The natural course of binge-eating disorder: findings from a prospective, community-based study of adults

Affiliations.

- 1 McLean Hospital, Belmont, MA, USA.

- 2 Department of Psychiatry, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA.

- 3 Department of Psychiatry, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC, USA.

- 4 Department of Medical Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden.

- 5 Department of Nutrition, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC, USA.

- 6 Department of Psychiatry, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN, USA.

- 7 Accanto Health, Saint Paul, MN, USA.

- 8 Lindner Center of HOPE, Mason, OH, USA.

- 9 Department of Psychiatry & Behavioral Neuroscience, University of Cincinnati College of Medicine, Cincinnati, OH, USA.

- PMID: 38803271

- DOI: 10.1017/S0033291724000977

Background: Epidemiological data offer conflicting views of the natural course of binge-eating disorder (BED), with large retrospective studies suggesting a protracted course and small prospective studies suggesting a briefer duration. We thus examined changes in BED diagnostic status in a prospective, community-based study that was larger and more representative with respect to sex, age of onset, and body mass index (BMI) than prior multi-year prospective studies.

Methods: Probands and relatives with current DSM-IV BED ( n = 156) from a family study of BED ('baseline') were selected for follow-up at 2.5 and 5 years. Probands were required to have BMI > 25 (women) or >27 (men). Diagnostic interviews and questionnaires were administered at all timepoints.

Results: Of participants with follow-up data ( n = 137), 78.1% were female, and 11.7% and 88.3% reported identifying as Black and White, respectively. At baseline, their mean age was 47.2 years, and mean BMI was 36.1. At 2.5 (and 5) years, 61.3% (45.7%), 23.4% (32.6%), and 15.3% (21.7%) of assessed participants exhibited full, sub-threshold, and no BED, respectively. No participants displayed anorexia or bulimia nervosa at follow-up timepoints. Median time to remission (i.e. no BED) exceeded 60 months, and median time to relapse (i.e. sub-threshold or full BED) after remission was 30 months. Two classes of machine learning methods did not consistently outperform random guessing at predicting time to remission from baseline demographic and clinical variables.

Conclusions: Among community-based adults with higher BMI, BED improves with time, but full remission often takes many years, and relapse is common.

Keywords: binge-eating disorder; eating disorders; epidemiology; machine learning; natural course; outcomes; predictors; relapse; remission.

Binge Eating Disorder

- First Online: 08 November 2017

Cite this chapter

- Erin E. Reilly 3 ,

- Lisa M. Anderson 3 ,

- Lauren Ehrlich 3 ,

- Sasha Gorrell 3 ,

- Drew A. Anderson 3 &

- Jennifer R. Shapiro 4

9575 Accesses

Despite the fact that Binge Eating Disorder was only recently introduced as a formal diagnosis in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders (DSM-5), there has been a substantial amount of research over the past decade investigating the prevalence, etiology, and treatment of binge eating and loss of control eating behaviors in children and adolescents. The present chapter provides a summary of the current literature on binge eating, loss of control eating, and overeating behaviors in youth. In particular, we aim to (1) provide an overview of different terms and definitions used in the study of binge eating and loss of control eating, (2) outline available assessment tools for measuring binge eating within child and adolescent populations, (3) review existing research in the etiology and treatment of binge eating behaviors in youth, and (4) discuss important trends in symptom presentation and course within this population. Overall, we hope to provide an informative summary of current work regarding eating-disordered behaviors in children, with the larger intent of highlighting the areas in which future research can enhance our understanding and treatment of this debilitating condition.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Overview of Binge Eating Disorder

Eating Disorders

Prevalence of binge-eating disorder among children and adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis

Ackard, D. M., Neumark-Sztainer, D., Story, M., & Perry, C. (2003). Overeating among adolescents: Prevalence and associations with weight-related characteristics and psychological health. Pediatrics , 111 , 67–74.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Adami, G. F., Gandolfo, P., Campostano, A., Cocchi, F., Bauer, B., & Scopinaro, N. (1995). Obese binge eaters: Metabolic characteristics, energy expenditure and dieting. Psychological Medicine , 25 , 195–198.

Adamo, K. B., Wilson, S. L., Ferraro, Z. M., Hadjiyannakis, S., Doucet, É., & Goldfield, G. S. (2014). Appetite sensations, appetite Signaling proteins, and glucose in obese adolescents with subclinical Binge eating disorder. ISRN Obesity , 2014 .

Google Scholar

Agras, W. S., Telch, C. F., Arnow, B., Eldredge, K., Detzer, M. J., Henderson, J., & Marnell, M. (1995). Does interpersonal therapy help patients with binge eating disorder who fail to respond to cognitive-behavioral therapy. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology , 63 , 356–360.

Allen, K. L., Byrne, S. M., La Puma, M., McLean, N., & Davis, E. A. (2008). The onset and course of binge eating in 8-to 13-year-old healthy weight, overweight and obese children. Eating Behaviors , 9 , 438–446.

Allen, K. L., Byrne, S. M., Oddy, W. H., & Crosby, R. D. (2013). Early onset binge eating and purging eating disorders: Course and outcome in a population-based study of adolescents. Journal of Abnormal Child Clinical Psychology , 41 , 1083–1096.

Article Google Scholar

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing.

Book Google Scholar

Berger, S. S., Elliott, C., Ranzenhofer, L. M., Shomaker, L. B., Hannallah, L., Field, S. E., … & Tanofsky-Kraff, M. (2014). Interpersonal problem areas and alexithymia in adolescent girls with loss of control eating. Comprehensive Psychiatry , 55 , 170–178.

Berkowitz, R., Stunkard, A. J., & Stallings, V. A. (1993). Binge-eating disorder in obese adolescent girls. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences , 699 , 200–206.

Birgegård, A., Norring, C., & Clinton, D. (2014). Binge Eating in Interview Versus Self-Report: Different Diagnoses Show Different Divergences. European Eating Disorders Review, 22, 170–175.

Blaine, B. E., Rodman, J., & Newman, J. M. (2007). Weight loss treatment and psychological well-being: A review and meta-analysis. Journal of Health Psychology , 12 , 66–82.

Boutelle, K. N., Peterson, C. B., Crosby, R. D., Rydell, S. A., Zucker, N., & Harnack, L. (2014). Overeating phenotypes in overweight and obese children. Appetite , 76 , 95–100.

Boutelle, K. N., Peterson, C. B., Rydell, S. A., Zucker, N. L., Cafri, G., & Harnack, L. (2011). Two novel treatments to reduce overeating in overweight children: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology , 79 , 759–771.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Boutelle, K., Wierenga, C. E., Bischoff-Grethe, A., Melrose, A. J., Grenesko-Stevens, E., Paulus, M. P., & Kaye, W. H. (2014). Increased brain response to appetitive tastes in the insula and amygdala in obese compared to healthy weight children when sated. International Journal of Obesity . Preview retrieved from: http://www.nature.com/ijo/journal/vaop/naam/abs/ijo2014206a.html

Braden, A., Rhee, K., Peterson, C. B., Rydell, S. A., Zucker, N., & Boutelle, K. (2014). Associations between child emotional eating and general parenting style, feeding practices, and parent psychopathology. Appetite , 80 , 35–40.

Braet, C., Tanghe, A., Veerle, D., Moens, E., & Rosseel, Y. (2004). Inpatient treatment for children with obesity: Weight loss, psychological well-being, and eating behavior. Journal of Pediatric Psychology , 29 , 519–529.

Bravender, T., Bryant-Waugh, R., Herzog, D., Katzman, D., Kreipe, R. D., Lask, B., … & Zucker, N. (2007). Classification of child and adolescent eating disturbances. Workgroup for classification of eating disorders in children and adolescents (WCEDCA). The International Journal of Eating Disorders , 40 , S117–S122.

Bravender, T., Bryant-Waugh, R., Herzog, D., Katzman, D., Kriepe, R. D., Lask, B., … Zucker, N. (2010). Classification of eating disturbance in children and adolescents: Proposed changes for the DSM-V. European Eating Disorders Review, 18, 79–89.

Brewerton, T. D., Rance, S. J., Dansky, B. S., O’Neil, P. M., & Kilpatrick, D. G. (2014). A comparison of women with child-adolescent versus adult onset binge eating: Results from the National Women’s Study. International Journal of Eating Disorders , 47 , 836–843.

Brownley, K. A., Shapiro, J. R., & Bulik, C. M. (2009). Evidence-informed strategies for binge eating disorder and obesity. In I. F. Dancyger & V. M. Fornari (Eds.), Evidence based treatments for eating disorders (pp. 231–256). Hauppauge, NY: Nova Science Publishers, Inc..

Bruce, A. S., Holsen, L. M., Chambers, R. J., Martin, L. E., Brooks, W. M., Zarcone, J. R., … Savage, C. R. (2010). Obese children show hyperactivation to food pictures in brain networks linked to motivation, reward and cognitive control. International Journal of Obesity, 34(10), 1494–1500.

Bryant-Waugh, R., & Lask, B. (1995). Annotation: Eating disorders in children. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry , 36 , 191–202.

Bulik, C. M., Brownley, K. A., & Shapiro, J. R. (2007). Diagnosis and management of binge eating disorder. World Psychiatry , 6 , 142–148.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Bulik, C. M., Sullivan, P. F., & Kendler, K. S. (1998). Heritability of binge-eating and broadly defined bulimia nervosa. Biological Psychiatry , 44 , 1210–1218.

Bulik, C. M., Sullivan, P. F., & Kendler, K. S. (2003). Genetic and environmental contributions to obesity and binge eating. International Journal of Eating Disorders , 33 , 293–298.

