Causes of the English Civil Wars

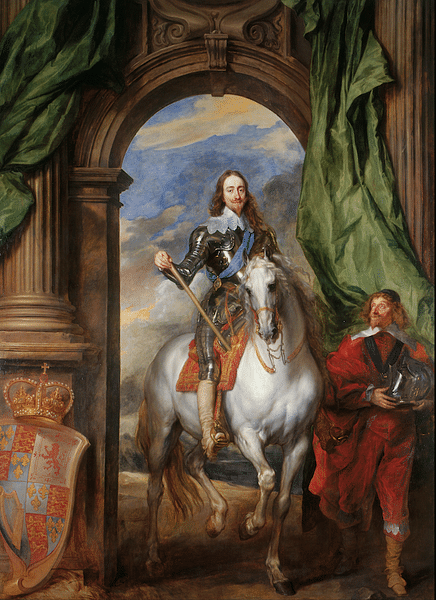

The English Civil Wars (1642-1651) were caused by a monumental clash of ideas between King Charles I of England (r. 1625-1649) and his parliament. Arguments over the powers of the monarchy, finances, questions of religious practices and toleration, and the clash of leaders with personalities, who passionately believed in their own cause but had little empathy towards any other view, all contributed to the decade-long conflict which saw over 600 battles and sieges, thousands of deaths, the execution of Charles, abolition of the monarchy, and the proclamation of England as a republic.

The Three Civil Wars

The conflict between the Royalists ('Cavaliers') and Parliamentarians ('Roundheads') which rocked Britain is usually divided into three distinct parts:

- The First English Civil War (1642-1646)

- The Second English Civil War (Feb-Aug 1648)

- The Third English Civil War or Anglo-Scottish War (1650-1651)

The causes of all three conflicts, sometimes collectively known as the Wars of the Three Kingdoms (England, Scotland , and Ireland ), were much the same except that following Charles I's execution in 1649, the figurehead for the Royalists during the Third Civil War became his son Charles II of Scotland.

Historians do not agree on the precise causes of the Civil Wars, and so the following is a summary of the various viewpoints with no particular weight given to one cause over another.

A Multitude of Causes

The principal causes of the English Civil Wars may be summarised as:

- Charles I's unshakeable belief in the divine right of kings to rule

- Parliament's desire to curb the powers of the king

- Charles I's need for money to fund his court and wars

- Religious differences between the monarch, Parliament, Scottish Covenanters, and Irish Catholics

- The personalities of key leaders on both sides, which did not allow for compromise

- A rise in the number and economic power of the new gentry who now sought political change

- A belief that the king was a wicked warmonger and had to be removed

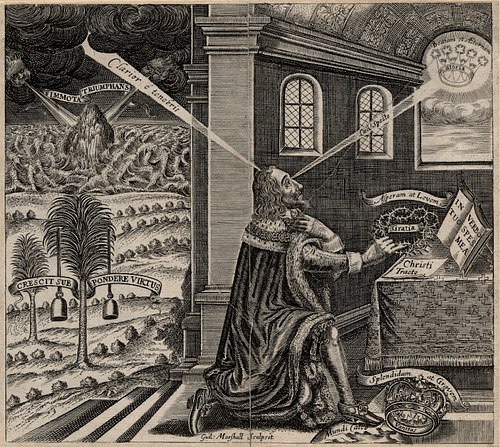

The Divine Right of Kings

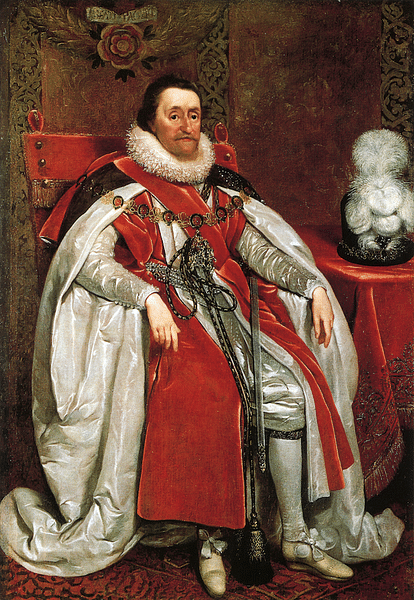

Charles was very much like his father James I of England (r. 1603-1625) in that he had an unshakeable belief in his divine right to rule, given to him, he thought, by God , and so no man, be it politician or soldier, should ever question his reign. The English king once stated: "Parliaments are altogether in my power…As I find the fruits of them good or evil, they are to continue or not to be" (McDowall, 88). This belief was never shaken throughout the wars, as seen in 1649 when he refused to recognise the authority of those who had put him on trial for treason:

I would know by what power I am called hither…I would know by what authority, I mean lawful…Remember, I am your king, your lawful king…a king cannot be tried by any superior jurisdiction on earth. (Ralph Lewis, 160)

Charles' personality had much to do with the crisis. A little shy and lacking confidence after a childhood away from the limelight when his elder brother was groomed for the crown, Charles was thrust into the glare of politics when Henry, Prince of Wales died of fever aged 18. Never quite trusting those around him, inflexible, repeatedly unwilling to make concessions, and not particularly receptive to criticism, Charles was perhaps led into making certain decisions that he himself did not whole-heartedly believe in or which were, at best, naive in their ignorance of opposing and more modern views. The king is also accused of being unaware of the different social, economic, and religious identities within his own kingdoms, particularly regarding Scotland, Wales, and Ireland, but also in parts of England where there were differences between regions and between rural and urban communities. In fairness, similar criticisms could be made of his opponents with such bullish MPs as John Pym (1583-1643) and Oliver Cromwell (1599-1658) who were utterly convinced God was on their side and not with the king.

There is also the argument that Charles inherited a difficult situation, his father being the first Stuart monarch after the Tudors. The kingdom was a united one in name only. There had been turbulent religious reforms going back to Henry VIII of England (r. 1509-1547), and the fallout of these was still being felt. Tensions between monarch and Parliament were not new either, and the antiquated system of state finances did not help smooth the relationship. Granted that the situation was not an easy one, some historians would accuse Charles of making it much worse, turning only potential problems into very real ones (Gaunt, 18).

The position of the king as an absolute monarch in Charles' own mind should have been seriously challenged by such events as the 1628 Petition of Right when Parliament demanded the king stop trying to raise money outside of that institution. Other demands included an end to both imprisonment without trial and the use of martial law against civilians. Desperately in need of money for his war with France, the king was obliged to agree to the demands but it in no way altered his opinion of his status as a monarch who had no need to consult anyone on how to govern his kingdom.

Disputes Over Finances

The monarchy traditionally required Parliament to meet and pass favour on royal requests for money, which typically entailed MPs deciding budgets and raising taxes. Charles grew tired of Parliament's obstinacy and insistence that money be accounted for and spending curbed. The king repeatedly called and dismissed parliaments but eventually grew tired of this situation and decided to rule alone. Parliament was not called between 1629 and 1640, a period often called the 'Personal Rule' of the king. This strategy worked well enough until the king desperately needed funds in 1639 to pay for his campaigns against a Scottish army, which had occupied the north of England, and a serious rebellion in Ireland, both fuelled by religious differences and the king's high-handed policies.

The king's efforts to raise money during his 'Personal Rule' had met with only limited success. He borrowed from bankers, extracted new customs duties, imposed forced loans on the wealthy, sold monopolies, and widened the extraction and use of Ship Money (originally imposed on coastal communities only to help fund the navy). He also imposed fines based on archaic forest laws and increased fines imposed by courts. Many of these measures were deeply unpopular with the merchant classes and local gentry, who were more numerous than ever before. Such men were keen to see a political role to match their importance to the economy , and they were unwilling to fund the whims of a monarch who caused what they saw as unnecessary wars and who supported a declining and outdated feudal aristocracy. It did not help that Charles spent grandly on new palaces and art collections. Parliament, knowing the king had nowhere else to go for more cash, could now force Charles into political reforms and concessions.

Charles called what became known as the Short Parliament in the spring of 1640 to help raise an army, but this failed after three frustrating weeks of discussion. As a result, the king could only muster a weak militia force against the Scots in the so-called Bishops' Wars (1639-1640). These wars ended in Charles making concessions to Scotland in the Treaty of Ripon in October 1640. Scotland was permitted its religious freedom, and the leaders on the battlefield were promised a handsome sum in cash to stand down. The king then had the practical problem of where exactly to get this money from without Parliament.

