Brown v. Board of Education: 70 Years of Progress and Challenges

- Share article

After 70 years, what is left to say about Brown v. Board of Education ?

A lot, it turns out. As the anniversary nears this week for the U.S. Supreme Court’s historic May 17, 1954, decision that outlawed racial segregation in public schools, there are new books, reports, and academic conferences analyzing its impact and legacy.

Just last year, members of the current Supreme Court debated divergent interpretations of Brown as they weighed the use of race in higher education admissions, with numerous references to the landmark ruling in their deeply divided opinions in the case that ended college affirmative action as it had been practiced for half a century.

Meanwhile, some school district desegregation cases remain active after more than 50 years, while the Supreme Court has largely gotten out of the business of taking up the issue. There are fresh reports that the nation’s K-12 schools, which are much more racially and ethnically diverse than they were in the 1950s, are nonetheless experiencing resegregation .

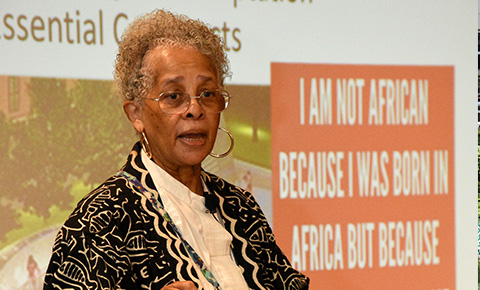

At an April 4 conference at Columbia University, speakers captured the mood about a historic decision that slowly but steadily led to the desegregation of schools in much of the country but faced roadblocks and new conditions that have left its promise unfulfilled.

“I think Brown permeates nearly every aspect of our current modern society,” said Janai Nelson, the president and director-counsel of the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, the organization led by Thurgood Marshall, who would later become a Supreme Court justice, during the Brown era.

“I hope that we see clearly now that there is an effort to roll back [the] gains” brought by the decision, said Nelson, whose organization was a conference co-sponsor. “There is an effort to recast Brown from what it was originally intended to produce. If we want to keep this multiracial democracy and actually have it fulfill its promise, because the status quo is still not satisfactory, we must look at the original intent of this all-important case and make sure we fulfill its promise.”

Celebrations at the White House, the Justice Department, and a Smithsonian Museum

On May 16, President Joe Biden will welcome to the White House descendants of the original plaintiffs in the cases that were consolidated into Brown , which dealt with cases from Delaware, Kansas, South Carolina, and Virginia. (The companion decision, Bolling v. Sharpe , decided the same day, struck down school segregation in the District of Columbia.) On May 17, the president will deliver remarks on the historic decision at the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of African American History and Culture.

Attorney General Merrick B. Garland and U.S. Secretary of Education Miguel Cardona marked the anniversary at an event at the U.S. Department of Justice on Tuesday.

“ Brown vs. Board and its legacy remind us who we want to be as a nation, a place that upholds values of justice and equity as its highest ideals,” Cardona said. “We normalize a culture of low expectations for some students and give them inadequate resources and support. Today, it’s still become all too normal for some to deny racism and segregation or ban books that teach Black history when we all know that Black history is American history.”

On May 17, 1954, then-Chief Justice Earl Warren announced the decision for a unanimous court that held that “in the field of public education, ‘separate but equal’ has no place. Separate educational facilities are inherently unequal.”

That opinion was a compromise meant to bring about unanimity, and the court did not even address a desegregation remedy until a year later in Brown II , when it called for lower courts to address local conditions “with all deliberate speed.”

“In short, the standard the court established for evaluating schools’ desegregation efforts was as vague as the schedule for achieving it was amorphous,” R. Shep Melnick, a professor of American politics at Boston College and the co-chair of the Harvard Program on Constitutional Government, says in an assessment of the Brown anniversary published this month by the American Enterprise Institute.

The paper distills a book by Melnick published last year, The Crucible of Desegregation: The Uncertain Search for Educational Equity , which takes a fresh look at the 70-year history of post-Brown desegregation efforts.

Melnick argues that even after 70 years, Brown and later Supreme Court decisions remain full of ambiguities as to even what it means for a school system to be desegregated. He highlights two competing interpretations of Brown embraced by lawyers, judges, and scholars—a “colorblind” approach prohibiting any categorization of students by race, and a perspective based on racial isolation and equal educational opportunity. “Neither was ever fully endorsed or rejected by the Supreme Court,” Melnick writes in the book. “Both could find some support in the court’s ambiguous 1954 opinion.”

The Supreme Court issued some 35 decisions on desegregation after Brown , but hasn’t taken up a case involving a court-ordered desegregation remedy since 1995 and last spoke on the issue of integration and student diversity in the K-12 context in 2007, when the court struck down two voluntary plans to increase diversity by considering race in assigning students to schools.

Citations to Brown pervade last year’s sharply divided opinions over affirmative action

Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr., in his plurality opinion in that voluntary integration case, Parents Involved in Community Schools v. Seattle School District , laid the groundwork for last year’s affirmative action decision, which fully embraced Brown’s “race-blind” interpretation.

Last term, the high court ruled that race-conscious admissions plans at Harvard and the University of North Carolina violated the 14th Amendment’s equal protection clause. (The vote was 6-2 in Students for Fair Admissions v. President and Fellows of Harvard College , with Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson not participating because of her recent membership on a Harvard governing board. The vote was 6-3 in SFFA v. University of North Carolina .)

The Brown decision was a running theme in the arguments in the case, and in the some 230 pages of opinions.

Roberts, in the majority opinion, said a fundamental lesson of Brown in 1954 and Brown II in 1955 was that “The time for making distinctions based on race had passed.”

Brown and a generation of high court decisions on race that followed, in education and other areas, “reflect the core purpose of the Equal Protection Clause: doing away with all governmentally imposed discrimination based on race,” the chief justice wrote.

Justice Clarence Thomas, who succeeded Thurgood Marshall, joined the majority opinion and wrote a lengthy concurrence that touched on views he had long expressed about the 1954 decision. He cited the language of legal briefs filed by the challengers of segregated schools in the Brown cases (led by Marshall) that embraced the view that the 14th Amendment barred all government consideration of race.

Thomas said those challenging segregated schools in Brown “embraced the equality principle.”

Justice Brett M. Kavanaugh also joined the majority and acknowledged in his concurrence that in Brown , the court “authorized race-based student assignments for several decades—but not indefinitely into the future.”

(The other justices in the majority were Samuel A. Alito Jr., Neil M. Gorsuch, and Amy Coney Barrett.)

Writing the main dissent, Justice Sonia Sotomayor rejected the view that Brown was race-blind.

“ Brown was a race-conscious decision that emphasized the importance of education in our society,” she wrote, joined by justices Elena Kagan and Jackson. “The desegregation cases that followed Brown confirm that the ultimate goal of that seminal decision was to achieve a system of integrated schools that ensured racial equality of opportunity, not to impose a formalistic rule of race-blindness.”

Jackson, in a separate dissent (joined by Sotomayor and Kagan), said, “The majority and concurring opinions rehearse this court’s idealistic vision of racial equality, from Brown forward, with appropriate lament for past indiscretions. But the race-linked gaps that the law (aided by this court) previously founded and fostered—which indisputably define our present reality— are strangely absent and do not seem to matter.”

Amid reports on resegregation, some legal efforts continue

As the Brown anniversary arrives, there are fresh reports about resegregation of the schools. Research released this month by Sean Reardon of Stanford University and Ann Owens of the University of Southern California found that students in the nation’s large school districts have become much more isolated racially and economically in recent years.

