COVID-19: Where we’ve been, where we are, and where we’re going

One of the hardest things to deal with in this type of crisis is being able to go the distance. Moderna CEO Stéphane Bancel

Where we're going

Living with covid-19, people & organizations, sustainable, inclusive growth, related collection.

The Next Normal: Emerging stronger from the coronavirus pandemic

Three Years Later: How the Pandemic Changed Us

From routines to deep losses, the global health crisis altered lives of staff and faculty

Since her father’s death from COVID-19 in 2021, Alexy Hernandez’s days have become emotional minefields. Any small thing can be a gut punch, reminding her of what’s lost.

Perhaps it’s a football highlight, since she and her father, Josue, shared a love of the sport. Coffee has become complicated since her dad always got a kick out of pictures she sent of the creative designs left in her latte foam.

Or maybe it will simply be the small pieces of her daily routine — getting into work in the morning, coming home at night — experiences that warranted a quick text to her dad, who always wrote back with love and encouragement.

“He was my best friend, my biggest supporter, my biggest cheerleader,” said Hernandez, 28, a clinical research coordinator with the Department of Population Health Sciences . “I am who I am because of him.”

The pandemic changed the way most of us lived. We learned how to work remotely or gained new appreciation for human connection. And, for the loved ones of the roughly 1 million Americans who died from the virus, life will forever feel incomplete.

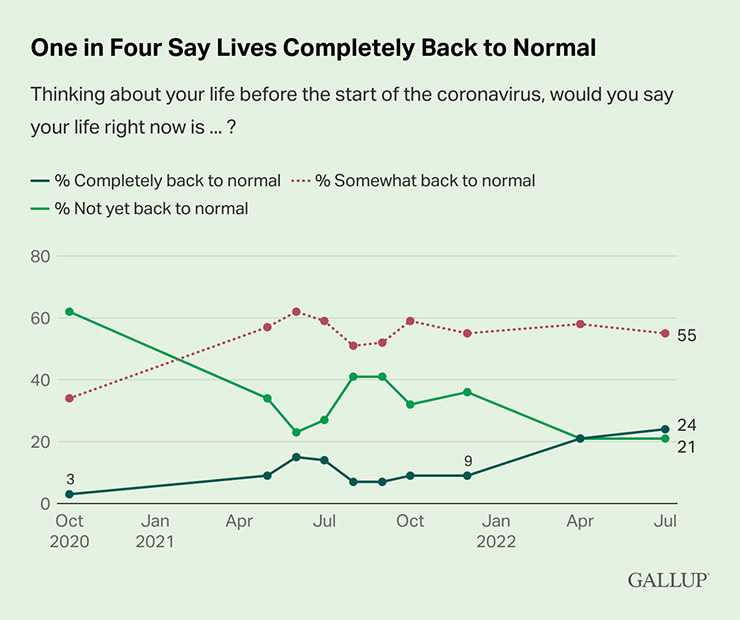

While the worst of the pandemic may be behind us, its effects linger. According to a Gallup poll , 53 percent of U.S. adults don’t expect their life to ever be the same as it was before the pandemic.

“We all felt this,” said Rachel Kranton, the James B. Duke Professor of Economics who, early in the pandemic, contributed to Project ROUSE , an independent Duke faculty research study that looked at how staff and faculty at Duke coped with changes to life, work, and well-being.

Project ROUSE showed that the pandemic had profound effects on everyone, including that, during the pandemic’s first year, roughly 40 percent of nearly 5,000 study respondents were at risk of moderate or severe depression.

As the pandemic’s difficult early days fade, Kranton said that other changes will likely endure, such as a willingness to connect in new ways, reassess careers, or build lives with more flexibility.

“I think there’s probably a new normal, and I think that new normal includes both good things and bad things,” Kranton said.

Hernandez’s life won’t be the same after her father’s death, but she is moving forward.

She’s learned not to stress about trivial things and thinks often about how she can make her father proud. Nothing, she said, can be taken for granted.

“Losing my dad has completely changed how I view and interact with the world and has given me more clarity on what I value,” said Hernandez, who has worked at Duke for four years.

We asked staff and faculty to share how the pandemic changed their lives, and here’s what some colleagues shared.

‘I’ve learned from students’

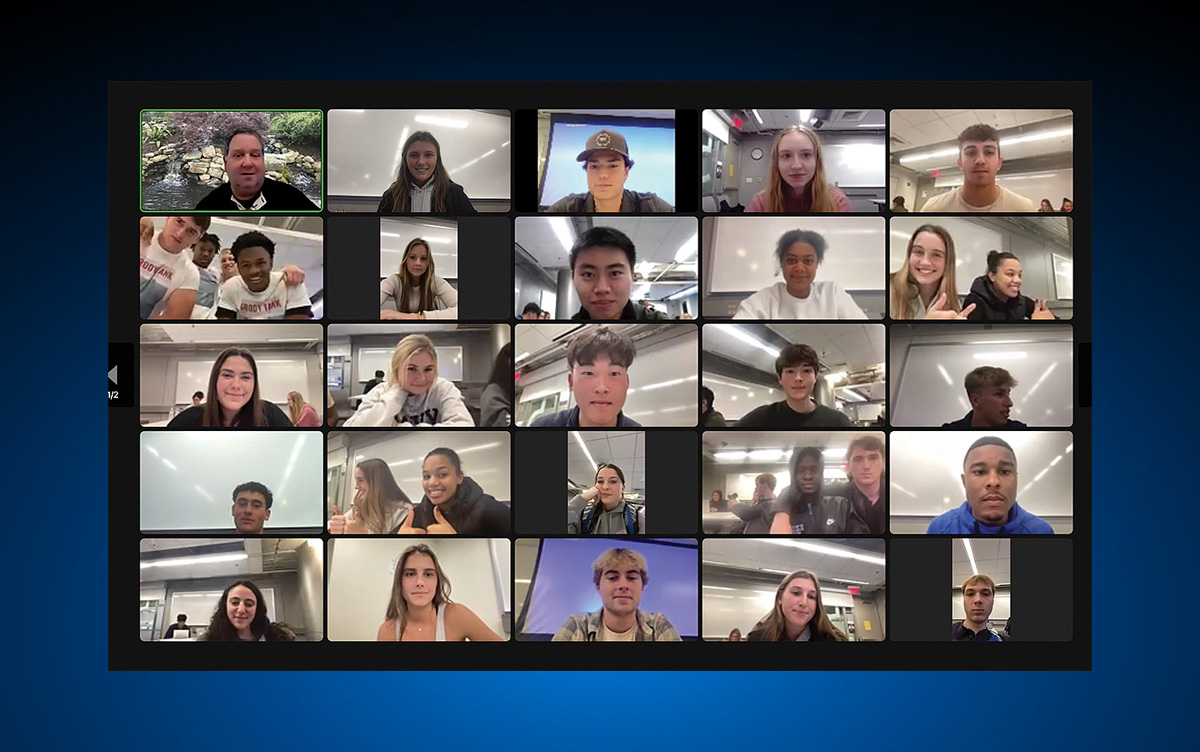

“It’s a new normal. You’ve got to deal with what you’ve got to deal with. Teaching markets and management, I’ve tried to move on and try to keep things fun. I like to make my courses interactive. So whether that’s changing materials or adding new things to a class, I’ve had to adapt. A lot of new stuff I’ve learned from students, whether it’s using polls, or Kahoot, or other activities. You’ve got to keep things fresh. The world is changing, you’ve got to change with it.”

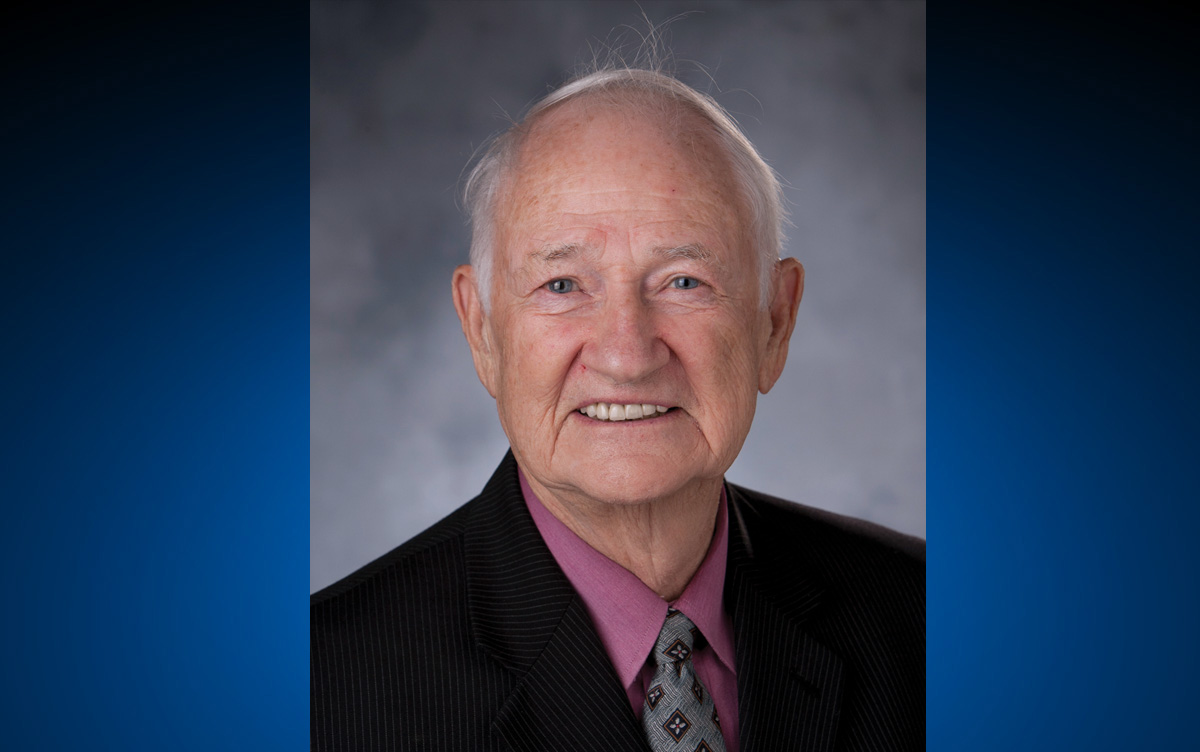

George Grody, 64, Lecturing Fellow of Markets & Management, Trinity College of Arts and Sciences

Value of Life

“I appreciate more than ever before, not only the value of life, but a strong appreciation for others in the respiratory field and healthcare. I have been a respiratory therapist 33 years, and I’ve worked at Duke 35 years. Many have come and some have gone from this world. It’s devastating when you’ve worked so hard on patients, and they don’t make it out. Nothing can replace the value of life and what it means. Life is so important, and each and every day that you work with your patients is important. This all taught me a lot about what it means to really care for your patients, and it taught me a great deal of humility in caring for those who needed me.”

