- Skip to main content

- Skip to secondary menu

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

A Plus Topper

Improve your Grades

Family History Essay | How to Write? and 400 Words Essay on Family History

February 14, 2024 by Prasanna

Family History Essay: A family involves individuals living respectively that structure a gathering of people inside a local area. Individuals making this gathering are dependent upon connections either by birth or blood, and it involves at any rate two grown-ups as guardians and grandparents, along with little youngsters. The relatives have a common association between them. Thus, an exposition about family ancestry is a rundown of a person’s social personality and the equal relationship(s) he/she imparts to individuals living respectively.

Adapting family ancestry is indispensable to comprehend our economic well-being, mankind, and variety. History saves our recollections for ages to comprehend what their identity is and their geographic beginning. Having decent information on family foundation allows you to see the value in the things or penances made before by grandparents to encounter better things throughout everyday life. A person’s underlying foundations and beginning bring a self-appreciation revelation. Likewise, expounding on your family ancestry is one method of protecting its legacy for people in the future.

You can also find more Essay Writing articles on events, persons, sports, technology and many more.

How to Write a Family History Essay?

When composing a, there is a consistent construction you should continue in giving out your contentions. An appropriate diagram will deliver an energizing show of each segment, and it will interest the peruser. The standard design of an article has a presentation, body, and end. Here is a magnificent illustration of a layout for a family ancestry article:

- Topic: My Family History

- Introduction (Outline): Write a short brief about your family background and why your family is important

- Body: Write about your family members, how you live together and who your neighbors

- Conclusion: Rehashing your conflict, Sum up your key thoughts, and Give a last remark or reflection about the paper

Essay on Family History 400 Words in English

Would you need to know how everything began until here? My grandpa disclosed to me that he met my grandmother at a show where probably the best craftsman was performing during one of the late spring occasions in London. As he was moving alone, my grandpa moved toward a wonderful woman (who might turn into his perfect partner) to request that she dance together. They later consented to meet for a supper date. Our family lives in London. Without a doubt, this is the best family, and it’s an honor to be essential for it.

Each individual includes different sides inside his/her family; my fatherly side begins from Canada, while the maternal side is from America. Despite the fact that my extraordinary granddad comes from Spain, my grandpa and grandmother live in London. My granddad is Indo-British who functioned as a barkeep, no big surprise he adored shows! My dad fills in as a traditionalist for amphibian fauna while my mom works in the bread kitchen. My mom and father met in a store when they were both shopping.

Despite the fact that we live in a similar city, my grandparents have their loft, a separation from our own. We live as a group of five; father, mum, and three youngsters. As we as a whole live in a similar city, we (me and my two sisters) incidentally visit our grandparents during the end of the week to invest some energy with them; grandpa and I were doing some planting while my sisters and grandmother do cook and other house tasks. The connection between our extraordinary guardians and our own is extremely phenomenal.

At Christmas, every one of my youngsters, mum, and father travel to our grandparents for an entire week. During the new year, we get together at our home, my parent’s home, to invite the year as a whole family. Now and again during the end of the week, we normally invest the majority of our energy on the seashore swimming, besides on chapel days. As a family, our number one food is rotisserie fish, rice, and vegetables. In any case, my grandpa likes chicken hash.

All in all, the social conjunction between us is fantastic, which has made a powerful common bond for the family. From visiting one another, investing energy in the seashore, getting together suppers to usher in the new year, and observing Christmas as a family, the bond continues to develop. I’m favored to be essential for a particularly incredible family.

FAQ’s on Family History Essay

Question 1. Why is it important to know family history?

Answer: Knowing your family ancestry is vital. It empowers one to self-find himself inside the general public and like the heredity. At the point when you find out about your family’s past, you will comprehend the things you see and experience today. Composing an article on family ancestry requires a ton of comprehension and consideration regarding the viewpoints you need to depict. The basic factor being the family foundation, at that point seeing how you need to design and scribble down your thoughts.

Question 2. What are the points that can be mentioned in a family history essay?

Answer: You can write about family members, relations, values and traditions of your family. Write down the places from where your ancestors belong or the origin of your family. Also, mention the family reunion or gatherings or the occasions when you all get together.

Question 3. What family really means?

Answer: Family implies having somebody to adore you unequivocally disregarding you and your weaknesses. Family is cherishing and supporting each other in any event when it is difficult to do as such. It’s being the best individual you could be with the goal that you may motivate your adoration ones.

Question 4. Why do we need family?

Answer: Family is the absolute most significant impact on a youngster’s life. From their first snapshots of life, kids rely upon guardians and family to ensure them and accommodate their necessities. Kids flourish when guardians can effectively advance their positive development and improvement.

- Picture Dictionary

- English Speech

- English Slogans

- English Letter Writing

- English Essay Writing

- English Textbook Answers

- Types of Certificates

- ICSE Solutions

- Selina ICSE Solutions

- ML Aggarwal Solutions

- HSSLive Plus One

- HSSLive Plus Two

- Kerala SSLC

- Distance Education

How to Write an Essay About My Family History

A family comprises of people living together that form a social group within a community. The people creating this group are subject to relationships either by birth or blood, and it comprises at least two adults as parents and grandparents, together with young children. The family members have a mutual connection between them. Therefore, an essay about family history is a synopsis of an individual's social identity and the reciprocal relationship(s) he/she shares with the people living together. Learning family history is vital to understand our social status, humanity, and diversity. History keeps our memories for generations to understand who they are and their geographic origin. Having a good knowledge of family background lets you appreciate the things or sacrifices made before by grandparents to experience better things in life. An individual's roots and origin bring a sense of self-discovery. Also, writing about your family history is one way of preserving its heritage for future generations.

How to Start A Family History Essay

Outline writing, tips concerning writing a family history essay introduction, how to write body paragraphs, how to write a conclusion for a family history essay, essay revision, essay proofreading, make citations, catchy titles for an essay about family history, short example of a college essay about family history.

- How to Get the Best Family History Essay

Buy Pre-written Essay Examples on The Topic

Use edujungles to write your essay from a scratch.

When writing an essay, there is a logical structure you must follow in giving out your arguments. A proper outline will produce an exciting presentation of every section, and it will fascinate the reader. The standard structure of an essay has an introduction, body, and conclusion. Here is an excellent example of an outline for a family history essay:

- Introduction

- Short family background information

- Importance of writing about the family

- Body (paragraphs)

- Family members; grandparents, parents, and children

- The community in which family resides

- Form of livelihood

- Conclusion (a summarizing paragraph)

- Restating your contention

- Summarize your key ideas

- Provide a final comment or reflection about the essay

When writing a presentation about family history, you need to provide a hook to the readers, to make them interested to know much about the family. You can start with facts or anecdotes about grandparents; for example, how they met on the first date and opted to make a family together, you can as well describe the circumstances. You can also provide an insight into a situation by your ancestors that impacted your life experience—the other thing to include in the short background information about your family. Remember to provide a clear and debatable thesis statement that will serve as the roadmap for your discussion in the paper.

WE WILL WRITE A CUSTOM ESSAY

SPECIALLY FOR YOU

FOR ONLY $11/PAGE

465 CERTIFICATED WRITERS ONLINE

The body paragraphs contain the arguments one needs to discuss the subject topic. Every section includes the main idea or explanatory statement as the first sentence; the primary purpose is a debatable point that you need to prove. The length of a paragraph depends on the accurate measurement of ideas. In most cases, a section has about five sentences; but it can be as short or long as you want, depending on what you discuss. A paragraph has the main statement, supporting sentence(s) with evidence, and concluding sentences. When crafting the body, ensure a clear flow of ideas, connecting from one argument to the other. Transitional words, when used accordingly, can provide a nice transition and flow of ideas from one paragraph to the other. The commonly used transitional words or phrases include moreover, also, therefore, consequently, hence, thus, finally, etc.

A conclusion is as crucial as the introduction; it is the final recap of what your essay entails. The ending paragraph contains three main parts that form a full section. First, remind the audience of your thesis statement and show its relation to the essay topic. Second, provide a summary of the key arguments that you discussed in the body paragraphs. Third, it is advisable to add a final comment or general reflection about the essay. It's important to state that you should use different wording in the conclusion when restating statements and arguments. Also, remember to use signal words at the start of concluding paragraphs like in conclusion, finish, etc.

