Development of self-concept in childhood and adolescence: How neuroscience can inform theory and vice versa

- Split-Screen

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

- Peer Review

- Open the PDF for in another window

- Get Permissions

- Cite Icon Cite

- Search Site

Eveline A. Crone , Lina van Drunen; Development of self-concept in childhood and adolescence: How neuroscience can inform theory and vice versa. Human Development 2024; https://doi.org/10.1159/000539844

Download citation file:

- Ris (Zotero)

- Reference Manager

Article PDF first page preview

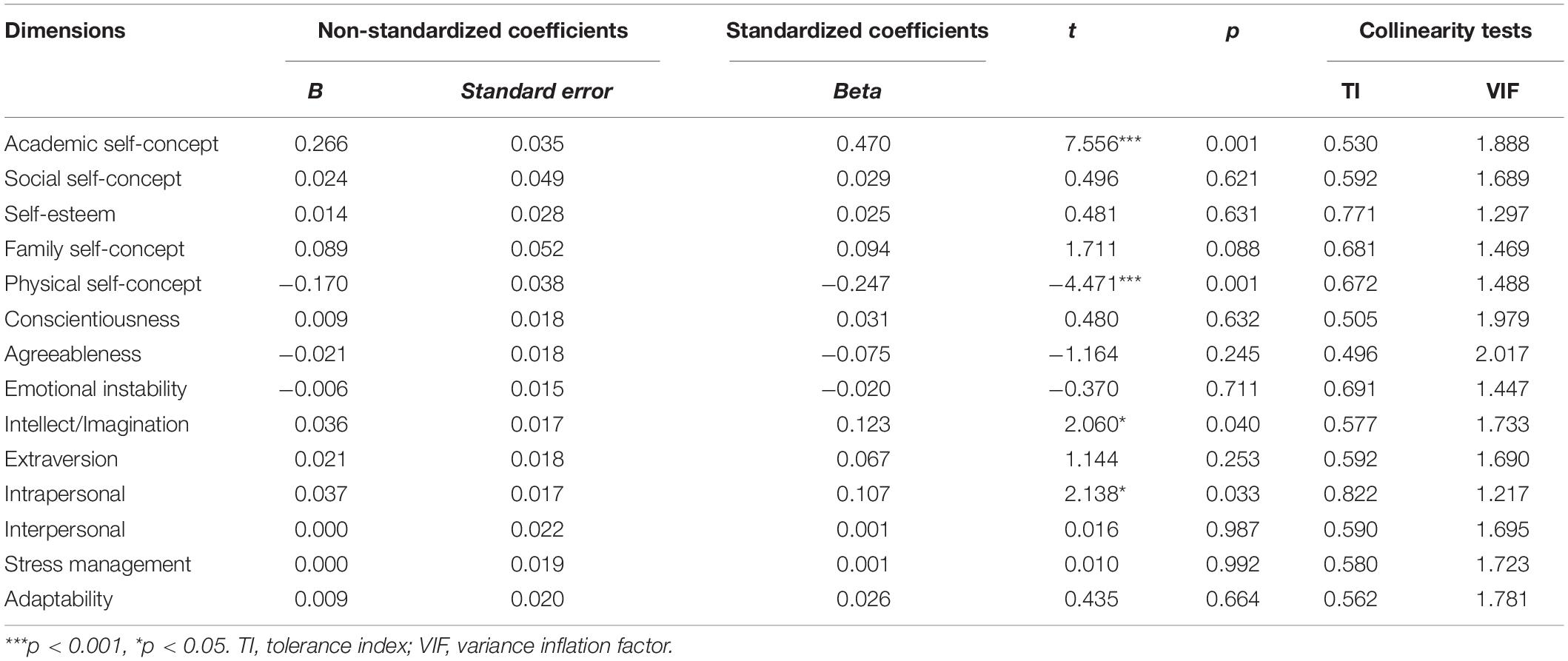

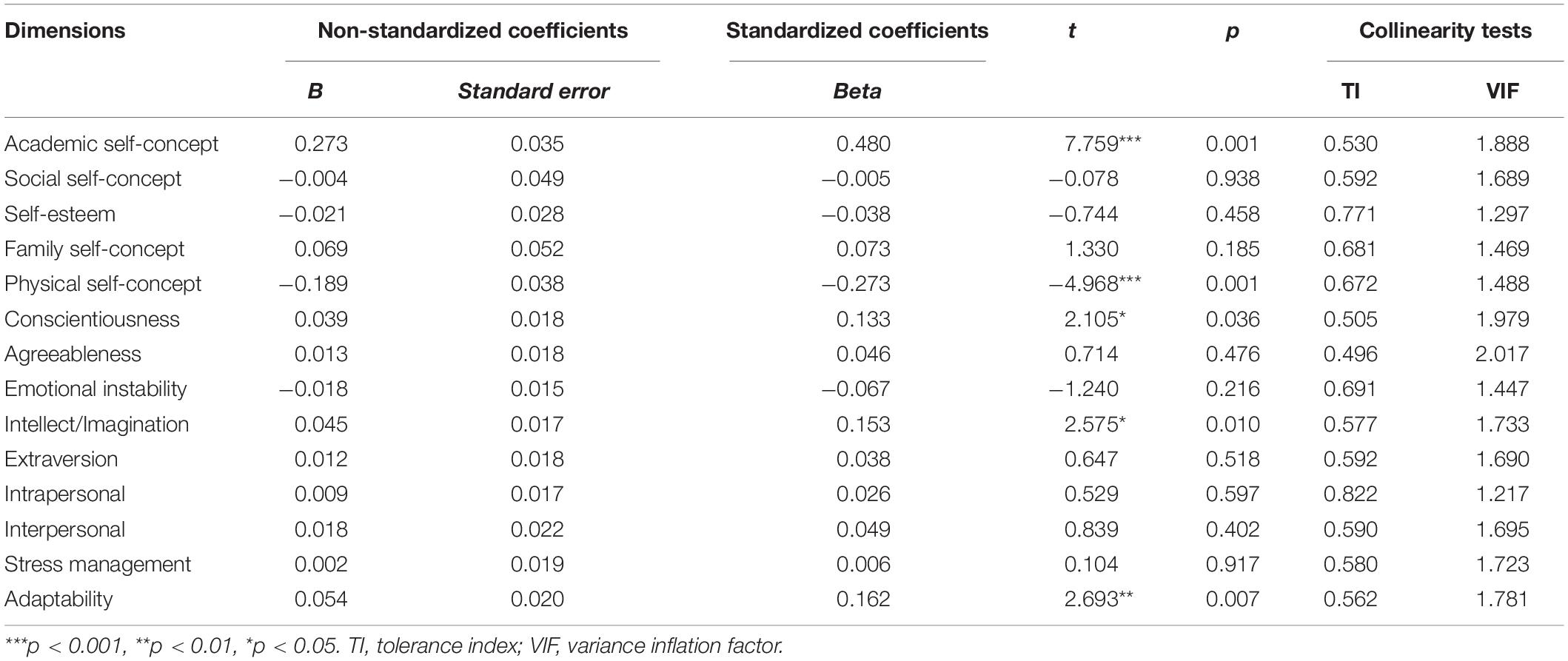

How do we develop a stable and coherent self-concept in contemporary times? Susan Harter’s original work The Construction of Self (1999; 2012) argues that cognitive and social processes are building blocks for developing a coherent sense of self, resulting in self-concept clarity across various domains in life (e.g., (pro-)social, academic, and physical). Here, we show how this framework guides and can benefit from recent findings on (1) the prolonged and non-linear structural brain development during childhood and adolescence, (2) insights from developmental neuroimaging studies using self-concept appraisal paradigms, (3) genetic and environmental influences on behavioral and neural correlates of self-concept development, and (4) youth’s perspectives on self-concept development in the context of 21st century global challenges. We examine how neuroscience can inform theory by testing several compelling questions related to stability versus change of neural, behavioral, and self-report measures and we reflect on the meaning of variability and change/growth.

Email alerts

Citing articles via, suggested reading.

- Online ISSN 1423-0054

- Print ISSN 0018-716X

INFORMATION

- Contact & Support

- Information & Downloads

- Rights & Permissions

- Terms & Conditions

- Catalogue & Pricing

- Policies & Information

- People & Organization

- Stay Up-to-Date

- Regional Offices

- Community Voice

SERVICES FOR

- Researchers

- Healthcare Professionals

- Patients & Supporters

- Health Sciences Industry

- Medical Societies

- Agents & Booksellers

Karger International

- S. Karger AG

- P.O Box, CH-4009 Basel (Switzerland)

- Allschwilerstrasse 10, CH-4055 Basel

- Tel: +41 61 306 11 11

- Fax: +41 61 306 12 34

- Contact: Front Office

- Experience Blog

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Use

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

Self-Concept: Determinants and Consequences of Academic Self-Concept in School Contexts

- First Online: 02 April 2016

Cite this chapter

- Ulrich Trautwein 6 &

- Jens Möller 7

Part of the book series: The Springer Series on Human Exceptionality ((SSHE))

4146 Accesses

41 Citations

Self-concepts are subjective beliefs about the qualities that characterize us, with academic self-concepts describing our self-beliefs about our intellectual strengths and weaknesses. The chapter attempts to answer some of the most pressing questions about the role of academic self-concept as a central construct in educational theory and practice: What is self-concept? What are the consequences of high or low self-concept? What are the determinants of high or low self-concept? What can be done to positively influence self-concept? The chapter starts by explaining the multidimensional and hierarchical nature of academic self-concept. It then identifies academic self-concepts as one of the most powerful predictors of academic behavior and academic outcomes and, thus, as highly relevant for researchers and practitioners. At the same time, the chapter highlights that the development of academic self-concept is influenced by many sources, and it describes how educational interventions have to deal with these different determinants of academic self-concept. The chapter concludes with a number of suggestions for educational practice and further research.

