Tune In Live: State Policy Efforts To Improve Prescription Drug Affordability for Consumers

Center for American Progress

Homework and Higher Standards

- Report PDF (736 KB)

How Homework Stacks Up to the Common Core

CAP analysis found that homework is generally aligned to Common Core State Standards, but additional policy changes would make it more valuable.

Education, Education, K-12, Modernizing and Elevating the Teaching Profession

Media Contact

Mishka espey.

Senior Manager, Media Relations

[email protected]

Sarah Nadeau

Associate Director, Media Relations

Government Affairs

Madeline shepherd.

Director, Federal Affairs

In this article

Introduction and summary

For as long as homework has been a part of school life in the United States, so too has the debate over its value. In 1900, a prominent magazine published an article on the evils of homework titled, “A National Crime at the Feet of Parents.” 1 The author, Edward Bok, believed that homework or too much school learning outside the classroom deprived children of critical time to play or participate in other activities at home. The very next year, California, influenced by those concerns, enacted a statewide prohibition on homework for students under the age of 15. 2 In 1917, the state lifted the ban, which has often been the case as districts have continually swung back and forth on the issue. 3

InProgress Stay informed on the most pressing issues of our time.

This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

More than 100 years later, homework remains a contentious issue, and the debate over its value rages on, with scholars coming down on both sides of the argument. Homework skeptic Alfie Kohn has questioned the benefit of homework, arguing that its positive effects are mythical, and in fact, it can disrupt the family dynamic. 4 He questions why teachers continue to assign homework given its mixed research base. Taking the opposite view, researchers Robert Marzano and Debra Pickering have voiced their support for purposeful homework that reinforces learning outside of school hours but still leaves time for other activities. 5

In 1989, prominent homework scholar Harris Cooper published a meta-analysis of more than 100 studies on homework in a survey that found a correlation between homework and performance on standardized tests, but only for certain grade levels. According to Cooper’s research, for students in late-elementary grades through high-school, there was a link between homework and improved standardized test performance. However, there was no evidence of the same correlation for younger students. 6 Even without a connection to academic achievement, Cooper still recommended assigning homework to younger students because it helps “develop good study habits, foster positive attitudes toward school, and communicate to students the idea that learning takes work at home as well as school.” 7

Far from academia, parents—not surprisingly—are some of homework’s most ardent supporters and, also, its most vocal critics. For better or worse, many parents help or are involved in their child’s homework in some way. As a result, homework can shape family dynamics and weeknight schedules. If a child receives too much homework, or only busywork, it can cause stress within families and resentment among parents. 8 Some parents report spending hours each night helping their children. For instance, a 2013 article in The Atlantic detailed a writer’s attempt to complete his 13-year-old daughter’s homework for a week. The headline simply read: “My Daughter’s Homework Is Killing Me.” 9 The father reported falling asleep trying to thoughtfully complete homework, which took around three hours per night. 10 On the other hand, some parents appreciate the glimpse into their child’s daily instruction and value homework’s ability to build positive learning habits.

It is no surprise that the debate over homework often spills onto the pages of newspapers and magazines, with calls to abolish homework regularly appearing in the headlines. In 2017, the superintendent of Marion County Public Schools in Florida joined districts in Massachusetts and Vermont in announcing a homework ban. To justify his decision, he used research from the University of Tennessee that showed that homework does not improve student achievement. 11 Most recently, in December 2018, The Wall Street Journal published a piece that argued that districts were “Down With Homework”—banning it, placing time caps or limiting it to certain days, or no longer grading it—in order to give students more time to sleep, read, and spend time with family. 12

Given the controversy long surrounding the issue of homework, in late spring 2018, the Center for American Progress conducted an online survey investigating the quality of students’ homework. The survey sought to better understand the nature of homework as well as whether the homework assigned was aligned to rigorous academic standards. Based on the best knowledge of the authors, the CAP survey and this report represent the first-ever national study of homework rigor and alignment to the Common Core State Standards—rigorous academic standards developed in a state-led process in 2010, which are currently in place in 41 states and Washington, D.C. The CAP study adds to existing research on homework by focusing on the quality of assignments rather than the overall value of homework of any type. There are previous studies that considered parental involvement and the potential stress on parents related to homework, but the authors believe that this report represents the first national study of parent attitudes toward homework. 13

For the CAP study, the authors used the Amazon Mechanical Turk (MTurk) online survey tool to collect from parents their child’s actual homework assignments. Specifically, as part of the survey, the authors asked parents to submit a sample of their child’s most recent math or language arts homework assignment and have the child complete questions to gauge if the assignment was challenging, as well as how long it took to complete the assignment. In all, 372 parents responded to the survey, with CAP analyzing 187 homework assignments.

Admittedly, the methodological approach has limitations. For one, it’s a convenience sample, which means people were not selected randomly; and broadly speaking, the population on the MTurk site is younger and whiter than the U.S. population as a whole. However, research has shown that MTurk yields high-quality, nationally representative results, with data that are at least as reliable as those obtained via traditional methods. 14

In addition, the homework sample is not from a single classroom or school over the course of a year; rather, it is a snapshot of homework across many classrooms during the span of a few weeks in May 2018. The assumption is that looking at assignments from many classrooms over a short period of time helps to construct a composite picture of mathematics and language arts homework.

Moreover, the design of the CAP study has clear advantages. Many of the previous existing studies evaluated homework in a single district, whereas the CAP study draws from a national sample, and despite its limitations, the authors believe that the findings are robust and contribute significantly to the existing research on homework.

Three key findings from the CAP survey:

- Homework is largely aligned to the Common Core standards. The authors found that the homework submitted is mostly aligned to Common Core standards content. The alignment index that the authors used evaluated both topic and skill. As previously noted, the analysis is a snapshot of homework and, therefore, does not allow the authors to determine if homework over the course of a year covered all the topics represented in the standards.

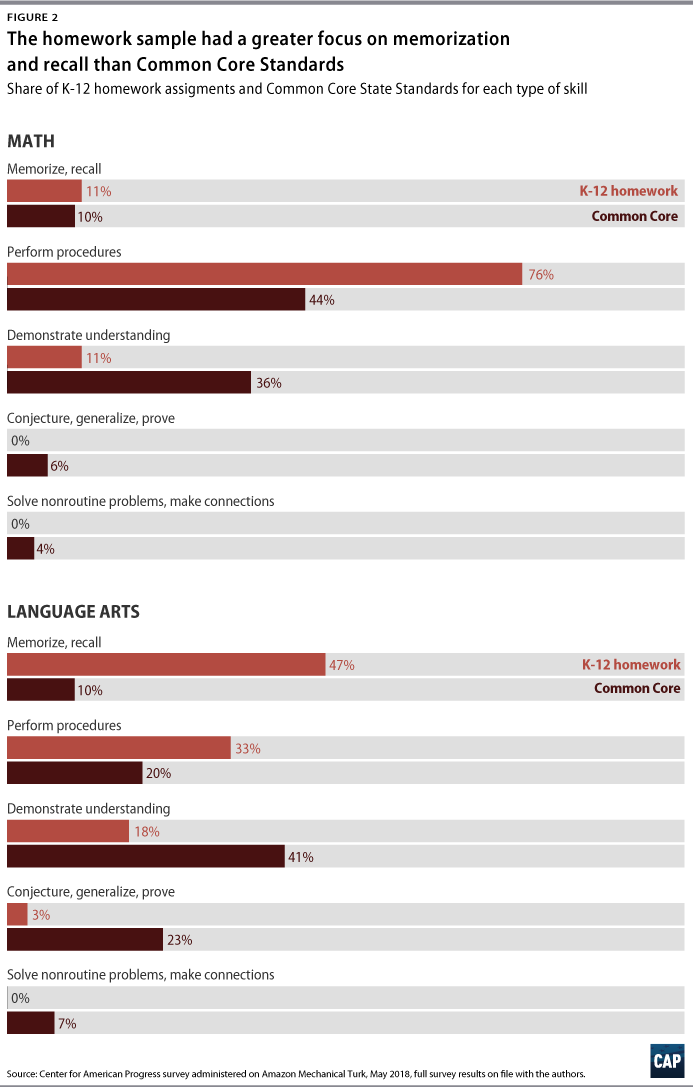

- Homework is often focused on low-level skills in the Common Core standards, particularly in the earlier grades. While the authors’ analysis shows that there was significant alignment between Common Core and the topics represented in the homework studied, most of the assignments were fairly rote and often did not require students to demonstrate the full depth of knowledge required of the content standards. There was clear emphasis on procedural knowledge, and an even stronger emphasis on memorization and recall in language arts. Common Core content standards, on the other hand, require students to demonstrate deeper knowledge skills, such as the ability to analyze, conceptualize, or generate. 15

