10.7 Body of the report

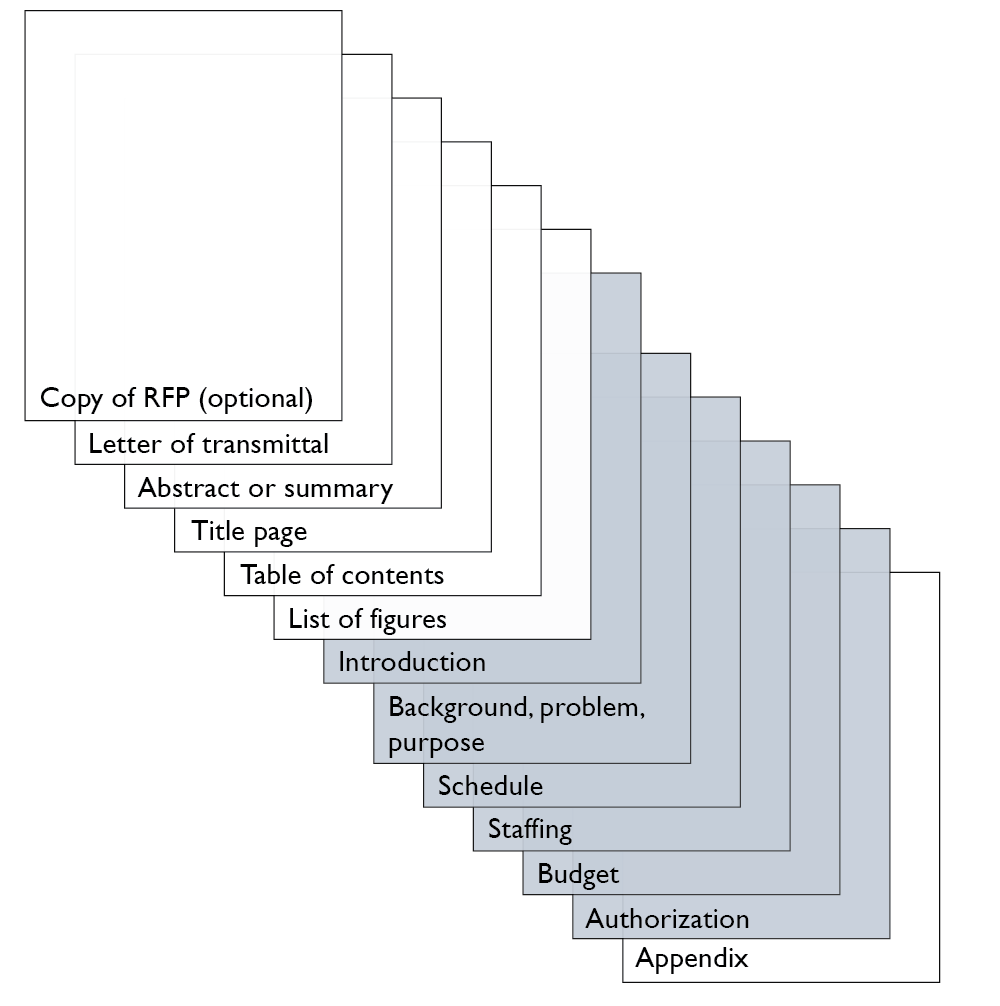

The body of the report is of course the main text of the report, the sections between the introduction and conclusion. Illustrated below are sample pages.

In all but the shortest reports (two pages or less), use headings to mark off the different topics and subtopics covered. Headings are the titles and subtitles you see within the actual text of much professional scientific, technical, and business writing. Headings are like the parts of an outline that have been pasted into the actual pages of the document.

Headings are an important feature of professional technical writing: they alert readers to upcoming topics and subtopics, help readers find their way around in long reports and skip what they are not interested in, and break up long stretches of straight text.

Headings are also useful for writers. They keep you organized and focused on the topic. When you begin using headings, your impulse may be to slap in the headings after you’ve written the rough draft. Instead, visualize the headings before you start the rough draft, and plug them in as you write.

Your task in this chapter is to learn how to use headings and to learn the style and format of a specific design of headings. Here are a number of helpful tips:

- Make the phrasing of headings self-explanatory: instead of “Background” or “Technical Information,” make it more specific, such as “Physics of Fiber Optics.”

- Make headings indicate the range of topic coverage in the section. For example, if the section covers the design and operation of a pressurized water reactor, the heading “Pressurized Water Reactor Design” would be incomplete and misleading.

- Avoid “stacked” headings—any two consecutive headings without intervening text.

- Avoid pronoun reference to headings. For example, if you have a heading “Torque,” don’t begin the sentence following it with something like this: “This is a physics principle…..”

- When possible, omit articles from the beginning of headings. For example, “The Pressurized Water Reactor” can easily be changed to “Pressurized Water Reactor” or, better yet, “Pressurized Water Reactors.”

- Don’t use headings as lead-ins to lists or as figure titles.

- Avoid “widowed” headings: that’s where a heading occurs at the bottom of a page and the text it introduces starts at the top of the next page. Keep at least two lines of body text with the heading, or force it to start the new page.

If you manually format each individual heading using the guidelines presented in the preceding list, you’ll find you’re doing quite a lot of repetitive work. The styles provided by Microsoft Word, OpenOffice Writer, and other software save you this work. You simply select Heading 1, Heading 2, Heading 3, and so on. You’ll notice the format and style are different from what is presented here. However, you can design your own styles for headings.

Bulleted and numbered lists

In the body of a report, also use bulleted, numbered, and two-column lists where appropriate. Lists help by emphasizing key points, by making information easier to follow, and by breaking up solid walls of text. Always introduce the list so that your audience understand the purpose and context of the list. Whenever practical, provide a follow-up comment, too. Here are some additional tips:

- Use lists to highlight or emphasize text or to enumerate sequential items.

- Use a lead-in to introduce the list items and to indicate the meaning or purpose of the list (and punctuate it with a colon).

- Use consistent spacing, indentation, punctuation, and caps style for all lists in a document.

- Make list items parallel in phrasing.

- Make sure that each item in the list reads grammatically with the lead-in.

- Avoid using headings as lead-ins for lists.

- Avoid overusing lists; using too many lists destroys their effectiveness.

- Use similar types of lists consistently in similar text in the same document.

Following up a list with text helps your reader understand context for the information distilled into list form. The tips above provide a practical guide to formatting lists.

Graphics and figure titles

In technical report, you are likely to need drawings, diagrams, tables, and charts. These not only convey certain kinds of information more efficiently but also give your report an added look of professionalism and authority. If you’ve never put these kinds of graphics into a report, there are some relatively easy ways to do so—you don’t need to be a professional graphic artist. For strategies for adding graphics and tables to reports, see the chapter on Creating and Using Visuals. See the chapter on visuals for more help with the principles for creating visuals.

Conclusions

For most reports, you will need to include a final section. When you plan the final section of your report, think about the functions it can perform in relation to the rest of the report. A conclusion does not necessarily just summarize a report. Instead, use the conclusion to explain the most significant findings you made in relation to your report topic.

