The four building blocks of change

Large-scale organizational change has always been difficult, and there’s no shortage of research showing that a majority of transformations continue to fail. Today’s dynamic environment adds an extra level of urgency and complexity. Companies must increasingly react to sudden shifts in the marketplace, to other external shocks, and to the imperatives of new business models. The stakes are higher than ever.

So what’s to be done? In both research and practice, we find that transformations stand the best chance of success when they focus on four key actions to change mind-sets and behavior: fostering understanding and conviction, reinforcing changes through formal mechanisms, developing talent and skills, and role modeling. Collectively labeled the “influence model,” these ideas were introduced more than a dozen years ago in a McKinsey Quarterly article, “ The psychology of change management .” They were based on academic research and practical experience—what we saw worked and what didn’t.

Digital technologies and the changing nature of the workforce have created new opportunities and challenges for the influence model (for more on the relationship between those trends and the model, see this article’s companion, “ Winning hearts and minds in the 21st century ”). But it still works overall, a decade and a half later (exhibit). In a recent McKinsey Global Survey, we examined successful transformations and found that they were nearly eight times more likely to use all four actions as opposed to just one. 1 1. See “ The science of organizational transformations ,” September 2015. Building both on classic and new academic research, the present article supplies a primer on the model and its four building blocks: what they are, how they work, and why they matter.

Fostering understanding and conviction

We know from research that human beings strive for congruence between their beliefs and their actions and experience dissonance when these are misaligned. Believing in the “why” behind a change can therefore inspire people to change their behavior. In practice, however, we find that many transformation leaders falsely assume that the “why” is clear to the broader organization and consequently fail to spend enough time communicating the rationale behind change efforts.

This common pitfall is predictable. Research shows that people frequently overestimate the extent to which others share their own attitudes, beliefs, and opinions—a tendency known as the false-consensus effect. Studies also highlight another contributing phenomenon, the “curse of knowledge”: people find it difficult to imagine that others don’t know something that they themselves do know. To illustrate this tendency, a Stanford study asked participants to tap out the rhythms of well-known songs and predict the likelihood that others would guess what they were. The tappers predicted that the listeners would identify half of the songs correctly; in reality, they did so less than 5 percent of the time. 2 2. Chip Heath and Dan Heath, “The curse of knowledge,” Harvard Business Review , December 2006, Volume 8, Number 6, hbr.org.

Therefore, in times of transformation, we recommend that leaders develop a change story that helps all stakeholders understand where the company is headed, why it is changing, and why this change is important. Building in a feedback loop to sense how the story is being received is also useful. These change stories not only help get out the message but also, recent research finds, serve as an effective influencing tool. Stories are particularly effective in selling brands. 3 3. Harrison Monarth, “The irresistible power of storytelling as a strategic business tool,” Harvard Business Review , March 11, 2014, hbr.org.

Even 15 years ago, at the time of the original article, digital advances were starting to make employees feel involved in transformations, allowing them to participate in shaping the direction of their companies. In 2006, for example, IBM used its intranet to conduct two 72-hour “jam sessions” to engage employees, clients, and other stakeholders in an online debate about business opportunities. No fewer than 150,000 visitors attended from 104 countries and 67 different companies, and there were 46,000 posts. 4 4. Icons of Progress , “A global innovation jam,” ibm.com. As we explain in “Winning hearts and minds in the 21st century,” social and mobile technologies have since created a wide range of new opportunities to build the commitment of employees to change.

Reinforcing with formal mechanisms

Psychologists have long known that behavior often stems from direct association and reinforcement. Back in the 1920s, Ivan Pavlov’s classical conditioning research showed how the repeated association between two stimuli—the sound of a bell and the delivery of food—eventually led dogs to salivate upon hearing the bell alone. Researchers later extended this work on conditioning to humans, demonstrating how children could learn to fear a rat when it was associated with a loud noise. 5 5. John B. Watson and Rosalie Rayner, “Conditioned emotional reactions,” Journal of Experimental Psychology , 1920, Volume 3, Number 1, pp. 1–14. Of course, this conditioning isn’t limited to negative associations or to animals. The perfume industry recognizes how the mere scent of someone you love can induce feelings of love and longing.

Reinforcement can also be conscious, shaped by the expected rewards and punishments associated with specific forms of behavior. B. F. Skinner’s work on operant conditioning showed how pairing positive reinforcements such as food with desired behavior could be used, for example, to teach pigeons to play Ping-Pong. This concept, which isn’t hard to grasp, is deeply embedded in organizations. Many people who have had commissions-based sales jobs will understand the point—being paid more for working harder can sometimes be a strong incentive.

Despite the importance of reinforcement, organizations often fail to use it correctly. In a seminal paper “On the folly of rewarding A, while hoping for B,” management scholar Steven Kerr described numerous examples of organizational-reward systems that are misaligned with the desired behavior, which is therefore neglected. 6 6. Steven Kerr, “On the folly of rewarding A, while hoping for B,” Academy of Management Journal , 1975, Volume 18, Number 4, pp. 769–83. Some of the paper’s examples—such as the way university professors are rewarded for their research publications, while society expects them to be good teachers—are still relevant today. We ourselves have witnessed this phenomenon in a global refining organization facing market pressure. By squeezing maintenance expenditures and rewarding employees who cut them, the company in effect treated that part of the budget as a “super KPI.” Yet at the same time, its stated objective was reliable maintenance.

Even when organizations use money as a reinforcement correctly, they often delude themselves into thinking that it alone will suffice. Research examining the relationship between money and experienced happiness—moods and general well-being—suggests a law of diminishing returns. The relationship may disappear altogether after around $75,000, a much lower ceiling than most executives assume. 7 7. Belinda Luscombe, “Do we need $75,000 a year to be happy?” Time , September 6, 2010, time.com.

Would you like to learn more about our People & Organizational Performance Practice ?

Money isn’t the only motivator, of course. Victor Vroom’s classic research on expectancy theory explained how the tendency to behave in certain ways depends on the expectation that the effort will result in the desired kind of performance, that this performance will be rewarded, and that the reward will be desirable. 8 8. Victor Vroom, Work and motivation , New York: John Wiley, 1964. When a Middle Eastern telecommunications company recently examined performance drivers, it found that collaboration and purpose were more important than compensation (see “Ahead of the curve: The future of performance management,” forthcoming on McKinsey.com). The company therefore moved from awarding minor individual bonuses for performance to celebrating how specific teams made a real difference in the lives of their customers. This move increased motivation while also saving the organization millions.

How these reinforcements are delivered also matters. It has long been clear that predictability makes them less effective; intermittent reinforcement provides a more powerful hook, as slot-machine operators have learned to their advantage. Further, people react negatively if they feel that reinforcements aren’t distributed fairly. Research on equity theory describes how employees compare their job inputs and outcomes with reference-comparison targets, such as coworkers who have been promoted ahead of them or their own experiences at past jobs. 9 9. J. S. Adams, “Inequity in social exchanges,” Advances in Experimental Social Psychology , 1965, Volume 2, pp. 267–300. We therefore recommend that organizations neutralize compensation as a source of anxiety and instead focus on what really drives performance—such as collaboration and purpose, in the case of the Middle Eastern telecom company previously mentioned.

Developing talent and skills

Thankfully, you can teach an old dog new tricks. Human brains are not fixed; neuroscience research shows that they remain plastic well into adulthood. Illustrating this concept, scientific investigation has found that the brains of London taxi drivers, who spend years memorizing thousands of streets and local attractions, showed unique gray-matter volume differences in the hippocampus compared with the brains of other people. Research linked these differences to the taxi drivers’ extraordinary special knowledge. 10 10. Eleanor Maguire, Katherine Woollett, and Hugo Spires, “London taxi drivers and bus drivers: A structural MRI and neuropsychological analysis,” Hippocampus , 2006, Volume 16, pp. 1091–1101.

Despite an amazing ability to learn new things, human beings all too often lack insight into what they need to know but don’t. Biases, for example, can lead people to overlook their limitations and be overconfident of their abilities. Highlighting this point, studies have found that over 90 percent of US drivers rate themselves above average, nearly 70 percent of professors consider themselves in the top 25 percent for teaching ability, and 84 percent of Frenchmen believe they are above-average lovers. 11 11. The art of thinking clearly, “The overconfidence effect: Why you systematically overestimate your knowledge and abilities,” blog entry by Rolf Dobelli, June 11, 2013, psychologytoday.com. This self-serving bias can lead to blind spots, making people too confident about some of their abilities and unaware of what they need to learn. In the workplace, the “mum effect”—a proclivity to keep quiet about unpleasant, unfavorable messages—often compounds these self-serving tendencies. 12 12. Eliezer Yariv, “‘Mum effect’: Principals’ reluctance to submit negative feedback,” Journal of Managerial Psychology , 2006, Volume 21, Number 6, pp. 533–46.

Even when people overcome such biases and actually want to improve, they can handicap themselves by doubting their ability to change. Classic psychological research by Martin Seligman and his colleagues explained how animals and people can fall into a state of learned helplessness—passive acceptance and resignation that develops as a result of repeated exposure to negative events perceived as unavoidable. The researchers found that dogs exposed to unavoidable shocks gave up trying to escape and, when later given an opportunity to do so, stayed put and accepted the shocks as inevitable. 13 13. Martin Seligman and Steven Maier, “Failure to escape traumatic shock,” Journal of Experimental Psychology , 1967, Volume 74, Number 1, pp. 1–9. Like animals, people who believe that developing new skills won’t change a situation are more likely to be passive. You see this all around the economy—from employees who stop offering new ideas after earlier ones have been challenged to unemployed job seekers who give up looking for work after multiple rejections.

Instilling a sense of control and competence can promote an active effort to improve. As expectancy theory holds, people are more motivated to achieve their goals when they believe that greater individual effort will increase performance. 14 14. Victor Vroom, Work and motivation , New York: John Wiley, 1964. Fortunately, new technologies now give organizations more creative opportunities than ever to showcase examples of how that can actually happen.

Role modeling

Research tells us that role modeling occurs both unconsciously and consciously. Unconsciously, people often find themselves mimicking the emotions, behavior, speech patterns, expressions, and moods of others without even realizing that they are doing so. They also consciously align their own thinking and behavior with those of other people—to learn, to determine what’s right, and sometimes just to fit in.