Revision is an opportunity for a student to review the content in his/her paper and identify parts that need improvement. Some students start revising as they begin drafting their essays. During revision, you need to restructure and rearrange sentences to enhance your work quality and ensure the message reaches your audience well. Revising gives you a chance to recheck whether the essay has a short main idea and a thesis statement, a specific purpose, whether the introduction is strong enough to hook the audience and organization of the article. Also, you check if there is a clear transition from one paragraph to another and ascertain if the conclusion is competent enough to emphasize the purpose of the paper.

Nothing is more frustrating than submitting an essay to earn dismal grade due to silly common mistakes. Proofreading is an essential stage in the editing process. It is an opportunity for reviewing the paper, identifying and correcting common mistakes such as typos, punctuation, grammatical errors, etc. Since proofreading is the final part of the editing, proofread only after finishing the other editing stages like revision. It is advisable to get help from another pair of eyes; you can send the paper to your friend to help you in the same process. There are online proofreading tools such as Grammarly and Hemingway, which you can use to proofread, but you should not only rely on grammar checkers. Remember to proofread the document at least three times.

Making citations is an essential way of keeping references for the sources of content you used. As you are editing, you may make several changes to the document. Do not forget to correctly provide citations for every fact or quote you obtained from other sources. There are different citation formats such as APA, MLA, etc.; therefore, you need to ensure correct usage of quotes depending on the requirement by your professor. The sources you cite present the list of references or bibliography at the end of your essay for easy reference.

- Generation to Generation

- The Origin of My Family

- Our Circle and Family Heritage

- A Lifetime of Love

- Because of Two Lovebirds, I Am Here

- The Family Archives

- The Family Ties

- Branches of The Family Tree

- The Generational Genes

- Forever as a Family

- It All Started with a Date

- Bits of Yesteryears

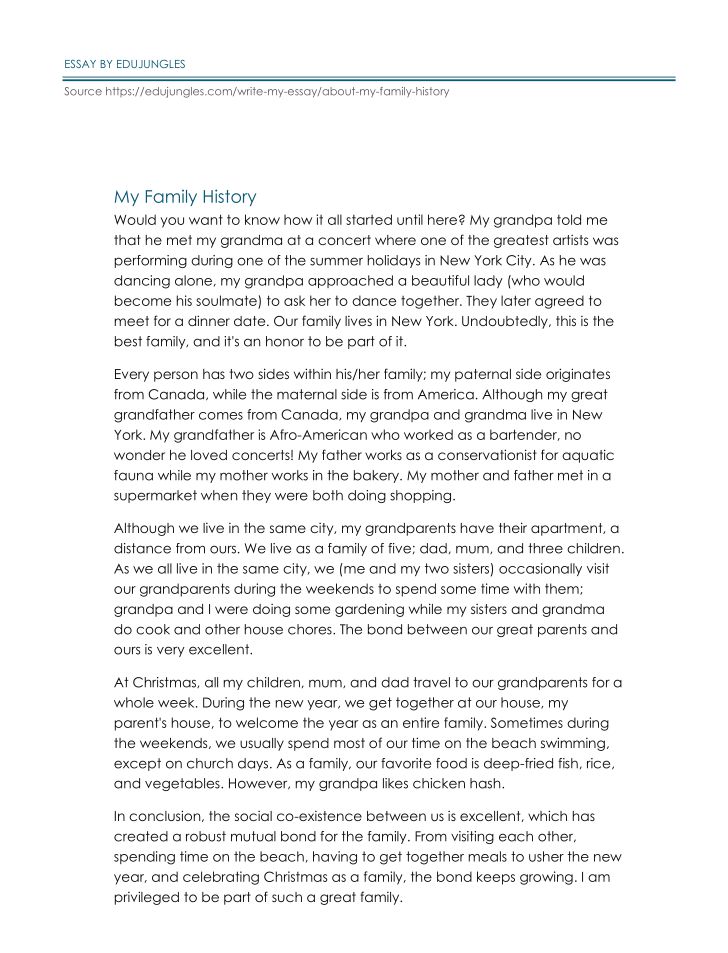

Would you want to know how it all started until here? My grandpa told me that he met my grandma at a concert where one of the greatest artists was performing during one of the summer holidays in New York City. As he was dancing alone, my grandpa approached a beautiful lady (who would become his soulmate) to ask her to dance together. They later agreed to meet for a dinner date. Our family lives in New York. Undoubtedly, this is the best family, and it's an honor to be part of it.

Every person has two sides within his/her family; my paternal side originates from Canada, while the maternal side is from America. Although my great grandfather comes from Canada, my grandpa and grandma live in New York. My grandfather is Afro-American who worked as a bartender, no wonder he loved concerts! My father works as a conservationist for aquatic fauna while my mother works in the bakery. My mother and father met in a supermarket when they were both doing shopping.

Although we live in the same city, my grandparents have their apartment, a distance from ours. We live as a family of five; dad, mum, and three children. As we all live in the same city, we (me and my two sisters) occasionally visit our grandparents during the weekends to spend some time with them; grandpa and I were doing some gardening while my sisters and grandma do cook and other house chores. The bond between our great parents and ours is very excellent.

At Christmas, all my children, mum, and dad travel to our grandparents for a whole week. During the new year, we get together at our house, my parent's house, to welcome the year as an entire family. Sometimes during the weekends, we usually spend most of our time on the beach swimming, except on church days. As a family, our favorite food is deep-fried fish, rice, and vegetables. However, my grandpa likes chicken hash.

In conclusion, the social co-existence between us is excellent, which has created a robust mutual bond for the family. From visiting each other, spending time on the beach, having to get together meals to usher the new year, and celebrating Christmas as a family, the bond keeps growing. I am privileged to be part of such a great family.

How to Get the Best Family History Essay?

Every student would want to produce the best essay possible to earn a better grade. One way of getting information is through previously written materials such as essay samples. Pre-written essay samples have become popular recently among college students due to the vital information they offer. There are several sites, such as Essay Kitchen, that provide pre-written essays on family history at affordable prices. Students can use the essay samples to obtain enough content and idea about paper outline the professor expect; thus, producing a quality article.

Essay writing is a daunting experience for most college students. The academic pressure, coupled with a lot of other activities, makes the whole experience an ordeal. Some students have a lot of responsibilities and find themselves with limited time to handle their academic essays. Consequently, the students use online essay writing service 12 hours at Edu Jungles to write my essay for me at an affordable rate.

Knowing your family history is very important. It enables one to self-discover himself within the society and appreciate the lineage. When you learn about your family's past, you will understand the things you see and experience today. Writing an essay on family history requires a lot of understanding and attention to the aspects you need to describe. The critical factor being family background, then understanding how you need to structure and jot down your ideas.

We use cookies. Read about how we use cookies and how you can control them by clicking cookie policy .

How to write an introduction for a history essay

Every essay needs to begin with an introductory paragraph. It needs to be the first paragraph the marker reads.

While your introduction paragraph might be the first of the paragraphs you write, this is not the only way to do it.

You can choose to write your introduction after you have written the rest of your essay.

This way, you will know what you have argued, and this might make writing the introduction easier.

Either approach is fine. If you do write your introduction first, ensure that you go back and refine it once you have completed your essay.

What is an ‘introduction paragraph’?

An introductory paragraph is a single paragraph at the start of your essay that prepares your reader for the argument you are going to make in your body paragraphs .

It should provide all of the necessary historical information about your topic and clearly state your argument so that by the end of the paragraph, the marker knows how you are going to structure the rest of your essay.

In general, you should never use quotes from sources in your introduction.

Introduction paragraph structure

While your introduction paragraph does not have to be as long as your body paragraphs , it does have a specific purpose, which you must fulfil.

A well-written introduction paragraph has the following four-part structure (summarised by the acronym BHES).

B – Background sentences

H – Hypothesis

E – Elaboration sentences

S - Signpost sentence

Each of these elements are explained in further detail, with examples, below:

1. Background sentences

The first two or three sentences of your introduction should provide a general introduction to the historical topic which your essay is about. This is done so that when you state your hypothesis , your reader understands the specific point you are arguing about.