Lipnevich, A., Preckel, F., & Roberts, R. (Eds.), Psychosocial skills and school systems in the twenty-first century: Theory, research, and applications . Berlin: Springer.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Albert, S. (1977). Temporal comparison theory. Psychological Review, 84 , 485–503.

Article Google Scholar

Archambault, I., Eccles, J. S., & Vida, M. N. (2010). Ability self-concepts and subjective value in literacy: Joint trajectories from grade 1 through 2. Journal of Educations Psychology, 102 (4), 804–816.

Asendorpf, J. B., & van Aken, M. A. G. (2003). Personality-relationship transaction in adolescence: Core versus surface personality characteristics. Journal of Personality, 71 , 629–662.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control . New York: Freeman.

Google Scholar

Baumeister, R. F., Campbell, J. C., Krueger, J. I., & Vohs, K. D. (2003). Does high self-esteem cause better performance, interpersonal success, happiness, or healthier lifestyles? Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 4 , 1–44.

Bong, M. (2001). Between- and within-domain relations of academic motivation among middle and high school students: Self-efficacy, task value, and achievement goals. Journal of Educational Psychology, 93 , 23–34.

Brunner, M., Keller, U., Dierendonck, C., Reichert, M., Ugen, S., Fischbach, A., et al. (2010). The structure of academic self-concepts revisited: The nested Marsh/Shavelson model. Journal of Educational Psychology, 102 , 964–981.

Byrne, B. M. (1996). Measuring self-concept across the life span: Issues and instrumentation . Washington, DC: APA Books.

Book Google Scholar

Calsyn, R. J., & Kenny, D. A. (1977). Self-concept of ability and perceived evaluation of others: Cause or effect of academic achievement? Journal of Educational Psychology, 69 , 136–145.

Chiu, M.-S. (2012). The internal/external frame of reference model, big-fish-little-pond effect, and combined model for mathematics and science. Journal of Educational Psychology, 104 , 87–107.

Chmielewski, K., Dumont, H., & Trautwein, U. (2013). Tracking effects depend on tracking type: An international comparison of academic self-concept. American Educational Research Journal, 50 , 925–957.

Cialdini, R. B., & Richardson, K. D. (1980). Two indirect tactics of image management: Basking and blasting. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 39 , 406–415.

Dai, D. Y., & Rinn, A. N. (2008). The big-fish-little-pond effect: What do we know and where do we go from here? Educational Psychology Review, 20 , 283–317.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). Handbook of self-determination research . Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press.

Denissen, J. J. A., Zarrett, N. R., & Eccles, J. S. (2007). I like to do it, I’m able, and I know I am: Longitudinal couplings between domain-specific achievement, self-concept, and interest. Child Development, 78 , 430–447.

Diener, E., & Fujita, F. (1997). Social comparison and subjective well-being. In B. P. Buunk & F. X. Gibbons (Eds.), Health, coping, and well-being: Perspectives from social comparison theory (pp. 329–358). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Dunlosky, J., & Rawson, K. (2012). Overconfidence produces underachievement: Inaccurate self-evaluations undermine students’ learning and retention. Learning and Instruction, 22 , 271–280.

Eccles, J. S. (1983). Expectancies, values, and academic choice: Origins and changes. In J. Spence (Ed.), Achievement and achievement motivation (pp. 87–134). San Francisco: W. H. Freeman.

Eccles, J.S., Wigfield, A., Harold, R.D., & Blumenfeld, P. (1993). Age and gender differences in children’s self- and task perceptions during elementary school. Child Development, 64, 830–847.

Eccles, J. S. (1994). Understanding women’s educational and occupational choices. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 11 , 135–172.

Eccles, J., Adler, T. F., Futterman, R., Goff, S. B., Kaczala, C. M., & Meece, J., et al. (1983). Expectancies, values and academic behaviors. In J. T. Spence (Ed.), Achievement and achievement motives (pp. 75–146) . San Francisco: W. H. Freeman.

Eccles, J. S., & Wigfield, A. (2002). Motivational beliefs, values, and goals. Annual Review of Psychology, 53 , 109–132.

European Commission. (2007). Science education now: A renewed pedagogy for the future of Europe (Community Research Expert Group, Vol. 22845). Luxembourg: EUR-OP.

Fauth, B., Decristan, J., Rieser, S., Klieme, E., & Büttner, G. (2014). Student ratings of teaching quality in primary school: Dimensions and prediction of student outcomes. Learning and Instruction, 29 , 1–9.

Festinger, L. (1954). A theory of social comparison processes. Human Relations, 7 , 117–140.

Försterling, F. (1985). Attributional retraining: A review. Psychological Bulletin, 98 , 495–512.

Friedrich, A., Flunger, B., Nagengast, B., Jonkmann, K., Schmitz, B., & Trautwein, U. (2015). Pygmalion effects in the classroom: Teacher expectancy effects on students’ math achievement. Contemporary Educational Psychology , 41, 1–12.

Frome, P. M., & Eccles, J. S. (1998). Parents’ influence on children’s achievement-related perceptions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74 , 435–452.

Gogol, K., Brunner, M., Goetz, T., Martin, R., Ugen, S., Keller, U., et al. (2014). “My questionnaire is too long!” The assessments of motivational-affective constructs with three-item and single-item measures. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 39 , 188–205.

Harter, S. (1998). The development of self-representations. In W. Damon (Series Ed.) & N. Eisenberg (Vol. Ed.), Handbook of child psychology: Vol. 3. Social, emotional, and personality development (5th ed., pp. 553–617). New York: Wiley.

Hattie, J. (1992). Self-concept . Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Helmke, A. (1990). Mediating processes between children’s self-concept of ability and mathematical achievement: A longitudinal study. In H. Mandl, E. de Corte, S. N. Bennett, & H. F. Friedrich (Eds.), Learning and instruction. European research in an international context. Volume 2.2: Analysis of complex skills and complex knowledge domains (pp. 537–549). Oxford: Pergamon Press.

Huang, C. (2011). Self-concept and academic achievement: A meta-analysis of longitudinal relations. Journal of School Psychology, 49 , 505–528.

Hulleman, C. S., Barron, K. E., Kosovich, J. J., & Lazowski, R. A. (2015). Student motivation: Current theories, constructs, and interventions within an expectancy-value framework. In A. A. Lipnevich, F. Preckel, & R. D. Roberts (Eds.), Psychosocial skills and school systems in the 21st century . Cham: Springer.

James, W. (1892/1999). The self. In R. F. Baumeister (Ed.), The self in social psychology (pp. 69–77). Philadelphia: Psychology Press. (Original: James, W. [1892/1948]. Psychology . Cleveland, OH: World Publishing).

Jussim, L., & Harber, K. D. (2005). Teacher expectations and self-fulfilling prophecies: Knowns and unknowns, resolved and unresolved controversies. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 9 , 131–155.

Kim, Y.-H., Chiu, C.-Y., & Zou, Z. (2010). Know thyself: Misperceptions of actual performance undermine achievement motivation, future performance, and subjective well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 99 (3), 395–409.

Kruger, J., & Dunning, D. (1999). Unskilled and unaware of it: How difficulties in recognizing one’s own incompetence lead to inflated self-assessments. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77 (6), 1121–1134.

Lüdtke, O., Köller, O., Marsh, H. W., & Trautwein, U. (2005). Teacher frame of reference and the big-fish-little-pond effect. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 30 , 263–285.

Makel, M. C., Lee, S. Y., Olszewski-Kubilius, P., & Putallaz, M. (2012). Changing the pond, not the fish: Following high ability students across different educational environments. Journal of Educational Psychology, 104 , 788–792.

Marsh, H.W., & Shavelson, R.J. (1985). Self-concept: Its multifaceted, hierarchical structure. Educational Psychologist, 20, 107–125.

Marsh, H. W. (1986). Verbal and math self-concepts: An internal/external frame of reference model. American Educational Research Journal, 23 , 129–149.

Marsh, H. W. (1987). The big fish little pond effect on academic self-concept. Journal of Educational Psychology, 79 , 280–295.

Marsh, H. W. (1989). Age and sex effects in multiple dimensions of self-concept: Preadolescence to early adulthood. Journal of Educational Psychology, 81 , 417–430.

Marsh, H. W. (1990). The structure of academic self-concept: The Marsh/Shavelson model. Journal of Educational Psychology, 82 , 623–636.

Marsh, H. W., Byrne, B. M., & Shavelson, R. J. (1988). A multifaceted academic self-concept: Its hierarchical structure and its relation to academic achievement. Journal of Educational Psychology, 80 , 366–380.

Marsh, H. W., Chessor, D., Craven, R., & Roche, L. (1995). The effects of gifted and talented programs on academic self-concept: The Big Fish strikes again. American Educational Research Journal, 32 , 285–319.

