2004

6 Citations

Art of writing articles and thesis, the process of undertaking a quantitative dissertation for a taught m.sc: personal insights gained from supporting and examining students in the uk and ireland, wasp (write a scientific paper): how to write a scientific thesis., wasp (write a scientific paper): structuring a scientific paper., master thesis supervision, putting pen to paper to publication, 2 references, writing a thesis: substance and style, assignment and thesis writing, related papers.

Showing 1 through 3 of 0 Related Papers

How To Write A Dissertation Or Thesis

8 straightforward steps to craft an a-grade dissertation.

By: Derek Jansen (MBA) Expert Reviewed By: Dr Eunice Rautenbach | June 2020

Writing a dissertation or thesis is not a simple task. It takes time, energy and a lot of will power to get you across the finish line. It’s not easy – but it doesn’t necessarily need to be a painful process. If you understand the big-picture process of how to write a dissertation or thesis, your research journey will be a lot smoother.

In this post, I’m going to outline the big-picture process of how to write a high-quality dissertation or thesis, without losing your mind along the way. If you’re just starting your research, this post is perfect for you. Alternatively, if you’ve already submitted your proposal, this article which covers how to structure a dissertation might be more helpful.

How To Write A Dissertation: 8 Steps

- Clearly understand what a dissertation (or thesis) is

- Find a unique and valuable research topic

- Craft a convincing research proposal

- Write up a strong introduction chapter

- Review the existing literature and compile a literature review

- Design a rigorous research strategy and undertake your own research

- Present the findings of your research

- Draw a conclusion and discuss the implications

Step 1: Understand exactly what a dissertation is

This probably sounds like a no-brainer, but all too often, students come to us for help with their research and the underlying issue is that they don’t fully understand what a dissertation (or thesis) actually is.

So, what is a dissertation?

At its simplest, a dissertation or thesis is a formal piece of research , reflecting the standard research process . But what is the standard research process, you ask? The research process involves 4 key steps:

- Ask a very specific, well-articulated question (s) (your research topic)

- See what other researchers have said about it (if they’ve already answered it)

- If they haven’t answered it adequately, undertake your own data collection and analysis in a scientifically rigorous fashion

- Answer your original question(s), based on your analysis findings

In short, the research process is simply about asking and answering questions in a systematic fashion . This probably sounds pretty obvious, but people often think they’ve done “research”, when in fact what they have done is:

- Started with a vague, poorly articulated question

- Not taken the time to see what research has already been done regarding the question

- Collected data and opinions that support their gut and undertaken a flimsy analysis

- Drawn a shaky conclusion, based on that analysis

If you want to see the perfect example of this in action, look out for the next Facebook post where someone claims they’ve done “research”… All too often, people consider reading a few blog posts to constitute research. Its no surprise then that what they end up with is an opinion piece, not research. Okay, okay – I’ll climb off my soapbox now.

The key takeaway here is that a dissertation (or thesis) is a formal piece of research, reflecting the research process. It’s not an opinion piece , nor a place to push your agenda or try to convince someone of your position. Writing a good dissertation involves asking a question and taking a systematic, rigorous approach to answering it.

If you understand this and are comfortable leaving your opinions or preconceived ideas at the door, you’re already off to a good start!

Step 2: Find a unique, valuable research topic

As we saw, the first step of the research process is to ask a specific, well-articulated question. In other words, you need to find a research topic that asks a specific question or set of questions (these are called research questions ). Sounds easy enough, right? All you’ve got to do is identify a question or two and you’ve got a winning research topic. Well, not quite…

A good dissertation or thesis topic has a few important attributes. Specifically, a solid research topic should be:

Let’s take a closer look at these:

Attribute #1: Clear

Your research topic needs to be crystal clear about what you’re planning to research, what you want to know, and within what context. There shouldn’t be any ambiguity or vagueness about what you’ll research.

Here’s an example of a clearly articulated research topic:

An analysis of consumer-based factors influencing organisational trust in British low-cost online equity brokerage firms.

As you can see in the example, its crystal clear what will be analysed (factors impacting organisational trust), amongst who (consumers) and in what context (British low-cost equity brokerage firms, based online).

Need a helping hand?

Attribute #2: Unique

Your research should be asking a question(s) that hasn’t been asked before, or that hasn’t been asked in a specific context (for example, in a specific country or industry).

For example, sticking organisational trust topic above, it’s quite likely that organisational trust factors in the UK have been investigated before, but the context (online low-cost equity brokerages) could make this research unique. Therefore, the context makes this research original.

One caveat when using context as the basis for originality – you need to have a good reason to suspect that your findings in this context might be different from the existing research – otherwise, there’s no reason to warrant researching it.

Attribute #3: Important

Simply asking a unique or original question is not enough – the question needs to create value. In other words, successfully answering your research questions should provide some value to the field of research or the industry. You can’t research something just to satisfy your curiosity. It needs to make some form of contribution either to research or industry.

For example, researching the factors influencing consumer trust would create value by enabling businesses to tailor their operations and marketing to leverage factors that promote trust. In other words, it would have a clear benefit to industry.

So, how do you go about finding a unique and valuable research topic? We explain that in detail in this video post – How To Find A Research Topic . Yeah, we’ve got you covered 😊

Step 3: Write a convincing research proposal

Once you’ve pinned down a high-quality research topic, the next step is to convince your university to let you research it. No matter how awesome you think your topic is, it still needs to get the rubber stamp before you can move forward with your research. The research proposal is the tool you’ll use for this job.

So, what’s in a research proposal?

The main “job” of a research proposal is to convince your university, advisor or committee that your research topic is worthy of approval. But convince them of what? Well, this varies from university to university, but generally, they want to see that:

- You have a clearly articulated, unique and important topic (this might sound familiar…)

- You’ve done some initial reading of the existing literature relevant to your topic (i.e. a literature review)

- You have a provisional plan in terms of how you will collect data and analyse it (i.e. a methodology)

At the proposal stage, it’s (generally) not expected that you’ve extensively reviewed the existing literature , but you will need to show that you’ve done enough reading to identify a clear gap for original (unique) research. Similarly, they generally don’t expect that you have a rock-solid research methodology mapped out, but you should have an idea of whether you’ll be undertaking qualitative or quantitative analysis , and how you’ll collect your data (we’ll discuss this in more detail later).

Long story short – don’t stress about having every detail of your research meticulously thought out at the proposal stage – this will develop as you progress through your research. However, you do need to show that you’ve “done your homework” and that your research is worthy of approval .

So, how do you go about crafting a high-quality, convincing proposal? We cover that in detail in this video post – How To Write A Top-Class Research Proposal . We’ve also got a video walkthrough of two proposal examples here .

Step 4: Craft a strong introduction chapter

Once your proposal’s been approved, its time to get writing your actual dissertation or thesis! The good news is that if you put the time into crafting a high-quality proposal, you’ve already got a head start on your first three chapters – introduction, literature review and methodology – as you can use your proposal as the basis for these.