Pamela Bowman, 63, recently retired Respiratory Care Practitioner, Duke Regional Hospital

Out of the Quiet

“Though it’s crazy to say, my life started to flourish during the pandemic in more ways than one. I went back to school at the beginning of the pandemic at Durham Technical Community College to study business. I got in the best shape of my life by focusing on clean eating, and I lost 35 pounds. I started earning more money by taking a job at Duke. The pandemic was a time for me to quiet down the noise around me. Personally, I was able to shut out the world, decide what I really wanted out of life, and for myself, and start making those things happen. Ever since things started getting back to how they were pre-pandemic, those progressions I’ve made slowly started to derail. I gained back the 35 pounds I lost once the world started to open up again, and it’s just been harder to do everything I was doing to better myself every day. I went into a bit of a depression, but now I’m finally coming out of it. I’m back down 20 pounds. I’m learning how to cope with things and get back to being able to do those things that progressed for me and made me happy, even though I’m not able to get the same quietness I once had.”

Sadie Horton, 27, Staff Assistant, Academic Support, Fuqua School of Business

Cherish Loved Ones

“My mom, Johnnie Mae Snipes, was put on hospice on Jan. 11, 2021, and she passed away on January 20, 2021, at age 83. Me and my sisters were holding her hand, and, needless to say, we lost the strongest woman we ever knew. Our queen was gone. My mother had six daughters, 17 grandchildren, 44 great grandchildren and seven great, great grandchildren. My mother passed away from dementia and COVID. The past few years have taught me to never take anything for granted and to cherish your loved ones. It also has showed me how the world can change in one day. But one thing I know for sure that will never change is God is still in charge.”

Clara Bailey, 58, Staff Assistant, Department of Medicine, Oncology

‘I don’t go anywhere without my mask’

“When Dr. Anthony Fauci came out and said we need to wear masks in public, I did it. I’m claustrophobic, so when I first started wearing the cloth masks, I would have panic and anxiety attacks, particularly at the grocery store. Over time, I got used to it, and I started feeling safer by wearing my mask. Now, I don't think I will ever go into another crowded event without a mask. As a woman, we have our purses. We don’t go anywhere without our purses. Now, I don’t go anywhere without my mask. Since wearing my mask, I haven't caught a cold, let alone anything else. It's a piece of cloth, no big deal.”

Sandy Ouellette, 62, Access Specialist, Consultation & Referral Center

Rethinking What’s Most Important

“During the pandemic, my wife got a new job in Virginia, and because I’ve been working remote since March 2020, it made it easy to move with her because, in the past, somebody would have had to quit their job, find a new job, and do all kinds of stuff. Personally, the pandemic has made me rethink what’s most important in life, such as making sure to set aside time for family and friends. Now, I get to spend more time with my wife. We can do house projects, take our dogs out and explore. Now that our parents are getting older, we try to take advantage of any time we can spend with them. The pandemic made spending time with people who are important to you a little extra important because they’re what helped me get through.”

Christopher Morgenstern, 39, Administrative Manager, Cardiology

‘180-degrees different’

“My wedding, honeymoon, and bachelorette party were all canceled due to COVID, so my husband, Brent Durden, and I got married in our backyard with just our parents. We were going to wait several years to start a family so we could travel but decided to seize the day during quarantine after buying a house. Now, we have a beautiful 18-month-old daughter, Eliana. As tragic as the losses we experienced as a country and community have been through this pandemic, my entire world is 180-degrees different than it was before COVID, and it makes me so grateful to have the family that I do.”

Tricia Smar, 36, Education and Training Coordinator, Duke Trauma Center

‘I’m fulfilling my bucket list’

“I have terminal prostate cancer. I live one day at a time. They gave me 18 months to live about six years ago. During the pandemic, I retired to fulfill my bucket list only to find disappointment. I made all sorts of plans, but everything was shut down so my plans were shot. I returned to work. I have a love for nursing and have no regrets coming back to patient care. I missed interacting with people. I missed my coworkers, I missed the patients. Now I travel, and I'm fulfilling my bucket list, but I always look forward to coming back to Duke for both my own care and to care for our patients.”

Doug Buehrle, 68, Clinical Nurse, Apheresis, Duke University Hospital

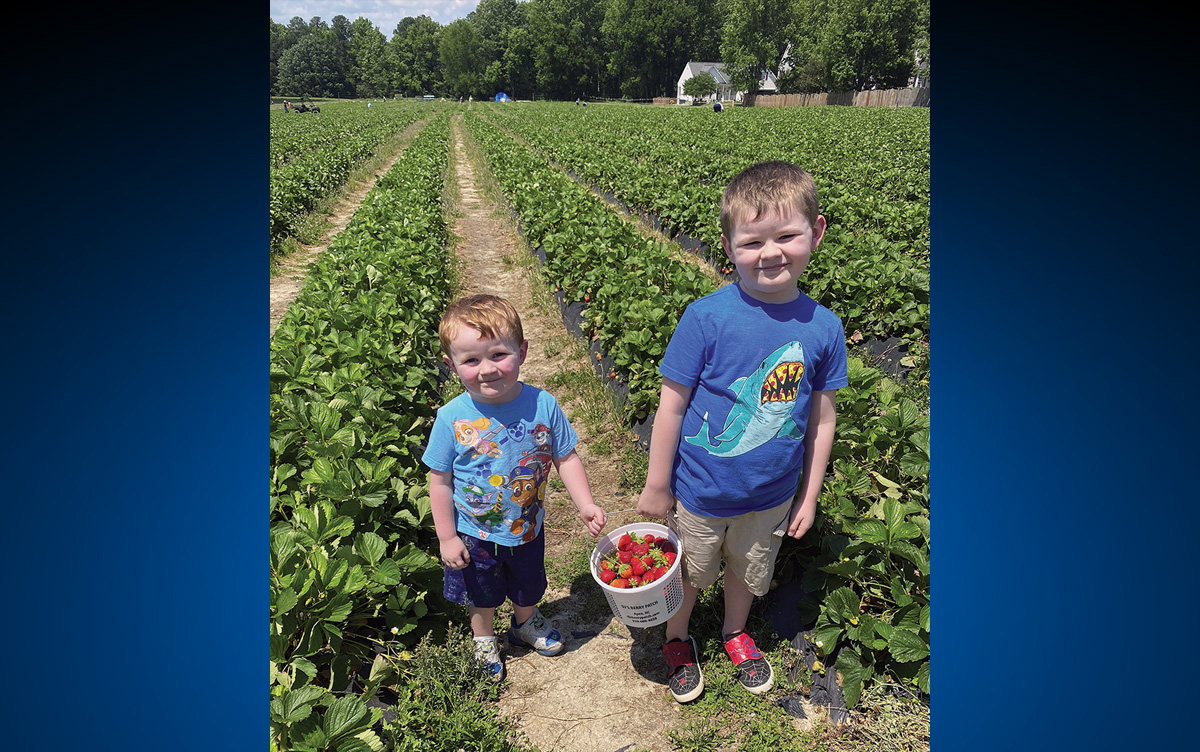

Savor Small Moments

“I learned to make the best out of a horrific situation. My kids, Derek and Joshua, were 5 and nearly 3 when COVID hit. In the clinical research field, we had to scramble to see which trials could keep going and which ones would have to go on pause. We had to be very flexible to work around each other’s schedules and everyone’s kid’s schedules. But I got to spend a lot more time with my kids than I ever would have if COVID didn't hit, so I'm grateful I was able to do it. We got to spend time going to the park and flying kites since the playgrounds were closed. We went hiking and exploring since the museums were closed. Those were memories I am thankful to have made, and I'm hoping they don't fade.”

Kristin Byrne, 41, Clinical Research Coordinator, Hematology

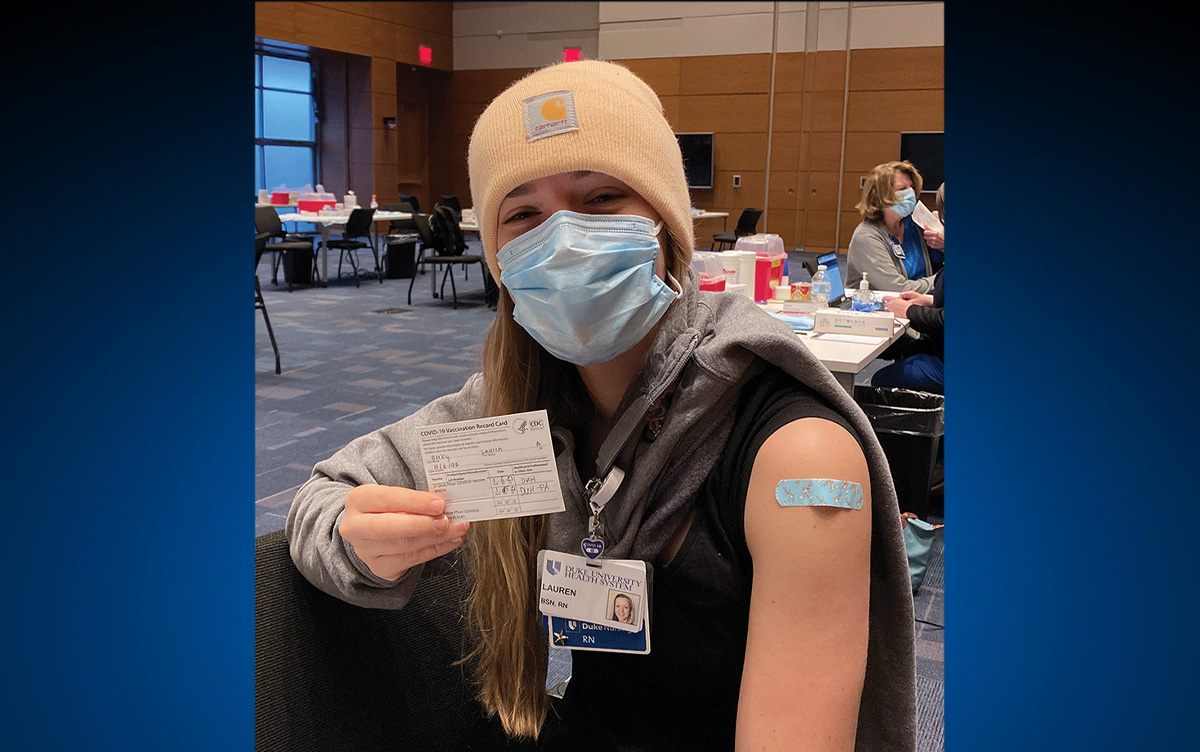

‘Packed up my car with as much as I could fit into it’

