Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

Banned by the law, practiced by the society: The study of factors associated with dowry payments among adolescent girls in Uttar Pradesh and Bihar, India

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Software, Validation

Affiliation Department of Mathematical Demography & Statistics, International Institute for Population Sciences, Mumbai, India

Roles Writing – original draft

Affiliation Department of Population Policies and Programmes, International Institute for Population Sciences, Mumbai, India

Affiliation Department of Public Health and Mortality Studies, International Institute for Population Sciences, Mumbai, India

Roles Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Software, Validation

* E-mail: [email protected]

Roles Formal analysis

Roles Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing

- Shobhit Srivastava,

- Shekhar Chauhan,

- Ratna Patel,

- Strong P. Marbaniang,

- Pradeep Kumar,

- Ronak Paul,

- Preeti Dhillon

- Published: October 15, 2021

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0258656

- Peer Review

- Reader Comments

Despite the prohibition by the law in 1961, dowry is widely prevalent in India. Dowry stems from the early concept of ’Stridhana,’ in which gifts were given to the bride by her family to secure some personal wealth for her when she married. However, with the transition of time, the practice of dowry is becoming more common, and the demand for a higher dowry becomes a burden to the bride’s family. Therefore, this study aimed to determine the factors associated with the practice of dowry in Bihar and Uttar Pradesh.

We utilized information from 5206 married adolescent girls from the Understanding the lives of adolescents and young adults (UDAYA) project survey conducted in two Indian states, namely, Uttar Pradesh and Bihar. Dowry was the outcome variable of this study. Univariate, bivariate, and multivariate logistic regression analyses were performed to explore the factors associated with dowry payment during the marriage.

The study reveals that dowry is still prevalent in the state of Uttar Pradesh and Bihar. Also, the proportion of dowry varies by adolescent’s age at marriage, spousal education, and household socioeconomic status. The likelihood of paid dowry was 48 percent significantly less likely (OR: 0.52; CI: 0.44–0.61) among adolescents who knew their husbands before marriage compared to those who do not know their husbands before marriage. Adolescents with age at marriage more than equal to legal age had higher odds to pay dowry (OR: 1.60; CI: 1.14–2.14) than their counterparts. Adolescents with mother’s who had ten and above years of education, the likelihood of dowry was 33 percent less likely (OR: 0.67; CI: 0.45–0.98) than their counterparts. Adolescents belonging to the richest households (OR: 1.48; CI: 1.13–1.93) were more likely to make dowry payments than adolescents belonging to poor households.

Limitation of the dowry prohibition act is one of the causes of continued practices of dowry, but major causes are deeply rooted in the social and cultural customs, which cannot be changed only using laws. Our study suggests that only the socio-economic development of women will not protect her from the dowry system, however higher dowry payment is more likely among women from better socio-economic class.

Citation: Srivastava S, Chauhan S, Patel R, Marbaniang SP, Kumar P, Paul R, et al. (2021) Banned by the law, practiced by the society: The study of factors associated with dowry payments among adolescent girls in Uttar Pradesh and Bihar, India. PLoS ONE 16(10): e0258656. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0258656

Editor: Nishith Prakash, University of Connecticut, UNITED STATES

Received: February 17, 2021; Accepted: October 3, 2021; Published: October 15, 2021

Copyright: © 2021 Srivastava et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Data Availability: The data can be found from the following link: https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataset.xhtml?persistentId=doi:10.7910/DVN/RRXQNT .

Funding: The author(s) received no specific funding for this work.

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Introduction

The preponderance of dowry and bride-price practices is culturally driven and existed as a way of marriage requirements [ 1 ]. In various traditional societies, the transfer of money or goods accompanies the initiation of marriage. When made to groom families from the bride families, such transfers are widely classified as dowry [ 2 ]. Historically, dowry served the fundamental purpose of inheritance for women as men were thought to inherit the family property in the Indian context [ 3 ]. Moreover, dowry has been seen as a way to compensate the groom’s family for the economic support they would provide to the new member of the family, i.e., the bride, as women tend to have a small role in the market economy and are dependent on their husbands [ 4 ]. The above interpretation holds true in the Indian scenario as historically; dowry has been practiced in upper-caste families where women’s economic opportunities are limited. In the lower caste; where women are seen as economic contributors, the bride-price’s custom was more common [ 5 ]. However, dowry dynamics have been changing in recent times, and people from the upper and lower caste are practicing dowry. Furthermore, recent studies noted that the dowry system is prevalent across many cultures and is no longer is treated as a contribution towards a suitable beginning of the practical life of newly married couples [ 6 ].

In India, dowry has been prevalent for ages. The custom of dowry in India is a deeply rooted cultural phenomenon [ 7 ]. The concept of Sanskritization was proposed by eminent sociologist Srinivas in 1952, and many communities that never took dowry before started practicing dowry probably due to the phenomenon of Sanskritization [ 8 ]. A study has noticed that dowry is being practiced in about 93 percent of Indian marriage and is almost universal [ 9 ]. Not only this, but studies have also noted that dowry payments have increased manifolds in India [ 10 , 11 ]. A clear explanation for rising dowry payments is the marriage squeeze [ 12 ]. However, in her study, Anderson refuted the claims of any association between marriage squeeze and dowry payments [ 11 ]. Marriage squeeze depicts tightness of marriage market. Chiplunkar and Weaver (2019) carefully documented the transition of dowry payments in India using the 1999 wave of the ARIS-REDS data and test which theories about dowry inflation are consistent with the data and which are not [ 13 ]. Chiplunkar and Weaver (2019) show that the theory of sanskritization cannot explain dowry inflation. Similarly, they also find that the REDS data offers limited support to the marriage squeeze hypothesis. Few researchers postulated the theory of ’sex ratios and dowry’ whereby changes in sex ratios due to population growth could alter dowry payments [ 8 , 14 , 15 ]. The spousal age gap difference remains a concern as male marry at older ages than women, so when population grows, as was the case in India in the 1950s and 1960s, there will be a surplus of women at marriageable ages relative to men at marriageable ages. In the resulting "marriage squeeze", competition over relatively scarce grooms may cause an increase in dowry [ 2 , 16 ]. Contrary to these predictions, Chiplunkar and Weaver do not find that sex ratio in the marriage market is related to increases in the prevalence or size of dowry [ 13 ]. Instead, the "squeeze" appears to be relieved by changes in the age of marriage, with a smaller average age difference between brides and grooms [ 11 ]. Zhang & Chan (1999) utilizing 1989 Taiwan Women and Family Survey data of 25–60 years old women stated that dowry improves the bride’s welfare in her family [ 17 ]. They further stated that dowry represents bequest by altruistic parents for a daughter which not only increases the wealth of new conjugal household but also enhances the bargaining power of the bride [ 17 ].

Researchers unanimously agreed that the issue of dowry could be associated with gender inequality and female deprivation [ 7 , 18 ]. Alfano (2017) argued that the presence of son preference resulting from deeply rooted attitudes that boys are more valuable than girls is mostly attributed to the dowry payments [ 19 ]. Alfano (2017) further stated that the economic intuition that sons are cheaper to raise than daughters stem from the dowry [ 19 ]. He opined that dowries increase the economic returns to sons and decrease the return to daughters [ 19 ]. Kumar (2020) is of the opinion that dowry prevails because of disempowerment of women, male dominance, and financial dependence on men [ 20 ]. He further stated that inability to give dowry causes victimization of brides; whereas, the glorification of dowry generates son preference leading to female feticide, sex-ratio imbalances, and gender inequality [ 20 ]. Prevailing son preference in Indian societies leads to female feticide so as to avoid the burden of dowry [ 21 – 23 ]. Bhalotra et al., (2020) found a positive relationship between gold prices and the value of dowry payments [ 21 ]. They stated that payment in gold is essential in Indian marriages and further validated that gold prices marked the financial burden of dowry [ 21 ]. Further, Bhalotra et al. (2020) evidently provided evidence that gold prices impact dowry value and, that parents react to unexpected increases in gold prices by committing girl abortion or neglecting girls in the first month of life, when neglect more easily translates into death [ 21 ].

