Advertisement

Corporate governance and sustainability: a review of the existing literature

- Published: 03 January 2021

- Volume 26 , pages 55–74, ( 2022 )

Cite this article

- Valeria Naciti 1 ,

- Fabrizio Cesaroni ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-2345-6225 1 &

- Luisa Pulejo 1

11k Accesses

73 Citations

8 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

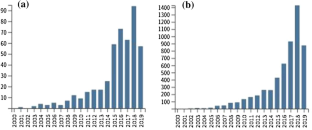

Over the last 2 decades, the literature on corporate governance and sustainability has increased substantially. In this study, we analyze 468 research studies published between 1999 and 2019 by employing three clustering analysis visualization techniques, namely keyword network clustering, co-citation network clustering, and overlay visualization. In addition, we provide a brief review of each cluster. We find that the number of published items that fall under our search criteria has grown over the years, having surged at various times including 2014. We identified three main thematic clusters, which we have called (1) corporate social responsibility and reporting, (2) corporate governance strategies, and (3) board composition. The weighted average years that major keywords appear in the literature published over the last 2 decades fall into a period of 4 years between 2014 and 2017. This is due to the massive increase in the number of publications on corporate governance and sustainability in recent years. By means of chronological analysis, we observe a transition from more abstract concepts—such as ‘society,’ ‘ethics,’ and ‘responsibility’—to more tangible and actionable terms such as ‘female director,’ ‘board size,’ and ‘independent director.’ Our review suggests that corporate governance and sustainability literature is evolving from quite a conceptual approach to rather more strategic and practical studies, while its theoretical roots can be traced back to a number of foundational studies in stakeholder theory, agency theory and socio-political theories of voluntary disclosure.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Criteria for Good Qualitative Research: A Comprehensive Review

Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) Implementation: A Review and a Research Agenda Towards an Integrative Framework

Environmental-, social-, and governance-related factors for business investment and sustainability: a scientometric review of global trends

Adams, B. (2008). Green development: Environment and sustainability in a developing world . New York: Routledge.

Book Google Scholar

Aguilera, R. V., Filatotchev, I., Gospel, H., & Jackson, G. (2008). An organizational approach to comparative corporate governance: Costs, contingencies, and complementarities. Organization Science, 19 (3), 475–492.

Article Google Scholar

Amran, A., Lee, S. P., & Devi, S. S. (2014). The influence of governance structure and strategic corporate social responsibility toward sustainability reporting quality. Business Strategy and the Environment, 23 (4), 217–235.

Aoki, M. (1984). The co-operative game theory of the firm . New York: Oxford University Press.

Google Scholar

Aras, G., & Crowther, D. (2009). Corporate sustainability reporting: A study in disingenuity? Journal of Business Ethics, 87 (1), 279.

Barnett, M. L., Henriques, I., & Husted, B. W. (2018). Governing the void between stakeholder management and sustainability. In S. Dorobantu, R. V. Aguilera, J. Luo, & F. J. Milliken (Eds.), Sustainability, stakeholder governance, and corporate social responsibility (pp. 121–143). Bingley, UK: Emerald Publishing Limited.

Chapter Google Scholar

Burke, R. J., & Mattis, M. C. (Eds.). (2013). Womenoncorporateboardsofdirectors:International challenges and opportunities (Vol. 14). Dordrecht, NL: Springer Science & Business Media.

Brundtland, G. H., Khalid, M., Agnelli, S., Al-Athel, S., & Chidzero, B. J. N. Y. (1987). Our common future (p. 8). New York. https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/5987our-common-future.pdf .

Carroll, A. B. (1991). The pyramid of corporate social responsibility: Toward the moral management of organizational stakeholders. Business Horizons, 34 (4), 39–48.

Carter, D. A., D’Souza, F., Simkins, B. J., & Simpson, W. G. (2010). The gender and ethnic diversity of US boards and board committees and firm financial performance. Corporate Governance: An International Review, 18 (5), 396–414.

Cetinkaya, B., Cuthbertson, R., Ewer, G., Klaas-Wissing, T., Piotrowicz, W., & Tyssen, C. (2011). Sustainable supply chain management: Practical ideas for moving towards best practice . Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Science & Business Media.

Clarkson, P. M., Li, Y., Richardson, G. D., & Vasvari, F. P. (2008). Revisiting the relation between environmental performance and environmental disclosure: An empirical analysis. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 33 (4–5), 303–327.

Cox, T. H., & Blake, S. (1991). Managing cultural diversity: Implications for organizational competitiveness. Academy of Management Perspectives, 5 (3), 45–56.

Davidson, F. (1996). Planning for performance: Requirements for sustainable development. Habitat international, 20 (3), 445–462.

Demirag, I. (Ed.). (2018). Corporate social responsibility, accountability and governance: Global perspectives . New York: Routledge.

Di Maggio, P. J., & Powell, W. W. (1983). The iron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. American Sociological Review, 48 (2), 147–160. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2095101 . Accessed 6 Dec 2020.

Du Plessis, J. J., Hargovan, A., & Harris, J. (2018). Principles of contemporary corporate governance . Port Melbourne: Cambridge University Press.

Epstein, M. J. (2018). Making sustainability work: Best practices in managing and measuring corporate social, environmental and economic impacts . Oxford: Routledge.

Erhardt, N. L., Werbel, J. D., & Shrader, C. B. (2003). Board of director diversity and firm financial performance. Corporate Governance: An International Review, 11 (2), 102–111.

Fernando, Y., Jabbour, C. J. C., & Wah, W. X. (2019). Pursuing green growth in technology firms through the connections between environmental innovation and sustainable business performance: Does service capability matter? Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 141, 8–20.

Figge, F., Hahn, T., Schaltegger, S., & Wagner, M. (2002). The sustainability balanced scorecard—Linking sustainability management to business strategy. Business Strategy and the Environment, 11 (5), 269–284.

Filatotchev, I., & Wright, M. (2005). The life cycle of corporate governance . Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Freeman, R. E. (1984). Strategic management: A stakeholder approach . Boston: Pitman.

Freeman, R. E., & Werhane, P. H. (2005). Corporate responsibility. In R. G. Frey & C. Heath Wellman (Eds.), A Companion to Applied Ethics (pp. 552–569). Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishing.

Friedman, M. (1970). A theoretical framework for monetary analysis. Journal of Political Economy, 78 (2), 193–238.

Giddings, B., Hopwood, B., & O’brien, G. (2002). Environment,economyandsociety:Fittingthem together into sustainable development. Sustainable Development, 10 (4), 187–196.

Gray, R., Owen, D., & Maunders, K. (1988). Corporate social reporting: Emerging trends in accountability and the social contract. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 1 (1), 6–20.

Gray, R., Kouhy, R., & Lavers, S. (1995). Corporate social and environmental reporting: A review of the literature and a longitudinal study of UK disclosure. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 8 (2), 47–77.

Hall, R. (1993). A framework linking intangible resources and capabiliites to sustainable competitive advantage. Strategic Management Journal, 14 (8), 607–618.

Haniffa, R. M., & Cooke, T. E. (2005). The impact of culture and governance on corporate social reporting. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, 24 (5), 391–430.

Hart, S. L., & Ahuja, G. (1996). Does it pay to be green? An empirical examination of the relationship between emission reduction and firm performance. Business Strategy and the Environment, 5 (1), 30–37.

Hildebrand, P. & Deese, B. (2019). Il futuro degli investimenti è sostenibile. Il sole 24ore.

Hill, C. W., & Jones, T. M. (1992). Stakeholder-agency theory. Journal of Management Studies, 29 (2), 131–154.

Iansiti, M., & Levien, R. (2004). Strategy as ecology. Harvard Business Review, 82 (3), 68–81.

