An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Literature Review on the Role of Uterine Fibroids in Endometrial Function

Deborah e. ikhena.

1 Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago, IL, USA

Serdar E. Bulun

Uterine fibroids are benign uterine smooth muscle tumors that are present in up to 8 out of 10 women by the age of 50. Many of these women experience symptoms such as heavy and irregular menstrual bleeding, early pregnancy loss, and infertility. Traditionally believed to be inert masses, fibroids are now known to influence endometrial function at the molecular level. We present a comprehensive review of published studies on the effect of uterine fibroids on endometrial function. Our goal was to explore the current knowledge about how uterine fibroids interact with the endometrium and how these interactions influence clinical symptoms. Our review shows that submucosal fibroids produce a blunted decidualization response with decreased release of cytokines critical for implantation such as leukocyte inhibitory factor and cell adhesion molecules. Furthermore, fibroids alter the expression of genes relevant for implantation, such as bone morphogenetic protein receptor type II, glycodelin, among others. With regard to heavy menstrual bleeding, fibroids significantly alter the production of vasoconstrictors in the endometrium, leading to increased menstrual blood loss. Fibroids also increase the production of angiogenic factors such as basic fibroblast growth factor and reduce the production of coagulation factors resulting in heavy menses. Understanding the crosstalk between uterine fibroids and the endometrium will provide key insights into implantation and menstrual biology and drive the development of new and innovative therapeutic options for the management of symptoms in women with uterine fibroids.

Introduction

Uterine fibroids are the most common gynecologic tumor, present in up to 80% of all women by the age of 50. 1 While most uterine fibroids do not cause symptoms, some women can experience severe symptoms that significantly impact their quality of life. Fibroid symptoms include heavy and irregular menstrual bleeding with accompanying anemia, pelvic pain, dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, increased urinary frequency, infertility, early pregnancy loss, among others. 2 , 3 Fibroids are the leading indication for hysterectomy in the United States and account for up to US$34.4 billion dollars annually in health-care costs. 4

The effects of fibroids on fertility were formerly believed to be exclusively as a result of their size; however, this perspective has changed as our understanding of fibroid pathogenesis at the molecular level has broadened. Fibroids influence endometrial gene expression through paracrine interactions. Additionally, the effect of fibroids on the endometrium is global and not localized to the endometrium overlying the fibroid itself. 5 We conducted a review of the literature to evaluate and discuss what is currently known about how uterine fibroids interact with the endometrium and how these interactions lead to clinical symptoms, specifically infertility, miscarriage, and heavy menstrual bleeding.

We performed a comprehensive review of the literature on uterine fibroids, the influences they exert on endometrial function, and the potential mechanisms through which these lead to the impaired implantation. PubMed and Google Scholar websites were used to identify relevant articles. Search terms such as “uterine fibroids,” “leiomyoma,” and “endometrium” were used in combination with “implantation,” “heavy menstrual bleeding,” “irregular menses,” “recurrent pregnancy loss,” “miscarriage,” “early pregnancy loss,” “infertility,” “subfertility,” and “fertility outcomes.” References from these articles were used to identify additional sources.

Only reports written in English were included in the literature review. We placed no restrictions on year of publication; we included all publications from the earliest database dates until March 2017. We described and expanded on what is currently known about the relationship between uterine fibroids and the endometrium as it pertains to fertility and menstrual bleeding.

Cellular Origins of Uterine Fibroids

Uterine fibroids are monoclonal tumors believed to arise from a single fibroid stem cell within the myometrium. 6 Three cell populations have been identified in uterine fibroids: fully differentiated fibroid smooth muscle cells, a cell population with intermediate characteristics, and fibroid stem cells. 7 Both myometrium and fibroid tissue have side population cells that possess cell surface markers characteristic of stem cells. 7 , 8 Fibroid stem cells are critical for fibroid growth and expansion. In fact, in a murine model, tumors composed only of fully differentiated or intermediate populations of fibroid cells demonstrate significantly slower growth rates than those tumors composed of fibroid stem cells. 7

It appears that fibroid stem cells occur as a result of a genetic hit to a myometrial stem cell, such as point mutations in the mediator complex subunit 12 ( MED12 ) gene or chromosomal rearrangements that affect the expression of the high-mobility group AT-hook 2 ( HMGA2 ) gene. 6 Chromosomal rearrangements involving HMGA2 on the long arm of chromosome 12 are believed to play a role in the induction of fibroid stem cells and fibroid tumorigenesis, especially in larger tumors. 6 , 9 Additionally, some fibroid stem cells possess MED12 mutations that have not been identified in the myometrial stem cell population. 10 Introduction of a MED12 mutation in murine uterine tissue has been shown to give rise to fibroid-like tumor formation. 11 These findings suggest that a genetic hit may be important for the initiation of fibroid tumors and their growth. Ethnicity and environmental factors are believed to play a role in tumorigenesis. Endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs) have been shown to interfere with growth and differentiation in different stem cell types. Recent studies suggest that exposure to EDCs may lead to genetic alterations in stem cells, which may be important in fibroid tumorigenesis. 12 - 14 With regard to ethnicity, studies reveal that the number of tumor-initiating myometrial stem cells is directly correlated with the likelihood of developing uterine fibroids, with the highest number being present in African American women with uterine fibroids and the lowest in Caucasian women without uterine fibroids. 15

Fibroids are hormonally responsive tumors. Mature fibroid cells possess estrogen receptors, and estradiol is associated with increased proliferation of uterine fibroid smooth muscle cells. 16 , 17 Uterine fibroids not only respond to systemic steroids but also to local steroids biosynthesized by aromatase within the fibroid itself. 18 Despite the hormonally dependent nature of fibroids, fibroid stem cells express low levels of estrogen and progesterone receptors, suggesting that steroid hormones utilize a paracrine mechanism to exert their tropic effects on fibroid stem cells ( Figure 1 ).

Illustration of stem cell populations in the myometrium and fibroid tissue. Stem cells are self-renewing and are involved in the proliferation of both normal myometrium and fibroid tissue. It is thought that a genetic hit, such as a mutation in the MED12 gene, can lead to the transformation of a myometrial stem cell into a fibroid stem cell. Fibroids are hormone-responsive tissues. However, fibroid stem cells, which are mainly responsible for proliferation and fibroid growth, are devoid of estrogen and progesterone receptors. Thus, stem cell replication and growth is likely regulated via paracrine signals, which lead to fibroid growth. ERα indicates estrogen receptor alpha; PR, progesterone receptor.

An important signaling pathway implicated in promoting fibroid growth is the wingless-type Mouse Mammary Tumor Virus (MMTV) integration site Wingless Type (WNT)/β-catenin pathway. 19 Because β-catenin targets the MED12 subunit, mutations in the MED12 gene can lead to alterations in the interactions between MED12 and β-catenin leading to inhibition of β-catenin transactivation in response to WNT signaling. 20 In the WNT/β-catenin pathway, secreted WNT proteins bind to frizzled family cell surface receptors, leading to decreased β-catenin degradation in the cytoplasm and a subsequent increase in nuclear β-catenin. 2 , 21 In the murine model, increased β-catenin level seen with increasing parity is correlated with the number of fibroid-like tumors present in the uteri of such mice, which exhibit both histologic and molecular characteristics of fibroids. 22 However, in this study, it was unclear whether the increased β-catenin level or the increased parity of these mice is the primary driver of the increase in fibroid-like tumors. Recent data show that MED12 knockdown in human fibroid cells leads to decreased cell proliferation via downregulation of the WNT/β-catenin signaling pathway. 23

Additionally, activation of the WNT/β-catenin pathway leads to increased levels of transforming growth factor β3 (TGF-β3). Fibroid cells secrete markedly elevated levels of TGF-β3 in a steroid-responsive manner when compared to myometrial cells. 24 Transforming growth factor β3 has also been shown to play a key role in cell proliferation and deposition of extracellular matrix. 22 Taylor and colleagues have demonstrated that TGF-β3 secreted by fibroid cells exerts paracrine effects on endometrial stromal cells (ESCs) and epithelial cells. 5 , 25 , 26

Clinical Fertility Outcomes in the Presence of Uterine Fibroids

One in every 10 women seeking fertility treatment has uterine fibroids. 27 - 29 The effect of uterine fibroids on infertility is largely dependent on the location of the fibroid, with submucosal and intramural fibroids having the most significant impact.

