Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

The relationship between workload and burnout among nurses: The buffering role of personal, social and organisational resources

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Institute of Occupational, Social and Environmental Medicine, University Medical Center of the Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz, Mainz, Germany

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Writing – review & editing

Roles Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Resources, Writing – review & editing

Roles Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Institute for Health Services Research in Dermatology and Nursing (IVDP), University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany

Roles Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Supervision, Writing – review & editing

Affiliations Institute for Health Services Research in Dermatology and Nursing (IVDP), University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany, Department for Occupational Medicine, Hazardous Substances and Health Science, Institution for Accident Insurance and Prevention in the Health and Welfare Services (BGW), Hamburg, Germany

Roles Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Writing – review & editing

¶ ‡ These authors are joint senior authors on this work.

Affiliations Institute of Occupational, Social and Environmental Medicine, University Medical Center of the Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz, Mainz, Germany, Federal Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (BAuA), Berlin, Germany

Roles Supervision, Writing – review & editing

* E-mail: [email protected]

- Elisabeth Diehl,

- Sandra Rieger,

- Stephan Letzel,

- Anja Schablon,

- Albert Nienhaus,

- Luis Carlos Escobar Pinzon,

- Pavel Dietz

- Published: January 22, 2021

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0245798

- Peer Review

- Reader Comments

Workload in the nursing profession is high, which is associated with poor health. Thus, it is important to get a proper understanding of the working situation and to analyse factors which might be able to mitigate the negative effects of such a high workload. In Germany, many people with serious or life-threatening illnesses are treated in non-specialized palliative care settings such as nursing homes, hospitals and outpatient care. The purpose of the present study was to investigate the buffering role of resources on the relationship between workload and burnout among nurses. A nationwide cross-sectional survey was applied. The questionnaire included parts of the Copenhagen Psychosocial Questionnaire (COPSOQ) (scale ‘quantitative demands’ measuring workload, scale ‘burnout’, various scales to resources), the resilience questionnaire RS-13 and single self-developed questions. Bivariate and moderator analyses were performed. Palliative care aspects, such as the ‘extent of palliative care’, were incorporated to the analyses as covariates. 497 nurses participated. Nurses who reported ‘workplace commitment’, a ‘good working team’ and ‘recognition from supervisor’ conveyed a weaker association between ‘quantitative demands’ and ‘burnout’ than those who did not. On average, nurses spend 20% of their working time with palliative care. Spending more time than this was associated with ‘burnout’. The results of our study imply a buffering role of different resources on burnout. Additionally, the study reveals that the ‘extent of palliative care’ may have an impact on nurse burnout, and should be considered in future studies.

Citation: Diehl E, Rieger S, Letzel S, Schablon A, Nienhaus A, Escobar Pinzon LC, et al. (2021) The relationship between workload and burnout among nurses: The buffering role of personal, social and organisational resources. PLoS ONE 16(1): e0245798. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0245798

Editor: Adrian Loerbroks, Universtiy of Düsseldorf, GERMANY

Received: July 30, 2020; Accepted: January 7, 2021; Published: January 22, 2021

Copyright: © 2021 Diehl et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Data Availability: According to the Ethics Committee of the Medical Association of Rhineland-Palatinate (Study ID: 837.326.16 (10645)), the Institute of Occupational, Social and Environmental Medicine of the University Medical Center of the University Mainz is specified as data holding organization. The institution is not allowed to share the data publically in order to guarantee anonymity to the institutions that participated in the survey because some institution-specific information could be linked to specific institutions. The data set of the present study is stored on the institution server at the University Medical Centre of the University of Mainz and can be requested for scientific purposes via the institution office. This ensures that data will be accessible even if the authors of the present paper change affiliation. Postal address: University Medical Center of the University of Mainz, Institute of Occupational, Social and Environmental Medicine, Obere Zahlbacher Str. 67, D-55131 Mainz. Email address: [email protected] .

Funding: The research was funded by the BGW - Berufsgenossenschaft für Gesundheitsdienst und Wohlfahrtspflege (Institution for Statutory Accident Insurance and Prevention in Health and Welfare Services). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Competing interests: I have read the journal’s policy and the authors of this manuscript have the following competing interests: The project was funded by the BGW - Berufsgenossenschaft für Gesundheitsdienst und Wohlfahrtspflege (Institution for Statutory Accident Insurance and Prevention in Health and Welfare Services). The BGW is responsible for the health concerns of the target group investigated in the present study, namely nurses. Prof. Dr. A. Nienhaus is head of the Department for Occupational Medicine, Hazardous Substances and Health Science of the BGW and co-author of this publication. All other authors declare to have no potential conflict of interest. This does not alter our adherence to PLOS ONE policies on sharing data and materials.

Introduction

Our society has to face the challenge of a growing number of older people [ 1 ], combined with an expected shortage of skilled workers, especially in nursing care [ 2 ]. At the same time, cancer patients, patients with non-oncological diseases, multimorbid patients [ 3 ] and patients suffering from dementia [ 4 ] are to benefit from palliative care. In Germany, palliative care is divided into specialised and general palliative care ( Table 1 ). The German Society for Palliative Medicine (DGP) estimated that 90% of dying people are in need of palliative care, but only 10% of them are in need of specialised palliative care, because of more complex needs, such as complex pain management [ 5 ]. The framework of specialised palliative care encompasses specialist outpatient palliative care, inpatient hospices and palliative care units in hospitals. In Germany, most nurses in specialised palliative care have an additional qualification [ 6 ]. Further, nurses in specialist palliative care in Germany have fewer patients to care for than nurses in other fields which results in more time for the patients [ 7 ]. Most people are treated within general palliative care in non-specialized palliative care settings, which is provided by primary care suppliers with fundamental knowledge of palliative care. These are GPs, specialists (e.g. oncologists) and, above all, staff in nursing homes, hospitals and outpatient care [ 8 ]. Nurses in general palliative care have basic skills in palliative care from their education. However, there is no data available on the extent of palliative care they provide, or information on an additional qualification in palliative care. Palliative care experts from around the world consider the education and training of all staff in the fundamentals of palliative care to be essential [ 9 ] and a study conducted in Italy revealed that professional competency of palliative care nurses was positively associated with job satisfaction [ 10 ]. Thus, it is possible that the extent of palliative care or an additional qualification in palliative care may have implications on the working situation and health status of nurses. In Germany, there are different studies which concentrate on people dying in hospitals or nursing homes and the associated burden on the institution’s staff [ 11 , 12 ], but studies considering palliative care aspects concentrate on specialised palliative care settings [ 6 , 13 , 14 ]. Because the working conditions of nurses in specialised and general palliative care are somewhat different, as stated above, this paper focuses on nurses working in general palliative care, in other words, in non-specialized palliative care settings.

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0245798.t001

Burnout is a large problem in social professions, especially in health care worldwide [ 19 ] and is consistently associated with nurses intention to leave their profession [ 20 ]. Burnout is a state of emotional, physical, and mental exhaustion caused by a long-term mismatch of the demands associated with the job and the resources of the worker [ 21 ]. One of the causes for the alarming increase in nursing burnout is their workload [ 22 , 23 ]. Workload can be either qualitative (pertaining to the type of skills and/or effort needed in order to perform work tasks) or quantitative (the amount of work to be done and the speed at which it has to be performed) [ 24 ].

Studies analysing burnout in nursing have recognised different coping strategies, self-efficacy, emotional intelligence factors, social support [ 25 , 26 ], the meaning of work and role clarity [ 27 ] as protective factors. Studies conducted in the palliative care sector identified empathy [ 28 ], attitudes toward death, secure attachment styles, and meaning and purpose in life as protective factors [ 29 ]. Individual factors such as spirituality and hobbies [ 30 ], self-care [ 31 ], coping strategies for facing the death of a patient [ 32 ], physical activity [ 33 ] and social resources, like social support [ 33 , 34 ], the team [ 6 , 13 ] and time for patients [ 32 ] were identified, as effectively protecting against burnout. These studies used qualitative or descriptive methods or correlation analyses in order to investigate the relationship between variables. In contrast to this statistical approach, fewer studies examined the buffering/moderating role of resources on the relationship between workload and burnout in nursing. A moderator variable affects the direction and/or the strength of the relationship between two other variables [ 35 ]. A previous study has showed resilience as being a moderator for emotional exhaustion on health [ 36 ], and other studies revealed professional commitment or social support moderating job demands on emotional exhaustion [ 37 , 38 ]. Furthermore, work engagement and emotional intelligence was recognised as a moderator in the work demand and burnout relationship [ 39 , 40 ].

