- Summary of Recommendations

- USPSTF Assessment of Magnitude of Net Benefit

- Practice Considerations

- Update of Previous USPSTF Recommendations

- Supporting Evidence

- Research Needs and Gaps

- Recommendations of Others

- Article Information

USPSTF indicates US Preventive Services Task Force.

eFigure. US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) Grades and Levels of Evidence

- USPSTF Recommendation: Depression and Suicide Risk Screening in Children and Adolescents JAMA US Preventive Services Task Force October 18, 2022 This 2022 Recommendation Statement from the US Preventive Services Task Force recommends screening for major depressive disorder (MDD) in adolescents aged 12 to 18 years (B recommendation) and concludes that current evidence is insufficient to assess the balance of benefits and harms of screening for MDD in children 11 years or younger (I statement) and of screening for suicide risk in children and adolescents (I statement). US Preventive Services Task Force; Carol M. Mangione, MD, MSPH; Michael J. Barry, MD; Wanda K. Nicholson, MD, MPH, MBA; Michael Cabana, MD, MA, MPH; David Chelmow, MD; Tumaini Rucker Coker, MD, MBA; Karina W. Davidson, PhD, MASc; Esa M. Davis, MD, MPH; Katrina E. Donahue, MD, MPH; Carlos Roberto Jaén, MD, PhD, MS; Martha Kubik, PhD, RN; Li Li, MD, PhD, MPH; Gbenga Ogedegbe, MD, MPH; Lori Pbert, PhD; John M. Ruiz, PhD; Michael Silverstein, MD, MPH; James Stevermer, MD, MSPH; John B. Wong, MD

- USPSTF Report: Screening for Depression and Suicide Risk in Children and Adolescents JAMA US Preventive Services Task Force October 18, 2022 This systematic review to support the 2022 US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement on screening for depression and suicide risk in children and adolescents summarizes published evidence on the benefits and harms of screening for and treatment of depression and suicide risk in children and adolescents 18 years or younger. Meera Viswanathan, PhD; Ina F. Wallace, PhD; Jennifer Cook Middleton, PhD; Sara M. Kennedy, MPH; Joni McKeeman, PhD; Kesha Hudson, PhD; Caroline Rains, MPH; Emily B. Vander Schaaf, MD, MPH; Leila Kahwati, MD, MPH

- USPSTF Review: Depression and Suicide Risk Screening JAMA US Preventive Services Task Force June 20, 2023 This systematic review to support the 2023 US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement on depression and suicide risk screening summarizes published evidence on the benefits and harms of screening for, and treatment of, depression and suicide risk in primary care settings, including during pregnancy and postpartum. Elizabeth A. O’Connor, PhD; Leslie A. Perdue, MPH; Erin L. Coppola, MPH; Michelle L. Henninger, PhD; Rachel G. Thomas, MPH; Bradley N. Gaynes, MD, MPH

- Reframing the Key Questions Regarding Screening for Suicide Risk JAMA Editorial June 20, 2023 Gregory E. Simon, MD, MPH; Julie E. Richards, PhD, MPH; Ursula Whiteside, PhD

- Screening for Depression and Suicide Risk in Adults JAMA JAMA Patient Page June 20, 2023 This JAMA Patient Page describes the pros and cons of screening for depression and suicide risk in adults. Jill Jin, MD, MPH

- Suicidality Screening Guidelines Highlight the Need for Intervention Studies JAMA Network Open Editorial June 20, 2023 Roy H. Perlis, MD, MSc

See More About

Select your interests.

Customize your JAMA Network experience by selecting one or more topics from the list below.

- Academic Medicine

- Acid Base, Electrolytes, Fluids

- Allergy and Clinical Immunology

- American Indian or Alaska Natives

- Anesthesiology

- Anticoagulation

- Art and Images in Psychiatry

- Artificial Intelligence

- Assisted Reproduction

- Bleeding and Transfusion

- Caring for the Critically Ill Patient

- Challenges in Clinical Electrocardiography

- Climate and Health

- Climate Change

- Clinical Challenge

- Clinical Decision Support

- Clinical Implications of Basic Neuroscience

- Clinical Pharmacy and Pharmacology

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Consensus Statements

- Coronavirus (COVID-19)

- Critical Care Medicine

- Cultural Competency

- Dental Medicine

- Dermatology

- Diabetes and Endocrinology

- Diagnostic Test Interpretation

- Drug Development

- Electronic Health Records

- Emergency Medicine

- End of Life, Hospice, Palliative Care

- Environmental Health

- Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion

- Facial Plastic Surgery

- Gastroenterology and Hepatology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Genomics and Precision Health

- Global Health

- Guide to Statistics and Methods

- Hair Disorders

- Health Care Delivery Models

- Health Care Economics, Insurance, Payment

- Health Care Quality

- Health Care Reform

- Health Care Safety

- Health Care Workforce

- Health Disparities

- Health Inequities

- Health Policy

- Health Systems Science

- History of Medicine

- Hypertension

- Images in Neurology

- Implementation Science

- Infectious Diseases

- Innovations in Health Care Delivery

- JAMA Infographic

- Law and Medicine

- Leading Change

- Less is More

- LGBTQIA Medicine

- Lifestyle Behaviors

- Medical Coding

- Medical Devices and Equipment

- Medical Education

- Medical Education and Training

- Medical Journals and Publishing

- Mobile Health and Telemedicine

- Narrative Medicine

- Neuroscience and Psychiatry

- Notable Notes

- Nutrition, Obesity, Exercise

- Obstetrics and Gynecology

- Occupational Health

- Ophthalmology

- Orthopedics

- Otolaryngology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Care

- Pathology and Laboratory Medicine

- Patient Care

- Patient Information

- Performance Improvement

- Performance Measures

- Perioperative Care and Consultation

- Pharmacoeconomics

- Pharmacoepidemiology

- Pharmacogenetics

- Pharmacy and Clinical Pharmacology

- Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation

- Physical Therapy

- Physician Leadership

- Population Health

- Primary Care

- Professional Well-being

- Professionalism

- Psychiatry and Behavioral Health

- Public Health

- Pulmonary Medicine

- Regulatory Agencies

- Reproductive Health

- Research, Methods, Statistics

- Resuscitation

- Rheumatology

- Risk Management

- Scientific Discovery and the Future of Medicine

- Shared Decision Making and Communication

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports Medicine

- Stem Cell Transplantation

- Substance Use and Addiction Medicine

- Surgical Innovation

- Surgical Pearls

- Teachable Moment

- Technology and Finance

- The Art of JAMA

- The Arts and Medicine

- The Rational Clinical Examination

- Tobacco and e-Cigarettes

- Translational Medicine

- Trauma and Injury

- Treatment Adherence

- Ultrasonography

- Users' Guide to the Medical Literature

- Vaccination

- Venous Thromboembolism

- Veterans Health

- Women's Health

- Workflow and Process

- Wound Care, Infection, Healing

Others Also Liked

- Download PDF

- X Facebook More LinkedIn

- CME & MOC

US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for Depression and Suicide Risk in Adults : US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement . JAMA. 2023;329(23):2057–2067. doi:10.1001/jama.2023.9297

Manage citations:

© 2024

- Permissions

Screening for Depression and Suicide Risk in Adults : US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement

- Editorial Reframing the Key Questions Regarding Screening for Suicide Risk Gregory E. Simon, MD, MPH; Julie E. Richards, PhD, MPH; Ursula Whiteside, PhD JAMA

- Editorial Suicidality Screening Guidelines Highlight the Need for Intervention Studies Roy H. Perlis, MD, MSc JAMA Network Open