Appendixes are those extra sections following the conclusion. What do you put in appendixes? Anything that does not comfortably fit in the main part of the report but cannot be left out of the report altogether. The appendix is commonly used for large tables of data, big chunks of sample code, fold-out maps, background that is too basic or too advanced for the body of the report, or large illustrations that just do not fit in the body of the report. Anything that you feel is too large for the main part of the report or that you think would be distracting and interrupt the flow of the report is a good candidate for an appendix. Notice that each one is given a letter (A, B, C, and so on).

Information sources

Documenting your information sources is all about establishing, maintaining, and protecting your credibility in the profession. You must cite (“document”) borrowed information regardless of the shape or form in which you present it. Whether you directly quote it, paraphrase it, or summarize it—it’s still borrowed information. Whether it comes from a book, article, a diagram, a table, a web page, a product brochure, an expert whom you interview in person—it’s still borrowed information.

Documentation systems vary according to professionals and fields. For a technical writing class in college, you may be using either MLA or APA style. Engineers use the IEEE system, examples of which are shown throughout this chapter. Another commonly used documentation system is provided by the American Psychological Association (APA).

Page numbering

Page-numbering style used in traditional report design differs from contemporary report design primarily in the former’s use of lowercase roman numerals in front matter (everything before the introduction).

- All pages in the report (within but excluding the front and back covers) are numbered; but on some pages, the numbers are not displayed.

- In the contemporary design, all pages throughout the document use arabic numerals; in the traditional design, all pages before the introduction (first page of the body of the report) use lowercase roman numerals.

- On special pages, such as the title page and page one of the introduction, page numbers are not displayed.

- Page numbers can be placed in one of several areas on the page. Usually, the best and easiest choice is to place page numbers at the bottom center of the page (remember to hide them on special pages).

- If you place page numbers at the top of the page, you must hide them on chapter or section openers where a heading or title is at the top of the page.

Chapter Attribution Information

This chapter was derived by Annemarie Hamlin, Chris Rubio, and Michele DeSilva, Central Oregon Community College, from Online Technical Writing by David McMurrey – CC: BY 4.0

Technical Writing Copyright © 2017 by Allison Gross, Annemarie Hamlin, Billy Merck, Chris Rubio, Jodi Naas, Megan Savage, and Michele DeSilva is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

The Report Body

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

The body of your report is a detailed discussion of your work for those readers who want to know in some depth and completeness what was done. The body of the report shows what was done, how it was done, what the results were, and what conclusions and recommendations can be drawn.

Introduction

The introduction states the problem and its significance, states the technical goals of the work, and usually contains background information that the reader needs to know in order to understand the report. Consider, as you begin your introduction, who your readers are and what background knowledge they have. For example, the information needed by someone educated in medicine could be very different from someone working in your own field of engineering.

The introduction might include any or all of the following.

- Problems that gave rise to the investigation

- The purpose of the assignment (what the writer was asked to do)

- History or theory behind the investigation Literature on the subject

- Methods of investigation

While academic reports often include extensive literature reviews, reports written in industry often have the literature review in an appendix.

Summary or background

This section gives the theory or previous work on which the experimental work is based if that information has not been included in the introduction.

Methods/procedures

This section describes the major pieces of equipment used and recaps the essential step of what was done. In scholarly articles, a complete account of the procedures is important. However, general readers of technical reports are not interested in a detailed methodology. This is another instance in which it is necessary to think about who will be using your document and tailor it according to their experience, needs, and situation.

A common mistake in reporting procedures is to use the present tense. This use of the present tense results in what is sometimes called “the cookbook approach” because the description sounds like a set of instructions. Avoid this and use the past tense in your “methods/procedures” sections.

This section presents the data or the end product of the study, test, or project and includes tables and/or graphs and a brief interpretation of what the data show. When interpreting your data, be sure to consider your reader, what their situation is and how the data you have collected will pertain to them.

Discussion of results

This section explains what the results show, analyzes uncertainties, notes significant trends, compares results with theory, evaluates limitations or the chance for faulty interpretation, or discusses assumptions. The discussion section sometimes is a very important section of the report, and sometimes it is not appropriate at all, depending on your reader, situation, and purpose.

It is important to remember that when you are discussing the results, you must be specific. Avoid vague statements such as “the results were very promising.”

Conclusions

This section interprets the results and is a product of thinking about the implications of the results. Conclusions are often confused with results. A conclusion is a generalization about the problem that can reasonably be deduced from the results.

Be sure to spend some time thinking carefully about your conclusions. Avoid such obvious statements as “X doesn’t work well under difficult conditions.” Be sure to also consider how your conclusions will be received by your readers, and as well as by your shadow readers—those to whom the report is not addressed, but will still read and be influenced by your report.

Recommendations

The recommendations are the direction or actions that you think must be taken or additional work that is need to expand the knowledge obtained in your report. In this part of your report, it is essential to understand your reader. At this point you are asking the reader to think or do something about the information you have presented. In order to achieve your purposes and have your reader do what you want, consider how they will react to your recommendations and phrase your words in a way to best achieve your purposes.

Conclusions and recommendations do the following.

- They answer the question, “So what?”

- They stress the significance of the work

- They take into account the ways others will be affected by your report

- They offer the only opportunity in your report for you to express your opinions

What are the differences between Results, Conclusions, and Recommendations?

Assume that you were walking down the street, staring at the treetops, and stepped in a deep puddle while wearing expensive new shoes. What results, conclusions, and recommendations might you draw from this situation?

Some suggested answers follow.

- Results : The shoes got soaking wet, the leather cracked as it dried, and the soles separated from the tops.

- Conclusions : These shoes were not waterproof and not meant to be worn when walking in water. In addition, the high price of the shoes is not closely linked with durability.

- Recommendations : In the future, the wearer of this type of shoe should watch out for puddles, not just treetops. When buying shoes, the wearer should determine the extent of the shoes’ waterproofing and/or any warranties on durability.

How to Write a Body of a Research Paper

The main part of your research paper is called “the body.” To write this important part of your paper, include only relevant information, or information that gets to the point. Organize your ideas in a logical order—one that makes sense—and provide enough details—facts and examples—to support the points you want to make.

Logical Order

Transition words and phrases, adding evidence, phrases for supporting topic sentences.

- Transition Phrases for Comparisons

- Transition Phrases for Contrast

- Transition Phrases to Show a Process

- Phrases to Introduce Examples

- Transition Phrases for Presenting Evidence

How to Make Effective Transitions

Examples of effective transitions, drafting your conclusion, writing the body paragraphs.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% off with 24start discount code.

- The third and fourth paragraphs follow the same format as the second:

- Transition or topic sentence.

- Topic sentence (if not included in the first sentence).

- Supporting sentences including a discussion, quotations, or examples that support the topic sentence.

- Concluding sentence that transitions to the next paragraph.

The topic of each paragraph will be supported by the evidence you itemized in your outline. However, just as smooth transitions are required to connect your paragraphs, the sentences you write to present your evidence should possess transition words that connect ideas, focus attention on relevant information, and continue your discussion in a smooth and fluid manner.

You presented the main idea of your paper in the thesis statement. In the body, every single paragraph must support that main idea. If any paragraph in your paper does not, in some way, back up the main idea expressed in your thesis statement, it is not relevant, which means it doesn’t have a purpose and shouldn’t be there.