We have analysed the working situation of nurses using the Rudow Stress-Strain-Resources model [ 41 ]. According to this model, the same stressor can lead to different strains in different people depending on available resources. These resources can be either individual, social or organisational. Individual resources are those resources which are owned by an individual. This includes for example personal capacities such as positive thinking as well as personal qualifications. Social resources consist of the relationships an individual has, this includes for example relationships at work as well as in his private life. Organisational resources refer to the concrete design of the workplace and work organisation. For example, nurses reporting a good working team may experience workload as less threatening and disruptive because a good working team gives them a feeling of security, stability and belonging. According to Rudow, individual, social or organisational resources can buffer/moderate the negative effects of job demands (stressors) on, for example, burnout (strain).

Nurses’ health may have an effect on the quality of the services offered by the health care system [ 42 ], therefore, it is of great interest to do everything possible to preserve their health. This may be achieved by reducing the workload and by strengthening the available resources. However, to the best of our knowledge, we are not aware of any study which considers palliative care aspects within general palliative care in Germany. Therefore, the aim of the study was to investigate the buffering role of resources on the relationship between workload (‘quantitative demands’) and burnout among nurses. Palliative care aspects, such as information on the extent of palliative care were incorporated to the analyses as covariates.

Study design and participants

An exploratory cross-sectional study was conducted in 2017. In Germany, there is no national register for nurses. Data for this study were collected from a stratified 10% random sample of a database with outpatient facilities, hospitals and nursing homes in Germany from the Institution for Statutory Accident Insurance and Prevention in Health and Welfare Services in Germany. This institution is part of the German social security system. It is the statutory accident insurer for nonstate institutions in the health and welfare services in Germany and thus responsible for the health concerns of the target group investigated in the present study, namely nurses. Due to data protection rules, this institution was also responsible for the first contact with the health facilities. 126 of 3,278 (3.8%) health facilities agreed to participate in the survey. They informed the study team about how many nurses worked in their institution, and whether the nurses would prefer to answer a paper-and-pencil questionnaire (with a pre-franked envelope) or an online survey (with an access code ). 2,982 questionnaires/access codes were sent out to the participating health facilities (656 to outpatient care, 160 to hospitals and 2,166 to nursing homes), where they were distributed to the nurses ( S1 Table ). Participation was voluntary and anonymous. Informed consent was obtained written at the beginning of the questionnaire. Approval to perform the study was obtained by the ethics committee of the State Chamber of Medicine in Rhineland-Palatinate (Clearance number 837.326.16 (10645)).

Questionnaire

The questionnaire contained questions regarding i) nurse’s sociodemographic information and information on current profession as well as ii) palliative care aspects. Furthermore, iii) parts of the German version of the Copenhagen Psychosocial Questionnaire (COPSOQ), iv) a resilience questionnaire [RS-13] and v) single questions relating to resources were added.

i) Sociodemographic information and information on current profession.

The nurse’s sociodemographic information and information on current profession included the variables ‘age’, ‘gender’, ‘marital status’, ‘education’, ‘professional qualification’, ‘working area’, ‘professional experience’ and ‘extent of employment’.

ii) Palliative care aspects.

Palliative care aspects included self-developed questions on ‘additional qualification in palliative care’, the ‘number of patients’ deaths within the last month (that the nurses cared for personally)’ and the ‘extent of palliative care’. The latter was evaluated by asking: how much of your working time (as a percentage) do you spend with care of palliative patients? The first two items were already used in the pilot study. The pilot study consisted of a qualitative part, where interviews with experts in general and specialised palliative care were performed [ 43 ]. These interviews were used to develop a standardized questionnaire which was used for a cross-sectional pilot survey [ 6 , 44 ].

iii) Copenhagen Psychosocial Questionnaire (COPSOQ).

The questionnaire included parts of the German standard version of the Copenhagen Psychosocial Questionnaire (COPSOQ) [ 45 ]. The COPSOQ is a valid and reliable questionnaire for the assessment of psychosocial work environmental factors and health in the workplace [ 46 , 47 ]. The scales selected were ‘quantitative demands’ (four items, for example: “Do you have to work very fast?”) measuring workload, ‘burnout’ (six items, for example: “How often do you feel emotionally exhausted?”), ‘meaning of work’ (three items, for example: “Do you feel that the work you do is important?”) and ‘workplace commitment’ (four items, for example: “Do you enjoy telling others about your place of work?”).

iv) Resilience questionnaire RS-13.

The RS-13 questionnaire is the short German version of the RS-25 questionnaire developed by Wagnild & Young [ 48 ]. The questionnaire postulates a two-dimensional structure of resilience formed by the factors “personal competence” and “acceptance of self and life”. The RS-13 questionnaire measures resilience with 13 items on a 7-point scale (1 = I do not agree, 7 = I totally agree with different statements) and has been validated in representative samples [ 49 , 50 ]. The results of the questionnaire were grouped into persons with low, moderate or high resilience.

v) Questions on resources.

Single questions on personal, social and organizational resources assessed the nurses’ views of these resources in being helpful in dealing with the demands of their work. Further, single questions collected the agreement to different statements such as ‘Do you receive recognition for your work from the supervisor? ’ (see Table 4 ). These resources were frequently reported in the pilot study by nurses in specialised palliative care [ 6 ].

Data preparation and analysis

The data from the paper-and-pencil and online questionnaires were merged, and data cleaning was done (e.g. questionnaires without specification to nursing homes, hospitals or outpatient care were excluded). The scales selected from the COPSOQ were prepared according to the COPSOQ guidelines. In general, COPSOQ items have a 5-point Likert format, which are then transformed into a 0 to 100 scale. The scale score is calculated as the mean of the items for each scale, if at least half of the single items had valid answers. Nurses who answered less than half of the items in a scale were recorded as missing. If at least half of the items were answered, the scale value was calculated as the average of the items answered [ 46 ]. High values for the scales ‘quantitative demands‘ and ‘burnout‘ were considered negative, while high values for the scales ‘meaning of work’ and ‘workplace commitment’ were considered positive. The proportion of missing values for single scale items was between 0.5% and 2.7%. Cronbach’s Alpha was used to assess the internal consistency of the scales. A Cronbach’s Alpha > 0.7 was regarded as acceptable [ 35 ]. The score of the RS-13 questionnaire ranges from 13 to 91. The answers were grouped according to the specifications in groups with low resilience (score 13–66), moderate resilience (67–72) and high resilience (73–91) [ 49 ]. The categorical resource variables were dichotomised (example: not helpful/little helpful vs. quite helpful/very helpful).

The study was conceptualised as an exploratory study. Consequently, no prior hypotheses were formulated, so the p-values merely enable the recognition of any statistically noteworthy findings [ 51 ]. Descriptive statistics (absolute and relative frequency, M = mean, SD = standard deviation) were used to depict the data. Bivariate analyses (Pearson correlation, t-tests, analysis of variance) were performed to infer important variables for the regression-based moderation analysis. Variables which did not fulfil all the conditions for linear regression analysis were recoded as categorical variables [ 35 ]. The variable ‘extent of palliative care’ was categorised as ‘≤ 20 percent of working time’ vs. ‘> 20 percent of working time’ due to the median of the variable (median = 20).

The first step with regard to the moderation analysis was to determine the resource variables. Therefore all resource variables that reached a p-value < 0.05 in the bivariate analysis with the scale ‘burnout’ were further analysed (scale ‘meaning of work’, scale ‘workplace commitment’, variables presented in Table 4 ). The moderator analysis was conducted using the PROCESS program developed by Andrew F. Hayes. First, scales were mean-centred to reduce possible scaling problems and multicollinearity. Secondly, for all significant resource variables the following analysis were done: the ‘quantitative demand’, one resource (one per model) and the interaction term between the ‘quantitative demand’ and the resource, as well as the covariates ‘age’, ‘gender’, ‘working area’, ‘extent of employment’, the ‘extent of palliative care’ and the ‘number of patient deaths within the last month’ were added to the moderator analysis, in order to control for confounding influence. If the interaction term between the ‘quantitative demand’ and the resource accounted for significantly more variance than without interaction term (change in R 2 denoted as ΔR 2 , p < 0.05), a moderator effect of the resource was present. The interaction of the variables (± 1 SD the mean or variable manifestation such as yes and no) was plotted.