Marsh, H. W., & Craven, R. (1997). Academic self-concept: Beyond the dustbowl. In G. D. Phye (Ed.), Handbook of classroom assessment (pp. 137–198). San Diego, CA: Academic.

Marsh, H. W., & Craven, R. (2002). The pivotal role of frames of reference in academic self-concept formation: The big-fish-little-pond effect. In F. Pajares & T. Urdan (Eds.), Adolescence and education (Vol. 2, pp. 83–123). Greenwich, CT: Information Age.

Marsh, H. W., Craven, R., & Debus, R. (1998). Structure, stability, and development of young children’s self-concepts: A multicohort-multioccasion study. Child Development, 69 , 1030–1053.

Marsh, H. W., & Craven, R. G. (2006). Reciprocal effects of self-concept and performance from a multidimensional perspective: Beyond seductive pleasure and unidimensional perspectives. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 1 , 133–162.

Marsh, H. W., & Hattie, J. (1996). Theoretical perspectives on the structure of self-concept. In B. A. Bracken (Ed.), Handbook of self-concept (pp. 38–90). New York: Wiley.

Marsh, H. W., & Hau, K.-T. (2003). Big-Fish-Little-Pond effect on academic self-concept: A cross-cultural (26-country) test of the negative effects of academically selective schools. American Psychologist, 58 , 364–376.

Marsh, H. W., Kong, C.-K., & Hau, K.-T. (2000). Longitudinal multilevel models of the big fish little pond effect on academic self-concept: Counterbalancing contrast and reflected-glory effects in Hong Kong schools. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 78 , 337–349.

Marsh, H. W., Kong, C.-K., & Hau, K.-T. (2001). Extension of the internal/external frame of reference model of self-concept formation: Importance of native and nonnative languages for Chinese students. Journal of Educational Psychology, 93 , 543–553.

Marsh, H. W., Kuyper, H., Seaton, M., Parker, P. D., Morin, A. J. S., Möller, J., et al. (2014). Dimensional comparison theory: An extension of the internal/external frame of reference effect on academic self-concept formation. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 39 , 326–341.

Marsh, H. W., Lüdtke, O., Nagengast, B., Trautwein, U., Abduljabbar, A.S., Abdelfattah, F., et al. (2015). Dimensional comparison theory: Paradoxical relations between self-beliefs and achievements in multiple domains. Learning and Instruction, 35 , 16–32.

Marsh, H. W., & Martin, A. J. (2011). Academic self-concept and academic achievement: Relations and causal ordering. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 81 , 59–77.

Marsh, H. W., Trautwein, U., Lüdtke, O., Baumert, J., & Köller, O. (2007). Big Fish Little Pond Effect: Persistent negative effects of selective high schools on self-concept after graduation. American Educational Research Journal, 44 , 631–669.

Marsh, H. W., Trautwein, U., Lüdtke, O., & Köller, O. (2008). Social comparison and big-fish-little-pond effects on self-concept and efficacy perceptions: Role of generalized and specific others. Journal of Educational Psychology, 100 , 510–524.

Marsh, H. W., Trautwein, U., Lüdtke, O., Köller, O., & Baumert, J. (2005). Academic self-concept, interest, grades and standardized test scores: Reciprocal effects models of causal ordering. Child Development, 76 , 397–416.

Marsh, H. W., & Yeung, A. S. (1997). Coursework selection: Relations to academic self-concept and achievement. American Educational Research Journal, 34 , 691–720.

Marsh, H. W., & Yeung, A. S. (1998). Longitudinal structural equation models of academic self-concept and achievement: Gender differences in the development of math and English constructs. American Educational Research Journal, 35 , 705–738.

Meece, J. L., Wigfield, A., & Eccles, J. S. (1990). Predictors of math anxiety and its influence on young adolescents’ course enrollment intentions and performance in mathematics. Journal of Educational Psychology, 82 , 60–70.

Möller, J., Helm, F., Müller-Kalthoff, H., Nagy, N., & Marsh, H. W. (2015). Dimensional comparisons: Theoretical assumptions and empirical results. In J. D. Wright (Ed.), International encyclopedia of the social and behavioral sciences (2nd ed., pp. 430–436). Oxford: Elsevier.

Möller, J., & Husemann, N. (2006). Internal comparisons in everyday life. Journal of Educational Psychology, 98 , 342–353.

Möller, J., & Köller, O. (2001). Dimensional comparisons: An experimental approach to the internal/external frame of reference model. Journal of Educational Psychology, 93 , 826–835.

Möller, J., & Marsh, H. W. (2013). Dimensional comparison theory. Psychological Review, 120 , 544–560.

Möller, J., & Pohlmann, B. (2010). Achievement differences and self-concept differences: Stronger associations for above or below average students? British Journal of Educational Psychology, 80 , 435–450.

Möller, J., Pohlmann, B., Köller, O., & Marsh, H. W. (2009). A meta-analytic path analysis of the internal/external frame of reference model of academic achievement and academic self-concept. Review of Educational Research, 79 , 1129–1167.

Möller, J., Retelsdorf, J., Köller, O., & Marsh, H. W. (2011). The reciprocal I/E model: An integration of models of relations between academic achievement and self-concept. American Educational Research Journal, 48 , 1315–1346.

Möller, J., & Savyon, K. (2003). Not very smart thus moral: Dimensional comparisons between academic self-concept and honesty. Social Psychology of Education, 6 , 95–106.

Möller, J., Zimmermann, F., & Köller, O. (2014). The reciprocal internal/external frame of reference model using grades and test scores. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 84 , 591–611.

Nagengast, B., Marsh, H.W., Scalas, L.F., Xu, M., Hau, K.-T., & Trautwein, U. (2011). Who took the “X” out of expectancy-value theory? A psychological mystery, a substantive-methodological synergy, and a cross-national generalization. Psychological Science, 22, 1058–1066.

Nagy, G., Trautwein, U., Baumert, J., Köller, O., & Garrett, J. (2006). Gender and course selection in upper secondary education: Effects of academic self-concept and intrinsic value. Educational Research and Evaluation, 12 , 323–345.

Niepel, C., Brunner, M., & Preckel, F. (2014). The longitudinal interplay of students’ academic self-concepts and achievements within and across domains: Replicating and extending the reciprocal internal/external frame of reference model. Journal of Educational Psychology, 106 , 1170–1191.

OECD (Ed.). (2001). Knowledge and skills for life: First results from PISA 2000. Paris: OECD.

O’Mara, A. J., Marsh, H. W., Craven, R. G., & Debus, R. (2006). Do self-concept interventions make a difference? A synergetic blend of construct validation and meta-analysis. Educational Psychologist, 41 , 181–206.

Oakes, J. (1985). Keeping tack: How schools structure inequality . New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Pianta, R. C., & Hamre, B. K. (2009). Classroom processes and positive youth development: Conceptualizing, measuring, and improving the capacity of interactions between teachers and students. New Directions for Youth Development, 121 , 33–46.

Pintrich, P. R. (2003). A motivational science perspective on the role of student motivation in learning and teaching contexts. Journal of Educational Psychology, 95 , 667–686.

Pinxten, M., Wouters, S., Preckel, F., Niepel, C., De Fraine, B., & Verschueren, K. (2015). The formation of academic self-concept in elementary education: A unifying model for external and internal comparisons. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 41 , 124–132.

Preckel, F., & Brüll, M. (2010). The benefit of being a big fish in a big pond: Contrast and assimilation effects on academic self-concept. Learning and Individual Differences, 20 , 522–531. doi: 10.1016/j.lindif.2009.12.007 .

Retelsdorf, J., Köller, O., & Möller, J. (2014). Reading achievement and reading self-concept: Testing the reciprocal effects model. Learning and Instruction, 29 , 21–30.

Rosenthal, R., & Jacobson, L. (1968). Pygmalion in the classroom . New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston.

Ross, M., & Wilson, A. E. (2003). Autobiographical memory and conceptions of self: Getting better all the time. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 12 , 66–69.

Ryan, R. M., & Weinstein, N. (2009). Undermining quality teaching and learning: A self-determination theory perspective on high-stakes testing. Theory and Research in Education, 7 , 224–233.

Schwarzer, R., Lange, B., & Jerusalem, M. (1982). Selbstkonzeptentwicklung nach einem Bezugsgruppenwechsel. Zeitschrift für Entwicklungspsychologie und Pädagogische Psychologie, 14 , 125–140.

Seaton, M., Marsh, H. W., Duman, F., Huguet, P., Monteil., J. M., Régner, I., et al. (2008). In search oft he big fish: Investigating the coexistence of the big-fish-little-pond effect with the positive effects of upward comparisons. British Journal of Social Psychology, 47 , 73–103.

Shavelson, R. J., Hubner, J. J., & Stanton, G. C. (1976). Validation of construct interpretations. Review of Educational Research, 46 , 407–441.

Simpkins, S. D., Davis-Kean, P. E., & Eccles, J. S. (2006). Math and science motivation: A longitudinal examination of the links between choices and beliefs. Developmental Psychology, 42 , 70–83.

Suls, J., & Wheeler, L. (2000). Handbook of social comparison: Theory and research . New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Press.

Tesser, A. (1988). Toward a self-evaluation maintenance model of social behavior. In L. Berkowitz (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 21, pp. 181–227). New York: Academic.