Parents desire their daughters to marry educated men with urban jobs, because such men have higher and more certain incomes, which are not subject to climatic cycles and which are paid monthly, and because the wives of such men will be freed from the drudgery of rural work and will usually live apart from their parents-in-law. In a sellers’ market, created by relative scarcity, there was no alternative but to offer a dowry with one’s daughter [ 24 ]. A different notion was put forward by Bloch & Rao (2002), where they stated that husbands are more likely to beat their wives when the wife’s family is rich because there are more resources to extract and the returns are greater [ 25 ]. A husband’s greater satisfaction with the marriage, indicated by higher numbers of male children, reduces the probability of violence against women [ 25 ]. Thus, it is likely that aspects of violent behavior are strongly linked to economic incentives [ 25 ]. Previous research has documented numerous factors associated with the dowry, such as socio-economic factors of the families [ 26 ], failure of the government in curbing the practice of dowry [ 27 ], first-born gender in the family [ 28 ]. A study showed that increasing the returns to women’s human capital could lead to the disappearance of marriage payments altogether [ 29 ]. Edlund (2006) hypothezing that rise in dowry payments in India has been associated with the disadvantaged position of women in the marriage market, has shown that in a much-used data set on dowry inflation, net dowries did not increase in the period after 1950 [ 30 ]. Moreover, the stagnation of net dowries after 1950 undermine claims that marriage market conditions for brides have worsened [ 30 ]. Answering the query of whether dowry is bequest or price, Arunachalam & Logam (2016) found that more than a quarter of marriages use dowry as bequests [ 31 ]. Arunachalam & Logam (2016) further noticed limited evidence on marriage squeeze as a factor for dowry [ 31 ].

It was around sixty years back when India enacted the Dowry Prohibition Act, 1961, to prohibit the giving or taking of the dowry. However, the act has been unsuccessful in curbing down the dowry’s menace and failed in its basic fundamental of eliminating the demand for dowry [ 7 ]. The dowry is so profoundly entrenched that a way out seems a bit tedious task; even well-educated families begin saving wealth for their daughter after she is born in anticipation of the futuristic dowry payments [ 6 ]. Traditional marriage institutions affect the household’s financial decisions and influence saving behaviour [ 28 ]. Despite acknowledging the problem of dowry widely, there is a paucity of empirical studies that systematically analyze the correlates of dowry among adolescent girls in recent times [ 13 ]. Given the growing concerns about the dowry’s socioeconomic consequences, it is imperative to explore the correlates of dowry in India. Therefore, we have tried to examine the factors associated with dowry in India. This study captures data from adolescents aged 15–19 years of age. While examining the correlates of dowry among adolescent girls, this study contributes to the existing literature examining factors associated with dowry.

This study’s data came from Understanding the lives of adolescents and young adults (UDAYA) project survey conducted in two Indian states Uttar Pradesh and Bihar, in 2016 by the Population Council under the guidance of the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India. The survey collected detailed information on family, media, community environment, assets acquired in adolescence, and quality of transitions to young adulthood indicators. A total of 150 primary sampling units (PSUs)—villages in rural areas and census wards in urban areas have been selected in the state in order to conduct interviews in the required number of households. The 150 PSUs were further divided equally into rural and urban areas, that is, 75 for rural respondents and 75 for urban respondents. Within each sampling domain, survey adopted a multi-stage systematic sampling design. The 2011 census list of villages and wards (each consisting of several census enumeration blocks [CEBs] of 100–200 households) served as the sampling frame for the selection of villages and wards in rural and urban areas, respectively. This list was stratified using four variables, namely, region, village/ward size, proportion of the population belonging to scheduled castes and scheduled tribes, and female literacy. The UDAYA provide the estimates for states as a whole as well as urban and rural areas of the states. The required sample for each sub-group of adolescents was determined at 920 younger boys, 2,350 older boys, 630 younger girls, 3,750 older girls, and 2,700 married girls in the state. The sample size for Uttar Pradesh and Bihar was 10,350 and 10,350 adolescents aged 10–19 years, respectively. The sample size for this study was 5,206 adolescent girls who were married at the time of the survey [ 32 , 33 ]. In the present study the unmarried boys and girls were dropped and only married adolescent girls were included in the sample. Fig 1 represents the sample selection procedure for the present study.

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0258656.g001

Outcome variables

Dowry was the outcome variable of this study, which was binary. The question was framed as: "whether dowry paid at the time of marriage or later"? the response was coded as 0 means "no" and 1 means "yes." The variable measures the response of dowry if demanded during marriage or after marriage.

Explanatory variables

- Interaction with husband before marriage was named as "Husband known before marriage" and was recoded as not known and known.

- Age at marriage was recoded as less than legal age (<18 years) and more than equals to legal age (≥18 years). The sample in 18 and above age category would be small as the dataset contained married adolescent’s girl aged 15–19 years.

- Spousal age gap was recoded wife older/almost the same age (wife older or one year younger than husband) and husband older (husband two or more years older than wife).

- Spousal education recoded both not educated, only husband educated, only wife educated, and both educated.

- Working status of the respondent was recoded as no and yes.

- Whether vocation training was received or not by the respondent

- Mother’s education of the respondent was recoded as no education, 1–7, 8–9, and 10 and above years of education.

- Land ownership among in-laws was coded as no and yes. The measurements about the land owned was not available in the data set.

- Caste was recoded as Scheduled Caste and Scheduled Tribe (SC/ST) and non-SC/ST. The Scheduled Caste include a group of population which is socially segregated and financially/economically by their low status as per Hindu caste hierarchy. The Scheduled Castes (SCs) and Scheduled Tribes (STs) are among the most disadvantaged socio-economic groups in India [ 34 ].

- Religion was recoded as Hindu and non-Hindu.

- Wealth index was recoded as poorest, poorer, middle, richer, and richest. The survey measured household economic status, using a wealth index composed of household asset data on ownership of selected durable goods, including means of transportation, as well as data on access to a number of amenities. The wealth index was constructed by allocating the following scores to a household’s reported assets or amenities. Principal component analysis technique was used for creating the wealth index variable. The scores were divided into five quintiles using xtile command in Stata 14.

- Residence was available in data as urban and rural.

- Data were available for two states, i.e., Uttar Pradesh and Bihar, as the survey was conducted in these two states only.

Statistical analysis

Univariate, bivariate, and multivariate logistic regression analysis [ 35 ] were performed to find the factors associated with dowry payment during marriage.

Where π is the expected proportional response for the logistic model; β 0 ,….., β M are the regression coefficient indicating the relative effect of a particular explanatory variable on the outcome. These coefficients change as per the context in the analysis in the study. Svyset command using Stata 14 was used to control for complex survey design. Additionally, individual weights were used to present the representative results. Further it was evident from the robustness check that logit model had a better fit. S4 and S5 Tables provide the summary statistics and correlation matrix along with plot of logistic predicted probabilities vs linear model ( S1 Fig ) and Plot of logistic predicted probabilities vs linear probability model (LPM) ( S2 Fig ).

Next, we check the stability of the regression coefficients and their sensitivity to selection bias using standard methods [ 36 , 37 ]. We obtain bias-adjusted coefficients and calculate the absolute deviation from the non-bias-adjusted regression estimates to understand the extent of bias. Further, we calculate Oster’s δ, whose value higher than one would indicate that the regression coefficients are insensitive to omitted variable bias and variable selection bias [ 37 ]. All estimates were obtained with the assumption that the bias-adjusted model would explain 1.3 times variation in dowry payment status compared to the non-bias-adjusted model. The statistical analyses for coefficient stability check were performed using the psacalc command by estimating linear probability models in STATA [ 38 ].