All the statistical calculations were performed using the Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS, version 23.5) and the PROCESS macro for SPSS (version 3.5 by Hayes) for the moderator analysis.

Of the 2,982 questionnaires/access codes sent out, 497 were eligible for the analysis. The response rate was 16.7% (response rate of outpatient care 14.6%, response rate of hospitals 18.1% and response rate of nursing homes 16.0%). Since only n = 29 nurses from hospitals participated, these were excluded from data analysis. After data cleaning , the final number of participants was n = 437.

Descriptive results

The basic characteristics of the study population are presented in Table 2 . The average age of the nurses was 42.8 years, and 388 (89.6%) were female. In total, 316 nurses answered the question how much working time they spend caring for palliative patients. Sixteen (5.1%) nurses reported spending no time caring for palliative patients, 124 (39.2%) nurses reported between 1% to 10%, 61 (19.30%) nurses reported between 11% to 20% and 115 (36.4%) nurses reported spending more than 20% of their working time for caring for palliative patients. Approximately one-third (n = 121, 27.7%) of the nurses in this study did not answer this question. One hundred seventeen (29.5%) nurses reported 4 or more patient deaths, 218 (54.9%) reported 1 to 3 patient deaths and 62 (15.6%) reported 0 patient deaths within the last month.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0245798.t002

Table 3 presents the mean values and standard deviations of the scales ‘quantitative demands’, ‘burnout’, and the resource scales ‘meaning of work’ and ‘workplace commitment’. All scales achieved a satisfactory level of internal consistency.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0245798.t003

Bivariate analyses

There was a strong positive correlation between the ‘quantitative demands’ and ‘burnout’ scales (r = 0.498, p ≤ 0.01), and a small negative correlation between ‘burnout’ and ‘meaning of work’ (r = -0.222, p ≤ 0.01) and ‘workplace commitment’ (r = -0.240, p ≤ 0.01). Regarding the basic and job-related characteristics of the sample shown in Table 2 , ‘burnout’ was significantly related to ‘extent of palliative care’ (≤ 20% of working time: n = 199, M = 46.06, SD = 20.28; > 20% of working time: n = 115, M = 53.80, SD = 20.24, t(312) = -3.261, p = 0.001). Furthermore, there was a significant effect regarding the ‘number of patient deaths during the last month’ (F (2, 393) = 5.197, p = 0.006). The mean of the burnout score was lower for nurses reporting no patient deaths within the last month than for nurses reporting four or more deaths (n = 62, M = 42.47, SD = 21.66 versus n = 116, M = 52.71, SD = 20.03). There was no association between ‘quantitative demands’ and an ‘additional qualification in palliative care’ (no qualification: n = 328, M = 55.77, SD = 21.10; additional qualification: n = 103, M = 54.39, SD = 20.44, p = 0.559).

The association between ‘burnout’ and the evaluated (categorical) resource variables is presented in Table 4 . Nurses mostly had a lower value on the ‘burnout’ scale when reporting various resources. Only the resources ‘family’, ‘religiosity/spirituality’, ‘gratitude of patients’, ‘recognition through patients/relatives’ and an ‘additional qualification in palliative care’ were not associated with ‘burnout’.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0245798.t004

Moderator analyses

In total, 16 moderation analyses were conducted. Table 5 presents the results of the moderation analyses where a significant moderation was found. For ‘workplace commitment’, there was a positive and significant association between ‘quantitative demands’ and ‘burnout’ (b = 0.47, SE = 0.051, p < 0.001). An increase of one value on the scale ‘quantitative demands’ increased the scale ‘burnout’ by 0.47. ‘Workplace commitment’ was negatively related to ‘burnout’, meaning that a higher degree of ‘workplace commitment’ was related to a lower level of ‘burnout’ (b = -0.11, SE = 0.048, p = 0.030). A model with the interaction term of ‘quantitative demands’ and the resource ‘workplace commitment’ accounted for significantly more variance in ‘burnout’ than a model without interaction term (ΔR 2 = 0.021, p = 0.004). The impact of ‘quantitative demands’ on ‘burnout’ was dependent on ‘workplace commitment’ (b = -0.01, SE = 0.002 p = 0.004). The variables explained 31.9% of the variance in ‘burnout’.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0245798.t005

Regarding the ‘good working team’ resource, the variables ‘quantitative demands’ and ‘burnout’ were positively and significantly associated (b = 0.76, SE = 0.154, p < 0.001), and the variables ‘good working team’ and ‘burnout’ were not associated (b = -3.15, SE = 3.52, p = 0.372). A model with the interaction term of ‘quantitative demands’ and the ‘good working team’ resource accounted for significantly more variance in ‘burnout’ than a model without interaction term (ΔR 2 = 0.011, p = 0.040). The ‘good working team’ resource moderated the impact of ‘quantitative demands’ on ‘burnout’ (b = -0.34, SE = 0.165, p = 0.004). The variables explained 29.7% of the variance in ‘burnout’.

The associations between ‘quantitative demands’ and ‘burnout’ (b = 0.63, SE = 0.085, p < 0.001), between ‘recognition supervisor’ and ‘burnout’ (b = -7.29, SE = 2.27, p = 0.001), and the interaction term of ‘quantitative demands’ and the resource ‘recognition supervisor’ (b = -0.34, SE = 0.108, p = 0.002) were significant. Again, a model with the interaction term accounted for significantly more variance in ‘burnout’ than a model without interaction term (ΔR 2 = 0.024, p = 0.002). ‘Recognition from supervisor’ influenced the impact of ‘quantitative demands’ on burnout for -0.34 on the 0 to 100 scale. The variables explained 33.7% of the variance in ‘burnout’.

Figs 1 – 3 demonstrates simple slopes of the interaction effects of ‘workplace commitment’ predicting ‘burnout’ at high, average and low levels ( Fig 1 ) respectively with and without the resource ‘good working team’ ( Fig 2 ) and ‘recognition from supervisor’ ( Fig 3 ). Higher ‘quantitative demands’ were associated with higher levels of ‘burnout’. At low ‘quantitative demands’, the ‘burnout’ level was quite similar for all nurses. However, when ‘quantitative demands’ increased, nurses who confirmed that they had the resources stated a lower ‘burnout’ level than nurses who denied having them. This trend is repeated by the resources ‘workplace commitment’, ‘good working team’ and ‘recognition from supervisor’.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0245798.g001

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0245798.g002

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0245798.g003

The palliative care aspect ‘extent of palliative care’ showed that spending more than 20 percent of working time in care for palliative patients increased burnout significantly by a value of approximately 5 on a 0 to 100 scale ( Table 5 ).

The aim of the present study was to analyse the buffering role of resources on the relationship between workload and burnout among nurses. This was done for the first time by considering palliative care aspects, such as information on the extent of palliative care.

The study shows that higher quantitative demands were associated with higher levels of burnout, which is in line with other studies [ 37 , 39 ]. Furthermore, the results of this study indicate that working in a good team, recognition from supervisor and workplace commitment is a moderator within the workload—burnout relationship. Although the moderator analyses revealed low buffering effect values, social resources were identified once more as important resources. This is consistent with the results of a study conducted in the field of specialised palliative care in Germany, where a good working team and workplace commitment moderated the impact of quantitative demands on nurses burnout [ 52 ]. A recently published review also describes social support from co-workers and supervisors as a fundamental resource in preventing burnout in nurses [ 53 ]. Workplace commitment was not only reported as a moderator between workload and health in the nurse setting [ 37 ], but also as a moderator between work stress and burnout [ 54 ] and between work stress and other health related aspects outside the nurse setting [ 55 ]. In the present study, the effect of high workload on burnout was reduced with increasing workplace commitment. Nurses reporting a high work commitment may experience workload as less threatening and disruptive because workplace commitment gives them a feeling of belonging, security and stability. However, there are also some correlation studies which observed no direct relationship between workplace commitment and burnout for occupations in the health sector [ 56 ]. A study from Serbia assessed workplace commitment by nurses and medical technicians as a protective factor against patient-related burnout, but not against personal and work-related burnout [ 57 ]. Furthermore, a study conducted in Estonia reported no relationship between workplace commitment and burnout amongst nurses [ 58 ]. As there are indications that workplace commitment is correlated with patient safety [ 59 ], the development and improving of workplace commitment needs further scientific investigation.

