- Open access

- Published: 18 May 2017

Virginity testing: a systematic review

- Rose McKeon Olson 1 &

- Claudia García-Moreno ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-0208-4119 2

Reproductive Health volume 14 , Article number: 61 ( 2017 ) Cite this article

67k Accesses

25 Citations

340 Altmetric

Metrics details

So-called virginity testing, also referred to as hymen, two-finger, or per vaginal examination, is the inspection of the female genitalia to assess if the examinee has had or has been habituated to sexual intercourse. This paper is the first systematic review of available evidence on the medical utility of virginity testing by hymen examination and its potential impacts on the examinee.

Ten electronic databases and other sources for articles published in English were systematically searched from database inception until January 2017. Studies reporting on the medical utility or impact on the examinee of virginity testing were included. Evidence was summarized and assessed via a predesigned data abstraction form. Meta-analysis was not possible.

Main Results

Seventeen of 1269 identified studies were included. Summary measures could not be computed due to study heterogeneity. Included studies found that hymen examination does not accurately or reliably predict virginity status. In addition, included studies reported that virginity testing could cause physical, psychological, and social harms to the examinee.

Conclusions

Despite the lack of evidence of medical utility and the potential harms, health professionals in multiple settings continue to practice virginity testing, including when assessing for sexual assault. Health professionals must be better informed and medical and other textbooks updated to reflect current medical knowledge. Countries should review their policies and move towards a banning of virginity testing.

Peer Review reports

Plain Language Summary

Language: english.

Virginity testing is a practice some communities use to detect which women or girls are ‘virgins’ (i.e. have not had sexual intercourse). People have different ways of trying to detect who are virgins. Some think you can tell by looking at the hymen (a piece of tissue that covers the vagina), while others think you can tell by looking at the size of the vagina. Communities often use the test to separate “pure” females from “impure” females. In some communities, only the “pure” females are to be married, have certain jobs, or be respected. This review searched ten different databases, and found 17 reports on virginity testing. We studied whether looking at the hymen can determine who is a ‘virgin’, and how the exam affects the girl or woman being tested. Our review found that virginity testing is not good at detecting who has not had sexual intercourse, and that it can hurt the person being tested – physically, mentally, and socially. Our hope is to make more people and countries aware of this to prevent harm to women and girls.

So-called virginity testing, also referred to as hymen, two-finger, or per vaginal examination, is the inspection of the female genitalia to determine if the individual has had or has been habituated to sexual intercourse [ 1 ]. The two most common techniques are inspection of the hymen for size or tears, and two-finger vaginal insertion to measure size of the introitus or laxity of the vaginal wall. Both techniques are performed under the belief that there is a specific appearance of genitalia that demonstrates habituation to sexual intercourse [ 1 , 2 ]. The prevailing social rationale for testing is that an unmarried female’s virginity is indicative of her moral character and social value, whether in the context of marriage eligibility, sexual assault assessment, employment application, or otherwise [ 1 , 2 ].

Virginity examinations are most commonly performed on unmarried females, often without consent or in situations where individuals are unable to give consent [ 1 ]. Depending on the region, the examiner may be a medical doctor, police officer, or community leader. Countries where this practice has been reported include Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Egypt, India, Indonesia, Iran, Jordan, Palestine, South Africa, Sri Lanka, Swaziland, Turkey, and Uganda [ 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 ]. Virginity testing is performed in various countries for reasons that vary by region. Certain communities in rural KwaZulu Natal in South Africa and Swaziland have performed virginity tests on school-aged girls with the aim to deter pre-marital sexual activity and reduce HIV prevalence [ 3 , 4 ]. In India, the test has been part of the sexual assault assessment of female rape victims [ 9 ]. In Indonesia, the exam has been part of the application process for women to join the Indonesian police force [ 12 , 13 ]. Due to increased globalization, reports of virginity testing are appearing in countries with no prior history, including Canada, Spain, Sweden, and the Netherlands [ 15 ]. Despite it being a long-standing tradition in some communities, formal assessments of the frequency of virginity testing are scarce. Thus, prevalence cannot be accurately described; however, anecdotes of its incidence occur in a variety of social settings in different countries.

The growing attention to eliminating sexual violence has raised awareness of the routine use of virginity testing in some settings [ 16 ]. This study was undertaken to systematically review all available published studies on virginity testing to determine its medical relevance and its impacts on the examinee. Ultimately, this review will inform the World Health Organization’s recommendations regarding virginity testing.

This systematic review followed PRISMA guidelines (Fig. 1 ) [ 17 ]. The available literature on virginity testing was identified by searching ten electronic databases: Pubmed, the Cochrane Library, the Campbell Collaboration, SSRN, Regional Indexes of the WHO Global Health Libraries, Sage, Science Direct, Cambridge Press, Oxford Press, and Elsevier. Databases were searched for articles published in English from inception of the database until January 14, 2017. The search terms used were “virginity testing”, “virginity examination”, “hymen examination”, “two-finger testing”, and “per vaginal examination”. Multiple combinations of these search terms were used, with and without thesaurus and MeSH terms. (The search strategy is described in more detail in the Additional file 1 ). The protocol was not registered with a systematic review registry. Researchers in relevant fields were contacted for assistance in identifying studies. The reference lists of the identified studies were manually reviewed for additional citations.

PRISMA flow diagram

The study population of interest was females who underwent any type of ‘virginity test’ and/or hymen examination. We did not enforce limitations on age, race/ethnicity, nationality, or other participant characteristics. Outcomes that were of interest in determining medical utility included physical exam findings of the female hymen (such as hymenal tear, perforation, or size of opening) that could indicate vaginal penetration, and the examiner’s ability to accurately and/or reliably identify hymenal features by physical exam. Outcomes that were of interest in determining impact on the examinee included personal or close-contact accounts of the effects of the virginity test on the examinee’s well-being (such as physical, psychological, and social consequences).

Two reviewers (Olson and García-Moreno) independently screened titles and abstracts and selected relevant studies for full text analysis. References of relevant articles were screened to find additional studies. RO then performed full text assessments, extracted data, and, in consultation with CGM, made decisions about study inclusion and exclusion. Any differences in opinion in the screening process, data extraction and in analysis were resolved through re-examination of the study and further discussion. If agreement had not been reached, the reviewers would have consulted a third reviewer.

Data were extracted using predesigned data extraction forms. The forms contained questions regarding study type, participant characteristics, role of examiner, method of examination, and outcomes measured. Data extracted from studies reporting on the impact of virginity testing on the examinee was synthesized with a thematic synthesis approach informed by the Cochrane Collaboration guidelines [ 18 ]. A spreadsheet was created of all the data extracted from these studies, and thematic analysis methods were used to develop broad themes.

The quality of each study was assessed using the grading system of the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) [ 19 , 20 ]. This grading system examines both study design and the internal validity of each study. (Additional information regarding the USPSTF grading criteria is provided in the Additional file 1 ). Internal validity measures how well the study was conducted, and a level of good, fair, or poor is assigned. Due to the lack of available research and presence of heterogeneity with respect to study design and aims, measures, and outcomes, a structured synthesis was undertaken, rather than a metaanalysis [ 21 ].

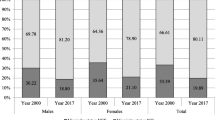

The search yielded 1269 articles, of which 69 full text articles were reviewed in full for eligibility. Of these, 17 met the inclusion criteria [ 4 , 6 , 14 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 ]. All studies reporting primary data on the medical relevance and/or impact of virginity testing on examinee were included ( n = 17). Studies with inappropriate study design were excluded ( n = 44). This included editorials, opinions, and any study that did not report primary data on virginity testing and/or hymen examination. Studies with inappropriate study population were also excluded, including those that did not study females with a history of vaginal penetration ( n = 4). Studies reporting on surgical interventions of the hymen not associated with virginity testing were excluded ( n = 4). Ten studies reported on the medical utility of virginity testing and key findings are presented in Table 1 [ 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 ]. Eight studies reported on the impact of virginity testing on the examinee and key findings are presented in Table 2 and presented again in Table 3 by theme identified [ 4 , 6 , 14 , 30 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 ].

