An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Diagnostics (Basel)

- PMC10178083

Sexually Transmitted Diseases—An Update and Overview of Current Research

Kristina wihlfahrt.

1 Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University Hospitals Schleswig-Holstein, Campus Kiel, Arnold-Heller-Strasse 3 (House C), 24105 Kiel, Germany

Veronika Günther

Werner mendling.

2 German Center for Infections in Gynecology and Obstetrics, at Helios University Hospital Wuppertal, Heusnerstrasse 40, 42283 Wuppertal, Germany

Anna Westermann

Damaris willer, georgios gitas.

3 Department of Gynecology-Robotic Surgery at European Interbalkan Medical Center, 57001 Thessaloniki, Greece

Zino Ruchay

Nicolai maass, leila allahqoli.

4 School of Public Health, Iran University of Medical Sciences (IUMS), Tehran 14167-53955, Iran

Ibrahim Alkatout

Associated data.

The datasets analyzed for the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

A rise in the rates of sexually transmitted diseases, both worldwide and in Germany, has been observed especially among persons between the ages of 15 and 24 years. Since many infections are devoid of symptoms or cause few symptoms, the diseases are detected late, may spread unchecked, and be transmitted unwittingly. In the event of persistent infection, the effects depend on the pathogen in question. Manifestations vary widely, ranging from pelvic inflammatory disease, most often caused by Chlamydia trachomatis (in Germany nearly 30% of PID) or Neisseria gonorrhoeae (in Germany <2% of PID), to the development of genital warts or cervical dysplasia in cases of infection with the HP virus. Causal treatment does exist in most cases and should always be administered to the sexual partner(s) as well. An infection during pregnancy calls for an individual treatment approach, depending on the pathogen and the week of pregnancy.

1. Introduction

According to the WHO, more than a million sexually transmitted infections (STI) are diagnosed every day throughout the world [ 1 ]. On average, every year 374 million persons contract a new infection with one of four leading sexually transmitted pathogens: Chlamydia trachomatis, Trichomonas vaginalis, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, or human papillomaviruses [ 2 ].

In the USA and in Germany, an increasing number of infections have been observed especially among adolescents and young adults between the ages of 15 and 24 years [ 3 ].

The transmission routes of viruses, bacteria, fungi, or parasites in connection with sexual intercourse usually occurs through the exchange of infectious fluids or through direct skin contact ( Table 1 ). However, many of these infections remain asymptomatic for a long period of time and are thus transmitted unwittingly or become persistent. This may cause long-term complications such as the pelvic inflammatory disease syndrome (PID), cervical dysplasia, or sterility. The gynecologist is then confronted with these conditions.

Spectrum of pathogens in STI [ 1 , 4 , 5 , 6 ].

In the following, the diagnosis, symptoms, treatment, and prevention of a selection of sexually transmitted diseases are presented. In addition, a case report is included in this review to provide a more clinical context.

2. Brief Case History

A 29-year-old patient with increased vaginal discharge for two weeks presented at a gynecologist’s office. She reported pain in the lower abdomen, fever, and chills during the last two days. She had recently started a relationship with a man who had had a male partner previously. Her partner had been combating a bladder infection for a significant period of time. The investigation of the patient revealed an increased quantity of greenish vaginal discharge. Intracervical and intravaginal swabs were obtained with the speculum. Palpation of the vagina disclosed cervical motion tenderness and significant pain on pressure in the right-sided adnexa. The laboratory investigation revealed elevated leukocytes (17,000/µL) and C-reactive protein (CRP) levels (97mg/L). How would you proceed ( Figure 1 )?

Flowchart of practical steps. Abbreviations: STI: Sexually transmitted infection, PID: Pelvic inflammatory disease; PCR: polymerase chain reaction.

3. Spectrum of Pathogens

Table 1 provides an overview of the spectrum of pathogens, divided into four groups: parasites, fungi, bacteria, and viruses. Furthermore, typical examples in each case are mentioned.

4. Etiology

Infection with a sexually transmitted disease usually occurs through the exchange of infectious fluids or by direct skin contact during sexual intercourse [ 1 ].

5. Predisposing Factors

The following risk factors apply to all sexually transmitted infections: frequent change of partners, young age, smoking, and drug abuse [ 7 ].

Furthermore, previous infections or a pre-existing infection may serve as predisposing factors for acquiring further pathogens [ 5 ]. For instance, a person infected with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is exposed to a higher risk of infection, persistence of infection, the upward migration of other pathogens from the cervix or the vagina towards the uterus, and further upward migration of germs into the peritoneum [ 7 ]. A persistent HPV infection also favors additional vaginal and cervical infections [ 8 ]. In the vagina of premenopausal women, the presence of lactobacilli is a prerequisite for maintaining an acidic environment with a physiological pH between 4 und 4.4, which prevents the augmentation of pathogenic or potentially pathogenic germs [ 8 ]. Any disruption of this natural microbiome of the vaginal tract increases the risk of infection [ 8 ]. Thus, vaginal dysbiosis is a risk factor for infection with sexually transmitted pathogens and the emergence of a PID, with the subsequent complications of subfertility and ectopic pregnancy [ 9 ].

Note: Young women are especially at risk [ 4 ].

6. Prevention

The best preventive measure is to enlighten the population about the benefits of condoms [ 10 ]. The latter do not merely protect sexual partners from undesired pregnancy but also effectively hinder the spread of STIs [ 10 ]. Female patients should use a condom during vaginal as well as anal sex, if it is not used by the male partner [ 10 ].

Regardless of the physician’s specialty, he/she is advised to record the patient’s sexual history as part of the patient’s general medical history. In asymptomatic patients with a positive history, the physician could then initiate diagnostic investigations and, if needed, appropriate treatment on a timely basis [ 11 ].

In the event of treatment for a diagnosed STI, simultaneous treatment of the patient’s partner is mandatory [ 11 ]. Women must be urged to inform their last sexual partners and also be advised to abstain from sexual intercourse until the treatment has been concluded [ 12 ].

Hepatitis B and HPV can be prevented by vaccination. The latter should ideally be given prior to first sexual intercourse [ 13 ]. An increase in HPV vaccination rates would be very desirable [ 14 ].

Postexposure prophylaxis with 1 × 200 mg doxycycline also appears to reduce the risk for STIs. Both advantages and disadvantages are discussed with regard to this therapy. At present, however, the advantages outweigh the disadvantages, so the therapy is recommended [ 15 ].

7. Clinical Symptoms and Diagnostic Investigation

Infections may be accompanied by a variety of symptoms. However, many infections remain asymptomatic. Therefore, it is important to establish the risk of an STI on the basis of a patient’s medical history and then initiate timely treatment.

The following questions may be asked: Do you currently have sexual intercourse? If yes, do you have intercourse with a single partner or with changing sexual partners? How many partners have you had in the last six months? What contraception do you use? Do you use condoms? What type of sexual intercourse do you have (oral, vaginal, and/or anal)? Incorporating these few questions in the general medical history of the patient yields crucial additional information about the patient in just a few minutes ( Table 2 ).

Sexual history.

The investigation of sexually transmitted diseases should be aligned to the respective risk situation, sexual practices, and the existing symptoms. However, an inspection of sexual organs and the perianal region should be a basic element of the investigation. In women, the speculum should be used for inspection, for obtaining the pH value from the vaginal wall, and for obtaining a swab of the cervix for the PCR investigation and a wet mount (phase contrast × 400), followed by palpation. The pH value and the wet mount must be obtained before any contact with the ultrasound gel. Finally, depending on the symptoms, an additional vaginal ultrasound investigation may aid the diagnosis. This would be especially important in women with abdominal symptoms of long duration. Depending on individual sexual practices, the patient’s mouth and throat should be inspected, and swab specimens should be obtained if necessary [ 16 ].

Note: A comprehensive examination must include an inspection of the mouth and a throat swab.

7.1. Human Papillomaviruses

Human papillomaviruses are a type of small DNA virus that infects the squamous epithelium of the skin or the mucous membranes. The majority of infections are eliminated by the body’s immune system. However, if the viruses persist the patient may develop condylomas, precancerous conditions, or even invasive cancer over time [ 17 , 18 ].

More than 200 types of the HP virus have been classified so far. A distinction is made between high-risk and low-risk types with regard to their carcinogenic potential.

The low-risk HPV types 6 and 11 are found most commonly in anogenital condyloma acuminata ( Figure 2 ) [ 19 ]. The incubation period is about two to three months [ 20 ]. The treatment of condyloma acuminata should be aligned to the location, number, and size of the warts. On the one hand, we have topical treatment, such as podophyllotoxin 0.5% solution, imiquimod 5% cream, or sinecatechins 10% ointment. A further alternative is surgery, which may consist of cryotherapy or the removal of the warts by means of electrocautery, laser, or scissors [ 21 ].

Perianal condylomata acuminata.

