Adjuvant and neoadjuvant breast cancer treatments: A systematic review of their effects on mortality

Affiliations.

- 1 Nuffield Department of Population Health, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK. Electronic address: [email protected].

- 2 Nuffield Department of Population Health, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK. Electronic address: [email protected].

- 3 Nuffield Department of Population Health, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK. Electronic address: [email protected].

- 4 Nuffield Department of Population Health, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK. Electronic address: [email protected].

- 5 St Luke's Radiation Oncology Network, St. James's Hospital, Dublin, Ireland. Electronic address: [email protected].

- 6 Nuffield Department of Population Health, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK. Electronic address: [email protected].

- 7 Nuffield Department of Population Health, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK. Electronic address: [email protected].

- 8 Nuffield Department of Population Health, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK. Electronic address: [email protected].

- PMID: 35367784

- PMCID: PMC9096622

- DOI: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2022.102375

Background: Adjuvant and neoadjuvant breast cancer treatments can reduce breast cancer mortality but may increase mortality from other causes. Information regarding treatment benefits and risks is scattered widely through the literature. To inform clinical practice we collated and reviewed the highest quality evidence.

Methods: Guidelines were searched to identify adjuvant or neoadjuvant treatment options recommended in early invasive breast cancer. For each option, systematic literature searches identified the highest-ranking evidence. For radiotherapy risks, searches for dose-response relationships and modern organ doses were also undertaken.

Results: Treatment options recommended in the USA and elsewhere included chemotherapy (anthracycline, taxane, platinum, capecitabine), anti-human epidermal growth factor 2 therapy (trastuzumab, pertuzumab, trastuzumab emtansine, neratinib), endocrine therapy (tamoxifen, aromatase inhibitor, ovarian ablation/suppression) and bisphosphonates. Radiotherapy options were after breast conserving surgery (whole breast, partial breast, tumour bed boost, regional nodes) and after mastectomy (chest wall, regional nodes). Treatment options were supported by randomised evidence, including > 10,000 women for eight treatment comparisons, 1,000-10,000 for fifteen and < 1,000 for one. Most treatment comparisons reduced breast cancer mortality or recurrence by 10-25%, with no increase in non-breast-cancer death. Anthracycline chemotherapy and radiotherapy increased overall non-breast-cancer mortality. Anthracycline risk was from heart disease and leukaemia. Radiation-risks were mainly from heart disease, lung cancer and oesophageal cancer, and increased with increasing heart, lung and oesophagus radiation doses respectively. Taxanes increased leukaemia risk.

Conclusions: These benefits and risks inform treatment decisions for individuals and recommendations for groups of women.

Keywords: Adjuvant treatments; Breast cancer; Neoadjuvant treatments; Treatment benefits; Treatment harms.

Copyright © 2022 The Authors. Published by Elsevier Ltd.. All rights reserved.

Publication types

- Systematic Review

- Breast Neoplasms* / drug therapy

- Breast Neoplasms* / pathology

- Chemotherapy, Adjuvant

- Neoadjuvant Therapy

- Tamoxifen / therapeutic use

Grants and funding

- A21133/CRUK_/Cancer Research UK/United Kingdom

Advertisement

Advancements in Oncologic Surgery of the Breast: A Review of the Literature

- Published: 27 February 2024

Cite this article

- Tiffany J. Nevill 1 ,

- Kelly C. Hewitt 2 &

- Rachel L. McCaffrey 2

42 Accesses

7 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Purpose of Review

This review article is an update on the state of surgical options in the treatment of breast cancer. We seek to provide readers with the best practices for oncologically safe and cosmetically superior breast surgery.

Recent Findings

This article reviews the latest technologies for partial mastectomy, advances in and oncologic safety of mastectomy including skin and nipple sparing techniques, and a review of oncoplastic breast surgery techniques.

Our goal is to inform all surgeons who treat patients with breast cancer that many options remain available for the surgical treatment of breast cancer.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

The Optimal Approach to Post-Mastectomy and Post-Lumpectomy Breast Reconstruction

Overview of Oncoplastic Breast Surgery Techniques for the Treatment of Breast Cancer with Review of Normal and Abnormal Postsurgical Imaging Findings

Mastectomy: Simple (Total), Modified, and Classical Radical

Data availability.

No datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Halsted WSI. The results of radical operations for the cure of carcinoma of the breast. Ann Surg. 1907;46(1):1–19. https://doi.org/10.1097/00000658-190707000-00001 .

Article MathSciNet CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Fisher B, Jeong JH, Anderson S, Bryant J, Fisher ER, Wolmark N. Twenty-five-year follow-up of a randomized trial comparing radical mastectomy, total mastectomy, and total mastectomy followed by irradiation. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(8):567–75. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa020128 .

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Effects of radiotherapy and surgery in early breast cancer. An overview of the randomized trials. N Engl J Med. 1995;333(22):1444–55. doi: https://doi.org/10.1056/nejm199511303332202 .

Fisher B, Bauer M, Margolese R, Poisson R, Pilch Y, Redmond C, et al. Five-year results of a randomized clinical trial comparing total mastectomy and segmental mastectomy with or without radiation in the treatment of breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 1985;312(11):665–73. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejm198503143121101 .

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Fisher B, Anderson S, Bryant J, Margolese RG, Deutsch M, Fisher ER, et al. Twenty-year follow-up of a randomized trial comparing total mastectomy, lumpectomy, and lumpectomy plus irradiation for the treatment of invasive breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(16):1233–41. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa022152 .

de Boniface J, Szulkin R, Johansson ALV. Survival after breast conservation vs mastectomy adjusted for comorbidity and socioeconomic status: a Swedish national 6-year follow-up of 48 986 women. JAMA Surg. 2021;156(7):628–37. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamasurg.2021.1438 .

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Elmore LC, Dietz JR, Myckatyn TM, Margenthaler JA. The landmark series: mastectomy trials (skin-sparing and nipple-sparing and reconstruction landmark trials). Ann Surg Oncol. 2021;28(1):273–80. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-020-09052-x .

Margenthaler JA, Dietz JR, Chatterjee A. The landmark series: breast conservation trials (including oncoplastic breast surgery). Ann Surg Oncol. 2021;28(4):2120–7. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-020-09534-y .

Kapoor MM, Patel MM, Scoggins ME. The wire and beyond: recent advances in breast imaging preoperative needle localization. Radiographics. 2019;39(7):1886–906. https://doi.org/10.1148/rg.2019190041 .

Black DM, Mittendorf EA. Landmark trials affecting the surgical management of invasive breast cancer. Surg Clin North Am. 2013;93(2):501–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.suc.2012.12.007 .

Mascaro A, Farina M, Gigli R, Vitelli CE, Fortunato L. Recent advances in the surgical care of breast cancer patients. World J Surg Oncol. 2010;8:5. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7819-8-5 .

Veronesi U, Cascinelli N, Mariani L, Greco M, Saccozzi R, Luini A, et al. Twenty-year follow-up of a randomized study comparing breast-conserving surgery with radical mastectomy for early breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(16):1227–32. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmoa020989 .

De La Cruz L, Blankenship SA, Chatterjee A, Geha R, Nocera N, Czerniecki BJ, et al. Outcomes after oncoplastic breast-conserving surgery in breast cancer patients: a systematic literature review. Ann Surg Oncol. 2016;23(10):3247–58. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-016-5313-1 .

Gwark S, Kim HJ, Kim J, Chung IY, Kim HJ, Ko BS, et al. Survival after breast-conserving surgery compared with that after mastectomy in breast cancer patients receiving neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2023;30(5):2845–53. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-022-12993-0 .

Hartmann-Johnsen OJ, Kåresen R, Schlichting E, Nygård JF. Survival is better after breast conserving therapy than mastectomy for early stage breast cancer: a registry-based follow-up study of Norwegian women primary operated between 1998 and 2008. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22(12):3836–45. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-015-4441-3 .

Hwang ES, Lichtensztajn DY, Gomez SL, Fowble B, Clarke CA. Survival after lumpectomy and mastectomy for early stage invasive breast cancer: the effect of age and hormone receptor status. Cancer. 2013;119(7):1402–11. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.27795 .

Wrubel E, Natwick R, Wright GP. Breast-conserving therapy is associated with improved survival compared with mastectomy for early-stage breast cancer: a propensity score matched comparison using the National Cancer Database. Ann Surg Oncol. 2021;28(2):914–9. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-020-08829-4 .

van Maaren MC, de Munck L, de Bock GH, Jobsen JJ, van Dalen T, Linn SC, et al. 10 year survival after breast-conserving surgery plus radiotherapy compared with mastectomy in early breast cancer in the Netherlands: a population-based study. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17(8):1158–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1470-2045(16)30067-5 .

Gradishar WJ, Moran MS, Abraham J, Aft R, Agnese D, Allison KH, et al. Breast cancer, version 3.2022, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2022;20(6):691–722. doi: https://doi.org/10.6004/jnccn.2022.0030 .

Bleicher RJ, Ruth K, Sigurdson ER, Daly JM, Boraas M, Anderson PR, Egleston BL. Breast conservation versus mastectomy for patients with T3 primary tumors (>5 cm): a review of 5685 medicare patients. Cancer. 2016;122(1):42–9. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.29726 .

Moran MS, Schnitt SJ, Giuliano AE, Harris JR, Khan SA, Horton J, et al. Society of Surgical Oncology-American Society for Radiation Oncology consensus guideline on margins for breast-conserving surgery with whole-breast irradiation in stages I and II invasive breast cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2014;88(3):553–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrobp.2013.11.012 .

Morrow M, Van Zee KJ, Solin LJ, Houssami N, Chavez-MacGregor M, Harris JR, et al. Society of Surgical Oncology-American Society for Radiation Oncology-American Society of Clinical Oncology Consensus Guideline on margins for breast-conserving surgery with whole-breast irradiation in ductal carcinoma in situ. Pract Radiat Oncol. 2016;6(5):287–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prro.2016.06.011 .

Gradishar WJ, Moran MS, et al.: NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: breast cancer. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/breast.pdf (2024). Accessed Feb 3 2024.

ACS Clinical Research Program; Alliance for Clinical Trials in Oncology; Nelson HDH, Kelly K. Operative standards for cancer surgery: volume I: breast, lung, pancreas, colon. LWW; 2015.