Tiedemann, J. (2000). Parents’ gender stereotypes and teachers’ beliefs as predictors of children’s concept of their mathematical ability in elementary school. Journal of Educational Psychology, 92 , 144–151.

Tiedemann, J. (2002). Gender-related beliefs of teachers in elementary school mathematics. Educational Studies in Mathematics, 41 , 191–207.

Trautwein, U., Köller, O., Lüdtke, O., & Baumert, J. (2005). Student tracking and the powerful effects of opt-in courses on self-concept: Reflected-glory effects do exist after all. In H. W. Marsh, R. G. Craven, & M. McInerney (Eds.), New frontiers for self research (International advances in self research, Vol. 2, pp. 307–327). Greenwich, CT: Information Age Press.

Trautwein, U., & Lüdtke, O. (2007). Students’ self-reported effort and time on homework in six school subjects: Between-student differences and within-student variation. Journal of Educational Psychology, 99 , 432–444.

Trautwein, U., Lüdtke, O., Kastens, C., & Köller, O. (2006). Effort on homework in grades 5 through 9: Development, motivational antecedents, and the association with effort on classwork. Child Development, 77 , 1094–1111.

Trautwein, U., Lüdtke, O., Köller, O., & Baumert, J. (2006). Self-esteem, academic self-concept, and achievement: How the learning environment moderates the dynamics of self-concept. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 90 , 334–349.

Trautwein, U., Lüdtke, O., Marsh, H. W., Köller, O., & Baumert, J. (2006). Tracking, grading, and student motivation: Using group composition and status to predict self-concept and interest in ninth grade mathematics. Journal of Educational Psychology, 98 , 788–806.

Trautwein, U., Lüdtke, O., Marsh, H. W., & Nagy, G. (2009). Within-school social comparison: How students’ perceived standing of their class predicts academic self-concept. Journal of Educational Psychology, 101 , 853–866.

Trautwein, U., Marsh, H. W., Nagengast, B., Lüdtke, O., Nagy, G., & Jonkmann, K. (2012). Probing for the multiplicative term in modern expectancy–value theory: A latent interaction modeling study. Journal of Educational Psychology, 104 , 763–777.

Valentine, J. C., DuBois, D. L., & Cooper, H. (2004). The relations between self-beliefs and academic achievement: A systematic review. Educational Psychologist, 39 , 111–133.

Wakslak, C. J., Nussbaum, S., Liberman, N., & Trope, Y. (2008). Representations of the self in the near and distant future. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 95 , 757–773.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Watt, H. M. G., & Eccles, J. S. (Eds.). (2008). Gender and occupational outcomes: Longitudinal assessments of individual, social, and cultural influences . Washington, DC: APA Books.

Wheeler, L., & Suls, J. (2005). Social comparison and self-evaluation of competence. In A. J. Elliot & C. S. Dweck (Eds.), Handbook of competence and motivation (pp. 566–578). New York: Guilford.

Wheeler, L., & Suls, J. (2007). Assimilation in social comparison: Can we agree on what it is? Revue Internationale de Psychologie Sociale, 20 , 31–51.

Wigfield, A., & Eccles, J. S. (1992). The development of achievement task values: A theoretical analysis. Developmental Review, 12 , 265–310.

Wigfield, A., & Eccles, J. S. (2000). Expectancy-value theory of motivation. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 25 , 68–81.

Wigfield, A., & Eccles, J. S. (2002). Children’s motivation during the middle school years. In J. Aronson (Ed.), Improving academic achievement: Contributions of social psychology . San Diego, CA: Academic.

Wigfield, A., Eccles, J. S., Yoon, K. S., Harold, R. D., Arbreton, A., Freedman-Doan, K., et al. (1997). Changes in childrens’ competence beliefs and subjective task values across the elementary school years: A three-year study. Journal of Educational Psychology, 89 , 451–469.

Wigfield, A., Tonks, S., & Klauda, S. L. (2009). Expectancy – value theory. In K. R. Wentzel & A. Wigfield (Eds.), Handbook of motivation at school (pp. 55-76). New York: Taylor Francis.

Wilson, A. E., & Ross, M. (2000). The frequency of temporal-self and social comparisons in people’s personal appraisals. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 78 , 928–942.

Wilson, A. E., & Ross, M. (2001). From chump to champ: People’s appraisals of their earlier and present selves. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 80 , 572–584.

Zell, E., & Alicke, M. D. (2009). Self-evaluative effects of temporal and social comparison. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 45 , 223–227.

Download references

Acknowledgment

Some parts of this chapter were informed by the authors’ chapter on self-concept in a German language textbook (Möller & Trautwein, 2015).

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Hector Research Institute of Education Sciences and Psychology, University of Tübingen, Europastraße 6, Tübingen, Germany

Ulrich Trautwein

Department of Psychology, University of Kiel, Olshausenstraße 75, 24118, Kiel, Germany

Jens Möller

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Ulrich Trautwein .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Educational Psychology, CUNY, Queens College and the Graduate Center,, Flushing, New York, USA

Anastasiya A Lipnevich

Department of Psychology, University of Trier, Trier, Germany

Franzis Preckel

Professional Examination Service, Center for Innovative Assessments, New York, New York, USA

Richard D. Roberts

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2016 Springer International Publishing Switzerland

About this chapter

Trautwein, U., Möller, J. (2016). Self-Concept: Determinants and Consequences of Academic Self-Concept in School Contexts. In: Lipnevich, A., Preckel, F., Roberts, R. (eds) Psychosocial Skills and School Systems in the 21st Century. The Springer Series on Human Exceptionality. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-28606-8_8

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-28606-8_8

Published : 02 April 2016

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-319-28604-4

Online ISBN : 978-3-319-28606-8

eBook Packages : Behavioral Science and Psychology Behavioral Science and Psychology (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Tools and Resources

- Customer Services

- Affective Science

- Biological Foundations of Psychology

- Clinical Psychology: Disorders and Therapies

- Cognitive Psychology/Neuroscience

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational/School Psychology

- Forensic Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems of Psychology

- Individual Differences

- Methods and Approaches in Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational and Institutional Psychology

- Personality

- Psychology and Other Disciplines

- Social Psychology

- Sports Psychology

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Article contents

Self and identity.

- Sanaz Talaifar Sanaz Talaifar Department of Psychology, University of Texas at Austin

- and William Swann William Swann Department of Psychology, University of Texas

- https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190236557.013.242

- Published online: 28 March 2018

Active and stored mental representations of the self include both global and specific qualities as well as conscious and nonconscious qualities. Semantic and episodic memory both contribute to a self that is not a unitary construct comprising only the individual as he or she is now, but also past and possible selves. Self-knowledge may overlap more or less with others’ views of the self. Furthermore, mental representations of the self vary whether they are positive or negative, important, certain, and stable. The origins of the self are also manifold and can be considered from developmental, biological, intrapsychic, and interpersonal perspectives. The self is connected to core motives (e.g., coherence, agency, and communion) and is manifested in the form of both personal identities and social identities. Finally, just as the self is a product of proximal and distal social forces, it is also an agent that actively shapes its environment.

- self-concept

- self-representation

- self-knowledge

- self-perception

- self-esteem

- personal identity

- social identity

Introduction

The concept of the self has beguiled—and frustrated—psychologists and philosophers alike for generations. One of the greatest challenges has been coming to terms with the nature of the self. Every individual has a self, yet no two selves are the same. Some aspects of the self create a sense of commonality with others whereas other aspects of the self set it apart. The self usually provides a sense of consistency, a sense that there is some connection between who a person was yesterday and who they are today. And yet, the self is continually changing both as an individual ages and he or she traverses different social situations. A further conundrum is that the self acts as both subject and object; it does the knowing about itself. With so many complexities, coupled with the fact that people can neither see nor touch the self, the construct may take on an air of mysticism akin to the concept of the soul (Epstein, 1973 ).

Perhaps the most pressing, and basic, question psychologists must answer regarding the self is “What is it?” For the man whom many regard as the father of modern psychology, William James, the self was a source of continuity that gave individuals a sense of “connectedness” and “unbrokenness” ( 1890 , p. 335). James distinguished between two components of the self: the “I” and the “me” ( 1910 ). The “I” is the self as agent, thinker, and knower, the executive function that experiences and reacts to the world, constructing mental representations and memories as it does so (Swann & Buhrmester, 2012 ). James was skeptical that the “I” was amenable to scientific study, which has been borne out by the fact that far more attention has been accorded to the “me.” The “me” is the individual one recognizes as the self, which for James included a material, social, and spiritual self. The material self refers to one’s physical body and one’s physical possessions. The social self refers to the various selves one may express and others may recognize depending on the social setting. The spiritual self refers to the enduring core of one’s being, including one’s values, personality, beliefs about the self, etc.

This article focuses on the “me” that will be referred to interchangeably as either the “self” or “identity.” We define the self as a multifaceted, dynamic, and temporally continuous set of mental self-representations. These representations are multifaceted in the sense that different situations may evoke different aspects of the self at different times. They are dynamic in that they are subject to change in the form of elaborations, corrections, and reevaluations (Diehl, Youngblade, Hay, & Chui, 2011 ). This is true when researchers think of the self as a sort of scientific theory in which new evidence about the self from the environment leads to adjustments to one’s self-theory (Epstein, 1973 ; Gopnick, 2003 ). It is also true when researchers consider the self as a narrative that can be rewritten and revised (McAdams, 1996 ). Finally, self-representations are temporally continuous because even though they change, most people have a sense of being the same person over time. Further, these self-representations, whether conscious or not, are essential to psychological functioning, as they organize people’s perceptions of their traits, preferences, memories, experiences, and group memberships. Importantly, representations of the self also guide an individual’s behavior.

