What Is Creative Writing? (Ultimate Guide + 20 Examples)

Creative writing begins with a blank page and the courage to fill it with the stories only you can tell.

I face this intimidating blank page daily–and I have for the better part of 20+ years.

In this guide, you’ll learn all the ins and outs of creative writing with tons of examples.

What Is Creative Writing (Long Description)?

Creative Writing is the art of using words to express ideas and emotions in imaginative ways. It encompasses various forms including novels, poetry, and plays, focusing on narrative craft, character development, and the use of literary tropes.

Table of Contents

Let’s expand on that definition a bit.

Creative writing is an art form that transcends traditional literature boundaries.

It includes professional, journalistic, academic, and technical writing. This type of writing emphasizes narrative craft, character development, and literary tropes. It also explores poetry and poetics traditions.

In essence, creative writing lets you express ideas and emotions uniquely and imaginatively.

It’s about the freedom to invent worlds, characters, and stories. These creations evoke a spectrum of emotions in readers.

Creative writing covers fiction, poetry, and everything in between.

It allows writers to express inner thoughts and feelings. Often, it reflects human experiences through a fabricated lens.

Types of Creative Writing

There are many types of creative writing that we need to explain.

Some of the most common types:

- Short stories

- Screenplays

- Flash fiction

- Creative Nonfiction

Short Stories (The Brief Escape)

Short stories are like narrative treasures.

They are compact but impactful, telling a full story within a limited word count. These tales often focus on a single character or a crucial moment.

Short stories are known for their brevity.

They deliver emotion and insight in a concise yet powerful package. This format is ideal for exploring diverse genres, themes, and characters. It leaves a lasting impression on readers.

Example: Emma discovers an old photo of her smiling grandmother. It’s a rarity. Through flashbacks, Emma learns about her grandmother’s wartime love story. She comes to understand her grandmother’s resilience and the value of joy.

Novels (The Long Journey)

Novels are extensive explorations of character, plot, and setting.

They span thousands of words, giving writers the space to create entire worlds. Novels can weave complex stories across various themes and timelines.

The length of a novel allows for deep narrative and character development.

Readers get an immersive experience.

Example: Across the Divide tells of two siblings separated in childhood. They grow up in different cultures. Their reunion highlights the strength of family bonds, despite distance and differences.

Poetry (The Soul’s Language)

Poetry expresses ideas and emotions through rhythm, sound, and word beauty.

It distills emotions and thoughts into verses. Poetry often uses metaphors, similes, and figurative language to reach the reader’s heart and mind.

Poetry ranges from structured forms, like sonnets, to free verse.

The latter breaks away from traditional formats for more expressive thought.

Example: Whispers of Dawn is a poem collection capturing morning’s quiet moments. “First Light” personifies dawn as a painter. It brings colors of hope and renewal to the world.

Plays (The Dramatic Dialogue)

Plays are meant for performance. They bring characters and conflicts to life through dialogue and action.

This format uniquely explores human relationships and societal issues.

Playwrights face the challenge of conveying setting, emotion, and plot through dialogue and directions.

Example: Echoes of Tomorrow is set in a dystopian future. Memories can be bought and sold. It follows siblings on a quest to retrieve their stolen memories. They learn the cost of living in a world where the past has a price.

Screenplays (Cinema’s Blueprint)

Screenplays outline narratives for films and TV shows.

They require an understanding of visual storytelling, pacing, and dialogue. Screenplays must fit film production constraints.

Example: The Last Light is a screenplay for a sci-fi film. Humanity’s survivors on a dying Earth seek a new planet. The story focuses on spacecraft Argo’s crew as they face mission challenges and internal dynamics.

Memoirs (The Personal Journey)

Memoirs provide insight into an author’s life, focusing on personal experiences and emotional journeys.

They differ from autobiographies by concentrating on specific themes or events.

Memoirs invite readers into the author’s world.

They share lessons learned and hardships overcome.

Example: Under the Mango Tree is a memoir by Maria Gomez. It shares her childhood memories in rural Colombia. The mango tree in their yard symbolizes home, growth, and nostalgia. Maria reflects on her journey to a new life in America.

Flash Fiction (The Quick Twist)

Flash fiction tells stories in under 1,000 words.

It’s about crafting compelling narratives concisely. Each word in flash fiction must count, often leading to a twist.

This format captures life’s vivid moments, delivering quick, impactful insights.

Example: The Last Message features an astronaut’s final Earth message as her spacecraft drifts away. In 500 words, it explores isolation, hope, and the desire to connect against all odds.

Creative Nonfiction (The Factual Tale)

Creative nonfiction combines factual accuracy with creative storytelling.

This genre covers real events, people, and places with a twist. It uses descriptive language and narrative arcs to make true stories engaging.

Creative nonfiction includes biographies, essays, and travelogues.

Example: Echoes of Everest follows the author’s Mount Everest climb. It mixes factual details with personal reflections and the history of past climbers. The narrative captures the climb’s beauty and challenges, offering an immersive experience.

Fantasy (The World Beyond)

Fantasy transports readers to magical and mythical worlds.

It explores themes like good vs. evil and heroism in unreal settings. Fantasy requires careful world-building to create believable yet fantastic realms.

Example: The Crystal of Azmar tells of a young girl destined to save her world from darkness. She learns she’s the last sorceress in a forgotten lineage. Her journey involves mastering powers, forming alliances, and uncovering ancient kingdom myths.

Science Fiction (The Future Imagined)

Science fiction delves into futuristic and scientific themes.

It questions the impact of advancements on society and individuals.

Science fiction ranges from speculative to hard sci-fi, focusing on plausible futures.

Example: When the Stars Whisper is set in a future where humanity communicates with distant galaxies. It centers on a scientist who finds an alien message. This discovery prompts a deep look at humanity’s universe role and interstellar communication.

Watch this great video that explores the question, “What is creative writing?” and “How to get started?”:

What Are the 5 Cs of Creative Writing?

The 5 Cs of creative writing are fundamental pillars.

They guide writers to produce compelling and impactful work. These principles—Clarity, Coherence, Conciseness, Creativity, and Consistency—help craft stories that engage and entertain.

They also resonate deeply with readers. Let’s explore each of these critical components.

Clarity makes your writing understandable and accessible.

It involves choosing the right words and constructing clear sentences. Your narrative should be easy to follow.

In creative writing, clarity means conveying complex ideas in a digestible and enjoyable way.

Coherence ensures your writing flows logically.

It’s crucial for maintaining the reader’s interest. Characters should develop believably, and plots should progress logically. This makes the narrative feel cohesive.

Conciseness

Conciseness is about expressing ideas succinctly.

It’s being economical with words and avoiding redundancy. This principle helps maintain pace and tension, engaging readers throughout the story.

Creativity is the heart of creative writing.

It allows writers to invent new worlds and create memorable characters. Creativity involves originality and imagination. It’s seeing the world in unique ways and sharing that vision.

Consistency

Consistency maintains a uniform tone, style, and voice.

It means being faithful to the world you’ve created. Characters should act true to their development. This builds trust with readers, making your story immersive and believable.

Is Creative Writing Easy?

Creative writing is both rewarding and challenging.

Crafting stories from your imagination involves more than just words on a page. It requires discipline and a deep understanding of language and narrative structure.

Exploring complex characters and themes is also key.

Refining and revising your work is crucial for developing your voice.

The ease of creative writing varies. Some find the freedom of expression liberating.

Others struggle with writer’s block or plot development challenges. However, practice and feedback make creative writing more fulfilling.

What Does a Creative Writer Do?

A creative writer weaves narratives that entertain, enlighten, and inspire.

Writers explore both the world they create and the emotions they wish to evoke. Their tasks are diverse, involving more than just writing.

Creative writers develop ideas, research, and plan their stories.

They create characters and outline plots with attention to detail. Drafting and revising their work is a significant part of their process. They strive for the 5 Cs of compelling writing.

Writers engage with the literary community, seeking feedback and participating in workshops.

They may navigate the publishing world with agents and editors.

Creative writers are storytellers, craftsmen, and artists. They bring narratives to life, enriching our lives and expanding our imaginations.

How to Get Started With Creative Writing?

Embarking on a creative writing journey can feel like standing at the edge of a vast and mysterious forest.

The path is not always clear, but the adventure is calling.

Here’s how to take your first steps into the world of creative writing:

- Find a time of day when your mind is most alert and creative.

- Create a comfortable writing space free from distractions.

- Use prompts to spark your imagination. They can be as simple as a word, a phrase, or an image.

- Try writing for 15-20 minutes on a prompt without editing yourself. Let the ideas flow freely.

- Reading is fuel for your writing. Explore various genres and styles.

- Pay attention to how your favorite authors construct their sentences, develop characters, and build their worlds.

