The #1 Sports Betting Research Platform In The World

Find Your Edge

We make sports betting easier for you.

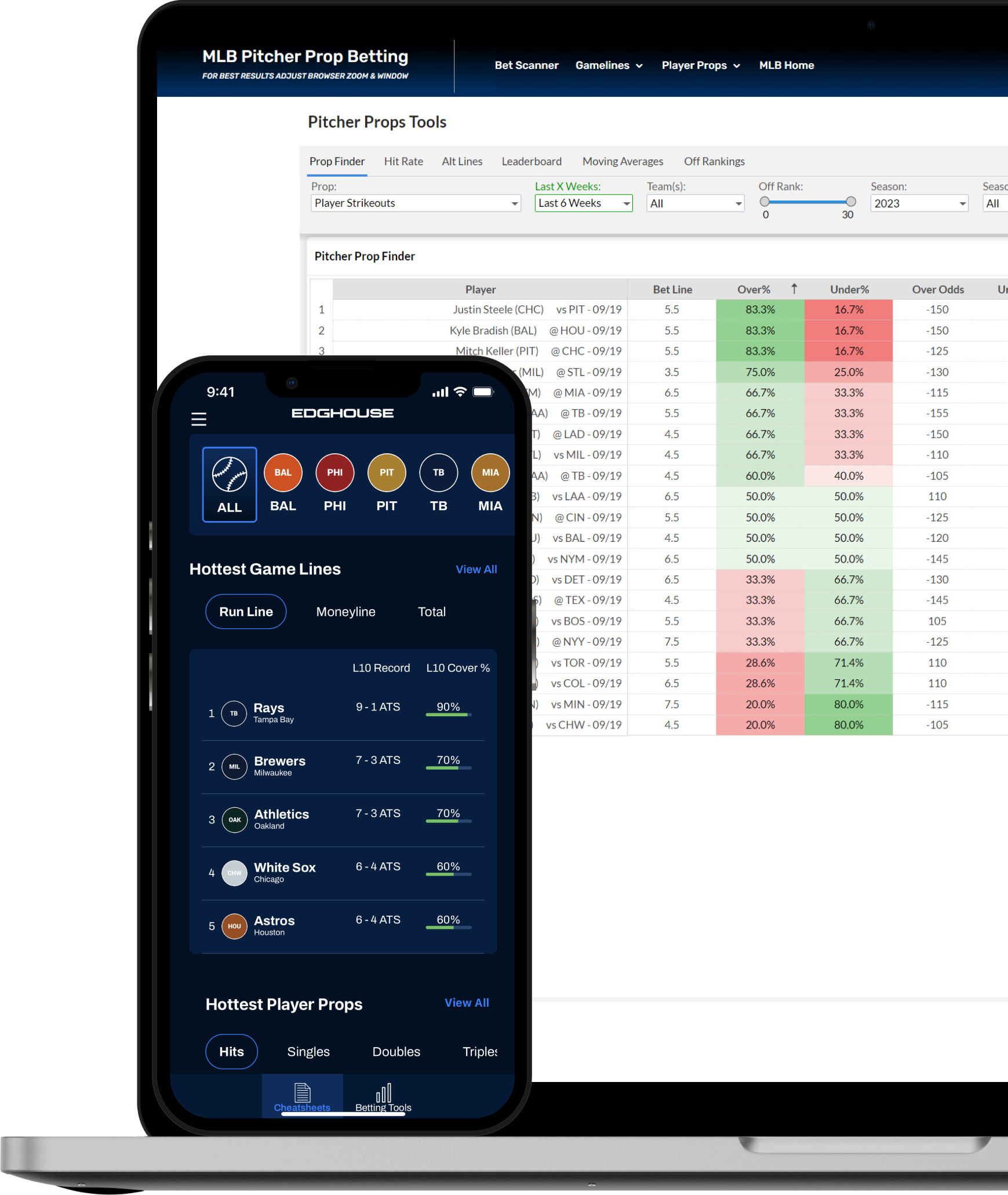

EdgHouse is a premium sports betting research platform. We currently cover NFL, NBA, MLB, NCAAM, & NCAAF betting and provide users with betting tools designed to help them make smarter data-driven betting decisions

Using our betting tools will cut your research time down significantly and help you gain a competitive advantage while finding an edge that is needed to beat the sportsbooks in the long run

"@EdgHouse really is the best. All the info you could want on.....I can do all the research I need for game bets and player props all in one place AND they have the best, most responsive customer service. What a treat to start my week."

"you guys seriously make it so easy to find high probability plays".

@DelphiCommish

"2nd to NOBODY, you folks are amazing!!!"

"love using every resource you guys supply. been loving it since day 1".

@donnie_roos

"With the stats I got from y’all I just need to sit back and watch the money roll in.... Appreciate it"

@WeinbergerBlake

"You beauty. Thanks for all your hard work!"

@Arana_Taha

"@EdgHouse strikes again...trend is my friend."

"love the platform".

@ZonaJsPlays

Transforming The Way You Research

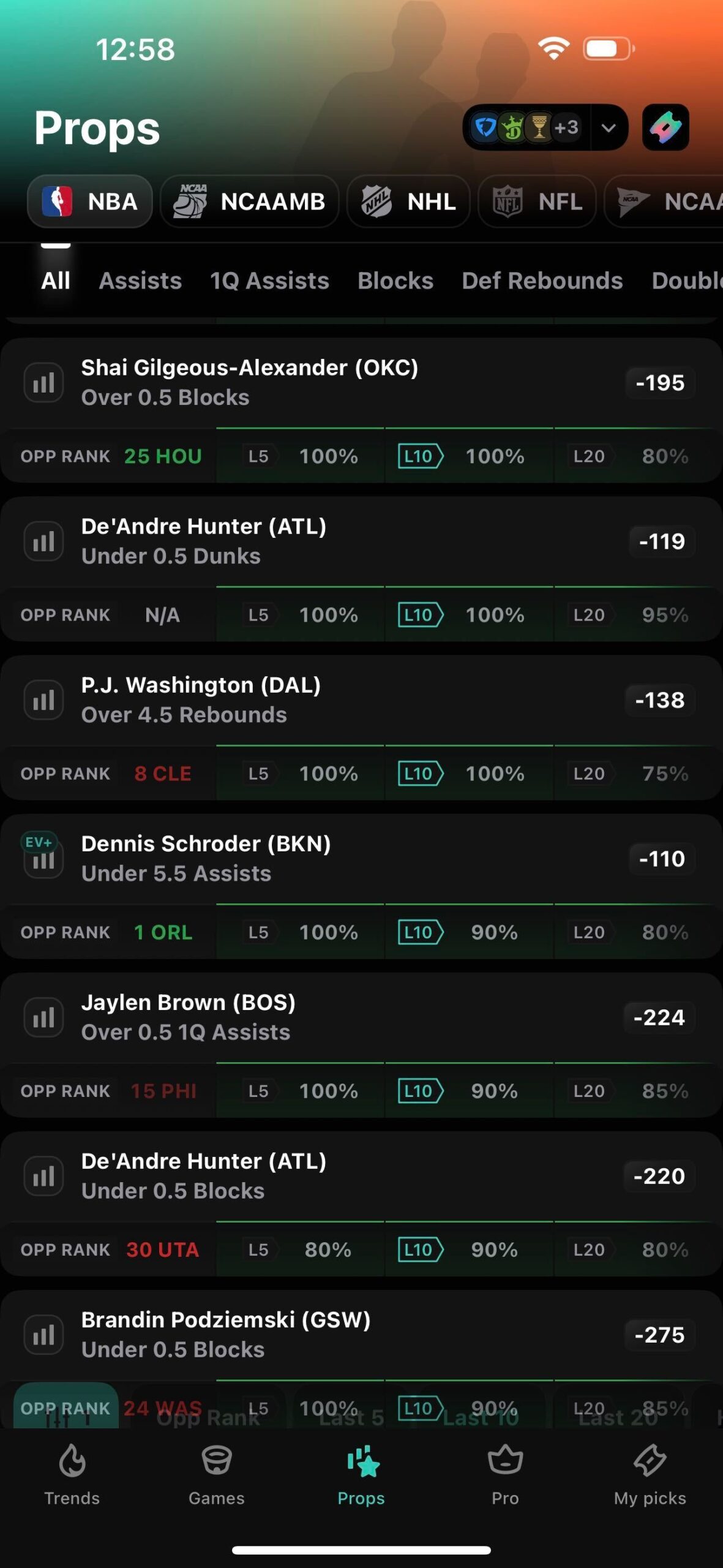

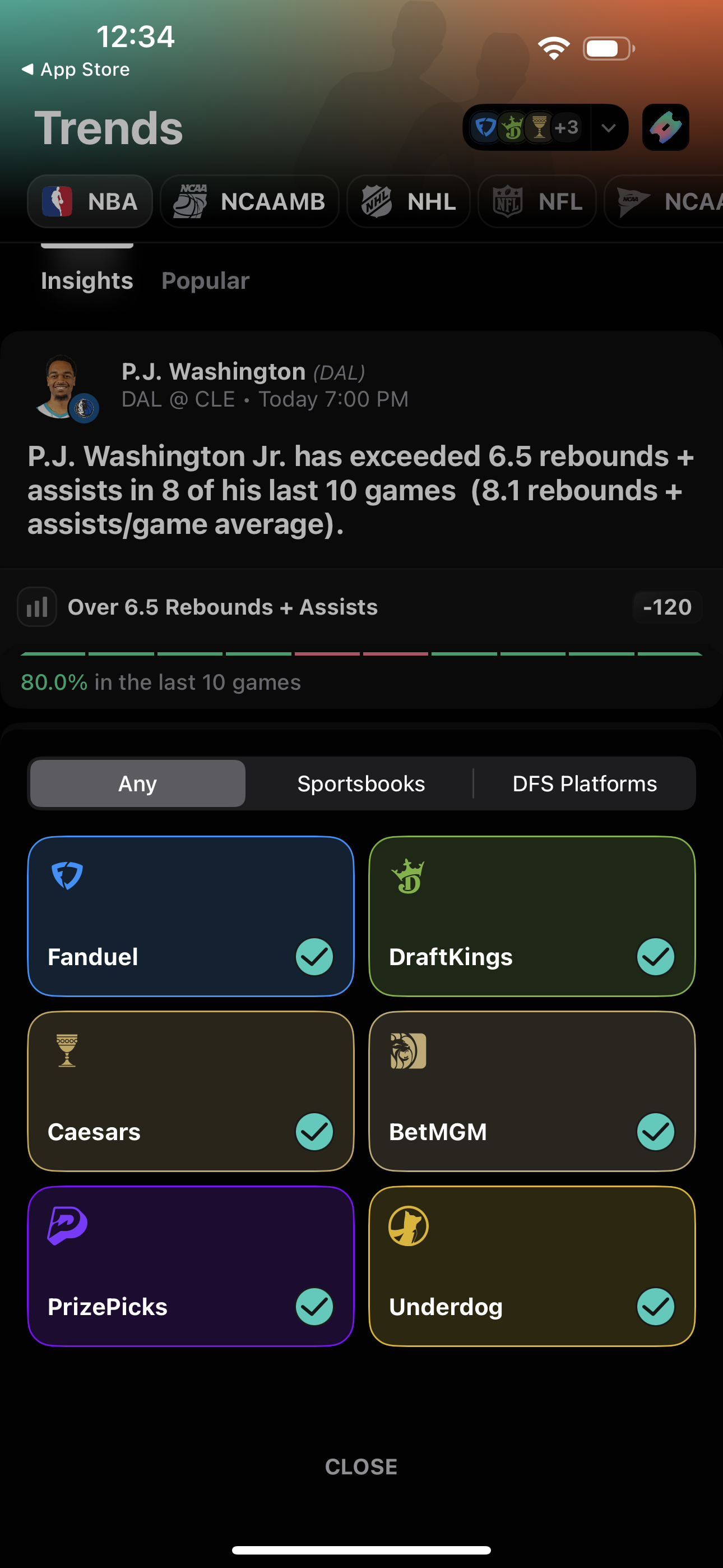

Our users are given exclusive access to our sports betting research platform (mobile & web) where all betting cheatsheets, tools, & insights are provided. EdgHouse makes finding and researching sports bets much easier and faster

Our Purpose

To provide you with the best sports betting research tools and make you a better bettor

The Best Betting Research Tools

Our betting tools are designed so you can research any bet, from any angle, at any time

Designed For Sports Bettors

EdgHouse is designed for sports bettors by sports bettors

Scan & Analyze

Scan by swping through bets available, find trends, and analyze further

Visualize & Explore

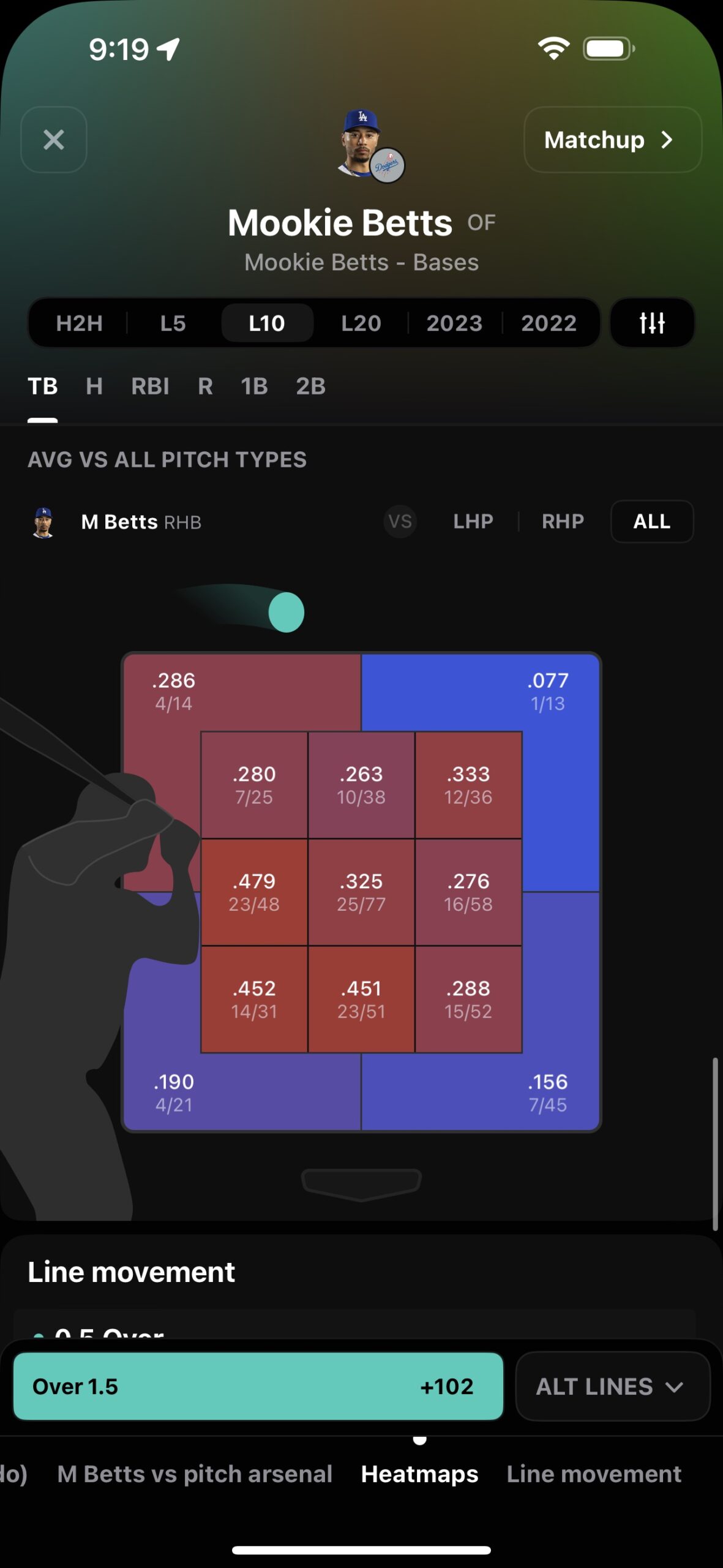

See the data and research through a new lens like never before

Multip le Sports & Leagues

We currently cover the NFL, NBA, MLB, NCAAM, & NCAAF betting

Easy To Use

Our platform is easy to understand, interactive, and bettor friendly

Web & Mobile

When you sign up for EdgHouse you get access to both our web platform and mobile app (iOS & Android)

Make better data-driven betting decisions and find your true edge

Plans For Everyone

Access to everything.

Pro Plan ($9.99 / week)

All-Star Plan ($19.99 / month)

Hall of Fame Plan ($149.99 / year)

- A ll sports betting research cheatsheets, tools, & insights

- Lines & odds updated in near real-time

- Web and mobile app (iOS & Android)

- NFL, NBA, MLB, NCAAM, & NCAAF coverage

- All future tools added, improvements, & updates

- All future leagues & sports we add

- Dedicated customer service

Have any questions? Please reach out to our support team and we will respond as soon as possible!

Our users are given exclusive access to our sports betting research platform (mobile & web) where all betting cheatsheets, tools, & insights are provided. EdgHouse makes finding and researching sports bets much easier and faster

Join The EdgHouse Community!

Subscribe to our mailing list to receive the latest news and updates from the EdgHouse team!

Homepage Subscribers Homepage Subscribers

You have successfully subscribed to receive EdgHouse news and updates!