Some psychologists (e.g., behaviorists and more recently Brubaker & Cooper, 2000 ) have questioned the need to implicate a construct as nebulous as the self to explain behavior. Certainly an individual can perform many complex actions without invoking his or her self-representations. Nevertheless, psychologists increasingly regard the self as one of the most important constructs in all of psychology. For example, the percentage of self-related studies published in the field’s leading journal, the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology , increased fivefold between 1972 and 2002 (Swann & Seyle, 2005 ) and has continued to grow to this day. The importance of the self becomes evident when one considers the consequences of a sense of self that is interrupted, damaged, or absent. Epstein ( 1973 ) offers a case in point with an example of a schizophrenic girl meeting her psychiatrist:

Ruth, a five year old, approached the psychiatrist with “Are you the bogey man? Are you going to fight my mother? Are you the same mother? Are you the same father? Are you going to be another mother?” and finally screaming in terror, “I am afraid I am going to be someone else.” [Bender, 1950 , p. 135]

To provide a more commonplace example, children do not display several emotions we consider uniquely human, such as empathy and embarrassment, until after they have developed a sense of self-awareness (Lewis, Sullivan, Stanger, & Weiss, 1989 ). As Darwin has argued ( 1872 / 1965 ), emotions like embarrassment exist only after one has a developed a sense of self that can be the object of others’ attention.

The self’s importance also is evident when one considers that it is a pancultural phenomenon; all individuals have a sense of self regardless of where they are born. Though the content of self-representations may vary by cultural context, the existence of the self is universal. So too is the structure of the self. One of the most basic structural dimensions of the self involves whether the knowledge is active or stored.

Forms of Self-Knowledge

Active and stored self-knowledge.

Although i ndividuals accumulate immeasurable amounts of knowledge over their lifespans, at any given moment they can access only a portion of that knowledge. The aspects of self-knowledge held in consciousness make up “active self-knowledge.” Other terms for active self-knowledge are the working self-concept (Markus & Kunda, 1986 ), the spontaneous self-concept (McGuire, McGuire, Child, & Fujioka, 1978 ), and the phenomenal self (Jones & Gerard, 1967 ). On the other hand, “stored self-knowledge” is information held in memory that one can access and retrieve but is not currently held in consciousness. Because different features of the self are active versus stored at different times depending on the demands of the situation, the self can be quite malleable without eliciting feelings of inconsistency or inauthenticity (Swann, Bosson, & Pelham, 2002 ).

Semantic and Episodic Representations of Self-Knowledge

People possess both episodic and semantic representations of themselves (Klein & Loftus, 1993 ; Tulving, 1983 ). Episodic self-representations refer to “behavioral exemplars” or relatively brief “cartoons in the head” involving one’s past life and experiences. For philosopher John Locke, the self was built of episodic memory. For some researchers interested in memory and identity, episodic memory has been of particular interest because it is thought to involve re-experiencing events from one’s past, providing a person with content through which to construct a personal narrative (see, e.g., Eakin, 2008 ; Fivush & Haden, 2003 ; Klein, 2001 ; Klein & Gangi, 2010 ). Recall of these episodic instances happens together with the conscious awareness that the events actually occurred in one’s life (e.g., Suddendorf & Corballis, 1997 ).

Episodic self-knowledge may shed light on the individual’s traits or preferences and how he or she will or should act in the future, but some aspects of self-knowledge do not require recalling any specific experiences. Semantic self-knowledge involves memories at a higher level abstraction. These self-related memories are based on either facts (e.g., I am 39 years old) or traits and do not necessitate remembering a specific event or experience (Klein & Lax, 2010 ; Klein, Robertson, Gangi, & Loftus, 2008 ). Thus, one may consider oneself intelligent (semantic self-knowledge) without recalling that he or she achieved stellar grades the previous term (episodic self-knowledge). In fact, Tulving ( 1972 ) suggested that the two types of knowledge may be structurally and functionally independent of each other. In support of this, case studies show that damage to the episodic self-knowledge system does not necessarily result in impairment of the semantic self-knowledge system. Evaluating semantic traits for self-descriptiveness is associated with activation in brain regions implicated in semantic, but not episodic, memory. In addition, priming a trait stored in semantic memory does not facilitate recall of corresponding episodic memories that exemplify the semantic self-knowledge (Klein, Loftus, Trafton, & Fuhrman, 1992 ). The tenuous relationship between episodic and semantic self-knowledge suggests that only a portion of semantic self-knowledge arises inductively from episodic self-knowledge (e.g., Kelley et al., 2002 ).

Recently some researchers have questioned the importance of memory’s role in creating a sense of identity. For example, at least when it comes to perceptions of others, people perceive a person’s identity to remain more intact after a neurodegenerative disease that affects their memory than one that affects their morality (Strohminger & Nichols, 2015 ).

Conscious and Nonconscious Self-Knowledge (Sometimes Confused With Explicit Versus Implicit)

Individuals may be conscious, or aware, of aspects of the self to varying degrees in different situations. Indeed sometimes it is adaptive to have self-awareness (Mandler, 1975 ) and other times it is not (Wegner, 2009 ). Nonconscious self-representations can influence behavior in that individuals may be unaware of the ways in which their self-representations affect their behavior (Greenwald & Banaji, 1995 ). Some researchers have even suggested that individuals can be unconscious of the contents of their self-representations (e.g., Devos & Banaji, 2003 ). It is important to remember that consciousness refers primarily to the level of awareness of a self-representation, rather than the automaticity of a given representation (i.e., whether the representation is retrieved in an unaware, unintentional, efficient, and uncontrolled manner) (Bargh, 1994 ).

A key ambiguity in recent work on implicit self-esteem is defining its criterial attributes. One view contends that the nonconscious and conscious self reflect fundamentally distinct knowledge systems that arise from different learning experiences and have independent effects on thought, emotion, and behavior (Epstein, 1994 ). Another perspective views the self as a singular construct that may nevertheless show diverging responses on direct and indirect measures of self due to factors such as the opportunity and motivation to control behavioral responses (Fazio & Twoles-Schwen, 1999 ). While indirect measures such as the Implicit Association Test do not require introspection and as a result may tap nonconscious representations, this is an assumption that should be supported with empirical evidence (Gawronski, Hofmann, & Wilbur, 2006 ).

Issues of direct and indirect measurement are a key consideration in research on the implicit and explicit self. Indirect measures of self allow researchers to infer an individual’s judgment about the self as a result of the speed or nature of their responses to stimuli that may be more or less self-related (De Houwer & Moors, 2010 ). Some researchers have argued that indirect measures of self-esteem are advantageous because they circumvent self-presentational issues (Farnham, Greenwald, & Banaji, 1999 ), but other researchers have questioned such claims (Gawronski, LeBel, & Peters, 2007 ) because self-presentational strivings can be automatized (Paulhus, 1993 ).

Recent findings have raised additional questions regarding the validity of some key assumptions regarding research inspired by interest in implicit self-esteem (for a more optimistic take on implicit self-esteem, see Dehart, Pelham, & Tennen, 2006 ). Although near-zero correlations between individuals’ scores on direct and indirect measures of self (e.g., Bosson, Swann, & Pennebaker, 2000 ) are often taken to mean that nonconscious and conscious self-representations are distinct, other factors, such as measurement error and lack of conceptual correspondence, can cause these low correlations (Gawronski et al., 2007 ). Some researchers have also taken evidence of negligible associations between measures of implicit self-esteem and theoretically related outcomes to mean that such measures may not measure self-esteem at all (Buhrmester, Blanton, & Swann, 2011 ). A prudent strategy is thus to consider that indirect measures reflect an activation of associations between the self and other stimuli in memory and that these associations do not require conscious validation of the association as accurate or inaccurate (Gawronski et al., 2007 ). Direct measures, on the other hand, do require validation processes (Strack & Deutsch, 2004 ; Swann, Hixon, Stein-Seroussi, & Gilbert, 1990 ).

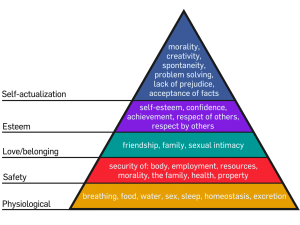

Global and Specific Self-Knowledge

Self-views vary in scope (Hampson, John, & Goldberg, 1987 ). Global self-representations are generalized beliefs about the self (e.g., I am a worthwhile person) while specific self-representations pertain to a narrow domain (e.g., I am a nimble tennis player). Self-views can fall anywhere on a continuum between these two extremes. Generalized self-esteem may be thought of as a global self-representation at the top of a hierarchy with individual self-concepts nested underneath in specific domains such as academic, physical, and social (Marsh, 1986 ). Individual self-concepts, measured separately, combine statistically to form a superordinate global self-esteem factor (Marsh & Hattie, 1996 ). When trying to predict behavior it is important not to use a specific self-representation to predict a global behavior or a global self-representation to predict a specific behavior (e.g., Donnellan, Trzesniewski, Robins, Moffitt, & Caspi, 2005 ; Swann, Chang-Schneider, & McClarty, 2007 ; Trzesniewski et al., 2006 ).

