Positive and Negative Media Effects on University Students’ Learning: Preliminary Findings and a Research Program

- First Online: 03 January 2020

Cite this chapter

- Marcus Maurer 2 ,

- Christian Schemer 2 ,

- Olga Zlatkin-Troitschanskaia 3 &

- Judith Jitomirski 4

556 Accesses

6 Citations

Research in communication science highlights positive as well as negative effects of news and social media on learning but focuses predominantly on the largely unintended knowledge acquisition of the overall population. Research in educational science deals with students’ knowledge acquisition but is largely limited to formal learning such as in university courses. In this paper, we report findings of a pilot study combining both approaches by dealing with mass and social media effects on university students’ learning. While this study reveals several effects, their influences and causality remain largely unclear. Therefore, we propose a research program to explain positive and negative media effects on students learning in higher education in a more detailed fashion. In this program, we aim to combine various research methods like content analyses, panel surveys, mobile experience samplings, and experiments to uncover the mechanisms behind the emergence of positive and negative effects on learning.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or Ebook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Media Effects on Positive and Negative Learning

Social Media and Higher Education: A Literature Review

Social Media in Higher Education: A Review of Their Uses, Benefits and Limitations

Brückner, S., & Pellegrino, J. W. (2016). Integrating the analysis of mental operations into multilevel models to validate an assessment of higher education students’ competency in business and economics. Journal of Educational Measurement, 53 , 293–312. https://doi.org/10.1111/jedm.12113

Article Google Scholar

Dalton, J. C., & Crosby, P. C. (2013). Digital identity: How social media are influencing student learning and development in college. Journal of College and Character, 14 (1), 1–4.

Fletcher, R., & Nielsen, R. K. (2017). Are news audiences increasingly fragmented? A cross-national comparative analysis of cross-platform news audience fragmentation and duplication. Journal of Communication, 67 (4), 476–498.

Graber, D. A. (2001). Processing politics: Learning from television in the internet age . Chicago, IL: Univ. of Chicago Press.

Book Google Scholar

Happ, R., Zlatkin-Troitschanskaia, O., & Schmidt, S. (2016). An analysis of economic learning among undergraduates in introductory economics courses in Germany. Journal of Economic Education, 47 (4), 300–310. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220485.2016.1213686

Kimmerle, J., Moskaliuk, J., Oeberst, A., & Cress, U. (2015). Learning and collective knowledge construction with social media: A process-oriented perspective. Educational Psychologist, 50 (2), 120–137.

Kunda, Z. (1990). The case for motivated reasoning. Psychological Bulletin, 108 (3), 480–498.

Madge, C., Meek, J., Wellens, J., & Hoole, T. (2009). Facebook, social integration and informal learning at university: ‘It is more for socialising and talking to friends about work than for actually doing work’. Learning, Media and Technology, 34 (2), 141–155.

Maurer, M. (2017). Media effects: Levels of analysis. In P. Rössler (Ed.), The international encyclopedia of media effects (pp. 984–995). New York, NY: Wiley-Blackwell.

Google Scholar

Maurer, M., & Oschatz, C. (2016). The influence of online media on political knowledge. In G. Vowe & P. Henn (Eds.), Political communication in the online world (pp. 73–87). New York, NY: Routledge.

Maurer, M., Quiring, O., & Schemer, C. (2018). Media effects on positive and negative learning. In O. Zlatkin-Troitschanskaia, G. Wittum, & A. Dengel (Eds.), Positive learning in the age of information – A blessing or a curse? (pp. 197–208). Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

Maurer, M., & Reinemann, C. (2006). Learning versus knowing: Effects of misinformation in televised debates. Communication Research, 33 , 489–506. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650206293252

Pariser, E. (2011). The filter bubble. What the internet is hiding from you . New York, NY: Penguin.

Pashler, H., Bain, P. M., Bottge, B. A., Graesser, A. C., Koedinger, K., McDaniel, M., et al. (2007). Organizing instruction and study to improve student learning . Washington, DC: National Center for Education Research, Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education.

Schmidt, S., Zlatkin-Troitschanskaia, O., & Fox, J.-P. (2016). Pretest-posttest-posttest multilevel IRT modeling of competence growth of students in higher education in Germany. Journal of Educational Measurement, 53 (3), 332–351. https://doi.org/10.1111/jedm.12115

Shadish, W. R., Cook, T. D., & Campbell, D. T. (2001). Experimental and quasi-experimental designs for generalized causal inference . Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin.

Shavelson, R. J., Zlatkin-Troitschanskaia, O., Beck, K., Schmidt, S., & Mariño, J. P. (2019). Assessment of University Students’ Critical Thinking: Next Generation Performance Assessment. International Journal of Testing . https://doi.org/10.1080/15305058.2018.1543309

Shavelson, R. J., Zlatkin-Troitschanskaia, O., & Mariño, J. P. (2018). Performance indicators of learning in higher-education institutions: An overview of the field. In E. Hazelkorn, H. Coates, & A. Cormick (Eds.), Research handbook on quality, performance and accountability in higher education (pp. 249–263). Cheltenham/Northampton: Edward Elgar.

Chapter Google Scholar

Sparrow, B., Liu, J., & Wegner, D. M. (2011). Google effects on memory: Cognitive consequences of having information at our fingertips. Science, 333 , 776–778.

Sundar, S. S. (2003). News features and learning. In J. Bryant, D. R. Roskos-Ewoldsen, & J. Cantor (Eds.), Communication and emotion. Essays in honor of Dolf Zillmann (pp. 275–296). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Walstad, W. B., Schmidt, S., Zlatkin-Troitschanskaia, O., & Happ, R. (2018). Pretest-posttest measurement of the economic knowledge of undergraduates – Estimating guessing effects (Discussion paper of the annual AEA conference on teaching and research in economic education). Philadelphia, PA: AEA.

Ward, A. F. (2013). One with the cloud: Why people mistake the internet’s knowledge for their own . Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University.

Ziegler, D. A., Mishra, J., & Gazzaley, A. (2015). The acute and chronic impact of technology on our brain. In L. D. Rosen, N. A. Cheever, & L. M. Carrier (Eds.), The Wiley handbook of psychology, technology and society (pp. 3–19). New York, NY: Wiley.

Zlatkin-Troitschanskaia, O., Pant, H. A., Kuhn, C., Toepper, M., & Lautenbach, C. (2016). Messung akademisch vermittelter Kompetenzen von Studierenden und Hochschulabsolventen. Ein Überblick zum nationalen und internationalen Forschungsstand . Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

Zlatkin-Troitschanskaia, O., Schmidt, S., Molerov, D., Shavelson, R. J., & Berliner, D. (2018). Conceptual fundamentals for a theoretical and empirical framework of positive learning. In O. Zlatkin-Troitschanskaia, G. Wittum, & A. Dengel (Eds.), Positive learning in the age of information – A blessing or a curse? (pp. 29–52). Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

Zlatkin-Troitschanskaia, O., Jitomirski, J., Happ, R., Molerov, D., Schlax, J., Kühling-Thees, C., Förster, M. and Brückner, S. (2019). Validating a test for measuring knowledge and understanding of economics among university students. Zeitschrift für pädagogische Psychologie (German Journal of Educational Psychology), 33 (2), 119–133.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Institute of Journalism and Communication Studies, Johannes Gutenberg University of Mainz, Mainz, Germany

Marcus Maurer & Christian Schemer

Department of Business and Economics Education, Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz, Mainz, Germany

Olga Zlatkin-Troitschanskaia

Institute for Educational Studies, Humboldt University of Berlin, Berlin, Germany

Judith Jitomirski

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Marcus Maurer .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations, rights and permissions.

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2019 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Maurer, M., Schemer, C., Zlatkin-Troitschanskaia, O., Jitomirski, J. (2019). Positive and Negative Media Effects on University Students’ Learning: Preliminary Findings and a Research Program. In: Zlatkin-Troitschanskaia, O. (eds) Frontiers and Advances in Positive Learning in the Age of InformaTiOn (PLATO). Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-26578-6_8

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-26578-6_8

Published : 03 January 2020

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-030-26577-9

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-26578-6

eBook Packages : Education Education (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Open access

- Published: 22 June 2023

Social media and mental health in students: a cross-sectional study during the Covid-19 pandemic

- Abouzar Nazari ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-2155-5438 1 ,

- Maede Hosseinnia ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-2248-7011 2 ,

- Samaneh Torkian 3 &

- Gholamreza Garmaroudi ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-7449-227X 4

BMC Psychiatry volume 23 , Article number: 458 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

67k Accesses

3 Citations

17 Altmetric

Metrics details

Social media causes increased use and problems due to their attractions. Hence, it can affect mental health, especially in students. The present study was conducted with the aim of determining the relationship between the use of social media and the mental health of students.

Materials and methods

The current cross-sectional study was conducted in 2021 on 781 university students in Lorestan province, who were selected by the Convenience Sampling method. The data was collected using a questionnaire on demographic characteristics, social media, problematic use of social media, and mental health (DASS-21). Data were analyzed in SPSS-26 software.

