The Author’s Purpose for students and teachers

What Is The Author’s Purpose?

When discussing the author’s purpose, we refer to the ‘why’ behind their writing. What motivated the author to produce their work? What is their intent, and what do they hope to achieve?

The author’s purpose is the reason they decided to write about something in the first place.

There are many reasons a writer puts pen to paper, and students must possess the necessary tools to identify these reasons and intents to react and respond appropriately.

Understanding why authors write is essential for students to navigate the complex landscape of texts effectively. The concept of author’s purpose encompasses the motivations behind a writer’s choice of words, style, and structure. By teaching students to discern these purposes, educators empower them to engage critically with various forms of literature and non-fiction.

Author’s Purpose Definition

The author’s purpose is his or her motivation for writing a text and their intent to Persuade, Inform, Entertain, Explain or Describe something to an audience.

Author’s Purpose Examples and Types

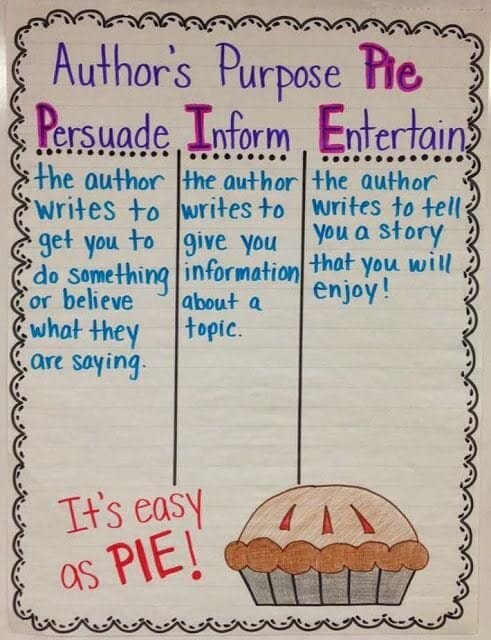

It is universally accepted there are three base categories of the Author’s Purpose: To Persuade, To Inform , and To Entertain . These can easily be remembered with the PIE acronym and should be the starting point on this topic. However, you may also encounter other subcategories depending on who you ask.

This table provides many author’s purpose examples, and we will cover the first five in detail in this article.

| Author’s Purpose | Author’s Purpose Examples |

|---|---|

| : | The author aims to convince the reader to agree with a particular viewpoint or take a specific action. This can be seen in opinion pieces, advertisements, or political speeches. |

| : | The author aims to provide factual information to the reader, such as in textbooks, news articles, or research papers. |

| : | The author aims to engage and amuse the reader through storytelling, humour, or other means. This includes genres such as fiction, poetry, and humour. |

| : | The author’s purpose is to provide step-by-step guidance or directions to the reader. Examples include manuals, how-to guides, and recipes. |

| : | The author uses vivid language to paint a picture in the reader’s mind. This can be found in travel writing, descriptive essays, or literature. |

| : | Some authors write primarily to express themselves, their thoughts, emotions, or experiences. This can be seen in personal essays, journals, or poetry. |

| : | Exploratory writing involves delving into a topic or idea to gain a deeper understanding or to provoke thought. This can be found in philosophical essays, literary analysis, or investigative journalism. |

| : | Authors may write to document events, experiences, or historical periods for posterity. This includes memoirs, autobiographies, and historical accounts. |

Author’s Purpose Teaching Unit

Teach your students ALL ASPECTS of the Author’s Purpose with this fully EDITABLE 63-page Teaching Unit.

⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐ ( 42 reviews )

Author’s Purpose 1: To Persuade

Definition: This is a prevalent purpose of writing, particularly in nonfiction. When a text is written to persuade, it aims to convince the reader of the merits of a particular point of view . In this type of writing, the author attempts to persuade the reader to agree with this point of view and/or subsequently take a particular course of action.

Examples: This purpose can be found in all kinds of writing. It can even be in fiction writing when the author has an agenda, consciously or unconsciously. However, it is most commonly the motivation behind essays, advertisements, and political writing, such as speech and propaganda.

Persuasion is commonly also found in…

- A political speech urges voters to support a particular candidate by presenting arguments for their suitability for the position, policies, and record of achievements.

- An advertisement for a new product that emphasizes its unique features and benefits over competing products, attempting to convince consumers to choose it over alternatives.

- A letter to the editor of a newspaper expressing a strong opinion on a controversial issue and attempting to persuade others to adopt a similar position by presenting compelling evidence and arguments.

How to Identify: To identify when the author’s purpose is to persuade, students should ask themselves if they feel the writer is trying to get them to believe something or take a specific action. They should learn to identify the various tactics and strategies used in persuasive writing, such as repetition, multiple types of supporting evidence, hyperbole, attacking opposing viewpoints, forceful phrases, emotive imagery, and photographs.

We have a complete persuasive writing guide if you want to learn more.

Strategies for being a more PERSUASIVE writer

To become a persuasive writer, students can employ several strategies to convey their arguments and influence their readers effectively. Here are five strategies for persuasive writing:

- Understand Your Audience: Know your target audience and tailor your persuasive arguments to appeal to their interests, values, and beliefs. Consider their potential objections and address them in your writing. Understanding your audience helps you create a more compelling and persuasive piece.

- Use Strong Evidence and Examples: Support your claims with credible evidence, statistics, and real-life examples. Persuasive writing relies on logic and facts to support your arguments. Conduct research to find reliable sources that strengthen your case and make your writing more convincing.

- Craft a Persuasive Structure: Organize your writing clearly and persuasively. Start with a compelling introduction that grabs the reader’s attention and states your main argument. Use body paragraphs to present evidence and supporting points logically. Finish with a strong conclusion that reinforces your main message and calls the reader to take action or adopt your viewpoint.

- Appeal to Emotions: Persuasive writing is not just about logic; emotions are crucial in influencing readers. Use emotional appeals to connect with your audience and evoke empathy, sympathy, or excitement. Be careful not to manipulate emotions but use them to reinforce your argument authentically.

- Anticipate Counterarguments: Acknowledge and address potential counterarguments to show that you have considered different perspectives. By addressing opposing viewpoints, you demonstrate that you have thoroughly thought about the issue and strengthen your credibility as a persuasive writer.

Bonus Tip: Use Persuasive Language: Pay attention to your choice of words and language. Use compelling language that evokes a sense of urgency or importance. Employ rhetorical devices, such as repetition, analogy, and rhetorical questions, to make your writing more persuasive and memorable.

Please encourage students to practice these strategies in their writing in formal essays and everyday persuasive situations. By mastering persuasive writing techniques, students can effectively advocate for their ideas, inspire change, and have a greater impact with their words.

Author’s Purpose 2: To Inform

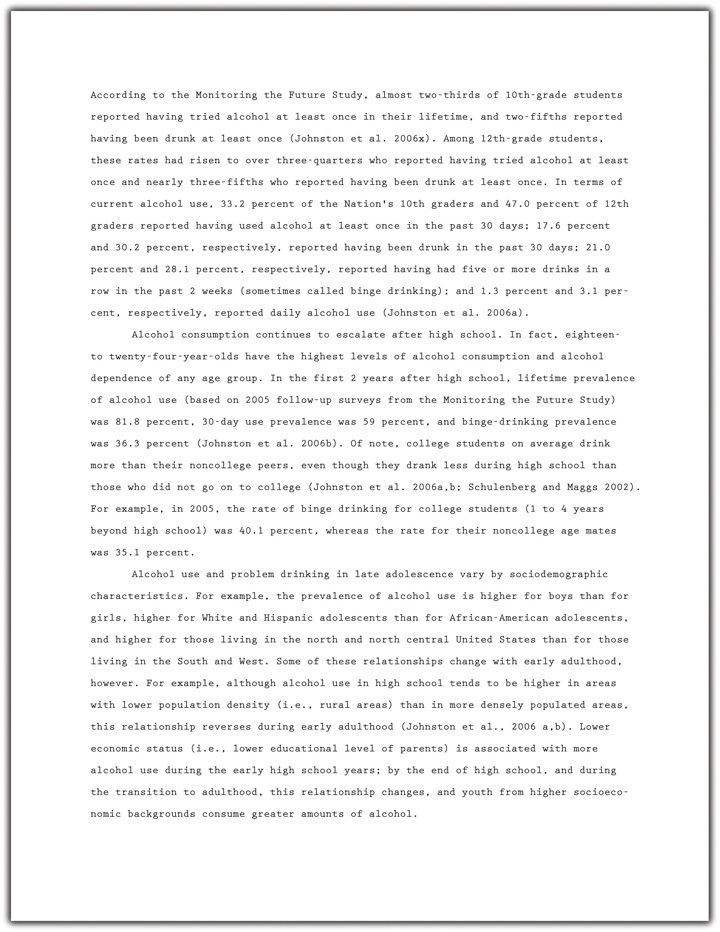

Definition: When an author aims to inform, they usually wish to enlighten their readership about a real-world topic. Often, they will do this by providing lots of facts. Informational texts impart information to the reader to educate them on a given topic.