Each paragraph also has a main idea of its own. That main idea is stated in a topic sentence, either at the beginning or somewhere else in the paragraph. Just as every paragraph in your paper supports your thesis statement, every sentence in each paragraph supports the main idea of that paragraph by providing facts or examples that back up that main idea. If a sentence does not support the main idea of the paragraph, it is not relevant and should be left out.

A paper that makes claims or states ideas without backing them up with facts or clarifying them with examples won’t mean much to readers. Make sure you provide enough supporting details for all your ideas. And remember that a paragraph can’t contain just one sentence. A paragraph needs at least two or more sentences to be complete. If a paragraph has only one or two sentences, you probably haven’t provided enough support for your main idea. Or, if you have trouble finding the main idea, maybe you don’t have one. In that case, you can make the sentences part of another paragraph or leave them out.

Arrange the paragraphs in the body of your paper in an order that makes sense, so that each main idea follows logically from the previous one. Likewise, arrange the sentences in each paragraph in a logical order.

If you carefully organized your notes and made your outline, your ideas will fall into place naturally as you write your draft. The main ideas, which are building blocks of each section or each paragraph in your paper, come from the Roman-numeral headings in your outline. The supporting details under each of those main ideas come from the capital-letter headings. In a shorter paper, the capital-letter headings may become sentences that include supporting details, which come from the Arabic numerals in your outline. In a longer paper, the capital letter headings may become paragraphs of their own, which contain sentences with the supporting details, which come from the Arabic numerals in your outline.

In addition to keeping your ideas in logical order, transitions are another way to guide readers from one idea to another. Transition words and phrases are important when you are suggesting or pointing out similarities between ideas, themes, opinions, or a set of facts. As with any perfect phrase, transition words within paragraphs should not be used gratuitously. Their meaning must conform to what you are trying to point out, as shown in the examples below:

- “Accordingly” or “in accordance with” indicates agreement. For example :Thomas Edison’s experiments with electricity accordingly followed the theories of Benjamin Franklin, J. B. Priestly, and other pioneers of the previous century.

- “Analogous” or “analogously” contrasts different things or ideas that perform similar functions or make similar expressions. For example: A computer hard drive is analogous to a filing cabinet. Each stores important documents and data.

- “By comparison” or “comparatively”points out differences between things that otherwise are similar. For example: Roses require an alkaline soil. Azaleas, by comparison, prefer an acidic soil.

- “Corresponds to” or “correspondingly” indicates agreement or conformity. For example: The U.S. Constitution corresponds to England’s Magna Carta in so far as both established a framework for a parliamentary system.

- “Equals,”“equal to,” or “equally” indicates the same degree or quality. For example:Vitamin C is equally as important as minerals in a well-balanced diet.

- “Equivalent” or “equivalently” indicates two ideas or things of approximately the same importance, size, or volume. For example:The notions of individual liberty and the right to a fair and speedy trial hold equivalent importance in the American legal system.

- “Common” or “in common with” indicates similar traits or qualities. For example: Darwin did not argue that humans were descended from the apes. Instead, he maintained that they shared a common ancestor.

- “In the same way,”“in the same manner,”“in the same vein,” or “likewise,” connects comparable traits, ideas, patterns, or activities. For example: John Roebling’s suspension bridges in Brooklyn and Cincinnati were built in the same manner, with strong cables to support a metallic roadway. Example 2: Despite its delicate appearance, John Roebling’s Brooklyn Bridge was built as a suspension bridge supported by strong cables. Example 3: Cincinnati’s Suspension Bridge, which Roebling also designed, was likewise supported by cables.

- “Kindred” indicates that two ideas or things are related by quality or character. For example: Artists Vincent Van Gogh and Paul Gauguin are considered kindred spirits in the Impressionist Movement. “Like” or “as” are used to create a simile that builds reader understanding by comparing two dissimilar things. (Never use “like” as slang, as in: John Roebling was like a bridge designer.) For examples: Her eyes shone like the sun. Her eyes were as bright as the sun.

- “Parallel” describes events, things, or ideas that occurred at the same time or that follow similar logic or patterns of behavior. For example:The original Ocktoberfests were held to occur in parallel with the autumn harvest.

- “Obviously” emphasizes a point that should be clear from the discussion. For example: Obviously, raccoons and other wildlife will attempt to find food and shelter in suburban areas as their woodland habitats disappear.

- “Similar” and “similarly” are used to make like comparisons. For example: Horses and ponies have similar physical characteristics although, as working farm animals, each was bred to perform different functions.

- “There is little debate” or “there is consensus” can be used to point out agreement. For example:There is little debate that the polar ice caps are melting.The question is whether global warming results from natural or human-made causes.

Other phrases that can be used to make transitions or connect ideas within paragraphs include:

- Use “alternately” or “alternatively” to suggest a different option.

- Use “antithesis” to indicate a direct opposite.

- Use “contradict” to indicate disagreement.

- Use “on the contrary” or “conversely” to indicate that something is different from what it seems.

- Use “dissimilar” to point out differences between two things.

- Use “diverse” to discuss differences among many things or people.

- Use “distinct” or “distinctly” to point out unique qualities.

- Use “inversely” to indicate an opposite idea.

- Use “it is debatable,” “there is debate,” or “there is disagreement” to suggest that there is more than one opinion about a subject.

- Use “rather” or “rather than” to point out an exception.

- Use “unique” or “uniquely” to indicate qualities that can be found nowhere else.

- Use “unlike” to indicate dissimilarities.

- Use “various” to indicate more than one kind.

Writing Topic Sentences

Remember, a sentence should express a complete thought, one thought per sentence—no more, no less. The longer and more convoluted your sentences become, the more likely you are to muddle the meaning, become repetitive, and bog yourself down in issues of grammar and construction. In your first draft, it is generally a good idea to keep those sentences relatively short and to the point. That way your ideas will be clearly stated.You will be able to clearly see the content that you have put down—what is there and what is missing—and add or subtract material as it is needed. The sentences will probably seem choppy and even simplistic.The purpose of a first draft is to ensure that you have recorded all the content you will need to make a convincing argument. You will work on smoothing and perfecting the language in subsequent drafts.

Transitioning from your topic sentence to the evidence that supports it can be problematic. It requires a transition, much like the transitions needed to move from one paragraph to the next. Choose phrases that connect the evidence directly to your topic sentence.

- Consider this: (give an example or state evidence).

- If (identify one condition or event) then (identify the condition or event that will follow).

- It should go without saying that (point out an obvious condition).

- Note that (provide an example or observation).

- Take a look at (identify a condition; follow with an explanation of why you think it is important to the discussion).

- The authors had (identify their idea) in mind when they wrote “(use a quotation from their text that illustrates the idea).”

- The point is that (summarize the conclusion your reader should draw from your research).

- This becomes evident when (name the author) says that (paraphrase a quote from the author’s writing).

- We see this in the following example: (provide an example of your own).

- (The author’s name) offers the example of (summarize an example given by the author).

If an idea is controversial, you may need to add extra evidence to your paragraphs to persuade your reader. You may also find that a logical argument, one based solely on your evidence, is not persuasive enough and that you need to appeal to the reader’s emotions. Look for ways to incorporate your research without detracting from your argument.

Writing Transition Sentences

It is often difficult to write transitions that carry a reader clearly and logically on to the next paragraph (and the next topic) in an essay. Because you are moving from one topic to another, it is easy to simply stop one and start another. Great research papers, however, include good transitions that link the ideas in an interesting discussion so that readers can move smoothly and easily through your presentation. Close each of your paragraphs with an interesting transition sentence that introduces the topic coming up in the next paragraph.