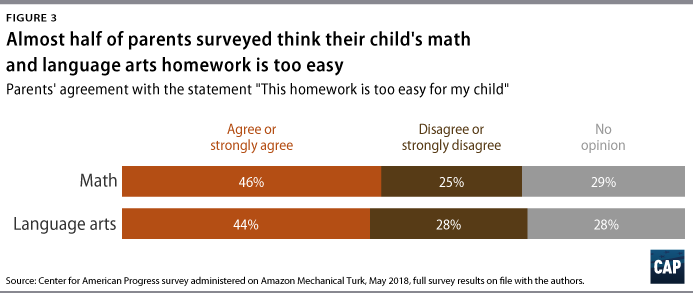

- Homework frequently fails to challenge students. Nearly half of the parents who responded to the CAP survey reported that homework is too easy for their child. In particular, parents of primary-grade children were most likely to agree or strongly agree that the homework assignment they submitted was too easy for their child.

Based on these key findings, CAP recommends that states, districts, and schools improve the quality of homework and increase opportunities for students to practice rigorous grade-level content at home. Specifically, the authors—drawing from this survey and other existing research on homework—recommend the following actions to improve the role of homework in education:

- Schools and districts should develop homework policies that emphasize strategic, rigorous homework. In many cases, the homework debate is limited and short-sighted. Currently, many arguments focus on whether or not students should have homework at all, and there are entire school districts that have simply banned homework. Instead of debating the merits of banning homework, reformers and practitioners should focus on improving the rigor and effectiveness of all instructional materials, including

Districts, schools, and teachers should ensure that the total amount of homework students receive does not exceed the 10-minute rule—that is to say, no more than 10 minutes of homework multiplied by the student’s grade level. 16 According to research, any more than that can be counterproductive. 17 Also, too much homework may be an unnecessary burden on families and parents. Homework should be engaging and aligned to Common Core standards, which allow students to develop deeper-level learning skills—such as analysis or conceptualization—that help them increase retention of content.

- Districts and schools should periodically audit homework to make sure it is challenging and aligned to standards. Rather than implementing homework bans, district policymakers and school principals should regularly review examples of homework assignments to ensure that it is aligned to grade-level standards and requires students to demonstrate conceptual learning. In instances where the district or school finds that homework assignments are not aligned or take too much or too little time to complete, they should help teachers improve homework assignments by recommending instructional materials that may make it easier for them to identify appropriate, grade-level homework assignments.

- Schools and districts should provide access to technology and other supports that can make it easier for students to complete rigorous schoolwork at home. Technology can also provide additional support or scaffolding at home, allowing more students to complete homework without help from adults or older siblings. For instance, programs such as the Khan Academy can give students rigorous homework that’s aligned to Common Core standards. 18 Unfortunately, many households across the nation still do not have adequate access to devices or internet at home. Schools and districts should consider options to ensure that all students can benefit from technology and broadband. Greater access to technology can help more students benefit from continual innovation and new tools. While most of these technologies are not yet research-based, and the use of devices may not be appropriate for younger children, incorporating new tools into homework may be a low-cost method to improve the quality of student learning.

- Curriculum reform and instructional redesign should focus on homework. There are many states and districts that are reforming curriculum or adopting different approaches to instruction, including personalized learning. Curriculum reform and personalized learning are tied to greater academic outcomes and an increase in motivation. Homework should also be a focus of these and other efforts; states and districts should consider how textbooks or other instructional materials can provide resources or examples to help teachers assign meaningful homework that will complement regular instruction.

The findings and recommendations of this study are discussed in detail below.

Homework must be rigorous and aligned to content standards

All homework is not created equal. The CAP study sought to evaluate homework quality—specifically, if homework is aligned to rigorous content standards. The authors believe that access to grade-level content at home will increase the positive impact of adopting more rigorous content standards, and they sought to examine if homework is aligned to the topics and skill level in the content standards.

The 10-minute rule

According to Harris Cooper, homework is a valuable tool, but there is such a thing as too much. In 2006, Cooper and his colleagues argued that spending a lot of time on homework can be counterproductive. He believes that research supports the 10-minute rule—that students should be able to complete their homework in no more than 10 minutes multiplied by their grade. For example, this would amount to 20 minutes for a second-grade student, 50 minutes for a fifth-grade student, and so on. 19

The Common Core, developed by the National Governors Association and the Council of Chief State School Officers, established a set of benchmarks for “what students should know and be able to do” in math and language arts by the end of the academic year in kindergarten through high school. 20 The math standards focus on fewer concepts but in more depth and ask students to develop different approaches to solve similar problems. In language arts, the standards moved students away from narrative-based assignments, instead concentrating on using evidence to build arguments and reading more nonfiction.

The Common Core is not silent in the cognitive demand needed to demonstrate mastery for each standard. 21 For example, a second grade math standard is “[s]olve word problems involving dollar bills, quarters, dimes, nickels, and pennies, using $ and ¢ symbols appropriately.” For this standard, a second-grader has not mastered the standard if they are only able to identifying the name and value of every.

Remember, apply, integrate: Levels of cognitive demand or depth of knowledge

There are numerous frameworks to describe levels of cognitive skills. One of the most prominent of these models, Bloom’s taxonomy, identifies six categories of cognition. The original levels and terms were knowledge, comprehension, application, analysis, synthesis, and evaluation; however, these terms have changed slightly over time. 22 Learning does not necessarily follow a linear process, and certainly, all levels of cognitive demand are important. Yet these categories require individuals to demonstrate a different level of working knowledge of a topic. With the advent of standards-based reform, the role of cognitive skill—particularly in the area of assessment—has become a much more explicit component of curriculum materials.

Over the past two decades, cognitive science has shown that individuals of any age retain information longer when they demonstrate deeper learning and make their own meaning with the content—using skills such as the abilities to conjecture, generalize, prove, and more—as opposed to only committing ideas to memory or performing rote procedures, using skills such as the ability to memorize or recall.

In essence, Common Core created rigorous expectations to guide the instruction of students in all states that chose to adopt its standards. These standards aimed to increase college preparedness and make students more competitive in the workforce. Policymakers, advocates, and practitioners hoped that Common Core would create greater consistency in academic rigor across states. In addition, with the classroom and homework aligned to these standards, many anticipated that students would graduate from high school prepared for college or career. As of 2017, 41 states and the District of Columbia have adopted and are working to implement the standards, although many of these states have modified them slightly. 23

In this study, the authors evaluated homework to determine if it was aligned to Common Core standards in two ways: First, does it reflect grade-level content standards; second, does it require students to use skills similar to those required to demonstrate proficiency in a content area. This multitiered approach is critical to evaluating alignment between standards and instruction—in this case homework. Instruction must teach content and help students develop necessary levels of cognitive skill. Curricula for each grade should include instructional materials that are sequenced and rigorous, thus enabling students to develop an understanding of all content standards.

In spring 2018, the Center for American Progress used Amazon Mechanical Turk (MTurk) to administer a survey. MTurk is a crowdsourcing marketplace managed by Amazon; it allows organizations to virtually administer surveys for a diverse sample. 24 The CAP survey asked parents to submit a sample of their child’s most recent math or language arts homework assignment and complete a few questions to gauge if the assignment was challenging, as well as how long it took for the student to complete the assignment. A total of 372 parents responded to the survey, and CAP analyzed 187 homework assignments.

Of the 372 parents who participated in the survey, 202, or about 54 percent of respondents, submitted samples of their child’s homework assignment. The researchers dropped a total of 15 homework submissions from analysis either because the subject matter was not math or language arts—but rather, science, music, or social studies—or because the authors could not examine the specific content, for example, in cases where parents only provided a copy of the cover of a textbook. Of the remaining homework samples submitted, 72 percent (134 samples) focused on mathematics content, while the remaining 28 percent (53 samples) represented language arts content.