Morrow M, Strom EA, Bassett LW, Dershaw DD, Fowble B, Giuliano A, et al. Standard for breast conservation therapy in the management of invasive breast carcinoma. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2002;52(5):277–300. doi: https://doi.org/10.3322/canjclin.52.5.277 .

Shirazi S, Hajiesmaeili H, Khosla M, Taj S, Sircar T, Vidya R. Comparison of wire and non-wire localisation techniques in breast cancer surgery: a review of the literature with pooled analysis. Medicina (Kaunas). 2023;59(7). doi: https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina59071297 .

Farha MJ, Simons J, Kfouri J, Townsend-Day M. SAVI Scout® system for excision of non-palpable breast lesions. Am Surg. 2023;89(6):2434–8. https://doi.org/10.1177/00031348221096576 .

Liang DH, Black D, Yi M, Luo CK, Singh P, Sahin A, et al. Clinical outcomes using magnetic seeds as a non-wire, non-radioactive alternative for localization of non-palpable breast lesions. Ann Surg Oncol. 2022;29(6):3822–8. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-022-11443-1 .

Srour MK, Kim S, Amersi F, Giuliano AE, Chung A. Comparison of wire localization, radioactive seed, and Savi Scout(®) radar for management of surgical breast disease. Breast J. 2020;26(3):406–13. https://doi.org/10.1111/tbj.13499 .

Choe AI, Ismail R, Mack J, Walter V, Yang AL, Dodge DG. Review of variables associated with positive surgical margins using scout reflector localizations for breast conservation therapy. Clin Breast Cancer. 2022;22(2):e232–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clbc.2021.07.003 .

Kelly BN, Webster AJ, Lamb L, Spivey T, Korotkin JE, Henriquez A, et al. Magnetic seeds: an alternative to wire localization for nonpalpable breast lesions. Clin Breast Cancer. 2022;22(5):e700–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clbc.2022.01.003 .

Jones C, Lancaster R. Evolution of operative technique for mastectomy. Surg Clin North Am. 2018;98(4):835–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.suc.2018.04.003 .

Surgeons TASoB: Performance and practice guidelines for mastectomy. 2018. https://breastsurgeons.org/docs/statements/Performance-and-Practice-Guidelines-for-Mastectomy.pdf . Accessed.

Morrow M, Jagsi R, Alderman AK, Griggs JJ, Hawley ST, Hamilton AS, et al. Surgeon recommendations and receipt of mastectomy for treatment of breast cancer. JAMA. 2009;302(14):1551–6. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2009.1450 .

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Hill EL, Ochoa D, Denham F, Merrill A, Lin-Duffy MF, Wilson AB, et al. The Angel Wings Incision: a novel solution for mastectomy patients with increased lateral adiposity. Breast J. 2019;25(4):687–90. https://doi.org/10.1111/tbj.13301 .

van Zeelst LJ, Ten Wolde B, van Eekeren R, Volders JH, de Wilt JHW, Strobbe LJA. Quilting following mastectomy reduces seroma, associated complications and health care consumption without impairing patient comfort. J Surg Oncol. 2022;125(3):369–76. https://doi.org/10.1002/jso.26739 .

Drivas E, Gachabayov M, Kajmolli A, Stadlan Z, Felsenreich DM, Castaldi M. Quilting suture technique after mastectomy: a meta-analysis. Am Surg. 2023;89(12):6045–52. https://doi.org/10.1177/00031348231173995 .

Baker JL, Dizon DS, Wenziger CM, Streja E, Thompson CK, Lee MK, et al. “Going Flat” after mastectomy: patient-reported outcomes by online survey. Ann Surg Oncol. 2021;28(5):2493–505. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-020-09448-9 .

Anderson C, Islam JY, Elizabeth Hodgson M, Sabatino SA, Rodriguez JL, Lee CN, et al. Long-term satisfaction and body image after contralateral prophylactic mastectomy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2017;24(6):1499–506. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-016-5753-7 .

Kim H, Yoon TI, Kim S, Lee SB, Kim J, Chung IY, et al. Age-related incidence and peak occurrence of contralateral breast cancer. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(12):e2347511. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.47511 .

Lee C, Sunu C, Pignone M. Patient-reported outcomes of breast reconstruction after mastectomy: a systematic review. J Am Coll Surg. 2009;209(1):123–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2009.02.061 .

Romanoff A, Zabor EC, Stempel M, Sacchini V, Pusic A, Morrow M. A Comparison of patient-reported outcomes after nipple-sparing mastectomy and conventional mastectomy with reconstruction. Ann Surg Oncol. 2018;25(10):2909–16. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-018-6585-4 .

Hieken TJ, Boolbol SK, Dietz JR. Nipple-sparing mastectomy: indications, contraindications, risks, benefits, and techniques. Ann Surg Oncol. 2016;23(10):3138–44. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-016-5370-5 .

Garcia-Etienne CA, Cody Iii HS, 3rd, Disa JJ, Cordeiro P, Sacchini V. Nipple-sparing mastectomy: initial experience at the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center and a comprehensive review of literature. Breast J. 2009;15(4):440- https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1524-4741.2009.00758.x

Agarwal S, Agarwal S, Neumayer L, Agarwal JP. Therapeutic nipple-sparing mastectomy: trends based on a national cancer database. The American Journal of Surgery. 2014;208(1):93–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjsurg.2013.09.030 .

Galimberti V, Vicini E, Corso G, Morigi C, Fontana S, Sacchini V, Veronesi P. Nipple-sparing and skin-sparing mastectomy: review of aims, oncological safety and contraindications. Breast. 2017;34 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):S82-s4. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.breast.2017.06.034 .

De La Cruz L, Moody AM, Tappy EE, Blankenship SA, Hecht EM. Overall survival, disease-free survival, local recurrence, and nipple-areolar recurrence in the setting of nipple-sparing mastectomy: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22(10):3241–9. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-015-4739-1 .

Donovan CA, Harit AP, Chung A, Bao J, Giuliano AE, Amersi F. Oncological and surgical outcomes after nipple-sparing mastectomy: do incisions matter? Ann Surg Oncol. 2016;23(10):3226–31. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-016-5323-z .

Stolier AJ, Wang J. Terminal duct lobular units are scarce in the nipple: implications for prophylactic nipple-sparing mastectomy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15(2):438–42. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-007-9568-4 .

Piato JR, de Andrade RD, Chala LF, de Barros N, Mano MS, Melitto AS, et al. MRI to predict nipple involvement in breast cancer patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2016;206(5):1124–30. https://doi.org/10.2214/ajr.15.15187 .

Ponzone R, Maggiorotto F, Carabalona S, Rivolin A, Pisacane A, Kubatzki F, et al. MRI and intraoperative pathology to predict nipple-areola complex (NAC) involvement in patients undergoing NAC-sparing mastectomy. Eur J Cancer. 2015;51(14):1882–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2015.07.001 .

Agha RA, Al Omran Y, Wellstead G, Sagoo H, Barai I, Rajmohan S, et al. Systematic review of therapeutic nipple-sparing<i>versus</i>skin-sparing mastectomy. BJS Open. 2019;3(2):135–45. https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs5.50119 .

Eisenberg RE, Chan JS, Swistel AJ, Hoda SA. Pathological evaluation of nipple-sparing mastectomies with emphasis on occult nipple involvement: the Weill-Cornell experience with 325 cases. Breast J. 2014;20(1):15–21. https://doi.org/10.1111/tbj.12199 .

Amara D, Peled AW, Wang F, Ewing CA, Alvarado M, Esserman LJ. Tumor involvement of the nipple in total skin-sparing mastectomy: strategies for management. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22(12):3803–8. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-015-4646-5 .

Galimberti V, Morigi C, Bagnardi V, Corso G, Vicini E, Fontana SKR, et al. Oncological outcomes of nipple-sparing mastectomy: a single-center experience of 1989 patients. Ann Surg Oncol. 2018;25(13):3849–57. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-018-6759-0 .

Mitchell SD, Willey SC, Beitsch P, Feldman S. Evidence based outcomes of the American Society of Breast Surgeons Nipple Sparing Mastectomy Registry. Gland Surg. 2018;7(3):247–57. https://doi.org/10.21037/gs.2017.09.10 .

Orzalesi L, Casella D, Santi C, Cecconi L, Murgo R, Rinaldi S, et al. Nipple sparing mastectomy: surgical and oncological outcomes from a national multicentric registry with 913 patients (1006 cases) over a six year period. Breast. 2016;25:75–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.breast.2015.10.010 .

Smith BL, Tang R, Rai U, Plichta JK, Colwell AS, Gadd MA, et al. Oncologic safety of nipple-sparing mastectomy in women with breast cancer. J Am Coll Surg. 2017;225(3):361–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2017.06.013 .

Daar DA, Abdou SA, Rosario L, Rifkin WJ, Santos PJ, Wirth GA, Lane KT. Is there a preferred incision location for nipple-sparing mastectomy? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2019;143(5):906e-e919. https://doi.org/10.1097/prs.0000000000005502 .

Peled AW, Peled ZM. Nerve preservation and allografting for sensory innervation following immediate implant breast reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2019;7(7):e2332. https://doi.org/10.1097/gox.0000000000002332 .

Toth BA, Lappert P. Modified skin incisions for mastectomy: the need for plastic surgical input in preoperative planning. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1991;87(6):1048–53.

Citgez B, Yigit B, Bas S. Oncoplastic and reconstructive breast surgery: a comprehensive review. Cureus. 2022. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.21763

Ayoub Z, Strom EA, Ovalle V, Perkins GH, Woodward WA, Tereffe W, et al. A 10-year experience with mastectomy and tissue expander placement to facilitate subsequent radiation and reconstruction. Ann Surg Oncol. 2017;24(10):2965–71. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-017-5956-6 .

Kaufman CS. Increasing role of oncoplastic surgery for breast cancer. Curr Oncol Rep. 2019;21(12):111. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11912-019-0860-9 .

Silverstein MJ, Mai T, Savalia N, Vaince F, Guerra L. Oncoplastic breast conservation surgery: the new paradigm. J Surg Oncol. 2014;110(1):82–9. https://doi.org/10.1002/jso.23641 .

