- Games & Quizzes

- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

- Introduction & Top Questions

Early years

- Declaring independence

- American in Paris

- Slavery and racism

- Party politics

- Cabinet of President Thomas Jefferson

Where was Thomas Jefferson educated?

What was thomas jefferson like, what is thomas jefferson remembered for.

Thomas Jefferson

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- Miller Center - Thomas Jefferson

- Thomas Jefferson's Monticello - Brief Biography of Thomas Jefferson

- Spartacus Educational - Biography of Thomas Jefferson

- USA 4 Kids - Biography of Thomas Jefferson

- Humanities LibreTexts - Jefferson as President

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy - Thomas Jefferson

- Lemelson-MIT - Biography of Thomas Jefferson

- Thomas Jefferson - Children's Encyclopedia (Ages 8-11)

- Thomas Jefferson - Student Encyclopedia (Ages 11 and up)

- Table Of Contents

Who was Thomas Jefferson?

Thomas Jefferson was the primary draftsman of the Declaration of Independence of the United States and the nation’s first secretary of state (1789–94), its second vice president (1797–1801), and, as the third president (1801–09), the statesman responsible for the Louisiana Purchase .

As a teenager, Thomas Jefferson boarded with the local schoolmaster to learn Latin and Greek. In 1760 he entered the College of William & Mary in Williamsburg , where he was influenced by, among others, George Wythe , the leading legal scholar in Virginia, with whom he read law from 1762 to 1767.

Thomas Jefferson was known for his shyness (apart from his two inaugural addresses as president , there is no record of Jefferson delivering any public speeches whatsoever) and for his zealous certainty about the American cause. He was full of contradictions, arguing for human freedom and equality while owning hundreds of enslaved people.

How was Thomas Jefferson influential?

Thomas Jefferson’s ideas about politics and government greatly influenced early American history. He believed that the American Revolution represented a clean break with the past and that the United States should reject all European versions of political discipline and resist efforts to create a strong central governmental authority.

Thomas Jefferson is remembered for being the primary writer of the Declaration of Independence and the third president of the United States. The fact that he owned over 600 enslaved people during his life while forcefully advocating for human freedom and equality made Jefferson one of America’s most problematic and paradoxical heroes.

Recent News

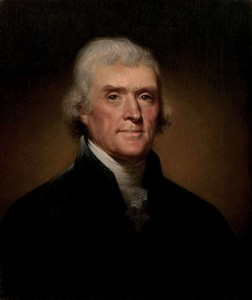

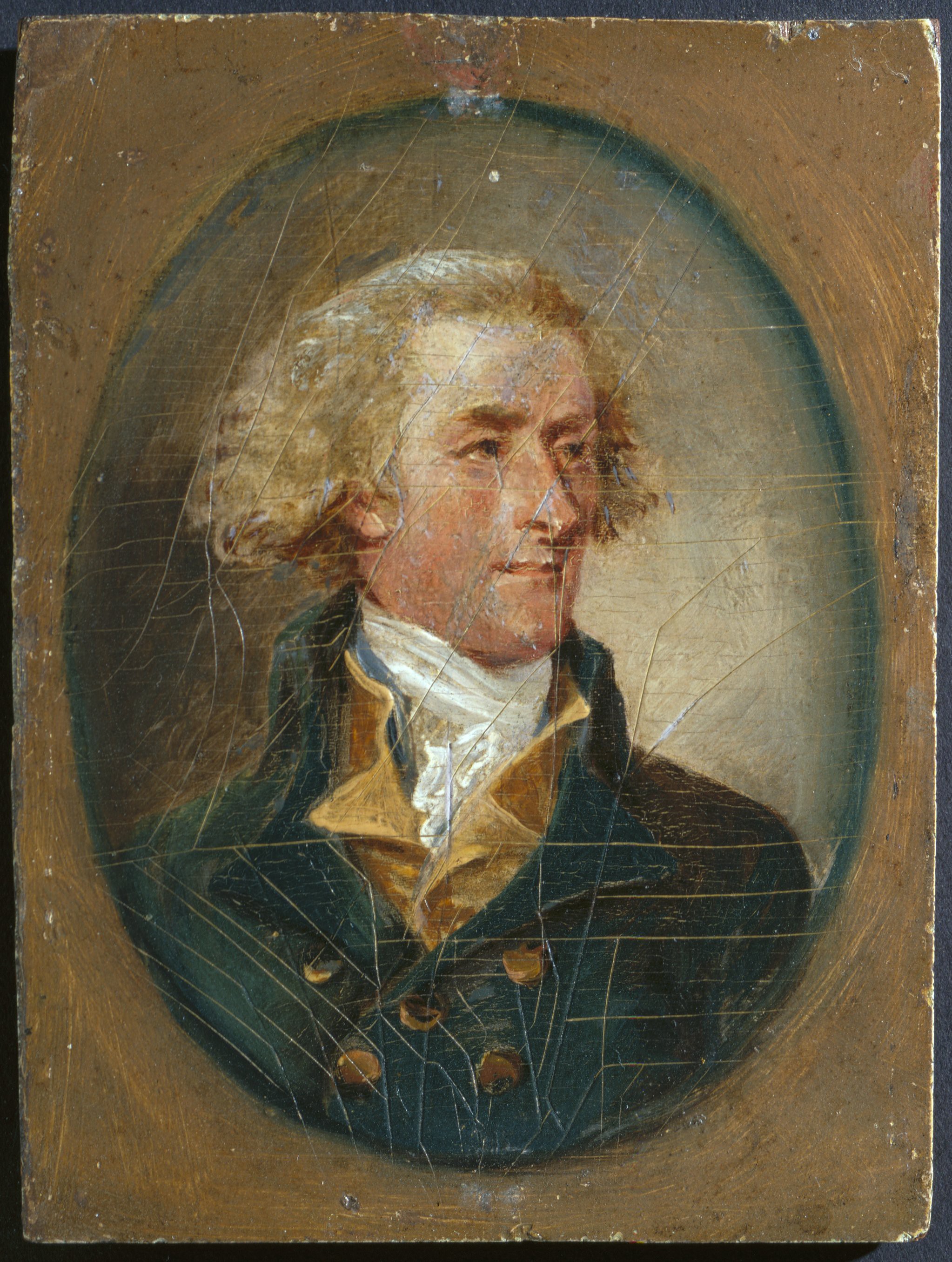

Thomas Jefferson (born April 2 [April 13, New Style], 1743, Shadwell, Virginia [U.S.]—died July 4, 1826, Monticello, Virginia, U.S.) was the draftsman of the Declaration of Independence of the United States and the nation’s first secretary of state (1789–94) and second vice president (1797–1801) and, as the third president (1801–09), the statesman responsible for the Louisiana Purchase . An early advocate of total separation of church and state , he also was the founder and architect of the University of Virginia and the most eloquent American proponent of individual freedom as the core meaning of the American Revolution .

Long regarded as America’s most distinguished “apostle of liberty,” Jefferson has come under increasingly critical scrutiny within the scholarly world. At the popular level, both in the United States and abroad, he remains an incandescent icon, an inspirational symbol for both major U.S. political parties, as well as for dissenters in communist China, liberal reformers in central and eastern Europe, and aspiring democrats in Africa and Latin America . His image has suffered, however, as the focus on racial equality has prompted a more negative reappraisal of his dependence upon slavery and his conviction that American society remain a white man’s domain. Especially disturbing to many were the DNA results of the 1998 study revealing that Jefferson had almost certainly fathered a child with his slave Sally Hemings , thirty years his junior. (For more on this story, see “Tom and Sally”: The Jefferson - Hemings paternity debate .) The huge gap between his lyrical expression of liberal ideals and the more attenuated reality of his own life has transformed Jefferson into America’s most problematic and paradoxical hero. The Jefferson Memorial in Washington, D.C. , was dedicated to him on April 13, 1943, the 200th anniversary of his birth.

(Read Joseph Ellis’s Britannica essay on the Sally Heming’s affair.)