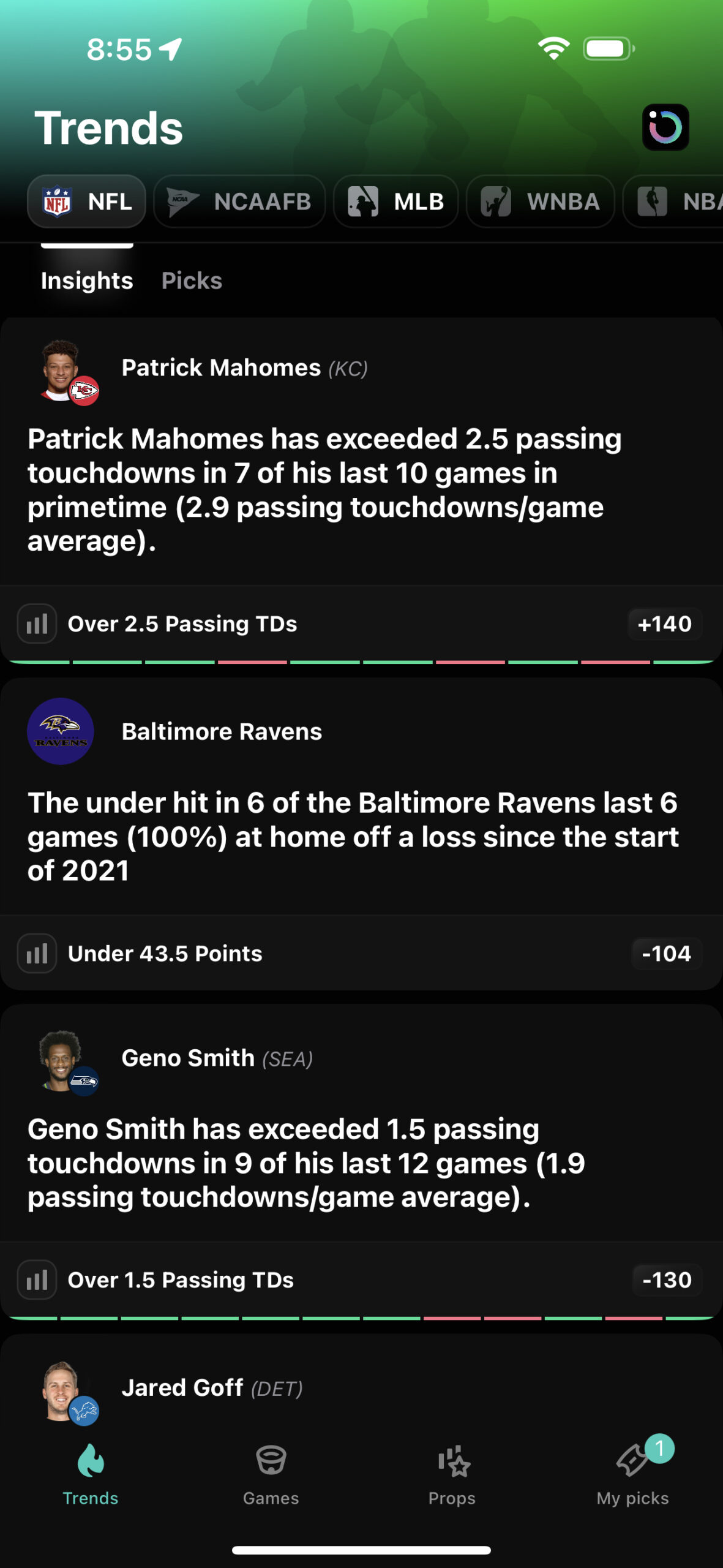

The first sports betting super app

Browse, analyze, and execute picks on major sportsbooks. All in one place.

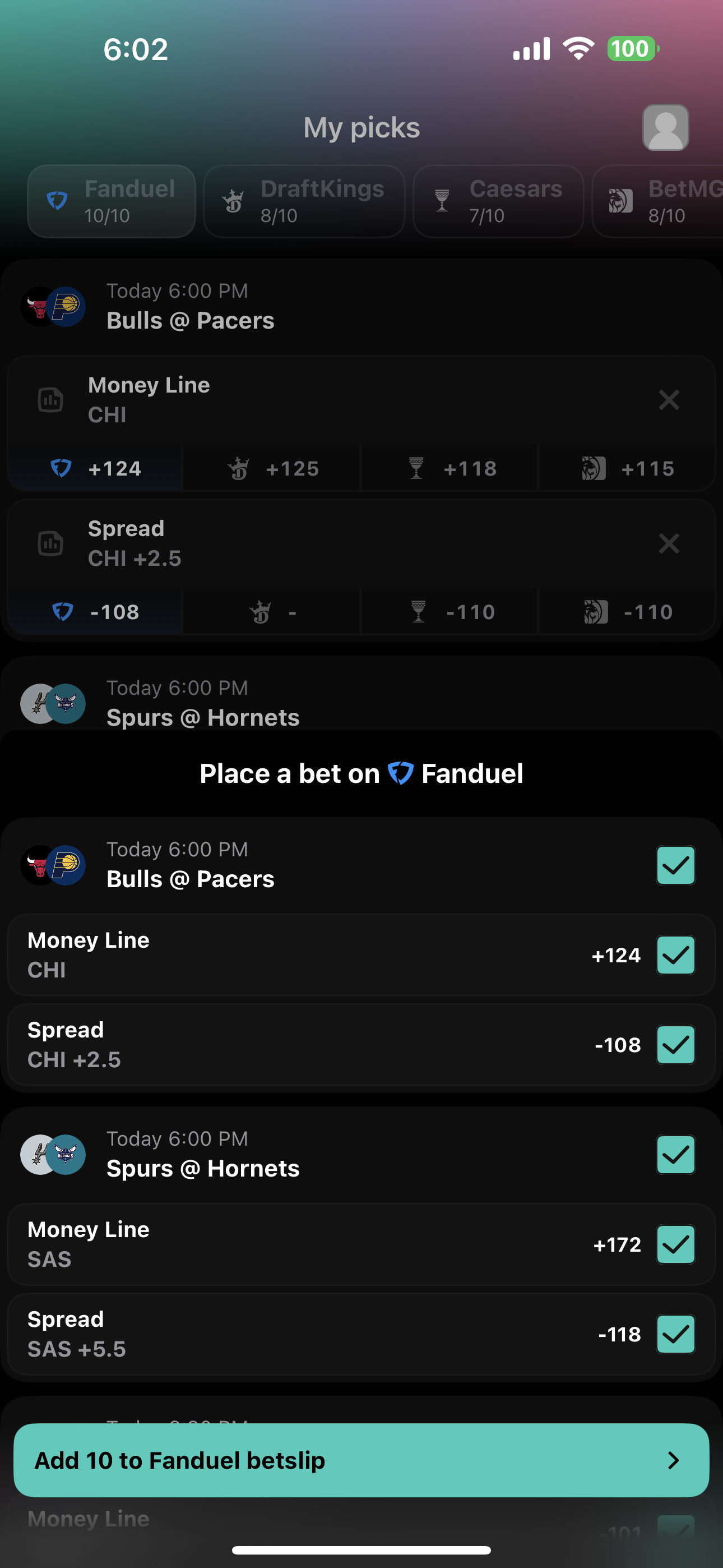

Integrated with your favorite sportsbooks to place bets faster than ever

The community has spoken

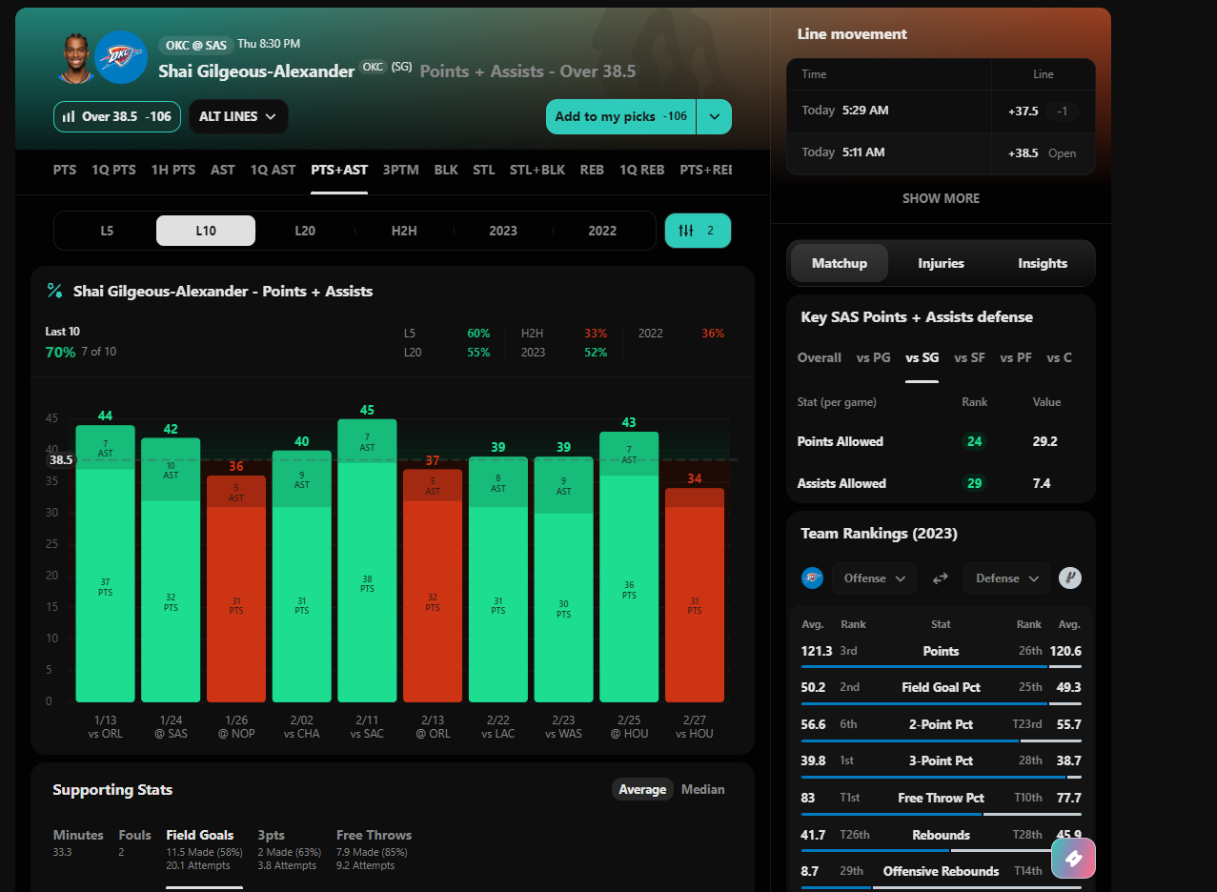

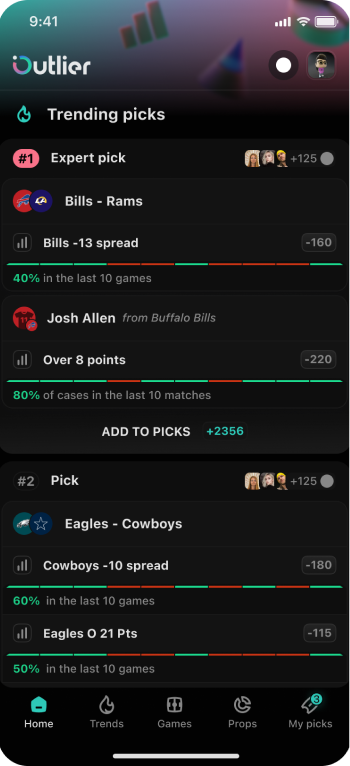

Get inspired. Comb through a curated feed of trending picks and insights to uncover smart betting opportunities.

Explore the markets. Browse thousands of gamelines and player props across leagues to find the perfect pick.

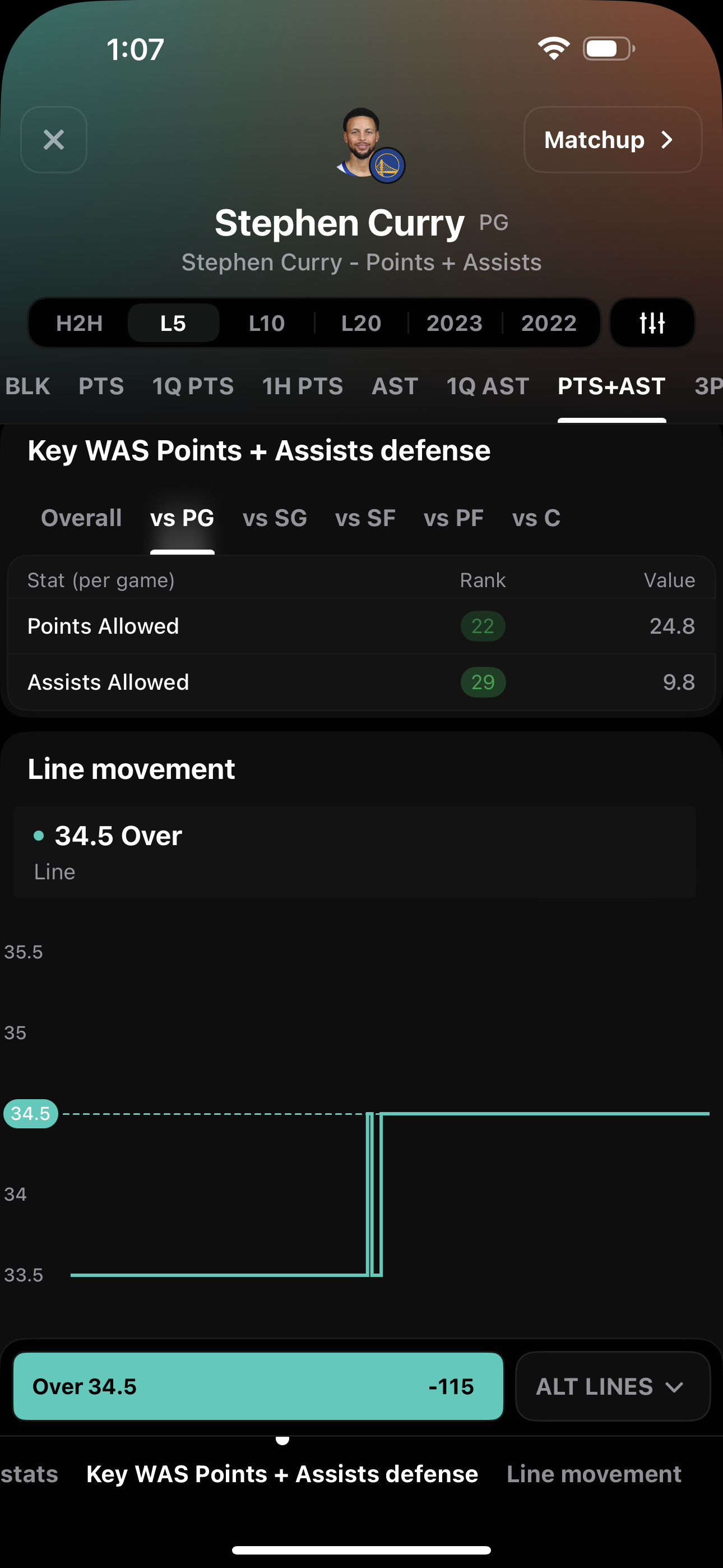

Evaluate the opportunity. Analyze performance trends, injuries, matchup data, public sentiment, and line movement to understand your picks.

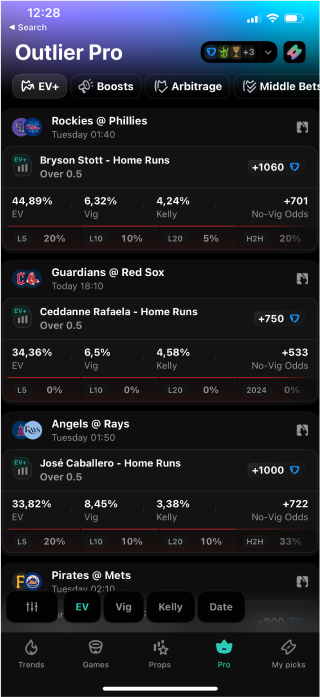

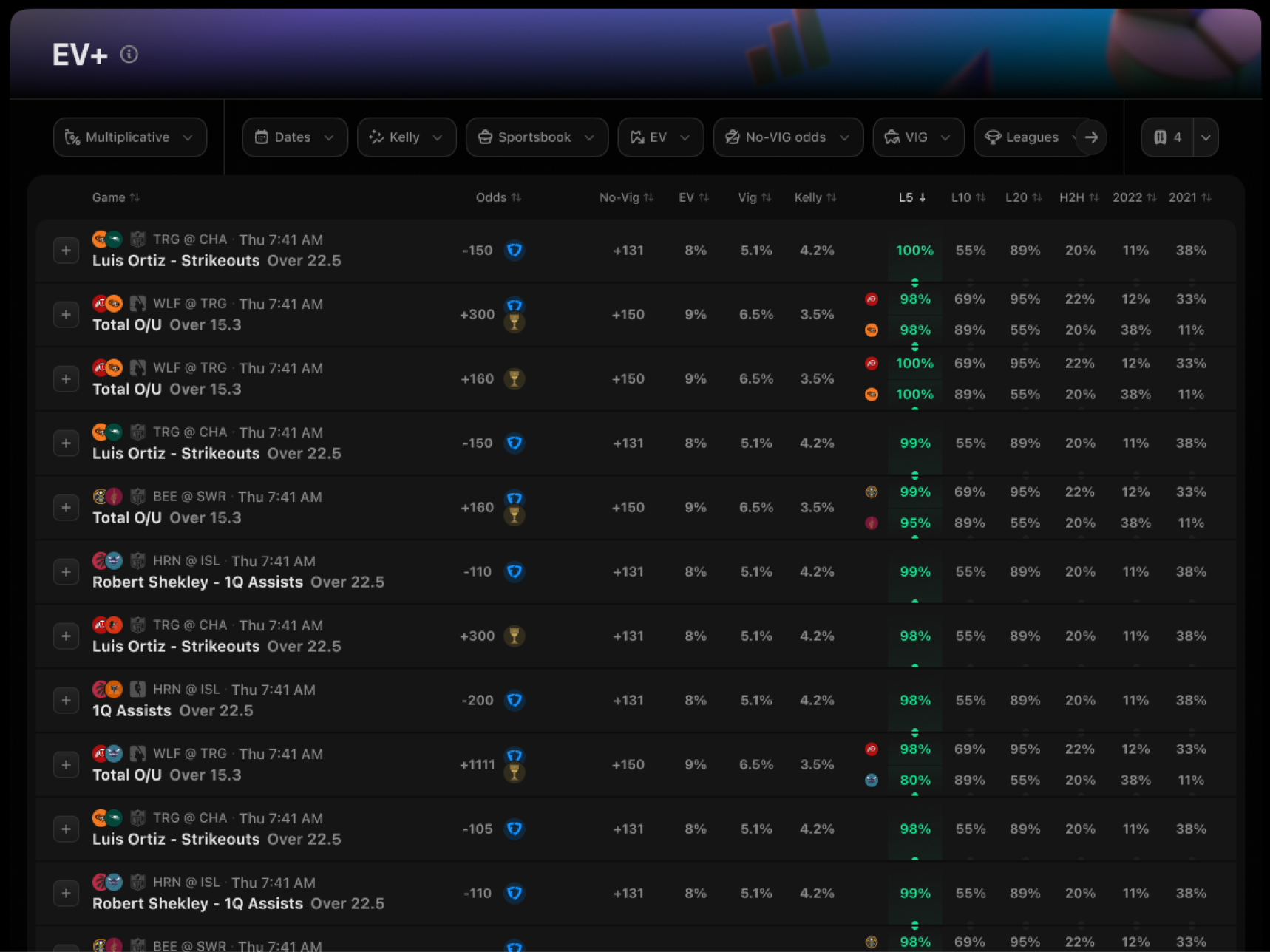

Find Your Edge with Outlier Pro. Take action on a live feed of Positive EV bets, filtered to your strategy.

Uncover the insights. Act on player performance and injury insights presented in the context of available betting markets.

Maximize your upside. Secure picks at the best price by comparing odds across your favorite sportsbooks & DFS apps.

Execute seamlessly. Place bets on FanDuel, DraftKings, BetMGM, or Caesars, in just two clicks.

Outlier Pro: Positive EV Betting Tools. Simplify betting and boost profits with Outlier's EV+ tools.

Which plan is right for you?

Our sports betting research platform will make you a smarter, more efficient, and more confident bettor. Get started with a 7 day free trial to all our tools.

Become a Smarter Sports Bettor

Merch. Loving Outlier? Stock up on gear and show off your favorite betting app.

Odds and Evens: The Science and Strategy of Successful Sports Betting

staffwriter

- Published January 22, 2024

- Updated January 2024

In the thrilling world of sports betting, enthusiasts often find themselves walking a fine line between chance and strategy. While luck undoubtedly plays a role, successful sports betting is far from a shot in the dark. Behind the scenes, a complex interplay of mathematics, statistics, and strategic decision-making shapes the landscape of profitable wagering. In exploring the science and strategy behind successful sports betting, we delve into the intricacies that can elevate your betting game and increase your chances of walking away with a win.

Understanding odds: The fundamental building blocks

At the heart of sports betting at 4 pound deposit casino sites in the United Kingdom lies the concept of odds, the numerical representation of the probability of a particular outcome. Whether expressed as fractional, decimal, or moneyline odds, grasping the fundamentals of these numerical representations is essential for any aspiring sports bettor.

Probability and expected value: The science behind the odds

While odds provide insight into potential winnings, understanding probability is the key to making informed betting decisions. The relationship between odds and probability is reciprocal—the higher the odds, the lower the implied probability, and vice versa. Calculating a bet’s expected value (EV) involves assessing the potential return against the likelihood of success.

Expected Value Formula: EV = (Probability of Winning * Potential Profit) – (Probability of Losing * Stake)

In essence, the Expected Value illuminates the path towards making well-informed betting decisions by balancing risk and reward in the intricate dance between odds and probability.

Bankroll management: Protecting your capital

Successful sports betting isn’t just about picking winners; it’s about managing your funds wisely. Bankroll management is a crucial aspect that prevents impulsive decisions and helps bettors navigate the inevitable swings in fortune.

- Set realistic goals : Establish achievable and measurable goals for your betting endeavours, whether it’s a daily, weekly, or monthly target.

- Risk percentage : Avoid risking more than 1-5% of your total bankroll on a single bet to protect against significant losses.

- Bet sizing : Adjust your bet sizes based on your confidence in a particular wager. Higher confidence can justify a larger bet, while uncertainty should lead to smaller stakes.

- Diversify wager types : Spread your bets across different types—straight bets, parlays, and prop bets—to mitigate risk and maximise potential returns.

- Track and analyse performance : Record your bets, wins, and losses meticulously. Regularly analyse your performance to identify trends and areas for improvement.

- Periodic assessments : Conduct periodic evaluations of your bankroll strategy, adjusting it as needed based on your evolving betting style and financial circumstances.

- Embrace patience : Recognise that success in sports betting is a marathon, not a sprint. Practice patience, and avoid chasing losses or overcommitting during hot streaks.

- Research and informed decisions : Invest time in thorough research before placing bets. Informed decisions based on solid analysis enhance your chances of success and contribute to effective bankroll management.

- Emergency fund : Set aside a portion of your bankroll as an emergency fund to cover unexpected expenses. This ensures that your betting activities don’t encroach on essential financial responsibilities.

Research and analysis: The foundation of informed betting

Research and analysis are the bedrock of informed decision-making in the intricate realm of sports betting. Thorough research unveils the nuances that escape casual observation, offering a deeper understanding of the variables influencing a game. Analytical tools and methodologies further refine this information, transforming raw data into actionable insights. Bettors gain a strategic edge by delving into injury reports, team strategies, and past head-to-head matchups. Informed sports betting isn’t a gamble; it’s a calculated endeavour that hinges on the diligent pursuit of knowledge.

Spotting value bets: Finding the edge

The concept of a “value bet” is central to successful sports betting. Identifying situations where bookmakers’ odds underestimate an outcome’s true probability is crucial for long-term profitability.

- Compare odds across bookmakers : Different bookmakers may offer varying odds for the same event. Comparing prices allows you to spot discrepancies and find the best value.

- Line movements : Track line movements to understand how public sentiment and sharp money influence odds. Quick shifts may indicate valuable opportunities.

- Be selective : Rather than betting on every available market, be selective. Focus on markets where you have expertise and can identify potential value.

Emotional discipline: Mastering the mental game

The psychological aspect of sports betting is often underestimated. Successful bettors maintain emotional discipline, avoiding impulsive decisions driven by excitement, frustration, or fear. Therefore, you should:

- Stick to your strategy : Develop and adhere to a clear betting strategy. Avoid deviating based on emotions or chasing losses.

- Learn from mistakes : Acknowledge that losses are inevitable, but view them as learning opportunities. Analyse errors and refine your approach.

- Avoid “gamblers fallacy” : Each bet is independent of the previous ones. Refrain from falling into the trap of thinking that past outcomes influence future results.

Live betting and in-play opportunities: Seizing the moment

In the evolving landscape of sports betting, live betting has emerged as a transformative force, inviting bettors to engage actively with the unfolding drama of a match. In-play odds undergo continuous adjustments as the game progresses, offering a real-time reflection of the unfolding events. This fluidity in odds presents a canvas of strategic possibilities for bettors who can discern favourable moments to place their wagers. This adaptability aligns with the unpredictability inherent in sports, providing a safety net for strategic wagering.

Specialising in niche markets: Finding your niche

While mainstream sports attract the majority of betting attention, specialising in niche markets or less popular sports can provide unique advantages:

- Less bookmaker attention : Niche markets may receive less attention from bookmakers, potentially leading to softer odds and more value.

- Specialist knowledge : Becoming an expert in a particular niche allows for more informed betting decisions, as you have a deeper understanding of the factors influencing outcomes.

- Reduced public influence : Niche markets may be less susceptible to the influence of public sentiment and media coverage, providing a more objective betting landscape.

In conclusion, the science and strategy of successful sports betting require a multifaceted approach that blends mathematical acumen, strategic decision-making, and emotional discipline. By understanding the intricacies of odds, grasping the science behind the expected value, practising effective bankroll management, conducting thorough research, and staying disciplined in the face of wins and losses, bettors can enhance their chances of long-term success in the dynamic world of sports wagering. Betting may have an element of chance, but with the right approach, it can evolve into a calculated and strategic pursuit beyond mere luck.

While it’s feasible to increase your chances of winning, we’d always remind you that sports betting is gambling and ultimately comes with a sizeable risk of losing your money. Never bet more than you can afford to lose.

Recent Posts

Phil Foden’s rise: generational talent and a feverish passion for football

Phil Foden is a 23 year old with no fewer than 6 Premier League titles to his name. Let’s take a look at how Foden became Foden.

Hiking in Canada – What You Need to Know

Canada is a huge place with some of the best hiking in the world. While we couldn’t possibly claim to be able to tell you EVERYTHING you need to know in once single sentence, we can certainly offer up some key information for those of you planning a hiking led adventure break in arguably the most beautiful part of North America.

Best Portable Charging Banks for Hiking

Traditionalists may not like it! But personally, I don’t like to risk being stuck on a hill or mountain with a dead phone or head torch battery. So I like to carry a portable charging device (or 2, or 3) with me. Here are the best portable charging banks for hiking that I’ve used. (And I’ve used a lot, by the way).

The Hiker’s Guide to Dovestone

Dovestone is a beautiful place in the Peak District’s Dark peak, nestled amongst the Saddleworth Hills. But there’s far more for hikers here than reservoir walks. Here’s a hiker’s guide to Dovestone Reservoir and the surrounding hills.

Across the website, Our Sporting Life uses affiliate links on some of its content. In a nutshell, it means that if you click one of those links and then go on to make a purchase, we may receive a commission (but you won’t be charged any more by the seller of that product or service). Importantly, though, opinions on products, services and so forth remain our own. We do not accept payment to review anything and we don’t accept payment to place editorial either.

- Online Sports Betting Market Size

Report on Industry Size & Market Share Analysis - Growth Trends & Forecasts (2024 - 2029)

Online Sports Betting is Experiencing Significant Transformations Due To Technological Advancements. Leading Firms are Enhancing Their Platforms, With Cashless Transactions and Increased Female Participation Expected To Boost the Market. The Sector's Growth is Also Driven by Virtual Reality and Blockchain Technologies. Digital Sports Betting is Popular in Events Like the FIFA World Cup and European Championships, and in Sports Like Horse Racing and Tennis. The Market is Segmented by Sports Type, Device, and Location, With Most Bets Placed On Football, Basketball, Horse Racing, and Cricket. The Convenience of Remote Sports Betting and Secure Transaction Methods are Key Market Drivers. The Market is Highly Competitive and Fragmented, With Players Adopting Strategies Like Expansions, Innovations, and New Product Launches To Maintain Competitiveness.

INSTANT ACCESS

Single User License

Team License

Corporate License

Need a report that reflects how COVID-19 has impacted this market and its growth?

Online Sports Betting Market Analysis

The Online Sports Betting Market size is estimated at USD 48.17 billion in 2024, and is expected to reach USD 83.58 billion by 2029, growing at a CAGR of 11.65% during the forecast period (2024-2029).

Sports betting involves gambling by predicting the outcome of a game and placing a wager. It is popular in various sports, including cricket, football, and horse racing. The proliferation of the internet is expected to drive advancements in the sports betting industry. European football generates the most revenue in online betting sports, with baseball trailing closely behind. The increasing popularity of online sports has revolutionized the methods of sports betting. However, numerous countries prohibit sports betting, which significantly hinders the expansion of the sports betting market. However, relaxation in the regulation framework of betting and gambling activities by governments worldwide is anticipated to provide favorable opportunities for betting operators. For instance, in 2023, as per the American Gaming Association in the United States, sports betting was legally permitted in 36 states, an increase from 32 in 2021. Within the first ten months of 2022, sports bettors in the United States legally wagered approximately USD 73 billion.

- Online Sports Betting Market Trends

Increasing Popularity of Online Gambling

The football segment of the international online sports betting market records a high betting volume, with a growing number of bets. It is especially prevalent in European countries such as Italy, France, and Spain, where football is more popular. The online betting segment is predominantly applied in sports, especially in football events like the Fédération Internationale de Football Association (FIFA) World Cup and European Championships. Moreover, the increased penetration of smartphones is leading to an increase in several mobile application-based lottery games. The end-user has the convenience and comfort of gambling within the comfort of their own space, which is one of the primary drivers of the segment. Casino gambling has been one of the rapidly growing gambling categories, owing to the convenience of usage and optimal user experience. Also, the rising adoption of online payment gateways has made payment options convenient for players. Online payment provides a safe and secure mode of transaction, boosting the growth of the online sports betting market.

Europe Dominates the Market

The market records a high demand from European betting consumers, who bet across multiple leagues, pre-match, and in-play. The market generates a significant portion of its revenue from the United Kingdom, Spain, Germany, and other European countries, as most companies are expanding into regulated markets to generate sustainable revenues. As online sports betting is predominantly applied in events such as the FIFA World Cup, the Wimbledon Championship, and the European Championships, the online sports betting market in Europe has grown significantly in the last few years. Companies are expanding their presence in the region based on various factors, including offerings, user experience, brand equity, personalized payoffs, and access to multiple platforms. For instance, in September 2023, global gaming operator Betsson entered the French online betting market. Betsson’s entrance into the French market results from collaborating with a local partner. It strategically aims to bring the company closer to the French sports betting arena. In the fourth quarter of 2023, the official launch of Betsson’s flagship brand took place.

Online Sports Betting Industry Overview

The market studied is fragmented due to the strong presence of regional and global players. Key players dominate the market, including Bet365, 888 Holdings PLC, Flutter Entertainment PLC, Entain PLC, and The Stars Group. Key players compete on various factors, including offerings, user experience, brand equity, personalized payoffs, and access to multiple platforms. The key strategies adopted by the players in the market are expansions, innovations, and product launches to maintain competitiveness in the market. They also focus on mergers to increase their market stake and improve profit margins.

Online Sports Betting Market Leaders

The Stars Group

888 holdings PLC

Flutter Entertainment PLC

*Disclaimer: Major Players sorted in no particular order

Online Sports Betting Market News

- December 2023: Betsson collaborated with Racing Club de Avellaneda for the upcoming 2023/2024 season. Starting May 19, the Swedish brand logo would be featured on the upper back of the men’s and women’s First Division football teams’ shirts for local and international matches.

- September 2023: Betsson was awarded a license to offer online sports betting on the locally regulated market in France. The operations in France would run in collaboration with a local partner. The launch in the country took place during the fourth quarter of 2023 under the Betsson brand.

- March 2023: OpenBet, a multinational company that provides sports betting entertainment, expanded its presence in the United States with a day-one launch in Massachusetts.

Online Sports Betting Market Report - Table of Contents

1. INTRODUCTION

1.1 Study Assumptions and Market Definition

1.2 Scope of the Study

2. RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

3. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

4. MARKET DYNAMICS

4.1 Market Drivers

4.1.1 Increasing Popularity of Online Gambling

4.1.2 Advancement In Security, Encryption, and Streaming Technology

4.2 Market Restraints

4.2.1 Regulatory Uncertainty And Compliance

4.3 Industry Attractiveness - Porter's Five Forces Analysis

4.3.1 Bargaining Power of Suppliers

4.3.2 Bargaining Power of Buyers/Consumers

4.3.3 Threat of New Entrants

4.3.4 Threat of Substitutes

4.3.5 Degree of Competition

5. MARKET SEGMENTATION

5.1 Sport Type

5.1.1 Football

5.1.2 Basketball

5.1.3 Horse Racing

5.1.4 Baseball

5.1.5 Tennis

5.1.6 Other Sport Types

5.2 End User

5.2.1 Desktop

5.2.2 Mobile

5.3 Geography

5.3.1 North America

5.3.1.1 United States

5.3.1.2 Canada

5.3.1.3 Mexico

5.3.1.4 Rest of North America

5.3.2 Europe

5.3.2.1 Spain

5.3.2.2 United Kingdom

5.3.2.3 Germany

5.3.2.4 France

5.3.2.5 Italy

5.3.2.6 Sweden

5.3.2.7 Rest of Europe

5.3.3 Asia-Pacific

5.3.3.1 Oceanic Countries

5.3.3.2 Rest of Asia-Pacific

5.3.4 Rest Of The World

5.3.4.1 South America

5.3.4.2 Middle East & Africa

6. COMPETITIVE LANDSCAPE

6.1 Most Adopted Strategies

6.2 Market Share Analysis

6.3 Company Profiles

6.3.1 888 holdings PLC

6.3.2 Entain PLC

6.3.3 BET 365

6.3.4 Betsson AB

6.3.5 Flutter Entertainment PLC

6.3.6 Draftkings Inc.

6.3.7 Kindred Group PLC

6.3.8 1XBET

6.3.9 22BET

6.3.10 Sportpesa

- *List Not Exhaustive

7. MARKET OPPORTUNITIES AND FUTURE TRENDS

Online Sports Betting Industry Segmentation

Sports betting is predicting sports results and placing a wager on the outcome. The frequency of sports bets varies by culture, with the vast majority placed on football, basketball, horse racing, cricket, and others. The online sports betting market is segmented by sports type, end user, and geography. Based on sports type, the market is segmented into football, basketball, horse racing, baseball, tennis, and other sports types. Based on end users, the market is segmented into desktop and mobile. Moreover, an analysis has been done based on emerging and established regions, including North America, Europe, Asia-Pacific, and the Rest of the World. The market sizing and forecasts have been done for each segment based on value (USD).

Online Sports Betting Market Research FAQs

How big is the online sports betting market.

The Online Sports Betting Market size is expected to reach USD 48.17 billion in 2024 and grow at a CAGR of 11.65% to reach USD 83.58 billion by 2029.

What is the current Online Sports Betting Market size?

In 2024, the Online Sports Betting Market size is expected to reach USD 48.17 billion.

Who are the key players in Online Sports Betting Market?

Entain PLC, The Stars Group, 888 holdings PLC, BET 365 and Flutter Entertainment PLC are the major companies operating in the Online Sports Betting Market.

Which is the fastest growing region in Online Sports Betting Market?

North America is estimated to grow at the highest CAGR over the forecast period (2024-2029).

Which region has the biggest share in Online Sports Betting Market?

In 2024, the Europe accounts for the largest market share in Online Sports Betting Market.

What years does this Online Sports Betting Market cover, and what was the market size in 2023?

In 2023, the Online Sports Betting Market size was estimated at USD 42.56 billion. The report covers the Online Sports Betting Market historical market size for years: 2019, 2020, 2021, 2022 and 2023. The report also forecasts the Online Sports Betting Market size for years: 2024, 2025, 2026, 2027, 2028 and 2029.