Examples: Many types of school books are written with the express purpose of informing the reader, such as encyclopedias, recipe books, newspapers and informative texts…

- A news article reporting on a recent event or development provides factual details about what happened, who was involved, and where and when it occurred.

- A scientific journal article describes a research study’s findings, explaining the methodology, results, and implications for further analysis or practical application.

- A travel guidebook that provides detailed information about a particular destination, including its history, culture, attractions, accommodation options, and practical advice for visitors.

How to Identify: In the process of informing the reader, the author will use facts, which is one surefire way to spot the intent to inform.

However, when the author’s purpose is persuasion, they will also likely provide the reader with some facts to convince them of the merits of their particular case. The main difference between the two ways facts are employed is that when the intention is to inform, facts are presented only to teach the reader. When the author aims to persuade, they commonly mask their opinions amid the facts.

Students must become adept at recognizing ‘hidden’ opinions through practice. Teach your students to beware of persuasion masquerading as information!

Please read our complete guide to learn more about writing an information report.

Strategies for being a more INFORMATIVE writer

To become an informative writer, students can employ several strategies to effectively convey information and knowledge clearly and engagingly. Here are five strategies for informative writing:

- Conduct Thorough Research: Before writing, gather information from credible sources such as books, academic journals, reputable websites, and expert interviews. Use reliable data and evidence to support your points. Ensuring the accuracy and reliability of your information is essential in informative writing.

- Organize Information Logically: Structure your writing clearly and logically. Use headings, subheadings, and bullet points to organize information into easily digestible chunks. A well-structured piece helps readers understand complex topics more quickly.

- Use Clear and Concise Language: Aim for clarity and avoid unnecessary jargon or complex language that might confuse your readers. Use simple and concise sentences to deliver information effectively. Make sure to define any technical terms or concepts unfamiliar to your audience.

- Provide Real-Life Examples: Illustrate your points with real-life examples, case studies, or anecdotes. Concrete examples make abstract concepts more understandable and relatable. They also help to keep the reader engaged throughout the piece.

- Incorporate Visual Aids: Whenever possible, use visual aids such as charts, graphs, diagrams, and images to complement your text. Visual elements enhance understanding and retention of information. Be sure to explain the significance of each visual aid in your writing.

Bonus Tip: Practice Summarization: After completing informative writing, practice summarizing the main points. Being able to summarize your work concisely reinforces your understanding of the topic and helps you identify any gaps in your information.

Encourage students to practice these strategies in various writing tasks, such as research papers, reports, and explanatory essays. By mastering informative writing techniques, students can effectively educate their readers, share knowledge, and contribute meaningfully to their academic and professional pursuits.

Author’s Purpose 3: To Entertain

Definition: When an author’s chief purpose is to entertain the reader, they will endeavour to keep things as interesting as possible. Things happen in books written to entertain, whether in an action-packed plot , inventive characterizations, or sharp dialogue.

Examples: Not surprisingly, much fiction is written to entertain, especially genre fiction. For example, we find entertaining examples in science fiction, romance, and fantasy.

Here are some more entertaining texts to consider.

- A novel that tells a compelling story engages the reader’s emotions and imagination through vivid characters, evocative settings, and unexpected twists and turns.

- A comedy television script that uses humour and wit to amuse the audience, often by poking fun at everyday situations or societal norms.

- A stand-up comedy routine that relies on the comedian’s storytelling ability and comedic timing to entertain the audience, often by commenting on current events or personal experiences.

How to Identify: When writers attempt to entertain or amuse the reader, they use various techniques to engage their attention. They may employ cliffhangers at the end of a chapter, for example. They may weave humour into their story or even have characters tell jokes. In the case of a thriller, an action-packed scene may follow an action-packed scene as the drama builds to a crescendo. Think of the melodrama of a soap opera here rather than the subtle touch of an arthouse masterpiece.

Strategies for being a more ENTERTAINING writer

To become an entertaining writer, students can use several strategies to captivate their readers and keep them engaged. Here are five effective techniques:

- Use Humor: Inject humour to tickle the reader’s funny bone. Incorporate witty remarks, funny anecdotes, or clever wordplay. Humour lightens the tone of your writing and makes it enjoyable to read. However, be mindful of your audience and ensure your humour is appropriate and relevant to the topic.

- Create Engaging Characters: Whether you’re writing a story, essay, or any other type of content, develop compelling and relatable characters. Readers love connecting with well-developed characters with distinct personalities, flaws, and strengths. Use descriptive language to bring them to life and make them memorable.

- Craft Intriguing Beginnings: Grab your reader’s attention from the very first sentence. Start with a compelling hook that sparks curiosity or creates intrigue. An exciting beginning sets the tone for the rest of the piece and encourages the reader to continue reading.

- Build Suspense and Surprise: Incorporate twists, turns, and surprises into your writing to keep readers on their toes. Building suspense creates anticipation and makes readers eager to discover what happens next. Surprise them with unexpected plot developments or revelations to keep them engaged throughout the piece.

- Use Imagery and Vivid Descriptions : Paint vivid pictures with your words to immerse readers in your writing. Use sensory language and descriptive imagery to transport them to different places, evoke emotions, and create a multisensory experience. Readers love to feel like they’re part of the story, and vivid descriptions help achieve that.

Bonus Tip: Read Widely and Analyze: To become an entertaining writer, read a variety of books, articles, and pieces from different genres and authors. Pay attention to the elements that make their writing engaging and entertaining. Analyze their use of humour, character development, suspense, and descriptions. Learning from the work of accomplished writers can inspire and improve your own writing.

By using these strategies and practising regularly, students can become more entertaining writers, captivating their audience and making their writing a joy to read. Remember, the key to entertaining writing is engaging your readers and leaving them with a positive and memorable experience.

Author’s Purpose 4: To Explain

Definition: When writers write to explain, they want to tell the reader how to do something or reveal how something works. This type of writing is about communicating a method or a process.

Examples: Writing to explain can be found in instructions, step-by-step guides, procedural outlines, and recipes such as these…

- A user manual explaining how to operate a piece of machinery or a technical device provides step-by-step instructions and diagrams to help users understand the process.

- A textbook chapter that explains a complex scientific or mathematical concept breaks it into simpler components and provides examples and illustrations to aid comprehension.

- A how-to guide that explains how to complete a specific task or achieve a particular outcome, such as cooking a recipe, gardening, or home repair. It provides a list of materials, step-by-step instructions, and tips to ensure success.

How to Identify: Often, this writing is organized into bulleted or numbered points. As it focuses on telling the reader how to do something, often lots of imperatives will be used within the writing. Diagrams and illustrations are often used to reinforce the text explanations too.

Read our complete guide to explanatory texts here.

Strategies for being a more EXPLANATORY WRITER

To become a more explanatory writer, students can employ several strategies to effectively clarify complex ideas and concepts for their readers. Here are five strategies for explanatory writing:

- Define Technical Terms: When writing about a specialized or technical topic, ensure that you define any relevant terms or jargon that might be unfamiliar to your readers. A clear and concise definition helps readers grasp the meaning of these terms and facilitates better understanding of the content.

- Use Analogies and Comparisons: Use analogies and comparisons to relate complex ideas to more familiar concepts. This technique makes abstract or difficult concepts more relatable and easier to understand. Analogies provide a frame of reference that helps readers connect new information to something they already know.

- Provide Step-by-Step Explanations: Break down complex processes or procedures into step-by-step explanations. This approach helps readers follow the sequence of events or actions and understand the logic behind each step. Use numbered lists or bullet points to make the process visually clear.

- Include Visuals and Diagrams: Supplement your explanatory writing with visual aids such as diagrams, flowcharts, or illustrations. Visuals can enhance understanding and retention of information by visually representing the concepts being discussed.

- Address “Why” and “How”: In explanatory writing, go beyond simply stating “what” happened or what a concept is. Focus on explaining “why” something occurs and “how” it works. Providing the underlying reasons and mechanisms helps readers better understand the subject matter.