Albermarle county, where Jefferson was born, lay in the foothills of the Blue Ridge Mountains in what was then regarded as a western province of the Old Dominion. His father, Peter Jefferson, was a self-educated surveyor who amassed a tidy estate that included 60 slaves. According to family lore, Jefferson’s earliest memory was as a three-year-old boy “being carried on a pillow by a mounted slave” when the family moved from Shadwell to Tuckahoe. His mother, Jane Randolph Jefferson, was descended from one of the most prominent families in Virginia . She raised two sons, of whom Jefferson was the eldest, and six daughters. There is reason to believe that Jefferson’s relationship with his mother was strained, especially after his father died in 1757, because he did everything he could to escape her supervision and had almost nothing to say about her in his memoirs. He boarded with the local schoolmaster to learn his Latin and Greek until 1760, when he entered the College of William & Mary in Williamsburg .

By all accounts he was an obsessive student, often spending 15 hours of the day with his books, 3 hours practicing his violin, and the remaining 6 hours eating and sleeping. The two chief influences on his learning were William Small, a Scottish-born teacher of mathematics and science , and George Wythe , the leading legal scholar in Virginia. From them Jefferson learned a keen appreciation of supportive mentors, a concept he later institutionalized at the University of Virginia. He read law with Wythe from 1762 to 1767, then left Williamsburg to practice, mostly representing small-scale planters from the western counties in cases involving land claims and titles. Although he handled no landmark cases and came across as a nervous and somewhat indifferent speaker before the bench, he earned a reputation as a formidable legal scholar. He was a shy and extremely serious young man.

In 1768 he made two important decisions: first, to build his own home atop an 867-foot- (264-metre-) high mountain near Shadwell that he eventually named Monticello and, second, to stand as a candidate for the House of Burgesses . These decisions nicely embodied the two competing impulses that would persist throughout his life—namely, to combine an active career in politics with periodic seclusion in his own private haven. His political timing was also impeccable , for he entered the Virginia legislature just as opposition to the taxation policies of the British Parliament was congealing. Although he made few speeches and tended to follow the lead of the Tidewater elite, his support for resolutions opposing Parliament’s authority over the colonies was resolute.

In the early 1770s his own character was also congealing. In 1772 he married Martha Wayles Skelton ( Martha Jefferson ), an attractive and delicate young widow whose dowry more than doubled his holdings in land and slaves. In 1774 he wrote A Summary View of the Rights of British America , which was quickly published, though without his permission, and catapulted him into visibility beyond Virginia as an early advocate of American independence from Parliament’s authority; the American colonies were tied to Great Britain, he believed, only by wholly voluntary bonds of loyalty to the king.

His reputation thus enhanced , the Virginia legislature appointed him a delegate to the Second Continental Congress in the spring of 1775. He rode into Philadelphia—and into American history—on June 20, 1775, a tall (slightly above 6 feet 2 inches [1.88 metres]) and gangly young man with reddish blond hair, hazel eyes, a burnished complexion, and rock-ribbed certainty about the American cause. In retrospect, the central paradox of his life was also on display, for the man who the following year was to craft the most famous manifesto for human equality in world history arrived in an ornate carriage drawn by four handsome horses and accompanied by three slaves.

Top of page

Collection Thomas Jefferson Papers, 1606 to 1827

American sphinx: the contradictions of thomas jefferson.

An essay by historian Joseph Ellis from the November-December 1994 issue of Civilization: The Magazine of the Library of Congress .

American Sphinx: The Character of Thomas Jefferson (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1997), which won the National Book Award for Nonfiction. This essay was originally published in the November-December 1994 issue of Civilization: The Magazine of the Library of Congress and bears a slightly different title from the book that followed it. This essay may not be reprinted in any other form or by any other source. For more recent writings by Ellis and others, see the Thomas Jefferson Memorial Foundation's Jefferson Web site, Monticello: The Home of Thomas Jefferson External , including discussion of Sally Hemings and the Hemings family External .

A Reincarnated Jefferson

The idea clicked into full consciousness one cold evening in November of 1993, in a large brick church in Worcester, Massachusetts. It was election night, and the streets of Worcester were clotted with drivers heading for the polls. The occasion that lured me into this morass was the public appearance of Thomas Jefferson. Or rather, the performance of an impersonator named Clay Jenkinson, who portrayed a reincarnated Jefferson, alive among us in the late 20th century.

I figured that a maximum of 40 or 50 hardy souls would show up. After all, this was a semischolarly affair, designed to bring Jefferson to life without fanfare or patriotic pageantry. Maybe down in Charlottesville or Richmond you could pack them in by murmuring, "Jefferson lives," but this was New England, which has a long outstanding suspicion of Virginia grandees.

As it turned out, about 400 enthusiastic New Englanders crowded into the church. Jenkinson began talking in the languid cadence of the Tidewater about Jefferson's early days at the College of William and Mary, his thoughts on the American Revolution, his love of French wine and French ideas, his accomplishments and frustrations as a political leader and president, his obsession with education, his elegiac correspondence with John Adams, his bottomless hope in America's democratic prospects. Jenkinson obviously knew his stuff. He was delivering an elegantly disguised history lecture that drew upon modern Jefferson scholarship quite deftly. The audience was entranced.

At the end, still in character and costume, Jenkinson took questions. What would you do about the health-care problem, Mr. Jefferson. Who is your favorite modern-day American president? Should we do something about the atrocities in Bosnia? Sprinkled into this mixture were several questions about American history and Jefferson's life: Why did you never remarry? What did you mean by "pursuit of happiness" in the Declaration of Independence? Why did you own slaves? This last question was the only one with a sharp edge, and Jenkinson handled it carefully. Slavery was a moral travesty, he said, an institution clearly at odds with the values of the American Revolution. He has tried his best to persuade his countrymen to end the slave trade and gradually end slavery itself. But he had failed. As for his own slaves, he treated them benevolently, as the fellow human beings they were. He concluded with a question of his own: What else would you have wanted me to do?

This seemed to satisfy the audience. But I was struck by the fact that when Jenkinson-as- Jefferson volunteered information on his less admirable features--his accommodation with slavery, his stiffbacked formality toward women, his tendency to gloss over complex social problems with felicitous language--the audience did not follow up. That's not what they had come to hear. If Jefferson was America's Mona Lisa, they had come to see him smiling.

Even so, I was surprised that no one asked a question about Sally Hemings, the young mulatto slave who was reputed to be Jefferson's lover and the mother of four of his children. My own experience as a college teacher suggested that most students could be counted on to know two things about Jefferson--that he wrote the Declaration of Independence and that he had been accused of an affair with Sally Hemings. This piece of scandalous gossip first surfaced when Jefferson was president, in 1802, and subsequently affixed itself to his reputation like a tin can that then rattled through the pages of history. A best-selling biography of Jefferson by Fawn Brodie, published in 1974, revived the old rumor for the modern generation, although in Brodie's version Jefferson and Sally loved each other, transforming the story of rape and subjugation (itself probably untrue) into a tragic but touching romance (an utter fabrication).

Jenkinson surprised me. He was neither historian nor an actor. A late-thirty-ish Midwesterner somewhat shorter than Jefferson's 6 feet 2 1/2 inches, he had graduated from the University of Minnesota and gone on to Oxford as a Rhodes scholar to study English literature. Currently on the faculty of the University of Nevada at Reno, he began assuming Jefferson's identity in 1984, when he helped found "the Great Plains Chautauqua," which was described as "a traveling humanities tent show" based in Bismark, North Dakota.

Jenkinson, who called himself a "scholar-impersonator," had somehow made Jefferson his own. Several state legislatures, scores of college and university audiences, and an even larger number of public gatherings like the one at Worcester had found his renderings of Jefferson impressive. A few months after I saw him, Jenkinson was the star attraction at a gala Jefferson celebration hosted by President Clinton, where he won the hearts of the White House staff by saying that Jefferson would have dismissed the entire Whitewater investigation as "absolutely nobody's business."

