- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 14 November 2019

The impact of interventions for youth experiencing homelessness on housing, mental health, substance use, and family cohesion: a systematic review

- Jean Zhuo Wang 1 ,

- Sebastian Mott 2 ,

- Olivia Magwood 3 ,

- Christine Mathew 4 ,

- Andrew Mclellan 5 , 6 ,

- Victoire Kpade 2 ,

- Priya Gaba 6 ,

- Nicole Kozloff 7 ,

- Kevin Pottie 8 &

- Anne Andermann 9

BMC Public Health volume 19 , Article number: 1528 ( 2019 ) Cite this article

58k Accesses

46 Citations

21 Altmetric

Metrics details

Youth often experience unique pathways into homelessness, such as family conflict, child abuse and neglect. Most research has focused on adult homeless populations, yet youth have specific needs that require adapted interventions. This review aims to synthesize evidence on interventions for youth and assess their impacts on health, social, and equity outcomes.

We systematically searched Medline, Embase, PsycINFO, and other databases from inception until February 9, 2018 for systematic reviews and randomized controlled trials on youth interventions conducted in high income countries. We screened title and abstract and full text for inclusion, and data extraction were completed in duplicate, following the PRISMA-E (equity) review approach.

Our search identified 11,936 records. Four systematic reviews and 18 articles on randomized controlled trials met the inclusion criteria. Many studies reported on interventions including individual and family therapies, skill-building, case management, and structural interventions. Cognitive behavioural therapy led to improvements in depression and substance use, and studies of three family-based therapies reported decreases in substance use. Housing first, a structural intervention, led to improvements in housing stability. Many interventions showed inconsistent results compared to services as usual or other interventions, but often led to improvements over time in both the intervention and comparison group. The equity analysis showed that equity variables were inconsistently measured, but there was data to suggest differential outcomes based upon gender and ethnicity.

Conclusions

This review identified a variety of interventions for youth experiencing homelessness. Promising interventions include cognitive behavioural therapy for addressing depression, family-based therapy for substance use outcomes, and housing programs for housing stability. Youth pathways are often unique and thus prevention and treatment may benefit from a tailored and flexible approach.

Peer Review reports

Youth homelessness is a major public health challenge worldwide, even in high income countries [ 1 ]. Youth experiencing homelessness are defined as, “youth between the ages of 13 to 24 who live independently of their parents or guardians, but do not have the means to acquire stable, safe or consistent residence, or the immediate prospect of it [ 2 ].” Youth pathways into homelessness are anomalous and seldom experienced as a single isolated event. Compared to the adult homeless population, youth experiencing homelessness are more likely to report leaving home due to parental conflicts, including: being “kicked out” of the home, abuse (physical, verbal, sexual and other), parental neglect due to mental health problems, or parental substance use [ 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 ]. The broader context of family dysfunction can lead to youth circumstances that further reinforce situations of homelessness, including desire for separation from unsupportive environments, financial independence, mental health challenges, substance use, and/or run-ins with the justice system [ 1 ].

Not only are youth’s pathways into homelessness different from the adult homeless population, but their experiences on the street are distinct as well. Once homeless, youth are exposed to many dangers and are at a high risk of further trauma [ 12 ]. Youth experiencing homelessness may face a number of daily stressors and have limited coping strategies and resources to deal with these stressors [ 13 ]. Youth homelessness is often invisible and includes vulnerable housing situations such as couchsurfing or staying with relatives [ 14 ]. Furthermore, youth experiencing homelessness are vulnerable to social and health inequities, which describe the fairness in the distribution of health opportunities and outcomes across populations [ 15 ]. Health inequities are differences in health status that are unfair and/or avoidable [ 16 ]. Often, the compounding effect of various stratifying characteristics can result in increased disparities between individuals.

Current research has largely focused on adult populations, with a gap in evidence on interventions for youth experiencing homelessness on a broad range of outcomes. Among the current interventions for individuals experiencing homelessness, non-abstinence contingent permanent supportive housing and case management have shown promising results in terms of improving housing stability and mental health outcomes [ 17 ]. However, youth are a distinct population and they require specifically tailored, context appropriate, equity-focused interventions and research attention [ 18 ]. From systematically searching the literature for youth interventions, this paper will introduce four main categories of interventions applied to youth experiencing homelessness: 1) individual and family therapies (ie. cognitive behavioural therapy, motivational interviewing, etc.) 2) skill building programs, 3) case management, and 4) structural interventions (such as housing support, drop-in centres, and shelters). These interventions are designed to address the complex, multifaceted pathways and contributors to youth homelessness, whether it be addressing substance use issues through motivational interviewing, mental health care through cognitive behavioural therapy, improving unstable family environments through family therapies, increasing access to resources through case management, and enhancing structural support such as income and housing support [ 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 ]. Given the complexity and interconnectedness of these outcomes, one would hope that these interventions would have an impact on not only the primary outcome, but also extend to other facets of a youth’s life. For instance, family therapies have shown promising results on both family functioning as well as substance use, by addressing the toxic family environment and thereby decreasing its contribution to unhealthy substance use patterns [ 24 ].

Current research on interventions for the population of youth experiencing homelessness lacks a comprehensive synthesis on a broad range of social and health outcomes. The objective of this review is to synthesize the existing scientific literature on interventions for homeless or vulnerably housed youth in high income countries, and assess the impacts of the interventions on housing, mental health, substance use, and family cohesion, with an equity perspective.

We established an expert working group consisting of homeless health researchers, academics, clinicians and youth with lived experience of homelessness to conduct this review. We report our results according to PRISMA-E [see Additional file 3 ] and published an open access protocol on the Campbell and Cochrane Equity Methods website [ 25 , 26 ].

Data sources and search strategy

Without language restrictions, we systematically searched the following databases from inception until February 9, 2018: Medline, Embase, CINAHL, PsycINFO, Epistemonikos, HTA database, NHSEED, DARE, and Cochrane Central. Combinations of relevant keywords and MeSH terms were searched, including “homeless” and “homeless youth” [see Additional file 1 for search strategy]. We hand-searched included studies for primary studies and consulted experts for additional papers. We conducted a grey literature search on homeless health and public health websites.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

We downloaded citation information into Rayyan online software [ 27 ]. All title and abstracts were screened according to our inclusion criteria (see Table 1 ) in duplicate by two independent reviewers, and any discrepancies were resolved. Throughout a process of several consultations, our working group, consisting of persons with lived experience and experts in the field, helped develop these inclusion criteria by identifying priority areas in which to focus this review. This study focused on youth between the ages of 13 to 24, however, the age categorizations of youth tend to differ between various definitions, with the medicolegal definition utilizing ages 16 to 21. It is important to note that the broader age range utilized in this paper may lead to risks of over-inclusion, but it was chosen as it is reflective of the currently literature on youth homelessness and includes both high school and university students who are generally still dependents living with family or relying on them for financial or moral support.

Data extraction and analysis

Data extraction proceeded in duplicate using a standardized data extraction form and a third reviewer resolved discrepancies [ 25 ]. We extracted data regarding the effectiveness of interventions on a broad range of social and health outcomes. We conducted a scoping exercise to identify key outcome categories in the literature and prioritized reported outcomes with our expert working group members, which included individuals of lived experience. The outcomes rated as being of highest priority (mental health, substance use, housing, and family outcomes) are reported in the body of this paper, and the remaining outcomes (violence, sexual health, personal and social, and health and social service utilization) are reported in the appendix [see Additional file 2 ]. To reduce overlap between single studies and systematic reviews, we reported the results of systematic reviews and supplemented with data from randomized control trials (RCTs) that were not included in the systematic reviews. Due to heterogeneity of interventions and outcomes studied, we qualitatively synthesized the results. We created a forest plot to summarize RCTs for mental health outcomes, as sufficient data were available and it was a highly ranked outcome.

Health equity analysis

We used the PROGRESS+ framework to apply a health equity lens and enable us to identify characteristics that socially stratify youth experiencing homelessness, and various drivers of homelessness [ 15 ]. In particular, we extracted the following from studies to inform our analysis: 1) study rationale for focusing on youth-centred interventions; 2) the measures used to assess differences in outcomes for women and men; 3) the study’s gender-related findings and conclusions; and 4) the study’s incorporation of equity considerations (e.g. race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status).

Critical appraisal

We assessed the methodological quality of systematic reviews with AMSTAR II and RCTs using the Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool [ 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 ]. When assessing the overall risk of bias of RCTs, we defined the risk of bias as “not serious” when there were low risk ratings in all categories or one or two unclear risk, “serious” with one or two high risk categories, and “very serious” with more than two high risk categories.