- Don’t pressure yourself to write a novel right away. Begin with short stories or poems.

- Small projects can help you hone your skills and boost your confidence.

- Look for writing groups in your area or online. These communities offer support, feedback, and motivation.

- Participating in workshops or classes can also provide valuable insights into your writing.

- Understand that your first draft is just the beginning. Revising your work is where the real magic happens.

- Be open to feedback and willing to rework your pieces.

- Carry a notebook or digital recorder to jot down ideas, observations, and snippets of conversations.

- These notes can be gold mines for future writing projects.

Final Thoughts: What Is Creative Writing?

Creative writing is an invitation to explore the unknown, to give voice to the silenced, and to celebrate the human spirit in all its forms.

Check out these creative writing tools (that I highly recommend):

Read This Next:

- What Is a Prompt in Writing? (Ultimate Guide + 200 Examples)

- What Is A Personal Account In Writing? (47 Examples)

- How To Write A Fantasy Short Story (Ultimate Guide + Examples)

- How To Write A Fantasy Romance Novel [21 Tips + Examples)

What Freud Said About Writing Fiction

"The creative writer does the same as the child at play," and other quips

- Scientific Mysteries, Illustrated

- When Darwin Hated Everyone

- Why It's Dark at Night

"Writing is a little door," Susan Sontag wrote in her diary . "Some fantasies, like big pieces of furniture, won't come through."

Sigmund Freud—key figure in the making of consumer culture , deft architect of his own myth , modern plaything —spent a fair amount of his career exploring the psychology of dreams . In 1908, he turned to the intersection of fantasies and creativity, and penned a short essay titled "Creative Writers and Day-Dreaming," eventually republished in the anthology The Freud Reader ( public library ). Though his theories have been the subject of much controversy and subsequent revision, they remain a fascinating formative framework for much of the modern understanding of the psyche.

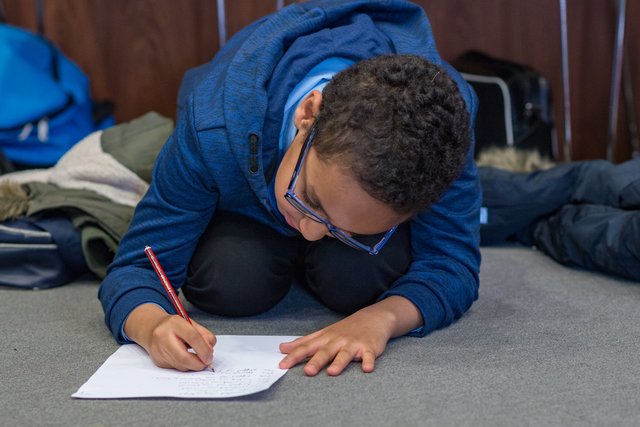

Predictably, Freud begins by tracing the subject matter to its roots in childhood, stressing, as Anaïs Nin eloquently did—herself trained in psychoanalysis—the importance of emotional investment in creative writing :

Should we not look for the first traces of imaginative activity as early as in childhood? The child's best-loved and most intense occupation is with his play or games. Might we not say that every child at play behaves like a creative writer, in that he creates a world of his own, or, rather, rearranges the things of his world in a new way which pleases him? It would be wrong to think he does not take that world seriously; on the contrary, he takes his play very seriously and he expends large amounts of emotion on it. The opposite of play is not what is serious but what is real. In spite of all the emotion with which he cathects his world of play, the child distinguishes it quite well from reality; and he likes to link his imagined objects and situations to the tangible and visible things of the real world. This linking is all that differentiates the child's 'play' from 'phantasying.' The creative writer does the same as the child at play. He creates a world of phantasy which he takes very seriously—that is, which he invests with large amounts of emotion—while separating it sharply from reality.

He then considers, as Henry Miller did in his famous creative routine three decades later, the time scales of the creative process:

The relation of phantasy to time is in general very important. We may say that it hovers, as it ware, between three times—the three moments of time which our ideation involves. Mental work is linked to some current impression, some provoking occasion in the present which has been able to arouse one of the subject's major wishes. From here it harks back to a memory of an earlier experience (usually an infantile one) in which this wish was fulfilled; and now it creates a situation relating to the future which represents the fulfillment of the wish. What it thus creates is a day-dream or phantasy, which carries about it traces of its origin from the occasion which provoked it and from the memory. Thus, past, present and future are strung together, as it were, on the thread of the wish that runs through them.

He synthesizes the parallel between creative writing and play:

[A] piece of creative writing, like a day-dream, is a continuation of, and a substitute for, what was once the play of childhood.

He goes on to explore the secretive nature of our daydreams, suggesting that an element of shame keeps us from sharing them with others—perhaps what Jack Kerouac meant when he listed the unspeakable visions of the individual as one of his iconic beliefs and techniques for prose —and considers how the creative writer transcends that to achieve pleasure in the disclosure of these fantasies:

How the writer accomplishes this is his innermost secret; the essential ars poetica lies in the technique of overcoming the feeling of repulsion in us which is undoubtedly connected with the barriers that rise between each single ego and the others. We can guess two of the methods used by this technique. The writer softens the character of his egoistic day-dreams by altering and disguising it, and he bribes us by the purely formal—that is, aesthetic—yield of pleasure which he offers us in the presentation of his phantasies. We give the name of an incentive bonus , or a fore-pleasure , to a yield of pleasure such as this, which is offered to us so as to make possible the release of still greater pleasure arising from deeper psychical sources. In my opinion, all the aesthetic pleasure which a creative writer affords us has the character of a fore-pleasure of this kind, and our actual enjoyment of an imaginative work proceeds from a liberation of tensions in our minds. It may even be that not a little of this effect is due to the writer's enabling us thenceforward to enjoy our own day-dreams without self-reproach or shame.

For more famous insights on writing, see Kurt Vonnegut's 8 rules for a great story , David Ogilvy's 10 no-bullshit tips , Henry Miller's 11 commandments , Jack Kerouac's 30 beliefs and techniques , John Steinbeck's six pointers , and Susan Sontag's synthesized learnings .

This post also appears on Brain Pickings , an Atlantic partner site.

The Writing For Pleasure Centre

– promoting research-informed writing teaching

The DfE and Writing For Pleasure: What happened and what should happen next?

When I was undertaking some reading recently, I came across a Department for Education paper titled ‘ What is the research evidence on writing? ’ (2012). While there have been other papers produced such as Moving English Forward (2012) and Excellence in English (2011) this is the most recent example which has an emphasis solely on writing. Its aim was to:

‘Report on the statistics and research evidence on writing both in and out of school, covering pupils in primary and secondary schools.’

It sought to answer several questions, but the ones which struck me were:

- What does effective teaching of writing look like?

- What are pupils’ attitudes toward writing, including enjoyment and confidence?

- In which types of writing activity do pupils engage out of school?

The practices highlighted came from research reviews of international evidence including:

- What Works Clearinghouse (2012)

- Gillespie & Graham (2010)

- Andrews et al (2009)

- Santangelo & Olinghouse (2009)

What I read reminded me that the approaches outlined then elide so smoothly with many of the principles of a Writing for Pleasure approach being articulated today ( Young & Ferguson 2021 ).

The research-informed practices that were suggested were listed as follows:

- Teach the writing processes

- Pursue writing for a variety of purposes and audiences

- Set writing goals and foster inquiry skills

- Provide daily time for children to write

- Create an engaged community of writers

- Teachers should model the writer’s life and share their writing with their class

- Give pupils personal responsibility for the topics they choose to write about

- Encourage the collaborative and social aspects of writing

- Ensure pupils give and receive constructive feedback throughout their writing process

- Publish pupils’ writing so it reaches external audiences

Music to the ears of Writing for Pleasure advocates for sure, as these approaches strike many of the same notes. And, perhaps not that surprising when you consider that a Writing for Pleasure approach, while being a newly-realised pedagogy ( Gusevik 2020 ), is in fact based on many decades of scientific research and case studies of the best performing writing teachers ( Young & Ferguson 2021 ).

Additionally, the DfE paper also highlighted a study by Myhill and her colleagues ( 2011 ) looking at the effect of contextualised grammar teaching on pupils’ writing development. The study showed a significant positive effect for pupils in the intervention group, taught in lessons using the principles outlined above. By contextualised grammar teaching the researchers referred to:

- Introducing grammatical constructions and terminology at a point which is relevant to the focus of the children’s developing writing.

- Placing emphasis on effects and sharing meaning, not on the feature or terminology itself.

- Grammar teaching opening up a ‘repertoire of possibilities’.