“I graduated from nursing school at George Fox University in Oregon about a month after lockdown happened. I have a grandmother in High Point, so I started applying to hospitals in North Carolina, and Duke turned out to be the best option. In October of 2020, I packed up my car with as much as I could fit into it, and I drove across the country with my dad. I left my family, friends, my church back in Portland, and I’ve had to build an entirely new life here. My first nursing job was working for the medical-surgical float pool at Duke University Hospital, which basically staffed the COVID-19 floors for a while. I was thrown into the thick of it, and I really had to stay on my toes all the time. It was really hard, and it was really a dark period in my life, until I started to get my feet settled. I just started to put myself out there out of my comfort zone, and I started inviting people to do things with me. I found Bright City Church too. Over time, I started to find those little sparks of hope, when you send a patient home instead of the ICU. I’ve learned a lot from my nursing career, and I’ve learned a lot about myself and how to take care of myself.”

Lauren Berky, 25, Clinical Nurse, Internal Staffing Resource Pool

‘More Openness to Change’

“I think COVID has opened the clinical community to change more than ever before. Sharing data has replaced hoarding data. Technology has come so far, and we had a hard time getting people to change the way they think about data. I think COVID opened their minds that we need other ways of dealing with data, particularly that the patient needs to be the centerpiece of everything that we’re doing. Some people have said to me, that five years ago we’d have been laughed at for some of the things we’re trying to do. But now, everybody is at least willing to have the conversation.”

William Edward Hammond, 88, Professor of Biostatistics and Bioinformatics, Family Medicine and Community Health

‘Never take tomorrow for granted’

“I am much more committed to ‘living in the moment,’ appreciating what I have, and looking inward. At home, I find joy with my husband. I walk much more. I cook at home almost all the time. And, maybe most important, I appreciate the beautiful natural environment around our home on Morgan Creek in Chapel Hill, where husband, David, and I began walking nearly every afternoon in January 2021. I’ve learned to never take tomorrow for granted. To appreciate friendships and family and the place where we are, now. To be OK with less ‘running around.’ To not take progress for granted, and to realize that things can get worse.”

Anne Mitchell Whisnant, 55, Director, Graduate Liberal Studies, and Associate Professor of the Practice, Social Science Research Institute

Bittersweet Milestones

“COVID was honestly a bittersweet time. My father-in-law, Mark, the president of North Georgia Technical College, passed away from COVID on September 13, 2020. Then in January 2021, my husband, Andrew, and I found out we were pregnant with our first child, Lilly, after a very long time. We thought we couldn’t have kids, so that was quite the surprise. When she was born on October 21, 2021, the joy of having her was indescribable. She just turned a year old, and I know she’ll never know her grandfather, and he’ll never know her. We want her to be happy and healthy and treat others the best way possible, and we’ll continue to tell her about her Papa when we can. We can’t wish Mark back because he’s not coming back. We’re living in the reality knowing that we can’t change it; it’s something Ecclesiastes calls our lot in life. COVID-19 brought out the worst for so many families, including ours, but it also brought so much good.”

Marissa Ivester, 34, Fellowship Program Coordinator, Office of Pediatrics

Send story ideas, shout-outs and photographs through our story idea form or write [email protected] .

Advertisement

Supported by

When Life Felt Normal: Your Pre-Pandemic Moments

Readers share memories, images and videos from before the coronavirus became a pandemic, and reflect on what they mean now.

- Share full article

By Hannah Wise

Our lives have been forever changed by the coronavirus pandemic. Hundreds of thousands of people around the world have died. Millions in the United States alone have lost their jobs.

Though the coronavirus outbreak was declared a pandemic just over a month ago, many of us are already feeling nostalgic for our lives before the virus went global. We asked you to send us photos and videos that captured those moments of normalcy. We received nearly 700 submissions from all over the world — from Wuhan, China, to Paris, Milan to Mumbai, and across the United States.

You shared photos from weddings, funerals, meals with friends, and powerful scenes from crowded places that feel almost unthinkable now.

Nearly every submission expressed a sense of gratitude and appreciation for the time before the pandemic. Many also conveyed worry and a longing to feel a sense of safety and normalcy again.

What follows is a selection of those snapshots. The responses have been edited for clarity and length.

We are having trouble retrieving the article content.

Please enable JavaScript in your browser settings.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access. If you are in Reader mode please exit and log into your Times account, or subscribe for all of The Times.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access.

Already a subscriber? Log in .

Want all of The Times? Subscribe .

Life after COVID-19: Making space for growth

In this time of grief, the theory of post-traumatic growth suggests people can emerge from trauma even stronger

Vol. 51, No. 4

In the traditional Japanese art of kintsugi, artisans fill the cracks in broken pottery with gold or silver, transforming damaged pieces into something more beautiful than they were when new. Post-traumatic growth is like kintsugi for the mind.

Developed in the 1990s by psychologists Richard Tedeschi, PhD, and Lawrence Calhoun, PhD, the theory of post-traumatic growth suggests that people can emerge from trauma or adversity having achieved positive personal growth. It’s a comforting idea in the best of times. But it holds particular appeal as we live through a pandemic that’s upending lives for people around the globe.

Growing from trauma isn’t unusual, says Tedeschi, now a professor emeritus at the University of North Carolina Charlotte and chair of the Boulder Crest Institute for Posttraumatic Growth in Bluemont, Virginia. “Studies support the notion that post-traumatic growth is common and universal across cultures,” he says. “We’re talking about a transformation—a challenge to people’s core beliefs that causes them to become different than they were before.”

And the COVID-19 pandemic may have the ingredients to foster such growth. “We’re still in the middle of this situation, and we don’t know yet what might happen—but there will be serious challenges to people’s lives,” Tedeschi says. While those effects may be devastating, it’s possible to emerge from such adversity for the better, he adds. “For some people, this event may be a shock to their core belief system. When that’s the case, it has the potential to result in significant positive changes.”

Resilience vs. post-traumatic growth

Research across a variety of disasters has shown that there are different trajectories for recovery, says Erika Felix, PhD, a psychologist at the University of California, Santa Barbara, who treats and studies trauma survivors. Some people need time to recover from a trauma before returning to normal functioning. A portion of people experience negative mental health impacts that become chronic, but the majority of people bounce back from a trauma pretty quickly, she says. “Most people will be resilient and return to their previous level of functioning.”

Resilience and post-traumatic growth are not the same thing, however. In fact, people who bounce back quickly from a setback aren’t the ones likely to experience positive growth, Tedeschi explains. Rather, people who experience post-traumatic growth are those who endure some cognitive and emotional struggle and then emerge changed on the other side.

This experience is measured by Tedeschi and Calhoun’s Posttraumatic Growth Inventory (PTGI) ( Journal of Traumatic Stress , Vol. 9, No. 3, 1996), which evaluates growth in five areas: appreciation of life, relating to others, personal strength, recognizing new possibilities and spiritual change. It’s not necessary or even typical to show change in all five areas, Tedeschi says. But growth in even one or two of those realms “can have a profound effect on a person’s life,” he says.

Some psychologists say the evidence for post-traumatic growth isn’t yet as robust as it could be. For example, Patricia Frazier, PhD, at the University of Minnesota, and colleagues followed undergraduates before and after a trauma. They found that participants’ self-reported perceived growth didn’t align with actual growth as measured by the PTGI. And while actual growth was related to positive coping, perceived growth was not, suggesting the construct may not fully reflect the way people are transformed by trauma ( Psychological Science , Vol. 20, No. 7, 2009).

But other evidence suggests that people do grow from trauma. A 2018 book by Tedeschi and colleagues summarizes more than 700 studies related to post-traumatic growth, including Tedeschi’s own research and work from other scientists (“ Posttraumatic Growth: Theory, Research, and Applications ,” Routledge, 2018). “When you look at how people respond to traumatic events, post-traumatic growth seems to be fairly common,” he says.

Planting the seeds for positive change

Post-traumatic growth isn’t something psychologists can prescribe or create, Tedeschi says. But they can facilitate it. “We see it as a natural tendency that we can watch for and encourage, without trying to make people feel pressured or that they’re failures if they don’t achieve this growth,” Tedeschi explains.

Most evidence-based trauma treatments provide a “manualized approach” to alleviating stress and symptoms such as anxiety, Tedeschi says. The post-traumatic growth framework he uses is an integrated approach that includes elements of cognitive-behavioral therapy, along with other aspects that emphasize personal growth. “It has elements of narrative and existential aspects, too, because traumas often present people with existential questions about what’s important in life.”

One way to help clients see the possibilities for growth is to be an “expert companion” during their struggle, he says. “That’s someone who accompanies their trauma, listens carefully to their story and learns from them about what has happened in their lives. By being that kind of expert, people start to open up and look at the possibilities in their lives more thoroughly.”

Yet post-traumatic growth isn’t something that can be rushed, and it often takes a long time to come to fruition. “As a clinician, you can plant the seeds that may germinate later,” Tedeschi says.

As we emerge from the COVID-19 crisis, clinicians and their clients may have opportunities to help those seeds begin to sprout. “This situation presents a challenge to people’s lives, and some people will be able to emerge from this for the better,” Tedeschi says.

One doesn’t necessarily need to experience trauma and existential struggle to learn from this crisis, however. For many people, the pandemic is shining a light on the things that are most important. “We might be making more time for things we find meaningful, simplifying our lives and making time for being connected in our relationships,” Felix says. “A stressor like this makes all of us think: What does this slowdown mean for our lives? We might be fundamentally changed in some ways that are beneficial.”