Campbell, I. C., Mill, J., Uher, R., & Schmidt, U. (2011). Eating disorders, gene–environment interactions and epigenetics. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews , 35 , 784–793.

Campfield, L. A. (2002). Leptin and body weight regulation. In C. G. Fairburn & K. D. Brownell (Eds.), Eating disorders and obesity: A comprehensive handbook (pp. 32–36). New York: Guilford Press.

Carper, J. L., Fisher, J. O., & Birch, L. L. (2000). Young girls’ emerging dietary restraint and disinhibition are related to parental control in child feeding. Appetite , 35 , 121–129.

Childress, A. C., Brewerton, T. D., Hodges, E. L., & Jarrell, M. P. (1993). The Kids’ Eating Disorders Survey (KEDS): a study of middle school students. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry , 32 , 843–850.

Colles, S. L., Dixon, J. B., & O’Brien, P. E. (2008). Loss of control is central to psychological disturbance associated with binge eating disorder. Obesity , 16 , 608–614.

Crandall, C. S. (1988). Social contagion of binge eating. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology , 55 , 588–598.

Croll, J., Neumark-Sztainer, D., Story, M., & Ireland, M. (2002). Prevalence and risk and protective factors related to disordered eating behaviors among adolescents: Relationship to gender and ethnicity. Journal of Adolescent Health , 31 , 166–175.

Czaja, J., Rief, W., & Hilbert, A. (2009). Emotion regulation and binge eating in children. International Journal of Eating Disorders , 42 , 356–362.

Dakanalis, A., Timko, C. A., Carrà, G., Clerici, M., Zanetti, M. A., Riva, G., & Caccialanza, R. (2014). Testing the original and the extended dual-pathway model of lack of control over eating in adolescent girls: A two-year longitudinal study. Appetite , 82 , 180–193.

Danese, A., Pariante, C. M., Caspi, A., Taylor, A., & Poulton, R. (2007). Childhood maltreatment predicts adult inflammation in a life-course study. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences , 104 , 1319–1324.

DeBar, L. L., Striegel-Moore, R. H., Wilson, T., Perrin, N., Yarborough, B. J., Dickerson, J., … & Kraemer, H. C. (2011). Guided self-help treatment for recurrent binge eating: Replication and extension. Psychiatric Services, 62 , 367–373.

Delacuwe, V., & Braet, C. (2003). Prevalence of binge-eating disorder in obese children and adolescents seeking weight-loss treatment. International Journal of Obesity , 27 , 406–409.

Decaluwé, V., & Braet, C. (2004). Assessment of eating disorder psychopathology in obese children and adolescents: interview versus self-report questionnaire. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 42, 799–811.

Decaluwé, V., & Braet, C. (2005). The cognitive behavioural model for eating disorders: A direct evaluation in children and adolescents with obesity. Eating Behaviors , 6 , 211–220.

Decaluwé, V., Braet, C., & Fairburn, C. G. (2003). Binge eating in obese children and adolescents. International Journal of Eating Disorders , 33 , 78–84.

Duchesne, M., Mattos, P., Appolinário, J. C., de Freitas, S. R., Coutinho, G., Santos, C., & Coutinho, W. (2010). Assessment of executive functions in obese individuals with binge eating disorder. Revista Brasileria de Psiquiatria , 32 , 381–3888.

Dunkley, D. M., & Grilo, C. M. (2007). Self-criticism, low self-esteem, depressive symptoms, and over-evaluation of shape and weight in binge eating disorder patients. Behaviour Research and Therapy , 45 , 139–149.

Eddy, K. T., Tanofsky-Kraff, M., Thompson-Brenner, H., Herzog, D. B., Brown, T. A., & Ludwig, D. S. (2007). Eating disorder pathology among overweight treatment-seeking youth: Clinical correlates and cross-sectional risk modeling. Behaviour Research and Therapy , 45 , 2360–2371.

Eisenberg, M. E., Wall, M., Shim, J. J., Bruening, M., Loth, K., & Neumark-Sztainer, D. (2012). Associations between friends’ disordered eating and muscle-enhancing behaviors. Social Science & Medicine , 75 , 2242–2249.

Elliott, C. A., Tanofsky-Kraff, M., Shomaker, L. B., Columbo, K. M., Wolkoff, L. E., Ranzenhofer, L. M., & Yanovski, J. A. (2010). An examination of the interpersonal model of loss of control eating in children and adolescents. Behaviour Research and Therapy , 48 , 424–428.

Epstein, L. H., Paluch, R. A., Saelen, B. E., Ernst, M. M., & Wilfley, D. E. (2001). Changes in eating disorder symptom with pediatric obesity treatment. The Journal of Pediatrics , 139 , 58–65.

Evers, C., Stok, F. M., & de Ridder, D. T. (2010). Feeding your feelings: Emotion regulation strategies and emotional eating. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin , 36 , 792–804.

Fairburn, C. G. (2008). Cognitive Behavior therapy and eating disorders . New York: Guilford Press.

Fairburn, C. G., & Cooper, Z. (1993). The eating disorder examination. In C. G. Fairburn & G. T. Wilson (Eds.), Binge eating: Nature, assessment and treatment (12th ed.pp. 317–360). New York: Guilford Press.

Fairburn, C. G., Cooper, Z., & Cooper, P. J. (1986). The clinical features and maintenance of bulimia nervosa. In K. D. Brownell & J. P. Foreyt (Eds.), Handbook of eating disorders: Physiology, psychology and treatment of obesity, anorexia and bulimia (pp. 389–404). New York: Basic Books.

Fairburn, C. G., Cooper, Z., & Shafran, R. (2003). Cognitive behaviour therapy for eating disorders: A “transdiagnostic” theory and treatment. Behaviour Research and Therapy , 41 , 509–528.

Fairburn, C. G., Wilson, G. T., & Schleimer, K. (1993). Binge eating: Nature, assessment, and treatment (pp. 333–360). New York: Guilford Press.

Field, A. E., Austin, S. B., Taylor, C. B., Malspeis, S., Rosner, B., Rockett, H. R., … & Colditz, G. A. (2003). Relation between dieting and weight change among preadolescents and adolescents. Pediatrics , 112 , 900–906.

Field, A. E., Camargo, C. A., Barr Taylor, C., Berkey, C. S., Frazier, A. L., Gillman, M. W., & Coldit, G. A. (1999). Overweight, weight concerns, and bulimic behaviors among girls and boys. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry , 38 , 754–760.

Fisher, J. O., & Birch, L. L. (2002). Eating in the absence of hunger and overweight in girls from 5 to 7 y of age. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition , 76 , 226–231.

Fitzsimmons-Craft, E. E., Ciao, A. C., Accurso, E. C., Pisetsky, E. M., Peterson, C. B., Byrne, C. E., & LeGrange, D. (2014). Subjective and objective binge eating in relation to eating disorder symptomatology, depressive symptoms, and self-esteem among treatment-seeking adolescents with bulimia nervosa. European Eating Disorders Review , 22 , 230–236.

Ford, E. S., Giles, W. H., & Mokdad, A. H. (2004). Increasing prevalence of the metabolic syndrome among US adults. Diabetes Care , 27 , 2444–2449.

French, S. A., Story, M., Neumark-Sztainer, D., Downes, B., Resnick, M., & Blum, R. (1997). Ethnic differences in psychosocial and health behavior correlates of dieting, purging, and binge eating in a population-based sample of adolescent females. International Journal of Eating Disorders , 22 , 315–322.

Frieling, H., Römer, K. D., Scholz, S., Mittelbach, F., Wilhelm, J., De Zwaan, M., … & Bleich, S. (2010). Epigenetic dysregulation of dopaminergic genes in eating disorders. International Journal of Eating Disorders , 43 , 577–583.

Geliebter, A., & Aversa, A. (2003). Emotional eating in overweight, normal weight and underweight individuals. Eating Behaviors , 3 , 341–347.

Geliebter, A., Yahav, E. K., Gluck, M. E., & Hashim, S. A. (2004). Gastric capacity, test meal intake, and appetitive hormones in binge eating disorder. Physiology and Behavior , 81 , 735–740.

Glasofer, D. R., Tanofsky-Kraff, M., Eddy, K. T., Yanovski, S. Z., Theim, K. R., Mirch, M. C., … Yanovski, J.A. (2007). Binge eating in overweight treatment-seeking adolescents. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 32 , 95–101.

Golan, M., & Crow, S. (2004). Parent are key players in the prevention and treatment of weight-related problems. Nutrition Review , 62 , 39–50.

Goldschmidt, A. B., Doyle, A. C., & Wilfley, D. E. (2007). Assessment of binge eating in overweight youth using a questionnaire version of the Child Eating Disorder Examination with instructions. International Journal of Eating Disorders , 40 , 460–467.

Goldschmidt, A. B., Wall, M. M., Choo, T. H. J., Bruening, M., Eisenberg, M. E., & Neumark-Sztainer, D. (2014). Examining associations between adolescent binge eating and binge eating in parents and friends. International Journal of Eating Disorders , 47 , 325–328.

Goldschmidt, A. B., Wall, M. M., Loth, K. A., Bucchianeri, M. M., & Neumark-Sztainer, D. (2014). The course of binge eating from adolescence to young adulthood. Health Psychology , 33 , 457–460.

Goldschmidt, A., Wilfley, D. E., Eddy, K. T., Boutelle, K., Zucker, N., Peterson, C. B., … & Le Grange, D. (2011). Overvaluation of shape and weight among overweight children and adolescents with loss of control eating. Behaviour Research and Therapy , 49 , 682–688.