Transition sentences should show a relationship between the two topics.Your transition will perform one of the following functions to introduce the new idea:

- Indicate that you will be expanding on information in a different way in the upcoming paragraph.

- Indicate that a comparison, contrast, or a cause-and-effect relationship between the topics will be discussed.

- Indicate that an example will be presented in the next paragraph.

- Indicate that a conclusion is coming up.

Transitions make a paper flow smoothly by showing readers how ideas and facts follow one another to point logically to a conclusion. They show relationships among the ideas, help the reader to understand, and, in a persuasive paper, lead the reader to the writer’s conclusion.

Each paragraph should end with a transition sentence to conclude the discussion of the topic in the paragraph and gently introduce the reader to the topic that will be raised in the next paragraph. However, transitions also occur within paragraphs—from sentence to sentence—to add evidence, provide examples, or introduce a quotation.

The type of paper you are writing and the kinds of topics you are introducing will determine what type of transitional phrase you should use. Some useful phrases for transitions appear below. They are grouped according to the function they normally play in a paper. Transitions, however, are not simply phrases that are dropped into sentences. They are constructed to highlight meaning. Choose transitions that are appropriate to your topic and what you want the reader to do. Edit them to be sure they fit properly within the sentence to enhance the reader’s understanding.

Transition Phrases for Comparisons:

- We also see

- In addition to

- Notice that

- Beside that,

- In comparison,

- Once again,

- Identically,

- For example,

- Comparatively, it can be seen that

- We see this when

- This corresponds to

- In other words,

- At the same time,

- By the same token,

Transition Phrases for Contrast:

- By contrast,

- On the contrary,

- Nevertheless,

- An exception to this would be …

- Alongside that,we find …

- On one hand … on the other hand …

- [New information] presents an opposite view …

- Conversely, it could be argued …

- Other than that,we find that …

- We get an entirely different impression from …

- One point of differentiation is …

- Further investigation shows …

- An exception can be found in the fact that …

Transition Phrases to Show a Process:

- At the top we have … Near the bottom we have …

- Here we have … There we have …

- Continuing on,

- We progress to …

- Close up … In the distance …

- With this in mind,

- Moving in sequence,

- Proceeding sequentially,

- Moving to the next step,

- First, Second,Third,…

- Examining the activities in sequence,

- Sequentially,

- As a result,

- The end result is …

- To illustrate …

- Subsequently,

- One consequence of …

- If … then …

- It follows that …

- This is chiefly due to …

- The next step …

- Later we find …

Phrases to Introduce Examples:

- For instance,

- Particularly,

- In particular,

- This includes,

- Specifically,

- To illustrate,

- One illustration is

- One example is

- This is illustrated by

- This can be seen when

- This is especially seen in

- This is chiefly seen when

Transition Phrases for Presenting Evidence:

- Another point worthy of consideration is

- At the center of the issue is the notion that

- Before moving on, it should be pointed out that

- Another important point is

- Another idea worth considering is

- Consequently,

- Especially,

- Even more important,

- Getting beyond the obvious,

- In spite of all this,

- It follows that

- It is clear that

- More importantly,

- Most importantly,

How to make effective transitions between sections of a research paper? There are two distinct issues in making strong transitions:

- Does the upcoming section actually belong where you have placed it?

- Have you adequately signaled the reader why you are taking this next step?

The first is the most important: Does the upcoming section actually belong in the next spot? The sections in your research paper need to add up to your big point (or thesis statement) in a sensible progression. One way of putting that is, “Does the architecture of your paper correspond to the argument you are making?” Getting this architecture right is the goal of “large-scale editing,” which focuses on the order of the sections, their relationship to each other, and ultimately their correspondence to your thesis argument.

It’s easy to craft graceful transitions when the sections are laid out in the right order. When they’re not, the transitions are bound to be rough. This difficulty, if you encounter it, is actually a valuable warning. It tells you that something is wrong and you need to change it. If the transitions are awkward and difficult to write, warning bells should ring. Something is wrong with the research paper’s overall structure.

After you’ve placed the sections in the right order, you still need to tell the reader when he is changing sections and briefly explain why. That’s an important part of line-by-line editing, which focuses on writing effective sentences and paragraphs.

Effective transition sentences and paragraphs often glance forward or backward, signaling that you are switching sections. Take this example from J. M. Roberts’s History of Europe . He is finishing a discussion of the Punic Wars between Rome and its great rival, Carthage. The last of these wars, he says, broke out in 149 B.C. and “ended with so complete a defeat for the Carthaginians that their city was destroyed . . . .” Now he turns to a new section on “Empire.” Here is the first sentence: “By then a Roman empire was in being in fact if not in name.”(J. M. Roberts, A History of Europe . London: Allen Lane, 1997, p. 48) Roberts signals the transition with just two words: “By then.” He is referring to the date (149 B.C.) given near the end of the previous section. Simple and smooth.

Michael Mandelbaum also accomplishes this transition between sections effortlessly, without bringing his narrative to a halt. In The Ideas That Conquered the World: Peace, Democracy, and Free Markets , one chapter shows how countries of the North Atlantic region invented the idea of peace and made it a reality among themselves. Here is his transition from one section of that chapter discussing “the idea of warlessness” to another section dealing with the history of that idea in Europe.

The widespread aversion to war within the countries of the Western core formed the foundation for common security, which in turn expressed the spirit of warlessness. To be sure, the rise of common security in Europe did not abolish war in other parts of the world and could not guarantee its permanent abolition even on the European continent. Neither, however, was it a flukish, transient product . . . . The European common security order did have historical precedents, and its principal features began to appear in other parts of the world. Precedents for Common Security The security arrangements in Europe at the dawn of the twenty-first century incorporated features of three different periods of the modern age: the nineteenth century, the interwar period, and the ColdWar. (Michael Mandelbaum, The Ideas That Conquered the World: Peace, Democracy, and Free Markets . New York: Public Affairs, 2002, p. 128)

It’s easier to make smooth transitions when neighboring sections deal with closely related subjects, as Mandelbaum’s do. Sometimes, however, you need to end one section with greater finality so you can switch to a different topic. The best way to do that is with a few summary comments at the end of the section. Your readers will understand you are drawing this topic to a close, and they won’t be blindsided by your shift to a new topic in the next section.

Here’s an example from economic historian Joel Mokyr’s book The Lever of Riches: Technological Creativity and Economic Progress . Mokyr is completing a section on social values in early industrial societies. The next section deals with a quite different aspect of technological progress: the role of property rights and institutions. So Mokyr needs to take the reader across a more abrupt change than Mandelbaum did. Mokyr does that in two ways. First, he summarizes his findings on social values, letting the reader know the section is ending. Then he says the impact of values is complicated, a point he illustrates in the final sentences, while the impact of property rights and institutions seems to be more straightforward. So he begins the new section with a nod to the old one, noting the contrast.