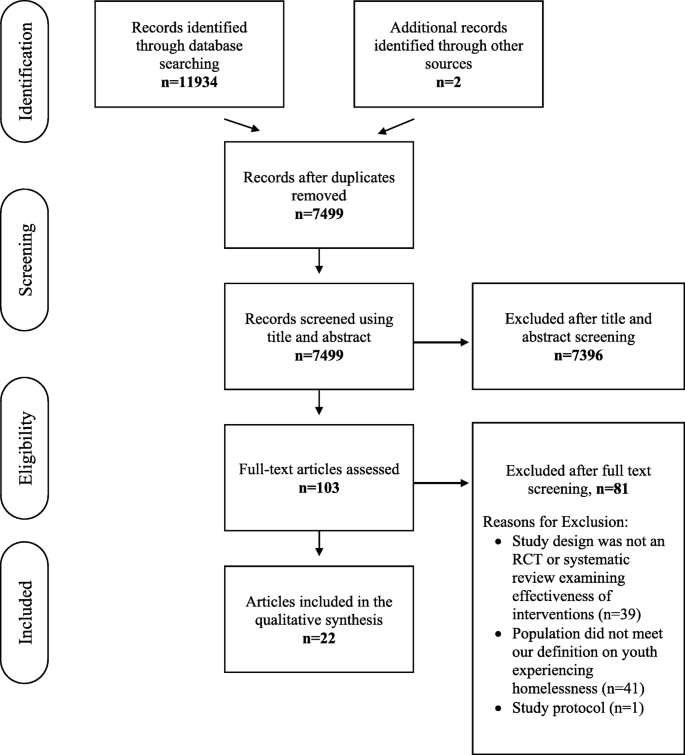

The search strategy yielded 11,934 potentially relevant citations. After we removed duplicates, we screened 7499 citations and assessed 103 full text articles. Twenty-two citations met the full inclusion criteria (See Fig. 1 ). Four of the included citations were systematic reviews [ 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 ] and the remaining 18 citations reported on 15 RCTs (see Table 2 for RCTs and Table 3 for SRs) [ 19 , 21 , 37 , 38 , 39 , 40 , 41 , 42 , 43 , 44 , 45 , 46 , 47 , 48 , 49 , 50 , 51 , 52 , 53 ].

PRISMA Flow Diagram

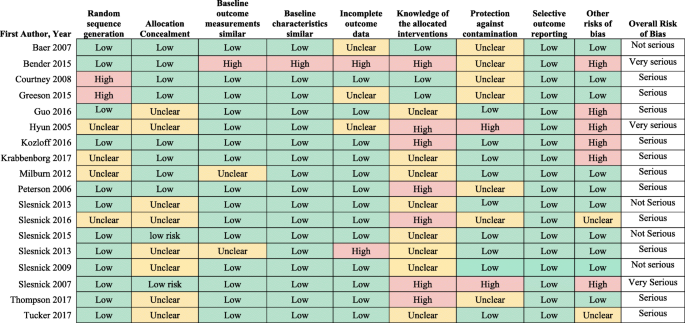

Methodological quality of the included studies was low or very low, with serious risk of bias across most included studies (see Fig. 2 for RCTs and Table 4 for SRs). The most common domain with a high level of risk was knowledge of the allocated interventions, as blinding was often not possible or difficult with the nature of the interventions.

Methodological Quality of Included RCTs using Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool

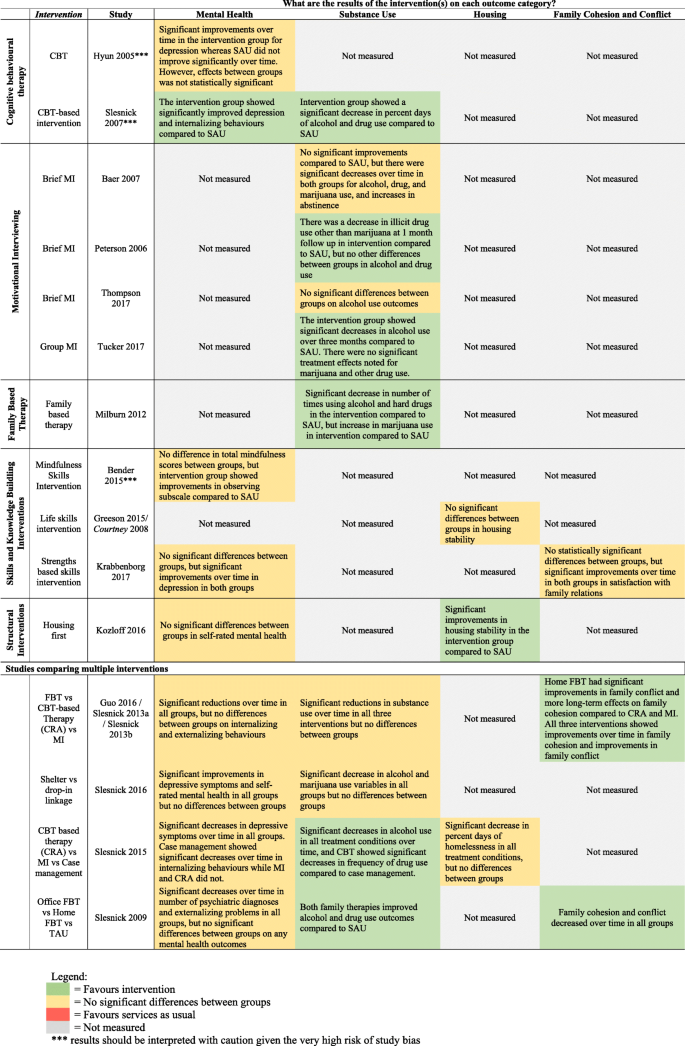

The main categories of interventions applied to youth homelessness included: 1) individual and family therapy (e.g. cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), motivational interviewing (MI), family therapy), 2) skills building (e.g. life skills, mindfulness), 3) case management and 4) structural interventions (e.g. housing support, drop-in centres, shelters). See Table 5 for the definitions of interventions. The results of RCTs have been summarized using a visual map (see Fig. 3 ).

Visual Summary of Results of RCTs by Outcome

Individual and family therapy

Cognitive behavioural therapy.

CBT led to improvements in substance use and depression, and one systematic review also reported improvements in internalizing behaviours and self-efficacy [ 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 ]. When a CBT-based therapy (community reinforcement approach) was delivered with case management in one study, there were improvements in percentage of days being housed, psychological distress, and substance use [ 33 ]. Two systematic reviews conducted meta-analyses on CBT and CBT-based interventions and found no statistically significant difference in mental health outcomes compared to services as usual, but noted that lack of a statistically significant difference may be due to heterogeneity between studies [ 34 , 35 , 36 ].

Family therapy

Family-based therapy was delivered in an office setting, known as functional family therapy, or in the home setting, called ecologically-based family therapy. Systematic reviews reported that all three family therapy RCTs showed a reduction in substance use [ 34 , 35 , 36 ]. However, Noh (2018) conducted a subgroup meta-analysis on two family intervention studies and found no significant effect on substance use [ 34 ]. Another meta-analysis found a statistically significant improvement in family cohesion, but called it a clinically marginal effect [ 36 ]. In a three arm RCT comparing home-based family therapy with MI and a CBT-based therapy, all three groups improved over time in internalizing and externalizing behaviours, family cohesion, and substance use [ 47 , 48 , 49 ]. Furthermore, when an RCT compared functional family therapy, home-based family therapy, and services as usual, all treatments showed improvements in days living at home at three, nine and 15 months, but no group was superior to another [ 52 ].

Motivational interviewing

Brief or group MI interventions were primarily designed to address substance use and/or risky sexual behaviours. A brief intervention showed declines in non-marijuana drug use at 1-month follow up, but the reduction was no longer significant after 3 months [ 33 , 34 , 35 ]. In another RCT, both the service as usual and intervention groups showed significant improvements over time, but there were no significant and durable results in favour of the experimental group [ 21 ]. A 16-week group MI intervention found significant declines in alcohol use and increased motivation to change drug use, but no significant decreases in marijuana use [ 37 ]. A two-session individual brief MI intervention compared to an education program reported significant improvements in readiness to change alcohol use [ 38 ].

Skill building

The interventions focused on vocational and life skills, mindfulness, and strengths-based skill building. One systematic review included one study evaluating a life skills intervention and found improvements in family contact and near significant improvements in depressive symptoms [ 33 ]. Another systematic review reported similar results but noted an increase in substance use over 6 months which could not be explained [ 35 ]. A training program based on a peer influence model showed non-statistically significant decreases in drug use in the treatment group. One study evaluated a strengths-based program deployed in a shelter to identify and make use of strengths in each youth [ 39 ]. This program showed no significant differences between groups but found improvements over time in depression, substance use, and satisfaction with family relations [ 39 ]. Two RCTs evaluated a vocational and life skills program and a mindfulness skills program, though did not report promising treatment effects [ 40 , 41 , 42 ].

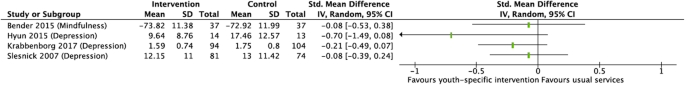

We attempted to conduct meta-analyses whenever possible, but due to the heterogeneity between studies, it was inappropriate to pool the results into a combined effect size. As such, we developed a forest plot for short-term mental health outcomes of a mindfulness intervention, CBT intervention, strengths-based intervention, and CBT-based intervention [ 39 , 42 , 50 , 51 , 52 , 53 ]. The figure depicts a general trend favouring the interventions but none reaching statistical significance compared to control (see Fig. 4 ).