Goossens, L., Braet, C., Bosmans, G., & Decaluwé, V. (2011). Loss of control over eating in pre-adolescent youth: The role of attachment and self-esteem. Eating Behaviors , 12 , 289–295.

Goossens, L., Braet, C., & Decaluwé, V. (2007). Loss of control over eating in obese youngsters. Behavior Research and Therapy , 45 , 1–9.

Goossens, L., Soenens, B., & Braet, C. (2009). Prevalence and characteristics of binge eating in an adolescent community sample. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology , 38 , 342–353.

Greeno, C. G., Wing, R. R., & Shiffman, S. (2000). Binge antecedents in obese women with and without binge eating disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology , 68 , 95–102.

Haedt-Matt, A. A., & Keel, P. K. (2011). Revisiting the affect regulation model of binge eating: A meta-analysis of studies using ecological momentary assessment. Psychological Bulletin , 137 , 660–681.

Hartmann, A. S., Czaja, J., Rief, W., & Hilbert, A. (2010). Personality and psychopathology in children with and without loss of control over eating. Comprehensive Psychiatry , 51 , 572–578.

Hartmann, A. S., Czaja, J., Rief, W., & Hilbert, A. (2012). Psychosocial risk factors of loss of control eating in primary school children: A retrospective case-control study. International Journal of Eating Disorders , 45 , 751–758.

Hausenblas, H. A., Campbell, A., Menzel, J. E., Doughty, J., Levine, M., & Thompson, J. K. (2013). Media effects of experimental presentation of the ideal physique on eating disorder symptoms: A meta-analysis of laboratory studies. Clinical Psychology Review , 33 , 168–181.

Hawkins, R. C., & Clement, P. F. (1984). Binge eating: Measurement problems and a conceptual model. In R. C. Hawkins, W. J. Fremouw, & P. F. Clement (Eds.), The Binge purge syndrome: Diagnosis, treatment, and research (pp. 229–251). New York: Springer.

Heatherton, T. F., & Baumeister, R. F. (1991). Binge eating as an escape from self-awareness. Psychological Bulletin , 110 , 86–108.

Helder, S. G., & Collier, D. A. (2011). The genetics of eating disorders. In Behavioral neurobiology of eating disorders (pp. 157–175). Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer.

Hilbert, A., & Brauhardt, A. (2014). Childhood loss of control eating over five-year follow-up. International Journal of Eating Disorders , 47 , 758–761.

Hilbert, A., & Czaja, J. (2009). Binge eating in primary school children: Towards a definition of clinical significance. International Journal of Eating Disorders , 42 , 235–243.

Hilbert, A., Rief, W., Tuschen-Caffier, B., de Zwaan, M., & Czaja, J. (2009). Loss of control eating and psychological maintenance in children: An ecological momentary assessment study. Behaviour Research and Therapy , 47 , 26–33.

Hudson, J. I., Coit, C. E., Lalonde, J. K., & Pope Jr., H. G. (2012). By how much will the proposed new DSM-5 criteria increase the prevalence of binge eating disorder? International Journal of Eating Disorders , 45 , 139–141.

Hutchinson, D. M., & Rapee, R. M. (2007). Do friends share similar body image and eating problems? The role of social networks and peer influences in early adolescence. Behaviour Research and Therapy , 45 , 1557–1577.

Holsen, L. M., Zarcone, J. R., Thompson, T. I., Brooks, W. M., Anderson, M. F., Ahluwalia, J. S., … Savage, C. R. (2005). Neural mechanisms underlying food motivation in children and adolescents. Neuroimage, 27 (3), 669–676.

Isnard, P., Michel, G., Frelut, M. L., Vila, G., Falissard, B., Naja, W., … & Mouren-Simeoni, M. C. (2003). Binge eating and psychopathology in severely obese adolescents. International Journal of Eating Disorders , 34 , 235–243.

Isomaa, B. O., Almgren, P., Tuomi, T., Forsén, B., Lahti, K., Nissen, M., … & Groop, L. (2001). Cardiovascular morbidity and mortality associated with the metabolic syndrome. Diabetes Care , 24 , 683–689.

Jansen, A. (1998). A learning model of binge eating: Cue reactivity and cue exposure. Behaviour Research and Therapy , 36 , 257–272.

Johnson, W. G., Grieve, F. G., Adams, C. D., & Sandy, J. (1999). Measuring binge eating in adolescents: adolescent and parent versions of the questionnaire of eating and weight patterns. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 26 , 301–314

Johnson, J. G., Cohen, P., Kasen, S., & Brook, J. S. (2002). Eating disorders during adolescence and the risk for physical and mental disorders during early adulthood. Archives of General Psychiatry , 59 , 545–552.

Johnson, W. G., Rohan, K. J., & Kirk, A. A. (2002). Prevalence and correlates of binge eating in while and African American adolescents. Eating Behaviors , 3 , 179–189.

Jones, M., Luce, K. H., Osborne, M. I., Taylor, K., Cunning, D., Doyle, A. C., … Taylor, C. B. (2008). Randomized, controlled trial of an internet-facilitated intervention for reducing binge eating and overweight in adolescents. Pediatrics , 121 , 453–462.

Kelly, N. R., Shank, L. M., Bakalar, J. L., & Tanofsky-Kraff, M. (2014). Pediatric feeding and eating disorders: Current state of diagnosis and treatment. Current Psychiatry Reports , 16 (446), 1–12.

Keys, A., Brozek, K., Henschel, A., Mickelson, O., & Taylor, H. L. (1950). The biology of human starvation . Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

Killgore, W. D., & Yurgelun-Todd, D. A. (2006). Affect modulates appetite-related brain activity to images of food. International Journal of Eating Disorders , 39 , 357–363.

Klump, K. L., Suisman, J. L., Burt, S. A., McGue, M., & Iacono, W. G. (2009). Genetic and environmental influences on disordered eating: An adoption study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology , 118 , 797–805.

Le Grange, D., Crosby, R. D., Rathouz, P. J., & Leventhal, B. L. (2007). A randomized controlled comparison of family-based treatment and supportive psychotherapy for adolescent bulimia nervosa. Archives of General Psychiatry , 64 , 1049–1056.

Ledoux, S., Choquet, M., & Manfredi, R. (1993). Associated factors for self-reported binge eating among male and female adolescents. Journal of Adolescence , 16 , 75–91.

Lourenço, B. H., Arthur, T., Rodrigues, M. D., Guazzelli, I., Frazzatto, E., Deram, S., … & Villares, S. M. (2008). Binge eating symptoms, diet composition and metabolic characteristics of obese children and adolescents. Appetite , 50 , 223–230.

Marcus, M. D., & Kalarchian, M. A. (2003). Binge eating in children and adolescents. International Journal of Eating Disorders , 34 , S47–S57.

Marcus, M. D., Moulton, M. M., & Greeno, C. G. (1995). Binge eating onset in obese patients with binge eating disorder. Addictive Behaviors , 20 , 747–755.

Mathes, W. F., Brownley, K. A., Mo, X., & Bulik, C. M. (2009). The biology of binge eating. Appetite , 52 , 545–553.

Maayan, L., Hoogendoorn, C., Sweat, V., & Convit, A. (2011). Disinhibited eating in obese adolescents is associated with orbitofrontal volume reductions and executive dysfunction. Obesity , 19 , 1382–1387.

Meyer, C., & Waller, G. (2001). Social convergence of disturbed eating attitudes in young adult women. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease , 189 , 114–119.

Michaelides, M., Thanos, P. K., Volkow, N. D., & Wang, G. J. (2012). Dopamine-related frontostriatal abnormalities in obesity and binge-eating disorder: emerging evidence for developmental psychopathology. Int Rev Psychiatry , 24 (3), 211–218.

Mirch, M. C., McDuffie, J. R., Yanovski, S. Z., Schollnberger, M., Tanofsky-Kraff, M., Theim, K. R., … & Yanovski, J. A. (2006). Effects of binge eating on satiation, satiety, and energy intake of overweight children. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition , 84 , 732–738.

Moens, E., & Braet, C. (2007). Predictors of disinhibited eating in children with and without overweight. Behaviour Research and Therapy , 45 , 1357–1368.

Mond, J., Hall, A., Bentley, C., Harrison, C., Gratwick-Sarll, K., & Lewis, V. (2014). Eating-disordered behavior in adolescent boys: Eating disorder examination questionnaire norms. International Journal of Eating Disorders , 47 , 335–341.

Monteleone, P., Tortorella, A., Castaldo, E., & Maj, M. (2006). Association of a functional serotonin transporter gene polymorphism with binge eating disorder. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part B: Neuropsychiatric Genetics , 141 , 7–9.

Morgan, C. M., Yanovski, S. Z., Nguyen, T. T., McDuffie, J., Sebring, N. G., Jorge, M. R., … Yanocski, J. A. (2002). Loss of control over eating, adiposity, and psychopathology in overweight children. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 31 , 430–441.

Munsch, S., Roth, B., Michael, T., Meyer, A. H., Biedart, E., Roth, S., …, Margraf, J. (2008). Randomized controlled comparison of two cognitive behavioral therapies for obese children: Mother versus mother-child cognitive behavioral therapy. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 77 , 235–246.

Murdoch, M., Payne, N., Samani-Radia, D., Rosen-Webb, K., Walker, L., Howe, M., & Lewis, P. (2011). Family-based behavioural management of childhood obesity: Service evaluation of a group programme run in a community setting in the United Kingdom. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition , 65 , 764–767.

Nederkoorn, C., Braet, C., Van Eijs, Y., Tanghe, A., & Jansen, A. (2006). Why obese children cannot resist food: The role of impulsivity. Eating Behaviors , 7 , 315–322.

