Reported Speech – Rules, Examples & Worksheet

| Candace Osmond

Candace Osmond

Candace Osmond studied Advanced Writing & Editing Essentials at MHC. She’s been an International and USA TODAY Bestselling Author for over a decade. And she’s worked as an Editor for several mid-sized publications. Candace has a keen eye for content editing and a high degree of expertise in Fiction.

They say gossip is a natural part of human life. That’s why language has evolved to develop grammatical rules about the “he said” and “she said” statements. We call them reported speech.

Every time we use reported speech in English, we are talking about something said by someone else in the past. Thinking about it brings me back to high school, when reported speech was the main form of language!

Learn all about the definition, rules, and examples of reported speech as I go over everything. I also included a worksheet at the end of the article so you can test your knowledge of the topic.

What Does Reported Speech Mean?

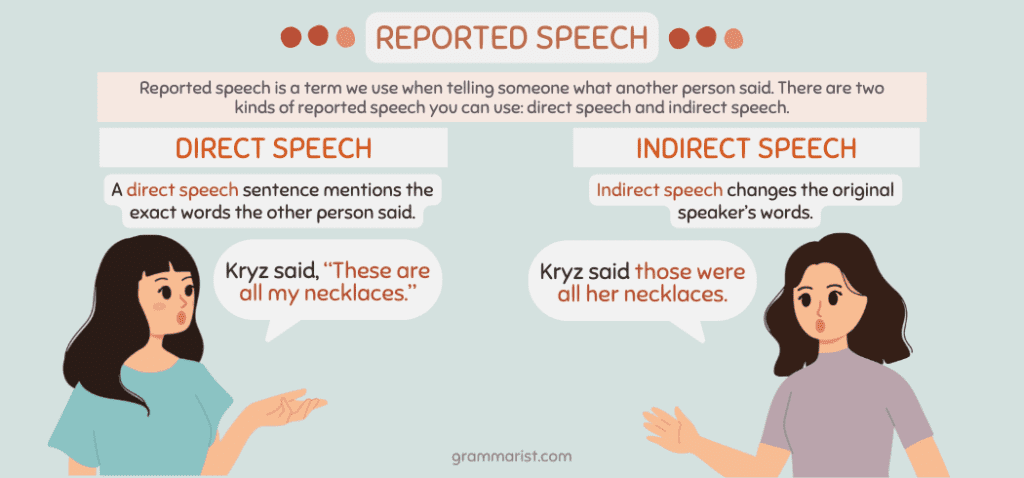

Reported speech is a term we use when telling someone what another person said. You can do this while speaking or writing.

There are two kinds of reported speech you can use: direct speech and indirect speech. I’ll break each down for you.

A direct speech sentence mentions the exact words the other person said. For example:

- Kryz said, “These are all my necklaces.”

Indirect speech changes the original speaker’s words. For example:

- Kryz said those were all her necklaces.

When we tell someone what another individual said, we use reporting verbs like told, asked, convinced, persuaded, and said. We also change the first-person figure in the quotation into the third-person speaker.

Reported Speech Examples

We usually talk about the past every time we use reported speech. That’s because the time of speaking is already done. For example:

- Direct speech: The employer asked me, “Do you have experience with people in the corporate setting?”

Indirect speech: The employer asked me if I had experience with people in the corporate setting.

- Direct speech: “I’m working on my thesis,” I told James.

Indirect speech: I told James that I was working on my thesis.

Reported Speech Structure

A speech report has two parts: the reporting clause and the reported clause. Read the example below:

- Harry said, “You need to help me.”

The reporting clause here is William said. Meanwhile, the reported clause is the 2nd clause, which is I need your help.

What are the 4 Types of Reported Speech?

Aside from direct and indirect, reported speech can also be divided into four. The four types of reported speech are similar to the kinds of sentences: imperative, interrogative, exclamatory, and declarative.

Reported Speech Rules

The rules for reported speech can be complex. But with enough practice, you’ll be able to master them all.

Choose Whether to Use That or If

The most common conjunction in reported speech is that. You can say, “My aunt says she’s outside,” or “My aunt says that she’s outside.”

Use if when you’re reporting a yes-no question. For example:

- Direct speech: “Are you coming with us?”

Indirect speech: She asked if she was coming with them.

Verb Tense Changes

Change the reporting verb into its past form if the statement is irrelevant now. Remember that some of these words are irregular verbs, meaning they don’t follow the typical -d or -ed pattern. For example:

- Direct speech: I dislike fried chicken.

Reported speech: She said she disliked fried chicken.

Note how the main verb in the reported statement is also in the past tense verb form.

Use the simple present tense in your indirect speech if the initial words remain relevant at the time of reporting. This verb tense also works if the report is something someone would repeat. For example:

- Slater says they’re opening a restaurant soon.

- Maya says she likes dogs.

This rule proves that the choice of verb tense is not a black-and-white question. The reporter needs to analyze the context of the action.

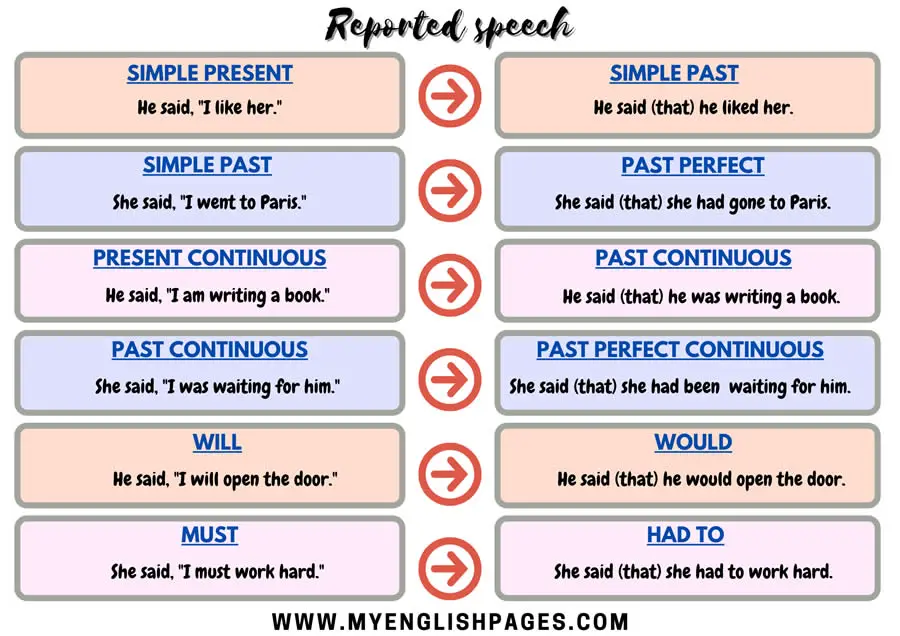

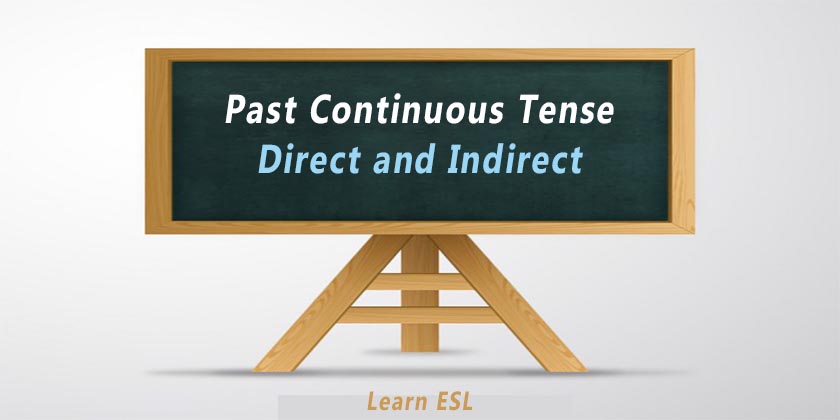

Move the tense backward when the reporting verb is in the past tense. That means:

- Present simple becomes past simple.

- Present perfect becomes past perfect.

- Present continuous becomes past continuous.

- Past simple becomes past perfect.

- Past continuous becomes past perfect continuous.

Here are some examples:

- The singer has left the building. (present perfect)

He said that the singers had left the building. (past perfect)

- Her sister gave her new shows. (past simple)

- She said that her sister had given her new shoes. (past perfect)

If the original speaker is discussing the future, change the tense of the reporting verb into the past form. There’ll also be a change in the auxiliary verbs.

- Will or shall becomes would.

- Will be becomes would be.

- Will have been becomes would have been.

- Will have becomes would have.

For example:

- Direct speech: “I will be there in a moment.”

Indirect speech: She said that she would be there in a moment.

Do not change the verb tenses in indirect speech when the sentence has a time clause. This rule applies when the introductory verb is in the future, present, and present perfect. Here are other conditions where you must not change the tense:

- If the sentence is a fact or generally true.

- If the sentence’s verb is in the unreal past (using second or third conditional).

- If the original speaker reports something right away.

- Do not change had better, would, used to, could, might, etc.

Changes in Place and Time Reference

Changing the place and time adverb when using indirect speech is essential. For example, now becomes then and today becomes that day. Here are more transformations in adverbs of time and places.

- This – that.