Intervention vs. Usual services for Short Term (0-6 months) Mental Health Outcomes)

Case management

Two systematic reviews reported on several case management programs, including intensive case management and multidisciplinary case management, and reported minimal additional benefit of the programs relative to their comparison interventions [ 33 , 34 , 35 ]. They noted that one program showed favourable results for substance use, but the study quality was very low due to low retention rates [ 33 ]. In a three-arm RCT, case management, a CBT-based intervention, and MI all showed significant improvements over time in housing stability, depression, and substance use, but no significant differences between groups [ 45 ]. Case management led to improvements over time in internalizing behaviours while the other groups did not [ 45 ]. Overall, there is evidence to suggest that case management may have impacts on substance use, depression, and housing stability, but different control conditions in each of the studies made it difficult to assess overall effectiveness of the intervention.

Structural support

Housing programs.

A subgroup analysis of young adults in an RCT of the housing first model for adults with mental illness found that, compared to treatment as usual, housing first significantly increased the proportion of days stably housed over the 24-month trial, but had no impact on self-rated mental health [ 43 ]. One systematic review included an independent living program and reported marginal results on psychological measures, however reported some positive outcomes on housing status [ 33 ]. The same systematic review also included a study evaluating a supportive housing program, which reported lower rates of substance abuse and improvements in self-reported health, but the study quality was noted to be low. Xiang evaluated the same supportive housing program and also concluded that the lower rates of substance use may be attributed to baseline differences between control and intervention groups instead of treatment effect [ 35 ].

Drop-in and shelter services

A systematic review included three shelter services studies, two evaluating residential services and one evaluating emergency shelter and crisis services [ 35 ]. The review showed some improvements in substance use but this was not consistent over the various studies and there were no enduring effects over time. An RCT compared referrals from case management made to drop-in versus shelter services programs [ 44 ]. There were no differential treatment effects, as both groups showed decreases in depression and substance use over time [ 44 ]. However, individuals assigned to the drop-in service had greater service contacts and access to care over 6 months [ 44 ].

Gender and equity analysis

Equity variables were not consistently measured, reported, or analyzed across studies. Several studies measured equity and PROGRESS+ factors with baseline sample characteristics, but very few included them as covariates. The most examined factors were gender and ethnicity/race, with some studies mentioning place of residence and occupation. A number of RCTs included equity variables in their analysis [ 21 , 37 , 39 , 40 , 41 , 43 , 44 , 45 , 46 , 47 , 48 , 49 ], as did three systematic reviews [ 34 , 35 , 36 ].

A number of studies indicated that females responded differently to services than males. Slesnick’s studies have showed that females initially reported higher rates of depression than males, with a greater reduction throughout the study [ 44 , 45 , 46 ]. Female adolescents showed a greater improvement in family cohesion subsequent to treatment regardless of the treatment condition [ 47 ] and appeared to derive greater benefit from shelter services than males [ 35 ].

Some variance in relation to ethnicity and employment emerged as well. While youth from ethnic minorities had greater reductions in substance use, they also relapsed more quickly than white youth [ 49 ] and had more HIV risk behaviours [ 44 ]. African Americans showed a greater reduction in percent days homeless than other ethnic groups [ 45 ]. Non-Hispanic white youth more quickly reduced their number of days drinking to intoxication [ 44 ]. Those employed or in school at baseline were more likely to remain employed at follow-up [ 39 ].

This review identified a wide variety of interventions for youth experiencing housing instability. Regarding individual and family therapies, CBT interventions showed improvements in depression and substance use outcomes [ 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 ]. Family interventions led to improvements in alcohol and drug use measures and may have had an impact on family cohesion [ 34 , 35 , 36 ]. Motivational interviewing, skill-building programs and case management showed inconsistent effects on mental health and substance use when compared with services as usual and other interventions [ 21 , 33 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 , 40 , 41 , 42 , 45 , 46 , 47 , 48 , 49 ]. Among the structural support interventions, housing first led to improved housing stability outcomes, while drop-in and shelter services led to inconsistent effects [ 43 , 44 ]. The equity analysis revealed differential treatment effects based upon gender and ethnicity, with females often deriving more treatment benefit than males [ 44 , 45 , 47 , 48 , 49 ]. Equity analyses were limited, with very little mention of important considerations such as sexual orientation status, as LGBTQ+ youth are disproportionately represented in the homeless population [ 58 , 59 ].

While in many circumstances, differences were not statistically significant between treatment groups, this does not preclude the lack of effectiveness of these interventions. It is important to note that a treatment as usual group was not the absence of an intervention, but rather involved referral to other community services and follow-up with researchers. This may lessen the differences between the intervention and control arms, and decrease the detectable effect of the intervention. Providing non-specific support for youth may be enough to improve outcomes and reduce the toxic effects of adverse childhood experiences. However, that regression to the mean may also potentially explain the changes observed over time [ 60 ]. As participants may enter the research studies during a point of crisis, they may naturally improve over time regardless of the study group, and this effect may lessen the observed differences between intervention and control groups.

Tailoring interventions to the needs of youth

The dynamics of youth homelessness are complex; pathways to housing are precarious, sociocultural backgrounds are becoming increasingly diverse and available resources are inconsistent. Research has shown that unstable family relationships underlie youth homelessness, and many youth have left homes where they experienced interpersonal violence and abuse [ 3 , 4 , 5 , 61 ]. Among these difficult family issues, other personal factors arise as a result of their environmental contexts, which can interplay and lead to increased distress. These challenges include substance use, depression, and disability, and can compoundly contribute to strain [ 10 ]. The interventions identified in this review may help to address the specific needs of youth and may be tailored to their situation.

One important consideration to note is that while we have defined youth as those ages 13 to 24 for the purposes of this study, this grouping brings together minors as well as young adults of legal age. While this age categorization is reflective of the literature on the youth population, we recognize that there are differences between the experiences of younger versus older youth. Furthermore, there are medicolegal implications of the mature minor and capacity to consent. Clinicians and program implementers who work directly with this population need to consider the ethical considerations of consent for treatment participation with mature minors as well as the legal obligations provided by their governing college [ 62 ].

Strengths and limitations of the review

We conducted a high quality search, complying to PRISMA-E guidelines [ 26 ]. This review included only high quality study designs: RCTs and systematic reviews. This may, however, have limited the types of interventions that were included. Limitations include a broad range of outcomes and, thus, too few studies available for meta-analyses. There was heterogeneity in the interventions, and the available evidence was insufficient to use network meta-analysis to answer the question of the relative advantages of the different types of interventions. In our systematic review, the studies did not use placebo designs and, instead, used several different interventions/comparisons. However, there was considerable heterogeneity in the outcome measures and this prevented a pooling of the effects. The services-as-usual comparisons were often not adequately described in the primary studies, limiting the comparisons that could be made across different studies. Furthermore, our definition of youth experiencing homelessness focused on unaccompanied youth and did not include accompanied youth that enter homeless situations along with their families, as this youth population has quite distinct circumstances and needs.

Implications for future research, policy, and practice

The results suggest that tailored interventions for youth may have impacts on depression, substance use and housing. Given the diverse pathways to youth homelessness, health care policy-makers, practitioners and other stakeholders should consider the specific needs of youth during prevention and delivery of care. Furthermore, we recommend additional high quality research to be conducted in the area of family-based therapies, CBT, and housing interventions, which have shown some positive results thus far. We further recommend additional considerations for equity factors. Few studies examined equity factors, and those that did were limited largely to gender and ethnicity. There remains a large gap in data regarding the intersectionality between a variety of PROGRESS+ factors contributing to youth experiences.

There is also a large gap in research on the impact of structural interventions such as housing and case management on youth experiencing homelessness. The predominance of psychological and family interventions in this paper suggests that more work could be done to study an area in which it may be more difficult to design studies. Nonetheless, future research on these interventions are important to addressing the root causes of poverty and homelessness. Furthermore, there are emerging models of housing which have not yet been evaluated rigorously in the literature. For instance, host homes provide safe and temporary housing for up to 6 months for youth while supporting them with a case manager to identify long term solutions [ 63 ]. Rapid re-housing programs provide short-term subsidies to allow persons experiencing homelessness to acquire stable housing as quickly as possible [ 64 , 65 ]. The landscape on housing models continues to evolve and future research will need to evaluate these in the context of youth experiencing homelessness.

This review identifies a variety of interventions targeted towards the unique needs of youth experiencing homelessness. CBT interventions may lead to improvements in depression and substance use, and family-based therapy may impact substance use and family outcomes. Housing programs may lead to improvements in housing support and stability. Other interventions such as skill building, case management, show inconsistent results on health and social outcomes.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

A MeaSurement Tool to Assess systematic Reviews

Cognitive Behavioural Therapy

Motivational Interviewing

Preferred Reporting Items for Equity-Focused Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses

Place of Residence- Race/ethnicity/culture/language- Occupation- Gender/sex- Religion- Education- Socioeconomic status- Social capital + refers to: 1) personal characteristics associated with discrimination (e.g. age, disability). 2) features of relationships (e.g. smoking parents, excluded from school). 3) time-dependent relationships (e.g. leaving the hospital, respite care, other instances where a person may be temporarily at a disadvantage)

Randomized Control Trial

Gaetz S, Gulliver T, Richter T. The state of homelessness in Canada 2014: Canadian Homelessness Research Network; 2014. https://www.homelesshub.ca/SOHC2013

Canadian Definition of Homelessness. Homeless Hub: Canadian Observatory on Homelessness. https://www.homelesshub.ca/resource/canadian-definition-homelessness . Accessed 20 Dec 2018.