The high-risk HPV types 16 and 18 are responsible for 70% of HPV-induced cervical cancers and their preliminary stages or cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) [ 22 ]. The interval between an infection with an HP virus and the emergence of invasive cervical cancer is about 10 years [ 17 ]. After acetic acid staining, changes in the cervix on colposcopy are graded as minor or major (these may have a mosaic or dotted pattern) and should be investigated by performing a biopsy ( Figure 3 ) [ 23 ]. This is usually done in the course of a so-called investigative colposcopy, which follows after an unusual PAP smear report and/or in case of a persistent HPV infection, as part of secondary prevention of cervical cancer [ 18 ].

CIN III with major changes.

Primary prophylaxis is provided by the previously mentioned vaccination against HP viruses in order to prevent an infection in the first place [ 17 ]. Since 2007, the vaccination is recommended twice for girls between the ages of 9 and 14 years, with an interval of 2–6 months between the two doses [ 17 ]. After the age of 14 years, the vaccination should be given three times in intervals of 2–6 months because the antibody response is weaker in older adolescents [ 17 ]. Since 2018, this recommendation also applies to boys [ 17 ]. Initially, there was a bivalent vaccine that only contained the high-risk types 16 and 18, but we now have a nonavalent vaccine that includes types 6, 11, 31, 33, 45, 52, and 58 [ 13 ].

Note: Girls and boys should be vaccinated between the ages of 9 and 14 years.

7.2. Chlamydia trachomatis (Serotypes D to K)

Chlamydia are the most common sexually transmitted pathogens and are mainly found in young women between the ages of 14 and 25 years [ 24 ].

A chlamydia infection is usually asymptomatic (70–90% of cases), which causes the pathogens to persist for as long as a few years [ 16 ]. Upward migration of the germs may trigger types of inflammation such as endomyometritis, urethritis, salpingitis, and PID, with the late sequelae of subfertility and infertility [ 24 ]. Chlamydia can be proven by the nucleic acid amplification test (NAAT), which can be performed on a first-void urine sample or an endocervical swab specimen. The latter is the method of choice because a higher concentration of pathogens is found in the cervix [ 16 ].

Once a chlamydia infection has been established, the patient as well as the patient’s sexual partner should be treated even in the absence of symptoms [ 25 ]. The partner should be treated by the general physician or the urologist. Sexual abstinence should be maintained until the treatment has been concluded and the success of treatment has been established (control investigation at the earliest after 4–6 weeks) in order to avoid a ping-pong effect [ 25 ]. The treatment may consist of a single dose of 1 g azithromycin or 100 mg doxocycline taken orally twice daily for seven to 10 days [ 16 ].

Caution: 70–90% of chlamydia infections remain subclinical [ 25 ].

Tip: The partner must also undergo treatment in order to avoid a ping-pong effect.

7.3. Mycoplasma genitalium

In the last few years, Mycoplasma genitalium has been recognized as a sexually transmitted pathogen responsible for genitourinary infections with a high risk of preterm birth [ 26 ]. Little is known about its prevalence among women in Germany because we lack comprehensive swab tests. However, among young men in the United Kingdom, it is found in 10–35% of patients with urethritis [ 26 ]. Mycoplasma genitalium is involved in cervicitis and PID in 20–25% of cases [ 26 ]. The symptoms are similar to those of Chlamydia trachomatis (discharge, urethritis (dysuria in 30%), cervicitis, salpingitis, and reactive arthritis), but 50% of these infections are also asymptomatic.

The swab is tested by the same method as that used for chlamydia, namely the nuclear acid amplification test (NAAT)/PCR [ 26 ].

7.4. Neisseria gonorrhoeae

Neisseria gonorrhoeae belongs to the group of Gram-negative diplococci. Gonococci possess fimbriae (pili) by which they can bind to the epithelial layer and are particularly adherent to the human urethral and cervical mucosa as well as the conjunctiva of the eyes [ 27 ]. Typical symptoms include dysuria, pollakisuria, and a purulent cervical or urethral discharge. The acute phase is followed by a chronic phase with much less suppuration. If the pathogens are spread in the body by the hematogenic route, the patient may develop monoarthritis or even gonococcal sepsis with pleuritis, meningitis, or endocarditis. Ascending infection may cause salpingitis or pelvic peritonitis and subsequent sterility or a high risk of ectopic pregnancy [ 12 , 27 ].

The recommended diagnostic procedure is to demonstrate the pathogen in cultures of urethral and cervical swab specimens of the gonococci. Gonorrhea can be evidenced very clearly during menstruation because the germs are especially prone to multiplication in a sanguineous milieu [ 27 ]. Due to increasing resistance, it is very important to test for resistance and initiate guideline-oriented antibiogram-based treatment in case first-line therapy fails [ 16 ]. Gonococci are highly sensitive and are able to survive in a culture transport medium for no longer than 2–4 h, especially in a warm environment. This problem does not exist in PCR testing, but the latter does not permit a resistance test [ 27 ].

The routine treatment is a single dose of 1–2 g ceftriaxone either by the intravenous or the intramuscular route. As co-infection with chlamydia is frequently present, patients with low compliance should also receive a single dose of 1 g azithromycin orally. In compliant patients, one may initially await the results of the swab test in order to address a proven co-infection in a targeted manner ( Table 3 ) [ 16 ]. Here again, the partner must be treated simultaneously. Repeat swabs to check the success of treatment should—if subjected to a culture test—be obtained on the 5th and 10th day after the start of therapy. If both tests are negative, the patient may be considered cured [ 12 ].

Antibiotic treatment of gonorrhea (modified according to [ 16 ]).

7.5. Trichomonas vaginalis

A trichomonas infection is one of the most common sexually transmitted infections throughout the world, but its prevalence in Germany is low [ 28 ].

Trichomonads are protozoa that exist in different species as parasites in water, animals, and humans [ 28 ]. A trichomonas vaginalis infection initially causes a marked reproduction of protozoa in the vagina and a subsequent inflammatory reaction. The cervical glands release immunoglobulins which trigger the inflammatory reaction. As this reaction does not occur after hysterectomy, the trichomonads are able to grow unchecked. In the presence of bacterial vaginosis, the pH increases from 4.5 to 5.5. This is a “feel-good pH” for trichomonads, which is the reason why they occur more commonly in the presence of bacterial vaginosis [ 27 ]. Typical symptoms include a greenish-yellow discharge, itching, burning in the vestibulum, dyspareunia, dysuria, or cervix bleeding on contact. Clinically, however, the infection is asymptomatic in half of cases; this is equally true of men and women [ 27 ]. Trichomonads are identified directly on a wet mount of vaginal discharge. Under the microscope, one finds increased leukocytes, and trichomonads double the size of leukocytes. Trichomonads are pear-shaped, with a horned process at one end and four flagella at the other end ( Figure 4 ) [ 28 ]. In comparison, Figure 5 shows a physiological wet mount with lactobacilli (Döderlein bacilli) and vaginal epithelial cells. The wet mount should be viewed soon after sampling because trichomonads do not survive cold temperatures or the incidence of light [ 28 ]. The sensitivity is strongly dependent on the investigator. Therefore, it would be advisable to obtain a swab from the vagina or urethra or a urine sample and demonstrate trichomonads by means of a nucleic acid amplification test (NAA) or a multiplex PCR or a biochemical bedside test [ 28 ].

Wet mount of a patient with a Trichomonas vaginalis infection (phase contrast microscopy, 400-fold magnification, in 0.8% NaCl solution).

Premenstrual physiological wet mount (phase contrast microscopy, 400-fold magnification, in 0.9% NaCl solution): Figure 4 and Figure 5 were kindly provided by co-author Werner Mendling.

Once the pathogen has been confirmed, the treatment of choice is 500 mg metronidazole, given orally twice daily for 7 days [ 16 ]. A control investigation should be performed no earlier than 3 weeks later. All sexual partners of the preceding 60 days should be treated simultaneously [ 29 ].

7.6. Herpes Simplex Virus (HSV), Types 1 and 2

A distinction is made between various herpes viruses (varicella-zoster virus, cytomegalovirus, HSV-1, and HSV-2). While HSV-1 (oral type) triggers labial herpes, according to the traditional view HSV-2 is responsible for genital symptoms [ 30 ]. According to reports from the USA, however, HSV-1 is now found more frequently in genital herpes infections than it was earlier. This is probably due to orogenital contact, which is particularly common among adolescents and young adults [ 31 ].

The viruses are transmitted by direct physical contact during sexual intercourse or orogenital intercourse. Transmission (viral shedding) may also occur without clinical symptoms. About a half of the infections are asymptomatic [ 32 ]. Typical clinical manifestations include an edema of the vulva with several small blisters on inflammatory skin after an incubation period of 3–8 days ( Figure 6 ). The blisters erode over time and lead to painful ulcerations. Furthermore, the patient may experience general symptoms such as pain in the extremities or muscle pain, fever, or vomiting [ 32 ]. The typical clinical appearance is usually sufficient to establish the diagnosis. The recommended treatment is 200 mg aciclovir taken orally for 5 days [ 30 ]. Aciclovir ointment is used frequently but is considered ineffective and promotes (increasing) resistance to aciclovir [ 30 ].

