What this handout is about

This handout will help you understand how paragraphs are formed, how to develop stronger paragraphs, and how to completely and clearly express your ideas.

What is a paragraph?

Paragraphs are the building blocks of papers. Many students define paragraphs in terms of length: a paragraph is a group of at least five sentences, a paragraph is half a page long, etc. In reality, though, the unity and coherence of ideas among sentences is what constitutes a paragraph. A paragraph is defined as “a group of sentences or a single sentence that forms a unit” (Lunsford and Connors 116). Length and appearance do not determine whether a section in a paper is a paragraph. For instance, in some styles of writing, particularly journalistic styles, a paragraph can be just one sentence long. Ultimately, a paragraph is a sentence or group of sentences that support one main idea. In this handout, we will refer to this as the “controlling idea,” because it controls what happens in the rest of the paragraph.

How do I decide what to put in a paragraph?

Before you can begin to determine what the composition of a particular paragraph will be, you must first decide on an argument and a working thesis statement for your paper. What is the most important idea that you are trying to convey to your reader? The information in each paragraph must be related to that idea. In other words, your paragraphs should remind your reader that there is a recurrent relationship between your thesis and the information in each paragraph. A working thesis functions like a seed from which your paper, and your ideas, will grow. The whole process is an organic one—a natural progression from a seed to a full-blown paper where there are direct, familial relationships between all of the ideas in the paper.

The decision about what to put into your paragraphs begins with the germination of a seed of ideas; this “germination process” is better known as brainstorming . There are many techniques for brainstorming; whichever one you choose, this stage of paragraph development cannot be skipped. Building paragraphs can be like building a skyscraper: there must be a well-planned foundation that supports what you are building. Any cracks, inconsistencies, or other corruptions of the foundation can cause your whole paper to crumble.

So, let’s suppose that you have done some brainstorming to develop your thesis. What else should you keep in mind as you begin to create paragraphs? Every paragraph in a paper should be :

- Unified : All of the sentences in a single paragraph should be related to a single controlling idea (often expressed in the topic sentence of the paragraph).

- Clearly related to the thesis : The sentences should all refer to the central idea, or thesis, of the paper (Rosen and Behrens 119).

- Coherent : The sentences should be arranged in a logical manner and should follow a definite plan for development (Rosen and Behrens 119).

- Well-developed : Every idea discussed in the paragraph should be adequately explained and supported through evidence and details that work together to explain the paragraph’s controlling idea (Rosen and Behrens 119).

How do I organize a paragraph?

There are many different ways to organize a paragraph. The organization you choose will depend on the controlling idea of the paragraph. Below are a few possibilities for organization, with links to brief examples:

- Narration : Tell a story. Go chronologically, from start to finish. ( See an example. )

- Description : Provide specific details about what something looks, smells, tastes, sounds, or feels like. Organize spatially, in order of appearance, or by topic. ( See an example. )

- Process : Explain how something works, step by step. Perhaps follow a sequence—first, second, third. ( See an example. )

- Classification : Separate into groups or explain the various parts of a topic. ( See an example. )

- Illustration : Give examples and explain how those examples support your point. (See an example in the 5-step process below.)

Illustration paragraph: a 5-step example

From the list above, let’s choose “illustration” as our rhetorical purpose. We’ll walk through a 5-step process for building a paragraph that illustrates a point in an argument. For each step there is an explanation and example. Our example paragraph will be about human misconceptions of piranhas.

Step 1. Decide on a controlling idea and create a topic sentence

Paragraph development begins with the formulation of the controlling idea. This idea directs the paragraph’s development. Often, the controlling idea of a paragraph will appear in the form of a topic sentence. In some cases, you may need more than one sentence to express a paragraph’s controlling idea.

Controlling idea and topic sentence — Despite the fact that piranhas are relatively harmless, many people continue to believe the pervasive myth that piranhas are dangerous to humans.

Step 2. Elaborate on the controlling idea

Paragraph development continues with an elaboration on the controlling idea, perhaps with an explanation, implication, or statement about significance. Our example offers a possible explanation for the pervasiveness of the myth.

Elaboration — This impression of piranhas is exacerbated by their mischaracterization in popular media.

Step 3. Give an example (or multiple examples)

Paragraph development progresses with an example (or more) that illustrates the claims made in the previous sentences.

Example — For example, the promotional poster for the 1978 horror film Piranha features an oversized piranha poised to bite the leg of an unsuspecting woman.

Step 4. Explain the example(s)

The next movement in paragraph development is an explanation of each example and its relevance to the topic sentence. The explanation should demonstrate the value of the example as evidence to support the major claim, or focus, in your paragraph.

Continue the pattern of giving examples and explaining them until all points/examples that the writer deems necessary have been made and explained. NONE of your examples should be left unexplained. You might be able to explain the relationship between the example and the topic sentence in the same sentence which introduced the example. More often, however, you will need to explain that relationship in a separate sentence.

Explanation for example — Such a terrifying representation easily captures the imagination and promotes unnecessary fear.

Notice that the example and explanation steps of this 5-step process (steps 3 and 4) can be repeated as needed. The idea is that you continue to use this pattern until you have completely developed the main idea of the paragraph.

Step 5. Complete the paragraph’s idea or transition into the next paragraph

The final movement in paragraph development involves tying up the loose ends of the paragraph. At this point, you can remind your reader about the relevance of the information to the larger paper, or you can make a concluding point for this example. You might, however, simply transition to the next paragraph.

Sentences for completing a paragraph — While the trope of the man-eating piranhas lends excitement to the adventure stories, it bears little resemblance to the real-life piranha. By paying more attention to fact than fiction, humans may finally be able to let go of this inaccurate belief.

Finished paragraph

Despite the fact that piranhas are relatively harmless, many people continue to believe the pervasive myth that piranhas are dangerous to humans. This impression of piranhas is exacerbated by their mischaracterization in popular media. For example, the promotional poster for the 1978 horror film Piranha features an oversized piranha poised to bite the leg of an unsuspecting woman. Such a terrifying representation easily captures the imagination and promotes unnecessary fear. While the trope of the man-eating piranhas lends excitement to the adventure stories, it bears little resemblance to the real-life piranha. By paying more attention to fact than fiction, humans may finally be able to let go of this inaccurate belief.

Troubleshooting paragraphs

Problem: the paragraph has no topic sentence.

Imagine each paragraph as a sandwich. The real content of the sandwich—the meat or other filling—is in the middle. It includes all the evidence you need to make the point. But it gets kind of messy to eat a sandwich without any bread. Your readers don’t know what to do with all the evidence you’ve given them. So, the top slice of bread (the first sentence of the paragraph) explains the topic (or controlling idea) of the paragraph. And, the bottom slice (the last sentence of the paragraph) tells the reader how the paragraph relates to the broader argument. In the original and revised paragraphs below, notice how a topic sentence expressing the controlling idea tells the reader the point of all the evidence.

Original paragraph

Piranhas rarely feed on large animals; they eat smaller fish and aquatic plants. When confronted with humans, piranhas’ first instinct is to flee, not attack. Their fear of humans makes sense. Far more piranhas are eaten by people than people are eaten by piranhas. If the fish are well-fed, they won’t bite humans.

Revised paragraph

Although most people consider piranhas to be quite dangerous, they are, for the most part, entirely harmless. Piranhas rarely feed on large animals; they eat smaller fish and aquatic plants. When confronted with humans, piranhas’ first instinct is to flee, not attack. Their fear of humans makes sense. Far more piranhas are eaten by people than people are eaten by piranhas. If the fish are well-fed, they won’t bite humans.

Once you have mastered the use of topic sentences, you may decide that the topic sentence for a particular paragraph really shouldn’t be the first sentence of the paragraph. This is fine—the topic sentence can actually go at the beginning, middle, or end of a paragraph; what’s important is that it is in there somewhere so that readers know what the main idea of the paragraph is and how it relates back to the thesis of your paper. Suppose that we wanted to start the piranha paragraph with a transition sentence—something that reminds the reader of what happened in the previous paragraph—rather than with the topic sentence. Let’s suppose that the previous paragraph was about all kinds of animals that people are afraid of, like sharks, snakes, and spiders. Our paragraph might look like this (the topic sentence is bold):

Like sharks, snakes, and spiders, piranhas are widely feared. Although most people consider piranhas to be quite dangerous, they are, for the most part, entirely harmless . Piranhas rarely feed on large animals; they eat smaller fish and aquatic plants. When confronted with humans, piranhas’ first instinct is to flee, not attack. Their fear of humans makes sense. Far more piranhas are eaten by people than people are eaten by piranhas. If the fish are well-fed, they won’t bite humans.