Medical relevance

Ten studies reported on the medical relevance of hymen examination as a method to determine history of vaginal intercourse, the most common type of virginity testing [ 1 ]. The study characteristics and key findings are summarized in Table 1 [ 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 ]. The available research on this topic comes chiefly from physician examination of prepubertal and adolescent girls after sexual abuse allegations to determine if evidence of vaginal penetration existed. Seven of the included papers studied the accuracy of abnormal genital examinations as an indicator for history of vaginal penetration [ 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 ]. Abnormal genital exams included findings such as a hymenal transection, laceration, enlarged opening, or scar. Two studies reviewed physician’s accuracy in determination of virginity by exam [ 29 , 30 ], and one study reported on pediatric chief residents’ ability to correctly identify the hymen by examination [ 31 ].

In a case-control study by Berenson et al. in the United States, genital features were compared between 192 girls with a history of vaginal penetration from sexual abuse and 200 who denied past penetration [ 22 ]. Presence or absence of 21 different hymenal or vulvar features was compared between the two groups, such as presence of hymenal tissue, transections, perforations, and notches. It was found that only 2.5% of physical exam findings were unique to the group with a history of penetration.

Kellog et al. studied a cohort in the United States with definitive evidence of previous vaginal penetration. In the study of 26 pregnant adolescents who reported sexual abuse, 22 participants (64%) had normal or nonspecific genital examination findings, eight (22%) had inconclusive findings, four (8%) had suggestive findings, and two (6%) had findings of definite evidence of vaginal penetration [ 23 ].

In one large cohort of 2384 children in the United States, 957 girls reported penetration from sexual abuse. Of these 957 girls, only 61 (6%) had abnormal genital examination findings [ 24 ]. The study’s parameters for abnormal examination included: “acute trauma, transections of the hymen that extended to the base of the hymen, scarring, sexually transmitted diseases, and positive forensics” [ 24 ].

In a retrospective case review in the United States of 213 girls who reported vaginal penetration/contact from sexual abuse, there was a normal genital exam in 59 cases (28%), non-specific findings in 104 cases (49%), and suspicious findings in 20 cases (9%) [ 25 ]. Size of hymenal opening was also measured on the study group (7.7 ± 2.6 mm) and compared to published data on non-abused children of the same age (6.9 ± 2.2 mm), and no significant difference was found in mean size [ 25 ].

Hymenal opening size was measured in a United States case-control study of 189 girls with, and 197 girls without, a history of penile or digital penetration from sexual abuse [ 26 ]. The former group had a larger mean transverse hymen diameter than the latter when examined in the knee-chest position but not supine position; hymenal orifice size also increased with age.

Healing of injuries to the hymen was reviewed in two studies, both in the contexts of sexual abuse allegations in the United States [ 27 , 28 ]. In a study of 75 girls with a history of a vaginal penetration or trauma, injuries to the hymen were found in 37 cases (49.3%), significant genital findings (i.e., a transection of the hymen) were found in 15 girls (20%), and in the remaining 80%, there was no increase in the hymenal diameter or irregularity or narrowing of the hymen [ 27 ]. In a study of 113 prepubertal girls and 126 pubertal girls with previous penetration that reported on healing of injuries to the hymen, it was found that hymenal injuries in both groups healed rapidly and often left little or no evidence of previous trauma [ 28 ].

A 1978 study in the United States reported on the accuracy of physicians in confirming virginity through hymen examination [ 29 ]. Two gynecologists inspected the hymens of a cohort of 28 self-declared virgins. The physicians reported that examination of the hymen confirmed virginity in 16 cases (58%), was inconclusive in nine cases (31%), and uncertain in three cases (11%) [ 29 ].

In a study of forensic physicians in Turkey, 66% of respondents reported that their findings from at least one virginity exam contradicted a recent virginity exam of the same patient [ 30 ].

Lastly, a study examined physician knowledge of hymen anatomy [ 31 ]. In 2005, 137 United States pediatric chief residents were asked to identify the hymen on a photograph of pediatric anatomy; 64% were able to correctly identify the structure [ 31 ].

Quality of the ten studies reporting on the medical relevance of virginity testing was assessed according to USPSTF guidelines and is reported in Table 1 . (Additional information regarding the USPSTF grading criteria is provided in the Additional file 1 ). The level of evidence ranged from level II-2 to level III. Seven studies were level II-2 [ 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 ], one study was level II-3 [ 29 ], and two studies were level III [ 30 , 31 ]. The internal validity of the studies reporting on medical relevance ranged from good to poor. Two studies had good internal validity [ 22 , 26 ], six had fair internal validity [ 24 , 25 , 27 , 28 , 30 , 31 ], and two had poor interval validity [ 23 , 29 ].

Impact on examinee

Eight studies provided evidence on the effects of virginity testing on the examinee [ 4 , 6 , 14 , 30 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 ]. The study characteristics and key findings are summarized in Table 2 . Included studies provided data on the experiences of the examinee and those who worked directly with the examinee (such as doctors, social workers, police officers, and lawyers). Six studies [ 4 , 6 , 14 , 32 , 33 , 35 ] provided data from interviews and focus group discussions and two studies [ 30 , 34 ] provided survey data from healthcare professionals. Three themes were constructed from the data: physical harm, psychological harm, and social harm. Themes are presented in Table 3 , and expanded on below with relevant study findings and rationale of theme selection.

Physical harm of virginity examinees was reported in four studies [ 6 , 14 , 32 , 33 ]. In a study of virginity testing in Palestine, a social worker present during her client’s virginity exam reported that, “the process was very painful, she was crying, screaming, holding my hands” [ 6 ]. Undergoing virginity exams also caused two of the social worker’s clients to become suicidal, with one reported attempted suicide [ 6 ]. When one examinee failed her virginity test, she was told that she would need to, “search for a way to save herself from the deadly consequences that awaited her” [ 6 ]. In a report of virginity testing in Iran, one medical examiner reported an exam that lead to death, “I told her that her hymen was not intact, and she said that she had done nothing. Then I heard she had committed suicide” [ 14 ]. A report on India’s two-finger test describes doctors who harmed the examinee during the test by aggravating existing injuries [ 32 ]. In South Africa, a report was made to Childline, a helpline that offers rape counseling, of an examinee’s relatives breaking both of her arms after she failed a virginity test [ 33 ].

Psychological harm was reported in five studies [ 6 , 14 , 30 , 32 , 34 ]. In a study of virginity testing in Palestine, focus group discussions revealed that women who underwent virginity testing were:

extremely fearful of and indeed felt terrorized by [the experience]. … Their feelings of fear and invasion were manifested in a variety of ways: by their refusal to sit on the examination chair, through crying, screaming, pushing, freezing-up, being silent, fainting, etc. [ 36 ]

One social worker described virginity exams as torture: “… I also felt it is so unfair to be sexually abused and then [have to] go through such a vicious process of torture” [ 6 ]. In depth interviews of medical professionals who performed virginity testing in Iran revealed that the virginity test resulted in the psychological distress of the examinee, causing “rejection, suicide, depression, and weakened self-confidence” [ 14 ]. A survey of forensic physicians in Turkey found that 93% of 118 respondents agreed that virginity tests are psychologically traumatic for the patient, 64% believed they were a violation of privacy, and 60% believed they result in loss of examinee’s self-esteem [ 30 ]. Interviews from a report on India’s two-finger test documented the fear and re-traumatization the examination causes [ 32 ]. In a study of 101 nurses and midwives in Turkey, 90% indicated they were opposed to virginity testing, and when asked why, nearly half agreed that they were opposed because the examinations are being done against the examinee’s will [ 34 ]. Sixty-two percent of the nurses and midwives also agreed that a forced virginity exam may result in severe negative effects such as anxiety, depression, isolation from society, a dysfunctional sex life, guilt, worsened self-respect, and fear of death [ 34 ].