Neumark-Sztainer, D., Story, M., Hannan, P. J., & Rex, J. (2003). New Moves: a school-based obesity prevention program for adolescent girls. Preventive Medicine , 37 , 41–51.

Neumark-Sztainer, D., Wall, M., Guo, J., Story, M., Haines, J., & Eisenberg, M. (2006). Obesity, disordered eating, and eating disorders in a longitudinal study of adolescents: How do dieters fare 5 years later? Journal of the American Dietetic Association , 106 , 559–568.

Nguyen-Michel, S. T., Unger, J. B., & Spruijt-Metz, D. (2007). Dietary correlates of emotional eating in adolescence. Appetite , 49 , 494–499.

Pasold, T. L., McCracken, A., & Ward-Begnoche, W. L. (2013). Binge eating in obese adolescents: Emotional and behavioral characteristics and impact on health-related quality of life. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry , 19 , 299–312.

Paxton, S. J., Schutz, H. K., Wertheim, E. H., & Muir, S. L. (1999). Friendship clique and peer influences on body image concerns, dietary restraint, extreme weight-loss behaviors, and binge eating in adolescent girls. Journal of Abnormal Psychology , 108 , 255–266.

Pearson, C. M., Combs, J. L., Zapolski, T. C., & Smith, G. T. (2012). A longitudinal transactional risk model for early eating disorder onset. Journal of Abnormal Psychology , 121 , 707.

Pike, K. M. (1995). Bulimic symptomatology in high school girls toward a model of cumulative risk. Psychology of Women Quarterly , 19c , 373–396.

Polivy, J., Heatherton, T. F., & Herman, C. P. (1988). Self-esteem, restraint, and eating behavior. Journal of Abnormal Psychology , 97 , 354.

Polivy, J., & Herman, C. P. (1985). Dieting and binging: A causal analysis. American Psychologist , 40 , 193–201.

Ranzenhofer, L. M., Columbo, K. M., Tanofsky-Kraff, M., Shomaker, L. B., Cassidy, O., Matheson, B. E., … & Yanovski, J. A. (2012). Binge eating and weight-related quality of life in obese adolescents. Nutrients , 4 , 167–180.

Reynolds, R. M., Godfrey, K. M., Barker, M., Osmond, C., & Phillips, D. I. (2007). Stress responsiveness in adult life: Influence of mother’s diet in late pregnancy. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism , 92 , 2208–2210.

Robin, A. L., Gilroy, M., & Dennis, A. B. (1998). Treatment of eating disorders in children and adolescents. Clinical Psychology Review , 18 , 421–446.

Rosas-Vargas, H., Martínez-Ezquerro, J. D., & Bienvenu, T. (2011). Brain-derived neurotrophic factor, food intake regulation, and obesity. Archives of Medical Research , 42 , 482–494.

Ross, H. E., & Ivis, F. (1999). Binge eating and substance use among male and female adolescents. International Journal of Eating Disorders , 26 , 245–260.

Russell, J., Hooper, M., & Hunt, G. (1996). Insulin response in bulimia nervosa as a marker of nutritional depletion. International Journal of Eating Disorders , 20 , 307–313.

Safer, D. L., Lively, T. J., Telch, C. F., & Agras, W. S. (2002). Predictors of relapse following successful dialectical behavior therapy for binge eating disorder. International Journal of Eating Disorders , 32 , 155–163.

Scherag, S., Hebebrand, J., & Hinney, A. (2010). Eating disorders: The current status of molecular genetic research. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry , 19 , 211–226.

Schienle, A., Schäfer, A., Hermann, A., & Vaitl, D. (2009). Binge-eating disorder: Reward sensitivity and brain activation to images of food. Biological Psychiatry , 65 , 654–661.

Schmidt, U., Lee, S., Beecham, J., Perkins, S., Treasure, J., Yi, I., … Eisler, I. (2007). A randomized controlled trial of family therapy and cognitive behavior therapy guided self-care for adolescents with bulimia nervosa and related disorders. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 164 , 591–598.

Shapiro, J. R., Woolson, S. L., Hamer, R. M., Kalarchian, M. A., Marcus, M. D., & Bulik, C. M. (2007). Evaluating binge eating disorder in children: Development of the Children’s Binge Eating Disorder Scale (C-BEDS). International Journal of Eating Disorders , 40 , 82–89.

Skinner, H. H., Haines, J., Austin, S. B., & Field, A. E. (2012). A prospective study of overeating, binge eating, and depressive symptoms among adolescent and young adult women. Journal of Adolescent Health , 50 , 478–483.

Sonneville, K. R., Horton, N. J., Micali, N., Crosby, R. D., Swanson, S. A., Solmi, F., & Field, A. E. (2013). Longitudinal associations between binge eating and overeating and adverse outcomes among adolescents and young adults: Does loss of control matter? JAMA Pediatrics , 167 , 149–155.

Spoor, S. T., Bekker, M. H., Van Strien, T., & van Heck, G. L. (2007). Relations between negative affect, coping, and emotional eating. Appetite , 48 , 368–376.

Spoor, S. T. P., Stice, E., Bekker, M. H. J., van Stien, T., Croon, M. A., & van Heck, G. L. (2006). Relations between dietary restraint, depressive symptoms, and binge eating. A longitudinal study. The International Journal of Eating Disorders , 39 , 700–707.

Spurrell, E. B., Wilfley, D. E., Tanofsky, M. B., & Brownell, K. D. (1997). Age of onset for binge eating: Are there different pathways to binge eating? International Journal of Eating Disorders , 21 , 55–65.

Stice, E. (1998). Relations of restraint and negative affect to bulimic pathology. A longitudinal test of three competing models. The International Journal of Eating Disorders , 23 , 243–260.

Stice, E. (2001). A prospective test of the dual-pathway model of bulimic pathology: Mediating effects of dieting and negative affect. Journal of Abnormal Psychology , 110 , 124.

Stice, E., & Agras, W. S. (1998). Predicting onset and cessation of bulimic behaviors during adolescence: A longitudinal grouping analysis. Behavior Therapy , 29 , 257–276.

Stice, E., Shaw, H. E., & Nemeroff, C. (1998). Dual pathway model differentiates, bulimics, subclinical bulimics, and controls. Testing the continuity hypothesis. Behavior Therapy , 27 , 531–549.

Stice, E., Agras, W. S., & Hammer, L. D. (1999). Risk factors for the emergence of childhood eating disturbances: A five-year prospective study. International Journal of Eating Disorders , 25 , 375–387.

Stice, E., Cameron, R. P., Killen, J. D., Hayward, C., & Taylor, C. B. (1999). Naturalistic weight-reduction efforts prospectively predict growth in relative weight and onset of obesity among female adolescents. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology , 67 , 967–974.

Stice, E., & Shaw, H. E. (2002). Role of body dissatisfaction in the onset and maintenance of eating pathology: A synthesis of research findings. Journal of Psychosomatic Research , 53 , 985–993.

Stice, E., Davis, K., Miller, N. P., & Marti, N. (2008). Fasting increases risk for onset of binge eating and bulimic pathology: A 5-year prospective study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology , 117 , 941–946.

Stice, E., Killen, J. D., Hayward, C., & Taylor, C. B. (1998). Age of onset for binge eating and purging during late adolescence: A 4-year survival analysis. Journal of Abnormal Psychology , 107 , 671–675.

Stice, E., Marti, C. N., Shaw, H., & Jaconis, M. (2009). An 8-year longitudinal study of the natural history of threshold, subthreshold, and partial eating disorders from a community sample of adolescents. Journal of Abnormal Psychology , 118 , 587–597.

Stice, E., Martinez, E. E., Presnell, K., & Groesz, L. M. (2006). Relation of successful dietary restriction to change in bulimic symptoms: A prospective study of adolescent girls. Health Psychology , 25 , 274–281.

Stice, E., Presnell, K., & Spangler, D. (2002). Risk factors for binge eating onset in adolescent girls: A 2-year prospective investigation. Health Psychology , 21 , 131–138.

Stice, E., Yokum, S., Burger, K. S., Epstein, L. H., & Small, D. M. (2011). Youth at risk for obesity show greater activation of striatal and somatosensory regions to food. Journal of Neuroscience , 31 , 4360–4366.

Stice, E., Yokum, S., Blum, K., & Bohon, C. (2010). Weight gain is associated with reduced striatal response to palatable food. Journal of Neuroscience , 30 , 13105–13109.

Striegel-Moore, R. H., & Franko, D. L. (2008). Should binge eating disorder be included in the DSM-V? A critical review of the state of the evidence. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology , 4 , 305–324.

Swanson, S. A., Crow, S. J., Le Grange, D., Swendsen, J., & Merikangas, K. R. (2011). Prevalence and correlates of eating disorders in adolescents: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication Adolescent Supplement. Archives of General Psychiatry , 68 , 714–723.

Tanofsky, M. B., Wilfley, D. E., Spurrell, E. B., Welch, R., & Brownell, K. D. (1997). Comparison of men and women with binge eating disorder. International Journal of Eating Disorders , 21 , 49–54.

Tanofsky-Kraff, M. (2008). Binge eating among children and adolescents. In E. S. Jelalian & R. Steele (Eds.), Handbook of child and adolescent obesity (pp. 43–59). New York: Springer.

Tanofsky-Kraff, M., Bulik, C. M., Marcus, M. D., Striegel, R. H., Wilfley, D. E., Wonderlich, S. A., & Hudson, J. I. (2013). Binge eating disorder: The next generation of research. International Journal of Eating Disorders , 46 , 193–207.