Without much choice in the matter, another Parliament was called in November 1640, and so began a period known as the 'Crisis of the Monarchy'. MPs seized their opportunity with the Long Parliament, as it became known, to guarantee their future survival. Money would be raised to pay off the Scots, but only on the condition that laws were passed which meant a parliament must be called at least once every three years, that it could not be dissolved by the monarch's wishes alone, royal ministers now had to be approved by Parliament, and Ship Money was made illegal. The king agreed but then blithely ignored his promises.

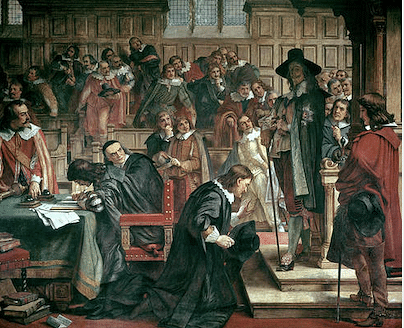

One of the decisions of Parliament which had particularly struck Charles and soured relations more than ever was the trial for treason and execution of his closest advisor Thomas Wentworth, Earl of Stafford (1593-1641) in May 1641. Stafford had been accused of preparing to bring an Irish army into England to aid the king, for which there was not much evidence. More significant, perhaps, was Parliament's fear of what exactly the gifted and utterly ruthless Stafford planned in the future regarding themselves. As far as Charles was concerned, Parliament had drawn first blood.

In October 1641 the king needed money for yet another army when a rebellion broke out against English rule (some would say tyranny) in Ireland, fuelled by grievances over massive English land confiscations and the exclusive employment of English and Scottish immigrants on many large estates. Ulster was a particularly bloody battleground while Charles and the English Parliament wrangled over the formation of an army necessary to quell the rebellion. Parliament was particularly anxious that the king use such a force in Ireland and not against themselves. These fears were perhaps not unfounded, and the king's attempted arrest of five MPs in January 1642 hardly instilled confidence. The group, who included John Pym, had written the Grand Remonstrance listing the king's abuses of power and which was passed by Parliament in November 1641. The Remonstrance was then made public. In retaliation for the arrests, the Parliamentarians locked the gates of London, preventing Charles from entering his own capital. However, the king was encouraged by the distinct lack of unity in Parliament as the Remonstrance had only been accepted by 159 votes to 148. Some MPs believed that the king's powers were being unjustly infringed upon (for example, that he could not choose his own counsellors or military leaders), while the more radical members were keen to curb those powers even further. A military solution to the deadlock might now be Charles' best tactic. The king relocated from Hampton Court to York and then to Nottingham in August 1642, where a royal army was formed.

Sign up for our free weekly email newsletter!

Religious Differences

As we have seen, the multiple threads of discord that caused the English Civil Wars were intertwined in a complex political, religious, and military knot. Charles frequently created new enemies because of his religious policies. In 1627, Charles began to promote the Arminians, a branch of the Anglican Church that emphasised ritual, sacraments, and the clergy, and not the style of preaching seen in other branches closer to Calvinism. Some saw this move as a dangerous shift back towards Catholicism, a sign of a secret Papist conspiracy to reverse the English Reformation , an idea which was widely circulated in the 17th century by word of mouth and the printing press, adding fictional fuel to a bonfire of conspiracy theories that went all the way back to the one real conspiracy: the Gunpowder Plot to blow up King and Parliament in 1605.

Charles was not, in fact, a Catholic but a High Anglican, that is he had certain sympathies with such aspects of the Christian Church as ceremony, the elevation of the clergy and bishops, and what he perceived as the beauty and order provided by certain decorations within the church building itself. For many, though, it was difficult to distinguish this from 'Popish' practices and Roman Catholic doctrine. There were, too, more concrete concerns over the Arminians' seeming support of an absolute monarchy.

In 1633, the king appointed William Laud (1573-1645), an Arminian, as the Archbishop of Canterbury, head of the Church of England. Laud was detested by the Puritans , who remained a rich and powerful section of English society and who had a strong presence in Parliament. Many MPs and army officers were Independents or Congregationalists, that is they wanted less power in the hands of bishops and more inclusion in the Church. Many wanted greater freedom for 'independent' congregations that assembled according to the individual believers' consciences and their own interpretation of the Bible . Laud outraged the Puritans when he reintroduced what were widely seen as Catholic practices into the more austere Anglican Church. These included decorating churches, railing off the altar or communion table to restrict access only for the clergy, and encouraging music . Laud banned preaching on any day other than a Sunday and replaced this with the Catechism. He also banned the weekday lectures that Puritans so valued. From Laud's and the king's perspective, these religious changes were slight and intended to emphasise ritual and order, but for the Puritans, this was a direct attack on the achievements of the Reformation . With no real means to protest or obstruct these measures, and with punishments and fines for non-compliance, many Puritans decided to emigrate and find greater religious freedom in North America or the Netherlands.

Charles also upset the Scottish Kirk and its Presbyterian church leaders by trying to install bishops there. The introduction of a new prayer book in 1637 was made without even consulting the Kirk. The Presbyterians (moderate Puritans who believed in a church hierarchy) much preferred to stick to their system where each congregation was led by a minister who in turn reported to the Synod, an elected supervisory council of elders. Further, the Scots believed Charles had no right to impose anything on the Scottish Church, a point many were willing to fight for.

Far from being a problem of ecclesiastical debate, these issues boiled over onto the battlefield in the Bishops' Wars mentioned above. The Scottish Presbyterian Church was determined to defend its independence and so became an active ally of the Parliamentarians in the English Civil Wars before switching sides in support of the Royalists when Parliament was deemed the greater threat. Those Scots who sought an alliance with England were known as the Covenanters from the agreement known as the National Covenant of February 1638. Those who signed the agreement swore to defend the Presbyterian Church, even by military means if necessary.

In England, meanwhile, as we have seen, the situation between King and Parliament had worsened considerably. By 1642, both sides were gathering arms, fortifying the cities they controlled, and preparing for war. The first major battle was at Edgehill in October. The result was indecisive, as it would be in many of the battles that followed. While often seen as a war that did not involve a great number of civilians, it is estimated that at least one in four adult male Britons fought at some point, one in ten people in urban areas lost their homes, and the vast majority of people had to bear heavy taxes, even if they themselves avoided the actual fighting. As the Civil War progressed so new motives arrived for supporters on both sides. Charles' policy in Ireland further alienated the king from many of his English subjects. The king had struck a deal with Irish rebels so that Irish Catholic troops might bolster his army. This never came about in reality as most of the troops from Ireland were Charles' English soldiers now released from policing duties there, and even these were few in number. The episode did raise the serious question as to Charles' loyalty to the Anglican Church.

More and more people came to see the king as a despot and wilful warmonger who no longer had his people's interests foremost in his mind. The capture of the king's personal writing cabinet at the Battle of Naseby in 1645 revealed that the king had no intention of ever compromising with Parliament. Already for many, there could be no peaceful resolution to the conflict. This was particularly so after the Second Civil War and the invasion of a Scottish army into England. The king, even in self-imposed exile on the Isle of Wight, came to be viewed as a 'man of blood', a biblical term for a ruler who waged war against his own people. In his treaty with the Scots known as the Engagement of December 1647, he had even promised to favour the Presbyterian Church in England, disband the English army and rely only on a Scottish one, and suppress radical religious groups. This was the final straw.

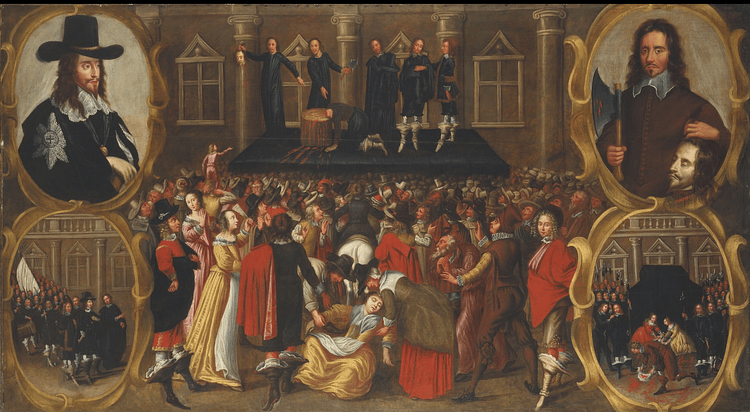

With more money and a more professional army, the Parliamentarians were the victors again at the Battle of Preston in 1648 . Charles I was tried and found guilty of treason to his own people and government. The king was executed on 30 January 1649. The monarchy and the House of Lords were abolished, and the Anglican Church was reformed. Scotland remained loyal to the crown, and Charles' eldest son Charles was, by right of birth, its king. However, a Scottish army was again defeated by an English one in the so-called Third English Civil War, and the would-be Charles II was obliged to flee to France.