Submucosal fibroids

Submucosal fibroids, which impinge into the uterine cavity, have been associated with impaired reproductive outcomes. In 2008, Klatsky et al performed a systematic review showing that women with submucosal fibroids had lower implantation rates (3.0%-11.5% vs 14%-30%) and a higher incidence of early pregnancy loss (47% vs 22%) compared to women without fibroids. 30 - 33 A meta-analysis by Pritts et al found that women with submucosal fibroids had significantly lower implantation rates, pregnancy rates, ongoing pregnancies, and live birth rates. In this meta-analysis, submucosal fibroids were associated with an increased risk of spontaneous abortion. 34 Although most of these data are from retrospective or prospective cohort studies, the consensus is to surgically remove submucosal fibroids in a woman who is actively pursuing pregnancy, regardless of other symptoms.

Intramural fibroids

Fibroids located within the wall of the myometrium are known as intramural fibroids. The data on the relationship between intramural fibroids and infertility are inconclusive at best. A meta-analysis by Pritts et al found higher rates of spontaneous abortions and significantly lower rates of implantation, ongoing pregnancies, and live births in women with intramural fibroids. 34 In 2017, Christopoulos et al showed decreased pregnancy rates after in vitro fertilization (IVF) in women with noncavity-distorting fibroids. Sagi-Dain and colleagues observed a similar trend in recipients of donor oocytes with uterine fibroids. 35 , 36 However, in this study, oocyte recipients with intramural fibroids received a significant lower percent of good quality embryos and this was not controlled for in the results. However, other studies show data to the contrary. Klatsky et al also studied pregnancy rates in recipients of donor oocytes and noted no difference in implantation or clinical pregnancy rates between women with and without uterine fibroids. 37 Additionally, the Assessment of Multiple Intrauterine Gestations from Ovarian Stimulation clinical trial by the Reproductive Medicine Network showed no difference in conception and live birth rates in women with noncavity-distorting intramural fibroids. 38 Given the conflicting data, there is still some debate about the clinical effect of noncavity-distorting intramural fibroids. Current data suggest that if a clinical effect is present, it may be unmasked by and as a result more clinically relevant for IVF cycles than with ovarian stimulation and intrauterine insemination.

In addition to the controversy on fibroid location, there is still some debate as to whether the degree of the detrimental effect of uterine fibroids’ endometrial function correlates with the size of the fibroid. A 2008 meta-analysis by Pritts et al both show no difference in effect due to fibroid size or number on outcomes. 34 However, fibroid size was only reported by 5 of the studies included in this meta-analysis.

The effect of myomectomy

These observations, specifically in the case of submucosal fibroids, raise the question of whether myomectomy leads to an improvement in fertility and early pregnancy outcomes. A 2013 Cochrane review concluded that hysteroscopic myomectomy improves clinical pregnancy rates with timed intercourse from a baseline of 21% to 39%. 39 Although these findings suggest that hysteroscopic myomectomy provides a clinical benefit in the presence of a submucosal fibroid, more data from randomized controlled trials with larger populations are needed to better understand the effect of hysteroscopic myomectomy on endometrial function and implantation.

Effect of Uterine Fibroids on the Endometrium and Implantation

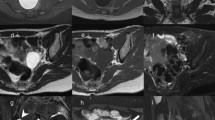

The narrow time period during which the endometrium is receptive to implantation of the embryo is known as the window of implantation (WOI). The WOI occurs between 7 and 10 days following the luteinizing hormone surge and it is when the endometrium prepares for the attachment of the blastocyst. 40 The steps necessary for successful implantation are apposition, adhesion, and invasion. A complex series of interactions between various processes are necessary for these steps to occur and any aberrations can result in recurrent implantation failure, early pregnancy loss, or infertility. The effects of uterine fibroids on implantation are summarized in Figure 2 and described in detail below.

Diagram summarizing the effects of submucosal and intramural fibroids on implantation. BMP2 indicates bone morphogenetic protein 2; HOXA10, Homeobox A10; IL-1β, interleukin 1 beta; IL-11, interleukin 11; LIF, leukemia inhibitory factor; TGF-β3, transforming growth factor beta 3; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor.

Cell adhesions molecules, homeobox genes, and other gene expression

Transcription factors known as homeobox genes, specifically homeobox A10 ( HOXA10 ) and homeobox A11 ( HOXA11 ), are expressed in the female reproductive system and are important for implantation. 41 In mice, HOXA10 expression increased during the WOI. Knockout mice for HOXA10 are infertile due to implantation failure, specifically embryos from HOXA10 knockout mice are able to grow normally in wild-type mice, demonstrating that the defect lies with endometrial receptivity and not with the embryos themselves. 42

The HOXA10 expression is decreased in the endometrium of women with submucosal fibroids. This decrease in HOXA10 expression is most prominent in the endometrium overlying the submucosal fibroid but is also observed throughout the endometrium. 5

Decreased expression of HOXA10 and the cell adhesion molecule E-cadherin have been described in the endometrium of women with noncavity-distorting intramural uterine fibroids during the WOI. 43 In fact, 68.8% of women with fibroids have low mid-secretory phase HOXA10 protein expression. 44 Furthermore, it appears that this decrease in HOXA10 expression reverses following myomectomy. Interestingly, the same study failed to show any improvement in HOXA10 expression following myomectomy for submucosal fibroids. 45 Bone morphogenetic protein type II (BMP2) mediates HOXA10 expression; thus, increased endometrial resistance to BMP2 may contribute to the low HOXA10 expression in the endometrium of these patients 25 ( Figure 2 ).

Ben-Nagi and colleagues evaluated levels of glycodelin, osteopontin, interleukin (IL) 6, IL-10, and tumor necrosis factor (TNF) α in uterine flushings of women with and without submucosal fibroids during the WOI. They found lower levels of glycodelin and IL-10 in uterine flushings from the mid-luteal endometrium of women with uterine fibroids and no differences in osteopontin, IL-6, and TNFα compared to women without fibroids. 46 However, this was a study of uterine flushings and the accuracy of the correlation between uterine flushings and secretions from ESCs is unclear.

Horcajadas et al performed gene expression analysis on endometrial tissue from women with or without intramural uterine fibroids during the WOI. They identified 3 genes that are dysregulated in women with intramural fibroids >5 cm compared to controls: glycodelin and aldehyde dehydrogenase 3 family member B2. 47 Glycodelin was dysregulated in women with intramural fibroids <5 cm. This suggests that larger fibroids may have a more profound effect on endometrial gene expression; however, additional studies are needed to better elucidate this point.

The rise in progesterone following ovulation is responsible for decidualization of the endometrium, which is marked by increasing amounts of prostaglandins and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF). 48 These prostaglandins and VEGF increase vessel permeability in endometrial blood vessels allowing for extravasation of polymorphonuclear cells, which also produce cytokines important for implantation, including leukocyte inhibitory factor (LIF).

Another effect of progesterone and estrogen on ESCs is the secretion of decidual markers such as prolactin and insulin-like growth factor-binding protein 1, which are associated with IL-11. 49 , 50 IL-11 is essential for implantation. 51 Both LIF and IL-11 are pleiotropic cytokines belonging to the IL-6 family and have been noted to be essential for embryo implantation in the murine model. Both LIF and IL-11 bind to ligand-specific receptors, LIFR and IL-11R, and share the same signal transduction target, gp130. The gp130 signaling pathway is important for embryo implantation, 41 , 52 with inactivation of gp130 in a murine model resulting in implantation failure. 53

The LIF-deficient mice show a complete failure of implantation due to defective decidualization. Interestingly, embryos from LIF-deficient mice are unable to implant in the endometrium of LIF-deficient mice, but they are able to implant in the endometrium of wild-type mice. 54 In humans, LIF expression increases in the luteal phase and peaks during the implantation window; however, in the presence of submucosal fibroids, the luteal phase increase in LIF protein expression is blunted. 55 Clinically, deregulation of LIF production in the secretory endometrium has been associated with unexplained infertility and recurrent abortions. 56

Interleukin 11 is essential for sustained decidualization. The IL-11-deficient mice are able to begin decidualization but cannot sustain or complete the decidual response, thus leading to pregnancy loss by day 8. 51 , 57 In humans, IL-11 plays a role in the regulation of trophoblast invasion, and low levels of IL-11 are associated with decreased numbers of uterine natural killer (NK) cells in the secretory endometrium. 58 , 59 The production of IL-11 is decreased during the WOI in the presence of submucosal fibroids. 55 Because of its known role in trophoblast invasion and decidualization, reduction in IL-11 may lead to defective implantation; however, further study is needed to determine the clinical correlation.