Tanofsky-Kraff, M., Cohen, M., Yanovski, S., Cox, C., Theim, K., Keil, M., et al. (2006). A prospective study of psychological predictors of body fat gain among children at high risk for adult obesity. Pediatrics , 117 , 1203–1209.

Tanofsky-Kraff, M., Faden, D., Yanovski, S., Wilfley, D., & Yanovski, J. (2005). The perceived onset of dieting and loss of control eating behaviors in overweight children. The International Journal of Eating Disorders , 38 , 112–122.

Tanofsky-Kraff, M., Han, J. C., Anandalingam, K., Shomaker, L. B., Columbo, K. M., Wolkoff, L. E., … & Yanovski, J. A. (2009). The FTO gene rs9939609 obesity-risk allele and loss of control over eating. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition , 90 , 1483–1488.

Tanofsky-Kraff, M., Marcus, M., Yanovski, S., & Yanovski, J. (2008). Loss of control eating disorder in children age 12 years and younger: Proposed research criteria. Eating Behaviors , 9 , 360–365.

Tanofsky-Kraff, M., Shomaker, L. B., Olsen, C., Roza, C. A., Wolkoff, L. E., Columbo, K. M., … & Yanovski, J. A. (2011). A prospective study of pediatric loss of control eating and psychological outcomes. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 120 , 108–118.

Tanofsky-Kraff, M., Shomaker, L. B., Stern, E. A., Miller, R., Sebring, N., DellaValle, D., … & Yanovski, J. A. (2012). Children’s binge eating and development of metabolic syndrome. International Journal of Obesity , 36 , 956–962.

Tanofsky-Kraff, M., Theim, K. R., Yanovski, S. Z., Bassett, A. M., Burns, N. P., Ranzenhofer, L. M., … Yanovski, Y. A. (2007). Validation of the emotional eating scale adapted for use in children and adolescents (EES-C). International Journal of Eating Disorders, 40 , 232–240.

Tanofsky-Kraff, M., Wilfley, D. E., Young, J. F., Mufson, L., Yanovski, S. Z., Glasofer, D. R., … Schvey, B. A. (2010). A pilot study of interpersonal psychotherapy for preventing excess weight gain in adolescent girls at-risk for obesity. International Journal of Eating Disorders , 43 , 701–706.

Tanofsky-Kraff, M., Yanovski, S., Wilfley, D., Marmarosh, C., Morgan, C., & Yanovski, J. (2004). Eating-disordered behaviors, body fat, and psychopathology in overweight and normal- weight children. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology , 72 , 53–61.

Tanofsky-Kraff, M., Yanovski, S. Z., Schvey, N. A., Olsen, C. H., Gustafson, J., & Yanovski, J. A. (2009). A prospective study of loss of control eating for body weight gain in children at high risk for adult obesity. The International Journal of Eating Disorders , 42 , 26–30.

Tao, Y. X., & Segaloff, D. L. (2003). Functional characterization of melanocortin-4 receptor mutations associated with childhood obesity. Endocrinology , 144 , 4544–4551.

Tschöp, M., Weyer, C., Tataranni, P. A., Devanarayan, V., Ravussin, E., & Heiman, M. L. (2001). Circulating ghrelin levels are decreased in human obesity. Diabetes , 50 , 707–709.

Tzischinsky, O., & Latzer, Y. (2006). Sleep–wake cycles in obese children with and without binge-eating episodes. Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health , 42 , 688–693.

Valette, M., Poitou, C., Le Beyec, J., Bouillot, J. L., Clement, K., & Czernichow, S. (2012). Melanocortin-4 receptor mutations and polymorphisms do not affect weight loss after bariatric surgery. PloS One , 7 , e48221.

Van Strien, T., Engels, R. C., Van Leeuwe, J., & Snoek, H. M. (2005). The Stice model of overeating: Tests in clinical and non-clinical samples. Appetite , 45 , 205–213.

Wang, G. J., Volkow, N. D., Thanos, P. K., & Fowler, J. S. (2004). Similarity between obesity and drug addiction as assessed by neurofunctional imaging: A concept review. Journal of Addictive Diseases , 23 , 39–53.

Whitaker, A., Davies, M., Shaffer, D., Johnson, J., Abrams, S., Walsh, B. T., & Kalikow, K. (1989). The struggle to be thin: A survey of anorexic and bulimic symptoms in a non-referred adolescent population. Psychological Medicine , 19 , 143–163.

Whiteside, U., Chen, E., Neighbors, C., Hunter, D., Lo, T., & Larimer, M. (2007). Difficulties regulating emotions: Do binge eaters have fewer strategies to modulate and tolerate negative affect? Eating Behaviors , 8 , 162–169.

Wildes, J. E., Marcus, M. D., Kalarchian, M. A., Levine, M. D., Houck, P. R., & Cheng, Y. (2010). Self-reported binge eating in severe pediatric obesity: Impact on weight change in a randomized controlled trial of family-based treatment. International Journal of Obesity , 34 , 1143–1148.

Wilfley, D. E., Bishop, M. E., Wilson, G. T., & Agras, W. S. (2007). Classification of eating disorders: Toward DSM-V. International Journal of Eating Disorders , 40 , S123–S129.

Wilfley, D. E., MacKenzie, K. R., Welch, R. R., & Ayres, V. E. (2007). Interpersonal psychotherapy for group . New York: Basic Books.

Wilfley, D. E., Vannucci, A., & White, E. K. (2010). Early intervention of eating and weight-related problems. Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings , 17 , 285–300.

Wilson, G. T., & Shafran, R. (2005). Eating disorders guidelines from NICE. Lancet , 365 , 79–81.

Wonderlich, S. A., Gordon, K. H., Mitchell, J. E., Crosby, R. D., & Engel, S. G. (2009). The validity and clinical utility of binge eating disorder. International Journal of Eating Disorders , 42 , 687–705.

Zocca, J. M., Shomaker, L. B., Tanofsky-Kraff, M., Columbo, K. M., Raciti, G. R., Brady, S. M., & Yanovski, J. A. (2011). Links between mothers’ and children’s disinhibited eating and children’s adiposity. Appetite , 56 , 324–331.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Psychology, Social Sciences 399, University at Albany, State University of New York, 1400 Washington Avenue, Albany, NY, 12222, USA

Erin E. Reilly, Lisa M. Anderson, Lauren Ehrlich, Sasha Gorrell & Drew A. Anderson

Dr. Jennifer Shapiro and Associates, 6540 Lusk Blvd Suite C239, San Diego, CA, 92121, USA

Jennifer R. Shapiro

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Erin E. Reilly .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Neurology, Learning and Behavior Center, Salt Lake City, Utah, USA

Sam Goldstein

Intermountain Healthcare, Salt Lake City, Utah, USA

Melissa DeVries

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2017 Springer International Publishing AG

About this chapter

E. Reilly, E., Anderson, L.M., Ehrlich, L., Gorrell, S., A. Anderson, D., Shapiro, J.R. (2017). Binge Eating Disorder. In: Goldstein, S., DeVries, M. (eds) Handbook of DSM-5 Disorders in Children and Adolescents. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-57196-6_18

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-57196-6_18

Published : 08 November 2017

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-319-57194-2

Online ISBN : 978-3-319-57196-6

eBook Packages : Behavioral Science and Psychology Behavioral Science and Psychology (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Published: 11 March 2002

Binge eating disorder: a review

- AE Dingemans 1 ,

- MJ Bruna 1 &

- EF van Furth 1

International Journal of Obesity volume 26 , pages 299–307 ( 2002 ) Cite this article

17k Accesses

159 Citations

13 Altmetric

Metrics details

Binge eating disorder (BED) is a new proposed eating disorder in the DSM-IV. BED is not a formal diagnosis within the DSM-IV, but in day-to-day clinical practice the diagnosis seems to be generally accepted. People with the BED-syndrome have binge eating episodes as do subjects with bulimia nervosa, but unlike the latter they do not engage in compensatory behaviours. Although the diagnosis BED was created with the obese in mind, obesity is not a criterion. This paper gives an overview of its epidemiology, characteristics, aetiology, criteria, course and treatment. BED seems to be highly prevalent among subjects seeking weight loss treatment (1.3–30.1%). Studies with compared BED, BN and obesity indicated that individuals with BED exhibit levels of psychopathology that fall somewhere between the high levels reported by individuals with BN and the low levels reported by obese individuals. Characteristics of BED seemed to bear a closer resemblance to those of BN than of those of obesity.

A review of RCT's showed that presently cognitive behavioural treatment is the treatment of choice but interpersonal psychotherapy, self-help and SSRI's seem effective. The first aim of treatment should be the cessation of binge eating. Treatment of weight loss may be offered to those who are able to abstain from binge eating.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

251,40 € per year

only 20,95 € per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Microdosing with psilocybin mushrooms: a double-blind placebo-controlled study

Associations of dietary patterns with brain health from behavioral, neuroimaging, biochemical and genetic analyses

Adults who microdose psychedelics report health related motivations and lower levels of anxiety and depression compared to non-microdosers

American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4th edn (DSM-IV). American Psychiatric Association: Washington, DC; 1994

Spitzer RL, Devlin M, Walsh BT, Hasin D, Wing R, Marcus MD, Stunkard A, Wadden T, Yanovski S, Agras WS, Mitchell J, Nonas C . Binge eating disorder: to be or not to be in DSM-IV Int J Eating Disord 1991 10 : 627–629.

Article Google Scholar

Spitzer RL, Devlin M, Walsh BT, Hasin D, Wing R, Marcus MD, Stunkard A, Wadden T, Yanovski S, Agras WS, Mitchell J, Nonas C . Binge eating disorder: a multiside field trial of the diagnostic criteria Int J Eating Disord 1992 11 : 191–203.