- These – those.

- Now – then.

- Here – there.

- Tomorrow – the next/following day.

- Two weeks ago – two weeks before.

- Yesterday – the day before.

Here are some examples.

- Direct speech: “I am baking cookies now.”

Indirect speech: He said he was baking cookies then.

- Direct speech: “Myra went here yesterday.”

Indirect speech: She said Myra went there the day before.

- Direct speech: “I will go to the market tomorrow.”

Indirect speech: She said she would go to the market the next day.

Using Modals

If the direct speech contains a modal verb, make sure to change them accordingly.

- Will becomes would

- Can becomes could

- Shall becomes should or would.

- Direct speech: “Will you come to the ball with me?”

Indirect speech: He asked if he would come to the ball with me.

- Direct speech: “Gina can inspect the room tomorrow because she’s free.”

Indirect speech: He said Gina could inspect the room the next day because she’s free.

However, sometimes, the modal verb should does not change grammatically. For example:

- Direct speech: “He should go to the park.”

Indirect speech: She said that he should go to the park.

Imperative Sentences

To change an imperative sentence into a reported indirect sentence, use to for imperative and not to for negative sentences. Never use the word that in your indirect speech. Another rule is to remove the word please . Instead, say request or say. For example:

- “Please don’t interrupt the event,” said the host.

The host requested them not to interrupt the event.

- Jonah told her, “Be careful.”

- Jonah ordered her to be careful.

Reported Questions

When reporting a direct question, I would use verbs like inquire, wonder, ask, etc. Remember that we don’t use a question mark or exclamation mark for reports of questions. Below is an example I made of how to change question forms.

- Incorrect: He asked me where I live?

Correct: He asked me where I live.

Here’s another example. The first sentence uses direct speech in a present simple question form, while the second is the reported speech.

- Where do you live?

She asked me where I live.

Wrapping Up Reported Speech

My guide has shown you an explanation of reported statements in English. Do you have a better grasp on how to use it now?

Reported speech refers to something that someone else said. It contains a subject, reporting verb, and a reported cause.

Don’t forget my rules for using reported speech. Practice the correct verb tense, modal verbs, time expressions, and place references.

Grammarist is a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for sites to earn advertising fees by advertising and linking to Amazon.com. When you buy via the links on our site, we may earn an affiliate commission at no cost to you.

2024 © Grammarist, a Found First Marketing company. All rights reserved.

Reported Speech: Rules, Examples, Exceptions

👉 Quiz 1 / Quiz 2

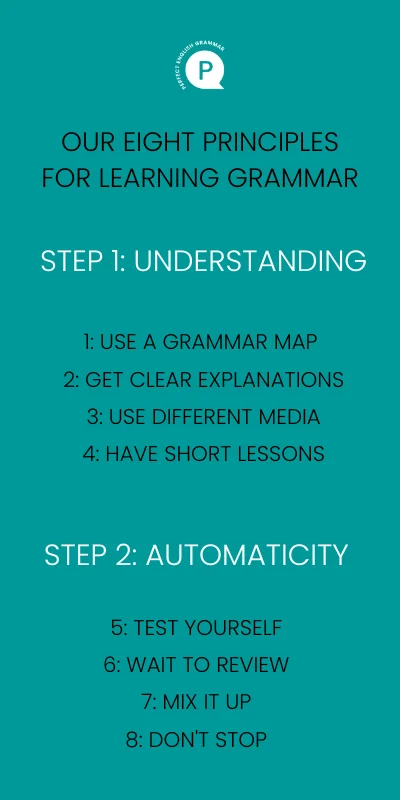

Advanced Grammar Course

What is reported speech?

“Reported speech” is when we talk about what somebody else said – for example:

- Direct Speech: “I’ve been to London three times.”

- Reported Speech: She said she’d been to London three times.

There are a lot of tricky little details to remember, but don’t worry, I’ll explain them and we’ll see lots of examples. The lesson will have three parts – we’ll start by looking at statements in reported speech, and then we’ll learn about some exceptions to the rules, and finally we’ll cover reported questions, requests, and commands.

So much of English grammar – like this topic, reported speech – can be confusing, hard to understand, and even harder to use correctly. I can help you learn grammar easily and use it confidently inside my Advanced English Grammar Course.

In this course, I will make even the most difficult parts of English grammar clear to you – and there are lots of opportunities for you to practice!

Backshift of Verb Tenses in Reported Speech

When we use reported speech, we often change the verb tense backwards in time. This can be called “backshift.”

Here are some examples in different verb tenses:

Reported Speech (Part 1) Quiz

Exceptions to backshift in reported speech.

Now that you know some of the reported speech rules about backshift, let’s learn some exceptions.

There are two situations in which we do NOT need to change the verb tense.

No backshift needed when the situation is still true

For example, if someone says “I have three children” (direct speech) then we would say “He said he has three children” because the situation continues to be true.

If I tell you “I live in the United States” (direct speech) then you could tell someone else “She said she lives in the United States” (that’s reported speech) because it is still true.

When the situation is still true, then we don’t need to backshift the verb.

He said he HAS three children

But when the situation is NOT still true, then we DO need to backshift the verb.

Imagine your friend says, “I have a headache.”

- If you immediately go and talk to another friend, you could say, “She said she has a headache,” because the situation is still true

- If you’re talking about that conversation a month after it happened, then you would say, “She said she had a headache,” because it’s no longer true.

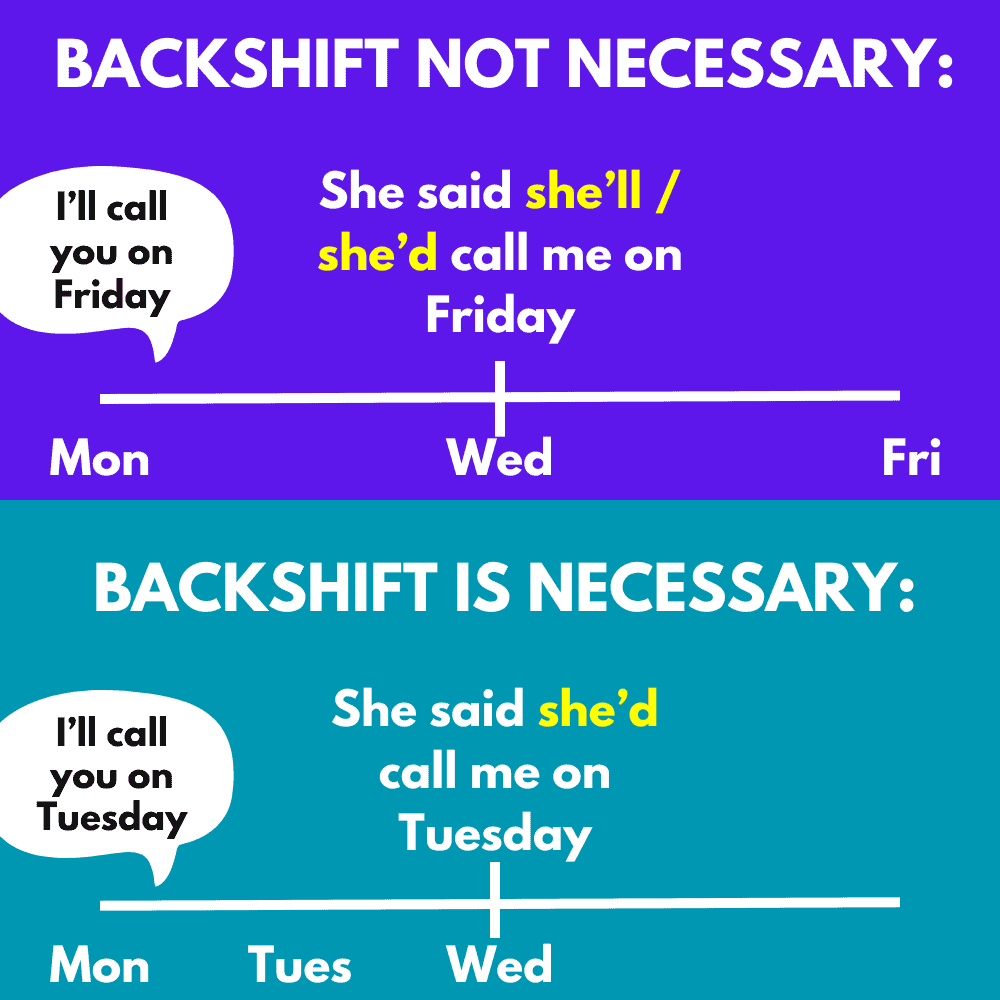

No backshift needed when the situation is still in the future

We also don’t need to backshift to the verb when somebody said something about the future, and the event is still in the future.

Here’s an example:

- On Monday, my friend said, “I ‘ll call you on Friday .”

- “She said she ‘ll call me on Friday”, because Friday is still in the future from now.

- It is also possible to say, “She said she ‘d (she would) call me on Friday.”

- Both of them are correct, so the backshift in this case is optional.

Let’s look at a different situation:

- On Monday, my friend said, “I ‘ll call you on Tuesday .”

- “She said she ‘d call me on Tuesday.” I must backshift because the event is NOT still in the future.