The socio-demographic profile of the study population (married adolescents aged 15–19 years) is presented in Table 1 . About 65 percent of adolescent girls did not know their husbands before marriage. Most husbands were older than their wives (91%) in the study population, and 64 percent of spouses (both) were educated. Only 11.7 percent of adolescent girls were working, and about 16 percent of adolescent girls received vocational training. Around 42 percent of girls’ in-laws had land ownership. Nearly 30 percent of adolescents belonged to the SC/ST group, and most adolescents were Hindu (82.5%) and lived in rural areas (86%).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0258656.t001

Table 2 depicts the distribution of adolescents who paid dowry by background characteristics. Overall, around 86 percent of adolescent girls reported that dowry was paid for their marriage. Bivariate results revealed that paid dowry was significantly higher among those who did not know their husbands before marriage (87.2%) than their counterparts (82.9%). It was more prevalent among those whose age at marriage was more than the legal age (89.1%). Similarly, dowry was more prevalent among married adolescent women whose husbands were older and higher if both husband and wife were educated. Interestingly, paid dowry was significantly higher among those who were not working (86%) and received vocational training (91%). Moreover, paid dowry was lower among the non-Hindu community (84.5%). Interestingly, the dowry was more prevalent in the richest households (88.7%). The rural-urban differential was observed for paid dowry. For instance, rural adolescents (86.8%) reported higher paid dowry than urban (78.7%) counterparts. S2 Table provides estimates for Uttar Pradesh and Bihar separately.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0258656.t002

Estimates from logistic regression analysis for adolescents who paid dowry by important predictors were presented in Table 3 . The likelihood of paid dowry was 48 percent significantly less likely (OR: 0.52; CI: 0.44–0.61) among adolescents who knew their husbands before marriage compared to those who do not know their husbands before marriage. Moreover, if adolescent girls who got marry after legal age (OR: 1.60; CI: 1.14–2.14) were 60 per cent more likely to pay dowry than their counterparts. The likelihood of paid dowry was 25 percent more likely among adolescents whose husband was older (OR: 1.25; CI: 1.03–1.67) than their counterparts. The odds of paid dowry were 39 percent, 47 percent, and 89 percent significantly more likely if only husband (OR: 1.39; CI: 1.05–1.83), only wife (OR: 1.47; CI: 1.11–1.96), and both were educated (OR: 1.89; CI: 1.48–2.4) respectively, than when both were not educated. Interestingly, if an adolescent’s mother was having ten and above years of education, the likelihood of dowry was 33 percent less likely (OR: 0.67; CI: 0.45–0.98) than their counterparts. Wealth quintile has a positive relationship with adolescents who paid dowry for marriage. For instance, the odds of paid dowry were 33 percent, 39 percent, and 48 percent more likely among adolescents whose family gave dowry to marry them in middle (OR: 1.33; CI: 1.03–1.73), richer (OR: 1.39; CI: 1.06–1.83), and richest (OR: 1.48; CI: 1.07–2.05) families respectively compared to poorest counterparts. Moreover, the likelihood of paid dowry was 54 percent more likely in rural areas (OR: 1.54; CI: 1.28–1.86) than urban areas. Importantly, Bihar has higher odds for paid dowry (OR: 1.42; CI: 1.19–1.70) compared to Uttar Pradesh. Additionally, the estimates were provided for urban and rural place of residence as many covariates may vary by place of residence ( S1 Table ). Moreover, stepwise regression analysis was used to check for sensitivity bias ( S3 Table ).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0258656.t003

Table 4 gives the results of the coefficient stability check of the explanatory variables of dowry payment among female adolescents. From the bias-adjusted estimates (see column 8), we observed that the multivariable association between husband familiar before marriage, age at marriage, spousal education, wealth index, residence and state with dowry payment is statistically significant (at 5% level) and lies in the same direction as the uncontrolled estimates. Moreover, from the difference shown in column 10, we can say that the bias-adjusted and non-bias-adjusted regression coefficients are similar. However, Oster’s delta revealed that the statistically significant multivariable association of age at marriage and state with dowry payment suffers from omitted-variable and selection bias.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0258656.t004

The practice of dowry is widely prevalent in India [ 9 ], despite the prohibition by the law in 1961. Dowry stems from the early concept of ’Stridhana,’ in which gifts were given to the bride by her family to secure some personal wealth for her when she married [ 39 ]. However, with the transition of time, dowry has become a common practice, and the demand for a higher dowry becomes a burden to the bride’s family. Srinivasan (2005) describes that modern dowry comprises demands that include gold, cash, and consumer goods that far exceed what families can afford, exploiting its obligatory symbolic nature and the fact that they are gifts of love woman from her natal family [ 40 ]. This study aimed to determine the factors associated with the practice of dowry among adolescent girls. The study reveals that the practice of dowry is still prevalent and is influenced by many factors such as spousal age gap, spousal education, and household socioeconomic status.

Our study report that a girl knowing her husband before marriage is less likely to pay dowry than those not known about the husband. This may be because the information about knowing each other is much better in a love match [ 41 ], and the practice of dowry is almost non-existent in the case of love marriage [ 40 , 42 ]. Other studies mentioned that in an arranged marriage where information about each other is limited, the groom’s quality is inferred through his education, associated with the dowry level [ 41 ]. The age of the bride is the main factor in marital negotiation, particularly in rural India. Our study found that a girl married to a husband older than her is more likely to pay dowry than an older girl or of similar age to her husband. One possible explanation by Maitra (2006) in his study on dowry inflation in India, argues that the excess supply of younger brides in the marriage market can leads to increase in dowry price when an older man marries the younger brides [ 43 ]. Another reason could be groom late age at marriage may be associated with pursuing of higher education [ 44 ]. Higher groom education is often found to be associated with higher dowry; this is because due to the competition among the brides for a particular groom leads to offers of higher and higher prices of dowries [ 41 ]. Also, suppose a potential bride’s cares about the qualities of the groom like commitment, sincerity, and loyalty which is important for a peaceful marriage, however if these qualities are unobservable and likely to be true, the brides may judge from the groom education as the signal of these qualities [ 45 ]. Hence, the bride’s family is ready to pay more dowries for a more educated person, not for higher education, but the underlying desirable qualities signals [ 45 ].

However, our study reveals contrasting results as girl education does not impact reducing the amount of dowry paid. Dalmia & Lawrence (2005) while examined the continued prevalence of dowry system in India explained that the amount of dowry or money transfer from brides and their families to grooms and their families does not decrease with increasing bride’s level of education [ 2 ]. Our results show that educated girls are more likely to pay dowry than the uneducated girls whose husband is also not educated. One possible explanation could be that the brides’ education is a good indicator of her household wealth. Hence, higher education and higher dowry are effects of bride’s household wealth [ 45 ]. Girl having a higher level of education tends to marry at a later age because they are more job aspirants than the lower educated girl [ 46 ]. The study of Dhamija & Chowdhury(2020) noted that a delay in marriage is associated with more education, low fertility, and possibly higher dowry for Indian women [ 47 ]. Findings by Field & Ambrus (2008) show that marriage opportunities curtail schooling investment suggest that the benefits to girls of delaying marriage come at a cost to the families, probably in higher dowry payments or less desirable spouses [ 48 ]. A more educated girl puts her parents in a difficult situation because it is very difficult to get a suitable boy for an educated girl. By virtue of her feminine status, a girl is expected to marry a man who should be in a better position and more educated than her. Drèze & Sen (1995) explained that if an educated girl marries a more educated boy, then the dowry payment will be more likely to increase with the groom’s education [ 49 ]. As Mathew (1987) explained, the expected dowry’s mean value increased with the prestige of the groom’s education [ 50 ]. Foreign degrees drew the highest dowries, Ph.D. degree received the lowest than engineering and medical degrees. However, on the other way, in the case of a rift, a more educated bride is more likely to walk out of the marriage, and the groom is bearing a greater risk of separation. So, given grooms value marital life’s stability or longevity, they will want to be paid a higher price for marrying with more educated brides as a premium for bearing the additional risk that such marriages entail [ 45 ].

The studies of Saroja & Chandrika (1991) found that as the bride, parental income increased, and dowry also increased [ 51 ]. This is consistent with our study’s findings, where the girls from the wealthier family were more likely to pay the dowry at marriage. The possible reason for this result is that the higher the parents’ income, the chance with which dowry demands can be agreed with ease, and more smoothly, the dowry payment can take place [ 52 ]. Our study shows that girls from Bihar were more likely to pay dowry than girls in Uttar Pradesh, this finding warrant qualitative study on dowry practices between these two states, because the information from the present study is not sufficient to draw a conclusion for this finding.

The study has some limitations as the study was conducted only in two Indian states, so the researchers could not establish a general conclusion from this study. Also, as our study in quantitative, we are unable to capture the individual social and cultural view point on dowry practice. Additionally, national representative data will be helpful for further study to understand the scenario of dowry practice in India, as because India is a country with diverse social and cultural practices, dowry will vary with respect to their cultural norms. Although the coefficient stability check revealed that the majority of the explanatory characteristics are insensitive to omitted-variable and selection bias, the results for age at marriage and state need to be interpreted with caution.