In commerce, war and politics, what was functional was often preferred [within Europe] to what was aesthetic or moral, and when it was not, natural selection saw to it that such pragmatism was never entirely absent in any society. . . . The contempt in which physical labor, commerce, and other economic activity were held did not disappear rapidly; much of European social history can be interpreted as a struggle between wealth and other values for a higher step in the hierarchy. The French concepts of bourgeois gentilhomme and nouveau riche still convey some contempt for people who joined the upper classes through economic success. Even in the nineteenth century, the accumulation of wealth was viewed as an admission ticket to social respectability to be abandoned as soon as a secure membership in the upper classes had been achieved. Institutions and Property Rights The institutional background of technological progress seems, on the surface, more straightforward. (Joel Mokyr, The Lever of Riches: Technological Creativity and Economic Progress . New York: Oxford University Press, 1990, p. 176)

Note the phrase, “on the surface.” Mokyr is hinting at his next point, that surface appearances are deceiving in this case. Good transitions between sections of your research paper depend on:

- Getting the sections in the right order

- Moving smoothly from one section to the next

- Signaling readers that they are taking the next step in your argument

- Explaining why this next step comes where it does

Every good paper ends with a strong concluding paragraph. To write a good conclusion, sum up the main points in your paper. To write an even better conclusion, include a sentence or two that helps the reader answer the question, “So what?” or “Why does all this matter?” If you choose to include one or more “So What?” sentences, remember that you still need to support any point you make with facts or examples. Remember, too, that this is not the place to introduce new ideas from “out of the blue.” Make sure that everything you write in your conclusion refers to what you’ve already written in the body of your paper.

Back to How To Write A Research Paper .

ORDER HIGH QUALITY CUSTOM PAPER

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

36 Body of the report

The body of the report is of course the main text of the report, the sections between the introduction and conclusion. Illustrated below are sample pages.

In all but the shortest reports (two pages or less), use headings (or captions) to mark off your topics and subtopics, that is, to visually signal the structure of the report. Think of headings as the entries of an outline that have been pasted into the actual text of the document.

Headings are an important feature of professional technical writing. They alert readers to upcoming topics and subtopics, help readers find their way around in long reports and skip what they are not interested in, and break up long stretches of straight text.

Headings are also useful for writers. They keep you organized and focused on the topic. When you begin using headings, your impulse may be to slap in the headings after you’ve written the rough draft. Instead, visualize the headings before you start the rough draft, and plug them in as you write.

- Avoid vague headings. For example, instead of “Background” or “Technical Information,” make it more specific.

- Make sure headings accurately indicate the range of topic coverage in the section.

- When possible, omit articles from the beginning of headings. For example, “The Pressurized Water Reactor” can easily be changed to “Pressurized Water Reactor” or, better yet, “Pressurized Water Reactors.”

- Avoid “widowed” headings: that’s where a heading occurs at the bottom of a page and the text it introduces starts at the top of the next page. Keep at least two lines of body text with the heading, or force it to start the new page.

If you manually format each individual heading using the guidelines presented in the preceding list, you’ll find you’re doing quite a lot of repetitive work. The styles provided by Microsoft Word, OpenOffice Writer, and other software save you this work. You simply select Heading 1, Heading 2, Heading 3, and so on. You’ll notice the format and style are different from what is presented here. However, you can design your own styles for headings.

Bulleted and numbered lists

In the body of a report, also use bulleted, numbered, and two-column lists where appropriate. Lists help by emphasizing key points, by making information easier to follow, and by breaking up solid walls of text. Always introduce the list so that your audience understand the purpose and context of the list. Whenever practical, provide a follow-up comment, too. Here are some additional tips:

- Use lists to highlight or emphasize text or to enumerate sequential items.

- Use a lead-in to introduce the list items and to indicate the meaning or purpose of the list (and punctuate it with a colon).

- Use consistent spacing, indentation, punctuation, and caps style for all lists in a document.

- Make list items parallel in phrasing.

- Make sure that each item in the list reads grammatically with the lead-in.

- Avoid using headings as lead-ins for lists.

- Avoid overusing lists; using too many lists destroys their effectiveness.

- Use similar types of lists consistently in similar text in the same document.

Following up a list with text helps your reader understand context for the information distilled into list form. The tips above provide a practical guide to formatting lists.

Graphics and figure titles

Conclusions.

Most reports are strengthened by an brief conclusion. A conclusion reinforces main points, stresses what you want the reader’s “takeaways” to be, note the next steps in the project, and can indicate desired follow-up actions.

Appendixes are those extra sections following the conclusion. What do you put in appendixes? Anything that does not comfortably fit in the main part of the report but cannot be left out of the report altogether. The appendix is commonly used for large tables of data, big chunks of sample code, fold-out maps, background that is too basic or too advanced for the body of the report, or large illustrations that just do not fit in the body of the report. Anything that you feel is too large for the main part of the report or that you think would be distracting and interrupt the flow of the report is a good candidate for an appendix. Notice that each one is given a letter (A, B, C, and so on).

Information sources

Documenting your information sources is all about establishing, maintaining, and protecting your credibility in the profession. You must cite (“document”) borrowed information regardless of the shape or form in which you present it. Whether you directly quote it, paraphrase it, or summarize it—it’s still borrowed information. Whether it comes from a book, article, a diagram, a table, a web page, a product brochure, an expert whom you interview in person—it’s still borrowed information.

Documentation systems vary according to professionals and fields. For a technical writing class in college, you may be using either MLA or APA style. Engineers use the IEEE system, examples of which are shown throughout this chapter. Another commonly used documentation system is provided by the American Psychological Association (APA).

Page numbering

Page-numbering style used in traditional report design differs from contemporary report design primarily in the former’s use of lowercase roman numerals in front matter (everything before the introduction).

- All pages in the report (within but excluding the front and back covers) are numbered; but on some pages, the numbers are not displayed.

- In the contemporary design, all pages throughout the document use arabic numerals; in the traditional design, all pages before the introduction (first page of the body of the report) use lowercase roman numerals.

- On special pages, such as the title page and page one of the introduction, page numbers are not displayed.

- Page numbers can be placed in one of several areas on the page. Usually, the best and easiest choice is to place page numbers at the bottom center of the page (remember to hide them on special pages).

- If you place page numbers at the top of the page, you must hide them on chapter or section openers where a heading or title is at the top of the page.

WTNG 311: Technical Writing Copyright © 2017 by Mel Topf is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

Margin Size

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

10.7: Body of the report

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 16461

- DeSilva et al.

- Central Oregon Community College via OpenOregon

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

The body of the report is of course the main text of the report, the sections between the introduction and conclusion. Illustrated below are sample pages.

In all but the shortest reports (two pages or less), use headings to mark off the different topics and subtopics covered. Headings are the titles and subtitles you see within the actual text of much professional scientific, technical, and business writing. Headings are like the parts of an outline that have been pasted into the actual pages of the document.

Headings are an important feature of professional technical writing: they alert readers to upcoming topics and subtopics, help readers find their way around in long reports and skip what they are not interested in, and break up long stretches of straight text.

Headings are also useful for writers. They keep you organized and focused on the topic. When you begin using headings, your impulse may be to slap in the headings after you’ve written the rough draft. Instead, visualize the headings before you start the rough draft, and plug them in as you write.

Your task in this chapter is to learn how to use headings and to learn the style and format of a specific design of headings. Here are a number of helpful tips:

- Make the phrasing of headings self-explanatory: instead of “Background” or “Technical Information,” make it more specific, such as “Physics of Fiber Optics.”