I met Jenkinson earlier that evening at a dinner put on by the American Antiquarian Society. The room was full of local business leaders, school superintendents and state politicians. Also present were two filmmaking groups. From Florentine Films came Camilla Rockwell, who told me that Ken Burns, the leading documentary filmmaker in the country, was planning to do a major project on Jefferson for public television. And from the Jefferson Legacy Foundation came Bud Leeds and Chip Stokes, who had recently launched a campaign to raise funds for a big-budget commercial film on Jefferson. Leeds and Stokes were flying out to Los Angeles the next morning to confer with Francis Ford Coppola and other Hollywood luminaries about scripts and actors. Their entourage also included an Iranian millionaire who told me that he had fallen in love with Jefferson soon after escaping the persecution of Islamic fundamentalists, an experience that made him appreciate the Jeffersonian belief in religious freedom and the separation of church and state.

I found myself wondering what other prominent historical figure could generate this kind of turnout. Certainly not George Washington. He has the biggest monument on the Mall, and the capital city itself carries his name, but he is just too patriarchal, too distant. Jefferson is Jesus, who came to live among us. Washington is Jehovah, aloof and alone in heaven.

Maybe Lincoln, usually the winner whenever polls try to measure public opinion on great American presidents, would draw such a crowd. Ordinary citizens tend to know as much about the Gettysburg Address as about the Declaration of Independence. Lincoln is magical too, but his is a different kind of magic, a more somber magic with a tragic dimension. Jefferson is light, graceful, inspiring. Lincoln is heavy, biblical, burdened. Lincoln is more respected, but Jefferson more loved.

That, at least, was what I was thinking as I drove home from Worcester that November evening. I even conjured up a picture of Jefferson atop some American version of Mount Olympus, dismissing competitors for the summit with a flick of that famous wrist, the one that wrote the Declaration of Independence--and that never healed properly after he broke it vaulting over a fountain in Paris while rushing to meet Maria Cosway, the object of his affections.

A silly thought, to be sure, but just the kind of extravagant enthusiasm that seemed to flower in the popular imagination wherever and whenever the Jefferson myth got planted. At the center of the silliness, however, is an idea that I had half-known but never fully appreciated until that night: Jefferson is America's special addiction, and something is going on out there in the minds and hearts of ordinary Americans at this moment in our national history to make that addiction particularly powerful. It is as if the American citizenry harbors some worrisome questions about the state of the republic and looks to him as America's oracle to provide reassuring answers.

Jefferson as "America's Everyman"

Once such an interpretive pattern lodges itself in the mind, of course, it quickly pulls half-forgotten odds and ends of one's memory and aligns them within the new grid-work. What came to my mind was a thesis advanced 30 years ago by Merrill Peterson in The Jefferson Image in the American Mind .

Peterson discovered that Jefferson had become America's Everyman, the cult hero for wildly divergent and often antagonistic political movements throughout the 19th and 20th centuries. The term Peterson used was "Protean Jefferson," which gave a respectably classical sound to what others might regard as Jefferson's disarming ideological promiscuity. Southern secessionists loved him; Northern abolitionists worshiped him; Gilded Age moguls echoed his warnings about federal power; Populists adored his advice about the evils of a banking conspiracy and the superiority of agrarian values. In the 1925 Scopes trial, both William Jennings Bryan and Clarence Darrow were sure that Jefferson agreed with their positions on evolution. Herbert Hoover and Franklin Roosevelt both claimed him as their guide to the problems of the Great Depression. In the 1930s isolationists and interventionists cited him as their spiritual mentor.

At some point, as this Jeffersonian procession passed by, I began to wonder whether there was anything Jefferson did not stand for. Was he a real historical person who once lived "back there" in time? Or was he a free-floating Rorschach test we carried around with us "up here" in the present?

These questions had ominous implication for anyone who harbored the traditional assumption that the quest to understand historical figures was a scholarly affair that would, albeit incrementally and gradually, contribute to the popular understanding of who they were and what they stood for. It seemed that Jefferson was simply too resonant, too interactive, too inherently elusive for that. The people who had gathered in Worcester carried assumptions about what Jefferson stood for that were infinitely more powerful than any set of historical facts. America's greatest historians and biographers could labor for decades to produce the most authoritative and sophisticated studies of Thomas Jefferson--Peterson, in fact, had proceeded to do precisely that--and their findings would bounce off the popular image of Jefferson without making a dent. Jefferson was not just a uniquely powerful touchstone, not just a seductively enigmatic historical hero. He was the Great Sphinx of American history. Coming to terms with Jefferson meant coming to terms with the most cherished convictions and contested truths in contemporary American culture.

My emerging hypothesis--that we are in the midst of a resurgent love affair with Jefferson that speaks, in some mysterious way, to our current ideological condition--evidently was shared by the political maestros at the White House, whose overnight polls provided up-to-the-minute readings of the American pulse. The week of his inauguration, Bill Clinton retraced Jefferson's trip from Monticello to Washington. And the White House staff made a point of apprizing the press that the new president was reading an advance copy of a soon-to-be-published popular biography of Jefferson by Willard Sterne Randall.

Clinton had also contributed, if unintentionally, to this interest in Jefferson during the presidential campaign. Allegations that Clinton was a womanizer prompted a flurry of newspaper and television reports on the sexual improprieties of past presidents, especially John F. Kennedy and Franklin D. Roosevelt. During the very month of the presidential election, The Atlantic Monthly put Thomas Jefferson on its cover and featured an essay by Douglas Wilson, a distinguished Jeffersonian scholar, titled "Thomas Jefferson and the Character Issue."

A month or two later, I received a letter from Mary Jo Salter, a good friend who also happens to be one of America's most respected poets. Mary Jo was in Paris, where she was continuing to perform her duties as poetry editor of The New Republic and completing a volume of new poems. The longest poem in the collection, it turned out, focused on none other than the ubiquitous Mr. Jefferson.

This seemed too coincidental. Could it be that politicians, propagandists, poets and impersonators were all plugged into the same cultural grid, which somehow had its main power source buried beneath the mountain at Monticello? Mary Jo said that she wanted me to suggest some books and articles about Jefferson and his time. I responded with a list of books, most of which she had already read. What I wanted in return was an answer to the simple question: Why Jefferson?

For a poet of Mary Jo's sensibility, it was clearly not a question of politics, at least in the customary sense of the term. She is not one to slide her mind into comfortable ideological grooves or sing patriotic hymns about freedom and democracy. Like any serious poet, she tends to defy trends, listen to her own internal voice, make her own music.

And that was just the kind of answer she gave to my question. "I knew I had the first part of a poem when I ran across a mention somewhere of TJ buying a thermometer on July 4, 1776--and recording a peak temperature of 76 degrees," Mary Jo recalled in a letter. It was a coincidence that caught her eye, a detail with poetic possibilities. Then she encountered one of history's eeriest coincidences--the deaths of Thomas Jefferson and John Adams on the same day, July 4, 1826, the 50th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence. For Mary Jo, it was perfect springboard for her imagination. As she put it, these coincidences were "poignant and eminently visual events."

Finally, she said that she was attracted to Jefferson's accessible complexity, what she called his "variousness." This was quite similar to Merrill Peterson's image of Protean Jefferson, but with a difference. Peterson emphasized the many meanings that posterity has imposed on Jefferson. Mary Jo was emphasizing the various and varied personae that actually existed inside Jefferson. "We love the fact that our favorite politician was a writer and a farmer and a scientists and an aesthete and a violinist," she wrote, "partly because we all wish to squeeze more out of our own 24-hour days...." Her Jefferson was a fascinating bundle of selves that beckoned to our modern sense of multiple identities. The poet, so it seemed to me, was getting closer to the essential appeal of Jefferson than were the biographers and historians.

The 250th Anniversary of Jefferson's Birth: Evocations

Meanwhile, the Jeffersonian flood was reaching new heights. During the year-long celebration of the 250th anniversary of Jefferson's birth, it seemed that every publishing house in America brought out a book on some aspect of his career or character. In addition to the full-length biography by Willard Sterne Randall, there were 17 new books with Jefferson's name in the title published in 1993. One of them, a novel by Max Byrd ( Jefferson ), offered an utterly captivating depiction of Jefferson's French phase and an evocation of his layered personality that rivaled Mary Jo's account in its imaginative power. (Byrd's novel supported my hunch that one needed the leeway provided by fiction or poetry to handle Jefferson's character compellingly.) Meanwhile, a major exhibition on "The Worlds of Thomas Jefferson at Monticello" attracted upwards of 600,000 visitors to Monticello last year (Elvis' Graceland just barely surpassed this figure.) And from Paris, Mary Jo wrote to say that James Ivory and Ismail Merchant had set up production there for a film called "Jefferson in Paris," focusing on the romantic interlude with Maria Cosway and, so I learned later, starring Nick Nolte in the title role.

