Library of Congress

Exhibitions.

- Ask a Librarian

- Digital Collections

- Library Catalogs

- Exhibitions Home

- Current Exhibitions

- All Exhibitions

- Loan Procedures for Institutions

- Special Presentations

Benjamin Franklin: In His Own Words Scientist and Inventor

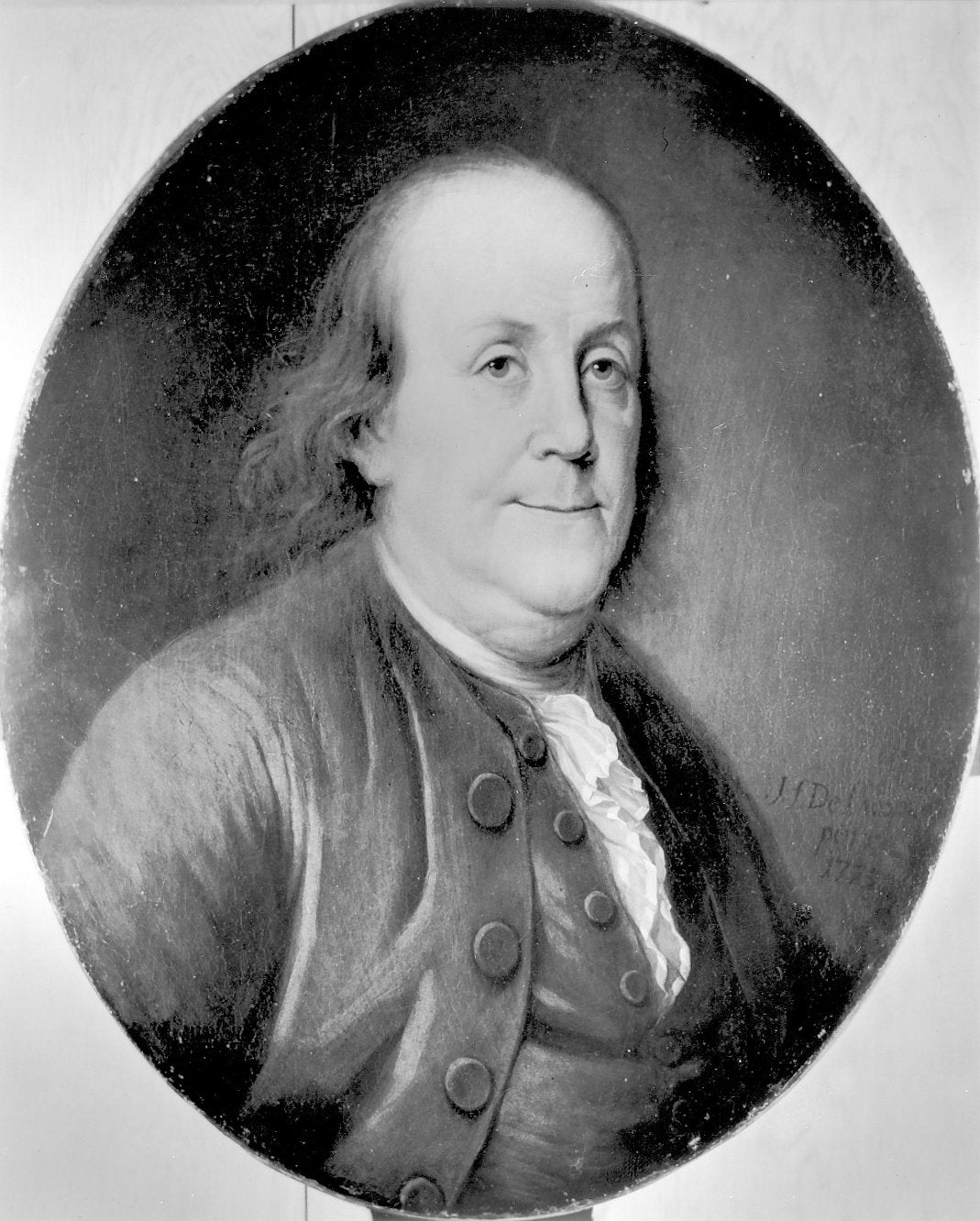

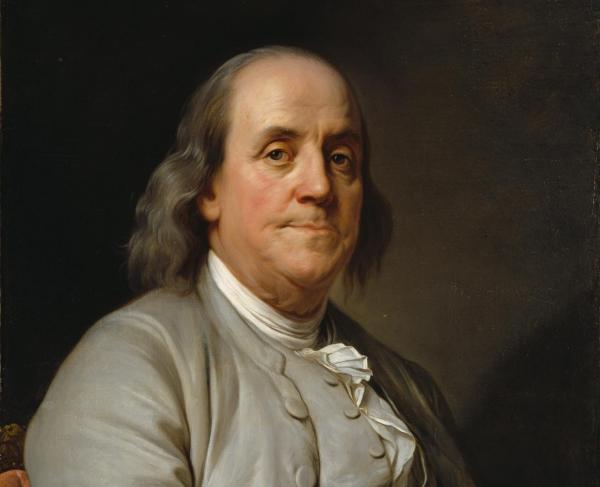

Benjamin Franklin

This portrait, which depicts Franklin as a learned scientist and inventor, was one of his favorites. Pictured on the left is the signal-bell apparatus Franklin devised to detect the presence of electrically-charged clouds. The bolt of lightning , seen through the open window, became an attribute closely identified with Franklin. At Franklin's death French philosopher/scientist Jacques Turgot wrote: “He seized the lightning from the sky and the scepter from the hand of tyrants.”

Edward Fisher (1730–ca. 1785), after Mason Chamberlin (d. 1787). Benjamin Franklin of Philadelphia, 1763. Mezzotint. Prints & Photographs Division , Library of Congress (32) LC-DIG-ppmsca-10083

Bookmark this item: //www.loc.gov/exhibits/franklin/franklin-scientist.html#obj32

The Franklin Stove

Franklin wrote this description of the stove he had invented to promote sales of a model being manufactured by his friend Robert Grace. A series of partitioned iron plates permits a continuous supply of fresh warm air, separated from the smoke, to be distributed equally throughout the room. By controlling the airflow, less heat is lost, and much less wood is needed. Franklin's stove became so popular in England and Europe that this essay was frequently reprinted and translated into several foreign languages.

Benjamin Franklin. An Account of the New Invented Pennsylvanian Fire-Places . An Account of the New Invented Pennsylvanian Fire-Places . Page 2. Philadelphia: Printed and Sold by B. Franklin, 1744. Rare Book & Special Collections Division, Library of Congress (35) //www.loc.gov/exhibits/franklin/images/bf0035p2s.jpg ">Page 2 . Philadelphia: Printed and Sold by B. Franklin, 1744. Rare Book & Special Collections Division , Library of Congress (35)

Bookmark this item: //www.loc.gov/exhibits/franklin/franklin-scientist.html#obj35

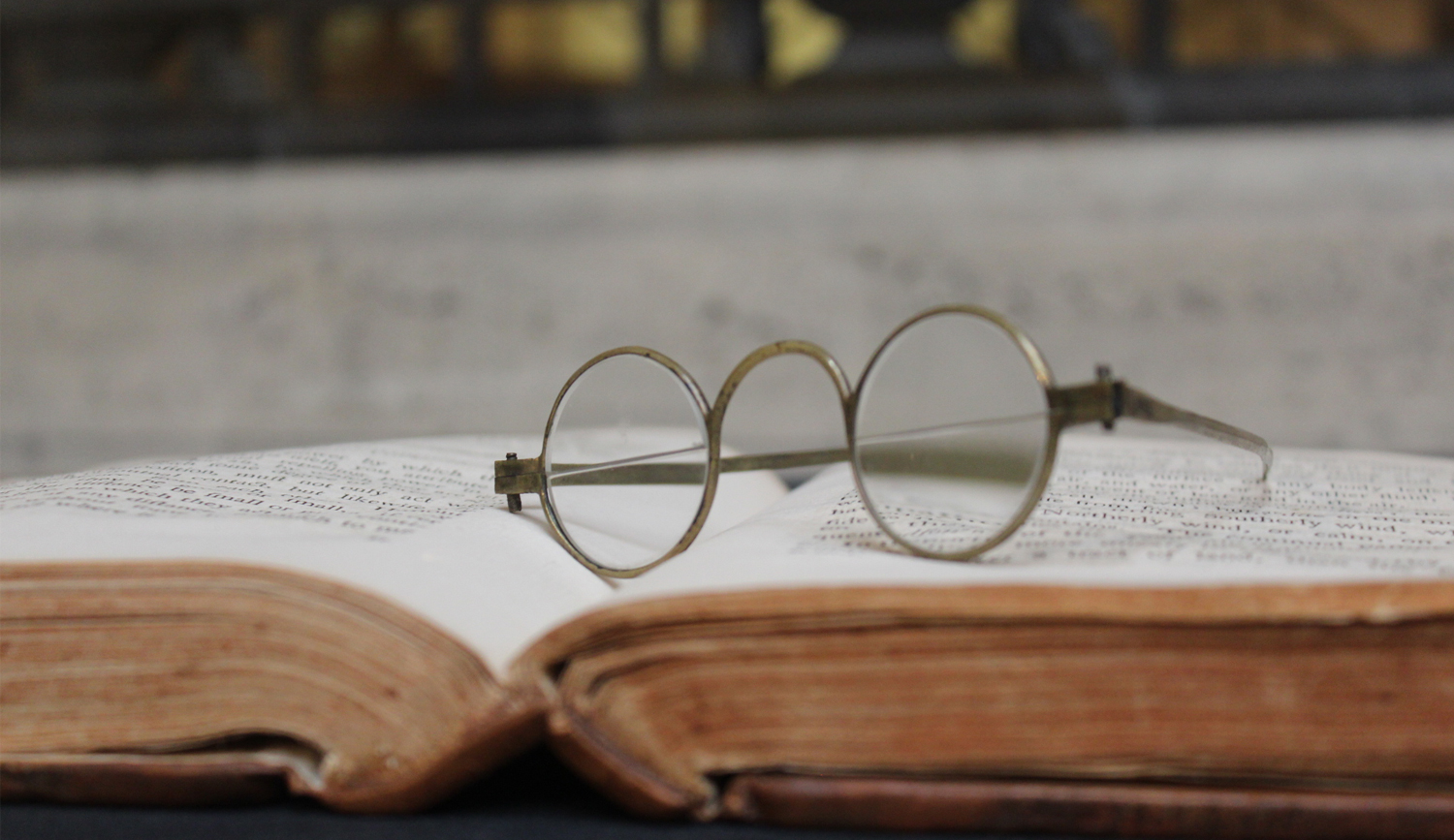

Franklin's Design for Bifocals

Benjamin Franklin is credited with the invention of bifocal glasses, which he sketched here for his friend George Whatley, a London merchant and pamphleteer. Franklin told Whately he found them particularly useful at dinner in France, where he could see the food he was eating and watch the facial expressions of those seated at the table with him, which helped interpret the words being said. He wrote: “I understand French better by the help of my Spectacles.”