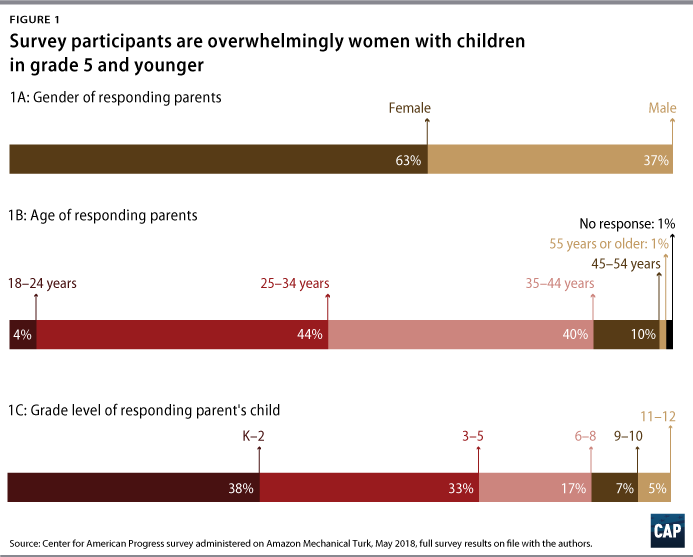

Of the 372 responding parents, 234—or 63 percent—were female, and 126—or 37 percent—were male. Forty-eight percent of parents responding to the survey were under the age of 34, while almost 90 percent of respondents were under the age of 45. There was an unequal distribution of parents representing elementary and secondary grade levels. Seventy-one percent of the total sample were parents with students in primary (K-2) and elementary (3-5) grades. (See Methodology section below)

Based on the analysis, the authors’ drew the following conclusions:

Homework is largely aligned to Common Core standards, especially the topics in the standards

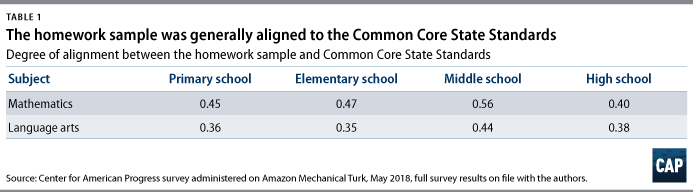

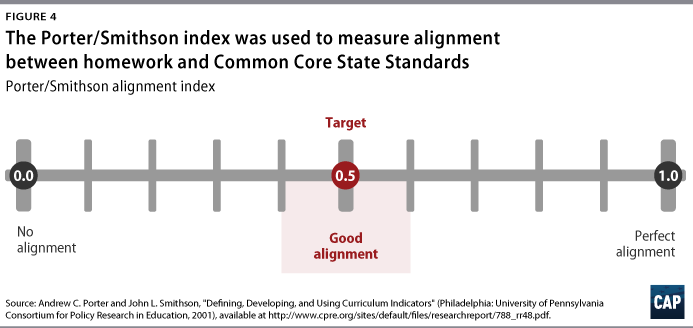

The authors found that the submitted homework, for the most part, was aligned to Common Core standards content or within the so-called “good” range based on content expert evaluations. As described in the Methodology, the authors used an alignment index that does not require a homework assignment to exactly mirror the content standards—both topic and skill level—for evaluators to note that it is within a good range. For context, the study’s alignment index has a range of 0.00 to 1.00, where 0.00 indicates no content in common whatsoever between the two descriptions—perfect misalignment—and 1.00 indicates complete agreement between the two descriptions—perfect alignment. Generally speaking, what one might call “good” alignment for instruction tends to range on the alignment index between 0.4 and 0.6, with a measure of 0.5 serving as a median indicator of good alignment.

The analysis is a snapshot of homework and, therefore, does not allow the authors to determine if homework over the course of a year covered all required standards. In other words, it is difficult to say how many of the standards for a given grade are covered across a full school year, simply because of the limited sample of assignments.

The alignment index evaluates both topic and skill, but there was particular alignment in topic areas. For instance, there was a strong emphasis in the topic areas of number sense and operations for primary math homework. When combined with the third-most emphasized topic, measurement, these three areas accounted for more than 90 percent of primary mathematics homework content. The actual math content standards for the primary grades also placed heavy emphasis on the topic areas of number sense, operations, and measurement—though they accounted for only about 80 percent of primary math content.

In general, across all age groups, math homework was more closely aligned to content standards—both topic and skill level—than language arts. The alignment results for middle school math were particularly strong, at 0.56, based on 27 homework samples. The stronger alignment among math homework samples may be in part due to the fact that there were more math assignments in the sample than language arts assignments. Larger samples offer more opportunities to show alignment. As a result, smaller samples may underestimate alignment.

The table below presents the alignment indices, which were calculated using the homework samples collected for each grade band.

Homework is often focused on low-level skills in the standards, particularly in younger grades

While the authors’ analysis shows that there was significant alignment in the topic of standards and homework assignments, most of the homework did not require students to demonstrate the full depth of knowledge required of content standards. The analysis uncovered an emphasis on procedural knowledge, with an even stronger emphasis on memorization and recall in language arts. Content standards, on the other hand, require students to demonstrate deeper-knowledge skills, such as the ability to analyze, conceptualize, or generate.

Of five performance expectation categories across math and language arts that the authors used to measure alignment between standards and homework, there was a disproportionate emphasis on skills that require a lower level of knowledge or understanding. In grades K-2, for instance, the content standards emphasize the performance expectations of “procedures,” or computation, and “demonstrate,” or understanding, but the homework samples submitted primarily emphasized the procedures level of performance expectation. Similarly, homework for grades three through five focused almost entirely on the performance expectation of procedures, rather than standards that emphasized both procedures and demonstrate. 25

As seen with the middle school grades, high school math standards—despite a continued emphasis on procedures—show increased emphasis on the more challenging performance expectations of “demonstrate understanding” and “conjecture, generalize, prove.” Interestingly, this shift toward more challenging performance expectations is most visible for the topic areas of geometric concepts and functions, in both the standards and the homework samples submitted by parents of high school students.

Parents report that homework frequently does not challenge students

Nearly half of parents that participated in the survey reported that homework does not challenge their child. In particular, parents of primary-grade children were most likely to agree or strongly agree that the homework assignment they submitted was too easy for their child—58 percent for language arts and 55 percent for math.

Parents’ opinions about homework difficulty varied between mathematics and language arts assignments. Forty-eight percent of parents who submitted a mathematics assignment and 44 percent of parents who submitted a language arts assignment reported that it was too easy for their child. There was some variance across grade spans as well. As noted above, parents of primary-grade children were most likely to find the homework assignments too easy for their child. Meanwhile, parents that submitted high school math homework were also more likely to agree or strongly agree that the assignments were too easy, with 50 percent agreeing or strongly agreeing and only 33 percent disagreeing or strongly disagreeing with the statement. While there were clear trends in parent opinions, it is important to acknowledge that the sample size for each subset was small.

The comments of surveyed parents echoed this finding. One parent noted that “most homework that they are assigned seems like nothing more than busy work.” Another parent said: “The homework is not strong enough to build conceptual knowledge. It assumes that the child already has that knowledge.” Meanwhile, another parent commented: “Homework is way oversimplified and they don’t seem to spend much time on it. It’s a bit sad that English and math don’t seem to require what they used to. I remember much longer and harder worksheets to complete when I was a child.” 26

Weak homework samples

Within the sample of homework assignments, there were some that fell short of rigorous. For instance, one assignment listed 24 pairs of numbers—three and nine, 24 and 21, and so on—and asked the student to circle the smaller number in order to build numbers sense. While homework can be critical when establishing foundational knowledge, repetitive activities such as this often fail to engage students and, instead, overemphasize rote learning. Asking a student to list or name a number of a lesser value, for instance, would make this assignment more interactive.