Social harm was reported in three studies [ 4 , 6 , 35 ]. Leclerc-Madlala reported in a study in South Africa that those who fail virginity tests are often expected to pay a fine for tainting the community [ 4 ]. They are also excluded from certain employment opportunities, illustrated by one factory owner who stated that her various franchises throughout KwaZulu-Natal and the Eastern Cape had tested and selectively employed over 4000 virgins, which she believed was a service to the community and state [ 4 ]. Social harms of positive virginity tests were also noted. In a focus group interview of 14 girls who were planning to attend a virginity testing event, the girls reported that their primary concern was that being “certified” a virgin would result in brothers, friends, or neighbors raping them. They spoke of previous cases in which this had occurred in their community. Rape in this context was reported most likely to occur as a gang rape by several boys who needed to “teach her a lesson” and show her “what men are all about” [ 4 ]. A study in Palestine detailed one examinee’s fear of adverse social consequences [ 6 ]. She was afraid that a failed virginity test would result in loss of honor and social condemnation. The examinee stated, “I wanted to do [the examination]. I wanted to know if I lost my honor. I paid to learn that I lost my honor” [ 6 ]. In another study of South Africa’s KwaZulu-Natal province by Leclerc-Madlala, those who failed a virginity test were subject to name-calling and social exclusion [ 35 ]. One respondent referred to a girl who failed as a "rotten potato" who must be kept away from the ‘virgin girls’ because she will surely “spoil the bunch.” Another respondent noted that being in close proximity to a girl who failed the test would, “cause the flowers of the nation to wilt” [ 35 ].

Quality of the eight studies reporting on the impact of virginity testing on examinee was assessed according to USPSTF guidelines and is reported in Table 2 . All eight studies were level III evidence [ 4 , 6 , 14 , 30 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 ]. The internal validity of the studies reporting on impact on examinee ranged from fair to poor. Four studies had fair internal validity [ 6 , 14 , 30 , 34 ] and four had poor internal validity [ 4 , 32 , 33 , 35 ].

The present review assessed 17 published studies on virginity testing, in particular its medical relevance and impact on the examinee.

The utility of hymen examination as a test for virginity was reviewed [ 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 ]. The studies indicated, as has been described in previous reviews, that the inspection of the hymen cannot give conclusive evidence of vaginal penetration or any other sexual history [ 36 , 37 ]. Normal hymen examination findings are likely to occur in those with and without a history of vaginal penetration [ 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 ]. A hymen exam with abnormal findings is also inconclusive: abnormal hymenal features such a hymenal transection, laceration, enlarged opening, or scars are found in females with and without a history of sexual intercourse [ 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 ].

One hymenal feature commonly examined in virginity testing is hymenal opening size. Hymenal opening size also was found to be an unreliable test for vaginal penetration [ 25 , 26 , 27 ]. Hymen opening size varies with the method of examination, the position of the examinee, the cooperation and relaxation of the examinee, and the examinee’s age, weight, and height [ 25 ]. With regards to healing of hymenal injuries, it was found that most hymenal injuries heal rapidly and leave no evidence of previous trauma [ 26 , 27 ].

Six studies reporting on medical utility included in the present review were limited by not having a control group [ 23 , 24 , 25 , 27 , 28 , 29 ]. Studies without control groups make it difficult to interpret whether exam findings were accurately labeled as indicative or suspicious of vaginal penetration, as limited information is known about the appearance of the hymen after injury [ 22 ]. Another limitation is that most studies that reported on the medical utility of hymen examination were performed on females from the United States to determine if evidence existed after sexual abuse allegations, whereas most routine use of virginity tests has been reported outside of the United States and for the purpose of assessing moral or social value [ 1 , 2 ]. The lack of data from outside the United States may affect the generalizability of results to females examined elsewhere. The ages of examinees of included studies were heterogeneous, with reported ages varying from 3 months to 48 years. Four studies combined females from different ages and stages of development [ 24 , 25 , 28 , 29 ]. The heterogeneity in age groups may have caused observed differences to be due to differences in age, as it is known that hymenal features vary with age [ 23 , 24 , 25 , 27 , 28 , 29 ]. Lastly, heterogeneity exists in regards to the knowledge and experience of examiner.

The search carried out for this review was comprehensive but did not include unpublished studies or studies in languages other than English, and thus there is potential to have missed relevant studies in other languages.

Another form of virginity testing is performed by insertion of two fingers into the vagina to examine its laxity [ 9 ]. This form of virginity testing was not included in the review of literature because the medical community has not considered vaginal laxity a clinical indicator of previous sexual intercourse. The vagina is a dynamic muscular canal that varies in size and shape depending on individual, developmental stage, physical position, and various hormonal factors such as sexual arousal and stress [ 38 , 39 ]. However, there are reports that the so-called ‘finger testing’ has been used in countries like India to assess evidence for sexual assault [ 32 ]. It can also be found in forensic examination forms in some countries.

Studies of the effects of virginity testing on the examinee are also limited. Eight studies on the effects of virginity testing were identified and reviewed [ 4 , 6 , 14 , 30 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 ]. The review found that the virginity exam itself had resulted in physical harm of the examinee. This is supported by news reports from Turkey in which five by students attempted suicide by consuming rat poison to avoid undergoing the virginity test [ 7 ]. Virginity exams also commonly resulted in psychological trauma with long-lasting adverse effects, including but not limited to anxiety, depression, loss of self-esteem, and suicidal ideation. Health professionals also identified violation of privacy and autonomy as adverse effects [ 6 , 34 ]. Lastly, virginity exams were reported to have an adverse social impact including social exclusion, perceived dishonor brought to family and community, employment discrimination, humiliation, and increased risk of sexual assault [ 4 , 6 , 35 ]. More research is needed to understand better the short and long term consequences of the virginity exam on the examinee.

Conclusions and Recommendations

This review found that virginity examination, also known as two-finger, hymen, or per-vaginal examination, is not a useful clinical tool, and can be physically, psychologically, and socially devastating to the examinee. From a human rights perspective, virginity testing is a form of gender discrimination, as well as a violation of fundamental rights, and when carried out without consent, a form of sexual assault.

A gap exists between current medical evidence of virginity testing and medical education and training [ 9 , 30 , 33 , 35 ]. Some forensic medical textbooks still include virginity testing as a standard procedure for assessment of sexual assault [ 38 , 40 , 41 , 42 ]. Medical schools and public health professionals must update their textbooks, courses, and training to eliminate any recommendations of virginity testing, and educate others on the lack of scientific evidence for and possible harms of its use.

Governments, medical establishments, and health professional associations in all countries, even those with no history of virginity testing, should take the initiative to ban the use of virginity testing and create national guidelines for health professionals, public officials, and community leaders. More research is urgently needed to understand the regional and cultural rationales for virginity testing, and to develop more robust and efficacious education strategies that involve communities.

Independent Forensic Expert Group. Statement on virginity testing. J Forensic Leg Med. 2015;33:121–4.

Article Google Scholar

Khambati N. India's two finger test after rape violates women and should be eliminated from medical practice. BMJ. 2014;348:g3336–g36.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Behrens K. Virginity testing in South Africa: a cultural concession taken too far? South African Journal of Philosophy. 2014;33(2):177–87.

Leclerc-Madlala S. Protecting girlhood? Virginity revivals in the era of AIDS. Agenda: Empowering Women for Gender Equality. 2003;56:16–25.

Google Scholar

Egypt women protesters forced to take 'virginity tests'. BBC. 24 March 2014. http://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-12854391 . Accessed 5 Aug 2015.

Shalhoub-Kevorkian N. Imposition of virginity testing: a life-saver or a license to kill? Soc Sci Med. 2005;60(6):1187–96.

Amnesty International. Stop Violence Against Women: It's In Our Hands. London: Amnesty International Publications; 2004. p. 18. https://www.amnesty.ie/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/Its-in-our-Hands.pdf . Accessed 5 Aug 2015.