The Posttraumatic Growth Workbook Tedeschi, R.G., & Moore, B.A. New Harbinger Publications, 2016

The Posttraumatic Growth Inventory: A Revision Integrating Existential and Spiritual Change Tedeschi R.G., et al., Journal of Traumatic Stress , 2017

Do Levels of Posttraumatic Growth Vary by Type of Traumatic Event Experienced? An Analysis of the Nurses’ Health Study II Lowe, S.R., et al., Psychological Trauma , 2020

Resiliency and Posttraumatic Growth Despotes, A.M., et al. In Wilson, L.C. (Ed.)The Wiley Handbook of the Psychology of Mass Shootings, John Wiley & Sons, 2017

Recommended Reading

Contact apa, you may also like.

Greater Good Science Center • Magazine • In Action • In Education

How Life Could Get Better (or Worse) After COVID

How do pandemics change our societies? It is tempting to believe that there will not be a single sector of society untouched by the COVID-19 pandemic . However, a quick look at previous pandemics in the 20th century reveals that such negative forecasts may be vastly exaggerated.

Prior pandemics have corresponded to changes in architecture and urban planning, and a greater awareness of public health . Yet the psychological and societal effects of the Spanish flu, the worst pandemic of the 20th century, were later perceived as less dramatic than anticipated, perhaps because it originated in the shadow of WWI. Austrian psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud described Spanish flu as a “ Nebenschauplatz ”—a sideshow in his life of that time, even though he eventually lost one of his daughters to the disease. Neither do we recall much more recent pandemics: the Asian flu of 1957 and the Hong Kong flu from 1968.

Imagining and planning for the future can be a powerful coping mechanism to gain some sense of control in an increasingly unpredictable pandemic life. Over the past year, some experts proclaimed that the world after COVID would be a completely different place , with changed values and a new map of international relations. The opinions of oracles who were not downplaying the virus were mostly negative . Societal unrest and the rise of totalitarian regimes, stunted child social development, mental health crises, exacerbated inequality, and the worst economic recession since the Great Depression were just a few worries discussed by pundits and on the news.

Other predictions were brighter—the disruptive force of the pandemic would provide an opportunity to reshape the world for the better, some said. To complement the voices of journalists, pundits, and policymakers, one of us (Igor Grossmann) embarked on a quest to gather opinions from the world’s leading scholars on behavioral and social science, founding the World after COVID project.

The World after COVID project is a multimedia collection of expert visions for the post-pandemic world, including scientists’ hopes, worries, and recommendations. In a series of 57 interviews, we invited scientists, along with futurists, to reflect on the positive and negative societal or psychological change that might occur after the pandemic, and the type of wisdom we need right now. Our team used a range of methodological techniques to quantify general sentiment, along with common and unique themes in scientists’ responses.

The results of this interview series were surprising, both in terms of the variability and ambivalence in expert predictions. Though the pandemic has and will continue to create adverse effects for many aspects of our society, the experts observed, there are also opportunities for positive change, if we are deliberate about learning from this experience.

Three opportunities after COVID-19

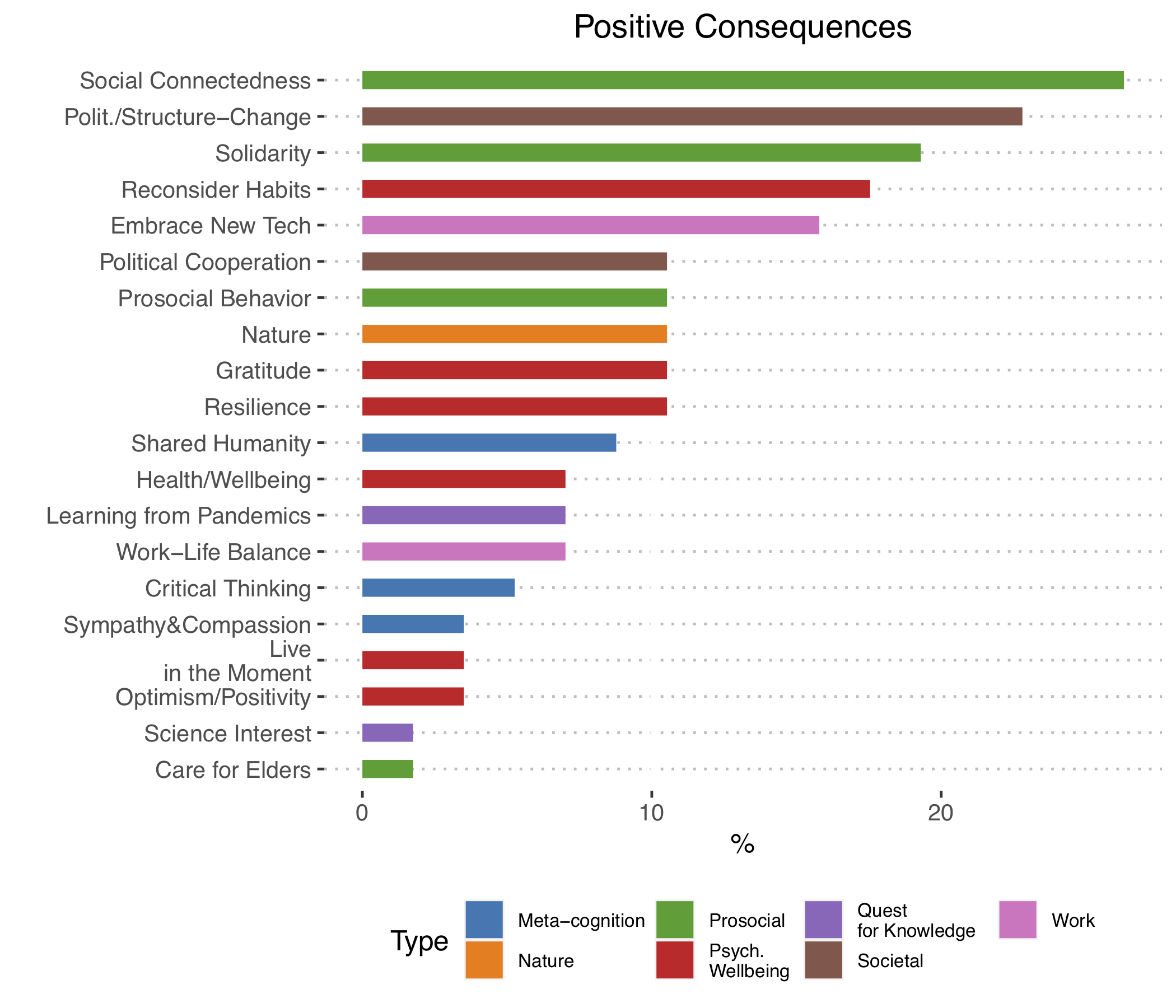

Scientists’ opinions about positive consequences were highly diverse. As the graph shows, we identified 20 distinct themes in their predictions. These predictions ranged from better care for elders, to improved critical thinking about misinformation, to greater appreciation of nature. But the three most common categories concerned social and societal issues.

1. Solidarity. Experts predicted that the shared struggles and experiences that we face due to the pandemic could foster solidarity and bring us closer together, both within our communities and globally. As clinical psychologist Katie A. McLaughlin from Harvard University pointed out, the pandemic could be “an opportunity for us to become more committed to supporting and helping one another.”

Similarly, sociologist Monika Ardelt from the University of Florida noted the possibility that “we realize these kinds of global events can only be solved if we work together as a world community.” Social identities—such as group memberships, nationality, or those that form in response to significant events such as pandemics or natural disasters—play an important role in fostering collective action. The shared experience of the pandemic could help foster a more global, inclusive identity that could promote international solidarity.

2. Structural and political changes. Early in the pandemic, experts also believed that we might also see proactive efforts and societal will to bring about structural and political changes toward a more just and diversity-inclusive society. Experts observed that the pandemic had exposed inequalities and injustices in our societies and hoped that their visibility might encourage societies to address them.

Philosopher Valerie Tiberius from the University of Minnesota suggested that the pandemic might bring about an “increased awareness of our vulnerability and mutual dependence.”

Fellow of the Royal Institute for International Affairs in the U.K. Anand Menon proposed that the pandemic might lead to growing awareness of economic inequality, which could lead to “greater sustained public and political attention paid to that issue.” Cultural psychologist Ayse Uskul from Kent University in the U.K. shared this sentiment and predicted that this awareness “will motivate us to pick up a stronger fight against the unfair distribution of resources and rights not just where we live, but much more globally.”

3. Renewed social connections. Finally, the most common positive consequence discussed was that we might see an increased awareness of the importance of our social connections. The pandemic has limited our ability to connect face to face with friends and families, and it has highlighted just how vulnerable some of our family members and neighbors might be. Greater Good Science Center founding director and UC Berkeley professor Dacher Keltner suggested that the pandemic might teach us “how absolutely sacred our best relationships are” and that the value of these relationships would be much higher in the post-pandemic world. Past president of the Society of Evolution and Human Behavior Douglas Kenrick echoed this sentiment by predicting that “tighter family relationships would be the most positive outcome of this [pandemic].”

Similarly, Jennifer Lerner—professor of decision-making from Harvard University—discussed how the pandemic had led people to “learn who their neighbors are, even though they didn’t know their neighbors before, because we’ve discovered that we need them.” These kinds of social relationships have been tied to a range of benefits, such as increased well-being and health , and could provide lasting benefits to individuals.