Review: Reported Speech, Backshift, & Exceptions

Quick review:

- Normally in reported speech we backshift the verb, we put it in a verb tense that’s a little bit further in the past.

- when the situation is still true

- when the situation is still in the future

Reported Requests, Orders, and Questions

Those were the rules for reported statements, just regular sentences.

What about reported speech for questions, requests, and orders?

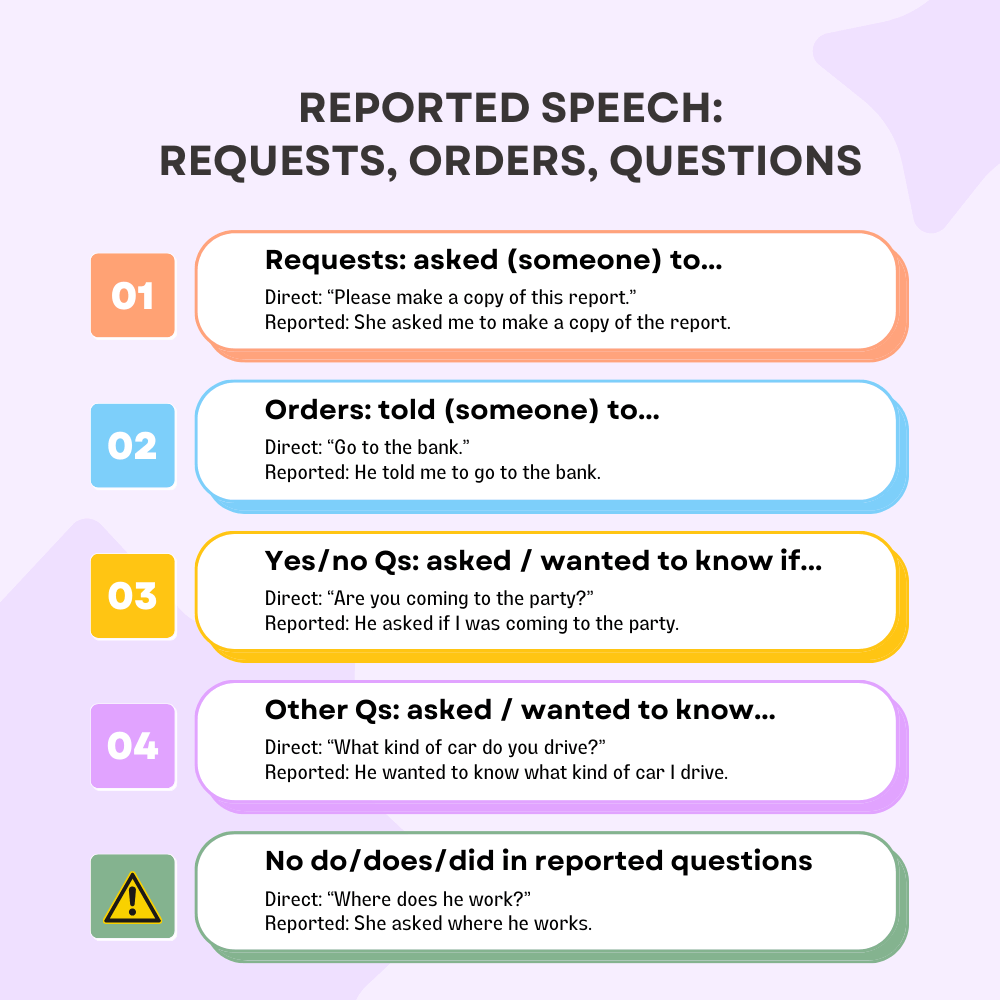

For reported requests, we use “asked (someone) to do something”:

- “Please make a copy of this report.” (direct speech)

- She asked me to make a copy of the report. (reported speech)

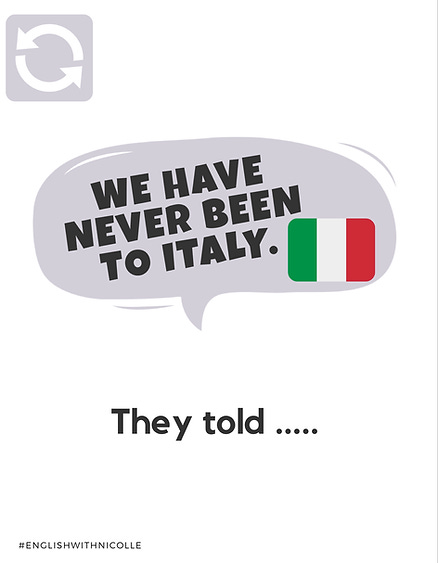

For reported orders, we use “told (someone) to do something:”

- “Go to the bank.” (direct speech)

- “He told me to go to the bank.” (reported speech)

The main verb stays in the infinitive with “to”:

- She asked me to make a copy of the report. She asked me make a copy of the report.

- He told me to go to the bank. He told me go to the bank.

For yes/no questions, we use “asked if” and “wanted to know if” in reported speech.

- “Are you coming to the party?” (direct)

- He asked if I was coming to the party. (reported)

- “Did you turn off the TV?” (direct)

- She wanted to know if I had turned off the TV.” (reported)

The main verb changes and back shifts according to the rules and exceptions we learned earlier.

Notice that we don’t use do/does/did in the reported question:

- She wanted to know did I turn off the TV.

- She wanted to know if I had turned off the TV.

For other questions that are not yes/no questions, we use asked/wanted to know (without “if”):

- “When was the company founded?” (direct)

- She asked when the company was founded.” (reported)

- “What kind of car do you drive?” (direct)

- He wanted to know what kind of car I drive. (reported)

Again, notice that we don’t use do/does/did in reported questions:

- “Where does he work?”

- She wanted to know where does he work.

- She wanted to know where he works.

Also, in questions with the verb “to be,” the word order changes in the reported question:

- “Where were you born?” ([to be] + subject)

- He asked where I was born. (subject + [to be])

- He asked where was I born.

Reported Speech (Part 2) Quiz

Learn more about reported speech:

- Reported speech: Perfect English Grammar

- Reported speech: BJYU’s

If you want to take your English grammar to the next level, then my Advanced English Grammar Course is for you! It will help you master the details of the English language, with clear explanations of essential grammar topics, and lots of practice. I hope to see you inside!

I’ve got one last little exercise for you, and that is to write sentences using reported speech. Think about a conversation you’ve had in the past, and write about it – let’s see you put this into practice right away.

Master the details of English grammar:

More Espresso English Lessons:

About the author.

Shayna Oliveira

Shayna Oliveira is the founder of Espresso English, where you can improve your English fast - even if you don’t have much time to study. Millions of students are learning English from her clear, friendly, and practical lessons! Shayna is a CELTA-certified teacher with 10+ years of experience helping English learners become more fluent in her English courses.

You are using an outdated browser. Please upgrade your browser or activate Google Chrome Frame to improve your experience.

Reported Speech in English

“Reported speech” might sound fancy, but it isn’t that complicated.

It’s just how you talk about what someone said.

Luckily, it’s pretty simple to learn the basics in English, beginning with the two types of reported speech: direct (reporting the exact words someone said) and indirect (reporting what someone said without using their exact words ).

Read this post to learn how to report speech, with tips and tricks for each, plenty of examples and a resources section that tells you about real world resources you can use to practice reporting speech.

How to Report Direct Speech

How to report indirect speech, reporting questions in indirect speech, verb tenses in indirect reported speech, simple present, present continuous, present perfect, present perfect continuous, simple past, past continuous, past perfect, past perfect continuous, simple future, future continuous, future perfect, future perfect continuous, authentic resources for practicing reported speech, novels and short stories, native english videos, celebrity profiles.

Download: This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you can take anywhere. Click here to get a copy. (Download)

Direct speech refers to the exact words that a person says. You can “report” direct speech in a few different ways.

To see how this works, let’s pretend that I (Elisabeth) told some people that I liked green onions.

Here are some different ways that those people could explain what I said:

Direct speech: “I like green onions,” Elisabeth said.

- Thousands of learner friendly videos (especially beginners)

- Handpicked, organized, and annotated by FluentU's experts

- Integrated into courses for beginners

Direct speech: “I like green onions,” she told me. — In this sentence, we replace my name (Elisabeth) with the pronoun she.

In all of these examples, the part that was said is between quotation marks and is followed by a noun (“she” or “Elisabeth”) and a verb. Each of these verbs (“to say,” “to tell [someone],” “to explain”) are ways to describe someone talking. You can use any verb that refers to speech in this way.

You can also put the noun and verb before what was said.

Direct speech: Elisabeth said, “I like spaghetti.”

The example above would be much more likely to be said out loud than the first set of examples.

Here’s a conversation that might happen between two people:

- Interactive subtitles: click any word to see detailed examples and explanations

- Slow down or loop the tricky parts

- Show or hide subtitles

- Review words with our powerful learning engine

1: Did you ask her if she liked coffee?

2: Yeah, I asked her.

1: What did she say?

2. She said, “Yeah, I like coffee.” ( Direct speech )

Usually, reporting of direct speech is something you see in writing. It doesn’t happen as often when people are talking to each other.

Direct reported speech often happens in the past. However, there are all kinds of stories, including journalism pieces, profiles and fiction, where you might see speech reported in the present as well.

