United States Institute of Peace

National high school essay contest.

USIP partners with the American Foreign Service Association (AFSA) on the annual National High School Essay Contest. The contest each year engages high school students in learning and writing about issues of peace and conflict, encouraging appreciation for diplomacy’s role in building partnerships that can advance peacebuilding and protect national security.

The winner of the contest receives a $2,500 cash prize, an all-expense paid trip to Washington, D.C. to meet U.S. Department of State and USIP leadership, and a full-tuition paid voyage with Semester at Sea upon the student’s enrollment at an accredited university. The runner-up receives a $1,250 cash prize and a full scholarship to participate in the International Diplomacy Program of the National Student Leadership Conference.

2023 National High School Essay Contest

The American Foreign Service Association’s national high school essay contest completed its twenty-third year with over 400 submissions from 44 states. Three randomized rounds of judging produced this year’s winner, Justin Ahn, a junior from Deerfield Academy in Deerfield, Massachusetts. In his essay, “Mending Bridges: U.S.-Vietnam Reconciliation from 1995 to Today,” Ahn focuses on the successful reconciliation efforts by the Foreign Service in transforming U.S.-Vietnam relations from post-war tension to close economic and strategic partnership.

Ahn will travel to Washington, D.C. to meet with a member of the Department of State’s leadership and receive a full tuition scholarship to an educational voyage with Semester at Sea.

Niccolo Duina was this year’s runner-up. He is currently a junior at Pulaski Academy in Little Rock, Arkansas. Duina will be attending the international diplomacy program of the National Student Leadership Conference this summer.

There were eight honorable mentions:

- Santiago Castro-Luna – Chevy Chase, Maryland

- Dante Chittenden – Grimes, Iowa

- Merle Hezel – Denver, Colorado

- Adarsh Khullar – Villa Hills, Kentucky

- Nicholas Nall – Little Rock, Arkansas

- Ashwin Telang – West Windsor, New Jersey

- Himani Yarlagadda – Northville, Michigan

- Sophia Zhang – San Jose, California

Congratulations! We thank all students and teachers who took the time to research and become globally engaged citizens who care about diplomacy, development and peacebuilding.

2023 National High School Essay Contest Topic

In 2024, the U.S. Foreign Service will celebrate its 100th birthday. The Foreign Service is an important element of the American approach to peacebuilding around the world. Over the last century, U.S. diplomats have been involved in some of the most significant events in history — making decisions on war and peace, responding to natural disasters and pandemics, facilitating major treaties, and more.

As AFSA looks back on their century-long history, we invite you to do the same. This year, students are asked to explore a topic that touches upon this important history and sheds light on how vital it is for America to have a robust professional corps focused on diplomacy, development and peace in the national interest.

In your essay, you will select a country or region in which the U.S. Foreign Service has been involved in at any point since 1924 and describe — in 1,500 words or less — how the Foreign Service was successful or unsuccessful in advancing American foreign policy goals, including promoting peace, in this country/region and propose ways in which it might continue to improve those goals in the coming years.

Contest deadline: April 3, 2023

Download the study guide for the 2023 National High School Essay Contest. This study guide provides students with a basic introduction to the topic and some additional context that can assist them in answering the question. It includes the essay question, prizes and rules for the contest; an introduction to diplomacy and peacebuilding; key terms; topics and areas students might explore; and a list of other useful resources.

Learn more about the contest rules and how to submit your essay on the American Foreign Service Association’s contest webpage .

2022 National High School Essay Contest

Katherine Lam, a freshman from University High School in Tucson, Arizona, is the 2022 National High School Essay Contest winner. In her essay, “Competition and Coaction in Ethiopia: U.S. and Chinese Partnerships for International Stabilization,” Lam focuses on how the Foreign Service has partnered with other U.S. government agencies, nongovernmental organizations and — most notably — China to promote peace and development in Ethiopia. Lam will travel to Washington, D.C., to meet with a member of the U.S. Department of State’s leadership and gain full tuition for an educational voyage with Semester at Sea.

Olivia Paulsen was this year’s runner-up. She is a currently a junior receiving a home-schooled education in Concord, Massachusetts. Paulsen will be attending the international diplomacy program of the National Student Leadership Conference this summer.

The 2022 honorable mentions were: Josh Diaz (Little Rock, AR); Grace Hartman (Bethlehem, PA); Elena Higuchi (Irvine, CA); Ovea Kaushik (Oklahoma City, OK); Evan Lindemann (Palm Desert, CA); Percival Liu (Tokyo, Japan); Alexander Richter (San Jose, CA); and Gavin Sun (Woodbury, MN).

USIP congratulates all the winners of the 2022 National High School Essay Contest.

Partnerships for Peace in a Multipolar Era

The current multipolar era poses challenges for U.S. foreign policy but also provides new opportunities for partnership across world powers—including emerging great powers like China and Russia—to build peace in conflict-affected countries. Describe a current situation where American diplomats and peacebuilders are working with other world powers, as well as local and/or regional actors, in a conflict-affected country to champion democracy, promote human rights, and/or resolve violent conflict. A successful essay will lay out the strategies and tactics U.S. Foreign Service Officers and American peacebuilders are employing to build successful partnerships with other world and regional powers and with local actors in the chosen current situation. The essay will also describe specific ways that these partnerships are helping to promote stability and build peace.

Contest deadline: April 4, 2022

Download the study guide for the 2022 National High School Essay Contest. This study guide provides students with a basic introduction to the topic and some additional context that can assist them in answering the question. It includes the essay question, prizes, and rules for the contest; an introduction to diplomacy and peacebuilding; key terms; topics and areas students might explore; and a list of other useful resources.

Learn more about the contest rules and how to submit your essay on the American Foreign Service Association’s contest webpage.

2021 National High School Essay Contest

Mariam Parray, a sophomore from Pulaski Academy in Little Rock, Arkansas, is the 2021 National High School Essay Contest winner. In her essay, “Diplomats and Peacebuilders in Tunisia: Paving the Path to Democracy,” Ms. Parray focuses on how the Foreign Service partnered with other U.S. government agencies and NGOs to effect a peaceful democratic transition in Tunisia. She emphasizes the importance of multifaceted approaches as well as the importance of bringing marginalized groups into the fold. Mariam will travel to Washington to meet with a member of the Department of State’s leadership and will also gain a full tuition to an educational voyage with Semester at Sea. Harrison McCarty was this year’s runner-up. Coincidentally, he is also a sophomore from Pulaski Academy in Little Rock, Arkansas. Harrison will be attending the international diplomacy program of the National Student Leadership Conference this summer. The 2021 honorable mentions were: Louisa Eaton (Wellesley, MA); Samuel Goldston (Brooklyn, NY); Lucy King (Bainbridge Island, WA); Haan Jun Lee (Jakarta, Indonesia); Khaled Maalouf (Beirut, Lebanon); Madeleine Shaw (Bloomington, IN); Allison Srp (Austin, MN); and Daniel Zhang (Cortland, NY).

USIP congratulates all the winners of the 2021 National High School Essay Contest.

Diplomats and Peacebuilders: Powerful Partners

What characteristics lead to a successful effort by diplomats and peacebuilders to mediate or prevent violent conflict? The United States Foreign Service—often referred to as America’s first line of defense—works to prevent conflict from breaking out abroad and threats from coming to our shores. Peacebuilders work on the ground to create the conditions for peace and resolve conflicts where they are most needed.

Successful essays will identify, in no more than 1,250 words, a situation where diplomats worked on a peacebuilding initiative with partners from the country/region in question, nongovernmental organizations, and other parts of the U.S. government, and then go on to analyze what characteristics and approaches made the enterprise a success.

Contest deadline: April 5, 2021

Download the study guide for the 2021 National High School Essay Contest. This study guide provides students with a basic introduction to the topic and some additional context that can assist them in answering the question. It includes key terms in conflict management and peacebuilding and examples of peacebuilding initiatives, with reflection questions for independent learners to dig more deeply or for teachers to encourage class reflection and discussion. We hope this study guide will be a useful resource for educators and students participating in this contest, and for educators who want their students to learn more about this year’s contest topic.