- US Preventive Services Task Force USPSTF Recommendation: Depression and Suicide Risk Screening in Children and Adolescents US Preventive Services Task Force; Carol M. Mangione, MD, MSPH; Michael J. Barry, MD; Wanda K. Nicholson, MD, MPH, MBA; Michael Cabana, MD, MA, MPH; David Chelmow, MD; Tumaini Rucker Coker, MD, MBA; Karina W. Davidson, PhD, MASc; Esa M. Davis, MD, MPH; Katrina E. Donahue, MD, MPH; Carlos Roberto Jaén, MD, PhD, MS; Martha Kubik, PhD, RN; Li Li, MD, PhD, MPH; Gbenga Ogedegbe, MD, MPH; Lori Pbert, PhD; John M. Ruiz, PhD; Michael Silverstein, MD, MPH; James Stevermer, MD, MSPH; John B. Wong, MD JAMA

- US Preventive Services Task Force USPSTF Report: Screening for Depression and Suicide Risk in Children and Adolescents Meera Viswanathan, PhD; Ina F. Wallace, PhD; Jennifer Cook Middleton, PhD; Sara M. Kennedy, MPH; Joni McKeeman, PhD; Kesha Hudson, PhD; Caroline Rains, MPH; Emily B. Vander Schaaf, MD, MPH; Leila Kahwati, MD, MPH JAMA

- US Preventive Services Task Force USPSTF Review: Depression and Suicide Risk Screening Elizabeth A. O’Connor, PhD; Leslie A. Perdue, MPH; Erin L. Coppola, MPH; Michelle L. Henninger, PhD; Rachel G. Thomas, MPH; Bradley N. Gaynes, MD, MPH JAMA

- JAMA Patient Page Screening for Depression and Suicide Risk in Adults Jill Jin, MD, MPH JAMA

Importance Major depressive disorder (MDD), a common mental disorder in the US, may have substantial impact on the lives of affected individuals. If left untreated, MDD can interfere with daily functioning and can also be associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular events, exacerbation of comorbid conditions, or increased mortality.

Objective The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) commissioned a systematic review to evaluate benefits and harms of screening, accuracy of screening, and benefits and harms of treatment of MDD and suicide risk in asymptomatic adults that would be applicable to primary care settings.

Population Asymptomatic adults 19 years or older, including pregnant and postpartum persons. Older adults are defined as those 65 years or older.

Evidence Assessment The USPSTF concludes with moderate certainty that screening for MDD in adults, including pregnant and postpartum persons and older adults, has a moderate net benefit. The USPSTF concludes that the evidence is insufficient on the benefit and harms of screening for suicide risk in adults, including pregnant and postpartum persons and older adults.

Recommendation The USPSTF recommends screening for depression in the adult population, including pregnant and postpartum persons and older adults. (B recommendation) The USPSTF concludes that the current evidence is insufficient to assess the balance of benefits and harms of screening for suicide risk in the adult population, including pregnant and postpartum persons and older adults. (I statement)

See the Summary of Recommendations figure.

Pathway to Benefit

To achieve the benefit of depression screening and reduce disparities in depression-associated morbidity, it is important that persons who screen positive are evaluated further for diagnosis and, if appropriate, are provided or referred for evidence-based care.

The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) makes recommendations about the effectiveness of specific preventive care services for patients without obvious related signs or symptoms to improve the health of people nationwide.

It bases its recommendations on the evidence of both the benefits and harms of the service and an assessment of the balance. The USPSTF does not consider the costs of providing a service in this assessment.

The USPSTF recognizes that clinical decisions involve more considerations than evidence alone. Clinicians should understand the evidence but individualize decision-making to the specific patient or situation. Similarly, the USPSTF notes that policy and coverage decisions involve considerations in addition to the evidence of clinical benefits and harms.

The USPSTF is committed to mitigating the health inequities that prevent many people from fully benefiting from preventive services. Systemic or structural racism results in policies and practices, including health care delivery, that can lead to inequities in health. The USPSTF recognizes that race, ethnicity, and gender are all social rather than biological constructs. However, they are also often important predictors of health risk. The USPSTF is committed to helping reverse the negative impacts of systemic and structural racism, gender-based discrimination, bias, and other sources of health inequities, and their effects on health, throughout its work.

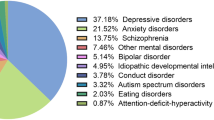

Major depressive disorder (MDD), a common mental disorder in the US, can have a substantial impact on the lives of affected individuals. 1 , 2 If left untreated, MDD can interfere with daily functioning and can be associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular events, exacerbation of comorbid conditions, or increased mortality. 1 , 3 - 5 In 2019, 7.8% (19.4 million) of adults in the US experienced at least 1 major depressive episode; 5.3% (13.1 million) experienced a major depressive episode with severe impairment. 1 , 6 Depression can be a chronic condition characterized by periods of remission and recurrence, often beginning in adolescence or early adulthood. However, full recovery may occur. 1 There is overwhelming evidence of racial and ethnic disparities in depression treatment and outcomes. 7

Depression is common in postpartum and pregnant persons and affects both the parent and infant. Depression during pregnancy increases the risk of preterm birth and low birth weight or small-for-gestational age. 8 , 9 Postpartum depression may interfere with parent-infant bonding. 10 Data from the Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System has shown a recent increase in self-reported depression during pregnancy, from 11.6% in 2016 to 14.8% in 2019. 11

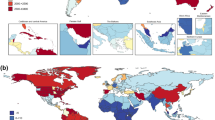

Suicide is the 10th leading cause of death in US adults (45 390 deaths [2019 data]). 12 From 2001 to 2017, there was a 31% increase in suicide deaths. 13 Over the last decade, there has been an increase; however, in recent years, suicide rates have declined. 14 In 2020, provisional suicide deaths numbered 45 855, which was 3% less than in 2019 (47 511 deaths). 15 , 16 However, rates did not decline among Black and Hispanic/Latino persons. 17 Rates of suicide attempts and deaths vary by sex, age, and race and ethnicity. 1 Psychiatric disorders and previous suicide attempts increase the risk of suicide. 1

The USPSTF concludes with moderate certainty that screening for MDD in adults, including pregnant and postpartum persons, as well as older adults, has a moderate net benefit .

The USPSTF concludes that the evidence is insufficient on the benefit and harms of screening for suicide risk in adults, including pregnant and postpartum persons, as well as older adults. As a result, the balance of benefits and harms cannot be determined.

See Table 1 and Table 2 for more information on the USPSTF recommendation rationale and assessment and the eFigure in Supplement for information on the recommendation grade. See the Figure for a summary of the recommendations for clinicians. For more details on the methods the USPSTF uses to determine the net benefit, see the USPSTF Procedure Manual. 18

This recommendation applies to adults 19 years or older who do not have a diagnosed mental health disorder or recognizable signs or symptoms of depression or suicide risk. Older adults are defined as those 65 years or older. This recommendation focuses on screening for MDD and does not address screening for other depressive disorders, such as minor depression or dysthymia.

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (Fifth Edition) defines MDD as having at least 2 weeks of mild to severe persistent feelings of sadness or a lack of interest in everyday activities. Depression can also present with irritability, poor concentration, and somatic complaints (eg, difficulty sleeping, decreased energy, and changes in appetite). 19

Perinatal depression is defined as depressive episodes that occur during pregnancy and the postpartum period (the first 12 months following delivery). 20 In addition to common symptoms of depressive disorders (eg, feeling sad or loss of interest in activities), other symptoms during the perinatal period may include difficulty bonding with the infant, persistent doubt in parenting abilities, and parental thoughts of death, suicide, self-harm, or harm to the infant. 21

Suicidal behavior includes suicidal ideation, suicide attempts, and suicide completion. Suicidal ideation refers to thinking about, considering, or planning suicide. Suicide attempts refer to nonfatal, self-directed, and potentially injurious behavior that is intended to result in death. Suicide completion is defined as a death caused by self-inflicted injurious behavior with the intent to cause death. 22

The USPSTF recommends screening for depression in all adults regardless of risk factors. Risk factors for depression include a combination of genetic, biological, and environmental factors, 1 , 23 such as a family history of depression, prior episode of depression or other mental health condition, a history of trauma or adverse life events, or a history of disease or illness (eg, cardiovascular disease). 24 - 30

Prevalence rates vary by sex, age, race, ethnicity, education, marital status, geographic location, poverty level, and employment status. 1 , 23 Women have twice the risk of depression compared with men. 31 , 32 Young adults, multiracial individuals, and Native American/Alaska Native individuals have higher rates of depression. 33

Risk factors for perinatal depression include life stress, low social support, history of depression, marital or partner dissatisfaction, and a history of abuse. 34

Many brief tools have been developed that screen for depression and are appropriate for use in primary care. All positive screening results should lead to additional assessments to confirm the diagnosis, determine symptom severity, and identify comorbid psychological problems.