This is sometimes done when the author of the piece wants you to feel that you’re experiencing events in the present moment.

- Learn words in the context of sentences

- Swipe left or right to see more examples from other videos

- Go beyond just a superficial understanding

For example, a profile of Kristen Stewart in Vanity Fair has a funny moment that describes how the actress isn’t a very good swimmer:

Direct speech: “I don’t want to enter the water, ever,” she says. “If everyone’s going in the ocean, I’m like, no.”

Here, the speech is reported as though it’s in the present tense (“she says”) instead of in the past (“she said”).

In writing of all kinds, direct reported speech is often split into two or more parts, as it is above.

Here’s an example from Lewis Carroll’s “ Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland ,” where the speech is even more split up:

Direct speech: “I won’t indeed!” said Alice, in a great hurry to change the subject of conversation. “Are you—are you fond—of—of dogs?” The Mouse did not answer, so Alice went on eagerly: “There is such a nice little dog near our house I should like to show you!”

Reporting indirect speech is what happens when you explain what someone said without using their exact words.

- FluentU builds you up, so you can build sentences on your own

- Start with multiple-choice questions and advance through sentence building to producing your own output

- Go from understanding to speaking in a natural progression.

Let’s start with an example of direct reported speech like those used above.

Direct speech: Elisabeth said, “I like coffee.”

As indirect reported speech, it looks like this:

Indirect speech: Elisabeth said she liked coffee.

You can see that the subject (“I”) has been changed to “she,” to show who is being spoken about. If I’m reporting the direct speech of someone else, and this person says “I,” I’d repeat their sentence exactly as they said it. If I’m reporting this person’s speech indirectly to someone else, however, I’d speak about them in the third person—using “she,” “he” or “they.”

You may also notice that the tense changes here: If “I like coffee” is what she said, this can become “She liked coffee” in indirect speech.

- Images, examples, video examples, and tips

- Covering all the tricky edge cases, eg.: phrases, idioms, collocations, and separable verbs

- No reliance on volunteers or open source dictionaries

- 100,000+ hours spent by FluentU's team to create and maintain

However, you might just as often hear someone say something like, “She said she likes coffee.” Since people’s likes and preferences tend to change over time and not right away, it makes sense to keep them in the present tense.

Indirect speech often uses the word “that” before what was said:

Indirect speech: She said that she liked coffee.

There’s no real difference between “She said she liked coffee” and “She said that she liked coffee.” However, using “that” can help make the different parts of the sentence clearer.

Let’s look at a few other examples:

Indirect speech: I said I was going outside today.

Indirect speech: They told me that they wanted to order pizza.

Indirect speech: He mentioned it was raining.

Indirect speech: She said that her father was coming over for dinner.

You can see an example of reporting indirect speech in the funny video “ Cell Phone Crashing .” In this video, a traveler in an airport sits down next to another traveler talking on his cell phone. The first traveler pretends to be talking to someone on his phone, but he appears to be responding to the second traveler’s conversation, which leads to this exchange:

Woman: “Are you answering what I’m saying?”

Man “No, no… I’m on the phone with somebody, sorry. I don’t mean to be rude.” (Direct speech)

Woman: “What was that?”

Man: “I just said I was on the phone with somebody.” (Indirect speech)

When reporting questions in indirect speech, you can use words like “whether” or “if” with verbs that show questioning, such as “to ask” or “to wonder.”

Direct speech: She asked, “Is that a new restaurant?”

Indirect speech: She asked if that was a new restaurant.

In any case where you’re reporting a question, you can say that someone was “wondering” or “wanted to know” something. Notice that these verbs don’t directly show that someone asked a question. They don’t describe an action that happened at a single point in time. But you can usually assume that someone was wondering or wanted to know what they asked.

Indirect speech: She was wondering if that was a new restaurant.

Indirect speech: She wanted to know whether that was a new restaurant.

It can be tricky to know how to use tenses when reporting indirect speech. Let’s break it down, tense by tense.

Sometimes, indirect speech “ backshifts ,” or moves one tense further back into the past. We already saw this in the example from above:

Direct speech: She said, “I like coffee.”

Indirect speech: She said she liked coffee.

Also as mentioned above, backshifting doesn’t always happen. This might seem confusing, but it isn’t that difficult to understand once you start using reported speech regularly.

What tense you use in indirect reported speech often just depends on when what you’re reporting happened or was true.

Let’s look at some examples of how direct speech in certain tenses commonly changes (or doesn’t) when it’s reported as indirect speech.

To learn about all the English tenses (or for a quick review), check out this post .

Direct speech: I said, “I play video games.”

Indirect speech: I said that I played video games (simple past) or I said that I play video games (simple present).

Backshifting into the past or staying in the present here can change the meaning slightly. If you use the first example, it’s unclear whether or not you still play video games; all we know is that you said you played them in the past.

If you use the second example, though, you probably still play video games (unless you were lying for some reason).

However, the difference in meaning is so small, you can use either one and you won’t have a problem.

Direct speech: I said, “I’m playing video games.”

Indirect speech: I said that I was playing video games (past continuous) or I said that I’m playing video games (present continuous).

In this case, you’d likely use the first example if you were telling a story about something that happened in the past.

You could use the second example to repeat or stress what you just said. For example:

Hey, want to go for a walk?

Direct speech: No, I’m playing video games.

But it’s such a nice day!

Indirect speech: I said that I’m playing video games!

Direct speech: Marie said, “I have read that book.”

Indirect speech: Marie said that she had read that book (past perfect) or Marie said that she has read that book (present perfect).

The past perfect is used a lot in writing and other kinds of narration. This is because it helps point out an exact moment in time when something was true.

The past perfect isn’t quite as useful in conversation, where people are usually more interested in what’s true now. So, in a lot of cases, people would use the second example above when speaking.

Direct speech: She said, “I have been watching that show.”

Indirect speech: She said that she had been watching that show (past perfect continuous) or She said that she has been watching that show (present perfect continuous).

These examples are similar to the others above. You could use the first example whether or not this person was still watching the show, but if you used the second example, it’d probably seem like you either knew or guessed that she was still watching it.

Direct speech: You told me, “I charged my phone.”

Indirect speech: You told me that you had charged your phone (past perfect) or You told me that you charged your phone (simple past).

Here, most people would probably just use the second example, because it’s simpler, and gets across the same meaning.

Direct speech: You told me, “I was charging my phone.”

Indirect speech: You told me that you had been charging your phone (past perfect continuous) or You told me that you were charging your phone (past continuous).

Here, the difference is between whether you had been charging your phone before or were charging your phone at the time. However, a lot of people would still use the second example in either situation.

Direct speech: They explained, “We had bathed the cat on Wednesday.”

Indirect speech: They explained that they had bathed the cat on Wednesday. (past perfect)

Once we start reporting the past perfect tenses, we don’t backshift because there are no tenses to backshift to.

So in this case, it’s simple. The tense stays exactly as is. However, many people might simplify even more and use the simple past, saying, “They explained that they bathed the cat on Wednesday.”

Direct speech: They said, “The cat had been going outside and getting dirty for a long time!”

Indirect speech: They said that the cat had been going outside and getting dirty for a long time. (past perfect continuous)

Again, we don’t shift the tense back here; we leave it like it is. And again, a lot of people would report this speech as, “They said the cat was going outside and getting dirty for a long time.” It’s just a simpler way to say almost the same thing.

Direct speech: I told you, “I will be here no matter what.”

Indirect speech: I told you that I would be here no matter what. (present conditional)

At this point, we don’t just have to think about tenses, but grammatical mood, too. However, the idea is still pretty simple. We use the conditional (with “would”) to show that at the time the words were spoken, the future was uncertain.

In this case, you could also say, “I told you that I will be here no matter what,” but only if you “being here” is still something that you expect to happen in the future.

What matters here is what’s intended. Since this example shows a person reporting their own speech, it’s more likely that they’d want to stress the truth of their own intention, and so they might be more likely to use “will” than “would.”

But if you were reporting someone else’s words, you might be more likely to say something like, “She told me that she would be here no matter what.”

Direct speech: I said, “I’ll be waiting for your call.”

Indirect speech: I said that I would be waiting for your call. (conditional continuous)

These are similar to the above examples, but apply to a continuous or ongoing action.

Direct speech: She said, “I will have learned a lot about myself.”

Indirect speech: She said that she would have learned a lot about herself (conditional perfect) or She said that she will have learned a lot about herself (future perfect).

In this case, using the conditional (as in the first example) suggests that maybe a certain event didn’t happen, or something didn’t turn out as expected.

However, that might not always be the case, especially if this was a sentence that was written in an article or a work of fiction. The second example, however, suggests that the future that’s being talked about still hasn’t happened yet.

Direct speech: She said, “By next Tuesday, I will have been staying inside every day for the past month.”

Indirect speech: She said that by next Tuesday, she would have been staying inside every day for the past month (perfect continuous conditional) or She said that by next Tuesday, she will have been staying inside every day for the past month (past perfect continuous).

Again, in this case, the first example might suggest that the event didn’t happen. Maybe the person didn’t stay inside until next Tuesday! However, this could also just be a way of explaining that at the time she said this in the past, it was uncertain whether she really would stay inside for as long as she thought.