This study observed slightly higher burnout rates among nurses who reported a ‘good working team’ for low workload. This fact is not decisive for the interpretation of the moderation effect of this resource because moderation is present. When workload increased, nurses who confirmed that they worked in a good working team stated a lower burnout level. However, the result of the current study showed that a good working team is particularly important when workload increases, in the most extreme cases team work in palliative care is necessary to save a person’s life. Because team work in today’s health care system is essential, health care organisations should foster team work in order to enhance their clinical outcomes [ 60 ], improve the quality of patient care as well as health [ 61 ] and satisfaction of nurses [ 62 ].

The bivariate analysis revealed that nurses who reported getting recognition from colleagues, through the social context, salary and gratitude from relatives of patients stated a lower value on the burnout scale. This is in accordance with the results of a qualitative study, which indicated that the feeling of recognition, and that one’s work is useful and worthwhile, is very important for nurses and a source of satisfaction [ 63 ]. Furthermore, self-care, self-reflection [ 64 ] and professional attitude/dissociation seem to play an important role in preventing burnout. The bivariate analysis also revealed a relationship between resilience and burnout. Nurses with high resilience reported lower values on the burnout scale, but a buffering role of resilience on burnout was not assessed. The present paper focuses solely on quantitative demands and burnout. In future studies, the different fields of nursing demands, like organisational or emotional demands, should be assessed in relation to burnout, job satisfaction and health.

Finally, we observed whether the consideration of palliative care aspects is associated with burnout. The bivariate analysis revealed a relationship between the extent of palliative care, number of patient deaths within the last month and burnout. Using regression analyses, only the extent of palliative care was associated with burnout. Since, to the best of our knowledge, the present study is the first study to consider palliative care aspects within general palliative care in Germany, these variables need further scientific investigation, not only within the demand—burnout relationship but also between the demand—health and the demand—job satisfaction relationship. Furthermore, palliative care experts from around the world considered the education and training of all members of staff in the fundamentals of palliative care to be essential [ 9 ]. One-fourth of the respondents in the present study had an additional qualification in palliative care, which was not obligatory. We assessed a relationship between quantitative demands and burnout but no relationship between an additional qualification and quantitative demands nor burnout. Nevertheless, we assessed a protective effect of the additional qualification within the pilot study in specialised palliative care, in relation both to organisational demands and demands regarding the care of relatives [ 6 ]. This suggests that the additional qualification is a resource, but one which depends on the field of demand. Further analyses would be required to review benefits achieved by additional qualifications in general palliative care.

The variable extent of palliative care is the one with the most missing values in the survey, thus future analyses should not only study larger samples but also reconsider the question on extent of palliative care.

Finally, it can be said that the main contribution of the present study is to make palliative care aspects in non-specialised palliative care settings a subject of discussion.

Limitations

The following potential limitations need to be stated: although a random sample was drawn, the sample is not representative for general palliative care in Germany due to a low participation rate of the health facilities, a low response rate of the nurses, the different responses of the health facilities and the exclusion of hospitals. One possible explanation for the low participation rate of the health facilities is the sampling procedure and data protection rules, which did not allowed the study team to contact the institutions in the sample. Due to the low participation rate, the results of the present study may be labelled as preliminary. Further, the data are based on a detailed and anonymous survey, and therefore the potential for selection bias has to be considered. It is possible that the institutions and nurses with the highest burden had no time for or interest in answering the questionnaire. It is also possible that the institutions which care for a high number of palliative patients may have taken particular interest in the survey. Additionally, some items of the questionnaire were self-developed and not validated but were considered valuable for our study as they answered certain questions that standardized questionnaires could not. The moderator analyses revealed low effect values and the variance explained by the interaction terms is rather low. However, moderator effects are difficult to detect, therefore, even those explaining as little as one percent of the total variance should be considered [ 65 ]. Consequently, the additional amount of variance explained by the interaction in the current study (2% for workplace commitment and recognition of supervisor and 1% for good working team) is not only statistically significant but also practically and theoretically relevant. When considering the results of the current study, it must be taken into account that the present paper focuses solely on quantitative demands and burnout. In future studies, the different fields of nursing demands have to be carried out on the role of resources. This not only pertains for burnout, but also for other outcomes such as job satisfaction and health. Finally, the cross-sectional design does not allow for casual inferences. Longitudinal and interventional studies are needed to support causality in the relationships examined.

Conclusions

The present study provides support to a buffering role of workplace commitment, good working teams and recognition from supervisors on the relationship between workload and burnout. Initiatives to develop or improve workplace commitment and strengthen collaboration with colleagues and supervisors should be implemented in order to reduce burnout levels. Furthermore, the results of the study provides first insights that palliative care aspects in general palliative care may have an impact on nurse burnout, and therefore they have gone unrecognised for too long in the scientific literature. They have to be considered in future studies, in order to improve the working conditions, health and satisfaction of nurses. As our study was exploratory, the results should be confirmed in future studies.

Supporting information

S1 table. number of questionnaires sent out to facilites and response rate..

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0245798.s001

Acknowledgments

We thank the nurses and the health care institutions for taking part in the study. We thank D. Wendeler, O. Kleinmüller, E. Muth, R. Amma and C. Kohring who were helpful in the recruitment of the participants and data collection.

- 1. OECD. Health at a glance 2015: OECD indicators. 2015th ed. Paris: OECD Publishing; 2015.

- View Article

- PubMed/NCBI

- Google Scholar

- 5. Melching H. Palliativversorgung—Modul 2 -: Strukturen und regionale Unterschiede in der Hospiz- und Palliativversorgung. Gütersloh; 2015.

- 8. German National Academy of Sciences Leopoldina and Union of German Academies of Sciences. Palliative care in Germany: Perspectives for practice and research. Halle (Saale): Deutsche Akademie der Naturforscher Leopoldina e. V; 2015.

- 12. George W, Siegrist J, Allert R. Sterben im Krankenhaus: Situationsbeschreibung, Zusammenhänge, Empfehlungen. Gießen: Psychosozial-Verl.; 2013.

- 15. Deutsche Krebsgesellschaft, Deutsche Krebshilfe, Arbeitsgemeinschaft der Wissenschaftlichen Medizinischen Fachgesellschaften (AWMF). Palliativmedizin für Patienten mit einer nicht heilbaren Krebserkrankung: Langversion 1.1; 2015.

- 16. Deutsche Gesellschaft für Palliativmedizin. Definitionen zur Hospiz- und Palliativversorgung. 2016. https://www.dgpalliativmedizin.de/images/DGP_GLOSSAR.pdf . Accessed 8 Sep 2020.

- 17. Deutscher Hospiz- und PalliativVerband e.V. Hospizarbeit und Palliativversorgung. 2020. https://www.dhpv.de/themen_hospiz-palliativ.html . Accessed 20 May 2020.

- 24. van Veldhoven Marc. Quantitative Job Demands. In: Peeters M, Jonge de J, editors. An introduction to contemporary work psychology. Chichester West Sussex UK: John Wiley & Sons; 2014. p. 117–143.

- 35. Field A. Discovering statistics using IBM SPSS statistics. 4th ed. Los Angeles, London, New Delhi, Singapore, Washington DC, Melbourne: SAGE; 2016.

- 41. Rudow B. Die gesunde Arbeit: Psychische Belastungen, Arbeitsgestaltung und Arbeitsorganisation. 3rd ed. Berlin, München, Boston: De Gruyter Oldenbourg; 2014.

- 45. Freiburger Forschungsstelle für Arbeits- und Sozialmedizin. Befragung zu psychosozialen Faktoren am Arbeitsplatz. 2016. https://www.copsoq.de/assets/COPSOQ-Standard-Fragebogen-FFAW.pdf . Accessed 6 Mar 2020.

- 60. O’Daniel M, Rosenstein AH. Patient Safety and Quality: An Evidence-Based Handbook for Nurses: Professional Communication and Team Collaboration. Rockville (MD); 2008.

- 61. Canadian Health Services Research Foundation. eamwork in healthcare: promoting effective teamwork in healthcare in Canada.: Policy synthesis and recommendations.; 2006.