Invernizzi, G., Milano, M., & Milano, E. G. E. A. (2004). Strategia e politica aziendale . Milan, IT: Mc Graw-Hill.

Jensen, M. C., & Meckling, W. H. (1976). Theory of the firm: Managerial behavior, agency costs and ownership structure. Journal of Financial Economics, 3 (4), 305–360.

John, K., & Senbet, L. W. (1998). Corporate governance and board effectiveness. Journal of Banking & Finance, 22 (4), 371–403.

Kang, H., Cheng, M., & Gray, S. J. (2007). Corporate governance and board composition: Diversity and independence of Australian boards. Corporate Governance: An International Review, 15 (2), 194–207.

Kemp, R. (1997). Environmental policy and technical change . Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Kolk, A. (2003). Trends in sustainability reporting by the Fortune Global 250. Business Strategy and the Environment, 12 (5), 279–291.

Kolk, A. (2008). Sustainability, accountability and corporate governance: Exploring multinationals’ reporting practices. Business Strategy and the Environment, 17 (1), 1–15.

Kolk, A., & Pinkse, J. (2008). A perspective on multinational enterprises and climate change: learning from “an inconvenient truth”? Journal of International Business Studies , 39 (8), 1359–1378.

Kotabe, M., & Murray, J. Y. (2004). Global sourcing strategy and sustainable competitive advantage. Industrial Marketing Management, 33 (1), 7–14.

Lankoski, L. (2006). Environmental performance and economic performance: The basic links. In S. Schaltegger & M. Wagner (Eds.), Managing the business case for sustainability: The integration of social, environmental and economic performance (pp. 32–46). Sheffield, UK: Greenleaf Publishing.

Lazzeretti, L., Capone, F., & Innocenti, N. (2017). Exploring the intellectual structure of creative economy research and local economic development: A co-citation analysis. European Planning Studies, 25 (10), 1693–1713.

Lee, S. Y. (2012). Corporate carbon strategies in responding to climate change. Business Strategy and the Environment, 21 (1), 33–48.

Maignan, I. (2001). Consumers’ perceptions of corporate social responsibilities: A cross-cultural comparison. Journal of Business Ethics, 30 (1), 57–72.

Marcus, A., & Geffen, D. (1998). The dialectics of competency acquisition: Pollution prevention in electric generation. Strategic Management Journal, 19 (12), 1145–1168.

Michelon, G., & Parbonetti, A. (2012). The effect of corporate governance on sustainability disclosure. Journal of Management & Governance, 16 (3), 477–509.

Milne, M. J. (1996). On sustainability; the environment and management accounting. Management Accounting Research, 7 (1), 135–161.

Morhardt, J. E. (2010). Corporate social responsibility and sustainability reporting on the internet. Business Strategy and the Environment, 19 (7), 436–452.

Naciti, V. (2019). Corporate governance and board of directors: The effect of a board composition on firm sustainability performance. Journal of Cleaner Production, 237, 117727.

Pelled, L. H. (1996). Demographic diversity, conflict, and work group outcomes: An intervening process theory. Organization Science, 7 (6), 615–631.

Poddar, A., Narula, S. A., & Zutshi, A. (2019). A study of corporate social responsibility practices of the top Bombay Stock Exchange 500 companies in India and their alignment with the Sustainable Development Goal s. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 26 (6), 1184–1205.

Rao, K., & Tilt, C. (2016). Board composition and corporate social responsibility: The role of diversity, gender, strategy and decision making. Journal of Business Ethics, 138 (2), 327–347.

Roberts, D. J., & Van den Steen, E. (2000). Shareholder interests, human capital investment and corporate governance. Stanford GSB Working. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.230019 .

Robinson, N. A. (1998). Comparative environmental law perspectives on legal regimes for sustainable development. Widener Law Symposium Journal, 3, 247–278.

Robinson, G., & Dechant, K. (1997). Building a business case for diversity. Academy of Management Perspectives, 11 (3), 21–31.

Rogelj, J., Den Elzen, M., Höhne, N., Fransen, T., Fekete, H., Winkler, H., et al. (2016). Paris Agreement climate proposals need a boost to keep warming well below 2 C. Nature, 534 (7609), 631.

Schaltegger, S., & Wagner, M. (2006). Integrative management of sustainability performance, measurement and reporting. International Journal of Accounting, Auditing and Performance Evaluation, 3 (1), 1–19.

Scherer, A. G., Rasche, A., Palazzo, G., & Spicer, A. (2016). Managing for political corporate social responsibility: New challenges and directions for PCSR 2.0. Journal of Management Studies, 53 (3), 273–298.

Seelos, C., & Mair, J. (2005). Entrepreneurs in service of the poor: Models for business contributions to sustainable development. Business Horizons, 48 (3), 241–246.

Testa, S., Massa, S., Martini, A., & Appio, F. P. (2020). Social media-based innovation: A review of trends and a research agenda. Information & Management, 57 (3), 103196.

Trujillo, C. M., & Long, T. M. (2018). Document co-citation analysis to enhance transdisciplinary research. Science Advances, 4 (1), e1701130.

Uhlaner, L., Wright, M., & Huse, M. (2007). Private firms and corporate governance: An integrated economic and management perspective. Small Business Economics, 29 (3), 225–241.

United Nations (UN). (2015). Countries reach historic agreement to generate financing for new sustainable development agenda. http://www.un.org/esa/ffd/ffd3/press-release/countries-reach-historic-agreement.html .

United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCC). (2008). Kyoto protocol reference manual on accounting of emissions and assigned amount . Germany: UNFCC.

Useem, M. (1986). The inner circle: Large corporations and the rise of business political activity in the US and UK . New York: Oxford University Press.

Van Eck, N. J., & Waltman, L. (2007). VOS: A new method for visualizing similarities between objects. In R. Decker & H. J. Lenz (Eds.), Advances in data analysis (pp. 299–306). Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer.

Van Eck, N., & Waltman, L. (2009). Software survey: VOSviewer, a computer program for bibliometric mapping. Scientometrics, 84 (2), 523–538.

Van Eck, N. J., & Waltman, L. (2017). Citation-based clustering of publications using CitNetExplorer and VOSviewer. Scientometrics, 111 (2), 1053–1070.

Van Eck, N. J., Waltman, L., Dekker, R., & van den Berg, J. (2010). A comparison of two techniques for bibliometric mapping: Multidimensional scaling and VOS. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 61 (12), 2405–2416.

Waddock, S. A., & Graves, S. B. (1997). The corporate social performance–financial performance link. Strategic Management Journal, 18 (4), 303–319.

Waltman, L., Van Eck, N. J., & Noyons, E. C. (2010). A unified approach to mapping and clustering of bibliometric networks. Journal of Informetrics, 4 (4), 629–635.

Williamson, O. E. (1985). The economic institutions of capitalism: Firms, markets, relational contracting . New York: Free Press.

Zadek, S. (2001). Third generation corporate citizenship . London: The Foreign Policy Centre.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Economics, University of Messina, Piazza Pugliatti, 1, 98122, Messina, Italy

Valeria Naciti, Fabrizio Cesaroni & Luisa Pulejo

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Fabrizio Cesaroni .