Background sentences explain the important historical period, dates, people, places, events and concepts that will be mentioned later in your essay. This information should be drawn from your background research .

Example background sentences:

Middle Ages (Year 8 Level)

Castles were an important component of Medieval Britain from the time of the Norman conquest in 1066 until they were phased out in the 15 th and 16 th centuries. Initially introduced as wooden motte and bailey structures on geographical strongpoints, they were rapidly replaced by stone fortresses which incorporated sophisticated defensive designs to improve the defenders’ chances of surviving prolonged sieges.

WWI (Year 9 Level)

The First World War began in 1914 following the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand. The subsequent declarations of war from most of Europe drew other countries into the conflict, including Australia. The Australian Imperial Force joined the war as part of Britain’s armed forces and were dispatched to locations in the Middle East and Western Europe.

Civil Rights (Year 10 Level)

The 1967 Referendum sought to amend the Australian Constitution in order to change the legal standing of the indigenous people in Australia. The fact that 90% of Australians voted in favour of the proposed amendments has been attributed to a series of significant events and people who were dedicated to the referendum’s success.

Ancient Rome (Year 11/12 Level)

In the late second century BC, the Roman novus homo Gaius Marius became one of the most influential men in the Roman Republic. Marius gained this authority through his victory in the Jugurthine War, with his defeat of Jugurtha in 106 BC, and his triumph over the invading Germanic tribes in 101 BC, when he crushed the Teutones at the Battle of Aquae Sextiae (102 BC) and the Cimbri at the Battle of Vercellae (101 BC). Marius also gained great fame through his election to the consulship seven times.

2. Hypothesis

Once you have provided historical context for your essay in your background sentences, you need to state your hypothesis .

A hypothesis is a single sentence that clearly states the argument that your essay will be proving in your body paragraphs .

A good hypothesis contains both the argument and the reasons in support of your argument.

Example hypotheses:

Medieval castles were designed with features that nullified the superior numbers of besieging armies but were ultimately made obsolete by the development of gunpowder artillery.

Australian soldiers’ opinion of the First World War changed from naïve enthusiasm to pessimistic realism as a result of the harsh realities of modern industrial warfare.

The success of the 1967 Referendum was a direct result of the efforts of First Nations leaders such as Charles Perkins, Faith Bandler and the Federal Council for the Advancement of Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders.

Gaius Marius was the most one of the most significant personalities in the 1 st century BC due to his effect on the political, military and social structures of the Roman state.

3. Elaboration sentences

Once you have stated your argument in your hypothesis , you need to provide particular information about how you’re going to prove your argument.

Your elaboration sentences should be one or two sentences that provide specific details about how you’re going to cover the argument in your three body paragraphs.

You might also briefly summarise two or three of your main points.

Finally, explain any important key words, phrases or concepts that you’ve used in your hypothesis, you’ll need to do this in your elaboration sentences.

Example elaboration sentences:

By the height of the Middle Ages, feudal lords were investing significant sums of money by incorporating concentric walls and guard towers to maximise their defensive potential. These developments were so successful that many medieval armies avoided sieges in the late period.

Following Britain's official declaration of war on Germany, young Australian men voluntarily enlisted into the army, which was further encouraged by government propaganda about the moral justifications for the conflict. However, following the initial engagements on the Gallipoli peninsula, enthusiasm declined.

The political activity of key indigenous figures and the formation of activism organisations focused on indigenous resulted in a wider spread of messages to the general Australian public. The generation of powerful images and speeches has been frequently cited by modern historians as crucial to the referendum results.

While Marius is best known for his military reforms, it is the subsequent impacts of this reform on the way other Romans approached the attainment of magistracies and how public expectations of military leaders changed that had the longest impacts on the late republican period.

4. Signpost sentence

The final sentence of your introduction should prepare the reader for the topic of your first body paragraph. The main purpose of this sentence is to provide cohesion between your introductory paragraph and you first body paragraph .

Therefore, a signpost sentence indicates where you will begin proving the argument that you set out in your hypothesis and usually states the importance of the first point that you’re about to make.

Example signpost sentences:

The early development of castles is best understood when examining their military purpose.

The naïve attitudes of those who volunteered in 1914 can be clearly seen in the personal letters and diaries that they themselves wrote.

The significance of these people is evident when examining the lack of political representation the indigenous people experience in the early half of the 20 th century.

The origin of Marius’ later achievements was his military reform in 107 BC, which occurred when he was first elected as consul.

Putting it all together

Once you have written all four parts of the BHES structure, you should have a completed introduction paragraph. In the examples above, we have shown each part separately. Below you will see the completed paragraphs so that you can appreciate what an introduction should look like.

Example introduction paragraphs:

Castles were an important component of Medieval Britain from the time of the Norman conquest in 1066 until they were phased out in the 15th and 16th centuries. Initially introduced as wooden motte and bailey structures on geographical strongpoints, they were rapidly replaced by stone fortresses which incorporated sophisticated defensive designs to improve the defenders’ chances of surviving prolonged sieges. Medieval castles were designed with features that nullified the superior numbers of besieging armies, but were ultimately made obsolete by the development of gunpowder artillery. By the height of the Middle Ages, feudal lords were investing significant sums of money by incorporating concentric walls and guard towers to maximise their defensive potential. These developments were so successful that many medieval armies avoided sieges in the late period. The early development of castles is best understood when examining their military purpose.

The First World War began in 1914 following the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand. The subsequent declarations of war from most of Europe drew other countries into the conflict, including Australia. The Australian Imperial Force joined the war as part of Britain’s armed forces and were dispatched to locations in the Middle East and Western Europe. Australian soldiers’ opinion of the First World War changed from naïve enthusiasm to pessimistic realism as a result of the harsh realities of modern industrial warfare. Following Britain's official declaration of war on Germany, young Australian men voluntarily enlisted into the army, which was further encouraged by government propaganda about the moral justifications for the conflict. However, following the initial engagements on the Gallipoli peninsula, enthusiasm declined. The naïve attitudes of those who volunteered in 1914 can be clearly seen in the personal letters and diaries that they themselves wrote.

The 1967 Referendum sought to amend the Australian Constitution in order to change the legal standing of the indigenous people in Australia. The fact that 90% of Australians voted in favour of the proposed amendments has been attributed to a series of significant events and people who were dedicated to the referendum’s success. The success of the 1967 Referendum was a direct result of the efforts of First Nations leaders such as Charles Perkins, Faith Bandler and the Federal Council for the Advancement of Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders. The political activity of key indigenous figures and the formation of activism organisations focused on indigenous resulted in a wider spread of messages to the general Australian public. The generation of powerful images and speeches has been frequently cited by modern historians as crucial to the referendum results. The significance of these people is evident when examining the lack of political representation the indigenous people experience in the early half of the 20th century.

In the late second century BC, the Roman novus homo Gaius Marius became one of the most influential men in the Roman Republic. Marius gained this authority through his victory in the Jugurthine War, with his defeat of Jugurtha in 106 BC, and his triumph over the invading Germanic tribes in 101 BC, when he crushed the Teutones at the Battle of Aquae Sextiae (102 BC) and the Cimbri at the Battle of Vercellae (101 BC). Marius also gained great fame through his election to the consulship seven times. Gaius Marius was the most one of the most significant personalities in the 1st century BC due to his effect on the political, military and social structures of the Roman state. While Marius is best known for his military reforms, it is the subsequent impacts of this reform on the way other Romans approached the attainment of magistracies and how public expectations of military leaders changed that had the longest impacts on the late republican period. The origin of Marius’ later achievements was his military reform in 107 BC, which occurred when he was first elected as consul.

Additional resources

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources.

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2024.

Contact via email

Essay about Family: What It Is and How to Nail It

Humans naturally seek belonging within families, finding comfort in knowing someone always cares. Yet, families can also stir up insecurities and mental health struggles.

Family dynamics continue to intrigue researchers across different fields. Every year, new studies explore how these relationships shape our minds and emotions.

In this article, our dissertation service will guide you through writing a family essay. You can also dive into our list of topics for inspiration and explore some standout examples to spark your creativity.