A second example from kindergarten asked a student to create an uppercase and lowercase letter “f” by filling in dots with paint. The parent who submitted it highlighted the limited utility of the assignment, emphasizing that it does not hold students to high expectations. What’s more, the homework only gave the student two opportunities to practice writing the letter, both in a nonauthentic way. Indeed, the assignment focused more on filling in circles than it did constructing letters. While this task might help build a kindergartener’s hand-eye coordination, it does little to support language arts.

Exemplary homework samples

While many of the assignments submitted focused on procedures and, for math, computation, it is worth acknowledging some of the more exemplary types of homework included in the samples. These offer examples of how homework can challenge students, engage rigorous cognitive processes, and demonstrate that content standards at all levels—not just middle and high school—can support challenging homework that pushes students to think critically.

For example, one math homework assignment asked a student to identify which individuals possessed each of four groups of shapes based on the following description:

Ally, Bob, Carl, and Dana each have a set of shapes.

- Bob has no triangles.

- The number of rectangles that Dana has is the same as the number of triangles that Carl has.

This example is interesting on two counts. First, the assignment goes beyond procedure, requiring the student to analyze the various sets of shapes in order to determine which set belongs to which individual. It is also interesting insofar as it demonstrates a common real-world situation: There is usually more than one way to solve a problem, and sometimes, there is more than one correct answer.

Similarly, another example asked a student to determine actions that would help students beautify the school. The header of the assignment read, “Make a Decision: Keep Our School Beautiful!” The assignment had various boxes, each with a question above, such as, “Should we recycle?” or “Should we make art?” The assignment asked the student to “(1) think about each choice, (2) consider how each choice would affect them and others in the school community, (3) write their ideas in boxes below.” In doing so, it required primary students to analyze and generate ideas—both of which are skills that promote deeper learning.

Recommendations

Homework offers a valuable window into the curricula, assessment practices, and instructional preferences of teachers. It provides insight into classroom learning as well as the types of knowledge and skills the teacher believes will reinforce that instruction at home.

This analysis shows that the content and value of homework varies. While most homework within the sample was aligned to content standards, there is still a significant need to increase the rigor of homework and create opportunities for students to use higher-order skills.

Overall, schools and districts should pay more attention to homework as a reform lever. A growing body of research shows that homework is connected to learning outcomes, and as a result, schools and districts should ensure that policies help teachers provide meaningful assignments. 27 Based on this survey and the existing research on homework quality, the authors identified recommendations that can help increase the quality of homework:

Schools and districts should develop homework policies that emphasize strategic, rigorous homework

In many cases, the current debate over homework is short-sighted. Many arguments focus on whether or not students should have homework. There are entire school districts that have simply banned homework altogether. However, the debate should move beyond the merit of homework. Research shows that homework is linked to better performance on standardized assessments, especially in higher grades. 28 Many homework scholars also believe that a reasonable homework load can help develop important work habits. 29 Therefore, instead of eliminating homework outright, schools, districts, and advocates should focus on improving its rigor and effectiveness. As discussed throughout, homework should be an extension of instruction during the school day. Accordingly, policymakers and schools must make changes to homework that are in concert with curriculum reform.

Like all instruction, homework should be aligned to states’ rigorous content standards and should engage students in order to promote deeper learning and retention. To do this, homework should ask students to use higher-order skills, such as the ability to analyze or evaluate.

However, schools and districts, rather than simply assigning longer, more complicated assignments to make homework seem more challenging, should make strategic shifts. Homework assignments should be thought-provoking. But there is a such thing as too much homework. Districts and schools should ensure that teachers follow the research-supported 10-minute rule. 30 Also, teachers, schools, and districts should consider resources to set all students up for success when faced with more rigorous home assignments; homework should never be a burden or source of stress for families and parents.

Districts and schools should audit homework to make sure it is challenging and aligned to standards

Rather than implementing homework bans, district policymakers and schools should regularly review homework samples to ensure that they are aligned to grade-level standards, are engaging, require students to demonstrate higher-order skills, and adhere to the 10-minute rule. The audit should review multiple homework assignments from each classroom and consider how much time children are receiving from all subject areas, when appropriate. The district or school should ask for ongoing feedback from students, parents, and guardians in order to collect a comprehensive representation of the learning experience at home.

In instances where the district or school principal finds that homework assignments are not aligned to grade-level standards or take too much or too little time to complete, they should help the school or teachers improve them by recommending instructional materials that may make it easier for teachers to identify appropriate, grade-level homework assignments. In addition, if parents or students identify challenges to complete assignments at home, the district or school should identify solutions to ensure that all students have access to the resources and support they need to complete homework.

Schools and districts should provide access to technology and other supports that make it easier for students to complete homework

Technology can go a long way to improve homework and provide additional support or scaffolding at home. For instance, programs such as the Khan Academy—which provides short lessons through YouTube videos and practice exercises—can give students rigorous homework that is aligned to the Common Core standards. Unfortunately, many households across the nation still do not have adequate access to devices or internet at home. A 2017 ACT survey found that 14 percent of students only have access to one technology device at home. 31 Moreover, federal data from 2013 found that about 40 percent of households with school-age children do not have access to broadband. 32 It is likely that the percentage has decreased with time, but internet access remains a significant problem.

Schools and districts should adopt programs to ensure that all students can benefit from technology and broadband. For instance, Salton City, California, installed a Wi-Fi router in a school bus. Every night, the bus parks near a neighborhood with low internet connectivity, serving as a hot spot for students. 33

Moreover, greater access to technology can help more students benefit from new innovative resources. While most of these technologies are not yet research-based, and the use of devices may not be appropriate for younger children, incorporating new tools into homework may be a low-cost option to improve the quality of student learning. For instance, ASSISTments is a free web-based tool that provides immediate feedback as students complete homework or classwork. It has been proven to raise student outcomes. 34 Other online resources can complement classroom learning as well. There are various organizations that offer students free lessons in the form of YouTube videos, while also providing supplementary practice exercises and materials for educators. LearnZillion, for example, provides its users with high-quality lessons that are aligned to the Common Core standards. 35

Curriculum reform and instruction design should focus on homework

There are many states and districts that are engaging in curriculum reform. Many of these recent reform efforts show promise. In an analysis of the curricula and instructional materials used by the nation’s 30 largest school districts, the Center for American Progress found that approximately one-third of materials adopted or recommended by these districts were highly rated and met expectations for alignment. 36

Homework should be a focus of curriculum reform, and states and districts should consider how textbooks or other instructional materials can provide resources or examples to help teachers assign meaningful homework that will complement regular classroom instruction.

Personalized learning—which tailors instruction and learning environments to meet each student’s individual interests and needs—is also gaining traction as a way to increase declining engagement in schools and increase student motivation. 37 These ideas are also relevant to homework quality. A 2010 study found that when students were offered a choice of homework assignment, they were more motivated to do the work, reported greater competence in the assignments, and performed better on unit tests, compared with peers that did not have choice in homework. 38 The study also suggested that offering students a choice improved the rate of completion of assignments. 39 Districts and schools should help implement more student-centered approaches to all instruction—in the classroom and at home.

When it comes to change management, experts often advise to look for low-hanging fruit—the simplest and easiest fixes. 40 In education, homework reform is low-hanging fruit. Research shows that quality homework and increasing student achievement are positively correlated; and yet, the authors’ analysis shows that some schools may not be taking advantage of a valuable opportunity to support student achievement. Instead of mirroring the cognitive demand in rigorous content standards, homework assigned to students is often weak or rote. But it does not have to be this way. More rigorous, insightful homework is out there. Policymakers and schools need to move beyond the debate of whether or not to assign work outside of school hours and do their own due diligence—or, put another way, their own homework—before assigning homework to students in this nation’s schools.

Methodology

As mentioned above, the authors used the Amazon Mechanical Turk (MTurk) online survey tool to collect from parents their child’s actual homework assignments. Specifically, as part of the survey, the authors asked parents to submit a sample of their child’s most recent math or language arts homework assignment and have the child complete questions to gauge if the assignment was challenging, as well as how long it took to complete the assignment. In all, 372 parents responded to the survey, with CAP analyzing 187 homework assignments. The submissions of samples were analyzed by a group of analysts under the supervision of John L. Smithson, researcher emeritus at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Measuring alignment

The homework samples were reviewed by two teams of content analysts—one for mathematics and one for language arts—who were asked to describe the academic content represented by the submitted homework, as well as the performance expectation. Each team consisted of three analysts who possessed the relevant content expertise and experience in methodology used to gather the descriptive data.