- Open access

- Published: 08 October 2022

Workload and quality of nursing care: the mediating role of implicit rationing of nursing care, job satisfaction and emotional exhaustion by using structural equations modeling approach

- Fatemeh Maghsoud 1 ,

- Mahboubeh Rezaei 2 ,

- Fatemeh Sadat Asgarian 3 &

- Maryam Rassouli 4

BMC Nursing volume 21 , Article number: 273 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

11k Accesses

17 Citations

Metrics details

Nursing workload and its effects on the quality of nursing care is a major concern for nurse managers. Factors which mediate the relationship between workload and the quality of nursing care have not been extensively studied. This study aimed to investigate the mediating role of implicit rationing of nursing care, job satisfaction and emotional exhaustion in the relationship between workload and quality of nursing care.

In this cross-sectional study, 311 nurses from four different hospitals in center of Iran were selected by convenience sampling method. Six self-reported questionnaires were completed by the nurses. The data were analyzed by SPSS version 16. Structural equation modeling was used to determine the relationships between the components using Stata 14 software.

Except direct and mutual relationship between workload and quality of nursing care ( P ≥ 0.05), the relationship between other variables was statistically significant ( P < 0.05). The hypothesized model fitted the empirical data and confirmed the mediating role of implicit rationing of nursing care, job satisfaction and emotional exhaustion in the relationship between workload and the quality of nursing care (TLI, CFI > 0.9 and RMSEA < 0.08 and χ 2 /df < 3).

Workload affects the quality of the provided nursing care by affecting implicit rationing of nursing care, job satisfaction and emotional exhaustion. Nurse managers need to acknowledge the importance of quality of nursing care and its related factors. Regular supervision of these factors and provision of best related strategies, will ultimately lead to improve the quality of nursing care.

Peer Review reports

Care is the core of the nursing profession and the main factor which distinguishes nursing from other health-related professions [ 1 , 2 ]. High-quality nursing care means the provision of easy and accessible care by competent qualified nurses [ 3 ]. Nowadays, the maintenance and improvement of the quality of nursing care is the most important challenge for nursing care systems around the world [ 4 ]. The first step in improving the quality of nursing care is to evaluate and analyze the quality of provided care and examine the factors affecting on it [ 5 ].

Various variables can affect the quality of nursing care [ 6 , 7 , 8 ]; one of which is workload. Zuniga et al. (2015) indicated in Switzerland that increased workload and, subsequently, increased stress could reduce the quality of nursing care [ 9 ]. However, there are contradictory findings in this regard. It was shown in another study that there was a high level of nursing care quality despite the high workload and inadequate human resources and equipment [ 6 ]. In another study, the workload was measured by total direct nursing hours. The results showed a significant correlation between total direct nursing hours and some indicators of nursing care quality such as incidence of patient restraint, and mortality rate. Nevertheless, there was no significant correlation with other indicators of nursing care quality like incidence density of pressure sores, the incidence of falls, the incidence of tube self-extraction, and incidence density of infection [ 10 ].

In addition to the correlation between workload and the quality of nursing care, a number of other factors can also be involved in this relationship. For example, workload can lead to implicit rationing of nursing care, thereby can affect the quality of care. In a study conducted in Lebanon, the level of perceived workload in all shifts had a positive relationship with the level of rationing of nursing care [ 11 ]. Because of many reasons such as high workload, nurses may find themselves in situations where they are forced to omit the necessary cares, do them briefly or with delay [ 11 , 12 ]. Nurses are unable to provide comprehensive care in accordance with professional standards, and it can affect the quality of nursing care [ 13 ]. A study conducted in China showed that the nurses who had a higher score in rationing of nursing care, had a lower score of the quality of nursing care [ 14 ]. Moreover, while increased rationing in rehabilitation, care, supervision and social care in nursing homes, decreases the quality of nursing care, increased rationing in the field of documentation increases the quality of nursing care [ 9 ].

Job satisfaction seems to be another factor mediating the relationship between workload and the quality of nursing care. Inegbedion et al. (2020) indicated that increased workload could be associated with decreased job satisfaction among nurses [ 15 ]. Workload as a strong stressor can negatively affect the job satisfaction of nurses [ 16 ]. Job satisfaction is a multidimensional emotional concept which reflects the interaction between nurses' expectations and values, their environment and personal characteristics [ 17 ]. Perception of the significance of nurses' job satisfaction and its improvement is essential in providing high-quality care with optimal clinical outcomes. In the study of Aron et al. (2015), 87.6% of nurses believed that the quality of care provided by nurses was affected by their job satisfaction [ 18 ]. According to another study, job satisfaction was a significant predictor of the quality of nursing care [ 19 ].

Workload may also affect the quality of nursing care by causing emotional exhaustion in nurses. The results of a study revealed that 55.4% of Canadian nurses suffered from emotional exhaustion. The high workload in this study was a predictor of emotional exhaustion and there was a positive and significant correlation between workload and emotional exhaustion [ 20 ]. Additionally, the findings of Nantsupawat et al. (2016) were indicative of the effect of emotional exhaustion on the quality of nursing care. While increased emotional exhaustion of nurses in their study increased the incidence of medication errors and infections, it decreased the quality of nursing care [ 21 ]. Findings of another study showed that among the components of job burnout, emotional exhaustion had the strongest relationship with the quality of nursing care [ 22 ].

Previous studies have mainly investigated the relationship of one or two variables with the quality of nursing care and the simultaneous effect of several mediating variables on the quality of nursing care has not been examined [ 23 , 24 , 25 ]. Many of these studies have not used a comprehensive questionnaire to assess all aspects of the quality of nursing care or have been conducted in other settings except hospital units [ 6 , 9 , 26 , 27 ]. Assessing the quality of nursing care with an incomplete questionnaire or with only one question does not cover all dimensions of quality of nursing care such as the care-related activities, nursing care environment, nursing process, and strategies that empower patients and will provide incomplete findings [ 28 , 29 ].

Accordingly, to improve the quality of nursing care, we need to determine these variables and their mediating roles, in order to better control them through applying effective interventions. Using Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) is one powerful tool for mediation analysis [ 30 , 31 ], this study was conducted to investigate the mediating role of implicit rationing of nursing care, job satisfaction, and emotional exhaustion in the relationship between workload and the quality of nursing care in Iran.

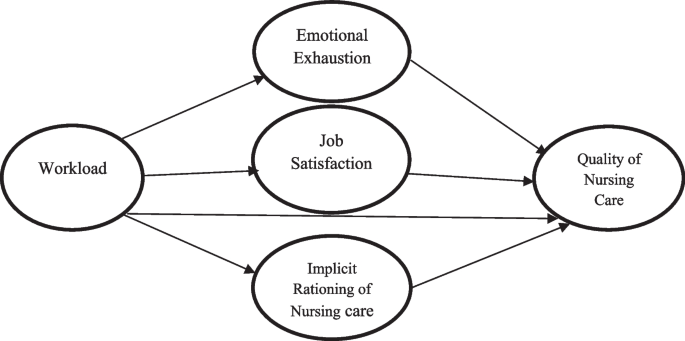

The theoretical model in this study was developed by reviewing the related literature (Fig. 1 ) to test three hypotheses:

Hypothesized model

H1: Implicit rationing of nursing care plays a mediating role in the relationship between workload and the quality of nursing care.

H2: Job satisfaction plays a mediating role in the relationship between workload and the quality of nursing care.

H3: Emotional exhaustion plays a mediating role in the relationship between workload and the quality of nursing care.

Study design and participants

This cross-sectional study was conducted from October to December 2020 in inpatient units of four selected hospitals in central Iran, Kashan city. According to the guidelines of structural equation modeling, the study required at least 300 participants [ 32 ]. As such, 311 employed nurses participated in the study by using the convenience sampling method. Inclusion criteria were as follows: willingness to participate in the study, having at least six months of work experience, having experience of direct clinical care of patients, and having at least a bachelor's degree in nursing. Exclusion criteria were failure to complete the questionnaire and decline to answer the questionnaires in the process of the study.

Instrumentation

Six tools were used to collect data and analyze the variables of this study:

Nurse's demographic information questionnaire which contains questions about age, gender, marital status, current workplace unit, employment status, nursing work experience, duration of working in the current unit, having overtime, average salary per month, being a nurse as a second job, having a second job beside nursing and the level of interest in the nursing.

The NASA Task Load Index (NASA-TLX) includes six areas of mental demand, physical demand, temporal demand, performance, effort and, frustration. The final score is calculated to be between zero and 100, where scores higher than 50 are indicative of a high overall subjective workload [ 33 ]. Using Cronbach's alpha coefficient, the reliability of this questionnaire has been reported to be above 0.8 in previous studies [ 34 , 35 ].