What is Family Essay

A family essay takes a close look at the bonds and experiences within families. It's a common academic assignment, especially in subjects like sociology, psychology, and literature.

.webp)

So, what's involved exactly? Simply put, it's an exploration of what family signifies to you. You might reflect on cherished family memories or contemplate the portrayal of families in various media.

What sets a family essay apart is its personal touch. It allows you to express your own thoughts and experiences. Moreover, it's versatile – you can analyze family dynamics, reminisce about family customs, or explore other facets of familial life.

If you're feeling uncertain about how to write an essay about family, don't worry; you can explore different perspectives and select topics that resonate with various aspects of family life.

Tips For Writing An Essay On Family Topics

A family essay typically follows a free-form style, unless specified otherwise, and adheres to the classic 5-paragraph structure. As you jot down your thoughts, aim to infuse your essay with inspiration and the essence of creative writing, unless your family essay topics lean towards complexity or science.

.webp)

Here are some easy-to-follow tips from our essay service experts:

- Focus on a Specific Aspect: Instead of a broad overview, delve into a specific angle that piques your interest, such as exploring how birth order influences sibling dynamics or examining the evolving role of grandparents in modern families.

- Share Personal Anecdotes: Start your family essay introduction with a personal touch by sharing stories from your own experiences. Whether it's about a favorite tradition, a special trip, or a tough time, these stories make your writing more interesting.

- Use Real-life Examples: Illustrate your points with concrete examples or anecdotes. Draw from sources like movies, books, historical events, or personal interviews to bring your ideas to life.

- Explore Cultural Diversity: Consider the diverse array of family structures across different cultures. Compare traditional values, extended family systems, or the unique hurdles faced by multicultural families.

- Take a Stance: Engage with contentious topics such as homeschooling, reproductive technologies, or governmental policies impacting families. Ensure your arguments are supported by solid evidence.

- Delve into Psychology: Explore the psychological underpinnings of family dynamics, touching on concepts like attachment theory, childhood trauma, or patterns of dysfunction within families.

- Emphasize Positivity: Share uplifting stories of families overcoming adversity or discuss strategies for nurturing strong, supportive family bonds.

- Offer Practical Solutions: Wrap up your essay by proposing actionable solutions to common family challenges, such as fostering better communication, achieving work-life balance, or advocating for family-friendly policies.

Family Essay Topics

When it comes to writing, essay topics about family are often considered easier because we're intimately familiar with our own families. The more you understand about your family dynamics, traditions, and experiences, the clearer your ideas become.

If you're feeling uninspired or unsure of where to start, don't worry! Below, we have compiled a list of good family essay topics to help get your creative juices flowing. Whether you're assigned this type of essay or simply want to explore the topic, these suggestions from our history essay writer are tailored to spark your imagination and prompt meaningful reflection on different aspects of family life.

So, take a moment to peruse the list. Choose the essay topics about family that resonate most with you. Then, dive in and start exploring your family's stories, traditions, and connections through your writing.

- Supporting Family Through Tough Times

- Staying Connected with Relatives

- Empathy and Compassion in Family Life

- Strengthening Bonds Through Family Gatherings

- Quality Time with Family: How Vital Is It?

- Navigating Family Relationships Across Generations

- Learning Kindness and Generosity in a Large Family

- Communication in Healthy Family Dynamics

- Forgiveness in Family Conflict Resolution

- Building Trust Among Extended Family

- Defining Family in Today's World

- Understanding Nuclear Family: Various Views and Cultural Differences

- Understanding Family Dynamics: Relationships Within the Family Unit

- What Defines a Family Member?

- Modernizing the Nuclear Family Concept

- Exploring Shared Beliefs Among Family Members

- Evolution of the Concept of Family Love Over Time

- Examining Family Expectations

- Modern Standards and the Idea of an Ideal Family

- Life Experiences and Perceptions of Family Life

- Genetics and Extended Family Connections

- Utilizing Family Trees for Ancestral Links

- The Role of Younger Siblings in Family Dynamics

- Tracing Family History Through Oral Tradition and Genealogy

- Tracing Family Values Through Your Family Tree

- Exploring Your Elder Sister's Legacy in the Family Tree

- Connecting Daily Habits to Family History

- Documenting and Preserving Your Family's Legacy

- Navigating Online Records and DNA Testing for Family History

- Tradition as a Tool for Family Resilience

- Involving Family in Daily Life to Maintain Traditions

- Creating New Traditions for a Small Family

- The Role of Traditions in Family Happiness

- Family Recipes and Bonding at House Parties

- Quality Time: The Secret Tradition for Family Happiness

- The Joy of Cousins Visiting for Christmas

- Including Family in Birthday Celebrations

- Balancing Traditions and Unconditional Love

- Building Family Bonds Through Traditions

Looking for Speedy Assistance With Your College Essays?

Reach out to our skilled writers, and they'll provide you with a top-notch paper that's sure to earn an A+ grade in record time!

Family Essay Example

For a better grasp of the essay on family, our team of skilled writers has crafted a great example. It looks into the subject matter, allowing you to explore and understand the intricacies involved in creating compelling family essays. So, check out our meticulously crafted sample to discover how to craft essays that are not only well-written but also thought-provoking and impactful.

Final Outlook

In wrapping up, let's remember: a family essay gives students a chance to showcase their academic skills and creativity by sharing personal stories. However, it's important to stick to academic standards when writing about these topics. We hope our list of topics sparked your creativity and got you on your way to a reflective journey. And if you hit a rough patch, you can just ask us to ' do my essay for me ' for top-notch results!

Having Trouble with Your Essay on the Family?

Our expert writers are committed to providing you with the best service possible in no time!

FAQs on Writing an Essay about Family

Family essays seem like something school children could be assigned at elementary schools, but family is no less important than climate change for our society today, and therefore it is one of the most central research themes.

Below you will find a list of frequently asked questions on family-related topics. Before you conduct research, scroll through them and find out how to write an essay about your family.

How to Write an Essay About Your Family History?

How to write an essay about a family member, how to write an essay about family and roots, how to write an essay about the importance of family.

Daniel Parker

is a seasoned educational writer focusing on scholarship guidance, research papers, and various forms of academic essays including reflective and narrative essays. His expertise also extends to detailed case studies. A scholar with a background in English Literature and Education, Daniel’s work on EssayPro blog aims to support students in achieving academic excellence and securing scholarships. His hobbies include reading classic literature and participating in academic forums.

is an expert in nursing and healthcare, with a strong background in history, law, and literature. Holding advanced degrees in nursing and public health, his analytical approach and comprehensive knowledge help students navigate complex topics. On EssayPro blog, Adam provides insightful articles on everything from historical analysis to the intricacies of healthcare policies. In his downtime, he enjoys historical documentaries and volunteering at local clinics.

.webp)

How to Write Your Family History

- Genealogy Fun

- Vital Records Around the World

- American History

- African American History

- African History

- Ancient History and Culture

- Asian History

- European History

- Latin American History

- Medieval & Renaissance History

- Military History

- The 20th Century

- Women's History

Choose a Format

Define the scope, set realistic deadlines.

- Choose a Plot and Themes

Do Your Background Research

- Don't Be Afraid to Use Records and Documents

Include an Index and Source Citations

- Certificate in Genealogical Research, Boston University

- B.A., Carnegie Mellon University

Writing a family history may seem like a daunting task, but when the relatives start nagging, you can follow these five easy steps to make your family history project a reality.

What do you envision for your family history project? A simple photocopied booklet shared only with family members or a full-scale, hard-bound book to serve as a reference for other genealogists? Perhaps you'd rather produce a family newsletter, cookbook, or website. Now is the time to be honest with yourself about the type of family history that meetings your needs and your schedule. Otherwise, you'll have a half-finished product nagging you for years to come.

Considering your interests, potential audience, and the types of materials you have to work with, here are some forms your family history can take:

- Memoir/Narrative: A combination of story and personal experience, memoirs, and narratives do not need to be all-inclusive or objective. Memoirs usually focus on a specific episode or time period in the life of a single ancestor, while a narrative generally encompasses a group of ancestors.