Spitzer RL, Yanovski SZ, Wadden T, Wing R . Binge eating disorder: its further validation in a multisite study Int J Eating Disord 1993 13 : 137–153.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Hay P . The epidemiology of eating disorder behaviors: an Australian community-based survey Int J Eating Disord 1998 23 : 371–382.

Basdevant A, Pouillon M, Lahlou N, Le Barzic M, Brillant M, Guy-Grand B . Prevalence of binge eating disorder in different populations of French women Int J Eating Disord 1995 18 : 309–315.

Götestam KG, Agras WS . General population-based epidemiological study of eating disorders in Norway Int J Eating Disord 1995 18 : 119–126.

Kinzl JF, Traweger C, Trefalt E, Mangweth B, Biebl W . Binge eating disorder in females: a population-based investigation Int J Eating Disord 1999 25 : 287–292.

Rosenvinge JH, Borgen JS, Borresen R . The prevalence and psychological correlates of anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa and binge eating among 15-year-old students: a controlled epidemiological study Eur Eating Disord Rev 1999 7 : 382–391.

Cotrufo P, Barretta V, Monteleone P, Maj M . Full-syndrome, partial-syndrome and subclinical eating disorders: an epidemiological study of female students in Southern Italy Acta Psychiatr Scand 1998 98 : 112–115.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Kinzl JF, Traweger C, Trefalt E, Mangweth B, Biebl W . Binge eating disorder in males: a population-based investigation Eating Weight Disord 1999 4 : 169–174.

Striegel-Moore RH . Psychological factors in the etiology of binge eating Addict Behav 1995 20 : 713–723.

Ramacciotti CE, Coli E, Passaglia C, Lacorte M, Pea E, Dell'Osso L . Binge eating disorder: prevalence and psychopathological features in a clinical sample of obese people in Italy Psychiat Res 2000 94 : 131–138.

Ricca V, Mannucci E, Moretti S, Di Bernardo M, Zucchi T, Cabras PL, Rotella CM . Screening for binge eating disorder in obese outpatients Comp Psychiat 2000 41 : 111–115.

Varnado PJ, Williamson DA, Bentz BG, Ryan DH, Rhodes SK, O'Neil PM, Sebastian SB . Prevalence of binge eating disorder in obese adults seeking weight loss treatment Eating Weight Disord 1997 2 : 117–124.

Fairburn CG, Doll HA, Welch SL, Hay PJ, Davies BA, O'Connor ME . Risk factors for binge eating disorder Arch Gen Psychiat 1998 55 : 425–432.

Telch CF, Agras WS, Rossiter EM . Binge eating increases with increasing adiposity Int J Eating Disord 1988 7 : 115–119.

Hay P, Fairburn C . The validity of the DSM-IV scheme for classifying bulimic eating disorders Int J Eating Disord 1998 23 : 7–15.

Herpertz S, Albus C, Lichtblau K, Kohle K, Mann K, Senf W . Relationship of weight and eating disorders in type 2 diabetic patients: a multicenter study Int J Eating Disord 2000 28 : 68–77.

Mannucci E, Bardini G, Ricca V, Tesi F, Piani F, Vannini R, Rotella CM . Eating attitudes and behaviour in patients with type II diabetes Diabet Nutr Metab 1997 10 : 275–281.

Google Scholar

Herpertz S, Albus C, Wagener R, Kocnar M, Wagner R, Henning A, Best F, Foerster H, Schleppinghoff BS, Thomas W, Kohle K, Mann K, Senf W . Comorbidity of diabetes and eating disorders—does diabetes control reflect disturbed eating behavior? Diabetes Care 1998 21 : 1110–1116.

Nielsen S, Molbak AG . Eating disorder and type 1 diabetes: overview and summing-up Eur Eating Disord Rev 1998 6 : 4–26.

Hodges EL, Cochrane CE, Brewerton TD . Family characteristics of binge-eating disorder patients Int J Eating Disord 1998 23 : 145–151.

Lee YH, Abbott DW, Seim HC, Crosby RD, Monson N, Burgard M, Mitchell JE . Eating disorders and psychiatric disorders in the first-degree relatives of obese probands with binge eating disorder and obese non-binge eating disorder controls Int J Eating Disord 1999 26 : 322–332.

Mussell MP, Mitchell JE, Fenna CJ, Crosby RD, Miller JP, Hoberman HM . A comparison of onset of binge eating versus dieting in the development of bulimia nervosa Int J Eating Disord 1997 21 : 353–360.

Marcus MD, Moulton MM, Greeno CG . Binge eating onset in obese patients with binge eating disorder Addict Behav 1995 20 : 747–755.

Haiman C, Devlin MJ . Binge eating before the onset of dieting: a distinct subgroup of bulimia nervosa? Int J Eating Disord 1999 25 : 151–157.

Grilo CM, Masheb RM . Onset of dieting vs binge eating in outpatients with binge eating disorder Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 2000 24 : 404–409.

Abbott DW, de Zwaan M, Mussell MP, Raymond NC, Seim HC, Crow SJ, Crosby RD, Mitchell JE . Onset of binge eating and dieting in overweight women: implications for etiology, associated features and treatment J Psychosom Res 1998 44 : 367–374.

Spurrell EB, Wilfley DE, Tanofsky MB, Brownell KD . Age of onset for binge eating: are there different pathways to binge eating? Int J Eating Disord 1997 21 : 55–65.

Mussell MP, Mitchell JE, Weller CL, Raymond NC, Crow SJ, Crosby RD . Onset of binge eating, dieting, obesity, and mood disorders among subjects seeking treatment for binge eating disorder Int J Eating Disord 1995 17 : 395–401.

Howard CE, Porzelius LK . The role of dieting in binge eating disorder: etiology and treatment implications Clin Psychol Rev 1999 19 : 25–44.

de Zwaan M, Mitchell JE . Binge eating in the obese Ann Med 1992 24 : 303–308.

Mitchell JE, Mussell MP . Comorbidity and binge eating disorder Addict Behav 1995 20 : 725–732.

Yanovski SZ, Nelson JE, Dubbert BK, Spitzer RL . Association of binge eating disorder and psychiatric comorbidity in obese subjects Am J Psychiat 1993 150 : 1472–1479.

Kuehnel RH, Wadden TA . Binge eating disorder, weight cycling, and psychopathology Int J Eating Disord 1994 15 : 321–329.

Striegel-Moore RH, Wilson GT, Wilfley DE, Elder KA, Brownell KD . Binge eating in an obese community sample Int J Eating Disord 1998 23 : 27–37.

Telch CF, Stice E . Psychiatric comorbidity in women with binge eating disorder: prevalence rates from a non-treatment-seeking sample J Consult Clin Psychol 1998 66 : 768–776.

Marcus MD, Wing R, Lamparski DM . Binge eating and dietary restraint in obese patients Addict Behav 1985 10 : 163–168.

Wadden T, Foster G, Letizia KA . Response of obese binge eaters to treatment by behavior therapy combined with very low calorie diet J Consult Clin Psychol 1992 60 : 808–811.

Marcus MD, Wing RR, Ewing L, Kern E, McDermott M, Gooding W . A double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of fluoxetine plus behavior modification in the treatment of obese binge-eaters and non-binge-eaters Am J Psychiat 1990 147 : 876–881.

Eldredge KL, Agras WS . The relationship between perceived evaluation of weight and treatment outcome among individuals with binge eating disorder Int J Eat Disord 1997 22 : 43–49.

de Zwaan M, Mitchell JE, Seim HC, Specker SM, Pyle RL, Raymond NC, Crosby RD . Eating related and general psychopathology in obese females with binge eating disorder Int J Eating Disord 1994 15 : 43–52.

Grissett NL, Fitzgibbon ML . The clinical significance of binge eating in an obese population: support for BED and questions regarding its criteria Addict Behav 1996 21 : 57–66.

Mussell MP, Mitchell JE, de Zwaan M, Crosby RD, Seim HC, Crow SJ . Clinical characteristics associated with binge eating in obese females: a descriptive study Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 1996 20 : 324–331.

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Masheb RM, Grilo CM . Accuracy of self-reported weight in patients with binge eating disorder Int J Eating Disord 2001 29 : 29–31.

Goldfein JA, Walsh BT, LaChaussee JL, Kissileff HR . Eating behavior in binge eating disorder Int J Eating Disord 1993 14 : 427–431.

Yanovski S, Leet M, Yanovski JA, Flood M, Gold PW, Kissileff HR, Walsh BT . Food selection and intake of obese women with binge-eating disorder Am J Clin Nutr 1992 56 : 975–980.

Mitchell JE, Crow S, Peterson CB, Wonderlich S, Crosby RD . Feeding laboratory studies in patients with eating disorders: a review Int J Eating Disord 1998 24 : 115–124.

Telch CF, Agras WS . Obesity, binge eating and psychopathology: are they related? Int J Eating Disord 1994 15 : 53–61.

Masheb RM, Grilo CM . Binge eating disorder: a need for additional diagnostic criteria Comp Psychiat 2000 41 : 159–162.

Marcus MD, Smith DE, Santelli R, Kaye W . Characterization of eating disordered behavior in obese binge eaters Int J Eating Disord 1992 12 : 249–255.

Kirkley BG, Kolotkin RL, Hernandez JT, Gallagher PN . A comparison of binge-purgers, obese binge eaters and obese nonbinge eaters on the MMPI Int J Eating Disord 1992 12 : 221–228.

Fichter MM, Quadflieg N, Brandl B . Recurrent overeating: an empirical comparison of binge eating disorder, bulimia nervosa, and obesity Int J Eating Disord 1993 14 : 1–16.