Problem: the paragraph has more than one controlling idea

If a paragraph has more than one main idea, consider eliminating sentences that relate to the second idea, or split the paragraph into two or more paragraphs, each with only one main idea. Watch our short video on reverse outlining to learn a quick way to test whether your paragraphs are unified. In the following paragraph, the final two sentences branch off into a different topic; so, the revised paragraph eliminates them and concludes with a sentence that reminds the reader of the paragraph’s main idea.

Although most people consider piranhas to be quite dangerous, they are, for the most part, entirely harmless. Piranhas rarely feed on large animals; they eat smaller fish and aquatic plants. When confronted with humans, piranhas’ first instinct is to flee, not attack. Their fear of humans makes sense. Far more piranhas are eaten by people than people are eaten by piranhas. A number of South American groups eat piranhas. They fry or grill the fish and then serve them with coconut milk or tucupi, a sauce made from fermented manioc juices.

Problem: transitions are needed within the paragraph

You are probably familiar with the idea that transitions may be needed between paragraphs or sections in a paper (see our handout on transitions ). Sometimes they are also helpful within the body of a single paragraph. Within a paragraph, transitions are often single words or short phrases that help to establish relationships between ideas and to create a logical progression of those ideas in a paragraph. This is especially likely to be true within paragraphs that discuss multiple examples. Let’s take a look at a version of our piranha paragraph that uses transitions to orient the reader:

Although most people consider piranhas to be quite dangerous, they are, except in two main situations, entirely harmless. Piranhas rarely feed on large animals; they eat smaller fish and aquatic plants. When confronted with humans, piranhas’ instinct is to flee, not attack. But there are two situations in which a piranha bite is likely. The first is when a frightened piranha is lifted out of the water—for example, if it has been caught in a fishing net. The second is when the water level in pools where piranhas are living falls too low. A large number of fish may be trapped in a single pool, and if they are hungry, they may attack anything that enters the water.

In this example, you can see how the phrases “the first” and “the second” help the reader follow the organization of the ideas in the paragraph.

Works consulted

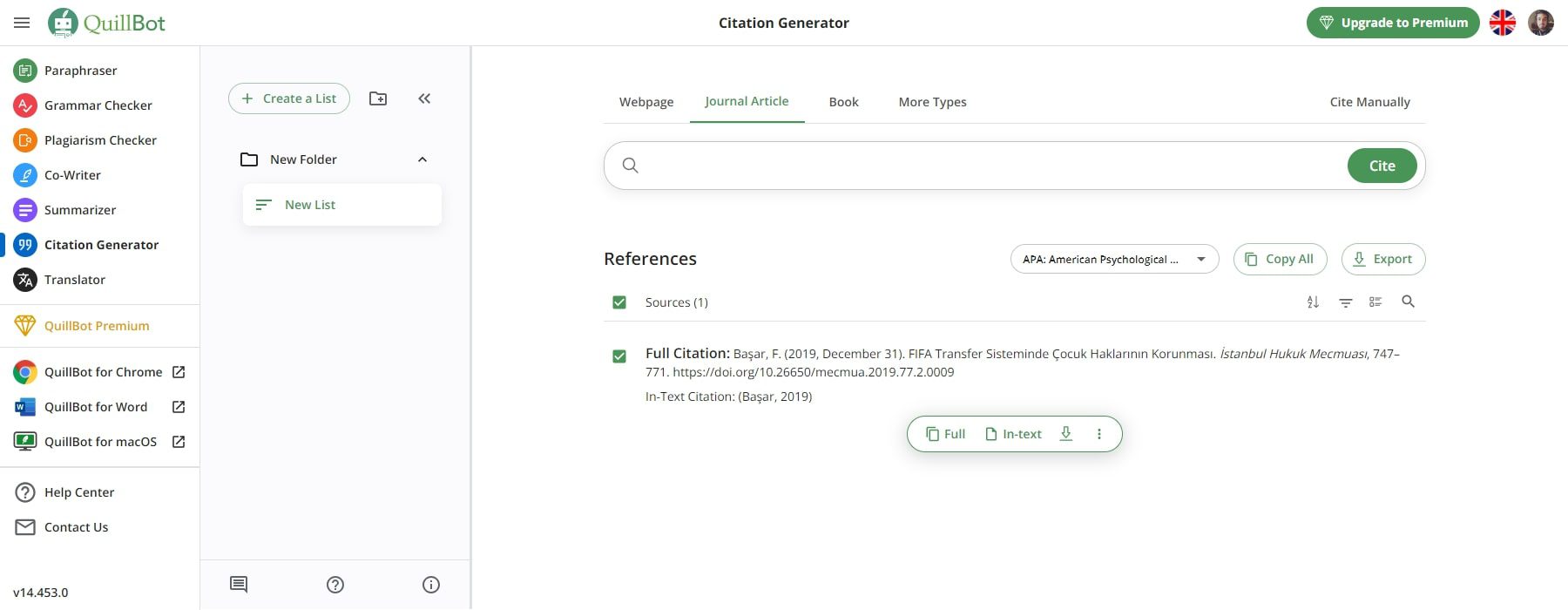

We consulted these works while writing this handout. This is not a comprehensive list of resources on the handout’s topic, and we encourage you to do your own research to find additional publications. Please do not use this list as a model for the format of your own reference list, as it may not match the citation style you are using. For guidance on formatting citations, please see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial . We revise these tips periodically and welcome feedback.

Lunsford, Andrea. 2008. The St. Martin’s Handbook: Annotated Instructor’s Edition , 6th ed. New York: St. Martin’s.

Rosen, Leonard J., and Laurence Behrens. 2003. The Allyn & Bacon Handbook , 5th ed. New York: Longman.

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Make a Gift

11 Rules for Essay Paragraph Structure (with Examples)

Chris Drew (PhD)

Dr. Chris Drew is the founder of the Helpful Professor. He holds a PhD in education and has published over 20 articles in scholarly journals. He is the former editor of the Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education. [Image Descriptor: Photo of Chris]

Learn about our Editorial Process

How do you structure a paragraph in an essay?

If you’re like the majority of my students, you might be getting your basic essay paragraph structure wrong and getting lower grades than you could!

In this article, I outline the 11 key steps to writing a perfect paragraph. But, this isn’t your normal ‘how to write an essay’ article. Rather, I’ll try to give you some insight into exactly what teachers look out for when they’re grading essays and figuring out what grade to give them.

You can navigate each issue below, or scroll down to read them all:

1. Paragraphs must be at least four sentences long 2. But, at most seven sentences long 3. Your paragraph must be Left-Aligned 4. You need a topic sentence 5 . Next, you need an explanation sentence 6. You need to include an example 7. You need to include citations 8. All paragraphs need to be relevant to the marking criteria 9. Only include one key idea per paragraph 10. Keep sentences short 11. Keep quotes short

Paragraph structure is one of the most important elements of getting essay writing right .

As I cover in my Ultimate Guide to Writing an Essay Plan , paragraphs are the heart and soul of your essay.

However, I find most of my students have either:

- forgotten how to write paragraphs properly,

- gotten lazy, or

- never learned it in the first place!

Paragraphs in essay writing are different from paragraphs in other written genres .

In fact, the paragraphs that you are reading now would not help your grades in an essay.

That’s because I’m writing in journalistic style, where paragraph conventions are vastly different.

For those of you coming from journalism or creative writing, you might find you need to re-learn paragraph writing if you want to write well-structured essay paragraphs to get top grades.

Below are eleven reasons your paragraphs are losing marks, and what to do about it!

Essay Paragraph Structure Rules

1. your paragraphs must be at least 4 sentences long.

In journalism and blog writing, a one-sentence paragraph is great. It’s short, to-the-point, and helps guide your reader. For essay paragraph structure, one-sentence paragraphs suck.

A one-sentence essay paragraph sends an instant signal to your teacher that you don’t have much to say on an issue.

A short paragraph signifies that you know something – but not much about it. A one-sentence paragraph lacks detail, depth and insight.

Many students come to me and ask, “what does ‘add depth’ mean?” It’s one of the most common pieces of feedback you’ll see written on the margins of your essay.

Personally, I think ‘add depth’ is bad feedback because it’s a short and vague comment. But, here’s what it means: You’ve not explained your point enough!

If you’re writing one-, two- or three-sentence essay paragraphs, you’re costing yourself marks.

Always aim for at least four sentences per paragraph in your essays.

This doesn’t mean that you should add ‘fluff’ or ‘padding’ sentences.

Make sure you don’t:

a) repeat what you said in different words, or b) write something just because you need another sentence in there.