I draw attention to this in such detail because teaching grammar functionally and illuminating a suite of options for children to use in their writing is a fundamental element of a Writing for Pleasure approach; however, this sits in contrast to the so-called ‘skill and drill’ decontextualised and exercise-based approaches to teaching grammar which still hold sway across many school curricula. Young & Ferguson’s review of the writing research reviews ( 2021 ) amply demonstrates that the formal teaching of grammar has always negatively impacted on children’s writing. So why does this practice persist? Perhaps the answer lies in the presence of the high-stakes Spelling, Punctuation and Grammar test in Year Six. It has had a deleterious percolating effect as schools have tended to isolate the teaching of grammatical terminology and divorce it from the act of meaningful writing at an ever younger age.

Despite the negative repercussions of the Key Stage 2 SATS, and their distorting nature, in my experience there is another significant issue: there is a distinct lack of awareness in the teaching profession at all levels of what makes for effective and affecting writing practice. This leaves me wondering:

- How do we draw attention to these principles and push them further by undertaking additional research?

- How do we influence powerful stakeholders (DfE, Ofsted), the teaching profession and literacy organisations, all of whom have a key role in defining the kind of practice that takes place in schools?

The answer to the first question has already been amply answered by Young ( 2019 ) and Young & Ferguson’s ( 2021 and here ) work. I know from experience that once you begin teaching writing effectively and affectively, you quickly develop an understanding of the interconnectedness and transformative nature of the approach. These principles are knitted together like your favourite cosy jumper, and once you start wearing it you don’t want to take off.

But the second question is more challenging. Should Ofsted be using its role to promote more effective and affecting models of teaching writing? Do they have the desire to do so? What assessment has been made of what impact national curriculum changes have had on the teaching of writing in primary schools? How can teachers find the time and inclination to develop their own practice? If we want to ensure teaching stays a vocation and a profession then we have to engage more honestly with the research and challenge the prevailing orthodoxy especially around writing. Why are other professional organisations not pointing to the evidence but rather promoting what sometimes feels like solely a book-planning and novel study approach to writing teaching? A review by the Department of Education is surely long overdue.

We also know that recruitment and retention is a perennial problem, certainly in English schools, and is particularly acute concerning early career teachers with ‘ over 20% of new teachers leav[ing] the profession within their first 2 years of teaching, and 33% leav[ing] within their first 5 years’ ( DfE 2019 ). However, I would contend that it is not just owing to a ‘ decline in the position of the teachers’ pay framework in the labour market for graduate professions ’ ( NEU 2019 ), or a burdensome workload, but it is at least partly due to the very nature of some aspects of the work itself. I believe that schools will better attract and retain staff if they can offer a different experience; one which challenges teachers to develop their practice in a framework of classroom-based action research (see here , here and here ), which can be both transformational for the children they teach as well as for themselves and their own motivation to remain in the classroom.

Being part of a community of Writing for Pleasure teachers within your own school, but also one which extends beyond the school boundary, creates solidarity with other teachers through the publication and sharing of examples of practice . This process itself contributes to a feeling of moving a pedagogy forward as a community of practitioners rather than being required to teach someone else’s ideas and choices. Working in this way would contribute significantly to restoring the primacy of human relationships to the teaching process and help repel the feelings of alienation engendered by ‘off the shelf’ writing schemes, which require little imagination or creative capacity on the part of the teacher or students as a collective.

A teacher’s essential product is their ability to meld their subject, curriculum and pedagogical knowledge with the needs of their pupils, and while this can often be contorted to fit the demands of the national curriculum and the individual school interpretation of this, often there is little or no place for the expression of personal values or communal construction. What happens then? Motivation, professional pride and satisfaction wane sometimes to the point where, when combined with pay and workload issues, enough is enough.

Working within a Writing for Pleasure approach encourages us to meet the human needs of our pupils, their development as agentive writers, and ultimately is an expression of our own human essence. Being a writer-teacher develops our sense of involvement and inserts our literary experiences into the classroom by teaching through our own craft. Writing for Pleasure is teaching for pleasure and has motivated me to see a long-term future in the classroom.

Reading for Pleasure has gained significant traction over the last few years and is now almost universally accepted as having a fundamental role in motivating children to become readers as well as developing teachers’ pedagogical knowledge of effective practice. Now it is time for Writing for Pleasure to become the beating heart of our education system too – for the benefit of all concerned.

By Tobias Hayden Twitter: @TobiasHayden

References:

- Andrews, R., & Torgerson, C., Low, G., & McGuinn, Nick., (2009) Teaching argument writing to 7- to 14-year-olds: An international review of the evidence of successful practice Cambridge Journal of Education 39. pp.291-310. 10.1080/03057640903103751.

- DfE (2012) What is the research evidence on writing? Education Standards Research Team, Department for Education: London

- DfE (2019) Teacher Recruitment and Retention Strategy Department for Education: London

- Graham, S., Bollinger, A., Olson, C. B, D’Aoust, C., MacArthur, C., McCutchen, D. & Olinghouse, N. (2012). Teaching elementary school students to be effective writers 1-103 United States of America: Institute of Education Sciences

- Graham, S., & Gillespie, A., & Mckeown, D., (2012) Writing: Importance, development, and instruction Reading and Writing 26

- Gusevik, R., (2020) Writing for Pleasure and the Teaching of Writing at the Primary Level: A Teacher Cognition Case Study Unpublished dissertation University of Stavanger

- Myhill, D., Jones, S., Lines, H., & Watson, A., (2012) Re-thinking grammar: The impact of embedded grammar teaching on students’ writing and students’ metalinguistic understanding Research Papers in Education 27 pp.139-166

- NEU (2019) Teacher recruitment and retention [Available online: https://neu.org.uk/policy/teacher-recruitment-and-retention%5D  ;

- Ofsted (2011) Excellence in English London: Ofsted

- Ofsted (2012) Moving English forward London: Ofsted

- Santangelo, T., & Olinghouse, N., (2009) Effective Writing Instruction for Students Who Have Writing Difficulties Focus on Exceptional Children 42 pp.1-20

- Young, R., (2019) What is it ‘Writing For Pleasure’ teachers do that makes the difference? The University Of Sussex: The Goldsmiths’ Company

- Young, R., Ferguson, F., (2021) Writing for pleasure: theory, research and practice London: Routledge

Share this:

Leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Notify me of follow-up comments by email.

Notify me of new posts by email.

Discover more from The Writing For Pleasure Centre

Subscribe now to keep reading and get access to the full archive.

Type your email…

Continue reading

VIDEO COURSE

Finish your draft in our 3-month master class. Sign up now to watch a free lesson!

Learn How to Write a Novel

Finish your draft in our 3-month master class. Enroll now for daily lessons, weekly critique, and live events. Your first lesson is free!

Guides • Perfecting your Craft

Last updated on Feb 14, 2023

10 Types of Creative Writing (with Examples You’ll Love)

A lot falls under the term ‘creative writing’: poetry, short fiction, plays, novels, personal essays, and songs, to name just a few. By virtue of the creativity that characterizes it, creative writing is an extremely versatile art. So instead of defining what creative writing is , it may be easier to understand what it does by looking at examples that demonstrate the sheer range of styles and genres under its vast umbrella.

To that end, we’ve collected a non-exhaustive list of works across multiple formats that have inspired the writers here at Reedsy. With 20 different works to explore, we hope they will inspire you, too.

People have been writing creatively for almost as long as we have been able to hold pens. Just think of long-form epic poems like The Odyssey or, later, the Cantar de Mio Cid — some of the earliest recorded writings of their kind.

Poetry is also a great place to start if you want to dip your own pen into the inkwell of creative writing. It can be as short or long as you want (you don’t have to write an epic of Homeric proportions), encourages you to build your observation skills, and often speaks from a single point of view .

Here are a few examples:

“Ozymandias” by Percy Bysshe Shelley

Nothing beside remains. Round the decay Of that colossal Wreck, boundless and bare The lone and level sands stretch far away.

This classic poem by Romantic poet Percy Shelley (also known as Mary Shelley’s husband) is all about legacy. What do we leave behind? How will we be remembered? The great king Ozymandias built himself a massive statue, proclaiming his might, but the irony is that his statue doesn’t survive the ravages of time. By framing this poem as told to him by a “traveller from an antique land,” Shelley effectively turns this into a story. Along with the careful use of juxtaposition to create irony, this poem accomplishes a lot in just a few lines.

“Trying to Raise the Dead” by Dorianne Laux

A direction. An object. My love, it needs a place to rest. Say anything. I’m listening. I’m ready to believe. Even lies, I don’t care.

Poetry is cherished for its ability to evoke strong emotions from the reader using very few words which is exactly what Dorianne Laux does in “ Trying to Raise the Dead .” With vivid imagery that underscores the painful yearning of the narrator, she transports us to a private nighttime scene as the narrator sneaks away from a party to pray to someone they’ve lost. We ache for their loss and how badly they want their lost loved one to acknowledge them in some way. It’s truly a masterclass on how writing can be used to portray emotions.