Genital herpes.

7.7. Salpingitis, Pelvic Inflammatory Disease (PID)

PID is defined as an inflammation of the female pelvic organs with involvement of the peritoneum in the abdominal cavity, especially in the lower abdomen [ 7 ]. It usually occurs due to the ascension of pathogens, which may be transmitted during sexual intercourse. The infection spreads per continuitatem through the vagina/cervix, uterus, adnexa, and further into the abdominal cavity [ 7 ]. Cervicitis, endometritis, and salpingitis or adnexitis frequently cannot be differentiated from one another in terms of etiology, clinical appearance, or therapy [ 27 ]. This is because it is always an ascending disease from the cervix, with the exception of hematogenic genital tuberculosis which is rare in Germany, or the carried-over form of tuberculosis as in appendicitis. The term commonly used in the international published literature—pelvic inflammatory disease (PID)—expresses the fact that, in terms of pathomorphology, one may find accompanying inflammations such as parametritis, perimetritis, peritonitis, perihepatitis, perinephritis, perisplenitis, and tubo-ovarian abscess (TOA), as well as abscesses in the pouch of Douglas [ 33 ].

The most common sexually transmitted pathogens are Chlamydia trachomatis, Mycoplasma genitalium, and Neisseria gonorrhoeea [ 1 ]. In addition to the characteristic symptoms of the respective germs, the patient may develop general symptoms such as pain in the lower abdomen, fever, dyspareunia, and bleeding disorders [ 34 ].

PID may run an acute, subclinical, or chronic course (>30 days). The acute form is marked by severe pain in the lower abdomen, whereas the chronic type is marked by intermittent and less severe pain in the lower abdomen [ 7 ]. Right-sided pain in the upper abdomen may be indicative of a chronic PID or a Fitz-Hugh–Curtis syndrome ( Figure 7 ). The latter is a form of perihepatitis with adhesions between the abdominal wall and the liver. Such adhesive bands in the peritoneum are usually discovered incidentally in a laparoscopy, several years after their emergence.

Fibrinous adhesions between the peritoneum and the liver surface (Fitz-Hugh–Curtis syndrome) [ 5 ].

Predisposing factors for PID include smoking and lack of immunocompetence, such as an HIV infection. The most important risk factor, however, is an abnormal vaginal microbiome, especially in cases of bacterial vaginosis, and an STI. An intact vaginal microbiome, on the other hand, has a protective effect [ 33 ].

As in the case described earlier, the patients primarily experience pain in the lower abdomen. During the diagnostic investigation of PID, all other potential gynecological and non-gynecological differential diagnoses should be taken into account and ruled out ( Table 4 ). A standard step is to obtain a urine sample and ensure the absence of a pregnancy.

Differential diagnosis of PID (modified according to [ 33 , 34 ].

The diagnosis of salpingitis/PID is unreliable and is established correctly by clinical investigation in a mere 60% of cases [ 33 ]. It is most reliably diagnosed by laparoscopy, which dates back to Jacobsen and Weström in Sweden as early as in 1969 [ 33 ]. In terms of method and the number of correctly diagnosed patients, this approach has not been superseded to date. One should obtain smears from the endings of the fimbriae (PCR test for Chlamydia trachomatis and Mycoplasma genitalium, PCR or culture including a general bacterial culture for gonococci). Fluid in the pouch of Douglas is not suitable for this purpose. The problem is that chlamydia, in the case of salpingitis, can be found at the fallopian tube in about 30% of cases but is seen in the cervix, urethra, or urine in just a half of these cases [ 35 ].

The diagnosis can be established with adequate certainty when the investigator finds a bacterial vaginosis or cervicitis either clinically or in the wet mount, in addition to pain in the lower abdomen and pressure-sensitive adnexa. If the patient also has fever in excess of 38.2 °C the diagnosis is accurate in about 80% of cases [ 34 ]. If one finds thickening of the adnexa and pathological inflammatory parameters in blood, the diagnosis is correct in more than 90% of cases [ 34 ]. A laparoscopy is considered unnecessary in this setting, especially in cases of mild disease [ 36 ].

In these instances, however, the clinician remains unaware of chlamydia at the fimbrial ends.

PID is treated with antibiotics. Mild disease may be treated on an outpatient basis with a combination of a single dose of 1–2 g ceftriaxone IV plus 100 mg doxycyclin given orally twice a day and 500 mg metronidazole given orally twice a day for 10 to 14 days [ 16 ]. In a case of more severe symptoms, the patient will need to undergo in-hospital treatment. The therapy initially consists of 2 g ceftriaxone given by the intravenous route once daily and 100 mg doxycyclin also given by the intravenous route twice daily for 3–5 days. This is followed by 100 mg doxycyclin taken orally twice a day and 500 mg metronidazole taken orally twice a day for a further 7–10 days [ 7 ].

Sexual abstinence is recommended until complete cure. Control swabs should be obtained from the patient and her sexual partner(s) at six weeks after conclusion of the antibiotic treatment [ 34 ].

8. Continuation of Case Report (Continued from Page 2)

The patient reported above also had elevated inflammatory parameters. The vaginal ultrasound investigation, which was unpleasant for the patient, and the abdomen ultrasound investigation showed a thickened fallopian tube (>10 mm) on the right side. The Doppler investigation revealed increased vascularity. A hyperechogenic fluid was noted in the pouch of Douglas. We suspected a tubo-ovarian abscess on the right side as a complication of PID ( Figure 8 ). We first initiated intravenous antibiotic therapy and then performed a secondary laparoscopy for drainage of the abscess after an interval of 3–4 days. Intraoperatively, we found a few adhesions; the right fallopian tube was adherent to the tubo-ovarian abscess. Therefore, we were unable to preserve the fallopian tube. In the region of the liver, we found adhesions to the abdominal wall by way of perihepatitis (Fitz-Hugh–Curtis syndrome). A surgical adhesiolysis is currently not recommended as a general measure because its value has not been clearly proven [ 36 ].

Vaginal ultrasound investigation showing the tubo-ovarian abscess in the right-sided adnexa. The uterus is marked with a star [ 5 ].

Table 5 summarizes the individual STIs.

Summary of STIs (modified according to [ 1 , 5 , 16 ].

9. Infertility

A further potential consequence of ascending infection, especially in the case of Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae, is infertility [ 4 ].

After a chlamydia infection and subsequent PID, the patient may develop a post-inflammatory occlusion of the fallopian tubes and intra-abdominal adhesions. One therefore finds higher rates of ectopic pregnancies or tubal factor infertility in these instances [ 37 ]. Furthermore, in some cases the fallopian tubes cannot be preserved after surgical treatment.

In Germany, all sexually active women below the age of 25 years are offered a chlamydia screening test at the expense of the health insurance in order to reduce the risk of infertility. However, it should be noted that in some cases, chlamydiae are only found in the funnel of the fimbriae and not in urine or in a swab specimen of the cervix [ 35 ].

10. Infections during Pregnancy

10.1. screening during pregnancy.

Sexually transmitted diseases may occur during pregnancy. Depending on the time point and the respective pathogen, the infection may be associated with a number of risks. The maternity guidelines of the Federal Joint Committee recommend a serum screening for syphilis with the TPHA test, a serological test for antibodies to the rubella virus, and a test for genital Chlamydia trachomatis infection. The patient may be offered a pooled culture of samples taken from the rectum and vagina for Streptococcus agalactiae (B streptococci) for intrapartal prevention of neonatal early-onset sepsis, separate tests for HSV 1 and HSV 2 (as recommended in the guidelines) in case of suspected genital herpes, and screening for toxoplasmosis or a cytomegalovirus infection.

10.2. Chlamydia trachomatis

If a patient contracts an infection with Chlamydia trachomatis during pregnancy, she is subject to a higher risk of abortion, preterm birth, and a low birth weight [ 25 ]. In the presence of an active chlamydia infection during vaginal delivery, the germs are passed on to the newborn infant in 2/3rds of cases. In the event of an infection, the neonate may develop inclusion conjunctivitis (18–50%) or atypical pneumonia (11–18%) [ 25 ]. At the screening investigation, all pregnant women in Germany are tested for chlamydia at the start of their pregnancy in order to initiate prompt antibiotic treatment [ 38 ]. The maternal risk of postpartum endometritis is higher in the presence of a chlamydia infection. The symptoms include fever, mild pain at the margins of the uterus, and, in the case of anaerobic bacteria, additional fetid lochia, lochial congestion, and dysfunctional uterine bleeding typically 4–6 weeks after the delivery [ 25 ]. Especially in cases of repeat bleeding, the clinician should first rule out differential diagnoses such as retained placenta and then take a chlamydia infection into account [ 38 ]. If the patient develops endometritis, the clinician should take a swab to demonstrate the pathogen in question and then use an agent to promote contractions as well as antibiotic treatment with ampicillin [ 39 ].