Macmillan RD, McCulley SJ. Oncoplastic breast surgery: what, when and for whom? Curr Breast Cancer Rep. 2016;8:112–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12609-016-0212-9 .

Crown A, Wechter DG, Grumley JW. Oncoplastic breast-conserving surgery reduces mastectomy and postoperative re-excision rates. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22(10):3363–8. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-015-4738-2 .

Kosasih S, Tayeh S, Mokbel K, Kasem A. Is oncoplastic breast conserving surgery oncologically safe? A meta-analysis of 18,103 patients. Am J Surg. 2020;220(2):385–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjsurg.2019.12.019 .

André C, Holsti C, Svenner A, Sackey H, Oikonomou I, Appelgren M, et al. Recurrence and survival after standard versus oncoplastic breast-conserving surgery for breast cancer. BJS Open. 2021;5(1). doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsopen/zraa013 .

Campbell EJ, Romics L. Oncological safety and cosmetic outcomes in oncoplastic breast conservation surgery, a review of the best level of evidence literature. Breast Cancer (Dove Med Press). 2017;9:521–30. https://doi.org/10.2147/bctt.S113742 .

Kopkash K, Clark P. Basic oncoplastic surgery for breast conservation: tips and techniques. Ann Surg Oncol. 2018;25(10):2823–8. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-018-6604-5 .

Yang JD, Lee JW, Cho YK, Kim WW, Hwang SO, Jung JH, Park HY. Surgical techniques for personalized oncoplastic surgery in breast cancer patients with small- to moderate-sized breasts (Part 1): Volume Displacement. J Breast Cancer. 2012;15(1):1. https://doi.org/10.4048/jbc.2012.15.1.1 .

Cantürk NZ, Şimşek T, Özkan GS. Oncoplastic breast-conserving surgery according to tumor location. Eur J Breast Health. 2021;17(3):220–33. https://doi.org/10.4274/ejbh.galenos.2021.2021-1-2 .

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Surgery, Franciscan Health, Olympia Fields, Chicago, IL, USA

Tiffany J. Nevill

Department of Surgery, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, 2220 Pierce Avenue, Preston Research Building 597, Nashville, TN, 37232-2730, USA

Kelly C. Hewitt & Rachel L. McCaffrey

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

TN and RM wrote the main manuscript. KH reviewed the manuscript for clinical content and contributed to table formation. All reviewed the final manuscript prior to submission.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Rachel L. McCaffrey .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors of this review article have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Human and animal rights

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Nevill, T.J., Hewitt, K.C. & McCaffrey, R.L. Advancements in Oncologic Surgery of the Breast: A Review of the Literature. Curr Breast Cancer Rep (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12609-024-00537-2

Download citation

Accepted : 18 February 2024

Published : 27 February 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s12609-024-00537-2

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Breast surgery

- Breast cancer

- Oncoplastic surgery

- Oncologic safety

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 16 December 2019

Current treatment landscape for patients with locally recurrent inoperable or metastatic triple-negative breast cancer: a systematic literature review

- Claire H. Li 1 na1 ,

- Vassiliki Karantza 1 ,

- Gursel Aktan 1 &

- Mallika Lala 1 na1

Breast Cancer Research volume 21 , Article number: 143 ( 2019 ) Cite this article

22k Accesses

79 Citations

5 Altmetric

Metrics details

Metastatic triple-negative breast cancer (mTNBC), an aggressive histological subtype, has poor prognosis. Chemotherapy remains standard of care for mTNBC, although no agent has been specifically approved for this breast cancer subtype. Instead, chemotherapies approved for metastatic breast cancer (MBC) are used for mTNBC (National Comprehensive Cancer Network Guidelines [NCCN] v1.2019). Atezolizumab in combination with nab-paclitaxel was recently approved for programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1)–positive locally advanced or metastatic TNBC. Published historical data were reviewed to characterize the efficacy of NCCN-recommended (v1.2016) agents as first-line (1L) and second-line or later (2L+) treatment for patients with locally recurrent inoperable or metastatic TNBC (collectively termed mTNBC herein).

A systematic literature review was performed, examining clinical efficacy of therapies for mTNBC based on NCCN v1.2016 guideline recommendations. Data from 13 studies, either published retrospective mTNBC subgroup analyses based on phase III trials in MBC or phase II trials in mTNBC, were included.

A meta-analysis of mTNBC subgroups from three phase III trials in 1L MBC reported pooled objective response rate (ORR) of 23%, median overall survival (OS) of 17.5 months, and median progression-free survival (PFS) of 5.4 months with single-agent chemotherapy. In two subgroup analyses from a phase III study and a phase II trial ( n = 40 each), median duration of response (DOR) to 1L chemotherapy for mTNBC was 4.4–6.6 months; therefore, responses were not durable. A meta-analysis of seven cohorts showed the pooled ORR for 2L+ chemotherapy was 11% (95% CI, 9–14%). Median DOR to 2L+ chemotherapy in mTNBC was also limited (4.2–5.9 months) per two subgroup analyses from a phase III study. No combination chemotherapy regimens recommended by NCCN v1.2016 for treatment of MBC showed superior OS to single agents.

Conclusions

Chemotherapies have limited effectiveness and are associated with unfavorable toxicity profiles, highlighting a considerable unmet medical need for improved therapeutic options in mTNBC. In addition to the recently approved combination of atezolizumab and nab-paclitaxel for PD-L1–positive mTNBC, new treatments resulting in durable clinical responses, prolonged survival, and manageable safety profile would greatly benefit patients with mTNBC.

Introduction

Breast cancer (BC) is the most common malignant neoplasm in females; an estimated 266,120 new diagnoses and 40,920 related deaths occurred in the USA in 2018 [ 1 ]. Approximately 10–20% of BCs do not express estrogen and progesterone receptors and lack amplification/overexpression of the human epidermal growth factor 2 receptor (HER2) [ 2 , 3 , 4 ]; therefore, they are known as triple-negative breast cancers (TNBCs) and constitute an aggressive histologic subtype. In patients with locally recurrent inoperable or metastatic disease (collectively referred to as mTNBC in this article), treatment options have primarily been chemotherapies based on recommended therapeutic approaches (National Comprehensive Cancer Network [NCCN] v1.2019 guidelines and the European School of Oncology-European Society for Medical Oncology [ESO-ESMO] 2018 guidelines) for metastatic breast cancer (MBC) [ 5 , 6 ]. In particular, anthracyclines, taxanes, capecitabine, and more recently, eribulin are commonly used as monotherapy or in combination with other agents and as standard/control arms in registration trials of new/investigational agents for TNBC. Anthracyclines and taxanes are both recommended, unless contraindicated, as first-line (1L) treatments for patients who have not previously received these agents as neoadjuvant or adjuvant treatment [ 5 , 6 ]. The efficacy of anthracyclines in mTNBC has been inferred from earlier studies that involved patients with MBC in which the TNBC subpopulation was not distinctly defined (mostly because of the absence of HER2 status reporting) [ 7 ]. Compared with taxanes, anthracyclines have not demonstrated overall survival (OS) benefit in mTNBC [ 8 ]. Because data on the effectiveness of anthracyclines are not available in the mTNBC population and anthracyclines and taxanes are generally considered similarly effective, anthracyclines are not discussed further in this review.

Overall prognosis for patients with mTNBC is worse than for the other BC subtypes, and more effective therapeutic options are needed. In a pooled analysis of two phase III trials in MBC, inferior outcomes were reported with 1L or later line physician choice of chemotherapy for patients with mTNBC than for the overall MBC population [ 9 ]. Chemotherapies are generally associated with unfavorable adverse events (AEs), more so in combination, that can lead to treatment discontinuation. Because combination regimens have not prolonged OS compared with monotherapies, the approach recommended by the NCCN v1.2019/ESO-ESMO 2018 guidelines [ 5 , 6 ] for the treatment of MBC (including mTNBC) remains sequential use of single-agent chemotherapy. Based on recent evidence that atezolizumab plus nab-paclitaxel improves progression-free survival (PFS), this combination was recently granted accelerated approval by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in patients with programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1)–positive (immune cell score, IC 1+) TNBC [ 5 , 10 , 11 ]. In general, clinical trials conducted only in patients with mTNBC are limited. No phase III trials have been conducted to specifically evaluate single agents as treatment for mTNBC in any line of therapy, and only a limited number of phase III trials have been conducted to evaluate combination therapies in the mTNBC population. The purpose of the current evidence synthesis was to systematically characterize the efficacy of commonly used chemotherapies, defined herein to be agents recommended in the NCCN v1.2016 guidelines (which were current at the time of this analysis) [ 12 ], as 1L and second-line or later (2L+) treatment for patients with mTNBC, thereby providing a summary of available historical data.

