The HCCI Home-Based Primary Care Implementation Model

According to estimates from the Small Business Administration, approximately 50% of small businesses fail within the first five years. Only 25% make it to 15 years or more. While a house call program isn’t an IT firm or subscription-based clothing firm, the challenges facing those organizations – that often prove insurmountable – are not all that different.

Research suggests that organizations, and practices, fail due to shortcomings in the following:

- Assessing the market

- Creating a viable business and financial plan

- Hiring enough of the right people

- Patient and caregiver satisfaction

- Flexibility and changing with the environment

Many well-intentioned practitioners who see a need in their area – patients who are no longer able to access traditional primary care – jump in with good intentions of meeting that need. They bring a much-needed model of care to a vulnerable population. What happens too often, however, is those same practitioners find themselves struggling months later, encountering issues with staffing, staff retention, and revenue generation. They work tireless hours for little financial return. The intrinsic rewards of home-based primary care are notable, and the care provided is life-changing for many patients and caregivers. But if the practice isn’t sustainable, all those good intentions and good work are at risk.

HCCI has developed a model for implementing and growing house call programs. Starting with the fundamentals of establishing a business, including researching the market and creating a business plan, the HCCI House Call Implementation Model guides practitioners through the multiple aspects of building and leading a successful practice. While the initial phases of the model are critical and not to be overlooked, the Model is interactive by design, and can be entered at any level. HCCI has developed a rich array of learning opportunities and tools to support practices as they grow and can provide expert assistance whenever additional guidance is requested.

HCCI is dedicated to increasing access to home-based primary care for the millions of chronically ill, medically complex patients who need it. The HCCI House Call Implementation Model supports the work of practitioners who seek to do that, helping them create thriving and sustainable house call practices equipped to provide long-term solutions for their patients.

Click here to download a copy of the model. Contact us to learn how HCCI can support your practice.

Categories:

- Benefits of HBPC

- Caregiver Stories

- CMS Updates

- Data Insights

- General Features

- Practice Management

- Practice Spotlight

- Training & Education

- February 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- February 2021

- December 2020

- October 2020

- August 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

Interest in home-based primary care is growing as payments increase, technology improves, and the population ages.

THOMAS CORNWELL, MD, FAAFP, AND BRIANNA PLENCNER, CPC, CPMA

Fam Pract Manag. 2021;28(3):22A-22G

Author disclosures: no relevant financial affiliations disclosed.

The United States is experiencing a resurgence of home-based primary care (HBPC) after a rapid decline during the last century. Steady growth in physician house calls started with the doubling of house call payment rates in 1998 and a doubling and tripling of domiciliary payment rates in 2006. Other factors include the aging of our society; increased technology that allows X-rays, ultrasounds, electrocardiograms, and lab tests to be done in the home; and new CPT payments that target complex patients such as those who need chronic care management, remote patient monitoring, and advance care planning.

HBPC's value has been demonstrated through improved outcomes and reduced costs for complex patients. Medicare's Independence at Home house call program improved outcomes and decreased costs by $2,000 per patient per year, and the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs' HBPC program reduced hospital days by 60%, readmissions by 21%, and nursing home use by an astounding 89%. 1 The data generated support for HBPC on Capitol Hill, at the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), from Medicare Advantage plans, and from investors.

More recently, the COVID-19 public health emergency (PHE) brought virtual care into patients' homes in a remarkable way. But telehealth is beyond the scope of this article. Currently, Congressional action is needed to enable telehealth to continue in the home after the PHE.

Still, family physicians can take advantage of the growing support for HBPC. This article outlines steps for adding house calls to an office-based practice. Reasons to do so include the following:

Continuity of care for patients who have difficulty getting to the office, ensuring they are not lost in the system.

Better quality of care, increased time with patients, and improved doctor-patient-caregiver relationships, resulting in increased patient satisfaction scores, increased referrals from family members, increased physician satisfaction, and decreased burnout.

Improved end-of-life care, fulfilling the wishes of the majority of patients who desire to be at home surrounded by loved ones at the time of death.

Improved value-based care performance from superior risk capture, reducing gaps in care, improving quality, and lowering the total cost of care.

Increased reimbursement for complex patient care.

Increased payment, improved technology, and the aging of the population have all contributed to steady growth in physician house calls.

House calls have been shown to improve patient outcomes and decrease costs by $2,000 per patient per year.

When adding house calls to an office-based practice, three ingredients necessary to success are patients, processes, and payments.

THREE INGREDIENTS FOR SUCCESS

A successful house call program requires three ingredients: patients, processes, and payments.

Patients . There is some flexibility in choosing which patients should receive home visits. Medicare has never required house call patients to meet the homebound definition that it requires for receiving skilled nursing and therapy services in the home. But until January 2019, Medicare required additional documentation of medical necessity for every home visit, describing why a house call was needed in “lieu of an office visit.” The 2019 Medicare Physician Fee Schedule Final Rule removed this requirement as of Jan. 1, 2019.

Still, most house call programs focus on complex patients who have difficulty getting to the office. Some practices use data analytics to identify and target high-risk patients. Common candidates for HBPC include the following:

Frail older adults with multiple (often five or more) chronic conditions and deficiencies in activities of daily living (ADL).

Younger homebound patients, usually with one principal neuromuscular condition such as multiple sclerosis, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, or cervical spine injuries (some on ventilators).

Patients with high-risk diagnoses like congestive heart failure and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Patients with high hospital and emergency department (ED) utilization in the past six to 12 months.

Patients with hierarchical condition category (HCC) scores greater than 2.0.

Another group well-suited for HBPC is post-acute, transitional care management (TCM) patients. During the high-risk transition period, these patients benefit from a short course of HBPC that reduces complications and readmissions. Payments for TCM (CPT codes 99495 and 99496) have increased more than 20% over the past two years. CMS has also unbundled virtually all care management services that previously were not billable within the 30-day TCM period. These include chronic care management, care plan oversight for home health and hospice services, face-to-face and non-face-to-face prolonged services, and more when reasonable and necessary. Numerous hospitals are partnering with HBPC programs to reduce their readmission rates.

Logistical considerations for choosing house call patients include the following:

Geography: A geographic radius should be determined for home visits based on driving time (e.g., no more than 20 minutes from the physician's office or home). Telehealth, at least while it is allowed under the PHE, is an excellent way to provide care for more distant patients.

Established vs. new house call patients: Some practices may decide to limit house calls to established patients. But if you desire to grow a house call practice, the largest referral source tends to be home health agencies, followed by hospital and rehabilitation discharge planners, social services, and word of mouth.

Place of service: Practices may offer house calls to patients at home or in domiciliary settings (e.g., assisted living facilities or group homes). There are economies of scale in domiciliary care because you can see multiple patients in the same location on the same day, and the payments are roughly the same as home visits.

Capacity: A good way to start is with a half day or one full day of house calls per week, and then increase that time as volume demands.

Operational processes . Practices will need to address operational issues such as scheduling, visit preparation, staffing, supply management, and safety.

Efficient scheduling is critical to reduce travel time, and can be achieved through the following steps:

Schedule patients in close proximity. This is facilitated by assigning days to specific geographic areas and using mapping/routing software.

Map and route patients one to two days before the visit, notify patients or caregivers of the approximate visit time (usually providing a two- to four-hour window or simply indicating morning or afternoon), and verify the address (sometimes the address on file is for mailing the bill and is not the patient's physical location).