10.3. Trichomonads

An infection with trichomonads during pregnancy raises the risk of preterm birth by a factor of 1.4 as well as the risk of premature rupture of the membranes. Therefore, treatment with metronidazole should be given during pregnancy [ 40 ].

10.4. Herpes Simplex Virus Types 1 and 2

Among mothers with an acute herpes simplex infection, only 5% of the fetuses are infected by the intauterine route, usually with HSV 2 [ 41 ]. Mothers with severe infection in the first trimester are subject to a high risk of abortion, stillbirth, or malformations in 50% of cases, and the risk of perinatal mortality is 50% [ 41 ].

In about 90% of cases, however, HSV (in about three fourths of cases it is HSV 2 that may cause a more severe course of disease) is transmitted during birth [ 41 ]. In a very small number of cases, the infection occurs during the first few hours or days after the delivery. In 50% of cases, the mother who passes on the infection to the infant has a primary HSV infection, whereas the transmission risk of an HSV recurrence during birth is just 2–5% [ 41 ]. However, it should be noted that in 70% of perinatal infections, the maternal HSV infection remains asymptomatic [ 41 ].

The child’s symptoms usually start 2 or 3 weeks after birth. Depending on the severity of disease, the infection is associated with a high lethality and a risk of permanent damage [ 41 ].

Therefore, the guidelines recommend that mothers with a primary infection be offered an elective Caesarean section; the risk of a perinatal herpes infection of the neonate is about 30% in these cases [ 41 ]. However, if a genital herpes infection is identified in the first or second trimester, one may anticipate maternal IgG antibodies with the ability to cross the placental barrier. In these cases, a vaginal delivery may be permitted in the presence of negative swab tests and no clinical symptoms [ 42 ]. Knowledge of the mother’s virus status helps in counseling the mother about the delivery. The father or any other infected person (midwife, obstetrician, nurse) may also infect the newborn.

11. Conclusions for Clinical Practice

- In the presence of a genitourinary infection, the clinician must take sexually transmitted pathogens and simultaneous treatment of the partner into account.

- The consequences of untreated STDs include, in addition to ascending infections, infertility and chronic recurrent lower abdominal pain.

- Early vaccination for HP viruses at the age of 9–14 years and, as far as possible prior to first sexual intercourse, is associated with a markedly lower risk of the sequelae of HPV infection as well as the acquisition of other STI.

- Young male and female patients should be informed early about the benefits of a condom in reducing and preventing the spread of STIs.

- The preventive potential of a balanced vaginal microbiome is being recognized to an increasing extent through the options of modern non-culture-based techniques.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge financial support by DFG within the funding programme Open Access Publikationskosten.

Abbreviations

Funding statement.

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sector.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.W., V.G., L.A., N.M. and I.A.; Project administration, W.M., A.W., D.W. and I.A.; Supervision, N.M. and I.A.; Visualization, G.G., Z.R. and L.A.; Writing—original draft, K.W. and I.A.; Writing—review and editing, V.G., A.W., D.W., G.G., Z.R. and L.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

All procedures involving human participants were performed in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee, as well as the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of interest.

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Review Article

- Published: 02 August 2022

Sexually transmitted infections and female reproductive health

- Olivia T. Van Gerwen ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-9362-6234 1 ,

- Christina A. Muzny ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-4005-3858 1 &

- Jeanne M. Marrazzo 1

Nature Microbiology volume 7 , pages 1116–1126 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

22k Accesses

40 Citations

452 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Applied microbiology

- Bacterial infection

- Microbiology

Women are disproportionately affected by sexually transmitted infections (STIs) throughout life. In addition to their high prevalence in women, STIs have debilitating effects on female reproductive health due to female urogenital anatomy, socio-cultural and economic factors. In this Review, we discuss the prevalence and impact of non-HIV bacterial, viral and parasitic STIs on the reproductive and sexual health of cisgender women worldwide. We analyse factors affecting STI prevalence among transgender women and women in low-income settings, and describe the specific challenges and barriers to improved sexual health faced by these population groups. We also synthesize the latest advances in diagnosis, treatment and prevention of STIs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Prevalence of STIs, sexual practices and substance use among 2083 sexually active unmarried women in Lebanon

Hormonal contraceptive use and the risk of sexually transmitted infections: a systematic review and meta-analysis

Antimicrobial treatment and resistance in sexually transmitted bacterial infections

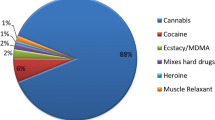

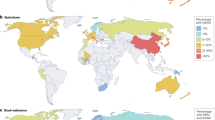

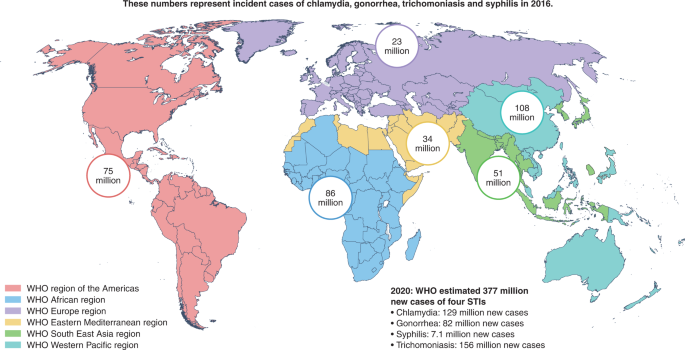

Sexually transmitted infections (STIs) cause reproductive morbidity worldwide. In 2019, the World Health Organization (WHO) estimated that there were 376 million new episodes of chlamydia, gonorrhoea, syphilis and trichomoniasis (Fig. 1 ) 1 . In 2019, the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported a nearly 30% increase in chlamydia, gonorrhoea and syphilis between 2015–2019 and a rising incidence of all STIs for the sixth consecutive year 2 . In the United States in 2018, several STIs were estimated to be more prevalent among women than men, including gonorrhoea, chlamydia and trichomoniasis 3 . Women often experience complications from STIs, including infertility and chronic pelvic pain, that can have lifelong impact 4 . STIs can increase peripartum morbidity and mortality in both industrialized areas and in rural and underserved areas of developed countries.

WHO global regions and the incident cases of four STIs (chlamydia, gonorrhoea, trichomoniasis and syphilis) from 2016 estimates. The WHO estimates of new cases of these four STIs worldwide in 2020 are shown at the bottom right of the figure.

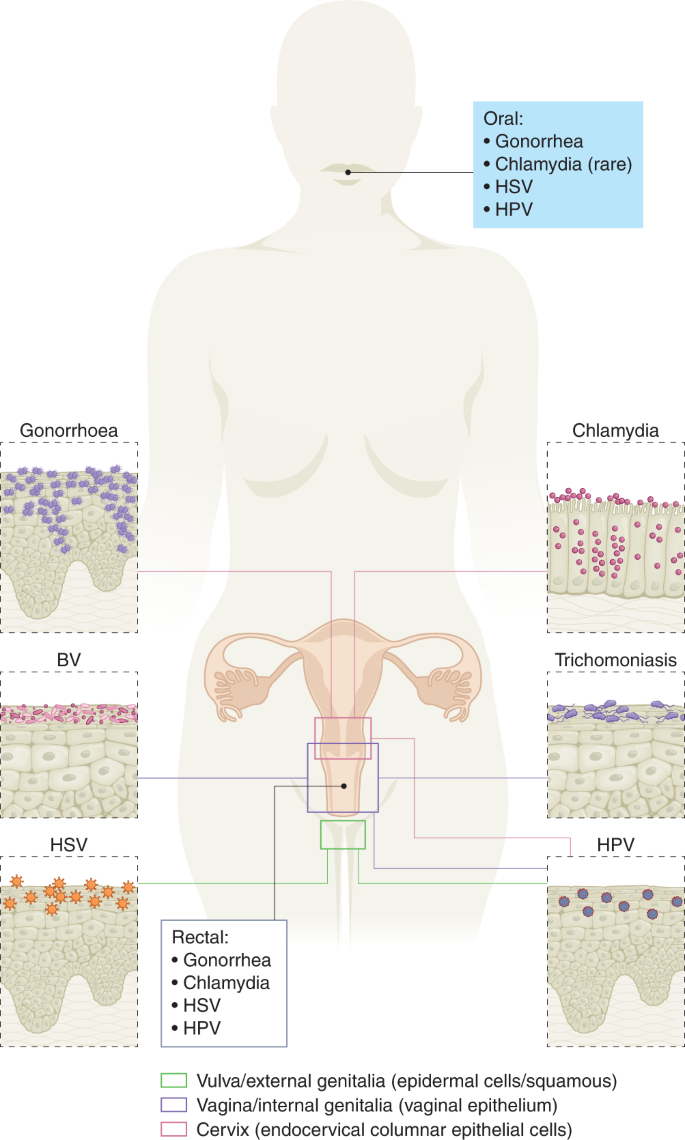

The larger impact of STIs in women compared with men is in part due to the female anatomy (Fig. 2 ). A woman’s urogenital anatomy is more exposed and vulnerable to STIs compared with the male urogenital anatomy, particularly because the vaginal mucosa is thin, delicate and easily penetrated by infectious agents 5 . The cervix at the distal end of the vagina leads to the upper genital tract including the uterus, endometrium, fallopian tubes and ovaries. STIs can produce a variety of symptoms and effects at different parts of the female reproductive tract, including genital ulcer disease, vaginitis, pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) and infertility 6 .