Oliver Cromwell (1599-1658) ruled the 'Commonwealth' republic as Lord Protector. When Cromwell died, his chosen successor, his son Richard Cromwell, was not supported for long, and so, to avert another civil war, there was the Restoration of the Monarchy in 1660. Charles returned from France to become Charles II of England (r. 1660-1685), but he now had to rule alongside a much more powerful Parliament.

Subscribe to topic Bibliography Related Content Books Cite This Work License

Bibliography

- Anderson, Angela & Scarboro, Dale. Stuart Britain. Hodder Education, 2015.

- Bennett, Martyn. The English Civil War 1640-1649 . Routledge, 2014.

- Gaunt, Peter. The English Civil Wars. Osprey Publishing, 2003.

- Hunt, Tristram. The English Civil War at First Hand. Penguin UK, 2011.

- Miller, John. Early Modern Britain, 1450–1750 . Cambridge University Press, 2017.

- Morrill, John. The Oxford Illustrated History of Tudor & Stuart Britain. Oxford University Press, 1996.

- Wanklyn, Malcolm. Decisive Battles of the English Civil War. Pen and Sword Military, 2007.

About the Author

Translations

We want people all over the world to learn about history. Help us and translate this article into another language!

Related Content

Oliver Cromwell

Thomas Cromwell

Charles I of England

English Civil Wars

Charles II of England

Battle of Dunbar in 1650

Free for the world, supported by you.

World History Encyclopedia is a non-profit organization. For only $5 per month you can become a member and support our mission to engage people with cultural heritage and to improve history education worldwide.

Recommended Books

| , published by Cambridge University Press (2017) |

| , published by Routledge (2015) |

| , published by Shotwell Publishing LLC (2020) |

| , published by Touchstone (1992) |

| , published by Wiley-Blackwell (1999) |

Cite This Work

Cartwright, M. (2022, February 04). Causes of the English Civil Wars . World History Encyclopedia . Retrieved from https://www.worldhistory.org/article/1939/causes-of-the-english-civil-wars/

Chicago Style

Cartwright, Mark. " Causes of the English Civil Wars ." World History Encyclopedia . Last modified February 04, 2022. https://www.worldhistory.org/article/1939/causes-of-the-english-civil-wars/.

Cartwright, Mark. " Causes of the English Civil Wars ." World History Encyclopedia . World History Encyclopedia, 04 Feb 2022. Web. 20 Jun 2024.

License & Copyright

Submitted by Mark Cartwright , published on 04 February 2022. The copyright holder has published this content under the following license: Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike . This license lets others remix, tweak, and build upon this content non-commercially, as long as they credit the author and license their new creations under the identical terms. When republishing on the web a hyperlink back to the original content source URL must be included. Please note that content linked from this page may have different licensing terms.

- Games & Quizzes

- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

- Introduction & Top Questions

Personal Rule and the seeds of rebellion (1629–40)

The bishops’ wars and the return of parliament (1640–42).

- The first English Civil War (1642–46)

- Conflicts in Scotland and Ireland

- Second and third English Civil Wars (1648–51)

- Cost and legacy

- What is Charles I known for?

- What was Charles I’s early life like?

- How did Charles I become king of Great Britain and Ireland?

- What was the relationship between Charles I and Parliament like?

- Why was Charles I executed?

English Civil Wars

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- World History Encyclopedia - English Civil Wars

- National Center for Biotechnology Information - PubMed Central - Misogyny, feminism, and sexual harassment

- NSCC Libraries Pressbooks - Western Civilization: A Concise History - The English Civil War and the Glorious Revolution

- History Learning Site - The English Civil War

- The Cormwwell Association - Causes of the English Civil War

- English Civil War - Children's Encyclopedia (Ages 8-11)

- English Civil Wars - Student Encyclopedia (Ages 11 and up)

- Table Of Contents

When did the English Civil Wars occur?

The English Civil Wars occurred from 1642 through 1651. The fighting during this period is traditionally broken into three wars: the first happened from 1642 to 1646, the second in 1648, and the third from 1650 to 1651.

What was the first major battle fought in the English Civil Wars?

The first major battle of the English Civil Wars fought on English soil was the Battle of Edgehill , which occurred in October 1642. Forces loyal to the English Parliament, commanded by Robert Devereux, 3rd earl of Essex , delayed Charles I’s march on London.

How many people died during the English Civil Wars?

An estimated 200,000 people lost their lives directly or indirectly as a result of the English Civil Wars, making it arguably the bloodiest conflict in the history of the British Isles.

When did the English Civil Wars come to an end?

The English Civil Wars ended on September 3, 1651, with Oliver Cromwell ’s victory at Worcester and the subsequent flight of Charles II to France.

English Civil Wars , (1642–51), fighting that took place in the British Isles between supporters of the monarchy of Charles I (and his son and successor , Charles II ) and opposing groups in each of Charles’s kingdoms, including Parliamentarians in England , Covenanters in Scotland , and Confederates in Ireland . The English Civil Wars are traditionally considered to have begun in England in August 1642, when Charles I raised an army against the wishes of Parliament , ostensibly to deal with a rebellion in Ireland. But the period of conflict actually began earlier in Scotland, with the Bishops’ Wars of 1639–40, and in Ireland, with the Ulster rebellion of 1641. Throughout the 1640s, war between king and Parliament ravaged England, but it also struck all of the kingdoms held by the house of Stuart —and, in addition to war between the various British and Irish dominions, there was civil war within each of the Stuart states. For this reason the English Civil Wars might more properly be called the British Civil Wars or the Wars of the Three Kingdoms. The wars finally ended in 1651 with the flight of Charles II to France and, with him, the hopes of the British monarchy.

Compared with the chaos unleashed by the Thirty Years’ War (1618–48) on the European continent, the British Isles under Charles I enjoyed relative peace and economic prosperity during the 1630s. However, by the later 1630s, Charles’s regime had become unpopular across a broad front throughout his kingdoms. During the period of his so-called Personal Rule (1629–40), known by his enemies as the “Eleven-Year Tyranny” because he had dissolved Parliament and ruled by decree, Charles had resorted to dubious fiscal expedients, most notably “ ship money ,” an annual levy for the reform of the navy that in 1635 was extended from English ports to inland towns. This inclusion of inland towns was construed as a new tax without parliamentary authorization. When combined with ecclesiastical reforms undertaken by Charles’s close adviser William Laud , the archbishop of Canterbury , and with the conspicuous role assumed in these reforms by Henrietta Maria , Charles’s Catholic queen, and her courtiers, many in England became alarmed. Nevertheless, despite grumblings, there is little doubt that had Charles managed to rule his other dominions as he controlled England, his peaceful reign might have been extended indefinitely. Scotland and Ireland proved his undoing.

In 1633 Thomas Wentworth became lord deputy of Ireland and set out to govern that country without regard for any interest but that of the crown. His thorough policies aimed to make Ireland financially self-sufficient; to enforce religious conformity with the Church of England as defined by Laud, Wentworth’s close friend and ally; to “civilize” the Irish; and to extend royal control throughout Ireland by establishing British plantations and challenging Irish titles to land. Wentworth’s actions alienated both the Protestant and the Catholic ruling elites in Ireland. In much the same way, Charles’s willingness to tamper with Scottish land titles unnerved landowners there. However, it was Charles’s attempt in 1637 to introduce a modified version of the English Book of Common Prayer that provoked a wave of riots in Scotland, beginning at the Church of St. Giles in Edinburgh . A National Covenant calling for immediate withdrawal of the prayer book was speedily drawn up on February 28, 1638. Despite its moderate tone and conservative format, the National Covenant was a radical manifesto against the Personal Rule of Charles I that justified a revolt against the interfering sovereign .