Nothing like this had accompanied the 250th birthday of George Washington, Benjamin Franklin or John Adams. Nor had Lincoln's 150th birthday generated anything like this popular outpouring. It was as if one had attended a Fourth of July fireworks display and, instead of the usual rockets and sparklers, witnessed the detonation of a 2-megaton bomb.

As a cultural phenomenon, the Jeffersonian explosion was not a movement controlled or shaped by scholars or professional historians. Jefferson was part of the public domain, with daring power outside the academic world. The folks who ran publishing houses, produced films and mounted exhibitions, as well as the foundation directors who gave away money for worthy causes, obviously regarded Jefferson as a sure bet. The market for things Jeffersonian was wide and deep and strikingly diverse. It was--well, what other word fit so nicely?--democratic, in the Jeffersonian sense of the term.

The admiration for Jefferson was as much a psychological as a political phenomenon. In the hands of a poet like Salter or a novelist like Byrd, Jefferson became not Everyman but Postmodern Man, a series of overlapping and interacting personae that talked to us but not to each other. He could walk past the slave quarters on Mulberry Row at Monticello without qualms or guilt while daydreaming about the rights of man with utter sincerity. He could purchase the finest and most expensive art and furniture for his many residences, all the while idealizing the pastoral virtues of the sturdy farmer. He could fall in love with beautiful women in fits of rhapsodic passion but never allow the deepest secrets of his soul to be shared with any living creature. He was, like us, layered and conflicted but, as we wish to be, always in control, the perfect model for his beloved ideal of "self-government."

Historians Rethink Jefferson

In the academic world, the winds were gusting in a different direction. Not that scholars had ignored Jefferson or consigned him to some second tier of historical significance. Far from it. The number of scholarly books and articles focusing on Jefferson or some aspect of his long career continued to grow at a geometric rate; it requires two full volumes just to list all the Jefferson scholarship, much of it coming in the last quarter century. The central scholarly project, The Papers of Thomas Jefferson , continues to appear from Princeton University Press at the stately pace of one volume every two years or so (25 volumes had appeared by 1993). And Dumas Malone's authoritative biography, Jefferson and His Time , is an equally stately six-volume behemoth that, thanks to introductory offers from the Book-of-the-Month Club and History Book Club, graces the libraries and coffee tables of countless American homes.

The problem, then, was not a lack of academic interest or scholarly attention. The problem was a lowered academic opinion of the man and his accomplishments. Jefferson's captivating contradictions had come to be seen by many historians as massive hypocrisies, his elegant articulations of the American creed as platitudinous nonsense. The love affair with Jefferson that flourishes in the public domain had finally turned sour in the academic world. Once the symbol of all that is right with America, Jefferson had become the symbol of much that is wrong.

You could look back and, with the advantage of hindsight--which is, after all, the historian's crucial intellectual asset--locate the moment when the tide began to turn. In 1968 Winthrop Jordan published White over Black , a magisterial reappraisal of race relations in early America that featured a section on Jefferson. Jordan's book, which won the major prizes, offered a subtle and psychologically sophisticated assessment of Jefferson's attitudes toward slavery and blacks, suggesting that he was emblematic of white American society in the way his deep-seated racist values were hidden within folds of his personality.

White over Black was hardly a heavy-handed indictment of Jefferson. Jordan's major point was that racism had infiltrated the American soul very early in our history and that Jefferson simply provided the most resonant example of the virulence of racist values and the commingling of racial and sexual drives. Jordan's interpretation adopted an agnostic attitude toward the allegations of a sexual liaison with Sally Hemings. It is one of those intriguing pieces of gossip that can never be proved or disproved. Regardless of his relationship with Hemings, Jordan argued, Jefferson's deepest feelings toward blacks had their origins in primal urges that, like the sex drive, came from deep within his subconscious. Many other scholarly books and articles soon took up related themes, but Jordan's account set the terms of the debate about the centrality of race and slavery in any appraisal of Jefferson. And once that became a chief measure of Jefferson's character, his stock was fated to fall.

Another symptom of imminent decline--again, all this in retrospect--was a 1970 essay by Eric McKitrick, a professor of history at Columbia University, in the New York Review of Books . McKitrick was reviewing the recent biographies of Jefferson by Dumas Malone and Merrill Peterson, who were not only experts on Jefferson but the avowed ringleaders of what has been called the "Charlottesville Mafia," scholarly keepers of the Jefferson flame. In the course of a fair-minded assessment, McKitrick had the temerity to ask whether it might not be time to declare a moratorium on the generally benign and gentlemanly posture toward Monticello Man that was the hallmark of Malone's and Peterson's works. "What about those traits of character that aren't heroic from an angle?" asked McKitrick, mentioning Jefferson's accommodation and dependence upon slavery as well as "the frequent smugness, the covert vindictiveness, ...the hand-washing, the downright hypocrisy." What about his very un-Churchillian performance as governor of Virginia during the American Revolution, when he failed to mobilize the militia and had to flee Monticello on horseback ahead of the marauding British army? What about the fiasco of his American Embargo in 1807, when he clung to the illusion that economic sanctions would keep us out of war with England, even after it was clear that they only devastated the American economy?

The list of critical questions went on, effectively making the general point that interpretations of the man guided by Jefferson's own world view, what McKitrick called "the view from Jefferson's camp," had just about exhausted their explanatory power. What we obviously needed from the next generation of Jeffersonian scholars were some less fastidious and less friendly biographers who did not have their hearts or headquarters at Charlottesville.

The 1992 "Jeffersonian Legacies" Conference

Rather amazingly, it was in Charlottesville that the scholarly reassessment of Jefferson reached a crescendo. It happened in October 1992, when the University of Virginia convened a conference to commemorate its founder under the apparently harmless rubric of "Jeffersonian Legacies." The result was an intellectual free-for-all that went on for six days and nights. The conference spawned a collection of 15 essays published in record time by the University Press of Virginia, an hour-long videotape of the proceedings shown on PBS, and a series of newspaper stories in the Richmond papers and The Washington Post . Advertised as a scholarly version of a birthday party, the conference assumed the character of a public trial, with Jefferson--and the version of American history he symbolized--cast in the role of defendant.

The chief argument for the prosecution was delivered by Paul Finkelman, a hard-charging historian from Virginia Tech. "Because he was the author of the Declaration of Independence," said Finkelman, "the test of Jefferson's position on slavery is not whether he was better than the worst of his generation, but whether he was the leader of the best." The answer had the clear ring of an indictment: "Jefferson fails the test." For Finkelman, historians like Malone and Peterson had been mesmerized by the "d-word," Jefferson as the apostle of democracy. The more appropriate d-words were dissimulation, duplicity and denial.

According to Finkelman, Jefferson was an out-and-out racist who believed that blacks were inherently inferior to whites and who rejected the possibility that blacks and whites could ever live together on an equal basis. Moreover, his several attempts to end the slave trade or restrict the expansion of slavery beyond the South were halfhearted, as was his contemplation of a program of gradual emancipation. His beloved Monticello and personal extravagances were possible only because of slave labor. Finkelman argued that it was misguided--worse, it was positively sickening--to celebrate Jefferson as the father of freedom. In Finkelman's view, Jefferson was the ultimate symbol of the discrepancy (another d-word) between American rhetoric and American reality.