While role modeling is commonly associated with high-power leaders such as Abraham Lincoln and Bill Gates, it isn’t limited to people in formal positions of authority. Smart organizations seeking to win their employees’ support for major transformation efforts recognize that key opinion leaders may exert more influence than CEOs. Nor is role modeling limited to individuals. Everyone has the power to model roles, and groups of people may exert the most powerful influence of all. Robert Cialdini, a well-respected professor of psychology and marketing, examined the power of “social proof”—a mental shortcut people use to judge what is correct by determining what others think is correct. No wonder TV shows have been using canned laughter for decades; believing that other people find a show funny makes us more likely to find it funny too.

Today’s increasingly connected digital world provides more opportunities than ever to share information about how others think and behave. Ever found yourself swayed by the number of positive reviews on Yelp? Or perceiving a Twitter user with a million followers as more reputable than one with only a dozen? You’re not imagining this. Users can now “buy followers” to help those users or their brands seem popular or even start trending.

The endurance of the influence model shouldn’t be surprising: powerful forces of human nature underlie it. More surprising, perhaps, is how often leaders still embark on large-scale change efforts without seriously focusing on building conviction or reinforcing it through formal mechanisms, the development of skills, and role modeling. While these priorities sound like common sense, it’s easy to miss one or more of them amid the maelstrom of activity that often accompanies significant changes in organizational direction. Leaders should address these building blocks systematically because, as research and experience demonstrate, all four together make a bigger impact.

Tessa Basford is a consultant in McKinsey’s Washington, DC, office; Bill Schaninger is a director in the Philadelphia office.

Explore a career with us

Related articles.

Winning hearts and minds in the 21st century

Changing change management

Digital hives: Creating a surge around change

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- J Healthc Leadersh

Where Do Models for Change Management, Improvement and Implementation Meet? A Systematic Review of the Applications of Change Management Models in Healthcare

Reema harrison.

1 School of Population Health, University of New South Wales, Sydney, NSW, Australia

Sarah Fischer

2 Clinical Excellence Commission, New South Wales Health, Sydney, NSW, Australia

3 School of Psychology, Deakin University, Melbourne, VIC, Australia

Ramesh L Walpola

Ashfaq chauhan, temitope babalola, stephen mears.

4 Hunter New England Medical Library, New Lambton, NSW, Australia

Huong Le-Dao

The increasing prioritisation of healthcare quality across the six domains of efficiency, safety, patient-centredness, effectiveness, timeliness and accessibility has given rise to accelerated change both in the uptake of initiatives and the realisation of their outcomes to meet external targets. Whilst a multitude of change management methodologies exist, their application in complex healthcare contexts remains unclear. Our review sought to establish the methodologies applied, and the nature and effectiveness of their application in the context of healthcare.

A systematic review and narrative synthesis was undertaken. Two reviewers independently screened the titles and abstracts followed by the full-text articles that were potentially relevant against the inclusion criteria. An appraisal of methodological and reporting quality of the included studies was also conducted by two further reviewers.

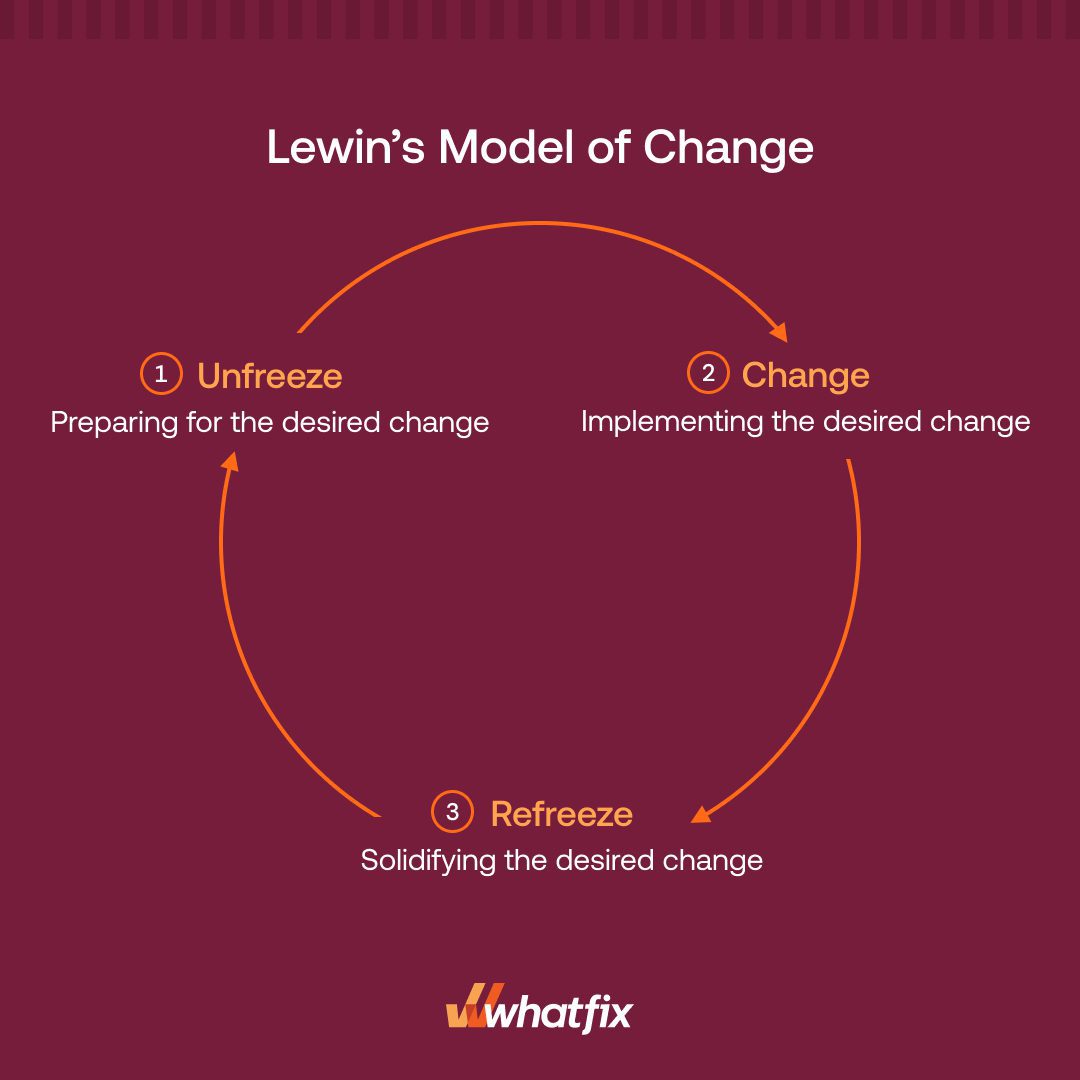

Thirty-eight studies were included that reported the use of 12 change management methodologies in healthcare contexts across 10 countries. The most commonly applied methodologies were Kotter’s Model (19 studies) and Lewin’s Model (11 studies). Change management methodologies were applied in projects at local ward or unit level (14), institutional level (12) and system or multi-system (6) levels. The remainder of the studies provided commentary on the success of change efforts that had not utilised a change methodology with reference to change management approaches.

Change management methodologies were often used as guiding principle to underpin a change in complex healthcare contexts. The lack of prescription application of the change management methodologies was identified. Change management methodologies were valued for providing guiding principles for change that are well suited to enable methodologies to be applied in the context of complex and unique healthcare contexts, and to be used in synergy with implementation and improvement methodologies.

Introduction

The ability to adapt and change is critical to contemporary health service delivery in order to meet changing population needs, the demands of increasing life expectancy and complex health conditions. 1 Increasing prioritisation of healthcare quality across the six domains of efficiency, safety, patient-centredness, effectiveness, timeliness and accessibility has given rise to accelerated change, both in the uptake of initiatives and the realisation of their outcomes to meet external targets. 2 Contemporary health systems thrive on efficient models of care and effective resource utilisation. 3–5 Strategies implemented centrally and locally across health systems to enhance efficiency and patient-reported experiences and outcomes require individuals, teams and organisations to quickly adopt, integrate and renew their behaviours, activities and approach to service planning. 6 , 7 Likewise, achieving patient-centred care requires a revitalisation of the system as a whole, with holistic changes to ways of working to enable and integrate patient contributions, preferences, experiences and outcomes to inform care delivery. 8 , 9 Realisation of healthcare organisations as intelligent systems that consider even everyday clinical work as learning and improvement opportunities have further integrated continuous quality improvement as business as usual for healthcare. 10

With high volume, rapid change required as a central and enduring feature, the healthcare sector has recognised change management as a core competency for healthcare leaders and managers; reflected in professional registration requirements internationally. 1 Despite extensive education and training around change management to healthcare leadership and management, change efforts often fail, change fatigue is substantial and lack of sufficient change management cited as a critical cause of initiatives that fail. 11 Healthcare is now recognised as a complex adaptive system; the whole of the system as more than the sum of its parts and characterised by a large number of elements that interact dynamically, non-linear interactions, history that influences behaviour and poor boundary definition. 12 This recognition has led to growing interest in use of methodologies that promote the adoption of changes in health service delivery through iterative planning and practice cycles and subsequent scaling where considered successful. 13 A plethora of evidence is now available regarding approaches to identify and test change ideas, with a parallel literature regarding how to embed evidence-based successful change practices, including through promoting behaviour change amongst healthcare staff and patients. 14 , 15

In a departure from the notion of planned, top-down and controlled change processes, arguably there has been reduced interest in and the use of “change management” models in healthcare. 16 In understanding healthcare systems as complex adaptive systems, the multiple variables and influences within the system and their unpredictability and uncertainty must be recognised in trying to create and manage any change process. 17 Yet concepts that underpin change management continue to feature as central to successful change in healthcare, from the engagement of stakeholders towards a shared change vision and basis for change through to the progression of the change effort and its implementation. 18–20 Acknowledgement of the critical role of clinician and consumer engagement to create sustained change for quality improvement further supports the continued relevance of change management concepts of shared vision, stakeholder engagement and person-centred thinking. 21 Despite this, there has been limited exploration of the opportunities for change management concepts to support contemporary approaches to implementation and improvement methodologies. The Institute for Healthcare Improvement highlights that the Model for Improvement is not intended to replace change models but rather to accelerate improvement. When integrated with improvement and implementation methodologies, change management models may support increased clinician and patient engagement with change initiatives in healthcare and their success. The contemporary application of change management models in healthcare and their potential value towards enabling change in the context of a complex adaptive system remains unclear. 22 This knowledge provides the evidence base required for exploring opportunities to integrate change management with improvement and implementation methodologies.