The study sought to explore the factors associated with the practice of dowry in Bihar and Uttar Pradesh. It is evident from this study that the practice of dowry is still widespread, and the results show that increasing age, education, and household economic status of girls are associated with the likelihood of high dowry payment. Limitation of the dowry prohibition act is one of the causes of continued practices of dowry [ 53 ]. However, significant causes are deeply rooted in social and cultural customs, which cannot be changed using laws. Our study suggests that socio-economic development of women will not protect her from the dowry system, however higher dowry payment is more likely among women from better socio-economic class.

Supporting information

S1 fig. plot of logistic predicted probabilities vs. linear model..

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0258656.s001

S2 Fig. Plot of logistic predicted probabilities vs. LPM.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0258656.s002

S1 Table. Logistic regression estimates for adolescents who paid dowry by background characteristics (15–19 years).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0258656.s003

S2 Table. Percentage distribution of adolescents who paid dowry by region, 15–19 years.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0258656.s004

S3 Table. Stepwise logistic regression estimates for adolescents who paid dowry by background characteristics (15–19 years).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0258656.s005

S4 Table. Summary statistics for LPM.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0258656.s006

S5 Table. Correlation index for robustness check of LPM.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0258656.s007

Acknowledgments

Authors are thankful to Population Council, India for providing UDAYA data for research. This paper was written using data collected as part of Population Council’s UDAYA study, which is funded by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and the David and Lucile Packard Foundation.

- 1. Conteh JA. Dowry and Bride-Price. The Wiley Blackwell Encyclopedia of Gender and Sexuality Studies. American Cancer Society; 2016. pp. 1–4. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118663219.wbegss548

- View Article

- Google Scholar

- 5. Srinivas MN 1916–1999. Religion and society among the Coorgs of South India. Oxford University Press; 2003.

- 7. Mathew MV. Dowry Customs. The Encyclopedia of Women and Crime. American Cancer Society; 2019. pp. 1–2. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118929803.ewac0097

- 13. Chiplunkar G, Weaver J. Prevalence and evolution of dowry in India. 2019. http://www.ideasforindia.in/topics/social-identity/prevalence-and-evolution-of-dowry-in-india.html .

- 16. Sautmann A. Partner Search and Demographics: The Marriage Squeeze in India. Rochester, NY: Social Science Research Network; 2011 Aug. Report No.: ID 1915158. 10.2139/ssrn.1915158.

- 20. Kumar R. Dowry System: Unequalizing Gender Equality. Gender Equality. Switzerland: Springer Nature; 2020. pp. 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-70060-1_21-1

- PubMed/NCBI

- 28. Anukriti S, Kwon S, Prakash N. Household Savings and Marriage Payments: Evidence from Dowry in India. Rochester, NY: Social Science Research Network; 2018 May. Report No.: ID 3170253. https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=3170253 .

- 35. Osborne JW. Best Practices in Quantitative Methods. SAGE; 2008.

- 38. Oster E. PSACALC: Stata module to calculate treatment effects and relative degree of selection under proportional selection of observables and unobservables.

- 43. Maitra S. Can Population Growth Cause Dowry Inflation. Princeton University; 2006.

- 49. Dreze J, Sen A. India: Economic Development and Social Opportunity. OUP Catalogue. Oxford University Press; 1999. https://ideas.repec.org/b/oxp/obooks/9780198295280.html .

- Search Menu

- Sign in through your institution

- Advance articles

- Editor's Choice

- Supplements

- Open Access Articles

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- For Reviewers

- About International Health

- About the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

1 introduction, 4 discussion, authors’ contributions, conflicts of interest, ethical approval.

- < Previous

Dowry deaths: a neglected public health issue in India

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Gopalan Retheesh Babu, Bontha Veerraju Babu, Dowry deaths: a neglected public health issue in India, International Health , Volume 3, Issue 1, March 2011, Pages 35–43, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.inhe.2010.12.002

- Permissions Icon Permissions

This paper appraises the public health burden of mortality in India caused by the practice of dowry and examines the association of some demographic and socio-economic factors with dowry deaths and dowry-related suicides. The paper is based on the data available on the public domains of the National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB), third National Family Health and Survey-2005-06, Planning Commission of India and Census of India 2001. In 2007, the total number of dowry deaths and dowry-related suicides reported in India were 8093 and 3148, respectively. There was a 74% increase in dowry-related deaths from1995 to 2007, while there was a 31% increase in the reporting of dowry-related suicides. Occurrence of dowry deaths has significant association with some demographic and socio-economic variables. The data reveal that the status of women is undesirable, and the burden of mortality and related morbidity is enormous. There should be a national injury surveillance system and reliable estimates of dowry-related homicides. However, available information can be used to design and implement some counter-measures to prevent dowry-related violence and deaths. The study warrants the undertaking of research to give insights into circumstances and triggers of such violence, the healthcare seeking of these victims, bottlenecks in seeking health care and reporting to the police.

Dowry has often been referred to either in a narrative or tale, but in the past, it might not have the prevailing negative connotations as a social evil. The purpose of this practice was meant to help new couples start their life in comfort. The dowry system, giving cash and kind from the bride's family to the groom or groom's family at the time of marriage, has a long history in India and other Asian societies. 1 The practice of dowry was not uncommon in Europe, East Asia, South Asia, and pockets of the Americas. Though the custom has largely disappeared in the western world, it remains in South Asia. 2 One feature of the dowry system in general, which applies specifically to India, is its association with socio-economic stratification. Dowry helps in perpetrating these divisions over generations. 3 Rao identified some fundamental patriarchal conditions that lie at the root of the problem in India; 4 they include: (i) a woman's primary role as a mother and daughter with limited options outside marriage, (ii) a daughter who stays unmarried beyond a certain age whose parents face high social costs, (iii) divorce is practically non-existent, (iv) women are customarily denied inheritance rights and (v) marriages are arranged by the parents of brides and grooms to largely reflect the interests of parents. Though India possesses several communities which are discrete in their geography, language and culture, marriage is perceived as a universal obligation, customarily arranged by parents or relatives of the bride and groom 5 and dowry became a major constituent in marriage negotiations. Now the money and property, as a tangible part of marriage settlements, has been accepted as a private family matter. It has become more private and confined to both families, due to the legal implications of giving and accepting dowry. Most of the time, its unfavourable and disastrous consequences are superficially weighed as individual destiny.

In a patriarchal society, women have little or no role in the market economy and are dependent upon their husbands and in-laws. 6 Today the practice of dowry, which was once limited among some communities, has become customary across caste and class groups in India due to changed economy. 7 Modernization has increased the desirability of consumer goods, and young married couples may see dowry as a way of obtaining them. Studies show that even parents of daughters see dowry as an opportunity to make status claims and to ensure good treatment of their daughters by their conjugal families. 8 Traditionally, dowry items mainly consisted of clothing and household items, but have now been replaced by cash or large consumer goods due to competition for ‘a better groom’. 5 Social scientists provided two major explanations of this shift, one demographic and the other status based. 4 The demographic explanation lays the blame on population growth; the other explanation is the drive towards social status as mentioned above. The practice of dowry has now become a depraved and an ignoble commercial transaction in which financial considerations receive preference over all other qualities of the bride. Even though the custom of dowry has become a source of serious threats to the life of women in many cases, paradoxically it receives support not only from society but also from women themselves. 7 The practice of giving and taking dowry was legally prohibited in 1961, but still continues in 2010.

1.1 Dowry deaths – a public health issue

Though the marriage deal is completed by paying dowry, there is no guarantee for the health and well-being of the bride after marriage. There are many instances reported in the public media of the groom or his family making another demand for dowry after marriage. This is usually due to lower-value dowries being given than the offer made during the deal or may be due to the influence of patriarchal factors to demand more dowries from the bride's family. Women whose families paid either fewer or lower-value dowries, those whose in-laws have expressed dissatisfaction with their dowries, and those who have faced post-marriage dowry requests have been repeatedly found to be more likely to report domestic violence against them. 9 – 12 The issue is not limited to number of deaths only. The magnitude of the morbidity in terms of deterioration of physical and mental health due to dowry-related conflicts is enormous. The family-level conflicts and associated violence have a significant role in determining many social and health conditions of women as well as children. 13 – 20 There are cases of poor utilisation of ante-natal care and child immunisation due to the inferior consideration of the women and conflicts within the family. 21 The issues of female foeticide, high infant mortality, maternal mortality, malnutrition of women and female children should also be read synchronically. Despite the enormous impact of dowries on women's health, little information is available in public health literature. In this context, the present paper examines the trend of the mortality in the form of dowry deaths and dowry-related suicides from India. The association of various demographic and socio-economic factors with these events are also examined.