If Finkelman was the chief prosecutor, the star witness for the prosecution was Robert Cooley, a middle-aged black man who claimed to be a direct descendant of Jefferson and Sally Hemings. Cooley offered himself as "living proof" that the story of Jefferson's sexual relationship with one of his slaves was true. No matter what the Charlottesville Mafia or the tour guides at Monticello said, several generations of blacks living in Ohio and Illinois were certain they had Jefferson's blood in their veins. Scholars always talk about the absence of documentation and hard evidence, but how could such evidence exist? "We couldn't write then," Cooley explained. "We were slaves." And Jefferson's white children had destroyed all written records of the relationship soon after his death. Cooley essentially pitted the oral tradition of the black community against the scholarly tradition of professional historians. Cooley's version of history might not have had the bulk of the hard evidence on its side, but it clearly had the political leverage. Whether or not Jefferson had an affair with Sally Hemings, he was guilty of so many other moral crimes that it hardly made any difference. The Hemings story was either true literally or true metaphorically. The Washington Post reporter covering the conference caught the mood: "What tough times these are for icons!"

If the historical profession had any final words of wisdom to offer in the wake of what was being called "the cacophony at Charlottesville," they came from Gordon Wood, generally regarded as the leading historian of the Revolutionary era. Wood, a conference participant, was asked to review the published collection of essays for The New York Review of Books .

Wood called for a halt to the appropriation of prominent historical figures like Jefferson to serve as rallying points for modern-day political constituencies on the left or right. "We Americans make a great mistake in idolizing...and making symbols of authentic historical figures," warned Wood, "who cannot and should not be ripped out of their own time and place." And Jefferson had been especially abused: "By turning Jefferson into the kind of transcendent moral hero that no authentic historically situated human being could ever be, we leave ourselves demoralized by the time-bound weaknesses of this eighteenth-century slaveholder." In effect, the canonization of Jefferson as our preeminent political saint, Wood was suggesting, virtually assured his eventual slide into the status of villain. Why? Because we know too much about him. And what we know would always undercut his saintly and heroic status, leaving us disappointed and then angry, much like a starry-eyed fan who makes the mistake of actually getting to know his idol. We invested too much in Jefferson. The core of the problem is not his inevitable flaws but our unrealistic expectations.

Coming from a historian of Wood's reputation, who had no special affection for Jefferson and no special ties with the Charlottesville Mafia, the assessment had the realistic ring of common sense, a welcome note of sobriety amid a band of shrill partisans. It was rooted in the sound scholarly recognition that the late 18th century is a foreign country with a separate culture of its own. The historian's job is not so much to protect Jefferson's reputation as to protect the integrity of the past from modern-day raiding parties with obvious ideological agendas.

All of which makes complete scholarly sense but absolutely no practical difference. Jefferson is not like most other historical subjects--dead, forgotten and nonchalantly entrusted to historians, who presumably serve as the gravekeepers for buried memories no one really cares about anymore. Jefferson has risen from the dead. Lots of Americans care about the meaning of his memory. Historians could not control his legacy because it has escaped from the past, which they oversee, and is living in the present, a foreign country for most of them.

Evidence of Jefferson's natural tendency to surge out of the past and into the present kept popping up in the press in the months after the Charlottesville conference. In The New York Review of Books , Garry Wills used his review of the exhibition at Monticello to paint an unflattering portrait of Jefferson as a compulsive consumer of expensive French wines, art and furniture, an indulged aristocrat whose exorbitant tastes belied his rustic rhetoric about yeoman farmers and republican virtue. A few months later, The New York Times reported on a mock trial of Jefferson by the Bar Association of New York City, presided over by none other than Chief Justice William Rehnquist. The indictment consisted of the following three counts: that he subverted the independence of the federal judiciary; that he lived in the lavish manner of Louis XIV (Wills' charge); and that he frequently violated the Bill of Rights. Though Jefferson was found not guilty on all charges, the salient fact was that he had been moved off his pedestal and into the witness box.

The "Jeffersonian Surge"

Whether the most appropriate command was "back to the future" or "forward to the past," many of the professional historians with whom I spoke were relieved when the 250th anniversary of Jefferson's birth was over. It meant that they could reclaim the historical Jefferson and "get on with their own work," free of the anachronistic questions about relevance and legacies. When I asked my academic colleagues about the phenomenon I was now calling the Jeffersonian Surge, most of them expressed bemused indifference. It was all hype, they observed, like one of the feeding frenzies in the contemporary talk-show culture--Jefferson as the historical equivalent of Michael Jackson or Tonya Harding. Or it could be explained pragmatically: Jefferson had managed to get himself institutionalized with a mansion at Monticello, a university at Charlottesville and a memorial on the Tidal Basin in Washington, so there were several permanent constituencies poised to plug his birthday for self-interested reasons. For a professional historian, the thing to do when confronted with this kind of loony sensationalism is to stand still, close one's eyes and wait for it to pass.

One exception to this general pattern was Peter Onuf, the successor to Merrill Peterson as Thomas Jefferson Memorial Foundation Professor at the University of Virginia. Onuf predicted that scholarly criticism of Jefferson would seep into popular thinking, as the idealization of racial and ethnic diversity became an essential measure of America's dedication to equality. In effect, the democratic revolution Jefferson helped launch had now expanded to include a form of human equality--racial equality and integration--that Jefferson clearly could never have countenanced or even imagined. The next generation of Americans was not likely to raze the Jefferson Memorial or chip his face off Mount Rushmore, but the scholarly trend boded badly for Jefferson's reputation with posterity. As more Americans became aware of Jefferson as a slave-owning white racist, Onuf suggested, this flaw had the potential to trump all his virtues. The critical, even hostile, judgement of scholars was a preview of coming attractions in the larger popular culture.

In the October 1993 issue of The William and Mary Quarterly , the leading journal of early-American historians, Onuf suggested that the fascination with Jefferson's psychological complexity was gradually changing to frustration. The famous paradoxes that so intrigued poets, novelists and devotees of the "postmodern Jefferson" were beginning to look more like outright contradictions. The most glaring contradiction, his words in the Declaration of Independence as opposed to his lifelong ownership of slaves, was merely the most obvious disjunction between Jeffersonian rhetoric and Jeffersonian reality. Onuf described the emerging scholarly portrait of Jefferson as "a monster of self-deception," a man whose felicitous style was a bit too felicitous, concealing often incompatible ideals or dressing up platitudes as pieces of political wisdom that, as Onuf put it,"now circulate as the debased coin of our democratic culture." For Onuf, the multiple personalities of Jefferson were looking less like different facets of a Renaissance man and more like the artful disguises of a confidence man.

It occurred to me that the scholarly frustration Onuf described might derive from the realization that Jefferson's enigmatic character was never going to yield to conventional biographical or historical techniques (if, after all this time and effort, he remained the American Sphinx, well then, to hell with him). Onuf's point, on the other hand, was that a deconstructed Jefferson, a Jefferson divided into several disjoined selves that flickered into focus whenever convenient, then faded away whenever accountability was required, was hardly the stuff of a national hero. At some point, obliviousness stops looking like serenity and starts looking like hypocrisy.

With Jefferson, however, just when you think you have him cornered in an escape-proof room and are about to make an arrest, a trapdoor always seems to appear out of nowhere and he slips away to another adventure. The same week that I wrote the preceding paragraph, my eye came upon the following statement in boldface type in The New York Times Book Review : "Is your self shattered, your life riddled with inconsistency? Cheer up. That means you are resilient, postmodern."

This tongue-in-cheek observation was part of a serious review of a new book by Robert Jay Lifton called The Protean Self . The title echoed Merrill Peterson's description of Protean Jefferson, but with a new twist on its positive implications. Apparently Lifton, a prominent psychiatrist, was announcing that the new psychological ideal for the postmodern world was, in the reviewer's words, "a shapeshifter capable of assuming multiple identities without pathological fragmentation." In a world of jarring, unpredictable change, a world lacking clear borders between illusion and reality, with no shared sense of truth or morality, a premium was put on the ability to keep on the move inside yourself. The emerging psychological model was the "willful eclectic" who could live comfortably with contradictions.

This, of course, is a perfect description of Jefferson, or at least the version of Jefferson that scholars find so frustrating and, if Onuf is right, so reprehensible. But if Lifton is right, hypocrisy is an outmoded concept and Jefferson's disjointed personality is becoming the role model for postmodern society. (The trapdoor was opening again.) At any rate, I was grateful for Lifton's intriguing thesis because it helped me to understand what I meant when I used the term "postmodern." It also helped explain why poets, novelists and filmmakers are more favorably disposed toward Jefferson than scholars. They are more patient with and fascinated by Protean Jefferson because as artists they are more attuned to the interchangeable identities of the postmodern world.