Percy J. Love crimes: what liberation looks like for Afghan women. Harper's Magazine. 2015:1–18. http://harpers.org/archive/2015/01/love-crimes/ . Accessed 28 July 2015

Ayotte B. State-control of female virginity in Turkey: the role of physicians. Journal of Ambulatory Care Management. 2000;23(1):89–91.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Bangladesh: Court Prohibits Use of the "Two-Finger Test" [website]. Avon Global Center for Women and Justice, Cornell Law School; 2015. http://www.lawschool.cornell.edu/womenandjustice/Featured-Cases/Bangladesh-Court-Prohibits-Use-of-the-Two-Finger-Test.cfm . Accessed 15 July 2015.

Jayaweera S, Sanmugam T. Impact of macro economic reforms on women in Sri Lanka. Colombo: Centre for Women's Research; 2001.

Kine P. Indonesia ‘Virginity Tests’ Run Amok. Human Rights Watch. 9 February 2015. https://www.hrw.org/news/2015/02/09/dispatches-indonesia-virginity-tests-run-amok . Accessed 10 Aug 2015.

Human Rights Watch. ‘Virginity Tests’ for Female Police in Indonesia. https://www.hrw.org/video-photos/video/2014/11/17/virginity-tests-female-police-indonesia . Accessed 10 Aug 2015.

Robatjazi M, Simbar M, Nahidi F, Gharehdaghi J, Emamhadi M, Vedadhir AA, Alavimajd H. Virginity Testing Beyond a Medical Examination. Glob J Health Sci. 2015;18;8(7):152–64.

Behrens K. Why physicians ought not to perform virginity tests. J Med Ethics. 2015;41(8):691–5.

United Nations. Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. New York: United Nations; 2015.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Higgins J, Green S. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell; 2008.

Book Google Scholar

Harris RP, Helfand M, Woolf SH, Lohr KN, Mulrow CD, Teutsch SM, et al. Current methods of the US Preventive Services Task Force: a review of the process. Am J Prev Med. 2001;20(3 Suppl):21–35.

US Preventive Services Task Force. Guide to Clinical Preventive Services: Report of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. 2nd ed. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1996.

Yeaton WH, Lagenbrunner JC, Smyth JM, Wortman PM. Exploratory research synthesis--methodological considerations for addressing limitations in data quality. Eval Health Prof. 1995;18(3):283.

Berenson A, Chacko M, Wiemann C, Mishaw C, Friedrich W, Grady J. A case–control study of anatomic changes resulting from sexual abuse. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;182(4):820–34.

Kellogg N, Menard S, Santos A. Genital anatomy in pregnant adolescents: "Normal" does not mean "Nothing Happened". PEDIATRICS. 2003;113(1):e67–9.

Heger A, Ticson L, Velasquez O, Bernier R. Children referred for possible sexual abuse: medical findings in 2384 children. Child Abuse Negl. 2002;26(6–7):645–59.

Adams J, Harper K, Knudson S, Revilla J. Examination findings in legally confirmed child sexual abuse: it's normal to be normal. PEDIATRICS. 1994;94(3):310–3.

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Berenson A, Chacko M, Wiemann C, Mishaw C, Friedrich W, Grady J. Use of hymenal measurements in the diagnosis of previous penetration. PEDIATRICS. 2002;109(2):228–35.

Heppenstall-Heger A, McConnell G, Ticson L, Guerra L, Lister J, Zaragoza T. Healing patterns in anogenital injuries: a longitudinal study of injuries associated with sexual abuse, accidental injuries, or genital surgery in the preadolescent child. PEDIATRICS. 2003;112(4):829–37.

McCann J, Miyamoto S, Boyle C, Rogers K. Healing of hymenal injuries in prepubertal and adolescent girls: a descriptive study. PEDIATRICS. 2007;119(5):e1094–106.

Underhill R, Dewhurst J. The doctor cannot always tell. Medical examination of the "intact" hymen. Lancet. 1978;1(8060):375–6.

Frank M, Bauer H, Arican N, Korur Fincanci S, Iacopino V. Virginity examinations in Turkey. JAMA. 1999;282(5):485.

Dubow S, Giardino A, Christian C, Johnson C. Do pediatric chief residents recognize details of prepubertal female genital anatomy: a national survey. Child Abuse Negl. 2005;29(2):195–205.

Dignity on Trial. New York City: Human Rights Watch; 2010. http://www.hrw.org/sites/default/files/reports/india0910webwcover.pdf . Accessed 19 July 2015.

Scared At School. New York City: Human Rights Watch: 2001. http://www.hrw.org/legacy/reports/2001/safrica/ . Accessed 21 July 2015

Gursoy E, Vural G. Nurses' and midwives' views on approaches to hymen examination. Nurs Ethics. 2003;10(5):485–96.

Leclerc-Madlala S. Virginity testing: managing sexuality in a maturing HIV/AIDS epidemic. Med Anthropol Q. 2001;15(4):533–52.

Berkoff MC, Zolotor AJ, Makoroff KL, Thackeray JD, Shapiro RA, Runyan DK. Has this prepubertal girl been sexually abused? JAMA. 2008;300(23):2779–92.

Pillaim M. Genital findings in prepubertal girls: what can be concluded from an examination? J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2008;21(4):177–85.

Padubidri V, Daftary S. Shaw's Textbook of Gynecology. 16th ed. New Delhi: Elsevier Health Sciences APAC; 2014.

Lloyd J, Crouch N, Minto C, Liao L, Creighton S. Female genital appearance: ‘normality’ unfolds. BJOG. 2005;112(5):643–6.

Subrahmanyam B, Modi J. Modi's medical jurisprudence and toxicology. 22nd ed. New Delhi: Butterworths India; 2001.

Parikh C. Parikh's textbook of medical jurisprudence and toxicology. 6th ed. New Delhi: CBS Publishers and Distributor; 2005.

Narayan Reddy K. The essentials of forensic medicine and toxicology. 26th ed. Hyderabad: K. Suguna Devi; 2007.

Download references

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

This work was undertaken while RO was an intern in the Department of Reproductive Health and Research of the World Health Organization. No specific funding was received for this work.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article (and its Additional file 1).

Authors’ contributions

CGM conceptualized and oversaw the review. RO carried out the search and data extraction and CGM reviewed the search and data extraction. Both authors were involved in writing the paper based on first draft of the report prepared by RO with input from CGM. Both authors reviewed and agreed on the final manuscript.

Author’s information

RO attends the University of Minnesota Medical School. She is a Duke University Global Health Fellow, and interned with the Reproductive Health and Research Department at the WHO under CGM. CGM coordinates the work on violence against women at the World Health Organization, Department of Reproductive Health and Research. She is a physician with an MSc in Community Medicine and has led research, policy and guidelines development work on women’s health, health and gender equality and violence against women.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests. The views expressed here are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views or policy of the World Health Organization.

Consent for publication

Ethics approval and consent to participate, publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

University of Minnesota, 100 Church Street Southeast Minneapolis, Minneapolis, MN, 55455, USA

Rose McKeon Olson

Department of Reproductive Health and Research, World Health Organization, 20 Ave Appia, Geneva, Switzerland, 1227

Claudia García-Moreno

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Claudia García-Moreno .

Additional file

Additional file 1:.

Search strategy. United States Preventive Services Task Force Grading System [ 18 ]. (DOCX 21 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Olson, R., García-Moreno, C. Virginity testing: a systematic review. Reprod Health 14 , 61 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-017-0319-0

Download citation

Received : 20 October 2016

Accepted : 28 April 2017

Published : 18 May 2017

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-017-0319-0

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Virginity testing

- Gynecological examination

Reproductive Health

ISSN: 1742-4755

- General enquiries: [email protected]

Articles on Virginity

Displaying all articles.