The Civil Rights Project at the University of California, Los Angeles, which has been sounding the alarm about resegregation for years, says in a new report that Black and Latino students were the most highly segregated demographic groups in 2021. Though U.S. schools were 45 percent white, Blacks, on average, attended 76 percent nonwhite schools, and Latino students went to 75 percent nonwhite schools.

The CRP says the Brown anniversary is worth celebrating, but “American schools have been moving away from the goal of Brown and creating more ‘inherently unequal’ schools for a third of a century. We need new thought about how inequality and integration work in institutions and communities with changing multiracial populations with very unequal experiences.”

At the Columbia conference, Samuel Spital, the litigation director and general counsel of the Legal Defense Fund, noted that many jurisdictions are still under desegregation orders, some going back decades.

He highlighted one where LDF lawyers have been in federal district court, involving the 7,200-student St. Martin Parish school district in western Louisiana. Black plaintiffs first sued over segregated schools in 1965. In a 2022 decision, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 5th Circuit, in New Orleans, noted that the case had been pending for “five decades,” though largely inactive for long stretches. The court nonetheless affirmed the district court’s continued supervision of a desegregation plan that addressed disparities in graduation tracks and student discipline, though it said the court overstepped in ordering the closure of an elementary school in a mostly white community.

As recently as this month, the LDF and the Department of Justice’s civil rights division joined with the St. Martin Parish school board in a proposed consent order for revised attendance zones for the district’s schools. The proposed order suggests that court supervision of student assignments could end sometime after June 2027.

“We try to make sure that with the vast docket of segregation cases we have, that we have not lost sight of what Brown’s ultimate intent was,” said LDF’s Nelson, which was not just “to make sure that Black and white children learn together” but also to foster principles of equity and citizenship.

With a hostile federal court climate, advocates more recently have turned to state constitutions and state courts to pursue desegregation. Last year, a state judge in New Jersey allowed key claims to proceed in a lawsuit that seeks to hold the state responsible for remedying racial segregation in its many “racially isolated” public schools. In December, the Minnesota Supreme Court allowed a suit under the state constitution to move forward, ruling that there was no need for plaintiffs to prove that the state itself had caused segregation in its schools.

“We see a path forward through state courts with the very specific goal of trying to challenge state practices, which really boil down to segregative school district lines,” Saba Bireda, the chief legal counsel of Brown’s Promise , said at the Columbia conference. Bireda, a former civil rights lawyer in the Education Department under President Barack Obama’s administration, co-founded the Washington-based organization last year to help address diversity and underfunding in public schools.

A Supreme Court exhibit offers the idealized take on Brown

At the Supreme Court, there has been no formal recognition of the 70th anniversary of Brown . But the court did open an exhibit on its ground floor late last year that tells the story of some of the first desegregation cases, including Brown .

The exhibit is primarily about the Little Rock integration crisis of 1957, when Arkansas Gov. Orval Faubus defied a federal judge’s order to desegregate Central High School. The exhibit is built around the actual bench used by Judge Ronald N. Davies when he heard a challenge to Faubus’ use of the Arkansas National Guard to prevent the nine Black high school students from entering the all-white high school that year. (Davies withstood threats and intense opposition from desegregation opponents, but he ruled for the Black students. The Supreme Court itself supported desegregation in Little Rock with its 1958 decision in Cooper v. Aaron .)

To tell the Little Rock story, the exhibit starts with Brown (and some of the prior history). A central feature is a 15-minute video featuring all current members of the court.

In the video, the justices set aside their differences over the meaning of Brown and provide a more idealized perspective on the 1954 decision.

“ Brown was a godsend,” Thomas says in the video. “Because it said that what was happening that we thought was wrong, they now know that this court said it was also wrong. It’s wrong not just morally, but under the Constitution of the United States. It was like a ray of hope.”

Kavanaugh says: “ Brown vs. Board of Education is the single greatest moment, single greatest decision in this court’s history. And the reason for that is that it enforced a constitutional principle, equal protection of the laws, equal justice under law. It made that real for all Americans. And it corrected a grave wrong, the separate but equal doctrine that the court had previously allowed.”

Jackson, the court’s third Black justice, who has spoken of her family moving in one generation from “segregation to the Supreme Court,” reflects in the video on Brown ‘s legacy.

“I think I’m most grateful for the fact that my parents have lived to see me in this position, after a history of them and others in our family and people from my background not having the opportunity to live to our fullest potential,” she says.

As the video comes to a close, Roberts speaks with evident pride in his voice.

“The Supreme Court building stands as a symbol of our country’s faith in the rule of law,” the chief justice says. “ Brown v. Board of Education , the great school desegregation case, was decided here.”

Sign Up for EdWeek Update

Edweek top school jobs.

Sign Up & Sign In

Clarence Thomas criticizes Brown v. Board of Education. It comes at an awkward moment

WASHINGTON − Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas this week criticized a piece of the landmark Brown v. Board of Education decision s that made racial segregation in schools illegal in arguing that courts should get out of the business of deciding if congressional maps discriminate against Black people.

His charge came just a week after the 70 th anniversary of the landmark case.

Thomas said the Supreme Court took a “boundless view of equitable remedies” when it told schools in 1955 how they needed to comply with the initial 1954 decision .

That may have justified temporary measures to overcome the schools’ widespread resistance, Thomas wrote. But it’s not backed up by the Constitution or by the nation’s “history and tradition.”

Federal courts, he said, do not have “the flexible power to invent whatever new remedies may seem useful at the time.”

Thomas made that case in arguing that courts have no role in deciding if congressional maps have been unfairly drawn to discriminate against Black people.

The court’s conservative majority dismissed a challenge to a South Carolina district that a civil rights group said had been drawn to limit the influence of Black voters.

Thomas agreed with that decision but separately argued courts don’t have the constitutional authority to get involved. He blamed the second Brown v. Board of Education decision – an attempt by the court to enforce the first ruling -- for starting such “extravagant uses of judicial power.”

Thomas has made similar points in the past. In a 1995 concurring opinion , Thomas wrote that the “extraordinary remedial measures” the court approved because of its impatience with the pace of desegregation and schools’ lack of good-faith effort should have been temporary and used only to overcome widespread resistance to following the Constitution.

Advertisement

Supported by

Biden Marks Landmark Desegregation Anniversary as Black Support Slips

President Biden commemorated Brown v. Board of Education during one of a series of events over the next several days to highlight his commitment to the Black community.

- Share full article

By Erica L. Green

Reporting from Washington

President Biden commemorated the 70th anniversary of Brown v. Board of Education on Thursday, meeting with plaintiffs and their families at the White House as he tries to shore up support among Black Americans, who helped deliver him the White House in 2020.

Mr. Biden thanked the litigants for their sacrifice in being part of what would become a major legal landmark — that racial segregation in schools was unconstitutional.

“He recognized that back in the ’50s, in the ’40s, when Jim Crow was still running rampant, that the folks that you see here were taking a risk when they signed on to be part of this case,” Cheryl Brown Henderson, one of the daughters of Oliver L. Brown, a lead plaintiff, told reporters after the meeting.

The Oval Office meeting was one of a series of events planned over the next several days to highlight Mr. Biden’s commitment to the Black community. The outreach culminates on Sunday with a highly anticipated commencement address at the prestigious Morehouse College, one of the oldest of the nation’s historically Black colleges and universities.

Mr. Biden plans to underscore past victories for Black Americans while also boosting the achievements that he has delivered, White House officials said, citing a 60 percent increase in Black household wealth and the lowest Black unemployment rate ever, last year.

We are having trouble retrieving the article content.

Please enable JavaScript in your browser settings.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access. If you are in Reader mode please exit and log into your Times account, or subscribe for all of The Times.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access.

Already a subscriber? Log in .

Want all of The Times? Subscribe .