Benjamin Franklin to George Whatley (ca. 1709–1791), May 23, 1785. Letterpress manuscript. Manuscript Division , Library of Congress (36)

Read the transcript

Bookmark this item: //www.loc.gov/exhibits/franklin/franklin-scientist.html#obj36

Experiments in Electricity

In 1751, Peter Collinson, President of the Royal Society, arranged for the publication of a series of letters from Benjamin Franklin, 1747 to 1750, describing his experiments on electricity. Franklin demonstrated his new theory of positive and negative charges, suggested the electrical nature of lightning, and proposed a tall, grounded rod as a protection against lightning. These experiments established Franklin's reputation as a scientist, and in 1753 he received the Copley Medal of the Royal Society for his contributions to the knowledge of lightning and electricity.

Benjamin Franklin. Experiments and Observations on Electricity, made at Philadelphia in America, By Benjamin Franklin . Experiments and Observations on Electricity, made at Philadelphia in America, By Benjamin Franklin . Page 2. London, Printed for David Henry, 1769. Rare Book & Special Collections Division, Library of Congress (37A) //www.loc.gov/exhibits/franklin/images/bf0037ap2s.jpg ">Page 2 . London, Printed for David Henry, 1769. Rare Book & Special Collections Division , Library of Congress (37A)

Bookmark this item: //www.loc.gov/exhibits/franklin/franklin-scientist.html#obj37a

On Electricity

Benjamin Franklin's formulation of a general theory of electrical “action” won him an international reputation in pure science in his own day. Writing to Dutch physician and scientist Jan Ingenhousz, Franklin responds to a number of his friend's questions about electricity and the Leyden jar, an early form of electrical condenser. In this draft scientific report, it appears that Franklin wrote his answers first using dark ink, leaving room for the questions, which he wrote in red ink.

Benjamin Franklin. “Queries from Dr. Ingenhousz, with my Answers, B.F.”. //www.loc.gov/exhibits/franklin/images/bf0038p2s.jpg ">Page 2 . //www.loc.gov/exhibits/franklin/images/bf0038p3s.jpg ">Page 3 . Holograph report with annotations, [1777]. Manuscript Division , Library of Congress (38)

Bookmark this item: //www.loc.gov/exhibits/franklin/franklin-scientist.html#obj38

Franklin Explains the Effects of Lightning

In this lengthy essay intended for his fellow scientist Jan Ingenhousz, Benjamin Franklin attempted to explain the effects of lightning on a church steeple in Cremona, Italy, by describing the effects of electricity on various metals. He based his hypothesis on other written accounts, and used this sketch of a tube of tin foil to aid in his explanation.

Benjamin Franklin to Jan Ingenhousz, 1777. Manuscript essay. Manuscript Division , Library of Congress (39)

Bookmark this item: //www.loc.gov/exhibits/franklin/franklin-scientist.html#obj39

Mapping the Gulf Stream

Although Spanish explorers had described the Gulf Stream, Franklin, fascinated by the fact that the sea journey from North America to England was shorter than the return trip, asked his cousin, Nantucket sea captain Timothy Folger, to map its dimensions and course. Franklin published this map and his directions for avoiding it in the Transactions of the American Philosophical Society in 1786. Systematic research, conducted by the U.S. Coast Survey, of the Gulf Stream did not occur until 1845.

Benjamin Franklin. “ Maritime Observations and A Chart of the Gulph Stream .” in Transactions of the American Philosophical Society . Philadelphia: 1796. Engraved map. Geography & Map Division , Library of Congress (40A) [gmd9/g9112/g9112g/ct000136]

Bookmark this item: //www.loc.gov/exhibits/franklin/franklin-scientist.html#obj40a

Franklin Battles the Common Cold

Despite his eminence in scientific circles, Benjamin Franklin remained concerned with the more practical applications of scientific study. This sheet entitled “Definition of a Cold” is one of a series bearing Franklin's notes for a paper he intended to write on the subject. Exercise, bathing, and moderation in food and drink consumption were just some of his steps to avoid the common cold.

Benjamin Franklin. “Hints concerning what is called Catching a Cold,” [1773]. //www.loc.gov/exhibits/franklin/images/bf0041p2s.jpg ">Page 2 . Manuscript document. Manuscript Division , Library of Congress (41)

Bookmark this item: //www.loc.gov/exhibits/franklin/franklin-scientist.html#obj41

The Aurora Borealis

Benjamin Franklin's interest in the mystery of the “Northern Lights” is said to have begun on his voyages across the North Atlantic to England. He ascribed the shifting lights to a concentration of electrical charges in the polar regions intensified by the snow and other moisture. He reasoned that this overcharging caused a release of electrical illumination into the air. In this essay, which he wrote in English and French, Franklin analyzed the causes of the Aurora Borealis. It was read at the French Académie des Sciences on April 14, 1779.

Benjamin Franklin (1706-1790). “Suppositions and Conjectures on the Aurora Borealis,” [ca. December 1778]. //www.loc.gov/exhibits/franklin/images/bf0042p2s.jpg ">Page 2 . //www.loc.gov/exhibits/franklin/images/bf0042p3s.jpg ">Page 3 . //www.loc.gov/exhibits/franklin/images/bf0042p4s.jpg ">Page 4 . Manuscript essay. Manuscript Division , Library of Congress (42)

Bookmark this item: //www.loc.gov/exhibits/franklin/franklin-scientist.html#obj42

Franklin's Armonica

Before leaving London in July 1762, Franklin wrote to the Italian philosopher Giambatista Beccaria. Not having anything new to report on their shared interest in electricity, Franklin described the improvements he had made to the musical glasses invented by Richard Puckeridge. By fitting a series of graduated glass discs on a spindle laid horizontal in a case and revolving the spindle by a foot treadle, Franklin could create bell-like tones by touching his wet fingers to the revolving glasses. Franklin's armonica became popular in Europe, with Mozart and Beethoven composing music for it.

L'Armonica: Lettera del Signor Beniamino Franklin al Padre Giambatista Beccaria, Regio Professore di Fisica nell' Univ. di Torino . L'Armonica: Lettera del Signor Beniamino Franklin al Padre Giambatista Beccaria, Regio Professore di Fisica nell' Univ. di Torino . Page 2. [Milano?:1776?]. Rare Book & Special Collections Division, Library of Congress (43) //www.loc.gov/exhibits/franklin/images/bf0043p2s.jpg ">Page 2 . [Milano?:1776?]. Rare Book & Special Collections Division , Library of Congress (43)

Bookmark this item: //www.loc.gov/exhibits/franklin/franklin-scientist.html#obj43

Back to Top

Connect with the Library

All ways to connect

Subscribe & Comment

- RSS & E-Mail

Download & Play

- iTunesU (external link)

About | Press | Jobs | Donate Inspector General | Legal | Accessibility | External Link Disclaimer | USA.gov

- Games & Quizzes

- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

Benjamin Franklin summary

Explore the life of benjamin franklin, his inventions, and contribution to public service.

Benjamin Franklin , (born Jan. 17, 1706, Boston, Mass.—died April 17, 1790, Philadelphia, Pa., U.S.), American printer and publisher, author, scientist and inventor, and diplomat. He was apprenticed at age 12 to his brother, a local printer. He taught himself to write effectively, and in 1723 he moved to Philadelphia, where he founded the Pennsylvania Gazette (1729–48) and wrote Poor Richard’s almanac (1732–57), often remembered for its proverbs and aphorisms emphasizing prudence, industry, and honesty. He became prosperous and promoted public services in Philadelphia, including a library, a fire department, a hospital, an insurance company, and an academy that became the University of Pennsylvania. His inventions include the Franklin stove and bifocal spectacles, and his experiments helped pioneer the understanding of electricity. He served as a member of the colonial legislature (1736–51). He was a delegate to the Albany Congress (1754), where he put forth a plan for colonial union. He represented the colony in England in a dispute over land and taxes (1757–62); he returned there in 1764. The issue of taxation gradually caused him to abandon his longtime support for continued American colonial membership in the British Empire. Believing that taxation ought to be the prerogative of the representative legislatures, he opposed the Stamp Act. He served as a delegate to the second Continental Congress and as a member of the committee to draft the Declaration of Independence. In 1776 he went to France to seek aid for the American Revolution. Lionized by the French, he negotiated a treaty that provided loans and military support for the U.S. He also played a crucial role in bringing about the final peace treaty with Britain in 1783. As a member of the 1787 Constitutional Convention, he was instrumental in achieving adoption of the Constitution of the U.S. He is regarded as one of the most extraordinary and brilliant public servants in U.S. history.