He’s the romantic lead but has never had sex: what The Bachelors has to say about virginity

Jodi McAlister , Deakin University

Zadie Smith: how the Wife of Willesden brings to life Chaucer’s tale of sex and power

Natalie Hanna , University of Liverpool

Is when you lose your virginity and have your first kid really written in your genes? Not quite

Andrew Shelling , University of Auckland, Waipapa Taumata Rau

Spinster, old maid or self-partnered – why words for single women have changed through time

Amy Froide , University of Maryland, Baltimore County

The backwards history of attitudes toward public breastfeeding

Eleanor Johnson , Columbia University

Losing your virginity: how we discovered that genes could play a part

John Perry , University of Cambridge and Ken Ong , University of Cambridge

How sexting is creating a safe space for curious millennials

Melissa Meyer , University of Cape Town

The obscure history of the ‘virgin’s disease’ that could be cured with sex

Helen King , The Open University

Is virgin birth possible? Yes (unless you are a mammal)

Jenny Graves , La Trobe University

Women suffer the myths of the hymen and the virginity test

Sherria Ayuandini , Washington University in St. Louis

Reliving virginity: sexual double standards and hymenoplasty

Meredith Nash , University of Tasmania

Related Topics

- Geoffrey Chaucer

- Reproduction

Top contributors

Distinguished Professor of Genetics and Vice Chancellor's Fellow, La Trobe University

Professor Emerita, Classical Studies, The Open University

Research affiliate, University of Amsterdam

Associate Professor of English, Columbia University

University of Cape Town

Senior Investigator Scientist, University of Cambridge

Group Leader of the Development Programme at the MRC Epidemiology Unit, University of Cambridge

Lecturer in English, University of Liverpool

Professor of History, University of Maryland, Baltimore County

Professor and Associate Dean (Research), University of Auckland, Waipapa Taumata Rau

Professor and Associate Dean - Diversity, Belonging, Inclusion, and Equity, Australian National University

Senior Lecturer in Writing, Literature and Culture, Deakin University

- X (Twitter)

- Unfollow topic Follow topic

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Wiley Open Access Collection

Hymen and virginity: What every paediatrician should know

Dehlia moussaoui.

1 Division of General Paediatrics, Department of Woman, Child and Adolescent Medicine, Geneva University Hospitals, Geneva Switzerland

3 Present address: Department of Paediatric and Adolescent Gynaecology, The Royal Children's Hospital Melbourne, Parkville Victoria, Australia

Jasmine Abdulcadir

2 Division of Gynaecology, Department of Woman, Child and Adolescent Medicine, Geneva University Hospitals, Geneva Switzerland

Michal Yaron

Paediatricians may face the notion of ‘virginity’ in various situations while caring for children and adolescents, but are often poorly prepared to address this sensitive topic. Virginity is a social construct. Despite medical evidence that there is no scientifically reliable way to determine virginity, misconceptions about the hymen and its supposed association with sexual history persist and lead to unethical practices like virginity testing, certificate of virginity or hymenoplasty, which can be detrimental to the health and well‐being of females of all ages. The paediatrician has a crucial role in providing evidence‐based information and promoting positive sexual education to children, adolescents and parents. Improving knowledge can help counter misconceptions and reduce harms to girls and women.

‘Virginity’ has no medical or scientific definition. It is a social, cultural and religious construct, which refers to the absence of former engagement in sexual intercourse. 1 However, it is not uncommon for the paediatrician to face virginity‐related concerns in various clinical situations: after an alleged sexual assault, during evaluations of post‐accidental traumas, in adolescents' well‐care visits, and following requests for virginity testing, certificates of virginity or hymenoplasty. This narrative review provides an overview of the notion of virginity through different perspectives such as culture, anatomy, forensic medicine, ethics and sex education. Our aim is to provide paediatricians with evidence‐based knowledge to improve their attitudes and practice when caring for young patients around the notion of virginity. Scientific information can help to reduce misconceptions and offer to children and adolescents the opportunity to grow and develop sexually in a healthy and respectful society.

Social Construction of Virginity

Virginity is a concept shared almost universally. The three monotheistic religions, as well as traditional cultures in different countries, value virginity before marriage. 2 Although not exclusively, the term ‘virginity’ is usually attributed to females. Controlling women's sexuality provides regulation of lineage since virginity before marriage helps prevent unfavourable alliances in patriarchal societies and provides reassurance about the paternity of children. Virginity is often considered as a virtue associated with purity, honour and morality. In some communities, it has an economic value as well, since a virgin bride brings money in dowry. 3

The recognition of women and children's human rights, the evolution of laws and the promotion of sex education have led to a change in attitudes and behaviours in pre‐marital sex in many parts of the world. However, even where pre‐marital virginity has lost some of its previous attributed value, the so‐called ‘loss of virginity’ remains a significant milestone in the adolescent and young adult's life. The issue of the first sexual intercourse is a central concern for teenagers of any gender and is associated with questioning, anxiety and expectations. In some circumstances, adolescents might feel ashamed to be considered still a ‘virgin’ and would like to get rid of this ‘embarrassing status’ as soon as possible. The myth that a male can feel with his penis if his female partner is virgin is widespread, although the feeling of ‘tightness’ is mostly due to anxiety and unvoluntary contraction of pelvic muscles rather than the absence of previous vaginal penetration. 4 Moreover, the misconception linking virginity to alterations of the female genital organs overlooks the fact that sexual encounters are not limited to the vagina, and not restricted to heterosexual practices.

Embryology and Anatomy of the Hymen

Virginity is commonly thought to be associated with the integrity of the hymen, which would rupture and bleed at first vaginal intercourse. 5 The hymen is a membranous tissue surrounding the vaginal introitus. Embryologically, the hymen is thought to derive from an invagination of the urogenital sinus. 6 , 7 The pelvic part of the urogenital sinus gives rise to the distal third of the vagina, which will join the utero‐vaginal canal arising from the fusion of the lower portion of the paramesonephric ducts around 12 weeks of gestation (Fig. 1 ). 7

Embryologic development of female genital organs. Left: Frontal view of female sex organs of a 4‐month fetus. The uterus and the upper part of the vagina (blue) come from the fusion of the paramesonephric ducts. The lower part of the vagina (yellow) comes from the urogenital sinus. Right: Sagittal view of female sex organs of a 5‐month fetus. The lumen of the vaginal canal is separated from the vaginal vestibule by the hymen (star), which will open around birth. (Reproduced from http://embryology.ch/anglais/ugenital/genitinterne05.html 7 , with permission.)

The hymen opens during the perinatal period. 5 If opening fails, a condition known as an imperforate hymen will ensue, which is the most common obstructive anomaly of the female reproductive tract, occurring in 1 of 1000 newborn girls. 6 Imperforate hymen may manifest at birth by a hydrocolpos. However, it often remains undiagnosed until adolescence and presents with primary amenorrhea and hematocolpos. The complete absence of the hymen is extremely rare and has been reported in cases of vaginal agenesis. 6

Hymenal anatomy has a wide range of shapes and appearances, such as annular (circumferential), crescentic (posterior rim), fimbriated, redundant (sleeve‐like), septate or cribriform (Fig. 2 ). 8 The hymen is a dynamic tissue, with morphological changes, also induced by hormonal variations. 8 Placental transfer of maternal hormones during pregnancy thickens and swells the hymen in the newborn. With the suppression of the hypothalamic‐pituitary‐gonadal axis in pre‐pubertal girls, the hymen may become thin, dry and smooth‐edged. During puberty, the exposure to oestrogen contributes to the thickening of the hymen and provides more elasticity, enabling it to stretch during penetration without leaving any trace of injury. 5 The post‐pubertal hymen has been compared to a scrunchy or a rubber band because of its elastic properties for educational purposes. 9

Physiological variations of hymenal anatomy (upper line) and variations requiring investigations and treatment (lower line). A septate, cribriform or microperforate hymen may lead to difficulty with tampon's insertion or vaginal penetrative sex.