Bonus Tip: Review and Revise: After completing your explanatory writing, review your work and assess whether the explanations are clear and comprehensive. Consider seeking feedback from peers or teachers to identify areas needing further clarification or expansion.

Please encourage students to practice these strategies in writing across different subjects and topics. By mastering explanatory writing techniques, students can effectively communicate complex ideas, promote better understanding, and excel academically and professionally.

Author’s Purpose 5: To Describe

Definition: Writers often use words to describe something in more detail than conveyed in a photograph alone. After all, they say a picture paints a thousand words, and text can help get us beyond the one-dimensional appearance of things.

Examples: We can find lots of descriptive writing in obvious places like short stories, novels and other forms of fiction where the writer wishes to paint a picture in the reader’s imagination. We can also find lots of writing with the purpose of description in nonfiction too – in product descriptions, descriptive essays or these text types…

- A travelogue that describes a particular place, highlighting its natural beauty, cultural attractions, and unique characteristics. The author uses sensory language to create a vivid mental picture in the reader’s mind.

- A painting analysis that describes the colors, shapes, textures, and overall impression of a particular artwork. The author uses descriptive language to evoke the emotions and ideas conveyed by the painting.

- A product review that describes the features, benefits, and drawbacks of a particular item. The author uses descriptive language to give the reader a clear sense of the product and whether it might suit their needs.

How to Identify: In the case of fiction writing which describes, the reader will notice the writer using lots of sensory details in the text. Our senses are how we perceive the world, and to describe their imaginary world, writers will draw heavily on language that appeals to these senses. In both fiction and nonfiction, readers will notice that the writer relies heavily on adjectives.

Strategies for being a more descriptive writer

Becoming a descriptive writer is a valuable skill that allows students to paint vivid pictures with words and immerse readers in their stories. Here are five strategies for students to enhance their descriptive writing:

- Sensory Language: Engage the reader’s senses by incorporating sensory language into your writing. Use descriptive adjectives, adverbs, and strong verbs to create a sensory experience for your audience. For example, instead of saying “the flower was pretty,” describe it as “the delicate, fragrant blossom with hues of vibrant pink and a velvety texture.”

- Show, Don’t Tell: Use the “show, don’t tell” technique to make your writing more descriptive and immersive. Rather than stating emotions or characteristics directly, use descriptive details and actions to show them. For instance, instead of saying “she was scared,” describe how “her heart raced, and her hands trembled as she peeked around the dark corner.”

- Use Metaphors and Similes: Integrate metaphors and similes to add depth and creativity to your descriptions. Compare two unrelated things to create a powerful visual image. For example, “the sun dipped below the horizon like a golden coin slipping into a piggy bank.”

- Focus on Setting: Pay attention to the setting of your story or narrative. Describe the environment, atmosphere, and surroundings in detail. Take the reader on a journey by clearly depicting the location. Let your words bring the setting to life, whether it’s a lush forest, a bustling city street, or a mystical castle.

- Practice Observation: Practice keen observation skills in your daily life. Take note of the world around you—the sights, sounds, smells, tastes, and textures. Observe people, places, and objects with a writer’s eye. By developing a habit of keen observation, you’ll have a rich bank of sensory details to draw from when you write.

Bonus Tip: Revise and Edit: Good descriptive writing often comes through revision and editing. After writing a draft, go back and read your work critically. Look for opportunities to add more descriptive elements, eliminate unnecessary adjectives or cliches, and refine your language to make it more engaging.

By applying these strategies and continually honing your descriptive writing skills, you’ll be able to transport readers to new worlds, evoke emotions, and make your writing more captivating and memorable.

Free Author’s Purpose Anchor Charts & Posters

Author’s Purpose Teaching Activities

The Author’s Purpose Task 1. The Author’s Purpose Anchor Chart

Whether introducing the general idea of the author’s purpose or working on identifying the specifics of a single purpose, a pie author’s purpose anchor chart can be an excellent resource for students when working independently. Compiling the anchor chart collaboratively with the students can be an effective way for them to reconstruct and reinforce their learning.

The Author’s Purpose Task 2. Gather Real-Life Examples

Challenging students to identify and collect real-life examples of the various types of writing as homework can be a great way to get some hands-on practice. Encourage your students to gather various forms of text together indiscriminately. They then sift through them to categorize them appropriately according to their purpose. The students will soon begin to see that all writing has a purpose. You may also like to make a classroom display of the gathered texts to serve as examples.

The Author’s Purpose Task 3. DIY

One of the most effective ways for students to recognize the authorial intent behind a piece of writing is to gain experience producing writing for various purposes. Design writing tasks with this in mind. For example, if you are focused on writing to persuade, you could challenge the students to produce a script for a radio advertisement. If the focus is entertaining, you could ask the students to write a funny story.

The Author’s Purpose Task 4. Classroom Discussion

When teaching author’s purpose, organize the students into small discussion groups of, say, 4 to 5. Provide each group with copies of sample texts written for various purposes. Students should have some time to read through the texts by themselves. They then work to identify the author’s purpose, making notes as they go. Students can discuss their findings as a group.

Remember: the various purposes are not mutually exclusive; sometimes, a text has more than one purpose. It is possible to be both entertaining and informative, for example. It is essential students recognize this fact. A careful selection of texts can ensure the students can discover this for themselves.

Students need to understand that regardless of the text they are engaged with, every piece of writing has some purpose behind it. It’s important that they work towards recognizing the various features of different types of writing that reveal to the reader just what that purpose is.

Initially, the process of learning to identify the different types of writing and their purposes will require conscious focus on the part of the student. Plenty of opportunities should be created to allow this necessary classroom practice.

However, this practice doesn’t have to be exclusively in the form of discrete lessons on the author’s purpose. Simply asking students what they think the author’s purpose is when reading any text in any context can be a great way to get the ‘reps’ in quickly and frequently.

Eventually, students will begin to recognize the author’s purpose quickly and unconsciously in the writing of others.

Ultimately, this improved comprehension of writing, in general, will benefit students in their own independent writing.

This video is an excellent introductory guide for students looking for a simple visual breakdown of the author’s purpose and how it can impact their approach to writing and assessment.

OTHER GREAT ARTICLES RELATED TO THE AUTHOR’S PURPOSE

Teaching Cause and Effect in Reading and Writing

The Writing Process

Elements of Literature

Teaching The 5 Story Elements: A Complete Guide for Teachers & Students

When You Write

What is the Author’s Purpose & Why Does it Matter?

There’s always a reason a writer decides to produce their work. We rarely think about it, but there’s always a motivating factor behind intent and goals they hope to achieve.

This “why” behind the author’s writing is what we call the author’s purpose, and it is the reason the author decided to write about something.

There are billions—maybe more—of reasons a writer decides to write something and when you understand the why behind the words, you can effectively and accurately evaluate their writing.

When you understand the why, you can apprehend what the author is trying to say, grasp the writer’s message, and the intent of a particular piece of literary work.

Without further ado, let me explain what the author’s purpose is and how you can identify it.

What is Author’s Purpose?

Just as I introduced the term, an author’s purpose is the author’s reason for or intent in writing.

In both fiction and non-fiction, the author selects the genre, writing format, and language to suit the author’s purpose.

The writing formats, genres, and vernacular are chosen to communicate a key message to the reader, to entertain the reader, to sway the reader’s opinion, et cetera.

The way an author writes about a topic fulfills their purpose; for example, if they intend to amuse, the writing will have a couple of jokes or anecdotal sections. The author’s purpose is also reflected in the way they title their works, write prefaces, and in their background.

In general, the purposes fall into three main categories, namely persuade, inform, and entertain. The three types of author’s purpose make the acronym PIE.

But, there are many reasons to write, the PIE just represents the three main classes of the author’s purpose .

In the next section, I’m going to elaborate on the various forms of the author’s purpose including the three broader categories that I have introduced.

How useful is the Author’s Purpose?

Understanding the author’s purpose helps readers understand and analyze writing. This analytical advantage helps the reader have an educated point of view. Titles or opening passages act as the text’s signposts, and we can assume what type of text we’re about to read.