The teams used a taxonomy-based methodology that was developed by education researchers Andrew Porter and John Smithson during Porter’s tenure as director of the Wisconsin Center for Education Research at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. 41 Researchers both nationally and internationally have subsequently used this approach to content description for decades in order to examine issues of alignment as well as to support program evaluation and inform school improvement efforts.

The U.S. Department of Education also recognizes the validity of this approach. Specifically, the Education Department completes a peer review of states’ annual assessment program’s alignment to state academic content standards. 42 The Porter/Smithson approach is one of a handful of alignment methodologies that has been determined to meet these federal requirements. 43

The Porter/Smithson approach is unique because it defines instructional content as a two-dimensional construct consisting of topic and cognitive demand, or skill. This approach to describing cognitive skill is similar to Bloom’s, which the authors have described above. It has five categories: recall, process, analyze, integrate, and conceptual understanding. The Porter/Smithson approach is the most stringent of alignment indicators, as it looks at both topic and cognitive demand; it is also possibly the most challenging to interpret because the final alignment score considers two dimensions.

The alignment index has a range of 0.00 to 1.00, where 0.00 indicates no content in common whatsoever between the two descriptions—perfect misalignment—and 1.00 indicates complete agreement between the two descriptions—perfect alignment. A measure of 1.00 is exceedingly unlikely, requiring perfect agreement across every cell that makes up the content description. In practice, this is only seen when comparing a document to itself. For instance, very high alignment measures—more than 0.70—have been noted when comparing different test forms used for a particular grade-level state assessment; but those are instances where high alignment is desired. In terms of instructional alignment—in other words, how well instruction is aligned to the standards—a measure of 1.00 is not the goal. For this reason, the authors did not expect any analysis of homework alignment, no matter how well designed, to have a measure of or close to 1.00.

Generally speaking, what one might call “good” alignment for instruction tends to range between 0.4 and 0.6 on the alignment index, with a measure of 0.5 serving as a median indicator of good alignment. The description of the content standards represents the goal of instructional practice—the destination, not the journey. As such, it does not indicate the best path for achieving those goals. The 0.5 indicator measure represents a middle road where teachers are balancing the expectations of the content standards with the immediate learning needs of their students.

Limitations

The authors acknowledge that the analysis has shortcomings. The sample was relatively small and does not directly mirror the national population of parents of elementary and secondary school students. As such, the sample does not necessarily reflect the views or homework experiences of the larger U.S. population.

Limited sample size

The current study analyzes a snapshot of homework across many classrooms, rather than homework from a single classroom or school. The assumption is that looking at individual homework assignments across many classrooms will help to construct a composite picture of mathematics and language arts homework that will be somewhat reflective of the picture one would get from following many classrooms for many days. If the sample is large enough with a wide enough geographical spread, that assumption serves researchers well enough.

For the current study, however, the number of homework samples available for each grade band were, in some cases, quite small—as low as five assignments each for middle and high school language arts. The largest sample sizes were for primary and elementary math, with 47 and 41 homework assignments collected, respectively. However, even 47 is a fairly small sample size for drawing inferences about a full year of homework.

Selection bias

The respondents that participated in this study were a reasonably diverse group in terms of age, gender, and ethnicity, but there are notable differences between the makeup of the parents represented in the study and the makeup of parents of school-age children more generally. Respondents were predominantly female, with women making up almost two-thirds—63 percent—of the sample. They also tended to be parents of younger school-age children, with 71 percent of the respondents reporting on children from the bottom half of the K-12 system—grades K-5. Finally, in terms of race and ethnicity, the sample overrepresented Asian American families and underrepresented African American families. These groups comprised 14 percent and 8 percent of respondents, respectively, compared with national averages of 6 percent and 12 percent.

Because the sample does not well reflect the population of parents of elementary and secondary students, the authors considered possible selection biases that may help to explain the differences in sample and overall population and that may have affected certain members of the population more than others.

For instance, the authors administered the survey using MTurk, which may have skewed the sample. In general, the population on the site is younger and whiter than the U.S. population as a whole. However, research has shown that MTurk yields high-quality, nationally representative results, with data that are at least as reliable as those obtained via traditional methods. 44 The researchers also targeted California and Texas in order to increase the diversity of the sample.

In addition, accessibility could have led to selection bias. Despite broad internet access in 2018, there remain families in low-income locales where internet access is not readily available for parents. It is also possible that older parents are less likely to be as active on the internet as younger parents, further contributing to selection bias.

About the authors

Ulrich Boser is a senior fellow at the Center for American Progress. He is also the founder and CEO of The Learning Agency.

Meg Benner is a senior consultant at the Center.

John Smithson is the researcher emeritus at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Sarah Shapiro, a former research assistant at the Center for American Progress, for her support developing the survey. They also appreciate the valuable feedback of Catherine Brown, senior fellow for Education Policy at the Center for American Progress; Tom Loveless, senior fellow at the Brookings Institution; Lisette Partelow, director of K-12 Special Initiatives at the Center; and Scott Sargrad, vice president of K-12 Education Policy at the Center.

Conflicts of interest

The author, Ulrich Boser, has a financial relationship with the creators of the online homework tool ASSISTments.

- Tom Loveless, “How Well Are American Students Learning?” (Washington: Brown Center on Education Policy , 2014), available at https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/2014-Brown-Center-Report_FINAL-4.pdf .

- Seema Mehta, “Some schools are cutting back on hoomework,” Los Angeles Times , March 22, 2009, available at http://articles.latimes.com/2009/mar/22/local/me-homework22 .

- Alfie Kohn, “Rethinking Homework,” Principal , January/February 2007, available at https://www.alfiekohn.org/article/rethinking-homework/ .

- Robert J. Marzano and Debra J. Pickering, “The Case For and Against Homework,” Educational Leadership 64 (6) (2007): 74–79, available at http://www.ascd.org/publications/educational-leadership/mar07/vol64/num06/The-Case-For-and-Against-Homework.aspx .

- Michael Winerip, “Homework Bound,” The New York Times , January 3, 1999, available at https://www.nytimes.com/1999/01/03/education/homework-bound.html .

- Marzano and Pickering, “The Case For and Against Homework.”

- Brian P. Gill and Seven L. Schlossman, “Villain or Savior? The American Discourse on Homework, 1850-2003,” Theory Into Practice 43 (3) (2004): 174–181, available at http://www.history.cmu.edu/docs/schlossman/Villiain-or-Savior.pdf .

- Karl Taro Greenfeld, “My Daughter’s Homework Is Killing Me,” The Atlantic , October 2013, available at https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2013/10/my-daughters-homework-is-killing-me/309514/ .

- Fox News, “Florida students in Marion County will no longer be assigned homework, superintendent says,” July 13, 2017, available at https://www.foxnews.com/us/florida-students-in-marion-county-will-no-longer-be-assigned-homework-superintendent-says ; Kate Edwards, “East Tennessee schools consider ‘no homework policy’,” WJHL, September 13, 2016, available at https://www.wjhl.com/news/east-tennessee-schools-consider-no-homework-policy/871720275 .

- Tawnell D. Hobbs, “Down With Homework, Say U.S. School Districts,” The Wall Street Journal, December 12, 2018, available at https://www.wsj.com/articles/no-homework-its-the-new-thing-in-u-s-schools-11544610600 .

- Marzano and Pickering, “The Case For and Against Homework”; Gill and Schlossman, “Villain or savior?”.

- Matthew J. C. Crump, John V. McDonnell, and Todd M. Gureckis, “Evaluating Amazon’s Mechanical Turk as a Tool for Experimental Behavioral Research,” PLOS ONE 8 (3) (2013): 1–18, available at https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article/file?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0057410&type=printable .

- Common Core requires students to demonstrate conceptual understanding of topics and use the information to analyze and make their own meaning. The abilities to analyze, conceptualize, and generate denote higher-order cognitive skills. The authors describe hierarchies of cognitive skills later in the report. Many of the standards use these verbs to describe what is expected. Common Core State Standards Initiative, “About the Standards,” available at http://www.corestandards.org/about-the-standards/ (last accessed January 2019).