The turn of events in Scotland horrified Charles, who determined to bring the rebellious Scots to heel. However, the Covenanters , as the Scottish rebels became known, quickly overwhelmed the poorly trained English army, forcing the king to sign a peace treaty at Berwick (June 18, 1639). Though the Covenanters had won the first Bishops’ War , Charles refused to concede victory and called an English parliament, seeing it as the only way to raise money quickly. Parliament assembled in April 1640, but it lasted only three weeks (and hence became known as the Short Parliament ). The House of Commons was willing to vote the huge sums that the king needed to finance his war against the Scots, but not until their grievances—some dating back more than a decade—had been redressed. Furious, Charles precipitately dissolved the Short Parliament. As a result, it was an untrained, ill-armed, and poorly paid force that trailed north to fight the Scots in the second Bishops’ War. On August 20, 1640, the Covenanters invaded England for the second time, and in a spectacular military campaign they took Newcastle following the Battle of Newburn (August 28). Demoralized and humiliated, the king had no alternative but to negotiate and, at the insistence of the Scots, to recall parliament.

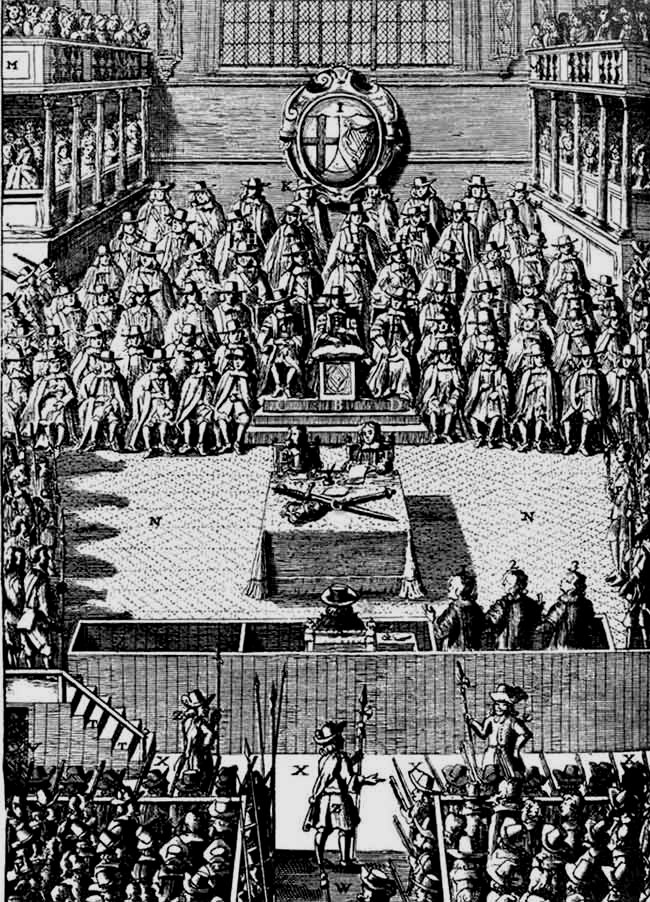

A new parliament (the Long Parliament ), which no one dreamed would sit for the next 20 years, assembled at Westminster on November 3, 1640, and immediately called for the impeachment of Wentworth, who by now was the earl of Strafford. The lengthy trial at Westminster, ending with Strafford’s execution on May 12, 1641, was orchestrated by Protestants and Catholics from Ireland, by Scottish Covenanters, and by the king’s English opponents, especially the leader of Commons, John Pym —effectively highlighting the importance of the connections between all the Stuart kingdoms at this critical junction.

To some extent, the removal of Strafford’s draconian hand facilitated the outbreak in October 1641 of the Ulster uprising in Ireland. This rebellion derived, on the one hand, from long-term social, religious, and economic causes (namely tenurial insecurity, economic instability, indebtedness, and a desire to have the Roman Catholic Church restored to its pre- Reformation position) and, on the other hand, from short-term political factors that triggered the outbreak of violence. Inevitably, bloodshed and unnecessary cruelty accompanied the insurrection, which quickly engulfed the island and took the form of a popular rising, pitting Catholic natives against Protestant newcomers. The extent of the “massacre” of Protestants was exaggerated, especially in England where the wildest rumours were readily believed. Perhaps 4,000 settlers lost their lives—a tragedy to be sure, but a far cry from the figure of 154,000 the Irish government suggested had been butchered. Much more common was the plundering and pillaging of Protestant property and the theft of livestock. These human and material losses were replicated on the Catholic side as the Protestants retaliated.

The Irish insurrection immediately precipitated a political crisis in England, as Charles and his Westminster Parliament argued over which of them should control the army to be raised to quell the Irish insurgents. Had Charles accepted the list of grievances presented to him by Parliament in the Grand Remonstrance of December 1641 and somehow reconciled their differences, the revolt in Ireland almost certainly would have been quashed with relative ease. Instead, Charles mobilized for war on his own, raising his standard at Nottingham in August 1642. The Wars of the Three Kingdoms had begun in earnest. This also marked the onset of the first English Civil War fought between forces loyal to Charles I and those who served Parliament. After a period of phony war late in 1642, the basic shape of the English Civil War was of Royalist advance in 1643 and then steady Parliamentarian attrition and expansion.

- Advertise with us

- History Magazine

- History of England

The Origins & Causes of the English Civil War

We English like to think of ourselves as gentlemen and ladies; a nation that knows how to queue, eat properly and converse politely. And yet in 1642 we went to war with ourselves…

Victoria Masson

We English like to think of ourselves as gentlemen and ladies; a nation that knows how to queue, eat properly and converse politely. And yet in 1642 we went to war with ourselves. Pitting brother against brother and father against son, the English civil war is a blot on our history. Indeed, there was barely an English ‘gentleman’ who was not touched by the war.

Yet how did it start? Was it simply a power struggle between king and Parliament? Were the festering wounds left by the Tudor religious roller coaster to blame? Or was it all about the money?

Divine right – the God given right of an anointed monarch to rule unhindered – was established firmly in the reign of James I (1603-25). He asserted his political legitimacy by decreeing that a monarch is subject to no earthly authority; not the will of his people, the aristocracy or any other estate of the realm, including Parliament. Under this definition any attempt to depose, dethrone or restrict the powers of the monarch goes against the will of God. The concept of a God given right to rule was not born in this period however; writings as far back as AD 600 infer that the English in their varied Anglo-Saxon states accepted those in power had God’s blessing.

This blessing should create an infallible leader – and there is the rub. Surely if you have been given power to rule by God, you should demonstrate an ability to wield this responsibility with a degree of success? By 1642 Charles I found himself nearly bankrupt, surrounded by blatant corruption and nepotism and desperate to hold onto the thin veil that masked his religious uncertainty. He was by no means an infallible leader, a fact that was glaringly obvious to both Parliament and the people of England.

Parliament had no tangible power at this point in English history. They were a collection of aristocrats who met at the King’s pleasure to offer advice and to help him collect taxes. This alone gave them some influence, as the king needed their seal of approval to legitimately set taxes in motion. In times of financial difficulty that meant the King had to listen to Parliament. Stretched thinly through the lavish lifestyles and expensive wars of the Tudor and Stuart period, the Crown was struggling. Coupled with his desire to extend his high Anglican (read here thinly disguised Catholic) policies and practices to Scotland, Charles I needed the financial support of Parliament. When this support was withheld, Charles saw it as an infringement on his Divine Right and as such, he dismissed Parliament in March 1629. The following eleven years, during which Charles ruled England without a Parliament, are referred to as the ‘personal rule’. Ruling without Parliament was not unprecedented but without access to Parliament’s financial pulling power, Charles’s ability to acquire funds was limited.

Charles’s personal rule reads like a ‘how to annoy your countrymen for dummies’. His introduction of a permanent Ship Tax was the most offensive policy to many. Ship Tax was an established tax that was paid by counties with a sea border in times of war. It was to be used to strengthen the Navy and so these counties would be protected by the money they paid in tax; in theory, it was a fair tax against which they could not argue.

Charles’s decision to extend a year-round Ship Tax to all counties in England provided around £150,000 to £200,000 annually between 1634 and 1638. The resultant backlash and popular opposition however proved that there was growing support for a check on the power of the King.