Use electronic health record flags/alerts for travel notes, communication preferences, and patient preferences. Special visit instructions should be noted on the schedule (e.g., “call daughter ahead,” “go in back door,” or “dogs need to be secured”).

Call when en route to the visit so the patient is ready and has medication out.

Give patients follow-up timeframes (e.g., four to six weeks or two to three months) instead of exact dates to allow the schedule to be fluid, to facilitate scheduling patients within the same geographic area, and to enable last-minute schedule changes based on patient acuity.

Make sure that clerical tasks are done before the visit, including obtaining signed forms and medical records (e.g., HIPAA forms, consent for treatment, or medical history forms) when possible.

Staffing considerations include the following:

Medical assistant (MA) support: Many physicians choose to do house calls solo, mainly because of the cost of including an MA. But having an MA route and drive saves the physician significant time and allows charting and phone calls while in transit. During the house call, the MA can check vitals, do immunizations, draw blood, assist with medication reconciliation and refills, get forms signed, review gaps in care, do assessments (such as PHQ-2/9, Mini-Cog, nutritional, and safety surveys), assist with wound care, help with orders (e.g., durable medical equipment, home health, and hospice), and increase safety. Making one extra house call a day covers the MA's cost, and the time savings more than allow for that one extra call.

Advanced practice provider visits: Nurse practitioner and physician assistant house calls have dramatically increased over the past decade; they are now the largest provider group making house calls. This is a cost-effective model with good outcomes, when provided with physician support.

Supply management involves keeping track of what supplies are used and restocking at the end of the day. Unlike in the office, you cannot walk down the hall to a storage closet if you run out of something during a home visit. Ensure equipment is sanitized and charged. Have a container in the car for standard supplies that are not damaged by temperature extremes (e.g., wound care items). Review schedules in advance to identify any special supply needs (e.g., a cooler for storing and transporting drawn labs).

Safety concerns include higher crime areas and homes with potentially dangerous patients, caregivers, or pets. Safety and emergency plans should include the following:

Handling car accidents and other incidents such as falls with injuries, needle-sticks, etc.

Handling pets in the home. Some HBPC programs require pets be caged during visits. Others leave it to the discretion of the pet owner and the physician.

Sitting on a hard surface chair to avoid unseen soiling, bedbugs, etc.

Washing or sanitizing hands before, during, and after the visit.

Noting safety issues on the schedule, including a history of multi-resistant organisms, bed bugs, or firearms (which should always be locked). During the PHE, conduct COVID-19 screening questions when notifying the patient of the appointment time and again when en route to the patient's home.

Seeing patients in higher crime areas during daylight hours. There is debate among HBPC clinicians about wearing clothing that identifies them as health care workers, such as a lab jacket. Some think it's better to avoid drawing attention to themselves. Others believe it is good for people to know they are there to provide care. Determine which is more comfortable for you.

Turning on smartphone location service apps, which enable the office to know the physician's location and allow the physician to quickly call in an emergency through a simple touch or verbal command.

Planning for inclement weather or natural disasters. Patients may need to be rescheduled.

Exiting the premises if the physician feels unsafe. Consider having a code word to alert staff if you need assistance.

Clinical processes . The Institute for Healthcare Improvement's Age-Friendly Health Systems' "4Ms" framework is an excellent approach to complex house call patients. The 4Ms are what matters , medication , mentation , and mobility. What matters is determined through conversations with patients about their goals of care, leading to advance directives. The home is an ideal setting to have these conversations. It is also the best place to reconcile and optimize medications , which often includes deprescribing in frail older adults. Mentation refers to diagnosing and managing dementia, depression, and delirium. Mobility focuses on ADLs, maintaining function, gait, safety, and independence. (See “ Common assessments in HBPC .”)

A house call's main clinical difference is that the exam room is in the patient's home. This requires bringing the office to the patient. The table below shows the modern-day “black bag.” The supply list will vary somewhat depending on what the physician is comfortable doing in the home. The home also provides tremendous information about the patient, including diet, safety (are there grab bars, fall hazards, etc.), social determinants of health, and what matters to the patient (pictures, religious objects, etc.). It is important to be culturally sensitive in patients' homes, which is best accomplished by asking about patient and caregiver preferences.

It is wise to review charts the day before the home visit to see if fasting blood work or any unique supplies are needed, such as injections, immunizations, or gastrostomy tubes. It also helps to review charts for complex, new, and TCM patients ahead of the visit and start pre-charting. Extensive prep time (more than 30 minutes) can be billed using CPT codes for prolonged evaluation and management (E/M) services. (See “ Commonly used CPT codes in home-based primary care .”)

House call practices commonly have 20% to 25% mortality rates, so it is critical to discuss goals of care such as the patient's desired medical decision-maker if needed, level of hospital care, cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR), and end-of-life wishes (e.g., desired place of death, hospice services, and funeral arrangements). These advance care planning (ACP) discussions can be billed with CPT code 99497 if a minimum of 16 minutes is spent and the patient consents to the conversation voluntarily (be sure to note this in your documentation). These discussions often take place over several visits, and there is no limit on how often ACP can be billed. Copays are waived for ACP done during annual wellness visits, but co-pays will apply if performed with another service.

House call patients are best served by an interdisciplinary team providing a range of services, often virtually, including the following:

Ancillary service providers (mobile X-ray, ultrasound, and phlebotomy).

Home health and hospice (Medicare pays physicians for the certification and recertification of home health and care plan oversight if they spend 30 minutes in a calendar month overseeing home health or hospice).

Care coordination departments (such as ED or hospital discharge planning).

Durable medical equipment companies.

Community organizations (Area Agencies on Aging can assist with Meals on Wheels, utilities, home maintenance, etc.; other community organizations may provide behavioral health, private duty, or respite care; and websites such as findhelp.org by Aunt Bertha list resources by ZIP code).

Other professionals making house calls (audiologists, dentists, optometrists, podiatrists, etc.).

PAYMENT FOR HOUSE CALLS

Medicare fee-for-service (FFS) payments fund most house call programs. The 2021 changes in office outpatient E/M documentation requirements do not apply to home or domiciliary visit codes, so you are still required to use the 1995 or 1997 E/M documentation guidelines for these visits. Billing by time still requires that more than 50% of the visit be spent in counseling and/or coordination of care. (See “ Home and domiciliary E/M codes and payment rates .”) Other commonly used CPT codes in HBPC and their payment rates are listed in the table above. Most of these CPT codes are new in the past decade.

Value-based care (VBC) payments are fueling the growth of house calls. Payments can vary, from shared savings with only upside potential and no downside risk, to global capitation with full risk for all patient care. Three things are essential for success: 1) capturing risk scores for accurate payment, 2) improving quality and the patient experience and closing gaps in care, and 3) lowering costs principally by reducing acute care utilization. House calls do all three exceedingly well and lower acute-care usage more than any other intervention. For family practices involved in Accountable Care Organizations or other forms of VBC, house calls can significantly contribute to the bottom line.

American Academy of Family Physicians Home-based Primary Care Member Interest Group (AAFP members only)

Rerucha CM, Salinas R, Shook J, Duane M. House calls . Am Fam Physician . 2020;102(4):211–220.