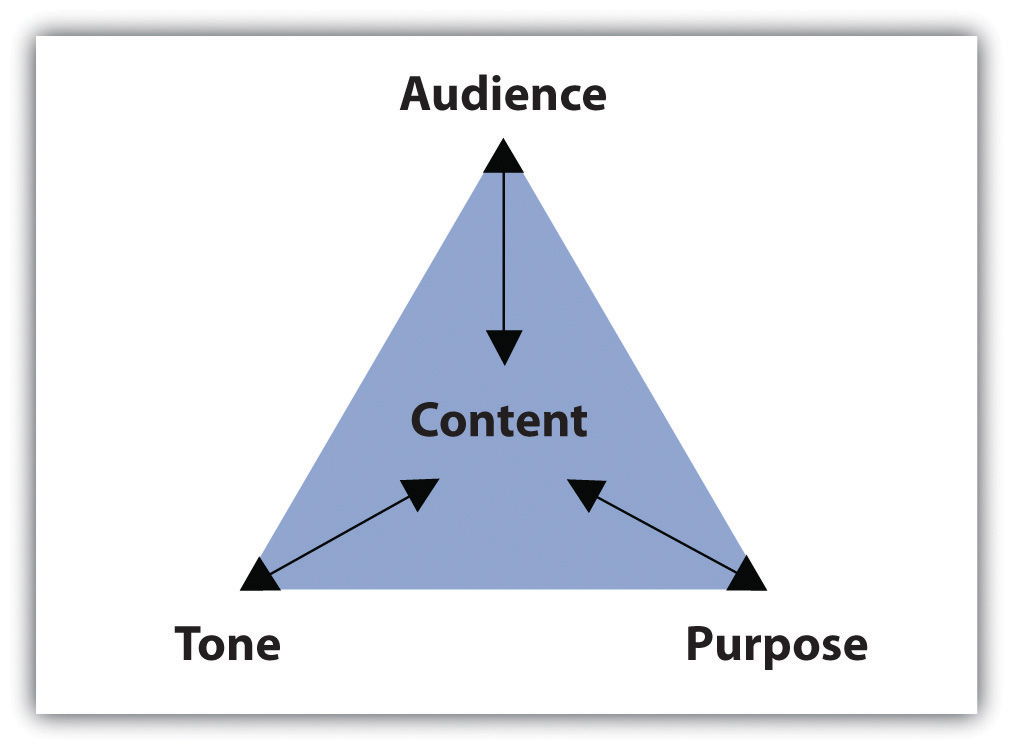

If you can identify the author’s purpose, it becomes easier to recognize the proficiencies used to achieve that particular purpose. So, once you identify the author’s purpose, you can recognize the style, tone, word, and content used by the author to communicate their message.

You also get to explore other people’s attitudes, beliefs, or perspectives.

Why does the Author’s Purpose Matter for the Writer?

The intent and manner in which a body of text is written determine how one perceives the information one reads.

Perception is especially important if the author aims to inform, educate, or explain something to the reader. For instance, an author writing an informative piece should provide relevant or reliable information and clearly explain his concepts; otherwise, the reader will think they are trying to be deceptive.

The readers—particularly those reading informative or persuasive pieces—expect authors to support their arguments and demonstrate validity by using autonomous sources as references for their writing.

Likewise, readers expect to be thoroughly entertained by works of fiction.

Types of Author’s Purpose

Mostly, reasons for writing are condensed into 5 broad categories, and here they are:

1. to Persuade

Using this form of author’s purpose, the author tries to sway the reader and make them agree with their opinion, declaration, or stance. The goal is to convince the reader and make them act in a specific way.

To convince a reader to believe a concept or to take a specific course of action, the author backs the idea with facts, proof, and examples.

Authors also have to be creative with their persuasive writing . For instance, apart from form complementary facts and examples, the author has to borrow some forms of entertaining elements and amuse their readers. This makes their writing enjoyable and relatable to some extent, increasing the likelihood of persuading people to take the required course of action.

2. to Inform

When the author’s purpose is to inform or teach the reader, they use expository writing. The author attempts to teach objectively by showing or explaining facts.

When you look at informative writing and persuasive writing, you can identify a common theme: the use of facts. However, the two forms of the author’s purpose use these facts differently. Unlike persuasive writing, which uses facts to convince the reader, informative writing uses facts to educate the reader about a particular subject. With persuasive writing, it’s like there’s a catch: the call to action. But, informative writing only uses facts to educate the reader, not to convince them to take a specific course of action.

Informative writing only seeks to “expose” factual information about a topic for enlightenment.

3. to Entertain

Most fiction books are written to entertain the reader—and, yes, including horror. On the other hand, non-fiction works combine an entertaining element with informative writing.

To entertain, the author tries to keep things as interesting as possible by coming up with fascinating characters , exciting plots, thrilling storylines, and sharp dialogue.

Most narratives, poetry, and plays are written to entertain. Be that as it may, these works of fiction can also be persuasive or informative, but if we fuse values and ideas, changing the reader’s perspective becomes an easier task.

Nonetheless, the entertaining purpose has to dominate, or else, readers are going to lose interest quickly and the informative purpose will be defeated.

4. to Explain

When the author’s purpose is to explain, they write with the intent of telling the reader how to do something or giving details on how something works.

This type of writing is about teaching a method or a process and the text contains explanations that teach readers how a particular process works or the procedure required to do or create something.

5. to Describe

When describing is the author’s purpose, the author uses words to complement images in describing something. This type of writing attempts to give a more detailed description of something, a bit more detail than the “thousand words that a picture paints.”

The writer uses adjectives and images to make the reader feel as though it were their own sensory experience.

Main elements and examples of Author’s Purpose

A great way to identify the author’s purpose is to analyze the whole piece of literature. The first step would be to ask “What is the point of this piece?” One can also look at why it was written, who it was written for, and what effect they wanted it to have on readers.

Another method is to break down the text into different categories of purpose. For example, if someone wants their writing to persuade, they would use rhetorical devices (i.e., logical appeals).

Below are the types of publications dominated by each purpose and the things to look for when identifying the author’s purpose.

Persuasive Purpose

Persuasion is usually found in non-fiction, but countless other fiction books have also been used to persuade the reader.

Propaganda works are top of the list when it comes to persuasion in writing. But we also have other works including:

- Political speeches

- Advertisements

- Infomercial scripts and news editorials meant to persuade the reader

- Fiction writing whose author has an agenda

How to Identify Persuasive Purpose

When trying to identify persuasion in writing, you should ask yourself if the author is attempting to convince the reader to take a specific course of action.

If the author is trying to persuade their readers, they employ several tactics and schemes including hyperboles, forceful phrases, repetition, supporting evidence, imagery, and photographs, and they attack opposing ideas or proponents.

Informative Purpose

Although some works of fiction are also informative, informative writing is commonly found on non-fiction shelves and dominates academic works.

Many types of academic textbooks are written with the primary purpose of informing the reader.

Informative writing is generally found in the following:

- Textbooks

- Encyclopedias

- Recipe books

How to identify Informative Purpose

Just like in persuasive writing, the writer will attempt to inform the reader by feeding them facts.

So, how can you spot a pure intent to inform?

The difference between the two is that an author whose purpose is persuasion is likely going to provide the reader with some facts in an attempt with the primary goal of convincing the reader of the worthwhileness or valuableness of a particular idea, item, situation, et cetera.

On the other hand, in informative writing, facts are used to inform and are not sugar-coated by the author’s opinion, like is the case when the author’s purpose is to persuade.

Entertaining Purpose

The entertaining purpose dominates fiction writing—there’s a huge emphasis placed on entertaining the reader in almost every fiction book.

In almost every type of fiction (be it science fiction, romance, or fantasy), the writer works on an exciting story that will leave his readers craving for more.

The only issue with this purpose is that the adjective ‘entertaining’ is subjective and what entertains one reader may not be so riveting for another.

For example, the type of ‘entertainment’ one gets from romance novels is different from the amusement another gets from reading science fiction.

Although entertainment in writing is mostly used in fiction, non-fiction works also use storytelling—now and then—to keep the reader engaged and drive home a specific point.

How to identify Entertaining Purpose

Identifying works meant to entertain is fairly easy: When an author intends to entertain or amuse the reader, they use a variety of schemes aimed at getting the readers engaged.

The author may insert some humor into their narrative or use dialogue to weave in some jokes.

The writer may also use cliffhangers at the end of a page or chapter to keep the reader interested in the story.

Explaining Purpose

Authors also write to explain a topic or concept, especially in the non-fiction category. Fiction writers also write to explain things, usually not for the sole purpose of explaining that topic, but to help readers understand the plot, an event, a setting, or a character.

This type of purpose is dominant in How-to books, texts with recipes, DIY books, company or school books for orientation, and others.

How to identify Explaining Purpose

Texts with explaining purpose typically have a list of points (using a numbered or bulleted format), use infographics, diagrams, or illustrations.

Explaining purpose also contains a lot of verbs that try to convey directions, instructions, or guidelines.