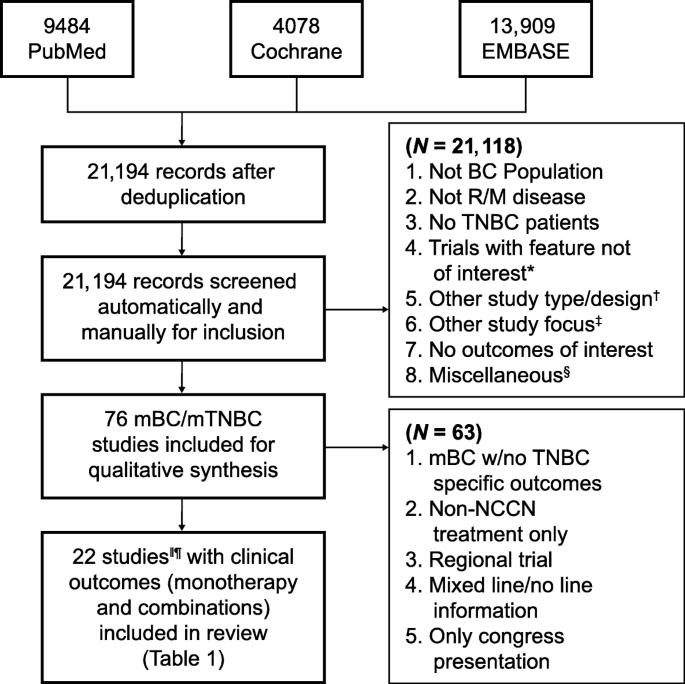

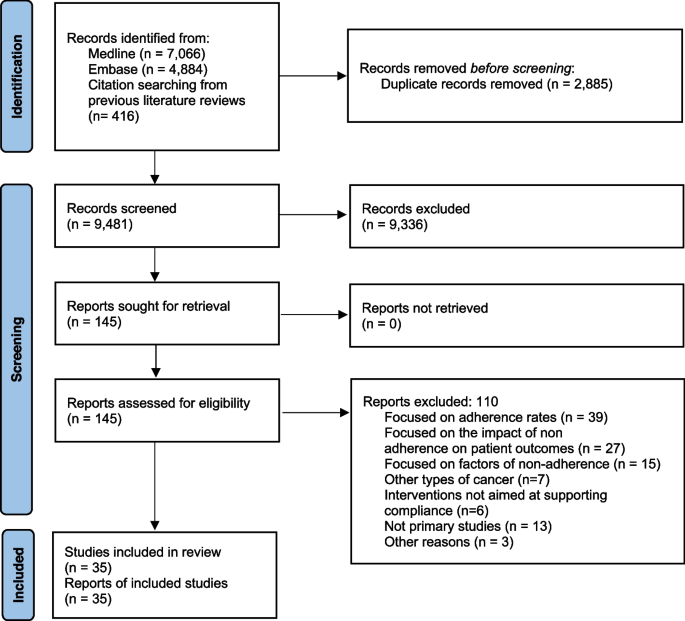

Systematic review

A systematic review of the literature was conducted to synthesize objective response rate (ORR), duration of response (DOR), PFS, and OS of commonly used chemotherapies as 1L or 2L+ treatment for patients with mTNBC. Commonly used chemotherapies were defined as agents recommended in the NCCN v1.2016 guidelines for the treatment of MBC (including mTNBC) as single agents or combinations thereof, including the combination of paclitaxel and bevacizumab [ 12 ]. Clinical trial results published in English between January 1, 1996, and August 21, 2016, were identified by searching the PubMed (MEDLINE), Cochrane, and Embase databases (Additional file 1 : Table S1, Additional file 2 : Table S2, Additional file 3 : Table S3). Identified publications were then manually screened for inclusion. Reports of phase III trials in either mTNBC or MBC (with mTNBC subgroup outcomes) populations, recent (2010 and later) phase II trials in mTNBC-only populations, and retrospective or meta-analyses of mTNBC subgroups based on phase III MBC trials were included. Details of the search inclusion and exclusion criteria are presented in Fig. 1 . Studies published after 21 August 2016 were evaluated separately for relevance based on recent guideline updates and were included for completeness [ 10 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 ].

Study selection process for the systematic literature review and meta-analysis of breast cancer ( BC ). *Exclusions include not phase II, not phase III or phase II with triple-negative breast cancer ( TNBC ) focus, phase II not TNBC focus, not phase II or phase III, and not TNBC focus phase II/I. † Exclusions include review articles, other study types, not recurrent/metastatic ( R/M ) of phase III/II data, and not TNBC-specific R/M. ‡ Exclusions include non-cancer outcomes focus, only quality-of-life data, study protocol, surgical intervention, model development, and only AE data. § Exclusions include other language, older report of the same study, and reference unavailable. ‖ Results from one study (phase III trial, study 301) based on internal communication with sponsor (Eisai); not published results. ¶ Results from Twelves et al.’s [ 9 ] and Pivot et al.’s [ 13 ] studies are both included based on the reported different treatment line outcomes

Study selection

There was substantial heterogeneity in the inclusion of 1L and 2L+ populations, between and within identified studies, with many studies including mixed patient populations in terms of prior therapy and current line of treatment. Studies were first classified by line of treatment (1L, 2L+, mixed line). Only those that reported clinical efficacy outcomes in mTNBC populations in which the majority of patients (≥ 80%) were given 1L or 2L+ treatment with chemotherapy, as single-agent and in combination regimens, were included in the review. Reports of clinical trials that were conducted regionally (limited to one geographic location) in a non-White population and reports that were limited to presentation at a congress but not published were excluded from the review.

Data analysis and meta-analysis

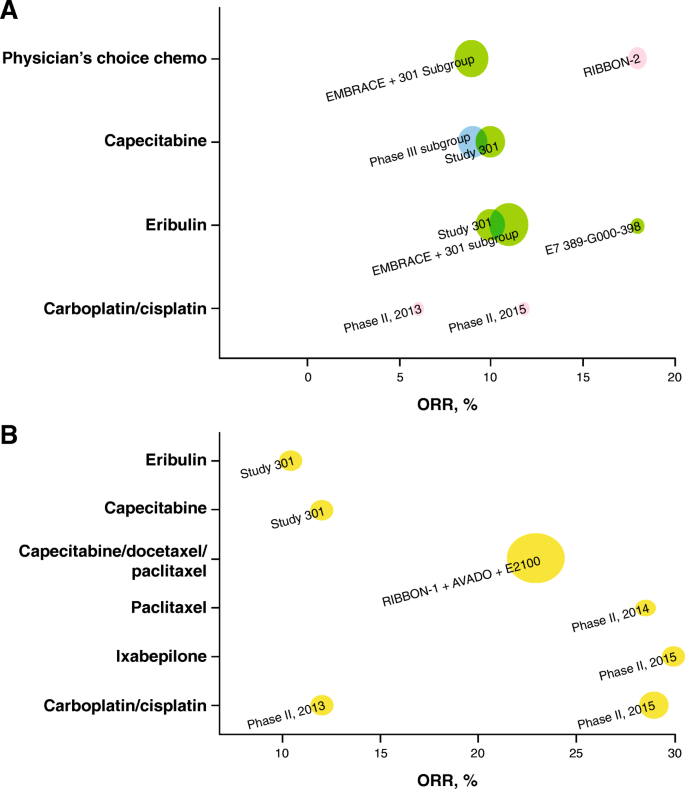

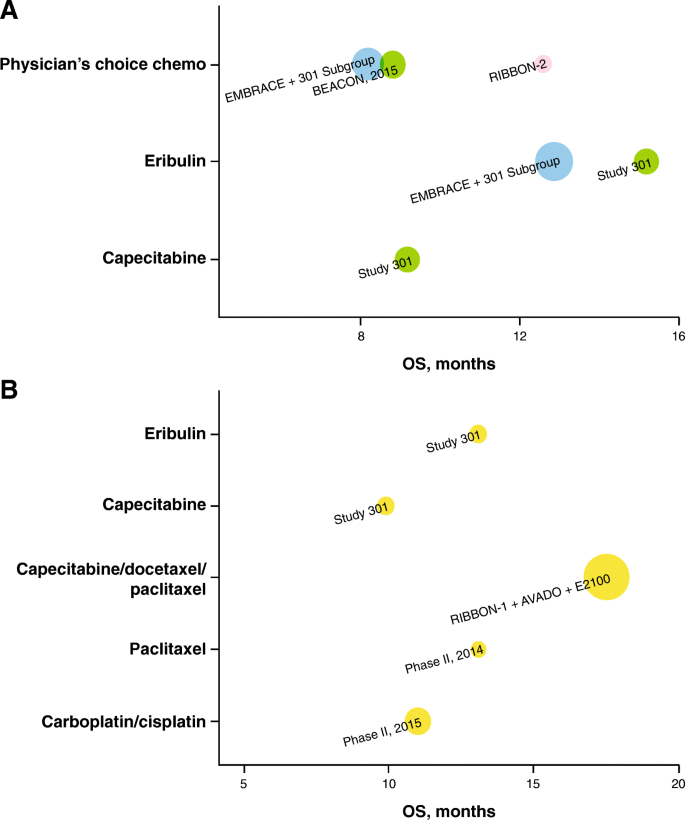

Clinical outcomes, including ORR and OS, were qualitatively represented by monotherapy as 1L and 2L+ therapy, as shown in Figs. 3 and 4 . Meta-analyses were performed to synthesize the pooled ORRs for single-agent chemotherapy among studies of 2L+ treatment. Inverse-variance fixed-effects and random-effects meta-analyses were explored. A DerSimonian and Laird random-effects model was used to account for between-trial heterogeneity; this model assumes that the true treatment effects of the included studies follow a distribution around an overall mean [ 20 ]. The sample size, ORR, 95% confidence interval (95% CI) for each treatment and study, and pooled ORR (95% CI) are presented as forest plots, per PRISMA guidelines [ 21 ]. The ORRs were re-estimated using the all-patients-as-treated (APaT) population to ensure common definition across studies. The ORR proportions were transformed to a logit scale to calculate 95% CIs and then transformed back to proportions.

Data sources and software

The PubMed, Cochrane, and Embase databases were searched for eligible studies/publications; Microsoft Office Excel (Redmond, WA, USA) was used to synthesize study records. As necessary, trial eligibility criteria were compared against the criteria listed on ClinicalTrials.gov . Meta-analyses of ORR were conducted in R (version 3.1.3) using the metafor package [ 22 ]. Qualitative graphical analyses of ORR, DOR, OS, and PFS across identified trials were performed using R (version 3.2.5).

A total of 21,194 references were collected from combined literature searches of PubMed, Cochrane, and Embase databases after filtering duplicate records (Fig. 1 ). From those references, 76 studies complied with the key inclusion criteria from qualitative synthesis. Of these 76 trials, 63 were excluded, as described in the “ Results ” section (Fig. 1 ). Finally, 21 studies that reported clinical outcomes of interest with chemotherapies for patients with mTNBC were reviewed in detail and are reported herein.

A summary of study outcomes of all included studies is given in Table 1 . ORRs based on the APaT populations were calculated to facilitate comparisons across studies. ORRs were re-estimated based on the APaT population (i.e., number of responders divided by number of patients composing the APaT population for studies in which ORR was reported based on the evaluable or intention-to-treat population [ITT]). The clinical outcomes for patients with mTNBC treated with NCCN-recommended (v1.2016) agents [ 6 , 12 ] as either 1L or 2L+ therapy were further separated based on whether the investigation therapy was monotherapy or combination therapy (Table 1 ).