What are the key regional trends shaping Online Sports Betting?

The increasing growth in emerging markets like Asia Pacific and Latin America, alongside regulations evolving in established markets are the key regional trends shaping Online Sports Betting.

What are the emerging technologies shaping the future of Online Sports Betting?

The emerging technologies shaping the future of Online Sports Betting are a) AI-powered personalization b) Virtual reality experiences as potential game-changers

Our Best Selling Reports

- Fly Ash Market

- Bio-Based Succinic Acid Market

- Lubricant Additives Market

- Aliphatic Hydrocarbon Solvents and Thinners Market

- Feed Preservatives Market

- Self-Healing Coatings Market

- China EV Market

- IoT Sensor Market

- Global Industrial Fasteners Market

- PC Based Automation Market

Online Sports Betting Industry Report

The global online sports betting market is experiencing significant growth due to the rapid adoption of internet-connected devices like smartphones and tablets. The development of online betting is expected to cause a significant increase in demand for the global sports betting industry over the projected period. The growth of high-speed internet services and the growing acceptance of online gambling, particularly in football-loving nations like Italy, France, and Spain, are driving this expansion. However, the increased negative effects on mental health and restrictions on online gambling in several countries are anticipated to hamper the market expansion. Despite these challenges, the growth of live e-sports coverage platforms is anticipated to create lucrative opportunities for the global market to expand. The market is divided into various segments based on type and sports type, with football and line-in-play segments owning the highest market shares. Statistics for the Online sports betting market share, size, and revenue growth rate, created by Mordor Intelligence™ Industry Reports. Online sports betting analysis includes a market forecast outlook and historical overview. Get a sample of this industry analysis as a free report PDF download.

Online Sports Betting Market Report Snapshots

- Online Sports Betting Market Share

- Online Sports Betting Companies

- Online Sports Betting News

Please enter a valid email id!

Please enter a valid message!

Online Sports Betting Market Size & Share Analysis - Growth Trends & Forecasts (2024 - 2029)

Online Sports Betting Market Get a free sample of this report

Please enter your name

Business Email

Please enter a valid email

Please enter your phone number

Get this Data in a Free Sample of the Online Sports Betting Market Report

Please enter your requirement

Thank you for your Purchase. Your payment is successful. The Report will be delivered in 2 - 4 hours. Our sales representative will reach you shortly with the details.

Please be sure to check your spam folder too.

Sorry! Payment Failed. Please check with your bank for further details.

Add Citation APA MLA Chicago

➜ Embed Code X

Get Embed Code

Want to use this image? X

Please copy & paste this embed code onto your site:

Images must be attributed to Mordor Intelligence. Learn more

About The Embed Code X

Mordor Intelligence's images may only be used with attribution back to Mordor Intelligence. Using the Mordor Intelligence's embed code renders the image with an attribution line that satisfies this requirement.

In addition, by using the embed code, you reduce the load on your web server, because the image will be hosted on the same worldwide content delivery network Mordor Intelligence uses instead of your web server.

Sports Betting

This article provides insights into the increasing interest in sports betting and its connection to consumer behavior, demographics, and personality traits. Understanding these dynamics is essential for businesses seeking to engage with this growing market.

- The increasing popularity of sports betting, driven by prominent platforms like FanDuel and DraftKings, is explored through data from the 2023 Prosper Media Behavior and Influence (MBI) study, encompassing 17,159 adults aged 18+.

- Two key questions were asked in the study: “Do you gamble on sports?” and “Do you play fantasy sports?” Responses were categorized as regularly, occasionally, or never.

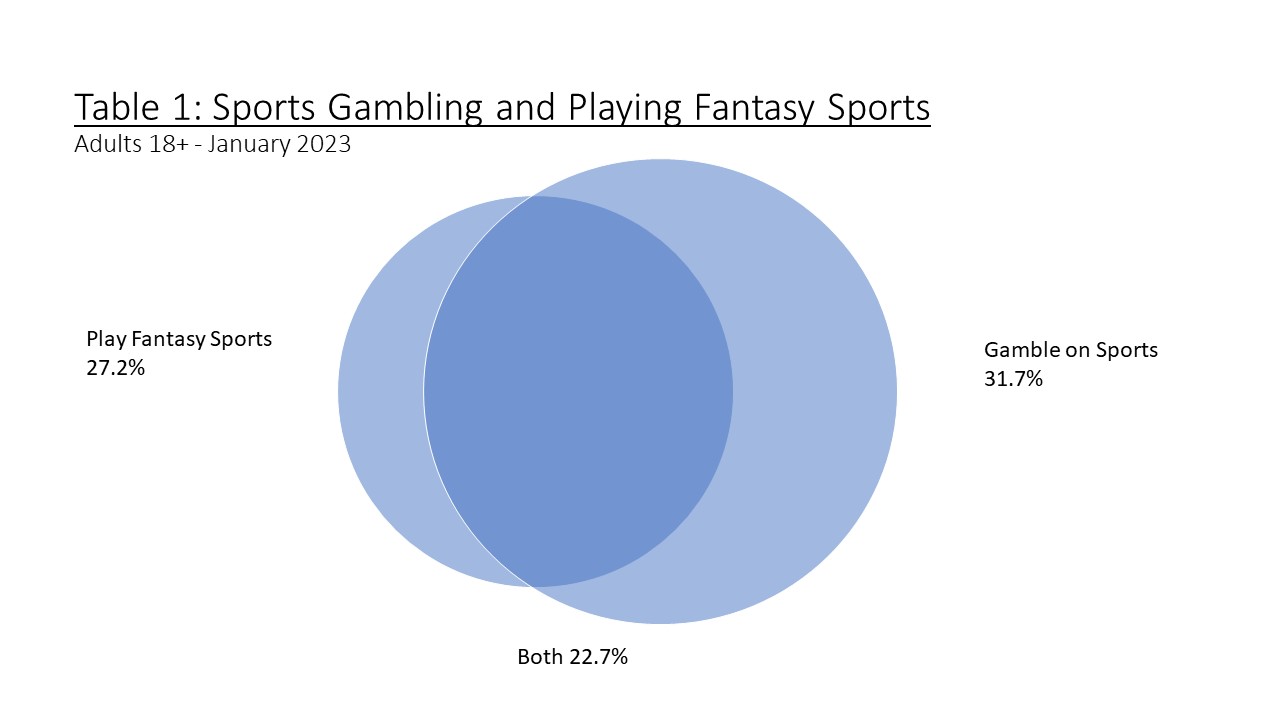

- 31.7% of respondents engage in sports gambling (regularly or occasionally), while 27.2% participate in fantasy sports, with a substantial overlap of 22.7% doing both.

- Within these categories, 71.7% of sports gamblers also play fantasy sports, and 83.4% of fantasy sports participants also gamble on sports.

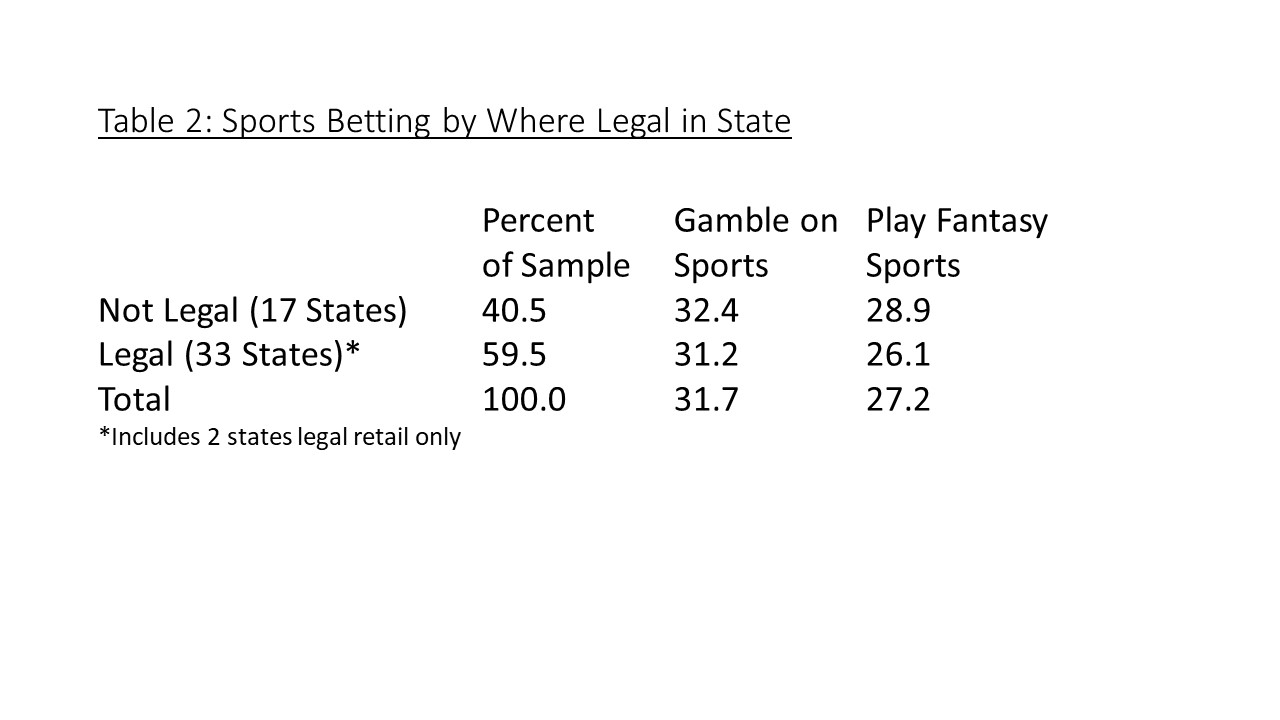

- Approximately 40% of the 2023 MBI study population resides in states where online sports betting is illegal, despite substantial legal concerns, especially in large states like California and Texas.

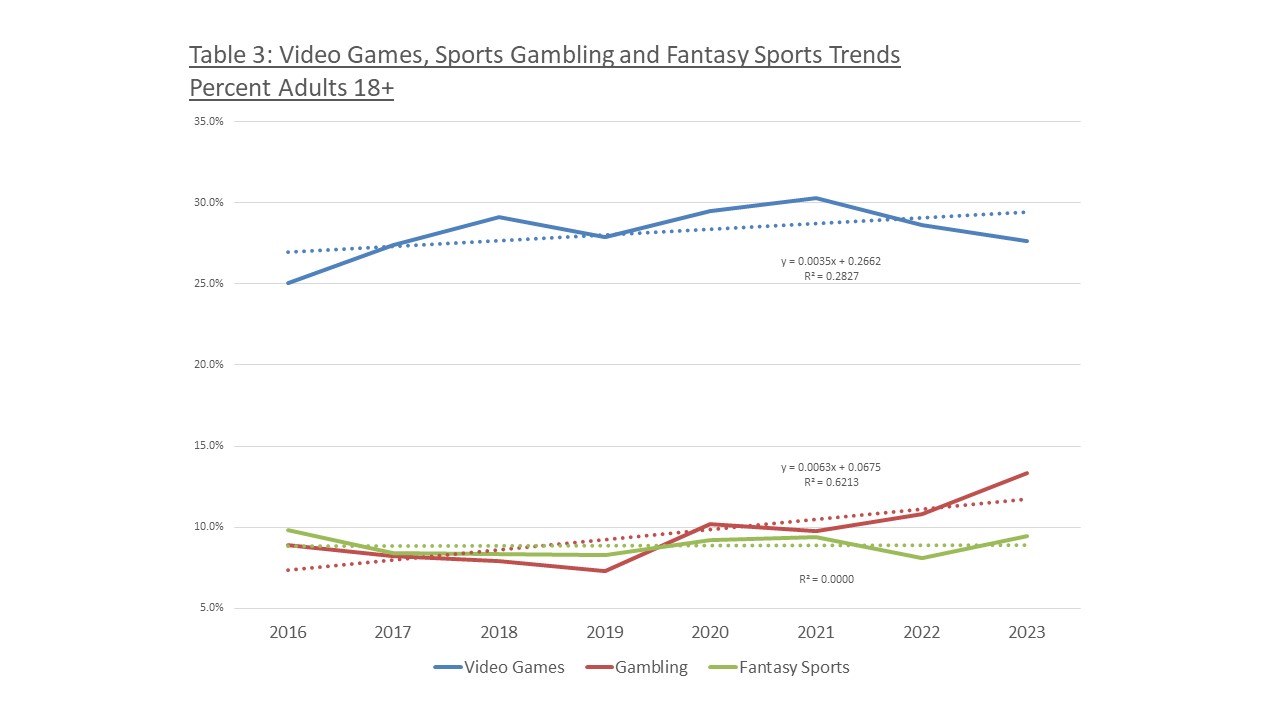

- Historical data reveals a steady increase in sports gambling, particularly in recent years, while fantasy sports participation has remained relatively stable.

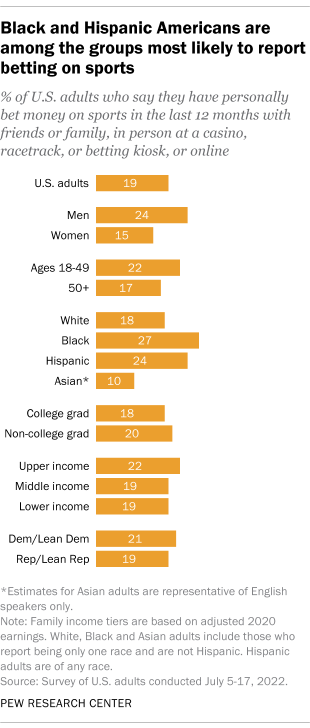

- In 2023, 42.1% of males reported gambling on sports compared to 21.5% of females, with both genders showing growth over the past three years, albeit at different rates.

- Demographic characteristics reveal higher sports gambling rates among Gen-Z, Millennials, and males, with connections to various occupations and a slight advantage for those with higher education.

- A classification regression tree (CRT) analysis identifies segments with high sports gambling rates, with age, gender, income, marital status, and ethnicity being significant predictors.

- Viewership patterns indicate that gambling on sports is related to specific sports categories, with minor sports and women’s sports exhibiting greater relative interest among gamblers. Additionally, sports bettors are more likely to engage in sports-related activities, favor alcoholic beverages, and display specific personality traits, including high extraversion and lower grit, demonstrating a distinct consumer profile.

Forward By Dr. Larry DeGaris, Executive Director, Medill Spiegel Research Center, Northwestern University

“Legalized sports gambling is the endgame. One-day fantasy delivers a similar fan experience to gambling, so I expect the current database of customers would provide a good foundation for sports gamblers.” I said this in 2015 when I was interviewed for the Bloomberg article “Daily Fantasy Sites Seen Positioned for Jump to Sports Gambling.”

This interview came on the heels of NBA commissioner Adam Silvers’s 2014 NYT op-ed, “Legalize and Regulate Sports Betting,” advocating legalizing sports betting; I knew it was just a matter of time before sports betting was legalized nationwide and DraftKings and FanDuel were planting the seeds.

Fast forward to 2023, and DraftKings and FanDuel are dominating the sports betting market while big sports brands like Fox and big gaming brands like MGM struggle or fail. I thought it was a good strategy. I didn’t realize how good.

The sports betting market highlights the value of customer data. DraftKings and FanDuel’s market domination is based on their customer data strategy. They bet that fantasy players, especially daily fantasy players, would be the most promising market for sports betting. As sports betting became legal in more states, they were ready. It was a big bet and a big win.

Similarly, brands are placing big bets on Retail Media Networks. The strategy is the same. As we enter the cookie-less world, customer data will become more valuable. That’s no fantasy.

More recently, Fanatics is getting into the sports betting game with its acquisition of Pointsbet, betting that its database of fans will help them compete where others have fallen short. I’m not sure I like the odds. Let’s reverse engineer DraftKings’s and FanDuel’s winning strategy. Martin Block’s nifty little sports betting paper shows us the way.

The relationship between betting on sports and playing fantasy sports is very high. The two groups are almost identical. Unlike the years it took Amazon to build a customer database, DraftKings and FanDuel had theirs built before sports betting became legal. As more states legalized sports betting, they were ready. That initial advantage has been difficult for other entrants to overcome.

Having a database of sports fans doesn’t measure up to a targeted list of fantasy sports players. Similarly, I reckon Fanatics has a great database of fans passionate about their teams, which likewise wouldn’t translate well to betting.

Digging deeper, we see the underlying mechanisms of sports betting and outline a path forward. DraftKings and FanDuel won the first round, but it ain’t over ‘til it’s over.

The women’s market in sports tends to be underserved in general because fan populations are more likely to be male. The difference in degree mistakenly is equated with a categorical difference. Sports bettors are more likely to be male, but there are a lot of women betting on sports.

Sports betting companies have been active as sponsors of sports properties. But sports betting is a fan activity and, as Martin points out, there are many product categories that index high for sports bettors. Creating a brand partnership strategy using sports betting as a platform could bring another revenue stream.

Sports bettors are highly social and competitive. That’s the underlying link between fantasy and betting. Fantasy was a natural connection for sports betting in that respect, but if sportsbooks can innovate ways to connect fans who weren’t playing fantasy, they can gain an entry point. What do you talk about when your team is having a bad year? This week’s parlays. Sports betting is a social experience for fans. Sports betting companies can create a social infrastructure for fans to interact, as they’ve done with fantasy leagues.

The story highlights both the importance and limitations of customer data. Customer data tells you who. Traditional market research can help understand the why.

We should keep this in mind as we watch retail media grow. First-party customer data is tremendously valuable but limited without a deeper understanding of shopper experiences and identities.