Every author’s purpose or motive should be more than just entertaining the reader, it should be about more than just telling a good story.

A lot of authors tell stories to accomplish different objectives – some want to teach, provoke thought and debate, or show people that they’re not alone in their struggles. Others—like yours truly—write an article about the different types of Author’s purpose and hope it changes your writing style accordingly.

Authors must take their audience’s needs and interests into account, as well as their purposes for writing when writing something they intend to publish.

The author should find a way to make a piece that both generates interest as well as provides value to their reader.

Recommended Reading...

4 things that will improve your writing imagination, how to write an affirmation, best cities for writers to live and write in, list of interesting places to write that evoke inspiration.

Keep in mind that we may receive commissions when you click our links and make purchases. However, this does not impact our reviews and comparisons. We try our best to keep things fair and balanced, in order to help you make the best choice for you.

As an Amazon Associate, I earn from qualifying purchases.

© 2024 When You Write

Understanding Author’s Purpose: Why It Matters in Writing

Share This Article

Welcome to our exploration of author’s purpose in writing! Have you ever wondered why authors write what they do?

Understanding an author’s purpose is like deciphering the code behind their words. It’s about uncovering the intentions and motivations that drive their writing. In this blog post, we’ll delve into the significance of author’s purpose, its impact on the reader, and why it’s essential for both writers and readers to grasp.

So, let’s embark on this journey to unravel the mysteries of author’s purpose in writing.

Now, let’s explore why authors write the way they do, and why it’s crucial for both writers and readers to understand this concept.

The purpose behind a piece of writing is like the North Star guiding a ship through the vast ocean of words. Every word, every sentence, every paragraph crafted by an author serves a purpose beyond mere communication. Whether it’s to inform, persuade, entertain, or provoke thought, the author’s purpose shapes the entire composition, influencing the tone, style, and content.

Consider a persuasive essay advocating for environmental conservation. The author’s purpose is to convince readers of the urgency to protect the planet. They employ rhetorical strategies, emotional appeals, and factual evidence to sway the audience towards their viewpoint. Understanding this purpose allows readers to engage critically with the text, evaluating the effectiveness of the author’s arguments and forming informed opinions.

Similarly, in a work of fiction, the author’s purpose might be to transport readers to a different world, evoke emotions, or convey universal truths about the human experience. By recognizing the underlying purpose, readers can immerse themselves more fully in the narrative, empathizing with characters, and grasping the deeper themes woven into the story.

For writers, clarity of purpose is paramount. Before putting pen to paper or fingers to keyboard, authors must ask themselves: What do I hope to achieve with this piece? Whether it’s to entertain, educate, inspire, or provoke change, a clear understanding of their purpose guides every decision—from choosing the right words to structuring the narrative.

Moreover, understanding author’s purpose fosters critical thinking skills essential in today’s information-saturated world. When readers approach a text with an awareness of the author’s intentions, they become active participants in the dialogue, questioning, analyzing, and interpreting the content more effectively.

What Is Authors Purpose?

The author’s purpose refers to the reason behind why a writer creates a particular piece of writing. It encompasses the goals, intentions, or objectives that drive the author to communicate their message to the audience. Understanding the author’s purpose is crucial for readers as it helps them comprehend the text better, evaluate its effectiveness, and engage critically with the content.

What are the different types of authors’ purpose?

There are several different types of author’s purposes, each serving a distinct function in communication. Here are the primary categories:

- To Inform : The author aims to impart knowledge, facts, or information to the audience. This purpose is prevalent in textbooks, news articles, research papers, and instructional manuals. The author seeks to educate the reader about a specific topic, event, or concept.

- To Persuade : In persuasive writing, the author endeavors to sway the audience’s beliefs, opinions, or actions. This could involve presenting arguments, making appeals to emotions or logic, and advocating for a particular viewpoint or course of action. Examples include opinion pieces, advertisements, political speeches, and editorials.

- To Entertain : Authors may write primarily to amuse, entertain, or engage the audience. Fictional works such as novels, short stories, poetry, and plays often serve this purpose. Through storytelling, humor, drama, or suspense, the author seeks to captivate readers and provide enjoyment.

- To Express : Sometimes, authors write to express themselves, their thoughts, feelings, or experiences. This purpose is common in personal narratives, journals, memoirs, and reflective essays. The author may use writing as a form of self-expression, catharsis, or exploration of identity.

- To Instruct : Writing with the intention to instruct involves providing guidance, directions, or step-by-step procedures to help readers learn or accomplish something. This purpose is evident in how-to guides, recipes, manuals, and tutorials. The author aims to facilitate understanding and skill acquisition in the audience.

- To Describe : Authors may write to describe a person, place, object, or event in vivid detail, appealing to the reader’s senses and imagination. Descriptive writing is often found in travelogues, nature writing, and creative non-fiction. The author aims to paint a rich, sensory picture for the reader.

- To Convey Emotion : Some authors write with the primary goal of evoking emotions in the reader. This purpose is prevalent in poetry, lyrical prose, and personal essays. Through the use of imagery, metaphor, and language, the author seeks to elicit feelings of joy, sadness, nostalgia, or empathy.

Understanding these different types of author’s purposes allows readers to engage more deeply with a variety of texts, discerning the intentions behind the writing and interpreting the messages effectively.

What are the key words for author’s purpose?

Key words for identifying the author’s purpose in a text vary depending on the specific purpose. Here are some key words associated with each purpose:

- To Inform : inform, explain, describe, report, detail, educate, illustrate, clarify

- To Persuade : persuade, convince, argue, advocate, influence, convince, sway, urge, recommend

- To Entertain : entertain, amuse, delight, captivate, engage, charm, entertain, divert, thrill

- To Express : express, share, reveal, convey, articulate, narrate, recount, reflect, disclose

- To Instruct : instruct, guide, teach, demonstrate, show, explain, clarify, direct, advise

- To Describe : describe, depict, portray, characterize, illustrate, paint, evoke, capture, depict

- To Convey Emotion : evoke, express, convey, evoke, stir, elicit, provoke, arouse, communicate

What are the characteristics of the author’s purpose?

- Clarity : The purpose should be clear and evident throughout the text.

- Consistency : The content should align with the stated purpose.

- Tone : The tone of the writing often reflects the author’s purpose (e.g., formal for informing, persuasive for persuading, emotive for conveying emotion).

- Content : The type of information, arguments, or storytelling techniques used correspond to the purpose.

- Audience Engagement : The author aims to engage the audience according to their purpose (e.g., providing information, sparking emotions, guiding actions).

Why does purpose matter in writing?

Understanding the purpose of writing is paramount because it serves as the guiding force behind every word, sentence, and paragraph. Here’s why purpose matters in writing:

- Clarity of Communication : Identifying the purpose helps writers articulate their message clearly and effectively. Whether the goal is to inform, persuade, entertain, or express, knowing the purpose ensures that the content is tailored to achieve that objective.

- Audience Engagement : Purpose-driven writing resonates with the intended audience, capturing their attention and maintaining their interest. By aligning the content with the audience’s expectations and needs, writers can create meaningful connections and foster engagement.

- Effectiveness of Communication : Understanding the purpose allows writers to choose the most appropriate language, tone, and style to convey their message. This enhances the effectiveness of communication, ensuring that the intended message is conveyed accurately and convincingly.

- Achieving Goals : Writing with a clear purpose helps writers achieve their goals, whether it’s to inform, persuade, entertain, or inspire action. By keeping the purpose in mind throughout the writing process, writers can stay focused and effectively achieve their objectives.

- Impact on Readers : Purposeful writing has a significant impact on readers, influencing their perceptions, beliefs, and actions. Whether the goal is to educate, motivate, or entertain, purpose-driven writing can inspire readers, provoke thought, and evoke emotions, leaving a lasting impression.

Overall, purpose serves as the compass that guides writers through the writing process, ensuring that their message is clear, engaging, and impactful.

What is a top priority for all proposal writers?

For proposal writers, a top priority is to clearly articulate the purpose and objectives of the proposal. Here’s why:

- Clarity of Intent : Clearly stating the purpose of the proposal helps stakeholders understand the goals, objectives, and desired outcomes. This ensures alignment and clarity of intent, reducing ambiguity and misinterpretation.

- Audience Engagement : Clearly defining the purpose of the proposal captures the attention of stakeholders and engages them in the proposed initiative or project. It communicates the relevance and importance of the proposal, motivating stakeholders to invest time and resources in its success.