Basel Extend of Rationing of Nursing Care (BERNCA) questionnaire which has 20 items based on a 4-point Likert scale. In this questionnaire, nurses assess themselves how many times in the past month they have not been able to perform the listed care activities and have been forced to ration them. The total mean score of rationing is 0–3, and the higher the score, the more will be the care that has been rationed. Cronbach's alpha coefficient was calculated to be 0.93 [ 36 ]. The reliability coefficient was calculated at 0.91 in the present study.

The Minnesota Satisfaction Questionnaire (MSQ) which was designed by Weiss et al. (1967) and has two long and short versions [ 37 ]. In this study, the short version of the questionnaire was used. This 18-item questionnaire is based on a 5-point Likert scale and higher scores are indicative of better job satisfaction. The reliability and validity of this questionnaire was determined in Iran [ 38 ]. Using Cronbach's alpha, the reliability of this questionnaire was calculated at 0.77 in the present study.

The emotional exhaustion subscale of the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI), includes nine items and is based on a 7-point Likert scale. Higher scores indicate higher emotional exhaustion [ 39 ]. The validity and reliability of this scale were examined in Iran and Cronbach's alpha coefficient was reported to be 0.88 [ 40 ]. Cronbach's alpha coefficient was calculated to be 0.90 in the study of Maslach et al. (1996) and 0.89 in the present study.

The Good Nursing Care Scale (GNCS) is a comprehensive questionnaire that examines all aspects of the quality of nursing care. It has two parallel versions for the nurse and the patient and the nurse's version was used in the present study. This questionnaire has 40 items and seven dimensions include nurses’ characteristics in providing care ( such as type of interaction with the patient, and accuracy ), care-related activities ( such as patient education, and emotional support ), care preconditions ( such as nurse’s knowledge, skill, and experience ), nursing care environment ( such as infection control, maintain patient safety, and patient privacy protection ), nursing process ( conditions related to patient’s admission, treatment and, discharge ), patient empowerment strategies in coping with the disease ( such as paying attention to the patient’s level of knowledge, answering the questions ), and collaboration with the patient's family and relatives ( such as providing sufficient information to the family, and family participation in treatment process ). The scale is based on a 5-point Likert scale and the higher the obtained score, the more will be the quality of provided care [ 28 , 29 ]. This scale has been psychometrically evaluated and used in different countries and Cronbach's alpha coefficient for the scale has been in the range of 0.80 to 0.94 in various studies [ 6 , 41 , 42 , 43 ]. Cronbach's alpha coefficient was calculated to be 0.93 in the present study.

Data collection

All six questionnaires were filled out by the participants based on their work performance in the past month. After obtaining the informed written and oral consent of the eligible nurses, they were explained how to complete the questionnaires. It order to prevent the nurses’ fatigue, the questionnaires were prepared in both online and paper format. The researcher asked each of the participants if they wanted to fill out the questionnaires online or on paper format. If the participants chose the paper format, the questionnaires were delivered to them and were collected at the appointed time. All of the questionnaires have been assessed immediately after the response of the participants and any missing data have been filled by them. But if the participants selected the online version, the link to the questionnaires was sent to their cellphone. This link was designed in such a way that a person could answer only once through the link of the questionnaire and until all the questions were answered, the questionnaire was not sent. Accordingly, there were no missing data. All data collection process was done by a researcher (first author).

Data analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS version 16 and Stata version 14. Categorical data were described by frequencies and percentages, and quantitative continuous data by mean and standard deviation (SD). The correlation between the variables was determined by the Pearson correlation coefficient test. Structural equation modeling was used to capture the structure of relationships among a web of latent and observed components. To understand the relationships between the variables, according to the theoretical model of the study, all variables were analyzed using Stata software and the structural model was developed. In this study, three types of absolute, comparative and, parsimony fit indices were examined. The Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), the Comparative Fit Index (CFI) Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI), and the ratio of chi-square to the degrees of freedom (χ2 / df) were considered for the good fit of the model. A model is considered to have good fit if the (χ2 / df) value is lower than 3, CFI and TLI are 0.90 or greater, and the RMSEA value is less than 0.08 [ 44 , 45 ]

Participants’ characteristics

All of 311 distributed questionnaires were completed and analyzed. The mean age of the nurses participating in the study was 32.68 ± 6.73 years. The majority of the participants were female (86.5%) and married (76.2%). The complete demographic information of the participants can be seen in Table 1 .

Bivariate analysis

According to the scoring of the questionnaires, the workload of the nurses was at a high level, implicit rationing of nursing care happened rarely, the job satisfaction of nurses was at a moderate level and emotional exhaustion was at a low level. Moreover, the quality of the provided nursing care was at a good level (Table 2 ).

According to the result of Pearson correlation coefficient, there was a statistically significant correlation between the various variables of the study (except workload and quality of nursing care) (Table 3 ).

Structural equation model

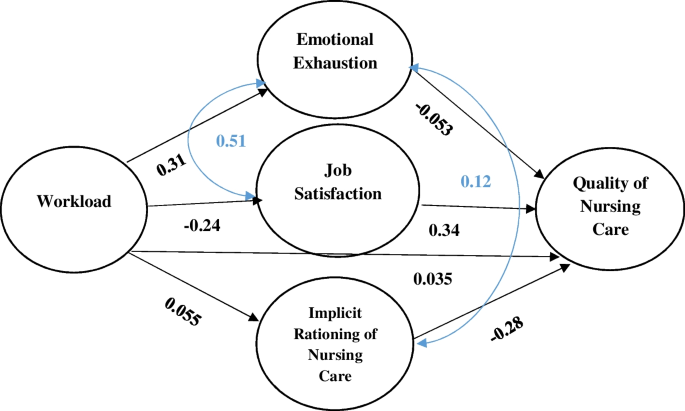

Based on the results of this study, the direct effect of workload on implicit rationing of nursing care, job satisfaction and emotional exhaustion was statistically significant ( p < 0.05). Moreover, implicit rationing of nursing care, job satisfaction, and emotional exhaustion had an indirect statistically significant effect on the relationship between workload and quality of nursing care ( p < 0.05) (Table 4 ).

The obtained good fit indices confirmed the mediating role of implicit rationing of nursing care (TLI = 0.94; CFI = 0.95; RMSEA = 0.05), job satisfaction (TLI = 1; CFI = 1; RMSEA = 0.01) and emotional exhaustion (TLI = 0.96; CFI = 0.95; RMSEA = 0.01) in the relationship between workload and the quality of nursing care.

As shown in Fig. 2 , the model fit the data well and was consistent with the hypothesized model. By putting together the three variables of implicit rationing of nursing care, job satisfaction, and emotional exhaustion as mediators in the model, a good fit was obtained (TLI = 0.95; χ2/df = 2.3; CFI = 0.96; and RMSEA = 0.05).

The final model

The results of this study supported the proposed hypothesized model. The findings shown in this structural equation model provided strong support for the study hypotheses.

Based on the findings, implicit rationing of nursing care played a mediating role in the relationship between workload and the quality of nursing care. Therefore, the H1 hypothesis was supported. When the nurses’ workload is high and they are responsible for caring for a large number of patients, they are inevitably forced to ration some important interventions which, in turn, can reduce the quality of nursing care [ 12 , 13 ]. An earlier study showed that implicit rationing of nursing care functions as a mediator between predictive variables such as workload and patient-related outcomes such as medication error and patients’ falling. These adverse events can reduce the quality of nursing care [ 20 ]. In other words, workload has an indirect effect on patient-related outcomes through care rationing and affecting the ability of nurses in completing their main tasks. In another study, nurse-to-patient ratio, as an important indicator in the workload of nurses, affected the quality of care and the incidence of adverse events through rationing of care. In other words, poor nurse staffing levels leads to the rationing of nursing care and, thereby, hinders the provision of high quality care [ 14 ]. Some other studies also referred to the mediating role of rationing of nursing care in the relationship between workload and patient safety [ 46 ] as well as in the relationship between workload and patients’ falling [ 47 ]. Accordingly, implicit rationing of nursing care seems to play a key role in the relationship between workload and the quality of nursing care.