Description of the study outcomes with NCCN-recommended (v1.2016) agents

Monotherapy.

No published data from randomized controlled phase III trials with single-agent chemotherapy as 1L or later lines of treatment for mTNBC were found. Thirteen published reports (disregarding congress presentations) of retrospective subgroup analyses in patients with mTNBC based on phase III trials in MBC or phase II trials in mTNBC with limited sample size were identified, considering all lines of treatment. Of these, six studies reported clinical efficacy outcomes in the 1L mTNBC patient population, as summarized in Table 1 [ 24 , 25 , 27 , 28 , 32 ]. Treatments included capecitabine, taxanes (docetaxel, paclitaxel), eribulin, ixabepilone, or platinum (carboplatin, cisplatin). Furthermore, nine studies, also summarized in Table 1 , reported clinical efficacy outcomes in the 2L+ mTNBC patient population; treatments included capecitabine, carboplatin, cisplatin, or eribulin [ 9 , 13 , 23 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 30 , 31 , 33 ].

Among the six studies on 1L treatment, five had published outcomes [ 24 , 25 , 27 , 28 , 32 ]. For one study (phase III trial, study 301), clinical outcomes for the mTNBC subgroup were available via internal communication. Notably, a meta-analysis of the mTNBC subgroups from three phase III trials in 1L MBC [ 28 ] reported a pooled ORR of 23% and median OS of 17.5 months. In trial 301, which compared eribulin with capecitabine for the treatment of MBC, in the mTNBC subgroup, ORR for 1L eribulin and capecitabine was 10% and 12%, respectively.

In addition, four phase II trials conducted to investigate single-agent chemotherapies for mTNBC with sample sizes of 28–69 were identified; the reported ORR ranged from 12 to 30%, and a median OS of 13.1 months was reported in only one [ 24 ] of these phase II trials. In studies that reported response duration (two subgroup analyses from a phase III study (study 301) and one phase II trial, all limited in sample size [ n = 40 each]), the median DOR to 1L chemotherapy in mTNBC ranged from 4.4 to 6.6 months (Table 1 ) [ 32 ]. Qualitative analyses of the sample sizes, ORR, and OS are shown graphically in Figs. 3 b and 4 b.

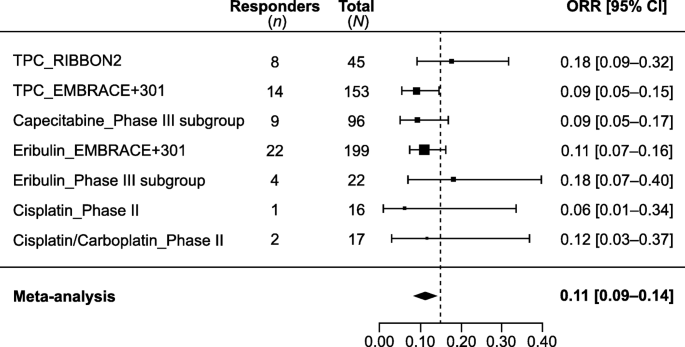

Second-line or later

Among the nine studies on 2L+ treatment, seven phase III studies in MBC reported clinical efficacy outcomes for mTNBC subgroups [ 9 , 13 , 23 , 26 , 30 , 31 , 33 ]. In these studies, ORR ranged from 9 to 18%; median OS, from 8.1 to 15.2 months. The median DOR to 2L+ chemotherapy in mTNBC was only available from two subgroup analyses of a phase III study (study 301) and ranged from 4.2 to 5.9 months. Two additional phase II studies reported ORR of 6% and 11.8% with platinum (cisplatin/carboplatin) [ 25 , 27 ]. A meta-analysis of ORR reported for seven cohorts from six of these studies (mTNBC subgroup analyses from five phase III trials in MBC and two phase II trials in mTNBC) resulted in a pooled ORR of 11% (95% CI, 9–14%) for chemotherapy in Fig. 2 . Qualitative analyses of the sample sizes, ORR, and OS are shown graphically in Figs. 3 a and 4 a.

Historical objective response rate (ORR) with chemotherapy in 2L+ mTNBC. Meta-analysis of the seven cohorts from six studies reporting ORR with single-agent chemotherapy in second or later line treatment settings

Graphical representations of objective response rates ( ORR s) for a trials of NCCN-recommended (v1.2016) second-line ( 2L ) plus monotherapy (including studies mixed with first-line [ 1L ]), and b trials of NCCN-recommended (v1.2016) first-line monotherapy; the size of the bubble is proportional to the study size (all-patients-as-treated population), and the color of the bubble indicates the line of therapy. Yellow = 1L, green = 2L–3L+, pink = 2L, blue = 1L–3L+ (including studies with ≤ 15% 1L patients). Study 301 result is based on internal communication with trial sponsor (Eisai); not published results

Graphical representation of overall survival (OS) for a trials of NCCN-recommended (v1.2016) second-line ( 2L ) plus monotherapy (including studies mixed with first-line [ 1L ]), and b trials of NCCN-recommended (v1.2016) 1L monotherapy; the size of the bubble is proportional to the study size (all-patients-as-treated population), and the color of the bubble indicates the line of therapy. Yellow = 1L, green = 2L–3L+, pink = 2L, blue = 1L–3L+ (including studies with ≤ 15% 1L patients). Study 301 result is based on internal communication with trial sponsor (Eisai); not published results. OS from phase II 2015 study is based on a total of 86 patients, including 80% 1L and 20% 2L+ patients

Combination therapy

Eleven published clinical studies reported efficacy outcomes in patients with mTNBC treated with NCCN-recommended (v1.2016) combination regimens [ 6 , 12 ], either as chemotherapy-only regimens or in combination with bevacizumab (Table 1 ) [ 28 , 30 , 31 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 , 40 , 41 ]. Only one phase III trial conducted specifically in the mTNBC population was identified, which evaluated the combination of gemcitabine, carboplatin, and iniparib/placebo as 1L–third-line (3L) treatment [ 40 ]. The overall reported ORR was 32%, and median OS was 11.1 months. In the 1L setting ( n = 149), median PFS and OS were 4.6 and 13.9 months, respectively, whereas in the 2L+ setting ( n = 109), median PFS and OS were 2.9 and 8.1 months, respectively.

In addition to monotherapy, as described previously herein, the meta-analysis of the mTNBC subgroups from three phase III trials in 1L MBC [ 28 ] also reported pooled outcomes for chemotherapy and bevacizumab combinations, including the NCCN-recommended (v1.2016) paclitaxel + bevacizumab regimen. In these studies, ORR was 42%; median OS, 18.9 months. Furthermore, two phase III trials in MBC included 20–25% patients with mTNBC and reported outcomes in their mTNBC subgroups [ 28 , 41 ] In addition, four phase II trials were also identified that investigated combination regimens in mTNBC [ 35 , 36 , 38 , 39 ]. Wide ranges of ORR (14.8–64.3%), median PFS (4.8–8.2 months), and median OS (16.5–21.5 months) were reported across these studies, in which trial designs varied and sample sizes were small (18–46 patients).

Two phase III trials in patients with MBC reported outcomes for mTNBC subgroups treated with ixabepilone + capecitabine [ 30 , 31 ]: median OS, 4.1–4.2 months, and ORR, 27% (reported in one study). An additional phase II study conducted specifically in the 2L+ mTNBC population was identified [ 37 ], which reported an ORR of 60% ( n = 50) with the paclitaxel + carboplatin combination.

The current standard of care for management of mTNBC is chemotherapy, although no chemotherapy agent is specifically approved for TNBC. Instead, chemotherapies approved for MBC (all subtypes) are also used for the treatment of mTNBC (NCCN v1.2019 guidelines and ESO-ESMO guidelines 2018) [ 5 , 6 ]. With the advent of immunotherapies, atezolizumab in combination with nab-paclitaxel was recently approved for PD-L1–positive locally advanced or metastatic TNBC [ 11 ]. In general, the number of clinical trials conducted only in patients with mTNBC is limited. Considering NCCN-recommended (v1.2016) treatments, there were no published phase III trials to specifically evaluate single-agent chemotherapy in mTNBC in any line of treatment and only one phase III trial that evaluated combination chemotherapy in mTNBC [ 40 ]. The most commonly used treatments were taxanes, capecitabine, and, more recently, eribulin. These agents were also used as standard/control arms in registration trials of new/investigational agents for mTNBC. The current systematic literature review was performed to determine effectiveness of treatments recommended for MBC in the NCCN v1.2016 guidelines, when used either as 1L or 2L+ therapy for mTNBC [ 6 , 12 ].

The wide range of ORRs (6–29% with single agents; 14.8–64.3% with combination regimens) to NCCN-recommended (v1.2016) therapies used as 1L and 2L+ treatments for mTNBC highlights a need for more precise determination of the efficacy of these therapies to inform clinical practice. The data reviewed here suggest that the variability in ORRs was not fully attributed to differences in the effectiveness of available therapies. Small study size and heterogeneity in the characteristics of the enrolled patients (reflective of real-world clinical settings) were also significant factors. Moreover, the observed responses were generally not durable and did not necessarily translate to survival benefit. A key focus of this review was to summarize clinical outcomes taking into consideration the heterogeneity among studies caused by mixed-line patient populations and different therapeutic approaches. Historical studies identified via a systematic literature search were categorized based on the patient population being closer to 1L or later line of treatment and the regimen being monotherapy or combination.

No published results of randomized controlled phase III trials in mTNBC in 1L or later lines of treatment were found for single-agent chemotherapy. Published reports of either retrospective mTNBC subgroup analyses based on phase III trials in MBC or phase II trials in mTNBC with limited sample size were identified. These formed the evidence base in this review of historical data. A notable meta-analysis of the mTNBC subgroups from three phase III trials in 1L MBC [ 28 ] reported a pooled ORR of 23% and a median OS of 17.5 months with chemotherapy. Among available historical data, this study is regarded as the most relevant to efficacy outcomes from available 1L treatments. The recent TNT trial also reported similar clinical outcomes (31–34% ORRs and median OS of 12 months) in 2L+ mTNBC subgroups treated with carboplatin or docetaxel [ 19 ].