2020 National High School Essay Contest

Jonas Lorincz, a junior from Marriotts Ridge High School in Marriottsville, MD, is the 2020 National High School Essay Contest winner. In his essay, “Verification, Mediation, and Peacebuilding: The Many Roles of the U.S. Foreign Service in Kosovo,” Mr. Lorincz focused on the importance of interagency cooperation in mediating the crisis in Kosovo – primarily looking into how diplomats and other civilian agencies engaged in peacebuilding throughout the conflict.

Claire Burke was this year’s runner-up. She is a junior at Mill Valley High School in Shawnee, KS.

The 2020 honorable mentions were: Grace Cifuentes (Concord, CA), Grace Lannigan (Easton, CT), Seryung Park (Tenafly, NJ), Vynateya Purimetla (Troy, MI), David Richman (Norfolk, VA), Madeleine Shaw (Bloomington, IN), Sara Smith (Fargo, ND), and Jack Viscuso (Northport, NY). USIP congratulates all the winners of the 2020 National High School Essay Contest.

2020 National High School Essay Contest Topic

Why Diplomacy and Peacebuilding Matter

How do members of the Foreign Service work with other civilian parts of the U.S. Government to promote peace, national security and economic prosperity?

Qualified essays focused on a specific challenge to U.S. peace and prosperity and included one example of the work of the Foreign Service and one or more examples of collaboration between America’s diplomats and other civilian (i.e. non-military) U.S. Government agencies or organizations.

2019 National High School Essay Contest

In its 21st year, the American Foreign Service Association (AFSA)’s National High School Essay Contest encouraged students to think about how and why the United States engages globally to build peace, and about the role that the Foreign Service plays in advancing U.S. national security and economic prosperity.

For the second year in a row, the National High School Essay Contest focused on an important aspect of operating in countries affected by or vulnerable to violent conflict: effective coordination of the many different foreign policy tools the United States has at its disposal. Whether you were addressing the prompt for a second year or new to the contest, the contest will have challenged you to expand your understanding of the role of the Foreign Service and other actors in foreign policy, identify case studies, and provide a sophisticated analysis in a concise manner.

The essay prompt and a helpful study guide are included below; you can find out more information about the rules and how to submit by checking out AFSA’s essay contest page .

2019 Essay Question

The United States has many tools to advance and defend its foreign policy and national security interests around the world—from diplomatic approaches pursued by members of the Foreign Service, to the range of options available to the U.S. military. In countries affected by or vulnerable to violent conflict, peacebuilding tools are important additions to the national security toolkit.

In such complex environments, cooperation across agencies and approaches is challenging, but it can also blend knowledge and skills in ways that strengthen the overall effort to establish a lasting peace. On the other hand, lack of coordination can lead to duplication of effort, inefficient use of limited resources and unintended consequences.

In a 1,000-1,250-word essay, identify two cases—one you deem successful and one you deem unsuccessful—where the U.S. pursued an integrated approach to build peace in a conflict-affected country. Analyze and compare these two cases, addressing the following questions:

- What relative strengths did members of the Foreign Service and military actors bring to the table? What peacebuilding tools were employed? Ultimately, what worked or did not work in each case?

- How was each situation relevant to U.S. national security interests?

- What lessons may be drawn from these experiences for the pursuit of U.S. foreign policy more broadly?

Download the study guide for the 2019 AFSA National High School Essay Contest

2018 National High School Essay Contest

Jennifer John from Redwood City, CA is the 2018 National High School Essay Contest winner, surpassing close to 1,000 other submissions. Her essay examined to what extent U.S. interagency efforts in Iraq and Bosnia were successful in building peace. Aislinn Niimi from Matthews, NC was the runner up.

The 2018 honorable mentions were: Alex, DiCenso (North Kingstown, RI),Alexandra Soo (Franklin, MI), Caroline Bellamy (Little Rock AR), Colin LeFerve (Indianapolis, IN), Elizabeth Kam (Burlingham, CA), Emma Singh (Tenafly NJ), Emma Chambers (Little Rock AR), Francesca Ciampa (Brooksville, ME), Greta Bunce (Franktown, VA), Isaac Che (Mount Vernon OH), Isabel Davis (Elk River MN), Katrina Espinoza (Watsonvile, CA), Molly Ehrig (Bethlehem, PA), Payton McGoldrick (Bristow, VA), Rachel Russell (Cabin John, MD), Sarah Chapman (Tucson, AZ), Shalia Lothe (Glen Allen VA), Sohun Modha (San Jose CA), Suhan Kacholia (Chandler, AZ), Supriya Sharma (Brewster, NY), Sydney Adams (Fort Wayne, IN), Tatum Smith (Little Rock AR), and William Milne (Fort Wayne, IN).

2017 National High School Essay Contest

Nicholas Deparle, winner of the 2017 AFSA National High School Essay Contest, comes from Sidwell Friends School in Washington DC. A rising senior at the time, Mr. Deparle covers the Internally Displaced Persons crisis in Iraq and potential ideas to help resolve the issue. Read his winning essay here . Mr. Manuel Feigl, a graduate of Brashier Middle College Charter High School in Simpsonville, SC took second place.

This year there were twenty honorable mentions: Mohammed Abuelem ( Little Rock, Ark.), Lucas Aguayo-Garber (Worcester, Mass.), Rahul Ajmera (East Williston, N.Y.), Taylor Gregory (Lolo, Mont.), Rachel Hildebrand (Sunnyvale, Calif.), Ryan Hulbert (Midland Park, N.J.), India Kirssin (Mason, Ohio), Vaibhav Mangipudy (Plainsboro, N.J.), William Marsh (Pittsburgh, Penn.), Zahra Nasser (Chicago, Ill.), Elizabeth Nemec (Milford, N.J.), David Oks (Ardsley, N.Y.), Max Pumilia (Greenwood Village, Colo.), Nikhil Ramaswamy (Plano, Texas), Aditya Sivakumar (Beaverton, Ore.), Donovan Stuard (Bethlehem, Penn.), Rachel Tanczos (Danielsville, Penn.), Isabel Ting (San Ramon, Calif.), Kimberley Tran (Clayton, Mo.), and Chenwei Wang (Walnut, Calif.).

2017 Essay Contest Topic

According to the United Nations, 65 million people worldwide have left their homes to seek safety elsewhere due to violence, conflict, persecution, or human rights violations. The majority of these people are refugees or internally displaced persons (IDPs).

Imagine you are a member of the U.S. Foreign Service —– a diplomat working to promote peace, support prosperity, and protect American citizens while advancing the interests of the United States abroad – and are now assigned to the U.S. embassy in one of these four countries.

- Turkey (Bureau of European and Eurasian Affairs)

- Kenya (Bureau of African Affairs)

- Afghanistan (Bureau of South and Central Asian Affairs)

- Iraq (Bureau of Near Eastern Affairs)

Your task is to provide recommendations to address the refugee/IDP crisis facing the country in which you are now posted. Using the resources available to you as a member of the Foreign Service, write a memo to your Ambassador outlining how the United States might help address the current unprecedented levels of displacement. You may choose to address issues related to the causes of refugee crisis, or to focus on the humanitarian crisis in your host country.

A qualifying memo will be 1,000-1,250 words and will answer the following questions:

- How does the crisis challenge U.S. interests in the country you are posted and more broadly?

- Specifically outline the steps you propose the U.S. should take to tackle the roots or the consequences of the crisis, and explain how it would help solve the issue or issues you are examining. How will your efforts help build peace or enhance stability?

- How do you propose, from your embassy/post of assignment, to foster U.S. government interagency cooperation and cooperation with the host-country government to address these issues? Among U.S. government agencies, consider U.S. Agency for International Development, the Foreign Commercial Service and the U.S. Institute of Peace.

Memo Template

TO: Ambassador ______________________

FROM: Only use your first name here

RE: Think of this as your title, make sure to include the country you are writing about

Here you want to lay out the problem, define criteria by which you will be deciding the best steps the U.S. could take, and include a short sentence or two on your final recommendation. Embassy leadership is very busy and reads many memos a day —– they should be able to get the general ““gist”” of your ideas by reading this section.

Background:

This section should provide any background information about the crisis or conflict relevant to your proposed policy. Here, you should mention why the issue is important to U.S. interests, especially peace and security.