The second example, on the other hand, would only be used if next Tuesday hadn’t happened yet.

Let’s take a look at where you can find resources for practicing reporting speech in the real world.

One of the most common uses for reported speech is in fiction. You’ll find plenty of reported speech in novels and short stories . Look for books that have long sections of text with dialogue marked by quotation marks (“…”). Once you understand the different kinds of reported speech, you can look for it in your reading and use it in your own writing.

Writing your own stories is a great way to get even better at understanding reported speech.

One of the best ways to practice any aspect of English is to watch native English videos. By watching English speakers use the language, you can understand how reported speech is used in real world situations.

FluentU takes authentic videos—like music videos, movie trailers, news and inspiring talks—and turns them into personalized language learning lessons.

You can try FluentU for free for 2 weeks. Check out the website or download the iOS app or Android app.

P.S. Click here to take advantage of our current sale! (Expires at the end of this month.)

Try FluentU for FREE!

Celebrity profiles, which you can find in print magazines and online, can help you find and practice reported speech, too. Celebrity profiles are stories that focus on a famous person. They often include some kind of interview. The writer will usually spend some time describing the person and then mention things that they say; this is when they use reported speech.

Because many of these profiles are written in the present tense, they can help you get used to the basics of reported speech without having to worry too much about different verb tenses.

While the above may seem really complicated, it isn’t that difficult to start using reported speech.

Mastering it may be a little difficult, but the truth is that many, many people who speak English as a first language struggle with it, too!

Reported speech is flexible, and even if you make mistakes, there’s a good chance that no one will notice.

Enter your e-mail address to get your free PDF!

We hate SPAM and promise to keep your email address safe

The Reported Speech

Table of Contents

What is reported speech.

Reported speech is when you tell somebody what you or another person said before. When reporting a speech, some changes are necessary.

For example, the statement:

- Jane said she was waiting for her mom .

is a reported speech, whereas:

- Jane said, “I’m waiting for my mom.”

is a direct speech.

Reported speech is also referred to as indirect speech or indirect discourse .

Before explaining how to report a discourse, let us first distinguish between direct speech and reported speech .

Direct speech vs reported speech

1. We use direct speech to quote a speaker’s exact words. We put their words within quotation marks. We add a reporting verb such as “he said” or “she asked” before or after the quote.

- He said, “I am happy.”

2. Reported speech is a way of reporting what someone said without using quotation marks. We do not necessarily report the speaker”‘s exact words. Some changes are necessary: the time expressions, the tense of the verbs, and the demonstratives.

- He said that he was happy.

More examples:

Different types of reported speech

When you use reported speech, you either report:

- Requests/commands

- Other types

A. Reporting statements

When transforming statements, check whether you have to change:

- place and time expression

1- Pronouns

In reported speech, you often have to change the pronoun depending on who says what.

She says, “My dad likes roast chicken.” => She says that her dad likes roast chicken.

- If the sentence starts in the present, there is no backshift of tenses in reported speech.

- If the sentence starts in the past, there is often a backshift of tenses in reported speech.

No backshift

Do not change the tense if the introductory clause (i.e., the reporting verb) is in the present tense (e. g. He says ). Note, however, that you might have to change the form of the present tense verb (3rd person singular).

- He says, “I write poems.” => He says that he writes English.

You must change the tense if the introductory clause (i.e., the reporting verb) is in the past tense (e. g. He said ).

- He said, “I am happy.”=> He said that he was happy.

Examples of the main changes in verb tense :

3. Modal verbs

The modal verbs could, should, would, might, needn’t, ought to, and used to do not normally change.

- He said: “She might be right.” => He said that she might be right.

- He told her: “You needn’t see a doctor.” => He told her that she needn’t see a doctor.

Other modal verbs such as can, shall, will, must, and ma y change:

4- Place, demonstratives, and time expressions

Place, demonstratives, and time expressions change if the context of the reported statement (i.e. the location and/or the period of time) is different from that of the direct speech.

In the following table, you will find the different changes of place; demonstratives, and time expressions.

B. Reporting Questions

When transforming questions, check whether you have to change:

- The pronouns

- The place and time expressions

- The tenses (backshift)

Also, note that you have to:

- transform the question into an indirect question

- use the question word ( where, when, what, how ) or if / whether

>> EXERCISE ON REPORTING QUESTIONS <<

C. Reporting requests/commands

When transforming requests and commands, check whether you have to change:

- place and time expressions

- She said, “Sit down.” – She asked me to sit down.

- She said, “don’t be lazy” – She asked me not to be lazy

D. Other transformations

- Expressions of advice with must , should, and ought are usually reported using advise / urge . Example: “You must read this book.” He advised/urged me to read that book.

- The expression let’s is usually reported using suggest . In this case, there are two possibilities for reported speech: gerund or statement with should . Example : “Let’s go to the cinema.” 1. He suggested going to the cinema. 2. He suggested that we should go to the cinema.

Main clauses connected with and/but

If two complete main clauses are connected with and or but , put that after the conjunction.

- He said, “I saw her but she didn’t see me.=> He said that he had seen her but that she hadn’t seen him.

If the subject is dropped in the second main clause (the conjunction is followed by a verb), do not use that .

- She said, “I am a nurse and work in a hospital.=> He said that she was a nurse and worked in a hospital.

punctuation rules of the reported speech

Direct speech:

We normally add a comma between the reporting verbs (e.g., she/he said, reported, he replied, etc.) and the reported clause in direct speech. The original speaker”s words are put between inverted commas, either single (“…”) or double (“…”).

- She said, “I wasn’t ready for the competition”.

Note that we insert the comma within the inverted commas if the reported clause comes first:

- “I wasn’t ready for the competition,” she said.

Indirect speech:

In indirect speech, we don’t put a comma between the reporting verb and the reported clause and we omit the inverted quotes.

- She said that she hadn’t been ready for the competition.

In reported questions and exclamations, we remove the question mark and the exclamation mark.

- She asked him why he looked sad?

- She asked him why he looked sad.

Can we omit that in the reported speech?

Yes, we can omit that after reporting verbs such as he said , he replied , she suggested , etc.

- He said that he could do it. – He said he could do it.

- She replied that she was fed up with his misbehavior. – She replied she was fed up with his misbehavior.

List of reporting verbs

Reported speech requires a reporting verb such as “he said”, she “replied”, etc.

Here is a list of some common reporting verbs:

- Cry (meaning shout)

- Demonstrate

- Hypothesize

- Posit the view that

- Question the view that

- Want to know

In reported speech, we put the words of a speaker in a subordinate clause introduced by a reporting verb such as – “ he said ” and “ she asked “- with the required person and tense adjustments.

Related pages

- Reported speech exercise (mixed)

- Reported speech exercise (questions)

- Reported speech exercise (requests and commands)

- Reported speech lesson

- English Grammar

- Reported Speech

Reported Speech - Definition, Rules and Usage with Examples

Reported speech or indirect speech is the form of speech used to convey what was said by someone at some point of time. This article will help you with all that you need to know about reported speech, its meaning, definition, how and when to use them along with examples. Furthermore, try out the practice questions given to check how far you have understood the topic.

Table of Contents

Definition of reported speech, rules to be followed when using reported speech, table 1 – change of pronouns, table 2 – change of adverbs of place and adverbs of time, table 3 – change of tense, table 4 – change of modal verbs, tips to practise reported speech, examples of reported speech, check your understanding of reported speech, frequently asked questions on reported speech in english, what is reported speech.

Reported speech is the form in which one can convey a message said by oneself or someone else, mostly in the past. It can also be said to be the third person view of what someone has said. In this form of speech, you need not use quotation marks as you are not quoting the exact words spoken by the speaker, but just conveying the message.

Now, take a look at the following dictionary definitions for a clearer idea of what it is.

Reported speech, according to the Oxford Learner’s Dictionary, is defined as “a report of what somebody has said that does not use their exact words.” The Collins Dictionary defines reported speech as “speech which tells you what someone said, but does not use the person’s actual words.” According to the Cambridge Dictionary, reported speech is defined as “the act of reporting something that was said, but not using exactly the same words.” The Macmillan Dictionary defines reported speech as “the words that you use to report what someone else has said.”

Reported speech is a little different from direct speech . As it has been discussed already, reported speech is used to tell what someone said and does not use the exact words of the speaker. Take a look at the following rules so that you can make use of reported speech effectively.

- The first thing you have to keep in mind is that you need not use any quotation marks as you are not using the exact words of the speaker.

- You can use the following formula to construct a sentence in the reported speech.

- You can use verbs like said, asked, requested, ordered, complained, exclaimed, screamed, told, etc. If you are just reporting a declarative sentence , you can use verbs like told, said, etc. followed by ‘that’ and end the sentence with a full stop . When you are reporting interrogative sentences, you can use the verbs – enquired, inquired, asked, etc. and remove the question mark . In case you are reporting imperative sentences , you can use verbs like requested, commanded, pleaded, ordered, etc. If you are reporting exclamatory sentences , you can use the verb exclaimed and remove the exclamation mark . Remember that the structure of the sentences also changes accordingly.

- Furthermore, keep in mind that the sentence structure , tense , pronouns , modal verbs , some specific adverbs of place and adverbs of time change when a sentence is transformed into indirect/reported speech.