By Dr. Martin Block, Professor Emeritus, Northwestern University, Retail Analytics Council

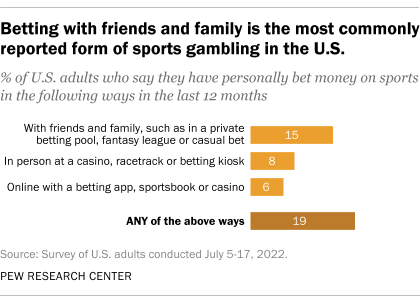

Interest in sports betting is increasing with the publicity that FanDuel and DraftKings have recently enjoyed. To better understand sports betting data from the annual Prosper Media Behavior and Influence (MBI) study collected in January of 2023 (n=17,159) of adults 18+ is analyzed. Two questions were asked: “Do you gamble on sports?” and “Do you play fantasy sports?” Both questions were supplied with answer options of regularly, occasionally, and never. Table 1 shows the proportion of the sample that gamble on sports combining regularly and occasionally at 31.7%, and those playing fantasy sports at 27.2%. There is substantial overlap between gambling and fantasy sports, with 22.7% reporting both. Of those who gamble, 71.7% say they also play fantasy sports. Of those who play fantasy sports, 83.4% say they also gamble. Not all respondents say they gamble and play exclusively online. Of those who say they gamble on sports, 66.0% say they also gamble online. Of those who play fantasy sports, 84.1% say they also play fantasy sports online.

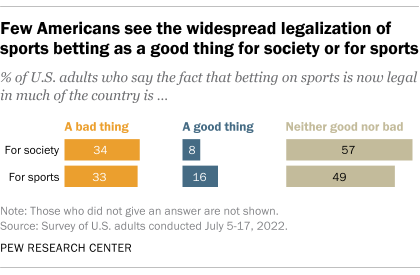

The legality of online sports betting has also been a topic of interest. Using FanDuel’s map of states where the service is legal, Table 2 shows that approximately 40% of the population as represented by the 2023 MBI are in states where it is not legal. Two big states, California and Texas are among the states where it is not legal. It should be noted that in states where it is not legal, the proportion is slightly higher than in states where it is legal. The difference, despite the very large sample sizes, is not statistically different. Legalizing online sports betting appears to have little influence.

The gambling and fantasy sports questions have been asked in the MBI for several years. Table 3 shows the trends over the last eight years for gambling, playing fantasy sports, and playing video games. Playing video games has slowly increased over the years but is showing a slight decline in 2023. Gambling on sports has steadily increased, especially in recent years. Playing fantasy sports has remained almost perfectly flat.

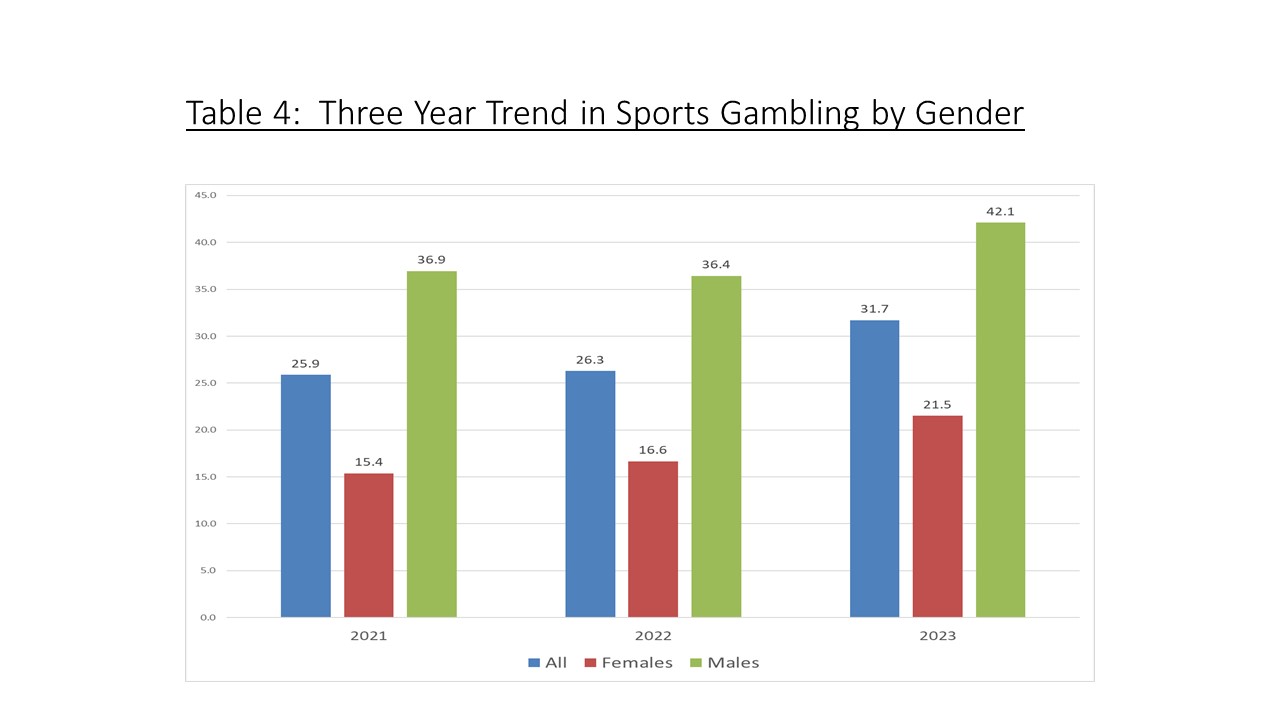

Considering just the last three years, as shown in Table 4 illustrates the recent growth, especially for 2023. It also shows a comparison of gambling by gender. In 2023, 42.1% of males reported gambling on sports compared to 21.5% of females. The average annual growth rate for males over the three years is 3.9%, compared to 4.0% for females.

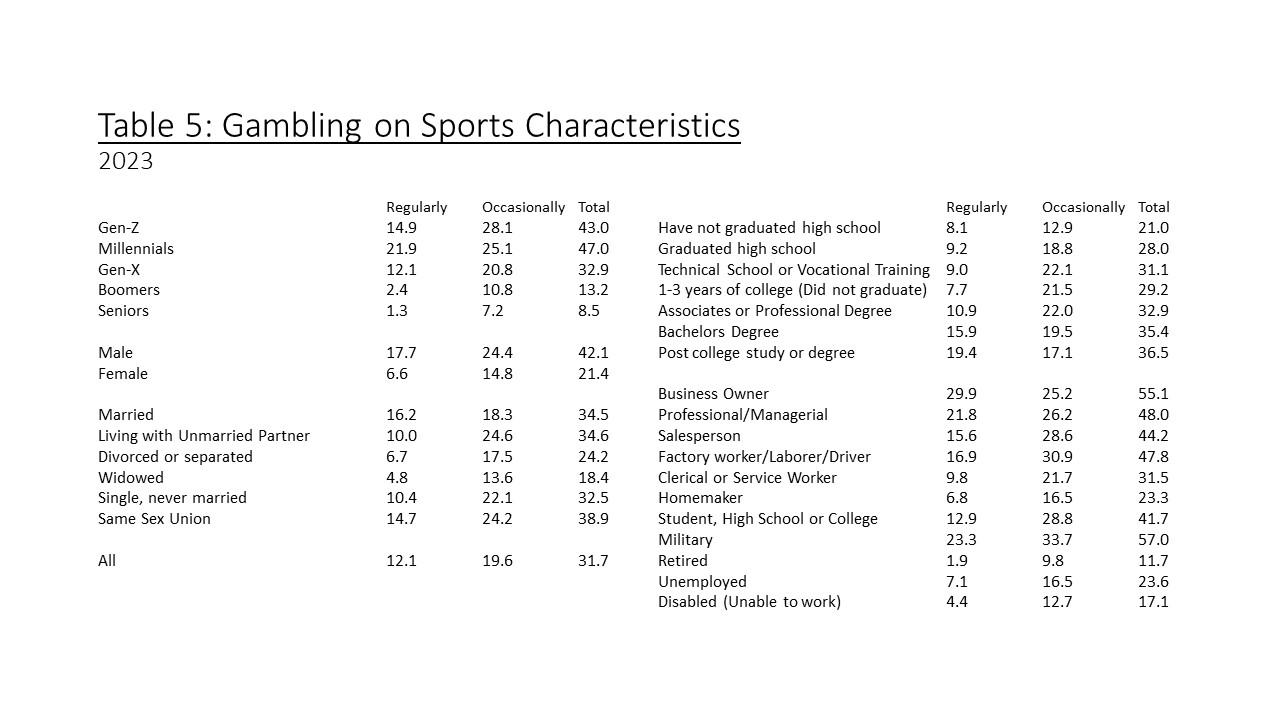

Table 5 shows some differences by various demographic characteristics and the breakdown by regularly and occasionally gambling on sports. Looking at the characteristic variables by themselves, it appears that sports gambling is highest among Gen-Z, Millennials, and males. There seems to be strong connections to occupation, especially business owners, professionals, salespersons, workers, students, and military. All these occupations have a social component. There is also a slight advantage for higher or more education.

Identifying the Sports Bettor

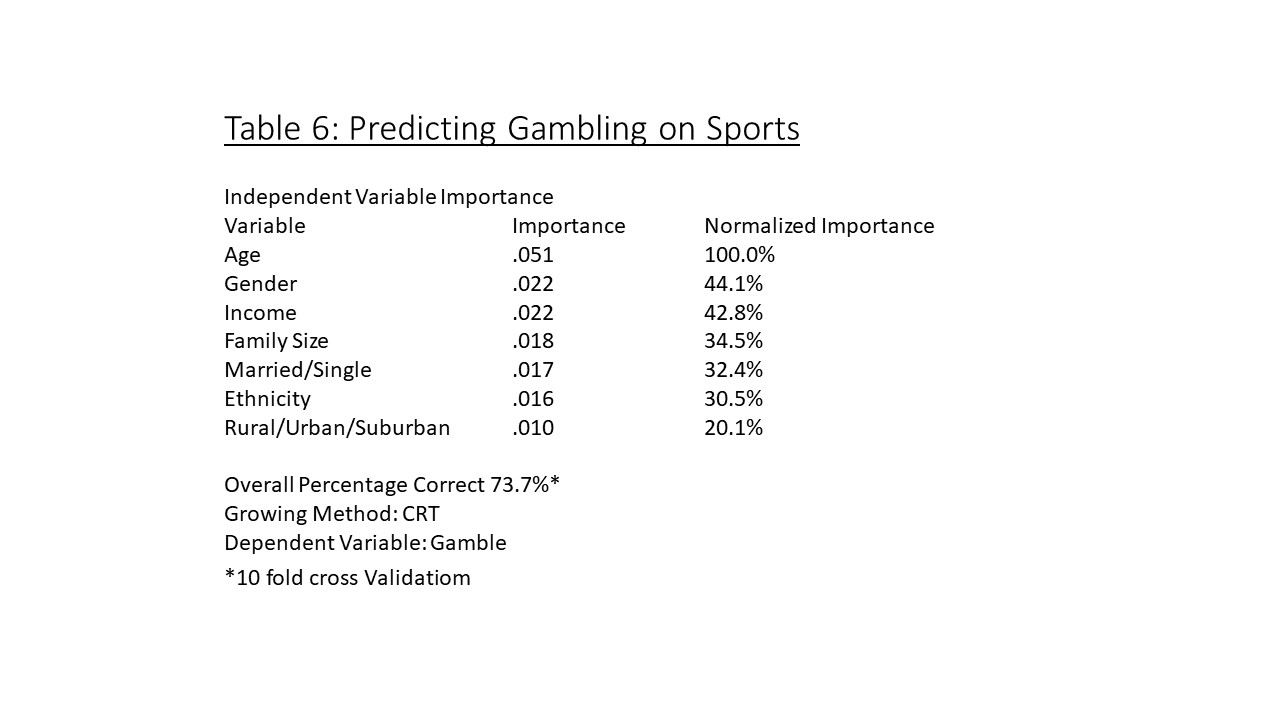

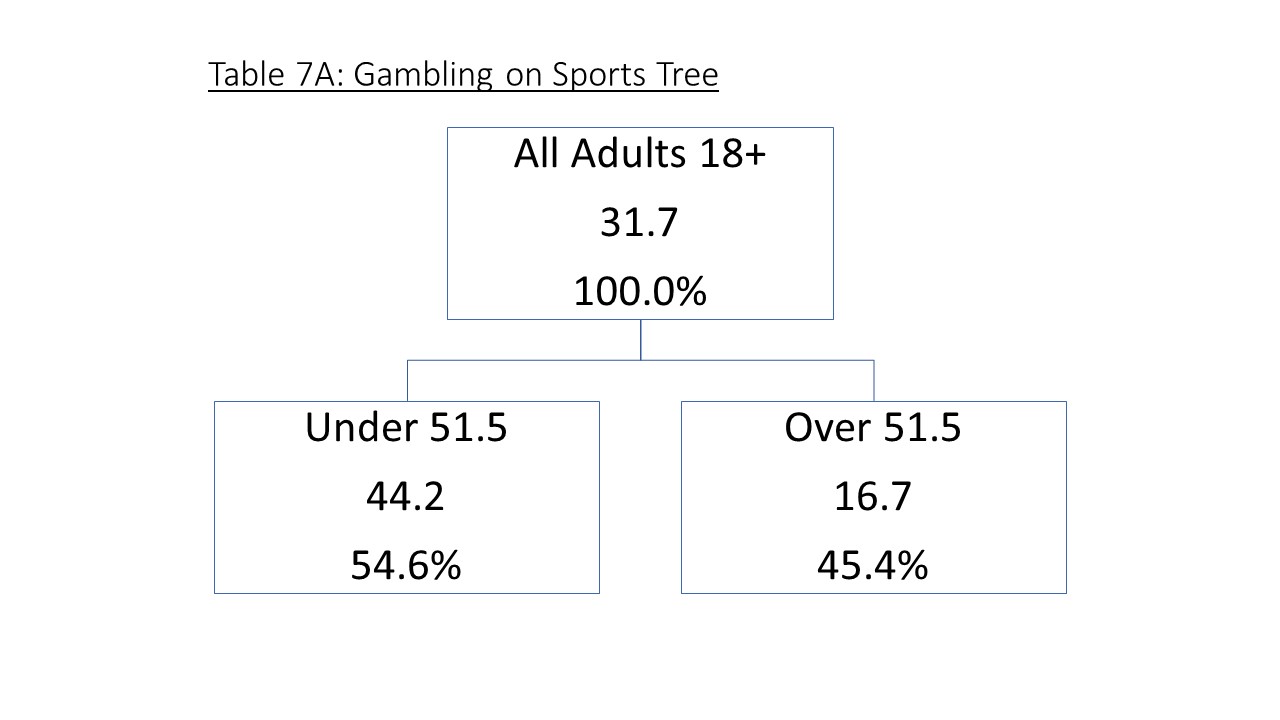

Using a classification regression tree (CRT) to predict gambling on sports allows for the identification of consumer segments that have high rates of gambling on sports. Table 6 shows the results of such analysis and the important predictor variables. The most important predictor, by far, is age. This is followed by gender, income, family size, marital status, ethnicity, and population density. The model itself is reasonably strong, predicting a bettor 73.7% of the time using 10-fold cross-validation.

The tree itself identifies the segments as terminal nodes, as shown in Table 7. The highest node, those under 44, male, incomes over $106.5K, and married report 81.2% betting on sports and comprise 5.3% of the total population of adults. Slight older, ranging from 44 to 51, report 67.7% betting. Under 51, males, over $1065k and are single (never married) report 60.9% and comprise 1.6% of adults. Males under the age of 51 with incomes between $53k and $106K living in an urban area report 64.0%, and males in suburban and rural areas report 50.6%. Males under the age of 51 with incomes less than $53K, who are non-white report 51.1% gambling on sports and comprise 6.3% of the total population. These are all the male segments above 40% of sports gambling.

The female side of the tree shows non-white with a family size of four or more at 45.3%, comprising 5.4% of the total sample. Non-white females, with a family size of less than four, and younger than 36 report 40.0% gambling and comprise 4.0% of the total sample. Among the older segments are males earning over $53K, aged 52 to 55, reporting 49.6% gambling, and African American males earning under $53K, aged 52 to 63, reporting 44.9% gambling.

Sports Program Viewing

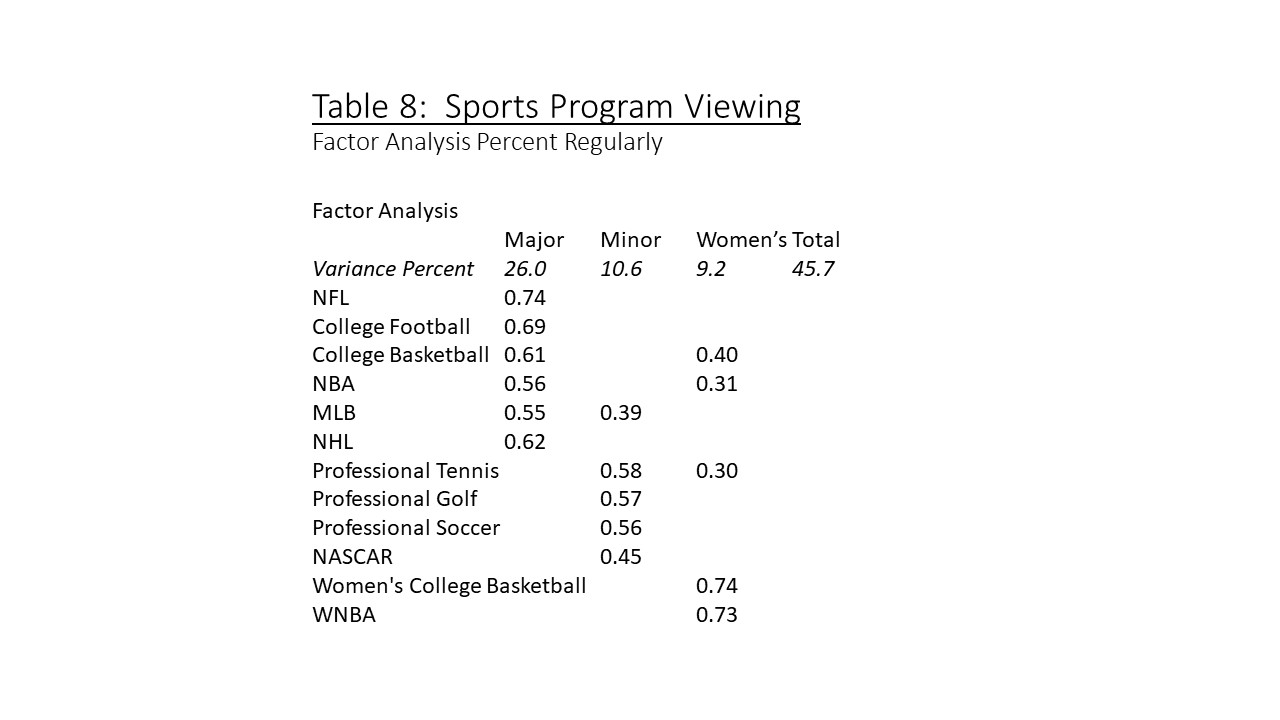

Respondents were asked if they regularly viewed 12 different sporting events. To establish a pattern, the 12 were factor-analyzed (principal component) as shown in Table 8. The viewing patterns are arranged in three groups labeled “major,” which includes the NFL, college football, and other team sports of broad interest. The analysis shows that those who report viewing the NFL are also likely to watch college football. The second group, labeled “minor,” includes professional tennis and golf and have a narrower level of interest and are not thought of as team sports. The third group is labelled “women’s” for woman’s sports..”