STIs can affect genital and extragenital sites in women. Gonorrhoea and chlamydia typically present as cervicitis. Bacterial vaginosis (BV) and trichomoniasis can also cause cervicitis, but more commonly manifest as vaginitis. HSV and HPV most typically affect the vulva or external genitalia of women.

In this Review, we focus on the impact of non-HIV bacterial, viral and parasitic STIs on the sexual and reproductive health of cisgender women (Table 1 ). We discuss adverse outcomes of STIs, treatment and prevention, including vaccine development. STIs in transgender women (TGW) are discussed in brief because an exhaustive review of STIs in this population has recently been published 7 , 8 . We do not review developments in HIV prevention or treatments in women and refer readers to reviews published elsewhere 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 . Hepatitis B was also excluded as it would merit its own dedicated review.

Human papilloma virus (HPV) is a small circular double-stranded DNA papilloma virus that infects cutaneous or mucosal epithelial tissues in humans 14 . More than 200 genotypes of HPV have been identified, including at least 40 that affect the genitals, and are grouped into high- or low-risk 15 . Although HPV infection is often asymptomatic and self-limiting, symptoms can include anogenital warts, respiratory papillomatosis, and precancerous or cancerous cervical, penile, vulvar, vaginal, anal and oropharyngeal lesions 16 . HPV is the most common STI worldwide, with most sexually active people exposed to it during their lifetime 17 . Among women, HPV prevalence is highest among those in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), peaking at <25 years old 18 . While most women clear HPV spontaneously, persistent infection can cause cervical, anal, or head and neck cancer 19 . Cervical cancer has been a leading cause of mortality among women for decades; in 2012, there were 266,000 HPV-related cervical cancer deaths worldwide, accounting for 8% of all female cancer deaths that year 20 . Cervical cancer also causes substantial genitourinary morbidity, including radiation treatment-related infertility and urinary or faecal incontinence 21 . Persistent infection with high-risk HPV types is responsible for 99.7% of cervical squamous cell cancer cases 22 .

In women with HPV, one factor that increases the risk of progression to cervical cancer is co-infection with a different STI 23 . HIV, for example, increased the oncogenic potential of HPV, especially in immunosuppressed women 24 . Women adherent to antiretroviral therapy are less likely to acquire high-risk HPV types, and progression to pre-malignant or malignant lesions is reduced 25 . In HIV-negative women, persistent HPV increases the risk of acquiring HIV, but the underlying mechanism is unclear 23 . Persistent HPV and Chlamydia trachomatis co-infection has also been proposed as a cofactor in the progression of cervical malignancy in women, with chronic inflammation as a mediating factor 26 . For these reasons, primary prevention using HPV vaccination is essential.

HPV vaccine development is one the most important medical achievements of the twenty-first century. Universal HPV vaccination has the potential to prevent between 70% to 90% of HPV-related disease, including anogenital warts and HPV-associated cancers 27 . The global strategy of the WHO is to vaccinate 90% of females by age 15, in addition to screening and treating older females, with the goal of eliminating cervical cancer in the next century 28 . There are four available HPV vaccines: Gardasil (Merck, 2006), Ceravrix (GlaxoSmithKline, 2007), Gardasil 9 (Merck, 2014) and Cecolin (Xiamen Innovax Biotech Co., 2021) 27 . All offer protection against HPV16 and HPV18 high-risk genotypes, which account for 66% of all cervical cancers (Table 2 ). Gardasil 9 targets 5 additional oncogenic HPV types (HPV31, 33, 45, 52, 58) that account for another 15% of cervical cancers. Gardasil products also offer protection against HPV6 and HPV11, which cause >90% of genital warts 16 . Cervarix and Cecolin offer protection only against HPV16 and HPV18 29 .

HPV vaccination programmes have resulted in a profound reduction in pre-malignant and malignant cancers in women 30 . In England since 2008, HPV immunization has been routinely recommended for girls aged 12–13 years, with a catch-up programme at 14–18 years. A 2019 observational study of this population reported that for those vaccinated at ages 12–13, there was an estimated 87% relative reduction in cervical cancer rates and a 97% risk reduction for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia 3 compared with a reference unvaccinated cohort. Among vaccinated cohorts in the same study, since 2008, investigators estimated 448 fewer cervical cancers and 17,235 fewer cervical intraepithelial neoplasia 3 cases than expected by 2019 31 . The study authors concluded that the immunization programme in England has almost eliminated cervical cancer in women born since 1995. Programmes in Denmark and Sweden have reported similar levels of success 30 .

These findings show that elimination of cervical cancer in the short term is possible with primary prevention programmes, at least in adequately resourced countries. In other settings, infrastructural and cultural challenges can make establishment of such programmes difficult. Efforts to implement HPV vaccination programmes in all areas are essential, especially to vaccinate girls before sexual debut and complete all doses in the vaccination series 32 .

HPV-related anal cancer is also of concern for women, especially those with HIV 33 . HPV has been linked to 80% of anal cancer cases in the United States 34 . Women living with HIV have a 7.8-fold higher risk of anal carcinoma in situ and a 10-fold higher risk of anal squamous cell carcinoma compared with women without HIV 35 , 36 . In contrast to cervical cancer, it is less clear whether screening for HPV-associated precancerous lesions will impact the incidence of anal cancers. The Anal Cancer HSIL Outcomes Research (ANCHOR) study is an ongoing trial investigating whether treatment of precancerous high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (HSIL) is effective in reducing the incidence of anal cancer in people with HIV, including women ( NCT02135419 ). Preliminary results in 4,446 participants demonstrated that removal of HSILs identified on screening anal Papanicolaou smears notably reduced the risk of progression to anal cancer 37 . Currently, there are no routine screening recommendations for anal cancer for women 16 .

Detection of high-risk HPV based on cytology screening of precancerous anal lesions is challenging because sensitivity is limited and diagnosis requires the provision of adequate follow-up infrastructure (for example, high-resolution anoscopy). Molecular assays might reduce the number of unnecessary high-resolution anoscopies performed 38 , 39 .

Genital herpes is caused by herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) or type 2 (HSV-2), which are members of the Herpesviridae family. In 2016, the WHO estimated that up to 192 million people were affected by genital HSV-1 and 491 million people by HSV-2 40 . Although HSV-1 is more commonly associated with oral disease (‘cold sores’), the proportion of sexually transmitted anogenital herpes attributed to HSV-1 has increased over time, especially among women aged 18–30 years old 41 . HSV-2 is the primary causative agent of genital herpes infections globally 42 . Although HSV infection is chronic and lifelong, many women experience few or no symptoms. When present, symptoms range from painful genital sores to discomfort that is sometimes misdiagnosed as recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis. HSV infections can be managed with oral antivirals including suppressive therapy, such as valacylovir (Table 3 ) 16 .

One devasting consequence of HSV infection in pregnant women is neonatal herpes. In the U.S., the incidence of neonatal HSV has increased, with 5.3/10,000 infants affected in 2015, up from 3.75/10,000 births in the early 2000s 43 , 44 . Neonatal herpes manifests when neonates are infected with HSV during vaginal birth. Neonatal infection can affect the skin, eyes or mouth, but the central nervous system or multiple organs can also become infected; incidence of central nervous system manifestations of neonatal herpes is estimated to be between 1 in 3,000 and 1 in 20,000 live births. Mortality in such cases without treatment is as high as 85%, with a high likelihood of long-term neurological sequalae in those infants who do survive 45 . Mother-to-child transmission is preventable by elective Caesarian-section delivery in mothers with active herpetic lesions.

HSV-2 infection in women is associated with a threefold increased risk of HIV acquisition and horizontal transmission 46 , 47 . One analysis concluded that an estimated 420,000/1.4 million HIV infections (population attributable fraction 29.6% (22.9–37.1)) were attributed to HSV-2 infections worldwide 48 .

Diagnosis of genital herpes is challenging because characteristic lesions often resolve by the time patients present to care. A presumptive diagnosis can be made by physical examination but should be confirmed with type-specific nucleic acid amplification testing (NAAT) or culture 16 . The use of HSV serologies is discussed in detail elsewhere 16 , 49 .