Home Centered Care Institute

HCCIntelligence™ Resource Center

American Academy of Home Care Medicine

Cornwell T. House calls are reaching the tipping point — now we need the workforce. J Patient Cent Res Rev . 2019;6(3):188-191.

Continue Reading

More in FPM

More in pubmed.

Copyright © 2021 by the American Academy of Family Physicians.

This content is owned by the AAFP. A person viewing it online may make one printout of the material and may use that printout only for his or her personal, non-commercial reference. This material may not otherwise be downloaded, copied, printed, stored, transmitted or reproduced in any medium, whether now known or later invented, except as authorized in writing by the AAFP. See permissions for copyright questions and/or permission requests.

Copyright © 2024 American Academy of Family Physicians. All Rights Reserved.

Don't bother with copy and paste.

Get this complete sample business plan as a free text document.

Home Health Care Business Plan

Start your own home health care business plan

CaringCompanion

Value proposition.

CaringCompanion provides high-quality, personalized home health care services to seniors and individuals with disabilities, letting them maintain independence and comfort within their own homes.

The Problem

Demand for reliable, high-quality and affordable home health care services is growing. Many seniors and individuals with disabilities face challenges in finding home health care providers that can effectively address their specific needs while also offering the necessary support to ensure a high quality of life at home.

The Solution

CaringCompanion offers a comprehensive and holistic approach to home health care by connecting clients with experienced, certified caregivers who possess the skills and expertise to provide personalized care and support. Our services include personalized care plans that ensure each client receives the appropriate level of assistance.

Target Market

The primary market for CaringCompanion is seniors and individuals with disabilities who want to maintain their independence while receiving assistance with daily living activities in the comfort of their own homes. This may include individuals recovering from surgery, facing chronic health conditions or dealing with cognitive impairments such as Alzheimer’s or dementia.

Competitors & Differentiation

Current alternatives.

- Traditional home health care agencies

- Independent caregivers

- Assisted living facilities and nursing homes

CaringCompanion stands out by offering personalized care plans and a thorough caregiver vetting process. Our customized care plans allow us to address each client’s specific needs and preferences, and our dedication to ongoing caregiver training and support ensures that our team stays up-to-date with the latest best practices while maintaining open communication with patients and their families.

Funding Needs

CaringCompanion requires $250,000 in initial funding to cover operating expenses, caregiver salaries, marketing efforts, insurance, and other startup costs.

Sales Channels

- Official CaringCompanion website

- Social media platforms

- Local senior centers and community organizations

- Referrals from existing clients

Marketing Activities

- Content marketing through blog posts and articles

- Social media campaigns

- Local advertising and sponsorships

- Networking with healthcare professionals and senior organizations

Financial Projections

2023: $180,000

2024: $250,000

2025: $325,000

Expenses/Costs

2023: $130,000

2024: $175,000

2025: $210,000

2023: $50,000

2024: $75,000

2025: $115,000

- Secure initial funding – June 1, 2023

- Launch official CaringCompanion website – July 1, 2023

- Hire and train first team of caregivers – August 1, 2023

- Acquire first 10 clients – September 30, 2023

- Establish partnerships with local healthcare providers – December 31, 2023

- Reach 50 active clients – June 30, 2024

- Expand service offerings and geographic reach – January 1, 2025

Team and Key Roles

Founder & ceo.

Responsible for overall business operations, client management, and strategic growth initiatives.

Care Coordinator

Oversees client intake, caregiver assignments, and care plan development.

Caregiver Team

Provides in-home care services, ensuring clients’ needs are met with compassion and professionalism.

Marketing Manager

Develops and executes marketing strategies to attract new clients and enhance brand visibility.

Partnerships & Resources

Local healthcare providers.

Collaborate with physicians, therapists, and other healthcare professionals to ensure coordinated care and support for our clients.

Senior Organizations

Partner with local senior centers, community organizations, and advocacy groups to provide resources, educational materials, and support to seniors and their families.

Insurance Companies

Establish relationships with insurance providers to offer our services as a covered benefit, making home health care more accessible and affordable for clients.

The quickest way to turn a business idea into a business plan

Fill-in-the-blanks and automatic financials make it easy.

No thanks, I prefer writing 40-page documents.

Discover the world’s #1 plan building software

Non-Medical Home care Business Plan Guide + Example

July 6, 2023

Adam Hoeksema

The in-home healthcare industry has been experiencing remarkable growth over the past few years, propelled by an aging population, increased life expectancy, and a growing preference for care within the comfort of one's own home. The Global In-Home Health Care market size was valued at around USD 305.9 billion in 2021 and is expected to reach approximately USD 629.3 billion by 2028, according to data from Fortune Business Insights. Key driving factors include the prevalence of chronic diseases, increased need for cost-effective healthcare delivery systems, technological advancements, and government initiatives promoting home healthcare. Moreover, the recent COVID-19 pandemic has put a spotlight on the importance and feasibility of home healthcare, further catalyzing its growth. The industry's trajectory suggests a promising future for businesses aiming to provide high-quality, personalized care services within a patient's home.

Read more: 9 Home Healthcare Industry Financial Stats

Based on the industry growth, there is no surprise that many are starting new businesses or considering starting a new home healthcare business.

There are two basic types of businesses that you could start:

- In Home Healthcare Business

- In Home Non-Medical Care Business

In this blog post I am going to guide you through the process of creating a business plan for a non medical home care business. You can also download our free non-medical home care business plan template and start creating your custom plan as you follow along. I plan to cover the following:

- Why Write a Business Plan for a Non-Medical Home Care Business?

What Should be Included in a Non-Medical Home Care Business Plan?

- Non-Medical Home Care Business Plan Outline

How to Analyze the Market Demand for a Non-Medical Home Care Business?

How to find and retain employees for a non-medical home care business, how to find customers for a non-medical home care business.

- How Much Working Capital is Needed for a Non-Medical Home Care Business?

- How to create financial projections for your non-medical home care business

- Non-Medical Home Care Example Business Plan

Non-Medical Home Care Business Plan FAQs

With that as the guide, let’s dive in!

Why Write a Business Plan for a Non-Medical Home Care Business?

I could say something like “if you fail to plan you plan to fail” or give you a long list of reasons why the business planning exercise could be beneficial for you, but at the end of the day, most people write a business plan because the people with the money ask for it. Your potential investors or lenders probably are asking for your business plan, so you just have to roll up your sleeves and get it done.

A non-medical home care business plan should include a Company Description, Market Analysis, Service Offerings, Marketing and Sales Strategy and Financial Projections. Our business plan template has the following outline.

Non-Medical Home Business Plan Outline

I. executive summary.

II. Business Concept

III. Market Analysis

IV. Competition Analysis

V. Marketing Strategy

VI. Menu and Kitchen Operations

VII. Service and Hospitality

VIII. Financial Plan

- Startup Costs:

Projected Financial Summary:

Annual sales, gross profit and net profit:, key financial ratios:, income statement:, balance sheet:, cash flow statement:.

IX. Organizational Structure

X. Conclusion

In order to analyze the market demand for a non-medical home care business, you first need to determine what services you might provide.

Non-Medical Home Care Services

Non-medical home care services focus on helping individuals with their daily activities and needs, improving their quality of life without necessarily providing healthcare-specific treatments. Here are some examples:

Personal Care: This includes assistance with activities of daily living (ADLs) such as bathing, dressing, grooming, toileting, and feeding.

Companionship: This involves providing social interaction to prevent loneliness and depression. Companions may engage the individual in conversations, read books, play games, or accompany them to social events.

Meal Preparation: Some non-medical care services involve preparing meals for individuals who may have difficulty cooking for themselves. They may also assist with grocery shopping.

Light Housekeeping: This can include help with tasks like doing laundry, dishes, taking out the trash, and general tidying up around the home.

Transportation Services: Non-medical home care providers can offer non-emergency medical transportation to and from appointments, social engagements, shopping trips, or other errands.

Medication Reminders: While non-medical home care providers do not administer medication, they can remind individuals to take their medication at the appropriate times to ensure adherence to their regimen.

Respite Care: These services provide temporary relief to primary caregivers, allowing them time off for rest, personal errands, or vacations.

Mobility Assistance: Helping individuals move around, whether it's transferring from the bed to a chair or assisting with ambulation around the house or outdoors.

Once you decide what services you might want to provide, you can use Google Keyword Planner Tool to search for keyword phrases related to those services in your area and get an estimate of the number of people searching for those services each month. This can really help analyze which services might be the most popular. For example, I did a search for home care in Chicago and found that there are roughly 320 monthly searches for that keyword phrase. There are roughly 90 monthly search for non-emergency medical transportation in Chicago and only 10 searches per month for companionship services in Chicago.

This should help you get a feel for the most in demand services in your area.

One of the biggest challenges for most non-medical home care businesses is finding and retaining employees. You will likely need some unique plans to recruit and retain good employees. Here are some ideas:

Recruitment:

Clear Job Descriptions: Ensure that the roles and responsibilities are clearly stated in your job advertisements. This way, potential employees will understand exactly what is expected of them.

Strong Online Presence: A well-designed website and active social media accounts can enhance your business's credibility and reach. Post job vacancies on your website, LinkedIn, job boards, and social media platforms to attract potential employees.

Partnerships with Local Institutions: Build relationships with vocational schools, nursing schools, and community colleges. They can provide a steady stream of potential candidates.

Employee Referral Program: Your current employees might know others who would be a good fit for your business. Offering incentives for successful referrals can be a productive recruitment tool.

Competitive Pay and Benefits: Offering competitive salaries and benefits, such as health insurance, retirement plans, paid time off, can significantly increase employee retention.

Employee Recognition and Rewards: Regularly acknowledge and reward the hard work and dedication of your employees. This could be through an "Employee of the Month" program, performance bonuses, or simply a thank you note.

Professional Development: Offer ongoing training and development opportunities. This will not only improve the quality of your services but will also show your employees that you value their personal and professional growth.

Supportive Work Environment: Create a culture that supports work-life balance. This could include flexible scheduling, mental health resources, and supportive management.

Open Communication: Foster a culture of open communication where employees feel comfortable voicing their ideas and concerns. Regularly ask for feedback and be responsive to it.

Career Advancement Opportunities: Provide clear pathways for career progression within your company. This gives employees something to work towards and helps them see a future with your organization.

By combining these effective recruitment and retention strategies, your non-medical home care business can build and maintain a reliable, motivated, and highly-skilled team.

Finding customers for your non-medical home care business is all about understanding your target audience, building awareness, and establishing trust in your services. Here are several strategies to help attract clients:

Referral Networks: Build strong relationships with healthcare professionals, such as doctors, nurses, physical therapists, social workers, and hospital discharge planners. They can refer patients to your service. Also, consider forming partnerships with senior centers, retirement communities, and organizations that cater to your target demographic.

Online Marketing: Ensure your business has a robust online presence. Create a professional website detailing your services, customer testimonials, pricing, and contact information. Utilize SEO strategies to ensure your site ranks highly in search results related to home care in your area. Also, leverage social media platforms to connect with potential clients and their families.

Community Outreach: Participate in local events and sponsor activities that resonate with your target audience. Giving talks on elder care topics or offering free workshops can help establish your business as an authority in the field.

Content Marketing: Write blogs or create videos on topics that your potential clients might search for online, such as "How to choose a home care provider" or "Benefits of non-medical home care." This helps position your business as a trusted resource.

Direct Mail and Brochures: Despite the digital age, direct mail campaigns can still be effective, particularly as many seniors may not be as internet-savvy. Distribute brochures or flyers in areas frequented by your target demographic.

Customer Testimonials and Reviews: Encourage satisfied customers to share their experiences online. Positive testimonials and reviews can be powerful tools for attracting new clients.

Networking: Attend industry-related events and join professional organizations to meet others in the field who might refer clients to you.

Paid Advertising: Consider paid advertising options like Google Ads or Facebook Ads targeting your local area and specific demographics.

Follow-up Services: If a client discontinues your service (e.g., because of hospitalization), ensure to follow up. They might need your service again when they are discharged.

Remember, trust and reliability are key in this industry. By delivering high-quality service, maintaining professional standards, and putting your clients' needs first, you can build a strong reputation that will attract and retain customers.

How Much Working Capital is Needed for a Non-Medical Home Care Business?

As we soon move into the financial projections section, one of the key questions for a non-medical home care business is how much working capital will be needed. I spent over 10 years leading an SBA Microloan Program and we funded many loans for home care services that needed working capital. The basic challenge was that companies often got paid through Medicare or Medicaid which could potentially have a significant delay between the time the service is provided and when you get paid. In the meantime you have to pay your employees. So the more clients you get the more working capital you actually need to float. I would expect that you should have at least 45 days worth of payroll available as working capital. So if your employees cost $50,000 per month, you should have access to a line of credit for at least $75,000 and you should be careful about how fast you grow.

Watch: How growing too fast can lead to bankruptcy even if you are profitable

How to Create Financial Projections for a Home Healthcare Business Plan

Just like in any industry, the in-home healthcare business has its unique factors that influence financial projections, such as client acquisition, reimbursement rates, and regulatory compliance. Utilizing an in-home healthcare financial projection template can simplify the process and increase your confidence. Creating accurate financial projections goes beyond showcasing your ability to provide in-home healthcare services; it's about illustrating the financial path to profitability and the realization of your mission to deliver quality care. To develop precise projections, consider the following key steps:

- Estimate startup costs for your in-home healthcare business, including licensing and certifications, insurance, office space or administrative setup, equipment, and initial marketing efforts.

- Forecast revenue based on projected client volume, reimbursement rates, and potential growth in service offerings or specialty areas.

- Project costs related to employee wages, training and development, supplies and equipment, transportation, and administrative expenses.

- Estimate operating expenses like rent, utilities, insurance premiums, software subscriptions, and marketing costs.

- Calculate the capital needed to launch and sustain your in-home healthcare business, covering initial expenses and providing working capital for continued growth and operations.

While financial projections are a vital component of your in-home healthcare business plan, seek guidance from experienced professionals in the industry. Adapt your projections based on real-world insights, leverage industry resources, and stay informed about regulatory changes, industry standards, and evolving healthcare models to ensure your financial plan aligns with your goals and positions your business for long-term success in providing exceptional in-home care.

Example Non-Medical Care Business Plan

Explore our comprehensive Non-Medical Home Care Business Plan Guide below, complete with an example template to jumpstart your planning process. Download the editable Google Doc version and follow our video walkthrough to tailor the plan to your unique business concept.

Table of Contents

Ii. company description, iv. service offerings, v. marketing and sales strategy, vi. financial projections, use of startup funds:, vii. conclusion.