- Robert J. Marzano and Debra J. Pickering, “The Case For and Against Homework.”

- Khan Academy, “Common Core,” available at https://www.khanacademy.org/commoncore (last accessed February 2019).

- Common Core State Standards Initiative, “What are educational standards?”, available at http://www.corestandards.org/faq/what-are-educational-standards/ (last accessed January 2019).

- William G. Huitt, “Bloom et al.’s Taxonomy of the Cognitive Domain” (Valdosta, GA: Valdosta State University, 2011), available at http://www.edpsycinteractive.org/topics/cognition/bloom.pdf .

- Solomon Friedberg and others, “The State of State Standards Post-Common Core” (Washington: Thomas B. Fordham Institute, 2018), available at http://edex.s3-us-west-2.amazonaws.com/publication/pdfs/(08.22)%20The%20State%20of%20State%20Standards%20Post-Common%20Core.pdf .

- Amazon Mechanical Turk, “Home,” available at https://www.mturk.com/ (last accessed January 2019).

- Common Core State Standards Initiative, “Read the Standards,” available at http://www.corestandards.org/read-the-standards/ (last accessed February 2019).

- Center for American Progress survey administered on Amazon Mechanical Turk, May 2018, full survey results on file with the authors.

- Lauraine Genota, “‘Homework Gap’ Hits Minority, Impoverished Students Hardest, Survey Finds,” Education Week , September 19, 2018, available at https://blogs.edweek.org/edweek/DigitalEducation/2018/09/homework_gap_education_equity_ACT_survey.html .

- John B. Horrigan, “The numbers behind the broadband ‘homework gap’,” Pew Research Center, April 20, 2015, available at http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2015/04/20/the-numbers-behind-the-broadband-homework-gap/ .

- Nichole Dobo, “What to do for kids with no internet at home? How about parking a wifi-enabled school bus near their trailer park?”, The Hechinger Report , December 23, 2014, available at https://hechingerreport.org/kids-no-internet-home-parking-wifi-enabled-school-bus-near-trailer-park/ .

- Alison Duffy, “Study Shows WPI-developed Math Homework Tool Closes the Learning Gap,” Worcester Polytechnic Institute, October 24, 2016, available at https://www.wpi.edu/news/study-shows-wpi-developed-math-homework-tool-closes-learning-gap .

- Sean Cavanagh, “LearnZillion Going After District Curriculum Business, Aims to Compete With Big Publishers,” EdWeek Market Brief, June 6, 2018, available at https://marketbrief.edweek.org/marketplace-k-12/learnzillion-going-district-curriculum-business-aims-compete-big-publishers/ .

- Lisette Partelow and Sarah Shapiro, “Curriculum Reform in the Nation’s Largest School Districts” (Washington: Center for American Progress, 2018), available at https://americanprogress.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2018/08/DistrictCurricula-report3.pdf .

- TNTP, “The Opportunity Myth” (New York: 2018), available at https://tntp.org/assets/documents/TNTP_The-Opportunity-Myth_Web.pdf ; Gallup, “Gallup Student Poll: Measure What Matters Most for Student Success,” available at https://www.gallup.com/education/233537/gallup-student-poll.aspx?utm_source=link_newsv9&utm_campaign=item_211028&utm_medium=copy&_ga=2.248421390.86741706.1543204564-175832835.1543204564 (last accessed January 2019).

- Erika A. Patall, Harris Cooper, and Susan R. Wynn, “The Effectiveness and Relative Importance of Choice in the Classroom,” Journal of Educational Psychology , 102 (4) (2010): 896–915, available at https://www.immagic.com/eLibrary/ARCHIVES/GENERAL/JOURNALS/E101100P.pdf .

- Jeremy Eden and Terri Long, “Forget the strategic transformation, going after the low-hanging fruit reaps more rewards,” The Globe and Mail, June 24, 2014, available at https://www.theglobeandmail.com/report-on-business/careers/management/bagging-simple-cheap-ideas/article19311957/ .

- U.S. Department of Education, “A State’s Guide to the U.S. Department of Education’s Assessment Peer Review Process” (Washington: 2018), available at https://www2.ed.gov/admins/lead/account/saa/assessmentpeerreview.pdf .

- Ellen Forte, “Evaluating Alignment in Large-Scale Standards-Based Assessment Systems” (Washington: Council of Chief State School Officers, 2017) available at https://ccsso.org/sites/default/files/2018-07/TILSA%20Evaluating%20Alignment%20in%20Large-Scale%20Standards-Based%20Assessment%20Systems.pdf .

- Kevin J. Mullinix and others, “The Generalizability of Survey Experiments,” Journal of Experimental Political Science 2 (2) (2015): 109–138, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/journal-of-experimental-political-science/article/generalizability-of-survey-experiments/72D4E3DB90569AD7F2D469E9DF3A94CB .

The positions of American Progress, and our policy experts, are independent, and the findings and conclusions presented are those of American Progress alone. A full list of supporters is available here . American Progress would like to acknowledge the many generous supporters who make our work possible.

Ulrich Boser

Former Senior Fellow

Senior Consultant

John Smithson

ChatGPT for Teachers

Trauma-informed practices in schools, teacher well-being, cultivating diversity, equity, & inclusion, integrating technology in the classroom, social-emotional development, covid-19 resources, invest in resilience: summer toolkit, civics & resilience, all toolkits, degree programs, trauma-informed professional development, teacher licensure & certification, how to become - career information, classroom management, instructional design, lifestyle & self-care, online higher ed teaching, current events, advice on creating homework policies.

Getting students to work on their homework assignments is not always a simple task. Teachers need to take the initiative to create homework policies that encourage students to work hard to improve their achievement in the classroom setting. Educational leadership starts with making a policy that helps students learn and achieve while competing with extracurricular activities and the interests of students.

Set high standards

Homework policies need to have high standards to encourage students to work hard on achieving the best possible results. Student achievement in school improves when teachers set high standards and tell students that they are expected to meet the standards set in the classroom.

By setting high standards for the homework policy, teachers are ensuring that the students will be more willing to work on getting assignments done. The policies for homework that teachers and parents create can help improve student understanding of materials and result in better grades and scores on standardized tests.

Focus on study skills

Teaching students in their early education is a complicated task. Teachers need to balance the age of the students with the expected school, state and federal educational standards. Although the temptation to create a homework policy that focuses on repetition and traditional assignments can make the policy easy to create, it also removes the focus from establishing strong study skills and habits to engage students in education.

Creating a homework policy for younger students in the elementary grades should avoid traditional assignments and focus on building study skills and encouraging learning. Older students after elementary school are ready to take on written assignments rather than using technology and other tools.

Putting more focus on study skills will set a stronger foundation for homework in the future. As students get into higher grades, the type of assignments will focus on writing with a pen or pencil. The age of the student must be considered and the goal is to create a strong foundation for the future.

Involve the parents

Getting parents involved in the homework policy will encourage students to study and complete the assigned tasks. Asking parents to get involved to facilitate assignments will ensure students are learning without the parents completing the assignment for their child.

The goal of involving the parents in the homework policy is getting the family to take an interest in ensuring the assignments are completed. The best assignments will allow the student to manage the work without seeking answers from a parent. That allows parents to supervise and encourage their child without giving the answers.

Give consequences for incomplete assignments

Homework is an important part of providing educational leadership in the classroom. Although parental involvement and high standards can help encourage students to study, it is also important to clearly state the consequences if assignments are incomplete or not turned in on time.

A clear homework policy will lay out the possible consequences of avoiding assignments or turning in incomplete work. Consequences can vary based on the student grade level and age, but can include lowering the grades on a report card or taking away classroom privileges.

Although it is important to provide details about the consequences of avoiding the assignments, teachers can also use a reward system to motivate students to complete their work. Rewards can focus on the entire class or on individual rewards, depending on the situation. For example, teachers can give a small candy when students complete five assignments in a row.

Consequences and rewards can serve as a motivating factor when it comes to the homework policy. By clearly stating the potential downsides and the benefits to the student, it is easier for students to focus on the work.