Commonly used depression screening instruments include the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ) in various forms in adults, the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D), the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) in older adults, and the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) in postpartum and pregnant persons. 1

Screening instruments for suicide risk include the Beck Hopelessness Scale, the SAD PERSONS Scale (Sex, Age, Depression, Previous attempt, Ethanol abuse, Rational thinking loss, Social supports lacking, Organized plan, No spouse, Sickness), and the SAFE-T (Suicide Assessment Five-step Evaluation and Triage). 1 Some depression screening instruments, such as the PHQ-9, incorporate questions that ask about suicidal ideation. 1

There is little evidence regarding the optimal timing for screening for depression; more evidence is needed in both perinatal and general adult populations. In the absence of evidence, a pragmatic approach might include screening adults who have not been screened previously and using clinical judgment while considering risk factors, comorbid conditions, and life events to determine if additional screening of patients at increased risk is warranted. Ongoing assessment of risks that may develop during pregnancy and the postpartum period is also a reasonable approach.

Effective treatment of depression in adults generally includes antidepressant medication or psychotherapy (eg, cognitive behavioral therapy or brief psychosocial counseling), alone or in combination. 1 Clinicians are encouraged to consider the unique balance of benefits and harms in the perinatal period when deciding the best treatment for depression for a pregnant or breastfeeding person.

Adequate systems and clinical staff are needed to ensure that patients are screened and, if they screen positive, are appropriately diagnosed and treated with evidence-based care or referred to a setting that can provide the necessary care. Inadequate support and follow-up may result in treatment failures or harm, including those indicated by the US Food and Drug Administration boxed warning for selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs). 1 These essential functions can be provided through a wide range of different arrangements of clinician types and settings, including primary care clinicians, mental health specialists, or both working collaboratively, such as within a collaborative care model. 1 , 35 Collaborative care is a multicomponent, health care system–level intervention that uses care managers to link primary care clinicians, patients, and mental health specialists. 1 , 35 Additional components of support include training and materials to improve clinicians’ knowledge and skills surrounding diagnosis and treatment of depression, facilitation or improvement of the referral process, and patient-specific treatment materials. 1 , 35

Potential barriers to screening include clinician knowledge and comfort level with screening, inadequate systems to support screening or to manage positive screening results, and impact on care flow, given the time constraints faced by primary care clinicians. Clinicians should be cognizant of stigma issues associated with mental health diagnoses and should aim to develop trusting relationships with patients, free of implicit bias, by being sensitive to cultural issues. 1

Clinicians should also be cognizant of the barriers that keep individuals with depression, particularly those identified through screening, from receiving adequate treatment. It is estimated that only 50% of patients with major depression are identified. 36 Only 35% of adults in the US with a depressive disorder receive care within the first year of condition onset. 37 Systemic barriers also exist, including lack of connection between mental health and primary care, patient hesitation to initiate treatment, and nonadherence to medication and therapy. 38 , 39

Racism and structural policies have contributed to wealth inequities in the US, 40 which can affect mental health services in underserved communities. 1 For example, wealth inequities may result in barriers to receiving mental health services, such as treatment costs and lack of insurance, which tend to have a greater impact on Black persons and other racial and ethnic groups than on White persons. 41 Black and Hispanic/Latino primary care patients are less likely to be diagnosed with depression or anxiety compared with White patients. 37 , 42 - 44 Black and Hispanic/Latino patients are also less likely to receive mental health services than Asian American or White patients. 45 , 46

Suicide is the second-leading cause of death in individuals aged 10 to 34 years. 2 Eighty-three percent of individuals who die by suicide were seen in primary care in the previous year; 24% had any mental health diagnosis in their medical records in the month prior to death. 47

Factors resulting in increased risk for suicide attempts include severe psychological distress, major depressive episodes, alcohol use disorder, marital status of being divorced or separated, or being unemployed. Important risk factors for suicide deaths include previous suicide attempts (strongest predictor of future suicide death), mental health disorders and substance abuse, family history of suicide or mental health disorders, life stressors, family violence or abuse, incarceration or legal problems, certain medical conditions, chronic pain, or being a military veteran. 1

Suicide risk varies by age, sex, and race and ethnicity. 1 Men are more than 3 times more likely to die by suicide than women. 48 The highest suicide rates for women occur between the ages of 45 and 54 years, while for men the highest rates occur after age 65 years. 48 In the US, the highest suicide rates occur among White adults, followed by Native American/Alaska Native adults. Between 2014 and 2019, suicide rates increased in Asian or Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander individuals by 16% and in Black individuals by 30%. 49

Although evidence on harms of screening for suicide risk is limited, potential harms of screening include false-positive screening results that may lead to unnecessary referrals and treatment (and associated time and economic burden), labeling, anxiety, and stigma. Studies of suicide prevention interventions generally demonstrate that they are no more effective than usual care 1 ; however, 1 large pragmatic trial demonstrated an increased risk of self-harm with a dialectical behavioral therapy skills-building intervention. 50

Evidence is limited on the implementation of routine mental health screening in primary care settings in the US. No information on screening rates for depression and suicide risk in the US was identified. Suicide screening likely occurs as part of depression screening within settings that screen for suicide risk.

Screening instruments for suicide risk usually include components related to current suicidal ideation, self-harm behaviors, and assessments of past attempts and behaviors. It is unknown how often primary care clinicians detect elevated suicide risk in adults. Thirty-six percent of US primary care clinicians discussed suicide in encounters with patients showing symptoms of major depression or adjustment disorders or seeking antidepressants. 51

The Community Preventive Services Task Force (CPSTF) has several recommendations related to mental health conditions in adults. The CPSTF recommends collaborative care for managing depressive disorders. It recommends both home-based depression care and depression care management in primary care clinics for older adults. The CPSTF also recommends mental health benefits legislation in increasing appropriate utilization of mental health services for persons with mental health conditions. More information about the CPSTF and its recommendations on depression interventions is available on its website ( https://www.thecommunityguide.org ).

The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration maintains a national registry of evidence-based programs and practices for substance abuse and mental health interventions ( https://www.samhsa.gov/resource-search/ebp ) that may be helpful for clinicians looking for models of how to implement depression screening. The Suicide Prevention Resource Center, supported by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, offers various resources on suicide prevention ( https://sprc.org/ ).

In 2021, the US Surgeon General released a Call to Action that seeks progress toward full implementation of the National Strategy for Suicide Prevention ( https://www.hhs.gov/surgeongeneral/reports-and-publications/suicide-prevention/index.html ).

Perinatal Psychiatry Access Programs are population-based programs that aim to increase access to perinatal mental health care ( https://www.umassmed.edu/lifeline4moms/Access-Programs/ ). These programs build the capacity of medical professionals to address perinatal mental health and substance use disorders.

The USPSTF has recommendations on other mental health topics pertaining to adults, including screening for anxiety, 52 preventive counseling interventions for perinatal depression, 53 screening for unhealthy drug use, 54 and screening and behavioral counseling interventions for alcohol use. 55

This recommendation will replace the 2014 USPSTF recommendation statement on screening for suicide risk in adults 56 and the 2016 recommendation statement on screening for MDD in adults. 57 Previously, the USPSTF concluded that there was insufficient evidence to assess the balance of benefits and harms of screening for suicide risk in adults and older adults in primary care (I statement). The USPSTF recommended screening for MDD in in the general adult population, including pregnant and postpartum persons, noting that screening should be implemented with adequate systems in place to ensure accurate diagnosis, effective treatment, and appropriate follow-up (B recommendation). The current recommendation statement is consistent with these previous recommendations.