Raymond NC, Mussell MP, Mitchell JE, de Zwaan M . An age-matched comparison of subjects with binge eating disorder and bulimia nervosa Int J Eating Disord 1995 18 : 135–143.

Tobin DL, Griffing A, Griffing S . An examination of subtype criteria for bulimia nervosa Int J Eating Disord 1997 22 : 179–186.

Mitchell JE, Mussell MP, Peterson CB, Crow S, Wonderlich S, Crosby RD, Davis T, Weller CL . Hedonics of binge eating in women with bulimia nervosa and binge eating disorder Int J Eating Disord 1999 26 : 165–170.

LaChaussee JL, Kissileff HR, Walsh BT, Hadigan CM . The single-item meal as a measure of binge-eating behavior in patients with bulimia nervosa Physiol Behav 1992 38 : 563–570.

Santonastaso P, Ferrara S, Favaro A . Differences between binge eating disorder and nonpurging bulimia nervosa Int J Eating Disord 1999 25 : 215–218.

Fitzgibbon ML, Blackman LR . Binge eating disorder and bulimia nervosa: differences in the quality and quantity of binge eating episodes Int J Eating Disord 2000 27 : 238–243.

Johnson WG, Boutelle KN, Torgrud L, Davig JP, Turner S . What is a binge? The influence of amount, duration, and loss of control criteria on judgments of binge eating Int J Eating Disord 2000 27 : 471–479.

Fairburn CG, Welch SL, Hay PJ . The classification of recurrent overeating: the ‘binge eating disorder’ proposal Int J Eating Disord 1993 13 : 155–159.

Cooper Z, Fairburn CG . The Eating Disorder Examination: a semi-structured interview for the assessment of the specific psychopathology of eating disorders Int J Eating Disord 1987 6 : 1–8.

Fairburn CG, Wilson GT . Binge eating: definition and classification. In: Fairburn CG, Wilson GT (eds) Binge eating: nature, assessment and treatment New York: The Guilford Press 1993 pp 3–14.

de Zwaan M, Mitchell JE, Specker SM, Pyle RL . Diagnosing binge eating disorder: level of agreement between self-report and expert-rating Int Eating Disord 1993 14 : 289–295.

de Zwaan M, Mitchell JE, Raymond NC, Spitzer RL . Binge eating disorder: clinical features and treatment of a new diagnosis Harv Rev Psychiat 1994 1 : 310–325.

de Zwaan M . Status and utility of a new diagnostic category: binge eating disorder Eur Eating Disord Rev 1998 5 : 226–240.

Schmidt U . The treatment of bulimia nervosa. In: Hoek HW, Treasure JL, Katzman MA (eds) Neurobiology in the treatment of eating disorders Chichester: John Wiley 1998 pp 331–362.

Wilfley DE, Cohen LR . Psychological treatment of bulimia nervosa and binge eating disorder Psychopharmac Bull 1997 33 : 437–454.

CAS Google Scholar

Romano SJ, Quinn L . Binge eating disorder: description and proposed treatment Eur Eating Disord Rev 1995 3 : 67–79.

Telch CF, Agras WS, Rossiter EM, Wilfley DE, Kenardy J . Group cognitive-behavioral treatment for the nonpurging bulimic: an initial evaluation J Consult Clin Psychol 1990 58 : 629–635.

Wilfley DE, Agras WS, Telch CF, Rossiter EM, Schneider JA, Golomb Cole A, Sifford L, Raeburn SD . Group cognitive-behavioral therapy and group interpersonal psychotherapy for the nonpurging bulimic individual: a controlled comparison J Consult Clin Psychol 1993 61 : 296–305.

Agras WS, Telch CF, Arnow B, Eldredge K, Wilfley DE, Raeburn SD, Henderson J, Marnell M . Weight loss, cognitive-behavioral, and desipramine treatments in binge eating disorder: an additive design Behav Ther 1994 25 : 225–238.

Agras WS, Telch CF, Arnow B, Eldredge K, Detzer MJ, Henderson J, Marnell M . Does interpersonal therapy help patients with binge eating disorder who fail to respond to cognitive-behavioral therapy? J Consult Clin Psychol 1995 63 : 356–360.

Eldredge KL, Agras WS, Arnow B, Telch CF, Bell S, Castonguay L, Marnell M . The effects of extending cognitive-behavioral therapy for binge eating disorder among initial treatment nonresponders Int J Eating Disord 1997 21 : 347–352.

Peterson CB, Mitchell JE, Engbloom S, Nugent S, Mussell MP, Miller JP . Group cognitive-behavioral treatment of binge eating disorder: a comparison of therapist-led versus self-help formats Int J Eating Disord 1998 24 : 125–136.

Carter JC, Fairburn CG . Cognitive-behavioral self-help for binge eating disorder: a controlled effectiveness study J Consult Clin Psychol 1998 66 : 616–623.

Fairburn CG . Overcoming binge eating The Guilford Press: New York 1993.

Fairburn CG . A cognitive behavioural approach to the treatment of bulimia Psychol Med 1981 11 : 707–711.

Klerman GL, Weissman MM, Rounsaville BJ, Chevron ES . Interpersonal psychotherapy of depression Basic Books: New York 1984.

Fairburn CG, Jones R, Peveler RC, Carr SJ, Solomon RA, O'Connor ME, Burton J, Hope RA . Three psychological treatments for bulimia nervosa Arch Gen Psychiat 1991 48 : 463–469.

Wilfley DE, Mackenzie KR, Welch RR, Ayres VE, Weissman MM . Interpersonal psychotherapy for group Basic Books: New York 2000.

Wilfley DE, Frank MA, Welch R, Borman Spurrell E, Rounsaville BJ . Adapting interpersonal psychotherapy to a group format (IPT-G) for binge eating disorder: toward a model for adapting empirically supported treatments Psychother Res 1998 8 : 379–391.

Greeno CG, Wing R . A double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of the effect of fluoxetine on dietary intake in overweight women with and without binge-eating disorder Am J Clin Nutr 1996 64 : 267–273.

Hudson JI, McElroy SL, Raymond NC, Crow S, Keck PEJ, Carter J, Mitchell J, Strakowski SM, Pope HGJ, Coleman BS, Jonas JM . Fluvoxamine in the treatment of binge-eating disorder: a multicenter placebo-controlled, double-blind trial Am J Psychiat 1998 155 : 1756–1762.

McElroy SL, Casuto LS, Nelson EB, Lake KA, Soutullo CA, Keck PE, Hudson JI . Placebo-controlled trial of sertraline in the treatment of binge eating disorder Am J Psychiatr 2000 157 : 1004–1006.

Stunkard A, Berkowitz R, Tanrikut C, Reiss E, Young L . D -Fenfluramine treatment of binge eating disorder Am J Psychiat 1996 153 : 1455–1459.

Fairburn CG, Cooper Z, Doll HA, Norman PA, O'Connor ME . The natural course of bulimia nervosa and binge eating disorder in young women Arch Gen Psychiat 2000 57 : 659–665.

Cachelin FM, Striegel-Moore RH, Elder KA, Pike KM, Wilfley DE, Fairburn CG . Natural course of a community sample of women with binge eating disorder Int J Eating Disord 1999 25 : 45–54.

Fichter MM, Quadflieg N, Gnutzmann A . Binge eating disorder: treatment outcome over a 6-year course J Psychosom Res 1998 44 : 385–405.

Fairburn CG, Welch SL, Norman PA, O'Connor ME, Doll HA . Bias and bulimia nervosa: how typical are clinic cases? Am J Psychiat 1996 153 : 386–391.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Robert-Fleury Stichting, National Centre for Eating Disorders, Leidschendam, The Netherlands

AE Dingemans, MJ Bruna & EF van Furth

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to AE Dingemans .

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Dingemans, A., Bruna, M. & van Furth, E. Binge eating disorder: a review. Int J Obes 26 , 299–307 (2002). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ijo.0801949

Download citation

Received : 06 December 2000

Revised : 14 March 2001

Accepted : 07 November 2001

Published : 11 March 2002

Issue Date : 01 March 2002

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ijo.0801949

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- binge eating disorder

This article is cited by

Investigation of the role of difficulty in emotion regulation in the relationship between attachment styles and binge eating disorder.

- Zehra Bekmezci

- Safiye Elif Çağatay

Current Psychology (2024)

Prevalence and associated factors of binge eating disorder among Bahraini youth and young adults: a cross-sectional study in a self-selected convenience sample

- Zahraa A. Rasool Abbas Abdulla

- Hend Omar Almahmood

- Adel Salman Alsayyad

Journal of Eating Disorders (2023)

Neural circuit control of innate behaviors

- Zhuo-Lei Jiao

- Xiao-Hong Xu

Science China Life Sciences (2022)

A review on association and correlation of genetic variants with eating disorders and obesity

- Sayed Koushik Ahamed

- Md Abdul Barek

- S. M. Naim Uddin

Future Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences (2021)

Deep Brain Stimulation in the Nucleus Accumbens for Binge Eating Disorder: a Study in Rats

- D. L. Marinus Oterdoom

- Gertjan van Dijk

Obesity Surgery (2020)

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

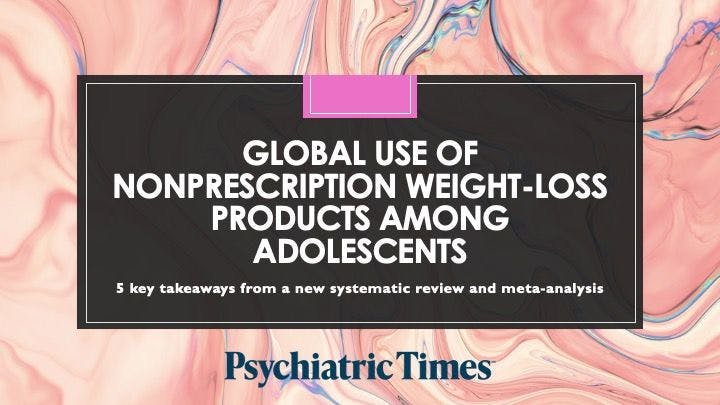

New Research: Revealing the True Duration of Binge-Eating Disorder

Investigators at McLean Hospital found 61% and 45% of individuals still experiencing binge-eating disorder after 2.5 and 5 years after their initial diagnoses, respectively.