- Alignment of Strategies : A clearly defined purpose enables proposal writers to develop strategies and action plans that align with the intended objectives. It provides a framework for decision-making and prioritization, ensuring that resources are allocated effectively to achieve the desired outcomes.

- Measurable Outcomes : Defining the purpose of the proposal allows for the establishment of measurable outcomes and success criteria. This enables stakeholders to assess the effectiveness and impact of the proposed initiative, facilitating accountability and evaluation.

Overall, clearly articulating the purpose of the proposal is essential for gaining stakeholder buy-in, guiding decision-making, and ultimately achieving the desired results.

In conclusion, understanding the purpose of writing is fundamental to effective communication. Whether informing, persuading, entertaining, or expressing, the purpose serves as the driving force behind every word penned by the author. It guides the tone, style, and content of the writing, ensuring clarity, engagement, and impact on the audience.

Recognizing the writer’s purpose and tone empowers readers to interpret and evaluate the content critically, fostering deeper engagement and meaningful dialogue. For proposal writers, clearly articulating the purpose of the proposal is paramount for gaining stakeholder buy-in, guiding decision-making, and ultimately achieving success.

In essence, purpose matters in writing because it provides direction, relevance, and significance to the text. By understanding the purpose behind the words, both writers and readers can navigate the complexities of communication with clarity, purpose, and effectiveness.

About Sara Cook

Hi, I am Sara! I am the founder of TheWritersHQ! I have loved writing and reading since I was a little kid! Stephen King has my heart! I started this site to share my knowledge and build on my passion!

Thewritershq

REVIEW GUIDELINES

THEWritershq 2023 ©

21 Author’s Purpose Examples

Chris Drew (PhD)

Dr. Chris Drew is the founder of the Helpful Professor. He holds a PhD in education and has published over 20 articles in scholarly journals. He is the former editor of the Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education. [Image Descriptor: Photo of Chris]

Learn about our Editorial Process

The author’s purpose of a text refers to why they wrote the text .

It;s important to know the author’s purpose for a range of reasons, including:

- Media Literacy : We want to make sure we’re not tricked by the author. When reading an article online, for example, we want to figure out what the author’s purpose is in order to determine whether they’re going to write with a particular political bias.

- Determining Meaning: We might also want to know the author’s purpose in order to infer and predict what the underlying message might be. If an author’s job is to inform, we can read the text closely in order to examine its logic; but if the purpose is to entertain, we can consume the text with less of a critical lens.

- Understand Genre Convention : If we know the author’s purpose, we can predict and develop expectations about how the piece will be written. For example, persuasive texts should cite sources, while in reflective texts, we should expect first-person language and more intimate language.

Below are a range of possible purposes that authors may have when writing texts.

Author’s Purpose Examples

1. to inform.

Common Text Genres: News articles, Research papers, Textbooks, Biographies, Manuals.

Texts designed to inform tend to seek an objective stance, where the author presents facts, data, or truths to the reader with the sole intention of educating or delivering important information to the reader. It is common, for example, in news articles, where journalists must adhere to journalistic ethics and ensure the information is entirely factual. This is also often the purpose of non-fiction books, academic writing, scientific articles, and of course, this very website you’re reading right now.

Example of an Informative Text A National Geographic article on climate change informs readers about the state of the planet, providing facts and figures about global warming, melting ice caps, and so on.

2. To Entertain

Common Text Genres: Novels, Short stories, Poetry, Plays, Comics

This type of writing is meant to captivate the reader’s imagination and provide enjoyment. Here, the content needs to be delivered in a way that doesn’t bore and keeps the reader compelled to keep reading. To do this, the writing might be humorous, suspenseful, mysterious, or touching, depending on the genre. The author may also create characters, plot, and settings to keep the reader engaged and entertained, as with novels.

Example of an Entertaining Text A well-known example is J.K. Rowling’s “Harry Potter” series, which was written with the primary goal of entertaining readers with its magical world and captivating story.

3. To Persuade

Common Text Genres: Advertisements, Speeches, Opinion columns, Cover letters, Product reviews

In persuasive texts, the author’s main purpose is to convince the reader to accept a particular point of view or to take a specific action. This involves the use of arguments, logic, evidence, and emotional appeals. Persuasive writing can be found in speeches, advertisements, and opinion editorials. To examine some key techniques and strategies authors use to persuade, consult my article on the thirty types of persuasion in literature .

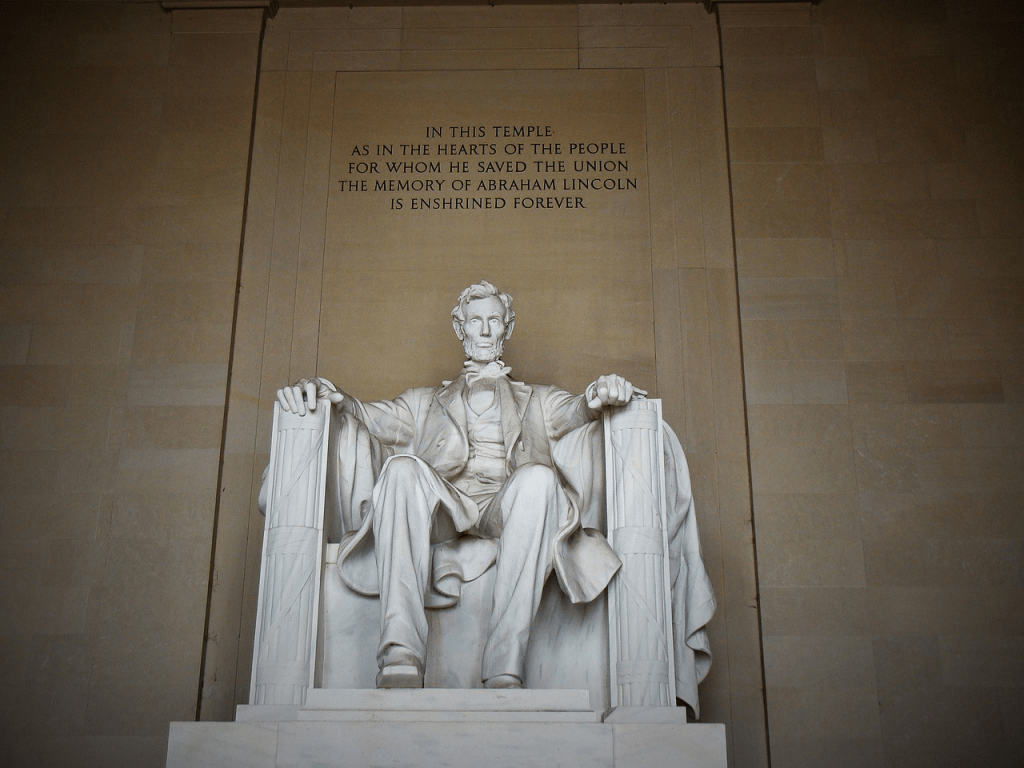

Example of a Persuasive Text A classic example is Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech, in which he persuasively argues for the end of racial discrimination in the United States.

4. To Describe

Common Text Genres: Travelogues, Food reviews, Personal essays, Descriptive poetry, Nature writing

Descriptive texts aim to paint a vivid picture in the reader’s mind. These sorts of texts can take us away to a different place and draw us into a complex world created by the author. For example, the author uses detailed and evocative descriptions to convey a scene, object, person, or feeling. The goal is to make the reader see, hear, smell, taste, or feel what is being described. This can be seen in many forms of writing, but is most evident in fiction, poetry, and travel writing, and can be paired with other author purposes, such as entertainment.

Example of a Descriptive Text An example of descriptive writing is F. Scott Fitzgerald’s “The Great Gatsby”, especially in its portrayal of the extravagant lifestyle of Jay Gatsby.

5. To Explain

Common Text Genres: How-to articles, Technical manuals, FAQs, Cookbooks, Explanatory journalism

In this type of writing, the author seeks to make the reader understand a process, concept, or idea. The writing breaks down complex subjects into simpler, more digestible parts. The author provides step-by-step explanations, examples, and definitions to aid understanding. This can be seen in how-to guides, tutorials, and expository essays . Of course, this purpose overlaps significantly with to inform , but tends to be more step-by-step or strips complex ideas into clear-to-understand chunks of information .

Example of an Explanatory Text A real-world example is Stephen Hawking’s “A Brief History of Time”, in which complex topics such as the Big Bang, black holes, and light cones are explained in a manner accessible to non-scientists.