Our non-medical home care business, named "Compassionate Care", aims to provide high-quality and affordable in-home care services to seniors and people with disabilities in the Dallas-Fort Worth area. Our mission is to help people live with dignity and independence in the comfort of their own homes, by providing compassionate and trustworthy care to meet their physical, emotional, and social needs.

The home care industry has experienced significant growth in recent years, driven by the aging of the population and the increasing demand for alternatives to institutional care. Compassionate Care will differentiate itself from competitors by offering a comprehensive suite of services, including personal care, homemaking, transportation, and companionship, tailored to the individual needs and preferences of each client. Our services will be delivered by a team of experienced and qualified caregivers, who will undergo rigorous background checks and training, and be bonded and insured.

Based on market research and financial projections, we expect Compassionate Care to generate $1 million in revenue in its first year of operations, and to achieve a net profit margin of 22% by the end of year three. To finance the business, we will seek a combination of debt and equity financing, from banks, angel investors, and family and friends.

Compassionate Care was founded by two friends, Jane Doe and John Doe, who have a combined 20 years of experience in the health care and social services industries. Jane has a Bachelor's degree in Nursing and has worked as a registered nurse for 10 years, while John has a Master's degree in Social Work and has been a social worker for 10 years. Both have a passion for helping people and a vision to create a company that provides compassionate and high-quality care to seniors and people with disabilities.

Compassionate Care will be incorporated as a Limited Liability Company (LLC) and will be headquartered in Dallas, Texas. The company will be owned and operated by Jane and John, who will act as the CEO and COO, respectively. The company will employ a team of 15 caregivers, who will be supervised by a director of nursing and a director of operations. The company will also have an office manager and a marketing and sales coordinator, who will handle administrative and marketing tasks.

The home care industry is a growing and dynamic market, with an estimated value of $100 billion in the United States. The demand for home care services is driven by the aging of the population, the increasing prevalence of chronic conditions, and the preference for home-based care over institutional care. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the number of people aged 65 and older is projected to increase from 56 million in 2020 to 84 million in 2050, representing a 50% increase. Moreover, the number of people with disabilities who require assistance with daily activities is also expected to grow, as a result of improved medical care and increased longevity.

Compassionate Care's target market will be seniors and people with disabilities in the Dallas-Fort Worth area, who need assistance with activities of daily living and desire to maintain their independence and quality of life at home. The target market will include individuals who live alone, as well as those who live with family or friends, who need additional support and companionship. The target market will also include those who are transitioning from hospital to home, who need short-term or intermittent care.

Compassionate Care will face competition from other home care agencies, as well as from informal care providers, such as family members, friends, and neighbors. However, Compassionate Care will differentiate itself from competitors by offering a comprehensive and customized approach to care, by involving clients and their families in the care planning process, and by ensuring that the caregivers are well-trained and compassionate. Our services will also be priced competitively, while maintaining high quality standards.

Compassionate Care will offer a range of in-home care services to meet the diverse needs and preferences of its clients. Our services will include the following:

- Personal Care: Assistance with activities of daily living, such as bathing, dressing, grooming, toileting, and transferring.

- Homemaking: Assistance with household tasks, such as light housekeeping, laundry, meal preparation, and shopping.

- Transportation: Assistance with errands, appointments, and recreational activities, using the client's or the company's vehicle.

- Companionship: Socialization and emotional support, through conversation, games, reading, and other activities of interest.

All of our services will be tailored to the individual needs and preferences of each client, and will be provided in accordance with a care plan that is developed in collaboration with the client and the caregiver. The care plan will be reviewed and updated regularly, based on the client's changing needs and preferences.

Compassionate Care will employ a multi-channel marketing strategy, to reach its target audience and generate leads. Our marketing and sales efforts will include the following:

- Website: A professional and user-friendly website, which will provide information about the company and its services, testimonials, and a contact form.

- Referral Network: Collaboration with hospitals, rehabilitation centers, senior centers, and other organizations that serve seniors and people with disabilities, to promote our services and receive referrals.

- Direct Mail: A targeted direct mail campaign, using mailing lists of seniors and people with disabilities in the Dallas-Fort Worth area, to introduce our services and offer a special promotion.

- Social Media: Active presence on social media platforms, such as Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram, to engage with our target audience and promote our services.

- Referral Program: A referral program, which will offer incentives to clients, caregivers, and referral sources who refer new clients to the company.

Compassionate Care expects to generate $1 million in revenue in its first year of operations, and to grow its revenue by 100% in each subsequent year. The revenue will come from the sale of home care services, which will be priced competitively, based on the number and type of services provided.

Compassionate Care expects to achieve a profit margin of 10% by the end of year three, and to reinvest a portion of the profits into the business to support its growth and expansion.

All of the unique financial projections you see below were generated using ProjectionHub’s Home Healthcare financial projection template . Use PH20BP to enjoy a 20% discount on the template.

Watch how to create financial projections for your very own home care business:

Compassionate Care is poised to capture a significant share of the home care market in the Dallas-Fort Worth area, by providing high-quality and customized care services to seniors and people with disabilities. The company's experienced and dedicated management team, its commitment to excellence, and its focus on client satisfaction, will set it apart from competitors and ensure its success. We look forward to serving the needs of our clients and their families, and to making a positive impact on their lives.

Compassionate Care will also be committed to giving back to the community, by participating in volunteer and fundraising activities, and by supporting organizations that serve seniors and people with disabilities. Our goal is to be not only a trusted and respected provider of home care services, but also a responsible and engaged member of the community.

With this comprehensive business plan, we are confident that Compassionate Care will become a leading provider of non-medical home care services in the Dallas-Fort Worth area. We are eager to launch this business and to make a positive difference in the lives of our clients and the community.

How do I start a non-medical home care business?

To start an non-medical home care business, obtain the necessary licenses and certifications, establish legal and regulatory compliance, develop policies and procedures, hire qualified caregivers or nurses, establish relationships with healthcare providers, and create a marketing strategy to reach potential clients.

What types of non-medical home care services can I offer?

Non-medical home care services can include personal care assistance, medication management, medical monitoring, wound care, physical therapy, occupational therapy, speech therapy, respite care, and end-of-life care, among others.

How can I attract clients to my non-medical home care business?

To attract clients, establish relationships with hospitals, nursing homes, churches, and healthcare professionals for referrals, create a professional website with informative content, participate in local healthcare events or fairs, network with community organizations, and provide exceptional and compassionate care.

What legal and regulatory requirements do I need to comply with in the non-medical home care industry?

Legal and regulatory requirements in the non-medical home care industry can include obtaining proper licensing, complying with privacy regulations (such as HIPAA in the United States), following state and federal guidelines for caregiver qualifications, and adhering to safety and health regulations.

About the Author

Adam is the Co-founder of ProjectionHub which helps entrepreneurs create financial projections for potential investors, lenders and internal business planning. Since 2012, over 50,000 entrepreneurs from around the world have used ProjectionHub to help create financial projections.

Other Stories to Check out

How to know if your financial projections are realistic.

It is important for financial projections for a small business or startup to be realistic or else an investor or lender may not take them seriously. More importantly, the founder may make a financial mistake without a reliable plan.

How to Finance a Small Business Acquisition

In this article we are going to walk through how to finance a small business acquisition and answer some key questions related to financing options.