Benjamin Franklin’s Inventions

Benjamin franklin was many things in his lifetime: a printer, a postmaster, an ambassador, an author, a scientist, and a founding father. above all, he was an inventor, creating solutions to common problems, innovating new technology, and even making life a little more musical..

Despite creating some of the most successful and popular inventions of the modern world, Franklin never patented a single one, believing that they should be shared freely:

"That as we enjoy great Advantages from the Inventions of others, we should be glad of an Opportunity to serve others by any Invention of ours; and this we should do freely and generously."

Here are some of Benjamin Franklin’s most significant inventions:

Lightning rod.

Franklin is known for his experiments with electricity - most notably the kite experiment - a fascination that began in earnest after he accidentally shocked himself in 1746. By 1749, he had turned his attention to the possibility of protecting buildings—and the people inside—from lightning strikes. Having noticed that a sharp iron needle conducted electricity away from a charged metal sphere, he theorized that such a design could be useful:

"May not the knowledge of this power of points be of use to mankind, in preserving houses, churches, ships, etc., from the stroke of lightning, by directing us to fix, on the highest parts of those edifices, upright rods of iron made sharp as a needle...Would not these pointed rods probably draw the electrical fire silently out of a cloud before it came nigh enough to strike, and thereby secure us from that most sudden and terrible mischief!"

Franklin’s pointed lightning rod design proved effective and soon topped buildings throughout the Colonies. Learn more about the lightning rod .

Like most of us, Franklin found that his eyesight was getting worse as he got older, and he grew both near-sighted and far-sighted. Tired of switching between two pairs of eyeglasses, he invented “double spectacles,” or what we now call bifocals. He had the lenses from his two pairs of glasses - one for reading and one for distance - sliced in half horizontally and then remade into a single pair, with the lens for distance at the top and the one for reading at the bottom.

An avid swimmer, Franklin was just 11 years old when he invented swimming fins—two oval pieces of wood that, when grasped in the hands, provided extra thrust through the water. He also tried out fins for his feet, but they weren’t as effective. He wrote about his childhood invention in an essay titled “On the Art of Swimming”:

“When I was a boy, I made two oval [palettes] each about 10 inches long and six broad, with a hole for the thumb in order to retain it fast in the palm of my hand. They much resembled a painter’s [palettes]. In swimming, I pushed the edges of these forward and I struck the water with their flat surfaces as I drew them back. I remember I swam faster by means of these [palettes], but they fatigued my wrists.”

Franklin Stove

The Franklin Stove.

In 1742, Franklin—perhaps fed up with the cold Pennsylvania winters—invented a better way to heat rooms. The Franklin stove, as it came to be called, was a metal-lined fireplace designed to stand a few inches away from the chimney. A hollow baffle at the rear let the heat from the fire mix with the air more quickly, and an inverted siphon helped to extract more heat. His invention also produced less smoke than a traditional fireplace, making it that much more desirable.

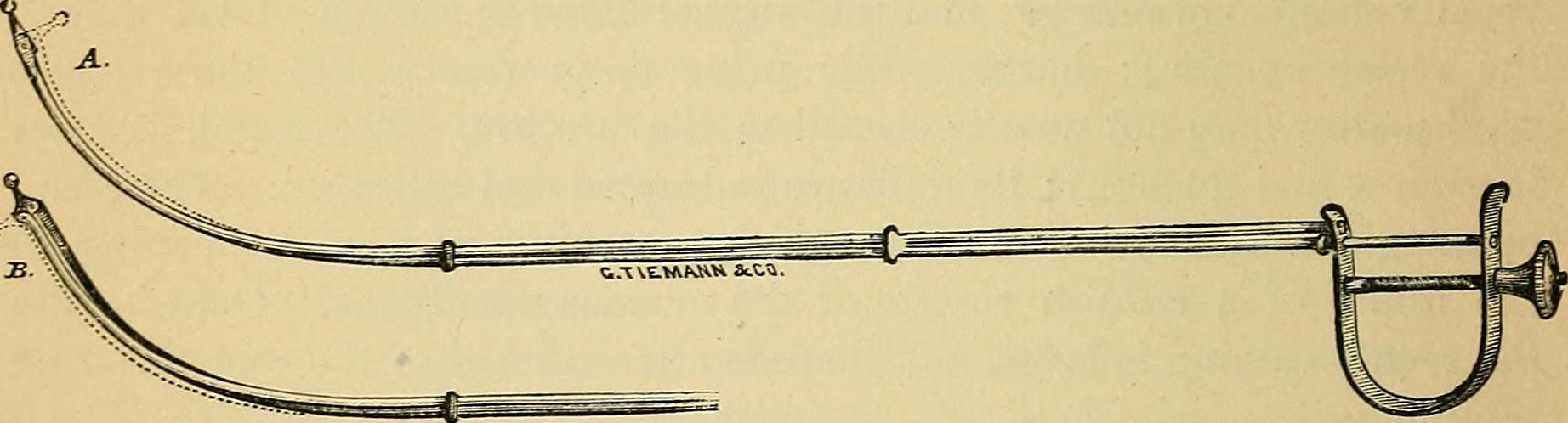

Urinary Catheter

Franklin was inspired to invent a better catheter in 1752 when he saw what his kidney (or bladder) stone-stricken brother had to go through. Catheters at the time were simply rigid metal tubes—none too pleasant. So Franklin devised a better solution: a flexible catheter made of hinged segments of tubes. He had a silversmith make his design and he promptly mailed it off to his brother with instructions and best wishes.

"Of all my inventions, the glass armonica has given me the greatest personal satisfaction."

So wrote Franklin about the musical instrument he designed in 1761. Inspired by English musicians who created sounds by passing their fingers around the brims of glasses filled with water, Franklin worked with a glassblower to re-create the music (“incomparably sweet beyond those of any other”) in a less cumbersome way.

The armonica (the name is derived from the Italian for “harmony”) was immediately popular, but by the 1820s it had been nearly forgotten. Get the full story here .

- Buy Tickets

- TFI Transformation

- Accessibility

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Itineraries

- Daily Schedule

- Getting Here

- Where to Eat & Stay

- All Exhibits & Experiences

- The Art of the Brick

- Wondrous Space

- Science After Hours

- Heritage Days

- Events Calendar

- Staff Scientists

- Benjamin Franklin Resources

- Scientific Journals of The Franklin Institute

- Professional Development

- The Current: Blog

- About Awards

- Ceremony & Dinner

- Sponsorship

- The Class of 2024

- Call for Nominations

- Committee on Science & The Arts

- Next Generation Science Standards

- Title I Schools

- Neuroscience & Society Curriculum

- STEM Scholars

- GSK Science in the Summer™

- Missions2Mars Program

- Children's Vaccine Education Program

- Franklin @ Home

- The Curious Cosmos with Derrick Pitts Podcast

- So Curious! Podcast

- A Practical Guide to the Cosmos

- Archives & Oddities

- Ingenious: The Evolution of Innovation

- The Road to 2050

- Science Stories

- Spark of Science

- That's B.S. (Bad Science)

- Group Visits

- Plan an Event

Open 365 days a year, Mount Vernon is located just 15 miles south of Washington DC.

From the mansion to lush gardens and grounds, intriguing museum galleries, immersive programs, and the distillery and gristmill. Spend the day with us!

Discover what made Washington "first in war, first in peace and first in the hearts of his countrymen".

The Mount Vernon Ladies Association has been maintaining the Mount Vernon Estate since they acquired it from the Washington family in 1858.

Need primary and secondary sources, videos, or interactives? Explore our Education Pages!

The Washington Library is open to all researchers and scholars, by appointment only.

Benjamin Franklin

| Born: | January 17, 1706 (New Style), Boston, Massachusetts |

| Died: | April 17, 1790, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania |

| Occupation: | Printer, author, scientist and inventor, politician, diplomat, postmaster general |

| Major Political Offices: | Representative in London for the Assembly of Pennsylvania and for the assemblies of Massachusetts, New Jersey, and Georgia; Deputy Postmaster for North America and 1st US Postmaster General; US Minister Plenipotentiary to France; President of Pennsylvania |

Digital Encyclopedia

Benjamin franklin in london.

From 1757 through 1775, Benjamin Franklin was happily settled in London. In England, he was renowned as a famous scientist, and until 1775 he staunchly believed that America and its mother country could be reconciled.

Historic Site

Benjamin franklin house, london.

Craven Street is the only one of Franklin’s many residences that still remains today. Almost approved for "redevelopment" in the late 20th century, it was saved by a charitable trust and reopened as a Museum and Education Center on the 300th anniversary of Franklin’s birth in 2006.

Franklin and Ballooning

In this clip, Dr. Tom Crouch, Senior Curator of Aeronautics at the National Air and Space Museum, introduces the viewer to Franklin's views on practical usage of balloons and flying.

George Washington may rightly be known as the " Father of his Country " but, for the two decades before the American Revolution, Benjamin Franklin was the world’s most famous American.