Examination of the Hymen

The hymen receives little consideration in medical schools and most paediatricians do not feel comfortable to examine it. 10 A cross‐sectional study showed that only 64% of 139 paediatric chief residents identified correctly the hymen on photographs of pre‐pubertal female genitalia. 11 Nevertheless, professional societies advocate that genital examination should be a routine part of a comprehensive physical examination in prepubertal girls, where it could provide not only useful clinical information but also the opportunity for health education to patients and family. 12 , 13 Evidence supports that children comfortable with the correct terminology of their genitalia are less vulnerable to sexual abuse and more likely to disclose any potential event. 14

Inspection does not require any special instrument and primary care setting is ideal. The patient is placed supine in a frog‐leg position on the examining table or, depending on her age and apprehension, seated on her caregiver, with legs bent in the same position. Inspection of the hymen, vaginal introitus, urethra and clitoris requires a separation and a slight diagonal traction of the external labia (Fig. 3 ). The hypoestrogenised hymen of the pre‐pubertal girl is atrophied, thus very thin and highly sensitive, so physicians should be careful not to touch it and cause pain inadvertently. 12 The prone knee‐chest position can confirm potential findings noted in the supine position, since gravity may unroll the hymenal folds, which may not have been visible in the frog‐leg position. Moreover, it improves visualisation of the inner vagina, sometimes up to the cervix.

Labelled diagram of the external female genitalia. Courtesy of Michal Yaron.

Genital Examination in Medicolegal Circumstances

In cases suspected for sexual abuse, referral to a trained professional is necessary. 15 Nevertheless, evidence‐based data show that the large majority of children and adolescents who were victims of confirmed sexual abuse, with and without genital penetration, have normal or non‐specific findings on genital examination. 16 , 17 , 18 In a prospective study of 1500 girls aged from birth to 17 years old with a history of sexual abuse, 93% had an unremarkable genital examination, while 7% had one or more diagnostic findings. 17 Diagnostic findings for abuse were detected 10 times more (21.4 vs. 2.2%, respectively) when examination took place within 72 h from the assault, when the victim was older, or when the assault included genital penetration by a penis, finger or object. 17 Some morphological features of the hymen are non‐specific, such as clefts or notches, bumps or mounds, and irregularities extending to less than half the width of the hymenal rim (Fig. 4 ). 15 , 19 Findings highly suggestive of an acute sexual abuse include laceration of the hymen, posterior fourchette or vestibule, bruising, petechiae or abrasions of the hymen and vaginal or perianal laceration. 15 The hymen has a remarkable healing capacity, with most hymenal injuries healing completely in a few days without any scarring except in complete transection. 18 , 20 According to child abuse group of experts, transection is the only non‐acute evidence of a past and healed injury (Fig. 4 ). 15

Morphological features of the hymen. Left: Mounds and superficial clefts extending to <50% of the hymenal width are non‐specific. A clock‐face representation is suggested for consistent description of hymen's morphological features. Middle: A deep cleft extends to >50% of the hymenal width. Right: A transection is a complete defect traversing through the entire width of the hymen, to the fossa navicularis.

Hymenal trauma can result from accidental penetrating injury. 18 , 20 Despite common myths, there is no evidence that sport practice such as horse riding or tampons use can cause hymenal injuries. 21 , 22

The documentation of genital examination and hymen anatomy should be precise, using standardised medical terminology and a clock‐face analogy. Improper terms such as ‘intact’ or ‘broken’ hymen should be discarded as they are not descriptive, but interpretative. 5 Moreover, the interpretation of genital examination should be cautious: an examination described as ‘ normal’ or ‘nonspecific’ must not be interpreted as ‘nothing happened’. 23 Sometimes the patient or her caregivers may feel disappointed that the examination did not reveal any lesions. Levelling expectations before examination, by giving appropriate information on possible results, is paramount. The most important evidence of sexual abuse and the pivotal element for conviction in court remains the history provided by the victim.

Virginity Testing, Certificate of Virginity and Hymenoplasty

Despite scientific evidence showing that the hymen is not a reliable marker for previous sexual activity, misconceptions persist and lead to unjustified procedures, such as virginity testing, certificate of virginity and hymenoplasty.

Virginity testing refers to the practice of genital examination for the sole purpose of determining if a woman has had sexual intercourse or not. 1 It consists usually in inspection of the hymen or two‐finger vaginal insertion to assess the size of introitus and the laxity of the vaginal wall. 1 Although more commonly performed before marriage to assess the bride's suitability, virginity testing has also been reported as a routine examination in school setting, a repression against women protesters or as a requirement for work application. 3 , 24 Virginity testing has been described world‐wide, 2 , 25 including in high‐income countries. 1 , 4 , 26 It relies on the misconception that penile penetration leads to predictable changes of the female genital organs and overlooks the fact that sexual encounters are not limited to the vagina. Sexual practices involving the anus or the oral cavity are commonly reported by women willing to ‘spare’ their hymens. 25

The result of such testing can have devastating consequences on women who ‘fail’ them, such as shaming, social exclusion, reduction of dowry, violence and sometimes murder. 2 , 3 According to the World Health Organization, virginity tests are a form of sexual violence. 27 They are harmful not only to individuals but also to societies as they promote discrimination and gender inequality, and lead to violence against women. 24

Physicians may face a request to provide a certificate of virginity. In such uncomfortable situations and in fear for the safety of their patient, some may feel inclined to deliver a certificate of virginity of convenience, regardless of the findings on examination or even without proceeding to an examination. Although the intention is noble, this practice does not meet bioethical and deontological requirements since the physician solicited to provide such certification is asked to attest something that cannot be certified. 25 In 2020, the French government approved a law against virginity certification by health professionals, who can now incur a prison sentence or a fine. 28 Such approval of law raised a heated debate as some physicians argued that specifically banning certificates of virginity would cause more harm to vulnerable women, who may be at risk for their lives. 29 The national French medical order published an informative document for health professionals, stating that virginity cannot be scientifically and medically certified, reprimanding the delivery of such certification and suggesting to replace them with education, guidance, social support and, when indicated, protection to patients and families. 30

Hymenoplasty is a surgical act modifying the shape of the hymen, aiming to reduce its opening after previous vaginal intercourse. 25 The procedure's main goal is to obtain genital bleeding on the wedding night, in order to convince the groom and family members that the bride had never had a sexual experience prior to marriage. 4 , 25 Hymenoplasty relies on the false belief that all women bleed after the first vaginal intercourse, when in fact only half do so. 31 The efficacy of this intervention is doubtful: in the Netherlands, a small‐scale study showed that 17 of 19 women who underwent hymenoplasty reported no bleeding at first marital intercourse. 31 Because hymenal shape varies greatly between women, hymenoplasty is ‘at best, the surgeon's creative vision of what she or he imagines a woman's hymen has previously presented’. 10 Hymenoplasty is a controversial procedure, which is not taught at medical schools and is not described in most gynaecological textbooks. There is no regulation and standardisation of this procedure because it is not part of standard medical care. 4 In fact, it is classified by several national professional associations as a form of female genital cosmetic surgery. 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 In some countries, it is performed secretly and/or illegally, because of the associated shame. 25 Over the last decades, high‐income countries have reported growing numbers of requests for this lucrative procedure, mainly in private settings. 4 , 26

Alternative tricks to mimic blood loss on the wedding night have been described, such as the use of a finger‐prick to produce drops of blood to be spread on the sheet or the insertion of a dissolvable capsule containing a red dye into the vagina. 36 Such products are easily available on the internet and sometimes even suggested by physicians. 31 However, no safety data are available on these practices and the insertion of poor‐quality material into the vagina is not without risk for woman's health. It is worth mentioning that the World Health Organization classifies all procedures to the female genitalia for non‐medical purposes, including the insertion of material into the vagina, as female genital mutilation type IV. 37 Scheduling the wedding date to coincide with the menstruations or manipulating oral contraceptives to obtain vaginal bleeding has also been reported. 4