Proposed Steps:

This is where you outline your proposed policy. Be specific in describing how the U.S. might address this issue and how these steps can contribute to peace and security. Include which organizations you propose partnering with and why.

Recommendation:

This is where you write your final recommendations for embassy leadership. Think of this as a closing paragraph.

Companion Guide for the 2017 National High School Essay Contest

It is no easy task to jump into the role of a diplomat, especially when confronted by such an urgent crisis. USIP, in consultation with AFSA, developed a guide to provide a basic introduction to the topic and some additional context that can assist you in answering the question, while still challenging you to develop your own unique response. As such, this guide should be used as a starting point to your own research and as you ultimately prepare a compelling memo outlining recommendations the U.S. government should follow to respond to the refugee and IDP crisis.

In the guide you will find: insights into the role of the Foreign Service; country, organization, and key-term briefs to provide a foundational understanding; and a list of other useful resources. Download the Companion Guide for the 2017 National High School Essay Contest (.pdf).

2016 National High School Essay Contest

USIP first partnered with AFSA for the 2016 contest and was pleased to welcome winner Dylan Borne to Washington in August. His paper describes his role as an economic officer in the U.S. Agency for International Development’s Bureau for Democracy, Conflict and Humanitarian Assistance. He writes about promoting education for girls in Afghanistan through on-line courses and dispersal of laptops. Read his winning essay (.pdf).

2021 NATIONAL HIGH SCHOOL - Diplomats and Peacebuilders: American ...

- Download HTML

- Download PDF

- Current Events

- Uncategorized

- IT & Technique

- Health & Fitness

- Government & Politics

- Home & Garden

- Food & Drink

- Hobbies & Interests

- Arts & Entertainment

What are your chances of acceptance?

Calculate for all schools, your chance of acceptance.

Your chancing factors

Extracurriculars.

The CollegeVine Ultimate Guide to High School Writing Contests

Do you have a plan for applying to college?

With our free chancing engine, admissions timeline, and personalized recommendations, our free guidance platform gives you a clear idea of what you need to be doing right now and in the future.

There are some unique skills that are harder than others to capture on the college application. Students who excel at sports will often have a long list of tangible achievements. Students who produce fine arts or participate in student leadership programs will easily find ways to highlight their participation in these extracurriculars on college applications. But writers will often have a harder time highlighting the skills, time, and energy put into perfecting the craft of writing. If you are a student who excels at writing, how can you draw attention to your abilities and dedication on your college application? Are high grades in the humanities and a well-written essay enough? How can you show that this skill is something you pursue as an extracurricular activity outside of regular school hours?

Writing contests are a great way to highlight your dedication to and success in writing.

Winning a writing contest does much more than simply look good on your college application. Many serious writing contests at the high school level offer prizes. Some are cash awards, and others come in the form of a scholarship, often to a summer writing program . Winning a writing contest can also help you to form and nurture a lasting relationship with the institute that hosts the contest. Additionally, numerous writing contests offer multiple levels of recognition, so you do not have to be the top winner to earn a title that will look good on your college application.

Although winning a writing contest is not easy, it can be the perfect way to show that you’re serious about your craft. Below are sixteen distinguished writing contests across all genres, open to high school students. Read on to learn about eligibility, prizes, submissions deadlines, and more!

1. The Atlantic & College Board Writing Prize

About: Hosted by the College Board in collaboration with the publication The Atlantic, the focus of this annual contest changes each year “to align with the introduction of a newly redesigned AP course and exam.”

Prizes: One grand prize winner receives $5,000 and has their winning submission printed in the September issue of The Atlantic. Two finalists also receive $2,500 each.

Who is Eligible: Students 16-19 years of age

Important Dates: January: Annual essay topic released. February 28: Submission deadline. May: Winners announced.

Genre of Writing: Essay, topics vary by year

Level of Competition: Most Competitive

Full Rules Available Here

2. National Council of Teachers of English Achievement Awards

About: Hosted annually by the National Council of Teachers of English, these awards seek to “encourage high school students in their writing and to publicly recognize some of the best student writers.”

Prizes: Students judged as having superior writing skills receive a certificate and a letter. Their names also appear on the NCTE website. In 2016, 533 high school juniors were nominated, and of them, 264 received Certificates for Superior Writing.

Who is Eligible: High school juniors who are nominated by their school’s English department. The number of nominees allowed from each school depends on their enrollment.

Important Dates: October: Writing theme released. November to Mid-February: Entries accepted. May: Winners announced.

Genre of Writing: Students submit one themed essay based on a given prompt, and one choice piece from any genre displaying their “best work”.

Level of Competition: Very Competitive

3. National Scholastic Art and Writing Awards

About: This contest begins regionally and progresses to the national level. Local organizations host regional competitions and winners from these are sent on for national consideration. This is a huge contest and it received nearly 320,000 entries in 29 categories across writing and the arts in 2016. Of those entries, 85,000 were recognized at the regional level and 2,500 received national medals. There is a submission fee of $5 per entry, or $20 per portfolio, but this can be waived for students who apply and meet the standards for financial assistance.

Prizes: At the regional level, students win Honorable Mentions, Silver or Gold Keys, or Nominations for the American Visions and Voices Medals. Regional Gold Key winners are then evaluated for national honors that include Gold and Silver Medals or the American Visions and Voices Medal, which serves as a “Best in Show” award for each region. National award winners are invited to a National Ceremony and celebration at Carnegie Hall in New York City. There are several sponsored cash awards at the national level, ranging by genre and sponsor, and some National Medal winners will be selected for scholarships to colleges or summer programs as well.

Who is Eligible: All U.S. students in grades 7-12.

Important Dates: Regional deadlines vary; search for yours here . National winners are announced in the spring and the National Ceremony is held in June each year.

Genre of Writing: Critical Essay, Dramatic Script, Flash Fiction, Humor, Journalism, Novel Writing, Personal Essay & Memoir, Poetry, Science Fiction & Fantasy, Short Story, Writing Portfolio (graduating seniors only)

Level of Competition: Regionally: Somewhat Competitive Nationally: Very Competitive

4. Letters About Literature

About: This is a reading and writing contest sponsored by the Center for the Book in the Library of Congress. It invites students to write a letter to the author (living or dead) of a book, poem, or speech that has affected them personally. Letters are judged at state and national levels.

Prizes: The National Winner at each level receives a $1,000 cash award. Two National Honor Winners at each level receive a $200 cash award.

Who is Eligible: Students in grades 4-12. (Grades 4-6 are in Level 1, Grades 7-8 are in Level 2, and Grades 9-12 are in Level 3.)

Important Dates: Submission deadline vary according to level and state.

Genre of Writing: Letters, written to a prompt.

5. Princeton University Contests

About: Princeton University hosts two contests for high school juniors. One is a poetry contest judged by members of the Princeton University Creative Writing faculty. The other is a Ten-Minute Play Contest judged by members of the Princeton University Program in Theater faculty. They offer no information about how many entrants they receive each year, but in the past 20 years, at least five winners have gone on to become Princeton students.

Prizes: Each contest has a first place prize of $500, second place prize of $250, and third place prize of $100.

Who is Eligible: High school juniors

Important Dates: The Poetry Contest submission period for 2017 is now closed; dates for 2018-2019 school year have not been announced. The Ten-Minute Play Contest will publish new application materials this fall; submissions are due April 2, 2018 with winners announced online by June 6, 2018.

Genre of Writing: Poetry and Playwriting

Level of Competition: Competitive

6. Ocean Awareness Student Contest

About: A relatively new competition, the Bow Seat Ocean Awareness Program and the Ocean Awareness Contest was founded in 2011 with a mission to “inspire the next generation of ocean caretakers through education and engagement with the arts, science, and advocacy.” It challenges entrants to think creatively about human impact on our oceans and coastal environment. An interdisciplinary contest, it welcomes art, poetry, prose, and film entries. Though it is only five years old, it is rapidly growing. It received over 2,100 entrants in 2015 and has already awarded more than $100,000 in scholarships. The theme changes each year, but it always relates to the connection between humans and the ocean.

Prizes: The contest is divided into high school and middle school levels, and there are 26 cash awards available for writing in each age group, ranging from $100 to $1,500.