Franklin was a celebrated scientist and inventor. 1 His electrical experiments had won him the Royal Society's Copley Medal, the 18 th Century equivalent of the Nobel Prize, and his inventions included the lightning conductor, the first map of the Gulf Stream and a new musical instrument in the glass armonica – for which Gluck, Mozart and Beethoven all composed concertos. Franklin’s genius was internationally acclaimed, with Immanuel Kant describing him as “The Prometheus of Modern Times” and David Hume hailing him as America’s “first great man of letters”. 2

Born on January 17, 1706 in Boston, Benjamin Franklin was the tenth and youngest son of an independent tallow chandler and soap maker. 3 He was apprenticed at the age of twelve to his printer brother James, but, following a dispute, Benjamin moved to Philadelphia in 1723. The next year the young printer was on the move again, this time to London, Britain's great imperial capital, and his eighteen-month stay would have a lasting influence. In 1726 he returned to America and made Philadelphia his permanent family home.

From as early as his mid-twenties, Franklin (in partnership with his wife Deborah) started to become successful, first as a printer, then also as a newspaper proprietor, writer, and merchant. In the years that followed, and inspired by his time in London, he founded some of America’s great institutions. These included the American Philosophical Society (based on the Royal Society), the Library Company of Philadelphia (the first successful public lending library in America), and the Academy of Philadelphia that would ultimately become the University of Pennsylvania. Following his retirement from daily involvement in his business and on taking up public service on a full time basis in 1748, Franklin also helped to establish America’s first public hospital and a system of Fire Insurance, having already created a Fire Service in 1736.

By 1757 Franklin was Deputy Postmaster for North America and a leading member of the Assembly of Pennsylvania, which sent him to London as its representative. During his time in Britain (1757- 1762 and 1764 to March 1775), he also took on representation for Massachusetts, New Jersey, and Georgia and fought hard for a reconciliation between Britain and its American colonies. Yet, when spurned by the anti-Americans in Lord North’s government and after fleeing Britain to escape arrest, he became a fierce American patriot.

Having returned to America, Franklin became an early advocate of confederation and was one of the committee of five appointed to draft the Declaration of Independence . His most striking contribution was his suggestion to Thomas Jefferson that the phrase ‘We hold these truths to be sacred and undeniable’ be changed to ‘We hold these truths to be self evident’, which thereby neatly substituted natural law for divine sanction. Franklin was the only man to sign the three key documents in the birth of the United States: the Declaration of Independence, the Treaty of Paris, and the Constitution.

To those can be added an important fourth, the 1778 Treaty of Alliance with France. As the United States’ minister in France from 1776, Franklin brought the French into the war against Britain and kept them there. This made him second only to Washington for his importance in winning the War of American Independence. John Adams inadvertently provided confirmation of the contemporary and near-contemporary understanding of Franklin’s wartime importance, with his acid comment in an 1815 letter to Thomas Jefferson: "The essence of the whole will be that Dr Franklin’s electric rod smote the earth and out sprang General Washington. Then Franklin electrified him, and thence forward those two conducted all the Policy, Negotiations, Legislations, and War." 4

After his return from France in 1785, Franklin became, at the age of seventy-nine, the President and effective Governor of Pennsylvania for three years. He was also a member of the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia in 1787. Though enfeebled by ill-health, his few contributions to the Convention were important. Together with George Washington, he acted as a senior statesman willing to lend his authority to the compromises they deemed necessary to forge a Constitution capable of serving the new nation.

Also in 1787, Franklin became President of the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society. In earlier years he had not only owned enslaved people but had profited from including slave advertisements in his newspapers. However, his views changed over time and he became first an advocate of "negro education" and then of abolition. He widely circulated Josiah Wedgwood’s "Am I not a Man and a Brother" anti-slavery medallions because he believed them to have "an Effect equal to that of the best written Pamphlet, in procuring Favour to those oppressed People." 5

George Goodwin, FRHistS., FRSA, FCIM Author in Residence at Benjamin Franklin House in London for Benjamin Franklin in London: The British Life of America’s Founding Father (Yale University Press).

1. In the 18th century, however, he was not called a "scientist," but the contemporary term "natural philosopher."

2. Immanuel Kant, Gesammelte Schriften, vol. 1 (Berlin: Georg Reimer, 1900), 472; David Hume to Benjamin Franklin, May 10, 1762, in Leonard W. Labaree et. al., eds., Papers of Benjamin Franklin , vol. 10 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1966), 81-82.

3. This date reflects the "new" style Gregorian calendar. Britain and its colonies switched from the Julian to the Gregorian calendar during Franklin's lifetime, in 1752. Under the Julian calendar, Franklin's birth was recorded as January 6, 1706.

4. John Adams to Benjamin Rush, April 4, 1790 , Founders Online, Library of Congress.

5. Benjamin Franklin to Josiah Wedgwood, May 15, 1787 , The Papers of Benjamin Franklin.

Quick Links

9 a.m. to 5 p.m.

The Papers of Benjamin Franklin

Sponsored by the american philosophical society and yale university, digital edition by the packard humanities institute, i agree to use this web site only for personal study and not to make copies except for my personal use under "fair use" principles of copyright law. click here if you agree to this license, if you wish to use materials on this site for purposes other than personal study click here to read license terms.

Home » Online Exhibits » Penn People » Penn People A-Z » Benjamin Franklin

Benjamin Franklin 1706 - 1790

Penn Connection

- Founder and trustee 1749-1790

- President of Board of Trustees 1749-1756 and 1789-1790

Born in Boston, Massachusetts, in 1706, Benjamin Franklin assisted his father, a tallow chandler and soap boiler, in his business from 1716 to 1718. In 1718 young Franklin was apprenticed to his brother James as a printer. Franklin ran away in 1723, heading for Philadelphia where he worked for the printer Samuel Keimer. After traveling to London in 1724 to continue learning his trade as a journeyman printer, Franklin returned to Philadelphia in 1726. By 1730, Franklin established himself as an independent master printer.

Franklin quickly became not only the most prominent printer in the colonies, but the figure who shaped and defined colonial and revolutionary Philadelphia. As one who believed that the phenomena of nature should serve human welfare, Franklin was greatly interested in applied scientific inquiry. Franklin’s groundbreaking discoveries and contributions to fundamental knowledge—most famously those involving lightning and the nature of electricity—made him internationally known for his experiments and insatiable curiosity. He was as renowned for the practical inventions that followed. Many of these profoundly altered everyday life for the better, including the lightning rod, bifocals, and the Franklin stove.

Franklin was equally interested in the improvement of individuals and society as well. He was the center of the Junto, an elite group of intellectuals who were at the core of Philadelphia politics and cultural life for some time and who became the basis for the American Philosophical Society. He was also instrumental in the improvement of the lighting and paving of Philadelphia and in the organization of a police force, fire companies, Pennsylvania Hospital, the Library Company of Philadelphia, as well as the Academy and College of Philadelphia.

Franklin was a key political leader at many levels. In 1736 he was chosen clerk of the Pennsylvania Assembly, which position he held until 1751. In 1737 he was made postmaster at Philadelphia. In 1754 he was sent to the Albany Convention where he submitted a plan for colonial unity. He provisioned Braddock’s army and in 1756 was put in charge of the northwestern frontier of the province by the governor. He was sent to London twice as agent for the Assembly, 1757-1762 and 1764-1775. With the outbreak of the Revolution, he was sent as commissioner to France, 1776-1785, and in 1781 was on the commission to make peace with Great Britain. Franklin was a member of the Continental Congress, a signer of the Declaration of Independence, and a framer of both the Pennsylvania and United States Constitutions. Franklin also served as the American ambassador to France.

Franklin was the primary founder and shaper of the new institution which became the University of Pennsylvania. His 1749 Proposals Relating to the Education of Youth in Pensilvania were the basis of the Academy which opened two years later. Franklin was responsible for the hiring of William Smith as the first provost in 1754. From 1749 to 1755 Benjamin Franklin was president of the Board of Trustees of the College, Academy, and Charitable School of Philadelphia, and he continued as a trustee of the College and then of the University of the State of Pennsylvania until his death in 1790. For most of this period he served as an elected trustee; but from 1785-1788 while president of Pennsylvania’s Supreme Executive Council (the equivalent of governor), Franklin was an ex officio trustee.

Franklin was also a well-known abolitionist later in life, but he only came to that position over many years. From as early as 1735 to as late as the 1770s, Franklin owned at least seven enslaved people. From 1729, when Franklin purchased the Pennsylvania Gazette , to 1790, the paper advertised slave auctions and notices of runaway slaves while also printing essays by authors deeply critical of slavery. In 1757, Franklin lent his vocal support for the creation of a school for African Americans in Philadelphia, the first of its kind in the colonies. In subsequent years, he began writing publicly against the institution of slavery. In 1787, Franklin became President of the Pennsylvania Society for Promoting the Abolition of Slavery. In February 1790, Franklin petitioned Congress for the abolition of slavery. In the petition, he argued that “the blessings of liberty” applied to all “People of the United States.”

It was among his final acts. Franklin died later that year in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania and is buried in the Christ Church burial ground.

Founders Online --> [ Back to normal view ]

Quick links.

- About Founders Online

- Major Funders

- Search Help

- How to Use This Site

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Teaching Resources

About the Papers of Benjamin Franklin

The Papers of Benjamin Franklin is a collaborative undertaking by a team of scholars at Yale University to collect, edit, and publish a comprehensive, annotated edition of Franklin’s writings and papers: everything he wrote and almost everything he received. In a life spanning from 1706 to 1790, Franklin explored nearly every aspect of his world, and he corresponded with an astonishing range of men and women of all social classes and professions in America, Great Britain, and Europe. His collected papers present a panoramic view of the eighteenth century, in addition to an unprecedented view into Franklin’s thoughts and activities reflecting his ever-curious and inventive mind.