But, you need to do some research and find something insightful to add to that two-sentence paragraph if you want to ace your essay.

Check out Points 5 and 6 for some advice on what to add to that short paragraph to add ‘depth’ to your paragraph and start moving to the top of the class.

- How to Make an Essay Longer

- How to Make an Essay Shorter

2. Your Paragraphs must not be more than 7 Sentences Long

Okay, so I just told you to aim for at least four sentences per paragraph. So, what’s the longest your paragraph should be?

Seven sentences. That’s a maximum.

So, here’s the rule:

Between four and seven sentences is the sweet spot that you need to aim for in every single paragraph.

Here’s why your paragraphs shouldn’t be longer than seven sentences:

1. It shows you can organize your thoughts. You need to show your teacher that you’ve broken up your key ideas into manageable segments of text (see point 10)

2. It makes your work easier to read. You need your writing to be easily readable to make it easy for your teacher to give you good grades. Make your essay easy to read and you’ll get higher marks every time.

One of the most important ways you can make your work easier to read is by writing paragraphs that are less than six sentences long.

3. It prevents teacher frustration. Teachers are just like you. When they see a big block of text their eyes glaze over. They get frustrated, lost, their mind wanders … and you lose marks.

To prevent teacher frustration, you need to ensure there’s plenty of white space in your essay. It’s about showing them that the piece is clearly structured into one key idea per ‘chunk’ of text.

Often, you might find that your writing contains tautologies and other turns of phrase that can be shortened for clarity.

3. Your Paragraph must be Left-Aligned

Turn off ‘Justified’ text and: Never. Turn. It. On. Again.

Justified text is where the words are stretched out to make the paragraph look like a square. It turns the writing into a block. Don’t do it. You will lose marks, I promise you! Win the psychological game with your teacher: left-align your text.

A good essay paragraph is never ‘justified’.

I’m going to repeat this, because it’s important: to prevent your essay from looking like a big block of muddy, hard-to-read text align your text to the left margin only.

You want white space on your page – and lots of it. White space helps your reader scan through your work. It also prevents it from looking like big blocks of text.

You want your reader reading vertically as much as possible: scanning, browsing, and quickly looking through for evidence you’ve engaged with the big ideas.

The justified text doesn’t help you do that. Justified text makes your writing look like a big, lumpy block of text that your reader doesn’t want to read.

What’s wrong with Center-Aligned Text?

While I’m at it, never, ever, center-align your text either. Center-aligned text is impossible to skim-read. Your teacher wants to be able to quickly scan down the left margin to get the headline information in your paragraph.

Not many people center-align text, but it’s worth repeating: never, ever center-align your essays.

Don’t annoy your reader. Left align your text.

4. Your paragraphs must have a Topic Sentence

The first sentence of an essay paragraph is called the topic sentence. This is one of the most important sentences in the correct essay paragraph structure style.

The topic sentence should convey exactly what key idea you’re going to cover in your paragraph.

Too often, students don’t let their reader know what the key idea of the paragraph is until several sentences in.

You must show what the paragraph is about in the first sentence.

You never, ever want to keep your reader in suspense. Essays are not like creative writing. Tell them straight away what the paragraph is about. In fact, if you can, do it in the first half of the first sentence .

I’ll remind you again: make it easy to grade your work. Your teacher is reading through your work trying to determine what grade to give you. They’re probably going to mark 20 assignments in one sitting. They have no interest in storytelling or creativity. They just want to know how much you know! State what the paragraph is about immediately and move on.

Suggested: Best Words to Start a Paragraph

Ideal Essay Paragraph Structure Example: Writing a Topic Sentence If your paragraph is about how climate change is endangering polar bears, say it immediately : “Climate change is endangering polar bears.” should be your first sentence in your paragraph. Take a look at first sentence of each of the four paragraphs above this one. You can see from the first sentence of each paragraph that the paragraphs discuss:

When editing your work, read each paragraph and try to distil what the one key idea is in your paragraph. Ensure that this key idea is mentioned in the first sentence .

(Note: if there’s more than one key idea in the paragraph, you may have a problem. See Point 9 below .)

The topic sentence is the most important sentence for getting your essay paragraph structure right. So, get your topic sentences right and you’re on the right track to a good essay paragraph.

5. You need an Explanation Sentence

All topic sentences need a follow-up explanation. The very first point on this page was that too often students write paragraphs that are too short. To add what is called ‘depth’ to a paragraph, you can come up with two types of follow-up sentences: explanations and examples.

Let’s take explanation sentences first.

Explanation sentences give additional detail. They often provide one of the following services:

Let’s go back to our example of a paragraph on Climate change endangering polar bears. If your topic sentence is “Climate change is endangering polar bears.”, then your follow-up explanation sentence is likely to explain how, why, where, or when. You could say:

Ideal Essay Paragraph Structure Example: Writing Explanation Sentences 1. How: “The warming atmosphere is melting the polar ice caps.” 2. Why: “The polar bears’ habitats are shrinking every single year.” 3. Where: “This is happening in the Antarctic ice caps near Greenland.” 4. When: “Scientists first noticed the ice caps were shrinking in 1978.”

You don’t have to provide all four of these options each time.

But, if you’re struggling to think of what to add to your paragraph to add depth, consider one of these four options for a good quality explanation sentence.

>>>RELATED ARTICLE: SHOULD YOU USE RHETORICAL QUESTIONS IN ESSAYS ?

6. Your need to Include an Example

Examples matter! They add detail. They also help to show that you genuinely understand the issue. They show that you don’t just understand a concept in the abstract; you also understand how things work in real life.

Example sentences have the added benefit of personalising an issue. For example, after saying “Polar bears’ habitats are shrinking”, you could note specific habitats, facts and figures, or even a specific story about a bear who was impacted.

Ideal Essay Paragraph Structure Example: Writing an ‘Example’ Sentence “For example, 770,000 square miles of Arctic Sea Ice has melted in the past four decades, leading Polar Bear populations to dwindle ( National Geographic, 2018 )

In fact, one of the most effective politicians of our times – Barrack Obama – was an expert at this technique. He would often provide examples of people who got sick because they didn’t have healthcare to sell Obamacare.

What effect did this have? It showed the real-world impact of his ideas. It humanised him, and got him elected president – twice!

Be like Obama. Provide examples. Often.

7. All Paragraphs need Citations

Provide a reference to an academic source in every single body paragraph in the essay. The only two paragraphs where you don’t need a reference is the introduction and conclusion .

Let me repeat: Paragraphs need at least one reference to a quality scholarly source .

Let me go even further:

Students who get the best marks provide two references to two different academic sources in every paragraph.

Two references in a paragraph show you’ve read widely, cross-checked your sources, and given the paragraph real thought.

It’s really important that these references link to academic sources, not random websites, blogs or YouTube videos. Check out our Seven Best types of Sources to Cite in Essays post to get advice on what sources to cite. Number 6 w ill surprise you!

Ideal Essay Paragraph Structure Example: In-Text Referencing in Paragraphs Usually, in-text referencing takes the format: (Author, YEAR), but check your school’s referencing formatting requirements carefully. The ‘Author’ section is the author’s last name only. Not their initials. Not their first name. Just their last name . My name is Chris Drew. First name Chris, last name Drew. If you were going to reference an academic article I wrote in 2019, you would reference it like this: (Drew, 2019).

Where do you place those two references?

Place the first reference at the end of the first half of the paragraph. Place the second reference at the end of the second half of the paragraph.

This spreads the references out and makes it look like all the points throughout the paragraph are backed up by your sources. The goal is to make it look like you’ve reference regularly when your teacher scans through your work.

Remember, teachers can look out for signposts that indicate you’ve followed academic conventions and mentioned the right key ideas.

Spreading your referencing through the paragraph helps to make it look like you’ve followed the academic convention of referencing sources regularly.

Here are some examples of how to reference twice in a paragraph:

- If your paragraph was six sentences long, you would place your first reference at the end of the third sentence and your second reference at the end of the sixth sentence.

- If your paragraph was five sentences long, I would recommend placing one at the end of the second sentence and one at the end of the fifth sentence.

You’ve just read one of the key secrets to winning top marks.

8. Every Paragraph must be relevant to the Marking Criteria

Every paragraph must win you marks. When you’re editing your work, check through the piece to see if every paragraph is relevant to the marking criteria.

For the British: In the British university system (I’m including Australia and New Zealand here – I’ve taught at universities in all three countries), you’ll usually have a ‘marking criteria’. It’s usually a list of between two and six key learning outcomes your teacher needs to use to come up with your score. Sometimes it’s called a:

- Marking criteria

- Marking rubric

- (Key) learning outcome

- Indicative content

Check your assignment guidance to see if this is present. If so, use this list of learning outcomes to guide what you write. If your paragraphs are irrelevant to these key points, delete the paragraph .