- Cookbook: Share your family's favorite recipes while writing about the people who created them. A fun project to assemble, cookbooks help carry on the family tradition of cooking and eating together.

- Scrapbook or Album: If you're fortunate enough to have a large collection of family photos and memorabilia, a scrapbook or photo album can be a fun way to tell your family's story. Include your photos in chronological order and include stories, descriptions, and family trees to complement the pictures.

Most family histories are generally narrative in nature, with a combination of personal stories, photos, and family trees.

Do you intend to write mostly about just one particular relative, or everyone in your family tree ? As the author, you need to choose a focus for your family history book. Some possibilities include:

- Single Line of Descent: Begin with the earliest known ancestor for a particular surname and follows him/her through a single line of descent (to yourself, for example). Each chapter of your book would cover one ancestor or generation.

- All Descendants Of...: Begin with an individual or couple and cover all of their descendants, with chapters organized by generation. If you're focusing your family history on an immigrant ancestor, this is a good way to go.

- Grandparents: Include a section on each of your four grandparents, or eight great-grandparents, or sixteen great-great-grandparents if you are feeling ambitious. Each individual section should focus on one grandparent and work backward through their ancestry or forward from his/her earliest known ancestor.

Again, these suggestions can easily be adapted to fit your interests, time constraints, and creativity.

Even though you'll likely find yourself scrambling to meet them, deadlines force you to complete each stage of your project. The goal here is to get each piece done within a specified time frame. Revising and polishing can always be done later. The best way to meet these deadlines is to schedule writing time, just as you would a visit to the doctor or the hairdresser.

Choose a Plot and Themes

Thinking of your ancestors as characters in your family story, ask yourself: what problems and obstacles did they face? A plot gives your family history interest and focus. Popular family history plots and themes include:

- Immigration/Migration

- Rags to Riches

- Pioneer or Farm Life

- War Survival

If you want your family history to read more like a suspense novel than a dull, dry textbook, it is important to make the reader feel like an eyewitness to your family's life. Even when your ancestors didn't leave accounts of their daily lives, social histories can help you learn about the experiences of people in a given time and place. Read town and city histories to learn what life was life during certain periods of interest. Research timelines of wars, natural disasters, and epidemics to see if any might have influenced your ancestors. Read up on the fashions, art, transportation, and common foods of the time. If you haven't already, be sure to interview all of your living relatives. Family stories told in a relative's own words will add a personal touch to your book.

Don't Be Afraid to Use Records and Documents

Photos, pedigree charts, maps, and other illustrations can also add interest to family history and help break up the writing into manageable chunks for the reader. Be sure to include detailed captions for any photos or illustrations that you incorporate.

Source citations are an essential part of any family book, to both provide credibility to your research, and to leave a trail that others can follow to verify your findings.

- Celebrate Family History Month and Explore Your Lineage

- 5 First Steps to Finding Your Roots

- Scrapbooking Your Family History

- 5 Great Ways to Share Your Family History

- 10 Top Genealogy Questions and Answers

- How to Begin Tracing Your Family Tree

- Fun Family History Activities for Family Reunions

- 10 Steps for Finding Your Family Tree Online

- Tracing Your Family Medical History

- 8 Places to Put Your Family Tree Online

- How To Research Latino Ancestry and Genealogy

- Best Things to Make With Desktop Publishing Software

- How Are Cousins Related?

- How to Trace American Indian Ancestry

- Steps to a Successful Family Reunion

- Top Genealogy Magazines for Family History Enthusiasts

ADVERTISEMENT

How to Create an Outline for Writing an Interesting Family History

Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you!

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

" * " indicates required fields

You might approach writing with a mixture of caution, excitement and dread. On one hand, you look forward to sharing sweeping tales about your ancestors, the journeys they have taken and the triumphs and trials they have faced.

On the other hand, though, writing can be downright hard. The saying goes that the pen is mightier than the sword (or, in our digital world, the laptop or other electronic device). But when you struggle to find the right words to describe a person who means a great deal to you, the pen might feel like little more than a blunt stick.

In fact, because family stories are so personal, writing about them can be harder than writing about something more scientific or technical. You may know more about Grandma Ethel and her childhood than anyone else—but you know so much that you fear you will gloss over something important. Every time you sit down to write about her, nagging thoughts arise: what if I’m not doing her story justice? What if I’m leaving out important details or homing in on the wrong details? What if I’m just not the writer for the job?

Fortunately, writing doesn’t have to feel like a long, uncertain battle. You can break the writing process down into manageable parts, turning it from stressful slog into an illuminating journey.

Creating a handy outline can help. Below are some strategies to guide you in creating an outline that covers all you want to share about your family history.

What is a Writing Outline?

A writing outline is a tangible plan in which you lay out:

- what you are writing

- about whom or what you are writing

- the structure or organization of your work

Outlines take many different forms. Some may be linear, plotting out exactly what happens from the beginning to the end. For example, a story of your grandfather’s immigration to America may begin with the moment he left his homeland and end with him stepping foot on unfamiliar land.

Other outlines have a more stream-of-consciousness structure; you simply write whatever comes to mind as you brainstorm and use your notes as your guide. In this case, you might highlight specific descriptions or moments of your grandfather’s voyage, but don’t connect the dots,” at least right away.

This article focuses mostly on structured outlines. But the “right” outline is whichever feels the most useful to you.

And whatever outline you create, nothing in it has to be set in stone. Even if you map out Grandpa’s life perfectly from its humble start to its glorious conclusion, you may decide as you write to change some parts around, to add details, or to omit entire swaths of time and text altogether.

That’s okay. What makes the writing process so rewarding is uncovering old fond memories that you thought had turned to dust, or making new, startling epiphanies that enliven your story.

Every time I write something new, be it a story or article or essay, I end up writing something very different than what I had initially envisioned. Even the final draft of this article looks quite different from my outline. I embrace these differences, and I also embrace my outlines for carrying me to the end.

Types of Outlines

What does an outline look like? Below I highlight several common types and provide examples of each. Your outline might look entirely different, or blend elements from several varieties. What’s important is that you find an outlining strategy that helps you write your family history the way you want.

The Alphanumeric Outline

The alphanumeric outline is exactly what it sounds like: It uses a combination of letters (lowercase or uppercase) and numbers (Arabic or Roman numerals) to denote hierarchies in your thought process.

For example, you might identify three main topics you want to highlight in your family history and number them 1, 2, and 3. Then you can expand upon a main topic with supporting, more-specific “sub-topics” that you label a, b and c under the main idea. To put it another way, the main topic serves as an “umbrella” over those sub-topics.

You’ve probably used this outline to write structured essays in school—ones with a clear introduction and thesis statement, a cohesive body and a compelling conclusion. The alphanumeric outline is ideal if you’re looking to write a chronological family history that has a clear order to your thoughts.

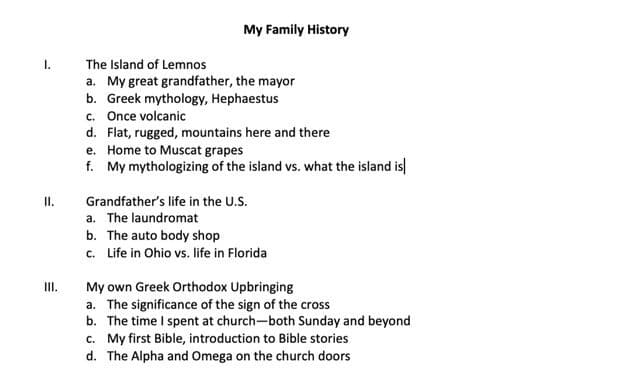

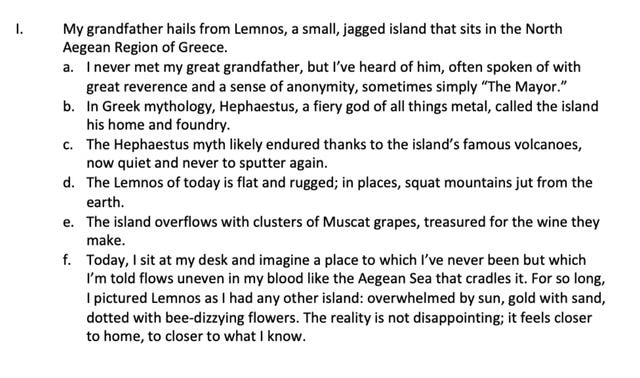

Below is an example of an alphanumeric outline I drafted up to write a piece on my own family history:

Note that my topics have different numbers of sub-topics beneath them. Your outline, too, might not look completely balanced. Some subjects might simply spur more inspiration or warrant a more-detailed discussion. I also gave my outline a temporary, working title to differentiate it from other outlines.