Who is Eligible: Individuals or groups in grades 6-12

Important Dates: The 2018 contest opened on Sept. 18, 2017 and entries must be received by June 18, 2018 11:59 p.m. ET. Winners are announced in January 2019.

Genre of Writing: Poetry or prose and an accompanying reflection piece.

Level of Competition: Somewhat Competitive

7. The Bennington Young Writers Awards

About: Bennington College boasts among its alumna seven Pulitzer Prize winners, three US poet laureates, and countless New York Times bestsellers. Judges for its young writers’ contest include faculty and students from Bennington College. In 2015, it received more than 2,300 submissions.

Prizes: First place winners in each category receive $500; second place winners receive $250

Who is Eligible: Students in grades 10-12

Important Dates: Submissions will be accepted starting September 4, 2018 until November 1, 2018. Winners announced after April 15, 2019.

Genre of Writing: Poetry, Fiction, and Nonfiction (personal or academic essay), fewer than 1500 words

8. The New Voices One-Act Competition for Young Playwrights

About: The New Voices One-Act Competition for Young Playwrights is hosted by YouthPLAYS, an organization that publishes plays and musicals for performance by schools and theaters for young audiences. The contest, founded in 2010, is designed to encourage young writers to create new pieces for the stage. There are also similar contests run at the regional and local level under the same “New Voice Playwrights” title, though rules, eligibility and prizes vary.

Prizes: The winner receives $200 in addition to representation of their play through YouthPLAYS publishing. The runner-up receives $50.

Who is Eligible: Authors 19 years old or younger

Important Dates: Submission deadline is May 1, 2018 and winners are announced in the fall.

Genre of Writing: 10-40 minute single act plays suitable for school productions

9. YoungArts

About: The National YoungArts Foundation was founded in 1981 with a mission to identify and support the next generation of artists in the visual, design, literary, and performing arts. Thousands of students apply each year and winners attend weeklong programs offered in Los Angeles, New York, and Miami. At these programs, students participate in workshops with master artists. It is also the only path to nomination for the U.S. Presidential Scholars in the Arts. There is a $35 application fee, but fee waivers are available for students who qualify.

Prizes: Regional Honorable Mentions are invited to participate in regional workshops. Finalists are invited to participate in National YoungArts week where they have the opportunity to meet with the panel of judges and can win cash prizes up to $10,000. Finalists are also eligible for a U.S. Presidential Scholar in the Arts nomination.

Who is Eligible: Students in grades 10-12 or ages 15-18, U.S. citizens or permanent residents only.

Important Dates: Applications open Spring 2018 and submissions are due by mid-October for the following year’s programs.

Genre of Writing: Creative nonfiction, novel, play or script, poetry, short story, or spoken word

10. The Patricia Grodd Poetry Prize for Young Writers

About: The Kenyon Review literary magazine of Kenyon College sponsors this writing contest aimed at encouraging and recognizing outstanding young poets.

Prizes: First place winner receives a full scholarship to the weeklong Kenyon Review summer program. Two runners-up receive partial scholarships. All three award-winning pieces are published in The Kenyon Review .

Who is Eligible: Students in grades 10-11

Important Dates: Submissions are open Nov 1- Nov 30 and winners are announced in February.

Genre of Writing: Poetry

11. The Claremont Review Writing Contest

About: The Claremont Review is an international magazine for young writers. It publishes poetry, short stories, short plays, graphic art, and photography twice annually in issues released in the spring and fall. Based in Canada, The Claremont Review was founded in 1992 by a group of editors who saw a need to “provide young adult artists with a legitimate venue to display their work.” Their contest is hosted annually, and there is a $20 USD fee for entries from outside Canada, and $20 CAD for entries inside Canada.

Prizes: Cash prizes between $400 CAD and $1,000 CAD are awarded in poetry, fiction, and visual arts categories. All winners and honorable mentions are published in the fall issue of the magazine.

Who is Eligible: Young adults aged 13-19 may submit previously unpublished work written in English.

Important Dates: Submissions are open from January 15 to March 15 each year. Winners are announced in May

Genre of Writing: Poetry and fiction

12. Richard G. Zimmerman Scholarship

About: Slightly different in structure, this award is a scholarship rather than a traditional writing contest. It was endowed by Richard G. Zimmerman, a member of the National Press Club who died in 2008. One annual scholarship is awarded to a high school senior who intends to pursue a career in journalism. Applicants must submit three samples of journalistic work along with three letters of recommendation, a high school transcript, a signed copy of the financial aid form (FAFSA), and a letter of acceptance to college or documentation of where you have applied.

Prizes: One-time $5,000 scholarship

Who is Eligible: High school seniors who seek to pursue a career in journalism

Important Dates: Applications must be postmarked by March 1 each year.

Genre of Writing: Journalism

13. Signet Classics Student Scholarship Essay Contest

About: Signet Classics, an imprint of Penguin Books, has hosted this high school essay contest annually for 21 years. Essays must be submitted by an English teacher on behalf of his or her student, and must respond to one of five prompts on the annually selected text. The 2017 text is The Tempest.

Prizes: Five cash prizes of $1,000 each are awarded to winners, with each winner’s school library also receiving a Signet Classics Library.

Who is Eligible: High school juniors and seniors, and home-schooled students who are between the ages of 16-18; students must reside in the fifty United States and the District of Columbia.

Important Dates: Entries for the 2018 contest must be postmarked by April 14, 2018 and received on or before April 21, 2018. Winners will be announced at the end of June.

Genre of Writing: Academic essay

14. National High School Essay Contest by the United States Institute of Peace

About: The United States Institute of Peace (USIP) partners with the American Foreign Service Association (AFSA) to host this annual contest aimed to engage “high school students in learning and writing about issues of peace and conflict, encouraging appreciation for diplomacy’s role in building partnerships that can advance peacebuilding and protect national security.” The 2017 theme asks students to put themselves in the place of U.S. diplomats addressing the refugee crisis in one of four countries: Turkey, Iraq, Kenya, or Afghanistan. Students should consult the contest Companion Guide to help shape their answers and must also submit a list of references used.

Prizes: One winner receives a $2,500 cash award, an all-expense paid trip to Washington, D.C. to meet the Secretary of State, and a full scholarship for one semester aboard the Semester at Sea Program upon enrollment at an accredited university. One runner-up receives a cash prize of $1,250 and a full scholarship to participate in the International Diplomacy Program of the National Student Leadership Conference.

Who is Eligible: “Students whose parents are not in the Foreign Service are eligible to participate if they are in grades nine through twelve in any of the fifty states, the District of Columbia, the U.S. territories, or if they are U.S. citizens attending high school overseas. Students may be attending a public, private, or parochial school. Entries from home-schooled students are also accepted.”

Important Dates: Entries must be submitted by March 15, 2018. Winners are announced in July.

Genre of Writing: Letter, written to address a prompt.

15. We the Students Essay Contest by Bill of Rights Institute

About: Sponsored by the Bill of Rights Institute, this essay contest challenges students to think critically and creatively about the rights of the people and how they impact the greater society. The 2017 prompt asks students to specifically consider civil disobedience and think critically about whether peaceful resistance to laws positively or negatively impacts a free society. Students are encouraged to use specific examples and current events to back up their thinking.

Prizes: One grand prize winner receives $5,000 and a scholarship to Constitutional Academy. Six runners-up receive $1,250 each, and eight honorable mentions receive $500 each.

Who is Eligible: U.S. citizens or legal residents between the ages of 14-19, attending school in the fifty United States, the District of Columbia, U.S. territories, or American Armed Forces schools abroad.

Important Dates: Submissions typically start in September and must be completed by early February. Winners are announced in April.

Genre of Writing: Essay

Level of Competition: Very Competitive.

16. Profile in Courage Essay Contest by JFK Presidential Library

About: Hosted annually, the Profile in Courage Essay Contest will be marking the 100th anniversary of John F. Kennedy’s birth in 2017, and is doubling prizes to celebrate. This contest is inspired by JFK’s book, Profiles in Courage , which recounted the stories of eight U.S. senators who displayed political courage in standing up for a greater good and risking their careers by doing so. The contest asks entrants to describe and analyze an act of political courage in the form of a similar profile.

Prizes: First place prize of $20,000. Twenty-five smaller cash awards ranging from $100 to $1,000.