Growth factors

Progesterone induces the secretion of BMP2 and its downstream target wingless-type MMTV integration site family, member 4 (WNT4) by ESCs. 60 This occurs via decidual signals from TGF-β3 family proteins such as heparin-binding epidermal growth factor. 61 The endometrium in BMP2-deficient mice is unable to undergo decidual differentiation due to the absence of BMP2 production. 62 , 63 Furthermore, although embryo attachment is possible in BMP2-deficient mice, impaired decidual differentiation leads to defective implantation and pregnancy loss. 60 , 63 When exposed to progesterone, WNT4 knockout mice have defective implantation as a result of impaired ESC survival and decidualization. 64 The activation of BMP2 in response to progesterone appears to be necessary for WNT4 activation and subsequently implantation.

In humans, BMP2 resistance is one of the proposed mechanisms by which submucosal fibroids impair implantation. Submucosal fibroids secrete high levels of TGF-β3, which downregulates BMP receptor type II expression in ESC and subsequently leads to ESC resistance to BMP2. 25 This resistance to BMP2 negatively affects cell proliferation and differentiation, causing impaired decidualization and implantation site formation. 63 Given the essential role of BMP2 and its downstream targets in decidualization and successful implantation, endometrial resistance to BMP2 in the presence of uterine fibroids has the potential to result in suboptimal decidualization and defective implantation. Clinically, this may manifest as a higher incidence of spontaneous abortions and a lower rate of implantation.

Immune cells

The progesterone-dependent increase in VEGF and prostaglandin secretion seen with decidualization promotes extravasation of immune cells into the endometrium. These cells consist mainly of macrophages and NK cells. 65 Macrophages produce cytokines, such as LIF, which as described above are essential for implantation. 58 , 66 Furthermore, macrophages play an integral role in trophoblast invasion and placental development. 67

The NK cells are the principal immune cells present during the WOI and are important for immune tolerance, angiogenesis, trophoblast migration, and invasion. 68 The NK cells produce pro-angiogenic factors such as VEGF and placental growth factor, which regulate maternal–uterine vasculature remodeling and trophoblast invasion. 69 , 70 Mice deficient in NK cells are still fertile, but their pregnancies are marked by fetal loss, severe intrauterine growth restriction, and preeclampsia. 71

Mid-secretory endometrium of women with uterine fibroids compared to women without fibroids show an increase in macrophage density and a decrease in the density of NK cells 72 ( Figure 2 ). These abnormalities in macrophage and NK cell density result in altered endometrial function and may impede endometrial receptivity to implantation.

Mechanical stretch, uterine wall contractility, and implantation

Uterine fibroids can place tremendous stress and stretch on the nearby myometrium and overlying endometrium, proportionate to the size and location of the fibroid. This increase in uterine stretch results in abnormal gene expression. 73 - 75

These abnormalities in gene expression, together with the physical presence of fibroids, contribute to impaired uterine contractility. Recent studies have implicated uterine contractility in implantation. Abnormal uterine contractions and peristalsis during the mid-luteal phase have been observed on cine magnetic resonance imaging of women with uterine fibroids. 76 Yoshino et al further described lower pregnancy rates in women with intramural fibroids and a higher frequency of uterine peristalsis during the WOI. In that study, 10 of the 29 women with intramural fibroids in the low-frequency peristalsis group achieved pregnancy compared to none of the 22 women in the high-frequency peristalsis group. 77 Although it was a small study, the data suggest that abnormal uterine peristalsis may play a role in implantation and pregnancy outcomes in women with intramural fibroids. However, additional larger studies are needed before these clinical relevance of these data can be determined.

Heavy Menstrual Bleeding and Dysmenorrhea Associated With Uterine Fibroids

Abnormal uterine bleeding is one of the most common symptoms in women with uterine fibroids. Normal menses occurs every 24 to 35 days. The American Congress of Obstetrics and Gynecology (ACOG) defines heavy menstrual bleeding as diagnosed when bleeding exceeds 80 mL, however, for clinical purposes, any level of menstrual bleeding which causes distress to the patient is managed as heavy menstrual bleeding. 78 The quantity of bleeding experienced with each menses depends on a complex interplay of vasoconstriction, angiogenesis, and coagulation. The most common type of abnormal uterine bleeding observed with fibroids is excessive menstrual bleeding that is frequently accompanied by dysmenorrhea. 2

Endothelin-1 (ET-1) and prostaglandin F 2alpha (PGF 2α ) are the 2 most important vasoconstrictors involved in menstruation. 79 Endothelin-1 is a potent vasoconstrictor that stimulates mitogenesis and myometrial contraction. 80 In the endometrium, ET-1 plays a role in spiral arteriole vasoconstriction and thus blood flow. Significantly higher levels of ET-1 are expressed in the endometrium compared to the myometrium and fibroid tissue. Endothelin-1 exerts its effects via its receptors ET A -R and ET B -R. Higher levels of ET A -R are found in fibroid tissue relative to the myometrium, but the opposite is observed for ET B -R. The alterations in receptor levels suggest that ET function is aberrant in the presence of uterine fibroids. 81 The altered myometrial expression of ET A -R and ET B -R may result in abnormal uterine contractions leading to defective vasoconstriction and increased menstrual blood flow, especially in the setting of intramural fibroids. Consistent with these data, the endometrial stroma in women with fibroids and heavy menstrual bleeding have been shown to have dilated endometrial stromal venous spaces compared to normal controls. This supports the idea that defective vasoconstriction is one of the mechanisms by which heavy menstrual bleeding occurs. 82 Prostaglandin F 2alpha receptors are present in normal myometrium and regulate uterine contractions. Uterine fibroids have increased PGF 2α production, which is accompanied by disordered uterine contraction and may play a role in the greater menstrual blood loss observed in women with uterine fibroids. 65

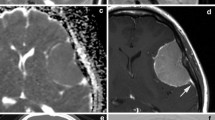

When compared to normal endometrium, fibroids overexpress basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF), an important regulator of angiogenesis. 83 Concurrently, the endometrial stroma of women with uterine fibroids expresses increased levels of basic fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 (FGFR1). 83 The combined increase in the expression of bFGF and FGFR1 may play a role in abnormal angiogenesis and excess bleeding during menses observed in women with uterine fibroids ( Figure 3 ).

Diagram summarizing the effects of submucosal and intramural fibroids on bleeding. ATIII indicates antithrombin III; bFGF, basic fibroblast growth factor; BMPR-2, bone morphogenetic receptor type II; ET-1, endothelin-1; FGFR1, basic fibroblast growth factor receptor 1; PAI1, plasminogen activator inhibitor 1; PGF2α, prostaglandin F 2-alpha; TGF-β3, transforming growth factor beta 3; TM, thrombomodulin.

As described previously, fibroids secrete TGF-β3. Increased TGF-β3 secretion impedes production of coagulation and thrombosis factors, such as thrombomodulin, antithrombin III, and plasminogen activator inhibitor 1. Therefore, disproportionately higher levels of TGF-β3 secreted by fibroids inhibit expression of genes related to fibrinolytic and anticoagulant activity, which results in heavy menstrual bleeding ( Figure 3 ).

Our understanding of the intricate communication between uterine fibroids and the endometrium continues to grow. Although a clear link exists between uterine fibroids and heavy menstrual bleeding, a causative relationship between uterine fibroids and fertility is less clear given that both conditions are relatively common. There is consensus that submucosal fibroids, which distort the uterine cavity, are associated with infertility and early pregnancy loss and should be removed in patients with infertility. In contrast, the clinical significance of intramural fibroids remains controversial.

Submucosal and intramural fibroids both exert significant effects on endometrial gene expression and function. The downstream effects of excessive TGF-β3 secretion from uterine fibroids influence the entire endometrium. This leads to decreased production of transcription factors necessary for implantation during the WOI and aberrant production of coagulation factors during menses. Fibroids also exert their effect on the endometrium through altered gene expression and changes to the immune environment and vasoconstrictive factors.

Despite the significant strides that have been made in this field in recent years, further study is warranted to better understand the crosstalk between uterine fibroids and the endometrium. Such knowledge has the potential to lead to new therapeutic options for the management of symptomatic uterine fibroids.

Authors’ Note: DEI designed the review, performed the literature search, and wrote the manuscript. SEB designed the manuscript, supervised and performed revisions, and critically discussed and reviewed the complete manuscript.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the NIH grants, POI-HD57877 and R37-HD38691 (to S.E.B) and the Friends of Prentice (to D.E.I).