How Public Schools Cherry-Pick Their Students

I n May 2022, an Arizona mom named Karrie got a heartbreaking message from the local public school: Her son Brayden wouldn’t be allowed to return as a second-grader in the fall. The reason? Brayden had been diagnosed on the autism spectrum, and the school claimed that it didn’t have any more room for kids with disabilities.

“It felt like they were looking for a reason to dismiss him,” Karrie told me, “and make him somebody else’s problem.”

Karrie and her family had recently moved just outside of the boundary line for the Tanque Verde School District just outside of Tucson. In accordance with Arizona’s Open Enrollment law, Brayden’s old school actually accepts many students outside of that boundary line. But that law has a troubling loophole that allows districts to reject the applications of students with disabilities, no matter how minimal the services they require. So the district said that Brayden couldn’t come back.

“This experience has really turned me off of public education,” says Karrie. It’s a hard lesson that many American families have learned over the years: The public schools are not as inclusive as we typically assume them to be, and they often turn children away for arbitrary or discriminatory reasons, violating the foundational promise of common schools that are open to all children.

Writing almost 70 years ago this week, Chief Justice Earl Warren issued the court’s ruling in Brown v. Board of Education , pledging that all public schools in the U.S. must be “available to all on equal terms.” But seven decades later, that promise remains unfulfilled.

Historically, the most coveted public schools in America use government-drawn maps to discriminate against students who live in “less desirable” parts of town. This type of geographic discrimination echoes the racist redlining policies of the early 20th century and allows many sought-after public schools to operate as quasi-private schools. The practice of “educational redlining” is one of the main reasons that a child’s zip code increasingly determines his or her fate in life.

Some of these coveted schools are protected by district boundary lines, like the Beverly Hills Unified School District in Southern California or the Grosse Pointe Public Schools just outside of Detroit. Others are protected by the boundaries of “attendance zones” or “catchment areas” drawn by bureaucrats at large urban districts. These maps determine who is—and who isn’t—eligible to attend coveted public schools. Look no further than Lincoln Elementary in Chicago, Ivanhoe Elementary in Los Angeles, P.S. 8 Robert Fulton in Brooklyn, Mary Lin Elementary in Atlanta, and many others.

Indeed, the shape of these school zones is often shockingly similar to the redlining maps drawn by the federal government nearly a century ago. And families are told—once again—that they aren’t eligible for valuable government services because they don’t live in the right part of town. Left out are the working-class families (disproportionately people of color and immigrants) who can’t afford the extra premium of $200,000 or more that people pay for a house within the coveted zone lines. This is often the real financial cost of a “free” public education.

Read More: How School Voucher Programs Hurt Students

As a result, it’s commonplace for Americans of all races and income levels to use a false address to get into a school that they aren’t zoned for. School districts then sometimes hire private eyes to spy on kids and even put parents in jail for crossing the lines.

But educational redlining is just one of the many ways that public schools try to cherry-pick their students. Connecticut, for example, built gleaming new magnet schools that were meant to end the racial divisions in the public schools . But most privileged students, who were predominantly white and Asian, already had access to high-performing schools (via educational redlining) and didn’t have an incentive to enroll in the new magnets. In order to get the racial mix that it wanted, Connecticut had to enforce a strict racial quota . Instead of enrolling African American kids—the group that the state was supposedly trying to help—the magnets ended up excluding them, despite hundreds of empty seats.

New York City has long harbored a dirty secret about public school enrollment. Alina Adams, an expert on admissions in the city’s public schools, says that cherry-picking students is common. “Anyone who tells you that a New York City public school waitlist follows a straight queue is lying,” she says, “either to you or to themselves.” A coveted school has the ability to pick which kids they want to serve by manipulating the waitlist queue , leaving everyone else scrambling for the scraps.

Charter schools have faced the most scrutiny for their admissions processes , and there is no doubt that some engage in cherry-picking. I’ve spoken to one former charter worker who discovered that the school’s enrollment director was turning away students who didn’t speak English very well. “She felt that those students would be harder to educate,” says the staffer. “But it’s a public school, and that’s against the law.”

She’s right: It is against the law. In most states, charter schools are held to a high legal standard of open access. They have to take all comers, and they’re required to hold a lottery if they have too many applicants. In addition, most charter schools are forbidden from discriminating against a child based on where they live. (The most common exception is zoned schools that convert to charter, which are most often required to continue operating the exclusionary zone.)

So when a charter school is found to be cherry-picking its students, there are consequences. Local ACLU chapters, including Southern California and Arizona , have published reports detailing how charter schools have either broken the law or violated its spirit. And many charters have altered their enrollment policies as a result.

But the rest of the public schools are held to a very low legal standard of access and face very little scrutiny of their enrollment practices. Yes, they are prohibited from excluding a child explicitly because of his or her race. But public school waitlists receive little attention, and school staff are often free to pick those families that they prefer. As in Arizona, many Open Enrollment laws have loopholes that allow school staff to turn kids away because they have a minor disability.

What’s more, magnet schools often use “socioeconomic status” as a proxy for race , giving wealthier students a better shot of admission in hopes that they can get their racial mix right. That’s the policy that Connecticut adopted after it was sued for racial discrimination. Its “solution” means that low-income students still face a disadvantage when they apply to the magnet schools. Similar policies have faced scrutiny in Indiana and Illinois .

It’s clear that our public education system is not “available to all on equal terms.” As a country, we desperately need to repair our social contract. One vital way to do that is to restore the promise of public education as a system of common schools that are truly open to all American children.

We need state laws that hold public schools to the highest standards of openness. We need district enrollment policies that are simple, fair, and transparent. These policies need to prevent local school staff from turning children away for arbitrary or discriminatory reasons. We also need the government, the media, and nonprofits to monitor the admissions and enrollment practices of the public schools. We need enforcement mechanisms that punish public schools for trying to cherry-pick their students.

It’s time we make good on Justice Warren’s promise.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Welcome to the Noah Lyles Olympics

- Melinda French Gates Is Going It Alone

- What to Do if You Can’t Afford Your Medications

- How to Buy Groceries Without Breaking the Bank

- Sienna Miller Is the Reason to Watch Horizon

- Why So Many Bitcoin Mining Companies Are Pivoting to AI

- The 15 Best Movies to Watch on a Plane

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at [email protected]

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Brown v. Board of Education: A First Step in the Desegregation of America’s Schools

By: Sarah Pruitt

Updated: May 17, 2024 | Original: May 16, 2018

On May 17, 1954, Chief Justice Earl Warren issued the Supreme Court ’s unanimous decision in Brown v. Board of Education , ruling that racial segregation in public schools violated the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment . The upshot: Students of color in America would no longer be forced by law to attend traditionally under-resourced Black-only schools.

The decision marked a legal turning point for the American civil-rights movement . But it would take much more than a decree from the nation’s highest court to change hearts, minds and two centuries of entrenched racism. Brown was initially met with inertia and, in most southern states, active resistance. Seventy years later, progress has been made, but the vision of Warren’s court has not been fully realized.

Supreme Court Rules 'Separate' Means Unequal

The landmark case began as five separate class-action lawsuits brought by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) on behalf of Black schoolchildren and their families in Kansas , South Carolina , Delaware , Virginia and Washington, D.C . The lead plaintiff, Oliver Brown, had filed suit against the Board of Education in Topeka, Kansas in 1951, after his daughter Linda was denied admission to a white elementary school.