- Make headings indicate the range of topic coverage in the section. For example, if the section covers the design and operation of a pressurized water reactor, the heading “Pressurized Water Reactor Design” would be incomplete and misleading.

- Avoid “stacked” headings—any two consecutive headings without intervening text.

- Avoid pronoun reference to headings. For example, if you have a heading “Torque,” don’t begin the sentence following it with something like this: “This is a physics principle…..”

- When possible, omit articles from the beginning of headings. For example, “The Pressurized Water Reactor” can easily be changed to “Pressurized Water Reactor” or, better yet, “Pressurized Water Reactors.”

- Don’t use headings as lead-ins to lists or as figure titles.

- Avoid “widowed” headings: that’s where a heading occurs at the bottom of a page and the text it introduces starts at the top of the next page. Keep at least two lines of body text with the heading, or force it to start the new page.

If you manually format each individual heading using the guidelines presented in the preceding list, you’ll find you’re doing quite a lot of repetitive work. The styles provided by Microsoft Word, OpenOffice Writer, and other software save you this work. You simply select Heading 1, Heading 2, Heading 3, and so on. You’ll notice the format and style are different from what is presented here. However, you can design your own styles for headings.

Bulleted and numbered lists

In the body of a report, also use bulleted, numbered, and two-column lists where appropriate. Lists help by emphasizing key points, by making information easier to follow, and by breaking up solid walls of text. Always introduce the list so that your audience understand the purpose and context of the list. Whenever practical, provide a follow-up comment, too. Here are some additional tips:

- Use lists to highlight or emphasize text or to enumerate sequential items.

- Use a lead-in to introduce the list items and to indicate the meaning or purpose of the list (and punctuate it with a colon).

- Use consistent spacing, indentation, punctuation, and caps style for all lists in a document.

- Make list items parallel in phrasing.

- Make sure that each item in the list reads grammatically with the lead-in.

- Avoid using headings as lead-ins for lists.

- Avoid overusing lists; using too many lists destroys their effectiveness.

- Use similar types of lists consistently in similar text in the same document.

Following up a list with text helps your reader understand context for the information distilled into list form. The tips above provide a practical guide to formatting lists.

Graphics and figure titles

In technical report, you are likely to need drawings, diagrams, tables, and charts. These not only convey certain kinds of information more efficiently but also give your report an added look of professionalism and authority. If you’ve never put these kinds of graphics into a report, there are some relatively easy ways to do so—you don’t need to be a professional graphic artist. For strategies for adding graphics and tables to reports, see the chapter on Creating and Using Visuals. See the chapter on visuals for more help with the principles for creating visuals.

Conclusions

For most reports, you will need to include a final section. When you plan the final section of your report, think about the functions it can perform in relation to the rest of the report. A conclusion does not necessarily just summarize a report. Instead, use the conclusion to explain the most significant findings you made in relation to your report topic.

Appendixes are those extra sections following the conclusion. What do you put in appendixes? Anything that does not comfortably fit in the main part of the report but cannot be left out of the report altogether. The appendix is commonly used for large tables of data, big chunks of sample code, fold-out maps, background that is too basic or too advanced for the body of the report, or large illustrations that just do not fit in the body of the report. Anything that you feel is too large for the main part of the report or that you think would be distracting and interrupt the flow of the report is a good candidate for an appendix. Notice that each one is given a letter (A, B, C, and so on).

Information sources

Documenting your information sources is all about establishing, maintaining, and protecting your credibility in the profession. You must cite (“document”) borrowed information regardless of the shape or form in which you present it. Whether you directly quote it, paraphrase it, or summarize it—it’s still borrowed information. Whether it comes from a book, article, a diagram, a table, a web page, a product brochure, an expert whom you interview in person—it’s still borrowed information.

Documentation systems vary according to professionals and fields. For a technical writing class in college, you may be using either MLA or APA style. Engineers use the IEEE system, examples of which are shown throughout this chapter. Another commonly used documentation system is provided by the American Psychological Association (APA).

Page numbering

Page-numbering style used in traditional report design differs from contemporary report design primarily in the former’s use of lowercase roman numerals in front matter (everything before the introduction).

- All pages in the report (within but excluding the front and back covers) are numbered; but on some pages, the numbers are not displayed.

- In the contemporary design, all pages throughout the document use arabic numerals; in the traditional design, all pages before the introduction (first page of the body of the report) use lowercase roman numerals.

- On special pages, such as the title page and page one of the introduction, page numbers are not displayed.

- Page numbers can be placed in one of several areas on the page. Usually, the best and easiest choice is to place page numbers at the bottom center of the page (remember to hide them on special pages).

- If you place page numbers at the top of the page, you must hide them on chapter or section openers where a heading or title is at the top of the page.

Chapter Attribution Information

This chapter was derived by Annemarie Hamlin, Chris Rubio, and Michele DeSilva, Central Oregon Community College, from Online Technical Writing by David McMurrey – CC: BY 4.0

Uncomplicated Reviews of Educational Research Methods

- Writing a Research Report

.pdf version of this page

This review covers the basic elements of a research report. This is a general guide for what you will see in journal articles or dissertations. This format assumes a mixed methods study, but you can leave out either quantitative or qualitative sections if you only used a single methodology.

This review is divided into sections for easy reference. There are five MAJOR parts of a Research Report:

1. Introduction 2. Review of Literature 3. Methods 4. Results 5. Discussion

As a general guide, the Introduction, Review of Literature, and Methods should be about 1/3 of your paper, Discussion 1/3, then Results 1/3.

Section 1 : Cover Sheet (APA format cover sheet) optional, if required.

Section 2: Abstract (a basic summary of the report, including sample, treatment, design, results, and implications) (≤ 150 words) optional, if required.

Section 3 : Introduction (1-3 paragraphs) • Basic introduction • Supportive statistics (can be from periodicals) • Statement of Purpose • Statement of Significance

Section 4 : Research question(s) or hypotheses • An overall research question (optional) • A quantitative-based (hypotheses) • A qualitative-based (research questions) Note: You will generally have more than one, especially if using hypotheses.

Section 5: Review of Literature ▪ Should be organized by subheadings ▪ Should adequately support your study using supporting, related, and/or refuting evidence ▪ Is a synthesis, not a collection of individual summaries

Section 6: Methods ▪ Procedure: Describe data gathering or participant recruitment, including IRB approval ▪ Sample: Describe the sample or dataset, including basic demographics ▪ Setting: Describe the setting, if applicable (generally only in qualitative designs) ▪ Treatment: If applicable, describe, in detail, how you implemented the treatment ▪ Instrument: Describe, in detail, how you implemented the instrument; Describe the reliability and validity associated with the instrument ▪ Data Analysis: Describe type of procedure (t-test, interviews, etc.) and software (if used)

Section 7: Results ▪ Restate Research Question 1 (Quantitative) ▪ Describe results ▪ Restate Research Question 2 (Qualitative) ▪ Describe results

Section 8: Discussion ▪ Restate Overall Research Question ▪ Describe how the results, when taken together, answer the overall question ▪ ***Describe how the results confirm or contrast the literature you reviewed

Section 9: Recommendations (if applicable, generally related to practice)

Section 10: Limitations ▪ Discuss, in several sentences, the limitations of this study. ▪ Research Design (overall, then info about the limitations of each separately) ▪ Sample ▪ Instrument/s ▪ Other limitations

Section 11: Conclusion (A brief closing summary)

Section 12: References (APA format)

Share this:

About research rundowns.