A systematic review was completed to establish the evidence regarding defined change management models currently adopted in healthcare and the implications of their use to support implementation and improvement methodologies. In this review, change management models are defined as a structured overall process for change from the inception of change to benefits realisation. The evidence base identified through this review is critical to inform health systems about how change management models currently support healthcare change and to consider the opportunities to integrate change management models with improvement and implementation science methods.

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews (PRISMA) was used to guide the reporting of this review. 23

Eligibility Criteria

Inclusion criteria.

Primary data that demonstrated the application of an identified change management process, defined as a structured overall process for change from the inception of change to benefits realisation (eg, PROCSI, ADKAR, AIM), towards healthcare delivery published in English between 1 st January 2009–31 st August 2020 were included in the review. No restrictions were placed on the health system, service setting or the study design for inclusion in the review.

Exclusion Criteria

Publications discussing a hypothetical change as a result of a planned intervention were excluded. Additionally, non-primary sources such as editorials, opinion pieces or letters were excluded. Review articles were excluded but their reference lists searched to identify additional relevant material. The expansive literature utilising the Model for Improvement was not included in this review given the definition by the IHI as a model to accelerate improvement models rather than as a change model in itself. Furthermore, an aim of this review was to explore how change management models may support the use of improvement models such as the Model for Improvement.

Study Identification

Synonyms and relevant concepts were developed for these two major concepts being evaluated in this review of change management and healthcare delivery. A search strategy ( supplementary file 1 ) was developed and applied to the following electronic databases in June 2019, updated in August 2020: MEDLINE, PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science. Results were merged using reference-management software (Endnote X9.2), duplicates were removed. The review process utilised the Covidence systematic review software (Veritas Health Innovation, Melbourne, Australia) for screening and extraction.

Study Selection and Data Extraction

Two reviewers (TB, RH) screened the titles and abstracts against the eligibility criteria. Full-text documents were obtained for all potentially relevant articles. The eligibility criteria were then applied to the articles by two reviewers (TB, RH). Two further reviewers conducted a face validity check on the final set of articles for inclusion (HLD, RW), with disagreements resolved via consultation. The following data were extracted from the included studies; author, date, study design, setting, sample, change management process/es and key findings.

Data Synthesis

A narrative empirical synthesis was undertaken in stages, based on the review objectives. 24 A quantitative analytic approach was not appropriate due to the heterogeneity of study designs, contexts, and types of literature included. Initial descriptions of eligible studies and results were tabulated ( Table 1 ). Common concepts were discussed between the review team members and patterns in the data explored to identify consistent findings in relation to the study objectives. In this process, interrogation of the findings explored relationships between study characteristics and their findings; the findings of different studies; and the influence of the use of different outcome measures, methods and settings on the resulting data. The literature was then subjected to a quality appraisal process before a narrative synthesis of the findings was produced.

Summary of Included Studies

| Lead Author | Date | Design | Method | Setting | Sample | Change Management Method | Objective | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abd El-Shafy | 2019 | Quantitative | Administrative data | Paediatric trauma Surgery Unit, New York, USA | All department and staff | Lewin’s change model | To reduce nonsurgical trauma admission rate and better align resources to provide care for injured children | Reduction of nonsurgical admission of trauma patients from 30% to 3% and Reduction in length of stay by 21% |

| Alonso | 2013 | Qualitative | Quality indicators | Medway Maritime Hospital emergency department (ED), Kent, UK | Employees working in the emergency department | Kotter’s 8-step | Address problems and inefficiencies with the triage system and to meet the latest ED quality clinical indicators | After six weeks, nursing staff decided to adopt navigation for 24 a day because it allowed them to identify high risk patients on arrival, and make quicker and safer assessments |

| Andersen | 2013 | Quantitative | Interrupted prospective method (time series analysis | Bispeberg Teaching hospital, Denmark | 510 beds - Hospital level data | Kotter’s 8-step | To optimise the use of antimicrobial medications | Immediate and sustained reduction in the use of cefuroxime, and an increase in the use of ertapenem, piperacillin/tazobactam and beta-lactamase sensitive penicillin, Although the consumption remained unaffected *instead maybe: an alternative approach to contain a problem with resistant bacteria that does not require ongoing antimicrobial stewardship was developed which resulted in a sustained change in the consumption of antimicrobials and a decreasing rate of ESBL-KP |

| Balluck | 2020 | Case study | Case study | State based healthcare system, US | 25 hospitals | ADKAR and CLARC Change Models | Discuss the methodological journey of transition from primary to team nursing. | The nurse executive deployed a successful transition for the new nurse care model using ADKAR and CLARC change models. |

| Baloh | 2018 | Qualitative | Semi-structured interview | Rural hospitals in Iowa, USA | 17 small rural hospitals; 47 key informants | Kotter’s 8-step | Implementation of team STEPPS | In half the hospitals, performance of the initial phase influenced the success of the other phases. In the other half, success was dependent on the scope of implementation and the strategies utilised. |

| Bousquet | 2019 | Quantitative | Research and obtained data | ARIA organisation | Hospitals using ARIA | Kotter’s 8-step | Providing an active and healthy life to patients with rhinitis and to those with asthma multimorbidity across the lifecycle irrespective of their sex or socioeconomic status to reduce health and social inequities incurred by the disease | ARIA Phases 1 and 2 were developed in accordance to the Kotter 8-step change model and can be used as a model of CM in patients with chronic diseases. However, there are still unmet needs for the management of rhinitis and asthma in real life. |

| Bowers | 2011 | Mixed methods | Autoethnography and audit | Community nurses seeing housebound patients | Seven community nurses | Lewin’s change model | Health gain; and encourage a new culture of clinical care | Increase in team engagement, teamwork and open discussion. Presence of a revert back into the handwritten caseload due to a lack in continues driving force thereby making resistance forces increase. |

| Bradley | 2013 | Mixed method | Quasi-experimental and Ethnographic interviewing | 3 Acute wards in 3 rural hospitals in South Australia | Nine self-selected inpatients and forty-eight self-selected nurses | Lewin’s change model | to empirically explore the process and outcome of implementation of nurse-to-nurse bedside handover | Patients preferred bedside handover rather than closed-door office handover approach, improving the patient/health provider relationship. Also, the level of patient involvement increased. |

| Burden | 2016 | quantitative | Pre-post surveillance data analysis | A NHS Trust, UK (not identified) | Surgical team | Kotter’s 8-step | To improve breast surgical site infection rates | Overall surgical site infection rate fell from 7% to 2% with inpatient and readmission rates dropping from 2.2% to 0% |

| Carman | 2019 | Qualitative | Interviews | Rural health centre, US | 21 interviews with administrators, physicians, support staff, care-coordinators | Kotter’s 8-Step Process | To understand and evaluate significant organizational change improve preventive care service delivery, close care gaps, and reduce health disparities among its patients. | Steps 1 through 7 of Kotter’s 8 steps of change in the POE implementation process showed evidence. Step 8, anchoring new approaches in the organizational culture, was an area for improvement |

| Chaboyer | 2009 | Qualitative | Semi-structured interview and survey | Regional hospital, Queensland, Australia | Patients and 27 Nurses | Lewin’s change model | Improving patient-centred care through bedside handover in nursing | Support from shift coordinators and team leaders, Improved patient safety,efficiency, teamwork and improved patient outcome through bedside handover |

| Champion | 2017 | quantitative | Surveys | Ottowa Hospital, Canada | Frontline staff in surgical unit | Kotter’s 8-step | To target high surgical site infection rates | Implementation of improved communication methods has resulted in short term wins. |

| Detwiller | 2014 | Qualitative | Observation | Interior Health, British Columbia, Canada | Multiple database | C.A.P. model | Moving a large healthcare organization from an old, non-standardized clinical information system to a new user-friendly standards-based system. | For a change to be successful, there must be authentic, committed leadership visible to everyone within the organization throughout the duration of an initiative. Leading change activities included having a sponsor or champion and team members who demonstrated visible, active, public commitment and were supportive of the change. |

| Dort | 2020 | Quantitative | Eight KPIs | Academic Teaching Hospital, Canada | Head and Neck surgery Department | Kotter’s 8-Step Process | Outline and describe a quality management program | Demonstrated sustained high clinical performance when compared to a non-pathway managed cohort using 7 years of prospective outcomes data. |

| Dredge | 2017 | Mixed Methods | Working party and survey | Calvary Health Care Bethlehem community palliative care service, NSW, Australia | Nurses in an outpatient palliative care service | Kotter’s 8-step | To change anticipatory medicine practices in palliative care | Study identified carers found it difficult to attend training however, found the step by step instructions useful to administer medicines in a timely manner without a nurse. |

| Gazarin | 2020 | Quasi-experimental | Surveillance data | Rural Teaching Hospital, Canada | 224 patients with urinary catheters | Influencer Change Model and the Choosing Wisely Canada toolkit | To create a bundle of interventions that would reduce the unnecessary use of urinary catheters in hospitalised patients | There was gradual improvement during PDSA cycle 2, with the percentage of inappropriate urinary catheter use dropping from an initial 31% before any interventions to less than 5% by the end of this study. |

| Hennerby | 2011 | Quantitative | Competency assessment tool | Acute children’s hospital, Dublin, Ireland | Registered general agency nurses | Young’s nine stage framework | Implementation of a competency assessment tool for registered general agency nurses | 18% of agency nurses scored below expected standard and were not employed. Communication with agency provider and undertaking of competency assessment to check for experience and skills before employing agency nurses |

| Henry | 2017 | Quantitative | Surveys | a 533 bed hospital in Pennsylvania, USA | Frontline staff in a 98 bed maternity ward | Kotter’s 8-step | To increase enculturation of frontline maternity staff with Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative practices. | Kotter's principles provided the structure to achieve the necessary changes to attitudes and behaviours. Intervention resulted in increased mothers breastfeeding on discharge and improved use of community support groups helped the maintenance of breast milk as the primary nutrition for newborns post discharge |