Who is Eligible: “The contest is open to United States high school students in grades nine through twelve attending public, private, parochial, or home schools; U.S. students under the age of twenty enrolled in a high school correspondence/GED program in any of the fifty states, the District of Columbia, or the U.S. territories; and U.S. citizens attending schools overseas.”

Important Dates: The contest deadline is in early January, though official dates for 2019 have not been posted yet.

Writing in all genres is an art form. Students who are passionate about it will find that writing contests provide them with a platform for highlighting their skills, receiving recognition at the local, regional and national levels, and even receiving valuable cash prizes or scholarships. Not to mention writing awards look great on your college application and draw attention to a sometimes overlooked art form.

Want access to expert college guidance — for free? When you create your free CollegeVine account, you will find out your real admissions chances, build a best-fit school list, learn how to improve your profile, and get your questions answered by experts and peers—all for free. Sign up for your CollegeVine account today to get a boost on your college journey.

Related CollegeVine Blog Posts

- Board of Directors and Member Institutions

- Volunteer Opportunities

- Pre-Collegiate Academy

- College and Career Information Centers (CCIC)

- Cash For College

- College Information Day

- I’m Going to College

- Transfer: Make It Happen

- Informational Workshops

- Who Qualifies?

- The California Dream Act

- Step-by-Step Guide to Financial Aid

- State Aid Programs

- Federal Aid Programs

- Accepting Student Loans

- Financial Aid from Schools and Colleges

- Steps to go to College

- College Entrance Exams

- Junior’s College Admissions Checklist

- Senior’s College Admissions Checklist

- Admission Requirements

- Top College Resources Online

- Printable Handouts

- Scholarships

- Student Testimonials

National Peace Essay Contest

Institution.

All fields of study. Essays are focused on peacebuilding

The National Peace Essay Contest is a yearly competition that provides scholarships to high school students. NPEC encourages high school students to explore peacebuilding. Many NPEC winners have gone on to study foreign policy issues in college or have pursued careers in international affairs. Up to 53 winners receive college scholarships and, in 2014, the three national winners will be invited to an Awards Program in Washington, D.C.

Students are eligible to participate if they are in grades nine through twelve in any of the fifty states, the District of Columbia, the U.S. territories, or if they are U.S. citizens attending high school overseas. Students may be attending a public, private, or parochial school. Entries from home-schooled students are also accepted. Previous first-place state winners and immediate relatives of directors or staff of the Institute are not eligible to participate. Previous honorable mention recipients are eligible to enter .

See website for essay prompt, requirement checklist, and essay submission directions.

Share This Scholarship

Summer II 2024 Application Deadline is June 26, 2024.

Click here to apply.

Featured Posts

National Science Foundation's High School Internship - 7 Reasons Why You Should Apply

10 Free Summer Programs for High School Students in New Jersey (NJ)

8 Summer STEM Programs for High School Students in Virginia

How to Write Your Personal Statement: A College Essay Expert’s Step-by-Step Process for Success

10 Mentorship Programs for High School Students in 2024-2025

10 Computer Science Camps for High School Students

7 Robotics Summer Camps for Middle School Students

9 Non-Profit Internships for High School Students

10 Best Hackathons for High School Students

10 International Olympiads for High School Students

- 11 min read

10 Awesome Essay Competitions for High School Students

Whether you’re interested in STEM or the humanities, if you are a high school student looking to bolster your college applications and resumes, be sure to check out these essay competitions! These competitions provide you with a platform to express your ideas, enhance your writing skills, and demonstrate your ability to think critically and creatively about various topics . Engaging in such contests not only sharpens your writing but also allows you to explore and articulate your thoughts on a range of subjects, showcasing your depth of knowledge and interest in broader worldly issues.

Winning or even just participating in these competitions can add significant value to your college applications. It highlights your initiative and intellectual curiosity, qualities that colleges and universities deeply value. Essay competitions also often come with accolades, scholarships, or opportunities to have your work published, further bolstering your academic profile.

In this blog, we cover 10 amazing essay competitions for high school students.

1. Profile in Courage Essay Contest by JFK Presidential Library

Deadline : January 12

Eligibility : All high school students are eligible

Prize : Grand prize of $10,000 cash award. If the John F. Kennedy Library Foundation holds the 2024 Profile in Courage Award event in person, the winner and her/his/their family will be invited to travel to Boston to accept her/his/their award in May 2024. Travel and lodging expenses will be paid for the trip to Boston for the winning student and her/his/their parents.

The Profile in Courage Essay Contest, hosted by the JFK Presidential Library, allows you to showcase your writing skills and your understanding of political courage. This contest challenges you to write an original and creative essay that reflects your grasp of the concept of political courage as described by John F. Kennedy in his book, "Profiles in Courage." You are tasked with exploring an act of political courage by a U.S. elected official who served during or after 1917, the year of Kennedy's birth. Your essay, with a word limit of 1,000 and a minimum of 700 words, excluding citations and bibliography, should not only describe the act but also delve into a detailed analysis of the obstacles, risks, and consequences associated with it . By participating in this contest, you are not just demonstrating your writing and analytical abilities; you are also engaging with important themes in American political history and contributing to the discourse on leadership and moral courage.

Winning the Profile in Courage Essay Contest comes with significant recognition and a substantial reward – a $10,000 cash award . This accolade is not only a testament to your academic and creative abilities but also a noteworthy achievement that can enhance your college applications and resumes. Moreover, the act of researching and writing about a U.S. elected official's courageous act allows you to delve into the intricacies of political decision-making and leadership. For tips on how to win, check out this article !

2. AFSA's National High School Essay Contest

Deadline : April 1

Eligibility : All high students whose parents are not in the Foreign Service

Prize : $2,500 to the writer of the winning essay, in addition to an all-expense paid trip to the nation’s capital from anywhere in the U.S. for the winner and his or her parents, and an all-expense paid educational voyage courtesy of Semester at Sea.

The AFSA's National High School Essay Contest is a prestigious competition organized jointly by the American Foreign Service Association (AFSA) and the United States Institute of Peace (USIP). This annual contest is designed to engage you in learning and writing about critical issues related to peace and conflict, emphasizing the importance of diplomacy in building partnerships for peacebuilding and protecting national security. Whether or not you have a background or family connection to the Foreign Service, this contest is open to you, offering a platform to explore and express your views on international relations and the vital role of diplomatic efforts. The challenge is to craft an essay that not only reflects depth of thought but also demonstrates a clear understanding of the complex dynamics of international diplomacy and peacekeeping.

If you win, you will receive a $2,500 cash prize, an all-expenses-paid trip to Washington, D.C., and a remarkable opportunity to enroll in the Semester at Sea Program with a full scholarship for one semester, contingent upon your admission to an accredited university. This experience offers an unparalleled opportunity to gain a global perspective, traveling the world while engaging in a rigorous academic program. The runner-up is also rewarded with a cash prize of $1,250 and a full scholarship to the National Student Leadership Conference's International Diplomacy Program, which is another exceptional avenue to deepen your understanding of global diplomacy and leadership . For a deep dive into this contest, check out this article !

3. We the Students Essay Contest by Bill of Rights Institute

Deadline : May 19

Eligibility : US citizens and US-based young people who are between the ages of 13 and 19 and enrolled in middle or high school

Prize : $10,000

The We the Students Essay Contest, sponsored by the Bill of Rights Institute, is an opportunity for you to dive into the world of civic understanding and appreciation. As a participant, you will explore the intricacies of the U.S. Constitution and the Bill of Rights, understanding not just their historical context but also their relevance in today's world. The contest challenges you to articulate your thoughts and arguments effectively, fostering a deeper understanding of the principles that underpin American democracy. By engaging in this essay contest, you will not only enhance your writing and critical thinking skills but also deepen your understanding of the foundational concepts of rights and liberties.

The grand prize winner will receive $5,000, a significant financial boost that acknowledges the quality of their work, in addition to a scholarship to the Constitutional Academy. Moreover, six runners-up will each be awarded $1,250, and eight honorable mentions will receive $500 each, ensuring that a range of participants are recognized and rewarded for their efforts . Eligibility for this contest extends to citizens or legal residents of the United States between the ages of 14 and 19, encompassing a broad spectrum of high school students. Participating in this contest is an opportunity to engage with critical issues surrounding individual rights and societal needs. For a deep dive into this contest, check out this article !