6. To Analyze

Common Text Genres: Critical essays, Business reports, Scientific research papers, Market research, Literary analysis

Authors who write to analyze seek to break down a complex concept, event, or piece of work into smaller parts in order to better understand it. Analytical writing looks closely at all the components of a topic and how they work together. It’s about making connections and recognizing patterns. It could, for example, aim to identify flaws in a topic, or draw connections, similarities and differences, between multiple different concepts. You’ll commonly find these types of texts in professional contexts, such as reports provided to a company to give them guidance that helps them make better business decisions.

Example of an Analytical Text “The Art of War” by Sun Tzu offers a comprehensive analysis of warfare strategies, breaking down the complexities of warfare into key principles.

7. To Teach

Common Text Genres: Textbooks, How-to guides, Cookbooks, Self-help books

The author aims to impart knowledge or skills to the reader. These texts often provide step-by-step instructions or delve deep into a topic to ensure understanding. The goal is not only to inform but to enable the reader to perform a task or understand a concept independently. Examples of texts like this can include self-help books and textbooks, which might also contain ‘tasks’, ‘homework’ or ‘revision quizzes’ at the end of each chapter.

Example of an Educational Text “On Writing: A Memoir of the Craft” by Stephen King teaches readers about the art of writing and the life of a writer.

8. To Argue

Common Text Genres: Opinion editorials, Political speeches, Legal briefs, Persuasive essays

For these sorts of texts, the author’s purpose is to persuade the reader to accept a particular perspective, worldview, or ideology, often presenting a thesis and supporting it with evidence and logical reasoning. The goal is to make a case and convince the reader of its validity. Authors could use pathos , meaning emotion , to argue a point (e.g. appealing to a person’s emotional side), or logos , meaning logic (e.g. setting out a clear and logical explanation of why the author’s perspective is correct).

Example of an Argumentative Text A famous example is “A Vindication of the Rights of Woman” by Mary Wollstonecraft, where she argues for women’s rights and equality.

9. To Inspire

Common Text Genres: Motivational speeches, Inspirational books, Success stories, Motivational posters

Authors with this purpose want to stimulate their readers to act or create a change, instill hope, or provoke a sense of awe. These writings often share success stories, motivational thoughts, or beautiful descriptions of nature or humanity. A wide range of texts aim to inspire, from novels about amazing journeys, biographies about great people from history, and even people writing sales copy for brands.

Example of an Inspirational Text “I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings” by Maya Angelou is a work meant to inspire readers through its tale of overcoming adversity.

10. To Reflect

Common Text Genres: Diaries or journals, Vlogs and blogs, Retirement speeches, Reflective essays

In a reflective piece, the aim of the author is to share personal experiences, thoughts, or insights in an introspective manner. The goal is to convey the author’s personal journey or internal thought process. These texts often give readers a window into the author’s mind, and they may invite readers to reflect on their own experiences as well. Sometimes, the author will write the piece as a tool for self-improvement , such as to identify where they made mistakes or weaknesses in their processes, so they don’t make those mistakes next time.

Example of a Reflective Text “Meditations” by Marcus Aurelius is a series of personal writings, reflecting the author’s stoic philosophy and ideas on life.

11. To Share

Common Text Genres: Personal Blogs, Social Media Posts, Personal Essays, Anecdotes , Letters.

In this type of writing, the author aims to share personal experiences, thoughts, ideas, or information with the reader. The writer may offer insights into their lives, discuss their passions, or recount an event that happened to them. We might see this, for example, for someone who writes detailed reflections on their travels in their travel blog, or even a personal email back to friends and family each week.

Example of a Text designed to Share Elizabeth Gilbert’s “Eat, Pray, Love” is a memoir where the author shares her journey of self-discovery as she travels through Italy, India, and Indonesia.

12. To Record

Common Text Genres: Historical Accounts, Diaries, Journals, Biographies, Documentaries.

When writing to record, the author aims to create a detailed and factual account of events or experiences, either for personal reflection or to inform future generations. This type of writing can also serve to preserve personal or historical memories. We see this, for example, in historians’ writing as well as in some journalistic work, such as in the New York Times, which has become known as the paper of record for its longevity in recording important moments in US history.

Example of a Text of Record Anne Frank’s “The Diary of a Young Girl” is a historical record of her experiences hiding during the Nazi occupation of the Netherlands.

13. To Provoke Thought

Common Text Genres: Philosophical Works, Thought-Provoking Novels, Reflective Essays, Social Commentaries.

Authors who write to provoke thought aim to challenge their readers, pushing them to think more deeply about certain topics or to see things from a different perspective. They may raise complex questions, explore ambiguities, or critique societal norms. Such authors might be even aiming to get the reader upset, animated, or otherwise achieving cognitive dissonance in order to shift their thinking in some way.

Example of a Thought-Provoking Text George Orwell’s “1984” provokes thought about totalitarianism, surveillance, and individual freedom.

14. To Criticize

Common Text Genres: Reviews, Critical Essays, Satire, Polemics, Critiques .

When authors write to criticize, their aim is to express disapproval, dissent, or disagreement. They may critique a person, an idea, a societal trend, a piece of work, etc. They typically present their criticisms in a structured, reasoned manner, often supported by evidence. We see this regularly, for example, in ‘letters to the editor’ in newspapers, where everyday people can write into a newspaper in order to share their thoughts or rants for everyone to read.

Example of a Critical Text In his essay “Self-Reliance,” Ralph Waldo Emerson criticizes societal conformity and advocates for individualism.

15. To Predict

Common Text Genres: Speculative Fiction, Futurism Articles, Predictive Analytics Reports, Science Fiction.

Authors who write to predict aim to forecast future events or trends. These predictions could be based on current data, societal trends, scientific understanding, or simply imaginative speculation. This can be anything from a piece written by an economist or political scientist who’s predicting social trends that are upcoming, to a sci-fi novel that attempts to predict a dystopian future where AI has taken over the world!

Example of a Predictive Text In Aldous Huxley’s “Brave New World,” the author predicts a future society characterized by technological advancements, consumerism, and a lack of individual freedom.

16. To Express Emotion

Common Text Genres: Poetry, Personal Essays, Novels, Letters, Memoirs.

When authors write to express emotion, their main goal is to convey their feelings, or the feelings of someone else, to the reader. They might explore their emotional reaction to events, or evoke emotion in the reader. This is a common purpose of poetry and song lyrics, which have long genre-histories of evoking emotions in audiences, especially when the lyrics are read or sung to a live audience.

Example of an Emotional Text Sylvia Plath’s poetry, such as in her collection “Ariel,” often expresses deep personal emotions, particularly her struggles with depression.

17. To Explore

Common Text Genres: Adventure Novels, Travel Writing, Scientific Papers, Experimental Poetry, Philosophy Books.

Authors who write to explore aim to delve deeply into a topic, concept, or place. This might involve exploring physical environments, such as in travel writing, or abstract concepts , as in philosophical or scientific texts. Exploratory writing may start without a clear end-goal, and can ramble its way to an unknown conclusion.

Example of an Exploratory Text Charles Darwin’s “On the Origin of Species” explores the concept of natural selection and evolution.

18. To Satirize

Common Text Genres: Satirical Novels, Political Cartoons, Satirical Essays, Parodies.

Satirical writing uses humor, irony, exaggeration, or ridicule to expose and criticize people’s stupidity or vices, particularly in the context of contemporary politics and other societal issues. It could, for example, be a satirical novel which tries to undermine or make a joke out of other famous texts or genres. This, obviously, overlaps with the author purpose of to entertain but may also have elements of social commentary.

Example of a Satirical Text Jonathan Swift’s “Gulliver’s Travels” satirizes human nature and the “travelers’ tales” literary subgenre.

19. To Commemorate

Common Text Genres: Eulogies, Obituaries, Commemorative Speeches, Historical Fiction.

Writing to commemorate aims to honor or remember a person, event, or idea. It often involves highlighting the subject’s significance or impact. For example, a person might write a piece that commemorates veterans on Vetertan’s Day. Similarly, an obituary commemorates a person’s life and attempts to sum up their achievements and the things that were of great importance to them.

Example of a Commemorative Text The Gettysburg Address by Abraham Lincoln was a speech to commemorate the lives lost during the Civil War and to reaffirm the principles of liberty and equality.

20. To Plead

Common Text Genres: Petitions, Open Letters, Advocacy Articles, Speeches.

When authors write to plead, they aim to make an urgent appeal or request for something. This could be a plea for action, support, change, etc. These texts commonly ask for social change or a change in perspective from the reader. The author may be pleading for themselves and their family (e.g. a refugee who pleads their case in a newspaper op-ed) or for the less advantaged (e.g. an activist pleading for people to donate to children in poverty).