Her all-Black school, Monroe Elementary, was fortunate—and unique—to be endowed with well-kept facilities, well-trained teachers and adequate materials. But the other four lawsuits embedded in the Brown case pointed to more common fundamental challenges. The case in Clarendon, South Carolina described school buildings as no more than dilapidated wooden shacks. In Prince Edward County, Virginia, the high school had no cafeteria, gym, nurse’s office or teachers’ restrooms, and overcrowding led to students being housed in an old school bus and tar-paper shacks.

Brown v. Board First to Rule Against Segregation Since Reconstruction Era

The Supreme Court’s decision in Brown v. Board marked a shining moment in the NAACP’s decades-long campaign to combat school segregation. In declaring school segregation as unconstitutional, the Court overturned the longstanding “separate but equal” doctrine established nearly 60 years earlier in Plessy v. Ferguson (1896). In his opinion, Chief Justice Warren asserted public education was an essential right that deserved equal protection, stating unequivocally that “separate educational facilities are inherently unequal.”

Still, Thurgood Marshall , head of the NAACP’s Legal Defense and Educational Fund and lead lawyer from the plaintiffs, knew the fight was far from over—and that the high court’s decision was only a first step in the long, complicated process of dismantling institutionalized racism. He warned his colleagues soon after the verdict came down: “The fight has just begun.”

In 1954, the Supreme Court unanimously strikes down segregation in public schools, sparking the Civil Rights movement.

Brown v. Board Does Not Instantly Desegregate Schools

In its landmark ruling, the Supreme Court didn’t specify exactly how to end school segregation, but rather asked to hear further arguments on the issue. The Court’s timidity, combined with steadfast local resistance, meant that the bold Brown v. Board of Education ruling did little on the community level to achieve the goal of desegregation. Black students, to a large degree, still attended schools with substandard facilities, out-of-date textbooks and often no basic school supplies.

In a 1955 case known as Brown v. Board II , the Court gave much of the responsibility for the implementation of desegregation to local school authorities and lower courts, urging that the process proceed “with all deliberate speed.” But many lower court judges in the South, who had been appointed by segregationist politicians, were emboldened to resist desegregation by the Court’s lackluster enforcement of the Brown decision.

In Prince Edward County, where one of the five class-action suits behind Brown was filed, the Board of Supervisors refused to appropriate funds for the County School Board, choosing to shut down the public schools for five years rather than integrate them.

This backlash against the Court’s verdict reached the highest levels of government: In 1956, 82 representatives and 19 senators endorsed a so-called “Southern Manifesto” in Congress, urging Southerners to use all “lawful means” at their disposal to resist the “chaos and confusion” that school desegregation would cause.

In 1964, a full decade after the decision, more than 98 percent of Black children in the South still attended segregated schools .

Brown Ruling Becomes a Catalyst for the Civil Rights Movement

For the first time since the Reconstruction Era , the Court’s ruling focused national attention on the subjugation of Black Americans. The result? The growth of the nascent civil rights movement , which would doggedly challenge segregation and demand legal equality for Black families through boycotts , sit-ins , freedom rides and voter-registration drives.

The Brown verdict inspired Southern Blacks to defy restrictive and punitive Jim Crow laws, however, the ruling also galvanized Southern whites in defense of segregation—including the infamous standoff at a high school in Little Rock , Arkansas in 1957. Violence against civil-rights activists escalated, outraging many in the North and abroad, helping to speed up the passage of major civil-rights and voting rights legislation by the mid-1960s.

Finally, in 1964, two provisions within the Civil Rights Act effectively gave the federal government the power to enforce school desegregation for the first time: The Justice Department could sue schools that refused to integrate, and the government could withhold funding from segregated schools. Within five years after the act took effect, nearly a third of Black children in the South attended integrated schools, and that figure reached as high as 90 percent by 1973.

Brown v. Board Impact and Legacy

Seventy years after the landmark ruling, assessing its impact remains a complicated endeavor. The Court’s verdict fell short of initial hopes that it would end school segregation in America for good, and some argued that larger social and political forces within the nation played a far greater role in ending segregation.

Both conservative and liberal Supreme Court justices have claimed the legacy of Brown v. Board to argue different sides in the constitutional debate. In 2007, the Court ruled 5-4 against allowing public schools to take race into account in their admission policies in order to achieve or maintain integration.

Chief Justice John Roberts, writing for the majority, asserted: “The way to stop discrimination on the basis of race is to stop discriminating on the basis of race.” And in a dissenting opinion, Justice John Paul Stevens wrote that the ruling “rewrites the history of one of this court’s most important decisions.”

The legacy of Brown v. Board has also echoed in rulings over college admission policies. In 2022, in a 6-3 decision , the Court struck down affirmative action admissions programs at Harvard University and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, ruling that colleges may not use race as a deciding factor in admissions. The Court's majority opinion, again written by Chief Justice Roberts, held that race-conscious admissions programs violated the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment .

In her dissenting opinion, Justice Sonia Sotomayor wrote , “The Court subverts the constitutional guarantee of equal protection by further entrenching racial inequality in education, the very foundation of our democratic government and pluralistic society.”

Continued Segregation in Schools

School segregation persists in America today, largely because many of the neighborhoods in which schools are still located are themselves segregated. Despite the passage of the Fair Housing Act in 1968 and later judicial decisions making racial discrimination illegal, exclusionary economic-zoning laws still bar low-income and working-class Americans from many neighborhoods, which in many cases reduces their access to higher quality schools.

According to a U.S. Government and Accountability Office Report , released in July 2022, more than a third of students (around 18.5 million students) attended schools where 75 percent or more of the student body was the same race or ethnicity.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

- DE Politics

- Investigations

- National Politics

Key takeaways as a Delaware panel marks 70th anniversary of Brown v. Board of Education

Most people understand the Brown v. Board of Education decision as one of the most definitive cases in education and American history. On Tuesday, though, a special panel looked to remind listeners of not only how closely Delaware is tied to that story — but how that relevance still echoes.

The decision, eventually stripping the country of its "separate but equal" doctrine across schools, just marked a 70th anniversary this month . Two cases from Delaware joined that landmark case at the Supreme Court, Bulah v. Gebhart and Gebhart v. Belton, led by Wilmington powerhouse attorney and civil rights advocate Louis L. Redding.

Delaware Division of Diversity, Equity & Inclusion invited several speakers to dive into this intersection. State officials were joined by the Rev. JB Redding, daughter of Louis L. Redding; René Ricks-Stamps, daughter of plaintiff Shirley Bulah; Justice C.J. Seitz Jr., of the Delaware Supreme Court and son of late judge Collins J. Seitz; and James “Sonny” Knott, a 94-year-old former student of the very school they sat in. More names lined the list.

Speakers and a small audience packed Hockessin Colored School #107C for two hours of discussion, and the public livestream can still be watched . Here are just some key takeaways.

"We're standing on hallowed ground today," said Ricard Potter Jr., chief diversity officer within Delaware's Department of Human Resources. "And hopefully this conversation will be one that enriches individuals who are in attendance, as well as an opportunity for us to have a call for action."

'Trail to Desegregation': How one Wilmington bus tour honors 70th anniversary of Brown v. Board of Education

The work is not over

This was never an instant solution.

Though the 1954 decision called for an "immediate" stop to segregated schools, the reality would play out much more slowly. And in the very state with two cases fueling arguments, school segregation persisted in some areas until the late '60s. Impact was clear, but progress painfully lagged for many.

And, Tuesday's speakers would argue, it has yet to be entirely achieved.

"Even today, Black students in our state and across the nation continue to face challenges that impact their academic success," said guest Rep. Kendra Johnson, speaking in opening comments. "Issues such as unequal funding, resource gaps and racial discrimination are reminders that the promise of Brown v. Board of Education is yet to be fully realized."

Redding echoed her thoughts as the panel heated up.