Episodic and suppressive treatments for HSV do not prevent recurrence. Even if indefinite suppressive antivirals are administered, HSV shedding can still occur 50 . Lifelong antivirals are not cost effective and perfect adherence can be challenging for patients 16 . Therefore, there is continued interest in developing vaccines for HSV-2 (Table 2 ). Despite extensive investigation of many candidate HSV vaccines, none have performed well enough in clinical trials to be brought to the market. In the 1990s, initial studies investigated subunit vaccines, which aimed to select targets that induce immune responses against HSV-2 51 . One such vaccine candidate, Simplirix (GSK), targeted the glycoprotein D subunit (gD), which facilitates host cell entry by HSV. Initial trials demonstrated 74% efficacy in HSV-1/HSV-2 seronegative women with seropositive partners, but these results were not replicated in seronegative men 52 . Given the promising initial efficacy findings among seronegative women, additional trials were performed in women; however, they largely failed to meet primary endpoints. Most notably, efficacy of the same GSK gD subunit vaccine in the Herpevac trial was only 58% and 20% against HSV-1 and HSV-2, respectively 53 . The discrepancy in results between these two studies is puzzling, but given that gD is known to elicit a strong immune response, it has been a component in several additional vaccine candidates 51 , 54 . A major concern with HSV subunit vaccines is cost, so research and development strategies have pivoted towards cheaper nucleic acid-based vaccine platforms and the potential of live-attenuated vaccines 55 , 56 , 57 . Given the complex immunology of HSV, there is interest in understanding the role of mucosal immunity in the genital tract to aid the development of a successful vaccine against HSV-2 58 .

Bacterial STIs

Syphilis is caused by the spirochaete Treponema pallidum subspecies pallidum . Main symptoms of syphilis include anogenital or oral painless chancres in primary syphilis, diffuse rash in secondary syphilis, aseptic meningitis and pan uveitis 59 . The impact of syphilis on women has intensified over the past decade. In the United States between 2014 and 2018, rates of primary and secondary syphilis among women doubled and similar trends have been noted globally 1 , 60 . Rates of primary and secondary syphilis are lower among US women compared with men who have sex with men (MSM), but cases among heterosexual women increased by 178.6% between 2015 and 2019, suggesting an epidemic mediated by heterosexual transmission 60 . Increasing primary and secondary syphilis cases among women are also predominant among those of childbearing age 60 . Therefore, the rising rates of congenital syphilis are not surprising; in 2013, congenital syphilis occurred in 9.2 cases per 100,000 live births and in 2020 increased to 57.3 cases per 100,000 live births 60 . Tragically, this trajectory has resulted in increasing numbers of syphilitic stillbirths and congenital syphilis-related infant deaths 60 . Syphilis in pregnancy is the second leading cause of stillbirth globally and has been associated with low birth weight, neonatal infections and preterm delivery 61 . Congenital syphilis is preventable with early detection and prompt treatment of maternal infection; however, many women lack access to adequate syphilis treatment, even with early diagnosis 62 . Limited prenatal care and timely syphilis testing are barriers to preventing congenital syphilis, especially in LMICs where prenatal care and syphilis screening resources are limited 63 . Currently, the CDC and WHO recommend routine serologic screening of pregnant women at their initial prenatal visit, at 28 weeks’ gestation and at the time of delivery in high-prevalence settings, although recommendations vary geographically 16 , 64 .

Consequences of untreated syphilis in pregnancy are dire for both mother and neonate. Options for effective treatment are straightforward because syphilis is treatable with penicillin G and antimicrobial resistance is essentially non-existent 16 . Depending on the stage and site of infection, treatment regimens differ in terms of penicillin dose frequency and route of administration, as discussed elsewhere 16 . Doxycycline can be given in certain situations to non-pregnant women (that is, in cases of true penicillin allergy) to effectively treat primary, secondary or latent syphilis; however, penicillin G is the only antimicrobial agent that has demonstrated efficacy in preventing congenital syphilis 65 . Thus, treatment of women with a true penicillin allergy and those who are unable to access penicillin G is challenging. The ideal dosing regimen of penicillin G for syphilis treatment during pregnancy is not clear, but evidence suggests that an additional injection of benzathine penicillin G after the initial dose reduces the risk of congenital syphilis 65 , 66 , 67 .

Chlamydia trachomatis is an obligate intracellular Gram-negative bacterium that can replicate only inside a host cell 68 . Although usually asymptomatic in women, C. trachomatis infection can result in reproductive damage, and when untreated, it can be associated with PID, ectopic pregnancy, chronic pelvic pain and tubal infertility. In the U.S., women <25 years account for most infections, so annual screening in this age group is recommended to reduce the frequency of PID and other adverse health outcomes 16 , 60 , 69 . Perinatal maternal Chlamydia infection is associated with preterm birth, stillbirth, low birth weight and neonatal infections such as pneumonia and conjunctivitis 69 , 70 , 71 .

The composition of the vaginal microbiome probably has a role in host defence against chlamydial infection. An optimal vaginal microbiota is dominated by Lactobacillus crispatus , which produces lactic acid that has antimicrobial properties and can inactivate C. trachomatis , decreasing the likelihood of ascension of this pathogen into the upper genital tract 72 . Women with bacterial vaginosis, defined by a paucity of L. crispatus and other favourable vaginal lactobacilli, and an increased abundance of facultative and strict anaerobes, may have reduced immune defence against C. trachomatis , leading to increased risk of acquiring this pathogen as well as Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Trichomonas vaginalis 73 .

Prompt diagnosis and treatment are the best approaches to preventing the reproductive morbidity and sequelae associated with chlamydia (Table 3 ). For decades, single-dose oral azithromycin (2 g) was a first-line treatment option for C. trachomatis , offering the option of directly observed therapy. Recent data suggest that this regimen is inferior to oral doxycycline given twice daily for 7 days, specifically for women and men with urogenital and rectal infection 74 . Thus, the only currently recommended first-line agent for uncomplicated urogenital or rectal chlamydia is multidose doxycycline 16 . This change in guidance in 2021 was driven by data related to men with chlamydia; more efficacy studies are needed in women 75 . However, rectal chlamydial infection has been found to occur in women more frequently than previously thought. In addition to receptive anal sex, auto-inoculation from cervicovaginal chlamydial infection may yield rectal infection 76 , 77 . While single-dose azithromycin is efficacious for urogenital C. trachomatis in women, the possibility that concomitant rectal infection that may not be adequately treated with this regimen is concerning 78 . Single-dose azithromycin is also recommended for the treatment of chlamydia in pregnant women as doxycycline is not safe in pregnancy 16 .

Currently, no vaccines are available for C. trachomatis 79 . Given the high rates of re-infection, especially among young women 80 , vaccines offer the promise of both protecting from disease and reducing antibiotic use, treatment burden, preventing development of antimicrobial resistance in other infections (for example, gonorrhoea) and decreasing reproductive morbidity 81 , 82 . A major challenge in C. trachomatis vaccine research has been targeting both humoral and cell-mediated immune responses in infected individuals; complete protection requires activity in both pathways 83 , 84 . Comprehensive monitoring of this complicated immune response is difficult. Despite approximately 220 chlamydial vaccine trials having been conducted from 1946 until the present—over seven decades—an effective vaccine remains elusive (Table 2 ).

Gonorrhoea is caused by N. gonorrhoeae , a Gram-negative diplococcal bacterium. N. gonorrhoeae can yield mucosal infections in epithelia of the urogenital tract and the ectocervix 85 . Gonorrhoea is extremely common worldwide, with an estimated global annual incidence of 86.9 million adults and a prevalence among women of 0.9%, with the greatest burden among women in LMICs 1 . Genitourinary gonorrhoea can present in women as cervicitis or urethritis but is mostly asymptomatic 86 . If untreated, gonococcal infections can result in serious complications such as PID, tubal infertility, ectopic pregnancy and disseminated gonococcal infection 87 , 88 , 89 . Gonorrhoea also facilitates transmission of HIV and other STIs 86 . Similar to other bacterial STIs, untreated gonorrhoea has been associated with adverse birth outcomes such as preterm birth, low birth weight and premature rupture of membranes 90 , 91 . Perinatal exposure to an infected cervix puts neonates at risk for serious complications such as gonococcal sepsis and ophthalmia neonatorum, the latter of which can lead to blindness if untreated 92 .

When detected in a timely manner, gonorrhoea can be treated and its negative sequelae can be avoided. The landscape of gonorrhoea treatment, however, has been in flux over the past several decades due to the emergence of resistance to multiple antimicrobials among gonococcal isolates worldwide 60 , 93 . The Gonococcal Isolate Surveillance Program (GISP) was established in the United States in 1986 to monitor trends in antimicrobial resistance among urethral N. gonorrhoeae isolates. This programme is integral in generating clinical guidance on gonococcal therapy 94 . Since the generation of GISP, notable gonococcal resistance has emerged to several antimicrobial drug classes, including fluoroquinolones (for example, ciprofloxacin) and macrolides (for example, azithromycin); use of these agents is no longer recommended in national treatment guidelines 16 , 95 . The 2021 CDC STI treatment guidelines currently recommend cephalosporins for first-line gonorrhoea treatment, specifically 500 mg intramuscular ceftriaxone for people weighing less than 150 kg 16 . Oral cephalosporins, such as cefixime, are not recommended as first-line treatment, given many instances of treatment failure and limited efficacy in treating pharyngeal gonococcal infection 96 , 97 , 98 , 99 , 100 . While ceftriaxone remains a reliable choice in most situations, there is growing concern for widespread ceftriaxone-resistant gonococcal isolates. Such strains have been reported in Denmark, France, Japan, Thailand and the United Kingdom; alternative treatment options are limited 101 , 102 , 103 , 104 .