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Naciti, V., Cesaroni, F. & Pulejo, L. Corporate governance and sustainability: a review of the existing literature. J Manag Gov 26 , 55–74 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10997-020-09554-6

Download citation

Accepted : 26 November 2020

Published : 03 January 2021

Issue Date : March 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s10997-020-09554-6

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Corporate governance

- Sustainability

- Corporate social responsibility

- Board of Directors

- Sustainability reporting

- Clustering analysis

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

- Open access

- Published: 01 November 2021

The impact of corporate governance measures on firm performance: the influences of managerial overconfidence

- Tolossa Fufa Guluma ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-1608-5622 1

Future Business Journal volume 7 , Article number: 50 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

59k Accesses

34 Citations

Metrics details

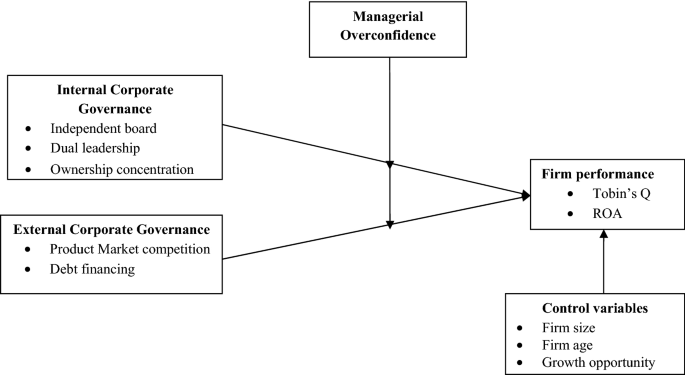

The paper aims to investigate the impact of corporate governance (CG) measures on firm performance and the role of managerial behavior on the relationship of corporate governance mechanisms and firm performance using a Chinese listed firm. This study used CG mechanisms measures internal and external corporate governance, which is represented by independent board, dual board leadership, ownership concentration as measure of internal CG and debt financing and product market competition as an external CG measures. Managerial overconfidence was measured by the corporate earnings forecasts. Firm performance is measured by ROA and TQ. To address the study objective, the researcher used panel data of 11,634 samples of Chinese listed firms from 2010 to 2018. To analyze the proposed hypotheses, the study employed system Generalized Method of Moments estimation model. The study findings showed that ownership concentration and product market competition have a positive significant relationship with firm performance measured by ROA and TQ. Dual leadership has negative relationship with TQ, and debt financing also has a negative significant association’s with both measures of firm performance ROA and TQ. Moreover, the empirical results also showed managerial overconfidence negatively influences the relationship of board independence, dual leadership, and ownership concentration with firm performance. However, managerial overconfidence positively moderates the impact of debt financing on firm performance measured by Tobin’s Q and negative influence on debt financing and operational firm performance relationship. These findings have several contributions: first, the study extends the literature on the relationship between CG and a firm’s performance by using the Chinese CG structure. Second, this study provides evidence that how managerial behavioral bias interacts with CG mechanisms to affect firm performance, which has not been studied in previous literature. Therefore, the results of this study contribute to the theoretical perspective by providing an insight into the influencing role of managerial behavior in the relationship between CG practices and firm performance in an emerging markets economy. Hence, the empirical result of the study provides important managerial implications for the practice and is important for policy-makers seeking to improve corporate governance in the emerging market economy.

Introduction

Corporate governance and its relation with firm performance, keep on to be an essential area of empirical and theoretical study in corporate study. Corporate governance has got attention and developed as an important mechanism over the last decades. The fast growth of privatizations, the recent global financial crises, and financial institutions development have reinforced the improvement of corporate governance practices. Well-managed corporate governance mechanisms play an important role in improving corporate performance. Good corporate governance is fundamental for a firm in different ways; it improves company image, increases shareholders’ confidence, and reduces the risk of fraudulent activities [ 67 ]. It is put together on a number of consistent mechanisms; internal control systems and external environments that contribute to the business corporations’ increase successfully as a complete to bring about good corporate governance. The basic rationale of corporate governance is to increase the performance of firms by structuring and sustaining initiatives that motivate corporate insiders to maximize firm’s operational and market efficiency, and long-term firm growth through limiting insiders’ power that can abuse over corporate resources.

Several studies are contributed to the effect of CG on firm performance using different market developments. However, there is no consensus on the role CG on firm performance, due to different contextual factors. The role of CG mechanisms is affected by different factors. Prior studies provided different empirical evidence such as [ 14 ], suggested that the monitoring efficiency of the board of directors is affected by internal and external factors like government regulation and internal firm-specific factors; the role of board monitoring is determined by ownership structure and firm-specific characters Boone et al. [ 8 ], and Liu et al. [ 57 ] and Bozec [ 10 ] also reported that external market discipline affects the internal CG role on firm performance. Moreover, several studies studied the moderation role of different variables in between CG and firm value. Mcdonald et al. [ 63 ] studied CEO experience moderating the board monitoring effectiveness, and [ 60 ] studied the moderating role of product market competition in between internal CG and firm performance. Bozec [ 10 ] studied market disciple as a moderator between the board of directors and firm performance. As to the knowledge of the researcher, no study considered the influencing role of managerial overconfidence in between CG mechanisms and firm corporate performance. Thus, this study aims to investigate the influence of managerial overconfidence in the relationship between CG mechanisms and firm performance by using Chinese listed firms.

Managers (CEOs) were able to valuable contributions to the monitoring of strategic decision making [ 13 ]. Behavioral decision theory [ 94 ] suggests that overconfidence, as one type of cognitive bias, encourages decision-makers to overestimate their information and problem-solving capabilities and underestimates the uncertainties facing their firms and the potential losses from litigation associated with claims against them. Several prior studies reported different results of the manager's role in corporate governance in different ways. Previous studies claimed that overconfidence is a dysfunctional behavior of managers that deals with unfavorable consequences for the firm outcome, such as value distraction through unprofitable mergers and suboptimal investment behavior [ 61 ], and unlawful activities (Mishina et al. [ 64 ]). Oliver [ 68 ] argued the human character of individual managers affects the effectiveness of corporate governance. Top managers' behaviors and experience are primary determinants of directors' ability to effectively evaluate their managerial decision-making [ 45 ]. In another way, [ 47 , 58 ] noted managerial overconfidence can encourage some risk and make up for managerial risk aversion, which leads to suboptimal investment decisions. Jensen [ 41 ] suggested in the presence of free cash flow, the manager may overinvest and they can accept a negative net present value project. Therefore, the existence of CG mechanisms aims to eliminate or reduce the effect of agency and asymmetric information on the CEO’s decisions [ 62 ]. This means that the objectives of CG mechanisms are to counterbalance the effect of such problems in the corporate organization that may affect the value of the firms in the long run. Even with the absence of agency conflicts and asymmetric information problems, there is evidence documented for distortions such as the case of corporate investment. Managers will over- or under-invest regarding their optimism level and the availability of internal cash flow.

Agency theory by Jensen and Meckling [ 42 ] has a very clear vision of the problems that exist in the company to know the disagreement of interests between shareholders and managers. Irrational behavior of management resulting from behavioral biases of executive managers is a great challenge in corporate governance [ 44 ]. Overconfidence may create more agency conflict than normal managers. It may lead internal and external CG mechanisms to decisions which damage firm value. The role of CG mechanisms mitigating corporate governance results from agency costs, information asymmetry, and their impact on corporate decisions. This means the behavior of overconfident executives may affect controlling and monitoring role of internal/external CG mechanisms. According to Baccar et al. [ 5 ], suggestion is that one of the roles of corporate governance is controlling such managerial behavioral bias and limiting their potential effects on the company’s strategies. These discussions lead to the conclusion that CEO overconfidence will negatively or positively influence the relationships of CG on firm performance. The majority of studies in the corporate governance field deal with internal problems associated with managerial opportunism, misalignment of objectives of managers and stakeholders. To deal with these problems, the firm may organize internal governance mechanisms, and in this section, the study provides a review of research focused on this specific aspect of corporate governance.