Transforming Direct Speech into Reported Speech

As discussed earlier, when transforming a sentence from direct speech into reported speech, you will have to change the pronouns, tense and adverbs of time and place used by the speaker. Let us look at the following tables to see how they work.

Here are some tips you can follow to become a pro in using reported speech.

- Select a play, a drama or a short story with dialogues and try transforming the sentences in direct speech into reported speech.

- Write about an incident or speak about a day in your life using reported speech.

- Develop a story by following prompts or on your own using reported speech.

Given below are a few examples to show you how reported speech can be written. Check them out.

- Santana said that she would be auditioning for the lead role in Funny Girl.

- Blaine requested us to help him with the algebraic equations.

- Karishma asked me if I knew where her car keys were.

- The judges announced that the Warblers were the winners of the annual acapella competition.

- Binsha assured that she would reach Bangalore by 8 p.m.

- Kumar said that he had gone to the doctor the previous day.

- Lakshmi asked Teena if she would accompany her to the railway station.

- Jibin told me that he would help me out after lunch.

- The police ordered everyone to leave from the bus stop immediately.

- Rahul said that he was drawing a caricature.

Transform the following sentences into reported speech by making the necessary changes.

1. Rachel said, “I have an interview tomorrow.”

2. Mahesh said, “What is he doing?”

3. Sherly said, “My daughter is playing the lead role in the skit.”

4. Dinesh said, “It is a wonderful movie!”

5. Suresh said, “My son is getting married next month.”

6. Preetha said, “Can you please help me with the invitations?”

7. Anna said, “I look forward to meeting you.”

8. The teacher said, “Make sure you complete the homework before tomorrow.”

9. Sylvester said, “I am not going to cry anymore.”

10. Jade said, “My sister is moving to Los Angeles.”

Now, find out if you have answered all of them correctly.

1. Rachel said that she had an interview the next day.

2. Mahesh asked what he was doing.

3. Sherly said that her daughter was playing the lead role in the skit.

4. Dinesh exclaimed that it was a wonderful movie.

5. Suresh said that his son was getting married the following month.

6. Preetha asked if I could help her with the invitations.

7. Anna said that she looked forward to meeting me.

8. The teacher told us to make sure we completed the homework before the next day.

9. Sylvester said that he was not going to cry anymore.

10. Jade said that his sister was moving to Los Angeles.

What is reported speech?

What is the definition of reported speech.

Reported speech, according to the Oxford Learner’s Dictionary, is defined as “a report of what somebody has said that does not use their exact words.” The Collins Dictionary defines reported speech as “speech which tells you what someone said, but does not use the person’s actual words.” According to the Cambridge Dictionary, reported speech is defined as “the act of reporting something that was said, but not using exactly the same words.” The Macmillan Dictionary defines reported speech as “the words that you use to report what someone else has said.”

What is the formula of reported speech?

You can use the following formula to construct a sentence in the reported speech. Subject said that (report whatever the speaker said)

Give some examples of reported speech.

Given below are a few examples to show you how reported speech can be written.

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Your Mobile number and Email id will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Request OTP on Voice Call

Post My Comment

Register with BYJU'S & Download Free PDFs

Register with byju's & watch live videos.

Search form

- B1-B2 grammar

Reported speech

Daisy has just had an interview for a summer job.

Instructions

As you watch the video, look at the examples of reported speech. They are in red in the subtitles. Then read the conversation below to learn more. Finally, do the grammar exercises to check you understand, and can use, reported speech correctly.

Sophie: Mmm, it’s so nice to be chilling out at home after all that running around.

Ollie: Oh, yeah, travelling to glamorous places for a living must be such a drag!

Ollie: Mum, you can be so childish sometimes. Hey, I wonder how Daisy’s getting on in her job interview.

Sophie: Oh, yes, she said she was having it at four o’clock, so it’ll have finished by now. That’ll be her ... yes. Hi, love. How did it go?

Daisy: Well, good I think, but I don’t really know. They said they’d phone later and let me know.

Sophie: What kind of thing did they ask you?

Daisy: They asked if I had any experience with people, so I told them about helping at the school fair and visiting old people at the home, that sort of stuff. But I think they meant work experience.

Sophie: I’m sure what you said was impressive. They can’t expect you to have had much work experience at your age.

Daisy: And then they asked me what acting I had done, so I told them that I’d had a main part in the school play, and I showed them a bit of the video, so that was cool.

Sophie: Great!

Daisy: Oh, and they also asked if I spoke any foreign languages.

Sophie: Languages?

Daisy: Yeah, because I might have to talk to tourists, you know.

Sophie: Oh, right, of course.

Daisy: So that was it really. They showed me the costume I’ll be wearing if I get the job. Sending it over ...

Ollie: Hey, sis, I heard that Brad Pitt started out as a giant chicken too! This could be your big break!

Daisy: Ha, ha, very funny.

Sophie: Take no notice, darling. I’m sure you’ll be a marvellous chicken.

We use reported speech when we want to tell someone what someone said. We usually use a reporting verb (e.g. say, tell, ask, etc.) and then change the tense of what was actually said in direct speech.

So, direct speech is what someone actually says? Like 'I want to know about reported speech'?

Yes, and you report it with a reporting verb.

He said he wanted to know about reported speech.

I said, I want and you changed it to he wanted .

Exactly. Verbs in the present simple change to the past simple; the present continuous changes to the past continuous; the present perfect changes to the past perfect; can changes to could ; will changes to would ; etc.

She said she was having the interview at four o’clock. (Direct speech: ' I’m having the interview at four o’clock.') They said they’d phone later and let me know. (Direct speech: ' We’ll phone later and let you know.')

OK, in that last example, you changed you to me too.

Yes, apart from changing the tense of the verb, you also have to think about changing other things, like pronouns and adverbs of time and place.

'We went yesterday.' > She said they had been the day before. 'I’ll come tomorrow.' > He said he’d come the next day.

I see, but what if you’re reporting something on the same day, like 'We went yesterday'?

Well, then you would leave the time reference as 'yesterday'. You have to use your common sense. For example, if someone is saying something which is true now or always, you wouldn’t change the tense.

'Dogs can’t eat chocolate.' > She said that dogs can’t eat chocolate. 'My hair grows really slowly.' > He told me that his hair grows really slowly.

What about reporting questions?

We often use ask + if/whether , then change the tenses as with statements. In reported questions we don’t use question forms after the reporting verb.

'Do you have any experience working with people?' They asked if I had any experience working with people. 'What acting have you done?' They asked me what acting I had done .

Is there anything else I need to know about reported speech?

One thing that sometimes causes problems is imperative sentences.

You mean like 'Sit down, please' or 'Don’t go!'?

Exactly. Sentences that start with a verb in direct speech need a to + infinitive in reported speech.

She told him to be good. (Direct speech: 'Be good!') He told them not to forget. (Direct speech: 'Please don’t forget.')

OK. Can I also say 'He asked me to sit down'?

Yes. You could say 'He told me to …' or 'He asked me to …' depending on how it was said.

OK, I see. Are there any more reporting verbs?

Yes, there are lots of other reporting verbs like promise , remind , warn , advise , recommend , encourage which you can choose, depending on the situation. But say , tell and ask are the most common.

Great. I understand! My teacher said reported speech was difficult.

And I told you not to worry!

Check your grammar: matching

Check your grammar: error correction, check your grammar: gap fill, worksheets and downloads.

What was the most memorable conversation you had yesterday? Who were you talking to and what did they say to you?

Sign up to our newsletter for LearnEnglish Teens

We will process your data to send you our newsletter and updates based on your consent. You can unsubscribe at any time by clicking the "unsubscribe" link at the bottom of every email. Read our privacy policy for more information.

EnglishPost.org

Reported Speech: Structures and Examples

Reported speech (Indirect Speech) is how we represent the speech of other people or what we ourselves say.

Reported Speech focuses more on the content of what someone said rather than their exact words

The structure of the independent clause depends on whether the speaker is reporting a statement, a question, or a command.

Table of Contents

Reported Speech Rules and Examples

Present tenses and reported speech, past tenses and reported speech, reported speech examples, reported speech and the simple present, reported speech and present continuous, reported speech and the simple past, reported speech and the past continuous, reported speech and the present perfect, reported speech and the past perfect, reported speech and ‘ can ’ and ‘can’t’, reported speech and ‘ will ’ and ‘ won’t ’, reported speech and could and couldn’t, reported speech and the future continuous, reported questions exercises online.

To turn sentences into Indirect Speech, you have to follow a set of rules and this is what makes reported speech difficult for some.

To make reported speech sentences, you need to manage English tenses well.

- Present Simple Tense changes into Past Simple Tense

- Present Progressive Tense changes into Past Progressive Tense

- Present Perfect Tense changes into Past Perfect Tense

- Present Perfect Progressive Tense changes into Past Perfect Tense

- Past Simple Tense changes into Past Perfect Tense

- Past Progressive Tense changes into Perfect Continuous Tense

- Past Perfect Tense doesn’t change

- Past Perfect Progressive Tense doesn’t change

- Future Simple Tense changes into would

- Future Progressive Tense changes into “would be”

- Future Perfect Tense changes into “would have·

- Future Perfect Progressive Tense changes into “would have been”

These are some examples of sentences using indirect speech

The present simple tense usually changes to the past simple

The present continuous tense usually changes to the past continuous.