The Sentence Outline

Like the alphanumeric outline, the sentence outline sorts ideas and subjects into subject groups. However, each topic and sub-topic is written as a complete sentence. Sometimes, I’m so overflowing with ideas that I break the rules and end up creating a (short) paragraph outline.

While it may seem like extra work, this outline is useful. It forces you to engage with your ideas just as you would while writing your actual family history. As a result, you can potentially identify at the outline level what you need to expand upon and what you could possibly pare down. For instance, if you struggle to write even one sentence to sum up the topic, you may consider reworking the topic altogether.

Another thing I appreciate about the sentence outline is that it allows me to play with language and tone. Most sentences from the outline won’t survive to the actual written family history, but they do help me uncover sensory images and valuable details that I might otherwise overlook during the writing process.

I also may notice certain themes that emerge organically and tie my story together. For example, I found that the concept of myths and mythologizing the past threaded many of the topics in my outline together. This revelation helped guide my narrative throughout the entire piece.

Here’s a sentence outline for the first top I laid out in my alphanumerical outline:

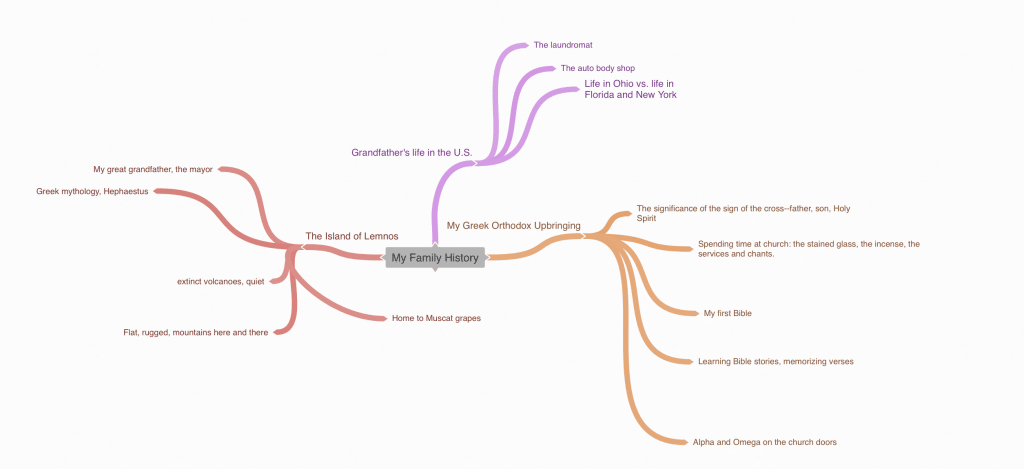

The Mind Map

If the outlines mentioned above feel too academic or rigid for you (or you just want something more visual), then the mind map may be right for you. The mind map usually begins with a single “seed” of a topic—something general, like “My Family History”—then branches off into many separate topics that intersect or sprout their own “sub-topics.” (It goes without saying, then, that a tree is an apt metaphor for the family history mind map!)

The mind map can help you visualize where your ideas are in relation to one another. As you add new ideas to your mind map, it grows, as does your understanding of what you are writing about.

Here’s a mind map outline that I created using a free version of Coggle:

Most mind-mapping tools allow you to create several free mind maps and use basic mapping capabilities. The paid versions of these tools offer unlimited maps and more complex features (for example, color-coding, more bubble shape options, etc).

Here’s a quick breakdown of five different mind-mapping tools: Coggle , GitMind , Microsoft Visio , MindMeister and Miro . You can review this chart for number of free maps, free features offered, paid features offers and price.

| Company | # of Free Mind Maps Offered | Free Features | Paid Features | Price |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coggle | 3 | Unlimited public diagrams, unlimited photo uploads, change history, several start points, branch auto-arrange feature | Unlimited private mind maps, control line path, change line style, more item shape options, high resolution photo downloads | $5/month |

| GitMind | 10 | Color themes, outline mode, slideshow capabilities | Free features + unlimited mind maps, nodes, and templates | $9/month |

| Microsoft Visio | Unlimited with 1 month trial | Enjoy all features during trial period | Many different templates and shapes, cross functional flowcharts, app to work anywhere | $5/month |

| MindMeister | 3 | Outline mode, customizable text colors and styles, custom icon color | Unlimited mind maps, file and image attachments, export PDFs and image, mind map printing | $4.99/month |

| Miro | 3 | Premade templates, integration with Google Drive, Microsoft and other programs | Unlimited mind maps, custom templates, project folders, high-resolution export capabilities, board version history | $8/month |

Beyond the Outline: Family History Writing Organization Strategies

You might want jump right into writing once you’ve got an outline. By all means, go ahead! But if you’re still apprehensive, here are tips that will help you ease into the writing process, both before and after you start drafting an outline.

Before the Outline

Determine the form and length of your project.

Few writers can accurately predict how many words a piece will be, so it’s okay if you’re unsure about the length of your family history. However, your outline will be more helpful if it reflects the scope of your project: how deep you plan to go into your family history and what kind of form it’s going to take.

For example, are you writing a book-length memoir that captures snapshots throughout an ancestor’s life? Or are you weaving a narrative that has a clear beginning, middle and end? Is your family history going to be a cohesive narrative, or (like mine) a collection of shorter essays or stories tied together by a theme?

Determine Who You are Going to Write About

This might go without saying, but you’ll need to know who is going to appear in your written family history before you start outlining it. With that decided, you can spend the outlining stage sketching an accurate portrait of the person(s).

Determine Where You Fit into the Story

When you read a book (especially a work of fiction), the narrative point of view is usually one of the first pieces of information you receive. Who is telling the story?

Your family history isn’t fiction, of course. But you’ll want to decide how personal your storytelling will be. Will you let readers get a closer look at who you (the author) are, through personal memories? Or will family stories be told from the point of view of an omniscient, impersonal narrator? There’s no right or wrong answer, but deciding on an approach will help you build your outline.

After the Outline

Organize and integrate research.

Once you have your outline in hand, you can start incorporating your research into it. This is more challenging than it first seems, since you probably have decades of research and plenty of facts that you want to share. It can be tempting to dump all of that information on the page during the outline stage, but I get less overwhelmed if I write my outline first , then match details and facts to specific topics mentioned in my outline.

Make sure that the research you include is relevant to the story and reflects your overall vision. You don’t want your narrative to be bogged down in unrelated details.

Identify Common Images and Narrative Threads

I mentioned above how, during the outlining process, I recognized and embraced the theme of mythology that had emerged from my outline. As you study your own, look out for those such motifs. They might not be broad (such as connections to mythology) or subtle (such as memories of the sky, sea or birds).

Of course, you shouldn’t force such imagery into your writing if it feels unnatural. But concrete images can enrich your story and provide an emotional connection that your readers will respond to.

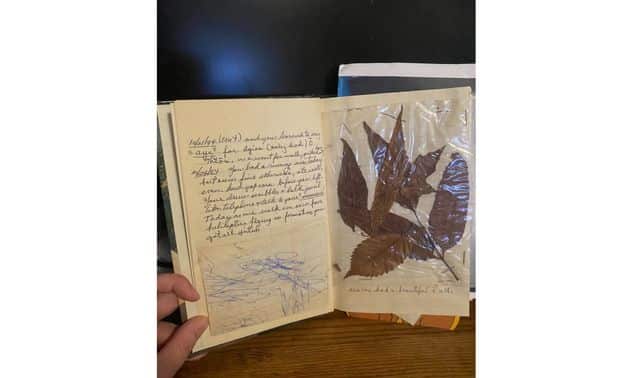

Find Photos, Heirlooms and Other Items That Can Help Strengthen Your Story

Consider looking through your family photos and keepsakes to find any objects that will help bring your story to life. While colorful descriptions of Grandma’s kitchen at Christmas can help readers visualize the scene (a flour-covered counter, or the smell of freshly baked cookies), an actual photo can transport them there.