Internal CG includes the controlling mechanism between various actors inside the firm: that is, the company management, its board, and shareholders. The shareholders delegate the controlling function to internal mechanisms such as the board or supervisory board. Effective internal CG is essential in accomplishing company strategic goals. Gillan [ 30 ] described internal mechanisms by dividing them into boards, managers, shareholders, debt holders, employees, suppliers, and customers. These internal mechanisms of CG work to check and balance the power of managers, shareholders, directors, and stakeholders. Accordingly, independent board, CEO duality, and ownership concentration are the main internal corporate governance controlling mechanisms suggested by various researchers in the literature. Thus, the study considered these three internal corporate structures in this study as internal control mechanisms that affect firm performance. Concurrently, external CG mechanisms are mechanisms that are not from the inside of the firm, which is from the outside of the firms and includes: market competition, take over provision, external audit, regulations, and debt finance. There are a lot of studies that examine and investigate the effect of external CG practices on the financial performance of a company, especially in developed nations. In this study, product market competition and debt financing have been taken as representatives of external CG mechanisms. Thus, the study used internal CG measures; independent board, dual leadership, ownership concentration, and product-market competition, and debt financing as a proxy of external CG measures.

Literature review and hypothesis building

Corporate governance and firm performance.

Corporate governance has got attention and developed as a significant mechanism more than in the last decades. The recent financial crises, the fast growth of privatizations, and financial institutions have reinforced the improvement of corporate governance practices in numerous institutions of different countries. As many studies revealed, well-managed corporate governance mechanisms play an important role in providing corporate performance. Good corporate governance is fundamental for a firm in several ways: OECD [ 67 ] indicates the good corporate governance increases the company image, reduces the risks, and boosts shareholders' confidence. Furthermore, good corporate governance develops a number of consistent mechanisms, internal control systems and external environments that contribute to the business corporations’ increase effectively as a whole to bring about good corporate governance.

The basic rationale of corporate governance is to increase the performance of companies by structuring and sustaining incentives that initiate corporate managers to maximize firm’s operational efficiency, return on assets, and long-term firm growth through limiting managers’ abuse of power over corporate resources.

Corporate governance mechanisms are divided into two broad categories: internal corporate governance and external corporate governance mechanisms. Supporting this concept, Keasey and Wright [ 43 ] indicated corporate governance as a framework for effective monitoring, regulation, and control of firms which permits alternative internal and external mechanisms for achieving the proposed company’s objectives. The achievement of corporate governance relies on the mechanism effectiveness of both internal and external governance structures. Gillan [ 30 ] suggested that corporate governance can be divided into two: the internal and external mechanisms. Gillan [ 30 ] described internal mechanisms by dividing into boards, managers, shareholders, debt holders, employees, suppliers, and customers, and also explain external corporate governance mechanisms by incorporating the community in which companies operate, the social and political environment, laws and regulations that corporations and governments involved in.

The internal mechanisms are derived from ownership structure, board structure, and audit committee, and the external mechanisms are derived from the capital market corporate control market, labor market, state status, and investors activate [ 26 ]. The balance and effectiveness of the internal and external corporate governance practices can enhance a better corporate operational performance [ 21 ]. Literature argued that integrated and complete governance mechanisms are better with multi-dimensional theoretical view [ 87 ]. Thus, the study includes both internal and external CG mechanisms to broadly show the connection of these components. Filatotchev and Nakajima [ 26 ] suggest that an integrated approach bringing external and internal mechanisms jointly enhances to build up a more general view on the effectiveness and efficiency of different corporate governance mechanisms. Thus, the study includes both internal and external CG mechanisms to broadly show the connection of these three components.

Board of directors and ownership concentration are the main internal corporate governance mechanisms and product market competition and debt finance also the main representative of external corporate governance suggested by many researchers in the literature that were used in this study. Therefore, the following sections provide a brief discussion of internal and external corporate governance from different angles.

Independent board and firm performance

Board of directors monitoring has been centrally important in corporate governance. Jensen [ 41 ] board of directors is described as the peak of the internal control system. The board represents a firm’s owners and is responsible for ensuring that the firm is managed effectively. Thus, the board is responsible for adopting control mechanisms to ensure that management’s behavior and actions are consistent with the interest of the owners. Mainly the responsibility of the board of directors is selection, evaluation, and removal of poorly performing CEO and top management, the determination of managerial incentives and monitoring, and assessment of firm performance [ 93 ]. The board of directors has the formal authority to endorse management initiatives, evaluate managerial performance, and allocate rewards and penalties to management on the basis of criteria that reflect shareholders’ interests.

According to the agency theory board of directors, the divergence of interests between shareholders and managers is addressed by adopting a controlling role over managers. The board of directors is one of the key governance mechanisms; the board plays a pivotal role in monitoring managers to reduce the problems associated with the separation of ownership and management in corporations [ 24 ]. According to Chen et al. [ 16 ], the strategic role of the board became increasingly important and going beyond the mere approval of strategic management decisions. The board of directors must serve to reconcile management decisions with the objectives of shareholders and stakeholders, which can at times influence strategic decisions (Uribe-Bohorquez [ 85 ]). Therefore, the board's responsibilities extend beyond controlling and monitoring management, ensuring that it takes decisions that are reliable with the corporations [ 29 ]. In the perspective of resource dependence theory, an independent director is often linked firm to outside environments, who are non-management members of the board. Independent boards of directors are more believed to be effective in protecting shareholders' interests resulting in high performance [ 26 ]. This focus on board independence is grounded in agency theory, which addresses inefficiencies that arise from the separation of ownership and control [ 24 ]. As agency theory perspective boards of directors, particularly independent boards are put in place to monitor managers on behalf of shareholders [ 59 ].

A large number of empirical studies are undertaken to verify whether independent directors perform their governance functions effectively or not, but their results are still inconclusive. Studies [ 2 , 50 , 52 , 56 , 85 ], reported the supportive arguments that independent board of directors and firm performance have a positive relationship; in other ways, a large number of studies [ 6 , 17 , 65 91 ], and findings indicated the independent director has a negative relation with firm performance. The positive relationship of independent board and firm performance argued that firms which empower outside directors may lead to their more effective monitoring and therefore higher firm performance. The negative relationship of independent board and firm performance results are based on the argument that external directors have no access to information about the internal business of the firms and their relation with internal management does not allow them to have a sufficient understanding of the firm’s day-to-day business activities or it may arise from the lack of knowledge of the business or the ability to monitor management actions [ 28 ].

Specifically in China, the corporate governance regulation code was approved in 2001 and required that the board of all Chinese listed domestic companies must include at least one-third of independent directors on their board by June 2003. Following this direction, many listed firms had appointed more independent directors, with a view to increase the independence of the board [ 54 ]. This proclamation is staying stable till now, and the number of independent directors in Chinese listed firms is increasing from time to time due to its importance. Thus, the following hypothesis is proposed.

Hypothesis 1

The proportion of independent directors in board members is positively related to firm performance.

Dual leadership and firm performance

CEO duality is one of the important board control mechanisms of internal CG mechanisms. It refers to a situation where the firm’s chief executive officer serves as chairman of the board of directors, which means a person who holds both the positions of CEO and the chair. Regarding leadership and firm performance relation, there are different arguments; there is not consistent conclusion among different researchers. There are two competitive views about dual leadership in corporate governance literature. Agency theory view proposed that duality could minimize the board’s effectiveness of its monitoring function, which leads to further agency problems and enhance poor performance [ 41 , 83 ]. As a result, dual leadership enhances CEO entrenchment and reduces board independence. In this condition, these two roles in one person made a concentration of power and responsibility, and this may result in busyness of CEO which affects the normal duties of a company. This means the CEO is responsible to execute a company’s strategies, monitoring and evaluating the managerial activities of a company. Thus, separating these two roles is better to avoid concentration of authority and power in one individual and separate leadership of board from the ruling of the business [ 72 ].