Handy sidenote – our free dissertation & thesis template is a great way to speed up your dissertation writing journey.

What’s the introduction chapter all about?

The purpose of the introduction chapter is to set the scene for your research (dare I say, to introduce it…) so that the reader understands what you’ll be researching and why it’s important. In other words, it covers the same ground as the research proposal in that it justifies your research topic.

What goes into the introduction chapter?

This can vary slightly between universities and degrees, but generally, the introduction chapter will include the following:

- A brief background to the study, explaining the overall area of research

- A problem statement , explaining what the problem is with the current state of research (in other words, where the knowledge gap exists)

- Your research questions – in other words, the specific questions your study will seek to answer (based on the knowledge gap)

- The significance of your study – in other words, why it’s important and how its findings will be useful in the world

As you can see, this all about explaining the “what” and the “why” of your research (as opposed to the “how”). So, your introduction chapter is basically the salesman of your study, “selling” your research to the first-time reader and (hopefully) getting them interested to read more.

How do I write the introduction chapter, you ask? We cover that in detail in this post .

Step 5: Undertake an in-depth literature review

As I mentioned earlier, you’ll need to do some initial review of the literature in Steps 2 and 3 to find your research gap and craft a convincing research proposal – but that’s just scratching the surface. Once you reach the literature review stage of your dissertation or thesis, you need to dig a lot deeper into the existing research and write up a comprehensive literature review chapter.

What’s the literature review all about?

There are two main stages in the literature review process:

Literature Review Step 1: Reading up

The first stage is for you to deep dive into the existing literature (journal articles, textbook chapters, industry reports, etc) to gain an in-depth understanding of the current state of research regarding your topic. While you don’t need to read every single article, you do need to ensure that you cover all literature that is related to your core research questions, and create a comprehensive catalogue of that literature , which you’ll use in the next step.

Reading and digesting all the relevant literature is a time consuming and intellectually demanding process. Many students underestimate just how much work goes into this step, so make sure that you allocate a good amount of time for this when planning out your research. Thankfully, there are ways to fast track the process – be sure to check out this article covering how to read journal articles quickly .

Literature Review Step 2: Writing up

Once you’ve worked through the literature and digested it all, you’ll need to write up your literature review chapter. Many students make the mistake of thinking that the literature review chapter is simply a summary of what other researchers have said. While this is partly true, a literature review is much more than just a summary. To pull off a good literature review chapter, you’ll need to achieve at least 3 things:

- You need to synthesise the existing research , not just summarise it. In other words, you need to show how different pieces of theory fit together, what’s agreed on by researchers, what’s not.

- You need to highlight a research gap that your research is going to fill. In other words, you’ve got to outline the problem so that your research topic can provide a solution.

- You need to use the existing research to inform your methodology and approach to your own research design. For example, you might use questions or Likert scales from previous studies in your your own survey design .

As you can see, a good literature review is more than just a summary of the published research. It’s the foundation on which your own research is built, so it deserves a lot of love and attention. Take the time to craft a comprehensive literature review with a suitable structure .

But, how do I actually write the literature review chapter, you ask? We cover that in detail in this video post .

Step 6: Carry out your own research

Once you’ve completed your literature review and have a sound understanding of the existing research, its time to develop your own research (finally!). You’ll design this research specifically so that you can find the answers to your unique research question.

There are two steps here – designing your research strategy and executing on it:

1 – Design your research strategy

The first step is to design your research strategy and craft a methodology chapter . I won’t get into the technicalities of the methodology chapter here, but in simple terms, this chapter is about explaining the “how” of your research. If you recall, the introduction and literature review chapters discussed the “what” and the “why”, so it makes sense that the next point to cover is the “how” –that’s what the methodology chapter is all about.

In this section, you’ll need to make firm decisions about your research design. This includes things like:

- Your research philosophy (e.g. positivism or interpretivism )

- Your overall methodology (e.g. qualitative , quantitative or mixed methods)

- Your data collection strategy (e.g. interviews , focus groups, surveys)

- Your data analysis strategy (e.g. content analysis , correlation analysis, regression)

If these words have got your head spinning, don’t worry! We’ll explain these in plain language in other posts. It’s not essential that you understand the intricacies of research design (yet!). The key takeaway here is that you’ll need to make decisions about how you’ll design your own research, and you’ll need to describe (and justify) your decisions in your methodology chapter.

2 – Execute: Collect and analyse your data

Once you’ve worked out your research design, you’ll put it into action and start collecting your data. This might mean undertaking interviews, hosting an online survey or any other data collection method. Data collection can take quite a bit of time (especially if you host in-person interviews), so be sure to factor sufficient time into your project plan for this. Oftentimes, things don’t go 100% to plan (for example, you don’t get as many survey responses as you hoped for), so bake a little extra time into your budget here.

Once you’ve collected your data, you’ll need to do some data preparation before you can sink your teeth into the analysis. For example:

- If you carry out interviews or focus groups, you’ll need to transcribe your audio data to text (i.e. a Word document).

- If you collect quantitative survey data, you’ll need to clean up your data and get it into the right format for whichever analysis software you use (for example, SPSS, R or STATA).

Once you’ve completed your data prep, you’ll undertake your analysis, using the techniques that you described in your methodology. Depending on what you find in your analysis, you might also do some additional forms of analysis that you hadn’t planned for. For example, you might see something in the data that raises new questions or that requires clarification with further analysis.

The type(s) of analysis that you’ll use depend entirely on the nature of your research and your research questions. For example:

- If your research if exploratory in nature, you’ll often use qualitative analysis techniques .

- If your research is confirmatory in nature, you’ll often use quantitative analysis techniques

- If your research involves a mix of both, you might use a mixed methods approach

Again, if these words have got your head spinning, don’t worry! We’ll explain these concepts and techniques in other posts. The key takeaway is simply that there’s no “one size fits all” for research design and methodology – it all depends on your topic, your research questions and your data. So, don’t be surprised if your study colleagues take a completely different approach to yours.

Step 7: Present your findings

Once you’ve completed your analysis, it’s time to present your findings (finally!). In a dissertation or thesis, you’ll typically present your findings in two chapters – the results chapter and the discussion chapter .

What’s the difference between the results chapter and the discussion chapter?

While these two chapters are similar, the results chapter generally just presents the processed data neatly and clearly without interpretation, while the discussion chapter explains the story the data are telling – in other words, it provides your interpretation of the results.

For example, if you were researching the factors that influence consumer trust, you might have used a quantitative approach to identify the relationship between potential factors (e.g. perceived integrity and competence of the organisation) and consumer trust. In this case:

- Your results chapter would just present the results of the statistical tests. For example, correlation results or differences between groups. In other words, the processed numbers.

- Your discussion chapter would explain what the numbers mean in relation to your research question(s). For example, Factor 1 has a weak relationship with consumer trust, while Factor 2 has a strong relationship.

Depending on the university and degree, these two chapters (results and discussion) are sometimes merged into one , so be sure to check with your institution what their preference is. Regardless of the chapter structure, this section is about presenting the findings of your research in a clear, easy to understand fashion.