- Neoplasms by Histologic Type

- Muscle Tissue Neoplasms

- Connective and Soft Tissue Neoplasms

A Comprehensive Review of Uterine Fibroids: Pathogenesis, Diagnosis, Treatment, And Future Perspectives

- November 2023

- Journal of Population Therapeutics and Clinical Pharmacology 30(18):1961–1974

- 30(18):1961–1974

- University of Karachi

Abstract and Figures

Discover the world's research

- 25+ million members

- 160+ million publication pages

- 2.3+ billion citations

- Int J Environ Res Publ Health

- INT J GYNECOL OBSTET

- Emma Giuliani

- Erica E. Marsh

- Geum Seon Sohn

- Yong Man Kim

- J Basic Clin Physiol Pharmacol

- Manoj Kumar

- Nihar Ranjan Bhoi

- BIOMED PHARMACOTHER

- Linjiao Chen

- Christine P West

- George A Vilos

- Angelos G Vilos

- Surg Tech Int

- Marcel Grube

- Recruit researchers

- Join for free

- Login Email Tip: Most researchers use their institutional email address as their ResearchGate login Password Forgot password? Keep me logged in Log in or Continue with Google Welcome back! Please log in. Email · Hint Tip: Most researchers use their institutional email address as their ResearchGate login Password Forgot password? Keep me logged in Log in or Continue with Google No account? Sign up

MARIA SYL D. DE LA CRUZ, MD, AND EDWARD M. BUCHANAN, MD

Am Fam Physician. 2017;95(2):100-107

Patient information : A handout on this topic is available at https://familydoctor.org/familydoctor/en/diseases-conditions/uterine-fibroids.html .

Author disclosure: No relevant financial affiliations.

Uterine fibroids are common benign neoplasms, with a higher prevalence in older women and in those of African descent. Many are discovered incidentally on clinical examination or imaging in asymptomatic women. Fibroids can cause abnormal uterine bleeding, pelvic pressure, bowel dysfunction, urinary frequency and urgency, urinary retention, low back pain, constipation, and dyspareunia. Ultrasonography is the preferred initial imaging modality. Expectant management is recommended for asymptomatic patients because most fibroids decrease in size during menopause. Management should be tailored to the size and location of fibroids; the patient's age, symptoms, desire to maintain fertility, and access to treatment; and the experience of the physician. Medical therapy to reduce heavy menstrual bleeding includes hormonal contraceptives, tranexamic acid, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists or selective progesterone receptor modulators are an option for patients who need symptom relief preoperatively or who are approaching menopause. Surgical treatment includes hysterectomy, myomectomy, uterine artery embolization, and magnetic resonance–guided focused ultrasound surgery.

Uterine fibroids, or leiomyomas, are the most common benign tumors in women of reproductive age. 1 Their prevalence is age dependent; they can be detected in up to 80% of women by 50 years of age. 2 Fibroids are the leading indication for hysterectomy, accounting for 39% of all hysterectomies performed annually in the United States. 3 Although many are detected incidentally on imaging in asymptomatic women, 20% to 50% of women are symptomatic and may wish to pursue treatment. 4

WHAT IS NEW ON THIS TOPIC: UTERINE FIBROIDS

Compared with total laparoscopic hysterectomy or laparoscopically assisted vaginal hysterectomy, vaginal hysterectomy is associated with shorter operative time, less blood loss, shorter paralytic ileus time, and shorter hospitalization.

In 2014, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration recommended limiting the use of laparoscopic power morcellation to reproductive-aged women who are not candidates for en bloc uterine resection. Morcellation should not be used in women with suspected or known uterine cancer.

An estimated 15% to 33% of fibroids recur after myomectomy, and approximately 10% of women undergoing myomectomy will undergo a hysterectomy within five to 10 years.

| Ultrasonography is the recommended initial imaging modality for diagnosis of uterine fibroids. | C | , |

| Management of uterine fibroids should be tailored to the size and location of fibroids; the patient's age, symptoms, desire to preserve fertility, and access to therapy; and the physician's experience. | C | , |

| Expectant management is appropriate for women with asymptomatic uterine fibroids. | C | |

| In women undergoing hysterectomy for treatment of uterine fibroids, the least invasive approach possible should be chosen. | B | , |

Epidemiology and Etiology

Fibroids are benign tumors that originate from the uterine smooth muscle tissue (myometrium) whose growth is dependent on estrogen and progesterone. 5 , 6 Fibroids are rare before puberty, increase in prevalence during the reproductive years, and decrease in size after menopause. 6 Aromatase in fibroid tissue allows for endogenous production of estradiol, and fibroid stem cells express estrogen and progesterone receptors that facilitate tumor growth in the presence of these hormones. 5 Protective factors and risk factors for fibroid development are listed in Table 1 . 7 – 9 The major risk factors for fibroid development are increasing age (until menopause) and African descent. 7 , 8 Compared with white women, black women have a higher lifetime prevalence of fibroids and more severe symptoms, which can affect their quality of life. 10

| Increased parity | African descent |

| Late menarche (older than 16 years) | Age greater than 40 years |

| Smoking | Early menarche (younger than 10 years) |

| Use of oral contraceptives | Family history of uterine fibroids |

| Nulliparity | |

| Obesity |

Clinical Features

Uterine fibroids are classified based on location: subserosal (projecting outside the uterus), intramural (within the myometrium), and submucosal (projecting into the uterine cavity). The symptoms and treatment options are affected by the size, number, and location of the tumors. 11 The most common symptom is abnormal uterine bleeding, usually excessive menstrual bleeding. 12 Other symptoms include pelvic pressure, bowel dysfunction, urinary frequency and urgency, urinary retention, low back pain, constipation, and dyspareunia. 13

Uterine fibroids may be associated with infertility, and some experts recommend that women with infertility be evaluated for fibroids, with potential removal if the tumors have a submucosal component. 14 However, there is no evidence from randomized controlled trials to support myomectomy to improve fertility. 15 One meta-analysis included two studies that showed improvement in spontaneous conception rates in women who underwent myomectomy for submucosal fibroids (relative risk [RR] = 2.034; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.081 to 3.826; P = .028). 16 However, no statistically significant difference was noted in the ongoing pregnancy/live birth rate. Women with intramural fibroids had no differences in pregnancy rates after undergoing myomectomy. Although studies have had conflicting results on the change in fibroid size during pregnancy, 17 , 18 a large retrospective study of women with uterine fibroids found a significantly increased risk of cesarean delivery compared with a control group (33.1% vs. 24.2%), as well as increases in the risk of breech presentation (5.3% vs. 3.1%), pre-term premature rupture of membranes (3.3% vs. 2.4%), delivery before 37 weeks' gestation (15.1% vs. 10.5%), and intrauterine fetal death with growth restriction (3.9% vs. 1.5%). 19 Therefore, fibroids in pregnant women warrant additional maternal and fetal surveillance.

In the postpartum period, women with fibroids have an increased risk of postpartum hemorrhage secondary to an increased risk of uterine atony. 20 The risk of malignancy for uterine fibroids is very low; the prevalence of leiomyosarcoma is estimated at about one in 400 (0.25%) women undergoing surgery for fibroids. 21 Because the natural course of fibroids involves growth and regression, enlarging fibroids are not an indication for removal. 22 , 23

The evaluation of fibroids is based mainly on the patient's presenting symptoms: abnormal menstrual bleeding, bulk symptoms, pelvic pain, or findings suggestive of anemia. Fibroids are sometimes found in asymptomatic women during routine pelvic examination or incidentally during imaging. 24 In the United States, ultrasonography is the preferred initial imaging modality for fibroids. 4 Transvaginal ultrasonography is about 90% to 99% sensitive for detecting uterine fibroids, but it may miss subserosal or small fibroids. 25 , 26 Adding sonohysterography or hysteroscopy improves sensitivity for detecting submucosal myomas. 25 There are no reliable means to differentiate benign from malignant tumors without pathologic evaluation. Some predictors of malignancy on magnetic resonance imaging include age older than 45 years (odds ratio [OR] = 20), intratumoral hemorrhage (OR = 21), endometrial thickening (OR = 11), T2-weighted signal heterogeneity (OR = 10), menopausal status (OR = 9.7), and nonmyometrial origin (OR = 4.9). 27 , 28 Risk factors for leiomyosarcoma include radiation of the pelvis, increasing age, and use of tamoxifen, 29 , 30 which has implications for surgical management of fibroids. Table 2 includes the differential diagnosis of uterine masses. 31

| Adenomyosis |

| Ectopic pregnancy |

| Endometrial carcinoma |

| Endometrial polyp |

| Endometriosis |

| Metastatic disease |

| Pregnancy |

| Uterine carcinosarcoma (considered an epithelial neoplasm) |

| Uterine fibroids |

| Uterine sarcoma (leiomyosarcoma, endometrial stromal sarcoma, mixed mesodermal tumor) |