Jefferson Today, A "Free-Floating Icon"

In the end, however, my thoughts returned to the faces of those ordinary Americans who had gathered at Worcester to celebrate Jefferson as their favorite Founding Father. They had absolutely no interest in deconstructing Jefferson or worshiping the disassembled parts of some engagingly incoherent hero. They were somewhat vulnerable, I suspect, to criticism of their idol as a racist. If the mounting scholarly case against Jefferson did filter down to the broader populace, it could do damage. But it seems clear to me that the deep reservoir of instinctive affection for Jefferson will probably remain intact. In its own way, the apparently unconditional love for Jefferson is every bit as mysterious as the enigmatic character of the man himself. Like a splendid sunset or a woman's beauty, it is simply there. It is the ultimate energy source for the Jeffersonian Surge.

Grass-roots Jeffersonianism, what we might also call Jeffersonian fundamentalism, has a long history of its own, but for our purposes its most instructive feature is the change in its character over the past 50 years. For most of American history, Jefferson was cast in the lead role in the dramatic clash between democracy and aristocracy, with Alexander Hamilton usually playing the opposite lead. If this dramatic formulation often had the suspicious odor of a soap opera, it also had the decided advantage of fitting neatly into the mainstream political categories and parties: It was the people against the interests, agrarians against the industrialists, the West against the East, Democrats against Republicans. Jefferson was one-half the American political dialogue, the liberal voice of "the many" holding forth against the conservative voice of "the few."

This version of American history always had the semifictional quality of an imposed plot line, but it stopped making much sense at all by the New Deal era, when Franklin Roosevelt invoked Hamiltonian methods (i.e., government intervention) to achieve Jeffersonians goals (i.e., economic equality). After the New Deal, most historians abandoned the Jefferson-Hamilton distinction altogether and most politicians stopped yearning for a Jeffersonian utopia free of all government influence. The disintegration of the old categories meant the demise of Jefferson as the symbolic leader of liberal partisans fighting valiantly against the entrenched interests. In a sense, what happened was that Jefferson ceased to function as the liberal half of the American political dialogue and became instead the presiding presence who stood above all political conflicts and parties.

And this, of course, is where he resides today, a kind of free-floating icon who hovers over the American political scene much like one of those dirigibles cruising above the Super Bowl, flashing words of encouragement to both teams. Formerly the property of liberal crusaders, he is now claimed by Democrats and Republicans alike. In fact, the most effective articulator of Jeffersonian rhetoric in the last half of the 20th century has been Ronald Reagan, the most conservative president since Calvin Coolidge, whose belief in less government, individual freedoms and American destiny came straight out of the Jeffersonian lexicon. Jefferson is not just an essential ingredient in the American political tradition, but the essence itself.

If you really press the issue, if you edit out all the extraneous voices and get to the core of Jefferson's thinking, the primal stuff consists of a single sentence of 35 simple words:

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain inalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness .

These are the magic words of American history. To question them is to commit some combination of sacrilege and treason. Actually, they are not quite the words Jefferson first composed in June of 1776. His original draft, the pure Jeffersonian version of the message before editorial changes were made by the Continental Congress, makes it even clearer that Jefferson intended to express an essentially moral or spiritual vision:

We hold these truths to be sacred & undeniable; that all men are created equal & independent, that from that equal creation they derive rights inherent & inalienable, among which are the preservation of life, & liberty, & the pursuit of happiness .

Two monumental claims are being made here, one explicit and the other implicit. The explicit claim is that the individual is the sovereign unit in society. His natural state is freedom and equality with all other individuals. This is the natural order of things. All restrictions on this natural order are illegal and immoral transgressions, violations of what God intended. The implicit claim is that the removal of those artificial and arbitrary restraints on individual freedom will release unprecedented amounts of energy into the world. The liberated individual will, in effect, interact with his fellows in a harmonious scheme that recovers the natural order and allows for the fullest realization of human potential.

Now if you say that these claims are wildly unrealistic and utopian, the kind of news that is just too good to be true, you would be completely correct. Jefferson was not a profound political thinker. As John Adams and James Madison sometimes tried to tell him, his efforts at political philosophy were often embarrassingly superficial and sometimes downright juvenile. But Jefferson was less a cogent or logical political thinker than a brilliant political theologian and visionary. The genius of his vision is first to propose that our deepest personal yearnings are in fact achievable, then to articulate opposing principles in a way that conceals their irreconcilability. Jefferson guards the American creed at an inspirational level, where all of us can congregate as individual Americans regardless of race, class or gender and speak the magic words together.

Here is the point where being a scholar and being an American divide. The natural instinct of the scholar is to pull Jefferson down from the high ground, to document the many ways that Jefferson himself failed to accept the full implications of his vision--slavery, racism and sexism are chief offenses--and to expose the inherent contradictions embedded within the creed.

The overwhelming feeling of ordinary Americans, however, is quite the opposite. That gathering of citizens in the Worcester church is illustrative. As they sat together in Jefferson's presence, they could simultaneously embrace the following propositions: that abortion is a woman's right, and than an unborn child cannot be killed; that health care for all Americans is a moral imperative, and that the government bureaucracies required to oversee health care (or welfare, or environmental protection) stifle individual freedom; that blacks and women (and gays and lesbians) cannot be denied their rights as citizens, and that affirmative-action programs are misguided violations of the egalitarian principle.

The Jeffersonian magic works because we permit it to function at a rarefied rhetorical level where real-world choices do not have to be made. As we segregate ourselves into a bewildering variety of racial, ethnic, gender and class categories, all defending our respective territories under the multicultural banner, there are precious few plots of common ground on which we can come together as Americans. Jefferson provides that space, which is actually not common ground at all, but a midair location floating above all the battle lines. In this Jefferson space we become, at least for a moment, an American chorus instead of an American cacophony.

What William James said about religious experience is also true for the Jeffersonian experience: If you have not had it, no one can explain it to you. But you do not need to be an American to feel the spirit move. In fact, the Jeffersonian Surge is probably stronger in parts of Central Europe than anywhere else. You could give a party for Jefferson in contemporary Gdansk, Prague or St. Petersburg and be pretty certain that an enthusiastic band of celebrants would show up seeking the same inspiration as those Worcester residents.

At the end of August, The Washington Post published a long story on a wealthy Iranian named Bahman Batmanghelidj. His picture looked familiar, and then I recognized him as the philanthropist I met in Worcester. It turned out that Batmanghelidj was rallying opposition to the Merchant and Ivory film on Jefferson, which supposedly sanctions the story of Jefferson's liaison with Sally Hemings.

"Americans don't realize," Batmanghelidj warned, "how profoundly Jefferson and his ideas live on in the hopes and dreams of people in other countries. This movie will undercut all that. People around the world will view it as the defining truth about Jefferson. And of course it is a lie."

Well, yes, it almost certainly is. But then so is a hefty portion of the more attractive sources of Jefferson's image. Batmanghelidj's crusade was just the latest skirmish in the escalating struggle over Jefferson's legacy. The stakes are high, as can be seen in the stark formulation of James Parton, one of Jefferson's earliest biographers: "If Jefferson is wrong, America is wrong. If America is right, Jefferson was right."