Importantly, your discussion here needs to link back to your research questions (which you outlined in the introduction or literature review chapter). In other words, it needs to answer the key questions you asked (or at least attempt to answer them).

For example, if we look at the sample research topic:

In this case, the discussion section would clearly outline which factors seem to have a noteworthy influence on organisational trust. By doing so, they are answering the overarching question and fulfilling the purpose of the research .

For more information about the results chapter , check out this post for qualitative studies and this post for quantitative studies .

Step 8: The Final Step Draw a conclusion and discuss the implications

Last but not least, you’ll need to wrap up your research with the conclusion chapter . In this chapter, you’ll bring your research full circle by highlighting the key findings of your study and explaining what the implications of these findings are.

What exactly are key findings? The key findings are those findings which directly relate to your original research questions and overall research objectives (which you discussed in your introduction chapter). The implications, on the other hand, explain what your findings mean for industry, or for research in your area.

Sticking with the consumer trust topic example, the conclusion might look something like this:

Key findings

This study set out to identify which factors influence consumer-based trust in British low-cost online equity brokerage firms. The results suggest that the following factors have a large impact on consumer trust:

While the following factors have a very limited impact on consumer trust:

Notably, within the 25-30 age groups, Factors E had a noticeably larger impact, which may be explained by…

Implications

The findings having noteworthy implications for British low-cost online equity brokers. Specifically:

The large impact of Factors X and Y implies that brokers need to consider….

The limited impact of Factor E implies that brokers need to…

As you can see, the conclusion chapter is basically explaining the “what” (what your study found) and the “so what?” (what the findings mean for the industry or research). This brings the study full circle and closes off the document.

Let’s recap – how to write a dissertation or thesis

You’re still with me? Impressive! I know that this post was a long one, but hopefully you’ve learnt a thing or two about how to write a dissertation or thesis, and are now better equipped to start your own research.

To recap, the 8 steps to writing a quality dissertation (or thesis) are as follows:

- Understand what a dissertation (or thesis) is – a research project that follows the research process.

- Find a unique (original) and important research topic

- Craft a convincing dissertation or thesis research proposal

- Write a clear, compelling introduction chapter

- Undertake a thorough review of the existing research and write up a literature review

- Undertake your own research

- Present and interpret your findings

Once you’ve wrapped up the core chapters, all that’s typically left is the abstract , reference list and appendices. As always, be sure to check with your university if they have any additional requirements in terms of structure or content.

Psst... there’s more!

This post was based on one of our popular Research Bootcamps . If you're working on a research project, you'll definitely want to check this out ...

You Might Also Like:

20 Comments

thankfull >>>this is very useful

Thank you, it was really helpful

unquestionably, this amazing simplified way of teaching. Really , I couldn’t find in the literature words that fully explicit my great thanks to you. However, I could only say thanks a-lot.

Great to hear that – thanks for the feedback. Good luck writing your dissertation/thesis.

This is the most comprehensive explanation of how to write a dissertation. Many thanks for sharing it free of charge.

Very rich presentation. Thank you

Thanks Derek Jansen|GRADCOACH, I find it very useful guide to arrange my activities and proceed to research!

Thank you so much for such a marvelous teaching .I am so convinced that am going to write a comprehensive and a distinct masters dissertation

It is an amazing comprehensive explanation

This was straightforward. Thank you!

I can say that your explanations are simple and enlightening – understanding what you have done here is easy for me. Could you write more about the different types of research methods specific to the three methodologies: quan, qual and MM. I look forward to interacting with this website more in the future.

Thanks for the feedback and suggestions 🙂

Hello, your write ups is quite educative. However, l have challenges in going about my research questions which is below; *Building the enablers of organisational growth through effective governance and purposeful leadership.*

Very educating.

Just listening to the name of the dissertation makes the student nervous. As writing a top-quality dissertation is a difficult task as it is a lengthy topic, requires a lot of research and understanding and is usually around 10,000 to 15000 words. Sometimes due to studies, unbalanced workload or lack of research and writing skill students look for dissertation submission from professional writers.

Thank you 💕😊 very much. I was confused but your comprehensive explanation has cleared my doubts of ever presenting a good thesis. Thank you.

thank you so much, that was so useful

Hi. Where is the excel spread sheet ark?

could you please help me look at your thesis paper to enable me to do the portion that has to do with the specification

my topic is “the impact of domestic revenue mobilization.

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

- Correspondence

- Open access

- Published: 05 December 2007

Medical theses as part of the scientific training in basic medical and dental education: experiences from Finland

- Pentti Nieminen 1 ,

- Kirsi Sipilä 2 , 3 ,

- Hanna-Mari Takkinen 1 ,

- Marjo Renko 4 &

- Leila Risteli 5

BMC Medical Education volume 7 , Article number: 51 ( 2007 ) Cite this article

11k Accesses

40 Citations

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

Teaching the principles of scientific research in a comprehensive way is important at medical and dental schools. In many countries medical and dental training is not complete until the candidate has presented a diploma thesis. The objective of this study was to evaluate the nature, quality, publication pattern and visibility of Finnish medical diploma theses.

A total of 256 diploma theses presented at the University of Oulu from 2001 to 2003 were analysed. Using a standardised questionnaire, we extracted several characteristics from each thesis. We used the name of the student to assess whether the thesis resulted in a scientific publication indexed in medical article databases. The number of citations received by each published thesis was also recorded.

A high proportion of the theses (69.5%) were essentially statistical in character, often combined with an extensive literature review or the development of a laboratory method. Most of them were supervised by clinical departments (55.9%). Only 61 theses (23.8%) had been published in indexed scientific journals. Theses in the fields of biomedicine and diagnostics were published in more widely cited journals. The median number of citations received per year was 2.7 and the range from 0 to 14.7.

The theses were seldom written according to the principles of scientific communication and the proportion of actually published was small. The visibility of these theses and their dissemination to the scientific community should be improved.

Peer Review reports

The teaching of scientific communication is an important part of basic medical education. Producing a thesis is an essential step for a student graduating from medical school [ 1 ]. It is also important that medical and dental undergraduate curricula should include the teaching of scientific thinking and the principles of scientific research [ 2 ]. In Finland, 10–20 weeks are reserved for advanced special studies in the medical and dental undergraduate curricula. These studies are compulsory and include an independent research project and the writing of a short diploma thesis [ 3 ]. Students are encouraged to consider research projects of any kind and mostly select their topic from ongoing scientific research projects in the university's departments and clinics. The academic staff at the departments act as supervisors for the theses.

Interest in the literature on this subject has focused on the role of writing a thesis as a part of medical education [ 1 , 4 – 6 ]. Teaching students to write effectively has been a major concern in education for many years [ 7 , 8 ]. Problems affecting such scientific writing have included variety in terms of scientific level and the requirements of the research projects as well as inadequate supervision. Problems have also arisen in the timing of the work, in that the courses that support scientific writing have been scheduled separately from the actual scientific work [ 9 ]. Hren et al. note, however, that medical students generally have a positive attitude towards science and scientific research [ 2 ]. Medical research and projects also have several benefits, such as improving students' ability to interpret the scientific literature critically when working as physicians or dentists, increasing the potential number of scientists who will pursue medical research and improving independent analytical problem-solving skills [ 6 , 10 ].