For example, my Yia Yia kept a journal that dates to when I was just a baby. In it, she recorded notable milestones, stowed away some fun projects we did together, and described some of our trips to church. I could describe this journal to you in great detail, but that probably wouldn’t be as interesting as seeing it for yourself!

Final Thoughts

Outlines don’t force your family history into a prescribed, write-by-number template. Instead they guide your thoughts, spark memories and move you through years of joys and sorrows. You can always deviate from your outline—you don’t have to commit to a certain topic just because your outline says so. The outline is only a foundation that you can build higher or reshape as you see fit. Keeping that in mind will leave you open to your own treasured memories: how peaceful you felt when you walked with your grandpa through the woods; the touch of his weathered hand in your own; the sound of his wise, booming voice; how his shadow disappeared into those of the trees.

A version of this article appeared in the May/June 2023 issue of Family Tree Magazine .

Related Reads

Melina Papadopoulos

related articles

Writing compelling characters in your family history.

Storytelling, Writing

7 creative writing forms for sharing your family history.

How to Share Family History Stories on the Big Genealogy Websites

Ancestry, FamilySearch, MyHeritage, Storytelling

10 story-building strategies from the finding your roots team.

Storytelling

0 articles left, 0 free articles left this month.

Get unlimited access. subscribe

0 free articles left this month

Don't miss the future..

Get unlimited access to premium articles.

How to Go From Boring to Brilliant Family History Writing

So, you’ve done so much family history research that you’re drowning in facts and you’ve decided – that’s it – I’ve got to start writing some of this up!

Only now you are stuck. Don’t worry, you are not alone.

Unless you’re a bit of a Marvin (from Hitchhikers Guide To The Galaxy) you are probably perfectly fine at telling stories. I mean, we tell snippets of stories all the time, whether it’s moaning to the postman about our encounter with a grumpy lady in Tesco’s. Or explaining our Great-Grandfather to our 3rd cousin twice removed. We tell stories daily.

It’s often only when we come to write these stories down that we struggle. We can’t find the “right” words. We lose our voice. We get bogged down in details. We forget about our core story. The thing that made us want to tell it in the first place. We either stare at a blank white page, unable to even start writing OR we write tons of words – read them back and decide we’d like to delete the lot.

In this article, I’ll share some tips that’ll transform your family history writing. I’m not saying you are going to become a world-renowned author. We’re not all JK Rowling. But, when you give your cousin Sue the story about your great-gran, you can be sure she’ll read it, enjoy it and therefore remember it.

Table of Contents

Before you start writing your family history, decide your audience.

Sometimes our audience is clear, such as I’m writing this for my children. But, we don’t always have a particular person in mind. You may be writing up your family history for fun, to check for gaps in your research, as ‘cousin bait’, as a blog for fellow genealogists or professional reasons.

That’s fine, but you need to try to imagine who might be reading. Let’s use my blog post on my Woodrow witch ancestor as an example. It could attract unknown cousins, fellow genealogists or person’s interested in family history. It might attract those that like reading true stories.

These readers all have some things in common. They are unlikely to be children. They are likely to enjoy history. Yet, some readers may have lots of family history knowledge, others none at all. I need to ensure I don’t alienate anyone. For example, I use language appropriate to their reading age but without jargon.

Envisioning your audience, their likes and dislikes will help inform your writing.

Decide On The Message For Each Piece of Family History Writing

Your writing doesn’t have to have a deep and meaningful message. But, it does have to have some sort of point. For example, my blog post ‘ Blue Blood ‘ explores my illegitimate ancestor. I wanted to make my research journey clear and to inform readers of the parentage of my ancestor. That was my message. Whereas, my blog post ‘A Hidden Victim of Ripper Mania ‘ had a statement at its heart. I wanted to use my ancestor’s story to explore the effect of constricted gender roles. I wanted to show her story of suicide as a possible consequence of Victorian rigidity.

Regardless of whether your message is divisive, exploratory or informative, decide it before you start. Don’t let it get lost or diluted. Keep checking on your message. Are you getting to the point? Is it clear?

Set A Plan & Avoid Tangents

Before writing your family history make a plan. Exactly which ancestors are you going to cover? Over what time? Who will you start with? How will you break up their story? How does this plan work with your decided audience? Where will you show your message?

Setting a plan will give your writing structure. It’ll ensure you cover all the points you want to explore. It’ll ensure your message comes through. It’ll help you weed out or avoid random tangents.

Odd pieces of off-topic text can be very distracting. It’s easy to fall into a trap of including things because they are ‘interesting’. This is an error. Adding random pieces of content dilutes your story. It starts to feel rambling and the message becomes lost.

Writing Your Family History

If you can't write it, say it.

One of my favourite writing styles, especially for short stories, is ‘conversational’. I like to feel like the writer is sat next to me, sharing their tale over a cuppa. That’s not always easy to emulate. So cheat! Record yourself whilst you explain the story.

You don’t need anything fancy to do this. Download the free app Otter ( Google Play or Apple Store ) onto your phone. This nifty programme will listen to you talk and convert your words into text. It’s not perfect but its accuracy is impressive.

Next, take that speech-to-text and edit it. Use it as a starting point and build upon it.

Pay special attention to the words you use or turns of phase. This is your real voice. Use those phases in your family history writing to make it feel more authentic.

Use Endnotes or Footnotes to separate your family history writing from sources

You don’t have to put all your details within the body of the text. I have read a lot of family histories that start like this:

“My ancestor, John Brown was born on 5th June 1857. He was christened on 10 June 1857 in St Michael’s Church, Basingstoke. His older brother, Thomas was christened on the same day. Thomas was born on 20th March 1855.”

For an instant win, try putting some of those details in footnotes or endnotes, alongside any source information. Doing so transforms our sentence, to something like this:

“John and his older brother Thomas were both christened in the summer of 1857 at St Michael’s Church, Basingstoke.”

Bring Your Family History Writing To Life

Reading a list of facts is boring. We need details to help spark our imagination. Writing family history is challenging because we need both accuracy and imagination.

Let’s look at our 1857 christening example. It took place in the summer and it’d be easy to presume that the weather was hot. We need to check though! That June may have been infamous for its terrible weather.

Our example took place in a church. We may look at a photo of that stone building and presume it looked the same way in 1857. Again we need to check. What if the church flooded that year? What if the building we see today is a replica?

Once we’ve got our confirmed details though, we can use them to create texts rich in detail:

“Summer 1857 was hot and the parishioners of St Michael’s Church must have felt relieved to sit within the cool of the church’s thick stone walls. On 10th June the Brown family filled the congregation. A generation of bottoms squashed into the tiny pews. I imagine the new Brown babies (Thomas and John) cried as the icy holy water splashed onto their foreheads. Three years before them, a daughter had been baptised using that same deep stone font. Her little bottom was missing from the row of Browns that watched the ceremony. Perhaps her mother, Elizabeth was thinking of her as she hushed her son’s bawl…”

Find The Right Words

Successful authors tend to have a fantastic vocabulary. Reading widely can help you to expand your own. But, you can also use a thesaurus to aid you – especially if you find you are using the same words repetitively. There are loads of free thesaurus’ online.

It is also worth bearing in mind that old adage, “show not tell”. If you find your text is full of adjectives (describing words) then start pruning them! Replacing those adjectives with strong nouns can actually enhance your writing.

I recommend reading “ Kill Your Adjectives “. It really explains this concept in much more detail and gives some great examples.

Use Tech To Help With Grammar

Even the very best of writers make mistakes. That’s why they have proof readers and editors. Now, whilst using a real-life person is always best, that’s not always possible. So, use apps to try to fill the gap. Hemingway is a free editor. Type in your text and using various colours, it’ll highlight sections that use a passive voice or are hard to read. It’ll point out your use of adverbs too. Fixing these errors will lead to better writing.