Treatment of uterine fibroids should be tailored to the size and location of the tumors; the patient's age, symptoms, desire to maintain fertility, and access to treatment; and the physician's experience 4 , 11 ( Table 3 32 – 42 and Table 4 4 , 16 , 34 , 38 , 40 – 44 ) . The ideal treatment satisfies four goals: relief of signs and symptoms, sustained reduction of the size of fibroids, maintenance of fertility (if desired), and avoidance of harm. Figure 1 presents an algorithm for the management of uterine fibroids. 4

| Gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists | Preoperative treatment to decrease size of tumors before surgery or in women approaching menopause | Decrease blood loss, operative time, and recovery time | Long-term treatment associated with higher cost, menopausal symptoms, and bone loss; increased recurrence risk with myomectomy | Depends on subsequent procedure |

| Levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (Mirena) | Treats abnormal uterine bleeding, likely by stabilization of endometrium | Most effective medical treatment for reducing blood loss; decreases fibroid volume | Irregular uterine bleeding, increased risk of device expulsion | Yes, if discontinued after resolution of symptoms |

| Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs | Anti-inflammatories and prostaglandin inhibitors | Reduce pain and blood loss from fibroids | Do not decrease fibroid volume; gastrointestinal adverse effects | Yes |

| Oral contraceptives | Treat abnormal uterine bleeding, likely by stabilization of endometrium | Reduce blood loss from fibroids; ease of conversion to alternate therapy if not successful | Do not decrease fibroid volume | Yes, if discontinued after resolution of symptoms |

| Selective progesterone receptor modulators , | Preoperative treatment to decrease size of tumors before surgery or in women approaching menopause | Decrease blood loss, operative time, and recovery time; not associated with hypoestrogenic adverse effects | Headache and breast tenderness, progesterone receptor modulator–associated endometrial changes; increased recurrence risk with myomectomy | Depends on subsequent procedure |

| Tranexamic acid (Cyklokapron) , | Antifibrinolytic therapy | Reduces blood loss from fibroids; ease of conversion to alternate therapy | Does not decrease fibroid volume; medical contraindications | Yes |

| Hysterectomy | Surgical removal of the uterus (transabdominally, transvaginally, or laparoscopically) | Definitive treatment for women who do not wish to preserve fertility; transvaginal and laparoscopic approach associated with decreased pain, blood loss, and recovery time compared with transabdominal surgery | Surgical risks higher with transabdominal surgery (e.g., infection, pain, fever, increased blood loss and recovery time); morcellation with laparoscopic approach increases risk of iatrogenic dissemination of tissue | No |

| Magnetic resonance–guided focused ultrasound surgery | In situ destruction by high-intensity ultrasound waves | Noninvasive approach; shorter recovery time with modest symptom improvement | Heavy menses, pain from sciatic nerve irritation, higher reintervention rate | Unknown |

| Myomectomy | Surgical or endoscopic excision of tumors | Resolution of symptoms with preservation of fertility | Recurrence rate of 15% to 30% at five years, depending on size and extent of tumors | Yes |

| Uterine artery embolization | Interventional radiologic procedure to occlude uterine arteries | Minimally invasive; avoids surgery; short hospitalization | Recurrence rate > 17% at 30 months; postembolization syndrome | Unknown |

| Asymptomatic women | Clinical surveillance |

| Infertile women with distorted uterine cavity (i.e., submucosal fibroids) who desire future fertility | Myomectomy |

| Symptomatic women who desire future fertility | Medical treatment or myomectomy , , |

| Symptomatic women who do not desire future fertility but wish to preserve the uterus | Medical treatment, myomectomy, uterine artery embolization, magnetic resonance–guided focused ultrasound surgery , , – |

| Symptomatic women who want definitive treatment and do not desire future fertility | Hysterectomy by least invasive approach possible , |

EXPECTANT THERAPY

About 3% to 7% of untreated fibroids in premenopausal women regress over six months to three years, and most decrease in size at menopause. Because there is minimal concern for malignancy in women with asymptomatic fibroids, watchful waiting is preferred - for management. 4 There are no studies that support - surveillance with imaging or repeat imaging in asymptomatic women with fibroids. 4 , 11

MEDICAL THERAPY

Hormonal Contraceptives . Women who use combined oral contraceptives have significantly less self-reported menstrual blood loss after 12 months compared with placebo. 33 However, the levonorgestrel-releasing intra-uterine system (Mirena) results in a significantly greater reduction in menstrual blood loss at 12 months vs. oral contraceptives (mean reduction = 91% vs. 13% per cycle; P < .001). 33 In six prospective observational studies, reported expulsion rates of intrauterine devices were between zero and 20% in women with uterine fibroids. 45 There is a lack of high-quality evidence regarding oral and injectable progestin for uterine fibroids. 46 – 48

Tranexamic Acid . Tranexamic acid (Cyklokapron) is an oral nonhormonal antifibrinolytic agent that significantly reduces menstrual blood loss compared with placebo (mean reduction = 94 mL per cycle; 95% CI, 36 to 151 mL). 37 , 38 One small nonrandomized study reported a higher rate of fibroid necrosis in patients who received tranexamic acid compared with untreated patients (15% vs. 4.7%; OR = 3.60; 95% CI, 1.83 to 6.07; P = .0003), with intralesional thrombi in one-half of the 22 cases involving fibroid necrosis (manifesting as apop-totic cellular debris with inflammatory cells, and usually hemorrhage). 49 However, in a systematic review of four studies with 200 patients who received tranexamic acid, none of the studies detailed the adverse effects of fibroid necrosis or thrombus formation. 50

Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs . Another medical option for the treatment of uterine fibroids is a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug. These agents significantly reduce blood loss (mean reduction = 124 mL per cycle; 95% CI, 62 to 186 mL) and improve pain relief compared with placebo, 34 but are less effective in decreasing blood loss compared with the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system or tranexamic acid at three months. 51

Hormone Therapy . Gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonists and selective progesterone receptor modulators (SPRMs) are options for patients who need temporary relief from symptoms preoperatively or who are approaching menopause. Preoperative administration of GnRH agonists (e.g., leuprolide [Lupron], goserelin [Zoladex], triptorelin [Trelstar Depot]) increases hemoglobin levels preoperatively by 1.0 g per dL (10 g per L) and postoperatively by 0.8 g per dL (8 g per L), as well as significantly decreases pelvic symptom scores. 32 Adverse effects resulting from the hypoestrogenized state, including hot flashes (OR = 6.5), vaginitis (OR = 4.0), sweating (OR = 8.3), and change in breast size (OR = 7.7), affect the long-term use of these agents. 32

Compared with placebo, the SPRM mife-pristone (Mifeprex) significantly decreases heavy menstrual bleeding (OR = 18; 95% CI, 6.7 to 47) and improves fibroid-specific quality of life, but does not affect fibroid volume. 35 Ulipristal (Ella) is an SPRM approved as a contraceptive in the United States but used in other countries for the treatment of fibroids in adult women who are eligible for surgery. Compared with placebo, a 5-mg dose of ulipristal significantly reduces mean blood loss (94% vs. 48% per cycle; 95% CI, 55% to 83%; P < .001), decreases fibroid volume by more than 25% (85% vs. 45%; 95% CI, 4% to 39%; P = .01), and induces amenorrhea in significantly more patients (94% vs. 48%; 95% CI, 50% to 77%; P < .001). 52 Treatment is limited to three months of continuous use. The most common adverse effects include headache and breast tenderness. The advantage of SPRMs over GnRH agonists for preoperative adjuvant therapy is their lack of hypoestrogenic adverse effects and bone loss. However, SPRMs can result in progesterone receptor modulator–associated endometrial changes, although these seem to be benign. 36

Other Agents . Other, less-studied options for the treatment of uterine fibroids include aromatase inhibitors and estrogen receptor antagonists. Aromatase inhibitors (e.g., letrozole [Femara], anastrozole [Arimidex], fadrozole [not available in the United States]) block the synthesis of estrogen. Limited data have shown that they help reduce fibroid size as well as decrease menstrual bleeding, with adverse effects including hot flashes, vaginal dryness, and musculoskeletal pain. 53 , 54 Overall, there is insufficient evidence to support the use of aromatase inhibitors for the treatment of uterine fibroids. 55 Selective estrogen receptor modulators act as partial estrogen receptor agonists in bone, cardiovascular tissue, and the endometrium. In a small prospective trial of 18 patients, tamoxifen did not reduce fibroid size or uterine volume, but did reduce menstrual blood loss by 40% to 50% and decrease pelvic pain compared with the control group. 56 Based on its adverse effects (e.g., hot flashes, dizziness, endometrial thickening), the authors concluded that its risks outweigh its marginal benefits for fibroid treatment. Another selective estrogen receptor modulator, raloxifene (Evista), has also shown inconsistent results, with two of three studies included in a Cochrane review showing significant benefit. 57