If you find yourself inspired to try out some poetry — and maybe even get it published — check out these poetry layouts that can elevate your verse!

Song Lyrics

Poetry’s closely related cousin, song lyrics are another great way to flex your creative writing muscles. You not only have to find the perfect rhyme scheme but also match it to the rhythm of the music. This can be a great challenge for an experienced poet or the musically inclined.

To see how music can add something extra to your poetry, check out these two examples:

“Hallelujah” by Leonard Cohen

You say I took the name in vain I don't even know the name But if I did, well, really, what's it to ya? There's a blaze of light in every word It doesn't matter which you heard The holy or the broken Hallelujah

Metaphors are commonplace in almost every kind of creative writing, but will often take center stage in shorter works like poetry and songs. At the slightest mention, they invite the listener to bring their emotional or cultural experience to the piece, allowing the writer to express more with fewer words while also giving it a deeper meaning. If a whole song is couched in metaphor, you might even be able to find multiple meanings to it, like in Leonard Cohen’s “ Hallelujah .” While Cohen’s Biblical references create a song that, on the surface, seems like it’s about a struggle with religion, the ambiguity of the lyrics has allowed it to be seen as a song about a complicated romantic relationship.

“I Will Follow You into the Dark” by Death Cab for Cutie

If Heaven and Hell decide that they both are satisfied Illuminate the no's on their vacancy signs If there's no one beside you when your soul embarks Then I'll follow you into the dark

You can think of song lyrics as poetry set to music. They manage to do many of the same things their literary counterparts do — including tugging on your heartstrings. Death Cab for Cutie’s incredibly popular indie rock ballad is about the singer’s deep devotion to his lover. While some might find the song a bit too dark and macabre, its melancholy tune and poignant lyrics remind us that love can endure beyond death.

Plays and Screenplays

From the short form of poetry, we move into the world of drama — also known as the play. This form is as old as the poem, stretching back to the works of ancient Greek playwrights like Sophocles, who adapted the myths of their day into dramatic form. The stage play (and the more modern screenplay) gives the words on the page a literal human voice, bringing life to a story and its characters entirely through dialogue.

Interested to see what that looks like? Take a look at these examples:

All My Sons by Arthur Miller

“I know you're no worse than most men but I thought you were better. I never saw you as a man. I saw you as my father.”

Arthur Miller acts as a bridge between the classic and the new, creating 20th century tragedies that take place in living rooms and backyard instead of royal courts, so we had to include his breakout hit on this list. Set in the backyard of an all-American family in the summer of 1946, this tragedy manages to communicate family tensions in an unimaginable scale, building up to an intense climax reminiscent of classical drama.

💡 Read more about Arthur Miller and classical influences in our breakdown of Freytag’s pyramid .

“Everything is Fine” by Michael Schur ( The Good Place )

“Well, then this system sucks. What...one in a million gets to live in paradise and everyone else is tortured for eternity? Come on! I mean, I wasn't freaking Gandhi, but I was okay. I was a medium person. I should get to spend eternity in a medium place! Like Cincinnati. Everyone who wasn't perfect but wasn't terrible should get to spend eternity in Cincinnati.”

A screenplay, especially a TV pilot, is like a mini-play, but with the extra job of convincing an audience that they want to watch a hundred more episodes of the show. Blending moral philosophy with comedy, The Good Place is a fun hang-out show set in the afterlife that asks some big questions about what it means to be good.

It follows Eleanor Shellstrop, an incredibly imperfect woman from Arizona who wakes up in ‘The Good Place’ and realizes that there’s been a cosmic mixup. Determined not to lose her place in paradise, she recruits her “soulmate,” a former ethics professor, to teach her philosophy with the hope that she can learn to be a good person and keep up her charade of being an upstanding citizen. The pilot does a superb job of setting up the stakes, the story, and the characters, while smuggling in deep philosophical ideas.

Personal essays

Our first foray into nonfiction on this list is the personal essay. As its name suggests, these stories are in some way autobiographical — concerned with the author’s life and experiences. But don’t be fooled by the realistic component. These essays can take any shape or form, from comics to diary entries to recipes and anything else you can imagine. Typically zeroing in on a single issue, they allow you to explore your life and prove that the personal can be universal.

Here are a couple of fantastic examples:

“On Selling Your First Novel After 11 Years” by Min Jin Lee (Literary Hub)

There was so much to learn and practice, but I began to see the prose in verse and the verse in prose. Patterns surfaced in poems, stories, and plays. There was music in sentences and paragraphs. I could hear the silences in a sentence. All this schooling was like getting x-ray vision and animal-like hearing.

This deeply honest personal essay by Pachinko author Min Jin Lee is an account of her eleven-year struggle to publish her first novel . Like all good writing, it is intensely focused on personal emotional details. While grounded in the specifics of the author's personal journey, it embodies an experience that is absolutely universal: that of difficulty and adversity met by eventual success.

“A Cyclist on the English Landscape” by Roff Smith (New York Times)

These images, though, aren’t meant to be about me. They’re meant to represent a cyclist on the landscape, anybody — you, perhaps.

Roff Smith’s gorgeous photo essay for the NYT is a testament to the power of creatively combining visuals with text. Here, photographs of Smith atop a bike are far from simply ornamental. They’re integral to the ruminative mood of the essay, as essential as the writing. Though Smith places his work at the crosscurrents of various aesthetic influences (such as the painter Edward Hopper), what stands out the most in this taciturn, thoughtful piece of writing is his use of the second person to address the reader directly. Suddenly, the writer steps out of the body of the essay and makes eye contact with the reader. The reader is now part of the story as a second character, finally entering the picture.

Short Fiction

The short story is the happy medium of fiction writing. These bite-sized narratives can be devoured in a single sitting and still leave you reeling. Sometimes viewed as a stepping stone to novel writing, that couldn’t be further from the truth. Short story writing is an art all its own. The limited length means every word counts and there’s no better way to see that than with these two examples:

“An MFA Story” by Paul Dalla Rosa (Electric Literature)

At Starbucks, I remembered a reading Zhen had given, a reading organized by the program’s faculty. I had not wanted to go but did. In the bar, he read, "I wrote this in a Starbucks in Shanghai. On the bank of the Huangpu." It wasn’t an aside or introduction. It was two lines of the poem. I was in a Starbucks and I wasn’t writing any poems. I wasn’t writing anything.

This short story is a delightfully metafictional tale about the struggles of being a writer in New York. From paying the bills to facing criticism in a writing workshop and envying more productive writers, Paul Dalla Rosa’s story is a clever satire of the tribulations involved in the writing profession, and all the contradictions embodied by systemic creativity (as famously laid out in Mark McGurl’s The Program Era ). What’s more, this story is an excellent example of something that often happens in creative writing: a writer casting light on the private thoughts or moments of doubt we don’t admit to or openly talk about.

“Flowering Walrus” by Scott Skinner (Reedsy)

I tell him they’d been there a month at least, and he looks concerned. He has my tongue on a tissue paper and is gripping its sides with his pointer and thumb. My tongue has never spent much time outside of my mouth, and I imagine it as a walrus basking in the rays of the dental light. My walrus is not well.

A winner of Reedsy’s weekly Prompts writing contest, ‘ Flowering Walrus ’ is a story that balances the trivial and the serious well. In the pauses between its excellent, natural dialogue , the story manages to scatter the fear and sadness of bad medical news, as the protagonist hides his worries from his wife and daughter. Rich in subtext, these silences grow and resonate with the readers.

Want to give short story writing a go? Give our free course a go!

FREE COURSE

How to Craft a Killer Short Story

From pacing to character development, master the elements of short fiction.

Perhaps the thing that first comes to mind when talking about creative writing, novels are a form of fiction that many people know and love but writers sometimes find intimidating. The good news is that novels are nothing but one word put after another, like any other piece of writing, but expanded and put into a flowing narrative. Piece of cake, right?