4. Engineer Girl Annual Essay Contest

Deadline : February 1

Eligibility : Students in grades 3-12

Prize : Grand prize of $1,000

The Engineer Girl Annual Essay Contest allows you to showcase your understanding of engineering's role in the world. Each year, this contest focuses on different aspects of engineering and its impact on our daily lives, challenging students to research and write about these topics creatively and informatively. Prize money of up to $500 is available, serving as a great incentive and recognition for your hard work and creativity. Participating in this contest is not just about winning prizes; it's also an opportunity to deepen your understanding of engineering concepts and their practical applications. As a high school student, engaging in this competition allows you to explore and articulate the significance of engineering in everyday life, enhancing your research and writing skills in the process.

For the 2024 EngineerGirl Writing Contest, the challenge is to write an essay exploring the lifecycle of an object that you use in your daily life. This topic prompts you to think critically about the products around you, from their creation and use to their eventual disposal or recycling. It's an invitation to consider the broader environmental, economic, and social impacts of these objects, reflecting on how engineering contributes to every stage of their lifecycle. The word limit for submissions varies depending on your grade level. Whether you are in elementary, middle, or high school, the contest is tailored to your level of education, ensuring that the challenge is appropriate and engaging. This contest is an excellent way for you to bridge the gap between technical understanding and expressive writing, skills that are invaluable in both academic and professional settings.

5. Jane Austen Society Essay Contest

Deadline : June 1

Prize : $1,000 scholarship, plus free registration and two nights’ lodging for JASNA’s upcoming Annual General Meeting .

If you have an interest in literature, the Jane Austen Society Essay Contest is a great opportunity for you. By entering this contest, you have the chance to win up to $1,000 by crafting an essay on a specified topic related to Jane Austen's novels. The 2024 contest topic presents a particularly intriguing challenge: you are to engage in a formal debate-style discussion on the resolution, "That Jane Austen’s novels are still relevant and speak to us after 200 years." This approach requires you to first attack this claim, scrutinizing and challenging the relevance of Austen's works in the modern context. Then, in the second part of your essay, you will shift gears to defend this claim, highlighting the enduring significance and impact of Austen's novels. As a participant, you will also receive a year of membership to the Jane Austen Society of North America (JASNA) and a collection of Norton Critical Editions of Austen's novels, enriching your literary journey.

To excel in this contest, you will need to demonstrate a deep understanding of Austen’s works, backing up your positions with quotations and examples from at least one of her novels. This requirement not only tests your knowledge of Austen's literature but also your ability to engage with the text in a meaningful and analytical manner. Citing Austen’s unfinished works is also permitted. This contest is not just about showcasing your writing skills; it's an opportunity to delve deeply into the literary world of Jane Austen, exploring how her novels, written over 200 years ago, continue to resonate in the contemporary world. The winning essays will be featured on the JASNA website, providing you with a platform to share your insights with a wider audience of Austen enthusiasts and literary scholars. For tips on how to win, check out this article !

6. DNA Day Essay Contest

Deadline : March 2024

Eligibility : All high schools students are eligible

Prize : $1,000 for student and $1,000 genetics materials grant

The ASHG's DNA Day Essay Contest is a fascinating opportunity for you to explore and deepen your understanding of genetics. DNA Day, celebrated to commemorate the completion of the Human Genome Project in April 2003 and the discovery of the double helix of DNA in 1953, serves as the backdrop for this contest. Open to students in grades 9-12 worldwide, the contest asks you to examine, question, and reflect on key concepts in genetics. The 2024 question focuses on the complex interplay between genetics and the environment in shaping human health. You are challenged to provide an example of how this interaction can influence diseases or health conditions. This task requires not only a deep understanding of scientific concepts related to genetics but also the ability to reason and argue effectively.

If your essay is selected as the first-place winner, you will receive a $1,000 prize. In addition, a $1,000 genetics materials grant is awarded, providing further support for your academic or research pursuits. The contest is evaluated by ASHG members through three rounds of scoring, ensuring a fair and thorough review of your work. Participating in this contest not only offers the chance for monetary rewards but also allows you to showcase your understanding of genetics to a panel of experts . This exposure can be invaluable, especially if you are considering a future career in genetics, medicine, or a related field. For tips on how to win, check out this article !

7. John Locke Essay Competition

Deadline : May 31

Prize : $2000 towards the cost of attending any John Locke Institute programme, and the essays will be published on the Institute's website

The John Locke Institute Essay Competition is designed to encourage young people like you to develop the qualities that define great writers and thinkers: independent thought, depth of knowledge, clear reasoning, critical analysis, and persuasive style . By entering this competition, you are not just participating in an academic exercise; you are stepping into an arena that challenges you to think deeply and critically about a range of complex and thought-provoking questions. These questions span across various disciplines, offering you the freedom to explore areas of interest in Philosophy, Politics, Economics, History, Psychology, Theology, and Law. This competition is an excellent way for you to delve into topics that fascinate you, fostering a deeper understanding and appreciation of these subjects.

Engaging in the John Locke Institute Essay Competition is more than just an academic endeavor; it is a chance to have your work evaluated by some of the most distinguished academics from renowned universities, including Oxford and Princeton . This not only provides you with invaluable feedback but also gives you a sense of the standards expected at the highest levels of academia. The competition is divided into several categories, ensuring that students of different ages and interests can participate and be recognized for their work. The judges will select a favorite essay from each subject category, as well as a junior category for those under 15, before choosing an overall 'best essay' across all subjects. Whether you win a prize or not, the experience gained from participating in the John Locke Institute Essay Competition is invaluable, setting you apart as a critical thinker and a persuasive writer. For tips on how to win, check out this article !

8. Bowseat Ocean Awareness Contest

Deadline : June 10

Eligibility : Students ages 11-18 who are enrolled in middle school or high school (or the homeschool equivalent) worldwide.

The 13th annual Ocean Awareness Contest offers you, a student aged 11-18, a unique platform to express your concerns and perspectives on environmental issues through the lens of art and creativity. The 2024 contest theme, "Tell Your Climate Story," invites you to become a climate witness, sharing your personal experiences, insights, or perceptions about the rapidly changing climate. This is more than just a competition; it's an opportunity for you to explore your relationship with the world as it evolves due to climate change. By participating in this contest, you are encouraged to delve into the impacts of the climate crisis on your family, community, and personal life. This is your chance to creatively express how these changes are affecting you and your surroundings.

Depending on your age at the time of entry, you can enter either the Junior Division (age 11-14) or the Senior Division (age 15-18) . This ensures that your work is evaluated alongside peers in a similar age range, making the competition fair and encouraging. You have the flexibility to participate as an individual or as part of a club, class, or group, allowing for collaborative as well as individual expressions of creativity . Your participation in this contest can be a significant step towards becoming a more informed and active environmental advocate. For tips on how to win, check out this article !

9. SPJ/JEA High School Essay Contest

Deadline : February 19

Prize : Scholarship awards are provided,

The SPJ/JEA High School Essay Contest, sponsored by the Society of Professional Journalists and the Journalism Education Association, is a great opportunity for you to contemplate the crucial role of the press in American society. You will be tasked with writing an essay, between 300 and 500 words, that explores the interconnectedness of media literacy and democracy . This topic is especially relevant in today's digital age, where the media plays a pivotal role in shaping public opinion and democracy. The challenge lies in proposing top strategies to engage people of all ages with media literacy and democracy, a task that will require you to think critically and creatively about the current media landscape and its impact on democratic processes.

Entering the SPJ/JEA High School Essay Contest is a chance for you to showcase your writing skills and your understanding of media literacy's role in supporting democracy. The competition is open to students in grades 9 through 12 across the United States, with a registration fee of just $5. The first-place winner receives a $1,000 scholarship, second-place a $500 award, and third-place a $300 prize. Participating in this contest is more than just a chance to win a scholarship; it's an opportunity to contribute to an important conversation about media literacy and its crucial role in a democratic society.

10. Atlas Shrugged Novel Essay Contest

Deadline : November 6

Eligibility : Open to all high school, college, and graduate students worldwide.