Hysterectomy . Hysterectomy provides a definitive cure for women with symptomatic fibroids who do not wish to preserve fertility, resulting in complete resolution of symptoms and improved quality of life. Hysterectomy by the least invasive approach possible is the most effective treatment for symptomatic uterine fibroids. 39 Vaginal hysterectomy is the preferred technique because it provides several statistically significant advantages, including shorter surgery time than total laparoscopic hysterectomy or laparoscopically assisted vaginal hysterectomy (70 minutes vs. 151 minutes vs. 130 minutes, respectively), decreased blood loss (183 mL vs. 204 mL vs. 358 mL), shorter hospitalization (51 hours vs. 77 hours vs. 77 hours), and shorter paralytic ileus time (19 hours vs. 28 hours vs. 26 hours); however, vaginal hysterectomy is limited by the size of the myomatous uterus. 43 Abdominal hysterectomy is an alternative approach, but the balance of risks and benefits must be individualized to each patient. 44

The laparoscopic extraction of the uterus may be performed with morcellation, whereby a rotating blade cuts the tissue into small pieces. This technique has come under scrutiny because of concerns about iatrogenic dissemination of benign and malignant tissue. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration recommends limiting the use of laparoscopic morcellation to reproductive-aged women who are not candidates for en bloc uterine resection. 58 The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends morcellation as an option, but emphasizes the importance of informed consent and notes that the technique should not be performed in women with suspected or known uterine cancer. 59 , 60 Approximately one in 10 women have new symptoms after hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy. 61

Myomectomy . Hysteroscopic myomectomy is the preferred surgical procedure for women with submucosal fibroids who wish to preserve their uterus or fertility. It is optimal for submucosal fibroids less than 3 cm when more than 50% of the tumor is intracavitary. 62 Laparoscopy is associated with less postoperative pain at 48 hours, less risk of postoperative fever (OR = 0.44; 95% CI, 0.26 to 0.77), and shorter hospitalization (mean of 67 fewer hours; 95% CI, 55 to 79 hours) compared with open myomectomy. 41 An estimated 15% to 33% of fibroids recur after myomectomy, and approximately 10% of women who undergo this procedure will have a hysterectomy within five to 10 years. 24

Uterine Artery Embolization . Uterine artery embolization is an option for women who wish to preserve their uterus or avoid surgery because of medical comorbidities or personal preference. 4 It is an interventional radiologic procedure in which occluding agents are injected into one or both of the uterine arteries, limiting blood supply to the uterus and fibroids. Compared with hysterectomy and myomectomy, uterine artery embolization has a significantly decreased length of hospitalization (mean of three fewer days), decreased time to normal activities (mean of 14 days), and a decreased likelihood of blood transfusion (OR = 0.07; 95% CI, 0.01 to 0.52). 42 Long-term studies show a reoperation rate of 20% to 33% within 18 months to five years. 24 Contraindications include pregnancy, active uterine or adnexal infections, allergy to intravenous contrast media, and renal insufficiency. The most common complication is postembolization syndrome, which is characterized by mild fever and pain, and vaginal expulsion of fibroids. 63

There is insufficient evidence on the effect of uterine artery embolization on future fertility. An observational study of 26 women treated with uterine artery embolization and 40 treated with hysterectomy found no difference in live birth rates. 42 In a retrospective study with five years of follow-up in women who received uterine artery embolization for fibroids, 27 (4.2%) had one (n = 20) or more (n = 7) pregnancies after uterine artery embolization. 64 Of these pregnancies, there were 15 miscarriages and 19 live births, 79% of which were cesarean deliveries because of complications. Further studies are needed on fertility outcomes after uterine artery embolization so that patients can be counseled appropriately.

Myolysis . Myolysis is a minimally invasive procedure targeting the destruction of fibroids via a focused energy delivery system such as heat, laser, or more recently, magnetic resonance–guided focused ultrasound surgery (MRgFUS). A study of 359 women treated with MRgFUS showed improved scores on the Uterine Fibroid Symptoms Quality of Life questionnaire at three months that persisted for up to 24 months ( P < .001). 40 In another study comparing women who underwent MRgFUS with those who underwent total abdominal hysterectomy, the groups had similar improvement in quality-of-life scores at six months, but the MRgFUS group had significantly fewer complications (14 vs. 33 events; P < .0001). 65 In a five-year follow-up study of 162 women, the reoperative rate was 59%. 66 Overall, this less-invasive procedure is well tolerated, although risks include localized pain and heavy bleeding. 40 Spontaneous conception has occurred in patients after MRgFUS, but further studies are needed to examine its effect on future fertility. 67

This article updates a previous article on this topic by Evans and Brunsell. 68

Data Sources: A PubMed search was completed in Clinical Queries using the key terms leiomyoma, uterine fibroids, diagnosis, management, power morcellation, and guidelines. The search included meta-analyses, randomized controlled trials, clinical trials, and reviews. Also searched were the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality evidence reports, Clinical Evidence, the Cochrane database, the Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects, Essential Evidence Plus, and the National Guideline Clearinghouse database. Search date: October 25, 2015.

Wallach EE, Vlahos NF. Uterine myomas: an overview of development, clinical features, and management. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;104(2):393-406.

Zimmermann A, Bernuit D, Gerlinger C, et al. Prevalence, symptoms and management of uterine fibroids: an international internet-based survey of 21,746 women. BMC Womens Health. 2012;12(1):6.

Whiteman MK, Hillis SD, Jamieson DJ, et al. Inpatient hysterectomy surveillance in the United States, 2000–2004. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;198(1):34.e1-34.e7.

Vilos GA, Allaire C, Laberge PY, et al. The management of uterine leiomyomas. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2015;37(2):157-181.

Bulun SE. Uterine fibroids. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(14):1344-1355.

Ishikawa H, Ishi K, Serna VA, et al. Progesterone is essential for maintenance and growth of uterine leiomyoma. Endocrinology. 2010;151(6):2433-2442.

Ross RK, Pike MC, Vessey MP, et al. Risk factors for uterine fibroids: reduced risk associated with oral contraceptives [published correction appears in Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) . 1986;293(6553):1027]. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1986;293(6543):359-362.

Ryan GL, Syrop CH, Van Voorhis BJ. Role, epidemiology, and natural history of benign uterine mass lesions. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2005;48(2):312-324.

Chiaffarino F, Parazzini F, La Vecchia C, et al. Use of oral contraceptives and uterine fibroids: results from a case-control study. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1999;106(8):857-860.

Stewart EA, Nicholson WK, Bradley L, et al. The burden of uterine fibroids for African-American women: results of a national survey. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2013;22(10):807-816.

Munro MG, Storz K, Abbott JA, et al. Practice guidelines for the management of hysteroscopic distending media. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2013;20(2):137-148.

Drayer SM, Catherino WH. Prevalence, morbidity, and current medical management of uterine leiomyomas. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2015;131(2):117-122.

Bukulmez O, Doody KJ. Clinical features of myomas. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2006;33(1):69-84.

Carranza-Mamane B, Havelock J, Hemmings R, et al. The management of uterine fibroids in women with otherwise unexplained infertility. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2015;37(3):277-288.

Metwally M, Cheong YC, Horne AW. Surgical treatment of fibroids for subfertility. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;11:CD003857.

Pritts EA, Parker WH, Olive DL. Fibroids and infertility: an updated systematic review of the evidence. Fertil Steril. 2009;91(4):1215-1223.

De Vivo A, Mancuso A, Giacobbe A, et al. Uterine myomas during pregnancy: a longitudinal sonographic study. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2011;37(3):361-365.

Hammoud AO, Asaad R, Berman J, et al. Volume change of uterine myomas during pregnancy: do myomas really grow?. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2006;13(5):386-390.

Stout MJ, Odibo AO, Graseck AS, et al. Leiomyomas at routine second-trimester ultrasound examination and adverse obstetric outcomes. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116(5):1056-1063.

Klatsky PC, Tran ND, Caughey AB, et al. Fibroids and reproductive outcomes: a systematic literature review from conception to delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;198(4):357-366.

Knight J, Falcone T. Tissue extraction by morcellation: a clinical dilemma. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2014;21(3):319-320.

ACOG practice bulletin. Alternatives to hysterectomy in the management of leiomyomas. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112(2 pt 1):387-400.

Practice Committee of American Society for Reproductive Medicine; Society of Reproductive Surgeons. Myomas and reproductive function. Fertil Steril. 2008;90(5 suppl):S125-S130.

Singh SS, Belland L. Contemporary management of uterine fibroids: focus on emerging medical treatments [published correction appears in Curr Med Res Opin . 2016;32(4):797]. Curr Med Res Opin. 2015;31(1):1-12.