Importance of Education by the Paediatrician

False ideas about the hymen and virginity persist among societies mainly because of the lack of education. Well‐child visits at the medical office are excellent opportunities to discuss sexual health. 38 Addressing this topic, like any other health matter, can reassure children and adolescents, who learn that any type of question can receive evidence‐based information in a confidential, safe and professional environment. Involving the patient while examining the genitalia by offering to look into a mirror or by using drawings or 3D models can help them understand genital anatomy. 39

Paediatricians should support sexual education within families, by also providing the parents with evidence‐based information and encouraging an open dialogue about sexual matters, appropriate to the age and development of the child. 40 While parents are often embarrassed and reluctant to address this delicate topic for fear of encouraging their adolescents to become sexually active, evidence suggests that sexual education and communication between parents and children are associated with a delay in sexual debut. 41

Sexuality should be addressed from a broad perspective. Sexual activity is much more than vaginal intercourse and considering the hymen as a biological marker of ‘virginity’ is not only wrong from a scientific point‐of‐view but also very limiting. Sexuality is expressed in diverse forms of behaviours, encompassing non‐penetrative gestures and penetrative sexual intercourse that can also be applied to same‐sex couples. Embracing a more nuanced view on sexuality is also useful when advocating for prevention of sexually transmitted infections that are possible with oral and anal sex. 42

It is also important to recognise that some terms such as ‘sexual activity’ or ‘virginity’ are often understood or interpreted differently. 42 , 43 For instance, among 925 adolescents, genital touching was considered to be abstinent behaviour by 83.5%, oral intercourse by 70.6% and anal sex by 16.1%, respectively. 43 It is therefore pertinent to ask for more precision and details when discussing sexual knowledge, attitudes and practices. The words associated with ‘virginity’ deserve to be chosen carefully. Expressions such as ‘losing or giving her virginity’ and ‘taking her virginity’ contribute to the perpetuation of misconceptions about the hymen and the female body, and of stereotypes about gender roles.

The notion of ‘virginity’ is a social construct, which has no physical foundation. The hymen is an elastic and changing tissue, with intra‐ and inter‐individual variations. It is not a marker of purity or sexual experience and there is no scientifically reliable way to determine virginity on examination. Requests for virginity testing, certificate of virginity or hymenoplasty should be declined but dealt with carefully by providing information and support that promote the psychophysical, social and sexual health of patients. Providing sexual education to children, adolescents and parents is part of the role of a paediatrician, who can improve sexual health and counter misconceptions, which are harmful to young women and more broadly to societies.

Acknowledgement

Open Access Funding provided by Universite de Geneve.

Conflict of interest: None declared.

Correlates of Disclosure of Virginity Status Among U.S. College Students

- Original Paper

- Published: 25 July 2022

- Volume 51 , pages 3141–3149, ( 2022 )

Cite this article

- Michael D. Barnett ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-0571-4884 1 ,

- Kennedy A. Millward 2 &

- Idalia V. Maciel 3

407 Accesses

Explore all metrics

Disclosure of virginity status (DVS) refers to the extent to which an individual reveals that they identify as a virgin or not to different individuals in their lives. The purpose of this study was to investigate how generalized self-disclosure, virginity beliefs, and religiosity, as well as interactions with gender and virginity status, relate to DVS to family, peers, and religious communities. Southern U.S. college students ( N = 690) took an online sexuality questionnaire. Generalized self-disclosure did not relate to DVS, suggesting that DVS represents a unique form of self-disclosure. Gender by virginity status interactions suggested that societal double standards of gender and virginity status (i.e., non-virgin women and virgin men being stigmatized for their virginity identifications) may be most relevant to one’s decision to disclose to family, and somewhat relevant to one’s decision to disclose to religious communities. Individuals high in religiosity overall tended to disclose their virginity status when they identified as a virgin, but not as a non-virgin. Virgins concealed their virginity status from religious communities when they stigmatized their own virginity but disclosed to family and peers when they viewed virginity as a gift. Overall, the results suggest that, although religiosity and virginity beliefs indeed play a role in DVS toward certain targets, one’s gender and virginity status appear to be most important. Increased education on the double standard regarding gender and virginity status may help reduce stigma and improve sexual well-being.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

“Coming Out” as a Virgin (or Not): The Disclosure of Virginity Status Scale

Disclosure of sexual identities across social-relational contexts: findings from a national sample of black sexual minority men.

"Like a virgin". Correlates of virginity among Italian university students

https://mfr.osf.io/render?url=https%3A%2F%2Fosf.io%2Fpebsk%2Fdownload .

Amer, A., Howarth, C., & Sen, R. (2015). Diasporic virginities: Social representations of virginity and identity formation amongst British Arab Muslim women. Culture & Psychology, 21 (1), 3–19.

Article Google Scholar

Barnett, M. D., Maciel, I. V., & Moore, J. M. (2021). “Coming out” as a virgin (or not): The disclosure of virginity status scale. Sexuality & Culture., 25 , 2142–2157.

Barnett, M. D., Melugin, P. R., & Cruze, R. M. (2016). Was it (or will it be) good for you? Expectations and experiences of first coitus among emerging adults. Personality and Individual Differences, 97 , 25–29.

Blank, H. (2008). Virgin: The untouched history . Bloomsbury Publishing.

Google Scholar

Carpenter, L. M. (2001). The ambiguity of “having sex”: The subjective experience of virginity loss in the united states. Journal of Sex Research, 38 (2), 127–139.

Carpenter, L. M. (2002). Gender and the meaning and experience of virginity loss in the contemporary United States. Gender & Society, 16 (3), 345–365.

Carpenter, L. M. (2005). Virginity lost: An intimate portrait of first sexual experiences . NYU Press.

Crawford, M., & Popp, D. (2003). Sexual double standards: A review and methodological critique of two decades of research. Journal of Sex Research, 40 (1), 13–26.

Eriksson, J., & Humphreys, T. P. (2011). Virginity Beliefs Scale. In T. D. Fisher, C. M. Davis, W. L. Yarber, & S. L. Davis (Eds.), Handbook of sexuality-related measures (pp. 638–639). Routledge.

Eriksson, J., & Humphreys, T. P. (2014). Development of the virginity beliefs scale. Journal of Sex Research, 51 (1), 107–120.

Essizoğlu, A., Yasan, A., Yildirim, E. A., Gurgen, F., & Ozkan, M. (2011). Double standard for traditional value of virginity and premarital sexuality in Turkey: A university student’s case. Women & Health, 51 (2), 136–150.

Fuller, M. A., Boislard, M. A., & Fernet, M. (2019). “You’re a virgin? Really!?”: A qualitative study of emerging adult female virgins’ experiences of disclosure. The Canadian Journal of Human Sexuality, 28 (2), 190–202.

Gesselman, A. N., Webster, G. D., & Garcia, J. R. (2017). Has virginity lost its virtue? Relationship stigma associated with being a sexually inexperienced adult. Journal of Sex Research, 54 (2), 202–213.

Greene, K., Derlega, V. J., & Mathews, A. (2006). Self-disclosure in personal relationships. In A. L. Vangelisti & D. Perlman (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of personal relationships (pp. 409–427). Cambridge University Press.

Chapter Google Scholar

Hayes, A. F. (2017). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach . Guilford Publications.

Herold, E. S., & Way, L. (1988). Sexual self-disclosure among university women. Journal of Sex Research, 24 (1), 1–14.

Higgins, J. A., Trussell, J., Moore, N. B., & Davidson, J. K. (2010). Virginity lost, satisfaction gained? Physiological and psychological sexual satisfaction at heterosexual debut. Journal of Sex Research, 47 (4), 384–394.

Huang, H. (2018). Cherry picking: Virginity loss definitions among gay and straight cisgender men. Journal of Homosexuality, 65 (6), 727–740.

Humphreys, T. P. (2013). Cognitive frameworks of virginity and first intercourse. Journal of Sex Research, 50 (7), 664–675.