1.2 Conceptual framework

Violence against women is often examined from an ecological perspective to understand its risk factors. 22 , 23 This ecological framework conceptualizes dowry-related deaths and other violence against women as multifaceted phenomena. Heise noted that this phenomenon is grounded in an interplay of individual, family and community-level factors. 23 The present study too uses this framework to examine the risk factors of dowry-related deaths.

Research suggests that some women are more likely to be victimized than others, because of individual differences in their abilities, resources and experiences. Literacy, for example, has an impact on coping with family conflicts and lessens the risk of victimization due to these conflicts. Education attainment in women improves access to knowledge and information, and brings about an openness to ideas and an increasing independence from traditional authority. 24 Age at marriage and teenage pregnancy also have an impact on the victimization of women. Early age at marriage jeopardizes women's status and is likely to make motherhood the sole focus of her life. It limits women's opportunities in education, occupational training and employment. Further, a lack of education and employment undermines the status of women in the family and community. Also, research revealed that the younger the woman marries, the more likely she is to experience marital conflicts. 25 Women's exposure to mass media makes them aware of their opportunities and rights with the result that they are less likely to experience dowry-related violence.

Some characteristics of couples and families influence a woman's likelihood of being victimized. Family-level characteristics include economic and decision making power and the role of women in the family. Family-level stressors like husband's unemployment and poverty also increase a woman's likelihood of being victimized. A husband's inability and lack of resources to meet the family's needs can cause stress and ultimately lead to frustration. Violence against women is a possible response to this frustration. There is the possibility of increase of alcohol abuse among these men and alcohol consumption among men is positively associated with the perpetration of violence against women. Also, the power dynamics in the family and women's empowerment have an impact on women's status and likelihood of victimization. This likelihood is lower among women who are involved in the family's decision making process. Similarly women's involvement in income-generation activities (like microfinance schemes) helps them, to an extent, to access knowledge and information and attain power to take part in decision making.

Communities have inherent features of protecting people from violence and conversely making people vulnerable to victimization in different contexts. Some community-level characteristics are a reflection of the lower status of women in the community; lower sex ratio is one such kind. Similarly rates of crimes and, specifically, those against women indicate the level of integrity of the community and to what extent the safety of women is assured by the community. The brunt of violence in the community is borne by women too.

Data of both outcome variables and independent variables were taken from the public domains of governmental and related organizations. Details of these data, including the source are presented herewith. India is a republic, consisting of 28 states and seven union territories with a democratic parliamentary system. Only 15 states (Andhra Pradesh, Assam, Bihar, Gujarat, Haryana, Karnataka, Kerala, Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra, Orissa, Punjab, Rajasthan, Uttar Pradesh, West Bengal, and Tamil Nadu), which possessed all the data have been considered for this analysis. These states are in the North, South, Central, East, West and North-Eastern zones of India.

Data of the outcome variables were taken from the public domain of the National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB). The NCRB, an organization under the government of India, functions as a clearing house for information related to crimes occurring in the country. Through Crime Criminal Information System (CCIS), NCRB developed a national network, with the police headquarters at 727 police districts and 35 state/union territory levels connected to one another, and to the central data repository at the NCRB in New Delhi, using standard input integrated investigation forms. The application resides at the NCRB office in New Delhi, and runs in district headquarters across the country. Records fed in at the district level are periodically updated at the centre through the offline/online system of data transfer. The integrated information forms serve as the backbone of the application, which links 140 tables, 120 forms and 160 parameters related to crimes, criminals and property. Thus, this network amassed data from 15 000 police stations through district and state/union territory levels for national figures at national level at the central data repository at the NCRB in New Delhi. 26

Data of the independent variables were taken from the third National Family Health Survey 2005–06, 27 the Planning Commission of India 28 and the Census of India 2001. 29 State-level values of these variables are available on their public domains as well as in the form of reports.

2.2 Outcome variables

Outcome variables considered for this paper are dowry deaths and suicide where dowry is a cause. Dowry death means the death of a married woman who was murdered by her husband and/or in-laws. Suicide-related dowry is a suicide in which dowry is the principal cause. Dowry-related suicides are included while counting the dowry deaths. These deaths have been recorded based on the first information report recorded by the police at community level. However, it is not known how many of these cases were proved in courts of justice.

2.3 Independent variables

Independent variables are considered based on the ecological framework mentioned under conceptual framework. The variables at three levels were included for the analysis. They are: individual-level variables of women (age at marriage, teenage pregnancy, literacy, unemployment and exposure to media), family-level variables (unemployment of men, per capita income, spousal violence, women's role in decision making in the family, women's access to microfinance schemes and men's alcohol habit) and community-level variables (sex ratio, crime rate and rate of crimes against women).

Age at marriage is the percentage of women aged 18–29 years who were first married by the age of 18. Teenage pregnancy is the percentage of women who have begun childbearing during the ages 15–19 years. Literacy rate is the percentage of women and men, aged 15–49 years, who can read a whole sentence or part of a sentence and women and men who completed Standard 6 or higher. Unemployment is the percentage of women and men aged 15-49 years who are not employed in the 12 months preceding the survey. 29 Exposure to mass media is the percentage of women aged 15–49 years who are not regularly exposed to any of the media. 27 Per capita income is the average income per individual. 28 Prevalence of spousal violence is the percentage of women aged 15–49 years, who have experienced physical domestic violence. 27 Women's decision making in the family is the percentage of currently married women who usually make four specific kinds of decisions (own health care, major household purchases, purchases for daily household needs and visits to her family or relatives) either by themselves or jointly with their husband. 27 Access to microfinance is the percentage of women who have membership of and/or have taken a loan from a microcredit scheme. 27 Men's alcohol use is the percentage of men aged 15–49 years who drink alcohol. 27 Sex ratio is the total number of women for 1000 male population in the State as per Census of India, 2001. 29 Crime rate is the percentage contribution of total crime to all of India in 2007. 26 Crime against women is the percentage contribution of crime against women to all in India in 2007. 26

2.4 Analysis

Outcome variables (dowry deaths and dowry-related suicides) and other independent variables of fifteen states were compiled. Univariate and multivariate regression analyses were conducted to examine the association of the independent variables. Dependent variables were two outcome variables: dowry deaths and dowry-related suicides. Separate regression analyses were carried out for each dependent variable. Initially, each independent variable was regressed against each dependent variable. Those variables with a minimum P value of 0.25 were considered for multiple regression analyses. Hosmer and Lemeshow recommended a P value of < 0.25 to be used as a screening criterion for variable selection. 30 Multiple regression models were run by stepwise procedure with a P value of >0.10 to exit. All analyses were done using SPSS 17.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, USA).

In 2007, the total number of dowry deaths and dowry-related suicides reported by NCRB in India were 8093 and 3148, respectively. Table 1 reveals the trend of year-wise occurrence of dowry deaths during 1995-2007 in India. There was a 74% increase in the occurrence of dowry deaths from 1995 to 2007, and there was a 31% increase in the occurrence of dowry-related suicides during this period. Table 2 shows the values of both outcome and independent variables of 15 Indian states. Dowry deaths and dowry-related suicides are shown in the form of number of cases per million population. Of all states, the highest occurrence of dowry deaths and dowry-related suicides are reported from Bihar (followed by Orissa, Uttar Pradesh and Madhya Pradesh), and West Bengal (followed by Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra and Haryana), respectively.

Occurrence of dowry deaths and dowry-related suicides in India from 1995–2007.

Distribution of dowry deaths, dowry-related suicides and some socio-economic and demographic variables in the selected fifteen states of India.

The univariate regression revealed that occurrence of dowry deaths has significant association with three individual-level variables namely, age at marriage, literacy rate and women's exposure to mass media, and with two family-level variables namely, per capita income and spousal violence ( Table 3 ). With respect to dowry-related suicides, no significant relation is established with any of the independent variables. Of the 14 independent variables, nine variables which met the required criterion were included in multiple regression analysis ( Table 4 ). However, only women's literacy rate is significantly and inversely associated with occurrence of dowry deaths. Similar multivariate regression was carried out with occurrence of dowry-related suicides by considering four independent variables, however, none of them yielded significant association.

Details of univariate regression analysis for association of dowry deaths and dowry-related suicides with some socio-economic and demographic variables.