Dueholm M, Lundorf E, Hansen ES, et al. Accuracy of magnetic resonance imaging and transvaginal ultrasonography in the diagnosis, mapping, and measurement of uterine myomas. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;186(3):409-415.

Cicinelli E, Romano F, Anastasio PS, et al. Transabdominal sonohysterography, transvaginal sonography, and hysteroscopy in the evaluation of submucous myomas. Obstet Gynecol. 1995;85(1):42-47.

Thomassin-Naggara I, Dechoux S, Bonneau C, et al. How to differentiate benign from malignant myometrial tumours using MR imaging. Eur Radiol. 2013;23(8):2306-2314.

Bonneau C, Thomassin-Naggara I, Dechoux S, et al. Value of ultra-sonography and magnetic resonance imaging for the characterization of uterine mesenchymal tumors. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2014;93(3):261-268.

Varelas FK, Papanicolaou AN, Vavatsi-Christaki N, et al. The effect of anastrazole on symptomatic uterine leiomyomata. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;110(3):643-649.

Wright JD, Tergas AI, Burke WM, et al. Uterine pathology in women undergoing minimally invasive hysterectomy using morcellation. JAMA. 2014;312(12):1253-1255.

Fleischer AC, James AE, Millis JB, et al. Differential diagnosis of pelvic masses by gray scale sonography. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1978;131(3):469-476.

Lethaby A, Vollenhoven B, Sowter M. Efficacy of pre-operative gonadotrophin hormone releasing analogues for women with uterine fibroids undergoing hysterectomy or myomectomy. BJOG. 2002;109(10):1097-1108.

Sayed GH, Zakherah MS, El-Nashar SA, et al. A randomized clinical trial of a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system and a low-dose combined oral contraceptive for fibroid-related menorrhagia. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2011;112(2):126-130.

Lethaby A, Duckitt K, Farquhar C. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for heavy menstrual bleeding. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;1:CD000400.

Tristan M, Orozco LJ, Steed A, et al. Mifepristone for uterine fibroids. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;8:CD007687.

Donnez J, Tatarchuk TF, Bouchard P, et al. Ulipristal acetate versus placebo for fibroid treatment before surgery. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(5):409-420.

Lethaby A, Farquhar C, Cooke I. Antifibrinolytics for heavy menstrual bleeding. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2000(4):CD000249.

Lukes AS, Moore KA, Muse KN, et al. Tranexamic acid treatment for heavy menstrual bleeding. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116(4):865-875.

Aarts JW, Nieboer TE, Johnson N, et al. Surgical approach to hysterectomy for benign gynaecological disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015(8):CD003677.

Stewart EA, Gostout B, Rabinovici J, et al. Sustained relief of leiomyoma symptoms by using focused ultrasound surgery. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;110(2 pt 1):279-287.

Bhave Chittawar P, Franik S, et al. Minimally invasive surgical techniques versus open myomectomy for uterine fibroids. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014(10):CD004638.

Gupta JK, Sinha A, Lumsden MA, et al. Uterine artery embolization for symptomatic uterine fibroids. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014(12):CD005073.

Sesti F, Cosi V, Calonzi F, et al. Randomized comparison of total laparoscopic, laparoscopically assisted vaginal and vaginal hysterectomies for myomatous uteri. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2014;290(3):485-491.

Hwang JL, Seow KM, Tsai YL, et al. Comparative study of vaginal, laparoscopically assisted vaginal and abdominal hysterectomies for uterine myoma larger than 6 cm in diameter or uterus weighing at least 450 g. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2002;81(12):1132-1138.

Zapata LB, Whiteman MK, Tepper NK, et al. Intrauterine device use among women with uterine fibroids. Contraception. 2010;82(1):41-55.

Venkatachalam S, Bagratee JS, Moodley J. Medical management of uterine fibroids with medroxyprogesterone acetate (Depo Provera). J Obstet Gynaecol. 2004;24(7):798-800.

Verspyck E, Marpeau L, Lucas C. Leuprorelin depot 3.75 mg versus lynestrenol in the preoperative treatment of symptomatic uterine myomas. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2000;89(1):7-13.

Ichigo S, Takagi H, Matsunami K, et al. Beneficial effects of dienogest on uterine myoma volume. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2011;284(3):667-670.

Ip PP, Lam KW, Cheung CL, et al. Tranexamic acid-associated necrosis and intralesional thrombosis of uterine leiomyomas. Am J Surg Pathol. 2007;31(8):1215-1224.

Peitsidis P, Koukoulomati A. Tranexamic acid for the management of uterine fibroid tumors. World J Clin Cases. 2014;2(12):893-898.

Milsom I, Andersson K, Andersch B, et al. A comparison of flurbiprofen, tranexamic acid, and a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine contraceptive device in the treatment of idiopathic menorrhagia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1991;164(3):879-883.

Carbonell Esteve JL, Acosta R, Heredia B, et al. Mifepristone for the treatment of uterine leiomyomas. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112(5):1029-1036.

Hilário SG, Bozzini N, Borsari R, et al. Action of aromatase inhibitor for treatment of uterine leiomyoma in perimenopausal patients. Fertil Steril. 2009;91(1):240-243.

Gurates B, Parmaksiz C, Kilic G, et al. Treatment of symptomatic uterine leiomyoma with letrozole. Reprod Biomed Online. 2008;17(4):569-574.

Song H, Lu D, Navaratnam K, et al. Aromatase inhibitors for uterine fibroids. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013(10):CD009505.

Sadan O, Ginath S, Sofer D, et al. The role of tamoxifen in the treatment of symptomatic uterine leiomyomata—a pilot study. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2001;96(2):183-186.

Deng L, Wu T, Chen XY, et al. Selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs) for uterine leiomyomas. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012(10):CD005287.

U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Updated: laparoscopic uterine power morcellation in hysterectomy and myomectomy: FDAsafety communication. http://www.fda.gov/MedicalDevices/Safety/AlertsandNotices/ucm424443.htm . Accessed January 20, 2016.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Power morcellation and occult malignancy in gynecologic surgery. http://www.acog.org/Resources-And-Publications/Task-Force-and-Work-Group-Reports/Power-Morcellation-and-Occult-Malignancy-in-Gynecologic-Surgery . Accessed January 20, 2016.

Bogani G, Cliby WA, Aletti GD. Impact of morcellation on survival outcomes of patients with unexpected uterine leiomyosarcoma. Gynecol Oncol. 2015;137(1):167-172.

Carlson KJ, Miller BA, Fowler FJ. The Maine women's health study: I. outcomes of hysterectomy. Obstet Gynecol. 1994;83(4):556-565.

Camanni M, Bonino L, Delpiano EM, et al. Hysteroscopic management of large symptomatic submucous uterine myomas. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2010;17(1):59-65.

Goodwin SC, Spies JB. Uterine fibroid embolization. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(7):690-697.

Hirst A, Dutton S, Wu O, et al. A multi-centre retrospective cohort study comparing the efficacy, safety and cost-effectiveness of hysterectomy and uterine artery embolisation for the treatment of symptomatic uterine fibroids. Health Technol Assess. 2008;12(5):1-248.

Taran FA, Tempany CM, Regan L, et al.; MRgFUS Group. Magnetic resonance-guided focused ultrasound (MRgFUS) compared with abdominal hysterectomy for treatment of uterine leiomyomas. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2009;34(5):572-578.

Quinn SD, Vedelago J, Gedroyc W, et al. Safety and five-year re-intervention following magnetic resonance-guided focused ultrasound (MRgFUS) for uterine fibroids. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2014;182:247-251.

Rabinovici J, David M, Fukunishi H, et al.; MRgFUS Study Group. Pregnancy outcome after magnetic resonance-guided focused ultrasound surgery (MRgFUS) for conservative treatment of uterine fibroids. Fertil Steril. 2010;93(1):199-209.

Evans P, Brunsell S. Uterine fibroid tumors: diagnosis and treatment. Am Fam Physician. 2007;75(10):1503-1508.

Continue Reading

More in AFP

More in pubmed.

Copyright © 2017 by the American Academy of Family Physicians.

This content is owned by the AAFP. A person viewing it online may make one printout of the material and may use that printout only for his or her personal, non-commercial reference. This material may not otherwise be downloaded, copied, printed, stored, transmitted or reproduced in any medium, whether now known or later invented, except as authorized in writing by the AAFP. See permissions for copyright questions and/or permission requests.

Copyright © 2024 American Academy of Family Physicians. All Rights Reserved.