The USPSTF commissioned a systematic review 1 , 58 to evaluate the benefits and harms of screening, accuracy of screening, and benefits and harms of treatment of MDD and suicide risk in asymptomatic adults that would be applicable to primary care settings.

The USPSTF examined evidence on the most widely used or recommended screening tools for depression: PHQ, any version; CES-D; EPDS for perinatal persons; and GDS for older adults. 1 , 58

The USPSTF found 14 primary studies (n = 8819) and 10 existing systematic reviews (n ≈ 75 000) on accuracy of screening tests for detecting depression. 1 , 58 The existing systematic reviews assessed different versions of the PHQ, 2- and 3-item Whooley screening questions, CES-D, and EPDS. 1 , 58 One study conducted a series of individual patient data meta-analyses to compare several versions of the PHQ with structured or semistructured interviews. In the individual patient data meta-analyses, the PHQ-9 identified 85% of participants with major depression and 85% of those without major depression, at the standard cutoff of 10 or greater, when compared with a semistructured interview reference standard (sensitivity, 0.85 [95% CI, 0.79-0.89]; specificity, 0.85 [95% CI, 0.82-0.87]; 47 studies [n = 11 234]). 1 , 58

At the standard cutoff of 2 or greater and when compared with a semistructured interview, the PHQ-2 was more sensitive than the PHQ-9, identifying 91% of participants with major depression (sensitivity, 0.91 [95% CI, 0.88-0.94]; 48 studies [n = 11 703]). However, specificity at that cutoff was lower, identifying 67% of participants without depression (specificity, 0.67 [95% CI, 0.64-0.71]; 48 studies [n = 11 703]). The Whooley screening questions and the CES-D demonstrated accuracy comparable with the PHQ-2. 1 , 58 The accuracy of the EPDS was also similar to that of the PHQ-2, with sensitivity ranging from 81% to 90% and specificity ranging from 83% to 88% at cutoffs of 11 and 12, compared with a fully structured diagnostic interview. 1 , 58

The 14 primary studies covered multiple versions of the GDS; the GDS-15 was the most common version. In the studies, participants were 55 years or older (mean age, 69-85 years). Fifty percent to 70% of participants were women. Race or ethnicity was reported in only 4 studies. In these 4 studies, patients were primarily White, although 1 study from the UK included only Afro-Caribbean participants. 1 , 58 The standard cutoff of 5 or greater had an acceptable balance of sensitivity and specificity. In a pooled analysis, the GDS-15 accurately identified participants with major depression (sensitivity, 0.94 [95% CI, 0.85-0.98]; I 2 = 85.7%; specificity, 0.81 [95% CI, 0.70-0.89]; I 2 = 99.2%), with a cutoff score of 5. 1 , 58

Three studies (n = 1801) assessed screening instruments for suicidal ideation. 1 , 58 - 61 Two studies evaluated general adult populations and 1 study evaluated older adults. The study with the most events was limited to older adults. 1 , 58 Individual screening tests (GDS-15, GDS-SI [GDS–Suicide Ideation], and SDDS-PC [Symptom Driven Diagnostic System for Primary Care]) were not examined in more than 1 study. Most screening instruments reported sensitivity and specificity above 0.80 for at least 1 reported cutoff score. 1 , 58

None of the studies on the accuracy of screening tests defined optimal screening timing or intervals for either general adult or perinatal populations.

Seventeen screening trials (n = 18 437 participants) directly addressed the benefits of screening for depression on health outcomes. Four trials included unscreened control groups. The remaining trials screened all participants but provided the screening results only to the intervention groups’ clinicians. 1 Trial participants included adults of all ages and perinatal populations; 6 studies included general adult populations, 4 studies were limited to older adults, 6 studies were limited to postpartum patients (between 2 and 12 weeks postpartum), and 1 study was limited to pregnant patients. 1 , 58

Nine of the studies were conducted in the US. The remaining studies were conducted in the UK, Hong Kong, and Northern European countries. 1 , 58 All studies took place in primary care, general practice, obstetrics-gynecology, or other maternal or child wellness settings. 1 , 58 The mean age of trial participants was 38.2 years. Across all studies, 93% of all participants were women. Women also comprised a majority of participants in studies focused on general adult populations (73% women) and older adults (66% women). Among studies conducted in the US, the proportion of Black participants ranged from 7.1% to 51.2% (6 studies); of Hispanic/Latino study participants, from 4.5% to 59.3% (4 studies); and of White study participants, from 29% to 94.1% (6 studies). Only 1 study reported the percentage of participants of Asian descent, and none reported the percentage who were Native American/Alaska Native. 1 , 58 Depression outcomes included the proportion of participants meeting criteria for depression or who were above a prespecified depression symptom score (“prevalence”), the proportion who no longer met criteria for depression or were below a prespecified symptom score (“remission”), the proportion whose depression symptoms were reduced by a specified amount (“response”), and mean symptom scores.

The direct evidence from the 17 screening trials demonstrated increased rates of depression remission or scoring below a specified symptom severity threshold after 6 to 12 months in general adult and perinatal populations. 1 , 58 Screening interventions, most of which also included other care management components, were associated with a lower prevalence of depression or clinically important depressive symptomatology at 6 months postbaseline or postpartum (or the closest follow-up to 6 months) (odds ratio [OR], 0.60 [95% CI, 0.50-0.73]; 8 randomized clinical trials [RCTs] [n = 10 244]; I 2 = 0%). Among participants scoring above a predefined symptom level at baseline, screening interventions were associated with a greater likelihood of remission or scoring below a specified level of depression symptomatology (OR, 1.58 [95% CI, 1.23-2.02]; 8 RCTs [n = 2302]; I 2 = 0%) after 6 months (or the closest follow-up to 6 months). However, no benefit in symptom severity measures was found (pooled mean difference in change, −1.0 [95% CI, −2.3 to 0.3]; 9 studies [n = 5543]; I 2 = 74.4%). 1 , 58

The evidence in older adult populations demonstrated smaller effects. Four trials examined screening only in older adults and only 1 trial used a depression measure that was specifically designed for older adults. Trials among general adult populations included older adults; however, none of the trials reported subgroup effects by age. 1 , 58 There was also a lack of evidence on the optimal time to screen or screening intervals.

Forty existing systematic reviews evaluated treatment for depression; 30 (≈346 RCTs [n ≈ 45 078]) addressed psychological treatment and 10 addressed pharmacologic treatment (≈522 studies [n ≈ 116 477]). One existing systematic review reported both psychological and pharmacotherapy treatment. 1 , 58 Psychotherapy treatment improved depression and other health outcomes such as anxiety symptoms, hopelessness, quality of life, and functioning in primary care patients, perinatal populations, and older adults. The broadest analysis (any type of psychotherapy compared with any kind of control condition, measuring the depression outcome immediately after treatment [typically 2-6 months postbaseline]) demonstrated a moderate to large effect on depression (standardized mean difference [SMD], −0.72 [95% CI, −0.78 to −0.67]; 385 studies [N not reported but estimated at ≈33 000]). The effect was smaller but still statistically significant when limited to studies in primary care patients (SMD, −0.42 [95% CI, −0.56 to −0.29]; 59 studies [N not reported]). 1 , 58 Remission and response to treatment were rarely reported. There were limited data for populations according to racial or ethnic group or whether participants were socially or economically disadvantaged. The limited evidence available suggested benefits of psychological treatment in these populations. 1 , 58

Pooled analyses of antidepressant medications demonstrated increased rates of remission and response to treatment and small but statistically significant reductions in depressive symptom severity in the short term (typically 8 weeks). 1 , 58 Fluoxetine (117 studies) was associated with a small reduction in symptom severity (SMD, −0.23 [95% CI, −0.28 to −0.19]), an increase in the odds of remission (OR, 1.46 [95% CI, 1.34-1.60]), and an increase in the odds of treatment response (OR, 1.52 [95% CI, 1.40-1.66]). 1 , 58 Limited evidence was available on the longer-term impact of antidepressants and on the benefits of pharmacologic treatment in older adults and pregnant persons. 1 , 58