Shows that marital status, major, and household income are significantly associated with lower DASS21 scores (a lower DASS21 score means better mental health status). Also, problematic use of social media (β = 3.54, 95% CI: (3.23, 3.85)) was significantly associated with higher mental health scores (a higher DASS21 score means worse mental health status). Income and social media use (β = 1.02, 95% CI: 0.78, 1.25) were significantly associated with higher DASS21 scores (a higher DASS21 score means worse mental health status). Major was significantly associated with lower DASS21 scores (a lower DASS21 score means better mental health status).

This study indicated that social media had a direct relationship with mental health. Despite the large amount of evidence suggesting that social media harms mental health, more research is still necessary to determine the cause and how social media can be used without harmful effects.

Peer Review reports

- Social media

Social media is one of the newest and most popular internet services, which has caused significant progress in the social systems of different countries in recent years [ 1 , 2 ]. The use of the Internet has become popular among people in such a way that its use has become inevitable and has made life difficult for those who use it excessively [ 3 ]. Social media has attracted the attention of millions of users around the world owing to the possibility of fast communication, access to a large amount of information, and its widespread dissemination [ 4 ]. Facebook, WhatsApp, Instagram, and Twitter are the most popular media that have attractive and diverse spaces for online communication among users, especially the young generation [ 5 , 6 ].

According to studies, at least 55% of the world’s population used social media in 2022 [ 7 ]. Iranian statistics also indicate that 78.5% of people use at least one social media. WhatsApp, with 71.1% of users, Instagram, with 49.4%, and Telegram, with 31.6% are the most popular social media among Iranians [ 8 , 9 ].

The use of social media has increased significantly in all age groups due to the origin of the COVID-19 pandemic [ 10 ] .It affected younger people, especially students, due to educational and other purposes [ 11 , 12 ]. Because of the sudden onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, educational institutions and learners had to accept e-learning as the only sustainable education option [ 13 ]. The rapid migration to E-learning has brought several challenges that can have both positive and negative consequences [ 14 ].

Unlike traditional media, where users are passive, social media enables people to create and share content; hence, they have become popular tools for social interaction [ 15 ].The freedom to choose to participate in the company of friends, anonymity, moderation, encouragement, the free exchange of feelings, and network interactions without physical presence and the constraints of the real world are some of the most significant factors that influence users’ continued activity in social media [ 16 ]. In social media, people can interact, maintain relationships, make new friends, and find out more about the people they know offline [ 17 ]. However, this popularity has resulted in significant lifestyle changes, as well as intentional or unintentional changes in various aspects of human social life [ 18 ]. Despite many advantages, the high use of social media brings negative physical, psychological, and social problems and consequences [ 19 ], but despite the use and access of more people to the Internet, its consequences and crises have been ignored [ 20 ].

Use of social media and mental health

Spending too much time on social media can easily become problematic [ 21 ]. Excessive use of social media, called problematic use, has symptoms similar to addiction [ 22 , 23 ]. Problematic use of social media represents a non-drug-related disorder in which harmful effects emerge due to preoccupation and compulsion to over-participate in social media platforms despite its highly negative consequences [ 24 , 25 , 26 ], which leads to adverse consequences of mental health, including anxiety, depression, lower well-being, and lower self-esteem [ 27 , 28 , 29 ].

Mental health & use of social media

Mental health is the main pillar of healthy human societies, which plays a vital role in ensuring the dynamism and efficiency of any society in such a way that other parts of health cannot be achieved without mental health [ 30 ]. According to World Health Organization’s (WHO) definition, mental health refers to a person’s ability to communicate with others [ 31 ]. Some researchers believe that social relationships can significantly affect mental health and improve quality of life by creating a sense of belonging and social identity [ 32 ]. It is also reported that people with higher social interactions have higher physical and mental health [ 33 ].

Scientific evidence also shows that social media affect people’s mental health [ 34 ]. Social studies and critiques often emphasize the investigation of the negative effects of Internet use [ 35 ]. For example, Kim et al. studied 1573 participants aged 18–64 years and reported that Internet addiction and social media use were associated with higher levels of depression and suicidal thoughts [ 36 ]. Zadar also studied adults and reported that excessive use of social media and the Internet was correlated with stress, sleep disturbances, and personality disorders [ 37 ]. Richards et al. reported the negative effects of the Internet and social media on the health and quality of life of adolescents [ 38 ]. There have been numerous studies that examine Internet addiction and its associated problems in young people [ 39 , 40 ], as well as reports of the effects of social media use on young people’s mental health [ 41 , 42 ].

A study on Iranian students showed that social media leads to depression, anxiety, and mental health decline [ 25 ]. A study on Iranian students showed that social media leads to depression, anxiety, and mental health decline [ 25 ]. But no study has investigated the effects of social media on the mental health of students from a more traditional province with lower individualism and higher levels of social support (where they were thought to have lower social media use and better mental health) during the COVID-19 pandemic. As social media became more and more vital to university students’ social lives during the lockdowns, students were likely at increased risk of social media addiction, which could harm their mental health. University students depended more on social media due to the limitations of face-to-face interactions. In addition, previous studies were conducted exclusively on students in specific fields. However, in our study, all fields, including medical and non-medical science fields were investigated.

The present study was conducted to determine the relationship between the use of social media and mental health in students in Lorestan Province during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Study design and participants

The current study was descriptive-analytical, cross-sectional, and conducted from February to March 2022 with a statistical population made up of students in all academic grades at universities in Lorestan Province (19 scientific and academic centers, including centers under the supervision of the Ministry of Health and the Ministry of Science).

Sample size

According to the convenience sampling method, 781 people were chosen as participants in the present study. During the sampling, a questionnaire was created and uploaded virtually on Porsline’s website, and then the questionnaire link was shared in educational and academic groups on social media for students to complete the questionnaire under inclusion criteria (being a student at the University of Lorestan and consenting to participate in the study).

The research tools included the demographic information questionnaire, the standard social media use questionnaire, and the mental health questionnaire.

Demographic information

The demographic information age, gender, ethnicity, province of residence, urban or rural, place of residence, semester, and the field of study, marital status, household income, education level, and employment status were recorded.

Psychological assessment

The students were subjected to the Persian version of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scale (DASS21). It consists of three self-report scales designed to measure different emotional states. DASS21 questions were adjusted according to their importance and the culture of Iranian students. The DASS21 scale was scored on a four-point scale to assess the extent to which participants experienced each condition over the past few weeks. The scoring method was such that each question was scored from 0 (never) to 3 (very high). Samani (2008) found that the questionnaire has a validity of 0.77 and a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.82 [ 43 ].

Use of social media questionnaire

Among the 13 questions on social media use in the questionnaire, seven were asked on a Likert scale (never, sometimes, often, almost, and always) that examined the problematic use of social media, and six were asked about how much time users spend on social media. Because some items were related to the type of social media platform, which is not available today, and users now use newer social media platforms such as WhatsApp and Instagram, the questionnaires were modified by experts and fundamentally changed, and a 22-item questionnaire was obtained that covered the frequency of using social media. Cronbach’s alpha was equal to 0.705 for the first part, 0.794 for the second part, and 0.830 for all questions [ 44 ]. Considering the importance of the problematic use of the social media, six questions about the problematic use were measured separately.

To confirm the validity of the questionnaire, a panel of experts with CVR 0.49 and CVI 0.70 was used. Its reliability was also obtained (0.784) using Cronbach’s alpha coefficient. Finally, the questionnaire was tested in a class with 30 students to check the level of difficulty and comprehension of the questionnaire. Finally, a 22-item questionnaire was obtained, of which six items were about the problematic use of social media and the remaining 16 questions were about the rate and frequency of using social media. Cronbach’s alpha was 0.705 for the first part, including questions about the problematic use of the social media, and 0.794 for the second part, including questions about the rate and frequency of using the social media. The total Cronbach’s alpha for all questions was 0.830. Six questions about the problematic use of social media were measured separately due to the importance of the problematic use of social media. Also, a separate score was considered for each question. The scores of these six questions on the problematic use of the social media were summed, and a single score was obtained for analysis.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 26.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The normal distribution of continuous variables was analyzed using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, histogram, and P-P diagram, which showed that they are not normally distributed. Descriptive statistics were calculated for all variables. Comparison between groups was done using Mann-Whitney and Kruskal-Wallis non-parametric tests. Multiple linear regression analysis was used to investigate the relationship between mental health, problematic use of social media, and social media use (The result of merging the Frequency of using social media and Time to use social media). Generalized Linear Models (GLM) were used to assess the association between mental health with the use of social media and problematic use of social media. Due to the high correlation (r = 0.585, p = < 0.001) between the use of social media and problematic use of social media, collinearity, we run two separate GLM models. Regression coefficients (β) and adjusted β (β*) with 95% CI and P-value were reported.

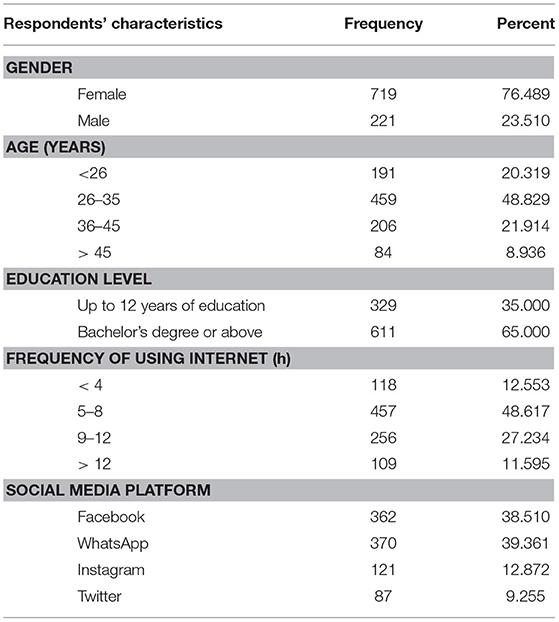

A total of 781 participants completed the questionnaires, of which 64.4% were women and 71.3% were single. The minimum age of the participants was 17 years, the maximum age was 45 years, and about half of them (48.9%) were between 21 and 25 years old. A total of 53.4% of the participants had bachelor’s degrees. The income level of 23.2% of participants was less than five million Tomans (the currency of Iran), and 69.7% of the participants were unemployed. 88.1% were living with their families and 70.8% were studying in non-medical fields. 86% of the participants lived in the city, and 58.9% were in their fourth semester or higher. Considering that the research was conducted in a Lorish Province, 43.8% of participants were from the Lorish ethnicity.

The mean total score of mental health was 12.30 with a standard deviation of 30.38, and the mean total score of social media was 14.5557 with a standard deviation of 7.74140.

Table 1 presents a comparison of the mean problematic use of social media and mental health with demographic variables. Considering the non-normality of the hypothesis H0, to compare the means of the independent variables, Mann-Whitney non-parametric tests (for the variables of gender, the field of study, academic semester, employment status, province of residence, and whether it is rural or urban) and Kruskal Wallis (for the variables age, ethnicity, level of education, household income and marital status). According to the obtained results, it was found that the score of problematic use of social media is significantly higher in women, the age group less than 20 years, unemployed, non-native students, dormitory students, and students living with friends or alone, Fars students, students with a household income level of fewer than 7 million Tomans(Iranian currency), and single, divorced, and widowed students were higher than the other groups(P < 0.05).

By comparing the mean score of mental health with demographic variables using non-parametric Mann-Whitney and Kruskal Wallis tests, it was found that there is a significant difference between the variable of poor mental health and all demographic variables (except for the semester variable), residence status (rural or urban) and education level. (There was a significant relationship (P < 0.05). In such a way that the mental health condition was worse in women, age group less than 20 years old, non-medical science, unemployed, non-native, and dormitory students. Also, Fars students, divorced, widowed, and students with a household income of fewer than 5 million Tomans (Iranian currency) showed poorer mental health status. (Table 1 ).

The final model shows that marital status, field, and household income were significantly associated with lower DASS21 scores (a lower DASS21 score means better mental health status). Being single (β* = -23.03, 95% CI: (-33.10, -12.96), being married (β* = -38.78, 95% CI: -51.23, -26.33), was in Medical sciences fields (β* = -8.15, 95% CI: -11.37, -4.94), and have income 7–10 million (β* = -5.66, 95% CI: -9.62, -1.71) were significantly associated with lower DASS21 scores (a lower DASS21 score means better mental health status). Problematic use of social media (β* = 3.54, 95% CI: (3.23, 3.85) was significantly associated with higher mental health scores (a higher DASS21 score means worse mental health status). (Table 2 )

Age, income, and use of social media (β* = 1.02, 95% CI: 0.78, 1.25) were significantly associated with higher DASS21 scores (a higher DASS21 score means worse mental health status). Marital status and field were significantly associated with lower DASS21 scores (a lower DASS21 score means better mental health status). Age groups < 20 years (β* = 6.36, 95% CI: 0.78, 11.95) and income group < 5 million (β* = 6.58, 95% CI: 1.47, 11.70) increased mental health scores. Being single (β* = -34.72, 95% CI: -47.06, -38.78), being married (β* = -38.78, 95% CI: -51.23, -26.33) and in medical sciences fields (β* = -8.17, 95% CI: -12.09, -4.24) decreased DASS21 scores. (Table 3 )

The main purpose of this study was to determine the relationship between social media use and mental health among students during the COVID-19 pandemic.

University students are more reliant on social media because of the limitations of in-person interactions [ 45 ]. Since social media has become more and more vital to the social lives of university students during the pandemic, students may be at increased risk of social media addiction, which may be harmful to their mental health [ 14 ].

During non-adulthood, peer relations and approval are critical and social media seems to meet these needs. For example, connection and communication with friends make them feel better and happier, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic and national lockdowns where face-to-face communication was restricted [ 46 ]. Kele’s study showed that the COVID-19 pandemic has increased the time spent on social media, and the frequency of online activities [ 47 ].

Because of the COVID-19 pandemic, e-learning became the only sustainable option for students [ 13 ]. This abrupt transition can lead to depression, stress, or anxiety for some students due to insufficient time to adjust to the new learning environment. The role of social media is also important to some university students [ 48 ].

Staying at home, having nothing else to do, and being unable to go out and meet with friends due to the lockdown measures increased the time spent on social media and the frequency of online activities, which influenced their mental health negatively [ 49 ]. These reasons may explain the findings of previous studies that found an increase in depression and anxiety among adolescents who were healthy before the COVID-19 pandemic [ 50 ].

According to the results, there was a statistically significant relationship between social media use and mental health in students, in such a way that one Unit increase in the score of social media use enhanced the score of mental health. These two variables were directly correlated. Consistent with the current study, many studies have shown a significant relationship between higher use of social media and lower mental health in students [ 45 , 51 , 52 , 53 , 54 ].

Inconsistent with the findings of the present study, some previous studies reported the positive effect of social media use on mental health [ 55 , 56 , 57 ]. The differences in findings could be attributed to the time and location of the studies. Anderson’s study in France in 2018 found no significant relationship between social media use and mental health. This may be because of the differences between the tools for measuring the ability to detect fake news and health literacy and the scales of the research [ 4 ].

The present study showed that the impact of using social media on the mental health of students was higher than Lebni’s study, which was conducted in 2020 [ 25 ]. Also, in Dost Mohammad’s study in 2018, the effect of using social media on the mental health of students was reported to be lower than in the present study [ 58 ]. Entezari’s study in 2021, was also lower than the present study [ 59 ]. It seems that the excessive use of social media during the COVID-19 pandemic was the reason for the greater effects of social media on students’ mental health.

The use of social media has positive and negative characteristics. Social media is most useful for rapidly disseminating timely information via widely accessible platforms [ 4 ]. Among the types of studies, at least one shows an inverse relationship between the use of social media and mental health [ 53 ]. While social media can serve as a tool for fostering connection during periods of physical isolation, the mental health implications of social media being used as a news source are tenuous [ 45 ].

The results of the GLM analysis indicated that there was a statistically significant relationship between the problematic use of social media and mental health in students in such a way that one-unit increase in the score of problematic use of social media enhanced the mental health score, and it was found that the two variables had a direct relationship. Consistent with our study, Boer’s study showed that problematic use of social media may highlight the potential risk to adolescent mental health [ 60 ]. Malaeb also reported that the problematic use of social media had a positive relationship with mental health [ 61 ], but that study was conducted on adults and had a smaller sample size before the COVID-19 pandemic.

Saputri’s study found that excessive social media use likely harms the mental health of university students since students with higher social media addiction scores had a greater risk of experiencing mild depression [ 62 ]. A systematic literature review before the COVID-19 pandemic (2019) found that the time spent by adolescents on social media was associated with depression, anxiety, and psychological distress [ 63 ]. Marino’s study (2018) reported a significant correlation between the problematic use of social media by students and psychological distress [ 64 ].

Social media has become more vital for students’ social lives owing to online education during the COVID-19 pandemic. Therefore, this group is more at risk of addiction to social media and may experience more mental health problems than other groups. Lebni also indicated that students’ higher use of the Internet led to anxiety, depression, and adverse mental health, but the main purpose of the study was to investigate the effects of such factors on student’s academic performance [ 25 ]. Previous studies indicated that individuals who spent more time on social media had lower self-esteem and higher levels of anxiety and depression [ 65 , 66 ]. In the present study, students with higher social media addiction scores were at higher mental health risk. Such a finding was consistent with research by Gao et al., who found that the excessive use of social media during the pandemic had adverse effects on social health [ 14 ]. Cheng et al. indicated that using the Internet, especially for communication with people, can harm mental health by changing the quality of social relationships, face-to-face communication, and changes in social support [ 24 ].

A reason for the significant relationship between social media use and mental health in students during the COVID-19 pandemic in the present study was probably the students’ intentional or unintentional use of online communication. Unfortunately, social media published information, which might be incorrect, in this pandemic that caused public fear and threatened mental health.

During the pandemic, social media played essential roles in learning and leisure activities. Due to electronic education, staying at home, and long leisure time, students had more time, frequency, and opportunities to use social media in this pandemic. Such a high reliance on social media may threaten student’s mental health. Lee et al. conducted a study during the COVID-19 pandemic and confirmed that young people who used social media had higher symptoms of depression and loneliness than before the COVID-19 pandemic [ 67 ].

The present study showed that there was a significant positive relationship between problematic use of social media and gender, so that women were more willing to use social media, probably because they had more opportunities to use social media as they stayed at home more than men; hence, they were more exposed to problematic use of social media. Consistent with our study, Andreassen reported that being a woman was an important factor in social media addiction [ 68 ]. In contrast to our study, Azizi’s study in Iran showed that male students use social media significantly more than female students, possibly due to differences in demographic variables in each population [ 69 ].

Moreover, there was a significant relationship between age and problematic use of social media in that people younger than 20 were more willing to use social media in a problematic way. Consistent with the present study, Perrin also indicated that younger people further used social media [ 70 ].

According to the findings, unemployed students used social media more than employed ones, probably because they had more time to spend in virtual space, leading to higher use and the possibility of problematic use of social media [ 71 ].

Moreover, non-native students were more willing to use the social media probably because students who lived far away from their families used social media problematically due to the lack of family control over hours of use and higher opportunities [ 72 ] .

The results showed that rural students have a greater tendency to use social Medias than urban students. Inconsistent with this finding, Perrin reported that urban people were more willing to use the social media. The difference was probably due to different research times and places or different target groups [ 70 ].

According to the current study, people with low household income were more likely to use social media, most likely because low-income people seek free information and services due to a lack of access to facilities and equipment in the real world or because they seek assimilation with people around them. Inconsistent with our findings, Hruska et al. reported that people with high household income levels made much use of social media [ 73 ], probably because of cultural, economic, and social differences or different information measurement tools.

Furthermore, single, divorced, and widowed students used social media more than married students. This is because they spend more time on social media due to the need for more emotional attention, the search for a life partner, or a feeling of loneliness. This also led to the problematic use of social media [ 74 ].

According to the results, Fars people used social media more than other ethnic groups, but this difference was insignificant. This finding was consistent with Perrin’s study, but the population consisted of people aged 18 to 65 [ 70 ].

In the current study, there was a significant relationship between gender and mental health, so that women had lower mental health than men. The difference was in health sociology. Consistent with the present study, Ghasemi et al. indicated that it appeared necessary to pay more attention to women’s health and create an opportunity for them to use health services [ 75 ].

The findings revealed that unemployed students had lower mental health than employed students, most likely because unemployed individuals have lower mental health due to not having a job and being economically dependent on others, as well as feeling incompetent at times. Consistent with the present study, Bialowolski reported that unemployment and low income caused mental disorders and threatened mental health [ 76 ].

According to this study, non-native students have lower mental health than native students because they live far from their families. The family plays an imperative role in improving the mental health of their children, and mental health requires their support. Also, the economic, social, and support problems caused by being away from the family have endangered their mental health [ 77 ].

Another important factor of the current study was that married people had higher mental health than single people. In addition, divorced and widowed students had lower mental health [ 78 ]. Possibly due to the social pressure they suffer in Iranian society. Furthermore, they received lower emotional support than married people. Therefore, their lower mental health seemed logical [ 79 , 80 , 81 ]. A large study in a European population also reported differences in the likelihood of mood, anxiety, and personality disorders between separated/divorced and married mothers [ 82 ].

A key point confirmed in other studies is the relationship between low incomes with mental health. A meta-analysis by Lorant indicated that economic and social inequalities caused mental disorders [ 83 ]. Safran also reported that the probability of developing mental disorders in people with low socioeconomic status is up to three times higher than that of people with the highest socioeconomic status [ 84 ]. Bialowolski’s study was consistent with the current study but Bialowolski’s study examined employees [ 76 ].

The present study was conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic and therefore had limitations in accessing students. Another limitation was the use of self-reporting tools. Participants may show positive self-presentation by over- or under-reporting their social media-related behaviors and some mental health-related items, which may directly or indirectly lead to social desirability bias, information bias, and reporting bias. Small sample sizes and convenience sampling limit student population representativeness and generalizability. This study was based on cross-sectional data. Therefore, the estimation results should be seen as associative rather than causative. Future studies would need to investigate causal effects using a longitudinal or cohort design, or another causal effect research design.

The findings of this study indicated that the high use of social media affected students’ mental health. Furthermore, the problematic use of the social media had a direct relationship with mental health. Variables such as age, gender, income level, marital status, and unemployment of non-native students had significant relationships with social media use and mental health. Despite the large amount of evidence suggesting that social media harms mental health, more research is still necessary to determine the cause and how social media can be used without harmful effects. It is imperative to better understand the relationship between social media use and mental health symptoms among young people to prevent such a negative outcome.

Data Availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Austin LL, Jin Y. Social media and crisis communication. Routledge New York; 2018.

Carr CT, Hayes RAJAjoc. Social media: defining, developing, and divining. 2015;23(1):46–65.

Fathi A, Sadeghi S, Maleki Rad AA, Sharifi Rahnmo S, Rostami H, Abdolmohammadi KJIJoP et al. The role of Cyberspace Use on Lifestyle promoting health and coronary anxiety in Young Peopl. 2020;26(3):332–47.

Anderson M, Jiang JJPRC. Teens, social media & technology 2018. 2018;31(2018):1673-89.

Nakaya ACJW. Internet and social media addiction. 2015;12(2):1–3.

Hemayatkhah M. The Impact Of Virtual Social Networks On Women’s Social Deviations. 2021.

Chaffey DJSISMM. Global social media research summary 2016. 2016.

Naderi N, Pourjamshidi HJJoBAR. The role of social networks on entrepreneurial orientation of students: a case study of Razi University. 2022;13(26):291–309.

Narmenji SM, Nowkarizi M, Riahinia N, Zerehsaz MJS. Investigating the behavior of sharing information of students in the virtual Social Networks: Instagram, Telegram and WhatsApp. Manage ToI. 2020;6(4):49–78.

Google Scholar

Zarocostas JJTl. How to fight an infodemic. 2020;395(10225):676.

de Ávila GB, Dos Santos ÉN, Jansen K. Barros FCJTip, psychotherapy. Internet addiction in students from an educational institution in Southern Brazil: prevalence and associated factors. 2020;42:302–10.

Cain JJAjope. It’s time to confront student mental health issues associated with smartphones and social media. 2018;82(7).

Cavus N, Sani AS, Haruna Y, Lawan AAJS. Efficacy of Social networking Sites for Sustainable Education in the era of COVID-19: a systematic review. 2021;13(2):808.

Gao J, Zheng P, Jia Y, Chen H, Mao Y, Chen S et al. Mental health problems and social media exposure during COVID-19 outbreak. 2020;15(4):e0231924.

Moreno MA, Kolb JJPC. Social networking sites and adolescent health. 2012;59(3):601–12.

Claval PJLEg. Marxism and space. 1993;1(1):73–96.

Thomas L, Orme E, Kerrigan FJC. Student loneliness: the role of social media through life transitions. Education. 2020;146:103754.

Dixon SJCSOhwscsg-s-n-r-b-n-o-u. Global social networks ranked by number of users 2022. 2022.

Sindermann C, Elhai JD, Montag CJPR. Predicting tendencies towards the disordered use of Facebook’s social media platforms: On the role of personality, impulsivity, and social anxiety. 2020;285:112793.

Zheng B, Bi G, Liu H, Lowry PBJH. Corporate crisis management on social media: A morality violations perspective. 2020;6(7):e04435.

Schou Andreassen C, Pallesen SJCpd. Social network site addiction-an overview. 2014;20(25):4053–61.

Hussain Z, Griffiths MDJIJoMH. Addiction. The associations between problematic social networking site use and sleep quality, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, depression. anxiety and stress. 2021;19:686–700.

Hussain Z, Starcevic, VJCoip. Problematic social networking site use: a brief review of recent research methods and the way forward. 2020;36:89–95.

Cheng C, Lau Y-c, Chan L, Luk JWJAB. Prevalence of social media addiction across 32 nations: Meta-analysis with subgroup analysis of classification schemes and cultural values. 2021;117:106845.

Lebni JY, Toghroli R, Abbas J, NeJhaddadgar N, Salahshoor MR, Mansourian M, et al. A study of internet addiction and its effects on mental health. A study based on Iranian University Students; 2020. p. 9.

Griffiths MD, Kuss DJ, Demetrovics ZJBa. Social networking addiction: An overview of preliminary findings. 2014:119 – 41.

O’reilly M, Dogra N, Whiteman N, Hughes J, Eruyar S, Reilly PJCcp et al. Is social media bad for mental health and wellbeing? Exploring the perspectives of adolescents. 2018;23(4):601–13.

Huang CJC, Behavior, Networking S. Time spent on social network sites and psychological well-being: a meta-analysis. 2017;20(6):346–54.

MPh MMJJMAT. Facebook addiction and its relationship with mental health among thai high school students. 2015;98(3):S81–S90.

Galderisi S, Heinz A, Kastrup M, Beezhold J. Sartorius NJWp. Toward a new definition of mental health. 2015;14(2):231.

Health WHODoM, Abuse S, Organization WH, Health WHODoM, Health SAM, Evidence WHOMH, et al. Mental health atlas 2005. World Health Organization; 2005.

Massari LJISF. Analysis of MySpace user profiles. 2010;12:361-7.

Chang P-J, Wray L, Lin YJHP. Social relationships, leisure activity, and health in older adults. 2014;33(6):516.

Cunningham S, Hudson C, Harkness K. Social media and depression symptoms: a meta-analysis. Res Child Adolesc Psychopathol. 2021;49(2):241–53.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Haand R, Shuwang ZJIJoA. Youth. The relationship between social media addiction and depression: a quantitative study among university students in Khost. Afghanistan. 2020;25(1):780–6.

Kim B-S, Chang SM, Park JE, Seong SJ, Won SH. Cho MJJPr. Prevalence, correlates, psychiatric comorbidities, and suicidality in a community population with problematic Internet use. 2016;244:249 – 56.

Zadra S, Bischof G, Besser B, Bischof A, Meyer C, John U et al. The association between internet addiction and personality disorders in a general population-based sample. 2016;5(4):691–9.

Richards D, Caldwell PH. Go HJJop, health c. Impact of social media on the health of children and young people. 2015;51(12):1152–7.

Al-Menayes JJJP, Sciences B. Dimensions of social media addiction among university students in Kuwait. 2015;4(1):23–8.

Hou Y, Xiong D, Jiang T, Song L, Wang QJCJoproc. Social media addiction: Its impact, mediation, and intervention. 2019;13(1).

Chen I-H, Pakpour AH, Leung H, Potenza MN, Su J-A, Lin C-Y et al. Comparing generalized and specific problematic smartphone/internet use: longitudinal relationships between smartphone application-based addiction and social media addiction and psychological distress. 2020;9(2):410–9.

Tang CS-k. Koh YYWJAjop. Online social networking addiction among college students in Singapore: Comorbidity with behavioral addiction and affective disorder. 2017;25:175–8.

Samani S, Jokar B. Validity and reliability short-form version of the Depression, Anxiety and Stress. 2001.

Taghavifard MT, Ghafurian Shagerdi A, Behboodi OJJoBAR. The Effect of Market Orientation on Business Performance. 2015;7(13):205–27.

Haddad JM, Macenski C, Mosier-Mills A, Hibara A, Kester K, Schneider M et al. The impact of social media on college mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic: a multinational review of the existing literature. 2021;23:1–12.

Fiacco A. Adolescent perspectives on media use: a qualitative study. Antioch University; 2020.

Keles B, Grealish A, Leamy MJCP. The beauty and the beast of social media: an interpretative phenomenological analysis of the impact of adolescents’ social media experiences on their mental health during the Covid-19 pandemic. 2023:1–17.

Lim LTS, Regencia ZJG, Dela Cruz JRC, Ho FDV, Rodolfo MS, Ly-Uson J et al. Assessing the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic, shift to online learning, and social media use on the mental health of college students in the Philippines: a mixed-method study protocol. 2022;17(5):e0267555.

Cohen ZP, Cosgrove KT, DeVille DC, Akeman E, Singh MK, White E et al. The impact of COVID-19 on adolescent mental health: preliminary findings from a longitudinal sample of healthy and at-risk adolescents. 2021:440.

Levita L, Miller JG, Hartman TK, Murphy J, Shevlin M, McBride O et al. Report1: Impact of Covid-19 on young people aged 13–24 in the UK-preliminary findings. 2020.

Conrad RC, Koire A, Pinder-Amaker S, Liu CHJJoPR. College student mental health risks during the COVID-19 pandemic: Implications of campus relocation. 2021;136:117 – 26.

Li Y, Zhao J, Ma Z, McReynolds LS, Lin D, Chen Z et al. Mental health among college students during the COVID-19 pandemic in China: a 2-wave longitudinal survey. 2021;281:597–604.

Zhao N, Zhou GJAPH, Well-Being. Social media use and mental health during the COVID‐19 pandemic: moderator role of disaster stressor and mediator role of negative affect. 2020;12(4):1019–38.

Saputri RAM, Yumarni, TJIJoMH. Addiction. Social media addiction and mental health among university students during the COVID-19 pandemic in Indonesia. 2021:1–15.

Glaser P, Liu JH, Hakim MA, Vilar R, Zhang RJNZJoP. Is social media use for networking positive or negative? Offline social capital and internet addiction as mediators for the relationship between social media use and mental health. 2018;47(3):12–8.

Nabi RL, Prestin A, So JJC. Behavior, networking s. Facebook friends with (health) benefits? Exploring social network site use and perceptions of social support, stress, and well-being. 2013;16(10):721–7.

Campisi J, Folan D, Diehl G, Kable T, Rademeyer CJPR. Social media users have different experiences, motivations, and quality of life. 2015;228(3):774–80.

Dost Mohammadi M, Khojaste S, Doukaneifard FJJoQRiHS. Investigating the relationship between the use of social networks with self-confidence and mental health of faculty members and students of Payam Noor University. Kerman. 2020;8(4):16–27.

Franco JA. Carrier LMJHb, technologies e. Social media use and depression, anxiety, and stress in Latinos: A correlational study. 2020;2(3):227 – 41.

Boer M, Stevens GW, Finkenauer C, de Looze ME, Eijnden RJJCiHB. Social media use intensity, social media use problems, and mental health among adolescents: Investigating directionality and mediating processes. 2021;116:106645.

Malaeb D, Salameh P, Barbar S, Awad E, Haddad C, Hallit R et al. Problematic social media use and mental health (depression, anxiety, and insomnia) among Lebanese adults: Any mediating effect of stress? 2021;57(2):539 – 49.

Saputri RAM, Yumarni TJIJoMH. Addiction. Social media addiction and mental health among university students during the COVID-19 pandemic in Indonesia. 2023;21(1):96–110.

Keles B, McCrae N, Grealish AJIJoA. Youth. A systematic review: the influence of social media on depression, anxiety and psychological distress in adolescents. 2020;25(1):79–93.

Marino C, Gini G, Vieno A, Spada MMJJoAD. The associations between problematic Facebook use, psychological distress and well-being among adolescents and young adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. 2018;226:274–81.

Vannucci A, Flannery KM. Ohannessian CMJJoad. Social media use and anxiety in emerging adults. 2017;207:163-6.

Huang CJC. behavior, networking s. Internet use and psychological well-being: A meta-analysis. 2010;13(3):241-9.

Lee Y, Yang BX, Liu Q, Luo D, Kang L, Yang F et al. Synergistic effect of social media use and psychological distress on depression in China during the COVID-19 epidemic. 2020;74(10):552.

Andreassen CS, Pallesen S, Griffiths MDJAb. The relationship between addictive use of social media, narcissism, and self-esteem: findings from a large national survey. 2017;64:287–93.

Azizi SM, Soroush A, Khatony AJBp. The relationship between social networking addiction and academic performance in iranian students of medical sciences: a cross-sectional study. 2019;7(1):1–8.

Perrin AJPrc. Social media usage. 2015;125:52–68.

Kemp. SJD-RAhdcrm-t-h-t-w-u-s-m. More than half of the people on earth now use social media. 2020.

Vejmelka L, Matković R, Borković DKJIJoC, Youth, Studies F. Online at risk! Online activities of children in dormitories: experiences in a croatian county. 2020;11(4):54–79.

Hruska J, Maresova PJS. Use of social media platforms among adults in the United States—behavior on social media. 2020;10(1):27.

Huo J, Desai R, Hong Y-R, Turner K, Mainous AG III, Bian JJCC. Use of social media in health communication: findings from the health information national trends survey 2013, 2014, and 2017. 2019;26(1):1073274819841442.

Ghasemi S, Delavaran A, Karimi ZJQEM. A comparative study of the total index of mental health in males and females through meta-analysis method. 2012;3(10):159–75.

Bialowolski P, Weziak-Bialowolska D, Lee MT, Chen Y, VanderWeele TJ, McNeely EJSS et al. The role of financial conditions for physical and mental health. Evidence from a longitudinal survey and insurance claims data. 2021;281:114041.

Moradi GJSWQ. Correlation between social capital and mental health among hostel students of tehran and shiraz universities. 2008;8(30):143–70.

Mohebbi Z, Setoodeh G, Torabizadeh C, Rambod MJIyeee. State of mental health and associated factors in nursing students from Southeastern Iran. 2019;37(3).

Grundström J, Konttinen H, Berg N, Kiviruusu OJS-ph. Associations between relationship status and mental well-being in different life phases from young to middle adulthood. 2021;14:100774.

Vaingankar JA, Abdin E, Chong SA, Shafie S, Sambasivam R, Zhang YJ et al. The association of mental disorders with perceived social support, and the role of marital status: results from a national cross-sectional survey. 2020;78(1):1–11.

McLuckie A, Matheson KM, Landers AL, Landine J, Novick J, Barrett T et al. The relationship between psychological distress and perception of emotional support in medical students and residents and implications for educational institutions. 2018;42:41–7.

Afifi TO, Cox BJ. Enns MWJSp, epidemiology p. Mental health profiles among married, never-married, and separated/divorced mothers in a nationally representative sample. 2006;41:122–9.

Lorant V, Deliège D, Eaton W, Robert A, Philippot P. Ansseau MJAjoe. Socioeconomic inequalities in depression: a meta-analysis. 2003;157(2):98–112.

Safran MA, Mays RA Jr, Huang LN, McCuan R, Pham PK, Fisher SK, et al. Mental health disparities. 2009;99(11):1962–6.

Download references

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express their gratitude to all academic officials of Lorestan universities and Mr. Mohsen Amani for their cooperation in data collection.

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Health Education and Promotion, Faculty of Health, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, 1417613151, Iran

Abouzar Nazari

Department of Health Education and Promotion, Faculty of Health, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Isfahan, Iran

Maede Hosseinnia

Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Faculty of Health, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, 1417613151, Iran

Samaneh Torkian

Department of Health Education and Promotion, School of Health, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, 1417613151, Iran

Gholamreza Garmaroudi

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

Abouzar Nazari and Maedeh Hossennia designed the study, collected the data and drafted the manuscript. Samaneh Torkian performed the statistical analysis and prepared the tables. Gholamreza Garmaroudi, as the responsible author, supervised the entire study. All authors reviewed and edited the draft manuscript and approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Gholamreza Garmaroudi .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

Permission was obtained from the Ethics Committee of the Tehran University of Medical Sciences (IR.TUMS.SPH.REC.1400.258) before starting the study and follows the principles outlined in the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its subsequent amendments. Participants were informed about the purpose and benefits of the study. Sending the completed questionnaire was considered as informed consent to participate in the research. The respondents’ participation was completely consensual, anonymous, and voluntary. (The present data were collected before social media filtering in Iran).

Consent for publication

Competing interests.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Nazari, A., Hosseinnia, M., Torkian, S. et al. Social media and mental health in students: a cross-sectional study during the Covid-19 pandemic. BMC Psychiatry 23 , 458 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-023-04859-w

Download citation

Received : 31 January 2023

Accepted : 10 May 2023

Published : 22 June 2023

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-023-04859-w

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Mental Health

BMC Psychiatry

ISSN: 1471-244X

- Submission enquiries: [email protected]

- General enquiries: [email protected]

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Effects of social media use on psychological well-being: a mediated model.

- 1 School of Finance and Economics, Jiangsu University, Zhenjiang, China

- 2 Research Unit of Governance, Competitiveness, and Public Policies (GOVCOPP), Center for Economics and Finance (cef.up), School of Economics and Management, University of Porto, Porto, Portugal

- 3 Department of Business Administration, Sukkur Institute of Business Administration (IBA) University, Sukkur, Pakistan

- 4 CETYS Universidad, Tijuana, Mexico

- 5 Department of Business Administration, Al-Quds University, Jerusalem, Israel

- 6 Business School, Shandong University, Weihai, China

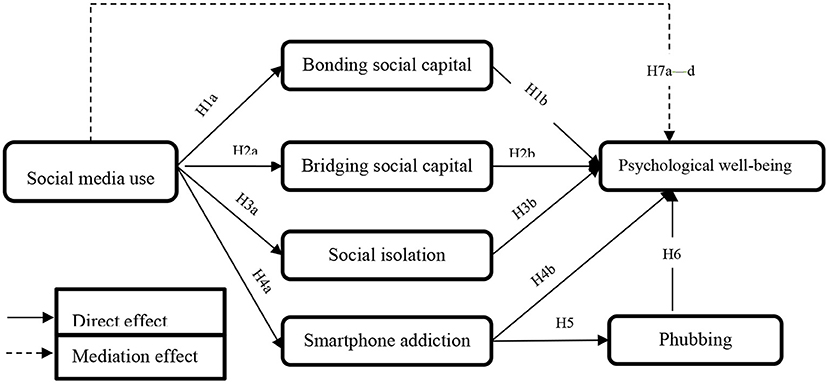

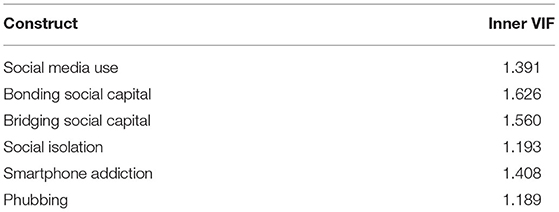

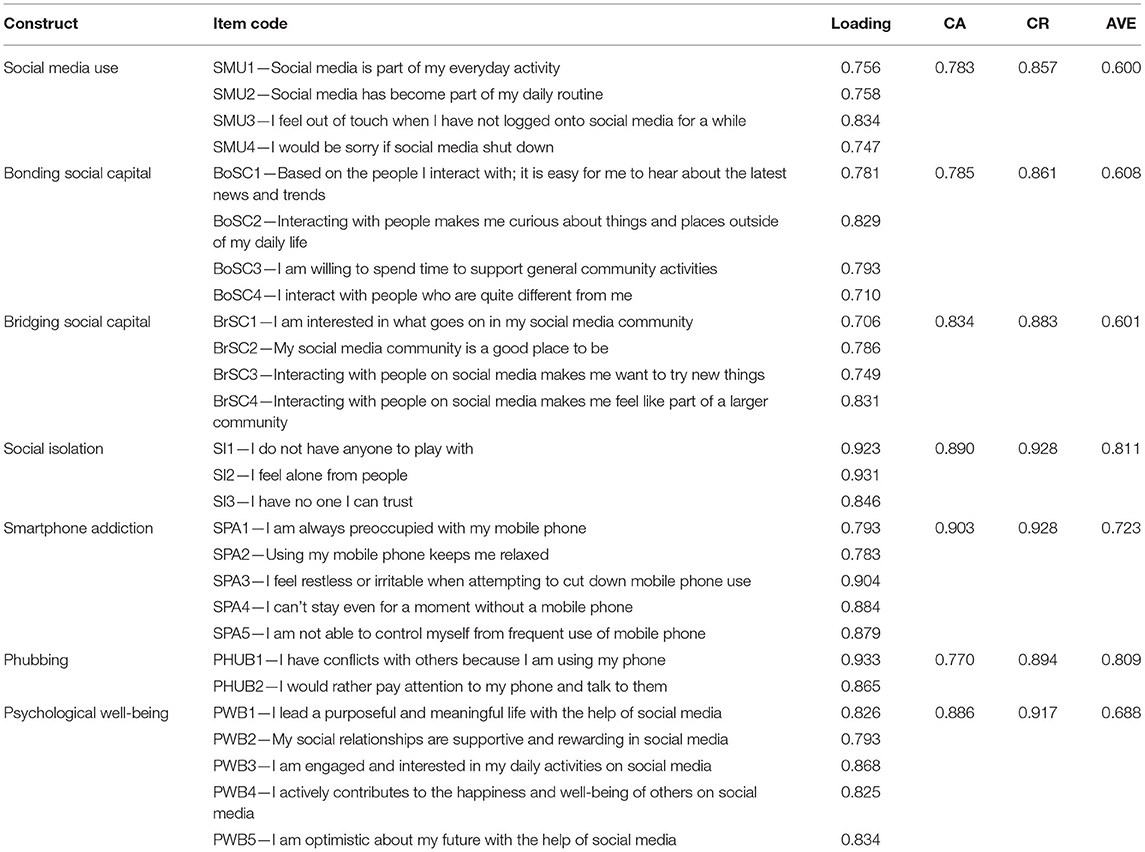

The growth in social media use has given rise to concerns about the impacts it may have on users' psychological well-being. This paper's main objective is to shed light on the effect of social media use on psychological well-being. Building on contributions from various fields in the literature, it provides a more comprehensive study of the phenomenon by considering a set of mediators, including social capital types (i.e., bonding social capital and bridging social capital), social isolation, and smartphone addiction. The paper includes a quantitative study of 940 social media users from Mexico, using structural equation modeling (SEM) to test the proposed hypotheses. The findings point to an overall positive indirect impact of social media usage on psychological well-being, mainly due to the positive effect of bonding and bridging social capital. The empirical model's explanatory power is 45.1%. This paper provides empirical evidence and robust statistical analysis that demonstrates both positive and negative effects coexist, helping to reconcile the inconsistencies found so far in the literature.

Introduction

The use of social media has grown substantially in recent years ( Leong et al., 2019 ; Kemp, 2020 ). Social media refers to “the websites and online tools that facilitate interactions between users by providing them opportunities to share information, opinions, and interest” ( Swar and Hameed, 2017 , p. 141). Individuals use social media for many reasons, including entertainment, communication, and searching for information. Notably, adolescents and young adults are spending an increasing amount of time on online networking sites, e-games, texting, and other social media ( Twenge and Campbell, 2019 ). In fact, some authors (e.g., Dhir et al., 2018 ; Tateno et al., 2019 ) have suggested that social media has altered the forms of group interaction and its users' individual and collective behavior around the world.

Consequently, there are increased concerns regarding the possible negative impacts associated with social media usage addiction ( Swar and Hameed, 2017 ; Kircaburun et al., 2020 ), particularly on psychological well-being ( Chotpitayasunondh and Douglas, 2016 ; Jiao et al., 2017 ; Choi and Noh, 2019 ; Chatterjee, 2020 ). Smartphones sometimes distract their users from relationships and social interaction ( Chotpitayasunondh and Douglas, 2016 ; Li et al., 2020a ), and several authors have stressed that the excessive use of social media may lead to smartphone addiction ( Swar and Hameed, 2017 ; Leong et al., 2019 ), primarily because of the fear of missing out ( Reer et al., 2019 ; Roberts and David, 2020 ). Social media usage has been associated with anxiety, loneliness, and depression ( Dhir et al., 2018 ; Reer et al., 2019 ), social isolation ( Van Den Eijnden et al., 2016 ; Whaite et al., 2018 ), and “phubbing,” which refers to the extent to which an individual uses, or is distracted by, their smartphone during face-to-face communication with others ( Chotpitayasunondh and Douglas, 2016 ; Jiao et al., 2017 ; Choi and Noh, 2019 ; Chatterjee, 2020 ).

However, social media use also contributes to building a sense of connectedness with relevant others ( Twenge and Campbell, 2019 ), which may reduce social isolation. Indeed, social media provides several ways to interact both with close ties, such as family, friends, and relatives, and weak ties, including coworkers, acquaintances, and strangers ( Chen and Li, 2017 ), and plays a key role among people of all ages as they exploit their sense of belonging in different communities ( Roberts and David, 2020 ). Consequently, despite the fears regarding the possible negative impacts of social media usage on well-being, there is also an increasing number of studies highlighting social media as a new communication channel ( Twenge and Campbell, 2019 ; Barbosa et al., 2020 ), stressing that it can play a crucial role in developing one's presence, identity, and reputation, thus facilitating social interaction, forming and maintaining relationships, and sharing ideas ( Carlson et al., 2016 ), which consequently may be significantly correlated to social support ( Chen and Li, 2017 ; Holliman et al., 2021 ). Interestingly, recent studies (e.g., David et al., 2018 ; Bano et al., 2019 ; Barbosa et al., 2020 ) have suggested that the impact of smartphone usage on psychological well-being depends on the time spent on each type of application and the activities that users engage in.

Hence, the literature provides contradictory cues regarding the impacts of social media on users' well-being, highlighting both the possible negative impacts and the social enhancement it can potentially provide. In line with views on the need to further investigate social media usage ( Karikari et al., 2017 ), particularly regarding its societal implications ( Jiao et al., 2017 ), this paper argues that there is an urgent need to further understand the impact of the time spent on social media on users' psychological well-being, namely by considering other variables that mediate and further explain this effect.

One of the relevant perspectives worth considering is that provided by social capital theory, which is adopted in this paper. Social capital theory has previously been used to study how social media usage affects psychological well-being (e.g., Bano et al., 2019 ). However, extant literature has so far presented only partial models of associations that, although statistically acceptable and contributing to the understanding of the scope of social networks, do not provide as comprehensive a vision of the phenomenon as that proposed within this paper. Furthermore, the contradictory views, suggesting both negative (e.g., Chotpitayasunondh and Douglas, 2016 ; Van Den Eijnden et al., 2016 ; Jiao et al., 2017 ; Whaite et al., 2018 ; Choi and Noh, 2019 ; Chatterjee, 2020 ) and positive impacts ( Carlson et al., 2016 ; Chen and Li, 2017 ; Twenge and Campbell, 2019 ) of social media on psychological well-being, have not been adequately explored.

Given this research gap, this paper's main objective is to shed light on the effect of social media use on psychological well-being. As explained in detail in the next section, this paper explores the mediating effect of bonding and bridging social capital. To provide a broad view of the phenomenon, it also considers several variables highlighted in the literature as affecting the relationship between social media usage and psychological well-being, namely smartphone addiction, social isolation, and phubbing. The paper utilizes a quantitative study conducted in Mexico, comprising 940 social media users, and uses structural equation modeling (SEM) to test a set of research hypotheses.

This article provides several contributions. First, it adds to existing literature regarding the effect of social media use on psychological well-being and explores the contradictory indications provided by different approaches. Second, it proposes a conceptual model that integrates complementary perspectives on the direct and indirect effects of social media use. Third, it offers empirical evidence and robust statistical analysis that demonstrates that both positive and negative effects coexist, helping resolve the inconsistencies found so far in the literature. Finally, this paper provides insights on how to help reduce the potential negative effects of social media use, as it demonstrates that, through bridging and bonding social capital, social media usage positively impacts psychological well-being. Overall, the article offers valuable insights for academics, practitioners, and society in general.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section Literature Review presents a literature review focusing on the factors that explain the impact of social media usage on psychological well-being. Based on the literature review, a set of hypotheses are defined, resulting in the proposed conceptual model, which includes both the direct and indirect effects of social media usage on psychological well-being. Section Research Methodology explains the methodological procedures of the research, followed by the presentation and discussion of the study's results in section Results. Section Discussion is dedicated to the conclusions and includes implications, limitations, and suggestions for future research.

Literature Review

Putnam (1995 , p. 664–665) defined social capital as “features of social life – networks, norms, and trust – that enable participants to act together more effectively to pursue shared objectives.” Li and Chen (2014 , p. 117) further explained that social capital encompasses “resources embedded in one's social network, which can be assessed and used for instrumental or expressive returns such as mutual support, reciprocity, and cooperation.”

Putnam (1995 , 2000) conceptualized social capital as comprising two dimensions, bridging and bonding, considering the different norms and networks in which they occur. Bridging social capital refers to the inclusive nature of social interaction and occurs when individuals from different origins establish connections through social networks. Hence, bridging social capital is typically provided by heterogeneous weak ties ( Li and Chen, 2014 ). This dimension widens individual social horizons and perspectives and provides extended access to resources and information. Bonding social capital refers to the social and emotional support each individual receives from his or her social networks, particularly from close ties (e.g., family and friends).

Overall, social capital is expected to be positively associated with psychological well-being ( Bano et al., 2019 ). Indeed, Williams (2006) stressed that interaction generates affective connections, resulting in positive impacts, such as emotional support. The following sub-sections use the lens of social capital theory to explore further the relationship between the use of social media and psychological well-being.

Social Media Use, Social Capital, and Psychological Well-Being

The effects of social media usage on social capital have gained increasing scholarly attention, and recent studies have highlighted a positive relationship between social media use and social capital ( Brown and Michinov, 2019 ; Tefertiller et al., 2020 ). Li and Chen (2014) hypothesized that the intensity of Facebook use by Chinese international students in the United States was positively related to social capital forms. A longitudinal survey based on the quota sampling approach illustrated the positive effects of social media use on the two social capital dimensions ( Chen and Li, 2017 ). Abbas and Mesch (2018) argued that, as Facebook usage increases, it will also increase users' social capital. Karikari et al. (2017) also found positive effects of social media use on social capital. Similarly, Pang (2018) studied Chinese students residing in Germany and found positive effects of social networking sites' use on social capital, which, in turn, was positively associated with psychological well-being. Bano et al. (2019) analyzed the 266 students' data and found positive effects of WhatsApp use on social capital forms and the positive effect of social capital on psychological well-being, emphasizing the role of social integration in mediating this positive effect.

Kim and Kim (2017) stressed the importance of having a heterogeneous network of contacts, which ultimately enhances the potential social capital. Overall, the manifest and social relations between people from close social circles (bonding social capital) and from distant social circles (bridging social capital) are strengthened when they promote communication, social support, and the sharing of interests, knowledge, and skills, which are shared with other members. This is linked to positive effects on interactions, such as acceptance, trust, and reciprocity, which are related to the individuals' health and psychological well-being ( Bekalu et al., 2019 ), including when social media helps to maintain social capital between social circles that exist outside of virtual communities ( Ellison et al., 2007 ).

Grounded on the above literature, this study proposes the following hypotheses:

H1a: Social media use is positively associated with bonding social capital.

H1b: Bonding social capital is positively associated with psychological well-being.

H2a: Social media use is positively associated with bridging social capital.

H2b: Bridging social capital is positively associated with psychological well-being.

Social Media Use, Social Isolation, and Psychological Well-Being

Social isolation is defined as “a deficit of personal relationships or being excluded from social networks” ( Choi and Noh, 2019 , p. 4). The state that occurs when an individual lacks true engagement with others, a sense of social belonging, and a satisfying relationship is related to increased mortality and morbidity ( Primack et al., 2017 ). Those who experience social isolation are deprived of social relationships and lack contact with others or involvement in social activities ( Schinka et al., 2012 ). Social media usage has been associated with anxiety, loneliness, and depression ( Dhir et al., 2018 ; Reer et al., 2019 ), and social isolation ( Van Den Eijnden et al., 2016 ; Whaite et al., 2018 ). However, some recent studies have argued that social media use decreases social isolation ( Primack et al., 2017 ; Meshi et al., 2020 ). Indeed, the increased use of social media platforms such as Facebook, WhatsApp, Instagram, and Twitter, among others, may provide opportunities for decreasing social isolation. For instance, the improved interpersonal connectivity achieved via videos and images on social media helps users evidence intimacy, attenuating social isolation ( Whaite et al., 2018 ).

Chappell and Badger (1989) stated that social isolation leads to decreased psychological well-being, while Choi and Noh (2019) concluded that greater social isolation is linked to increased suicide risk. Schinka et al. (2012) further argued that, when individuals experience social isolation from siblings, friends, family, or society, their psychological well-being tends to decrease. Thus, based on the literature cited above, this study proposes the following hypotheses:

H3a: Social media use is significantly associated with social isolation.

H3b: Social isolation is negatively associated with psychological well-being.

Social Media Use, Smartphone Addiction, Phubbing, and Psychological Well-Being

Smartphone addiction refers to “an individuals' excessive use of a smartphone and its negative effects on his/her life as a result of his/her inability to control his behavior” ( Gökçearslan et al., 2018 , p. 48). Regardless of its form, smartphone addiction results in social, medical, and psychological harm to people by limiting their ability to make their own choices ( Chotpitayasunondh and Douglas, 2016 ). The rapid advancement of information and communication technologies has led to the concept of social media, e-games, and also to smartphone addiction ( Chatterjee, 2020 ). The excessive use of smartphones for social media use, entertainment (watching videos, listening to music), and playing e-games is more common amongst people addicted to smartphones ( Jeong et al., 2016 ). In fact, previous studies have evidenced the relationship between social use and smartphone addiction ( Salehan and Negahban, 2013 ; Jeong et al., 2016 ; Swar and Hameed, 2017 ). In line with this, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H4a: Social media use is positively associated with smartphone addiction.

H4b: Smartphone addiction is negatively associated with psychological well-being.

While smartphones are bringing individuals closer, they are also, to some extent, pulling people apart ( Tonacci et al., 2019 ). For instance, they can lead to individuals ignoring others with whom they have close ties or physical interactions; this situation normally occurs due to extreme smartphone use (i.e., at the dinner table, in meetings, at get-togethers and parties, and in other daily activities). This act of ignoring others is called phubbing and is considered a common phenomenon in communication activities ( Guazzini et al., 2019 ; Chatterjee, 2020 ). Phubbing is also referred to as an act of snubbing others ( Chatterjee, 2020 ). This term was initially used in May 2012 by an Australian advertising agency to describe the “growing phenomenon of individuals ignoring their families and friends who were called phubbee (a person who is a recipients of phubbing behavior) victim of phubber (a person who start phubbing her or his companion)” ( Chotpitayasunondh and Douglas, 2018 ). Smartphone addiction has been found to be a determinant of phubbing ( Kim et al., 2018 ). Other recent studies have also evidenced the association between smartphones and phubbing ( Chotpitayasunondh and Douglas, 2016 ; Guazzini et al., 2019 ; Tonacci et al., 2019 ; Chatterjee, 2020 ). Vallespín et al. (2017 ) argued that phubbing behavior has a negative influence on psychological well-being and satisfaction. Furthermore, smartphone addiction is considered responsible for the development of new technologies. It may also negatively influence individual's psychological proximity ( Chatterjee, 2020 ). Therefore, based on the above discussion and calls for the association between phubbing and psychological well-being to be further explored, this study proposes the following hypotheses:

H5: Smartphone addiction is positively associated with phubbing.

H6: Phubbing is negatively associated with psychological well-being.

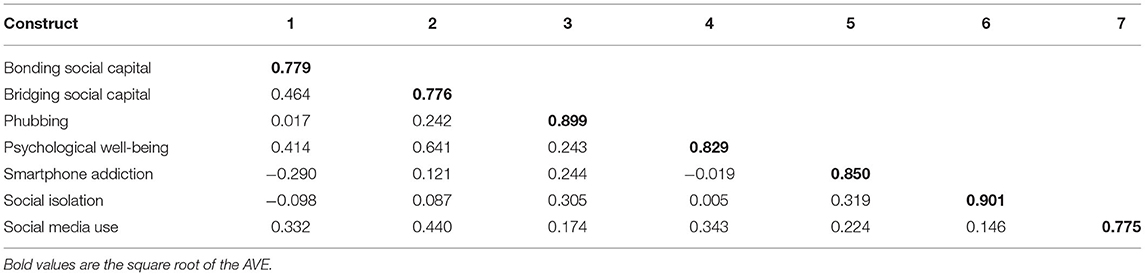

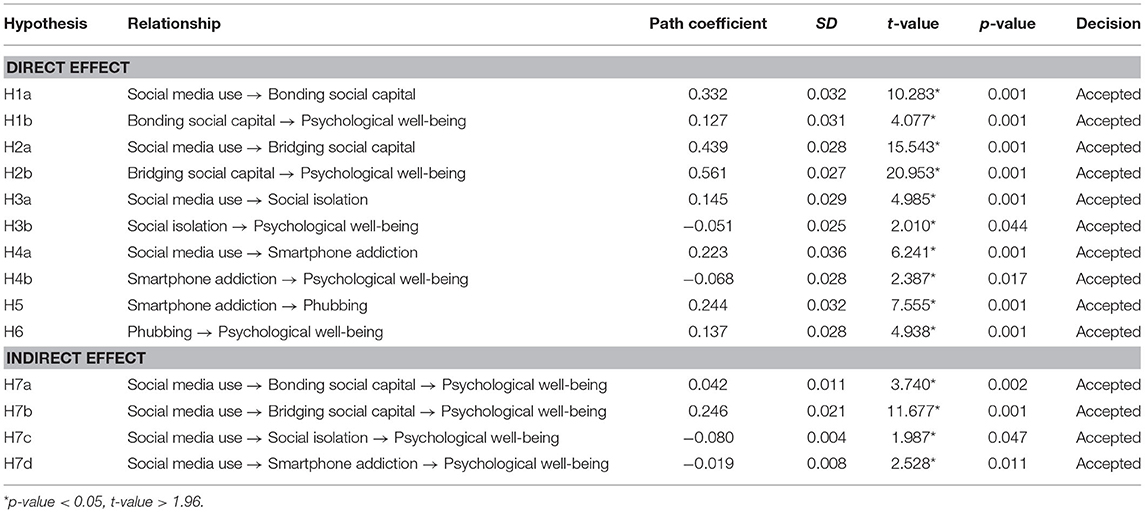

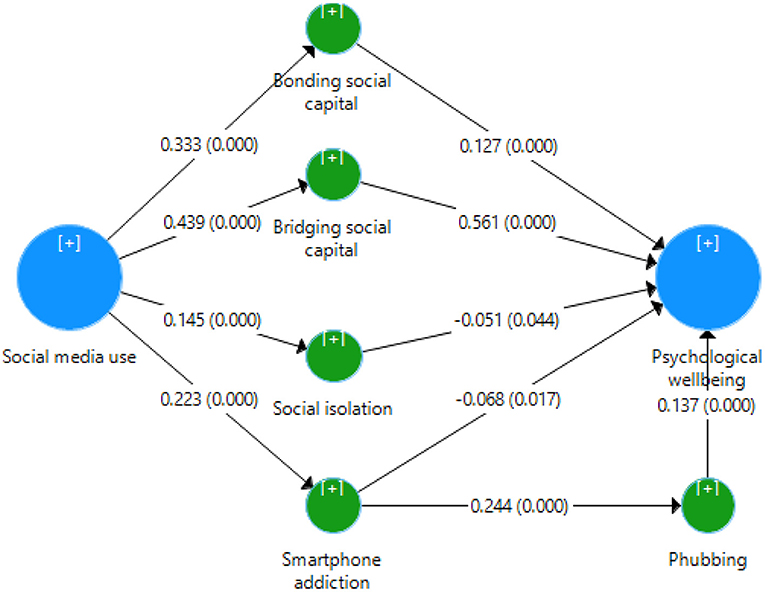

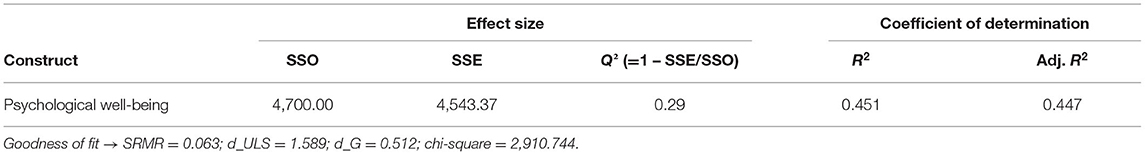

Indirect Relationship Between Social Media Use and Psychological Well-Being