Ballon BC, Courbasson CM, Psych C, Smith PD. Physical and sexual abuse issues among youths with substance use problems. Can J Psychiatr. 2001;46:617–21.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Gaetz S, O’Grady B. Making money: exploring the economy of young homeless workers. Work Employ Soc. 2002;16:433–56.

Article Google Scholar

Karabanow J. Being young and homeless: understanding how youth enter and exit street life. New York: Peter Lang; 2004.

Karabanow J. Getting off the street: exploring the processes of young People’s street exits. Am Behav Sci. 2008;51:772–88. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764207311987 .

Rew L, Taylor-Seehafer M, Thomas NY, Yockey RD. Correlates of resilience in homeless adolescents. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2001;33:33–40.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Thrane LE, Hoyt DR, Whitbeck LB, Yoder KA. Impact of family abuse on running away, deviance, and street victimization among homeless rural and urban youth. Child Abuse Negl. 2006;30:1117–28.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Tyler KA, Bersani BE. A longitudinal study of early adolescent precursors to running away. J Early Adolesc. 2008;28:230–51.

van den Bree MB, Shelton K, Bonner A, Moss S, Thomas H, Taylor PJ. A longitudinal population-based study of factors in adolescence predicting homelessness in young adulthood. J Adolesc Health. 2009;45:571–8.

Whitbeck LB. Nowhere to grow: homeless and runaway adolescents and their families: Routledge; 2017.

Homelessness in America: Focus on Youth. United States Interagency Council on Homelessness; 2018. https://www.usich.gov/resources/uploads/asset_library/Homelessness_in_America_Youth.pdf .

Google Scholar

Unger JB, Kipke MD, Simon TR, Johnson CJ, Montgomery SB, Iverson E. Stress, coping, and social support among homeless youth. J Adolesc Res. 1998;13:134–57.

McLoughlin PJ. Couch surfing on the margins: the reliance on temporary living arrangements as a form of homelessness amongst school-aged home leavers. J Youth Stud. 2013;16:521–45. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2012.725839 .

O’Neill J, Tabish H, Welch V, Petticrew M, Pottie K, Clarke M, et al. Applying an equity lens to interventions: using PROGRESS ensures consideration of socially stratifying factors to illuminate inequities in health. J Clin Epidemiol. 2014;67:56–64.

Whitehead M. The concepts and principles of equity and health. Health Promot Int. 1991;6:217–28.

Hwang SW, Burns T. Health interventions for people who are homeless. Lancet. 2014;384:1541–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61133-8 .

Dawson A, Jackson D. The primary health care service experiences and needs of homeless youth: a narrative synthesis of current evidence. Contemp Nurse. 2013;44:62–75.

Cognitive behavioural therapy. Centre for Addictions and Mental Health. 2018. https://www.camh.ca/en/health-info/mental-illness-and-addiction-index/cognitive-behavioural-therapy .

Gaetz S, Redman M. Towards an Ontario youth homelessness strategy. Canadian observatory on homelessness policy brief. Toronto: The Homeless Hub Press; 2016.

Baer JS, Garrett SB, Beadnell B, Wells EA, Peterson PL. Brief motivational intervention with homeless adolescents: evaluating effects on substance use and service utilization. Psychol Addict Behav. 2007;21:582.

De Vet R, Van Luijtelaar M, Brilleslijper-Kater S, Vanderplasschen W, Beijersbergen M, Wolf J. Effectiveness of case Management for Homeless Persons: a systematic review. Am J Public Health. 2013;103:e13–26.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Tsemberis S. Housing first: The pathways model to end homelessness for people with mental illness and addiction manual. Eur J Homelessness. 2011;5:11-18.

Pergamit M. Family Interventions for Youth Experiencing or at Risk of Homelessness. :107.

Wang J, Mott S, Mathew C, Magwood O, Pinto N, Pottie K, et al. Impact of Interventions for Homeless Youth: A Narrative Review using Health, Social, Gender, and Equity Outcomes.

Welch V, Petticrew M, Tugwell P, Moher D, O’Neill J, Waters E, et al. PRISMA-equity 2012 extension: reporting guidelines for systematic reviews with a focus on health equity. PLoS Med. 2012;9:e1001333. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1001333 .

Ouzzani M, Hammady H, Fedorowicz Z, Elmagarmid A. Rayyan—a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst Rev. 2016;5:210.

Higgins JPT, Sterne JAC, Savović J, Page MJ, Hróbjartsson A. A revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomized trials In: Chandler J, McKenzie J, Boutron I, Welch V (editors). Cochrane Methods. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;10(Suppl 1).

Tanner-Smith EE, Wilson SJ, Lipsey MW. The comparative effectiveness of outpatient treatment for adolescent substance abuse: a meta-analysis. J Subst Abus Treat. 2013;44:145–58.

Stanton B, Cole M, Galbraith J, Li X, Pendleton S, Cottrel L, et al. Randomized trial of a parent intervention: parents can make a difference in long-term adolescent risk behaviors, perceptions, and knowledge. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2004;158:947–55.

Luchenski S, Maguire N, Aldridge RW, Hayward A, Story A, Perri P, et al. What works in inclusion health: overview of effective interventions for marginalised and excluded populations. Lancet. 2018;391:266–80.

Shea BJ, Reeves BC, Wells G, Thuku M, Hamel C, Moran J, et al. AMSTAR 2: a critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. BMJ. 2017;358:j4008.

Altena AM, Brilleslijper-Kater SN, Wolf JR. Effective interventions for homeless youth: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2010;38:637–45.

Noh D. Psychological interventions for runaway and homeless youth. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2018;50:465–72.

Xiang X. A review of interventions for substance use among homeless youth. Res Soc Work Pract. 2013;23:34–45.

Coren E, Hossain R, Pardo JP, Bakker B. Interventions for promoting reintegration and reducing harmful behaviour and lifestyles in street-connected children and young people. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;2:CD009823.

Tucker JS, D’Amico EJ, Ewing BA, Miles JN, Pedersen ER. A group-based motivational interviewing brief intervention to reduce substance use and sexual risk behavior among homeless young adults. J Subst Abus Treat. 2017;76:20–7.

Thompson RG Jr, Elliott JC, Hu M-C, Aivadyan C, Aharonovich E, Hasin DS. Short-term effects of a brief intervention to reduce alcohol use and sexual risk among homeless young adults: results from a randomized controlled trial. Addict Res Theory. 2017;25:24–31.

Krabbenborg MA, Boersma SN, van der Veld WM, van Hulst B, Vollebergh WA, Wolf JR. A cluster randomized controlled trial testing the effectiveness of Houvast: a strengths-based intervention for homeless young adults. Res Soc Work Pract. 2017;27:639–52.

Courtney ME, Zinn A, Zielewski EH, Bess RJ, Malm KE, Stagner M, et al. Evaluation of the life skills training program. Administration for children & families: Los Angeles; 2008.

Greeson JK, Garcia AR, Kim M, Thompson AE, Courtney ME. Development & maintenance of social support among aged out foster youth who received independent living services: results from the multi-site evaluation of Foster youth programs. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2015;53:1–9.

Bender K, Begun S, DePrince A, Haffejee B, Brown S, Hathaway J, et al. Mindfulness intervention with homeless youth. J Soc Soc Work Res. 2015;6:491–513.

Kozloff N, Adair CE, Lazgare LIP, Poremski D, Cheung AH, Sandu R, et al. “ Housing first” for homeless youth with mental illness. Pediatrics. 2016;138(4):e20161514.

Slesnick N, Feng X, Guo X, Brakenhoff B, Carmona J, Murnan A, et al. A test of outreach and drop-in linkage versus shelter linkage for connecting homeless youth to services. Prev Sci. 2016;17:450–60.

Slesnick N, Guo X, Brakenhoff B, Bantchevska D. A comparison of three interventions for homeless youth evidencing substance use disorders: results of a randomized clinical trial. J Subst Abus Treat. 2015;54:1–13.

Slesnick N, Guo X, Feng X. Change in parent-and child-reported internalizing and externalizing behaviors among substance abusing runaways: the effects of family and individual treatments. J Youth Adolesc. 2013;42:980–93.

Guo X, Slesnick N, Feng X. Changes in family relationships among substance abusing runaway adolescents: a comparison between family and individual therapies. J Marital Fam Ther. 2016;42:299–312.

Peterson PL, Baer JS, Wells EA, Ginzler JA, Garrett SB. Short-term effects of a brief motivational intervention to reduce alcohol and drug risk among homeless adolescents. Psychol Addict Behav. 2006;20:254.

Slesnick N, Erdem G, Bartle-Haring S, Brigham GS. Intervention with substance-abusing runaway adolescents and their families: results of a randomized clinical trial. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2013;81:600.

Hyun M-S, Chung H-IC, Lee Y-J. The effect of cognitive–behavioral group therapy on the self-esteem, depression, and self-efficacy of runaway adolescents in a shelter in South Korea. Appl Nurs Res. 2005;18:160–6.