The Papers of Benjamin Franklin was established in 1954 under the joint auspices of Yale University and the American Philosophical Society. It is housed in Yale’s Franklin Collection, the world’s finest collection of printed, manuscript, and visual materials dedicated to the study of Franklin and his times, which was assembled by Yale alumnus William Smith Mason. Launched with a generous gift from Henry Luce in the name of Life Magazine, the project has been sustained by numerous grants from individuals; private foundations, including the Packard Humanities Institute, The Pew Charitable Trusts, the Florence Gould Foundation, the Mellon Foundation, and the Cinco Hermanos Fund; and two federal agencies, the National Historical Publications and Records Commission and the National Endowment for the Humanities. Forty volumes have been published to date, bringing the edition to September, 1783, when Franklin and his colleagues signed the Treaty of Paris that ended the American Revolution and established the United States of America. The entire edition is projected to reach 47 volumes and will encompass approximately 30,000 extant papers.

A Digital Franklin Papers edition has been freely available on the web since 2006, sponsored by the Packard Humanities Institute, at www.franklinpapers.org . This database contains texts of all documents that have been published (current through volume 37), and preliminary transcriptions of all texts that will appear in future volumes, through the end of Franklin’s life. In addition, the database includes transcriptions of the documents that were not printed in full, translations of many of the French texts, a biographical dictionary of all Franklin’s correspondents, and an introduction written for the digital edition by Edmund S. Morgan.

A preliminary cumulative index to the published volumes is available on the project’s website. Please visit that website for more information on the project, links to order volumes, and information on Yale’s Franklin Collection.

See a complete list of Franklin Papers volumes included in Founders Online, with links to the documents.

The letterpress edition of The Papers of Benjamin Franklin is available from Yale University Press .

Copyright © by the American Philosophical Society Held at Philadelphia for Promoting Useful Knowledge and by Yale University.

We thank Michael D. Hattem of Yale University, and Erica Cavanaugh and Patricia Searl of the University of Virginia, for their assistance in proofreading the Franklin documents in Founders Online.

- Skip to global NPS navigation

- Skip to this park navigation

- Skip to the main content

- Skip to this park information section

- Skip to the footer section

Exiting nps.gov

Alerts in effect, benjamin franklin and science.

| Early in his life, Franklin’s flair for innovation and youthful love of swimming led him to produce “a method in which a swimmer may pass to greater distances with much facility, by means of a sail.” Centuries before windsurfing, Franklin discovered he could harness the power of the wind with his kite and be pulled effortlessly across a mile-wide pond. At the age of 11, he also created an early version of what we now know as swim fins. “I made two oval palettes… They much resembled a painter’s palette… I also fitted the soles of my feet a kind of sandals.” In 1968, Franklin’s swim fin invention earned him a place in the International Swimming Hall of Fame. Franklin crossed the Atlantic by ship eight times during his life, voyages that provided him with ample opportunity to observe the ocean and the weather. His charting of the Gulf Stream contributed to an understanding of how the ocean’s currents could affect global trade by helping ship captains sail within the Gulf Stream and thus reduce the lengthy ocean crossing. Because he was interested in improving travel to make it more efficient, comfortable, and convenient, he imagined various ways to streamline vessels for speedier voyages. Franklin was fascinated by electricity and devoted much of his time after he retired to studying its properties. Some of his research resulted in “tricks” that he used to amuse others, like a charged metal spider that moved like the real thing and an electrified fence that created sparks. He coined the terms “battery,” “positive charge,” and “negative charge,” and discovered new ways to generate, store, and deploy electricity. His design and promotion of the use of lightning rods helped prevent untold numbers of structural fires throughout the world. His famous kite experiment occurred in June 1752, and though it is said to have taken place in Philadelphia, the exact location remains unclear. Franklin asked his son William to fly a silk kite, to which he had attached a wire on top and a key at the end of a string. Ultimately, the kite—and therefore the key—amassed an electric charge from a storm cloud. Franklin was then able to collect some of the charge and compare it to the electricity he had created in other experiments. He did not publicly mention the experiment until October, four months after it took place, at which point Franklin did not clarify that he had conducted the experiment himself—an issue that has caused some scholars to doubt Franklin’s story. Franklin’s electrical experiments launched him into an international network of men (and some women) who worked in fields today known as physics, chemistry, biology, botany, and paleontology. To share and exchange such knowledge, Franklin proposed a society “to be called the ” which remains today a world-renowned institution headquartered in Philadelphia. Benjamin Franklin was no stranger to the pleasures of food and drink—he liked good wine, and he liked good food. He also knew that the economic stability for the colonies depended on agriculture, exports, and trade. So he gathered information about which types of crops would thrive in the climates and conditions of the colonies, and he imagined the possibilities of growing plants for medical help, protein, and his own culinary pleasure. Whether he was in Philadelphia or London, Franklin drew on his network of friends and scientists across the globe and eagerly participated in a whirlwind of botanical exchange. John Bartram, in Philadelphia, sent acorn, magnolia, and honey locust seeds to Franklin in London. Franklin sent naked oats and Swiss barley seeds from London to Deborah in Philadelphia, who gave some to Bartram. Bartram sent seeds to Franklin in London, and Franklin sent seeds back to Bartram. Seeds were sent from East India to London to Savannah, from Philadelphia to Amsterdam and Bordeaux, from London to Turkey to Philadelphia, and on and on until the colonies had been thoroughly pollinated by Franklin and his friends! The year was 1783. Europe had been wallowing in a dense fog for months. The sun was unable to penetrate the thick cloud layer and there was hardly a summer at all that year. The first snow of the winter, unable to melt, had frozen to the ground, and every snow since had only accumulated. Franklin, in France at the time, had witnessed the bizarre fog. But for Franklin, the fog had to have a rational explanation. It was a puzzle to be solved. In May of 1784, Franklin suggested a possible cause, theorizing that “ His theory was correct. Iceland’s Laki fissures had been continuously spewing lava since June of that year, one of the largest volcanic eruptions that had ever been recorded. The eruptions released tons of toxic gases into the atmosphere. The change in atmosphere, combined with what had already been an unusually warm summer, caused major weather shifts in the weather throughout Europe and North America for months. Silk dresses were in vogue throughout Europe and the colonies, and the finest silk came from Asia. But Benjamin Franklin wanted to make silk right here at home. He figured that if the colonists succeeded, they could make money and have inexpensive access to fine silk. The process of making silk, however, is no easy task. Silk comes from the larvae of a moth called the Bombyx mori. This moth can neither see nor fly, and it lays about 500 eggs in only a few days before dying. These eggs produce about 30,000 worms, which may only be kept alive by a diet of the ever-so-slightly wilted leaves of the White Mulberry Tree, which is only found in Asia. The American Philosophical Society offered cash prizes for colonists who could succeed in making silk. Sadly, the White Mulberry tree did not flourish in the colonies and the process of making silk was just too laborious for the colonists—not to mention the silkworms. Never one to miss a lunar eclipse, Franklin set himself up one evening in 1743, ready to watch his favorite nighttime show. His very own almanac had predicted that the eclipse would begin around 9 o’clock that evening. A strong wind began to blow, thick clouds and rain blew in blocking his view… and the eclipse went on without him. Much to his astonishment, he later read about the eclipse as having been seen farther northeast in Boston: “…what surpriz’d me, was to find in the Boston Newspaper an Account … of that Eclipse … for I thought, as the Storm came from the NE. it must have begun sooner at Boston than with us, and consequently have prevented such Observation. I wrote my Brother about it, and he inform’d me, that the Eclipse was over there, an hour before the storm began!” This led him to study the path of storms, and he deduced that storms which seem to blow from the northeast are actually moving from the southwest as the winds are moving from the northeast, making them especially powerful storms that blow from south to north. In Franklin’s time, the shape and design of our solar system was already well-known, but the actual size was still a mystery. What was missing was a single measurement: the distance between any two heavenly bodies could provide them with the size of the solar system. It was predicted that with the help of relatively simple mathematics, the distance between the Earth and the Sun could be measured during the Transits of Venus in 1761 and 1769, in which Venus passes between the Earth and the Sun. European nations and North American colonies spent fortunes sending explorers to the far corners of the Earth to witness the rare cosmic event. Scientists risked their lives sneaking past enemy war ships, battling diseases, and journeying the open seas for years at a time to record Venus’ measurements. In Philadelphia, scientists set up an observatory in the Pennsylvania State House Yard (now known as Independence Square) to view the phenomenon. Their measurements, along with calculations from over 170 other observers at over 70 locations around the globe, enabled scientists to figure out the distance between the Earth and the Sun (Astronomical Unit or AU), and begin to understand the size of our solar system. Once the observations were documented, someone needed to publish and disseminate the findings for the entire world to see—someone well-connected, and well-versed in both science and astronomy. Benjamin Franklin took the lead, making certain that the American Philosophical Society published the Transit of Venus reports and disseminated them far and wide, formally establishing the size of our solar system. |

Last updated: August 24, 2021

Park footer

Contact info, mailing address:.

143 S. 3rd Street Philadelphia, PA 19106

215-965-2305

Stay Connected

Benjamin Franklin

Benjamin Franklin was born in Boston, Massachusetts on January 17, 1706. Growing up, Franklin came from a modest family and was one of seventeen children. He began his formal education at eight when his father enrolled him in the Boston Latin School. While in school, Franklin showed strong leadership skills and was an avid reader and writer. Since his family could only afford Franklin's education for two years, he dropped out and began working for his father at age ten. At 15, Franklin's older brother James accepted him as an apprentice at his print shop in Boston. Under James, Franklin began working for one of the first newspapers in America, The New England Courant. While working at the print shop, Franklin wrote under the pseudonym Silence Dogood. He became an advocate for free speech, despite his brother's wishes. At age 17, Franklin ran away from his family to Philadelphia. In doing so, he broke his apprenticeship, making him a fugitive. While in Philadelphia, Franklin found work as a printer and began making connections, including meeting his future wife, Deborah Reed. Franklin sailed to London, England, a year later and began working as a typesetter in a print shop. He returned in 1726 and opened his own print shop in Philadelphia, where he published a newspaper called the Pennsylvania Gazette and the "Poor Richard's Almanack."