Only 1 short-term RCT (n = 443) examined screening for suicide risk, which was limited to primary care patients who had screened positive for depression. 1 , 58 This trial reported no statistically significant group differences in suicidal ideation at 2 weeks’ follow-up, with 1 suicide attempt among all study participants. 1 , 58

Twenty-three RCTs (n = 22 632) of suicide prevention among persons at increased risk of suicide were included. 1 , 58 One trial evaluated lithium; the remaining trials studied behavioral interventions. The effectiveness of psychological interventions for suicide prevention on suicide deaths and suicide attempts could not be determined due to the small number of events. One suicide death was reported. Most studies reported 5 or fewer suicide attempts per study group, and the pooled effect was not statistically significant (OR, 0.94 [95% CI, 0.73-1.22]; 12 RCTs [n = 14 573]; I 2 = 11.2%) 1 , 58 Pooled analyses did not demonstrate improvement over usual care for suicidal ideation, self-harm, or depression symptom severity. 1 , 58

One depression screening RCT (n = 462) evaluated harms. This trial was among postpartum patients, and no adverse events were reported in the intervention and placebo groups. Across all other depression screening studies that evaluated the benefits of screening, there was no pattern of effects indicating that screening might paradoxically worsen any outcomes the interventions were intending to benefit. 1 , 58

Four existing systematic reviews (≈63 RCTs [n ≈ 8466]) addressed the harms of psychotherapy in the general adult and perinatal populations. Psychological interventions with any psychological treatment, self-guided internet-based cognitive behavioral therapy, or guided internet-based interventions did not increase the risk of harm, measured as a worsening of depressive symptoms. 1 , 58 In 3 existing systematic reviews, the deterioration rates were lower with psychological interventions or did not differ statistically from the control group. In an existing systematic review of older adults, 14 included trials did not report safety data. 1 , 58

Twenty-two existing systematic reviews (≈522 RCTs and 175 observational studies [n > 9 million]) and 1 cohort study (n = 358 351) addressed the harms of pharmacotherapy in adults of all ages and perinatal persons. 1 , 58 Two existing systematic reviews assessed perinatal patients, 4 evaluated older adults, and the remaining reviews included adults of any age. 1 , 58 Pharmacologic agents evaluated included SSRIs and other second-generation antidepressants. Harm outcomes included any adverse events, dropout due to adverse events, serious adverse events, suicide deaths, suicide attempts, and suicidal ideation. 1 , 58

Pharmacologic treatment was associated with a higher risk of dropout due to adverse events. There was also an increased risk of serious adverse events with SSRI use compared with placebo (OR, 1.39 [95% CI 1.12-1.72]; 44 RCTs [n not reported]; I 2 = 0%). The absolute risk of serious adverse events was low, and evidence for specific serious adverse events was limited. There were too few suicide deaths to examine the association between antidepressant use and suicide death. However, RCT and observational evidence demonstrated a small absolute increase in risk of suicide attempts with second-generation antidepressant use among adults up to age 65 years (OR, 1.53 [95% CI, 1.09-2.15] [n = 41 861]; 0.7% of antidepressants users vs 0.3% of placebo users). Evidence of other harmful outcomes (eg, cardiovascular-related, bleeding, mortality, risk of falls, fractures, or dementia) was limited and mostly included observational evidence. Evidence was also almost entirely limited to observational studies for serious harms of pharmacotherapy in pregnant or postpartum persons (eg, preeclampsia, gestational diabetes, postpartum hemorrhage, and spontaneous abortion). 1 , 58

A short-term study (2 weeks’ follow-up) among primary care patients (n = 443) who screened positive for depression assessed the harms of suicide risk screening. 62 Although absolute scores were higher on 2 of the 3 suicidal ideation measures, compared with no screening, the findings were not statistically significant. 1 , 58

Two RCTs of suicide prevention treatment reported on harms. There were no differences between groups at follow-up on an instrument developed to evaluate the perceived level of coercion experienced by service users during hospital admission. 63 , 64 A lithium trial found a higher rate of nonserious adverse events (75.7% with lithium, 69% with placebo; P value not reported) and of serious adverse events (38.8% with lithium, 34.1% with placebo; P value not reported). 64 However, there was no difference in withdrawals due to adverse events (1.2% with lithium, 1.5% with placebo; P value not reported). Treatment trials did not show results indicating paradoxical harms.

One large trial (n = 18 882) assessed 2 suicide prevention interventions among adults with an elevated risk of suicide based on the PHQ-9 (question 9). 65 A care management intervention, compared with usual care, had no impact on the rate of suicide attempts (hazard ratio, 1.07 [97.5% CI, 0.84 to 1.37]; P = .52). A low-intensity online skills training intervention was associated with an increased risk of suicide attempts (hazard ratio, 1.29 [97.5% CI, 1.02 to 1.64]; P = .02). 1 , 50 , 58

A draft version of this recommendation statement was posted for public comment on the USPSTF website from September 20, 2022, to October 17, 2022. In response to comments, the USPSTF added text in the Practice Considerations section to address barriers to screening such as lack of clinician training, time constraints, and lack of systems to ensure adequate follow-up. The USPSTF added language about treatment harms of suicide interventions to the Suggestions for Practice Regarding the I Statement and Supporting Evidence sections. The USPSTF incorporated additional language regarding screening intervals into the Practice Considerations section and highlighted it as an evidence gap. The USPSTF addressed the use of pharmacotherapy in pregnant and postpartum persons in the Practice Considerations section and added a resource to help clinicians in the Additional Tools and Resources section.

More evidence on whether and how screening for suicide risk can improve health outcomes is needed. There are several critical evidence gaps; more research is needed on the following.

Epidemiology and natural history of suicide risk. Persons who attempt suicide and survive and those who die by suicide are overlapping populations. More research is needed to understand these groups and to determine how primary care can improve health outcomes in these groups.

Foundational research is needed in primary care populations and pregnant and postpartum persons, including determining which tools should be used and how screening for suicide risk should be implemented.

Accuracy of single-item suicide screeners within depression screening instruments among patients who have screened positive for depression.

Whether more individuals with screen-detected suicidal ideation could be helped before they act.

Treatment studies in populations with screen-detected suicide risk in all age groups.

Potential harms of suicide risk interventions.

Benefits and potential harms of targeted vs general screening for suicide risk.

Targeting persons at high risk for suicide, such as Hispanic/Latino and Native American/Alaska Native persons or persons with depression, may help determine whether tailored therapies are more effective in these populations.

Although the evidence is clear that providing depression screening in adults and pregnant and postpartum patients is beneficial, more research is needed to ensure that all patients receive depression screening equitably. Studies are needed that provide more information on the following.

The effect of depression screening and the most accurate screening tools among Asian American, Black, Hispanic/Latino, and Native American/Alaska Native communities and other underrepresented groups (eg, populations defined by sex, race and ethnicity, sexual orientation, and gender identity).

Barriers to establishing adequate systems of care and how these barriers can be addressed; there are also limitations to understanding the direct effect of screening relative to other depression management supports.

Rigorous examination of implementation programs is needed that reports the percentage of patients being screened, referred, and treated for depression, as well as patient health outcomes.

The American College of Physicians recommends depression screening in all adults. It defines adults who are postpartum, have a personal or family history of depression, or have comorbid medical illnesses as being at increased risk. 66 The American College of Preventive Medicine recommends universal screening for depression for all adults. 67 The Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement recommends universal screening for suspected depression based on patient presentation, risk factors, and special populations (eg, pregnant and postpartum persons and individuals with cognitive impairment). 68 The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends screening patients at least once during the perinatal period for depression and anxiety symptoms using a standardized, validated tool. 20 It also recommends that clinicians complete a full assessment of mood and emotional well-being (including screening for postpartum depression and anxiety with a validated instrument) during the comprehensive postpartum visit for each patient. 20 The US Department of Veterans Affairs recommends universal screening for suicide risk in veterans. 69

Accepted for Publication: May 12, 2023.