Prize : Grand prize of $10,000

The Atlas Shrugged novel essay contest offers you a unique opportunity to delve into the provocative and philosophically rich world of Ayn Rand's "Atlas Shrugged." This contest is open to students globally and challenges you to engage deeply with Rand's heroic mystery novel by choosing one of the provided prompts to write an 800-1,600 word essay in English . Your essay will require you to critically analyze and interpret the novel's concepts, making connections to your own experiences or societal observations. This is a chance to not only showcase your understanding of one of the 20th century’s most influential novels but also to express your own perspectives and insights in a well-crafted essay.

The contest boasts a generous first prize of $10,000, along with three second prizes of $2,000, five third prizes of $1,000, 25 finalist awards of $100, and 50 semifinalist prizes of $50 . With entry being free, this contest is an accessible way for you to demonstrate your analytical and writing skills while competing for noteworthy awards. This experience will not only enhance your critical thinking and writing skills but also provide you with a deeper understanding of Rand's influential ideas, potentially shaping your perspectives on literature and philosophy.

One other option - Lumiere Research Scholar Program

If you would like to further enhance your applications, you should also consider applying to the Lumiere Research Scholar Program , a selective online high school program for students founded with researchers at Harvard and Oxford. Last year, we had over 4000 students apply for 500 spots in the program! You can find the application form here.

Also check out the Lumiere Research Inclusion Foundation , a non-profit research program for talented, low-income students.

Jessica attends Harvard University where she studies Neuroscience and Computer Science as a Coca-Cola, Elks, and Albert Shankar Scholar. She is passionate about educational equity and hopes to one day combine this with her academic interests via social entrepreneurship. Outside of academics, she enjoys taking walks, listening to music, and running her jewelry business!

Image Source: Profile in Courage

- competitions

Transforming the understanding and treatment of mental illnesses.

Información en español

Celebrating 75 Years! Learn More >>

- Science News

- Meetings and Events

- Social Media

- Press Resources

- Email Updates

- Innovation Speaker Series

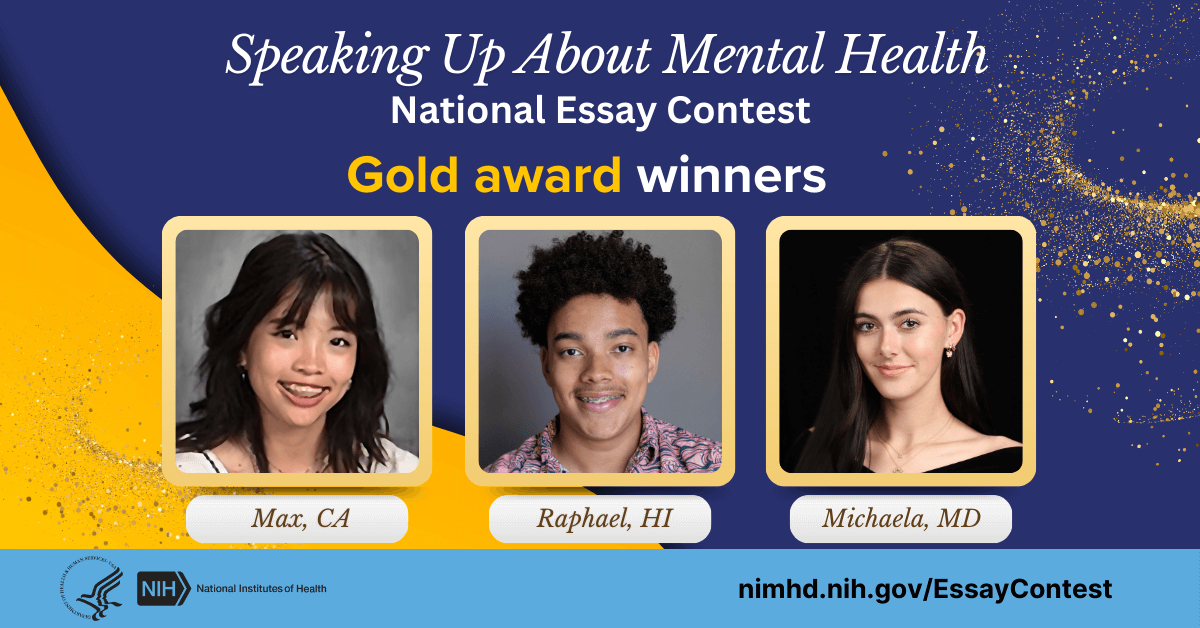

NIH Announces Winners of 2023-2024 High School Mental Health Essay Contest

May 31, 2024 • Institute Update

The National Institutes of Health (NIH) is pleased to announce the winners of the 2024 Speaking Up About Mental Health essay contest. Out of more than 370 submissions across 33 states, NIH awarded 24 youth (ages 16-18) finalists with gold, silver, bronze, and honorable mention prizes.

Supported by the National Institute of Mental Health, the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities, and the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, the essay contest invited youth to address mental health and reduce mental health stigma that young people may face when seeking mental health treatment.

The winning essays addressed complicated topics such as stigma, trauma, resilience, equity, anxiety, and more. Teens also wrote about specific ideas for improving well-being, such as broader access to leisure sports, reducing time spent on social media, and normalizing mental health treatment and care.

NIH awarded a total of $15,000 in cash prizes to gold, silver, bronze, and honorable mention recipients. Read the winning essays at nimhd.nih.gov/EssayContest .

Gold winners

- Max, California - Tenacity Through Tumultuousness

- Michaela, Maryland - Exposing the Impact of Social Media on Teenage Mental Health: A Journey of Self-Discovery

- Raphael, Hawaii - Let's CHAT: Mental Health Impact on Teens Living with Speech Challenges

Silver winners

- Aditi, California – Embracing Authenticity

- Anna, New York - Change Our Approach: How Sports Can Play a Role in Mental Health

- Ciniyah, Illinois - The Roots Affect the Fruit: A Personal Journey of Trauma to Triumph

- Kathleen, Maryland - Behind A Perfect Life

- Paige, Texas - Learn to Live and Accept Your Journey

- Rylie, Maryland - Drowning in Plain Sight

Bronze winners

- Argiro, Pennsylvania - Out in the Open: A Conversation about Mental Health

- Dresden, Maryland - Normalize the Care to Destigmatize the Conditions

- Gabriel, New Jersey - Keeping My Head Up: My Experience with Dad's Brain Cancer

- Hailey, Arkansas - Access for Adolescent Athletes

- Jordan, New Jersey - A Weighted Wait

- Kathryne, North Carolina - Embracing Openness: Unveiling Silent Struggles Surrounding Mental Health

- Maya, Maryland - Speaking up for Change

- Rachel, California - Embracing the Journey Towards Mental Health Acceptance

- Savannah, New Jersey - Taking a Step Today, for a Better Tomorrow

Honorable mentions

- Agaana, Maryland – Accountability for Authority: The Responsibilities of Schools

- Gisele, Pennsylvania - Breaking the Silence

- Jillian, Illinois - Navigating Mental Illness in Teens

- Kyle, North Carolina - How the Neglect of Mental Health Within Black Communities Causes Underlying Issues

- Mason, Maryland - Social Media as a Possible Method to Reduce Mental Health Stigma

- Minsung, Georgia - Hope to Bridge the Gap

If you are in crisis and need immediate help, call or text the 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline at 988 (para ayuda en español, llame al 988) to connect with a trained crisis counselor. The Lifeline provides 24-hour, confidential support to anyone in suicidal crisis or emotional distress. The deaf and hard of hearing can contact the Lifeline using their preferred relay service or by dialing 711 and then 988.