Although achieving clinical response is important, long-term clinical benefit of a treatment is linked with durability of the response. In two subgroup analyses from a phase III study (study 301) and one phase II trial [ 32 ], all limited in sample size ( n = 40 each), that reported response duration, median DOR to 1L chemotherapy for mTNBC ranged from 4.4 to 6.6 months (Table 1 ), indicating that the responses were not durable. Considering later lines (2L+) of treatment, the efficacy of chemotherapies was lower than in the 1L setting. Based on a meta-analysis of seven cohorts, the pooled ORR for chemotherapy was 11% (95% CI, 9–14%) [ 13 , 23 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 30 ]. Median DOR to 2L+ chemotherapy in mTNBC was also limited, ranging from 4.2 to 5.9 months, based on two subgroup analyses from a phase III study.

NCCN-recommended (v1.2016) combination regimens (including paclitaxel + bevacizumab) have not been proven superior to single-agent chemotherapy in terms of OS [ 5 ]. Only one global phase III trial of a combination regimen was found. This trial evaluated the gemcitabine, carboplatin, and iniparib/placebo combination as 1L–3L treatment for mTNBC [ 40 ]. Although the ORR to gemcitabine + carboplatin (32%) exceeded clinical response rates seen with monotherapy, the combination did not prolong OS (median OS, 11.1 months in 1L–3L) but was instead accompanied by higher toxicity (86% of patients had AEs of grade 3 or higher toxicities, and 10% discontinued treatment because of AEs).

In addition, the meta-analysis of the mTNBC subgroups from three phase III trials in 1L MBC [ 28 ] also reported pooled outcomes for chemotherapy and bevacizumab combinations with an ORR of 42%, which is higher than that for monotherapy, but a median OS (18.9 months) similar to that with monotherapy. The meta-analysis included patients treated with bevacizumab in combination with several chemotherapies, among which only the bevacizumab + paclitaxel combination is recommended by the NCCN v1.2016 guidelines. For 2L+ treatment of patients with mTNBC, although the ORR for combination therapies was superior to that of monotherapy, survival (median OS, 4.1–4.2 months) was poor. The current NCCN v1.2019 guidelines continue to state that the recommended approach to treatment of mTNBC remains sequential use of single-agent chemotherapy, except in patients with PD-L1–positive mTNBC, for whom atezolizumab plus nab-paclitaxel may be considered [ 5 ].

Not only do commonly used chemotherapies for MBC result in short-lived responses in patients with mTNBC, but they are also associated with toxicity, such as myelosuppression and neuropathy, which can compromise quality of life and lead to early treatment discontinuation. A pooled analysis of two phase III trials in patients with MBC (including mTNBC) receiving either single-agent physician’s choice chemotherapy (~ 70% had capecitabine) or eribulin as 2L+ treatment reported inferior outcomes with 1L or later-line chemotherapy for mTNBC than with overall MBC (ORR, 10.3% vs 16.4%; OS, 8.2 vs 12.8 months; PFS, 2.6 vs 3.4 months for chemotherapy of physician’s choice and ORR, 12.0% vs 14.9%; OS, 12.9 vs 15.2 months; PFS, 2.8 vs 4.0 months for eribulin) [ 9 ]. The study also reported that 47% and 66% of patients, respectively, for physician choice chemotherapy and eribulin, had treatment-emergent AEs of grades 3 to 4 toxicity, with neutropenia and leukopenia being the most prominent, whereas discontinuations because of treatment-emergent AEs were 13.6% and 11.3%, respectively [ 9 ]. The RIBBON-1 phase III trial [ 42 ] in patients with MBC (including mTNBC) treated in the 1L setting reported that 22% of participants in the capecitabine cohort and 38% in the taxane cohort had AEs of grade 3–5 toxicity, with sensory neuropathy, neutropenia, and venous thromboembolism being the most common. The rates of discontinuations because of AEs were 11.9% and 7.8%, respectively.

Specifically in the mTNBC population, AEs and treatment discontinuations because of toxicity have been reported in phase II studies as follows: ixabepilone (1L treatment), 45% of patients had AEs of grade ≥ 3 toxicity (neutropenia and leukopenia most common) with 20% discontinuations because of AEs [ 32 ]; paclitaxel (1L treatment), 10.7% discontinuations because of AEs [ 24 ]; and platinum (carboplatin/cisplatin, 1L or 2L treatment), 11.6% discontinuations because of AEs [ 27 ]. However, caution is required when drawing conclusions regarding the therapeutic index of different agents based on grade 3 or 4 toxicities, given that in some cases these toxicities may have minimal clinical consequence (e.g., grade 3 neutropenia in the absence of infection) whereas other chronic grade 2 toxicities may be intolerable or have a substantial impact on a patient’s quality of life.

New agents and agents in development

New treatment options for mTNBC are emerging with the advent of immune checkpoint programmed death 1 (PD-1)/PD-L1 inhibitors, antibody drug conjugates (ADCs), and other immune therapies under investigation that could become essential for the treatment of mTNBC, either as monotherapy or in combination with other agents (Table 2 ). Targeted therapies and other chemotherapies under investigation, mostly in phase II studies, as 1L and later lines of treatment for mTNBC are primarily single arm and often include mixed-line patient populations; hence, efficacy outcomes are challenging to interpret [ 24 , 43 , 44 , 45 , 46 , 47 ].

Immune checkpoint inhibitors

Compared with nab-paclitaxel alone, atezolizumab in combination with nab-paclitaxel prolonged PFS in patients with mTNBC (ITT population: median PFS of 7.2 months vs 5.5 months; Table 2 ) in the IMpassion 130 trial. Median PFS among the subpopulation of that trial with PD-L1–positive tumors was 7.5 months in the atezolizumab group and 5.0 months in the placebo group [ 10 ]. PD-L1 positivity in that trial was determined using the Ventana PD-L1 [SP142] immunohistochemical assay (Roche Diagnostics USA) and was defined based on the percentage of PD-L1–expressing immune cells as a percentage of tumor area: IC3 (≥ 10%), IC2 (≥ 5% to < 10%), IC1 (≥ 1% and < 5%), and IC0 (< 1%). Combination atezolizumab plus nab-paclitaxel is now approved by the FDA for the treatment of PD-L1–positive (IC1+) mTNBC (with PD-L1 positivity established using an FDA-approved test) and is included in the most recent NCCN v1.2019 guidelines [ 5 , 11 ]. Results of KEYNOTE-355, a phase III study of pembrolizumab in combination with one of (nab)-paclitaxel, gemcitabine, or carboplatin as 1L therapy for mTNBC, are pending.

Immune checkpoint inhibitors are also being investigated for monotherapy, and atezolizumab and pembrolizumab both have shown durable responses but in limited patient subsets. Results from the single-arm atezolizumab monotherapy trial in mTNBC were promising, with an ORR of 26% and 7% in the 1L and 2L+ settings, respectively; median DOR was 21 months (range 8+ to 26+ months) in the 1L setting, and DOR ranged from 3 to 13+ months in the 2L+ setting [ 48 ]. In KEYNOTE-086, a phase II study of pembrolizumab monotherapy for heavily pretreated mTNBC reported an overall ORR of 5% in a 2L+ subset of patients. The median DOR was 6.3 months (range, 1.2+ to 10.3+ months), with a median PFS and OS of 2 months and 8.9 months, respectively [ 49 ].

PARP inhibitors

When the NCCN guidelines were updated in 2018 and 2019, after this systematic review was conducted, two poly adenosine diphosphate (ADP) ribose polymerase (PARP) inhibitors, olaparib and talazoparib, were added for the treatment of germline BRCA -mutated HER2-negative MBC [ 50 ]. In the recent phase 3 OlympiAD trial of single-agent olaparib versus physician choice chemotherapy as 1L+ treatment for patients with germline BRCA -mutant and HER2-negative MBC (50% of patients with mTNBC), use of olaparib showed improvement in ORR (60% vs 29%) and median PFS (7.0 months vs 4.2 months) compared with chemotherapy [ 17 ]. Similarly, the EMBRACA trial of talazoparib versus chemotherapy as a 2L+ treatment in a similar patient population (45% mTNBC) reported that, compared with chemotherapy, talazoparib conferred a significantly higher ORR (62.6% vs 27.2%; P < 0.001) and significantly longer median PFS (8.6 months vs 5.6 months; P < 0.001) (Table 2 ) [ 16 ].

AKT inhibitors

Addition of AKT inhibitors to chemotherapy is also being investigated as 1L treatment for patients with mTNBC. A recent combination trial of the AKT inhibitor ipatasertib plus paclitaxel as 1L treatment for mTNBC (LOTUS trial) reported a median PFS of 6.2 months with the ipatasertib combination (vs 4.9 months with the placebo combination; P = 0.037; Table 2 ). After a follow-up of 23 months, median OS was 23.1 months with ipatasertib (vs 18.4 months with placebo plus paclitaxel) and the 1-year OS rate increased from 70 to 83% with the addition of ipatasertib; OS seemed to be independent of PTEN expression status [ 14 , 15 ]. Furthermore, the AKT inhibitor AZD5363 (capivasertib) is being investigated in combination with paclitaxel in patients with previously untreated mTNBC (PAKT) [ 51 ]. After a median follow-up of 18.2 months, PFS and OS were both longer with capivasertib plus paclitaxel than with placebo plus paclitaxel (PFS, 5.9 months vs 4.2 months; OS, 19.1 months vs 12.6 months).

Antibody drug conjugates

Among ADCs, on February 5, 2016, the FDA granted breakthrough therapy designation to sacituzumab govitecan (IMMU-132) as 3L treatment for mTNBC based on the results of a phase I/II clinical trial, which demonstrated an ORR of 34%, a median PFS of 5.5 months, and a median OS of 12.7 months [ 52 ]. In the EMERGE phase II trial with the 3L+ mTNBC subpopulation treated with another ADC, glembatumumab vedotin (GV), reporting an ORR of 18% (vs 0% for the chemotherapy-treated counterparts), these figures were 40% and 0%, respectively, for patients with mTNBC overexpressing glycoprotein NMB (gpNMB) [ 53 ]. There was a suggestion of possible improvement in survival (PFS and OS) with GV compared with chemotherapy in this population of the EMERGE study (PFS: 3.5 months vs 1.5 months; OS, 10.0 months vs 5.5 months) [ 53 ]. However, a recent trial of GV versus capecitabine in a similar population of patients with gpNMB-overexpressing mTNBC (METRIC) did not meet its primary PFS objective, with no improvement in PFS with GV compared with capecitabine, and no OS benefit [ 54 ].