Post-pandemic risks

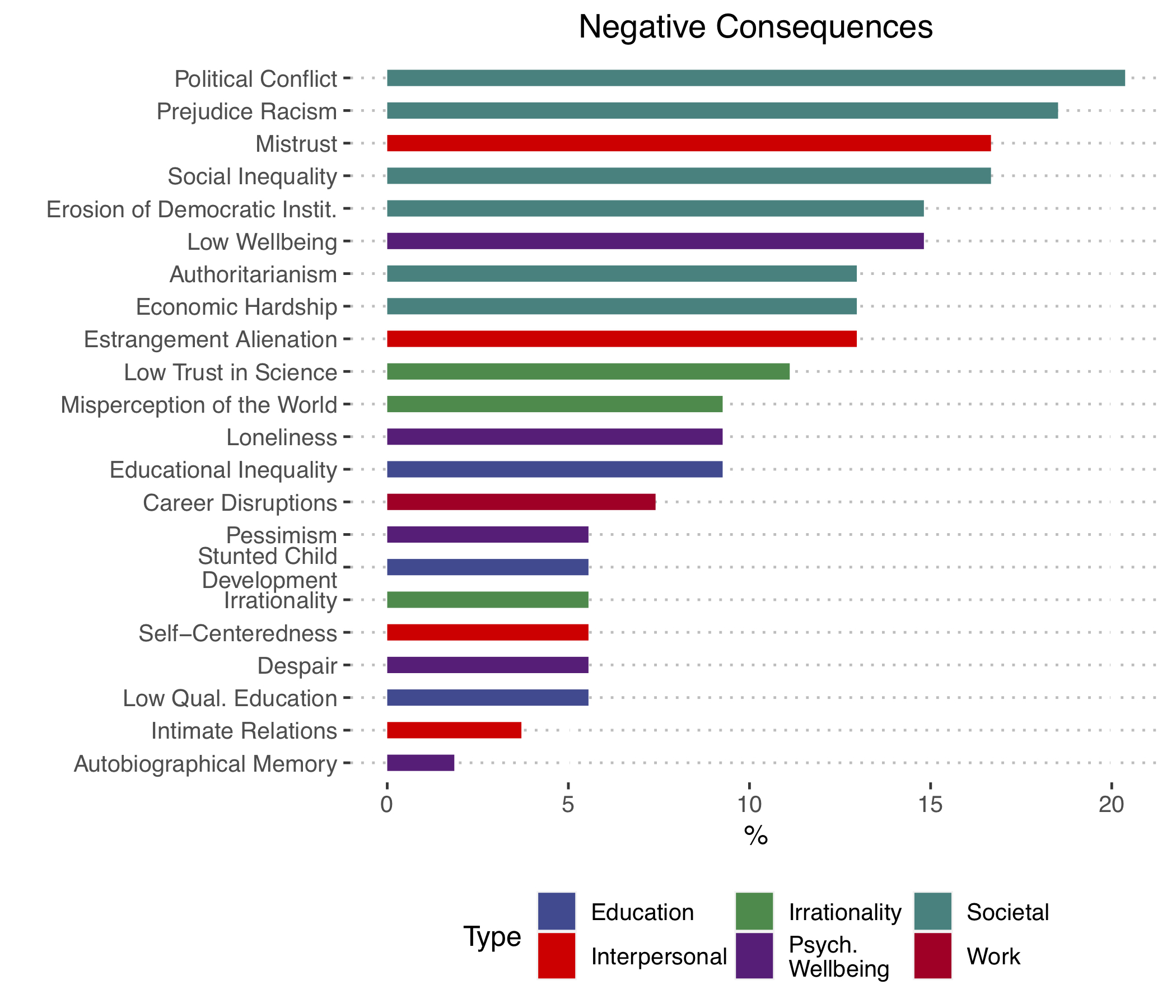

How about predictions for negative consequences of the pandemic? Again, opinions were variable, with more than half of the themes were mentioned by less than 10% of our interviewees. Only two predictions were mentioned by at least ten experts: the potential for political unrest and increased prejudice or racism. These predictions highlight a tension in expert predictions: Whereas some scholars viewed the future bright and “diversity-inclusive,” others fear the rise in racism and prejudice. Before we discuss this tension, let us examine what exactly scholars meant by these two worries.

1. Increased prejudice or racism. Many experts discussed how the conditions brought about by the pandemic could lead us to focus on our in-group and become more dismissive of those outside our circles. Incheol Choi, professor of cultural and positive psychology from Seoul National University, discussed that his main area of concern was that “stereotypes, prejudices against other group members might arise.” Lisa Feldman Barrett, fellow of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences and the Royal Society of Canada, echoed this sentiment, noting that previous epidemics saw “people become more entrenched in their in-group and out-group beliefs.”

2. Political unrest. Similarly, many experts discussed how a greater focus on our in-groups might also exacerbate existing political divisions. Past president of the Society for Philosophy and Psychology Paul Bloom discussed how a greater dismissiveness toward out-groups was visible both within countries and internationally, where “countries are blaming other countries and not working together enough.” Dilip Jeste, past president of the American Psychiatric Association, discussed his concerns that the tendency to view both candidates and supporters as winners and losers in elections could mean that the “political polarization that we are observing today in the U.S. and the world will only increase.”

These predictions were not surprising— pundits and other public figures have been discussing these topics, too. However, as we analyzed and compared predictions for positive and negative consequences, we found something unexpected.

The yin and yang of COVID’s effects

Almost half of the interviewees spontaneously mentioned that the same change could be a force for good and for bad . In other words, they were dialectical , recognizing the multidetermined nature of predictions and acknowledging that context matters—context that determines who may be the winners and losers in the years to come. For example, experts predicted that we may see greater acceptance of digital technologies at home and at work. But besides the benefits of this—flexible work schedules, reduced commutes—they also mentioned likely costs, such as missing social information in virtual communication and disadvantages for people who cannot afford high-speed internet or digital devices.

Share Your Perspective

Curious about the world after COVID? So are we, and we'd love your opinion about possible changes ahead. Fill out this short survey to offer your perspective on the hopes and worries of a post-pandemic world.

Amid this complexity, experts weighed in on what type of wisdom we need to help bring about more positive changes ahead. Not only do we need the will to sustain political and structural change, many argued, but also a certain set of psychological strategies promoting sound judgment: perspective taking, critical thinking, recognizing the limits of our knowledge, and sympathy and compassion.

In other words, experts’ recommended wisdom focuses on meta-cognition, which underlies successful emotion regulation, mindfulness, and wiser judgment about complex social issues. The good news is that these psychological strategies are malleable and trainable ; one way we can cultivate wisdom and perspective, for example, is by adopting a third-person, observer perspective on our challenges.

On the surface, the “it depends” attitude of many experts about the world after COVID may be dissatisfying. However, as research on forecasting shows, such a dialectical attitude is exactly what distinguishes more accurate forecasters from the rest of the population. Forecasting is hard and predictions are often uncertain and likely wrong. In fact, despite some hopes for the future, it is equally possible that the change after the pandemic will not even be noticeable. Not because changes will not happen, but because people quickly adjust to their immediate circumstances.

The future will tell whether and how the current pandemic has altered our societies. In the meantime, the World after COVID project provides a time-stamped window into experts’ apartments and their minds. As we embrace another pandemic spring, these insights can serve as a reminder that the pandemic may lead not only to worries but also to hopes for the years ahead.

About the Authors

Igor Grossmann

Igor Grossmann, Ph.D. , studies people and cultures, sometimes together, and often across time. He is an associate professor of psychology at the University of Waterloo, where he directs the Wisdom and Culture Lab.

Oliver Twardus

Oliver Twardus is the lab manager for the Wisdom and Culture lab and an aspiring researcher. He will be starting his master’s in neuroscience and applied cognitive science in September 2021.

You May Also Enjoy

What Will the World Look Like After Coronavirus?

Can the Lockdown Push Schools in a Positive Direction?

Five Skills We Need for the Year Ahead

Five Lessons to Remember When Lockdown Ends

Four Reasons Why Zoom Can Be Exhausting

What Will Work Look Like After COVID-19?

Read these 12 moving essays about life during coronavirus

Artists, novelists, critics, and essayists are writing the first draft of history.

by Alissa Wilkinson

The world is grappling with an invisible, deadly enemy, trying to understand how to live with the threat posed by a virus . For some writers, the only way forward is to put pen to paper, trying to conceptualize and document what it feels like to continue living as countries are under lockdown and regular life seems to have ground to a halt.

So as the coronavirus pandemic has stretched around the world, it’s sparked a crop of diary entries and essays that describe how life has changed. Novelists, critics, artists, and journalists have put words to the feelings many are experiencing. The result is a first draft of how we’ll someday remember this time, filled with uncertainty and pain and fear as well as small moments of hope and humanity.

- The Vox guide to navigating the coronavirus crisis

At the New York Review of Books, Ali Bhutto writes that in Karachi, Pakistan, the government-imposed curfew due to the virus is “eerily reminiscent of past military clampdowns”:

Beneath the quiet calm lies a sense that society has been unhinged and that the usual rules no longer apply. Small groups of pedestrians look on from the shadows, like an audience watching a spectacle slowly unfolding. People pause on street corners and in the shade of trees, under the watchful gaze of the paramilitary forces and the police.

His essay concludes with the sobering note that “in the minds of many, Covid-19 is just another life-threatening hazard in a city that stumbles from one crisis to another.”

Writing from Chattanooga, novelist Jamie Quatro documents the mixed ways her neighbors have been responding to the threat, and the frustration of conflicting direction, or no direction at all, from local, state, and federal leaders:

Whiplash, trying to keep up with who’s ordering what. We’re already experiencing enough chaos without this back-and-forth. Why didn’t the federal government issue a nationwide shelter-in-place at the get-go, the way other countries did? What happens when one state’s shelter-in-place ends, while others continue? Do states still under quarantine close their borders? We are still one nation, not fifty individual countries. Right?

- A syllabus for the end of the world

Award-winning photojournalist Alessio Mamo, quarantined with his partner Marta in Sicily after she tested positive for the virus, accompanies his photographs in the Guardian of their confinement with a reflection on being confined :

The doctors asked me to take a second test, but again I tested negative. Perhaps I’m immune? The days dragged on in my apartment, in black and white, like my photos. Sometimes we tried to smile, imagining that I was asymptomatic, because I was the virus. Our smiles seemed to bring good news. My mother left hospital, but I won’t be able to see her for weeks. Marta started breathing well again, and so did I. I would have liked to photograph my country in the midst of this emergency, the battles that the doctors wage on the frontline, the hospitals pushed to their limits, Italy on its knees fighting an invisible enemy. That enemy, a day in March, knocked on my door instead.

In the New York Times Magazine, deputy editor Jessica Lustig writes with devastating clarity about her family’s life in Brooklyn while her husband battled the virus, weeks before most people began taking the threat seriously:

At the door of the clinic, we stand looking out at two older women chatting outside the doorway, oblivious. Do I wave them away? Call out that they should get far away, go home, wash their hands, stay inside? Instead we just stand there, awkwardly, until they move on. Only then do we step outside to begin the long three-block walk home. I point out the early magnolia, the forsythia. T says he is cold. The untrimmed hairs on his neck, under his beard, are white. The few people walking past us on the sidewalk don’t know that we are visitors from the future. A vision, a premonition, a walking visitation. This will be them: Either T, in the mask, or — if they’re lucky — me, tending to him.