Details of multivariate regression analysis for association of dowry deaths and dowry-related suicides with selected socio-economic and demographic variables.

The analysis revealed that female literacy has a significant relationship with dowry deaths. From the selected fifteen states, the percentage of women's literacy rate is very low in Bihar (37%), Madhya Pradesh (44%), Uttar Pradesh (45%) and Orissa (52%), where more dowry deaths are reported. In univariate analysis, significant relationships with women's exposure to media and dowry death are found ( P = 0.004) . When there are higher proportions of women without exposure to media, the occurrence of dowry deaths are higher. In Bihar, more than 58% of women have no regular exposure to any kind of media and the total number of dowry deaths in 2007 was 1172. A similar situation is noted in Madhya Pradesh and Uttar Pradesh. Per capita income is another variable found significant during univariate analysis on the occurrence of dowry deaths ( P = 0.017). Data shows that where the per capita income is low dowry death has been reported high. Physical domestic violence is another variable found significant in univariate regression with dowry-related deaths ( P = 0.029). More dowry deaths have been reported in the states of Bihar, Madhya Pradesh and Uttar Pradesh than in other states where the prevalence of domestic violence is low. In these states 39%, 37% and 30.3% of women, respectively, have experienced domestic violence.

The present analysis reveals the increase of both dowry-related deaths and suicides in India during 1995–2007. There is no doubt that many dowry death cases are not reported and so the actual deaths and atrocities due to dowry are more than the present figures show. There are approximately 15 000 dowry deaths estimated per year, 31 which are mostly in kitchen fires designed to look like accidents. 32 Since India does not have a national injury surveillance system and the official records of these incidents are low, the only source of information about the incidence of burn morbidity and mortality is from police reports. 33 Sanghvi et al. 34 reported that 65% of fire-related deaths among women occurred in those aged 15–34 years and were likely to be caused by: kitchen accidents related to use of kerosene and flammability of garments, self-immolation or suicides and homicides related to domestic violence. Another study based on autopsy data of 5933 unnatural deaths over 25 years revealed that females (61%) outnumbered males (39%) in deaths for which cause of death was burns. 35 This autopsy study also revealed that 55.4% of the total unnatural deaths of women and only 12.8% of unnatural deaths in men occurred due to burns. Some micro-studies revealed that the injuries resulting from kitchen accidents, 36 , 37 self-immolation 38 and domestic violence 36 , 39 which could include dowry related harassment have lead to death. Also, there were instances in which fire-related homicides are disguised as accidents and suicides. 34

The number of dowry-related deaths in Kerala is lower than in many other Indian states. The literacy rate among men and women in Kerala is highest among all Indian states which could be one of the reasons for the relatively lower number of dowry-related deaths. Studies show that the dowry system is more rigid in the northern Hindi-speaking region consisting of Bihar, Uttar Pradesh and Rajasthan states. 40 Among the selected fifteen states, the highest number of dowry deaths occurred in Uttar Pradesh followed by Bihar and Madhya Pradesh, which are major Hindi-speaking northern states. Mukherjee et al. made an attempt to understand the regional variations in dowry deaths and other crimes against women. 41 Based on the NCRB data of three years (1995 to 1997), they concluded that the spatial concentration of dowry deaths is in the northern part of India. Age at marriage of women is an important factor with respect to her family life. To avoid giving too much dowry and to get rid of the burden of daughters, parents are marrying off their daughters at the earliest opportunity. As a result the very young bride is not able to resist and cope with the harassment of her husband and in-laws for dowry. The young woman is often helpless and, facing negative experiences of her family life or being victimised by her conjugal family, ultimately thinks that there is no option except committing suicide. Women's exposure to media is an important factor which may empower women to a great extent in their daily life. It is true that women who have more exposure will be able to resist and protest against the atrocities which they have been faced with due to the patriarchal norms. Women who are regularly exposed to media and with more access to modern educational systems challenge conventional thinking and lifestyles. Employed women are more likely to be exposed to media, and their financial resources allow them to question traditional practices which make them a burden to their families and undermine their status. 42 Women may also value the enhanced status in their conjugal families when they are given better dowries. The influences of modernization and self-interest may be paradoxical.

Poverty has multiple impacts in terms of everyone's life. Dowry is considered as one of the means to get rid of poverty, within the same class structure. Violence against women in the family was considered a family problem and never acknowledged as a crime or as a public health problem. It is discussed that women's lack of autonomy could be a major determinant of victimisation due to domestic violence. 43 There are reports of violence against women whose dowries are deemed insufficient by their husbands or the husbands’ families. 44 Some socio-economic characteristics like lower education and lower family income of women have a significant association with the occurrence of domestic violence, and harassment by in-laws has been reported in some cases. 45 The third National Family Health Survey reported that more than 33% of women in India have been physically mistreated by their husbands or other family members. 27 Dowry related issues could be one of the reasons for this mistreatment.

Thus, this study attempted to identify some determinants of dowry-related deaths and suicides. However, before discussing the implications of the findings, it is important to note the limitations, as usual to this type of data and analysis. Like any analysis based on the information collected by different agencies under different governments, there might be reporting bias across the states in reporting of deaths. Also, the yearly increases of dowry deaths and suicides may partially be due to improved reporting practices. Another limitation is data of cross-sectional type from different sources, which do not allow us to establish cause-and-effect relationships. The associations observed during regression analyses could be the function of some prior cause. Also, there is the possibility of multicollinearity in multiple regression models used. Theoretically one can assume an association between two independent variables included in the model. Though this will not affect the overall prediction efficacy of the model, this will affect the coefficients of the individual predictors. Despite these limitations, this analysis had methodological strengths including the use of nation-level data from well-established surveys and from fifteen varied states to generalise the results to the country.

Reports reveal that the rates of dowry deaths and related crimes have been rising. Studies have been addressed in an attempt to try to understand the factors that make young women vulnerable to dowry-related violence. Dowry death might simply be a result of several factors including marriage patterns (especially hypergamy), the economic dependency of women and cultural norms that make the state's enacting agencies, such as the police and judiciary, hesitant to intervene in cases of domestic violence. 46 Present day prevailing dowry and dowry deaths are related to the frustration of urban middle class people, unable to afford the status and lifestyle they desire on their own earnings. 47

It is evident that the conflict usually starts early in the marriage. A new bride is harassed when she brings a small amount of dowry and is compelled to bring more dowry from her family. However, her in-laws often remain unsatisfied and react to the situation with an attempt on the bride's life. 48 In order to curb this evil practice, The Dowry Prohibition Act 1961 was enacted, and amended in 1984 and 1986. The Act has been already questioned in terms of its existing ambiguity by experts. Most marriage negotiations are done as a confidential matter. Apart from this, both givers and takers of dowry are subject to criminal liability and so even if the bride is harassed by her in laws this will rarely be reported. Even after the legal recognition of crime, sometimes the concerned legal authorities consider violence against women in the home a private family matter. 49 Apart from the attitude of these authorities, the transformative law, which is supposed to make social transformation, has not considered the social customs, beliefs and values that would resist enforcement of these laws. 50 Since transformative law like The Dowry Prohibition Act has its own social, cultural and legislative limitations, there should be action-oriented initiatives and a comprehensive approach from all concerned individuals and institutions against dowry. The recent initiative from a gram panchayat (village-level self-government) in Kerala is a notable one. 51 Nilambur Grama Panchayat in Malappuram District of Kerala is expected to emerge as the first dowry-free panchayat in India. The Panchayat kicked off the campaign of being a ‘dowry-free village’ and set a new standard by pledging to ‘neither ask for nor give any dowry’ and has started a unique project against dowry. The Panchayat made initiatives to promote dowry-free marriages and to rehabilitate the victims of dowry abuse.

This analysis warrants that more research is required to better understand many societal, socio-cultural and economic issues responsible for this problem. In addition, there should be interventions from the health and welfare sectors of the government. Judicial stakeholders are also needed to look into the existing legislative deficiencies to combat the culturally-rooted malpractice in a better way. Moreover, the mindset of people is important and there should be strategies addressing discrimination against girls and women and the social norms that make dowry and dowry-related domestic violence acceptable within society. In addition, the present study warrants the addressing of the health consequences of dowry and dowry-related violence by the public health system. As advocated by earlier researchers, 34 there should be a national injury surveillance system. Also, there should be reliable estimates of dowry-related homicides. Despite the lack of such a system and estimates, efforts should be made to assess the present situation of the problem from other sources such as NCRB, 26 and other methods such as the compilation of data of medical certification of cause of death in urban hospitals, 52 surveys of causes of death 53 and the sample registration systems of births and deaths. 54 This information can be used to design and implement counter-measures to prevent dowry-related violence and deaths. Research among survivors of such violence, and family and neighbours of victims will give some insight into circumstances and triggers of this violence. Also, this research will provide insight into healthcare seeking of these victims, difficulties in seeking health care and reporting to the police. This type of information is more likely to translate into some preventive interventions.