On the other hand, stewardship theory suggests that managers are good stewards of company resources, which could benefit a firm [ 9 ]. This theory advocates that there is no conflict of interest between shareholders and managers, if the role of CEO and chairman vests on one person, rather CEO duality would promote a clear sense of strategic direction by unifying and strengthening leadership.

In the Chinese firm context, there are different conflicting conclusions about the relationship between CEO duality and firm performance.

Hypothesis 2

CEO duality is negatively associated with firm performance.

Ownership concentration and firm performance

The ownership structure is which has a profound effect on business strategy and performance. Agency theory [ 81 ] argued that concentrated ownership can monitor corporate operating management effectively, alleviate information problems and agency costs, consequently, improve firm performance. The concentration of ownership as a large number of studies grounded in agency theory suggests that it has both the incentive and influence to assure that managers and directors operate in the interests of shareholders [ 19 ]. Concentrated ownership presence among the firm’s investors provides an important driver of good CG that should lead to efficiency gains and improvement in performance [ 81 ].

Due to shareholder concentrated economic risk, these shareholders have a strong encouragement to watch strictly over management, making sure that management does not engage in activities that are damaging the wealth of shareholders. Similarly, Shleifer and Vishny [ 80 ] argue that large share blocks reduce managerial opportunism, resulting in lower agency conflicts between management and shareholders.

In other ways, some researchers have indicated, block shareholders harmfully on the value of the firm, especially when majority shareholders can abuse their position of dominant control at the expense of minority shareholders [ 25 ]. As a result, at some level of ownership concentration the distinction between insiders and outsiders becomes unclear, and block-holders, no matter what their identity is, may have strong incentives to switch resources to the ways that make them better off at the cost of other shareholders. However, concentrated shareholding may create a new set of agency conflicts that may provide a negative impact on firm performance.

In the emerging market context, studies [ 77 , 90 ] find a positive association between ownership concentration and accounting profit for Chinese public companies. As Yu and Wen [ 92 ] argued, Chinese companies have a concentrated ownership structure, limited disclosure, poor investor protection, and reliance on the banking system. As this study argues, this concentration is more controlled by the state, institution, and private shareholders. Thus, ownership concentration in Chinese firms may be an alternative governance tool to reduce agency problems and enhance efficiency.

Hypothesis 3

The ownership concentration is positively related to firm performance.

Product market competition and firm performance

Theoretical models have argued that competition in product markets is a powerful force for overcoming the agency problem between shareholders and managers [ 78 ]. Competition in product markets plays the role of a takeover [ 3 ], and well-managed firms take over the market from poorly managed firms. According to this study finding, competition helps to build the best management team. Competition acts as a substitute for internal governance mechanisms, practically the market for corporate control [ 3 ]. Chou et al. [ 18 ] provided evidence that product market competition has a substantial impact on corporate governance and that it substitutes for corporate governance quality, and they provide evidence that the disciplinary force of competition on the management of the firm is from the fear of insolvency. For instance, Ibrahim [ 39 ] reported firms to operate in competitive industries record more returns of share compared with the concentrated industries. Hart [ 33 ] stated that competition inspires managers to work harder and, thus, reduces managerial slack. This study suggests that in high competition, the selling prices of products or services are more likely to fall because managers are concerned with their economic interest, which may tie up with firm performance. Managers are more focused on enhancing productivity that is more likely to reduce cost and increase firm performance. Thus, competition in product market can reduce agency problems between owners and managers and can enhance performance.

Hypothesis 4

Product market competition is positively associated with firm performance.

Debt financing and firm performance

Debt financing is one of the important governance mechanisms in aligning the incentives of corporate managers with those of shareholders. According to agency theory, debt financing can increase the level of monitoring over self-serving managers and that can be used as an alternative corporate governance mechanism [ 40 ]. This theory argues two ways through debt finance can minimize the agency cost: first the potential positive impact of debt comes from the discipline imposed by the obligation to continually earn sufficient cash to meet the principal and interest payment. It is a commitment device for executives. Second leverage reduces free cash flows available for managers’ discretionary expenses. Literature suggests that when leverage increases, managers may invest in high-risk projects in order to meet interest payments; this action leads lenders to monitor more closely the manager’s action and decision to reduce the agency cost. Koke and Renneboog [ 48 ] have found empirical support that a positive impact of bank debt on productivity growth in German firms. Also, studies like [ 77 , 86 ] examine empirically the effect of debt on firm investment decisions and firm value; reveal that debt finance is a negative effect on corporate investment and firm values [ 69 ] find that there is a significant and negative relationship between debt intensity and firm productivity in the case of Indian firms.

In the Chinese financial sectors, banks play a great role and use more commercial judgment and consideration in their leading decision, and even they monitor corporate activities [ 82 ]. In China listed company [ 77 , 82 ] found that an increase in bank loans increases the size of managerial perks and free cash flows and decreases corporate efficiency, especially in state control firms. The main source of debts is state-owned banks for Chinese listed companies [ 82 ]. This shows debt financing can act as a governance mechanism in limiting managers’ misuse of resources, thus reducing agency costs and enhance firm values. However, in China still government plays a great role in public listed company management, and most banks in China are also governed by the central government. However, the government is both a creditor and a debtor, especially in state-controlled firms. Meanwhile, the government as the owner has multiple objectives such as social welfare and some national (political) issues. Therefore, when such an issue is considerable, debt financing may not properly play its governance role in Chinese listed firms.

Hypothesis 5

Debt financing has a negative association with firm performance

Influence of managerial overconfidence on the relationship of corporate governance and firm performance

Corporate governance mechanisms are assumed to be an appropriate solution to solve agency problems that may derive from the potential conflict of interest between managers and officers, on the one hand, and shareholders, on the other hand [ 42 ].

Overconfidence is an overestimation of one’s own abilities and outcomes related to one’s own personal situation [ 74 ]. This study proposed from the behavioral finance view that overconfidence is typical irrational behavior and that a corporate manager tends to show it when they make business decisions. Overconfident CEOs tend to think they have more accurate knowledge about future events than they have and that they are more likely to experience favorable future outcomes than they are [ 35 ]. Behavioral finance theory incorporates managerial psychological biases and emotions into their decision-making process. This approach assumes that managers are not fully rational. Concurrently, several reasons in the literature show managerial irrationality. This means that the observed distortions in CG decisions are not only the result of traditional factors. Even with the absence of agency conflicts and asymmetric information problems, there is evidence documented for distortions such as the case of corporate investment. Managers will over- or under-invest regarding their optimism level and the availability of internal cash flow. Such a result push managers to make sub-optimal decisions and increase observed corporate distortions as a result. The view of behavioral decision theory [ 94 ] suggests that overconfidence, as one type of cognitive bias, encourages decision-makers to overestimate their own information and problem-solving capabilities and underestimates the uncertainties facing their firms and the potential losses from proceedings related with maintains against them.

Researchers [ 34 , 61 ] discussed the managerial behavioral bias has a great impact on firm corporate governance practices. These studies carefully analyzed and clarified that managerial overconfidence is a major source of corporate distortions and suggested good CG practices can mitigate such problems.

In line with the above argument and empirical evidence of several researchers, therefore, the current study tried to investigate how the managerial behavioral bias (overconfidence) positively or negatively influences the effect of CG on firm performance using Chinese listed firms.