One indicator of the scientific value of a thesis and of the acceptability of its content to the international scientific community is whether the work has been published in a peer-reviewed journal. The quality of the theses can be judged by the proportion of published papers [ 5 ]. These peer-reviewed articles also give positive information about the integration of teaching and research within medical and dental education.

Our aim was to evaluate the graduate theses completed at a Finnish university and to examine their publication pattern and utility. Special attention was focused on supervision, the nature and quality of the theses and whether they were later published in the scientific literature.

Our research material consisted of 256 consecutive medical and dental theses completed at the Medical Faculty of the University of Oulu in 2001–2003.

We reviewed the printed copy of each thesis supplied by the student to the faculty and evaluated several characteristics including language, department, supervisors and examiners. The theses were classified as 1) extensive analyses of quantitative material, 2) brief quantitative analyses of the authors' own material linked with a literature review or the development of a laboratory method, 3) pure literature reviews or 4) others (case reports, experimental generation of a laboratory procedures, analyses of qualitative material, descriptions of health organisations, or combinations of these).

Using a protocol for data collection, the following information was also obtained: does the report follow the structure of a scientific article (no, yes or printed publication), and what is its technical quality (unsatisfactory/satisfactory, good or excellent)? The shortcomings in technical quality were related to elementary word processing techniques and included the following: (i) disturbing variations in font, font style and font size, (ii) indefinite or inconsistent margins, (iii) inconsistent line spacing, (iv) unfinished tables and figures, (v) unfinished table of contents, or (vi) deficiencies in reference format, and (vii) others. The technical quality was evaluated as poor (several shortcomings), good (no more than two shortcomings) or excellent (no shortcomings). The technical quality of the printed publications was not evaluated.

The theses were categorized as using statistical methods if descriptive statistics (distributions, means, medians, standard deviations, etc.) or the results of formal tests of statistical significance were reported. The usage of tables and figures was also assessed. The presence or absence of special advanced statistical procedures and techniques was reviewed in each thesis. The same classification was used as in the study by Miettunen et al. [ 11 ]. Multivariate methods and survival time analyses, for example, were considered to be special methods. To evaluate the quality of the statistical reporting information was obtained on whether the data analysis procedures were completely described in the methods section. The description of methods was considered adequate if it satisfactorily explained what approaches and methods had been used to answer the main question posed in the research and why these had been chosen [ 12 ]. Reliability of the evaluation of this information in medical research articles has been shown to be good [ 13 ].

The theses were reviewed by one out of four assessors (PN, KS, MR and LR). Where the interpretation of the paper was ambiguous, it was appraised by other assessors and the conclusions reconciled in a group discussion.

The name of the student was then used to determine whether the thesis had resulted in a scientific publication indexed in the Medline, Scopus or Medic databases. The Medic database indexes were used to find scientific articles published in Finnish medical, dental and nursing journals. We searched for all articles that included the name of the student as an author and then browsed through these to find potential matches with the thesis. A thesis was considered to have been published if the title of one of these articles or the content of its abstract was consistent with the characteristics of the thesis. It was possible that some studies published in lower visibility journals not indexed in major databases were missed.

The journal impact factor as reported by the Journal Citation Reports of the ISI Web of Knowledge for the publication year was obtained from the journal that published the article. Journals not included in the ISI Web of Science system were assigned the impact factor value zero. These included all theses published in Finnish journals.

Citation counts for each published article were obtained from the Web of Science databases and the Scopus database in November 2006. The total number of citations received by each article counts the number of times other researchers have cited it in their subsequent publications during the period from the publication date to November 2006. Since the citation counts are affected by the follow-up time, which in this case ranged from 1 (published in 2005) to 6 (published in 2000) years, we used the average number of citations received per year to assess the utility of an article.

Statistical methods

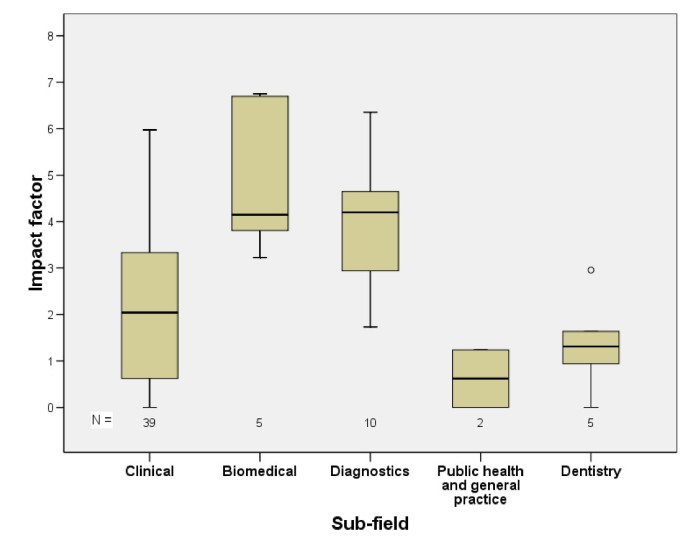

The data were analysed using SPSS for Windows 14.0 (SPSS Inc.; Chicago, Illinois, USA) software. Frequency distributions and cross-tabulations were used as the main tools for presentation and analysis. The distribution of the journal impact factor was visualised with box-plots.

Characteristics of the theses

Of the 256 theses evaluated, 143 (55.9%) were clinical, 9 (3.5%) biomedical, 33 (12.9%) from a diagnostic department (Clinical Chemistry, Medical Microbiology, Forensic Medicine, Pathology or Diagnostic Radiology) or from the Department of Pharmacology and Toxicology, 22 (8.6%) from the Department of Public Health Science and General Practice, and 49 (19.1%) from the Institute of Dentistry.

In most cases the supervisor was a professor or adjunct professor (60.6%). The language was English in 71 cases (27.7%), Swedish in one, and the rest of the theses were written in Finnish.

A total of 119 theses (46.5%) reported quantitative research with samples mainly consisting of patient material, or in some cases experimental animals (n = 6). Quantitative research was linked with an extensive literature review or a report on the development of a laboratory procedure in 59 brief quantitative works (23.0%). Pure literature reviews accounted for 29 theses (11.3%). The number of reports of other type was 49 (19.1%), including five that were purely qualitative. Twenty reported extensive laboratory work, nine presented case reports or other descriptions and the rest were case reports accompanied by a literature review (n = 5), descriptions of laboratory procedure (n = 8) or analyses of qualitative material (n = 2).