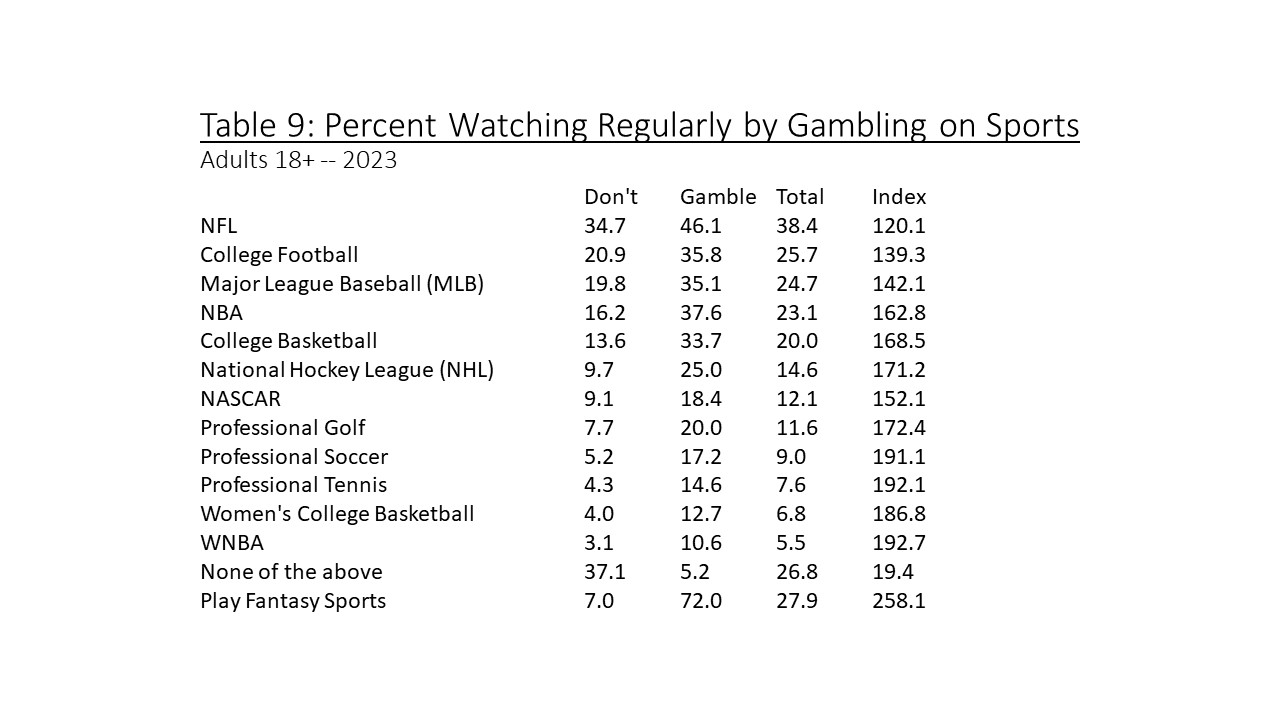

Relating the viewing to gambling on sports is shown in Table 9. Overall, 73.2% of adults report viewing at least one of the categories of sports programming. The NFL is viewed by 38.4% of adults, followed by college football, major league baseball, and the NBA. Sports betting is certainly related to viewing, as in the case of the NFL, where 46.1% of the viewers compared to 34.7% of the viewers do not gamble, providing a gambling index of 120.1. The major sports have an average index of 150.7, minor sports have an average index of 176.9, and women’s sports have the highest average index of 189.8. Minor, less team-oriented sports, and especially women’s sports, are of greater relative interest to gamblers.

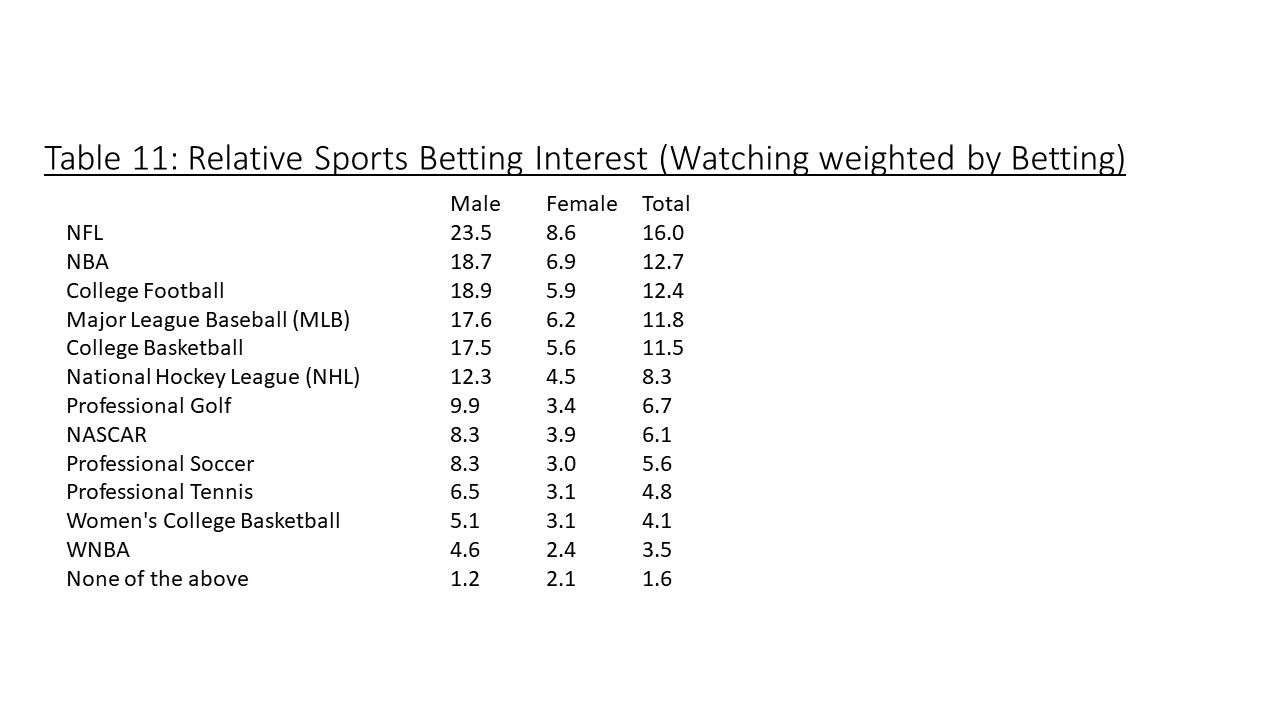

Weighting sports betting by regular viewing demonstrates the relative interest in the sports category, as shown in Table 11. The NFL overall leads sports betting activity, followed by the NBA, college football, major league baseball, and college basketball. All these categories are team-oriented and of broad interest.

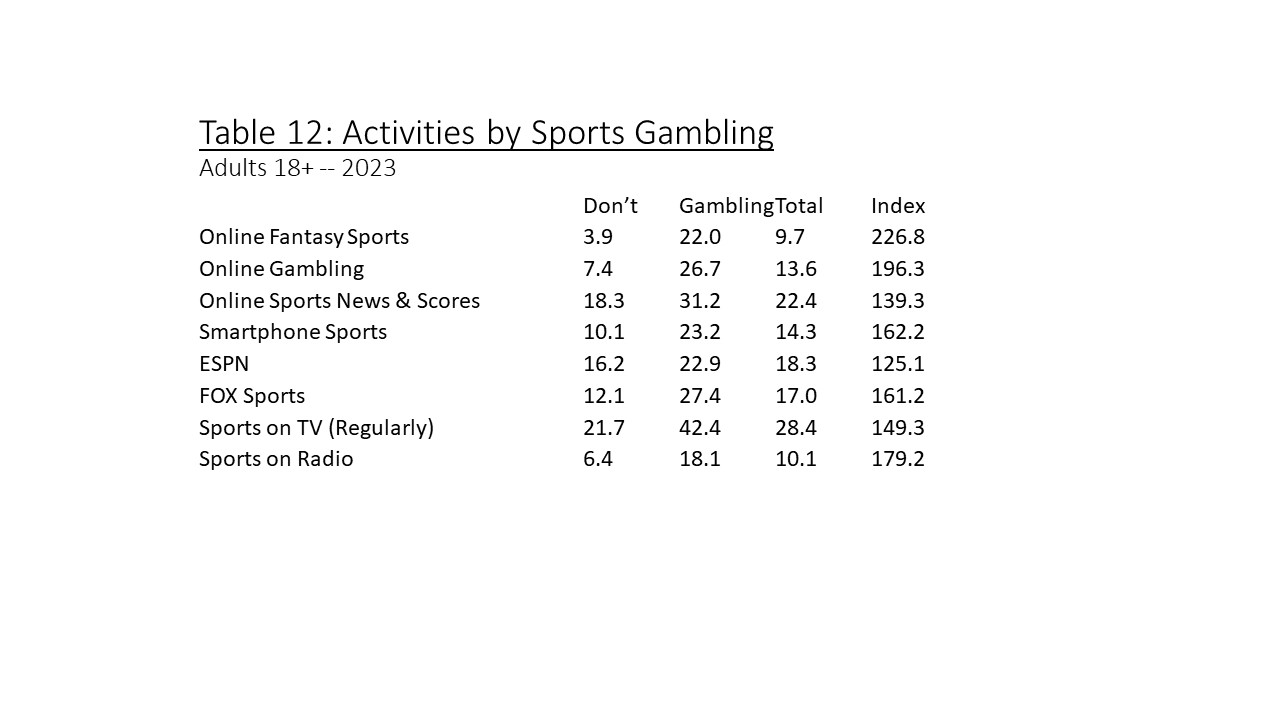

Those who report gambling on sports are more likely to engage in a variety of sports-related activities, as shown in Table 12. Engaging in online fantasy sports and online gambling index at almost double. Sports on the radio and smartphones are higher than regularly watching sports on TV. Fox Sports indexes higher than ESPN.

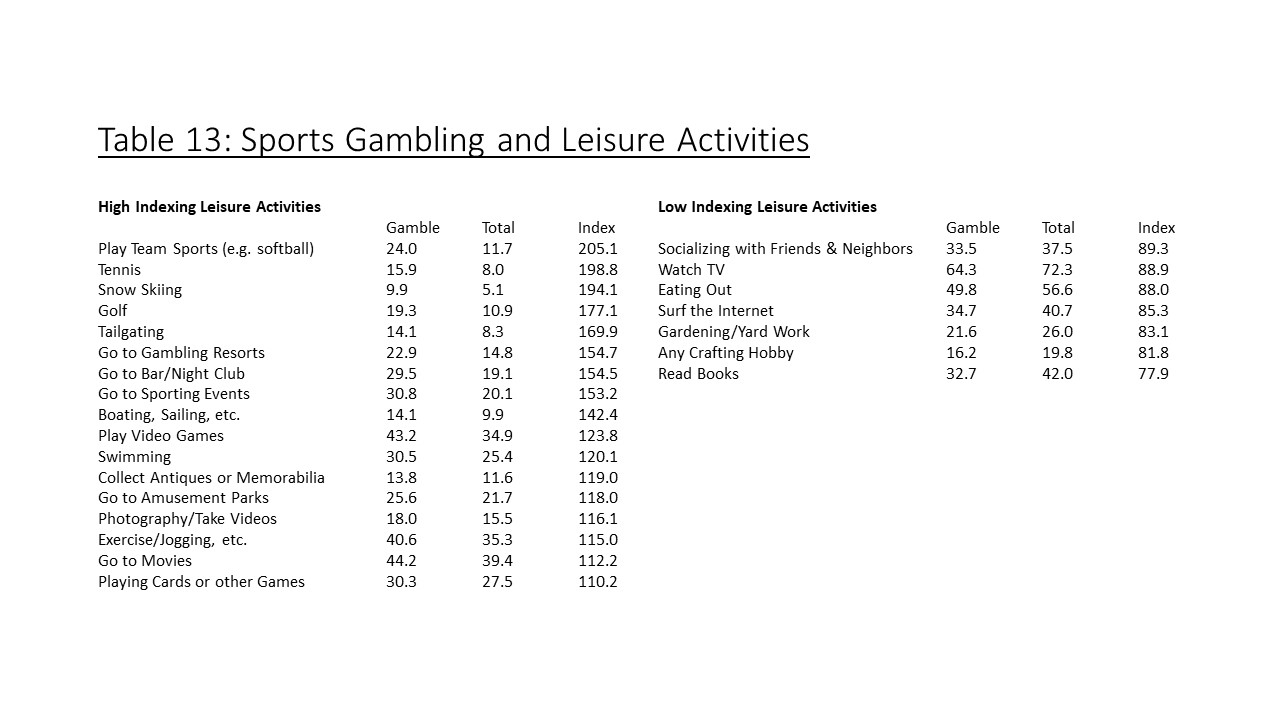

Respondents were also asked about 31 different leisure activities, which are compared to reported gambling on sports, as shown in Table 13. The highest indexing activity is playing team sports. Also high are very active categories such as tennis and snow skiing. Social activities, such as tailgating and going to gambling resorts, bars, and sporting events are also high. The image of sports betting is being social, interested in competition, and physically active. On the other hand, those indexing low is generally passive and perhaps a bit more solitary, reporting activities such as watching TV, surfing the internet, crafting hobbies, and reading books. Those activities are indexed at nearly the same (not shown) as going shopping, online communities, and travel.

Product Consumption

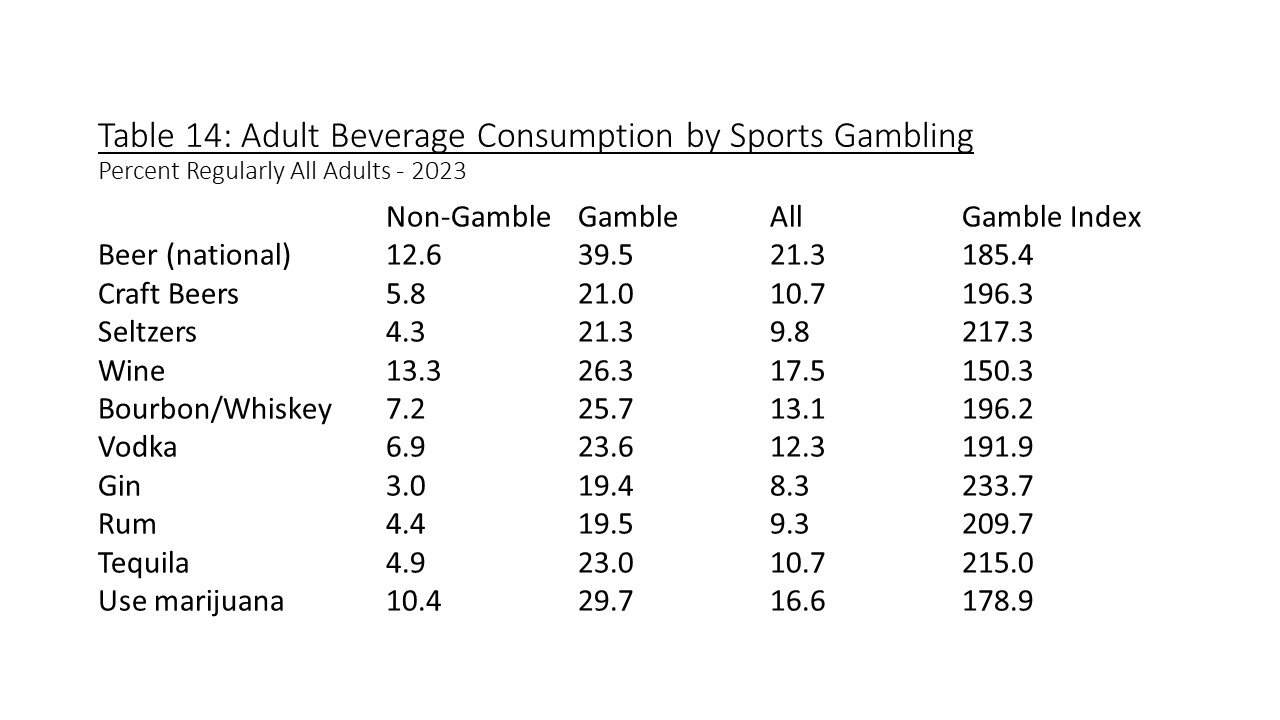

Consumption of alcoholic drinks is commonly associated with viewing and gambling on sports. Table 14 shows this to be true as most categories of drinks index at almost double among those that gamble. The lowest index is wine.