Creating homework policies is part of educational leadership in the classroom. Although homework must focus on helping students achieve, it also needs to clearly state the expectations and give details about the benefits and consequences of different actions. By giving a clear policy from the first day of school, the students will know what to expect and can gain motivation to work on achieving the best results.

You may also like to read

- The Homework Debate: How Homework Benefits Students

- Creating Better Online Students: A Guide for Teachers

- Ending the Homework Debate: Expert Advice on What Works

- Elementary Students and Homework: How Much Is Too Much?

- The Homework Debate: The Case Against Homework

- FERPA Advice for New Teachers

Categorized as: Tips for Teachers and Classroom Resources

Tagged as: Leadership and Administration

- Online & Campus Doctorate (EdD) in Administra...

- Early Childhood Education: Resources, Theorie...

- Online & Campus Bachelor's in Early Childhood...

Homework Guidelines for Elementary and Middle School Teachers

- Homework Tips

- Learning Styles & Skills

- Study Methods

- Time Management

- Private School

- College Admissions

- College Life

- Graduate School

- Business School

- Distance Learning

- M.Ed., Educational Administration, Northeastern State University

- B.Ed., Elementary Education, Oklahoma State University

Homework; the term elicits a myriad of responses. Students are naturally opposed to the idea of homework. No student ever says, “I wish my teacher would assign me more homework.” Most students begrudge homework and find any opportunity or possible excuse to avoid doing it.

Educators themselves are split on the issue. Many teachers assign daily homework seeing it as a way to further develop and reinforce core academic skills, while also teaching students responsibility. Other educators refrain from assigning daily homework. They view it as unnecessary overkill that often leads to frustration and causes students to resent school and learning altogether.

Parents are also divided on whether or not they welcome homework. Those who welcome it see it as an opportunity for their children to reinforce critical learning skills. Those who loathe it see it as an infringement of their child’s time. They say it takes away from extra-curricular activities, play time, family time, and also adds unnecessary stress.

Research on the topic is also inconclusive. You can find research that strongly supports the benefits of assigning regular homework, some that denounce it as having zero benefits, with most reporting that assigning homework offers some positive benefits, but also can be detrimental in some areas.

The Effects of Homework

Since opinions vary so drastically, coming to a consensus on homework is nearly impossible. We sent a survey out to parents of a school regarding the topic, asking parents these two basic questions:

- How much time is your child spending working on homework each night?

- Is this amount of time too much, too little, or just right?

The responses varied significantly. In one 3 rd grade class with 22 students, the responses regarding how much time their child spends on homework each night had an alarming disparity. The lowest amount of time spent was 15 minutes, while the largest amount of time spent was 4 hours. Everyone else fell somewhere in between. When discussing this with the teacher, she told me that she sent home the same homework for every child and was blown away by the vastly different ranges in time spent completing it. The answers to the second question aligned with the first. Almost every class had similar, varying results making it really difficult to gauge where we should go as a school regarding homework.

While reviewing and studying my school’s homework policy and the results of the aforementioned survey, I discovered a few important revelations about homework that I think anyone looking at the topic would benefit from:

1. Homework should be clearly defined. Homework is not unfinished classwork that the student is required to take home and complete. Homework is “extra practice” given to take home to reinforce concepts that they have been learning in class. It is important to note that teachers should always give students time in class under their supervision to complete class work. Failing to give them an appropriate amount of class time increases their workload at home. More importantly, it does not allow the teacher to give immediate feedback to the student as to whether or not they are doing the assignment correctly. What good does it do if a student completes an assignment if they are doing it all incorrectly? Teachers must find a way to let parents know what assignments are homework and which ones are classwork that they did not complete.

2. The amount of time required to complete the same homework assignment varies significantly from student to student. This speaks to personalization. I have always been a big fan of customizing homework to fit each individual student. Blanket homework is more challenging for some students than it is for others. Some fly through it, while others spend excessive amounts of time completing it. Differentiating homework will take some additional time for teachers in regards to preparation, but it will ultimately be more beneficial for students.

The National Education Association recommends that students be given 10-20 minutes of homework each night and an additional 10 minutes per advancing grade level. The following chart adapted from the National Education Associations recommendations can be used as a resource for teachers in Kindergarten through the 8 th grade.

|

|

Kindergarten | 5 – 15 minutes |

1 Grade | 10 – 20 minutes |

2 Grade | 20 – 30 minutes |

3 Grade | 30 – 40 minutes |

4 Grade | 40 – 50 minutes |

5 Grade | 50 – 60 minutes |

6 Grade | 60 – 70 minutes |

7 Grade | 70 – 80 minutes |

8 Grade | 80 – 90 minutes |

It can be difficult for teachers to gauge how much time students need to complete an assignment. The following charts serve to streamline this process as it breaks down the average time it takes for students to complete a single problem in a variety of subject matter for common assignment types. Teachers should consider this information when assigning homework. While it may not be accurate for every student or assignment, it can serve as a starting point when calculating how much time students need to complete an assignment. It is important to note that in grades where classes are departmentalized it is important that all teachers are on the same page as the totals in the chart above is the recommended amount of total homework per night and not just for a single class.

Kindergarten – 4th Grade (Elementary Recommendations)

|

|

Single Math Problem | 2 minutes |

English Problem | 2 minutes |

Research Style Questions (i.e. Science) | 4 minutes |

Spelling Words – 3x each | 2 minutes per word |

Writing a Story | 45 minutes for 1-page |

Reading a Story | 3 minutes per page |

Answering Story Questions | 2 minutes per question |

Vocabulary Definitions | 3 minutes per definition |

*If students are required to write the questions, then you will need to add 2 additional minutes per problem. (i.e. 1-English problem requires 4 minutes if students are required to write the sentence/question.)

5th – 8th Grade (Middle School Recommendations)

|

|

Single-Step Math Problem | 2 minutes |

Multi-Step Math Problem | 4 minutes |

English Problem | 3 minutes |

Research Style Questions (i.e. Science) | 5 minutes |

Spelling Words – 3x each | 1 minutes per word |

1 Page Essay | 45 minutes for 1-page |

Reading a Story | 5 minutes per page |

Answering Story Questions | 2 minutes per question |

Vocabulary Definitions | 3 minutes per definition |

*If students are required to write the questions, then you will need to add 2 additional minutes per problem. (i.e. 1-English problem requires 5 minutes if students are required to write the sentence/question.)

Assigning Homework Example

It is recommended that 5 th graders have 50-60 minutes of homework per night. In a self-contained class, a teacher assigns 5 multi-step math problems, 5 English problems, 10 spelling words to be written 3x each, and 10 science definitions on a particular night.

|

|

|

|

Multi-Step Math | 4 minutes | 5 | 20 minutes |

English Problems | 3 minutes | 5 | 15 minutes |

Spelling Words – 3x | 1 minute | 10 | 10 minutes |

Science Definitions | 3 minutes | 5 | 15 minutes |

|

|

3. There are a few critical academic skill builders that students should be expected to do every night or as needed. Teachers should also consider these things. However, they may or may not, be factored into the total time to complete homework. Teachers should use their best judgment to make that determination:

- Independent Reading – 20-30 minutes per day

- Study for Test/Quiz - varies

- Multiplication Math Fact Practice (3-4) – varies - until facts are mastered

- Sight Word Practice (K-2) – varies - until all lists are mastered

4. Coming to a general consensus regarding homework is almost impossible. School leaders must bring everyone to the table, solicit feedback, and come up with a plan that works best for the majority. This plan should be reevaluated and adjusted continuously. What works well for one school may not necessarily be the best solution for another.

- How Much Homework Should Students Have?