How to Acquire a Business in 11 Steps

Many people don't realize that acquiring a business can be a great way to become a business owner if they prefer not to start one from scratch. But the acquisition process can be a little intimidating so here is a guide helping you through it!

Have some questions? Let us know and we'll be in touch.

Everything that you need to know to start your own business. From business ideas to researching the competition.

Practical and real-world advice on how to run your business — from managing employees to keeping the books.

Our best expert advice on how to grow your business — from attracting new customers to keeping existing customers happy and having the capital to do it.

Entrepreneurs and industry leaders share their best advice on how to take your company to the next level.

- Business Ideas

- Human Resources

- Business Financing

- Growth Studio

- Ask the Board

Looking for your local chamber?

Interested in partnering with us?

Start » business ideas, how to start a home care business.

Starting a home care business can be a lucrative opportunity for anyone with health care experience. Learn the seven steps you’ll need to take to get started.

Home care businesses provide a valuable service to the community, which is why the industry is expected to double in size over the next 15 years. But the job is demanding, and it’s essential to perform your due diligence before getting started.

What is a home care business?

Home care businesses offer home health and medical services to aging or sick individuals. It’s an umbrella term used to refer to multiple types of services.

A home care business could provide the following services:

- Companionship to seniors.

- Assisting clients with daily activities like housekeeping and cooking.

- Home therapy services, like physical and occupational therapy.

- Hospice care.

7 tips to starting a home care business

Find out what certifications you need.

Before starting a home care business, you must certify your business through the state and obtain a license. It’s also a good idea to check your local health department to find out if you need any additional licenses. This is not an overnight process and could take as long as a year to complete.

Decide what services you’ll offer

Home care businesses can cover a wide variety of services. You want to decide which type of services you will provide based on your experience and your staff.

If you’re not sure what service you want to offer, spend some time researching the top growing trends in the health care field. This can be an excellent way to match your skills with the current market demand.

As a home care worker, you cannot discuss health records with family or friends.

Identify your target market

Next, you’ll want to spend some time thinking about your target market. This is not necessarily the clients you’ll be serving, but the individuals who will be hiring you. For instance, if you offer hospice services, your target market is the adult children who will hire you to care for their parents.

Create a business plan

The best way to set yourself up for success is by coming up with a detailed business plan. A business plan will outline your target market, your financial plan and how you plan to market your business.

Having a business plan can make it easier to qualify for a small business loan. A loan can help you get your business off the ground faster and let you avoid having to dip into your savings.

[ Read more: How to Write a One-Page Business Plan in a Hurry ]

Make sure you understand HIPAA laws

HIPAA compliance can be one of the most challenging aspects of starting a home care business. HIPAA laws protect the patient's privacy and ensure that third parties can’t access their records without their consent.

As a home care worker, you cannot discuss health records with family or friends. This could frustrate some family members and friends and make it harder for you to do your job. Make sure you have a thorough understanding of HIPAA laws before starting your business.

Come up with a marketing plan

Once you have your business set up and have applied for the appropriate licenses, you should begin marketing your business. You can promote your business on social media and invest in local advertising.

And don’t forget to ask current clients for referrals. Referrals are an excellent―and free―way to grow your business.

[ Read more: The Difference Between Sales and Marketing ]

Hire your staff

If you want to grow your home care business, then at some point you’ll have to bring on staff. You should choose your employees carefully since they directly represent the quality care you will provide.

Conduct a thorough interview process and run background checks on all employees. You can find potential employees through a staffing agency or through personal recommendations.

[ Read more: The Best Interview Questions to Ask, According to Franchise Owners ]

CO— aims to bring you inspiration from leading respected experts. However, before making any business decision, you should consult a professional who can advise you based on your individual situation.

Follow us on Instagram for more expert tips & business owners’ stories.

CO—is committed to helping you start, run and grow your small business. Learn more about the benefits of small business membership in the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, here .

Subscribe to our newsletter, Midnight Oil

Expert business advice, news, and trends, delivered weekly

By signing up you agree to the CO— Privacy Policy. You can opt out anytime.

For more business ideas

11 self-care business ideas for entrepreneurs, how to start a brewery, how to start your own real estate business.

By continuing on our website, you agree to our use of cookies for statistical and personalisation purposes. Know More

Welcome to CO—

Designed for business owners, CO— is a site that connects like minds and delivers actionable insights for next-level growth.

U.S. Chamber of Commerce 1615 H Street, NW Washington, DC 20062

Social links

Looking for local chamber, stay in touch.

Healthcare Business Plan Template

Written by Dave Lavinsky

Healthcare Business Plan

You’ve come to the right place to create your Healthcare business plan.

We have helped over 10,000 entrepreneurs and business owners create business plans and many have used them to start or grow their Healthcare companies.

Below is a template to help you create each section of your Healthcare business plan.

Executive Summary

Business overview.

Riverside Medical is a family medical clinic located in San Francisco, California. Our goal is to provide easy access to quality healthcare, especially for members of the community who have low to moderate incomes. Our clinic provides a wide range of general and preventative healthcare services, including check-ups, minor surgeries, and gynecology. Anyone of any age or group is welcome to visit our clinic to get the healthcare that they need.

Our medical practitioners and supporting staff are well-trained and have a passion for helping improve the health and well-being of our clients. We serve our patients not just with our knowledge and skills but also with our hearts. Our clinic was founded by Samantha Parker, who has been a licensed doctor for nearly 20 years. Her experience and compassion will guide us throughout our mission.

Product Offering

Riverside Medical will provide extensive general care for all ages, creating a complete healthcare solution. Some of the services included in our care include the following:

- Primary care: annual checkups, preventative screenings, health counseling, diagnosis and treatment of common conditions

- Gynecology: PAP tests, annual well-woman exam, and family planning

- Pediatrics: infant care, annual physicals, and immunizations

- Minor procedures: stitches, casts/splints, skin biopsies, cyst removals, and growth lacerations

- Health and wellness: weight loss strategies, nutrition guidance, hormone balance, and preventive and routine services

The costs will depend upon the materials used, the physician’s time, and the amount designated for each procedure. Medical bills will be billed either directly to the patient or to their insurance provider.

Customer Focus

Riverside Medical will primarily serve the community living and working within the San Francisco bay area. The city is diverse and growing and includes people of all ages, ethnicities, and backgrounds. Everyone is welcome to visit our clinic to receive the health care they need.

Management Team

Riverside Medical’s most valuable asset is the expertise and experience of its founder, Samantha Parker. Samantha has been a licensed family doctor for 20 years now. She spent the most recent portion of her career on medical mission trips, where she learned that many people are not privileged to have access to quality medical services. Samantha will be responsible for ensuring the general health of her patients and creating a viable and profitable business medical practice.

Riverside Medical will also employ nurses, expert medical staff, and administrative assistants that also have a passion for healthcare.

Success Factors

Riverside Medical will be able to achieve success by offering the following competitive advantages:

- Location: Riverside Medical’s location is near the center of town. It’s visible from the street with many people walking to and from work on a daily basis, giving them a direct look at our clinic, most of which are part of our target market.

- Patient-oriented service: Riverside Medical will have a staff that prioritizes the needs of the patients and educates them on the proper way how to take care of themselves.

- Management: Samantha Parker has a genuine passion for helping the community, and because of her previous experience, she is fully equipped and overqualified to open this practice. Her unique qualifications will serve customers in a much more sophisticated manner than our competitors.