Paragraphs that don’t link to the marking criteria are pointless. They won’t win you marks.

For the Americans: If you don’t have a marking criteria / rubric / outcomes list, you’ll need to stick closely to the essay question or topic. This goes out to those of you in the North American system. North America (including USA and Canada here) is often less structured and the professor might just give you a topic to base your essay on.

If all you’ve got is the essay question / topic, go through each paragraph and make sure each paragraph is relevant to the topic.

For example, if your essay question / topic is on “The Effects of Climate Change on Polar Bears”,

- Don’t talk about anything that doesn’t have some connection to climate change and polar bears;

- Don’t talk about the environmental impact of oil spills in the Gulf of Carpentaria;

- Don’t talk about black bear habitats in British Columbia.

- Do talk about the effects of climate change on polar bears (and relevant related topics) in every single paragraph .

You may think ‘stay relevant’ is obvious advice, but at least 20% of all essays I mark go off on tangents and waste words.

Stay on topic in Every. Single. Paragraph. If you want to learn more about how to stay on topic, check out our essay planning guide .

9. Only have one Key Idea per Paragraph

One key idea for each paragraph. One key idea for each paragraph. One key idea for each paragraph.

Don’t forget!

Too often, a student starts a paragraph talking about one thing and ends it talking about something totally different. Don’t be that student.

To ensure you’re focussing on one key idea in your paragraph, make sure you know what that key idea is. It should be mentioned in your topic sentence (see Point 3 ). Every other sentence in the paragraph adds depth to that one key idea.

If you’ve got sentences in your paragraph that are not relevant to the key idea in the paragraph, they don’t fit. They belong in another paragraph.

Go through all your paragraphs when editing your work and check to see if you’ve veered away from your paragraph’s key idea. If so, you might have two or even three key ideas in the one paragraph.

You’re going to have to get those additional key ideas, rip them out, and give them paragraphs of their own.

If you have more than one key idea in a paragraph you will lose marks. I promise you that.

The paragraphs will be too hard to read, your reader will get bogged down reading rather than scanning, and you’ll have lost grades.

10. Keep Sentences Short

If a sentence is too long it gets confusing. When the sentence is confusing, your reader will stop reading your work. They will stop reading the paragraph and move to the next one. They’ll have given up on your paragraph.

Short, snappy sentences are best.

Shorter sentences are easier to read and they make more sense. Too often, students think they have to use big, long, academic words to get the best marks. Wrong. Aim for clarity in every sentence in the paragraph. Your teacher will thank you for it.

The students who get the best marks write clear, short sentences.

When editing your draft, go through your essay and see if you can shorten your longest five sentences.

(To learn more about how to write the best quality sentences, see our page on Seven ways to Write Amazing Sentences .)

11. Keep Quotes Short

Eighty percent of university teachers hate quotes. That’s not an official figure. It’s my guestimate based on my many interactions in faculty lounges. Twenty percent don’t mind them, but chances are your teacher is one of the eight out of ten who hate quotes.

Teachers tend to be turned off by quotes because it makes it look like you don’t know how to say something on your own words.

Now that I’ve warned you, here’s how to use quotes properly:

Ideal Essay Paragraph Structure Example: How To Use Quotes in University-Level Essay Paragraphs 1. Your quote should be less than one sentence long. 2. Your quote should be less than one sentence long. 3. You should never start a sentence with a quote. 4. You should never end a paragraph with a quote. 5 . You should never use more than five quotes per essay. 6. Your quote should never be longer than one line in a paragraph.

The minute your teacher sees that your quote takes up a large chunk of your paragraph, you’ll have lost marks.

Your teacher will circle the quote, write a snarky comment in the margin, and not even bother to give you points for the key idea in the paragraph.

Avoid quotes, but if you really want to use them, follow those five rules above.

I’ve also provided additional pages outlining Seven tips on how to use Quotes if you want to delve deeper into how, when and where to use quotes in essays. Be warned: quoting in essays is harder than you thought.

Follow the advice above and you’ll be well on your way to getting top marks at university.

Writing essay paragraphs that are well structured takes time and practice. Don’t be too hard on yourself and keep on trying!

Below is a summary of our 11 key mistakes for structuring essay paragraphs and tips on how to avoid them.

I’ve also provided an easy-to-share infographic below that you can share on your favorite social networking site. Please share it if this article has helped you out!

11 Biggest Essay Paragraph Structure Mistakes you’re probably Making

1. Your paragraphs are too short 2. Your paragraphs are too long 3. Your paragraph alignment is ‘Justified’ 4. Your paragraphs are missing a topic sentence 5 . Your paragraphs are missing an explanation sentence 6. Your paragraphs are missing an example 7. Your paragraphs are missing references 8. Your paragraphs are not relevant to the marking criteria 9. You’re trying to fit too many ideas into the one paragraph 10. Your sentences are too long 11. Your quotes are too long

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 101 Class Group Name Ideas (for School Students)

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 19 Top Cognitive Psychology Theories (Explained)

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 119 Bloom’s Taxonomy Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ All 6 Levels of Understanding (on Bloom’s Taxonomy)

4 thoughts on “11 Rules for Essay Paragraph Structure (with Examples)”

Hello there. I noticed that throughout this article on Essay Writing, you keep on saying that the teacher won’t have time to go through the entire essay. Don’t you think this is a bit discouraging that with all the hard work and time put into your writing, to know that the teacher will not read through the entire paper?

Hi Clarence,

Thanks so much for your comment! I love to hear from readers on their thoughts.

Yes, I agree that it’s incredibly disheartening.

But, I also think students would appreciate hearing the truth.

Behind closed doors many / most university teachers are very open about the fact they ‘only have time to skim-read papers’. They regularly bring this up during heated faculty meetings about contract negotiations! I.e. in one university I worked at, we were allocated 45 minutes per 10,000 words – that’s just over 4 minutes per 1,000 word essay, and that’d include writing the feedback, too!

If students know the truth, they can better write their essays in a way that will get across the key points even from a ‘skim-read’.

I hope to write candidly on this website – i.e. some of this info will never be written on university blogs because universities want to hide these unfortunate truths from students.

Thanks so much for stopping by!

Regards, Chris

This is wonderful and helpful, all I say is thank you very much. Because I learned a lot from this site, own by chris thank you Sir.

Thank you. This helped a lot.

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

TRY OUR FREE APP

Write your book in Reedsy Studio. Try the beloved writing app for free today.

Craft your masterpiece in Reedsy Studio

Plan, write, edit, and format your book in our free app made for authors.

Blog • Perfecting your Craft

Posted on Mar 13, 2024

How Many Sentences Are in a Paragraph?

In most forms of writing, paragraphs tend to be around four to eight sentences long . This general range will vary depending on the type of writing in question and the effect the writer is aiming to achieve.

In this guide, we’ll look at the length of paragraphs in various types of writing and see what determines whether they should be 20 sentences long, or stand alone as single sentences.

Which writing app is right for you?

Find out here! Takes 30 seconds

A paragraph should be as long as it needs to be

Reedsy editor Rebecca Heyman says a paragraph generally begins when a new idea is introduced. “A single sentence can stand on its own as a paragraph if its treatment of a specific theme or motif is complete. Conversely, denser, more complex topics may require a substantial number of sentences to adequately unpack meaning.” For example, in this very paragraph that you’re reading right now, we’re dealing with a fairly abstract concept which requires multiple sentences for clarification. In other words, a paragraph should be as long as it needs to be in order to convey its point.

Let’s now examine this idea from different perspectives, and look at how writers use paragraph breaks for different purposes.

In nonfiction, paragraphs tend to be longer

In nonfiction writing , where the purpose is often to explain new concepts and ideas, paragraphs tend to be a bit on the longer side. They will often introduce an idea, explore it, and then draw conclusions based on that exploration.

In this paragraph from Stefano Mancuso’s The Revolutionary Genius of Plants , he introduces, explores, and concludes upon the intelligence of plants:

Even though they have nothing akin to a central brain, plants exhibit unmistakable attributes of intelligence. They are able to perceive their surroundings with a greater sensitivity than animals do. They actively compete for the limited resources in the soil and atmosphere; they evaluate their circumstances with precision; they perform sophisticated cost-benefit analyses; and, finally, they define and then take appropriate adaptive actions in response to environmental stimuli. Plants embody a model that is much more durable and innovative than that of animals; they are the living representation of how stability and flexibility can be combined. Their modular, diffused construction is the epitome of modernity: a cooperative, shared structure without any command centers, able to flawlessly resist repeated catastrophic events without losing functionality and adapt very quickly to huge environmental changes.