Milburn NG, Iribarren FJ, Rice E, Lightfoot M, Solorio R, Rotheram-Borus MJ, et al. A family intervention to reduce sexual risk behavior, substance use, and delinquency among newly homeless youth. J Adolesc Health. 2012;50:358–64.

Slesnick N, Prestopnik JL. Comparison of family therapy outcome with alcohol-abusing, runaway adolescents. J Marital Fam Ther. 2009;35:255–77.

Slesnick N, Prestopnik JL, Meyers RJ, Glassman M. Treatment outcome for street-living, homeless youth. Addict Behav. 2007;32:1237–51.

Community Reinforcement Approach. Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addictions; 2017. www.ccdus.ca/Resource Library/CCSA-Community-Reinforcement-Approach-Summary-2017-en.pdf. Accessed 20 Dec 2018.

Dialectical Behavioural Therapy. Centre for Addictions and Mental Health. https://www.camh.ca/en/health-info/mental-illness-and-addiction-index/dialectical-behaviour-therapy .

Chanut F, Brown T, Dongier M. Motivational interviewing and clinical psychiatry - Florence Chanut, Thomas G Brown, Maurice Dongier. Can J Psychiatr. 2005;50:548–54.

Dieterich M, Irving CB, Bergman H, Khokhar MA, Park B, Marshall M. Intensive case management for severe mental illness. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD007906.pub3 .

Rice E, Fulginiti A, Winetrobe H, Montoya J, Plant A, Kordic T. Sexuality and Homelessness in Los Angeles Public Schools. Am J Public Health. 2012;102:200a–3201.

Article PubMed Central Google Scholar

corliss H, Goodenow C, Nichols L, Austin S. High burden of homelessness among sexual-minority adolescents: findings from a representative Massachusetts high school sample. Am J Public Health. 2011;101:1683–9. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2011.300155 .

Barnett AG, van der Pols JC, Dobson AJ. Regression to the mean: what it is and how to deal with it. Int J Epidemiol. 2005;34:215–20. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyh299 .

Braitstein P, Li K, Tyndall M, Spittal P, O’Shaughnessy MV, Schilder A, et al. Sexual violence among a cohort of injection drug users. Soc Sci Med. 2003;57:561–9.

Medical decision-making in paediatrics: Infancy to adolescence. Canadian Paediatric Society; 2018. https://www.cps.ca/en/documents/position/medical-decision-making-in-paediatrics-infancy-to-adolescence . Accessed 14 Aug 2019.

Point Source Youth. Host Homes Handbook: A Resource Guide for Host Home Programs | The Homeless Hub. 2018. https://homelesshub.ca/resource/host-homes-handbook-resource-guide-host-home-programs . Accessed 9 Oct 2019.

NAEH. Can You Use Rapid Re-Housing to Serve Homeless Youth? Some Providers Already Are. In: National Alliance to End Homelessness; 2015. https://endhomelessness.org/can-you-use-rapid-re-housing-to-serve-homeless-youth-some-providers-already/ . Accessed 9 Oct 2019.

The Homeless Hub. Rapid Re-Housing. 2019. https://www.homelesshub.ca/solutions/housing/rapid-re-housing . Accessed 9 Oct 2019.

Download references

Acknowledgements

Nicole Pinto for expert data extraction and critical appraisal.

Published on Cochrane Equity Methods Website - https://methods.cochrane.org/equity/projects/homeless-health-guidelines

This study was funded by the Inner City Health Associates. ICHA was not involved in conducting the study including study design, data collection, analysis, interpretation, and writing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

University of Ottawa Faculty of Medicine, Bruyere Research Institute, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, ON, Canada

Jean Zhuo Wang

McGill University Faculty of Medicine, Montreal, QC, Canada

Sebastian Mott & Victoire Kpade

C.T. Lamont Primary Health Care Research Centre, Bruyere Research Institute, Ottawa, ON, Canada

Olivia Magwood

Bruyere Research Institute, Ottawa, ON, Canada

Christine Mathew

University of Toronto, Faculty of Nursing, Toronto, ON, Canada

Andrew Mclellan

Department of Family Medicine, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, ON, Canada

Andrew Mclellan & Priya Gaba

Centre for Addiction and Mental Health, Department of Psychiatry and Institute of Health Policy, Management and Evaluation, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada

Nicole Kozloff

Departments of Family Medicine and Epidemiology and Community Medicine, Bruyere Research Institute, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, ON, Canada

Kevin Pottie

Department of Family Medicine and Department of Epidemiology, Biostatistics and Occupational Health, Faculty of Medicine, McGill University, Montreal, QC, Canada

Anne Andermann

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

JZW, SM, CM, OM, KP and AA were involved in the conception and funding of this study. JZW, SM, CM, AM, KP and AA helped screen articles and determine their inclusion and exclusion in this study. JZW, SM, CM, OM, AM, NK, KP, and AA were involved in extracting data from randomized control trials and systematic reviews on relevant outcomes. JZW, SM, OM, AM, VK, PG, NK, KP, and AA were involved in critical appraisal of the quality of articles using AMSTAR and Cochrane risk of bias tool. All authors were involved in data analysis, writing the manuscript, and revisions. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Kevin Pottie .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

This article was a review of published primary studies, ethics approval not required.

Consent for publication

Competing interests.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1..

Search Strategy.

Additional file 2.

Interventions for Social, Personal, Health and Social Service Utilization, and Sexual Health Outcomes.

Additional file 3.

PRISMA Equity Checklist.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Wang, J.Z., Mott, S., Magwood, O. et al. The impact of interventions for youth experiencing homelessness on housing, mental health, substance use, and family cohesion: a systematic review. BMC Public Health 19 , 1528 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-7856-0

Download citation

Received : 19 March 2019

Accepted : 28 October 2019

Published : 14 November 2019

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-7856-0

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Homelessness

- Vulnerably housed

- Interventions

BMC Public Health

ISSN: 1471-2458

- General enquiries: [email protected]

Information

- Author Services

Initiatives

You are accessing a machine-readable page. In order to be human-readable, please install an RSS reader.

All articles published by MDPI are made immediately available worldwide under an open access license. No special permission is required to reuse all or part of the article published by MDPI, including figures and tables. For articles published under an open access Creative Common CC BY license, any part of the article may be reused without permission provided that the original article is clearly cited. For more information, please refer to https://www.mdpi.com/openaccess .

Feature papers represent the most advanced research with significant potential for high impact in the field. A Feature Paper should be a substantial original Article that involves several techniques or approaches, provides an outlook for future research directions and describes possible research applications.

Feature papers are submitted upon individual invitation or recommendation by the scientific editors and must receive positive feedback from the reviewers.

Editor’s Choice articles are based on recommendations by the scientific editors of MDPI journals from around the world. Editors select a small number of articles recently published in the journal that they believe will be particularly interesting to readers, or important in the respective research area. The aim is to provide a snapshot of some of the most exciting work published in the various research areas of the journal.

Original Submission Date Received: .

- Active Journals

- Find a Journal

- Proceedings Series

- For Authors

- For Reviewers

- For Editors

- For Librarians

- For Publishers

- For Societies

- For Conference Organizers

- Open Access Policy

- Institutional Open Access Program

- Special Issues Guidelines

- Editorial Process

- Research and Publication Ethics

- Article Processing Charges

- Testimonials

- Preprints.org

- SciProfiles

- Encyclopedia

Article Menu

- Subscribe SciFeed

- Recommended Articles

- Google Scholar

- on Google Scholar

- Table of Contents

Find support for a specific problem in the support section of our website.

Please let us know what you think of our products and services.

Visit our dedicated information section to learn more about MDPI.

JSmol Viewer

Unpacking the discourse on youth pathways into and out of homelessness: implications for research scholarship and policy interventions.

1. Introduction

2. contextualizing youth homelessness: what do we know, 2.1. individual factors, 2.2. structural causes and systems failures, 2.3. the new orthodoxy, 2.4. the pathways discourse and youth homelessness.

Homelessness is not just a matter of lack of shelter or lack of abode, a lack of a roof over one’s head. It involves deprivation across a number of different dimensions—physiological (lack of bodily comfort or warmth), emotional (lack of love or joy), territorial (lack of privacy), ontological (lack of rootedness in the world, anomie) and spiritual (lack of hope, lack of purpose). (p. 384)

3. The Characteristics of the Pathways Approach

3.1. the social construction of homelessness, 3.2. the whatness vs. howness.

for the large majority of the youth, homelessness was not the product of a single event, nor did it lead immediately to the streets. Rather, homelessness for most of the youth resulted in a number of different living arrangements that reflected the use, and perhaps even the “burning out”, of their available social networks. On average, a youth experienced 6 of the 9 living arrangements listed, reflecting a pattern of unstable and diminishing options. [ 83 ] (p. 74)

3.3. The Temporal Dimension

3.4. pathways into and out of homelessness, 3.5. heterogeneity of homelessness experiences, 4. implications for research and practice, 5. conclusions, institutional review board statement, informed consent statement, data availability statement, acknowledgments, conflicts of interest.

- Karabanow, J.; Kidd, S.A.; Frederick, T.; Hughes, J. Homeless Youth and the Search for Stability ; Wilfrid Laurier University Press: Waterloo, ON, Canada, 2018. [ Google Scholar ]

- Zerger, S.; Strehlow, A.J.; Gundlapalli, A.V. Homeless Young Adults and Behavioral Health: An Overview. Am. Behav. Sci. 2008 , 51 , 824–841. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Gaetz, S. Safe Streets for Whom? Homeless Youth, Social Exclusion, and Criminal Victimization. Can. J. Criminol. Crim. Justice 2004 , 46 , 423–455. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Thompson, S.J.; Bender, K.; Windsor, L.; Cook, M.S.; Williams, T. Homeless Youth: Characteristics, Contributing Factors, and Service Options. J. Hum. Behav. Soc. Environ. 2010 , 20 , 193–217. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Grant, R.; Gracy, D.; Goldsmith, G.; Shapiro, A.; Redlener, I.E. Twenty-Five Years of Child and Family Homelessness: Where Are We Now? Am. J. Public Health 2013 , 103 (Suppl. S2), 1–10. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Ferguson, K.M.; Bender, K.; Thompson, S.J. Gender, Coping Strategies, Homelessness Stressors, and Income Generation among Homeless Young Adults in Three Cities. Soc. Sci. Med. 2015 , 135 , 47–55. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- O’Grady, B.; Gaetz, S. Street Survival: A Gendered Analysis of Youth Homelessness in Toronto. In Finding Home: Policy Options for Addressing Homelessness in Canada ; Hulchanski, J.D., Campsie, P., Chau, S.B.Y., Hwang, S.W., Paradis, E., Eds.; Cities Centre Press: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2009. [ Google Scholar ]

- Nooe, R.M.; Patterson, D.A. The Ecology of Homelessness. J. Hum. Behav. Soc. Environ. 2010 , 20 , 105–152. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Gaetz, S.; Schwan, K.; Redman, M.; French, D.; Dej, E. The Roadmap for the Prevention of Youth Homelessness ; Buchnea, A., Ed.; Canadian Observatory on Homelessness Press: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2018. [ Google Scholar ]

- Martijn, C.; Sharpe, L. Pathways to Youth Homelessness. Soc. Sci. Med. 2006 , 62 , 1–12. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Karabanow, J. Being Young and Homeless: Understanding How Youth Enter and Exit Street Life ; Peter Lang: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [ Google Scholar ]

- Morton, M.H.; Dworsky, A.; Matjasko, J.L.; Curry, S.R.; Schlueter, D.; Chávez, R.; Farrell, A.F. Prevalence and Correlates of Youth Homelessness in the United States. J. Adolesc. Health 2018 , 62 , 14–21. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Quigley, J.M.; Raphael, S.; Smolensky, E. Homeless in America. Rev. Econ. Stat. 2001 , 83 , 37–51. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- O’Flaherty, B. An Economic Theory of Homelessness and Housing. J. Hous. Econ. 1995 , 4 , 13–49. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Lee, B.A.; Price-Spratlen, T.; Kanan, J.W. Determinants of Homelessness in Metropolitan Areas. J. Urban Aff. 2003 , 25 , 335–356. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Gaetz, S.; Dej, E. A New Direction: A Framework for Homelessness Prevention ; Canadian Observatory on Homelessness Press: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2017. [ Google Scholar ]

- Nichols, N. Nobody “Signs Out of Care.” Exploring Institutional Links between Child Protection Services & Homelessness. In Youth Homelessness in Canada: Implications for Policy and Practice ; Gaetz, S., O’Grady, B., Buccieri, K., Karabanow, J., Eds.; Canadian Homelessness Research Network Press: Toronto, ON, Canada, Canada, 2013; pp. 75–93. [ Google Scholar ]

- Baskin, C. Aboriginal Youth Talk about Structural Determinants as the Causes of Their Homelessness. First Peoples Child Fam. Rev. 2007 , 3 , 31–42. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Alberton, A.M.; Angell, G.B.; Gorey, K.M.; Grenier, S. Homelessness among Indigenous Peoples in Canada: The Impacts of Child Welfare Involvement and Educational Achievement. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2020 , 111 , 104846. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Pleace, N. The New Consensus, the Old Consensus and the Provision of Services for People Sleeping Rough. Hous. Stud. 2000 , 15 , 581–594. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- May, J. Housing Histories and Homeless Careers: A Biographical Approach. Hous. Stud. 2000 , 15 , 613–638. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Fitzpatrick, S. Explaining Homelessness: A Critical Realist Perspective. Hous. Theory Soc. 2005 , 22 , 1–17. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Pleace, N. Researching Homelessness in Europe: Theoretical Perspectives. Eur. J. Homelessness 2016 , 10 , 19–44. [ Google Scholar ]

- Somerville, P. Understanding Homelessness. Hous. Theory Soc. 2013 , 30 , 384–415. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Clapham, D. Pathways Approaches to Homelessness Research. J. Community Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2003 , 13 , 119–127. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Clapham, D. The Meaning of Housing: A Pathways Approach ; Policy Press: Bristol, UK, 2005. [ Google Scholar ]

- Rittel, H.W.J.; Webber, M.M. Dilemmas in a General Theory of Planning. Policy Sci. 1973 , 4 , 155–169. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Bonakdar, A. Reflective Practice in Homelessness Research and Practice: Implications for Researchers and Practitioners in the COVID-19 Pandemic Era. Int. J. Homelessness 2022 , 3 , 124–136. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Gaetz, S.; O’Grady, B.; Buccieri, K.; Karabanow, J.; Marsolais, A. Youth Homelessness in Canada: Implications for Policy and Practice ; Gaetz, S.A., O’Grady, B., Buccieri, K., Karabanow, J., Marsolais, A., Eds.; The Canadian Homelessness Research Network: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2013. [ Google Scholar ]

- van den Bree, M.B.M.; Shelton, K.; Bonner, A.; Moss, S.; Thomas, H.; Taylor, P.J. A Longitudinal Population-Based Study of Factors in Adolescence Predicting Homelessness in Young Adulthood. J. Adolesc. Health 2009 , 45 , 571–578. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Rosenthal, D.; Mallett, S.; Myers, P. Why Do Homeless Young People Leave Home? Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 2006 , 30 , 281–285. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Mallett, S.; Rosenthal, D.; Keys, D. Young People, Drug Use and Family Conflict: Pathways into Homelessness. J. Adolesc. 2005 , 28 , 185–199. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Brakenhoff, B.; Jang, B.; Slesnick, N.; Snyder, A. Longitudinal Predictors of Homelessness: Findings from the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth-97. J. Youth Stud. 2015 , 18 , 1015–1034. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Heerde, J.A.; Bailey, J.A.; Toumbourou, J.W.; Rowland, B.; Catalano, R.F. Longitudinal Associations Between Early-Mid Adolescent Risk and Protective Factors and Young Adult Homelessness in Australia and the United States. Prev. Sci. 2020 , 21 , 557–567. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Tyler, K.A.; Cauce, A.M.; Whitbeck, L. Family Risk Factors and Prevalence of Dissociative Symptoms among Homeless and Runaway Youth. Child Abus. Negl. 2004 , 28 , 355–366. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Keeshin, B.R.; Campbell, K. Screening Homeless Youth for Histories of Abuse: Prevalence, Enduring Effects, and Interest in Treatment. Child Abus. Negl. 2011 , 35 , 401–407. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Ballon, B.C.; Courbasson, C.M.A.; Smith, P.D. Physical and Sexual Abuse Issues among Youths with Substance Use Problems. Can. J. Psychiatry 2001 , 46 , 617–621. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Dawson-Rose, C.; Shehadeh, D.; Hao, J.; Barnard, J.; Khoddam-Khorasani, L.; Leonard, A.; Clark, K.; Kersey, E.; Mousseau, H.; Frank, J.; et al. Trauma, Substance Use, and Mental Health Symptoms in Transitional Age Youth Experiencing Homelessness. Public Health Nurs. 2020 , 37 , 363–370. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Forge, N.; Hartinger-Saunders, R.; Wright, E.; Ruel, E. Out of the System and onto the Streets: LGBTQ-Identified Youth Experiencing Homelessness with Past Child Welfare System Involvement. Child Welf. 2018 , 96 , 47–74. [ Google Scholar ]

- Nicholls, C.M.N. Agency, Transgression and the Causation of Homelessness: A Contextualised Rational Action Analysis. Eur. J. Hous. Policy 2009 , 9 , 69–84. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Pleace, N.; O’Sullivan, E.; Johnson, G. Making Home or Making Do: A Critical Look at Homemaking without a Home. Hous. Stud. 2022 , 37 , 315–331. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Parsell, C.; Parsell, M. Homelessness as a Choice. Hous. Theory Soc. 2012 , 29 , 420–434. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Hyde, J. From Home to Street: Understanding Young People’s Transitions into Homelessness. J. Adolesc. 2005 , 28 , 171–183. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Quigley, J.M.; Raphael, S. The Economics of Homelessness: The Evidence from North America. Int. J. Hous. Policy 2001 , 1 , 323–336. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Crane, M.; Byrne, K.; Fu, R.; Lipmann, B.; Mirabelli, F.; Rota-Bartelink, A.; Ryan, M.; Shea, R.; Watt, H.; Wames, A.M. The Causes of Homelessness in Later Life: Findings from a 3-Nation Study. J. Gerontol. Ser. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2005 , 60 , 152–159. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Gaetz, S.; Gulliver, T.; Richter, T. The State of Homelessness in Canada 2014 ; The Homeless Hub Press: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2014. [ Google Scholar ]

- Abramovich, A. Understanding How Policy and Culture Create Oppressive Conditions for LGBTQ2S Youth in the Shelter System. J. Homosex. 2017 , 64 , 1484–1501. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Shelton, J.; DeChants, J.; Bender, K.; Hsu, H.-T.; Santa Maria, D.; Petering, R.; Ferguson, K.; Narendorf, S.; Barman-Adhikari, A. Homelessness and Housing Experiences among LGBTQ Young Adults in Seven U.S. Cities. Cityscape A J. Policy Dev. Res. 2018 , 20 , 2005. [ Google Scholar ]

- McCann, E.; Brown, M. Homelessness among Youth Who Identify as LGBTQ+: A Systematic Review. J. Clin. Nurs. 2019 , 28 , 2061–2072. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Robinson, B.A. Coming Out to the Streets: LGBTQ Youth Experiencing Homelessness ; University of California Press: Oakland, CA, USA, 2020. [ Google Scholar ]

- Berzin, S.C.; Rhodes, A.M.; Curtis, M.A. Housing Experiences of Former Foster Youth: How Do They Fare in Comparison to Other Youth? Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2011 , 33 , 2119–2126. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Bonakdar, A.; Gaetz, S.; Banchani, E.; Schwan, K.; Kidd, S.A.; Grady, B.O. Child Protection Services and Youth Experiencing Homelessness: Findings of the 2019 National Youth Homelessness Survey in Canada. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2023 , 153 , 107088. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Bender, K.; Yang, J.; Ferguson, K.; Thompson, S. Experiences and Needs of Homeless Youth with a History of Foster Care. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2015 , 55 , 222–231. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Dworsky, A.; Napolitano, L.; Courtney, M.; Napolitano, L.; Courtney, M. Homelessness during the Transition from Foster Care to Adulthood. Am. J. Public Health 2013 , 103 (Suppl. S2), 318–323. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Dworsky, A.; Courtney, M. Homelessness during the Transition from Foster Care to Adulthood. Child Welf. 2009 , 88 , 23–56. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/45400428 (accessed on 22 May 2024). [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Goldstein, A.L.; Amiri, T.; Vilhena, N.; Wekerle, C.; Thornton, T.; Tonmyr, L. Youth on the Street and Youth Involved with Child Welfare: Maltreatment, Mental Health and Substance Use ; University of Toronto: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2011. [ Google Scholar ]

- Brandon, D.; Wells, K.; Francis, C.; Ramsay, E. The Survivors: A Study of Homeless Young Newcomers to London and the Responses Made to Them ; Routledge: London, UK, 1980. [ Google Scholar ]

- Liddiard, M. Explaining Youth Homelessness: Issues and Approaches. In New Approaches to Homelessness ; Kennett, P., Ed.; University of Bristol: Bristol, UK, 1992. [ Google Scholar ]

- Shinn, M. International Homelessness: Policy, Socio-Cultural, and Individual Perspectives. J. Soc. Issues 2007 , 63 , 657–677. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Fitzpatrick, S.; Christian, J. Comparing Homelessness Research in the US and Britain. Eur. J. Hous. Policy 2006 , 6 , 313–333. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Farrugia, D.; Gerrard, J. Academic Knowledge and Contemporary Poverty: The Politics of Homelessness Research. Sociology 2016 , 50 , 267–284. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Peck, J.; Tickell, A. Neoliberalizing Space. Antipode 2002 , 34 , 380–404. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Pleace, N.; Quilgars, D. Led Rather than Leading? Research on Homelessness in Britain. J. Community Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2003 , 13 , 187–196. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Fitzpatrick, S.; Bramley, G.; Johnsen, S. Pathways into Multiple Exclusion Homelessness in Seven UK Cities. Urban Stud. 2013 , 50 , 148–168. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Ross-brown, S.; Leavey, G. Understanding Young Adults’ Pathways into Homelessness in Northern Ireland: A Relational Approach. Eur. J. Homelessness 2021 , 15 , 59–82. [ Google Scholar ]

- Pinder, R. Turning Points and Adaptations: One Man’s Journey into Chronic Homelessness. Ethos 1994 , 22 , 209–239. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Gaetz, S.; O’Grady, B.; Buccieri, K.; Karabanow, J.; Marsolais, A. Introduction. In Youth Homelessness in Canada: Implications for Policy and Practice ; Gaetz, S., O’Grady, B., Buccieri, K., Karabanow, J., Marsolais, A., Eds.; Canadian Observatory on Homelessness Press: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2013; pp. 1–13. [ Google Scholar ]

- Berger, P.L.; Luckmann, T. The Social Construction of Reality: A Treatise in the Sociology of Knowledge ; Penguin Books: London, 1966. [ Google Scholar ]

- Blumer, H. Social Problems as Collective Behavior. Soc. Probl. 1971 , 18 , 298–306. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Jacobs, K.; Kemeny, J.; Manzi, T. The Struggle to Define Homelessness: A Constructivist Approach. In Homelessness: Public Policies and Private Troubles ; Hutson, S., Clapham, D., Eds.; Cassell: London, UK, 1999; pp. 11–28. [ Google Scholar ]

- Cronley, C. Unraveling the Social Construction of Homelessness. J. Hum. Behav. Soc. Environ. 2010 , 20 , 319–333. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Clapham, D. Housing Pathways: A Post Modern Analytical Framework. Hous. Theory Soc. 2002 , 19 , 57–68. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Ravenhill, M. The Culture of Homelessness ; Ashgate Publishing: Aldershot, UK, 2008. [ Google Scholar ]

- Wolfe, S.M.; Toro, P.A.; McCaskill, P.A. A Comparison of Homeless and Matched Housed Adolescents on Family Environment Variables. J. Res. Adolesc. 1999 , 9 , 53–66. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Whitbeck, L.B.; Hoyt, D.R.; Ackley, K.A. Abusive Family Backgrounds and Later Victimization among Runaway and Homeless Adolescents. J. Res. Adolesc. 1997 , 7 , 375–392. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Karabanow, J. Getting off the Street: Exploring the Processes of Young People’s Street Exits. Am. Behav. Sci. 2008 , 51 , 772–788. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Abramovich, A. No Safe Place to Go LGBTQ Youth Homelessness in Canada: Reviewing the Literature. Can. J. Fam. Youth 2012 , 4 , 29–51. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Durso, L.E.; Gates, G.J. Serving Our Youth: Findings from a National Survey of Services Providers Working with Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Youth Who Are Homeless or At Risk of Becoming Homeless ; The University of California, Los Angeles: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2010. [ Google Scholar ]

- Abramovich, A. Preventing, Reducing and Ending LGBTQ2S Youth Homelessness: The Need for Targeted Strategies. Soc. Incl. 2016 , 4 , 86. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Thompson, S.J. Factors Associated with Trauma Symptoms among Runaway/Homeless Adolescents. Stress. Trauma Cris. 2005 , 8 , 143–156. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Williams, N.R.; Lindsey, E.W.; Kurtz, P.D.; Jarvis, S. From Trauma to Resiliency: Lessons from Former Runaway and Homeless Youth. J. Youth Stud. 2001 , 4 , 233–253. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Tomas, A.; Dittmar, H. The Experience of Homeless Women: An Exploration of Housing Histories and the Meaning of Home. Hous. Stud. 1995 , 10 , 493–515. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Coates, J.; Mckenzie-Mohr, S. Out of the Frying Pan, Into the Fire: Trauma in the Lives of Homeless Youth Prior to and During Homelessness. J. Sociol. Soc. Welf. 2010 , 37 , 65–96. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Anderson, I. Pathways through Homelessness: Towards a Dynamic Analysis. In Urban Frontiers Programme ; University of Western Sydney: Sydney, NSW, Canada, 2001; pp. 1–18. [ Google Scholar ]

- Anderson, I.; Tulloch, D. Pathways Through Homelessness: A Review of the Research Evidence ; Scottish Homes: Edinburgh, UK, 2000. [ Google Scholar ]

- Gaetz, S.; O’Grady, B.; Kidd, S.A.; Schwan, K. Without a Home: The National Youth Homelessness Survey ; Canadian Observatory on Homelessness Press: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2016. [ Google Scholar ]

- Kuhn, R.; Culhane, D.P. Applying Cluster Analysis to Test a Typology of Homelessness by Pattern of Shelter Utilization: Results from the Analysis of Administrative Data. Am. J. Community Psychol. 1998 , 26 , 207–232. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Kidd, S.A.; Frederick, T.; Karabanow, J.; Hughes, J.; Naylor, T.; Barbic, S. A Mixed Methods Study of Recently Homeless Youth Efforts to Sustain Housing and Stability. Child Adolesc. Soc. Work J. 2016 , 33 , 207–218. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Karabanow, J.; Taylor, N. Pathways towards Stability: Young People’s Transitions Off of the Streets. In Youth Homelessness in Canada: Implications for Policy and Practice ; Gaetz, S., O’Grady, B., Buccieri, K., Karabanow, J., Marsolais, A., Eds.; The Canadian Homelessness Research Network: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2013; pp. 39–52. [ Google Scholar ]

- Thulien, N.S.; Gastaldo, D.; Hwang, S.W.; McCay, E. The Elusive Goal of Social Integration: A Critical Examination of the Socio-Economic and Psychosocial Consequences Experienced by Homeless Young People Who Obtain Housing. Can. J. Public Health 2018 , 109 , 89–98. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Winland, D. Reconnecting with Family and Community: Pathways Out of Youth Homelessness. In Youth Homelessness in Canada: Implications for Policy and Practice ; The Canadian Homelessness Research Network: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2013; pp. 15–38. [ Google Scholar ]

- Miller, P.; Donahue, P.; Este, D.; Hofer, M. Experiences of Being Homeless or at Risk of Being Homeless among Canadian Youths. Adolescence 2004 , 39 , 735–755. [ Google Scholar ]

- O’Grady, B.; Gaetz, S. Homelessness, Gender and Subsistence: The Case of Toronto Street Youth. J. Youth Stud. 2004 , 7 , 397–416. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Barker, J. A Habitus of Instability: Youth Homelessness and Instability. J. Youth Stud. 2016 , 19 , 665–683. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- MacDonald, C.; Sohn, J.; Bonakdar, A.; Traher, C. A Roof over Your Head Is Not a Home: Youth Homelessness in Canada. In The Routledge International Handbook of Child and Adolescent Grief in Contemporary Contexts ; Traher, C., Breen, L.J., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 180–191. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Moxley, D.P.; Feen, H. Arts-Inspired Design in the Development of Helping Interventions in Social Work: Implications for the Integration of Research and Practice. Br. J. Soc. Work 2016 , 46 , 1690–1707. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Lenette, C. Why Arts-Based Research? In Arts-Based Methods in Refugee Research: Creating Sanctuary ; Lenette, C., Ed.; Springer: Singapore, 2019; pp. 27–55. [ Google Scholar ]

- Nathan, S.; Hodgins, M.; Wirth, J.; Ramirez, J.; Walker, N.; Cullen, P. The Use of Arts-Based Methodologies and Methods with Young People with Complex Psychosocial Needs: A Systematic Narrative Review. Health Expect. 2023 , 26 , 795–805. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Barone, T.; Eisner, E.W. Arts Based Research ; Sage Publications: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2012. [ Google Scholar ]

- Leavy, P. Method Meets Art, Third Edition: Arts-Based Research Practice , 3rd ed.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [ Google Scholar ]

- Ansloos, J.P.; Wager, A.C.; Dunn, N.S. Preventing Indigenous Youth Homelessness in Canada: A Qualitative Study on Structural Challenges and Upstream Prevention in Education. J. Community Psychol. 2022 , 50 , 1918–1934. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Wager, A.C.; Ansloos, J.P. Street Wisdom: A Critical Study on Youth Homelessness and Decolonizing Arts-Based Research. In Engaging Youth in Critical Arts Pedagogies and Creative Research for Social Justice: Opportunities and Challenges of Arts-Based Work and Research with Young People ; Goessling, K.P., Wright, D.E., Wager, A.C., Dewhurst, M., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2021; pp. 84–105. [ Google Scholar ]

- Elder, G.H., Jr.; Johnson, M.K.; Crosnoe, R. The Emergence and Development of Life Course Theory. In Handbook of the Life Course ; Mortimer, J.T., Shanahan, M.J., Eds.; Kluwer Academic Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 2003; pp. 3–19. [ Google Scholar ]

- Elder, G.H., Jr. The Life Course as Developmental Theory. Child Dev. 2009 , 69 , 1–12. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Watkins, J.F.; Hosier, A.F. Conceptualizing Home and Homelessness: A Life Course Perspective. In Home and Identity in Late Life: International Perspectives ; Rowles, G.D., Chaudhury, H., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2005; pp. 197–216. [ Google Scholar ]

- Mackie, P.K. Homelessness Prevention and the Welsh Legal Duty: Lessons for International Policies. Hous. Stud. 2015 , 30 , 40–59. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Culhane, D.P.; Metraux, S.; Byrne, T. A Prevention-Centered Approach to Homelessness Assistance: A Paradigm Shift? Hous. Policy Debate 2011 , 21 , 295–315. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Milaney, K. The 6 Dimensions of Promising Practice for Case Managed Supports to End Homelessness, Part 1: Contextualizing Case Management for Ending Homelessness. Prof. Case Manag. 2011 , 16 , 281–287. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Milaney, K. The 6 Dimensions of Promising Practice for Case Managed Supports to End Homelessness: Part 2: The 6 Dimensions of Quality. Prof. Case Manag. 2012 , 17 , 4–12. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Baskin, C. Shaking Off the Colonial Inheritance: Homeless Indigenous Youth Resist, Reclaim and Reconnect. In Youth Homelessness in Canada: Implications for Policy and Practice ; Gaetz, S., O’Grady, B., Buccieri, K., Karabanow, J., Marsolais, A., Eds.; Canadian Homelessness Research Network Press: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2013; pp. 405–424. [ Google Scholar ]

- Mackie, P.K.; Thomas, I.; Bibbings, J. Homelessness Prevention: Reflecting on a Year of Pioneering Welsh Legislation in Practice. Eur. J. Homelessness 2017 , 11 , 81–107. [ Google Scholar ]

| The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

Share and Cite

Bonakdar, A. Unpacking the Discourse on Youth Pathways into and out of Homelessness: Implications for Research Scholarship and Policy Interventions. Youth 2024 , 4 , 787-802. https://doi.org/10.3390/youth4020052

Bonakdar A. Unpacking the Discourse on Youth Pathways into and out of Homelessness: Implications for Research Scholarship and Policy Interventions. Youth . 2024; 4(2):787-802. https://doi.org/10.3390/youth4020052

Bonakdar, Ahmad. 2024. "Unpacking the Discourse on Youth Pathways into and out of Homelessness: Implications for Research Scholarship and Policy Interventions" Youth 4, no. 2: 787-802. https://doi.org/10.3390/youth4020052

Article Metrics

Article access statistics, further information, mdpi initiatives, follow mdpi.

Subscribe to receive issue release notifications and newsletters from MDPI journals

Meaningfully Engaging Homeless Youth in Research

- First Online: 06 May 2020

Cite this chapter

- Annie Smith 3 ,

- Maya Peled 3 &

- Stephanie Martin 3

748 Accesses

1 Citations

Meaningfully engaging young people in decisions that affect them benefits not only those youth but also the adults and agencies that support them, as well as the wider community. Youth participatory action research (YPAR) is an approach to facilitate youth engagement in research which has been increasingly implemented to enable young people to collaborate and influence decisions in areas where their voices are commonly excluded. This chapter offers examples of youth engagement projects and YPAR initiatives with vulnerable youth. It then focuses on an effective approach to engaging homeless youth in research, includes a discussion of the challenges and benefits of doing so, and offers some lessons learned for future projects wishing to engage homeless young people in the participatory action research process.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Engaging Youth in Research

Speaking Out: Youth Led Research as a Methodology Used with Homeless Youth

Checkoway B. What is youth participation? Child Youth Serv Rev. 2011;33:340–5.

Article Google Scholar

Smith A, Peled M, Hoogeveen C, Cotman S, McCreary Centre Society. A seat at the table: a review of youth Engagement in Vancouver. Vancouver: McCreary Centre Society; 2009.

Google Scholar

BC Healthy Communities. Provincial youth engagement scan. 2011. http://bchealthycommunities.ca/res/download.php?id=961 . Accessed 23 Aug 2018.

Paglia A, Room R. Preventing substance use problems among youth: a literature review & recommendations. J Prim Prev. 1998;20(1):3–50.

Libby M, Rosen M, Sedonaen M. Building youth-adult partnerships for community change: lessons from the youth leadership institute. J Community Psychol. 2005;33(1):111–20.

Ramey H, Rose-Krasnor L. The new mentality: youth-adult partnerships in community mental health promotion. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2015;50:28–37.

Zeldin S, Petrokubi J, McCart S, Khanna N, Collura J, Christens B. Strategies for sustaining quality youth-adult partnerships in organizational decision making: multiple perspectives. Prev Res. 2011;18(Suppl):7–11.

Ramey HL. Organizational outcomes of youth involvement in organizational decision making: a synthesis of qualitative research. J Community Psychol. 2013;41(4):488–504.

Hart RA. Children’s participation: from tokenism to citizenship. 1992. http://www.unicef-irc.org/publications/pdf/childrens_participation.pdf . Accessed 1 Aug 2018.

Zeldin S, Camino L, Mook C. The adoption of innovation in youth organizations: creating the conditions for youth-adult partnerships. J Community Psychol. 2005;33(1):121–35.

Zeldin S, Christens BD, Powers JL. The psychology and practice of youth-adult partnership: bridging generations for youth development and community change. Am J Community Psychol. 2013;51:385–97.

Thomason JD, Kuperminc G. Cool girls, inc. and self-concept: the role of social capital. J Early Adolesc. 2014;34(6):816–36.