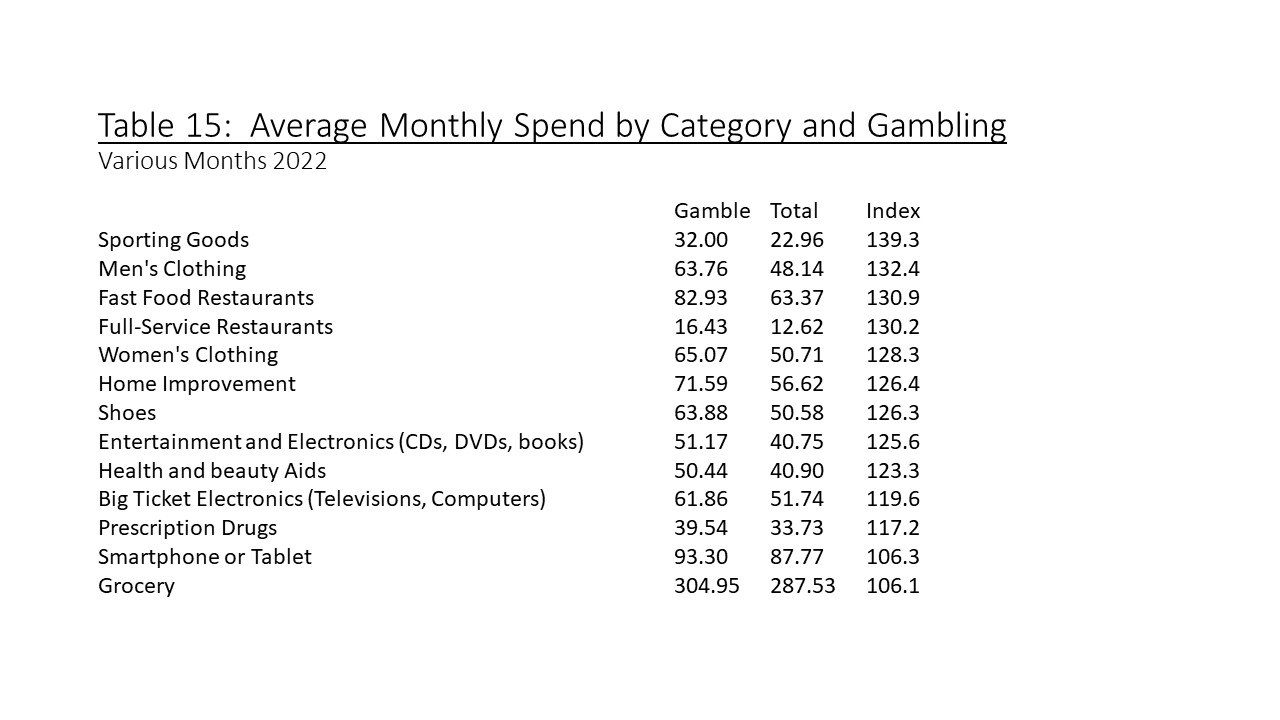

Average monthly product spending is collected monthly, with the categories rotating across different months. The data from the monthly surveys (average n=7,500) needs to be integrated with the annual MBI, which is done using decision tree equations from available demographic variables common to both the monthly and MBI studies. Shown in Table 15 are the average reported household monthly spending across a variety of product categories. The months are taken from 2022 prior to the 2023 MBI. The averages include zero if the respondent reports no spending in that category. The highest indexing category is sporting goods, followed by men’s clothing and both fast food and full-service restaurants. It is worth noting the home improvement spending indexes highly note the characteristics of the sports gambler. Smartphone and grocery spending is almost the same. Overall, those who gamble on sports spend more on average than those who do not.

Personality

Several personality measures were also collected in the MBI including the five-factor personality inventory commonly referred to as OCEAN, grit, and impulsiveness. The personality inventory used by Prosper in the MBI is taken from the short-form version developed by the Gosling Laboratory at the University of Texas. The five factors include:

- Extraversion: Extraversion is characterized by excitability, sociability, talkativeness, assertiveness, and high amounts of emotional expressiveness. People who are high in extroversion are outgoing and tend to gain energy in social situations. People who are low in extroversion (or introverted) tend to be more reserved and must expend energy in social settings.

- Agreeableness: This personality dimension includes attributes such as trust, altruism, kindness, affection, and other prosocial behaviors. People who are high in agreeableness tend to be more cooperative, while those low in this trait tend to be more competitive and even manipulative.

- Conscientiousness: Standard features of this dimension include high levels of thoughtfulness, with good impulse control and goal-directed behaviors. Those high on conscientiousness tend to be organized and mindful of details.

- Neuroticism: Neuroticism is a trait characterized by sadness, moodiness, and emotional instability. Individuals who are high in this trait tend to experience mood swings, anxiety, moodiness, irritability, and sadness. Those low in this trait tend to be more stable and emotionally resilient. This trait is sometimes inversely reported as “emotional stability.” The Prosper database uses the “emotional stability” terminology.

- Openness: This trait features characteristics such as imagination and insight, and those high in this trait also tend to have a broad range of interests. People who are high in this trait tend to be more adventurous and creative. People low in this trait are often much more traditional and may struggle with abstract thinking.

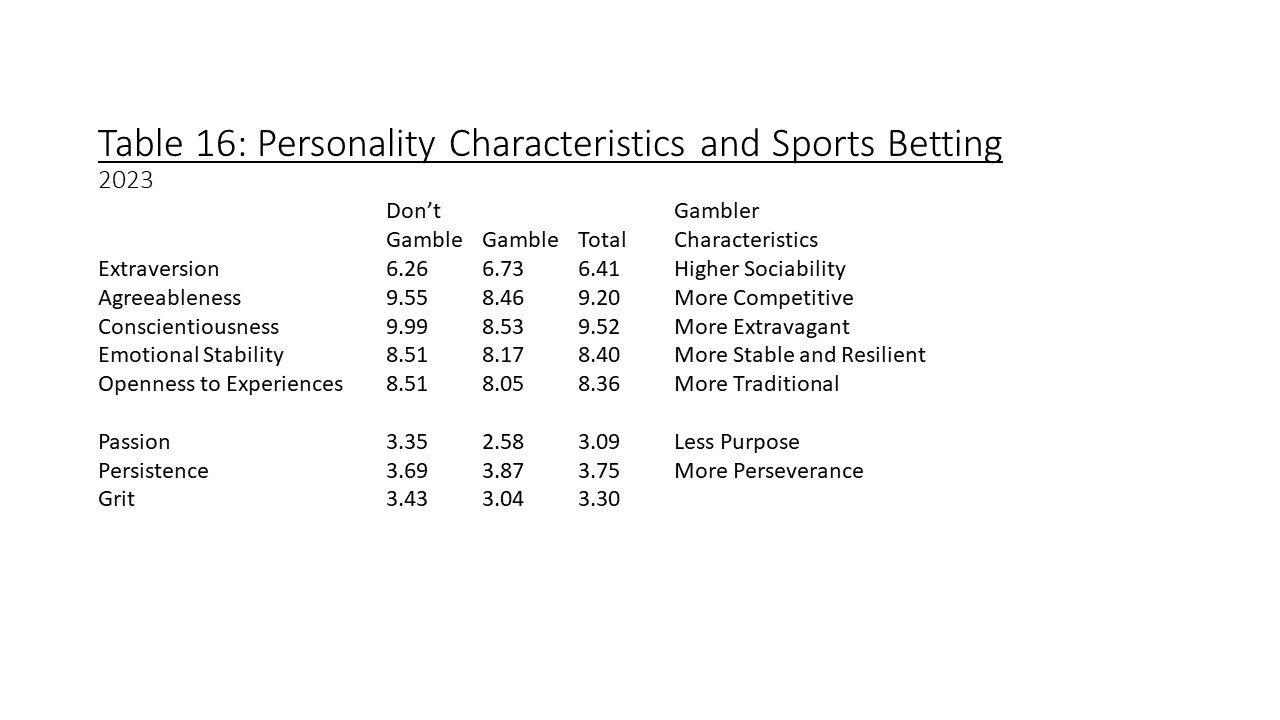

Table 16 shows a comparison of sports gamblers by the five personality traits. All five are statistically different. The biggest differences are gamblers are more competitive and more extravagant with less impulse control. Gamblers also have higher sociability, are more traditional, and are less likely to think abstractly. They are also more emotionally stable and resilient.

A non-cognitive predictor of success in life, such as grit, like having a clear inner compass that guides all your decisions and actions. Grit is defined as the disposition to demonstrate perseverance and passion for long-term goals (Angela Duckworth, Grit: The Power of Passion and Perseverance , Scribner, 2016). Passion is a deep, enduring knowledge of what you want. Perseverance is hard work and resilience. All three predictors are expressed as a five-point scale, with higher values being stronger on the characteristics developed from a series of five-points. Prosper used the short-scale version.

Again, shown in Table 16 is the comparison of sports gamblers. All the differences are statistically different. Gamblers have lower overall grit, meaning they are less oriented toward long-term goals. The biggest difference for gamblers is lower passion, that is knowledge of what they want. Gamblers are higher in perseverance.

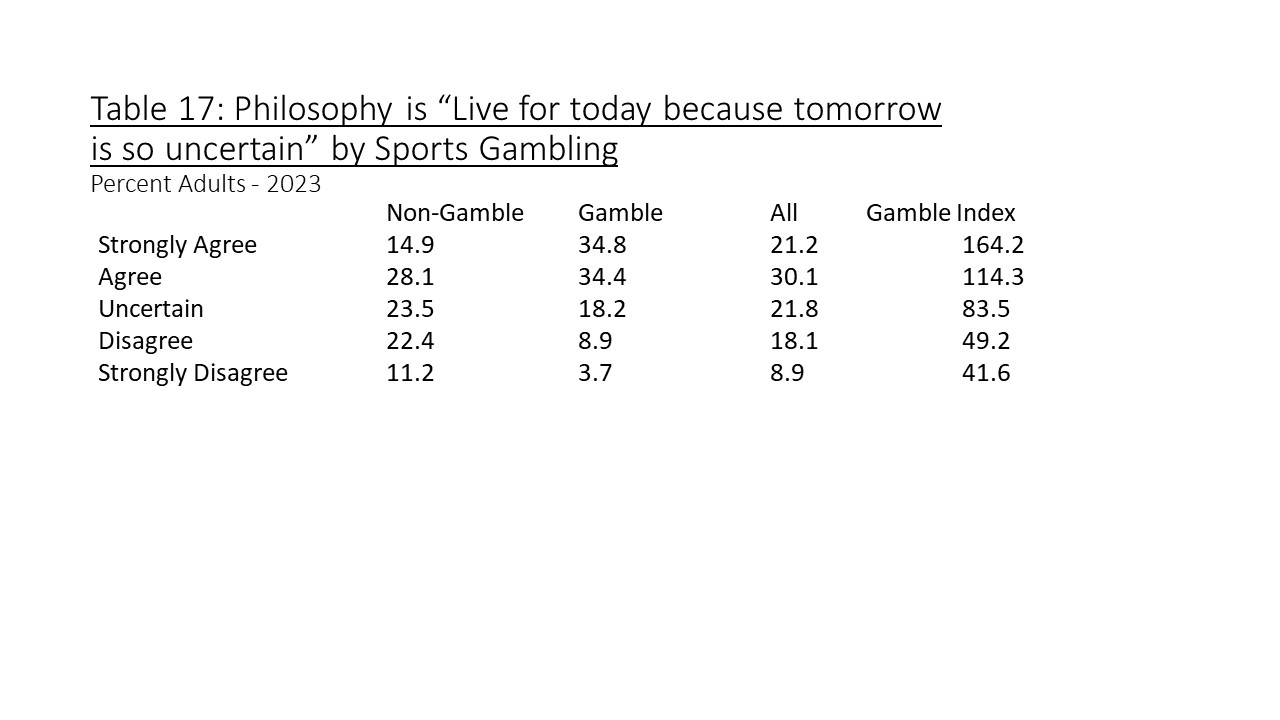

Impulsivity, as measured by agreement with the statement “Live for today because tomorrow is so uncertain,” also demonstrates a difference among gamblers, as shown in Table 17. Gamblers are much more likely to strongly agree with the statement and, conversely, strongly disagree. This reinforces the lack of long-term orientation among gamblers.

The Prosper Media Behavior and Influence study from January 2023 unveils the rising interest in sports betting, emphasizing the convergence of sports gambling and fantasy sports. The analysis explores demographic predictors, revealing age, gender, income, and marital status as key factors influencing sports betting engagement. Furthermore, the study uncovers correlations between sports program viewing, personality traits, leisure activities, and product consumption, painting a comprehensive picture of the diverse profile of sports gamblers.

Articles on Sports betting

Displaying 1 - 20 of 59 articles.

How the 18th-century ‘probability revolution’ fueled the casino gambling craze

John Eglin , University of Montana

Professional sport commissioners are fighting to preserve league integrity amid gambling scandals

Craig Greenham , University of Windsor

Sports gambling creates a windfall, but raises questions of integrity – here are three lessons from historic sports-betting scandals

Jared Bahir Browsh , University of Colorado Boulder

March Madness brings unique gambling risks for college students

M. Dolores Cimini , University at Albany, State University of New York

Why March Madness is a special time of year for state budgets

Jay L. Zagorsky , Boston University

Ads, food and gambling galore − 5 essential reads for the Super Bowl

Nick Lehr , The Conversation

The Super Bowl gets the Vegas treatment, with 1 in 4 American adults expected to gamble on the big game

Thomas Oates , University of Iowa

Colleges face gambling addiction among students as sports betting spreads

Jason W. Osborne , Miami University

How AI and AR could increase the risk of problem gambling for online sports betting

Philip Newall , University of Bristol and Jamie Torrance , University of Chester

Australia has a strong hand to tackle gambling harm. Will it go all in or fold?

Charles Livingstone , Monash University

Sport is being used to normalise gambling. We should treat the problem just like smoking

Grattan on Friday: Peter Dutton warns of threat to ‘working poor’ in budget reply lacking a big picture

Michelle Grattan , University of Canberra

Premier League’s front-of -shirt gambling ad ban is a flawed approach. Australia should learn from it

Samantha Thomas , Deakin University ; Hannah Pitt , Deakin University , and Simone McCarthy , Deakin University

As March Madness looms, growth in legalized sports betting may pose a threat to college athletes

How the push to end tobacco advertising in the 1970s could be used to curb gambling ads today

Carolyn Holbrook , Deakin University and Thomas Kehoe

Gambling Act review: how EU countries are tightening restrictions on ads and why the UK should too

Raffaello Rossi , University of Bristol ; Agnes Nairn , University of Bristol ; Ben Ford , University of Bristol , and Jamie Wheaton , University of Bristol

A boon for sports fandom or a looming mental health crisis? 5 essential reads on the effects of legal sports betting

Data from New Jersey is a warning sign for young sports bettors

Lia Nower , Rutgers University

Millions of Americans are problem gamblers – so why do so few people ever seek treatment?

James P. Whelan , University of Memphis

I treat people with gambling disorder – and I’m starting to see more and more young men who are betting on sports

Tori Horn , University of Memphis

Related Topics

- Gambling addiction

- Gambling harm

- Gambling in America

- Gambling reform

- Online gambling

- Problem gambling

Top contributors

Associate Professor, School of Public Health and Preventive Medicine, Monash University

Knight Chair in Sports Journalism and Society, Penn State

Lecturer and Researcher in Psychology, Swansea University

Professor of Public Health, Deakin University

PhD Student in Clinical Psychology, University of Memphis

Principal Research Fellow, CQUniversity Australia

Professor and Director, Center for Gambling Studies, Rutgers University

Clinical Psychologist, University of Sydney

Associate Professor of Markets, Public Policy and Law, Boston University

Researcher, School of Psychology, University of Sydney

Postdoctoral Research Fellow, Deakin University

Research Professor of Clinical Health, University of Memphis

VicHealth Postdoctoral Research Fellow, Deakin University

Assistant Professor of Psychology, East Tennessee State University

Lecturer in the School of Psychological Science, University of Bristol

- X (Twitter)

- Unfollow topic Follow topic

Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

A statistical theory of optimal decision-making in sports betting

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliation Dept of Biomedical Engineering, City College of New York, New York, NY, United States of America

- Jacek P. Dmochowski

- Published: June 28, 2023

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0287601

- Peer Review

- Reader Comments

The recent legalization of sports wagering in many regions of North America has renewed attention on the practice of sports betting. Although considerable effort has been previously devoted to the analysis of sportsbook odds setting and public betting trends, the principles governing optimal wagering have received less focus. Here the key decisions facing the sports bettor are cast in terms of the probability distribution of the outcome variable and the sportsbook’s proposition. Knowledge of the median outcome is shown to be a sufficient condition for optimal prediction in a given match, but additional quantiles are necessary to optimally select the subset of matches to wager on (i.e., those in which one of the outcomes yields a positive expected profit). Upper and lower bounds on wagering accuracy are derived, and the conditions required for statistical estimators to attain the upper bound are provided. To relate the theory to a real-world betting market, an empirical analysis of over 5000 matches from the National Football League is conducted. It is found that the point spreads and totals proposed by sportsbooks capture 86% and 79% of the variability in the median outcome, respectively. The data suggests that, in most cases, a sportsbook bias of only a single point from the true median is sufficient to permit a positive expected profit. Collectively, these findings provide a statistical framework that may be utilized by the betting public to guide decision-making.

Citation: Dmochowski JP (2023) A statistical theory of optimal decision-making in sports betting. PLoS ONE 18(6): e0287601. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0287601

Editor: Baogui Xin, Shandong University of Science and Technology, CHINA

Received: December 19, 2022; Accepted: June 8, 2023; Published: June 28, 2023

Copyright: © 2023 Jacek P. Dmochowski. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Data Availability: Data is available at https://github.com/dmochow/optimal_betting_theory .

Funding: The author received no specific funding for this work.

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Introduction

The practice of sports betting dates back to the times of Ancient Greece and Rome [ 1 ]. With the much more recent legalization of online sports wagering in many regions of North America, the global betting market is projected to reach 140 billion USD by 2028 [ 2 ]. Perhaps owing to its ubiquity and market size, sports betting has historically received considerable interest from the scientific community [ 3 ].

A topic of obvious relevance to the betting public, and one that has also been the subject of multiple studies, is the efficiency of sports betting markets [ 4 ]. While multiple studies have reported evidence for market inefficiencies [ 5 – 11 ], others have reached the opposite conclusion [ 12 , 13 ]. The discrepancy may signify that certain, but not all, sports markets exhibit inefficiencies. Research into sports betting has also revealed insights into the utility of the “wisdom of the crowd” [ 14 – 16 ], the predictive power of market prices [ 17 – 20 ], quantitative rating systems [ 21 , 22 ], and the important finding that sportsbooks exploit public biases to maximize their profits [ 13 , 23 ].