In the present study, nurses’ job satisfaction was the second variable that mediated the relationship between workload and quality of nursing care. Hence, the H2 hypothesis was supported. When the workload is increased, nurses cannot meet some of the needs of patients despite the effort they make. So, nurses do not have a positive attitude toward their performances, leading to less job satisfaction [ 23 , 48 ]. In these circumstances, nurses do not have the necessary peace of mind and precision in the workplace which may negatively affect their efficiency and performance, decreasing the quality of the provided care [ 49 ]. Job satisfaction is an important variable that mediates the relationship between workload and other variables such as intention to leave the job and position [ 50 , 51 ]. Therefore, this is affecting the quality of nursing care indirectly. However, more research is required to investigate the mediating role of job satisfaction.

Emotional exhaustion was another mediating variable in the relationship between workload and quality of nursing care in this study. Therefore, the H3 hypothesis was supported. Emotional exhaustion is considered to be the most important component of job burnout and nurses who experience high levels of emotional exhaustion will suffer from job burnout and have a lower ability and tendency to provide high-quality care [ 39 , 52 ]. According to Van Bogaert et al. (2009), emotional exhaustion plays a mediating role in the relationship between nurses’ workplace conditions and the quality of nursing care [ 53 ]. Liu et al. (2018) also indicated that emotional exhaustion mediates the relationship between workload and patient safety. When nurses are constantly exposed to stressful work environments, their reactions become more chronic and serious, and they need more time to recover [ 46 ]. Additionally, because of high workload and regular attendance at the hospital, nurses do not have much opportunity to rest and regain their energy and, thus, will experience a perpetual emotional exhaustion [ 54 ].

It is noticed from this study that there was no significant correlation between workload and quality of nursing care. This finding is interesting and in line with an earlier study in which despite the high levels of workload and insufficiency of human resources and equipment, the quality of nursing care was at a high level [ 6 ]. Considering that both the nurse’s workload and the quality of nursing care have been investigated from the nurse's point of view, more reliable results have been obtained in this study. It should be noted that the final model in this study is a full mediation model, as the three variables (rationing of nursing care, job satisfaction, and emotional exhaustion) fully mediate the effect of workload on the quality of nursing care. So, after controlling for this mediation effect, there is no direct effect of workload on quality of nursing care [ 55 ].

Also, it seems that experience of high levels of workload for a long period of time and fall into the habit of these conditions lead to nurses can manage difficult situations. According to this finding, it is suggested that temporary or permanent high nursing workload should be taken into consideration in the next researches. Also, social desirability bias which is the tendency to respond in a pleasing way, in answering the questions related to quality of nursing care may also have been influential.

Study limitations

This study has several limitations: a) the present study was confined to frontline nurses in four selected governmental hospitals in a small city in the country; so, generalization of the findings may be limited; b) given the limited number of available participants, the convenience sampling method was used to provide the minimum sample size. It is suggested that future studies be conducted in different cities of the country and private and public hospitals with more participants, to be able to compare the findings; c) the use of self-report questionnaires and nurses’ perceptions to obtain data on the study variables may be a potential limitation because of social desirability bias [ 56 , 57 ]. It is recommended that future studies use more precise data collection strategies with observation or retrospective methodology; d) because the questionnaires filled out by the participants based on their work performance in the past month, recall bias may be another limitation of this study; e) although SEM approach was used in this study, causation cannot be established with the cross-sectional study design.

Implication for clinical practice

Nurse managers have a prominent position related to issues such as nursing workload, rationing of nursing care, job satisfaction and emotional exhaustion. Providing any intervention in these fields, will ultimately effect on the quality of nursing care. Nursing workload, which was at high level, is a major concern in this study. Some strategies such as staffing and resource adequacy assessment and hiring more nurses to increase staffing levels can be useful [ 58 ]. Moderate levels of job satisfaction and emotional exhaustion were another important finding of this study. Administering flexible work schedules, increasing monthly salary, suggesting some mental health resources, and modification of work environment may be improving nurses’ job satisfaction and decrease their emotional exhaustion. Regular supervision of clinical nursing care activities and provision of continuous feedback are important to ensure that essential nursing care tasks are provided and prevent any compromise of nursing care [ 59 ] .

Despite the limitations, this study highlighted that the three variables of implicit rationing of nursing care, job satisfaction and emotional exhaustion played a mediating role in the relationship between workload and quality of nursing care. In other words, the effect of workload was applied to the quality of nursing care through these three variables. Therefore, the assumed theoretical model was approved and provided a theoretical basis for quality of nursing care. Nurse managers should pay special attention to the three mediating variables and monitor them periodically and try to solve problems in these areas. Nurse managers should be aware that support of nurses means the support of high-quality care of the patients and overlooking the issues and problems of nurses will have negative effect on the patients.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

Basel Extend of Rationing of Nursing Care

Comparative Fit Index

Good Nursing Care Scale

Maslach Burnout Inventory

Minnesota Satisfaction Questionnaire

NASA Task Load Index

Root Mean Square Error of Approximation

Standard Deviations

Tucker-Lewis Index

Labrague LJ, McEnroe-Petitte DM, Papathanasiou IV, Edet OB, Arulappan J, Tsaras K. Nursing students’ perceptions of their own caring behaviors: a multicountry mtudy. Int J Nurs Knowl. 2017;28(4):225–32. https://doi.org/10.1111/2047-3095.12108 .

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Ross-Kerr JC, Wood MJ. Canadian nursing: issues and perspectives. 5th ed. Canada: Mosby Publisher; 2010.

Google Scholar

Charalambous A, Papadopoulos IR, Beadsmoore A. Listening to the voices of patients with cancer, their advocates and their nurses: a hermeneutic-phenomenological study of quality nursing care. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2008;12(5):436–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejon.2008.05.008 .

Vinckx MA, Bossuyt I, Dierckx de Casterlé B. Understanding the complexity of working under time pressure in oncology nursing: a grounded theory study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2018;87:60–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2018.07.010 .

Jaramillo Santiago LX, Osorio Galeano SP, Salazar Blandón DA. Quality of nursing care: perception of parents of newborns hospitalized in neonatal units. Invest Educ Enferm. 2018;36(1):e08. https://doi.org/10.17533/udea.iee.v36n1e08 .

Gaalan K, Kunaviktikul W, Akkadechanunt T, Wichaikhum OA, Turale S. Factors predicting quality of nursing care among nurses in tertiary care hospitals in Mongolia. Int Nurs Rev. 2019;66(2):176–82. https://doi.org/10.1111/inr.12502 .

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Labrague LJ, De Los Santos JAA, Tsaras K, Galabay JR, Falguera CC, Rosales RA, et al. The association of nurse caring behaviors on missed nursing care, adverse patient events and perceived quality of care: A cross-sectional study. J Nurs Manag. 2020;28(8):2257–65. https://doi.org/10.1111/jonm.12894 .

Guirardello EB. Impact of critical care environment on burnout, perceived quality of care and safety attitude of the nursing team. Rev Lat Am Enfermagem. 2017;25:e2884. https://doi.org/10.1590/1518-8345.1472.2884 .

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Zúñiga F, Ausserhofer D, Hamers JP, Engberg S, Simon M, Schwendimann R. Are staffing, work environment, work stressors, and rationing of care related to care workers’ perception of quality of care? A cross-sectional study. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2015;16(10):860–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2015.04.012 .

Chang LY, Yu HH, Chao YC. The Relationship between nursing workload, quality of care, and nursing payment in intensive care units. J Nurs Res. 2019;27(1):1–9. https://doi.org/10.1097/jnr.0000000000000265 .

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Dhaini SR, Simon M, Ausserhofer D, Al Ahad MA, Elbejjani M, Dumit N, et al. Trends and variability of implicit rationing of care across time and shifts in an acute care hospital: a longitudinal study. J Nurs Manag. 2020;28(8):1861–72. https://doi.org/10.1111/jonm.13035 .

Kalisch BJ, Landstrom GL, Hinshaw AS. Missed nursing care: a concept analysis. J Adv Nurs. 2009;65(7):1509–17. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2009.05027.x .

Cho SH, Lee JY, You SJ, Song KJ, Hong KJ. Nurse staffing, nurses prioritization, missed care, quality of nursing care, and nurse outcomes. Int J Nurs Pract. 2020;26(1):e12803. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijn.12803 .

Zhu X, Zheng J, Liu K, You L. Rationing of nursing care and its relationship with nurse staffing and patient outcomes: the mediation effect tested by structural equation modeling. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(10):1672. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16101672 .