| Hopkins | 2015 | Quantitative | Administrative data | New Jersey Hospital Association and the Greater New York Hospital Association, USA | Physicians in both hospital | Kotter’s 8-step | Achieve a successful gainsharing culture which capitalizes on creativity, knowledge and problem-solving ability | Resolving problems related to large-scale implementation, operation, and administration of gainsharing, achieved improvements in efficiency, promoted patient safety and quality of care, provided support for care redesign saving $822 per admission on average. |

| Jacelon | 2011 | Qualitative | Unstructured interview | Jewish Geriatric Services, Massachusett, America | Multidisciplinary health team and residents | Lewin’s change model | Creating a model which can be used to organize the entire system including the residential facilities and nursing components. | Implementing the JGS-CCM with Lewin’s model has transformed the way care is provided; framework of interaction and communication between informed residents, families and knowledgeable interdisciplinary teams led by nurses resulted in better patient centred care |

| John | 2017 | Quantitative | Administrative data on service user access | Kent and Medway NHS and Social Care Partnership Trust, UK | nurses in acute inpatient mental health units | Kotter’s 8-step | Setting up recovery clinics and promoting service user involvement | Initial results show that the initiative has driven an increase involvement between nurses and service users. |

| Kuhlman | 2019 | Quantitative | Surveillance data | State Hospital, US | 200,691 patients identified as adults with chest pain | Advent Health Clinical Transformation (ACT) cycle. | Develop a clinical pathway for management of adults with chest pain in ED | Baseline-Year was compared with the Performance-Year, chest pain patients discharged from the ED increased by 99%, those going to the ‘Observation’ status decreased by 20%, and inpatient admissions decreased by 63% (p b 0.0001) |

| Lin | 2011 | Multi-method | Documentation, direct observation, physical artefacts, interviews, progress metrics | 4 medical-surgical units in two Northern California Kaiser Permanente hospitals (Sacramento and Clara), USA | 150 participants from multi-disciplinary groups | Cake model, Concerns-Based, and Lewin’s Model | How to implement and spread service design concept (Nurse Knowledge Exchange) in large, complex organizations | Application of change management theories resulted in a redesign of implementation methods and inspired a more human-centred approach to spread the service design concept |

| Manchester | 2014 | 2 Case studies | Chart reviews and Cohorts | Geriatric Education Centres in Maine and Virginia USA | All stakeholders e.g medical director, nurse director, registered nurse, chief nurse officer for the hospital, pharmacists, social workers, physical therapist, clerk and administrative assistant | Lewin’s change model | To understand the contextual factors themselves, surrounding health professions’ ability to change and adopted practices to be sustained | Early involvements of stakeholders and the planning for both the intended and unintended effects can improve the likelihood of change. |

| Mork | 2018 | Qualitative | Pre- and postintervention staff surveys, quality indicators, leadership rounding | 592 Academic Medical centre, Wisconsin, USA | 24-bed medical/surgical intensive care unit | Kotter’s 8-step | To describe the process of implementing and sustaining complementary quality initiatives in a medical surgical, level 1 trauma intensive care unit (ICU) | Active partnership with the patient and the family during these changes promoted a strong intensive care unit culture of patient- and family-centred care |

| Radtke | 2013 | Qualitative | Survey and Interview | Medical/surgical intermediate care unit, Wisconsin, USA | Patients and Nurses | Lewin’s change model | To determine if standardizing shift report improves patient satisfaction with nursing communication | A rise in patient satisfaction in nursing communication to 87.6%, an increase from 75% in the previous 6 months |

| Rafman | 2013 | Quantitative | Outcome measures | Emergency department, 977 bed national hospital, Singapore, | Emergency department | Kotter’s 8-step | To provide timelier access to inpatient and urgent outpatient specialist care for emergency patients. To influence multiple stakeholders to modify their traditional practices and sustain changes. | Specialist outpatient appointments given within the timeframe requested by the ED doctor increased from 51.7% to 80.8%. Early discharges increased from 11.9% to 26.6% and were sustained at 27.2%. 84% of eligible patients received earlier defined specialist care at the ED. The change management achieved excellent clinician compliance rates ranging from 84% to 100%. Median wait for admission remained unchanged. |

| Reddeman | 2016 | Qualitative | Documentation, direct observation, physical artefacts, interviews, progress metrics and adaptation | Cancer Care Ontario, Canada | 14 regional cancer centres | Kotter’s 8-step | To increase peer review of plans for patients receiving radical intent RT. | The initiative is ongoing, but early results indicate that the proportion of radical intent RT courses peer reviewed province wide increased from 43.5% (April 2013) to 68.0% in (March 2015) |

| Sale | 2019 | Case study | Not available | Radiology department, Australia | Radiotherapy department staff | Riches four-stage model of change | To describe the successful move of the radiation therapy department to its new site | The move to the new site was a great success with a transition period working across two sites enabling a slower ramp up of activity at the new site supporting staff and patients in adjusting to the new environment. The four-stage model of change assisted in the smooth implementation of a transition plan for radiation oncology. |

| Small | 2016 | Quantitative | Survey | Isreal Deaconess Medical Centre, Boston, Massachusetts, USA | Surgical orthopaedic trauma unit. | Kotter’s 8-step | To describe the implementation of a bedside handoff process using Kotter’s change model and the DMS to report the implementation effects on nurse compliance, patient and nurse satisfaction, and their perceptions of the process. | Thirty (88%) of the patients reported that a bedside communication occurred between 2 nurses at change of shift. Twenty-nine (96%) were satisfied or very satisfied that nurses per- formed this communication at the bedside. Furthermore, all of the patients expressed satisfaction in the manner the information was shared |

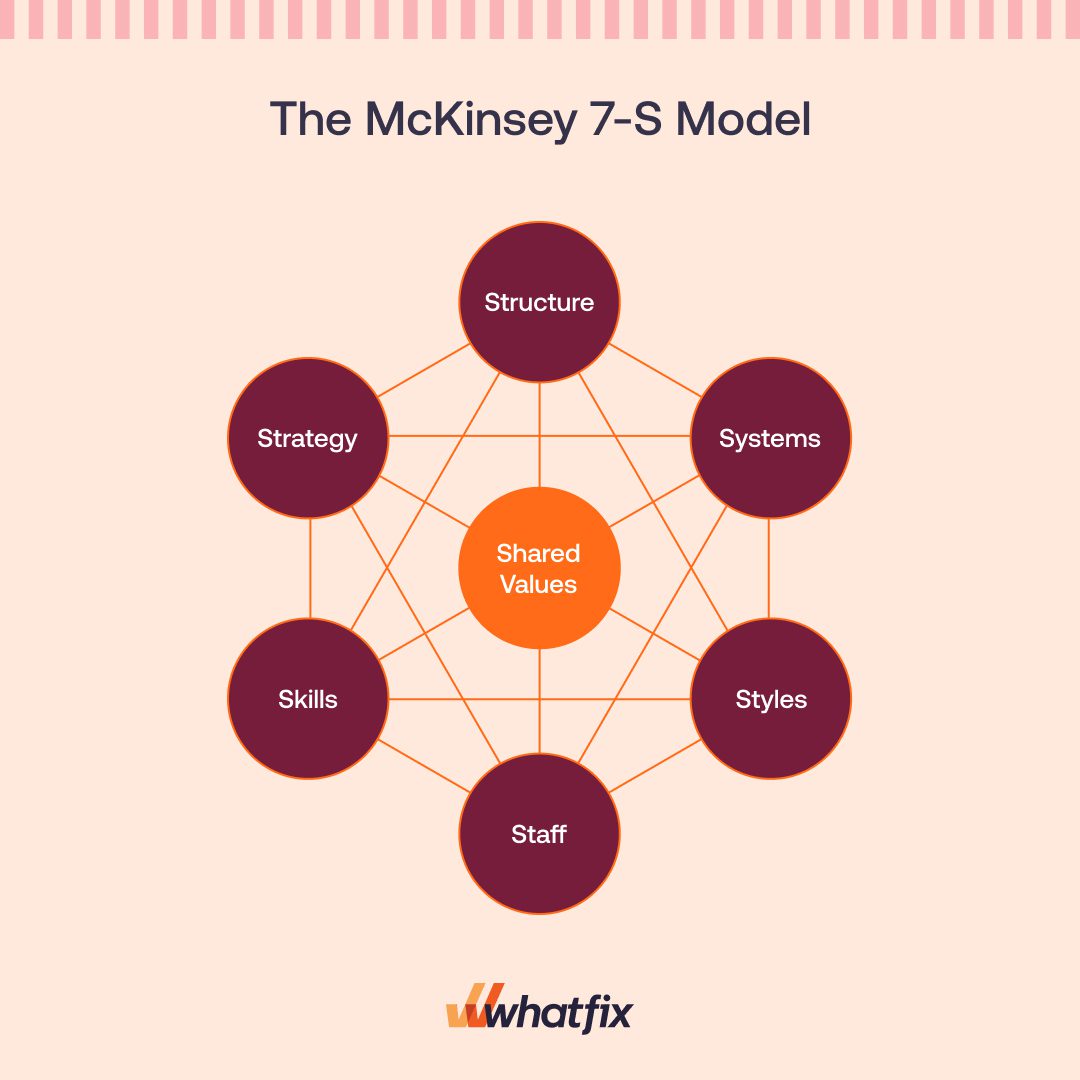

| Sokol | 2020 | Case Study | Surveillance data | Academic health care centre, US | Family medicine clinic | Lewin’s Three-Step Change Theory, and McKinsey 7S Model of Change | Describe our 5-year process of using cultural and structural elements to support change management for safe opioid prescribing and opioid use disorder treatment. | Change management theory to support both safe opioid prescribing and treating patients with OUD over the past 5 years resulted in changes to the practices, people, skills, and infrastructure in the clinic. |

| Sorensen | 2016 | Qualitative | Semi-structured group interview | Ambulatory care clinics, Minnesota, United States of America | Pharmacists and medical practitioners from six health systems with a well-established medication management program | Kotter’s 8-step | To describe the influencing the adoption, growth and sustainability of medication management services | A supportive culture and team-based collaborative care are necessary for medication management services’ sustainability. |

| Spira | 2017 | Quantitative | Surveillance data and surveys | Two hospitals, Uganda | Maternity Departments | Accelerated Implementation Method | To increase the use of intrapartum and postnatal essential interventions (EIs) in two hospitals in Uganda | EIs that were regularly used had no improvement, however, seldom used EIs had a significant improvement in use due to the implementation package of activities developed |