"I think the first thing to say is where we are not," said the daughter of Delaware's first Black attorney. "That whatever brown the board did, it did not desegregate America. That right now, straight across the nation, north and south, any of our big cities but also rural areas, are as segregated as they were at the time required."

The state's own Redding Consortium has rooted its recent work in this reality, having been created in 2019 to recommend policies aimed at educational equity in Wilmington and the northern county. Legal and political decisions over decades, members write, have left the city with several racially identifiable, high-poverty schools — plagued with higher rates of crime, housing instability and poverty, alongside educator turnover and persistent underachievement.

Another familiar face on the panel came in Mark Holodick, secretary of the Delaware Department of Education.

"Equality and fairness have changed, and I would say improved, since the Brown decision," Holodick said. "However, opportunities and outcomes for students of color — not so much."

He nodded to this consortium work, exploring how redistricting could be a first step in more systemic reform for Wilmington schools, which he senses an appetite for from the state board. He also called on necessary impact from a very similar body, charged with improving city schools: the Wilmington Learning Collaborative.

But statewide, Delaware is battling low proficiency among students of color, not leading such students to high levels of success in math and reading in particular. His department, Holodick told the panel, is particularly focused on trying to bolster elementary reading levels.

"We need to do something about our literacy rates in Delaware, particularly among students of color," he said, also quoting some counsel from activist Bebe Coker. "Because we all know reading opens the door for everything else."

Justice Seitz, of the Delaware Supreme Court, also noted the ongoing need for diversity in the law — having formed the Delaware Bench and Bar Diversity Project, back on the 67th anniversary of Brown. There's hope changemakers like his father won't be far and in between again.

"We have a huge amount of work and resources going in to education because that is, as we said today, that is the key to a long-term solution to getting greater diversity in the Delaware bar," the justice said.

Wilmington with two school districts? Delaware’s latest redistricting vision to take shape

Remember Delaware's history

When asked if segregation made him angry as a child, Louis L. Redding said no.

"It was not anger he felt," said Claire DeMatteis, Delaware's secretary of human resources, moderating the panel, "but instead: 'Curiosity.'"

During the more than 50 years that he practiced law in Delaware, Redding handled cases that challenged discrimination in housing, public accommodations, employment and criminal justice. His two Delaware cases that consolidated under Brown v. Board of Education played out on New Castle County soil.

In 1951, the families of Ethel Louise Belton and Shirley Barbara Bulah hired Redding in separate cases, suing the state for refusing to provide transportation to attend the schools closest to their homes. Belton was required to attend Howard High School, a forced 20-mile round trip on public transportation, while living just blocks from all-white Claymont High. Bulah attended Hockessin Colored School #107-C, even though a white school would have been much closer for the 7-year-old.

"The quest to satisfy this curiosity changed the face of Delaware and shaped laws within our nation," DeMatteis said, noting the very decision joining this panel.

Sonny Knott, alongside nearly every speaker, stressed Delaware cannot forget this history. That is, both what these parents went through for their children's education, as well as the stories within the state's Black schools.

He remembers a vibrant community, in a close-knit one-room school with six grades and one teacher. But he also remembers missing pages in school books, given as hand-me-downs if the white schools upgraded.

"I love the opportunity to talk about the 107, and I encourage each and every one of you: Forget about today," the former student said to the crowd. "Think about tomorrow and the next day in our future. Bring your kids here. There's a lot of history here. There's only about five of us left that spent their entire career at the 107."

Knott's stories and many more fill the pages of another panelist's book. Lanette Edwards, author and school historian, published " Hockessin Colored School #107C (Images of America) " just last year.

Hockessin Colored School #107C ceased operations after desegregation. After a rocky road, the school has now been restored and transformed into a Center for Diversity and Social Equity. In 2022, President Joe Biden protected the site, having signed a law incorporating Hockessin Colored School #107 into the National Park System among other additions.

Redding House Museum and Community Center, maintained by its own foundation, is now a historic landmark located near downtown Wilmington. Today's Howard High School of Technology was once the only high school serving Black students in the state and one of the earliest in the nation. Once-Claymont High is now the Claymont Community Center.

"The remarks you quoted from my father are what I would say are hopeful remarks," said Justice Seitz, noting passages from his father, who ruled on the Delaware Gebhart v. Belton case that conditions were unequal, and the only remedy to suffice would be integration.

"And I think he'd recognize the reality that the solutions to race relations in the United States are not going to be found in the courts; as he said, 'They have to be found in the hearts of people.' And I think events like today are so important because they eliminate or reduce complacency."

Got a story? Kelly Powers covers race, culture and equity for Delaware Online/The News Journal and USA TODAY Network Northeast, with a focus on education. Contact her at [email protected] or (231) 622-2191, and follow her on X @kpowers01.

These Researchers Study the Legacy of the Segregation Academies They Grew Up Around

Three young academics in alabama are examining these mostly white private schools through the lenses of economics, education and history to better understand the persistent division of schools in the south..

- Twitter Twitter

- Facebook Facebook

- https://www.propublica.org/article/alabama-researchers-segregation-academies-school-vouchers Link Copied! Link Copy

ProPublica is a nonprofit newsroom that investigates abuses of power. Sign up for Dispatches , a newsletter that spotlights wrongdoing around the country, to receive our stories in your inbox every week.

One young researcher from Alabama is unearthing the origin stories of schools known as “segregation academies” to understand how that history fosters racial divisions today.

Another is measuring how much these private schools — which opened across the Deep South to facilitate white flight after the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education ruling — continue to drain public school enrollment.

And a third is examining how these academies, operating in a “landscape marred by historical racial tensions,” receive public money through Alabama’s voucher-style private school tuition grants.

All three researchers are white women raised in Alabama, close in age, who grew up near these academies. The women — one recently received a doctorate and the other two are working on theirs — approach their research from the varied disciplines of economics, education and history. Their inquiries are probing the very schools some of their family and friends attended.

In an ongoing series this year, ProPublica is examining the continued effects of hundreds of segregation academies still operating in the South . One of the three researchers played a key role in our initial story. Her experiences, both personally and academically, provided essential context to understanding how one segregation academy in rural Alabama has kept an entire community separated by race.

The research conducted by all three women is especially important now. It comes at a time when Southern legislatures are creating and expanding school-voucher-style programs that will pour hundreds of millions of public dollars into the coffers of private schools, including segregation academies, over the coming years.

Segregation Academies and Voucher Programs

Annah Rogers was working on her undergraduate degree at Auburn University in 2013 when Republican lawmakers suddenly rushed to pass the Alabama Accountability Act. The legislation created a voucher-style system to pay private school tuition for low-income students. As Rogers followed the debates, she wondered just how accessible private schools are to families with few resources, especially in rural areas. She knew that some of those communities don’t have private schools — and where they do exist, they’re often segregation academies.

Rogers hails from Eutaw, Alabama, a town of 3,000 people located in the Black Belt, a stretch of counties whose dark, rich soil once fueled large cotton plantations. Her parents sent her 45 minutes away to a private Catholic school. (Catholic schools generally aren’t considered segregation academies because most dioceses integrated willingly.) Rogers’ father attended a now-defunct local segregation academy, and her mother went to one in another county.

While working on her doctorate in political science at the University of Alabama, she devoted her 2022 dissertation to examining the state’s voucher-style program and its effects on private schools , including segregation academies. She had expected segregation academies to balk at participating in the program given that more than 60% of students who use it are Black. Yet she found that many do. In fact, they take part at a slightly higher rate — 8% more often — than other private schools.

That discovery prompted more questions: Are the tuition grants enabling Black students to attend segregation academies, making the schools more diverse? Or are the academies merely siphoning off the white students who use the grants?