Actual, Possible, Ideal, and Ought Selves

The self does not just include who a person is in the present but also includes past and future iterations of the self. In addition, people tend to hold “ought” or “ideal” beliefs about the self. The former includes one’s beliefs about who they should be according to their own and others’ standards while the latter includes beliefs about who they would like to be (Higgins, 1987 ). In a related vein, possible selves are the future-oriented positive or negative aspects of the self-concept, selves that one hopes to become or fears becoming (Markus & Nurius, 1986 ). Some research has even shown that distance between one’s feared self and actual self is a stronger predictor of life satisfaction than proximity between one’s ideal self and actual self (Ogilvie, 1987 ). Possible selves vary in how far in the future they are, how detailed they are, and how likely they are to become an actual self (Oyserman & James, 2008 ). Many researchers have studied the content of possible selves, which can be as idiosyncratic as a person’s imagination is. The method used to measure possible selves (close-ended versus open-ended questions) will affect which possible selves are revealed (Lee & Oyserman, 2009 ). The content of possible selves is also socially and contextually grounded. For example, as a person ages, career-focused possible selves become less important while health-related possible selves become increasingly important (Cross & Markus, 1991 ; Frazier, Hooker, Johnson, & Kaus, 2000 ).

Researchers have been interested in not just the content but the function of possible selves. Thinking about successful possible selves is mood enhancing (King, 2001 ) because it is a reminder that the current self can be improved. In addition, possible selves may play a role in self-regulation. By linking present and future selves, they may promote desired possible selves and avoid feared possible selves. Possible selves may be in competition with each other and with a person’s actual self. For example, someone may envision one possible self as an artist and another possible self as an airline pilot, and each of these possible selves might require the person to take different actions in the present moment. Goal striving requires employing limited resources and attention, so working toward one possible self may require shifting attention and resources away from another possible self (Fishbach, Dhar, & Zhang, 2006 ). Possible selves may have other implications as well. For example, Alesina and La Ferrara ( 2005 ) show how expected future income affects a person’s preferences for economic redistribution in the present.

Accuracy of Self-Knowledge and Feelings of Authenticity

Most individuals have had at least one encounter with an individual whose self-perception seemed at odds with “reality.” Perhaps it is a friend who believes himself to be a skilled singer but cannot understand why everyone within earshot grimaces when he starts singing. Or the boss who believes herself to be an inspiring leader but cannot motivate her workers. One potential explanation for inaccurate self-views is a disjunction between episodic and semantic memories; the image of grimacing listeners (episodic memory) may be quite independent of the conviction that one is a skilled singer (semantic memory). Of course, if self-knowledge is too disjunctive with reality it ceases to be adaptive; self-views must be moderately accurate to be useful in allowing people to predict and navigate their worlds. That said, some researchers have questioned the desirability of accurate self-views. For example, Taylor and Brown ( 1988 ) have argued that positive illusions about the self promote mental health. Similarly, Von Hippel and Trivers ( 2011 ) have argued that certain kinds of optimistic biases about the self are adaptive because they allow people to display more confidence than is warranted, consequently allowing them to reap the social rewards of that confidence.

Studying the accuracy of self-knowledge is challenging because objective criteria are often scarce. Put another way, there are only two vantage points from which to assess a person: self-perception and the other’s perception of the self. This is true even of supposedly “objective” measures of the self. An IQ test is still a measure of intelligence from the vantage point of the people who developed the test. Both vantage points can be subject to error. For example, self-perceptions may be biased to protect one’s self-image or due to self-comparison to an inappropriate referent. Others’ perceptions may be biased because of a lack of cross-situational information about the person in question or lack of insight into that person’s motives. Because of the advantages and disadvantages of each vantage point, self-reports may be better for assessing some traits (e.g., those low in observability, like neuroticism) while informant reports may be better for others (such as traits high in observability, like extraversion) (Vazire, 2010 ).

Furthermore, self-perceptions and others’ perceptions of the self may overlap to varying degrees. The “Johari window” provides a useful way of thinking about this (Luft & Ingham, 1955 ). The window’s first quadrant consists of things one knows about oneself that others also know about the self (arena). The second quadrant includes knowledge one has about the self that others do not have (façade). The third quadrant consists of knowledge one does not have about the self but others do have (blindspot). The fourth quadrant consists of information about the self that is not known to oneself or to others (unknown).

Which of these quadrants contains the “true self”? If I believe myself to be kind, but others do not, who is right? Which is a reflection of the “real me”? One set of attempts to answer this question has focused on perceptions of authenticity. The authentic self (Johnson & Boyd, 1995 ) is alternatively termed the “true self” (Newman, Bloom, & Knobe, 2014 ), “real self” (Rogers, 1961 ), “intrinsic self” (Schimel, Arndt, Pyszczynski, & Greenberg, 2001 ), “essential self” (Strohminger & Nichols, 2014 ), or “deep self” (Sripada, 2010 ). Recent research has addressed both what aspects of the self other people describe as belonging to a person’s true self and how individuals judge their own authenticity.

Though authenticity has long been the subject of philosophical thought, only recently have researchers begun addressing the topic empirically, and definitional ambiguities abound (Knoll, Meyer, Kroemer, & Schroeder-Abe, 2015 ). Some studies use unidimensional measures that equate authenticity to feeling close to one’s true self (e.g., Harter, Waters, & Whitesell, 1997 ). A more elaborate and philosophically grounded approach proposes four necessary factors for trait authenticity: awareness (the extent of one’s self-knowledge, motivation to expand it, and ability to trust in it), unbiased processing (the relative absence of interpretative distortions in processing self-relevant information), behavior (acting consistently with one’s needs, preferences, and values), and relational orientation (valuing and achieving openness in close relationships) (Kernis, 2003 ). Authenticity is related to feelings of self-alienation (Gino, Norton, & Ariely, 2010 ). Being authentic is also sometimes thought to be equivalent to low self-monitoring (Snyder & Gangestad, 1982 )— someone who does not alter his or her behavior to accommodate changing social situations (Grant, 2016 ). Authenticity and self-monitoring, however, are orthogonal constructs; being sensitive to environmental cues can be compatible with acting in line with one’s true self.

Although some have argued that the ability to behave in a way that contradicts one’s feelings and mental states is a developmental accomplishment (Harter, Marold, Whitesell, & Cobbs, 1996 ), feelings of authenticity have been associated with many positive outcomes such as positive self-esteem, positive affect, and well-being (Goldman & Kernis, 2002 ; Wood, Linley, Maltby, Baliousis, & Joseph, 2008 ). One interesting line of research examines the interaction of authenticity, power, and well-being. Power can increase feelings of authenticity in social interactions (Kraus, Chen, & Keltner, 2011 ), and that increased authenticity in turn can result in higher well-being (Kifer, Heller, Peruvonic, & Galinsky, 2013 ). Another line of research examines the relationship between beliefs about authenticity (at least in the West) and morality. Gino, Kouchaki, and Galinsky ( 2015 ) suggest that dishonesty and inauthenticity share a similar source: dishonesty involves being untrue to others while inauthenticity involves being untrue to the self.

Metacognitive Aspects of Self

Valence and importance of self-views.

Self-knowledge may be positively or negatively valenced. Having more positive self-views and fewer negative ones are associated with having higher self-esteem (Brown, 1986 ). Both bottom-up and top-down theories have been used to explain this association. The bottom-up approach posits that the valence of specific self-knowledge drives the valence of one’s global self-views (e.g., Marsh, 1990 ). In this view, someone who has more positive self-views in specific domains (e.g., I am intelligent and attractive) should be more likely to develop high self-esteem overall (e.g., I am worthwhile). In contrast, the top-down perspective holds that the valence of global self-views drive the valence of specific self-views such that someone who thinks they are a worthwhile person is more likely to view him or herself as attractive and intelligent (e.g., Brown, Dutton, & Cook, 2001 ). The reasoning is grounded in the view that global self-esteem develops quite early in life and thus determines the later development of domain-specific self-views.

A domain-specific self-view can vary not only in its valence but also in its importance. Domain-specific self-views that one believes are important are more likely to affect global self-esteem than those self-views that one considers unimportant (Pelham, 1995 ; Pelham & Swann, 1989 ). As James wrote, “I, who for the time have staked my all on being a psychologist, am mortified if others know much more psychology than I. But I am contented to wallow in the grossest ignorance of Greek” ( 1890 / 1950 , p. 310). Of course not all self-views matter to the same extent for all people. A professor of Greek studies is likely to place a great deal of importance on his knowledge of Greek. Furthermore, changes to features that are perceived to be more causally central than others are believed to be more disruptive to identity (Chen, Urminsky, & Bartels, 2016 ). Individuals try to protect their important self-views by, for example, surrounding themselves with people and environments who confirm those important self-views (Chen, Chen, & Shaw, 2004 ; Swann & Pelham, 2002 ) or distancing themselves from close friends who outperform them in these areas (Tesser, 1988 ).

Certainty and Clarity of Self-Views

Individuals may feel more or less certain about some self-views as compared to others. And just as they are motivated to protect important self-views, people are also motivated to protect the self-views of which they are certain. People are more likely to seek (Pelham, 1991 ) and receive (Pelham & Swann, 1994 ) feedback consistent with self-views that are highly certain than those about which they feel less certain. They also actively resist challenges to highly certain self-views (Swann & Ely, 1984 ).