Altogether 204 theses (81%) followed the structure of a scientific article, including an introduction, a description of the methods, a presentation of the results and a discussion section. In 142 cases (55.5%) the literature review made up more than half of the thesis. The technical quality was only satisfactory in 55 cases (21.5%), good in 124 (48.4%) and excellent in 63 (24.6%). Common shortcomings were variations in font size and style (30.9%), indistinct and unfinished figures and tables (17.6%), inconsistent line spacing (15.6%), indefinite margins (14.5%), inadequate use of references or a deficient list of references (12.1%), an unfinished table of contents (5.1%) and other defects (24.2%) such as the lack of an abstract, information lacking from the title page, or an otherwise disorganized report. A total of 14 theses (5.5%) were already available as printed publications and a further 52 (20.3%) were written according to the instructions of a specific scientific journal.

Statistical methods of at least some kind of were used in 178 (69.5%) theses that reported quantitative research. More than one fifth of those that had used statistical analyses included special methods such as survival analyses and multivariate models. Statistical figures and tests of statistical significance were presented in approximately half of the theses. Extensive description of the statistical methods used were presented in 69 theses (38.8%).

Number and citation frequency of publications

A total of 61 theses (23.8%) resulted in a scientific publication, most of them were quantitative (62.3%). Those that were of excellent technical quality or originally written in English were more often published as scientific articles than those of poor technical quality or written in Finnish (Table 1 ). The distribution of publication by other characteristics is also shown in Table 1 .

The student was the first author in 30 articles (49.2%), the second author in 21 (34.4%) and the third or later-mentioned author in 10 (16.4%). The supervisor was a co-author in 60 out of the 61 papers.

The distribution of impact factors by fields is shown in Figure 1 . Theses in biomedical or diagnostic fields were more often published in highly cited journals than the others. Papers in purely clinical or dental fields were published in journals with lower impact factor than the others.

Distribution of impact factor by field. The horizontal line in the middle of the box is the median value for the journal impact factor and the lower and upper boundaries indicate the 25th and 75th percentiles. The largest and smallest observed values that are not outliers are also shown. Lines are drawn from the ends of the box to those values.

The median number of citations received per paper per year was 2.7, ranging from 0 to 14.7. There were four papers that were cited very often (more than 10 citations per year), three of which were quantitative and one of another type.

The present paper investigated the basic characteristics, publication pattern and utility of medical theses completed at the Faculty of Medicine, University of Oulu, Finland. The traditional format of reporting statistical analyses of medical data was most common, often combined with an extensive review of the literature or the development of a laboratory method. Most of these theses were supervised by university hospital clinicians. Shortcomings in the them were related to the technical quality and the description of the research methods. Most of the theses were not published, but the frequency of publishing the research findings in a scientific journal was higher for theses produced in more biomedical disciplines. The publications resulting from the theses received a moderate number of citations, which means that they were utilized quite well by other researchers.

For most physicians and dentists the thesis included in their basic medical and dental basic education is the only contact they have with the producing of new scientific information. The present analysis showed that regrettably often the student did not command the basics of scientific communication. These results are in agreement with other reports concerning the level of basic medical scientific education [ 8 , 14 ].

In 2001–2003, when these theses projects were carried out, the regulations regarding theses for the MD and DMD degree at the University of Oulu were somewhat cursory. They simply stated that the preparation of the thesis should include participation in data collection, preliminary observations and their processing in a research project and writing of a report on the research project. They also included requirements for the extent of the thesis and general instructions for writing it. No instructions were available for supervisors. This insufficiency of instructions for students and supervisors could partly explain some of the weaknesses in the theses.

Numerous books, articles and Internet sites offer recommendations and instructions for the students on how to write and organize a research paper or thesis. Medical and dental curricula often include introductions to the principles of scientific research, the retrieval of medical literature and data analysis, as in the University of Oulu [ 15 ]. Despite the existence of courses in medical informatics, guides and thesis regulations, many students do not understand the process of scientific writing [ 16 ]. Some medical schools have developed student-oriented courses and programmes to overcome the perceived difficulties and improve the quality of theses and promote their publication [ 7 , 8 , 17 ]. Our findings show that it is important to teach undergraduate students the full scientific publishing process, including the peer review process, the format for scientific articles and the necessary skills in word processing.

The weaknesses reported concerning the preparation of the theses may be associated with the lack of time [ 4 ]. Students' use of time in the undergraduate curriculum can be guided, and enough time should be reserved for this writing process. The courses of relevance to scientific education, such as scientific theory, information search and biostatistics, give tools for both completing the thesis and reading the scientific literature. These studies should be timetabled so that they support the actual work on the thesis in the best possible way.

The supervision of research is highly important, and the frequent lack of supervision is considered problematic [ 4 , 9 ]. The present analysis showed that the supervision was unevenly distributed within the clinics and departments: the proportion available in biomedical institutions being quite small, whereas a considerable amount of work was done in the clinical units. This is understandable, as thesis work usually takes place in the final stages of qualifying, when the students are studying clinical subjects. Furthermore, the variety in technical quality and content suggested that the supervisors were not fully aware of their responsibilities. Clear instructions and pedagogical education for supervisors could improve the quality of the theses and the fluency of the students' learning process. The supervisors and their departments and clinics should also be given proper acknowledgement for their work.

The strengthening of scientific education is a key component in developing competent physicians who will not only ask the right questions but also be able to apply current treatment methodologies [ 6 ]. The inclusion of research work in medical education can promote physicians' use of evidence-based medicine and their involvement in clinical trials. Lloyd et al. noted that participation in medical research as a student may be an important determinant of future involvement in clinical research [ 18 ]. In addition, experience from medical schools that have had student research programs suggests that these can and do encourage medical students to take an interest in research and possibly an academic career [ 19 ].

The diploma theses written by medical and dental students in Finland are not currently available on the Internet. In order to maximize the visibility and usage of student's work, medical and dental schools should make their reviewed diploma theses accessible to any potential users on the Internet. The full digital text of all theses can be deposited in the university's self-archive.

The percentage of diploma theses actually published (23.8%) is somewhat higher than the figures in two other European countries. A study in France showed that 17% of theses presented between 1993 and 1997 had resulted in publication by 1999 [ 5 ]. Frkovic et al. reported data on master theses defended at two Croatian medical schools [ 20 ]. They found that 14% of those prepared by medical students in 1990–1999 had subsequently been published in scientific journals indexed in Medline. The higher proportion of publications from the University of Oulu could be associated with the increase in medical publishing in Finland since the 1990s [ 21 ].

Publication in a peer-reviewed journal indicates that the content of the thesis is acceptable to the international scientific community. Our study showed that especially theses with a literature review were not published later in scientific journals. Writing a review of high scientific quality is a demanding process, and students may not have enough experience for this. The reasons for the thesis not resulting in publication may often lie elsewhere, however, and not in the quality or content of the project. The publication process is usually slow, and the student's most important goal at this stage may be graduation, the thesis being just a mandatory part of this. Also the publication process demands time and resources from the supervisor. On the other hand, publication is an additional merit for the supervisors, which should encourage them to aim at getting theses published.

One limitation of this study should be noted. It was performed in a local setting in one medical faculty in Finland – and each educational setting is unique. Nevertheless, in spite of the limited scope, our findings might be helpful when considering possible educational and training interventions in medical and dental schools which require the writing of a mandatory thesis, especially in Europe.

Students and supervisors should be encouraged to aim at publishing the degree theses. The production of the thesis could mimic the scientific publishing process more closely than is currently the case. Requiring students to write their theses according to the guidelines of a few selected journals, improving the supervisor's engagement in the reporting and improving students' understanding of the peer review process would add a new dimension to the thesis process and provide additional opportunities for publication. The full digital text of the completed and reviewed thesis should be made visible and accessible in the institution's self-archive.

Tollan A, Magnus JH: Writing a scientific paper as part of the medical curriculum. Med Educ. 1993, 27: 461-464.

Article Google Scholar

Hren D, Lukic IK, Marusic A, Vodopivec I, Vujaklija A, Hrabak M, Marusic M: Teaching research methodology in medical schools: students' attitudes towards and knowledge about science. Med Educ. 2004, 38: 81-86. 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2004.01735.x.

Hietala EL, Karjalainen A, Raustia A: Renewal of the clinical-phase dental curriculum to promote better learning at the University of Oulu. Eur J Dent Educ. 2004, 8: 120-126. 10.1111/j.1600-0579.2004.00329.x.

Diez C, Arkenau C, Meyer-Wentrup F: The German medical dissertation--time to change?. Acad Med. 2000, 75: 861-863. 10.1097/00001888-200008000-00024.

Salmi LR, Gana S, Mouillet E: Publication pattern of medical theses, France, 1993-98. Med Educ. 2001, 35: 18-21. 10.1046/j.1365-2923.2001.00768.x.

Ogunyemi D, Bazargan M, Norris K, Jones-Quaidoo S, Wolf K, Edelstein R, Baker RS, Calmes D: The development of a mandatory medical thesis in an urban medical school. Teach Learn Med. 2005, 17: 363-369. 10.1207/s15328015tlm1704_9.

Marusic A, Marusic M: Teaching students how to read and write science: a mandatory course on scientific research and communication in medicine. Acad Med. 2003, 78: 1235-1239. 10.1097/00001888-200312000-00007.

Guilford WH: Teaching peer review and the process of scientific writing. Adv Physiol Educ. 2001, 25: 167-175.

Google Scholar

Remes V, Helenius I, Sinisaari I: A medical student as a researcher--how many, why and how? [Finnish]. Duodecim. 1998, 114: 705-709.

Weihrauch M, Strate J, Pabst R: [The medical dissertation--no definitive model. Results of a survey about obtaining a doctorate contradict frequently stated opinions]. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 2003, 128: 2583-2587. 10.1055/s-2003-45206.

Miettunen J, Nieminen P, Isohanni I: Statistical methodology in major general psychiatric journals. Nord J Psychiatry. 2002, 56: 223-228. 10.1080/080394802317607219.

Nieminen P, Miettunen J, Koponen H, Isohanni M: Statistical methodologies in psychopharmacology: a review. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2006, 21 (3): 195-203. 10.1002/hup.759.

Nieminen P, Carpenter J, Rucker G, Schumacher M: The relationship between quality of research and citation frequency. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2006, 6: 42-10.1186/1471-2288-6-42.

Frishman WH: Student research projects and theses: should they be a requirement for medical school graduation?. Heart Dis. 2001, 3: 140-144. 10.1097/00132580-200105000-00002.

Virtanen JI, Nieminen P: Information and communication technology among undergraduate dental students in Finland. Eur J Dent Educ. 2002, 6: 147-152. 10.1034/j.1600-0579.2002.00251.x.

Cunningham SJ: How to write a thesis. J Orthod. 2004, 31: 144-148. 10.1179/146531204225020445.

Cunningham D, Viola D: Collaboration to teach graduate students how to write more effective theses. J Med Libr Assoc. 2002, 90: 331-334.

Lloyd T, Phillips BR, Aber RC: Factors that influence doctors' participation in clinical research. Med Educ. 2004, 38: 848-851. 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2004.01895.x.

Solomon SS, Tom SC, Pichert J, Wasserman D, Powers AC: Impact of medical student research in the development of physician-scientists. J Investig Med. 2003, 51: 149-156.

Frkovic V, Skender T, Dojcinovic B, Bilic-Zulle L: Publishing scientific papers based on Master's and Ph.D. theses from a small scientific community: case study of Croatian medical schools. Croat Med J. 2003, 44: 107-111.

Lehvo A, Nuutinen A: Publications of the Academy of Finland. Finnish science in international comparison. A bibliometric analysis. 2006, Helsinki, Academy of Finland

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here: http://www.biomedcentral.com/1472-6920/7/51/prepub

Download references

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the contributions of Hanna Pesonen, Chief Academic Officer at the Medical Faculty, University of Oulu, who provided support throughout the evaluation process. This study has been supported by a grant from the Teaching Development Unit, University of Oulu, Finland.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Medical Informatics Group, University of Oulu, P.O. Box 5000, FIN-90014, Oulu, Finland

Pentti Nieminen & Hanna-Mari Takkinen

Institute of Dentistry, University of Oulu, P.O. Box 5000, FIN-90014, Oulu, Finland

Kirsi Sipilä

Oral and Maxillofacial Department, Oulu University Hospital, Aapistie 3, FIN-90220, Oulu, Finland

Department of Paediatrics, University of Oulu, P.O. Box 5000, FIN-90014, Oulu, Finland

Marjo Renko

Research and Innovation Services, University of Oulu, P.O. Box 8000, FIN-90014, Oulu, Finland

Leila Risteli

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Pentti Nieminen .

Additional information

Competing interests.

The author(s) declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

PN and KS had the idea for the article. PN initiated the project, contributed to the data collection and statistical analysis and wrote the paper. KS, MR and LR contributed to the study design, data collection and writing of the paper. H-MT performed the bibliometric data collection and statistical analyses and contributed to the and writing of the paper. All the authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Authors’ original file for figure 1

Authors’ original file for figure 2, rights and permissions.

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Nieminen, P., Sipilä, K., Takkinen, HM. et al. Medical theses as part of the scientific training in basic medical and dental education: experiences from Finland. BMC Med Educ 7 , 51 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6920-7-51

Download citation

Received : 16 July 2007

Accepted : 05 December 2007

Published : 05 December 2007

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6920-7-51

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Scientific Article

- Technical Quality

- Journal Impact Factor

- Peer Review Process

- Dental School

BMC Medical Education

ISSN: 1472-6920

- Submission enquiries: [email protected]

- General enquiries: [email protected]

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- How to Write a Thesis Statement | 4 Steps & Examples

How to Write a Thesis Statement | 4 Steps & Examples

Published on January 11, 2019 by Shona McCombes . Revised on August 15, 2023 by Eoghan Ryan.

A thesis statement is a sentence that sums up the central point of your paper or essay . It usually comes near the end of your introduction .