- Mission and Vision

- Scientific Advancement Plan

- Science Visioning

- Research Framework

- Minority Health and Health Disparities Definitions

- Organizational Structure

- Staff Directory

- About the Director

- Director’s Messages

- News Mentions

- Presentations

- Selected Publications

- Director's Laboratory

- Congressional Justification

- Congressional Testimony

- Legislative History

- NIH Minority Health and Health Disparities Strategic Plan 2021-2025

- Minority Health and Health Disparities: Definitions and Parameters

- NIH and HHS Commitment

- Foundation for Planning

- Structure of This Plan

- Strategic Plan Categories

- Summary of Categories and Goals

- Scientific Goals, Research Strategies, and Priority Areas

- Research-Sustaining Activities: Goals, Strategies, and Priority Areas

- Outreach, Collaboration, and Dissemination: Goals and Strategies

- Leap Forward Research Challenge

- Future Plans

- Research Interest Areas

- Research Centers

- Research Endowment

- Community Based Participatory Research Program (CBPR)

- SBIR/STTR: Small Business Innovation/Tech Transfer

- Solicited and Investigator-Initiated Research Project Grants

- Scientific Conferences

- Training and Career Development

- Loan Repayment Program (LRP)

- Data Management and Sharing

- Social and Behavioral Sciences

- Population and Community Health Sciences

- Epidemiology and Genetics

- Medical Research Scholars Program (MRSP)

- Coleman Research Innovation Award

- Health Disparities Interest Group

- Art Challenge

- Breathe Better Network

- Healthy Hearts Network

- DEBUT Challenge

- Healthy Mind Initiative

- Mental Health Essay Contest

- Science Day for Students at NIH

- Fuel Up to Play 60 en Español

- Brother, You're on My Mind

- Celebrating National Minority Health Month

- Reaching People in Multiple Languages

- Funding Strategy

- Active Funding Opportunities

- Expired Funding Opportunities

- Technical Assistance Webinars

- Community Health and Population Sciences

- Clinical and Health Services Research

- Integrative Biological and Behavioral Sciences

- Intramural Research Program

- Training and Diverse Workforce Development

- Inside NIMHD

- ScHARe HDPulse PhenX SDOH Toolkit Understanding Health Disparities For Research Applicants For Research Grantees Research and Training Programs Reports and Data Resources Health Information for the Public Science Education

- NIMHD Programs

- Education and Outreach

- 2024 Awardees

- Extramural Research

- Intramural Research

- NIMHD Collaborations

- Fuel Up to Play 60 en Espanol

- COVID-19 Information and Resources

2024 Essay Contest Awardees

Speaking up about mental health.

Gold Winners

Tenacity through tumultuousness.

Max, California

In this essay I recount my past: from hospitalizations to advocacy, mental health is not something we just have to "survive" with but rather a tool we leverage to help others thrive, an unabashed reminder against preconceived stigma. As Kelly Clarkson once sang, "'What doesn't kill you makes you stronger,'" and mental health has not only made me more resilient but my community as well.

Exposing the Impact of Social Media on Teenage Mental Health: A Journey of Self-Discovery

Michaela, Maryland

This essay explores the detrimental effects of social media on teenage mental health, tracing a personal journey from immersion in virtual reality to self-discovery. The author, grappling with the toxic influences of platforms like Instagram and Snapchat, ultimately breaks free from the cycle of comparison and seeks to raise awareness and implement measures to combat social media addiction among youth, advocating for education, support, and regulation.

Let's CHAT: Mental Health Impact on Teens Living With Speech Challenges

Raphael, Hawaii

Navigating through a fluid world as a young stutterer tests one's mental stability on a regular basis. This essay highlights the link between teens with speech challenges and mental health while fostering a communal environment of normalcy for those with speech differences.

Silver Winners

Embracing authenticity.

Aditi, California

Self respect is often overshadowed by societal expectations, but in this essay, I aim to promote inclusivity and emphasize the significance of individuality. Through personal reflections and insights, I underscore the importance of awareness, destigmatizing mental health issues, and increasing access to mental health resources to foster a supportive and meaningful environment.

Change Our Approach: How Sports Can Play a Role in Mental Health

Anna, New York

Physical activity is an important health behavior that can affect many different aspects of physical health, but also mental health. In my essay, I describe how sports have impacted me and how having more open, informal team sports can benefit others.

The Roots Affect the Fruit: A Personal Journey of Trauma to Triumph

Ciniyah, Illinois

This essay addresses how generational trauma has negatively impacted the foundation of the Black family. By doing so, I examine the brokenness within my own family, the trauma my father has given me, and how poor experiences can make an individual even more powerful.

Behind a Perfect Life

Kathleen, Maryland

It is important to remember that mental health disorders affect many people, but not everyone is open about their struggles. In my essay, I describe what schools can do to destigmatize mental health conditions and teach students how to reach out for help.

Learn to Live and Accept Your Journey

Paige, Texas

I have been battling my anxiety for as long as I can remember whether it was stress over a test, a nervous tick, or worry about my athletic performance. Getting help for my anxiety was the best decision my parents and I ever made because it helped take a massive burden off of me, so that I could go back to enjoying my everyday life.

Drowning in Plain Sight

Rylie, Maryland

By sharing my journey, I hope to bring awareness to youth mental health and what it’s like to feel trapped in your thoughts. My hope by speaking up about mental health is to provide more mental health resources and reduce the stigma around mental health.

Bronze Winners

Normalize the care to destigmatize the conditions.

Dresden, Maryland

Destigmatizing mental health issues will only occur if the dialogue surrounding them departs from the current dramatization and glamourization that plagues online media. The first step in building a healthier societal relationship with mental health issues—especially among teens—is to normalize seeking treatment for them.

Keeping My Head Up: My Experience with Dad's Brain Cancer

Gabriel, New Jersey

Last year, my father was diagnosed with terminal brain cancer, and I had sunken into a crippling, hopeless depression. This is my story on how changing my mindset led to a happier life for us all.

Access for Adolescent Athletes

Hailey, Arkansas

I want to spread awareness about the importance of mental health awareness, especially regarding athletes. Mental health in athletes is typically unmentioned and disregarded, so I wrote this essay to highlight the significance on taking care of yourself.

Out in the Open: A Conversation About Mental Health

Iro, Pennsylvania

Blindness and negligence are the main reasons mental health is stigmatized, thus they should be eliminated with the aim of creating a safer environment for all students to express themselves freely. By addressing it openly and changing school policies, such as implementing anonymous support groups, mandatory mental health classes, and clubs that provide healthy coping mechanisms, we can reduce the negative perception and educate students and teachers alike on the subject.

A Weighted Wait

Jordan, New Jersey

When most people think of hospice, they only imagine patients who are physically ill, such as those with end-stage cancer, kidney failure, or a traumatic brain injury. However, loneliness within the hospice setting is a serious mental health concern as well, and it is imperative that we compassionately care for these patients in their final months so they may leave this earth in peace and with a sense of comfort and fulfillment.

Embracing Openness: Unveiling Silent Struggles Surrounding Mental Health

Kathryne, North Carolina

Individuals should never compromise their mental health for cultural expectations; my essay explores the intersection of mental health barriers and cultural norms, specifically highlighting the silent struggles faced by Asian American students. By advocating for accountability among educators and fostering diverse school environments, my solutions aim to empower students to seek support without feeling burdened by shame or cultural expectations.

Speaking Up for Change

Maya, Maryland

Personal experience with the American mental health system has given me first hand evidence that something within needs to change. The magnitude of the issue including stigma and long wait times to see certified professionals is a system wide issue, leaving caring providers and patients alike struggling.

Embracing the Journey Towards Mental Health Acceptance

Rachel, California

When I watched my brother be silenced by the world around him, I felt the need to speak up against the stigmas that suppress the realities of mental health. Writing this essay allowed me to navigate through the often-neglected topic of youth mental illness and discover possible solutions with modern-day technological advancements.

Taking a Step Today, for a Better Tomorrow

Savannah, New Jersey

My essay consists of informing people what can cause mental health problems and what contributing factors involve the rise of mental health. Also, contains information about how we can fix or lower mental health issues for teens and adults.

Honorable Mentions

Accountability for authority: the responsibilities of schools.

Agaana, Maryland

In discussing why schools need to address students' mental health issues, my essay considers how schools can influence students through academic pressures, social struggles, and management of time within and out of school. While alluding to a personal anecdote of generalized anxiety disorder, I also suggest courses of action that schools can take to mitigate the mental health issues that they contribute to.

Breaking the Silence

Gisele, Pennsylvania

A writing that delves into the crucial topic of dismantling mental health sigmas, ultimately providing valuable insights on how to overcome them. Additionally, this piece sheds light on the collective responsibility of society to foster inclusivity and a supportive environment for individuals facing these challenges.

Navigating Mental Illness in Teens

Jillian, Illinois