Jourard, S. M., & Lasakow, P. (1958). Some factors in self-disclosure. The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 56 (1), 91–98.

Kaufmann, L. M., Williams, B., Hosking, W., Anderson, J. R., & Pedder, D. J. (2015). Identifying as in, out, or sexually inexperienced: Perception of sex-related personal disclosures. Sensoria, 11 (1), 28–40.

Maciel, I. V., & Barnett, M. D. (2021). Generalized self-disclosure explains variance in outness beyond internalized sexual prejudice among young adults. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 50 (3), 1121–1128.

Mak, H. K., & Tsang, J. A. (2008). Separating the “sinner” from the “sin”: Religious orientation and prejudiced behavior toward sexual orientation and promiscuous sex. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 47 (3), 379–392.

Pachankis, J. E. (2007). The psychological implications of concealing a stigma: A cognitive-affective-behavioral model. Psychological Bulletin, 133 (2), 328–345.

Paul, C., Fitzjohn, J., Eberhart-Phillips, J., Herbison, P., & Dickson, N. (2000). Sexual abstinence at age 21 in New Zealand: The importance of religion. Social Science & Medicine, 51 (1), 1–10.

Pew Research Center. (2015). America’s changing religious landscape . Pew Research Center.

Raphael, K. G., & Dohrenwend, B. P. (1987). Self-disclosure and mental health: A problem of confounded measurement. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 96 (3), 214–217.

Sabia, J. J., & Rees, D. I. (2008). The effect of adolescent virginity status on psychological well-being. Journal of Health Economics, 27 (5), 1368–1381.

Sprecher, S., & Treger, S. (2015). Virgin college students’ reasons for and reactions to their abstinence from sex: Results from a 23-Year study at a Midwestern U.S. university. Journal of Sex Research, 52 (8), 936–948.

Stranges, M., & Vignoli, D. (2020). “Like a virgin”. Correlates of virginity among Italian university students. Genus, 76 (1), 1–23.

Tang, N., Bensman, L., & Hatfield, E. (2013). Culture and sexual self-disclosure in intimate relationships. Interpersona: An International Journal on Personal Relationships, 7 (2), 227–245.

Ullrich, P. M., Lutgendorf, S. K., & Stapleton, J. T. (2003). Concealment of homosexual identity, social support and CD4 cell count among HIV-seropositive gay men. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 54 (3), 205–212.

Willems, Y. E., Finkenauer, C., & Kerkhof, P. (2020). The role of disclosure in relationships. Current Opinion in Psychology, 31 , 33–37.

Worthington, E. L., Jr., Wade, N. G., Hight, T. L., Ripley, J. S., McCullough, M. E., Berry, J. W., Schmitt, M. M., Berry, J. T., Bursley, K. H., & O’Connor, L. (2003). The Religious Commitment Inventory-10: Development, refinement, and validation of a brief scale for research and counseling. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 50 (1), 84–96.

Zeyneloğlu, S., Kısa, S., & Yılmaz, D. (2013). Turkish nursing students’ knowledge and perceptions regarding virginity. Nurse Education Today, 33 (2), 110–115.

Download references

This study did not receive any funding.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Psychology and Counseling, The University of Texas at Tyler, 3900 University Boulevard HPR 235B, Tyler, TX, 75799, USA

Michael D. Barnett

School of Behavioral and Brain Sciences, The University of Texas at Dallas, 800 W Campbell Rd, Richardson, TX, 75080, USA

Kennedy A. Millward

Department of Psychology, University of Michigan, 500 S. State Street, Ann Arbor, MI, 48109, USA

Idalia V. Maciel

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Michael D. Barnett .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants in the study.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Barnett, M.D., Millward, K.A. & Maciel, I.V. Correlates of Disclosure of Virginity Status Among U.S. College Students. Arch Sex Behav 51 , 3141–3149 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-022-02343-2

Download citation

Received : 15 March 2021

Revised : 16 April 2022

Accepted : 17 April 2022

Published : 25 July 2022

Issue Date : August 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-022-02343-2

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Virginity beliefs

- Religiosity

- Self-disclosure

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Choose Your Test

Sat / act prep online guides and tips, 113 great research paper topics.

General Education

One of the hardest parts of writing a research paper can be just finding a good topic to write about. Fortunately we've done the hard work for you and have compiled a list of 113 interesting research paper topics. They've been organized into ten categories and cover a wide range of subjects so you can easily find the best topic for you.

In addition to the list of good research topics, we've included advice on what makes a good research paper topic and how you can use your topic to start writing a great paper.

What Makes a Good Research Paper Topic?

Not all research paper topics are created equal, and you want to make sure you choose a great topic before you start writing. Below are the three most important factors to consider to make sure you choose the best research paper topics.

#1: It's Something You're Interested In

A paper is always easier to write if you're interested in the topic, and you'll be more motivated to do in-depth research and write a paper that really covers the entire subject. Even if a certain research paper topic is getting a lot of buzz right now or other people seem interested in writing about it, don't feel tempted to make it your topic unless you genuinely have some sort of interest in it as well.

#2: There's Enough Information to Write a Paper

Even if you come up with the absolute best research paper topic and you're so excited to write about it, you won't be able to produce a good paper if there isn't enough research about the topic. This can happen for very specific or specialized topics, as well as topics that are too new to have enough research done on them at the moment. Easy research paper topics will always be topics with enough information to write a full-length paper.

Trying to write a research paper on a topic that doesn't have much research on it is incredibly hard, so before you decide on a topic, do a bit of preliminary searching and make sure you'll have all the information you need to write your paper.

#3: It Fits Your Teacher's Guidelines

Don't get so carried away looking at lists of research paper topics that you forget any requirements or restrictions your teacher may have put on research topic ideas. If you're writing a research paper on a health-related topic, deciding to write about the impact of rap on the music scene probably won't be allowed, but there may be some sort of leeway. For example, if you're really interested in current events but your teacher wants you to write a research paper on a history topic, you may be able to choose a topic that fits both categories, like exploring the relationship between the US and North Korea. No matter what, always get your research paper topic approved by your teacher first before you begin writing.

113 Good Research Paper Topics

Below are 113 good research topics to help you get you started on your paper. We've organized them into ten categories to make it easier to find the type of research paper topics you're looking for.

Arts/Culture

- Discuss the main differences in art from the Italian Renaissance and the Northern Renaissance .

- Analyze the impact a famous artist had on the world.

- How is sexism portrayed in different types of media (music, film, video games, etc.)? Has the amount/type of sexism changed over the years?

- How has the music of slaves brought over from Africa shaped modern American music?

- How has rap music evolved in the past decade?

- How has the portrayal of minorities in the media changed?

Current Events

- What have been the impacts of China's one child policy?

- How have the goals of feminists changed over the decades?

- How has the Trump presidency changed international relations?

- Analyze the history of the relationship between the United States and North Korea.

- What factors contributed to the current decline in the rate of unemployment?

- What have been the impacts of states which have increased their minimum wage?

- How do US immigration laws compare to immigration laws of other countries?

- How have the US's immigration laws changed in the past few years/decades?

- How has the Black Lives Matter movement affected discussions and view about racism in the US?

- What impact has the Affordable Care Act had on healthcare in the US?

- What factors contributed to the UK deciding to leave the EU (Brexit)?

- What factors contributed to China becoming an economic power?

- Discuss the history of Bitcoin or other cryptocurrencies (some of which tokenize the S&P 500 Index on the blockchain) .

- Do students in schools that eliminate grades do better in college and their careers?

- Do students from wealthier backgrounds score higher on standardized tests?

- Do students who receive free meals at school get higher grades compared to when they weren't receiving a free meal?

- Do students who attend charter schools score higher on standardized tests than students in public schools?

- Do students learn better in same-sex classrooms?

- How does giving each student access to an iPad or laptop affect their studies?

- What are the benefits and drawbacks of the Montessori Method ?

- Do children who attend preschool do better in school later on?