The ongoing debate about Jefferson is less an argument about the man himself than about what he stands for. It is not even an argument about whether what he stands for is a viable idea or a seductive illusion. After all, every great nation draws inspiration from illusions. The debate is about whether those illusions still work for us and whether the abiding Jeffersonian optimism that underlies them is still justified.

by Joseph J. Ellis

Books and Articles Discussed in this Essay

Fawn Brodie. Thomas Jefferson: An Intimate History . New York: Norton, 1974. LC Call Number: E332 .B787

Merrill Peterson. The Jefferson Image in the American Mind . New York: Oxford University Press, 1960. LC Call Number: E332.2 .P4

Douglas L. Wilson, "Thomas Jefferson and the Character Issue," The Atlantic Monthly , 270:5 (November 1992), 57-74. LC Call Number: AP2 .A8

Willard Sterne Randall. Thomas Jefferson: A Life . New York: H. Holt, 1993. LC Call Number: E332 .R196 1993

Max Byrd. Jefferson: A Novel . New York: Bantam Books, c1993. LC Call Number: PS3552 .Y675 J44 1993

Garry Wills, "The Aesthete," The New York Review of Books , August 12, 1993. LC Call Number: AP2 .N6552

Susan R. Stein. The Worlds of Thomas Jefferson at Monticello . New York: H. N. Abrams, in association with the Thomas Jefferson Memorial Foundation, 1993. LC Call Number: E332.2 .S84 1993

The Papers of Thomas Jefferson. Ed., Julian P. Boyd. Vols. 1-. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1950- LC Call Number: E 302 .J442 1950a

Dumas Malone. Jefferson and His Time . 6 vols. Boston: Little, Brown, 1948-1981. LC Call Number: E332 .M25

Wintrop Jordan, White Over Black: American Attitudes toward the Negro, 1550-1812 . Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1968; New York: Norton, 1977. LC Call Numbers: E185 .J69; E446 .J68, 1977

Eric McKitrick, "The View from Jefferson's Camp," The New York Review of Books , December 17, 1970. LC Call Number: AP2 .N6552

Peter S. Onuf, ed. Jeffersonian Legacies . Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1993. LC Call Number: E332.2 .J48 1993

Gordon S. Wood, "Jefferson at Home," New York Review of Books , 1993. LC Call Number: AP2 .N6552

Peter Onuf, "The Scholars' Jefferson," William and Mary Quarterly 3d Series, L:4 (October 1993), 671-699. LC Call Number: F221 .W71

James Parton. Life of Thomas Jefferson, Third President of the United States . Boston: J. R. Osgood and Company, 1874; New York: Da Capo Press, 1971. LC Call Number: E322 .P27 1971

- Subject List

- Take a Tour

- For Authors

- Subscriber Services

- Publications

- African American Studies

- African Studies

American Literature

- Anthropology

- Architecture Planning and Preservation

- Art History

- Atlantic History

- Biblical Studies

- British and Irish Literature

- Childhood Studies

- Chinese Studies

- Cinema and Media Studies

- Communication

- Criminology

- Environmental Science

- Evolutionary Biology

- International Law

- International Relations

- Islamic Studies

- Jewish Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Latino Studies

- Linguistics

- Literary and Critical Theory

- Medieval Studies

- Military History

- Political Science

- Public Health

- Renaissance and Reformation

- Social Work

- Urban Studies

- Victorian Literature

- Browse All Subjects

How to Subscribe

- Free Trials

In This Article Expand or collapse the "in this article" section Thomas Jefferson

Introduction.

- Papers of Thomas Jefferson

- Papers of Thomas Jefferson, Second Series

- Other Book-Length Works

- Reference Books

- Biographies

- Books and Reading

- General Studies

- Declaration of Independence

- Notes on the State of Virginia

- Other Writings

- Race and Gender

- Essay Collections

Related Articles Expand or collapse the "related articles" section about

About related articles close popup.

Lorem Ipsum Sit Dolor Amet

Vestibulum ante ipsum primis in faucibus orci luctus et ultrices posuere cubilia Curae; Aliquam ligula odio, euismod ut aliquam et, vestibulum nec risus. Nulla viverra, arcu et iaculis consequat, justo diam ornare tellus, semper ultrices tellus nunc eu tellus.

- J. Hector St. John de Crèvecœur

- Joel Barlow

- Mercy Otis Warren

- Music of the American Revolution

- Roger Williams

- Royall Tyler

- The Federalist Papers

- Thomas Paine

Other Subject Areas

Forthcoming articles expand or collapse the "forthcoming articles" section.

- Mary Boykin Chesnut

- Phillis Wheatley Peters

- Richard Selzer

- Find more forthcoming articles...

- Export Citations

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Thomas Jefferson by Kevin J. Hayes LAST REVIEWED: 24 July 2018 LAST MODIFIED: 24 July 2018 DOI: 10.1093/obo/9780199827251-0180

A chronological list of the various positions Thomas Jefferson held over the course of his lengthy public career can serve as a rough outline of his life: member of the Virginia House of Burgesses, delegate to the Continental Congress, member of the Virginia House of Delegates, governor of Virginia, minister to France, US secretary of state, president of the American Philosophical Society, US vice president, US president, and founder and rector of the University of Virginia. All these positions do not touch upon the numerous other roles Jefferson played in his life: architect, author, bookman, farmer, father, grandfather, lawyer, scientist, and traveler. As an author, for example, Jefferson is best known for the Declaration of Independence and Notes on the State of Virginia , but he wrote much else, as well. He is one of the finest and most prolific letter writers in American literature. He wrote an autobiography; a secular life of Jesus of Nazareth; the Manual of Parliamentary Practice ; numerous acts of legislation; and many pamphlets, including Observation on the Whale Fishery , Proceedings and Report of the Commissioners for the University of Virginia , and Summary View of the Rights of British America ; and The Anas , a compilation of conversation recorded while he was a member of George Washington’s cabinet. Students interested in nearly any topic about American history, literature, or culture can look to Thomas Jefferson to find an exciting subject for research. The works listed here are designed to provide useful starting points for research in many different fields of study. The list of primary texts provides works written by Jefferson, but they all contain detailed introductions and annotations to help put Jefferson’s writings into their biographical, cultural, and historical contexts. The remainder of this article is devoted to secondary works, that is, writings about Thomas Jefferson. Discussed are reference books, biographies, and volumes devoted to the following major topics: books and reading, critical studies, political science, race and gender, and science. Collections of critical and historical essays are grouped together, as are works that view Jefferson’s enduring influence on the nation and the world.

Primary Texts

The primary bibliography that constitutes this section is subdivided into four parts. One section lists the two separate series of the Papers of Thomas Jefferson , the First Series and the Retirement Series. The Second Series of the Papers , which is composed of stand-alone works, gets its own section. Other book-length works that have not been or will not be included in the Papers of Thomas Jefferson are listed in the third section, and the fourth section provides a highly selective list of Jefferson’s letters.

back to top

Users without a subscription are not able to see the full content on this page. Please subscribe or login .

Oxford Bibliographies Online is available by subscription and perpetual access to institutions. For more information or to contact an Oxford Sales Representative click here .

- About American Literature »

- Meet the Editorial Board »

- Adams, Alice

- Adams, Henry

- African American Vernacular Tradition

- Agee, James

- Alcott, Louisa May

- Alexie, Sherman

- Alger, Horatio

- American Exceptionalism

- American Grammars and Usage Guides

- American Literature and Religion

- American Magazines, Early 20th-Century Popular

- "American Renaissance"

- American Revolution, Music of the

- Amiri Baraka (LeRoi Jones)

- Anaya, Rudolfo

- Anderson, Sherwood

- Angel Island Poetry

- Antin, Mary

- Anzaldúa, Gloria

- Austin, Mary

- Baldwin, James

- Barlow, Joel

- Barth, John

- Bellamy, Edward

- Bellow, Saul

- Bible and American Literature, The

- Bierce, Ambrose

- Bishop, Elizabeth

- Bourne, Randolph

- Bradford, William

- Bradstreet, Anne

- Brockden Brown, Charles

- Brooks, Van Wyck

- Brown, Sterling

- Brown, William Wells

- Butler, Octavia

- Byrd, William

- Cahan, Abraham

- Callahan, Sophia Alice

- Captivity Narratives

- Cather, Willa

- Cervantes, Lorna Dee

- Chesnutt, Charles Waddell

- Child, Lydia Maria

- Chopin, Kate

- Cisneros, Sandra

- Civil War Literature, 1861–1914

- Clark, Walter Van Tilburg

- Connell, Evan S.

- Cooper, Anna Julia

- Cooper, James Fenimore

- Copyright Laws

- Crane, Stephen

- Creeley, Robert

- Cruz, Sor Juana Inés de la

- Cullen, Countee

- Culture, Mass and Popular

- Davis, Rebecca Harding

- Dawes Severalty Act

- de Burgos, Julia

- de Crèvecœur, J. Hector St. John

- Delany, Samuel R.