Essayist Leslie Jamison writes in the New York Review of Books about being shut away alone in her New York City apartment with her 2-year-old daughter since she became sick:

The virus. Its sinewy, intimate name. What does it feel like in my body today? Shivering under blankets. A hot itch behind the eyes. Three sweatshirts in the middle of the day. My daughter trying to pull another blanket over my body with her tiny arms. An ache in the muscles that somehow makes it hard to lie still. This loss of taste has become a kind of sensory quarantine. It’s as if the quarantine keeps inching closer and closer to my insides. First I lost the touch of other bodies; then I lost the air; now I’ve lost the taste of bananas. Nothing about any of these losses is particularly unique. I’ve made a schedule so I won’t go insane with the toddler. Five days ago, I wrote Walk/Adventure! on it, next to a cut-out illustration of a tiger—as if we’d see tigers on our walks. It was good to keep possibility alive.

At Literary Hub, novelist Heidi Pitlor writes about the elastic nature of time during her family’s quarantine in Massachusetts:

During a shutdown, the things that mark our days—commuting to work, sending our kids to school, having a drink with friends—vanish and time takes on a flat, seamless quality. Without some self-imposed structure, it’s easy to feel a little untethered. A friend recently posted on Facebook: “For those who have lost track, today is Blursday the fortyteenth of Maprilay.” ... Giving shape to time is especially important now, when the future is so shapeless. We do not know whether the virus will continue to rage for weeks or months or, lord help us, on and off for years. We do not know when we will feel safe again. And so many of us, minus those who are gifted at compartmentalization or denial, remain largely captive to fear. We may stay this way if we do not create at least the illusion of movement in our lives, our long days spent with ourselves or partners or families.

- What day is it today?

Novelist Lauren Groff writes at the New York Review of Books about trying to escape the prison of her fears while sequestered at home in Gainesville, Florida:

Some people have imaginations sparked only by what they can see; I blame this blinkered empiricism for the parks overwhelmed with people, the bars, until a few nights ago, thickly thronged. My imagination is the opposite. I fear everything invisible to me. From the enclosure of my house, I am afraid of the suffering that isn’t present before me, the people running out of money and food or drowning in the fluid in their lungs, the deaths of health-care workers now growing ill while performing their duties. I fear the federal government, which the right wing has so—intentionally—weakened that not only is it insufficient to help its people, it is actively standing in help’s way. I fear we won’t sufficiently punish the right. I fear leaving the house and spreading the disease. I fear what this time of fear is doing to my children, their imaginations, and their souls.

At ArtForum , Berlin-based critic and writer Kristian Vistrup Madsen reflects on martinis, melancholia, and Finnish artist Jaakko Pallasvuo’s 2018 graphic novel Retreat , in which three young people exile themselves in the woods:

In melancholia, the shape of what is ending, and its temporality, is sprawling and incomprehensible. The ambivalence makes it hard to bear. The world of Retreat is rendered in lush pink and purple watercolors, which dissolve into wild and messy abstractions. In apocalypse, the divisions established in genesis bleed back out. My own Corona-retreat is similarly soft, color-field like, each day a blurred succession of quarantinis, YouTube–yoga, and televized press conferences. As restrictions mount, so does abstraction. For now, I’m still rooting for love to save the world.

At the Paris Review , Matt Levin writes about reading Virginia Woolf’s novel The Waves during quarantine:

A retreat, a quarantine, a sickness—they simultaneously distort and clarify, curtail and expand. It is an ideal state in which to read literature with a reputation for difficulty and inaccessibility, those hermetic books shorn of the handholds of conventional plot or characterization or description. A novel like Virginia Woolf’s The Waves is perfect for the state of interiority induced by quarantine—a story of three men and three women, meeting after the death of a mutual friend, told entirely in the overlapping internal monologues of the six, interspersed only with sections of pure, achingly beautiful descriptions of the natural world, a day’s procession and recession of light and waves. The novel is, in my mind’s eye, a perfectly spherical object. It is translucent and shimmering and infinitely fragile, prone to shatter at the slightest disturbance. It is not a book that can be read in snatches on the subway—it demands total absorption. Though it revels in a stark emotional nakedness, the book remains aloof, remote in its own deep self-absorption.

- Vox is starting a book club. Come read with us!

In an essay for the Financial Times, novelist Arundhati Roy writes with anger about Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s anemic response to the threat, but also offers a glimmer of hope for the future:

Historically, pandemics have forced humans to break with the past and imagine their world anew. This one is no different. It is a portal, a gateway between one world and the next. We can choose to walk through it, dragging the carcasses of our prejudice and hatred, our avarice, our data banks and dead ideas, our dead rivers and smoky skies behind us. Or we can walk through lightly, with little luggage, ready to imagine another world. And ready to fight for it.

From Boston, Nora Caplan-Bricker writes in The Point about the strange contraction of space under quarantine, in which a friend in Beirut is as close as the one around the corner in the same city:

It’s a nice illusion—nice to feel like we’re in it together, even if my real world has shrunk to one person, my husband, who sits with his laptop in the other room. It’s nice in the same way as reading those essays that reframe social distancing as solidarity. “We must begin to see the negative space as clearly as the positive, to know what we don’t do is also brilliant and full of love,” the poet Anne Boyer wrote on March 10th, the day that Massachusetts declared a state of emergency. If you squint, you could almost make sense of this quarantine as an effort to flatten, along with the curve, the distinctions we make between our bonds with others. Right now, I care for my neighbor in the same way I demonstrate love for my mother: in all instances, I stay away. And in moments this month, I have loved strangers with an intensity that is new to me. On March 14th, the Saturday night after the end of life as we knew it, I went out with my dog and found the street silent: no lines for restaurants, no children on bicycles, no couples strolling with little cups of ice cream. It had taken the combined will of thousands of people to deliver such a sudden and complete emptiness. I felt so grateful, and so bereft.

And on his own website, musician and artist David Byrne writes about rediscovering the value of working for collective good , saying that “what is happening now is an opportunity to learn how to change our behavior”:

In emergencies, citizens can suddenly cooperate and collaborate. Change can happen. We’re going to need to work together as the effects of climate change ramp up. In order for capitalism to survive in any form, we will have to be a little more socialist. Here is an opportunity for us to see things differently — to see that we really are all connected — and adjust our behavior accordingly. Are we willing to do this? Is this moment an opportunity to see how truly interdependent we all are? To live in a world that is different and better than the one we live in now? We might be too far down the road to test every asymptomatic person, but a change in our mindsets, in how we view our neighbors, could lay the groundwork for the collective action we’ll need to deal with other global crises. The time to see how connected we all are is now.

The portrait these writers paint of a world under quarantine is multifaceted. Our worlds have contracted to the confines of our homes, and yet in some ways we’re more connected than ever to one another. We feel fear and boredom, anger and gratitude, frustration and strange peace. Uncertainty drives us to find metaphors and images that will let us wrap our minds around what is happening.

Yet there’s no single “what” that is happening. Everyone is contending with the pandemic and its effects from different places and in different ways. Reading others’ experiences — even the most frightening ones — can help alleviate the loneliness and dread, a little, and remind us that what we’re going through is both unique and shared by all.

Most Popular

Stop setting your thermostat at 72, the lawsuit accusing trump of raping a 13-year-old girl, explained, leaks about joe biden are coming fast and furious, do other democrats actually poll better against trump than biden, the baffling case of karen read, today, explained.

Understand the world with a daily explainer plus the most compelling stories of the day.

More in Culture

Simone Biles is so back

Diljit Dosanjh is one of India’s biggest stars. Now he’s taking on America.

Food is no longer a main character on The Bear

Chappell Roan spent 7 years becoming an overnight success

The Spotify conspiracy theories about "Espresso," explained

TikTok is full of bad health “tricks”

Why American politicians are so old

Why is everyone talking about Kamala Harris and coconut trees?

Did the media botch the Biden age story?

Life before COVID-19: how was the World actually performing?

- Published: 11 January 2021

- Volume 55 , pages 1871–1888, ( 2021 )

Cite this article

- Salvatore F. Pileggi ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-9722-2205 1 , 2

34k Accesses

10 Citations

8 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

The COVID-19 pandemic has suddenly and deeply changed our lives in a way comparable with the most traumatic events in history, such as a World war. With millions of people infected around the World and already thousands of deaths, there is still a great uncertainty on the actual evolution of the crisis, as well as on the possible post-crisis scenarios, which depend on a number of key variables and factors (e.g. a treatment, a vaccine or some kind of immunity). Despite the optimism enforced by the positive results recently achieved to produce a vaccine, uncertainty is probably still somehow the predominant feeling. From a more philosophical perspective, the COVID-19 drama is also a kind of stress-test for our global system and, probably, an opportunity to reconsider some aspects underpinning it, as well as its sustainability. In this article we focus on the pre-crisis situation by combining a number of selected global indicators that are likely to represent measures of different aspects of life. How was the World actually performing? We have defined 6 macro-categories and inferred their relevance from different sources. Results show that economic-oriented priorities correspond to positive performances, while all other distributions point to a negative performance. Additionally, balanced and economy-focused distributions of weights propose an optimistic interpretation of performance regardless of the absolute score.

Similar content being viewed by others

Looking Beyond the COVID-19 Pandemic: What Does Our Future Hold?

Conclusion: COVID-19 Pandemic, Crisis Responses and the Changing World—Perspectives in Humanities and Social Sciences

The Long Shadow of COVID-19

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The unpredictable and overwhelming COVID-19 pandemic has completely and radically changed our lives and lifestyle in a way comparable with the most traumatic events in history, such as a World war. With millions of people infected around the World and already thousands of deaths (Dong et al. 2020 ), there is still a great uncertainty on the actual evolving of the crisis, as well as on the possible post-crisis scenarios, which depend on a number of key variables and factors (e.g. a treatment Felsenstein et al. 2020 , a vaccine Le et al. 2020 or some kind of immunity Weitz et al. 2020 ). Despite the optimism enforced by the positive results recently achieved to produce a vaccine, uncertainty is probably still somehow the predominant feeling (Chater 2020 ).