- Relationships: Having lived in the community for 25 years, Samantha Parker knows many of the local leaders, newspapers, and other influences. Furthermore, she will be able to draw from her ties to previous patients from her work at other clinics to establish a starting clientele.

Financial Highlights

Riverside Medical is seeking a total funding of $800,000 of debt capital to open its clinic. The capital will be used for funding capital expenditures and location build-out, acquiring basic medical supplies and equipment, hiring initial employees, marketing expenses, and working capital.

Specifically, these funds will be used as follows:

- Clinic design/build: $100,000

- Medical supplies and equipment: $150,000

- Six months of overhead expenses (rent, salaries, utilities): $450,000

- Marketing: $50,000

- Working capital: $50,000

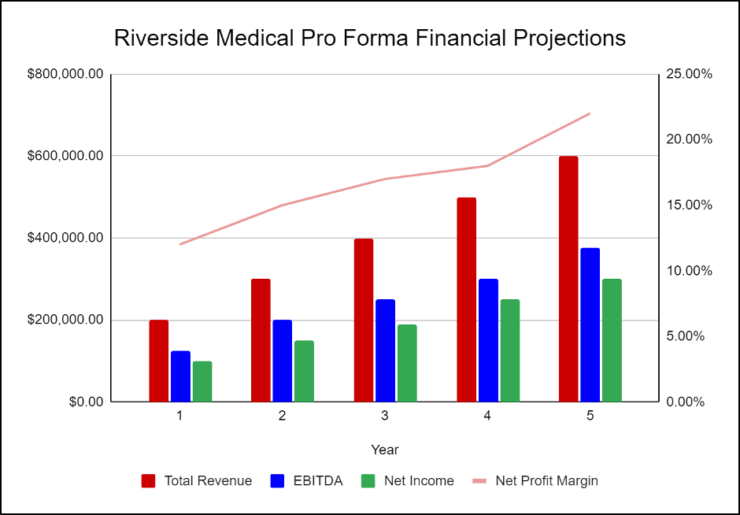

The following graph below outlines the pro forma financial projections for Riverside Medical.

Company Overview

Who is riverside medical, riverside medical history.

Samantha Parker started the clinic with the goal of providing easy access to good quality health service, especially to those members of the community with low to moderate income. After years of planning, she finally started to build Riverside Medical in 2022. She gathered a group of professionals to fund the project and was able to incorporate and register Riverside Medical with their funding support.

Since its incorporation, Riverside Medical has achieved the following milestones:

- Found clinic space and signed Letter of Intent to lease it

- Developed the company’s name, logo, and website

- Hired a contractor for the office build-out

- Determined equipment and fixture requirements

- Began recruiting key employees with previous healthcare experience

- Drafted marketing campaigns to promote the clinic

Riverside Medical Services

Industry analysis.

The global healthcare market is one of the largest and highest-valued industries in the world. According to Global Newswire, the global healthcare services market is currently valued at $7548.52 billion and is expected to reach $10414.36 billion in 2026. This growth is expected to continue for the foreseeable future.

The biggest drivers of industry growth throughout the next decade will be a continual increase in illnesses and diseases as well as a quickly aging population. With more people aging and needing daily/frequent care, hospitals and medical clinics are bound to be in even more demand than they already are.

One obstacle for the industry is the rising cost of care. Though this results in greater profits, more and more Americans cannot afford basic medical care. Therefore, they are opting out of procedures they believe are unnecessary or unimportant.

Despite the challenges of the next decade, the industry is still expected to see substantial growth and expansion.

Customer Analysis

Demographic profile of target market.

Riverside Medical will serve the residents of the San Francisco bay area as well as those who work in the area.

The population of the area experiences a large income gap between the highest earners and the lowest earners. Therefore, it is hard for middle and lower-class families to find quality care that is affordable. As a result, they are in need of the services that we offer and are looking for accessible medical care.

The precise demographics of San Francisco are as follows:

Customer Segmentation

Our clinic is a general family practice and will treat patients of all ages, incomes, physical abilities, races, and ethnicities. As such, there is no need to create marketing materials targeted at only one or two of these groups, but we can appeal to all with a similar message.

Competitive Analysis

Direct and indirect competitors.

Riverside Medical will face competition from other companies with similar business profiles. A description of each competitor company is below.

City Medical

Founded in 2008, City Medical is a membership-based, primary-care practice in the heart of the city. City Medical offers a wide range of primary care services for patients who subscribe to the practice for an annual fee. Patients enjoy personalized care, including office visits, as well as the diagnosis and treatment of common health problems. The patient membership fee covers the services listed below, and most care is received in-office. However, some additional services, such as lab testing and vaccinations, are billed separately. Furthermore, though the annual fee is convenient for some, it is too high for many families, so many are priced out of care at this facility.

Bay Doctors

Bay Doctors is a primary care practice that provides highly personalized medical care in the office or patients’ homes. Bay Doctors includes a team of dedicated healthcare professionals with dual residency in Emergency Medicine and Internal Medicine. The practice offers same-day/next-day appointments, telemedicine, office visits, and home visits. Some of the medical care services they provide are primary care, urgent care, emergency care, gynecology, pediatrics, and minor procedures.

Community Care

Established in 1949, Community Care is a non-profit regional healthcare provider serving the city and surrounding suburbs. This facility offers a wide variety of medical services, including 24-hour emergency care, telemedicine, primary care, and more. In addition to their medical care, they have a wide variety of fundraising activities to raise money to operate the hospital and help families cover the costs of their care.

Competitive Advantage

Riverside Medical enjoys several advantages over its competitors. These advantages include:

Marketing Plan

Brand & value proposition.

The Riverside Medical brand will focus on the company’s unique value proposition:

- Client-focused healthcare services, where the company’s interests are aligned with the customer

- Service built on long-term relationships

- Big-hospital expertise in a small-clinic environment

Promotions Strategy

The promotions strategy for Riverside Medical is as follows:

Riverside Medical understands that the best promotion comes from satisfied customers. The company will encourage its patients to refer their friends and family by providing healthcare benefits for every new client produced. This strategy will increase in effectiveness after the business has already been established.

Direct Mail

The company will use a direct mail campaign to promote its brand and draw clients, as well. The campaign will blanket specific neighborhoods with simple, effective mail advertisements that highlight the credentials and credibility of Riverside Medical.

Website/SEO

Riverside Medical will invest heavily in developing a professional website that displays all of the clinic’s services and procedures. The website will also provide information about each doctor and medical staff member. The clinic will also invest heavily in SEO so the brand’s website will appear at the top of search engine results.

Social Media

Riverside Medical will invest heavily in a social media advertising campaign. The marketing manager will create the company’s social media accounts and invest in ads on all social media platforms. It will use targeted marketing to appeal to the target demographics.

Riverside Medical’s pricing will be lower than big hospitals. Over time, client testimonials will help to maintain our client base and attract new patients. Furthermore, we will be able to provide discounts and incentives for lower-income families by connecting with foundations and charities from people who are interested in helping.

Operations Plan

The following will be the operations plan for Riverside Medical.

Operation Functions:

- Samantha Parker is the founder of Riverside Medical and will operate as the sole doctor until she increases her patient list and hires more medical staff. As the clinic grows, she will operate as the CEO and take charge of all the operations and executive aspects of the business.