Indeed, the decisions made by sportsbooks to set the offered odds and payouts have been previously analyzed [ 13 , 23 , 24 ]. On the other hand, arguably less is known about optimality on the side of the bettor . The classic paper by Kelly [ 25 ] provides the theory for optimizing betsize (as a function of the likelihood of winning the bet) and can readily be applied to sports wagering. The Kelly bet sizing procedure and two heuristic bet sizing strategies are evaluated in the work of Hvattum and Arntzen [ 26 ]. The work of Snowberg and Wolfers [ 27 ] provides evidence that the public’s exaggerated betting on improbable events may be explained by a model of misperceived probabilities. Wunderlich and Memmert [ 28 ] analyze the counterintuitive relationship between the accuracy of a forecasting model and its subsequent profitability, showing that the two are not generally monotonic. Despite these prior works, idealized statistical answers to the critical questions facing the bettor, namely what games to wager on, and on what side to bet, have not been proposed. Similarly, the theoretical limits on wagering accuracy, and under what statistical conditions they may be attained in practice, are unclear.

To that end, the goal of this paper is to provide a statistical framework by which the astute sports bettor may guide their decisions. Wagering is cast in probabilistic terms by modeling the relevant outcome (e.g. margin of victory) as a random variable. Together with the proposed sportsbook odds, the distribution of this random variable is employed to derive a set of propositions that convey the answers to the key questions posed above. This theoretical treatment is complemented with empirical results from the National Football League that instantiate the derived propositions and shed light onto how closely sportsbook prices deviate from their theoretical optima (i.e., those that do not permit positive returns to the bettor).

Importantly, it is not an objective of this paper to propose or analyze the utility of any specific predictors (“features”) or models. Nevertheless, the paper concludes with an attempt to distill the presented theorems into a set of general guidelines to aid the decision making of the bettor.

Problem formulation: “Point spread” betting

For positive s (home team favored), the home team is said to “cover the spread” if m > s , whereas the visiting team has “beat the spread” otherwise. Conversely, for negative s (visiting team favored), the visiting team covers the spread if m < s , and the home team has beat the spread otherwise. The home (visiting) team is said to win “against the spread” if m − s is positive (negative).

Denote the profit (on a unit bet) when correctly wagering on the home and visiting teams by ϕ h and ϕ v , respectively. Assuming a bet size of b placed on the home team, the conventional payout structure is to award the bettor with b (1 + ϕ h ) when m > s . The entire wager is lost otherwise. The total profit π is thus bϕ h when correctly wagering on the home team (− b otherwise). When placing a bet of b on the visiting team, the bettor receives b (1 + ϕ v ) if m < s and 0 otherwise. Typical values of ϕ h and ϕ v are 100/110 ≈ 0.91, corresponding to a commission of 4.5% charged by the sportsbook.

In practice, the event m = s (termed a “push”) may have a non-zero probability and results in all bets being returned. In keeping with the modeling of m by a continuous random variable, here it is assumed that P ( m = s ) = 0. This significantly simplifies the development below. Note also that for fractional spreads (e.g. s = 3.5), the probability of a push is indeed zero.

Wagering to maximize expected profit.

Consider first the question of which team to wager on to maximize the expected profit. As the profit scales linearly with b , a unit bet size is assumed without loss of generality.

Corollary 1 . Assuming equal payouts for home and visiting teams ( ϕ h = ϕ v ), maximization of expected profit is achieved by wagering on the home team if and only if the spread is less than the median margin of victory .

A subtle but important point is that knowledge of which side to bet on for each match is insufficient for maximizing overall profit. The reason is that even if wagering on the side with higher expected profit, it is possible (and in fact quite common, see empirical results below) that the “optimal” wager carries a negative expectation. Thus, an understanding of when wagering should be avoided altogether is required. This is the subject of the theorem below.

It is instructive to consider the conditions above for typical values of ϕ h and ϕ v . When wagering on the home team with ϕ h = 0.91, positive expectation requires the spread to be no larger than the 0.476 quantile of m . When wagering on the visiting team, the spread must exceed the 0.524 quantile. This means that, if the spread is contained within the 0.476-0.524 quantiles of the margin of victory, wagering should be avoided . Practically, it is thus important to obtain estimates of this interval and its proximity to the median score in units of points .

The result of Theorem 2 is reminiscent of the “area of no profitable bet” scenario described in [ 28 ]. Whereas the latter result is presented in terms of outcome probabilities estimated by the bettor and the sportsbook, Theorem 2 here delineates the conditions under which the sportsbook’s point spread assures a negative expectation on the bettor’s side.

Optimal estimation of the margin of victory.

Theorem 3 . Define an “error” as a wager that is placed on the team that loses against the spread. The probability of error is bounded according to : min{ F m ( s ), 1 − F m ( s )} ≤ p (error) ≤ max{ F m ( s ), 1 − F m ( s )}.

The result of Theorem ( 8 ) provides both the best- and worst-case scenario of a given wager. When F m ( s ) is close to 1/2, both the minimum and maximum error rates are near 50%, and wagering is reduced to an event akin to a coin flip. On the other hand, when the true median is far from the spread (i.e., F m ( s ) deviates from 1/2), the minimum and maximum error rates diverge, increasing the highest achievable accuracy of the wager.

Optimality in “moneyline” wagering

Corollary 4 . Define an “error” as a wager that is placed on the team that loses the match outright. The probability of error in moneyline wagering is bounded according to : min{ F m (0), 1 − F m (0)} ≤ p (error) ≤ max{ F m (0), 1 − F m (0)}.

Notice that optimal decision-making in moneyline wagers requires knowledge of quantiles that may be near 0 (if ϕ v ≫ ϕ h ) or near 1 (if ϕ h ≫ ϕ v ). More subtly, the required quantiles will differ for matches that exhibit different payout ratios. For example, a match with two even sides will require knowledge of central quantiles, while a match with a 4:1 favorite will require knowledge of the 80th and 20th percentiles. The implications of this property on quantitative modeling are described in the Discussion .

The moneyline wagering considered in this section is a two-alternative bet that is popular in North American sports. In European betting markets, the most common type of wager is the three-alternative “Home-Draw-Away” bet where there is no point spread and the task of the bettor is to forecast one of the three potential outcomes: m > 0, m = 0, or m < 0, each of which are endowed with a payout (see, for example, [ 26 , 29 , 30 ]). Clearly the the probability p ( m = 0) will be non-zero in this context. As a result, the methodology here, which models m by a continuous random variable, cannot be straightforwardly applied to the case of the Home-Draw-Away bet. The extension of the present findings to the case of multi-way bets with discrete m is a potential topic of future research.

Optimality in “over-under” betting

The following two results may be proven by replacing m with τ , ϕ h with ϕ o , and ϕ v with ϕ u in the Proofs of Theorems 1 and 2, respectively.

In the special case of ϕ o = ϕ u , one should bet on the over only if and only if the sportsbook total τ falls below the median of t .

Define F t ( τ ) as the CDF of the true point total evaluated at the sportsbook’s proposed total. The following corollary may be proven by following the Proof of Theorem 3.

Corollary 8 . Define an “error” in over-under betting as a wager that is placed on the “over” when t < τ or on the “under” when t > τ. The probability of error is bounded according to : min{ F t ( τ ), 1 − F t ( τ )} ≤ p (error) ≤ max{ F t ( τ ), 1 − F t ( τ )}.

Empirical results from the National Football League

In order to connect the theory to a real-world betting market, empirical analyses utilizing historical data from the National Football League (NFL) were conducted. The margins of victory, point totals, sportsbook point spreads, and sportsbook point totals were obtained for all regular season matches occurring between the 2002 and 2022 seasons ( n = 5412). The mean margin of victory was 2.19 ± 14.68, while the mean point spread was 2.21 ± 5.97. The mean point total was 44.43 ± 14.13, while the mean sportsbook total was 43.80 ± 4.80. The standard deviation of the margin of victory is nearly 7x the mean, indicating a high level of dispersion in the margin of victory, perhaps due to the presence of outliers. Note that the standard deviation of a random variable provides an upper bound on the distance between its mean and median [ 31 ], which is relevant to the problem at hand.

To estimate the distribution of the margin of victory for individual matches, the point spread s was employed as a surrogate for θ . The underlying assumption is that matches with an identical point spread exhibit margins of victory drawn from the same distribution. Observations were stratified into 21 groups ranging from s o = −7 to s o = 10. This procedure was repeated for the analysis of point totals, where observations were stratified into 24 groups ranging from t o = 37 to t o = 49.

How accurately do sportsbooks capture the median outcome?

It is important to gain insight into how accurately the point spreads proposed by sportsbooks capture the median margin of victory. For each stratified sample of matches, the median margin of victory was computed and compared to the sample’s point spread. The distribution of margin of victory for matches with a point spread s o = 6 is shown in Fig 1a , where the sample median of 4.34 (95% confidence interval [2.41,6.33]; median computed with kernel density estimation to overcome the discreteness of the margin of victory; confidence interval computed with the bootstrap) is lower than the sportsbook point spread. However, the sportsbook value is contained within the 95% confidence interval.

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

( a ) The distribution of margin of victory for National Football League matches with a consensus sportsbook point spread of s = 6. The median outcome of 4.26 (dashed orange line, computed with kernel density estimation) fell below the sportsbook point spread (dashed blue line). However, the 95% confidence interval of the sample median (2.27-6.38) contained the sportsbook proposition of 6. ( b ) Same as (a), but now showing the distribution of point total for all matches with a sportsbook point total of 46. Although the sportsbook total exceeded the median outcome by approximately 1.5 points, the confidence interval of the sample median (42.25-46.81) contained the sportsbook’s proposition. ( c ) Combining all stratified samples, the sportsbook’s point spread explained 86% of the variability in the median margin of victory. The confidence intervals of the regression line’s slope and intercept included their respective null hypothesis values of 1 and 0, respectively. ( d ) The sportsbook point total explained 79% of the variability in the median total. Although the data hints at an overestimation of high totals and underestimation of low totals, the confidence intervals of the slope and intercept contained the null hypothesis values.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0287601.g001

Aggregating across stratified samples, the sportsbook point spread explained 86% of the variability in the true median margin of victory ( r 2 = 0.86, n = 21; Fig 1c ). Both the slope (0.93, 95% confidence interval [0.81,1.04]) and intercept (-0.41, 95% confidence interval [-1.03,0.16]) of the ordinary least squares (OLS) line of best fit (dashed blue line) indicate a slight overestimation of the margin of victory by the point spread. This is most apparent for positive spreads (i.e., a home favorite). Nevertheless, the confidence intervals of both the slope and intercept did include the null hypothesis values of 1 and 0, respectively. The data for all sportsbook point spreads with at least 100 matches is provided in Table 1 .

Regular season matches from the National Football League occurring between 2002-2022 were stratified according to their sportsbook point spread. Each set of 3 grouped rows corresponds to a subsample of matches with a common sportsbook point spread. The “level” column indicates whether the row pertains to the 95% confidence interval (0.025 and 0.975 quantiles) or the mean value across bootstrap resamples. The dependent variables include the 0.476, 0.5, and 0.524 quantiles, as well as the expected profit of wagering on the side with higher likelihood of winning the bet for hypothetical point spreads that deviate from the median outcome by 1, 2, and 3 points, respectively.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0287601.t001

The distribution of observed point totals for matches with a sportsbook total of τ = 46 is shown in Fig 1b , where the computed median of 44.45 (95% confidence interval [42.25,46.81]) is suggestive of a slight overestimation of the true total. Combining data from all samples, the sportsbook point total explained 79% of the variability in the median point total ( r 2 = 0.79, n = 24; Fig 1d ).

Interestingly, the data hints at the sportsbook’s proposed point total underestimating the true total for relatively low totals (i.e., black line is below the blue for sportsbook totals below 43), while overestimating the total for those matches expected to exhibit high scoring (i.e., black line is above the blue line for sportsbook totals above 43). Note, however, that the confidence intervals of the regression line (slope: [0.72,1.02], intercept: [-1.14, 12.05]) did contain the null hypothesis values. The data for all sportsbook point total with at least 100 samples is provided in Table 2 .

Matches were stratified into 24 subsamples defined by the value of the sportsbook total. The dependent variables are the 0.476, 0.5, and 0.524 quantiles of the true point total, as well as the expected profit of wagering conditioned on the amount of bias in the sportsbook’s total.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0287601.t002

Do sportsbook estimates deviate from the 0.476-0.524 interval?

In the common case of ϕ = 0.91, a positive expected profit is only feasible if the point spread (or point total) is either below the 0.476 or above the 0.524 quantiles of the outcome’s distribution. It is thus interesting to consider how often this may occur in a large betting market such as the NFL. To that end, the 0.476 and 0.524 quantiles of the margin of victory were estimated in each stratified sample (horizontal bars in Fig 2 ; the point spread is indicated with an orange marker; all quantiles are listed in Table 1 ).

With a standard payout of ϕ = 0.91, achieving a positive expected profit is only feasible if the sportsbook point spread falls outside of the 0.476-0.524 quantiles of the margin of victory. The 0.476 and 0.524 quantiles were thus estimated for each stratified sample of NFL matches. Light (dark) black bars indicate the 95% confidence intervals of the 0.476 (0.524) quantiles. Orange markers indicate the sportsbook point spread, which fell within the quantile confidence intervals for the large majority of stratifications. An exception was s = 5, where the sportsbook appeared to overestimate the margin of victory. For two other stratifications ( s = 3 and s = 10), the 0.524 quantile tended to underestimate the sportsbook spread, with the 95% confidence intervals extending to just above the spread.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0287601.g002

For the majority of samples, the confidence intervals of the 0.476 and 0.524 quantiles contained the sportsbook spread. One exception was the spread s = 5, where the margin of victory fell below the sportsbook value (95% confidence interval of the 0.524 quantile: [0.87,4.85]). The margin of victory for s = 3 (95% confidence interval of the 0.524 quantile: [0.78,3.08]) and s = 10 (95% confidence interval of the 0.524 quantile: [6.42,10.06]) also tended to underestimate the sportsbook spread, with the confidence intervals just containing the sportsbook value.

The analysis was repeated for point totals ( Fig 3 , all quantiles listed in Table 2 ). All but one stratified sample exhibited 0.476 and 0.524 quantiles whose confidence intervals contained the sportsbook total ( t = 47, [41.59, 45.42]). Examination of the sample quantiles suggests that NFL sportsbooks are very adept at proposing point totals that fall within 2.4 percentiles of the median outcome.

The 0.476 and 0.524 quantiles of the true point total were estimated for each stratified sample of NFL matches. For all but one stratification ( t = 47, 95% confidence interval [41.59-45.42], sportsbook overestimates the total), the confidence intervals of the sample quantiles contained the sportsbook proposition. Visual inspection of the data suggests that, in the NFL betting market at least, sportsbooks are very adept at proposing totals that fall within the critical 0.476-0.524 quantiles.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0287601.g003

How large of a discrepancy from the median is required for profit?

In practice, it is desirable to have an understanding of how large of a sportsbook bias, in units of points, is required to permit a positive expected profit. To address this, the value of the empirically measured CDF of the margin of victory was evaluated at offsets of 1, 2, and 3 points from the true median in each direction. The resulting value was then converted into the expected value of profit (see Materials and Methods ). The computation was performed separately within each stratified sample, and the height of each bar in Fig 4 indicates the hypothetical expected profit of a unit bet when wagering on the team with the higher probability of winning against the spread . For the sake of clarity, only the four largest samples ( s ∈ {−3, 2.5, 3, 7}) are shown in the Figure, with data for all samples listed in Table 1 .

In order to estimate the magnitude of the deviation between sportsbook point spread and median margin of victory that is required to permit a positive profit to the bettor, the hypothetical expected profit was computed for point spreads that differ from the true median by 1, 2, and 3 points in each direction. The analysis was performed separately within each stratified sample, and the figure shows the results of the four largest samples. For 3 of the 4 stratifications, a sportsbook bias of only a single point is required to permit a positive expected return (height of the bar indicates the expected profit of a unit bet assuming that the bettor wagers on the side with the higher probability of winning; error bars indicate the 95% confidence intervals as computed with the bootstrap). For a sportsbook spread of s = 3 (dark black bars), the expected profit on a unit bet is 0.021 [0.008-0.035], 0.094 [0.067-0.119], and 0.166 [0.13-0.2] when the sportsbook’s bias is +1, +2, and +3 points, respectively (mean and confidence interval over 500 bootstrap resamples).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0287601.g004

The expected profit is negative (i.e., ( ϕ − 1)/2 = −0.045) when the spread equals the median (center column). Interestingly however, for 3 of the 4 largest stratified samples, a positive profit is achievable with only a single point deviation from the median in either direction (the confidence intervals indicated by error bars do not extend into negative values). Averaged across all n = 21 stratifications, the expected profit of a unit bet is 0.022 ± 0.011, 0.090 ± 0.021, and 0.15 ± 0.030 when the spread exceeds the median by 1, 2, and 3 points, respectively (mean ± standard deviation over n = 21 stratifications, each of which is an average over 1000 bootstrap ensembles). Similarly, the expected return is 0.023 ± 0.013, 0.089 ± 0.026, and 0.15 ± 0.037 when the spread undershoots the median by 1, 2, and 3 points respectively. This indicates that sportsbooks must estimate the median outcome with high precision in order to prevent the possibility of positive returns.

The analysis was repeated on the data of point totals. A deviation from the true median of only 1 point was sufficient to permit a positive expected profit in all four of the largest stratifications ( Fig 5 ; t ∈ {41, 43, 44, 45}; error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals; data for all samples is provided in Table 2 ). When the sportsbook overestimates the median total by 1, 2, and 3 points, the expected profit on a unit bet is 0.014 ± 0.0071, 0.073 ± 0.014, and 0.13 ± 0.020, respectively (mean ± standard deviation over n = 24 samples, each of which is a average over 1000 bootstrap resamples). When the sportsbook underestimates the median, the expected profit on a unit bet is 0.015±0.0071, 0.076± 0.014, and 0.14± 0.020, for deviations of 1, 2, and 3 points, respectively. Note that despite the dependent variable having a larger magnitude (compared to margin of victory), the required sportsbook error to permit positive profit is the same as shown by the analysis of point spreads.