The idea is established simply in the first sentence: “plants exhibit unmistakable attributes of intelligence”. Mancuso then elaborates on this idea by discussing their perceptual and analytical properties, before concluding that plants' intelligence is an example of innovative and durable adaptability to the environment.

You’ll see a similar pattern across nonfiction and other types of expository writing, whether you’re reading books on military history, self-help guides , or gardening manuals. Where the intention of the work is to inform or educate the reader, this tried-and-true way of structuring paragraphs allows information to be passed on in manageable chunks.

However, when you’re writing with the intention of telling a story in an enjoyable fashion, paragraph breaks tend to happen more often, and for different reasons.

Perfect your self-help manuscript

Work with a professional to take your book to the next level.

In fiction, they can be as short as a sentence

With artistic works of writing, where the focus is on storytelling providing the reader with a satisfying narrative experience , you will often see the greatest range of paragraph length within a single work. A novelist might have three pages of unbroken narrative, punctuated by a one-word paragraph.

In general, fiction writers will start a new paragraph whenever something new happens. For example:

Whenever dialogue or action switches between characters

In this extract from Gillian Flynn’s Gone Girl , the narrator, Nick, is being spoken to by his sister.

‘We were lost in the rain,’ she said in a voice that was pleading on the way to peeved. I finished the shrug. McMann’s, Nick. Remember, when we got lost in the rain in Chinatown[...]’

The first paragraph is a quick line of dialogue with a tag that indicates who is speaking. Nick then reacts with an action beat (his shrug) — which is in its own paragraph. Then there is another paragraph break to indicate that the next line is spoken once again by his sister.

In this context, paragraph breaks show the reader that we’re switching characters, allowing an author to avoid having to start every other sentence with “Margo said” or “I said”.

FREE COURSE

How to Write Believable Dialogue

Master the art of dialogue in 10 five-minute lessons.

When the narration changes between action and reflection

In a narrative, paragraph transitions can also be a way to indicate that the narrator is changing their perspective — often from describing the action of a scene, to remarking on a character’s thoughts or inner reactions.

In this passage from All Quiet on the Western Front , Erich Maria Remarque uses short paragraphs — sometimes single sentences — to paint an impressionistic vignette of a man’s death in the trenches.

But every gasp strips my heart bare. The dying man is the master of these hours, he has an invisible dagger to stab me with: the dagger of time and my own thoughts. I would give a lot for him to live. It is hard to lie here and have to watch and listen to him. By three in the afternoon he is dead. I breathe again. But only for a short time. Soon the silence seems harder for me to bear than the groans. I would even like to hear the gurgling again; in fits and starts, hoarse, sometimes a soft whistling noise and then hoarse and loud again.

Remarque utilizes paragraph transitions to depict the shift in Paul’s ( the main character ) focus, moving from the immediate sensory details of the scene to his internal reflections and emotional turmoil. Paul’s desire for the dying man to live, juxtaposed with the harsh reality of death in wartime, highlights the juxtaposition between his internal empathy and the tragic experience of war.

Whenever there’s a time jump

Time jumps are often a good place to start a new paragraph to make it visually clear that some amount of time has passed. In this passage from Oliver Twist, Dickens starts a new paragraph to indicate time jumps.

They were sad rags, to tell the truth; and Oliver had never had a new suit before. One evening, about a week after the affair of the picture, as he was sitting talking to Mrs. Bedwin, there came a message down from Mr. Brownlow, that if Oliver Twist felt pretty well, he should like to see him in his study, and talk to him a little while.

Without a paragraph change, it would feel odd that the narrator is suddenly taking us forward by a week right in the middle of telling us about Oliver’s clothes. Instead, the paragraph break indicates that one part of the story is over and that the next part is about to begin.

GET ACCOUNTABILITY

Meet writing coaches on Reedsy

Industry insiders can help you hone your craft, finish your draft, and get published.

Paragraphs' length affects the pace of the writing

Paragraph length (along with sentence length) has a profound effect on the pace of one’s writing . A page or two of block paragraphs will take readers far longer to get through than several shorter paragraphs and often reflects whether something is occurring quickly or slowly within the narrative.

For example, in The Great Gatsby , Fitzgerald takes his time to describe a road that will play a significant role in the story.

‘About half way between West Egg and New York the motor-road hastily joins the railroad and runs beside it for a quarter of a mile, so as to shrink away from a certain desolate area of land. This is a valley of ashes—a fantastic farm where ashes grow like wheat into ridges and hills and grotesque gardens where ashes take the forms of houses and chimneys and rising smoke and finally, with a transcendent effort, of men who move dimly and already crumbling through the powdery air. Occasionally a line of gray cars crawls along an invisible track, gives out a ghastly creak and comes to rest, and immediately the ash-gray men swarm up with leaden spades and stir up an impenetrable cloud which screens their obscure operations from your sight.’

This longer style paragraph is used to great effect in representing this pastoral stretch of land between the party hubs of West Egg and New York City. Think of this long paragraph as the wide establishing shot in a movie, everything looks a bit slower from that perspective!

Equally, when Fitzgerald wants to pick up the pace, he uses shorter paragraphs, as seen in the following example:

‘What do you want money for, all of a sudden?’ ‘I’ve been here too long. I want to get away. My wife and I want to go west.’ ‘Your wife does!’ exclaimed Tom, startled. ‘She’s been talking about it for ten years.’ He rested for a moment against the pump, shading his eyes. ‘And now she’s going whether she wants to or not. I’m going to get her away.’ The coupé flashed by us with a flurry of dust and the flash of a waving hand. ‘What do I owe you?’ demanded Tom harshly. ‘I just got wised up to something funny the last two days,’ remarked Wilson. ‘That’s why I want to get away. That’s why I been bothering you about the car.’ ‘What do I owe you?’ ‘Dollar twenty.’

Tom realizes both his mistress and wife are slipping from his grasp (image: Warner Bros)

During this part of the novel, Tom Buchanan (the antagonist ) is feeling cornered as both his wife and mistress are slipping away from him. The short paragraphs in quick succession show his irritability, giving readers an insight into how unsettled he is. Even the coupé driven by Gatsby flashes by him, the speed of which is also heightened by use of short paragraphs.

Shorter paragraphs introduce more white space on the page, which accelerates the pace of reading. This can be used powerfully, as in the examples above, to match the narrative when fast, uncontrollable, or sudden events happen or to give readers a wide, slow, or sluggish feeling.

Many paragraphs later, we hope you found this helpful. If you’ve struggled with how to determine your paragraph lengths, know that it’s something that many writers find challenging! By roughly following the advice in this post you’ll be able to powerfully use varying paragraph lengths to hook readers throughout your work.

Continue reading

Recommended posts from the Reedsy Blog

450+ Powerful Adjectives to Describe a Person (With Examples)

Want a handy list to help you bring your characters to life? Discover words that describe physical attributes, dispositions, and emotions.

How to Plot a Novel Like a NYT Bestselling Author

Need to plot your novel? Follow these 7 steps from New York Times bestselling author Caroline Leavitt.

How to Write an Autobiography: The Story of Your Life

Want to write your autobiography but aren’t sure where to start? This step-by-step guide will take you from opening lines to publishing it for everyone to read.

What is the Climax of a Story? Examples & Tips

The climax is perhaps a story's most crucial moment, but many writers struggle to stick the landing. Let's see what makes for a great story climax.

What is Tone in Literature? Definition & Examples

We show you, with supporting examples, how tone in literature influences readers' emotions and perceptions of a text.

Writing Cozy Mysteries: 7 Essential Tips & Tropes

We show you how to write a compelling cozy mystery with advice from published authors and supporting examples from literature.

Join a community of over 1 million authors

Reedsy is more than just a blog. Become a member today to discover how we can help you publish a beautiful book.

We made a writing app for you

Yes, you! Write. Format. Export for ebook and print. 100% free, always.

1 million authors trust the professionals on Reedsy. Come meet them.

Enter your email or get started with a social account:

- Features for Creative Writers

- Features for Work

- Features for Higher Education

- Features for Teachers

- Features for Non-Native Speakers

- Learn Blog Grammar Guide Community Events FAQ

- Grammar Guide

How Many Sentences Should There Be in a Paragraph?

Ashley Shaw

There are a lot of writing rules out there, and they can be restricting, especially when they start to feel a little formulaic. If you’ve ever been told that a paragraph should always be at least three sentences long, but ideally five to seven, then you know what I mean.

Why does it have to be so specific?