Other apps that can help include, Grammarly (a free app or chrome extension). It will point out all your spelling and grammatical errors. Underlined. In red. I hate it. I love it. It’s one of those kinds of relationships.

Editing and Proof-Reading

Apps aside, nothing beats a human eye on your work. In an ideal world, once completed, put your writing away. Leave it for at least a couple of weeks before you pick it up and start editing. Then finally hand it to someone else to read. Proof-reading is a talent. It’s why people get paid to do it! So, do what you can. Pass it to who you can. Don’t beat yourself up if 3 months later you look at it again and there’s an apostrophe in the wrong place.

Enhance Your Family History Writing

An image is worth 1000 words.

Those of us writing up our family history today have a huge advantage over our ancestors. We have the mighty power of the internet. Within seconds we can have access to quality photographs to add to our work.

Use images to “back up” the detail you’ve written or to separate large pieces of writing. These don’t have to be images of your ancestors. Use photos of buildings, maps, artwork, newspapers. Mix it up!

On a practical note, ensure you are not breaking any copyright laws. On Google Images select Settings-Advanced Search and filter by ‘Usage Rights’ to find images marked as shareable. Read the different levels of copyright and attribute your images as appropriate. If in doubt, check with whoever owns the image before you use it. If you can’t find someone to ask and are still unsure, then don’t use it. And yes, I know exactly how frustrating that can be!

Geograph is great for free images of places and buildings within the UK. You can also utilise sites like Unsplash , Pixabay and Pexels to find free pictures. Use Canva to curate your own images and text graphics.

Add Charts To Your Family History Writing

Make use of another advantage available to modern genealogists. Create and add family tree diagrams to your text. These not only break up long passages but make the text itself easier to follow. Use charts to explain genetic relationships. Create these either within your family tree package or using Microsoft PowerPoint or Excel, or your Mac or Google equivalent.

Break Up Your Family History Writing

Depending on the length of your family history writing, consider using tools to make it easier to navigate. Very long works benefit from contents pages and indexes. All easily created in Word.

Shorter pieces may benefit from section breaks and sub-headings.

Give It A Title

People make snap decisions about what to read. Give your text the very best chance by giving it a great title. Use the Headline Analyser to see which of your ideas is worth pursuing. Or browse these 100+ blog title ideas to get your creative juices flowing.

Do You Enjoy Writing Your Family History Stories?

Writing up your family history should be enjoyable. Be honest with yourself. If writing your family history feels like a form of torture then don’t do it! It’ll come through in your writing anyway. Writing up your ancestors’ lives is not the only method of recording their histories. You could simply do some oral recordings. You could try making a presentation.

Or you could join my Curious Descendants Club! With regular workshops and challenges, this Club is designed to help you write your family history. You can find all the details here, including testimonials from existing members .

Stay in touch...

I send semi-regular emails packed with family history writing tips, ideas and stories. Plus you’ll never miss one of my articles (or an episode of #TwiceRemoved) ever again.

STAY IN TOUCH

Never miss a blog post or an episode of #TwiceRemoved ever again. Plus get semi-regular family history writing tips delivered straight to your inbox. All for FREE!

More Posts:

- Write Your Family History With Style

- Why Everyone Should Write Their Family History

- #TwiceRemoved with Matthew Roberts

- #TwiceRemoved with Justin Bengry

- 5 Tips to Make The Most of Genealogy Research Rabbit Holes

Purchases made via these links may earn me a small commission – helping me to keep blogging!

Read my other articles

The learning centre.

- CURIOUS DESCENDANTS CLUB

Start writing your family history today. Turn your facts into narratives with the help of the Curious Descendants Club workshops and community.

TALKS & WORKSHOPS

Looking for a guest speaker? Or a tutor on your family history course? I offer a range of talks with a focus on technology, writing and sharing genealogy stories.

HOW I CAN HELP

- TALKS & WORKSHOPS

- [email protected]

CONNECT WITH ME

Copyright © 2020 Genealogy Stories | All Rights Reserved | Privacy Policy | Cookies

Privacy Overview

Get semi-regular emails packed with family history writing challenges, hints, tips and ideas. All delivered straight to your inbox FREE! Never miss a blog posts or episode of #TwiceRemoved ever again.

p.s. I hate spam so I make sure that you can unsubscribe from my emails at any time (or adjust your settings to hear more / less from me).

My Family History Essay Example

Family history is a journey that can take many different shapes. For some, it’s the story of how they became who they are today. For others, it might be simple curiosity about their roots or where their last name came from. It could also be an investigation into family secrets and mysteries for those with a more adventurous personality.

Writing an essay on family history is really challenging when it comes to describing every important aspect of it. That is why the essay sample serves an important purpose for the students here.

Essay Sample on My Family History

- Thesis Statement of My Family History Essay

- Introduction of My Family History Essay

- How Did Our Family use to live under a Single Roof?

- What are the Values that we learn by living in Joint Family?

- Causes that Separated the Family into little pieces

Thesis Statement of My Family History Essay This essay talks about my joint family or family tree in which we used to have a lot of fun and enjoy being together. Various glimpses of this happiness of togetherness is described in the essay below. Introduction of My Family History Essay Like every other family, we have our own family history which is illustrated herein details to the readers. The essay talks about how we used to live under a single roof and we have no need to set appointments to ask our elders for dinner. These joys of togetherness bring certain values in us as well like how to be happy among the people of different nature and hope. What is the result of being in togetherness that could be found in this essay? Readers will come to know about the instances that separate us from a joint family to a nuclear family in recent times. Main Body of My Family History Essay Here a detailed description of the family history is given to let you know about the era of happiness that used to exist in our life. Each and every single detail is given in this essay for better clarity of things. How Did Our Family use to live under a Single Roof? It dates back to the days when we were small kids and our grandmother used to feed us with a variety of dishes. Every day was like a festival for us as we were not supposed to go out for school and used to sit in the vicinity of our grandmother to listen to the different stories from her. We used to dine together and no one was supposed to watch television at the time of food. This is how we were spending our days happily. My parents were also very melodious towards us and everyone who visits our home at that time was bringing some refreshments to us. Hire USA Experts for My Family History Essay Order Now What are the Values that we learn by living in Joint Family? The joint family not only gave us happiness but at the same time, we adopt many values from our elders as well. For instance, living happily and ignoring the mistakes of others is the most important feature of residing in a joint family. That is what happened to us. We never fight with each other our siblings and always used to abide by the instructions of the parents whatever they ask us to do. More patience, compromise for small things, and becoming happy in the joy of others are some important things that we gained from our family history. The roots of love between the family members could easily be traced in those days. Causes that Separated the Family into little pieces As well said by a great philosopher that every good thing comes to an end eventually similar happened in our case as well. My grandmother died of cholera and we remain behind with the parents. As our age was gradually increasing we were sent to a school where the boring routine makes us remind of the old days and then the pressure of study starts suppressing our joy of being with the grandmother. We used to miss her for the entire long day, be that in the school hours or in the evening. Even the parents fail to continue the same routine of dining together owing to their jobs and all that we find around us was chaos in life. Buy Customized Essay on My Family History At Cheapest Price Order Now Conclusion The above essay draws a conclusion that it is a very positive thing to live in a joint family as it teaches values to us. But at the same time due to time constraints and technology-driven lifestyle we cannot suppose to cope up our life in joint families. This is how the family history has been narrated and it gives us a lesson that we should do something to save the ancient culture of staying together happily.

Get online essay writing services in just one click from Students Assignment Help

The above-written essay sample is based on my family history. If you need more free essay samples , visit our website and get narrative essay samples like About My Life Essay , Divorce Essay , Sleeping Disorder Essay and etc.

Need help finishing your essay? You can get it by hiring our experts at Students Assignment Help. We know how to write an essay and we will deliver before the deadline!

We have been providing custom writing services to students from high school, college, and university levels for a long time. We provide a wide range of academic assistance including thesis writing help , coursework writing services , and research paper writing services .

Explore More Relevant Posts

- Nike Advertisement Analysis Essay Sample

- Mechanical Engineer Essay Example

- Reflective Essay on Teamwork

- Career Goals Essay Example

- Importance of Family Essay Example

- Causes of Teenage Depression Essay Sample