Article PubMed Central Google Scholar

Inegbedion H, Inegbedion E, Peter A, Harry L. Perception of workload balance and employee job satisfaction in work organizations. Heliyon. 2020;6(1):e03160. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e03160 .

Bautista JR, Lauria PAS, Contreras MCS, Maranion MMG, Villanueva HH, Sumaguingsing RC, et al. Specific stressors relate to nurses’ job satisfaction, perceived quality of care, and turnover intention. Int J Nurs Pract. 2020;26(1):e12774. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijn.12774 .

Misener TR, Cox DL. Development of the Misener nurse practitioner job satisfaction scale. J Nurs Meas. 2001;9(1):91–108.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Aron S. Relationship between nurses’ job satisfaction and quality of healthcare they deliver [thesis]. Mankato: Minnesota State University; 2015.

Al-Hamdan Z, Smadi E, Ahmad M, Bawadi H, Mitchell AM. Relationship between control over nursing practice and job satisfaction and quality of patient care. J Nurs Care Qual. 2019;34(3):E1–6. https://doi.org/10.1097/NCQ.0000000000000390 .

MacPhee M, Dahinten VS, Havaei F. The impact of heavy perceived nurse workloads on patient and nurse outcomes. Adm Sci. 2017;7(1):1–17. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci7010007 .

Article Google Scholar

Nantsupawat A, Nantsupawat R, Kunaviktikul W, Turale S, Poghosyan L. Nurse burnout, nurse-reported quality of care, and patient outcomes in Thai hospitals. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2016;48(1):83–90. https://doi.org/10.1111/jnu.12187 .

Salyers MP, Bonfils KA, Luther L, Firmin RL, White DA, Adams EL, et al. The relationship between professional burnout and quality and safety in healthcare: a meta-analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(4):475–82. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-016-3886-9 .

Farman A, Kousar R, Hussain M, Waqas A, Gillani SA. Impact of job satisfaction on quality of care among nurses on the public hospital of lahore, pakistan. Saudi J Med Pharm Sci. 2017;3(6):511–9.

Ball JE, Murrells T, Rafferty AM, Morrow E, Griffiths P. “Care left undone” during nursing shifts: associations with workload and perceived quality of care. BMJ Qual Saf. 2014;23(2):116–25. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2012-001767 .

Starc J, Erjavec K. Impact of the dimensions of diversity on the quality of nursing care: the case of Slovenia. Open Access Maced J Med Sci. 2017;5(3):383–90. https://doi.org/10.3889/oamjms.2017.086 .

Boonpracom R, Kunaviktikul W, Thungjaroenkul P, Wichaikhum O. A causal model for the quality of nursing care in Thailand. Int Nurs Rev. 2019;66(1):130–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/inr.12474 .

Rochefort CM, Clarke SP. Nurses’ work environments, care rationing, job outcomes, and quality of care on neonatal units. J Adv Nurs. 2010;66(10):2213–24. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2010.05376.x .

Leino-Kilpi H, Vuorenheimo J. The patient’s perspective on nursing quality: developing a framework for evaluation. Int J Qual Health Care. 1994;6(1):85–95. https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/6.1.85 .

Stolt M, Katajisto J, Anders Kottorp A, Leino-Kilpi H. Measuring the quality of care: a Rasch validity analysis of the good nursing care scale. J Nurs Care Qual. 2019;34(4):E1–6. https://doi.org/10.1097/NCQ.0000000000000391 .

Byrne BM. Structural equation modeling with AMOS: basic concepts, applications, and programming. New York, NY: Routledge; 2016.

Book Google Scholar

Gunzler D, Chen T, Wu P, Zhang H. Introduction to mediation analysis with structural equation modeling. Shanghai Arch Psychiatry. 2013;25:390–4. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1002-0829.2013.06.009 .

Jackson DL. Revisiting sample size and number of parameter estimates: Some support for the N: q hypothesis. Struct Equ Modeling. 2003;10(1):128–41.

Hart SG, Staveland LE. Development of NASA-TLX (Task Load Index): Results of empirical and theoretical research. Adv Psychol. 1988;52:139–83.

Xiao YM, Wang ZM, Wang MZ, Lan YJ. The appraisal of reliability and validity of subjective workload assessment technique and NASA-task load index. Chin J Ind Hyg Dis. 2005;23(3):178–81.

Mohammadi M, Nasl Seraji J, Zeraati H. Developing and accessing the validity and reliability of a questionnaire to assess the mental workload among ICUs nurses in one of the Tehran University of medical sciences hospitals. J Sch Public Health Inst Public Health Res. 2013;11(2):87–96 ([in Persian]).

Schubert M, Glass TR, Clarke SP, Schaffert-Witvliet B, De Geest S. Validation of the basel extent of rationing of nursing care instrument. Nurs Res. 2007;56(6):416–24. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.NNR.0000299853.52429.62 .

Weiss DJ, Dawis RV, England GW. Manual for the Minnesota satisfaction questionnaire: Minnesota studies in vocational rehabilitation. University of Minnesota: Minneapolis: industrial relations center; 1967. p. 1–120.

Azadi R, Eydi H. The effects of social capital and job satisfaction on employee performance with organizational commitment mediation role. Organ Behav Manage Sport Stud. 2015;2(4):11–24 ([in Persian]).

Maslach C, Jackson S, Leiter M. The Maslach burnout inventory manual. 3rd ed. Palo Alto: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1996. p. 191–210.

Azizi L, Feyzabadi Z, Salehi M. Exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis of maslach burnout inventory among tehran universitys employees. J Psychol Stud. 2008;4(3):73–92 ([inPersian]).

Zhao SH, Akkadechanunt T, Xue XL. Quality nursing care as perceived by nurses and patients in a Chinese hospital. J Clin Nurs. 2009;18(12):1722–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2702.2008.02315.x .

Istomina N, Suominen T, Razbadauskas A, Martinkėnas A, Meretoja R, Leino-Kilpi H. Competence of nurses and factors associated with it. Medicina (Kaunas). 2011;47(4):230–7.

Esmalizadeh A, Heidarzadeh M, Karimollahi M. Translation and psychometric properties of good nursing care scale from nurses’ perspective in Ardabil educational centers, 2018. J Health Care. 2019;21(3):252–62 ([in Persian]).

Fabrigar LR, Porter RD, Norris ME. Some things you should know about structural equation modeling but never thought to ask. J Consum Psychol. 2010;20(2):221–5.

Sivo SA, Fan X, Witta EL, Willse JT. The search for “optimal” cutoff properties: Fit index criteria in structural equation modeling. J Exp Educ. 2006;74(3):267–88.

Liu X, Zheng J, Liu K, Baggs JG, Liu J, Wu Y, et al. Hospital nursing organizational factors, nursing care left undone, and nurse burnout as predictors of patient safety: a structural equation modeling analysis. Int J Nurs Stud. 2018;86:82–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2018.05.005 .

Kalisch BJ, Tschannen D, Lee KH. Missed nursing care, staffing, and patient falls. J Nurs Care Qual. 2012;27(1):6–12. https://doi.org/10.1097/NCQ.0b013e318225aa23 .

Semachew A, Belachew T, Tesfaye T, Adinew YM. Predictors of job satisfaction among nurses working in Ethiopian public hospitals, 2014: institution-based cross-sectional study. Hum Resour Health. 2017;15(1):31. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12960-017-0204-5 .

Safavi M, Abdollahi SM, Salmani Mood M, Rahimh H, Nasirizadeh M. Relationship between nurses’ quality performance and their job satisfaction. Q J Nurs Manag. 2017;6(1):53–61.

Chen YC, Guo YL, Chin WS, Cheng NY, Ho JJ, Shiao JS. Patient-nurse ratio is related to nurses’ intention to leave their job through mediating factors of burnout and job dissatisfaction. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(23):4801. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16234801 .

Holland P, Tham TL, Sheehan C, Cooper B. The impact of perceived workload on nurse satisfaction with work-life balance and intention to leave the occupation. Appl Nurs Res. 2019;49:70–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apnr.2019.06.001 .

Poghosyan L, Clarke SP, Finlayson M, Aiken LH. Nurse burnout and quality of care: cross-national investigation in six countries. Res Nurs Health. 2010;33(4):288–98. https://doi.org/10.1002/nur.20383 .