Corresponding Author: Michael J. Barry, MD, Informed Medical Decisions Program, Massachusetts General Hospital, 50 Staniford St, Boston, MA 02114 ( [email protected] )

The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) Members: Michael J. Barry, MD; Wanda K. Nicholson, MD, MPH, MBA; Michael Silverstein, MD, MPH; David Chelmow, MD; Tumaini Rucker Coker, MD, MBA; Karina W. Davidson, PhD, MASc; Esa M. Davis, MD, MPH; Katrina E. Donahue, MD, MPH; Carlos Roberto Jaén, MD, PhD, MS; Li Li, MD, PhD, MPH; Gbenga Ogedegbe, MD, MPH; Lori Pbert, PhD; Goutham Rao, MD; John M. Ruiz, PhD; James J. Stevermer, MD, MSPH; Joel Tsevat, MD, MPH; Sandra Millon Underwood, PhD, RN; John B. Wong, MD.

Affiliations of The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) Members: Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts (Barry); George Washington University, Washington, DC (Nicholson); Brown University, Providence, Rhode Island (Silverstein); Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond (Chelmow); University of Washington, Seattle (Coker); Feinstein Institutes for Medical Research at Northwell Health, Manhasset, New York (Davidson); University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania (Davis); University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (Donahue); The University of Texas Health Science Center, San Antonio (Jaén, Tsevat); University of Virginia, Charlottesville (Li); New York University, New York, New York (Ogedegbe); University of Massachusetts Medical School, Worcester (Pbert); Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, Ohio (Rao); University of Arizona, Tucson (Ruiz); University of Missouri, Columbia (Stevermer); University of Wisconsin, Milwaukee (Underwood); Tufts University School of Medicine, Boston, Massachusetts (Wong).

Author Contributions: Dr Barry had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. The USPSTF members contributed equally to the recommendation statement.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: Authors followed the policy regarding conflicts of interest described at https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Name/conflict-of-interest-disclosures . Dr Silverstein reported receiving a research grant on a community-based approach to maternal depression. All members of the USPSTF receive travel reimbursement and an honorarium for participating in USPSTF meetings.

Funding/Support: The USPSTF is an independent, voluntary body. The US Congress mandates that the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) support the operations of the USPSTF.

Role of the Funder/Sponsor: AHRQ staff assisted in the following: development and review of the research plan, commission of the systematic evidence review from an Evidence-based Practice Center, coordination of expert review and public comment of the draft evidence report and draft recommendation statement, and the writing and preparation of the final recommendation statement and its submission for publication. AHRQ staff had no role in the approval of the final recommendation statement or the decision to submit for publication.

Disclaimer: Recommendations made by the USPSTF are independent of the US government. They should not be construed as an official position of AHRQ or the US Department of Health and Human Services.

Additional Contributions: We thank Iris Mabry-Hernandez, MD, MPH (AHRQ), who contributed to the writing of the manuscript, and Lisa Nicolella, MA (AHRQ), who assisted with coordination and editing.

Additional Information: Published by JAMA®—Journal of the American Medical Association under arrangement with the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). ©2023 AMA and United States Government, as represented by the Secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), by assignment from the members of the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF). All rights reserved.

- Register for email alerts with links to free full-text articles

- Access PDFs of free articles

- Manage your interests

- Save searches and receive search alerts

Transforming the understanding and treatment of mental illnesses.

Información en español

Celebrating 75 Years! Learn More >>

- Health Topics

- Brochures and Fact Sheets

- Help for Mental Illnesses

- Clinical Trials

What is depression?

Depression (also known as major depression, major depressive disorder, or clinical depression) is a common but serious mood disorder. It causes severe symptoms that affect how a person feels, thinks, and handles daily activities, such as sleeping, eating, or working.

To be diagnosed with depression, the symptoms must be present for at least 2 weeks.

There are different types of depression, some of which develop due to specific circumstances.

- Major depression includes symptoms of depressed mood or loss of interest, most of the time for at least 2 weeks, that interfere with daily activities.

- Persistent depressive disorder (also called dysthymia or dysthymic disorder) consists of less severe symptoms of depression that last much longer, usually for at least 2 years.

- Perinatal depression is depression that occurs during pregnancy or after childbirth. Depression that begins during pregnancy is prenatal depression, and depression that begins after the baby is born is postpartum depression.

- Seasonal affective disorder is depression that comes and goes with the seasons, with symptoms typically starting in the late fall or early winter and going away during the spring and summer.

- Depression with symptoms of psychosis is a severe form of depression in which a person experiences psychosis symptoms, such as delusions (disturbing, false fixed beliefs) or hallucinations (hearing or seeing things others do not hear or see).

People with bipolar disorder (formerly called manic depression or manic-depressive illness) also experience depressive episodes, during which they feel sad, indifferent, or hopeless, combined with a very low activity level. But a person with bipolar disorder also experiences manic (or less severe hypomanic) episodes, or unusually elevated moods, in which they might feel very happy, irritable, or “up,” with a marked increase in activity level.

Other depressive disorders found in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5-TR) include disruptive mood dysregulation disorder (diagnosed in children and adolescents) and premenstrual dysphoric disorder (that affects women around the time of their period).

Who gets depression?

Depression can affect people of all ages, races, ethnicities, and genders.

Women are diagnosed with depression more often than men, but men can also be depressed. Because men may be less likely to recognize, talk about, and seek help for their feelings or emotional problems, they are at greater risk of their depression symptoms being undiagnosed or undertreated.

Studies also show higher rates of depression and an increased risk for the disorder among members of the LGBTQI+ community.

What are the signs and symptoms of depression?

If you have been experiencing some of the following signs and symptoms, most of the day, nearly every day, for at least 2 weeks, you may have depression:

- Persistent sad, anxious, or “empty” mood

- Feelings of hopelessness or pessimism

- Feelings of irritability, frustration, or restlessness

- Feelings of guilt, worthlessness, or helplessness

- Loss of interest or pleasure in hobbies and activities

- Fatigue, lack of energy, or feeling slowed down

- Difficulty concentrating, remembering, or making decisions

- Difficulty sleeping, waking too early in the morning, or oversleeping

- Changes in appetite or unplanned weight changes

- Physical aches or pains, headaches, cramps, or digestive problems without a clear physical cause that do not go away with treatment

- Thoughts of death or suicide or suicide attempts

Not everyone who is depressed experiences all these symptoms. Some people experience only a few symptoms, while others experience many. Symptoms associated with depression interfere with day-to-day functioning and cause significant distress for the person experiencing them.

Depression can also involve other changes in mood or behavior that include:

- Increased anger or irritability

- Feeling restless or on edge

- Becoming withdrawn, negative, or detached

- Increased engagement in high-risk activities

- Greater impulsivity

- Increased use of alcohol or drugs

- Isolating from family and friends

- Inability to meet the responsibilities of work and family or ignoring other important roles

- Problems with sexual desire and performance

Depression can look different in men and women. Although people of all genders can feel depressed, how they express those symptoms and the behaviors they use to cope with them may differ. For example, men (as well as women) may show symptoms other than sadness, instead seeming angry or irritable. And although increased use of alcohol or drugs can be a sign of depression in anyone, men are more likely to use these substances as a coping strategy.

In some cases, mental health symptoms appear as physical problems (for example, a racing heart, tightened chest, ongoing headaches, or digestive issues). Men are often more likely to see a health care provider about these physical symptoms than their emotional ones.

Because depression tends to make people think more negatively about themselves and the world, some people may also have thoughts of suicide or self-harm.

Several persistent symptoms, in addition to low mood, are required for a diagnosis of depression, but people with only a few symptoms may benefit from treatment. The severity and frequency of symptoms and how long they last will vary depending on the person, the illness, and the stage of the illness.

If you experience signs or symptoms of depression and they persist or do not go away, talk to a health care provider. If you see signs or symptoms of depression in someone you know, encourage them to seek help from a mental health professional.

If you or someone you know is struggling or having thoughts of suicide, call or text the 988 Suicide and Crisis Lifeline at 988 or chat at 988lifeline.org . In life-threatening situations, call 911 .

What are the risk factors for depression?

Depression is one of the most common mental disorders in the United States . Research suggests that genetic, biological, environmental, and psychological factors play a role in depression.

Risk factors for depression can include:

- Personal or family history of depression

- Major negative life changes, trauma, or stress

Depression can happen at any age, but it often begins in adulthood. Depression is now recognized as occurring in children and adolescents, although children may express more irritability or anxiety than sadness. Many chronic mood and anxiety disorders in adults begin as high levels of anxiety in childhood.

Depression, especially in midlife or older age, can co-occur with other serious medical illnesses, such as diabetes, cancer, heart disease, chronic pain, and Parkinson’s disease. These conditions are often worse when depression is present, and research suggests that people with depression and other medical illnesses tend to have more severe symptoms of both illnesses. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has also recognized that having certain mental disorders, including depression and schizophrenia, can make people more likely to get severely ill from COVID-19.

Sometimes a physical health problem, such as thyroid disease, or medications taken for an illness cause side effects that contribute to depression. A health care provider experienced in treating these complicated illnesses can help determine the best treatment strategy.

How is depression treated?

Depression, even the most severe cases, can be treated. The earlier treatment begins, the more effective it is. Depression is usually treated with psychotherapy , medication , or a combination of the two.

Some people experience treatment-resistant depression, which occurs when a person does not get better after trying at least two antidepressant medications. If treatments like psychotherapy and medication do not reduce depressive symptoms or the need for rapid relief from symptoms is urgent, brain stimulation therapy may be an option to explore.

Quick tip : No two people are affected the same way by depression, and there is no "one-size-fits-all" treatment. Finding the treatment that works best for you may take trial and error.

Psychotherapies

Several types of psychotherapy (also called talk therapy or counseling) can help people with depression by teaching them new ways of thinking and behaving and helping them change habits that contribute to depression. Evidence-based approaches to treating depression include cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) and interpersonal therapy (IPT). Learn more about psychotherapy .

The growth of telehealth for mental health services , which offers an alternative to in-person therapy, has made it easier and more convenient for people to access care in some cases. For people who may have been hesitant to look for mental health care in the past, virtual mental health care might be an easier option.

Medications

Antidepressants are medications commonly used to treat depression. They work by changing how the brain produces or uses certain chemicals involved in mood or stress. You may need to try several different antidepressants before finding the one that improves your symptoms and has manageable side effects. A medication that has helped you or a close family member in the past will often be considered first.

Antidepressants take time—usually 4–8 weeks—to work, and problems with sleep, appetite, and concentration often improve before mood lifts. It is important to give a medication a chance to work before deciding whether it’s right for you. Learn more about mental health medications .

New medications, such as intranasal esketamine , can have rapidly acting antidepressant effects, especially for people with treatment-resistant depression. Esketamine is a medication approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for treatment-resistant depression. Delivered as a nasal spray in a doctor’s office, clinic, or hospital, it acts rapidly, typically within a couple of hours, to relieve depression symptoms. People who use esketamine will usually continue taking an oral antidepressant to maintain the improvement in their symptoms.

Another option for treatment-resistant depression is to take an antidepressant alongside a different type of medication that may make it more effective, such as an antipsychotic or anticonvulsant medication. Further research is needed to identify the role of these newer medications in routine practice.

If you begin taking an antidepressant, do not stop taking it without talking to a health care provider . Sometimes people taking antidepressants feel better and stop taking the medications on their own, and their depression symptoms return. When you and a health care provider have decided it is time to stop a medication, usually after a course of 9–12 months, the provider will help you slowly and safely decrease your dose. Abruptly stopping a medication can cause withdrawal symptoms.

Note : In some cases, children, teenagers, and young adults under 25 years may experience an increase in suicidal thoughts or behavior when taking antidepressants, especially in the first few weeks after starting or when the dose is changed. The FDA advises that patients of all ages taking antidepressants be watched closely, especially during the first few weeks of treatment.

If you are considering taking an antidepressant and are pregnant, planning to become pregnant, or breastfeeding, talk to a health care provider about any health risks to you or your unborn or nursing child and how to weigh those risks against the benefits of available treatment options.

To find the latest information about antidepressants, talk to a health care provider and visit the FDA website .

Brain stimulation therapies

If psychotherapy and medication do not reduce symptoms of depression, brain stimulation therapy may be an option to explore. There are now several types of brain stimulation therapy, some of which have been authorized by the FDA to treat depression. Other brain stimulation therapies are experimental and still being investigated for mental disorders like depression.

Although brain stimulation therapies are less frequently used than psychotherapy and medication, they can play an important role in treating mental disorders in people who do not respond to other treatments. These therapies are used for most mental disorders only after psychotherapy and medication have been tried and usually continue to be used alongside these treatments.

Brain stimulation therapies act by activating or inhibiting the brain with electricity. The electricity is given directly through electrodes implanted in the brain or indirectly through electrodes placed on the scalp. The electricity can also be induced by applying magnetic fields to the head.

The brain stimulation therapies with the largest bodies of evidence include:

- Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT)

- Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS)

- Vagus nerve stimulation (VNS)

- Magnetic seizure therapy (MST)

- Deep brain stimulation (DBS)

ECT and rTMS are the most widely used brain stimulation therapies, with ECT having the longest history of use. The other therapies are newer and, in some cases, still considered experimental. Other brain stimulation therapies may also hold promise for treating specific mental disorders.

ECT, rTMS, and VNS have authorization from the FDA to treat severe, treatment-resistant depression. They can be effective for people who have not been able to feel better with other treatments; people for whom medications cannot be used safely; and in severe cases where a rapid response is needed, such as when a person is catatonic, suicidal, or malnourished.

Additional types of brain stimulation therapy are being investigated for treating depression and other mental disorders. Talk to a health care provider and make sure you understand the potential benefits and risks before undergoing brain stimulation therapy. Learn more about these brain stimulation therapies .

Natural products

The FDA has not approved any natural products for treating depression. Although research is ongoing and findings are inconsistent, some people use natural products, including vitamin D and the herbal dietary supplement St. John’s wort, for depression. However, these products can come with risks. For instance, dietary supplements and natural products can limit the effectiveness of some medications or interact in dangerous or even life-threatening ways with them.

Do not use vitamin D, St. John’s wort, or other dietary supplements or natural products without talking to a health care provider. Rigorous studies must be conducted to test whether these and other natural products are safe and effective.

Daily morning light therapy is a common treatment choice for people with seasonal affective disorder (SAD). Light therapy devices are much brighter than ordinary indoor lighting and considered safe, except for people with certain eye diseases or taking medications that increase sensitivity to sunlight. As with all interventions for depression, evaluation, treatment, and follow-up by a health care provider are strongly recommended. Research into the potential role of light therapy in treating non-seasonal depression is ongoing.

How can I find help for depression?

A primary care provider is a good place to start if you’re looking for help. They can refer you to a qualified mental health professional, such as a psychologist, psychiatrist, or clinical social worker, who can help you figure out next steps. Find tips for talking with a health care provider about your mental health.

You can learn more about getting help on the NIMH website. You can also learn about finding support and locating mental health services in your area on the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) website.

Once you enter treatment, you should gradually start to feel better. Here are some other things you can do outside of treatment that may help you or a loved one feel better:

- Try to get physical activity. Just 30 minutes a day of walking can boost your mood.

- Try to maintain a regular bedtime and wake-up time.

- Eat regular, healthy meals.

- Break up large tasks into small ones; do what you can as you can. Decide what must get done and what can wait.