The whole scientific community is currently committed to face the challenging situation and to provide solutions and mitigation plans as a response to the complex dynamics at different levels. Indeed, the actual impact of COVID-19 on the different aspects of life (e.g. socio-economic Bashir et al. 2020 , environmental Collivignarelli et al. 2020 and psycological Fofana et al. 2020 ) is still not completely clear. Even relatively obvious or largely predictable macro-effects, such as a huge economic recession, present great elements of uncertainty at the moment (Altig et al. 2020 ). Additionally, a large number of studies have been conducted to explore the role of different factors [e.g. temperature Jamil et al. 2020 and air pollution Fattorini and Regoli ( 2020 )].

From a more philosophical perspective, the COVID-19 drama is also a kind of stress-test for our system and, probably, an opportunity to reconsider some aspects underpinning it, as well as its sustainability (Naidoo and Fisher 2020 ). However, in order to re-design the World and our lives accordingly, we should first of all fully understand them. We definitely recognise the importance of cultural factors, opinions, personal values and beliefs. At the same time, we believe that it would be valuable to understand global performance in a data-driven and relatively systematic way.

In this article we focus on the pre-crisis situation by combining a number of selected global indicators to represent macro-categories that are likely to represent measures of different aspects of life: how was the World actually performing before pandemic?

We believe that answering the previously stated research question by adopting a relatively unbiased and customizable analysis framework can first of all (1) contribute to have a concise understanding of global development evolution and its priorities in the pre-pandemic period; additionally, it should (2) facilitate a better holistic understanding of the post-pandemic scenario; last but not least, (3) a similar approach can be adopted to estimate and analyse more specific aspects (e.g. global or country resilience to pandemic).

Previous work and background This paper is based on the method proposed in Pileggi ( 2020 ) which adopts a Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis (MCDA) philosophy (Ishizaka and Nemery 2013 ; Velasquez and Hester 2013 ). That paper focuses on the method in itself, which is explained in detail and applied to a number of examples using real data. This work is conceptually different and addresses the result, as the method previously defined has been applied to concretely measure global performance from heterogeneous criteria with emphasis on sustainable development (Hopwood et al. 2005 ). The idea of indices in such an area (e.g. Bravo 2014 ; Shaker 2018 ; Barrera-Roldán and Saldıvar-Valdés 2002 ) is a well consolidated concept. Furthermore, many studies explicitely focus on underlying correlations (e.g. Shaker 2018 , 2015 ).

As discussed later on in the paper, the original method has been slightly modified for this concrete application: on one side, the definition of the categories and their relation with numerical indicators has been simplified (see Sect. 3.1 ); on the other side, some extension has been provided in the weighting phase to better model the trade-offs existing among the different aspects considered (see Sect. 4.1 ). Last but not least, the interpretation of computations has been better formalised (see Sect. 5 ).

Structure of the paper This introductory part is followed by a detailed description of the research methodology. Each of the three phases identified in the methodological section is object of one of the core sections which deal, respectively, with the selection of criteria (Sect. 3 ), the weighting of such criteria (Sect. 4 ) and the performance analysis based on the resulting computations (Sect. 5 ). The paper finishes with a typical conclusions and future work section.

2 Methodology and approach

The methodology adopted in this study is summarised in concept in Fig. 1 . The target system is modelled by selecting a number of categorised indicators, which are global indicators in this study. The model also assumes weights and semantics associated with indicators and it’s the input for the computational method (Pileggi 2020 ). Interpretations are based on both qualitative and quantitative metrics. The three main seamless phases are briefly discussed in this section both with key design decisions, possible biases and uncertainties.

Method in concept. The target system is modelled by a number of categorised indicators and by the weights and the semantics associated. Such a model is the input for the computational method. Results are analysed by adopting qualitative and quantitative metrics

Criteria selection: macro-categories and representative indicators The normal approach (adopted also in previous work (Pileggi 2020 ) as well as by many reputable studies and publications, such as Our World in Data ) is to group the different indicators in classes which represent, therefore, an abstracted categorization of the considered indicators. It is very useful, especially considering the great availability of data, dependencies and the need to consider multiple aspects together.

In the context of this work, we have defined a number of categories of interest, each one represented by one single indicator that should be chosen to effectively characterise the target category. In terms of model (Fig. 1 ), given M categories and N indicators, we are assuming \(N=M\) and cardinality 1:1. Such a simplification allows an easier weighting and modelling within the method adopted (Pileggi 2020 ). We are assuming the definition of categories and the selection of representative indicators as an intrinsic bias, which is referred to as selection bias . Additionally, as the different indicators are expressed by different units and scales which don’t necessarily reflect their relevance in the resulting system or model, we assume a second kind of bias called numerical bias . The latter will be further discussed in Sect. 3.1 .

Weighting Weighting the target categories or indicators is a critical step. Indeed, while indicators themselves may be considered objective measures, their weighting should reflect the different relevance/importance of the various criteria in the context of the considered system or model. Weights may be estimated in different ways. For instance, they may reflect the opinions within a given group or community, normally elicited by surveys or interviews. Alternatively, weights may be inferred by capturing input parameters by the users of tools that adopt the method (Pileggi 2020 ). Either ways, to be relevant, the weighting should be based on a significant number of samples. Moreover, in general, survey/interview defines a static approach as it is based on a concrete selection of indicators. Changing indicators implies the need to re-estimate weights. Such a process is very demanding and definitely it is not agile.

In this study we have adopted a more pragmatic and, at the same time, flexible approach to establish weights that are inferred by analysing reports on global priorities, issues or challenges. Although, due to the different intent and extent of the selected reports, it is not possible to define a systematic method to infer weights, this approach assures weighting according to different foci and perspectives. As proposed later on in the paper, the analysis of different reports leads to weight configurations that may vary very much from each other.

Last but not least, unlike in the original method, in this work we assume finite resource for weighting to better model the trade-offs raising in a limited resource world (see Sect. 4 ).

Computation and analysis The final step is the computation of the results based on the input as defined in the two previous phases. The computational method should support the systematic combination of heterogeneous indicators and associated semantics, measure uncertainty and biases, as well as provide a framework for the interpretation of results. Results based on the application of the original method (Pileggi 2020 ) with the modifications previously explained are discussed in Sect. 5 .

3 Categories and indicators

The very first logical step of the study assumes the definition of macro-categories and the consequent selection of representative indicators. Such a step is described in the following subsection, while Sect. 3.2 deals with numerical bias and its minimization.

3.1 Categories

Inspired by Our World in Data , we have defined our own marco-categories (summary in Table 1 ) reflecting different aspects of life as follows:

Environment/sustainability Several indicators might represent this macro-category as either global environmental measures (e.g. temperature anomaly or CO2 emissions) or indicators in sub-categories (e.g. energy) potentially express the performance trend. In the context of this work, we consider temperature anomaly (Morice et al. 2012 ; Ritchie and Roser 2017 ) as a representative indicator which we want, evidently, to decrease.

Health/demographic change Life expectancy (Temperature 2020 ; Riley 2005 ; Zijdeman and Ribeira da Silva 2005 ; Max Roser and Ritchie 2013 ) has been selected to represent this macro-category. Indeed, an increasing life expectancy reflects, normally, an improved healthcare, as well as it implies population increasing. In terms of wished trend, we want life expectancy to increase, although an higher population may have negative implications in terms of global sustainability.

Economy It is represented by the classic GDP per capita (World Development Indicators, Roser 2013b ), as more sophisticated indicators (e.g. Economic Complexity Index Hausmann et al. 2014 ) are normally understood at a country level and might be not very indicative if considered globally. The GDP represents somehow an economical model that assumes never ending growing. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on global economy is expected to be much more consistent than in recent crisis (Kotz 2009 ) and to be comparable with the second World war.

Poverty/inequality We consider that the number of people living in extreme poverty (Roser and Ortiz-Ospina 2013 ; Ravallion 2015 ) is the ideal measure to properly integrate economic indicators that express a generic increasing well-being by introducing the concept of inequality. Although we recognise an intrinsic interdependency, we prefer to keep this category separated from the previous one as we want to be able to differentiate ideas and concerns related to the economic growth in itself from the others that explicitly address poverty and inequality.

Human rights/freedom By considering democracy as one of the most relevant achievements of all times, we believe that the number of people living in democracy (Roser 2013a ) may be an effective representative for human rights and, more in general, freedom. Indeed, we consider democracy as a condition necessary (although not always sufficient) to create a socio-political environment in which individual freedom and human rights are likely to be fully respected.

Violence/instability The selection of a single indicator to express violence and instability in general terms is not easy. Looking at recent happenings, we consider that measures related to terrorism (Ritchie et al. 2013 ) may be a very reasonable choice. From one side, it’s not always easy to understand terrorism and classify terrorist attacks according to the same criteria worldwide. However, a clear definition for terrorism and a number of unanimously recognised principles currently exist (Ritchie et al. 2013 ). Terrorism is normally generated by situations of war or local conflict and it definitely causes uncertainty, violence and instability.

All indicators selected are based on objective measures, while others that result from perceptions or opinions (e.g. happiness Frey and Stutzer 2012 ) have not been included.

For the numerical analysis proposed in the paper, we are considering recent years and, more concretely, the time range 2000–2015. Unfortunately, it is not possible to include in the study later years as the indicator measuring people currently living in democracy is available only up to 2015. As per previous explanations, we consider such an indicator as very relevant for the extent and the intent of this research, so we prefer to keep it and reduce the target time range. Additionally, the indicator on people living in extreme poverty is measured at a different granularity of all others, which are available by year. We have indeed adopted approximations considering the available values for the years 2002, 2005, 2008, 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013 and 2015.

In terms of wished trends (Table 1 ), we want the temperature anomaly, people living in poverty and deaths caused by terrorism to decrease, while an increasing trend is wanted for life expectancy, people living in democracy and GDP. The actual trends in the considered time range is shown in Fig. 2 on the left. In the same figure, the contribution to global performance by considering the wished trends (Pileggi 2020 ) is shown on the right. According to this view, positive trends in the chart contributes positively to global performance. Likewise, negative trends have a negative impact on the performance.