| Spira | 2018 | Quantitative | Surveillance data | Two tertiary teaching hospitals, Nepal | Maternity Departments | Accelerated Implementation Method | To increase the use of intrapartum and postnatal essential interventions (EIs) in two hospitals in Nepal | Only the timely administration of antibiotics caesarean increased, with all other EIs not showing improvement |

| Stoller | 2010 | Mixed method | Randomised control trail, observational and in-person interviews | Respiratory therapy department, Cleveland clinic, Cleveland, Ohio | RCT on 145 patients, 71 RTCS groups and 74 physicians. Interviews on 8 RT department leaders | Kotter’s 8-step, and Silversin and Kornacki’s model - Amicus | Implementing respiratory care protocols to reduce misallocation of respiratory care | There were 11 desired featured to the change. Understanding and embracing change is important. |

| Tetef | 2017 | Multi method | Surveys and feedback interviews | Union hospital, southern California, USA | The organization as a whole | Lewin’s change model and Roger’s diffusion of innovation theory | Implement a successful bronchial thermoplastic program, while maintain patient safety and ensuring staff competency | The program was success at a union level by using Roger’s theory, the BT program was successful because planning and development of the program. Also, with leadership of change which includes acknowledging the feelings and social and emotional aspects of the staff |

| Townsend | 2016 | Quantitative | Retrospective Review | Emergency Department, Southern New Jersey, United States of America | 1000 patients per quarter over 2 years | Kotter’s 8-step | To reduce ED falls by implementing fall reduction plan and a specific risk fall assessment | During the first quarter of the intervention there was an increase in falls without injury (potentially due to staff awareness) and a decrease in falls with injury. In the second and third quarters of the intervention, the number of falls significantly dropped, with zero falls with injury in the third quarter. |

| Westerlund | 2015 | Qualitative | Survey and Interview | 3 hospitals within a Region in Sweden | Change Facilitation Staff, managers and clinic staff | Lewin’s change model | To achieve a system wide organisational change | The study highlighted the need to clarify the division of roles and responsibilities between managers, facilitators and others, as well as ownership of the change process |

Assessment of Study Quality

Due to heterogeneity of the study types selected, appraisal of methodological and reporting quality of the included studies and overall body of evidence was carried out using the revised version of the Quality Assessment for Diverse Studies tool (QuADS), which has demonstrated reliability and validity. 25 , 26 This tool awarded the score of 0–3 where 0 is the minimum score and 3 is the highest score against each of the 13 criterion. 26 Interrater reliability between two reviewers (RH, AC) revealed substantial agreement in the quality appraisal (k = 0.68). 27 , 28

Results of the Search

After duplicates were removed, 2012 papers were extracted from Endnote into Covidence. After title and abstract screening, 285 papers fulfilled the inclusion criteria and copies of full texts were obtained. Full-text screening led to a total of 38 papers included in the review. Figure 1 demonstrates the screening and selection process.

Flow chart of the study search and selection process.

Excluded Studies

The most common reasons for excluding papers at full-text review were because they did not discuss a formal change management method explicitly (144), were not in a healthcare setting, 16 were commentary, protocol or editorial pieces, 11 or were not in health service delivery. 6 Many studies alluded to common concepts or techniques identified in change management methodologies but were excluded if no explicit model or framework was utilised. The distinct and expansive literature employing the Model for Improvement as a methodology was excluded because, whilst the model intersects with change management methodologies, the focus is determining the nature of changes and adaptations to introduce through incremental introduction and analysis of changes rather than the process of managing the change. This body of work was therefore beyond the scope of the present review.

Characteristics of Included Studies

A total of 38 articles emerged; 35 were from OECD countries including the United States of America (18 studies), Canada (5 studies), Australia (4 studies), the United Kingdom (4 studies), Denmark (1 study), Ireland (1 study), Singapore (1 study) and Sweden (1 study). Two articles emerged from non-OECD countries: Nepal (1 study) and Uganda (1 study); and one study did not specify the country. Most studies were conducted in hospital settings (29 studies), with more than half of these at a department or unit level (17 studies). Other settings included regional level health organisations health centres or clinics, education centres, community health settings and one in a residential aged care facility. Most studies only involved a single institution, 28 seven studies involved in between 2 and 9 institutions, and three studies involved more than ten institutions with the largest number being 25 institutes.

The impetus for change for the majority of studies came from within the organisation (34 studies). Of these, changes in 17 studies were part of quality improvement programs/projects, 13 were due to changes required as a result of changes in organisational policies or demands and four were as part of the implementation of an organisational strategy. In two further studies, change was due to a directive from the state or national health department. In the final two studies, both conducted in non-OECD countries, the impetus for change was from healthcare professional associations.

Study Quality

The included studies varied widely in their scores using the QUADS criteria. Most studies performed strongly in reporting their theoretical and conceptual underpinning, and in reporting of research aims and the involvement of stakeholders in the process of change. Many studies were case examples of change models and presented in a non-traditional research format. This limited their suitability for quality appraisal regarding the reporting of recruitment methods, data collection and data analyses. Studies often performed poorly on reporting of sampling to address research aims, description of data collection procedure, recruitment and critical discussion of strength and limitations of the study. The findings of the quality appraisal may be indicative of the nature of the publications identified but highlight a lack of transparency regarding the quality of the research design and methods used to gather the data, which must be acknowledged in interpreting the review findings.

Review Findings

Change management models utilised.

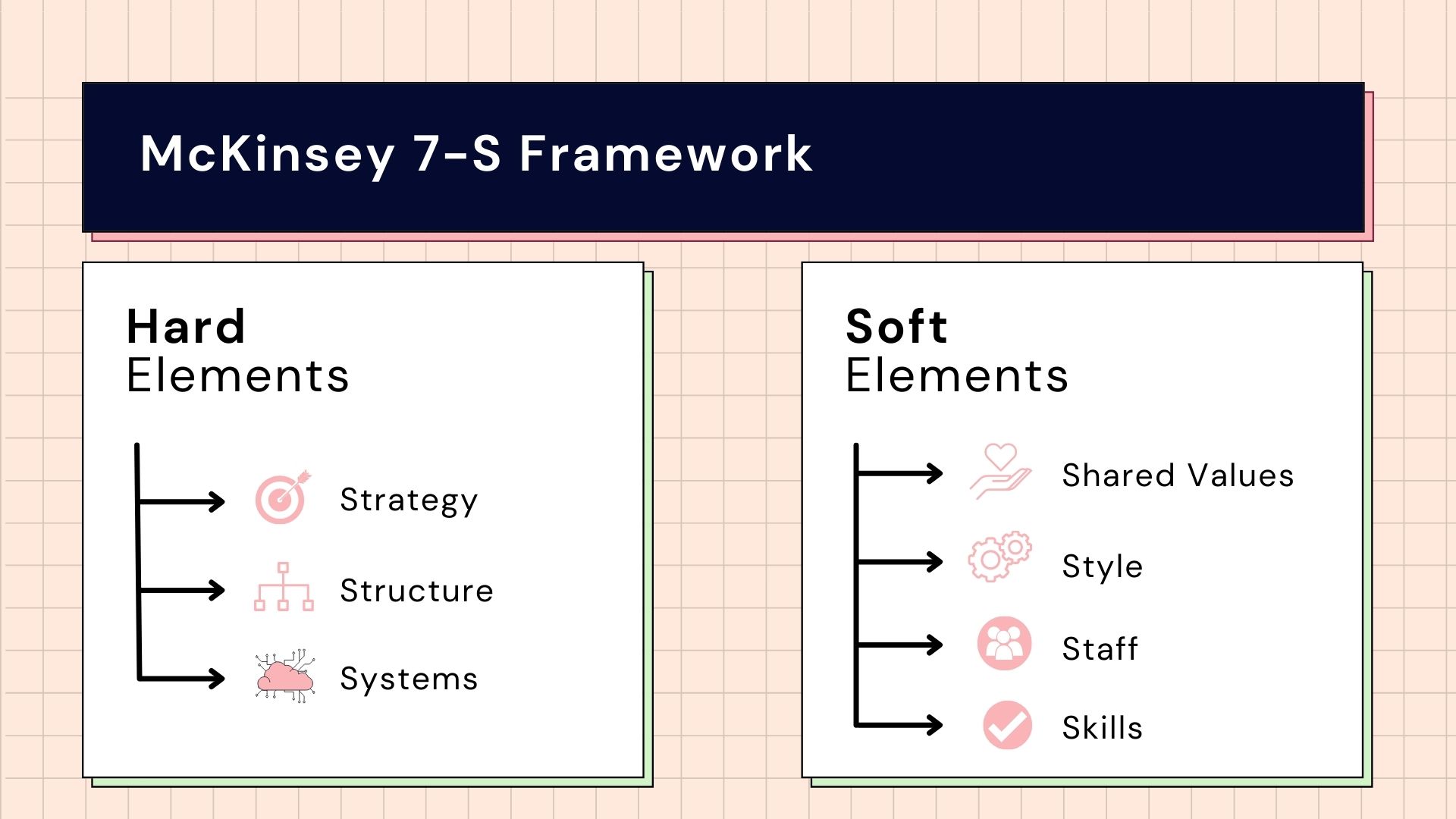

Thirty-eight of the identified articles described applications of change management models predominantly applied from the discipline of management into healthcare. Most of the studies utilised either Kotter’s 8-Step Model (19 studies) or Lewin’s 3-Stage Model of Change (11 studies). Eighteen studies utilised the Kotter 8-Step Model for managing change, with one further study that integrated the Kotter model with Silversin and Kornacki’s model. 29–47 Eight studies referenced their application of the Lewin 3-Stage Model of Change into a healthcare setting, 48–55 with three further studies that integrated the Lewin model with a concern-based change management approach, McKinsey 7S Model of Change, and Roger’s Diffusion of Innovation Theory, respectively. 56–58 A further eight articles reported the use of six further models for managing and leading change: Influencer Change Model (1 study); 59 Prosci ADKAR (1 study); 60 Accelerated Implementation Methodology (AIM) (2 studies); 61 , 62 Advent Health Clinical Transformation Model (1 study); 63 Riches 4 stage model (1 study); 64 Youngs Nine Stage Framework (1 study), 65 and the CAP model (1 study). 66