“The biggest problem is that we don’t know,” said Rogers, who’s now an assistant professor at the University of West Alabama’s education college. She hit a huge hurdle when the state refused to break down by school the demographics of students who use the publicly funded program to pay private school tuition.

Despite that roadblock, she continues to probe these questions while working on related studies, including one that demonstrates how school segregation patterns have continued and even worsened across Alabama’s Black Belt over the last three decades.

Her research will become more critical in the coming years, as more students, including students from wealthier families, will be receiving state money to attend private schools. In March, Alabama lawmakers created a universal voucher-style program to fund private school tuition. It will be open to all children, regardless of household income, starting in 2027.

Segregation Academies and Public School Enrollment

Danielle Graves grew up in Mobile on the Gulf Coast, where she attended a mostly white private Episcopal school. Although it opened long enough before the Brown v. Board ruling that academics don’t label it a segregation academy, its enrollment still grew substantially during desegregation.

Graves left the South to pursue her master’s and doctorate in economics at Boston University, where she is a fourth-year Ph.D. student. While in the Northeast, she realized that private schools there tend to be much older than in the South. The private school tradition didn’t really catch on in the South until white people thought Black students might arrive at their children’s public schools.

Graves also realized how few people outside of the South knew about segregation academies. Economics literature rarely mentioned them at all.

“I felt like it was this missing piece,” she said.

A lot of economic research on school desegregation and white flight focuses on cities rather than on rural areas “where segregation academies really play a big role,” Graves said. She jumped into that largely empty research lane.

Graves tackles questions like: How have segregation academies affected the average public school enrollment? Are there differences between rural and urban areas?

She taught a class on the economics and history of school segregation at Harvard University this spring and has spent the last two years researching and presenting her work on the impact that segregation academies have on local public schools.

For the dissertation she is finishing, Graves found that on average, when segregation academies opened in Alabama and Louisiana, they caused white enrollment in neighboring public schools to drop by about a third — and the white population did not return over the 15 years that followed.

Now she is measuring the effects of segregation academies on local public school funding, the students who attended them and the communities where they operate.

Segregation Academies and History

Unlike the other two researchers, Amberly Sheffield went to her local public schools, which were predominantly Black. As she watched other white families pay to send their children to segregation academies, she wondered: why?

Sheffield grew up in Grove Hill, a town of 2,000 people, where her father briefly attended a local segregation academy. After earning her undergraduate degree, she landed a job teaching history at a segregation academy in neighboring Wilcox County. ProPublica’s first story in its series on these academies focused on Wilcox County and the lasting effect that school segregation has had on community members — including, for a time, Sheffield.

Almost all of her students at Wilcox Academy were white. The entire faculty was white. Yet Wilcox County is 70% Black .

Like most segregation academies, Wilcox Academy doesn’t advertise itself as such. Some of these schools include their founding years on their websites or entrance signs — as Wilcox Academy does — but mention nothing about the fact that they opened to avoid desegregation.

Sheffield wanted to shed light on the context of the schools’ openings. In her 2022 master's thesis at Auburn University , she chronicled Wilcox County’s history of sharecropping, violence against civil rights advocates, and resistance to school integration.

She also documented the many fundraisers white people held to pay for the segregation academies they rushed to open before many Black students arrived at the white public schools. Families forming one academy held a skit night, barbeque, fish fry, bingo party, pet show and pancake supper. The money raised paid for school equipment and salaries “but equally important, it created a new community for its founders, sponsors, and families,” she wrote.

The schools also joined a new group that provided their accreditation and organized sports events. “These academies allowed whites to gain complete control over their children’s education — they no longer had to answer to any form of government but their own,” Sheffield wrote.

Today, she is continuing her research as a doctoral student in history at the University of Mississippi.

“History is very important in understanding how we’ve gotten to where we are today, especially when you look at public schools in rural communities in Alabama,” Sheffield said. Many of these schools are mostly Black, underfunded and struggling. “I want people to understand how it got that way, and the answer usually is segregation academies.”

Help ProPublica Report on Education

ProPublica is building a network of educators, students, parents and other experts to help guide our reporting about education. Take a few minutes to join our source network and share what you know.

Mollie Simon contributed research.

Greg Abbott’s School Voucher Crusade Is Three Decades in the Making

Greg Abbott has campaigned against members of his own party who do not support voucher programs. This fall, he may finally get the votes needed to pass a bill.

by Jeremy Schwartz , June 21, 5 a.m. CDT

How Illinois’ Hands-Off Approach to Homeschooling Leaves Children at Risk

At 9 years old, L.J. started missing school. His parents said they would homeschool him. It took two years — during which he was beaten and denied food — for anyone to notice he wasn’t learning.

by Molly Parker and Beth Hundsdorfer , Capitol News Illinois , June 5, 8 a.m. EDT

Local Reporting Network

New York Education Department Hindered an Abuse Investigation at Boarding School for Autistic Youth

A state judge ruled that the agency must cooperate in a disability rights investigation into Shrub Oak International School. A ProPublica investigation found that would-be whistleblowers could not get state authorities to intervene at the school.

by Jennifer Smith Richards and Jodi S. Cohen , May 31, 6 a.m. EDT

How an Alabama Town Staved Off School Resegregation

In the 1970s, Black students organized protests and a boycott that cost local white businesses money. Today, many families who could afford private school still choose Thomasville’s public schools.

by Jennifer Berry Hawes , May 29, 5 a.m. EDT

How Residents in a Rural Alabama County Are Confronting the Lasting Harm of Segregation Academies

In Wilcox County, Alabama, many people say they want to bridge racial divides created by their segregated schools. But they must face a long and painful history.

by Jennifer Berry Hawes , photography by Sarahbeth Maney , May 24, 6 a.m. EDT

“I Refuse to Be Told What to Do”: Facebook Posts Show a Conservative School Board Member Rejecting Extremism

When reporter Jeremy Schwartz first learned of a local Texas activist who ran for school board on a far-right education platform, she seemed to embody the extremist movement he’d covered since 2021. Then her Facebook posts took a surprising turn.

by Jeremy Schwartz , May 22, 5 a.m. CDT

Some Surprises in the No Surprises Act

A law to protect individual patients from sky-high medical bills has already helped millions of Americans but may result in higher health insurance premiums for all.

by T. Christian Miller , June 28, 5 a.m. EDT

Trump Built a National Debt So Big That It’ll Weigh Down the Economy for Years

The “King of Debt” promised to reduce the national debt — then his tax cuts made it surge. Add in the pandemic, and he oversaw the third-biggest deficit increase of any president.

by Allan Sloan , ProPublica, and Cezary Podkul for ProPublica , Jan. 14, 2021, 5 a.m. EST

New Yorkers Were Choked, Beaten and Tased by NYPD Officers. The Commissioner Buried Their Cases.

New York City’s Police Commissioner Edward Caban has repeatedly used a little-known authority called “retention” to prevent officers accused of misconduct from facing public disciplinary trials. Victims are never told their cases have been buried.

by Eric Umansky , June 27, 5 a.m. EDT

How 3M Execs Convinced a Scientist the Forever Chemicals She Found in Human Blood Were Safe

Decades ago, Kris Hansen showed 3M that its PFAS chemicals were in people’s bodies. Her bosses halted her work.

by Sharon Lerner , photography by Haruka Sakaguchi , special to ProPublica , May 20, 6 a.m. EDT

The Delusion of “Advanced” Plastic Recycling

The plastics industry has heralded a type of chemical recycling it claims could replace new shopping bags and candy wrappers with old ones — but not much is being recycled at all, and this method won’t curb the crisis.

by Lisa Song , illustrations by Max Guther , special to ProPublica , June 20, 5 a.m. EDT

Republish This Story for Free

Creative Commons License (CC BY-NC-ND 3.0)

Thank you for your interest in republishing this story. You are free to republish it so long as you do the following:

- You have to credit ProPublica and any co-reporting partners . In the byline, we prefer “Author Name, Publication(s).” At the top of the text of your story, include a line that reads: “This story was originally published by ProPublica.” You must link the word “ProPublica” to the original URL of the story.