Your thesis will look a bit different depending on the type of essay you’re writing. But the thesis statement should always clearly state the main idea you want to get across. Everything else in your essay should relate back to this idea.

You can write your thesis statement by following four simple steps:

- Start with a question

- Write your initial answer

- Develop your answer

- Refine your thesis statement

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

What is a thesis statement, placement of the thesis statement, step 1: start with a question, step 2: write your initial answer, step 3: develop your answer, step 4: refine your thesis statement, types of thesis statements, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about thesis statements.

A thesis statement summarizes the central points of your essay. It is a signpost telling the reader what the essay will argue and why.

The best thesis statements are:

- Concise: A good thesis statement is short and sweet—don’t use more words than necessary. State your point clearly and directly in one or two sentences.

- Contentious: Your thesis shouldn’t be a simple statement of fact that everyone already knows. A good thesis statement is a claim that requires further evidence or analysis to back it up.

- Coherent: Everything mentioned in your thesis statement must be supported and explained in the rest of your paper.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

The thesis statement generally appears at the end of your essay introduction or research paper introduction .

The spread of the internet has had a world-changing effect, not least on the world of education. The use of the internet in academic contexts and among young people more generally is hotly debated. For many who did not grow up with this technology, its effects seem alarming and potentially harmful. This concern, while understandable, is misguided. The negatives of internet use are outweighed by its many benefits for education: the internet facilitates easier access to information, exposure to different perspectives, and a flexible learning environment for both students and teachers.

You should come up with an initial thesis, sometimes called a working thesis , early in the writing process . As soon as you’ve decided on your essay topic , you need to work out what you want to say about it—a clear thesis will give your essay direction and structure.

You might already have a question in your assignment, but if not, try to come up with your own. What would you like to find out or decide about your topic?

For example, you might ask:

After some initial research, you can formulate a tentative answer to this question. At this stage it can be simple, and it should guide the research process and writing process .

Now you need to consider why this is your answer and how you will convince your reader to agree with you. As you read more about your topic and begin writing, your answer should get more detailed.

In your essay about the internet and education, the thesis states your position and sketches out the key arguments you’ll use to support it.

The negatives of internet use are outweighed by its many benefits for education because it facilitates easier access to information.

In your essay about braille, the thesis statement summarizes the key historical development that you’ll explain.

The invention of braille in the 19th century transformed the lives of blind people, allowing them to participate more actively in public life.

A strong thesis statement should tell the reader:

- Why you hold this position

- What they’ll learn from your essay

- The key points of your argument or narrative

The final thesis statement doesn’t just state your position, but summarizes your overall argument or the entire topic you’re going to explain. To strengthen a weak thesis statement, it can help to consider the broader context of your topic.

These examples are more specific and show that you’ll explore your topic in depth.

Your thesis statement should match the goals of your essay, which vary depending on the type of essay you’re writing:

- In an argumentative essay , your thesis statement should take a strong position. Your aim in the essay is to convince your reader of this thesis based on evidence and logical reasoning.

- In an expository essay , you’ll aim to explain the facts of a topic or process. Your thesis statement doesn’t have to include a strong opinion in this case, but it should clearly state the central point you want to make, and mention the key elements you’ll explain.

If you want to know more about AI tools , college essays , or fallacies make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples or go directly to our tools!

- Ad hominem fallacy

- Post hoc fallacy

- Appeal to authority fallacy

- False cause fallacy

- Sunk cost fallacy

College essays

- Choosing Essay Topic

- Write a College Essay

- Write a Diversity Essay

- College Essay Format & Structure

- Comparing and Contrasting in an Essay

(AI) Tools

- Grammar Checker

- Paraphrasing Tool

- Text Summarizer

- AI Detector

- Plagiarism Checker

- Citation Generator

A thesis statement is a sentence that sums up the central point of your paper or essay . Everything else you write should relate to this key idea.

The thesis statement is essential in any academic essay or research paper for two main reasons:

- It gives your writing direction and focus.

- It gives the reader a concise summary of your main point.

Without a clear thesis statement, an essay can end up rambling and unfocused, leaving your reader unsure of exactly what you want to say.

Follow these four steps to come up with a thesis statement :

- Ask a question about your topic .

- Write your initial answer.

- Develop your answer by including reasons.

- Refine your answer, adding more detail and nuance.

The thesis statement should be placed at the end of your essay introduction .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, August 15). How to Write a Thesis Statement | 4 Steps & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved June 25, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/academic-essay/thesis-statement/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, how to write an essay introduction | 4 steps & examples, how to write topic sentences | 4 steps, examples & purpose, academic paragraph structure | step-by-step guide & examples, what is your plagiarism score.

Reference management. Clean and simple.

How to write a thesis statement + examples

What is a thesis statement?

Is a thesis statement a question, how do you write a good thesis statement, how do i know if my thesis statement is good, examples of thesis statements, helpful resources on how to write a thesis statement, frequently asked questions about writing a thesis statement, related articles.

A thesis statement is the main argument of your paper or thesis.

The thesis statement is one of the most important elements of any piece of academic writing . It is a brief statement of your paper’s main argument. Essentially, you are stating what you will be writing about.

You can see your thesis statement as an answer to a question. While it also contains the question, it should really give an answer to the question with new information and not just restate or reiterate it.

Your thesis statement is part of your introduction. Learn more about how to write a good thesis introduction in our introduction guide .

A thesis statement is not a question. A statement must be arguable and provable through evidence and analysis. While your thesis might stem from a research question, it should be in the form of a statement.

Tip: A thesis statement is typically 1-2 sentences. For a longer project like a thesis, the statement may be several sentences or a paragraph.

A good thesis statement needs to do the following:

- Condense the main idea of your thesis into one or two sentences.

- Answer your project’s main research question.

- Clearly state your position in relation to the topic .

- Make an argument that requires support or evidence.

Once you have written down a thesis statement, check if it fulfills the following criteria:

- Your statement needs to be provable by evidence. As an argument, a thesis statement needs to be debatable.

- Your statement needs to be precise. Do not give away too much information in the thesis statement and do not load it with unnecessary information.

- Your statement cannot say that one solution is simply right or simply wrong as a matter of fact. You should draw upon verified facts to persuade the reader of your solution, but you cannot just declare something as right or wrong.

As previously mentioned, your thesis statement should answer a question.

If the question is:

What do you think the City of New York should do to reduce traffic congestion?

A good thesis statement restates the question and answers it:

In this paper, I will argue that the City of New York should focus on providing exclusive lanes for public transport and adaptive traffic signals to reduce traffic congestion by the year 2035.

Here is another example. If the question is:

How can we end poverty?

A good thesis statement should give more than one solution to the problem in question:

In this paper, I will argue that introducing universal basic income can help reduce poverty and positively impact the way we work.

- The Writing Center of the University of North Carolina has a list of questions to ask to see if your thesis is strong .

A thesis statement is part of the introduction of your paper. It is usually found in the first or second paragraph to let the reader know your research purpose from the beginning.