An official website of the United States government

Here's how you know

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- U.S. Department of Health & Human Services

Call the OWH HELPLINE: 1-800-994-9662 9 a.m. — 6 p.m. ET, Monday — Friday OWH and the OWH helpline do not see patients and are unable to: diagnose your medical condition; provide treatment; prescribe medication; or refer you to specialists. The OWH helpline is a resource line. The OWH helpline does not provide medical advice.

Please call 911 or go to the nearest emergency room if you are experiencing a medical emergency.

Uterine fibroids

Fibroids are muscular tumors that grow in the wall of the uterus (womb). Fibroids are almost always benign (not cancerous). Not all women with fibroids have symptoms. Women who do have symptoms often find fibroids hard to live with. Some have pain and heavy menstrual bleeding. Treatment for uterine fibroids depends on your symptoms.

What are fibroids?

Fibroids are muscular tumors that grow in the wall of the uterus (womb). Another medical term for fibroids is leiomyoma (leye-oh-meye-OH-muh) or just "myoma". Fibroids are almost always benign (not cancerous). Fibroids can grow as a single tumor, or there can be many of them in the uterus. They can be as small as an apple seed or as big as a grapefruit. In unusual cases they can become very large.

Why should women know about fibroids?

About 20 percent to 80 percent of women develop fibroids by the time they reach age 50. Fibroids are most common in women in their 40s and early 50s. Not all women with fibroids have symptoms. Women who do have symptoms often find fibroids hard to live with. Some have pain and heavy menstrual bleeding. Fibroids also can put pressure on the bladder, causing frequent urination, or the rectum, causing rectal pressure. Should the fibroids get very large, they can cause the abdomen (stomach area) to enlarge, making a woman look pregnant.

Who gets fibroids?

There are factors that can increase a woman's risk of developing fibroids.

- Age. Fibroids become more common as women age, especially during the 30s and 40s through menopause. After menopause, fibroids usually shrink.

- Family history. Having a family member with fibroids increases your risk. If a woman's mother had fibroids, her risk of having them is about three times higher than average.

- Ethnic origin. African-American women are more likely to develop fibroids than white women.

- Obesity. Women who are overweight are at higher risk for fibroids. For very heavy women, the risk is two to three times greater than average.

- Eating habits. Eating a lot of red meat (e.g., beef) and ham is linked with a higher risk of fibroids. Eating plenty of green vegetables seems to protect women from developing fibroids.

Where can fibroids grow?

Most fibroids grow in the wall of the uterus. Doctors put them into three groups based on where they grow:

- Submucosal (sub-myoo-KOH-zuhl) fibroids grow into the uterine cavity.

- Intramural (ihn-truh-MYOOR-uhl) fibroids grow within the wall of the uterus.

- Subserosal (sub-suh-ROH-zuhl) fibroids grow on the outside of the uterus.

Some fibroids grow on stalks that grow out from the surface of the uterus or into the cavity of the uterus. They might look like mushrooms. These are called pedunculated (pih-DUHN-kyoo-lay-ted) fibroids.

What are symptoms of fibroids?

Most fibroids do not cause any symptoms, but some women with fibroids can have:

- Heavy bleeding (which can be heavy enough to cause anemia ) or painful periods

- Feeling of fullness in the pelvic area (lower stomach area)

- Enlargement of the lower abdomen

- Frequent urination

- Pain during sex

- Lower back pain

- Complications during pregnancy and labor, including a six-time greater risk of cesarean section

- Reproductive problems, such as infertility , which is very rare

What causes fibroids?

No one knows for sure what causes fibroids. Researchers think that more than one factor could play a role. These factors could be:

- Hormonal (affected by estrogen and progesterone levels)

- Genetic (runs in families)

Because no one knows for sure what causes fibroids, we also don't know what causes them to grow or shrink. We do know that they are under hormonal control — both estrogen and progesterone. They grow rapidly during pregnancy, when hormone levels are high. They shrink when anti-hormone medication is used. They also stop growing or shrink once a woman reaches menopause.

Can fibroids turn into cancer?

Fibroids are almost always benign (not cancerous). Rarely (less than one in 1,000) a cancerous fibroid will occur. This is called leiomyosarcoma. (leye-oh-meye-oh-sar-KOH-muh) Doctors think that these cancers do not arise from an already-existing fibroid. Having fibroids does not increase the risk of developing a cancerous fibroid. Having fibroids also does not increase a woman's chances of getting other forms of cancer in the uterus.

What if I become pregnant and have fibroids?

Women who have fibroids are more likely to have problems during pregnancy and delivery. This doesn't mean there will be problems. Most women with fibroids have normal pregnancies. The most common problems seen in women with fibroids are:

- Cesarean section. The risk of needing a c-section is six times greater for women with fibroids.

- Baby is breech. The baby is not positioned well for vaginal delivery.

- Labor fails to progress.

- Placental abruption. The placenta breaks away from the wall of the uterus before delivery. When this happens, the fetus does not get enough oxygen.

- Preterm delivery.

Talk to your obstetrician if you have fibroids and become pregnant. All obstetricians have experience dealing with fibroids and pregnancy. Most women who have fibroids and become pregnant do not need to see an OB who deals with high-risk pregnancies.

How do I know for sure that I have fibroids?

Your doctor may find that you have fibroids when you see her or him for a regular pelvic exam to check your uterus, ovaries, and vagina. The doctor can feel the fibroid with her or his fingers during an ordinary pelvic exam, as a (usually painless) lump or mass on the uterus. Often, a doctor will describe how small or how large the fibroids are by comparing their size to the size your uterus would be if you were pregnant. For example, you may be told that your fibroids have made your uterus the size it would be if you were 16 weeks pregnant. Or the fibroid might be compared to fruits, nuts, or a ball, such as a grape or an orange, an acorn or a walnut, or a golf ball or a volleyball.

Your doctor can do imaging tests to confirm that you have fibroids. These are tests that create a "picture" of the inside of your body without surgery. These tests might include:

- Ultrasound – Uses sound waves to produce the picture. The ultrasound probe can be placed on the abdomen or it can be placed inside the vagina to make the picture.

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) – Uses magnets and radio waves to produce the picture

- X-rays – Uses a form of radiation to see into the body and produce the picture

- Cat scan (CT) – Takes many X-ray pictures of the body from different angles for a more complete image

- Hysterosalpingogram (hiss-tur-oh-sal-PIN-juh-gram) (HSG) or sonohysterogram (soh-noh-HISS-tur-oh-gram) – An HSG involves injecting x-ray dye into the uterus and taking x-ray pictures. A sonohysterogram involves injecting water into the uterus and making ultrasound pictures.

You might also need surgery to know for sure if you have fibroids. There are two types of surgery to do this:

- Laparoscopy (lap-ar-OSS-koh-pee) – The doctor inserts a long, thin scope into a tiny incision made in or near the navel. The scope has a bright light and a camera. This allows the doctor to view the uterus and other organs on a monitor during the procedure. Pictures also can be made.

- Hysteroscopy (hiss-tur-OSS-koh-pee) – The doctor passes a long, thin scope with a light through the vagina and cervix into the uterus. No incision is needed. The doctor can look inside the uterus for fibroids and other problems, such as polyps. A camera also can be used with the scope.

What questions should I ask my doctor if I have fibroids?

- How many fibroids do I have?

- What size is my fibroid(s)?

- Where is my fibroid(s) located (outer surface, inner surface, or in the wall of the uterus)?

- Can I expect the fibroid(s) to grow larger?

- How rapidly have they grown (if they were known about already)?

- How will I know if the fibroid(s) is growing larger?

- What problems can the fibroid(s) cause?

- What tests or imaging studies are best for keeping track of the growth of my fibroids?

- What are my treatment options if my fibroid(s) becomes a problem?

- What are your views on treating fibroids with a hysterectomy versus other types of treatments?

A second opinion is always a good idea if your doctor has not answered your questions completely or does not seem to be meeting your needs.

How are fibroids treated?

Most women with fibroids do not have any symptoms. For women who do have symptoms, there are treatments that can help. Talk with your doctor about the best way to treat your fibroids. She or he will consider many things before helping you choose a treatment. Some of these things include:

- Whether or not you are having symptoms from the fibroids

- If you might want to become pregnant in the future

- The size of the fibroids

- The location of the fibroids

- Your age and how close to menopause you might be

If you have fibroids but do not have any symptoms, you may not need treatment. Your doctor will check during your regular exams to see if they have grown.

Medications

If you have fibroids and have mild symptoms, your doctor may suggest taking medication. Over-the-counter drugs such as ibuprofen or acetaminophen can be used for mild pain. If you have heavy bleeding during your period, taking an iron supplement can keep you from getting anemia or correct it if you already are anemic.