In the past 10 years, several novel anti-gonococcal antimicrobials have been conceptualized and developed 105 , 106 , 107 . One example is zoliflodacin, a single-dose spiropyrimidinetrione antimicrobial that works by inhibiting DNA biosynthesis through blocking gyrase complex cleavage 108 . In a multicentre Phase 2 trial in the United States, most patients who received zoliflodacin for uncomplicated urogenital and rectal gonococcal infection were successfully treated. Efficacy for treating pharyngeal infections was less impressive, with only 50% and 82% of those who received 2 g and 3 g of zoliflodacin, respectively, achieving cure. Regardless, several studies have shown that zoliflodacin continues to have excellent in vitro activity against multidrug-resistant gonococcal isolates, including those with resistance to extended-spectrum cephalosporins 109 , 110 .

Given global increases in antimicrobial resistance, vaccines preventing acquisition of gonorrhoea are urgently needed. Modelling studies have demonstrated that a gonococcal vaccine of moderate efficacy and duration would have a substantial impact on disease prevalence and prevention of adverse reproductive sequelae 111 . The WHO has named N. gonorrhoeae as a global priority, hence increasing interest and funding have been funnelled into development of candidate gonorrhoea vaccines ( Table 2 ) . Fortunately, available tools for other gonococcal species may offer opportunity for N. gonorrhoeae prevention, an approach currently under study. The rMenB+OMV NZ vaccine (Bexsero) was first licensed in the European Union in 2013 and in the United States in 2015 for prevention of meningococcal disease caused by N. meningitidis serogroup B 112 . An earlier version of a vaccine aimed at a meningococcal B outbreak (MeNZB) was introduced in New Zealand in the early 2000s. A retrospective case-control study revealed that this vaccine programme not only led to a decrease in meningococcal disease, as expected, but had an estimated reduction of future gonorrhoea acquisition of 31% (95% CI: 21–39) in those who received 3 doses of vaccine 113 . Clinical trials are ongoing to assess the efficacy of Bexsero in preventing urogenital and/or rectal gonorrhoea (NCT 04350138).

Parasitic STIs

Trichomoniasis.

Globally, trichomoniasis has an enormous impact on women as the most common non-viral STI 1 . It is caused by the parasitic protozoan Trichomonas vaginalis , and results in vaginal discharge and dysuria when symptomatic 114 . T. vaginalis has also been associated with adverse birth outcomes (for example, preterm birth, low birth weight, preterm rupture of membranes) 115 and an increased risk of HIV acquisition and transmission, PID and cervical cancer related to HPV infection 116 , 117 , 118 , 119 . Despite these significant health impacts, has been viewed as a nuisance infection and investigation has been limited until recent years. Globally, trichomoniasis is not currently reportable 120 , 121 . Marked racial and geographic disparities have also been described in relation to T. vaginalis infection. In the United States, according to the most recent National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey data, the overall prevalence of T. vaginalis in women in the United States is 1.8% 122 , being 6.8% among black women compared with 0.4% among women of other racial/ethnic backgrounds 122 . The global epidemiology of trichomoniasis is less well-defined, but one systematic review including men and women noted a prevalence range of 3.9%–24.6% in LMICs from Latin America and Southern Africa 123 .

Diagnosis of T. vaginalis has greatly improved in women (and men) over the past decade with the use of highly sensitive and specific NAAT tests 124 , 125 , 126 , 127 . Treatment recommendations for women with T. vaginalis have been largely unchanged for decades, with 5-nitroimidazoles such as metronidazole (MTZ) and tinidazole (TDZ) remaining mainstays of therapy (Table 3 ). Guidelines published by the WHO in June 2021 recommend treatment with either a single dose of MTZ (2 g orally) or twice-daily dose of MTZ (500 mg orally) for 7 days 128 . In LMIC and other resource-limited settings where adherence to a multidose MTZ regimen may be difficult, a single-dose treatment option may be advantageous. Accumulating data suggest, however, that single-dose treatment with MTZ for women may not be optimal 129 , 130 . A recent multicentre randomized controlled trial in the United States compared the multidose oral MTZ regimen to the single-dose regimen among HIV-negative women. Participants who received the multidose regimen were significantly less likely to re-test positive for T. vaginalis at 1 month compared with women in the single-dose group; adherence among both groups were similar 130 . Thus, the multidose oral MTZ regimen is now the recommended regimen for all women; this update may influence future global guidelines moving forward 16 . Notably, MTZ is safe for pregnant women at all stages of pregnancy 131 . Therefore, to prevent adverse birth outcomes associated with this infection, prompt treatment is essential 115 , 131 .

Due to limited clinical trial data in men, the single 2 g dose of oral MTZ remains the recommended treatment regimen for T. vaginalis in men 16 . This is the first time there has been a discrepancy in the treatment of an STI based on gender. Such a situation could lead to complicated public health logistics in partner treatment of infected women and additional studies are needed to discover the optimal treatment regimen for men 132 . Women are re-infected by their male sex partners if they are either not treated or are inadequately treated for trichomoniasis 133 .

Oral secnidazole (SEC) was recently approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for treatment of T. vaginalis in both men and women. Given its microbiologic cure rate of 92.2% in a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled delayed-treatment study, SEC offers a promising new single-dose treatment option for trichomoniasis 134 .

STI prevention challenges and disparities in minority populations

Gender minority women.

STI prevention poses challenges for women in general, but some populations face additional barriers to sexual healthcare (Table 4 ). Gender minority women, including transgender women (TGW), or people who were assigned male sex at birth but whose gender identity is female, are at high risk of acquiring STIs through engagement in sexual behaviours such as commercial sex work and condomless anal receptive intercourse 135 . Consequently, STIs disproportionally affect TGW; an estimated 14% of TGW in the United States are living with HIV 136 , and global bacterial STI prevalence has been reported to be as high as 50%, 19% and 25% for syphilis, gonorrhoea and chlamydia, respectively 8 , 135 , 136 . These high rates may be related to the limited engagement of TGW with effective sexual health services—for example, regular HIV/STI screening—and underutilization of pre-exposure prophylaxis 137 , 138 . This lack of engagement arises from a suite of factors, including stigma, mistrust of the healthcare system, limited trans-affirming clinical services, previous sexual trauma or competing healthcare priorities such as hormone replacement therapy for gender-affirming therapy 139 , 140 .

Given the combination of this population’s unique sexual health needs and mistrust of the medical establishment, community-driven patient-centred prevention efforts are necessary. One qualitative study assessing attitudes related to HIV prevention among TGW in the Southeastern United States found that limited trans-affirming sexual health resources are a major barrier to engaging in care 141 . In addition, an individualized approach to affirming sexual history-taking should be employed by providers when caring for TGW. More broadly, another driver of sexual health disparities among TGW is their limited representations in research studies and clinical trials in the field. Data for TGW are often aggregated together with those of cisgender MSM and thus difficult to interpret. Study design and trial recruitment planning efforts must be made to appropriately report data on TGW.

Women in LMICs

Women living in LMICs face additional STI prevention challenges largely due to limited healthcare infrastructure, availability of sexual health resources and misogynistic cultural attitudes towards sexuality 142 . African countries have been particularly impacted, with the most recent WHO STI global prevalence estimates reporting the highest rates worldwide for gonorrhoea, trichomoniasis and syphilis among women in the region 1 . In addition, until very recently, distribution of HPV vaccines has been largely limited to European and North American nations, with LMICs receiving little support until approximately 2019. Even when HPV vaccines were introduced in many LMICs, uptake of the full series has been limited due to logistical challenges, highlighting an enormous, missed opportunity to curtail the rates of cervical cancer worldwide 32 .

Affordable STI testing that can be performed at the point-of-care is an important tool that needs to be made available to women in LMICs. Concurrent availability and accessibility of appropriate treatment for STIs are also essential. Clinics or other community settings need to provide confidential diagnostics and treatment to mitigate restricted access owing to stigma and the potential for gender-based violence that sometimes occurs when male sexual partners find out about sexual health diagnoses. Vaccines against STIs such as C. trachomatis and HSV-2 also hold great promise for women of LMICs, offering both disease prevention and a reduction in the need for diagnosis and treatment. Continued pursuit of safe and effective STI vaccines should be prioritized.