This support did not just come from the general tax paying population but also from the Puritanical forces within Protestant England. After Mary I , all subsequent English monarchs have been overtly Protestant. This stabilization of the religious roller coaster calmed the fears of many in Tudor times who believed if a civil war was to be fought in England it would be fought along religious lines.

While outwardly a Protestant, Charles I was married to a staunch Catholic, Henrietta Maria of France. She heard Roman Catholic mass every day in her own private chapel and frequently took her children, the heirs to the English throne, to mass. Furthermore, Charles’ support for his friend Archbishop William Laud’s reforms to the English Church were seen by many as a move backwards to the popery of Catholicism. The re-introduction of stained glass windows and finery within churches was the last straw for many Puritans and Calvinists.

To prosecute those who opposed his reforms, Laud used the two most powerful courts in the land, the Court of High Commission and the Court of Star Chamber. The courts became feared for their censorship of opposing religious views and were unpopular among the propertied classes for inflicting degrading punishments on gentlemen. For example, in 1637 William Prynne, Henry Burton and John Bastwick were pilloried, whipped, mutilated by cropping and imprisoned indefinitely for publishing anti-episcopal pamphlets.

Charles’s continued support for these types of policies continued to pile on support for those that were looking to put a limit on his power.

By October 1640, Charles’ unpopular religious policies and attempts to extend his power north had resulted in a war with the Scots. This was a disaster for Charles who had neither the money nor the men to fight a war. He rode north to lead the battle himself, suffering a crushing defeat that left Newcastle upon Tyne and Durham occupied by Scottish forces.

Public demands for a Parliament were growing and Charles realised that whatever his next step was to be, it would require a financial backbone. After the conclusion of the humiliating Treaty of Ripon that let the Scots remain in Newcastle and Durham whilst being paid £850 a day for the privilege, Charles summoned Parliament. Being called upon to help King and country instilled a sense of purpose and power into this new Parliament. They now presented an alternative power in the country to the King. The two sides in the English Civil war had been established.

The slide to war becomes more pronounced from this stage onwards. That is not to say it was inevitable, or that the subsequent removal and execution of Charles I was even a notion in the heads of those who opposed him. However, the balance of power had begun to shift. Parliament wasted no time arresting and putting on trial the Kings closest advisers, including Archbishop Laud and Lord Strafford.

In May 1641 Charles conceded an unprecedented act, which forbade the dissolution of the English Parliament without Parliament’s consent. Thus emboldened, Parliament now abolished Ship Tax and the courts of The Star Chamber and The High Commission.

Over the next year Parliament began to introduce increased emboldened demands, and by June 1642 these were too much for Charles to bear. His bullish response in barging into the House of Commons and attempting to arrest five MPs lost him the last remnants of support among undecided MPs. The sides were crystallized and the battle lines were drawn. Charles I raised his standard on 22nd August 1642 in Nottingham: the Civil War had begun.

So the origins of the English Civil War are complex and intertwined. England had managed to escape the Reformation relatively unscathed, avoiding much of the heavy fighting that raged in Europe as Catholic and Protestant forces battled in The Thirty Year War. However, the scars of the Reformation were still present beneath the surface and Charles did little to avert public fears about his intentions for the religious future of England.

Money had also been an issue from the outset, especially as the royal coffers had been emptied during the reigns of Elizabeth I and James I. These issues were exacerbated by Charles’s mismanagement of the public coffers and through introducing new and ‘unfair’ taxes he simply added to the already growing anti-Crown sentiment up and down the country.

These two points demonstrate the fact that Charles believed in his Divine Right, a right to rule unchallenged. Through the study of money, religion and power at this time it is clear that one factor is woven through them all and must be noted as a major cause of the English Civil War; that is the attitude and ineptitude of Charles I himself, perhaps the antithesis of an infallible monarch.

Battles of the First English Civil War:

| 23 October, 1642 | |

| 19 January, 1643 | |

| 19 March, 1643 | |

| 16 May, 1643 | |

| 18 June, 1643 | |

| 30 June, 1643 | |

| 5 July, 1643 | |

| 13 July, 1643 | |

| 11 October, 1643 | |

| 25 January, 1644 | |

| 29 March, 1644 | |

| 29 June, 1644 | |

| 2 July, 1644 | |

| 14 June, 1645 | |

| 10 July 1645 | |

| 24 September, 1645 | |

| 21 March, 1646 |

History in your inbox

Sign up for monthly updates

Advertisement

Next article

Oliver Cromwell

The year 2011 marked the 350th anniversary of the execution of Oliver Cromwell, Lord Protector of England - two and half years AFTER his death..

Popular searches

- Castle Hotels

- Coastal Cottages

- Cottages with Pools

- Kings and Queens

- TOP CATEGORIES

- AS and A Level

- University Degree

- International Baccalaureate

- Uncategorised

- 5 Star Essays

- Study Tools

- Study Guides

- Meet the Team

- British History: Monarchy & Politics

The causes of the English civil war.

Melroy Satkunarajah

The causes of the English civil war

In this essay I am going to explain why the civil war broke out in 1642. The English civil war broke out on 22 nd August 1642. It caused many deaths and divided some families. There were many reasons for this, including religious arguments, financial arguments, the actions of Charles himself, all the causes were linked together, (Parliamentarian and Royalist) some of the events of 1642 and the demands made by parliaments for more power and also I am going to explain the long – term causes and the short – term causes also know as the triggers.

There are many different reasons for the causes of the English civil war but first I will start with the religious disputes over archbishops Laud’s reforms of the church. Reforms were introduced that made churches more decorated (like catholic churches) Charles I collected customs duties without parliaments permission, he married a French catholic who was unpopular with his people. The Bishops' Wars were fought between the Scots and English forces led by . These conflicts paved the way for the uprising of Parliament that began the English civil wars.

Charles I was attempting to enforce Anglican reforms onto the Scottish church. However the Scots were opposed to this, and even wanted to destroy the control that bishops had over the church. To this end, Charles' reforms were rejected by the Scottish Assembly at Glasgow in 1638.

Charles was furious that the Scots had rejected his proposals, and hastily formed an English force with which to march on Scotland in 1639. He did not have the funds for such a military expedition, nor confidence in his troops, so he was forced to leave Scotland without fighting a battle.

The unrest continued in Scotland, and when Charles discovered that they had been plotting with the French he again decided to mount a military expedition. This time, Charles called Parliament in order to get funds (1640).

This is a preview of the whole essay

The second cause was the financial quarrels between the king and parliament. When parliament formed, they immediately wanted to discuss grievances against the government, and were generally opposed to any military operation. This angered Charles and he dismissed parliament again, hence the name "Short Parliament" that it is commonly given.

Charles went ahead with his military operation without Parliament's support, and was beaten by the Scots. The Scots, taking advantage of this, went on to seize Northumberland and Durham.

Charles found himself in a desperate position, and was forced to call parliament again in November, 1640. This parliament is known as the "Long Parliament".

The third cause was the demands made by parliament for greater share government. The tension between Charles and Parliament was still great, since none of the issues raised by the Short Parliament had been resolved. This tension was brought to a head on January 4th, 1642 when Charles attempted to arrest five members of parliament. This attempt failed, since they were spirited away before the king's troops arrived.

Charles left London and both he and parliament began to stockpile military resources and recruit troops.

Charles officially began the war by raising his standard at Nottingham in August, 1642. At this stage of the wars, parliament had no wish to kill the king. It was hoped that Charles could be reinstated as ruler, but with a more constructive attitude to parliament. Parliaments were supported by the richer South and East, including London. Parliament also held most of the ports, since the merchants that ran them saw more profit in a parliament-lead country.

Parliament definitely had access to more resources than the king, and could collect taxes. Charles had to depend on donations from his supporters to fund his armies.

The fourth cause was that Charles I ruled without parliament. Charles I dissolved parliament because of all the disputes and ruled without it for 11 years. King did not like the wealth, power or ideas of parliament. He began making the decisions about taxes without parliament.

The fifth cause was that the ship money argument. Without parliament, Charles had to think up new pays of raising money, e.g. ship money which was paid in times of war by people living the coast, now had to pay by all people even though there was no war.

The sixth cause was that the parliament was recalled and demanded reforms. King Charles I wanted money, so he reopened the parliament to get money but they demanded the reforms e.g. never to be shut down again.

These are called the long – term cases.

Some M.P.S demanded more reforms from the king in a new list called ‘the grand remonstrance’ other M.P.S stick up for the king because he has already greed to some reforms.