In general, a thesis statement should have one or two sentences. But the length really depends on the overall length of your project. Take a look at our guide about the length of thesis statements for more insight on this topic.

Here is a list of Thesis Statement Examples that will help you understand better how to write them.

Every good essay should include a thesis statement as part of its introduction, no matter the academic level. Of course, if you are a high school student you are not expected to have the same type of thesis as a PhD student.

Here is a great YouTube tutorial showing How To Write An Essay: Thesis Statements .

- Resources Home 🏠

- Try SciSpace Copilot

- Search research papers

- Add Copilot Extension

- Try AI Detector

- Try Paraphraser

- Try Citation Generator

- April Papers

- June Papers

- July Papers

What is a thesis | A Complete Guide with Examples

Table of Contents

A thesis is a comprehensive academic paper based on your original research that presents new findings, arguments, and ideas of your study. It’s typically submitted at the end of your master’s degree or as a capstone of your bachelor’s degree.

However, writing a thesis can be laborious, especially for beginners. From the initial challenge of pinpointing a compelling research topic to organizing and presenting findings, the process is filled with potential pitfalls.

Therefore, to help you, this guide talks about what is a thesis. Additionally, it offers revelations and methodologies to transform it from an overwhelming task to a manageable and rewarding academic milestone.

What is a thesis?

A thesis is an in-depth research study that identifies a particular topic of inquiry and presents a clear argument or perspective about that topic using evidence and logic.

Writing a thesis showcases your ability of critical thinking, gathering evidence, and making a compelling argument. Integral to these competencies is thorough research, which not only fortifies your propositions but also confers credibility to your entire study.

Furthermore, there's another phenomenon you might often confuse with the thesis: the ' working thesis .' However, they aren't similar and shouldn't be used interchangeably.

A working thesis, often referred to as a preliminary or tentative thesis, is an initial version of your thesis statement. It serves as a draft or a starting point that guides your research in its early stages.

As you research more and gather more evidence, your initial thesis (aka working thesis) might change. It's like a starting point that can be adjusted as you learn more. It's normal for your main topic to change a few times before you finalize it.

While a thesis identifies and provides an overarching argument, the key to clearly communicating the central point of that argument lies in writing a strong thesis statement.

What is a thesis statement?

A strong thesis statement (aka thesis sentence) is a concise summary of the main argument or claim of the paper. It serves as a critical anchor in any academic work, succinctly encapsulating the primary argument or main idea of the entire paper.

Typically found within the introductory section, a strong thesis statement acts as a roadmap of your thesis, directing readers through your arguments and findings. By delineating the core focus of your investigation, it offers readers an immediate understanding of the context and the gravity of your study.

Furthermore, an effectively crafted thesis statement can set forth the boundaries of your research, helping readers anticipate the specific areas of inquiry you are addressing.

Different types of thesis statements

A good thesis statement is clear, specific, and arguable. Therefore, it is necessary for you to choose the right type of thesis statement for your academic papers.

Thesis statements can be classified based on their purpose and structure. Here are the primary types of thesis statements:

Argumentative (or Persuasive) thesis statement

Purpose : To convince the reader of a particular stance or point of view by presenting evidence and formulating a compelling argument.

Example : Reducing plastic use in daily life is essential for environmental health.

Analytical thesis statement

Purpose : To break down an idea or issue into its components and evaluate it.

Example : By examining the long-term effects, social implications, and economic impact of climate change, it becomes evident that immediate global action is necessary.

Expository (or Descriptive) thesis statement

Purpose : To explain a topic or subject to the reader.

Example : The Great Depression, spanning the 1930s, was a severe worldwide economic downturn triggered by a stock market crash, bank failures, and reduced consumer spending.

Cause and effect thesis statement

Purpose : To demonstrate a cause and its resulting effect.

Example : Overuse of smartphones can lead to impaired sleep patterns, reduced face-to-face social interactions, and increased levels of anxiety.

Compare and contrast thesis statement

Purpose : To highlight similarities and differences between two subjects.

Example : "While both novels '1984' and 'Brave New World' delve into dystopian futures, they differ in their portrayal of individual freedom, societal control, and the role of technology."

When you write a thesis statement , it's important to ensure clarity and precision, so the reader immediately understands the central focus of your work.

What is the difference between a thesis and a thesis statement?

While both terms are frequently used interchangeably, they have distinct meanings.

A thesis refers to the entire research document, encompassing all its chapters and sections. In contrast, a thesis statement is a brief assertion that encapsulates the central argument of the research.

Here’s an in-depth differentiation table of a thesis and a thesis statement.

Aspect | Thesis | Thesis Statement |

Definition | An extensive document presenting the author's research and findings, typically for a degree or professional qualification. | A concise sentence or two in an essay or research paper that outlines the main idea or argument. |

Position | It’s the entire document on its own. | Typically found at the end of the introduction of an essay, research paper, or thesis. |

Components | Introduction, methodology, results, conclusions, and bibliography or references. | Doesn't include any specific components |

Purpose | Provides detailed research, presents findings, and contributes to a field of study. | To guide the reader about the main point or argument of the paper or essay. |

Now, to craft a compelling thesis, it's crucial to adhere to a specific structure. Let’s break down these essential components that make up a thesis structure

15 components of a thesis structure

Navigating a thesis can be daunting. However, understanding its structure can make the process more manageable.

Here are the key components or different sections of a thesis structure:

Your thesis begins with the title page. It's not just a formality but the gateway to your research.

Here, you'll prominently display the necessary information about you (the author) and your institutional details.

- Title of your thesis

- Your full name

- Your department

- Your institution and degree program

- Your submission date

- Your Supervisor's name (in some cases)

- Your Department or faculty (in some cases)

- Your University's logo (in some cases)

- Your Student ID (in some cases)

In a concise manner, you'll have to summarize the critical aspects of your research in typically no more than 200-300 words.

This includes the problem statement, methodology, key findings, and conclusions. For many, the abstract will determine if they delve deeper into your work, so ensure it's clear and compelling.

Acknowledgments

Research is rarely a solitary endeavor. In the acknowledgments section, you have the chance to express gratitude to those who've supported your journey.

This might include advisors, peers, institutions, or even personal sources of inspiration and support. It's a personal touch, reflecting the humanity behind the academic rigor.

Table of contents

A roadmap for your readers, the table of contents lists the chapters, sections, and subsections of your thesis.

By providing page numbers, you allow readers to navigate your work easily, jumping to sections that pique their interest.

List of figures and tables

Research often involves data, and presenting this data visually can enhance understanding. This section provides an organized listing of all figures and tables in your thesis.

It's a visual index, ensuring that readers can quickly locate and reference your graphical data.

Introduction

Here's where you introduce your research topic, articulate the research question or objective, and outline the significance of your study.

- Present the research topic : Clearly articulate the central theme or subject of your research.

- Background information : Ground your research topic, providing any necessary context or background information your readers might need to understand the significance of your study.

- Define the scope : Clearly delineate the boundaries of your research, indicating what will and won't be covered.