- Creating a Homework Policy With Meaning and Purpose

- How to Deal With Late Work and Makeup Work

- Collecting Homework in the Classroom

- Effective Classroom Policies and Procedures

- Innovative Ways to Teach Math

- Essential Strategies to Help You Become an Outstanding Student

- Tips for Teachers to Make Classroom Discipline Decisions

- The 10 Things That Worry Math Teachers the Most

- 4 Tips for Completing Your Homework On Time

- Appropriate Consequences for Student Misbehavior

- Classroom Assessment Best Practices and Applications

- How Teachers Must Handle a "Lazy" Student

- Topics for a Lesson Plan Template

- Tips for Remembering Homework Assignments

- An Overview of Renaissance Learning Programs

- Featured Articles

- Report Card Comments

- Needs Improvement Comments

- Teacher's Lounge

- New Teachers

- Our Bloggers

- Article Library

- Featured Lessons

- Every-Day Edits

- Lesson Library

- Emergency Sub Plans

- Character Education

- Lesson of the Day

- 5-Minute Lessons

- Learning Games

- Lesson Planning

- Subjects Center

- Teaching Grammar

- Leadership Resources

- Parent Newsletter Resources

- Advice from School Leaders

- Programs, Strategies and Events

- Principal Toolbox

- Administrator's Desk

- Interview Questions

- Professional Learning Communities

- Teachers Observing Teachers

- Tech Lesson Plans

- Science, Math & Reading Games

- Tech in the Classroom

- Web Site Reviews

- Creating a WebQuest

- Digital Citizenship

- All Online PD Courses

- Child Development Courses

- Reading and Writing Courses

- Math & Science Courses

- Classroom Technology Courses

- Spanish in the Classroom Course

- Classroom Management

- Responsive Classroom

- Dr. Ken Shore: Classroom Problem Solver

- A to Z Grant Writing Courses

- Worksheet Library

- Highlights for Children

- Venn Diagram Templates

- Reading Games

- Word Search Puzzles

- Math Crossword Puzzles

- Geography A to Z

- Holidays & Special Days

- Internet Scavenger Hunts

- Student Certificates

Newsletter Sign Up

Prof. Development

- General Archive

- Have Some Fun

- Expert Interviews

- Math Corner

- New Teacher Advisor

- Strategies That Work

- Voice of Experience

- Improvement

- Lessons from Our Schools

- Whatever it Takes

- School Climate Archive

- Classroom Mgmt. Tips

- Behavior Management Tips

- Motivating Kids

- Fit to Be Taught

- Rural Education

- Urban Education

- Community Involvement

- Best Idea Ever

- Read About It

- Book Report Makeover

- Bulletin Board

- Parent Issues

- Goal Setting/Achieving

- Teacher Lifestyle Tips

- Classroom Problem Solver

- Strategy of the Week

- Teacher’s Lounge

- Grouping/Scheduling

- In a Sub’s Shoes

- SchoolDoodles

- Teach for America Diaries

- Teaming Up to Achieve

- Earth Science Demos

- Interdisciplinary

- Language Arts

- The Reading Room

- All Columnists...

- Dr. Fred Jones

- Emma McDonald

- Dr. Ken Shore

- School Issues: Glossary

- Top PD Features

- Books in Education

- Reader's Theater

- Reading Coach

- Teacher Feature

- School Improvement

- No Educator Left Behind

- Turnaround Tales

- School Climate

- Responsive Classroom Archive

- Community Context

- School Choice

- School to Work

- Problem Solving Archive

- Homework Hassles

- Teacher’s Lounge

- Virtual Workshop

- In a Sub’s Shoes

- Academic Subjects

- Readers’ Theater

- Math Mnemonics

- Math Cats Math Chat

- Prof. Dev. Columnists

Search form

build flexibility into your homework policy.

Any teacher who has ever given out homework has certainly encountered a student the next day saying, “I don’t have my assignment.” Whether pitiful or indifferent, this admission often places us in the unfortunate position of asking why, which puts us in the even more unfortunate position of having to determine whether the student’s excuse is creative (or pathetic) enough to warrant an extension or excusal (or, perhaps just as often, a lecture or punishment).

It took me a woefully long time to break the habit of asking “why,” and it might not have happened unless one of my students told me that a tornado had taken his paper out of his lunchbox! Regardless of your feelings about the value of homework (or its lack thereof), should you decide to give homework, it will be worth your while to develop a policy that eliminates excuses and minimizes stress to you and your students.

A few things to keep in mind:

- Consider the value of the homework you give and make sure that intentions go beyond simply wanting them to practice or be prepared for the next lesson. Keep in mind the importance of engaging (and maintaining) a love of learning and a curiosity about life and the world beyond the subject itself. Some of the best types of homework assignments are those that help the students apply what they are learning, or challenge them within the range of their actual abilities and resources.

- Keep drillwork to a minimum. If doing five problems will adequately strengthen and reinforce a particular skill, why assign 20?

- Keep tabs on how your students are doing with a particular skill. To whatever degree possible, match assignments to student needs and abilities. If I can’t do long division problems in class, how successful am I likely to be doing a page of them after school?

- Be realistic about the amount of time your assignments will require. Many researchers recommend about 10 minutes per grade level per night—total! If you’re only one of your students’ teachers, remember that other teachers’ assignments will be competing for their time.

- Offer students choices to engage their autonomy and individual learning preferences. Allow students to pick a certain number of problems on a particular page, for example, or to choose between the problems on two different pages. Some students will be perfectly happy writing spelling words a certain number of times each; others will learn better by using the same words in a story or puzzle.

- Because students can indeed have a bad night, rather than relying on excuses, build some flexibility into your policy, right up front. You might want to run your idea by an administrator or department chair, and ask parents to sign off as well. You’ll get a lot farther with their support. (And parents will appreciate not having to write excuses.)

Here are some of the policies other teachers have shared with me. Try using these strategies to build flexibility into your homework policies and avoid having to ask for (or deal with) excuses:

- Requesting that a certain percentage of assignments be turned in on time: “You are responsible for 37 out of 40 of the assignments you’ll be getting this semester.” BONUS: Giving extra credit for any of the extras that are turned in, even if late!

- Giving some token for one free “excuse” which does not need any explanation for its use: “Here is a ‘Get Out of Jail Free’ card, which you can use if you forget your homework any time during the semester.” BONUS: Not requiring kids to actually SHOW the card to get off the hook.

- Giving kids a break after a certain number of assignments are completed: “If you turn in completed homework 10 days in a row, you can have the next night off (or you can do the work for extra credit).”

- Having a specific date for assignments to be turned in. (Similar to deadlines used in many college classes, this strategy may work best for specific assignments or projects, or with advanced-level classes and self-managing kids.) “As long as you get your homework in two weeks before the end of the grading period, you’ll get credit for it.”

- Not counting one or more missed assignments, or the lowest score on a series of assignments or quizzes—for example: “You can drop your lowest grade each semester.”

- Extending daily deadlines beyond the end of class, giving kids until the end of the following day to turn in work: “You have until the 3:30 bell tomorrow to turn in this assignment.”

- Getting away from using punishments, penalties, or other negative consequences for not doing homework and offering positive outcomes instead. One school saw a change in students’ attitudes about homework—and a big shift in the amount of work being turned in—by simply shifting from giving a minus when the work wasn’t done to giving a plus when it was.

- Not requiring homework at all but instead, giving extra credit for any that is turned in. (One teacher increased his percentage from 10% to 85% of assignments completed, simply by using this strategy.)

Discussions about homework can become pretty heated, and both pros and cons are worth considering. I do believe there is a way to find some balance and sanity, a way to accommodate kids’ needs for free time and skill practice. Let’s do our homework to find out what the research says and bring mindfulness—of the demands on kids’ lives and time, as well as their future academic needs—to the choices we make about this important issue.

Related resources

Help for Homework Hassles Homework: A Place for Rousing Reform Special Theme Page: Homework

Also from Dr. Bluestein: Is Your School Emotionally Safe? Accommodating Student Sensory Differences Tips for Positive Teacher-Parent Interaction The Art of Setting Boundaries The Beauty of Losing Control Stressful Student Experiences: What Not to Do

COMMENTS

A school's homework policy should reflect this philosophy; ultimately guiding teachers to give their students reasonable, meaningful, purposeful homework assignments. Sample School Homework Policy Homework is defined as the time students spend outside the classroom in assigned learning activities.

A growing body of research shows that homework is connected to learning outcomes, and as a result, schools and districts should ensure that policies help teachers provide meaningful assignments ...

The policies for homework that teachers and parents create can help improve student understanding of materials and result in better grades and scores on standardized tests. Focus on study skills. Teaching students in their early education is a complicated task. Teachers need to balance the age of the students with the expected school, state and ...