The past simple tense usually changes to the past perfect

The past continuous tense usually changes to the past perfect continuous.

The present perfect tense usually changes to the past perfect tense

The past perfect tense does not change

‘ Can ’ and ‘can’t’ in direct speech change to ‘ could ’ and ‘ couldn’t ’

‘ Will ’ and ‘ won’t ’ in direct speech change to ‘ would ’ and ‘ wouldn’t ’

Could and couldn’t doesn’t change

Will ’ and ‘ won’t ’ in direct speech change to ‘ would ’ and ‘ wouldn’t ’

These are some online exercises to learn more about reported questions

- Present Simple Reported Yes/No Question Exercise

- Present Simple Reported Wh Question Exercise

- Mixed Tense Reported Question Exercise

- Present Simple Reported Statement Exercise

- Present Continuous Reported Statement Exercise

I am Jose Manuel, English professor and creator of EnglishPost.org, a blog whose mission is to share lessons for those who want to learn and improve their English

Related Posts

Questions with How Many and How Much

![reported speech the past continuous 100 Simple Present Questions [Do & Does]](https://englishpost.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/more-english-examples.png)

100 Simple Present Questions [Do & Does]

100 Linking Words Examples

What is Reported Speech and how to use it? with Examples

Published by

Olivia Drake

Reported speech and indirect speech are two terms that refer to the same concept, which is the act of expressing what someone else has said.

On this page:

Reported speech is different from direct speech because it does not use the speaker’s exact words. Instead, the reporting verb is used to introduce the reported speech, and the tense and pronouns are changed to reflect the shift in perspective. There are two main types of reported speech: statements and questions.

1. Reported Statements: In reported statements, the reporting verb is usually “said.” The tense in the reported speech changes from the present simple to the past simple, and any pronouns referring to the speaker or listener are changed to reflect the shift in perspective. For example, “I am going to the store,” becomes “He said that he was going to the store.”

2. Reported Questions: In reported questions, the reporting verb is usually “asked.” The tense in the reported speech changes from the present simple to the past simple, and the word order changes from a question to a statement. For example, “What time is it?” becomes “She asked what time it was.”

It’s important to note that the tense shift in reported speech depends on the context and the time of the reported speech. Here are a few more examples:

- Direct speech: “I will call you later.”Reported speech: He said that he would call me later.

- Direct speech: “Did you finish your homework?”Reported speech: She asked if I had finished my homework.

- Direct speech: “I love pizza.”Reported speech: They said that they loved pizza.

When do we use reported speech?

Reported speech is used to report what someone else has said, thought, or written. It is often used in situations where you want to relate what someone else has said without quoting them directly.

Reported speech can be used in a variety of contexts, such as in news reports, academic writing, and everyday conversation. Some common situations where reported speech is used include:

News reports: Journalists often use reported speech to quote what someone said in an interview or press conference.

Business and professional communication: In professional settings, reported speech can be used to summarize what was discussed in a meeting or to report feedback from a customer.

Conversational English: In everyday conversations, reported speech is used to relate what someone else said. For example, “She told me that she was running late.”

Narration: In written narratives or storytelling, reported speech can be used to convey what a character said or thought.

How to make reported speech?

1. Change the pronouns and adverbs of time and place: In reported speech, you need to change the pronouns, adverbs of time and place to reflect the new speaker or point of view. Here’s an example:

Direct speech: “I’m going to the store now,” she said. Reported speech: She said she was going to the store then.

In this example, the pronoun “I” is changed to “she” and the adverb “now” is changed to “then.”

2. Change the tense: In reported speech, you usually need to change the tense of the verb to reflect the change from direct to indirect speech. Here’s an example:

Direct speech: “I will meet you at the park tomorrow,” he said. Reported speech: He said he would meet me at the park the next day.

In this example, the present tense “will” is changed to the past tense “would.”

3. Change reporting verbs: In reported speech, you can use different reporting verbs such as “say,” “tell,” “ask,” or “inquire” depending on the context of the speech. Here’s an example:

Direct speech: “Did you finish your homework?” she asked. Reported speech: She asked if I had finished my homework.

In this example, the reporting verb “asked” is changed to “said” and “did” is changed to “had.”

Overall, when making reported speech, it’s important to pay attention to the verb tense and the changes in pronouns, adverbs, and reporting verbs to convey the original speaker’s message accurately.

How do I change the pronouns and adverbs in reported speech?

1. Changing Pronouns: In reported speech, the pronouns in the original statement must be changed to reflect the perspective of the new speaker. Generally, the first person pronouns (I, me, my, mine, we, us, our, ours) are changed according to the subject of the reporting verb, while the second and third person pronouns (you, your, yours, he, him, his, she, her, hers, it, its, they, them, their, theirs) are changed according to the object of the reporting verb. For example:

Direct speech: “I love chocolate.” Reported speech: She said she loved chocolate.

Direct speech: “You should study harder.” Reported speech: He advised me to study harder.

Direct speech: “She is reading a book.” Reported speech: They noticed that she was reading a book.

2. Changing Adverbs: In reported speech, the adverbs and adverbial phrases that indicate time or place may need to be changed to reflect the perspective of the new speaker. For example:

Direct speech: “I’m going to the cinema tonight.” Reported speech: She said she was going to the cinema that night.

Direct speech: “He is here.” Reported speech: She said he was there.

Note that the adverb “now” usually changes to “then” or is omitted altogether in reported speech, depending on the context.

It’s important to keep in mind that the changes made to pronouns and adverbs in reported speech depend on the context and the perspective of the new speaker. With practice, you can become more comfortable with making these changes in reported speech.

How do I change the tense in reported speech?

In reported speech, the tense of the reported verb usually changes to reflect the change from direct to indirect speech. Here are some guidelines on how to change the tense in reported speech:

Present simple in direct speech changes to past simple in reported speech. For example: Direct speech: “I like pizza.” Reported speech: She said she liked pizza.

Present continuous in direct speech changes to past continuous in reported speech. For example: Direct speech: “I am studying for my exam.” Reported speech: He said he was studying for his exam.

Present perfect in direct speech changes to past perfect in reported speech. For example: Direct speech: “I have finished my work.” Reported speech: She said she had finished her work.

Past simple in direct speech changes to past perfect in reported speech. For example: Direct speech: “I visited my grandparents last weekend.” Reported speech: She said she had visited her grandparents the previous weekend.

Will in direct speech changes to would in reported speech. For example: Direct speech: “I will help you with your project.” Reported speech: He said he would help me with my project.

Can in direct speech changes to could in reported speech. For example: Direct speech: “I can speak French.” Reported speech: She said she could speak French.

Remember that the tense changes in reported speech depend on the tense of the verb in the direct speech, and the tense you use in reported speech should match the time frame of the new speaker’s perspective. With practice, you can become more comfortable with changing the tense in reported speech.

Do I always need to use a reporting verb in reported speech?

No, you do not always need to use a reporting verb in reported speech. However, using a reporting verb can help to clarify who is speaking and add more context to the reported speech.

In some cases, the reported speech can be introduced by phrases such as “I heard that” or “It seems that” without using a reporting verb. For example:

Direct speech: “I’m going to the cinema tonight.” Reported speech with a reporting verb: She said she was going to the cinema tonight. Reported speech without a reporting verb: It seems that she’s going to the cinema tonight.

However, it’s important to note that using a reporting verb can help to make the reported speech more formal and accurate. When using reported speech in academic writing or journalism, it’s generally recommended to use a reporting verb to make the reporting more clear and credible.

Some common reporting verbs include say, tell, explain, ask, suggest, and advise. For example:

Direct speech: “I think we should invest in renewable energy.” Reported speech with a reporting verb: She suggested that they invest in renewable energy.

Overall, while using a reporting verb is not always required, it can be helpful to make the reported speech more clear and accurate

How to use reported speech to report questions and commands?

1. Reporting Questions: When reporting questions, you need to use an introductory phrase such as “asked” or “wondered” followed by the question word (if applicable), subject, and verb. You also need to change the word order to make it a statement. Here’s an example:

Direct speech: “What time is the meeting?” Reported speech: She asked what time the meeting was.

Note that the question mark is not used in reported speech.

2. Reporting Commands: When reporting commands, you need to use an introductory phrase such as “ordered” or “told” followed by the person, to + infinitive, and any additional information. Here’s an example:

Direct speech: “Clean your room!” Reported speech: She ordered me to clean my room.

Note that the exclamation mark is not used in reported speech.

In both cases, the tense of the reported verb should be changed accordingly. For example, present simple changes to past simple, and future changes to conditional. Here are some examples:

Direct speech: “Will you go to the party with me?”Reported speech: She asked if I would go to the party with her. Direct speech: “Please bring me a glass of water.”Reported speech: She requested that I bring her a glass of water.

Remember that when using reported speech to report questions and commands, the introductory phrases and verb tenses are important to convey the intended meaning accurately.

How to make questions in reported speech?