Limitations

No mTNBC-specific randomized controlled trials directly comparing NCCN-recommended (v1.2016) chemotherapies for the treatment of MBC were identified in this search, allowing only indirect comparison between studies. Furthermore, no phase III trial studying single-agent chemotherapy for the treatment of mTNBC in any line of therapy was found. Given that results from only one global phase III trial to evaluate combination chemotherapy in mTNBC are available [ 40 ], retrospective (and in one case prospective [ 41 ]) subgroup analyses of the mTNBC subpopulation from larger phase III MBC trials and smaller phase II trials, including single-arm trials, were included in this evidence synthesis. Furthermore, for the meta-analysis of 2L+ chemotherapies, quantitative adjustment for differences in patient characteristics across trials was not feasible because of the paucity of such historical trials. It should also be noted that these clinical trial results are representative of a very select group of patients with mTNBC. Therefore, worse outcomes are likely in the general population of patients, many of whom would not meet the stringent eligibility criteria specified in these clinical trials (e.g., exclusion of patients with brain metastases at screening, exclusion of patients with early recurrences in first-line studies).

Adequately controlled historical data on the treatment of mTNBC are limited, which may be attributed to the lack of therapies specific to mTNBC. Among the available historical data, commonly used chemotherapies have demonstrated limited durability of response, limited survival benefit, and challenging toxicity profiles, suggesting a considerable unmet medical need in mTNBC. The recent approval of the combination of nab-paclitaxel and atezolizumab for the treatment of PD-L1–positive (IC1+) mTNBC is a positive development for a subset of patients with mTNBC (41% by the Ventana PD-L1 [SP142] assay). However, therapeutic regimens that result in improved, sustainable clinical responses and longer survival, along with more manageable safety profiles, are still needed for patients with mTNBC, including those with PD-L1–negative tumors. Ongoing and future studies with immune therapies, targeted agents, and ADCs, either as monotherapy or combination treatment, can provide new opportunities for improved outcomes in patients with this difficult-to-treat BC subtype.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

Second-line or higher

Adverse event

All patients as treated

Breast cancer

Confidence interval

Duration of response

European School of Oncology-European Society for Medical Oncology

US Food and Drug Administration

Glycoprotein NMB

Glembatumumab vedotin

Metastatic breast cancer

- Metastatic triple-negative breast cancer

National Comprehensive Cancer Network

Objective response rate

Overall survival

Programmed death 1

Programmed death-ligand 1

Progression-free survival

Triple-negative breast cancer

Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2018. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:7–30.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Bauer KR, Brown M, Cress RD, Parise CA, Caggiano V. Descriptive analysis of estrogen receptor (ER)-negative, progesterone receptor (PR)-negative, and HER2-negative invasive breast cancer, the so-called triple-negative phenotype: a population-based study from the California Cancer Registry. Cancer. 2007;109:1721–8.

Carey LA, Perou CM, Livasy CA, Dressler LG, Cowan D, et al. Race, breast cancer subtypes, and survival in the Carolina Breast Cancer Study. JAMA. 2006;295:2492–502.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Dent R, Trudeau M, Pritchard KI, Hanna WM, Kahn HK, et al. Triple-negative breast cancer: clinical features and patterns of recurrence. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:4429–34.

National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology (NCCN guidelines): breast cancer (Version 1.2019). Accessed 8 July 2019.

Cardoso F, Senkus E, Costa A, Papadopoulos E, Aapro M, et al. 4th ESO-ESMO International Consensus Guidelines for Advanced Breast Cancer (ABC 4). Ann Oncol. 2018;29:1634–57.

Zeichner SB, Terawaki H, Gogineni K. A review of systemic treatment in metastatic triple-negative breast cancer. Breast Cancer. 2016;10:25–36.

CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Piccart-Gebhart MJ, Burzykowski T, Buyse M, Sledge G, Carmichael J, et al. Taxanes alone or in combination with anthracyclines as first-line therapy of patients with metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:1980–6.

Twelves C, Cortes J, Vahdat L, Olivo M, He Y, Kaufman PA, Awada A. Efficacy of eribulin in women with metastatic breast cancer: a pooled analysis of two phase 3 studies. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2014;148:553–61.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Schmid P, Adams S, Rugo HS, Schneeweiss A, Barrios CH, et al. Atezolizumab and nab-paclitaxel in advanced triple-negative breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:2108–21.

TECENTRIQ® (atezolizumab) injection, for intravenous use [prescribing information]. South San Francisco, CA, USA: Genentech, Inc.; 2019.

National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology (NCCN guidelines): breast cancer (Version 1.2016). Accessed 8 July 2019.

Pivot X, Marme F, Koenigsberg R, Guo M, Berrak E, Wolfer A. Pooled analyses of eribulin in metastatic breast cancer patients with at least one prior chemotherapy. Ann Oncol. 2016;27:1525–31.

Dent R, Seock-Ah IM, Espie M, Blau S, Tan AR, et al. Overall survival (OS) update of the double-blind placebo (PBO)-controlled randomized phase 2 LOTUS trial of first-line ipatasertib (IPAT) + paclitaxel (PAC) for locally advanced/metastatic triple-negative breast cancer (mTNBC). J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(15_suppl):1008.

Article Google Scholar

Kim SB, Dent R, Im SA, Espie M, Blau S, et al. Ipatasertib plus paclitaxel versus placebo plus paclitaxel as first-line therapy for metastatic triple-negative breast cancer (LOTUS): a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18:1360–72.

Litton JK, Rugo HS, Ettl J, Hurvitz SA, Gonçalves A, et al. Talazoparib in patients with advanced breast cancer and a germline BRCA mutation. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:753–63.

Robson M, Im SA, Senkus E, Xu B, Domchek SM, et al. Olaparib for metastatic breast cancer in patients with a germline BRCA mutation. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:523–33.

Robson ME, Tung N, Conte P, Im SA, Senkus E, et al. OlympiAD final overall survival and tolerability results: Olaparib versus chemotherapy treatment of physician's choice in patients with a germline BRCA mutation and HER2-negative metastatic breast cancer. Ann Oncol. 2019;30(4):558–66.

Tutt A, Tovey H, Cheang MCU, Kernaghan S, Kilburn L, et al. Carboplatin in BRCA1/2-mutated and triple-negative breast cancer BRCAness subgroups: the TNT Trial. Nat Med. 2018;24:628–37.

DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7:177–88.

Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gotzsche PC, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000100.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Vermorken JB, Herbst RS, Leon X, Amellal N, Baselga J. Overview of the efficacy of cetuximab in recurrent and/or metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck in patients who previously failed platinum-based therapies. Cancer. 2008;112:2710–9.

Aftimos P, Polastro L, Ameye L, Jungels C, Vakili J, et al. Results of the Belgian expanded access program of eribulin in the treatment of metastatic breast cancer closely mirror those of the pivotal phase III trial. Eur J Cancer. 2016;60:117–24.

Awada A, Bondarenko IN, Bonneterre J, Nowara E, Ferrero JM, et al. A randomized controlled phase II trial of a novel composition of paclitaxel embedded into neutral and cationic lipids targeting tumor endothelial cells in advanced triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC). Ann Oncol. 2014;25:824–31.

Baselga J, Gomez P, Greil R, Braga S, Climent MA, et al. Randomized phase II study of the anti-epidermal growth factor receptor monoclonal antibody cetuximab with cisplatin versus cisplatin alone in patients with metastatic triple-negative breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:2586–92.

Brufsky A, Valero V, Tiangco B, Dakhil S, Brize A, et al. Second-line bevacizumab-containing therapy in patients with triple-negative breast cancer: subgroup analysis of the RIBBON-2 trial. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;133:1067–75.

Isakoff SJ, Mayer EL, He L, Traina TA, Carey LA, et al. TBCRC009: a multicenter phase II clinical trial of platinum monotherapy with biomarker assessment in metastatic triple-negative breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:1902–9.

Miles DW, Dieras V, Cortes J, Duenne AA, Yi J, O'Shaughnessy J. First-line bevacizumab in combination with chemotherapy for HER2-negative metastatic breast cancer: pooled and subgroup analyses of data from 2447 patients. Ann Oncol. 2013;24:2773–80.

Perez EA, Awada A, O'Shaughnessy J, Rugo HS, Twelves C, et al. Etirinotecan pegol (NKTR-102) versus treatment of physician's choice in women with advanced breast cancer previously treated with an anthracycline, a taxane, and capecitabine (BEACON): a randomised, open-label, multicentre, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16:1556–68.

Pivot XB, Li RK, Thomas ES, Chung HC, Fein LE, et al. Activity of ixabepilone in oestrogen receptor-negative and oestrogen receptor-progesterone receptor-human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-negative metastatic breast cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:2940–6.

Sparano JA, Vrdoljak E, Rixe O, Xu B, Manikhas A, et al. Randomized phase III trial of ixabepilone plus capecitabine versus capecitabine in patients with metastatic breast cancer previously treated with an anthracycline and a taxane. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:3256–63.

Tredan O, Campone M, Jassem J, Vyzula R, Coudert B, et al. Ixabepilone alone or with cetuximab as first-line treatment for advanced/metastatic triple-negative breast cancer. Clin Breast Cancer. 2015;15:8–15.

von Minckwitz G, Puglisi F, Cortes J, Vrdoljak E, Marschner N, et al. Bevacizumab plus chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone as second-line treatment for patients with HER2-negative locally recurrent or metastatic breast cancer after first-line treatment with bevacizumab plus chemotherapy (TANIA): an open-label, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:1269–78.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Brodowicz T, Lang I, Kahan Z, Greil R, Beslija S, et al. Selecting first-line bevacizumab-containing therapy for advanced breast cancer: TURANDOT risk factor analyses. Br J Cancer. 2014;111:2051–7.

Dieras V, Campone M, Yardley DA, Romieu G, Valero V, et al. Randomized, phase II, placebo-controlled trial of onartuzumab and/or bevacizumab in combination with weekly paclitaxel in patients with metastatic triple-negative breast cancer. Ann Oncol. 2015;26:1904–10.