- Try to connect with people. Talk with people you trust about how you are feeling.

- Delay making important decisions, such as getting married or divorced, or changing jobs until you feel better. Discuss decisions with people who know you well.

- Avoid using alcohol, nicotine, or drugs, including medications not prescribed for you.

How can I find a clinical trial for depression?

Clinical trials are research studies that look at new ways to prevent, detect, or treat diseases and conditions, including depression. The goal of a clinical trial is to determine if a new test or treatment works and is safe. Although people may benefit from being part of a clinical trial, they should know that the primary purpose is to gain new scientific knowledge so that others can be better helped in the future.

Researchers at NIMH and around the country conduct many studies with people with and without depression. We have new and better treatment options today because of what clinical trials have uncovered. Talk to a health care provider about clinical trials, their benefits and risks, and whether one is right for you.

To learn more or find a study, visit:

- Clinical Trials – Information for Participants : Information about clinical trials, why people might take part in a clinical trial, and what people might experience during a clinical trial

- Clinicaltrials.gov: Current Studies on Depression : List of clinical trials funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) being conducted across the country

- Join a Study: Depression—Adults : List of studies currently recruiting adults with depression being conducted on the NIH campus in Bethesda, MD

- Join a Study: Depression—Children : List of studies currently recruiting children with depression being conducted on the NIH campus in Bethesda, MD

- Join a Study: Perimenopause-Related Mood Disorders : List of studies on perimenopause-related mood disorders being conducted on the NIH campus in Bethesda, MD

- Join a Study: Postpartum Depression : List of studies on postpartum depression being conducted on the NIH campus in Bethesda, MD

Where can I learn more about depression?

Free brochures and shareable resources.

- Chronic Illness and Mental Health: Recognizing and Treating Depression : This fact sheet provides information about the link between depression and chronic disease. It describes what a chronic disease is, symptoms of depression, and treatment options, and presents resources to find help for yourself or someone else.

- Depression : This brochure provides information about depression, including different types of depression, signs and symptoms, how it is diagnosed, treatment options, and how to find help for yourself or a loved one.

- Depression in Women: 4 Things to Know : This fact sheet provides information about depression in women, including signs and symptoms, types of depression unique to women, and how to get help.

- Perinatal Depression : This brochure provides information about perinatal depression, including how it differs from “baby blues,” causes, signs and symptoms, treatment options, and how to find help for yourself or a loved one.

- Seasonal Affective Disorder : This fact sheet provides information about seasonal affective disorder, including signs and symptoms, how it is diagnosed, causes, and treatment options.

- Seasonal Affective Disorder (SAD): More Than the Winter Blues : This infographic provides information about how to recognize the symptoms of SAD and what to do to get help.

- Teen Depression: More Than Just Moodiness : This fact sheet is for teens and young adults and provides information about how to recognize the symptoms of depression and what to do to get help.

- Digital Shareables on Depression : These digital resources, including graphics and messages, can be used to spread the word about depression and help promote depression awareness and education in your community.

Federal resources

- Depression (MedlinePlus - also en español )

- Moms’ Mental Health Matters: Depression and Anxiety Around Pregnancy ( Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development)

Research and statistics

- Journal Articles : This webpage provides articles and abstracts on depression from MEDLINE/PubMed (National Library of Medicine).

- Statistics: Major Depression : This webpage provides the statistics currently available on the prevalence and treatment of depression among people in the United States.

- Depression Mental Health Minute : Take a mental health minute to watch this video on depression.

- NIMH Experts Discuss the Menopause Transition and Depression : Learn about the signs and symptoms, treatments, and latest research on depression during menopause.

- NIMH Expert Discusses Seasonal Affective Disorder : Learn about the signs and symptoms, treatments, and latest research on seasonal affective disorder.

- Discover NIMH: Personalized and Targeted Brain Stimulation Therapies : Watch this video describing repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation and electroconvulsive therapy for treatment-resistant depression. Brain stimulation therapies can be effective treatments for people with depression and other mental disorders. NIMH supports studies exploring how to make brain stimulation therapies more personalized while reducing side effects.

- Discover NIMH: Drug Discovery and Development : One of the most exciting breakthroughs from research funded by NIMH is the development of a fast-acting medication for treatment-resistant depression based on ketamine. This video shares the story of how ketamine infusions meaningfully changed the life of a participant in an NIMH clinical trial.

- Mental Health Matters Podcast: Depression: The Case for Ketamine : Dr. Carlos Zarate Jr. discusses esketamine—the medication he helped discover—for treatment-resistant depression. The podcast covers the history behind the development of esketamine, how it can help with depression, and what the future holds for this innovative line of clinical research.

Last Reviewed: March 2024

Unless otherwise specified, the information on our website and in our publications is in the public domain and may be reused or copied without permission. However, you may not reuse or copy images. Please cite the National Institute of Mental Health as the source. Read our copyright policy to learn more about our guidelines for reusing NIMH content.

- See us on facebook

- See us on twitter

- See us on youtube

- See us on linkedin

- See us on instagram

Stanford Medicine-led research identifies a subtype of depression

Using surveys, cognitive tests and brain imaging, researchers have identified a type of depression that affects about a quarter of patients. The goal is to diagnose and treat the condition more precisely.

June 22, 2023 - By Emily Moskal

Knowing what type of depression a patient has can help clinicians provide the best treatment. Yurchanka Siarhei/Shutterstock.com

Scientists at Stanford Medicine conducted a study describing a new category of depression — labeled the cognitive biotype — which accounts for 27% of depressed patients and is not effectively treated by commonly prescribed antidepressants.

Cognitive tasks showed that these patients have difficulty with the ability to plan ahead, display self-control, sustain focus despite distractions and suppress inappropriate behavior; imaging showed decreased activity in two brain regions responsible for those tasks.

Because depression has traditionally been defined as a mood disorder, doctors commonly prescribe antidepressants that target serotonin (known as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors or SSRIs), but these are less effective for patients with cognitive dysfunction. Researchers said that targeting these cognitive dysfunctions with less commonly used antidepressants or other treatments may alleviate symptoms and help restore social and occupational abilities.

The study , published June 15 in JAMA Network Open , is part of a broader effort by neuroscientists to find treatments that target depression biotypes, according to the study’s senior author, Leanne Williams , PhD, the Vincent V.C. Woo Professor and professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences.

“One of the big challenges is to find a new way to address what is currently a trial-and-error process so that more people can get better sooner,” Williams said. “Bringing in these objective cognitive measures like imaging will make sure we’re not using the same treatment on every patient.”

Finding the biotype

In the study, 1,008 adults with previously unmedicated major depressive disorder were randomly given one of three widely prescribed typical antidepressants: escitalopram (brand name Lexapro) or sertraline (Zoloft), which act on serotonin, or venlafaxine-XR (Effexor), which acts on both serotonin and norepinephrine. Seven hundred and twelve of the participants completed the eight-week regimen.

Leanne Williams

Before and after treatment with the antidepressants, the participants’ depressive symptoms were measured using two surveys one, clinician-administered, and the other, a self-assessment, which include questions related to changes in sleep and eating. Measures on social and occupation functioning, as well as quality of life, were tracked as well.

The participants also completed a series of cognitive tests, before and after treatment, measuring verbal memory, working memory, decision speed and sustained attention, among other tasks.

Before treatment, scientists scanned 96 of the participants using functional magnetic resonance imaging as they engaged in a task called the “GoNoGo” that requires participants to press a button as quickly as possible when they see “Go” in green and to not press when they see “NoGo” in red. The fMRI tracked neuronal activity by measuring changes in blood oxygen levels, which showed levels of activity in different brain regions corresponding to Go or NoGo responses. Researchers then compared the participants’ images with those of individuals without depression.

The researchers found that 27% of the participants had more prominent symptoms of cognitive slowing and insomnia, impaired cognitive function on behavioral tests, as well as reduced activity in certain frontal brain regions — a profile they labeled the cognitive biotype.