GRB compiled the data, analysed and interpreted the data and wrote the first draft. BVB developed the data analysis plan, interpreted the results and refined the manuscript. Both the authors read and approved the final version. GRB is guarantor of the paper.

None declared.

Not required.

Google Scholar

Google Preview

- precipitating factors

- socioeconomic factors

- family health

- public health medicine

- surveillance, medical

| Month: | Total Views: |

|---|---|

| December 2016 | 2 |

| January 2017 | 3 |

| February 2017 | 12 |

| March 2017 | 12 |

| April 2017 | 11 |

| May 2017 | 3 |

| June 2017 | 3 |

| August 2017 | 14 |

| September 2017 | 4 |

| October 2017 | 26 |

| November 2017 | 25 |

| December 2017 | 8 |

| January 2018 | 1 |

| February 2018 | 12 |

| March 2018 | 14 |

| April 2018 | 9 |

| May 2018 | 6 |

| June 2018 | 3 |

| July 2018 | 4 |

| August 2018 | 10 |

| September 2018 | 3 |

| October 2018 | 19 |

| November 2018 | 10 |

| December 2018 | 4 |

| January 2019 | 5 |

| February 2019 | 9 |

| March 2019 | 11 |

| April 2019 | 15 |

| May 2019 | 14 |

| June 2019 | 9 |

| July 2019 | 8 |

| August 2019 | 30 |

| September 2019 | 12 |

| October 2019 | 8 |

| November 2019 | 15 |

| December 2019 | 14 |

| January 2020 | 13 |

| February 2020 | 6 |

| March 2020 | 7 |

| April 2020 | 17 |

| May 2020 | 6 |

| June 2020 | 61 |

| July 2020 | 74 |

| August 2020 | 63 |

| September 2020 | 86 |

| October 2020 | 162 |

| November 2020 | 172 |

| December 2020 | 139 |

| January 2021 | 102 |

| February 2021 | 150 |

| March 2021 | 176 |

| April 2021 | 182 |

| May 2021 | 157 |

| June 2021 | 271 |

| July 2021 | 296 |

| August 2021 | 202 |

| September 2021 | 275 |

| October 2021 | 297 |

| November 2021 | 318 |

| December 2021 | 249 |

| January 2022 | 194 |

| February 2022 | 253 |

| March 2022 | 199 |

| April 2022 | 245 |

| May 2022 | 266 |

| June 2022 | 148 |

| July 2022 | 103 |

| August 2022 | 94 |

| September 2022 | 164 |

| October 2022 | 156 |

| November 2022 | 163 |

| December 2022 | 179 |

| January 2023 | 185 |

| February 2023 | 173 |

| March 2023 | 75 |

| April 2023 | 77 |

| May 2023 | 57 |

| June 2023 | 42 |

| July 2023 | 61 |

| August 2023 | 39 |

| September 2023 | 50 |

| October 2023 | 59 |

| November 2023 | 64 |

| December 2023 | 82 |

| January 2024 | 53 |

| February 2024 | 63 |

| March 2024 | 105 |

| April 2024 | 104 |

| May 2024 | 78 |

| June 2024 | 18 |

Email alerts

Citing articles via.

- Contact RSTMH

- Recommend to your Library

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1876-3405

- Copyright © 2024 Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Dowry Death and Dowry System in India – Research Paper by Dev Raizada

Dowry Death is one of the most hideous or gruesome and burning issues in India. There have been Laws and Acts that have been enacted and incorporated by the legal system of the country; also there have been campaigns and awareness programs initiated by the Governmental and Non-Governmental Organisations against the Dowry Deaths and Dowry System in India, but in-spite the presence of such initiatives the statistics on dowry-related deaths have only increased in the country. Despite the rapid increase of the middle-class society and youth population, steps towards modernization, enormous privileged economic development, better education system and etc., there are still certain grey areas where the country is still lacking the growth and one of such issues is the prevalent Dowry System and related Deaths, which continues to rise with time. There is the Dowry Prohibition Act, 1961 which is enacted, and in addition the laws have been made more stringent namely, Section 304 B (dowry death) and Section 498 A (cruelty by husband or his relatives) have been integrated into the Indian Penal Code (I.P.C.) and also Section 113 B (presumption as to dowry death) have been made part of the Indian Evidence Act (I.E.A.) in order to eradicate or at-least lower down this heinous act of dowry system and related deaths. This research paper has made an effort to scrutinize and evaluate legal provisions which have been adapted and adopted by the Indian Legal System to minimize nuisance of Dowry Deaths, highlight loopholes and along-with its betterment in the legal system & the society and also to spotlight the available remedies as also how to further augment such remedies so as to be beneficial to the genuinely aggrieved party. Keywords: - Dowry Death; Dowry Prohibition Act, 1961; Dowry System; Government; Section 113–B of I.E.A.; Section 302–B of I.P.C.; Section 498–A of I.P.C.

Related Papers

The Medico-legal journal

Jagadish Rao

Marriage in India is a voluntary union for life of one man and one woman to the exclusion of all others. It is a social association where the husband has the responsibility to take care of and maintain his wife and not to neglect his duties. But in relation to this great institution, the problem of the "dowry" still persists. Women are ill-treated, harassed, killed or divorced for the simple reason that they do not get a dowry or do not get a sufficiently large one. To safeguard the interest of women against the cruelty they face within the four walls of their matrimonial home, the Indian Penal Code 1860 was amended in 1983 and section 498A was added. This deals with "Matrimonial Cruelty" to a woman. Matrimonial Cruelty in India is a cognizable, non-bailable and non-compoundable offence. Notwithstanding that the practice of demanding dowries was made illegal in India over 50 years ago, the (London) Times on 18 January 2012 reported that a study in 2007 concluded ...

PNMLEGAL ADVOCATES

Dipa Dube , Mukesh Yadav

Abstract Dowry Death has been one of the most barbaric forms of cruelty inflicted on young brides in the matrimonial home. Over the years, it assumed dangerous proportions calling for immediate legislative changes. Supreme Court judgment dated 11th Oct 2006 held that the demand for dowry or money from the parents of the bride has shown a phenomenal increase in last few years. Cases are frequently coming before the Courts, where the husband or in-laws have gone to the extent of killing the bride if the demand is not met. These crimes are generally committed in complete secrecy inside the house and it becomes very difficult for the prosecution to lead evidence. Forensic medical evidence has proved to be a crucial area in establishing the fact of ‘unnatural’ death before the Indian courts. An evaluation of cases indicates that proper scientific evidence has assisted the courts to establish the cause of deaths, while the absence of it has created a dilemma, leading to the acquittal of the accused. The paper emphasizes on the significance and indispensability of forensic medical evidence for the purpose of prosecuting an accused for the offence. Key Words: Dowry, Medical Evidence, Death, Forensic Evidence, Cause of Death

Preethi Nayak

Amrita Mukhopadhyay

This paper examines a judgment of the Supreme Court of India on the misuse of Section 498A as the 'weapon of disgruntled wives'. It examines the gendered provisions of the criminal law of India with regard to the institution of marriage.

Tribeni Saikia

Crimes are as old as human civilization and Crimes against Women have been in existence since then. Crimes against Women are ubiquitous. Nature of Crimes against Women, its types, dimensions and rate of change vary from country to country and time to time. Even within a country it varies from region to region. This study covers a period of two decades from 1994 – 2013. It has focused on analysing the trends of Crimes against Women after the advent of the era of Liberalisation, Privatisation and Globalisation. Here, crimes refer to only those crimes which are prescribed in criminal laws that have been taken up for analysis. Some of the special laws related to Crimes against Women have been analysed in addition to the general offences enumerated under IPC.

Biswajit Ghosh

kuldeep singh thind

Loading Preview

Sorry, preview is currently unavailable. You can download the paper by clicking the button above.