Fan Y, Xu BH, Yuan P, Ma F, Wang JY, et al. Docetaxel-cisplatin might be superior to docetaxel-capecitabine in the first-line treatment of metastatic triple-negative breast cancer. Ann Oncol. 2013;24:1219–25.

Halim IIA, El-Sadda W, El-Ebrashy M, El Ashry M. Phase II study of weekly paclitaxel and carboplatin followed by oral navelbine in patients with triple negative metastatic/recurrent breast cancer previously treated with adjuvant anthracycline and taxotere. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(15_suppl):e12557.

Li Q, Li Q, Zhang P, Yuan P, Wang J, et al. A phase II study of capecitabine plus cisplatin in metastatic triple-negative breast cancer patients pretreated with anthracyclines and taxanes. Cancer Biol Ther. 2015;16:1746–53.

Liao Y, Fan Y, Wan Y, Li J, Peng L. Acceptable but limited efficacy of capecitabine-based doublets in the first-line treatment of metastatic triple-negative breast cancer: a pilot study. Chemotherapy. 2013;59:207–13.

O'Shaughnessy J, Schwartzberg L, Danso MA, Miller KD, Rugo HS, et al. Phase III study of iniparib plus gemcitabine and carboplatin versus gemcitabine and carboplatin in patients with metastatic triple-negative breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:3840–7.

Rugo HS, Barry WT, Moreno-Aspitia A, Lyss AP, Cirrincione C, et al. Randomized phase III trial of paclitaxel once per week compared with nanoparticle albumin-bound nab-paclitaxel once per week or ixabepilone with bevacizumab as first-line chemotherapy for locally recurrent or metastatic breast cancer: CALGB 40502/NCCTG N063H (Alliance). J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:2361–9.

Robert NJ, Dieras V, Glaspy J, Brufsky AM, Bondarenko I, et al. RIBBON-1: randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase III trial of chemotherapy with or without bevacizumab for first-line treatment of human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-negative, locally recurrent or metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:1252–60.

Carey LA, Rugo HS, Marcom PK, Mayer EL, Esteva FJ, et al. TBCRC 001: randomized phase II study of cetuximab in combination with carboplatin in stage IV triple-negative breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:2615–23.

Duda DG, Ziehr DR, Guo H, Ng M, Barry WT, et al. Effect of cabozantinib treatment on circulating immune cell populations in patients with metastatic triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC). J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(15_suppl):1093.

Hu X, Zhang J, Xu B, Jiang Z, Ragaz J, et al. Multicenter phase II study of apatinib, a novel VEGFR inhibitor in heavily pretreated patients with metastatic triple-negative breast cancer. Int J Cancer. 2014;135:1961–9.

Tolaney SM, Tan S, Guo H, Barry W, Van AE, et al. Phase II study of tivantinib (ARQ 197) in patients with metastatic triple-negative breast cancer. Investig New Drugs. 2015;33:1108–14.

Tutt A, Robson M, Garber JE, Domchek SM, Audeh MW, et al. Oral poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitor olaparib in patients with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations and advanced breast cancer: a proof-of-concept trial. Lancet. 2010;376:235–44.

Emens LA, Braiteh FS, Cassier P, Delord J-P, Eder JP, et al. Inhibition of PD-L1 by MPDL3280A leads to clinical activity in patients with metastatic triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC). Cancer Res. 2015;75(15_suppl):2859.

Google Scholar

Adams S, Schmid P, Rugo HS, Winer EP, Loirat D, et al. Phase 2 study of pembrolizumab (pembro) monotherapy for previously treated metastatic triple-negative breast cancer (mTNBC): KEYNOTE-086 cohort A. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(15_suppl):1008.

National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology (NCCN guidelines): breast cancer (Version 1.2018). Accessed 8 July 2019.

Schmid P, Abraham J, Chan S, Wheatley D, Brunt M, et al. AZD5363 plus paclitaxel versus placebo plus paclitaxel as first-line therapy for metastatic triple-negative breast cancer (PAKT): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase II trial. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(15_suppl):1007.

Bardia A, Vahdat L, Diamond J, Kalinsky K, O'Shaughnessy J, et al. Abstract GS1–07: Sacituzumab govitecan (IMMU-132), an anti-Trop-2-SN-38 antibody-drug conjugate, as ≥3rd-line therapeutic option for patients with relapsed/refractory metastatic triple-negative breast cancer (mTNBC): efficacy results [abstract]. Cancer Res. 2018;78(suppl 4):Abstract GS1-07.

Yardley DA, Weaver R, Melisko ME, Saleh MN, Arena FP, et al. EMERGE: a randomized phase II study of the antibody-drug conjugate glembatumumab vedotin in advanced glycoprotein NMB-expressing breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:1609–19.

Vahdat LT, Forero-Torres A, Schmid P, Blackwell K, Telli ML, et al. A randomized international phase 2b study of the antibody-drug conjugate (ADC) glembatumumab vedotin (GV) in gpNMB-overexpressing, metastatic, triple-negative breast cancer (mTNBC). J Clin Oncol. 2019;79(4_suppl):P6–20 01.

Download references

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the study 301 research team. Medical writing and/or editorial assistance was provided by Amy McQuay, PhD, of the ApotheCom pembrolizumab team (Yardley, PA, USA). This assistance was funded by Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp., a subsidiary of Merck & Co., Inc., Kenilworth, NJ, USA.

Funding for this research was provided by Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp., a subsidiary of Merck & Co., Inc., Kenilworth, NJ, USA.

Author information

Claire H. Li and Mallika Lala contributed equally to this work.

Authors and Affiliations

Merck & Co., Inc., Kenilworth, NJ, USA

Claire H. Li, Vassiliki Karantza, Gursel Aktan & Mallika Lala

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

CHL, VK, and ML conceived and designed the analysis; CHL, GA, and ML collected the data; CHL, GA, and ML analyzed the data; and CHL, VK, GA, and ML interpreted the data. All authors were involved in the drafting, critical review, and approval of the final manuscript and the decision to submit for publication.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Mallika Lala .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate, consent for publication.

CHL, VK, GA, and ML have consented to the publication of this manuscript.

Competing interests

CHL, VK, GA, and ML are employees of Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp., a subsidiary of Merck & Co., Inc., Kenilworth, NJ, USA.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1:.

Table S1. PubMed search queries.

Additional file 2:

Table S2. Cochrane search queries.

Additional file 3:

Table S3. Embase search queries.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Li, C.H., Karantza, V., Aktan, G. et al. Current treatment landscape for patients with locally recurrent inoperable or metastatic triple-negative breast cancer: a systematic literature review. Breast Cancer Res 21 , 143 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13058-019-1210-4

Download citation

Received : 24 January 2019

Accepted : 15 October 2019

Published : 16 December 2019

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s13058-019-1210-4

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Chemotherapy

- Immune checkpoint inhibitor

- PARP inhibitor

Breast Cancer Research

ISSN: 1465-542X

- Submission enquiries: [email protected]

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 18 May 2024

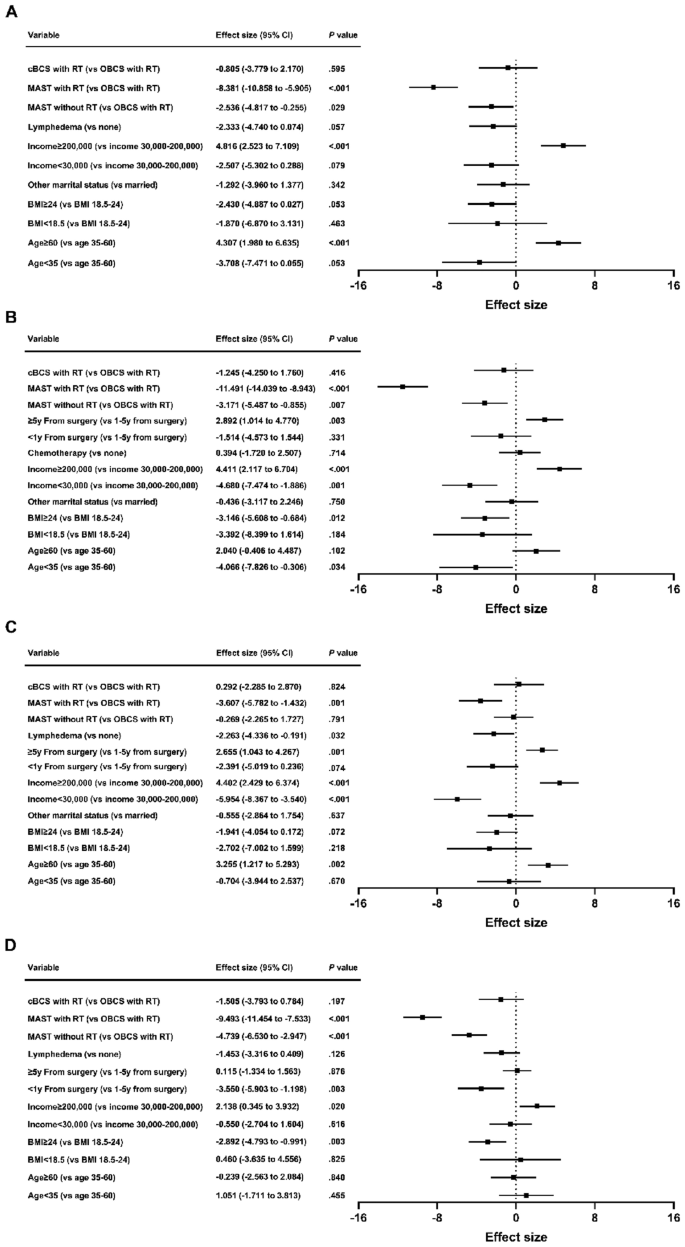

Disparities in quality of life among patients with breast cancer based on surgical methods: a cross-sectional prospective study

- Yi Wang 1 ,

- Yibo He 1 ,

- Shiyan Wu 1 &

- Shangnao Xie 1

Scientific Reports volume 14 , Article number: 11364 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

229 Accesses

Metrics details

- Breast cancer

- Quality of life