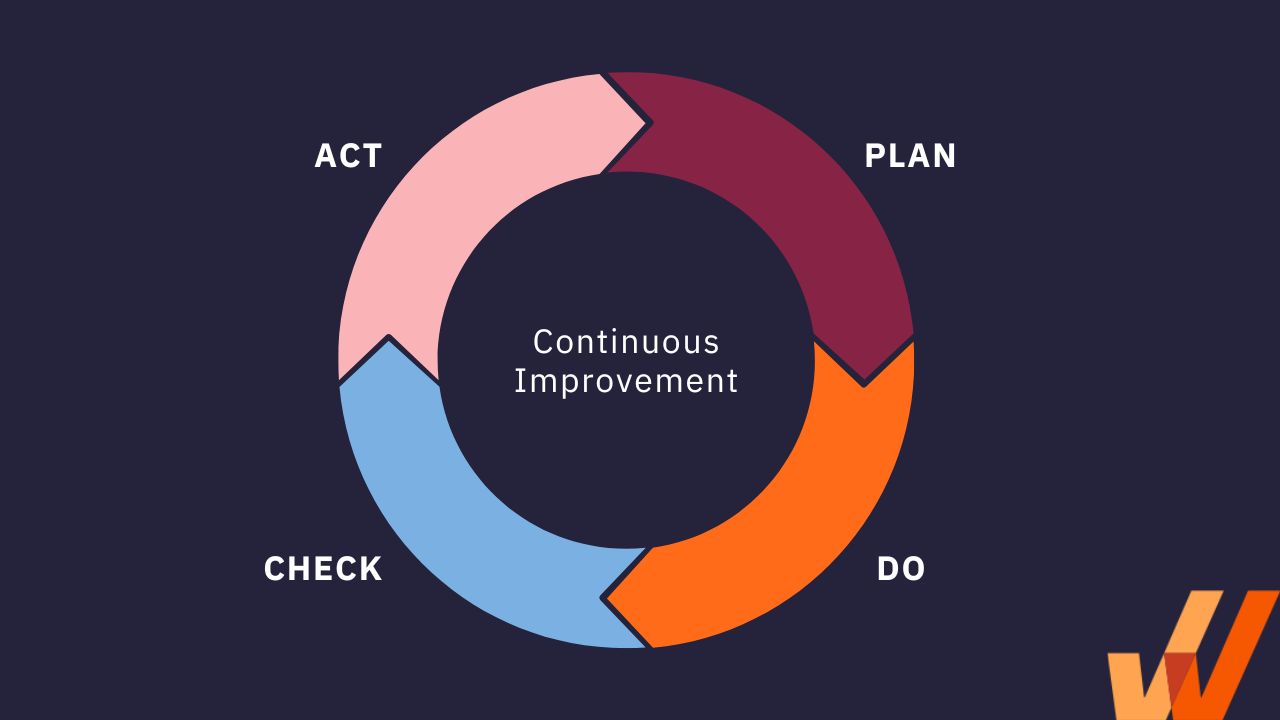

Local-Level Change

Applications of the Kotter model were primarily identified in nurse-led, local level, single unit or site quality improvement projects. 29 , 43 , 45 , 47 , 67 One US and one UK study applied the model to the full project lifecycle in emergency departments to increase the number of risk assessments undertaken by nurses for falls and to enhance the triage system, respectively. 29 , 45 Both projects reported success in creating change, with a significant increase in fall assessments reported following the project 45 and the adoption of the triage system into routine practice. 29 Two further US-based projects utilised the model to bring about change to bedside handoffs in an intensive care unit and a surgical orthopaedic trauma unit, noting significant improvements reported by the nurses on those units following project completion. 43 , 47 Young’s Nine Stage Framework was also used in a nurse-led local-level quality improvement project in an acute paediatric setting to introduce a competency assessment tool. 65 The authors described in detail the models, issues and actions arising through the stages of pre-change, stimulus, consideration, validate need, preparation, commit, do-check-act, results and into the new normal. 65 The application of the model enabled a considered change process which analysed organisational and systems influences impacting the change proposed, leading to full uptake of the assessment tool at 18–24 months. 65

The Kotter model was also applied in a quality improvement program in head and neck surgery in a Canadian surgical department, with authors concluding the model provided a guiding principle to support the change process. 36 In a further leadership-focused change program, the Comprehensive Unit-Based Safety Program (CUSP) model within the Division of General Surgery applied the Kotter 8-step and five principles of dual-operating systems to the development and implementation of surgical quality improvement initiatives. 35 A guiding coalition of leaders that included staff and resident surgeons, nursing leaders, allied health and hospital administrators was brought together to tackle two key quality issues identified around surgical site infection (SSI) by front-line staff of wound care and poor team communication. 35 This ongoing structure to identify and address quality issues was supported by reporting of improvement data and regular meeting to build a quality improvement culture, yet data to determine the success of this initiative was not provided. 35 Reduction in SSI’s was the focus of a change project in a UK NHS Trust breast surgery team that engaged the Kotter 8-step principles, with each step operationalised in the Trust, demonstrating reduced SSI’s in the first quarter of the project implementation year from 7%-3.1% of inpatients and readmission rates from 2.2% to 0% in this period. 33 This trend continued into the second quarter, with the need to maintain momentum and embed this change identified as critical to ongoing success. 33

Lewin’s Model of Change was similarly applied in two nurse-led change projects to enhance bedside handover in four Australian hospitals across multiple wards. 50 , 51 The application of the model was as a way to describe the process of change rather than to guide the activities to be undertaken during the change effort, with model descriptively aligned by the authors to reflect the periods of data collection at baseline (unfreezing stage), changes being made to the handover process and policies and the post-intervention data collection regarding the handover process (refreezing). 50 , 51 In a further nurse-led change project regarding the implementation of an electronic patient caseload tool in a community setting, Lewin’s Model was employed as a structured change process through a series of steps, yet the primary stages reported were unfreezing and moving. 49 A key benefit of the application of this model was the focus it provided to the nurse leader to actively contemplate the change process and its progression. 49 Lewin’s Model was also drawn upon to frame the steps taken in implementing and evaluating a bedside reporting intervention in the US that sought to enhance nursing communication. 54 As such, patient satisfaction with nursing communication increased from 75% to 87.6% over a six-month period. 54

One physician-led study focused on bringing about change in the management of chest pain in a US emergency department using their locally developed AdventHealth Clinical Transformation method. 63 This approach integrates common components of major change management models in the period of designing and planning for change, with piloting, implementation and sustainment periods. A key value of taking this planned approach was the ability to maintain clinician engagement in the project and achieving outcomes at a timed accountable follow-up. 63 A multidisciplinary team reported the use of the Influencer Change Model, which seeks to address both motivation and ability across personal, social and structural levels, to enhance appropriate use of urinary catheters in a hospital in Canada. 59 This behaviourally focused approach was combined with PDSA cycles and led to a significant reduction in inappropriate catheter use. 59 A key factor identified by the authors in the success of the approach was the multi-modal change techniques to address more than just informational needs.

Institutional Change

Twelve institutional-level projects were identified. 30 , 37 , 38 , 40 , 41 , 46 , 48 , 52 , 56 , 58 , 68 , 69 The first was a hospital-wide multi-faceted intervention to reduce in-hospital transmission of antimicrobial resistance in Denmark, which recorded immediate and sustained change in antimicrobial consumption and the rate of Bacteria-producing extended spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL-KP) resulting from a project guided by Kotter from inception to completion. 30 The second hospital-wide project emerged from Singapore and aimed to enhance timely access to outpatient specialist care requested by the emergency department. 41 Utilising a change management process guided by the Kotter steps, the organisation realised the benefits of the change project in improving the proportion of specialist outpatient appointments given within the timeframe requested from 51.7% to 80.8%, early discharge from 11.9% to being sustained at 27.2%, and clinician compliance rates in performing the changes required of between 84% and 100%. 41 In the third hospital-level project, a project to achieve a baby-friendly hospital in relation to breast-feeding utilised the Kotter 8-steps to bring together a Breastfeeding Task Force and transform the hospital. 38 A pre- and post-project survey indicated that the change goals were realised over a 12-month period. 38 In the Kent and Medway NHS Trust, recovery clinics were implemented by nurses using Kotter’s model to enable greater user engagement in their care and enhance nursing care opportunities by protecting their time. 40 After three months of the project, administrative organisational data indicated evidence of enhanced user involvement in the service. 40

Stoller et al reported a teamwork enhancement intervention across four respiratory departments of a US hospital to implement and optimise utilisation of the Respiratory Therapy Consult Service (RTCS). The project was underpinned by organisational and individual change theories integrating Kotter's 8-step model with Silversin and Kornacki’s Amicus Model, and the Intentional Change Theory of Boyatzis. 46 The use of the RTCS significantly enhanced the allocation of respiratory therapy services in the hospital and has been embedded in institutional practice. 46 In a community-based palliative organisation in Australia, the term emergency medication was replaced with anticipatory medication over several years. 37 The Kotter model was applied to support the change process, primarily in building momentum around the perceived need for change and a guiding coalition to facilitate buy-in and direct to the change process. 37 The application of the latter components of the model, particularly with regard to how change was embedded, was not reported. 37

In a paediatric trauma centre, Lewin’s Model was utilised to guide a change process in which a collaborative care model led by surgical services with medical service consultation was introduced to manage trauma patients reducing the need for non-surgical admissions across the institution. 48 The project achieved a reduction in non-surgical trauma admissions from 30% to 3% of admissions over a three-and-a-half-year project period. 48 The model was applied closely to guide the change activities within this project, with a range of activities at each stage seeking to set the basis for change and its embedding in practice. 48 Lewin was also used in geriatric care settings to embed a new approach to the management of chronic conditions. However, the application of the model in this context was primarily focused on the moving stage, with few activities that appeared to address the first and third stages of the model and limited data reported of the outcomes of this change project. 52

Combining the Lewin Model with Roger’s Diffusion of Innovation Theory, Tetef et al, implemented the new technology of a bronchial thermoplasty program. 58 Lewin’s Model was used to couch all of the change activities. It was notable that unfreezing activities identified the development of new policies and procedures, with the overall project primarily focused on bringing in the new technology and the moving stage. 58 Data of the project impacts and success were not reported in detail. Across four medical-surgical units in two Kaiser Permanente hospitals in the US, a Nurse Knowledge Exchange (NKE) was developed to integrate change management methods into the implantation of practice change. 56 Lewin’s Model was introduced along with the Concerns-Based Model and Force-Field Models and integrated with design-centric methods in approaches to implement service-design changes. 56 Although limited in its initial success, when underpinned with the addition of The cake model for change that more gradually introduced the participating nurses to change management concepts, the NKE achieved increased patient engagement and in-room shift exchange over a 7-month period. 56

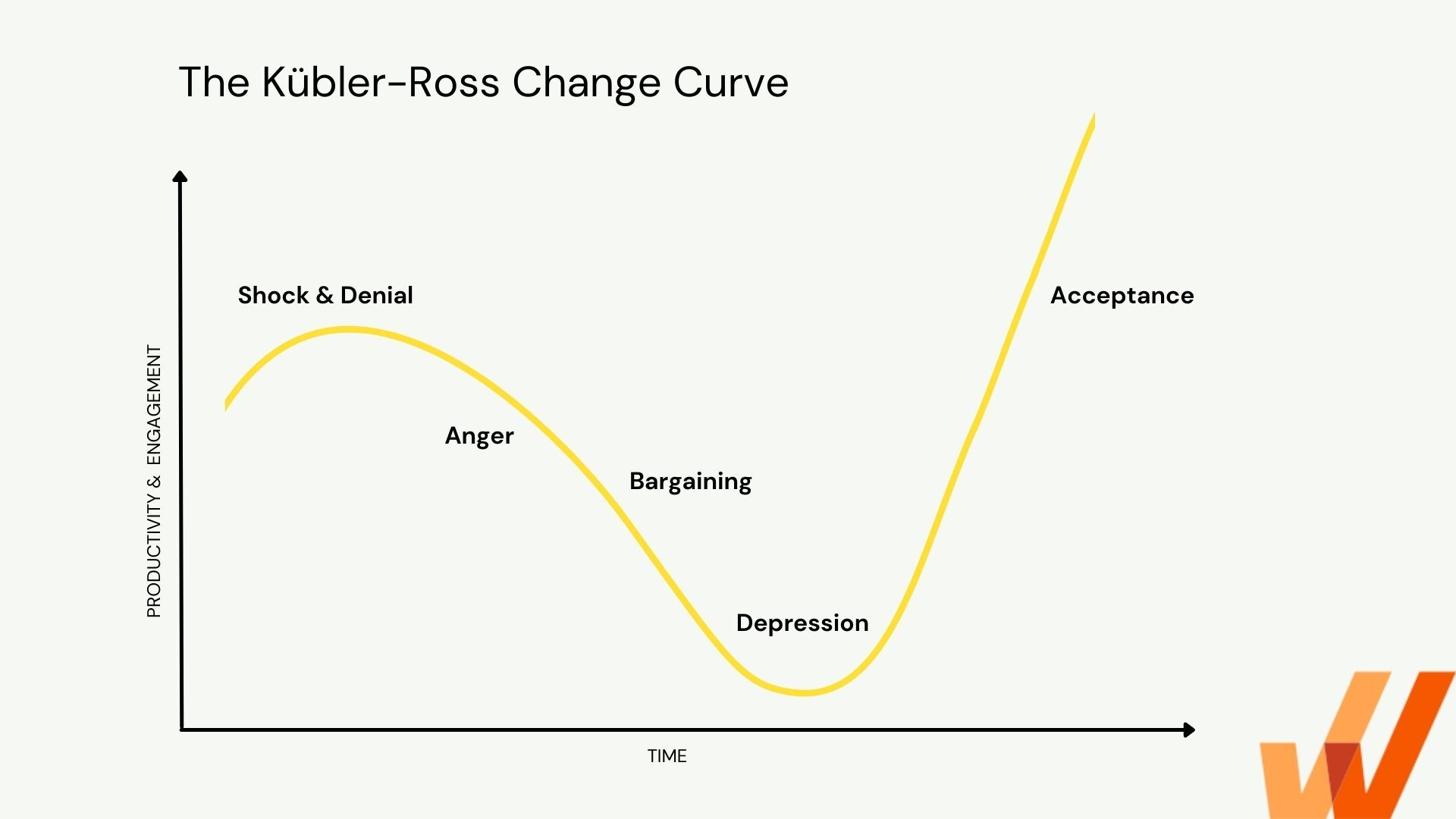

In a larger scale institutional project, Riches 4 Stages Model was applied to transitioning a radiation therapy department to a new hospital site. 64 The model identifies key feelings and experiences of people moving through change and was used as a grounding for developing approaches to mitigate any negative feelings arising and to support the change to come about. The authors reported the model as valuable in supporting smooth transition. 64

A final study of a large four-year change project introducing technology upgrades into a healthcare organisation utilised the Change Acceleration Process (CAP) model. 66 Critically, this study identified the core value of utilising change management methodology as addressing the foundational basis for change; and clinician engagement in a shared need and vision. 66 The authors reported that clinical engagement, and the considerations regarding the time required to be engaged, were important components of successful change. 66

System-Wide and Multi-System Change

Six national or system-wide projects were identified. 42 , 53 , 55 , 70–72 Kotter’s model was employed to bring about change in one of these through the use of peer-review models in radiation oncology across 14 cancer treatment centres in Canada. 42 Over a two-year period, the proportion of radical-intent radiation therapy courses peer reviewed increased from 43.5% to 68%, with some sites reaching over 95% use of peer-review. 42 In a Swedish region, 26 clinics participated in an examination of how local level change agents worked as a development unit group across the clinics. 55 The notion of the change agent is drawn from the Lewin Model, with links to change generators which are highlighted by the study as key within change efforts. In this study, it should be noted that the model was not applied to explore the role throughout the study. 55 In a further project across Geriatric Education Centres in the US, Lewin’s Model was applied to explore the relationship between changing practice and changes in an organisational context. 53 The model was retrofitted to two projects rather than applied prospectively to manage the change process. 53

One international multi-system project was identified that reported the management of change in a World Health Organisation (WHO) project seeking to shift Allergic Rhinitis and its Impact on Asthma (ARIA) from a guideline to integrated care pathways using mobile technology in patients with allergic rhinitis and asthma multimorbidity. 32 Employing Kotter’s model, the WHO working group employed a broad range of approaches and activities across more than 70 countries, engaging with national allergy programs and agencies to bring about change reporting substantial success over an 18-year period. 32 The project continues to engage the Kotter steps for each change cycle.

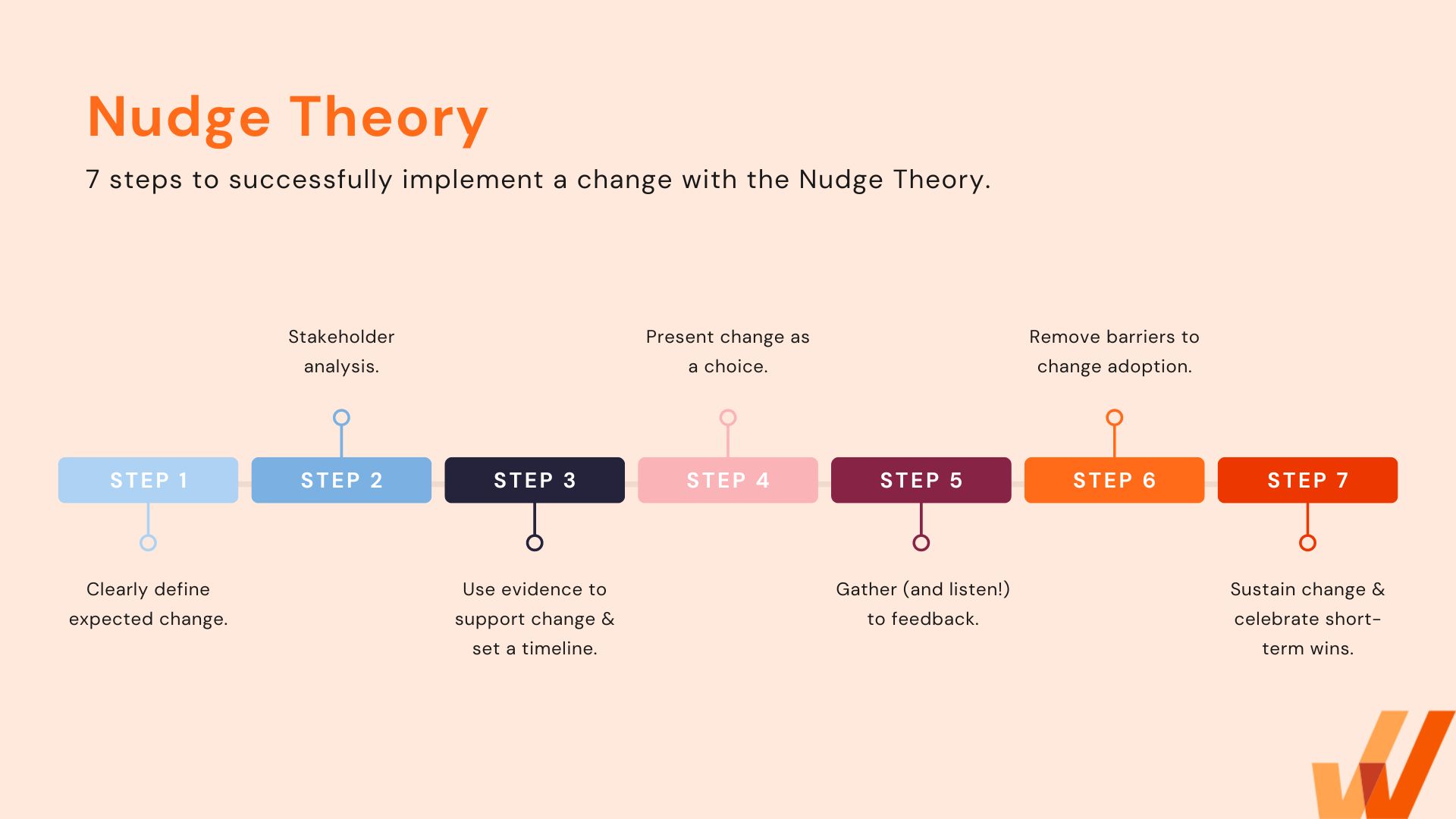

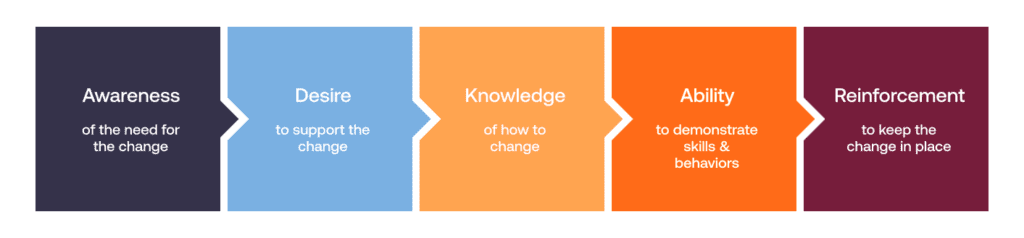

Balluck et al reporting the use of the Prosci ADKAR model along with the CLARC model through the CoVID-19 pandemic to transition from primary to team nursing, in which a team of health professionals manage a patient under one registered nurse, across 25 hospitals in US health system. 60 The study primarily reported a range of activities to undertake to align to each element of the models and concluded that the application of these models enabled leaders to plan for change more systematically, leading to successful change. 60 In a non-OECD context, two studies led by the same author reported the application of AIM to bring about change in two hospitals in Uganda and two hospitals in Nepal. In maternity services in Uganda and Nepal, change occurred through dissemination workshops, reminders, case reviews, practical workshops and team building guided by AIM methodology. The operationalisation of AIM was not detailed in the studies. 61 , 62

Applications of Change Management Models

Whilst many studies utilised structured change management models reported successful change, it was not possible to detect whether the use of a model, method or process contributed to the success. In five qualitative studies, analysis and commentary pieces explored the change management of successful and/or less successful projects against the Kotter steps in an attempt to explore whether the application of change management models differed in successful and/or unsuccessful projects in terms of the number of steps completed or the way in which they were completed. 31 , 34 , 39 , 44 , 57

Baloh et al followed eight hospitals in the US through a two-year implementation of team huddles (TeamSTEPPS) to explore, through interviews with 47 leader and change managers or champions, how they performed in relation to the three overarching Kotter phases. 31 Half of the hospitals progressed along all of the three broad phases and components within, with adherence to the Kotter steps in the first phase influencing the success of the final two phases. 31 Hospitals that did not adhere to the Kotter phases did however demonstrate successful change, with the scope and strategies used for implementation identified as key factors in successful change in these instances; linking the huddles to performance indicators, having a local-level scope or having a strong strategic approach to gain staff buy-in for projects of broader scope all contributed to successful change. 31 Similarly, Carman et al mapped, through interviews with key change agents, the application of Kotter’s model to organisational change in a US health centre. 34 The application of all eight stages of this model was apparent through the interviews and reported as central to the successful change effort to ensure a systematic process. 34

Using the Lewin and McKinsey 7S models together, Sokol et al described the application of change management theory to office-wide culture and structural support to meet the twin goals of safe opioid prescribing and treating patients with opioid-use disorder. 73 Integrating two approaches enabled the team to address specific change management issues under a broader framework of the overall change management process under the Lewin model. 73

In a larger scale project, a multidisciplinary group of staff involved in the development of the medication management services in each of six health systems across Minnesota were interviewed to explore the degree to which Kotter’s steps were followed during the development of the service change. 44 Thirteen emerging themes were grouped against the Kotter model and highlighted that supportive culture and team-based collaborative care were critical to the success of their change. Specifically, the programs reported as successful were those introduced in systems that used change management methods aligned more closely with the Kotter model. 44 In the final qualitative piece, Hopkins et al provided a commentary analysis on implementing a gainsharing program to incentivise value- over volume-based practice in two hospital and health systems in one US state. 39 This study reinforced the other qualitative works indicating that change management approaches that more comprehensively mapped to the Kotter model were associated with successful change projects in the implementation of gainsharing. 39

Our findings identify multiple change management models that are applied to bring about change in healthcare teams, services and organisations. In the reviewed articles, it was apparent that change management models provided a frame of reference for change agents to support them to consider key elements required for change to occur and be sustained. Key elements include exploring why change is needed and crafting the right messages for stakeholders at every step to bring them along on the change journey. In the included studies, models that included a series of stages or steps, eg, Lewin or Kotter provided change agents with a series of goal posts to monitor and to create moments of celebration along the change journey. Notably, there was little emphasis on reliance on the models to overcome resistance or develop specific change activities; their value was consistently in providing a broad guiding framework for clinicians creating change. 32

Drawing upon change management models as a guiding framework rather than as a prescriptive management process is in keeping with contemporary thinking regarding healthcare as a complex adaptive system. A complex adaptive system seeks to draw out and mobilize the natural creativity of health care professionals to adapt to circumstances and to evolve new and better ways of achieving quality akin to bottom-up change and requires change agents to shift away from the reliance on top-down, highly controlled change processes. 18 On this basis, we propose that when change management models are adopted with sufficient flexibility to be relevant to the context in which they are being applied and empower local level change agents, change management models may be used to compliment and support improvement and implementation methodologies. For example, Baloh et al in exploring the introduction and implementation of huddles in rural US hospitals noted the value of integrating broad concepts from change management models, particularly in relation to the earlier model steps, with appropriate implementation scope and strategies. 31

The primary change methodologies identified in this review were Kotter’s 8-Steps and Lewin’s Freeze – Unfreeze – Freeze model. Methods also emerged from this review that are not as prominent as other change management models and methods but appeared to be used successfully to create and sustain change in healthcare delivery models and services. These methods include Accelerated Implementation Methodology, Young’s Nine Stage Framework, Riches four-stage model of change, and General Electric’s proprietary change management model known as Change Acceleration Process (CAP), among others. This review has not determined one change management model as preferred over another. This finding suggests that the guiding framework and flexibility within this to enable a range of activities and actions suited to the particular circumstance is of key value rather than a particular change management approach. It was notable that in the context of healthcare, change management models were often used by clinicians in local-level projects. The models were rarely used to address issues of resistance and more often used to provide a framework to house a broad and diverse range of activities to facilitate successful sustained change.

Clinician engagement in the change process emerged as a critical factor for change to take hold and be sustained. Projects that were successful were often led by clinicians and/or positioned in terms of the benefits for patients or staff. 74–76 Our findings confirm existing evidence that suggests that when the patient or staff benefits are unclear, clinicians may be less engaged with the change activities leading to challenges in gaining and sustaining momentum with the change. 77

Change is naturally challenging for humans, particularly when it is rapid and ongoing. 78 , 79 Our findings reinforce current knowledge that those directly and indirectly affected by change are more likely to commit to and embrace change when they contribute to the decision-making about the change, and understand why and how the change is going to improve patient and/or staff experiences or the healthcare environment. 80 This is particularly noted in the context of change for quality enhancement. 74 , 81

Implications

The review findings suggest that when exploring evidence-based methodologies for creating and sustaining change, an integrative approach that draws upon models for change to support applications of models for improvement and/or implementation may be valuable for change agents. The common guiding principles found in many of the models utilised in the review, such as Kotter and Lewin’s models, highlight core common principles of involving people in change from the outset, working with their feelings about change and supporting change through good communication and collaboration behaviours. 82 , 83 These fundamental steps for change can be operationalised through drawing upon the Model for Improvement, which is underpinned by Deming’s System of Profound Knowledge and “Psychology of Change” principles. 84 The Model for Improvement highlights leveraging individuals’ motivation, or agency, as well as the collective agency of the team and a system that enables individuals and teams to exercise that agency. 82 , 83

The guiding principles of the change management models we identified as commonly used in healthcare seek to create an enabling culture for change; seen through shared ways of thinking, assumptions and visible manifestations. 85 Characteristics of an enabling culture in the reviewed studies included supportive and authentic leadership and sponsorship, engaged and committed staff, multi-disciplinary team involvement, a collaborative approach to work, strong communication behaviours and models, the ability to resolve conflict and capable staff with the capacity to engage in further development. The reviewed articles suggest an enabling culture for change is central to creating opportunities for and supporting clinician engagement from decision-making about change through to change implementation. 74 , 85 As such, there are implications for implementation research and appear to be opportunities to integrate change management and implementation models to enhance processes of healthcare change. It is well established that implementation research is focused to more than translation of evidence from bench to bedside. As the scientific study of methods to promote the systematic uptake of clinical research findings and other evidence-based practices into routine practice, and hence to improve the quality (effectiveness, reliability, safety, appropriateness, equity, efficiency) of health care, it is inextricably linked with healthcare change and its management. 86 Knowledge of influences on clinician and organisational behaviour gained through implementation research may provide substantial insight into approaches to operationalise change management.

One artefact of organisations with cultures supportive of change is the presence of co-design efforts. 87 Co-design is a method to meaningfully engage about a process or service change with service users, which can include staff, patients and caregivers. 88 The concept of co-design aligns well with change management, improvement and implementation science principles that converge on the centrality of stakeholder-led or support change. 89 Co-design approaches therefore provide one mechanism through which change management, improvement and implementation methods may be integrated for the purpose of creating change for quality improvement. Such approaches are however contingent on appropriate supports to ensure participants have both the capability and capacity to engage. 90

Limitations

Our findings must be considered in terms of the limitations of the included studies and the review process. It is possible that some relevant studies were not captured by the database search or were made available after the search date. The included studies were often case examples of change initiatives with limited breadth of sample and a lack of detail reported about the research methods. The quality of such studies was therefore challenging to appraisal due to the limited reported information. The ability to generalise findings from such studies was also limited when case examples were utilised. We do note however that the wide range of included studies demonstrated consistent commonalities across change principles and applications of change management models across multiple settings and change projects in health.

Change management models are commonly applied to guide change processes at local, institutional and system-levels in healthcare. Clinician-led change is common, with the value of change management models being primarily to provide a supportive yet flexible framework to direct change processes. The review also highlights the potential opportunities to integrate models for change management with models commonly applied for improvement and implementation to support positive changes in healthcare.

Funding Statement

No funding linked to this submission.

Data Sharing Statement

All data included in the review are publicly available research findings.

Author Contributions