The boards of directors as central internal CG mechanisms have the responsibility to monitor, control, and supervise the managerial activities of firms. Thus, the board of directors has the responsibility to monitor and initiate managers in the company to increase the wealth of ownership and firm value. The capability of the board composition and diversity may be important to control and monitor the internal managers' based on the nature of internal executives behaviors, managerial behavior bias that may hinder or smooth the progress of corporate decisions of the board of directors. Accordingly, several studies suggested different arguments; Delton et al. [ 20 ] argued managerial behavior is influencing the allocation of board attention to monitoring. According to this argument, board of directors or concentrated ownership is not activated all the time continuously, and board members do not keep up a constant level of attention to supervise CEOs. They execute their activities according to firm and CEO status. While the current performance of the firm desirable the success confers celebrity status on CEOs and board will be liable to trust the CEOs and became idle. In other ways, overconfidence managers are irrational behaviors that tend to consider themselves better than others on different attributes. They do not always form beliefs logically [ 73 ]. They blame the external advice and supervision, due to overestimating their skills and abilities, underestimate their risks [ 61 ]. Similarly, CEOs are the most decision-makers in the firm strategies. While managers are highly overconfident, board members (especially external) face information limitations on a day-to-day activities of internal managers. In other way, CEOs have a strong aspiration to increase the performance of their firm; however, if they achieve their goals, they may build their empire. This situation will pronounce where the market for corporate control is not matured enough like China [ 27 ]. So, this fact affects the effectiveness of board activities in strategic decision-making. In contrast, as the study [ 7 ] indicated, as the number of the internal board increases, the impact of managerial overconfidence in the firm became increasing and positively correlated with the leadership duality. In other ways, agency theory, many opponents suggest that CEO duality reduces the monitoring role of the board of directors over the executive manager, and this, in turn, may harm corporate performance. In line with this Khajavi and Dehghani, [ 44 ] found that as the number of internal board increases, the managerial overconfidence bias will increase in Tehran Stock Exchange during 2006–2012.

This shows us the controlling and supervising role of independent directors are less likely in the firms managed by overconfident managers than normal managers; conversely, the power of CEO duality is more salient in the case of overconfident managers than normal managers.

Hypothesis 2a

Managerial overconfidence negatively influences the relationship of independent board and firm performance.

Hypothesis 2b

Managerial overconfidence strengthens the negative relationships of CEO duality and firm performance.

An internal control mechanism ownership concentration believes in the existence of strong control against the managers’ decisions and choices. Ownership concentration can reduce managerial behaviors such as overconfidence and optimism since it contributes to the installation of a powerful control system [ 7 ]. They documented that managerial behavior affects the monitoring activities of ownership concentration on firm performance. Ownership can affect the managerial behavioral bias in different ways, for instance, when CEOs of the firm become overconfident for a certain time, the block ownership controlling attention is weakened [ 20 ], and owners trust the internal managers that may damage the performance of the firms in an emerging market where external market control is weak. Overconfidence CEOs have the quality that expresses their behavior up on their company [ 36 ]. In line with this fact, the researcher can predict that the impact of concentrated ownership on firm performance is affected by overconfident managers.

Hypothesis 2c

Managerial overconfidence negatively influences the impact of ownership concentration on firm performance.

Theoretical literature has argued that product market competition forces management to improve firm performance and to make the best decisions for the future. In high competition, managers try their best due to fear of takeover [ 3 ], well-managed firms take over the market from poorly managed firms, and thus, competition helps to build the best management team. In the case of firms operating in the competitive industry, overconfidence CEO has advantages, due to its too simple to motivate overconfident managerial behaviors due to being overconfident managers assume his/her selves better than others. Overconfident CEOs are better at investing for future investments like research and development, so it plays a strategic role in the competition. Englmaier [ 23 ] argues firms in a more competitive industry better hire a manager who strongly believes in better future market outcomes.

Therefore, the following hypothesis was proposed:

Hypothesis 2d

Managerial overconfidence moderates the effect of product market competition on firm performance.

Regarding debt financing, existing empirical evidence shows no specific pattern in the relation of managerial overconfidence and debt finance. Huang et al. [ 38 ] noted that overconfident managers normally overestimate the profitability of investment projects and underestimate the related risks. So, this study believes that firms with overconfident managers will have lower debt. Then, creditors refuse to provide debt finance when firms are facing high liquidity risks. Abdullah [ 1 ] also argues that debt financers may refuse to provide debt when a firm is having a low credit rating. Low credit rating occurs when bankers believe firms are overestimating the investment projects. Therefore, creditors may refuse to provide debt when managers are overconfident, due to under-estimating the related risk which provides a low credit rating.

However, in China, the main source of debt financers for companies is state banks [ 82 ], and most overconfidence CEOs in Chinese firms have political connections [ 96 ] with the state and have a better relationship with external financial institutions and public banks. Hence, overconfident managers have better in accessing debt rather than rational managers in the context of China that leads creditors to allow to follow and influence the firm investments through collecting information about the firm and supervise the firms directly or indirectly. Thus, managerial overconfidence could have a positive influence on relationships between debt finance and firm performance; thus, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 2e

Managerial overconfidence moderates the relationship between debt financing and firm performance.

To explore the impact of CG on firm performance and whether managerial behavior (managerial overconfidence) influences the relationships of CG and firm performance, the following research model framework was developed based on theoretical suggestions and empirical evidence.

Data sources and sample selection

The data for this study required are accessible from different sources of secondary data, namely China Stock Market and Accounting Research (CSMAR) database and firm annual reports. The original data are obtained from the CSMAR, and the data are collected manually to supplement the missing value. CSMAR database is designed and developed by the China Accounting and Financial Research Center (CAFC) of Honk Kong Polytechnic University and by Shenzhen GTA Information Technology Limited company. All listed companies (Shanghai and Shenzhen stock Exchange) financial statements are included in this database from 1990 and 1991, respectively. All financial data, firm profile data, ownership structure, board structure, composition data of listed companies are included in the CSMAR database. The research employed nine consecutive years from 2010 to 2018 that met the condition that financial statements are available from the CSMAR database. This study sample was limited to only listed firms on the stock market, due to hard to access reliable financial and corporate governance data of unlisted firms. All data collected from Chinese listed firms only issued on A shares in domestic stoke market exchange of Shanghai and Shenzhen. The researcher also used only non-financial listed firms’ because financial firms have special regulations. The study sample data were unbalanced panel data for nine consecutive years from 2010 to 2018. To match firms with industries, we require firms with non-missing CSRC top-level industry codes in the CSMAR database. After applying all the above criteria, the study's final observations are 11,634 firm-year observations.

Measurement of variables

Dependent variable.

- Firm performance

To measure firm performance, prior studies have been used different proxies, by classifying them into two groups: accounting-based and market-based performance measures. Accordingly, this study measures firm performance in terms of accounting base (return on asset) and market-based measures (Tobin’s Q). The ROA is measured as the ratio of net income or operating benefit before depreciation and provisions to total assets, while Tobin’s Q is measured as the sum of the market value of equity and book value of debt, divided by book value of assets.

Independent Variables

Board independent (bind).

Independent is calculated as the ratio of the number of independent directors divided by the total number of directors on boards. In the case of the Chinese Security Regulatory Commission (2002), independent directors are defined as the “directors who hold no position in the company other than the position of director, and no maintain relation with the listed company and its major shareholders that might prevent them from making objective judgment independently.” In line with this definition, many previous studies used a proportion of independent directors to measure board independence [ 56 , 79 ].

CEO Duality

CEO duality refers to a position where the same person serves the role of chief executive officer of the form and as the chairperson of the board. CEO duality is a dummy variable, which equals 1 if the CEO is also the chairman of the board of directors, and 0 otherwise.