Example of a Text that Pleads a Case In “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” Martin Luther King Jr. pleads for an end to racial segregation and appeals for justice and equality.

21. To Celebrate

Common Text Genres: Commendatory Speeches, Reviews, Praises, Tributes.

Authors who write to celebrate aim to acknowledge, praise, or express gratitude for someone or something. They might celebrate a person, a culture, a historical event, an achievement, or a simple joy of life. A celebratory text, for example, might be a speech someone gives at a graduation ceremony, with the intention of celebrating the graduates’ successes in finally completing their degree.

Example of a Celebratory Text Maya Angelou’s poem “Still I Rise” celebrates the resilience and strength of African American women.

See Also: Examples of Text Types

Texts are written for a range of reasons. By determining the intentions of the author, we can begin to infer genre expectations, whether there will be much bias, or indeed, whether we can simply read for entertainment and throw caution to the wind! Similarly, if you want to be a writer, it’s worth examining other author’s texts that have similar purposes, and take notes on their style and turns-of-phrase to learn from them.

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 101 Class Group Name Ideas (for School Students)

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 19 Top Cognitive Psychology Theories (Explained)

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 119 Bloom’s Taxonomy Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ All 6 Levels of Understanding (on Bloom’s Taxonomy)

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Reading Skills

Analyzing author’s purpose and point of view.

- The Albert Team

- Last Updated On: June 16, 2023

Introduction

Do you ever wonder why writers write the way they do? Why they pick certain words or tell a story in a specific way? The reason behind this is called the author’s purpose and point of view. It’s like a secret code that helps you understand what they really mean.

In this blog post, we’ll learn about this secret code. You’ll learn to figure out what an author is trying to say, and how they see the world. This will help you understand books, articles, and even posts on social media even better!

What is the Author’s Point of View?

When you read a text, it’s important to think about the author’s point of view. The author’s point of view refers to their unique perspective, opinions, beliefs, and biases that shape how they present information or tell a story. They might see things in a way that’s different from you because of their own experiences, beliefs, and backgrounds.

Understanding an author’s point of view allows us to dig deeper into the underlying motivations and intentions behind their words. It can also help you find hidden messages in the text. So, how do we figure out an author’s point of view? Let’s talk about some ways to do this.

How to Determine the Author’s Point of View

You might think figuring out an author’s point of view is hard, but it can be fun, like solving a mystery! Here are some tips to help you do it:

- Look at the Words : Notice the words the author uses. Are they showing strong feelings or opinions? The way they write can give you hints about what they think and feel.

- Learn About the Author : Knowing more about the author can help you understand their point of view. What kind of job do they have? Where are they from? What are some important things that have happened to them?

- Think About Why the Author Wrote the Text: Why do you think the author wrote this? Do they want to teach you something, make you think, or make you laugh? Knowing this can help you understand what they’re trying to say.

- Notice Patterns: Look for ideas that come up again and again. These can tell you a lot about what the author thinks is important.

- Think About Who the Author is Writing For: Authors often write for specific groups of people. The way they write can tell you a lot about who they are trying to talk to.

Remember, figuring out an author’s point of view is about understanding the text better, not about deciding if they are right or wrong.

Why is the Author’s Point of View Important?

Why should we care about the author’s point of view? Here are some good reasons:

- Contextual Understanding : The author’s point of view helps us make sense of the text. It shows us why they chose to write the way they did and what they want us to learn.

- Uncovering Bias: No author can be totally unbiased. By understanding their point of view, we can see their own opinions in the text. This helps us think critically about what we’re reading.

- Evaluating Objectivity: Knowing the author’s point of view helps us see if the text is objective (without personal feelings) or subjective (based on personal feelings). This can help us decide if we can trust the information in the text.

- Enhancing Interpretation: Understanding the author’s point of view helps us understand what the text really means. We can see what arguments the author is making and think more deeply about the text.

- Encouraging Empathy and Perspective: By seeing things from the author’s point of view, we can better understand people who are different from us. This helps us be more understanding and open-minded.

As you can see, knowing the author’s point of view helps us understand and think about what we read in a deeper way. It makes us better readers and thinkers!

How to Determine the Author’s Purpose

In addition to analyzing the author’s point of view, it is also key to examine the author’s purpose. Here are some tips to help you figure out the author’s purpose:

- Check the Type of Text: Look at what kind of text it is. Is it a story, a news article, or maybe an essay? This can give you clues about why the author wrote it.

- Look at the Words and Tone: Pay attention to the words the author uses and how they write. If they use a lot of emotion, they might be trying to persuade you. If they give a lot of facts, they’re probably trying to inform you.

- Think About Who It’s Written For: Who is the author writing for? For example, a text for experts might be trying to give new information, while a text for kids might be trying to teach something in a fun way.

- Look for Main Ideas: What are the big ideas in the text? What is the author trying to say? This can give you a hint about why they wrote it.

- Check for Facts or Stories: Does the author use a lot of facts and data? Or do they tell stories? This can also help you figure out the author’s purpose.

- Think About the Time and Place: When and where was the text written? Sometimes, this can tell you a lot about why the author wrote the text.

Remember, you might not always see the author’s purpose right away. But if you look closely, you can usually find clues that will help you figure it out.

How Text Structure Contributes to the Author’s Purpose

Text structure, or the way a text is put together, plays a significant role in conveying the author’s purpose and shaping the overall message of a written piece. The way a text is organized and structured can greatly influence how the information is presented and how the reader engages with it. Here are some ways that text structure contributes to the author’s purpose

- Order of Ideas: Authors choose how to order their ideas for a reason. They might use a time order, cause and effect, or compare and contrast to help get their point across.

- Important Points Stand Out: Authors use things like headings or bullet points to show important ideas. This can tell us what the author thinks is most important.

- Storytelling Techniques: In stories, authors might play with the order of events, use flashbacks, or tell the story from different viewpoints. This can make the story more interesting or help make a point.

- Persuasion Techniques: If the author is trying to convince you of something, they will present their arguments in a careful order. They might present a problem, then give evidence, then propose a solution.

- Easy to Follow: A well-organized text is easier to understand. The way the author organizes the text can help you follow their ideas and understand what they want to say.

By looking at how a text is structured, you can get a better idea of what the author’s purpose is. So, next time you read something, pay attention to how it’s put together!

Classroom Application: What is the Author’s Purpose in this Passage?

Analyzing the author’s purpose becomes more engaging and relatable when you can apply your skills to historical speeches. One exemplary text for this exercise is Abraham Lincoln’s Second Inaugural Address. Use this step-by-step guide to analyze the author’s purpose in this significant piece of writing:

Step 1: Background Research:

First, start by gathering some background information about Abraham Lincoln, his presidency, and the context of the Second Inaugural Address. Learn about the Civil War and how it impacted the nation during that time.

Step 2: Reading and Annotation:

Next, read the Second Inaugural Address carefully, highlighting or underlining key statements and phrases. Take note of any repeated themes or arguments and mark moments where Lincoln’s perspective or tone seems particularly important.

Step 3: Identifying the Type of Text:

Consider the type of text you are analyzing, which is a presidential inauguration speech. Think about the common purposes associated with such speeches, like inspiring unity, expressing gratitude, or outlining a vision for the nation.

Step 4: Analyzing Language and Tone:

Pay close attention to Lincoln’s choice of language and tone throughout the address. Look for emotional or persuasive language and note instances of unity, humility, or calls for reconciliation. Consider how these choices contribute to Lincoln’s purpose.

Step 5: Reflecting on Historical Context:

Think about the historical context surrounding the Second Inaugural Address. For example, you could reflect on the divided nation during the Civil War and how it affected Lincoln’s presidency. Then, connect these historical events to Lincoln’s purpose in addressing the nation during such a critical time.

Step 6: Identifying Key Statements and Arguments:

Identify the central statements and arguments made by Lincoln in the address. Consider how these statements reflect his purpose and the message he wanted to convey. Think critically about the implications of these arguments.

Step 7: Considering the Audience:

Reflect on the intended audience of the Second Inaugural Address, which includes both supporters and opponents of Lincoln. Analyze how Lincoln’s purpose might have been influenced by this diverse audience and how he aimed to unite the nation through his words.

Step 8: Drawing Conclusions:

Based on the evidence you gathered from the text analysis and understanding of the historical context, draw conclusions about Lincoln’s purpose in delivering the Second Inaugural Address. Make sure to support your conclusions with evidence from the text.

Step 9: Classroom Discussion and Reflection: