ENCYCLOPEDIC ENTRY

Charles darwin.

Charles Darwin and his observations while aboard the HMS Beagle , changed the understanding of evolution on Earth.

Biology, Earth Science, Geography, Physical Geography

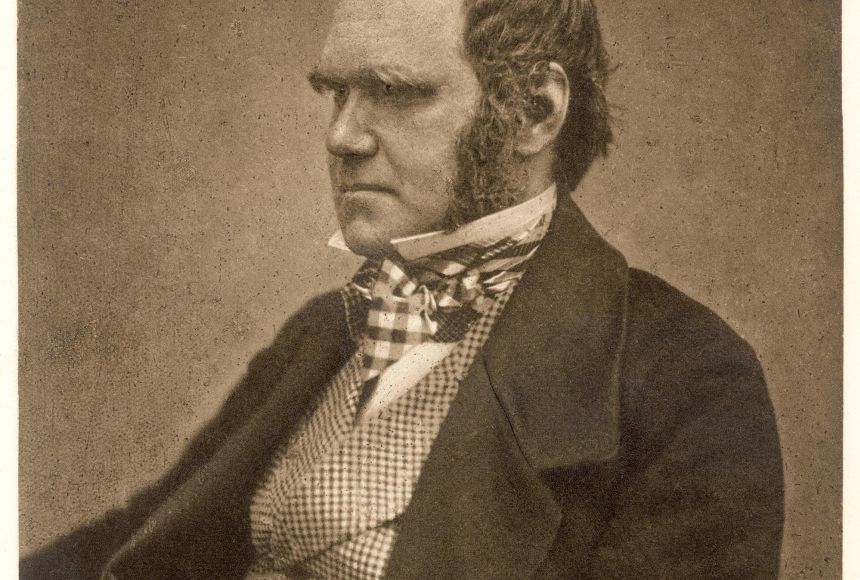

Historic photograph of Charles Darwin in profile.

Photograph by Chronical/Alamy Stock Photo

Charles Darwin was born in 1809 in Shrewsbury, England. His father, a doctor, had high hopes that his son would earn a medical degree at Edinburgh University in Scotland, where he enrolled at the age of sixteen. It turned out that Darwin was more interested in natural history than medicine—it was said that the sight of blood made him sick to his stomach. While he continued his studies in theology at Cambridge, it was his focus on natural history that became his passion.

In 1831, Darwin embarked on a voyage aboard a ship of the British Royal Navy, the HMS Beagle, employed as a naturalist . The main purpose of the trip was to survey the coastline of South America and chart its harbors to make better maps of the region. The work that Darwin did was just an added bonus.

Darwin spent much of the trip on land collecting samples of plants, animals, rocks, and fossils . He explored regions in Brazil, Argentina, Chile, and remote islands such as the Galápagos. He packed all of his specimens into crates and sent them back to England aboard other vessels.

Upon his return to England in 1836, Darwin’s work continued. Studies of his samples and notes from the trip led to groundbreaking scientific discoveries. Fossils he collected were shared with paleontologists and geologists, leading to advances in the understanding of the processes that shape the Earth’s surface. Darwin’s analysis of the plants and animals he gathered led him to question how species form and change over time. This work convinced him of the insight that he is most famous for— natural selection . The theory of natural selection says that individuals of a species are more likely to survive in their environment and pass on their genes to the next generation when they inherit traits from their parents that are best suited for that specific environment. In this way, such traits become more widespread in the species and can lead eventually to the development of a new species .

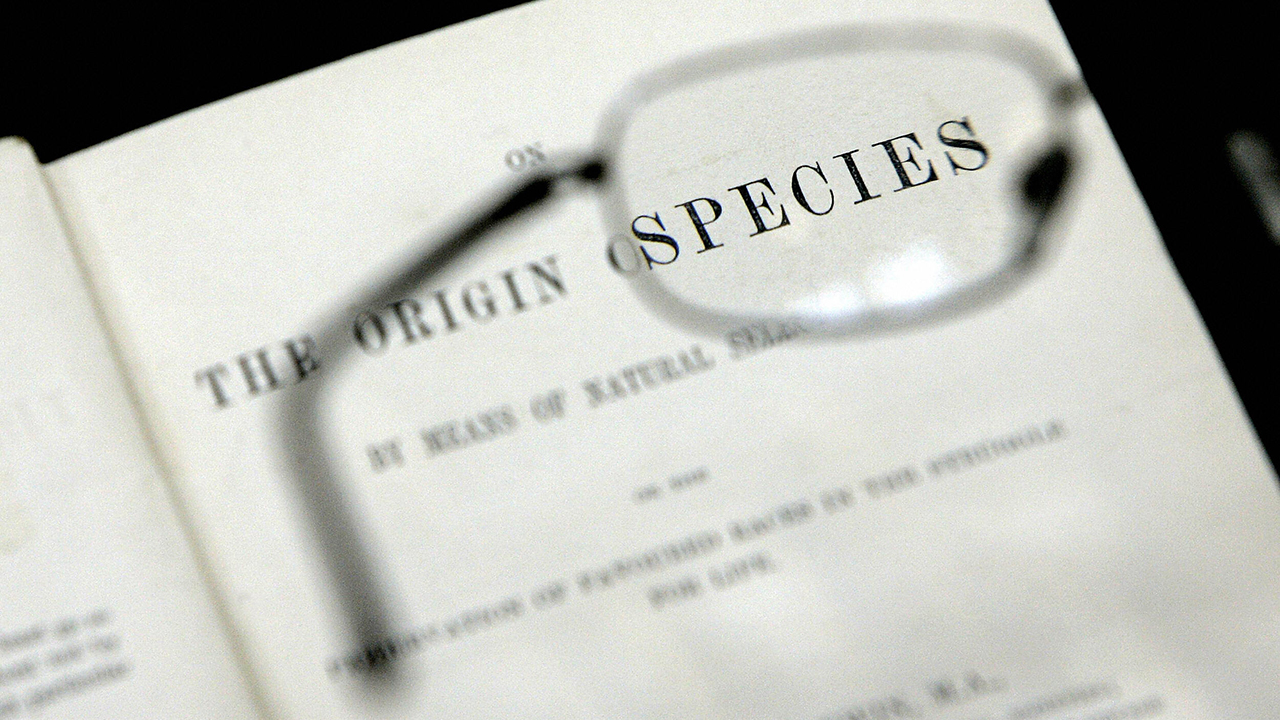

In 1859, Darwin published his thoughts about evolution and natural selection in On the Origin of Species . It was as popular as it was controversial. The book convinced many people that species change over time—a lot of time—suggesting that the planet was much older than what was commonly believed at the time: six thousand years.

Charles Darwin died in 1882 at the age of seventy-three. He is buried in Westminster Abbey in London, England.

Media Credits

The audio, illustrations, photos, and videos are credited beneath the media asset, except for promotional images, which generally link to another page that contains the media credit. The Rights Holder for media is the person or group credited.

Production Managers

Program specialists, last updated.

October 19, 2023

User Permissions

For information on user permissions, please read our Terms of Service. If you have questions about how to cite anything on our website in your project or classroom presentation, please contact your teacher. They will best know the preferred format. When you reach out to them, you will need the page title, URL, and the date you accessed the resource.

If a media asset is downloadable, a download button appears in the corner of the media viewer. If no button appears, you cannot download or save the media.

Text on this page is printable and can be used according to our Terms of Service .

Interactives

Any interactives on this page can only be played while you are visiting our website. You cannot download interactives.

Related Resources

Charles Darwin

(1809-1882)

Who Was Charles Darwin?

Charles Robert Darwin was a British naturalist and biologist known for his theory of evolution and his understanding of the process of natural selection. In 1831, he embarked on a five-year voyage around the world on the HMS Beagle , during which time his studies of various plants and an led him to formulate his theories. In 1859, he published his landmark book, On the Origin of Species .

Darwin was born on February 12, 1809, in the tiny merchant town of Shrewsbury, England. A child of wealth and privilege who loved to explore nature, Darwin was the second youngest of six kids.

Darwin came from a long line of scientists: His father, Dr. R.W. Darwin, was a medical doctor, and his grandfather, Dr. Erasmus Darwin, was a renowned botanist. Darwin’s mother, Susanna, died when he was only eight years old.

His father hoped he would follow in his footsteps and become a medical doctor, but the sight of blood made Darwin queasy. His father suggested he study to become a parson instead, but Darwin was far more inclined to study natural history.

While Darwin was at Christ's College, botany professor John Stevens Henslow became his mentor. After Darwin graduated Christ's College with a bachelor of arts degree in 1831, Henslow recommended him for a naturalist’s position aboard the HMS Beagle .

The ship, commanded by Captain Robert FitzRoy, was to take a five-year survey trip around the world. The voyage would prove the opportunity of a lifetime for the budding young naturalist.

On December 27, 1831, the HMS Beagle launched its voyage around the world with Darwin aboard. Over the course of the trip, Darwin collected a variety of natural specimens, including birds, plants and fossils.

DOWNLOAD BIOGRAPHY'S CHARLES DARWIN FACT CARD

Darwin in the Galapagos

Through hands-on research and experimentation, he had the unique opportunity to closely observe principles of botany, geology and zoology. The Pacific Islands and Galapagos Archipelago were of particular interest to Darwin, as was South America.

Upon his return to England in 1836, Darwin began to write up his findings in the Journal of Researches , published as part of Captain FitzRoy's larger narrative and later edited into the Zoology of the Voyage of the Beagle .

The trip had a monumental effect on Darwin’s view of natural history. He began to develop a revolutionary theory about the origin of living beings that ran contrary to the popular view of other naturalists at the time.

Theory of Evolution

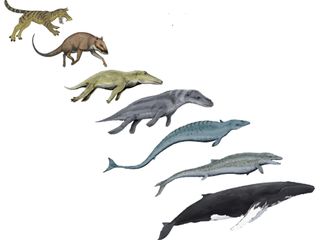

Darwin’s theory of evolution declared that species survived through a process called "natural selection," where those that successfully adapted or evolved to meet the changing requirements of their natural habitat thrived and reproduced, while those species that failed to evolve and reproduce died off.

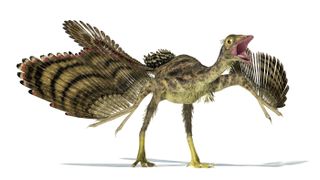

Through his observations and studies of birds, plants and fossils, Darwin noticed similarities among species all over the globe, along with variations based on specific locations, leading him to believe that the species we know today had gradually evolved from common ancestors.

Darwin’s theory of evolution and the process of natural selection later became known simply as “Darwinism.”

At the time, other naturalists believed that all species either came into being at the start of the world or were created over the course of natural history. In either case, they believed species remained much the same throughout time.

'Origin of Species'

In 1858, after years of scientific investigation, Darwin publicly introduced his revolutionary theory of evolution in a letter read at a meeting of the Linnean Society . On November 24, 1859, he published a detailed explanation of his theory in his best-known work, On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection.

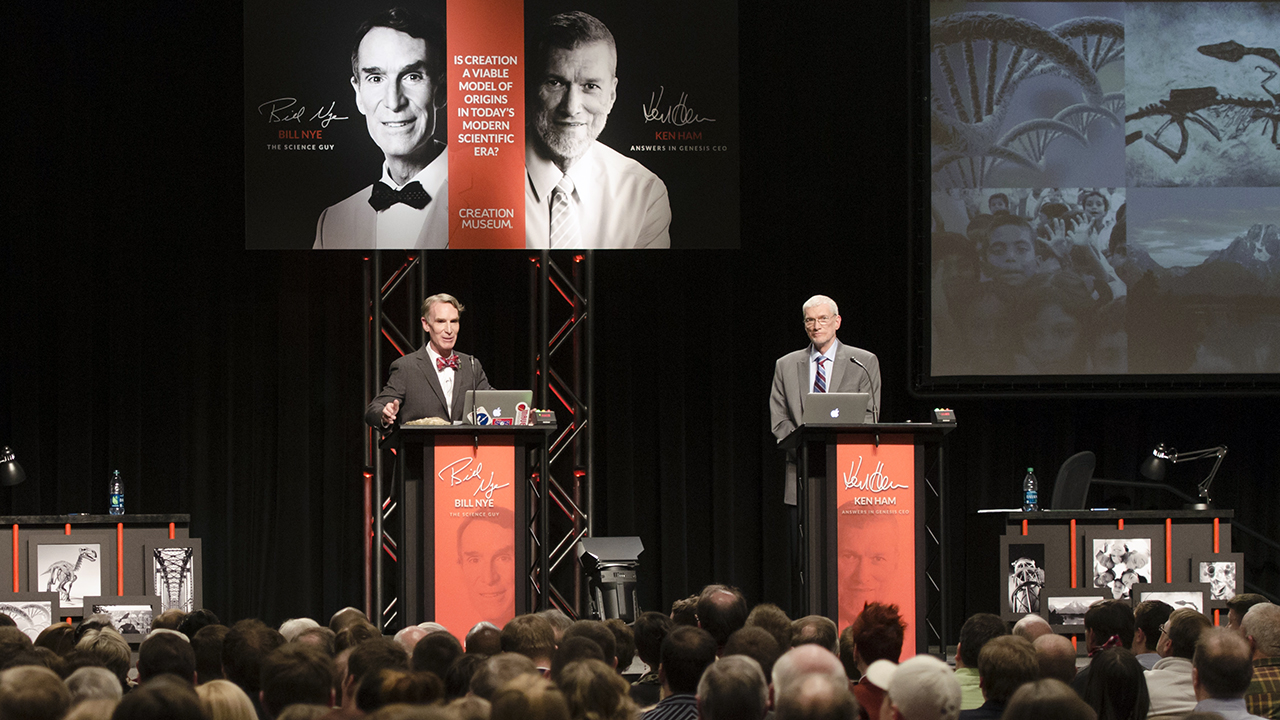

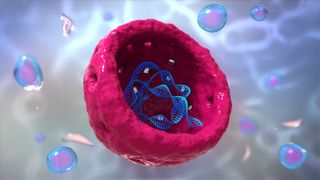

In the next century, DNA studies provided scientific evidence for Darwin’s theory of evolution. However, controversy surrounding its conflict with Creationism — the religious view that all of nature was born of God — is still found among some people today.

Social Darwinism

Social Darwinism is a collection of ideas that emerged in the late 1800s that adopted Darwin’s theory of evolution to explain social and economic issues.

Darwin himself rarely commented on any connections between his theories and human society. But while attempting to explain his ideas to the public, Darwin borrowed widely understood concepts, such as “survival of the fittest” from sociologist Herbert Spencer.

Over time, as the Industrial Revolution and laissez faire capitalism swept across the world, social Darwinism has been used as a justification for imperialism, labor abuses, poverty, racism, eugenics and social inequality.

Following a lifetime of devout research, Charles Darwin died at his family home, Down House, in London, on April 19, 1882. He was buried at Westminster Abbey .

More than a century later, Yale ornithologist Richard Brum sought to revive Darwin's lesser-known theory on sexual selection in The Evolution of Beauty .

While Darwin's original attempts to cite female aesthetic mating choices as a driving force of evolution was criticized, Brum delivered an effective argument via his expertise in birds, earning selection to The New York Times ' list of 10 best books of 2017.

QUICK FACTS

- Name: Charles Darwin

- Birth Year: 1809

- Birth date: February 12, 1809

- Birth City: Shrewsbury

- Birth Country: England

- Gender: Male

- Best Known For: Charles Darwin was a British naturalist who developed a theory of evolution based on natural selection. His views and “social Darwinism” remain controversial.

- Science and Medicine

- Astrological Sign: Aquarius

- University of Edinburgh

- Interesting Facts

- Although Charles Darwin originally went to college to be a physician, he changed career paths when he realized that he couldn't stomach the sight of blood.

- Charles Darwin had a mountain named after him, Mount Darwin, in Tierra del Fuego for his 25th birthday. The monumental gift was given by Captain FitzRoy.

- Death Year: 1882

- Death date: April 19, 1882

- Death City: Downe

- Death Country: England

We strive for accuracy and fairness.If you see something that doesn't look right, contact us !

CITATION INFORMATION

- Article Title: Charles Darwin Biography

- Author: Biography.com Editors

- Website Name: The Biography.com website

- Url: https://www.biography.com/scientists/charles-darwin

- Access Date:

- Publisher: A&E; Television Networks

- Last Updated: March 29, 2021

- Original Published Date: April 3, 2014

- A man who dares to waste one hour of time has not discovered the value of life.

- [How great the] difference between savage and civilized man is—it is greater than between a wild and [a] domesticated animal.

- If all men were dead, then monkeys make men. Men make angels.

- I am a complete millionaire in odd and curious little facts.

- Multiply, vary, let the strongest live and the weakest die.

- For the shield may be as important for victory, as the sword or spear.

- I see no good reason why the views given in this volume should shock the religious feelings of anyone."[In 'Origin of the Species']

- A grain in the balance may determine which individuals shall live and which shall die—which variety or species shall increase in number, and which shall decrease, or finally become extinct.

- If it could be demonstrated that any complex organ existed, which could not possibly have been formed by numerous, successive, slight modifications, my theory would absolutely break down. But I can find out no such case.

- The extinction of species and of whole groups of species, which has played so conspicuous a part in the history of the organic world, almost inevitably follows from the principle of natural selection.

- There is grandeur in this view of life...from so simple a beginning endless forms most beautiful and most wonderful have been, and are being, evolved.

Famous British People

Mick Jagger

Agatha Christie

Alexander McQueen

The Real Royal Scheme Depicted in ‘Mary & George’

William Shakespeare

Anya Taylor-Joy

Kate Middleton, Princess of Wales

Kensington Palace Shares an Update on Kate

Prince William

Where in the World Is Kate Middleton?

- Table of Contents

- Random Entry

- Chronological

- Editorial Information

- About the SEP

- Editorial Board

- How to Cite the SEP

- Special Characters

- Advanced Tools

- Support the SEP

- PDFs for SEP Friends

- Make a Donation

- SEPIA for Libraries

- Entry Contents

Bibliography

Academic tools.

- Friends PDF Preview

- Author and Citation Info

- Back to Top

Darwin: From the Origin of Species to the Descent of Man

This entry offers a broad historical review of the origin and development of Darwin’s theory of evolution by natural selection through the initial Darwinian phase of the “Darwinian Revolution” up to the publication of the Descent of Man in 1871. The development of evolutionary ideas before Darwin’s work has been treated in the separate entry evolutionary thought before Darwin . Several additional aspects of Darwin’s theory of evolution and his biographical development are dealt with in other entries in this encyclopedia (see the entries on Darwinism ; species ; natural selection ; creationism ). The remainder of this entry will focus on aspects of Darwin’s theory not developed in the other entries. It will also maintain a historical and textual approach. Other entries in this encyclopedia cited at the end of the article and the bibliography should be consulted for discussions beyond this point. The issues will be examined under the following headings:

1.1 Historiographical Issues

1.2 darwin’s early reflections, 2.1. the concept of natural selection.

- 2.2. The Argument of the Published Origin

3.1 The Popular Reception of Darwin’s Theory

3.2 the professional reception of darwin’s theory, 4.1 the genesis of darwin’s descent, 4.2 darwin on mental powers, 4.3 the ethical theory of the descent of man.

- 4.4 The Reception of the Descent

5. Summary and Conclusion

Other internet resources, related entries, acknowledgments, 1. the origins of darwin’s theory.

Charles Darwin’s version of transformism has been the subject of massive historical and philosophical scholarship almost unparalleled in any other area of the history of science. This includes the continued flow of monographic studies and collections of articles on particular aspects of Darwin’s theory (Prestes 2023; R. J. Richards and Ruse 2016; Ruse 2013a, 2009a,b,c; Ruse and Richards 2009; Hodge and Radick 2009; Hösle and Illies 2005; Gayon 1998; Bowler 1996; Depew and Weber 1995; Kohn 1985a). The continuous production of popular and professional biographical studies on Darwin provides ever new insights (Ruse et al. 2013a; Johnson 2012; Desmond and Moore 1991, 2009; Browne 1995, 2002; Bowlby 1990; Bowler 1990). In addition, major editing projects on Darwin’s manuscripts and the completion of the Correspondence , project through the entirety of Darwin’s life, continue to reveal details and new insights into the issues surrounding Darwin’s own thought (Keynes [ed.] 2000; Burkhardt et al. [eds] 1985–2023; Barrett et al. [eds.] 1987). The Cambridge Darwin Online website (see Other Internet Resources ) serves as an international clearinghouse for this worldwide Darwinian scholarship, functioning as a repository for electronic versions of all the original works of Darwin, including manuscripts and related secondary materials. It also supplies a continuously updated guide to current literature.

A long tradition of scholarship has interpreted Darwin’s theory to have originated from a framework defined by endemic British natural history, a British tradition of natural theology defined particularly by William Paley (1743–1805), the methodological precepts of John Herschel (1792–1871), developed in his A Preliminary Discourse on the Study of Natural Philosophy (1830 [1987]), and the geological theories of Charles Lyell (1797–1875). His conversion to the uniformitarian geology of Charles Lyell and to Lyell’s advocacy of “deep” geological time during the voyage of the HMS Beagle (December 1831–October 1836), has been seen as fundamental in his formation (Norman 2013; Herbert 2005; Hodge 1983). Complementing this predominantly anglophone historiography has been the social-constructivist analyses emphasizing the origins of Darwin’s theories in British Political Economy (Young 1985: chps. 2, 4, 5). It has also been argued that a primary generating source of Darwin’s inquiries was his involvement with the British anti-slavery movement, a concern reaching back to his revulsion against slavery developed during the Beagle years (Desmond and Moore 2009).

A body of recent historiography, on the other hand, drawing on the wealth of manuscripts and correspondence that have become available since the 1960s (online at Darwin online “Papers and Manuscripts” section, see Other Internet Resources ) has de-emphasized some of the novelty of Darwin’s views and questions have been raised regarding the validity of the standard biographical picture of the early Darwin. These materials have drawn attention to previously ignored aspects of Darwin’s biography. In particular, the importance of his Edinburgh period from 1825–27, largely discounted in importance by Darwin himself in his late Autobiography , has been seen as critical for his subsequent development (Desmond and Moore 1991; Hodge 1985). As a young medical student at the University of Edinburgh (1825–27), Darwin developed a close relationship with the comparative anatomist Robert Edmond Grant (1793–1874) through the student Plinian Society, and in many respects Grant served as Darwin’s first mentor in science in the pre- Beagle years (Desmond and Moore 1991, chp. 1). Through Grant he was exposed to the transformist theories of Jean Baptiste Lamarck and the Cuvier-Geoffroy debate centered on the Paris Muséum nationale d’histoire naturelle (see entry on evolutionary thought before Darwin , Section 4).

These differing interpretive frameworks make investigations into the origins of Darwin’s theory an active area of historical research. The following section will explore these origins.

In its historical origins, Darwin’s theory was different in kind from its main predecessors in important ways (Ruse 2013b; Sloan 2009a; see also the entry on evolutionary thought before Darwin ). Viewed against a longer historical scenario, Darwin’s theory does not deal with cosmology or the origins of the world and life through naturalistic means, and therefore was more restricted in its theoretical scope than its main predecessors influenced by the reflections of Georges Louis LeClerc de Buffon (1707–1788), Johann Herder (1744–1803, and German Naturphilosophen inspired by Friederich Schelling (1775–1854) . This restriction also distinguished Darwin’s work from the grand evolutionary cosmology put forth anonymously in 1844 by the Scottish publisher Robert Chambers (1802–1871) in his immensely popular Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation , a work which in many respects prepared Victorian society in England, and pre-Civil War America for the acceptance of a general evolutionary theory in some form (Secord 2000; MacPherson 2015). It also distinguishes Darwin’s formulations from the theories of his contemporary Herbert Spencer (1820–1903).

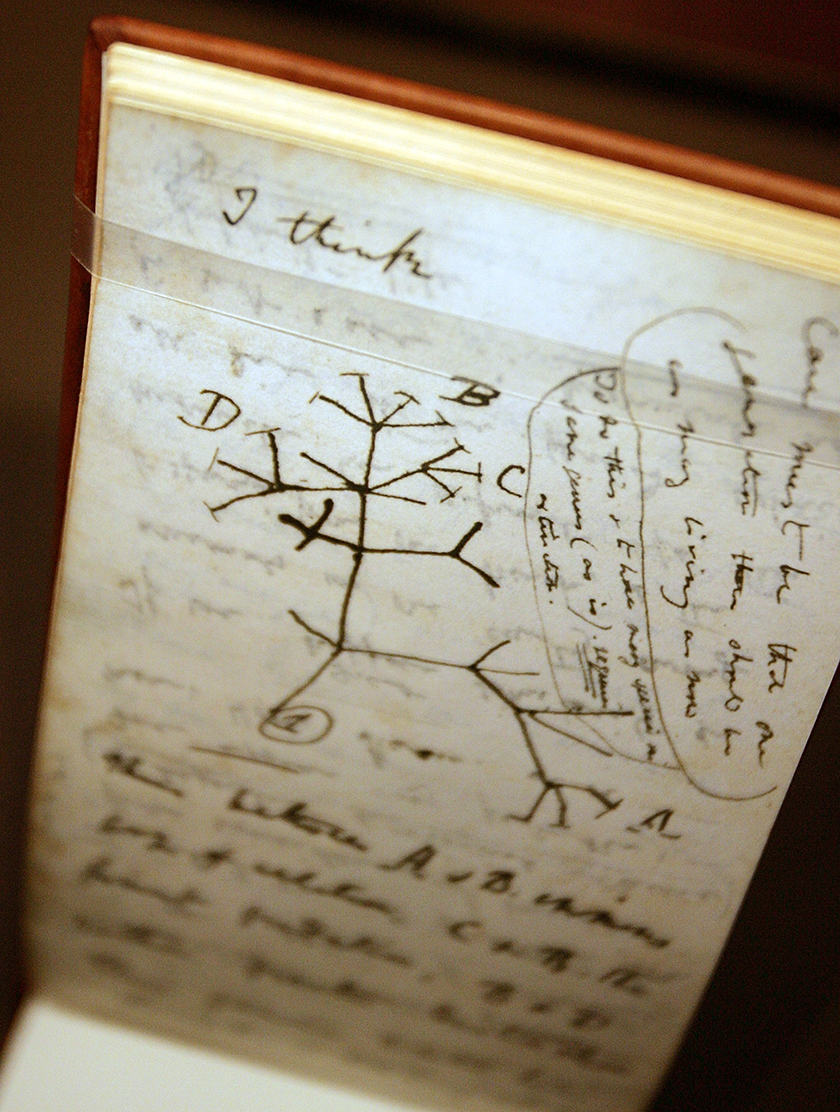

Darwin’s theory first took written form in reflections in a series of notebooks begun during the latter part of the Beagle voyage and continued after the return of the Beagle to England in October of 1836 (Barrett et al., 1987). His reflections on the possibility of species change are first entered in March of 1837 (“Red Notebook”) and are developed in the other notebooks (B–E) through July of 1839 (Barrett et al. 1987; Hodge 2013a, 2009). Beginning with the reflections of the third or “D” “transmutation” Notebook, composed between July and October of 1838, Darwin first worked out the rudiments of what was to become his theory of natural selection. In the parallel “M” and “N” Notebooks, dating between July of 1838 and July of 1839, and in a loose collection called “Old and Useless Notes”, dating from approximately 1838–40, he also developed many of his main ideas on human evolution that would only be made public in the Descent of Man of 1871 (below, Section 4).

To summarize a complex issue, these Notebook reflections show Darwin proceeding through a series of stages in which he first formulated a general theory of the transformation of species by historical descent from common ancestors. He then attempted to work out a causal theory of life that would explain the tendency of life to complexify and diversify (Hodge 2013a, 2009, 1985; Sloan 1986). This causal inquiry into the underlying nature of life, and with it the search for an explanation of life’s innate tendency to develop and complexify, was then replaced by a dramatic shift in focus away from these inquiries. This concern with a causal theory of life was then replaced by a new emphasis on external forces controlling population, a thesis developed from his reading of Thomas Malthus’s (1766–1834) Essay on the Principle of Population (6th ed. 1826). For Malthus, human populaton was assumed to expand geometrically, while food supply expanded arithmetically, leading to an inevitable struggle of humans for existence. The impact of Darwin’s reading of this edition of the Essay in August of 1838, was dramatic. It enabled him to theorize the existence of a constantly-acting dynamic force behind the transformation of species.

Darwin’s innovation was to universalize the Malthusian “principle of population” to apply to all of nature. In so doing, Darwin effectively introduced what may be termed an “inertial” principle into his theory, although such language is never used in his text. Newton’s first law of motion, set forth in his Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy (1st ed. 1687), established his physical system upon the tendency of all material bodies to persist eternally either at rest or in uniform motion in a straight line, requiring a causal force explanation for any deviations from this initial state. But Newton did not seek a deeper metaphysical explanation of this inertial state. Law One is simply an “axiom” in Newton’s Principia. Similarly, the principle of population supplied Darwin with the assumption of an initial dynamic state of affairs that was not itself explained within the theory—there is no attempt to account causally for this tendency of living beings universally to reproduce geometrically. Similarly for Darwin, the principle of population functions axiomatically, defining a set of initial conditions from which any deviance from this ideal state demands explanation.

This theoretical shift enabled Darwin to bracket his earlier efforts to develop a causal theory of life, and focus instead on the means by which the dynamic force of population was controlled. This allowed him to emphasize how controls on population worked in company with the phenomenon of slight individual variation between members of the same species, in company with changing conditions of life, to produce a gradual change of form and function over time, leading to new varieties and eventually to new species. This opened up the framework for Darwin’s most important innovation, the concept of “natural” selection.

2. Darwinian Evolution

The primary distinguishing feature of Darwin’s theory that separates it from previous explanations of species change centers on the causal explanation he offered for how this process occurred. Prior theories, such as the theory of Jean-Baptiste Lamarck (see entry on evolutionary thought before Darwin ), relied on the inherent dynamic properties of matter. The change of species was not, in these pre-Darwinian efforts, explained through an adaptive process. Darwin’s emphasis after the composition of Notebook D on the factors controlling population increase, rather than on a dynamic theory of life grounded in vital forces, accounts for many of the differences between Darwin’s theory and those of his predecessors and contemporaries.

These differences can be summarized in the concept of natural selection as the central theoretical component of Darwinian theory. However, the exact meaning of this concept, and the varying ways he stated the principle in the Origin over its six editions (1859–1872), has given rise to multiple interpretations of the meaning of this principle in the history of Darwinism, and the different understandings of his meaning deeply affected different national and cultural receptions of his theory (see below, Section 3 .1).

One way to see the complexity of Darwin’s own thinking on these issues is to follow the textual development of this concept from the close of the Notebook period (1839) to the publication of the Origin of Species in 1859. This period of approximately twenty years involved Darwin in a series of reflections that form successive strata in the final version of his theory of the evolution of species. Understanding the historical sequence of these developments also has significance for subsequent controversies over this concept and the different readings of the Origin as it went through its successive revisions. This historical development of the concept also has some bearing on assessing Darwin’s relevance for more general philosophical questions, such as those surrounding the relevance of his theory for such issues as the concept of a more general teleology of nature.

The earliest set of themes in the manuscript elaboration of natural selection theory can be characterized as those developed through a particular form of the argument from analogy. This took the form of a strong “proportional” form of the analogical argument that equated the relation of human selection to the development of domestic breeds as an argument of the basic form: human selection is to domestic variety formation as natural selection is to natural species formation (White, Hodge and Radick 2021, chps. 4–5). This makes a direct analogy between the actions of nature with those of humans in the process of selection. The specific expressions, and changes, in this analogy are important to follow closely. As this was expressed in the first coherent draft of the theory, a 39-page pencil manuscript written in 1842, this discussion analogized the concept of selection of forms by human agency in the creation of the varieties of domestic animals and plants, to the active selection in the natural world by an almost conscious agency, a “being infinitely more sagacious than man (not an omniscient creator)” who acts over “thousands and thousands of years” on “all the variations which tended towards certain ends” (Darwin 1842 in Glick and Kohn 1996, 91). This agency selects out those features most beneficial to organisms in relation to conditions of life, analogous in its action to the selection by man on domestic forms in the production of different breeds. Interwoven with these references to an almost Platonic demiurge are appeals to the selecting power of an active “Nature”:

Nature’s variation far less, but such selection far more rigid and scrutinizing […] Nature lets <<an>> animal live, till on actual proof it is found less able to do the required work to serve the desired end, man judges solely by his eye, and knows not whether nerves, muscles, arteries, are developed in proportion to the change of external form. (Ibid., 93)

These themes were continued in the 230 page draft of his theory of 1844. Again he referred to the selective action of a wise “Being with penetration sufficient to perceive differences in the outer and innermost organization quite imperceptible to man, and with forethought extending over future centuries to watch with unerring care and select for any object the offspring of an organism produced” (Darwin 1844 in ibid., 101). This selection was made with greater foresight and wisdom than human selection. As he envisions the working of this causal agency,

In accordance with the plan by which this universe seems governed by the Creator, let us consider whether there exist any secondary means in the economy of nature by which the process of selection could go on adapting, nicely and wonderfully, organisms, if in ever so small a degree plastic, to diverse ends. I believe such secondary means do exist. (Ibid., 103).

Darwin returned to these issues in 1856, following a twelve-year period in which he published his Geological Observations on the Volcanic Islands (1844), the second edition of his Journal of Researches (1845), Geological Observations on South America (1846), the four volumes on fossil and living barnacles ( Cirripedia ) (1851, 54, 55), and Geological Observations on Coral Reefs (1851). In addition, he published several smaller papers on invertebrate zoology and on geology, and reported on his experiments on the resistance of seeds to salt water, a topic that would be of importance in his explanation of the population of remote islands.

These intervening inquiries positioned Darwin to deal with the question of species permanence against an extensive empirical background. The initial major synthesis of these investigations takes place in his long manuscript, or “Big Species Book”, commenced in 1856, known in current scholarship as the “Natural Selection” manuscript. This formed the immediate background text behind the published Origin . Although incomplete, the “Natural Selection” manuscript provides insights into many critical issues in Darwin’s thinking. It was also prepared with an eye to the scholarly community. This distinguishes its content and presentation from that of the subsequent “abstract” which became the published Origin of Species . “Natural Selection” contained tables of data, references to scholarly literature, and other apparatus expected of a non-popular work, none of which appeared in the published Origin .

The “Natural Selection” manuscript also contained some new theoretical developments of relevance to the concept of natural selection that are not found in earlier manuscripts. Scholars have noted the introduction in this manuscript of the “principle of divergence”, the thesis that organisms under the action of natural selection will tend to radiate and diversify within their “conditions of life”—the contemporary name for the complex of environmental and species-interaction relationships (Kohn 1985b, 2009). Although the concept of group divergence under the action of natural selection might be seen as an implication of Darwin’s theory from his earliest formulations of the 1830s, nonetheless Darwin’s explicit definition of this as a “principle”, and its discussion in a long late insertion in the “Natural Selection” manuscript, suggests its importance for Darwin’s mature theory. The principle of divergence was now seen by Darwin to form an important link between natural variation and the conditions of existence under the action of the driving force of population increase.

Still evident in the “Natural Selection” manuscript is Darwin’s implicit appeal to some kind of teleological ordering of the process. The action of the masculine-gendered “wise being” of the earlier manuscripts, however, has now been given over entirely to the action of a selective “Nature”, now referred to in the traditional feminine gender. This Nature,

…cares not for mere external appearance; she may be said to scrutinise with a severe eye, every nerve, vessel & muscle; every habit, instinct, shade of constitution,—the whole machinery of the organisation. There will be here no caprice, no favouring: the good will be preserved & the bad rigidly destroyed.… Can we wonder then, that nature’s productions bear the stamp of a far higher perfection than man’s product by artificial selection. With nature the most gradual, steady, unerring, deep-sighted selection,—perfect adaption [sic] to the conditions of existence.… (Darwin 1856–58 [1974: 224–225])

The language of this passage, directly underlying statements about the action of “natural selection” in the first edition of the published Origin , indicates the complexity in the exegesis of Darwin’s meaning of “natural selection” when viewed in light of its historical genesis (Ospovat 1981). The parallels between art and nature, the intentionality implied in the term “selection”, the notion of “perfect” adaptation, and the substantive conception of “nature” as an agency working toward certain ends, all render Darwin’s views on teleological purpose more complex than they are typically interpreted from the standpoint of contemporary Neo-selectionist theory (Lennox 1993, 2013). As will be discussed below, the changes Darwin subsequently made in his formulations of this concept over the history of the Origin have led to different conceptions of what he meant by this principle.

The hurried preparation and publication of the Origin between the summer of 1858 and November of 1859 was prompted by the receipt on June 18 of 1858 of a letter and manuscript from Alfred Russel Wallace (1823–1913) that outlined his remarkably similar views on the possibility of continuous species change under the action of a selection upon natural variation (Wallace 1858 in Glick and Kohn 1996, 337–45). This event had important implications for the subsequent form of Darwin’s published argument. Rapidly condensing the detailed arguments of the unfinished “Natural Selection” manuscript into shorter chapters, Darwin also universalized several claims that he had only developed with reference to specific groups of organisms, or which he had applied only to more limited situations in the manuscript. This resulted in a presentation of his theory at the level of broad generalization. The absence of tables of data, detailed footnotes, and references to the secondary literature in the published version also resulted in predictable criticisms which will be discussed below in Section 3.2 .

2.2. The Central Argument of the Published Origin

The Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservaton of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life was issued in London by the publishing house of John Murray on November 24, 1859 (Darwin 1859 [1964]). The structure of the argument presented in the published Origin has been the topic of considerable literature and can only be summarized here. Although Darwin himself described his book as “one long argument”, the exact nature of this argument is not immediately transparent, and alternative interpretations have been made of his reasoning and rhetorical strategies in formulating his evolutionary theory. (Prestes 2023; White, Hodge and Radick 2021; Hodge 2013b, 1977; Hoquet 2013; Hull 2009; Waters 2009; Depew 2009; Ruse 2009; Lennox 2005; Hodge 1983b).

The scholarly reconstruction of Darwin’s methodology employed in the Origin has taken two primary forms. One approach has been to reconstruct it from the standpoint of currently accepted models of scientific explanation, sometimes presenting it as a formal deductive model (Sober 1984). Another, more historical, approach interprets his methodology in the context of accepted canons of scientific explanation found in Victorian discussions of the period (see the entry on Darwinism ; Prestes 2023; White, Hodge and Radick 2021; Hodge 2013b, 1983b, 1977; Hoquet 2013; Hull 2009; Waters 2009; Depew 2009; Lennox 2005). The degree to which Darwin did in fact draw from the available methodological discussions of his contemporaries—John Herschel, William Whewell, John Stuart Mill—is not fully clear from available documentary sources. The claim most readily documented, and defended particularly by White, Hodge and Radick (2021) and M. J. S. Hodge (1977, 1983a), has emphasized the importance of John Herschel’s A Preliminary Discourse on the Study of Natural Philosophy (1830 [1987]), which Darwin read as a young student at Cambridge prior to his departure on the HMS Beagle in December of 1831.

In Herschel’s text he would have encountered the claim that science seeks to determine “true causes”— vera causae— of phenomena through the satisfaction of explicit criteria of adequacy (Herschel, 1830 [1987], chp. 6). This concept Newton had specified in the Principia as the third of his “Rules of Reasoning in Philosophy” (see the entry on Newton’s philosophy , Section 4). Elucidation of such causes was to be the goal of scientific explanation. Vera causae , in Herschel’s formulation, were those necessary to produce the given effects; they were truly active in producing the effects; and they adequately explained these effects.

The other plausible methodological source for Darwin’s mature reasoning was the work of his older contemporary and former Cambridge mentor, the Rev. William Whewell (1794–1866), whose three-volume History of the Inductive Sciences (Whewell 1837) Darwin read with care after his return from his round-the-world voyage (Ruse 2013c, 1975). On this reading, a plausible argument has been made that the actual structure of Darwin’s text is more closely similar to a “Whewellian” model of argument. In Whewell’s accounts of his philosophy of scientific methodology (Whewell 1840, 1858), the emphasis of scientific inquiry is, as Herschel had also argued, to be placed on the discovery of “true causes”. But evidence for the determination of a vera causa was to be demonstrated by the ability of disparate phenomena to be drawn together under a single unifying “Conception of the Mind”, exemplified for Whewell by Newton’s universal law of gravitation. This “Consilience of Inductions”, as Whewell termed this process of theoretical unification under a few simple concepts, was achieved only by true scientific theories employing true causes (Whewell 1840: xxxix). It has therefore been argued that Darwin’s theory fundamentally produces this kind of consilience argument, and that his methodology is more properly aligned with that of Whewell.

A third account, related to the Whewellian reading, is that of David Depew. Building on Darwin’s claim that he was addressing “the general naturalist public,” Darwin is seen as developing what Depew has designated as “situated argumentation”, similar to the views developed by contemporary Oxford logician and rhetorical theorist Richard Whately (1787–1863) (Depew 2009). This rhetorical strategy proceeds by drawing the reader into Darwin’s world by personal narration as it presents a series of limited issues for acceptance in the first three chapters, none of which required of the reader a considerable leap of theoretical assent, and most of which, such as natural variation and Malthusian population increase, had already been recognized in some form in the literature of the period.

As Darwin presented his arguments to the public, he opens with a pair of chapters that draw upon the strong analogy developed in the manuscripts between the action of human art in the production of domestic forms, and the actions of selection “by nature.” The resultant forms are presumed to have arisen through the action of human selection on the slight variations existing between individuals within the same species. The interpretation of this process as implying directional, and even intentional, selection by a providential “Nature” that we have seen in the manuscripts was, however, downplayed in the published work through the importance given by Darwin to the role of “unconscious” selection, a concept not encountered in the Natural Selection manuscript. Such selection denotes the practice even carried out by aboriginal peoples who simply seek to maintain the integrity and survival of a breed or species by preserving the “best” forms.

The domestic breeding analogy is, however, more than a decorative rhetorical strategy. It repeatedly functions for Darwin as the principal empirical example to which he could appeal at several places in the text as a means of visualizing the working of natural selection in nature, and this appeal remains intact through the six editions of the Origin.

From this model of human selection working on small individual natural variations to produce the domestic forms, Darwin then developed in the second chapter the implications of “natural” variation, delaying discussion of the concept of natural selection until Chapter IV. The focus of the second chapter introduces another important issue. Here he extends the discussion of variation developed in Chapter I into a critical analysis of the common understanding of classification as grounded on the definition of species and higher groups based on the possession of essential defining properties. It is in this chapter that Darwin most explicitly develops his own position on the nature of organic species in relation to his theory of descent. It is also in this chapter that he sets forth the ingredients for his attack on one meaning of species “essentialism”.

Darwin’s analysis of the “species question” involves a complex argument that has many implications for how his work was read by his contemporaries and successors, and its interpretation has generated a considerable literature (see the entries on species and Darwinism ; Mallet 2013; R. A. Richards 2010; Wilkins 2009; Stamos 2007; Sloan 2009b, 2013; Beatty 1985).

Prior tradition had been heavily affected by eighteenth-century French naturalist Buffon’s novel conception of organic species in which he made a sharp distinction between “natural” species, defined primarily by fertile interbreeding, and “artificial” species and varieties defined by morphological traits and measurements upon these (see the entry on evolutionary thought before Darwin , Section 3.3). This distinction was utilized selectively by Darwin in an unusual blending of two traditions of discussion that are conflated in creative ways in Darwin’s analysis.

Particularly as the conception of species had been discussed by German natural historians of the early nineteenth-century affected by distinctions introduced by philosopher Immanuel Kant (1724–1804), “Buffonian” species were defined by the material unity of common descent and reproductive continuity. This distinguished them by their historical and material character from the taxonomic species of the “Linnean” tradition of natural history. This distinction between “natural” and “logical” species had maintained a distinction between problems presented in the practical classification of preserved specimens, distinguished by external characters, and those relating to the unity of natural species, which was grounded upon reproductive unity and the sterility criterion (Sloan 2009b).

Remarkable in Darwin’s argument is the way in which he draws selectively in his readings from these two preexistent traditions to undermine the different grounds of species “realism” assumed within both of these traditions of discourse. One framework—what can be considered in his immediate context the “Linnean” tradition—regarded species in the sense of universals of logic or class concepts, whose “reality” was often grounded on the concept of divine creation. The alternative “Buffonian” tradition viewed species more naturalistically as material lineages of descent whose continuity was determined by some kind of immanent principle, such as the possession of a conserving “internal mold” or specifying vital force (see evolutionary thought before Darwin 3.3). The result in Darwin’s hands is a complex terminological interweaving of concepts of Variety, Race, Sub-species, Tribe, and Family that can be shown to be a fusion of different traditions of discussion in the literature of the period. This creative conflation also led to many confusions among his contemporaries about how Darwin actually did conceive of species and species change in time.

Darwin addresses the species question by raising the problems caused by natural variation in the practical discrimination of taxa at the species and varietal levels, an issue with which he had become closely familiar in his taxonomic revision of the Sub-class Cirripedia (barnacles) in his eight-year study on this group. Although the difficulty of taxonomic distinctions at this level was a well-recognized problem in the literature of the time, Darwin subtly transforms this practical problem into a metaphysical ambiguity—the fuzziness of formal taxonomic distinctions created by variation in preserved specimens is seen to imply a similar ambiguity of “natural” species boundaries.

We follow this in reading how natural variation is employed by Darwin in Chapter Two of the Origin to break down the distinction between species and varieties as these concepts were commonly employed in the practical taxonomic literature. The arbitrariness apparent in making distinctions, particularly in plants and invertebrates, meant that such species were only what “naturalists having sound judgment and wide experience” defined them to be ( Origin 1859 [1964], 47). These arguments form the basis for claims by his contemporaries that Darwin was a species “nominalist”, who defined species only as conventional and convenient divisions of a continuum of individuals.

But this feature of Darwin’s discussion of species captures only in part the complexity of his argument. Drawing also on the tradition of species realism developed within the “Buffonian” tradition, Darwin also affirmed that species and varieties are defined by common descent and material relations of interbreeding. Darwin then employed the ambiguity of the distinction between species and varieties created by individual variation in practical taxonomy to undermine the ontological fixity of “natural” species. Varieties are not simply the formal taxonomic subdivisions of a natural species as conceived in the Linnaean tradition. They are, as he terms them, “incipient” species (ibid., 52). This subtly transformed the issue of local variation and adaptation to circumstances into a primary ingredient for historical evolutionary change. The full implications to be drawn from this argument were, however, only to be revealed in Chapter Four of the text.

Before assembling the ingredients of these first two chapters, Darwin then introduced in Chapter Three the concept of a “struggle for existence”. This concept is introduced in a “large and metaphorical sense” that included different levels of organic interactions, from direct struggle for food and space to the struggle for life of a plant in a desert. Although described as an application of Thomas Malthus’s parameter of geometrical increase of population in relation to the arithmetical increase of food supply, Darwin’s use of this concept in fact reinterprets Malthus’s principle, which was formulated only with reference to human population in relation to food supply. It now becomes a general principle governing all of organic life. Thus all organisms, including those comprising food for others, would be governed by the tendency to geometrical increase.

Through this universalization, the controls on population become only in the extreme case grounded directly on the traditional Malthusian limitations of food and space. Normal controls are instead exerted through a complex network of relationships of species acting one on another in predator-prey, parasite-host, and food-web relations. This profound revision of Malthus’s arguments rendered Darwin’s theory deeply “ecological” as this term would later be employed. We can cite two thought experiments employed by Darwin himself as illustrations (ibid., 72–74). The first concerns the explanation of the abundance of red clover in England. This Darwin sees as dependent on the numbers of pollinating humble bees, which are controlled in turn by the number of mice, and these are controlled by the number of cats, making cats the remote determinants of clover abundance. The second instance concerns the explanation of the abundance of Scotch Fir. In this example, the number of fir trees is limited indirectly by the number of cattle.

With the ingredients of the first three chapters in place, Darwin was positioned to assemble these together in his grand synthesis of Chapter Four on “natural” selection. In this long discussion, Darwin develops the main exposition of his central theoretical concept. For his contemporaries and for the subsequent tradition, however, the meaning of Darwin’s concept of “natural” selection was not unambiguously evident for reasons we have outlined above, and these unclarities were to be the source of several persistent lines of disagreement and controversy.

The complexities in Darwin’s presentation of his central principle over the six editions of the published Origin served historically to generate several different readings of his text. In the initial introduction of the principle of natural selection in the first edition of Darwin’s text, it is characterized as “preservation of favourable variations and the rejection of injurious variations” (ibid., 81). When Darwin elaborated on this concept in Chapter Four of the first edition, he continued to describe natural selection in language suggesting that it involved intentional selection, continuing the strong art-nature analogy found in the manuscripts. For example:

As man can produce and certainly has produced a great result by his methodical and unconscious means of selection, what may not nature effect? Man can act only on external and visible characters: nature cares nothing for appearances, except in so far as they may be useful to any being. She can act on every internal organ, on every shade of constitutional difference, on the whole machinery of life. Man selects only for his own good; Nature only for that of the being which she tends. Every selected character is fully exercised by her; and the being is placed under well-suited conditions of life. (Ibid., 83)

The manuscript history behind such passages prevents the simple discounting of these statements as mere rhetorical imagery. As we have seen, the parallel between intentional human selectivity and that of “nature” formed the proportional analogical model upon which the concept of natural selection was originally constructed.

Criticisms that quickly developed over the overt intentionality embedded in such passages, however, led Darwin to revise the argument in editions beginning with the third edition of 1861. From this point onward he explicitly downplayed the intentional and teleological language of the first two editions, denying that his appeals to the selective role of “nature” were anything more than a literary figure. Darwin then moved decisively in the direction of defining natural selection as the description of the action of natural laws working upon organisms rather than as an efficient or final cause of life. He also regrets in his Correspondence his mistake in not utilizing the designation “natural preservation” rather than “natural selection” to characterize his principle (letter to Lyell 28 September 1860, Burkhardt Correspondence 8, 397; also see Darwin Correspondence Project in Other Internet Resources ). In response to criticisms of Alfred Russel Wallace, Darwin then adopted in the fifth edition of 1869 his contemporary (1820–1903) Herbert Spencer’s designator, “survival of the fittest”, as a synonym for “natural selection” (Spencer 1864, 444–45; Darwin 1869, 72). This redefinition further shifted the meaning of natural selection away from the concept that can be extracted from the early texts and drafts. These final statements of the late 1860s and early 70s underlie the tradition of later “mechanistic” and non-teleological understandings of natural selection, a reading developed by his disciples who, in the words of David Depew, “had little use for either his natural theodicy or his image of a benignly scrutinizing selection” (Depew 2009, 253). The degree to which this change preserved the original strong analogy between art and nature can, however, be questioned. Critics of the use of this analogy had argued since the original formulations that the comparison of the two modes of selection actually worked against Darwin’s theory (Wallace 1858 in Glick and Kohn 1997, 343). This critique would also be leveled against Darwin in the critical review of 1867 by Henry Fleeming Jenkin discussed below.

The conceptual synthesis of Chapter Four also introduced discussions of such matters as the conditions under which natural selection most optimally worked, the role of isolation, the causes of the extinction of species, and the principle of divergence. Many of these points were made through the imaginative use of “thought experiments” in which Darwin constructed possible scenarios through which natural selection could bring about substantial change.

One prominent way Darwin captured for the reader the complexity of this process is reflected in the single diagram to appear in all the editions of the Origin . In this illustration, originally located as an Appendix to the first edition, but thereafter moved into Chapter Four, Darwin summarized his conception of how species were formed and diverged from common ancestral points. This image also served to depict the frequent extinction of most lineages, an issue developed in detail in Chapter Ten. It displayed pictorially the principle of divergence, illustrating the general tendency of populations to diverge and fragment under the pressure of population increase. It supplied a way of envisioning relations of taxonomic affinity to time, and illstrated the persistence of some forms unchanged over long geological periods in which stable conditions prevail.

Figure: Tree of life diagram from Origin of Species ( Origin 1859:“Appendix”.

Remarkable about Darwin’s diagram of the tree of life is the relativity of its coordinates. It is first presented as applying only to the divergences taking place in taxa at the species level, with varieties represented by the small lower-case letters within species A–L of a “wide ranging genus”, with the horizontal lines representing time segments measured in terms of a limited number of generations. However, the attentive reader could quickly see that Darwin’s destructive analysis of the distinction between “natural” and “artificial” species in Chapter Two, implied the relativity of the species-variety distinction, this diagram could represent eventually all organic relationships, from those at the non-controversial level of diverging varieties within fixed species, to those of the relations of Species within different genera. Letters A–L could also represent taxa at the level of genera, families or orders. The diagram can thus be applied to relationships between all levels of the Linnaean hierarchy with the time segments representing potentially vast expanses of time, and the horizontal spread of branches the degree of taxonomic divergence over time. In a very few pages of argument, the diagram was generalized to represent the most extensive group relations, encompassing the whole of geological time. Extension of the dotted lines at the bottom could even suggest, as Darwin argues in the last paragraph of the Origin , that all life was a result of “several powers, having been originally breathed into a few forms or into one” (Darwin 1859 [1964], 490). This could suggest a single naturalistic origin of all original forms either by material emergence, or through the action of a vitalistic power of life. Darwin’s use of Biblical language could also be read as allowing for the action of a supernatural cause.

In response to criticisms concerning this latter point, Darwin quickly added to the final paragraph in the second edition of 1860 the phrase “by the Creator” (1860: 484), which remained in all subsequent editions. as did the quotations on the frontispiece from familiar discussions in British natural theology concerning creation by secondary causation. Conceptual space was thereby created for the reading of the Origin by some contemporaries, notably by the Harvard botanist Asa Gray (1810–88), as compatible with traditional natural theology (Gray 1860).

The sweep of the theoretical generalization that closed the natural selection chapter, one restated even more generally in the final paragraph of the book, required Darwin to deal with several obvious objections to the theory that constitute the main “defensive” chapters of the Origin (Five–Nine), and occupy him through the numerous revisions of the text between 1859 and 1872. As suggested by David Depew, the rhetorical structure of the original text developed in an almost “objections and response” structure that resulted in a constant stream of revisions to various editions of the original text as Darwin engaged his opponents (Depew 2009; Peckham 2006). Anticipating at first publication several obvious lines of objection, Darwin devoted much of the text of the original Origin to offering a solution in advance to predictable difficulties. As Darwin outlined these main lines of objection, he discussed, first, the apparent absence of numerous slight gradations between species, both in the present and in the fossil record, of the kind that would seem to be predictable from the gradualist workings of the theory (Chps. Six, Nine). Second, the gradual development of organs and structures of extreme complexity, such as the vertebrate eye, an organ which had since Antiquity served as a mainstay of the argument for external teleological design (Chp. Six). Third, the evolution of the elaborate instincts of animals and the puzzling problem of the evolution of social insects that developed sterile neuter castes, proved to be a particularly difficult issue for Darwin in the manuscript phase of his work and needed some account (Chp. Seven). As a fourth major issue needing attention, the traditional distinction between natural species defined by interfertility, and artificial species defined by morphological differences, required an additional chapter of analysis in which he sought to undermine the absolute character of the interbreeding criterion as a sign of fixed natural species (Chp. Eight).

In Chapter Ten, Darwin developed his interpretation of the fossil record. At issue was the claim by Lamarckian and other transformists, as well as Cuvierian catastrophists such as William Buckland (1784–1856) (see the entry on evolutionary thought before Darwin , Section 4.1), that the fossil record displayed a historical sequence beginning with simpler plants and animals, arriving either by transformism or replacement, at the appearance of more complex forms in geological history. Opposition to this thesis of “geological progressionism” had been made by none other than Darwin’s great mentor in geology, Charles Lyell in his Principles of Geology (Lyell 1832 [1990], vol. 2, chp. xi; Desmond 1984; Bowler 1976). Darwin defended the progressionist view against Lyell’s arguments in this chapter.

To each of the lines of objection to his theory, Darwin offered his contemporaries plausible replies. Additional arguments were worked out through the insertion of numerous textual insertions over the five revisions of the Origin between 1860 and 1872, including the addition of a new chapter to the sixth edition dealing with “miscellaneous” objections, responding primarily to the criticisms of St. George Jackson Mivart (1827–1900) developed in his Genesis of Species (Mivart 1871).

For reasons related both to the condensed and summary form of public presentation, and also as a reflection of the bold conceptual sweep of the theory, the primary argument of the Origin could not gain its force from the data presented by the book itself. Instead, it presented an argument from unifying simplicity, gaining its force and achieving assent from the ability of Darwin’s theory to draw together in its final synthesizing chapters (Ten–Thirteen) a wide variety of issues in taxonomy, comparative anatomy, paleontology, biogeography, and embryology under the simple principles worked out in the first four chapters. This “consilience” argument might be seen as the best reflection of the impact of William Whewell’s methodology (see above).

As Darwin envisioned the issue, with the acceptance of his theory, “a grand untrodden field of inquiry will be opened” in natural history. The long-standing issues of species origins, if not the the explanation of the ultimate origins of life, as well as the causes of their extinction, had been brought within the domain of naturalistic explanation. It is in this context that he makes the sole reference in the text to the claim that “light will be thrown on the origin of man and his history”. And in a statement that will foreshadow the important issues of the Descent of Man of 1871, he speaks of how “Psychology will be based on a new foundation, that of the necessary acquirement of each mental power and capacity by gradation” (ibid., 488)

3. The Reception of the Origin

The broad sweep of Darwin’s claims, the brevity of the empirical evidence actually supplied in the Origin , and the implications of his theory for several more general philosophical and theological issues, opened up a controversy over Darwinian evolution that has waxed and waned over more than 160 years. The theory was inserted into a complex set of different national and cultural receptions the study of which currently forms a scholarly industry in its own right. European, Latin American and Anglophone receptions have been most deeply studied (Bowler 2013a; Gayon 2013; Largent 2013; Glick 1988, 2013; Glick and Shaffer 2014; Engels and Glick 2008; Gliboff 2008; Numbers 1998; Pancaldi, 1991; Todes 1989; Kelly 1981; Hull 1973; Mullen 1964). To these have been added analyses of non-Western recptions (Jin 2020, 2019 a,b; Yang 2013; Shen 2016; Elshakry 2013; Pusey 1983). These analyses display common patterns in both Western and non-Western readings of Darwin’s theory, in which these receptions were conditioned, if not determined, by the pre-existing intellectual, scientific, religious, social, and political contexts into which his works were inserted.

In the anglophone world, Darwin’s theory fell into a complex social environment that in the United States meant into the pre-Civil War slavery debates (Largent 2013; Numbers 1998). In the United Kingdom it was issued against the massive industrial expansion of mid-Victorian society, and the development of professionalized science. To restrict focus to aspects of the British reading public context, the pre-existing popularity of the anonymous Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation of 1844, which had reached 11 editions and sold 23,350 copies by December of 1860 (Secord “Introduction” to Chambers 1844 [1994], xxvii]), with more editions to appear by the end of the century, certainly prepared the groundwork for the general notion of the evolutionary origins of species by the working of secondary natural laws. The Vestiges ’s grand schema of a teleological development of life, from the earliest beginnings of the solar system in a gaseous nebula to the emergence of humanity under the action of a great “law of development”, had also been popularized for Victorian readers by Alfred Lord Tennyson’s epic poem In Memoriam (1850). This Vestiges backdrop provided a context in which some could read Darwin as supplying additional support for the belief in an optimistic historical development of life under teleological guidance of secondary laws with the promise of ultimate historical redemption. Such readings also rendered the Origin seemingly compatible with the progressive evolutionism of Darwin’s contemporary Herbert Spencer (see the entry on Herbert Spencer ). Because of these similarities, Spencer’s writings served as an important vehicle by which Darwin’s views, modified to fit the progressivist views expounded by Spencer, were first introduced in non-Western contexts (Jin 2020, 2019 a,b; Lightman [ed.] 2015; Pusey 1983). Such popular receptions ignored or revised Darwin’s concept of evolution by natural selection to fit these progressivist alternatives.

Outside the United Kingdom, the receptions of Darwin’s work display the importance of local context and pre-existent intellectual and social conditions. Three examples—France, Germany, and China—can be elaborated upon. In France, Darwin’s theory was received against the background of the prior debates over transformism of the 1830s that pitted the theories of Lamarck and Etienne Geoffroy St. Hilaire against Cuvier (Gayon 2013; entry on evolutionary thought before Darwin , 4.1). At least within official French Academic science, these debates had been resolved generally in favor of Cuvier’s anti-transformism. The intellectual framework provided by the “positive philosophy” of Auguste Comte (1798–1857) also worked both for and against Darwin. On one hand, Comte’s emphasis on the historical progress of science over superstition and metaphysics allowed Darwin to be summoned in support of a theory of the progress of science. The Origin was so interpreted in the preface to the first French translation of the Origin made by Clémence Royer (Harvey 2008). On the other hand, the Comtean three stages view of history, with its claim of the historical transcendence of speculative and metaphysical periods of science by a final period of experimental science governed by determinate laws, placed Darwinism in a metaphysical phase of speculative nature philosophy. This view is captured by the assessment of the leading physiologist and methodologist of French Science, Claude Bernard (1813–78). As he stated this in his 1865 treatise on scientific methodology, Darwin’s theory was to be regarded with those of “a Goethe, an Oken, a Carus, a Geoffroy Saint Hilaire”, locating it within speculative philosophy of nature rather than granting it the status of “positive” science (Bernard 1865 [1957], 91–92]).

In the Germanies, Darwin’s work entered a complex social, intellectual and political situation in the wake of the failed efforts to establish a liberal democracy in 1848. It also entered an intellectual culture strongly influenced by the pre-existent philosophical traditions of Kant, Schelling’s Naturphilosophie , German Romanticism, and the Idealism of Fichte and Hegel (R. J. Richards 2002, 2008, 2013; Gliboff 2007, 2008; Mullen 1964). These factors formed a complex political and philosophical environment into which Darwin’s developmental view of nature and theory of the transformation of species was quickly assimilated, if also altered. Many readings of Darwin consequently interpreted his arguments against the background of Schelling’s philosophy of nature. The marshalling of Darwin’s authority in debates over scientific materialism were also brought to the fore by the enthusiastic advocacy of Darwinism in Germany by University of Jena professor of zoology Ernst Heinrich Haeckel (1834–1919). More than any other individual, Haeckel made Darwinismus a major player in the polarized political and religious disputes of Bismarckian Germany (R. J. Richards 2008). Through his polemical writings, such as the Natural History of Creation (1868), Anthropogeny (1874), and Riddle of the Universe (1895–99), Haeckel advocated a materialist monism in the name of Darwin, and used this as a stick with which to beat traditional religion. Much of the historical conflict between religious communities and evolutionary biology can be traced back to Haeckel’s polemical writings, which went through numerous editions and translations, including several English and American editions that appeared into the early decades of the twentieth century.

To turn to a very different context, that of China, Darwin’s works entered Chinese discussions by a curious route. The initial discussions of Darwinian theory were generated by the translation of Thomas Henry Huxley’s 1893 Romanes Lecture “Evolution and Ethics” by the naval science scholar Yan Fu (1854–1921), who had encountered Darwinism while being educated at the Royal Naval College in Greenwich from 1877 to 1879. This translation of Huxley’s lecture, published in 1898 under the name of Tianyan Lun , was accompanied with an extensive commentary by Yan Fu that drew heavily upon the writings of Herbert Spencer which Yan Fu placed in opposition to the arguments of Huxley. This work has been shown to have been the main vehicle by which the Chinese learned indirectly of Darwin’s theory (Jin 2020, 2019 a, b; Yang 2013; Pusey 1983). In the interpretation of Yan Fu and his allies, such as Kan Yuwei (1858–1927), Darwinism was given a progressivist interpretation in line with aspects of Confucianism.

Beginning in 1902, a second phase of Darwinian reception began with a partial translation of the first five chapters of the sixth edition of the Origin by the Chinese scientist, trained in chemistry and metallurgy in Japan and Germany, Ma Junwu (1881–1940). This partial translation, published between 1902 and 1906, again modified the text itself to agree with the progressive evolutionism of Spencer and with the progressivism already encountered in Yan Fu’s popular Tianyan Lun. Only in September of 1920 did the Chinese have Ma Junwu’s full translation of Darwin’s sixth edition. This late translation presented a more faithful rendering of Darwin’s text, including an accurate translation of Darwin’s final views on natural selection (Jin 2019 a, b). As a political reformer and close associate of democratic reformer Sun Yat-Sen (1866–1925), Ma Junwu’s interest in translating Darwin was also was involved with his interest in revolutionary Chinese politics (Jin 2019a, 2022).

The reception of the Origin by those who held positions of professional research and teaching positions in universities, leadership positions in scientific societies, and employment in museums, was complex. These individuals were typically familiar with the empirical evidence and the technical scientific issues under debate in the 1860s in geology, comparative anatomy, embryology, biogeography, and classification theory. This group can usually be distinguished from lay interpreters who may not have made distinctions between the views of Lamarck, Chambers, Schelling, Spencer, and Darwin on the historical development of life.

If we concentrate attention on the reception by these professionals, Darwin’s work received varied endorsement (Hull 1973). Many prominent members of Darwin’s immediate intellectual circle—Adam Sedgwick, William Whewell, Charles Lyell, Richard Owen, and Thomas Huxley—had previously been highly critical of Chambers’s Vestiges in the 1840s for its speculative character and its scientific incompetence (Secord 2000). Darwin himself feared a similar reception, and he recognized the substantial challenge facing him in convincing this group and the larger community of scientific specialists with which he interacted and corresponded widely. With this group he was only partially successful.

Historical studies have revealed that only rarely did members of the scientific elites accept and develop Darwin’s theories exactly as they were presented in his texts. Statistical studies on the reception by the scientific community in England in the first decade after the publication of the Origin have shown a complicated picture in which there was neither wide-spread conversion of the scientific community to Darwin’s views, nor a clear generational stratification between younger converts and older resisters, counter to Darwin’s own predictions in the final chapter of the Origin (Hull et al. 1978). These studies also reveal a distinct willingness within the scientific community to separate acceptance of Darwin’s more general claim of species descent with modification from common ancestors from the endorsement of his explanation of this descent through the action of natural selection on slight morphological variations.

Of central importance in analyzing this complex professional reception was the role assigned by Darwin to the importance of normal individual variation as the source of evolutionary novelty. As we have seen, Darwin had relied on the novel claim that small individual variations—the kind of differences considered by an earlier tradition as merely “accidental”—formed the raw material upon which, by cumulative directional change under the action of natural selection, major changes could be produced sufficient to explain the origin and subsequent differences in all the various forms of life over time. Darwin, however, left the specific causes of this variation unspecified beyond some effect of the environment on the sexual organs. Variation was presented in the Origin with the statement that “the laws governing inheritance are quite unknown” (Darwin 1859 [1964], 13). In keeping with his commitment to the gradualism of Lyellian geology, Darwin also rejected the role of major “sports” or other sources of discontinuous change in this process.

As critics focused their attacks on the claim that such micro-differences between individuals could be accumulated over time without natural limits, Darwin began a series of modifications and revisions of the theory through a back and forth dialogue with his critics that can be followed in his revisions to the text of the Origin . In the fourth edition of 1866, for example, Darwin inserted the claim that the continuous gradualism depicted by his branching diagram was misleading, and that transformative change does not necessarily go on continuously. “It is far more probable that each form remains for long periods unaltered, and then again undergoes modification” (Darwin 1866, 132; Peckham 2006, 213). This change-stasis-change model allowed variation to stabilize for a period of time around a mean value from which additional change could then resume. Such a model would, however, presumably require even more time for its working than the multi-millions of years assumed in the original presentation of the theory.

The difficulties in Darwin’s arguments that had emerged by 1866 were highlighted in a lengthy and telling critique in 1867 by the Scottish engineer Henry Fleeming Jenkin (1833–1885) (typically Fleeming Jenkin). Using an argument previously raised in the 1830s by Charles Lyell against Lamarck, Fleeming Jenkin cited empirical evidence from domestic breeding that suggested a distinct limitation on the degree to which normal variation could be added upon by selection (Fleeming Jenkin 1867 in Hull 1973). Using a loosely mathematical argument, Fleeming Jenkin argued that the effects of intercrossing would continuously swamp deviations from the mean values of characters and result in a tendency of the variation in a population to return to mean values over time. It is also argued that domestic evidence does not warrant an argument for species change. For Fleeming Jenkin, Darwin’s reliance on continuous additive deviation was presumed to be undermined by these arguments, and only more dramatic and discontinuous change—something Darwin explicitly rejected—could account for the origin of new species.

Fleeming Jenkin also argued that the time needed by Darwin’s theory to account for the history of life under the gradual working of natural selection was simply unavailable from scientific evidence, supporting this claim by an appeal to the physical calculations of the probable age of the solar system presented in publications by his mentor, the Glasgow physicist William Thompson (Lord Kelvin, 1824–1907) (Burchfield 1975). On the basis of Thompson’s quantitative physical arguments concerning the age of the sun and solar system, Fleeming Jenkin judged the time since the presumed first beginnings of life to be insufficient for the Darwinian gradualist theory of species transformation to have taken place.

Jenkin’s multi-pronged argument gave Darwin considerable difficulties and set the stage for more detailed empirical inquiries into variation and its causes by Darwin’s successors. The time difficulties were only resolved in the twentieth-century with the discovery of radioactivity that could explain why the sun did not lose heat in accord with Newtonian principles.

As a solution to the variation question, Darwin developed his “provisional hypothesis” of pangenesis, which he presented the year after the appearance of the Fleeming Jenkin review in his two-volume Variation of Plants and Animals Under Domestication (Darwin 1868; Olby 2013). Although this theory had been formulated independently of the Jenkin review (Olby 1963), in effect it functioned as Darwin’s reply to Jenkin’s critique. The pangenesis theory offered a causal theory of variation and inheritance through a return to a theory resembling Buffon’s theory of the organic molecules proposed in the previous century (see entry on evolutionary thought before Darwin section 3.2). Invisible material “gemmules” were presumed to exist within the cells. According to theory, these were subject to external alteration by the environment and other external causes. The gemmules were then shed continually into the blood stream (the “transport” hypothesis) and assembled by “mutual affinity for each other, leading to their aggregation either into buds or into the sexual elements” (Darwin 1868, vol. 2, 375). In this form they were then transmitted—the details were not explained—by sexual generation to the next generation to form the new organism out of “the modified physiological units of which the organism is built” (ibid., 377). In Darwin’s view, this hypothesis united together numerous issues into a coherent and causal theory of inheritance and explained the basis of variation. It also explained how use-disuse inheritance, a theory which Darwin never abandoned, could work.

The pangenesis theory, although not specifically referred to, seems to be behind an important distinction Darwin inserted into the fifth edition of the Origin of 1869 in his direct reply to the criticisms of Jenkin. In this textual revision, Darwin distinguished “certain variations, which no one would rank as mere individual differences”, from ordinary variations (Darwin1869, 105; Peckham 2006, 178–179). This revision shifted Darwin’s emphasis away from his early reliance on normal slight individual variation, and gave new status to what he now termed “strongly marked” variations. The latter were now the forms of variation to be given primary evolutionary significance. Presumably this strong variation was more likely to be transmitted to the offspring, although details are left unclear, and in this form major variation could presumably be maintained in a population against the tendency to swamping by intercrossing as Fleeming Jenkin had argued.