To make questions in reported speech, you need to use an introductory phrase such as “asked” or “wondered” followed by the question word (if applicable), subject, and verb. You also need to change the word order to make it a statement. Here are the steps to make questions in reported speech:

Identify the reporting verb: The first step is to identify the reporting verb in the sentence. Common reporting verbs used to report questions include “asked,” “inquired,” “wondered,” and “wanted to know.”

Change the tense and pronouns: Next, you need to change the tense and pronouns in the sentence to reflect the shift from direct to reported speech. The tense of the verb is usually shifted back one tense (e.g. from present simple to past simple) in reported speech. The pronouns should also be changed as necessary to reflect the shift in perspective from the original speaker to the reporting speaker.

Use an appropriate question word: If the original question contained a question word (e.g. who, what, where, when, why, how), you should use the same question word in the reported question. If the original question did not contain a question word, you can use “if” or “whether” to introduce the reported question.

Change the word order: In reported speech, the word order of the question changes from the inverted form to a normal statement form. The subject usually comes before the verb, unless the original question started with a question word.

Here are some examples of reported questions:

Direct speech: “Did you finish your homework?”Reported speech: He wanted to know if I had finished my homework. Direct speech: “Where are you going?”Reported speech: She wondered where I was going.

Remember that when making questions in reported speech, the introductory phrases and verb tenses are important to convey the intended meaning accurately.

Here you can find more examples of direct and indirect questions

What is the difference between reported speech an indirect speech?

In reported or indirect speech, you are retelling or reporting what someone said using your own words. The tense of the reported speech is usually shifted back one tense from the tense used in the original statement. For example, if someone said, “I am going to the store,” in reported speech you would say, “He/she said that he/she was going to the store.”

The main difference between reported speech and indirect speech is that reported speech usually refers to spoken language, while indirect speech can refer to both spoken and written language. Additionally, indirect speech is a broader term that includes reported speech as well as other ways of expressing what someone else has said, such as paraphrasing or summarizing.

Examples of direct speech to reported

- Direct speech: “I am hungry,” she said. Reported speech: She said she was hungry.

- Direct speech: “Can you pass the salt, please?” he asked. Reported speech: He asked her to pass the salt.

- Direct speech: “I will meet you at the cinema,” he said. Reported speech: He said he would meet her at the cinema.

- Direct speech: “I have been working on this project for hours,” she said. Reported speech: She said she had been working on the project for hours.

- Direct speech: “What time does the train leave?” he asked. Reported speech: He asked what time the train left.

- Direct speech: “I love playing the piano,” she said. Reported speech: She said she loved playing the piano.

- Direct speech: “I am going to the grocery store,” he said. Reported speech: He said he was going to the grocery store.

- Direct speech: “Did you finish your homework?” the teacher asked. Reported speech: The teacher asked if he had finished his homework.

- Direct speech: “I want to go to the beach,” she said. Reported speech: She said she wanted to go to the beach.

- Direct speech: “Do you need help with that?” he asked. Reported speech: He asked if she needed help with that.

- Direct speech: “I can’t come to the party,” he said. Reported speech: He said he couldn’t come to the party.

- Direct speech: “Please don’t leave me,” she said. Reported speech: She begged him not to leave her.

- Direct speech: “I have never been to London before,” he said. Reported speech: He said he had never been to London before.

- Direct speech: “Where did you put my phone?” she asked. Reported speech: She asked where she had put her phone.

- Direct speech: “I’m sorry for being late,” he said. Reported speech: He apologized for being late.

- Direct speech: “I need some help with this math problem,” she said. Reported speech: She said she needed some help with the math problem.

- Direct speech: “I am going to study abroad next year,” he said. Reported speech: He said he was going to study abroad the following year.

- Direct speech: “Can you give me a ride to the airport?” she asked. Reported speech: She asked him to give her a ride to the airport.

- Direct speech: “I don’t know how to fix this,” he said. Reported speech: He said he didn’t know how to fix it.

- Direct speech: “I hate it when it rains,” she said. Reported speech: She said she hated it when it rained.

Share this:

Leave a reply cancel reply, i’m olivia.

Welcome to my virtual classroom! Join me on a journey of language and learning, where we explore the wonders of English together. Let’s discover the joy of words and education!

Let’s connect

Join the fun!

Stay updated with our latest tutorials and ideas by joining our newsletter.

Type your email…

Recent posts

Going to and present continuous for future plans and arrangements, difference between present simple vs. present continuous with example, questions in present continuous tense with examples, present continuous negative sentences with examples, present continuous sentences with examples, present perfect vs past perfect exercises with answers, discover more from fluent english grammar.

Subscribe now to keep reading and get access to the full archive.

Continue reading

Accessibility links

- Skip to content

- Accessibility Help

Learning English

Inspiring language learning since 1943.

- Courses home Courses

- Grammar home Grammar

- Pronunciation home Pronunciation

- Vocabulary home Vocabulary

- News home News

- Quizzes More...

- Test Your Level More...

- Downloads More...

- Teachers More...

- For Children More...

- Podcasts More...

- Drama More...

- Business English More...

- Afaan Oromoo

Unit 2: Reported speech in 90 seconds! Move the tense back

Select a unit

- 1 Go beyond intermediate with our new video course

- 2 Reported speech in 90 seconds!

- 3 If or whether?

- 4 5 ways to use 'would'

- 5 Let and allow

- 6 Passive voice

- 8 Mixed conditionals

- 9 The zero article - in 90 seconds

- 10 The indefinite article - in 90 seconds

- 11 The. That's right - the! Learn all about it in 90 seconds

- 12 The continuous passive

- 13 Future perfect

- 14 Need + verb-ing

- 15 Have something done

- 17 Word stress

- 18 Different ways of saying 'if'

- 19 Passive reporting structures

- 20 The subjunctive

- 21 When and if

- 22 Inversion

- 23 Phrasal verbs

- 24 The future

- 25 Modals in the past

- 26 Narrative tenses

- 27 Phrasal verb myths

- 28 Conditionals review

- 29 Used to - review

- 30 Linking words of contrast

- Vocabulary reference

- Grammar reference

Do you have 90 seconds? Do you want to learn something useful about reported speech? Then join Finn as he attempts to give you one useful tip against the clock!

Sessions in this unit

Session 1 score.

- 0 / 5 Activity 1

BBC English Class: Reported speech

Welcome to another BBC English Class video. This is the programme where one of our presenters tries to give you a top grammar tip in just 90 seconds.

This time Finn looks at reported speech . But can he do it in time?

Watch the video and complete the activity

You are a busy person. I'm a busy person. English grammar takes a long time to learn.

Today we're going to look at reported speech. But we're not going to go through a whole book. We're not going to learn everything. We're going to learn one point that you need to remember when you forget everything else. This is the one most important thing. And we're going to do it in 90 seconds because I know how busy you are.

This clock is going to start now.

Reported speech - what's the tip? What is the secret? Just four words: Move the tense back .

Now what does that mean? That means, for example:

We're at a party, we're having a great time. You come and ask me, "Finn would you like a cigarette?" And I say, "No, I don't want a cigarette, in fact, I've never smoked a cigarette in my life." Wow, that's quite interesting, you think. I'm going to tell my friend. Right, OK, there's your friend. How do you tell them? You use reported speech.

OK, so if I said, "I've never smoked a cigarette in my life," what tense is that? I've never smoked is present perfect. Right, if you want to tell your friend what do you do? Using reported speech? You move the tense back.

So you say: Finn said he had never smoked a cigarette in his life.

There it is. I've still got 20 seconds... what about that? We moved the tense back.

So if the sentence is in the present simple, move it to the past simple. Easy.

Remember that, you won't go far wrong in life. We're really busy, but hey - six seconds to go, you're looking great - remember my point - move the tense back. See you.

The main point

- So - what was Finn's tip? Simple: Move the tense back .

What do we mean by that? Well, if the original statement was in the present perfect tense, the reported statement goes one tense back in time - to the past perfect tense, like this:

Finn: I have never smoked a cigarette in my life.

Reported speech: Finn said he had never smoked a cigarette in his life.

And if the original statement was in the present continuous, the reported statement would be in the... past continuous.

Finn: I am writing a novel.

Reported speech: Finn said he was writing a novel.

Which tense should this sentence change to in reported speech?

Kim: I'm planning to meet Jin in Berlin.

The answer is past continuous:

Reported speech: Kim said she was planning to meet Jin in Berlin.

There are a few exceptions to this rule. For more information, check out our Grammar Reference .

Now - time for a quick test to see if you've understood this point.

Finn said it was easy...

5 Questions

So, how confident do you feel at moving the tense back? Test yourself with this quiz! Each question has a statement - you have to change it into reported speech by moving the tense back.

Question 1 of 5

Question 2 of 5

Question 3 of 5

Question 4 of 5

Question 5 of 5

End of Session 1

That's the end of our BBC English Class activity. Next, join us as we explore the language of the news, in News Review.

Session Grammar

Reported speech.

One thing to remember: Move the tense back!

1) Present simple -> past simple

"I know you." -> She said she knew him.

2) Present continuous -> past continuous

"I am having coffee" -> He said he was having coffee.

3) Present perfect -> past perfect

"I have finished my homework" -> He said he had finished his homework.

4) Present perfect continuous -> past perfect continuous