A rebellion starts in Ireland where Catholics murdered 200,000 Protestants.

The England wondered if Charles supported the Catholics.

Charles I try to arrest five M.P.S while parliament is in session, but they had escaped before hand. This lost the king a lot of respect and showed he wanted to control parliament after all. Parliament and the king argued over who control the Army. Only six days after trying to arrest the five Members of Parliament, Charles left London to head for Oxford to raise an army to fight Parliament for control of England. A could not be avoided.

By 1642, relations between Parliament and had become very bad. Charles had to do as Parliament wished as they had the ability to raise the money that Charles needed. However, as a firm believer in the "divine right of kings", such a relationship was unacceptable to Charles.

These are called the short – term causes.

From the beginning of his reign, King Charles quarrelled with parliament about power.

King Charles dismissed parliament in 1629 and ruled without it for 11 years.

In 1635, King Charles made everyone pay the ship money tax.

The Scots rebelled against the new prayer book which the king and archbishop laud introduced in Scotland.

In 1638, the Scots invaded England.

King Charles asked parliament for money to raise an army.

Parliament made King Charles agree to reforms in 1641.

King Charles and archbishop laud made changes of the Church of England which were unpopular.

The puritans were angry about the king’s Catholic sympathies.

These are shot – term causes and long – term causes, they are linked together between causes and how they lead to civil war.

I think there were almost as many reasons for people to fight the civil war as there were people fighting. Briefly, however, the main reason for the war was the king Charles I and his various parliaments did not agree about anything – religion, how the country should be run, how England should behave towards other countries and so on. This was made worse by the fact that Charles I, believing that kings got their power from god and so could rule as they chose, made no attempt to keep his parliament happy. He spent eleven years ruling without parliament at all. When the long parliament, called in 1640, tried to make him change his ways and he refused, war broke out. (Some important things may not have set off the war, without the small triggers).

Document Details

- Word Count 1226

- Page Count 3

- Level AS and A Level

- Subject History

Related Essays

The Origins of the English Civil War

English Civil War

english civil war

What were the causes of the civil war?

Home — Essay Samples — History — Civil War — Causes of the Civil War

Causes of The Civil War

- Categories: Civil War

About this sample

Words: 572 |

Published: Jan 30, 2024

Words: 572 | Page: 1 | 3 min read

Table of contents

Economic factors, political factors, social factors, the role of leadership.

- McPherson, J. M. (1988). Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era. Oxford University Press.

- Goldfield, D. R. (2005). America Aflame: How the Civil War Created a Nation. Bloomsbury Press.

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Prof. Kifaru

Verified writer

- Expert in: History

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

2 pages / 1060 words

6 pages / 2599 words

3 pages / 1286 words

2 pages / 821 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Civil War

The Missouri Compromise, enacted in 1820, was a pivotal legislative agreement in the history of the United States, aiming to balance the power between free and slave states. As the country expanded westward, the issue of [...]

The Civil War was a pivotal moment in American history, a time of great conflict and division. It was a time when the power of rhetoric was at its peak, as leaders on both sides of the conflict used speeches and propaganda to [...]

The Civil War, which took place from 1861 to 1865, is a pivotal event in American history that significantly shaped American society and solidified the national identity of the United States. While the primary cause of the war [...]

Harriet Tubman's greatest achievement lies in her ability to inspire hope and instill a sense of agency in those who had been stripped of their humanity by the institution of slavery. Her unwavering commitment to freedom and [...]

“War is what happens when language fails” said Margaret Atwood. Throughout history and beyond, war has been contemplated differently form one nation to another, or even, one person to another. While some people believe in what [...]

The Civil War is one of the most pivotal moments in the shaping of our country today. In 1858, a Republican candidate for a senator named Abraham Lincoln remarked, “A house divided against itself cannot stand.” Lincoln, [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

More results...

The Causes of the English Civil War

Charles I Oliver Cromwell

The English Civil War has many causes but the personality of Charles I must be counted as one of the major reasons. Few people could have predicted that the civil war, that started in 1642, would have ended with the public execution of Charles. His most famous opponent in this war was Oliver Cromwell – one of the men who signed the death warrant of Charles.

No king had ever been executed in England and the execution of Charles was not greeted with joy. How did the English Civil War break out?

As with many wars, there are long and short term causes.

Long term causes :

The status of the monarchy had started to decline under the reign of James I. He was known as the “wisest fool in Christendom”. James was a firm believer in the “divine right of kings”. This was a belief that God had made someone a king and as God could not be wrong, neither could anyone appointed by him to rule a nation. James expected Parliament to do as he wanted; he did not expect it to argue with any of his decisions.

However, Parliament had one major advantage over James – they had money and he was continually short of it. Parliament and James clashed over custom duties . This was one source of James income but Parliament told him that he could not collect it without their permission. In 1611, James suspended Parliament and it did not meet for another 10 years. James used his friends to run the country and they were rewarded with titles. This caused great offence to those Members of Parliament who believed that they had the right to run the country.

In 1621, James re-called Parliament to discuss the future marriage of his son, Charles, to a Spanish princess. Parliament was outraged. If such a marriage occurred, would the children from it be brought up as Catholics? Spain was still not considered a friendly nation to England and many still remembered 1588 and the Spanish Armada. The marriage never took place but the damaged relationship between king and Parliament was never mended by the time James died in 1625.

Short term causes :

Charles had a very different personality compared to James. Charles was arrogant, conceited and a strong believer in the divine rights of kings. He had witnessed the damaged relationship between his father and Parliament, and considered that Parliament was entirely at fault. He found it difficult to believe that a king could be wrong. His conceit and arrogance were eventually to lead to his execution.

From 1625 to 1629, Charles argued with parliament over most issues, but money and religion were the most common causes of arguments.

In 1629, Charles copied his father. He refused to let Parliament meet. Members of Parliament arrived at Westminster to find that the doors had been locked with large chains and padlocks. They were locked out for eleven years – a period they called the Eleven Years Tyranny.

Charles ruled by using the Court of Star Chamber. To raise money for the king, the Court heavily fined those brought before it. Rich men were persuaded to buy titles. If they refused to do so, they were fined the same sum of money it would have cost for a title anyway!

In 1635 Charles ordered that everyone in the country should pay Ship Money. This was historically a tax paid by coastal towns and villages to pay for the upkeep of the navy. The logic was that coastal areas most benefited from the navy’s protection. Charles decided that everyone in the kingdom benefited from the navy’s protection and that everyone should pay.

In one sense, Charles was correct, but such was the relationship between him and the powerful men of the kingdom, that this issue caused a huge argument between both sides. One of the more powerful men in the nation was John Hampden. He had been a Member of Parliament. He refused to pay the new tax as Parliament had not agreed to it. At this time Parliament was also not sitting as Charles had locked the MP’s out. Hampden was put on trial and found guilty. However, he had become a hero for standing up to the king. There is no record of any Ship Money being extensively collected in the areas Charles had wanted it extended to.

Charles also clashed with the Scots. He ordered that they should use a new prayer book for their church services. This angered the Scots so much that they invaded England in 1639. As Charles was short of money to fight the Scots, he had to recall Parliament in 1640 as only they had the necessary money needed to fight a war and the required authority to collect extra money.

In return for the money and as a display of their power, Parliament called for the execution of “Black Tom Tyrant” – the Earl of Strafford, one of the top advisors of Charles. After a trial, Strafford was executed in 1641. Parliament also demanded that Charles get rid of the Court of Star Chamber.

By 1642, relations between Parliament and Charles had become very bad. Charles had to do as Parliament wished as they had the ability to raise the money that Charles needed. However, as a firm believer in the “divine right of kings”, such a relationship was unacceptable to Charles.

In 1642, he went to Parliament with 300 soldiers to arrest his five biggest critics. Someone close to the king had already tipped off Parliament that these men were about to be arrested and they had already fled to the safety of the city of London where they could easily hide from the king. However, Charles had shown his true side. Members of Parliament represented the people. Here was Charles attempting to arrest five Members of Parliament simply because they dared to criticise him. If Charles was prepared to arrest five Members of Parliament, how many others were not safe? Even Charles realised that things had broken down between him and Parliament. Only six days after trying to arrest the five Members of Parliament, Charles left London to head for Oxford to raise an army to fight Parliament for control of England. A civil war could not be avoided.

Related Posts

- Charles II Charles II, son of Charles I, became King of England, Ireland, Wales and Scotland in 1660 as a result of the Restoration Settlement. Charles ruled…

- Charles I Charles I was born in 1600 in Fife, Scotland. Charles was the second son of James I. His elder brother, Henry, died in 1612. Like…

- Timeline for causes of the English Civil War The causes of the English Civil War covered a number of years. The reign of Charles I had seen a marked deterioration in the relationship…

To what extent can the outbreak of civil war in 1642 be blamed on Charles I?

04 July, 2013 • History

The causes of the English Revolution have long been a subject of historiographical debate. One of the central questions has been that of the existence of a “high road to civil war”; that is, whether the causes of revolution can be traced back to the reigns of James, Elizabeth, or even earlier, or whether the causes were more immediate, surfacing during Charles’ reign. This essay will therefore address the question of the extent to which it was caused by the actions of Charles — which is to say, whether the causes originated after 1625 and, furthermore, whether Charles could reasonably be said to be responsible, or whether the events were out of his control.

The early Stuarts had in common with one another a number of conflicts with Parliament, among them constitutional issues, religion and finance. Not all of these were new problems but a number of factors increased the tendency towards conflict.

The question of constitutional issues can be addressed first, as it exacerbated the others. According to a traditional, “Whig” point of view, the roots of the revolution are traced back to the increasing absolutism introduced to the English monarchy by James and developed further by Charles. In this view, James ‘sowed the seeds of revolution and disaster’ 1 and Charles continued on this path; the early Stuarts were, therefore, both at fault, with Charles inheriting an already-restless kingdom. However, more recently, it has been pointed out that this interpretation was ‘utterly at odds with James’s widely praised performance as king of Scotland’; 2 by the time he inherited the English throne he had successfully managed the various hostile factions of Scotland for sixteen years.

To establish the truth of this claim (that there was a distinct change in the mode of government between Elizabeth and James) we can look at several facts. Firstly, there is the number of Parliamentary sessions held: James’ reign saw nine sessions in 22 years. Elizabeth’s reign, on the other hand, had 13 sessions in forty-four years, 3 sitting for a total of only two and a half years compared to three and a half under James. It has further been argued that when James wrote Basilikon Doron in 1599, arguing for the absolute power of the monarch, he was inspired by, and perhaps envious of, his cousin’s ability to rule her kingdom with so little interference. 4 Thus, the roots of absolutism in England predated both Charles and James; in fact, according to Smith, despite James’ problems ‘his style of kingship generally fostered stability’, 5 but he quotes Reeve’s description of Charles as ‘fundamentally unsuited for kingship’. 6

James’ outspoken views on the role of the monarch in relation to Parliament undoubtedly made contemporaries uncomfortable; he showed particular lack of tact in lecturing Parliament (on several occasions) on the limitations of its rights, sparking fears that ‘we are not like to leave to our successors that freedome we receved from our forefathers’. 7 Nevertheless, he was also an experienced ruler; Smith refers to his ‘shrewd political realism’, citing his abandonment of his plans for a union of the two kingdoms as an example of this. 8 He regularly showed discretion in this manner, seeming well-aware of how his words and actions were perceived; countless examples are given by Smith and others of his diplomatic withdrawals. This can be contrasted strongly with Charles.

Charles inherited his father’s belief in a divine right to rule (indeed, Basilikon Doron , in which those beliefs were set out, had been written specifically by James to teach his sons). However, he did not inherit James’ tact and diplomacy; unlike his father, he was unwilling to bend or negotiate unless forced — a failing which increased the perception of weakness, ’encouraging his subjects to believe that …he would retreat further’. 9 However, even this was not inevitable; his earliest dealings with Parliament, during the last years of his father’s reign, were successful, and it was a short time into his own reign before the problems began to manifest.

It has long been argued that by the early seventeenth century the finances of the crown were wholly inadequate; not simply in their magnitude, but structurally flawed as well. Morton describes them as ‘medieval in character’ and requiring on Elizabeth’s part ’the most extreme parsimony’ 10 to make ends meet. Inflation had driven prices up significantly during the sixteenth century, but Crown revenues, based primarily on rents and fines, had not risen in proportion. 11 Early in James’ reign a major restructuring of Crown finances was proposed, whereby the Crown would give up certain of its revenue sources in return for a guaranteed grant. However, this plan fell through and questions have been raised as to whether it would have been a success — Woolrych argues that it would have required greater frugality than James generally displayed. The inability of King and Parliament to agree on financial reform (according to Morton, due to the lack of economic understanding at the time) led to repeated conflicts over subsidies to the Crown, and to James’ increasing use of other sources of income — for example, the sale of titles and Crown lands.

The financial difficulties for Charles began in his first Parliament, which refused to grant Tonnage and Poundage to the King for life as was traditional, instead granting it for just a year with the intention of revisiting the royal financial arrangements. A clash of personalities ensued, with Charles inclined to see disagreement as a sign of a conspiracy against him. 12 His grievances were not unfounded, as England was currently engaged in a war against France, with the vocal support of Parliament, yet with the King expected to pay for it; Parliament attempted to use this as leverage to have the unpopular Duke of Buckingham removed from office. The dispute remained unresolved until an attempted impeachment of Buckingham led to Charles dissolving Parliament, and so Charles augmented his income with a ‘forced loan’ instead.

This set the scene for the remainder of the decade, with Charles’ attempts to raise money creating further conflicts which made Parliament unwilling to co-operate. Charles’ next Parliament introduced a Petition of Right, which agreed to finance the Crown so long as a number of grievances were addressed, but Charles accepted only grudgingly, doing his best to undermine it. Once again this aligns with Russell’s description of ‘a political style which tended to advertise the fact that concessions were made unwillingly’, 13 and did nothing to improve Parliament’s trust in him; they carried on and passed three resolutions against his continued flouting of the Petition of Right, whereupon he cited ‘seditious carriage’ sparked by ‘some few vipers’ 14 and dissolved Parliament.

This was the beginning of Charles’ personal rule. While opinion is divided as to whether it was a tyranny (see, for example, Kevin Sharpe 15 for an argument that it was not), it was certainly marked by continuing financial problems, among other things. Fundamentally the problem was that, since Charles could not impose taxation without Parliament, he needed to find ever more novel ways of generating revenue without new taxes. He had a particular talent for obeying the letter of the law while ignoring its spirit; for example, Ship Money was generally accepted to be within his power to raise, but his imposition of it on inland counties was an unwelcome innovation, 16 as was his designation of a significant part of Essex as royal forest, upon which landowners were then fined for encroaching. 17

However, these only increased the grievances against him; when Charles finally called a new Parliament in 1640, it was because of a lack of money to fund the war effort against Scotland. For its part, Parliament, once called, was more concerned with discussing the King’s attempts at taxation, among other things, than in giving him more money.

The second recurring conflict throughout the early Stuart period was religion; again, this was an issue which did not begin with the Stuarts, but rather dated back to Henry VIII. A settlement had been reached under Elizabeth, but the issue was raised again by the Millenary Petition early in James’ reign, from Puritans who saw the opportunity, under a new monarch, to push for further reform. However, the religious situation remained relatively stable, with James opposing major changes in either direction. His adherence to a middle way is evidenced by the opposition from both sides — although there was ongoing suspicion about his Catholic sympathies, particularly around the time of the Spanish Match, he was also (famously) the target of a Catholic assassination plot and firmly Protestant in his own convictions. 18

Charles again differed from his father, both in his religious convictions and his policies. His inclination towards the ceremony of Arminianism, seen as dangerously close to Catholicism by suspicious Protestants, along with his marriage to a French Catholic princess, increased tensions with Puritans. However, it is easy to judge him harshly on his inflexibility in this regard: Charles’ religious convictions were sincere, and not easily abandoned; while his pursuit of them may be seen as tactless, and he may have benefited from his father’s ability to know when to back down, it should be remembered that he was not setting out to be unreasonable.

His appointment of the Arminian Laud as Archbishop of Canterbury in 1633, against the advice of his father, further incited discontent. As well as the “popish” tendencies he displayed, he was a strong proponent of uniformity in the Anglican church, which inevitably brought him (and by extension Charles) into conflict with the various Dissenting movements of the period. In particular, his plans to introduce the Anglican prayerbook in Scotland can be argued to be one of the more direct causes of the conflict.