Women are disproportionately affected by STIs throughout their lives compared with men. This is mainly owing to the higher efficiency of male-to-female transmission of STIs and the biology of the female reproductive tract. In addition, the social and structural barriers to women realizing full sexual health include limited availability of HPV immunization in many parts of the world, barriers to contraception access, lack of confidential evaluation and counselling services, and lack of STI diagnostics. Finally, women are generally less well-resourced, both financially and socially, than men. This restricts their access to the resources required for sexual safety such as comprehensive sexual healthcare and HIV/STI prevention services, and the financial security that is fundamental to sexual health. Ensuring access to diagnostics and therapies on its own will not address the yawning gap in sexual health between men and women but would be a good start.

Rowley, J. et al. Chlamydia, gonorrhoea, trichomoniasis and syphilis: global prevalence and incidence estimates, 2016. Bull. World Health Organ. 97 , 548–562 (2019).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Reported STDs reach all-time high for 6th consecutive year. CDC (3 April 2021); https://www.cdc.gov/nchhstp/newsroom/2021/2019-std-surveillance-report-press-release.html

Kreisel, K. M. et al. Sexually transmitted infections among US women and men: prevalence and incidence estimates, 2018. Sex. Transm. Dis . https://doi.org/10.1097/OLQ.0000000000001355 (2021).

Rietmeijer, C. A. et al. Report from the national academies of sciences, engineering and medicine–STI: adopting a sexual health paradigm–a synopsis for sti practitioners, clinicians, and researchers. Sex. Transm. Dis . https://doi.org/10.1097/olq.0000000000001552 (2021).

CDC Fact Sheet: 10 Ways STDs Impact Women Differently from Men (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2011); https://www.cdc.gov/std/health-disparities/stds-women-042011.pdf

Smolarczyk, K. et al. The impact of selected bacterial sexually transmitted diseases on pregnancy and female fertility. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22 , 2170 (2021).

Van Gerwen, O. T., Aryanpour, Z., Selph, J. P. & Muzny, C. A. Anatomical and sexual health considerations among transfeminine individuals who have undergone vaginoplasty: a review. Int. J. STD AIDS 33 , 106–113 (2022).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Van Gerwen, O. T. et al. Prevalence of sexually transmitted infections and human immunodeficiency virus in transgender persons: a systematic review. Transgend. Health 5 , 90–103 (2020).

Deese, J. et al. Recent advances and new challenges in cisgender women’s gynecologic and obstetric health in the context of HIV. Clin. Obstet. Gynecol. 64 , 475–490 (2021).

Hodges-Mameletzis, I. et al. Pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV prevention in women: current status and future directions. Drugs 79 , 1263–1276 (2019).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

O’Leary, A. Women and HIV in the twenty-first century: how can we reach the UN 2030 goal? AIDS Educ. Prev. 30 , 213–224 (2018).

Heumann, C. L. Biomedical approaches to HIV prevention in women. Curr. Infect. Dis. Rep. 20 , 11 (2018).

Kharsany, A. B. & Karim, Q. A. HIV infection and AIDS in Sub-Saharan Africa: current status, challenges and opportunities. Open AIDS J. 10 , 34–48 (2016).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Burk, R. D., Harari, A. & Chen, Z. Human papillomavirus genome variants. Virology 445 , 232–243 (2013).

Burd, E. M. Human papillomavirus and cervical cancer. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 16 , 1–17 (2003).

Workowski, K. A. et al. Sexually transmitted infections treatment guidelines, 2021. MMWR Recomm. Rep. 70 , 1–187 (2021).

Human Papilloma Virus Statistics (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2021); https://www.cdc.gov/std/hpv/stats.htm

Bruni, L. et al. Cervical human papillomavirus prevalence in 5 continents: meta-analysis of 1 million women with normal cytological findings. J. Infect. Dis. 202 , 1789–1799 (2010).

Brianti, P., De Flammineis, E. & Mercuri, S. R. Review of HPV-related diseases and cancers. New Microbiol . 40 , 80–85 (2017).

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

de Martel, C., Plummer, M., Vignat, J. & Franceschi, S. Worldwide burden of cancer attributable to HPV by site, country and HPV type. Int. J. Cancer 141 , 664–670 (2017).

Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar

Serrano, B., Brotons, M., Bosch, F. X. & Bruni, L. Epidemiology and burden of HPV-related disease. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 47 , 14–26 (2018).

Walboomers, J. M. et al. Human papillomavirus is a necessary cause of invasive cervical cancer worldwide. J. Pathol. 189 , 12–19 (1999).

Liu, G. et al. Prevalent HPV infection increases the risk of HIV acquisition in African women: advancing the argument for HPV immunization. AIDS https://doi.org/10.1097/qad.0000000000003004 (2021).

Liu, G., Sharma, M., Tan, N. & Barnabas, R. V. HIV-positive women have higher risk of human papilloma virus infection, precancerous lesions, and cervical cancer. AIDS 32 , 795–808 (2018).

Kelly, H., Weiss, H. A., Benavente, Y., de Sanjose, S. & Mayaud, P. Association of antiretroviral therapy with high-risk human papillomavirus, cervical intraepithelial neoplasia, and invasive cervical cancer in women living with HIV: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet HIV 5 , e45–e58 (2018).

Smith, J. S. et al. Evidence for Chlamydia trachomatis as a human papillomavirus cofactor in the etiology of invasive cervical cancer in Brazil and the Philippines. J. Infect. Dis. 185 , 324–331 (2002).

Wang, R. et al. Human papillomavirus vaccine against cervical cancer: opportunity and challenge. Cancer Lett. 471 , 88–102 (2020).

Cervical Cancer Elimination Initiative (WHO, 2022); https://www.who.int/initiatives/cervical-cancer-elimination-initiative

Monie, A., Hung, C.-F., Roden, R. & Wu, T. C. Cervarix: a vaccine for the prevention of HPV 16, 18-associated cervical cancer. Biologics 2 , 97–105 (2008).

PubMed Google Scholar

Lei, J. et al. HP V vaccination and the risk of invasive cervical cancer. N. Eng. J. Med. 383 , 1340–1348 (2020).

Article CAS Google Scholar

Falcaro, M. et al. The effects of the national HPV vaccination programme in England, UK, on cervical cancer and grade 3 cervical intraepithelial neoplasia incidence: a register-based observational study. Lancet https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(21)02178-4 (2021).

Bruni, L. et al. HPV vaccination introduction worldwide and WHO and UNICEF estimates of national HPV immunization coverage 2010-2019. Prev. Med . 144 , 106399 (2021).

Clifford, G. M. et al. Toward a unified anal cancer risk scale. Int. J. Cancer 148 , 38–47 (2021). A meta-analysis of anal cancer incidence by risk group .

Chin-Hong, P. V. & Palefsky, J. M. Human papillomavirus anogenital disease in HIV-infected individuals. Dermatol. Ther. 18 , 67–76 (2005).

Frisch, M., Biggar, R. J. & Goedert, J. J. Human papillomavirus-associated cancers in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 92 , 1500–1510 (2000).

Silverberg, M. J. et al. Risk of anal cancer in HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected individuals in North America. Clin. Infect. Dis. 54 , 1026–1034 (2012).

Palefsky, J. et al. Treatment of anal high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions to prevent anal cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 386 , 2273–2282 (2022).

Ellsworth, G. B. et al. Xpert HPV as a screening tool for anal histologic high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions in women living with HIV. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 87 , 978–984 (2021).

Chiao, E. Y. et al. Screening strategies for the detection of anal high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions in women living with HIV. AIDS 34 , 2249–2258 (2020).

Herpes Simplex Virus (WHO, 2022); https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/herpes-simplex-virus

Bernstein, D. I. et al. Epidemiology, clinical presentation, and antibody response to primary infection with herpes simplex virus type 1 and type 2 in young women. Clin. Infect. Dis. 56 , 344–351 (2012).

James, C. et al. Herpes simplex virus: global infection prevalence and incidence estimates, 2016. Bull. World Health Organ. 98 , 315–329 (2020).

Mahant, S. et al. Neonatal herpes simplex virus infection among medicaid-enrolled children: 2009–2015. Pediatrics https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2018-3233 (2019).

Kimberlin, D. W. Neonatal herpes simplex infection. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 17 , 1–13 (2004).

Kimberlin, D. Herpes simplex virus, meningitis and encephalitis in neonates. Herpes 11 , 65a–76a (2004).

Masese, L. et al. Changes in the contribution of genital tract infections to HIV acquisition among Kenyan high-risk women from 1993 to 2012. AIDS 29 , 1077–1085 (2015).

Freeman, E. E. et al. Herpes simplex virus 2 infection increases HIV acquisition in men and women: systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. AIDS 20 , 73–83 (2006).

Looker, K. J. et al. Global and regional estimates of the contribution of herpes simplex virus type 2 infection to HIV incidence: a population attributable fraction analysis using published epidemiological data. Lancet Infect. Dis. 20 , 240–249 (2020).