The truth is that these rules are meant to be guidelines to make writing easier for you. If they start to do the opposite, though, they defeat the purpose.

How Long Should a Paragraph Be?

What do teachers want to see in a paragraph, how do i structure a paragraph, how long should an introduction paragraph be, what do you include in a conclusion paragraph, can a paragraph be one sentence.

So here is what you really need to know: There is no general rule for how long your paragraphs should be. In fact, you probably want to vary your lengths in order to make your writing feel less like a robot wrote it and more human-friendly. A good paragraph isn’t one that has a set amount of sentences. It’s one that has a good, focused idea.

So, in this post, I’m going to talk about what makes a good paragraph, regardless of length. However, despite what I just said, sometimes you just have to follow the formula, so I’ll also point out some best practices on paragraph length. While I am going to focus on academic papers, I’ll also talk about good paragraphs in web writing, professional writing, and fiction.

Before you start thinking about length, you should first start thinking about what makes a good paragraph . Throughout this section, I’ll be using a lot of food analogies, so you should probably grab a snack whilst you read.

A good paragraph is like a bite of a sandwich. If you bite off too much, then you might choke. However, if you just take a tiny little nibble, you will barely taste it at all. In the same way, if your paragraph has too much information in it, then it is just going to be confusing and hard to swallow (get it?). However, if there is only one sentence, then there won’t be enough meat to let your reader know what your point is. So, you have to find the balance between those two things.

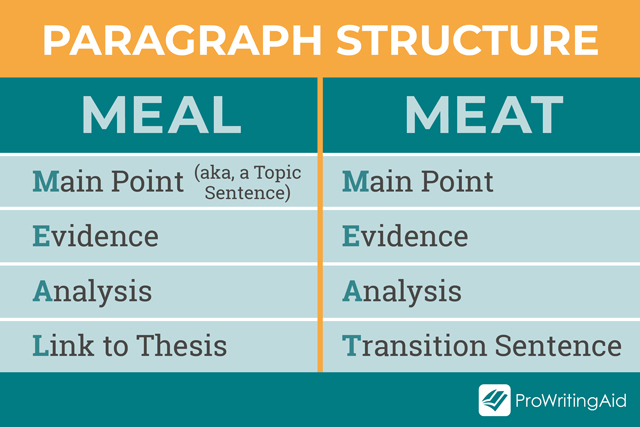

There are many acronyms that help determine paragraph structure. In school, you might have learned something like ICE for body paragraphs, which stands for introduce, cite, and explain evidence. However, to fit my sandwich theme, I use MEAL or MEAT.

A good body paragraph in an academic paper should do one of these:

MEAL : Main Point , Evidence , Analysis , Link to Thesis

MEAT : Main Point , Evidence , Analysis , Transition Sentence

Only the last letters of these are different, so let’s talk a bit about what each acronym means.

A good paragraph should have a main point or topic sentence. This is kind of like a mini-thesis statement for your paragraph or the paragraph’s controlling idea. You should have a single controlling idea in your paragraph.

A good way to test this is to do what is called a reverse outline: Summarize each of your paragraphs into one simple topic sentence. (Don’t combine two sentences with a conjunction . That’s cheating!)

If you cannot get a complete sentence to sum up your paragraph, then it is too short. If you can’t fit the point into one sentence, then you likely have two main ideas, which should be broken into multiple paragraphs.

After you get the topic sentence of the paragraph, you need some supporting sentences to help you prove your claim. This is where your outside sources come into the picture. You can put in a sentence or two explaining how you know your main sentence is true.

Don’t just put evidence up without explaining how it proves your point. Somebody might read the same quote, data, or theory as you and come to a completely different conclusion about what it means. So once you add in some evidence, take another two or three sentences and explain how that evidence proves your point.

Link to Thesis/Transition Sentence

Once you’ve finished the information in your paragraph, you can’t just move on. You need a good ending to your paragraph. This is where you have a few options. In your concluding sentence, you might want to show how the main point you are making in that section of the paper helps prove your thesis statement. This fits your paragraph into the premise of your writing.

Alternatively, you might want to focus on getting into your next main point. You can do this by creating a transition sentence that will bridge the gap between the previous paragraph and the one that follows it, creating a logical progression.

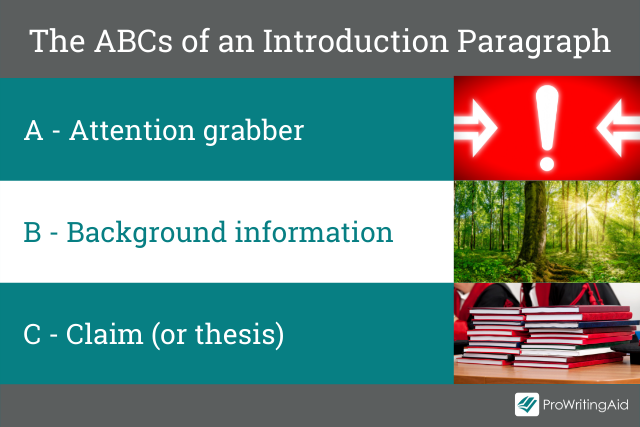

A Special Note on Introduction/Conclusion Paragraphs

Think of an academic paper as a funnel. When you first start writing, your audience has no idea what you are discussing, so they need you to draw them in first. Then, once you get into the body, you should be narrow and focused on your topic. Finally, at the end, you should send your reader back out to the rest of the world with a better understanding of your topic and what they should do about it.

Because the body paragraphs are narrower, the MEAL/MEAT plan works best for these. However, introductions and conclusions are a little different. Let’s discuss.

Again, there's no right or wrong answer here. It's all about the content.

Just like body paragraphs, there is a good acronym to help you remember what goes into an introduction paragraph, though this one isn’t food-centric: ABC.

A: Attention grabber , also known as a hook. You want to get your readers interested in your topic and let them know why they want to keep reading.

B: Background information . This is where you will give the reader enough information to catch them up on the topic. Let them know what they need to know to understand and follow your paper.

C: Claim, or the thesis statement . What is the main argument your paper will be making? What are you trying to prove or say? This should be really clear and straightforward.

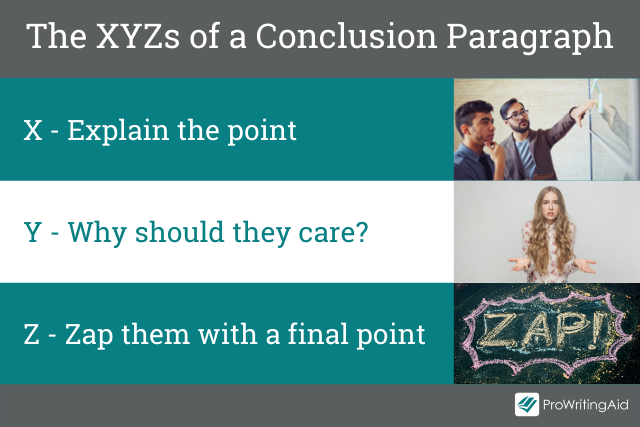

If you start with ABC, then it makes sense that you should end with XYZ. Notice that these are different letters. You don’t want to just repeat the introduction.

X: Explain what they should do with all of this information once they are done. This is sometimes called a "Call to Action". Likely, you want them to go away from academic writing being convinced about your thesis statement.

Y: Let them know why (y) they should care about all the information they just read.

Z: Zap them with a final hook in the concluding sentence so they don’t forget what you just taught them.

OK. But Really, How Many Sentences Should an Academic Paragraph Have?

I know I just spent a lot of time telling you that the content matters more than the amount of sentences in a paragraph, and I stand by that. However, I also acknowledge that there are best practices when it comes to paragraph length, and it helps to know them.

So, on average, there will be about 3 to 7 sentences in a paragraph . This is how many it takes to convey all of the necessary information I mentioned above into a paragraph without putting in too much.

You could also think of it as about half a page long, though that depends on how many words are in your sentences. More than that, and it will be harder to follow. Shorter than that, and it won’t feel like it has enough depth (and if you have a page-length requirement, it’ll be harder to hit it).

TIP: When I am teaching, I find that people who tend to turn in papers that are too short also have really short paragraphs. It’s usually because they don’t have enough sentences in their analysis section. So if you have this problem, then you might want to make sure you have enough of your own explanations about why the evidence you use supports your claims.

That depends on where you’re writing.

I spent a lot of time talking about a good paragraph in academic writing because that tends to be more formulaic than other types of writing. However, the answer to what makes a good paragraph (and how many sentences that paragraph should have) really depends on the type of writing you are doing. So here is where I will talk more about some other common types of writing that you may do.

How Long Are Paragraphs in Web/News Articles?

In web articles and news stories, can a good paragraph ever be a single sentence long?

One-sentence paragraphs are great for web writing. When people are online, they skim more. Thus, it is always smart to break up paragraphs more than you would in a paper.

On the web, short paragraphs are good. However, each paragraph still needs to have good information in it. If your readers can skim your writing and still get the important information you want to relay to them, then you are doing a good job.

This is also true in journalism. You likely want to keep your paragraphs tight and to the point. You don’t need a lot of sentences to give readers the facts.

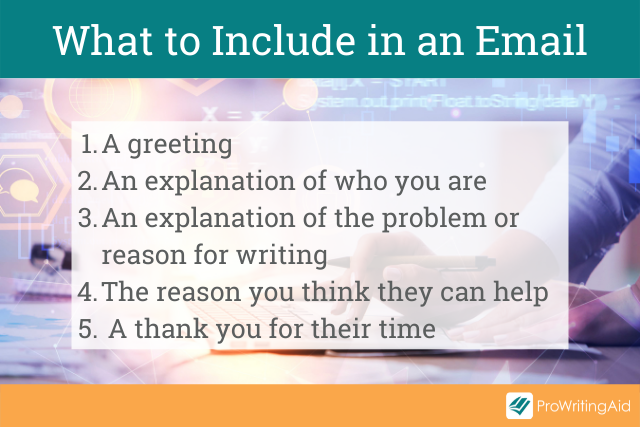

Should I Use Short Paragraphs in Emails?

The answer to how long a good paragraph in a professional writing task should be is going to vary widely based on the task and industry. Your best bet is to find some good samples that will help you see what is expected of you.

However, let’s talk a little bit about a professional writing task almost everyone will have at some point: the email .

A good email paragraph in a professional context is one that gives the reader enough information to understand the problem and to figure out the question being asked. That question should be directly stated so that it is more likely to get answered.

In other words, it should be exactly how long it needs to be and no longer. People are busy, they don’t have time for a five-page email!

Here are the basic components of most business emails:

- An explanation of who you are.

- An explanation of the problem or reason for writing.

- The reason you think they can help.

- A thank you for their time.

This is really all that is needed in the paragraph(s) of an email.

How Long Should a Fiction Paragraph Be?

To be honest with you, this is going to be the hardest part of this whole post to write. The reason for this is because creative writing is like the Wild West: There are no rules, and you might get into a showdown if you try to suggest any.

Seriously, creative writing is just that, creative. Well-known books have paragraphs as short as one word and as long as the entire novel! A big part of what makes a good paragraph in creative writing is personal style. In other words, BE YOU.

Still, though, if you want to get published and develop an audience, you might have to stick to some best practices sometimes. Try starting a new paragraph if you do any of the following:

Create any type of change

Introduce a new character or place

Add dialogue

While that isn’t a complete list, it is a good starting point.

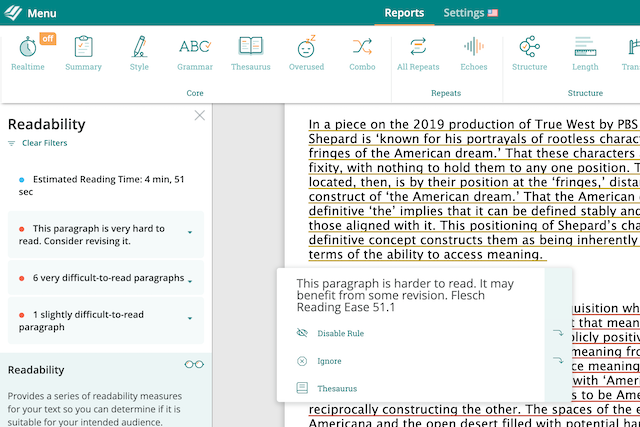

Of course, if you are still worried about the length of your paragraphs, you can always let ProWritingAid help. For example, check out the Readability Report , which will help you figure out which paragraphs are hard to read.

If it’s very difficult, it might mean there is too much information in there. Try breaking it down and running the report again to see if it improves your score.

Test your writing’s readability now with a free ProWritingAid account.

Now is a wonderful time to be a copywriter. Download this free book to learn how:

This guide breaks down the three essential steps you must take if you think copywriting is the career for you.

Be confident about grammar

Check every email, essay, or story for grammar mistakes. Fix them before you press send.

Ashley Shaw is a former editor and marketer/current PhD student and teacher. When she isn't studying con artists for her dissertation, she's thinking of new ways to help college students better understand and love the writing process. You can follow her on Twitter, or, if you prefer animal accounts, follow her rabbits, Audrey Hopbun and Fredra StaHare, on Instagram.

Get started with ProWritingAid

Drop us a line or let's stay in touch via :

- Link to facebook

- Link to linkedin

- Link to twitter

- Link to youtube

- Writing Tips

How Many Paragraphs Should an Essay Have?

- 6-minute read

- 19th May 2023

You have an essay to write. You’ve researched the topic and crafted a strong thesis statement . Now it’s time to open the laptop and start tapping away on the keyboard. You know the required word count, but you’re unsure of one thing: How many paragraphs should you have in the essay? Gee, it would’ve been nice if your professor had specified that, huh?

No worries, friend, because in this post, we’ll provide a guide to how many paragraphs an essay should have . Generally, the number of paragraphs will depend on how many words and how many supporting details you need (more on that later). We’ll also explore the concept of paragraphs if you’re wondering what they’re all about. And remember, paragraphs serve a purpose. You can’t submit an essay without using them!

What Is a Paragraph?

You likely know what a paragraph is, but can you define it properly in plain English? Don’t feel bad if that question made you shake your head. Off the top of our heads, many of us can’t explain what a paragraph is .

A paragraph comprises at least five sentences about a particular topic. A paragraph must begin with a well-crafted topic sentence , which is then followed by ideas that support that sentence. To move the essay forward, the paragraph should flow well, and the sentences should be relevant.

Why Are Paragraphs Important?

Paragraphs expand on points you make about a topic, painting a vivid picture for the reader. Paragraphs break down information into chunks, which are easier to read than one giant, uninterrupted body of text. If your essay doesn’t use paragraphs, it likely won’t earn a good grade!

How Many Paragraphs Are in an Essay?

As mentioned, the number of paragraphs will depend on the word count and the quantity of supporting ideas required. However, if you have to write at least 1,000 words, you should aim for at least five paragraphs. Every essay should have an introduction and a conclusion. The reader needs to get a basic introduction to the topic and understand your thesis statement. They must also see key takeaway points at the end of the essay.

As a rule, a five-paragraph essay would look like this:

- Introduction (with thesis statement)

- Main idea 1 (with supporting details)

- Main idea 2 (with supporting details)

- Main idea 3 (with supporting details)

Your supporting details should include material (such as quotations or facts) from credible sources when writing the main idea paragraphs.

If you think your essay could benefit from having more than five paragraphs, add them! Just make sure they’re relevant to the topic.

Professors don’t care so much about the number of paragraphs; they want you to satisfy the minimum word requirement. Assignment rubrics rarely state the number of required paragraphs. It will be up to you to decide how many to write, and we urge you to research the assigned topic before writing the essay. Your main ideas from the research will generate most of the paragraphs.

When Should I Start a New Paragraph?

Surprisingly, some students aren’t aware that they should break up some of the paragraphs in their essays . You need to start new paragraphs to keep your reader engaged.

As well as starting a new paragraph after the introduction and another for the conclusion, you should do so when you’re introducing a new idea or presenting contrasting information.

Find this useful?

Subscribe to our newsletter and get writing tips from our editors straight to your inbox.

Starting a paragraph often involves using transitional words or phrases to signal to the reader that you’re presenting a new idea. Failing to use these cues may cause confusion for the reader and undermine your essay’s coherence.

Let’s consider examples of transitional words and phrases in action in a conclusion. Note that the essay is about too much mobile device screen time and that transitional words and phrases can occur later in a paragraph too:

Thanks to “In conclusion” and “Additionally,” the reader clearly knows that they are now in the conclusion stage. They can also follow the logic and development of the essay more easily.

How Do I Know Whether I Have Enough Paragraphs?

While no magic number exists for how many paragraphs you need, you should know when you have enough to satisfy the requirements of the assignment. It helps if you can answer yes to the following questions:

- Does my essay have both an introduction and a conclusion?

- Have I provided enough main ideas with supporting details, including quotes and cited information?

- Does my essay develop the thesis statement?

- Does my essay adequately inform the reader about the topic?

- Have I provided at least one takeaway for the reader?

Conclusion

Professors aren’t necessarily looking for a specific number of paragraphs in an essay; it’s the word count that matters. You should see the word count as a guide for a suitable number of paragraphs. As a rule, five paragraphs should suffice for a 1,000-word essay. As long as you have an introduction and a conclusion and provide enough supporting details for the main ideas in your body paragraphs, you should be good to go.

Remember to start a new paragraph when introducing new ideas or presenting contrasting information. Your reader needs to be able to follow the essay throughout, and a single, unbroken block of text would be difficult to read. Transitional words and phrases help start new paragraphs, so don’t forget to use them!

As with any writing, we always recommend proofreading your essay after you’ve finished it. This step will help to detect typos, extra spacing, and grammatical errors. A second pair of eyes is always useful, so we recommend asking our proofreading experts to review your essay . They’ll correct your grammar, ensure perfect spelling, and offer suggestions to improve your essay. You can even submit a 500-word document for free!

1. What is a paragraph and what is its purpose?

A paragraph is a group of sentences that expand on a single idea. The purpose of a paragraph is to introduce an idea and then develop it with supporting details.

2. What are the benefits of paragraphs?

Paragraphs make your essay easy to read by providing structure and flow. They let you transition from one idea to another. New paragraphs allow you to tell your reader that you’ve covered one point and are moving on to the next.

3. How many paragraphs does a typical essay have?

An essay of at least 1,000 words usually has five paragraphs. It’s best to use the required word count as a guide to the number of paragraphs you’ll need.

Share this article:

Post A New Comment

Got content that needs a quick turnaround? Let us polish your work. Explore our editorial business services.

9-minute read

How to Use Infographics to Boost Your Presentation

Is your content getting noticed? Capturing and maintaining an audience’s attention is a challenge when...

8-minute read

Why Interactive PDFs Are Better for Engagement

Are you looking to enhance engagement and captivate your audience through your professional documents? Interactive...

7-minute read

Seven Key Strategies for Voice Search Optimization

Voice search optimization is rapidly shaping the digital landscape, requiring content professionals to adapt their...

4-minute read

Five Creative Ways to Showcase Your Digital Portfolio

Are you a creative freelancer looking to make a lasting impression on potential clients or...

How to Ace Slack Messaging for Contractors and Freelancers

Effective professional communication is an important skill for contractors and freelancers navigating remote work environments....

3-minute read

How to Insert a Text Box in a Google Doc

Google Docs is a powerful collaborative tool, and mastering its features can significantly enhance your...

Make sure your writing is the best it can be with our expert English proofreading and editing.

Daily Writing Tips

How many sentences in a paragraph.

A DWT reader, exasperated by an online newspaper article formatted as eleven one-sentence “paragraphs,” asks for a definition of “paragraph” and wants to know how long a paragraph should be.

A paragraph is a unit of thought that develops an idea. A traditional paragraph contains a topic sentence that states the idea to be developed, plus additional sentences that develop the idea stated by the topic sentence.

A newspaper lead (or lede if you prefer) can do its job in one sentence, but with few exceptions, a paragraph will contain more than one sentence. The OWL site, aimed at college students, suggests a length of from three to five or more sentences.

We all know that online writing calls for techniques different from those of the print media. Web readers do not tolerate long expanses of text. They expect short paragraphs, subheads, and bulleted lists. Nevertheless, they require the organization and coherence that paragraphs provide.

The article that prompted this post is an instructive example of a badly-organized piece which would have benefited from placing related ideas in paragraphs. Take a look and see what you think.

Eleven-sentence/paragraph story OWL on paragraphs

Stop making those embarrassing mistakes! Subscribe to Daily Writing Tips today!

You will improve your English in only 5 minutes per day, guaranteed!

Each newsletter contains a writing tip, word of the day, and exercise!

You'll also get three bonus ebooks completely free!

30 thoughts on “How Many Sentences in a Paragraph?”

I’ve always felt that a paragraph should be at least three sentences: one subject sentence plus two or three sentences that expand on the subject’s thought.

“A subject sentence is the most important sentence in a paragraph. It provides the main idea behind the paragraph. There is no hard and fast rule for the order in which it will appear amongst the other sentences. Sometimes it can be the last sentence in the paragraph, used to drive the idea home conclusively.”

Thank you, Maeve.

Yes it’s a terribly written piece. But that’s not to say single sentence paragraphs don’t have their place. They’re just another tool in the writer’s arsenal. Perhaps their application is what requires the discussion.

Great site.

Was going to comment, but I felt so strongly about this issue I was inspired to respond on my own blog.

I took several years of journalism classes in college and they actually teach you NOT to write big paragraphs. To journalism teachers a one sentence paragraph is perfectly acceptable.

That article you mention though is awful. You need to balance those one sentence paragraphs with a 2-3 sentence ones if you want it to be an article and not a list.

Clare, Thanks for the link. I read your post (which has planted seeds of future posts of my own). I agree with your itemized list of outdated rules such as not ending a sentence with a preposition or never splitting an infinitive. I don’t agree that paragraphing belongs in that category.

We’ll have to agree to disagree on the paragraph question, but I’m glad my post has inspired ideas for future posts. I look forward to reading them – and commenting on them, of course!

Newspaper “English” has nothing to do with fine writing techniques and style.

Newspaper “English” seeks to pack the most information into the least amount of space, which means eliminating as many uppercase letters as possible, cutting out commas and periods, and placing modifiers before the nouns and verbs, which also saves commas and spaces.

The width of the newspaper column is equally as important, which might be only two inches wide, and rarely wider than three inches. Adding spaces means knocking text onto the next line, and that’s a waste of space and money.

An example newspaper sentence: Beloved long-time Frederick HS football coach John Jones died today in a fiery car wreck along US Hwy 37 around 9 pm in a collision with a stalled cattle truck whose trailer extended into the inside traffic lane.

But when a newspaper story goes on-line, there are other considerations, which is usually too much space to fill. That’s why every sentence is treated like a whole paragraph.

I’m sorry—I wasn’t finished.

In an “on-line” story, the goal is to have the reader scroll down down down until all the advertising banners have been made visible, so the text is extended by making every sentence stand alone.

Advertising, in print or on-line, pays for the medium. And it’s a tough market these days for the advertisers, because their success depends on the contents of the medium. Lose 30-40% of your readers (due to content) and advertisers will fall off accordingly.

Cassie, I stand corrected. “Badly written” it is.

We’ll throw in our two cents (don’t we always?).

How many sentences does a paragraph need? At least one.

Here are 2 bits quoted from our training manual, with some additional commentary:

a. One paragraph = one central idea. Has someone ever said to you, “Hey, you’ve got a good point there”? Well, that’s what your paragraph does. It makes a point, one point, which is the central idea of the paragraph. You might think of it as the purpose for the paragraph. That one point of a paragraph may be supported by several other ideas, and the paragraph, itself, may be written to support a broader idea, but its purpose remains the same. It stands alone as the vehicle to express one complete idea to the reader.

What is the idea expressed by the paragraph? The length of your paragraph depends on the complexity of that idea and its scope. When you have completed discussing that idea, stop. If you haven’t completed the discussion, keep going.

b. Perhaps you had an English teacher tell you that a paragraph must have a thesis statement at the beginning. This is partially true. It must have a thesis statement. Your thesis statement is the point you are trying to communicate, but you have a couple of choices about its placement: beginning and end. You can start with the central idea and then build the internal and external supports, or you can provide the supports and lead up to your point.

Long paragraphs become manageable to the reader and to the writer when the supporting ideas are relevant to the main idea and are paced appropriately with context sentences, discussion, and an impact statement (but that’s a different article, I believe).

FYI: Henry David Thoreau used long paragraphs very effectively. See . As an exercise, identify the single main idea of each paragraph. Then find the supporting ideas by their context sentences, discussion, and impact statements. Have fun!

I used to proofread for a court reporting service (that produced, e.g., deposition transcripts).

The hard-and-fast rule there was to create a new paragraph once the testimony, as transcribed, ran over 5-7 lines. It was more about readability than expressing ideas in a paragraph block. Actually, I kind of enjoyed the challenge of interpreting testimony and defining paragraphs on my own.

And, there’s something to be said for readability — similar to the type of Web writing that Maeve pointed out.

(Oh, and I do believe it’s “a badly written piece,” without the hyphen. Yes? :-))

A paragraph should more precisely contain a central thought correlated to the preceeding paragraph (title if it is the first para).

If you wish to change the direction of your thought, or bring in a new dimension to your writing; you ought to know how to play with a paragraphs.

A very long paragraph is bad and so is a very small one., but nothing is rigid when it comes to writing.

So, experiment more and create newer styles.