RELATED PAPERS

sudipto dhaivat

sanya kishwar

Shalu Nigam

Adv. Imran Ahmad

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

- Open access

- Published: 21 April 2022

Domestic violence in Indian women: lessons from nearly 20 years of surveillance

- Rakhi Dandona 1 , 2 ,

- Aradhita Gupta 1 ,

- Sibin George 1 ,

- Somy Kishan 1 &

- G. Anil Kumar 1

BMC Women's Health volume 22 , Article number: 128 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

24k Accesses

11 Citations

63 Altmetric

Metrics details

Prevalence of self-reported domestic violence against women in India is high. This paper investigates the national and sub-national trends in domestic violence in India to prioritise prevention activities and to highlight the limitations to data quality for surveillance in India.

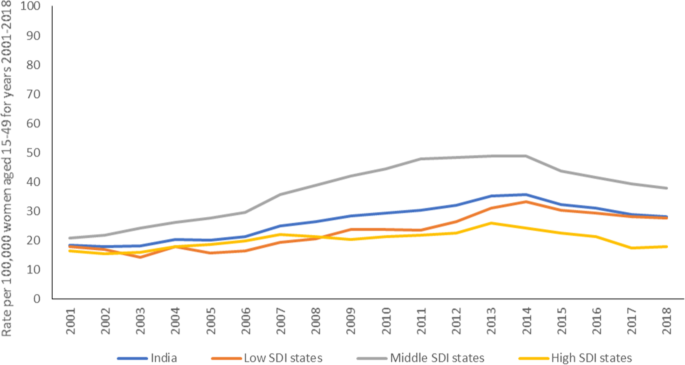

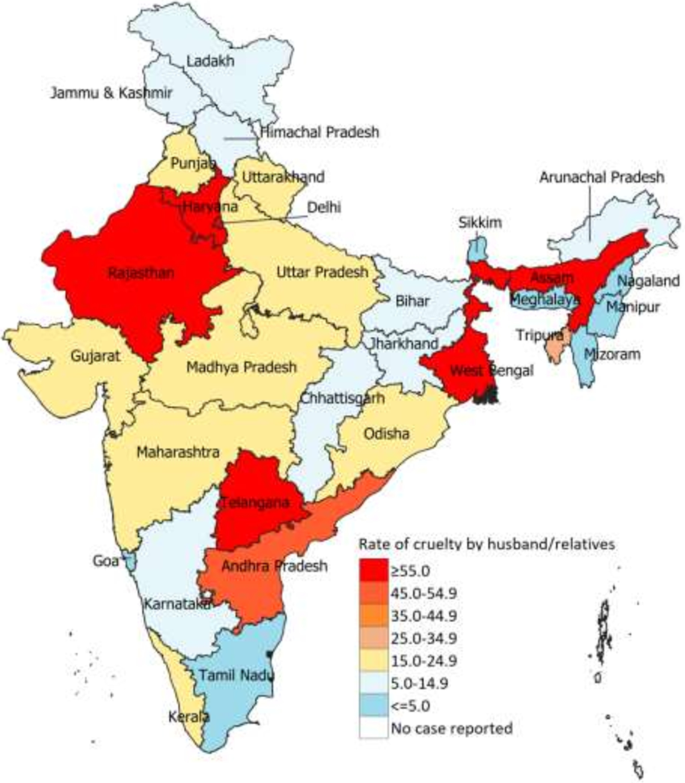

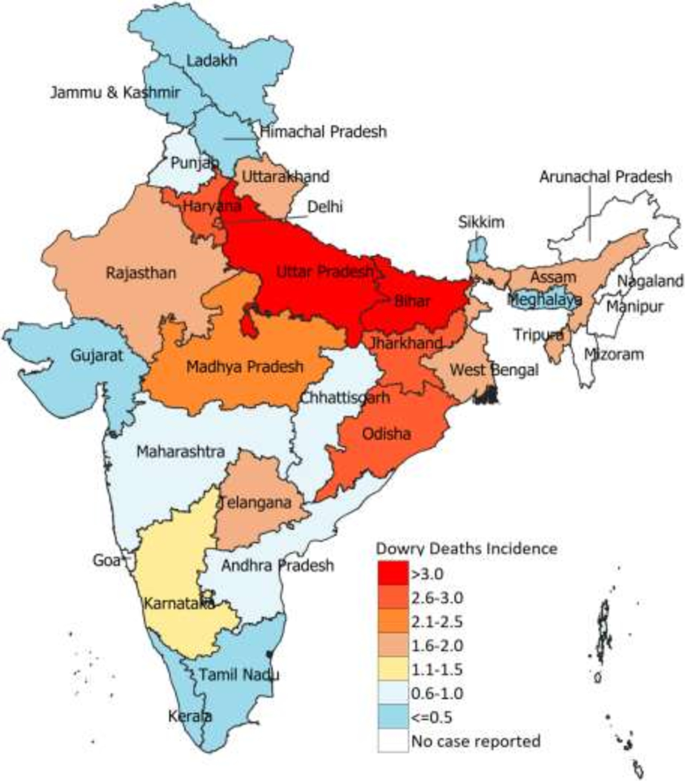

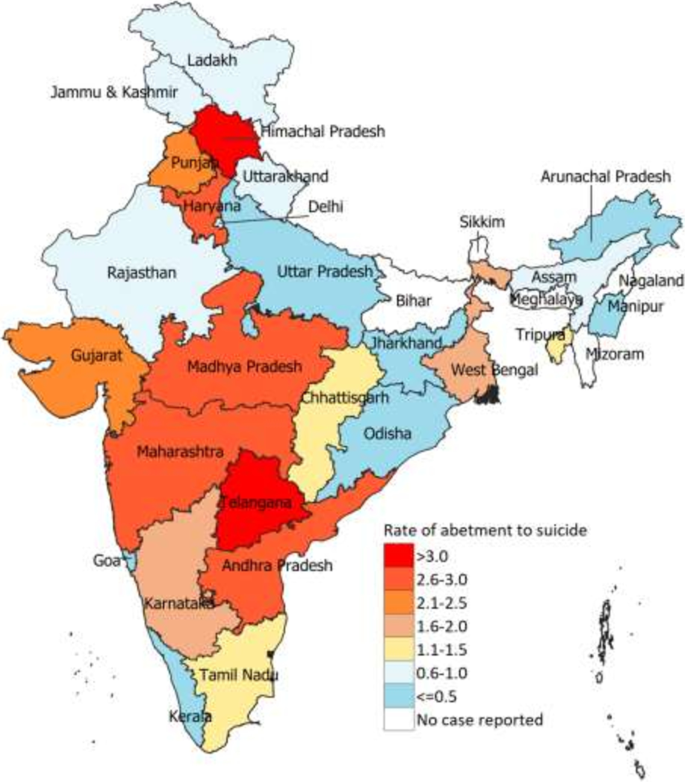

Data were extracted from annual reports of National Crimes Record Bureau (NCRB) under four domestic violence crime-headings—cruelty by husband or his relatives, dowry death, abetment to suicide, and protection of women against domestic violence act. Rate for each crime is reported per 100,000 women aged 15–49 years, for India and its states from 2001 to 2018. Data on persons arrested and legal status of the cases were extracted.

Rate of reported cases of cruelty by husband or relatives in India was 28.3 (95% CI 28.1–28.5) in 2018, an increase of 53% from 2001. State-level variations in this rate ranged from 0.5 (95% CI − 0.05 to 1.5) to 113.7 (95% CI 111.6–115.8) in 2018. Rate of reported dowry deaths and abetment to suicide was 2.0 (95% CI 2.0–2.0) and 1.4 (95% CI 1.4–1.4) in 2018 for India, respectively. Overall, a few states accounted for the temporal variation in these rates, with the reporting stagnant in most states over these years. The NCRB reporting system resulted in underreporting for certain crime-headings. The mean number of people arrested for these crimes had decreased over the period. Only 6.8% of the cases completed trials, with offenders convicted only in 15.5% cases in 2018. The NCRB data are available in heavily tabulated format with limited usage for intervention planning. The non-availability of individual level data in public domain limits exploration of patterns in domestic violence that could better inform policy actions to address domestic violence.

Conclusions

Urgent actions are needed to improve the robustness of NCRB data and the range of information available on domestic violence cases to utilise these data to effectively address domestic violence against women in India.

Peer Review reports