Research Rundowns was made possible by support from the Dewar College of Education at Valdosta State University .

- Experimental Design

- What is Educational Research?

- Writing Research Questions

- Mixed Methods Research Designs

- Qualitative Coding & Analysis

- Qualitative Research Design

- Correlation

- Effect Size

- Instrument, Validity, Reliability

- Mean & Standard Deviation

- Significance Testing (t-tests)

- Steps 1-4: Finding Research

- Steps 5-6: Analyzing & Organizing

- Steps 7-9: Citing & Writing

Blog at WordPress.com.

- Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

- Subscribe Subscribed

- Copy shortlink

- Report this content

- View post in Reader

- Manage subscriptions

- Collapse this bar

- Research Report: Definition, Types + [Writing Guide]

One of the reasons for carrying out research is to add to the existing body of knowledge. Therefore, when conducting research, you need to document your processes and findings in a research report.

With a research report, it is easy to outline the findings of your systematic investigation and any gaps needing further inquiry. Knowing how to create a detailed research report will prove useful when you need to conduct research.

What is a Research Report?

A research report is a well-crafted document that outlines the processes, data, and findings of a systematic investigation. It is an important document that serves as a first-hand account of the research process, and it is typically considered an objective and accurate source of information.

In many ways, a research report can be considered as a summary of the research process that clearly highlights findings, recommendations, and other important details. Reading a well-written research report should provide you with all the information you need about the core areas of the research process.

Features of a Research Report

So how do you recognize a research report when you see one? Here are some of the basic features that define a research report.

- It is a detailed presentation of research processes and findings, and it usually includes tables and graphs.

- It is written in a formal language.

- A research report is usually written in the third person.

- It is informative and based on first-hand verifiable information.

- It is formally structured with headings, sections, and bullet points.

- It always includes recommendations for future actions.

Types of Research Report

The research report is classified based on two things; nature of research and target audience.

Nature of Research

- Qualitative Research Report

This is the type of report written for qualitative research . It outlines the methods, processes, and findings of a qualitative method of systematic investigation. In educational research, a qualitative research report provides an opportunity for one to apply his or her knowledge and develop skills in planning and executing qualitative research projects.

A qualitative research report is usually descriptive in nature. Hence, in addition to presenting details of the research process, you must also create a descriptive narrative of the information.

- Quantitative Research Report

A quantitative research report is a type of research report that is written for quantitative research. Quantitative research is a type of systematic investigation that pays attention to numerical or statistical values in a bid to find answers to research questions.

In this type of research report, the researcher presents quantitative data to support the research process and findings. Unlike a qualitative research report that is mainly descriptive, a quantitative research report works with numbers; that is, it is numerical in nature.

Target Audience

Also, a research report can be said to be technical or popular based on the target audience. If you’re dealing with a general audience, you would need to present a popular research report, and if you’re dealing with a specialized audience, you would submit a technical report.

- Technical Research Report

A technical research report is a detailed document that you present after carrying out industry-based research. This report is highly specialized because it provides information for a technical audience; that is, individuals with above-average knowledge in the field of study.

In a technical research report, the researcher is expected to provide specific information about the research process, including statistical analyses and sampling methods. Also, the use of language is highly specialized and filled with jargon.

Examples of technical research reports include legal and medical research reports.

- Popular Research Report

A popular research report is one for a general audience; that is, for individuals who do not necessarily have any knowledge in the field of study. A popular research report aims to make information accessible to everyone.

It is written in very simple language, which makes it easy to understand the findings and recommendations. Examples of popular research reports are the information contained in newspapers and magazines.

Importance of a Research Report

- Knowledge Transfer: As already stated above, one of the reasons for carrying out research is to contribute to the existing body of knowledge, and this is made possible with a research report. A research report serves as a means to effectively communicate the findings of a systematic investigation to all and sundry.

- Identification of Knowledge Gaps: With a research report, you’d be able to identify knowledge gaps for further inquiry. A research report shows what has been done while hinting at other areas needing systematic investigation.

- In market research, a research report would help you understand the market needs and peculiarities at a glance.

- A research report allows you to present information in a precise and concise manner.

- It is time-efficient and practical because, in a research report, you do not have to spend time detailing the findings of your research work in person. You can easily send out the report via email and have stakeholders look at it.

Guide to Writing a Research Report

A lot of detail goes into writing a research report, and getting familiar with the different requirements would help you create the ideal research report. A research report is usually broken down into multiple sections, which allows for a concise presentation of information.

Structure and Example of a Research Report

This is the title of your systematic investigation. Your title should be concise and point to the aims, objectives, and findings of a research report.

- Table of Contents

This is like a compass that makes it easier for readers to navigate the research report.

An abstract is an overview that highlights all important aspects of the research including the research method, data collection process, and research findings. Think of an abstract as a summary of your research report that presents pertinent information in a concise manner.

An abstract is always brief; typically 100-150 words and goes straight to the point. The focus of your research abstract should be the 5Ws and 1H format – What, Where, Why, When, Who and How.

- Introduction

Here, the researcher highlights the aims and objectives of the systematic investigation as well as the problem which the systematic investigation sets out to solve. When writing the report introduction, it is also essential to indicate whether the purposes of the research were achieved or would require more work.

In the introduction section, the researcher specifies the research problem and also outlines the significance of the systematic investigation. Also, the researcher is expected to outline any jargons and terminologies that are contained in the research.

- Literature Review

A literature review is a written survey of existing knowledge in the field of study. In other words, it is the section where you provide an overview and analysis of different research works that are relevant to your systematic investigation.

It highlights existing research knowledge and areas needing further investigation, which your research has sought to fill. At this stage, you can also hint at your research hypothesis and its possible implications for the existing body of knowledge in your field of study.

- An Account of Investigation

This is a detailed account of the research process, including the methodology, sample, and research subjects. Here, you are expected to provide in-depth information on the research process including the data collection and analysis procedures.

In a quantitative research report, you’d need to provide information surveys, questionnaires and other quantitative data collection methods used in your research. In a qualitative research report, you are expected to describe the qualitative data collection methods used in your research including interviews and focus groups.

In this section, you are expected to present the results of the systematic investigation.

This section further explains the findings of the research, earlier outlined. Here, you are expected to present a justification for each outcome and show whether the results are in line with your hypotheses or if other research studies have come up with similar results.

- Conclusions

This is a summary of all the information in the report. It also outlines the significance of the entire study.

- References and Appendices

This section contains a list of all the primary and secondary research sources.

Tips for Writing a Research Report

- Define the Context for the Report

As is obtainable when writing an essay, defining the context for your research report would help you create a detailed yet concise document. This is why you need to create an outline before writing so that you do not miss out on anything.

- Define your Audience

Writing with your audience in mind is essential as it determines the tone of the report. If you’re writing for a general audience, you would want to present the information in a simple and relatable manner. For a specialized audience, you would need to make use of technical and field-specific terms.

- Include Significant Findings

The idea of a research report is to present some sort of abridged version of your systematic investigation. In your report, you should exclude irrelevant information while highlighting only important data and findings.