While in Philadelphia, Franklin created the first volunteer firefighting company and became involved with public affairs. In 1743, he founded the American Philosophical Society and began researching electricity. During his lifetime, Franklin continued to study science, including oceanography, engineering, meteorology, and physics. While studying, he created experiments, including the kite experiment, and invent products like the lighting rod based on his research. In addition to science, Franklin was interested in education and caring for society. Due to his wealth, Franklin organized the Pennsylvania militia and founded the first hospital in the colonies. Under Franklin's influence, the city streets were clean, and colonists in Philadelphia had homeowners' insurance. Franklin's popularity grew when he aided in founding the Academy of Philadelphia, later known as the University of Pennsylvania.

Since the French and Indian War, Franklin supported the American cause. In 1754, during the Albany Congress, he used the press to circulate the famous "Join or Die" cartoon in an attempt for the colonies to rally against the French. While at the congress, Franklin proposed the Albany Plan, which failed then but later inspired the Articles of Confederation and a uniting of the colonies. As tensions rose in the colonies, the Franklin press continued to publish pro-independence articles and stories. In 1751, Franklin was elected to represent the Pennsylvania assembly in the British parliament in London. He made connections in England with parliament officials and worked to settle disputes between the colonies and Britain. Franklin temporarily returned home until he was sent back to London in 1765 to testify against the Stamp Act. During Franklin's second mission to England in 1775, the British fired upon colonists at Lexington and Concord, officially beginning the American Revolution.

Upon hearing the news, Franklin returned to the colonies. He arrived in Philadelphia in May of 1775, and the Pennsylvania Assembly elected Franklin to the Second Continental Congress . The congress met to discuss the revolution's goals and plan the next steps for the colonies. While serving as a delegate for Pennsylvania, Franklin served as the United States' first postmaster general, suffered from gout, and missed most of the delegations. In early 1776, he was elected to the "Committee of Five," alongside Thomas Jefferson , John Adams , Robert Livingston, and Rodger Sherman was assigned to write the Declaration of Independence. Although Thomas Jefferson wrote most of the declaration, Franklin made "small but important changes." On July 4, the Declaration of Independence was signed, and the colonies readied to take the next step toward independence. In October 1776, Franklin was assigned the duty of Ambassador to France. To beat the British, the colonist needed European aid, and it was Franklin's mission to convince France to help the United States.

While in France, Franklin made connections with French politicians and the monarchy. France was willing to aid the colonies but needed proof that the American Revolution was not a lost cause. In October 1777, the Continental Army won a significant victory over the British during the Battle of Saratoga , forcing a British army to surrender. The battle showed that the United States had the potential to win and the French to sign the 1 778 Alliance Treaty , solidifying the Franco-American alliance. French troops arrived in the colonies under the command o f Jean-Baptiste, Comte de Rochambeau . The Continental and the French army worked together and were victorious during the Battle of Yorktown . In 1783, Franklin aided in the surrender under the Treaty of Paris . He remained in France for another two years, continuing to serve as the American minister for France and Sweden, despite never visiting. In 1785, Franklin returned to the United States and was immediately assigned to represent Pennsylvania in the Constitutional Convention.

At age 81, Franklin was the oldest representative at the convention. As a supporter of the United States Constitution, Franklin urged his fellow delegates to support the document. The Constitution was ratified in 1788, and the following year George Washington was selected as the United States' first President. On April 17, 1790, Franklin died in his Philadelphia home. Over 20,000 people attended his funeral in Pennsylvania to celebrate his life, accomplishments, and impact on the founding of the United States.

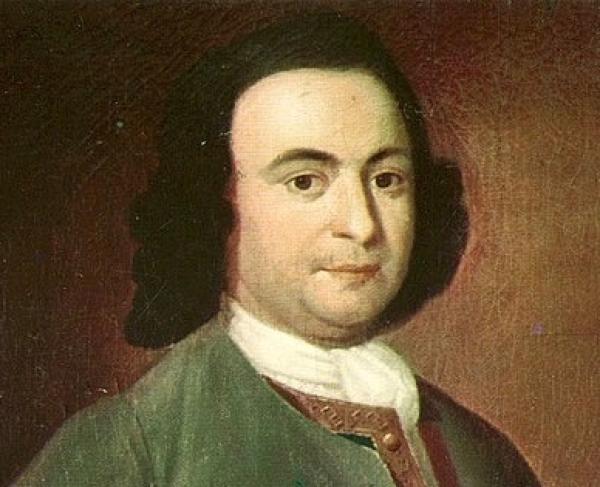

George Mason

Peyton Randolph

Armand Louis de Gontaut

You may also like.

- Fundamentals NEW

- Biographies

- Compare Countries

- World Atlas

Benjamin Franklin

Introduction.

Printer and Inventor

Franklin was born in Boston, Massachusetts, on January 17, 1706. He left school at age 10. At age 12 he went to work in his brother’s printing shop.

In 1723 Franklin moved to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. He worked there as a printer. His most popular publication was Poor Richard’s Almanack . The almanac featured Franklin’s witty sayings and verses. A famous one was “Early to bed and early to rise, makes a man healthy, wealthy, and wise.”

Franklin started many public services in Philadelphia. They included a fire department, a hospital, an insurance company, and a library. A school he founded became the University of Pennsylvania.

Franklin became a respected political leader in the years leading up to the American Revolution . In 1765 the British Parliament passed the Stamp Act, a tax on printing in the colonies. The act angered the colonists. Franklin persuaded the British to withdraw it.

In his last years Franklin wrote his autobiography. He also worked to end slavery. He died in Philadelphia on April 17, 1790.

It’s here: the NEW Britannica Kids website!

We’ve been busy, working hard to bring you new features and an updated design. We hope you and your family enjoy the NEW Britannica Kids. Take a minute to check out all the enhancements!

- The same safe and trusted content for explorers of all ages.

- Accessible across all of today's devices: phones, tablets, and desktops.

- Improved homework resources designed to support a variety of curriculum subjects and standards.

- A new, third level of content, designed specially to meet the advanced needs of the sophisticated scholar.

- And so much more!

Want to see it in action?

Start a free trial

To share with more than one person, separate addresses with a comma

Choose a language from the menu above to view a computer-translated version of this page. Please note: Text within images is not translated, some features may not work properly after translation, and the translation may not accurately convey the intended meaning. Britannica does not review the converted text.

After translating an article, all tools except font up/font down will be disabled. To re-enable the tools or to convert back to English, click "view original" on the Google Translate toolbar.

- Privacy Notice

- Terms of Use

June 21, 6am - 10am, all library hosted applications, including Franklin and Colenda, will be down for maintenance.

The main entrance to the Van Pelt-Dietrich Library Center is now open. Van Pelt Library and the Fisher Fine Arts Library are currently open to Penn Card holders, Penn affiliates, and certain visitors. See our Service Alerts for details.

- Notable Collections

Benjamin Franklin Papers

The Benjamin Franklin Papers (over 800 items) include correspondence and documents, 1705-1788, primarily relating to Franklin's stay in France during the American Revolution and his role in the negotiations between France and the Continental Congress. Some earlier documents and printed materials are also part of the collection.

Collection Overview

Franklin papers at the university of pennsylvania and the american philosophical society.

A collection of approximately 14,000 items arrived at the American Philosophical Society in 1840, becoming the nucleus of the current Benjamin Franklin Collections at the APS. At the time of Franklin's death in 1790, the papers were stored at Champlost, a country estate outside of Philadelphia owned by George Fox. A much smaller group of Franklin papers remained at the Fox home after the transfer of the Franklin Papers to the American Philosophical Society. In 1887, this collection of papers passed from Mary Fox to Thomas Hewson Bache. The papers were purchased by the University of Pennsylvania in 1903.

Scope and Content of the Benjamin Franklin Papers at the University of Pennsylvania

The Benjamin Franklin papers primarily contains correspondence during Franklin's tenure in France. The Papers are divided into three series: letters to Franklin; letters from Franklin; and miscellaneous. Materials are arranged chronologically within each series.

Description and Catalog of the Franklin Papers at the University of Pennsylvania

The Franklin Papers held in the Kislak Center are described in 1908 publication, Calendar of the papers of Benjamin Franklin in the University of Pennsylvania. Being the appendix to the "Calendar of the papers of Benjamin Franklin in the library of the American philosophical society," edited by I. Minis Hays (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania, 1908.) View this item in the online catalog .

For more information, view the finding aid for the Franklin Papers at the University of Pennsylvania .

Related sites

Accordion list, exhibit / web site.

- Educating the Youth of Pennsylvania: Worlds of Learning in the Age of Franklin (2006 exhibition)

- The Rebirth of Aquila Rose: Benjamin Franklin's First Philadelphia Printing Job (2017 exhibit)

Publication

- "The Good Education of Youth": Worlds of Learning in the Age of Learning (Philadelphia, 2009)

Finding aid

- Finding for the Benjamin Franklin Papers at the University of Pennsylvania (Ms. Coll. 900)

- Finding Aid for the Benjamin Franklin Papers at the American Philosophical Society (Mss.B.F85)

Related Collections at Penn

- Curtis Collection of Franklin Imprints (University of Pennsylvania)

- American Studies, History, and Literature: North America, Colonial Era to ca. 1800

John Pollack

- Kislak Center

- LIBRA - Penn Libraries Research Annex

- Van Pelt-Dietrich Library Center

- 1700-1799 C.E.

- Early Federal

- Correspondence

Thomas Jefferson's Monticello

- Research & Education

- Thomas Jefferson Encyclopedia

Benjamin Franklin

“The succession to Dr. Franklin at the court of France, was an excellent school of humility.” So Thomas Jefferson reflected as he prepared notes for a eulogy that would be read in memory of Benjamin Franklin (January 17 (January 6 O.S. ), 1706 – April 17, 1790) at the American Philosophical Society on March 1, 1791. Yet this “school of humility” was never one that Jefferson seemed to begrudge. He lauded Franklin as scientist, statesman, and a “great and dear friend, whom time will be making greater while it is spunging us from it’s records.” [1]

As neither man has been expunged from history, it is interesting to consider the nine months they spent together in Paris , a time when they renewed the relationship begun in the Continental Congress of 1775-1776 and when the younger Jefferson again had the opportunity to work closely with Franklin, seasoned veteran of international diplomacy, science, and letters.

When Jefferson arrived in August 1784 to assist in the negotiation of commercial treaties, Franklin had been in France for more than seven years. He had arrived late in 1776, primarily to secure French support for the American colonies in their fight for independence from Great Britain. By 1783, he was concluding the peace treaty that formally ended the conflict.

Podcast - "An Excellent School of Humility" - Jefferson and Franklin

Monticello guide Kyle Chattleton looks at the brief, yet important relationship between Thomas Jefferson and Benjamin Franklin, who came from two different worlds and generations, yet helped forge a new nation together.

Jefferson’s arrival was little noticed amid the fanfare and notoriety that surrounded Franklin. “No one was more fashionable, more sought after in Paris than Doctor Franklin. The crowd chased after him in parks and public places; hats, canes, and snuffboxes were designed in the Franklin style, and people thought themselves very lucky if they were invited to the same dinner party as this famous man,” one Parisian observed. [2]

Franklin’s reputation as a man of science and as a statesman had preceded him. His Experiments and Observations on Electricity had been translated into French in 1752 and endorsed by King Louis XV, who requested that his compliments be conveyed to the author. Other of Franklin’s essays and writings were available in French as well. His testimony before the House of Commons in 1766 in rebuttal of the Stamp Act had been reprinted in France with the advice to readers that “they will see what constitutes the superiority of intelligence, the presence of mind and the nobility of character of this illustrious philosopher, appearing before an assembly of legislators.” Franklin was described as “one of the greatest and the most enlightened and the noblest men the New World had seen born and the Old World has ever admired.” [3] And the French had watched carefully his negotiations on America’s behalf with their traditional enemy, England.

Jefferson had given similar voice to Franklin’s abilities in his own Notes on the State of Virginia , in which he rebuffed European charges that America, among other things, was devoid of genius. “In physics we have produced a Franklin, than whom no one of the present age has made more important discoveries, nor has enriched philosophy with more, or more ingenious solutions of the phenomena of nature,” Jefferson wrote. [4]

But despite his avid defense of American genius, Jefferson upon settling in Paris was drawn to the stimulating, intellectual atmosphere of the French salons and scientific circles. He hoped introductions initiated by Franklin would open “a door of admission for me to the circle of literati.” [5] It was at the salon of Madame Helvétius, a very close and particular friend of Franklin’s, where Jefferson met and established lasting relationships with members of the French literati such as the Comte de Volney, Destutt de Tracy, and Pierre-Georges Cabanis, among others. [6]

Jefferson’s only observation of a deficiency in Franklin’s diplomatic skills was his elder friend’s lack of training in the law. Jefferson cited a consular agreement made between Franklin and France’s foreign minister, the Comte de Vergennes, that allowed privileges and exemptions to French consuls assigned to the United States contrary to the laws of many of the states. Jefferson, trained in the law, would later renegotiate these points. [7] However, Jefferson recognized this same deficiency as one of Franklin’s strengths. Unlike lawyers, “whose trade it is to question every thing, yield nothing, & talk by the hour,” Jefferson noted that when he had served in the Continental Congress, Franklin never spoke as much as ten minutes at a time and then only addressed the main point to be decided. [8] Along with this ability to listen carefully, Jefferson listed among Franklin’s diplomatic skills his amiable temperament and reasonable disposition, “sensible that advantages are not all to be on one side.” [9]

During Jefferson’s first nine months in Paris, there were few accomplishments in negotiating commercial treaties. He fretted that Europe did not respect the U.S. government and looked upon it as lacking “tone and energy,” and recognized that Franklin’s cachet had been a major factor in the previous interest afforded the cause of the United States. [10] As preparations were made for Franklin’s departure and his own step into the position of minister plenipotentiary, Jefferson cautioned in letters to the United States that “Europe fixes an attentive eye on your reception of Doctr. Franklin.” [11] Despite some old political opponents who questioned Franklin’s loyalty to the United States because of the number of years he had been away, Franklin was welcomed back for the most part with accolades, and his appointment to the Constitutional Convention to assist in the drafting of the new constitution indicated a continued confidence in his abilities.

Soon after Jefferson’s own return to the United States four years later, he visited the “beloved and venerable Franklin” at his home in Philadelphia and tried to soothe his anxieties about his acquaintances who he feared were caught up in the political upheavals that erupted into the French Revolution . Upon hearing the news from France, Franklin’s “animation [was] almost too much for his strength,” Jefferson noted. Nonetheless, Jefferson still encouraged Franklin to complete his autobiography. [12]

This would be their last visit, as Franklin died a month later, on April 17, 1790. Jefferson maintained his lasting respect and admiration for Franklin, and concluded his notes for his eulogy with a confession: “On being presented to any one as the Minister of America, the common-place question, used in such cases, was ‘c’est vous, Monsieur, qui remplace le Docteur Franklin?’ ‘It is you, Sir, who replace Doctor Franklin?’ I generally answered ‘no one can replace him, Sir; I am only his successor.’” [13]

- Gaye Wilson, 2005. Originally published as Gaye Wilson, “Benjamin Franklin, Jefferson's ‘Beloved and Venerable’ Friend,” Monticello Newsletter 16 (Winter 2005). References added by Anna Berkes, April 20, 2012.

Further Sources

- Benjamin Franklin Home in London .

- Library of Congress. Benjamin Franklin Resource Guide . A selected list of sources for research on Franklin provided by the staff of the Library of Congress.

- Papers of Benjamin Franklin . Full text of Benjamin Franklin's letters, published by Yale University.

- Schiff, Stacy. A Great Improvisation: Franklin, France, and the Birth of America . New York: Henry Holt, 2005.

- Look for further sources on Benjamin Franklin in the Thomas Jefferson Portal .

- ^ Jefferson to Reverend William Smith, February 19, 1791, in PTJ , 19:113. Transcription available at Founders Online.

- ^ Elisabeth Vigée-Le Brun, Memoirs of Elisabeth Vigée-Le Brun , trans. Siân Evans (London: Camden, 1989), 319.

- ^ Âphémérides du Citoyen 4, no. 2 (1769): 39-52, quoted in Alfred Owen Aldridge, Franklin and His French Contemporaries (New York: New York University Press, 1957), 29.

- ^ Notes , ed. Peden, 64.

- ^ Jefferson to Abigail Adams , June 21, 1785, in PTJ , 8:241. Transcription available at Founders Online.

- ^ Howard C. Rice, Thomas Jefferson's Paris (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1976), 94.

- ^ Jefferson, Autobiography, in Ford , 1:117-18. Transcription available at Founders Online.

- ^ Ford , 1:82. Transcription available at Founders Online.

- ^ Jefferson to Robert Walsh, December 4, 1818, in PTJ:RS , 13:466-67. Transcription available at Founders Online.

- ^ Jefferson to Elbridge Gerry, November 11, 1784, in PTJ , 7:502. Transcription available at Founders Online.

- ^ Jefferson to James Monroe , July 5, 1785, in PTJ , 8:261. Transcription available at Founders Online.

- ^ Jefferson, Autobiography, in Ford , 1:151. Transcription available at Founders Online.

- ^ Jefferson to Reverend William Smith, February 19, 1791, in PTJ , 19:113. Transcription available at Founders Online.

Related Articles

- Benjamin Franklin Bust by Houdon (Sculpture)

- Benjamin Franklin (Painting)

- Benjamin Franklin Randolph

ADDRESS: 931 Thomas Jefferson Parkway Charlottesville, VA 22902 GENERAL INFORMATION: (434) 984-9800

History | April 11, 2024

The Real Story Behind Apple TV+’s ‘Franklin’

A new limited series starring Michael Douglas as Benjamin Franklin revisits the founding father’s years as the American ambassador to France

:focal(700x527:701x528)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/67/09/67093a85-b160-42fc-b0d1-19e3712e2fdf/benf.jpg)

Vanessa Armstrong

History Correspondent

In December 1776, nearly six months after the Thirteen Colonies declared their independence from British rule, 70-year-old Benjamin Franklin landed on the shores of France with two of his grandsons, 16-year-old William Temple Franklin and 7-year-old Benjamin Franklin Bache .

Franklin wasn’t the first American delegate to make his way to Versailles to lobby for France’s support in the nascent nation’s war against Britain. (The lawyer Silas Deane had arrived in Paris on July 7.) But over the next eight and a half years, he was the individual who secured the European country’s financial and military support. Without Franklin and the relationship he cultivated with the French minister of foreign affairs, France would not have funded the American war effort as robustly, and Britain might very well have won the war .

Stacy Schiff ’s 2005 book, A Great Improvisation: Franklin, France and the Birth of America , chronicles the famed polymath’s time in France, from his first clandestine meeting at Versailles in December 1776 to the end of his ambassadorship in May 1785. Now, Apple TV+ is releasing an eight-episode limited series based on Schiff’s biography. The show, titled “ Franklin ,” centers on its titular character’s “considerable efforts to charm, cajole and bamboozle the French into paying for the American Revolution,” says writer and executive producer Howard Korder .