The prayerbook had been introduced with little consultation, and along with Scotland’s pride in its independence from England and its discontent as the junior partner of the personal union, it was said that the Reformation in England was “verrie far inferior” to that of Scotland; 19 the strength of this opinion can be demonstrated by the rioting it provoked at St Giles’, and the later, more organised resistance in the form of the National Covenant. Charles’ attempts to bring this resistance under control were hampered by his usual inflexibility. His tendency was to refuse absolutely to negotiate, only to be left with no choice but to back down, a tendency remarked upon even by his supporters: “those particulars which I have so often sworn and said your Matie would never condiscend to, will now be granted, therefore they will give no credit to what I shall say ther after, but will still hope and believe, that all their desires will be given way to”.

The failure to negotiated escalated to the point where the Covenanters raised an army against Charles; the need to raise money to defend against this forced Charles to summon a Parliament at last. However, as noted above, this Parliament had other priorities; and beyond the financial disputes, the Short Parliament itself had a strong Puritan element and opposed Charles’ religious innovations. Charles, given the choice of negotiating with the Scots or with Parliament, chose to do neither, dissolving Parliament within three weeks and continuing to raise an army against Scotland. This spectacularly poor decision led to the occupation of New- castle by a Scottish army and the summoning of another Parliament within six months.

The Long Parliament was even less inclined to negotiate than the Short Parliament had been, immediately setting about a series of reforms, such as the Triennial act, and proceeding to impeach Laud and Strafford, Charles’ most unpopular advisors. After disagreement over the handling of the Irish Uprising, Parliament (led by Pym) issued the Grand Remonstrance, detailing the many grievances since the start of the reign and positioning itself as the true de- fender of English liberty; Charles once more perceived dissent as a conspiracy against him and eventually retaliated by attempting to round up the ringleaders, marching to Parliament with armed soldiers. The resulting outcry led to his flight from London to Oxford and can be seen as the start of the civil war in England. Parliament declared itself to have no need of royal assent and the King eventually summoned an alternative Parliament at Oxford.

Across a range of themes it can be seen that Charles was rarely, if ever, the fundamental cause of the conflict. The social, political, and economic problems of his reign were structural, dating back a century or more, with religious differences developing from the reigns of Henry VIII and especially Mary, and economic problems starting possibly even earlier than that. 20 The transition to James’ reign and personal union with Scotland marked a watershed and James became a convenient scapegoat, but more recently attention has been paid to 1625, or even later, as the point of no return. It is hard to lay all the blame on Charles, given the presence of these century-old structural issues, but also difficult to ignore his personal weaknesses that led him to fail so drastically (and terminally) at addressing them. Perhaps if Henry, Prince of Wales, had not died in 1612 and had succeeded his father in place of his younger brother, the middle part of the century would have looked drastically different. There are, however, no simple solutions to the question of blame in the English Revolution.

Samuel R. Gardiner, History of England from the Accession of James I to the Outbreak of the Civil War (Longmans, Green & Co., 1883), [v]{.smallcaps}, p. 316. ↩︎

David Lawrence Smith, ‘Politics in Early Stuart Britain, 1603–1640’, in A Companion to Stuart Britain , ed. by Barry Coward (Oxford: Blackwell, 2003), pp. 233–52. ↩︎

R. E. Foster, ‘Conflicts and Loyalties: The Parliaments of Elizabeth I’, History Review , 56, 2006 < https://www.historytoday.com/archive/conflicts-and-loyalties-parliaments-elizabeth-i >. ↩︎

I read this during the research for this essay, but have since been unable to find the reference again. ↩︎

Smith. ↩︎

L. J. Reeve, Charles I and the Road to Personal Rule (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989), p. 173. ↩︎

Megan Mondi, ‘The Speeches and Self-Fashioning of King James VI and I to the English Parliament, 1604-1624’, Constructing the Past , 8.1 (2007), 139–82 < https://digitalcommons.iwu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1009&context=constructing >. ↩︎

Conrad Russell, ‘The British Problem and the English Civil War’, History , 72, 1987, 395 < https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-229X.1987.tb01469.x >. ↩︎

Arthur Leslie Morton, A People’s History of England , 3rd edn (Lawrence & Wishart, 1989), p. 179. ↩︎

Austin Herbert Woolrych, Britain in Revolution: 1625–1660 (Oxford University Press, 2002), pp. 16–17. ↩︎

Russell. ↩︎

The Personal Rule of Charles I (Yale University Press, 1992). ↩︎

R.H Fritze and W. B. Robison, Historical Dictionary of Stuart England: 1603–1689 (Greenwood, 1996), p. 201. ↩︎

Woolrych. ↩︎

Woolrych; Morton. ↩︎

The English Civil War: Causes, Costs and Benefits Term Paper

- To find inspiration for your paper and overcome writer’s block

- As a source of information (ensure proper referencing)

- As a template for you assignment

Factors that led to civil war

The number of people who perished, gains or advantages, works cited.

The English Civil War broke out in 1642 and lasted for nine years (Coates 1-2). The parliament and monarchial administration disagreed on the ideals and principles upheld by each side and their unwillingness to cede ground on any issue (Henry and Delf 2). In the end, a war became the only option to settle their issues (Henry and Delf 2-6). The war occurred in three stages or periods. The first two stages occurred in 1642–1646 and in 1648–1649 (Backman 1-10) involving the Long Legislature and King Charles the first. The final stage occurred in 1649–1651 and involved the Rump Legislature and the Royal leadership under King Charles the second (Backman 3).

Ultimately, the Parliament emerged victorious and made changes both to justice and governance system. When it comes to the law, the English Civil War acted as a platform for establishing governance standards for future English leaders. That is, they had to derive consent or approval from Parliament whenever they wanted to pursue in issue of national interest (Henry and Delf 4). This paper discusses the English civil war in terms of causative factors, costs/disadvantages, and advantages/benefits.

Whig school of thought

According to Whig school of thought, the Civil War resulted from a protracted struggle between the Monarchial rule and parliamentary rule (White 3-5). In this case, the parliament wanted the conventional rights of people preserved, whilst the royal leadership wanted to expand its right in a way that would allow it to dictate issues (Backman 4-6).

Marxist school of thought

According to Marxist school of thought, the English Civil War was purely a class war (Henry and Delf 5-7). That is, those who benefited a lot from the dictatorship of Charles the first such as lords and church leaders, strongly defended his leadership, whilst parliament with the support of middle classes such as industrial and trading groups strongly resisted the monarchial leadership (Coates 2).

Revisionist school of thought

Revisionist, on the other hand, indicated that the English civil war arose from different factors each having a significant impact. For instance, Anglican doctrines were to be imposed on the Scottish and were strongly resisted (Coates 4). King Charles then had to use the military to enforce his directive. With this, he also forced the legislature to raise the tax in order to get sufficient amount of money to sustain the army (Backman 7). However, other groups still resisted his directive as no side was willing to compromise.

Local demands and problems

The monarchial leadership was also resisted as a result of local displeasures (Backman 10-13). For instance, the livelihood of many people was negatively impacted after the enforcement of drainage-schemes. With this, many people thought that King Charles was too insensitive to local grievances (White 4). This aspect saw many easterners join parliament a group that played a role in resisting the tyrannical leadership of King Charles.

Unwilling to convene parliament

Since the King was not able to raise money or revenue through the legislature, he was not willing to convene it (Henry and Delf 23-25). This meant that he would use other orthodox means to raise money. He started by bringing back into effect some outdated principles. For example, those who failed to turn up for coronation of the king were to pay a certain fine. The King also introduced ship tax payable by inlanders for sustenance of the Royal Navy. The wealthy were also compelled to purchase titles. Those who refused were fined heavily (Henry and Delf 9). Some people refused to pay any of these taxes arguing that they were unlawful. They were taken to courts and fined heavily for refusing to abide by the set laws (Backman 5). This aspect provoked widespread fury against the king’s leadership.

The constitutionality of parliament and a show of power

Before the civil war, the English Parliament did not have any permanent responsibility provided for in law and constitution. The parliament only convened on temporary basis and only served as an advisory committee to the royal leadership (White 6-10). The king also would dissolve it whenever he wanted. As such it lacked legal powers to force its will upon the government. This issue did not please many people especially parliamentarians.