- Samantha is assisted by Elizabeth O’Reilly. Elizabeth has experience working as a receptionist at a fast-paced hospital and will act as the receptionist/administrative assistant for the clinic. She will be in charge of the administrative and marketing aspects of the business.

- Samantha is in the process of hiring doctors, nurses, and other medical staff to help with her growing patient list.

Milestones:

The following are a series of path steps that will lead to the vision of long-term success. Riverside Medical expects to achieve the following milestones in the following twelve months:

3/202X Finalize lease agreement

5/202X Design and build out Riverside Medical location

7/202X Hire and train initial staff

9/202X Kickoff of promotional campaign

11/202X Reach break-even

1/202X Reach 1000 patients

Financial Plan

Key revenue & costs.

Riverside Medical’s revenues will come primarily from medical services rendered. The clinic will either bill the patients directly or their insurance providers.

The major cost drivers for the clinic will include labor expenses, lease costs, equipment purchasing and upkeep, and ongoing marketing costs.

Funding Requirements and Use of Funds

Key assumptions.

Below are the key assumptions required to achieve the revenue and cost numbers in the financials and to pay off the startup business loan.

- Year 1: 120

- Year 2: 150

- Year 3: 200

- Year 4: 275

- Year 5: 400

- Annual lease: $50,000

Financial Projections

Income statement, balance sheet, cash flow statement, healthcare business plan faqs, what is a healthcare business plan.

A healthcare business plan is a plan to start and/or grow your healthcare business. Among other things, it outlines your business concept, identifies your target customers, presents your marketing plan and details your financial projections.

You can easily complete your Healthcare business plan using our Healthcare Business Plan Template here .

What are the Main Types of Healthcare Businesses?

There are a number of different kinds of healthcare businesses , some examples include: Nursing care, Physical home health care, or Home health care aides:

How Do You Get Funding for Your Healthcare Business Plan?

Healthcare businesses are often funded through small business loans. Personal savings, credit card financing and angel investors are also popular forms of funding.

What are the Steps To Start a Healthcare Business?

Starting a healthcare business can be an exciting endeavor. Having a clear roadmap of the steps to start a business will help you stay focused on your goals and get started faster.

1. Develop A Healthcare Business Plan - The first step in starting a business is to create a detailed healthcare business plan that outlines all aspects of the venture. This should include potential market size and target customers, the services or products you will offer, pricing strategies and a detailed financial forecast.

2. Choose Your Legal Structure - It's important to select an appropriate legal entity for your healthcare business. This could be a limited liability company (LLC), corporation, partnership, or sole proprietorship. Each type has its own benefits and drawbacks so it’s important to do research and choose wisely so that your healthcare business is in compliance with local laws.

3. Register Your Healthcare Business - Once you have chosen a legal structure, the next step is to register your healthcare business with the government or state where you’re operating from. This includes obtaining licenses and permits as required by federal, state, and local laws.

4. Identify Financing Options - It’s likely that you’ll need some capital to start your healthcare business, so take some time to identify what financing options are available such as bank loans, investor funding, grants, or crowdfunding platforms.

5. Choose a Location - Whether you plan on operating out of a physical location or not, you should always have an idea of where you’ll be based should it become necessary in the future as well as what kind of space would be suitable for your operations.

6. Hire Employees - There are several ways to find qualified employees including job boards like LinkedIn or Indeed as well as hiring agencies if needed – depending on what type of employees you need it might also be more effective to reach out directly through networking events.

7. Acquire Necessary Healthcare Equipment & Supplies - In order to start your healthcare business, you'll need to purchase all of the necessary equipment and supplies to run a successful operation.

8. Market & Promote Your Business - Once you have all the necessary pieces in place, it’s time to start promoting and marketing your healthcare business. This includes creating a website, utilizing social media platforms like Facebook or Twitter, and having an effective Search Engine Optimization (SEO) strategy. You should also consider traditional marketing techniques such as radio or print advertising.

Other Helpful Business Plan Templates

Nonprofit Business Plan Template Non-Emergency Medical Transportation Business Plan Template Medical Practice Business Plan Template Home Health Care Business Plan Template

Healthcare Business Plan Template

Written by Dave Lavinsky

There are several types of Healthcare businesses, from family medicine practices to urgent care centers to home health care agencies. Regardless of the type of healthcare business you have, a business plan will keep you on track and help you grow your healthcare business in an organized way. In addition, if you plan to seek funding, investors and lenders will use your business plan to determine the level of risk.

Download our Ultimate Business Plan Template here >

Below is the business plan outline you should use to create a business plan for your healthcare company. Also, here are links to several healthcare business plan templates:

- Assisted Living Business Plan

- Counseling Private Practice Business Plan Template

- Dental Business Plan

- Home Health Care Business Plan

- Medical Practice Business Plan Template

- Medical Spa Business Plan Template

- Non Medical Home Care Business Plan Template

- Nursing Home Business Plan Template

- Pharmacy Business Plan

- Urgent Care Business Plan

Finish Your Business Plan Today!

Healthcare business plan example outline, executive summary.

Although it serves as the introduction to your business plan, your executive summary should be written last. The first page helps financiers decide whether to read the full plan, so provide the most important information. Give a clear and concise description of your healthcare company. Provide a summary of your market analysis that proves the need for another healthcare business, and explain your company’s unique qualifications to meet that need.

Company Analysis

Your company analysis explains your healthcare business as it exists right now. Describe the company’s founding, current stage of business, and legal structure. Highlight any past milestones, such as lining up clients or hiring healthcare providers with a proven track record. Elaborate on your unique qualifications, such as expertise in a currently underserved niche market.

Industry Analysis

The healthcare industry is incredibly large and diverse, but your analysis should focus on your specific segment of the market. Do you specialize in pediatric healthcare? senior healthcare? emergency medicine? family medicine? Figure out where your healthcare company fits in, and then research the current trends and market projections that affect your niche. Create a detailed strategy for overcoming any obstacles that you uncover.

Customer Analysis

Who will your healthcare company serve? Are they families? The elderly? What is important to them in a healthcare business? How do they select a healthcare provider? Narrow down their demographics as closely as you can, and then figure out what their unique needs are and how you can fulfill them.

Finish Your Healthcare Business Plan in 1 Day!

Don’t you wish there was a faster, easier way to finish your business plan?

With Growthink’s Ultimate Business Plan Template you can finish your plan in just 8 hours or less!

Competitive Analysis

Your direct competitors are those healthcare companies that fulfill the same needs for the same target market as yours. Your indirect competitors are healthcare businesses that target a different market, or other companies that fulfill a different need for your target market. Describe each of your direct competitors individually, and talk about the things that set your healthcare company apart. Categorize your indirect competitors as a group and talk about them as a whole.

Marketing Plan

A solid marketing plan is based on the four P’s: Product, Price, Promotion, and Place. The Product section describes the healthcare you sell along with any other services you provide. Price will change according to the specifics of the property, but you can delineate your fees here. Promotion is your means of getting new business. Place is your physical office location, along with your web presence and the areas where you sell. Another category, Customer retention, refers to the ways you will build loyalty.

Operations Plan

Your operations plan explains your methods for meeting the goals you set forth. Everyday short-term processes include all of the daily tasks involved in servicing clients. Long-term processes are the ways you will meet your defined business goals, such as expanding into new markets or new types of service.

Management Team