Wanlee/AdobeStock

A new 5-year study from investigators at McLean Hospital shows that binge-eating disorder lasts much longer and the likelihood of relapse is much higher than previously suggested, with 61% of individuals still experiencing binge-eating disorder after 2.5 years and 45% still experiencing it 5 years after their initial diagnoses. 1

"It's noteworthy that in high-quality randomized clinical trials of specific treatments for binge-eating disorder, the percentage of participants still experiencing binge eating several years after the treatment ended was lower than the analogous percentage of participants in our naturalistic study, few of whom were probably receiving evidence-based treatments,” study first author Kristin Javaras, DPhil, PhD, an assistant psychologist in the Division of Women’s Mental Health at McLean, exclusively told Psychiatric Times . “This suggests that adults with binge-eating disorder may be more likely to get better if they receive evidence-based care than if they do not undergo treatment.”

Investigators studied 137 adult community members with binge-eating disorder for 5 years in order to better understand the duration of this disorder. Participants included individuals who aged anywhere from 19 to 74 and had an average BMI of 36. They were assessed for binge-eating disorder at the study outset and reexamined both 2.5 and 5 years later.

After 5 years, most participants still experienced binge-eating episodes, with 46% of participants meeting the full criteria and a further 33% experiencing clinically significant but subthreshold symptoms. After 2.5 years, 61% of participants still met the full criteria for binge-eating disorder at the time the study was conducted, and a further 23% experienced clinically significant symptoms, although they were below the threshold for binge-eating disorder. Furthermore, approximately 35% of the participants in remission at the 2.5-year follow-up had relapsed to either full or subthreshold binge-eating disorder at the 5-year follow-up. Following the study’s completion, the criteria for diagnosing binge-eating disorder changed and under these new guidelines, an even larger percentage of the study’s participants would have been diagnosed with the disorder at the 2.5 and 5-year follow-ups.

“The big takeaway is that binge-eating disorder does improve with time, but for many people it lasts years,” Javaras shared in a press release. “As a clinician, oftentimes the clients I work with report many, many years of binge-eating disorder, which felt very discordant with studies that suggested that it was a transient disorder. It is very important to understand how long binge-eating disorder lasts and how likely people are to relapse so that we can better provide better care.” 2

Previous prospective studies had limitations, including a small sample size (less than 50 participants), and they focused only on adolescent or young-adult females, most of whom had BMIs less than 30, whereas around two-thirds of individuals with binge-eating disorder have BMIs of 30 or more.

Also worth noting is the study’s more accurate representation of binge-eating disorder’s natural duration, as the participants were community members who were possible receiving treatment, not actual patients enrolled in a treatment program. In comparing the community sample with those in treatment studies, it appears that treatments lead to faster remission. This reinforces the need for intervention in patients with eating disorders.

Investigators were unable to identify strong clinical or demographic predictors for the duration of binge-eating disorder. “This suggests that no one is much less or more likely to get better than anyone else,” Javaras said. 2

Binge-eating disorder is the most prevalent eating disorder, with 1% to 3% of US adults affected.3 Following the study’s completion, investigators have been working to develop treatment options and screening methods for this common disorder to best improve patient outcomes.

“We are studying binge-eating disorder with neuroimaging to get a better understanding of the neurobiology involved, which could help enhance or develop new treatments,” said Javaras. “We are also examining ways to catch people earlier, because many do not even realize they have binge-eating disorder, and there is a major need for increased awareness and screening so that intervention can begin earlier.” 2

Full results were published today, May 28, in Psychological Medicine .

1. Javaras KN, Franco VF, Ren B, et al. The natural course of binge-eating disorder: findings from a prospective, community-based study of adults. Psychol Med . 2024:1-11.

2. Binge-eating disorder not as transient as previously thought. News release. May 28, 2024.

3. Eating disorders. National Institute of Mental Health. Accessed May 24, 2024. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/eating-disorders

Recap: Eating Disorders 2024

Eating Disorders: Research and Future Directions

Eating Disorders in BIPOC Communities

Treatment for Eating Disorders and the Path to Wellness

Global Use of Nonprescription Weight-Loss Products Among Adolescents: 5 Key Takeaways

Eating Disorders in Psychiatric Times

2 Commerce Drive Cranbury, NJ 08512

609-716-7777

- May 31, 2024 | Witnessing Cosmic Dawn: Webb Captures Birth of Universe’s Earliest Galaxies for First Time

- May 31, 2024 | Ancient Roots, Modern Insights: New Study Reveals Age-Old Secrets of Camas Cultivation

- May 31, 2024 | Venus Erupts: Fresh Volcanic Activity Revealed in NASA’s Magellan Data

- May 31, 2024 | Rewriting the Rules of Power: Korean Researchers Develop Revolutionary New Lightweight Structure for Lithium Batteries

- May 31, 2024 | The Future of Contraception: Scientists Develop Potential Non-Hormonal Birth Control Pill for Men

Persistent Cravings: What a Five-Year Study Reveals About Binge-Eating Disorder

By McLean Hospital May 28, 2024

A five-year study by McLean Hospital found that binge-eating disorder persists longer than previously thought, with significant percentages of individuals still affected after 2.5 and 5 years. This challenges earlier research suggesting quicker remission and highlights the importance of continued intervention and improved treatment strategies.

McLean Hospital researchers show that binge-eating disorder lasts longer than expected and relapse is common, with many still affected years after diagnosis.

In the United States, binge-eating disorder is the most prevalent eating disorder. However, previous studies have presented conflicting views of the disorder’s duration and the likelihood of relapse.

A new five-year study led by investigators from McLean Hospital, part of the Mass General Brigham healthcare system, revealed that 61% of individuals continued to experience symptoms of binge-eating disorder 2.5 years after being diagnosed, and 45% still exhibited symptoms after five years. These findings challenge earlier prospective studies that suggested quicker recovery times, the researchers noted.

Key Findings and Implications

“The big takeaway is that binge-eating disorder does improve with time, but for many people it lasts years,” said first author Kristin Javaras, DPhil, PhD, assistant psychologist in the Division of Women’s Mental Health at McLean. “As a clinician, oftentimes the clients I work with report many, many years of binge-eating disorder, which felt very discordant with studies that suggested that it was a transient disorder. It’s very important to understand how long binge-eating disorder lasts and how likely people are to relapse so that we can better provide better care.”

The results were published May 28 in Psychological Medicine , published by Cambridge University Press.

Disorder Characteristics and Study Methodology

Binge-eating disorder, which is estimated to impact somewhere between 1 percent and 3 percent of U.S. adults, is characterized by episodes during which people feel a loss of control over their eating. The average age of onset is 25 years.

While previous retrospective studies, which rely on people’s sometimes-faulty memories, have reported that binge-eating disorder lasts seven to sixteen years on average, prospective studies tracking individuals with the disorder over time have suggested that many individuals with the disorder enter remission within a much smaller timeframe—from one to two years.

However, the researchers noted that most previous prospective studies had limitations, including a small sample size (<50 participants), and they were not representative because they focused only on adolescent or young-adult females, most of whom had BMIs less than 30, whereas around two-thirds of individuals with binge-eating disorder have BMIs of 30 or more.

Long-Term Trends and Treatment Insights

To better understand the time-course of binge-eating disorder, the researchers followed 137 adult community members with the disorder for five years. Participants, who ranged in age from 19 to 74 and had an average BMI of 36, were assessed for binge-eating disorder at the beginning of the study and re-examined 2.5 and 5 years later.

After five years, most of the study participants still experienced binge-eating episodes, though many showed improvements. After 2.5 years, 61 percent of participants still met the full criteria for binge-eating disorder at the time the study was conducted, and a further 23 percent experienced clinically significant symptoms, although they were below the threshold for binge-eating disorder. After 5 years, 46 percent of participants met the full criteria and a further 33 percent experienced clinically significant but sub-threshold symptoms. Notably, 35 percent of the individuals who were in remission at the 2.5-year follow-up had relapsed to either full or sub-threshold binge-eating disorder at the 5-year follow-up. The criteria for diagnosing binge-eating disorder have changed since the study was conducted, and Javaras notes that under the new guidelines, an even larger percentage of the study’s participants would have been diagnosed with the disorder at the 2.5 and 5-year follow-ups.

Javaras added that because participants in the study were community members who may or may not have been receiving treatment, rather than patients enrolled in a treatment program, the study’s results are more representative of binge-eating disorder’s natural time-course. When comparing this community sample to those in treatment studies, treatment appeared to lead to faster remission, suggesting that people with binge-eating disorders will benefit from intervention. There are major inequities in who receives treatment for eating disorders, according to Javaras.

Though there was variation amongst participants in the likelihood of remission and how long it took, the researchers were unable to find any strong clinical or demographic predictors for duration of the disorder.

“This suggests that no one is much less or more likely to get better than anyone else,” said Javaras.

Research Directions and Future Treatment

Since the study’s conclusion, the researchers have been investigating and developing treatment options for binge-eating disorder, and examining screening methods to better identify individuals who would benefit from treatment.