- Dick, Philip K.

- Dickinson, Emily

- Doctorow, E. L.

- Douglass, Frederick

- Dreiser, Theodore

- Dubus, Andre

- Dunbar, Paul Laurence

- Dunbar-Nelson, Alice

- Dune and the Dune Series, Frank Herbert’s

- Eastman, Charles

- Eaton, Edith Maude (Sui Sin Far)

- Eaton, Winnifred

- Edwards, Jonathan

- Eliot, T. S.

- Emerson, Ralph Waldo

- Environmental Writing

- Equiano, Olaudah

- Erdrich (Ojibwe), Louise

- Faulkner, William

- Fauset, Jessie

- Federalist Papers, The

- Ferlinghetti, Lawrence

- Fiedler, Leslie

- Fitzgerald, F. Scott

- Frank, Waldo

- Franklin, Benjamin

- Freeman, Mary Wilkins

- Frontier Humor

- Fuller, Margaret

- Gaines, Ernest

- Garland, Hamlin

- Garrison, William Lloyd

- Gibson, William

- Gilman, Charlotte Perkins

- Ginsberg, Allen

- Glasgow, Ellen

- Glaspell, Susan

- González, Jovita

- Graphic Narratives in the U.S.

- Great Awakening(s)

- Griggs, Sutton

- Hansberry, Lorraine

- Harper, Frances Ellen Watkins

- Harte, Bret

- Hawthorne, Nathaniel

- Hawthorne, Sophia Peabody

- H.D. (Hilda Doolittle)

- Hellman, Lillian

- Hemingway, Ernest

- Higginson, Ella Rhoads

- Higginson, Thomas Wentworth

- Hughes, Langston

- Indian Removal

- Irving, Washington

- James, Henry

- Jefferson, Thomas

- Jesuit Relations

- Jewett, Sarah Orne

- Johnson, Charles

- Johnson, James Weldon

- Kerouac, Jack

- King, Martin Luther

- Kirkland, Caroline

- Knight, Sarah Kemble

- Larsen, Nella

- Lazarus, Emma

- Le Guin, Ursula K.

- Lewis, Sinclair

- Literary Biography, American

- Literature, Italian-American

- London, Jack

- Longfellow, Henry Wadsworth

- Lost Generation

- Lowell, Amy

- Magazines, Nineteenth-Century American

- Mailer, Norman

- Malamud, Bernard

- Manifest Destiny

- Mather, Cotton

- Maxwell, William

- McCarthy, Cormac

- McCullers, Carson

- McKay, Claude

- McNickle, D'Arcy

- Melville, Herman

- Merrill, James

- Millay, Edna St. Vincent

- Miller, Arthur

- Moore, Marianne

- Morrison, Toni

- Morton, Sarah Wentworth

- Mourning Dove (Syilx Okanagan)

- Mukherjee, Bharati

- Murray, Judith Sargent

- Native American Oral Literatures

- New England “Pilgrim” and “Puritan” Cultures

- New Netherland Literature

- Newspapers, Nineteenth-Century American

- Norris, Zoe Anderson

- Northup, Solomon

- O'Brien, Tim

- Occom, Samson and the Brotherton Indians

- Olsen, Tillie

- Olson, Charles

- Ortiz, Simon

- Paine, Thomas

- Piatt, Sarah

- Pinsky, Robert

- Plath, Sylvia

- Poe, Edgar Allan

- Porter, Katherine Anne

- Proletarian Literature

- Realism and Naturalism

- Reed, Ishmael

- Regionalism

- Rich, Adrienne

- Rivera, Tomás

- Robinson, Kim Stanley

- Roth, Henry

- Roth, Philip

- Rowson, Susanna Haswell

- Ruiz de Burton, María Amparo

- Russ, Joanna

- Sanchez, Sonia

- Schoolcraft, Jane Johnston

- Sentimentalism and Domestic Fiction

- Sexton, Anne

- Silko, Leslie Marmon

- Sinclair, Upton

- Smith, John

- Smith, Lillian

- Spofford, Harriet Prescott

- Stein, Gertrude

- Steinbeck, John

- Stevens, Wallace

- Stoddard, Elizabeth

- Stowe, Harriet Beecher

- Tate, Allen

- Terry Prince, Lucy

- Thoreau, Henry David

- Time Travel

- Tourgée, Albion W.

- Transcendentalism

- Truth, Sojourner

- Twain, Mark

- Tyler, Royall

- Updike, John

- Vallejo, Mariano Guadalupe

- Viramontes, Helena María

- Vizenor, Gerald

- Walker, David

- Walker, Margaret

- War Literature, Vietnam

- Warren, Mercy Otis

- Warren, Robert Penn

- Wells, Ida B.

- Welty, Eudora

- Wendy Rose (Miwok/Hopi)

- Wharton, Edith

- Whitman, Sarah Helen

- Whitman, Walt

- Whitman’s Bohemian New York City

- Whittier, John Greenleaf

- Wideman, John Edgar

- Wigglesworth, Michael

- Williams, Roger

- Williams, Tennessee

- Williams, William Carlos

- Wilson, August

- Winthrop, John

- Wister, Owen

- Woolman, John

- Woolson, Constance Fenimore

- Wright, Richard

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

Powered by:

- [185.66.14.133]

- 185.66.14.133

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

27 Thomas Jefferson (1743-1826)

Samuel Metivier

Introduction

Mr. Thomas Jefferson was born on April 13th, 1743 in Shadwell, Virginia, where he lived on a slave plantation with his family. His father’s name was Peter and his mother’s name was Jane Randolph Jefferson, who was the daughter of a popular Virginia family. In the year of 1760, Jefferson went to the College of William and Mary. He studied and practiced law for many years. Jefferson was the main director in writing the Declaration of Independence. Although there were other men who helped write the draft, most historians say that Jefferson had the most input and control on the original draft. According to Charles A. Miller, Jefferson felt all humans were morally equal, but on the other hand he believed that african americans, Native Americans, and women were not culturally, physically, or intellectually equal to white males.

Jefferson’s first real important political treatise, A Summary View of the Rights of British America, showed his concept of natural rights—that people have certain inalienable (not transferrable to another) rights superior to civil law. During Jefferson’s time as governor of Virginia, he wrote An Act for Establishing Religious Freedom, Passed in the Assembly of Virginia in the Beginning of the Year 1786. Essentially stating that each individual’s conscience, rather than any singular institution, should control religious matters, and the disagreement that civil liberties should stand alone from that of religious beliefs.

Once Jefferson’s father died, he left Thomas around 3,000 acres of land. Jefferson was the governor of Virginia from the year 1779-1781. When he was elected, the American people were fighting the over the Revolutionary War. While governor he also produced his only full-length book, titled, Notes on the State of Virginia (1785). Jefferson’s work essentially covers the geography, flora, and fauna of Virginia, as well as descriptive components of its social, economic, and political structure.

In 1782, his wife Martha died. She left three daughters, Martha, Mary and Lucy. Jefferson was overcome with sadness by the death of his wife. He became a hard working father to his daughters and never remarried. His daughter Lucy died two years after her mother. Four years later, Thomas Jefferson became the President. His opponent was John Adams. Adams leaned toward a government run by the wealthy. Jefferson wanted a government run by men only. Jefferson’s election showed that Americans wanted a leader who believed that all men were equal. Jefferson was president from 1801-1809. He also started the University of Virginia. On July 4, 1826 Jefferson died at his home. He was eighty-three years old. The day was ironically the fiftieth anniversary of the signing of the Declaration of Independence.

Works Cited:

“Thomas Jefferson Essay – Critical Essays – ENotes.com.” Enotes.com . Enotes.com, 2015. Web. 22 Oct. 2015.

Thomas Jefferson Foundation. “Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello.” Thomas Jefferson, A Brief Biography . N.p., 2007. Web. 22 Oct. 2015.

THE DECLARATION OF INDEPENDENCE*

*jefferson’s draft.