To get an idea of the format’s breadth of scope, take a look at these two (very different) satirical novels:

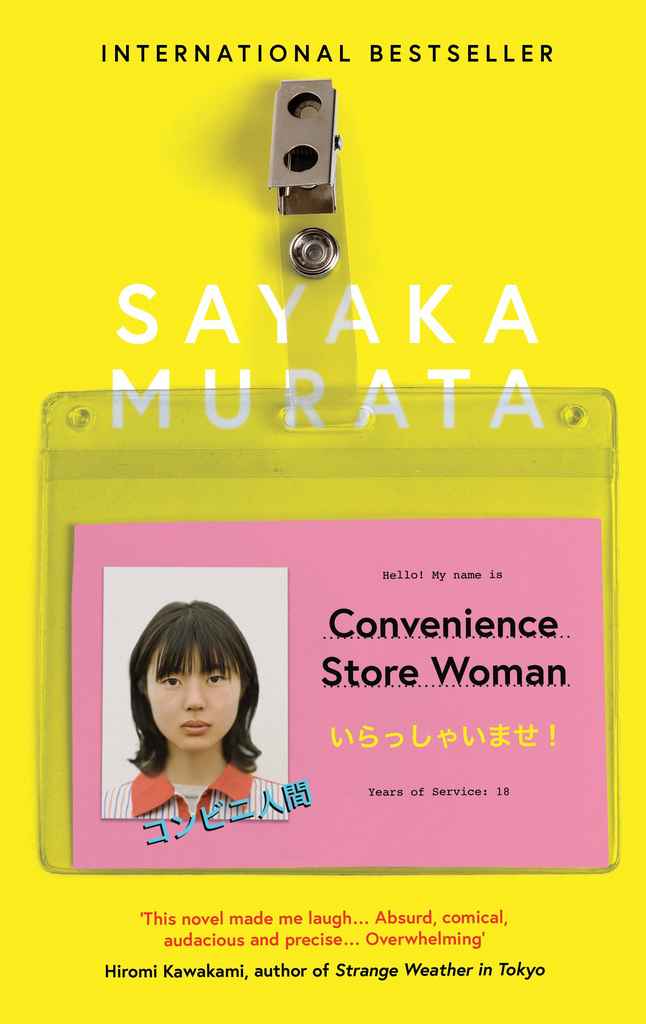

Convenience Store Woman by Sayaka Murata

I wished I was back in the convenience store where I was valued as a working member of staff and things weren’t as complicated as this. Once we donned our uniforms, we were all equals regardless of gender, age, or nationality — all simply store workers.

Keiko, a thirty-six-year-old convenience store employee, finds comfort and happiness in the strict, uneventful routine of the shop’s daily operations. A funny, satirical, but simultaneously unnerving examination of the social structures we take for granted, Sayaka Murata’s Convenience Store Woman is deeply original and lingers with the reader long after they’ve put it down.

Erasure by Percival Everett

The hard, gritty truth of the matter is that I hardly ever think about race. Those times when I did think about it a lot I did so because of my guilt for not thinking about it.

Erasure is a truly accomplished satire of the publishing industry’s tendency to essentialize African American authors and their writing. Everett’s protagonist is a writer whose work doesn’t fit with what publishers expect from him — work that describes the “African American experience” — so he writes a parody novel about life in the ghetto. The publishers go crazy for it and, to the protagonist’s horror, it becomes the next big thing. This sophisticated novel is both ironic and tender, leaving its readers with much food for thought.

Creative Nonfiction

Creative nonfiction is pretty broad: it applies to anything that does not claim to be fictional (although the rise of autofiction has definitely blurred the boundaries between fiction and nonfiction). It encompasses everything from personal essays and memoirs to humor writing, and they range in length from blog posts to full-length books. The defining characteristic of this massive genre is that it takes the world or the author’s experience and turns it into a narrative that a reader can follow along with.

Here, we want to focus on novel-length works that dig deep into their respective topics. While very different, these two examples truly show the breadth and depth of possibility of creative nonfiction:

Men We Reaped by Jesmyn Ward

Men’s bodies litter my family history. The pain of the women they left behind pulls them from the beyond, makes them appear as ghosts. In death, they transcend the circumstances of this place that I love and hate all at once and become supernatural.

Writer Jesmyn Ward recounts the deaths of five men from her rural Mississippi community in as many years. In her award-winning memoir , she delves into the lives of the friends and family she lost and tries to find some sense among the tragedy. Working backwards across five years, she questions why this had to happen over and over again, and slowly unveils the long history of racism and poverty that rules rural Black communities. Moving and emotionally raw, Men We Reaped is an indictment of a cruel system and the story of a woman's grief and rage as she tries to navigate it.

Cork Dork by Bianca Bosker

He believed that wine could reshape someone’s life. That’s why he preferred buying bottles to splurging on sweaters. Sweaters were things. Bottles of wine, said Morgan, “are ways that my humanity will be changed.”

In this work of immersive journalism , Bianca Bosker leaves behind her life as a tech journalist to explore the world of wine. Becoming a “cork dork” takes her everywhere from New York’s most refined restaurants to science labs while she learns what it takes to be a sommelier and a true wine obsessive. This funny and entertaining trip through the past and present of wine-making and tasting is sure to leave you better informed and wishing you, too, could leave your life behind for one devoted to wine.

Illustrated Narratives (Comics, graphic novels)

Once relegated to the “funny pages”, the past forty years of comics history have proven it to be a serious medium. Comics have transformed from the early days of Jack Kirby’s superheroes into a medium where almost every genre is represented. Humorous one-shots in the Sunday papers stand alongside illustrated memoirs, horror, fantasy, and just about anything else you can imagine. This type of visual storytelling lets the writer and artist get creative with perspective, tone, and so much more. For two very different, though equally entertaining, examples, check these out:

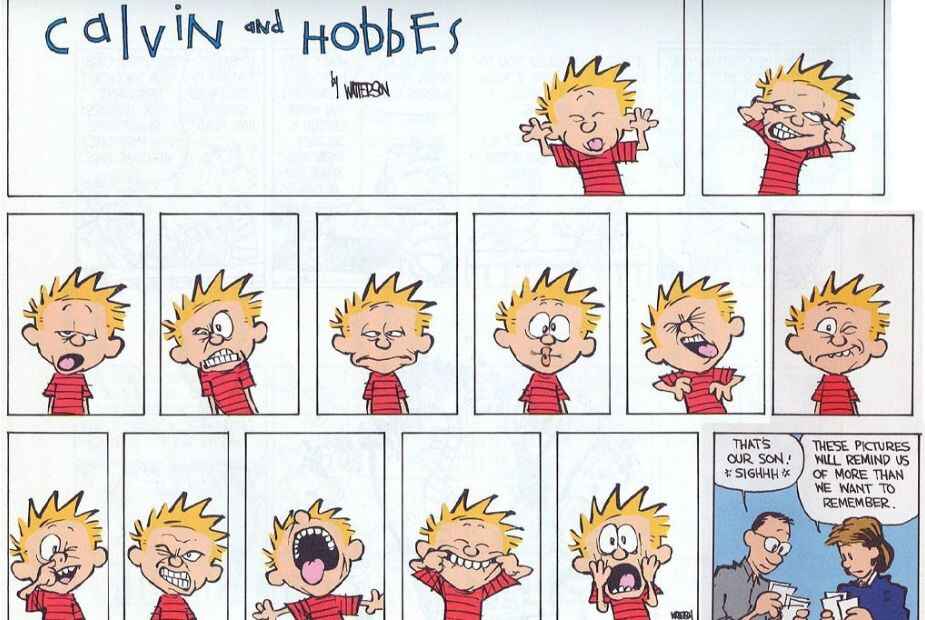

Calvin & Hobbes by Bill Watterson

"Life is like topography, Hobbes. There are summits of happiness and success, flat stretches of boring routine and valleys of frustration and failure."

This beloved comic strip follows Calvin, a rambunctious six-year-old boy, and his stuffed tiger/imaginary friend, Hobbes. They get into all kinds of hijinks at school and at home, and muse on the world in the way only a six-year-old and an anthropomorphic tiger can. As laugh-out-loud funny as it is, Calvin & Hobbes ’ popularity persists as much for its whimsy as its use of humor to comment on life, childhood, adulthood, and everything in between.

From Hell by Alan Moore and Eddie Campbell

"I shall tell you where we are. We're in the most extreme and utter region of the human mind. A dim, subconscious underworld. A radiant abyss where men meet themselves. Hell, Netley. We're in Hell."

Comics aren't just the realm of superheroes and one-joke strips, as Alan Moore proves in this serialized graphic novel released between 1989 and 1998. A meticulously researched alternative history of Victorian London’s Ripper killings, this macabre story pulls no punches. Fact and fiction blend into a world where the Royal Family is involved in a dark conspiracy and Freemasons lurk on the sidelines. It’s a surreal mad-cap adventure that’s unsettling in the best way possible.

Video Games and RPGs

Probably the least expected entry on this list, we thought that video games and RPGs also deserved a mention — and some well-earned recognition for the intricate storytelling that goes into creating them.