Another construct related to certainty is self-concept clarity. Not only are people with high self-concept clarity confident and certain of their self-views, they also are clear, internally consistent, and stable in their convictions about who they are (Campbell et al., 1996 ). The causes of low self-concept clarity have been theorized to be due to a discrepancy between one’s current self-views and the social feedback one has received in childhood (Streamer & Seery, 2015 ). Both high self-concept certainty and self-concept clarity are associated with higher self-esteem (Campbell, 1990 ).

Stability of Self-Views

The self is constantly accommodating, assimilating, and immunizing itself against new self-relevant information (Diehl et al., 2011 ). In the end, the self may remain stable (i.e., spatio-temporally continuous; Parfit, 1971 ) in at least two ways. First, the self may be stable in one’s absolute position on a scale. Second, there may be stability in one’s rank ordering within a group of related others (Hampson & Goldberg, 2006 ).

The question of the self’s stability can only be answered in the context of a specified time horizon. For example, like personality traits, self-views may not be particularly good predictors of behavior at a given time slice (perhaps an indication of the self’s instability) but are good predictors of behavior over the long term (Epstein, 1979 ). Similarly, more than others, some people experience frequent, transient changes in state self-esteem (Kernis, Cornell, Sun, Berry, & Harlow, 1993 ). Furthermore, there is a difference between how people perceive the stability of their self-views and the actual stability of their self-knowledge. Though previous research has explored the benefits of perceived self-esteem stability (e.g., Kernis, Paradise, Whitaker, Wheatman, & Goldman, 2000 ; Kernis, Grannemann, & Barclay, 1989 ), a recent program of research on fixed versus growth mindsets explores the benefits of the malleability of self-views in a variety of domains (Dweck, 1999 , 2006 ). For example, teaching adolescents to have a more malleable (i.e., incremental) theory of personality that “people change” led them to react less negatively to an immediate experience of social adversity, have lower overall stress and physical illness eight months later, and better academic performance over the school year (Yeager et al., 2014 ). Thus, believing that the self can be unstable can have positive effects in that one negative social interaction, or an instance of poor performance is not an indication that the self will always be that way, and this may, in turn, increase effort and persistence.

Organization of Self-Views

Though we have already touched on some aspects of the organization of self (e.g., specific self-views nested within global self-views), it is important to consider other aspects of organization including the fact that some self-views may be more assimilated within each other. Integration refers to the tendency to store both positive and negative self-views together, and is thought to promote resilience in the face of stress or adversity (Showers & Zeigler-Hill, 2007 ). Compartmentalization refers to the tendency to store positive and negative self-views separately. But both integration and compartmentalization can have positive and negative consequences and can interact with other metacognitive aspects of the self, like importance. For example, compartmentalization has been associated with higher self-esteem and less depression among people for whom positive components of the self are important (Showers, 1992 ). On the other hand, for those whose negative self-views are important, compartmentalization has been associated with lower self-esteem and higher depression.

Origins and Development of the Self

Developmental approaches.

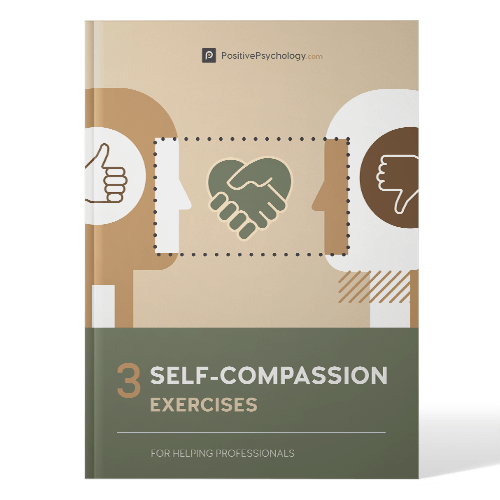

Psychologists have long been interested in when and how infants develop a sense of self. One very basic question is whether selfhood in infancy is comparable to selfhood in adulthood. The answer depends on definitions of selfhood. For example, some researchers have measured and defined selfhood in infants as the ability to self-regulate and self-organize, which even animals can do. This definition bears little resemblance to selfhood in adulthood. Nativist and constructivist debates within developmental psychology (and language development in particular) that grapple with the problem of the origins of knowledge also have implications for understanding origins of the self. A nativist account (e.g., Chomsky, 1975 ) that considers the human mind to be innately constrained to formulate a very small set of representations would suggest that the mind is designed to develop a self. Information from the environment may form specific self-representations, but a nativist account would posit that the structure of the self is intrinsic. A constructivist account would reject the notion that there are not enough environmental stimuli to explain the development of a construct like the self unless one invokes a specific innate cognitive structure. Rather, constructivists might suggest that a child develops a theory of self in the same way scientific theories are developed (Gopnik, 2003 ).

Because infants and children cannot self-report their mental states as adults can, psychologists must use other methods to study the self in childhood. One method involves studying the development of children’s use of the personal pronouns “me,” “mine,” and “I” (Harter, 1983 ; Hobson, 1990 ). Another method that is used cross-culturally, mirror self-recognition (Lewis & Brooks-Gunn, 1979 ; Lewis & Ramsay, 2004 ), has been associated with brain maturation (Lewis, 2003 ) and myelination of the left temporal region (Carmody & Lewis, 2006 , 2010 ; Lewis & Carmody, 2008 ). Pretend play, which occurs between 15 and 24 months, is an indication that the self is developing because it requires the toddler’s ability to understand its own and others’ mental states (Lewis, 2011 ). The development of self-esteem has also historically been difficult to study due to a lack of self-esteem measures that can be used across the lifespan. Recently, psychologists have developed a lifespan self-esteem scale (Harris, Donnellan, & Trzesniewski, 2017 ) suitable for measuring global self-esteem from ages 5 to 93.

The development of theory of mind, the understanding that others have minds separate from one’s own, is also closely related to the development of the self. For example, people cannot make social comparisons until they have developed the required cognitive abilities, usually by middle childhood (Harter, 1999 ; Ruble, Boggiano, Feldman, & Loebl, 1980 ). Finally, developmental psychology is also useful in understanding the self beyond childhood and into adolescence and beyond. Adolescence is a time where goals of autonomy from parents and other adults become particularly salient (Bryan et al., 2016 ), adolescents experiment with different identities to see which fit best, and many long-term goals and personal aspirations are established (Crone & Dahl, 2012 ).

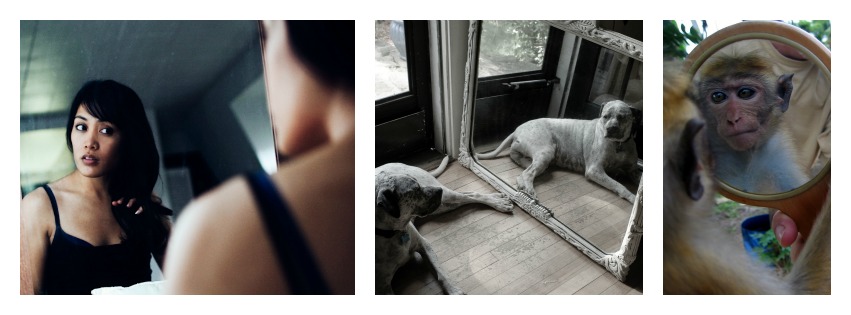

Biological Approaches

Biological approaches to understanding the origins of the self consider neurological, genetic, and hormonal underpinnings. These biological underpinnings are likely evolutionarily driven (Penke, Denissen, & Miller, 2007 ). Neuroscientists have debated the extent to which self-knowledge is “special,” or processed differently than other kinds of knowledge. What is clear is that no brain region by itself is responsible for our sense of self, but different aspects of the self-knowledge may be associated with different brain regions. Furthermore, the same region that is implicated in self-related processing can also be implicated in other types of processing (Ochsner et al., 2005 ; Saxe, Moran, Scholz, & Gabrieli, 2006 ). Specifically, the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) and the posterior cingulate cortex (PCC) have been associated with self-related processing (Northoff Heinzel, De Greck, Bermpohl, Dobrowolny, & Panksepp, 2006 ). But meta-analyses have found that the mPFC and PCC are recruited during the processing of both self-specific and familiar stimuli more generally (e.g., familiar others) (Qin & Northoff, 2011 ).

Twin studies of personality traits can shed light on the genetic bases of self. For example, genes account for about 40% to 60% of the population variance in self-reports of the Big Five personality factors (for a review, see Bouchard & Loehlin, 2001 ). Self-esteem levels also seem to be heritable, with 30–50% of population variance accounted for by genes (Kamakura, Ando, & Ono, 2007 ; Kendler, Gardner, & Prescott, 1998 ).

Finally, hormones are unlikely to be a cause of the self but may affect the expression of the self. For example, testosterone and cortisol levels interact with personality traits to predict different levels of aggression (Tackett et al., 2015 ). Differences in levels of and in utero exposure to certain hormones also affect gender identity (Berenbaum & Beltz, 2011 ; Reiner & Gearhart, 2004 ).

Intrapsychic Approaches

Internal processes, including self-perception and introspection, also influence the development of the self. One of the most obvious ways to develop knowledge about the self (especially when existing self-knowledge is weak) is to observe one’s own behavior across different situations and then make inferences about the aspects of the self that may have caused those behaviors (Bem, 1972 ). And just as judgments about others’ attributes are less certain when multiple possible causes exist for a given behavior, the same is true of one’s own behaviors and the amount of information they yield about the self (Kelley, 1971 ).

Conversely, introspection involves understanding the self from the inside outward rather than from the outside in. Though surprisingly little thought (only 8%) is expended on self-reflection (Csikszentmihalyi & Figurski, 1982 ), people buttress self-knowledge through introspection. For example, contemporary psychoanalysis can increase self-knowledge, even though an increase in self-knowledge on its own is unlikely to have therapeutic effects (Reppen, 2013 ). Writing is one form of introspection that does have psychological and physical therapeutic benefits (Pennebaker, 1997 ). Research shows that brief writing exercises can result in fewer physician visits (e.g., Francis & Pennebaker, 1992 ), and depressive episodes (Pennebaker, Kiecolt-Glaser, & Glaser, 1988 ), better immune function (e.g., Esterling, Kiecolt-Glaser, Bodnar, & Glaser, 1994 ), and higher grade point average (e.g., Cameron & Nicholls, 1998 ) and many other positive outcomes.

Experiencing the “subjective self” is yet another way that individuals gain self-knowledge. Unlike introspection, experiencing the subjective self involves outward engagement, a full engagement in the moment that draws attention away from the self (e.g., Csikszentmihalyi, 1990 ). Being attentive to one’s emotions and thoughts in the moment can reveal much about one’s preferences and values. Apparently, people rely more on their subjective experiences than on their overt behaviors when constructing self-knowledge (Andersen, 1984 ; Andersen & Ross, 1984 ).

Interpersonal Approaches

At the risk of stating the obvious, humans are social animals and thus the self is rarely cut off from others. In fact, many individuals would rather give themselves a mild electric shock than be alone with their thoughts (Wilson et al., 2014 ). The myth of finding oneself by eschewing society is dubious, and one of the most famous proponents of this tradition, transcendentalist Henry David Thoreau, actually regularly entertained visitors during his supposed seclusion at Walden (Schulz, 2015 ). As early as infancy, the reactions of others can lay the foundation for one’s self-views. Attachment theory (Bowlby, 1969 ; Hazan & Shaver, 1994 ) holds that children’s earliest interactions with their caregivers lead them to formulate schemas about their lovability and worth. This occurs outside of the infant’s awareness, and the schemas are based on the consistency and responsiveness of the care they receive. Highly consistent responsiveness to the infant’s needs provide the basis for the infant to develop feelings of self-worth (i.e., high global self-esteem) later in life. Though the mechanisms by which this occur are still being investigated, it may be that self-schemas developed during infancy provide the lens through which people interpret others’ reactions to them (e.g., Hazan & Shaver, 1987 ). Note, however, that early attachment relationships are in no way deterministic: 30–45% of people change their attachment style (i.e., their pattern of relating to others) across time (e.g., Cozzarelli, Karafa, Collins, & Tagler, 2003 ).

Early attachment relationships provide a working model for how an individual expects to be treated, which is associated with perceptions of self-worth. But others’ appraisals of the self are also a more direct source of self-knowledge. An extremely influential line of thought from sociology, symbolic interactionism (Cooley, 1902 ; Mead, 1934 ), emphasized the component of the self that James referred to as the social self. He wrote, “a man has as many social selves as there are individuals who recognize him and carry an image of him in their mind” ( 1890 / 1950 , p. 294). The symbolic interactionists proposed that people come to know themselves not through introspection but rather through others’ reactions and perceptions of them. This “looking glass self” sees itself as others do (Yeung & Martin, 2003 ). People’s inferences about how others view them become internalized and guide their behavior. Thus the self is created socially and is sustained cyclically.

Research shows, however, that reflected appraisals may not tell the whole story. While it is clear that people’s self-views correlate strongly with how they believe others see them, self-views are not necessarily perfectly correlated with how people actually view them (Shrauger & Schoeneman, 1979 ). Further, people’s self-views may inform how they believe others see them rather than the other way around (Kenny & DePaulo, 1993 ). Lastly, individuals are better at knowing how people see them in general rather than knowing how specific others view them (Kenny & Albright, 1987 ).

Though others’ perceptions of the self are not an individual’s only source of self-knowledge, they are an important source, and in more than one way. For example, others’ provide a reference point for “social comparison.” According to Festinger’s social comparison theory ( 1954 ), people compare their own traits, preferences, abilities, and emotions to those of similar others, making both upward and downward comparisons. These comparisons tend to happen spontaneously and effortlessly. The direction of the comparison influences how one views and feels about the self. For example, comparing the self to someone worse off boosts self-esteem (e.g., Helgeson & Mickelson, 1995 ; Marsh & Parker, 1984 ). In addition to increasing self-knowledge, social comparisons are also motivating. For instance, those undergoing difficult or painful life events can cope better when they make downward comparisons (Wood, Taylor, & Lichtman, 1985 ). When motivated to improve the self in a given domain, however, people may make upward comparisons to idealized others (Blanton, Buunk, Gibbons, & Kuyper, 1999 ). Sometimes individuals make comparisons to inappropriate others, but they have the ability (with mental effort) to undo the changes made to the self-concept as a result of this comparison (Gilbert, Giesler, & Morris, 1995 ).

Others can influence the self not only through interactions and comparisons but also when an individual becomes very close to a significant other. In this case, according to self-expansion theory (Aron & Aron, 1996 ), as intimacy increases, people experience cognitive overlap between the self and the significant other. People can acquire novel self-knowledge as they subsume attributes of the close other into the self.

Finally, the origins and development of the self are interpersonally influenced to the extent that our identities are dependent on the social roles we occupy (e.g., as mother, student, friend, professional, etc.). This will be covered in greater detail in the section on “The Social Self.” Here it is important simply to recognize that as the social roles of an individual inevitably change over time, so too does their identity.

Cultural Approaches

Markus and Kitayama’s seminal paper ( 1991 ) on differences in expression of the self in Eastern and Western cultures spawned an incredible amount of work investigating the importance of culture on self-construals. Building on the foundational work of Triandis ( 1989 ) and others, this work proposed that people in Western cultures see themselves as autonomous individuals who value independence and uniqueness more so than connectedness and harmony with others. In contrast to this individualism, people in the East were thought to be more collectivist, valuing interdependence and fitting in. However, the theoretical relationship between self-construals and the continuous individualism-collectivism variable have been treated in several different ways in the literature. Some have described individualism and collectivism as the origins of differences in self-construals (e.g., Gudykunst et al., 1996 ; Kim, Aune, Hunter, Kim, & Kim, 2001 ; Singelis & Brown, 1995 ). Others have considered self-construals as synonymous with individualism and collectivism (Oyserman, Coon, & Kemmelmeier, 2002 ; Taras et al., 2014 ) or have used individualism-collectivism at the individual level as an analog of the variable at the cultural level (Smith, 2011 ).

However, in contrast to perspectives that treat individualism and collectivism as a unidimensional variable (e.g., Singelis, 1994 ), individualism and collectivism have also been theorized to be multifaceted “cultural syndromes” that include normative beliefs, values, and practices, as well as self-construals (Brewer & Chen, 2007 ; Triandis, 1993 ). In this view, there are many ways of being independent or collectivistic depending on the domain of functioning under consideration. For example, a person may be independent or interdependent when defining the self, experiencing the self, making decisions, looking after the self, moving between contexts, communicating with others, or dealing with conflicting interests (Vignoles et al., 2016 ). These domains of functioning are orthogonal such that being interdependent in one domain does not require being interdependent in another. This multidimensional picture of individual differences in individualism and collectivism is actually more similar to Markus and Kitayama’s ( 1991 ) initial treatment aiming to emphasize cultural diversity and contradicts the prevalent unidimensional approach to cultural differences that followed.

Recent research has pointed out other shortcomings of this dichotomous approach. There is a great deal of heterogeneity among the world’s cultures, so simplifying all culture to “Eastern” and “Western” or collectivistic versus individualistic types may be invalid. Vignoles and colleagues’ ( 2016 ) study of 16 nations supports this. They found that neither a contrast between Western and non-Western, nor between individualistic and collectivistic cultures, sufficiently captured the complexity of cross-cultural differences in selfhood. They conclude that “it is not useful to characterize any culture as ‘independent’ or ‘interdependent’ in a general sense” and rather advocate for research that identifies what kinds of independence and interdependence may be present in different contexts ( 2016 , p. 991). In addition, there is a great deal of within culture heterogeneity in self-construals For example, even within an individualistic, Western culture like the United States, working-class people and ethnic minorities tend to be more interdependent (Markus, 2017 ), tempering the geographically based generalizations one might draw about self-construals.

Another line of recent research on the self in cultural context that has explored self-construals beyond the East-West dichotomy is the study of multiculturalism and individuals who are a member of multiple cultural groups (Benet-Martinez & Hong, 2014 ). People may relate to each of the cultures to which they belong in different ways, and this may in turn have important effects. For example, categorization, which involves viewing one cultural identity as dominant over the others, is associated positively with well-being but negatively with personal growth (Yampolsky, Amiot, & de la Sablonnière, 2013 ). Integration involves cohesively connecting multiple cultures within the self while compartmentalization requires keeping one’s various cultures isolated because they are seen to be in opposition. Each of these strategies has different consequences.