Ownership concentration (OWCON)

The most common way to measure ownership concentration is in terms of the percentage of shareholdings held by shareholders. The percentage of shares is usually calculated as each shareholder’s shareholdings held in the total outstanding shares of a company either by volume or by value in a stock exchange. Thus, the distribution of control power can be measured by calculating the ownership concentration indices, which are used to measure the degree of control or the power of influence in corporations [ 88 ]. These indices are calculated based on the percentages of a number of top shareholders’ shareholdings in a company, usually the top ten or twenty shareholders. Following the previous studies [ 22 ], Wei Hu et al. [ 37 ], ownership concentration is measured through the total percentage of the 10 top block holders' ownership.

Product market competition (PMC)

Previous studies measure it through different methods, such as market concentration, product substitutability and market size. Following the previous work in developed and emerging markets [product substitutability [ 31 , 57 ], the current study measured using proxies of market concentration (Herfindahl–Hirschman Index (HHI)). The market share of every firm is calculated by dividing the firm's net sale by the total net sale of the industry, which is calculated for each industry separately every year. This index measures the degree of concentration by industry. The bigger this index is, the more the concentration and the less the competition in that industry will be, vice versa.

Debt Financing (DF)

The debt financing proxy in this study is measured by the percentage of a total asset over the total debt of the firm following the past studies [ 69 , 95 ].

Interaction variable

Managerial overconfidence (moc).

To measure MOC, several researchers attempt to use different proxies, for instance CEO’s shareholdings [ 61 ] and [ 46 ]; mass media comments [ 11 ], corporate earnings forecast [ 36 ], executive compensation [ 38 ], and managers individual characteristics index [ 53 ]. Among these, the researcher decided to follow a study conducted in emerging markets [ 55 ] and used corporate earnings forecasts as a better indicator of managerial overconfidence. If a company’s actual earnings are lower than the earnings expected by managers, the managers are defined as overconfident with a dummy variable of (1), and as not overconfident (0) otherwise.

Control variables

The study contains three control variables: firm size, firm age, and firm growth opportunities. Firm size is an important component while dealing with firm performance because larger firms have more agency issues and need strong CG. Many studies confirmed that a large firm has a large board of directors, which increases the monitoring costs and affects a firm’s value (Choi et al., 2007). In other ways, large firms are easier to generate funds internally and to gain access to funds from an external source. Therefore, firm size affects the performance of firms. Firm size can be measured in many ways; common measures are market capitalization, revenue volume, number of employments, and size of total assets. In this study, firm size is measured by the logarithm of total assets following a previous study. Firm age is the number of years that a firm has operated; it was calculated from the time that the company first appeared on the Chinese exchange. It indicates how long a firm in the market and indicates firms with long age have long history accumulate experience and this may help them to incur better performance [ 8 ]. Firm age is a measure of a natural logarithm of the number of years listed from the time that company first listed on the Chinese exchange market. Growth opportunity is measured as the ratio of current year sales minus prior year sales divided by prior year sales. Sales growth enhances the capacity utilization rate, which spreads fixed costs over revenue resulting in higher profitability [ 49 ].

Data analysis methods

Empirical model estimations.

Most of the previous corporate governance studies used OLS, FE, or RE estimation methods. However, these estimations are better when the explanatory variables are exogenous. Otherwise, a system generalized moment method (GMM) approach is more efficient and consistent. Arellano and Bond [ 4 ] suggested that system GMM is a better estimation method to address the problem of autocorrelation and unobservable fixed effect problems for the dynamic panel data. Therefore, to test the endogeneity issue in the model, the Durbin–Wu–Hausman test was applied. The result of the Hausman test indicated that the null hypothesis was rejected ( p = 000), so there was an endogeneity problem among the study variables. Therefore, OLS and fixed effects approaches could not provide unbiased estimations, and the GMM model was utilized.

The system GMM is the econometric analysis of dynamic economic relationships in panel data, meaning the economic relationships in which variables adjust over time. Econometric analysis of dynamic panel data means that researchers observe many different individuals over time. A typical characteristic of such dynamic panel data is a large observation, small-time, i.e., that there are many observed individuals, but few observations over time. This is because the bias raised in the dynamic panel model could be small when time becomes large [ 75 ]. GMM is considered more appropriate to estimate panel data because it removes the contamination through an identified finite-sample corrected set of equations, which are robust to panel-specific autocorrelation and heteroscedasticity [ 12 ]. It is also a useful estimation tool to tackle the endogeneity and fixed-effect problems [ 4 ].

A dynamic panel data model is written as follows:

where y it is the current year firm performance, α is representing the constant, y it−1 is the one-year lag performance, i is the individual firms, and t is periods. β is a vector of independent variable. X is the independent variable. The error terms contain two components, the fixed effect μi and idiosyncratic shocks v it .

Accordingly, to test the impact of corporate governance mechanisms on firm performance and influencing role of the overconfident executive on the relationship between corporate governance mechanisms and firm performance, the following base models were used:

ROA / TQ i ,t = α + yROA /TQ i,t−1 + β 1 INDBRD + β 2 DUAL + β 3 OWCON + β 4 DF + β 5 PMC + β 6 MOC + β 7 FSIZE + β 8 FAGE + β 9 SGTH + β 10–14 MOC * (INDBRD, DUAL, OWCON, DF, and PMC) + year dummies + industry Dummies + ή + Ɛ it .

where i and t represent firm i at time t, respectively, α represents the constant, and β 1-9 is the slope of the independent and control variables which reflects a partial or prediction for the value of dependent variable, ή represents the unobserved time-invariant firm effects, and Ɛ it is a random error term.

Descriptive statistics

Descriptive statistics of all variables included in the model are described in Table 1 . Accordingly, the value of ROA ranges from −0.17 to 0.23, and the average value of ROA of the sample is 0.05 (5.4%). Tobin Q’s value ranges from 0.88 to 10.06, with an average value of 2.62. The ratio of the independent board ranges from 0.33 to 0.57. The average value of the independent board of directors’ ratio was 0.374. The proportion of the CEO serving as chairperson of the board is 0.292 or 29.23% over the nine years. Top 10 ownership concentration of the study ranged from 22.59% to 90.3%, and the mean value is 58.71%. Product market competition ranges from 0.85% to 40.5%, with a mean value of 5.63%. The debt financing also has a mean value of 40.5%, with a minimum value of 4.90% and a maximum value of 87%. The mean value of managerial overconfidence is 0.589, which indicates more than 50% of Chinese top managers are overconfident.

The study sample has an average of 22.15 million RMB in total book assets with the smallest firms asset 20 million RMB and the biggest owned 26 million RMB. Study sample average firms’ age was 8.61 years old. The growth opportunities of sample firms have an average value of 9.8%.

Table 2 presents the correlation matrix among variables in the regression analysis in the study. As a basic check for multicollinearity, a correlation of 0.7 or higher in absolute value may indicate a multicollinearity issue [ 32 ]. According to Table 2 results, there is no multicollinearity problem among variables. Additionally, the variance inflation factor (VIF) test also shows all explanatory variables are below the threshold value of 10, [ 32 ] which indicates that no multicollinearity issue exists.

Main results and discussion

Impact of cg on firm performance.

Accordingly, Tables 3 and 4 indicate the results of two-step system GMM employing the xtabond2 command introduced by Roodman [ 75 ]. In this, the two-step system GMM results indicated the CG and performance relationship, with the interaction of managerial overconfidence. One-year lag of performance has been included in the model and two to three periods lagged independent variables were used as an instrument in the dynamic model, to correct for simultaneity, control for the fixed effect, and to tackle the endogeneity problem of independent variables. In this model, all variables are taken as endogenous except control variables.

Tables 3 and 4 report the results of three model specification tests to determine whether an appropriate estimation model was applied. These tests are: 1) the Arellano–Bond test for the first-order (AR (1)) and second-order correlation (AR (2)). This test indicates the result of AR (1) and AR (2) is tested for the first-order and second-order serial correlation in the first-differenced residuals, AR (2) test accepted under the null of no serial correlation. The model results show AR (2) test yields a p-value of 0.511 and 0.334, respectively, for ROA and TQ firm performance measurement, which indicates that the models cannot reject the null hypothesis of no second-order serial correlation. 2) Hansen test over-identification is to detect the validity of the instrument in the models. The Hansen test of over-identification is accepted under the null that all instruments are valid. Tables 3 and 4 indicate the p-value of Hansen test over-identification 0.139 and 0.132 for ROA and TQ measurement of firm performance, respectively, so that these models cannot reject the hypothesis of the validity of instruments. 3) In the difference-in-Hansen test of exogeneity, it is acceptable under the null that instruments used for the equations in levels are exogenous. Table 3 shows p-values of 0.313 and 0.151, respectively, for ROA and TQ. These two models cannot reject the hypothesis that the equations in levels are exogenous.

Tables 3 and 4 report the results of the one-year lag values of ROA and TQ are positive (0.398, 0.658) and significant at less than 1% level. This indicates that the previous year's performance of a Chinese firm has a significant impact on the current firm's performance. This study finding is consistent with the previous studies: Shao [ 79 ], Nguyen [ 66 ] and Wintoki et al. [ 89 ], which considered previous year performance as one of the significant independent variables in the case of corporate governance mechanisms and firm performance relationships.

The results indicate board independence has no relation with firm performance measured by ROA and TQ. However, hypothesis 1 indicated that there is a positive and significant relationship between independent board and firm performance, which is not supported. The results are conflicting with the assumption that high independent board on board room should better supervise managers, alleviate the information asymmetry between agents and owners, and improve the firm performance by their proficiency. This result is consistent with several previous studies [ 56 , 79 ], which confirms no relation between board independence and firm performance.

This result is consistent with the argument that those outside directors are inefficient because of the lack of enough information concerning the daily activities of internal managers. Specifically, Chinese listed companies may simply include the minimum number of independent directors on board to fulfill the institutional requirement and that independent boards are only obligatory and fail to perform their responsibilities [ 56 , 79 ]. In this study sample, the average of independent board of all firms included in this study has only 37 percent, and this is one of concurrent evidence as to the independent board in Chinese listed firm simple assigned to fulfill the institutional obligation of one-third ratio.

CEO duality has a negative significant relationship with firm performance measured by TQ ( β = 0.103, p < 0.000), but has no significant relationship with accounting-based firm performance (ROA). Therefore, this result supports our hypothesis 2, which proposed there is a negative relationship between dual leadership and firm performance. This finding is also in line with the agency theory assumption that suggests CEO duality could reduce the board’s effectiveness of its monitoring functions, leading to further agency problems and ultimately leads poor firm performance [ 41 , 83 ]. This finding consistent with prior studies [ 15 , 56 ] that indicated a negative relationship between CEO dual and firm performance, against to this result the studies [ 70 ] and [ 15 ] found that duality positively related to firm performance.

Hypothesis 3 is supported, which proposes there is a positive relationship between ownership concentration and firm performance. Table 3 result shows that there is a positive and significant relationship between the top ten concentrated ownership and ROA and TQ (0.00046 & 0.06) at 1% and 5% significance level, respectively. These findings are consistent with agency theory, which suggests that the shareholders who hold large ownership alleviate agency costs and information problems, monitor managers effectively, consequently enhance firm performance [ 81 ]. This finding is in line with Wu and Cui [ 90 ], and Pant et al. [ 69 ]. Concentrated shareholders have a strong encouragement to watch strictly over management, making sure that management does not engage in activities that are damaging to the wealth of shareholders [ 80 ].

The result indicated in Table 3 PMC and firm performance (ROA) relationship was positive, but statistically insignificant. However, PMC has positive ( β = 2.777) and significant relationships with TQ’s at 1% significance level. Therefore, this result does not support hypothesis 4, which predicts product market competition has a positive relationship with firm performance in Chinese listed firms. In this study, PMC is measured by the percentage of market concentration, and a highly concentrated product market means less competition. Though this finding shows high product market concentration positively contributed to market-based firm performance, this result is consistent with the previous study; Liu et al. [ 57 ] reported high product market competition associated with poor firm performance measured by TQ in Chinese listed firms. The study finding is against the theoretical model argument that competition in product markets is a powerful force for overcoming the agency problem between shareholders and managers, and enhances better firm performance (Scharfstein and [ 78 ]).

Regarding debt finance and firm performance relationship, the impact of debt finance was found to be negative on both firm performances as expected. Thus, this hypothesis is supported. Table 3 shows a negative relationship with both firm performance measurements (0.059 and 0.712) at 1% and 5% significance level. Thus, hypothesis 5, which predicts a negative relationship between debt financing and firm performance, has been supported. This finding is consistent with studies ([ 86 ]; Pant et al., [ 69 ]; [ 77 , 82 ]) that noted that debt financing has a negative effect on firm values.

This could be explained by the fact that as debt financing increases in external loans, the size of managerial perks and free cash flows increase and corporate efficiency decrease. In another way, because the main source of debt financers is state-owned banks for Chinese listed firms, these banks are mostly governed by the government, and meanwhile, the government as the owner has multiple objectives such as social welfare and some national issues. Therefore, debt financing fails to play its governance role in Chinese listed firms.

Regarding control variables, firm age has a positive and significant relationship with both TQ and ROA. This finding supported by the notion indicates firms with long age have long history accumulate experience, and this may help them to incur better performance (Boone et al. [ 8 ]). Firm size has a significant positive relationship with firm performance ROA and negative significant relation with TQ. The positive result supported the suggestion that large firms get a higher market valuation from the markets, while the negative finding indicates large firms are more complex; they may have several agency problems and need additional monitoring, which results in higher operating costs [ 84 ]. Growth opportunity was found to be in positive and significant association with ROA; this indicates that a firm high growth opportunity can increase its performance.

Influences of managerial overconfidence in the relationship between CG measures and firm performance

It predicts that managerial overconfidence negatively influences the relationship of independent board and firm performance. The study findings indicate a negative significant influence of managerial overconfidence when the firm is measure by Tobin’s Q ( β = −4.624, p < 0.10), but a negative relationship is insignificant when the firm is measured by ROA. Therefore, hypothesis 2a is supported when firm value is measured by TQ. This indicates that the independent directors in Chinese firms are not strong enough to monitor internal CEOs properly, due to most Chinese firms merely include the minimum number of independent directors on a board to meet the institutional requirement and that independent directors on boards are only perfunctory. Therefore, the impact of independent board on internal directors is very weak, in this situation overconfident CEO becoming more powerful than others, and they can enact their own will and avoid compromises with the external board or independent board. In another way, the weakness of independent board monitoring ability allows CEOs overconfident that may damage firm value.

The interaction of managerial overconfidence and CEO duality has a significant negative effect on operational firm performance (0.0202, p > 0.05) and a negative insignificant effect on TQ. Thus, Hypothesis 2b predicts that the existence of overconfident managers strengthens the negative relationships of dual leadership and firm performance has been supported. This finding indicates the negative effect of CEO duality amplified when interacting with overconfident CEOs. According to Legendre et al. [ 51 ], argument misbehaviors of chief executive officers affect the effectiveness of external directors and strengthen the internal CEO's power. When the CEOs are getting more powerful, boards will be inefficient and this situation will result in poor performance, due to high agency problems created between managers and ownerships.

Hypothesis 2c is supported