- If you’re republishing online, you must link to the URL of this story on propublica.org, include all of the links from our story, including our newsletter sign up language and link, and use our PixelPing tag .

- If you use canonical metadata, please use the ProPublica URL. For more information about canonical metadata, refer to this Google SEO link .

- You can’t edit our material, except to reflect relative changes in time, location and editorial style. (For example, “yesterday” can be changed to “last week,” and “Portland, Ore.” to “Portland” or “here.”)

- You cannot republish our photographs or illustrations without specific permission. Please contact [email protected] .

- It’s okay to put our stories on pages with ads, but not ads specifically sold against our stories. You can’t state or imply that donations to your organization support ProPublica’s work.

- You can’t sell our material separately or syndicate it. This includes publishing or syndicating our work on platforms or apps such as Apple News, Google News, etc.

- You can’t republish our material wholesale, or automatically; you need to select stories to be republished individually. (To inquire about syndication or licensing opportunities, contact [email protected] .)

- You can’t use our work to populate a website designed to improve rankings on search engines or solely to gain revenue from network-based advertisements.

- We do not generally permit translation of our stories into another language.

- Any website our stories appear on must include a prominent and effective way to contact you.

- If you share republished stories on social media, we’d appreciate being tagged in your posts. We have official accounts for ProPublica on Twitter , Facebook and Instagram .

Northwestern Pritzker Law Co-Hosts “Brown v. Board of Education at 70: An Evolving Legacy” Event

Seventy years after the Supreme Court found segregated schools unconstitutional, Brown vs. Board of Education continues to shape education policy and practice as well as the legal field. Northwestern Pritzker School of Law Dean Hari Osofsky and Associate Dean of Research and Intellectual Life Paul Gowder took part in a Northwestern University event exploring the complex outcomes around the landmark verdict marking the 70th anniversary of the decision.

Hosted by Northwestern Pritzker School of Law and the School of Education and Social Policy, the two-day event was held at Evanston Township High School and the Orrington Hotel in Evanston. The series of seminars and professional development workshops brought together scholars, students, educators, legal experts and Evanston community members for candid conversations around the purpose of education.

In 1954 when Brown was decided, many Black families felt optimistic. Others were skeptical, wondering how it would actually look in practice. As the years passed, both responses turned out to have merit.

Four generations later, many of the country’s schools are even more split across racial lines. And while the country is now more ethnically and racially diverse, the policies that resulted from the ruling – be it bussing Black students to far away schools or offering tracked classes – have also had mixed outcomes.

Today, educators and researchers are still grappling with the aftermath and the overall influence of Brown v. Board as it relates to providing educational equity.

“Our goal is not only to understand the impact of Brown vs. Board of Education as a historical event, but also to forge a path forward,” Nichole Pinkard, the Alice Hamilton Professor of Learning Sciences told attendees. “We are not just commemorating a legal milestone.”

Confronting the ‘complexities of the past’

In exploring the legacy of Brown, it’s clear that simply allowing Black children to sit next to white kids in public schools isn’t enough, Northwestern School of Education and Social Policy Professor Emerita Carol Lee said.

“The goal now is to create equitable systems and harness the opportunities of public education, no matter who is seated in a classroom next to whom,” said Lee, who urged the audience to take a wider view on the ruling to understand how to move forward. Lee’s assessment of the impact of Brown on education policy and practic also featured School of Education and Social Policy Dean Bryan Brayboy.

“With a 400-year history of segregation, expecting change after just 70 years doesn’t take in the complexities of the past,” Lee said.

“Have we really moved on? “

For several faculty members, the Brown decision played a major role in their lives. Political scientist Sally Nuamah, associate professor of human development and social policy, recalled attending a mostly white middle school on Chicago’s North side in the 1990s.

As one of the only Black students at the school, she was assigned to an English as a Second Language class – even though English was her first language. Looking back, it affected her “self-worth and deservingness” as she continued her education, Nuamah said during a round table discussion called “Have We Really Moved on From Separate but Equal?”

Another speaker, Marcus Campbell, discussed how attending predominantly Black schools gave him a stronger sense of self. “My experience in a segregated environment was good,” said Campbell, now superintendent of Evanston Township High School District 202. “Normalizing achievement as a Black kid was just how I grew up.”

Evanston community members also weighed in on the local influence of Brown. Gilo Kwese Logan, an equity and inclusion consultant and a fifth generation Evanston resident, says the 1967 closing of Foster School in Evanston’s historically Black Fifth Ward set off a string of difficult events.

While praised as the first suburban district to integrate its schools, Evanston’s approach of bussing Black children to mostly white schools took away from the close-knit communities that formed over generations.

“On one block children attended four different elementary schools,” adding that local stores–including his family’s–also shut down. “When we lost these pillars of our community we lost portions of our village.” (A new school in Evanston’s Fifth Ward is scheduled to open in 2026.)

‘The two trajectories of Brown’

Even as participants look back on Brown v. Board, many other Civil Rights-era protections are now in question, Pritzker School of Law Dean Hari Osofsky, added during a discussion assessing the legal influence of the decision. “There are so many rollbacks in Civil Rights protections,” Osofsky told the audience. “Having legal protections of equity is important.”

Paul Gowder, associate dean of research and intellectual life at Pritzker, pointed to the “two histories and two trajectories of Brown” that have evolved since the ruling.

Most recently, the Students for Fair Admissions v. Harvard case in 2003 struck down race-based affirmative action in college admissions and pointed to Brown. And a 2007 case that also invoked Brown, Parents Involved in Community Schools v. Seattle School District No. 1, found it unconstitutional to use race as a factor for assigning students to schools.

On one side, the Brown v. Board precedent gets used in the courts to say that “taking race into account is a form of discriminating by race” while on the other it says that “people of color are entitled to be included in educational institutions as citizens,” Gowder explained. In his view, acknowledging racial inequities is more compatible with Brown.

A path forward

Another participant, LaToya Baldwin-Clark, professor at the University of California, Los Angeles School of Law, pointed out how a change in funding may be required for this kind of equitable education. Today’s public schools depend on local tax dollars, deepening inequities between schools in economically disadvantaged neighborhoods, said Baldwin-Clark. For parents without the economic means, the cycle of being left out of neighborhoods with well-funded schools continues.

“It allows private taxpayers to control the most basic aspect of schooling – exactly the process that Brown was meant to interrupt,” she added.

Many attendees also encouraged a deeper understanding of the intention of schools beyond just learning the basics. Academic success often stems from feelings of safety and belonging in the classroom.

“There is a big takeaway here about what functions the school serve,” said School of Education and Social Policy Dean Bryan McKinley Jones Brayboy. “Obviously, in some ways we are preparing children for the world they are going to live in, but it’s also about the future of community.”

This article originally appeared in SESP News .

Related Articles

Professor Genevieve Tokíc Elected as Fellow of the American College of Tax Counsel

Professor Genevieve Tokíc, Senior Lecturer and Associate Director at Northwestern Pritzker School of Law’s Tax Program, has been honored as a Fellow of the American College of Tax Counsel (ACTC). ...

Celebrating Pride Month: A Conversation With Kara Ingelhart

This year, Northwestern Pritzker School of Law’s Bluhm Legal Clinic launched the LGBTQI+ Rights Clinic to advance advocacy in support of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, and intersex ...