Essentially gamified adventure stories, without attention to plot, characters, and a narrative arc, these games would lose a lot of their charm, so let’s look at two examples where the creative writing really shines through:

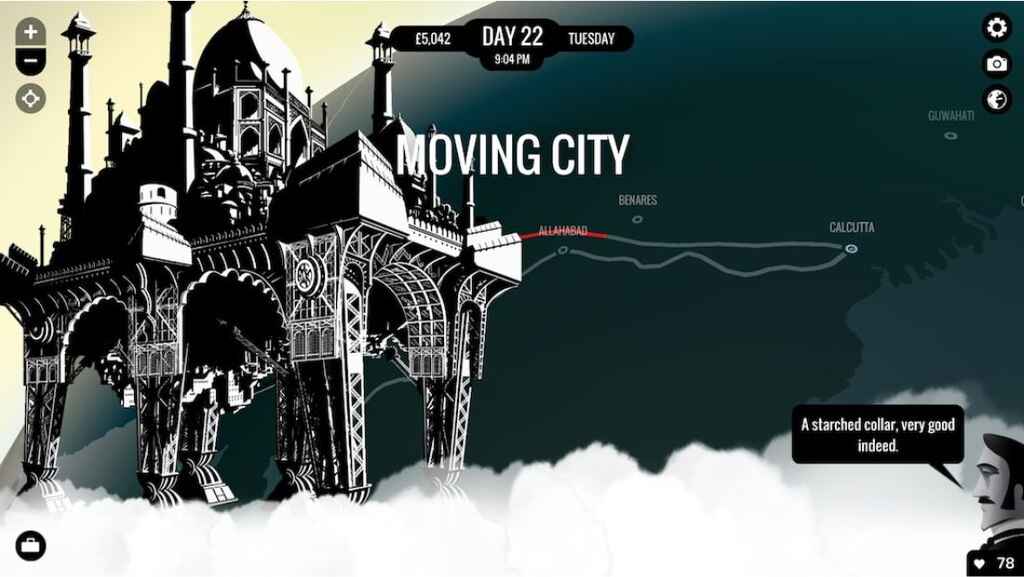

80 Days by inkle studios

"It was a triumph of invention over nature, and will almost certainly disappear into the dust once more in the next fifty years."

Named Time Magazine ’s game of the year in 2014, this narrative adventure is based on Around the World in 80 Days by Jules Verne. The player is cast as the novel’s narrator, Passpartout, and tasked with circumnavigating the globe in service of their employer, Phileas Fogg. Set in an alternate steampunk Victorian era, the game uses its globe-trotting to comment on the colonialist fantasies inherent in the original novel and its time period. On a storytelling level, the choose-your-own-adventure style means no two players’ journeys will be the same. This innovative approach to a classic novel shows the potential of video games as a storytelling medium, truly making the player part of the story.

What Remains of Edith Finch by Giant Sparrow

"If we lived forever, maybe we'd have time to understand things. But as it is, I think the best we can do is try to open our eyes, and appreciate how strange and brief all of this is."

This video game casts the player as 17-year-old Edith Finch. Returning to her family’s home on an island in the Pacific northwest, Edith explores the vast house and tries to figure out why she’s the only one of her family left alive. The story of each family member is revealed as you make your way through the house, slowly unpacking the tragic fate of the Finches. Eerie and immersive, this first-person exploration game uses the medium to tell a series of truly unique tales.

Fun and breezy on the surface, humor is often recognized as one of the trickiest forms of creative writing. After all, while you can see the artistic value in a piece of prose that you don’t necessarily enjoy, if a joke isn’t funny, you could say that it’s objectively failed.

With that said, it’s far from an impossible task, and many have succeeded in bringing smiles to their readers’ faces through their writing. Here are two examples:

‘How You Hope Your Extended Family Will React When You Explain Your Job to Them’ by Mike Lacher (McSweeney’s Internet Tendency)

“Is it true you don’t have desks?” your grandmother will ask. You will nod again and crack open a can of Country Time Lemonade. “My stars,” she will say, “it must be so wonderful to not have a traditional office and instead share a bistro-esque coworking space.”

Satire and parody make up a whole subgenre of creative writing, and websites like McSweeney’s Internet Tendency and The Onion consistently hit the mark with their parodies of magazine publishing and news media. This particular example finds humor in the divide between traditional family expectations and contemporary, ‘trendy’ work cultures. Playing on the inherent silliness of today’s tech-forward middle-class jobs, this witty piece imagines a scenario where the writer’s family fully understands what they do — and are enthralled to hear more. “‘Now is it true,’ your uncle will whisper, ‘that you’ve got a potential investment from one of the founders of I Can Haz Cheezburger?’”

‘Not a Foodie’ by Hilary Fitzgerald Campbell (Electric Literature)

I’m not a foodie, I never have been, and I know, in my heart, I never will be.

Highlighting what she sees as an unbearable social obsession with food , in this comic Hilary Fitzgerald Campbell takes a hilarious stand against the importance of food. From the writer’s courageous thesis (“I think there are more exciting things to talk about, and focus on in life, than what’s for dinner”) to the amusing appearance of family members and the narrator’s partner, ‘Not a Foodie’ demonstrates that even a seemingly mundane pet peeve can be approached creatively — and even reveal something profound about life.

We hope this list inspires you with your own writing. If there’s one thing you take away from this post, let it be that there is no limit to what you can write about or how you can write about it.

In the next part of this guide, we'll drill down into the fascinating world of creative nonfiction.

Join a community of over 1 million authors

Reedsy is more than just a blog. Become a member today to discover how we can help you publish a beautiful book.

We have an app for that

Build a writing routine with our free writing app.

1 million authors trust the professionals on Reedsy. Come meet them.

Enter your email or get started with a social account:

- Architecture and Design

- Asian and Pacific Studies

- Business and Economics

- Classical and Ancient Near Eastern Studies

- Computer Sciences

- Cultural Studies

- Engineering

- General Interest

- Geosciences

- Industrial Chemistry

- Islamic and Middle Eastern Studies

- Jewish Studies

- Library and Information Science, Book Studies

- Life Sciences

- Linguistics and Semiotics

- Literary Studies

- Materials Sciences

- Mathematics

- Social Sciences

- Sports and Recreation

- Theology and Religion

- Publish your article

- The role of authors

- Promoting your article

- Abstracting & indexing

- Publishing Ethics

- Why publish with De Gruyter

- How to publish with De Gruyter

- Our book series

- Our subject areas

- Your digital product at De Gruyter

- Contribute to our reference works

- Product information

- Tools & resources

- Product Information

- Promotional Materials

- Orders and Inquiries

- FAQ for Library Suppliers and Book Sellers

- Repository Policy

- Free access policy

- Open Access agreements

- Database portals

- For Authors

- Customer service

- People + Culture

- Journal Management

- How to join us

- Working at De Gruyter

- Mission & Vision

- De Gruyter Foundation

- De Gruyter Ebound

- Our Responsibility

- Partner publishers

Your purchase has been completed. Your documents are now available to view.

Writing with Pleasure

- Helen Sword

- Illustrator: Selina Tusitala Marsh

- X / Twitter

Please login or register with De Gruyter to order this product.

- Language: English

- Publisher: Princeton University Press

- Copyright year: 2023

- Main content: 328

- Other: 40 b/w illus.

- Keywords: Writing with Pleasure ; helen sword ; Selina Tusitala Marsh ; essential guide ; professional writing ; learning how to write ; how to write ; personal writing ; skills for scholars ; princeton university press ; creative writing ; compelling narratives ; scholarly article ; an administrative email ; a love letter ; illustrated by prizewinning graphic memoirist ; WriteSPACE ; pleasurable writing ; creatively challenging ; research-based principles ; hands-on strategies ; writing prompts ; writing skills ; learn to write ; make writing fun ; how to make writing fun ; creative space ; be a better writer ; books about writing

- Published: February 7, 2023

- ISBN: 9780691229416

Pleasure and Spaciousness: Poet Naomi Shihab Nye’s Advice on Writing, Discipline, and the Two Driving Forces of Creativity

By maria popova.

“A self-respecting artist must not fold his hands on the pretext that he is not in the mood,” Tchaikovsky wrote to his patron as he contemplated the interplay of discipline and creativity . A century later, James Baldwin echoed the sentiment in his advice on writing , observing: “Talent is insignificant. I know a lot of talented ruins. Beyond talent lie all the usual words: discipline, love, luck, but most of all, endurance.”

But for those of us who show up to do what we do day after day, inner rain or shine, as the days unspool into years — Brain Pickings turns 15 this year — there is something more than white-knuckle discipline making the steadfast labor not only bearable, not only sustainable, but vitalizing, inspiriting, joyful. What fuels the engine of endurance is a passionate enchantment — something of which Baldwin’s “love” reflects a glimmer but does not fully capture.

The most marvelous part of it is this: It is an enchantment we cast upon ourselves.

How to cast that enchantment and how to couple it with the requisite endurance is what Your People’s Poet Laureate Naomi Shihab Nye , composer of the existentially symphonic “Kindness,” explores in a short, splendid prose reflection tucked into the final pages of her altogether soul-broadening collection Everything Comes Next: Collected and New Poems ( public library ).

In a sentiment evocative of Bertrand Russell’s lovely notion of “largeness of contemplation” in calibrating the relationship between intuition and the intellect, Nye writes:

Two helpful words to keep in mind at the beginning of any writing adventure are pleasure and spaciousness. If we connect a sense of joy with our writing, we may be inclined to explore further. What’s there to find out? Perhaps too much stock has been placed in big ideas or even small ones — a myth! — but regularity seems like a key. Don’t start with a big idea. Start with a phrase, a line, a quote. Questions are very helpful. Begin with a few you’re carrying right now.

In consonance with John Steinbeck’s life-tested, Nobel-earning conviction that “in writing, habit seems to be a much stronger force than either willpower or inspiration,” she adds:

Small increments of writing time may matter more than we could guess. One thing leads to many — swerving off, linking up, opening of voices and images and memories. Nearby notebooks — or iPads or tablets or laptops — are surely helpful.

With this, Nye turns to the ongoing dialogue between the magic of creation and the mechanics of discipline:

Make a plan, and return to it. It’s a party to which we keep inviting ourselves. And we have so many realms of material that are very close by: Families Neighborhoods Changes Memories Spoken language woven into poems — something someone said to you a long time ago and you still remember it — why, out of all the talk, do you remember that thing? Pets Losses First Times Last Times Fears Friends Being Sick, Being Well What we see out our windows Gifts History — what used to be in this very place where we are sitting now? Start anywhere.

Although such constructed starting points might seem mechanistic, they are the lever that unlatches the expanse where the unexpected can begin to unfurl. That incubus where ideas collide with one another into the unconscious combinatorial process we call creativity is also the place where the joy of all creative labor lives.

Returning to the twin consecrating forces of discipline, pleasure and spaciousness, Nye writes:

Spaciousness — any page is wider than it looks. You have no idea where this thing might be going. Write in nuggets — here are my questions, here are some details I saw within the last 24 hours, here are some quotes I heard people say today. Gather material first — then select and connect from it… Each thing gives us something else. The more any of us writes, the more our words will “come to us.” If we trust in the words and their own mysterious relationship with one another, they will help us find things out… Consider the pleasure we feel when we go to a beach. The broad beach, the bigger air, the endless swish of movement and backdrop of sound. We feel uplifted, exhilarated. Writing regularly can help us feel that way too.

In a short poem from the same book, calling to mind poet Ross Gay’s reflection on writing by hand as an instrument of thought , Nye considers the practical tools that carve out this observant spaciousness in which impressions can collide and coalesce into ideas:

ALWAYS BRING A PENCIL by Naomi Shihab Nye There will not be a test. It does not have to be a Number 2 pencil. But there will be certain things — the quiet flush of waves, ripe scent of fish, smooth ripple of the wind’s second name — that prefer to be written about in pencil. It gives them more room to move around.

For more practical and philosophical reflections on the craft from great poets, savor Mary Oliver’s advice on writing , Elizabeth Alexander on language as a vehicle for the poetry of personhood , and Rilke on the relationship between solitude, love, and creativity , then revisit Rachel Carson on the sacred loneliness of writing and Walt Whitman on the discipline of creative self-esteem .

— Published July 11, 2021 — https://www.themarginalian.org/2021/07/11/naomi-shihab-nye-writing/ —

www.themarginalian.org

PRINT ARTICLE

Email article, filed under, books creativity culture naomi shihab nye writing, view full site.

The Marginalian participates in the Bookshop.org and Amazon.com affiliate programs, designed to provide a means for sites to earn commissions by linking to books. In more human terms, this means that whenever you buy a book from a link here, I receive a small percentage of its price, which goes straight back into my own colossal biblioexpenses. Privacy policy . (TLDR: You're safe — there are no nefarious "third parties" lurking on my watch or shedding crumbs of the "cookies" the rest of the internet uses.)

Writing with Pleasure

- Helen Sword

50% off with code FIFTY

Before you purchase audiobooks and ebooks

Please note that audiobooks and ebooks purchased from this site must be accessed on the Princeton University Press app. After you make your purchase, you will receive an email with instructions on how to download the app. Learn more about audio and ebooks .

Support your local independent bookstore.

- United States

- United Kingdom

- Selina Tusitala Marsh

An essential guide to cultivating joy in your professional and personal writing

- Skills for Scholars

- Look Inside

- Request Exam Copy

- Download Cover

Writing should be a pleasurable challenge, not a painful chore. Writing with Pleasure empowers academic, professional, and creative writers to reframe their negative emotions about writing and reclaim their positive ones. By learning how to cast light on the shadows, you will soon find yourself bringing passion and pleasure to everything you write. Acclaimed international writing expert Helen Sword invites you to step into your “WriteSPACE”—a space of pleasurable writing that is socially balanced, physically engaged, aesthetically nourishing, creatively challenging, and emotionally uplifting. Sword weaves together cutting-edge findings in the sciences and social sciences with compelling narratives gathered from nearly six hundred faculty members and graduate students from across the disciplines and around the world. She provides research-based principles, hands-on strategies, and creative “pleasure prompts” designed to help you ramp up your productivity and enhance the personal rewards of your writing practice. Whether you’re writing a scholarly article, an administrative email, or a love letter, this book will inspire you to find delight in even the most mundane writing tasks and a richer, deeper pleasure in those you already enjoy. Exuberantly illustrated by prizewinning graphic memoirist Selina Tusitala Marsh, Writing with Pleasure is an indispensable resource for academics, students, professionals, and anyone for whom writing has come to feel like a burden rather than a joy.

Awards and Recognition

- A Choice Outstanding Academic Title of the Year

"This book will be valuable for any writers—not only academics—who wish to experience more pleasure in their writing. Sword's engaging and personable writing style makes the book a pleasure to read."— Choice Reviews

“Intrinsic motivations like joy and fascination can and should propel our writing—all the more so when extrinsic rewards seem few. In this generous, generative book, Helen Sword offers us ample encouragement and insight on how, even in difficult times, we can dare to seek delight.”—Margy Thomas, founder of ScholarShape

“At last, a writing guide that doesn’t scold or ridicule, but treats the challenge of writing well as a form of pleasurable mastery.”—Steven Pinker, Johnstone Professor of Psychology, Harvard University, author of The Sense of Style: The Thinking Person’s Guide to Writing in the 21st Century

“Sword is the prophetic voice crying out in academia’s wilderness: ‘Write with pleasure! It can be done! Come and see!’ Through enviable prose, enticing poems, and elegant illustrations, readers see the pleasure, feel it, apply it to their own writing and, when all is read and done, cannot resist repenting.”—Patricia Goodson, Texas A&M University

“Helen Sword has been helping me improve my writing for more than a decade. In Writing with Pleasure , she finally taught me how to love it—and keep loving it. If you want to make writing a painless habit, this book is for you.”—Inger Mewburn, Australian National University

“ Writing with Pleasure —itself a pleasure in the reading—opens exciting vistas onto the great expanse of writing: the aesthetics in the written, the corporeality of the writer, the emotions felt for and from writing. This original and inventive book charts new territory for anyone who writes and for everyone who researches writing.”—Daniel Shea, Karlsruhe Institute of Technology, Germany

Author website: https://www.helensword.com/

Workshop suggestions for writing with pleasure [download .docx] .

Writing with Pleasure provides faculty and student writers with a refreshing antidote to the “shut up and write” school of academic productivity, which squashes out creativity, color, and joy in the name of scholarly seriousness. Through cutting-edge research, inspiring examples, and playful prose, international writing expert Helen Sword shows academic writers from across the disciplines that productivity and pleasure are bedfellows, not enemies.

Dr. Sword offers an array of online workshops, courses, retreats, and community events via her website at www.helensword.com . Below are some suggestions for using Writing with Pleasure in a campus-based academic writing program, course, or workshop.

1. Pleasure Prompts

Writing with Pleasure contains a sequence of 18 short reflective writing exercises called “Pleasure Prompts,” each of which precedes or follows a key section or chapter of the book.

The entire sequence is well suited for a semester-long faculty writing group, graduate research seminar, or undergraduate writing course.

Individual or paired Pleasure Prompts can also be used to anchor individual writing workshops or discussions. Popular pairings include:

- Butterflies and Cocoons and Sea of Islands (Pleasure Prompts #4 and #14): On society, solitude, and work-life balance. (Chapters 1 and 10)

- Bodies of Writing and Analog Anchors (Pleasure Prompts #5 and #10): On the physical and material pleasures of writing. (Chapters 2 and 6)

- Climbing the C-Curve and Tradewinds and Doldrums (Pleasure Prompts #7 and #12): On the challenges and joys of the creative process. (Chapters 4 and 8)

- Penguin Time and Compass Points (Pleasure Prompts #8 and #13): On passion, play, praise, and personal identity. (Chapters 5 and 9)

2. The SPACE of Writing

Writing with Pleasure is structured around the acronym SPACE, which encourages writers to develop a writing practice that is s ocially balanced, p hysically engaging, a esthetically nourishing, c reatively challenging, and e motionally fulfilling.