Looking at the data reported, health/demographics, economy, poverty/inequality and freedom/human rights are positively performing. On the other side, environment/sustainability and violence/instability present strongly negative performance.

Selected indicators expressed as the percentage of variation with respect to the initial state (left). The contribution of the different indicators to performance as the function of the associated wished trend is reported on the right

3.2 Dealing with numerical bias

At a more theoretical level, the definition of a restricted number of meaningful categories in the extent and intent of the current study can be considered a kind of bias in itself. It’s somehow inherent in study design.

At a practical level, it is almost impossible to provide a numerically balanced set of indicators. Indeed, indicators are normally very heterogeneous, adopts their own units of measure and may present very different numerical variations. In general, the variation of a given indicator is not comparable in terms of relevance with the variation of another indicators. Therefore, numerical proportions are not semantically relevant for the purpose of the considered study, meaning that numerical variations are not necessarily proportional with the relevance in the system or model.

We have represented all indicators uniformly as the percentage variation with respect to the initial state. As shown in Fig. 2 , for the considered set of indicators, the variation of deaths by terrorism is numerically much more relevant than any other. Also the temperature anomaly presents a strong pattern in this sense. However, it is not numerically comparable with the previous. As both indicators contribute potentially in a negative way on global performance, the resulting indicator framework is strongly biased (numerically) in this case and may affect the fairness of the computation.

The numerical differences among the considered indicators imply the need to deal with different scales when computing the different aspects together. In order to minimise numerical biases, we adopt the mechanism described in Pileggi ( 2020 ) in addition to weighting. A detailed description of such an adaptive mechanism is out of the scope of the paper. An example of the numerical bias using and not using the mechanism is reported in Fig. 3 .

Visualization of numerical bias by considering a linear combination of the different criteria by adopting the reference computational method (Pileggi 2020 ) (left). Such numerical bias can be reduced by applying adaptive tuning as per reference method (Pileggi 2020 ) (right)

4 Weighting

Once target criteria are defined, the weighting stage may result extremely subjective. The most natural way to weight criteria is probably by survey, as it is relatively simple to map weights into an opinion-based survey. In such a way, opinions from a generic public as well as opinions within defined communities may be captured and converted in a corresponding set of weights.

However, capturing people’s opinions in a meaningful way requires a large number of samples. Therefore, we have preferred to adopt a completely different and more pragmatic approach that aims to infer weights from the analysis of popular reports (e.g. from United Nations Footnote 1 and Global Economic Forum Footnote 2 ). On one side, the simplified approach adopted in the selection phase allows to weight categories rather than single indicators. It makes the mapping much easier. On the other side, the interpretation of certain kind of report may be subjective.

In the following subsections, we first describe an extension to the reference method to better model existing trade-offs and, then, we discuss the inference of weight sets from different sources of information.

4.1 Finite-resource assumption to model trade-offs

The original method (Pileggi 2020 ) doesn’t assume specific constraints for weights: the different indicators are weighted independently within a minimum value \(W_{min}\) and a maximum value \(W_{max}\) . Thus, any indicator i is associated with the corresponding weight \(W_{min} \leqslant w_i \leqslant W_{max}\) , for instance in a range [0,10].

That independent weighting intrinsically assumes an infinite resource model. For instance, it is possible to associate the maximum weight with all indicators ( \(w_i=W_{max},\forall i\) ). It doesn’t force decisions which should model the trade-offs existing among the different aspects of life. In order to model such trade-offs in a more effective way, we introduce a constraint for the overall weighting value, \(W_{tot}=\sum _{i=1}^{n}{w_i} \leq nk\) , where n is the number of considered criteria and k is a value between \(W_{min}\) and \(W_{max}\) . In the context of this work we are using six different criteria ( \(n=6\) ) and weighting in the range [1,10] ( \(1 \leq w_i \leq 10, \forall {i}\) ) rather than [0,10] as we want all criteria to contribute to overall performance. We consider \(k=5\) , which implies \(W_{tot}=30\) .

4.2 Weighting based on report analysis

In this sub-section we propose different weightings based on the analysis of different sources of information. As previously explained, probably such an inference cannot be completely objective. In order to minimise the impact of interpretations and biases in the analysis, for each case considered, the criteria and conclusions are explained and briefly discussed. Additionally, we have restricted the analysis to sources of information that allow a relative easy mapping. We have excluded those sources that potentially provide very good insight but are objectively hard to be converted in a clear weight set to the target criteria.

A summary of the weights produced by analysing the different reports is proposed in Fig. 4 . Each case is separately analysed and explained in the remaining part of this sub-section.

Weighting based on the analysis of different sources. Each weights set is compared with an homogeneous distribution of the resources—i.e. Neutral Weighting

Weighting based on the analysis of UN Global Issues The UN Global Issues report proposes 22 different global issues. Each issue in the report can be associated to no-one, one or more than one of the categories identified in this study.

According to our analysis, the category Environment/Sustainability is associated with 5 issues from the report (Atomic Energy, Climate Change, Food, Water), Health/Demography with 5 issues (Africa, Ageing, AIDS, Health, Population), Economy with no issue directly, Poverty/Inequality with 6 issues (Africa, Children, Decolonization, Ending Poverty, Food, Water), Human Rights/Freedom with 6 issues (Africa, Democracy, Gender Equality, Human Rights, International Law and Justice, Refugees) and Violence/Instability with 2 issues (Africa, Peace&Security). Resulting weights are reported in Table 2 . As previously discussed, the minimum weight assumed is 1.

Weighting based on the analysis of WEF 10 biggest global challenges (2016) The WEF 10 biggest global challenges [8] is a report with a much more economic focus. The criteria to map the 10 challenges in the report into weights are the same as in the previous case.

From our analysis, Environment/Sustainability is directly related to 2 challenges (Food Security, Climate Change), Health/Demographics to 1 challenge (Healthcare), Economy to 5 challenges (Inclusive Growth, Unemployment, Financial Crisis, Global Trade, Investment Strategy), Poverty/Inequality to 2 challenges (Food Security, Inclusive Growth), Human Rights/Freedom to 1 challenge (Gender Equality) and Violence/Instability to no challenge. The resulting weighing is reported in Table 3 .

Weighting based on the analysis of 10 most important global issues from The Borgen Project The Borgen Project, a nonprofit organization that is addressing poverty and hunger, has provided a list of 10 most important global issues [5].

According to our analysis of such a source, Environment/Sustainability is directly associated with 3 of the 10 issues (Climate Change, Pollution), Health/Demographics with 4 (Pollution, Security and Wellbeing, Malnourishment and Hunger, Substance Abuse), Economy with 1 (Unemployment), Poverty/Inequality with 3 (Lack of Education, Malnourishment and Hunger, Security and Wellbeing), Human Rights/Freedom with 1 (Government Corruption) and Violence/Instability with 3 (Violence, Security and Wellbeing, Terrorism). The resulting weights are reported in Table 4 .

Weighting based on the analysis of Global Shapers Survey 2017 Global Shapers Survey 2017 by WEF reflects opinion of millennials. Business Insider Australia has recently provided a list of the 10 most critical problems in the World according to millennials based on the Global Shapers Survey. In order to assure uniformity and consistency with previous cases, we have considered the list of problems provided but not the relevance associated with each of them.

According to our analysis, Environment/Sustainability matches with 2 problems (Food and water security, Climate change/Destruction of nature), Health/Demographics with 1 (Safety/Security/Wellbeing), Economy with 1 (Lack of economic opportunity and unemployment), Poverty/Inequality with 4 (Lack of education, Food and water security, Poverty, Inequality), Human Rights/Freedom with 1 (Government accountability and transparency/Corruption) and Violence/Instability with 3 (Safety/Security/Wellbeing, Religious conflicts, Large scale conflict/Wars ). Weights are reported in Table 5 .

5 Performance analysis

Performance analysis is based on two main metrics as follows:

Score This is the primary metric for analysis and it is based uniquely on the absolute performance according to computations (Pileggi 2020 ): positive scores are associated with positive performance, as well as negative scores correspond to negative performance.

Interpretation It is a relative metric defined by comparing the score of a given computation with the corresponding neutral computation, which assumes fair weighting (Pileggi 2020 ). In qualitative terms, scores higher than neutral computation correspond to an optimistic interpretation, while lower scores are associated with a pessimistic interpretation.

The two metrics as defined are completely independent as all qualitative combinations of the two metrics (positive/optimistic, positive/pessimistic, negative/optimistic and negative/pessimistic) are possible.

Looking at the analysis framework more holistically, two additional analysis factors may be considered:

Uncertainty In the context of this study, rather than a proper uncertainty, such a metric defines higher and lower bounds based on the potential weighting variance. Such an estimation provides a more consistent support for analysis in context.

Numerical bias Even though it is limited by the method adopted, numerical bias directly affects the absolute result. It is expressed by the neutral computation and can play a relevant role not only in the analysis phase but also when selecting criteria, as it can drive the selection of balanced set of indicators.

Computations for the different weight sets are presented in Fig. 5 , while a qualitative summary of results is presented in Table 6 .

Looking at Fig. 5 , the score associated with the different weight sets is represented by the blue line. Such a score is compared with the corresponding neutral computations in the charts on the left, while it is represented both with extreme computations in the charts on the right.

Weights from the analysis of UN Global Issues propose a relatively balanced distribution with a priority on Poverty/Inequality, Human Rights/Freedom, Health/Demographics and Environment/Sustainability. Additionally, there is a relative low priority for Violence/Instability and no economical focus. The resulting computation shows contrasting results, including a negative performance but also an optimistic interpretation. The weight set resulting from the analysis of the 10 biggest global challenges by WEF presents a much more economic oriented focus with a significant attention also for Environment/Sustainability and Poverty/Inequality. Human Rights/Freedom is still considered a kind of priority, while there is no explicit attention for Violence/Instability. Such a distribution of weights result in a very positive understanding of global performance. By focusing explicitly on addressing poverty, the weights from The Borgen Project proposes an interesting case study. The priority is clearly on 3 criteria, Health/Demographics, Poverty/Inequality and Violence/Instability. The computations associated show a clear negative trend in terms of either performance and interpretation (pessimistic). The analysis based on opinions of Millennials proposes a much more radical distribution with a clear priority on Poverty/Inequality and a significant attention on Environment/Sustainability and Violence/Instability. Final results are very similar to the ones related to the previous case (negative/pessimistic).