Academy Award winner Michael Douglas plays Franklin, while Noah Jupe , whose previous credits include A Quiet Place and Ford v Ferrari , plays Temple. Here’s what you need to know about the real history behind “Franklin” ahead of the show’s three-episode premiere on April 12.

The making of “Franklin”

By 1776, Franklin was internationally renowned as an inventor , scientist , scholar and statesman. He took a huge risk by embarking on the secret voyage to France. If caught by the British, he could be hanged as a traitor for signing the Declaration of Independence. But he “saw democracy as the penultimate truth, as a new future where the world really had to go,” and he was willing to put his life on the line for the cause, Douglas tells IGN .

According to writer and executive producer Kirk Ellis , “Franklin” dramatizes “the intergenerational conflict between both the Old World and the New,” as well as Franklin and his oldest grandson. This approach gave the creative team “a chance to explore, through Temple’s eyes, what a young man’s journey through the French court might be,” says Ellis.

The illegitimate son of Franklin’s own illegitimate son, Temple “has no idea who he is,” Jupe tells IGN. “He’s got no idea really where he’s from and what matters to him. He’s just trying to discover that and find his purpose in the world.” Complicating matters further was the fact that Temple’s father, William , was a Loyalist, exiled to England in 1782 for his political views.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/cd/c7/cdc7b7d8-6b08-45ef-aeda-652951ff43b8/franklin_photo_010401.jpg)

“Franklin” streamlines the number of players involved in negotiations with France, reducing the roles of diplomats like Deane and Arthur Lee . “There were a lot of people who came and went over the eight years that [Franklin] was in France,” says Korder. “You have to decide which one of these horses you are going to try and ride to the end of the story.”

Deane arrived in France in July 1776 and was “in over his head” from the start, struggling to covertly procure clothes and munitions for America, Schiff tells Smithsonian magazine. Lee, meanwhile, traveled from London to Paris, arriving shortly after Franklin in December 1776. As Schiff writes in her book, he was “ideally suited for the mission in every way save for his personality, which was rancid.”

Franklin’s negotiations with France

A major reason why Franklin was a more effective diplomat than Deane and Lee was his relative ease in navigating the French court, particularly his relationship with the French foreign minister, Charles Gravier , Comte de Vergennes.

“He just loved to charm people, and he had such a gift for it,” says Lorraine Smith Pangle , author of The Political Philosophy of Benjamin Franklin . “At the same time, he was making the case for American principles, including things like free trade and equal respect of countries and individual freedoms. … He was just wonderfully deft at doing all those things at the same time.”

Franklin was the only American delegate to earn Vergennes’ respect. “It’s almost like a buddy movie,” Schiff says. “They end up being profoundly, deeply in admiration of one another … and it’s very clear that Vergennes realizes that he, as a master statesman, has met his equal in Benjamin Franklin.” In contrast, Schiff adds, the other American delegates were “cloddish in every respect.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/2d/91/2d918cd5-f4e2-4285-af58-735a2112844f/800px-silas_deane_-_du_simitier_and_bl_prevost.jpg)

Vergennes shared Franklin’s desire to humiliate Britain, France’s longtime rival for supremacy in Europe. But he maintained an official stance of not directly helping the Americans, preferring to provide aid through covert channels so as not to provoke Britain into declaring war on France, too.

America’s victory at the Battle of Saratoga on October 17, 1777, marked a turning point in the revolution. When news of the British defeat reached Paris on December 6, Vergennes wrote that he and the French minister of state, Jean Frédéric Phélypeaux , Comte de Maurepas, agreed that Versailles must strengthen its relationship “with a friend who could be useful if bound to us, dangerous if neglected.”

Negotiations for the Franco-American Treaty of Alliance began in January 1778, with representatives of both countries signing the agreement the following month. The treaty stipulated that neither America nor France would seek a separate peace with Britain and set American independence as a requirement for any future agreements. The two parties also signed a Treaty of Amity and Commerce, which gave the colonies favorable trade status with France.

Franklin’s fellow diplomats, Deane and Lee, didn’t get along with him or each other. Within a year of the treaty’s signing, Congress recalled both men, leaving Franklin as the main representative of his country’s interests abroad.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/09/7f/097ff758-085c-4fa1-a60e-8ef481f29924/treaty_of_alliance_1778_signatures.jpeg)

Spying on Franklin

Franklin succeeded in securing France’s support despite the fact that he was surrounded by double agents and spies, both English and French. “We know about this incredibly efficient intelligence network that’s built up around Franklin,” says Schiff. “He walks through that in this almost serene way, where he basically just shrugs his shoulders and says, ‘I’m just going to assume that everyone is spying on me and comport myself as if my valet is also a spy.’”

As it turns out, Franklin was right to be suspicious: One of his closest confidants, the American physician Edward Bancroft , was a British spy who worked under the pseudonym Edward Edwards. Bancroft conspired with master spy Paul Wentworth to copy almost every letter that made its way across Franklin’s desk. “Bancroft and Wentworth actually had known each other from both being in Suriname in the 1750s,” says Korder. “Bancroft was working as some sort of overseer for a plantation there, and Wentworth was acting as a British agent in some capacity.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/7e/4f/7e4f93d3-ba58-4a1d-aca6-7698b94c2ba7/receptiontif.jpg)

Franklin likely didn’t know that Bancroft was a spy, as his duplicity wasn’t uncovered until the late 1880s. Regardless, the statesman viewed his openness in diplomatic dealings as a defense against espionage.

During Franklin’s time in France, he faced multiple threats to his safety. “We don’t know the actual details, but we do know … there are attempts to assassinate him, because it would have been a tremendous loss to the American cause for Franklin to be eliminated,” says Schiff.

The end of the American Revolution

Despite the danger, Franklin persevered in his diplomatic work. Following Deane’s recall, he worked with future president John Adams , who came to France as a replacement envoy in 1778 . The men had radically different views regarding diplomacy and often clashed.

“Franklin thought honesty is the best policy because people who are dishonest are going to be found out,” says Pangle. “They won’t be trusted. They’ll be isolated, and frankness is almost always disarming, and it helps you to find the common ground with people. … That was very much his policy toward the French court for most of the time that he was there.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/df/8c/df8cd11c-99e5-47b2-9c9a-9a9d5f181922/john-adams.jpg)

Adams, on the other hand, believed that countries will always act in their own interest, making negotiations a battle of wills in which each party pushes hard for its rights. He was suspicious of and had little patience for the elaborate inner workings of the French court, so much so that Vergennes at one point refused to communicate with him.

Luckily for America, the Treaty of Alliance was already signed by the time Adams arrived on the scene. It enabled France to start openly sending over arms, ammunitions and troops. Temple hoped to contribute to the cause directly: In 1779, he was slated to participate in a French raid of England, serving as the Marquis de Lafayette ’s aide-de-camp, but the invasion was canceled due to sick crews and bad weather.

It wasn’t until 1780 that France’s support truly made a difference in the American Revolution. That July, Jean-Baptiste Donatien de Vimeur, Comte de Rochambeau , landed in Rhode Island with nearly 6,000 soldiers ready to fight alongside George Washington’s Continental Army. In the fall of 1781, French and American troops defeated the British at the Battle of Yorktown , essentially ending the war.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/c9/53/c953492b-e022-4672-9623-10a94e53010b/battleofvirginiacapes.jpeg)

Getting a signed peace agreement, however, would take two more years. After Yorktown, Congress assigned Franklin, Adams, John Jay and Henry Laurens to negotiate with Britain in partnership with France, per the terms of the 1778 treaty. Confoundingly for the Americans, Lafayette pushed to be involved in the talks.

“Lafayette’s primary relationship isn’t with either Temple or with Franklin, but with this idea of liberty,” says Schiff. “He’s the emblematic French noble who’s been thirsting to prove himself, to prove his worth by fighting [for] a worthy cause.”

The Americans managed to shut Lafayette out. But Franklin faced dissension from within his own ranks. Adams and Jay wanted to forgo the French treaty’s obligations, as well as the directive from Congress, and negotiate directly with Britain. (Laurens wasn’t eager to be part of the negotiations and didn’t arrive in Paris until the proceedings were essentially over .) Franklin disagreed with this approach. “As to our treating separately and quitting our present alliance … it is impossible,” he wrote to Laurens in April 1782. “Our treaties and our instructions, as well as the honor and interest of our country, forbid it.”

But Franklin soon accepted the fact that he had little power to overrule his fellow diplomats. “He realizes that he’s going to essentially make this deal with colleagues who feel differently from him, and they’re going [to] outvote him, and he’s simply going to have to do it their way,” says Schiff. “And then he makes the best of this lousy hand that they have dealt him.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/dd/11/dd111ed4-9947-4ac6-b687-0edbb1689585/treaty_of_paris_by_benjamin_west_1783.jpeg)

The negotiations—with not only Britain but also Jay and Adams—put a strain on Franklin, who was already in poor health . Tim Van Patten , director of the “Franklin” series, says he drew inspiration from the 1957 movie 12 Angry Men while filming, hoping to visualize “the physical and mental toll that [period] had on [Franklin] over time. He was really fighting for his life, for his health. He could barely stand up.”

After two months of negotiations, the Americans agreed to a preliminary deal with Britain—without consulting France—on November 30, 1782. Called the Treaty of Paris , the agreement was officially ratified on September 3, 1783. Its terms gave America more than France would have liked, including control of the land east of the Mississippi River and fishing rights off Newfoundland.