The following Pleasure Prompts have been designed to work together as a sequence, prompting writers first to excavate their own past pleasure in writing, then to evaluate the emotions that they currently associate with academic writing, and finally to develop a “SPACE map” and action plan for bringing more pleasure into their writing life.

- A Time in Your Life (Pleasure Prompt #2): Write about a time in your life when writing gave you pleasure. (10 minutes; pp 18-19)

- Pleasure Prompt #3 (“Pastimes and Peeves”): Using the SPACE rubric, compare a favorite pastime or hobby with an aspect of your academic writing that does not give you pleasure. (10 minutes; pp 23-24).

- Pleasure Prompt #9 (“Mapping the WriteSPACE”): Use the SPACE rubric and five differently colored pencils or markers to draw and label the social, physical, aesthetic, creative, and emotional components of your ideal WriteSPACE (10 minutes; pp 128-29)

You can find a 20-minute online video tutorial called “Mapping the WriteSPACE” in the online SPACE Gallery ( https://www.helensword.com/spacegallery ), along with a curated collection of SPACE maps produced by academic writers from around the world. (Click on “Your Gallery” for the tutorial).

3. Metaphors for Writing

The concluding chapter of Writing with Pleasure , “Making SPACE,” prompts readers to develop a personal metaphor for writing that they can use to guide and empower them through times of frustration and challenge. Each of the following Pleasure Prompts works well on its own, or they can be undertaken as a three-part sequence:

- Pleasure Prompt #15 (“Lifelines, Leylines, Desire Lines”)

- Pleasure Prompt #16 (“Touchstones”)

- Pleasure Prompt #17 (“Chiaroscuro”)

See “Making SPACE,” pp. 229-47.

4. Diving for Treasure

Writing with Pleasure contains forty illustrations produced by prize-winning graphic memoirist Selina Tusitala Marsh in collaboration with Helen Sword. Many of these drawings include some text: a poem, an anecdote, a conversation. All are intended to be evocative, not prescriptive.

The following exercise can be used as a playful icebreaker for any writing workshop:

- Photocopy each of the thirty illustrations titled “The Pleasures of …” (listed on pp ix-x).

- Fold up the pages and invite each workshop participant to draw one from a hat.

- Working in pairs or groups, ask the participants to compare their illustrations, then to report back to the larger group. What writing-related pleasures does each drawing address? What stories are told or emotions evoked that could not have been communicated in the same way via standard academic prose?

Stay connected for new books and special offers. Subscribe to receive a welcome discount for your next order.

50% off sitewide with code FIFTY | May 7 – 31 | Some exclusions apply. See our FAQ .

- ebook & Audiobook Cart

British Council India

Boost your happiness with creative writing.

Beautiful writing isn’t about the words we use, it’s about the emotions we evoke – Katie Ganshert

For Katie, an author of several novels and works of short fiction, life is a journey we’re all traveling, and like any worthwhile adventure, it’s filled with valleys and peaks, detours and shortcuts, highways and jaw-dropping scenery. Her happiness comes from the keys of her computer and her total mental health depends on it, like it is for the most of us who cherish writing.

To say the past year has been a difficult one for people is somewhat an understatement. But, despite the colossal devastation and the resulting decline in mental health, people who took to writing as a solace or wrote professionally were perhaps the happiest beings in the world.

Writing has powerful mental health benefits that promote happiness, creative thinking, language development and memory building. You don’t have to be Jeffrey Archer, Jane Austen or Khushwant Singh to consider yourself as a writer. Whether you are a scribbler, a secret diarist, a blogger, a would-be journalist, or simply jotting down personal future plans, all have proven links to happiness according to research. Find out few reasons how writing can help you lead a happier life.

- Writing promotes well-being and helps express emotions fluidly - Simply writing for the sake of opening up your thoughts and jotting them down on a page has huge therapeutic benefits that include increased feeling of happiness and reduced stress. A recent study examined the effects of writing in a sample group of 81 undergraduates. The students wrote for 20 minutes each day for four consecutive days on topics such as traumatic experiences in life and future plans. By the end, the project revealed a significant increase in well-being and improved mood among participants.

So, try to use creative writing as a tool to express your positive thoughts.

- Writing may lead to increased gratitude - According to a study, people who reflect on the good things in their life once a week by writing them down were found to be more positive and motivated about their current situation and their future. It is interesting to note that writing about the good things in life can have such an impact, perhaps because it forces you to really look at why those things make you so happy. Furthermore, according to Psychology Today, writing leads to better learning because we tend to retain and recall information better when we write. It also keeps our thinking sharper even as we age because writing, much like a physical exercise, keeps our brain cells active.

So, what are you planning to write today?

If you see yourself struggling with the writer’s block or want to sharpen your creative talents, you might want to consider taking up the popular nine-week Creative Writing course at the British Council.

Click here to know more

What is Creative Writing? A Key Piece of the Writer’s Toolbox

Not all writing is the same and there’s a type of writing that has the ability to transport, teach, and inspire others like no other.

Creative writing stands out due to its unique approach and focus on imagination. Here’s how to get started and grow as you explore the broad and beautiful world of creative writing!

What is Creative Writing?

Creative writing is a form of writing that extends beyond the bounds of regular professional, journalistic, academic, or technical forms of literature. It is characterized by its emphasis on narrative craft, character development, and the use of literary tropes or poetic techniques to express ideas in an original and imaginative way.

Creative writing can take on various forms such as:

- short stories

- screenplays

It’s a way for writers to express their thoughts, feelings, and ideas in a creative, often symbolic, way . It’s about using the power of words to transport readers into a world created by the writer.

5 Key Characteristics of Creative Writing

Creative writing is marked by several defining characteristics, each working to create a distinct form of expression:

1. Imagination and Creativity: Creative writing is all about harnessing your creativity and imagination to create an engaging and compelling piece of work. It allows writers to explore different scenarios, characters, and worlds that may not exist in reality.

2. Emotional Engagement: Creative writing often evokes strong emotions in the reader. It aims to make the reader feel something — whether it’s happiness, sorrow, excitement, or fear.

3. Originality: Creative writing values originality. It’s about presenting familiar things in new ways or exploring ideas that are less conventional.

4. Use of Literary Devices: Creative writing frequently employs literary devices such as metaphors, similes, personification, and others to enrich the text and convey meanings in a more subtle, layered manner.

5. Focus on Aesthetics: The beauty of language and the way words flow together is important in creative writing. The aim is to create a piece that’s not just interesting to read, but also beautiful to hear when read aloud.

Remember, creative writing is not just about producing a work of art. It’s also a means of self-expression and a way to share your perspective with the world. Whether you’re considering it as a hobby or contemplating a career in it, understanding the nature and characteristics of creative writing can help you hone your skills and create more engaging pieces .

For more insights into creative writing, check out our articles on creative writing jobs and what you can do with a creative writing degree and is a degree in creative writing worth it .

Styles of Creative Writing

To fully understand creative writing , you must be aware of the various styles involved. Creative writing explores a multitude of genres, each with its own unique characteristics and techniques.

Poetry is a form of creative writing that uses expressive language to evoke emotions and ideas. Poets often employ rhythm, rhyme, and other poetic devices to create pieces that are deeply personal and impactful. Poems can vary greatly in length, style, and subject matter, making this a versatile and dynamic form of creative writing.

Short Stories

Short stories are another common style of creative writing. These are brief narratives that typically revolve around a single event or idea. Despite their length, short stories can provide a powerful punch, using precise language and tight narrative structures to convey a complete story in a limited space.

Novels represent a longer form of narrative creative writing. They usually involve complex plots, multiple characters, and various themes. Writing a novel requires a significant investment of time and effort; however, the result can be a rich and immersive reading experience.

Screenplays

Screenplays are written works intended for the screen, be it television, film, or online platforms. They require a specific format, incorporating dialogue and visual descriptions to guide the production process. Screenwriters must also consider the practical aspects of filmmaking, making this an intricate and specialized form of creative writing.

If you’re interested in this style, understanding creative writing jobs and what you can do with a creative writing degree can provide useful insights.

Writing for the theater is another specialized form of creative writing. Plays, like screenplays, combine dialogue and action, but they also require an understanding of the unique dynamics of the theatrical stage. Playwrights must think about the live audience and the physical space of the theater when crafting their works.