Kyle Rozema Publishes Study on Affirmative Action Bans and Law School Diversity

Kyle Rozema, Professor of Law and Co-Director of the JD/PhD Program and Academic Placement at Northwestern Pritzker School of Law, has a new working paper titled “Affirmative Action and Racial ...

March 7, 2024

10:00 am - 5:00 pm , Eastern Time

70 Years Later: Revisiting Brown v. Board of Education and the Struggle for Racial Equity in Education

This was a symposium with a number of speakers discussing the continuing impact of racial inequity in education, the ongoing legacy of Brown v. Board, and the coming impacts of Students for Fair Admissions v. Harvard. Keynote speaker: Karla McKanders . Co-Hosted with: Georgetown Racial Justice Institute, Georgetown Black Law Students Association, Georgetown Law Racial Equity in Education Law & Policy Clinic, and Latin American Law Students Association.

Educating About Race: A Back-to-School Conversation

September Speaker Series - Discussion with Professor Hadar Aviram

Small Group Networking Discussion with Professor Justin Hansford

Get Involved

Get ACS News and Updates

Find Your Local Chapter

Become a Member of ACS

Breaking News

OPINION ANALYSIS

Supreme court strikes down chevron , curtailing power of federal agencies.

This article was updated on June 28 at 3:46 p.m.

In a major ruling, the Supreme Court on Friday cut back sharply on the power of federal agencies to interpret the laws they administer and ruled that courts should rely on their own interpretion of ambiguous laws. The decision will likely have far-reaching effects across the country, from environmental regulation to healthcare costs.

By a vote of 6-3, the justices overruled their landmark 1984 decision in Chevron v. Natural Resources Defense Council , which gave rise to the doctrine known as the Chevron doctrine. Under that doctrine, if Congress has not directly addressed the question at the center of a dispute, a court was required to uphold the agency’s interpretation of the statute as long as it was reasonable. But in a 35-page ruling by Chief Justice John Roberts, the justices rejected that doctrine, calling it “fundamentally misguided.”

Justice Elena Kagan dissented, in an opinion joined by Justices Sonia Sotomayor and Ketanji Brown Jackson. Kagan predicted that Friday’s ruling “will cause a massive shock to the legal system.”

When the Supreme Court first issued its decision in the Chevron case more than 40 years ago, the decision was not necessarily regarded as a particularly consequential one. But in the years since then, it became one of the most important rulings on federal administrative law, cited by federal courts more than 18,000 times.

Although the Chevron decision – which upheld the Reagan-era Environmental Protection Agency’s interpretation of the Clean Air Act that eased regulation of emissions – was generally hailed by conservatives at the time, the ruling eventually became a target for those seeking to curtail the administrative state, who argued that courts, rather than federal agencies, should say what the law means. The justices had rebuffed earlier requests (including by one of the same lawyers who argued one of the cases here) to consider overruling Chevron before they agreed last year to take up a pair of challenges to a rule issued by the National Marine Fisheries Service. The agency had required the herring industry to pay for the costs, estimated at $710 per day, associated with carrying observers on board their vessels to collect data about their catches and monitor for overfishing.

The agency stopped the monitoring in 2023 because of a lack of funding. While the program was in effect, the agency reimbursed fishermen for the costs of the observers.

After two federal courts of appeals rebuffed challenges to the rules, two sets of commercial fishing companies came to the Supreme Court, asking the justices to weigh in.

The justices took up their appeals, agreeing to address only the Chevron question in Relentless v. Department of Commerce and Loper Bright Enterprises v. Raimondo . (Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson dissented in the Relentless case but was recused from the Loper-Bright case, presumably because she had heard oral argument in the case while she was still a judge on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit.)

Chevron deference, Roberts explained in his opinion for the court on Friday, is inconsistent with the Administrative Procedure Act, a federal law that sets out the procedures that federal agencies must follow as well as instructions for courts to review actions by those agencies. The APA, Roberts noted, directs courts to “decide legal questions by applying their own judgment” and therefore “makes clear that agency interpretations of statutes — like agency interpretations of the Constitution — are not entitled to deference. Under the APA,” Roberts concluded, “it thus remains the responsibility of the court to decide whether the law means what the agency says.”

Roberts rejected any suggestion that agencies, rather than courts, are better suited to determine what ambiguities in a federal law might mean. Even when those ambiguities involve technical or scientific questions that fall within an agency’s area of expertise, Roberts emphasized, “Congress expects courts to handle technical statutory questions” – and courts also have the benefit of briefing from the parties and “friends of the court.”

Moreover, Roberts observed, even if courts should not defer to an agency’s interpretation of an ambiguous statute that it administers, it can consider that interpretation when it falls within the agency’s purview, a doctrine known as Skidmore deference.

Stare decisis – the principle that courts should generally adhere to their past cases – does not provide a reason to uphold the Chevron doctrine, Roberts continued. Roberts characterized the doctrine as “unworkable,” one of the criteria for overruling prior precedent, because it is so difficult to determine whether a statute is indeed ambiguous.

And because of the Supreme Court’s “constant tinkering with” the doctrine, along with its failure to rely on the doctrine in eight years, there is no reason for anyone to rely on Chevron . To the contrary, Roberts suggested, the Chevron doctrine “allows agencies to change course even when Congress has given them no power to do so.”

Roberts indicated that the court’s decision on Friday would not require earlier cases that relied on Chevron to be overturned. “Mere reliance on Chevron cannot constitute a ‘special justification’ for overruling” a decision upholding agency action, “because to say a precedent relied on Chevron is, at best, just an argument that the precedent was wrongly decided” – which is not enough, standing along, to overrule the case.

The Supreme Court is expected to rule on Monday on when the statute of limitations to challenge agency action begins to run. The federal government has argued in that case, Corner Post v. Federal Reserve , that if the challenger prevails, it would open the door for a wide range of “belated challenges to agency regulation.”

Justice Clarence Thomas penned a brief concurring opinion in which he emphasized that the Chevron doctrine was inconsistent not only with the Administrative Procedure Act but also with the Constitution’s division of power among the three branches of government. The Chevron doctrine, he argued, requires judges to give up their constitutional power to exercise their independent judgment, and it allows the executive branch to “exercise powers not given to it.”

Justice Neil Gorsuch filed a longer (33-page) concurring opinion in which he emphasized that “[t]oday, the Court places a tombstone on Chevron no one can miss. In doing so, the Court returns judges to interpretative rules that have guided federal courts since the Nation’s founding.” He sought to downplay the impact of Friday’s ruling, contending that “all today’s decision means is that, going forward, federal courts will do exactly as this Court has since 2016, exactly as it did before the mid-1980s, and exactly as it had done since the founding: resolve cases and controversies without any systemic bias in the government’s favor.”

Kagan, who read a summary of her dissent from the bench, was sharply critical of the decision to overrule the Chevron doctrine. Congress often enacts regulatory laws that contain ambiguities and gaps, she observed, which agencies must then interpet. The question, as she framed it, is “[w]ho decides which of the possible readings” of those laws should prevail?

For 40 years, she stressed, the answer to that question has generally been “the agency’s,” with good reason: Agencies are more likely to have the technical and scientific expertise to make such decisions. She emphasized the deep roots that Chevron has had in the U.S. legal system for decades. “It has been applied in thousands of judicial decisions. It has become part of the warp and woof of modern government, supporting regulatory efforts of all kinds — to name a few, keeping air and water clean, food and drugs safe, and financial markets honest.”

By overruling the Chevron doctrine, Kagan concluded, the court has created a “jolt to the legal system.”