- Include Illustrations

Your research report should include illustrations and other visual representations of your data. Graphs, pie charts, and relevant images lend additional credibility to your systematic investigation.

- Choose the Right Title

A good research report title is brief, precise, and contains keywords from your research. It should provide a clear idea of your systematic investigation so that readers can grasp the entire focus of your research from the title.

- Proofread the Report

Before publishing the document, ensure that you give it a second look to authenticate the information. If you can, get someone else to go through the report, too, and you can also run it through proofreading and editing software.

How to Gather Research Data for Your Report

- Understand the Problem

Every research aims at solving a specific problem or set of problems, and this should be at the back of your mind when writing your research report. Understanding the problem would help you to filter the information you have and include only important data in your report.

- Know what your report seeks to achieve

This is somewhat similar to the point above because, in some way, the aim of your research report is intertwined with the objectives of your systematic investigation. Identifying the primary purpose of writing a research report would help you to identify and present the required information accordingly.

- Identify your audience

Knowing your target audience plays a crucial role in data collection for a research report. If your research report is specifically for an organization, you would want to present industry-specific information or show how the research findings are relevant to the work that the company does.

- Create Surveys/Questionnaires

A survey is a research method that is used to gather data from a specific group of people through a set of questions. It can be either quantitative or qualitative.

A survey is usually made up of structured questions, and it can be administered online or offline. However, an online survey is a more effective method of research data collection because it helps you save time and gather data with ease.

You can seamlessly create an online questionnaire for your research on Formplus . With the multiple sharing options available in the builder, you would be able to administer your survey to respondents in little or no time.

Formplus also has a report summary too l that you can use to create custom visual reports for your research.

Step-by-step guide on how to create an online questionnaire using Formplus

- Sign into Formplus

In the Formplus builder, you can easily create different online questionnaires for your research by dragging and dropping preferred fields into your form. To access the Formplus builder, you will need to create an account on Formplus.

Once you do this, sign in to your account and click on Create new form to begin.

- Edit Form Title : Click on the field provided to input your form title, for example, “Research Questionnaire.”

- Edit Form : Click on the edit icon to edit the form.

- Add Fields : Drag and drop preferred form fields into your form in the Formplus builder inputs column. There are several field input options for questionnaires in the Formplus builder.

- Edit fields

- Click on “Save”

- Form Customization: With the form customization options in the form builder, you can easily change the outlook of your form and make it more unique and personalized. Formplus allows you to change your form theme, add background images, and even change the font according to your needs.

- Multiple Sharing Options: Formplus offers various form-sharing options, which enables you to share your questionnaire with respondents easily. You can use the direct social media sharing buttons to share your form link to your organization’s social media pages. You can also send out your survey form as email invitations to your research subjects too. If you wish, you can share your form’s QR code or embed it on your organization’s website for easy access.

Conclusion

Always remember that a research report is just as important as the actual systematic investigation because it plays a vital role in communicating research findings to everyone else. This is why you must take care to create a concise document summarizing the process of conducting any research.

In this article, we’ve outlined essential tips to help you create a research report. When writing your report, you should always have the audience at the back of your mind, as this would set the tone for the document.

Connect to Formplus, Get Started Now - It's Free!

- ethnographic research survey

- research report

- research report survey

- busayo.longe

You may also like:

Assessment Tools: Types, Examples & Importance

In this article, you’ll learn about different assessment tools to help you evaluate performance in various contexts

21 Chrome Extensions for Academic Researchers in 2022

In this article, we will discuss a number of chrome extensions you can use to make your research process even seamless

How to Write a Problem Statement for your Research

Learn how to write problem statements before commencing any research effort. Learn about its structure and explore examples

Ethnographic Research: Types, Methods + [Question Examples]

Simple guide on ethnographic research, it types, methods, examples and advantages. Also highlights how to conduct an ethnographic...

Formplus - For Seamless Data Collection

Collect data the right way with a versatile data collection tool. try formplus and transform your work productivity today..

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Section 1- Evidence-based practice (EBP)

Chapter 6: Components of a Research Report

Components of a research report.

Partido, B.B.

Elements of research report

The research report contains four main areas:

- Introduction – What is the issue? What is known? What is not known? What are you trying to find out? This sections ends with the purpose and specific aims of the study.

- Methods – The recipe for the study. If someone wanted to perform the same study, what information would they need? How will you answer your research question? This part usually contains subheadings: Participants, Instruments, Procedures, Data Analysis,

- Results – What was found? This is organized by specific aims and provides the results of the statistical analysis.

- Discussion – How do the results fit in with the existing literature? What were the limitations and areas of future research?

Formalized Curiosity for Knowledge and Innovation Copyright © by partido1. All Rights Reserved.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

6.6: Formal Report—Conclusion, Recommendations, References, and Appendices

Learning objectives.

- Examine the remaining report sections: conclusion, recommendation, reference list, appendices

What Are the Remaining Report Sections?

Conclusions and recommendations.

The conclusions and recommendations section conveys the key results from the analysis in the discussion section. Up to this point, readers have carefully reviewed the data in the report; they are now logically prepared to read the report’s conclusions and recommendations.

According to OACETT (2021), “Conclusions are reasoned judgment and fact, not opinion. Conclusions consider all of the variables and relate cause and effect. Conclusions analyze, evaluate, and make comparisons and contrasts” (p. 7) and “Recommendation(s) (if applicable) suggest a course of action and are provided when there are additional areas for study, or if the reason for the Technology Report was to determine the best action going forward” (p. 7).

You may present the conclusions and recommendations in a numbered or bulleted list to enhance readability.

Reference Page

All formal reports should include a reference page; this page documents the sources cited within the report. The recipient(s) of the report can also refer to this page to locate sources for further research.

Documenting your information sources is all about establishing, maintaining, and protecting your credibility in the profession. You must cite (“document”) borrowed information regardless of the shape or form in which you present it. Whether you directly quote it, paraphrase it, or summarize it—it’s still borrowed information. Whether it comes from a book, article, a diagram, a table, a web page, a product brochure, an expert whom you interview in person—it’s still borrowed information.

Documentation systems vary according to professionals and fields. In ENGL 250, we follow APA. Refer to a credible APA guide for support.

Appendices are those extra sections in a report that follow the conclusion. According to OACETT (2021), “Appendices can include detailed calculations, tables, drawings, specifications, and technical literature” (p. 7).

Anything that does not comfortably fit in the main part of the report but cannot be left out of the report altogether should go into the appendices. They are commonly used for large tables of data, big chunks of sample code, background that is too basic or too advanced for the body of the report, or large illustrations that just do not fit in the body of the report. Anything that you feel is too large for the main part of the report or that you think would be distracting and interrupt the flow of the report is a good candidate for an appendix.

References & Attributions

Blicq, R., & Moretto, L. (2012). Technically write. (8th Canadian Ed.). Pearson Canada.

OACETT. (2021). Technology report guidelines . https://www.oacett.org/getmedia/9f9623ac-73ab-4f99-acca-0d78dee161ab/TR_GUIDELINES_Final.pdf.aspx

Attributions

Content is adapted from Technical Writing by Allison Gross, Annemarie Hamlin, Billy Merck, Chris Rubio, Jodi Naas, Megan Savage, and Michele DeSilva, which is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Writing in a Technical Environment (First Edition) Copyright © 2022 by Centennial College is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

Margin Size

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants